ハームリダクション

Harm reduction

★

ハームリダクション(害の最小化)とは、合法・非合法を問わず、さまざ

まな人間の行動に伴う社会的および/または身体的悪影響を軽減することを目的とした、意図的な実践や公衆衛生政策の総称である。ハームリダクションは、禁

欲を求めることなく、娯楽目的の薬物使用や性行為の悪影響を軽減するために用いられる。薬物使用を止められない人や止めようとし

ない人でも、自分自身や他者を保護するために前向きな変化を起こすことができることを認識している。ハームリダクションは、薬物使用による悪影響を軽減す

るアプローチに最も一般的に適用されており、ハームリダクションプログラムは現在、さまざまなサービ

スや世界のさまざまな地域で実施されている。2020年現在、約86カ国が薬物使用に対するハームリダクションアプローチを用いた1つ以上のプログラムを

実施しており、主に汚染された注射器具の使用による血液感染症の予防を目的としている。

注射針交換プログラムは、ヘロインやその他の薬物を注射器で使用する人々が注射器を共有し、それを複数回使用する可能性を低減する。注射器の共用は、感染

した血液で汚染された注射器の再使用により、HIVやC型肝炎などの感染症が人から人へと容易に広がる原因となることが多い。一部の地域では、注射針・注

射器プログラム(NSP)やオピオイドアゴニスト療法(OAT)の施設が基本的なプライマリーヘルスケアを提供している。

監督下注射施設は、薬物使用者に安全で衛生的、ストレスのない環境を提供することを目的とした、法的にも認められた医療監督下施設である。

これらの施設では、滅菌注射器具、薬物に関する情報、基本的なヘルスケア、治療の紹介、医療スタッフへのアクセスを提供している。

オピオイド作動薬療法(OAT)とは、ヘロインなどの違法なオピオイドを使用する人々のオピオイドへの渇望を軽減するために、メサドンやブプレノルフィン

などの多幸感を大幅に減少させる害の少ないオピオイドを使用する医療処置である。ブプレノルフィンとメサドンは医師の管理下で投与される。もう一つのアプ

ローチはヘロイン補助療法で、ヘロイン依存症の人々に医薬用ヘロイン(ジアセチルモルヒネ)が処方される。

メディアキャンペーンでは、飲酒運転の危険性をドライバーに知らせている。現在では、アルコールを娯楽として摂取するほとんどの人がこうした危険性を認識

しており、また「指名ドライバー」や無料タクシープログラムなどの安全運転テクニックにより、飲酒運転による事故件数は減少している。多くの学校では現

在、性行為を行う可能性のある10代および10代前の生徒を対象に、より安全な性教育を実施している。思春期の若者の中にはセックスをする者もいるため、

望まない妊娠や性感染症の感染を防ぐために、コンドームやデンタルダムなどの保護具の使用を強調する性教育が、害悪低減主義(harm minimization)のアプローチによって支持され ている。1999年以降、ドイツ(2002年)やニュージーランド(2003年)など、売春を合法化または非犯罪化した国もある。

路上レベルでの多くの危険回避戦略は、薬物を注射する人々や性労働者におけるHIV感染の減少に成功している。HIV教育、HIV検査、コンドームの使用、セーフセックスの交渉は、HIVウイルスの感染と伝播のリスクを大幅に減少させる。

☆ 以下は外国語ウィキペディアによる「ハームリダクション」とりわけ、英語(Harm reduction) のものからの翻訳である。

| Harm reduction, or

harm minimization, refers to a range of intentional

practices and

public health policies designed to lessen the negative social and/or

physical consequences associated with various human behaviors, both

legal and illegal.[1] Harm reduction is used to decrease negative

consequences of recreational drug use and sexual activity without

requiring abstinence, recognizing that those unable or unwilling to

stop can still make positive change to protect themselves and

others.[2][3] Harm reduction is most commonly applied to approaches that reduce adverse consequences from drug use, and harm reduction programs now operate across a range of services and in different regions of the world. As of 2020, some 86 countries had one or more programs using a harm reduction approach to substance use, primarily aimed at reducing blood-borne infections resulting from use of contaminated injecting equipment.[4] Needle-exchange programmes reduce the likelihood of people who use heroin and other substances sharing the syringes and using them more than once. Syringe-sharing often leads to the spread of infections such as HIV or hepatitis C, which can easily spread from person to person through the reuse of syringes contaminated with infected blood. Needle and syringe programmes (NSP) and Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) outlets in some settings offer basic primary health care. Supervised injection sites are legally sanctioned, medically supervised facilities designed to provide a safe, hygienic, and stress-free environment for people who use substances. The facilities provide sterile injection equipment, information about substances and basic health care, treatment referrals, and access to medical staff. Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) is the medical procedure of using a harm-reducing opioid that produces significantly less euphoria, such as methadone or buprenorphine to reduce opioid cravings in people who use illegal opioids, such as heroin; buprenorphine and methadone are taken under medical supervision. Another approach is heroin assisted treatment, in which medical prescriptions for pharmaceutical heroin (diacetylmorphine) are provided to people who are dependent on heroin. Media campaigns inform drivers of the dangers of driving drunk. Most people who recreationally consume alcohol are now aware of these dangers and safe ride techniques like 'designated drivers' and free taxicab programmes are reducing the number of drunk-driving crashes. Many schools now provide safer sex education to teen and pre-teen students, who may engage in sexual activity. Since some adolescents are going to have sex, a harm-reductionist approach supports a sexual education which emphasizes the use of protective devices like condoms and dental dams to protect against unwanted pregnancy and the transmission of STIs. Since 1999, some countries have legalized or decriminalized prostitution, such as Germany (2002) and New Zealand (2003). Many street-level harm-reduction strategies have succeeded in reducing HIV transmission in people who inject substances and sex-workers.[5] HIV education, HIV testing, condom use, and safer-sex negotiation greatly decreases the risk of acquiring and transmitting the HIV virus.[5] |

ハームリダクション(害の最小化)とは、合法・非合法を問わず、さまざ

まな人間の行動に伴う社会的および/または身体的悪影響を軽減することを目的とした、意図的な実践や公衆衛生政策の総称である。[1]

ハームリダクションは、禁欲を求めることなく、娯楽目的の薬物使用や性行為の悪影響を軽減するために用いられる。薬物使用を止められない人や止めようとし

ない人でも、自分自身や他者を保護するために前向きな変化を起こすことができることを認識している。[2][3] ハームリダクションは、薬物使用による悪影響を軽減するアプローチに最も一般的に適用されており、ハームリダクションプログラムは現在、さまざまなサービ スや世界のさまざまな地域で実施されている。2020年現在、約86カ国が薬物使用に対するハームリダクションアプローチを用いた1つ以上のプログラムを 実施しており、主に汚染された注射器具の使用による血液感染症の予防を目的としている。 注射針交換プログラムは、ヘロインやその他の薬物を注射器で使用する人々が注射器を共有し、それを複数回使用する可能性を低減する。注射器の共用は、感染 した血液で汚染された注射器の再使用により、HIVやC型肝炎などの感染症が人から人へと容易に広がる原因となることが多い。一部の地域では、注射針・注 射器プログラム(NSP)やオピオイドアゴニスト療法(OAT)の施設が基本的なプライマリーヘルスケアを提供している。 監督下注射施設は、薬物使用者に安全で衛生的、ストレスのない環境を提供することを目的とした、法的にも認められた医療監督下施設である。 これらの施設では、滅菌注射器具、薬物に関する情報、基本的なヘルスケア、治療の紹介、医療スタッフへのアクセスを提供している。 オピオイド作動薬療法(OAT)とは、ヘロインなどの違法なオピオイドを使用する人々のオピオイドへの渇望を軽減するために、メサドンやブプレノルフィン などの多幸感を大幅に減少させる害の少ないオピオイドを使用する医療処置である。ブプレノルフィンとメサドンは医師の管理下で投与される。もう一つのアプ ローチはヘロイン補助療法で、ヘロイン依存症の人々に医薬用ヘロイン(ジアセチルモルヒネ)が処方される。 メディアキャンペーンでは、飲酒運転の危険性をドライバーに知らせている。現在では、アルコールを娯楽として摂取するほとんどの人がこうした危険性を認識 しており、また「指名ドライバー」や無料タクシープログラムなどの安全運転テクニックにより、飲酒運転による事故件数は減少している。多くの学校では現 在、性行為を行う可能性のある10代および10代前の生徒を対象に、より安全な性教育を実施している。思春期の若者の中にはセックスをする者もいるため、 望まない妊娠や性感染症の感染を防ぐために、コンドームやデンタルダムなどの保護具の使用を強調する性教育が、害悪低減主義のアプローチによって支持され ている。1999年以降、ドイツ(2002年)やニュージーランド(2003年)など、売春を合法化または非犯罪化した国もある。 路上レベルでの多くの危険回避戦略は、薬物を注射する人々や性労働者におけるHIV感染の減少に成功している。[5] HIV教育、HIV検査、コンドームの使用、セーフセックスの交渉は、HIVウイルスの感染と伝播のリスクを大幅に減少させる。[5] |

Needle exchange programs provide people who inject substances with new needles and injection equipment to reduce the harm (e.g., HIV infection) from needle drug use. |

注射針交換プログラムは、薬物を注射する人々に新しい注射針と注射器具を提供し、注射針の使用による害(HIV感染など)を軽減する。(ワシントンDC) |

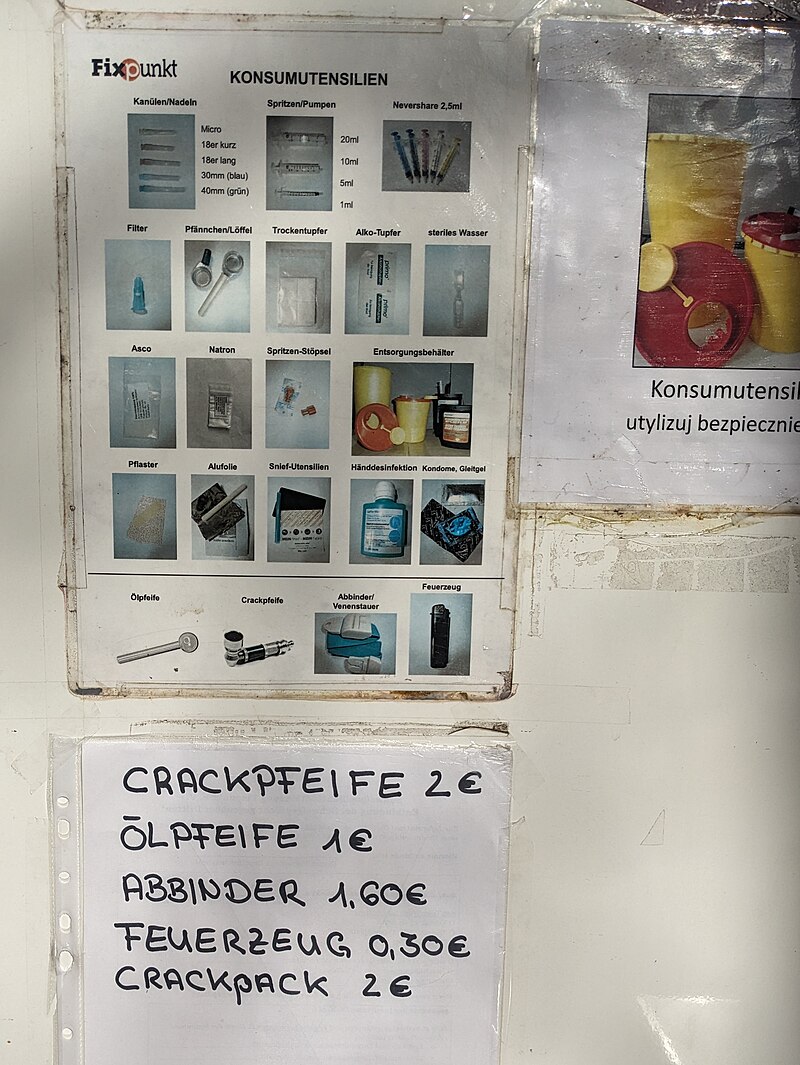

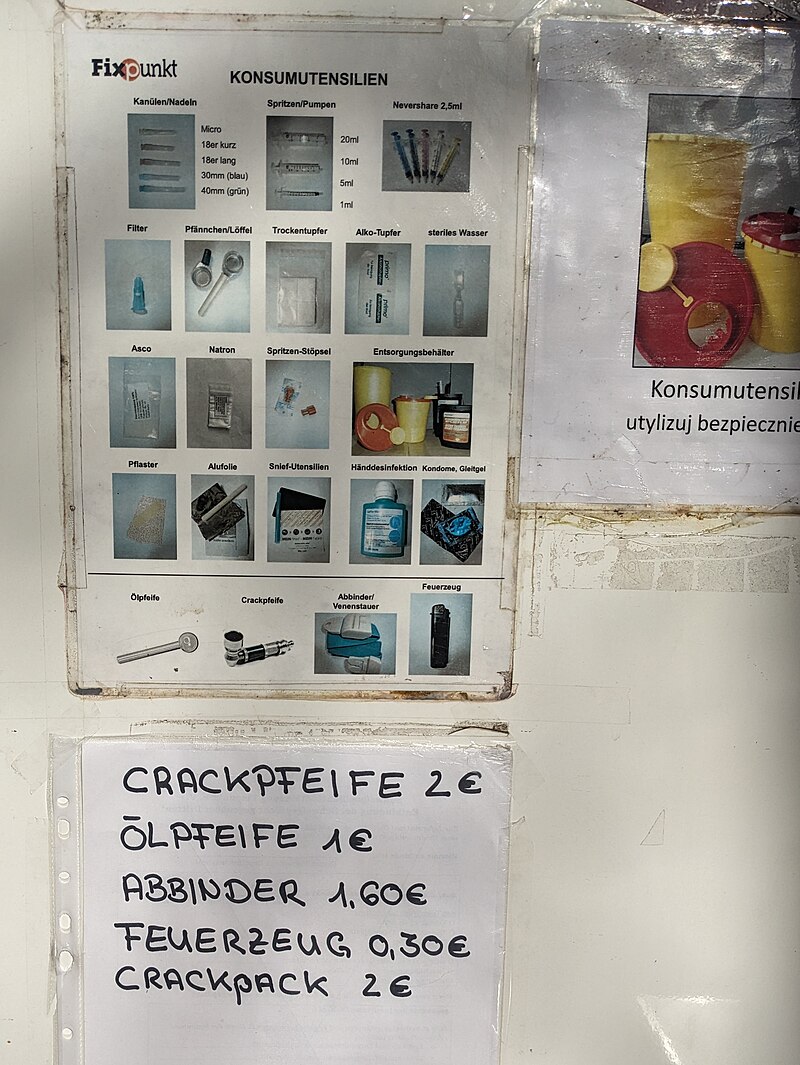

Drug paraphernalia available from a harm reduction NGO at a mobile supervised injection site in Berlin, Germany. |

ドイツ・ベルリンの移動式管理注射施設で、薬物関連器具が入手できる。 |

| Substance use See also: Responsible drug use and Drug liberalization In the case of recreational substance use, harm reduction is put forward as a useful perspective alongside the more conventional approaches of demand and supply reduction.[6] Many advocates argue that prohibitionist laws criminalise people for suffering from a disease and cause harm for example, by obliging people who use substances to obtain substances of unknown purity from unreliable criminal sources at high prices, thereby increasing the risk of overdose and death.[7] The web forum Bluelight allows users to share information and first-hand experience reports about various psychoactive substances and harm reduction practices.[8] The website Erowid collects and publishes information and first-hand experience reports about all kinds of substances to educate people who use or may use substances.[9] While the vast majority of harm reduction initiatives are educational campaigns or facilities that aim to reduce substance-related harm, a unique social enterprise was launched in Denmark in September 2013 to reduce the financial burden of illicit substance use for people with a drug dependence. Michael Lodberg Olsen, who was previously involved with the establishment of a substance consumption facility in Denmark, announced the founding of the Illegal magazine that will be sold by people who use substances in Copenhagen and the district of Vesterbro, who will be able to direct the profits from sales towards drug procurement. Olsen explained: "No one has solved the problem of drug addiction, so is it not better that people find the money to buy their drugs this way than through crime and prostitution?"[10] |

薬物の使用 関連情報: 責任ある薬物の使用、薬物の自由化 娯楽目的の薬物使用の場合、需要と供給の削減という従来のアプローチに加えて、害の軽減という視点が有益なアプローチとして提唱されている。[6] 多くの擁護派は、禁止主義的な法律は、病気に苦しむ人々を犯罪者扱いし、例えば、信頼できない犯罪者から純度の不明な薬物を高額で購入することを使用者に 義務付けることによって、 過剰摂取や死亡のリスクを高めることになる、と主張している。[7] ウェブフォーラム「Bluelight」では、ユーザーがさまざまな向精神物質や害の軽減に関する実践についての情報や直接的な経験報告を共有することが できる。[8] ウェブサイト「Erowid」では、あらゆる種類の物質に関する情報や直接的な経験報告を収集し、公開しており、物質を使用している人や使用する可能性の ある人々への教育を目的としている。[9] 薬物関連の害を軽減することを目的とした教育キャンペーンや施設が、害の軽減を目指す取り組みの大半を占めているが、2013年9月には、薬物依存症患者 の違法薬物使用による経済的負担を軽減することを目的としたユニークなソーシャル・エンタープライズがデンマークで立ち上げられた。デンマークで薬物使用 施設の設立に関わった経験を持つマイケル・ロズベルグ・オルセン氏は、コペンハーゲンとヴェスターブロ地区で薬物を使用する人々が販売する雑誌 『Illegal』の創刊を発表した。販売による利益を薬物の購入に充てることができる。オルセンは次のように説明している。「麻薬中毒の問題を解決でき た者はいない。それならば、犯罪や売春に手を染めるよりも、こうして麻薬を買うお金を手に入れる方がましではないだろうか?」[10] |

| Substances Depressants Alcohol See also: Fomepizole and Denatured alcohol § Toxicity Traditionally, homeless shelters ban alcohol. In 1997, as the result of an inquest into the deaths of two people experiencing homelessness who recreationally used alcohol two years earlier, Toronto's Seaton House became the first homeless shelter in Canada to operate a "wet shelter" on a "managed alcohol" principle in which clients are served a glass of wine once an hour unless staff determine that they are too inebriated to continue. Previously, people experiencing homelessness who consumed excessive amounts of alcohol opted to stay on the streets often seeking alcohol from unsafe sources such as mouthwash, rubbing alcohol or industrial products which, in turn, resulted in frequent use of emergency medical facilities. The programme has been duplicated in other Canadian cities, and a study of Ottawa's "wet shelter" found that emergency room visit and police encounters by clients were cut by half.[11] The study, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 2006, found that serving people experiencing long-term homelessness and who consume excessive amounts of alcohol controlled doses of alcohol also reduced their overall alcohol consumption. Researchers found that programme participants cut their alcohol use from an average of 46 drinks a day when they entered the programme to an average of 8 drinks and that their visits to emergency rooms dropped from 13.5 to an average of 8 per month, while encounters with the police fall from 18.1 to an average of 8.8.[12][13] Downtown Emergency Service Center (DESC),[14] in Seattle, Washington, operates several Housing First programmes which utilize the harm reduction model. University of Washington researchers, partnering with DESC, found that providing housing and support services for homeless alcoholics costs taxpayers less than leaving them on the street, where taxpayer money goes towards police and emergency health care. Results of the study funded by the Substance Abuse Policy Research Program (SAPRP) of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation[15] appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association in April 2009.[16] This first controlled assessment in the U.S. of the effectiveness of Housing First, specifically targeting chronically homeless alcoholics, showed that the programme saved taxpayers more than $4 million over the first year of operation. During the first six months, the study reported an average cost-savings of 53 percent (even after considering the cost of administering the housing's 95 residents)—nearly $2,500 per month per person in health and social services, compared to the per month costs of a wait-list control group of 39 homeless people. Further, despite the fact residents are not required to be abstinent or in treatment for alcohol use, stable housing also results in reduced drinking among people experiencing homelessness who recreationally use alcohol. Alcohol-related programmes A high amount of media coverage exists informing people of the dangers of driving drunk. Most people who recreationally consume alcohol are now aware of these dangers and safe ride techniques like 'designated drivers' and free taxicab programmes are reducing the number of drunk-driving crashes. Many cities have free-ride-home programmes during holidays involving high amounts of alcohol use, and some bars and clubs will provide a visibly drunk patron with a free cab ride. In New South Wales groups of licensees have formed local liquor accords and collectively developed, implemented and promoted a range of harm minimisation programmes including the aforementioned 'designated driver' and 'late night patron transport' schemes. Many of the transport schemes are free of charge to patrons, to encourage them to avoid drink-driving and at the same time reduce the impact of noisy patrons loitering around late night venues. Moderation Management is a programme which helps drinkers to cut back on their consumption of alcohol by encouraging safe drinking behaviour. Harm reduction in alcohol dependency could be instituted by use of naltrexone.[17] |

物質(サブスタンス=薬物の意味がある) 鎮静剤 アルコール 参照:ホメピゾールと変性アルコール § 毒性 従来、ホームレス・シェルターではアルコール類は禁止されていた。1997年、2年前にアルコールを娯楽目的で摂取したホームレス2人の死亡に関する調査 の結果、トロントのシートン・ハウスは、カナダで初めて「管理されたアルコール」の原則に基づいて「ウェット・シェルター」を運営するホームレス・シェル ターとなった。この原則では、利用者が酩酊しすぎていて継続できないとスタッフが判断しない限り、1時間に1杯のワインが提供される。それまでは、ホーム レス状態にある人々が過剰な量のアルコールを摂取した場合、路上で過ごすことを選択することが多く、洗口液、消毒用アルコール、工業製品など、安全でない 入手先からアルコールを入手することが多かった。その結果、救急医療施設が頻繁に利用されることになっていた。このプログラムは他のカナダの都市でも導入 されており、オタワ市の「ウェットシェルター」に関する研究では、利用者の救急外来への来院や警察沙汰が半減したことが分かった。[11] 2006年にカナダ医師会ジャーナル誌に掲載されたこの研究では、長期にわたってホームレス状態にあり、過剰な量のアルコールを摂取している人々に適量の アルコールを供給することで、アルコール摂取量全体が減少することが分かった。研究者は、プログラム参加者の飲酒量が、プログラム参加時に1日平均46杯 だったのが平均8杯に減り、救急外来への来院が13.5回から月平均8回に減り、警察沙汰が18.1回から平均8.8回に減少したことを発見した。 [12][13] ワシントン州シアトルのダウンタウン緊急サービスセンター(DESC)[14]は、害悪低減モデルを活用したハウジングファーストプログラムを複数運営し ている。ワシントン大学の研究者は、DESCと提携し、ホームレスのアルコール依存症患者に住宅と支援サービスを提供することは、彼らを路上に放置し、税 金が警察や緊急医療ケアに費やされるよりも、納税者の負担が少ないことを発見した。ロバート・ウッド・ジョンソン財団の薬物乱用政策研究プログラム (SAPRP)が資金提供したこの研究の結果は、2009年4月に『Journal of the American Medical Association』誌に掲載された。[16] これは、慢性的なホームレス状態にあるアルコール依存症者を対象とした「ハウジング・ファースト」の有効性を検証した、米国初の対照試験であり、このプロ グラムにより、最初の1年で400万ドル以上の節約が実現したことが示された。最初の6か月間では、平均53パーセントのコスト削減(95人の入居者の管 理費用を考慮しても)が報告された。これは、待機リストに登録されている39人のホームレスの人々の1か月あたりの費用と比較すると、1人あたり毎月 2,500ドル近くに相当する。さらに、入居者に対してアルコールの禁酒や治療を義務づけていないにもかかわらず、安定した住居は、レクリエーション目的 でアルコールを摂取しているホームレスの人々の飲酒量も減少させる結果となった。 アルコール関連プログラム 飲酒運転の危険性については、多くのメディアで報道されている。現在では、アルコールを娯楽として摂取する人の大半がその危険性を認識しており、また「指 名ドライバー」や無料タクシープログラムなどの安全運転テクニックにより、飲酒運転による事故は減少している。多くの都市では、アルコール摂取量の多い休 日には、無料の送迎プログラムを実施している。また、一部のバーやクラブでは、明らかに酔っている客にはタクシー代を無料にしている。 ニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州では、免許保有者のグループが地元の酒類協定を結成し、前述の「指名ドライバー」や「深夜の顧客送迎」制度を含む、さまざま な害の最小化プログラムを共同で開発、実施、推進している。 これらの送迎制度の多くは、顧客に無料で提供されており、飲酒運転を回避するよう顧客に促すと同時に、深夜の施設周辺にたむろする騒々しい顧客による影響 を軽減することを目的としている。 節度ある飲酒管理(Moderation Management)は、安全な飲酒行動を奨励することで、飲酒者のアルコール摂取量を減らすことを支援するプログラムである。 アルコール依存症における害の低減は、ナルトレキソンを使用することで実現できる可能性がある。[17] |

| Opioids Heroin maintenance programmes (HAT) Main article: Heroin assisted treatment Providing medical prescriptions for pharmaceutical heroin (diacetylmorphine) to heroin-dependent people has been employed in some countries to address problems associated with the illicit use of the drug, as potential benefits exist for the individual and broader society. Evidence has indicated that this form of treatment can greatly improve the health and social circumstances of participants, while also reducing costs incurred by criminalisation, incarceration and health interventions.[18][19] In Switzerland, heroin assisted treatment is an established programme of the national health system. Several dozen centres exist throughout the country and heroin-dependent people can administer heroin in a controlled environment at these locations. The Swiss heroin maintenance programme is generally regarded as a successful and valuable component of the country's overall approach to minimising the harms caused by illicit drug use.[20] In a 2008 national referendum, a majority of 68 per cent voted in favour of continuing the Swiss programme.[21] The Netherlands has studied medically supervised heroin maintenance.[22] A German study of long-term heroin addicts demonstrated that diamorphine was significantly more effective than methadone in keeping patients in treatment and in improving their health and social situation.[23] Many participants were able to find employment, some even started a family after years of homelessness and delinquency.[24][25] Since then, treatment had continued in the cities that participated in the pilot study, until heroin maintenance was permanently included into the national health system in May 2009.[26] As of 2021, the country offers heroin-assisted treatment by prescribing medical-grade heroin is typically prescribed in combination with methadone and psychosocial counseling.[27] A heroin maintenance programme has existed in the United Kingdom (UK) since the 1920s, as drug addiction was seen as an individual health problem. Addiction to opiates was rare in the 1920s and was mostly limited to either middle-class people who had easy access due to their profession, or people who had become addicted as a side effect of medical treatment. In the 1950s and 1960s a small number of doctors contributed to an alarming increase in the number of people who are experiencing addiction in the U.K. through excessive prescribing—the U.K. switched to more restrictive drug legislation as a result.[28] However, the British government is again moving towards a consideration of heroin prescription as a legitimate component of the National Health Service (NHS). Evidence has shown that methadone maintenance is not appropriate for all people who are dependent on opioids and that heroin is a viable maintenance drug that has shown equal or better rates of success.[29] A committee appointed by the Norwegian government completed an evaluation of research reports on heroin maintenance treatment that were available internationally. In 2011 the committee concluded that the presence of numerous uncertainties and knowledge gaps regarding the effects of heroin treatment meant that it could not recommend the introduction of heroin maintenance treatment in Norway.[30] Critics of heroin maintenance programmes object to the high costs of providing heroin to people who use it. The British heroin study cost the British government £15,000 per participant per year, roughly equivalent to average person who uses heroin's expense of £15,600 per year.[31] Drug Free Australia[32] contrast these ongoing maintenance costs with Sweden's investment in, and commitment to, a drug-free society where a policy of compulsory rehabilitation of people who are experiencing drug addiction is integral, which has yielded to one of the lowest reported illicit drug use levels in the developed world,[33] a model in which successfully rehabilitated people who use substances present no further maintenance costs to their community, as well as reduced ongoing health care costs.[32] King's Health Partners notes that the cost of providing free heroin for a year is about one-third of the cost of placing the person in prison for a year.[dead link][34][35] Naloxone distribution Naloxone is a drug used to counter an overdose from the effect of opioids; for example, a heroin or morphine overdose. Naloxone displaces the opioid molecules from the brain's receptors and reverses the respiratory depression caused by an overdose within two to eight minutes.[36] The World Health Organization (WHO) includes naloxone on their "List of Essential Medicines", and recommends its availability and utilization for the reversal of opioid overdoses.[37][38] Formal programs in which the opioid inverse agonist drug naloxone is distributed have been trialled and implemented. Established programs distribute naloxone, as per WHO's minimum standards, to people who use substances and their peers, family members, police, prisons, and others. These treatment programs and harm reduction centres operate in Afghanistan, Australia, Canada, China, Germany, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Norway, Russia, Spain, Tajikistan, the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US), Vietnam,[39] India, Thailand, Kyrgyzstan,[40] Denmark and Estonia.[41] Many reviews of the literature support the effectiveness of naloxone based interventions in reducing overdose deaths where it is available at the time of the overdose event.[42][43] This effectiveness has been explained in a Realist Evaluation which explained the effectiveness through bystander effect, social identity theory, and skills training such that universal access to training supports social identity and in-group norms (of people who use drugs), which supports the conditions for the success of a peer-to-peer distribution model of naloxone-based interventions. Stigma and stigmatising attitudes reduced the effectiveness of naloxone based interventions.[44] Medication assisted treatment (MAT): Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) and Opioid substitution therapy (OST) Medication assisted treatment (MAT) is the prescription of legal, prescribed opioids or other drugs, often long-acting, to diminish the use of illegal opioids. Many types of MAT exist, including opioid agonist therapy (OAT) where a safer opioid agonist is employed or opioid substitution therapy (OST) which employs partial opioid agonists. However, MAT, OAT, OST are often used synonymously.[45] Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) involves the use of a full opioid agonist treatment like methadone and is generally taken daily at a clinic.[46][47] Opioid substitution therapy (OST) involves the use of the partial agonist buprenorphine or a combination of buprenorphine/naloxone (brand name Suboxone). Oral/sublingual formulations of buprenorphine incorporate the opioid antagonist naloxone to prevent people from crushing the tablets and injecting them.[46] Unlike methadone treatment, buprenorphine therapy can be prescribed month-to-month and obtained at a traditional pharmacy rather than a clinic.[48] The driving principle behind OAT/OST is the program's capacity to facilitate a resumption of stability in the person's life, while they experience reduced symptoms of withdrawal symptoms and less intense drug cravings; however, a strong euphoric effect is not experienced as a result of the treatment drug.[46] In some countries, such as Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia, patients are treated with slow-release morphine when methadone is deemed inappropriate due to the individual's circumstances. In Germany, dihydrocodeine has been used off-label in OAT for many years, however it is no longer frequently prescribed for this purpose. Extended-release dihydrocodeine is again in current use in Austria for this reason.[citation needed] Research into the usefulness of piritramide, extended-release hydromorphone (including polymer implants lasting up to 90 days), dihydroetorphine and other substances for OAT is at various stages in a number of countries.[46] In 2020 in Vancouver, Canada, health authorities began vending machine dispensing of hydromorphone tablets as a response to elevated rates of fatal overdose from street drugs contaminated with fentanyl and fentanyl analogues.[49] In some countries (not the US, UK, Canada, or Australia),[46] regulations enforce a limited time period for people on OAT/OST programs that conclude when a stable economic and psychosocial situation is achieved. (Patients with HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C are usually excluded from this requirement.) In practice, 40–65% of patients maintain complete abstinence from opioids while receiving opioid agonist therapy, and 70–95% are able to reduce their use significantly, while experiencing a concurrent elimination or reduction in medical (improper diluents, non-sterile injecting equipment), psychosocial (mental health, relationships), and legal (arrest and imprisonment) issues that can arise from the use of illicit opioids.[46] OAT/OST outlets in some settings also offer basic primary health care. These are known as 'targeted primary health care outlet'—as these outlets primarily target people who inject drugs and/or 'low-threshold health care outlet'—as these reduce common barriers clients often face when they try to access health care from the conventional health care outlets.[50][51] For accessing sterile injecting equipment clients frequently visit NSP outlets, and for receiving pharmacotherapy (e.g. methadone, buprenorphine) they visit OST clinics; these frequent visits are used opportunistically to offer much needed health care.[52][53] These targeted outlets have the potential to mitigate clients' perceived barriers to access to healthcare delivered in traditional settings. The provision of accessible, acceptable and opportunistic services which are responsive to the needs of this population is valuable, facilitating a reduced reliance on inappropriate and cost-ineffective emergency department care.[54][55] |

オピオイド ヘロイン維持療法プログラム(HAT) 詳細は「ヘロイン補助治療」を参照 ヘロイン依存症患者に医薬用ヘロイン(ジアセチルモルヒネ)を処方する治療法は、違法なヘロイン使用に伴う問題に対処するために、個人および社会全体に潜 在的な利益をもたらす可能性があるとして、一部の国々で採用されている。この種の治療法は、参加者の健康状態や社会環境を大幅に改善し、同時に犯罪化や投 獄、医療介入によるコストを削減できることが実証されている。 スイスではヘロイン補助治療は国の医療制度の確立したプログラムである。国内に数十のセンターが存在し、ヘロイン依存者はこれらの場所で管理された環境下 でヘロインを摂取することができる。スイスのヘロイン維持プログラムは、一般的に、違法薬物の使用による害を最小限に抑えるという同国の全体的なアプロー チにおける成功した貴重な要素であるとみなされている。[20] 2008年の国民投票では、68%の国民がスイスのプログラムの継続に賛成票を投じた。[21] オランダでは、医療管理下でのヘロイン維持療法が研究されている。[22] ドイツにおける長期ヘロイン中毒患者を対象とした研究では、ジアモルフィンは患者を治療に留め置くこと、および患者の健康状態と社会状況を改善することに おいて、メサドンよりもはるかに効果的であることが実証された。[23] 多くの参加者が就職することができ、中には長年のホームレス生活と非行を経て、家庭を持つようになった者もいた。[24][2 それ以来、パイロット研究に参加した都市では治療が継続され、2009年5月にヘロイン維持療法が恒久的に国の医療制度に組み入れられるまで続いた。 [26] 2021年現在、この国では医療用ヘロインの処方によるヘロイン補助療法が提供されており、通常はメサドンや心理社会的カウンセリングと併用して処方され る。[27] 薬物中毒は個人の健康問題と見なされていたため、ヘロイン維持療法プログラムは1920年代から英国(UK)で存在していた。1920年代には、アヘンへ の依存症はまれであり、職業上容易に手に入る中流階級の人々か、または医療治療の副作用として依存症になった人々に限られていた。1950年代と1960 年代には、少数の医師が過剰な処方をしたことで、英国で薬物中毒になる人の数が驚異的に増加した。その結果、英国では薬物に関する法律がより厳格なものに 変更された。[28] しかし、英国政府は、国民保健サービス(NHS)の合法的な構成要素としてヘロイン処方を検討する方向へと再び動き出している。メサドン維持療法はオピオ イド依存症の人すべてに適しているわけではないこと、またヘロインは同等の成功率、あるいはそれ以上の成功率を示している有効な維持薬であることが証明さ れている。 ノルウェー政府が任命した委員会は、国際的に入手可能なヘロイン維持療法に関する研究報告の評価を完了した。2011年、委員会はヘロイン治療の効果に関 する多くの不確実性と知識のギャップがあるため、ノルウェーでのヘロイン維持療法の導入を推奨できないと結論づけた。 ヘロイン維持プログラムの批判者たちは、ヘロインを使用する人々にヘロインを供給するコストの高さを問題視している。英国のヘロイン研究では、参加者に年 間15,000ポンドの費用がかかったが、これはヘロインを使用する平均的な人々の年間費用15,600ポンドとほぼ同等である。[31] 薬物を使わないオーストラリア(Drug Free Australia)[32]は、これらの継続的な維持コストと、薬物を使わない社会へのスウェーデンの投資と取り組みとを比較している。 薬物中毒患者に強制的なリハビリテーションを施す政策が不可欠である薬物を使わない社会への投資と取り組みを挙げている。この取り組みにより、先進国の中 で報告されている違法薬物の使用率が最も低いレベルのひとつにまで減少した[33]。薬物を使用していた人々が社会復帰に成功し、地域社会に維持費をかけ ずに済むようになり、継続的な医療費も削減されたというモデルである[32]。 キングス・ヘルス・パートナーズは、ヘロインを1年間無料で提供する費用は、その人物を1年間刑務所に収監する費用の約3分の1であると指摘している。 [リンク切れ][34][35] ナロキソンの配布 ナロキソンは、オピオイドの影響による過剰摂取、例えばヘロインやモルヒネの過剰摂取に対処するために使用される薬物である。ナロキソンは、脳の受容体か らオピオイド分子を追い出し、2分から8分以内に過剰摂取による呼吸抑制を回復させる。[36] 世界保健機関(WHO)は、ナロキソンを「必須医薬品リスト」に含めており、オピオイド過剰摂取の回復に利用可能で利用すべきであると推奨している。 [37][38] オピオイド拮抗薬であるナロキソンが配布される正式なプログラムが試験的に実施されている。確立されたプログラムでは、WHOの最低基準に従って、薬物使 用者とその仲間、家族、警察、刑務所職員などにナロキソンを配布している。これらの治療プログラムと害削減センターは、アフガニスタン、オーストラリア、 カナダ、中国、ドイツ、グルジア、カザフスタン、ノルウェー、ロシア、スペイン、タジキスタン、英国(UK)、米国(US)、ベトナム、インド、タイ、キ ルギス、デンマーク、エストニアで運営されている。[39][40][41] ナルコキシンの使用に基づく介入が、過剰摂取の際に利用可能である場合、過剰摂取による死亡を減少させる効果があることを裏付ける文献のレビューは数多く ある。。[42][43] この有効性は、傍観者効果、社会的アイデンティティ理論、技能訓練などを通じて説明されるリアリスト評価によって説明されており、訓練への普遍的なアクセ スが社会的アイデンティティと(薬物使用者の)内集団規範を支え、ナロキソンベースの介入のピア・トゥ・ピア配布モデルの成功の条件を支える。スティグマ やスティグマを伴う態度は、ナロキソンをベースとした介入の効果を低下させる。[44] 薬物療法による治療(MAT):オピオイド作動薬療法(OAT)およびオピオイド置換療法(OST) 薬物療法(MAT)は、違法なオピオイドの使用を減らすために、合法的な処方オピオイドまたは他の薬物(多くの場合、長時間作用型)を処方することであ る。 オピオイド作動薬療法(OAT)ではより安全なオピオイド作動薬が用いられ、部分オピオイド作動薬が用いられるオピオイド置換療法(OST)など、多くの 種類のMATが存在する。 しかし、MAT、OAT、OSTはしばしば同義語として用いられる。[45] オピオイド作動薬療法(OAT)は、メサドンなどの完全オピオイド作動薬治療の使用を含み、通常はクリニックで毎日投与される。[46][47] オピオイド置換療法(OST)は、部分作動薬であるブプレノルフィン、またはブプレノルフィン/ナロキソン(商品名Suboxone)の併用を使用する。 経口/舌下投与のブプレノルフィン製剤にはオピオイド拮抗薬のナロキソンが配合されており、錠剤を砕いて注射することを防ぐことができる。[46] メサドン治療とは異なり、ブプレノルフィン療法は月単位で処方され、クリニックではなく従来の薬局で入手できる。[48] OAT/OSTの推進原理は、離脱症状の軽減と薬物への強い渇望の減少を経験しながら、その人の生活に安定性が再び戻ってくるのを促進するプログラムの能 力である。しかし、治療薬の使用によって強い多幸感が生じることはない。 スイス、オーストリア、スロベニアなどの国々では、患者の状況によりメサドンが不適切であると判断された場合、徐放性モルヒネが使用される。ドイツでは、 長年にわたりジヒドロコデインがOATで適応外使用されてきたが、現在ではこの目的で頻繁に処方されることは少なくなっている。徐放性ジヒドロコデイン は、この理由により、現在オーストリアで再び使用されている。[要出典] オピオイド依存症治療におけるピリトラミド、徐放性ヒドロモルフォン(最長90日間持続するポリマーインプラントを含む)、ジヒドロエトルフィン、および その他の物質の有用性に関する研究は、 段階にある。[46] 2020年、カナダのバンクーバーでは、フェンタニルおよびフェンタニル類似物質で汚染されたストリートドラッグによる致死量の過剰摂取率の上昇を受け て、保健当局がヒドロモルフォン錠剤の自動販売機による販売を開始した。[49] 一部の国々(米国、英国、カナダ、オーストラリアを除く)では、[46] 経済的および心理社会的状況が安定した時点で終了する、OAT/OSTプログラム利用者に限られた期間の規制が適用される。(HIV/AIDSまたはC型 肝炎の患者は、通常この要件の対象外となる。) 実際には、オピオイド作動薬療法を受けている患者の40~65%がオピオイドの完全な断薬を維持し、70~95%が使用量を大幅に減らすことができる。そ の一方で、違法なオピオイドの使用から生じる医療(不適切な希釈剤、非滅菌注射器具)、心理社会的(精神衛生、人間関係)、および法的(逮捕、投獄)問題 の排除または軽減も同時に実現している。[46] 一部の環境では、OAT/OSTの施設が基本的なプライマリーヘルスケアも提供している。 これらの施設は「対象を絞ったプライマリーヘルスケア施設」として知られている。これは、これらの施設が主に薬物を注射する人々を対象としているためであ る。また、「敷居の低いヘルスケア施設」として知られている。これは、従来のヘルスケア施設からヘルスケアを受けようとする際に、利用者が直面する一般的 な障壁を軽減しているためである。[50][51] 利用者は滅菌注射器具を入手するために NSPの店舗を訪れ、薬物療法(例:メサドン、ブプレノルフィン)を受けるために薬物依存症リハビリテーション施設を訪れる。こうした頻繁な訪問は、必要 とされているヘルスケアを提供するために機動的に利用されている。[52][53] こうした対象を絞った店舗は、従来の環境で提供されるヘルスケアへのアクセスに対する利用者の認識上の障壁を軽減する可能性がある。この集団のニーズに応 える、利用しやすく、受け入れられやすく、機会主義的なサービスの提供は価値があり、不適切で費用対効果の悪い救急外来への依存を減らすのに役立つ。 [54][55] |

| Cannabis Further information: Cannabis (drug), Legal issues of cannabis, and Health issues and the effects of cannabis Specific harms associated with cannabis include increased crash-rate while driving under intoxication, dependence, psychosis, detrimental psychosocial outcomes for adolescents who use substances, and respiratory disease.[56] Some safer cannabis usage campaigns including the UKCIA (United Kingdom Cannabis Internet Activists) encourage methods of consumption shown to cause less physical damage to a person's body, including oral (eating) consumption, vaporization, the usage of bongs which cool and to some extent filters the smoke, and smoking the cannabis without mixing it with tobacco. The fact that cannabis possession carries prison sentences in most developed countries is also pointed out as a problem by European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), as the consequences of a conviction for otherwise law-abiding people who use substances arguably is more harmful than any harm from the substance itself. For example, by adversely affecting employment opportunities, impacting civil rights,[57] and straining personal relationships.[58] Some people like Ethan Nadelmann of the Drug Policy Alliance have suggested that organized marijuana legalization would encourage safe use and reveal the factual adverse effects from exposure to this herb's individual chemicals.[59] The way the laws concerning cannabis are enforced is also very selective, even discriminatory. Statistics show that the socially disadvantaged, immigrants and ethnic minorities have significantly higher arrest rates.[58] Drug decriminalisation, such as allowing the possession of small amounts of cannabis and possibly its cultivation for personal use, would alleviate these harms.[58] Where decriminalisation has been implemented, such as in several states in Australia and United States, as well as in Portugal and the Netherlands no, or only very small adverse effects have been shown on population cannabis usage rate.[58] The lack of evidence of increased use indicates that such a policy shift does not have adverse effects on cannabis-related harm while, at the same time, decreasing enforcement costs.[58] In the last few years certain strains of the cannabis plant with higher concentrations of THC and drug tourism have challenged the former policy in the Netherlands and led to a more restrictive approach; for example, a ban on selling cannabis to tourists in coffeeshops suggested to start late 2011.[60] Sale and possession of cannabis is still illegal in Portugal[61] and possession of cannabis is a federal crime in the United States. |

大麻 さらに詳しい情報:大麻(薬物)、大麻の法的問題、健康問題と大麻の影響 大麻に関連する具体的な害としては、酩酊状態での運転中の衝突率の増加、依存症、精神病、薬物を使用する青少年の有害な心理社会的結果、呼吸器疾患などが ある。[56] UKCIA(英国大麻インターネット活動家)をはじめとする一部の安全な大麻使用キャンペーンでは )は、経口摂取(食べる)、気化、煙を冷却しある程度フィルターする水キセルの使用、タバコと混ぜずにマリファナを吸うなど、人体への物理的ダメージが少 ないとされる摂取方法を推奨している。 大麻の所持がほとんどの先進国で実刑判決につながるという事実も、欧州麻薬薬物監視センター(EMCDDA)によって問題として指摘されている。法を遵守 している人々が物質を使用したことによる有罪判決の結果は、物質そのものによる害よりも有害である可能性が高い。例えば、雇用機会に悪影響を及ぼしたり、 市民権に影響を与えたり[57]、人間関係にひずみを生じさせたりする[58]。 薬物政策連合のイーサン・ナデルマン(Ethan Nadelmann)氏のように、組織的なマリファナ合法化が安全な使用を促し、この薬草の個々の化学物質への暴露による事実上の悪影響を明らかにするだ ろうと提案する人もいる[59]。 大麻に関する法律の施行方法は、非常に選択的であり、差別的ですらある。統計によると、社会的弱者、移民、少数民族の逮捕率が著しく高いことが示されてい る。[58] 少量の大麻の所持や、個人使用目的での栽培を認めるなど、薬物の非犯罪化は、これらの弊害を緩和するだろう。[58] オーストラリアや米国の一部の州、 ポルトガルやオランダなど、非犯罪化が実施された国々では、大麻の使用率にほとんど悪影響が見られないか、あってもごくわずかであることが示されている。 [58] 使用率の増加を示す証拠がないことは、このような政策転換が大麻関連の害悪に悪影響を与えないことを示している。同時に、取締りコストの削減にもつながっ ている。[58] ここ数年、THCの含有量が高い特定の品種のマリファナと薬物目的の観光が、オランダの従来の政策に異議を唱え、より制限的なアプローチへと導いた。例え ば、2011年後半に開始が提案された、観光客へのマリファナの販売禁止などである。[60] ポルトガルでは、マリファナの販売と所持はいまだに違法であり[61]、米国ではマリファナの所持は連邦犯罪である。 |

| Psychedelics The Zendo Project conducted by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies uses principles from psychedelic therapy to provide safe places and emotional support for people having difficult experiences on psychedelic drugs at select festivals such as Burning Man, Boom Festival, and Lightning in a Bottle without medical or law enforcement intervention.[62] |

サイケデリクス(幻覚系の薬物) 多分野サイケデリクス研究会(Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies)が実施するゼンド・プロジェクト(Zendo Project)では、サイケデリクス療法の原則を応用し、医療や法執行機関の介入なしに、バーニングマン、ブーム・フェスティバル、ライトニング・イ ン・ア・ボトルなどの厳選されたフェスティバルで、サイケデリクス薬物を使用して困難な経験をしている人々に安全な場所と精神的なサポートを提供してい る。[62] |

| Stimulants The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime states, "While medical models of treatment for individuals with alcohol or opioid use disorders are well accepted and implemented worldwide, in most countries there is no parallel, long-term medical model of treatment for individuals with stimulant use disorders."[63] The neglect of stimulant-users has been widely considered to be related to the popularity of stimulants among systemically-oppressed groups, such as methamphetamine use among gay men and transgender people, and crack cocaine use among Black people.[64][65] The crack epidemic in the United States demonstrates a discrepancy between sentencing lengths of crack cocaine and heroin users, with crack users imprisoned for longer periods of time than heroin users. In 2012, 88% of imprisonments from crack cocaine were of African American people.[66] Stimulant users have increasingly been at risk for opioid overdose since 2006, due to the nonconsensual presence of fentanyl in their substances.[67] |

覚醒剤 国連薬物犯罪事務所は、「アルコールまたはオピオイド使用障害を持つ個人に対する治療の医学モデルは世界中で広く受け入れられ実施されているが、ほとんど の国では、覚醒剤使用障害を持つ個人に対する治療の医学モデルは長期的なものは存在しない」と述べている。[63] 覚醒剤使用者の無視は、 例えば、ゲイ男性やトランスジェンダーの人々によるメタンフェタミン使用、黒人によるクラック・コカイン使用など、抑圧的な状況下にある集団における覚醒 剤の人気と関連していると考えられている。[64][65] 米国におけるクラック・コカインの蔓延は、クラック・コカイン使用者とヘロイン使用者の判決期間の長さの相違を示しており、クラック・コカイン使用者はヘ ロイン使用者よりも長期にわたって投獄されている。2012年には、クラック・コカインによる投獄の88%がアフリカ系アメリカ人であった。[66] 覚醒剤使用者は、2006年以降、フェンタニルが非合意的に混入しているため、オピオイドの過剰摂取のリスクが高まっている。[67] |

| Tobacco Main article: Tobacco harm reduction Tobacco harm reduction describes actions taken to lower the health risks associated with using tobacco, especially combustible forms, without abstaining completely from tobacco and nicotine. Some of these measures include switching to safer (lower tar) cigarettes, switching to snus or dipping tobacco, or using a non-tobacco nicotine delivery systems. In recent years, the growing use of electronic cigarettes (or vaping) for smoking cessation, whose long-term safety remains uncertain, has sparked an ongoing controversy among medical and public health between those who seek to restrict and discourage all use until more is known and those who see them as a useful approach for harm reduction, whose risks are most unlikely to equal those of smoking tobacco.[68] "Their usefulness in tobacco harm reduction as a substitute for tobacco products is unclear",[69] but in an effort to decrease tobacco related death and disease, they have a potential to be part of the strategy.[70] |

タバコ 主な記事 タバコのハームリダクション タバコのハームリダクションとは、タバコやニコチンを完全に断つことなく、タバコ、特に可燃性タバコの使用に伴う健康リスクを下げるために取られる行動を 指す。このような対策には、より安全な(タールの低い)タバコへの切り替え、スヌースやディッピングタバコへの切り替え、タバコ以外のニコチンデリバリー システムの使用などがある。近年、禁煙のために電子タバコ(またはVAPE)の使用が増加しているが、その長期的な安全性はまだ不明であるため、医学およ び公衆衛生の間で、より多くのことが判明するまですべての使用を制限し、思いとどまらせようとする人々と、そのリスクが喫煙タバコのリスクと同等になる可 能性が最も低いハームリダクションのための有用なアプローチとみなす人々との間で、継続的な論争が巻き起こっている。 [68]「タバコ製品の代替品としてのタバコのハームリダクションにおける有用性は不明確である」[69]が、タバコに関連する死亡や疾病を減少させる努 力においては、戦略の一部となる可能性を秘めている[70]。 |

| Routes of administration Needle exchange programmes (NEP)  A bin allowing for safe disposal of needles in a public toilet in Caernarfon, Wales Main article: Needle-exchange programme The use of some illicit drugs can involve hypodermic needles. In some areas (notably in many parts of the US), these are available solely by prescription. Where availability is limited, people who use heroin and other substances frequently share the syringes and use them more than once or participate in unsafe practices such as blood flashing. As a result, infections such as HIV or hepatitis C can spread from person to person through the reuse of syringes contaminated with infected blood.[71] The principles of harm reduction propose that syringes should be easily available or at least available through a needle and syringe programmes (NSP). Where syringes are provided in sufficient quantities, rates of HIV are much lower than in places where supply is restricted. In many countries people who use substances are supplied equipment free of charge, others require payment or an exchange of dirty needles for clean ones, hence the name. A 2010 review found insufficient evidence that NSP prevents transmission of the hepatitis C virus, tentative evidence that it prevents transmission of HIV and sufficient evidence that it reduces self-reported injecting risk behaviour.[72] It has been shown in the many evaluations of needle-exchange programmes that in areas where clean syringes are more available, illegal drug use is no higher than in other areas. Needle exchange programmes have reduced HIV incidence by 33% in New Haven and 70% in New York City.[73] The Melbourne, Australia inner-city suburbs of Richmond and Abbotsford are locations in which the use and dealing of heroin has been concentrated for a protracted time period. Research organisation the Burnet Institute completed the 2013 'North Richmond Public Injecting Impact Study' in collaboration with the Yarra Drug and Health Forum, City of Yarra and North Richmond Community Health Centre and recommended 24-hour access to sterile injecting equipment due to the ongoing "widespread, frequent and highly visible" nature of illicit drug use in the areas. During the period between 2010 and 2012 a four-fold increase in the levels of inappropriately discarded injecting equipment was documented for the two suburbs. In the local government area the City of Yarra, of which Richmond and Abbotsford are parts of, 1550 syringes were collected each month from public syringe disposal bins in 2012. Furthermore, ambulance callouts for heroin overdoses were 1.5 times higher than for other Melbourne areas in the period between 2011 and 2012 (a total of 336 overdoses), and drug-related arrests in North Richmond were also three times higher than the state average. The Burnet Institute's researchers interviewed health workers, residents and local traders, in addition to observing the drug scene in the most frequented North Richmond public injecting locations.[74] On 28 May 2013, the Burnet Institute stated in the media that it recommends 24-hour access to sterile injecting equipment in the Melbourne suburb of Footscray after the area's drug culture continues to grow after more than ten years of intense law enforcement efforts. The institute's research concluded that public injecting behaviour is frequent in the area and inappropriately discarding injecting paraphernalia has been found in carparks, parks, footpaths and drives. Furthermore, people who inject drugs have broken open syringe disposal bins to reuse discarded injecting equipment.[75] The British public body, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), introduced a new recommendation in early April 2014 due to an increase in the presentation of the number of young people who inject steroids at UK needle exchanges. NICE previously published needle exchange guidelines in 2009, in which needle and syringe services are not advised for people under the age of 18 years, but the organisation's director Professor Mike Kelly explained that a "completely different group" of people were presenting at programs. In the updated guidance, NICE recommended the provision of specialist services for "rapidly increasing numbers of steroid users", and that needles should be provided to people under the age of 18—a first for NICE—following reports of 15-year-old steroid injectors seeking to develop their muscles.[76] |

投与経路 針交換プログラム(NEP)  ウェールズ、ケルナーフォンの公衆トイレにある注射針を安全に廃棄できるゴミ箱。 主な記事 注射針交換プログラム 一部の違法薬物の使用には皮下注射針が使われることがある。一部の地域(特に米国の多くの地域)では、皮下注射針は処方箋でのみ入手可能である。入手可能 な場所が限られている場合、ヘロインやその他の薬物を使用する人々は、注射器を頻繁に共有し、複数回使用したり、血液をフラッシュするような危険な行為に 参加したりする。その結果、HIVやC型肝炎などの感染症が、感染した血液で汚染された注射器の再使用を通じて人から人へと広がる可能性がある[71]。 ハームリダクションの原則は、注射器が容易に入手できるか、少なくとも注射針・注射器プログラム(NSP)を通じて入手できるようにすることを提案してい る。注射器が十分な量提供されている場合、HIV感染率は、供給が制限されている場所よりもはるかに低い。多くの国では、物質を使用する人々に無料で器具 が提供されるが、他の国では、代金を支払うか、汚れた注射針を清潔な注射針と交換する必要がある。 2010年のレビューでは、NSPがC型肝炎ウイルスの感染を防ぐという十分な証拠はなく、HIVの感染を防ぐという暫定的な証拠と、自己申告による注射 のリスク行動を減らすという十分な証拠が見つかった[72]。針交換プログラムの多くの評価で、清潔な注射器がより多く入手できる地域では、違法薬物の使 用は他の地域よりも高くないことが示されている。針交換プログラムは、ニューヘイブンでは33%、ニューヨーク市では70%のHIV発症率を減少させた [73]。 オーストラリアのメルボルン市郊外のリッチモンドとアボッツフォードは、ヘロインの使用と取引が長期にわたって集中している場所である。研究機関のバー ネット研究所は、ヤラ・ドラッグ・アンド・ヘルス・フォーラム、ヤラ市、ノース・リッチモンド・コミュニティ・ヘルスセンターと共同で、2013年に 「ノース・リッチモンド公共注射影響調査」を実施し、この地域で違法薬物の使用が「広範囲に、頻繁に、非常に目につく」状態が続いていることから、無菌注 射器具を24時間利用できるようにすることを推奨した。2010年から2012年の間に、不適切に廃棄された注射器具のレベルが、この2つの郊外で4倍に 増加したことが記録されている。リッチモンドとアボッツフォードが属するヤラ市では、2012年、毎月1550本の注射器が公共の注射器回収箱から回収さ れた。さらに、2011年から2012年にかけてのヘロインの過剰摂取による救急車の出動件数は、メルボルンの他の地域よりも1.5倍多く(合計336件 の過剰摂取)、ノース・リッチモンドにおける薬物関連の検挙件数も州平均の3倍であった。バーネット研究所の研究者は、最も頻繁にノース・リッチモンドの 公共の注射場所で薬物シーンを観察することに加えて、医療従事者、住民、地元の商人にインタビューを行った[74]。 2013年5月28日、バーネット研究所はメディアで、メルボルン郊外のフッツクレイで24時間無菌注射器へのアクセスを推奨すると述べた。研究所の調査 によると、この地域では公共の場での注射行為が頻繁に行われており、不適切に注射器具が捨てられているのが、駐車場、公園、歩道、車道で発見されている。 さらに、薬物を注射する人々は、注射器廃棄ボックスを壊して、廃棄された注射器を再利用している[75]。 英国の公的機関であるNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence(NICE)は、英国の注射針交換所においてステロイドを注射する若者の数の提示が増加したため、2014年4月初旬に新たな勧告を 導入した。NICEは2009年に針交換ガイドラインを発表しており、そこでは18歳未満の人々には針と注射器のサービスを勧めないとしていたが、同組織 のディレクターであるマイク・ケリー教授は、「まったく異なるグループ」の人々がプログラムに参加していると説明している。更新されたガイダンスの中で、 NICEは「急速に増加しているステロイド使用者」のために専門的なサービスを提供することを推奨し、15歳のステロイド注射者が筋肉を発達させようとし ているという報告を受けて、NICEとしては初めて18歳未満の人々に注射針を提供することを推奨した[76]。 |

| Supervised injection sites (SIS) A clandestine kit containing materials to inject drugs Injection kit obtained from a needle-exchange programme Main article: Supervised injection site Supervised injection sites (SIS), or Drug consumption rooms (DCR), are legally sanctioned, medically supervised facilities designed to address public nuisance associated with drug use and provide a hygienic and stress-free environment for drug consumers. The facilities provide sterile injection equipment, information about drugs and basic health care, treatment referrals, and access to medical staff. Some offer counseling, hygienic and other services of use to itinerant and impoverished individuals. Most programmes prohibit the sale or purchase of illegal drugs. Many require identification cards. Some restrict access to local residents and apply other admission criteria, such as they have to be people who inject substances, but generally in Europe they do not exclude people with substance use disorders who consume their substances through other means. The Netherlands had the first staffed injection room, although they did not operate under explicit legal support until 1996. Instead, the first center where it was legal to inject drugs was in Berne, Switzerland, opened 1986. In 1994, Germany opened its first site. Although, as in the Netherlands they operated in a "gray area", supported by the local authorities and with consent from the police until the Bundestag provided a legal exemption in 2000.[77] In Europe, Luxembourg, Spain and Norway have opened facilities after year 2000.[78] Sydney's Medically Supervised Injecting Center (MSIC) was established in May 2001 as a trial and Vancouver's Insite opened in September 2003.[79][80][81] In 2010, after a nine-year trial, the Sydney site was confirmed as a permanent public health facility.[82][83] As of late 2009 there were a total of 92 professionally supervised injection facilities in 61 cities.[78] In North American, as of 2023 there are supervised injection sites operating in a number of Canadian cities,[84] and two in United States. The sites in United States opened in 2021.[85] The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction's latest systematic review from April 2010 did not find any evidence to support concerns that DCR might "encourage drug use, delay treatment entry or aggravate problems of local drug markets."[78] Jürgen Rehm and Benedikt Fischer explained that while evidence show that DCR are successful, that "interpretation is limited by the weak designs applied in many evaluations, often represented by the lack of adequate control groups." Concluding that this "leaves the door open for alternative interpretations of data produced and subsequent ideological debate."[86] The EMCDDA review noted that research into the effects of the facilities "faces methodological challenges in taking account of the effects of broader local policy or ecological changes", still they concluded "that the facilities reach their target population and provide immediate improvements through better hygiene and safety conditions for injectors." Further that "the availability of safer injecting facilities does not increase levels of drug use or risky patterns of consumption, nor does it result in higher rates of local drug acquisition crime." While its usage is "associated with self-reported reductions in injecting risk behaviour such as syringe sharing, and in public drug use" and "with increased uptake of detoxification and treatment services."[78] However, "a lack of studies, as well as methodological problems such as isolating the effect from other interventions or low coverage of the risk population, evidence regarding DCRs—while encouraging—is insufficient for drawing conclusions with regard to their effectiveness in reducing HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence." Concluding with that "there is suggestive evidence from modelling studies that they may contribute to reducing drug-related deaths at a city level where coverage is adequate, the review-level evidence of this effect is still insufficient."[78] Critics of this intervention, such as drug prevention advocacy organisations, Drug Free Australia and Real Women of Canada[83][87][88] point to the most rigorous evaluations,[89] those of Sydney and Vancouver. Two of the centers, in Sydney, Australia and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada cost $2.7 million[90] and $3 million per annum to operate respectively,[91] yet Canadian mathematical modeling, where there was caution about validity, indicated just one life saved from fatal overdose per annum for Vancouver,[92][93] while the Drug Free Australia analysis demonstrates the Sydney facility statistically takes more than a year to save one life.[94] The Expert Advisory Committee of the Canadian Government studied claims by journal studies for reduced HIV transmission by Insite but "were not convinced that these assumptions were entirely valid."[92] The Sydney facility showed no improvement in public injecting and discarded needles beyond improvements caused by a coinciding heroin drought,[95] while the Vancouver facility had an observable impact.[92] Drug dealing and loitering around the facilities were evident in the Sydney evaluation,[96] but not evident for the Vancouver facility.[92] |

監視下注射施設(SIS) 薬物を注射するための材料が入った秘密のキット 注射針交換プログラムから入手した注射キット 主な記事 監視下注射施設 監視下注射施設(SIS)、または薬物消費室(DCR)は、薬物使用に伴う公共の迷惑に対処し、薬物消費者に衛生的でストレスのない環境を提供するために 設計された、法的に認可された、医学的に監視された施設である。 この施設では、無菌の注射器、薬物や基本的な健康管理に関する情報、治療の紹介、医療スタッフへのアクセスなどが提供される。旅人や貧困層にカウンセリン グや衛生管理などのサービスを提供しているところもある。ほとんどのプログラムでは、違法薬物の売買を禁止している。身分証明書が必要なものも多い。地域 住民にアクセスを制限したり、薬物を注射する人でなければならないなど、他の入所基準を適用しているところもあるが、ヨーロッパでは一般的に、他の手段で 薬物を摂取する薬物使用障害のある人を排除していない。 オランダには最初の有人注射室があったが、1996年までは明確な法的支援のもとで運営されていたわけではない。代わりに、薬物注射が合法となった最初の センターは、1986年に開設されたスイスのベルンであった。1994年には、ドイツが最初の施設を開設した。しかし、オランダと同様、2000年に連邦 議会が法的免除を与えるまでは、地元当局の支援と警察の同意のもと、「グレーゾーン」で運営されていた[77]。 ヨーロッパでは、ルクセンブルク、スペイン、ノルウェーが2000年以降に施設を開設している[78]。シドニーのMedically Supervised Injecting Center (MSIC)は2001年5月に試験的に設立され、バンクーバーのInsiteは2003年9月に開設された[79][80][81]。2010年、9年 間の試験期間を経て、シドニーの施設が恒久的な公衆衛生施設であることが確認された。 [北米では、2023年現在、カナダの多くの都市で管理された注射施設が運営されており[84]、米国では2つの施設が運営されている。米国の施設は 2021年にオープンした[85]。 2010年4月に行われた欧州薬物・薬物中毒モニタリングセンターの最新のシステマティックレビューでは、DCRが「薬物使用を助長し、治療への参加を遅 らせ、地域の薬物市場の問題を悪化させる」という懸念を裏付ける証拠は見つからなかった[78]。ユルゲン・レームとベネディクト・フィッシャーは、 DCRが成功していることを示す証拠はあるものの、「多くの評価で適用されているデザインが弱く、適切な対照群がないことに代表されるように、その解釈に は限界がある」と説明している。このことは、「作成されたデータの別解釈や、それに続くイデオロギー的な議論に門戸を開いたままにしている」と結論づけて いる[86]。 EMCDDAのレビューでは、施設の効果に関する研究は「より広範な地域の政策や生態系の変化の影響を考慮するという方法論的な課題に直面している」とし ながらも、「施設はその対象集団に到達し、注射者にとってより良い衛生・安全条件を通じて直接的な改善をもたらしている」と結論づけている。さらに、「よ り安全な注射施設が利用可能になったからといって、薬物使用レベルや危険な消費パターンが増加することはなく、地域の薬物取得犯罪率が高くなることもない 」と結論づけた。一方、DCRの利用は、「自己報告による、注射器の共有などの注射リスク行動の減少や、公共の場での薬物使用と関連しており」、「解毒・ 治療サービスの利用率の増加とも関連している」[78]。しかし、「研究数の不足に加え、他の介入からの効果の切り分けや、リスク集団のカバー率の低さな どの方法論的問題もあり、DCRに関するエビデンスは、勇気づけられるものではあるが、HIVやC型肝炎ウイルス(HCV)の罹患率を減少させる効果に関 して結論を出すには不十分である。モデル化研究からは、DCRが十分な普及率のある都市レベルでは薬物関連死の減少に寄与する可能性があるという示唆的な エビデンスがあるが、この効果に関するレビューレベルのエビデンスはまだ不十分である」[78]と結んでいる。 薬物乱用防止擁護団体であるドラッグ・フリー・オーストラリアやリアル・ウーマン・オブ・カナダ[83][87][88]など、この介入を批判する人々 は、最も厳密な評価である[89]シドニーとバンクーバーの評価を指摘している。オーストラリアのシドニーとカナダのブリティッシュコロンビア州バンクー バーにある2つのセンターの運営費は、それぞれ年間270万ドル[90]と300万ドル[91]であったが、カナダの数学的モデリングでは、妥当性につい ては注意が必要であり、バンクーバーでは年間わずか1人の命が致死的な過剰摂取から救われたとしている[92][93]。 [94]。カナダ政府の専門家諮問委員会は、インサイトによるHIV感染の減少に関する学術誌の研究による主張を調査したが、「これらの仮定が完全に妥当 であるとは確信できなかった」[92]。シドニー施設では、同時期のヘロイン干ばつによる改善以上の公共の場での注射と廃棄された針の改善は見られなかっ た[95]が、バンクーバー施設では観察可能な影響があった[92]。 |

| Safer supply Safer supply programs prescribe medications (including stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines) to people at high risk of overdose. This is meant to provide a safer alternative to an illegal drug supply that contains high levels of fentanyl and other dangerous chemicals.[97] The structure of such programs is more flexible than opioid agonist therapy.[97] The drugs dispensed by these programs can result in intoxication, unlike methadone or buprenorphine.[98] Safer supply projects exist in a number of Canadian cities.[84] Critics of these programs point to the risk of drug diversion and argue that patients should be encouraged to enter drug rehabilitation programs instead of being given drugs.[98] |

より安全な供給 より安全な供給プログラムは、過剰摂取のリスクが高い人々に薬物(覚せい剤、オピオイド、ベンゾジアゼピン系を含む)を処方するものである。これは、フェ ンタニルやその他の危険な化学物質を多量に含む違法な薬物供給に対して、より安全な代替手段を提供することを意図している[97]。こうしたプログラムの 仕組みは、オピオイド作動薬療法よりも柔軟である[97]。こうしたプログラムによって調剤される薬物は、メタドンやブプレノルフィンとは異なり、中毒を 引き起こす可能性がある。 [98]より安全な供給プロジェクトはカナダの多くの都市に存在する[84]。これらのプログラムの批判者は、薬物転用のリスクを指摘し、患者に薬物を与 えるのではなく、薬物リハビリテーションプログラムへの入所を促すべきだと主張している[98]。 |

| Sex Safer sex programmes Many schools now provide safer sex education to teen and pre-teen students, who may engage in sexual activity. Since some adolescents are going to have sex, a harm-reductionist approach supports a sexual education which emphasizes the use of protective devices like condoms and dental dams to protect against unwanted pregnancy and the transmission of STIs. This runs contrary to abstinence-only sex education, which teaches that educating children about sex can encourage them to engage in it. These programmes have been found to decrease risky sexual behaviour and prevent sexually transmitted infections.[99] They also reduce rates of unwanted pregnancies.[100] Abstinence-only programmes do not appear to affect HIV risks in developed countries with no evidence available for other areas.[101] Legalized prostitution Main article: Legality of prostitution Since 1999, some countries have legalized prostitution, such as Germany (2002) and New Zealand (2003). However, in most countries the practice is prohibited. Gathering accurate statistics on prostitution and human trafficking is extremely difficult. This has resulted in proponents of legalization claiming that it reduces organized crime rates while opponents claim exactly the converse. The Dutch prostitution policy, which is one of the most liberal in the world, has gone back and forth on the issue several times. In the period leading up to 2015 up to a third of officially sanctioned work places had been closed down again after reports of human trafficking. Prostitutes themselves are generally opposed to what they see as "theft of their livelihood".[102] Legal prostitution means prostitutes can contact police in instances of abuse or violence without fear of arrest or prosecution because of what they are doing being illegal. A legal and regulated system can also provide licensed brothels as opposed to prostitutes working on the streets, in which the owners or staff of the premises can call the police in instances of violence against sex workers without fear of workers or the business facing criminal charges or being shut down. Legal and regulated prostitution can require prostitutes to undergo regular health checks for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by law. Sex workers in Nevada for instance have to get monthly tests for syphilis and HIV and weekly tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia.[103] Sex-work and HIV Despite the depth of knowledge of HIV/AIDS, rapid transmission has occurred globally in sex workers.[73] The relationship between these two variables greatly increases the risk of transmission among these populations, and also to anyone associated with them, such as their sexual partners, their children, and eventually the population at large.[73] Many street-level harm-reduction strategies have succeeded in reducing HIV transmission in injecting drug users and sex-workers.[5] HIV education, HIV testing, condom use, and safer-sex negotiation greatly decreases the risk to the disease.[5][104] Peer education as a harm reduction strategy has especially reduced the risk of HIV infection, such as in Chad, where this method was the most cost-effective per infection prevented.[5] Decriminalisation as a harm-reduction strategy gives the ability to treat substance use disorder solely as a public health issue rather than a criminal activity. This enables other harm-reduction strategies to be employed, which results in a lower incidence of HIV infection.[105] One of the first harm reduction models was called the "Mersey Harm Reduction Model" in 1980s Liverpool, and the success of utilizing outreach workers, distribution of education, and providing clean equipment to drug users was shown in the fact that an HIV epidemic did not happen in Mersey.[106] The AIDS epidemic, which began in the 80s and peaked in 1995, further complicated the politicization of drug users and drug use in the US. The implementation of harm reduction faced much resistance within the US due to the demonization of particular drugs associated with stigmatized groups, such as sex workers and drug-injecting users.[107] |

セックス より安全な性教育プログラム 現在多くの学校では、性行為を行う可能性のある10代や10代前の生徒に対して、より安全な性教育を行っている。青少年の中には性行為をする者もいるた め、害悪削減主義的アプローチは、望まない妊娠やSTI感染から守るために、コンドームやデンタルダムといった保護具の使用を強調する性教育を支持する。 これは、セックスについて子どもたちに教育することは、子どもたちにセックスをすることを促すことになると教える禁欲のみの性教育とは相反するものであ る。 こうしたプログラムは、危険な性行動を減らし、性感染症を予防することが分かっている[99]。また、望まない妊娠の割合も減らすことができる [100]。禁欲のみのプログラムは、先進国ではHIVリスクに影響を与えないようであるが、他の地域では証拠がない[101]。 売春の合法化 主な記事 売春の合法化 1999年以降、ドイツ(2002年)やニュージーランド(2003年)のように売春を合法化した国もある。しかし、ほとんどの国では売春は禁止されてい る。売春や人身売買に関する正確な統計を取ることは非常に困難である。そのため、合法化推進派は組織犯罪率を下げると主張し、反対派はその逆を主張する結 果となっている。世界で最もリベラルな国のひとつであるオランダの売春政策は、この問題で何度も行きつ戻りつしている。2015年までの期間には、人身売 買の報告を受けて、公的に認可された仕事場の3分の1までが再び閉鎖された。売春婦自身は一般的に「生計の窃盗」とみなすものに反対している[102]。 合法的な売春とは、売春婦が虐待や暴力を受けた場合に、自分たちのしていることが違法であるという理由で逮捕や起訴を恐れることなく警察に連絡できること を意味する。合法的で規制された制度は、路上で働く売春婦とは対照的に、認可された売春宿を提供することもできる。このような売春宿では、施設の所有者や スタッフは、労働者や事業が刑事責任を問われたり閉鎖されたりすることを恐れることなく、セックス労働者に対する暴力の事例において警察に通報することが できる。合法的に規制された売春は、法律により売春婦に性感染症(STI)の定期的な健康診断を受けることを義務付けることができる。例えばネバダ州の セックスワーカーは、梅毒とHIVの検査を毎月、淋病とクラミジアの検査を毎週受けなければならない[103]。 セックスワークとHIV HIV/AIDSに関する知識の深さにもかかわらず、セックス・ワーカーにおける急速な感染は世界的に発生している[73]。これら2つの変数の関係は、 これらの集団の間での感染の危険性を大幅に高め、また、性的パートナー、その子ども、ひいては一般の人々など、これらの集団に関連する人々への感染の危険 性をも高めている[73]。 HIV教育、HIV検査、コンドームの使用、セーファーセックス交渉は、この病気に対するリスクを大幅に減少させる[5][104]。ハームリダクション 戦略としてのピアエデュケーションは、特にHIV感染のリスクを減少させており、例えばチャドでは、この方法が予防された感染あたり最も費用対効果が高 かった[5]。 ハームリダクション戦略としての非犯罪化は、薬物使用障害を犯罪行為としてではなく、公衆衛生上の問題としてのみ扱う能力を与える。これにより、他のハー ムリダクション戦略を採用することが可能になり、HIV感染の発生率が低下する[105]。 最初のハームリダクションモデルのひとつは、1980年代のリバプールにおける「マージー・ハームリダクション・モデル」と呼ばれるもので、アウトリーチ ワーカーを活用し、教育を配布し、薬物使用者に清潔な器具を提供することの成功は、マージーではHIVの流行が起こらなかったという事実で示された [106]。 80年代に始まり1995年にピークを迎えたエイズの流行は、アメリカにおける薬物使用者と薬物使用の政治化をさらに複雑にした。ハームリダクションの実 施は、セックスワーカーや薬物注射使用者など、汚名を着せられた集団に関連する特定の薬物の悪魔化により、米国内で多くの抵抗に直面した[107]。 |

| Decriminalisation Decriminalisation as a harm-reduction strategy gives the ability to treat substance use disorder solely as a public health issue rather than a criminal activity. This enables other harm-reduction strategies to be employed, which results in a lower incidence of HIV infection.[5] |

非犯罪化 ハームリダクション戦略としての非犯罪化は、薬物使用障害を犯罪行為としてではなく、公衆衛生上の問題としてのみ扱う能力を与える。これにより、他のハー ムリダクション戦略を採用することが可能となり、結果としてHIV感染の発生率が低下する[5]。 |

| Criticism Critics, such as Drug Free America Foundation and other members of network International Task Force on Strategic Drug Policy, state that a risk posed by harm reduction is by creating the perception that certain behaviours can be partaken of safely, such as illicit drug use, that it may lead to an increase in that behaviour by people who would otherwise be deterred. The signatories of the drug prohibitionist network International Task Force on Strategic Drug Policy stated that they oppose drug use harm reduction "...strategies as endpoints that promote the false notion that there are safe or responsible ways to use drugs. That is, strategies in which the primary goal is to enable drug users to maintain addictive, destructive, and compulsive behavior by misleading users about some drug risks while ignoring others."[108] In 2008, the World Federation Against Drugs stated that while "...some organizations and local governments actively advocate the legalization of drugs and promote policies such as "harm reduction" that accept drug use and do not help people who use substances to become free from substance use. This undermines the international efforts to limit the supply of and demand for drugs." The Federation states that harm reduction efforts often end up being "drug legalization or other inappropriate relaxation efforts, a policy approach that violates the UN Conventions."[109] Critics furthermore reject harm reduction measures for allegedly trying to establish certain forms of drug use as acceptable in society. The Drug Prevention Network of Canada states that harm reduction has "...come to represent a philosophy in which illicit substance use is seen as largely unpreventable, and increasingly, as a feasible and acceptable lifestyle as long as use is not 'problematic'", an approach which can increase "acceptance of drug use into the mainstream of society". They say harm reduction "...sends the wrong message to ... children and youth" about drug use.[110] In 2008, the Declaration of World Forum Against Drugs criticized harm reduction policies that "...accept drug use and do not help drug users to become free from drug abuse", which the group say undermines "...efforts to limit the supply of and demand for drugs." They state that harm reduction should not lead to less efforts to reduce drug demand.[111] Pope Benedict XVI criticised harm reduction policies with regards to HIV/AIDS, saying that it was "a tragedy that cannot be overcome by money alone, that cannot be overcome through the distribution of condoms, which even aggravates the problems".[112] This position was in turn widely criticised for misrepresenting and oversimplifying the role of condoms in preventing infections.[113][114] |

批判 ドラッグ・フリー・アメリカ財団や「戦略的薬物政策に関する国際タスクフォース」ネットワークのメンバーなどの批評家は、ハームリダクションがもたらすリ スクは、違法薬物使用のような特定の行動が安全に行えるという認識を植え付けることであり、そうでなければ抑止されるはずの行動が増加する可能性があると 述べている。薬物禁止派のネットワーク「戦略的薬物政策に関する国際タスクフォース」の署名者は、薬物使用ハームリダクションに反対すると述べている。つ まり、薬物のリスクについてユーザーを誤解させる一方で、他のリスクについては無視することで、薬物使用者が中毒的、破壊的、強迫的な行動を維持できるよ うにすることを第一の目標とする戦略である」[108]。 2008年、世界反薬物連盟は、「...一部の団体や地方自治体は、薬物の合法化を積極的に提唱し、薬物使用を容認する「ハームリダクション」のような政 策を推進する一方で、薬物を使用する人々が薬物使用から自由になることを支援しない。これは、薬物の供給と需要を制限するための国際的な努力を損なうもの である。」 同連合会は、ハームリダクションの努力は、しばしば「薬物合法化やその他の不適切な緩和努力、国連条約に違反する政策アプローチ」に終わるとしている [109]。 批評家たちはさらに、特定の形態の薬物使用を社会で容認されるものとして確立しようとしているとして、ハームリダクションの措置を拒否している。カナダ薬 物乱用防止ネットワークは、ハームリダクションは「...違法薬物使用はほとんど予防不可能であり、使用さえ『問題』でなければ、ますます実現可能で容認 可能なライフスタイルと見なされるようになった」という哲学を代表するものであり、「社会の主流への薬物使用の容認」を増加させうるアプローチであると述 べている。2008年、薬物対策世界フォーラム宣言は、ハームリダクションが「薬物使用を受け入れ、薬物使用者が薬物乱用から解放される手助けをしない」 政策を批判した。彼らは、ハームリダクションが薬物需要を減らす努力を減らすことにつながってはならないと述べている[111]。 ローマ法王ベネディクト16世は、HIV/AIDSに関してハームリダクション政策を批判し、それは「お金だけでは克服できない悲劇であり、問題を悪化さ せるコンドームの配布では克服できない」と述べた[112]。 |

| Aubri Esters Bluelight (web forum) Demand reduction Erowid Harm reduction in the United States Low-threshold treatment programs Mitigation Supervised injection site Supply reduction |

オーブリ・エスターズ ブルーライト(ウェブフォーラム) 需要削減 エロウィッド 米国におけるハームリダクション 閾値の低い治療プログラム 緩和 監視下注射サイト 供給削減 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harm_reduction |

|

| 1. Marshall, Zack; B.R. Smith,

Christopher (2016). Critical Approaches to Harm Reduction: Conflict,

Institutionalization, (de-)politicization, and Direct Action. New York:

Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-63484-902-9. OCLC 952337014. Archived from