ラ・マリンチェ

La Malinche,

ca.1500-ca.1529

Malintzin,

in an engraving dated 1886.

☆

マリーナ([maˈɾina])またはマリンツィンあるいはラ・マリンチェ[La Malinche]([maˈlintsin];約1500年 -

約1529年)は、メキシコ湾岸出身のナワ族の女性である。1500年頃 - 1529年頃)は、通称ラ・マリンチェ([la

maˈlintʃe])として知られるメキシコ湾岸出身のナワ族の女性である。スペインの征服者エルナン・コルテスの通訳、助言者、仲介者として活動し、

アステカ帝国征服(1519年-1521年)に貢献したことで知られる。[1]

彼女は1519年にタバスコ地方の先住民からスペイン人に献上された20人の奴隷女性の一人であった。[2]

コルテスは彼女を側室に選び、後に彼女はその最初の息子マルティンを出産した。マルティンはヌエバ・エスパーニャにおける最初のメスティソ(ヨーロッパ人

とアメリカ先住民の混血)の一人である。[3]

ラ・マリンチェの評価は時代と共に変化してきた。様々な人々が、自国の社会や政治的視点の変化に応じて彼女の役割を評価してきたからだ。特に1821年に

メキシコがスペインから独立したメキシコ独立戦争後は、演劇や小説、絵画で彼女が悪意ある狡猾な誘惑者として描かれるようになった。[4]

現代のメキシコにおいて、ラ・マリンチェは依然として強力な象徴的存在だ。裏切りの体現者、究極の犠牲者、あるいは新たなメキシコ国民の象徴的な母といっ

た、多様でしばしば矛盾する側面で理解されている。「マリンチスタ」という言葉は、特にメキシコにおいて、不忠実な同胞を指す。

| Marina ([maˈɾina])

or Malintzin ([maˈlintsin]; c. 1500 – c. 1529), more popularly known as

La Malinche ([la maˈlintʃe]), was a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf

Coast, who became known for contributing to the Spanish conquest of the

Aztec Empire (1519–1521), by acting as an interpreter, advisor, and

intermediary for the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés.[1] She was one

of 20 enslaved women given to the Spaniards in 1519 by the natives of

Tabasco.[2] Cortés chose her as a consort, and she later gave birth to

their first son, Martín – one of the first Mestizos (people of mixed

European and Indigenous American ancestry) in New Spain.[3] La Malinche's reputation has shifted over the centuries, as various peoples evaluate her role against their own societies' changing social and political perspectives. Especially after the Mexican War of Independence, which led to Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821, dramas, novels, and paintings portrayed her as an evil or scheming temptress.[4] In Mexico today, La Malinche remains a powerful icon – understood in various and often conflicting aspects as the embodiment of treachery, the quintessential victim, or the symbolic mother of the new Mexican people. The term malinchista refers to a disloyal compatriot, especially in Mexico. |

マリーナ([maˈɾina])またはマリンツィンあるいはラ・マリンチェ[La Malinche] ([maˈlintsin];約1500年 - 約1529年)は、メキシコ湾岸出身のナワ族の女性である。1500年頃 -

1529年頃)は、通称ラ・マリンチェ([la

maˈlintʃe])として知られるメキシコ湾岸出身のナワ族の女性である。スペインの征服者エルナン・コルテスの通訳、助言者、仲介者として活動し、

アステカ帝国征服(1519年-1521年)に貢献したことで知られる。[1]

彼女は1519年にタバスコ地方の先住民からスペイン人に献上された20人の奴隷女性の一人であった。[2]

コルテスは彼女を側室に選び、後に彼女はその最初の息子マルティンを出産した。マルティンはヌエバ・エスパーニャにおける最初のメスティソ(ヨーロッパ人

とアメリカ先住民の混血)の一人である。[3] ラ・マリンチェの評価は時代と共に変化してきた。様々な人々が、自国の社会や政治的視点の変化に応じて彼女の役割を評価してきたからだ。特に1821年に メキシコがスペインから独立したメキシコ独立戦争後は、演劇や小説、絵画で彼女が悪意ある狡猾な誘惑者として描かれるようになった。[4] 現代のメキシコにおいて、ラ・マリンチェは依然として強力な象徴的存在だ。裏切りの体現者、究極の犠牲者、あるいは新たなメキシコ国民の象徴的な母といっ た、多様でしばしば矛盾する側面で理解されている。「マリンチスタ」という言葉は、特にメキシコにおいて、不忠実な同胞を指す。 |

| Name Malinche is known by many names,[5][6] though her birth name is unknown.[7][8][9] Malinche was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church and given the Christian name "Marina",[7][10] often preceded by the honorific doña.[11][12] The Nahua called her Malintzin, derived from Malina, a Nahuatl rendering of her Spanish name, and the honorific suffix -tzin.[13] According to historian Camilla Townsend, the vocative suffix -e is sometimes added at the end of the name, giving the form Malintzine, which would be shortened to Malintze, and heard by the Spaniards as Malinche.[13][a] Another possibility is that the Spaniards simply did not hear the “whispered” -n of the name Malintzin.[15] The title Tenepal was often assumed to be part of her name. In the annotation made by Nahua historian Chimalpahin on his copy of Gómara's biography of Cortés, Malintzin Tenepal is used repeatedly about Malinche.[16][17] According to linguist and historian Frances Karttunen, Tenepal is probably derived from the Nahuatl root tene, which means "lip-possessor, one who speaks vigorously",[8] or "one who has a facility with words",[18] and postposition -pal, which means "through".[8] Historian James Lockhart, however, suggests that Tenepal might be derived from tenenepil, "somebody’s tongue".[19] In any case, Malintzin Tenepal appears to have been a literal translation of Spanish doña Marina la lengua,[15][19] with la lengua, "the interpreter", literally meaning "the tongue",[20] being her Spanish sobriquet.[16] Since at least the 19th century,[16] she was believed to have originally been named Malinalli,[b] (Nahuatl for "grass"), after the day sign on which she was supposedly born.[23] If so, Marina would have been chosen as her baptismal name because of its phonetic similarity.[21] Modern historians have rejected such mythic suggestions,[7][16] noting that the Nahua associate the day sign Malinalli with bad or "evil" connotations,[7][23][24] and they are known to avoid using such day signs as personal names.[7][25] Moreover, there would be little reason for the Spaniards to ask the natives what their names were before they were christened with new names after Catholic saints.[26] |

名前 マリンチェは多くの名前で知られているが[5][6]、彼女の本名は不明である[7][8][9]。マリンチェはローマ・カトリック教会で洗礼を受け、キ リスト教名として「マリーナ」を与えられた[7][10]。しばしば敬称のドニャが前に付く[11]。[12] ナワ族は彼女をマリンチンと呼んだ。これはマリーナ(スペイン語名のナワトル語訳)と敬称接尾辞-tzinから派生したものである。[13] 歴史家カミラ・タウンゼンドによれば、呼称接尾辞-eが名前の末尾に付加されることもあり、マリンツィネという形となる。これが短縮されてマリンツェとな り、スペイン人によってマリンチェと聞き取られたのである。[13][a] 別の可能性として、スペイン人たちが単にマリンチンという名前の「ささやくような」-n音を聞き取れなかったという説もある。[15] テネパルという称号は、しばしば彼女の名の一部と見なされてきた。ナワ族の歴史家チマルパヒンがゴマラのコルテス伝記写本に記した注釈では、マリンチェに ついて繰り返し「マリンチン・テネパル」という表記が使われている。[16][17] 言語学者兼歴史家フランセス・カートゥーネンによれば、テネパルはおそらくナワトル語の語根「テネ」(「唇を持つ者、力強く語る者」[8] あるいは「言葉に長けた者」[18] を意味する)と、後置詞「-パル」(「~を通して」を意味する)から派生したものである。[8] しかし歴史家ジェームズ・ロックハートは、テネパルは「誰かの舌」を意味するテネネピルに由来する可能性を示唆している[19]。いずれにせよ、マリント シン・テネパルはスペイン語のドニャ・マリーナ・ラ・レンガ(doña Marina la lengua)[15][19]の直訳と見られ、ラ・レンガ(「通訳者」を意味する)は文字通り「舌」を意味し[20]、彼女のスペイン語での通称であっ た。[16] 少なくとも19世紀以降[16]、彼女は本来マリナリ(ナワトル語で「草」を意味する)という名であったと信じられてきた。これは彼女が生まれたとされる 日の印に由来すると言われる[23]。もしそうなら、マリナは発音の類似性から洗礼名として選ばれたことになる[21]。現代の歴史家たちはこうした神話 的な説を退けている。[7][16] ナワ族は日印マリナリを悪い、あるいは「邪悪」な意味と結びつけており[7][23][24]、そのような日印を個人的な人名として避けることが知られて いる[7][25]。さらに、カトリックの聖人に因んだ新しい名前で洗礼を受ける前に、スペイン人が先住民に彼らの名前を尋ねる理由はほとんどなかっただ ろう[26]。 |

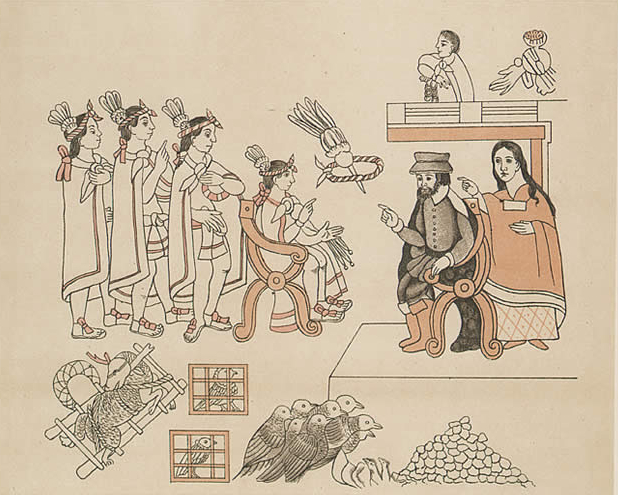

| Life Background  Codex Azcatitlan, Hernán Cortés and Malinche (far right), early 16th-century indigenous pictorial manuscript of the conquest of Mexico Malinche's birthdate is unknown,[21] but it is estimated to be around 1500, and likely no later than 1505.[27][28][c] She was born in an altepetl that was either a part of or a tributary of a Mesoamerican state whose center was located on the bank of the Coatzacoalcos River to the east of the Aztec Empire.[29][d] Records disagree about the exact name of the altepetl where she was born.[33][34] In three unrelated legal proceedings that occurred not long after her death, various witnesses who claimed to have known her personally, including her daughter, said that she was born in Olutla. The probanza of her grandson also mentioned Olutla as her birthplace.[33] Her daughter added that the altepetl of Olutla was related to Tetiquipaque, although the nature of this relationship is unclear.[35] In the Florentine Codex, Malinche's homeland is mentioned as "Teticpac", which is most likely the singular form of Tetiquipaque.[36] Gómara writes that she came from "Uiluta" (presumably a variant of Olutla). He departs from other sources by writing that it was in the region of Jalisco. Díaz, on the other hand, gives "Painalla" as her birthplace.[37][33] Her family is reported to have been of noble background;[37] Gómara writes that her father was related to a local ruler,[38] while Díaz recounts that her parents were rulers.[39] Townsend notes that while Olutla at the time probably had a Popoluca-speaking majority, the ruling elite, which Malinche supposedly belonged to, would have been Nahuatl-speaking.[40] Another hint that supports her noble origin is her apparent ability to understand the courtly language of tecpillahtolli ("lordly speech"), a Nahuatl register that is significantly different from the commoner's speech and has to be learned.[41][42] The fact that she was often referred to as a doña, at the time a term in Spain not commonly used when referring to someone outside of the aristocracy, indicates that she was viewed as a noblewoman.[22] But she may have been given this honorific by the Spanish because of recognition of her important role in the conquest.[9] Malinche was probably between the ages of 8 and 12[43] when she was either sold or kidnapped into slavery.[15][44] Díaz wrote that after her father's death, she was given away to merchants by her mother and stepfather so that their son (Malinche's halfbrother) would have the rights of an heir.[45][46] Scholars, historians, and literary critics alike have cast doubt upon Díaz's account of her origin, in large part due to his strong emphasis on Catholicism throughout his narration of the events.[22][45][47] In particular, historian Sonia Rose de Fuggle analyzes Díaz's over-reliance on polysyndeton (which mimics the sentence structure of many Biblical stories) as well as his overarching portrayal of Malinche as an ideal Christian woman.[48] But Townsend believes that it was likely that some of her people were complicit in trafficking her, regardless of the reason.[43] Malinche was taken to Xicalango,[49] a major port city in the region.[50] She was later purchased by a group of Chontal Maya who brought her to the town of Potonchán. It was here that Malinche started to learn the Chontal Maya language, and perhaps also Yucatec Maya.[51][e] Her acquisition of the language later enabled her to communicate with Jerónimo de Aguilar, another interpreter for Cortes who also spoke Yucatec Maya, as well as his native Spanish.[54] |

人生 背景  『アスカティトラン写本』エルナン・コルテスとマリンチェ(右端)、16世紀初頭のメキシコ征服を描いた先住民の絵入写本 マリンチェの出生年は不明だが[21]、1500年頃と推定され、遅くとも1505年以前である可能性が高い[27][28][c]。彼女はアステカ帝国 の東、コアツァコアルコス川河畔に中心を置くメソアメリカ国家の一部もしくは属国であったアルテペトルで生まれた。[29][d] 彼女の出生地となったアルテペトルの正確な名称については記録が一致しない。[33][34] 彼女の死後間もなく行われた三つの無関係な法廷手続きにおいて、娘を含む彼女を個人的に知っていたと主張する複数の証人が、彼女がオルトラで生まれたと証 言した。孫の相続訴訟記録もまた、彼女の出生地としてオルトラを挙げている。[33] 娘はさらに、オルトラのアルテペトルがテティキパケと関係があると付け加えたが、この関係の性質は不明である。[35] 『フィレンツェ写本』では、マリンチェの故郷は「テティパク」と記されており、これはおそらくテティキパケの単数形である。[36] ゴマーラは彼女が「ウイルタ」(おそらくオルトラの異形)出身だと記している。彼は他の資料とは異なり、その地がハリスコ地方にあったと書いている。一方 ディアスは彼女の出生地を「パイナヤ」としている。[37] [33] 彼女の家族は貴族の血筋であったと伝えられている。[37]ゴマラは彼女の父親が地元の支配者と縁故があったと記し、[38]ディアスは両親が支配者で あったと述べている。[39]タウンゼンドは、当時のオルトラではポポルカ語話者が多数派であったが、マリンチェが属していたとされる支配層はナワトル語 話者であったと指摘している。[40] 貴族出身を示すもう一つの手がかりは、彼女が「貴族の言語」テクピヤトルリを理解できたことだ。これは一般民衆の言語とは大きく異なり、習得が必要なナワ トル語の格調高い表現である。[41][42] 当時スペインでは貴族以外を指す際に「ドニャ」という呼称が一般的ではなかったが、彼女が頻繁にそう呼ばれていた事実は、貴族と見なされていたことを示し ている[22]。ただし征服における彼女の重要な役割をスペイン人が認めた結果、この敬称を与えられた可能性もある。[9] マリンチェが奴隷として売られたか誘拐されたのは、おそらく8歳から12歳の頃だった[43]。[15][44] ディアスは、彼女の父親が死んだ後、母親と継父が彼女を商人たちに譲り渡したと記している。その目的は、彼らの息子(マリンチェの異母兄弟)が相続権を得 るためだった。[45][46] 学者、歴史家、文学批評家らは、ディアスの記述における彼女の出自について疑念を呈している。その主な理由は、事件の叙述全体を通じてカトリック教義を強 く強調している点にある。[22][45] [47] 特に歴史家ソニア・ローズ・デ・ファグルは、ディアスがポリシンデトン(多くの聖書物語の文構造を模倣したもの)に過度に依存している点、およびマリン チェを理想的なキリスト教女性として包括的に描いている点を分析している。[48] しかしタウンゼンドは、理由の如何にかかわらず、彼女の部族の何人かが彼女の人身売買に加担していた可能性が高いと考えている。[43] マリンチェは地域の主要港湾都市シカランゴへ連行された。[49][50] その後、彼女を買い取ったチョンタル・マヤ族の一団によってポトンチャン村へ連れて行かれた。ここでマリンチェはチョンタル・マヤ語を学び始め、おそらく ユカテコ・マヤ語も習得した。[51][e] この言語習得が後に、コルテスの通訳でユカテコ・マヤ語と母語のスペイン語を話したヘロニモ・デ・アギラールとの意思疎通を可能にしたのである。[54] |

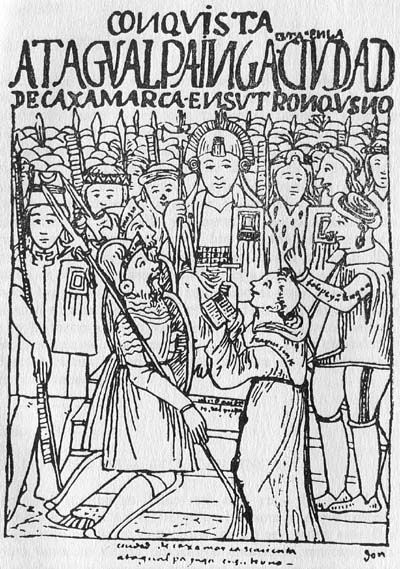

| The conquest of Mexico Motecuçoma was told how the Spaniards were bringing along with them a Mexica [Nahuatl-speaking] Indian woman called Marina, a citizen of the settlement of Teticpac, on the shore of the North Sea [Caribbean], who served as interpreter and said in the Mexican language everything that Captain don Hernando Cortés told her to. — Report from the emissaries to Moctezuma. Florentine Codex, Book XII, Chapter IX[55] Early in his expedition to Mexico, Cortés was confronted by the Maya at Potonchán.[39] In the ensuing battle, the Mayas suffered significant loss of lives and asked for peace. In the following days, they presented the Spaniards with gifts of food and gold, as well as twenty enslaved women, including Malinche.[56][57] The women were baptized and distributed among Cortés's men, who expected to use them as servants and sexual objects.[58][54][59] Malinche was given to Alonso Hernández Puertocarrero, one of Cortés' captains.[54] He was a first cousin to the count of Cortés's hometown, Medellín.[60] Malinche's language skills were discovered[61] when the Spaniards encountered the Nahuatl-speaking people at San Juan de Ulúa.[54][62] Moctezuma's emissaries had come to inspect the peoples,[63] but Aguilar could not understand them.[62][64] Historian Gómara wrote that, when Cortés realized that Malinche could talk with the emissaries, he promised her "more than liberty" if she would help him find and communicate with Moctezuma.[37][62] Cortés took Malinche from Puertocarrero.[54] He was later given another Indigenous woman before he returned to Spain.[65][66] Aided by Aguilar and Malinche, Cortés talked with Moctezuma's emissaries. The emissaries also brought artists to make paintings of Malinche, Cortés, and the rest of the group, as well as their ships and weapons, to be sent as records for Moctezuma.[67][68] Díaz later said that the Nahua addressed Cortés as "Malinche";[69][54] they took her as a point of reference for the group.[70][f] From then on, Malinche worked with Aguilar to bridge communication between the Spaniards and the Nahua;[34][67] Cortés would speak Spanish with Aguilar, who translated into Yucatec Maya for Malinche, who in turn translated into Nahuatl, before reversing the process.[73] The translation chain grew even longer when, after the emissaries left, the Spaniards met the Totonac,[74] whose language was not understood by either Malinche or Aguilar. There, Malinche asked for Nahuatl interpreters.[75][76] Karttunen remarks that "it is a wonder any communication was accomplished at all", for Cortés' Spanish words had to be translated into Maya, Nahuatl, and Totonac before reaching the locals, whose answers went back through the same chain.[75] Meeting with the Totonac was how the Spaniards first learned of opponents to Moctezuma.[76][74] |

メキシコ征服 モテクツァマは、スペイン人たちがメキシカ(ナワトル語を話す)のインディオ女性マリーナを連れてきていると伝えられた。彼女は北海(カリブ海)の岸辺に あるテティクパックの集落の住民で、通訳を務め、ドン・エルナンド・コルテス隊長が命じたことをメキシコ語で全て伝えた。 — 使節団によるモクテスマへの報告。『フィレンツェ写本』第12巻第9章[55] メキシコ遠征の初期、コルテスはポトンチャンでマヤ族と対峙した[39]。その後の戦闘でマヤ族は大きな犠牲を出し、和平を求めた。その後数日間、彼らは 食糧や金、そしてマリンチェを含む二十人の奴隷女性をスペイン人に献上した[56][57]。女性たちは洗礼を受け、コルテスの部下たちに分配された。彼 らは彼女たちを使用人兼性的対象として利用するつもりだった[58][54][59]。マリンチェはコルテスの副官の一人、アロンソ・エルナンデス・プエ ルトカレロに与えられた。[54] 彼はコルテスの故郷メデリンの伯爵の従兄弟であった。[60] マリンチェの言語能力は、スペイン人たちがサン・フアン・デ・ウルアでナワトル語を話す人々に出会った際に明らかになった。[54][62] モクテスマの使節団は現地調査のために派遣されていたが、アギラールは彼らの言葉を理解できなかった。[62][64] 歴史家ゴマラによれば、コルテスはマリンチェが使者と会話できると知ると、モクテスマの所在を突き止め連絡を取る手助けをすれば「自由以上のもの」を与え ると約束した[37][62]。コルテスはプエルトカレロからマリンチェを連れ去った[54]。後にスペインへ帰国する前に、別の先住民女性を与えられた [65]。[66] アギラールとマリンチェの助けを得て、コルテスはモクテスマの使者と会談した。使者はまた、マリンチェ、コルテス、一行の者たち、そして彼らの船や武器を 描いた絵をモクテスマへの記録として送るため、画家たちも連れてきていた。[67][68] ディアスは後に、ナワ族がコルテスを「マリンチェ」と呼んだと述べている。[69][54] 彼らは彼女を一行の代表者と見なしていた。[70][f] その後、マリンチェはアギラールと共にスペイン人とナワ族の間の橋渡し役を務めた。[34][67] コルテスはアギラールとスペイン語で話し、アギラールがユカタン・マヤ語に翻訳すると、マリンチェがナワトル語に翻訳し、逆の過程も同様に行われた。 [73] 使節団が去った後、スペイン人たちがトトナック族と出会った時、翻訳の連鎖はさらに長くなった。[74] 彼らの言語はマリンチェにもアギラルにも理解できなかった。そこでマリンチェはナワトル語の通訳を求めた。[75][76] カルトゥネンは「コミュニケーションが成立したこと自体が奇跡だ」と指摘する。コルテスのスペイン語は現地人に届く前にマヤ語、ナワトル語、トトナク語へ と翻訳され、現地人の返答も同様の翻訳経路を辿ったからだ。[75] トトナク族との接触により、スペイン人たちは初めてモクテスマの敵対勢力の存在を知ったのである。[76][74] |

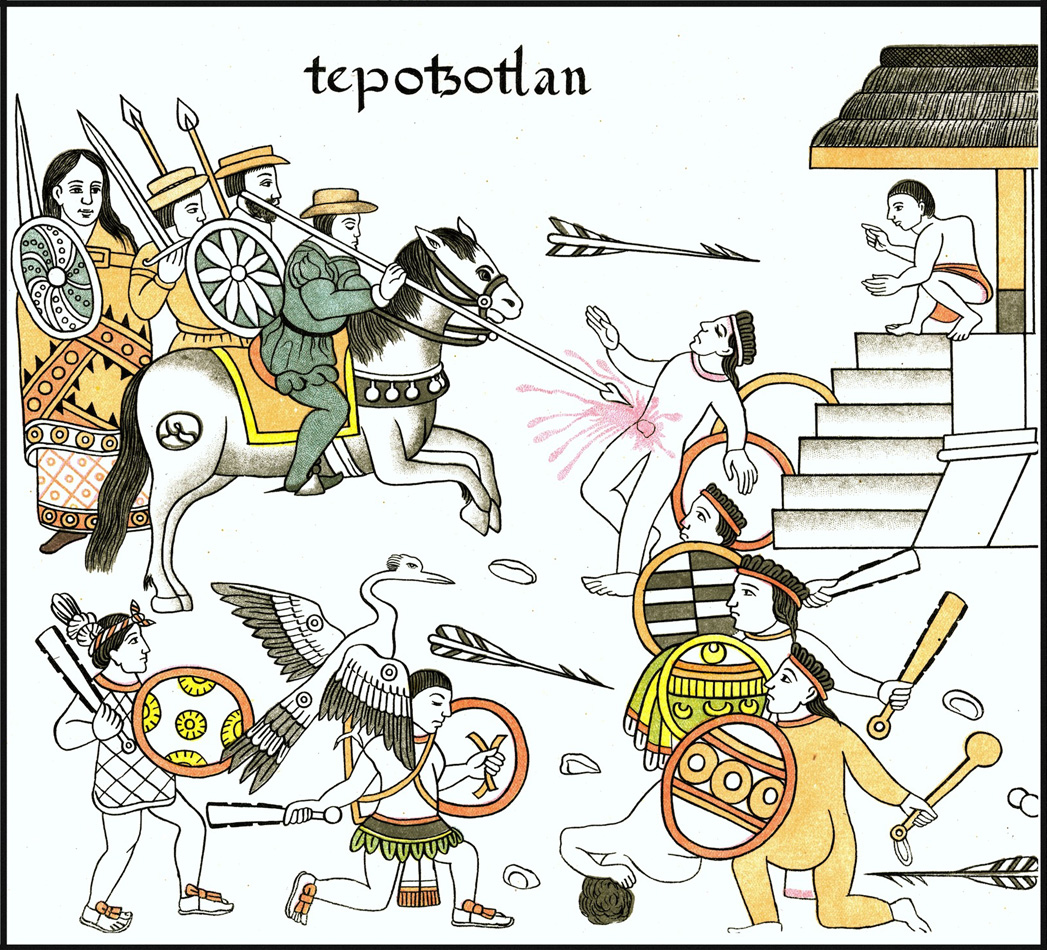

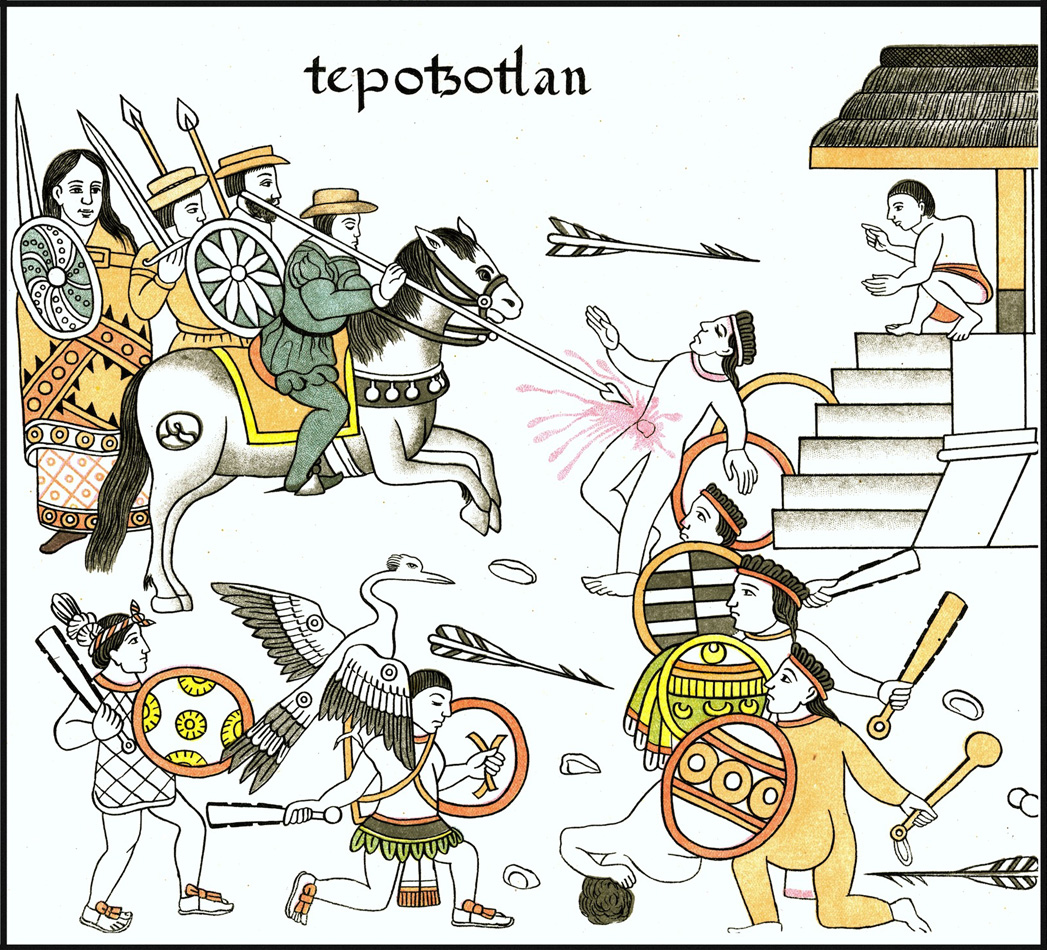

Malinche depicted with weapons during the Battle of Tepotzotlán. After founding the town of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz to be freed from the legal restriction of what was supposed to be an exploratory mission,[77] the Spaniards stayed for two months in a nearby Totonac settlement. They secured a formal alliance with the Totonac and prepared for a march toward Tenochtitlan.[78][79] The first major polity that they encountered on the way to Tenochtitlan was Tlaxcala.[80] Although the Tlaxcaltec were initially hostile to the Spaniards and their allies,[81] they later permitted the Spaniards to enter the city.[82][83] The Tlaxcalans negotiated an alliance with the Spaniards through Malinche and Aguilar. Later Tlaxcalan visual records of this meeting feature Malinche as a prominent figure. She appears to bridge communication between the two sides, as the Tlaxcalan presented the Spaniards with gifts of food and noblewomen to cement the alliance.[69][84] After several days in Tlaxcala, Cortés continued the journey to Tenochtitlan by the way of Cholula. By then he was accompanied by a large number of Tlaxcalan soldiers.[69][85] The Spaniards were received at Cholula and housed for several days. The explorers claimed that the Cholulans stopped giving them food, dug secret pits, built a barricade around the city, and hid a large Aztec army in the outskirts to prepare for an attack against the Spaniards.[86][69] Somehow, the Europeans learned of this and, in a preemptive strike, assembled and massacred the Cholulans.[87] Later accounts claimed that Malinche had uncovered the plot. According to Díaz, she was approached by a Cholulan noblewoman who promised her a marriage to the woman's son if she were to switch sides. Pretending to go along with the suggestion, Malinche was told about the plot and later reported all the details to Cortés.[88][89] In later centuries, this story has often been cited as an example of Malinche's "betrayal" of her people.[15] But modern historians such as Hassig and Townsend[89][90] have suggested that Malinche's "heroic" discovery of the purported plot was likely already a fabricated story intended to provide Cortés with political justification for his actions, to distant Spanish authorities.[89] In particular, Hassig suggests that Cortés, seeking stronger native alliances leading to the invasion of Tenochtitlan, worked with the Tlaxcalans to coordinate the massacre. Cholula had supported Tlaxcala before joining the Aztec Empire one or two years prior, and losing them as an ally had been a severe blow to the Tlaxcalans. Their state was now completely encircled by the Aztecs.[91][90][92] Hassig and other historians assert that Tlaxcalans considered the attack on the Cholulans as a "litmus test" of the Spanish commitment to them.[93][92] |

テポツォトランの戦いで武器を携えたマリンチェの描写。 探検任務という法的制約から解放されるため、ビジャ・リカ・デ・ラ・ベラ・クルスという町を設立した後[77]、スペイン人たちは近くのトトナック集落に二か月間滞在した。彼らはトトナック族との正式な同盟を結び、テノチティトランへの進軍準備を整えた[78]。[79] テノチティトランへ向かう途中で最初に遭遇した主要な政治共同体はトラスカラであった[80]。トラスカラ族は当初スペイン人とその同盟者に対して敵対的 であったが[81]、後にスペイン人の都市進入を許可した[82][83]。トラスカラ人はマリンチェとアギラールを通じてスペイン人との同盟交渉を行っ た。後にトラスカラ人が残したこの会合の視覚記録では、マリンチェが重要な人物として描かれている。彼女は両者の間の意思疎通の架け橋となったようで、ト ラスカラ人は同盟を固めるため、スペイン人たちに食糧や貴族の女性を贈り物として捧げた。[69][84] トラスカラで数日を過ごした後、コルテスはチョルラを経由してテノチティトランへの旅を続けた。この頃には、多数のトラスカラ兵が同行していた。[69] [85] チョルラではスペイン人一行は数日間もてなされた。しかし探検隊によれば、チョルラ人は食糧供給を停止し、秘密の穴を掘り、城壁を築き、郊外に大規模なア ステカ軍を隠してスペイン人への攻撃を準備していたという。[86][69] ヨーロッパ人たちは何らかの方法でこの計画を察知し、先制攻撃でチョルラ人を集結させて虐殺した。[87] 後世の記録によれば、この陰謀を暴いたのはマリンチェであったとされる。ディアスによれば、チョルラの貴族の女性がマリンチェに接触し、敵側に寝返ればそ の息子との結婚を約束すると申し出た。マリンチェは提案に乗るふりをし、陰謀の詳細を聞き出した後、コルテスに全てを報告したという。[88][89] 後世において、この話はしばしばマリンチェが同胞を「裏切った」例として引用されてきた。[15] しかしハシグやタウンゼンド[89][90]といった現代史家たちは、マリンチェによる陰謀の「英雄的」発見は、コルテスの行動を遠方のスペイン当局に政 治的に正当化するための作り話であった可能性が高いと示唆している。[89] 特にハシグは、テノチティトラン侵攻に向けたより強固な先住民同盟を求めたコルテスが、トラスカラ人と共謀して虐殺を計画したと示唆している。チョルラは 1~2年前にアステカ帝国に加盟する前までトラスカラを支援しており、同盟国を失ったことはトラスカラ人にとって深刻な打撃だった。彼らの国家は今やアス テカに完全に包囲されていた。[91][90][92] ハシグら歴史家は、トラスカラ人がチョルラ人への攻撃をスペインの忠誠心を試す「試金石」と見なしていたと主張する。[93][92] |

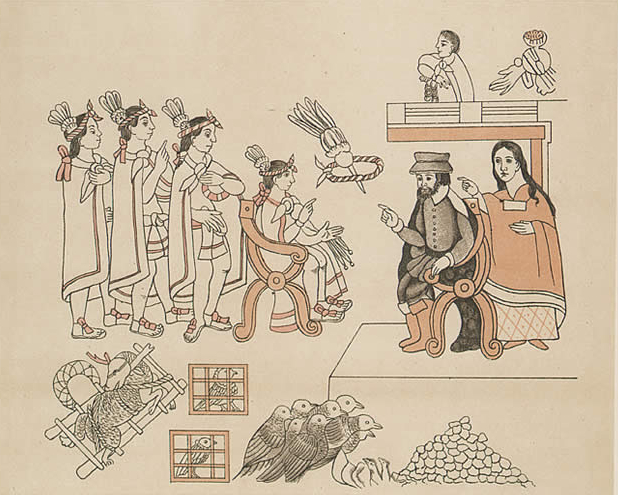

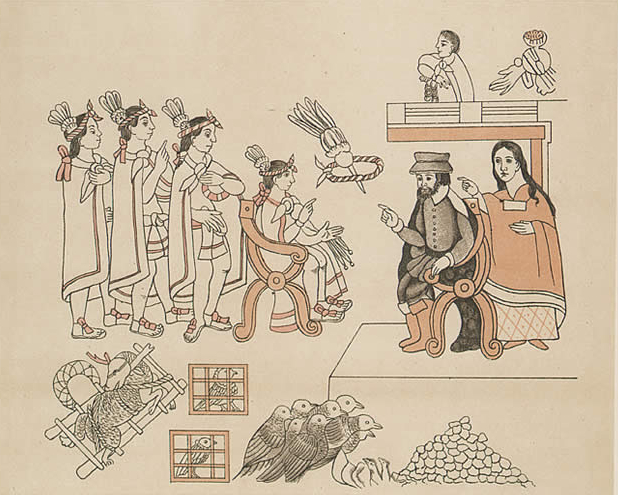

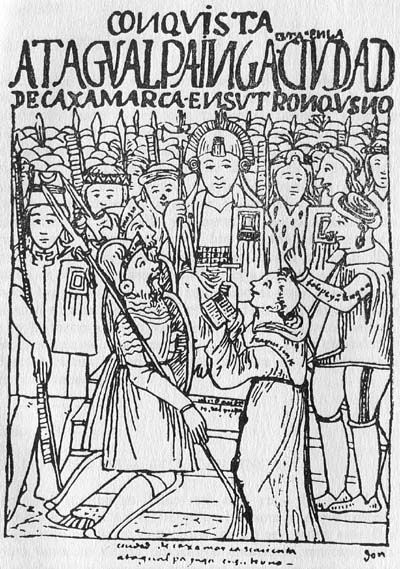

The meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma II, with Malinche acting as interpreter. The combined forces reached Tenochtitlan in early November 1519, where they were met by Moctezuma on a causeway leading to the city.[94] Malinche was in the middle of this event, translating the conversation between Cortés and Moctezuma.[44][95] Gomara writes that Moctezuma was "speaking through Malinche and Aguilar", although other records indicate that Malinche was already translating directly,[44] as she had quickly learned some Spanish herself.[54][96] Moctezuma's flowery speech, delivered through Malinche at the meeting, has been claimed by the Spaniards to represent a submission, but this interpretation is not followed by modern historians.[42][95] The deferential nature of the speech can be explained by Moctezuma's usage of tecpillahtolli, a Nahuatl register known for its indirection and complex set of reverential affixes.[42][97] Despite Malinche's apparent ability to understand tecpillahtolli, it is possible that some nuances were lost in translation.[42] The Spaniards, deliberately or not, may have misinterpreted Moctezuma's words.[95] Tenochtitlán fell in late 1521 and Marina's son by Cortes, Martín Cortés was born in 1522. During this time Malinche or Marina stayed in a house Cortés built for her in the town of Coyoacán, eight miles south of Tenochtitlán. The Aztec capital city was being redeveloped to serve as Spanish-controlled Mexico City. Cortés took Marina to help quell a rebellion in Honduras in 1524–1526 when she again served as interpreter (she may have known Mayan languages beyond Chontal and Yucatec). While in the mountain town of Orizaba in central Mexico, she married Juan Jaramillo, a Spanish hidalgo.[98] Some contemporary scholars have estimated that she died less than a decade after the conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, at some point before February 1529.[99][100] She was survived by her son Don Martín, who would be raised primarily by his father's family, and a daughter Doña María, who would be raised by Jaramillo and his second wife Doña Beatriz de Andrada.[101] Although Martín was Cortés's first-born son and eventual heir, his relation to Marina was poorly documented by prominent Spanish historians such as Francisco López de Gómara. He never referred to Marina by name, even in her work as Cortés's translator.[102] Even during Marina's lifetime, she spent little time with Martín. But many scholars and historians have marked her multiracial child with Cortés as the symbolic beginning of the large mestizo population that developed in Mesoamerica.[103] |

コルテスとモクテスマ2世の面会。マリンチェが通訳を務めた。 連合軍は1519年11月初旬にテノチティトランに到着し、モクテスマが都市へ続く堤防で出迎えた[94]。マリンチェはこの場面の中心にいて、コルテス とモクテスマの会話を翻訳していた[44][95]。ゴマラはモクテスマが「マリンチェとアギラールを通じて話した」と記しているが、他の記録によればマ リンチェは既に直接通訳していた[44]。彼女自身が短期間でスペイン語を習得していたためである[54][96]。会談でマリンチェを通じて発せられた モクテスマの華麗な演説は、スペイン人によって降伏の意思表示と主張されたが、この解釈は現代の歴史家には支持されていない。[42][95] この言葉の恭順的な性質は、モクテスマがナワトル語の「テクピヤトルリ」という間接的で複雑な敬語接辞体系を用いたことに起因すると説明できる。[42] [97] マリンチェがテクピヤトルリを理解していたように見えても、翻訳過程でニュアンスが失われた可能性はある。[42] スペイン人たちは、意図的か否か、モクテスマの言葉を誤解した可能性がある。[95] テノチティトランは1521年末に陥落し、コルテスとの間に生まれた娘マリーナの息子マルティン・コルテスは1522年に誕生した。この間、マリンチェあ るいはマリーナは、テノチティトランの南8マイルにあるコヨアカン村にコルテスが彼女のために建てた家に滞在していた。アステカの首都はスペイン支配下の メキシコシティとして再開発されていた。コルテスは1524年から1526年にかけてホンジュラスで起きた反乱を鎮圧するためマリーナを同行させ、彼女は 再び通訳を務めた(彼女はチョンタル語とユカテコ語以外のマヤ語も知っていた可能性がある)。メキシコ中央部の山岳都市オリサバに滞在中、彼女はスペイン のイダルゴフアン・ハラミージョと結婚した。[98] 近代の研究者の中には、彼女がメキシコ・テノチティトラン征服から10年も経たないうちに、1529年2月以前に死去したと推定する者もいる。[99] [100] 彼女には息子ドン・マルティンと娘ドニャ・マリアがいた。マルティンは主に父方の家族に育てられ、マリアはハラミージョとその再婚相手ドニャ・ベアトリ ス・デ・アンドラーダに育てられた。[101] マルティンはコルテスの長男であり後継者となるはずだったが、フランシスコ・ロペス・デ・ゴマラなどの著名なスペイン史家によるマリーナとの関係の記録は 乏しい。ゴマラは、マリーナがコルテスの通訳として働いていた時期でさえ、彼女の名前を一度も言及していない。[102] マリーナが生きている間も、彼女はマルティンと過ごす時間はほとんどなかった。しかし多くの学者や歴史家は、コルテスとの間に生まれた彼女の混血児を、メ ソアメリカで発展した大規模なメスティーソ人口の象徴的な始まりとして位置づけている。[103] |

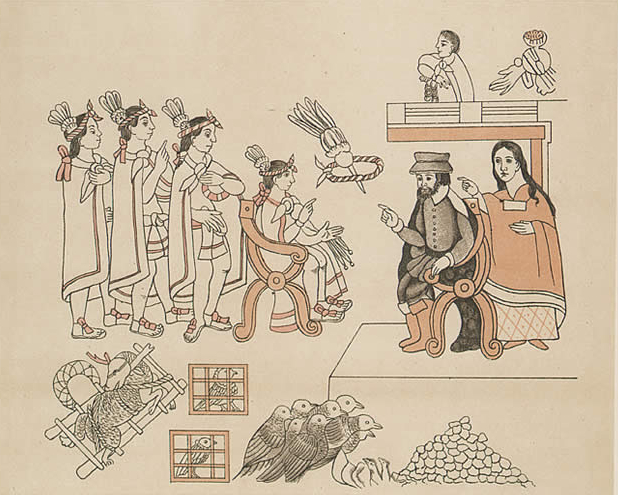

Debates about influence and importance in the conquest of Mexico La Malinche and Hernán Cortés in the city of Xaltelolco, in a drawing from the late 16th-century codex History of Tlaxcala For the conquistadores, having a reliable interpreter was important enough, but there is evidence that Marina's role and influence were larger still. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier who, as an old man, produced the most comprehensive of the eye-witness accounts, the Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España ("True Story of the Conquest of New Spain"), speaks repeatedly and reverentially of the "great lady" Doña Marina (always using the honorific title Doña). "Without the help of Doña Marina", he writes, "we would not have understood the language of New Spain and Mexico." Rodríguez de Ocaña, another conquistador, relates Cortés' assertion that after God, Marina was the main reason for his success. The evidence from Indigenous sources is even more interesting, both in the commentaries about her role, and in her prominence in the codex drawings made of conquest events. Although to some Marina may be known as a traitor, she was not viewed as such by all the Tlaxcalan. In some depictions they portrayed her as "larger than life," sometimes larger than Cortés, in rich clothing, and an alliance is shown between her and the Tlaxcalan instead of them and the Spaniards. They respected and trusted her and portrayed her in this light generations after the Spanish conquest.[104] In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (History of Tlaxcala), for example, not only is Cortés rarely portrayed without Marina poised by his side, but she is shown at times on her own, seemingly directing events as an independent authority. If she had been trained for court life, as in Díaz's account, her relationship with Cortés may have followed the familiar pattern of marriage among native elite classes. The role of the Nahua wife acquired through an alliance would have been to assist her husband achieve his military and diplomatic objectives.[105][106] Today's historians give great credit to Marina's diplomatic skills, with some "almost tempted to think of her as the real conqueror of Mexico."[107] Old conquistadors on various occasions recalled that one of her greatest skills had been her ability to convince other natives of what she could perceive, that it was useless in the long run to stand against Spanish metal (arms) and Spanish ships. In contrast to earlier parts of Díaz del Castillo's account, after Marina began assisting Cortés, the Spanish were forced into combat on one more occasion.[108] Had La Malinche not been part of the Conquest of Mexico for her language skills, communication between the Spanish and the Indigenous peoples would have been much harder. La Malinche knew how to speak in different registers and tones among certain Indigenous tribes and classes of people. For the Nahua audiences, she spoke rhetorically, formally, and high-handedly. This shift into formality gave the Nahua the impression that she was a noblewoman who knew what she was talking about.[109] |

メキシコ征服における影響力と重要性についての議論 16世紀後半の写本『トラスカラの歴史』に描かれた、サルテロコの街におけるラ・マリンチェとエルナン・コルテス 征服者たちにとって、信頼できる通訳がいることは十分に重要だったが、マリーナの役割と影響力がさらに大きかったことを示す証拠がある。ベルナル・ディア ス・デル・カスティーヨは、老齢になって最も包括的な目撃者記録『新スペイン征服の実話』を著した兵士である。彼は「偉大な女性」ドニャ・マリーナ(常に 敬称ドニャを用いて)について繰り返し、敬意を込めて語っている。「ドニャ・マリーナの助けがなければ」と彼は記す、「我々は新スペインとメキシコの言語 を理解できなかっただろう」。別の征服者ロドリゲス・デ・オカーニャは、コルテスが『神に次いでマリーナこそが成功の主因だ』と断言したと伝えている。 先住民側の記録はさらに興味深い。彼女の役割に関する記述も、征服事件を描いた古写本の挿絵における彼女の存在感も同様だ。一部の人々には裏切り者として 知られるマリーナだが、トラスカラ族全員からそう見られていたわけではない。いくつかの描写では、彼女は「現実を超えた存在」として描かれ、時にはコルテ スよりも大きく、豪華な衣装をまとっている。そして彼女とトラスカラ族の同盟関係が、スペイン人との同盟ではなく描かれている。彼らは彼女を尊敬し信頼 し、スペイン征服から何世代も経った後も、彼女をそのような光の中で描いたのである。[104] 例えば『トラスカラの絵巻(トラスカラの歴史)』では、コルテスがマリーナを傍らに置かずに描かれることは稀であり、時には単独で登場し、独立した権威と して事態を主導しているように見える。ディアスの記述のように宮廷生活のための訓練を受けていたなら、コルテスとの関係は先住民エリート階級における結婚 の慣例に沿ったものだったかもしれない。同盟によって得たナワ族の妻の役割は、夫の軍事的・外交的目標達成を助けることだったのだ[105][106]。 現代の歴史家たちはマリーナの外交手腕を高く評価しており、中には「彼女こそが真のメキシコ征服者だったと考える誘惑に駆られる」と述べる者もいる [107]。古参の征服者たちは度々、彼女の最大の才能は、スペインの金属(武器)や船に抵抗しても長期的には無意味だと、他の先住民を説得する能力に あったと回想している。ディアス・デル・カスティーヨの記述の前半部とは対照的に、マリーナがコルテスを支援し始めてからは、スペイン軍が戦闘を強いられ たのはあと一度だけだった。[108] ラ・マリンチェが言語能力のためにメキシコ征服に参加していなければ、スペイン人と先住民の間の意思疎通ははるかに困難だっただろう。ラ・マリンチェは特 定の先住民部族や階級ごとに、異なる口調やトーンで話す術を知っていた。ナワ族の聴衆に対しては、修辞的で形式張った高圧的な口調で話した。この形式的な 語り口の変化が、ナワ族に「彼女は自分の言っていることを理解している貴族の女性だ」という印象を与えたのである。 |

Image in contemporary Mexico Modern statue of Cortés, Marina, and their son Martín, which was moved from a prominent place of display to an obscure one, due to protests Malinche's image has become a mythical archetype that artists have represented in various forms of art. Her figure permeates historical, cultural, and social dimensions of Mexican cultures.[110] In modern times and several genres, she is compared with La Llorona (folklore story of the woman weeping for lost children), and the Mexican soldaderas (women who fought beside men during the Mexican Revolution)[111] for their brave actions. La Malinche's legacy is one of myth mixed with legend and the opposing opinions of the Mexican people about the legendary woman. Some see her as a founding figure of the Mexican nation, while others continue to see her as a traitor—as may be assumed from a legend that she had a twin sister who went North, and from the pejorative nickname La Chingada associated with her twin.[citation needed] Feminist interventions into the figure of Malinche began in the 1960s. The work of Rosario Castellanos was particularly significant; Chicanas began to refer to her as a "mother" as they adopted her as symbolism for duality and complex identity.[112] Castellanos's subsequent poem "La Mallinche" recast her not as a traitor but as a victim.[113] Mexican feminists defended Malinche as a woman caught between cultures, forced to make complex decisions, who ultimately served as a mother of a new race.[114] Today in Mexican Spanish, the term malinchismo and its adjetive malinchista are used to denounce Mexicans who are perceived as denying their cultural heritage by preferring foreign cultural expressions.[115] Some historians believe that La Malinche saved her people from the Aztecs, who held a hegemony throughout the territory and demanded tribute from its inhabitants. Some Mexicans also credit her with having brought Christianity to the New World from Europe, and for having influenced Cortés to be more humane than he would otherwise have been. It is argued, however, that without her help, Cortés would not have been successful in conquering the Aztecs as quickly, giving the Aztec people enough time to adapt to new technology and methods of warfare. From that viewpoint, she is seen as one who betrayed the Indigenous people by siding with the Spaniards. Recently, several feminists have decried such categorization as scapegoating.[116] President José López Portillo commissioned a sculpture of Cortés, Doña Marina, and their son Martín, which was placed in front of Cortés' house in the Coyoacán section of Mexico City. Once López Portillo left office, the sculpture was removed to an obscure park in the capital.[117] |

現代メキシコにおけるイメージ コルテス、マリーナ、そして彼らの息子マルティンの現代的な像は、抗議活動により目立つ展示場所から目立たない場所へ移された マリンチェのイメージは、芸術家たちが様々な芸術形式で表現してきた神話的な原型となった。彼女の人物像はメキシコ文化の歴史的、文化的、社会的側面に浸 透している。[110] 近代において、また様々なジャンルで、彼女はラ・ジョローナ(失われた子供を嘆く女性の民話)や、メキシコ革命時に男性と共に戦った女性戦士「ソルダデラ ス」[111] と、その勇敢な行動ゆえに比較される。 ラ・マリンチェの遺産は、神話と伝説が混ざり合い、伝説の女性に対するメキシコ国民の対立する意見が交錯するものである。彼女をメキシコ国家の創設者とす る見方がある一方、裏切り者と見なす見方も根強い。これは、彼女の双子の妹が北へ渡ったという伝説や、その妹に付けられた蔑称「ラ・チンガーダ」からも推 測できる。 フェミニストによるマリンチェ像への介入は1960年代に始まった。ロサリオ・カステジャノスの著作は特に重要で、チカーナたちは彼女を「母」と呼び始 め、二面性と複雑なアイデンティティの象徴として受け入れた[112]。カステジャノスの後年の詩「ラ・マリンチェ」は彼女を裏切り者ではなく犠牲者とし て再解釈した。[113] メキシコのフェミニストたちは、文化の狭間で複雑な決断を迫られ、最終的に新たな人種の母となった女性としてマリンチェを擁護した。[114] 今日のメキシコスペイン語では、「マリンチズモ」とその形容詞形「マリンチスタ」という用語が、外国の文化的表現を好み自らの文化的遺産を否定していると見なされるメキシコ人を非難するために用いられる。[115] 一部の歴史家は、ラ・マリンチェが自民族をアステカから救ったと考える。アステカは全土にヘゲモニーを敷き、住民に貢ぎ物を強要していた。また一部のメキ シコ人は、彼女がヨーロッパから新大陸にキリスト教をもたらし、コルテスに本来より人道的な行動を取るよう影響を与えたと評価する。しかし、彼女の助力が なければコルテスはアステカをこれほど迅速に征服できず、アステカ人は新技術や戦法に適応する時間を得られたはずだと反論される。この観点では、彼女は先 住民を裏切りスペイン側に付いた者と見なされる。近年、複数のフェミニストがこうした分類をスケープゴート化だと非難している。[116] ホセ・ロペス・ポルティージョ大統領は、コルテス、ドニャ・マリーナ、そして彼らの息子マルティンの彫像を制作し、メキシコシティのコヨアカン地区にあるコルテスの家の前に設置した。しかし、ロペス・ポルティージョが退任すると、その彫像は首都の無名の公園に移された。 |

In popular culture La Malinche, as part of the Monumento al Mestizaje in Mexico City  La Malinche, in Villa Oluta, Veracruz A reference to La Malinche as Marina is made in the novel The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by the Polish author Jan Potocki, in which she is cursed for yielding her "heart and her country to the hateful Cortez, chief of the sea-brigands."[118] La Malinche appears in the adventure novel Montezuma's Daughter (1893) by H. Rider Haggard. Doña Marina appears in the Henry King film Adventure Captain from Castile (1947) played Estela Inda. La Malinche is portrayed as a Christian and protector of her fellow native Mexicans in the novel Tlaloc Weeps for Mexico (1939) by László Passuth, and is the main protagonist in such works as the novels The Golden Princess (1954) by Alexander Baron and Feathered Serpent: A Novel of the Mexican Conquest (2002) by Colin Falconer. In contrast, she is portrayed as a duplicitous traitor in Gary Jennings' novel Aztec (1980). A novel published in 2006 by Laura Esquivel portrays the main character as a pawn of history who becomes Malinche. In 1949, choreographer José Limón premiered the dance trio "La Milanche" to music by Norman Lloyd. It was the first work created by Limón for his company and was based on his memories as a child of Mexican fiestas.[119] The story of La Malinche is told in Cortez and Marina (1963) by Edison Marshall. In the 1973 Mexican film Leyendas macabras de la colonia, La Malinche's mummy is in the possession of Luisa, her daughter by Hernán Cortés, while her spirit inhabits a cursed painting. La Malinche is referred to in the songs "Cortez the Killer" from the 1975 album Zuma by Neil Young, and "La Malinche" by the French band Feu! Chatterton from their 2015 album Ici le jour (a tout enseveli) In the animated television series The Mysterious Cities of Gold (1982), which chronicles the adventures of a Spanish boy and his companions traveling throughout South America in 1532 to seek the lost city of El Dorado, a woman called Marinche becomes a dangerous adversary. The series was originally produced in Japan and then translated into English. In the fictional Star Trek universe, a starship, the USS Malinche, was named for La Malinche and appeared in the 1997 "For the Uniform" episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. This was done by Hans Beimler, a native of Mexico City, who together with friend Robert Hewitt Wolfe later wrote a screenplay based on La Malinche called The Serpent and the Eagle. La Malinche is the main character in the 2002 French novel L'Indienne de Cortés (English: Cortés' Indian Woman) by Carole Achache.[120] La Malinche is a key character in the opera La Conquista (2005) by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero. Malinalli is the main character in a 2011 historical novel by Helen Heightsman Gordon, Malinalli of the Fifth Sun: The Slave Girl Who Changed the Fate of Mexico and Spain. Author Octavio Paz traces the root of mestizo and Mexican culture to La Malinche's child with Cortés in The Labyrinth of Solitude (1950). He uses her relation to Cortés symbolically to represent Mexican culture as originating from rape and violation, but also holds Malinche accountable for her "betrayal" of the indigenous population, which Paz claims "the Mexican people have not forgiven."[121] The novel Night of Sorrows by Frances Sherwood is an account of the life of La Malinche (called Malitzín within the novel). Malinal is a character in Graham Hancock's series of novels War God: Nights of the Witch (2013) and War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent (2014), which is a fictional story describing the events related to the Hernan Cortés' expedition to Mexico and the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire. Malinche is a character in Edward Rickford's The Serpent and the Eagle, referred to variously as Dona Marina and Malintze. The depiction of her character was praised by historical novelists and bloggers. La Malinche appears in the biographical Mexican series Malinche in 2018, where she is portrayed by María Mercedes Coroy. La Malinche appears in the Amazon Prime series Hernán. She is portrayed by Ishbel Bautista. Malintzin: The Story of an Enigma. Documentary of 2019 based on the life of La Malinche. Malintzin is a character in Álvaro Enrigue's novel You dreamed of Empires (2022), a fictional re-imagining of the first few days of the encounter between Hernán Cortes and Moctezuma. La Malinche is referenced in the Disney+ series National Treasure: Edge of History. In the series, she is portrayed as a double agent working to protect Aztec treasures from Cortés.[122] In 2022, Spanish musician Nacho Cano produced Malinche, a stage musical in Madrid. The show will be produced in Mexico with a Mexican cast.[123][124] Malinche, by Haniel Long was published in 1938 |

ポピュラー・カルチャーにおける メキシコシティの「メスティサヘの記念碑」の一部としてのラ・マリンチェ  ベラクルス州ビジャ・オルタにあるラ・マリンチェ ポーランドの作家ヤン・ポトツキの小説『サラゴサで発見された手稿』では、ラ・マリンチェがマリーナとして言及されている。彼女は「憎むべき海賊の首領コルテスに心と祖国を捧げた」として呪われている。[118] ラ・マリンチェはH・ライダー・ハガードの冒険小説『モンテスマの娘』(1893年)に登場する。 ドニャ・マリーナはヘンリー・キング監督の映画『カスティーリャの冒険船長』(1947年)にエストラ・インダ演じる役で登場する。 ラ・マリンチェは、ラズロ・パスースの小説『トラロックはメキシコのために泣く』(1939年)では、キリスト教徒であり、メキシコ人の同胞の保護者とし て描かれている。また、アレクサンダー・バロンの小説『黄金の王女』(1954年)や、コリン・ファルコナーの小説『羽のある蛇:メキシコ征服の物語』 (2002年)などの作品では、主人公として登場している。一方、ゲイリー・ジェニングスの小説『アステカ』(1980年)では、彼女は二面性のある裏切 り者として描かれている。2006年にローラ・エスキベルが発表した小説では、主人公は歴史の駒としてラ・マリンチェになる。 1949 年、振付師のホセ・リモンは、ノーマン・ロイドの音楽に合わせて、ダンストリオ「ラ・ミランチェ」を初演した。これは、リモンが自身のカンパニーのために制作した最初の作品であり、メキシコのお祭りを子供時代に体験した思い出に基づいていた。 ラ・マリンチェの物語は、エジソン・マーシャルの『コルテスとマリーナ』(1963年)で語られている。 1973年のメキシコ映画『Leyendas macabras de la colonia』では、ラ・マリンチェのミイラは、エルナン・コルテスとの娘であるルイーザが所有しており、彼女の魂は呪われた絵画に宿っている。 ラ・マリンチェは、ニール・ヤングの1975年のアルバム『Zuma』収録曲「Cortez the Killer」や、フランスのバンド、Feu! チャタートンが2015年のアルバム『Ici le jour (a tout enseveli)』で発表した楽曲「ラ・マリンチェ」でも言及されている。 1982年のテレビアニメ『黄金都市の謎』では、1532年にエルドラドを探すため南米を旅するスペイン人少年と仲間たちの冒険が描かれている。この作品に登場するマリンチェという女性は危険な敵役となる。このシリーズは日本で制作され、後に英語に翻訳された。 『スタートレック』の架空宇宙では、宇宙船「USSマリンチェ」がラ・マリンチェに因んで命名され、1997年の『スタートレック:ディープ・スペース・ ナイン』「制服のために」のエピソードに登場した。これはメキシコシティ出身のハンス・バイムラーによるもので、彼は後に友人ロバート・ヒューイット・ウ ルフと共にラ・マリンチェを題材にした脚本『蛇と鷲』を執筆した。 ラ・マリンチェは、2002年のフランス人作家キャロル・アシャシュの小説『コルテスのインディアン女』(原題:L'Indienne de Cortés)の主人公である。 ラ・マリンチェは、イタリア人作曲家ロレンツォ・フェッレロのオペラ『征服』(2005年)の主要人物である。 マリンアリは、ヘレン・ハイツマン・ゴードンによる2011年の歴史小説『第五の太陽のマリンアリ:メキシコとスペインの運命を変えた奴隷の少女』の主人公である。 作家オクタビオ・パスは、『孤独の迷宮』(1950年)において、メスティーソとメキシコ文化の根源を、ラ・マリンチェとコルテスの間に生まれた子に遡 る。彼はラ・マリンチェとコルテスの関係を象徴的に用い、メキシコ文化がレイプと侵害に起源を持つことを表現すると同時に、先住民に対する彼女の「裏切 り」についても責任を問う。パスは「メキシコ国民はこれを許していない」と主張している。[121] フランセス・シャーウッドの小説『悲しみの夜』は、ラ・マリンチェ(小説内ではマリツィンと呼ばれる)の生涯を描いたものである。 マリンアルは、グラハム・ハンコックの小説シリーズ『戦神:妖術師の夜』(2013年)および『戦神:羽飾りの蛇の帰還』(2014年)に登場する人物である。これはエルナン・コルテスのメキシコ遠征とアステカ帝国征服に関連する出来事を描いたフィクション作品である。 マリンチェはエドワード・リックフォードの『蛇と鷲』に登場する人物で、ドナ・マリーナやマリンツェなど様々な名称で呼ばれる。彼女のキャラクター描写は歴史小説家やブロガーから称賛された。 ラ・マリンチェは2018年のメキシコ伝記ドラマ『マリンチェ』に登場し、マリア・メルセデス・コロイが演じた。 ラ・マリンチェはAmazon Primeシリーズ『エルナン』にも登場する。イシュベル・バウティスタが演じた。 『マリンチン:謎の女』2019年のドキュメンタリー。ラ・マリンチェの生涯を基にしている。 マリンチンは、アルバロ・エンリケの小説『帝国の夢』(2022年)に登場する人物である。この作品は、エルナン・コルテスとモクテスマの出会い初日を再構築したフィクションである。 ラ・マリンチェは、Disney+シリーズ『ナショナル・トレジャー:エッジ・オブ・ヒストリー』で言及されている。同シリーズでは、アステカの財宝をコルテスから守る二重スパイとして描かれている。 2022年、スペイン人音楽家ナチョ・カノはマドリードで舞台ミュージカル『マリンチェ』を制作した。この作品はメキシコ人キャストでメキシコでも上演される予定だ。 ハニエル・ロング著『マリンチェ』は1938年に出版された。 |

Felipillo History of Mexico Pocahontas – a Powhatan woman notable for her interaction as an interpreter for the English colonists of Jamestown, Virginia. Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire Women in Mexico |

フェリピージョ メキシコの歴史 ポカホンタス – バージニア州ジェームズタウンのイギリス人入植者たちの通訳として交流したことで知られるポウハタン族の女性だ。 スペインによるアステカ帝国の征服 メキシコの女性たち |

| Notes a. The vocative form is used when addressing someone, so "Malintzine" and "Malintze" are more or less equivalent to "O Marina". Although the shortened form “Malintze” is unusual, it appears repeatedly in the Annals of Tlatelolco, alongside “Malintzine”[14] b. Also Malinal,[21] Ce-Malinalli,[6][22] and so forth. c. Karttunen (1994) gives "ca. 1500" for her birth year,[28] while Townsend (2006) writes that she was born before Charles V (who was born in February 1500) turned five.[27] d. Malinche's homeland never became part of the Aztec Empire.[30][31] Around the time of the conquest, the region probably consisted of "small, loosely allied city-states"[30] with some degree of influences from the Aztec and various Maya states, but most are relatively autonomous and paid tribute to no one.[32] e. Chontal is closely related to Yucatecan, but they are sufficiently distinct to hamper intelligibility.[52][53] Around this time, traders from the Yucatán Peninsula (who spoke Yucatecan) often were active in this region,[32] and Malinche may have learned the language from them.[52] Alternatively, she may have done some adjustment to be able to converse with speakers of other Maya varieties. (This would have been unusual.)[41] f Díaz explained this phenomenon by positing that "Malinche" in reference to Cortés was a shorthand for "Marina's Captain", because she was always in his company.[71] But Townsend said that possessive construction in Nahuatl cannot be shortened that way. Moreover, Díaz's theory does not explain the fact that "Malinche" was also applied to Juan Perez de Arteaga,[70] another Spaniard learning Nahuatl from her.[72] |

注記 a. 呼びかけ形は誰かに話しかける際に用いられる。したがって「マリントシネ」と「マリントセ」はほぼ「おお、マリーナよ」に相当する。短縮形「マリントセ」は珍しいが、トラテロルコ年代記には「マリントシネ」と共に繰り返し登場する[14] b. マルイナル[21]、セ・マリンアリ[6][22]などとも表記される。 c. カルトゥネン(1994)は彼女の生年を「約1500年」と記す[28]。一方タウンゼンド(2006)は、カルロス5世(1500年2月生まれ)が5歳になる前に生まれたと記述している。[27] d. マリンチェの故郷はアステカ帝国の一部にはならなかった。[30][31]征服当時、この地域はおそらく「小規模で緩やかに同盟した都市国家群」[30] で構成され、アステカや様々なマヤ国家からの影響をある程度受けていたが、大半は比較的自治的で誰にも貢ぎ物を納めていなかった。[32] e. チョンタル語はユカタン語と近縁だが、相互理解を妨げるほどに異なる。[52][53] 当時、ユカタン半島(ユカタン語話者)の商人たちがこの地域で活動することが多く[32]、マリンチェは彼らからこの言語を学んだ可能性がある。[52] あるいは、他のマヤ語方言話者と会話できるよう、何らかの調整を行ったのかもしれない。(これは珍しいことだっただろう。)[41] f ディアスは、コルテスを指す「マリンチェ」は「マリーナの船長」の略称だと説明した。彼女は常にコルテスに付き従っていたからだ。[71] しかしタウンゼンドは、ナワトル語の所有構文はそう簡単に短縮できないと指摘した。さらにディアスの説では、「マリンチェ」が別のスペイン人であるフア ン・ペレス・デ・アルテアガ[70]にも適用された事実を説明できない。彼は彼女からナワトル語を学んでいたのである[72]。 |

| References Citations 1. Hanson, Victor Davis (2007-12-18). Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8. Thomas (1993), p. 171–172. Cypess (1991), p. 7. Cypess (1991), p. 12-13. Cypess (1991), p. 2. Herrera-Sobek (2005), pp. 112–113. Townsend (2006), p. 12. Karttunen (2001), p. 352. Restall (2018), p. xiii. 10. Karttunen (1997), p. 292. Cypess (1991), p. 27. Townsend (2006), pp. 42, 180–182, 242. Townsend (2006), p. 55. Townsend (2006), p. 242. Karttunen (2001), p. 353. Karttunen (1997), p. 302. Schroeder et al. (2010), pp. 23, 105. Cypess (1991), p. 181. Schroeder et al. (2010), p. 32. 20. Karttunen (1994), p. 4. Cypess (1991), p. 33. Valdeón (2013), pp. 163–164. Downs (2008), p. 398. Cypess (1991), pp. 60–61. Evans (2004), p. 191. Karttunen (1994), p. 6. Townsend (2006), p. 11. Karttunen (1994), p. 1. Townsend (2006), pp. 13–14. 30. Evans (2004), p. 522. Townsend (2006), p. 14. Chapman (1957), pp. 116–117. Townsend (2006), pp. 230–232. Karttunen (1997), pp. 299–301. Townsend (2006), p. 13. Townsend (2006), p. 231. Karttunen (1997), p. 299. Townsend (2006), pp. 17, 233. Karttunen (1994), p. 5. 40. Townsend (2006), p. 16. Karttunen (1997), pp. 300–301. Restall (2003), pp. 97–98. Townsend (2006), p. 22. Restall (2003), p. 82. Townsend (2006), pp. 23–24. Karttunen (1997), pp. 299–300. Franco (1999), pp. 76–78. de Fuggle, Sonia Rose (2016). "Bernal Díaz del Castillo Cuentista: La Historia de Doña Marina". Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Townsend (2006), pp. 24–25. 50. Chapman (1957), pp. 135–136. Townsend (2006), pp. 25–26. Townsend (2006), p. 26. Karttunen (1997), p. 300. Restall (2003), p. 83. Lockhart (1993), p. 87. Hassig (2006), pp. 61–63. Townsend (2006), pp. 35–36. Karttunen (1997), pp. 301–302. Townsend (2006), p. 36. 60. Townsend (2006), p. 37. Karttunen (1997), p. 301. Townsend (2006), pp. 40–41. Hassig (2006), p. 65. Townsend (2019), pp. 93. Townsend (2006), p. 53. Karttunen (1994), p. 7. Townsend (2006), p. 42. Hassig (2006), p. 67. Karttunen (1994), pp. 8–9. 70. Townsend (2006), pp. 56, 242. Karttunen (1997), pp. 293–294. Karttunen (1994), p. 22. Restall (2003), pp. 84–85. Hassig (2006), p. 68. Karttunen (1997), p. 303. Townsend (2006), p. 43. Hassig (2006), pp. 69–70. Townsend (2006), p. 45. Hassig (2006), pp. 70–74, 77. 80. Townsend (2006), p. 59. Hassig (2006), p. 79. Townsend (2006), pp. 62–63. Hassig (2006), pp. 86–89. Townsend (2006), pp. 69–72. Hassig (2006), p. 93. Hassig (2006), pp. 43, 94–96. Hassig (2006), pp. 94–96. Karttunen (1994), p. 10. Hassig (2006), pp. 97–98. 90. Townsend (2006), pp. 81–82. Hassig (2006), pp. 43, 96. Restall (2018), p. 210. Hassig (2006), p. 96. Restall (2003), p. 77. Townsend (2006), pp. 86–88. Townsend (2019), pp. 99, 243. Karttunen (1994), p. 11. Gordon, Helen. Voice of the Vanquished: The Story of the Slave Marina and Hernan Cortés. Chicago: University Editions, 1995, page 454. Chaison, Joanne. "Mysterious Malinche: A Case of Mistaken Identity," The Americas 32, N. 4 (1976). 100. Townsend (2006), p. 263. Townsend (2006), pp. 168–187. Montaudon, Yvonne. "Doña Marina: las fuentes literarias de la construcción bernaldiana de la intérprete de Cortés". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-12-09. Tate, Julee (2017). "La Malinche: The Shifting Legacy of a Transcultural Icon". The Latin Americanist. 61: 81–92. doi:10.1111/tla.12102. S2CID 148798608. Townsend (2006), pp. 74–76. Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest "Mesolore: A research & teaching tool on Mesoamerica". www.mesolore.org. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2017-10-21. Brandon, William (2003). The Rise and Fall of North American Indians. Lanham, MD: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 9781570984525. Brandon, William (2003). The Rise and Fall of North American Indians. Lanham, MD: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 9781570984525. Townsend (2006), pp. 58. 110. Cypess (1991), p. Intro.. Salas[page needed] Castellanos, Rosario (1963). "Otra vez Sor Juana" ("Once Again Sor Juana")". {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) Rolando Romero (2005-01-01). Feminism, Nation and Myth: La Malinche. Arte Publico Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-1-61192-042-0. Don M. Coerver; Suzanne B. Pasztor; Robert Buffington (2004). Mexico: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Culture and History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-1-57607-132-8. Fortes De Leff, J. (2002). Racism in Mexico: Cultural Roots and Clinical Interventions1. Family Process, 41(4), 619-623. Cypess (1991), p. 12. It is time to stop vilifying the "Spanish father of Mexico", accessed 10 June 2019 Potocki, Jan; trans. Ian Maclean (1995). The Manuscript Found at Saragossa. Penguin Books. "Repertory". chnm.gmu.edu. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2022. 120. "L'indienne de Cortés, roman de Carole Achache". Hisler (in French). Retrieved 27 November 2023. "Dona Marina, Cortes' Translator: Nonfiction, Octavio Paz". chnm.gmu.edu. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2022. Claire Spellberg Lustig (December 14, 2022). "National Treasure: Edge of History Complicates the Nicolas Cage Movies, To Thrilling Results". Primetimer. Retrieved December 21, 2022. "Malinche: así puedes acceder a las becas para mexicanos y estudiar en la escuela de musicales en Madrid". El Heraldo de México. October 3, 2023. 124. "Malinche de Nacho Cano lanza becas en Madrid para mexicanos: ¿De qué se trata y cómo obtener una?". www.poresto.net. 3 October 2023. |

参考文献 引用 1. ハンソン、ビクター・デイヴィス (2007-12-18)。『大虐殺と文化:西洋の台頭における画期的な戦い』 Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group。ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8。 トーマス (1993)、171-172 ページ。 サイプレス (1991)、7 ページ。 サイプレス (1991)、12-13 ページ。 サイプレス (1991)、2 ページ。 エレラ=ソベック (2005)、112-113 ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、12ページ。 カルトゥネン(2001)、352ページ。 レストール(2018)、xiiiページ。 10. カルトゥネン(1997)、292ページ。 サイペス(1991)、27ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、42、180-182、242頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、55頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、242頁。 カルトゥネン(2001)、353頁。 Karttunen (1997), p. 302. Schroeder et al. (2010), pp. 23, 105. Cypess (1991)、181 ページ。 Schroeder et al. (2010)、32 ページ。 20. Karttunen (1994)、4 ページ。 Cypess (1991)、33 ページ。 Valdeón (2013)、163-164 ページ。 ダウンズ(2008)、398 ページ。 サイペス(1991)、60-61 ページ。 エヴァンス(2004)、191 ページ。 カルトゥネン(1994)、6 ページ。 タウンゼント(2006)、11 ページ。 Karttunen (1994)、1 ページ。 Townsend (2006)、13-14 ページ。 30. Evans (2004)、522 ページ。 Townsend (2006)、14 ページ。 チャップマン(1957)、116-117 ページ。 タウンゼント(2006)、230-232 ページ。 カルトゥネン(1997)、299-301 ページ。 タウンゼント(2006)、13 ページ。 タウンゼント (2006)、231 ページ。 カルトゥネン (1997)、299 ページ。 タウンゼント (2006)、17、233 ページ。 カルトゥネン (1994)、5 ページ。 40. タウンゼント (2006)、16 ページ。 カルトゥネン(1997)、300–301頁。 レストール(2003)、97–98頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、22頁。 レストール(2003)、82頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、23–24頁。 Karttunen (1997), pp. 299–300. Franco (1999), pp. 76–78. de Fuggle, Sonia Rose (2016). 「Bernal Díaz del Castillo Cuentista: La Historia de Doña Marina」. アリカンテ: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Townsend (2006), pp. 24–25. 50. チャップマン (1957)、pp. 135–136。 タウンゼント (2006)、pp. 25–26。 タウンゼント (2006)、p. 26。 カルトゥネン (1997)、p. 300。 レストール(2003)、83 ページ。 ロックハート(1993)、87 ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、61-63 ページ。 タウンゼント(2006)、35-36 ページ。 カルトゥネン(1997)、301-302 ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、36ページ。 60. タウンゼンド(2006)、37ページ。 カルトゥネン(1997)、301ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、40–41ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、65ページ。 タウンゼンド(2019)、93ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、53ページ。 カルトゥネン(1994)、7ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、42ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、67ページ。 カルトゥネン(1994)、8-9頁。 70. タウンゼンド(2006)、56頁、242頁。 カルトゥネン(1997)、293-294頁。 カルトゥネン(1994)、22頁。 レストール(2003)、84-85頁。 ハシグ(2006)、68頁。 カルトゥネン(1997)、303頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、43頁。 ハシグ(2006)、69-70頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、45ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、70–74ページ、77ページ。 80. タウンゼンド(2006)、59ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、79ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、62–63ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、86-89ページ。 タウンゼンド(2006)、69-72ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、93ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、43、94-96ページ。 ハシグ(2006)、94-96頁。 カルトゥネン(1994)、10頁。 ハシグ(2006)、97-98頁。 90. タウンゼンド(2006)、81-82頁。 ハシグ(2006)、43、96頁。 レストール(2018)、210頁。 ハシグ(2006)、96頁。 レストール(2003)、77頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、86–88頁。 タウンゼンド(2019)、99, 243頁。 カルトゥネン(1994)、11頁。 ゴードン、ヘレン。『敗者の声:奴隷マリーナとエルナン・コルテスの物語』。シカゴ:ユニバーシティ・エディションズ、1995年、454頁。 チェイソン、ジョアン。「謎めいたマリンチェ:誤認の事例」『アメリカ大陸』32巻4号(1976年)。 100. タウンゼンド(2006)、263頁。 タウンゼンド(2006)、168–187頁。 モントードン、イヴォンヌ。「ドニャ・マリーナ:コルテスの通訳者に関するベルナルディの構築における文学的源泉」。ミゲル・デ・セルバンテス仮想図書館(スペイン語)。2020年12月9日取得。 テイト、ジュリー(2017)。「ラ・マリンチェ:トランスカルチュラルな象徴の変遷する遺産」。『ラテンアメリカニスト』。61: 81–92頁。doi:10.1111/tla.12102。S2CID 148798608。 タウンゼンド(2006)、74–76頁。 レストール、マシュー。『スペイン征服の七つの神話』 「メゾロア:メソアメリカ研究・教育ツール」。www.mesolore.org。2020年11月12日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年10月21日に取得。 ブランドン、ウィリアム (2003)。『北米インディアンの興亡』。メリーランド州ラナム:ロバーツ・ラインハート出版社。88 ページ。ISBN 9781570984525。 ブランドン、ウィリアム (2003). 『北米インディアンの興亡』. メリーランド州ラナム: ロバーツ・ラインハート出版社. p. 88. ISBN 9781570984525. タウンゼント(2006)、58 ページ。 110. サイプレス(1991)、序文。 サラス[ページが必要] カステラーノス、ロサリオ(1963)。「オトラ・ベス・ソル・フアナ」(「再び、ソル・フアナ」)。{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) ロランド・ロメロ(2005-01-01)。『フェミニズム、国家、神話:ラ・マリンチェ』。アルテ・プブリコ・プレス。pp. 28–。ISBN 978-1-61192-042-0。 ドン・M・コーヴァー; スザンヌ・B・パストル; ロバート・バフィントン(2004)。『メキシコ:現代文化と歴史の百科事典』。ABC-CLIO. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-1-57607-132-8. フォルテス・デ・レフ, J. (2002). メキシコにおける人種主義:文化的根源と臨床的介入1. 家族プロセス, 41(4), 619-623. サイプレス (1991), p. 12. 「メキシコのスペイン人父」を誹謗するのを止める時だ、2019年6月10日閲覧 ポトツキ、ヤン;訳:イアン・マクリーン(1995)。『サラゴサで発見された写本』。ペンギンブックス。 「レパートリー」。chnm.gmu.edu。2020年6月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年2月7日取得。 120. 「コルテスのインディアン女、キャロル・アシャシュの小説」。ヒスラー(フランス語)。2023年11月27日閲覧。 「ドナ・マリーナ、コルテスの通訳:ノンフィクション、オクタビオ・パス」。chnm.gmu.edu。2016年5月10日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年2月7日閲覧。 クレア・スペルバーグ・ルスティグ(2022年12月14日)。「国宝:歴史の境界線がニコラス・ケイジの映画を複雑にし、スリリングな結果をもたらす」。プライムタイマー。2022年12月21日閲覧。 「マリンチェ:メキシコ人向け奨学金へのアクセス方法とマドリードのミュージカル学校で学ぶ方法」。エル・エラルド・デ・メヒコ。2023年10月3日。 124. 「ナチョ・カノのマリンチェ、メキシコ人向け奨学金をマドリードで募集:内容と申請方法」。www.poresto.net。2023年10月3日。 |

| Bibliography Chapman, Anne M. (1957). "Port of Trade Enclaves in Aztec and Maya Civilizations". In Karl Polanyi; Conrad M. Arensberg; Harry W. Pearson (eds.). Trade and Market in the Early Empires: Economies in History and Theory. New York: Free Press. Cypess, Sandra Messinger (1991). La Malinche in Mexican Literature: From History to Myth. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292751347. Downs, Kristina (2008). "Mirrored Archetypes: The Contrasting Cultural Roles of La Malinche and Pocahontas". Western Folklore. 67 (4). Long Beach, CA: Western States Folklore Society: 397–414. ISSN 0043-373X. JSTOR 25474939. Evans, Susan Toby (2004). Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500284407. Franco, Jean (1999). "La Malinche: from gift to sexual contract". In Mary Louise Pratt; Kathleen Newman (eds.). Critical Passions: Selected Essays. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 66–82. ISBN 9780822322481. Hassig, Ross (2006). Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806182087. Herrera-Sobek, María (2005). "In Search of La Malinche: Pictorial Representations of a Mytho-Historical Figure". In Rolando J. Romero; Amanda Nolacea Harris (eds.). Feminism, Nation and Myth: La Malinche. Houston, TX: Arte Público Press. ISBN 9781611920420. Karttunen, Frances (1994). Between Worlds: Interpreters, Guides, and Survivors. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813520315. ——— (1997). "Rethinking Malinche". Indian Women: Gender Differences and Identity in Early Mexico. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806129600. ——— (2001) [1997]. "Malinche and Malinchismo". Concise Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 352–355. ISBN 9781579583378. Lockhart, James, ed. (1993). We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Repertorium Columbianum. Vol. 1. Translated by James Lockhart. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520078758. Restall, Matthew (2003). Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176117. ——— (2018). When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting that Changed History. New York: Ecco. ISBN 9780062427267. Schroeder, Susan; Cruz, Anne J.; Roa-de-la-Carrera, Cristián; Tavárez, David E., eds. (2010). Chimalpahin's Conquest: A Nahua Historian's Rewriting of Francisco Lopez de Gomara's La conquista de Mexico. Translated by Susan Schroeder; Anne J. Cruz; Cristián Roa-de-la-Carrera; David E. Tavárez. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804775069. Townsend, Camilla (2006). Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826334053. ——— (2019). Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190673062. Valdeón, Roberto A. (2013). "Doña Marina/La Malinche: A Historiographical Approach to the Interpreter/Traitor". Target: International Journal of Translation Studies. 25 (2). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company: 157–179. doi:10.1075/target.25.2.02val. hdl:10651/19605. ISSN 0924-1884. |

参考文献 チャップマン、アン・M(1957)。「アステカ文明とマヤ文明における貿易の飛び地」。カール・ポラニー、コンラッド・M・アレンズバーグ、ハリー・W・ピアソン(編)。『初期帝国における貿易と市場:歴史と理論における経済』。ニューヨーク:フリープレス。 サイプレス、サンドラ・メッシンガー (1991). 『メキシコ文学におけるラ・マリンチェ:歴史から神話へ』. テキサス州オースティン:テキサス大学出版局. ISBN 9780292751347. ダウンズ、クリスティーナ(2008)。「鏡に映った原型:ラ・マリンチェとポカホンタスの対照的な文化的役割」。『ウエスタン・フォークロア』67 (4)。カリフォルニア州ロングビーチ:ウエスタン・ステーツ・フォークロア協会:397–414。ISSN 0043-373X。JSTOR 25474939。 エヴァンス、スーザン・トビー (2004)。『古代メキシコと中央アメリカ:考古学と文化史』。ロンドン:テムズ&ハドソン。ISBN 9780500284407。 フランコ、ジャン (1999)。「ラ・マリンチェ:贈り物から性的契約へ」。メアリー・ルイーズ・プラット、キャスリーン・ニューマン (編)『 『批判的激情:選集』所収。ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版。66-82 ページ。ISBN 9780822322481。 ハシグ、ロス (2006)。『メキシコとスペインによる征服』所収。オクラホマ州ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版。ISBN 9780806182087。 ヘレラ・ソベック、マリア(2005)。「ラ・マリンチェを求めて:神話的歴史上の人物の絵画的表現」。ロランド・J・ロメロ、アマンダ・ノラセア・ハリ ス(編)。フェミニズム、国家、神話:ラ・マリンチェ。テキサス州ヒューストン:アルテ・プブリコ・プレス。ISBN 9781611920420。 Karttunen, Frances (1994). 『世界の狭間で:通訳者、ガイド、そして生存者たち』. ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック:ラトガース大学出版局. ISBN 9780813520315. ——— (1997). 「マリンチェを再考する」. 『インディアン女性:初期メキシコにおけるジェンダーとアイデンティティ』. オクラホマ州ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版局. ISBN 9780806129600。 ——— (2001) [1997]。「マリンチェとマリンチズモ」。『メキシコ簡明百科事典』。シカゴ:フィッツロイ・ディアボーン。352-355 ページ。ISBN 9781579583378。 ロックハート、ジェームズ編 (1993). 『我ら、ここにいる者たち:メキシコ征服に関するナワトル語の記述』. レパートリウム・コロンビアヌム. 第 1 巻. ジェームズ・ロックハート訳. カリフォルニア州バークレー: カリフォルニア大学出版. ISBN 9780520078758. レスタル、マシュー (2003). 『スペイン征服の七つの神話』オックスフォード・ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 9780195176117。 ———(2018)。『モンテスマとコルテスの出会い:歴史を変えた真実の物語』ニューヨーク:エッコ。ISBN 9780062427267。 シュレーダー、スーザン;クルス、アン・J.; ロア=デ=ラ=カレラ、クリスティアン;タバレズ、デイビッド・E. 編(2010)。『チマルパヒンの征服:ナワ族歴史家によるフランシスコ・ロペス・デ・ゴマラ『メキシコ征服』の再記述』。スーザン・シュレーダー、ア ン・J・クルス、クリスティアン・ロア=デ=ラ=カレラ、デイビッド・E・タバレズ訳。カリフォルニア州パロアルト:スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 9780804775069。 タウンゼンド、カミラ(2006)。『マリンツィンの選択:メキシコ征服における一人のインディアン女性』。アルバカーキ:ニューメキシコ大学出版局。ISBN 9780826334053。 ——— (2019). 『第五の太陽:アステカの新歴史』. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 9780190673062. バルデオン, ロベルト・A. (2013). 「ドニャ・マリーナ/ラ・マリンチェ:通訳者/裏切り者への歴史記述学的アプローチ」. ターゲット:国際翻訳研究ジャーナル。25 (2)。アムステルダム:ジョン・ベンジャミンズ出版:157–179頁。doi:10.1075/target.25.2.02val。 hdl:10651/19605。 ISSN 0924-1884。 |

| Further reading Agogino, George A.; Stevens, Dominique E.; Carlotta, Lynda (1973). "Dona Marina and the legend of La Llorona". Anthropological Journal of Canada. 2 (1): 27–29. Calafell, Bernadette M. (2005). "Pro(re)claiming Loss: a Performance Pilgrimage in Search of Malintzin Tenepal". Text and Performance Quarterly. 25 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1080/10462930500052327. S2CID 191613689. Del Rio, Fanny (2009). La verdadera historia de Malinche. México, D.F.: Grijalbo. ISBN 978-607-429-593-1. Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1963) [1632]. The Conquest of New Spain. Translated by J.M. Cohen. London: The Folio Society. Fuentes, Patricia de (1963). The Conquistadors: First Person Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. New York: Orion. Maura, Juan Francisco (1997). Women in the Conquest of the Americas. Translated by John F. Deredita. New York: Peter Lang. Paz, Octavio (1961). The Labyrinth of Solitude. New York: Grove Press. Somonte, Mariano G. (1971). Doña Marina: "La Malinche". Mexico City: Edimex. Thomas, Hugh (1993). Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the Fall of Old Mexico. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671705183. Vivancos Pérez, Ricardo F. (2012). "Malinche". In María Herrera-Sobek (ed.). Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions. Vol. II. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 750–759. Henderson, James D. (1978). Ten notable women of Latin America. Chicago: Nelson Hall. ISBN 9780882294261. |

追加文献(さらに読む) アゴジーノ、ジョージ・A.;スティーブンス、ドミニク・E.;カルロッタ、リンダ(1973)。「ドナ・マリーナとラ・ジョローナの伝説」。『カナダ人類学雑誌』。2巻1号:27–29頁。 カラフェル、ベルナデット・M.(2005)。「喪失の再主張:マリンチン・テネパルを探してのパフォーマンス巡礼」『テキスト・アンド・パフォーマン ス・クォータリー』25巻1号:43–56頁。doi:10.1080/10462930500052327。S2CID 191613689。 デル・リオ、ファニー(2009)。『マリンチェの真実の物語』。メキシコシティ:グリハルボ。ISBN 978-607-429-593-1。 ディアス・デル・カスティーヨ、ベルナル(1963)[1632年]。『新スペイン征服記』。J.M.コーエン訳。ロンドン:フォリオ・ソサエティ。 フエンテス、パトリシア・デ(1963)。『征服者たち:メキシコ征服の第一人称記録』。ニューヨーク:オリオン。 マウラ、フアン・フランシスコ(1997)。『アメリカ大陸征服における女性たち』。ジョン・F・デレディタ訳。ニューヨーク:ピーター・ラング。 パス、オクタビオ(1961)。孤独の迷宮。ニューヨーク:グローブ・プレス。 ソモンテ、マリアノ・G.(1971)。ドニャ・マリーナ:「ラ・マリンチェ」。メキシコシティ:エディメックス。 トーマス、ヒュー(1993)。征服:モンテスマ、コルテス、そして古メキシコの没落。ニューヨーク:サイモン&シュスター。ISBN 9780671705183。 ビバンコス・ペレス、リカルド・F.(2012)。「マリンチェ」。マリア・エレラ=ソベック(編)。『ラティーノ民俗学を祝う:文化伝統事典』第II巻。カリフォルニア州サンタバーバラ:ABC-CLIO。750–759頁。 ヘンダーソン、ジェームズ・D.(1978年)。『ラテンアメリカにおける十人の著名な女性』シカゴ:ネルソン・ホール。ISBN 9780882294261。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Malinche |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099