あたらしい人種科学について

On

New Race Science

あたらしい人種科学について

On

New Race Science

★「日本人の起源」論:文化ナショナリ ズムか、科学レイシズムか?︎▶︎科学人種主義・科学レイシズム▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| Sociogenomics,

also known as social genomics, is the field of research that examines

why and how different social factors and processes (e.g., social

stress, conflict, isolation, attachment, etc.) affect the activity of

the genome.[1][2] Social genomics as a field is very young (< 20

years old) and was spurred by the scientific understanding that the

expression of genes to their gene products, though not the DNA sequence

itself, is affected by the external environment.[3] Social genomics

researchers have thus examined the role of social factors (e.g.

isolation, rejection) on the expression of individual genes, or more

commonly, clusters of many genes (i.e. gene profiles, or gene programs). |

ソシオゲノミクスは、社会ゲノム学としても知られ、様々な社会的要因や

プロセス(例えば、社会的ストレス、葛藤、孤立、愛着など)が、なぜ、そしてどのようにゲノムの活性に影響を与えるのかを検討する研究分野である[1]

[2]、

社会ゲノミクスは非常に歴史が浅く(20年未満)、DNAの塩基配列そのものではないが、遺伝子の発現やその遺伝子産物が外部環境の影響を受けるという科

学的理解に拍車をかけた。

[社会ゲノミクスの研究者たちは、個々の遺伝子、あるいはより一般的には多くの遺伝子のクラスター(すなわち遺伝子プロファイル、あるいは遺伝子プログラ

ム)の発現に対する社会的要因(例えば、孤立、拒絶)の役割を調べてきた。) |

| History In the early 2000s, initial work on this topic was conducted in animal model systems, such as zebra finch, honeybee, and cichlid, by Gene E. Robinson[1][4] at the University of Illinois among others. In 2007, Steve Cole at UCLA published the first study of social factors, in this case social connection, on the immune cell gene expression among healthy older adults.[5] Shortly thereafter, a series of papers were published by Youssef Idaghdour and his colleagues looking at the role of environmental factors on gene expression throughout the genome where they found that only 5% of the variation in genomic expression was attributable to genetic factors (i.e. sequence variation in the genome) whereas, as much as half was due to the living environment of the individual, either urban or rural.[6] These studies set the stage for looking at environmental modulation of gene expression including social influences. |

歴史 2000年代初頭、このテーマに関する初期の研究は、イリノイ大学のジーン・E・ロビンソン(Gene E. Robinson)[1][4] 氏をはじめとする研究者らによって、キンカチョウ、ミツバチ、シクリッドなどの動物モデルシステムで実施された。2007年には、UCLAのスティーブ・ コールが、健康な高齢者の免疫細胞の遺伝子発現における社会的要因(この場合は社会的つながり)に関する最初の研究を発表した。[5] その後まもなく、ユセフ・イダグドゥールと彼の同僚たちは、ゲノム全体の遺伝子発現における環境要因の役割を調査した一連の論文を発表した。そこで彼ら は、ゲノム全体の遺伝子発現における変動のわずか5%のみが遺伝的要因(すなわちゲノムの配列変異)に起因し、一方で半分近くが都市部か農村部かといった 個人の生活環境に起因することを発見した。[6] これらの研究は、社会的影響を含む遺伝子発現の環境調節を調べるための土台となった。 |

| Biological pathways The 23 pairs of DNA molecules called chromosomes contain the approximately 21,000 genes comprising the “human blueprint.” For this blueprint to have any biological affect however, it must be transcribed to RNA and then into proteins. This process of translation, or “turning on” of a gene to its final gene products is termed gene expression. Genetic expression is far from random, allowing the differentiation and specialization of different cell types with identical genomes. Transcription factors are the proteins which control gene expression, and they can either increase (i.e. an activator) or decrease (i.e. a repressor) expression. Multiple transcription factors exist that are responsive to the internal environment of the cell (e.g. to maintain cell differentiation), but several also appear to be responsive to external factors including several hormones, neurotransmitters, and growth factors. The sum total of genes expressed into RNA in a particular population of cells is referred to as the transcriptome. Research has shown that the activity of gene profiles or gene programs can be affected by the physical and social environments that humans inhabit. The pattern of social stress-related changes in gene expression has been termed by Steve Cole and George Slavich at UCLA as a conserved transcriptional response to adversity (CTRA).[7] In healthy situations, the human immune system is biased towards anti-viral readiness. However under conditions of social stress there appears to be a shift towards pro-inflammatory immunological processes including the production of various pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and IL-6. Simultaneously, social stress is associated with the down-regulation of anti-viral gene products including interferon type 1 and specific antibody isotypes (e.g. immunoglobulin G). This pattern of up-regulated pro-inflammatory transcription coupled with down-regulated anti-viral transcription challenged the previously held belief that social stress was generally immunosuppressive. An evolutionary explanation for the origin of the CTRA, characterized by increased pro-inflammatory gene expression and a suppression of anti-viral gene expression, has been proposed. From an evolutionary perspective, the frequent social contact of homo-sapiens increases the probability of viral infection. Thus a bias towards anti-viral readiness would be adaptive. In conditions of social stress however, the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression prepares the body to better deal with bodily injury and bacterial infection which is more likely under conditions of social stress either through hostile human contact, or increased predatory vulnerability due to separation from the social group. In the modern age however, the chronic elevation of pro-inflammatory gene expression produced by social stress is more likely to result in inflammation-related diseases including various cancers, cardiovascular disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Concurrently, the down-regulation of anti-viral gene expression leaves the individual more vulnerable to viral infection such as the flu and the common cold. Social signal transduction is the process through which social factors influence the transcriptome. This process is mediated by the central nervous system via changes in hormonal and neurotransmitter signals. For example catecholamines, the class of neurotransmitters that includes dopamine and norepinephrine, have been linked with responses to acute stressors including the fight-or-flight response, and also appear to modulate the transcription of multiple transcription factors that impact inflammatory and anti-viral genes. Norepinephrine release, for example, results in the activation of the transcription factor CREB, via the activity of β-adrenergic receptors. CREB then is able to up-regulate the transcription of many different genes. Thus, through effects of canonical neurotransmitter systems such as catecholamines, social stressors are able to penetrate the nucleus of various cell types and alter the gene transcription profiles within these cells. Other transcription factors that have been known to respond to social factors include some factors broadly related to the neurobiology of threat including NF-κB (which, in addition to CREB, is a widely implicated transcription factor affecting pro-inflammatory gene expression), cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), glucocorticoids (in particular glucocorticoid insensitivity, where inflammatory pathways are unusually insensitive to negative regulation by glucocorticoids), and interferon transcription factors (which mediate the depression of anti-viral immunity). Epigenetic factors including DNA methylation and histone modification have also been proposed as possible biological mechanisms. For example, childhood maltreatment in rodent models and humans has been shown to alter the epigenetics of the glucocorticoid receptor gene.[8][9] The epigenetic influences on social genomic outcomes are still largely unknown at present and require additional research. |

生物学的経路 染色体と呼ばれる23対のDNA分子には、「人間の設計図」を構成する約21,000個の遺伝子が含まれている。しかし、この設計図が生物学的に影響を及 ぼすためには、まずRNAに転写され、さらにタンパク質に転写されなければならない。この翻訳プロセス、すなわち遺伝子を「オン」にして最終的な遺伝子産 物に変えるプロセスは、遺伝子発現と呼ばれる。遺伝子発現はランダムではなく、同一のゲノムを持つさまざまな細胞タイプの分化と特化を可能にする。転写因 子は遺伝子発現を制御するタンパク質であり、発現を増大させる(すなわち活性化因子)か、または減少させる(すなわち抑制因子)かのいずれかである。細胞 の内部環境(例えば、細胞分化の維持)に反応する転写因子は多数存在するが、いくつかのホルモン、神経伝達物質、成長因子などの外部因子に反応するものも ある。特定の細胞集団においてRNAに転写された遺伝子の総体はトランスクリプトームと呼ばれる。 研究により、遺伝子プロファイルまたは遺伝子プログラムの活動は、人間が生活する物理的および社会的環境の影響を受けることが示されている。遺伝子発現に おける社会的ストレス関連の変化パターンは、UCLAのスティーブ・コールとジョージ・スラビッチにより、逆境に対する保存された転写応答(CTRA)と 名付けられた。[7] 健康な状態では、人間の免疫システムはウイルスに対する備えに偏っている。しかし、社会的ストレス下では、IL-1βやIL-6などのさまざまな炎症促進 性サイトカインの産生を含む炎症促進性の免疫プロセスへとシフトする傾向がある。同時に、社会的ストレスは、インターフェロン1型や特定の抗体アイソタイ プ(例えば免疫グロブリンG)などの抗ウイルス性遺伝子産物の発現抑制と関連している。この炎症促進性転写の活性化と抗ウイルス性転写の抑制というパター ンは、社会ストレスは一般的に免疫抑制的であるというこれまでの考え方に疑問を投げかけた。 炎症促進性遺伝子発現の増加と抗ウイルス性遺伝子発現の抑制という特徴を持つCTRAの起源について、進化論的な説明が提案されている。進化論的な観点か ら見ると、ホモサピエンスが頻繁に社会的に接触することはウイルス感染の確率を高める。したがって、抗ウイルスへの備えに偏ることは適応的である。しか し、社会的なストレス下では、炎症促進遺伝子の発現が増加することで、身体的な損傷や細菌感染への対処能力が高まる。これは、敵対的な人間との接触や、社 会集団からの分離による捕食に対する脆弱性の増大など、社会的なストレス下で起こりやすい。しかし現代では、社会的なストレスによって引き起こされる炎症 促進遺伝子の慢性的な発現上昇は、各種の癌、心血管疾患、関節リウマチなどの炎症関連疾患を引き起こす可能性が高くなっている。同時に、抗ウイルス遺伝子 の発現低下により、インフルエンザや風邪などのウイルス感染に対する抵抗力が低下する。 社会的シグナル伝達とは、社会的要因がトランスクリプトームに影響を与えるプロセスである。このプロセスは、ホルモンおよび神経伝達物質のシグナルの変化 を介して中枢神経系によって媒介される。例えば、ドーパミンやノルエピネフリンを含むカテコールアミンという神経伝達物質の一種は、闘争または逃走反応を 含む急性ストレス因子への反応と関連しており、また、炎症および抗ウイルス遺伝子に影響を与える複数の転写因子の転写を調節しているようである。例えば、 ノルエピネフィリンの放出は、β-アドレナリン受容体の活性を介して転写因子CREBを活性化させる。CREBは、多くの異なる遺伝子の転写を促進するこ とができる。このように、カテコールアミンなどの標準的な神経伝達物質システムの効果により、社会的ストレス要因はさまざまな細胞の核に浸透し、これらの 細胞内の遺伝子転写プロファイルを変化させることができる。 社会的要因に反応することが知られている他の転写因子には、NF-κB(CREB とともに、炎症促進遺伝子の発現に広く影響を及ぼす転写因子として広く知られている)や、環状アデノシン一リン酸(cAMP)、グルココルチコイド(特に グルココルチコイド不応症、炎症経路がグルココルチコイドによる負の調節に異常に反応しない)、インターフェロン転写因子(抗炎症経路の抑制を媒介する) など、脅威の神経生物学に広く関連する因子が含まれる (cAMP)、グルココルチコイド(特にグルココルチコイド不応症、炎症経路がグルココルチコイドによる負の調節に異常に反応しない)、およびインター フェロン転写因子(抗ウイルス免疫の抑制を媒介する)など、脅威の神経生物学に広く関連するいくつかの要因が挙げられる。 DNAメチル化やヒストン修飾などのエピジェネティック因子も、生物学的メカニズムの可能性として提案されている。例えば、齧歯類モデルやヒトにおける幼 少期の虐待は、グルココルチコイド受容体遺伝子のエピジェネティクスを変化させることが示されている。[8][9] 社会ゲノムの結果に対するエピジェネティクスの影響は、現時点ではまだほとんど分かっておらず、さらなる研究が必要である。 |

| Longitudinal effects While the majority of experimental social genomics research has elucidated the role of acute social stress on the CTRA, it has been proposed that social factors can, under some circumstances, promote more persistent modulation of the human transcriptome. Several pro-inflammatory gene products, including multiple cytokines, exist in a recursive system wherein their presence promotes their own transcription. From a psychological standpoint, the experience of social stressors can, in certain individuals, promote the experience of future social stressors, as in the stress-generation theory of depression, wherein depressive symptoms increase the likelihood of future stressful events.[10][11] Future studies are needed to test whether individual differences in the magnitude of the CTRA are biologically related to stress-generation. |

縦断的効果 実験的社会ゲノミクス研究の大半は、急性の社会的ストレスがCTRAに及ぼす影響を解明してきたが、社会的要因が、ある状況下では、ヒトのトランスクリプ トームのより持続的な変調を促進しうることが提案されている。複数のサイトカインを含むいくつかの炎症促進性遺伝子産物は、それらの存在が自身の転写を促 進する再帰的なシステムに存在している。心理学的観点から見ると、社会的なストレス要因を経験した特定の個人においては、将来の社会的なストレス要因を経 験する可能性が高まる可能性がある。これは、うつ病のストレス生成理論と同様であり、うつ病の症状は将来のストレス要因の可能性を高める。[10] [11] 今後の研究では、CTRAの大きさにおける個人差がストレス生成と生物学的に関連しているかどうかを検証する必要がある。 |

| Relationship with health Epidemiological research has demonstrated that social factors including social isolation can have large effects on various diseases and all-cause mortality.[12] Social genomics represents a plausible mechanism subserving this link between the social environment and disease risk. For example, individuals who have chronic social isolation have different transcriptome profiles for genes related to immune system factors including elevated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes and depressed expression of anti-viral genes.[5] Chronically isolated individuals are also more likely to develop inflammation-related diseases thus providing a plausible biological connection between social variables (e.g. isolation, rejection, social stress, and socioeconomic status) and disease risk and mortality, namely heightened inflammation mediated by differential gene expression.[13][14] Though this line of research is relatively young, acute and chronic social stressors have been linked with altered gene expression in various tissues in addition to immune cells including breast tissue, lymph nodes, and brain cells, and in diseased tissues including ovarian, prostate, and breast cancer. Simultaneously, chronic social stressors results in the individual being more susceptible to viral infection as a consequence of the down-regulation of anti-viral gene expression. The enhanced susceptibility to various viral infections maintained the hypothesis that social stress was generally immunosuppressive and only recently, through social genomic research, has the immunosuppressive hypothesis been challenged. One consistent observation in social genomics research is that the perception of social stressors is a stronger and more reliable predictor of the CTRA than the objective presence of social stressor.[15] For example, the subjective perception of isolation is a stronger predictor of pro-inflammatory gene expression than is the objective size of one's social network. This neurocognitive control of the CTRA suggests that altering one's perception of their social situation, for example by utilizing skills honed in cognitive therapy may be able to alleviate the negative consequences of the social stress and the CTRA.[16] |

健康との関係 疫学研究により、社会的孤立を含む社会的要因がさまざまな疾患や全死因死亡率に大きな影響を及ぼすことが実証されている。[12] 社会ゲノミクスは、社会的環境と疾患リスクの関連を裏付ける妥当なメカニズムを示している。例えば、慢性的に社会的孤立状態にある人々は、炎症性サイトカ イン遺伝子の発現上昇や抗ウイルス遺伝子の発現低下など、免疫系因子に関連する遺伝子のトランスクリプトームプロファイルが異なることが分かっている。 [5] 慢性的に孤立している人は炎症性疾患を発症する可能性も高いため、社会的変数(孤立、拒絶、社会的ストレス、社会経済的地位など)と疾患リスクおよび死亡 率との間に生物学的な関連がある可能性が示唆される。すなわち、遺伝子発現の差異によって媒介される炎症の増大である。[13][14] この研究分野は比較的新しいが、急性および慢性の社会的ストレス要因は、乳房組織、リンパ節、脳細胞などの免疫細胞に加え、卵巣がん、前立腺がん、乳がん などの病変組織を含むさまざまな組織における遺伝子発現の変化と関連していることが分かっている。 同時に、慢性的な社会的ストレスは、抗ウイルス遺伝子の発現の抑制を招く結果、個人がウイルス感染にかかりやすくなる。さまざまなウイルス感染に対する感 受性の高まりは、社会的ストレスが一般的に免疫抑制的であるという仮説を裏付けるものであり、免疫抑制仮説が最近になって、社会的ゲノム研究を通じて初め て疑問視されるようになった。 社会ゲノム研究における一貫した観察結果のひとつは、社会的なストレス要因の知覚は、客観的な社会的なストレス要因の存在よりも、より強く、より信頼性の 高いCTRAの予測因子であるということである。[15] 例えば、孤立感の主観的な知覚は、客観的な社会ネットワークの規模よりも、炎症促進遺伝子の発現のより強い予測因子である。この神経認知制御による CTRAは、認知療法で磨かれたスキルを活用するなどして、自身の社会的状況に対する認識を変えることで、社会的ストレスとCTRAによる負の結果を緩和 できる可能性を示唆している。[16] |

| Eugenics Dysgenics Genoeconomics Human reproductive ecology Income and fertility Intelligence and fertility Psychogenomics |

優生学 劣生学 ゲノエコノミクス ヒト生殖生態学 所得と出生率 知能と出生率 心理ゲノミクス |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociogenomics |

++

| Racism There have been many connections between pseudoscientific writers and researchers and their anti-semitic, racist and neo-Nazi backgrounds. They often use pseudoscience to reinforce their beliefs. One of the most predominant pseudoscientific writers is Frank Collin, a self-proclaimed Nazi who goes by Frank Joseph in his writings.[89] The majority of his works include the topics of Atlantis, extraterrestrial encounters, and Lemuria as well as other ancient civilizations, often with white supremacist undertones. For example, he posited that European peoples migrated to North America before Columbus, and that all Native American civilizations were initiated by descendants of white people.[90] The Alt-Right using pseudoscience to base their ideologies on is not a new issue. The entire foundation of anti-semitism is based on pseudoscience, or scientific racism. In an article from Newsweek by Sander Gilman, Gilman describes the pseudoscience community's anti-semitic views. "Jews as they appear in this world of pseudoscience are an invented group of ill, stupid or stupidly smart people who use science to their own nefarious ends. Other groups, too, are painted similarly in 'race science', as it used to call itself: African-Americans, the Irish, the Chinese and, well, any and all groups that you want to prove inferior to yourself".[91] Neo-Nazis and white supremacist often try to support their claims with studies that "prove" that their claims are more than just harmful stereotypes. For example Bret Stephens published a column in The New York Times where he claimed that Ashkenazi Jews had the highest IQ among any ethnic group.[92] However, the scientific methodology and conclusions reached by the article Stephens cited has been called into question repeatedly since its publication. It has been found that at least one of that study's authors has been identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a white nationalist.[93] The journal Nature has published a number of editorials in the last few years warning researchers about extremists looking to abuse their work, particularly population geneticists and those working with ancient DNA. One article in Nature, titled "Racism in Science: The Taint That Lingers" notes that early-twentieth-century eugenic pseudoscience has been used to influence public policy, such as the Immigration Act of 1924 in the United States, which sought to prevent immigration from Asia and parts of Europe. Research has repeatedly shown that race is not a scientifically valid concept, yet some scientists continue to look for measurable biological differences between 'races'.[94] [89]Frank Joseph". Inner Traditions. [90]Colavito, Jason. "Review of "Power Places And The Master Builders of Antiquity" By Frank Joseph". Jason Colavito. [91]Gilman, Sander (3 January 2018). "The Alt-Right's Jew-Hating Pseudoscience Is Not New" [92]Stephens, Bret (28 December 2019). "The Secrets of Jewish Genius". The New York Times.-> The controversy over Bret Stephens’s Jewish genius column, explained. [93]Shapiro, Adam (27 January 2020). "The Dangerous Resurgence in Race Science". American Scientist. [94]Nelson, Robin (2019). "Racism in Science: The Taint That Lingers". Nature. 570 (7762): 440–441. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..440N. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01968-z |

人種主義 疑似科学の作家や研究者と、反ユダヤ主義者、人種差別主義者、ネオナチの背景には多くのつながりがある。彼らはしばしば、自分たちの信念を補強するために 疑似科学を利用する。最も優勢な疑似科学作家の一人がフランク・コリンであり、自称ナチスであり、著作ではフランク・ヨセフと名乗っている[89]。彼の 作品の大半は、アトランティス、地球外生命体との遭遇、レムリア、その他の古代文明をテーマにしており、白人至上主義的なニュアンスを含んでいることが多 い。例えば、ヨーロッパ人はコロンブス以前に北アメリカに移住しており、アメリカ先住民の文明はすべて白人の子孫によって始まった と仮定している[90]。 オルト・ライトが自分たちのイデオロギーの基礎に疑似科学を用いることは、新しい問題ではない。反ユダヤ主義の基盤はすべて疑似科学、つまり科学的人種差 別に基づいている。サンダー・ギルマンによる『ニューズウィーク』誌の記事の中で、ギルマンは疑似科学コミュニティーの反ユダヤ主義的見解を述べている。 「この疑似科学の世界に登場するユダヤ人は、自分たちの邪悪な目的のために科学を利用する、病気で愚かな、あるいは愚かなほど賢い、作り出された集団であ る。他のグループも、かつてそう呼ばれていたように、『人種科学』では同じように描かれている: アフリカ系アメリカ人、アイルランド人、中国人、そしてまあ、自分より劣っていると証明したいあらゆる集団だ」[91]。ネオナチや白人至上主義者はしば しば、自分たちの主張が有害なステレオタイプ以上のものであることを「証明」する研究で、自分たちの主張を支えようとする。例えば、ブレット・スティーブ ンスは『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙にコラムを掲載し、アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人はあらゆる民族の中で最もIQが高いと主張した[92]。しかし、ス ティーブンスが引用した論文で得られた科学的方法論と結論は、その発表以来何度も疑問視されてきた。その研究の著者の少なくとも一人は、南部貧困法律セン ターによって白人ナショナリストと認定されていることが判明している[93]。 学術誌『ネイチャー』はここ数年、特に集団遺伝学者や古代のDNAを扱う研究者に対し、自分たちの研究を悪用しようとする過激派について警告する論説を数 多く発表している。科学における人種差別: 20世紀初頭の優生学的疑似科学が、アジアやヨーロッパの一部からの移民を阻止しようとしたアメリカの1924年の移民法などの公共政策に影響を与えるた めに利用されてきたことを指摘している。人種が科学的に妥当な概念ではないことは研究によって繰り返し示されているが、一部の科学者は「人種」間の測定可 能な生物学的差異を探し続けている[94]。 |

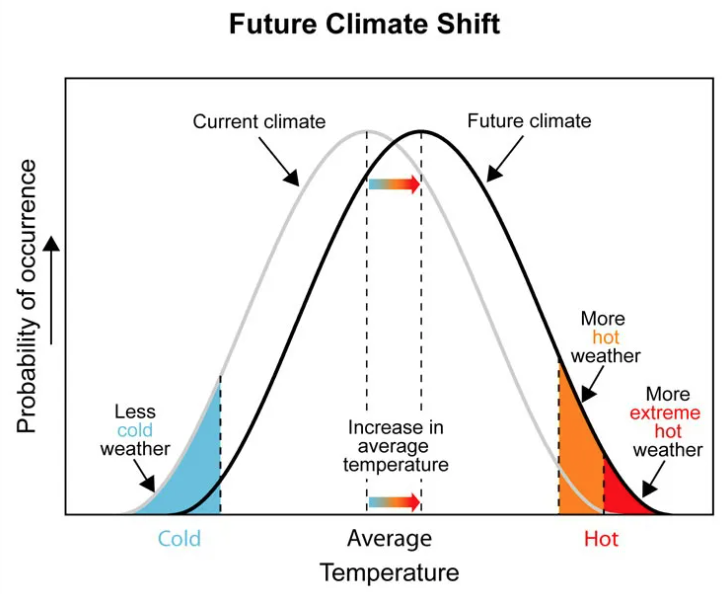

An important

thing to note, however, is that small average differences

can have big impacts on outliers. Many people, for example, struggle

intuitively to understand why a 3- or 4-degrees Celsius increase in

average global temperatures could be catastrophic given that

temperatures swing by that much all the time. An important

thing to note, however, is that small average differences

can have big impacts on outliers. Many people, for example, struggle

intuitively to understand why a 3- or 4-degrees Celsius increase in

average global temperatures could be catastrophic given that

temperatures swing by that much all the time.The reason, as shown here, is that even a small rightward shift of a bell curve leads to a wildly disproportionate increase in the number of extreme climate events. That’s a chart about climate change specifically, but the same logic applies broadly to all kinds of domains. A difference in average intelligence levels that is not particularly large or noteworthy could lead to a drastic difference in the share of the group that is capable of doing Nobel-level work. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/12/30/21042733/bret-stephens-jewish-iq-new-york-times |

しかし、注意すべき重要な点は、

平均気温のわずかな差が異常値に大きな影響を与える可能性があるということである。例えば、世界の平均気温が3~4℃上昇すると、なぜ壊滅的な打撃を受け

るのか、多くの人々は直感的に理解できない。 しかし、注意すべき重要な点は、

平均気温のわずかな差が異常値に大きな影響を与える可能性があるということである。例えば、世界の平均気温が3~4℃上昇すると、なぜ壊滅的な打撃を受け

るのか、多くの人々は直感的に理解できない。その理由は、ここに示されているように、ベルカーブが少し右にずれるだけで、極端な気候現象の数が不釣り合いに増加するからである。 これは気候変動に特化したグラフだが、同じ論理があらゆる分野に広く当てはまる。平均的な知能水準に特に大きな差や特筆すべき差がなくても、ノーベル賞級 の仕事ができる集団の割合に劇的な差が生じる可能性がある。 |

| Racism in

science: the taint that lingers Angela Saini’s book indicts a destructive bias in research, writes Robin G. Nelson.BOOKS AND ARTS 25 June 2019, by Naure. Superior: The Return of Race Science Angela Saini Beacon (2019) In her latest book, Superior, Angela Saini investigates how the history and preservation of dubious science has justified and normalized the idea of hierarchies between ‘racial’ groups. In a reflection on power and conquest, Superior opens in the halls of London’s British Museum, among collections from Lower Nubia and ancient Egypt. This overture to imperialism sets the stage for an eminently readable history lesson on the origins, rise, disavowal and resurgence of race research in Western science. That story spans the survival of German doctor Johann Blumenbach’s eighteenth-century regionally based characterization of five human ‘races’ (Caucasians, Mongolians, Ethiopians, Americans and Malays), and modern discussions about presumed correlations between race and intelligence. Saini’s celebrated 2017 Inferior investigated the troubling relationship between sexism and scientific research. Pivoting deftly from personal reflection to technical exposition, she now explores a similarly persistent taint: the search by some scientists for measurable biological differences between ‘races’, despite decades of studies yielding no supporting evidence. Research has repeatedly shown that race is not a scientifically valid concept. Across the world, humans share 99.9% of their DNA. The characteristics that have come to define our popular understanding of race — hair texture, skin colour, facial features — represent only a few of the thousands of traits that define us as a species. Visible traits tell us something about population histories and gene–environment interactions. But we cannot consistently divide humans into discrete groups. Yet, despite its lack of scientific rigour or reproducibility, this reliance on race as a biological concept persists in fields from genetics to medicine. The consequences of that reliance have ranged from justifications for school and housing segregation, to support for the Atlantic slave trade of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, genocidal policies against Indigenous communities around the world, and the Holocaust. Saini reminds us that in early-nineteenth-century Europe, the dehumanization of people of colour allowed for the caging and public exhibition of a South African Khoikhoi woman. Sara Baartman (her birth name is unknown) was insultingly dubbed “the Hottentot Venus” owing to a fascination with her genitalia. A century later, early-twentieth-century eugenic pseudoscience came to influence US policy. The US Immigration Act of 1924 was consciously designed to discourage southern and Eastern Europeans from entering the United States, and barred Asian immigrants outright. In Superior, one cannot help but see similarities between the twentieth-century movement of race-making ideologies from laboratories to political stages, and the current rise of xenophobic politics around the world. Long history The book, Saini tells us, reflects her childhood dream to understand and speak about the history and social context of the race concept. She does so accessibly and cogently, tracing the trajectory from that history to knotty topics such as research on the emergence of Homo sapiens, or the production of pharmaceuticals targeting people of colour. (For instance, the heart-failure medication BiDil (isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine), approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2005, was marketed solely to African Americans.) The durability of the race concept transcends disciplines, colouring everything from data collection to policy recommendations regarding immigration. In a chapter entitled ‘Race Realists’, Saini paints a vivid picture of the palpable fear that Barry Mehler, a Jewish historian of eugenics and genocide, felt in the 1980s on discovering an active network of ‘race scientists’ working long after the end of the Second World War. She points to shadow financing by the extremist US non-profit Pioneer Fund, which supports studies on eugenics, race and intelligence, and outlets such as the pro-eugenics so-called science journal Mankind Quarterly. She also notes that in the 1980s, the academic Ralph Scott, a contributor to that outlet, was appointed by the administration of US President Ronald Reagan to serve on the Iowa Advisory Commission on Civil Rights. Aside from a brief discussion of the slave trade and profits in the pharmaceuticals industry, the role of capitalist and colonialist expansion in propping up the race concept is not given much analysis here. Yet Saini does show that our current moment is part of a broader and longer span of social experience. She posits that the racial categories that many perceive as immutable could be transformed, as they have been in the past. These categories shift and align with the social ‘needs’ of the moment and have ranged, for example, from Celtic, to Hispanic, to the current US census categorization of people from the Middle East as white. That mutability might make racial categories seem random and purposeless. However, they have long served as the scaffolding for the creation and maintenance of empires. I wondered whom Saini imagines her primary audience to be. She uses the royal ‘we’, perhaps as a way of creating community with readers, whom I sense she sees as scientifically literate white people. This is perhaps due to the lack of diversity in science and science writing. At the same time, she reminds us that she is a Briton of Indian origin, and so would be a subject in race-based inquiries. In her discussion of Mankind Quarterly, she earnestly uses the term “political correctness” — which has been levelled disparagingly at those calling for more inclusive dialogue. And in a reflection on the Human Genome Diversity Project, which aimed to collect DNA from Indigenous communities around the world, she references the 1990s as the dawn of “identity politics” — a term often used to denigrate the perspectives of minoritized individuals. She does not question these tropes. In this way, Saini seems surprisingly willing to couch her critical analysis of race science in language often used by those more interested in silencing such critiques. A generous reading of her approach might be that it is a subversive attempt to appeal to sceptical readers. However, I am unsure that that is her intent. It is less clear what Saini makes of contemporary practitioners of race science. For her, it seems, there is a difference between past scientists who used financing from the Pioneer Fund to support eugenics research, and current researchers, those “race realists”, who continue to search for a biological component of race. She does explore the shortcomings of current research and openly questions why people persist with this field of fruitless inquiry. This tension between the deadly legacy of historical race science and the ethically troubling reification of racial frameworks in current research emerges in a lengthy interview with David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, known for his work on ancient DNA and human evolution. Reich tells her: “There are real ancestry differences across populations that correlate to the social constructions we have.” He adds: “We have to deal with that.” But, as Saini notes, when racism is embedded in society’s core structures, such research is born of the same social relations. |

スペリオール 人種科学の復権 アンジェラ・サイニ

ビーコン社(2019年) 最新刊『スペリオール』でアンジェラ・サイニは、怪しげな科学の歴史と保存が、「人種」グループ間のヒエラルキーという考えをいかに正当化し、常態化して きたかを調査している。 権力と征服についての考察の中で、『スペリオール』はロンドンの大英博物館のホールで、下層ヌビアと古代エジプトのコレクションの中で幕を開ける。この帝 国主義への序曲は、西洋科学における人種研究の起源、台頭、否定、そして復活に関する、非常に読み応えのある歴史レッスンの舞台となる。その物語は、ドイ ツの医師ヨハン・ブルーメンバッハが18世紀に地域別に5つの人間の「人種」(白人、モンゴル人、エチオピア人、アメリカ人、マレー人)を分類したことか ら、人種と知能の推定相関性に関する現代の議論に至るまで、存続している。 サイニの有名な2017年の『Inferior』は、性差別と科学研究の間の厄介な関係を調査した。個人的な考察から技術的な説明へと巧みに軸足を移しな がら、彼女は今回、同様に根強く残る汚点、つまり、何十年にもわたる研究にもかかわらず、「人種」間の測定可能な生物学的差異を一部の科学者が探し求める ことで、裏付けとなる証拠が得られないことを探求している。 人種は科学的に有効な概念ではないことは、研究によって繰り返し明らかにされてきた。世界中で、人間は99.9%のDNAを共有している。髪の毛の質感、 肌の色、顔の特徴など、私たちの一般的な人種理解を定義するようになった特徴は、私たちを種として定義する何千もの特徴のほんの一部に過ぎない。目に見え る形質は、集団の歴史や遺伝子と環境の相互作用について教えてくれる。しかし、人間を一貫して個別のグループに分けることはできない。 しかし、科学的な厳密さや再現性が欠けているにもかかわらず、遺伝学から医学に至るまで、生物学的概念としての人種への依存は続いている。その結果、学校 や住居の隔離を正当化するものから、16世紀から19世紀にかけての大西洋奴隷貿易の支持、世界中の先住民コミュニティに対する虐殺政策、ホロコーストに 至るまで、さまざまな影響を及ぼしてきた。 サイニは、19世紀初頭のヨーロッパで、有色人種の非人間化が、南アフリカのコイコイ族の女性を檻に入れ、公に展示することを許したことを思い起こさせ る。サラ・バートマン(出生名は不明)は、その性器に魅了され、侮辱的に「ホッテントットのヴィーナス」と呼ばれた。それから1世紀後、20世紀初頭の優 生学的疑似科学がアメリカの政策に影響を与えるようになった。1924年に制定されたアメリカ移民法は、南ヨーロッパや東ヨーロッパの人々のアメリカ入国 を意識的に阻止するように作られ、アジアからの移民は全面的に禁止された。 スーペリオールでは、20世紀に人種差別イデオロギーが研究室から政治の舞台へと移動したことと、現在世界中で外国人排斥政治が台頭していることの間に、 類似点を見ずにはいられない。 長い歴史 この本は、人種概念の歴史と社会的背景を理解し、語りたいという彼女の幼い頃からの夢を反映したものだとサイニは語る。その歴史から、ホモ・サピエンスの 出現に関する研究や、有色人種をターゲットにした医薬品の製造といった厄介なトピックに至る軌跡をたどりながら、彼女はわかりやすく、かつ理路整然とそう している(例えば、2005年に米国食品医薬品局から承認された心不全治療薬BiDil(硝酸イソソルビド/ヒドララジン)は、アフリカ系アメリカ人のみ を対象として販売された)。人種概念の耐久性は学問分野を超え、データ収集から移民に関する政策提言まで、あらゆるものを彩っている。 人種の現実主義者たち」と題された章で、サイニは、優生学と大量虐殺のユダヤ人歴史家であるバリー・メーラーが、1980年代に第二次世界大戦終結後も長 く活動している「人種科学者」の活発なネットワークを発見した際に感じた、手に取るような恐怖を鮮明に描いている。彼女は、優生学、人種、知能に関する研 究を支援する米国の過激派非営利団体パイオニア・ファンドによる影の資金提供や、優生学寄りのいわゆる科学雑誌『Mankind Quarterly』などの出版物を指摘している。また、1980年代には、この雑誌の寄稿者である学者のラルフ・スコットが、ロナルド・レーガン米大統 領政権によって、アイオワ州公民権諮問委員会の委員に任命されたことも指摘している。 奴隷貿易と製薬産業における利益についての短い議論を除けば、人種概念を支える資本主義と植民地主義の拡大の役割は、ここではあまり分析されていない。し かし、サイニは、私たちの現在が、より広く長い社会経験の一部であることを示している。彼女は、多くの人々が不変のものとして認識している人種的カテゴ リーは、過去にそうであったように、変容する可能性があると仮定している。このようなカテゴリーは、その時々の社会的「ニーズ」に合わせて変化し、例え ば、ケルト人からヒスパニック、そして現在のアメリカの国勢調査における中東出身者の白人への分類に至るまで様々である。 このような変わりやすさが、人種カテゴリーを無作為で無目的なものに思わせるのかもしれない。しかし、人種分類は長い間、帝国の創造と維持の足場として機 能してきた。 サイニが想像する主な読者は誰なのだろうか。彼女は、おそらく読者との共同体を作る方法として、「私たち」というロイヤルネームを使っている。これはおそ らく、科学やサイエンス・ライティングにおける多様性の欠如によるものだろう。同時に彼女は、自分がインド出身のイギリス人であり、人種に基づく調査の対 象となることを思い出させてくれる。季刊人類』についての考察の中で、彼女は「ポリティカル・コレクトネス(政治的正しさ)」という言葉を真摯に用いてい る。また、世界中の先住民コミュニティからDNAを収集することを目的としたヒトゲノム多様性プロジェクトについての考察の中で、彼女は1990年代を 「アイデンティティ・ポリティクス」の幕開けとして言及している。彼女はこうした常套句に疑問を投げかけることはない。 このようにサイニは、人種科学に対する批判的な分析を、そのような批判を封じ込めようとする人々がよく使う言葉で表現することを、驚くほど厭わないよう だ。彼女のアプローチを寛大に読めば、それは懐疑的な読者に訴えかける破壊的な試みだと言えるかもしれない。しかし、それが彼女の意図であるかどうかはわ からない。 サイニが現代の人種科学の実践者たちをどう見ているのかは、あまり明確ではない。彼女にとって、パイオニア基金からの資金で優生学研究を支援した過去の科 学者と、人種の生物学的要素を探求し続ける「人種現実主義者」である現在の研究者との間には違いがあるようだ。彼女は現在の研究の欠点を探り、なぜ人々が この実りのない分野に固執するのか、率直に疑問を投げかけている。 歴史的な人種科学の致命的な遺産と、現在の研究における人種的枠組みの倫理的に問題のある再定義との間のこの緊張は、古代のDNAと人類の進化に関する研 究で知られるマサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジにあるハーバード大学の遺伝学者、デイヴィッド・ライヒとの長いインタビューの中で浮かび上がってきた。ライ ヒは彼女に言う: 「私たちが抱いている社会的解釈と相関するような、集団間の祖先の違いが実際に存在するのです」。彼はこう付け加えた: 「私たちはそれに対処しなければなりません しかし、サイニが指摘するように、人種差別が社会の中核的構造に埋め込まれている場合、そのような研究は同じ社会的関係から生まれる。 ・科学の人種主義とたたかう : 人種概念の起源から最新のゲノム科学まで / アンジェラ・サイニー著 ; 東郷えりか訳、作品社 , 2020年 ・科学の女性差別とたたかう : 脳科学から人類の進化史まで / アンジェラ・サイニー著 ; 東郷えりか訳, 作品社 , 2019年 |

| Collective denial In my view, too many scholarly voices provide this kind of cover for their peers. This unwillingness to reckon with the possibility that racism actually underpins research that has been proved to have demonstrably deleterious outcomes left me longing for a stronger take-away message. Ultimately, Superior is most impactful in describing the persistence of support for ideas of hierarchal differences from the Enlightenment onwards, in the face of political backlash and researchers’ inability to even define the primary variable at play: race. Saini rightly calls out the denial that runs through so much of our public dialogue. She reveals how shame about an unreconciled past affects our ability to engage in tough conversations about its long shadows. Superior is perhaps best understood as continuing in a tradition of groundbreaking work that contextualizes the deep and problematic history of race science. These include the 2011 Fatal Invention by Dorothy Roberts and The Social Life of DNA (2016) by Alondra Nelson (see F. L. C. Jackson Nature 529, 279–280; 2016). Saini contributes to this conversation by linking the desire to make race real, particularly with regards to measurable health disparities, to society’s underlying desire to let itself off the hook for these very inequalities. She closes by arguing that researchers must at least know what it is they are measuring when they use race as a proxy. I would add that they should have to contend with what it isn’t — and what they have created instead. Nature 570, 440-441 (2019) doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01968-z |

集団的否定 私に言わせれば、このような隠れ蓑を提供する学者の声があまりにも多い。人種差別が、明らかに有害な結果をもたらすことが証明された研究の根底に実際に存 在するという可能性を考慮しようとしないこの姿勢に、私はもっと強力なメッセージを待ち望んでいた。 結局のところ、『スペリオール』は、政治的反発や研究者たちが主要な変数である人種を定義することさえできない中で、啓蒙主義以降、階層的差異に関する考 え方が支持され続けてきたという記述において、最も衝撃的であった。サイニは、私たちの公的な対話の多くを貫く否定を正しく指摘している。彼女は、和解で きない過去に対する羞恥心が、その長い影について厳しい対話をする私たちの能力にいかに影響しているかを明らかにする。 スペリオール』は、人種科学の深く問題のある歴史を文脈化する画期的な作品の伝統を受け継ぐものとして、おそらく最もよく理解されるだろう。ドロシー・ロ バーツによる2011年の『Fatal Invention』や、アロンドラ・ネルソンによる『The Social Life of DNA』(2016年)などがそれである(F. L. C. Jackson Nature 529, 279-280; 2016参照)。サイニは、特に測定可能な健康格差に関して、人種を現実のものにしたいという願望を、まさにこうした不平等から解放されたいという社会の 根底にある願望と結びつけることで、この会話に貢献している。 彼女は最後に、研究者は少なくとも、人種を代用品として使うときに何を測定しているのかを知らなければならないと主張している。私は、研究者たちはそれが 何でないのか、そしてその代わりに何を作り出してしまったのかに直面しなければならないと付け加えたい。 Nature 570, 440-441 (2019) doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01968-z |

| Shapiro, Adam (27 January 2020).

"The

Dangerous Resurgence in Race Science". American Scientist. |

|

| “The Secrets of Jewish Genius” At first glance, columnist Bret Stephens’s last New York Times column of 2019, “The Secrets of Jewish Genius”* might seem like a welcome act of defiance following years of increased anti-Semitism in the United States and elsewhere. Jews, Stephens claims, particularly Ashkenazi Jews whose historical roots lay in northern and eastern Europe, have highly developed intelligence in part because it was a necessary survival strategy in the face of centuries of oppression. With Jews of various backgrounds targeted by a variety of hate crimes, and the violence of those acts increasing, a column about Jewish “genius” would seem to be an affirmation of Jewish worth and value to society. Perhaps that was the intention behind the column: to provide frightened Jews with a weird silver lining to the surge in anti-Semitism they are witnessing (It’ll make you smarter!) while also suggesting to non-Jews that anti-Semitism is wrong because countries benefit from their Jewish geniuses. https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/macroscope/the-dangerous-resurgence-in-race-science |

「ユダヤ人の天才の秘密」 一 見すると、コラムニスト、ブレット・スティーブンスの2019年最後のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のコラム「ユダヤ人の天才の秘密」(※)は、米国やその他 の地域で反ユダヤ主義が強まった数年後の反抗的な行為として歓迎されるように見えるかもしれない。ユダヤ人、特に北欧や東欧に歴史的ルーツを持つアシュケ ナージ系ユダヤ人は、何世紀にもわたる抑圧の中で必要な生存戦略だったこともあり、高度に発達した知性を持っているとスティーブンスは主張する。さまざま な背景を持つユダヤ人がさまざまなヘイトクライムの標的にされ、そうした行為の暴力性が増している今、ユダヤ人の「天才」についてのコラムは、ユダヤ人の 価値と社会にとっての価値を肯定しているように見える。恐らく、それがこのコラムの背後にある意図なのだろう。怯えるユダヤ人に、彼らが目撃している反ユ ダヤ主義の急増に対する奇妙な明るい兆しを提供する一方で(それはあなたを賢くする!)、非ユダヤ人には、各国がユダヤ人の天才から利益を得ているのだか ら反ユダヤ主義は間違っていると示唆するのだ。 |

But

if that were Stephens’s intention, then it was thoroughly misguided.

Anti-Semitism is rarely justified by a belief in Jewish intellectual

inferiority—and so debunking such a claim does little to help the

current climate. If anything, it serves to reinforce a variety of

anti-Semitic tropes that portray Jews as cunning tricksters, using

their intelligence to manipulate the media, accrue wealth, or exert

outsized political influence. Attitudes toward Jews are not likely to

be improved by claims that “Ashkenazi Jews might have a marginal

advantage over their gentile peers when it comes to thinking better.” But

if that were Stephens’s intention, then it was thoroughly misguided.

Anti-Semitism is rarely justified by a belief in Jewish intellectual

inferiority—and so debunking such a claim does little to help the

current climate. If anything, it serves to reinforce a variety of

anti-Semitic tropes that portray Jews as cunning tricksters, using

their intelligence to manipulate the media, accrue wealth, or exert

outsized political influence. Attitudes toward Jews are not likely to

be improved by claims that “Ashkenazi Jews might have a marginal

advantage over their gentile peers when it comes to thinking better.” |

し

かし、それがスティーブンスの意図であったとすれば、それは完全に見当違いである。反ユダヤ主義が、ユダヤ人の知的劣等感によって正当化されることはめっ

たにない。むしろ、ユダヤ人を狡猾な策略家として描き、その知性を利用してメディアを操り、富を築き、政治的に大きな影響力を行使するという、さまざまな

反ユダヤ主義的表現を強化することになる。"アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人は、思考力が優れているという点では、同世代の異邦人よりわずかに有利かもしれない

"という主張によって、ユダヤ人に対する態度が改善されることはないだろう。 し

かし、それがスティーブンスの意図であったとすれば、それは完全に見当違いである。反ユダヤ主義が、ユダヤ人の知的劣等感によって正当化されることはめっ

たにない。むしろ、ユダヤ人を狡猾な策略家として描き、その知性を利用してメディアを操り、富を築き、政治的に大きな影響力を行使するという、さまざまな

反ユダヤ主義的表現を強化することになる。"アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人は、思考力が優れているという点では、同世代の異邦人よりわずかに有利かもしれない

"という主張によって、ユダヤ人に対する態度が改善されることはないだろう。 |

| But

at worst, Stephens’s column is a cynical and disingenuous attempt to

portray anti-Jewish hate acts as exceptional and unrelated to other

acts of racism and ethnic violence that are also fueled by resurgent

white nationalism and white supremacy movements. In so doing, it

suggests that the antidote to anti-Semitism is not a broad coalition

against the ideology of white supremacy that works across racial and

religious lines, but instead proposes an alternative Jewish supremacy

(justified by high IQ) that applies primarily to Jews most likely to

pass as or identify as “white” (coded here as Ashkenazi, although not

all Ashkenazi Jews are white). In short, Stephens argues for (white)

Jewish inclusion within white supremacy. Regardless of his intentions, Stephens’s line of argument displays a particularly problematic use of science (or at least an appeal to scientific authority) as a tool to justify specious claims. The original version of the column (now removed from the New York Times website and replaced with an edited version) made reference to a study published in 2006 that claimed that the disproportionate number of famous Jewish “geniuses”—Nobel laureates, chess champions, and others—was exemplary of the paper’s claim (quoted by Stephens) that “Ashkenazi Jews have the highest average IQ of any ethnic group for which there are reliable data.” Stephens fully embraces this apparently empirical claim, writing: “The common answer is that Jews are, or tend to be, smart. When it comes to Ashkenazi Jews, it’s true.” The scientific methodology and conclusions reached by the article Stephens cited has been called into question repeatedly since its publication. At least one of that study’s authors has been identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a white nationalist. Critics have observed that this isn’t the first time Stephens has been caught cherry-picking sources solely to back up his preconceived notions. The New York Times appended an Editors’ Note to the online column and removed both references to and quotations from that study as well as all references to the word Ashkenazi as a reference to a particular subset of Jews. The Note attempted to clarify: Mr. Stephens was not endorsing the study or its authors’ views, but it was a mistake to cite it uncritically. The effect was to leave an impression with many readers that Mr. Stephens was arguing that Jews are genetically superior. That was not his intent. He went on instead to argue that culture and history are crucial factors in Jewish achievements… But as a result of this effort to walk back the most overt racism, the resulting column no longer has anything to argue. Even in the redacted version of the column, Stephens writes: “These explanations for Jewish brilliance aren’t necessarily definitive. Nor are they exclusive to the Jews.” Stephens moderates the tone of his claim by acknowledging that non-Jewish people can also be smart, but his primary goal is still to consider “explanations for ‘Jewish brilliance.’” But without this discredited study, there’s no remaining evidence that there is exceptional “Jewish [Ashkenazi, white] brilliance” to be explained. The problems with Stephens’s column go well beyond the questionable scientific merit of a cherry-picked article. Much more troubling is the invocation of science as a neutral arbiter of truths about race and intelligence. https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/macroscope/the-dangerous-resurgence-in-race-science |

し

かし最悪の場合、スティーブンスのコラムは、反ユダヤ憎悪行為を、復活しつつある白人ナショナリズムや白人至上主義運動によって煽られている他の人種差別

や民族的暴力行為とは無関係で、例外的なものであるかのように描こうとする皮肉で不誠実な試みである。そうすることで、反ユダヤ主義への解毒剤は、人種や

宗教の違いを超えて機能する白人至上主義のイデオロギーに対抗する広範な連合ではなく、その代わりに、主に「白人」(ここではアシュケナージ・ユダヤ人と

するが、すべてのアシュケナージ・ユダヤ人が白人であるわけではない)として認められる可能性の高いユダヤ人に適用される、(高いIQによって正当化され

る)代替的なユダヤ人至上主義を提案することになる。要するにスティーブンスは、白人至上主義の中に(白人の)ユダヤ人が含まれることを主張しているので

ある。 彼の意図がどうであれ、スティーブンスの主張は、科学(あるいは少なくとも科学的権威へのアピール)を、まやかしの主張を正当化するための道具として使う という、特に問題のある使い方をしている。このコラムの原文(現在はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のウェブサイトから削除され、編集されたバージョンに差し替 えられている)は、2006年に発表された研究に言及し、ノーベル賞受賞者やチェスのチャンピオンなど、有名なユダヤ人の "天才 "の数が不釣り合いであることを主張している。"アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人の平均IQは、信頼できるデータが存在するあらゆる民族の中で最も高い "という論文の主張(スティーブンスが引用している)を例証している。スティーブンスはこの一見経験的な主張を全面的に受け入れ、こう書いている: 「一般的な答えは、ユダヤ人は頭がいい、あるいはその傾向がある、というものだ。アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人に関して言えば、それは真実である」。 スティーブンスが引用した論文の科学的方法論と結論は、発表以来何度も疑問視されてきた。その研究の著者の少なくとも一人は、南部貧困法律センターによっ て白人ナショナリストと認定されている。スティーブンスが自分の先入観を支持するためだけにソースを選んでいることが発覚したのは、今回が初めてではない と批評家たちは指摘している。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙はオンライン・コラムに編集者注を付け、ユダヤ人の特定のサブセットを指すアシュケナージという言 葉への言及と、その研究からの引用を削除した。この注釈では、次のことを明確にしようとしている: スティーブンス氏はその研究や著者の見解を支持したわけではないが、無批判に引用したのは誤りだった。多くの読者に、スティーブンス氏がユダヤ人は遺伝的 に優れていると主張しているかのような印象を与えてしまった。それは彼の意図するところではなかった。彼はその代わりに、ユダヤ人の業績には文化と歴史が 決定的な要因であると主張した。 しかし、このようにあからさまな人種差別を後退させようとした結果、このコラムはもはや反論のしようがない。再編集されたコラムの中でさえ、スティーブン スはこう書いている。また、ユダヤ人だけのものでもない」。スティーブンスは、ユダヤ人以外の人々も頭が良いことを認めることで、彼の主張のトーンを和ら げているが、彼の第一の目的は依然として"「ユダヤ人の優秀さ」の説明 "を検討することである。しかし、この信用できない研究がなければ、例外的な「ユダヤ人(アシュケナージ、白人)の優秀さ」を説明する証拠は残らない。 スティーブンスのコラムの問題点は、科学的根拠が疑わしいという点だけではない。もっと問題なのは、人種と知能に関する真実の中立的な裁定者として科学を 持ち出していることである。 |

| Generations of Debates The Editors’ Note in the New York Times tries to wave away the question of whether such brilliance was due to genetics or culture. But this nature-versus-nurture argument has plagued intelligence science since its inception. The science of defining and understanding intelligence has always been fraught with debates about the effects of heredity, environment, and culture. In 1792, French physician François-Emmanuel Fodéré published an “Essay on Goiter and Cretinism” studying the development and persistence of “cretins” and their underdeveloped mental and physical attributes, including intelligence. The condition is now known to be shaped by iodine deficiency and persisted especially in parts of southern France and other “goiter belts” where low levels of iodine are present in groundwater. Fodéré argued that the causes of cretinism seemed to be environmental, but in the days before genes were understood as they are today, he also argued that these environmental effects could become internalized and over the course of about three generations become hereditary. Later critics claimed that Fodéré’s assertion that intervention could reduce cretinism was ideologically shaped by the egalitarianism of the French Revolution and its commitment to rapid and radical change. Even as scientific theories of biological inheritance and the effects of the environment to influence offspring changed over the course of the 19th century, the idea remained that a trait that persisted through three generations was inheritable. Most famously, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1927 that the Commonwealth of Virginia had the right to forcibly sterilize Carrie Buck on the grounds that she, her mother, and her newborn child were all classified as “feeble-minded.” In his book about Buck, Three Generations No Imbeciles, legal historian Paul Lombardo demonstrates that the “feeble-minded” diagnosis was false and most probably deliberately fraudulent, and that her relatives used the claim of her mental deficiency to cover up her rape. But taking the scientific evidence at face value, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes infamously opined: “Three generations of imbeciles is enough." Holmes may well have meant “enough” in the sense that three generations were sufficient to determine that Buck’s feeblemindedness was due to hereditary rather than some environmental or cultural factor, rather than the more common interpretation that Holmes was saying that three generations were enough of a drain on state resources. But either interpretation presumes the legitimacy of Buck’s diagnosis as “feeble-minded” and that in turn relied on the new scientific tool of the Intelligence Quotient (IQ). While today IQ and similar intelligence tests are most used for identifying the learning needs of individual children, when it was first developed, IQ was devised as a statistical tool used to implement eugenic programs. (The Lady Science podcast episode featuring Safiya Umoja Noble features an excellent extended discussion of the racist origins of IQ testing.) “Imbecile” was a technical category used to describe someone with a measured IQ between 26 and 50. (In contrast to “idiots” [0–25] and “morons” [51–75].) The terms were introduced by the intelligence researcher and eugenicist Henry Goddard, who used his tests and the results they produced to institutionalize, deport and restrict the rights and freedoms of those deemed “feebleminded.” Goddard’s tests, taken to be the scientific standard of their day, overwhelmingly found higher proportions of feebleminded among immigrants from Southern Europe, Jews, and blacks. Goddard’s language and methods were also highly influenced by gendered views of intelligence and morality that tended to define the behavior of women as evidence of feeblemindedness while excusing or passing as normal the same or worse behavior in men. It’s not just the application of intelligence testing that has racist and sexist overtones. The content of questions and tasks, as well as the standards that have been used to calibrate such tests, have long been criticized for bias, sometimes invisible to those who develop the tests, sometimes intentional. The question of whether the scientific study of intelligence can ever be purged of its racist and sexist origins, is one that psychologists, educators, and social scientists continue to struggle with. https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/macroscope/the-dangerous-resurgence-in-race-science |

世代を超えた論争 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の編集者注は、このような才能が遺伝によるものなのか、それとも文化によるものなのかという疑問を振り払おうとしている。しか し、この自然対育成の議論は、知能科学が始まった当初から悩まされてきた。知能を定義し理解する科学は、遺伝、環境、文化の影響に関する議論と常に隣り合 わせだった。1792年、フランスの医師フランソワ=エマニュエル・フォデレは、「甲状腺腫とクレチン症に関する小論」を発表し、「クレチン」の発達と持 続性、および知能を含む彼らの未発達な精神的・身体的特性について研究した。現在では、この症状はヨウ素欠乏によって形成されることが知られており、特に 地下水中のヨウ素濃度が低い南フランスやその他の「甲状腺腫ベルト」の地域で持続していた。フォデレは、クレチン症の原因は環境的なものであると主張した が、今日のように遺伝子が解明される前の時代には、こうした環境的な影響が内面化し、3世代にわたって遺伝する可能性があるとも主張した。後の批評家たち は、介入によってクレチン症を減らすことができるというフォデレの主張は、フランス革命の平等主義と、急速で急進的な変化へのコミットメントによってイデ オロギー的に形成されたものだと主張した。 生物学的遺伝や環境が子孫に及ぼす影響に関する科学的理論が19世紀の間に変化しても、3世代にわたって持続する形質は遺伝するという考え方は変わらな かった。最も有名なのは、1927年に連邦最高裁判所が、キャリー・バックとその母親、そして生まれたばかりの子供がすべて "feeble-minded "に分類されるという理由で、バージニア州にキャリー・バックを強制不妊手術する権利があるという判決を下したことである。バックに関する著書 『Three Generations No Imbeciles』(邦題『3世代に不治の病なし』)の中で、法制史家のポール・ロンバードは、"feeble-minded "という診断が虚偽であり、おそらく意図的な詐欺であったこと、そして彼女の親族がレイプを隠蔽するために彼女の精神的欠陥の主張を利用したことを実証し ている。しかし、科学的証拠を額面通りに受け取ると、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ判事は悪名高い見解を示した: "無能者は3世代で十分だ"。 ホームズが "十分 "と言ったのは、バックの精神薄弱が環境や文化的要因ではなく、遺伝によるものだと判断するには3世代で十分だという意味であったかもしれない。しかし、 いずれの解釈もバックの「気が弱い」という診断の正当性を前提とし、その正当性は知能指数(IQ)という新しい科学的手段に依存している。今日、IQや類 似の知能テストは、個々の子供の学習ニーズを特定するために最も使用されているが、IQが開発された当初は、優生プログラムを実施するための統計ツールと して考案された。(サフィヤ・ウモジャ・ノーブルが出演したポッドキャスト『レディ・サイエンス』のエピソードでは、IQテストの人種差別的起源について 素晴らしい拡大議論がなされている)。 "Imbecile "は、測定されたIQが26から50の間の人を表すのに使われる技術的なカテゴリーだった。(この用語は、知能研究者であり優生学研究者でもあったヘン リー・ゴダードによって導入された。ゴダードは、自身のテストとその結果を用いて、"feebleinded "とみなされた人々を施設に収容し、国外追放し、権利と自由を制限した。当時の科学的基準とされたゴダードのテストは、南ヨーロッパからの移民、ユダヤ 人、黒人に圧倒的に高い割合で心の弱さを発見した。ゴダードの言葉や方法はまた、ジェンダーに基づく知性や道徳観の影響を強く受けており、女性の行動を心 の弱さの証拠と定義する一方で、男性の同じかそれ以上の行動を弁解したり、正常なこととして受け流したりする傾向があった。人種差別的で性差別的な含みを 持つのは、知能検査の適用だけではない。設問や課題の内容、そしてそのようなテストを校正するために使われてきた基準は、長い間偏向があると批判されてき た。知能の科学的研究が、その人種差別的・性差別的な起源を取り除くことができるのかどうかという問題は、心理学者、教育者、社会科学者たちが今もなお悩 み続けている問題である。 |

| Is This Eugenics? Over the course of the 20th century, with the advocacy of Goddard and other like-minded scientists, eugenic sterilization laws were passed by a number of U.S. states. Over time (especially but not exclusively in the South) these became increasingly racist in their application. Laws that were on paper in the 1910s and 1920s, meant to apply to the “feeble-minded” of any race, were by the 1940s and 1950s almost exclusively used on black women, Native Americans, and other people of color. “Intelligence” and the alleged objectivity and impartiality of its measurement became used as a proxy for race. The legacy is so recent that victims of racist and sexist eugenic sterilization are still alive today, and just a few years ago, North Carolina announced efforts to compensate surviving victims of its eugenics sterilizations. It’s not just for historical reasons that readers of the Stephens column saw his claim about Jewish IQ as “eugenics.” The identification of intelligence as inherited (and perhaps acted upon by some sort of selection principle) and the association of intelligence with distinct racial groups is all part of the eugenic ideology. Defenders of Stephens’s column claim he can’t be advocating eugenics because it’s claiming Jews are superior not inferior. This argument ignores the fact that some eugenicists (including some German scientists before World War II) made similar arguments about superior Ashkenazi Jewish intelligence. Writing soon after the 2006 study was published, Sander Gilman pointed out that such apparently positive interpretations of Jewish traits had a long history of anti-Semitic undercurrents, and have particular appeal among people whose theology places Jews at the center of a Christian narrative about apocalypse and redemption. And with the State of Israel considering using genetics as a measure of Jewish identity (at least for Ashkenazi Jews), concerns about “Jewgenics” are perhaps more politically fraught than ever. Pretending that this isn’t eugenics is also a byproduct of a fallacy of letting Nazi eugenics stand as the basis by which all eugenics are judged. The history of eugenics is rife with less extreme examples of coordinated efforts to change the demographics of a society, often aligned with racist and ableist standards of fitness, beauty, and social value. Eugenic ideas about improving the genome were behind the popularity of child beauty pageants in the 20th century. The advent of new genetic techniques and technologies of childbirth raise a variety of ethical questions. These kinds of eugenic actions don’t directly result in the kind of individual violations of human rights comparable to what happened to Carrie Buck or to victims of Nazis. But what makes something eugenics isn’t the invasion of individual human dignity but the intention to impact the genome of an entire population. Abuses of individuals that include sterilization or worse—or which reward them for beauty standards or other talents—are eugenics when they are intended to be part of a cumulative effect. https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/macroscope/the-dangerous-resurgence-in-race-science |

これは優生学か? 20世紀にかけて、ゴダードや志を同じくする科学者たちの提唱により、優生不妊手術法がアメリカの多くの州で制定された。やがて(特に南部だけではない が)、これらの法律は人種差別的に適用されるようになっていった。1910年代や1920年代には、あらゆる人種の「心の弱い人」に適用されるはずだった 法律が、1940年代や1950年代には、黒人女性やネイティブ・アメリカン、その他の有色人種にほとんど独占的に適用されるようになったのである。「知 性」とその測定の客観性と公平性が、人種の代用として使われるようになったのである。つい数年前、ノースカロライナ州は、優生不妊手術の犠牲者を補償する 取り組みを発表した。 スティーブンスのコラムの読者が、ユダヤ人のIQに関する彼の主張を "優生学 "と捉えたのは、歴史的な理由だけではない。知能が遺伝する(そしておそらくはある種の淘汰原理が作用する)ものであるという認識や、知能を別個の人種集 団と結びつけることは、すべて優生思想の一部なのである。スティーブンスのコラムを擁護する人々は、ユダヤ人は劣っているのではなく優れていると主張して いるのだから、優生学を提唱しているはずがないと主張する。この主張は、(第二次世界大戦前のドイツの科学者を含む)一部の優生学者が、アシュケナージ系 ユダヤ人の知能が優れていると同様の主張をしていたという事実を無視している。サンダー・ギルマンは、2006年の研究が発表された直後に執筆し、ユダヤ 人の特質に関するこのような一見肯定的な解釈には、反ユダヤ主義的な長い歴史があり、終末と救済に関するキリスト教の物語の中心にユダヤ人を据える神学を 持つ人々の間では特に魅力的であると指摘した。また、イスラエルがユダヤ人のアイデンティティを測る尺度として遺伝学を用いることを検討していることから (少なくともアシュケナージ系ユダヤ人については)、「ユダヤ人遺伝学」に対する懸念は、おそらくこれまで以上に政治的に危ういものとなっている。 これが優生学でないかのように装うのは、ナチスの優生学をすべての優生学が判断される基準として立脚させるという誤謬の副産物でもある。優生学の歴史に は、社会の人口統計を変えようとする、それほど極端ではない協調的な努力の例が数多くあり、多くの場合、人種差別的で能力主義的な体力、美しさ、社会的価 値の基準に沿っている。20世紀に子どもの美人コンテストが流行した背景には、ゲノムを改良するという優生思想があった。新たな遺伝技術や出産技術の出現 は、さまざまな倫理的問題を提起している。この種の優生学的行為は、キャリー・バックやナチスの犠牲者に起こったような個人の人権侵害を直接もたらすもの ではない。しかし、優生学を優生学たらしめているのは、個人の人間としての尊厳の侵害ではなく、集団全体のゲノムに影響を与えようとする意図なのである。 不妊手術やそれ以上のことを含む個人への虐待、あるいは美の基準やその他の才能に対して報酬を与えるような虐待は、それが累積的な効果の一部となることを 意図している場合、優生学となる。 |

| The rise and resurgence of race

science The rise and resurgence of race science is a consequence of science being seen as the more respectable and valued way to justify racism. Today, the language of science is considered impartial, truth seeking, and authoritative. Claims, even fallacious ones, couched in such language are more easily accepted. The ability to use scientific language to spread doubt and misinformation is the very basis for pseudoscience. In effect, the rise and resurgence of race science is a consequence of science being seen as the more respectable and valued way to justify racism. What’s changed is the type of language and arguments we value, not the conclusions. These most recent efforts to reassert biological or scientific justifications for racism, have been aligned with rhetoric of science’s moral purity—that scientific facts are objective and shouldn’t be rejected because they are politically unfashionable. This rhetoric suggests that science can be separated from its politics—even though what it’s really doing is framing some scientific practices as “political” while obscuring its own politics by presenting them as tacit and normal rather than ideological. Posturing as bold contrarians rebelling against established norms and asserting that pure science compels hard truths are standard fare in the pseudoscience playbook. These scientific racists invoke claims of scientific “objectivity” that ignore the (objective empirical evidence that) political and historical forces, including racial and gendered biases that made objectivity into the most esteemed scientific virtue. But just because some racist claims are pseudoscience does not mean that science can’t also be racist. From using racist justifications to justify the use of people’s bodies or lands to obtain scientific knowledge to the attempt to use scientific methods to define and impose categories of race and identity, science has frequently benefited from and been used to justify racist power structures. Efforts to dismiss this connection by claiming that all racism is a misapplication or abuse of science (as, for example, Stephen Jay Gould attempted to do in his Mismeasure of Man) is the flip side of the same science-purity arguments that are used elsewhere to justify scientific racism. One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is the way that its advocates respond to refutation and new scientific discoveries. When one hypothesis is shown to be incompatible with reality, a new theory may be seized on to justify claims that are functionally similar to what came before. Perhaps the most notable example of this pattern is the early history of the intelligent design movement in the 1990s, which despite its historical roots in older forms of antievolutionism claimed that it was distinct because it was a “science.” Advocates of intelligent design also claimed that new discoveries about genes justified their conclusion of an intelligent designer who was more scientific than the theological arguments for divine design of previous centuries. In a very similar way, scientific racists have abandoned some of their other exploded theories about climate or geography accounting for alleged race differences in intelligence and turned to genetics. When the New York Times stripped away the problematic claim that the “Jewish brilliance” that Stephens claims to explain has a genetic basis, it left an expurgated column that is largely incoherent. But even more incoherent are the defenses of race-realist apologists, who claim that they are following norms of scientific objectivity and that nature doesn’t care about the racial, ethnic, or gender identity of the scientist, that it doesn’t matter how people of different backgrounds think—all to justify an apparently scientific claim that because of their culture, history, and background, Jewish genius is “about thinking different.” The views and opinions expressed in this post are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of American Scientist or its publisher, Sigma Xi. https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/macroscope/the-dangerous-resurgence-in-race-science |

人種科学の勃興と再燃 人種科学の台頭と復活は、人種差別を正当化する方法として科学がより尊敬され、評価されるようになった結果である。 今日、科学の言葉は公平で、真実を追求し、権威があると考えられている。誤った主張であっても、そのような言葉で表現されたものは受け入れられやすい。疑 いや誤った情報を広めるために科学的な言葉を使う能力は、まさに疑似科学の基盤である。事実上、人種科学の台頭と復活は、人種差別を正当化する方法とし て、科学がより尊敬され、評価されるようになった結果である。変化したのは、私たちが重視する言葉や議論の種類であって、結論ではない。 人種差別を生物学的あるいは科学的に正当化しようとする最近の努力は、科学の道徳的純粋性、つまり科学的事実は客観的であり、政治的に好ましくないからと いって否定されるべきではないというレトリックに沿ったものである。科学的事実は客観的であり、政治的に好ましくないからといって否定されるべきではない というものだ。このレトリックは、科学がその政治性から切り離されることを示唆している。既成の規範に反旗を翻す大胆な反体制派を装い、純粋な科学が厳し い真実を突きつけると主張するのは、疑似科学の常套手段である。こうした科学的差別主義者たちは、客観性を最も尊敬される科学的美徳とした人種的・ジェン ダー的偏見を含む政治的・歴史的な力(客観的な経験的証拠)を無視した科学的「客観性」の主張を展開する。 しかし、人種差別的な主張が疑似科学だからといって、科学が人種差別的であってはならないということにはならない。科学的知識を得るために人々の身体や土 地を利用することを正当化するために人種差別的な正当化を用いることから、人種やアイデンティティのカテゴリーを定義し、押し付けるために科学的手法を用 いようとする試みまで、科学は人種差別的な権力構造から恩恵を受け、それを正当化するためにしばしば用いられてきた。すべての人種差別は科学の誤用や乱用 であると主張することで、この関連性を否定しようとする努力(例えば、スティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドが『人間の測り違い』で試みたように)は、科学的人 種差別を正当化するために他の場所で使われているのと同じ、科学純粋論の裏返しである。 疑似科学の特徴のひとつは、その擁護者が反論や新たな科学的発見にどのように対応するかということである。ある仮説が現実と相容れないことが示されると、 新しい理論を持ち出して、それ以前と機能的に類似した主張を正当化することがある。このパターンの最も顕著な例は、1990年代のインテリジェント・デザ イン運動の初期の歴史であろう。インテリジェント・デザイン運動は、その歴史的ルーツが旧来の反進化主義にあるにもかかわらず、"科学 "であることから区別されると主張した。インテリジェント・デザインの支持者たちはまた、遺伝子に関する新たな発見が、それ以前の何世紀にもわたる神学的 な設計論よりも科学的な知的設計者という結論を正当化すると主張した。これとよく似た方法で、科学的人種差別主義者たちは、気候や地理が人種間の知能の差 を説明するという、他の爆発的な理論のいくつかを放棄し、遺伝学に目を向けた。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙が、スティーブンスが説明したいと主張する「ユダヤ人の優秀さ」が遺伝的根拠を持つという問題のある主張を取り除いたとき、ほ とんど支離滅裂なコラムが残された。科学的客観性の規範に従っているのであり、自然は科学者の人種、民族、性別など気にしていない、異なる背景を持つ人々 がどのように考えるかは問題ではないのだ、と主張する人種現実主義者の弁明はさらに支離滅裂である。 この投稿で述べられている見解や意見は筆者個人のものであり、必ずしもAmerican Scientistやその発行元であるSigma Xiの見解を代表するものではありません。 |

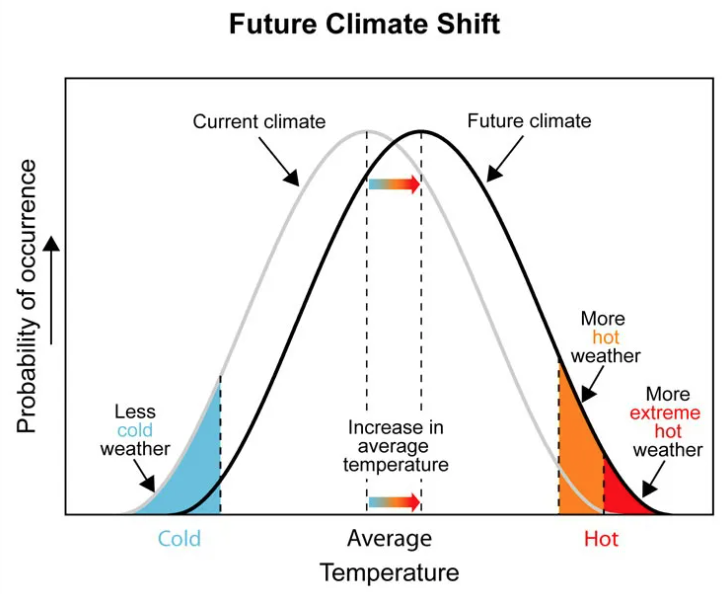

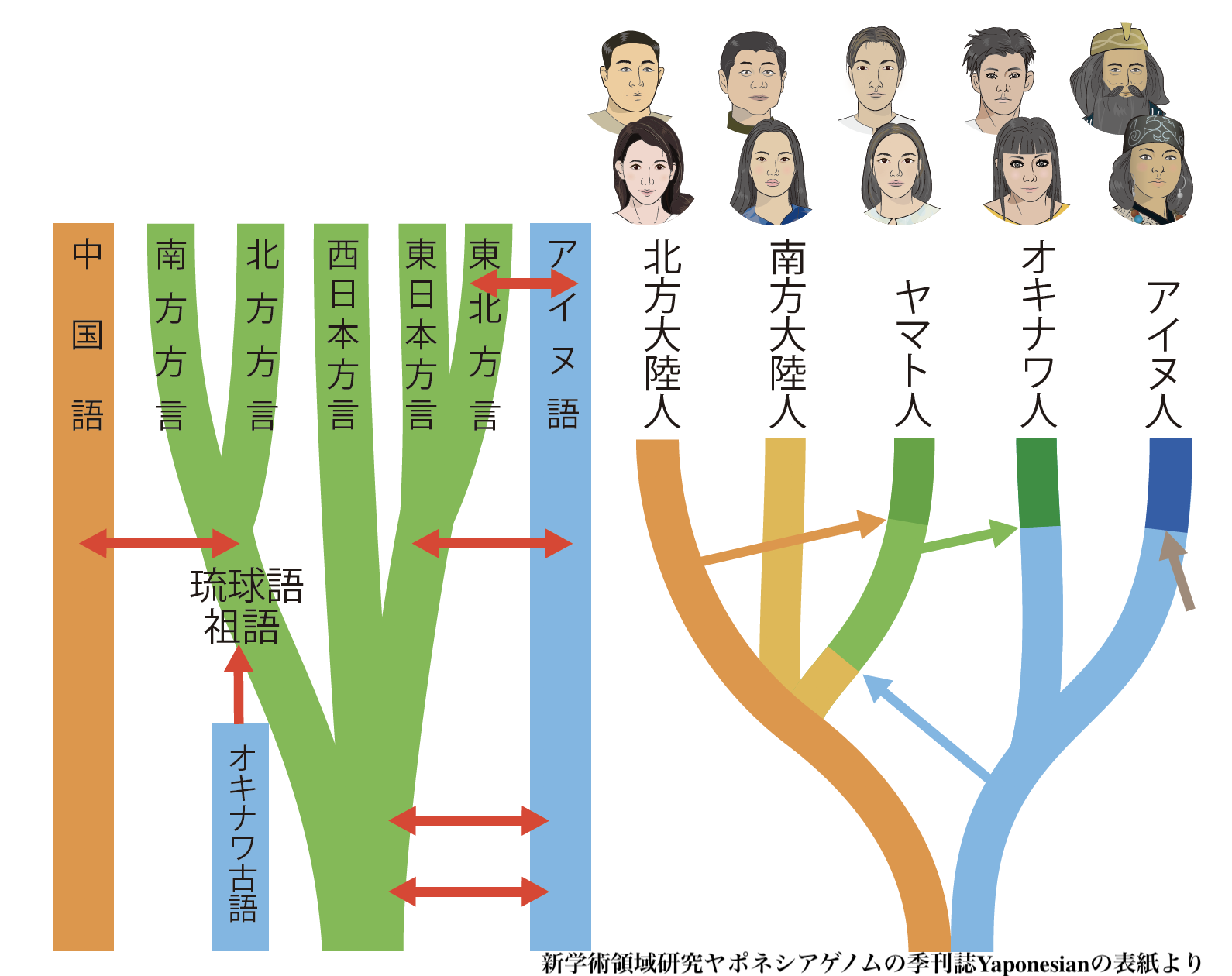

●検証課題02:「新学術領域研究ヤポネシアゲノム」研究は、はたして、科学人種主義の特徴 を持つのか?

新学術領域研究である「ヤポネシアゲノム」研究の ホームページには、下記のような人種の歴史的発展についてのイラストがある。これは、ユネスコ「人種問題」(1950年)において、人種の本質主義に基づ き、「人種の生物学的事実と『人種』の神話は、すべての実際的な社会的目的から見て、「人種」は生物学的現象というよりも社会的神話である。「人種」の神 話は、人的および社会的に多大な損害をもたらしました。近年、この神話には多大な影響が及んでいます。人命に犠牲を払い、計り知れない苦しみを引き起こし た」という記述からは、「強い人種差別」イデオロギーはみることことはできず、一見(人種差別主義思想からはかなり)「遠くに」あるように思える。しかし ながら、この研究グループの見解では、アイヌ、オキナワ、ヤマトという「生物学的人種的区分」は厳然として存在している。また、それらの集団を顔貌状の違 い、民族衣装などの文化的差異、さらには、言語的な差異にも見事にマッチして配分されている。

このホームページでの研究の目的は以下のように記載

されている:「ヤポネシア(日本列島)

には約4万年前に最初のヒトが渡来し、その後も何度か渡来の波がありました。この枠組みの中で、ヤポネシア人(日本列島人)はどのような集団にその起源を

もつのか、ヤポネシアにおける成立・発展の過程はどうであったのかを、多地域から選別した現代人500個体と旧石器時代~歴史時代の古代人100

名のゲノム配列を決定し比較解析することで、ヤポネシア人ゲノム史の解明をめざします。ヒトとともにヤポネシアに移ってきた動植物についても、それらのゲ

ノム配列の比較から歴史を解明します。過去の人口増減の詳細な歴史を、ゲノム配列から推定する既存の方法や新規に開発する方法を用いて、再構築します。ヤ

ポネシア人の歴史を多方向から検討するために、これらゲノム研究と、年代測定を取り入れた考古学研究や、日本語・琉球語の方言解析を含む言語学の研究グ

ループとの共同研究を行ないます。これらから、文理融合のあらたな研究領域を確立します」文部科学省科学研究費補助金新学術領域研究「ゲノム配列を核としたヤポネシア人の

起源と成立の解明」(領域略称名:ヤポネシアゲノム)。

+++

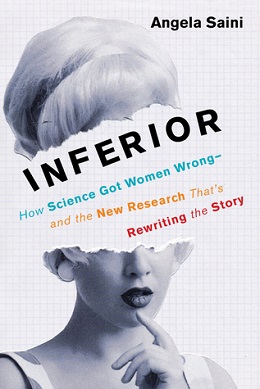

●科学の女性差別とたたかう : 脳科学から人類の進化史まで / アンジェラ・サイニー著 ; 東郷えりか訳, 作品社 , 2019年

内容説明

「“女脳”は論理的ではなく感情的」「子育ては母親の仕事」「人類の繁栄は男のおかげ」—間 違っている!旧来の「科学」がもたらしてきた偏見に真っ向から挑む!最新の科学が明らかにする、まったく新しい女性像。

目次

Inferior: How Science Got

Women Wrong and the New Research That's Rewriting the Story is a 2017

book by science journalist Angela Saini. The book discusses the effect

of sexism on scientific research, and how that sexism influences social

beliefs.[1][2] Inferior: How Science Got

Women Wrong and the New Research That's Rewriting the Story is a 2017

book by science journalist Angela Saini. The book discusses the effect

of sexism on scientific research, and how that sexism influences social

beliefs.[1][2]Inferior was launched in June 2017 at the Royal Academy of Engineering.[3] The book was published by Beacon Press in the United States and Fourth Estate Books in the United Kingdom.[4] Reception According to journalist Chantal Da Silva of The Independent, Angela Saini "paints a disturbing picture of just how deeply sexist notions have been woven into the fabric of scientific research" and concluded that her work "presents the rest of the scientific community with an important challenge: to acknowledge and correct a deep-rooted bias – and to help rewrite the role of women in the story of human evolution".[1] Science journalist Nicola Davis writing for The Guardian stated that Saini "discovers that many of society’s traditional beliefs about women are built on shaky ground" and that "Saini’s scrutiny of the stereotype of men as hunters, leaving women to tend hearth and home, is eye-opening".[2] Journalist Anjana Vaswani in the Ahmedabad Mirror wrote that Saini "exposes Charles Darwin's prejudices and how his views on a woman's place in society tinted, or rather tainted, his theories."[5] In a review by Chemistry World, journalist Jennifer Newton wrote that "Saini’s narrative is sharp, engaging and admirably tempered" "I cannot recommend it highly enough".[6] A month after its release, Inferior was recommended by Scientific American.[7] It was a finalist in the Goodreads Choice Awards for "Best Science and Technology" in 2017 but ultimately lost to Astrophysics for People in a Hurry.[8] Inferior was chosen as the Physics World "Book of the Year" for 2017 by the editor Tushna Commissariat who called it "[i]ntrepid, detailed [and] upbeat".[9] Egyptologist Julien Delhez, writing for the journal Evolution, Mind and Behaviour in 2019, criticized Inferior for being "imprecise", "hazy", stating that "[w]hile researchers often benefit from listening to those who disagree with them, innuendos and vague claims such as these will certainly not help". He also wrote that the book creates confusion that could potentially "seriously deteriorate the dialogue between the public and the scientific community", unless "evolutionary psychologists, personality researchers, and intelligence researchers take the time to respond to such critics [i.e. Saini]".[10] Psychologist Felipe Carvalho Novaes in the Portuguese journal Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, wrote that the book was well-written, but that it suffers from excessive biases and several contradictions.[11] Novaes also recommended reading other books, such as The Sexual Paradox, so the reader could get different perspectives on the subject.[11] After the release of Inferior, Angela Saini was invited to speak at universities and schools around the country, in what became a "scientific feminist book tour".[12][13][14][15] |

Inferior: How Science Got

Women Wrong and the New Research That's Rewriting the

Story』は、科学ジャーナリストのアンジェラ・サイニによる2017年の著書である。本書は、科学研究に対する性差別の影響と、その性差別が社会的信

念にどのような影響を与えるかを論じている[1][2]。 Inferior: How Science Got

Women Wrong and the New Research That's Rewriting the

Story』は、科学ジャーナリストのアンジェラ・サイニによる2017年の著書である。本書は、科学研究に対する性差別の影響と、その性差別が社会的信

念にどのような影響を与えるかを論じている[1][2]。Inferior』は2017年6月に王立工学アカデミーで発表された[3]。 本書は米国のBeacon Pressと英国のFourth Estate Booksから出版された[4]。 レセプション インディペンデント紙のジャーナリスト、シャンタル・ダ・シルヴァによると、アンジェラ・サイニは「性差別的な観念が科学研究の織物の中にどれほど深く織 り込まれてきたかについて、不穏な絵を描いている」とし、彼女の仕事は「科学界の他の人々に、根深い偏見を認めて修正し、人類の進化の物語における女性の 役割を書き直す手助けをするという、重要な課題を突きつけている」と結論づけた[1]。 科学ジャーナリストのニコラ・デイヴィスは『ガーディアン』紙に寄稿し、サイニについて「女性に関する社会の伝統的な信念の多くが、不安定な基盤の上に築 かれていることを発見した」と述べ、「男性は狩猟民族であり、女性は囲炉裏や家庭の世話をしているという固定観念に対するサイニの精査は、目を見張るもの がある」と述べている[2]。 Ahmedabad Mirror』紙のジャーナリスト、アンジャナ・ヴァスワニは、サイニが「チャールズ・ダーウィンの偏見と、社会における女性の地位に関する彼の見解が、 彼の理論をどのように染めているか、むしろ汚しているかを暴いている」と書いている[5]。 ケミストリー・ワールド』誌の書評で、ジャーナリストのジェニファー・ニュートンは「サイニの語りは鋭く、魅力的で、見事に抑制されている」「とても推薦 できない」と書いている[6]。 発売から1カ月後、『Inferior』はサイエンティフィック・アメリカン誌に推薦された[7]。 2017年のグッドリーズ・チョイス・アワードの「ベスト科学・技術賞」の最終選考に残ったが、最終的に『Astrophysics for People in a Hurry(急ぐ人のための天体物理学)』に敗れた[8]。『Inferior』は、編集者のトゥシュナ・コミサリアットによって、2017年のフィジッ クス・ワールドの「ブック・オブ・ザ・イヤー」に選ばれ、「(i)ntrepid, detailed [and] upbeat(勇敢で、詳細で、明るい)」と評された[9]。 エジプト学者のジュリアン・デレズは、2019年に『Evolution, Mind and Behaviour』誌に寄稿し、『Inferior』は「不正確」、「ぼんやり」していると批判し、「研究者はしばしば、自分たちと意見の異なる人々の 意見に耳を傾けることで利益を得るが、このような当てこすりやあいまいな主張は、確かに助けにならないだろう」と述べた。また、「進化心理学者、人格研究 者、知能研究者がこのような批評家(=サイニ)に答える時間をとらない限り」、この本は「一般大衆と科学界との対話を深刻に悪化させる」可能性のある混乱 を引き起こすとも書いている[10]。 ポルトガルの雑誌『Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho』に掲載された心理学者フェリペ・カルヴァーリョ・ノヴァエスは、この本はよく書かれているが、過度の偏見といくつかの矛盾に苦しんでい ると書いている[11]。ノヴァエスはまた、読者がこのテーマについて異なる視点を得ることができるように、『セクシュアル・パラドックス』などの他の本 を読むことを勧めている[11]。 Inferior』の発売後、アンジェラ・サイニは「科学的フェミニスト・ブックツアー」となり、国内の大学や学校に招かれて講演を行った[12] [13][14][15]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inferior_(book) |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報