親密な関係

Intimate relationship

☆

親密な関係とは、人々の間に感情的または身体的な親密さを伴う対人関係であり、恋愛感情やプラトニックな愛情、性的親密さを含むことがある。[1]

親密な関係は相互依存的であり、関係者は互いに影響し合う。[2]

その質と性質は個人間の相互作用に依存し、時間をかけて築かれる独自の文脈と歴史から派生する。[3][4][5]

結婚などの社会的・法的制度は、人々の間の親密な関係を認め支える。しかし、親密な関係が一夫一婦制であるとか性的であるとは限らず、人々の間の親密さの

規範や慣行には社会的・文化的に大きな多様性がある。

親密な関係の過程には、相互の惹かれ合いと、次第に深まる親密さや親しみの感覚によって促される形成期が含まれる。親密な関係は維持される中で時間ととも

に変化し、関係者はより深く関与し、関係へのコミットメントを強めることがある。健全な親密な関係は心理的・身体的健康に有益であり、人生全体の幸福に寄

与する。[6] しかし、関係上の葛藤、外部ストレス、不安感、嫉妬といった課題が関係を乱し、苦痛や関係の解消を招くこともある。

| An intimate

relationship is an interpersonal relationship that involves emotional

or physical closeness between people and can include feelings of

romantic or platonic love and sexual intimacy.[1] Intimate

relationships are interdependent, and the members of the relationship

mutually influence each other.[2] The quality and nature of the

relationship depends on the interactions between individuals, and is

derived from the unique context and history that builds between people

over time.[3][4][5] Social and legal institutions such as marriage

acknowledge and uphold intimate relationships between people. However,

intimate relationships are not necessarily monogamous or sexual, and

there is wide social and cultural variability in the norms and

practices of intimacy between people. The course of an intimate relationship includes a formation period prompted by interpersonal attraction and a growing sense of closeness and familiarity. Intimate relationships evolve over time as they are maintained, and members of the relationship may become more invested in and committed to the relationship. Healthy intimate relationships are beneficial for psychological and physical well-being and contribute to overall happiness in life.[6] However, challenges including relationship conflict, external stressors, insecurity, and jealousy can disrupt the relationship and lead to distress and relationship dissolution. |

親密な関係とは、人々の間に感情的または身体的な親密さを伴う対人関係

であり、恋愛感情やプラトニックな愛情、性的親密さを含むことがある。[1] 親密な関係は相互依存的であり、関係者は互いに影響し合う。[2]

その質と性質は個人間の相互作用に依存し、時間をかけて築かれる独自の文脈と歴史から派生する。[3][4][5]

結婚などの社会的・法的制度は、人々の間の親密な関係を認め支える。しかし、親密な関係が一夫一婦制であるとか性的であるとは限らず、人々の間の親密さの

規範や慣行には社会的・文化的に大きな多様性がある。 親密な関係の過程には、相互の惹かれ合いと、次第に深まる親密さや親しみの感覚によって促される形成期が含まれる。親密な関係は維持される中で時間ととも に変化し、関係者はより深く関与し、関係へのコミットメントを強めることがある。健全な親密な関係は心理的・身体的健康に有益であり、人生全体の幸福に寄 与する。[6] しかし、関係上の葛藤、外部ストレス、不安感、嫉妬といった課題が関係を乱し、苦痛や関係の解消を招くこともある。 |

| Intimacy Intimacy is the feeling of being in close, personal association with another person.[7] Emotional intimacy is built through self-disclosure and responsive communication between people,[8] and is critical for healthy psychological development and mental health.[9] Emotional intimacy produces feelings of reciprocal trust, validation, vulnerability, and closeness between individuals.[10] Physical intimacy—including holding hands, hugging, kissing, and sex—promotes connection between people and is often a key component of romantic intimate relationships.[11] Physical touch is correlated with relationship satisfaction[12] and feelings of love.[13] While many intimate relationships include a physical or sexual component, the potential to be sexual is not a requirement for the relationship to be intimate. For example, a queerplatonic relationship is a non-romantic intimate relationship that involves commitment and closeness beyond that of a friendship.[14] Among scholars, the definition of an intimate relationship is diverse and evolving. Some reserve the term for romantic relationships,[15][16] whereas other scholars include friendship and familial relationships.[17] In general, an intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship in which physically or emotionally intimate experiences occur repeatedly over time.[9] |

親密さ 親密さとは、他者と密接で個人的な結びつきを感じることである。[7] 感情的な親密さは、自己開示と相互的なコミュニケーションを通じて築かれる。[8] これは健全な心理的発達と精神的健康にとって極めて重要である。[9] 感情的な親密さは、相互の信頼、承認、無防備さ、そして親密さという感情を生む。[10] 身体的親密さ——手をつなぐ、抱擁、キス、性行為など——は人と人とのつながりを促進し、しばしば恋愛的親密関係の重要な要素となる。[11] 身体的接触は関係満足度[12]や愛情の感情[13]と相関する。多くの親密な関係には身体的・性的要素が含まれるが、性的関係の可能性は親密な関係であ るための必須条件ではない。例えば、クィアプラトニックな関係は、友情を超えた献身と親密さを伴う非恋愛的な親密な関係である。[14] 学者の間では、親密な関係の定義は多様で進化している。この用語を恋愛関係に限定する学者もいる[15][16]一方、友情や家族関係も含める学者もいる [17]。一般的に、親密な関係とは、時間をかけて身体的または感情的に親密な体験が繰り返し起こる対人関係である[9]。 |

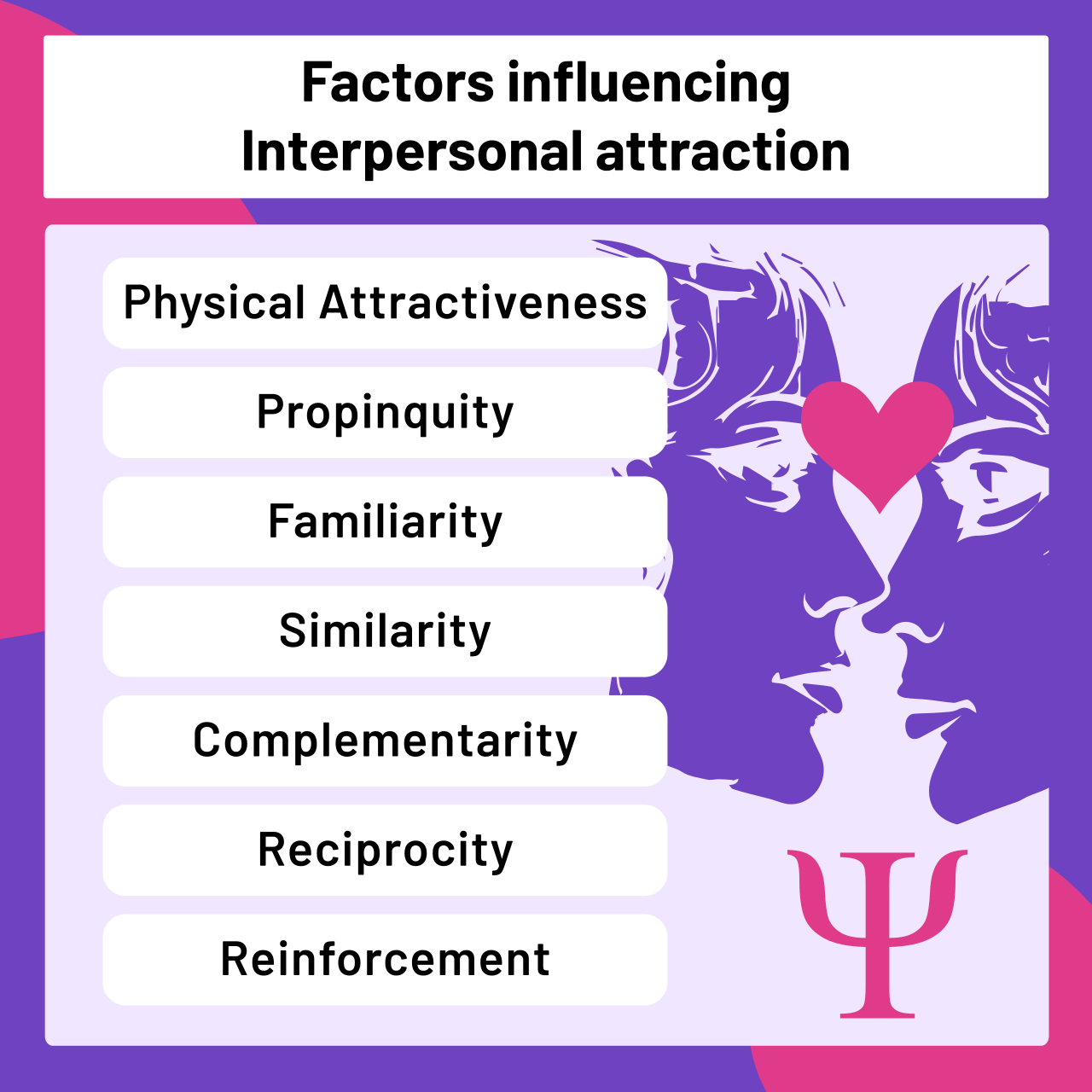

Course of intimate relationships Factors influencing Interpersonal attraction Formation Attraction Interpersonal attraction is the foundation of first impressions between potential intimate partners. Relationship scientists suggest that the romantic spark, or "chemistry", that occurs between people is a combination of physical attraction, personal qualities, and a build-up of positive interactions between people.[18] Researchers find physical attractiveness to be the largest predictor of initial attraction.[19] From an evolutionary perspective, this may be because people search for a partner (or potential mate) who displays indicators of good physical health.[20] Yet, there is also evidence that couples in committed intimate relationships tend to match each other in physical attractiveness, and are rated as similarly physically attractive by both the members of the couple and by outside observers.[21][16] An individual's perception of their own attractiveness may therefore influence who they see as a realistic partner.[16] Beyond physical appearance, people report desirable qualities they look for in a partner such as trustworthiness, warmth, and loyalty.[22] However, these romantic ideals are not necessarily good predictors of actual attraction or relationship success. Research has found little evidence for the success of matching potential partners based on personality traits, suggesting that romantic chemistry involves more than compatibility of traits.[23] Rather, repeated positive interactions between people and reciprocity of romantic interest seem to be key components in attraction and relationship formation. Reciprocal liking is most meaningful when it is displayed by someone who is selective about who they show liking to.[24] |

親密な関係の過程 対人魅力に影響する要因 形成 魅力 対人魅力は、潜在的な親密なパートナー間の第一印象の基盤である。関係科学者は、人々の間に生じるロマンチックな火花、すなわち「化学反応」は、身体的魅 力、個人的な資質、そして人々の間のポジティブな相互作用の積み重ねの組み合わせであると示唆している。[18] 研究者らは、身体的魅力が初期の魅力の最大の予測因子であると考えている。[19] 進化論的観点では、これは人々が良好な身体の健康の指標を示すパートナー(または潜在的な配偶者)を探すためかもしれない。[20] しかし、真剣な親密な関係にあるカップルは、身体的魅力において互いに一致する傾向があり、カップル双方および外部観察者によって同様に身体的に魅力的と 評価されるという証拠もある。[21] [16] したがって、個人が自覚する自身の魅力度は、現実的なパートナー候補像に影響を与える可能性がある。[16] 外見以上に、人々は信頼性、温かさ、忠誠心など、パートナーに求める望ましい資質を挙げる。[22] しかし、こうした恋愛観念は実際の魅力や関係性の成功を必ずしも予測しない。研究によれば、個人的な性格特性に基づくパートナー候補のマッチングが成功す る証拠はほとんど見られず、恋愛の相性には単なる特性の適合以上の要素が関与していることが示唆されている。[23] むしろ、人同士の繰り返される好ましい相互作用と、恋愛感情の相互性が、惹かれ合いや関係形成の重要な要素であるようだ。相互的な好意は、好意を示す相手 を厳選する人物から示された場合に最も意味を持つ。[24] |

| Initiation strategies When potential intimate partners are getting to know each other, they employ a variety of strategies to increase closeness and gain information about whether the other person is a desirable partner. Self-disclosure, the process of revealing information about oneself, is a crucial aspect of building intimacy between people.[25] Feelings of intimacy increase when a conversation partner is perceived as responsive and reciprocates self-disclosure, and people tend to like others who disclose emotional information to them.[26] Other strategies used in the relationship formation stage include humor, initiating physical touch, and signaling availability and interest through eye contact, flirtatious body language, or playful interactions.[27][28] Engaging in dating, courtship, or hookup culture as part of the relationship formation period allows individuals to explore different interpersonal connections before further investing in an intimate relationship.[29] |

接近戦略 潜在的な親密なパートナーが互いを知る過程では、親密さを高め、相手が望ましいパートナーかどうかを判断するための様々な戦略が用いられる。自己開示、す なわち自身に関する情報を明かす行為は、人間関係の親密さを築く上で重要な要素である[25]。会話相手が反応を示し、自己開示を返してくれると親密感は 増し、感情的な情報を開示してくれる相手を人は好む傾向がある。[26] 関係形成段階で使用される他の戦略には、ユーモア、身体的接触の開始、視線接触・軽妙なボディランゲージ・遊び心のある交流を通じた「空き状態」や「関 心」の示唆が含まれる。[27][28] 関係形成期間の一部としてデートや求愛、あるいはフックアップ文化に参加することは、個人が親密な関係にさらに投資する前に、異なる対人関係を探索するこ とを可能にする。[29] |

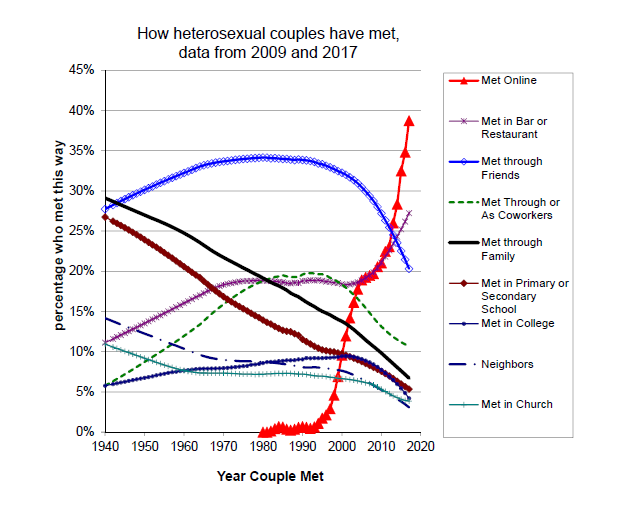

Context The internet has become a popular avenue for meeting an intimate partner. Context, timing, and external circumstances influence attraction and whether an individual is receptive to beginning an intimate relationship. Readiness for a relationship varies across the lifespan, and external pressures such as family expectations, peers being in committed relationships, and cultural norms can affect when people decide to pursue an intimate relationship.[30] Being in close physical proximity is a powerful facilitator for formation of relationships because it allows people to get to know each other through repeated interactions. Intimate partners commonly meet at college or school, as coworkers, as neighbors, at bars, or through religious community.[31] Speed dating, matchmakers, and online dating services are more structured formats used to begin relationships. The internet in particular has significantly changed how intimate relationships begin as it allows people to access potential partners beyond their immediate proximity.[32][33] In 2023, Pew Research Center found that 53% of people under 30 have used online dating, and one in ten adults in a committed relationship met their partner online.[34] However, there remains skepticism about the effectiveness and safety of dating apps due to their potential to facilitate dating violence.[34] |

文脈 インターネットは親密なパートナーと出会うための一般的な手段となった。 文脈、タイミング、外部環境は、惹かれる気持ちや親密な関係を始める意思に影響する。関係への準備態勢は生涯を通じて変化し、家族の期待、周囲の交際状況、文化的規範といった外部からの圧力が、親密な関係を追求する決断時期に影響する。[30] 物理的に近い距離にいることは、繰り返しの交流を通じて互いを知る機会を与えるため、関係形成の強力な促進要因となる。親密なパートナーは、大学や学校、 職場、近隣住民、バー、宗教コミュニティなどで出会うことが多い。[31] スピードデート、仲人、オンラインデートサービスは、より構造化された関係開始の形式である。特にインターネットは、身近な範囲を超えた潜在的なパート ナーへのアクセスを可能にしたことで、親密な関係の始まり方を大きく変えた。[32][33] 2023年、ピュー・リサーチ・センターは30歳未満の53%がオンラインデートを利用したことがあり、真剣な関係にある成人の10人に1人がオンライン でパートナーと出会ったと報告した。[34] しかし、デートアプリがデート暴力を助長する可能性があるため、その有効性と安全性に対する懐疑的な見方は依然として存在する。[34] |

| Maintenance Main article: Relationship maintenance Once an intimate relationship has been initiated, the relationship changes and develops over time, and the members may engage in commitment agreements and maintenance behaviors. In an ongoing relationship, couples must navigate protecting their own self-interest alongside the interest of maintaining the relationship.[35] This necessitates compromise, sacrifice, and communication.[36] In general, feelings of intimacy and commitment increase as a relationship progresses, while passion plateaus following the excitement of the early stages of the relationship.[37] Engaging in ongoing positive shared communication and activities is important for strengthening the relationship and increasing commitment and liking between partners. These maintenance behaviors can include providing assurances about commitment to the relationship, engaging in shared activities, openly disclosing thoughts and feelings, spending time with mutual friends, and contributing to shared responsibilities.[38][39] Physical intimacy including sexual behavior also increases feelings of closeness and satisfaction with the relationship.[40] However, sexual desire is often greatest early in a relationship, and may wax and wane as the relationship evolves.[41] Significant life events such as the birth of a child can drastically change the relationship and necessitate adaptation and new approaches to maintaining intimacy. The transition to parenthood can be a stressful period that is generally associated with a temporary decrease in healthy relationship functioning and a decline in sexual intimacy.[42][43] |

関係維持 詳細な記事: 関係維持 親密な関係が始まると、その関係は時間とともに変化し発展する。関係者はコミットメントの合意や維持行動を取ることもある。継続的な関係では、カップルは 自己の利益を守りつつ、関係維持の利益も考慮しなければならない[35]。これには妥協、犠牲、コミュニケーションが不可欠だ[36]。一般的に、親密さ やコミットメントの感覚は関係が進むにつれて高まるが、情熱は関係の初期段階の興奮期を過ぎると頭打ちになる。 継続的な前向きな共有コミュニケーションや活動は、関係を強化し、パートナー間のコミットメントと好意を高める上で重要だ。こうした維持行動には、関係へ のコミットメントを保証すること、共有活動に従事すること、思考や感情を率直に開示すること、共通の友人と時間を過ごすこと、共有責任に貢献することが含 まれる。[38][39] 性的行動を含む身体的親密さも、関係の親密感や満足感を高める。[40] ただし性的欲求は関係初期に最も高まり、関係の進展と共に増減する傾向がある。[41] 子供の誕生といった重大な人生イベントは関係を劇的に変え、親密さを維持するための適応や新たなアプローチを必要とする。親になる過程はストレスの多い時 期であり、一般的に健全な関係機能の一時的な低下や性的親密さの減退と関連している。[42][43] |

Commitment Marriage is a form of relationship maintenance that signals commitment between partners. As a relationship develops, intimate partners often engage in commitment agreements, ceremonies, and behaviors to signal their intention to remain in the relationship.[44] This might include moving in together, sharing responsibilities or property, and getting married. These commitment markers increase relationship stability because they create physical, financial, and symbolic barriers and consequences to dissolving the relationship.[45] In general, increases in relationship satisfaction and investment are associated with increased commitment.[46] |

コミットメント 結婚とは、パートナー間のコミットメントを示す関係維持の一形態である。 関係が発展するにつれ、親密なパートナーはしばしば、関係を維持する意思を示すために、コミットメントの合意や儀式、行動を取る。[44] これには同居、責任や財産の共有、結婚などが含まれる。こうしたコミットメントの指標は、関係を解消することに対する物理的、経済的、象徴的な障壁や結果 を生み出すため、関係の安定性を高める。[45] 一般的に、関係の満足度や投資の増加は、コミットメントの強化と関連している。[46] |

| Evaluating the relationship Individuals in intimate relationships evaluate the relative personal benefits and costs of being in the relationship, and this contributes to the decision to stay or leave. The investment model of commitment is a theoretical framework that suggests that an evaluation of relationship satisfaction, relationship investment, and the quality of alternatives to the relationship impact whether an individual remains in a relationship.[35] Because relationships are rewarding and evolutionarily necessary, and rejection is a stressful process, people are generally biased toward making decisions that uphold and further facilitate intimate relationships.[47] These biases can lead to distortions in the evaluation of a relationship. For instance, people in committed relationships tend to dismiss and derogate attractive alternative partners, thereby validating the decision to remain with their more attractive partner.[48] |

関係性の評価 親密な関係にある個人は、その関係に身を置くことの相対的な個人的利益とコストを評価し、これが関係を継続するか離れるかの決定に寄与する。コミットメン トの投資モデルは、関係満足度、関係への投資、および関係に代わる選択肢の質の評価が、個人が関係を継続するかどうかに影響を与えると示唆する理論的枠組 みである。 [35] 関係は報酬をもたらし進化的に必要であり、拒絶はストレスの多いプロセスであるため、人々は一般的に親密な関係を維持し促進する決断に偏る傾向がある。 [47] こうした偏りは関係評価の歪みを引き起こしうる。例えば、固い関係にある人々は魅力的な代替パートナーを軽視し貶める傾向があり、それによってより魅力的 なパートナーと留まる決断を正当化する。[48] |

| Dissolution The decision to leave a relationship often involves an evaluation of levels of satisfaction and commitment in the relationship.[49] Relationship factors such as increased commitment and feelings of love are associated with lower chances of breakup, whereas feeling ambivalent about the relationship and perceiving many alternatives to the current relationship are associated with increased chances of dissolution.[50] Predictors of dissolution Specific individual characteristics and traits put people at greater risk for experiencing relationship dissolution. Individuals high in neuroticism (the tendency to experience negative emotions) are more prone to relationship dissolution,[51] and research also shows small effects of attachment avoidance and anxiety in predicting breakup.[50] Being married at a younger age, having lower income, lower educational attainment, and cohabiting before marriage are also associated with risk of divorce and relationship dissolution. These characteristics are not necessarily the inherent causes of dissolution. Rather, they are traits that impact the resources that individuals are able to draw upon to work on their relationships as well as reflections of social and cultural attitudes toward relationship institutions and divorce.[52] Strategies and consequences Common strategies for ending a relationship include justifying the decision, apologizing, avoiding contact (ghosting), or suggesting a "break" period before revisiting the decision.[51] The dissolution of an intimate relationship is a stressful event that can have a negative impact on well-being, and the rejection can elicit strong feelings of embarrassment, sadness, and anger.[53] Following a relationship breakup, individuals are at risk for anxiety, depressive symptoms, problematic substance use, and low self-esteem.[54][55] However, the period following a break-up can also promote personal growth, particularly if the previous relationship was not fulfilling.[56] |

関係の解消 関係を離れる決断には、往々にしてその関係における満足度やコミットメントの度合いが評価される。[49] コミットメントの高まりや愛情といった関係要因は別れが起こりにくいことと関連している一方、関係に対する両価的な感情や現在の関係に代わる選択肢が多い という認識は、解消の可能性が高まることと関連している。[50] 解消の予測因子 特定の個人の特性や性質は、関係解消を経験するリスクを高める。神経症的傾向(ネガティブな感情を経験しやすい性質)が強い個人は関係解消を起こしやすい [51]。また、愛着回避や愛着不安が別れを予測する上でわずかな影響を持つことも研究で示されている[50]。若年結婚、低所得、低学歴、婚前同居も離 婚や関係解消のリスクと関連している。これらの特性は必ずしも解消の根本原因ではない。むしろ、関係修復に活用できる個人の資源に影響を与える特性である と同時に、関係制度や離婚に対する社会的・文化的態度の反映でもある。[52] 戦略と結果 関係を終わらせる一般的な戦略には、決断を正当化すること、謝罪すること、連絡を避けること(ゴーストング)、あるいは決断を再考する前に「休憩」期間を 提案することが含まれる。[51] 親密な関係の解消はストレスの多い出来事であり、幸福度に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があり、拒絶は強い恥ずかしさ、悲しみ、怒りの感情を引き起こす。[53] 関係解消後、個人は不安、抑うつ症状、問題のある物質使用、低い自尊心のリスクに晒される。[54][55] しかし、別れた後の期間は、特に以前の関係が満たされていなかった場合、個人的な成長を促進することもある。[56] |

| Benefits Psychological well-being  Intimate relationships impact well-being. Intimate relationships impact happiness and satisfaction with life.[6] While people with better mental health are more likely to enter intimate relationships, the relationships themselves also have a positive impact on mental health even after controlling for the selection effect.[57] In general, marriage and other types of committed intimate relationships are consistently linked to increases in happiness.[58] Furthermore, due to the interdependent nature of relationships, one partner's life satisfaction influences and predicts change in the other person's life satisfaction even after controlling for relationship quality.[59] Social support Social support from an intimate partner is beneficial for coping with stress and significant life events.[60] Having a close relationship with someone who is perceived as responsive and validating helps to alleviate the negative impact of stress,[61] and shared activities with an intimate partner aids in regulating emotions associated with stressful experiences.[62] Support for positive experiences can also improve relationship quality and increase shared positive emotions between people. When a person responds actively and constructively to their partner sharing good news (a process called "capitalization"), well-being for both individuals increases.[63][64] Sexual intimacy In intimate relationships that are sexual, sexual satisfaction is closely tied to overall relationship satisfaction.[65] Sex promotes intimacy, increases happiness,[66] provides pleasure, and reduces stress.[67][68] Studies show that couples who have sex at least once per week report greater well-being than those who have sex less than once per week.[69] Research in human sexuality finds that the ingredients of high quality sex include feeling connected to your partner, good communication, vulnerability, and feeling present in the moment. High quality sex in intimate relationships can both strengthen the relationship and improve well-being for each individual involved.[70] Physical health High quality intimate relationships have a positive impact on physical health,[71] and associations between close relationships and health outcomes involving the cardiovascular, immune, and endocrine systems have been consistently identified in the scientific literature.[72] Better relationship quality is associated lower risk of mortality[73] and relationship quality impacts inflammatory responses such as cytokine expression and intracellular signaling.[74][75] Furthermore, intimate partners are an important source of social support for encouraging healthy behaviors such as increasing physical activity[76] and quitting smoking.[77] Sexual activity and other forms of physical intimacy also contribute positively to physical health,[78] while conflict between intimate partners negatively impacts the immune and endocrine systems and can increase blood pressure.[72] Laboratory experiments show evidence for the association between support from intimate partners and physical health. In a study assessing recovery from wounds and inflammation, individuals in relationships high in conflict and hostility recovered from wounds more slowly than people in low-hostility relationships.[79] The presence or imagined presence of an intimate partner can even impact perceived pain. In fMRI studies, participants who view an image of their intimate partner report less pain in response to a stimulus compared to participants who view the photo of a stranger.[80][81] In another laboratory study, women who received a text message from their partner showed reduced cardiovascular response to the Trier Social Stress Test, a stress-inducing paradigm.[82] |

利点 心理的幸福感  親密な関係は幸福感に影響する。 親密な関係は幸福感と人生への満足度に影響する。[6] 精神的に健康な人は親密な関係に入りやすいが、選択効果を調整した後でも、関係そのものが精神的な健康に良い影響を与える。[57] 一般的に、結婚やその他の種類の献身的な親密な関係は、幸福度の向上と一貫して関連している。[58] さらに、関係性の相互依存的な性質により、関係品質を調整した後でも、一方のパートナーの生活満足度は他方の生活満足度の変化に影響を与え、予測する。 [59] 社会的支援 親密なパートナーからの社会的支援は、ストレスや重大な人生イベントへの対処に有益である。[60] 反応的で承認してくれると認識される人物との親密な関係は、ストレスの負の影響を軽減するのに役立つ。[61] また、親密なパートナーとの共有活動は、ストレス体験に伴う感情の調節を助ける。[62] ポジティブな体験への支援は、関係性の質を向上させ、人々の間で共有されるポジティブな感情を増大させることもできる。パートナーが良い知らせを共有した 際に、積極的かつ建設的に応答する(「資本化」と呼ばれるプロセス)と、双方の幸福感が増す。[63][64] 性的親密さ 性的関係を含む親密な関係において、性的満足度は関係全体の満足度と密接に関連している。[65] セックスは親密さを促進し、幸福感を高め[66]、快楽をもたらし、ストレスを軽減する。[67][68] 研究によれば、週に1回以上性行為を持つカップルは、それ以下の頻度の人々より幸福度が高いと報告されている。[69] 人間の性に関する研究では、質の高い性行為の要素として、パートナーとの繋がりを感じること、良好なコミュニケーション、心の弱さをさらけ出すこと、その 瞬間に没頭している感覚が挙げられている。親密な関係における質の高い性行為は、関係性を強化すると同時に、関わる各個人の幸福度を向上させ得る。 [70] 身体の健康 質の高い親密な関係は身体の健康に好影響を与える[71]。科学文献では、親密な関係と心血管・免疫・内分泌系に関わる健康結果との関連性が一貫して確認 されている[72]。良好な関係性は死亡リスク低下と関連し[73]、サイトカイン発現や細胞内シグナル伝達といった炎症反応にも影響を及ぼす。[74] [75] さらに、親密なパートナーは、身体活動の増加[76]や禁煙[77]といった健康的な行動を促す社会的支援の重要な源である。性的活動やその他の身体的親 密さも身体の健康に好影響を与える[78]一方、親密なパートナー間の葛藤は免疫系や内分泌系に悪影響を及ぼし、血圧上昇を引き起こす可能性がある。 [72] 実験室での研究は、親密なパートナーからの支援と身体的健康の関連性を示している。傷や炎症からの回復を評価した研究では、対立や敵意の強い関係にある人 々は、敵意の少ない関係にある人々に比べて傷の回復が遅かった。[79] 親密なパートナーの実際の存在や想像上の存在は、痛みの知覚にも影響を与える。fMRI研究では、親密なパートナーの画像を見た被験者は、見知らぬ人の写 真を見た被験者と比べて刺激に対する痛みの報告が少なかった。[80][81] 別の実験室研究では、パートナーからテキストメッセージを受け取った女性は、ストレス誘導パラダイムであるトライアー社会ストレステストに対する心血管反 応が低下した。[82] |

| Challenges Conflict Disagreements within intimate relationships are a stressful event,[83] and the strategies couples use to navigate conflict impact the quality and success of the relationship.[84] Common sources of conflict between intimate partners include disagreements about the balance of work and family life, frequency of sex, finances, and household tasks.[85] Psychologist John Gottman's research has identified three stages of conflict in couples. First, couples present their opinions and feelings on the issue. Next, they argue and attempt to persuade the other of their viewpoint, and finally, the members of the relationship negotiate to try to arrive at a compromise.[86] Individuals vary in how they typically engage with conflict.[86] Gottman describes that happy couples differ from unhappy couples in their interactions during conflict: unhappy couples tend to use more frequent negative tone of voice, show more predictable behavior during communication, and get stuck in cycles of negative behavior with their partner.[87][16] Other unproductive strategies within conflict include avoidance and withdrawal, defensiveness, and hostility.[88] These responses may be salient when an individual feels threatened by the conflict, which can be a reflection of insecure attachment orientation and previous negative relationship experiences.[83] When conflicts go unresolved, relationship satisfaction is negatively impacted.[89] Constructive conflict resolution strategies include validating the other person's point of view and concerns, expressing affection, using humor, and active listening. However, the effectiveness of these strategies depend on the topic and severity of the conflict and the characteristics of the individuals involved.[84] Repeated stressful instances of unresolved conflict might cause intimate partners to seek couples counseling, consult self-help resources, or consider ending the relationship.[90] |

課題 葛藤 親密な関係における意見の相違はストレスの多い出来事だ[83]。そしてカップルが葛藤に対処する戦略は、関係の質と成功に影響を与える[84]。親密な パートナー間の葛藤の一般的な原因には、仕事と家庭生活のバランス、性行為の頻度、経済問題、家事分担に関する意見の相違が含まれる[85]。心理学者 ジョン・ゴットマンの研究は、カップルの葛藤を三つの段階に分類している。第一に、カップルは問題に対する意見や感情を表明する。次に、議論し相手の立場 を説得しようとする。最後に、関係者は妥協点を見出すため交渉を試みる。[86] 個人が対立にどう関わるかは人によって異なる。[86] ゴットマンは、幸福なカップルと不幸なカップルでは対立時の相互作用が異なることを述べる:不幸なカップルは否定的な口調をより頻繁に使い、コミュニケー ション中に予測可能な行動をより多く示し、パートナーとの間で否定的な行動のサイクルに陥りがちだ。[87][16] 対立におけるその他の非生産的な戦略には、回避や引きこもり、防御的態度、敵意が含まれる。[88] こうした反応は、個人が葛藤によって脅威を感じた際に顕著になる。これは不安定な愛着指向や過去の否定的関係経験の反映である可能性がある。[83] 葛藤が未解決のまま放置されると、関係満足度は悪影響を受ける。[89] 建設的な葛藤解決戦略には、相手の視点や懸念を認めること、愛情表現、ユーモアの使用、積極的傾聴が含まれる。ただし、これらの戦略の有効性は、対立の主 題や深刻度、関与する個人の特性に依存する。[84] 解決されない対立によるストレスが繰り返されると、親密なパートナーはカップルカウンセリングを求めたり、自助リソースを参照したり、関係を終わらせるこ とを検討したりする可能性がある。[90] |

| Attachment insecurity Attachment orientations that develop from early interpersonal relationships can influence how people behave in intimate relationships, and insecure attachment can lead to specific issues in a relationship. Individuals vary in attachment anxiety (the degree to which they worry about abandonment) and avoidance (the degree to which they avoid emotional closeness).[91] Research shows that insecure attachment orientations that are high in avoidance or anxiety are associated with experiencing more frequent negative emotions in intimate relationships.[92] Individuals high in attachment anxiety are particularly prone to jealousy and experience heightened distress about whether their partner will leave them.[93] Highly anxious individuals also perceive more conflict in their relationships and are disproportionately negatively affected by those conflicts.[94] In contrast, avoidantly attached individuals may experience fear of intimacy or be dismissive of the potential benefits of a close relationship and thus have difficulty building an intimate connection with a partner.[95] Stress Stress that occurs both within and outside an intimate relationship—including financial issues, familial obligations, and stress at work—can negatively impact the quality of the relationship.[3] Stress depletes the psychological resources that are crucial for developing and maintaining a healthy relationship. Rather than spending energy investing in the relationship through shared activities, sex and physical intimacy, and healthy communication, couples under stress are forced to use their psychological resources to manage other pressing issues.[96] Low socioeconomic status is a particularly salient stressful context that constrains an individual's ability to invest in maintaining a healthy intimate relationship. Couples with lower socioeconomic status are at risk for experiencing increased rates of dissolution and lower relationship satisfaction.[97] Infidelity Infidelity and sex outside a monogamous relationship are behaviors that are commonly disapproved of, a frequent source of conflict, and a cause of relationship dissolution.[98] Low relationship satisfaction may cause people to desire physical or emotional connection outside their primary relationship.[98] However, people with more sexual opportunities, greater interest in sex, and more permissive attitudes toward sex are also more likely to engage in infidelity.[99] In the United States, research has found that between 15 and 25% of adults report ever cheating on a partner.[100] When one member of a relationship violates agreements of sexual or emotional exclusivity, the foundation of trust in the primary relationship is negatively impacted, and individuals may experience depression, low self-esteem, and emotional dysregulation in the aftermath of an affair.[101] Infidelity is ultimately tied to increased likelihood of relationship dissolution or divorce.[100] Intimate partner violence Violence within an intimate relationship can take the form of physical, psychological, financial, or sexual abuse. The World Health Organization estimates that 30% of women have experienced physical or sexual violence perpetrated by an intimate partner.[102] The strong emotional attachment, investment, and interdependence that characterizes close relationships can make it difficult to leave an abusive relationship.[103] Research has identified a variety of risk factors for and types of perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Individuals who are exposed to violence or experience abuse in childhood are more likely to become perpetrators or victims of intimate partner violence as adults as part of the intergenerational cycle of violence.[104] Perpetrators are also more likely to be aggressive, impulsive, prone to anger, and may show pathological personality traits such as antisocial and borderline traits.[105] Patriarchal cultural scripts that depict men as aggressive and dominant may be an additional risk factor for men engaging in violence toward an intimate partner,[106] although violence by female perpetrators is also a well-documented phenomenon[107] and research finds other contextual and demographic characteristics to be more salient risks factors.[108] Contextual factors such as high levels of stress can also contribute to risk of violence. Within the relationship, high levels of conflict and disagreements are associated with intimate partner violence, particularly for people who react to conflict with hostility.[109] |

愛着不安 幼少期の対人関係から形成される愛着指向は、親密な関係における行動に影響を与える。不安定な愛着は、関係において特定の問題を引き起こす可能性がある。 個人によって、愛着不安(見捨てられることへの心配の度合い)と回避(感情的な親密さを避ける度合い)は異なる。[91] 研究によれば、回避性や不安性が高い不安定な愛着指向は、親密な関係においてより頻繁にネガティブな感情を経験することと関連している。[92] 愛着不安の高い個人は特に嫉妬に駆られやすく、パートナーに捨てられるのではないかという強い苦痛を経験する。[93] 不安性の高い個人はまた、関係における葛藤をより強く認識し、それらの葛藤によって不釣り合いなほど否定的な影響を受ける。[94] 対照的に、回避的愛着を持つ個人は親密さを恐れたり、親密な関係の潜在的な利益を軽視したりするため、パートナーとの親密な絆を築くことに困難を覚える。 [95] ストレス 親密な関係の内外で生じるストレス——経済的問題、家族的義務、職場のストレスなど——は関係の質に悪影響を及ぼす。[3] ストレスは健全な関係を発展・維持するために不可欠な心理的資源を消耗させる。ストレス下にあるカップルは、共有活動や性・身体的親密さ、健全なコミュニ ケーションを通じて関係にエネルギーを注ぐ代わりに、他の差し迫った問題を管理するために心理的資源を費やさざるを得なくなる。[96] 低い社会経済的地位は、個人が健全な親密な関係を維持するために投資する能力を制約する、特に顕著なストレス要因である。社会経済的地位の低いカップル は、関係解消率の上昇や関係満足度の低下リスクに晒される。[97] 不貞行為 不貞行為や一夫一婦制関係外の性行為は、一般的に非難される行動であり、頻繁な衝突の原因となり、関係解消の要因となる。[98] 関係満足度の低さは、主要な関係の外で身体的・感情的な繋がりを求める原因となり得る。[98] しかし、性的機会が多く、性への関心が強く、性に対する寛容な態度を持つ人々もまた、不貞行為に及ぶ可能性が高い。[99] 米国では、成人の15~25%がパートナーを裏切った経験があると報告している。[100] 関係の一方が性的・感情的な排他性の合意を破ると、主要な関係における信頼の基盤が損なわれ、不倫の余波で個人は抑うつ、低い自尊心、感情の調節困難を経験する可能性がある。[101] 不貞行為は最終的に、関係解消や離婚の可能性を高めることにつながる。[100] 親密なパートナー間暴力 親密な関係内での暴力は、身体的、心理的、経済的、性的虐待の形態をとる。世界保健機関(WHO)の推計によれば、女性の30%が親密なパートナーによる 身体的または性的暴力を経験している。[102] 親密な関係の特徴である強い感情的結びつき、投資、相互依存性は、虐待的な関係から離れることを困難にする。[103] 研究により、親密なパートナー間暴力の加害者に関する様々な危険因子と加害者の類型が特定されている。幼少期に暴力に晒されたり虐待を経験した個人は、暴 力の世代間連鎖の一環として、成人後に親密なパートナー間暴力の加害者または被害者となる可能性が高い。[104] 加害者はまた、攻撃的で衝動的、怒りっぽく、反社会的・境界性などの病的な人格特性を示す傾向が強い。[105] 男性を攻撃的で支配的と描く家父長的な文化的規範は、男性が親密なパートナーに対して暴力を行使する追加的な危険因子となり得る[106]。ただし女性加 害者による暴力も十分に記録された現象である[107]。また研究では、他の状況的・人口統計学的特性がより顕著な危険因子であることが示されている [108]。高レベルのストレスといった状況的要因も暴力のリスクに寄与し得る。関係内では、高いレベルの対立や意見の相違が親密なパートナーに対する暴 力と関連している。特に、対立に敵意をもって反応する人々において顕著である[109]。 |

| Social and cultural variability Culture Cultural context has influence in many domains within intimate relationships including norms in communication, expression of affection, commitment and marriage practices, and gender roles.[110] For example, cross-cultural research finds that individuals in China prefer indirect and implicit communication with their romantic partner, whereas European Americans report preferring direct communication. The use of a culturally appropriate communication style influences anticipated relationship satisfaction.[111] Culture can also impact expectations within a relationship and the relative importance of various relationship-centered values such as emotional closeness, equity, status, and autonomy.[112] While love has been identified as a universal human emotion,[113] the ways love is expressed and its importance in intimate relationships vary based on the culture within which a relationship takes place. Culture is especially salient in structuring beliefs about institutions that recognize intimate relationships such as marriage. The idea that love is necessary for marriage is a strongly held belief in the United States,[114] whereas in India, a distinction is made between traditional arranged marriages and "love marriages" (also called personal choice marriages).[115] LGBTQ+ intimacy Same-sex intimate relationships Advances in legal relationship recognition for same-sex couples have helped normalize and legitimize same-sex intimacy.[116] Broadly, same-sex and different-sex intimate relationships do not differ significantly, and couples report similar levels of relationship satisfaction and stability.[117] However, research supports a few common differences between same-sex and different-sex intimacy. In the relationship formation period, the boundaries between friendship and romantic intimacy may be more nuanced and complex among sexual minorities.[118] For instance, many lesbian women report that their romantic relationships developed from an existing friendship.[119] Certain relationship maintenance practices also differ. While heterosexual relationships might rely on traditional gender roles to divide labor and decision-making power, same-sex couples are more likely to divide housework evenly.[117] Lesbian couples report lower frequency of sex compared to heterosexual couples, and gay men are more likely to engage in non-monogamy.[120] Same-sex relationships face unique challenges with regards to stigma, discrimination, and social support. As couples cope with these obstacles, relationship quality can be negatively affected.[121] Unsupportive policy environments such as same-sex marriage bans have a negative impact on well-being,[122] while being out as a couple and living in a place with legal same-sex relationship recognition have a positive impact on individual and couple well-being.[123] Asexuality Some asexual people engage in intimate relationships that are solely emotionally intimate, but other asexual people's relationships involve sex as part of negotiations with non-asexual partners.[124][125] A 2019 study of sexual minority individuals in the United States found that while asexual individuals were less likely to have recently had sex, they did not differ from non-asexual participants in rates of being in an intimate relationship.[126] Asexual individuals face stigma and the pathologization of their sexual orientation,[127] and report difficulty navigating assumptions about sexuality in the dating scene.[125] Various terms including "queerplatonic relationship" and "squish" (a non-sexual crush) have been used by the asexual community to describe non-sexual intimate relationships and desires.[128] Non-monogamy Non-monogamy, including polyamory, open relationships, and swinging, is the practice of engaging in intimate relationships that are not strictly monogamous, or consensually engaging in multiple physically or emotionally intimate relationships. The degree of emotional and physical intimacy between different partners can vary. For example, swinging relationships are primarily sexual, whereas people in polyamorous relationships might engage in both emotional and physical intimacy with multiple partners.[129] Individuals in consensually non-monogamous intimate relationships identify several benefits to their relationship configuration including having their needs met by multiple partners, engaging in a greater variety of shared activities with partners, and feelings of autonomy and personal growth.[130] |

社会的・文化的変異性 文化 文化的背景は、親密な関係における多くの領域に影響を与える。これには、コミュニケーションの規範、愛情表現、コミットメントや結婚慣行、そしてジェン ダー役割などが含まれる。[110] 例えば、異文化間研究によれば、中国人は恋愛相手との間接的・暗示的なコミュニケーションを好むのに対し、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人は直接的なコミュニケー ションを好むと報告されている。文化的に適切なコミュニケーションスタイルの使用は、関係満足度の予測に影響を与える。[111] 文化はまた、関係内の期待や、感情的な親密さ、公平性、地位、自律性といった様々な関係中心の価値観の相対的な重要性にも影響を及ぼす。[112] 愛は普遍的な人間の感情として認識されているが、[113] 愛の表現方法や親密な関係におけるその重要性は、関係が成立する文化によって異なる。文化は、結婚のような親密な関係を認める制度に関する信念を形作る上 で特に顕著だ。アメリカでは結婚に愛が必要だという考えが強く根付いている[114]。一方、インドでは伝統的な見合い結婚と「恋愛結婚」(個人の選択に よる結婚とも呼ばれる)が区別される[115]。 LGBTQ+の親密性 同性間の親密な関係 同性カップルの法的関係承認の進展は、同性間の親密性を正常化し正当化するのに寄与した[116]。大まかに言えば、同性間と異なる性間の親密な関係に大 きな差異はなく、カップルは同様の関係満足度と安定性を報告している[117]。しかし、研究は同性間と異なる性間の親密性におけるいくつかの共通する差 異を支持している。関係形成期において、性的少数者間では友情と恋愛的親密さの境界がより微妙で複雑になり得る。[118] 例えば、多くのレズビアン女性は恋愛関係が既存の友情から発展したと報告している。[119] 特定の関係維持の慣行も異なる。異性愛関係が労働分担や意思決定権を伝統的ジェンダー役割に依存する一方、同性カップルは家事労働を均等に分担する傾向が 強い。[117] レズビアンカップルは異性愛カップルに比べて性交頻度が低く、ゲイ男性は非一夫一婦制の関係を築く傾向が強い。[120] 同性愛関係は、スティグマ、差別、社会的支援に関して特有の課題に直面する。カップルがこれらの障害に対処する過程で、関係性の質は悪影響を受けることが ある。[121] 同性婚禁止のような支援的でない政策環境は幸福度に悪影響を及ぼす一方、カップルとしてカミングアウトし、同性関係を法的に認める地域で生活することは、 個人およびカップルの幸福度に好影響を与える。[123] 無性愛 一部の無性愛者は、純粋に感情的な親密さのみを伴う親密な関係を持つが、他の無性愛者の関係では、非無性愛のパートナーとの交渉の一部として性行為が含ま れる場合がある。[124][125] 2019年に米国で性的少数者を対象に行った研究では、無性愛者は最近性行為を行った可能性が低かったものの、親密な関係にある割合は非無性愛の参加者と の間に異なる点はなかった。[126] 無性愛者は自らの性的指向に対するスティグマや病理化に直面し[127]、交際場面における性に関する先入観への対応に困難を訴えている[125]。 「クィアプラトニックな関係」や「スクイッシュ」(性的でない片思い)など、無性愛コミュニティでは非性的な親密な関係や欲求を表す様々な用語が使われて いる[128]。 非一夫一婦制 ポリアモリー、オープンリレーションシップ、スウィンギングを含む非一夫一婦制とは、厳密な一夫一婦制ではない親密な関係、あるいは合意に基づく複数の身 体的・感情的な親密な関係を持つ実践を指す。異なるパートナー間の感情的・身体的な親密さの度合いは様々である。例えば、スウィンギング関係は主に性的で あるのに対し、ポリアモリー関係にある人々は複数のパートナーと感情的・身体的親密さの両方に関わる可能性がある。[129] 合意に基づく非一夫一婦制の親密な関係にある個人は、複数のパートナーによって自身のニーズが満たされること、パートナーとより多様な共有活動に従事でき ること、自律性と個人的な自己成長の感覚など、自身の関係構成にいくつかの利点を見出している。[130] |

| Attachment theory Breakup Couples therapy Dating Emotional intimacy Friendship Homogamy (sociology) Human bonding Hypergamy Interpersonal attraction Intimate partner violence Marriage Monogamy Open relationship Outline of relationships Physical intimacy Polyamory Relationship science Romance Same-sex relationship Sexual attraction Significant other Social buffering |

愛着理論 別れ カップルセラピー 交際 感情的な親密さ 友情 同質婚(社会学) 人間的絆 上婚 対人魅力 親密なパートナーによる暴力 結婚 一夫一婦制 オープンな関係 人間関係の概要 身体的親密さ ポリアモリー 人間関係科学 恋愛 同性愛関係 性的魅力 大切な人 社会的緩衝 |

| References | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intimate_relationship |

| Wong, D. W.; Hall, K. R.;

Justice, C.A.; Wong, L. (2014). Counseling Individuals Through the

Lifespan. SAGE Publications. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-4833-2203-2. Intimacy:

As an intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship that

involves physical or emotional intimacy. Physical intimacy is

characterized by romantic or passionate attachment or sexual activity. Rusbult, Caryl E. (2003), Fletcher, Garth J. O.; Clark, Margaret S. (eds.), "Interdependence in Close Relationships", Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Interpersonal Processes (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 357–387, doi:10.1002/9780470998557.ch14, ISBN 978-0-631-21228-7, retrieved 30 October 2023 Finkel, Eli J.; Simpson, Jeffry A.; Eastwick, Paul W. (3 January 2017). "The Psychology of Close Relationships: Fourteen Core Principles". Annual Review of Psychology. 68 (1): 383–411. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044038. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 27618945. S2CID 207567096. Wiecha, Jan (2023). "Intimacy". Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior. Springer, Cham. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_1240-1. ISBN 978-3-031-08956-5. Jankowiak, William (2015). "Intimacy". The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality. pp. 583–625. doi:10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs242. ISBN 978-1-4051-9006-0. Proulx, Christine M.; Helms, Heather M.; Buehler, Cheryl (2007). "Marital Quality and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Marriage and Family. 69 (3): 576–593. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00393.x. ISSN 0022-2445. Mashek, D.J.; Aron, A. (2004). Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy. Psychology Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-1-135-63240-3. Forest, Amanda L.; Sigler, Kirby N.; Bain, Kaitlin S.; O'Brien, Emily R.; Wood, Joanne V. (1 August 2023). "Self-esteem's impacts on intimacy-building: Pathways through self-disclosure and responsiveness". Current Opinion in Psychology. 52 101596. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101596. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 37348388. S2CID 258928012. Gaia, A. Celeste (2002). "Understanding Emotional Intimacy: A Review of Conceptualization, Assessment and the Role of Gender". International Social Science Review. 77 (3/4): 151–170. ISSN 0278-2308. JSTOR 41887101. Timmerman, Gayle M. (1991). "A concept analysis of intimacy". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 12 (1): 19–30. doi:10.3109/01612849109058207. ISSN 0161-2840. PMID 1988378. "The Power of Touch: Physical Affection is Important in Relationships, but Some People Need More Than Others – Kinsey Institute Research & Institute News". blogs.iu.edu. Retrieved 17 November 2023. Gallace, Alberto; Spence, Charles (1 February 2010). "The science of interpersonal touch: An overview". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Touch, Temperature, Pain/Itch and Pleasure. 34 (2): 246–259. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.004. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 18992276. S2CID 1092688. Sorokowska, Agnieszka; Kowal, Marta; Saluja, Supreet; Aavik, Toivo; Alm, Charlotte; Anjum, Afifa; Asao, Kelly; Batres, Carlota; Bensafia, Aicha; Bizumic, Boris; Boussena, Mahmoud; Buss, David M.; Butovskaya, Marina; Can, Seda; Carrier, Antonin (2023). "Love and affectionate touch toward romantic partners all over the world". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 5497. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.5497S. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31502-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10073073. PMID 37015974. "Queerplatonic Relationships: A New Term for an Old Custom | Psychology Today". www.psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 10 November 2023. Miller, Rowland (2022). Intimate Relationships (9th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1-260-80426-3. Bradbury, Thomas N.; Karney, Benjamin R. (1 July 2019). Intimate Relationships (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-64025-0. McCarthy, Jane Ribbens; Doolittle, Megan; Sclater, Shelley Day (2012). Understanding Family Meanings: A Reflective Text. Policy Press. pp. 267–268. ISBN 978-1-4473-0112-7. Eastwick, Paul W.; Finkel, Eli J.; Joel, Samantha (2023). "Mate evaluation theory". Psychological Review. 130 (1): 211–241. doi:10.1037/rev0000360. ISSN 1939-1471. PMID 35389716. S2CID 248024402. Eastwick, Paul W.; Luchies, Laura B.; Finkel, Eli J.; Hunt, Lucy L. (2014). "The predictive validity of ideal partner preferences: A review and meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 140 (3): 623–665. doi:10.1037/a0032432. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 23586697. Graziano, William G.; Bruce, Jennifer Weisho, "Attraction and the Initiation of Relationships: A Review of the Empirical Literature", Handbook of Relationship Initiation, Psychology Press, pp. 275–301, 5 September 2018, doi:10.4324/9780429020513-24, ISBN 978-0-429-02051-3, S2CID 210531741 Feingold, Alan (1988). "Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique". Psychological Bulletin. 104 (2): 226–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.104.2.226. ISSN 1939-1455. Campbell, Lorne; Fletcher, Garth JO (2015). "Romantic relationships, ideal standards, and mate selection". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationship science. 1: 97–100. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.007. ISSN 2352-250X. Eastwick, Paul W; Joel, Samantha; Carswell, Kathleen L; Molden, Daniel C; Finkel, Eli J; Blozis, Shelley A (2023). "Predicting romantic interest during early relationship development: A preregistered investigation using machine learning". European Journal of Personality. 37 (3): 276–312. doi:10.1177/08902070221085877. ISSN 0890-2070. S2CID 241096185. Eastwick, Paul W.; Finkel, Eli J.; Mochon, Daniel; Ariely, Dan (2007). "Selective Versus Unselective Romantic Desire: Not All Reciprocity Is Created Equal". Psychological Science. 18 (4): 317–319. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01897.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 17470256. S2CID 2843605. Collins, Nancy L.; Miller, Lynn Carol (1994). "Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 116 (3): 457–475. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.457. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 7809308. S2CID 13919881. Laurenceau, Jean-Philippe; Barrett, Lisa Feldman; Pietromonaco, Paula R. (1998). "Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (5): 1238–1251. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1238. ISSN 0022-3514. PMID 9599440. S2CID 1209571. Clark, Catherine L.; Shaver, Phillip R.; Abrahams, Matthew F. (1999). "Strategic Behaviors in Romantic Relationship Initiation". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 25 (6): 709–722. doi:10.1177/0146167299025006006. ISSN 0146-1672. S2CID 146305141. Moore, Monica M. (24 March 2010). "Human Nonverbal Courtship Behavior—A Brief Historical Review". Journal of Sex Research. 47 (2–3): 171–180. doi:10.1080/00224490903402520. ISSN 0022-4499. PMID 20358459. S2CID 15115115. Skipper, James K.; Nass, Gilbert (1966). "Dating Behavior: A Framework for Analysis and an Illustration". Journal of Marriage and Family. 28 (4): 412–420. doi:10.2307/349537. ISSN 0022-2445. JSTOR 349537. Agnew, Christopher R.; Hadden, Benjamin W.; Tan, Kenneth (2020), Agnew, Christopher R.; Machia, Laura V.; Arriaga, Ximena B. (eds.), "Relationship Receptivity Theory: Timing and Interdependent Relationships", Interdependence, Interaction, and Close Relationships, Advances in Personal Relationships, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 269–292, doi:10.1017/9781108645836.014, ISBN 978-1-108-48096-3, S2CID 225698943, retrieved 8 November 2023 Sprecher, Susan; Felmlee, Diane; Metts, Sandra; Cupach, William (2015), "Relationship initiation and development.", APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 3: Interpersonal relations., Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 211–245, doi:10.1037/14344-008, ISBN 978-1-4338-1703-8 Rosenfeld, Michael J.; Thomas, Reuben J. (2012). "Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary". American Sociological Review. 77 (4): 523–547. doi:10.1177/0003122412448050. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 145539089. Wu, Shangwei; Trottier, Daniel (3 April 2022). "Dating apps: a literature review". Annals of the International Communication Association. 46 (2): 91–115. doi:10.1080/23808985.2022.2069046. ISSN 2380-8985. S2CID 248618275. Vogels, Emily A.; McClain, Colleen (2 February 2023). "Key findings about online dating in the U.S." Pew Research Center. Retrieved 30 October 2023. Rusbult, Caryl E.; Olsen, Nils; Davis, Jody L.; Harmon, Peggy A. (2001). "Commitment and Relationship Maintenance Mechanisms". In Harvey, John H.; Wenzel, Amy (eds.). Close Romantic Relationships: Maintenance and Enhancement. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-135-65942-4. Agnew, C. R., & VanderDrift, L. E. (2015). Relationship maintenance and dissolution. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. A. Simpson, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 581–604). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14344-021 García, C.Y. (1998). "Temporal course of the basic components of love throughout relationships" (PDF). Psychology in Spain. 2 (1): 76–86. Stafford, Laura; Canary, Daniel J. (1991). "Maintenance Strategies and Romantic Relationship Type, Gender and Relational Characteristics". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 8 (2): 217–242. doi:10.1177/0265407591082004. ISSN 0265-4075. S2CID 145391340. Ogolsky, Brian G.; Bowers, Jill R. (2013). "A meta-analytic review of relationship maintenance and its correlates". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 30 (3): 343–367. doi:10.1177/0265407512463338. ISSN 0265-4075. S2CID 145683192. Birnbaum, Gurit E; Finkel, Eli J (2015). "The magnetism that holds us together: sexuality and relationship maintenance across relationship development". Current Opinion in Psychology. 1: 29–33. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.11.009. Impett, Emily A.; Muise, Amy; Rosen, Natalie O. (2019), Ogolsky, Brian G.; Monk, J. Kale (eds.), "Sex as Relationship Maintenance", Relationship Maintenance: Theory, Process, and Context, Advances in Personal Relationships, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 215–239, ISBN 978-1-108-41985-7, retrieved 8 November 2023 Doss, Brian D; Rhoades, Galena K (1 February 2017). "The transition to parenthood: impact on couples' romantic relationships". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationships and stress. 13: 25–28. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.003. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 28813289. Woolhouse, Hannah; McDonald, Ellie; Brown, Stephanie (1 December 2012). "Women's experiences of sex and intimacy after childbirth: making the adjustment to motherhood". Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 33 (4): 185–190. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2012.720314. ISSN 0167-482X. PMID 22973871. S2CID 37025280. Stanley, Scott M.; Rhoades, Galena K.; Whitton, Sarah W. (2010). "Commitment: Functions, Formation, and the Securing of Romantic Attachment". Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2 (4): 243–257. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00060.x. PMC 3039217. PMID 21339829. Rollie, Stephanie S.; Duck, Steve (2013). "Divorce and Dissolution of Romantic Relationships: Stage Models and Their Limitations". In Fine, Mark A.; Harvey, John H. (eds.). Handbook of Divorce and Relationship Dissolution. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-317-82421-3. Rusbult, Caryl E (1980). "Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 16 (2): 172–186. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4. ISSN 0022-1031. S2CID 21707015. Joel, Samantha; MacDonald, Geoff (2021). "We're Not That Choosy: Emerging Evidence of a Progression Bias in Romantic Relationships". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 25 (4): 317–343. doi:10.1177/10888683211025860. ISSN 1088-8683. PMC 8597186. PMID 34247524. Ritter, Simone M.; Karremans, Johan C.; van Schie, Hein T. (1 July 2010). "The role of self-regulation in derogating attractive alternatives". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (4): 631–637. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.02.010. hdl:2066/90614. ISSN 0022-1031. Joel, Samantha; MacDonald, Geoff; Page-Gould, Elizabeth (2018). "Wanting to Stay and Wanting to Go: Unpacking the Content and Structure of Relationship Stay/Leave Decision Processes". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 9 (6): 631–644. doi:10.1177/1948550617722834. ISSN 1948-5506. S2CID 148797874. Le, Benjamin; Dove, Natalie L.; Agnew, Christopher R.; Korn, Miriam S.; Mutso, Amelia A. (2010). "Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis". Personal Relationships. 17 (3): 377–390. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01285.x. Vangelisti, Anita L. (2013). "Relationship Dissolution: Antecedents, Processes, and Consequences". In Noeller, Patricia; Feeney, Judith A. (eds.). Close Relationships: Functions, Forms and Processes. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-134-95333-2. Rodrigues, A.E.; Hall, J.G.; Fincham, F.D. (2006). "What Predicts Divorce and Relationship Dissolution?". In Fine, M.A.; Harvey, J.H. (eds.). Handbook of divorce and relationship dissolution. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. pp. 85–112. Berscheid, Ellen; Hatfield, Elaine (1974), "A Little Bit about Love", Foundations of Interpersonal Attraction, Elsevier, pp. 355–381, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-362950-0.50021-5, ISBN 978-0-12-362950-0 Whisman, Mark A.; Salinger, Julia M.; Sbarra, David A. (1 February 2022). "Relationship dissolution and psychopathology". Current Opinion in Psychology. 43: 199–204. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.016. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 34416683. Kansky, Jessica; Allen, Joseph P. (2018). "Making Sense and Moving On: The Potential for Individual and Interpersonal Growth Following Emerging Adult Breakups". Emerging Adulthood. 6 (3): 172–190. doi:10.1177/2167696817711766. ISSN 2167-6968. PMC 6051550. PMID 30034952. Lewandowski, Gary W.; Bizzoco, Nicole M. (2007). "Addition through subtraction: Growth following the dissolution of a low quality relationship". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2 (1): 40–54. doi:10.1080/17439760601069234. ISSN 1743-9760. S2CID 145109937. Braithwaite, Scott; Holt-Lunstad, Julianne (2017). "Romantic relationships and mental health". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationships and stress. 13: 120–125. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.001. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 28813281. Stack, Steven; Eshleman, J. Ross (1998). "Marital Status and Happiness: A 17-Nation Study". Journal of Marriage and Family. 60 (2): 527–536. doi:10.2307/353867. ISSN 0022-2445. JSTOR 353867. Gustavson, Kristin; Røysamb, Espen; Borren, Ingrid; Torvik, Fartein Ask; Karevold, Evalill (1 June 2016). "Life Satisfaction in Close Relationships: Findings from a Longitudinal Study". Journal of Happiness Studies. 17 (3): 1293–1311. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9643-7. ISSN 1573-7780. S2CID 254703008. Sullivan, Kieran T.; Davila, Joanne (11 June 2010). Support Processes in Intimate Relationships. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-045229-2. Raposa, Elizabeth B.; Laws, Holly B.; Ansell, Emily B. (2016). "Prosocial Behavior Mitigates the Negative Effects of Stress in Everyday Life". Clinical Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science. 4 (4): 691–698. doi:10.1177/2167702615611073. ISSN 2167-7026. PMC 4974016. PMID 27500075. Lakey, Brian; Orehek, Edward (2011). "Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health". Psychological Review. 118 (3): 482–495. doi:10.1037/a0023477. ISSN 1939-1471. PMID 21534704. S2CID 20717156. Peters, Brett J.; Reis, Harry T.; Gable, Shelly L. (2018). "Making the good even better: A review and theoretical model of interpersonal capitalization". Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 12 (7). doi:10.1111/spc3.12407. ISSN 1751-9004. S2CID 149686889. Donato, Silvia; Pagani, Ariela; Parise, Miriam; Bertoni, Anna; Iafrate, Raffaella (2014). "The Capitalization Process in Stable Couple Relationships: Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Benefits". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 140: 207–211. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.411. Maxwell, Jessica A.; McNulty, James K. (2019). "No Longer in a Dry Spell: The Developing Understanding of How Sex Influences Romantic Relationships". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 28 (1): 102–107. doi:10.1177/0963721418806690. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 149470236. Cheng, Zhiming; Smyth, Russell (1 April 2015). "Sex and happiness". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 112: 26–32. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.030. ISSN 0167-2681. Meston, Cindy M.; Buss, David M. (3 July 2007). "Why Humans Have Sex". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 36 (4): 477–507. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2. ISSN 0004-0002. PMID 17610060. S2CID 6182053. Ein-Dor, Tsachi; Hirschberger, Gilad (2012). "Sexual healing: Daily diary evidence that sex relieves stress for men and women in satisfying relationships". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 29 (1): 126–139. doi:10.1177/0265407511431185. ISSN 0265-4075. S2CID 73681719. Muise, Amy; Schimmack, Ulrich; Impett, Emily A. (2016). "Sexual Frequency Predicts Greater Well-Being, But More is Not Always Better". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 7 (4): 295–302. doi:10.1177/1948550615616462. ISSN 1948-5506. S2CID 146679264. Kleinplatz, Peggy J.; Menard, A. Dana; Paquet, Marie-Pierre; Paradis, Nicolas; Campbell, Meghan; Zuccarino, Dino; Mehak, Lisa (2009). "The components of optimal sexuality: A portrait of "great sex"". Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 18 (1–2). Slatcher, Richard B.; Selcuk, Emre (2017). "A Social Psychological Perspective on the Links Between Close Relationships and Health". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 26 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1177/0963721416667444. ISSN 0963-7214. PMC 5373007. PMID 28367003. Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K.; Newton, Tamara L. (2001). "Marriage and health: His and hers". Psychological Bulletin. 127 (4): 472–503. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 11439708. Robles, Theodore F.; Slatcher, Richard B.; Trombello, Joseph M.; McGinn, Meghan M. (2014). "Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 140 (1): 140–187. doi:10.1037/a0031859. ISSN 1939-1455. PMC 3872512. PMID 23527470. GRAHAM, JENNIFER E.; CHRISTIAN, LISA M.; KIECOLT-GLASER, JANICE K. (2007), "Close Relationships and Immunity", Psychoneuroimmunology, Elsevier, pp. 781–798, doi:10.1016/b978-012088576-3/50043-5, ISBN 978-0-12-088576-3 Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K.; Gouin, Jean-Philippe; Hantsoo, Liisa (1 September 2010). "Close relationships, inflammation, and health". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Psychophysiological Biomarkers of Health. 35 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.09.003. ISSN 0149-7634. PMC 2891342. PMID 19751761. Berli, Corina; Bolger, Niall; Shrout, Patrick E.; Stadler, Gertraud; Scholz, Urte (2018). "Interpersonal Processes of Couples' Daily Support for Goal Pursuit: The Example of Physical Activity". Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 44 (3): 332–344. doi:10.1177/0146167217739264. hdl:2164/9760. ISSN 1552-7433. PMID 29121824. S2CID 5399890. Britton, Maggie; Haddad, Sana; Derrick, Jaye L. (2019). "Perceived Partner Responsiveness Predicts Smoking Cessation in Single-Smoker Couples". Addictive Behaviors. 88: 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.026. ISSN 0306-4603. PMC 7027992. PMID 30176500. Jakubiak, Brett K.; Feeney, Brooke C. (2017). "Affectionate Touch to Promote Relational, Psychological, and Physical Well-Being in Adulthood: A Theoretical Model and Review of the Research". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 21 (3): 228–252. doi:10.1177/1088868316650307. ISSN 1088-8683. PMID 27225036. S2CID 40786746. Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K.; Loving, Timothy J.; Stowell, Jeffrey R.; Malarkey, William B.; Lemeshow, Stanley; Dickinson, Stephanie L.; Glaser, Ronald (2005). "Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (12): 1377–1384. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 16330726. Younger, Jarred; Aron, Arthur; Parke, Sara; Chatterjee, Neil; Mackey, Sean (13 October 2010). "Viewing Pictures of a Romantic Partner Reduces Experimental Pain: Involvement of Neural Reward Systems". PLOS ONE. 5 (10) e13309. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513309Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013309. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2954158. PMID 20967200. Master, Sarah L.; Eisenberger, Naomi I.; Taylor, Shelley E.; Naliboff, Bruce D.; Shirinyan, David; Lieberman, Matthew D. (2009). "A Picture's Worth: Partner Photographs Reduce Experimentally Induced Pain". Psychological Science. 20 (11): 1316–1318. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02444.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 19788531. S2CID 14948326. Hooker, Emily D.; Campos, Belinda; Pressman, Sarah D. (1 July 2018). "It just takes a text: Partner text messages can reduce cardiovascular responses to stress in females". Computers in Human Behavior. 84: 485–492. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.033. ISSN 0747-5632. S2CID 13840189. Feeney, Judith A; Karantzas, Gery C (2017). "Couple conflict: insights from an attachment perspective". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationships and stress. 13: 60–64. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.017. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 28813296. Overall, Nickola C; McNulty, James K (2017). "What type of communication during conflict is beneficial for intimate relationships?". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationships and stress. 13: 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.002. ISSN 2352-250X. PMC 5181851. PMID 28025652. Risch, Gail S.; Riley, Lisa A.; Lawler, Michael G. (2003). "Problematic Issues in the Early Years of Marriage: Content for Premarital Education". Journal of Psychology and Theology. 31 (3): 253–269. doi:10.1177/009164710303100310. ISSN 0091-6471. S2CID 141072191. Gottman, John M. (30 November 2017), "The Roles of Conflict Engagement, Escalation, and Avoidance in Marital Interaction: A Longitudinal View of Five Types of Couples", Interpersonal Development, Routledge, pp. 359–368, doi:10.4324/9781351153683-21, ISBN 978-1-351-15368-3 Gottman, J.M. (1979). Marital Interaction: Experimental Investigations. New York, NY: Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-6598-8. Overall, Nickola C.; McNulty, James K. (2017). "What Type of Communication during Conflict is Beneficial for Intimate Relationships?". Current Opinion in Psychology. 13: 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.002. ISSN 2352-250X. PMC 5181851. PMID 28025652. Cramer, Duncan (2000). "Relationship Satisfaction and Conflict Style in Romantic Relationships". The Journal of Psychology. 134 (3): 337–341. doi:10.1080/00223980009600873. ISSN 0022-3980. PMID 10907711. S2CID 9245525. Doss, Brian D.; Rhoades, Galena K.; Stanley, Scott M.; Markman, Howard J. (2009). "Marital Therapy, Retreats, and Books: The Who, What, When, and Why of Relationship Help-Seeking". Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 35 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00093.x. ISSN 0194-472X. PMID 19161581. Simpson, Jeffry A; Rholes, W Steven (1 February 2017). "Adult attachment, stress, and romantic relationships". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationships and stress. 13: 19–24. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006. ISSN 2352-250X. PMC 4845754. PMID 27135049. Simpson, Jeffry A. (1990). "Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 59 (5): 971–980. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.971. ISSN 1939-1315. Martínez-León, Nancy Consuelo; Peña, Juan José; Salazar, Hernán; García, Andrea; Sierra, Juan Carlos (2017). "A systematic review of romantic jealousy in relationships". Terapia psicológica. 35 (2): 203–212. doi:10.4067/s0718-48082017000200203. hdl:20.500.12495/3466. ISSN 0718-4808. Campbell, Lorne; Simpson, Jeffry A.; Boldry, Jennifer; Kashy, Deborah A. (2005). "Perceptions of Conflict and Support in Romantic Relationships: The Role of Attachment Anxiety". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 88 (3): 510–531. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 15740443. S2CID 21042397. Bartholomew, Kim (1990). "Avoidance of Intimacy: An Attachment Perspective". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 7 (2): 147–178. doi:10.1177/0265407590072001. ISSN 0265-4075. S2CID 146379254. Karney, Benjamin R.; Neff, Lisa A. (2013). "Couples and stress: How demands outside a relationship affect intimacy within the relationship". In Simpson, J.A.; Campbell, L. (eds.). The Oxford handbook of close relationships. Oxford University Press. pp. 664–684. Karney, Benjamin R. (2021). "Socioeconomic Status and Intimate Relationships". Annual Review of Psychology. 72 (1): 391–414. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-051920-013658. PMC 8179854. PMID 32886585. S2CID 221503060. Blow, Adrian J.; Hartnett, Kelley (2005). "Infidelity in Committed Relationships II: A Substantive Review". Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 31 (2): 217–233. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01556.x. ISSN 0194-472X. PMID 15974059. Treas, Judith; Giesen, Deirdre (2000). "Sexual Infidelity among Married and Cohabiting Americans". Journal of Marriage and Family. 62 (1): 48–60. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00048.x. ISSN 0022-2445. JSTOR 1566686. "Who Cheats More? The Demographics of Infidelity in America". Institute for Family Studies. Retrieved 7 November 2023. Rokach, Ami; Chan, Sybil H. (2023). "Love and Infidelity: Causes and Consequences". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 20 (5): 3904. doi:10.3390/ijerph20053904. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 10002055. PMID 36900915. "Violence against women". www.who.int. Retrieved 24 November 2023. Kim, Jinseok; Gray, Karen A. (2008). "Leave or Stay?: Battered Women's Decision After Intimate Partner Violence". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 23 (10): 1465–1482. doi:10.1177/0886260508314307. ISSN 0886-2605. PMID 18309037. S2CID 263537650. Chen, Ping-Hsin; Jacobs, Abbie; Rovi, Susan L D (1 September 2013). "Intimate partner violence: childhood exposure to domestic violence". FP Essentials. 412: 24–27. ISSN 2161-9344. PMID 24053262. Finkel, Eli J.; Eckhardt, Christopher I. (12 April 2013). "Intimate Partner Violence". In Simpson, Jeffry A.; Campbell, Lorne (eds.). Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398694.013.0020. Ali, Parveen Azam; Naylor, Paul B. (1 November 2013). "Intimate partner violence: A narrative review of the feminist, social and ecological explanations for its causation". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 18 (6): 611–619. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.009. ISSN 1359-1789. Carney, Michelle; Buttell, Fred; Dutton, Don (1 January 2007). "Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 12 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2006.05.002. ISSN 1359-1789. Ehrensaft, Miriam K. (1 March 2008). "Intimate partner violence: Persistence of myths and implications for intervention". Children and Youth Services Review. Recent Trends in Intimate Violence: Theory and Intervention. 30 (3): 276–286. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.005. ISSN 0190-7409. Capaldi, Deborah M.; Knoble, Naomi B.; Shortt, Joann Wu; Kim, Hyoun K. (2012). "A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence". Partner Abuse. 3 (2): 231–280. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. PMC 3384540. PMID 22754606. Rokach, Ami (2023). "Love Culturally: How Does Culture Affect Intimacy, Commitment & Love". The Journal of Psychology. 158 (1): 84–114. doi:10.1080/00223980.2023.2244129. ISSN 0022-3980. PMID 37647358. S2CID 261394941. Ge, Fiona; Park, Jiyoung; Pietromonaco, Paula R. (2022). "How You Talk About It Matters: Cultural Variation in Communication Directness in Romantic Relationships". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 53 (6): 583–602. doi:10.1177/00220221221088934. ISSN 0022-0221. S2CID 247959876. Cionea, Ioana A.; Van Gilder, Bobbi J.; Hoelscher, Carrisa S.; Anagondahalli, Deepa (2 October 2019). "A cross-cultural comparison of expectations in romantic relationships: India and the United States". Journal of International and Intercultural Communication. 12 (4): 289–307. doi:10.1080/17513057.2018.1542019. ISSN 1751-3057. S2CID 150097472. Treger, Stanislav; Sprecher, Susan; Hatfield, Elaine C. (2014), "Love", in Michalos, Alex C. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 3708–3712, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1706, ISBN 978-94-007-0752-8, retrieved 21 November 2023 Simpson, Jeffry A.; Campbell, Bruce; Berscheid, Ellen (1986). "The Association between Romantic Love and Marriage: Kephart (1967) Twice Revisited". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 12 (3): 363–372. doi:10.1177/0146167286123011. ISSN 0146-1672. S2CID 145051003. Cardona, Betty; Bedi, Robinder P.; Crookston, Bradley J. (2019). "Choosing Love Over Tradition: Lived Experiences of Asian Indian Marriages". The Family Journal. 27 (3): 278–286. doi:10.1177/1066480719852994. ISSN 1066-4807. S2CID 195554512. Hopkins, Jason J.; Sorensen, Anna; Taylor, Verta (2013). "Same-Sex Couples, Families, and Marriage: Embracing and Resisting Heteronormativity 1". Sociology Compass. 7 (2): 97–110. doi:10.1111/soc4.12016. ISSN 1751-9020. Peplau, Letitia Anne; Fingerhut, Adam W. (2007). "The Close Relationships of Lesbians and Gay Men". Annual Review of Psychology. 58 (1): 405–424. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085701. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 16903800. Diamond, Lisa M.; Dubé, Eric M. (2002). "Friendship and Attachment Among Heterosexual and Sexual-Minority Youths: Does the Gender of Your Friend Matter?". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 31 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1023/A:1014026111486. ISSN 0047-2891. S2CID 142987585. Vetere, Victoria A. (1982). "The Role of Friendship in the Development and Maintenance of Lesbian Love Relationships". Journal of Homosexuality. 8 (2): 51–65. doi:10.1300/J082v08n02_07. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 7166643. Parsons, Jeffrey T.; Starks, Tyrel J.; Gamarel, Kristi E.; Grov, Christian (2012). "Non-monogamy and sexual relationship quality among same-sex male couples". Journal of Family Psychology. 26 (5): 669–677. doi:10.1037/a0029561. ISSN 1939-1293. PMID 22906124. Rostosky, Sharon Scales; Riggle, Ellen DB (1 February 2017). "Same-sex relationships and minority stress". Current Opinion in Psychology. Relationships and stress. 13: 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.011. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 28813290. Tatum, Alexander K. (16 April 2017). "The Interaction of Same-Sex Marriage Access With Sexual Minority Identity on Mental Health and Subjective Wellbeing". Journal of Homosexuality. 64 (5): 638–653. doi:10.1080/00918369.2016.1196991. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 27269121. S2CID 20843197. Wight, Richard G.; LeBlanc, Allen J.; Lee Badgett, M. V. (2013). "Same-Sex Legal Marriage and Psychological Well-Being: Findings From the California Health Interview Survey". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (2): 339–346. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301113. PMC 3558785. PMID 23237155. "Understanding the Asexual Community". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 17 November 2023. Chasin, CJ DeLuzio (2015). "Making Sense in and of the Asexual Community: Navigating Relationships and Identities in a Context of Resistance". Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 25 (2): 167–180. doi:10.1002/casp.2203. ISSN 1052-9284. Rothblum, Esther D.; Krueger, Evan A.; Kittle, Krystal R.; Meyer, Ilan H. (1 February 2020). "Asexual and Non-Asexual Respondents from a U.S. Population-Based Study of Sexual Minorities". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 49 (2): 757–767. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-01485-0. ISSN 1573-2800. PMC 7059692. PMID 31214906. Hille, Jessica J. (1 February 2023). "Beyond sex: A review of recent literature on asexuality". Current Opinion in Psychology. 49 101516. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101516. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 36495711. S2CID 253534170. Fine, Julia Coombs (2023). "From crushes to squishes: Affect and agency on r/ AskReddit and r/ Asexual". Journal of Language and Sexuality. 12 (2): 145–172. doi:10.1075/jls.22004.fin. ISSN 2211-3770. S2CID 259866691. Scoats, Ryan; Campbell, Christine (1 December 2022). "What do we know about consensual non-monogamy?". Current Opinion in Psychology. 48 101468. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101468. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 36215906. S2CID 252348893. Moors, Amy C.; Matsick, Jes L.; Schechinger, Heath A. (2017). "Unique and Shared Relationship Benefits of Consensually Non-Monogamous and Monogamous Relationships". European Psychologist. 22 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000278. |

ウォン、D. W.;ホール、K.

R.;ジャスティス、C.A.;ウォン、L. (2014). 『生涯を通じた個人カウンセリング』. SAGE Publications. p.

326. ISBN 978-1-4833-2203-2.

親密性:親密な関係とは、身体的または感情的な親密さを伴う対人関係である。身体的親密性は、ロマンチックまたは情熱的な愛着、あるいは性的活動によって