ループ量子重力論の歴史

ループ量子重力論の歴史

☆History of loop quantum gravity(ループ量子重力論の歴史)

| Loop quantum

gravity (LQG) is a theory of quantum gravity that incorporates

matter of the Standard Model into the framework established for the

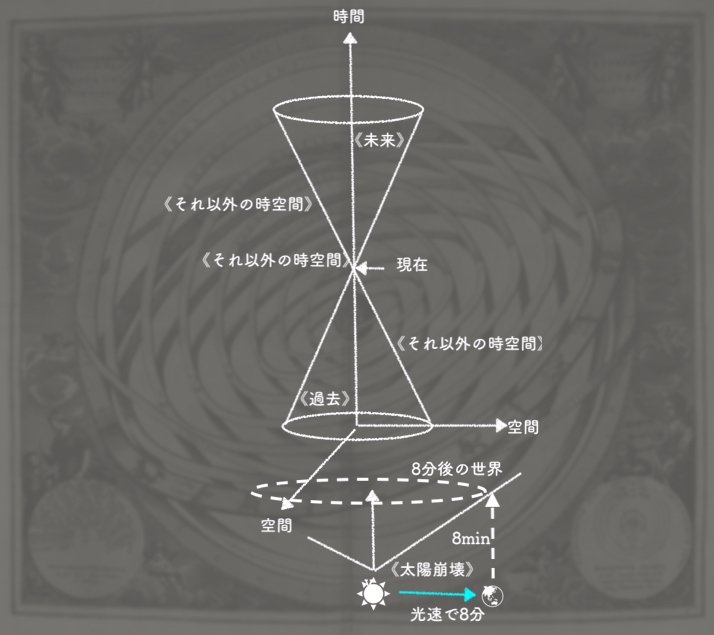

intrinsic quantum gravity case. It is an attempt to develop a quantum theory of gravity based directly on Albert Einstein's geometric formulation, general relativity. As a theory, LQG postulates that the structure of space and time is composed of finite loops woven into an extremely fine fabric or network. These networks of loops are called spin networks. The evolution of a spin network, or spin foam, has a scale on the order of a Planck length, approximately 10−35 meters, and smaller scales are meaningless. Consequently, not just matter, but space itself, prefers an atomic structure. The areas of research, which involve about 30 research groups worldwide,[1] share the basic physical assumptions and the mathematical description of quantum space. Research has evolved in two directions: the more traditional canonical loop quantum gravity, and the newer covariant loop quantum gravity, called spin foam theory. The most well-developed theory that has been advanced as a direct result of loop quantum gravity is called loop quantum cosmology (LQC). LQC advances the study of the early universe, incorporating the concept of the Big Bang into the broader theory of the Big Bounce, which envisions the Big Bang as the beginning of a period of expansion, that follows a period of contraction, which has been described as the Big Crunch. |

ループ量子重力理論(LQG)は、標準模型の物質を、本質的な量子重力

の場合のために確立された枠組みに組み込んだ量子重力理論である。 これは、アルバート・アインシュタインの幾何学的定式化である一般相対性理論に直接基づいて、量子重力理論を発展させようとする試みである。理論として、 LQGは時空の構造が極めて微細な織物やネットワークに織り込まれた有限ループで構成されていると仮定する。これらのループのネットワークはスピンネット ワークと呼ばれる。スピンネットワーク、すなわちスピンフォームの進化はプランク長(約10−35メートル)のオーダーのスケールを持ち、それより小さい スケールは無意味である。結果として、物質だけでなく空間そのものが原子構造を好む。 世界中の約30の研究グループが関わるこの研究分野は、基本的な物理的前提と量子空間の数学的記述を共有している。研究は二方向に進展した:より伝統的な 標準ループ量子重力理論と、新しい共変ループ量子重力理論(スピンフォーム理論と呼ばれる)。ループ量子重力の直接的な成果として最も発展した理論は、 ループ量子宇宙論(LQC)と呼ばれる。LQCは初期宇宙の研究を推進し、ビッグバン概念をビッグバウンス理論というより広範な枠組みに組み込む。この理 論では、ビッグバンは収縮期(ビッグクランチ)に続く膨張期の始まりと位置づけられる。 |

| History Main article: History of loop quantum gravity In 1986, Abhay Ashtekar reformulated Einstein's general relativity in a language closer to that of the rest of fundamental physics, specifically Yang–Mills theory.[2] Shortly after, Ted Jacobson and Lee Smolin realized that the formal equation of quantum gravity, called the Wheeler–DeWitt equation, admitted solutions labelled by loops when rewritten in the new Ashtekar variables. Carlo Rovelli and Smolin defined a nonperturbative and background-independent quantum theory of gravity in terms of these loop solutions. Jorge Pullin and Jerzy Lewandowski understood that the intersections of the loops are essential for the consistency of the theory, and the theory should be formulated in terms of intersecting loops, or graphs. In 1994, Rovelli and Smolin showed that the quantum operators of the theory associated to area and volume have a discrete spectrum.[3] That is, geometry is quantized. This result defines an explicit basis of states of quantum geometry, which turned out to be labelled by Roger Penrose's spin networks, which are graphs labelled by spins. The canonical version of the dynamics was established by Thomas Thiemann, who defined an anomaly-free Hamiltonian operator and showed the existence of a mathematically consistent background-independent theory. The covariant, or "spin foam", version of the dynamics was developed jointly over several decades by research groups in France, Canada, UK, Poland, and Germany. It was completed in 2008, leading to the definition of a family of transition amplitudes, which in the classical limit can be shown to be related to a family of truncations of general relativity.[4] The finiteness of these amplitudes was proven in 2011.[5][6] It requires the existence of a positive cosmological constant, which is consistent with observed acceleration in the expansion of the Universe. |

歴史 主な記事:ループ量子重力理論の歴史 1986年、アベイ・アシュテカーは、アインシュタインの一般相対性理論を、他の基礎物理学、特にヤン・ミルズ理論の言語に近い形で再定式化した[2]。 その直後、テッド・ジェイコブソンとリー・スモーリンは、ウィーラー・デウィット方程式と呼ばれる量子重力の形式的な方程式が、新しいアシュテカー変数で 書き直すと、ループでラベル付けされた解を認めることに気づいた。カルロ・ロヴェッリとスモーリンは、これらのループ解を用いて、非摂動的で背景に依存し ない量子重力理論を定義した。ホルヘ・プリンとイェジ・レヴァンドフスキは、ループの交点が理論の一貫性にとって不可欠であり、理論は交差するループ、す なわちグラフを用いて定式化されるべきであると理解した。 1994年、ロヴェッリとスモーリンは、面積と体積に関連する理論の量子演算子が離散的なスペクトルを持つことを示した[3]。つまり、幾何学は量子化さ れる。この結果は、量子幾何学の状態の明確な基礎を定義するものであり、それはロジャー・ペンローズのスピンネットワーク、すなわちスピンでラベル付けさ れたグラフによってラベル付けされることが判明した。 この力学の標準的なバージョンは、トーマス・ティーマンによって確立された。彼は、異常のないハミルトン演算子を定義し、数学的に一貫した背景独立の理論 の存在を示した。この力学の共変的な、あるいは「スピンフォーム」のバージョンは、フランス、カナダ、イギリス、ポーランド、ドイツの研究グループによっ て数十年にわたって共同で開発された。これは 2008 年に完成し、遷移振幅の族の定義につながった。これは、古典的な限界では、一般相対性理論の切り捨ての族に関連していることが示される。[4] これらの振幅の有限性は 2011 年に証明された。[5][6] これは、宇宙の膨張における観測された加速と一致する、正の宇宙定数の存在を必要とする。 |

| Background independence LQG is formally background independent, meaning the equations of LQG are not embedded in, or dependent on, space and time (except for its invariant topology). Instead, they are expected to give rise to space and time at distances which are 10 times the Planck length. The issue of background independence in LQG still has some unresolved subtleties. For example, some derivations require a fixed choice of the topology, while any consistent quantum theory of gravity should include topology change as a dynamical process.[citation needed] Spacetime as a "container" over which physics takes place has no objective physical meaning and instead the gravitational interaction is represented as just one of the fields forming the world. This is known as the relationalist interpretation of spacetime. In LQG this aspect of general relativity is taken seriously and this symmetry is preserved by requiring that the physical states remain invariant under the generators of diffeomorphisms. The interpretation of this condition is well understood for purely spatial diffeomorphisms. However, the understanding of diffeomorphisms involving time (the Hamiltonian constraint) is more subtle because it is related to dynamics and the so-called "problem of time" in general relativity.[7] A generally accepted calculational framework to account for this constraint has yet to be found.[8][9] A plausible candidate for the quantum Hamiltonian constraint is the operator introduced by Thiemann.[10] |

背景独立性 LQGは形式的に背景独立である。つまりLQGの方程式は、不変の位相を除き、時空に埋め込まれておらず、時空に依存しない。代わりに、それらはプランク 長度の10倍の距離において時空を生み出すと予想される。LQGにおける背景独立性の問題には、未解決の微妙な点が残っている。例えば、一部の導出ではト ポロジーの固定選択が必要となるが、一貫した量子重力理論はトポロジー変化を動的過程として包含すべきである。[出典必要] 物理現象が展開される「容器」としての時空は客観的物理的意味を持たず、代わりに重力相互作用は世界を構成する場の一つとして表現される。これは時空の関 係論的解釈として知られる。LQG では、一般相対性理論のこの側面が真剣に受け止められており、この対称性は、物理状態が微分同相変換の生成元の下で不変であるということを要求することに よって保たれている。この条件の解釈は、純粋に空間的な微分同相変換についてはよく理解されている。しかし、時間を含む微分同相変換(ハミルトニアン制 約)の理解は、一般相対性理論における力学およびいわゆる「時間の問題」に関連しているため、より微妙である。この制約を説明するための、一般に受け入れ られている計算の枠組みはまだ見出されていない。量子ハミルトニアン制約の有力な候補は、ティーマンが導入した演算子である。 |

| Citations 1. Rovelli 2008. 2. Ashtekar, Abhay (3 November 1986). "New Variables for Classical and Quantum Gravity". Physical Review Letters. 57 (18): 2244–2247. Bibcode:1986PhRvL..57.2244A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2244. PMID 10033673. 3. Rovelli, Carlo; Smolin, Lee (1995). "Discreteness of area and volume in quantum gravity". Nuclear Physics B. 442 (3): 593–619. arXiv:gr-qc/9411005. Bibcode:1995NuPhB.442..593R. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(95)00150-Q. 4. Rovelli 2011. 5. Muxin 2011, p. 064010. 6. Fairbairn & Meusburger 2011. 7. Kauffman & Smolin 1997. 8. Smolin 2006, pp. 196ff. 9. Rovelli 2004[2003?], pp. 13ff. 10. Thiemann 1996, pp. 257–264. |

引用文献 1. Rovelli 2008. 2. Ashtekar, Abhay (1986年11月3日). 「New Variables for Classical and Quantum Gravity」. Physical Review Letters. 57 (18): 2244–2247. Bibcode:1986PhRvL..57.2244A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2244. PMID 10033673. 3. ロヴェッリ, カルロ; スモーリン, リー (1995). 「量子重力における面積と体積の離散性」. 核物理学B. 442 (3): 593–619. arXiv:gr-qc/9411005. Bibcode:1995NuPhB.442..593R. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(95)00150-Q. 4. Rovelli 2011. 5. Muxin 2011, p. 064010. 6. フェアベーン&メウスバーガー 2011. 7. カウフマン&スモーリン 1997. 8. スモーリン 2006, pp. 196ff. 9. ロヴェッリ 2004, pp. 13ff. 10. ティーマン 1996, pp. 257–264. |

| Rovelli, Carlo (August 2008).

"Loop Quantum Gravity" (PDF). Living Reviews in Relativity. 11 (1) 5.

Bibcode:2008LRR....11....5R. doi:10.12942/lrr-2008-5. PMC 5256093. PMID

28179822 Rovelli, Carlo (2011). "Zakopane lectures on loop gravity". arXiv:1102.3660 [gr-qc]. Muxin, H. (2011). "Cosmological constant in loop quantum gravity vertex amplitude". Physical Review D. 84 (6) 064010. arXiv:1105.2212. Fairbairn, W. J.; Meusburger, C. (2011). "q-Deformation of Lorentzian spin foam models". arXiv:1112.2511 [gr-qc]. Kauffman, S.; Smolin, L. (7 April 1997). "A Possible Solution For The Problem Of Time In Quantum Cosmology". Edge.org. Smolin, Lee (2006). "The Case for Background Independence". In Rickles, D.; French, S.; Saatsi, J. T. (eds.). The Structural Foundations of Quantum Gravity. Clarendon Press. pp. 196ff. arXiv:hep-th/0507235. Bibcode:2005hep.th....7235S. ISBN 978-0-19-926969-3. Rovelli, Carlo (2003). "A Dialog on Quantum Gravity". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 12 (9): 1509–1528. arXiv:hep-th/0310077. Bibcode:2003IJMPD..12.1509R. doi:10.1142/S0218271803004304. S2CID 119406493. Thiemann, Thomas (1996). "Anomaly-free formulation of non-perturbative, four-dimensional Lorentzian quantum gravity". Physics Letters B. 380 (3–4): 257–264. arXiv:gr-qc/9606088. Bibcode:1996PhLB..380..257T. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(96)00532-1. S2CID 8691449. |

ロヴェッリ、カルロ(2008年8月)。「ループ量子重力理論」

(PDF)。Living Reviews in

Relativity。11巻1号、5頁。Bibcode:2008LRR....11....5R。doi:10.12942/lrr-2008-5。

PMC 5256093。PMID 28179822 ロヴェッリ、カルロ (2011). 「ループ重力に関するザコパネ講義」. arXiv:1102.3660 [gr-qc]. ムクシン、H. (2011). 「ループ量子重力頂点振幅における宇宙定数」. Physical Review D. 84 (6) 064010. arXiv:1105.2212. Fairbairn, W. J.; Meusburger, C. (2011). 「ローレンツスピンフォームモデルのq変形」. arXiv:1112.2511 [gr-qc]. カウフマン, S.; スモーリン, L. (1997年4月7日). 「量子宇宙論における時間問題の解決策の可能性」. Edge.org. スモーリン, リー (2006). 「背景独立性の主張」. リクルズ, D.; フレンチ, S.; サーツィ, J. T. (編). 『量子重力の構造的基礎』. クラレンドン・プレス. pp. 196ff. arXiv:hep-th/0507235. Bibcode:2005hep.th....7235S. ISBN 978-0-19-926969-3. ロヴェッリ、カルロ (2003). 「量子重力に関する対話」. 国際現代物理学ジャーナル D. 12 (9): 1509–1528. arXiv:hep-th/0310077. Bibcode:2003IJMPD..12.1509R. doi:10.1142/S0218271803004304. S2CID 119406493. ティーマン, トーマス (1996). 「非摂動的4次元ローレンツ量子重力の異常のない定式化」. 物理学レターB. 380 (3–4): 257–264. arXiv:gr-qc/9606088. Bibcode:1996PhLB..380..257T. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(96)00532-1. S2CID 8691449. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loop_quantum_gravity | |

| The history

of loop quantum gravity spans more than three decades of intense

research. |

ループ量子重力理論の歴史は、30年以上にわたる激しい研究の積み重ね

である。 |

| History Classical theories of gravitation General relativity is the theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915. According to it, the force of gravity is a manifestation of the local geometry of spacetime. Mathematically, the theory is modelled after Bernhard Riemann's metric geometry, but the Lorentz group of spacetime symmetries (an essential ingredient of Einstein's own theory of special relativity) replaces the group of rotational symmetries of space. (Later, loop quantum gravity inherited this geometric interpretation of gravity, and posits that a quantum theory of gravity is fundamentally a quantum theory of spacetime.) In the 1920s, the French mathematician Élie Cartan formulated Einstein's theory in the language of bundles and connections,[1] a generalization of Riemannian geometry to which Cartan made important contributions. The so-called Einstein–Cartan theory of gravity not only reformulated but also generalized general relativity, and allowed spacetimes with torsion as well as curvature. In Cartan's geometry of bundles, the concept of parallel transport is more fundamental than that of distance, the centerpiece of Riemannian geometry. A similar conceptual shift occurs between the invariant interval of Einstein's general relativity and the parallel transport of Einstein–Cartan theory. |

歴史 重力の古典理論 一般相対性理論は、1915年にアルバート・アインシュタインが発表した重力理論である。これによれば、重力は時空の局所的な幾何学的性質の現れである。 数学的には、この理論はベルンハルト・リーマンの計量幾何学をモデルとしているが、時空の回転対称性群(アインシュタイン自身の特殊相対性理論の重要な要 素)が空間の回転対称性群に取って代わっている。(後に、ループ量子重力は重力のこの幾何学的解釈を継承し、重力の量子理論は根本的に時空の量子理論であ ると提唱した。) 1920年代、フランスの数学者エリー・カルタンは、束と接続の言語を用いてアインシュタインの理論を定式化した[1]。これはリーマン幾何学の一般化で あり、カルタンはこれに重要な貢献をした。いわゆるアインシュタイン=カルタン重力理論は、一般相対性理論を再定式化しただけでなく一般化し、曲率だけで なくねじれを持つ時空を許容した。カルタンの束の幾何学において、平行移送の概念は距離の概念よりも根本的である。距離はリーマン幾何学の中心概念であっ た。同様の概念的転換が、アインシュタインの一般相対性理論における不変区間と、アインシュタイン=カルタン理論における平行移送との間でも生じている。 |

| Spin networks In 1971, physicist Roger Penrose explored the idea of space arising from a quantum combinatorial structure.[2][3] His investigations resulted in the development of spin networks. Because this was a quantum theory of the rotational group and not the Lorentz group, Penrose went on to develop twistors.[4] |

スピンネットワーク 1971年、物理学者ロジャー・ペンローズは空間が量子組合せ構造から生じるという考えを探求した[2][3]。彼の研究はスピンネットワークの構築へと つながった。これは回転群の量子理論であってローレンツ群の理論ではなかったため、ペンローズはその後ツイスター理論を発展させた[4]。 |

| Loop quantum gravity In 1982, Amitabha Sen tried to formulate a Hamiltonian formulation of general relativity based on spinorial variables, where these variables are the left and right spinorial component equivalents of Einstein–Cartan connection of general relativity.[5] Particularly, Sen discovered a new way to write down the two constraints of the ADM Hamiltonian formulation of general relativity in terms of these spinorial connections. In his form, the constraints are simply conditions that the spinorial Weyl curvature is trace free and symmetric. He also discovered the presence of new constraints which he suggested to be interpreted as the equivalent of Gauss constraint of Yang–Mills field theories. But Sen's work fell short of giving a full clear systematic theory and particularly failed to clearly discuss the conjugate momenta to the spinorial variables, its physical interpretation, and its relation to the metric (in his work he indicated this as some lambda variable). In 1986–87, physicist Abhay Ashtekar completed the project which Amitabha Sen began. He clearly identified the fundamental conjugate variables of spinorial gravity: The configuration variable is as a spinoral connection (a rule for parallel transport; technically, a connection) and the conjugate momentum variable is a coordinate frame (called a vierbein) at each point.[6][7] So these variable became what we know as Ashtekar variables, a particular flavor of Einstein–Cartan theory with a complex connection. General relativity theory expressed in this way, made possible to pursue quantization of it using well-known techniques from quantum gauge field theory. The quantization of gravity in the Ashtekar formulation was based on Wilson loops, a technique developed by Kenneth G. Wilson in 1974[8] to study the strong-interaction regime of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). It is interesting in this connection that Wilson loops were known to be ill-behaved in the case of standard quantum field theory on (flat) Minkowski space, and so did not provide a nonperturbative quantization of QCD. However, because the Ashtekar formulation was background-independent, it was possible to use Wilson loops as the basis for nonperturbative quantization of gravity. Due to efforts by Sen and Ashtekar, a setting in which the Wheeler–DeWitt equation was written in terms of a well-defined Hamiltonian operator on a well-defined Hilbert space was obtained. This led to the construction of the first known exact solution, the so-called Chern–Simons form or Kodama state. The physical interpretation of this state remains obscure. In 1988–90, Carlo Rovelli and Lee Smolin obtained an explicit basis of states of quantum geometry, which turned out to be labeled by Penrose's spin networks.[9][10] In this context, spin networks arose as a generalization of Wilson loops necessary to deal with mutually intersecting loops. Mathematically, spin networks are related to group representation theory and can be used to construct knot invariants such as the Jones polynomial. Loop quantum gravity (LQG) thus became related to topological quantum field theory and group representation theory. In 1994, Rovelli and Smolin showed that the quantum operators of the theory associated to area and volume have a discrete spectrum.[11] Work on the semi-classical limit, the continuum limit, and dynamics was intense after this, but progress was slower. On the semi-classical limit front, the goal is to obtain and study analogues of the harmonic oscillator coherent states (candidates are known as weave states). |

ループ量子重力 1982年、アミターバ・センは、スピン変数に基づく一般相対性理論のハミルトニアン定式化を試みた。このスピン変数は、一般相対性理論のアイシュタイ ン・カルタン結合の左右スピン成分に相当するものである[5]。特に、センは、一般相対性理論のADMハミルトニアン定式化の2つの制約を、これらのスピ ン結合を用いて記述する新しい方法を発見した。彼の形式では、制約は単にスピノリアル・ワイル曲率がトレースフリーで対称であるという条件である。また、 彼は、ヤン・ミルズ場理論のガウス制約と同等と解釈できる新しい制約の存在を発見した。しかし、センの研究は、完全で明確な体系的な理論を提示するには至 らず、特に、スピノリアル変数に対する共役運動量、その物理的解釈、およびメトリックとの関係について明確に論じることに失敗した(彼の研究では、これを あるラムダ変数として示していた)。 1986年から1987年にかけて、物理学者アビ・アシュテカルは、アミタブ・センが始めたプロジェクトを完成させた。彼は、スピノリアル重力の基本的な 共役変数を明確に特定した。構成変数はスピノリアル接続(平行輸送の規則、技術的には接続)であり、共役運動量変数は各点における座標系 (vierbein と呼ばれる)である。[6][7] したがって、これらの変数は、アシュテカー変数として知られるもの、つまり、複素接続を持つアインシュタイン・カルタン理論の特定の形態となった。このよ うに表現された一般相対性理論は、量子ゲージ場理論のよく知られた手法を用いてその量子化を追求することを可能にした。 アシュテカーの定式化における重力の量子化は、1974年にケネス・G・ウィルソンが量子色力学(QCD)の強相互作用領域を研究するために開発した手法 であるウィルソンループに基づいていた[8]。この点に関して興味深いのは、ウィルソンループは(平坦な)ミンコフスキー空間上の標準的な量子場理論の場 合、挙動が不安定であることが知られており、QCD の非摂動的量子化には利用できなかったことだ。しかし、アシュテカーの定式化は背景に依存しないため、ウィルソンループを重力の非摂動的量子化の基礎とし て利用することが可能であった。 センとアシュテカーの努力により、ウィーラー・デウィット方程式が、明確に定義されたヒルベルト空間上の明確に定義されたハミルトニアン演算子を用いて記 述される設定が得られた。これにより、最初の既知の正確な解、いわゆるチェルン・サイモンズ形式またはコダマ状態が構築された。この状態の物理的解釈は依 然として不明である。 1988年から1990年にかけて、カルロ・ロヴェッリとリー・スモーリンは、量子幾何学の状態の明示的な基底を得た。これは、ペンローズのスピンネット ワークによってラベル付けされることが判明した[9][10]。この文脈では、スピンネットワークは、相互に交差するループを扱うために必要なウィルソン ループの一般化として生じた。数学的には、スピンネットワークは群の表現論に関連しており、ジョーンズ多項式などの結び目不変量を構築するために使用する ことができる。こうして、ループ量子重力理論(LQG)は、位相的量子場理論および群の表現論に関連するものとなった。 1994年、ロヴェッリとスモーリンは、面積と体積に関連する理論の量子演算子が離散スペクトルを持つことを示した[11]。その後、半古典的限界、連続 限界、および力学に関する研究が活発に行われたが、その進展は遅かった。 半古典的限界の分野では、調和振動子のコヒーレント状態(候補はウィーブ状態として知られている)の類似体を取得し、研究することが目標である。 |

| Hamiltonian dynamics LQG was initially formulated as a quantization of the Hamiltonian ADM formalism, according to which the Einstein equations are a collection of constraints (Gauss, Diffeomorphism and Hamiltonian). The kinematics are encoded in the Gauss and Diffeomorphism constraints, whose solution is the space spanned by the spin network basis. The problem is to define the Hamiltonian constraint as a self-adjoint operator on the kinematical state space. The most promising work[according to whom?] in this direction is Thomas Thiemann's Phoenix Project.[12] |

ハミルトン力学 LQG は当初、ハミルトン ADM 形式の量子化として定式化された。これによれば、アインシュタイン方程式は一連の制約(ガウス、微分同相、ハミルトン)の集合である。運動学はガウス制約 と微分同相制約にコード化されており、その解はスピンネットワーク基底によって生成される空間である。問題は、運動学的状態空間上で自己共役演算子として ハミルトニアン制約を定義することである。この方向性で最も有望な研究は、トーマス・ティーマンのフェニックス・プロジェクトである。 |

| Covariant dynamics Much of the recent[as of?] work in LQG has been done in the covariant formulation of the theory, called "spin foam theory." The present version of the covariant dynamics is due to the convergent work of different groups, but it is commonly named after a paper by Jonathan Engle, Roberto Pereira and Carlo Rovelli in 2007–08.[13] Heuristically, it would be expected that evolution between spin network states might be described by discrete combinatorial operations on the spin networks, which would then trace a two-dimensional skeleton of spacetime. This approach is related to state-sum models of statistical mechanics and topological quantum field theory such as the Turaeev–Viro model of 3D quantum gravity, and also to the Regge calculus approach to calculate the Feynman path integral of general relativity by discretizing spacetime. |

共変力学 LQGにおける最近の研究の多くは、「スピンフォーム理論」と呼ばれる共変形式で進められている。現在の共変力学の形式は、異なる研究グループの収束した 成果によるものであるが、一般にジョナサン・エングル、ロベルト・ペレイラ、カルロ・ロヴェッリによる2007-08年の論文に因んで名付けられている [13]。直観的には、スピンネットワーク状態間の進化は、スピンネットワークに対する離散的組み合わせ操作によって記述され、それが時空の二次元骨格を トレースすると予想される。このアプローチは、統計力学の状態和モデルや、3次元量子重力のトゥラエフ・ヴィロモデルなどのトポロジカル量子場理論に関連 している。また、時空を離散化することで一般相対性理論のファインマン経路積分を計算するレッジェ計算法のアプローチとも関連している。 |

| History

of string theory |

弦理論の歴史 |

| References 1. Élie Cartan. "Sur une généralisation de la notion de courbure de Riemann et les espaces à torsion." C. R. Acad. Sci. (Paris) 174, 593–595 (1922); Élie Cartan. "Sur les variétés à connexion affine et la théorie de la relativité généralisée." Part I: Ann. Éc. Norm. 40, 325–412 (1923) and ibid. 41, 1–25 (1924); Part II: ibid. 42, 17–88 (1925). 2. Penrose, Roger (1971). "Applications of negative dimensional tensors". Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-743350-3. 3. Penrose, Roger (1971). "Angular momentum: an approach to combinatorial space-time". In Bastin, Ted (ed.). Quantum Theory and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07956-X. 4. Penrose, Roger (1987). "On the Origins of Twistor Theory". In Rindler, Wolfgang; Trautman, Andrzej (eds.). Gravitation and Geometry, a Volume in Honour of Ivor Robinson. Bibliopolis. ISBN 88-7088-142-3. 5. Amitabha Sen, "Gravity as a spin system," Phys. Lett. B119:89–91, December 1982. 6. Abhay Ashtekar, "New variables for classical and quantum gravity," Phys. Rev. Lett., 57, 2244-2247, 1986. 7. Abhay Ashtekar, "New Hamiltonian formulation of general relativity," Phys. Rev. D36, 1587-1602, 1987. 8. Wilson, K. (1974). "Confinement of quarks". Physical Review D. 10 (8): 2445. Bibcode:1974PhRvD..10.2445W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.2445. 9. Carlo Rovelli and Lee Smolin, "Knot theory and quantum gravity," Phys. Rev. Lett., 61 (1988) 1155. 10. Carlo Rovelli and Lee Smolin, "Loop space representation of quantum general relativity," Nuclear Physics B331 (1990) 80-152. 11. Carlo Rovelli, Lee Smolin, "Discreteness of area and volume in quantum gravity" (1994): arXiv:gr-qc/9411005. 12. Thiemann, T (2006). "The Phoenix Project: Master constraint programme for loop quantum gravity". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 23 (7): 2211–2247. arXiv:gr-qc/0305080. Bibcode:2006CQGra..23.2211T. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/23/7/002. S2CID 16304158. 13. Jonathan Engle, Roberto Pereira, Carlo Rovelli, "Flipped spinfoam vertex and loop gravity". Nucl. Phys. B798 (2008). 251–290. arXiv:0708.1236. |

参考文献 1. Élie Cartan. 「リーマン曲率の概念の一般化とねじれ空間について」 C. R. Acad. Sci. (Paris) 174, 593–595 (1922); Élie Cartan. 「アフィン接続を持つ多様体と一般相対性理論について」 Part I: Ann. Éc. Norm. 40, 325–412 (1923) および同上 41, 1–25 (1924); Part II: 同上 42, 17–88 (1925)。 2. ペンローズ、ロジャー (1971)。「負の次元テンソルの応用」。Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-743350-3. 3. ペンローズ、ロジャー (1971). 「角運動量:組み合わせ時空へのアプローチ」. バスティン、テッド (編). Quantum Theory and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07956-X. 4. ペンローズ、ロジャー(1987)。「ツイスター理論の起源について」。リンドラー、ウォルフガング、トラウトマン、アンジェイ(編)。『重力と幾何学、 アイヴァー・ロビンソンに捧げる一冊』。ビブリオポリス。ISBN 88-7088-142-3。 5. Amitabha Sen, 「Gravity as a spin system,」 Phys. Lett. B119:89–91, December 1982. 6. Abhay Ashtekar, 「New variables for classical and quantum gravity,」 Phys. Rev. Lett., 57, 2244-2247, 1986. 7. Abhay Ashtekar, 「New Hamiltonian formulation of general relativity,」 Phys. Rev. D36, 1587-1602, 1987. 8. Wilson, K. (1974). 「Confinement of quarks」. Physical Review D. 10 (8): 2445. Bibcode:1974PhRvD..10.2445W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.2445. 9. Carlo Rovelli and Lee Smolin, 「Knot theory and quantum gravity,」 Phys. Rev. Lett., 61 (1988) 1155. 10. カルロ・ロヴェッリ、リー・スモーリン、「量子一般相対性理論のループ空間表現」、Nuclear Physics B331 (1990) 80-152。 11. カルロ・ロヴェッリ、リー・スモーリン、「量子重力における面積と体積の離散性」 (1994): arXiv:gr-qc/9411005。 12. ティーマン、T (2006)。「フェニックス・プロジェクト:ループ量子重力のためのマスター制約プログラム」。古典および量子重力。23 (7): 2211–2247。arXiv:gr-qc/0305080。Bibcode:2006CQGra..23.2211T. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/23/7/002. S2CID 16304158. 13. Jonathan Engle、Roberto Pereira、Carlo Rovelli、「反転スピンフォーム頂点とループ重力」。Nucl. Phys. B798 (2008)。251–290。arXiv:0708.1236。 |

| Further reading Topical reviews Carlo Rovelli, "Loop Quantum Gravity," Living Reviews in Relativity 1, (1998), 1, online article, 2001 version. Thomas Thiemann, "Lectures on Loop Quantum Gravity," e-print available as gr-qc/0210094 Abhay Ashtekar and Jerzy Lewandowski, "Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report," e-print available as gr-qc/0404018 Carlo Rovelli and Marcus Gaul, "Loop Quantum Gravity and the Meaning of Diffeomorphism Invariance," e-print available as gr-qc/9910079. Lee Smolin, "The Case for Background Independence," e-print available as hep-th/0507235. Popular books Julian Barbour, The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Our Understanding of the Universe (1999). Lee Smolin, Three Roads to Quantum Gravity (2001). Carlo Rovelli, Che cos'è il tempo? Che cos'è lo spazio?, Di Renzo Editore, Roma, 2004. French translation: Qu'est ce que le temps? Qu'est ce que l'espace?, Bernard Gilson ed, Brussel, 2006. English translation: What is Time? What is space?, Di Renzo Editore, Roma, 2006. Magazine articles Lee Smolin, "Atoms in Space and Time", Scientific American, January 2004. Easier introductory, expository or critical works Abhay Ashtekar, "Gravity and the Quantum," e-print available as gr-qc/0410054. John C. Baez and Javier P. Muniain, Gauge Fields, Knots and Quantum Gravity, World Scientific (1994). Carlo Rovelli, "A Dialog on Quantum Gravity," e-print available as hep-th/0310077. More advanced introductory/expository works Carlo Rovelli, Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (2004); draft available online. Thomas Thiemann, "Introduction to Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity," e-print available as gr-qc/0110034. Abhay Ashtekar, New Perspectives in Canonical Gravity, Bibliopolis (1988). Abhay Ashtekar, Lectures on Non-Perturbative Canonical Gravity, World Scientific (1991). Rodolfo Gambini and Jorge Pullin, Loops, Knots, Gauge Theories and Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (1996). Hermann Nicolai, Kasper Peeters, Marija Zamaklar, "Loop Quantum Gravity: An Outside View," e-print available as hep-th/0501114. "Loop and Spin Foam Quantum Gravity: A Brief Guide for beginners" arXiv:hep-th/0601129 H. Nicolai and K. Peeters. Edward Witten, "Quantum Background Independence In String Theory," e-print available as hep-th/9306122. Conference proceedings John C. Baez (ed.), Knots and Quantum Gravity (1993). |

さらに読む トピックレビュー Carlo Rovelli, 「Loop Quantum Gravity,」 Living Reviews in Relativity 1, (1998), 1, オンライン記事、2001年版。 Thomas Thiemann, 「Lectures on Loop Quantum Gravity,」 e-print gr-qc/0210094 アベイ・アシュテカーとイェジ・レヴァンドフスキ、「背景独立量子重力:現状報告」、電子版は gr-qc/0404018 として入手可能。 カルロ・ロヴェッリとマーカス・ゴール、「ループ量子重力と微分同相不変性の意味」、電子版は gr-qc/9910079 として入手可能。 リー・スモーリン、「背景独立性の主張」、e-print は hep-th/0507235 として入手可能。 一般向け書籍 ジュリアン・バーバー、『時間の終わり:宇宙の理解における次の革命』(1999年)。 リー・スモーリン、『量子重力への三つの道』(2001年)。 カルロ・ロヴェッリ『時間とは何か?空間とは何か?』(Di Renzo Editore, ローマ, 2004年)。仏訳:ベルナール・ジルソン編『時間とは何か?空間とは何か?』(Brussel, 2006年)。英訳:ロレンツォ・ディ・レンツォ社刊『時間とは何か?空間とは何か?』(ローマ, 2006年)。 雑誌記事 リー・スモーリン「時空における原子」『サイエンティフィック・アメリカン』2004年1月号。 入門的・解説的・批判的著作 アベイ・アシュテカー「重力と量子」電子版はgr-qc/0410054として入手可能。 ジョン・C・ベイズとハビエル・P・ムニアイン共著『ゲージ場、結び目、量子重力』ワールドサイエンティフィック社(1994年)。 カルロ・ロヴェッリ「量子重力に関する対話」電子版はhep-th/0310077として入手可能。 より高度な入門・解説書 カルロ・ロヴェッリ『量子重力』ケンブリッジ大学出版局(2004年);オンラインで草稿が入手可能。 トーマス・ティーマン「現代カノニカル量子一般相対性理論入門」電子版はgr-qc/0110034として入手可能。 アベイ・アシュテカー『規範重力の新たな展望』ビブリオポリス(1988年)。 アベイ・アシュテカー『非摂動的規範重力講義』ワールドサイエンティフィック(1991年)。 ロドルフォ・ガンビーニ、ホルヘ・プリン『ループ、結び目、ゲージ理論と量子重力』ケンブリッジ大学出版局(1996年)。 ヘルマン・ニコライ、カスパー・ピーターズ、マリヤ・ザマクラク、「ループ量子重力:外部からの視点」、電子版はhep-th/0501114として入手 可能。 「ループとスピンフォーム量子重力:初心者向け簡明ガイド」arXiv:hep-th/0601129 H. ニコライとK. ピーターズ。 エドワード・ウィッテン、「弦理論における量子背景独立性」、電子版は hep-th/9306122 として入手可能。 会議録 ジョン・C・ベイズ(編)、『結び目と量子重力』(1993年)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_loop_quantum_gravity |

History of loop quantum gravity(ループ量子重力論の歴史) |

★なぜ時間は存在しないのか / ジュリアン・バーバー著 ; 川崎秀高, 高良富夫訳, 東京 : 青土社 , 2020.2

ヘ ラクレイトス、パルメニデス、ガリレオ、ニュートン、アインシュタインからジョン・ホイーラー、ロジャー・ペンローズ、スティーヴン・ホーキングまでの時 間の考え方を俯瞰しアインシュタインの唱えた時空連続体の概念に疑念を投げかけ、現代物理学のパラドックスの一つである相対性理論と量子力学のあいだの隙 間を埋め、現代物理学に革命を起こす画期の書。

★時間は存在しない / カルロ・ロヴェッリ著 ; 冨永星訳, 東京 : NHK出版 , 2019.8

時 間はいつでもどこでも同じように経過するわけではなく、過去から未来へと流れるわけでもない—。“ホーキングの再来”と評される天才物理学者が、本書の前 半で「物理学的に時間は存在しない」という驚くべき考察を展開する。後半では、それにもかかわらず私たちはなぜ時間が存在するように感じるのかを、哲学や 脳科学などの知見を援用して論じる。詩情あふれる筆致で時間の本質を明らかにする、独創的かつエレガントな科学エッセイ。

| アナクシマンドロス(古代ギリシャ語: Ἀναξίμανδρος, ラテン文字転写: Anaximandros; 紀元前610年頃 - 紀元前546年)は、古代ギリシアの哲学者。 |

|

| 生涯と業績 アナクシマンドロスは、プラクシアデスを父とするミレトスの人で、哲学者。タレス、アナクシメネスと共にミレトス学派(イオニア学派)の代表とされる。タ レスの縁者であり、彼の弟子にして後継者であった。自然哲学について考察し、アルケーを「無限なるもの」(ト・アペイロン)とした(後述#ト・アペイロ ン)。はじめて日時計を使って、夏至・冬至と、春分・秋分を識別したとされる[1]。スパルタで地震が起こることを予言し、実際に地震が起きた、というエ ピソードも伝わる。ギリシア世界で、人が住まっている全地域を地図に描くことを、はじめてなし遂げた。 主要著作に、『自然について』、『大地周航記』、『彷徨わぬ者たち(恒星)について』、『天球論』などがあったとされるが、いずれも現在に伝わっていない[2]。 |

|

| 学説 ト・アペイロン 存在するものの元のもの(始源・アルケー)が「無限なるもの」(ト・アペイロン, τὸ ἄπειρον)であることを論じた[3]。著作断片には以下のように記されている。 |

|

| 存在する諸事物の元のもの(アルケー)は、無限なるもの(ト・アペイロ

ン)である。……存在する諸事物にとってそれから生成がなされる源、その当のものへと、消滅もまた必然に従ってなされる。なぜなら、それらの諸事物は、交

互に時の定めに従って、不正に対する罰を受け、償いをするからである。 — シンプリキオス、『アリストテレス「自然学」注解』24.13[4] |

|

| アナクシマンドロスによれば、始源たる無限なるものは単一であり運動す

るものである。無限なるものから存在する諸事物は生成され、存在する諸事物は無限なるものへと消滅する。ここでの生成消滅は、対立相反しあうものが永遠の

動をつづけながら分離することによるのであり、この円環運動は無限の劫初から行われている。そして人間の営みも存在するものの中に含め、生成消滅を罰と償

いで説明しようとした。 |

|

| 宇宙論 アナクシマンドロスの宇宙論も同様な枠組みのもとで展開される。宇宙の生成を遠心分離運動と捉え、あらゆるものが無限に廻り、星や大地もその過程で生成されたとした。 彼の宇宙論には、始まりという概念がなく、万物は無限から生じ常に生成され続ける、という特徴を持っている。まず、永遠なるものから無限の運動の過程で、 熱いもの・冷たいものとを生み出すものが分離した。あらゆる天体は熱いものから分離し、空気に閉じ込められた火の環である。円柱状の大地を取り巻く火の環 には筒状の噴出孔があり、そこから見えるものが天体の姿である。日蝕や月蝕は、その孔が塞がることで起こる。月の満ち欠けも同様である[5]。大地での自 然現象としては、大地が形成された原初の湿った状態が海であり[6]、風は、極めて軽い蒸気が空気から分離することで生じるか、あるいは、蒸気が凝縮する ときに動くことで生じる。雷は、風が雲を引き裂くことで生じ、雨は、大地から蒸発したものが上昇することで起こる[7]。干ばつや雨によって大地に亀裂が 広がると、そこに空気が大量に侵入し、その激しい風により大地が震動し、地震が起こる[8]。生物は湿ったものの中から太陽の蒸発作用によって発生する。 人間は、魚に似た動物から発生した。その魚の中で成長するまで養育され、じきに分裂し、男女として分かれ生きられるようになった。そしてその時初めて陸に 上がったとされる[9]。 現代物理学者であるロヴェッリの評によれば、アナクシマンドロスは「地球」が空に浮いており地球の下側にも空が広がっていること、動物や植物は環境の変化 に対応して進化することなど、現代人に共有されている世界を理解するために必要な基本原理を築きあげたと考えられている[10]。 |

|

| 後世への影響 ハイデッガーによると、ソクラテス以前の自然哲学(イオニア学派)についての通説的理解は、哲学の未熟な表現とするものが広く見られるが、そうした通説的 理解には現代的人間の先入観が混入していると指摘する。ここで言う自然についての概念は、現代では製作(ポイエーシス)として理解されるが、本来は存在そ のものとして理解せねばならない[11]。製作とは、人間が自然に手を加えることであり、この自然は、存在と存在者の対比における存在者に区分される。し かし元来、自然とは、存在そのものであり、製作ではなく生成として捉えなければならない、とハイデッガーは考える[12]。 ハイデッガーは、西洋形而上学が誕生する以前の根源的哲学者として、アナクシマンドロスを評価している。そのことは、『形而上学入門』(1953)および 『ヒューマニズムについて』(1947)から窺い知ることができる。『形而上学入門』では、ギリシャ語における自然は、元来、生成や誕生を意味し、自然そ のものを存在として捉えていたが、キリスト教の伝統以降で、神による創造/被創造という製作の観点から語られるようになった、と主張される[13]。 『ヒューマニズムについて』では、自然を製作する技術とは、本来の自然の故郷喪失であり、こうした現代において、自然=生成という概念を復興させることに よって、ヒューマニズム(人間中心主義)を覆すことが試みられた[14]。 |

|

| 脚注 1.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 161. 2.^ 『スーダ』α 1986 3.^ “デジタル大辞泉の解説”. コトバンク. 2018年8月27日閲覧。 4.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 181. 5.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 167. 6.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 178. 7.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 168. 8.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 179. 9.^ ディールス & クランツ 1996, p. 180. 10.^ C・ロヴェッリ『すごい物理学講義』河出書房、2017年、18頁。 11.^ ハイデッガー 1957, pp. 117–118. 12.^ ハイデッガー 1957, p. 98. 13.^ ハイデッガー 1960, p. 22. 14.^ ハイデッガー 1974, pp. 60–61. |

|

| 参考文献 ディールス, H、クランツ, W『ソクラテス以前哲学者断片集』岩波書店、1996年。 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス『ギリシア哲学者列伝(上)』岩波書店〈岩波文庫〉。ISBN 400336631X。 ハイデッガー『アナクシマンドロスの言葉』理想社、1957年。 ハイデッガー『形而上学入門』理想社、1960年。 ハイデッガー『ヒューマニズムについて』理想社、1974年。 |

|

| https://x.gd/4gvoQ |

☆カルロ・ロベッリ(Carlo Rovelli, b.1956)

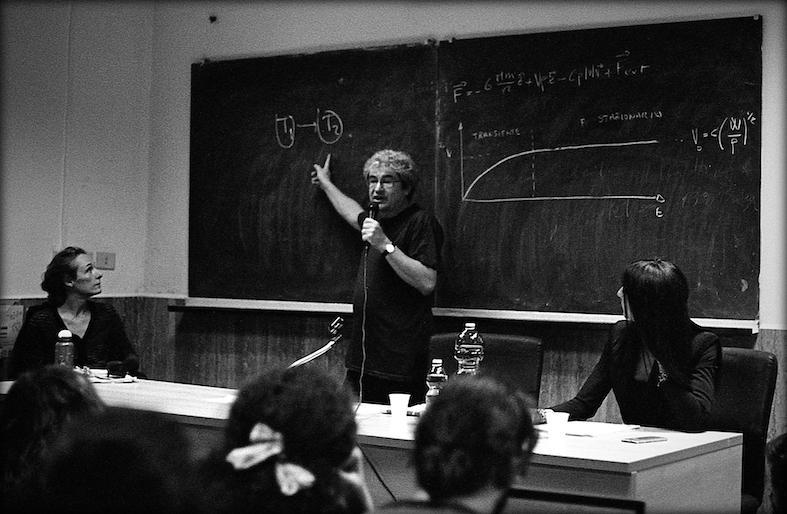

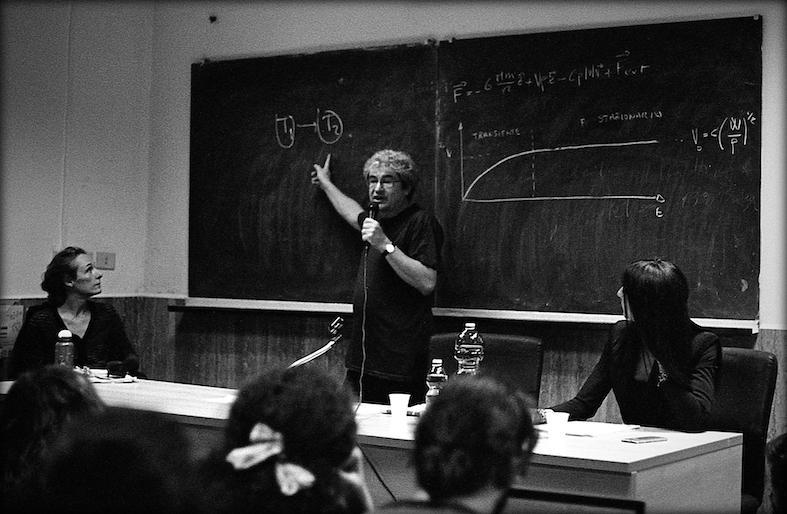

| Carlo

Rovelli (born 3 May 1956) is an Italian theoretical physicist and

writer who has worked in Italy, the United States, France, and

Canada.[1] He is currently Emeritus Professor at the Centre de Physique

Théorique of Marseille in France, a Distinguished Visiting Research

Chair at the Perimeter Institute,[2] core member of the Rotman

Institute of Philosophy of Western University in Canada,[3] and Fractal

Faculty of the Santa Fe Institute in The United States.[4] Rovelli works mainly in the field of quantum gravity and is a founder of the theory of loop quantum gravity. He has also worked in the history and philosophy of science, formulating the relational quantum mechanics and the notion of thermal time. He collaborates with several Italian newspapers, including the cultural supplements of the Corriere della Sera, Il Sole 24 Ore, and La Repubblica. His popular science book, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, was originally published in Italian in 2014. It has sold over two million copies worldwide.[5] In 2019, he was included by Foreign Policy magazine in the list of the 100 most influential global thinkers.[6] In 2021, he was included by Prospect magazine in the list of the 50 world's top thinkers.[7] |

カルロ・ロヴェッリ(1956年5月3日生まれ)は、イタ

リアの理論物理学者であり作家である。イタリア、アメリカ、フランス、カナダで活動してきた。[1]

現在、フランス・マルセイユ理論物理学センターの名誉教授、ペリメーター研究所の特別客員研究教授[2]、カナダ・ウェスタン大学ロットマン哲学研究所の

コアメンバー[3]、米国サンタフェ研究所フラクタル学部[4]を兼任している。 ロヴェッリは主に量子重力理論を研究対象とし、ループ量子重力理論の創始者の一人である。科学史・科学哲学の分野でも活動し、関係性量子力学や熱時間概念 を提唱した。コリエーレ・デラ・セーラ紙、イル・ソーレ24オーレ紙、ラ・レプッブリカ紙の文化欄を含む複数のイタリア紙に寄稿している。著書『物理学の 七つの短い講義』は2014年にイタリア語で刊行され、全世界で200万部以上を売り上げた。[5] 2019年には『フォーリン・ポリシー』誌が選ぶ「世界で最も影響力のある思想家100人」に選出された[6]。2021年には『プロスペクト』誌が選ぶ「世界のトップ思想家50人」に名を連ねた[7]。 |

| Life and career Carlo Rovelli was born in Verona, Italy, on 3 May 1956. He attended the Liceo Classico Scipione Maffei in Verona. In the 1970s, he participated in the student political movements in Italian universities. He was involved with the free political radio stations Radio Alice in Bologna and Radio Anguana in Verona, which he helped found.[8] In conjunction with his political activity, he was charged, but later released, for crimes of opinion related to the book Fatti Nostri, which he co-authored with Enrico Palandri, Maurizio Torrealta, and Claudio Piersanti.[9] Rovelli has credited his use of LSD at this time with sparking his interest in theoretical physics,[10] saying of his experience: "it was an extraordinarily strong experience that touched me also intellectually... Among the strange phenomena was the sense of time stopping. Things were happening in my mind but the clock was not going ahead; the flow of time was not passing any more... And I thought: ‘Well, it's a chemical that is changing things in my brain. But how do I know that the usual perception is right, and this is wrong? If these two ways of perceiving are so different, what does it mean that one is the correct one?"[11] In 1981, Rovelli graduated with a BS/MS in physics from the University of Bologna, and in 1986 he obtained his PhD at the University of Padova, Italy. Rovelli refused military service, which was compulsory in Italy at the time, and was therefore briefly detained in 1977.[12] He held postdoctoral positions at the University of Rome, the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, and Yale University. Rovelli was on the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh from 1990 to 2000,[13] where he was also affiliated with the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. Since 2000 he has been a professor at the Centre de Physique Théorique de Luminy of Aix-Marseille University in France.[14] |

生涯と経歴 カルロ・ロヴェッリは1956年5月3日、イタリアのヴェローナで生まれた。ヴェローナのシピオーネ・マッフェイ古典高校に通った。1970年代にはイタ リアの大学で学生政治運動に参加した。ボローニャの自由政治ラジオ局「ラジオ・アリス」やヴェローナの「ラジオ・アンガーナ」に関わり、後者の設立にも協 力した[8]。政治活動と並行して、エンリコ・パランドリ、マウリツィオ・トリアルタ、クラウディオ・ピエルサンティと共著した書籍『ファッティ・ノスト リ』に関連する思想犯罪で起訴されたが、後に釈放された。[9] ロヴェッリは、この時期にLSDを使用したことが理論物理学への関心を喚起したと述べている[10]。彼はその体験についてこう語っている。「それは知的 に私を揺さぶる、並外れて強烈な体験だった…奇妙な現象の一つに、時間の停止感があった。心の中では物事が進行しているのに時計は進まず、時間の流れが止 まったのだ…そして思った。『これは脳内の化学物質が変化を起こしているに違いない。だが通常の知覚が正しく、これが間違っているとどうして断言できる? 二つの知覚がこれほど異なるなら、どちらが正しいと言えるのか?』」と述べている[11]。 1981年、ロヴェッリはボローニャ大学で物理学の学士・修士号を取得し、1986年にはイタリアのパドヴァ大学で博士号を得た。当時イタリアで義務付け られていた兵役を拒否したため、1977年に一時拘留された[12]。ローマ大学、トリエステの高等研究所、イェール大学で博士研究員を務めた。1990 年から2000年までピッツバーグ大学の教員を務め、[13] 科学史・科学哲学学科にも所属していた。2000年以降はフランス・エクス=マルセイユ大学リュミニー理論物理学センターの教授である。[14] |

| Main contributions Loop quantum gravity In 1988, Rovelli, Lee Smolin and Abhay Ashtekar introduced a theory of quantum gravity called loop quantum gravity. In 1995, Rovelli and Smolin obtained a basis of states of quantum gravity, labelled by Penrose's spin networks, and using this basis they were able to show that the theory predicts that area and volume are quantized. This result indicates the existence of a discrete structure of space on a very small scale. In 1997, Rovelli and Michael Reisenberger introduced a "sum over surfaces" formulation of the theory, which has since evolved into the currently covariant "spin foam" version of loop quantum gravity. In 2008, in collaboration with Jonathan Engle and Roberto Pereira, he has introduced the spin foam vertex amplitude which is the basis of the current definition of the loop quantum gravity covariant dynamics. Loop theory is today considered a candidate for a quantum theory of gravity. It finds applications in quantum cosmology, spinfoam cosmology and quantum black hole physics. |

主な貢献 ループ量子重力理論 1988年、ロヴェッリ、リー・スモーリン、アベイ・アシュテカーはループ量子重力理論と呼ばれる量子重力理論を提唱した。1995年、ロヴェッリとス モーリンはペンローズのスピンネットワークでラベル付けされた量子重力の状態基底を得て、この基底を用いて理論が面積と体積の量子化を予測することを示し た。この結果は、非常に微小なスケールにおいて空間の離散構造が存在することを示唆している。1997年、ロヴェッリとマイケル・ライゼンバーガーは「曲 面総和」形式の理論を導入した。これはその後、現在のループ量子重力の共変的な「スピンフォーム」版へと発展した。2008年にはジョナサン・エングル、 ロベルト・ペレイラとの共同研究で、スピンフォーム頂点振幅を導入した。これは現在のループ量子重力共変力学の定義の基礎となっている。ループ理論は今 日、量子重力理論の有力候補と見なされている。量子宇宙論、スピンフォーム宇宙論、量子ブラックホール物理学に応用されている。 |

| Physics without time In his 2004 book, Quantum Gravity, Rovelli developed a formulation of classical and quantum mechanics that does not make explicit reference to the notion of time. The first step towards a theory of quantum gravity without a time variable is described by Wheeler–DeWitt equation. The timeless formalism is used to describe the world in the regimes where the quantum properties of the gravitational field cannot be disregarded. This is because the quantum fluctuation of spacetime itself makes the notion of time unsuitable for writing physical laws in the conventional form of evolution laws in time. This position led him to face the following problem: if time is not part of the fundamental theory of the world, then how does time emerge? In 1993, in collaboration with Alain Connes, Rovelli proposed a solution to this problem called the thermal time hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, time emerges only in a thermodynamic or statistical context. If this is correct, the flow of time is not fundamental, deriving from the incompleteness of knowledge. Similar conclusions had been reached earlier in the context of nonequilibrium statistical mechanics, in particular in the work of Robert Zwanzig, and in Caldeira-Leggett models used in quantum dissipation.[15][16] |

時間のない物理学 ロヴェッリは2004年の著書『量子重力』において、時間の概念を明示的に参照しない古典力学と量子力学の定式化を展開した。時間変数を持たない量子重力 理論への第一歩は、ウィーラー=デウィット方程式によって記述される。この時間のない形式主義は、重力場の量子的な性質を無視できない領域における世界を 記述するために用いられる。これは時空そのものの量子揺らぎが、時間の経過に伴う進化法則という従来形式で物理法則を記述するのに時間の概念を不適切にす るためだ。 この立場は彼に次の問題に向き合わせる:もし時間が世界の基本理論の一部でないなら、時間はどのように現れるのか?1993年、アラン・コンヌとの共同研 究でロヴェッリはこの問題への解決策として熱時間仮説を提案した。この仮説によれば、時間は熱力学的あるいは統計的な文脈においてのみ現れる。これが正し ければ、時間の流れは根本的なものではなく、知識の不完全性から派生するものである。同様の結論は以前、非平衡統計力学の文脈、特にロバート・ツヴァン ツィグの研究や、量子散逸で用いられるカルデイラ=レゲットモデルにおいて導かれていた。[15][16] |

| Relational quantum mechanics In 1994, Rovelli introduced the relational interpretation of quantum mechanics, based on the idea that the quantum state of a system must always be interpreted relative to another physical system (in the same way that the "velocity of an object" is always relative to another object, in classical mechanics).[17] The idea has been developed and analyzed in particular by Bas van Fraassen[18] and by Michel Bitbol. Among other important consequences, it provides a solution of the EPR paradox that does not violate locality.[19] Rovelli has expressed the main idea of relational quantum mechanics in the popular book Helgoland. |

関係性量子力学 1994年、ロヴェッリは関係性解釈を提唱した。これは量子状態は常に別の物理系を基準に解釈されねばならないという考えに基づく(古典力学で「物体の速 度」が常に別の物体を基準とするのと同様である)。[17] この考え方は特にバス・ファン・フラッセン[18]とミシェル・ビットボルによって発展・分析された。重要な帰結の一つとして、局所性を損なわないEPR パラドックスの解決策を提供する。[19] ロヴェッリは一般向け書籍『ヘルゴラント島』で関係性量子力学の主要な考え方を説明している。 |

| Relative information Rovelli won the second prize in the 2013 FQXi contest "It From Bit or Bit From It?" for his essay about "relative information". His paper, Relative Information at the Foundation of Physics, discusses how "Shannon's notion of relative information between two physical systems can function as [a] foundation for statistical mechanics and quantum mechanics, without referring to subjectivism or idealism...[This approach can] represent a key missing element in the foundation of the naturalistic picture of the world."[20] In 2017, Rovelli elaborated further upon the subject of relative information, writing that: In nature, variables are not independent; for instance, in any magnet, the two ends have opposite polarities. Knowing one amounts to knowing the other. So we can say that each end "has information" about the other. There is nothing mental in this; it is just a way of saying that there is a necessary relation between the polarities of the two ends. We say that there is "relative information" between two systems anytime the state of one is constrained by the state of the other. In this precise sense, physical systems may be said to have information about one another, with no need for a mind to play any role. Such "relative information" is ubiquitous in nature: The colour of the light carries information about the object the light has bounced from; a virus has information about the cell it may attach, and neurons have information about one another. Since the world is a knit tangle of interacting events, it teems with relative information. When this information is exploited for survival, extensively elaborated by our brain, and may be coded in a language understood by a community, it becomes mental, and it acquires the semantic weight that we commonly attribute to the notion of information. But the basic ingredient is down there in the physical world: physical correlation between distinct variables. The physical world is not a set of self-absorbed entities that do their selfish things. It is a tightly knitted net of relative information, where everybody's state reflects somebody else's state. We understand physical, chemical, biological, social, political, astrophysical, and cosmological systems in terms of these nets of relations, not in terms of individual behaviour. Physical relative information is a powerful basic concept for describing the world. Before "energy," "matter," or even "entity."[21] |

相対情報 ロヴェッリは2013年のFQXiコンテスト「It From Bit or Bit From It?」において、「相対情報」に関する論文で二等賞を受賞した。彼の論文『物理学の基礎における相対情報』は、「二つの物理系間の相対情報というシャノ ンの概念が、主観主義や観念論に依拠することなく、統計力学と量子力学の基礎として機能し得る」ことを論じている。[このアプローチは]自然主義的世界観 の基礎において欠けていた重要な要素を補完し得る」[20]。2017年、ロヴェッリは相対情報についてさらに論を展開し、次のように記している: 自然界において変数は独立していない。例えば磁石では両端の極性が相反する。一方を知れば他方も知ることになる。つまり各端は他方について「情報を持つ」 と言える。これは精神的な要素を一切含まない。単に両端の極性間に必然的な関係が存在すると言っているに過ぎない。一方の状態が他方の状態によって制約さ れる場合、常に二つのシステム間に「相対情報」が存在すると言うのである。この厳密な意味において、物理的システムは互いに情報を持っていると言える。そ こに精神が関与する必要はない。このような「相対情報」は自然界に遍在する:光の色は、光が反射した物体についての情報を運ぶ。ウイルスは、自身が付着す る可能性のある細胞についての情報を持つ。神経細胞は互いについての情報を持つ。世界は相互作用する事象の絡み合った網であるため、相対情報に満ちている のだ。この情報が生存のために利用され、我々の脳によって高度に精緻化され、共同体が理解する言語で符号化されると、それは精神的なものとなり、我々が情 報の概念に通常帰する意味論的重みを獲得する。しかし基本要素は物理世界の底辺にある:異なる変数間の物理的相関だ。物理世界は自己中心的な存在が利己的 な行動を取る集合体ではない。それは密に編まれた相対情報の網であり、あらゆる存在の状態が他の存在の状態を反映している。我々は物理的・化学的・生物学 的・社会的・政治的・天体物理学的・宇宙論的システムを、個々の行動ではなくこうした関係性の網によって理解する。物理的相対情報は世界を記述する強力な 基本概念である。「エネルギー」「物質」、あるいは「実体」よりも先に存在する概念だ。[21] |

History and philosophy of science Rovelli in Rome, 2015 Rovelli has written a book on the Greek philosopher Anaximander, published in France, Italy, US[22] and Brazil. The book analyses the main aspects of scientific thinking and articulates Rovelli's views on science. Anaximander is presented in the book as a main initiator of scientific thinking – it is almost a hagiography. For Rovelli, science is a continuous process of exploring novel possible views of the world;[23] this happens via a "learned rebellion", which always builds and relies on previous knowledge but at the same time continuously questions aspects of this received knowledge.[24] The foundation of science, therefore, is not certainty but the very opposite, a radical uncertainty about our own knowledge, or equivalently, an acute awareness of the extent of our ignorance.[24] |

科学の歴史と哲学 ローマのロヴェッリ、2015年 ロヴェッリはギリシャの哲学者アナクシマンドロスに関する本を執筆し、フランス、イタリア、アメリカ[22]、ブラジルで出版された。この本は科学的思考 の主要な側面を分析し、ロヴェッリの科学観を明確にしている。アナクシマンドロスは科学的思考の主要な先駆者として描かれており、ほぼ聖人伝に近い内容 だ。 ロヴェッリにとって、科学とは世界に対する新たな可能性を探求する継続的なプロセスである[23]。これは「学識ある反逆」を通じて起こる。それは常に過 去の知識を基盤とし依存するが、同時にその既得知識の諸側面を絶えず問い直す[24]。したがって科学の基盤は確実性ではなく、むしろその正反対、すなわ ち自らの知識に対する根本的な不確実性、あるいは同義的に言えば、我々の無知の深さに対する鋭い自覚にある[24]。 |

| Religious views Rovelli defines himself as "serenely atheist".[25] He discussed his religious views in several articles and in his book on Anaximander. He argues that the conflict between rational/scientific thinking and structured religion may find periods of truce ("there is no contradiction between solving Maxwell's equations and believing that God created Heaven and Earth"),[26] but it is ultimately unsolvable, because most religions demand the acceptance of some unquestionable truths, while scientific thinking is based on the continuous questioning of any truth. Thus, for Rovelli, the source of the conflict is not the pretense of science to give answers – for Rovelli, the universe is full of mystery and a source of awe and emotions – but, on the contrary, the source of the conflict is the acceptance of our ignorance at the foundation of science, which clashes with religions' pretense to be depositories of certain knowledge.[26] |

宗教観 ロヴェッリは自らを「穏やかな無神論者」と定義している。[25] 彼はいくつかの論文やアナクシマンドロスに関する著書で自身の宗教観について論じている。合理的・科学的思考と体系化された宗教の間の対立は休戦期間を見 出すこともある(「マクスウェルの方程式を解くことと、神が天地を創造したと信じることに矛盾はない」)と主張するが、[26] 結局は解決不能だとする。なぜなら、ほとんどの宗教は疑いようのない真理の受容を要求する一方、科学的思考はあらゆる真理に対する継続的な疑問を基盤とし ているからだ。したがってロヴェッリにとって、この対立の根源は科学が答えを与えるという主張にあるのではない。宇宙は神秘に満ち、畏敬と感動の源である と彼は考える。むしろ対立の根源は、科学の基盤にある我々の無知の受容にある。これが、確かな知識の保管庫であるという宗教の主張と衝突するのである。 [26] |

| Political engagement, pacifism, and controversies Rovelli's first book was on the Italian student political movements in the 1970s.[27] He later refused Italy's compulsory military draft and was briefly detained. In 2021, he coordinated the Global Peace Dividend, an open letter signed by more that 50 Nobel Laureates, including the Dalai Lama, calling for all countries to negotiate a balanced cut on their military spending by 2% a year for the next five years, and put half the saved money in a UN fund to combat pandemics, the climate crisis, and extreme poverty.[28] On 1 May 2023, Rovelli gave a political speech at the large Italian Labour Day concert in Rome, inviting the youth to engage politically for the environment, economical equality and peace, and criticizing the Italian Defence Minister Guido Crosetto for what he claims was his direct involvement with what he calls the industrial military complex. The speech raised a large controversy.[29] As a consequence, his invitation to represent Italy at the 2024 Frankfurt Book Fair was cancelled; the cancellation itself was widely criticized, leading to his re-invitation,[30] and the resignation of the Italian Commissary for the Buchmesse.[31] Rovelli repeated his call for reduced military spending and improved international cooperation following the outbreak of the Gaza war.[32] That same year, he was one of the signatories of the International Peace Conference manifesto, which accuses the United States, the European Union, and NATO of being a driving force behind the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[33] |

政治的関与、平和主義、そして論争 ロヴェッリの最初の著書は、1970年代のイタリア学生政治運動に関するものだった[27]。彼は後にイタリアの徴兵制を拒否し、一時的に拘束された。 2021年には、ダライ・ラマを含む50人以上のノーベル賞受賞者が署名した公開書簡「グローバル・ピース・ディビデンド」を主導した。この書簡は、今後 5年間にわたり各国が軍事費を年2%ずつ均衡的に削減し、節約した資金の半分を国連基金に拠出するよう求めている。その基金はパンデミック対策、気候危機 対策、極度の貧困対策に充てられる。[28] 2023年5月1日、ロヴェッリはローマで開催された大規模なイタリア労働者の日コンサートで政治演説を行い、若者に対し環境保護、経済的平等、平和のた めに政治的に関与するよう呼びかけた。また、イタリア国防相グイド・クロセッティが「軍産複合体」と呼ぶものへの直接関与を主張し、これを批判した。この 演説は大きな論争を巻き起こした[29]。結果として、2024年フランクフルト・ブックフェアにおけるイタリア代表としての彼の招待は取り消された。こ の取り消し自体も広く批判され、再招待[30]とブックフェア担当イタリア委員の辞任[31]につながった。ガザ戦争勃発後、ロヴェッリは軍事費削減と国 際協力強化の呼びかけを繰り返した。[32] 同年、彼は国際平和会議宣言の署名者の一人となった。この宣言は、米国、欧州連合、NATOがロシアのウクライナ侵攻の背後にある推進力であると非難して いる。[33] |

| Main awards 2024 Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing About Science ("In the conflicted world of 2024, the abiding, idealistic voice of Rovelli’s essay collection There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness feels especially valuable.") [34] 1995 International Xanthopoulos Award of the International Society for General Relativity and Gravitation, "for outstanding contributions to theoretical physics"[35] Senior member of the Institut Universitaire de France Laurea Honoris Causa National University of General San Martín[36] Honorary Professor of the Beijing Normal University in China Member of the Académie Internationale de Philosophie des Sciences Honorary member of the Accademia di Scienze Arti e Lettere di Verona 2009 First "community" prize of the FQXi contest on the "nature of time" 2013 Second prize of the FQXi contest on the "relation between physics and information" 2014 Premio Letterario Merck [it] for the book Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity 2015 Premio Pagine di Scienza di Rosignano for the book Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity[37] 2015 Premio Alassio centolibri per l’informazione culturale[38] 2015 Premio Larderello[39] 2015 Premio letterario Galileo per la divulgazione scientifica [it] for the book Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity |

主な受賞歴 2024年 ルイス・トーマス科学著作賞(「2024年の対立する世界において、ロヴェッリのエッセイ集『この世にはルールより優しさが大切だ』が放つ、揺るぎない理想主義的な声は特に貴重だ」と評された) [34] 1995年 国際一般相対性理論・重力学会より国際ザンソプロス賞を授与。「理論物理学への卓越した貢献に対して」[35] フランス大学研究所上級会員 サン・マルティン国立大学より名誉博士号[36] 中国・北京師範大学名誉教授 国際科学哲学アカデミー会員 ヴェローナ科学芸術文学アカデミー名誉会員 2009年 FQXi「時間の本質」コンテスト第1回「コミュニティ」賞 2013年 FQXi「物理学と情報の関係」コンテスト第2位 2014年 メルク文学賞(イタリア)『現実は見かけとは違う:量子重力への旅』に対して 2015年 ロジニャーノ科学ページ賞『現実は見かけとは違う:量子重力への旅』に対して 2015年 アラッシオ・チェントリブリ文化情報賞[38] 2015年 ラルデレロ賞[39] 2015年 ガリレオ科学普及文学賞[it](著書『現実は見かけとは違う:量子重力への旅』に対して) |

| In popular culture Rovelli appeared as a Disney character in a Mickey Mouse story in the Italian Disney publication of Topolino.[40] In November 2022 Carlo Rovelli and rock band Belladonna released the single "Nothing Shines Unless It Burns".[41][42][43] In October 2023 the song entered the Grammy Awards ballot in the Best Rock Performance category.[44] In the science fiction novel Mars Trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson, set in a future century, Rovelli and Lee Smolin appear as historical characters in the history of physics. In the novel, Loop quantum gravity has merged to string theory to give a comprehensive physical theory of the world. The book The Order of Time has been published in audiobook format read by the British actor Benedict Cumberbatch.[45] In Treacle Walker (2021) Alan Garner chose a quote from Rovelli's The Order of Time (L'ordine del tempo, 2017) as the epigraph for his book. The 2023 film The Order of Time, directed by Liliana Cavani, is inspired by Rovelli's book of the same title. Rovelli collaborated with the screenwriting.[46] Interviews on BBC radio: The BBC Radio 4 show Desert Island Discs in summer 2017.[47] The BBC Radio 4 show The Life Scientific in 2018 (discussing his career in science).[48] The BBC Radio 3 show Private Passions in 2020 (discussing time in music and science)[49] The BBC Radio 4 show A Good Read in 2020 (discussing books).[50] In 2022 Rovelli appeared in the Netflix documentary A Trip to InfinityA Trip to Infinity,[51] discussing the mathematical implications of infinity. He appeared on BBC Radio 4's The Museum of Curiosity in February 2023.[52] His hypothetical donation to this imaginary museum was a white hole. |

ポピュラー・カルチャーにおいて ロヴェッリは、イタリアのディズニー出版物『トポリーノ』のミッキーマウス物語に登場したディズニーキャラクターとして描かれた[40]。 2022年11月、カルロ・ロヴェッリとロックバンドのベラドンナはシングル「燃えなければ輝かない」をリリースした[41][42][43]。2023年10月、この楽曲はグラミー賞の最優秀ロック・パフォーマンス部門にノミネートされた。[44] キム・スタンリー・ロビンソンのSF小説『火星三部作』では、未来世紀を舞台に、ロヴェッリとリー・スモーリンが物理学史上の歴史的人物として登場する。小説内ではループ量子重力が弦理論と融合し、世界を包括する物理理論を形成している。 著書『時間の秩序』は、英国俳優ベネディクト・カンバーバッチによる朗読でオーディオブック化された。[45] アラン・ガーナーは2021年の作品『トレークル・ウォーカー』において、ロヴェッリの著書『時間の秩序』(原題:L'ordine del tempo, 2017年)からの引用を自著のエピグラフに選んだ。 2023年公開の映画『時間の秩序』は、リリアーナ・カヴァーニ監督による作品で、ロヴェッリの同名著書に着想を得ている。ロヴェッリは脚本制作に協力した。[46] BBCラジオでのインタビュー: 2017年夏放送のBBCラジオ4番組『砂漠の島ディスク』 [47] 2018年BBCラジオ4『ザ・ライフ・サイエンティフィック』(科学者としての経歴について議論)。[48] 2020年BBCラジオ3『プライベート・パッションズ』(音楽と科学における時間について議論)。[49] 2020年BBCラジオ4『ア・グッド・リード』(書籍について議論)。[50] 2022年、ロヴェッリはNetflixドキュメンタリー『無限への旅』に出演し、無限の数学的含意について論じた。 2023年2月にはBBCラジオ4『好奇心の博物館』に出演した。彼がこの架空の博物館に寄贈すると仮定したものはホワイトホールであった。 |

| Books and articles Rovelli has written more than 200 scientific articles published in international journals. He has published two monographs on loop quantum gravity and several popular science books. His book, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, has been translated into 41 languages. Scientific books Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-83733-2 With Francesca Vidotto, Covariant Loop Quantum Gravity: An Elementary Introduction to Quantum Gravity and Spinfoam Theory, Cambridge University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1107069626 |

書籍と論文 ロヴェッリは国際誌に200本以上の科学論文を発表している。ループ量子重力理論に関する専門書2冊と、一般向け科学書数冊を出版した。著書『物理学の七つの短い講義』は41言語に翻訳されている。 科学書 『量子重力』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2004年、ISBN 0-521-83733-2 フランチェスカ・ヴィドットとの共著『共変ループ量子重力:量子重力とスピンフォーム理論の初歩的入門』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2014年、ISBN 978-1107069626 |

| Popular books icon This section lacks ISBNs for books it lists. Please help add this information or run the citation bot. Anaximander: And the Birth of Science, Penguin Random House, 2023[53] (republication of The First Scientist: Anaximander and his legacy, Westholme Publishing, 2011) Helgoland, Penguin Random House 2021 / Helgoland, Adelphi, 2020. There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness, Penguin Random House, 2020 / Ci sono luoghi al mondo dove più che le regole è importante la gentilezza, Solferino, 2020. The Order of Time, Penguin Random House, 2018 / L'ordine del tempo, Adelphi, 2017. Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity, Penguin Random House, 2016 / La realtà non è come ci appare: La struttura elementare delle cose, Raffaello Cortina Editore, 2014. Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, Penguin Random House, 2015 / Sette brevi lezioni di fisica, Adelphi, 2014. Marion Lignana Rosenberg (translator), The First Scientist: Anaximander and his legacy, Westholme Publishing, 2011 / Che cos'è la Scienza. La rivoluzione di Anassimandro., Mondadori, 2012. What is time, what is space? (interview), Di Renzo Editore, 2006 / Che cos'è il tempo, che cos'é lo spazio?, Di Renzo Editore, 2004. Bologna, marzo 1977 ...fatti nostri..., a cura di e con Enrico Palandri, Claudio Piersanti [it], Maurizio Torrealta et alii, Verona, Bertani, 1977; Rimini, NdA press, 2007, ISBN 978-88-89035-17-7. General Relativity: The Essentials, Cambridge University Press, 2021. White Holes, Penguin Random House, 2023 |

人気書籍 アイコン このセクションには掲載されている書籍のISBNが不足している。この情報を追加するか、引用ボットを実行してほしい。 アナクシマンドロス:そして科学の誕生、ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2023年[53](『最初の科学者:アナクシマンドロスとその遺産』ウェストホルム出版、2011年の再刊) ヘルゴラント、ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2021年 / ヘルゴラント、アデルフィ、2020年。 この世にはルールより優しさが大切だとされる場所がある、ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2020年 / この世にはルールより優しさが大切だとされる場所がある、ソルフェリーノ、2020年。 『時間の秩序』ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2018年/『時間の秩序』アデルフィ、2017年。 『現実は見かけとは違う:量子重力への旅』ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2016年/『現実は見かけとは違う:物事の根本構造』ラファエロ・コルティーナ出版社、2014年。 物理学の七つの短い講義、ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2015年/物理学の七つの短い講義、アデルフィ、2014年。 マリオン・リニャーナ・ローゼンバーグ(訳)、最初の科学者:アナクシマンドロスとその遺産、ウェストホルム出版、2011年/科学とは何か。アナクシマンドロスの革命、モンダドーリ、2012年。 時間とは何か、空間とは何か?(インタビュー)、ディ・レンツォ・エディトーレ、2006年/『時間とは何か、空間とは何か?』ディ・レンツォ・エディトーレ、2004年。 ボローニャ、1977年3月...私たちの出来事...、エンリコ・パランドリ、クラウディオ・ピエルサンティ[イタリア語]、マウリツィオ・トリアルタ 他編、ヴェローナ、ベルターニ社、1977年;リミニ、NdAプレス、2007年、ISBN 978-88-89035-17-7。 一般相対性理論:基本概念、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2021年。 ホワイトホール、ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2023年。 |

| References 01. "Resume" (PDF). www.cpt.univ-mrs.fr. "Facultypage". www.perimeterinstitute.ca. "Faculty". www.rotman.uwo.ca. "Fractal faculty". www.santafe.edu/people/profile/carlo-rovelli. Carlo Rovelli (25 July 2017). "Carlo Rovelli: 'I felt the beautiful adventure of physics was a story that had to be told'". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2018. "2019 Global Thinkers". Foreign Policy. 12 January 2019. "The world's top 50 thinkers 2021". Prospect Magazine. 13 July 2021. Carlo Rovelli, "Fatti Nostri". "Fatti Nostri", Bertani editore, 1977, (re-edited Rimini, Nda Press, 2007), ISBN 978-88-89035-17-7 10. "Send us your questions for Carlo Rovelli", The Guardian, 5-3-2019. Retrieved 1-6-2023. Higgins, Charlotte (14 April 2018). "'There is no such thing as past or future': physicist Carlo Rovelli on changing how we think about time". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 January 2022. Carlo Rovelli, "Cos'è il tempo? Cos'è lo spazio?". "Artista". archivio.festivaldelleletterature.it. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2022. Laurent, Lionel (29 February 2008). "Is Time Just A Trick Of The Mind?". Forbes.com. Retrieved 4 January 2011. - Carlo Rovelli. "Carlo Rovelli forecasts the future". New Scientist. Retrieved 4 January 2011. Zwanzig, R. (1973). "Nonlinear generalized Langevin equations". Journal of Statistical Physics. 9 (3): 215–220. Bibcode:1973JSP.....9..215Z. doi:10.1007/BF01008729. S2CID 121594079. Caldeira, A. O.; Leggett, A. J. (1981). "Influence of Dissipation on Quantum Tunneling in Macroscopic Systems". Physical Review Letters. 46 (4): 211–214. Bibcode:1981PhRvL..46..211C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.46.211. ISSN 0031-9007. "Relational Quantum Mechanics" The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition). van Fraassen, Bas C. (11 July 2009). "Rovelli's World" (PDF). Foundations of Physics. 40 (4): 390–417. Bibcode:2010FoPh...40..390V. doi:10.1007/s10701-009-9326-5. S2CID 17217776. Smerlak, Matteo; Rovelli, Carlo (3 February 2007). "Relational EPR". Foundations of Physics. 37 (3): 427–445. arXiv:quant-ph/0604064. Bibcode:2007FoPh...37..427S. doi:10.1007/s10701-007-9105-0. S2CID 11816650. 20. Carlo Rovelli, Relative information at the foundation of physics (Marseille, CPT & Toulon U.). October 31, 2013. 3 pp.; Published in "It from Bit or Bit from It? On Physics and information", A Aguirre, B Foster and Z Merali eds., 79-86 (Springer 2015) - Carlo Rovelli, Relative information at the foundation of physics, Arxiv.org. Retrieved 2019-10-01. Archived 2020-07-27 at the Wayback Machine "What scientific term or concept ought to be more widely known? - Relative Information", Edge.org, 2017. Retrieved 13-9-2019 Carlo Rovelli, Anaximandre de Millet, ou la naissance de la science, Dunod, 2009; Che cos'è la scienza. La rivoluzione di Anassimandro, Mondadori Università, 2011; Carlo Rovelli, The first scientist. Anaximander and his legacy, Westholme Publishing, 2011. Anaximandre de Millet, ou la naissance de la science, pg. 180. Anaximandre de Millet, ou la naissance de la science, pg. 75. There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness, Penguin Random House, 2020 The First Scientist, pg. 153. Bologna, marzo 1977 ...fatti nostri..., Bertani, 1978 "‘Colossal waste’: Nobel laureates call for 2% cut to military spending worldwide", The Guardian 14-12-2-2021, 2017. Retrieved 1-6-2023 "Rovelli: «Al Primo Maggio ho detto quello che pensavo: non sono filorusso, ma questo governo fa scelte bellicose»", Corriere della Sera 23-5-2023, 2017. Retrieved 1-6-2023 "Caso Rovelli, la retromarcia di Levi: il fisico sarà alla Fiera di Francoforte", Corriere della Sera, 23-3-2023. 30. "Ricardo Franco Levi, lettera di dimissioni a Sangiuliano dopo il caso Rovelli e le polemiche sul figlio", Il Messaggero 26-5-2023, 2017. Retrieved 1-6-2023 Rovelli, Carlo (26 October 2023). "The new global arms race will lead to catastrophe. The west can pursue it — or choose peace". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 October 2023. "International Initiative for Peace". International Initiative for Peace. 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2025. "Theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli to receive 2024 Lewis Thomas Prize". www.rockefeller.edu. "Award list". ISGRG. "Carlo Rovelli, doctor Honoris Causa de la UNSAM » Noticias UNSAM". noticias.unsam.edu.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 April 2018. "Il progetto Pagine di scienza premia il prof Rovelli". Il Tirreno (in Italian). 23 March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2018. "Consegnato a Carlo Rovelli il premio "Alassio per l'Informazione Culturale"". Ecodisavona (in Italian). Retrieved 6 April 2018. "Il quarto Premio Larderello al fisico Carlo Rovelli". il Tirreno (in Italian). 18 August 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2018. 40. Topolino no. 3175, 2016. ItalianPostNews (23 November 2022). "Belladonna are auctioning off a song with Carlo Rovelli as Nft". Italian Post. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022. s.r.l, Rockol com. "√ Belladonna, all'asta un NFT con Carlo Rovelli". Rockol (in Italian). Retrieved 27 November 2022. Adnkronos (23 November 2022). "I Belladonna mettono all'asta come Nft un brano con Carlo Rovelli". Adnkronos. Retrieved 27 November 2022. Adnkronos (18 October 2023). "√ Musica, i Belladonna e Carlo Rovelli nel ballott dei Grammy Awards". Adnkronos (in Italian). Retrieved 18 October 2023. Alan Lightman (14 May 2018). "Benedict Cumberbatch Meets Albert Einstein in Carlo Rovelli's New Audiobook". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 October 2019. "Carlo Rovelli e l'incontro con la Cavani: «È la mia regista mito. A 17 anni vidi 'Il portiere di notte' e fu una fucilata»". Corriere della Sera. 25 August 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2024. "Professor Carlo Rovelli". BBC Radio 4. BBC. Retrieved 1 October 2019. "Carlo Rovelli on why time is not what it seems". BBC Radio 4. The Life Scientific. BBC. Retrieved 30 January 2020. "Carlo Rovelli". BBC Radio 3. 2020. 50. "A Good Read Nick Hornby & Carlo Rovelli". BBC Radio 4. A Good Read. BBC. Retrieved 30 January 2020. Halperin, Jonathan; Takahashi, Drew (26 September 2022), A Trip to Infinity (Documentary), Makemake, Room 608, retrieved 8 November 2023 "The Museum of Curiosity - Series 17 - Episode 1". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC Sounds. Retrieved 4 March 2023. "Anaximander: And the Birth of Science Kindle Edition". amazon.com. Retrieved 18 May 2022. |

参考文献 01. 「履歴書」(PDF)。www.cpt.univ-mrs.fr。 「教員ページ」。www.perimeterinstitute.ca。 「教員」。www.rotman.uwo.ca。 「フラクタル教員」。www.santafe.edu/people/profile/carlo-rovelli。 カルロ・ロヴェッリ (2017年7月25日). 「カルロ・ロヴェッリ:『物理学の美しい冒険は語られるべき物語だと感じた』」. ガーディアン. 2018年4月5日閲覧. 「2019年世界の思想家」. フォーリン・ポリシー. 2019年1月12日. 「2021年世界の思想家トップ50」. プロスペクト・マガジン。2021年7月13日。 カルロ・ロヴェッリ、「ファッティ・ノストリ」。 「ファッティ・ノストリ」、ベルターニ出版社、1977年、(再版 リミニ、Ndaプレス、2007年)、ISBN 978-88-89035-17-7 10. 「カルロ・ロヴェッリへの質問を送ってください」『ガーディアン』2019年3月5日。2023年6月1日取得。 ヒギンズ、シャーロット(2018年4月14日)。「『過去も未来も存在しない』:物理学者カルロ・ロヴェッリが語る時間の概念の変革」。『ガーディアン』。2022年1月10日取得。 カルロ・ロヴェッリ「時間とは何か?空間とは何か?」 「アーティスト」archivio.festivaldelleletterature.it. 2012年5月21日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年1月14日閲覧。 ローラン、ライオネル(2008年2月29日)「時間は単なる心のトリックなのか?」フォーブス・ドットコム。2011年1月4日閲覧。 - カルロ・ロヴェッリ. 「カルロ・ロヴェッリが未来を予測する」. ニュー・サイエンティスト. 2011年1月4日閲覧。 ツヴァンツィグ, R. (1973). 「非線形一般化ランジュバン方程式」. Journal of Statistical Physics. 9 (3): 215–220. Bibcode:1973JSP.....9..215Z. doi:10.1007/BF01008729. S2CID 121594079. カルデイラ, A. O.; レゲット, A. J. (1981). 「巨視的系における量子トンネル効果への散逸の影響」. 物理レビューレターズ. 46 (4): 211–214. Bibcode:1981PhRvL..46..211C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.46.211. ISSN 0031-9007. 「関係性量子力学」スタンフォード哲学百科事典(2021年冬版)。 ファン・フラッセン、バス・C.(2009年7月11日)。「ロヴェッリの世界」 (PDF)。物理学基礎。40 (4): 390–417。Bibcode:2010FoPh...40..390V. doi:10.1007/s10701-009-9326-5. S2CID 17217776. Smerlak, Matteo; Rovelli, Carlo (2007年2月3日). 「関係性EPR」. Foundations of Physics. 37 (3): 427–445. arXiv:quant-ph/0604064. Bibcode:2007FoPh...37..427S. doi:10.1007/s10701-007-9105-0. S2CID 11816650. 20. カルロ・ロヴェッリ, 物理学の基礎における相対情報 (マルセイユ, CPT & トゥーロン大学). 2013年10月31日. 3頁; 「ビットからイットか、イットからビットか?物理学と情報について」A Aguirre, B Foster, Z Merali 編, 79-86頁 (Springer 2015) に収録 - カルロ・ロヴェッリ, 物理学の基礎における相対情報, Arxiv.org. 2019年10月1日取得. 2020年7月27日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ 「より広く知られるべき科学用語や概念は何か? - 相対情報」, Edge.org, 2017年. 2019年9月13日取得 カルロ・ロヴェッリ『アナクシマンドロス・ド・ミレー、あるいは科学の誕生』デュノド社、2009年;『科学とは何か。アナクシマンドロスの革命』モンダ ドーリ大学出版、2011年;カルロ・ロヴェッリ『最初の科学者。アナクシマンドロスとその遺産』ウェストホルム出版、2011年。 アナクシマンドロス・ド・ミレー、あるいは科学の誕生、180ページ。 アナクシマンドロス・ド・ミレー、あるいは科学の誕生、75ページ。 この世界には、ルールより優しさが大切だとされる場所がある、ペンギン・ランダムハウス、2020年 最初の科学者、153ページ。 ボローニャ、1977年3月...fatti nostri..., ベルターニ社、1978年 「『途方もない浪費』:ノーベル賞受賞者らが世界の軍事費2%削減を要求」『ガーディアン』2021年12月14日、2017年。2023年6月1日取得 「ロヴェッリ:『メーデーで思ったことを言っただけだ。俺は親ロシア派じゃないが、この政府は好戦的な選択をしている』」『コリエーレ・デラ・セラ』2023年5月23日、2017年。2023年6月1日取得 「ロヴェッリ事件、レヴィの撤回:物理学者はフランクフルト見本市に出席する」『コリエーレ・デラ・セラ』2023年3月23日 30. 「リカルド・フランコ・レヴィ、ロヴェッリ事件と息子をめぐる論争を受けサンジュリアーノに辞表」『イル・メッサッジェロ』2023年5月26日 2023年6月1日取得 ロヴェッリ、カルロ(2023年10月26日)。「新たな世界的な軍拡競争は破滅を招く。西側諸国はそれを追求するか、平和を選ぶかだ」。ガーディアン。ロンドン、イギリス。ISSN 0261-3077。2023年10月26日取得。 「国際平和イニシアチブ」。国際平和イニシアチブ。2023年。2025年12月7日取得。 「理論物理学者カルロ・ロヴェッリ、2024年ルイス・トーマス賞受賞」。www.rockefeller.edu。 「受賞者一覧」。ISGRG。 「カルロ・ロヴェッリ、UNSAM名誉博士号授与」『UNSAMニュース』. noticias.unsam.edu.ar (スペイン語). 2018年4月6日閲覧. 「科学ページプロジェクト、ロヴェッリ教授を表彰」『イル・ティレノ』 (イタリア語). 2015年3月23日. 2018年4月6日閲覧. 「カルロ・ロヴェッリに『文化情報アッラッシオ賞』授与」。エコディサヴォーナ(イタリア語)。2018年4月6日閲覧。 「第4回ラルデレロ賞、物理学者カルロ・ロヴェッリに授与」。イル・ティレノ(イタリア語)。2015年8月18日。2018年4月6日閲覧。 40. トポリーノ第3175号、2016年。 ItalianPostNews(2022年11月23日)。「ベラドンナ、カルロ・ロヴェッリをフィーチャーした楽曲をNFTとしてオークション出品」。Italian Post。2022年11月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年11月27日閲覧。 s.r.l, Rockol com. 「ベラドンナ、カルロ・ロヴェッリとのNFTをオークションへ」. Rockol (イタリア語). 2022年11月27日閲覧. Adnkronos (2022年11月23日). 「ベラドンナ、カルロ・ロヴェッリとの楽曲をNFTとしてオークションへ」. Adnkronos. 2022年11月27日閲覧. Adnkronos (2023年10月18日). 「√ ミュージック、ベラドンナとカルロ・ロヴェッリがグラミー賞候補に」. Adnkronos (イタリア語). 2023年10月18日閲覧。 アラン・ライトマン (2018年5月14日). 「ベネディクト・カンバーバッチ、カルロ・ロヴェッリの新オーディオブックでアルバート・アインシュタインと出会う」. ニューヨーク・タイムズ。2019年10月1日閲覧。 「カルロ・ロヴェッリとカヴァーニ監督の出会い:『彼女は私の憧れの監督だ。17歳の時に『夜番』を見て衝撃を受けた』」。コリエーレ・デラ・セーラ。2023年8月25日。2024年9月16日閲覧。 「カルロ・ロヴェッリ教授」BBCラジオ4。BBC。2019年10月1日取得。 「カルロ・ロヴェッリが語る、時間が思われているものとは違う理由」BBCラジオ4。『ザ・ライフ・サイエンティフィック』。BBC。2020年1月30日取得。 「カルロ・ロヴェッリ」BBCラジオ3。2020年。 50. 「グッド・リード ニック・ホーンビー&カルロ・ロヴェッリ」. BBCラジオ4. A Good Read. BBC. 2020年1月30日閲覧. ハルペリン, ジョナサン; 高橋ドリュー (2022年9月26日), 『無限への旅』(ドキュメンタリー), マケマケ, Room 608, 2023年11月8日閲覧 「好奇心の博物館 - シリーズ17 - 第1話」。www.bbc.co.uk。BBC Sounds。2023年3月4日閲覧。 「アナクシマンドロス:そして科学の誕生 Kindle版」。amazon.com。2022年5月18日閲覧。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlo_Rovelli |

★

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆