首狩・首刈・ヘッドハンティング

Headhunting

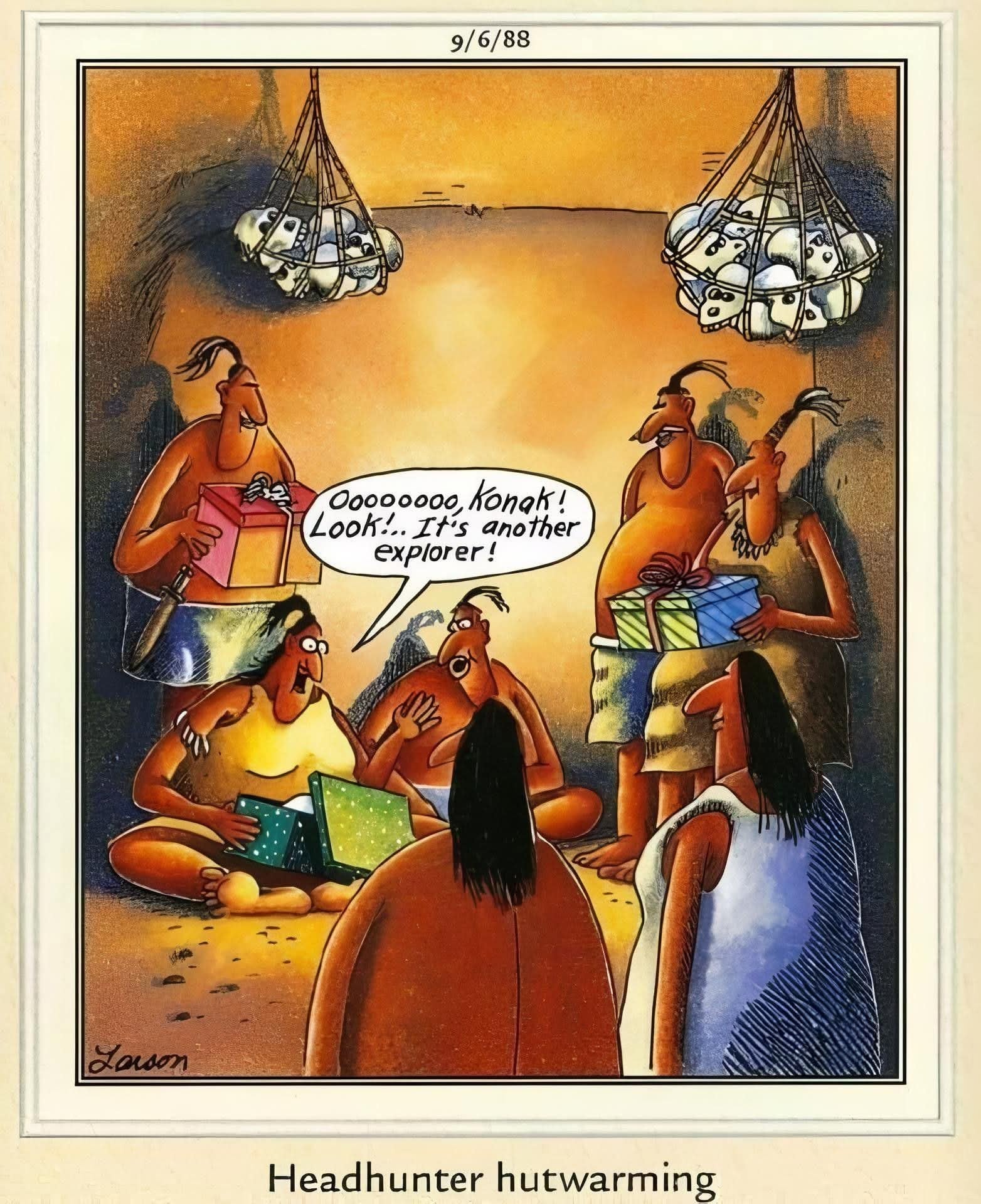

Headhunter hutwarming (首狩族の心あたたまる*話)「おおお、コナック!これは見なよ!!別の探検家のもの[生首]だ」——Gary Larson, Far side シリーズより

* hartwarming (心温まる)を hutwarming [小屋を温める]にダジャレしている

★このページには、残酷と思われるシーン

や写真があります。このページの情報にアクセスするためには、自己責任において下にスクロールしてお読みください。

★[このページの製作者からの注意]人類社会が知り尽くしているはずの首狩りの知識や解釈は、エ ドワード・サイードが指摘する「オリエンタリズム」の思考法である 可能性がある。そのため、首狩りの知識と西洋人が非西洋文化をみるまなざしという権力的布置についても、首狩り研究者は細心の注意を払うべきである。

☆ 首狩りとは、人間を狩り、殺害後に切り落とした頭部を収集する慣習である。代わりに、耳や鼻、頭皮など携帯しやすい身体部位を戦利品として持ち帰ることも ある。首狩りは歴史上、ヨーロッパ、東アジア、オセアニア、東南アジア、南アジア、メソアメリカ、南アメリカ、西アフリカ、中央アフリカの一部地域で実践 されてきた。 この慣習は人類学界で集中的に研究対象とされ、学者たちはその社会的役割・機能・動機を評価・解釈しようとしている。人類学文献では、敵対者への屈辱、儀 礼的暴力、宇宙的均衡、男らしさの誇示、 生前及び死後の敵の肉体と魂に対する支配権、殺害の証(狩猟における功績)としての戦利品、偉大さの誇示、敵対者の精神と力を取り込むことによる威信の獲 得、そして死後の世界で犠牲者を奴隷として従属させる手段としての役割などが挙げられる。[1] 現代の学者は概ね、首狩りの主たる機能が儀礼的・儀礼的であったと認めている。これは共同体と個人間の階層的関係を構築し、強化し、防衛する過程の一部で あった。[出典必要] 一部の専門家は、この慣習が「頭部には犠牲者の『魂の物質』あるいは生命力が宿っており、それを捕獲することで利用可能となる」という信念に由来すると理 論づけている。[2]

☆Digital painting of a Mississippian-era priest, with a ceremonial flint mace and a severed head, based on a repousse copper plate./ ミシシッピ文化時代の司祭を描いたデジタル絵画。儀式用の火打石の棍棒と切断された頭部を持つ。レポセ加工の銅版画を基にしている。///Seh-Dong-Hong-Beh, leader of the Dahomey Amazons, holding a severed head.

《店

主敬白》

首狩りは、上掲のように地球上のひろい地域でおこなわれてきた慣行である。ただし、[首を狩るという狩猟の意味があるにも関わらず]狩猟採集民は首狩をお

こなわない。首狩り慣行は農耕の誕生、あるいは、農耕の比喩——首狩り=刈りを収穫のメタファーで語ったり、豊穣の祈願と関係するという主張は、単に民族

学者の解釈のみならず、首狩りを実践する人たちもそのように説明してきた。ただし、首狩り行為の、ローカル名はさまざまなであり、民族間の相違を超えて首

狩りという共通語彙と、首狩りに付与される共通の解釈や理解があるわけではない。首狩りは、いわゆる、多様な現地語で表現され、多様に解釈されるために、

人類に共通する首狩りの説明原理があるわけではない。首狩りというテクニカルタームをつけたのは、西洋からやってきた異邦人であり、多くは、自分たちが忘

れたあるいはかって実践したが、文明化した自分たちが行わない野蛮な行為だという価値判断がこの用語には、染み付いている。生類の首(頭)を切ると、死ぬ

ために、首狩りは殺人あるいは殺害行為にあたるために、首狩り慣行があった民族には、特別な意味や解釈が付与されたことは間違いない。首狩りの代わりに、

他の動物の首を刈る。そのために、首狩りの言葉を聞いた時点で嫌悪感を覚えることは、首狩りをおこなう/なっていた人たちの内在的理解からは、遠いところ

にある。そのため、人類社会が知り尽くしているはずの首狩りの知識や解釈は、エ

ドワード・サイードが指摘する「オリエンタリズム」の思考法である

可能性がある。そのため、首狩りの知識と西洋人が非西洋文化をみるまなざしという権力的布置についても、首狩り研究者は細心の注意を払うべきである。

| Headhunting is

the

practice of hunting a human and collecting the severed head after

killing the victim. More portable body parts (such as ear, nose, or

scalp) can be taken as trophies, instead. Headhunting was practiced in

historic times across parts of Europe, East Asia, Oceania, Southeast

Asia, South Asia, Mesoamerica, South America, West Africa, and Central

Africa. The headhunting practice has been the subject of intense study within the anthropological community, where scholars try to assess and interpret its social roles, functions, and motivations. Anthropological writings explore themes in headhunting that include mortification of the rival, ritual violence, cosmological balance, the display of manhood, cannibalism, dominance over the body and soul of his enemies in life and afterlife, as a trophy and proof of killing (achievement in hunting), show of greatness, prestige by taking on a rival's spirit and power, and as a means of securing the services of the victim as a slave in the afterlife.[1] Today's scholars generally agree that headhunting's primary function was ritual and ceremonial. It was part of the process of structuring, reinforcing, and defending hierarchical relationships between communities and individuals.[citation needed] Some experts theorize that the practice stemmed from the belief that the head contained the victim's "soul matter" or life force, which could be harnessed through its capture.[2] |

首狩りとは、人間を狩り、殺害後に切り落とした頭部を収集する慣習であ

る。代わりに、耳や鼻、頭皮など携帯しやすい身体部位を戦利品として持ち帰ることもある。首狩りは歴史上、ヨーロッパ、東アジア、オセアニア、東南アジ

ア、南アジア、メソアメリカ、南アメリカ、西アフリカ、中央アフリカの一部地域で実践されてきた。 この慣習は人類学界で集中的に研究対象とされ、学者たちはその社会的役割・機能・動機を評価・解釈しようとしている。人類学文献では、敵対者への屈辱、儀 礼的暴力、宇宙的均衡、男らしさの誇示、 生前及び死後の敵の肉体と魂に対する支配権、殺害の証(狩猟における功績)としての戦利品、偉大さの誇示、敵対者の精神と力を取り込むことによる威信の獲 得、そして死後の世界で犠牲者を奴隷として従属させる手段としての役割などが挙げられる。[1] 現代の学者は概ね、首狩りの主たる機能が儀礼的・儀礼的であったと認めている。これは共同体と個人間の階層的関係を構築し、強化し、防衛する過程の一部で あった。[出典必要] 一部の専門家は、この慣習が「頭部には犠牲者の『魂の物質』あるいは生命力が宿っており、それを捕獲することで利用可能となる」という信念に由来すると理 論づけている。[2] |

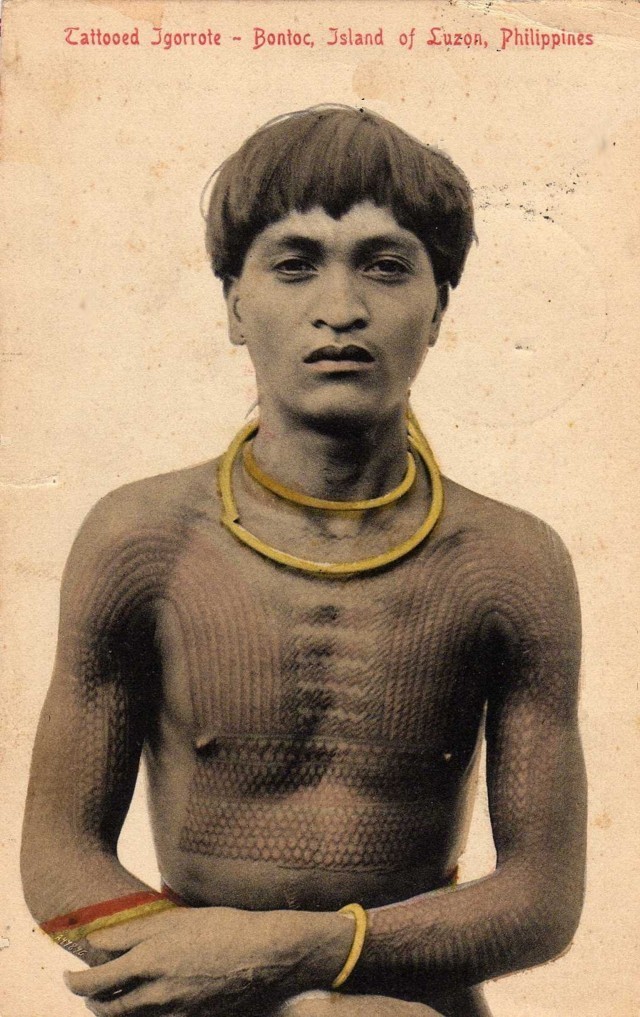

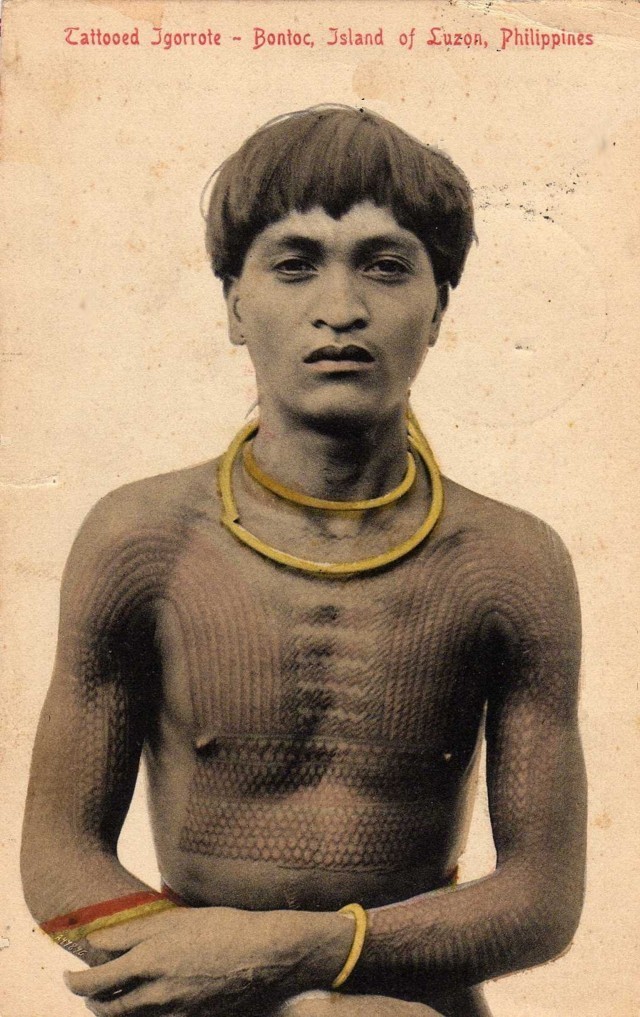

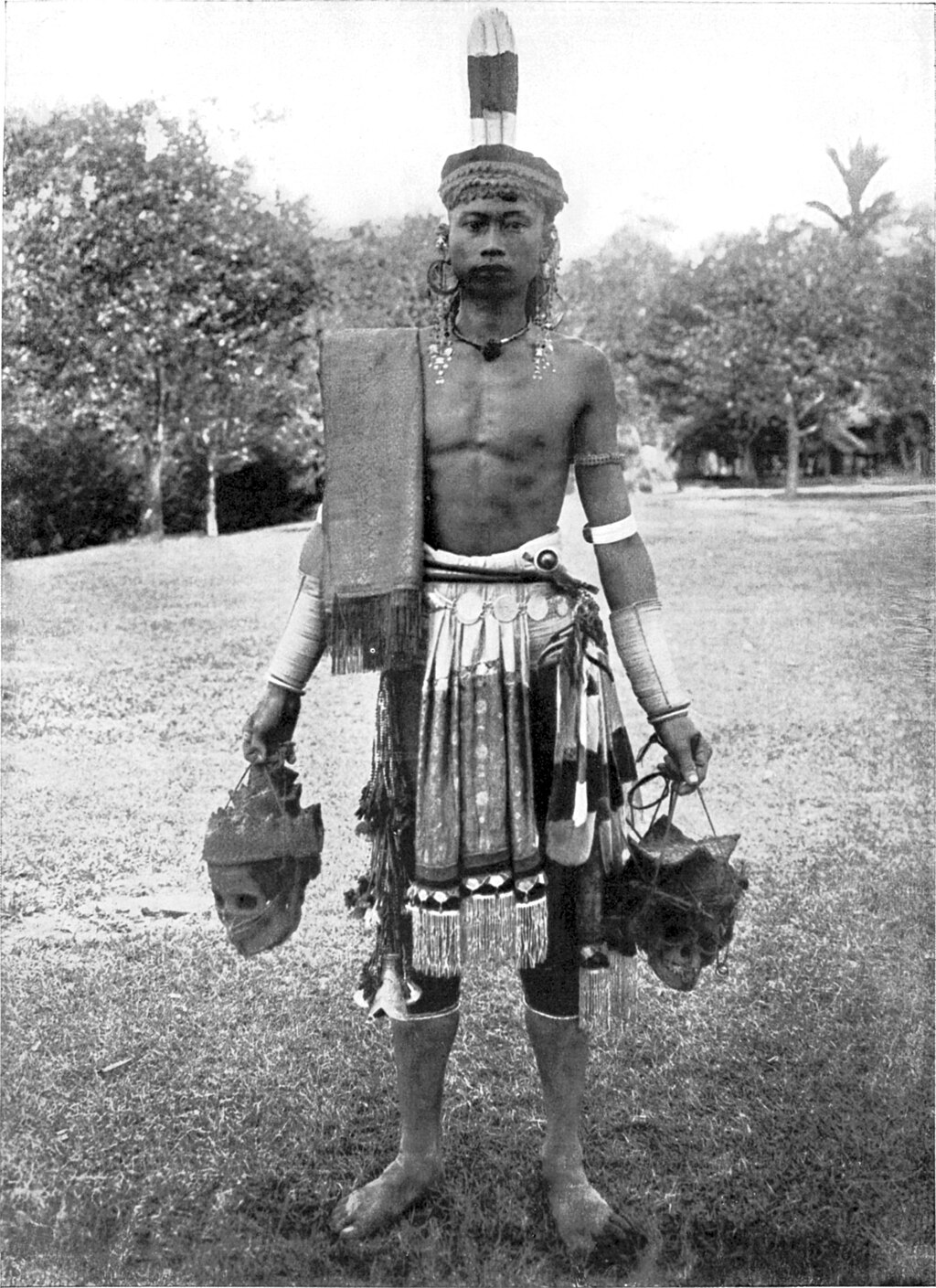

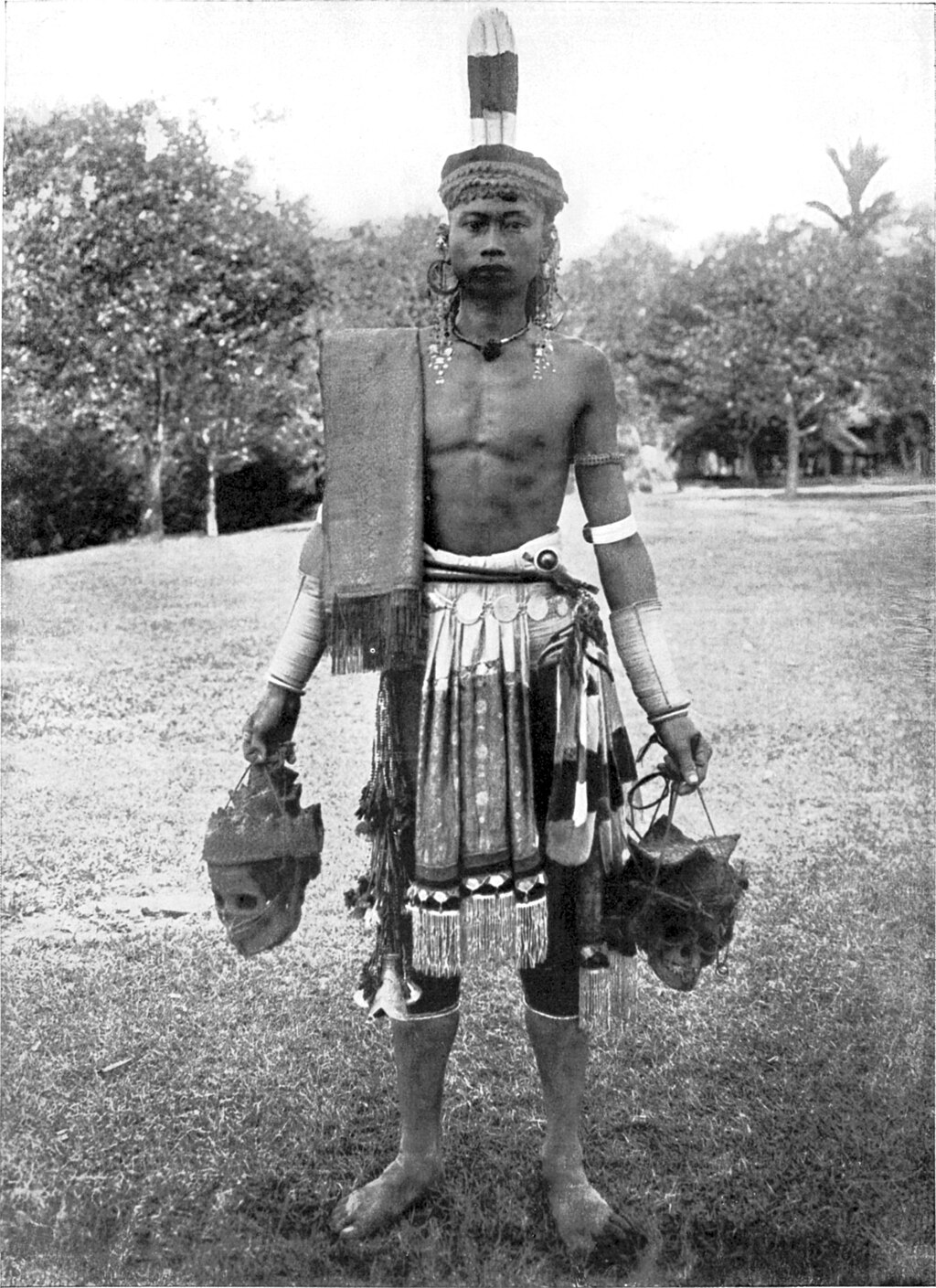

Austronesia A 1908 photo of a Bontoc warrior bearing a headhunter's chaklag chest tattoo Among the various Austronesian peoples, head-hunting raids were strongly tied to the practice of tattooing. In head-hunting societies, tattoos were records of how many heads the warriors had taken in battle, and was part of the initiation rites into adulthood. The number and location of tattoos, therefore, were indicative of a warrior's status and prowess.[3] Indonesia and Malaysia In Southeast Asia, anthropological writings have explored headhunting and other practices of the Murut, Dusun Lotud, Iban, Berawan, Wana and Mappurondo tribes. Among these groups, headhunting was usually a ritual activity rather than an act of war or feuding. A warrior would take a single head. Headhunting acted as a catalyst for the cessation of personal and collective mourning for the community's dead. Ideas of manhood and marriage were encompassed in the practice, and the taken heads were highly prized. Other reasons for headhunting included capture of enemies as slaves, looting of valuable properties, intra and inter-ethnic conflicts, and territorial expansion. Italian anthropologist and explorer Elio Modigliani visited the headhunting communities in South Nias (an island to the west of Sumatra) in 1886; he wrote a detailed study of their society and beliefs. He found that the main purpose of headhunting was the belief that, if a man owned another person's skull, his victim would serve as a slave of the owner for eternity in the afterlife. Human skulls were a valuable commodity.[1] Sporadic headhunting continued in Nias island until the late 20th century, the last reported incident dating from 1998.[4] Headhunting was practiced among Sumba people until the early 20th century. It was done only in large war parties. When the men hunted wild animals, by contrast, they operated in silence and secrecy.[5] The skulls collected were hung on the skull tree erected in the center of village. Kenneth George wrote about annual headhunting rituals that he observed among the Mappurondo religious minority, an upland tribe in the southwest part of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Heads are not taken; instead, surrogate heads in the form of coconuts are used in a ritual ceremony. The ritual, called pangngae, takes place at the conclusion of the rice-harvesting season. It functions to bring an end to communal mourning for the deceased of the past year; express intercultural tensions and polemics; allow for a display of manhood; distribute communal resources; and resist outside pressures to abandon Mappurondo ways of life.  Punan Bah heads taken by Sea Dayaks In Sarawak, the north-western region of the island of Borneo, the first "White Rajah" James Brooke and his descendants established a dynasty. They eradicated headhunting in the hundred years before World War II. Before Brooke's arrival, the Iban had migrated from the middle Kapuas region into the upper Batang Lupar river region by fighting and displacing the small existing tribes, such as the Seru and Bukitan. Another successful migration by the Iban was from the Saribas region into the Kanowit area in the middle of the Batang Rajang river, led by the famous Mujah "Buah Raya". They fought and displaced such tribes as the Kanowit and Baketan.[citation needed] Brooke first encountered the headhunting Iban of the Saribas-Skrang in Sarawak at the Battle of Betting Maru in 1849. He gained the signing of the Saribas Treaty with the Iban chief of that region, who was named Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana "Bayang". Subsequently, the Brooke dynasty expanded their territory from the first small Sarawak region to the present-day state of Sarawak. They enlisted the Malay, Iban, and other natives as a large unpaid force to defeat and pacify any rebellions in the states. The Brooke administration prohibited headhunting (ngayau in Iban language) and issued penalties for disobeying the Rajah-led government decree. During expeditions sanctioned by the Brooke administration, they allowed headhunting. The natives who participated in Brooke-approved punitive expeditions were exempted from paying annual tax to the Brooke administration and/or given new territories in return for their service. There were intra-tribal and intertribal headhunting.[citation needed] The most famous Iban warrior to resist the authority of the Brooke administration was Libau "Rentap". The Brooke government had to send three successive punitive expeditions in order to defeat Rentapi at his fortress on the top of Sadok Hill. Brooke's force suffered major defeats during the first two expeditions. During the third and final expedition, Brooke built a large cannon called Bujang Sadok (Prince of Sadok Mount) to rival Rentap's cannon nicknamed Bujang Timpang Berang (The One Arm Bachelor) and made a truce with the sons of a famous chief, who supported Rentap in not recognizing the government of Brooke due to his policies.[citation needed] The Iban performed a third major migration from upper Batang Ai region in the Batang Lupar region into the Batang Kanyau (Embaloh) onwards the upper Katibas and then to the Baleh/Mujong regions in the upper Batang Rajang region. They displaced the existing tribes of the Kayan, Kajang, Ukit, etc. The Brooke administration sanctioned the last migrations of the Iban, and reduced any conflict to a minimum. The Iban conducted sacred ritual ceremonies with special and complex incantations to invoke god's blessings, which were associated with headhunting. An example was the Bird Festival in the Saribas/Skrang region and Proper Festival in the Baleh region, both required for men of the tribes to become effective warriors.[citation needed] During the Japanese occupation of British Borneo during the Second World War, headhunting was revived among the natives. The Sukarno-led Indonesian forces fought against the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. Forces of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak fought in addition, and headhunting was observed during the communist insurgency in Sarawak and what was then Malaya. The Iban were noted for headhunting, and were later recognised as good rangers and trackers during military operations, during which they were awarded fourteen medals of valour and honour.[citation needed] Since 1997 serious inter-ethnic violence has erupted on the island of Kalimantan, involving the indigenous Dayak peoples and immigrants from the island of Madura. Events have included the Sambas riots and Sampit conflict. In 2001, during the Sampit conflict in the Central Kalimantan town of Sampit, at least 500 Madurese were killed and up to 100,000 Madurese were forced to flee. Some Madurese bodies were decapitated in a ritual reminiscent of the Dayak headhunting tradition.[6] The Moluccans (especially Alfurs in Seram), an ethnic group of mixed Austronesian-Papuan origin living in the Maluku Islands, were fierce headhunters until the Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia suppressed the practice.[7] |

オーストロネシア 1908年のボントック族戦士の写真。首狩り族のチャクラグ胸タトゥーを刻んでいる 様々なオーストロネシア系民族において、首狩り襲撃は刺青の慣習と強く結びついていた。首狩り社会では、刺青は戦士が戦いで何個の首を取ったかの記録であ り、成人への通過儀礼の一部であった。したがって、刺青の数と位置は、戦士の地位と武勇を示すものだった。[3] インドネシアとマレーシア 東南アジアでは、人類学の文献がムルット族、ドゥスン・ロトゥド族、イバン族、ベラワン族、ワナ族、マプルンド族の首狩りやその他の慣習を調査してきた。 これらの集団において、首狩りは通常、戦争や抗争の行為というより、儀礼的活動であった。戦士は一つの頭部だけを奪った。首狩りは、共同体の死者に対する 人格や集団の喪の終結を促す触媒として機能した。男らしさや結婚の概念がこの慣習に込められており、奪われた頭部は非常に貴重とされた。首狩りの他の理由 には、敵を奴隷として捕獲すること、貴重な財産の略奪、部族内および部族間の紛争、領土拡大などが含まれた。 イタリアの人類学者で探検家のエリオ・モディリアーニは1886年、スマトラ島西方のニアス島南部にある首狩りを行う共同体を訪問した。彼はその社会と信 仰について詳細な研究を記している。首狩りの主目的は、他人の人格の頭蓋骨を所有すれば、その犠牲者が来世で永遠に所有者の奴隷として仕えるという信仰に あると彼は発見した。人間の頭蓋骨は貴重な商品であった[1]。ニアス島では20世紀後半まで散発的な首狩りが続き、最後の記録は1998年のものである [4]。 スンバ族の間では20世紀初頭まで首狩りが行われていた。これは大規模な戦争集団でのみ実施された。対照的に、男たちが野生動物を狩る際は、沈黙と秘密裏 に行動した。[5] 収集された頭蓋骨は、村の中心に立てられた頭蓋骨の木に吊るされた。 ケネス・ジョージは、インドネシア・スラウェシ島南西部の高地部族であるマプルンド宗教的少数派の間で観察した、毎年行われる首狩りの儀礼について記して いる。実際の頭部は取らず、代わりにココナッツで作った代用頭部が儀礼の儀礼で使用される。パンンガイと呼ばれるこの儀礼は稲刈りシーズンの終わりに行わ れる。その目的は、過去1年間の死者を悼む共同体の喪に終止符を打つこと、異文化間の緊張や論争を表明すること、男らしさを示す機会とすること、共同体の 資源を分配すること、そしてマプルンドの生活様式を放棄するよう外部から加えられる圧力に抵抗することにある。  シー・ダヤク族に奪われたプナン・バ族の頭蓋骨 ボルネオ島北西部のサラワクでは、初代「白人ラジャ」ジェームズ・ブルックとその子孫が王朝を築いた。彼らは第二次世界大戦前の百年間に首狩りを根絶し た。ブルック到来以前、イバン族はカプアス川中流域からバタン・ルパル川上流域へ移住し、セル族やブキタン族といった小規模部族を戦い追い出した。イバン 族のもう一つの成功した移住は、有名なムジャハ「ブア・ラヤ」率いるサリバス地域からバタン・ラジャン川中流域のカノウィット地域への移動であった。彼ら はカノウィット族やバケタン族といった部族と戦い、追い出した。[出典が必要] ブルックは1849年のベッティンマルの戦いで、サラワクの首狩り族であるサリバス・スクラングのイバン族と初めて遭遇した。彼はその地域のイバン族首 長、オラン・カヤ・ペマンチャ・ダナ「バヤン」とサリバス条約の調印を得た。その後、ブルック王朝は最初の小さなサラワク地域から現在のサラワク州に至る まで領土を拡大した。彼らはマレー人、イバン族、その他の先住民を大規模な無給の軍隊として徴用し、州内のあらゆる反乱を鎮圧した。ブルック政権は首狩り (イバン語でンガヤウ)を禁止し、ラジャ主導の政府令に違反した場合の罰則を定めた。ただしブルック政権が認可した遠征では首狩りを容認した。ブルック公 認の懲罰遠征に参加した先住民は、ブルック政権への年貢納付が免除されるか、あるいはその功績と引き換えに新たな領地を与えられた。部族内および部族間の 首狩りが存在した。[出典が必要] ブルック政権の権威に抵抗した最も有名なイバン族の戦士はリバウ・「レンタップ」である。ブルック政府はサドック丘頂上の要塞に籠城するレンタップを撃破 するため、三度にわたる懲罰遠征を派遣せざるを得なかった。ブルック軍は最初の二度の遠征で大きな苦悩を喫した。三度目にして最後の遠征では、ブルックは レンタプの砲「ブジャン・ティンパン・ベラン(片腕の独身者)」に対抗するため「ブジャン・サドク(サドク山の王子)」と呼ばれる大砲を建造し、ブルック の政策に反発して彼を支持していた著名な首長の息子たちと休戦協定を結んだ。[出典が必要] イバン族は第三次大規模移住を行い、バタン・ルパル地域のバタン・アイ川上流域からバタン・カニャウ(エンバロー)を経てカティバス川上流域へ、さらにバ タン・ラジャン川上流域のバレ/ムジョン地域へと移動した。彼らはカヤン族、カジャン族、ウキット族など既存の部族を駆逐した。ブルック政権はイバン族の 最後の移住を認可し、衝突を最小限に抑えた。イバン族は神々の加護を呼び起こすため、特殊で複雑な呪文を用いた神聖な儀礼的な儀式を行った。これらは首狩 りに関連していた。例として、サリバス/スクラング地域での鳥祭りやバレ地域でのプロパー祭りが挙げられ、いずれも部族の男性が有能な戦士となるために必 要とされた。[出典必要] 第二次世界大戦中の日本による英領ボルネオ占領期、先住民の間で首狩りが復活した。スカルノ率いるインドネシア軍はマレーシア連邦結成に反対して戦った。 マレー、シンガポール、サバ、サラワクの軍隊も参戦し、サラワクと当時のマレー地域における共産主義反乱の際には首狩りが確認された。イバン族は首狩りで 知られ、後に軍事作戦において優秀な偵察兵・追跡者として認められ、14個の勇気と名誉の勲章を授与された。[出典が必要] 1997年以降、カリマンタン島では先住民のダヤク族とマドゥラ島からの移民を巻き込んだ深刻な民族間暴力が発生している。サンバス暴動やサンピット紛争 などがその例だ。2001年、中部カリマンタン州サンピット市でのサンピット紛争では、少なくとも500人のマドゥラ人が殺害され、最大10万人が避難を 余儀なくされた。一部のマドゥラ人の遺体は、ダヤクの首狩り伝統を彷彿とさせる儀礼で首を切断されていた。[6] モルッカ人(特にセラム島のアルフル族)は、マルク諸島に住むオーストロネシア系とパプア系の混血の民族である。オランダの植民地支配がインドネシアでこ の慣習を抑制するまで、彼らは獰猛な首狩り族であった。[7] |

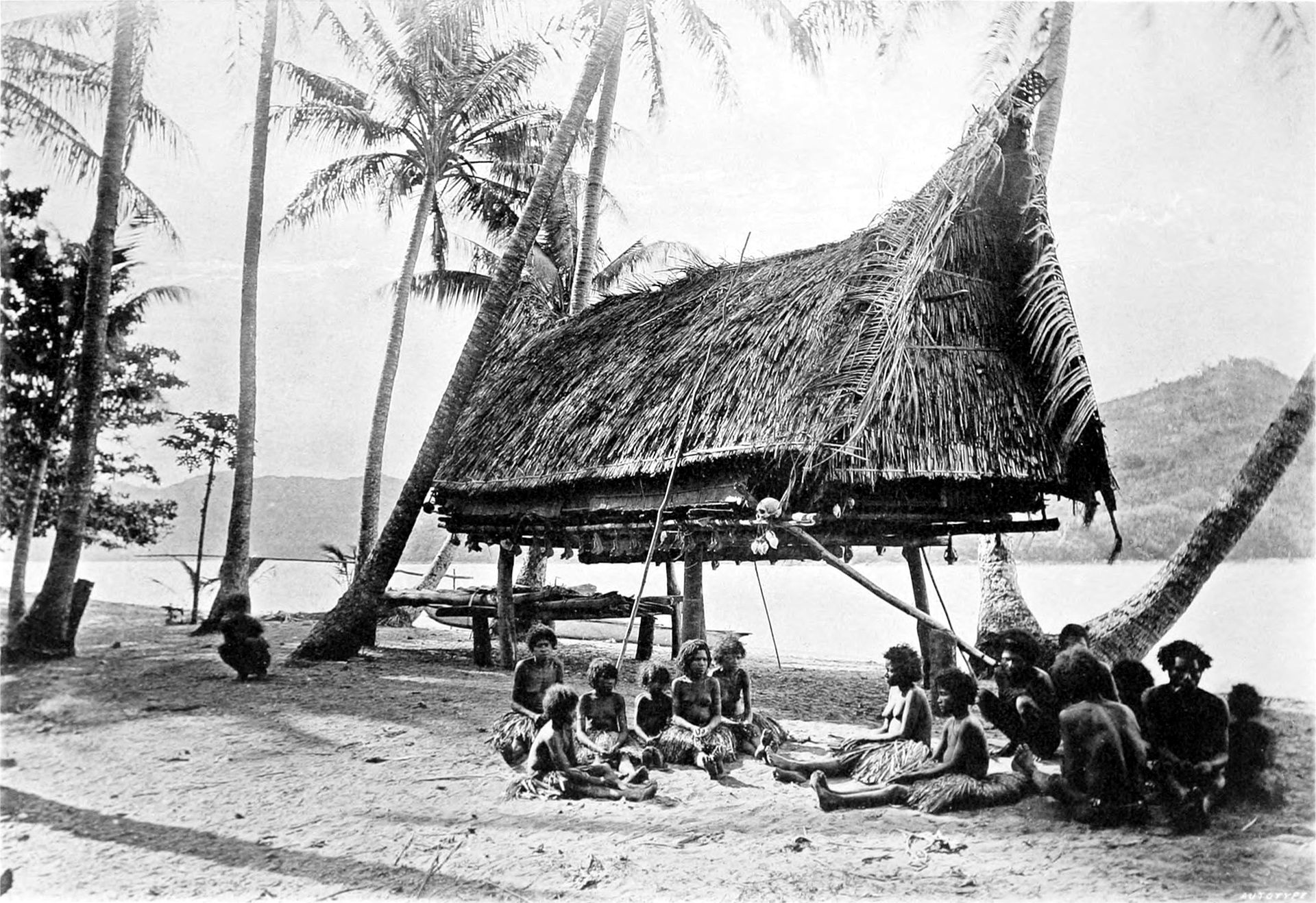

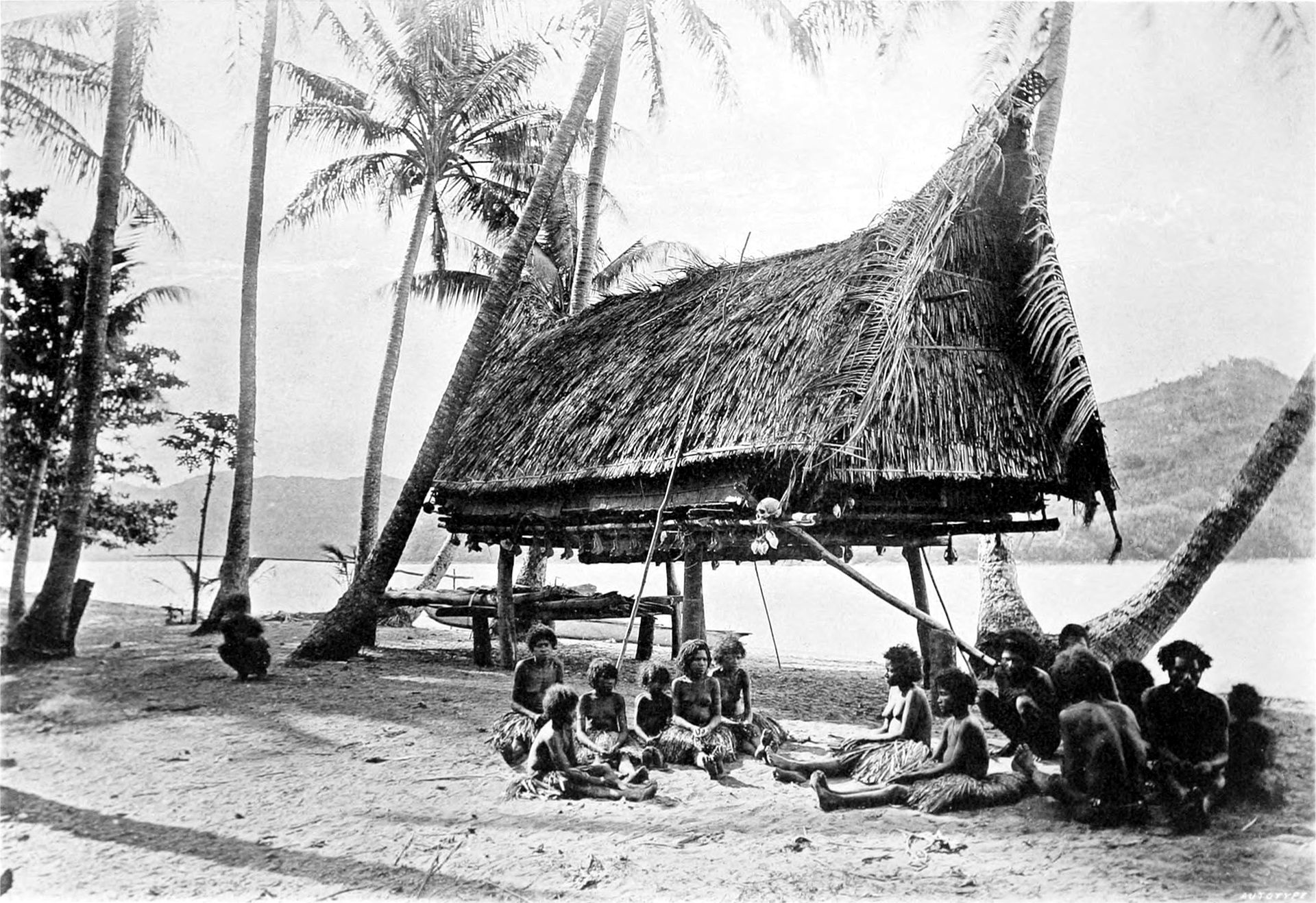

Melanesia Human skulls in a tribal village. Photograph taken in colonial Papua in 1885. Headhunting was practiced by many Austronesian people in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Headhunting has at one time or another been practiced among most of the peoples of Melanesia,[8] including New Guinea.[9] A missionary found 10,000 skulls in a community longhouse on Goaribari Island in 1901.[10] Historically, the Marind-anim in New Guinea were famed because of their headhunting.[11] The practice was rooted in their belief system and linked to the name-giving of the newborn.[12] The skull was believed to contain a mana-like force.[13] Headhunting was not motivated primarily by cannibalism, but the dead person's flesh was consumed in ceremonies following the capture and killing.[14] The Korowai, a Papuan tribe in the southeast of Irian Jaya, live in tree houses, some nearly 40 metres (130 ft) high. This was originally believed to be a defensive practice, presumably as protection against the Citak, a tribe of neighbouring headhunters.[15] Some researchers believe that the American Michael Rockefeller, who disappeared in New Guinea in 1961 while on a field trip, may have been taken by headhunters in the Asmat region. He was the son of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. In The Cruise of the Snark (1911), the account by Jack London of his 1905 adventure sailing in Micronesia, he recounted that headhunters of Malaita attacked his ship during a stay in Langa Langa Lagoon, particularly around Laulasi Island. His and other ships were kidnapping villagers as workers on plantations, a practice known as blackbirding. Captain Mackenzie of the ship Minolta was beheaded by villagers as retribution for the loss of village men during an armed labour "recruiting" drive. The villagers believed that the ship's crew "owed" several more heads before the score was even.[16] |

メラネシア 部族の村にある人間の頭蓋骨。1885年に植民地時代のパプアで撮影された写真。 首狩りは東南アジアと太平洋諸島の多くのオーストロネシア系民族によって行われていた。メラネシアの大部分の人民、ニューギニアを含む、いずれかの時期に 首狩りが行われていたことがある。[9] 1901年、ゴアリバリ島の共同長屋で宣教師が1万個の頭蓋骨を発見した。[10] 歴史的に、ニューギニアのマリンド・アニム族は首狩りで有名だった。[11] この慣習は彼らの信仰体系に根ざし、新生児の名付けと結びついていた。[12] 頭蓋骨にはマナのような力が宿ると信じられていた。[13] 頭狩りの主たる動機は人肉食ではなかったが、捕獲・殺害後の儀式では死者の肉が食された。[14] イリアンジャヤ南東部に住むパプア族のコロワイ族は、樹上住居に住んでいる。中には高さ約40メートル(130フィート)に達するものもある。これは元々 防御策と考えられており、おそらく近隣の首狩り部族シタックからの保護が目的だった[15]。一部の研究者は、1961年にニューギニアでの現地調査中に 失踪したアメリカ人マイケル・ロックフェラーが、アスマット地方の首狩り族に連れ去られた可能性を指摘している。彼はニューヨーク州知事ネルソン・ロック フェラーの息子であった。 ジャック・ロンドンが1905年にミクロネシアで体験した航海記『スナーク号の航海』(1911年)には、ラングラング・ラグーン(特にラウラシ島周辺) 停泊中にマライタ島の首狩り族が彼の船を襲撃した記録がある。彼の船を含む複数の船は、プランテーション労働者として村人を拉致する「ブラックバーディン グ」と呼ばれる行為を行っていた。ミノルタ号のマッケンジー船長は、武装した労働「徴用」作戦で村の男たちを失った報復として、村人たちに首を刎ねられ た。村人たちは、船の乗組員が「借り」を返すには、まだ何人もの首が必要だと信じていたのだ。 |

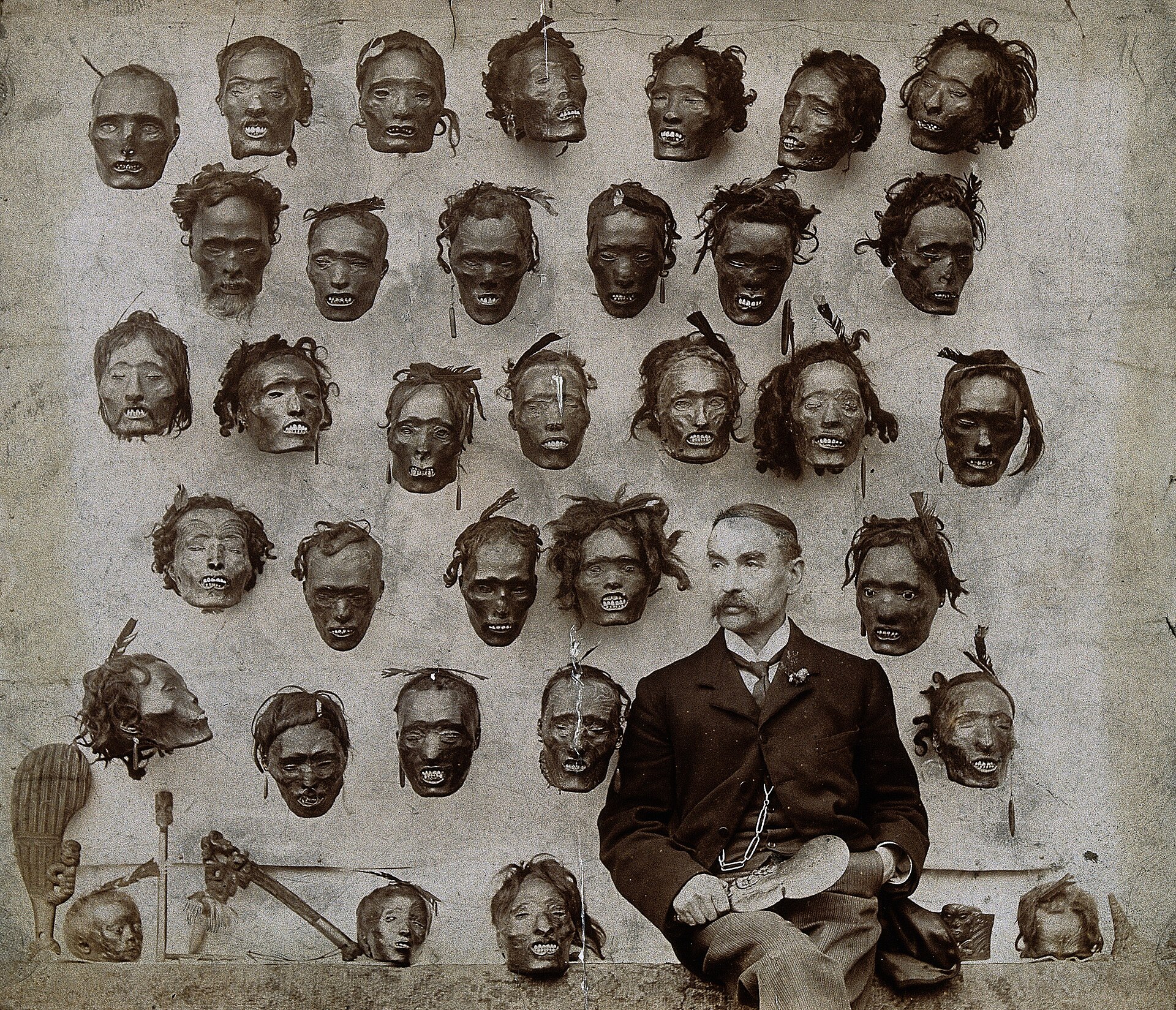

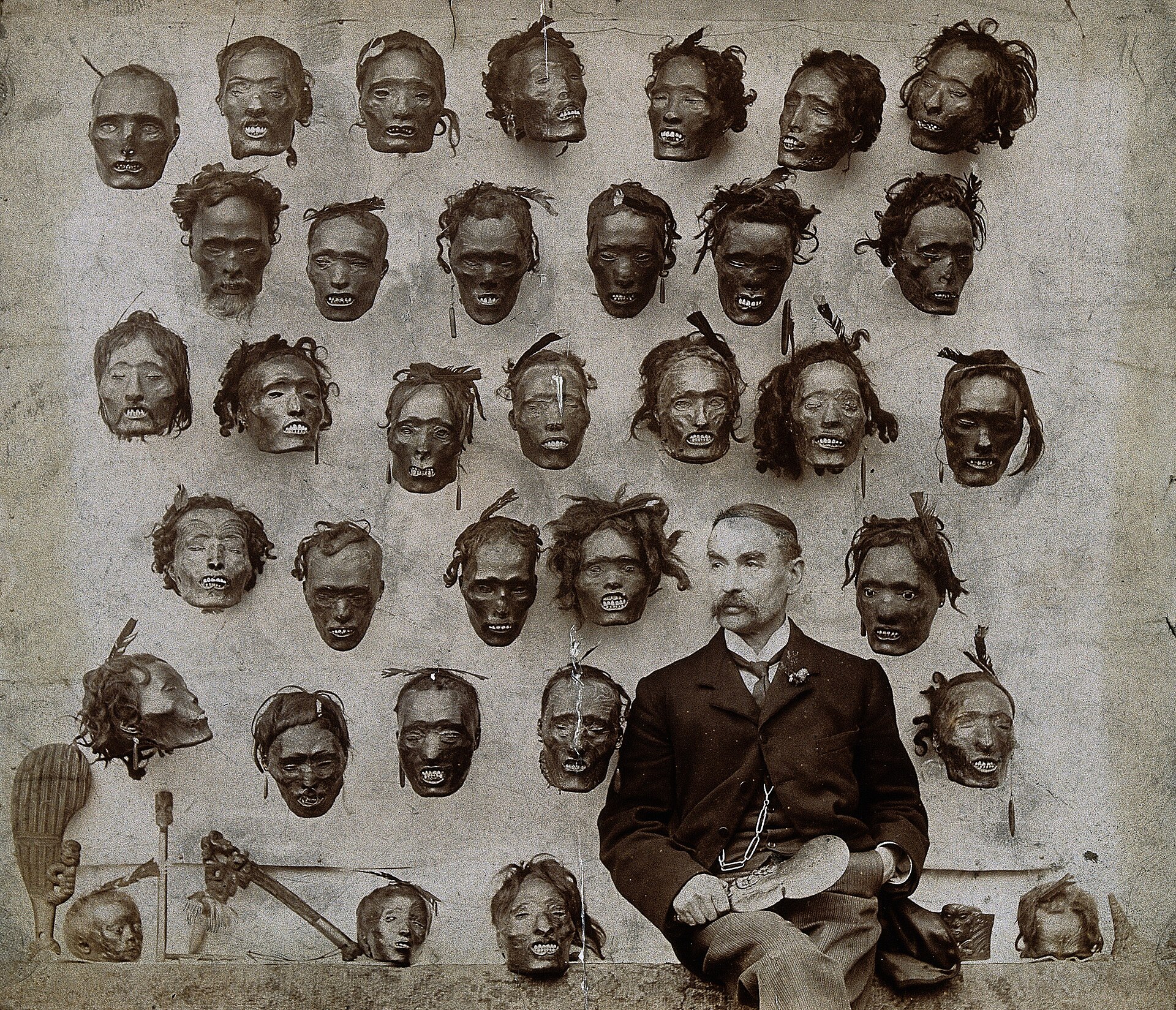

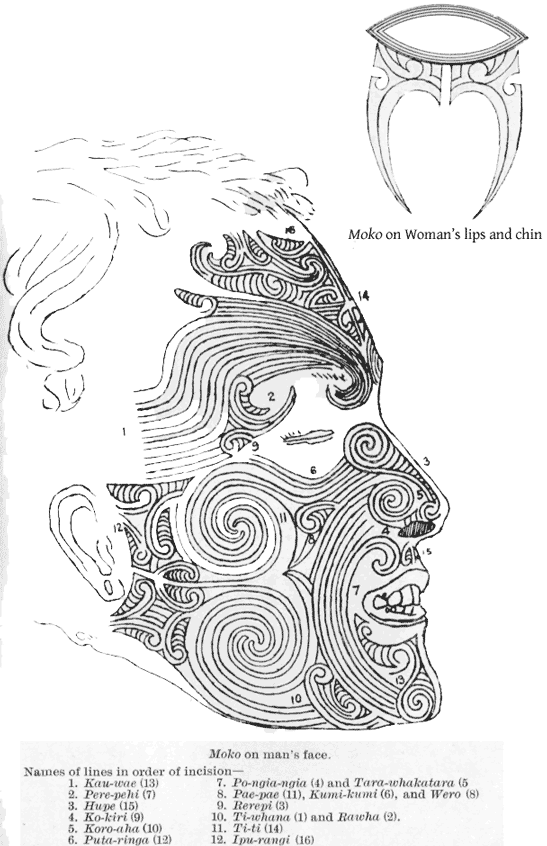

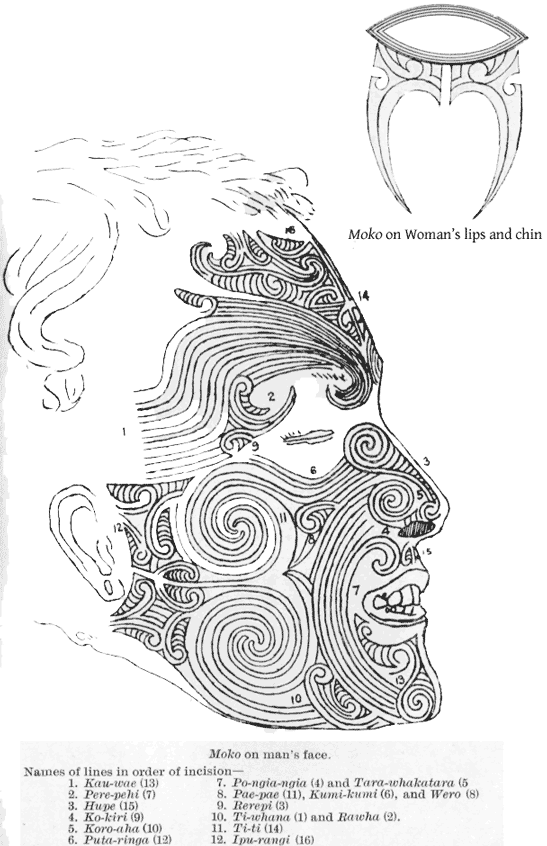

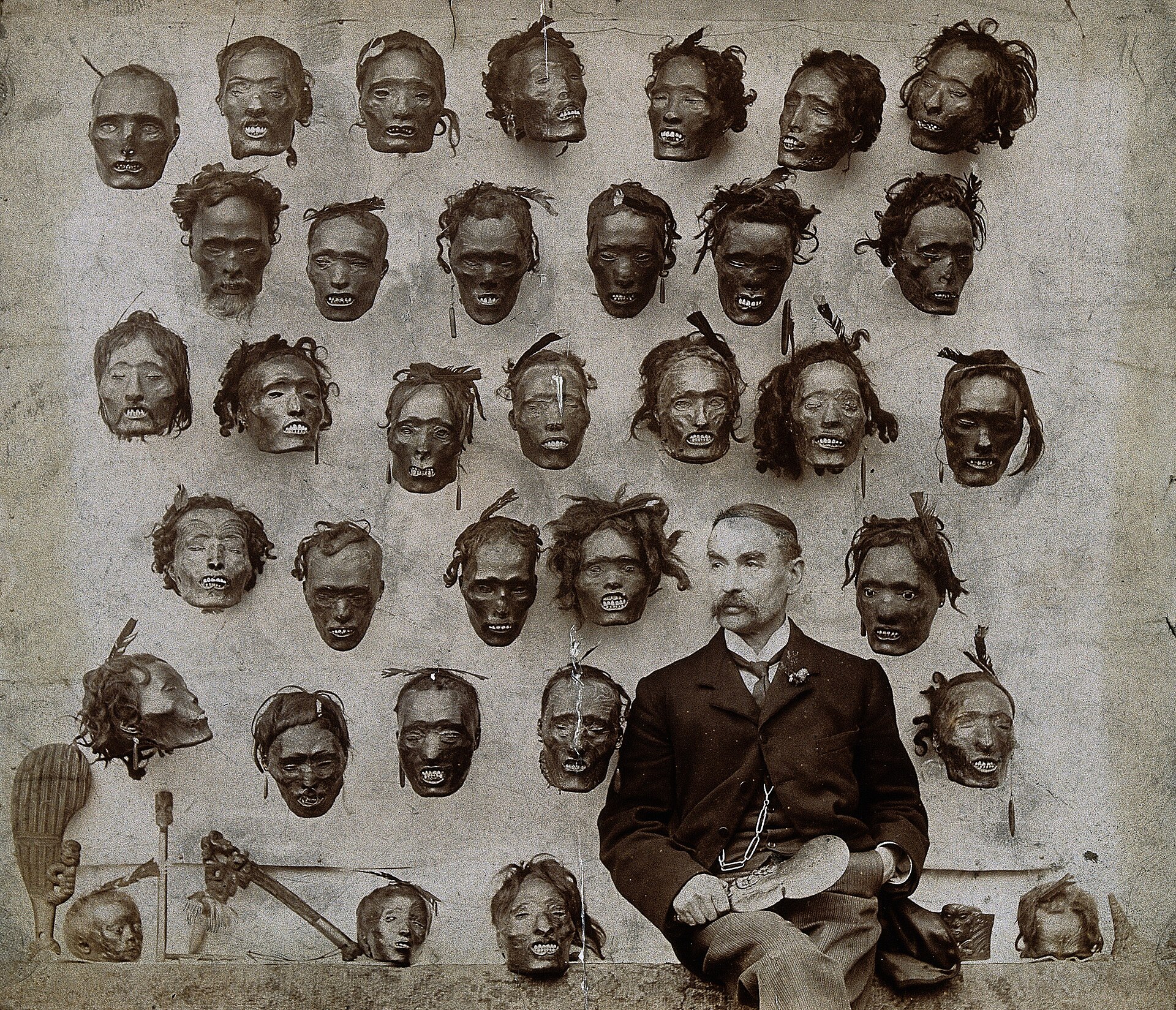

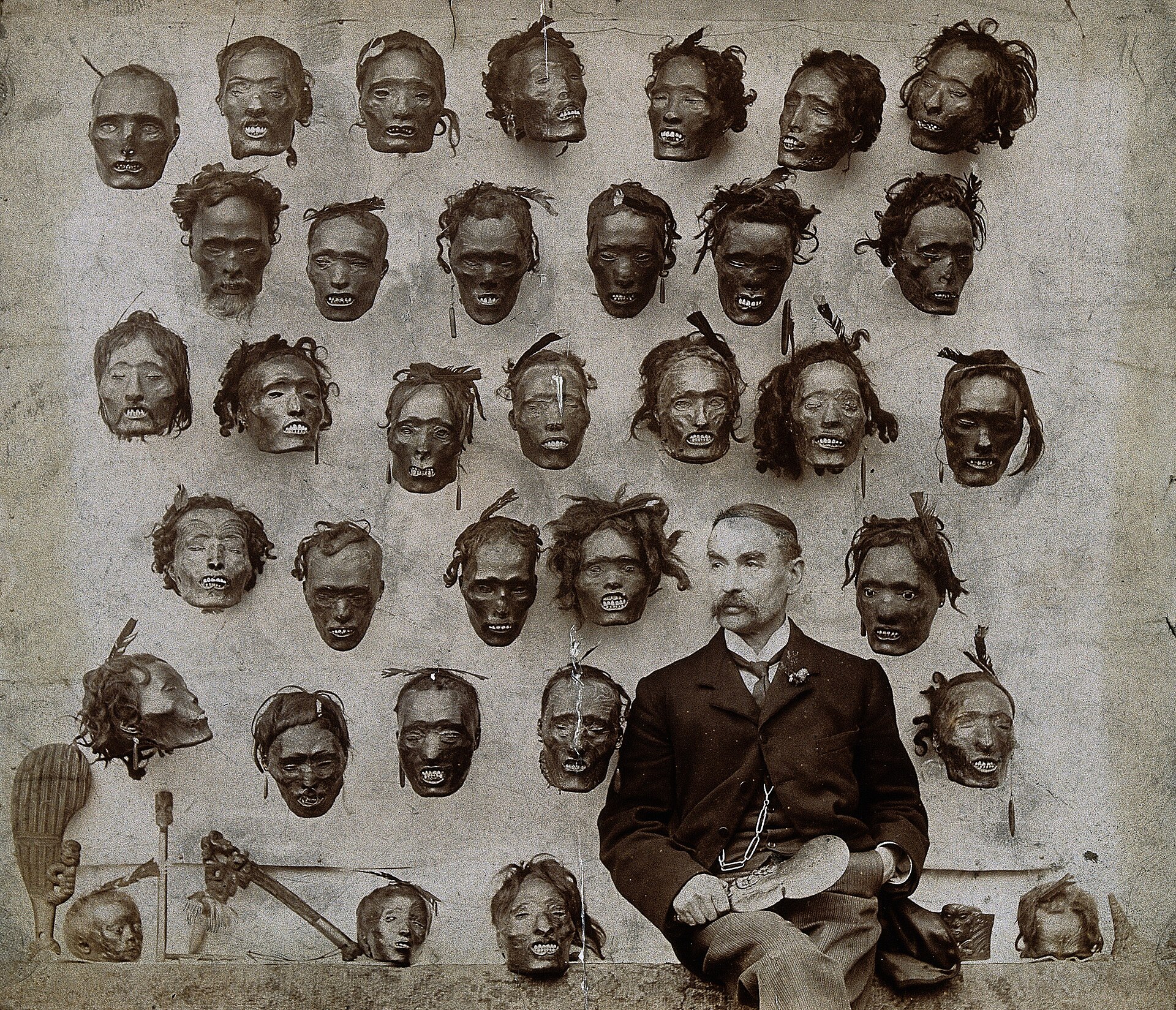

| New Zealand Main article: Mokomokai  H. G. Robley with his mokomokai collection In New Zealand, the Maori preserved the heads of some of their ancestors as well as certain enemies in a form known as mokomokai. They removed the brain and eyes, and smoked the head, preserving the moko tattoos. The heads were sold to European collectors in the late 1800s, in some instances having been commissioned and "made to order".[17] |

ニュージーランド 主な記事: モコモカイ  H・G・ロブリーと彼のモコモカイコレクション ニュージーランドでは、マオリ族は祖先や特定の敵の頭部をモコモカイと呼ばれる形で保存した。脳と目を除去し、頭部を燻製にしてモコの刺青を保存したので ある。これらの頭部は1800年代後半にヨーロッパの収集家に販売され、中には注文を受けて「特注品」として制作された例もある。[17] |

Philippines Headhunting skulls collected as trophies during blood feuds in Ifugao. Headhunting was banned in the Philippines in 1913. In the Philippines, headhunting was extensive among the various Cordilleran peoples (also known as "Igorot") of the Luzon highlands. It was tied with rites of passage, rice harvests, religious rituals to ancestor spirits, blood feuds, and indigenous tattooing. Cordilleran tribes used specific weapons for beheading enemies in raids and warfare, specifically the uniquely shaped head axes and various swords and knives. Though some Cordilleran tribes living near Christianized lowlanders during the Spanish colonial period had already abandoned the practice by the 19th century, they were still rampant in more remote areas beyond the reach of Spanish colonial authorities. The practices were finally suppressed in the early 20th century by the United States during the American colonial period of the Philippines.[18] |

フィリピン イフガオ族の血の争いにおいて戦利品として収集された狩人頭蓋骨。フィリピンでは1913年に狩人が禁止された。 フィリピンでは、ルソン島高地のコルディリェラ地方に住む様々な民族(イゴロットとも呼ばれる)の間で首狩りが広く行われていた。これは通過儀礼、稲作の 収穫、祖先の霊への宗教的儀礼、血の復讐、そして先住民の刺青と結びついていた。コルディリェラの部族は、襲撃や戦争で敵の首を落とすために特定の武器を 使用していた。具体的には独特の形状をした頭斧や様々な剣やナイフである。スペイン植民地時代、キリスト教化された低地住民の近くに住む一部のコルディ リェラ部族は19世紀までにこの慣習を放棄していたが、スペイン植民地当局の手の届かないより辺境の地域では依然として横行していた。この慣習は20世紀 初頭、フィリピンがアメリカの植民地となった時期に、ついにアメリカによって抑圧されたのである。[18] |

| Taiwan See also: Siege of Fort Zeelandia, Rover incident, Formosa Expedition, Mudan Incident (1871), Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1874), Battle of Tamsui, Keelung Campaign, and Wushe Incident  The headhunting ritual of aborigines in Taiwan Headhunting was a common practice among Taiwanese aborigines. All tribes practiced headhunting except the Yami people, who were previously isolated on Orchid Island, and the Ivatan people. It was associated with the peoples of the Philippines. Taiwanese Plains Aborigines, Han Taiwanese and Japanese settlers were choice victims of headhunting raids by Taiwanese Mountain Aborigines. The latter two groups were considered invaders, liars, and enemies. A headhunting raid would often strike at workers in the fields, or set a dwelling on fire and then kill and behead those who fled from the burning structure. The practice continued during the Japanese rule of Taiwan, but ended in the 1930s due to brutal suppression by the Japanese colonial government.  Seediq aboriginal rebels beheaded by pro-Japanese aborigines in the Second Musha Incident The Taiwanese Aboriginal tribes, who were allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652, turned against the Dutch in turn during the Siege of Fort Zeelandia. They defected to Koxinga's Chinese forces.[19] The Aboriginals (Formosans) of Sincan defected to Koxinga after he offered them amnesty. The Sincan Aboriginals fought for the Chinese and beheaded Dutch people in executions. The frontier aboriginals in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese on May 17, 1661, celebrating their freedom from compulsory education under Dutch rule. They hunted down Dutch people, beheading them and trashing their Christian school textbooks.[20] At the Battle of Tamsui in the Keelung Campaign during the Sino-French War on 8 October 1884, the Chinese took prisoners and beheaded 11 French marines who were injured, in addition to La Galissonnière's captain Fontaine. The heads were mounted on bamboo poles and displayed to incite anti-French feelings. In China, pictures of the beheading of the Frenchmen were published in the Tien-shih-tsai Pictorial Journal in Shanghai.[21] A most unmistakable scene in the market place occurred. Some six heads of Frenchmen, heads of the true French type were exhibited, much to the disgust of foreigners. A few visited the place where they were stuck up, and were glad to leave it—not only on account of the disgusting and barbarous character of the scene, but because the surrounding crowd showed signs of turbulence. At the camp also were eight other Frenchmen's heads, a sight which might have satisfied a savage or a Hill-man, but hardly consistent with the comparatively enlightened tastes, one would think, of Chinese soldiers even of to-day. It is not known how many of the French were killed and wounded; fourteen left their bodies on shore, and no doubt several wounded were taken back to the ships. (Chinese accounts state that twenty were killed and large numbers wounded.) In the evening Captain Boteler and Consul Frater called on General Sun, remonstrating with him on the subject of cutting heads off, and allowing them to be exhibited. Consul Frater wrote him a despatch on the subject strongly deprecating such practices, and we understand that the general promised it should not occur again, and orders were at once given to bury the heads. It is difficult for a general even situated as Sun is—having to command troops like the Hillmen, who are the veriest savages in the treatment of their enemies—to prevent such barbarities. It is said the Chinese buried the dead bodies of the Frenchmen after the engagement on 8th instant by order of General Sun. The Chinese are in possession of a machine gun taken or found on the beach. — James Wheeler Davidson, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present: History, people, resources, and commercial prospects. Tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions[22] Han Taiwanese and Taiwanese Aboriginals revolted against the Japanese in the Beipu Uprising in 1907 and Tapani Incident in 1915. The Seediq aboriginals revolted against the Japanese in the 1930 Musha Incident and resurrected the practice of headhunting, beheading Japanese during the revolt. |

台湾 関連項目:ゼーランディア要塞包囲戦、ローバー号事件、フォルモサ遠征、牡丹事件(1871年)、日本による台湾侵攻(1874年)、淡水戦、基隆作戦、 烏社事件  台湾原住民の首狩り儀礼 首狩りは台湾原住民の間で一般的な慣習であった。オーキッド島で孤立していたヤミ族とイバタン族を除く全ての部族が首狩りを行っていた。この慣習はフィリ ピンの諸人民とも関連していた。 台湾平原部族、漢人台湾人、日本人入植者は、台湾山岳部族による首狩り襲撃の標的となった。後者の二つの集団は侵略者、嘘つき、敵と見なされていた。狩頭 襲撃は、しばしば野原で働く労働者を襲ったり、住居に火を放ち、燃え盛る建物から逃げ出した者を殺害し首を刎ねたりした。この慣習は日本の台湾統治下でも 続いたが、日本植民地政府による残酷な弾圧により1930年代に終焉を迎えた。  第二霧社事件で親日派原住民に首を刎ねられたセディク族の反乱者たち 1652年の郭懐義の乱ではオランダ側について中国軍と戦った台湾原住民部族は、後にゼーランディア要塞包囲戦でオランダに背いた。彼らは鄭成功率いる中 国軍に寝返った[19]。新山の原住民(フォルモサ人)は鄭成功が恩赦を約束したため、彼に降伏した。新山の原住民は中国側で戦い、処刑でオランダの人民 を斬首した。山地や平野の辺境部族も1661年5月17日に降伏し中国側に寝返り、オランダ支配下の強制教育からの解放を祝った。彼らはオランダの人民を 追跡し斬首し、キリスト教の教科書を破棄した。[20] 1884年10月8日、清仏戦争における基隆作戦の淡水戦では、中国側が捕虜を捕らえ、負傷したフランス海軍兵11名とラ・ガリソニエール艦長のフォン テーヌを斬首した。首は竹竿に掲げられ、反仏感情を煽るために晒し者にされた。中国では、フランス人斬首の絵が上海の『天地時報』に掲載された。[21] 市場で最も紛れもない光景が起きた。フランス人らしい頭部のフランス人6人の首が展示され、外国人を大いに嫌悪させた。数人がその展示場所を訪れたが、す ぐに立ち去った。その光景が不快で野蛮だっただけでなく、周囲の群衆が騒動を起こす気配を見せていたからだ。陣営にはさらに8人のフランス人の首が並べら れていた。この光景は野蛮人や山岳民族なら満足したかもしれないが、今日の中国兵士でさえ比較的教養があると思われる彼らの趣味にはそぐわないだろう。フ ランス人の死傷者数は不明だ。十四人が遺体を岸に残し、数人の負傷者は船に連れ戻されたに違いない。(中国側の記録では二十人が死亡し、多数の負傷者が出 たとしている。) 夕刻、ボテラー艦長とフレイター領事は孫将軍を訪ね、首を切り落とし展示することを強く抗議した。フレイター領事はこの件について、そのような行為を強く 非難する書簡を孫将軍に送った。我々の理解では、将軍は再発防止を約束し、直ちに首を埋葬するよう命令が出された。孫将軍のような立場の将軍でさえ——敵 に対する扱いが最も野蛮な山岳民族のような部隊を指揮しなければならない——このような残虐行為を防ぐのは難しい。 今月8日の戦闘後、孫将軍の命令により中国軍がフランス兵の遺体を埋葬したと言われている。中国軍は海岸で押収または発見した機関銃を保持している。 — ジェームズ・ウィーラー・デイヴィッドソン著『台湾島 過去と現在:歴史・人々・資源・商業展望 茶・樟脳・砂糖・金・石炭・硫黄・有用植物その他の 産物』[22] 漢台湾人と台湾原住民は、1907年の北埔蜂起と1915年のタパニ事件で日本に対して反乱を起こした。1930年の霧社事件ではセディク族が反乱を起こ し、首狩りの慣習を復活させ、反乱中に日本人の首を斬った。 |

Mainland Asia Yataro Kojima (vassal of Kenshin Uesugi) with hunted head China During the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, Qin soldiers frequently collected their defeated enemies' heads as a means to accumulate merits. After Shang Yang's reforms, the Qin armies adopted a meritocracy system that awards the average soldiers, most of whom were conscripted serfs and were not paid, an opportunity to earn promotions and rewards from their superiors by collecting the heads of enemies, a type of body count. In this area, authorities also displayed heads of executed criminals in public spaces up to the early 20th century. The Wa people, a mountain ethnic minority in Southwest China, eastern Myanmar (Shan State) and northern Thailand, were once known as the "Wild Wa" by British colonists due to their traditional practice of headhunting.[23] Japan Tom O'Neill wrote: Samurai also sought glory by headhunting. When a battle ended, the warrior, true to his mercenary origins, would ceremoniously present trophy heads to a general, who would variously reward him with promotions in rank, gold or silver, or land from the defeated clan. Generals displayed the heads of defeated rivals in public squares.[24] |

アジア大陸 小島弥太郎(上杉謙信の家臣)の首刈り頭部(国芳) 中国 春秋戦国時代、秦の兵士は戦功を積む手段として、敗れた敵の首を頻繁に収集した。商鞅の改革後、秦軍は功績主義制度を採用した。これは徴用された農奴が大 部分を占める無給の兵士たちに、敵の首を集めることで(一種の戦果報告として)上司から昇進や報酬を得る機会を与える制度だった。この地域では、20世紀 初頭まで当局が処刑された犯罪者の首を公共の場に展示することも行われていた。 中国南西部、ミャンマー東部(シャン州)、タイ北部に住む山岳少数民族であるワ人民は、その伝統的な狩頭(頭狩り)の慣習から、かつて英国植民者たちから 「野生のワ族」と呼ばれていた。[23] 日本 トム・オニールはこう書いている。 侍も首狩りで栄誉を求めた。戦いが終わると、戦士は傭兵としての本分に忠実に、戦利品の首を将軍に厳かに献上した。将軍は、階級の上昇、金や銀、あるいは 敗北した氏族の土地など、さまざまな形で戦士に報いた。将軍は、敗北した敵の首を公共の広場に展示した。[24] |

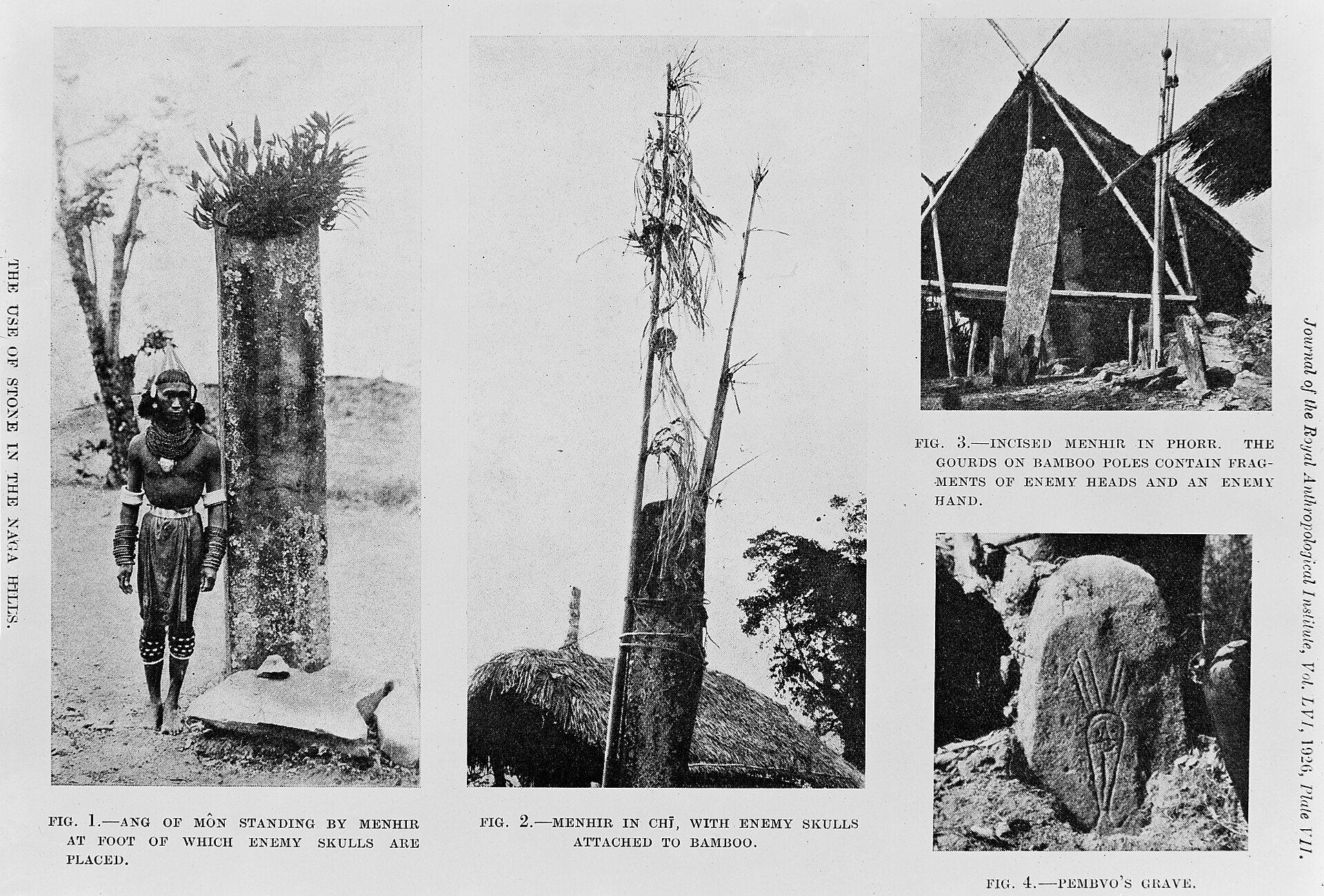

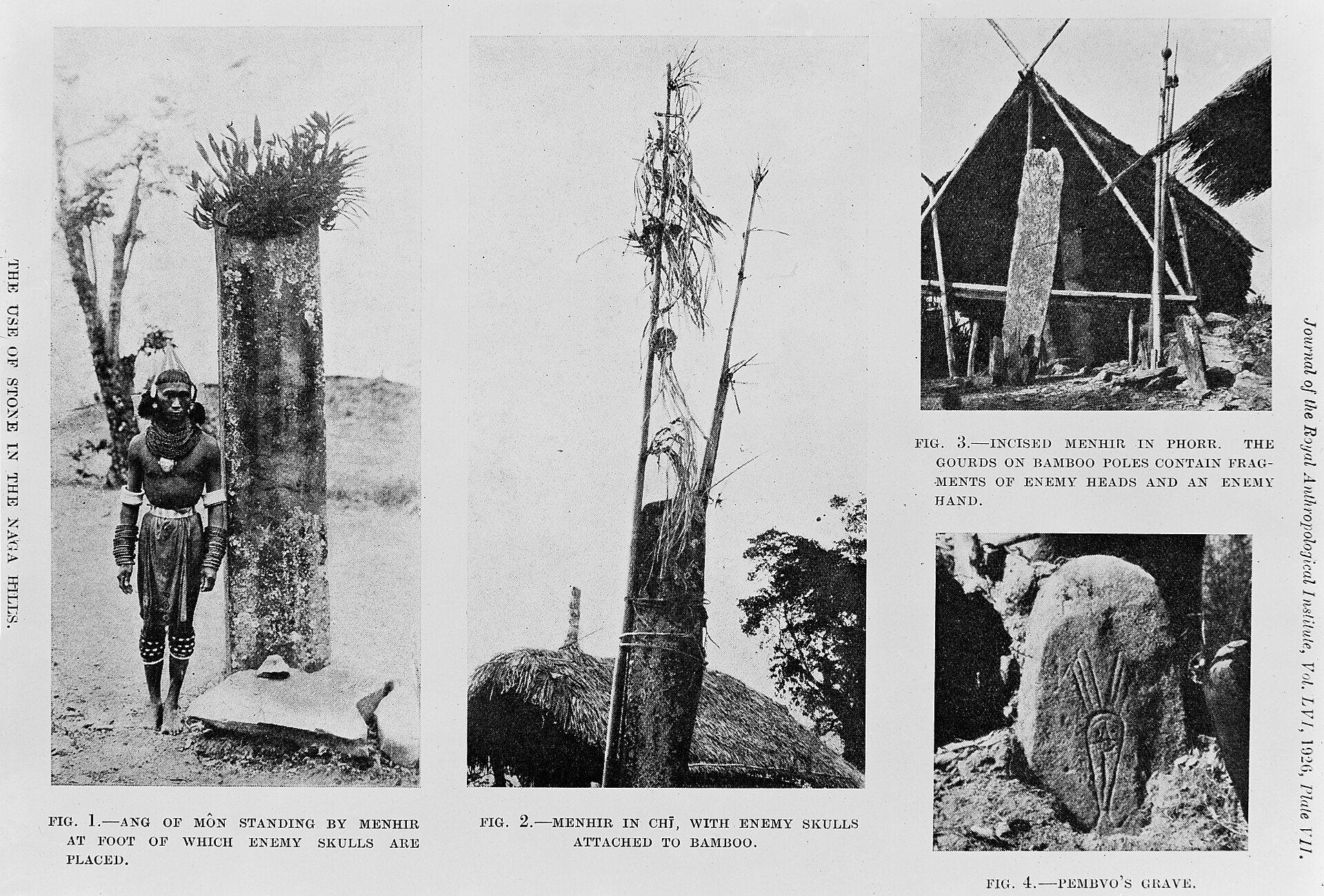

Indian subcontinent and Indochina Headhunting among the Naga people Headhunting has been a practice among the Kukis,[25] the Wa,[23] Mizo, the Garo and the Naga ethnic groups of India, Bangladesh and Myanmar till the 19th century.[26] Nuristanis in eastern Afghanistan were headhunters until the late 19th century.[25] |

インドの亜大陸とインドシナ ナガ族における首狩り 首狩りは、19世紀までインド、バングラデシュ、ミャンマーのクキ族[25]、ワ族[23]、ミゾ族、ガロ族、ナガ族の間で行われていた慣習である [26]。アフガニスタン東部のヌリスタニ族も19世紀後半まで首狩りを行っていた[25]。 |

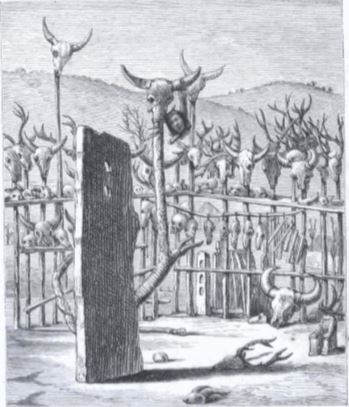

Mizo people Illustration of Chief Vanhnuailiana's tomb with a head observed during the Lushai Expedition. Mizo warfare would often rely on secret attacks and ambushing in surprise of their enemies.[27] This led to superstitions as to the time and auspciciousness to conduct a raid. A headhunting expedition would concern stargazing where the crescent of the moon would be studied as an omen. If a star accompanied the new moon on its right side, this was considered "the moon is brandishing a knife" hence not permitting a raid to occur. If the star appeared left of the crescent moon then this would be perceived as "the moon is carrying a head" which was auspicious for a raid.[28] Another superstition concerned the minivet. If on a journey to raid, the minivet flew away from the village it was a sign of success. If it flew to the village while screeching then the omen would lead the party to turn back.[29] A portion of men would be assigned to a raid and a portion to remain home to defend the village. After killing one's enemies, the victor was required to place their foot on the corpse and shout their name three times and sing a Bawhhla (battle song). This was due to the belief that doing so would enable the killed warrior to become the victor's slave in the afterlife. By proclaiming his name and singing a song, the slave would recognise his master's voice. Following this, the heads would be decapitated. If the journey home was too long then the scalps of the heads would be taken instead as proof of their victory.[29] Returning to the village, it was a taboo to bring the heads in during daylight. The war party would remain outside the village and delay their entrance. Only after dinner and the courtship hours between young men and women in the evening would permit for the party to enter. The arrival with the heads would announce themselves with gunshots and a bawhhla of their victory. Village maidens would then take initiative throughout the night to make an Arkeziak to tie on the heads, necks, wrists, ankles or upper arms of the warriors. The Arkeziak was made with a white spun cotton not boiled with rice and plaited into a pattern with tassels.[30] The rest of the village would not meet the party out of taboo while the return was being celebrated with battle songs and gunshots.[31] The following morning, the women tied the Arkeziak made during the night. The village chief and upas would honour the warriors with necklaces of amber and semi-precious stones. Even if a warrior had failed to bring back a head or scalp, any assistance in procuring the heads of the corpses would see them on equal footing with the rest of the warriors, however, with less rewards. The heads would be accompanied with other spoils of war such as guns, gongs, spears and knives distributed to the families of the warriors via small payments. It was forbidden to ask for trophies or receive them as a gift.[31] The heads of the warriors would be stored in the Thirdengsa (blacksmiths forge). After breakfast, a ceremony would be held. The heads would be retrieved from the forge and each warrior would carry the head they procured from slaying and assemble in front of the chief's house in the village square. A small table would be made for the heads to be placed. A broken piece of pottery would be placed with stale rice in it. A ritual dance would be performed for the ceremony.[32] Young women would alsojoin the ritual dance.[33] The warriors would surround the table to perform another custom. The party leader would have a boiled egg in his bag. Half of the egg would be consumed with the other half squeezed and sprinkled into the stale rice in the broken pot. A spell would be chanted to curse the heads on the table. A battle song would be sung and the gun would be fired three times. Music and song would then play following this.[34] The warriors would also during this period taunt, gloat and scoff at the heads. Guns would be loaded with gunpowder but no bullets as they were fired at the heads. Following this, a pot of zu would be placed in the village square. A mithun would be killed and offered to the warriors. A feast would be held with the customs of serving zu.[35] After the complete ceremony, the heads would be taken and fixed on the ends of freshly cut poles. The poles would be placed on the west side of the village and erected in a row in the lungdawh (cemetery). Some heads would be suspended to the entrance to the village. Any tree hanging the heads of enemies would be known as Sah-lam. A headhunter was also expected to sacrifice a mithun or a pig under a superstition that doing so would not engage the spirit of the head to turn the headhunter insane.[36] Wa people The Wa people, whose domain straddles the Burma-China border, were once known to Europeans as the "Wild Wa" for their "savage" behavior. Until the 1970s, the Wa practiced headhunting.[37] |

ミゾ族の人民 ルシャイ遠征中に観察された、首長ヴァンヌアイリアナの墓と頭部の図解。 ミゾ族の戦法は、しばしば秘密攻撃や奇襲による待ち伏せに依存していた[27]。これにより、襲撃を行う時期や吉凶に関する迷信が生まれた。首狩り遠征で は星占いが重要視され、三日月が前兆として観察された。新月の右側に星が伴う場合、「月が刃物を振るっている」と解釈され襲撃は禁忌とされた。三日月左側 に星が現れると「月が首を携えている」と見なされ、襲撃に吉兆とされた[28]。別の迷信はミズナギドリに関するものだ。襲撃の途上でミズナギドリが村か ら離れて飛ぶのは成功の兆しとされた。もし鳴き声をあげながら村に向かって飛んでいくなら、その前兆は襲撃隊を引き返させるものだった。[29] 襲撃には一部の男たちが割り当てられ、残りは村を守るために留守番となった。敵を殺した後、勝者はその死体に足を置き、三度その名を叫び、バウッラ(戦い の歌)を歌うことが義務づけられていた。これは、そうした行為によって殺された戦士が死後の世界で勝者の奴隷になれるという信仰に基づくものだ。名前を宣 言し歌を歌うことで、奴隷は主人の声を認識する。その後、首は切り落とされる。帰路が長すぎる場合、勝利の証として代わりに頭皮が持ち帰られた。[29] 村へ戻るとき、昼間に首を持ち込むのはタブーだった。戦隊は村の外に留まり、入村を遅らせた。夕食後、そして夕方の若者たちの求愛時間が過ぎて初めて、戦 隊は村に入ることが許された。首を持った到着は、銃声と勝利のバウラで自らを告げた。村の娘たちは夜通し、戦士の頭や首、手首、足首、上腕に結ぶアルケジ アックを作る。アルケジアックは米で煮ていない白い綿糸で編み、房付きの模様を施す[30]。帰還を祝う戦いの歌と銃声が響く間、村の他の者たちはタブー のため出迎えない。[31] 翌朝、女たちは夜中に作ったアルケジアックを結びつけた。村長とウパスは琥珀や半貴石の首飾りで戦士たちを称えた。たとえ戦士が首や頭皮を持ち帰れなくて も、死体の首の入手に関わった者は他の戦士と同等に扱われたが、報酬は少なかった。頭部は銃、鉦、槍、ナイフなどの戦利品と共に、少額の支払いを通じて戦 士たちの家族に分配された。戦利品を要求したり、贈り物として受け取ったりすることは禁じられていた。[31] 戦士たちの頭部は、テルデンサ(鍛冶屋の鍛冶場)に保管された。朝食後、儀式が行われる。鍛冶場から頭部を取り出し、各戦士は自身が斬り取った頭部を携 え、村の広場にある首長の家の前に集結する。頭部を置くための小さな卓が設けられる。割れた土器に古米が入れられる。儀礼の舞が捧げられる[32]。若い 女性たちも舞に加わる。[33] 戦士たちはテーブルを取り囲み、別の慣習を執り行う。隊長は袋にゆで卵を携えている。卵の半分は食べられ、残りの半分は割れた壺の中の古い米に絞りかけら れる。テーブル上の首を呪う呪文が唱えられる。戦いの歌が歌われ、銃が三度発砲される。その後、音楽と歌が奏でられた。[34] この間、戦士たちは首を嘲り、ほくそ笑い、嘲笑した。銃は火薬のみ装填され、弾丸なしで首に向けて発射された。続いて、ズー(豚肉料理)の鍋が村の広場に 置かれた。ミトゥン(水牛)が屠殺され、戦士たちに供された。ズーを供する慣習に従い、宴が開かれた。[35] 儀式が完全に終わると、首は切り取られたばかりの棒の先端に取り付けられる。棒は村の西側に置かれ、ルンダウ(墓地)に一列に立てられる。一部の首は村の 入口に吊るされる。敵の首が吊るされた木はサ・ラムと呼ばれる。 |

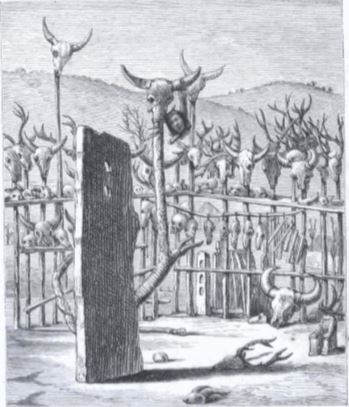

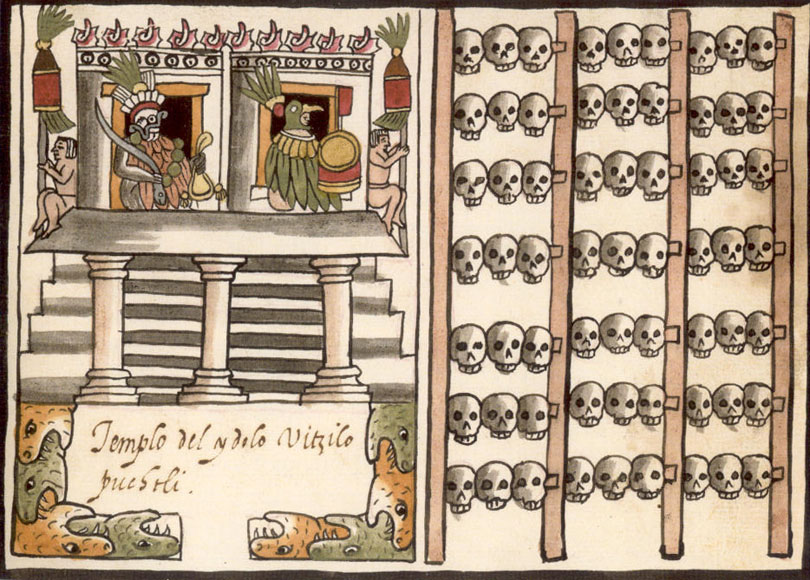

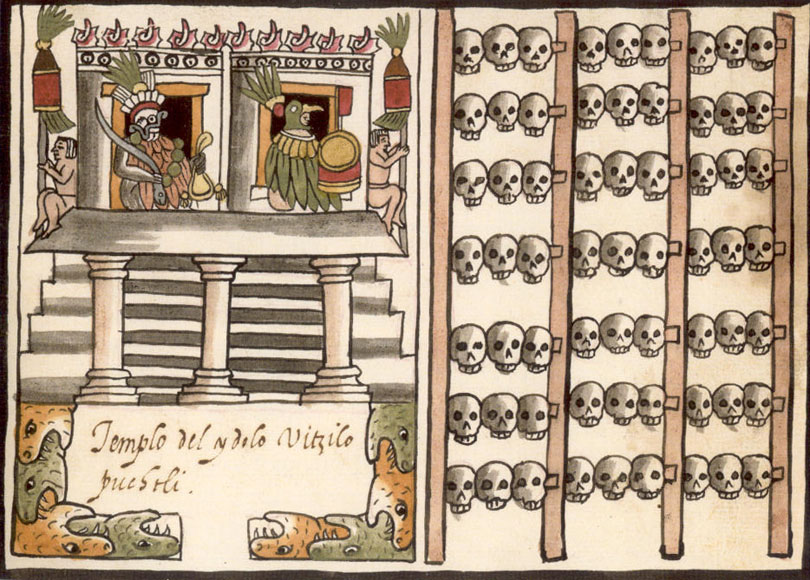

| Americas Amazon  Shrunken head from the upper Amazon region Several tribes of the Jivaroan group, including the Shuar in Eastern Ecuador and Northern Peru, along the rivers Chinchipe, Bobonaza, Morona, Upano, and Pastaza, main tributaries of the Amazon, practiced headhunting for trophies. The heads were shrunk, and were known locally as Tzan-Tzas. The people believed that the head housed the soul of the person killed. In the 21st century, the Shuar produce Tzan-tza replicas. They use their traditional process on heads of monkeys and sloths, selling the items to tourists. It is believed that splinter groups in the local tribes continue with these practices when there is a tribal feud over territory or as revenge for a crime of passion. [citation needed] The Kichwa-Lamista people in Peru used to be headhunters.[38] Mesoamerican civilizations  A tzompantli is illustrated to the right of a depiction of an Aztec temple dedicated to the deity Huitzilopochtli; from Juan de Tovar's 1587 manuscript, also known as the Ramírez Codex. A tzompantli is a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations. It was used for the public display of human skulls, typically those of war captives or other sacrificial victims.[39] A tzompantli-type structure has been excavated at the La Coyotera, Oaxaca site. It is dated to the Proto-Classic Zapotec civilization, which flourished from c. 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE.[40] Tzompantli are also noted in other Mesoamerican pre-Columbian cultures, such as the Toltec and Mixtec. Based on numbers given by the conquistador Andrés de Tapia and Fray Diego Durán, Bernard Ortiz de Montellano[41] has calculated in the late 20th century that there were at most 60,000 skulls on the Hueyi Tzompantli (great Skullrack) of Tenochtitlan. There were at least five more skullracks in Tenochtitlan, but, by all accounts, they were much smaller. Other examples are indicated from Maya civilization sites. A particularly fine and intact inscription example survives at the extensive Chichen Itza site.[42] Nazca culture The Nazca used severed heads, known as trophy heads, in various religious rituals.[43] Late Nazca iconography suggests that the prestige of the leaders of Late Nazca society was enhanced by successful headhunting.[44] |

アメリカ大陸 アマゾン  アマゾン上流域の縮み頭 アマゾンの主要な支流であるチンチペ川、ボボナザ川、モロナ川、ウパノ川、パスタサ川沿いに住む、エクアドル東部とペルー北部のシュアル族を含む、ヒバロ 族グループのいくつかの部族は、戦利品として首狩りを実践していた。頭部は縮められ、現地ではツァンツァとして知られていた。人民は、頭部が殺害された人 格の魂を宿すと信じていた。 21世紀の現在、シュアル族はツァンツァのレプリカを製作している。彼らは伝統的な技法を用いてサルやナマケモノの頭部を加工し、観光客向けに販売してい る。現地部族の分派集団は、領土をめぐる部族間の争いや激情による犯罪への復讐として、こうした慣習を継続しているとされている。[出典が必要] ペルーのキチュワ・ラミスタの人民もかつては首狩りを行っていた。[38] メソアメリカ文明  右図はアステカの神ウィツィロポチトリに捧げられた神殿の描写で、その右側にツォンパントリが描かれている。フアン・デ・トバルの1587年の写本(ラミ レス写本としても知られる)より。 ツォンパントリとは、メソアメリカの複数の文明で確認されている木製の棚または柵の一種である。これは人間の頭蓋骨、特に戦争捕虜やその他の生贄の犠牲者 の頭蓋骨を公に展示するために用いられた。[39] ツォンパントリ型の構造物は、オアハカ州ラ・コヨテラ遺跡で発掘されている。これは紀元前2世紀頃から紀元後3世紀にかけて栄えた、プロト古典期サポテカ 文明の時代に遡る。[40] ツォンパントリは、トルテカやミシュテカなど、他のメソアメリカ先コロンブス期文化でも確認されている。 征服者アンドレス・デ・タピアと修道士ディエゴ・デュランの記録に基づき、ベルナール・オルティス・デ・モンテジャーノ[41]は20世紀末に、テノチ ティトランの大頭蓋骨棚(ウエウィ・ツォンパントリ)には最大6万個の頭蓋骨が掲げられていたと推定した。テノチティトランには少なくともさらに5つの頭 蓋骨棚があったが、あらゆる記録によれば、それらははるかに小規模であった。 マヤ文明の遺跡からも他の例が示されている。特に精巧で完全な状態の碑文例が、広大なチチェン・イッツァ遺跡に現存している。[42] ナスカ文化 ナスカ人は、トロフィーヘッドとして知られる切断された頭部を様々な宗教儀礼で使用した。[43] 後期ナスカの図像からは、首狩りの成功によって後期ナスカ社会の指導者の威信が高められたことが示唆されている。[44] |

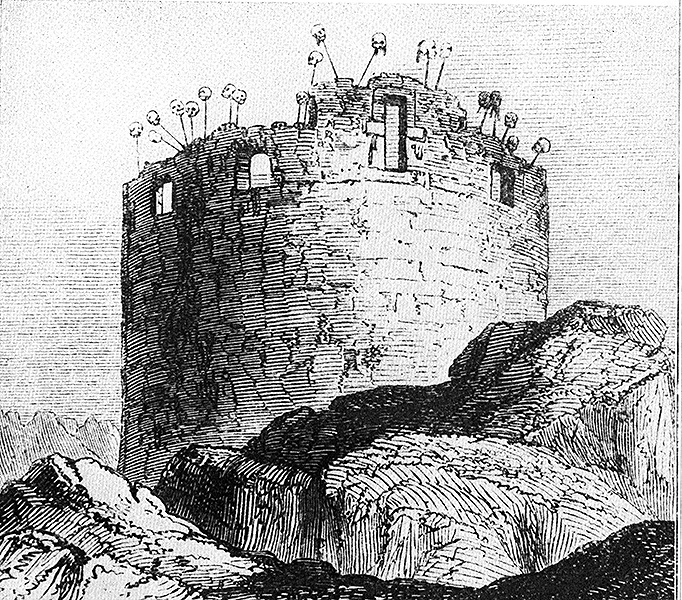

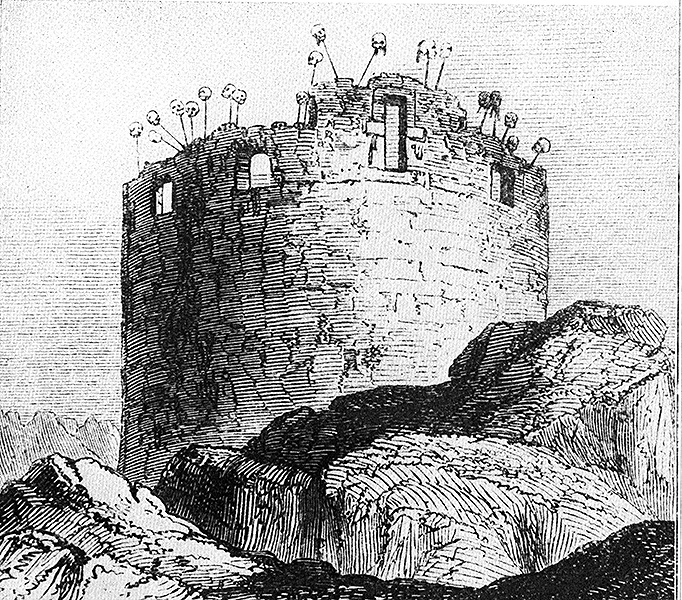

Europe Roquepertuse. The pillars of the portico, with cavities designed for receiving skulls. III-II B.C. Musée d'archéologie méditerranéenne in Marseille. Celts See also: Celtic decapitation The Celts of Europe practiced headhunting as the head was believed to house a person's soul. Ancient Romans and Greeks recorded the Celts' habits of nailing heads of personal enemies to walls or dangling them from the necks of horses.[45] The Celtic Gaels practiced headhunting a great deal longer. In the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, the demigod Cúchulainn beheads the three sons of Nechtan and mounting their heads on his chariot. This is believed to have been a traditional warrior, rather than religious, practice. The practice continued approximately to the end of the Middle Ages among the Irish clans and even later among the Border Reivers of the Anglo-Scottish marches.[46] The pagan religious reasons for headhunting were likely lost after the Celts' conversion to Christianity, even though the practice continued.[citation needed] In former Celtic areas, cephalophore representations of saints (miraculously carrying their severed heads) were common.[47] Heads were also taken among the Germanic tribes and among Iberians, but the purpose is unknown. Montenegrins  A painting of the Tablja Tower adorned with Ottoman soldier heads, which was located above the Cetinje Monastery in the old royal capital of Cetinje. The Montenegrins are an ethnic group in Southeastern Europe who are centered around the Dinaric mountains and are extremely closely related to Serbs.[48][49] They practiced headhunting until 1876, allegedly carrying the head from a lock of hair grown specifically for that purpose.[50] In the 1830s, Montenegrin ruler Petar II Petrović-Njegoš started building a tower called "Tablja" above Cetinje Monastery. The tower was never finished, and Montenegrins used it to display Turkish heads taken in battle, as they were in frequent conflict with the Ottoman Empire. In 1876 King Nicholas I of Montenegro ordered that the practice should end. He knew that European diplomats considered it to be barbaric. The Tablja was demolished in 1937. Scythians The Scythians were excellent horsemen. Ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that some of their tribes practiced human sacrifice, drinking the blood of victims, scalping their enemies, and drinking wine from the enemies' skulls.[51] |

ヨーロッパ ロケペルテュス。頭蓋骨を収めるための窪みを持つ柱廊の柱。紀元前3~2世紀。マルセイユ地中海考古学博物館所蔵。 ケルト人 関連項目: ケルト人の斬首 ヨーロッパのケルト人は、頭部が人格を宿すと信じられていたため、首狩りを実践した。古代ローマ人とギリシャ人は、ケルト人が人格の敵の首を壁に釘付けに したり、馬の首からぶら下げたりする習慣を記録している[45]。ケルト系ゲール人は、はるかに長く首狩りを実践した。アイルランド神話のアルスター叙事 詩では、半神クー・フーリンがネクターンの三人の息子を斬首し、その首を戦車に掲げている。これは宗教的ではなく、伝統的な戦士の慣習と考えられている。 この慣習はアイルランドの氏族の間では中世末期まで、アングロ・スコットランド国境地帯のボーダー・リーバーズの間ではさらに後まで続いた[46]。ケル ト人がキリスト教に改宗した後、首狩りの異教的な宗教的理由は失われた可能性が高いが、慣習自体は継続した[出典必要]。かつてのケルト地域では、聖人の 頭部保持者像(奇跡的に切断された自身の頭部を携える姿)が広く見られた[47]。ゲルマン部族やイベリア人の中にも頭部採取の慣習は存在したが、その目 的は不明である。 モンテネグロ人  旧王都ツェティニェのツェティニェ修道院上部に位置した、オスマン兵士の頭部で飾られたタブリャ塔の絵画。 モンテネグロ人は南東ヨーロッパの民族集団で、ディナール山脈周辺に集中し、セルビア人と極めて近縁である。[48][49] 彼らは1876年まで首狩りを実践し、その目的のために特別に育てた髪の毛の束から頭部を運んだと伝えられる。[50] 1830年代、モンテネグロの統治者ペタル2世ペトロヴィッチ=ニェゴシュはチェティンジェ修道院の上に「タブリャ」と呼ばれる塔の建設を始めた。塔は完 成せず、モンテネグロ人はオスマン帝国との頻繁な衝突で戦利品として得たトルコ人の首を展示するために使用した。1876年、モンテネグロのニコライ1世 は、この慣習を終わらせるよう命じた。彼は、ヨーロッパの外交官たちがこれを野蛮と見なしていることを知っていた。タブリャは1937年に取り壊された。 スキタイ人 スキタイ人は優れた騎手であった。古代ギリシャの歴史家ヘロドトスは、彼らの部族の一部が人身供犠を行い、犠牲者の血を飲み、敵の頭皮を剥ぎ取り、敵の頭 蓋骨からワインを飲んだと記している。[51] |

Modern times A Dayak headhunter, Borneo. Second Sino-Japanese War Nanjing Massacre Main article: Nanjing Massacre Many Chinese soldiers and civilians were beheaded by some Japanese soldiers, who even made contests to see who would kill more people (see Hundred man killing contest), and took photos with the piles of heads as souvenirs. World War II Main article: American mutilation of Japanese war dead  An American posing with a Japanese skull in World War II During World War II, Allied (specifically including American) troops occasionally collected the skulls of dead Japanese as personal trophies, as souvenirs for friends and family at home, and for sale to others. (The practice was unique to the Pacific theater; United States forces did not take skulls of German and Italian soldiers.) In September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet mandated strong disciplinary action against any soldier who took enemy body parts as souvenirs. But such trophy-hunting persisted: Life published a photograph in its issue of May 22, 1944, of a young woman posing with the autographed skull sent to her by her Navy boyfriend. There was public outrage in the US in response.[52][53] Historians have suggested that the practice related to Americans viewing the Japanese as lesser people, and in response to mutilation and torture of American war dead.[54] In Borneo, retaliation by natives against the Japanese was based on atrocities having been committed by the Imperial Japanese Army in that area. Following their ill treatment by the Japanese, the Dayak of Borneo formed a force to help the Allies. Australian and British special operatives of Z Special Unit developed some of the inland Dayak tribesmen into a thousand-strong headhunting army. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers.[55] |

近代 ボルネオのダヤック族の首狩り族。 日中戦争 南京大虐殺 詳細記事:南京大虐殺 多くの中国兵士や民間人が日本兵によって斬首された。日本兵は殺害数を競う「百人殺し競争」まで行い、記念に山積みになった首と写真を撮った。 第二次世界大戦 詳細記事: アメリカ軍による日本戦没者の遺体損壊  第二次世界大戦中に日本の頭蓋骨とポーズを取るアメリカ兵 第二次世界大戦中、連合国軍(特にアメリカ軍)の兵士は、死んだ日本人の頭蓋骨を個人的な戦利品として、あるいは故郷の友人や家族への土産として、あるい は他人に売るために収集することがあった。(この慣行は太平洋戦域に特有のものであり、アメリカ軍はドイツ兵やイタリア兵の頭蓋骨は収集しなかった。) 1942年9月、太平洋艦隊司令官は敵の身体の一部を記念品として持ち帰る兵士に対し、厳しい懲戒処分を命じた。しかし、こうした戦利品狩りは続いた。 1944年5月22日号の『ライフ』誌には、海軍の恋人が送ったサイン入りの頭蓋骨と一緒にポーズをとる若い女性の写真が掲載された。これに対し、アメリ カ国内では公の怒りが巻き起こった。[52] [53] 歴史家たちは、この慣行はアメリカ人が日本人を劣った人々として見なしていたこと、そしてアメリカ人戦没者に対する切断や拷問への報復として行われたと指 摘している。[54] ボルネオでは、原住民による日本軍への報復は、その地域で日本帝国陸軍が犯した残虐行為に基づいていた。日本軍による虐待を受けた後、ボルネオのダヤク族 は連合国を支援する部隊を結成した。オーストラリアと英国の特殊部隊「Z特殊部隊」は、内陸部のダヤク族部族民の一部を千人規模の首狩り部隊に育成した。 この部族民部隊は約1,500名の日本兵を殺害または捕虜とした。[55] |

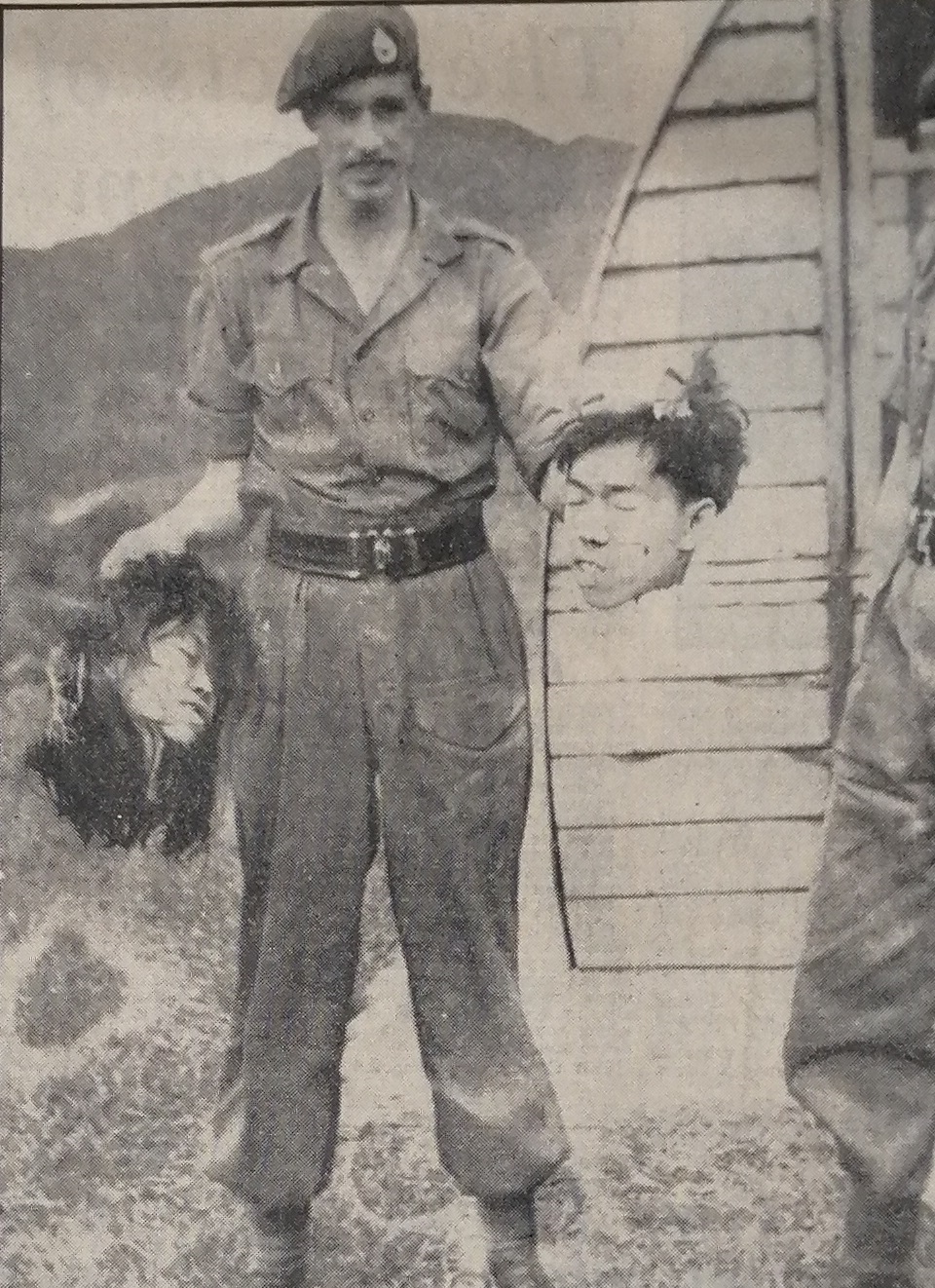

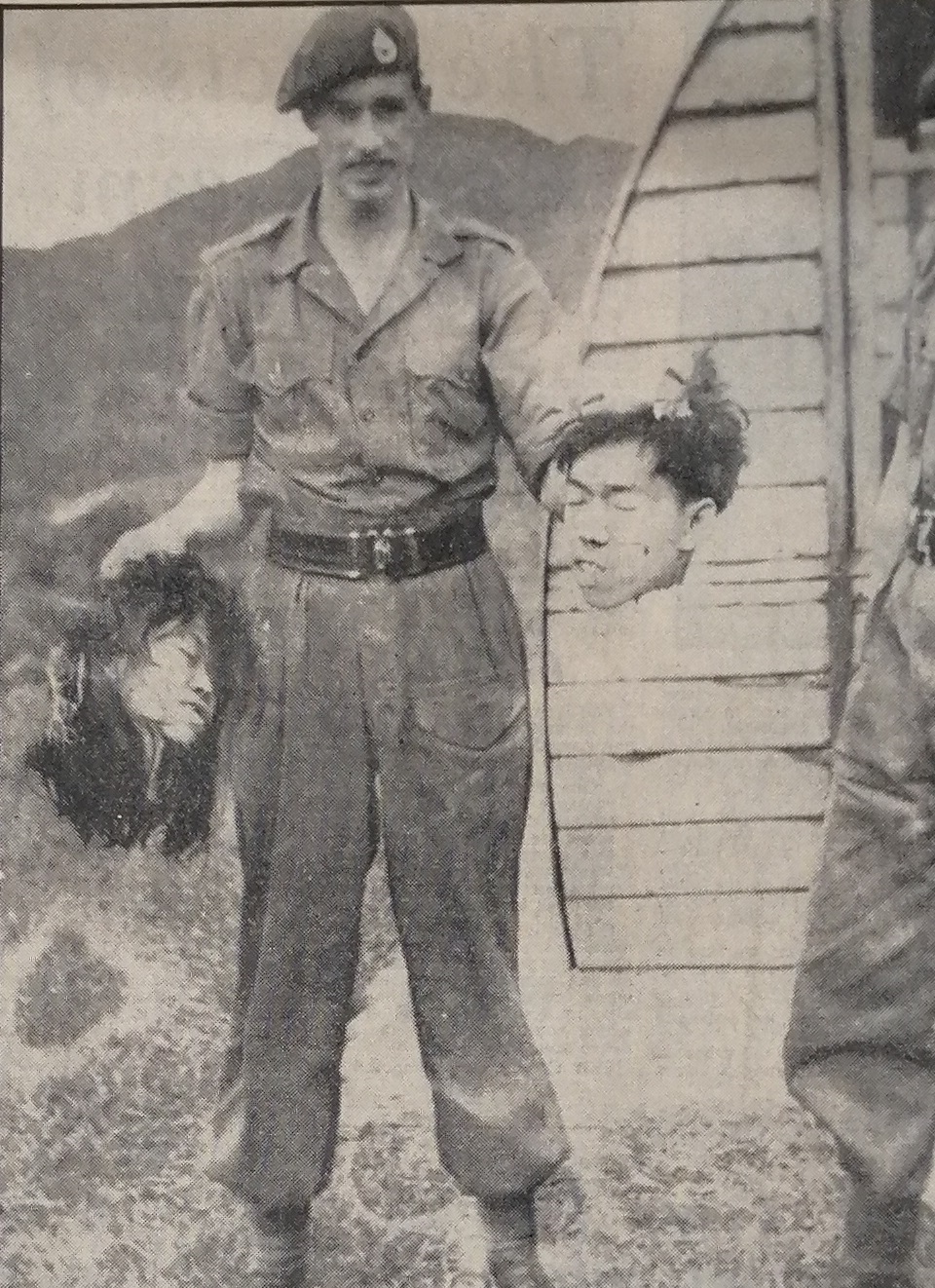

A Royal Marine holding the severed heads of suspected pro-independence fighters during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) Malayan Emergency During the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960), British and Commonwealth forces recruited Iban (Dayak) headhunters from Borneo to fight and decapitate suspected guerrillas of the socialist and pro-independence Malayan National Liberation Army, officially claiming this was done for "identification" purposes.[56] Iban headhunters were permitted to keep the scalps of corpses as trophies.[57][56] Privately, the Colonial Office noted that "there is no doubt that under international law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime".[58][59][60] Skull fragments from a trophy skull was later found to have been displayed in a British regimental museum.[56] In April 1952, the British Communist Party's official newspaper the Daily Worker (today known as the Morning Star) published a photograph of Royal Marines in a British military base in Malaya openly posing with severed human heads.[56][61] Initially, British government spokespersons belonging to the Admiralty and the Colonial Office denied the newspaper's claims and insisted that the photograph was a forgery.[60] In response, the Daily Worker released yet another photograph taken in Malaya showing other British soldiers posing with a severed human head. In response, Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttelton was forced to admit before the House of Commons that the Daily Worker headhunting photographs were indeed genuine.[62] In response to the Daily Worker articles, headhunting was banned by Winston Churchill, who feared that further photographs would continue being exploited for communist propaganda.[56][63] Despite the shocking imagery of the photographs of soldiers posing with severed heads in Malaya, the Daily Worker was the only British newspaper to publish them during the 20th century, and the photographs were virtually ignored by the mainstream British press.[60] European colonialist powers also engaged in headhunting, under the guise of phrenology and so-called scientific inquiry. Especially during the 19th century, at the height of Europe's oppression of Indigenous peoples internationally. During this time, English, French and German colonialists engaged in routine practices whereby "remains were commissioned, exchanged, and traded as objects between institutions and individuals. In some cases, colonial forces beheaded local chiefs and kings or members of resistance forces and collected the skulls as trophies." |

マラヤ非常事態(1948年~1960年)において、独立派戦闘員の首級を掲げる王立海兵隊員 マラヤ非常事態 マラヤ非常事態(1948年~1960年)の間、英国および英連邦軍は、社会主義・独立派のマラヤ国民解放軍(MNLA)のゲリラ容疑者を戦闘で倒し、首 を斬るために、ボルネオ島のイバン族(ダヤク族)の狩人(ヘッドハンター)を徴用した。公式には「身元確認」のためと主張していた[56]。イバン族の狩 人たちは、戦利品として死体の頭皮を保持することを許可されていた。[57][56] 植民地省は非公式に「国際法上、戦時下で同様の行為が行われた場合、戦争犯罪に該当することは疑いない」と記していた。[58][59][60] 戦利品の頭蓋骨の一部が、後に英国連隊博物館に展示されていたことが判明した。[56] 1952年4月、英国共産党の機関紙『デイリー・ワーカー』(現『モーニング・スター』)は、マラヤの英国軍基地で王立海兵隊員が切断された人間の頭部と 公然とポーズを取る写真を掲載した。[56][61]当初、海軍省と植民地省の英国政府スポークスパーソンは同紙の主張を否定し、写真は偽造だと主張し た。[60] これに対しデイリー・ワーカーは、マレーで撮影された別の写真をさらに公開した。そこには他の英国兵が切断された人頭と共にポーズを取る様子が写ってい た。これを受けて植民地大臣オリバー・リットルトンは、下院でデイリー・ワーカーの首狩り写真が確かに本物であることを認めざるを得なかった。[62] デイリー・ワーカーの記事を受けて、ウィンストン・チャーチルは首狩りを禁止した。彼は、さらなる写真が共産主義プロパガンダに利用され続けることを恐れ たのである。[56] [63] マラヤで兵士が切断された頭部とポーズを取る衝撃的な写真にもかかわらず、20世紀においてこれらを掲載した英国の新聞はデイリー・ワーカーのみであり、 主流の英国メディアはこれらの写真を事実上無視した。[60] ヨーロッパの植民地主義勢力も、骨相学やいわゆる科学的調査を名目に、首狩りに従事した。特に19世紀、ヨーロッパによる先住民への国際的抑圧が頂点に達 した時期に顕著だった。この時代、英仏独の植民地主義者たちは「遺骸が機関や個人間で物品として発注・交換・取引される」慣行を日常的に行っていた。場合 によっては植民地軍が現地の首長や王、抵抗勢力のメンバーを斬首し、頭蓋骨を戦利品として収集した事例もある。 |

| Interpretations of Headhunting Headhunting attracts attention to cultures uninvolved in the ritualism of its practice. Early Western observers often considered it taboo, claiming the behavior to be evident of savage intent. Due to the tradition’s misunderstanding across most colonial Euro-American cultures, it fueled discrimination. Headhunting was easily attributed to an interpreted primitive life in the cultures that engaged in the behaviors. The belief that cultures performing headhunting rituals late into human history were savage led to forcible attempts of religious conversation made by Western colonizers. Ecocentric perspective created a divide between parties involved in these rituals and those witnessing from outside. [64] |

首狩りの解釈 首狩りは、その儀礼的な実践に関わらない文化の注目を集める。初期の西洋の観察者はしばしばこれをタブーと見なし、その行為が野蛮な意図の証拠だと主張し た。この伝統はほとんどの植民地時代の欧米文化で誤解されたため、差別を助長した。首狩りは、その行為を行う文化における原始的な生活様式と容易に結びつ けられた。人類史の遅い時期まで狩人儀礼を行う文化が野蛮だという信念は、西洋の植民地支配者による強制的な宗教改宗の試みにつながった。生態中心主義的 視点が、これらの儀礼に関わる当事者と外部から観察する者との間に隔たりを生んだ。[64] |

| Cultural Impact Art Headhunting appears frequently in many forms of tribal art. Trophy heads have been depicted in numerous cultures’ artwork, including sculptures, carvings, tattoos, and ceremonial masks. Each culture depicts their headhunting rituals distinctly through different art forms. In all art forms, the works depict powerful symbolic and cultural significance, varying in stylistic design. Mediums vary from wood to skin to textile. Fashion and dance are even recorded to depict representations of pride, sometimes even involving the severed heads, themselves. Mask usage in these ritualistic dances often depicted social status, power, and pride in affiliation with headhunting.[65] |

文化的影響 芸術 首狩りは様々な部族芸術に頻繁に現れる。戦利品の頭部は、彫刻、彫刻、刺青、儀式用仮面など、数多くの文化の芸術作品に描かれてきた。各文化は異なる芸術 形式を通じて、独自の首狩りの儀礼を描写している。あらゆる芸術形式において、作品は力強い象徴的・文化的意義を描き出しており、様式的なデザインは様々 である。素材は木材から皮革、織物まで様々だ。ファッションや舞踊で誇りを表現した記録もあり、時には切断された頭部そのものが用いられることもある。こ うした儀式舞踊における仮面の使用は、しばしば社会的地位や権力、狩猟への帰属意識を誇示するものだった[65]。 |

| Vietnam War During the Vietnam War, some American soldiers engaged in the practice of taking "trophy skulls".[66][67] |

ベトナム戦争 ベトナム戦争中、一部のアメリカ兵は「戦利品の頭蓋骨」を収集する行為に及んだ。[66][67] |

| Shrunken head Scalping Decapitation Skull cup Human sacrifice Human trophy collecting Macheteros de Jara Laulasi Island Beheading in Islam Headless Horseman Plastered human skulls Crypteia, a Spartan organization who routinely practised headhunting against the servile Helot population. Tribal warfare |

縮んだ頭 頭皮剥ぎ 斬首 頭蓋骨杯 人身供犠 人間のトロフィー収集 マチェテロス・デ・ハラ ラウサリ島 イスラム教における斬首 首なしの騎手 漆喰で固められた人間の頭蓋骨 クリプテイア、奴隷階級のヘイロットに対して日常的に狩頭を行っていたスパルタの組織。 部族間戦争 |

| Citations 1. Modigliani, Elio (1890). Un viaggio a Nias [A Journey to Nias] (in Italian). Milano: Fratelli Treves Editori. 2. Hutton, J. H. "The Significance of Head-Hunting in Assam." The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 58, 1928, pp. 399–408. 3. DeMello, Margo (2014). Inked: Tattoos and Body Art around the World. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-1-61069-076-8. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020. 4. Puccioni, Vanni. (2013). Fra i tagliatori di teste : Elio Modigliani : un fiorentino all'esplorazione di Nias Salatan, 1886. Marsilio. ISBN 978-88-317-1710-6. OCLC 909365265. 5. Hoskins, Janet. The Play of Time: Kodi Perspectives on Calendars, History, and Exchange. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0x0n99tc/ p.312-314 6. "Behind Ethnic War, Indonesia's Old Migration Policy". Globalpolicy.org. March 1, 2001. Retrieved May 25, 2010. 7. Bartels, Dieter. "Politicians and Magicians: Power, Adaptive Strategies, and Syncretism in the Central Moluccas" (PDF). Retrieved February 8, 2024. 8. Van Der Kroef, Justus M. (1952). "Some Head-Hunting Traditions of Southern New Guinea". American Anthropologist. 54 (2): 221–235. doi:10.1525/aa.1952.54.2.02a00060. JSTOR 663912. 9. "Hunter Gatherers – New Guinea". Climatechange.umaine.edu. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2010. 10. Laurence Goldman (1999).The Anthropology of Cannibalism. p.19. 11. Nevermann 1957, p. 9. 12. Nevermann 1957, p. 111. 13 Nevermann 1957, blurb. 14. Nevermann 1957, p. 13. 15. "Head-Hunters Drove Papuan Tribe Into Tree-Houses". Sciencedaily.com. March 9, 1998. Retrieved May 25, 2010. 16. Jack London (1911). The Cruise of the Snark. Harvard University Digitized Jan 19, 2006. 17. "Weather delays return of toi-moko", TNVZ (national news) 18. Worcester, Dean C. (October 1906). "The Non-Christian Tribes of Northern Luzon". The Philippine Journal of Science. 1 (8): 791–875. 19. Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. pp. 96–97. ISBN 0932727905. Retrieved December 10, 2014. 20. Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624 - 1662. Vol. 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 222. ISBN 978-9004165076. Retrieved December 10, 2014. 21. Maritime Taiwan. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765641892. 22. Davidson, James Wheeler (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. Macmillan & Company. 23. "Headhunting days are over for Myanmar's 'Wild Wa'". Reuters. September 10, 2007. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2021. 24. Tom O'Neill, "Samurai: Japan's Way of the Warrior", National Geographic Magazine. 25. "Headhunting (anthropology)". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 26. Crudelli, Chris (October 1, 2008). The Way of the Warrior. Dorling Kindersley. p. 23. ISBN 978-1405330954. 27. Lalthangliana, B. (2005). Culture and Folklore of Mizoram. India: Publicans Division, Ministry of information and broadcasting. ISBN 978-81-230-1309-1. Retrieved February 12, 2025. 28. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 285. 29. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 286. 30. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 287. 31. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 288. 32. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 289. 33. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 290. 34. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 291. 35. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 292. 36 Lalthangliana 2005, p. 294. 37. "Soldiers of Fortune", TIME Asia 38. Hsu, Elisabeth; Harris, Stephen (May 15, 2012). Plants, Health And Healing. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9780857456342. 39. "Tower of human skulls in Mexico casts new light on Aztecs". Reuters. July 1, 2017. 40. Spencer 1982, pp. 236–239. 41. Ortíz de Montellano 1983. 42. Miller & Taube 1993, p. 176. 43. "The Body Context: Interpreting Early Nasca Decapitation Burials" DeLeonardis, Lisa. Latin American Antiquity. 2000. Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 363–368. 44. "A Cache of 48 Nasca Trophy Heads From Cerro Carapo, Peru" by David Browne, Helaine Silverman, and Ruben Garcia, Latin American Antiquity (1993), Volume 4, No. 3: 274–294 45. see e.g. Diodorus Siculus, 5.2 46. "Info for Headhunters". www.lard.net. 47. "The stories of St. Edmund, St. Kenelm, St. Osyth, and St. Sidwell in England, St. Denis in France, St. Melor and St. Winifred in Celtic territory, preserve the pattern and strengthen the link between legend and folklore," Beatrice White observes. (White 1972, p. 123). 48. "eHRAF World Cultures". eHRAF World Cultures. January 22, 2025. Retrieved January 22, 2025. 49. "Montenegro". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Self-Determination. May 21, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2025. 50. Edith Durham, M. (December 24, 2004). Albania and the Albanians. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781850439394. 51. Jona Lendering. "Summary of and commentary on Herodotus' Histories, book 4". Livius.org. Retrieved May 25, 2010. 52. Fussell 1990, p. 117. 53. Harrison 2006, p. 817ff. 54. Weingartner 1992, p. 67. 55. "'Guests' can succeed where occupiers fail", International Herald Tribune, 9 November 2007 56. Harrison, Simon (2012). Dark Trophies: Hunting and the Enemy Body in Modern War. Oxford: Berghahn. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-78238-520-2. 57. Hack 2022, p. 318. 58. Fujio Hara (December 2002). Malaysian Chinese & China: Conversion in Identity Consciousness, 1945–1957. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 61–65. 59. Mark Curtis (August 15, 1995). The Ambiguities of Power: British Foreign Policy Since 1945. pp. 61–71. 60. Hack 2022, p. 316. 61. Hack 2022, p. 315. 62. Peng, Chin; Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. Singapore: Media Masters. p. 302. ISBN 981-04-8693-6. 63. Hack 2022, p. 317. 64. McKinley, Robert (September 2015). "Human and proud of it!: A structural treatment of headhunting rites and the social definition of enemies". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 5 (2): 443–483. doi:10.14318/hau5.2.031. ISSN 2575-1433. 65. MIGULSKI, BOGDAN (December 9, 2024). "The Gruesome Tradition of Headhunting in History & Art". Retrieved May 13, 2025. 66. Michelle Boorstein (July 3, 2007). "Eerie Souvenirs From the Vietnam War". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved June 26, 2010. 67. "Signs of the Times – Trophy Skulls". George.loper.org. August 8, 1996. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2010. |

引用文献 1. モディリアーニ、エリオ(1890年)。『ニアス島への旅』(イタリア語)。ミラノ:フラテッリ・トレヴェス社。 2. ハットン、J. H. 「アッサムにおける首狩りの意義」 英国王立人類学協会誌、第58巻、1928年、399–408頁。 3. デメロ、マーゴ(2014)。『インクド:世界のタトゥーとボディアート』第1巻。ABC-CLIO。272–274頁。ISBN 978-1-61069-076-8。2020年7月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年6月4日に取得。 4. プッチオーニ、ヴァンニ(2013)。『首狩り人たちの間で:エリオ・モディリアーニ:ニアス・サラタン探検のフィレンツェ人、1886年』。マルシリオ 社。ISBN 978-88-317-1710-6。OCLC 909365265。 5. ホスキンス、ジャネット。『時間の遊び:カレンダー、歴史、交換に関するコディ族の視点』。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局、c1993 1993年。http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0x0n99tc/ p.312-314 6. 「民族戦争の背景にあるインドネシアの古い移住政策」. Globalpolicy.org. 2001年3月1日. 2010年5月25日取得. 7. Bartels, Dieter. 「政治家と魔術師:中部モルッカ諸島における権力、適応戦略、およびシンクレティズム」 (PDF). 2024年2月8日取得。 8. ファン・デル・クロエフ、ユストゥス・M. (1952). 「南ニューギニアのいくつかの狩頭習慣」. American Anthropologist. 54 (2): 221–235. doi:10.1525/aa.1952.54.2.02a00060. JSTOR 663912. 9. 「狩猟採集民 – ニューギニア」. Climatechange.umaine.edu. 2012年8月1日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2010年5月25日閲覧. 10. ローレンス・ゴールドマン (1999).『人食いの民族学』. p.19. 11. ネバーマン 1957, p. 9. 12. ネバーマン 1957, p. 111. 13 ネバーマン 1957, 帯文. 14. ネバーマン 1957, p. 13. 15. 「首狩り族がパプア部族を樹上住居へ追いやった」. Sciencedaily.com. 1998年3月9日. 2010年5月25日閲覧. 16. ジャック・ロンドン (1911). 『スナーク号の航海』. ハーバード大学 2006年1月19日デジタル化. 17. 「天候不良でトイモコの返還が遅れる」TNVZ(国民ニュース) 18. ウースター、ディーン・C.(1906年10月)。「北ルソン島の非キリスト教部族」。『フィリピン科学ジャーナル』1巻8号:791–875頁。 19. コベル、ラルフ・R.(1998年)。『台湾の丘のペンテコステ:原住民におけるキリスト教信仰』(図版付版)。ホープ出版社。96–97頁。ISBN 0932727905。2014年12月10日閲覧。 20. 邱新輝(2008)。『オランダ統治下の台湾における「文明化プロセス」:1624-1662年』。アジア・ヨーロッパ交流史に関するTANAPモノグラ フ第10巻(図版付)。ブリル社。222頁。ISBN 978-9004165076。2014年12月10日取得。 21. Maritime Taiwan. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765641892. 22. Davidson, James Wheeler (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. Macmillan & Company. 23. 「ミャンマーの『ワ族』の首狩りの時代は終わった」. ロイター. 2007年9月10日。2018年5月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年7月5日取得。 24. トム・オニール、「侍:日本の武士の道」、ナショナルジオグラフィック誌。 25. 「狩人(人類学)」。ブリタニカ国際大百科事典。 26. クリス・クルデッリ(2008年10月1日)。『戦士の道』。ドーリング・キンダースリー社。23ページ。ISBN 978-1405330954。 27. B. ラルタンリアナ(2005)。『ミゾラムの文化と民俗』。インド:情報放送省出版局。ISBN 978-81-230-1309-1。2025年2月12日取得。 28. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 285. 29. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 286. 30. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 287. 31. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 288. 32. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 289. 33. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 290. 34. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 291. 35. Lalthangliana 2005, p. 292. 36 Lalthangliana 2005, p. 294. 37. 「傭兵たち」, TIME Asia 38. Hsu, Elisabeth; Harris, Stephen (2012年5月15日). 『植物、健康、そして癒し』. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9780857456342。 39. 「メキシコの人骨の塔がアステカ文明に新たな光を当てる」。ロイター通信。2017年7月1日。 40. Spencer 1982, pp. 236–239. 41. Ortíz de Montellano 1983. 42. Miller & Taube 1993, p. 176. 43. 「身体の文脈:初期ナスカの斬首埋葬の解釈」DeLeonardis, Lisa. 『ラテンアメリカ古代』2000年. 第11巻第4号, pp. 363–368. 44. 「ペルー・セロ・カラポ出土 48体のナスカ戦利首の貯蔵庫」デイヴィッド・ブラウン、ヘレイン・シルバーマン、ルーベン・ガルシア共著、『ラテンアメリカ古代史』1993年、第4巻 第3号: 274–294頁 45. 例えばディオドロス・シクルス『歴史叢書』5巻2章を参照せよ 46. 「首狩り族のための情報」 www.lard.net. 47. 「イングランドの聖エドマンド、聖ケネルム、聖オシース、聖シドウェル、フランスの聖デニス、ケルト地域の聖メロルと聖ウィニフレッドの物語は、伝説と民 俗伝承の結びつきを強化し、そのパターンを保存している」とベアトリス・ホワイトは指摘する。(ホワイト 1972, p. 123)。 48. 「eHRAF World Cultures」。eHRAF World Cultures。2025年1月22日。2025年1月22日閲覧。 49. 「モンテネグロ」。The Princeton Encyclopedia of Self-Determination。2006年5月21日。2025年1月22日閲覧。 50. エディス・ダーラム, M. (2004年12月24日). 『アルバニアとアルバニア人』. ブルームズベリー・アカデミック. ISBN 9781850439394. 51. ヨナ・レンデリング. 「ヘロドトス『歴史』第4巻の要約と解説」. Livius.org. 2010年5月25日閲覧. 52. フッセル 1990, p. 117. 53. ハリソン 2006, p. 817ff. 54. ワインガートナー 1992, p. 67. 55. 「『客人』は占領者が失敗するところで成功できる」『インターナショナル・ヘラルド・トリビューン』2007年11月9日 56. ハリソン、サイモン(2012)。『暗い戦利品:近代戦争における狩猟と敵の身体』。オックスフォード:ベルハーン。158頁。ISBN 978-1-78238-520-2。 57. ハック 2022, p. 318. 58. 原藤雄(2002年12月)。『マレーシア華人と中国:アイデンティティ意識の転換、1945–1957年』。ハワイ大学出版局。61–65頁。 59. マーク・カーティス(1995年8月15日)。『権力の曖昧さ:1945年以降の英国外交政策』。61–71頁。 60. Hack 2022, p. 316. 61. Hack 2022, p. 315. 62. Peng, Chin; Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. Singapore: Media Masters. p. 302. ISBN 981-04-8693-6. 63. Hack 2022, p. 317. 64. McKinley, Robert (September 2015). 「Human and proud of it!: A structural treatment of headhunting rites and the social definition of enemies」. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 5 (2): 443–483. doi:10.14318/hau5.2.031. ISSN 2575-1433. 65. MIGULSKI, BOGDAN (2024年12月9日). 「歴史と芸術における首狩りの恐ろしい伝統」. 2025年5月13日取得. 66. ミシェル・ブールスタイン(2007年7月3日)。「ベトナム戦争の不気味な戦利品」。ワシントンポスト・ドットコム。2010年6月26日取得。 67. 「時代の兆し – トロフィー頭蓋骨」. George.loper.org. 1996年8月8日. 2009年10月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2010年5月25日に取得. |

| Sources Davidson, James Wheeler (1903). The Island of Formosa: Past and Present: History, People, Resources, and Commercial Crospects. Tea, Camphor, Sugar, Gold, Coal, Sulphur, Economical Plants, and other Productions. London and New York: Macmillan & Co. Davidson, James Wheeler (1903). The Island of Formosa: Historical View From 1430 to 1900. Fussell, Paul (1990). Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199840359. George, Kenneth (1996). Showing Signs of Violence: The Cultural Politics of a Twentieth-Century Headhunting Ritual. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20041-1. Hack, Karl (2022). The Malayan Emergency: Revolution and Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Harrison, Simon (2006). "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: Transgressive Objects of remembrance". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 12 (4): 817–836. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2006.00365.x. Miller, Mary; Taube, Karl (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317. Nevermann, Hans (1957). Söhne des tötenden Vaters. Dämonen- und Kopfjägergeschichten aus Neu-Guinea [Sons of the killing father. Stories about demons and headhunting, recorded in New Guinea]. Das Gesicht der Völker (in German). Vol. 23. Eisenach • Kassel: Erich Röth-Verlag. Ortíz de Montellano, Bernard R. (1983). "Counting Skulls: Comment on the Aztec Cannibalism Theory of Harner-Harris". American Anthropologist. 85 (2): 403–406. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130. Rubenstein, Steven L. (2006). "Circulation, Accumulation, and the Power of Shuar Shrunken Heads". Cultural Anthropology. 22 (3): 357–399. doi:10.1525/can.2007.22.3.357. Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2009). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0765623287. Spencer, C. S. (1982). The Cuicatlán Cañada and Monte Albán: A Study of Primary State Formation. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-656680-2. Weingartner, James J. (1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3640788. White, Beatrice (Summer 1972). "A Persistent Paradox". Folklore. 83 (2): 122–131. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1972.9716461. PMID 11614481. Yamada, Hitoshi (2015). Religionsethnologie der Kopfjagd (in Japanese). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo. ISBN 978-4480843050. |

出典 デイヴィッドソン、ジェームズ・ウィーラー(1903年)。『台湾島:過去と現在―歴史、人民、資源、商業展望。茶、樟脳、砂糖、金、石炭、硫黄、経済植 物、その他の産物』。ロンドン及びニューヨーク:マクミラン社。 デイヴィッドソン、ジェームズ・ウィーラー(1903年)。『台湾島:1430年から1900年までの歴史的展望』。 ファッセル、ポール(1990年)。『戦時下:第二次世界大戦における理解と行動』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 9780199840359。 ジョージ、ケネス(1996)。『暴力の痕跡を示す:20世紀の首狩り儀礼の文化政治学』。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 0-520-20041-1。 ハック、カール(2022)。『マラヤ非常事態:帝国の終焉における革命と反乱鎮圧』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ハリソン、サイモン(2006)。「太平洋戦争の頭蓋骨戦利品:記憶の越境的対象」。王立人類学協会誌。12巻4号:817–836頁。doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2006.00365.x。 ミラー、メアリー;タウベ、カール(1993)。『古代メキシコとマヤの神々と象徴:メソアメリカ宗教図解辞典』。ロンドン:テムズ・アンド・ハドソン。 ISBN 0-500-05068-6。OCLC 27667317。 ネヴァーマン、ハンス(1957)。『殺す父の子ら。ニューギニアにおける悪魔と首狩りの物語』[Söhne des tötenden Vaters. Dämonen- und Kopfjägergeschichten aus Neu-Guinea]。民族の顔(ドイツ語)。第23巻。アイゼナハ・カッセル:エーリッヒ・レート出版社。 オルティス・デ・モンテヤノ、バーナード・R. (1983). 「頭蓋骨を数える:ハーナー=ハリスによるアステカ人食理論へのコメント」. アメリカ人類学者. 85 (2): 403–406. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130. ルーベンスタイン、スティーブン・L.(2006)。「流通、蓄積、そしてシュアル族の縮み頭の力」。『文化人類学』。22巻3号:357–399頁。 doi:10.1525/can.2007.22.3.357。 ツァイ、シーシャン・ヘンリー(2009)。『海上の台湾:東西との歴史的遭遇』(図版付版)。M.E.シャープ。ISBN 978-0765623287。 スペンサー、C. S.(1982)。『クイカトラン・カニャダとモンテ・アルバン:原始国家形成の研究』。ニューヨーク: アカデミック・プレス。ISBN 978-0-12-656680-2。 ワインガートナー、ジェームズ・J. (1992). 「戦利品:米軍と日本戦没者の遺体損壊、1941–1945年」. 『太平洋歴史評論』. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788。ISSN 0030-8684。JSTOR 3640788。 ホワイト、ベアトリス(1972年夏)。「持続するパラドックス」。『フォークロア』83巻2号:122–131頁。doi: 10.1080/0015587X.1972.9716461. PMID 11614481. 山田仁 (2015). 『首狩りの宗教民族学』. 東京: 筑摩書房. ISBN 978-4480843050. |

| Further reading Head-Hunting Roman Cavalry - article about single combat and the taking of heads and scalps as trophies by Roman warriors Les Romains, chasseurs de têtes - paper by Jean-Louis Voisin about the Roman practice of head hunting Cornélis De Witt Willcox (1912). The head hunters of northern Luzon: from Ifugao to Kalinga, a ride through the mountains of northern Luzon : with an appendix on the independence of the Philippines. Vol. 31 of Philippine culture series. Franklin Hudson Publishing Co. ISBN 9781465502544. Retrieved April 24, 2014. |

さらに読む 首狩りを行うローマ騎兵 - ローマ戦士による一騎打ちと、戦利品としての首や頭皮の採取に関する記事 Les Romains, chasseurs de têtes - ジャン=ルイ・ヴォワザンによる、ローマ人の首狩りの慣習に関する論文 Cornélis De Witt Willcox (1912)。北ルソン島の狩人:イフガオからカリンガまで、北ルソン島の山々を旅して:フィリピン独立に関する付録付き。フィリピン文化シリーズ第 31 巻。フランクリン・ハドソン出版。ISBN 9781465502544。2014年4月24日取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headhunting |

★首狩の宗教民族学 / 山田仁史著, 筑摩書房 , 2015

「首 狩」とそれに関連する「首取」、「頭蓋崇拝」、「頭皮剥ぎ」、「人身供犠」のなぜ?首狩の精神的背景と意味を、フィールドワークと膨大な文献から解き明か す、世界初の研究書。

序 章 首狩と日本人(首狩の復活?;日本の首狩? ほか)

第 1章 生業と世界観—宗教民族学の見取図(宗教民族学とは;狩猟採集民の世界観 ほか)

第 2章 首狩・頭骨・カニバリズム—世界を視野に入れて(関連する諸習俗;首狩の研究史 ほか)

第 3章 東南アジアの首狩(“首狩文化複合”;近現代史における首狩 ほか)

第 4章 台湾原住民の首狩(台湾の原住民;探検の時代 ほか)

終

章 なぜ首を狩ったのか?—農耕・神話・シンボリズム(イェンゼンの学説;起源神話と世界像 ほか)

☆

☆

| 首狩りとは、人間の頭部を取り外し保存する慣

習である。首狩りは、あらゆる生命の根源となる物質的な魂の物質が存在するという信仰から、一部の文化で生まれた。人間の場合、この魂の物質は特に頭部に

存在すると考えられており、頭部を取り除くことでその内部の魂の物質を捕らえ、共同体に属する魂の物質の総量に加えることができると信じられている。これ

により、人間、家畜、作物の豊穣に寄与するとされる。したがって、首狩りは頭部を魂の座とする思想、犠牲者の魂の物質を食する者に移すための身体またはそ

の一部を摂取する形態の食人行為、そして土地に生産性を吹き込むことを目的とした男根崇拝や豊穣儀礼と関連付けられてきた。こうしてそれは人間生贄へと発

展しうる。この慣行は一般的に農業社会と結びつけられてきた。 首狩りは世界中で行われ、旧石器時代まで遡る可能性がある。バイエルン州オフネトで発見された後期旧石器時代のアジリアン文化の遺跡では、丁寧に首を切ら れた頭部が胴体とは別に埋葬されており、頭部の特別な神聖性や重要性を信じる思想を示している。 ヨーロッパでは、この慣習は20世紀初頭までバルカン半島で存続した。そこでは首を取る行為は、斬首された者の魂の物質が斬首者に移ることを意味してい た。モンテネグロでは1912年まで完全な頭部が採取され、その目的のために着用されたとされる一房の髪に運ばれていた。イギリス諸島では、アイルランド とスコットランド国境地帯において、この慣習は中世の終わり頃まで続いた。 アフリカではナイジェリアで首狩りが知られており、インドネシアと同様に、作物の豊穣、結婚、そして犠牲者が来世で僕として奉仕する義務と結びついてい た。 アフガニスタン東部のクフィリストン(現ヌルスタン)では、19世紀末まで首狩りが行われていた。インド北東部ではアッサムが首狩りで有名であり、ブラフ マプトラ川以南に住むガロ族、カシ族、ナガ族、クキ族など全ての民族がかつて首狩りを行っていた。アッサムにおける首狩りは通常、奇襲戦術に依存する襲撃 者集団によって行われた。 ミャンマー(ビルマ)では複数の集団が、インドの首狩り部族と同様の慣習に従っていた。ワ人民は明確な首狩り季節を設けており、成長中の作物に肥沃な魂の 物質が必要とされる時期には、旅人は危険を冒して移動しなければならなかった。ボルネオ、インドネシアの大部分、フィリピン、台湾でも同様の首狩り方法が 実践されていた。この慣習は1577年にマルティン・デ・ラダによってフィリピンで報告され、ルソン島のイゴロット人々やカリンガ人々によって正式に放棄 されたのは20世紀初頭になってからである。インドネシアでは、アルフル族が狩頭を行っていたセレム島を経て、モトゥ族が狩頭を行っていたニューギニアま で広がっていた。インドネシアのいくつかの地域、例えばバタク地方やタニムバル諸島では、狩頭は人食いに取って代わられたようだ。 オセアニア全域で狩頭は人食いに覆い隠される傾向があったが、多くの島々では頭部への重要性が明白だった。ミクロネシアの一部では、殺害した敵の首を踊り ながら見せびらかすことがあった。これは首長が公共支出を賄うための資金調達を正当化する口実となった。後に同じ目的で首を他の首長に貸し出すこともあっ た。メラネシアでは、死者の魂を宿すため、首はしばしばミイラ化され、時には仮面として着用された。同様に、オーストラリア先住民は殺害した敵の魂が殺害 者に宿ると信じていたと伝えられる。ニュージーランドでは敵の頭部を乾燥保存し、刺青や顔の特徴が判別できるようにした。この慣習が頭狩りの発展につなが り、刺青のある頭部が珍品として求められるようになると、ヨーロッパでのマオリ族の戦利品需要により「漬物状態の頭部」が船積み目録の常連品となった。 南アメリカでは、ジャボ族のように頭蓋骨を取り除き、皮膚を熱い砂で詰めて保存することが多かった。これにより皮膚は小型の猿の頭ほどの大きさに縮むが、 顔の特徴はそのまま保たれた。ここでも、首狩りは儀式的な形態の食人行為と結びついていた可能性が高い。 首狩り行為が禁止されたにもかかわらず、そのような慣行に関する散発的な報告は20世紀半ばまで続いた。 |

|

| 1996 Encyclopaedia Britannica,

Inc、からの翻訳 |

|

| A shrunken head

is a severed and specially-prepared human head with the skull removed –

many times smaller than its original size – that is used for trophy,

ritual, trade, or other purposes. Headhunting is believed to have occurred in many regions of the world since time immemorial, but the practice of head shrinking has only been documented in the northwestern region of the Amazon rainforest.[1] Jivaroan peoples, which includes the Shuar, Achuar, Huambisa and Aguaruna tribes from Ecuador and Peru, are known to keep shrunken human heads.[citation needed] While many were probably made from the remains of these peoples, the Shuar people are the only culture in the world that practiced ritualistic head shrinking.[2] Shuar people call a shrunken head a tsantsa,[3] also transliterated tzantza. Many tribe leaders would display their heads to scare enemies. Shrunken heads are known for their mandibular prognathism, facial distortion, and shrinkage of the lateral sides of the forehead; these are artifacts of the shrinking process. Among the Shuar, the reduction of the heads was followed by a series of feasts centered on important rituals.[citation needed]  Shrunken heads in the permanent collection of Ye Olde Curiosity Shop, Seattle |

縮んだ頭(干し首)とは、切り取られ特別に加工された人間の頭部で、頭

蓋骨が除去され元のサイズの何分の一かに縮小されたものである。戦利品、儀礼、交易、その他の目的で使用される。 狩猟は太古の昔から世界の多くの地域で行われてきたと考えられているが、頭部縮小の慣習が記録されているのはアマゾン熱帯雨林の北西部地域のみである。エ クアドルとペルーに居住するシュアル族、アチュアル族、ワンビサ族、アグアルナ族を含むヒバロ族は、縮んだ人間の頭部を保管することで知られている。[出 典が必要] 多くの頭部はこれらの民族の遺体から作られたものと思われるが、儀式的な頭部縮小を行った文化はシュアル族が世界で唯一である。[2] シュアル人民は縮んだ頭部をツァンツァと呼ぶ[3]。多くの部族長は敵を威嚇するため、捕虜の頭部を展示した。 縮んだ頭部は、下顎前突、顔面変形、額の外側部分の収縮といった特徴で知られる。これらは頭部縮小過程で生じる変形である。シュアル族の間では、頭部の縮 小後、重要な儀礼を中心とした一連の祝宴が行われた。[出典が必要]  シアトルの「古き好奇心商店」の常設展示品にある縮んだ頭部 |

Technique Shrunken head from the Shuar people, on display in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. The process of creating a shrunken head begins with removing the skull from the neck. An incision is made on the back of the ear and all the skin and flesh is removed from the cranium. Red seeds are placed underneath the nostrils and the lips are sewn shut. The mouth is held together with three palm pins. Fat from the flesh of the head is removed. Then a wooden ball is placed under the flesh to keep the form. The flesh is then boiled in water that has been saturated with a number of herbs containing tannins. The head is then dried with hot rocks and sand while molding it to retain its human features. The skin is then rubbed with charcoal ash. Decorative beads may be added to the head.[4] In the head shrinking tradition, it is believed that coating the skin in ash keeps the muisak, or avenging soul, from seeping out. |

技法 シュアル人民の縮み頭。オックスフォードのピット・リバース博物館に展示されている。 縮み頭の製作過程は、まず首から頭蓋骨を取り除くことから始まる。耳の後ろに切開を入れ、頭蓋骨から皮膚と肉を全て除去する。赤い種子を鼻孔の下に置き、 唇を縫い閉じる。口は三本のヤシの針で固定する。頭の肉から脂肪を取り除く。次に肉の下に木製の球体を置き、形を保たせる。その後、タンニンを含む複数の 薬草で煮出した湯で肉を煮る。熱した石と砂で乾燥させながら形を整え、人間の特徴を保つ。最後に皮膚を木炭の灰で擦り込む。装飾用のビーズを頭部に加える 場合もある。[4] 頭部縮小の伝統では、皮膚を灰で覆うことで「ムイサック」(復讐の魂)が漏れ出ないよう防ぐと考えられている。 |

Significance Shrunken head exhibited at the Lightner Museum in St. Augustine, Florida. The practice of preparing shrunken heads originally had religious significance; shrinking the head of an enemy was believed to harness the spirit of that enemy and compel him to serve the shrinker. It was said to prevent the soul from avenging his death.[5] Shuar believed in the existence of three fundamental spirits: Wakani – innate to humans thus surviving their death. Arutam – literally "vision" or "power", protects humans from a violent death. Muisak – vengeful spirit, which surfaces when a person carrying an Arutam spirit is murdered. To block a Muisak spirit from using its powers, they severed their enemies' heads and shrank them. The process also served as a way of warning their enemies. Despite these precautions, the owner of the trophy did not keep it for long. Many heads were later used in religious ceremonies and feasts that celebrated the victories of the tribe. Accounts vary as to whether the heads were discarded or stored.[citation needed] |

重要性 フロリダ州セントオーガスティンのライトナー博物館に展示されている縮み頭。 縮み頭の作成は元々宗教的な意味を持っていた。敵の頭を縮めることでその敵の魂を支配し、縮めた者に従わせると信じられていた。これにより魂が死の復讐を 企てるのを防ぐと言われている。[5] シュアル族は三つの根本的な精霊の存在を信じていた: ワカニ – 人間に生まれつき宿るため、死後も存続する。 アルタム – 文字通り「視力」または「力」を意味し、人間を暴力的な死から守る。 ムイサック – 復讐の精霊であり、アルタム精霊を持つ者が殺害された時に現れる。 ムイサクの力を封じるため、彼らは敵の首を切り落とし、それを縮めた。この行為は敵への警告でもあった。しかし、戦利品の所有者は長く保持しなかった。多 くの頭部は後に、部族の勝利を祝う宗教儀式や祝宴で使用された。頭部が廃棄されたか保管されたかについては、諸説ある。[出典が必要] |

| Trade When Westerner curio collectors created an economic incentive for shrunken heads, there was a sharp increase in the rate of killings in an effort to supply tourists and collectors of ethnographic items.[6][7] The terms 'headhunting' and 'headhunting parties' come from this practice. Guns were usually what the Shuar acquired in exchange for their shrunken heads, the rate being one gun per head.[citation needed] But weapons were not the only items exchanged. Around 1910, shrunken heads were being sold by a curio shop in Lima for one Peruvian gold pound, equal in value to a British gold sovereign (equivalent to $129 in 2023).[8] By 1919, the price in Panama's curio shop for shrunken heads had risen to £5.[8] By the 1930s, when heads were freely exchanged, a shrunken head could be purchased for about 25 U.S. dollars. This was stopped when the Peruvian and Ecuadorian governments cooperated to outlaw head trafficking.[citation needed] Also encouraged by this trade, people in Colombia and Panama unconnected to the Jívaros began to make counterfeit tsantsas. They used corpses from morgues, or the heads of monkeys or sloths. Some used goatskin. Kate Duncan wrote in 2001, "It has been estimated that about 80 percent of the tsantsas in private and museum hands are fraudulent", including almost all that are female or include an entire torso rather than just a head.[5] Thor Heyerdahl recounts in The Kon-Tiki Expedition (1948) the various problems of getting into the Jívaro (Shuar) area in Ecuador to get balsa wood for his expedition raft. Local people would not guide his team into the jungle for fear of being killed and having their heads shrunk. In 1951 and 1952 sales of such items in London were being advertised in The Times; one example was priced at $250, a hundredfold appreciation since the early 20th century.[8] In 1999, the National Museum of the American Indian repatriated the authentic shrunken heads in its collection to Ecuador.[5] Most other countries have also banned the trade. Currently, replica shrunken heads are manufactured as curios for the tourist trade. These are made from leather and animal hides formed to resemble the originals.[citation needed] In 2019 Mercer University repatriated a shrunken head from its collections, crediting the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act as inspiration.[9] In 2020, the Pitt Rivers Museum of Oxford University removed its collection of shrunken heads after an ethical review begun in 2017, as part of an effort to decolonize its collections and avoid stereotyping.[10] |

交易 西洋の骨董品収集家が縮頭(シュルンケン・ヘッド)に経済的価値を見出した時、観光客や民族誌的品々の収集家への供給を目的とした殺害率が急激に上昇し た。[6][7] 「狩頭(ヘッドハンティング)」や「狩頭隊(ヘッドハンティング・パーティ)」という用語はこの慣習に由来する。 シュアル族が縮頭と交換に得るものは通常銃であり、その交換比率は頭一つにつき銃一丁であった。[出典必要] しかし交換品は武器だけではない。1910年頃、リマの骨董品店では縮み頭がペルー金ポンド1枚(英国金ソブリンと同価値、2023年換算で約129ド ル)で販売されていた。[8] 1919年までにパナマの骨董品店では縮み頭の価格が5ポンドまで上昇した。[8] 1930年代には頭蓋骨が自由に取引されるようになり、縮み頭は約25米ドルで購入可能となった。この取引はペルーとエクアドル政府が協力して頭蓋骨取引 を非合法化したことで終焉を迎えた。[出典必要] この取引に刺激され、ジバロ族と無関係なコロンビアやパナマの人々も偽物のツァンツァ製作を始めた。彼らは死体安置所の遺体や、サルやナマケモノの頭部を 使用した。ヤギの皮を使う者もいた。ケイト・ダンカンは2001年に「個人や博物館が所有するツァンツァの約80%が偽物と推定されている」と記してい る。これには女性の頭部や、頭部だけではなく胴体全体を含むもののほとんどが含まれる。[5] トール・ヘイエルダールは『コン・ティキ号航海記』(1948年)で、エクアドルのヒバロ(シュアル)地域に入り、遠征用筏の材料となるバルサ材を入手す る際に直面した様々な困難を記している。現地の人々は、殺されて頭部を縮められてしまうことを恐れて、彼のチームをジャングルへ案内しようとしなかった。 1951年と1952年には、ロンドンでのこうした品々の販売がタイムズ紙で広告されていた。一例は250ドルで、20世紀初頭から百倍の値上がりだっ た。[8] 1999年、アメリカン・インディアン国立博物館は所蔵していた本物の縮み頭をエクアドルに返還した。[5] 他のほとんどの国も取引を禁止している。現在、観光土産としてレプリカの縮頭が製造されている。これらは革や動物の皮を加工し、原本に似せて作られてい る。[出典必要] 2019年にはマーサー大学が所蔵していた縮頭を返還し、その背景には「先住民墓地保護・返還法」の影響があったと述べている。[9] 2020年には、オックスフォード大学ピット・リバース博物館が、2017年に開始した倫理的見直しを経て、収蔵品の植民地主義的要素の除去と固定観念の 回避の一環として、収蔵していた縮頭部を撤去した。[10] |

In popular culture Shrunken head in the Knight Bus, The Wizarding World of Harry Potter In the novel Moby-Dick, the character Queequeg sells shrunken heads and gives his last as a gift to the narrator, Ishmael, who subsequently sells it himself. In the 1949 children's novel Amazon Adventure by Willard Price, the character John Hunt buys a shrunken head for the American Museum of Natural History from a Jivaro chief, who explains the shrinking process. The scene mirrors Price's own experience with the Jivaro, described in his 1948 travel book Roving South. In 1955, Disneyland opened its Jungle Cruise ride. Until 2021, the attraction featured a trader selling shrunken heads (three of his for one of yours).[11][12] In 1975, Whiting (a Milton Bradley company) released Vincent Price's Shrunken Head Apple Sculpture Kit.[13] In the 1946 movie The Devil's Mask, a crashed plane with a shrunken head aboard is the only clue to a mystery involving a secret code. The 1979 movie Wise Blood (film), a shrunken head from Mercer University is stolen from a museum and used as a "new Jesus" that "don't look like any other man so you'll look at it." The 1988 movie Beetlejuice featured a ghost of a hunter whose head had been shrunken. At the end of the movie, the title character suffers the same fate. The film's 2024 sequel, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, features the return of the hunter with the shrunken head, named Bob, alongside many other ghosts with shrunken heads now employed at Betelgeuse's personal call centre. One of the North American television commercials for the 1990 video game Dr. Mario featured head shrinking, as well as a cover of the song Witch Doctor with slightly different lyrics.[14] The Goosebumps book, How I Got My Shrunken Head, released in 1996, is about a boy who gets a shrunken head from his aunt that gives him jungle powers. In the 2004 film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Lenny Henry voices Dre Head, a Jamaican accented shrunken head on the magical Knight Bus. The same film features three more shrunken heads, voiced by Brian Bowles and Peter Serafinowicz, inside the wizard pub The Three Broomsticks.[15] Both Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (2006) and Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End (2007) feature shrunken heads.[16] |

大衆文化における縮み頭 ハリー・ポッターの魔法の世界にあるナイトバス内の縮み頭 小説『白鯨』では、登場人物クイークェグが縮み頭を売り、最後の1つを語り手イシュマエルに贈る。イシュマエルはその後、その縮み頭を自ら売り払う。 1949年の児童小説『アマゾン冒険記』(ウィラード・プライス著)では、主人公ジョン・ハントがアメリカ自然史博物館のためにヒバロ族の首長から縮んだ 頭を購入する。首長は縮小の工程を説明する。この場面はプライス自身のヒバロ族との体験を反映しており、1948年の旅行記『南へ彷徨う』で記述されてい る。 1955年、ディズニーランドはジャングルクルーズのアトラクションを開設した。2021年まで、このアトラクションでは、縮んだ頭(3つで1つと交換) を販売する商人が登場していた。 1975年、Whiting(Milton Bradley社)は、Vincent Priceの縮んだ頭リンゴ彫刻キットを発売した。 1946年の映画『悪魔の仮面』では、縮小頭が搭載された墜落機が、秘密の暗号に関する謎の唯一の手がかりとなっている。 1979年の映画『賢者の血』では、マーサー大学の縮小頭が博物館から盗まれ、「他の誰とも似ていない、だから見ずにはいられない」という「新しいイエ ス」として使われる。 1988年の映画『ビートルジュース』では、頭部を縮められた狩人の幽霊が登場する。映画の終盤で、タイトルキャラクターは苦悩する運命を辿る。2024 年の続編『ビートルジュース ビートルジュース』では、縮められた頭を持つ狩人ボブが再登場し、ベテルギウスの個人コールセンターに雇われた他の多くの縮頭幽霊たちと共に描かれる。 1990年のビデオゲーム『ドクターマリオ』の北米向けテレビCMの一つでは、頭部縮小の演出が用いられ、曲『ウィッチ・ドクター』のカバーが若干異なる 歌詞で流れた。[14] 1996年刊行の『グースバンプス』シリーズ『縮んだ頭を手に入れた話』は、叔母から縮んだ頭を受け取りジャングルの力を得る少年の物語だ。 2004年映画『ハリー・ポッターとアズカバンの囚人』では、レニー・ヘンリーが呪術的なナイトバスに乗るジャマイカ訛りの縮んだ頭「ドレ・ヘッド」の声 を担当している。同じ映画では、魔法使いの酒場「三本の箒」の中に、ブライアン・ボウルズとピーター・セラフィノウィッツが声を担当するさらに三つの縮ん だ頭が登場する。[15]『パイレーツ・オブ・カリビアン/デッドマンズ・チェスト』(2006年)と『パイレーツ・オブ・カリビアン/ワールド・エン ド』(2007年)の両方にも縮んだ頭が登場する。[16] |

| Mokomokai, preserved

Māori heads also used as trade goods |

|

| 1. "National Geographic:

Images of Animals, Nature, and Cultures". nationalgeographic.com.