人間動物園

Human Zoo

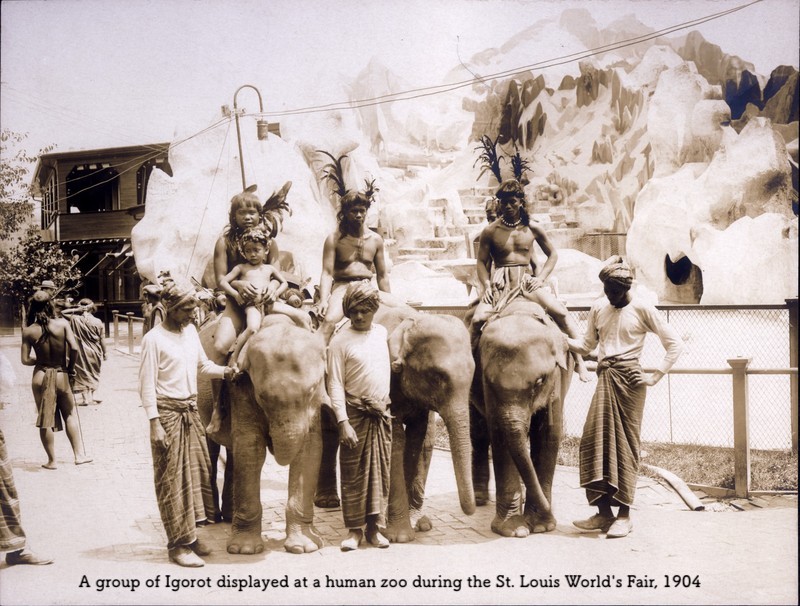

A group of Igorot displayed at a human zoo during the St.

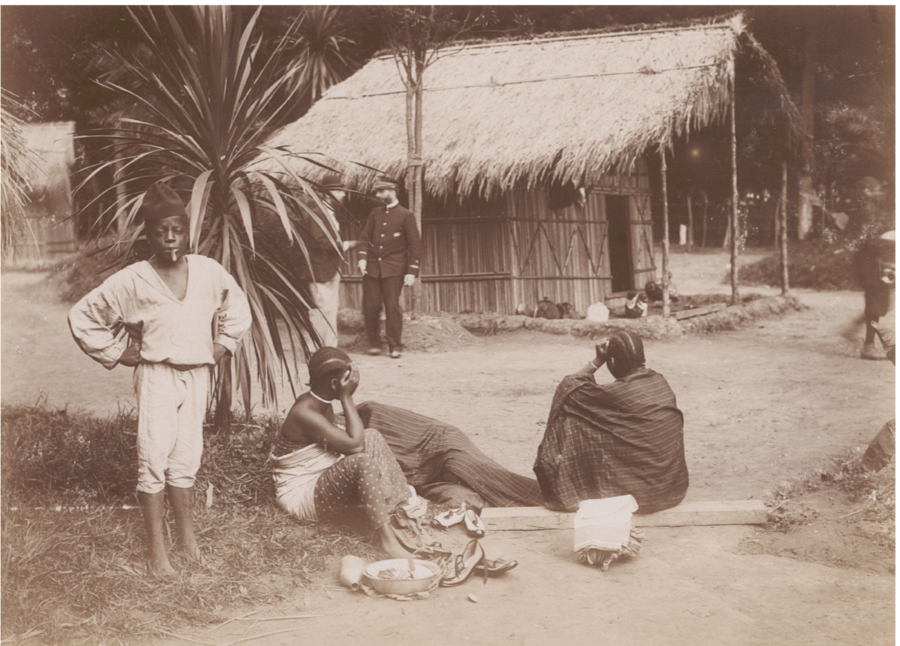

Louis World's Fair, 1904/ Exposición General de las Filipinas in Madrid (1887).

人間動物園

Human Zoo

A group of Igorot displayed at a human zoo during the St.

Louis World's Fair, 1904/ Exposición General de las Filipinas in Madrid (1887).

●Human zoo(人間動物園)あるいは、民族的展示は、いわゆる「自然」状態にある人、あるいは「未開」状態にある人を、(いわゆる文明人の)公衆の前に晒す行為であった。現在では、人権への配慮から、これらの「展示」行為はおこなわれていない。

| Human zoos, also

known as ethnological expositions, were public displays of people,

usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state.[4] They were

most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries.[4] These displays

sometimes emphasized the supposed inferiority of the exhibits' culture,

and implied the superiority of "Western society", through tropes that

purported marginalized groups as "savage".[5][6] The idea of a "savage"

derives from Columbus's voyages that deemed European culture remained

pure, while other cultures were titled impure or "wild", and this

stereotype relies heavily on the idea that different ways of living

were "cast out by God", as other cultures do not recognize Christianity

in relation to Creation.[6] Throughout their existence such exhibitions

garnered controversy over their demeaning, derogatory, and dehumanizing

nature.[7] They began as a part of circuses and "freak shows" which

displayed exotic humans in a manner akin to a caricature which

exaggerated their differences.[4] They then developed into independent

displays emphasizing the exhibits' inferiority to western culture and

providing further justification for their subjugation.[8] Such displays

featured in multiple colonial exhibitionss and at temporary exhibitions

in animal zoos.[9] One imperialist view of the whole non-Western world portrayed it as a vast animal park in which Whites could function as zookeepers—managers of the indigenous human and non-human inhabitants.[10] Animal zoos provide many controversies spanning to the modern day, as human expositions diminished in prominence in the 20th century.[7]  A group of Igorot displayed at a human zoo during the St. Louis World's Fair[1][2] |

これらの展示は時に展示物の文化の劣等性を強調し、疎外されたグループ

を「野蛮人」と称する表現を通して「西洋社会」の優越性を暗示した[4][5][6]。

[5][6]「野蛮人」という考えは、コロンブスの航海によってヨーロッパ文化が純粋なままであると見なされたことに由来し、他の文化は不純物や「野生」

と称され、このステレオタイプは、他の文化が創造との関係でキリスト教を認めていないことから、異なる生活様式は「神によって追い出された」という考えに

大きく依存している。 [6] このような展示はその存在を通して、その屈辱的、軽蔑的、非人間的な性質について論争を巻き起こした[7]

異国の人間をその違いを誇張する戯画に似た方法で展示するサーカスや「フリークショー」の一部として始まった[4]

その後、西洋文化に対する展示者の劣等性を強調し彼らの支配をさらに正当化する独立した展示へと発展した[8]

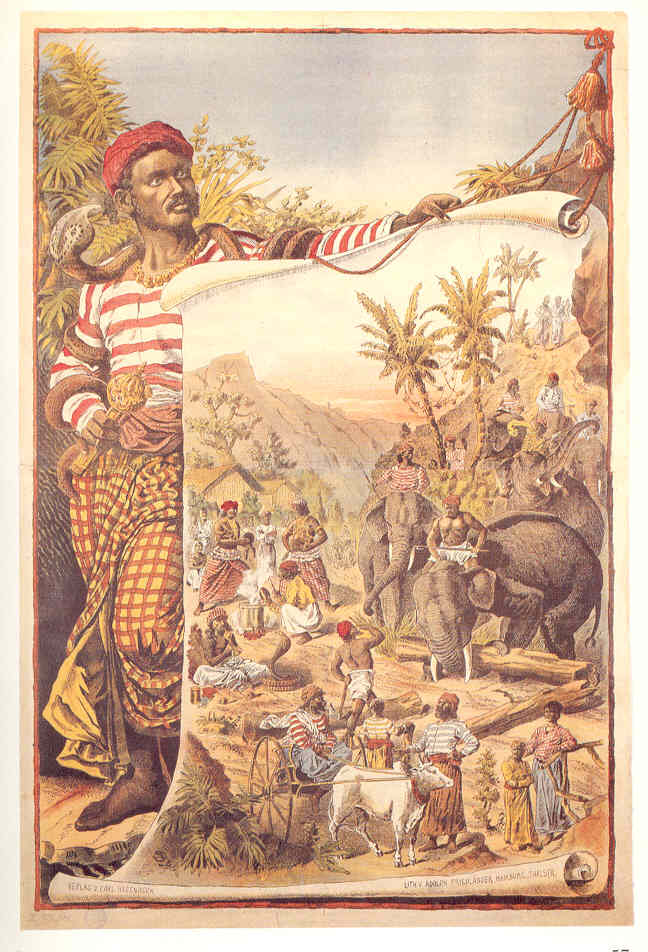

その展示は複数の植民地の展示や動物園での臨時展示で特集されていた[9]。 非西洋世界全体に対するある帝国主義的な見方は、それを広大な動物公園として描き、そこでは白人が動物園の飼育係として、先住民の人間や非人間の住民の管 理者として機能することができるとした[10]。 動物園は、20世紀に人間の博覧会の重要性が低下するにつれて、現代に至るまで多くの論争を提供している[7]。  Ad for a Carl Hagenbeck show (1886) |

| Circuses and freak shows The notion of the human curiosity has a history at least as long as colonialism[citation needed]. In the Western Hemisphere, one of the earliest-known zoos, that of Moctezuma in Mexico, consisted not only of a vast collection of animals, but also exhibited humans, for example, dwarves, albinos and hunchbacks.[11] During the Renaissance, the Medici developed a large menagerie in the Vatican. In the 16th century, Cardinal Hippolytus Medici had a collection of people of different races as well as exotic animals. He is reported as having a troupe of so-called Savages, speaking over twenty languages; there were also Moors, Tartars, Indians, Turks and Africans.[12] In 1691, Englishman William Dampier exhibited a tattooed native of Miangas whom he bought when he was in Mindanao. He also intended to exhibit the man's mother to earn more profit, but the mother died at sea. The man was named Jeoly, falsely branded as "Prince Giolo" to attract more audience, and was exhibited for three months straight until he died of smallpox in London.[13] Ad for a Carl Hagenbeck show (1886) One of the first modern public human exhibitions was P.T. Barnum's exhibition of Joice Heth on 25 February 1835[14] and, subsequently, the Siamese twins Chang and Eng Bunker. These exhibitions were common in freak shows.[15] Another famous example was that of Saartjie Baartman of the Namaqua, often referred to as the Hottentot Venus, who was displayed in London and France until her death in 1815. During the 1850s, Maximo and Bartola, two microcephalic children from El Salvador, were exhibited in the US and Europe under the names Aztec Children and Aztec Lilliputians.[16] However, human zoos would become common only in the 1870s in the midst of the New Imperialism period.  Natives of Tierra del Fuego, brought to Paris by the Maître in 1889 |

サーカスと見世物小屋 人間の好奇心という概念は、少なくとも植民地支配と同じくらい長い歴史を持っている[要出典]。西半球では、最も古くから知られている動物園の1つである メキシコのモクテスマの動物園は、膨大な動物のコレクションで構成されていただけでなく、例えば小人、アルビノ、せむし男など、人間も展示されていた [11]。 ルネサンス期には、メディチ家がバチカンに大規模な動物園を展開した。16世紀、ヒッポリュトス・メディチ枢機卿は、エキゾチックな動物だけでなく、さま ざまな人種の人々を集めていた。1691年、イギリス人のウィリアム・ダンピアはミンダナオ島で購入した刺青のあるミアンガスの原住民を展示した。彼はさ らに利益を得るためにその男の母親も出品するつもりだったが、母親は海で死んでしまった。この男はジェオリーと名付けられ、より多くの観客を集めるために 「プリンス・ジョロ」と偽の烙印を押され、ロンドンで天然痘で死亡するまで3ヶ月間連続で展示された[13]。 カール・ハーゲンベック展の広告(1886年)最初の近代的な人体公開のひとつは、1835年2月25日のP・T・バーナムのジョイス・ヘス展[14]、 その後、シャムの双子チャンとエン・バンカー展であった。このような展示は見世物小屋ではよくあることだった[15]。もう一つの有名な例は、しばしば ホッテントットのヴィーナスと呼ばれたナマクアのサールジエ・バートマンのもので、彼女は1815年に死ぬまでロンドンとフランスで展示されていた。 1850年代には、エルサルバドルの小頭症児マキシモとバルトラも「アステカの子ども」「アステカのリリプーチン」という名前でアメリカやヨーロッパで展 示された[16]。 しかし、人間動物園が一般化するのは新帝国主義の時代となった1870年代に入ってからである。  A caricature of Saartjie Baartman, called the Hottentot Venus. Born to a Khoisan family, she was displayed in European cities in the early 19th century. |

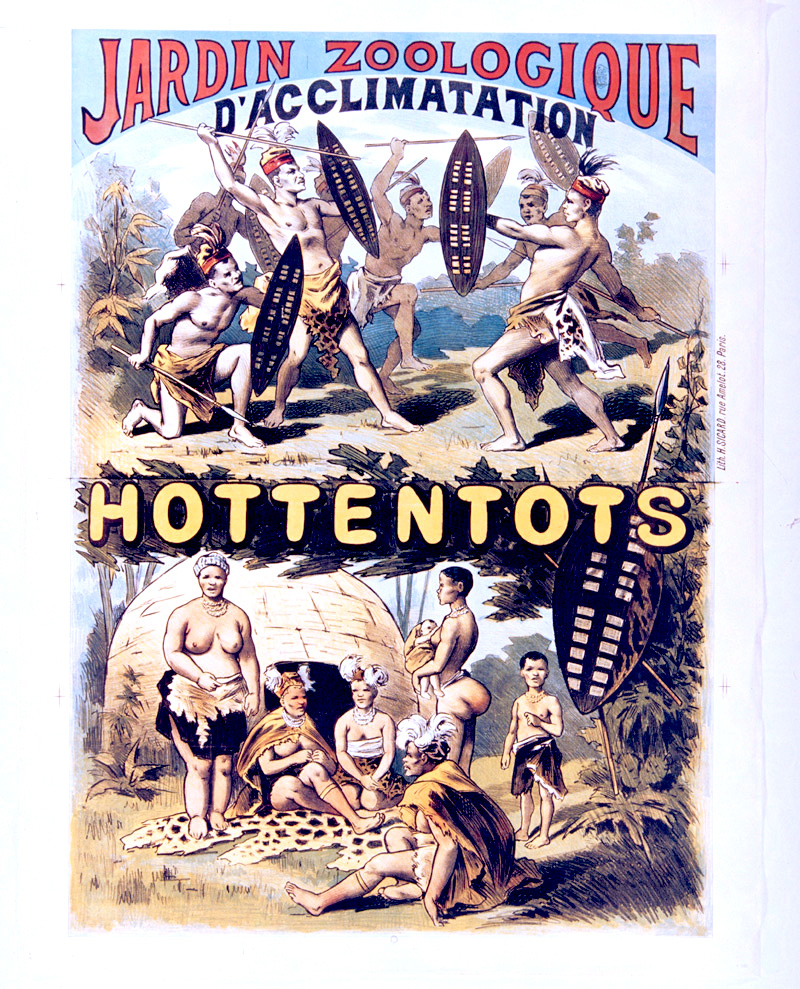

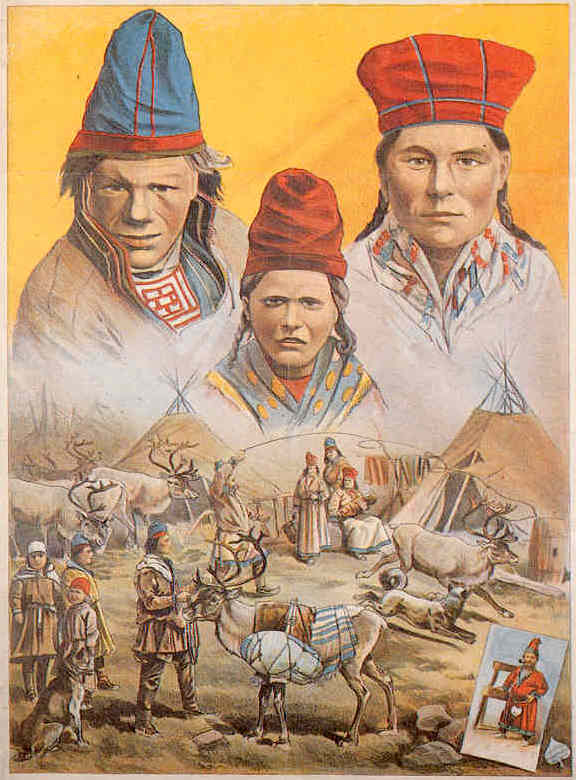

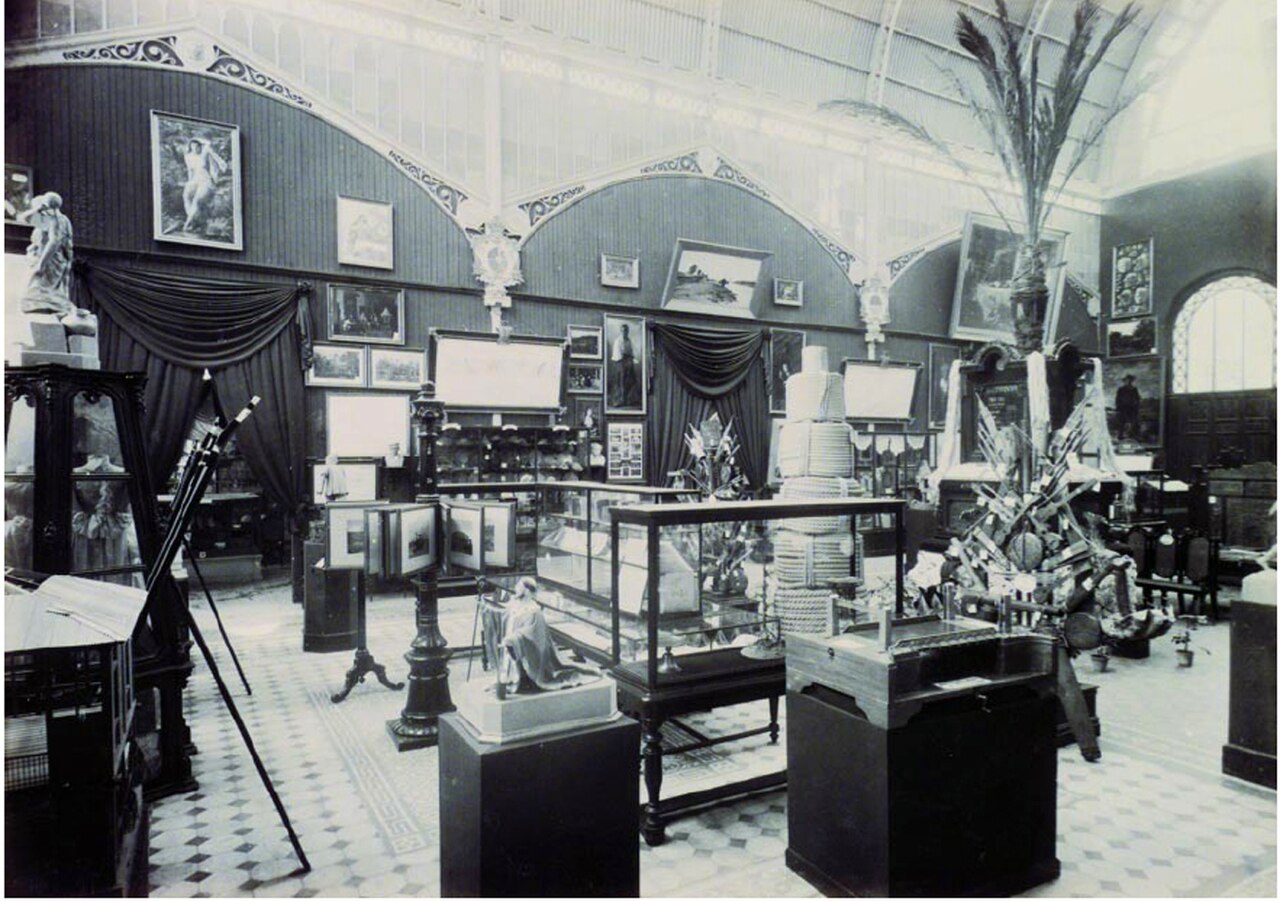

| Start of human exhibits In the 1870s, exhibitions of so-called "exotic populations" became popular throughout the western world.[7] Human zoos could be seen in many of Europe's largest cities, such as Paris, Hamburg, London, Milan as well as American cities such as New York City and Chicago.[7] Carl Hagenbeck, an animal trader, was one of the early proponents of this trend, when in 1874, at the suggestion of Heinrich Leutemann, he decided to exhibit Sami people with the 'Laplander Exhibition'.[9] What differentiated Hagenbeck's exhibit from others, was the fact that he showed these people, with animals and plants, to "re-create", their "natural environment."[9] He sold people the feeling of having travelled to these areas by witnessing his exhibits.[17] These exhibits were a massive success, and only became larger and more elaborate.[17] From this point forward human exhibitions would lean towards stereotyping, and projecting western superiority.[9] Greater feeding into the Imperialist narrative, that these people's culture merited subjugation.[18] It also promoted scientific racism, where they were classified as more or less 'civilized' on a scale, from great apes to western Europeans.[19] Hagenbeck would go on to launch a Nubian Exhibit in 1876, and an Inuit exhibit in 1880.[20] These were also massively successful. Aside from Hagenbeck, the Jardin d'Acclimatation was also a hotspot of ethnological exhibits. Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Jardin d'Acclimatation, decided in 1877 to organize two ethnological exhibits that also presented Nubians and Inuit. That year, the audience of the Jardin d'acclimatation' doubled to one million. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty ethnological exhibitions were presented at the Jardin zoologique d'acclimatation.[21] These displays were so successful they were incorporated into both the 1878 and the 1889 Parisian World's Fair, which presented a 'Negro Village'. Visited by 28 million people, the 1889 World's Fair displayed 400 indigenous people as the major attraction. In Amsterdam the International Colonial and Export Exhibition had a display of people native to Suriname, in 1883. In 1886, the Spanish displayed natives of the Philippines in an exhibition, as people whom they "civilized". This event added flame to the 1896 Philippine revolution.[22] Queen Consort of Spain, Maria Cristina of Austria, afterwards institutionalized the business of human zoos. By 1887, indigenous Igorot people & animals were sent to Madrid and were exhibited in a human zoo at the newly constructed Palacio de Cristal del Retiro.[23] At both the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition[24] Little Egypt a bellydancer, was photographed as a catalogued "type" by Charles Dudley Arnold and Harlow Higginbotha.[25] At the 1895 African Exhibition in The Crystal Palace, around eighty people from Somalia were displayed in an "exotic" setting.[26] German ethnographs Ethnology studies in Germany took a new approach in the 1870s as human displays were incorporated into zoos. These exhibits were lauded as 'educational' to the general population by the scientific community. Very quickly, the exhibits were used as a way to show that Europeans had "evolved" into a 'superior', 'cosmopolitan' life.[27] In the late 19th century, German ethnographic museums were seen as an empirical study of human culture. They contained artifacts from cultures around the world organized by continent allowing visitors to see the similarities and differences between the groups and "form their own ideas".[27] Objectification in human zoos Within the history of human zoos, there are patterns of overt sexual representation of displayed peoples, most frequently women. These objectifications often lead to treatment that reflect a lack of privacy and respect, including the dissection and display of bodies after death without consent. An example of the sexualization of ethnically diverse women in Europe is Saartje Baartman, often referred to as her anglicized name Sarah Bartmann. Bartmann was displayed both when she was alive throughout England and Ireland and after her death in The Musée de l'Homme.[28] While alive, she participated in a traveling show depicting her as a "savage female" with a large focus on her body. The clothes she was put in were tight and close to her skin color, and spectators were encouraged to "see for themselves" if Bartmann's body, particularly her buttocks, were real through "poking and pushing".[28] Her living display was financially compensated but there is no record of her consenting to be examined and displayed after death. Dominika Czarnecka theorizes of the relationship between the radicalization and sexualization of black female bodies in her journal article, "Black Female Bodies and the 'White' View."[29] Czarnecka focuses on ethnographic shows that were prominent in Polish territory in the late 19th century. She argues that an essential part of why these shows were so popular is the display of the black female body. Although the women in the shows were meant to be depicting Amazon warriors, their wardrobe was not similar to amazonian dress, and there are several documentations of comments from spectators about their revealing clothes and their bodies.[29] Although women were most frequently objectified, there are a few instances of "exotic" men being displayed due to their favorable appearance. Angelo Solimann was brought to Italy as a slave from Central Africa in the 18th century, but ended up gaining a reputation in Viennese society for his fighting skills and vast knowledge about language and history. Upon his death in 1796, this positive association did not prevent his body being "stuffed and exhibited in the Viennese Natural History Museum" for almost a decade.[30]  Poster for an anthropological exhibition in Paris, c. 1870 |

人体展示の開始 1870年代、いわゆる「外来種」の展示が西欧諸国で盛んになった[7]。パリ、ハンブルク、ロンドン、ミラノといったヨーロッパの大都市や、ニューヨー ク、シカゴといったアメリカの都市で、人間動物園が見られるようになった[7]...。 [1874年、ハインリッヒ・ロイテマンの提案で、サーミの人々を「ラップランド人展」として展示することを決めた。 ハゲンベックの展示が他と異なっていたのは、動物や植物を使って、彼らの「自然環境を再現」して見せたことであった[9]。 「これらの展示は大成功を収め、より大きく、より精巧になった[17]。この時点から、人間の展示はステレオタイプ化し、西洋の優越性を投影する方向に傾 いた[17]。 [また、科学的な人種差別を推進し、類人猿から西ヨーロッパ人までのスケールで、多かれ少なかれ「文明人」として分類された[18]。 ハーゲンベックはその後、1876年にヌビア展、1880年にイヌイット展を立ち上げることになる。 これらも大成功を収めた[20]。 ハーゲンベック以外にも、順化の庭は民族学的展示のホットスポットであった。1877年、順化庭園館長のジェフロワ・ド・サン=ヒレールは、ヌビア人とイ ヌイットを紹介する2つの民族学的展示を企画することを決定した。その年、「順化の庭」の観客は2倍の100万人に達した。1877年から1912年の間 に、約30の民族学的展示が順化植物園で行われた[21]。 これらの展示は非常に成功し、1878年と1889年のパリ万国博覧会に組み込まれ、「ニグロ村」が紹介された。1889年の万国博覧会では、2,800 万人が訪れ、400人の先住民が主要なアトラクションとして展示されました。 アムステルダムの国際植民地・輸出博覧会では、1883年にスリナムの先住民が展示された。 1886年、スペインはフィリピンの先住民を「文明化」した人々として展示した。この出来事は1896年のフィリピン革命に火をつけた[22]。その後、 スペイン王妃マリア・クリスティーナが人間動物園の事業を制度化した。1887年には、先住民であるイゴロット族の人々と動物がマドリードに送られ、新し く建設されたパラシオ・デ・クリスタル・デル・レティロの人間動物園に展示された[23]。 1893年の世界コロンビア博覧会と1901年のパンアメリカン博覧会の両方で[24]ベリーダンサーのリトル・エジプトは、チャールズ・ダドリー・アー ノルドとハーロウ・ヒギンボタによってカタログの「タイプ」として写真に撮られた[25]。 1895年のクリスタルパレスでのアフリカ展では、ソマリアから来た約80人の人々が「エキゾチックな」設定で展示された[26]。 ドイツの民族誌 1870年代、ドイツの民族学研究は、人間展示が動物園に取り入れられるという新しいアプローチをとった。これらの展示は、科学界から一般人に対する「教 育的」なものとして称賛された。非常に迅速に、展示物はヨーロッパ人が「優れた」「国際的な」生活へと「進化」したことを示す方法として使われるように なった[27]。 19世紀後半、ドイツの民族誌学博物館は、人間文化の実証的な研究として捉えられていた。それらは大陸によって整理された世界中の文化からの芸術品を含ん でおり、訪問者が集団間の類似点と相違点を見て「自分自身の考えを形成する」ことを可能にしていた[27]。 動物園におけるオブジェクト化 人間動物園の歴史には、展示された民族、特に女性があからさまに性的な対象とされるパターンがある。これらの対象化は、死後の遺体を同意なしに解剖・展示 するなど、プライバシーと尊重の欠如を反映した扱いにつながることが多い。 ヨーロッパで多様な民族の女性が性的に表現された例として、Saartje Baartman(英語名Sarah Bartmann)が挙げられる。バートマンは、生前はイギリスとアイルランド全土で、死後はフランス国立美術館で展示された[28]。着せられた服はタ イトで肌の色に近く、観客は「突いたり押したり」することでバルトマンの身体、特に臀部が本物かどうか「自分の目で確かめる」よう促された[28]。 生前の展示は金銭的に補償されていたが、死後に検査・展示を承諾した記録はない。 ドミニカ・チャルネッカは、雑誌論文「黒人女性の身体と『白人』観」[29]において、黒人女性の身体の過激化と性的化の関係を理論化している。チャル ネッカは、19世紀末にポーランド領で顕著だった民族誌のショーに焦点を当てている。彼女は、これらのショーが人気を博した理由の本質的な部分は、黒人の 女性の身体の展示にあると主張する。ショーの女性たちはアマゾンの戦士を描いているつもりだったが、彼女たちの衣装はアマゾンの服装とは似て非なるもので あり、観客から彼女たちの露出度の高い服や身体についてコメントされた文書がいくつか残っている[29]。 女性が最も頻繁に対象化されたが、好ましい外見のために「エキゾチックな」男性が展示された例もいくつかある。アンジェロ・ソリマンは、18世紀に中央ア フリカから奴隷としてイタリアに連れてこられたが、結局、戦闘能力と言語や歴史に関する膨大な知識でウィーンの社会で評判となった。1796年に死亡した 後も、彼の遺体は「剥製にされてウィーン自然史博物館に展示される」のを10年近く阻止できなかった[30]。  Ad for an 1893/1894 ethnological exposition of Sámi in Hamburg-Saint Paul |

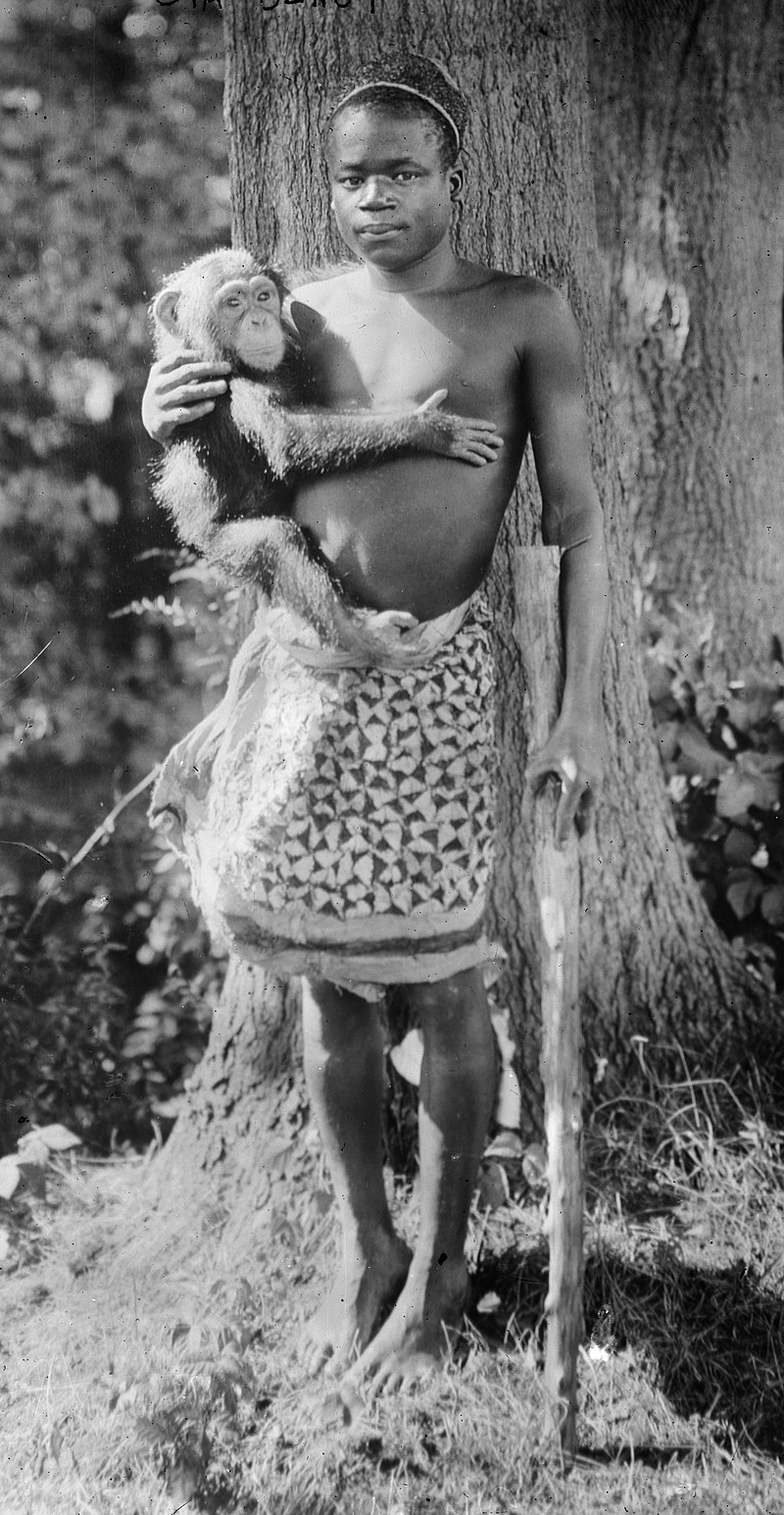

| Around the turn of the century In 1896, to increase the number of visitors, the Cincinnati Zoo invited one hundred Sioux Native Americans to establish a village at the site. The Sioux lived at the zoo for three months.[31] The 1900 World's Fair presented the famous diorama living in Madagascar, while the Colonial exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) also displayed humans in cages, often nude or semi-nude. The 1931 exhibition in Paris was so successful that 34 million people attended it in six months, while a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth on the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party, attracted very few visitors—in the first room, it recalled Albert Londres and André Gide's critiques of forced labour in the colonies. Nomadic Senegalese Villages were also presented.[citation needed] In 1906, Madison Grant—socialite, eugenicist, amateur anthropologist, and head of the New York Zoological Society—had Congolese pygmy Ota Benga put on display at the Bronx Zoo in New York City alongside apes and other animals. At the behest of Grant, the zoo director William Hornaday placed Benga displayed in a cage with the chimpanzees, then with an orangutan named Dohong, and a parrot, and labeled him The Missing Link, suggesting that in evolutionary terms Africans like Benga were closer to apes than were Europeans. It triggered protests from the city's clergymen, but the public reportedly flocked to see it.[32][33] On Monday, 8 September 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."[34] First organized backlash According to The New York Times, although "few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions", controversy erupted as black clergymen in the city took great offense. "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes", said the Reverend James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. "We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."[34] New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen, drawing the praise of Hornaday, who wrote to him: "When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage."[34] As the controversy continued, Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an ethnological exhibition. In another letter, he said that he and Grant—who ten years later would publish the racist tract The Passing of the Great Race—considered it "imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to" by the black clergymen.[34] 1903 saw one of the first widespread protests against human zoos, at the "Human Pavilion" of an exposition in Osaka, Japan. The exhibition of Koreans and Okinawans in "primitive" housing incurred protests from the governments of Korea and Okinawa, and a Formosan woman wearing Chinese dress angered a group of Chinese students studying abroad in Tokyo. An Ainu schoolteacher was made to exhibit himself in the zoo to raise money for his schoolhouse, as the Japanese government refused to pay. The fact that the schoolteacher made eloquent speeches and fundraised for his school while wearing traditional dress confused the spectators. An anonymous front-page column in a Japanese magazine condemned these examples and the "Human Pavilion" in total, calling it inhumane to exhibit people as spectacles.[35] |

世紀末の頃 1896年、シンシナティ動物園は、来園者を増やすために、100人のスー族のネイティブアメリカンを招き、この地に村を作りました。スー族は3ヶ月間、 動物園に住みました[31]。 1900年の万国博覧会ではマダガスカルに住む有名なジオラマが展示され、マルセイユ(1906年と1922年)とパリ(1907年と1931年)の植民 地時代の展示でも檻の中の人間が、しばしばヌードまたはセミヌードで展示された。1931年のパリ展は半年間で3,400万人を動員するほどの成功を収め たが、共産党が企画した「植民地の真実」と題する小規模な反対展にはほとんど人が集まらず、第1展示室ではアルベール・ロンドルやアンドレ・ジドの植民地 での強制労働に関する批判が想起される。セネガルの遊牧民の村も紹介された[citation needed]。 1906年、マディソン・グラント(社交家、優生学者、アマチュア人類学者、ニューヨーク動物学会の会長)は、コンゴのピグミーであるオタ・ベンガを ニューヨークのブロンクス動物園で猿や他の動物と一緒に展示するように指示した。動物園の園長であるウィリアム・ホーナデーは、グラントの指示でベンガを チンパンジー、オランウータンのドホン、オウムと一緒に檻に入れ、「ミッシングリンク」と名付け、進化の観点からベンガのようなアフリカ人はヨーロッパ人 よりも類人猿に近いと示唆したのである。それは、市の聖職者からの抗議を引き起こしたが、一般市民はそれを見るために群がったと伝えられている[32] [33]。 1906年9月8日(月)、わずか2日でホーナデーは展示を終了することを決め、ベンガは動物園の敷地を歩き、しばしば「吠え、嫉妬し、叫ぶ」群衆に付き まとわれているのを見つけることができました[34]。 最初の組織的反発 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙によると、「人間が猿と一緒に檻の中に入っている光景に、はっきりと異議を唱える者はほとんどいなかった」ものの、市内の黒人聖 職者が大きな不快感を示したため、論争が勃発したのである。ブルックリンのハワード孤児院の管理人であるジェームス・H・ゴードン牧師は、「我々の人種 は、猿と一緒に展示しなくても、十分に落ち込んでいると思う」と述べている。「私たちは、魂を持った人間とみなされるに値すると思っています」[34]。 ニューヨーク市長のジョージ・B・マクレラン・ジュニアは聖職者たちとの面会を拒否し、ホーネデイから賞賛を浴び、マクレランは彼に手紙を出した。「動物 園の歴史が書かれるとき、この事件はその最も愉快な一節を形成するだろう」[34]と書いている。 論争が続く中、ホーンデイは、自分の意図は民族学的な展示会を開くことだけだと主張し、謝らないままであった。別の手紙では、彼とグラント(10年後に人 種差別的な小冊子『偉大なる人種の通過』を出版)は、黒人聖職者によって「社会が指示されているようにさえ見えないことが必須」だと考えていると述べてい る[34]。 1903年、日本の大阪で開催された博覧会の「人間館」において、人間動物園に対する最初の広範な抗議が行われた。原始的な」住居に住む朝鮮人と沖縄人の 展示は、朝鮮と沖縄の政府から抗議を受け、中国風の服を着たタイワンアカシアの女性は、東京に留学中の中国人学生のグループを怒らせることになった。ま た、アイヌの学校教師が、校舎の建設費を捻出するために動物園に出演したところ、日本政府が支払いを拒否した。その学校教師が民族衣装を着て雄弁な演説を し、資金集めをしたことが、見物人を混乱させた。日本の雑誌の匿名の一面コラムは、これらの例と「人間館」全体を非難し、人間を見世物として展示すること は非人道的であるとした[35]。 |

| St. Louis World's Fair In 1904, over 1,100 Filipinos were displayed at the St. Louis World's Fair in association with the 1904 Summer Olympics. Following the Spanish-American War, the United States had just acquired new territories such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico.[36] William H. Taft was the civil governor of the Philippines at the time and allowed the U.S. to put together a Philippines exhibition in an attempt to "showcase the new colony."[37] Filipinos were put into villages, known generally by fair attendees as the "Igorrote Village," despite the variety of ethnic groups represented.[37] While the exhibit was promoted as a display of U.S. power and growth, it is believed that to achieve this perspective, the Filipinos themselves were construed as "racially inferior and incapable of national self-determination in the near future."[38] This was done by encouraging the performance of tribal customs that were seen as bizarre and 'savage' by Americans, such as eating dog. The villages also took part in western-influenced demonstrations, such as attending model school and participating in police drill teams.[39] One of the activities the indigenous people held in the zoo had to participate in were the "Special Olympics." This was an activity decided by the organizers of the zoos at the 1904 world's fair.[40] The people that were kept in the zoos were a symbol for the U.S. latest victory, keeping groups of people in the zoo to look at and showcase their newest territories. Igorot, Negrito, Visayan, and Moro were the four tribes that were brought over from the Philippines to show the diversity of the Filipino people.[39] When originally transported to St. Louis people put in the zoos were originally only given rations of rice, some hardtack, and canned goods. A lot of the Filipinos who arrived came coughing and ill from their travels on the train to St. Louis. They were given temporary live quarters while their traditional huts were being built in the zoo for them to live in during the fair.[37] While being a part of the fair the members of the tribes that were brought to the zoo were made to showcase their unique traditions during the fair to entertain. There was also a school made for the children in these tribes, where visitors could observe from an elevated balcony and view the children learning.[37]  Congolese village at 1897 Brussels International Exposition (Alphonse Gautier)  Grand Colonial Exhibition (Meiji Memorial Takushoku Expo) at Tennoji Park, Osaka in 1913 (明治記念拓殖博覧会(台湾土人ノ住宅及其風俗))——絵葉書のようだが、これは人形に衣装を着せて展示しているようにも見える |

セントルイス万国博覧会 1904年、夏季オリンピックに関連して開催されたセントルイス万国博覧会では、1,100人以上のフィリピン人が展示された。米西戦争の後、アメリカは グアム、フィリピン、プエルトリコなどの新しい領土を獲得したばかりだった[36] ウィリアム・H・タフトは当時フィリピンの民間総督で、アメリカは「新しい植民地を紹介する」試みとしてフィリピン展を許可した[37] フィリピン人は村に分けられ、その民族的な多様性にかかわらず、フェア参加者は一般に「イゴロテ村」として知られるようになった。 [この展示はアメリカの力と成長を示すものとして宣伝されたが、このような観点を達成するために、フィリピン人自身が「人種的に劣り、近い将来に民族自決 をすることができない」と解釈されたと考えられている[38] これは、犬を食べるなどアメリカ人から奇妙で「野蛮」だと見られる部族の習慣を行うよう促すことによって行われていた。また、村々はモデル・スクールへの 参加や警察演習チームへの参加など、西洋の影響を受けたデモに参加した[39]。 動物園で開催された先住民が参加しなければならない活動のひとつに、"Special Olympics "があった。これは1904年の万国博覧会で動物園の主催者が決めた活動だった[40]。動物園で飼われていた人々は、アメリカの最新の勝利の象徴とし て、動物園に人々のグループを飼って、新しい領土を見て見せようとしたのである。イゴロット、ネグリート、ビサヤ、モロの4つの部族は、フィリピンの人々 の多様性を示すためにフィリピンから連れてこられた部族である[39]。もともとセントルイスに運ばれたとき、動物園に入れられた人々は、米、いくつかの 乾パンと缶詰の配給しか与えられていなかった。到着したフィリピン人の多くは、セントルイスまでの汽車の旅で咳をし、病気になっていた。フェアの一環とし て、動物園に集められた部族のメンバーは、フェアの期間中、彼らのユニークな伝統を披露し、楽しませることになった。また、これらの部族の子供たちのため に学校が作られ、訪問者は高いバルコニーから観察し、子供たちが学んでいる様子を見ることができた[37]。  Ota Benga, a human exhibit, in 1906. Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches (150 cm). Weight, 103 pounds (47 kg). Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Central Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Exhibited each afternoon during September. – according to a sign outside the primate house at the Bronx Zoo, September 1906.[30] |

| France and Great Britain Between 1 May and 31 October 1908 the Scottish National Exhibition, opened by one of Queen Victoria's grandsons, Prince Arthur of Connaught, was held in Saughton Park, Edinburgh. One of the attractions was the Senegal Village with its French-speaking Senegalese residents, on show demonstrating their way of life, art and craft while living in beehive huts.[41][42] In 1909, the infrastructure of the 1908 Scottish National Exhibition in Edinburgh was used to construct the new Marine Gardens to the coast near Edinburgh at Portobello. A group of Somali men, women and children were shipped over to be part of the exhibition, living in thatched huts.[43][44] In 1925, a display at Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester, England, was entitled "Cannibals" and featured black Africans in supposedly native dress.[45] In 1931, around 100 other New Caledonian Kanaks, were put on display at the Jardin d'Acclimatation in Paris.[46] United States (1930s) By the 1930s, a new kind of human zoo appeared in America, nude shows masquerading as education. These included the Zoro Garden Nudist Colony at the Pacific International Exposition in San Diego, California (1935–36) and the Sally Rand Nude Ranch at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco (1939). The former was supposedly a real nudist colony, which used hired performers instead of actual nudists. The latter featured nude women performing in western attire. The Golden Gate fair also featured a "Greenwich Village" show, described in the Official Guide Book as "Model artists' colony and revue theatre."[47] Ethnological expositions during Nazi Germany As ethnogenic expositions were discontinued in Germany around 1931,[17] there were many repercussions for the performers. Many of the people brought from their homelands to work in the exhibits had created families in Germany, and there were many children that had been born in Germany. Once they no longer worked in the zoos or for performance acts, these people were stuck living in Germany where they had no rights and were harshly discriminated against. During the rise of the Nazi party, the foreign actors in these stage shows were typically able to stay out of concentration camps because there were so few of them that the Nazis did not see them as a real threat.[48] Although they were able to avoid concentration camps, they were not able to participate in German life as citizens of ethnically German origin could. The Hitler Youth did not allow children of foreign parents to participate, and adults were rejected as German soldiers.[48] Many ended up working in war industry factories or foreign laborer camps.[48] |

フランスとイギリス 1908年5月1日から10月31日にかけて、ヴィクトリア女王の孫であるコンノート公アーサーが開会したスコットランド国立博覧会がエディンバラのソー トンパークで開催された。見どころのひとつはセネガル村で、フランス語圏のセネガル人が蜂の巣小屋に住みながら、彼らの生活様式、芸術、工芸を実演してい た[41][42]。 1909年、エディンバラで開催された1908年のスコットランド万国博覧会のインフラを使い、エディンバラ近郊のポートベローの海岸に新しいマリンガー デンが建設された。この展覧会に参加するため、ソマリアの男性、女性、子供のグループが輸送され、藁葺き屋根の小屋で生活した[43][44]。 1925年、イギリスのマンチェスターにあるベルヴュー動物園の展示は「人食い人種」と題され、原住民と思われる服を着たアフリカの黒人を特集していた [45]。 1931年、パリの順化庭園に約100人のニューカレドニアのカナック族が展示された[46]。 アメリカ(1930年代) 1930年代になると、アメリカでは新しいタイプの人間動物園が登場しました。教育を装ったヌードショーです。カリフォルニア州サンディエゴの太平洋国際 博覧会(1935-36年)のゾロ・ガーデン・ヌーディスト・コロニーやサンフランシスコのゴールデンゲート国際博覧会(1939年)のサリー・ランド・ ヌードランチなどがそれです。前者は本物のヌーディスト・コロニーとされ、実際のヌーディストの代わりに雇われたパフォーマーが使われた。後者は、西部劇 の衣装を着た裸の女性が出演していました。ゴールデンゲートフェアでは「グリニッジビレッジ」のショーも行われ、公式ガイドブックでは「モデルアーティス トコロニーとレヴューシアター」と説明されている[47]。 ナチス・ドイツ時代の民族学的博覧会 1931年頃にドイツで民族学博覧会が廃止されると[17]、出演者にも多くの反響があった。民族博で働くために母国から連れてこられた人々の多くは、ド イツで家庭を築き、ドイツで生まれた子供も多くいた。動物園で働けなくなった人たちは、ドイツで何の権利もなく、厳しい差別を受けて生きていくしかなかっ た。ナチス党の台頭期には、これらの舞台の外国人俳優は、数が少ないためにナチスが本当の脅威と見なさないため、通常強制収容所から逃れることができた [48]。ヒトラーユーゲントでは外国人を親に持つ子供の参加を認めず、成人はドイツ兵として拒否された[48]。 多くの者は戦争産業の工場や外国人労働者収容所で働くことになった[48]。 |

| Modern exhibitions As part of the Portuguese World Exhibition in 1940, members of a tribe from the Bissagos Islands of Guinea-Bissau were displayed on an island in a lake in the Lisbon Tropical Botanical Garden.[49] A Congolese village was displayed at the Brussels 1958 World's Fair.[50] In April 1994, an example of an Ivory Coast village was presented as part of an African safari in Port-Saint-Père, near Nantes, in France, later called Planète Sauvage.[51] In July 2005, the Augsburg Zoo in Germany hosted an "African village" featuring African crafts and African cultural performances. The event was subject to widespread criticism.[52] Defenders of the event argued that it was not racist since it did not involve exhibiting Africans in a debasing way, as had been done at zoos in the past. Critics argued that presenting African culture in the context of a zoo contributed to exoticizing and stereotyping Africans, thus laying the ground work for racial discrimination.[53] In August 2005, London Zoo displayed four human volunteers wearing fig leaves (and bathing suits) for four days.[54] In 2007, Adelaide Zoo ran a Human Zoo exhibition which consisted of a group of people who, as part of a study exercise, had applied to be housed in the former ape enclosure by day, but then returned home by night.[55] The inhabitants took part in several exercises, and spectators were asked for donations towards a new ape enclosure. Also in 2007, pygmy performers at the Festival of Pan-African Music (Fespam) were housed at a zoo in Brazzaville, Congo. Although members of the group of 20 people—among them an infant, age three months—were not officially on display, it was necessary for them to "collect firewood in the zoo to cook their food, and [they] were being stared at and filmed by tourists and passers-by".[56] In 2012, a video surfaced showing a safari trip to the Bay of Bengal. The safari trip included showcasing the Jarawa tribe of the Andaman Islands in their own home. This indigenous tribe had not had much contact with outsiders, and some were asked to perform dances for the tourists. At the beginning of the safari trip there were signs stating not to "feed" the tribespeople, but tourists still brought food to give to the tribespeople. In 2013, the Indian Supreme Court banned these safari trips. In August 2014, as part of the Edinburgh International Festival, South African theatre-maker Brett Bailey's show Exhibit B was performed in the Playfair Library Hall, University of Edinburgh; then in September at The Barbican in London. This explored the nature of Human Zoos and raised much controversy both amongst the performers and the audiences.[57] With a view to tackling the morality of Human Zoo exhibits, 2018 saw the poster exhibition, Putting People on Display, tour Glasgow School of Art, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Stirling, the University of St Andrews and the University of Aberdeen. Additional posters were added to a selection from the French ACHAC's exhibition, Human Zoos: the Invention of the Savage, in relation to the Scottish dimension in hosting such shows.[58]  Exposición General de las Filipinas in Madrid (1887). |

現代の展覧会 1940年のポルトガル万国博覧会の一環として、ギニアビサウのビサゴス諸島の部族の人々がリスボン熱帯植物園の湖の中の島に展示された[49]。 1958年のブリュッセル万国博覧会ではコンゴの村が展示された[50]。 1994年4月、フランスのナント近郊のポルト・サンペールでアフリカンサファリの一部としてコートジボワールの村の例が展示され、後にプラネテ・ソバー ジュと呼ばれた[51]。 2005年7月、ドイツのアウグスブルク動物園では、アフリカの工芸品やアフリカ文化のパフォーマンスを特徴とする「アフリカ村」が開催された。イベント の擁護者は、それが過去の動物園で行われていたような卑下した方法でアフリカ人を展示することを伴わないので、人種差別的ではないと主張した[52]。批 評家は、動物園という文脈でアフリカ文化を紹介することは、アフリカ人をエキゾチック化しステレオタイプ化することに貢献し、その結果、人種差別の土台を 築くことになると主張した[53]。 2005年8月、ロンドン動物園は、4日間、イチジクの葉(と水着)を着た4人の人間のボランティアを展示した[54]。 2007年、アデレード動物園は、研究の一環として、昼は旧猿の囲いに収容されることを申請し、夜には帰宅する人々からなる人間動物園の展示を行った [55]。 住人たちはいくつかの演習に参加し、観客は新しい猿の囲いのための寄付を求められた。 また、2007年には、コンゴのブラザビルにある動物園に、汎アフリカ音楽祭(Fespam)のピグミーパフォーマーが収容された。20人のグループのメ ンバー(中には生後3ヶ月の乳児もいた)は公式には展示されていなかったが、「食事を作るために動物園内で薪を集める必要があり、(彼らは)観光客や通行 人に見つめられたり撮影されたりしていた」[56]。 2012年、ベンガル湾へのサファリ旅行を紹介する動画が表面化した。このサファリ旅行には、アンダマン諸島のジャラワ族を自分たちの故郷で紹介すること が含まれていました。この先住民族は外部との接触が少なく、観光客に踊りを披露するように頼まれた者もいた。サファリ旅行の冒頭には、部族に「餌を与えな い」旨のサインがあったが、それでも観光客は部族に与えるための食料を持参した。2013年、インドの最高裁判所は、こうしたサファリ旅行を禁止しまし た。 2014年8月、エディンバラ国際フェスティバルの一環として、南アフリカの演劇人ブレット・ベイリーのショー「Exhibit B」がエディンバラ大学プレイフェア図書館ホールで、その後9月にロンドンのバービカンで上演されました。これは人間動物園の本質を探るものであり、演者 と観客の間で多くの論争を巻き起こした[57]。 人間動物園の展示の道徳性に取り組むという観点から、2018年にはポスター展「Putting People on Display」がグラスゴー美術学校、エジンバラ大学、スターリング大学、セントアンドリュース大学、アバディーン大学を巡回した。フランスの ACHACの展覧会「Human Zoos: the Invention of the Savage」からのセレクションに、このような展覧会を主催するスコットランドの次元に関連して、追加のポスターが追加された[58]。 |

| Human safari The threatening, exploitative and degrading practice of "human safari" tourism has been a prevalent problem particularly for indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation, such as the Sentinelese.[59] |

ヒューマンサファリ 「人間サファリ」観光の脅威的、搾取的、劣化的な実践は、特にセンチネル人のような自主的に孤立している先住民族に広く見られる問題であった[59]。 |

| Abraham Ulrikab – Inuk man and

his family Cultural appropriation Living history museum Natural state Noble savage Orientalism Othering Primitivism Racial fetishism Reality television Romantic racism Scramble for Africa Wild man |

|

| Bibliography Ankerl, Guy. Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharatai, Chinese, and Western, Geneva, INU Press, 2000, ISBN 2881550045. Conklin, Alice L., and Ian Christopher Fletcher. European Imperialism, 1830–1930: Climax and Contradiction. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning,1999. ISBN 0395903858 Dreesbach, Anne. Colonial Exhibitions:'Völkerschauen' and the Display of the 'Other', European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2012. Grant, Kevin. A Civilised Savagery: Britain and the New Slaveries in Africa, 1884–1926. New York ; Oxfordshire, England: Routledge, 2005. India's Jarawa Tribe Facing Extinction, AlJazeera, 2012. Lewis, R. Barry. Understanding humans : introduction to physical anthropology and archaeology. Belmont, Calif. Wadsworth Cengage Learning. 2010. Oliveira, Cinthya. Human Rights & Exhibitions, 1789–1989, Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 29, 2016, pp. 71–94. Penny, H. Glenn. Objects of Culture : Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany, The University of North Carolina Press, 2002. Porter, Louis, Porter, A. N., and Louis, William Roger. The Oxford History of the British Empire. Volume III, The Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Oxford History of the British Empire. Web. Qureshi, Sadiah. Robert Gordon Latham, Displayed Peoples, and the Natural History of Race: 1854–1866, The Historical Journal, vol. 54, no. 1, 2011, pp. 143–166. Rothfels, Nigel. Savages and Beasts : The Birth of the Modern Zoo, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. Schofield, Hugh. Human Zoos: When Real People Were Exhibits, BBC News, 2011. India Andaman Jarawa Tribe in 'Shocking' Tourist Video, BBC News, 2012. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_zoo |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

リンク

Bibliography

Other informations