Not Ghost

in Machine but Ghost in Human

Not Ghost

in Machine but Ghost in Human

「今日は特別に媽 祖様にお伺いを立てにきました。20年後の台湾を考えれば、2020年の選挙はとても重要であり、私が出馬すべきかどうか。 実は、媽祖様は数日前、夢で私に掲示を与えてくださった。媽祖は夢に託して出馬を求めてきた。私は彼女の命ずるところに従う」—— 2019年4月17日テ リー・ゴウ(ホンハイ創業者)

テリー・ゴウ(郭台銘[Terry

Gou], 1950- )の中に媽祖は現れ、総統(=大統領に相当)選挙に出馬せよとお告げをした報道である。媽祖を「亡霊」と呼ぶの

はその崇敬者に失礼だが、目に見えない実体のないものという意味でのゴースト(亡霊)である。亡霊は人間の中におわしましたのである。そして、人間の行動

を変えることに成功する。

ちなみに「機械の中の幽霊」とは、デカルトの、内的に省察 する自己のドグマ(身体=機械から切り離された内省する自己=幽霊)に関 するギルバート・ライル(Gilbert Ryle, 1900-1976)による批判の表現である。デカルトは心(res cogitans)と身体(res extensa)をわけ、前者に、直観、自由、分割不能、破壊不能そして自由意志という特権的な立場を与え、自己としての同一性の根拠も 心にあるものとして扱われる。にもかかわらず、我々は心と身体の両方をもつ存在としてある。あるいは、他方で、私というものは、私の身体と関連づけられて はじめて意味をもつ。このような矛盾が共存する、デカルトの人間観を嘲笑して、ギルバート・ライルは、我々は機械(身体)の中に住む幽 霊(心)なのだと表現した(→「機械の中の幽霊」)。

人間の中のゴーストは、明らかにデカルト

的でオカルト的な心の概念(「機械の中の幽霊」)を隠喩するテーマと

議論がさまざまなところで交錯す

る。

++++++++++++

媽祖(莆仙語:Mâ-cô;閩南語:Má-tsoó͘;閩東語: Mā-cū)是以中國華南、臺灣為中心、擴及東亞(琉球、日本及新加坡等東南亞地區)沿海一帶的海神信仰(又稱天上聖母 、天后、天妃、天妃娘娘、湄洲娘媽、媽祖婆等)。媽祖影響力由福建湄洲傳播,歷經千百年,對東亞海洋文化及南中國海產生重大影響,稱為媽祖文化」- 媽祖.

Matsu (mitología);

Matsu (en chino: 媽祖), también conocida entre

otros nombres como Tian Fei o Tianfei y Tian Hou, es la diosa del mar

en la mitología china y ampara y protege a pescadores y marineros.

Tiene un lugar en los panteones taoísta y budista mahayana.- Matsu

(mitología).

++++++++++++

| Mazu or Matsu

is a sea goddess in Chinese folk religion, Chinese Buddhism,

Confucianism, and Taoism. She is also known by several other names and

titles. Mazu is the deified form of Lin Moniang (Chinese: 林默娘; pinyin:

Lín Mòniáng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lîm Be̍k-niû / Lîm Bia̍k-niû / Lîm Be̍k-niô͘),

a shamaness from Fujian who is said to have lived in the late 10th

century. After her death, she became revered as a tutelary deity of

Chinese seafarers, including fishermen and sailors. Her worship spread throughout China's coastal regions and overseas Chinese communities throughout Southeast Asia, where some Mazuist temples are affiliated with famous Taiwanese temples. Mazu was traditionally thought to roam the seas, protecting her believers through miraculous interventions. She is now generally regarded by her believers as a powerful and benevolent Queen of Heaven. Mazu worship is popular in Taiwan because many early Chinese settlers in Taiwan were Hoklo people from Fujian. Her temple festival is a major event in Taiwan, with the largest celebrations occurring in and around her temples at Dajia and Beigang. |

媽

祖は、中国の民間宗教、中国仏教、儒教、道教における海の女神である。媽祖は、林茂名(中国語:林默娘。媽祖は、林茂名(中国語:林默娘、ピンイン:

Lín Mòniáng、Pe̍-ōe-jī:

10世紀後半に生きたとされる福建省出身の巫女である。彼女の死後、漁師や船乗りなど中国の船乗りの守護神として崇められるようになった。 媽祖信仰は、中国の沿岸地域や東南アジアの華僑社会に広まり、台湾の有名な寺院と提携している媽祖廟もある。媽祖は伝統的に海を彷徨い、奇跡的な介入によって信者を守護すると考えられていた。現在では、媽祖は強力で慈悲深い天の女王と信者にみなされている。 媽祖信仰は台湾で人気があるが、これは台湾に入植した初期の中国人の多くが福建省出身のホクロ人だったからである。媽祖廟の祭りは台湾の一大イベントであり、大甲と北港の媽祖廟とその周辺で最大の祭りが行われる。 |

| Names and titles In addition to Mazu [1][2] or Ma-tsu, meaning "Maternal Ancestor"[3] "Mother",[4] "Granny", or "Grandmother",[5] Lin Moniang is worshipped under other names and titles: Mazupo [6][1] (妈祖婆; 媽祖婆; 'Granny Mazu') or Ma Cho Po in Hokkien, a popular name in Fujian[6][1] A-Ma, also spelled Ah-Ma (阿媽; 'Mother', 'Grandmother'), a popular name in Macau[7] Linghui Furen[6] ("Lady of Numinous Grace"), an official title conferred in 1156.[6][8] Linghui Fei[6] ("Princess of Numinous Grace"), an official title conferred in 1192.[6] Tianfei ("Princess of Heaven", Wu Chinese: Thi-fi),[1][9] fully Huguo Mingzhu Tianfei[6] ("Illuminating Princess of Heaven who Protects the Nation"), an official title conferred in 1281.[6][10] Huguo Bimin Miaoling Zhaoying Hongren Puji Tianfei ("Heavenly Princess who Protects the Nation and Shelters the People, of Marvelous Numen, Brilliant Resonance, Magnanimous Kindness, and Universal Salvation"), an official title conferred in 1409.[8] Tianhou or Tianhou Shengmu (title used mostly in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Vietnam), also called Tin Hau in Cantonese, Thean Hou in Min Chinese and Thiên Hậu in Vietnamese (天后; 'Queen/Empress of Heaven'),[2] an official title conferred in 1683.[10] Tianshang Shengmu ("Holy Heavenly Mother"; title used mostly in Taiwan)[10] Tongxian Lingnü (通贤灵女; 通賢靈女; 'Worthy & Efficacious Lady')[11] Shennü (神女; 'Divine Woman')[12] Zhaoxiao Chunzheng Fuji Ganying Shengfei[6] ("Holy Princess of Clear Piety, Pure Faith, and Helpful Response"), an official title conferred during the reign of the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming.[6] Gupozu (姑婆祖; 'Great-Grandaunt'), an unofficial title used by descendants whose surname is "Lin(林)", due to sharing the same surname Lin. Although many of Mazu's temples honor her titles Tianhou and Tianfei, it became customary to never pray to her under those names during an emergency since it was believed that, hearing one of her formal titles, Mazu might feel obligated to groom and dress herself as properly befitting her station before receiving the petition. Prayers invoking her as Mazu were thought to be answered more quickly.[13] |

名前と称号 媽祖」[1][2]、「母祖」[3]、「母」[4]、「おばあさん」[5]を意味する「媽祖」[6][6][7]に加えて、林聞江は他の名前や称号でも崇拝されている: マズポ[6][1](妈祖婆;「媽祖婆」)、あるいは福建省[6][1]でよく使われる福建語のマー・チョー・ポー(Ma Cho Po)である。 阿媽は阿媽とも表記され、マカオで人気のある名前である[7]。 1156年に授けられた公式称号である[6][8]。 霊妃飛[6](「ヌミナスグレイスのプリンセス」)は1192年に授けられた公式称号である[6]。 天妃(てんひ)[1][9]は、1281年に授けられた官位である[6][10]。 天后賓妙玲招英紅蓮普済天妃(「国民を守り、人民を庇護する天妃、驚嘆すべき沼、燦然たる響き、雄大な優しさ、万民を救済する」)は、1409年に授けられた官位である[8]。 天后または天后聖武(主に中国本土、香港、ベトナムで使用される称号)は、広東語ではティン・ハウ(Tin Hau)、ミン語ではテアン・ホウ(Thean Hou)、ベトナム語ではティエン・ハウ(Thiên Hậu)(天后;「天后」)とも呼ばれ[2]、1683年に授与された公式称号である[10]。 天后聖母(てんしょうしょうぼ)[10]。 通賢靈女(通贤灵女、通賢靈女)[11]。 神女(しんめ)[12]。 明の洪武帝の時代に授けられた公式称号である[6]。 姑婆祖」(姑婆祖、「大祖母」)は、「林」という同じ姓を持つことから、「林」という姓を持つ子孫が使う非公式の称号である。 媽祖の廟の多くは「天后」と「天妃」を称えているが、媽祖の正式な称号を聞くと、媽祖が身だしなみを整え、身なみを整えてから祈願を受けなければならない と思われるため、緊急時にはこれらの称号で祈願しないのが慣例となっている。媽祖として祈願すれば、より早く答えられると考えられていた[13]。 |

History The alleged tomb of Lin Moniang in Nangan in the Matsu Islands Very little is known of the historical Lin Moniang.[3] She was apparently a shamaness from a small fishing village on Meizhou Island, part of Fujian's Putian County,[6] in the late 10th century.[3] She probably did not live there, but on the nearby mainland.[14][a] During this era, Fujian was greatly sinicized by influxes of refugees fleeing invasions of northern China and it has been hypothesised that Mazu's cult represented a hybridization of Chinese and native indigenous culture.[16] The earliest record of her cult is from two centuries later, an 1150 inscription that mentions "she could foretell a man's good and ill luck" and, "after her death, the people erected a temple for her on her home island".[3] |

歴史 馬祖の南竿にある林望の墓とされる場所 彼女は10世紀後半に福建省福田県の一部である梅州島の小さな漁村[6]に住んでいた巫女であったようだ。[14][a]この時代、福建省は中国北部の侵 略から逃れてきた難民の流入によって大きく中国化しており、媽祖の信仰は中国と先住民の文化の混成であったという仮説が立てられている[16]。彼女の信 仰に関する最古の記録は2世紀後の1150年の碑文であり、「彼女は人の吉凶を予言することができた」「彼女の死後、人民は故郷の島に彼女のための寺院を 建立した」と記されている[3]。 |

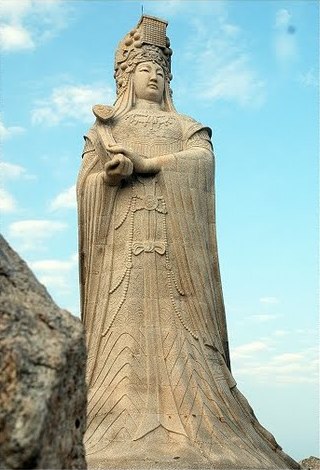

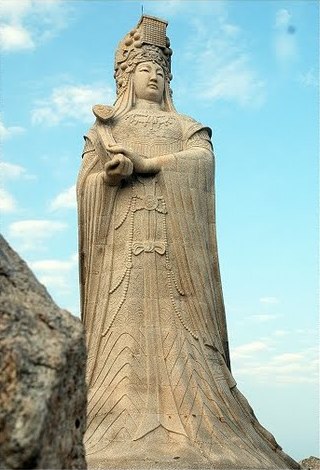

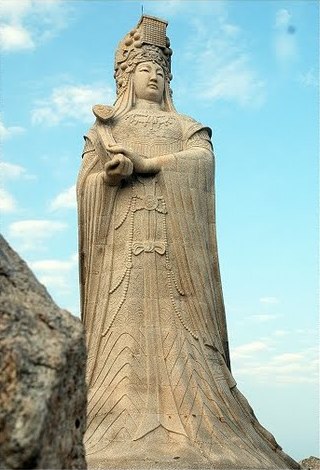

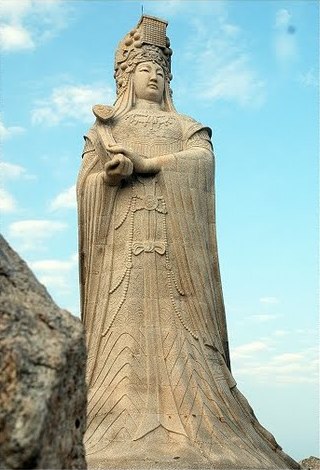

Legend A statue of Mazu Goddess near Meizhou Mazu Temple grounds in Meizhou Island, Fujian, China The legends around Lin Moniang's life were broadly established by the 12th century.[3] She was said to have been born under the reign of the Quanzhounese warlord Liu Congxiao (d. 962), in the Min Kingdom,[3] which eventually developed into the specific date of the 23rd day of the third month of the Chinese lunar calendar[11][b] in AD 960, the first year of the Song.[c] The late Ming Great Collection of the Three Teachings' Origin and Development and Research into the Divine, placed her birth much earlier, in 742.[19] The early sources speak of her as "Miss Lin". Her given name Mo ("Silent One")[20] or Moniang ("the Silent Girl") appeared later. It was said to have been chosen when she did not cry during birth[4] or during the first month afterwards. She remained a quiet and pensive child as late as four.[20] She was said to have been the sixth[4] or seventh daughter of Lin Yuan (林願). He is now usually remembered as one of the local fishermen,[4] although the 1593 edition of the Records of Research into the Divine made him Putian's chief military inspector.[10] The family was helpful and popular within their village.[4] Late legends intended to justify Mazu's presence in Buddhist temples held that her parents had prayed to Guanyin for a son but received yet another daughter.[4] In one version, her mother dreamt of Guanyin giving her a magical pill to induce pregnancy and woke to find the pill still in her hand.[4] Rather than being born in the conventional way, Mazu shot from her mother at birth in the form of a fragrant flash of red light.[20] Mazu was said to have been especially devoted to Guanyin or was even an incarnation of Guanyin.[21][22] For her part, Mazu was said to have been entranced by a statue of Guanyin at a temple she visited as a child, after which she became an ardent Buddhist.[20] She is now often said to have studied religious literature,[23] mastering Confucius by 8 and the principal Buddhist sutras by 11.[5] The Account of the Blessings Revealed by the Princess of Heaven (天妃顯聖錄; 天妃显圣录; Tiānfēi Xiǎnshèng Lù) collected by her supposed descendants Lin Yaoyu (林堯俞; 林尧俞; Lín Yáoyú; fl. 1589) and Lin Linchang (林麟焻; Lín Línchàng; fl. 1670) claimed that, while still a girl, she was visited by a Taoist master (elsewhere a Buddhist monk)[20] named Xuantong (玄通; Xuántōng) who recognized her Buddha nature. By 13, she had mastered the book of lore he had left her (玄微袐法; Xuánwēi Bìfǎ)[8] and gained the abilities to see the future and visit places in spirit without travel.[20] She was able to manifest herself at a distance as well and used this power to visit gardens in the surrounding countryside, although she asked owners' permission before gathering any flowers to take home.[20] Although she only started swimming at the relatively late age of 15, she soon excelled at it. She was said to have stood on the shore in red garments to guide fishing boats home, regardless of harsh or dangerous weather. She met a Taoist immortal at a fountain[20] at sixteen and received an amulet[8] or two bronze tablets, which she translated[20] or used to exorcize demons, to heal the sick,[5] and to avert disasters.[20] She was said to be a rainmaker during times of drought.[23] Mazu's principal legend concerns her saving one or some members of her family, when they were caught offshore during a typhoon, usually when she was 16.[23] It appears in several forms. In one, the women at home feared Lin Yuan and his son were lost but Mazu fell into a trance while weaving at her loom. Her spiritual power began to save the men from drowning but her mother roused her, causing her to drop her brother into the sea. The father returned and told the other villagers of the miracle. This version of the story is preserved in murals at Fengtin in Fujian.[22] One variant is that her brothers were saved, but her father was lost.[23] She then spent three days and nights searching for his body before finding it.[13] Another version is that all the men returned safely.[23] Another is that Mazu was praying to Guanyin; another that she was sleeping and assisting her family through her dream.[21] Another is that the boats were crewed by her four brothers and that she saved three of them, securing their boats together, with the eldest lost owing to the interference of her parents, who mistook her trance for a seizure and woke her.[19] In earlier records, Mazu died unmarried at 27 or 28.[3] Her celibacy was sometimes ascribed to a vow she took after losing her brother at sea.[19] The date of her passing eventually became the specific date of the Double Ninth Festival in 987,[24] making her 27 by western reckoning and 28 by traditional Chinese dating. She was said to have died in meditation.[19] In some accounts she did not die, but climbed a mountain alone and ascended into Heaven as a goddess[23] in a beam of bright light.[24] In others, she died protesting an unwanted betrothal.[3] Another places her death at age 16, saying she drowned after exhausting herself in a failed attempt to find her lost father, underlining her filial piety.[8][23] Her corpse then washed ashore on Nangan Island, which preserves a gravesite said to be hers. |

伝説 中国福建省梅州島の梅州媽祖廟近くにある媽祖像 林望の生涯にまつわる伝説は、12世紀には広く確立されていた[3]。 彼女はミン王国の全州人の武将である劉公暁(962年没)の治世下で生まれたとされ[3]、最終的には宋の元年である西暦960年の旧暦3月23日[11][b]という具体的な日付に発展した[c]。 初期の資料では、彼女は「ミス・リン」と呼ばれていた。彼女の名である莫(「無言の者」)[20]あるいは聞香(「無言の少女」)は後に登場した。出産時 [4]、あるいは出産後の最初の1ヶ月間、彼女が泣かなかったことから名付けられたと言われている。彼女は4歳になっても物静かで物思いにふける子供で あった[20]。林元の6女[4]あるいは7女であったと言われている。1593年版の『神皇紀』では普天の軍監とされているが[10]、現在では地元の 漁師の一人として記憶されている[4]。 媽祖が仏教寺院にいることを正当化するための後世の伝説では、媽祖の両親は観音菩薩に男児を祈願したが、また別の娘を授かったとされている[4]。[4] 媽祖は通常の方法で生まれるのではなく、香ばしい赤い閃光の形で母親から生まれた。[20]媽祖は特に観音に帰依していたとも、観音の化身であったとも言 われている。 現在、彼女はしばしば宗教文学を学んだと言われ[23]、8歳までに孔子を、11歳までに仏教の主要な経典をマスターした。[5]彼女の子孫とされる林堯 俞(りんぎょう;林剾俞)と林林昌(りんりんしょう;林剾俞)が集めた『天妃聖錄』(てんひしょうろく;天妃显圣录;Tiānfēi Xiǎnshèng Lù)がある。 1589年)と林林昌(林麟焻; Lín Línchàng; 1670年)は、彼女がまだ少女の頃、玄通(Xuántōng; Xuantong)という名の道教の師(仏教の僧侶)の訪問を受けたと主張している[20]。13歳までに、彼女は彼の残した伝承書(玄微袐法; Xuánwēi Bìfǎ)をマスターし[8]、未来を見たり、旅をせずに霊的な場所を訪れたりする能力を得た[20]。 彼女は遠く離れた場所にも姿を現すことができ、この力を使って周辺の田園地帯の庭園を訪れたが、花を採取して持ち帰る際には持ち主の許可を得ていた [20]。彼女は、厳しい天候や危険な天候に関係なく、漁船を家まで導くために赤い衣を着て海岸に立っていたと言われている。彼女は16歳のときに泉 [20]で道教の仙人に出会い、お守り[8]や2枚の青銅の石版をもらい、それを翻訳[20]したり、悪魔を祓ったり、病気を治したり[5]、災いを避け るために使ったりした[20]。 媽祖の主な伝説は、台風の際に沖合で巻き込まれた家族の一人または数人を彼女が救ったというもので、通常は彼女が16歳の時であった[23]。媽祖は機織 りをしているときに恍惚状態に陥り、媽祖の霊力が男たちを救い始めた。彼女の霊力は男たちを溺れから救おうとし始めたが、母親が彼女を奮い立たせ、弟を海 に落としてしまった。父親は戻ってきて、他の村人たちに奇跡を伝えた。この説話は福建省の鳳潭の壁画に残されている[22]。 別の説では、媽祖は観音に祈りを捧げていたという説もあり[23]、また別の説では、媽祖は眠っていて、夢を通して家族を助けたという説もある[21]。 [21]また別の説では、媽祖の船には4人の兄弟が乗り組んでいたが、媽祖はそのうちの3人を助け、船を一緒に固定し、長女は発作と間違えて起こした両親 の妨害によって失ったという[19]。 それ以前の記録では、媽祖は27歳か28歳で未婚のまま亡くなっている[3]。彼女の独身は、兄を海で失った後に立てた誓いのためとされることもあった [19]。彼女は瞑想中に死んだと言われている[19]。ある説では、彼女は死なず、一人で山に登り、明るい光を浴びて女神として天に昇った[23]。 [3]また、16歳で亡くなったとする説もあり、行方不明の父親を探すのに失敗し、溺れ死んだとして、彼女の親孝行を強調している[8][23]。 |

Myths A statue of Mazu (center), carrying a lantern and ceremonial ruyi, in Weihai In addition to the legends surrounding her earthly life, Mazu figures in a number of Chinese myths: In one, the demons Qianliyan ("Thousand-Mile Eye") and Shunfeng'er ("Wind-Following Ear") both fell in love with her and she conceded that she would marry the one who defeated her in combat. Using her martial arts skills, however, she subdued them both and, after becoming friends, hired them as her guardian generals.[25] In a book of the Taoist Canon (太上老君說天妃救苦靈驗經; 太上老君说天妃救苦灵验经; Tàishàng Lǎojūn Shuō Tiānfēi Jiùkǔ Língyàn Jīng), the Jade Woman of Marvelous Deeds (妙行玉女) is a star from the Big Dipper brought to earth by Laojun, the divine form of Laozi, to show his compassion for those who might be lost at sea. She is incarnated as Mazu and swears not only to protect sailors but to oversee all facets of life and death, providing help to anyone who might call upon her.[8] |

神話 ランタンと儀式用の如意棒を持った媽祖像(中央)。 媽祖の地上での生涯にまつわる伝説に加え、媽祖は中国の神話にも数多く登場する: 千里眼と順風耳が媽祖に恋をし、媽祖は自分を打ち負かした者と結婚することを認めた。しかし、彼女は武術の技を駆使して二人を制圧し、友人になった後、二人を自分の守護将軍として雇った[25]。 太上老君說天妃救苦靈驗經;太上老君说天妃救苦灵验经; Tàishàng Lǎojūn Shuō Tiānfēi Jiùkǔ Língyàn Jīng)では、玉女(妙行玉女)は北斗七星の星で、老子の神体である老君が海で遭難しそうな人々に慈悲を示すために地上に連れてきた。彼女は媽祖の化身 であり、船乗りを守るだけでなく、生と死のあらゆる面を監督し、彼女に助けを求める者に救いを与えると誓っている[8]。 |

| Legacy Worship Main article: List of Mazu temples Dressed in red, she shows her divine power. In the fourth year of the Xuanhe period of emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty, with the cyclical signs ren yin (1122), the Supervising Secretary Lu Yundi received an order to go on a mission to Korea. On his way through the Eastern Sea, he ran into a hurricane. Of the eight ships, seven were wrecked. Only Lu's ship did not capsize in the turbulent waves. As he prayed ardently to heaven for protection, he saw a goddess appear above the mast. Dressed in red, she was sitting still in a formal manner. Lu kowtowed and begged for protection. In the midst of the seething sea, the wind and waves calmed down suddenly, so that Lu was saved. After he had returned from Korea, he told his story to everyone. The Gentleman who Guards Righteousness, Li Zhen, a man who had visited (Sheng)dun for a long time, told him everything about the merciful manifestations of the holy princess. Lu said: "In this world, it is only my parents who have always shown endless kindness. Yet, when in the course of my vagrant life I almost arrived at the brink of death, not even my father and mother, in spite of their utmost parental love, could help me, while a divine girl, by simply breathing, was able to reach out to me. That day, I truly received the gift of rebirth." When Lu reported on his mission to the court, he memorialized the merciful manifestation of the goddess. He received the order to allow the words "Smooth crossing" to be used on a temple tablet, remit taxes on the temple fields, and make temple offerings at Jiangkou. — Tianfei Xiansheng Lu (early 17th century) about Lu Yundi's encounter with the goddess [26] Part of a series on Chinese folk religion Stylisation of the 禄 lù or 子 zi grapheme, respectively meaning "prosperity", "furthering", "welfare" and "son", "offspring". 字 zì, meaning "word" and "symbol", is a cognate of 子 zi and represents a "son" enshrined under a "roof". The symbol is ultimately a representation of the north celestial pole (Běijí 北极) and its spinning constellations, and as such it is equivalent to the Eurasian symbol of the swastika, 卍 wàn. Mazuism is first attested in Huang Gongdu's c. 1140 poem "On the Shrine of the Smooth Crossing"[27] (順濟廟; 顺济庙; Shùnjì Miào), which considered her a menial and misguided shamaness whose continued influence was inexplicable.[28] He notes that her devotees danced and sang together and with their children.[29] Shortly afterwards, Liao Pengfei (廖鵬飛)'s 1150 inscription at the village of Ninghai (now Qiaodou Village) in Putian was more respectful.[3][d] It states that, "after her death, the people erected a temple for her on her home island"[3] and that the Temple of the Sacred Mound (聖墩廟; 圣墩庙; Shèngdūn Miào) was raised in 1086 after some people in Ninghai saw it glowing, discovered a miraculous old raft[27] or stump,[28] and experienced a vision of "the goddess of Meizhou".[27][e] This structure had been renamed the Smooth Crossing Temple by Emperor Huizong of Song in 1123 after his envoy Lu Yundi (路允迪; Lù Yǔndí) was miraculously saved during a storm the year before while on an official mission to pay respects to the court of Goryeo upon the death of its king, Yejong,[27] and to replace the Liao dynasty as the formal suzerains investing his successor, Injong.[32][f] Her worship subsequently spread: Li Junfu's early-13th century Putian Bishi records temples on Meizhou and at Qiaodou, Jiangkou, and Baihu.[33] By 1257, Liu Kezhuang was noting Putian's "large market towns and small villages all have... shrines to the Princess" and that they had spread to Fengting to the south.[31] By the end of the Song dynasty, there were at least 31 temples to Mazu,[34] reaching at least as far as Shanghai in the north and Guangzhou in the south.[31] The power of the goddess, having indeed been manifested in previous times, has been abundantly revealed in the present generation. In the midst of the rushing waters it happened that, when there was a hurricane, suddenly a divine lantern was seen shining at the masthead, and as soon as that miraculous light appeared the danger was appeased, so that even in the peril of capsizing one felt reassured and that there was no cause for fear. — Admiral Zheng He and his associates (Changle inscription, early 15th century) about witnessing the goddess' divine lantern, which represented the natural phenomena Saint Elmo's fire [35]  Sanchong Yi Tian Temple at Sanchong District, New Taipei, Taiwan. As Mazuism spread, it began to absorb the cults of other local shamanesses such as the other two of Xianyou's "Three Princesses"[36] and even some lesser maritime and agricultural gods, including Liu Mian[31] and Zhang the Heavenly Instructor.[36] By the 12th century, she had already become a guardian to the people of Qiaodou when they suffered drought, flood, epidemic, piracy,[36] or brigandage.[5] She protected women during childbirth[29] and assisted with conception.[5] As the patron of the seas, her temples were among the first erected by arriving overseas Chinese, as they gave thanks for their safe passage. Despite his Islamic upbringing, the Ming admiral and explorer Zheng He credited Mazu for protecting one of his journeys, prompting a new title in 1409.[8] He patronized the Mazu temples of Nanjing and prevailed upon the Yongle Emperor to construct the city's Tianfei Palace; because of its imperial patronage and prominent location in the empire's southern capital, this was long the largest and highest-status center of Mazuism in China.[24] During the Southern Ming resistance to the Qing, Mazu was credited with helping Koxinga's army capture Taiwan from the Dutch; she was later said to have personally aided some of Shi Lang's men in defeating Liu Guoxuan at Penghu in 1683, ending the independent kingdom of Koxinga's descendants and placing Taiwan under Qing control.[24] The Ming prince Zhu Shugui's palace was converted into Tainan's Grand Matsu Temple, the first to bear her new title of "Heavenly Empress".[citation needed] In late imperial China, sailors often carried effigies of Mazu to ensure safe crossings.[23] Some boats still carry small shrines on their bows.[5] Mazu charms are also used as medicine, including as salves for blistered feet.[37] As late as the 19th century, the Qing government officially credited her divine intervention with their 1884 victory over the French at Tamsui District during the Sino-French War and specially honored the town's temple to her, which had served as General Sun Kaihua's headquarters during the fighting.[13] When US forces bombed Taiwan during World War II, Mazu was said to intercept bombs and defend the people.[38]  Thean Hou Temple in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Today, Mazuism is practiced in about 1,500 temples in 26 countries around the world, mostly in the Sinosphere or the overseas Chinese communities such as that of the predominantly Hokkien Philippines. Of these temples, almost 1000 are on Taiwan,[39] representing a doubling of the 509 temples recorded in 1980 and more than a dozen times the number recorded before 1911.[1] These temples are generally registered as Taoist, although some are considered Buddhist.[10] There are more than 90 Mazu Temples in Hong Kong. In Mainland China, Mazuism is formally classified as a cult outside of Buddhism and Taoism, although numerous Buddhist, Confucianist and Taoist temples include shrines to her. Her worship is generally permitted but not encouraged, with most surviving temples concentrated around Putian in Fujian. Including the twenty on Meizhou Island, there are more than a hundred in the prefecture and another 70 elsewhere in the province, mostly in the settlements along its coast. There are more than 40 temples in Guangdong and Hainan and more than 30 in Zhejiang and Jiangsu, but many historical temples are now treated as museums and operated by local parks or cultural agencies.[40] From the early 2000s, pilgrimages from Taiwan to temples in Fujian have been permitted, particularly to the one in Yongchun, where Taiwan's Xingang Mazu Temple has been allowed to open a branch temple.[40] A major project to build the world's tallest Mazu statue at Tanjung Simpang Mengayau in Kudat, Borneo, was officially launched[when?] by Sabah. The statue was to be 10 stories high, but was canceled due to protests from Muslims in Sabah and political interference.[41] Informal centers of pilgrimage for Mazu's believers include Meizhou Island, the Zhenlan Temple in Taichung on Taiwan, and Xianliang Temple in Xianliang Harbor, Putian. Together with Meizhou Island, the Xianliang Temple is considered the most sacred place to Mazu, whose supposed death happened on the seashore of Xianliang Harbor. A ceremony attended by pilgrims from different provinces of China and from Taiwan commemorates this legendary event each year in October.[40] |

レガシー 礼拝 主な記事 媽祖廟のリスト 赤い服に身を包み、神通力を示す。 宋の恵宗皇帝の宣和4年(1122年)、魯雲棣監督に朝鮮出兵の命が下った。東の海を通る途中、彼はハリケーンに遭遇した。8隻の船のうち7隻が難破し た。呂の船だけが乱波の中で転覆しなかった。彼が天の守護を熱心に祈っていると、マストの上に女神が現れた。赤い服を着た女神は、正装してじっと座ってい た。呂はお辞儀をして守護を乞うた。荒れ狂う海の中、風と波が急に静まったので、魯は助かった。朝鮮から帰国後、彼は皆にその話をした。義を守る紳士であ る李振は、長い間(聖)敦を訪れていたので、聖なる姫の慈悲深い現れについてすべて話した。呂は言った: 「この世で、私の両親だけがいつも限りない優しさを示してくれた。しかし、私が放浪の生活の中で死の淵に立たされそうになったとき、父と母でさえ、最大限 の親愛にもかかわらず、私を助けることができなかった。その日、私は本当に再生の贈り物を受け取った」。呂は宮廷に使命を報告する際、女神の慈悲深い顕現 を記念した。そして、廟の位牌に 「円滑渡海 」の文字を使用すること、廟の田畑の税金を送金すること、江口で廟の供え物をすることを許可する命令を受けた。 - 呂運繹と女神の出会いについて書かれた『天妃献生録』(17世紀初頭)[26]。 に関するシリーズの一部である。 中国の民間宗教 それぞれ「繁栄」、「促進」、「福祉」、「息子」、「子孫」を意味する。字zìは「言葉」「象徴」を意味し、子ziの同義語で、「屋根」の下に祀られた 「息子」を表す。このシンボルは究極的には北極(Běijí北极)とその回転する星座を表しており、ユーラシアのシンボルである卍wànに相当する。 媽祖は黄公主の1140年頃の詩「順濟廟; 顺济֙; Shùnjì Miào」に初めて登場する。[28] He notes that her devotees danced and sang together and with their children.[29] Shortly afterwards, Liao Pengfei (廖鵬飛)'s 1150 inscription at the village of Ninghai (now Qiaodou Village) in Putian was more respectful.[3][d]そこには、「彼女の死後、人民は彼女のために故郷の島に廟を建立した」と記されており[3]、聖墩廟(聖墩廟、圣墩 庙; 聖墩廟(Shèngdūn Miào)は、寧海の人民が光るのを見て、奇跡的な古いいかだ[27]や切り株を発見し[28]、「明州の女神」の幻を見た後、1086年に建てられたと いう。[27][e] この建造物は、1123年に宋の恵宗皇帝が、高麗の王であった耶宗の死去に伴い、高麗の宮廷に敬意を表するために公式の使節として赴いた使節の陸雲迪(路 允迪;Lù Yǔndí)が嵐の中で奇跡的に助かり[27]、遼王朝に代わって彼の後継者である仁宗を正式に宗主としたことから、滑渡寺と改名された[32][f]。 その後、彼女の崇拝は広まった: 李俊甫の13世紀初頭の『普天志』には、梅州、橋頭、江口、白湖に廟があったと記されている[33]。宋代末までには、媽祖を祀る寺院は少なくとも31カ所あり[34]、少なくとも北は上海、南は広州にまで及んでいた[31]。 女神の力は、確かに以前の時代にも現れていたが、現在の時代にも豊かに現れている。荒れ狂う海の中で、ハリケーンがあったとき、突然、マストヘッドに神の ランタンが輝いているのが見え、その奇跡的な光が現れるや否や、危険は鎮まり、転覆の危機にあっても、人は安心し、恐れる理由はないと感じたということが あった。 - 鄭和提督とその仲間たち(長楽碑文、15世紀初頭)は、自然現象である聖エルモの火を象徴する女神の神灯を目撃したことについて述べている[35]。  台湾の新北市三中区にある三中益天宮。 媽祖信仰が広まるにつれて、仙遊の「三姫」[36]の他の2人や、劉棉[31]、張天師[36]などの海神や農神など、他の地方の巫女の信仰も吸収し始め た。[36]12世紀までに、彼女はすでに喬堂の人民が干ばつ、洪水、疫病、海賊[36]、山賊[5]などの苦悩に見舞われたときの守護神となっていた。 出産の際には女性を守り[29]、妊娠を助けた[5]。 海の守護神である彼女の寺院は、到着した華僑が最初に建立した寺院のひとつであり、彼らは安全な航路に感謝を捧げた。明の提督であり探検家であった鄭和 は、イスラム教の教育を受けていたにもかかわらず、媽祖が彼の旅の安全を守ってくれたことを信じ、1409年に新しい称号を与えた[8]。 後に、媽祖は自ら石琅の部下を助けて1683年に澎湖で劉国軒を破り、石琅の子孫の独立王国を終わらせ、台湾を清の支配下に置いたと言われている。[24]明の王子であった朱淑貴の宮殿は台南の大媽祖廟に改築され、「天后」という新しい称号が初めて付けられた[要出典]。 媽祖のお守りは薬としても使われ、足に水ぶくれができたときの軟膏としても使われた[37]。[37]19世紀末、清朝政府は公式に、1884年の中仏戦 争で淡水地区でフランス軍に勝利したのは媽祖のおかげであるとし、戦闘中に孫開華将軍の司令部として使用された町の媽祖廟を媽祖に捧げた[13]。  マレーシアのクアラルンプールにある媽祖廟 今日、媽祖廟は世界26カ国の約1,500の寺院で修行されており、そのほとんどが中国圏、あるいは福建人が多いフィリピンなどの華僑社会で信仰されてい る。これらの寺院のうち、ほぼ1000が台湾にあり[39]、1980年に記録された509の寺院の2倍、1911年以前に記録された数の十数倍に相当す る[1]。これらの寺院は一般に道教として登録されているが、仏教とみなされるものもある[10]。 香港には90以上の媽祖廟がある。中国本土では、媽祖は仏教と道教以外のカルトとして正式に分類されているが、仏教、儒教、道教の寺院には媽祖を祀る廟が 数多くある。媽祖崇拝は一般的に許されているが、奨励はされておらず、現存する寺院の多くは福建省の普天周辺に集中している。福建省の福田周辺に集中して いる。梅州島にある20の寺院を含めると、福建省には100以上の寺院があり、その他にも70の寺院が福建省の海岸沿いの集落にある。広東省と海南省には 40以上、浙江省と江蘇省には30以上の寺院があるが、歴史的な寺院の多くは現在、博物館として扱われ、地元の公園や文化機関が運営している[40]。 2000年代初頭から、台湾から福建省の寺院への巡礼が許可されるようになり、特に永春にある永春媽祖廟への巡礼が許可された。 ボルネオ島クダットのタンジュン・シンパン・メンガヤウに世界一高い媽祖像を建立する一大プロジェクトが、サバ州によって正式に開始された[いつ?像は10階建てになる予定だったが、サバ州のイスラム教徒からの抗議と政治的干渉のために中止された[41]。 媽祖信仰の非公式な巡礼地としては、梅州島、台湾の台中にある鎮瀾寺、普天の仙良港にある仙良寺などがある。仙良寺は梅州島とともに媽祖の最も神聖な場所 とされており、媽祖は仙良港の海辺で亡くなったとされている。毎年10月には、中国の異なる省や台湾からの巡礼者が参加し、この伝説的な出来事を記念する 儀式が行われる[40]。 |

Pilgrimages 南方澳南天宮玉媽祖側面01  南方澳南天宮金媽祖側面02 Statue of Mazu made by Gold and Jade in Nantian Temple, Nanfang'ao, Su'ao Township, Yilan County, Taiwan The primary temple festival in Mazuism is Lin Moniang's traditional birthday on the 23rd day of the 3rd month of the Chinese lunar calendar. In Taiwan, there are two major pilgrimages made in her honor, the Dajia Mazu Pilgrimage and the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage. In both festivals, pilgrims walk more than 300 kilometers to carry a litter containing statues of the goddess between two temples.[42][43] Another major festival is that around the Tianhou Temple in Lukang.[44] Depending on the year, Mazu's festival day may fall as early as mid-April or as late as mid-May.[45] The anniversary of her death or supposed ascension into Heaven is also celebrated, usually on the Double Ninth Festival (the ninth day of the ninth month of the lunar calendar).[10] CCP influence operations Further information: United front in Taiwan The United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) utilizes Mazu as a tool to advocate for Chinese unification.[46][47][48][49][50] According to academic Chang Kuei-min of National Taiwan University, the CCP has created a narrative that it is a champion of Chinese folk religion and Mazu has become part of that narrative.[47] In 2011, CCP general secretary Xi Jinping instructed cadres to "make full use" of Mazu for Chinese unification efforts.[48] Temples in Taiwan, especially in rural areas, have been the most prominent targets for influence operations as they are meeting grounds for prominent local figures and financial donations to temples remain unregulated.[51][52][53] CCP-linked groups have sponsored paid trips for Taiwanese to visit Mazu-related temples in Fujian.[54] |

巡礼 南方澳南天宮玉媽祖側面01  南方澳南天宮金媽祖側面02 台湾宜蘭県蘇澳郷南方澳南天宮の金玉媽祖像 媽祖廟の主な祭典は、旧暦3月23日の林茂陽の誕生日である。台湾では、林茂名にちなんで「大甲媽祖巡礼」と「白沙屯媽祖巡礼」という2つの大きな巡礼祭 が行われる。この2つの祭りでは、巡礼者は女神の像を載せた駕籠を2つの廟の間に運ぶために300キロ以上歩く[42][43]。もう1つの大きな祭り は、鹿港の天后宮周辺の祭りである[44]。年によって、媽祖の祭りの日は早ければ4月中旬、遅ければ5月中旬になることもある[45]。 また、媽祖の命日や天に昇ったとされる記念日も祝われ、通常は二重九節(旧暦9月9日)に行われる[10]。 中国共産党の影響工作 さらなる情報 台湾の統一戦線 中国共産党中央委員会統一戦線工作部は、媽祖を中華統一を主張するための道具として利用している[46][47][48][49][50]。ナショナリズ ム学者の張桂民によれば、中国共産党は中国の民間宗教の擁護者であるという物語を作り上げ、媽祖はその物語の一部となっている。[47]2011年、中国 共産党の習近平総書記は、中国統一の努力のために媽祖を「フル活用」するよう幹部に指示した[48]。台湾の寺院、特に農村部の寺院は、地元の著名人の集 会場であり、寺院への金銭的な寄付が規制されていないため、影響力工作の最も顕著な標的となっている[51][52][53]。 中国共産党に関連する団体は、台湾人が福建省の媽祖関連の寺院を訪問する有料の旅行を後援している[54]。 |

In art Detail of an 18th-century painting depicting Mazu during her rescue of the Song embassy to Goryeo of 1123 on the high seas After her death, Mazu was remembered as a young lady who wore a red dress as she roamed over the seas.[6] In religious statuary, she is usually clothed in the attire of an empress, and decorated with accessories such as a ceremonial hu tablet and a flat-topped imperial cap (冕冠; mian'guan) with rows of beads (liu) hanging from the front and back.[55] Her temples are usually protected by the door gods Qianliyan (千里眼) and Shunfeng'er (順風耳). These vary in appearance but are frequently demons, Qianliyan red with two horns and two yellow sapphire eyes and Shunfeng'er green with one horn and two ruby eyes.[25] Lin Moniang (2000), a minor Fujianese TV series, was a dramatization of Mazu's life as a mortal. Mazu (海之傳說媽祖, 2007) was a Taiwanese animated feature film from the Chinese Cartoon Production Co. depicting her life as a shamaness and goddess. Its production director Teng Chiao admitted the limited appeal to the domestic market: "If young people were our primary target audience, we wouldn't tell the story of Mazu in the first place since they are not necessarily interested in the ancient legend[;] neither do they have loyalty to made-in-Taiwan productions". Instead, "when you look to global markets, the question that foreign buyers always ask is what can best represent Taiwan". Mazu, with its story about "a magic girl and two cute sidekicks [Mazu's door gods Qianliyan and Shunfeng'er] spiced up with a strong local flavor", was instead designed with an intent to appeal to international markets interested in Taiwan.[56] |

美術 1123年、高麗への宋の使節を公海上で救助した媽祖を描いた18世紀の絵画の詳細。 媽祖の死後、媽祖は赤いドレスを着て海を彷徨った若い女性として記憶されるようになった[6]。宗教的な彫像では、媽祖は通常、皇后の服装を身にまとい、 儀式用の胡の石版や、前後に数珠の列を垂らした平らな天冠(冕冠;mian'guan)などの装飾品で飾られている。[55]彼女の廟は通常、扉神である 千里眼と順風耳によって守られている。これらの神々の外見は様々であるが、しばしば鬼であり、乾隆は赤色で2本の角と2つの黄色いサファイアの目を持ち、 順風耳は緑色で1本の角と2つのルビーの目を持つ[25]。 媽祖の人間としての人生をドラマ化したのが、福建省のマイナーなテレビシリーズ『林聞香』(2000年)である。媽祖(海之傳說媽祖、2007年)は、中 国の漫画制作公司による台湾の長編アニメ映画で、巫女と女神としての媽祖の人生を描いている。制作ディレクターのテン・チャオは、国内市場へのアピールが 限られていることを認めた: 「もし若い人民が主なターゲットであれば、そもそも媽祖の物語は描かないでしょう。なぜなら、彼らは古代の伝説に必ずしも興味を持っていないからです。そ の代わり、「世界市場に目を向けると、海外のバイヤーが常に尋ねるのは、台湾を最もよく表現できるものは何かということだ」。媽祖』は、「呪術的な少女と 2人のかわいい相棒(媽祖の扉神である乾聯と順風兒)の物語に、強烈なローカル・テイストのスパイスを加えた」作品であり、その代わりに、台湾に興味を持 つ国際市場にアピールする意図主義でデザインされた[56]。 |

| Air pollution in Hong Kong#Joss paper and incense burning List of Mazu temples around the world Dragon King Ngaleima Tin Hau temples in Hong Kong Hung Shing Ye (洪聖爺) Qianliyan & Shunfeng'er Queen Mother of the West |

香港の大気汚染#ジョスペーパーと焼香 世界の媽祖廟リスト 龍王 ンガレイマ 香港のティンハウ寺院 洪聖爺 銭淵と順風兒 西太后 |

| Bibliography Boltz, Judith Magee (1986), "In Homage to T'ien-fei", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 106, Sinological Studies, pp. 211–232, doi:10.2307/602373, JSTOR 602373. Bosco, Joseph; Ho, Puay-peng (1999), Temples of the Empress of Heaven, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195903553 Boltz, Judith Magee (2008), "Mazu", The Encyclopedia of Taoism, vol. II, Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 741–744, ISBN 9781135796341. Clark, Hugh R. (2006), "The Religious Culture of Southern Fujian, 750–1450: Preliminary Reflections on Contacts across a Maritime Frontier" (PDF), Asia Major, vol. XIX, Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, archived (PDF) from the original on November 26, 2016, retrieved November 28, 2016. Clark, Hugh R. (2007), Portrait of a Community: Society, Culture, and the Structures of Kinship in the Mulan River Valley (Fujian) from the Late Tang through the Song, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, ISBN 978-9629962272. Clark, Hugh R. (2015), "What Makes a Chinese God? or, What Makes a God Chinese?", Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbors, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 111–139, ISBN 9789814620536. Crook, Steven (2014), "Mazu", Taiwan (2nd ed.), Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, pp. 32–33, ISBN 9781841624976. Dreyer, Edward L. (2007), Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433, New York: Pearson Longman, ISBN 9780321084439. Duyvendak, Jan Julius Lodewijk (1938), "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century", T'oung Pao, vol. XXXIV, Brill, pp. 341–413, doi:10.1163/156853238X00171, JSTOR 4527170. Giuffrida, Noelle (2004), "Tianhou", Holy People of the World, vol. II, Santa Barbara: ABC Clio, ISBN 9781576073551. Irwin, Lee (1990), "Divinity and Salvation: The Great Goddesses of China", Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 49, Nanzan University, pp. 53–68, doi:10.2307/1177949, JSTOR 1177949. Ruitenbeek, Klaas (1999), "Mazu, Patroness of Sailors, in Chinese Pictorial Art", Artibus Asiae, vol. 58, Artibus Asiae Publishers, pp. 281–329, doi:10.2307/3250021, JSTOR 3250021. Shu, Tenjun (1996), Massō to Chūgoku no Minken Shinkō 媽祖と中國の民間信仰 (in Japanese), Tokyo: Heika Shuppansha, ISBN 9784892032745. Soo Khin Wah (1990), "The Cult of Mazu in Peninsular Malaysia", The Preservation and Adaption of Tradition: Studies of Chinese Religious Expression in Southeast Asia, Contributions to Southeast Asian Ethnography, Columbus: OSU Department of Anthropology, pp. 29–51, ISSN 0217-2992. Yuan Haiwang (2006), "Mazu, Mother Goddess of the Sea", The Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales from the Han Chinese, World Folklore Series, Westport: Libraries Unlimited, ISBN 9781591582946. Zhang Xun (1993), Incense-Offering and Obtaining the Magical Power of Qi: The Mazu (Heavenly Mother) Pilgrimage in Taiwan (Thesis, Ph.D. in Anthropology), Berkeley: University of California, OCLC 31154698. |

参考文献 Boltz, Judith Magee (1986), 「In Homage to T'ien-fei」, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol.106, Sinological Studies, pp.211-232, doi:10.2307/602373, JSTOR 602373. Bosco, Joseph; Ho, Puay-peng (1999), Temples of the Empress of Heaven, Hong Kong: オックスフォード大学出版局, ISBN 9780195903553 Boltz, Judith Magee (2008), 「Mazu」, The Encyclopedia of Taoism, vol. II, Abingdon: Routledge, pp.741-744, ISBN 9781135796341. Clark, Hugh R. (2006), "The Religious Culture of Southern Fujian, 750-1450: Preliminary Reflections on Contacts across a Maritime Frontier" (PDF), Asia Major, vol.XIX, Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, archived (PDF) from the original on November 26, 2016, November 28, 2016. Clark, Hugh R. (2007), Portrait of a Community: 中国大学出版会、ISBN 978-999-999、香港: Chinese University Press, ISBN 978-9629962272. Clark, Hugh R. (2015), 「What Makes a Chinese God? or, What Makes a God Chinese?」, Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbors, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp.111-139, ISBN 9789814620536. Crook, Steven (2014), 「Mazu」, Taiwan (2nd ed.), Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, pp.32-33, ISBN 9781841624976. Dreyer, Edward L. (2007), Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433, New York: Pearson Longman, ISBN 9780321084439. Duyvendak, Jan Julius Lodewijk (1938), 「The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century」, T'oung Pao, vol.XXXIV, Brill, pp.341-413, doi:10.1163/156853238X00171, JSTOR 4527170. Giuffrida, Noelle (2004), 「Tianhou」, Holy People of the World, vol. II, Santa Barbara: ABC Clio, ISBN 9781576073551. Irwin, Lee (1990), "Divinity and Salvation: The Great Goddesses of China", Asian Folklore Studies, vol.49, Nanzan University, pp.53-68, doi:10.2307/1177949, JSTOR 1177949. Ruitenbeek, Klaas (1999), 「Mazu, Patroness of Sailors, in Chinese Pictorial Art」, Artibus Asiae, vol.58, Artibus Asiae Publishers, pp.281-329, doi:10.2307/3250021, JSTOR 3250021. 秀天順(1996)『大衆と中國の民間信仰』平河出版社、東京: 平河出版社, ISBN 9784892032745. Soo Khin Wah (1990), 「The Cult of Mazu in Peninsular Malaysia」, The Preservation and Adaption of Tradition: 東南アジアにおける中国系宗教表現の研究、東南アジア民族誌への貢献、コロンバス: OSU Department of Anthropology, pp.29-51, ISSN 0217-2992. Yuan Haiwang (2006), 「Mazu, Mother Goddess of the Sea」, The Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales from the Han Chinese, World Folklore Series, Westport: Libraries Unlimited, ISBN 9781591582946. Zhang Xun (1993), Incense-Offering and Obtaining the Magical Power of Qi: The Mazu (Heavenly Mother) Pilgrimage in Taiwan (Thesis, Ph.D. in Anthropology), Berkeley: University of California, OCLC 31154698. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mazu |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but

[Re]Think our message for all undergraduate

students!!!

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆