先住民遺骨副葬品返還の研究倫理

Research Ethics and the repatriation of the Ainu human remains

レ

イシズムと遺骨返還と墓地保全におけるマイケル・ブレイキー博士

先住民遺骨副葬品返還の研究倫理

Research Ethics and the repatriation of the Ainu human remains

レ

イシズムと遺骨返還と墓地保全におけるマイケル・ブレイキー博士

”IN 2017, ON HIS SECOND DAY in an archaeology class held at the Penn Museum, Francisco Diaz looked to his right and found himself staring at a skull with the label “Maya from Yucatan” pasted to its forehead. Diaz, an anthropology doctoral student at Penn, is Yucatec Maya, born on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. In class, skulls from Black and Indigenous people were “just made part of classroom décor,” he recalls. “You have this institution that has done this type of work on Indigenous people, and then one of you shows up,” he says. Seeing that skull in his classroom, “It’s kind of like saying, do you really belong here?” This year, he wrote an essay on how study and display of the skulls dehumanized the people they belonged to.” -by Lizzie Wade., A racist scientist built a collection of human skulls. Should we still study them?. Scinece Jul. 8, 2021.

「2017年、ペンシルベニア博物館で行われた考古

学の授業の2日目、フランシスコ・ディアスは右を見ると、額に「ユカタンのマヤ」というラベルが貼られた頭蓋骨を見つめていることに気づいた。ペンシルバ

ニア大学の人類学博士課程に在籍するディアスは、メキシコのユカタン半島で生まれたユカテク・マヤ人である。授業では、黒人や先住民の頭蓋骨が「教室の装

飾品の一部になっていた」と振り返る。「先住民族についてこのような研究をしてきた機関に、あなた方の研究対象の先住民の1人が現れたのです」と彼は指摘

する。教室に置かれた頭蓋骨を見て、「あなたは本当にここ(=先住民を研究する側)に属しているのかと批判されているようなものです」。今年、彼は、頭蓋

骨の研究と展示が、それらが属していた先住民の人間性をいかに奪ったかについてのエッセイを書きました。」DeepL( https://www.deepl.com/ )による翻訳を元に加筆した。

以下の文章(またはそのエッセンス)を読ん で、先住民の人骨の「返還」の問題がどのように訴えられているのか、読解の上で、みんなで考察してみよう(研究倫理入門特別講義)。

| 遺骨や副葬品を取り戻しつつある先住民のための試論 |

A Prolegomena for

repatriation of remain and burial materials by indigenous people in

Japan |

この文章は、世界の先住民遺骨返還運動の

現状とその

背景にある社会思想を明らかにして、「琉球遺骨返還請求訴訟」への理解を深め、その歴史的ならびに社会的意義をより多くの人に知ってもらうために構想され

ました。 |

| 先

住民遺骨副葬品返還の研究倫理 |

esearch Ethics and

the repatriation of the Ainu human remains |

以下の、3つの文章(またはそのエッセン

ス)を読ん で、先住民の人骨の「返還」の問題がどのように訴えられているのか、読解の上で、みんなで考察してみよう(研究倫理入門特別講義)。 |

| 琉球人遺骨返還運動と文化人類学者の反省 |

Reflection of a

cultural anthropologist on repatoriation activism by Ryukyuan

Indigenous People at Autumn of 2020. |

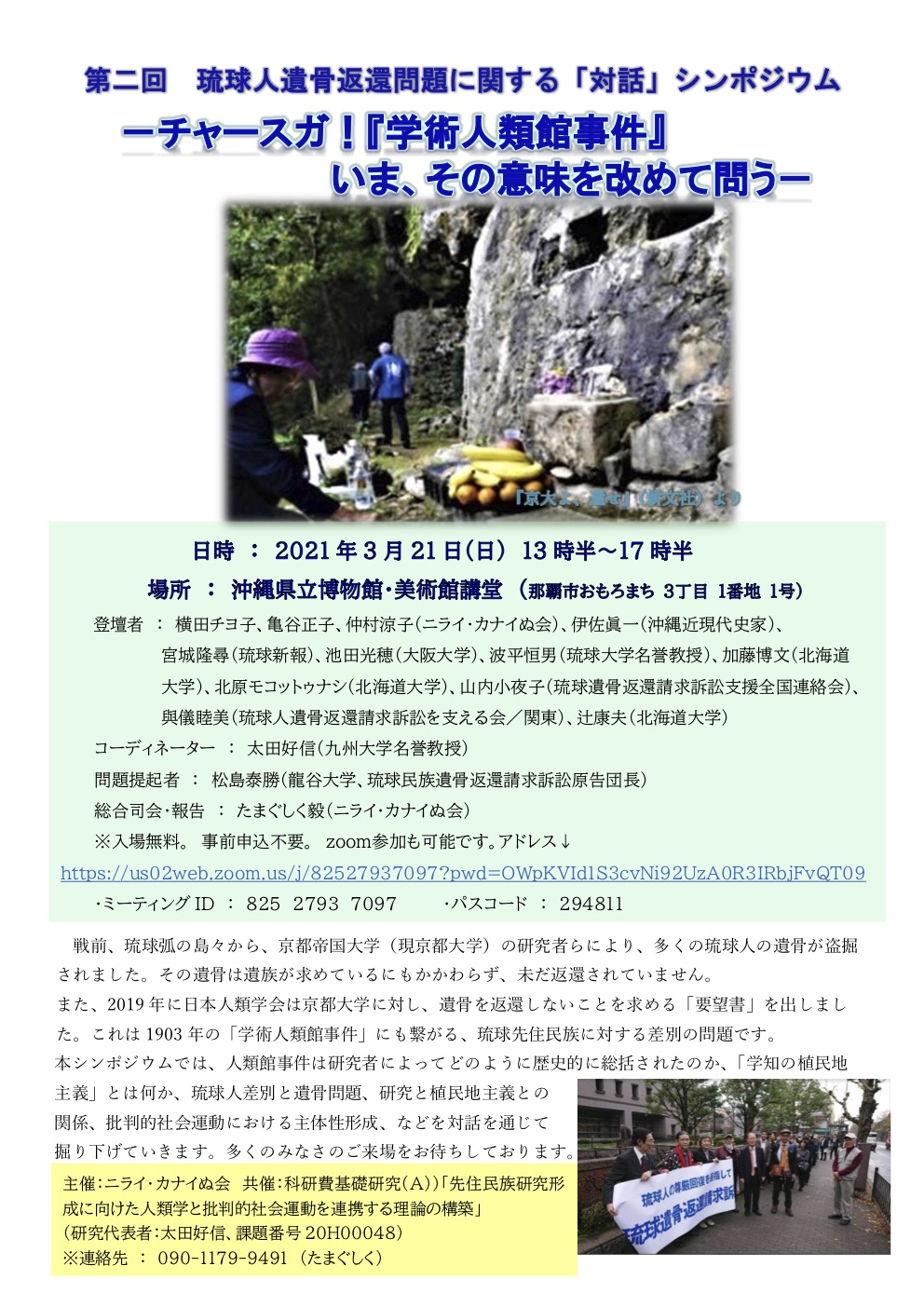

2018年12月に京都地裁に提訴され

た、いわゆる

琉球民族遺骨返還請求訴訟に関心をもち、そのおよそ2019年夏以降私は、その心情的な支援者になった。昨年11月のバンクーバーでのアメリカ人類学連合

大会では、本シンポジウムでもご一緒している、太田好信さん、瀬口典子さんが主宰する学会の分科会の発表者として、琉球とアイヌへの遺骨の返還にまつわる

研究倫理の問題について論じた。 |

| アイヌ遺骨等返還の手続きについて考えるページ |

On repatriation of

Ainu human remains in 2017-2018 |

(各種ウェブページについて引用紹介して

いる) |

| 【この続きは】「遺骨と副葬品の返還」で!!! |

Repatriation for Indigenous Pooples' remain and burial materials | 【この続きは】「遺骨と副葬品の返還」で!!! 論文「「学問の暴力」という糾弾がわれわれに向けられるとき」 |

現在、アイヌ民族の有志——北大開示文書研究会等 ——が、北海道大学ならびに全国の大学・研究機関に、日本の先住民アイヌの人骨の「返還」を求めている。その訴えの根拠はさまざまな理由から示されてい る。具体的には、......

1)さまざまな歴史的経緯から、アイヌは研究対象と して扱われることがあっても、人格・人権をもった対象として扱われてこなかった。その例は、戦前から続く人骨の「収集」であり、自然人類学者や考古学者に よる、伝統的埋葬地からの「盗掘」であり、「人種標本」としての写真の撮影、さらには「民族の起源」研究のための血液やDNAサンプルの採集である。それ らの多くは、アイヌ民族の研究がもたらす情報としてもまた研究資料を「提供してきた」貢献としての福利の還元ですらない——アイヌ民族に対する研究という 名の搾取。

2)上記の研究にかかわる自然科学的な研究のほか に、社会調査や民族学調査においても、その実態の調査に関する報告書が書かれたとしても、アイヌ民族が直面するさまざまな文化的あるいは政治経済的「窮 状」に、人間的な共感をもつ和人研究者はいても、その成果をもとに、アイヌと共に、国や地方自治体あるいは、研究を実施する大学・研究機関に対して、適切 な措置を講じるように、調査結果とともに訴えることは少数の例をとおしてなく、理念的なものに留まっていた。

3)アイヌの祖先に対する崇敬に関する伝統的な観念 と、和人や外国人によるさまざまな宗教の受容により、祖先の遺骨や遺体に対しては、多様な思いがある。また、日本政府はアイヌ民族を先住民として認めてい る事実がある。それらのことに鑑みて、個人が特定化された遺骨に関しては、遺族や祭祀継承者のもとに返還請求があれば速やかに返却すべきである。また、地 域のアイヌ民族集団として、その祭祀あるいは葬礼に関して集合的な崇敬の念をもって、研究材料から「解放」され、同胞として敬意をもって遺骨が処遇される ことは、アイヌ民族としての集団的な先住民権が国連宣言等(UNDRIP, 2007)で も認めるところである。

以下の、3つの文献(またはそのエッセンス)を読ん で、上記の問題がどのように訴えられているのか、読解の上で、みんなで考察してみよう。

(1)アイヌ民族からの請求により北海道大学がまと めた遺骨の収集や保存状況について書かれた文献:北海道大学『北海道大学医学部アイヌ人骨収蔵経緯に関する調査報告書』北海道大学、183pp., 2013年(→ hokudai_jinkotsu_report2013.pdf 9.8MB pdf)パスワードなし

(2)北大開示文書研究会に与る、市川守弘ら弁護士

らによる、内閣総理大臣安倍晋三らに宛てた「人権救済申立書」:出典は北大開示文書研究会編『アイヌの遺骨はコタンの土へ』緑風出版、2016年,

Pp.276-295. pdf パスワード付: Ainu_jinken_kyusai_2015.pdf

(3)葛野辰次郎エカシ(1910-2001)が遺 した、大自然の尊さと人間の悪との仲裁の口頭伝承(あるいは唱え歌)「シオイナ・ネワ・ハヲツルン・オルスペ(抜粋)」:出典は北大開示文書研究会編『ア イヌの遺骨はコタンの土へ』緑風出版、2016年, Pp.59-88. pdf パスワード付:Kuzuno_Ekashi_Sioina.pdf:: →関連ページ:「遺骨は自らの帰還を訴えることができるのか?」

続きは「アイヌ遺骨等返還の研究倫理」にてご覧ください。

●「北大人骨事件, 1995」

北大人骨事件(ほくだいじんこつじけん)とは、1995年(平成7年)7月26日 に北海道大学構内の古河記念講堂旧標本庫において、段ボール箱に納められた6つの頭骨が発見された事件である。

| 1 |

「韓国東学党」と墨書き |

「韓国東学党」と墨書きされた頭骨は東学

農民革命軍指導者遺骸奉還委員会に返還 |

| 2 |

「オタスの杜・風葬オロッコ」01 |

田中了らの仲介によってサハリンに返還さ

れた |

| 3 |

「オタスの杜・風葬オロッコ」02 | 田中了らの仲介によってサハリンに返還さ れた |

| 4 |

「オタスの杜・風葬オロッコ」03 | 田中了らの仲介によってサハリンに返還さ れた |

| 5 |

日本男子20才 |

2006年札幌市の浄土真宗本願派大乗寺 に、焼骨を行わずに納骨するという形で仮安置 |

| 6 |

「寄贈頭骨出土地不明」 |

2006年札幌市の浄土真宗本願派大乗寺

に、焼骨を行わずに納骨するという形で仮安置 |

●「大学の保管するアイヌ遺骨等の出土地域への返還 手続に関するガイドライン」から PW181226_chiiki-guidelines.pdf (開錠はアラビア数字6桁)

「国(北海道白老郡白老町に整備する民族共生象徴空

間を構成するアイヌ遺骨等の

慰霊及び管理のための施設(以下「慰霊施設」としづ。)に出土地域特定遺骨等を

集約する前にあっては、当該出土地域特定遺骨等を保管する大学(以下「関係大学」

としづ。))は、基本的な考え方、地域返還基本方針及び出土地域特定遺骨等に係る

裁判上の事例等を考慮し、「先住民族の権利に関する国際連合宣言」(国連総会第61

会期2007 年9 月13 日採択(国連文書A/RES/61/295 付属文書))の関連条項を参

照しつつ実施されるアイヌ政策の一環として、出土地域特定遺骨等については、ア

イヌの精神文化やアイヌの人々の心情等を踏まえ、尊厳ある慰霊の実現を図るため、

出土地域に居住するアイヌの人々を中心に構成された団体(以下「出土地域アイヌ

関係団体」という。)が返還を希望する場合には、本ガイドラインの定めに従い、

地域返還の手続を行うものとする」(2.本ガイドラインにおける遺骨返還の考え方)

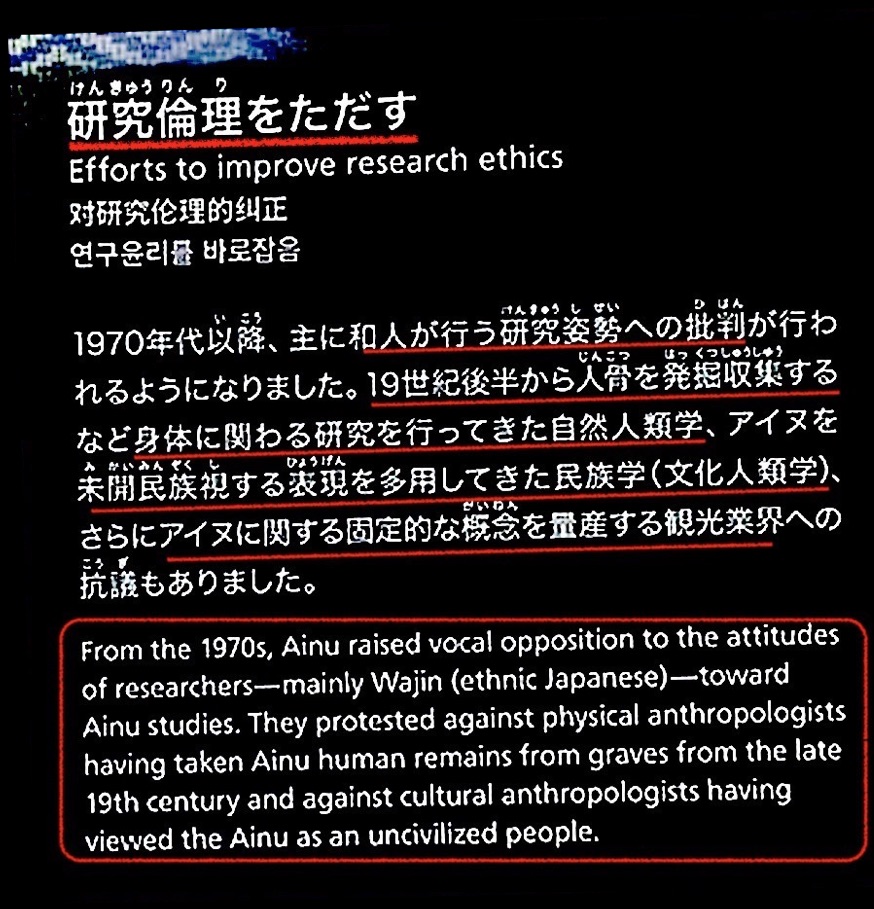

●2020年にウポポイ(国立アイヌ民族博物館)にて撮影(画像は階調を反転し赤の下線や枠 は追記)

画面クリックで拡大

● 最近の新聞記事より

「東京大の解剖学者らが北海道浦幌町のアイヌ民族の

墓地から持ち去った6体の遺骨を巡り、返還を求めて提訴していた地元のアイヌ団体と東京大が[2020年]8月7日にも和解する見通しになったことが21

日、関係者への取材で分かった。東京大側が遺骨6体と副葬品を返還し、団体側が慰霊行為を妨げられたとして求めていた50万円の賠償請求を放棄する内容と

いう。/8月下旬までに浦幌町のアイヌ団体「ラポロアイヌネイション」(旧・浦幌アイ

ヌ協会)に返還される。同団体が先祖の遺骨の返還を求めて北海道大、札幌医

科大、東京大を提訴していた一連の訴訟は、遺骨計102体を取り戻して終結することになる。」共同2020.07.21)

● アイヌ民族葛野次雄さん「(遺骨は)アイヌプリ (=アイヌの風習)で大地に眠らせてあげたいというのは私の願いです」2020年7月20日

「遺骨はすべからく返還すべし」を参照してください

● 遺骨返還の動き(クリーブランド自然史博物館HPより:https://www.cmnh.org/hamann-todd-biography-project)

| Museum

researchers look into the lives of individuals in the world-famous

osteological collection. |

博物館の研究者たちは、世界的に有名な骨学コレクションに含まれる個人

の生涯を調べている。 |

| BY EBETH SAWCHUK, PH.D.,

ASSISTANT CURATOR OF HUMAN EVOLUTION & CHRISTINE BAILEY, M.A., COLLECTIONS MANAGER OF BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY |

(著者名) |

| On October 21, 1925, 71-year-old

George Maus was working as a teamster (someone who drove teams of

horses) and living in Cleveland when he unexpectedly passed away from a

chronic health condition. Unfortunately, his family could not be

reached within the 36 hours required by law at the time to claim his

body. As a result, Maus was sent to Western Reserve University—now Case

Western Reserve University (CWRU)—to undergo anatomical dissection and

study by medical students. This is how he ultimately became one of the

more than 3,000 individuals in the Hamann-Todd Osteological Collection,

now curated by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The collection was started by surgeon Carl Hamann, who moved to Cleveland from Pennsylvania in 1893 to teach at Western Reserve University’s medical school. However, it was his successor, Thomas Wingate Todd, who vastly expanded the collection when he took over Hamann’s position in 1912. Fascinated by differences among people and variation in the human skeleton, Todd contributed enormously to the development of the field now known as biological (or physical) anthropology, which is the study of human and nonhuman primate biology and evolution. While many universities and museums were establishing skeletal collections in the 1920s, the Hamann-Todd Collection is exceptional in the sheer amount of associated information. Todd meticulously recorded as much as he could, including the person’s age at death, cause of death, body size and measurements, and often their name. After Todd’s sudden death in 1938, CWRU kept all the individuals and ultimately reached an agreement with the Cleveland Museum of Natural History for them to be housed and curated at the Museum. Many decades later, we are preparing to move these individuals again into a new, custom-built space as part of the Museum’s transformation project. All collections are currently closed to researchers while we busily prepare behind the scenes for this monumental move. This pause provides the perfect opportunity for us to revise our policies for research and access and consider how this collection may benefit communities today. For more than a century, the Hamann-Todd individuals have helped advance countless research studies, resulting in everything from better-fitting army helmets and orthopedic implants to improved forensic and anthropological methods for identifying unknown individuals and learning about the past. Recently, the Hamann-Todd Collection was in the news for helping us better understand mortality patterns during the 1918 flu epidemic, with important implications for public health today. However, such research tends to investigate broader patterns and variation, rarely focusing on individuals and their unique stories. And aside from researchers, many people may not even know this collection exists. Two years ago, we initiated the Hamann-Todd Biography Project to try to learn more about the individuals in the collection. Our team has since grown to three Museum anthropologists, four undergraduate students, and a roster of enthusiastic volunteers. Our approach has two components. First, we carefully digitize the century-old paper records associated with each individual, which are stored in numbered folders. Many only contain handwritten notes from Todd, but these files provide a crucial link to the people in the collection and the circumstances of their lives and deaths. Second, we use these records to search genealogy databases like FamilySearch.com and Ancestry.com to find additional information, such as death records and family relationships. Our goal is to build a more complete picture of who these people were for the purposes of research, sharing their stories, and perhaps even identifying descendants. Kimber Watkins, a fourth-year anthropology major at Cleveland State University (CSU), became involved in the Biography Project after taking a forensic anthropology class that involved working with CSU’s teaching collection of human remains. “It really bothered me that when I asked my professor who the bones belong to, she was unable to give me an answer,” Watkins says. Curious about other historical skeletal collections, Watkins contacted the Museum and learned about the Hamann-Todd individuals. She ultimately became the project’s first work-study student, developing the genealogical research protocols now being used by the entire team. “The project is important to me because I feel it’s taking a very large step in the right direction. I hope this work will help rebuild trust in what we as anthropologists do, bring closure and peace to the families of the individuals in the collection, and encourage other institutions to do the same so we can all benefit from a future we can be proud of.” Kate Gorodovich, another returning student and a third-year psychology and medical anthropology major at CWRU, got involved in the project last year for similar reasons. “This work is meaningful and emotional for me, but also for the general community and the families these people belong to,” Gorodovich says. “With every person I work with, I feel connected to them and thankful for the opportunity to give back in any way I can. It is with deep gratitude that I can be a part of restoring personhood and identity to the people in the collection.” Jana Ashour, a freshman at CWRU with a background in art and design, is a newcomer to the project and this kind of work. “I chose to join this project because it resonated with my passions for human health and social justice and ethics,” Ashour says. “Though gathering data on a collection of human remains wasn't something I ever anticipated, this project has been a rich learning experience for me, not just regarding the technical aspects of data collection but also in broadening my understanding of individuals, individuals’ diverse narratives, and the ethical complexities of research.” Nick Burkart, a CWRU sophomore majoring in physics and engineering, rounds out the student research team. The results of this project, which will run for the next several years, are already improving how we curate and care for the collection while helping to establish ethical best practices for the future. In the coming years, we plan to share stories from Hamann-Todd individuals that honor the contributions they have made to science and foster greater awareness of the collection in Cleveland and beyond. Our goal is to build connections between these individuals and present-day people and communities who can learn from and appreciate them. As part of this process, we anticipate some may even discover a long-lost relative in our museum. In 2022, nearly 100 years after George Maus passed away, one of his family members contacted the Museum upon finding his death certificate on FamilySearch.com. After confirming that “HTH 1292” (Todd gave everyone a number) was in fact George, the family member shared photos of him in life and gave us their blessing to continue to learn from him and share his story. We hope to establish more of these connections in the future, and to engage in meaningful consultations with descendants and engaged communities on what is now best for their relatives. While the families of the Hamann-Todd individuals weren’t able to claim them 100 years ago, today’s interconnected world provides another chance to mend broken connections from the past. Interested in learning more? Join us for a free public lecture at the Museum on Thursday, February 8, 2024, at 6:30pm. Dr. Carlina de la Cova, Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of South Carolina, will speak on “Restoring Cleveland’s Silenced Voices.” |

1925年10月21日、71歳のジョージ・マウスはチームスター(馬

のチームを運転する人)として働きながらクリーブランドに住んでいたが、持病のために突然この世を去った。残念なことに、彼の遺体を引き取るために当時の

法律で定められていた36時間以内に彼の家族と連絡が取れなかった。その結果、マウスはウェスタン・リザーブ大学(現在のケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ大

学(CWRU))に送られ、解剖と医学生による研究を受けることになった。こうして彼は、現在クリーブランド自然史博物館が所蔵する3,000体以上のハ

マン・トッド骨学コレクションの1体となった。 このコレクションは、ウェスタン・リザーブ大学の医学部で教えるために1893年にペンシルベニアからクリーブランドに移り住んだ外科医カール・ハマンに よって始められた。しかし、1912年にハーマンの後を継いだトーマス・ウィンゲート・トッド(Thomas Wingate Todd) が、コレクションを大幅に拡大した。人間の違いや骨格の変異に魅了されたトッドは、現在生物人類学(または物理人類学)として知られる、ヒトやヒト以外の 霊長類の生物学と進化を研究する分野の発展に多大な貢献をした。1920年代には、多くの大学や博物館が骨格コレクションを設立していたが、ハマン=トッ ド・コレクションは、関連情報の膨大さにおいて群を抜いている。トッドは、死亡時の年齢、死因、体の大きさ、寸法、そして多くの場合、その人の名前など、 できる限りの情報を丹念に記録した。1938年にトッドが急逝した後、CWRUはすべての個体を保管し、最終的にはクリーブランド自然史博物館と合意し て、同博物館で保管・管理されることになった。 それから何十年も経ち、私たちは博物館の改築プロジェクトの一環として、これらの個体を特注の新しいスペースに再び移す準備をしています。この記念碑的な 移転の舞台裏で慌ただしく準備を進めている間、すべてのコレクションは現在研究者に非公開となっている。この一時休止は、研究およびアクセスに関する方針 を見直し、このコレクションが今日の地域社会にどのように役立つかを検討する絶好の機会となります。一世紀以上にわたって、ハーマン・トッドの個人は数え 切れないほどの研究の発展に貢献し、よりフィットした軍用ヘルメットや整形外科用インプラントから、未知の個人を特定し過去を知るための法医学的・人類学 的手法の改善まで、あらゆるものを生み出してきた。最近では、ハーマン・トッド・コレクションが1918年のインフルエンザ流行時の死亡パターンをより深 く理解するのに役立ち、今日の公衆衛生に重要な示唆を与えたことが話題になった。しかし、このような研究は、より広範なパターンや変動を調査する傾向があ り、個人やその人独自のストーリーに焦点を当てることはほとんどない。研究者は別として、多くの人はこのコレクションの存在すら知らないかもしれない。 私たちは2年前、このコレクションに収められている個人のことをもっと知ろうと、ハーマン・トッド・バイオグラフィー・プロジェクトを立ち上げた。それ以 来、私たちのチームは3人の博物館人類学者、4人の学部生、そして熱心なボランティアに成長しました。私たちのアプローチには2つの要素があります。ま ず、各個人に関連する100年以上前の紙の記録を慎重にデジタル化する。その多くはトッドの手書きのメモしか残っていないが、これらのファイルは、コレク ションに収められている人々や彼らの生と死の状況との重要なつながりを提供してくれる。次に、これらの記録を使ってFamilySearch.comや Ancestry.comなどの系図データベースを検索し、死亡記録や家族関係などの追加情報を見つけます。私たちの目標は、研究、彼らのストーリーの共 有、そしておそらくは子孫の特定を目的として、これらの人々が誰であったかをより完全に把握することです」。 クリーブランド州立大学(CSU)で人類学を専攻する4年生のキンバー・ワトキンスは、CSUの教育用人骨コレクションを扱う法医人類学の授業を受けた 後、バイオグラフィ・プロジェクトに参加するようになった。 「この骨が誰のものか教授に尋ねても、答えてもらえなかったことがとても気になりました」とワトキンスは言う。 他の歴史的な骨格コレクションに興味を持ったワトキンスは、博物館に問い合わせ、ハマン=トッドの個人について知った。彼女は最終的に、このプロジェクト の最初のワーホリ生となり、現在チーム全体で使用されている系図調査プロトコルを開発した。 「このプロジェクトが私にとって重要なのは、正しい方向に非常に大きな一歩を踏み出していると感じるからです。このプロジェクトが、人類学者としての私た ちの活動に対する信頼を回復し、コレクションに含まれる個人の家族に終結と平穏をもたらし、他の研究機関にも同様の活動を奨励することで、私たち全員が誇 りを持てる未来から恩恵を受けられるようになることを願っています」。 同じく帰国子女で、CWRUで心理学と医療人類学を専攻する3年生のケイト・ゴロドヴィッチも、同様の理由で昨年このプロジェクトに参加した。 「この仕事は、私にとって意義深く、感情的なものですが、一般のコミュニティや彼らの家族にとっても意義深いものです」とゴロドビッチは言う。「一緒に働 くすべての人たちとのつながりを感じ、少しでも恩返しができることに感謝しています。コレクションにある人々の人格とアイデンティティを回復する一端を担 えることに、深い感謝の念を抱いています」。 アートとデザインのバックグラウンドを持つCWRUの1年生、ヤナ・アシュールは、このプロジェクトとこの種の仕事を始めたばかりだ。 「このプロジェクトに参加することにしたのは、人間の健康、社会正義、倫理に対する私の情熱に共鳴したからです」とアシュールは言う。「このプロジェクト は、データ収集の技術的な側面だけでなく、個人、個人の多様な語り、研究の倫理的な複雑さについての理解を深めるという意味でも、私にとって豊かな学びの 経験となりました」。 物理学と工学を専攻するCWRUの2年生、ニック・バーカートが学生研究チームの最後を飾る。 今後数年間実施されるこのプロジェクトの成果は、すでにコレクションの管理・保管方法を改善し、将来の倫理的ベストプラクティスの確立に役立っています。 今後数年間は、ハーマン・トッド個人が科学に貢献したことを称えるストーリーを共有し、クリーブランド内外でコレクションに対する認識を深める予定です。 私たちの目標は、これらの個人と、彼らから学び感謝できる現代の人々や地域社会とのつながりを築くことです。このプロセスの一環として、当館で長い間行方 不明になっていた親戚を発見する方もいらっしゃるかもしれません。 ジョージ・マウスの死後100年近く経った2022年、家族の一人がFamilySearch.comで彼の死亡診断書を見つけ、博物館に連絡してきた。 HTH1292」(トッドは全員に番号を与えた)が実際にジョージであることを確認した後、その家族は生前の彼の写真を共有し、彼から学び、彼の物語を共 有し続けることを祝福してくれた。私たちは今後、このようなつながりをさらに築き、子孫や関与するコミュニティと、彼らの親族にとって今何が最善なのかに ついて有意義な協議を行いたいと考えている。100年前、ハーマン・トッドの遺族はその権利を主張することができなかったが、今日の相互接続された世界 は、過去の壊れたつながりを修復する新たな機会を提供している。 もっと詳しく知りたいですか?2024年2月8日(木)午後6時30分より当館で開催される無料公開講座にご参加ください。サウスカロライナ大学人類学部 教授のカーリナ・デ・ラ・コバ博士が、"Restoring Cleveland's Silenced Voices"(クリーブランドの沈黙した声の回復)と題して講演します。 |

| https://www.cmnh.org/hamann-todd-biography-project |

|

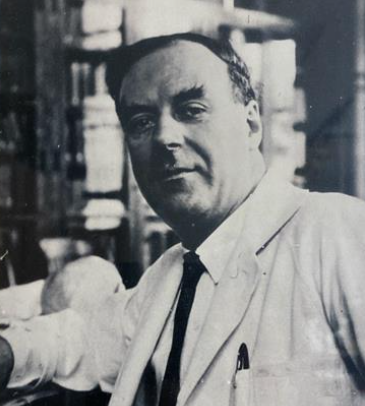

Thomas Wingate

Todd

(January 15, 1885 – December 28, 1938) was an English orthodontist who

is known for his contributions towards the growth studies of children

during early 1900s. Due to his efforts, Charles Bingham Bolton Fund was

established. He served as editor in chief of several journals over his

lifetime.[1][2] Thomas Wingate

Todd

(January 15, 1885 – December 28, 1938) was an English orthodontist who

is known for his contributions towards the growth studies of children

during early 1900s. Due to his efforts, Charles Bingham Bolton Fund was

established. He served as editor in chief of several journals over his

lifetime.[1][2]Life He was born in Sheffield to James Todd and Katherine Todd. His father was a Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal minister. He attended Nottingham High School and then went to University of Manchester and received his Medical Degree in 1907. After graduation he continued teaching Anatomy through 1912. He served as House Surgeon at Manchester Royal Infirmary in 1909–1910. During this time, Dr. Todd published several papers on inter-relationship of skeleton and nerves. Due to his efforts a new curriculum for Diploma in Dentistry and a degree of Dental Science was created at the University of Manchester. He also worked with Dr. A.H. Young, G. Elliot Smith and Sir Arthur Keith in organizing collections of bones coming from Egypt to England by the Nubian Archaeological Survey. Dr. Todd eventually moved to Western Reserve University and became the Professor of Anatomy and Physical Anthropology at the Western Reserve University School of Medicine.[3] He taught anatomy to both dental and medical students at that time. During this time he published his first book, called Mammalian Dentition. His teaching was interrupted by his military service in World War I as a captain in Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps . Career In 1920, became the Director of Hamann Museum of Comparative Anthropology and Anatomy at Cleveland Museum of Natural History . Under his direction, the museum became the largest document museum on human and mammalian growth in the world. In 1928, he started his research under the Brush Foundation where he studied 4500 healthy children. In 1929, due to his efforts Charles Bingham Bolton Fund was started. On 20 April 1923, Todd presented a lecture to the Harvey Club of London entitled "Forecasting the Future of the White Race" in which he agreed with Julian Huxley that education and environment were less important than heredity in the development of any people.[4] However, by the 1930s, he opposed the prevailing theories of racial determinism espoused by physical anthropologists when training William Montague Cobb, the first African-American physical anthropology PhD, who studied Jesse Owens to show that training, rather specific "racial traits," accounted for athletic success.[5] He was honorary member of Cleveland Dental Society, American Academy of Pediatrics, Southern Society of Orthodontists, Cleveland Neurological Society and Cleveland Allergy Society . Over his lifetime, Dr. Todd held appointments and was affiliated with sixty scientific societies of which some of them are mentioned below. Dr. Todd married Eleanor Pearson had three children, Arthur, Donald and Eleanor. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wingate_Todd |

トー

マス・ウィンゲート・トッド(Thomas Wingate Todd、1885年1月15日 -

1938年12月28日)は、イギリスの歯科矯正医で、1900年代初頭に子供の成長研究に貢献したことで知られている。彼の努力により、チャールズ・ビ

ンガム・ボルトン基金が設立された。彼は生涯を通じていくつかの雑誌の編集長を務めた[1][2]。 トー

マス・ウィンゲート・トッド(Thomas Wingate Todd、1885年1月15日 -

1938年12月28日)は、イギリスの歯科矯正医で、1900年代初頭に子供の成長研究に貢献したことで知られている。彼の努力により、チャールズ・ビ

ンガム・ボルトン基金が設立された。彼は生涯を通じていくつかの雑誌の編集長を務めた[1][2]。生涯 シェフィールドでジェームズ・トッドとキャサリン・トッドの間に生まれる。父親はウェスレアン・メソジスト・エピスコパルの牧師だった。ノッティンガム高 校を経てマンチェスター大学に進学し、1907年に医学博士号を取得。卒業後、1912年まで解剖学を教える。1909年から1910年にかけては、マン チェスター王立診療所のハウス・サージョンを務めた。この間、トッド博士は骨格と神経の相互関係に関する論文をいくつか発表した。彼の努力により、マン チェスター大学では、歯科学ディプロマと歯科科学の学位を取得するための新しいカリキュラムが作成された。また、A.H.ヤング博士、G.エリオット・ス ミス博士、アーサー・キース卿とともに、ヌビア考古学調査団がエジプトからイギリスに寄贈した骨のコレクションの整理にも携わった。 トッド博士はやがてウェスタン・リザーブ大学に移り、ウェスタン・リザーブ大学医学部の解剖学および身体人類学の教授となった[3]。この間、彼は哺乳類 の歯列という最初の本を出版した。彼の教育は、王立カナダ陸軍医療部隊の大尉として第一次世界大戦に従軍したことにより中断された。 経歴 1920年、クリーブランド自然史博物館のハマン比較人類学・解剖学博物館の館長に就任。彼の指揮の下、同博物館は人間と哺乳類の成長に関する世界最大の 資料館となった。1928年、彼はブラシ財団のもとで研究を開始し、4500人の健康な子供たちを調査した。1929年、彼の努力によりチャールズ・ビン ガム・ボルトン基金が設立された。 1923年4月20日、トッドはロンドンのハーヴェイ・クラブで「白人種の未来予測」と題する講演を行い、その中で彼はジュリアン・ハクスリーと同意見 で、教育と環境はどのような民族の成長においても遺伝よりも重要ではないという見解を示した。 [しかし、1930年代には、ジェシー・オーエンズを研究した最初のアフリカ系アメリカ人の身体人類学博士であるウィリアム・モンタギュー・コブを訓練 し、トレーニングが、むしろ特定の「人種的特徴」が運動競技の成功を説明することを示したことで、身体人類学者によって支持された一般的な人種決定論の理 論に反対した[5]。 彼は、クリーブランド歯科学会、アメリカ小児科学会、南部矯正歯科学会、クリーブランド神経学会、クリーブランドアレルギー学会の名誉会員であった。トッ ド博士は生涯に渡り、60もの学会に所属し、そのうちのいくつかを以下に紹介する。 トッド博士はエレノア・ピアソンと結婚し、アーサー、ドナルド、エレノアの3人の子供をもうけた。 |

■クレジット:池田光穂「先住民遺骨副葬品返還の研

究倫理」ですが、このページは、旧版である「アイヌ遺骨等返還の研

究倫

理」(人文社会系のための研究倫理入門(リテラシー

G)

2018、第7回授業)を改造したものです。

用語集

リンク(研究倫理と先住民主権)

リンク(先住民学)

リンク(文化遺産)

リンク(アイヌ研究・アイヌ遺骨返還のテーマ)

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099