異民族を生きたまま展示することの倫理問題

Ethical problem of the Human

Exposition

dedicated

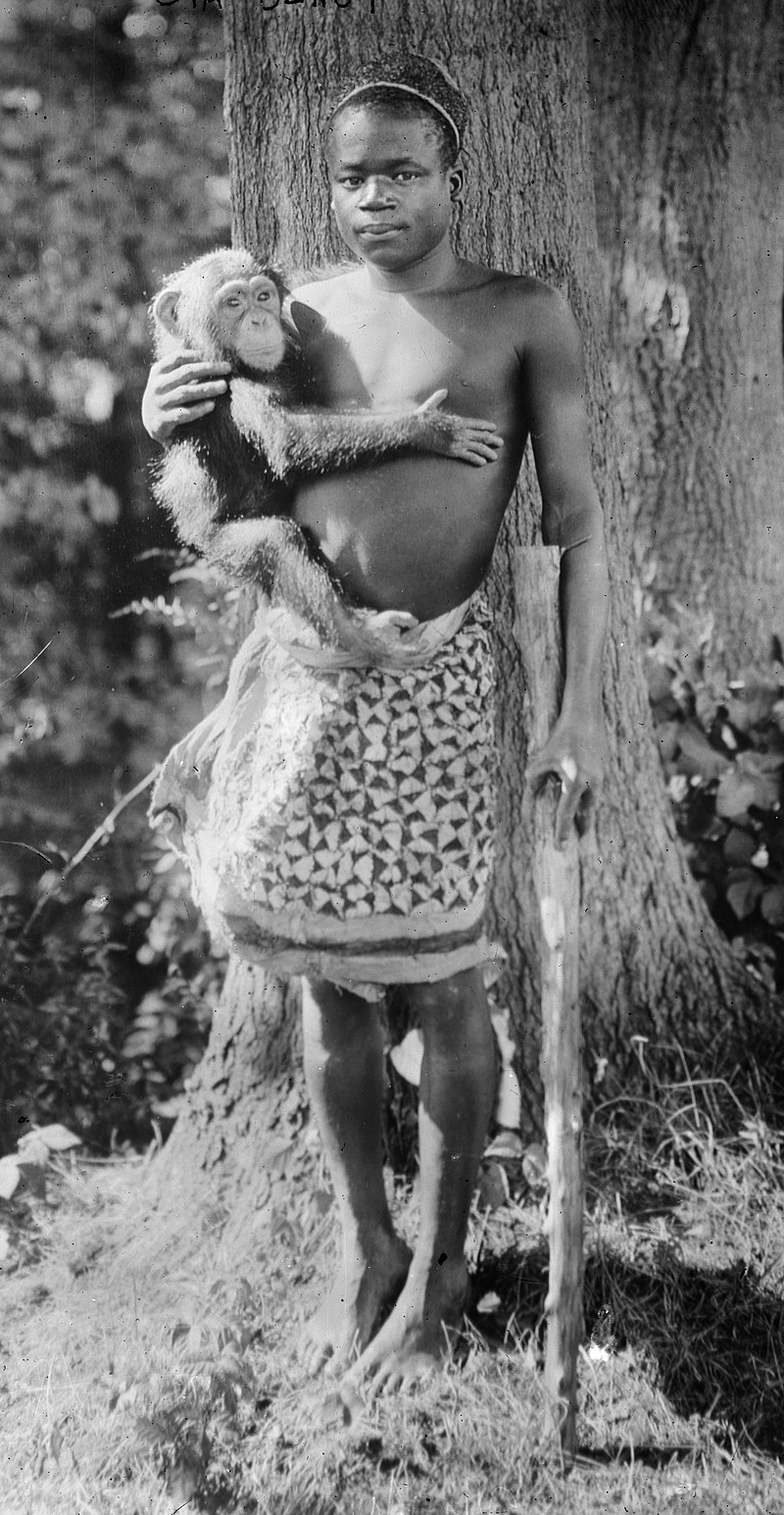

for the memory of Mr. Ota

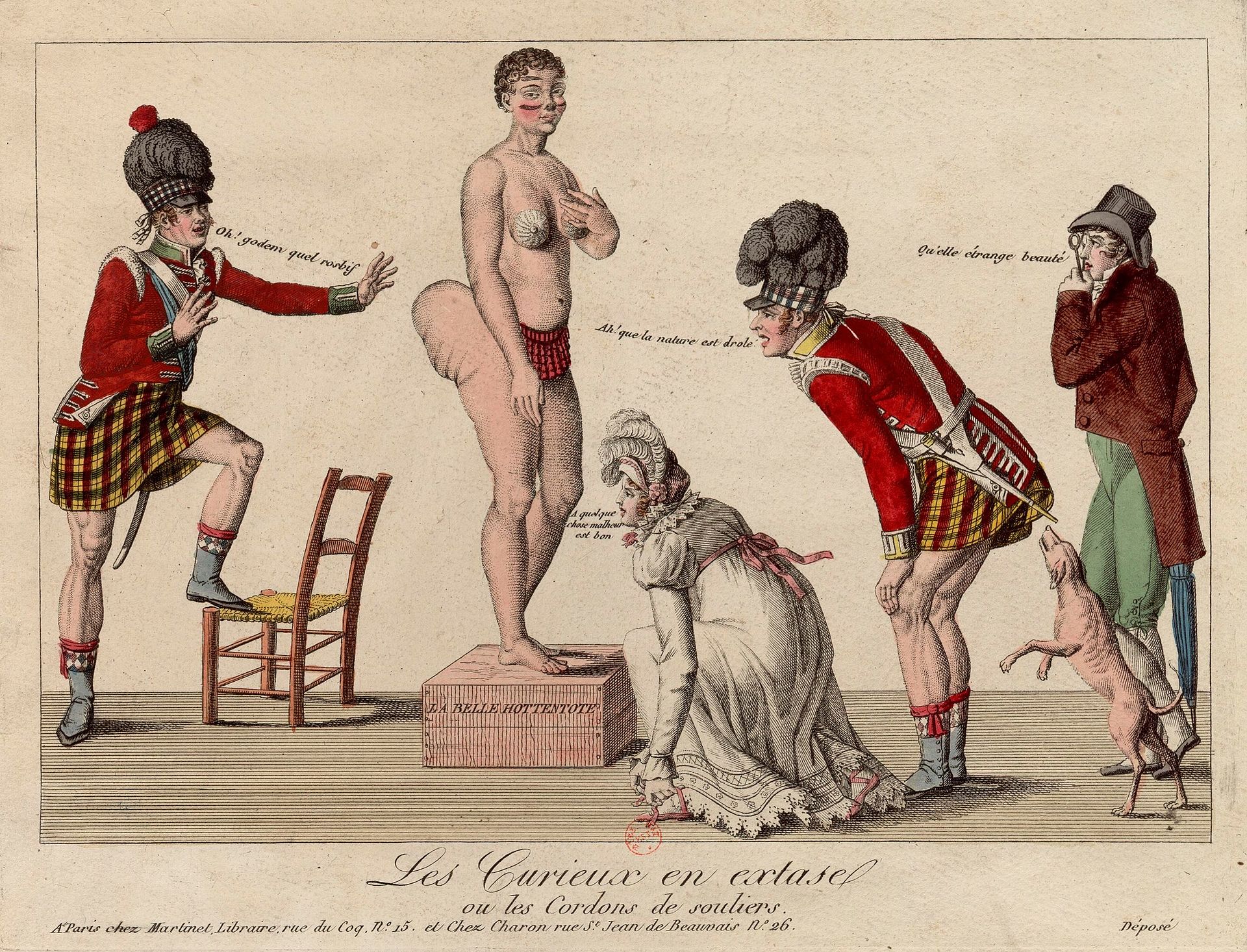

Benga, 1883-1916/ Les Curieux en extase ou les Cordons de souliers/

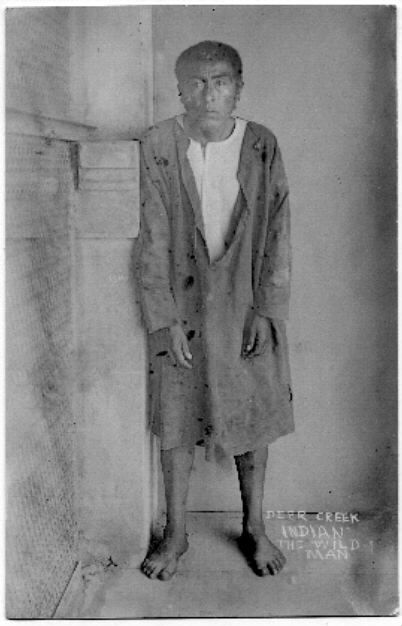

Ishi, ca. 1861-1916.

「1903年に大阪・天王寺で開かれた第5回内国勧 業博覧会の「学術人類館」において、アイヌ・台湾高砂族(生蕃)・沖 縄県(琉 球人)・朝鮮(大韓帝国)・清国・インド・ジャワ・バルガリー(ベンガル)・トルコ・アフリカなど合計32名の人々が、民族衣装姿で一定の区域内に住みな がら日常生活を見せる展示を行った」。このことにより、沖縄県と清国が自分たちの展示に抗議し、問題となった事件を「人類館事件」と呼ぶ。ここでは、ウィキペディアの記事に再掲しながら、この事件の 倫理的問題について考える。

●1903年の「学術人類館」事件に関してはこちらにどうぞ→「学術人類館への長い旅」

●前史ならびにその後の展示(アイヌを中心に)

| 博覧会 | 会期 |

開催地 |

主催 |

入場人数 |

アイヌに関する事項 |

| 湯島聖堂博覧会 |

1872(明治5)年3月10日〜4月

30日 |

湯島聖堂、東京 |

文部省博物局 |

ヒグマ飼育係として石狩アイヌが参加 |

|

| ウィーン万国博覧会 |

1873(明治6)年5月1日〜11月2

日 |

オーストリア |

北海道物産としてアイヌ民族の展示 |

||

| 第

五回内国勧業博覧会 |

1903

(明治36)年3月1日〜7月30日 |

天

王寺、大阪 |

政

府 |

435 万人 | 場

外展示、学術人類館:伏古、胆振7〜12名 |

| セントルイス万国博覧会 |

1904(明治37)年4月30日〜12

月1日 |

アメリカ |

1,969万人 |

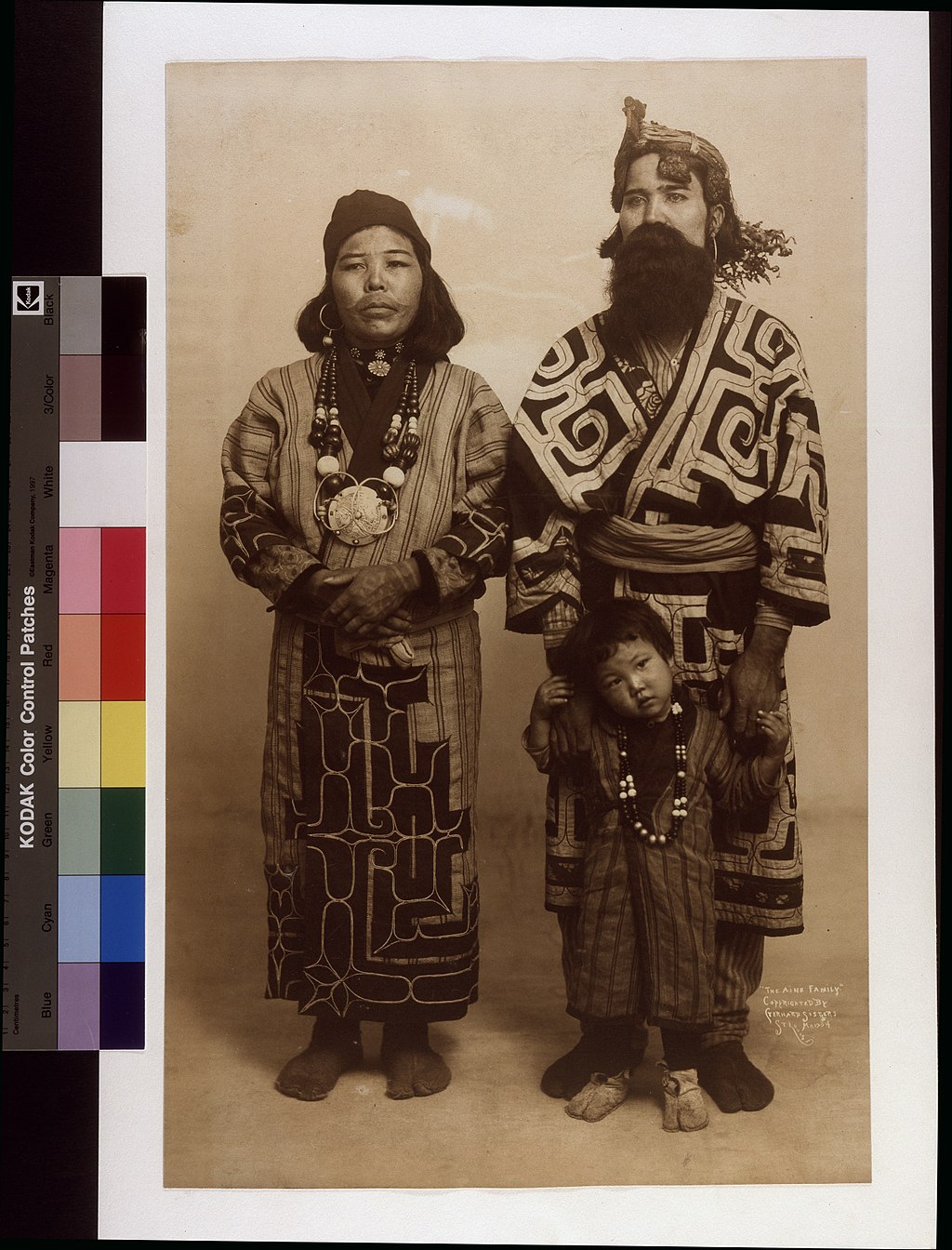

人類学展示場、日高ほか9名。同時参加の

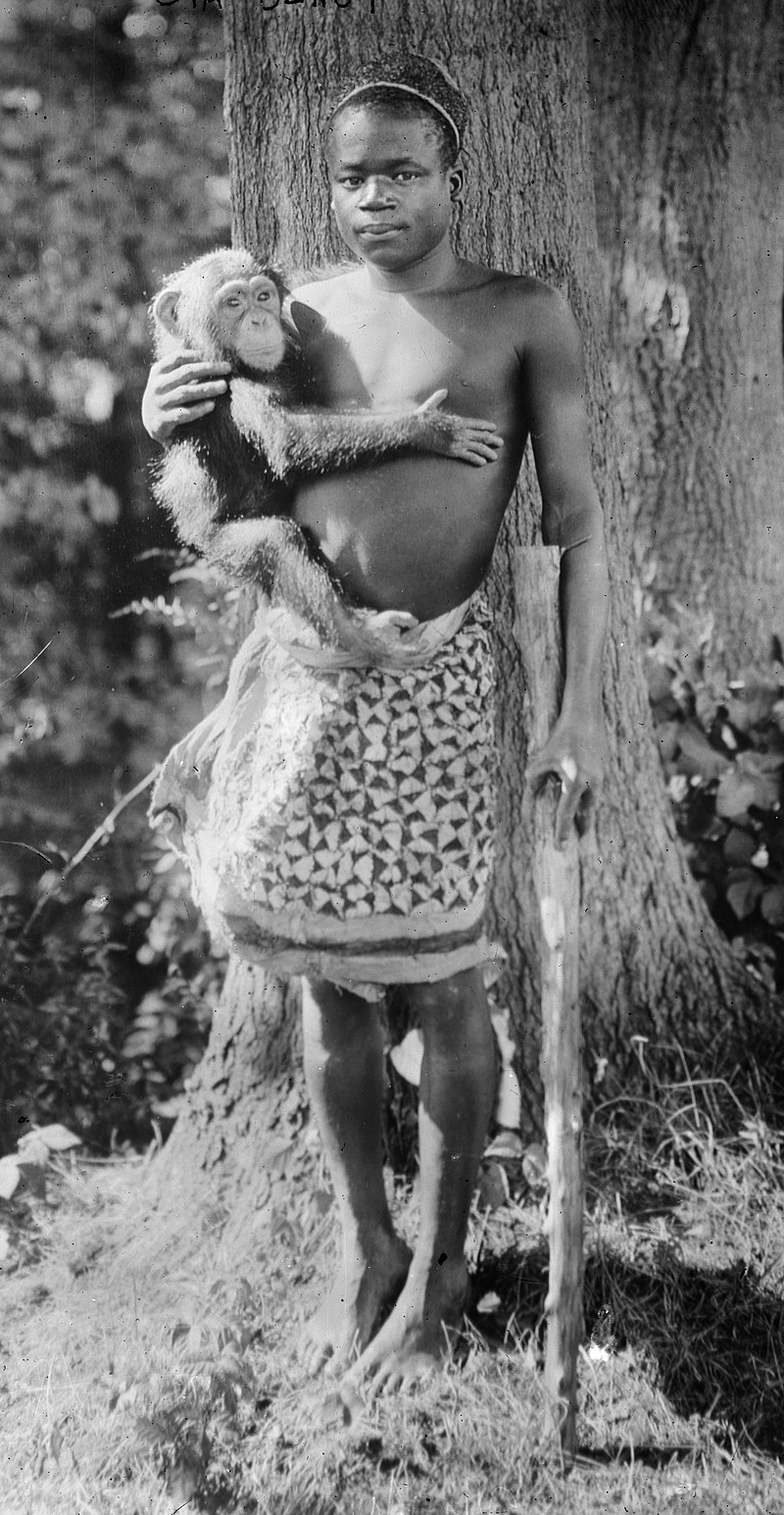

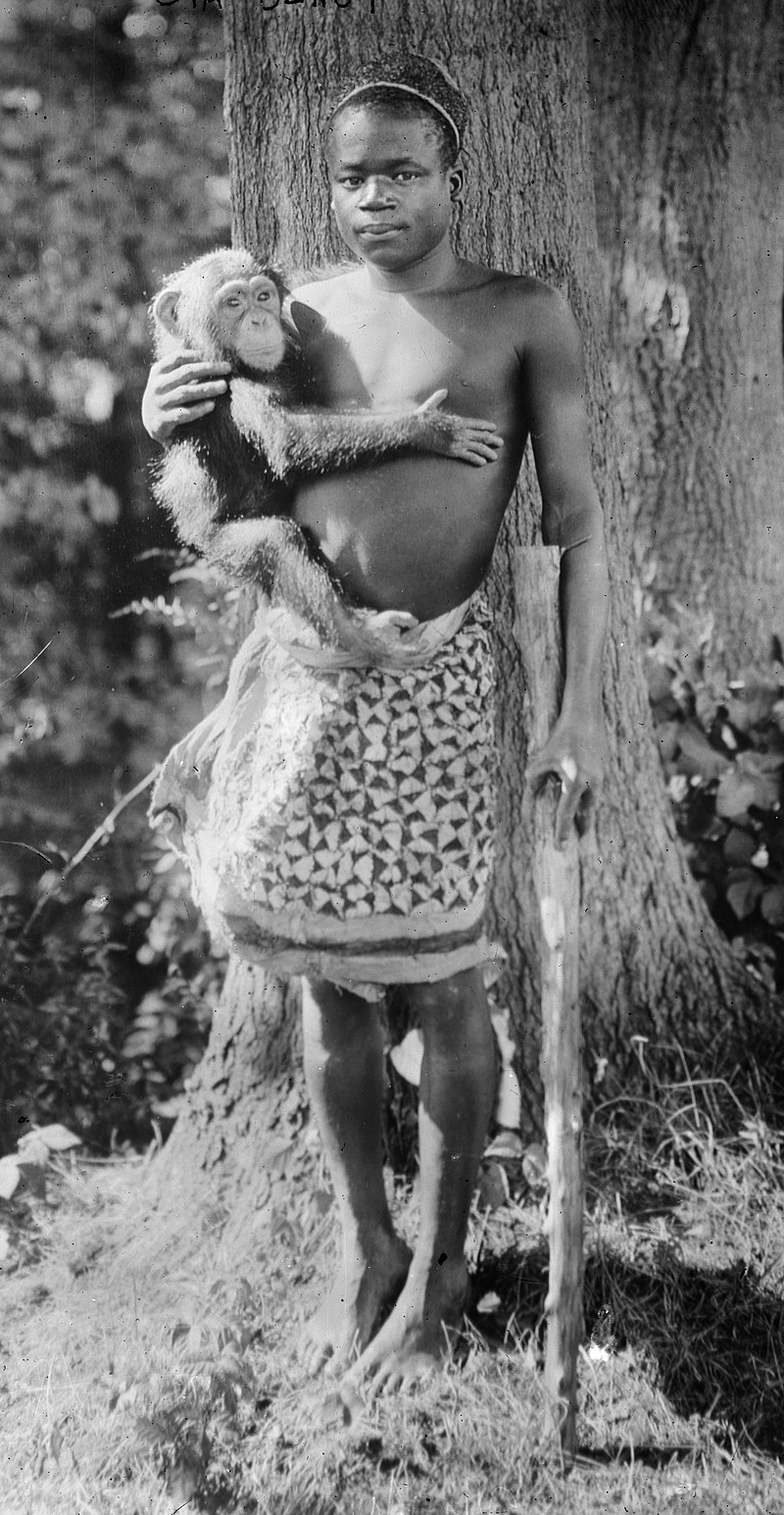

オリンピックにも参加 平取村からセントルイス万国博覧会に派遣された平村夫妻と娘。1904年(Wiki「平取町」 より) Ota Benga (1883-1916), a human exhibit, in 1906. Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches (150 cm). Weight, 103 pounds (47 kg). Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Central Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Exhibited each afternoon during September. - according to a sign outside the primate house at the Bronx Zoo, September 1906.[23] - Human zoo ・「オタ・ベンガ(1883 年ごろ[1] - 1916年3月20日)はコンゴのムブティ・ピグミーであり、ミズーリ州セントルイスで開かれた万国博覧会(1904年)の人類学展で展示品となったアフ リカ人の一人として」 |

|

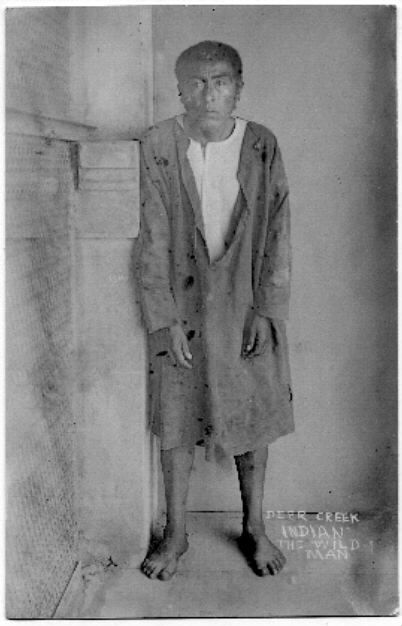

| イシ、(ヤヒ先住民) |

1908 |

・イシ(ishi, c1861-1916)が 発見された年 | |||

| スコットランド・ナショナル・エキシビ

ション |

1908 |

・

「1908年5月1日から10月31日にかけて、ヴィクトリア女王の孫の一人であるコノート公アーサー王子が開幕させたスコットランド全国博覧会が、エ

ディンバラのソーントン・パークで開催された。見どころのひとつはセネガル村で、フランス語を話すセネガル人たちが蜂の巣小屋に住みながら、彼らの生活様

式、芸術、工芸を実演していた。」 ・Between 1 May and 31 October 1908 the Scottish National Exhibition, opened by one of Queen Victoria's grandsons, Prince Arthur of Connaught, was held in Saughton Park, Edinburgh. One of the attractions was the Senegal Village with its French-speaking Senegalese residents, on show demonstrating their way of life, art and craft while living in beehive huts.[25][26]- Human zoo |

|||

| エジンバラのスコットランド国立展覧会

|

1909 |

・

「1909年、エジンバラで開催された1908年のスコットランド万国博覧会のインフラを利用して、エジンバラ近郊のポートベローの海岸に新しいマリン・

ガーデンズが建設された。ソマリア人の男性、女性、子供たちが、この博覧会に参加するために輸送され、藁葺き小屋で生活した。」 ・In 1909, the infrastructure of the 1908 Scottish National Exhibition in Edinburgh was used to construct the new Marine Gardens to the coast near Edinburgh at Portobello. A group of Somalian men, women and children were shipped over to be part of the exhibition, living in thatched huts.[27][28]- Human zoo |

|||

| 明治記念拓殖博覧会 | 1913 |

Grand Colonial

Exhibition (Meiji Memorial Takushoku Expo) at Tennoji Park, Osaka in

1913 (明治記念拓殖博覧会(台湾土人ノ住宅及其風俗)) |

|||

| イギリス、マンチェスターのベルビュー動

物園 |

1925 |

・「1925年、イギリスのマンチェス

ターにあるベルヴュー動物園の展示は「食人族」と題され、野蛮人として描かれたアフリカ黒人を特集していた。」 ・In 1925, a display at Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester, England, was entitled "Cannibals" and featured black Africans depicted as savages.[29]- Human zoo |

|||

| ドイツでの展示 |

1931-1930 |

・

「1931年頃にドイツで民族博覧会が廃止されると、出演者たちにもさまざまな影響があった。博覧会で働くために祖国から連れてこられた人々の多くは、ド

イツで家庭を築き、ドイツで生まれた子供もたくさんいた。動物園やパフォーマンスで働かなくなると、これらの人々は何の権利もないドイツで暮らすことにな

り、厳しい差別を受けることになった。ナチスが台頭してきた時代、このような舞台で活躍する外国人俳優は、ナチスが彼らを真の脅威と見なさないほど数が少

なかったため、通常、強制収容所から逃れることができた。強制収容所を免れたとはいえ、ドイツ民族の市民ができるようなドイツ生活への参加はできなかっ

た。ヒトラーユーゲントでは、外国人の親を持つ子供の参加を認めず、大人はドイツ兵として拒否された。その多くは、戦争産業の工場や外国人労働者収容所で

働くことになった。第二次世界大戦が終わると、ドイツにおける人種差別は隠蔽され、見えなくなっていったが、なくなったわけではない。外国系の人々の多く

は戦後にドイツを離れるつもりであったが、ドイツ国籍であったため、移住することは困難であった。」 ・As Ethnogenic expositions were discontinued in Germany around 1931,[31] there were many repercussions for the performers. Many of the people brought from their homelands to work in the exhibits had created families in Germany, and there were many children that had been born in Germany. Once they no longer worked in the zoos or for performance acts, these people were stuck living in Germany where they had no rights and were harshly discriminated against. During the rise of the Nazi party, the foreign actors in these stage shows were typically able to stay out of concentration camps because there were so few of them that the Nazis did not see them as a real threat.[32] Although they were able to avoid concentration camps, they were not able to participate in German life as citizens of ethnically German origin could. The Hitler Youth did not allow children of foreign parents to participate, and adults were rejected as German soldiers.[32] Many ended up working in war industry factories or foreign laborer camps.[32] After World War II ended, racism in Germany became more concealed or invisible, but it did not go away. Many people of foreign descent intended to leave after the war, but because of their German nationality, it was difficult for them to emigrate.- Human zoo |

|||

| カリフォルニア州サンディエゴで開催され

た太平洋国際博覧会のゾロ・ガーデン・ヌーディスト・コロニー |

1935-36 |

・

「1930年代になると、アメリカでは教育を装ったヌードショーという新しいタイプの人間動物園が登場した。カリフォルニア州サンディエゴの太平洋国際博

覧会におけるゾロ・ガーデン・ヌーディスト・コロニー(1935-6年)や、サンフランシスコのゴールデンゲート国際博覧会におけるサリー・ランド・ヌー

ド・ランチ(1939年)などがそれだ。前者は本物のヌーディスト・コロニーと思われたが、実際のヌーディストの代わりに雇われたパフォーマーを使ってい

た。後者では、西部劇の衣装を着たヌード女性が出演した。ゴールデンゲート博覧会では「グリニッジ・ヴィレッジ」のショーも行われ、公式ガイドブックには

"モデル・アーティスト・コロニーとレヴュー・シアター "と記されていた。」 ・By the 1930s, a new kind of human zoo appeared in America, nude shows masquerading as education. These included the Zoro Garden Nudist Colony at the Pacific International Exposition in San Diego, California (1935-6) and the Sally Rand Nude Ranch at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco (1939). The former was supposedly a real nudist colony, which used hired performers instead of actual nudists. The latter featured nude women performing in western attire. The Golden Gate fair also featured a "Greenwich Village" show, described in the Official Guide Book as “Model artists’ colony and revue theatre.”[30]- Human zoo |

「1903年(明治36年)、第5回の大阪今宮での

博覧会は、日本が「工業所有権の保護に関するパリ条約(Convention

de Paris pour la protection de la propriété industrielle)」に加盟したことから海

外からの出品が可能となり、14か国18地域が参加し、出品点数31,064点[7]と予想以上の出品が集まった。この数字は、1900年(明治33年)パリ万博の37か国、1902年(明治35年)グラス

ゴー万国博覧会の14か国と比べてもあまり遜色なく、事実上小さな万国博覧会とみなしても差し支えないだろう[8][9][10]。

当初、1899年に開催予定だったが、1900年のパリ万博、1901年のグラスゴー万博への参加準備のため延期された[10]。

3月1日から7月31日まで。観覧人530万余。会場のイルミネーションと冷蔵庫などの新製品が評判となった。雅邦「瀟湘八景」、広業「滝口入道」、岡田

「読書」、和田「こだま」、米原雲海「幼児と林檎」、赤塚自得「荒磯図額」、濤川惣助「雲月額」など。

博覧会跡地は日露戦争中に陸軍が使用したのち、1909年(明治42年)に東側の約

5万坪が大阪市によって天王寺公園となった。西側の約2万8千坪は大阪財界出資の大阪土地建物会社に払い下げられ、1912年(明治45年)7月3日、

「大阪の新名所」というふれこみで「新世界」が誕生。通天閣とルナパークが開業した。」

"Staged in Tennōji-ku,

Osaka, from 1 March to 31 July 1903, the fifth and final National

Industrial Exhibition ran for 153 days and drew 4,350,693 visitors, an

average of 28,436 visitors per day.[7] For the first time, overseas

exhibitors were permitted (eight foreign cars featured).[7] There was

some controversy over the Human Pavilion (人類館事件).[8]

Due to financial constraints after the Russo-Japanese War, a planned

sixth National Industrial Exhibition was cancelled, and the next

nation-wide initiative of this order was the 1970 Osaka Expo, Japan's

first world's fair.[7]"

「19世紀半ばから20世紀初頭における博覧会は 「帝国主義の巨大なディスプレイ装置」であったといわれる。博覧会は元々その開催国の国力を誇示するという性格を有していたが、帝国主義列強の植民地支配 が拡大すると、その支配領域の広大さを内外に示すために様々な物品が集められ展示されるようになる。生きた植民地住民の展示もその延長上にあった。 人間そのものの展示が博覧会に登場したのは、1889年のパリ万国博覧会である。欧米での万博では日本人を展示品とした日本人村もあった。パリ万博では展 示役を務めた芸者に一目惚れした青年がプロポーズを申し出たり、着物を譲って欲しいと願い出た女性の存在の記録もあり、日本においては人種差別意識より純 粋な民族文化の展示と受け取られた。」

●沖縄県の反発

「沖縄県からつれてきた遊女を「琉球婦人」として展

示し、説明者が動物の見世物さながらに「此奴は、此奴は」と鞭で指しながら、沖縄の生活様式などを説明した。これを見た県人の一人が、琉球新報に投書した

ことから、地元で抗議の声があがった[3]。たとえば当時の『琉球新報』(明治36年4月11日)では「我を生蕃アイヌ視したるものなり(私たちをアイヌ

なんかと一緒にするな)」という理由から、激しい抗議キャンペーンが展開された。特に、沖縄県出身の言論人太田朝敷が、「陳列されたる二人の本県婦人は正

しく辻遊廓の娼妓にして、当初本人又は家族への交渉は大阪に行ては別に六ヶ敷[4]事もさせず、勿論顔晒す様なことなく、只品物を売り又は客に茶を出す位

ひの事なり云々と、種々甘言を以て誘ひ出したるのみか、斯の婦人を指して琉球の貴婦人と云ふに至りては如何に善意を以て解釈するも、学術の美名を藉りて以

て、利を貪らんとするの所為と云ふの外なきなり。我輩は日本帝国に斯る冷酷なる貪欲の国民あるを恥つるなり。彼等が他府県に於ける異様な風俗を展陳せずし

て、特に台湾の生蕃、北海のアイヌ等と共に本県人を撰みたるは、是れ我を生蕃アイヌ視したるものなり。我に対するの侮辱、豈これより大なるものあらんや」

であると抗議し、沖縄県全体に非難の声が広がり、県出身者の展覧を止めさせた。

当時の世情として太田朝敷や沖縄県民は、大日本帝国の一員であり帝国臣民として積極的に「同化」しようとの意識が広まりつつあったため、他の民族と同列に

扱うことへの抗議であった。」

●清国の反発

「清国側からも同様に激しい抗議がいくつか寄せられ た。まず宣伝によって事前に、学術人類館に漢民族の展示が予定されていることを知った在日留学生や清国在神戸領事館員から抗議をうけて、日本政府はその展 示を取りやめた。博覧会開催前に清国の皇族や高官を招待していたため、すぐに外交問題となったためであった。その学術人類館に「展示」される予定だったの は、阿片吸引の男性と纏足の女性であった。清国人の展示が中止された後、今度は人類館に出演している台湾女性が実際には中国湖南省の人ではないか、という 疑いが清国留学生からかけられた。しかし、その留学生が自分で確かめたところ、台湾女性は本当に台湾出身であることが判明し、一件落着となった。」

| 「西欧近代社会が科学技術と産業の発展を誇示する目的で開催した万国博

覧会

が、植民地統治の成果を展示する機会でもあったということは、今日ではよく

知られている。明治時代以降の日本も、西欧を手本にして何度も博覧会を開催

し、各地の特産品を展示しながら産業の発達を満天下に宣伝することが行われ

てきた。日本が植民地を獲得する段階になると、博覧会では植民地を展示する

試みも行われるようになった。/ 1903(明治36)年、「第五回内国勧業博覧会」が大阪の天王寺で開催さ れたとき、北海道アイヌや沖縄県民とともに、台湾先住民が会場入り口近くの 「人類館」に集められ、好奇の眼差しを受けながら、「展示」されるという 出来事が起こった。このような見世物は、1912(大正元)年に東京の上野公 園で開催された「拓殖博覧会」、その翌年に大阪で開かれた「明治記念拓殖博 会」でも出現した。// 大正初期に行われた拓殖博覧会は、植民地の産業や風物、あるいは住民など を紹介するための展示会であり、北海道・樺太・台湾・朝鮮・満洲からの出展 が陳列室にかざられた。このときにも、植民地の住民が招かれ、会場内にそれ ぞれの家屋が建てられ、そこで寝泊りをして生活状況を大衆の視線にさらすこ とが行われた。東京で開かれた拓殖博覧会で招かれた人たちは、北海道・樺太 からウイルタ族・ニヴヒ族・樺太アイヌ族、それに北海道アイヌ族、台湾から は福佬(ふくろう)人とタイヤル族との男女老幼総数18人であった。この企画を積極的に 推進したのは坪井正五郎であって、坪井は多民族国家としての日本を強調し、 多様な民族の存在を一般大衆に啓蒙することが自己の責務である、と自認して いた。坪井は、こう語っている。 『此頃からして何かの折りに帝国版図内の諸人種を一ヶ所に集める事が出来 たら宜かろうと思って居ったのでありますが、今回聞かれた拓殖博覧会は 斯(か)かる催しに対し絶好の機会を与えたもので有ります。博覧会幹部の人か らして帝国版図内諸人種召集の相談が有った時、私は賛成の意を表したの みならず、話しの進むに従って喜んで此事に関する設計を引き受けた次第//です。(坪井正五郎「明治年代と日本版図内の人種」『人類学雑誌』29巻1号、 3 ページ)』 人類学を一般に啓蒙しようとしていた坪井にとって拓殖博覧会は絶好の機会 であった。書物のなかで説いてきたことが、今や現実のものとして目前で大衆 に説明することができる。人間の展示というおぞましさを自覚することなく、 講壇の高見から教養をたれる坪井には、この催しは満足のいく企画であった。 不幸にも、坪井はこの博覧会の直後にロシアで客死する。坪井の後継者として、 人類学教室の運営責任をとったのは松村瞭(あきら, 1880-1936)という自然人類学者であった。 松村瞭もまた博覧会での人間の展示に関心をもっていた。ただし彼は、坪井 よりも醒めた感性の持ち主であったようである。1914(大正3)年に、大正 天皇の即位を記念して大正博覧会が東京で開催されたとき、やはり生身の人間 の展示が企画されたが、松村はいたって冷静で見世物展示には関心を示さず、 このときに来日したマレー半島のセノイ族の身体計測に熱心に取り組み、その 資料を論文にして発表している。海外に赴いての調査活動が高嶺の花であった 時代、この自然人類学者は背に腹は変えられないと思ったのであろうか、見世 物小屋での調査であっても満足しなければならなかったのである(山路 2006:20-23)」 |

●小説のなかにある人間展示

・ディディエ・デナンクス『カ

ニバル』高橋啓訳、青土社、2003年。「1931

年パリ。植民地博覧会=人間動物園に送り込まれて見世物になったニューカレドニアの人々をさらなる苦難が待ち受ける…。フランス「帝国」が無垢な楽園の人

々に与えた癒されぬ傷を語り継ぐ、暗い輝きを放つ物語の傑作」

+++

●オタ・ベンガ(ca. 1883-1916)

| オタ・ベンガ(1883

年ごろ[1] -

1916年3月20日)はコンゴのムブティ・ピグミーであり、ミズーリ州セントルイスで開かれた万国博覧会(1904年)の人類学展で展示品となったアフ

リカ人の一人として知られる。ベンガは1906年にもブロンクス動物園に設置されて物議を醸した人間動物園の呼び物となった。ブロンクス動物園では構内の

サル園に「展示」される時間帯以外は自由に敷地を動き回ることができたが、このように非西欧人を人類の進化における「初期段階」の生きた標本として展示す

ることは、進化生物学の概念と人種理論がなめらかに結びつくこともしばしばであった20世紀はじめには奇習としては扱われなかったのである。 伝道師サミュエル・フィリップス・ヴェルナーによってコンゴの奴隷商人から買い出され自由の身になったベンガはヴェルナーに連れられてアメリカへ行き、ミ ズーリ州で展示品となった。全国のアフリカ系アメリカ人向けの新聞はベンガの扱いに強く抗議する論説を発表し、黒人教会代表団のスポークスマンである R.S. マッカーサー博士がニューヨーク市長にベンガの解放を求める嘆願書を提出した。最終的に市長はベンガを解放してジェームズ・M・ゴードン牧師の手に委ね た。ブルックリンのハワード黒人孤児院を監督するゴードンは居室を提供するだけでなく、同じ年に彼がバージニアで保護が受けられるように手配し、金を用立 ててアメリカ人と変わらない衣服を身につけさせ歯におおいをさせたためこのアフリカの青年は地域社会の成員になることができた。その後ベンガは家庭教師に 英語を教わり、工員の仕事を始めている。しかし数年後には第一次世界大戦が勃発し、航路は一旅行者には使えなくなった。アフリカに帰ることができなくなり 憂鬱状態になったベンガは1916年、32歳のときに自ら死を選んだ[2]。 |

|

| アフリカ ムブティ族の一員である[3]オタ・ベンガは当時ベルギー領であったコンゴのカサイ川にほど近い赤道直下の熱帯林で暮らしていた。彼の仲間はベルギー王レ オポルド2世の創設した公安軍に殺された(この部隊は、コンゴの現地人を統制するとともに豊富に産出するゴムを搾取するための組織だった)。ベンガは妻と 二人の子供を失ったが、公安軍が村を攻撃してきたときは狩りで遠出していたため運良く生き延びることができた。奴隷商人に捕まったのはその後である [4]。 アメリカ人の実業家であり宣教師でもあったサミュエル・フィリップス・ヴェルナーは、セントルイス万国博覧会からピグミー族の集団を展示品の一部にするた め連れ帰るという仕事を請け負い、1904年にアフリカへと出発した[5] 。出来て間もない人類学の世界をありありと示すため、著名な科学者であったウィリアム・ジョン・マッギーには「最も小さいピグミー族から最も巨大な人間ま で、最も黒い人種から支配集団の白人まで世界中のあらゆる人々の代表」を展示し、一種の文化的進化を表現しようと目論んでいたのである[6]。ヴェルナー がオタ・ベンガを発見したのは彼が過去にも訪れたことのあるバトワ族の村へ向かう途中だった。ベンガは交渉の末1ポンドの塩と1反の織物と交換されて自由 の身になり[7]、二人は村へ到着するまでの数週間を共に過ごした。しかし目的地の村ではレオポルト2世の軍の虐遇により「ムズング」(白人男性)への不 信感が植え付けられていた。ヴェルナーは自分についてくる村人を一人も集められなかったが、この「ムズング」が自分の命を救ったのだとベンガが村人たちに 語ったことで説得が可能になった。二人の間には友情が芽生え始め、同時にベンガにはヴェルナーがいた世界への好奇心が高まっていた。さらに4人のバトワ族 の男たちが二人に同行することを決めた。バクバの4人(その中にはンドンベ王の息子もいた)をはじめピグミー以外からも現代の人類学者に「レッド・アフリ カン」と総称される男たちが集まった[8][9]。 |

|

万国博覧会 万国博覧会セントルイスのベンガ(左から2番目)とバトワ族 マラリアにかかったヴェルナー以外の一行がミズーリ州セントルイスに到着したのは1904年の6月後半だった。セントルイス万国博覧会はすでに始まってい たが、彼らはすぐに注目の的になった。「アルティバ」、「オートバンク」[10]、「オタ・バング」、「オタベンガ」とマスコミはさまざまな呼び方をした が、オタ・ベンガは非常に人気があった。ベンガの愛想のよさも手伝ってか、来場者は熱心に彼の歯を見ていこうとした。彼の歯は儀式を兼ねた装飾として幼い 頃に先が鋭く磨がれていたのである。アフリカ人たちは写真やパフォーマンスに金をとることを学んでいて、ある新聞の記事ではベンガを「アメリカで唯一人の 正真正銘の人食い人種」として売り出し、「〔彼の歯は〕観光客が払う5セントの見物料の価値はある」と主張していた[8]。 一ヶ月後にやってきたヴェルナーは、ピグミーたちが演者というよりも囚人に近い扱いになっていることに気づいた。彼らが日曜には静かに森に集まろうとして も、「真面目」で科学的な展示物にしたかったマッギーの思惑と裏腹の観衆たちの熱狂がそれを許さなかった。彼らが「野蛮」だという先入観をもった観光客へ の見世物は人気を集め、7月28日には群衆を整理するために第1イリノイ連隊が招集されるという事態にまでいたった。ベンガたちはしだいに軍隊式のパ フォーマンスをするようになり、さらにはインディアンのそれを模倣しはじめた[11]。一方でインディアンの指導者であったジェロニモ(「虎」ともてはや され、陸軍省からも例外的な扱いを受けていた)[10]はベンガを尊敬し始めており、自分の矢の一つを彼に贈っている。功績が認められたヴェルナーは博覧 会の終わりには人類学部門における金メダルを受賞した[11]。 |

|

| 自然史博物館 その後ヴェルナーはアフリカ人たちを帰還させるためコンゴに向かい、それにベンガも同行した。アフリカでの冒険旅行の最中も二人は一緒であり、バトワ族に 囲まれて短い期間ながら共に過ごした。ベンガはバトワ族の女性と結婚しているが、後にこの妻が蛇に噛まれた傷がもとで亡くなるという事以外、この2度目の 結婚についてはほとんどわかっていない。ついにバトワ族に帰属感を覚えることのなかったベンガは、ヴェルナーとともにアメリカに帰ることを決める [12]。 ヴェルナーは他の仕事にも手をだしながら最終的にベンガの住処としてニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館の空き部屋を用意した。館員のヘンリー・バンプス との交渉はアフリカから彼を連れてくるまでや展示では何ができるのかといった話を材料に進んだ。バンプスは月に175ドルという法外な高給をヴェルナーに 求められて気分を悪くした上にこの男の人となりにもよい印象も持っていなかったが、ベンガには興味を持った。来場者の心をくすぐるために南部式のリネンの スーツを着ることになったベンガは初めのうちこそ博物館で楽しい時間を過ごしていた。しかし彼はホームシックにかかる[13]。 作家のブラッドフォードとブルームはこのときのベンガの心情に迫ろうとしている。 はじめ好奇心をかきたてたものが、今では彼に逃れたいという感情を芽生え

させていた。長い間、園内にいれられて―まるで丸呑みにされたかのよう―おかしくなりそうだった。心の中の自分は剥製にされ、ガラスでまわりを囲まれ、そ

れでも何とか命をながらえ、つくりものの焚き火の前に腰かけ、生気の無い赤子に肉を与えていた。博物館の静寂は苦痛の種になり、騒音にも等しかった。彼に

は鳥の歌が、そよ風が、木々が必要だった[14]

不平をかこつベンガは、雇い主が自分の売り文句にした「野蛮」さを徹底することに慰めを見いだそうとしはじめた。大群衆が移動するのにあわせて警備の目を すり抜けようとも試みた。裕福な後援者の妻に席を用意するように言われたときは、指示を誤ったふりをして椅子を部屋の反対側へと投げつけその女性の頭をか すめたりした。またそのころヴェルナーは資金繰りに苦労し、博物案との交渉にもほとんど進展がなかった。すぐにピグミーの家を別の場所に見つけなければな らなかった[13]。 |

|

ブロンクス動物園 ブロンクス動物園バンプスの提言にしたがってヴェルナーは1906年にベンガをブロンクス動物園に連れて行った。彼はここでは敷地を自由に歩き回ることができた。ベンガは 「サル園を仕切る才覚の持ち主」[15]であるドーホン(Dohong)という名前のオラウータンを好きになり、その成り行きから次第にいくつかの芸や人 間の行動のマネを教え込まれていたドーホンと肩を並べての「展示」が生まれた[4]。ベンガはサル園の展示品としてしばらく過ごしたが、動物園側はベンガ にそこのハンモックにゆられ、弓と矢で的を射ることを奨励した。展覧会の初日である1906年9月8日にベンガはサル園におり[4] それを見に来た来場者にはこんな看板が立てられていた。 ブロンクス動物園のオタ・ベンガ(1906年) この時代のベンガには5枚の宣伝写真があるのみであり、カメラが許可されなかった「サル園」のものは存在しない[16] アフリカ人のピグミー、「オタ・ベンガ」 年齢:23歳 身長:4フィート11インチ 体重:103ポンド カサイ川,コンゴ自由国、南中央のアフリカから、 サミュエルP.ベルネル博士によって持って来られた。 9月中、霊長類厩舎の外側に各午後に展示。 1906年9月、ブロンクス動物園[17] |

|

|

ブロンクス動物園の園長だったウィリアム・ホーナディはこの展示が観光客にとって得がたい見世物になると考えていたし、それを支持するニューヨーク動物学

会の幹事だったマディソン・グラントはオタ・ベンガをブロンクス動物園の類人猿と並べて展示するよう働きかけた(10年後にグラントは人種主義人類学およ

び優生学者として有名になる人物である[18])。一方でアフリカ系アメリカ人の聖職者はすぐに動物園の職員にこの展示に関して抗議を行った。ジェーム

ズ・H・ゴードンは次のように語った。「私たちの仲間を類人猿と並べて展示する以前から、私たちの人種はひどく貶められています…。私たちには魂をもった

人間とみなされるだけの価値がある。そう私は思います」[4]。またゴードンはこの展示がキリスト教と相容れぬものであり、ダーウィニズムの宣伝活動に等

しいとも考えていた。「ダーウィンの理論はキリスト教とは完全に対立するものであり、それに利する形で公衆を前に実演してみせることは許されるべきではな

い」[4]。多くの聖職者がゴードンに続いた[19]。ベンガを下等な人間として扱うことを擁護して、ニューヨークタイムズの社説は次のような議論を行っ

た。 私たちはこの問題に関して他人の顔に浮かぶ感情の全てをはっきりと理解しているわけではない…。ベンガが受けているという辱めや罵りを想像し、それに不平 をいうとはばかげている。ピグミーは…人間的な尺度でみれば非常に劣っているし、ベンガを檻のかわりに学校へいれるべきだという主張が無視しているのは、 高い可能性で学校という場所から…彼は何一つ有益なことを引き出せないだろうという点だ。人は皆同じであり、本を読んで勉強する機会があったかどうかの違 いしかないという考え方は、今ではまったく時代遅れだ[20] 論争後、ベンガは動物園の敷地を散策することを許可されたが、ただ展示されるばかりでなく群衆からは言葉や身ぶりで何かと催促されることに対して、ベンガ のいたずらは頻度を増し、いくらか暴力的にさえなった[21]。この頃に出たニューヨークタイムズのある記事では「児童愛護協会のような組織がないという のは残念なことだ。我々はアフリカ人をキリスト教化するために宣教師を彼の地へ送ったが、今度は同じ人間を野蛮にするためにこちらへ連れてきている [22]」という主張が掲載された。 最終的に動物園はベンガを敷地から退去させた。ヴェルナーはそれまで続けていた仕事探しこそ上手くいっていなかったが、折に触れてベンガと話し合いを持っ ていた。動物園では不愉快な注目の浴び方をしたもののアメリカに留まることがベンガにとっての第一の希望だという点で二人の考えは一致していた[23]。 1906年の終わりごろに、ベンガはゴードン牧師の保護下にはいった[4]。114年の月日が経った2020年、同動物園はベンガに対して謝罪した。 |

|

| 晩年 ゴードンは、教会が支援していた施設であり、自身の監督していたハワード黒人孤児院にベンガを入れた。マスコミからは相変わらず快いとはいえない扱いを受 けたが、1910年1月にゴードンはベンガをリンチバーグに送り、マクレイ家と生活を共にさせた[24]。ここでベンガの歯につけるおおいやアメリカ人風 の服を用意したので、ベンガは地域社会の一員になることができた。リンチバーグの詩人であるアン・スペンサーに教えを受けて英語も上達し[25]、地元の バプテスト神学校初等科へ通うことも始めた[20]。 しかし自分の英語が十分に上手くなったと考えたベンガは、正規の教育を受けることをやめてしまい、リンチバーグのタバコ工場で働き始めた。背こそ低かった が、タバコの葉をとるために梯子なしでポールを登ることができるベンガはすぐれた労働力だった(仲間の労働者たちは彼を「ビンゴ」と呼んでいた)。ルート ビアやサンドイッチと引き換えに、ベンガはよく自分の身の上話をした。そしてこの頃の彼はアフリカに帰る計画を立てはじめていた[26]。 しかし1914年に第一次世界大戦が勃発し、コンゴに帰国することは不可能になった。かねてからの願いが絶たれたベンガは憂鬱状態に陥った[26]。 1916年3月20日、32歳のベンガは儀式にみたてて炎を燃やし、歯のおおいを削り落とし、盗んだ拳銃で自分の胸を撃って死んだ[27]。 ベンガの遺体は、オールドシティ・セメタリーの黒人用地区へ、彼を支援したグレゴリー・ヘイズのそばに墓標もないまま埋められた。ある時期に二人の遺体は 行方がわからなくなっている。この地域に伝わる逸話によれば、オタ・ベンガとヘイズはオールド・セメタリーからホワイトロック・セメタリーへと移され、そ の後墓は打ち棄てられてしまったのだという[28]。 |

|

| その後 サミュエル・フィリップス・ヴェルナーの孫であるフィリップス・ヴェルナー・ブラッドフォードは、このコンゴ人についての本「Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo」(1992)を出版している。その取材中にベンガのライフマスクとボディキャストを保有しているニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館を訪れている が、展示品はいまも彼の名前を示さないままただ「ピグミー」と分類されていた。ヴェルナーが1世紀近く前から抗議を行い、彼以外の人間にも繰り返し非難さ れているにもかかわらずである[29]。 オタ・ベンガと同様にイシも部族の最後の一人だった オタ・ベンガと最後のネイティヴアメリカンであるイシとの共通点を見て取ることは容易い。ベンガと同時期にイシもまたカリフォルニアで展示され、観察され た(さらには関わりのあった学者の子孫が彼をテーマに本を出版している)[30]。しかし「文化的な尺度から人種、民族、種の違いを明らかにする」という のが展示会の発案者の意図だったが、むしろ「来場者は、人種のヒエラルキーやそれを成立させる進化という物語に占める自分たちの位置への疑いに至った」と アダムスが主張しているように、これらの出来事によって単にアメリカ社会のレイシズムが暴き出されたというよりも、展示という文化が より人間的なものへ近づいたというほうが適当なのかもしれない[31]。イシはオタ・ベンガが死んだ5日後の1916年3月25日に亡くなった。 |

イシの物語(1861年ごろ〜1916年)

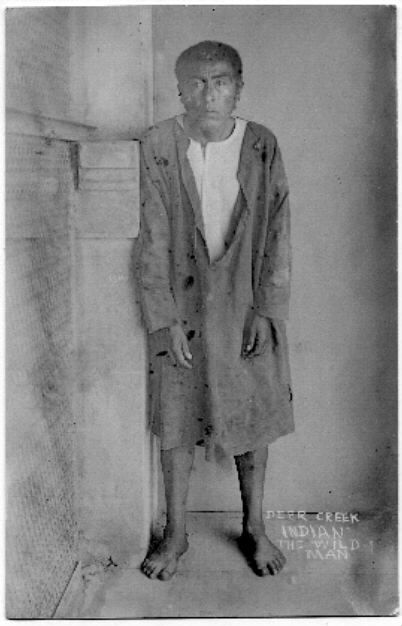

| ●Ishi. ca. 1861-1916 | |

| Ishi (c. 1861 – March 25, 1916) was the last known member of the Native American Yahi people from the present-day state of California in the United States. The rest of the Yahi (as well as many members of their parent tribe, the Yana) were killed in the California genocide in the 19th century. Ishi, who was widely acclaimed as the "last wild Indian" in the United States, lived most of his life isolated from modern American culture. In 1911, aged 50, he emerged at a barn and corral, 2 mi (3.2 km) from downtown Oroville, California. | イシ(1861年頃-1916年3月25日)は、現在のア メリカ合衆国カリフォルニア州に住んでいたネイティブアメリカンのヤヒ族の最後のメンバーとして知られている。19世紀のカリフォルニア大虐殺で、他のヤ ヒ族(およびその親部族であるヤナ族の多くの人々)は殺害された。イシは「アメリカ最後の野生のインディアン」と呼ばれ、その生涯の大半をアメリカの近代 文化から隔絶された場所で過ごしました。1911年、50歳の彼は、カリフォルニア州オロビルのダウンタウンから2マイル(3.2km)離れた納屋と家畜 小屋に姿を現しました。 |

| Ishi, which means "man" in the Yana language, is an adopted name. The anthropologist Alfred Kroeber gave him this name because in the Yahi culture, tradition demanded that he not speak his own name until formally introduced by another Yahi.[2] When asked his name, he said: "I have none, because there were no people to name me," meaning that there was no other Yahi to speak his name on his behalf. | ヤナ語で「男」を意味する「イシ」は、養子縁組した名前である。人類学者アルフレッド・クルーバーがこの名前をつけたのは、ヤヒ族の文化では、他のヤヒ族 から正式に紹介されるまでは自分の名前を口にしてはいけないという伝統があったからだ[2]。「つまり、彼の名前を代弁するヤヒ族がいなかったのだ。 |

| Ishi was taken in by anthropologists at the University of California, Berkeley, who both studied him and hired him as a janitor. He lived most of his remaining five years in a university building in San Francisco. His life was depicted and discussed in multiple films and books, notably the biographical account Ishi in Two Worlds published by Theodora Kroeber in 1961.[3][4][5][6] | イシはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の人類学者に引き取られ、研究されるとともに清掃員として雇われた。そして、残りの5年間をサンフランシスコの大学 の建物で過ごすことになった。1961年に出版されたセオドラ・クローバーの伝記『Ishi in Two Worlds』を筆頭に、彼の人生は複数の映画や本で描かれ、議論されている[3][4][5][6]。 |

|

|

| Early

life In 1865,[8] Ishi and his family were attacked in the Three Knolls Massacre, in which 40 of their tribesmen were killed. Although 33 Yahi survived to escape, cattlemen killed about half of the survivors. The last survivors, including Ishi and his family, went into hiding for the next 44 years. Their tribe was popularly believed to be extinct.[9] Prior to the California Gold Rush of 1848–1855, the Yahi population numbered 404 in California, but the total Yana in the larger region numbered 2,997.[10] |

初期の生活 1865年[8]、イシとその家族はスリーノルズ大虐殺に襲われ、40人の部族民が殺害された。33人のヤヒ族が逃げ延びたが、生存者の約半数が牛飼いに 殺された。イシとその家族を含む最後の生存者は、その後44年間身を隠すことになった。1848年から1855年のカリフォルニア・ゴールドラッシュ以 前、ヤヒ族はカリフォルニアに404人いたが、より広い地域のヤナ族は2,997人であった[10]。 |

| The gold rush brought tens of thousands of miners and settlers to northern California, putting pressure on native populations. Gold mining damaged water supplies and killed fish; the deer left the area. The settlers brought new infectious diseases such as smallpox and measles.[11] The northern Yana group became extinct while the central and southern groups (who later became part of Redding Rancheria) and Yahi populations dropped dramatically. Searching for food, they came into conflict with settlers, who set bounties of 50 cents per scalp and 5 dollars per head on the natives. In 1865, the settlers attacked the Yahi while they were still asleep.[12] | ゴールドラッシュは何万人もの鉱夫と入植者を北カリフォルニアにもたらし、先住民の人口に圧力をかけた。金鉱は水源を破壊し、魚を殺し、鹿はその地域から 去っていった。入植者は天然痘や麻疹などの新しい伝染病をもたらした[11]。 北部のヤナ族は絶滅し、中部と南部のグループ(後にレディング・ランチェリアの一部となる)とヤヒ族は劇的に減少した。彼らは食料を求め、先住民に頭皮1 枚50セント、頭5ドルの賞金をかけた入植者と対立するようになった。1865年、入植者たちはヤヒ族がまだ眠っている間に攻撃した[12]。 |

Richard Burrill wrote, in Ishi Rediscovered: "In 1865, near the Yahi's special place, Black Rock, the waters of Mill Creek turned red at the Three Knolls Massacre. 'Sixteen' or 'seventeen' Indian fighters killed about forty Yahi, as part of a retaliatory attack for two white women and a man killed at the Workman's household on Lower Concow Creek near Oroville. Eleven of the Indian fighters that day were Robert A. Anderson, Harmon (Hi) Good, Sim Moak, Hardy Thomasson, Jack Houser, Henry Curtis, his brother Frank Curtis, as well as Tom Gore, Bill Matthews, and William Merithew. W. J. Seagraves visited the site, too, but some time after the battle had been fought. |

Richard Burrillは『Ishi Rediscovered』の中でこう書いている。 「1865年、ヤヒ族の特別な場所、ブラックロックの近くで、ミルクリークの水はスリーノールズ虐殺で真っ赤になった。オロビル近くのコンコウ・クリーク 下流のワークマン家で白人女性2人と男性1人が殺された報復として、「16人」または「17人」のインディアン戦士が約40人のヤヒ族を殺したのである。 W・J・シーグレーブスもこの地を訪れましたが、戦いが終わってからしばらく経ってからであった。 |

Robert Anderson wrote, "Into the stream they leaped, but few got out alive. Instead many dead bodies floated down the rapid current." One captive Indian woman named Mariah from Big Meadows (Lake Almanor today), was one of those who did escape. The Three Knolls massacre is also described in Theodora Kroeber's Ishi in Two Worlds. |

ロバート・アンダーソンは、「彼らは小川に飛び込んだが、生きて出られた者はほとんどいなかった。代わりに多くの死体が急流を下っていった」と書いてい る。ビッグ・メドウズ(現在のレイク・アルマナー)出身のマライアという捕虜のインディアン女性も、脱出した一人だった。スリーノルズの大虐殺は、セオド ラ・クローバーの「二つの世界の石」にも書かれている。 |

| Since then more has been learned. It is estimated that with this

massacre, Ishi's entire cultural group, the Yana/Yahi, may have been

reduced to about sixty individuals. From 1859 to 1911, Ishi's remote

band became more and more infiltrated by non-Yahi Indian

representatives, such as Wintun, Nomlaki, and Pit River individuals. In 1879, the federal government started Indian boarding schools in California. Some men from the reservations became renegades in the hills. Volunteers among the settlers and military troops carried out additional campaigns against the northern California Indian tribes during that period.[13] In late 1908, a group of surveyors came across the camp inhabited by two men, a middle-aged woman, and an elderly woman. These were Ishi, his uncle, his younger sister, and his mother, respectively. The former three fled while the latter hid herself in blankets to avoid detection, as she was sick and unable to flee. The surveyors ransacked the camp, and Ishi's mother died soon after his return. His sister and uncle never returned.[14] |

それ以来、さらに多くのことが判明している。この虐殺によって、イシの全文化集団であるヤナ/ヤヒ族は、約60人にまで減少したと推測されている。

1859年から1911年にかけて、イシの遠隔地のバンドには、ウィントゥン、ノムラキ、ピットリバーなど、ヤヒ族以外のインディアンの代表がどんどん入

り込んでくるようになった。 1879年、連邦政府はカリフォルニアにインディアン寄宿舎学校を設立した。居留地から丘陵地帯で反逆者となった者もいた。入植者の中の有志と軍隊は、こ の時期、北カリフォルニアのインディアン部族に対してさらなる作戦を行った[13]。 1908年末、測量隊の一団が、2人の男性、中年の女性、老婆が住むキャンプに出くわした。彼らはそれぞれイシ、彼の叔父、妹、母親であった。前3人は逃 げ、後者は病気で逃げられないので、毛布で身を隠していた。測量隊は陣屋を荒らし、イシの母は石井の帰国後すぐに死んだ。妹と叔父は帰らぬ人となった [14] |

| Arrival into European American

society After the 1908 encounter, Ishi spent three more years alone in the wilderness. Starving and with nowhere to go, Ishi, at around the age of 50, was found pre-sunset[16][17] by Floyd Hefner, son of the next-door dairy owner (who was in town), who was "hanging out", and who went to harness the horses to the wagon for the ride back to Oroville, for the workers and meat deliveries.[18] Later, after Sheriff J.B. Webber arrived, the Sheriff directed Adolph Kessler, a nineteen-year-old slaughterhouse worker, to handcuff Ishi, who smiled and complied[19][20][21][22][23] on August 29, 1911, at the Charles Ward[24] slaughterhouse back corral[25] near Oroville, California, after forest fires in the area.[26][27][28] Witnessing slaughterhouse workers included Lewis "Diamond Dick" Cassings, a "drugstore cowboy". The local sheriff took Ishi into custody.[18] The "wild man" caught the imagination and attention of thousands of onlookers and curiosity seekers. University of California, Berkeley anthropology professors read about him and "brought him"[29] to the Affiliated Colleges Museum (1903—1931),[26] in an old law school building on the University of California's Affiliated Colleges campus[30] on Parnassus Heights, San Francisco. Studied by the university,[31] Ishi also worked as a janitor and lived at the museum for most of the remaining five years of his life. In October 1911, Ishi, Sam Batwi, T. T. Waterman, and A. L. Kroeber, went to the Orpheum Opera House in San Francisco to see Lily Lena (Alice Mary Ann Mathilda Archer, born 1877)[32][33][34][35] the "London Songbird," known for "kaleidoscopic" costume changes. Lena gave Ishi a piece of gum as a token.[36] On May 13, 1914,[37] Ishi, T.T. Waterman , A.L. Kroeber, Dr. Saxton Pope, and Saxton Pope Jr., 11-years-old, took Southern Pacific's Cascade Limited overnight train, from the Oakland Mole and Pier to Vina, California, on a trek in the homelands of the Deer Creek area of Tehama county,[38] researching and mapping for the University of California,[10][39] fleeing on May 30, 1914 during the Lassen Peak volcano eruption. T.T. Waterman and A.L. Kroeber, director of the museum, studied Ishi closely over the years and interviewed him at length in an effort to reconstruct Yahi culture. He described family units, naming patterns, and the ceremonies that he knew. Much tradition had already been lost when he was growing up, as there were few older survivors in his group. He identified material items and showed the techniques by which they were made. In February 1915, during the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, Ishi was filmed in the Sutro Forest with Grace Darling for Hearst-Selig News Pictorial, No. 30.[40][41] In June 1915, for three months,[10] Ishi lived in Berkeley with the anthropologist Thomas Talbot Waterman and his family.[42] Ishi, 1915[43] In the summer of 1915,[10] Ishi was interviewed on his native Yana language, which was recorded and studied by the linguist Edward Sapir, who had previously done work on the northern dialects.[44] These wax cylinders have had their sound recovered by Carl Haber's and Vitaliy Fadeyev's optical IRENE technology.[45][46][47][48] |

ヨーロッパ・アメリカ社会への到着 1908年の出会いの後、イシはさらに3年間を荒野で孤独に過ごした。飢えと行き場のない50歳前後のイシは、日没前に、隣の酪農家の息子(町にいた)フ ロイド・ヘフナーが「ぶらぶらしていた」ところを発見され、労働者と肉の配達のために、オロビルに戻るための馬車に馬をつなぎに行った[18] 後に保安官J.B.ウェバーが到着した後、保安官は19歳の屠殺場労働者であるアドルフ・ケスラーに石に手錠をかけるよう指示し、石は微笑んで応じた [19][20][21][22][23] 1911年8月29日、カリフォルニア州オロビル近くのチャールズ・ワード[24]の屠殺場裏家畜小屋で、地域の山火事後に目撃している[26][27] [28]。この「野生の男」は、何千人もの見物人や好奇心の強い人々の想像力と関心を集めた。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の人類学教授が彼について読 み、サンフランシスコのパルナサスハイツにあるカリフォルニア大学付属カレッジキャンパス[30]の古い法律学校の建物にある付属カレッジ博物館 (1903-1931)に「彼を連れてきた」[29]のであった。大学で学んだイシは、清掃員としても働き、残りの5年間のほとんどをこの美術館で暮らし た[31]。 1911年10月、イシは、サム・バトウィ、T・T・ウォーターマン、A・L・クローバーとともに、サンフランシスコのオーファム・オペラハウスに、「万 華鏡のような」衣装替えで知られる「ロンドンの歌姫」リリー・レナ(Alice Mary Ann Mathilda Archer、1877年生)[32][33][34][35]を見に行くことになった。レナはトークンとして石にガムを渡した[36]。 1914年5月13日[37]、イシ、T.T.ウォーターマン、A.L.クルーバー、サクストン・ポープ博士、サクストン・ポープJr, 11歳)は、サザン・パシフィックのカスケード・リミテッド夜行列車に乗り、オークランド・モール&ピアからカリフォルニア州ヴィナまで、テハマ郡のディ アクリーク地域の故郷をトレッキングし、カリフォルニア大学のための調査・地図作成を行っていたが[38]、1914年5月30日、ラッセンピークの火山 噴火のため逃亡した[39][40][41]。 T.T.ウォーターマンとA.L.クローバー館長は、長年にわたってイシを綿密に研究し、ヤヒ文化を再構築するために彼に長いインタビューを行った。彼は 家族構成、名前の付け方、儀式について知っていることを説明した。彼のグループには年配の生存者がほとんどいなかったため、彼が育った頃にはすでに多くの 伝統が失われていたのです。彼は、材料となる品物を特定し、それを作る技術を示した。 1915年2月、パナマ・パシフィック万国博覧会の際、イシはグレース・ダーリンと共にサットロの森で撮影され、『ハースト=セリグ・ニュースピクトリア ル』第30号に掲載された[40][41]。 1915年6月、3ヶ月間[10]、イシは人類学者トーマス・タルボット・ウォーターマンと彼の家族とバークレーで暮らした[42]。 イシ、1915年[43]。 1915年夏、[10] 石は母国語のヤナ語についてインタビューを受け、それを以前から北方方言について研究していた言語学者エドワード・サピアが録音し研究した[44] この蝋引きシリンダーはカール・ハーバーとヴィタリー・ファデイフの光学IRENE技術によって音が復元されている[45][46][47][48] 。 |

| Death Lacking acquired immunity to common diseases, Ishi was often ill. He was treated by Saxton T. Pope, a professor of medicine at UCSF. Pope became close friends with Ishi, and learned from him how to make bows and arrows in the Yahi way. He and Ishi often hunted together. Ishi died of tuberculosis on March 25, 1916.[49][50][1][51][52] It is said his last words were "You stay. I go."[53] His friends at the university tried to prevent an autopsy on Ishi's body, since Yahi tradition called for the body to remain intact. However, the doctors at the University of California medical school performed an autopsy before Waterman could prevent it. Ishi's brain was preserved and his body cremated. His friends placed grave goods with his remains before cremation: "one of his bows, five arrows, a basket of acorn meal, a boxfull of shell bead money, a purse full of tobacco, three rings, and some obsidian flakes." Ishi's remains were interred at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Colma, California, near San Francisco.[54] Kroeber put Ishi's preserved brain in a deerskin-wrapped Pueblo Indian pottery jar and sent it to the Smithsonian Institution in 1917. It was held there until August 10, 2000, when the Smithsonian repatriated it to the descendants of the Redding Rancheria and Pit River tribes. This was in accordance with the National Museum of the American Indian Act of 1989 (NMAI).[55] According to Robert Fri, director of the National Museum of Natural History, "Contrary to commonly-held belief, Ishi was not the last of his kind. In carrying out the repatriation process, we learned that as a Yahi–Yana Indian his closest living descendants are the Yana people of northern California."[56] His remains were also returned from Colma, and the tribal members intended to bury them in a secret place.[55] |

死 イシは、一般的な病気に対する後天性免疫を持たないため、よく病気になった。そこで、UCSFの医学部教授であったサクストン・T・ポープが治療にあたっ た。ポープはイシと親しくなり、ヤヒ流の弓と矢の作り方をイシから教わった。ポープとイシはよく一緒に狩りをした。1916年3月25日、イシは結核で死 亡した[49][50][1][51][52] 最後の言葉は「You stay. 私は行く」[53]。ヤヒ族の伝統では遺体をそのまま残すことになっていたため、大学の友人たちはイシの遺体を解剖することを阻止しようとした。しかし、 カリフォルニア大学医学部の医師たちは、ウォーターマンが阻止する前に解剖を行った。 イシは脳を保存し、遺体は火葬に付された。火葬の前に、友人たちが遺骨と一緒に墓標を置いた。「弓1本、矢5本、どんぐり籠、箱いっぱいの貝の玉のお金、 タバコの入った財布、指輪3個、黒曜石の薄片などである。イシの遺骨は、サンフランシスコ近郊のカリフォルニア州コルマにあるマウント・オリベット墓地に 埋葬された[54]。クローバーはイシの脳を鹿皮で包んだプエブロ・インディアン陶器の壺に入れ、1917年にスミソニアン博物館に送った。2000年8 月10日にスミソニアンがレディング・ランチェリアとピット・リバー部族の子孫に本国送還するまで、同機関で保管された。これは1989年の国立アメリカ ンインディアン博物館法(NMAI)に基づくものである[55]。国立自然史博物館のロバート・フリ館長によれば、「一般に信じられていることに反して、 イシは彼の種の最後のものではなかった」。彼の遺骨もコルマから返還され、部族は秘密の場所に埋葬するつもりであった[55]。 |

| Possible multi-ethnicity Steven Shackley of UC Berkeley learned in 1994 of a paper by Jerald Johnson, who noted morphological evidence that Ishi's facial features and height were more typical of the Wintu and Maidu. He theorized that under pressure of diminishing populations, members of groups that were once enemies had intermarried to survive. Johnson also referred to oral histories of the Wintu and Maidu that told of the tribes' intermarrying with the Yahi.[57] The theory is still debated, and this remains unresolved. In 1996, Shackley announced work based on a study of Ishi's projectile points and those of the northern tribes. He had found that points made by Ishi were not typical of those recovered from historical Yahi sites. Because Ishi's production was more typical of points of the Nomlaki or Wintu tribes, and markedly dissimilar to those of Yahi, Shackley suggested that Ishi had been of mixed ancestry, and related to and raised among members of another of the tribes.[57] He based his conclusion on a study of the points made by Ishi, compared to others held by the museum from the Yahi, Nomlaki and Wintu cultures. Among Ishi's techniques was the use of what is known as an Ishi stick, used to run long pressure flakes.[58] This is known to be a traditional technique of the Nomlaki and Wintu tribes. Shackley suggests that Ishi learned the skill directly from a male relative of one of those tribes. These people lived in small bands, close to the Yahi. They were historically competitors with and enemies of the Yahi.[58] |

多民族性である可能性 カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のSteven Shackleyは、1994年にJerald Johnsonの論文に触れ、イシの顔立ちや身長はウィントゥ族やメイドゥ族に典型的であるという形態学的な証拠を指摘しました。ジョンソン氏は、人口減 少の圧力の中で、かつて敵対していた集団のメンバーが生き残るために婚姻関係を結んだと推論しています。ジョンソンはまた、ウィントゥとマイドゥの部族が ヤヒ族と婚姻関係にあったことを伝える口伝を参照した[57]。この説にはまだ議論があり、これは未解決のままである。 1996年、シャックリーはイシの投石器と北方部族の投石器の研究に基づく研究成果を発表した。彼は、イシの作ったポイントは歴史的なヤヒの遺跡から出土 するものとは典型的なものではないことを発見した。シャックレーは、イシの製作した投石器はノムラキ族やウィントゥ族のものに典型的であり、ヤヒ族のもの とは著しく異なっていたことから、イシは混血であり、他の部族のメンバーと関わりながら育ったのではないかと考えた[57]。彼は、博物館が所蔵するヤ ヒ、ノムラキ、ウィントゥ文化の他のものと比較したイシの製作したポイントの研究に基づいて、この結論を出したのであった。 イシの技法の中には、長い圧力フレークを走らせるために使用されるイシ・スティックとして知られるものがあった[58]。これはノムラキ族とウィントゥ族 の伝統的な技法として知られている。シャックリー氏は、イシがこれらの部族の男性の親族から直接この技術を学んだと示唆している。これらの部族は、ヤヒ族 に近い小さなバンドで生活していた。彼らは歴史的にヤヒ族と競合し、敵対していた[58]。 |

| Similar case Ishi's story has been compared to that of Ota Benga, an Mbuti pygmy from Congo. His family had died and were not given a mourning ritual. He was taken from his home and culture. During one period, he was displayed as a zoo exhibit. Ota shot himself in the heart on March 20, 1916, five days before Ishi's death.[59] |

類似のケース イシは、コンゴのムブティ・ピグミー族のオタ・ベンガと比較されることがある。彼の家族は亡くなったが、弔いの儀式を受けることはなかった。彼は故郷と文 化を奪われたのだ。一時期は動物園の展示品にされていた。オタは石が亡くなる5日前の1916年3月20日に心臓を撃って自殺した[59]。 |

| Films Ishi: The Last of His Tribe, aired December 20, 1978, on NBC, with Eloy Casados as Ishi, written by Christopher Trumbo and Dalton Trumbo, and directed by Robert Ellis Miller.[68][69] The Last of His Tribe (1992), with Graham Greene as Ishi, is a Home Box Office movie.[70][71] Ishi: The Last Yahi (1992), is a documentary film by Jed Riffe.[72][73][74] In Search of History: Ishi, the Last of His Kind (1998), television documentary about him.[75] Literature Apperson, Eva Marie Englent (1971). "We Knew Ishi". Red Bluff, California: Walker Lithograph Co.[76] daughter-in-law of "One-Eyed" Jack Apperson, who in 1908, sacked Ishi's Yahi village Collins, David R.; Bergren, Kristen (2000). Ishi: The Last of His People. Greensboro, NC: Morgan Reynolds. ISBN 978-1-883846-54-1. OCLC 43520986. (Young Adult Biography)[77] Kroeber wrote about Ishi in two books: Kroeber, Theodora; Kroeber, Karl (2002). Ishi in Two Worlds: a biography of the last wild Indian in North America. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22940-2. OCLC 50805975.[78] A mass-market, second-hand account of Ishi's life story, published in 1961, after the death of her husband Alfred, who had worked with Ishi, but had refused to write or talk about him. Ishi: Last of His Tribe. Illus. Ruth Robbins. (1964). Parnassus Press,[79][80] Berkeley, California. a juvenile fiction version of his life.[81] Ishi the Last Yahi: A Documentary History (1981), edited by Robert Heizer and Theodora Kroeber, contains additional scholarly materials[82] Merton, Thomas (1976). Ishi Means Man. Unicorn keepsake series. Vol. 8. Greensboro, N. C.: Unicorn Press. Novels Othmar Franz Lang. Meine Spur löscht der Fluss (1978)[83] (young adult novel in German) Lawrence Holcomb. The Last Yahi: A Novel About Ishi (2000).[84] |

映画 『イシ:部族の最後の者』(1978年12月20日NBC放送)。イシ役はエロイ・カサドス。脚本はクリストファー・トランボとダルトン・トランボ、監督はロバート・エリス・ミラー。[68][69] 『部族の最後』(1992年)は、グラハム・グリーンがイシ役を演じたホーム・ボックス・オフィス映画である。[70][71] 『イシ:最後のヤヒ族』(1992年)は、ジェド・リッフェによるドキュメンタリー映画である。[72][73][74] 『歴史を探して:イシ、その種の最後』(1998年)は、彼に関するテレビドキュメンタリーである。[75] 文献 アパーソン、エヴァ・マリー・エングレント (1971). 「我々はイシを知っていた」. カリフォルニア州レッドブラフ: ウォーカー・リソグラフ社[76] 1908年にイシのヤヒ族の村を略奪した「片目の」ジャック・アパーソンの義理の娘 コリンズ、デイヴィッド・R.、ベルグレン、クリステン(2000)。『イシ:彼の民族の最後の人民』。ノースカロライナ州グリーンズボロ:モーガン・レ イノルズ。ISBN 978-1-883846-54-1。OCLC 43520986。(ヤングアダルト向け伝記)[77] クロエバーは 2 冊の本でイシについて書いている。 クロエバー、セオドラ、クロエバー、カール (2002)。『二つの世界に住んだイシ:北米最後の野生のインディアン伝』。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 978-0-520-22940-2。OCLC 50805975。[78] イシの生涯を扱った大衆向け二次資料。1961年、イシと協力関係にあったが彼について書いたり話したりすることを拒んだ夫アルフレッドの死後に出版された。 イシ:部族最後の者。イラスト:ルース・ロビンス。(1964)。パルナッソス・プレス[79][80]、カリフォルニア州バークレー。 [81] 彼の生涯を題材とした児童向けフィクション版。 ロバート・ハイザーとセオドラ・クローバー編『最後のヤヒ族イシ:ドキュメンタリー史』(1981年)には追加の学術資料が含まれる[82] マートン、トーマス(1976年)。『イシは人間を意味する』。ユニコーン記念シリーズ第8巻。ノースカロライナ州グリーンズボロ:ユニコーン出版社。 小説 オットマー・フランツ・ラング『川が私の跡を消す』(1978年)[83](ドイツ語のヤングアダルト小説) ローレンス・ホルコム『最後のヤヒ族:イシを題材にした小説』(2000年)。[84] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishi. |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishi |

+++

◎人間展示と人種主義

人間展示をしようとする発想は、次の3つの前提が満 たされた時になされてきた。1)「純粋」な民族や人種が存在して、それらを、多数派の集団あるいは全世界の人に「リアル」に見せたいという動機があり、そ のような行為が「可能」であると考えたこと。2)動物園の発想ではあるが、それはコミュニケーション可能な「被展示民族・被展示人種」の合意、金銭の授受 を含む契約があれば、人権問題は「クリア」できる思考(ある種の「契約倫理」概念)。3)これらの人間展示を可能にする、モノ・ヒト・イデオロギーのロジ スティクスがすでに出来上がっていること、である。

★倫理的課題:現在では「人間展示」は、非人道的な 行為として非難されるが、歴史的には「当時はそのような人権保護の概念がなかったのだから止むを得ない」ということも可能である。しかし、そのことの意味 を、時空を超えて、現在の時点から、倫理概念の相対性を超えて考えることも重要である。いかなる「負の歴史」も、現在を生きる我々には、「善く」生きよう とする我々に対する指針になるはずだ。

◎「純粋民族」を展示できるという学問上の誤り

★人種的「純粋」性:この問題は、「単一人種が単一 民族である」という概念が狭量で誤った考え方に繋がるという認識の誕生とその膾炙により、徐々に克服されつつあった。しかし、21世紀以降、世界中でネオ ナチ的思想が拡散すると、人種的「純粋」性の概念が復活してきた。例えば、2010年代以降、北海道でみられる政治発言の中に「純粋なアイヌなんていな い」 と主張して、アイヌ民族に対してヘイトする人たちがあらわれてきた。これは、民族の定義を「帰属する集団に対するアイデンティティ」から構成されるもの と、長く理解し、そのように定義してきた文化人類学者や社会人類学者(一般)には、反論しにくい厄介な問題である。人間の集団は、近隣集団のあいだに通婚 が可能なのであり、その家族や生まれた個人がどちらのあるいは双方の「文化」を獲得し ていくのか、あるいはそれ以外の「文化」を獲得していくのかはさまざまな個別条件によ る、としかいいようがないからである。

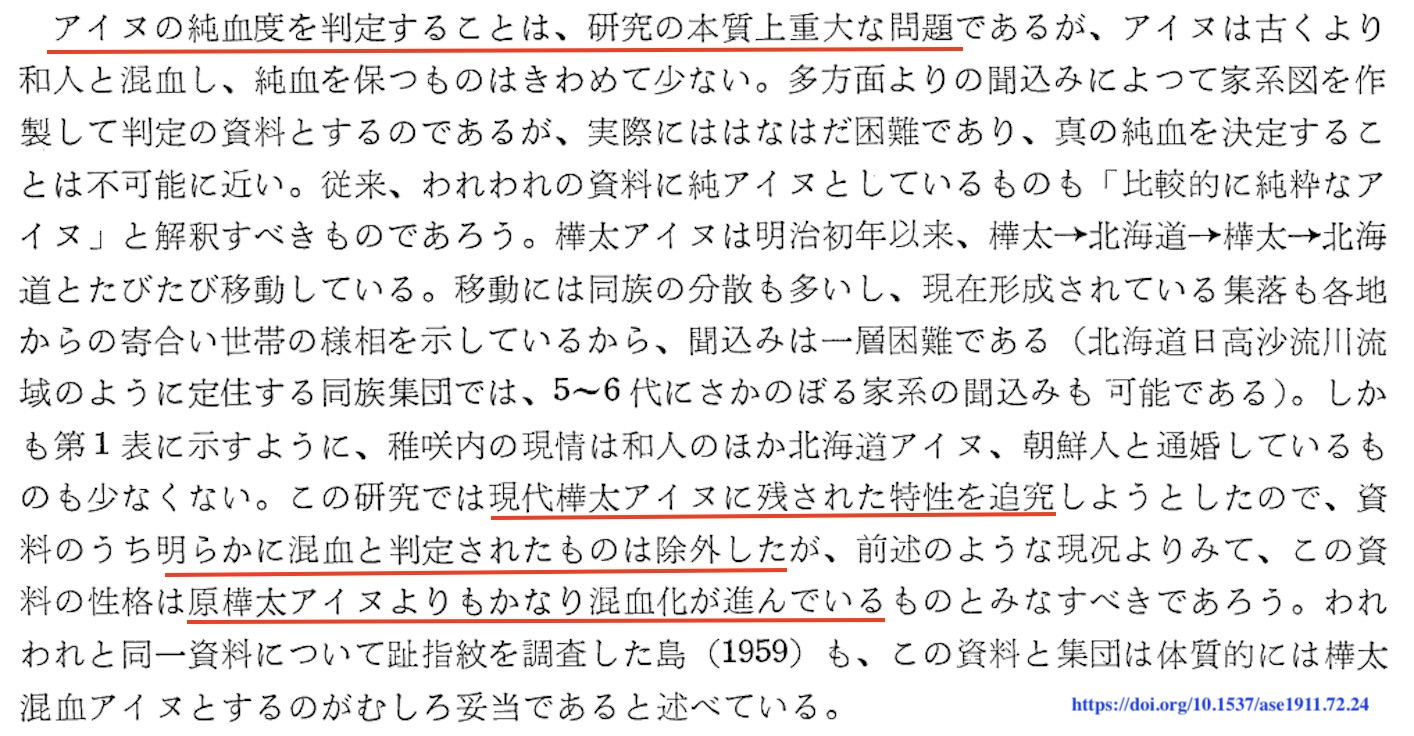

1875年に北海道に強制移動させられ、1905年 に樺太に(この時は移動の選択が選べたが)復 帰し、1945年に(敗戦により)ふたたび北海道に移動、定着してきた、樺太アイヌ・サハリンアイヌは、現在の民族の定義によると「樺太にルーツをもつア イヌ」と呼ぶほうが適切であろうが、1964年にその「純潔度」を推測しようと努力し人体計測データを分析した自然人類学者(小浜 基次, 加藤 昌太良, 欠田 早苗)は苦慮している。その時に、彼らは、「現代樺太アイヌの形質のうちで原樺太アイヌの特徴として残されている形質は、顔高と鼻高の大きいこと」と、よ り古い採集資料から仮想的に「原樺太アイヌ」を想定(=モデル化)して、「諸特性は認めがたく、恐らくは混血によってその特性を失ったもの」と主張してい る。つまり、このような主張は、後のヘイト論者にとって、「純粋の樺太アイヌなどいない」という主張の格好の「傍証材料」になってしまう。この自然学者た ちの研究方法に対する態度はきわめて客観的だが、「純粋の樺太アイヌ」を想定したことで、我々(和人やそれ以外の人びと)が普通に行なっている遠くの人び とや集団(=民族)との通婚というごく当たり前のことが、「純粋民族」を想定した時に、純粋さを阻害する変動要因としてみなされるということを示してい る。そのために、この論文の著者たちは、その抄録に「現代樺太アイヌの諸形質を総合すれば、北海道混血アイヌにもつとも近似する。体部は北海道純アイヌに やや近く、樺太和人とは遠いが、頭部、顔部は北海道純アイヌよりも和人に接近し、ギリヤーク、オロッコとはもつとも離れている」と結論せざるをえないので ある。

出典:小浜 基次, 加藤 昌太良, 欠田

早苗「北海道に移住した樺太アイヌの形質人類学的研究」人類学雑誌、1964 年 72 巻 1 号 p. 24-36 https://doi.org/10.1537/ase1911.72.24

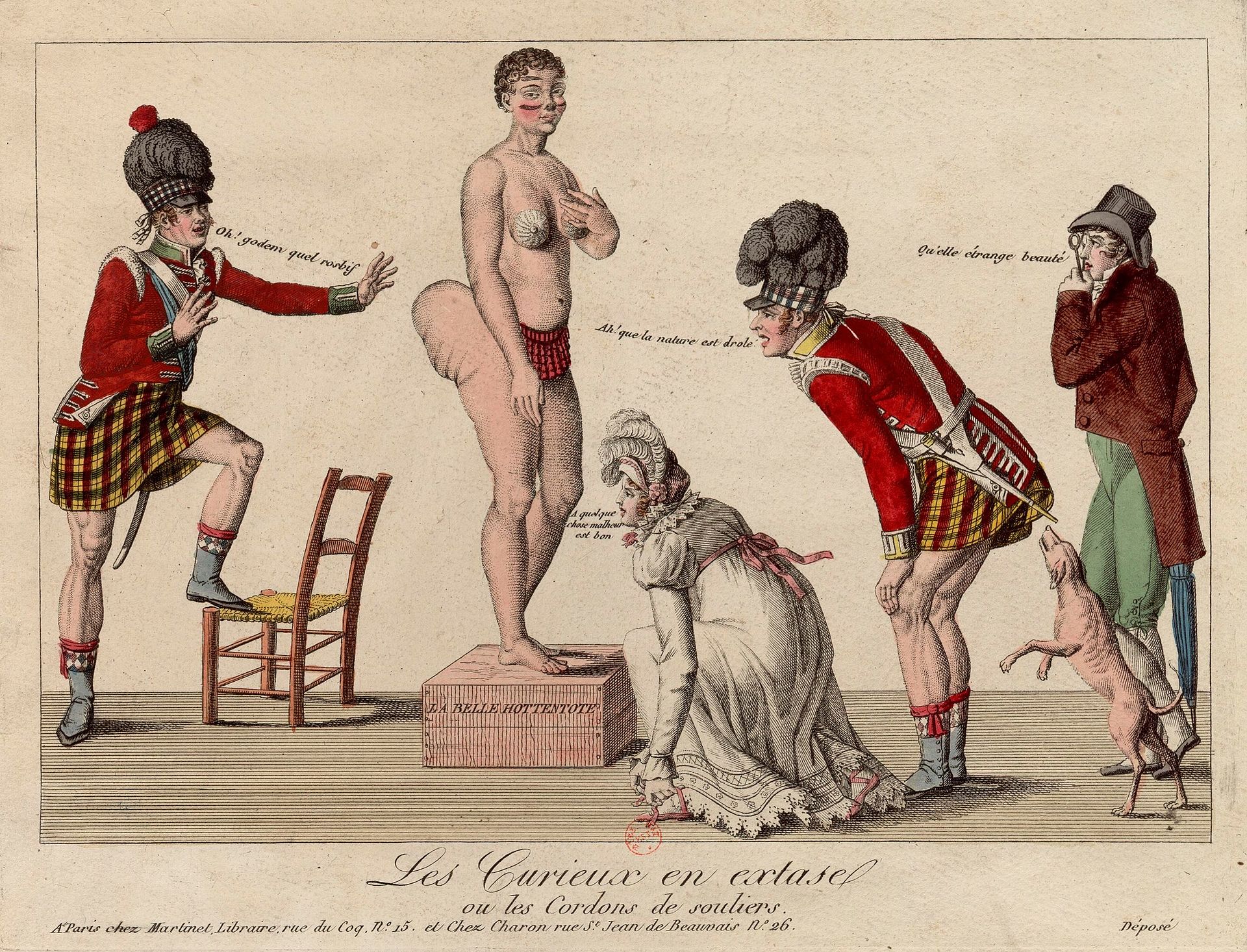

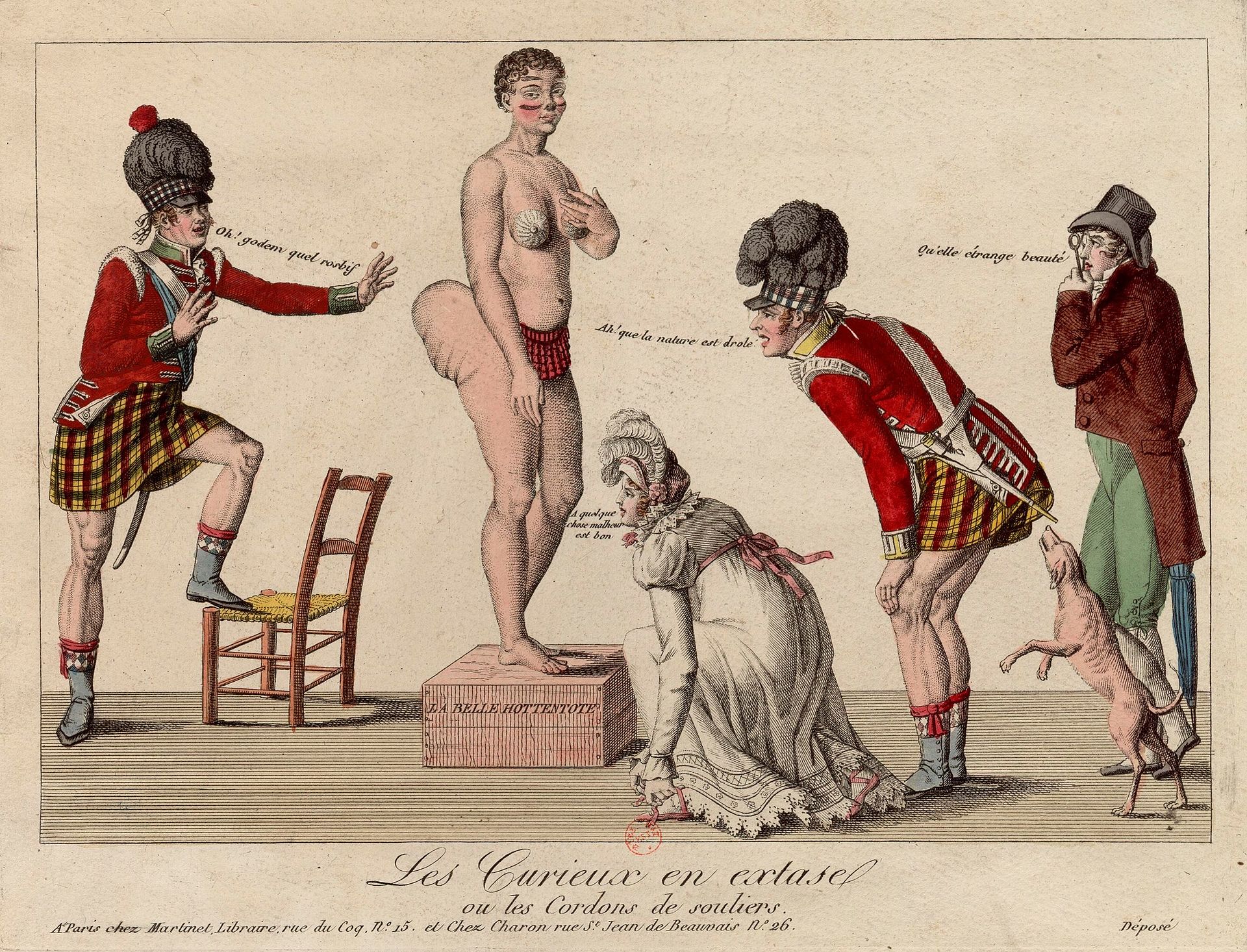

●「ホッテントット・ヴィーナス」ことサラ・バートマン(Sarah Baartman, ca. 1789-1815)

Sarah

Baartman (Afrikaans: [ˈsɑːra ˈbɑːrtman]; c.1789– 29 December 1815),

also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (Afrikaans

pronunciation: [ˈsɑːrtʃi]), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a

Khoikhoi woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in

19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus, a name which was

later attributed to at least one other woman similarly exhibited. The

term "Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoekoe

(formerly known as Khoikhoi) people of the southwestern area of Africa.

The women were exhibited for their steatopygic body type uncommon in

Western Europe which not only was perceived as a curiosity at that

time, but became subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias

frequently, as well as of erotic projection. However, it has been

suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once more

widespread in humans, based on carvings of idealised female forms

dating to the Paleolithic era collectively known as Venus figurines,

also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses. Sarah

Baartman (Afrikaans: [ˈsɑːra ˈbɑːrtman]; c.1789– 29 December 1815),

also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (Afrikaans

pronunciation: [ˈsɑːrtʃi]), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a

Khoikhoi woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in

19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus, a name which was

later attributed to at least one other woman similarly exhibited. The

term "Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoekoe

(formerly known as Khoikhoi) people of the southwestern area of Africa.

The women were exhibited for their steatopygic body type uncommon in

Western Europe which not only was perceived as a curiosity at that

time, but became subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias

frequently, as well as of erotic projection. However, it has been

suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once more

widespread in humans, based on carvings of idealised female forms

dating to the Paleolithic era collectively known as Venus figurines,

also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses."Venus" is sometimes used to designate representations of the female body in arts and cultural anthropology, referring to the Roman goddess of love and fertility. "Hottentot" was the name for the Khoi people, now usually considered an offensive term. The Sarah Baartman story is often regarded as the epitome of racist colonial exploitation, and of the commodification of the dehumanization of black people.[citation needed] |

サラ・バートマン(Afrikaans: [ˈra ˁˈbɑ;

c.1789 -

1815年12月29日)※バールトマンとも表記;サラ、時には短縮形のサーティエ(アフリカーンス語の発音:[ˁsɑi])、サーティエ、バートマン、

バートマンとも表記されたコイコイの女性で、19世紀のヨーロッパでホッテントットのヴィーナスと呼ばれ、見世物にされていた。ホッテントット」とは、ア

フリカ南西部の先住民コエコエ(旧名コイコイ)の植民地時代の呼称である。彼女たちは、西ヨーロッパでは珍しいステトピーの体型で展示され、当時は珍しが

られただけでなく、しばしば人種差別的なバイアスがかかるものの、科学的関心の対象となり、またエロティックな投影の対象にもなった。しかし、旧石器時代

の理想的な女性像が彫られたヴィーナスフィギア(Steatopygian

Venuses)とも呼ばれる彫刻から、この体型がかつて人類に広く存在していたことが人類学者によって示唆されている。 「ヴィーナス」は、芸術や文化人類学において、ローマ神話に登場する愛と豊穣の女神を意味し、女性の身体の表現を示すために用いられることがある。 "Hottentot "はコイ族の名前で、現在では通常、不快な言葉とされている。サラ・バートマンの物語は、人種差別的な植民地搾取、黒人の非人間化の商品化の縮図とみなさ れることが多い[要出典]。 |

| Early life in the Cape Colony Baartman was born to a Khoekhoe family in the vicinity of the Camdeboo in what is now the Eastern Cape of South Africa[2][3] (then the Dutch Cape Colony; a British colony by the time she was an adult). Saartjie is the diminutive form of Sarah; in Cape Dutch the use of the diminutive form commonly indicated familiarity, endearment or contempt. Her birth name is unknown.[4] Her surname has also been spelt Bartman and Bartmann.[1][2]: 184 Her mother died when she was an infant[5] and her father was later killed by Bushmen (San people) while driving cattle.[6] Baartman spent her childhood and teenage years on Dutch European farms. She went through puberty rites, and kept the small tortoise shell necklace, probably given to her by her mother, until her death in France. In the 1790s, a free black (a designation for individuals of enslaved descent) trader named Peter Cesars (also recorded as Caesar[5]) met her and encouraged her to move to Cape Town. Records do not show whether she was made to leave, went willingly, or was sent by her family to Cesars. She lived in Cape Town for at least two years working in households as a washerwoman and a nursemaid, first for Peter Cesars, then in the house of a Dutch man in Cape Town. She finally moved to be a wet-nurse in the household of Peter Cesars' brother, Hendrik Cesars, outside of Cape Town in present day Woodstock.[2][7] There is evidence that she had two children, though both died as babies.[2] She had a relationship with a poor Dutch soldier, Hendrik van Jong, who lived in Hout Bay near Cape Town, but the relationship ended when his regiment left the Cape.[2] Hendrik Cesars began to show her at the city hospital in exchange for cash, where surgeon Alexander Dunlop worked. Dunlop,[8] (sometimes wrongly cited as William Dunlop[5]), a Scottish military surgeon in the Cape slave lodge, operated a side business in supplying showmen in Britain with animal specimens, and suggested she travel to Europe to make money by exhibiting herself. Baartman refused. Dunlop persisted, and Baartman said she would not go unless Hendrik Cesars came too. He also refused, but he finally agreed in 1810 to go to Britain to make money by putting Baartman on stage. The party left for London in 1810. It is unknown whether Baartman went willingly or was forced.[2] Dunlop was the frontman and conspirator behind the plan to exhibit Baartman. According to a British legal report of 26 November 1810, an affidavit supplied to the Court of King's Bench from a "Mr. Bullock of Liverpool Museum" stated: "some months since a Mr. Alexander Dunlop, who, he believed, was a surgeon in the army, came to him to sell the skin of a Camelopard, which he had brought from the Cape of Good Hope.... Some time after, Mr. Dunlop again called on Mr. Bullock, and told him, that he had then on her way from the Cape, a female Hottentot, of very singular appearance; that she would make the fortune of any person who shewed her in London, and that he (Dunlop) was under an engagement to send her back in two years..."[9] Lord Caledon, governor of the Cape, gave permission for the trip, but later said regretted it after he fully learned the purpose of the trip.[10] |

ケープ植民地での幼少期 バートマンは現在の南アフリカ共和国東ケープ州[2][3](当時はオランダ領ケープ植民地、成人後はイギリス領)のカムデブー近郊でコエホ族の家庭に生 まれた。ケープタッチ語では、親しさ、愛らしさ、軽蔑を表すために小形化することが一般的であった。出生名は不明[4]。姓はバートマン、バートマンとも 表記される[1][2]。 184 幼少時に母親を亡くし[5]、父親はその後、牛の運搬中にブッシュマン(サン族)に殺害された[6]。 バートマンは幼少期から10代をオランダのヨーロッパの農場で過ごす。思春期の儀式を経て、フランスで亡くなるまで、おそらく母親から贈られた小さな亀甲 の首飾りを持ち続けた。1790年代、ピーター・シーザース(シーザー[5]という記録もある)という自由黒人(奴隷の血を引く個人の呼称)の貿易商が彼 女に出会い、ケープタウンに移住するよう勧められる。記録には、彼女が強制的に連れて行かれたのか、自ら進んで行ったのか、それとも家族がシーザーズに送 り届けたのかは記されていない。彼女は少なくとも2年間はケープタウンに住み、最初はピーター・シーザースのもとで、次にケープタウンのオランダ人男性の 家で洗濯婦や保母として働いていた。最終的にはケープタウン郊外の現在のウッドストックにあるピーター・シーザースの弟ヘンドリック・シーザースの家で乳 母として働くようになった[2][7]。 彼女には2人の子供がいたが、いずれも赤ちゃんの時に亡くなっている証拠がある[2]。 ケープタウン近くのハウトベイに住む貧しいオランダ兵ヘンドリック・ファンジョンと関係を持ったが、彼の連隊がケープから離れたため関係は終了している [2]。 ヘンドリック・セザースは現金と引き換えに彼女を市立病院に案内するようになり、そこには外科医アレクサンダー・ダンロップが勤務していた。ダンロップ [8](ウィリアム・ダンロップと間違って表記されることもある[5])はケープの奴隷宿のスコットランド人軍医で、イギリスの興行師に動物標本を提供す るサイドビジネスを行っており、彼女にヨーロッパに行って自分を展示してお金を稼ぐよう勧めた。バートマンはこれを拒否した。ダンロップは粘り強く説得 し、バートマンはヘンドリック・シーザースも来なければ行かない、と言い出した。彼もまた拒否したが、1810年になってようやく、バートマンを舞台にあ げて金を稼ぐためにイギリスに行くことを承諾した。一行は1810年にロンドンに向けて出発した。バートマンが自ら進んで行ったのか、強制されたのかは不 明である[2]。 ダンロップはバートマン出品計画の表看板であり、共謀者であった。1810年11月26日のイギリスの法律報告によると、「リバプール博物館のブロック 氏」からキングズベンチ裁判所に提出された宣誓供述書には次のように記されている。「数ヶ月前、陸軍の外科医であったと思われるアレキサンダー・ダンロッ プ氏が、喜望峰から持ち込んだカメレオパールの皮を売りに来た。それからしばらくして、ダンロップ氏は再びブリック氏を呼び、その時、岬から向かっている 途中に、非常に珍しい外見のホッテントットの女性がいること、ロンドンで彼女を見せた者は誰でも幸運になれること、彼(ダンロップ)は彼女を2年後に送り 返す約束になっていることを話した...」[9] 岬の知事のロード・カリドンはこの旅行を許可したが、後に旅行の目的を十分に知って後悔していると語った[10]。 |

| On display in Europe Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in 1810.[4] The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James, the most expensive part of London. In the household were Sarah Baartman, Hendrik Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.[2] Dunlop had to have Baartman exhibited and Cesars was the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room at the London residence of Thomas Hope at No. 10 Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London. Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners' lack of familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman's pejoratively perceived large buttocks. Crais and Scully say: "People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world".[2] She became known as the "Hottentot Venus" (as was at least one other woman, in 1829[11]). A handwritten note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably reproduced some of the language from the exhibition; thus the following origin story should be treated with skepticism: "Sartjee is 22 Years old is 4 feet 10 Inches high, and has (for a Hottentot) a good capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape, the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for a mere trifle. A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle & fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot them whenever they found them. 9 Jany, 1811. [H.C.?]"[12] The tradition of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed.[2] Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude,[13] and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.[14] She became a subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as well as of erotic projection.[15] She was marketed as the "missing link between man and beast".[8] Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act, which abolished the slave trade, created a scandal. Numerous Britons expressed discontent over a Dutch settler exhibiting an enslaved woman in the country.[16] A British abolitionist society, the African Association, conducted a newspaper campaign for her release. The British abolitionist Zachary Macaulay led the protest, with Hendrik Cesars protesting in response that Baartman was entitled to earn her living, stating: "has she not as good a right to exhibit herself as an Irish Giant or a Dwarf?"[4] Cesars was comparing Baartman to the contemporary Irish giants Charles Byrne and Patrick Cotter O'Brien.[17] Macaulay and The African Association took the matter to court and on 24 November 1810 at the Court of King's Bench the Attorney-General began the attempt "to give her liberty to say whether she was exhibited by her own consent." In support he produced two affidavits in court. The first, from a William Bullock of Liverpool Museum, was intended to show that Baartman had been brought to Britain by individuals who referred to her as if she were property. The second, by the Secretary of the African Association, described the degrading conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of coercion.[14] Baartman was then questioned before an attorney in Dutch, in which she was fluent, via interpreters. Historians have subsequently stated doubts on the veracity and independence of the statement that Baartman then made.[16] She stated that she in fact was not under restraint, had not been sexually abused and had come to London on her own free will.[17] She also did not wish to return to her family and understood perfectly that she was guaranteed half of the profits. The case was therefore dismissed.[16] She was questioned for three hours. The statements directly contradict accounts of her exhibitions made by Zachary Macaulay of the African Institution and other eyewitnesses.[13] A written contract was produced,[18] which is considered by some modern commentators to be a legal subterfuge.[2][4] The publicity given by the court case increased Baartman's popularity as an exhibit.[4] She later toured other parts of England and was exhibited at a fair in Limerick, Ireland in 1812. She also was exhibited at a fair at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.[2] On 1 December 1811 Baartman was baptised at Manchester Cathedral and there is evidence that she got married on the same day.[19][20] |

ヨーロッパでの展示 1810年、ヘンドリック・シーザースとアレクサンダー・ダンロップはバートマンをロンドンに連れてきた[4]。 一行はロンドンで最も高級なセント・ジェームス地区のデューク通りに同居していた。その家にはサラ・バートマン、ヘンドリック・シーザース、アレクサン ダー・ダンロップ、そしておそらくダンロップがケープタウンの奴隷宿から不法に連れてきたアフリカ人の少年2人が住んでいた[2]。 ダンロップはバートマンを展示する必要があり、シーザースは興行師となった。ダンロップはロンドンのキャベンディッシュ・スクエア、ダッチェス・ストリー ト10番地のトーマス・ホープの邸宅にあるエジプシャン・ルームでバートマンを展示した。ダンロップは、ロンドン市民がアフリカ人になじみがないことと、 バートマンが侮蔑的に認識されている大きな臀部のために、お金を稼ぐことができると考えたのである。クレイズとスカリーは言う。「彼女は「ホッテントット のヴィーナス」として知られるようになった(1829年に少なくとももう一人の女性がそうであった[11])。1811年1月にロンドンでバートマンを見 た人が展覧会のチラシに書いた手書きのメモには、彼女の出自についての好奇心が示されており、おそらく展覧会の言葉の一部が再現されている。したがって、 以下の出自の話は懐疑的に扱われるべきである。「Sartjeeは22歳で、身長は4フィート10インチ、(ホッテントットにしては)器量が良い。彼女は 喜望峰で料理人をやっていた。彼女の国は岬から600マイル弱のところにあり、その住民は牛が豊富で、物々交換でほんのわずかな金額で売っている。ブラン デー1瓶、またはタバコの小巻で、羊数頭を購入することができる。- この民族の向こうには、小柄で非常に繊細かつ獰猛な別の民族がいる。オランダ人は彼らを服従させることができず、見つけるたびに撃ち殺した。9 Jany, 1811. [バートマンは裸で展示されることを決して許さなかった[13]。1810年にロンドンに現れた彼女の記録では、ぴったりしたものではあるが衣服を身に着 けていたことが明らかである[14]。 [14] 彼女は、しばしば人種差別的な偏見を持っていたとはいえ、エロティックな投影と同様に科学的な興味の対象となった[15]。 彼女は「人間と獣の間のミッシングリンク」として売り出された[8]。 奴隷貿易を廃止した1807年の奴隷貿易法の成立からわずか数年後にロ ンドンで行われた彼女の展示はスキャンダルを引き起こした。多くのイギリス人が、オランダ人入植者が国内で奴隷の女性を展示したことに不満を表明した [16]。 イギリスの奴隷廃止運動団体であるアフリカ協会が、彼女の解放を求める新聞キャンペーンを実施した。イギリスの奴隷廃止論者ザカリー・マコーレーが抗議を 主導し、それに対してヘンドリック・シーザースは、バートマンには生計を立てる権利があると抗議し、次のように述べている[16]。「マコーレーとアフリ カ協会はこの問題を法廷に持ち込み、1810年11月24日、キングスベンチ法廷で検事総長は「彼女自身の同意によって展示されたのかどうかを語る自由を 与える」試みを開始した[17]。法廷では2つの宣誓供述書が提出された。最初のものはリバプール博物館のウィリアム・ブロックによるもので、バートマン が彼女を所有物であるかのように言っていた人物によってイギリスに持ち込まれたことを示すためのものであった。その後、バートマンは、通訳を介して、彼女 が堪能であったオランダ語で弁護士の前で尋問を受けることになった[14]。 歴史家はその後、バートマンがその後行った陳述の真実性と独立性に疑念を述べている[16]。 彼女は実際には拘束されておらず、性的虐待も受けておらず、自由意志でロンドンに来たと述べている[17]。また家族の元に戻ることを望まず、利益の半分 を保証されていることを完全に理解していた。そのため、この事件は却下された[16]。彼女は3時間にわたって尋問を受けた。アフリカン・インスティ テュートのザッカリー・マコーレーや他の目撃者による彼女の展示会の証言と直接的に矛盾する供述をしている[13]。 契約書が作成されたが、これは現代の論者によって法的裏技であると考えられている[18][2][4]。 裁判による宣伝はバートマンの展示品としての人気を高めた[4]。 その後、イングランドの他の地域を巡り、1812年にはアイルランドのリメリックのフェアに展示された。1811年12月1日にはマンチェスター大聖堂で 洗礼を受け、同日に結婚した形跡がある[19][20]。 |

| Later life A man called Henry Taylor took Baartman to France around September 1814. Taylor then sold her to a man sometimes reported as an animal trainer, S. Réaux,[21] but whose name was actually Jean Riaux and belonged to a ballet master who had been deported from the Cape Colony for seditious behaviour.[5] Riaux exhibited her under more pressured conditions for 15 months at the Palais Royal in Paris. In France she was in effect enslaved. In Paris, her exhibition became more clearly entangled with scientific racism. French scientists were curious about whether she had the elongated labia which earlier naturalists such as François Levaillant had purportedly observed in Khoisan at the Cape.[21] French naturalists, among them Georges Cuvier, head keeper of the menagerie at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, and founder of the discipline of comparative anatomy visited her. She was the subject of several scientific paintings at the Jardin du Roi, where she was examined in March 1815: as naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Frédéric Cuvier, a younger brother of Georges, reported: "she was obliging enough to undress and to allow herself to be painted in the nude". This was not really true: Although by his standards she appeared to be naked, she wore a small apron-like garment which concealed her genitalia throughout these sessions, in accordance with her own cultural norms of modesty.[22] She steadfastly refused to remove this even when offered money by one of the attending scientists.[4][2]: 131–134 She was brought out as an exhibit at wealthy people's parties and private salons.[8] In Paris, Baartman's promoters did not need to concern themselves with slavery charges. Crais and Scully state: "By the time she got to Paris, her existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally treated like an animal. There is some evidence to suggest that at one point a collar was placed around her neck."[2] At the end of her life she was a prostitute, and penniless.[23][24] |

その後の人生 1814年9月頃、ヘンリー・テイラーと呼ばれる男がバートマンをフランスに連れて行った。テイラーはその後、動物調教師のS.Réauxと報道されるこ ともあったが[21]、実際にはJean Riauxといい、扇動的な行動でケープコロニーから追放されたバレエ団の師匠に属していた。 Riauxは15ヶ月間パリのパレ・ロワイヤルでより厳しい条件の下で彼女を展示していた[5] 。フランスでは、彼女は事実上奴隷のようなものであった。パリでは、彼女の展示は、科学的な人種差別とより明確に絡んでいた。フランスの科学者たちは、フ ランソワ・レヴァイヤンなどの博物学者がケープでコイサンに観察したとされる細長い陰唇が彼女にあるかどうか知りたがった[21]。フランスの博物学者、 中でも国立自然史博物館の動物園長であり比較解剖学の創始者のジョルジュ・キュヴィエは彼女を訪れた。1815年3月、王宮庭園に展示された彼女の絵画 は、自然科学者のエティエンヌ・ジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールとジョルジュの弟であるフレデリック・キュヴィエの報告によるものであった。自然科学者のエチ エンヌ・ジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールとジョルジュの弟フレデリック・キュヴィエは、「彼女は服を脱ぎ、裸体で描かれることを十分承知していた」と報告して いる。しかし、これは真実ではない。彼の基準では彼女は裸に見えるが、彼女自身の文化的な慎み深さの規範に従って、セッション中は性器を隠す小さなエプロ ンのような衣服をしていた[22]。彼女は、出席した科学者の一人がお金を提示しても、これを外すことを頑なに拒否した[4][2]。 131-134 彼女は裕福な人々のパーティーや個人のサロンで展示物として引き出された[8]。パリでは、バートマンのプロモーターは奴隷の罪を気にする必要はなかっ た。クレイズとスカリーは次のように述べている。「パリに着くまで、彼女の存在は実に惨めで、非常に貧しいものであった。サラは文字通り動物のように扱わ れていた。ある時、首輪が彼女の首にかけられたことを示唆するいくつかの証拠がある」[2] 生涯の終わりに、彼女は売春婦で、無一文だった[23][24]。 |

| Death and aftermath Baartman died on 29 December 1815 around age 26,[1] of an undetermined[25] inflammatory ailment, possibly smallpox,[26][27] while other sources suggest she contracted syphilis,[3] or pneumonia. Cuvier conducted a dissection but no autopsy to inquire into the reasons for Baartman's death.[2] The French anatomist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville published notes on the dissection in 1816, which were republished by Georges Cuvier in the Memoires du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle in 1817. Cuvier, who had met Baartman, notes in his monograph that its subject was an intelligent woman with an excellent memory, particularly for faces. In addition to her native tongue, she spoke fluent Dutch, passable English, and a smattering of French. He describes her shoulders and back as "graceful", arms "slender", hands and feet as "charming" and "pretty". He adds she was adept at playing the jew's harp,[28] could dance according to the traditions of her country, and had a lively personality.[29] Despite this, Cuvier interpreted her remains, in accordance with his theories on racial evolution, as evidencing ape-like traits. He thought her small ears were similar to those of an orangutan and also compared her vivacity, when alive, to the quickness of a monkey.[4] He was part of a movement of scientists who were aiming to codify a hierarchy of races with the white man at the top.[8] |

死とその余波 1815年12月29日、バートマンは26歳の時に死亡した[1]。原因不明の[25]炎症性疾患、おそらく天然痘[26][27]、他の資料では梅毒、 または肺炎に感染したとされている。キュヴィエはバートマンの死因を調べるために解剖を行ったが、剖検は行わなかった[2]。 フランスの解剖学者アンリ・マリー・デュクロテ・ド・ブランヴィルは1816年に解剖の記録を発表し、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエは1817年に 『Memoires du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle』に再掲載した。バートマンと面識のあったキュヴィエは、そのモノグラフの中で、解剖対象が知的な女性で、特に顔に関する記憶力に優れ ていたことを記している。彼女は母国語に加えて、流暢なオランダ語、流暢な英語、そしてフランス語を少し話すことができた。肩と背中は「優美」、腕は 「ほっそり」、手と足は「チャーミング」「かわいい」と書いている。それにもかかわらず、キュヴィエは彼女の遺骨を人種進化論に則って、猿に似た形質を示 すと解釈した[29]。彼は彼女の小さな耳はオランウータンの耳に似ていると考え、また生きている時の活発さを猿の素早さに例えた[4]。 彼は白人を頂点とする人種の階層を成文化しようとする科学者の運動の一員であった[8]。 |

| Display of remains Saint-Hilaire applied on behalf of the Muséum d' Histoire Naturelle to retain her remains (Cuvier had preserved her brain, genitalia and skeleton[8]), on the grounds that it was of singular specimen of humanity and therefore of special scientific interest.[4] The application was approved and Baartman's skeleton and body cast were displayed in Muséum d'histoire naturelle d’Angers. Her skull was stolen in 1827 but returned a few months later. The restored skeleton and skull continued to arouse the interest of visitors until the remains were moved to the Musée de l'Homme, when it was founded in 1937, and continued up until the late 1970s. Her body cast and skeleton stood side by side and faced away from the viewer which emphasised her steatopygia (accumulation of fat on the buttocks) while reinforcing that aspect as the primary interest of her body. The Baartman exhibit proved popular until it elicited complaints for being a degrading representation of women. The skeleton was removed in 1974, and the body cast in 1976.[4] From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her remains. A poem written in 1978 by South African poet Diana Ferrus, herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home", played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to her birth soil.[3] The case gained world-wide prominence only after American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote The Mismeasure of Man in the 1980s. Mansell Upham, a researcher and jurist specializing in colonial South African history, also helped spur the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to South Africa.[2] After the victory of the African National Congress (ANC) in the 1994 South African general election, President Nelson Mandela formally requested that France return the remains. After much legal wrangling and debates in the French National Assembly, France acceded to the request on 6 March 2002. Her remains were repatriated to her homeland, the Gamtoos Valley, on 6 May 2002,[30] and they were buried on 9 August 2002 on Vergaderingskop, a hill in the town of Hankey over 200 years after her birth.[31] Baartman became an icon in South Africa as representative of many aspects of the nation's history. The Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children,[32] a refuge for survivors of domestic violence, opened in Cape Town in 1999. South Africa's first offshore environmental protection vessel, the Sarah Baartman, is also named after her.[33] On 8 December 2018, the University of Cape Town made the decision to rename Memorial Hall, at the centre of the campus, to Sarah Baartman Hall.[34] This follows the earlier removal of "Jameson" from the former name of the hall. |

遺骨の展示 サン=ヒレールは自然博物館 に代わり、バートマンの遺骨(キュヴィエは脳、生殖器、骨格を保存していた[8])を、人類で唯一の標本であり、科学的に特別な関心があるとして保存を申 請した[4]。 この申請は認められ、骨格と遺体はアンジェ自然史博物館に展示されることになる。彼女の頭蓋骨は1827年に盗まれたが、数ヵ月後に戻ってきた。復元され た骨格と頭蓋骨は、1937年に設立された人間博物館に移されるまで、来館者の関心を集め続け、1970年代後半まで展示が続けられた。また、バートマン の遺体は、遺体と骨格が背中合わせになるように展示され、彼女の脂肪が臀部に蓄積していることを強調し、そのことが彼女の身体への関心事であることを強調 するものであった。バートマンの展示は人気を博したが、女性を卑下する表現であるとの苦情が寄せられた。骨格は1974年に取り除かれ、遺 体は1976年に石膏型取された[4]。 1940年代から、彼女の遺骨の返還を求める声が散見されるようになった。1978年にコイサン族出身の南アフリカの詩人ダイアナ・フェラスが書いた詩 「I've come to take you home」が、バートマンの遺骨を生家に戻す運動に重要な役割を果たした[3]。 この事件が世界的に知られるようになったのは、1980年代にアメリカの古生物学者スティーブン・ジェイ・グールドが「人間の尺度(The Mismeasure of Man)」を書いてからであった。1994年の南アフリカ総選挙でアフリカ民族会議(ANC)が勝利すると、ネルソン・マンデラ大統領はフランスに遺骨の 返還を正式に要請した[2]。多くの法的論争とフランス国民議会での議論の後、フランスは2002年3月6日にその要求に応じました。彼女の遺骨は2002年5月6日に彼女の故郷であるガムトゥース・バレーに送還され[30]、 2002年8月9日にハンケイの町の丘、バーガデリングスコップに生後200年以上経ってから埋葬された[31]。(※「フリクワ民族会 議」) バートマンは、南アフリカの歴史の様々な側面を代表する存在として、南アフリカの象徴となった。1999年、ケープタウンにDV被害者のための避難所 「Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children」[32]が開設された[33]。南アフリカ初の洋上環境保護船「サラ・バートマン号」も彼女の名前にちなんでいる[33]。 2018年12月8日、ケープタウン大学はキャンパスの中心にあるメモリアルホールをサラ・バートマンホールに改名する決定を下した[34]。 これは、先にホールの旧名から「ジェイムソン」が削除されたことを受けたものである。 |

| Symbolism Sarah Baartman was not the only Khoikhoi to be taken from her homeland. Her story is sometimes used to illustrate social and political strains, and through this, some facts have been lost. Dr. Yvette Abrahams, professor of women and gender studies at the University of the Western Cape, writes, "we lack academic studies that view Sarah Baartman as anything other than a symbol. Her story becomes marginalized, as it is always used to illustrate some other topic." Baartman is used to represent African discrimination and suffering in the West although there were many other Khoikhoi people who were taken to Europe. Historian Neil Parsons writes of two Khoikhoi children 13 and six years old respectively, who were taken from South Africa and displayed at a holiday fair in Elberfeld, Prussia, in 1845. Bosjemans, a travelling show including two Khoikhoi men, women, and a baby, toured Britain, Ireland, and France from 1846 to 1855. P. T. Barnum's show "Little People" advertised a 16-year-old Khoikhoi girl named Flora as the "missing link" and acquired six more Khoikhoi children later.[citation needed] Baartman's tale may be better known because she was the first Khoikhoi taken from her homeland, or because of the extensive exploitation and examination of her body by scientists such as Georges Cuvier, an anatomist, and the public as well as the mistreatment she received during and after her lifetime. She was brought to the West for her "exaggerated" female form, and the European public developed an obsession with her reproductive organs. Her body parts were on display at the Musée de l'Homme for 150 years, sparking awareness and sympathy in the public eye. Although Baartman was the first Khoikhoi to land in Europe, much of her story has been lost, and she is defined by her exploitation in the West.[35] |

シンボリズム 故郷を追われたコイコイは、サラ・バートマンだけではない。彼女の物語は、社会的、政治的な歪みを説明するために使われることがあり、これを通して、いく つかの事実が失われてきた。西ケープ大学の女性学・ジェンダー学教授であるイヴェット・アブラハムズ博士は、「サラ・バートマンを象徴以外のものとしてと らえる学術的な研究が不足している」と書いている。彼女の物語は、常に他のテーマを説明するために使われるため、疎外されてしまうのです」。バートマン は、西洋におけるアフリカ人の差別と苦しみの象徴として使われているが、ヨーロッパに連れて行かれたコイコイ族は他にもたくさんいた。歴史家のニール・ パーソンズは、1845年にプロイセンのエルバーフェルトで開かれた見本市に、南アフリカから連れて行かれた13歳と6歳のコイコイの子供たちについて書 いている。2人のコイ族の男性、女性、赤ん坊を含む旅芝居「Bosjemans」は、1846年から1855年にかけてイギリス、アイルランド、フランス を巡業しました。P・T・バーナムのショー「リトル・ピープル」はフローラという16歳のコイコイの少女を「ミッシング・リンク」として宣伝し、その後さ らに6人のコイコイの子供を獲得した[citation needed]。 バートマンの物語は、彼女が故郷から連れ去られた最初のコイ族であることや、解剖学者ジョルジュ・キュヴィエなどの科学者や一般人による彼女の体の大規模 な搾取と検査、また彼女が生前と生後に受けた虐待のためによく知られているかもしれない。彼女はその「誇張された」女性像のために西洋にもたらされ、ヨー ロッパの人々は彼女の生殖器官に執着するようになった。彼女の体の一部は150年間、人間博物館に展示され、世間に認識と共感を呼び起こした。バートマン はヨーロッパに上陸した最初のコイコイ人であったが、彼女の物語の多くは失われ、彼女は西洋での搾取によって定義されている[35]。 |

| Her body as a foundation for

scientific racism Julien-Joseph Virey used Sarah Baartman's published image to validate racial typologies. In his essay "Dictionnaire des sciences medicales" (Dictionary of medical sciences), he summarizes the true nature of the black female within the framework of accepted medical discourse. Virey focused on identifying her sexual organs as more developed and distinct in comparison to white female organs. All of his theories regarding sexual primitivism are influenced and supported by the anatomical studies and illustrations of Sarah Baartman which were created by Georges Cuvier.[36] It has been suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once more widespread in humans, based on carvings of idealised female forms dating to the Paleolithic era which are collectively known as Venus figurines, also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses.[3] |

科学的人種差別の基礎となる彼女の身体 ジュリアン=ジョセフ・ヴィレイは、サラ・バートマンの公開された画像を用いて、人種的類型を検証している。彼は『医学辞典』というエッセイの中で、黒人 女性の本質を医学的言説の枠組みの中で要約している。ヴィレは、白人女性の性器に比べ、彼女の性器がより発達し、特徴的であることに注目した。性的原始主 義に関する彼の理論はすべて、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエが作成したサラ・バートマンの解剖学的研究と図版に影響を受け、支持されている[36]。 旧石器時代の理想的な女性の姿の彫刻に基づいて、この体型がかつて人類に広く存在していたことが人類学者によって示唆されており、それらは総称してヴィー ナスの置物として知られており、ステアトピーのヴィーナスとも呼ばれている[3]。 |

| Sexism From 1814 to 1870, there were at least seven scientific descriptions of the bodies of black women done in comparative anatomy. Cuvier's dissection of Baartman helped shape European science. Baartman, along with several other African women who were dissected, were referred to as Hottentots, or sometimes Bushwoman. The "savage woman" was seen as very distinct from the "civilised female" of Europe, thus 19th-century scientists were fascinated by "the Hottentot Venus". In the 1800s, people in London were able to pay two shillings apiece to gaze upon her body. Baartman was considered a freak of nature. For extra pay, one could even poke her with a stick or finger. |

性差別 1814年から1870年にかけて、比較解剖学で行われた黒人女性の身体に関する科学的記述は少なくとも7つあった。キュヴィエによるバートマンの解剖 は、ヨーロッパの科学の形成に貢献した。バートマンは、解剖された他の数人のアフリカ人女性とともに、ホッテントット、または時にはブッシュウーマンと呼 ばれた。未開の女性」は、ヨーロッパの「文明化された女性」とは全く異なる存在として捉えられていたため、19世紀の科学者は「ホッテントットのヴィーナ ス」に魅了されたのである。1800年代には、ロンドンの人々が1人2シリングを支払って彼女の体を眺めることができたという。バートマンは自然界の怪物 と見なされていた。さらにお金を払えば、棒や指で彼女をつつくこともできた。 |

| Colonialism There has been much speculation and study about colonialist influence that relates to Baartman's name, social status, her illustrated and performed presentation as the "Hottentot Venus" though considered an extremely offensive term, and the negotiation for her body's return to her homeland.[2][4] These components and events in Baartman's life have been used by activists and theorists to determine the ways in which 19th-century European colonists exercised control and authority over Khoikhoi people and simultaneously crafted racist and sexist ideologies about their culture.[16] In addition to this, recent scholars have begun to analyze the surrounding events leading up to Baartman's return to her homeland and conclude that it is an expression of recent contemporary post colonial objectives.[4] In Janet Shibamoto's book review of Deborah Cameron's book Feminism and Linguistic Theory, Shibamoto discusses Cameron's study on the patriarchal context within language, which consequentially influences the way in which women continue to be contained by or subject to ideologies created by the patriarchy.[37] Many scholars have presented information on how Baartman's life was heavily controlled and manipulated by colonialist and patriarchal language.[2]: 131–134 Baartman grew up on a farm. There is no historical documentation of her indigenous Khoisan name.[35] She was given the Dutch name "Saartjie" by Dutch colonists who occupied the land she lived on during her childhood. According to Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully: Her first name is the Cape Dutch

form for "Sarah" which marked her as a colonialist's servant. "Saartje"

the diminutive, was also a sign of affection. Encoded in her first name

were the tensions of affection and exploitation. Her surname literally

means "bearded man" in Dutch. It also means uncivilized, uncouth,

barbarous, savage. Saartjie Baartman – the savage servant.[2]: 9

Dutch colonisers also bestowed the term "Hottentot", which is derived from "hot" and "tot", Dutch approximations of common sounds in the Khoi language.[38] The Dutch used this word when referencing Khoikhoi people because of the clicking sounds and staccato pronunciations that characterise the Khoikhoi language; these components of the Khoikhoi language were considered strange and "bestial" to Dutch colonisers.[4] The term was used until the late 20th century, at which point most people understood its effect as a derogatory term.[39] Travelogues that circulated in Europe would describe Africa as being "uncivilised" and lacking regard for religious virtue.[4] Travelogues and imagery depicting Black women as "sexually primitive" and "savage" enforced the belief that it was in Africa's best interest to be colonised by European settlers. Cultural and religious conversion was considered to be an altruistic act with imperialist undertones; colonisers believed that they were reforming and correcting Khoisan culture in the name of the Christian faith and empire.[4] Scholarly arguments discuss how Baartman's body became a symbolic depiction of "all African women" as "fierce, savage, naked, and untamable" and became a crucial role in colonising parts of Africa and shaping narratives.[40] During the lengthy negotiation to have Baartman's body returned to her home country after her death, the assistant curator of the Musée de l'Homme, Philippe Mennecier, argued against her return, stating: "We never know what science will be able to tell us in the future. If she is buried, this chance will be lost ... for us she remains a very important treasure." According to Sadiah Qureshi, due to the continued treatment of Baartman's body as a cultural artifact, Philippe Mennecier's statement is contemporary evidence of the same type of ideology that surrounded Baartman's body while she was alive in the 18th century.[4] |

植民地主義 バートマンの名前、社会的地位、「ホッテントットのヴィーナス」という極めて不快な言葉でありながらイラストやパフォーマンスで表現したこと、そして彼女 の身体を祖国に返すための交渉に関連する植民地主義の影響については多くの推測や研究がなされてきた[2][4]。 [バートマンの人生におけるこれらの構成要素や出来事は、活動家や理論家によって、19世紀のヨーロッパの植民者がコイコイ族に対して支配と権威を行使 し、同時に彼らの文化について人種差別的、性差別的なイデオロギーを作り上げた方法を決定するために用いられてきた[16]。これに加えて、最近の学者た ちはバートマンが祖国に戻るまでの周辺の出来事を分析し、それが最近の現代のポスト植民地の目的の表現であると結論付け始めている[4]。 ジャネット柴本はデボラ・キャメロンの著書『フェミニズムと言語理論』の書評の中で、キャメロンの言語内の家父長制的文脈に関する研究を取り上げ、その結 果、女性が家父長制によって作られたイデオロギーに含まれ続ける、あるいは従う方法に影響を与えていると述べている[37] 多くの学者が、バートマンの人生がいかに植民主義者と家父長制的言語によって大きく制御され、操作されていたかを情報として示している[2]: 131- 134 バートマンは農家で育った。彼女の先住民コイサン族の名前に関する歴史的資料はない[35]。 彼女は幼少期に住んでいた土地を占領していたオランダ人入植者によって「サートジィ」というオランダ名を与えられた。クリフトン・クレイスとパメラ・スカ リーによる。 「彼女のファーストネームは、ケープタッチ語で「サラ」を意味するもの

で、植民地時代の使用人であることを表している。また、「Saartje」という短縮形は、愛情を示すものでもあった。彼女のファーストネームには、愛情

と搾取の緊張関係が内包されている。彼女の苗字は、オランダ語で文字通り「ひげを生やした男」を意味する。また、未開の、野生の、野蛮な、野蛮人という意

味もある。Saartjie Baartman - 野蛮な使用人[2]: 9」

オランダの植民者は「ホッテントット」という言葉も与えた。これは、コイ語の一般的な音をオランダ語で近似した「ホット」と「トット」に由来する [38]。 [この言葉はコイ語の特徴であるクリック音と澱んだ発音のため、オランダ人がコイ族を指す際に使用された[4]。 ヨーロッパで流布した旅行記はアフリカを「未開」であり宗教的な美徳を無視していると描写していた[4]。黒人女性を「性的に原始的」で「野蛮な」ものと して描いた旅行記やイメージは、ヨーロッパの入植者によって植民地にされることがアフリカにとって最善の利益であるという確信を強めていた。文化的、宗教 的な転換は、帝国主義的な含みを持つ利他的な行為と考えられていた。植民者はキリスト教の信仰と帝国の名の下にコイサン文化を改革し修正していると信じて いた[4]。学者たちの議論は、バートマンの身体が「すべてのアフリカ女性」の象徴的描写として「激しく、野蛮で裸で手懐けない」ものになり、アフリカの 一部を植民地にし物語りを形成する重要な役割になっていることを論じている[40]。 バートマンの死後、彼女の遺体を母国に戻すための長い交渉の間、人間博物館の学芸員補佐であるフィリップ・メネシエは彼女の返還に反対し、次のように述べ た。「科学が将来何を解明してくれるかは分からない。もし彼女が埋もれてしまったら、このチャンスは失われてしまう......私たちにとって、彼女はと ても重要な宝物であることに変わりはないのです」。サディア・クレシによれば、バートマンの遺体が文化財として扱われ続けていることから、フィリップ・メ ネシエの発言は、18世紀に生存していたバートマンの遺体を取り巻くのと同じ種類のイデオロギーを現代に伝える証拠である[4]。 |

| Traditional iconography of Sarah

Baartman and feminist contemporary art Many African female diasporic artists have criticised the traditional iconography of Baartman. According to the studies of contemporary feminists, traditional iconography and historical illustrations of Baartman are effective in revealing the ideological representation of black women in art throughout history. Such studies assess how the traditional iconography of the black female body was institutionally and scientifically defined in the 19th century.[36] Renee Cox, Renée Green, Joyce Scott, Lorna Simpson, Cara Mae Weems and Deborah Willis are artists who seek to investigate contemporary social and cultural issues that still surround the African female body. Sander Gilman, a cultural and literary historian states: "While many groups of African Blacks were known to Europeans in the 19th century, the Hottentot remained representative of the essence of the Black, especially the Black female. Both concepts fulfilled the iconographic function in the perception and representation of the world."[36] His article "Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in the Late Nineteenth Century Art, Medicine and Literature" traces art historical records of black women in European art, and also proves that the association of black women with concupiscence within art history has been illustrated consistently since the beginning of the Middle Ages.[36] Lyle Ashton Harris and Renee Valerie Cox worked in collaboration to produce the photographic piece Hottentot Venus 2000. In this piece, Harris photographs Victoria Cox who presents herself as Baartman while wearing large, sculptural, gilded metal breasts and buttocks attached to her body.[41] According to Deborah Willis, the paraphernalia attached to Cox's body are markers for the way in which Baartman's sexual body parts were essential for her constructed role or function as the "Hottentot Venus". Willis also explains that Cox's side-angle shot makes reference to the "scientific" traditional propaganda used by Cuvier and Julian-Joseph Virey, who sourced Baartman's traditional illustrations and iconography to publish their "scientific" findings.[41] Reviewers of Harris and Cox's work have commented that the presence of "the gaze" in the photograph of Cox presents a critical engagement with previous traditional imagery of Baartman.[4] bell hooks has elaborated further on the function of the gaze: The gaze has been and is a site of resistance for colonized black people globally. Subordinates in relations of power learn experientially that there is a critical gaze, one that "looks" to document, one that is oppositional. In resistance struggle, the power of the dominated to assert agency by claiming and cultivating "awareness" politicizes "looking" relations – one learns to look a certain way in order to resist.[42] "Permitted" is an installation piece created by Renée Green inspired by Sarah Baartman. Green created a specific viewing arrangement to investigate the European perception of the black female body as "exotic", "bizarre" and "monstrous". Viewers were prompted to step onto the installed platform which was meant to evoke a stage, where Baartman may have been exhibited. Green recreates the basic setting of Baartman's exhibition. At the centre of the platform, which there is a large image of Baartman, and wooden rulers or slats with an engraved caption by Francis Galton encouraging viewers to measure Baartman's buttocks. In the installation there is also a peephole that allows viewers to see an image of Baartman standing on a crate. According to Willis, the implication of the peephole, demonstrates how ethnographic imagery of the black female form in the 19th century functioned as a form of pornography for Europeans present at Baartmans exhibit.[41] In her film Reassemblage: From the firelight to the screen, Trinh T. Minh-ha comments on the ethnocentric bias that the colonisers eye applies to the naked female form, arguing that this bias causes the nude female body to be seen as inherently sexually provocative, promiscuous and pornographic within the context of European or western culture.[43] Feminist artists are interested in re-representing Baartman's image, and work to highlight the stereotypes and ethnocentric bias surrounding the black female body based on art historical representations and iconography that occurred before, after and during Baartman's lifetime.[41] |