マーシャル・マクルーハン

Marshall McLuhan,

1911-1980

☆

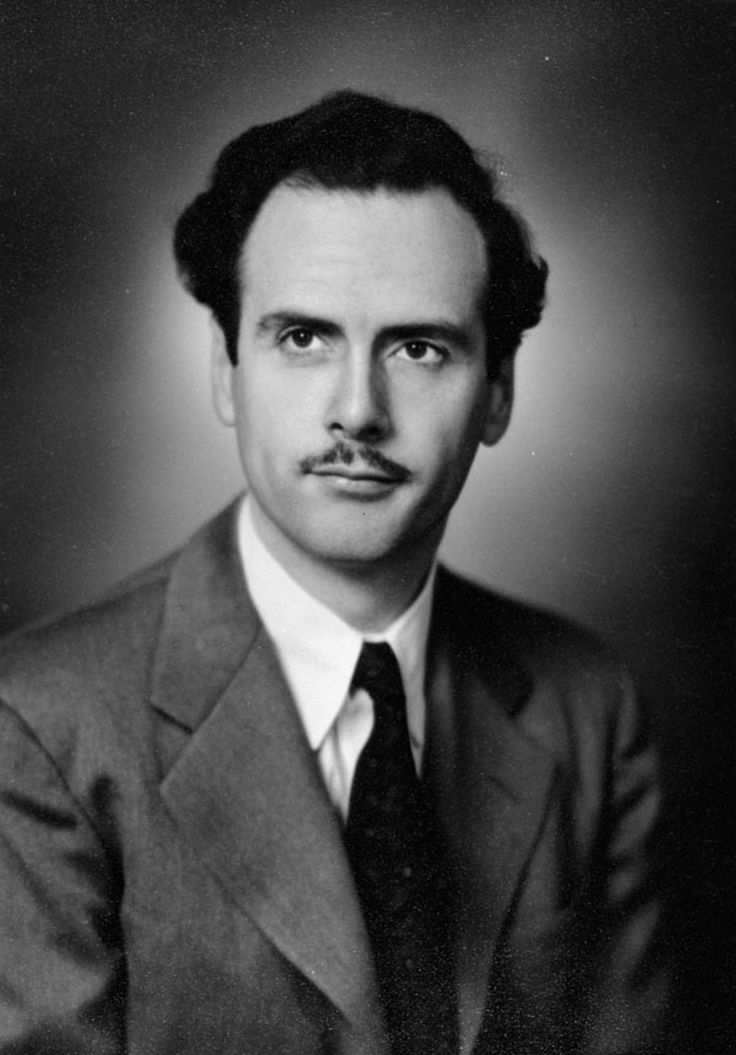

ハーバート・マーシャル・マクルーハン(Herbert Marshall

McLuhan

CC、/məˈkluːən/、mə-KLOO-ən、1911年7月21日 -

1980年12月31日)は、メディア論の基礎を築いたカナダの哲学者である。マニトバ大学とケンブリッジ大学で学んだ。彼は、1946年にトロント大学

に移るまで、米国とカナダの複数の大学で英語の教授として教鞭をとり、その後はトロント大学で生涯を過ごした。彼は「メディア研究の父」として知られてい

る。マクルーハンは著書『メディア論:人間拡張の諸相』の第1章で「メディアはメッセージである」という表現を考案し、また「グローバル・ヴィレッジ」と

いう用語も生み出した。彼は、WWWが発明されるほぼ30年前に、その存在を予言していた。1960年代後半には、マクルーハンはメディア論の議論の中心

人物であったが、1970年代初頭にはその影響力は衰え始めた。[15] 。彼の死後も、学術界では物議を醸す人物であり続けた。

しかし、インターネットとワールドワイドウェブの登場により、彼の作品と視点への関心が再び高まった。

| Herbert Marshall

McLuhan CC (/məˈkluːən/, mə-KLOO-ən; July 21, 1911 – December 31,

1980)

was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the

study of media theory.[7][8][9][10] He studied at the University of

Manitoba and the University of Cambridge. He began his teaching career

as a professor of English at several universities in the United States

and Canada before moving to the University of Toronto in 1946, where he

remained for the rest of his life. He is known as the "father of media

studies".[11] McLuhan coined the expression "the medium is the message"[12] in the first chapter in his Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man[13] and the term global village. He predicted the World Wide Web almost 30 years before it was invented.[14] He was a fixture in media discourse in the late 1960s, though his influence began to wane in the early 1970s.[15] In the years following his death, he continued to be a controversial figure in academic circles.[16] However, with the arrival of the Internet and the World Wide Web, interest was renewed in his work and perspectives.[17][18][19] |

ハーバート・マーシャル・マクルーハン(Herbert

Marshall McLuhan CC、/məˈkluːən/、mə-KLOO-ən、1911年7月21日 -

1980年12月31日)は、メディア論の基礎を築いたカナダの哲学者である。マニトバ大学とケンブリッジ大学で学んだ。彼は、1946年にトロント大学

に移るまで、米国とカナダの複数の大学で英語の教授として教鞭をとり、その後はトロント大学で生涯を過ごした。彼は「メディア研究の父」として知られてい

る。[11] マクルーハンは著書『メディア論:人間拡張の諸相』の第1章で「メディアはメッセージである」という表現を考案し[12]、また「グローバル・ヴィレッ ジ」という用語も生み出した。彼は、WWWが発明されるほぼ30年前に、その存在を予言していた。[14] 1960年代後半には、マクルーハンはメディア論の議論の中心人物であったが、1970年代初頭にはその影響力は衰え始めた。[15] 。彼の死後も、学術界では物議を醸す人物であり続けた。[16] しかし、インターネットとワールドワイドウェブの登場により、彼の作品と視点への関心が再び高まった。[17][18][19] |

| Life and career McLuhan was born on July 21, 1911, in Edmonton, Alberta, and was named "Marshall" from his maternal grandmother's surname. His brother, Maurice, was born two years later. His parents were both also born in Canada: his mother, Elsie Naomi (née Hall), was a Baptist school teacher who later became an actress; and his father, Herbert Ernest McLuhan, was a Methodist with a real-estate business in Edmonton. When the business failed at the start of World War I, McLuhan's father enlisted in the Canadian Army. After a year of service, he contracted influenza and remained in Canada, away from the front lines. After Herbert's discharge from the army in 1915, the McLuhan family moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where Marshall grew up and went to school, attending Kelvin Technical School before enrolling in the University of Manitoba in 1928. [20] Undergraduate education After studying for one year as an engineering student, he changed majors and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree (1933), winning a University Gold Medal in Arts and Sciences.[21] He went on to receive a Master of Arts degree (1934) in English from the university as well. He had long desired to pursue graduate studies in England and was accepted by Trinity Hall, Cambridge, having failed to secure a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford.[22] Though having already earned his BA and MA in Manitoba, Cambridge required him to enroll as an undergraduate "affiliated" student, with one year's credit towards a three-year bachelor's degree, before entering any doctoral studies.[a][24] He went up to Cambridge in the autumn of 1934, studied under I. A. Richards and F. R. Leavis, and was influenced by New Criticism.[22] Years afterward, upon reflection, he credited the faculty there with influencing the direction of his later work because of their emphasis on the "training of perception", as well as such concepts as Richards' notion of "feedforward".[25] These studies formed an important precursor to his later ideas on technological forms.[26] He received the required bachelor's degree from Cambridge in 1936[27] and entered their graduate program. Conversion to Catholicism At the University of Manitoba, McLuhan explored his conflicted relationship with religion and turned to literature to "gratify his soul's hunger for truth and beauty,"[28] later referring to this stage as agnosticism.[29] While studying the trivium at Cambridge, he took the first steps toward his eventual conversion to Catholicism in 1937,[30] founded on his reading of G. K. Chesterton.[31] In 1935, he wrote to his mother:[32] Had I not encountered Chesterton I would have remained agnostic for many years at least. Chesterton did not convince me of religious faith, but he prevented my despair from becoming a habit or hardening into misanthropy. He opened my eyes to European culture and encouraged me to know it more closely. He taught me the reasons for all that in me was simply blind anger and misery. At the end of March 1937,[b] McLuhan completed what was a slow but total conversion process, when he was formally received into the Catholic Church. After consulting a minister, his father accepted the decision to convert. His mother, however, felt that his conversion would hurt his career and was inconsolable.[33] McLuhan was devout throughout his life, but his religion remained a private matter.[34] He had a lifelong interest in the number three[35] (e.g., the trivium, the Trinity) and sometimes said that the Virgin Mary provided intellectual guidance for him.[c] For the rest of his career, he taught in Catholic institutions of higher education. Early career, marriage, and doctorate  McLuhan at Cambridge, c. 1940 Unable to find a suitable job in Canada, he went to the United States to take a job as a teaching assistant at the University of Wisconsin–Madison for the 1936–37 academic year.[37] From 1937 to 1944, he taught English at Saint Louis University (with an interruption from 1939 to 1940 when he returned to Cambridge). There he taught courses on Shakespeare,[38] eventually tutoring and befriending Walter J. Ong, who would write his doctoral dissertation on a topic that McLuhan had called to his attention, as well as become a well-known authority on communication and technology.[citation needed] McLuhan met Corinne Lewis in St. Louis,[39] a teacher and aspiring actress from Fort Worth, Texas, whom he married on August 4, 1939. They spent 1939–40 in Cambridge, where he completed his master's degree (awarded in January 1940)[27] and began to work on his doctoral dissertation on Thomas Nashe and the verbal arts. While the McLuhans were in England, World War II had erupted in Europe. For this reason, he obtained permission to complete and submit his dissertation from the United States, without having to return to Cambridge for an oral defence. In 1940, the McLuhans returned to Saint Louis University, where they started a family as he continued teaching. He was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy degree in December 1943.[40] He next taught at Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario, from 1944 to 1946, then moved to Toronto in 1946 where he joined the faculty of St. Michael's College, a Catholic college of the University of Toronto, where Hugh Kenner would be one of his students. Canadian economist and communications scholar Harold Innis was a university colleague who had a strong influence on his work. McLuhan wrote in 1964: "I am pleased to think of my own book The Gutenberg Galaxy as a footnote to the observations of Innis on the subject of the psychic and social consequences, first of writing then of printing."[41] Later career and reputation  McLuhan with a television showing his own image, 1967 In the early 1950s, McLuhan began the Communication and Culture seminars at the University of Toronto, funded by the Ford Foundation. As his reputation grew, he received a growing number of offers from other universities.[26] During this period, he published his first major work, The Mechanical Bride (1951), in which he examines the effect of advertising on society and culture. Throughout the 1950s, he and Edmund Carpenter also produced an important academic journal called Explorations.[42] McLuhan and Carpenter have been characterized as the Toronto School of communication theory, together with Harold Innis, Eric A. Havelock, and Northrop Frye. During this time, McLuhan supervised the doctoral thesis of modernist writer Sheila Watson on the subject of Wyndham Lewis. Hoping to keep him from moving to another institute, the University of Toronto created the Centre for Culture and Technology (CCT) in 1963.[26] From 1967 to 1968, McLuhan was named the Albert Schweitzer Chair in Humanities at Fordham University in the Bronx.[d] While at Fordham, he was diagnosed with a benign brain tumor, which was treated successfully. He returned to Toronto where he taught at the University of Toronto for the rest of his life and lived in Wychwood Park, a bucolic enclave on a hill overlooking the downtown where Anatol Rapoport was his neighbour.[citation needed] In 1970, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada.[43] In 1975, the University of Dallas hosted him from April to May, appointing him to the McDermott Chair.[44] Marshall and Corinne McLuhan had six children: Eric, twins Mary and Teresa, Stephanie, Elizabeth, and Michael. The associated costs of a large family eventually drove him to advertising work and accepting frequent consulting and speaking engagements for large corporations, including IBM and AT&T.[26] Death In September 1979, McLuhan suffered a stroke which affected his ability to speak. The University of Toronto's School of Graduate Studies tried to close his research center shortly thereafter, but was deterred by substantial protests. McLuhan never fully recovered from the stroke and died in his sleep on December 31, 1980.[45] He is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Thornhill, Ontario, Canada.[citation needed] |

生涯とキャリア マクルーハンは1911年7月21日、アルバータ州エドモントンで生まれ、母方の祖母の姓から「マーシャル」と名付けられた。2年後に弟のモーリスが生ま れた。両親もカナダ生まれで、母親のエルシー・ナオミ(旧姓ホール)はバプテスト派の学校教師で、後に女優となった。父親のハーバート・アーネスト・マク ルーハンはエドモントンで不動産業を営むメソジスト派の信者であった。第一次世界大戦の勃発により、マクルーハンの父親の不動産業は失敗に終わり、父親は カナダ軍に入隊した。1年間の兵役の後、インフルエンザに感染し、前線から離れたカナダ国内にとどまることとなった。1915年にハーバートが除隊した 後、マクルーハン一家はカナダのマニトバ州ウィニペグに移住し、マーシャルはそこで育ち、学校に通った。1928年にマニトバ大学に入学する前は、ケルビ ン・テクニカル・スクールに通っていた。[20] 学部教育 1年間工学を学んだ後、専攻を変更し、1933年に文学士号を取得し、人文科学の大学金メダルを受賞した。[21] その後、同大学で英語学の修士号(1934年)も取得した。彼はかねてよりイギリスで大学院の研究を希望しており、オックスフォード大学へのローズ奨学金 の獲得に失敗したが、ケンブリッジ大学のトリニティ・ホールに合格した。 マニトバ州で既に学士号と修士号を取得していたにもかかわらず、ケンブリッジ大学では博士課程に進む前に、3年間の学士号取得に必要な単位のうち1年分を 取得する「提携」学部生として入学することが義務付けられていた。[a][24] 1934年の秋にケンブリッジ大学に入学した彼は、I. A. リチャーズとF. R. レヴィスのもとで学び、新批評派の影響を受けた。[22] 何年も経ってから、彼は振り返って、その学部の教授陣が「知覚の訓練」やリチャーズの「フィードフォワード」の概念などを強調していたため、その後の自身 の研究の方向性に影響を与えたと述べている。[25] これらの研究は、テクノロジーの形態に関する彼の後の考え方の重要な先駆けとなった。[26] 1936年にケンブリッジ大学から学士号を取得し、[27] 大学院課程に入学した。 カトリックへの改宗 マニトバ大学在学中、マクルーハンは宗教との葛藤する関係を探求し、文学に目を向けた。「真実と美に対する魂の飢えを満たすため」であったが[28]、後 にこの段階を不可知論と呼んでいる[29]。 ケンブリッジ大学でトリビウムを学んでいる間、彼は1937年にカトリックに改宗する第一歩を踏み出した。[30] これはG. K. チェスタートンの著作を読んだことがきっかけであった。[31] 1935年、彼は母親に手紙を書き、次のように述べている。 もしチェスタートンに出会っていなかったら、少なくとも何年もの間、不可知論者であり続けていただろう。チェスタートンは私に宗教的信仰を納得させたわけ ではないが、絶望が習慣化したり、人間嫌いへと固まっていくのを防いでくれた。彼は私の目を開かせ、ヨーロッパ文化をより深く知るように促してくれた。そ して、私の中にあったのは単に盲目の怒りと不幸だったのだということを、その理由とともに教えてくれた。 1937年3月の終わりに、[b]マクルーハンは、ゆっくりではあるが完全な改宗プロセスを完了し、正式にカトリック教会に受け入れられた。牧師に相談し た後、父親は改宗の決断を受け入れた。しかし、彼の母親は息子の改宗がキャリアに悪影響を与えると感じ、悲嘆に暮れた。[33] マクルーハンは生涯を通じて敬虔な信者であったが、信仰はあくまで個人的な問題であった。[34] 彼は生涯を通じて「3」という数字に興味を持ち続け(例えば、三学、三位一体)、時には聖母マリアが自身の知的指導者であったと語った。[c] その後は、カトリック系の高等教育機関で教鞭をとった。 初期の経歴、結婚、博士号  ケンブリッジ時代のマクルーハン、1940年頃 カナダで適当な仕事が見つからなかったため、彼は米国に渡り、1936年から1937年の学年度にウィスコンシン大学マディソン校で教務補助員として職を 得た。[37] 1937年から1944年にかけて、彼はセントルイス大学で英語を教えた(1939年から1940年にかけてケンブリッジに戻った期間を除く)。そこで彼 はシェイクスピアのコースを教え[38]、最終的にはウォルター・J・オングの家庭教師となり、友人となった。オングは、マクルーハンが注目させたトピッ クを博士論文のテーマとし、コミュニケーションとテクノロジーの著名な権威となった人物である[要出典]。 マクルーハンは、セントルイスでコリン・ルイス(Corinne Lewis)と出会った。彼女はテキサス州フォートワース出身の教師で女優志望であり、1939年8月4日に結婚した。1939年から1940年にかけて はケンブリッジで過ごし、修士号を取得(1940年1月に授与)[27]し、トマス・ナッシュと言語芸術に関する博士論文の執筆を開始した。マクルーハン 夫妻が英国に滞在している間に、ヨーロッパでは第二次世界大戦が勃発した。そのため、彼は口頭試問のためにケンブリッジに戻る必要なく、論文を完成させ、 米国から提出する許可を得た。1940年、マクルーハン夫妻はセントルイス大学に戻り、そこで家庭を築きながら、彼は教鞭をとり続けた。1943年12 月、彼は博士号を授与された。 その後、1944年から1946年までオンタリオ州ウィンザーのアサンプション・カレッジで教鞭をとり、1946年にトロントに移り、トロント大学のカト リック系カレッジであるセント・マイケルズ・カレッジの教員となった。同カレッジには、ヒュー・ケナーが学生として在籍していた。カナダの経済学者でコ ミュニケーション学者のハロルド・イニスは、彼の研究に強い影響を与えた大学の同僚であった。マクルーハンは1964年に「『グーテンベルク・ギャラク シー』という私の著書が、イニスの『精神と社会への影響』という主題に関する観察の脚注となることを嬉しく思う。 その主題とは、まず文字、次に印刷である」と書いている。[41] その後の経歴と評価  自身の映像が映し出されるテレビとマクルーハン、1967年 1950年代初頭、マクルーハンはフォード財団の資金援助を受け、トロント大学で「コミュニケーションと文化」セミナーを開始した。彼の名声が高まるにつ れ、他の大学からもオファーが増加した。[26] この時期、彼は初の主要著作『機械の花嫁』(1951年)を出版し、広告が社会と文化に与える影響について考察した。1950年代を通じて、マクルーハン とエドマンド・カーペンターは学術誌『Explorations』を共同で発行した。[42] マクルーハンとカーペンターは、ハロルド・イニス、エリック・A・ハヴェロック、ノースロップ・フライらとともに、トロント学派のコミュニケーション理論 家として知られている。この時期、マクルーハンはモダニズム作家シーラ・ワトソンのウィンダム・ルイスに関する博士論文の指導を行った。彼が他の研究機関 に移るのを阻止しようと、トロント大学は1963年に文化とテクノロジーセンター(CCT)を設立した。 1967年から1968年にかけて、マクルーハンはブロンクス区のフォーダム大学で人文科学のアルバート・シュバイツァー講座の教授に任命された。フォー ダム大学在籍中に良性の脳腫瘍と診断されたが、無事に治療された。トロントに戻った彼は、その後生涯をトロント大学で教え、ダウンタウンを見下ろす丘の上 の牧歌的な一角であるウィッチウッド・パークに住んだ。アナトール・ラポポートは彼の隣人であった。 1970年にはカナダ勲章のコンパニオンに叙せられた。1975年にはダラス大学が4月から5月にかけて彼を招き、マクダーモット教授職に任命した。大家 族の養育費が嵩んだため、彼は広告の仕事や、IBMやAT&Tなどの大企業からのコンサルティングや講演の依頼を頻繁に受けるようになった。 死 1979年9月、マクルーハンは脳卒中に見舞われ、言語能力に影響が出るようになった。トロント大学の大学院研究科はその後間もなく彼の研究センターを閉 鎖しようとしたが、大規模な抗議活動により思いとどまった。マクルーハンは脳卒中から完全に回復することはなく、1980年12月31日に就寝中に死去し た。[45] 彼はカナダのオンタリオ州ソーンヒルにあるホーリークロス墓地に埋葬されている。[要出典] |

| Major works During his years at Saint Louis University (1937–1944), McLuhan worked concurrently on two projects: his doctoral dissertation and the manuscript that was eventually published in 1951 as a book, titled The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man, which included only a representative selection of the materials that McLuhan had prepared for it. McLuhan's 1942 Cambridge University doctoral dissertation surveys the history of the verbal arts (grammar, logic, and rhetoric—collectively known as the trivium) from the time of Cicero down to the time of Thomas Nashe.[e] In his later publications, McLuhan at times uses the Latin concept of the trivium to outline an orderly and systematic picture of certain periods in the history of Western culture. McLuhan suggests that the Late Middle Ages, for instance, were characterized by the heavy emphasis on the formal study of logic. The key development that led to the Renaissance was not the rediscovery of ancient texts, but a shift in emphasis from the formal study of logic to rhetoric and grammar. Modern life is characterized by the re-emergence of grammar as its most salient feature—a trend McLuhan felt was exemplified by the New Criticism of Richards and Leavis.[f] McLuhan also began the academic journal Explorations with anthropologist Edmund "Ted" Carpenter. In a letter to Walter Ong, dated 31 May 1953, McLuhan reports that he had received a two-year grant of $43,000 from the Ford Foundation to carry out a communication project at the University of Toronto involving faculty from different disciplines, which led to the creation of the journal.[46] At a Fordham lecture in 1999, Tom Wolfe suggested that a major under-acknowledged influence on McLuhan's work is the Jesuit philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose ideas anticipated those of McLuhan, especially the evolution of the human mind into the "noosphere."[47] In fact, McLuhan warns against outright dismissing or whole-heartedly accepting de Chardin's observations early on in his second published book The Gutenberg Galaxy: This externalization of our senses creates what de Chardin calls the "noosphere" or a technological brain for the world. Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as in an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and super-imposed co-existence.[48] In his private life, McLuhan wrote to friends saying: "I am not a fan of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The idea that anything is better because it comes later is surely borrowed from pre-electronic technologies." Further, McLuhan noted to a Catholic collaborator: "The idea of a Cosmic thrust in one direction ... is surely one of the lamest semantic fallacies ever bred by the word 'evolution'.… That development should have any direction at all is inconceivable except to the highly literate community."[49] Some of McLuhan's main ideas were influenced or prefigured by anthropologists like Edward Sapir and Claude Lévi-Strauss, arguably with a more complex historical and psychological analysis.[50] The idea of the retribalization of Western society by the far-reaching techniques of communication, the view on the function of the artist in society, and the characterization of means of transportation, like the railroad and the airplane, as means of communication, are prefigured in Sapir's 1933 article on Communication in the Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences,[51] while the distinction between "hot" and "cool" media draws from Lévi-Strauss' distinction between hot and cold societies.[52][53] |

主要作品 セントルイス大学在学中(1937年~1944年)、マクルーハンは博士論文と、最終的に1951年に『機械の花嫁:産業人のフォークロア』という題で書 籍として出版された原稿の2つのプロジェクトを並行して進めていた。 マクルーハンの1942年のケンブリッジ大学博士論文は、キケロの時代からトマス・ナッシュの時代までの言語芸術(文法、論理学、修辞学、総称して「三 学」と呼ばれる)の歴史を概観している。[e] その後の著作において、マクルーハンは西洋文化の歴史における特定の時代を秩序立てて体系的に概説するために、ラテン語の「三学」の概念を時折使用してい る。例えば、中世後期は形式的な論理学の研究が重視されていた時代であったとマクルーハンは指摘している。ルネサンスにつながる重要な発展は、古代のテキ ストの再発見ではなく、形式的な論理学の研究から修辞学や文法への重点の移行であった。現代の生活は、文法が再び浮上したことが最も顕著な特徴である。マ クルーハンは、リチャーズとリーヴィスの新批評がこの傾向を体現していると感じていた。 また、マクルーハンは人類学者エドモンド・「テッド」・カーペンターとともに学術誌『エクスプロレーションズ』を創刊した。1953年5月31日付のウォ ルター・オング宛ての手紙で、マクルーハンは、トロント大学でさまざまな学部の教員が関わるコミュニケーションプロジェクトを実施するために、フォード財 団から2年間にわたって4万3000ドルの助成金を受け取ったことを報告しており、これが学術誌創刊のきっかけとなった。 1999年のフォーダム大学での講演で、トム・ウルフは、マクルーハンの作品に大きな影響を与えたにもかかわらず、あまり知られていない人物として、イエ ズス会の哲学者ピエール・テイヤール・ド・シャルダンを挙げた。シャルダンの考えは、特に人間の精神が「ノースフィア」へと進化するというマクルーハンの 考えを先取りしていた。実際、マクルーハンは、2冊目の著書『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』の序文で、シャルダンの観察を全面的に否定したり、無条件に 受け入れたりすることに警告を発している。 この感覚の外部化によって、ド・シャルダンが「ヌースフィア」と呼ぶもの、つまり世界のためのテクノロジーによる脳が生まれる。世界は膨大なアレクサンド リア図書館へと向かうのではなく、幼児向けのSF小説のように、コンピュータ、電子脳へと変化した。そして、私たちの感覚が外部へと向かう一方で、ビッグ ブラザーは内部へと向かう。したがって、このダイナミクスを認識しない限り、私たちはたちまちパニックに陥り、まさに部族の太鼓の音が鳴り響く小さな世 界、完全な相互依存、重なり合う共存にふさわしい恐怖の段階へと突入することになるだろう。 マクルーハンは私生活では、友人たちに次のように書いていた。「私はピエール・テイヤール・ド・シャルダンのファンではない。後から出てきたものの方が優 れているという考え方は、電子技術以前の技術から借用したものであることは明らかだ。」さらに、マクルーハンはカトリックの協力者に対して、「宇宙の推進 力が一方向に働くという考え方は...、進化という言葉によって生み出された最もお粗末な意味論的誤謬のひとつである。... その発展が何らかの方向性を持つなどということは、高度な識字能力を持つ社会を除いては考えられない。」と指摘している。[49] マクルーハンの主要な考えのいくつかは、おそらくより複雑な歴史的および心理的分析を伴う形で、エドワード・サピアやクロード・レヴィ=ストロースといっ た人類学者の影響を受けたり、彼らによって先取りされていたりした。[50] 広範囲にわたるコミュニケーション技術による西洋社会の再原始化という考え、社会における芸術家の機能に関する見解、 鉄道や飛行機などの交通手段をコミュニケーションの手段として特徴づけるという考え方は、1933年にサピアが『社会科学百科事典』に発表したコミュニ ケーションに関する論文で予見されているが[51]、「ホット」メディアと「クール」メディアの区別は、レヴィ=ストロースによる「ホットな社会」と 「クールな社会」の区別から着想を得たものである[52][53]。 |

| The Mechanical Bride (1951) Main article: The Mechanical Bride This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) McLuhan's first book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (1951), is a pioneering study in the field now known as popular culture. In the book, McLuhan turns his attention to analysing and commenting on numerous examples of persuasion in contemporary popular culture. This followed naturally from his earlier work as both dialectic and rhetoric in the classical trivium aimed at persuasion. At this point, his focus shifted dramatically, turning inward to study the influence of communication media independent of their content. His famous aphorism "the medium is the message" (elaborated in his Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964) calls attention to this intrinsic effect of communications media.[g] His interest in the critical study of popular culture was influenced by the 1933 book Culture and Environment by F. R. Leavis and Denys Thompson, and the title The Mechanical Bride is derived from a piece by the Dadaist artist Marcel Duchamp. The Mechanical Bride is composed of 59 short essays[55] that may be read in any order—what he styled the "mosaic approach" to writing a book. Each essay begins with a newspaper or magazine article, or an advertisement, followed by McLuhan's analysis thereof. The analyses bear on aesthetic considerations as well as on the implications behind the imagery and text. McLuhan chose these ads and articles not only to draw attention to their symbolism, as well as their implications for the corporate entities who created and disseminated them, but also to mull over what such advertising implies about the wider society at which it is aimed. Roland Barthes's essays 1957 Mythologies, echoes McLuhan's Mechanical Bride, as a series of exhibits of popular mass culture (like advertisements, newspaper articles and photographs) that are analyzed in a semiological way.[56][57] |

『機械の花嫁』(1951年) 詳細は「機械の花嫁」を参照 この節では検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、削除される場合がありま す。 (2018年1月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) マクルーハンの最初の著書『機械の花嫁:産業人のフォークロア』(1951年)は、現在では大衆文化として知られる分野における先駆的な研究である。この 本の中で、マクルーハンは現代の大衆文化における説得の数多くの例を分析し、論評することに注目した。これは、説得を目的とした古典的な三学問における弁 証法と修辞学としての彼の初期の研究から自然に導かれたものである。この時点で、彼の関心は劇的に変化し、内容とは無関係なコミュニケーション・メディア の影響を研究する内省的なものへと転換した。彼の有名な格言「メディアはメッセージである」(『メディア論:人間拡張の諸相』1964年で詳述)は、コ ミュニケーション・メディアの本質的な効果に注目している。 大衆文化の批判的研究に対する彼の関心は、1933年に出版されたF. R. レヴィスとデニス・トンプソンの著書『文化と環境』の影響を受けている。また、『機械の花嫁』というタイトルは、ダダイズムの芸術家マルセル・デュシャン の作品から取られたものである。 『機械の花嫁』は59の短いエッセイから構成されており[55]、どの順番で読んでもよい。これは、彼が「モザイク的アプローチ」と呼ぶ本の書き方であ る。各エッセイは新聞や雑誌の記事、あるいは広告から始まり、それに続くのがマクルーハンの分析である。分析は、イメージやテキストの背後にある含意だけ でなく、審美的な考察にも及んでいる。マクルーハンは、これらの広告や記事を、その象徴性や、それらを作成し普及させた企業体への含意に注目させるためだ けでなく、そうした広告が対象とするより広い社会について、それが何を暗示しているかを熟考させるために選んだ。ロラン・バルトの1957年のエッセイ 『神話』は、マクルーハンの『機械の花嫁』と同様に、大衆的な大衆文化(広告、新聞記事、写真など)を一連の展示品として記号論的に分析している。 [56][57] |

| The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) Main article: The Gutenberg Galaxy Written in 1961 and first published by University of Toronto Press, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1962) is a pioneering study in the fields of oral culture, print culture, cultural studies, and media ecology. Throughout the book, McLuhan makes efforts to reveal how communication technology (i.e., alphabetic writing, the printing press, and the electronic media) affects cognitive organization, which in turn has profound ramifications for social organization:[58] [I]f a new technology extends one or more of our senses outside us into the social world, then new ratios among all of our senses will occur in that particular culture. It is comparable to what happens when a new note is added to a melody. And when the sense ratios alter in any culture then what had appeared lucid before may suddenly become opaque, and what had been vague or opaque will become translucent. Movable type McLuhan's episodic history takes the reader from pre-alphabetic, tribal humankind to the electronic age. According to McLuhan, the invention of movable type greatly accelerated, intensified, and ultimately enabled cultural and cognitive changes that had already been taking place since the invention and implementation of the alphabet, by which McLuhan means phonemic orthography. (McLuhan is careful to distinguish the phonetic alphabet from logographic or logogramic writing systems, such as Egyptian hieroglyphs or ideograms.) Print culture, ushered in by the advance in printing during the middle of the 15th century when the Gutenberg press was invented, brought about the cultural predominance of the visual over the aural/oral. Quoting (with approval) an observation on the nature of the printed word from William Ivins' Prints and Visual Communication, McLuhan remarks:[59] In this passage [Ivins] not only notes the ingraining of lineal, sequential habits, but, even more important, points out the visual homogenizing of experience of print culture, and the relegation of auditory and other sensuous complexity to the background.… The technology and social effects of typography incline us to abstain from noting interplay and, as it were, "formal" causality, both in our inner and external lives. Print exists by virtue of the static separation of functions and fosters a mentality that gradually resists any but a separative and compartmentalizing or specialist outlook. The main concept of McLuhan's argument (later elaborated upon in The Medium Is the Massage) is that new technologies (such as alphabets, printing presses, and even speech) exert a gravitational effect on cognition, which in turn, affects social organization: print technology changes our perceptual habits—"visual homogenizing of experience"—which in turn affects social interactions—"fosters a mentality that gradually resists all but a…specialist outlook". According to McLuhan, this advance of print technology contributed to and made possible most of the salient trends in the modern period in the Western world: individualism, democracy, Protestantism, capitalism, and nationalism. For McLuhan, these trends all reverberate with print technology's principle of "segmentation of actions and functions and principle of visual quantification."[60][verification needed] Global village In the early 1960s, McLuhan wrote that the visual, individualistic print culture would soon be brought to an end by what he called "electronic interdependence" wherein electronic media replaces visual culture with aural/oral culture. In this new age, humankind would move from individualism and fragmentation to a collective identity, with a "tribal base." McLuhan's coinage for this new social organization is the global village.[h] The term is sometimes described as having negative connotations in The Gutenberg Galaxy, but McLuhan was interested in exploring effects, not making value judgments:[48] Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence.… Terror is the normal state of any oral society, for in it everything affects everything all the time.… In our long striving to recover for the Western world a unity of sensibility and of thought and feeling we have no more been prepared to accept the tribal consequences of such unity than we were ready for the fragmentation of the human psyche by print culture. Key to McLuhan's argument is the idea that technology has no per se moral bent—it is a tool that profoundly shapes an individual's and, by extension, a society's self-conception and realization:[62] Is it not obvious that there are always enough moral problems without also taking a moral stand on technological grounds?… Print is the extreme phase of alphabet culture that detribalizes or decollectivizes man in the first instance. Print raises the visual features of alphabet to highest intensity of definition. Thus, print carries the individuating power of the phonetic alphabet much further than manuscript culture could ever do. Print is the technology of individualism. If men decided to modify this visual technology by an electric technology, individualism would also be modified. To raise a moral complaint about this is like cussing a buzz-saw for lopping off fingers. "But", someone says, "we didn't know it would happen." Yet even witlessness is not a moral issue. It is a problem, but not a moral problem; and it would be nice to clear away some of the moral fogs that surround our technologies. It would be good for morality. The moral valence of technology's effects on cognition is, for McLuhan, a matter of perspective. For instance, McLuhan contrasts the considerable alarm and revulsion that the growing quantity of books aroused in the latter 17th century with the modern concern for the "end of the book." If there can be no universal moral sentence passed on technology, McLuhan believes that "there can only be disaster arising from unawareness of the causalities and effects inherent in our technologies".[63] Though the World Wide Web was invented almost 30 years after The Gutenberg Galaxy, and 10 years after his death, McLuhan prophesied the web technology seen today as early as 1962:[64] The next medium, whatever it is—it may be the extension of consciousness—will include television as its content, not as its environment, and will transform television into an art form. A computer as a research and communication instrument could enhance retrieval, obsolesce mass library organization, retrieve the individual's encyclopedic function and flip into a private line to speedily tailored data of a saleable kind. Furthermore, McLuhan coined and certainly popularized the usage of the term surfing to refer to rapid, irregular, and multidirectional movement through a heterogeneous body of documents or knowledge, e.g., statements such as "Heidegger surf-boards along on the electronic wave as triumphantly as Descartes rode the mechanical wave." Paul Levinson's 1999 book Digital McLuhan explores the ways that McLuhan's work may be understood better through using the lens of the digital revolution.[14] McLuhan frequently quoted Walter Ong's Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue (1958), which evidently had prompted McLuhan to write The Gutenberg Galaxy. Ong wrote a highly favorable review of this new book in America.[65] However, Ong later tempered his praise, by describing McLuhan's The Gutenberg Galaxy as "a racy survey, indifferent to some scholarly detail, but uniquely valuable in suggesting the sweep and depth of the cultural and psychological changes entailed in the passage from illiteracy to print and beyond."[66] McLuhan himself said of the book, "I'm not concerned to get any kudos out of [The Gutenberg Galaxy]. It seems to me a book that somebody should have written a century ago. I wish somebody else had written it. It will be a useful prelude to the rewrite of Understanding Media [the 1960 NAEB report] that I'm doing now."[67] McLuhan's The Gutenberg Galaxy won Canada's highest literary award, the Governor-General's Award for Non-Fiction, in 1962. The chairman of the selection committee was McLuhan's colleague at the University of Toronto and oftentime intellectual sparring partner, Northrop Frye.[68] |

『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』(1962年) 詳細は「グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー」を参照 1961年に執筆され、トロント大学出版局から初版が出版された『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー:タイポグラフィック・マンの誕生』(1962年)は、口 承文化、印刷文化、カルチュラル・スタディーズ、メディア生態学の分野における先駆的な研究である。 マクルーハンは、この本の中で、コミュニケーション技術(すなわち、アルファベット文字、印刷機、電子メディア)が認知の組織にどのような影響を与えるか を明らかにしようと試みている。そして、それは社会組織に重大な影響を及ぼす。 新しいテクノロジーが、私たちの感覚のひとつまたは複数を、私たち自身から社会へと拡張するならば、その特定の文化において、私たちの感覚のすべてにわ たって新しい比率が生じるだろう。それは、メロディに新しい音が加わったときに起こることに似ている。そして、感覚の比率が文化の中で変化するとき、それ まで明晰に見えていたものが突如として不透明になり、曖昧であったり不透明であったものが半透明になる。 活字 マクルーハンのエピソード的な歴史は、読者をアルファベット以前の部族的な人類から電子時代へと導く。マクルーハンによれば、活字印刷の発明は、アルファ ベットの発明と実用化以来すでに起こり始めていた文化と認識の変化を、大幅に加速し、強化し、最終的に可能にした。マクルーハンが言うアルファベットと は、音素表記を意味する。(マクルーハンは、エジプトの象形文字や表意文字のような表語文字や表語文字体系と表音文字を区別するよう注意している。) 15世紀半ばにグーテンベルクが印刷機を発明したことにより印刷文化が発展し、視覚が聴覚/口頭よりも文化的に優位に立つようになった。ウィリアム・アイ ヴィンズ著『印刷物と視覚コミュニケーション』から印刷された文字の性質に関する観察を引用し(承認の意を表して)、マクルーハンは次のように述べてい る。 この文章で、[アイヴィンスは]直線的、連続的な習慣が根付いていることを指摘しているだけでなく、さらに重要なこととして、活字文化における視覚的な経 験の均質化、そして聴覚やその他の感覚的な複雑性の背景への追いやりを指摘している。 タイポグラフィの技術と社会的影響は、私たちが内面と外面の両方において、相互作用や、いわば「形式的な」因果関係を指摘することを控えさせる傾向にあ る。印刷物は機能の静的な分離によって存在し、分離や区分、専門家の見解以外のものに徐々に抵抗するメンタリティを育む。 マクルーハンの主張の主な概念(後に『メディアはマッサージである』でさらに詳しく説明されている)は、新しいテクノロジー(例えば、アルファベット、印 刷機、さらには音声)が認知に引力のような影響を及ぼし、それが社会組織に影響を与えるというものである。印刷技術は、私たちの知覚の習慣、「視覚的な経 験の均質化」を変え、それが社会的な相互作用に影響を与える。「専門家の見解以外には徐々に抵抗する考え方を助長する」のである。マクルーハンによれば、 印刷技術の進歩は西洋世界における近代の顕著な傾向のほとんどに貢献し、それを可能にした。すなわち、個人主義、民主主義、プロテスタンティズム、資本主 義、そしてナショナリズムである。マクルーハンにとって、これらの傾向はすべて印刷技術の原則である「行動と機能の細分化と視覚的数値化の原則」と共鳴し ている。[60][検証が必要] グローバル・ヴィレッジ 1960年代初頭、マクルーハンは、視覚的で個人主義的な活字文化は、電子メディアが視覚文化を聴覚・口承文化に置き換える「電子相互依存」によって、間 もなく終焉を迎えるだろうと書いた。この新しい時代において、人類は個人主義と断片化から「部族的基盤」を持つ集団的アイデンティティへと移行するだろ う。マクルーハンがこの新しい社会組織に与えた造語は「グローバル・ヴィレッジ」である。 この用語は『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』では否定的な意味合いで説明されているが、マクルーハンは価値判断を下すのではなく、その影響を探求すること に関心を持っていた。[48] 世界は膨大なアレクサンドリア図書館に向かうのではなく、コンピュータ、電子頭脳となった。まさに幼児向けのSF小説の通りだ。そして、私たちの感覚が外 に向かうにつれ、ビッグブラザーは内に向かう。したがって、この力学を認識しない限り、私たちはたちまちパニックに陥るだろう。それはまさに、部族の太鼓 の音が鳴り響き、完全に相互依存し、重なり合う共存が繰り広げられる小さな世界にふさわしい恐怖である。恐怖は、口承社会における通常の状態である。なぜ なら、そこではすべてが常にすべてに影響を及ぼすからだ。 西洋世界が感覚、思考、感情の統一性を回復しようと長い間努力してきた中で、私たちは、活字文化による人間の精神の断片化に備える以上に、そのような統一 性から生じる部族的帰結を受け入れる準備ができていなかった。 マクルーハンの主張の要点は、テクノロジーそれ自体には道徳的な傾向はないという考え方である。テクノロジーは、個人、ひいては社会の自己概念と自己実現 を形作るツールである。 テクノロジーの観点から道徳的な立場を取らないとしても、常に十分な道徳的な問題があることは明らかではないだろうか? 印刷は、まず第一に、人間を部族化または集団化から解放するアルファベット文化の極限的な段階である。印刷は、アルファベットの視覚的特徴を最大限に明確 にする。したがって、印刷は、音声アルファベットの個別化能力を、手書き文化がこれまでなし得たことよりもはるかに遠くまで運ぶ。印刷は個人主義の技術で ある。人間がこの視覚的技術を電気技術によって修正することを決めた場合、個人主義も修正されるだろう。これについて道徳的な不満を述べるのは、指を切り 落とすための電動のこぎりをののしるようなものだ。しかし、誰かが言うように、「私たちはそれが起こるとは知らなかった」のだ。しかし、無知でさえも道徳 的な問題ではない。それは問題ではあるが、道徳的な問題ではない。そして、私たちの技術を取り巻く道徳的な霧を晴らすことは素晴らしいことだ。それは道徳 にとって良いことだろう。 マクルーハンにとって、テクノロジーが認知に及ぼす影響の道徳的価値は、視点の問題である。例えば、マクルーハンは、17世紀後半に書籍の量が増加したこ とによって引き起こされた大きな不安や嫌悪感と、現代における「本の終焉」への懸念とを対比させている。テクノロジーに対する普遍的な道徳的判断を下すこ とはできないが、マクルーハンは「テクノロジーに内在する因果関係や影響に対する認識の欠如から生じる災厄だけは避けられない」と考えている。[63] マクルーハンは『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』を世に送り出してからほぼ30年、彼が亡くなってから10年後にWWWが発明されたが、マクルーハンは 1962年にはすでに今日のウェブテクノロジーを予言していた。[64] 次のメディアは、それが何であれ、意識の拡張であるかもしれないが、コンテンツとしてテレビを含み、環境としてテレビを含まない。そして、テレビを芸術の 形に変えるだろう。研究および通信機器としてのコンピュータは、検索を向上させ、大量の図書館の整理を時代遅れにし、個人の百科事典的な機能を回復させ、 販売可能な種類のデータを迅速にカスタマイズするプライベート回線に切り替えることができる。 さらに、マクルーハンは、異質な文書や知識の集合体を高速かつ不規則に、多方向に移動することを指す「サーフィン」という用語を考案し、広く普及させた。 例えば、「ハイデガーは、デカルトが機械の波に乗ったように、電子の波に乗って堂々とサーフボードに乗っている」というような表現である。ポール・レビン ソン(Paul Levinson)の1999年の著書『デジタル・マクルーハン』では、デジタル革命のレンズを通してマクルーハンの著作をより深く理解する方法が探求さ れている。[14] マクルーハンはウォルター・オングの著書『ラマス、方法、そして対話の衰退』(1958年)を頻繁に引用しており、この本がマクルーハンに『グーテンベル ク・ギャラクシー』を書かせたことは明らかである。オングはアメリカでこの新刊書について非常に好意的な書評を書いた。[65] しかし、オングは後にマクルーハンの『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』について「刺激的で、学術的な詳細には無頓着だが、 読み書きのできない状態から活字文化への移行、そしてさらにその先へと至る過程で生じる文化と心理の変化の広がりと深さを示唆する点で、他に類を見ないほ ど価値がある」と評した。[66] マクルーハン自身は、この本について次のように述べている。「私は『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』で称賛を得ようとは思っていない。これは100年前に 誰かが書くべきだった本のように思える。誰かが書いてくれていたらよかったのに。これは、私が今書いている『メディアの理解』(1960年のNAEBレ ポート)の改訂版の有益な序章となるだろう」[67] マクルーハンの『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』は、1962年にカナダで最も権威のある文学賞である総督文学賞(ノンフィクション部門)を受賞した。選 考委員長は、マクルーハンのトロント大学時代の同僚であり、知的な議論を交わすパートナーでもあったノースロップ・フライであった。[68] |

| Understanding Media (1964) Main article: Understanding Media McLuhan's best-known work, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), is a seminal study in media theory. Dismayed by the way in which people approach and use new media such as television, McLuhan famously argues that in the modern world "we live mythically and integrally…but continue to think in the old, fragmented space and time patterns of the pre-electric age."[69] McLuhan proposes that media themselves, not the content they carry, should be the focus of study—popularly quoted as "the medium is the message". His insight is that a medium affects the society in which it plays a role not by the content it delivers, but by its own characteristics. McLuhan points to the light bulb as a clear demonstration of this. A light bulb does not have content in the way that a newspaper has articles, or a television has programs, but it is a medium that has a social effect; that is, a light bulb enables people to create spaces at night that would otherwise be enveloped by darkness. He describes the light bulb as a medium without any content. McLuhan writes, "a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence."[70] More controversially, he postulates that content has little effect on society—for example, whether television broadcasts children's shows or violent programming, its effect on society is identical.[71] He notes that all media have characteristics that engage the viewer in different ways; for instance, a passage in a book can be reread at will, but a movie must be screened again in its entirety to study any part of it. "Hot" and "cool" media In the first part of Understanding Media, McLuhan writes that different media invite different degrees of participation on the part of a person who chooses to consume a medium. Using terminology derived from French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss's distinction between hot and cold societies,[52][53] McLuhan argues that a cool medium requires increased involvement due to decreased description, while a hot medium is the opposite, decreasing involvement and increasing description. In other words, a society that appears to be actively participating in streaming content but does not consider the tool's effects is not allowing an "extension of ourselves".[72] A movie is thus said to be "high definition", demanding a viewer's attention, and a comic book "low definition", requiring much more conscious participation by the reader to extract value:[73] "Any hot medium allows of less participation than a cool one, as a lecture makes for less participation than a seminar, and a book for less than a dialogue."[74] Some media, such as movies, are hot—that is, they enhance a single sense, in this case vision, in such a manner that a person does not need to exert much effort to perceive a detailed moving image. Hot media usually, but not always, provide complete involvement with considerable stimulus. In contrast, "cool" print may also occupy visual space, using visual senses, but require focus and comprehension to immerse readers. Hot media creation favour analytical precision, quantitative analysis and sequential ordering, as they are usually sequential, linear, and logical. They emphasize one sense (for example, of sight or sound) over the others. For this reason, hot media include film (especially silent films), radio, the lecture, and photography. McLuhan contrasts hot media with cool—specifically, television [of the 1960s i.e. small black-and-white screens], which he claims requires more effort from the viewer to determine meaning; and comics, which, due to their minimal presentation of visual detail, require a high degree of effort to fill in details the cartoonist may have intended to portray. Cool media are usually, but not always, those that provide little involvement with substantial stimulus. They require more active participation on the part of the user, including the perception of abstract patterning and simultaneous comprehension of all parts. Therefore, in addition to television, cool media include seminars and cartoons. McLuhan describes the term cool media as emerging from jazz and popular music used, in this context, to mean "detached".[75] This appears to force media into binary categories, but McLuhan's hot and cool exist on a continuum: they are more correctly measured on a scale than as dichotomous terms.[26] Critiques of Understanding Media Some theorists have attacked McLuhan's definition and treatment of the word "medium" for being too simplistic. Umberto Eco, for instance, contends that McLuhan's medium conflates channels, codes, and messages under the overarching term of the medium, confusing the vehicle, internal code, and content of a given message in his framework.[76] In Media Manifestos, Régis Debray also takes issue with McLuhan's envisioning of the medium. Like Eco, he is ill at ease with this reductionist approach, summarizing its ramifications as follows:[77] The list of objections could be and has been lengthened indefinitely: confusing technology itself with its use of the media makes of the media an abstract, undifferentiated force and produces its image in an imaginary "public" for mass consumption; the magical naivete of supposed causalities turns the media into a catch-all and contagious "mana"; apocalyptic millenarianism invents the figure of a homo mass-mediaticus without ties to historical and social context, and so on. Furthermore, when Wired magazine interviewed him in 1995, Debray said he saw McLuhan "more as a poet than a historian, a master of intellectual collage rather than a systematic analyst.… McLuhan overemphasizes the technology behind cultural change at the expense of the usage that the messages and codes make of that technology."[78] Dwight Macdonald, in turn, reproached McLuhan for his focus on television and for his "aphoristic" prose style, which he believes leaves Understanding Media filled with "contradictions, non-sequiturs, facts that are distorted and facts that are not facts, exaggerations, and chronic rhetorical vagueness."[79] Brian Winston's Misunderstanding Media, published in 1986, chides McLuhan for what he sees as his technologically deterministic stances.[79] Raymond Williams furthers this point of contention, claiming:[80] The work of McLuhan was a particular culmination of an aesthetic theory which became, negatively, a social theory ... It is an apparently sophisticated technological determinism which has the significant effect of indicating a social and cultural determinism.… For if the medium—whether print or television—is the cause, all other causes, all that men ordinarily see as history, are at once reduced to effects. David Carr wrote that there has been a long line of "academics who have made a career out of deconstructing McLuhan’s effort to define the modern media ecosystem", whether it be due to what they see as McLuhan's ignorance of sociohistorical context or the style of his argument.[81] While some critics have taken issue with McLuhan's writing style and mode of argument, McLuhan himself urged readers to think of his work as "probes" or "mosaics" offering a toolkit approach to thinking about media. His eclectic writing style has also been praised for its postmodern sensibilities[82] and suitability for virtual space.[83] |

『メディアを理解する』(1964年) 詳細は「メディア論」を参照 マクルーハンの最も有名な著作『メディア論:人間拡張の諸相』(1964年)は、メディア論における画期的な研究である。マクルーハンは、人々がテレビな どの新しいメディアに接し、利用する方法に驚き、現代社会では「私たちは神話的かつ統合的に生きているが、電気の発明以前の古い、断片的な空間と時間パ ターンで思考し続けている」と主張したことで有名である。 マクルーハンは、研究の対象はメディア自体であり、そのメディアが伝えるコンテンツではないと提唱した。これは一般的に「メディアはメッセージである」と いう言葉で引用されている。彼の洞察は、メディアはそれが果たす役割において、そのメディアが伝えるコンテンツではなく、そのメディア自体の特性によって 社会に影響を与えるというものである。マクルーハンは、このことを明確に示している例として電球を挙げている。電球には、新聞の記事やテレビの番組のよう なコンテンツはないが、社会に影響を与えるメディアである。つまり、電球は、暗闇に包まれてしまう夜の空間を人々が作り出すことを可能にする。彼は、電球 をコンテンツを持たないメディアと表現している。マクルーハンは「電球は、その存在だけで環境を作り出す」と書いている。[70] さらに物議を醸す主張として、マクルーハンは、コンテンツが社会に与える影響は少ないと仮定している。例えば、テレビが子供向け番組を放送しようが暴力的 な番組を放送しようが、社会に対する影響は 同一である」と主張している。[71] 彼は、すべてのメディアには視聴者を異なる方法で引き込む特性があることを指摘している。例えば、本の1つの章は自由に読み返すことができるが、映画のど の部分を研究する場合でも、映画全体をもう一度最初から最後まで上映しなければならない。 「ホット」なメディアと「クール」なメディア 『メディア論』の冒頭で、マクルーハンは、メディアを消費する人々は、そのメディアによって異なる程度の参加を求められると書いている。フランスの人類学 者クロード・レヴィ=ストロースによる「ホットな社会」と「クールな社会」の区別から派生した用語を使用して、マクルーハンは、クールなメディアは記述が 減少するため、より深い関与が必要であるが、ホットなメディアは逆で、関与が減少し、記述が増加すると論じている。言い換えれば、ストリーミング・コンテ ンツに積極的に参加しているように見えても、そのツールの効果を考慮していない社会では、「自己の拡張」は実現されていないのである。[72] 映画は「高解像度」であり、視聴者の注意を必要とする。また、漫画は 「クールなメディアよりもホットなメディアの方が、参加の度合いが少ない。講義はセミナーよりも、本は対話よりも参加の度合いが少ない」[74] 映画などの一部のメディアはホットである。つまり、視覚という一つの感覚を強化し、詳細な動画像を認識するために、人は多くの努力を必要としない。ホット メディアは、必ずしもそうとは限らないが、通常はかなりの刺激とともに完全な没入感を提供する。これに対し、「クール」な印刷物は、視覚領域を占め、視覚 感覚を利用するが、読者を没頭させるには集中力と理解力が必要となる。ホットメディアの制作は、通常、連続的、直線的、論理的であるため、分析的精度、量 的分析、順序付けを好む。また、他の感覚よりも特定の感覚(例えば視覚や聴覚)を強調する。このため、ホットメディアには映画(特にサイレント映画)、ラ ジオ、講演、写真などが含まれる。 マクルーハンは、ホットメディアとクールメディアを対比させている。具体的には、テレビ(1960年代の、つまり小さな白黒画面のテレビ)は、視聴者が意 味を理解するのにより多くの努力を必要とするとしている。また、漫画は視覚的な詳細が最小限に抑えられているため、漫画家が表現しようとしたであろう詳細 を補うのに高度な努力が必要である。クールメディアは、必ずしもそうとは限らないが、通常、実質的な刺激への関与が少ないものを指す。抽象的なパターン認 識や、すべての部分の同時理解など、ユーザーのより積極的な参加を必要とする。したがって、テレビに加えて、クールメディアにはセミナーや漫画などが含ま れる。マクルーハンは、クールメディアという用語を、ジャズやポピュラー音楽から生まれたものとして説明している。この文脈では、「クール」とは「距離を 置いた」という意味である。[75] これはメディアを二元的なカテゴリーに分類することを強いるように見えるが、マクルーハンのいうホットとクールは連続体上に存在する。つまり、二項対立的 な用語としてよりも、尺度によってより正確に測定されるべきものである。 『メディア論』への批判 一部の理論家は、マクルーハンの「メディア」という言葉の定義と扱い方が単純すぎると批判している。例えば、ウンベルト・エーコは、マクルーハンのメディ ア論では、チャネル、コード、メッセージがメディアという包括的な用語の下に混同され、彼の枠組みでは、特定のメッセージの媒体、内部コード、コンテンツ が混同されていると主張している。 メディア宣言』の中で、レジス・ドブレもまた、マクルーハンのメディアの概念化に異議を唱えている。エコと同様に、彼はこの還元主義的なアプローチに不快 感を示しており、その影響を次のようにまとめている。 反対意見のリストは際限なく長くなる可能性があり、実際そうなっている。テクノロジーそのものとメディアの利用を混同することは、メディアを抽象的で未分 化な力とし、そのイメージを想像上の「大衆」に大量消費させる。因果関係を想定する魔法のような素朴さは、メディアをあらゆるものを受け入れ、伝染する 「マナ」に変える。終末論的千年王国説は、歴史的・社会的文脈とのつながりを持たない「マス・メディアの人間」という概念を創り出す。 さらに、1995年にワイアード誌が彼にインタビューした際、ドブレは「マクルーハンは歴史家というよりも詩人であり、体系的分析者というよりも知的コ ラージュの達人である」と述べた。「マクルーハンは、メッセージやコードがその技術をどのように利用しているかという点をおろそかにして、文化の変化の背 後にある技術を過度に強調している」[78] ドワイト・マクドナルドは、マクルーハンがテレビに焦点を当てたことと、彼の「格言的」な散文スタイルを非難した。マクドナルドは、マクルーハンの『メ ディア論』には「矛盾、前提不整合、歪曲された事実と事実でない事実、誇張、そして慢性的な修辞的曖昧さ」が満ちていると考えている。 1986年に出版されたブライアン・ウィンストンの著書『メディアの誤解』は、マクルーハンが技術的に決定論的な立場を取っていると批判している。 [79] レイモンド・ウィリアムズはさらにこの論争の論点を深め、次のように主張している。[80] マクルーハンの業績は、否定的な意味で社会理論となった美学理論の特別な集大成であった。それは一見洗練された技術決定論であり、社会および文化決定論を 示す重要な効果をもたらしている。もし印刷物であれテレビであれ、メディアが原因であるならば、他のすべての原因、人々が通常歴史として認識しているもの はすべて、同時に結果へと還元されることになる。 デイヴィッド・カーは、「マクルーハンが現代のメディア生態系を定義しようとした試みを脱構築することをキャリアの目的とする学者」が長い列をなしている と書いた。それは、彼らがマクルーハンが社会史的文脈を無視していると見なしているためか、あるいは彼の議論のスタイルのためである。 マクルーハンの文章のスタイルや論調を批判する批評家もいるが、マクルーハン自身は、自身の著作を「探針」や「モザイク」として捉え、メディアを考えるた めのツールキットとして活用するよう読者に呼びかけている。また、彼の折衷的な文章スタイルはポストモダン的な感性[82]と仮想空間への適合性[83] を評価されている。 |

| The Medium Is the Massage (1967) Main article: The Medium Is the Massage The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects, published in 1967, was McLuhan's best seller,[18] "eventually selling nearly a million copies worldwide."[84] Initiated by Quentin Fiore,[85] McLuhan adopted the term "massage" to denote the effect each medium has on the human sensorium, taking inventory of the "effects" of numerous media in terms of how they "massage" the sensorium.[i] Fiore, at the time a prominent graphic designer and communications consultant, set about composing the visual illustration of these effects which were compiled by Jerome Agel. Near the beginning of the book, Fiore adopted a pattern in which an image demonstrating a media effect was presented with a textual synopsis on the facing page. The reader experiences a repeated shifting of analytic registers—from "reading" typographic print to "scanning" photographic facsimiles—reinforcing McLuhan's overarching argument in this book: namely, that each medium produces a different "massage" or "effect" on the human sensorium. In The Medium Is the Massage, McLuhan also rehashed the argument—which first appeared in the Prologue to 1962's The Gutenberg Galaxy—that all media are "extensions" of our human senses, bodies and minds. Finally, McLuhan described key points of change in how man has viewed the world and how these views were changed by the adoption of new media. "The technique of invention was the discovery of the nineteenth [century]", brought on by the adoption of fixed points of view and perspective by typography, while "[t]he technique of the suspended judgment is the discovery of the twentieth century," brought on by the bard abilities of radio, movies and television.[87] The past went that-a-way. When faced with a totally new situation we tend always to attach ourselves to the objects, to the flavor of the most recent past. We look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backward into the future. Suburbia lives imaginatively in Bonanza-land.[88] An audio recording version of McLuhan's famous work was made by Columbia Records. The recording consists of a pastiche of statements made by McLuhan interrupted by other speakers, including people speaking in various phonations and falsettos, discordant sounds and 1960s incidental music in what could be considered a deliberate attempt to translate the disconnected images seen on TV into an audio format, resulting in the prevention of a connected stream of conscious thought. Various audio recording techniques and statements are used to illustrate the relationship between spoken, literary speech and the characteristics of electronic audio media. McLuhan biographer Philip Marchand called the recording "the 1967 equivalent of a McLuhan video."[89] "I wouldn't be seen dead with a living work of art."—'Old man' speaking "Drop this jiggery-pokery and talk straight turkey."—"Middle-aged man" speaking |

『メディアはマッサージである』(1967年) 詳細は「『メディアはマッサージである』」を参照 1967年に出版された『メディアはマッサージである:効果の目録』は、マクルーハンのベストセラーとなり[18]、「最終的に世界中で100万部近くを 売り上げた」[84]。クエンティン・フィオーレが発案した[85]この本で、マクルーハンは「マッサージ」という用語を採用し、各メディアが人間の感覚 に与える影響を意味するものとした。また、数多くのメディアが感覚を「マッサージ」する方法という観点から、それらの「効果」を一覧化した[i]。 当時著名なグラフィックデザイナーであり、コミュニケーションコンサルタントでもあったフィオーレは、ジェローム・エイジェルがまとめたこれらの効果の視 覚的図解の作成に取り掛かった。本の冒頭近くで、フィオーレはメディア効果を示すイメージを、その対向ページにテキストの要約を添えて提示するというパ ターンを採用した。読者は、タイポグラフィの活字を「読む」ことから写真の複製を「スキャン」するといったように、分析のレベルを繰り返し変えることを経 験する。これは、各メディアが人間の感覚に対して異なる「メッセージ」や「効果」を生み出すという、この本におけるマクルーハンの包括的な主張を補強する ものである。 『メディアはマッサージである』では、マクルーハンは、1962年の『グーテンベルク・ギャラクシー』の序文で初めて提示した、すべてのメディアは人間の 感覚、身体、精神の「拡張」であるという主張を繰り返している。 最後に、マクルーハンは、人間が世界をどのように見てきたか、そして新しいメディアの採用によってそれらの見方がどのように変化したかという変化の要点を 説明した。「固定された視点と観点の採用によってもたらされた活版印刷術による『19世紀の発明の技術』に対し、」ラジオ、映画、テレビの詩的表現能力に よってもたらされた「判断保留の技術は20世紀の発見である」[87]。 過去はそうだった。まったく新しい状況に直面したとき、私たちはつねに、最も最近の過去の事物や雰囲気に固執しがちである。私たちは現在をバックミラー越 しに眺めている。私たちは未来に向かって後退しながら進む。郊外は想像力豊かに『ボナンザ』の世界に生きている。 マクルーハンの有名な著作の音声録音版がコロンビア・レコードによって制作された。録音は、マクルーハンによる発言のパッチワークで構成されており、他の 話し手による発言が挿入されている。その中には、さまざまな音声やファルセットで話す人々、不協和音、1960年代のBGMなどが含まれており、これは、 テレビで断片的に見られるイメージを音声フォーマットに変換しようとする意図的な試みであると考えられ、結果として、意識的な思考の流れが途切れることに なる。話し言葉、文学的な話し言葉、電子音声メディアの特性の関係性を示すために、さまざまな録音技術や発言が用いられている。マクルーハン伝記作家の フィリップ・マーチャンドは、この録音を「1967年のマクルーハン・ビデオ」と呼んだ。 「私は生きた芸術作品と一緒に死ぬつもりはない。」—「老人」のセリフ 「このごまかしをやめて、正直に話せ。」—「中年男性」のセリフ |

| War and Peace in the Global

Village (1968) Main article: War and Peace in the Global Village In War and Peace in the Global Village, McLuhan used James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, an inspiration for this study of war throughout history, as an indicator as to how war may be conducted in the future. Joyce's Wake is claimed to be a gigantic cryptogram that reveals a cyclic pattern for human history through its Ten Thunders. Each "thunder" below is a 100-character portmanteau of other words to create a statement McLuhan likens to an effect that each technology has on the society into which it is introduced. In order to glean the most understanding out of each, the reader must break the portmanteau into separate words (many of these themselves portmanteaus of words taken from multiple languages other than English) and speak them aloud for the spoken effect of each word. There is much dispute over what each portmanteau truly denotes. McLuhan claims that the ten thunders in Wake represent different stages in the history of man:[90] Thunder 1: Paleolithic to Neolithic. Speech. Split of East/West. From herding to harnessing animals. Thunder 2: Clothing as weaponry. Enclosure of private parts. First social aggression. Thunder 3: Specialism. Centralism via wheel, transport, cities: civil life. Thunder 4: Markets and truck gardens. Patterns of nature submitted to greed and power. Thunder 5: Printing. Distortion and translation of human patterns and postures and pastors. Thunder 6: Industrial Revolution. Extreme development of print process and individualism. Thunder 7: Tribal man again. All characters end up separate, private man. Return of choric. Thunder 8: Movies. Pop art, pop Kulch via tribal radio. Wedding of sight and sound. Thunder 9: Car and Plane. Both centralizing and decentralizing at once create cities in crisis. Speed and death. Thunder 10: Television. Back to tribal involvement in tribal mood-mud. The last thunder is a turbulent, muddy wake, and murk of non-visual, tactile man. |

グローバル・ヴィレッジの戦争と平和(1968年) 詳細は「グローバル・ヴィレッジの戦争と平和」を参照 グローバル・ヴィレッジの戦争と平和』において、マクルーハンは、歴史上の戦争研究のインスピレーションとなったジェイムズ・ジョイスの『フィネガンズ・ ウェイク』を、将来の戦争のあり方を示す指標として用いた。 ジョイスの『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』は、その「十の雷」を通して人類の歴史の循環的パターンを明らかにする巨大な暗号文であると主張されている。以下に 示すそれぞれの「雷」は、他の単語を組み合わせた100文字の混成語であり、マクルーハンはこれを、それぞれの技術が導入された社会に与える影響に例えて いる。各々の内容を最大限に理解するためには、読者はこれらの混成語を個々の単語に分解し(これらの多くは、英語以外の複数の言語から取られた単語の混成 語である)、それぞれの単語の口語的な効果を理解するために、それらの単語を声に出して発音する必要がある。各々の混成語が実際に何を意味するのかについ ては、多くの論争がある。 マクルーハンは、『覚醒』の「十の雷鳴」が人類の歴史における異なる段階を表していると主張している。 雷1:旧石器時代から新石器時代。 言語。 東西の分裂。 家畜化から動物利用へ。 雷2:武器としての衣服。 私的部位の囲い込み。 最初の社会的攻撃。 雷3:専門化。 車輪、輸送、都市による中央集権:市民生活。 雷4:市場と家庭菜園。 強欲と権力に従属する自然のパターン。 雷鳴5:印刷。人間のパターンや姿勢、牧師の歪曲と翻訳。 雷鳴6:産業革命。印刷プロセスと個人主義の極端な発展。 雷鳴7:再び部族の人間。すべてのキャラクターは、最終的には別々の個人主義的な人間になる。コーラスの復活。 雷鳴8:映画。部族のラジオを通じたポップアート、ポップカルチャー。視覚と音の融合。 雷9:車と飛行機。集中化と分散化が同時に起こり、危機的な都市が生まれる。スピードと死。 雷10:テレビ。部族の気分と泥沼への関わりに戻る。最後の雷は、激動の泥の航跡であり、視覚的でない、触覚的な人間の濁りである。 |

| From Cliché to Archetype (1970) Main article: From Cliché to Archetype Collaborating with Canadian poet Wilfred Watson[91] in From Cliché to Archetype (1970), McLuhan approaches the various implications of the verbal cliché and of the archetype. One major facet in McLuhan's overall framework introduced in this book that is seldom noticed is the provision of a new term that actually succeeds the global village: the global theater. In McLuhan's terms, a cliché is a "normal" action, phrase, etc. which becomes so often used that we are "anesthetized" to its effects. McLuhan provides the example of Eugène Ionesco's play The Bald Soprano, whose dialogue consists entirely of phrases Ionesco pulled from an Assimil language book: "Ionesco originally put all these idiomatic English clichés into literary French which presented the English in the most absurd aspect possible."[92] McLuhan's archetype "is a quoted extension, medium, technology, or environment." Environment would also include the kinds of "awareness" and cognitive shifts brought upon people by it, not totally unlike the psychological context Carl Jung described. McLuhan also posits that there is a factor of interplay between the cliché and the archetype, or a "doubleness":[93] Another theme of the Wake [Finnegans Wake] that helps in the understanding of the paradoxical shift from cliché to archetype is 'past time are pastimes.' The dominant technologies of one age become the games and pastimes of a later age. In the 20th century, the number of 'past times' that are simultaneously available is so vast as to create cultural anarchy. When all the cultures of the world are simultaneously present, the work of the artist in the elucidation of form takes on new scope and new urgency. Most men are pushed into the artist's role. The artist cannot dispense with the principle of 'doubleness' or 'interplay' because this type of hendiadys dialogue is essential to the very structure of consciousness, awareness, and autonomy. McLuhan relates the cliché-to-archetype process to the Theater of the Absurd:[94] Pascal, in the seventeenth century, tells us that the heart has many reasons of which the head knows nothing. The Theater of the Absurd is essentially a communicating to the head of some of the silent languages of the heart which in two or three hundred years it has tried to forget all about. In the seventeenth century world the languages of the heart were pushed down into the unconscious by the dominant print cliché. The "languages of the heart", or what McLuhan otherwise defined as oral culture, were thus made archetype by means of the printing press, and turned into cliché. According to McLuhan, the satellite medium encloses the Earth in a man-made environment, which "ends 'Nature' and turns the globe into a repertory theater to be programmed."[95] All previous environments (book, newspaper, radio, etc.) and their artifacts are retrieved under these conditions ("past times are pastimes"). McLuhan thereby meshes this into the term global theater. This updates his concept of the global village, which, in its own definitions, can be said to be subsumed into the overall condition of the global theater. |

クリシェからアーキタイプへ(1970年) 詳細は「クリシェからアーキタイプへ」を参照 1970年の『クリシェからアーキタイプへ』で、マクルーハンはカナダの詩人ウィルフレッド・ワトソンと共同作業を行い、言語上のクリシェとアーキタイプ のさまざまな含意にアプローチした。この本で紹介されたマクルーハンの全体的な枠組みの中で、あまり注目されていないものの重要な側面は、グローバル・ ヴィレッジに実際に取って代わる新しい用語、すなわちグローバル・シアターの概念である。 マクルーハンによれば、クリシェとは「通常」の行動や言い回しなどであり、あまりにも頻繁に使用されるため、その影響に対して「麻痺」してしまうものであ る。マクルーハンは、ユージン・イヨネスコの戯曲『はげソプラノ』を例に挙げている。この戯曲の台詞は、すべてイヨネスコが『アッシミラー』という言語学 習書から引用したフレーズで構成されている。「イヨネスコは、これらの慣用句的な英語の決まり文句をすべて文学的なフランス語に置き換えた。これにより、 英語は可能な限り最も不条理な様相を呈することになった」[92] マクルーハンのアーキタイプとは、「引用された拡張、媒体、技術、環境」である。環境には、それによって人々にもたらされる「気づき」や認識の変化も含ま れる。それは、カール・ユングが説明した心理的背景とまったく異ならない。 また、マクルーハンは、決まり文句と原型の間に相互作用の要素、すなわち「二重性」があるとも主張している。 決まり文句から原型への逆説的な転換を理解する上で役立つ『ウェイク』[『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』]のもう一つのテーマは、「過ぎ去った時間は娯楽であ る」というものである。ある時代の支配的なテクノロジーは、後の時代のゲームや娯楽となる。20世紀には、同時に利用可能な「過ぎ去った時間」の数が膨大 になり、文化的な無政府状態が生み出された。世界のあらゆる文化が同時に存在する現在、形を解明する芸術家の仕事は、新たな広がりと新たな緊急性を帯びて いる。ほとんどの人間が芸術家の役割を担わされているのだ。芸術家は「二重性」や「相互作用」の原則を無視することはできない。なぜなら、この種のヘン ディアディスの対話は、意識、認識、そして自律性の構造そのものに不可欠だからだ。 マクルーハンは、陳腐な表現から原型へのプロセスを不条理劇と関連付けている。 17世紀のパスカルは、心には頭が知らない多くの理由がある、と語っている。不条理劇の本質は、心にある沈黙の言語のいくつかを、頭に伝えることである。 この言語は、2、3百年もの間、すべてを忘れるように試みられてきた。17世紀の世界では、支配的な印刷の決まり文句によって、心の言語は無意識の領域へ と押しやられていた。 マクルーハンが「口承文化」と定義した「心の言語」は、印刷機によって原型が作られ、陳腐なものとなった。 マクルーハンによると、衛星メディアは地球を人工的な環境で囲い込み、「『自然』を終わらせ、地球をプログラム可能なレパートリーシアターに変える」 [95]。 これまでのあらゆる環境(書籍、新聞、ラジオなど)とその人工物は、この状況下で回収される(「過去の時代は娯楽」)。 マクルーハンは、これを「グローバルシアター」という用語に組み込んだ。これは、彼自身の定義によれば、グローバル・ヴィレッジという概念を更新するもの であり、グローバル・シアターの全体的な状況に包含されるものであると言える。 |

| The Global Village (1989) Main article: Global village In his posthumous book, The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century (1989), McLuhan, collaborating with Bruce R. Powers, provides a strong conceptual framework for understanding the cultural implications of the technological advances associated with the rise of a worldwide electronic network. This is a major work of McLuhan's as it contains the most extensive elaboration of his concept of acoustic space, and provides a critique of standard 20th-century communication models such as the Shannon–Weaver model. McLuhan distinguishes between the existing worldview of visual space—a linear, quantitative, classically geometric model—and that of acoustic space—a holistic, qualitative order with an intricate, paradoxical topology: "Acoustic Space has the basic character of a sphere whose focus or center is simultaneously everywhere and whose margin is nowhere."[96] The transition from visual to acoustic space was not automatic with the advent of the global network, but would have to be a conscious project. The "universal environment of simultaneous electronic flow"[97] inherently favors right-brain Acoustic Space, yet we are held back by habits of adhering to a fixed point of view. There are no boundaries to sound. We hear from all directions at once. Yet Acoustic and Visual Space are inseparable. The resonant interval is the invisible borderline between Visual and Acoustic Space. This is like the television camera that the Apollo 8 astronauts focused on the Earth after they had orbited the Moon. McLuhan illustrates how it feels to exist within acoustic space by quoting from the autobiography of Jacques Lusseyran, And There Was Light.[98] Lusseyran lost his eyesight in a violent accident as a child, and the autobiography describes how a reordering of his sensory life and perception followed: When I came upon the myth of objectivity in certain modern thinkers, it made me angry. So, there was only one world for these people, the same for everyone. And all the other worlds were to be counted as illusions left over from the past. Or why not call them by their name—hallucinations? I had learned to my cost how wrong they were. From my own experience I knew very well that it was enough to take from a man a memory here, an association there, to deprive him of hearing or sight, for the world to undergo immediate transformation, and for another world, entirely different, but entirely coherent, to be born. Another world? Not really. The same world, rather, but seen from a different angle, and counted in entirely new measures. When this happened all the hierarchies they called objective were turned upside down, scattered to the four winds, not even theories but like whims.[99] Reading, writing, and hierarchical ordering are associated with the left brain and visual space, as are the linear concept of time and phonetic literacy. The left brain is the locus of analysis, classification, and rationality. The right brain and acoustic space are the locus of the spatial, tactile, and musical. "Comprehensive awareness" results when the two sides of the brain are in true balance. Visual Space is associated with the simplified worldview of Euclidean geometry, the intuitive three dimensions useful for the architecture of buildings and the surveying of land. It is linearly rational and has no grasp of the acoustic. Acoustic Space is multisensory. McLuhan writes about robotism in the context of Japanese Zen Buddhism and how it can offer us new ways of thinking about technology. The Western way of thinking about technology is too related to the left brain, which has a rational and linear focus. What he called robotism might better be called androidism in the wake of Blade Runner and the novels of Philip K. Dick. Robotism-androidism emerges from the further development of the right brain, creativity and a new relationship to spacetime (most humans are still living in 17th-century classical Newtonian physics spacetime). Robots-androids will have much greater flexibility than humans have had until now, in both mind and body. Robots-androids will teach humanity this new flexibility. And this flexibility of androids (what McLuhan calls robotism) has a strong affinity with Japanese culture and life. McLuhan quotes from Ruth Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the Sword an anthropological study of Japanese culture published in 1946:[100] Occidentals cannot easily credit the ability of the Japanese to swing from one behavior to another without psychic cost. Such extreme possibilities are not included in our experience. Yet in Japanese life the contradictions, as they seem to us, are as deeply based in their view of life as our uniformities are in ours. The ability to live in the present and instantly readjust. Beyond existing communication models "All Western scientific models of communication are—like the Shannon–Weaver model—linear, sequential, and logical as a reflection of the late medieval emphasis on the Greek notion of efficient causality."[101] McLuhan and Powers criticize the Shannon-Weaver model of communication as emblematic of left-hemisphere bias and linearity, descended from a print-era perversion of Aristotle's notion of efficient causality. A third term of The Global Village that McLuhan and Powers develop at length is The Tetrad. McLuhan had begun development on the Tetrad as early as 1974.[102] The tetrad is an analogical, simultaneous, fourfold pattern of transformation. "At full maturity the tetrad reveals the metaphoric structure of the artifact as having two figures and two grounds in dynamic and analogical relationship to each other."[103] Like the camera focused on the Earth by the Apollo 8 astronauts, the tetrad reveals figure (Moon) and ground (Earth) simultaneously. The right-brain hemisphere thinking is the capability of being in many places at the same time. Electricity is acoustic. It is simultaneously everywhere. The Tetrad, with its fourfold Möbius topological structure of enhancement, reversal, retrieval and obsolescence, is mobilized by McLuhan and Powers to illuminate the media or technological inventions of cash money, the compass, the computer, the database, the satellite, and the global media network. |

グローバル・ヴィレッジ(1989年) 詳細は「グローバル・ヴィレッジ」を参照 マクルーハンは、ブルース・R・パワーズとの共著『グローバル・ヴィレッジ:21世紀の世界生活とメディアの変容』(1989年)という死後に出版された 著書で、世界的な電子ネットワークの台頭に伴う技術的進歩の文化的影響を理解するための強力な概念的枠組みを提供している。これは、マクルーハンの主要な 著作であり、音響空間に関する彼の概念を最も広範に展開したものであり、シャノン=ウィーバーモデルのような20世紀の標準的なコミュニケーションモデル の批判を提供している。 マクルーハンは、既存の視覚的空間(直線的、量的、古典的幾何学モデル)と音響的空間(全体的、質的、複雑かつ逆説的なトポロジー)を区別している。「音 響的空間は、焦点または中心が同時にあらゆる場所であり、境界がどこにもない球の基本的な性質を持つ」[96]。視覚的空間から音響的空間への移行は、グ ローバルネットワークの出現によって自動的に起こるものではなく、意識的なプロジェクトとして取り組む必要がある。「同時進行の電子の流れの普遍的環境」 [97] は、本質的に右脳の音響空間を好むが、私たちは固定観念に固執する習慣によって妨げられている。音には境界がない。私たちはあらゆる方向から同時に音を聞 く。しかし、音響空間と視覚空間は切り離せない。共鳴音程は、視覚空間と音響空間の間の見えない境界線である。これは、アポロ8号の宇宙飛行士たちが月を 周回した後、地球に焦点を合わせたテレビカメラのようだ。 マクルーハンは、ジャック・ルセイランの自伝『そして、光があった』[98] を引用し、音響空間の中で存在する感覚を説明している。ルセイランは幼少時に事故で失明し、その自伝では、彼の感覚生活と知覚がどのように再編されたかが 説明されている。 私は、ある近代思想家の客観性の神話に出くわしたとき、怒りを覚えた。 彼らにとって世界はただ一つであり、それは誰にとっても同じだった。 そして、それ以外の世界はすべて、過去から残された幻想として数えられるべきものだった。 あるいは、それを幻覚と呼んでもいいだろう。私は、それがいかに間違っているかを身をもって学んだ。自分の経験から、ある記憶や連想を奪うだけで、聴覚や 視覚を奪うだけで、世界は即座に変容し、まったく異なるが、まったく首尾一貫した別の世界が生まれることを私はよく知っていた。別の世界? そうではない。同じ世界だが、別の角度から見られ、まったく新しい尺度で計られているのだ。こうなると、彼らが客観的と呼んでいたすべてのヒエラルキーは ひっくり返り、四方八方に散らばり、理論ですらない気まぐれのようなものになる。 読み書きやヒエラルキーの順序付けは、左脳と視覚空間に関連しており、直線的な時間概念や音声識字も同様である。左脳は分析、分類、合理性の中心である。 右脳と音響空間は、空間、触覚、音楽の中心である。「包括的な認識」は、脳の両側が真のバランスを保っているときに生じる。視覚空間は、ユークリッド幾何 学の単純化された世界観、建築物の設計や土地の測量に役立つ直感的な三次元と関連している。直線的な合理性があり、音響の把握はできない。音響空間は多感 覚的である。マクルーハンは、日本の禅仏教の文脈におけるロボット主義について、それがテクノロジーに関する新しい考え方を私たちに提供できる可能性につ いて書いている。西洋のテクノロジーに対する考え方は、左脳に偏りすぎており、合理的かつ直線的な思考に重点が置かれている。マクルーハンが「ロボット主 義」と呼んだものは、映画『ブレードランナー』やフィリップ・K・ディックの小説に登場する「アンドロイド」と呼ぶ方がふさわしいかもしれない。ロボット 主義・アンドロイド主義は、右脳のさらなる発達、創造性、時空との新たな関係性から生まれるものである(ほとんどの人間は、17世紀の古典的なニュートン 物理学の時空に今も生きている)。ロボットやアンドロイドは、心と身体の両面において、これまで人間が持っていたものよりもはるかに高い柔軟性を持つこと になるだろう。ロボットやアンドロイドは、人類にこの新しい柔軟性を教えてくれるだろう。そして、アンドロイドの持つこの柔軟性(マクルーハンがロボット 主義と呼ぶもの)は、日本文化や日本人の生活と強い親和性を持っている。マクルーハンは、1946年に発表された日本文化の文化人類学的研究であるルー ス・ベネディクト著『菊と刀』から次のように引用している。 西洋人は、日本人が精神的な負担なしに、ある行動から別の行動へと容易に切り替える能力を持っているとは信じがたい。このような極端な可能性は、我々の経 験には含まれていない。しかし、日本人の生活においては、我々には矛盾と見えるものが、彼らの人生観においては、我々における均一性と同じくらい深く根付 いている。 現在を生き、即座に再調整する能力 既存のコミュニケーションモデルを超えて 「西洋の科学的なコミュニケーションモデルはすべて、シャノン=ウィーバーモデルのように、直線的、逐次的、論理的であり、これはギリシャの効率的因果関 係の概念を重視した中世末期の反映である」[101] マクルーハンとパワーズは、シャノン=ウィーバーのコミュニケーションモデルを、左半球の偏りや直線性を象徴するものとして批判している。これは、活字時 代の歪みから生まれたもので、アリストテレスの効率的因果関係の概念に由来する。 マクルーハンとパワーズが詳しく論じているグローバル・ビレッジの第三の要素は「四象限」である。マクルーハンは1974年にはすでに四象限の研究を始め ていた。[102] 四象限とは、類似した、同時進行する、4つのパターンによる変容である。「四象限が完全に成熟すると、人工物の隠喩的な構造が、2つの図と2つの地が互い に動的かつ類似した関係にあるものとして明らかになる」[103] アポロ8号の宇宙飛行士が地球にカメラを向けたように、四象限は図(月)と地(地球)を同時に明らかにする。右脳的な思考は、同時に多くの場所に存在でき る能力である。電気は音響である。それは同時にあらゆる場所にある。4つのメビウスの位相構造(強化、反転、検索、陳腐化)を持つ4象限は、マクルーハン とパワーズによって、現金、コンパス、コンピュータ、データベース、衛星、グローバルなメディアネットワークといったメディアや技術的発明を明らかにする ために活用されている。 |

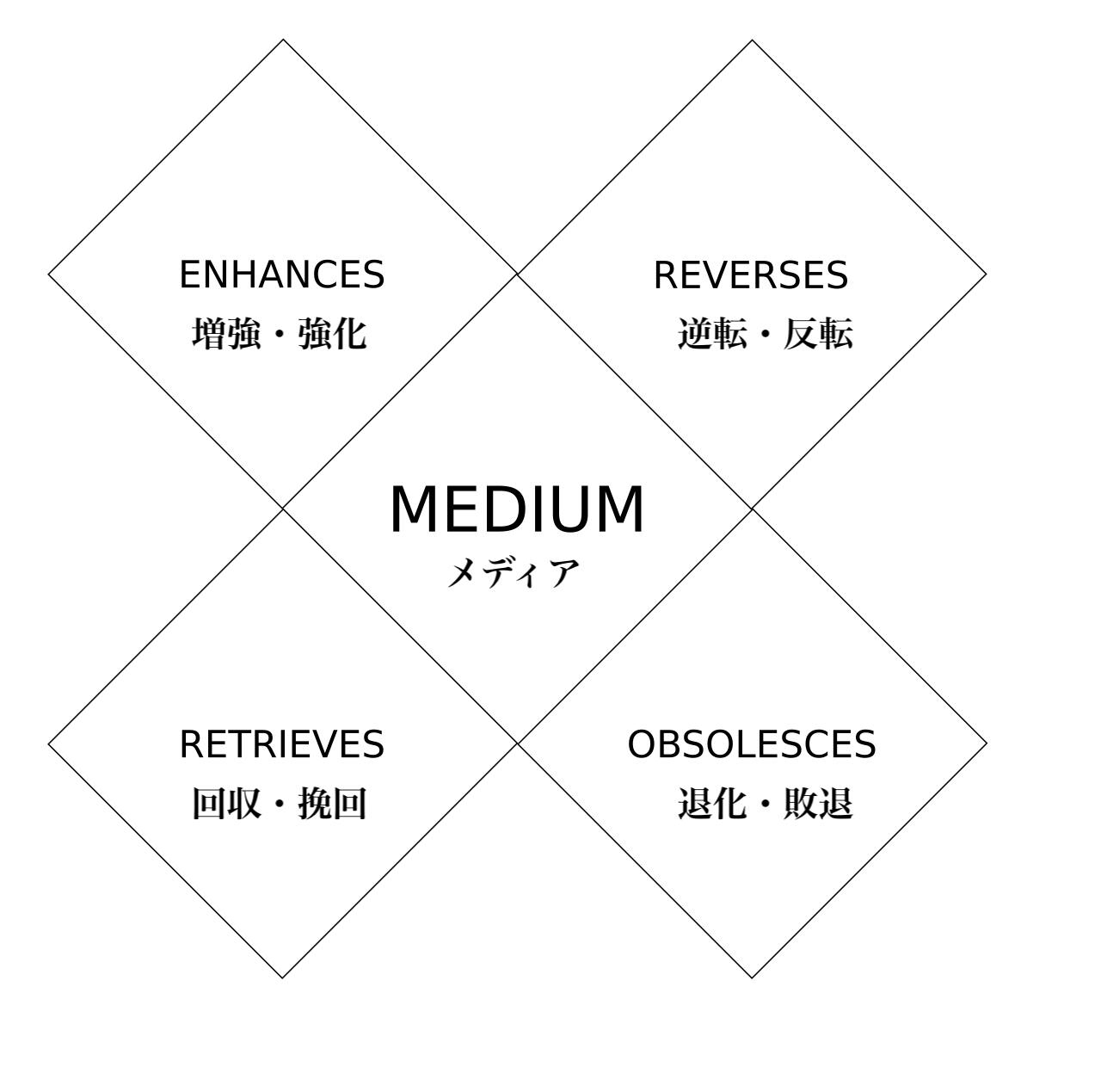

| Key concepts Tetrad of media effects Main article: Tetrad of media effects In Laws of Media (1988), published posthumously by his son Eric, McLuhan summarized his ideas about media in a concise tetrad of media effects. The tetrad is a means of examining the effects on society of any technology (i.e., any medium) by dividing its effects into four categories and displaying them simultaneously. McLuhan designed the tetrad as a pedagogical tool, phrasing his laws as questions with which to consider any medium: What does the medium enhance? What does the medium make obsolete? What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier? What does the medium flip into when pushed to extremes? The laws of the tetrad exist simultaneously, not successively or chronologically, and allow the questioner to explore the "grammar and syntax" of the "language" of media. McLuhan departs from his mentor Harold Innis in suggesting that a medium "overheats," or reverses into an opposing form, when taken to its extreme.[26]  Visually, a tetrad can be depicted as four diamonds forming an X, with the name of a medium in the centre. The two diamonds on the left of a tetrad are the Enhancement and Retrieval qualities of the medium, both Figure qualities. The two diamonds on the right of a tetrad are the Obsolescence and Reversal qualities, both Ground qualities.[104] A blank tetrad diagram Using the example of radio: Enhancement (figure): What the medium amplifies or intensifies. Radio amplifies news and music via sound. Obsolescence (ground): What the medium drives out of prominence. Radio reduces the importance of print and the visual. Retrieval (figure): What the medium recovers which was previously lost. Radio returns the spoken word to the forefront. Reversal (ground): What the medium does when pushed to its limits. Acoustic radio flips into audio-visual TV. Figure and ground Main article: Figure and ground (media) McLuhan adapted the Gestalt psychology idea of a figure and a ground, which underpins the meaning of "the medium is the message." He used this concept to explain how a form of communications technology, the medium, or figure, necessarily operates through its context, or ground. McLuhan believed that in order to grasp fully the effect of a new technology, one must examine figure (medium) and ground (context) together, since neither is completely intelligible without the other. McLuhan argued that we must study media in their historical context, particularly in relation to the technologies that preceded them. The present environment, itself made up of the effects of previous technologies, gives rise to new technologies, which, in their turn, further affect society and individuals.[26] All technologies have embedded within them their own assumptions about time and space. The message which the medium conveys can only be understood if the medium and the environment in which the medium is used—and which, simultaneously, it effectively creates—are analysed together. He believed that an examination of the figure-ground relationship can offer a critical commentary on culture and society.[26] Opposition between optic and haptic perception In McLuhan's (and Harley Parker's) work, electric media have an affinity with haptic and hearing perception, while mechanical media have an affinity with visual perception. This opposition between optic and haptic had previously been formulated by art historians Alois Riegl in his 1901 Late Roman Art Industry, and by Erwin Panofsky, in his 1927 Perspective as Symbolic Form. In his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935), Walter Benjamin observed how, in perceptions of modern Western culture, from about the 19th century a shift began from the optic toward the haptic.[105] This shift is one of the main recurring topics in McLuhan's work, which McLuhan attributes to the advent of the electronic era. |

主要概念 メディア効果の四象限 詳細は「メディア効果の四象限」を参照 マクルーハンは、息子のエリックによって死後に出版された『メディアの法則』(1988年)の中で、メディアに関する自身の考えを簡潔なメディア効果の四 象限にまとめている。四象限とは、あらゆるテクノロジー(すなわち、あらゆるメディア)が社会に与える影響を検証する手段であり、その影響を4つのカテゴ リーに分けて同時に表示するものである。マクルーハンは、この四象限図表を教育的なツールとして考案し、あらゆるメディアについて考察するための質問とし て、彼の法則を次のように表現した。 メディアは何かを増幅させるか? メディアは何かを時代遅れにするか? メディアは何かを、以前に時代遅れになったものから取り戻すか? メディアは極限まで追い込まれたときに何に変化するか? 四象限の法則は同時に存在し、連続的または時系列的に存在するものではなく、質問者はメディアの「言語」の「文法と構文」を探求することができる。マク ルーハンは、メディアが極端な状態にまで至ると「過熱」し、または反対の形に逆転するという考えを、師であるハロルド・イニスから引き継いでいる。  視覚的には、4象限は4つのダイヤモンドがX字形を形成し、その中心にメディアの名称が置かれる形で表される。4象限の左側の2つのダイヤモンドは、メ ディアの「拡張」と「挽回」の性質であり、どちらも「図」の性質である。4象限の右側の2つのダイヤモンドは、「陳腐化(退化)」と「逆転」の性質であ り、どちらも「地」の性質である。 空白の四象限ダイアグラム ラジオを例にすると、 強化(図):メディアが拡大または強化するもの。ラジオは音を通じてニュースや音楽を増幅する。 陳腐化(地):メディアが目立たなくさせるもの。ラジオは印刷物や視覚の重要性を低下させる。 回復(図):メディアが以前に失われたものを回復するもの。ラジオは音声による言葉を前面に押し出す。 反転(地):メディアが限界に達したときに起こる現象。音響ラジオはオーディオビジュアルテレビへと変化する。 図と地 詳細は「図と地(メディア)」を参照 マクルーハンは、「メディアはメッセージである」という意味を支えるゲシュタルト心理学の「図と地」の概念を応用した。彼は、この概念を用いて、コミュニ ケーション技術の形態であるメディア、すなわち「図」が、必然的にその文脈、すなわち「地」を通じて機能する方法を説明した。 マクルーハンは、新しいテクノロジーの影響を完全に理解するためには、図(メディア)と地(コンテクスト)を一緒に検討しなければならないと信じていた。 なぜなら、どちらか一方だけでは完全に理解できないからである。マクルーハンは、メディアは歴史的なコンテクストの中で、特に先行するテクノロジーとの関 連で研究されなければならないと主張した。現在の環境は、それ自体が過去のテクノロジーの影響で構成されており、それが新たなテクノロジーを生み出し、そ れがさらに社会や個人に影響を与えるのである。 すべてのテクノロジーには、時間と空間に関する独自の前提が組み込まれている。メディアが伝えるメッセージは、メディアと、そのメディアが使用される環境 (同時に、メディアが効果的に作り出す環境)を同時に分析することではじめて理解できる。彼は、図と地の関係を分析することで、文化と社会に関する重要な 論評を提供できると信じていた。 視覚と触覚の知覚の対立 マクルーハン(およびハーレー・パーカー)の著作では、電気メディアは触覚と聴覚の知覚と親和性があり、機械メディアは視覚の知覚と親和性がある。この視 覚と触覚の対立は、美術史家のアロイス・リーグルが1901年の著書『後期ローマ時代の芸術産業』で、またエルヴィン・パノフスキーが1927年の著書 『象徴形態としての遠近法』で、すでに理論化していた。 ウォルター・ベンヤミンは著書『複製技術時代の芸術作品』(1935年)の中で、19世紀頃から近代西洋文化の認識において視覚から触覚へのシフトが始 まったことを観察している。[105] このシフトは、マクルーハンが電子時代の到来に帰する、マクルーハンの著作における主な繰り返しテーマのひとつである。 |

Legacy A portion of Toronto's St. Joseph Street is co-named Marshall McLuhan Way. Influence After the publication of Understanding Media, McLuhan received an astonishing amount of publicity, making him perhaps the most-publicized 20th-century English teacher and arguably the most controversial.[according to whom?][106] This publicity began with the work of two California advertising executives, Howard Gossage and Gerald Feigen, who used personal funds to fund their practice of "genius scouting".[107][108] Much enamoured of McLuhan's work, Feigen and Gossage arranged for McLuhan to meet with editors of several major New York magazines in May 1965 at the Lombardy Hotel in New York. Philip Marchand reports that, as a direct consequence of these meetings, McLuhan was offered the use of an office in the headquarters of both Time and Newsweek anytime he wanted it.[107] In August 1965, Feigen and Gossage held what they called a "McLuhan festival" in the offices of Gossage's advertising agency in San Francisco. During this "festival", McLuhan met with advertising executives, members of the mayor's office, and editors from the San Francisco Chronicle and Ramparts magazine. More significant was the presence at the festival of Tom Wolfe, who wrote about McLuhan in a subsequent article, "What If He Is Right?", published in New York magazine and Wolfe's own The Pump House Gang. According to Feigen and Gossage, their work had only a moderate effect on McLuhan's eventual celebrity: they claimed that their work only "probably speeded up the recognition of his genius by about six months."[109] In any case, McLuhan soon became a fixture of media discourse. Newsweek magazine did a cover story on him; articles appeared in Life, Harper's, Fortune, Esquire, and others. Cartoons about him appeared in The New Yorker.[18] In 1969, Playboy magazine published a lengthy interview with him.[110] In a running gag on the popular sketch comedy Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In, the "poet" Henry Gibson would randomly say, "Marshall McLuhan, what are you doin'?"[111] McLuhan was credited with coining the phrase Turn on, tune in, drop out by its popularizer, Timothy Leary, in the 1960s. In a 1988 interview with Neil Strauss, Leary said the slogan was "given to him" by McLuhan during a lunch in New York City. Leary said McLuhan "was very much interested in ideas and marketing, and he started singing something like, 'Psychedelics hit the spot / Five hundred micrograms, that’s a lot,' to the tune of a Pepsi commercial. Then he started going, 'Tune in, turn on, and drop out.'"[112] During his lifetime and afterward, McLuhan heavily influenced cultural critics, thinkers, and media theorists such as Neil Postman, Jean Baudrillard, Timothy Leary, Terence McKenna, William Irwin Thompson, Paul Levinson, Douglas Rushkoff, Jaron Lanier, Hugh Kenner, and John David Ebert, as well as political leaders such as Pierre Elliott Trudeau[113] and Jerry Brown. Andy Warhol was paraphrasing McLuhan with his now famous "15 minutes of fame" quote. When asked in the 1970s for a way to sedate violence in Angola, he suggested a massive spread of TV devices.[114] Douglas Coupland argued that McLuhan "was conservative, socially, but he never let politics enter his writing or his teaching".[115] Popular culture Woody Allen's Oscar-winning Annie Hall (1977) featured McLuhan in a cameo as himself. In the film, a pompous academic is arguing with Allen in a cinema queue when McLuhan suddenly appears and silences him, saying, "You know nothing of my work."[116] The character "Brian O'Blivion" in David Cronenberg's 1983 film Videodrome is a "media oracle" based on McLuhan.[117] In 1991, McLuhan was named the "patron saint" of Wired magazine and a quote of his appeared on the masthead[citation needed] for the first ten years of its publication.[118] McLuhan's perspective on the cycle of cultural identity inspired Duke Ellington's album The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse.[119] He is mentioned by name in a Peter Gabriel–penned lyric in the song "Broadway Melody of 1974", on Genesis's concept album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway: "Marshall McLuhan, casual viewin', head buried in the sand."[citation needed] McLuhan is jokingly referred to in an episode of The Sopranos titled "House Arrest".[120] Despite his death in 1980, someone claiming to be McLuhan posted on a Wired mailing list in 1996. The information this person provided convinced one Wired writer that "if the poster was not McLuhan himself, it was a bot programmed with an eerie command of McLuhan's life and inimitable perspective."[118] McLuhan is the subject of the 1993 play The Medium, the first major work by the Saratoga International Theater Institute and director Anne Bogart. The play was revived by SITI Company for a farewell tour in 2022.[121] Recognition A new centre known as the McLuhan Program in Culture and Technology, formed soon after his death in 1980, was the successor to McLuhan's Centre for Culture and Technology at the University of Toronto. Since 1994, it has been part of the University of Toronto Faculty of Information. In 2008, the centre incorporated in the Coach House Institute, which was subsequently renamed The McLuhan Centre for Culture and Technology. In 2011, at the time of his centenary, the centre established a "Marshall McLuhan Centenary Fellowship" program in his honour, and each year appoints up to four fellows for a maximum of two years.[citation needed] In Toronto, Marshall McLuhan Catholic Secondary School is named after him.[122] The media room at Canada House in Berlin is called the Marshall McLuhan Salon.[123] It includes a multimedia information centre and an auditorium, and hosts a permanent exhibition dedicated to McLuhan, based on its collection of film and audio items by and about him.[124] |