Repatriation for Indigenous Pooples' remain and burial materials

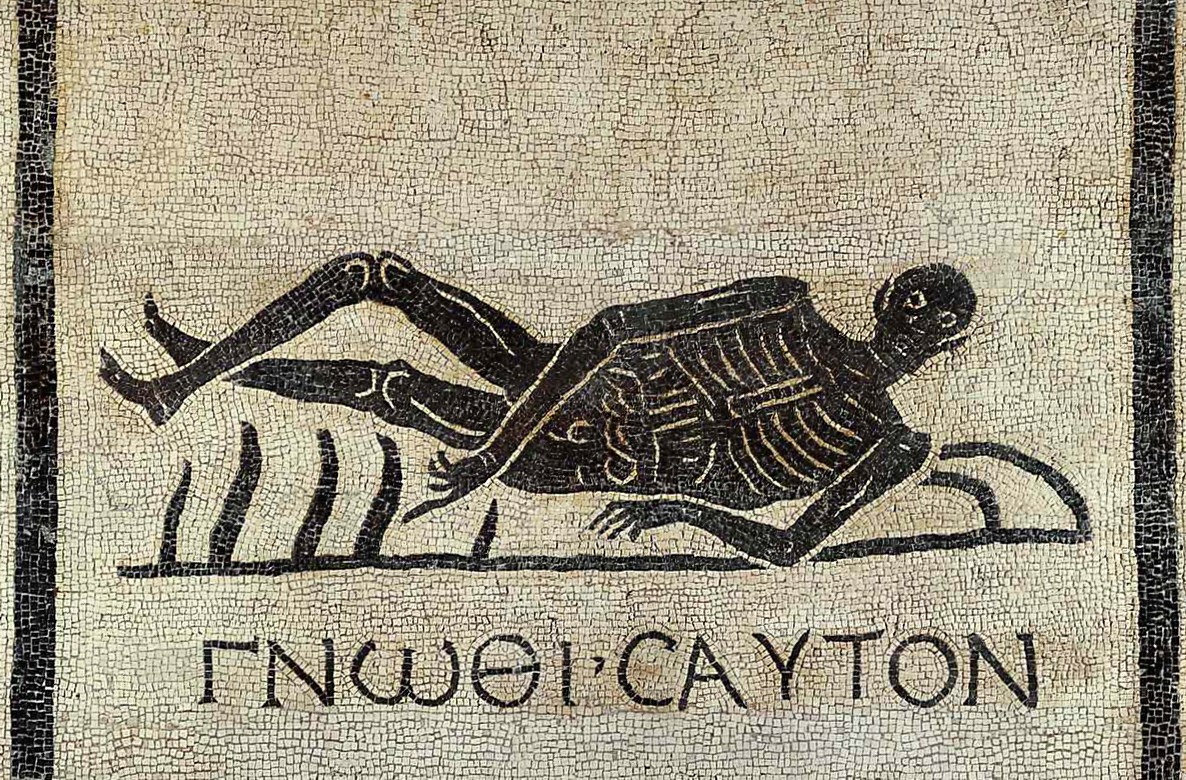

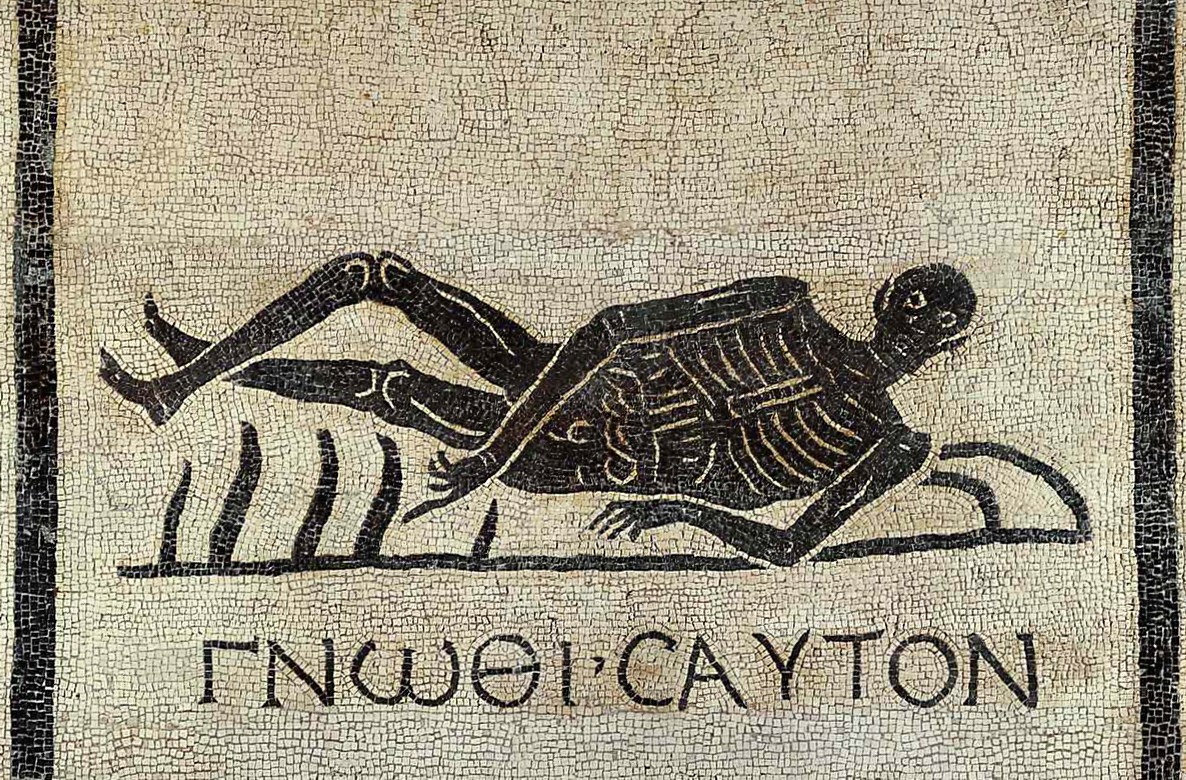

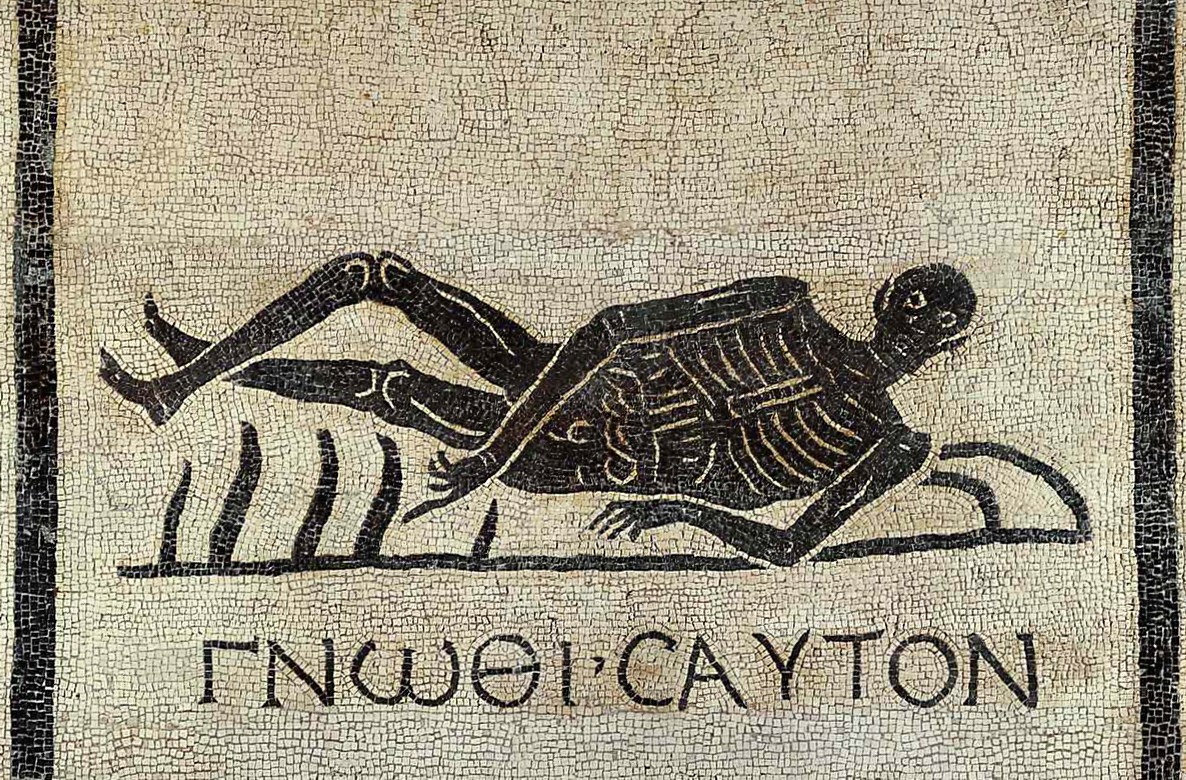

γνῶθι σεαυτόν ( グノーティ・セアウトン =汝自身を知れ)

遺骨と副葬品の返還

Repatriation for Indigenous Pooples' remain and burial materials

γνῶθι σεαυτόν ( グノーティ・セアウトン =汝自身を知れ)

池田光穂

日本は衆参両院で、アイヌ民族を日本の 「先住民族」であることをみとめた「ア イヌ民族を先住民族とすることを求める決議」ともに2008年6月 6日(衆 議院/参議院) をおこなったにもかかわらず、日本の大学においては、盗掘を含むアイヌの遺骨を、実験研究用に収集保管し、アイヌ側からの遺骨返還をめぐってもなかなか大 学行政全般を管理・統括する文科省ならびに日本国政府は、返還(repatriation)に真摯に応じようとしていない(→「アイヌ遺骨等返還の手続きについて考えるページ」)。遺骨問題や、先住民の文化遺産 の返還については、日本での対応のみならず、米国の「ネイティブ・アメリカン墳墓保護と返還に関 する法律(NAGPRA)」の施行(1990- )などを除いて、それほどスムースにいっているわけではない(→「遺骨 や副葬品を取り戻しつつある先住民のための試論」「琉球遺骨の収集に関する裁判所第一審の認定事実等」 「「琉球民族遺骨返還請求事件」解説」「先住民学への招待」「新しい「先住民学」の提唱」)。

| 0 |

先住民あるいは民族的マイノリティに対する国家の謝罪と和解のための提

言としての「遺骨と副葬品の返還」の哲学についてかんがえる |

| 1 |

先住民あるいは民族的マイノリティに対する国家の謝罪が必要になるため の倫理的基盤 |

| 2 |

先住民あるいは民族的マイノリティに対する国家の謝罪が必要になるため の法的基盤 |

| 3 |

先住民あるいは民族的マイノリティに対する諸学問の反省と謝罪 |

| 4 |

先住民あるいは民族的マイノリティに対する国家とそれに支えられた諸学 問からの対話の申し入れ |

| 5 |

先住民あるいは民族的マイノリティに対する代表的組織の確立とそのため の支援(=多様な価値観の調停) |

このような現在の、先住民問題のホット・ イシューである「遺骨と副葬品の返還」について理解するためにも、まず、先住民とは誰か?また 先住民 「問題」が、なぜ世界でこれほど、重要 なテーマになったのかについて、大まかなアウトラインを知ることが[地球市民にとっては]重要である。

| 遺骨や副葬品を取り戻しつつある先住民のための試論 |

A Prolegomena for

repatriation of remain and burial materials by indigenous people in

Japan |

この文章は、世界の先住民遺骨返還運動の

現状とその

背景にある社会思想を明らかにして、「琉球遺骨返還請求訴訟」への理解を深め、その歴史的ならびに社会的意義をより多くの人に知ってもらうために構想され

ました。 |

| 先住民遺骨副葬品返還の研究倫理 |

Research Ethics

and

the repatriation of the Ainu human remains |

以下の、3つの文章(またはそのエッセン

ス)を読ん で、先住民の人骨の「返還」の問題がどのように訴えられているのか、読解の上で、みんなで考察してみよう(研究倫理入門特別講義)。 |

| 琉球人遺骨返還運動と文化人類学者の反省 |

Reflection of a

cultural anthropologist on repatoriation activism by Ryukyuan

Indigenous People at Autumn of 2020. |

2018年12月に京都地裁に提訴され

た、いわゆる

琉球民族遺骨返還請求訴訟に関心をもち、そのおよそ2019年夏以降私は、その心情的な支援者になった。昨年11月のバンクーバーでのアメリカ人類学連合

大会では、本シンポジウムでもご一緒している、太田好信さん、瀬口典子さんが主宰する学会の分科会の発表者として、琉球とアイヌへの遺骨の返還にまつわる

研究倫理の問題について論じた。 |

| アイヌ遺骨等返還の手続きについて考えるページ |

On repatriation of

Ainu human remains in 2017-2018 |

(各種ウェブページについて引用紹介して

いる) |

| 個人が特定されないアイヌ遺骨等の地域返還手続きに関するガイドラ

イン(案) |

On repartriation

of bones of the Ainu people from universities and museums |

(このことにまつわる情報を整理する) |

| アイヌ遺骨等返還の研究倫理 |

Research Ethics

and the repatriation of the Ainu human remains |

以下の、3つの文献(またはそのエッセン

ス)を読ん で、日本の先住民アイヌの人骨の「返還」の問題がどのように訴えられているのか、読解の上で、みんなで考察してみよう。 |

| 遺骨は自らの帰還を訴えることができるのか? |

Can human remains

claim for their return and reburial from the University Collection Room

to their land of origin? |

平村ペンリウク氏(Penriuku

Hiramura, 1832-1903) は平取(ビラトリ)のアイヌ共同体(コタン)の首長(コタンコロクル)であっ

た。そして、彼は、1876年イギリス人宣教師ウォルター・デニング(Walter Dening,

1846-1913)、1879年以降は同ジョン・バチェラー(John Batchelor,

1854-1944)にアイヌ語を教え、また初期の人類学や民俗学の調査のインフォーマントとして、アイヌ研究に多大な貢献をしたことでも知られるべき

(バチラー 2008)で あるが、残念ながら2017年3月の曾孫の土橋芳美(Yoshimi Dobashi,

)氏の長編叙事詩『痛みのペンリウク』が発表されるまでは、バチェラー、金田一京助(1882-1971)、知里幸恵(1903-1922)、知里真志保

(1909-1961)に比べてアイヌ研究の重要な功労者として光が当てられることはなかった。 |

| 松島泰勝・木村朗編『大学による盗骨:研究利用され続ける琉球人・アイヌ遺骨』耕文社、

2019 年;研究ノート |

Violence of

Colonial Academy vs. Postcolonial Academy of Resistance |

今日における日本の先住民研究は、その

フィールドの

場所いかんにかかわらず、学問の植民地的性格に根ざしている。そのような知の枠組みを、さまざまな文化的収奪をうけてきた先住民研究者の立場から厳しく批

判するのが松島泰勝(Yasukatsu MATSUHIMA, 1963-

)氏である。彼の『琉球 奪われた骨』(2018)にも焦点を当てて、その批判的言説の可能性について検証しよう。 |

| 松島泰勝『琉球 奪われた骨:遺骨に刻まれた植民地主義』岩波書店、

2018年;研究ノート |

Violence of

Colonial Academy vs. Postcolonial Academy of Resistance |

はじめに言っておきますが、この書物を文

化人類学のテキストあるいは理論歴史書として読む必要はないということです。むしろ、日本の自然人類学を含めた文化人類学批判、あるいは、日本のアカデミ

ズムに対する批判の書として、読む必要があるということです。 |

| 霊性と物質性:アイヌと琉球の遺骨副葬品返還運動から |

Spirituality and

Materiality among Human Remains: Reflection on repatriation activism

for the Ainu and the Ryukyu |

この発表のタイトルは「霊性と物質性:ア

イヌと琉球の遺骨副葬品返還運動から」とも称すべきものです。 |

| Spirituality and Materiality among Human Remains: Reflection on repatriation activism for the Ainu and the Ryukyu | This paper

examines the ethical, legal, and social aspects of the debates on the

repatriation of the human remains and burial materials of the Ainu and

the Ryukyuan-Okinawan. |

|

| 「学問の暴力」という糾弾がわれわれに向けられるとき |

When the

accusation of "academic violence" is directed at us, we Japanese

Anthropologists |

私は、2018年12月に京都地裁に提訴

された、

いわゆる琉球民族遺骨返還請求訴訟に関心をもち、2019年夏以降その心情的な支援者になった。この発表では文化人類学(医療人類学)の一研究者として、

自分がもつ学問の来歴と、この遺骨返還請求訴訟が私たち文化人類学徒に投げかける研究倫理上の反省——倫理的・法的・社会的連累(Ethnical,

Legal and Social Implications, ELSI)——について考える。 |

| 琉球遺骨返還運動にみる倫理的・法的・社会的連累 (ELSI) |

Ethical, Legal,

and Social Implication of the Ryukyuan Repatriation Movement for Human

Remain |

アメリカ人類学会連合年次大会(カナダ・

バンクーバー、2019年)で発表したタイトルは、“Stealing remains is criminal”: Ethical, Legal,

and Social Issues of the repatriation of human remains to Ryukyu

islands, southern Japan(リンク先は発表予稿)でした。今回、これを改造して、日本平和学会2020

年秋季研究集会(オンライン開催、2020年11月7-8日、横浜市立大学)にて分科会「琉球人遺骨にとっての平和とはー『研究による暴力』に対する先住

民族の抵抗と祈り」(仮題:松島泰勝座長)の中で発表することになりました。そのための、論文構想発表ノートです。 |

| 遺骨返還における「皮肉なこと」 |

Great Irony of

Affair on repartriation activists and the authorites in Ryukyu, Dec. 5,

2020. |

|

| 金関丈夫と琉球の人骨 |

Dr. Takeo Kanaseki

and Ryukyuan Remains |

このページでは、人類学者として多大な業

績を残し た、金関丈夫(かなせき・たけお;1897-1983)が収集した、沖縄(琉球)の人骨とその返還について検討する |

| 京都大学と南西諸島の遺骨の収蔵ならびにそれらの返還について |

On Repatriation of

Ryukyuan remains and the responsibilities of Japanese cultural

anthropologists |

同志社大学の板垣竜太さんによると「京都

大学構内に眠る遺骨のうち、奄美に関わるものは約270例あると推定され、一地域からの『コレクション』としては最大規模」ということだ。その収集をおこ

なった主人公は、京都帝大医学部病理学教室の清野謙次人類学研究室によるもので、1933から35年におこなわれた「南島」調査(担当は講師の三宅宗悦)

によるという。 |

| 人類学者と研究対象者の4つのタイプ |

Four types of

Anthropologist from colonial to post-colonical periods |

Joe Watkins

教授(オクラホマ大学先住民研究センター所長―当時)による、人 類学者と研究対象の4つのタイプ(ハドソン

2010:136)。1.植民地主義的(colonial);2.合意的(consensual);3.契約的(covenantal);4.協力的

(collaborative) |

| 返還の人類学について |

On Anthropology of

Repatriation |

事物を所有すること。これは現在の日本社

会にとって

は自明のこととなっているが、近代啓蒙が事物を個人が所有することができるようになるための理解には、長い間の、所有権概念の成立、私的所有の概念、購入

した事物の転売か可処分を可能にする社会的条件、事物の売買市場の成立、事物の専有権や貸借概念などの整備、物件法に関する整備など、長い歴史を振り返ら

ないとならな い。 |

| 世界の先住民について知る |

World of

Indigenous Pooples |

先住民学(Indigenous

Studies) は、19世紀に北米ではじまる北米先住民の民族学研究からはじまるが、長く「先住民(先住民族)」

を研究対象にする非先住民あるいは(先住民の参加に

おいても)民族学/民俗学の専門教育をうけた専門家による研究であり、それらの研究の成果が「直接」先住民への知識や福利に寄与することは稀であった。し

かしながら、先住民の人権、法的権利についての長い間の論争や(犠牲者を伴う)抵抗運動という長い歴史的経験を通して、先住民学はたんに先住民を研究する

という自己目的のみならず、先住民による/先住民のための/先住民の研究であるべきだと、国際社会はようやく認識しつつある。 |

| Work_Place: 先住民の視点からグ ローバル・スタディーズを再考する |

Cross-boundary

Studies of Rethinking of Global Studies from the Indigenous people's

points of views |

本研究は、日本と海外を研究対象地域とし

て、先住民が実践し

ている(1)「遺骨や副葬品等の返還運動」、博物館における先住民による文化提示の際の敬意への要求といった(2)「文化復興運動」、および先住民アイデ

ンティティの復興のシンボルとなった(3)「先住民言語教育運動」という、3つの大きなテーマの現状を探る。 |

| Cross-boundary

Studies of Rethinking of Global Studies from the Indigenous people's

points of view |

||

| 清野謙次 |

Kenji

KIYONO, August 14, 1885 - December 27,1955 |

清野謙次(Kenji KIYONO,

1885-1955)年譜(ウィキペディア日本語等からの引用)ならびに「清野謙次とインドネ シアの民族医学(1943)について」より |

| グローバル・イシューズと先住民 |

UN Sustainable

Development Goals and World Indigenous Peoples |

このページは、科学研究費補助金・基盤

(B)「先住民の視

点からグローバル・スタディーズを再構築する領域横断研究(KAKEN)」(課題番号:18KT0005)の資料編です。このページの上位の親

ページは「先 住民の視点からグ ローバル・スタディーズを再考する」にあります。 |

| アイヌとシサムための 文化略奪史入門 |

Introduction to

The Ainu culture and history for the Sisamu and the Ainu |

シサムとは、アイヌ語でアイヌ以外の日本

人を指して

いう言葉である。シサムは「となり人」のような表現で、対面した相手にも使う。アイヌ語には日本人を指す言葉としてシャモがあるが、これはシサムが訛音

(かおん)化した、つまり、訛(なま)った言葉なので、同じ意味だが、現在ではより柔和で友好的なニュアンスのある表現である。 |

| 意⾒書(内閣官房アイヌ総合政策室・⽂部科学省・⽂化庁・国

⼟交通省宛) pdf |

Memoramdum on the

Ainu human remain repatriation |

私は「先住⺠族アイヌの声実現!実⾏委員

会」ならびに「⽇本⼈類学会のアイヌ遺⾻研究を考える会(通称・チャランケの会)」の活動の社会的意味について考え、基本的にその理念と⾏動を⽀持する者

であります。この度、同会の事務局、出原昌志⽒の慫慂により意⾒書をまとめることになりましたので、本状に添付します。 |

| 先住民と四分類人類学 |

World Indigenous

Peoples and Quadran/ General Anthropology |

人類学の守備範囲は、その学問がどの国で

発達してきたかによって微妙に異なり、民族学、民俗

学、文化研究、比較文明学などさまざまな類義語がある。日本では、人類学というと生物人類学(=形質人類学や自然人類学という旧名がある)と文化人類学の

2つの領域をさすことが一般的である。 |

| 憑在論 |

hauntology |

憑在論(ひょうざいろん:ハウントロ

ジー:hauntology, L'hantologie)とは、ジャッ ク・デリダの『マルクスの亡霊』(原著,

1993/2007a:37)に登場する用語で、「存在でもないが、かといって不在でもない、死んでいるのでもないが、かといって生きているでも

ない」ような亡霊の姿をとってあらわれる、延期されたオリジナル(res extensa)ではないものよっ

て表現される、置き換えられた、時間的・歴史的・存在論的脱節(temporal, historical, and ontological

disjunction)の状態のことをさす。 |

| 司法人類学者 |

forensic

anthropologist |

司法人類学とは法医学人類学とも言われ

る。被害者(おもに死体)を鑑定することで、年齢、性別、生前の持病や障害、死因 (事件か事故か)などを科学的に明らかにする仕事である。 |

| アメリカ先住

民の墳墓保護と返還に関する法律 |

NAGPRA, Native American Graves

Protection and Repatriation Act, 1990. |

この法律は、連邦政府機関および連邦政府から資金提供を受けている機関

[1]に対して、アメリカ先住民の「文化財」を直系卑属および文化的に提携しているアメリカインディアン部族、アラスカ先住民村、ハワイ先住民の組織に返

還することを義務付けている。文化的遺物には、遺骨、葬祭用具、聖なるもの、文化的財産となるものなどが含まれる。連邦政府の補助金プログラムは、本国送

還のプロセスを支援し、内務長官は、これに従わない博物館に対して民事罰を科すことができる。 |

| 遺骨返還の倫理をめぐる旅 |

A Journey through the Ethics

of Repatriation of Remains |

|

| 人間の遺骨の返還と再埋葬 |

Repatriation and reburial of

human remains |

● 池田光穂のこれまでの学会・研究発表の時系列リスト

| 2019年4月 2019年10月 |

Repatriation of

human remains and burial materials: Who owns cultural

heritage and dignity? The Spring meeting of the Korean Society of

Cultural Anthropology, Seoul National University, Seoul, South Korea,

April 26, 2019. "Spirituality and Materiality among Human Remains--Reflection from repatriation activism of the Ainu and the Ryukyu" Mitsuho IKEDA, テーマセッション「再帰的近代における宗教と社会・個人」(座長:安達智史)、第92回日本社会学会大会(東京都杉並区)、2019年10月5日 |

| 2019年11月 |

“Stealing remains

is criminal”: Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues of the Repatriation of

Remains to Ryukyu Islands, southern Japan. Mitsuho Ikeda (Osaka

University) in "HARKENING VOICES OF THE OTHER: ETHICS AND

STRUGGLES FOR REPATRIATION OF HUMAN REMAINS ON THE MARGINS OF

JAPAN"(5-1140) Annual Meeting of American Anthropological Association,

November 24, 2019. Vancouver, Canada. |

| 2019年12月 |

霊性と物質性:アイヌと琉球の遺骨副葬

品返還運動から、第三回豊中地区研究交流会(大阪大学基礎工学部シグマホール) |

| 2020年3月 |

Repatriation of

human remains and burial materials of Indigenous peoples: Who owns

cultural heritage and dignity ? CO*Design 7:1-20, 2020年3月

info:doi/10.18910/75574 |

| 2020年5月 |

霊性と物質性の研究倫理:先住民が訴え

る遺骨副葬品返還運動、日本文化人類学会第54回研究大会(主催校:早稲田大学)オンライン開催 |

| 2020年7月 |

遺骨や副葬品を取り戻しつつある先住民

のための試論、琉球人遺骨返還請求訴訟・支援集会、キャンパスプラザ京都(京都市下京区) |

| 2020年9月 |

『京大よ還せ:琉球人骨は訴える』松島

泰勝・山内小夜子編、耕文社(担当箇所「遺骨や副葬品を取り戻しつつある先住民のための試論」Pp.202-211)ISBN

978-4863770607, 256pp, 2020年9月 |

| 2020年9月 |

先住民が訴える遺骨副葬品返還運動、科

学研究費補助金「先住民族研究形成に向けた人類学と批判的社会運動を連携する理論の構築」(基盤(A))(代表者:太田好信)主催共同研究会、北海道大学

アイヌ先住民研究センター |

| 2020年11月 |

先住民運動からみた日本の保守とリベラ

ルの位相、第93回日本社会学会、会場:権力・政治(司会:中澤秀雄)、2020年11月1日 |

| 2020年11月 |

琉球人遺骨返還運動と文化人類学者の反

省、日本平和学会2020年度秋季研究大会, 2020年11月8日 |

| 2021年5月 |

「学問の暴力」という糾弾がわれわれに向けられるとき、第55回日本文

化人類学研究大会、2021年5月29日 |

| 2022年5月31日 |

朝日新聞「交論:先住民へ 学問の何よる暴力」(mieda220531S.pdf)with password |

| 2022年10月21日 |

⼤阪高等裁判所第6民事部に「琉球民族遺⾻返還請求事件」裁判の意見書

を提出(court_opinion_221021mikeda.pdf)with

password |

● NAGPRAに関する文献リスト

● Chip Colwell, Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America's Culture. University of Chicago Pres, 2017.

●Indigenous archaeologies : a reader on decolonization, editors, Margaret M. Bruchac, Siobhan M. Hart, and H. Martin Wobst. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016(→書籍情報)

"This

comprehensive reader on indigenous archaeology shows that

collaboration has become a key part of archaeology and heritage

practice worldwide. Collaborative projects and projects directed and

conducted by indigenous peoples independently have become standard,

community concerns are routinely addressed, and oral histories are

commonly incorporated into research. This volume begins with a

substantial section on theoretical and philosophical underpinnings,

then presents key articles from around the globe in sections on

Oceania, North America, Mesoamerica and South America, Africa, Asia,

and Europe. Editorial introductions to each piece con textualize them

in the intersection of archaeology and indigenous studies. This major

collection is an ideal text for courses in indigenous studies,

archaeology, heritage management, and related fields."- https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB28491817

先住民族の考古学に関するこの包括的な読

本は、コラボレーションが世界中の考古学と遺産保護の実践の重要な部分となっていることを示している。

共同プロジェクトや先住民が独自に指揮・実施するプロジェクトは標準的なものとなり、コミュニティの懸念は日常的に取り上げられ、オーラル・ヒストリーは

一般的に研究に取り入れられている。本書は、理論的・哲学的背景に関する充実したセクションに始まり、オセアニア、北米、メソアメリカと南米、アフリカ、

アジア、ヨーロッパのセクションで、世界各地の主要な論文を紹介している。また、各論文の序文では、考古学と先住民族研究の接点として、これらの論文をテ

キスト化している。先住民研究、考古学、遺産管理、および関連分野の講義に最適なテキストである。

| The repatriation

and reburial of human remains

is a current issue in archaeology and museum management, centering on

ethical issues and cultural sensitivities regarding human remains of

long-deceased ancestors which have ended up in museums and other

institutions. Historical trauma as a result of colonialism is often

involved. Various indigenous peoples around the world, such as Native

Americans and Indigenous Australians, have requested that human remains

from their respective communities be repatriated to their local areas

and burial sites from various institutions, often in other countries,

for reburial. Several requests for repatriation have developed into controversies which sometimes involve court cases, such as the Kennewick Man in the United States. The modern druids' request for the reburial of ancient human remains in the British Isles raised much debate. There is an ongoing program by the Australian government supporting the repatriation of Indigenous peoples' remains from institutions around the world. |

遺骨の本国送還と再埋葬は、考古学や博物館管理における現在の課題

であ

り、博物館やその他の施設に保管されている、長い間亡くなった先祖の遺骨に関する倫理的な問題や文化的な感受性が中心である。植民地支配による歴史的なト

ラウマが絡んでいることが多い。アメリカ先住民やオーストラリア先住民など、世界中のさまざまな先住民が、それぞれのコミュニティの遺骨を、さまざまな機

関(多くは他国)から自分たちの地域や埋葬地に送還し、再埋葬することを要求している。 いくつかの送還要求は、アメリカの「ケ ネウィック・マン」のように、時に裁判沙汰になる論争に発展している。また、現代のドルイド教団がイギリス諸島で 行った古代人骨の再埋葬の依頼は、多くの議論を呼んだ。また、オーストラリア政府は、先住民の遺骨の送還を支援するプログラムを世界各地で展開している。 |

| Ethical considerations The controversy of Archaeological ethics arises from the fact that some believe that it is disrespectful to the dead and to their contemporary descendants for their remains to be displayed in a museum or stored in other ways.[1] Historical trauma According to Hubert and Fforde (2002), the first and foremost undercurrent of repatriation is the ill-treatment of people in the past, the repatriation of human remains being to a degree part of a healing process aimed at repairing some of the traumas of history.[2] It is important that this ill-treatment is addressed, but with the repatriation and reburial of remains, they are essentially lost to the world as a reminder of that part of the history or biography of those remains. Repatriation presents an opportunity for people to lay claim to their own past and actively decide what is and what is not a part of their cultural heritage. The basis for the treatment of remains as objects for display and study in museums was that the people were seen as sufficiently "other" that they could be studied without any ethical considerations.[3] The contesting of ownership of human remains and demands of return to cultural groups is largely fuelled by the difference in the handling of "white" and indigenous remains. Where the former were reburied, the latter were subjects of study, eventually ending up in museums. In a sense one cultural group assumed the right to carry out scientific research upon another cultural group[4] This disrespectful and unequal treatment stems from a time when race and cultural differences had huge social implications, and centuries of inequality cannot be easily corrected. Repatriation and ownership claims have increased in recent years.[5] The “traumas of history” can be addressed by reconciliation, repatriation and formal governmental apologies disapproving of conducts in the past by the institutions they now represent. A good example of a repatriation case is described by Thornton, where a large group of massacred Northern Cheyenne Native Americans were returned to their tribe, showing the healing power of the repatriation gesture.[6] |

倫理的考察 考古学の倫理に関する論争は、遺骨が博物館に展示されたり、他の方法で保管されることは、死者やその子孫に対して失礼であるという考え方があることから生 じている[1]。 歴史的トラウマ Hubert and Fforde(2002)によれば、送還の第一の根底には、過去における人々の不当な扱いがあり、遺骨の送還は、ある程度、歴史のトラウマを修復すること を目的とした治癒プロセスの一部である[2]。この不当な扱いに取り組むことは重要であるが、遺骨の送還と再埋葬によって、その歴史や経歴の一部を思い起 こさせ、本質的に世界から失われることになる。本国送還は、人々が自らの過去を主張し、何が自分たちの文化遺産の一部であり、何がそうでないかを積極的に 決定する機会を提供するものである。博物館において遺骨が展示や研究の対象として扱われる根拠は、人々が十分に「他者」であると見なされ、倫理的な配慮な しに研究することが可能であるということであった[3]。 遺骨の所有権の争いと文化集団への返還要求は、「白人」と先住民の遺骨の取り扱いの違いによって大きく煽られている。前者は再埋葬され、後者は研究の対象 となり、最終的には博物館に収蔵された。ある意味で、ある文化集団が他の文化集団に対して科学的研究を行う権利を有していたのです[4]。この無礼で不平 等な扱いは、人種や文化の違いが社会的に大きな意味を持っていた時代に由来しており、数世紀に及ぶ不平等を簡単に正すことはできないのです。近年、返還と 所有権の主張が増加しています[5]。「歴史のトラウマ」は、和解、返還、そして現在彼らが代表する機関による過去の行為を認めない政府の正式な謝罪に よって対処することができます。 本国送還の事例として、虐殺された北シャイアン族のネイティブアメリカンの大集団が部族に戻され、本国送還というジェスチャーの治癒力を示したソーントン が良い例として述べている[6]。 |

| Australia Indigenous Australians' remains were removed from graves, burial sites, hospitals, asylums and prisons from the 19th century through to the late 1940s. Most of those which ended up in other countries are in the United Kingdom, with many also in Germany, France and other European countries as well as in the US. Official figures do not reflect the true state of affairs, with many in private collections and small museums. More than 10,000 corpses or part-corpses were probably taken to the UK alone.[7] Australia has no laws directly governing repatriation, but there is a government programme relating to the return of Aboriginal remains, the International Repatriation Program (IRP), administered by the Department of Communications and the Arts. This programme "supports the repatriation of ancestral remains and secret sacred objects to their communities of origin to help promote healing and reconciliation" and assists community representatives work towards repatriation of remains in various ways.[8][7][9] As of April 2019, it was estimated that around 1,500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral remains had been returned to Australia in the previous 30 years.[10] The government website showed that over 2,500 ancestral remains had been returned to their community of origin.[8] The Queensland Museum's program of returning and reburying ancestral remains which had been collected by the museum between 1870 and 1970 has been under way since the 1970s.[11] As of November 2018, the museum had the remains of 660 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people stored in their "secret sacred room" on the fifth floor.[12] In March 2019, 37 sets of Australian Aboriginal ancestral remains were set to be returned, after the Natural History Museum in London officially gave back the remains by means of a solemn ceremony. The remains would be looked after by the South Australian Museum and the National Museum of Australia until such time as reburial can take place.[13] In April 2019, work began to return more than 50 ancestral remains from five different German institutes, starting with a ceremony at the Five Continents Museum in Munich.[10] The South Australian Museum reported in April 2019 that it had more than 4,600 Old People in storage, awaiting reburial. Whilst many remains had been shipped overseas by its 1890s director Edward C. Stirling, many more were the result of land clearing, construction projects or members of the public. With a recent change in policy at the museum, a dedicated Repatriation Officer will implement a program of repatriation.[14] In April 2019, the skeletons of 14 Yawuru and Karajarri people which had been sold by a wealthy Broome pastoralist and pearler to a museum in Dresden in 1894 were brought home to Broome, in Western Australia. The remains, which had been stored in the Grassi Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig, showed signs of head wounds and malnutrition, a reflection of the poor conditions endured by Aboriginal people forced to work on the pearling boats in the 19th century. The Yawuru and Karajarri people are still in negotiations with the Natural History Museum in London to enable the release of the skull of the warrior known as Gwarinman.[15] On 1 August 2019, the remains of 11 Kaurna people which had been returned from the UK were laid to rest at a ceremony led by elder Jeffrey Newchurch at Kingston Park Coastal Reserve, south of the city of Adelaide.[16] In March 2020, a documentary titled Returning Our Ancestors was released by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council based on the book Power and the Passion: Our Ancestors Return Home (2010) by Shannon Faulkhead and Uncle Jim Berg,[17] partly narrated by award-winning musician Archie Roach. It was developed primarily as a resource for secondary schools in the state of Victoria, to help develop an understanding of Aboriginal history and culture by explaining the importance of ancestral remains.[18][19] In November 2021, the South Australian Museum apologised to the Kaurna people for having taken their ancestors' remains, and buried 100 of them a new 2 ha (4.9-acre) site at Smithfield Memorial Park, donated by Adelaide Cemeteries. The memorial site is in the shape of the Kaurna shield, to protect the ancestors now buried there.[20] |

オーストラリア オーストラリア先住民の遺骨は、19世紀から1940年代後半にかけて、墓、埋葬地、病院、精神病院、刑務所などから持ち出されました。海外に渡った遺骨 の多くは英国にあり、ドイツ、フランスなどの欧州諸国や米国にも多くあります。公式の数字は実態を反映しておらず、多くは個人のコレクションや小さな博物 館に所蔵されている。イギリスだけでも10,000体以上の死体や一部死体が持ち去られたと思われる[7]。 オーストラリアには送還を直接規定する法律はないが、アボリジニの遺骨の返還に関連する政府のプログラムとして、通信芸術省が運営する国際送還プログラム (IRP)が存在する。このプログラムは「癒しと和解を促進するために、先祖代々の遺骨や秘密の聖具を元のコミュニティへ送還することを支援」し、コミュ ニティの代表が様々な方法で遺骨の送還に向けた作業を支援するものです[8][7][9]。 2019年4月現在、アボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の祖先の遺骨は、過去30年間に約1,500体がオーストラリアに返還されたと推定されている [10]。 政府のウェブサイトでは、2,500体以上の祖先の遺骨が出身コミュニティに返還されていることが示された[8]。 クイーンズランド博物館が1870年から1970年の間に収集した祖先の遺骨を返還・改葬するプログラムは1970年代から行われており[11]、 2018年11月時点で660人のアボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の遺体が5階にある「秘密の神聖室」に保管されている[12]。 2019年3月、ロンドンの自然史博物館が厳粛な式典によって正式に遺骨を返還し、37組のオーストラリア・アボリジニの祖先の遺骨が返還されることが決 定した。遺骨は、再埋葬が可能になるまで、南オーストラリア博物館とオーストラリア国立博物館によって管理されることになった[13]。 2019年4月、ミュンヘンの五大陸博物館での式典を皮切りに、ドイツの5つの機関から50体以上の祖先の遺骨を返還する作業が開始された[10]。 南オーストラリア博物館は2019年4月に、4,600体以上のオールドピープルが保管され、再埋葬を待っていると報告した。多くの遺骨は1890年代の 館長エドワード・C・スターリングによって海外に運ばれたものである一方、多くの遺骨は土地の開墾や建設プロジェクト、一般市民によってもたらされたもの であった。最近の博物館の方針変更に伴い、専門のレパトリエーション・オフィサーがレパトリエーションのプログラムを実施する予定です[14]。 2019年4月、ブルームの裕福な牧民と真珠採取者が1894年にドレスデンの博物館に売却した14人のヤウル族とカラジャリ族の骸骨が、西オーストラリ ア州のブルームに持ち帰られました。ライプチヒのグラッシ民族学博物館に保管されていた遺骨には、頭の傷や栄養失調の跡があり、19世紀に真珠採取船で働 かされていたアボリジニの劣悪な環境を反映しているようでした。ヤウル族とカラジャリ族は、グワリンマンと呼ばれる戦士の頭蓋骨の公開を可能にするため に、ロンドンの自然史博物館とまだ交渉中である[15]。 2019年8月1日、アデレード市の南にあるキングストンパーク沿岸保護区で、長老ジェフリー・ニューチャーチが率いる式典で、英国から返還された11人 のカウルナ族の遺骨が安置された[16]。 2020年3月、『Power and the Passion』という書籍に基づき、『Returning Our Ancestors』というドキュメンタリー映画がビクトリア州アボリジニ遺産協議会から公開された。シャノン・フォークヘッドとジム・バーグおじさんに よる『Our Ancestors Return Home』(2010年)に基づき、受賞歴のあるミュージシャン、アーチー・ローチが一部ナレーションを担当した[17]。主にビクトリア州の中等学校の 教材として開発され、先祖の遺骨の重要性を説明することでアボリジニの歴史や文化への理解を深めることを目的としている[18][19]。 2021年11月、南オーストラリア博物館は、先祖の遺骨を持ち去ったことをカウルナ族に謝罪し、アデレード墓地が寄贈したスミスフィールド記念公園の 2ha(4.9エーカー)の新しい敷地に100体の遺骨を埋葬した。この記念地は、現在埋葬されている先祖を守るため、カウルナの盾の形をしている [20]。 |

| Head of a Tasmanian known as "Shiney" preserved in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, presented by Dr. John Frederick Clarke, F.R.C.S.I, Inspector General of Hospitals, about 1845–6. "This head had been placed in spirit which evaporated, and the air being very dry no decomposition took place." Photographed in 1896. | 【図版】アイルランド王立外科医学校の博物館に保存されている

「シャイ

ニー」と呼ばれるタスマニア人の頭部で、1845~6年頃に病院総監のジョン・フレデリック・クラーク博士(F.R.C.S.I)が寄贈した。「この頭部

は蒸留酒の中に置かれていたが蒸発し、空気が非常に乾燥していたため腐敗は起こらなかった。1896年に撮影されたもの。 |

| France During the French colonisation of Algeria, 24 Algerians fought the colonial forces in 1830 and in an 1849 revolt. They were decapitated and their skulls were taken to France as trophies. In 2011, Ali Farid Belkadi, an Algerian historian, discovered the skulls at the Museum of Man in Paris and alerted Algerian authorities that consequently launched the formal repatriation request, the skulls were returned in 2020. Between the remains were those of revolt leader Sheikh Bouzian, who was captured in 1849 by the French, shot and decapitated, and the skull of resistance leader Mohammed Lamjad ben Abdelmalek, also known as Cherif Boubaghla (the man with the mule).[21][22] |

フランス フランスによるアルジェリア植民地時代、1830年と1849年の反乱で、24人のアルジェリア人が植民地軍と戦った。彼らは首を切られ、その頭蓋骨は戦 利品としてフランスに持ち去られた。2011年、アルジェリアの歴史家アリ・ファリド・ベルカディがパリの人間博物館で頭蓋骨を発見し、アルジェリア当局 に警告した結果、正式な返還要請が開始され、2020年に返還された。遺骨の間には、1849年にフランス軍に捕まり、銃で撃たれて首を切られた反乱軍の 指導者シェイク・ブジアンのものと、チェリフ・ブバグラ(ラバを持った男)とも呼ばれるレジスタンスの指導者モハメド・ラムジャド・ベン・アブデルマレッ クの頭蓋骨があった[21][22]。 |

| Ireland The British anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon removed 13 skulls from a graveyard on Inishmore, and more skulls from Inishbofin, County Galway,[23][24] and a graveyard in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry, as part of the Victorian-era study of "racial types". The skulls are still in storage at Trinity College Dublin and their return to the cemeteries of origin has been requested,[25][23][26] and the board of Trinity College has signalled its willingness to work with islanders to return the remains to the island.[27] |

アイルランド イギリスの人類学者アルフレッド・コート・ハドンは、ヴィクトリア朝時代の「人種型」の研究の一環として、イニシュモアの墓地から13体の頭蓋骨を、ゴー ルウェイ州イニシュボフィン[23][24]とケリー州バリンスケリッグスの墓地からさらに頭蓋骨を持ち去った。頭蓋骨は現在もトリニティ・カレッジ・ダ ブリンに保管されており、出身地の墓地への返還が要請されている[25][23][26]。トリニティ・カレッジの理事会は島民と協力して遺骨を返還する 意向を示している[27]。 |

| United Kingdom The skeleton of the "Irish Giant" Charles Byrne (1761–1783) is on public display in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow despite it being Byrne's express wish to be buried at sea. Author Hilary Mantel called in 2020 for his remains to be returned to Ireland.[28] |

イギリス 「アイルランドの巨人」チャールズ・バーン(1761-1783)の骸骨は、バーンが海への埋葬を希望したにもかかわらず、グラスゴーのハンタリアン博物 館に展示されている。作家のヒラリー・マンテルは2020年に彼の遺骨をアイルランドに返還するよう呼びかけた[28]。 |

| Druids The Neo-druidic movement is a modern religion, with some groups originating in the 18th century and others in the 20th century. They are generally inspired by either Victorian-era ideas of the druids of the Iron Age, or later neopagan movements. Some practice ancestor veneration, and because of this may believe that they have a responsibility to care for the ancient dead where they now live. In 2006 Paul Davies requested that the Alexander Keiller Museum in Avebury, Wiltshire rebury their Neolithic human remains, and that storing and displaying them was "immoral and disrespectful".[29] The National Trust refused to allow reburial, but did allow for Neo-druids to perform a healing ritual in the museum.[30][31] The archaeological community has voiced criticism of the Neo-druids, making statements such as "no single modern ethnic group or cult should be allowed to appropriate our ancestors for their own agendas. It is for the international scientific community to curate such remains." An argument proposed by archaeologists is that: "Druids are not the only people who have feelings about human remains... We don't know much about the religious beliefs of these [Prehistoric] people, but know that they wanted to be remembered, their stories, mounds and monuments show this. Their families have long gone, taking all memory with them, and we archaeologists, by bringing them back into the world, are perhaps the nearest they have to kin. We care about them, spending our lives trying to turn their bones back into people... The more we know the better we can remember them. Reburying human remains destroys people and casts them into oblivion: this is at best, misguided, and at worse cruel."[32] Mr. Davies thanked English Heritage for their time and commitment given to the whole process and concluded that the dialogue used within the consultation focussed on museum retention and not reburial as requested.[33] |

ドルイド教 ネオドルイド運動は、18世紀に生まれたグループと20世紀に生まれたグループがあり、現代の宗教である。鉄器時代のドルイドに対するビクトリア朝時代の 思想や、その後のネオペイガン運動に影響を受けているのが一般的です。祖先崇拝を実践している者もおり、そのため、自分たちは今住んでいる場所で古代の死 者をケアする責任があると信じている場合もある。2006年、ポール・デイヴィスはウィルトシャーのエイブベリーにあるアレクサンダー・キーラー博物館に 新石器時代の人骨を再埋葬し、保管・展示することは「不道徳かつ無礼」であると要請した[29]。ナショナル・トラストは再埋葬を拒否したが、ネオドルイ ドが博物館内で癒しの儀式をすることは許可した[30][31]。 考古学界はネオ・ドルイドを批判し、「いかなる現代の民族集団や教団も、自分たちの目的のために先祖を利用することを許してはならない」といった声明を出 している[31]。このような遺跡を管理するのは、国際的な科学界である "と述べている。考古学者が提唱している議論では 「ドルイドだけが遺骨に思い入れを持っているわけではない......。しかし、彼らの物語や塚、モニュメントがそれを示していることは確かです。私たち 考古学者は、彼らをこの世に蘇らせることで、おそらく彼らにとって最も身近な親族になるのです。私たちは、彼らの骨を人間に戻すことに人生を費やし、彼ら を気にかけているのです。そして、より多くのことを知れば知るほど、彼らをよりよく思い出すことができるのです。遺骨を埋め戻すことは、人々を破壊し、忘 却の彼方へ追いやる。これはよくても見当違いであり、悪くすれば残酷である」[32]。 デイヴィス氏は、イングリッシュ・ヘリテージの全プロセスに与えられた時間と献身に感謝し、協議の中で使われた対話は博物館の保持に焦点を当てたものであ り、要求された再埋葬ではなかったと結論づけた[33]。 |

| United States The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, provides a process for museums and federal agencies to return certain cultural items such as human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, etc. to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organisations.[34][35][36] Kennewick Man The Kennewick Man is the name generally given to the skeletal remains of a prehistoric Paleoamerican man found on a bank of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, United States, on 28 July 1996,[37][38] which became the subject of a controversial nine-year court case between the United States Army Corps of Engineers, scientists, the Umatilla people and other Native American tribes who claimed ownership of the remains.[39] The remains of Kennewick Man were finally removed from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture on 17 February 2017. The following day, more than 200 members of five Columbia Plateau tribes were present at a burial of the remains.[40] |

米国 1990年に成立したアメリカ先住民の墓の保護と返還に関する法律(NAGPRA)は、 博物館や連邦機関が、人骨、葬儀用具、聖なる物などの特定の文化財を直系の子孫や文化的に提携しているインディアン部族やハワイ先住民の組織に返還する手 続きを定めたものである[34][35][36]。 ケネウィック・マン ケネウィックマン(Kennewick Man)は、1996年7月28日にアメリカ合衆国ワシントン州ケネウィックのコロンビア川の土手で発見された先史時代の古アメリカ人の骨格に一般的に与 えられた名称である[37][38]。この遺跡はアメリカ合衆国工兵隊、科学者、ウマティラ人、および遺跡の所有権を主張する他のネイティブアメリカンの 部族の間で9年間に及ぶ論争の的となる裁判の対象となった[39]。 ケネウィックマンの遺骨は、2017年2月17日にバーク自然史・文化博物館から最終的に搬出された。翌日、コロンビア高原の5つの部族の200人以上の メンバーが、遺骨の埋葬に立ち会った[40]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repatriation_and_reburial_of_human_remains |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

リンク(関係者・研究者・実践者・事件・ 行動)

++

リンク(→「世界の先住民について知る」)

文献

その他の情報

クレジット:「世界の先住民について知る(リテラシー

G)

2019」:Literacy G: World of

Indigenous Pooples, 2019

---------------------------------

****

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆