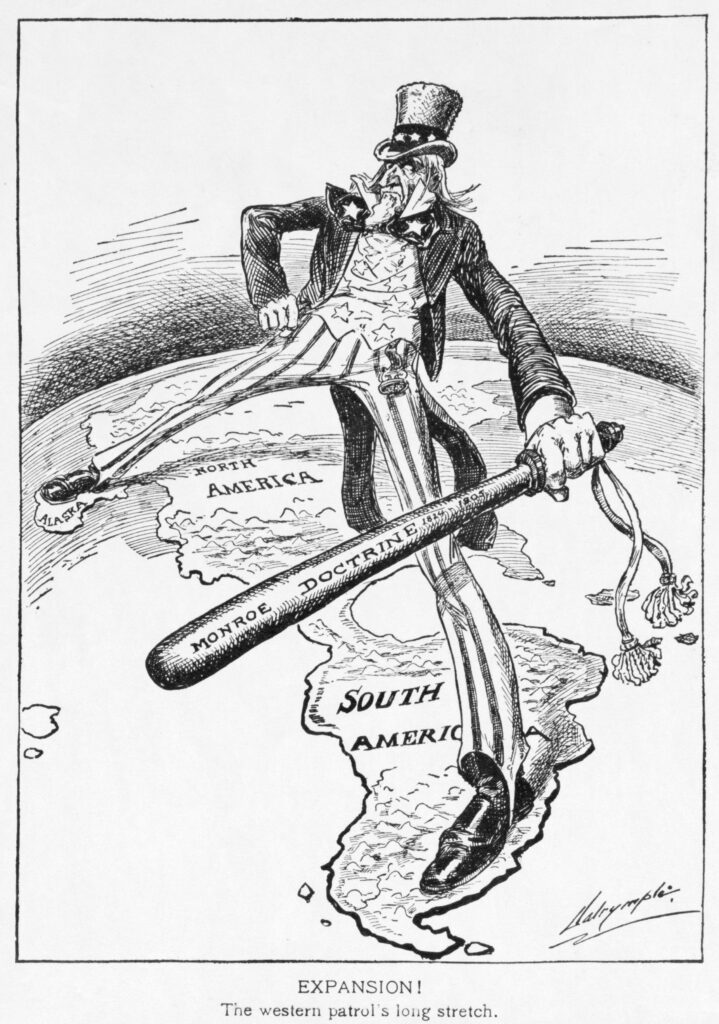

モンロー主義 / モンロードクトリン

Monroe Doctrine

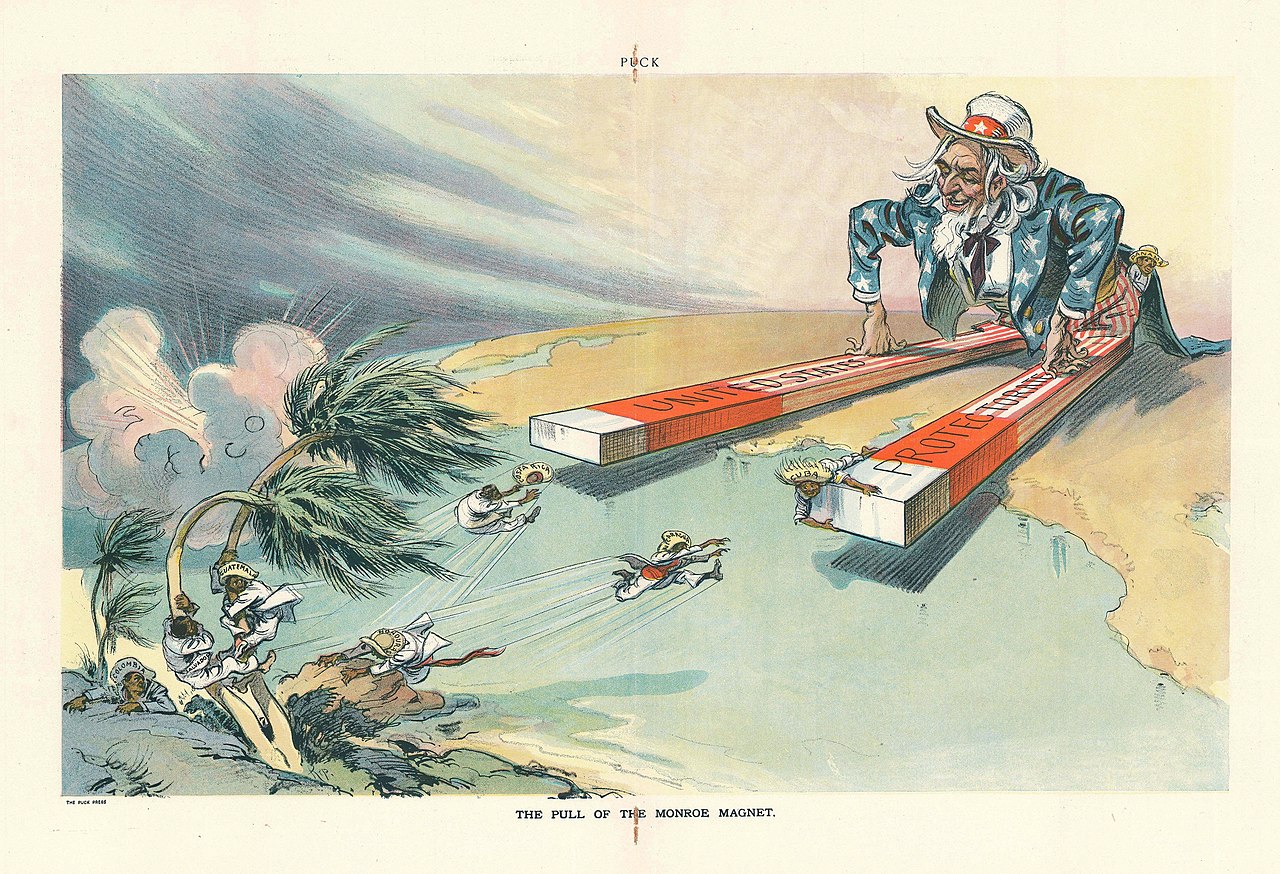

Political

cartoon by Louis

Dalrymple about U.S. expansionism

☆

モンロー主義[Monroe Doctrine]とは、西半球における外国の干渉に反対する米国の外交政策の立場である。元来は欧州の植民地主義を対象としていたが、外国勢力による米州の政

治問題への介入は、米国に対する潜在的な敵対行為であると主張する[1]。この主義は20世紀の米国の大戦略の中核をなした。[2]

ジェームズ・モンロー大統領は1823年12月2日、議会への第7回一般教書演説においてこの原則を初めて表明した(ただし、彼の名を冠する名称が定着し

たのは1850年である)。[3]

当時、アメリカ大陸のスペイン植民地のほぼ全てが独立を達成していたか、あるいは独立間近の状態にあった。モンローは新世界と旧世界が明確に分離された勢

力圏として存続すべきだと主張した[4]。したがって欧州列強がこの地域の主権国家を支配・影響下に置こうとするさらなる試みは、米国の安全保障に対する

脅威と見なされる[5][6]。その見返りとして米国は、既存の欧州植民地を承認し干渉せず、欧州諸国の内政にも干渉しない。

この教義が発表された当時、米国には信頼できる海軍も陸軍もなかったため、植民地支配国からはほとんど無視された。英国が自らの「パックス・ブリタニカ」

政策を推進する機会として利用した部分では成功裏に施行されたものの、19世紀を通じて教義は幾度も無視され、特にフランスによるメキシコへの二度目の介

入が顕著な例である。20世紀初頭までに、アメリカ自身がこの原則を成功裏に適用できるようになり、これはアメリカ外交政策における決定的な瞬間であり、

最も長く続いている基本方針の一つと見なされるようになった。この原則は、ユリシーズ・S・グラント、セオドア・ルーズベルト、ジョン・F・ケネディ、ロ

ナルド・レーガンなど、多くの米国の政治家や大統領によって引用され、2020年代にはドナルド・トランプによって実質的に再解釈されている。

1898年以降、モンロー主義は、多国間主義と不干渉主義を推進するものとして、法律家や知識人によって再解釈された。1933年、フランクリン・D・

ルーズベルト大統領の下、米国は米州機構の共同創設を通じて、この新しい解釈を再確認した[7]。21世紀に入っても、この主義は、さまざまな形で非難さ

れたり、復活したり、再解釈されたりし続けている。

| The Monroe Doctrine

is a United States foreign policy position that opposes any foreign

interference in the Western Hemisphere. Originally concerning European

colonialism, it holds that any intervention in the political affairs of

the Americas by foreign powers is a potentially hostile act against the

United States.[1] The doctrine was central to American grand strategy

in the 20th century.[2] President James Monroe first articulated the doctrine on December 2, 1823, during his seventh annual State of the Union Address to Congress (though it was not named after him until 1850).[3] At the time, nearly all Spanish colonies in the Americas had either achieved or were close to independence. Monroe asserted that the New World and the Old World were to remain distinctly separate spheres of influence,[4] and thus further efforts by European powers to control or influence sovereign states in the region would be viewed as a threat to U.S. security.[5][6] In turn, the United States would recognize and not interfere with existing European colonies nor meddle in the internal affairs of European countries. Because the U.S. lacked both a credible navy and army at the time of the doctrine's proclamation, it was largely disregarded by the colonial powers. While it was successfully enforced in part by the United Kingdom, who used it as an opportunity to enforce its own Pax Britannica policy, the doctrine was ignored several times over the course of the 19th century, notably with the second French intervention in Mexico. By the beginning of the 20th century, the United States itself was able to successfully enforce the doctrine, and it became seen as a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States and one of its longest-standing tenets. It has been invoked by many U.S. statesmen and several U.S. presidents, including Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and is being substantively reinterpreted in the 2020s by Donald Trump. After 1898, the Monroe Doctrine was reinterpreted by lawyers and intellectuals as promoting multilateralism and non-intervention. In 1933, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the United States reaffirmed this new interpretation, through co-founding the Organization of American States.[7] Into the 21st century, the doctrine continues to be variably denounced, reinstated, or reinterpreted. |

モンロー主義[Monroe Doctrine]とは、西半球における外国の干渉に反対する米国の外交政策

の立場である。元来は欧州の植民地主義を対象としていたが、外国勢力による米州の政治問題への介入は、米国に対する潜在的な敵対行為であると主張する

[1]。この主義は20世紀の米国の大戦略の中核をなした。[2] ジェームズ・モンロー大統領は1823年12月2日、議会への第7回一般教書演説においてこの原則を初めて表明した(ただし、彼の名を冠する名称が定着し たのは1850年である)。[3] 当時、アメリカ大陸のスペイン植民地のほぼ全てが独立を達成していたか、あるいは独立間近の状態にあった。モンローは新世界と旧世界が明確に分離された勢 力圏として存続すべきだと主張した[4]。したがって欧州列強がこの地域の主権国家を支配・影響下に置こうとするさらなる試みは、米国の安全保障に対する 脅威と見なされる[5][6]。その見返りとして米国は、既存の欧州植民地を承認し干渉せず、欧州諸国の内政にも干渉しない。 この教義が発表された当時、米国には信頼できる海軍も陸軍もなかったため、植民地支配国からはほとんど無視された。英国が自らの「パックス・ブリタニカ」 政策を推進する機会として利用した部分では成功裏に施行されたものの、19世紀を通じて教義は幾度も無視され、特にフランスによるメキシコへの二度目の介 入が顕著な例である。20世紀初頭までに、アメリカ自身がこの原則を成功裏に適用できるようになり、これはアメリカ外交政策における決定的な瞬間であり、 最も長く続いている基本方針の一つと見なされるようになった。この原則は、ユリシーズ・S・グラント、セオドア・ルーズベルト、ジョン・F・ケネディ、ロ ナルド・レーガンなど、多くの米国の政治家や大統領によって引用され、2020年代にはドナルド・トランプによって実質的に再解釈されている。 1898年以降、モンロー主義は、多国間主義と不干渉主義を推進するものとして、法律家や知識人によって再解釈された。1933年、フランクリン・D・ ルーズベルト大統領の下、米国は米州機構の共同創設を通じて、この新しい解釈を再確認した[7]。21世紀に入っても、この主義は、さまざまな形で非難さ れたり、復活したり、再解釈されたりし続けている。 |

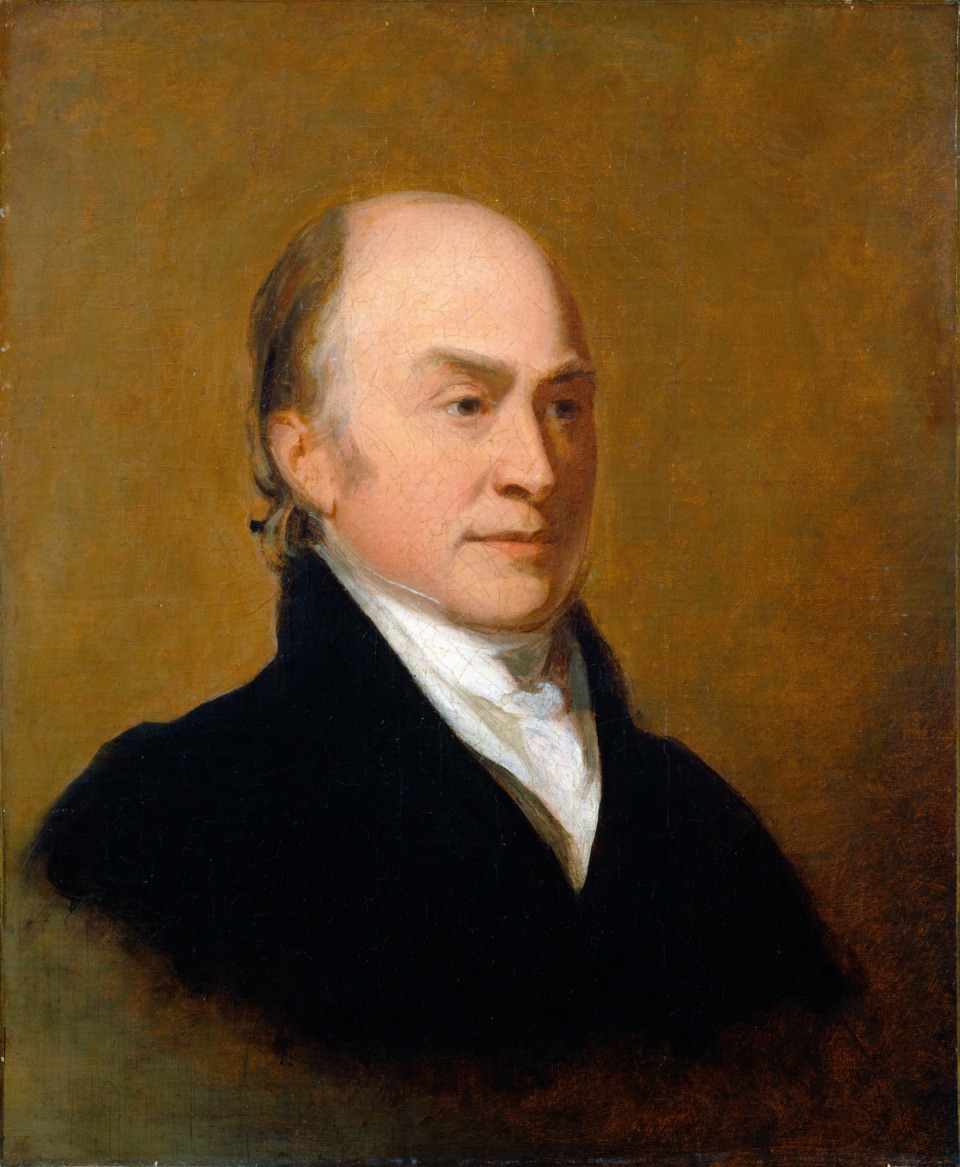

Seeds of the Monroe Doctrine James Monroe, 5th President of the United States  Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, author of the Monroe Doctrine and 6th President of the United States According to Samuel Eliot Morison, "as early as 1783, then, the United States adopted the policy of isolation and announced its intention to keep out of Europe. The supplementary principle of the Monroe Doctrine, that Europe must keep out of America, was still over the horizon".[8] Despite the United States' beginnings as an isolationist country, the foundation of the Monroe Doctrine was already being laid almost immediately after the end of the American Revolution. Alexander Hamilton, writing in The Federalist Papers, was already wanting to establish the United States as a world power and hoped that it would suddenly become strong enough to keep the European powers outside of the Americas, despite the fact that the European countries controlled much more of the Americas than the U.S. herself.[8] Hamilton expected that the United States would become the dominant power in the New World and would, in the future, act as an intermediary between the European powers and any new countries blossoming near the U.S.[8]  Portrait of the Chilean declaration of independence Proclamation of the Chilean Declaration of Independence on February 18, 1818 A note from James Madison (Thomas Jefferson's secretary of state and a future president) to the U.S. ambassador to Spain, expressed the U.S. government's opposition to further territorial acquisition by European powers.[9] Madison's sentiment might have been meaningless because, as was noted before, the European powers held much more territory in comparison to the territory held by the U.S. Although Jefferson was pro-French, in an attempt to keep the U.S. out of any European conflicts, the federal government under Jefferson made it clear to its ambassadors that the U.S. would not support any future colonization efforts on the North American continent. The U.S. feared the victorious European powers that emerged from the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) would revive monarchical government. France had already agreed to restore the Spanish monarchy in exchange for Cuba.[10][verification needed] As the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) came to an end, Prussia, Austria, and Russia formed the Holy Alliance to defend monarchism. In particular, the Holy Alliance authorized military incursions to re-establish Bourbon rule over Spain and its colonies, which were establishing their independence.[11]: 153–5 British foreign policy was compatible with the general objective of the Monroe Doctrine. Britain went as far as covertly assisting the South Americans in their fight against Spain. Britain offered to declare a joint statement concerning the doctrine, as they feared trade with the Americas would be damaged if other European powers further colonized it. In fact, for many years after the doctrine took effect, Britain, through the Royal Navy, was the sole nation enforcing it, as the United States Navy was a comparatively small force.[12] The U.S. government did not issue a joint statement due to the recent War of 1812; however, the immediate provocation was the Russian Ukase of 1821[13] asserting rights to the Pacific Northwest and forbidding non-Russian ships from approaching the coast.[14][15] |

モンロー主義の萌芽 ジェームズ・モンロー、アメリカ合衆国第5代大統領  国務長官ジョン・クインシー・アダムズ、モンロー主義の提唱者でありアメリカ合衆国第6代大統領 サミュエル・エリオット・モリソンによれば、「1783年には早くも、米国は孤立主義政策を採用し、ヨーロッパに関与しない意向を表明していた。ヨーロッパはアメリカに関与してはならないという、モンロー主義の補足的な原則は、まだ地平線の彼方にあった」[8]。 アメリカ合衆国は孤立主義国家として始まったにもかかわらず、モンロー主義の基礎は、アメリカ独立戦争の終結直後にすでに築かれつつあった。アレクサン ダー・ハミルトンは『フェデラリスト論文』の中で、アメリカ合衆国を世界的大国として確立したいと考えており、ヨーロッパ諸国がアメリカ大陸の大部分を支 配していたにもかかわらず、アメリカ大陸からヨーロッパ列強を締め出すほどに、アメリカ合衆国が突然強大になることを望んでいた。[8] ハミルトンは、米国が新世界における支配的な勢力となり、将来、欧州列強と米国周辺で台頭する新しい国々の間の仲介役となることを期待していた。[8]  チリの独立宣言の肖像(→南北アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化) 1818年2月18日のチリ独立宣言の公布 ジェームズ・マディソン(トーマス・ジェファーソンの国務長官であり、後に大統領となる人物)がスペイン駐在の米国大使に送った書簡は、欧州列強によるさ らなる領土獲得に対する米国政府の反対を表明していた。[9] マディソンの見解は無意味だったかもしれない。前述の通り、欧州列強が保有する領土は米国が持つものよりはるかに広大だったからだ。ジェファーソンは親仏 派だったが、米国を欧州紛争に巻き込まないため、連邦政府は大使に対し、北米大陸における今後の植民地化を支持しないことを明確にした。 アメリカは、ウィーン会議(1814-1815年)で台頭した勝利した欧州列強が君主制政府を復活させることを恐れた。フランスは既にキューバと引き換え にスペイン王政の復権に合意していた[10][検証必要]。ナポレオン戦争(1803-1815年)終結後、プロイセン、オーストリア、ロシアは君主制防 衛のため神聖同盟を結成した。特に神聖同盟は、独立を確立しつつあったスペインとその植民地に対するブルボン王朝の支配を再確立するため、軍事侵攻を承認 した[11]: 153–5 英国の外交政策はモンロー主義の一般的な目的と一致していた。英国はスペインに対する南米諸国の戦いを密かに支援するほどであった。英国は、他の欧州列強 がアメリカ大陸をさらに植民地化すれば貿易が損なわれると懸念し、この教義に関する共同声明を発表することを提案した。実際、教義発効後長年にわたり、米 国海軍が比較的小規模な勢力であったため、英国海軍を通じて英国だけがこれを執行する唯一の国であった。[12] 米国政府は1812年の戦争が終結したばかりだったため共同声明を発表しなかった。しかし直接の引き金は、1821年のロシア勅令[13]であった。この 勅令は太平洋岸北西部の権利を主張し、非ロシア船の沿岸接近を禁じていたのである。[14][15] |

| Doctrine The full document of the Monroe Doctrine, written chiefly by future president and then secretary of state John Quincy Adams, is long and couched in diplomatic language, but its essence is expressed in two key passages. The first is the introductory statement, which asserts that the New World is no longer subject to colonization by the European countries:[16] The occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers. The second key passage, which contains a fuller statement of the Doctrine, is addressed to the "allied powers" of Europe; it clarifies that the U.S. remains neutral on existing European colonies in the Americas but is opposed to "interpositions" that would create new colonies among the newly independent Spanish American republics:[6] We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power, we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States. Monroe's speech did not entail a coherent and comprehensive foreign policy.[2][17] It was mostly ignored until proponents of the European non-intervention in the Americas tried to craft a cohesive "Monroe doctrine" decades later.[2] It was not until the mid-20th century that the doctrine became a key component of U.S. grand strategy.[2] |

ドクトリン モンロー主義の全文は、将来の大統領であり当時の国務長官ジョン・クインシー・アダムズが主に起草したもので、長文かつ外交的な表現で書かれているが、そ の本質は二つの重要な箇所で示されている。一つ目は冒頭の声明であり、新世界がもはやヨーロッパ諸国による植民地化の対象ではないと主張している: [16] この機会に、合衆国の権利と利益に関わる原則として、アメリカ大陸は自由かつ独立した状態を確立し維持している以上、今後いかなる欧州列強による植民地化の対象ともみなされるべきではないと宣言するのが適切であると判断された。 第二の核心部分は、この原則をより詳細に述べたもので、ヨーロッパの「同盟諸国」に向けたものである。ここでは、アメリカ大陸における既存のヨーロッパ植 民地については中立を保つが、新たに独立したスペイン系アメリカ諸共和国において新たな植民地を生み出すような「介入」には反対する立場を明確にしてい る: [6] したがって我々は、米国と諸国との間に存在する誠実かつ友好的な関係に照らし、諸国が自国の体制をこの半球のいかなる地域へも拡大しようとする試みを、我 が国の平和と安全に対する脅威と見なすことを宣言せねばならない。既存の欧州列強の植民地もしくは属領については、我々は干渉しておらず、今後も干渉しな い。しかし、独立を宣言し維持している政府、そして我々が慎重な検討と正当な原則に基づきその独立を認めた政府に対して、いかなる欧州列強による、彼らを 圧迫する目的、あるいは他のいかなる方法であれ彼らの運命を支配しようとする介入も、米国に対する敵対的意図の表れ以外の何物でもないと見なすほかない。 モンローの演説は、一貫した包括的な外交政策を意味するものではなかった[2][17]。数十年後、アメリカ大陸への欧州非介入を主張する者たちがまとま りのある「モンロー主義」を構築しようとするまで、この演説はほとんど無視されていた[2]。この主義が米国の大戦略の重要な要素となったのは、20世紀 半ばになってからである[2]。 |

Effects Victor Gillam's 1896 political cartoon depicting Uncle Sam standing with a rifle between the Europeans and Latin Americans International response Because the United States lacked both a credible navy and army at the time, the doctrine was largely disregarded internationally.[4] Prince Klemens von Metternich of Austria was angered by the statement, and wrote privately that the doctrine was a "new act of revolt" by the U.S. that would grant "new strength to the apostles of sedition and reanimate the courage of every conspirator."[11]: 156 The doctrine, however, met with tacit approval from Britain, which enforced it tactically as part of the wider Pax Britannica, which included enforcing the freedom of the seas. This was in line with the developing British policy of supporting laissez-faire free trade and opposing mercantilism. Britain's fast-growing industries sought markets for their manufactured goods, and, if the newly independent Latin American states became Spanish colonies again, British access to these markets would be cut off by Spanish mercantilist policies.[18] |

影響 ヴィクター・ギラムによる1896年の風刺画。ヨーロッパ諸国とラテンアメリカ諸国の間に立ち、ライフルを構えるアンクル・サムを描いている 国際的な反応 当時、米国には信頼できる海軍も陸軍もなかったため、この教義は国際的にほとんど無視された。[4] オーストリアのクレメンス・フォン・メッテルニヒ公はこの声明に激怒し、私的に「この教義は米国の新たな反逆行為であり、反乱の使徒たちに新たな力を与 え、あらゆる陰謀家の勇気を蘇らせるだろう」と記した。[11]: 156 しかしこの教義は、大英帝国による黙認を得た。英国はこれを、海洋の自由を保障する広範な「パックス・ブリタニカ」の一環として戦術的に運用した。これは 自由放任主義の自由貿易を支持し重商主義に反対する、英国が発展させていた政策と一致していた。急成長する英国の産業は製造品の市場を求めており、新たに 独立したラテンアメリカ諸国が再びスペイン植民地となれば、スペインの重商主義政策によって英国はこれらの市場へのアクセスを遮断されることになる。 [18] |

| Latin American reaction The reaction in Latin America to the Monroe Doctrine was generally favorable but on some occasions suspicious. John A. Crow, author of The Epic of Latin America, states, "Simón Bolívar himself, still in the midst of his last campaign against the Spaniards, Santander in Colombia, Rivadavia in Argentina, Victoria in Mexico—leaders of the emancipation movement everywhere—received Monroe's words with sincerest gratitude".[19] Crow argues that the leaders of Latin America were realists. They knew that the president of the United States wielded very little power at the time, particularly without an alliance with Britain, and figured that the Monroe Doctrine was unenforceable if the U.S. stood alone against the Holy Alliance.[19] While Latin Americans appreciated and praised their support in the north, they knew that the future of their independence was in the hands of the British and their powerful navy. In 1826, Bolivar called upon his Congress of Panama to host the first "Pan-American" meeting. In the eyes of Bolivar and his men, the Monroe Doctrine was to become nothing more than a tool of national policy. According to Crow, "It was not meant to be, and was never intended to be a charter for concerted hemispheric action".[19] At the same time, some people questioned the intentions behind the Monroe Doctrine. Diego Portales, a Chilean businessman and minister, wrote to a friend: "But we have to be very careful: for the Americans of the north [from the United States], the only Americans are themselves".[20] |

ラテンアメリカの反応 モンロー主義に対するラテンアメリカの反応は概ね好意的だったが、時に疑念も示された。『ラテンアメリカの叙事詩』の著者ジョン・A・クロウはこう述べて いる。「シモン・ボリバル自身は、スペイン軍に対する最後の戦いの最中であり、コロンビアのサンタンデール、アルゼンチンのリバダビア、メキシコのビクト リア――各地の解放運動指導者たちは、モンローの言葉を心からの感謝をもって受け止めた」[19] クロウは、ラテンアメリカの指導者たちは現実主義者だったと論じる。彼らは当時のアメリカ大統領が、特にイギリスとの同盟なしではほとんど権力を持たない ことを理解しており、聖同盟に対してアメリカが単独で立ち向かうならモンロー主義は実行不可能だと見抜いていたのだ[19]。 ラテンアメリカ諸国は北からの支援を評価し称賛しつつも、自らの独立の未来はイギリスとその強力な海軍の手に委ねられていることを認識していた。1826 年、ボリバルはパナマ議会に対し、初の「汎米」会議の開催を要請した。ボリバルとその側近たちの目には、モンロー主義は単なる国家政策の道具に過ぎないと 映っていた。クロウによれば「それは、半球規模の協調行動の憲章となることを意図したものではなく、またそのような意図も決してなかった」のである。 [19] 同時に、モンロー主義の真意を疑う声もあった。チリの実業家兼大臣ディエゴ・ポルタレスは友人にこう書き送っている。「だが我々は警戒すべきだ。北米(ア メリカ合衆国)のアメリカ人にとって、真のアメリカ人とは彼ら自身だけなのだ」[20] |

Post-Bolívar events Surrender of the Spanish Army at the Battle of Tampico in 1829 In Spanish America, royalist guerrillas continued the war in several countries, and Spain attempted to retake Mexico in 1829. Only Cuba and Puerto Rico remained under Spanish rule, until the Spanish–American War in 1898. In early 1833, the British reasserted their sovereignty over the Falkland islands, thus violating the Monroe Doctrine.[21] No action was taken by the U.S. and the historian George C. Herring wrote that inaction "confirmed Latin American and especially Argentine suspicions of the United States."[11]: 171 [22] From 1838 to 1850, the Río de la Plata of Argentina was blockaded first by the French navy and then by the British and French navies. As before, no action was undertaken by the U.S. to support Argentina as stipulated in the doctrine.[23][21] In 1842, U.S. president John Tyler applied the Monroe Doctrine to the Hawaiian Kingdom and warned Britain not to interfere there. This began the process of annexing Hawaii to the U.S.[24] On December 2, 1845, U.S. president James K. Polk announced that the principle of the Monroe Doctrine should be strictly enforced, reinterpreting it to argue that no European nation should interfere with American western expansion ("manifest destiny").[25]  French intervention in Mexico, 1861–1867 In 1861, Dominican military commander and royalist politician Pedro Santana signed a pact with the Spanish Crown and reverted the Dominican nation to colonial status. Spain was wary at first, but with the United States occupied with its own civil war, Spain believed it had an opportunity to reassert control in Latin America. On March 18, 1861, the Spanish annexation of the Dominican Republic was announced. The American Civil War ended in 1865, and following the reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine by the U.S. government, this prompted Spanish forces stationed within the Dominican Republic to extradite back to Cuba within that same year.[26] In 1862, French forces under Napoleon III invaded and conquered Mexico, giving control to the puppet monarch Maximilian I. Washington denounced this as a violation of the doctrine but was unable to intervene because of the American Civil War. This marked the first time the Monroe Doctrine was widely referred to as a "doctrine".[citation needed] In 1865 the U.S. garrisoned an army on its border to encourage Napoleon III to leave Mexican territory, and they did subsequently remove their forces, which was followed by Mexican nationalists capturing and then executing Maximilian.[27] After the expulsion of France from Mexico, Secretary of State William H. Seward proclaimed in 1868 that the "Monroe doctrine, which eight years ago was merely a theory, is now an irreversible fact."[28] In 1865, Spain occupied the Chincha Islands in violation of the Monroe Doctrine.[21] In 1862, the remaining British colonies within modern-day Belize were merged into a single crown colony known as British Honduras. The U.S. government did not express disapproval for this action, either during or after the Civil War.[29] In the 1870s, President Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish endeavored to supplant European influence in Latin America with that of the U.S. In 1870, the Monroe Doctrine was expanded under the proclamation "hereafter no territory on this continent [referring to Central and South America] shall be regarded as subject to transfer to a European power."[11]: 259 Grant invoked the Monroe Doctrine in his failed attempt to annex the Dominican Republic in 1870.[30] |

ボリバル後の出来事 1829年、タンピコの戦いでスペイン軍が降伏 スペイン領アメリカでは、王党派のゲリラが複数の国で戦争を継続し、スペインは1829年にメキシコ奪還を試みた。1898年の米西戦争まで、スペインの支配下に残ったのはキューバとプエルトリコのみであった。 1833年初頭、英国はフォークランド諸島に対する主権を再主張し、これによりモンロー主義に違反した[21]。米国は何の行動も取らず、歴史家ジョー ジ・C・ヘリングは、この不作為が「ラテンアメリカ、特にアルゼンチンの米国に対する疑念を確かなものにした」と記している。[11]: 171 [22] 1838年から1850年にかけて、アルゼンチンのリオ・デ・ラ・プラタはまずフランス海軍、次いで英仏両海軍によって封鎖された。前回と同様、米国はド クトリンに定められた通りアルゼンチンを支援する行動を取らなかった。[23] [21] 1842年、ジョン・タイラー米大統領はモンロー主義をハワイ王国に適用し、英国に対し干渉しないよう警告した。これがハワイの米国併合プロセスを開始し た。[24] 1845年12月2日、ジェームズ・K・ポーク米大統領はモンロー主義の原則を厳格に適用すべきだと宣言し、これを再解釈して「欧米諸国はアメリカの西部 開拓(マニフェスト・デスティニー)に干渉すべきでない」と主張した。[25]  1861-1867年 メキシコへのフランス介入 1861年、ドミニカ共和国の軍司令官で王党派政治家ペドロ・サンタナはスペイン王室と協定を結び、ドミニカ共和国を植民地状態に戻した。スペインは当初 警戒していたが、アメリカが内戦で手一杯だったため、ラテンアメリカ支配を再確立する機会と見た。1861年3月18日、スペインによるドミニカ共和国併 合が発表された。アメリカ南北戦争は1865年に終結し、米国政府によるモンロー主義の再確認を受けて、ドミニカ共和国に駐留していたスペイン軍は同年中 にキューバへ引き揚げた。[26] 1862年、ナポレオン3世率いるフランス軍がメキシコに侵攻し征服、傀儡君主マクシミリアン1世に支配権を与えた。ワシントンはこれをドクトリン違反と 非難したが、南北戦争のため介入できなかった。これがモンロー主義が広く「ドクトリン」と呼ばれた最初の事例である[出典必要]。1865年、アメリカは 国境に軍隊を駐屯させナポレオン3世にメキシコ領からの撤退を促し、その後フランス軍は撤退した。これに続きメキシコナショナリストたちがマクシミリアン を捕らえ処刑した。[27] フランスがメキシコから追放された後、ウィリアム・H・スワード国務長官は1868年に「8年前には単なる理論に過ぎなかったモンロー主義は、今や不可逆 的事実となった」と宣言した。[28] 1865年、スペインはモンロー主義に違反してチンチャ諸島を占領した[21]。1862年、現在のベリーズにある残りの英国植民地は、英領ホンジュラス として単一の王室直轄植民地に統合された。米国政府は、南北戦争中も戦後も、この行動に対して不承認の意を表明しなかった。[29] 1870年代、ユリシーズ・S・グラント大統領とハミルトン・フィッシュ国務長官は、ラテンアメリカにおけるヨーロッパの影響力を米国の影響力で置き換え ようと努めた。1870年、モンロー主義は「今後、この大陸(中南米を指す)のいかなる領土も、ヨーロッパ列強への譲渡の対象とはみなされない」という宣 言の下で拡大された。[11]: 259 グラントは 1870 年にドミニカ共和国を併合しようとしたが失敗し、その際にモンロー主義を引用した。[30] |

President Grover Cleveland twisting the tail of the British Lion; cartoon in Puck by J. S. Pughe, 1895 The Venezuelan crisis of 1895 became "one of the most momentous episodes in the history of Anglo-American relations in general and of Anglo-American rivalries in Latin America in particular."[31] Venezuela sought to involve the U.S. in a territorial dispute with Britain and hired former U.S. ambassador William Lindsay Scruggs to argue that Britain's actions over the issue violated the Monroe Doctrine. President Grover Cleveland, through Secretary of State Richard Olney, cited the doctrine in 1895, threatening strong action against Britain if the British failed to arbitrate their dispute with Venezuela. In a July 20, 1895, note to Britain, Olney stated, "The United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition."[11]: 307 British prime minister Lord Salisbury took strong exception to the American language. The U.S. subsequently objected to a British proposal for a joint meeting to clarify the scope of the Monroe Doctrine. Herring wrote that by failing to pursue the issue further, the British "tacitly conceded the U.S. definition of the Monroe Doctrine and its hegemony in the hemisphere."[11]: 307–8 German chancellor Otto von Bismarck did not agree and in October 1897 called the doctrine an "uncommon insolence".[32] Sitting in Paris, the Tribunal of Arbitration finalized its decision on October 3, 1899.[31] The award was unanimous, but gave no reasons for the decision, merely describing the resulting boundary, which gave Britain almost 90% of the disputed territory[33] and all of the gold mines.[34]  Political cartoon depicting Theodore Roosevelt using the Monroe Doctrine to keep European powers out of the Dominican Republic. The reaction to the award was of surprise, with the award's lack of reasoning a particular concern.[33] The Venezuelans were keenly disappointed with the outcome, though they honored their counsel for their efforts (their delegation's secretary, Severo Mallet-Prevost, received the Order of the Liberator in 1944), and abided by the award.[33] The boundary dispute asserted for the first time a more outward-looking U.S. foreign policy, particularly in the Americas, marking the United States as a world power. This was the earliest example of modern interventionism under the Monroe Doctrine in which the U.S. exercised its claimed prerogatives in the Americas.[35] In 1898, the U.S. intervened in support of Cuba during its war for independence from Spain. The resulting Spanish–American War ended in a peace treaty requiring Spain to cede Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the U.S. in exchange for $20 million. Spain was additionally forced to recognize Cuban independence, though the island remained under U.S. occupation until 1902.[36] |

グロバー・クリーブランド大統領が英国の獅子を尻尾を捻る;J・S・ピュー作『パック』誌掲載風刺画、1895年 1895年のベネズエラ危機は「英米関係史全般、特にラテンアメリカにおける英米対立史において最も重大な出来事の一つ」となった。[31] ベネズエラは、英国との領土紛争に米国を巻き込もうと、元米国大使ウィリアム・リンゼイ・スクラッグスを雇い、この問題に関する英国の行動はモンロー主義 に違反していると主張させた。グローバー・クリーブランド大統領は、リチャード・オルニー国務長官を通じて、1895年にこの主義を引用し、英国がベネズ エラとの紛争を仲裁しなかった場合、英国に対して強力な措置を講じることを警告した。1895年7月20日、オルニーは英国宛の書簡で、「米国は実質的に この大陸の主権者であり、その介入が及ぶ対象については、米国の決定が法律である」と述べた[11]: 307。 英国のソールズベリー首相は、米国のこの表現に強い異議を唱えた。その後、米国は、モンロー主義の範囲を明確にするための合同会議の開催という英国の提案 に反対した。ヘリングは、この問題をさらに追求しなかったことで、英国は「モンロー主義の定義と、この半球における米国のヘゲモニーを暗黙のうちに認め た」と記している。[11]: 307–8 ドイツのオットー・フォン・ビスマルク首相はこれに同意せず、1897年10月にはこの教義を「並外れた厚か ましさ」と呼んだ。[32]パリに設置された仲裁裁判所は1899年10月3日に最終判決を下した。[31] 裁定は全会一致であったが、その理由を一切示さず、単に結果としての境界線を記述した。これにより英国は係争地域のほぼ90%[33]と全ての金鉱山 [34]を獲得した。  セオドア・ルーズベルトがモンロー主義を用いて欧州列強をドミニカ共和国から締め出す様子を描いた風刺画。 裁定への反応は驚きであり、特に理由説明の欠如が懸念された[33]。ベネズエラ側は結果に深く失望したが、自国弁護団の尽力(代表団書記セベロ・マレ= プレヴォストは1944年に解放者勲章を受章)を称え、裁定を順守した。[33] この境界紛争は、特に米州において、より対外的な米国外交政策を初めて主張するものであり、米国を世界的大国として位置づけた。これはモンロー主義に基づ く近代的介入主義の最も初期の事例であり、米国が米州における自国の主張する特権を行使したものである。[35] 1898年、米国はスペインからの独立戦争中のキューバを支援するため介入した。その結果生じた米西戦争は、スペインが2000万ドルと引き換えにプエル トリコ、フィリピン、グアムを米国に割譲することを求める平和条約で終結した。スペインはさらにキューバの独立を承認することを余儀なくされたが、同島は 1902年まで米国の占領下に置かれた。[36] |

| Big Brother The "Big Brother" policy was an extension of the Monroe Doctrine formulated by James G. Blaine in the 1880s that aimed to rally Latin American nations behind U.S. leadership and open their markets to U.S. traders. Blaine served as Secretary of State in 1881 under President James A. Garfield and again from 1889 to 1892 under President Benjamin Harrison. As a part of the policy, Blaine arranged and led the First International Conference of American States in 1889.[37] Olney Corollary Main article: Olney interpretation The Olney Corollary, also known as the Olney interpretation or Olney declaration was U.S. secretary of state Richard Olney's interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine when the border dispute for the Essequibo occurred between the British and Venezuelan governments in 1895. Olney claimed that the Monroe Doctrine gave the U.S. authority to mediate border disputes in the Western Hemisphere. Olney extended the meaning of the Monroe Doctrine, which had previously stated merely that the Western Hemisphere was closed to additional European colonization. The statement reinforced the original purpose of the Monroe Doctrine, that the U.S. had the right to intervene in its own hemisphere and foreshadowed the events of the Spanish–American War three years later. The Olney interpretation was defunct by 1933.[38] Canada In 1902, Canadian prime minister Wilfrid Laurier acknowledged that the Monroe Doctrine was essential to his country's protection. The doctrine provided Canada with a de facto security guarantee by the United States; the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, and the Royal Navy in the Atlantic, made invading North America almost impossible. Because of the peaceful relations between the two countries, Canada could assist Britain in a European war without having to defend itself at home.[39] |

ビッグ・ブラザー 「ビッグ・ブラザー」政策は、1880年代にジェームズ・G・ブレインが策定したモンロー主義の延長であり、ラテンアメリカ諸国を米国の指導力の下に結束 させ、米国貿易業者に市場を開放することを目的としていた。ブレインは、1881年にジェームズ・A・ガーフィールド大統領の下で国務長官を務め、 1889年から1892年までベンジャミン・ハリソン大統領の下で再び国務長官を務めた。この政策の一環として、ブレインは1889年に第1回米州国際会 議を主催し、主導した[37]。 オルニー補則 主な記事:オルニー解釈 オルニー補則は、オルニー解釈またはオルニー宣言としても知られ、1895年に英国とベネズエラ政府の間でエセキボの境界紛争が発生した際に、リチャー ド・オルニー米国務長官がモンロー主義を解釈したものである。オルニーは、モンロー主義は米国に西半球の境界紛争を仲介する権限を与えていると主張した。 オルニーは、西半球はヨーロッパによる追加的な植民地化に閉ざされていると単に述べていたモンロー主義の意味を拡大した。この声明は、米国が自国の半球に 介入する権利を有するというモンロー主義の本来の目的を強化し、3年後の米西戦争の出来事を予見するものであった。オルニー解釈は1933年までに廃止さ れた。 カナダ 1902年、カナダのウィルフリッド・ローリエ首相は、モンロー主義が自国の保護に不可欠であることを認めた。この主義は、カナダに米国による事実上の安 全保障をもたらした。太平洋の米海軍と大西洋の英国海軍の存在により、北米への侵攻は事実上不可能となった。両国の平和的な関係により、カナダは自国を防 衛する必要なく、欧州での戦争において英国を支援することができた。[39] |

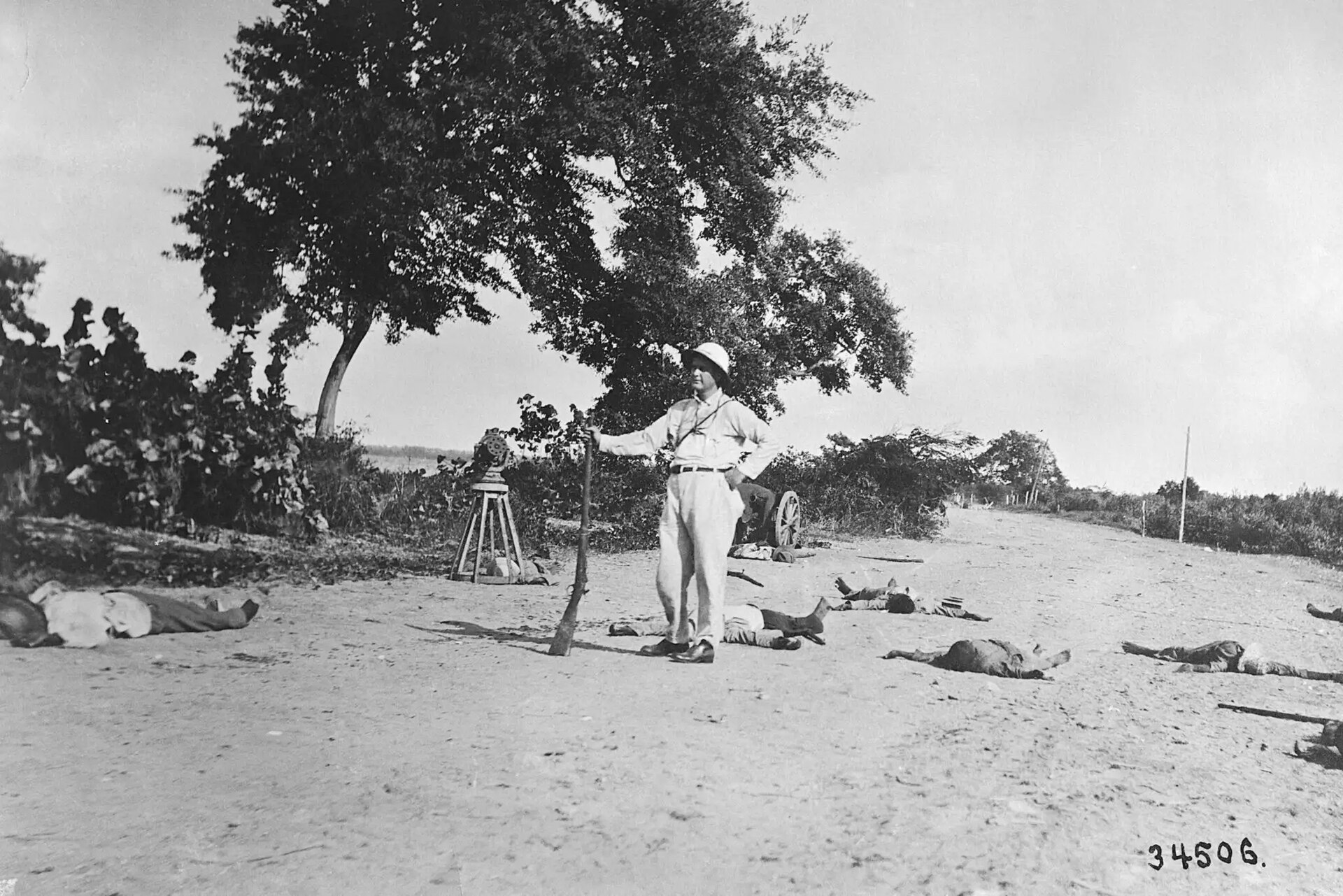

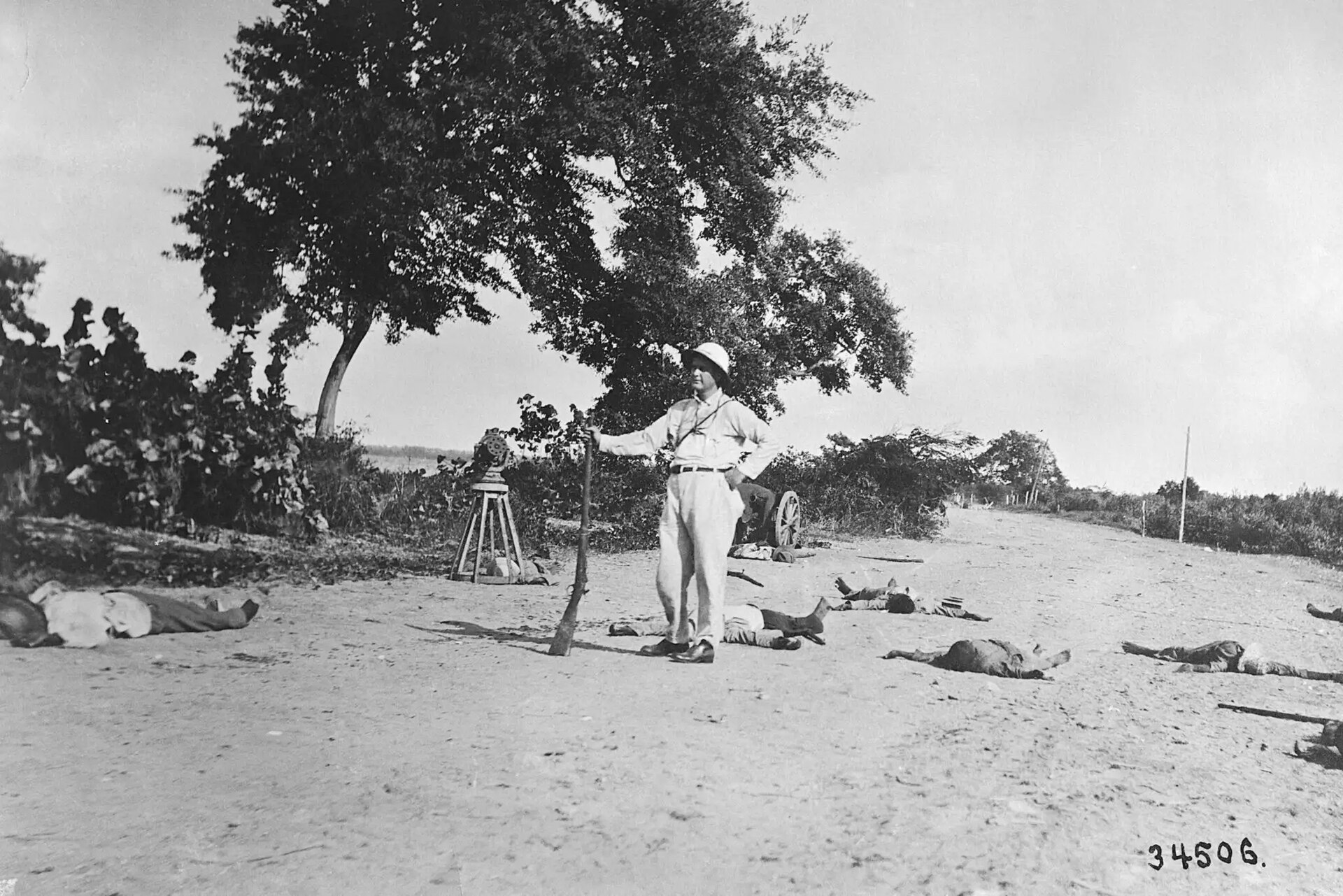

| Roosevelt Corollary Main article: Roosevelt Corollary  1903 cartoon: "Go Away, Little Man, and Don't Bother Me". President Theodore Roosevelt intimidating Colombia to acquire the Panama Canal Zone The doctrine has subsequently been reinterpreted and applied in a variety of instances. As the U.S. began to emerge as a world power, the Monroe Doctrine came to define a recognized sphere of control that few dared to challenge.[4] Before becoming president, Theodore Roosevelt had proclaimed the rationale of the Monroe Doctrine in supporting intervention in the Spanish colony of Cuba in 1898.[citation needed] The Venezuela crisis of 1902–1903 showed the world that the U.S. was willing to use its naval strength to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of small states in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts, in order to preclude European intervention to do so.[40] The Venezuela crisis, and in particular the arbitral award, were key in the development of the Corollary.[40] In Argentine foreign policy, the Drago Doctrine was announced on December 29, 1902, by Argentine foreign minister Luis María Drago. The doctrine itself was a response to the actions of Britain, Germany, and Italy, which, in 1902, had blockaded Venezuela in response to the Venezuelan government's refusal to pay its massive foreign debt that had been acquired under previous administrations before President Cipriano Castro took power. Drago set forth the policy that no European power could use force against an American nation to collect debt owed. Roosevelt rejected this policy as an extension of the Monroe Doctrine, declaring, "We do not guarantee any state against punishment if it misconducts itself".[11]: 370  A map of Middle America showing the places affected by Theodore Roosevelt's Big stick policy. Instead, Roosevelt added the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904, asserting the right of the U.S. to intervene in Latin America in cases of "flagrant and chronic wrongdoing by a Latin American Nation" to preempt intervention by European creditors. This reinterpretation of the Monroe Doctrine went on to be a useful tool to take economic benefits by force when Latin American nations failed to pay their debts to European and U.S. banks and business interests. This was also referred to as the big stick ideology because of the oft-quoted phrase from Roosevelt, "speak softly and carry a big stick".[4][11]: 371 [41] The Roosevelt Corollary provoked outrage across Latin America.[42] The Corollary was invoked to intervene militarily in Latin America to stop the spread of European influence.[41] It was the most significant amendment to the original doctrine and was widely opposed by critics, who argued that the Monroe Doctrine was originally meant to stop European influence in the Americas.[4] Christopher Coyne has argued that the addition of the Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine began the second phase of "American Liberal Empire" and "can be understood as a foreign policy declaration based on military primacy." It initiated a tectonic shift in the political and economic relations between the United States and Latin America, and with European governments.[43] Other critics have argued that the Corollary asserted U.S. domination in the area, effectively making them a "hemispheric policeman".[44] The early decades of the 20th century saw a number of interventions in Latin America by the U.S. government often justified under the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.[45] President William Howard Taft viewed dollar diplomacy as a way for American corporations to benefit while assisting in the national security goal of preventing European powers from filling any possible financial power vacuum.[46] U.S. Marine posing with dead Haitian revolutionaries during the United States occupation of Haiti |

ルーズベルト補則 詳細な記事: ルーズベルト補則  1903年の風刺画: 「さっさと失せろ、小僧。邪魔するな」。セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領がパナマ運河地帯を獲得するためコロンビアを威嚇する様子 この教義はその後、様々な事例で再解釈され適用されてきた。米国が世界的大国として台頭するにつれ、モンロー主義は公認された支配圏を定義するに至り、これに挑む者はほとんどいなかった[4]。 大統領就任前、セオドア・ルーズベルトは1898年のスペイン植民地キューバへの介入を支持する根拠としてモンロー主義を宣言していた[出典必要]。 1902年から1903年にかけてのベネズエラ危機は、カリブ海及び中央アメリカの小国が国際債務を返済不能に陥った場合、米国が海軍力を用いて介入し経 済情勢を安定化させ、欧州諸国の介入を阻止する意思があることを世界に示した。[40] ベネズエラ危機、特に仲裁裁定は、補則の発展において重要な役割を果たした。[40] アルゼンチン外交政策において、ドラゴ・ドクトリンは1902年12月29日にルイス・マリア・ドラゴ外相によって発表された。このドクトリン自体は、 1902年にベネズエラ政府がシプリアーノ・カストロ大統領以前の政権下で負った巨額の対外債務の支払いを拒否したことを受け、英国、ドイツ、イタリアが ベネズエラを封鎖した行動への対応であった。ドラゴは、いかなる欧州列強も債務回収のために米州諸国に対して武力を行使してはならないとする政策を打ち出 した。ルーズベルトはこの政策をモンロー主義の延長として拒否し、「自国が不正行為を行った場合、いかなる国民に対しても処罰を免除する保証はしない」と 宣言した。[11]: 370  セオドア・ルーズベルトのビッグ・スティック政策の影響を受けた地域を示す中米地図。 代わりにルーズベルトは1904年、モンロー主義に「ルーズベルト補則」を追加した。これは「ラテンアメリカ諸国による露骨かつ慢性的な不正行為」が発生 した場合、欧州債権国の介入を先制するため米国がラテンアメリカに介入する権利を主張するものだった。このモンロー主義の再解釈は、ラテンアメリカ諸国が 欧米の銀行や企業への債務を返済不能に陥った際、武力による経済的利益獲得の手段として機能した。ルーズベルトの「柔らかく語り、大きな棒を携えよ」とい う有名な言葉から、これは「大棒イデオロギー」とも呼ばれた。[4] [11]: 371 [41] ルーズベルト補則はラテンアメリカ全域で激しい反発を招いた。[42] 補則は欧州勢力の拡大を阻止するため、ラテンアメリカへの軍事介入を正当化する根拠として用いられた。[41] これはモンロー主義の根本的修正であり、批判派からは「モンロー主義は元々アメリカ大陸における欧州勢力の排除を目的としていた」として広く反対された。 [4] クリストファー・コイーンは、モンロー主義への補則の追加が「アメリカ自由主義帝国」の第二段階を開始し、「軍事的優位性に基づく外交政策宣言と理解でき る」と論じている。これは米国とラテンアメリカ、そして欧州諸国との政治的・経済的関係に地殻変動をもたらした。[43] 他の批判者は、この補則が同地域における米国の支配を主張し、事実上米国を「半球の警察官」にしたと論じている。[44] 20世紀初頭の数十年間、米国政府はモンロー主義のルーズベルト補則を根拠に、ラテンアメリカへの介入を数多く行った。[45] ウィリアム・ハワード・タフト大統領は、ドル外交を米国企業の利益確保と、欧州列強による金融力の空白地帯の埋没を防ぐという国家安全保障目標の達成を両 立させる手段と見なした。[46] ハイチ占領中の米海兵隊員が、死亡したハイチ革命軍兵士と共にポーズをとる |

U.S. Marine posing with dead Haitian revolutionaries during the United States occupation of Haiti The United States launched multiple interventions into Latin America, resulting in U.S. military presence in Cuba, Honduras, Panama (via the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty and Isthmian Canal Commission),[47] Haiti (1915–1935),[48] the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) and Nicaragua (1912–1925 and 1926–1933).[49] U.S. marines began to specialize in long-term military occupation of these countries, primarily to safeguard customs revenues which were the cause of local civil wars.[50] The Platt Amendment amended a treaty between the U.S. and the Republic of Cuba after the Spanish–American War, virtually making Cuba a U.S. protectorate. The amendment outlined conditions for the U.S. to intervene in Cuban affairs and permitted the United States to lease or buy lands for the purpose of establishing naval bases, including Guantánamo Bay.[51] |

アメリカ海兵隊員がハイチ占領中に死んだハイチ革命家とポーズを取っている アメリカはラテンアメリカに複数回介入し、その結果としてキューバ、ホンジュラス、パナマ(ヘイ=ブナウ=バリラ条約及び地峡運河委員会を通じて)、 [47] ハイチ(1915年~1935年)、[48] ドミニカ共和国(1916年~1924年)、ニカラグア(1912年~1925年および1926年~1933年)に駐留した。[49] 米海兵隊はこれらの国々における長期軍事占領を専門化し、主に内戦の原因となった関税収入の確保に当たった。[50] プラット修正条項は米西戦争後の米国とキューバ共和国間の条約を修正し、事実上キューバを米国の保護領とした。この修正条項は米国がキューバ内政に介入する条件を定め、グアンタナモ湾を含む海軍基地設置目的での土地の賃貸または購入を米国に許可した。[51] |

| Lodge Corollary The so-called "Lodge Corollary" was passed[52] by the U.S. Senate on August 2, 1912, in response to a reported attempt by a Japan-backed private company to acquire Magdalena Bay in Baja California Sur. It extended the reach of the Monroe Doctrine to cover actions of corporations and associations controlled by foreign states.[53] Clark Memorandum The Clark Memorandum, written on December 17, 1928, by President Calvin Coolidge's undersecretary of state J. Reuben Clark, concerned American use of military force to intervene in Latin American nations. This memorandum was officially released in 1930 by the administration of President Herbert Hoover. The Clark Memorandum rejected the view that the Roosevelt Corollary was based on the Monroe Doctrine. However, it was not a complete repudiation of the Roosevelt Corollary but was rather a statement that any intervention by the U.S. was not sanctioned by the Monroe Doctrine but rather was the right of the U.S. as a state. This separated the Roosevelt Corollary from the Monroe Doctrine by noting that the doctrine only applied to situations involving European countries. One main point in the Clark Memorandum was to note that the Monroe Doctrine was based on conflicts of interest only between the United States and European nations, rather than between the U.S. and Latin American nations. |

ロッジ補則 いわゆる「ロッジ補則」は、1912年8月2日に米国上院で可決された[52]。これは、日本が支援する民間企業がバハ・カリフォルニア・スル州のマグダ レナ湾を取得しようとしたとの報告を受けての対応であった。この補則は、モンロー主義の適用範囲を拡大し、外国政府が支配する企業や団体の行動も対象とし た。[53] クラーク覚書 クラーク覚書は、1928年12月17日にカルビン・クーリッジ大統領の国務次官J・ルーベン・クラークによって作成された。これはラテンアメリカ諸国への米軍介入に関する覚書である。この覚書は1930年にハーバート・フーヴァー大統領政権によって公式に公表された。 クラーク覚書は、ルーズベルト補則がモンロー主義に基づくという見解を否定した。しかし、ルーズベルト補則を完全に否定したわけではなく、米国のいかなる 介入もモンロー主義によって認可されたものではなく、国家としての米国の権利であるとの声明であった。これにより、モンロー主義は欧州諸国に関わる状況に のみ適用されるという点を明記し、ルーズベルト補則をモンロー主義から切り離したのである。クラーク覚書の主要な論点は、モンロー主義が米国と欧州諸国間 の利益相反に基づくものであり、米国とラテンアメリカ諸国間のそれではないと指摘した点にあった。 |

World War II American servicemen in Greenland during World War II After World War II began, a majority of Americans supported defending the entire Western Hemisphere against foreign invasion. A 1940 national survey found that 81% supported defending Canada; 75% Mexico and Central America; 69% South America; 66% West Indies; and 59% Greenland.[54] The December 1941 conquest of Saint Pierre and Miquelon by Free French forces from the control of Vichy France was seen as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine by Secretary of State Cordell Hull.[55] During World War II, the US invoked its Monroe Doctrine and occupied Greenland to prevent use by Germany following the German occupation of Denmark. The US military remained in Greenland after the war, and by 1948, Denmark abandoned attempts to persuade the US to leave. The following year, both countries became members of the NATO military alliance. A 1951 treaty gave the US a significant role in Greenland's defense. As of 2025, the US Space Force maintains Pituffik Space Base in Greenland, and the US military frequently takes part in NATO exercises in Greenlandic waters. |

第二次世界大戦 第二次世界大戦中のグリーンランドにおけるアメリカ軍兵士 第二次世界大戦が始まると、大多数のアメリカ人は外国の侵略から西半球全体を守ることを支持した。1940年の全国調査では、カナダ防衛を支持する者が 81%、メキシコと中央アメリカは75%、南アメリカは69%、西インド諸島は66%、グリーンランドは59%であった[54]。 1941年12月、自由フランス軍がヴィシー政権からサンピエール・ミクロン諸島を奪取したことは、コルデル・ハル国務長官によってモンロー主義の違反と見なされた。[55] 第二次世界大戦中、米国はモンロー主義を根拠にグリーンランドを占領した。これはドイツによるデンマーク占領後、同地がドイツに利用されるのを防ぐためで あった。戦後も米軍はグリーンランドに駐留を続け、1948年までにデンマークは米軍の撤退を求める試みを断念した。翌年、両国はNATO軍事同盟に加盟 した。1951年の条約により、米国はグリーンランド防衛において重要な役割を担うこととなった。2025年現在、米国宇宙軍はグリーンランドにピトゥ フィック宇宙基地を維持しており、米軍はグリーンランド海域で行われるNATO演習に頻繁に参加している。 |

| Latin American reinterpretation After 1898, jurists and intellectuals in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay, especially Luis María Drago, Alejandro Álvarez, and Baltasar Brum, reinterpreted the Monroe Doctrine. They sought a fresh continental approach to international law in terms of multilateralism and non-intervention. Indeed, an alternative Spanish American origin of the idea was proposed, attributing it to Manuel Torres.[56] However, U.S. officials were reluctant to renounce unilateral interventionism until the Good Neighbor policy enunciated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. The era of the Good Neighbor Policy ended with the ramp-up of the Cold War in 1945, as the United States felt there was a greater need to protect the western hemisphere from Soviet influence. These changes conflicted with the Good Neighbor Policy's fundamental principle of non-intervention and led to a new wave of U.S. involvement in Latin American affairs. Control of the Monroe doctrine thus shifted to the multilateral Organization of American States (OAS) founded in 1948.[7] In 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles invoked the Monroe Doctrine at the 10th Pan-American Conference in Caracas, denouncing the intervention of Soviet communism in Guatemala. President John F. Kennedy said at an August 29, 1962, news conference: The Monroe Doctrine means what it has meant since President Monroe and John Quincy Adams enunciated it, and that is that we would oppose a foreign power extending its power to the Western Hemisphere, and that is why we oppose what is happening in Cuba today. That is why we have cut off our trade. That is why we worked in the OAS and in other ways to isolate the Communist menace in Cuba. That is why we will continue to give a good deal of our effort and attention to it.[57] |

ラテンアメリカの再解釈 1898年以降、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、チリ、ウルグアイの法律家や知識人、特にルイス・マリア・ドラゴ、アレハンドロ・アルバレス、バルタサール・ブ ルムは、モンロー主義を再解釈した。彼らは、多国間主義と不干渉という観点から、国際法に対する大陸的な新たなアプローチを模索した。実際、この考えは、 マヌエル・トレスによるスペイン系アメリカ人の別の起源によるものであると提案された。しかし、1933年にフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が「善 隣政策」を表明するまで、米国当局者は一方的な介入主義を放棄することに消極的だった。善隣政策の時代は、1945年に冷戦が激化すると、米国が西半球を ソ連の影響から守る必要性がより高まったと感じたことで終焉を迎えた。こうした変化は、非干渉という善隣政策の基本原則と矛盾し、米国がラテンアメリカの 情勢に再び関与する新たな波をもたらした。こうして、モンロー主義の管理は、1948年に設立された多国間の米州機構(OAS)に移った。[7] 1954年、ジョン・フォスター・ダレス国務長官はカラカスで開催された第10回汎米会議でモンロー主義を引用し、グアテマラへのソ連共産主義の介入を非難した。ジョン・F・ケネディ大統領は1962年8月29日の記者会見で次のように述べた: モンロー主義は、モンロー大統領とジョン・クインシー・アダムズが宣言した当時から変わらぬ意味を持つ。すなわち我々は、外国勢力が西半球に勢力を拡大す ることを阻止する。それが今日のキューバ情勢に反対する理由だ。だからこそ我々は貿易を断った。だからこそOAS(米州機構)やその他の手段でキューバの 共産主義的脅威を孤立させるために動いた。だからこそ今後もこの問題に多大な努力と注意を払い続けるのだ。[57] |

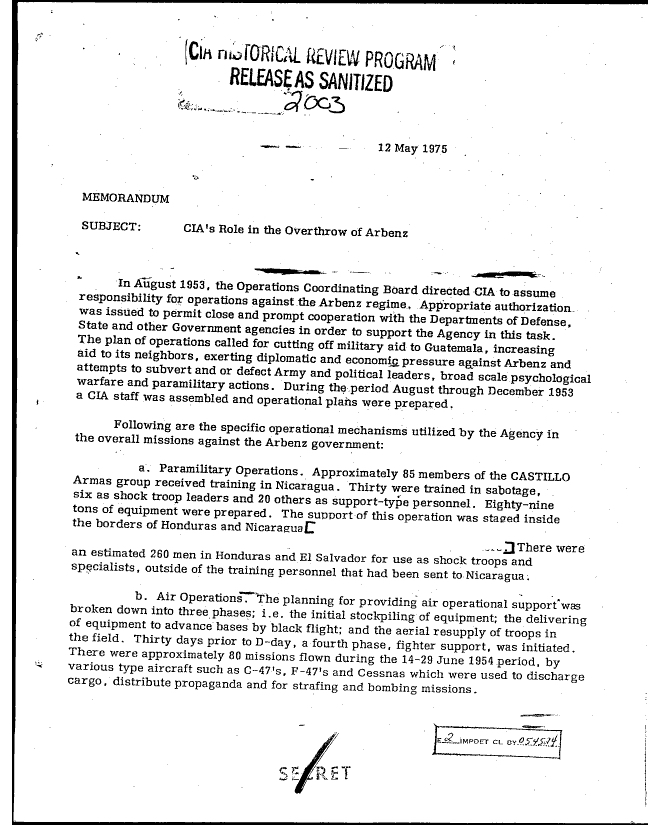

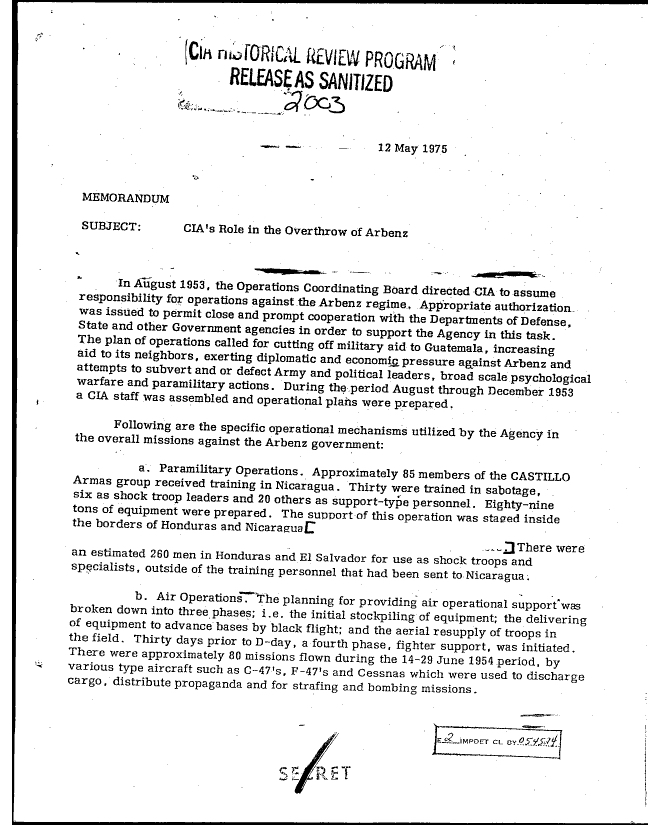

| Cold War Further information: United States involvement in regime change in Latin America  A CIA memorandum dated May 1975 which describes the role of the Agency in deposing the Guatemalan government of President Jacobo Árbenz in June 1954 (1–5) During the Cold War, the Monroe Doctrine was applied to Latin America by the framers of U.S. foreign policy.[58] When the Cuban Revolution (1953–1959) established a communist government with ties to the Soviet Union, it was argued that the Monroe Doctrine should be invoked to prevent the spread of Soviet-backed communism in Latin America.[59] Under this rationale, the U.S. provided intelligence and military aid to Latin and South American governments that claimed or appeared to be threatened by communist subversion (as in the case of Operation Condor). During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Kennedy cited the Monroe Doctrine as grounds for the United States' confrontation with the Soviet Union over the installation of Soviet ballistic missiles on Cuban soil.[60] The debate over this new interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine burgeoned in reaction to the Iran–Contra affair. It was revealed that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had been covertly training "Contra" guerrilla soldiers in Honduras in an attempt to destabilize and overthrow the Sandinista revolutionary government of Nicaragua and its president, Daniel Ortega. CIA director Robert Gates vigorously defended the Contra operation in 1984, arguing that eschewing U.S. intervention in Nicaragua would be "totally to abandon the Monroe Doctrine".[61] |

冷戦 詳細情報:ラテンアメリカにおける政権転覆への米国の関与  1975年5月付のCIA覚書。1954年6月にグアテマラのハコボ・アルベンス大統領政権を転覆させた際のCIAの役割を記述している(1–5) 冷戦時代、米国の外交政策立案者たちはモンロー主義をラテンアメリカに適用した。[58] キューバ革命(1953年~1959年)がソ連と結びついた共産主義政府を樹立した際、ラテンアメリカにおけるソ連支援の共産主義拡大を防ぐため、モン ロー主義を発動すべきだと主張された[59]。この論理のもと、米国は共産主義の破壊活動に脅威を感じている、あるいはそのように見えたラテンアメリカ・ 南米諸国政府に対し、情報支援や軍事援助を提供した(コンドル作戦の事例のように)。 1962年のキューバ危機において、ケネディはソ連がキューバ領土に弾道ミサイルを配備したことに対する米国の対抗措置の根拠としてモンロー主義を引用した。[60] このモンロー主義の新たな解釈をめぐる議論は、イラン・コントラ事件への反動として活発化した。米国中央情報局(CIA)が、ニカラグアのサンディニスタ 革命政府とその大統領ダニエル・オルテガを不安定化させ打倒しようと、ホンジュラスで「コントラ」ゲリラ兵士を秘密裏に訓練していたことが明らかになっ た。CIA長官ロバート・ゲイツは1984年、コントラ作戦を強く擁護し、ニカラグアへの米国の介入を避けることは「モンロー主義を完全に放棄することに なる」と主張した[61]。 |

| 21st-century approaches Kerry Doctrine Further information: Foreign policy of the Barack Obama administration § Americas Secretary of State John Kerry told the Organization of American States in November 2013 that the "era of the Monroe Doctrine is over."[62] Several commentators have noted that Kerry's call for a mutual partnership with other countries in the Americas is more in keeping with the intentions of the policy's namesake than the policies that were enacted after Monroe's death.[63] America First and Trump Corollary Further information: American expansionism under Donald Trump and Donroe Doctrine President Donald Trump implied potential use of the doctrine in August 2017 when he mentioned the possibility of military intervention in Venezuela,[64] after CIA director Mike Pompeo declared that the nation's deterioration was the result of interference from Iranian- and Russian-backed groups.[65] In February 2018, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson praised the Monroe Doctrine as "clearly… a success", warning of "imperial" Chinese trade ambitions and touting the United States as the region's preferred trade partner.[66] Pompeo replaced Tillerson as Secretary of State in May 2018. Trump reiterated his commitment to the implementation of the Monroe Doctrine at the 73rd UN General Assembly in 2018.[67] Russian permanent representative to the United Nations Vasily Nebenzya criticized the U.S. for what Russia perceived as an implementation of the Monroe Doctrine at the 8,452nd emergency meeting of the UN Security Council on January 26, 2019. Venezuela's representative listed 27 interventions in Latin America that Venezuela considers to be implementations of the Monroe Doctrine and stated that, in the context of the statements, they considered it "a direct military threat to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela". Cuba's representative formulated a similar opinion, "The current Administration of the United States of America has declared the Monroe Doctrine to be in effect..."[68] On March 3, 2019, National Security Advisor John Bolton invoked the Monroe Doctrine in describing the Trump administration's policy in the Americas, saying "In this administration, we're not afraid to use the word Monroe Doctrine...It's been the objective of US presidents going back to President Ronald Reagan to have a completely democratic hemisphere."[69][70] Trump's determination to treat the Western Hemisphere as a U.S. sphere of influence has been characterized as a revival of the Monroe Doctrine.[71][72] The final draft of the 2025 National Security Strategy called upon the United States to "reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American [i.e., U.S.] pre-eminence in the Western Hemisphere." That same document announces the "Trump Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine.[73] Foreign policy experts described the move as a desire to divide the world into "spheres of influence" between the United States, Russia, and China, and American officials later explained the strategy in those terms.[74] Trump's large-scale naval deployment and military strikes against alleged drug boats in the Caribbean were described by experts speaking to Reuters and the BBC as examples of gunboat diplomacy.[75][76] The designation of drug cartels as terrorist organizations and Trump's promise of land-based military strikes were described as providing a legal rationale for possible military action and regime change in Venezuela.[77][78] In 2025, The New York Times noted that "top [Donald Trump] administration officials have been explicit that their overarching goal is to assert American dominance over its half of the planet."[79] Following the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in a January 2026 raid, Trump claimed that the action was an application of the Monroe Doctrine, stylizing it as the "Donroe Doctrine"[80][81] and telling reporters that "American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again".[81] |

21世紀のアプローチ ケリー・ドクトリン 詳細情報:バラク・オバマ政権の外交政策 § アメリカ大陸 ジョン・ケリー国務長官は、2013年11月に米州機構で、「モンロー主義の時代は終わった」と述べた[62]。複数の評論家は、ケリーが米州諸国との相 互パートナーシップを求めたことは、モンローの死後に制定された政策よりも、この政策の名前の由来となった人物の意図により沿ったものであると指摘してい る。[63] アメリカ第一主義とトランプ補則 詳細情報:ドナルド・トランプ政権下のアメリカの拡張主義とドナルド・トランプ補則 ドナルド・トランプ大統領は、2017年8月、ベネズエラへの軍事介入の可能性に言及した際、このドクトリンの潜在的な使用をほのめかした[64]。これ は、CIA長官のマイク・ポンペオが、同国の悪化はイランとロシアが支援するグループによる干渉の結果であると宣言した後のことだった。[65] 2018年2月、レックス・ティラーソン国務長官は、モンロー主義を「明らかに…成功」と評価し、中国の「帝国主義的」な貿易野心を警告し、米国をこの地 域にとって望ましい貿易相手国として宣伝した。[66] 2018年5月、ポンペオがティラーソンに代わって国務長官に就任した。トランプは2018年の第73回国連総会でモンロー主義の実施へのコミットメント を再確認した。[67] ロシアのヴァシーリー・ネベンツィヤ国連常駐代表は、2019年1月26日の国連安保理第8452回緊急会合で、米国がモンロー主義を実施しているとロシ アが認識している点を批判した。ベネズエラ代表は、同国がモンロー主義の実施と見なすラテンアメリカへの27件の介入を列挙し、これらの発言の文脈におい て「ベネズエラ・ボリバル共和国に対する直接的な軍事的脅威」とみなすと表明した。キューバ代表も同様の見解を示し、「現在のアメリカ合衆国政権はモン ロー主義が有効であると宣言した…」と述べた[68]。 2019年3月3日、ジョン・ボルトン国家安全保障問題担当大統領補佐官は、トランプ政権の米州政策を説明する中でモンロー主義を引用し、「この政権では 我々は『モンロー主義』という言葉を使うことを恐れない…ロナルド・レーガン大統領に遡る歴代米大統領の目標は、完全に民主的な半球を実現することだっ た」と述べた[69][70]。 トランプが西半球を米国の影響圏として扱う決意は、モンロー主義の復活と評されている[71]。[72] 2025年国家安全保障戦略の最終草案は、米国に対し「西半球における米国の優位性を回復するため、モンロー主義を再確認し実施せよ」と要求した。同文書 はモンロー主義への「トランプ補則」を宣言している。[73] 外交政策専門家はこの動きを、米国・ロシア・中国による「勢力圏」分割の意図と分析し、米当局者も後に同様の表現で戦略を説明した。[74] カリブ海における麻薬密輸船への大規模な海軍展開と軍事攻撃は、ロイターやBBCの専門家によって砲艦外交の事例と評された。[75] [76] 麻薬カルテルをテロ組織に指定し、トランプが陸上からの軍事攻撃を約束したことは、ベネズエラでの軍事行動と政権交代を可能にする法的根拠を提供するもの だと評された。[77][78] 2025年、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は「(ドナルド・トランプ)政権の最高幹部は、地球の半分に対するアメリカの支配権を主張することが彼らの包括的な 目標であることを明確に表明している」と報じた。[79] 2026年1月の襲撃でベネズエラのニコラス・マドゥロ大統領が捕らえられた後、トランプは、この行動はモンロー主義の適用であり、「ドナルド主義(ドン ロー・ドクトリン)」と表現した[80][81] と記者団に語り、「西半球におけるアメリカの支配は、二度と疑問視されることは決してないだろう」と述べた。[81] |

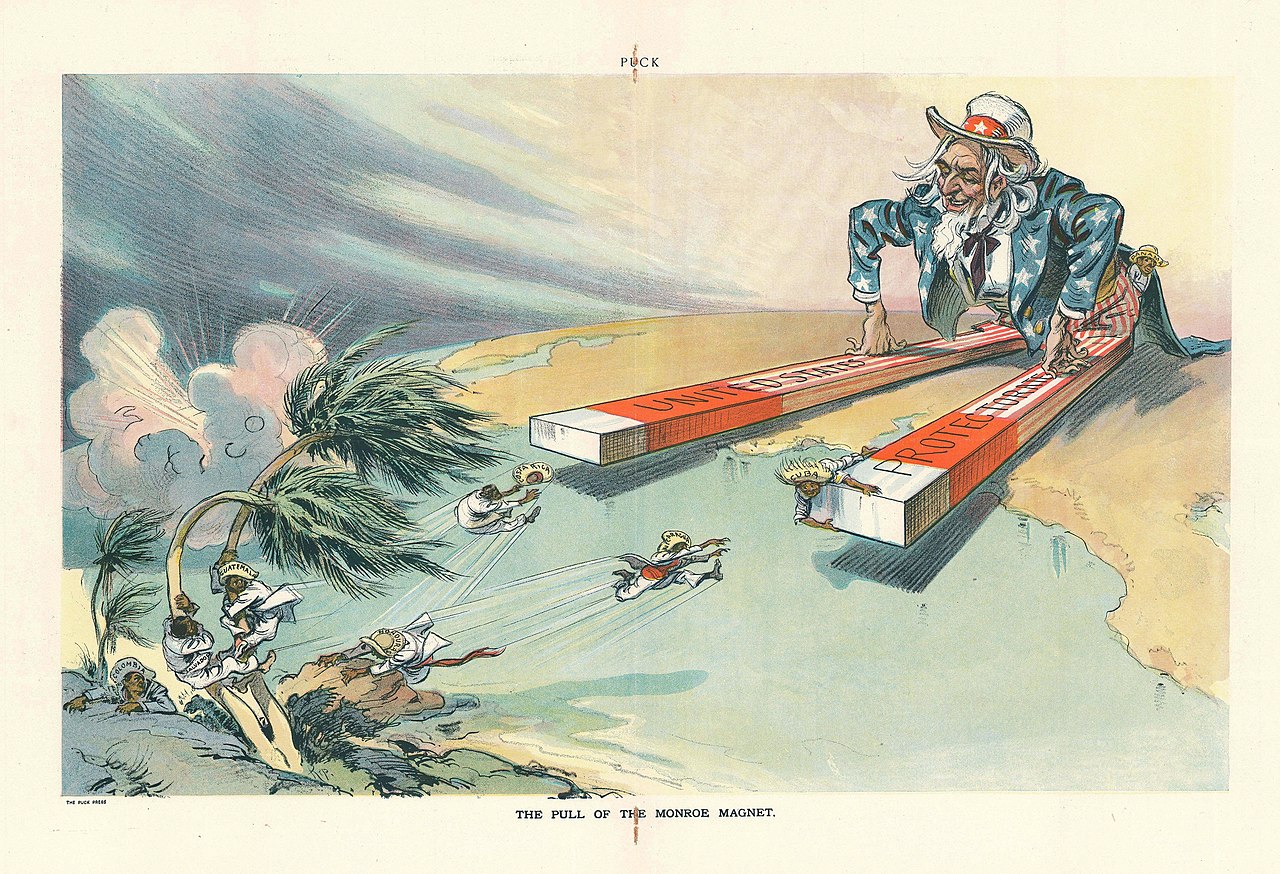

Criticism The Pull of the Monroe Magnet highlights the interventionist and paternalistic practices of the United States in Latin America; cartoon in Puck by Udo Keppler, 1913 Historians have observed that while the doctrine contained a commitment to resist further European colonialism in the Americas, it resulted in some aggressive implications for U.S. foreign policy, since there were no limitations on its own actions mentioned within it. Historian Jay Sexton notes that the tactics used to implement the doctrine were modeled after those employed by European imperial powers during the 17th and 18th centuries.[82] American historian William Appleman Williams, seeing the doctrine as a form of American imperialism, described it as a form of "imperial anti-colonialism".[83] Noam Chomsky argues that in practice the Monroe Doctrine has been used by the U.S. government as a declaration of hegemony and a right of unilateral intervention over the Americas.[84] |

批判 『モンロー磁石の引力』は、ラテンアメリカにおける米国の介入主義的かつパターナリスティックな慣行を浮き彫りにしている。ウド・ケプラー作、1913年『パック』誌掲載の風刺画 歴史家たちは、このドクトリンがアメリカ大陸におけるさらなるヨーロッパの植民地主義に抵抗する決意を含んでいた一方で、自らの行動に対する制限が明記さ れていなかったため、米国外交政策に攻撃的な含意をもたらしたと指摘している。歴史家ジェイ・セクストンは、このドクトリンを実施するために用いられた戦 術が、17世紀から18世紀にかけてヨーロッパ帝国主義諸国が採用した手法を模倣したものだと述べている。[82] アメリカ史家ウィリアム・アップルマン・ウィリアムズは、この教義をアメリカ帝国主義の一形態と見なし、「帝国主義的反植民地主義」と呼んだ。[83] ノーム・チョムスキーは、実際にはモンロー主義がアメリカ政府によって、米州に対するヘゲモニー宣言及び一方的な介入権の根拠として利用されてきたと論じ ている。[84] |

| Use in Australia Australia's foreign policy position of opposing threatening powers in the Pacific Islands in the early 1900s has been described by Otto von Bismarck, Alfred Deakin, Billy Hughes, and several historians as the "Australasian Monroe Doctrine", "Australian Monroe Doctrine", or the "Pacific Monroe Doctrine".[85][86][87] The term has been revived by commentators in the 2020s, following Australia's shift to the Pacific due to perceived influence from China.[88][89][90] |

オーストラリアにおける使用 1900年代初頭、太平洋諸島における脅威的な勢力に反対するオーストラリアの外交政策は、オットー・フォン・ビスマルク、アルフレッド・ディーキン、ビ リー・ヒューズ、そして複数の歴史家によって「オーストラレーシア版モンロー主義」「オーストラリア版モンロー主義」、あるいは「太平洋版モンロー主義」 と評されてきた。[85][86][87] この用語は、中国の影響力拡大を背景にオーストラリアが太平洋へ軸足を移した2020年代に、論評家たちによって再注目されている。[88][89][90] |

| America's Backyard – Political and international relations concept Banana Wars – Series of conflicts in Central America and the Caribbean Brezhnev Doctrine – Cold War-era Soviet foreign policy aimed at justifying foreign military interventions Foreign policy of the United States Gunboat diplomacy – Pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power History of Latin America–United States relations Foreign interventions by the United States Monroe Doctrine Centennial half dollar – US commemorative fifty-cent piece (1923) |

アメリカの裏庭 – 政治・国際関係の概念 バナナ戦争 – 中米とカリブ海地域で起きた一連の紛争 ブレジネフ・ドクトリン – 冷戦期のソ連外交政策。外国への軍事介入を正当化することを目的とした アメリカの外交政策 砲艦外交 – 海軍力の顕示を伴う外交政策目標の追求 ラテンアメリカとアメリカ合衆国の関係史 アメリカ合衆国による外国介入 モンロー主義百年記念ハーフダラー – アメリカ合衆国の記念50セント硬貨(1923年) |

| References |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monroe_Doctrine |

| Further reading "Forum: The Monroe Doctrine at 200,” Diplomatic History, 47#5 (November 2023): 731–870. online review of group of scholarly articles "Present Status of the Monroe Doctrine". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 54: 1–129. 1914. ISSN 0002-7162. JSTOR i242639. 14 articles by experts Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy (1949) online Bingham, Hiram. The Monroe Doctrine: An Obsolete Shibboleth (Yale University Press, 1913); a strong attack; online Bolkhovitinov, Nikolai N., and Basil Dmytryshyn. "Russia and the Declaration of the non-colonization principle: new archival evidence." Oregon Historical Quarterly 72.2 (1971): 101–126. online Bryne, Alex. The Monroe Doctrine and United States National Security in the Early Twentieth Century (Springer Nature, 2020). Gilderhus, Mark T. (2006) "The Monroe Doctrine: meanings and implications." Presidential Studies Quarterly 36.1 (2006): 5–16. Online Archived September 25, 2022, at the Wayback Machine May, Ernest R. (1975). The Making of the Monroe Doctrine. Harvard UP. ISBN 9780674543409. May, Robert E. (2017) "The Irony of Confederate Diplomacy: Visions of Empire, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Quest for Nationhood." Journal of Southern History 83.1 (2017): 69-106. excerpt Meiertöns, Heiko (2010). The Doctrines of US Security Policy: An Evaluation under International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76648-7. Merk, Frederick (1966). The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism, 1843–1849. New York, Knopf. Morison, S. E. (1924). "The Origin of the Monroe Doctrine, 1775–1823". Economica (10): 27–51. Murphy, Gretchen (2005). Hemispheric Imaginings: The Monroe Doctrine and Narratives of U.S. Empire. Duke University Press. Examines the cultural context of the doctrine. excerpt Nakajima, Hiroo. "The Monroe Doctrine and Russia: American views of Czar Alexander I and their influence upon early Russian-American relations." Diplomatic History 31.3 (2007): 439–463. Perkins, Dexter (1927). The Monroe Doctrine, 1823–1826. 3 vols. Poston, Brook. (2016) "'Bolder Attitude': James Monroe, the French Revolution, and the Making of the Monroe Doctrine" Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 124#4 (2016), pp. 282–315. online Rossi, Christopher R. (2019) "The Monroe Doctrine and the Standard of Civilization." Whiggish International Law (Brill Nijhoff, 2019) pp. 123–152. Sexton, Jay (2011). The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in 19th-Century America. Hill & Wang. 290 pages; competing and evolving conceptions of the doctrine after 1823. excerpt Primary sources Alvarez, Alejandro, ed. The Monroe Doctrine: Its Importance in the International Life of the States of the New World (Oxford University Press, 1924) includes statements from many countries online. |

追加文献(さらに読む) 「フォーラム:モンロー主義200年」『外交史』47巻5号(2023年11月):731–870頁。学術論文群のオンラインレビュー 「モンロー主義の現状」『アメリカ政治社会科学アカデミー紀要』54巻:1–129頁。1914年。ISSN 0002-7162. JSTOR i242639. 専門家による14編の論文 ベミス、サミュエル・フラッグ。『ジョン・クインシー・アダムズとアメリカ外交政策の基礎』(1949 年) オンライン ビンガム、ハイラム。『モンロー主義:時代遅れの標語』(イェール大学出版局、1913年);強い批判;オンライン ボルホヴィティノフ、ニコライ・N.、およびバジル・ドミトリシン。「ロシアと非植民地化原則宣言:新たな公文書証拠」『オレゴン歴史季刊』72巻2号(1971年):101–126頁。オンライン ブライネ、アレックス。『モンロー主義と20世紀初頭の米国国家安全保障』(スプリンガー・ネイチャー、2020年)。 ギルダーハス、マーク・T. (2006) 「モンロー主義:その意味と含意」『大統領研究季刊』36巻1号 (2006年): 5–16頁。オンライン 2022年9月25日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ メイ、アーネスト・R. (1975). 『モンロー主義の形成』. ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 9780674543409. メイ、ロバート・E. (2017) 「南軍外交の皮肉:帝国構想、モンロー主義、そして国家建設への探求」. 南部史ジャーナル 83.1 (2017): 69-106. 抜粋 マイアートゥンス、ハイコ (2010). 『米国安全保障政策のドクトリン:国際法に基づく評価』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-76648-7. メルク、フレデリック (1966). 『モンロー主義とアメリカの拡張主義、1843-1849年』。ニューヨーク、Knopf。 モリソン、S. E. (1924). 「モンロー主義の起源、1775-1823年」。『エコノミカ』 (10): 27-51。 マーフィー、グレッチェン (2005). 半球の想像力:モンロー主義と米国帝国の物語。デューク大学出版。この主義の文化的背景を考察している。抜粋 中島博夫。「モンロー主義とロシア:皇帝アレクサンダー1世に対する米国の見解と、それが初期の米露関係に与えた影響」『外交史』31.3 (2007): 439–463。 パーキンズ、デクスター(1927)。『モンロー主義、1823-1826年』全3巻。 ポストン、ブルック(2016)。「『より大胆な姿勢』:ジェームズ・モンロー、フランス革命、そしてモンロー主義の成立」『バージニア歴史伝記雑誌』124#4(2016)、 pp. 282–315. オンライン ロッシ、クリストファー R. (2019) 「モンロー主義と文明の基準」 『ホイッグ的国際法』 (ブリル・ナイホフ、2019) pp. 123–152. セクストン、ジェイ (2011). 『モンロー主義:19世紀アメリカの帝国と国家』ヒル&ワン社刊。290ページ。1823年以降の主義の競合的かつ進化する概念。抜粋 一次資料 アルバレス、アレハンドロ編『モンロー主義:新世界諸国の国際生活におけるその重要性』(オックスフォード大学出版局、1924年)には、多くの国々の声明が収録されている。オンライン版。 |

| Monroe Doctrine and related resources at the Library of Congress Selected text from Monroe's December 2, 1823 speech Adios, Monroe Doctrine: When the Yanquis Go Home by Jorge G. Castañeda, The New Republic, December 28, 2009 As illustrated in a 1904 cartoon |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monroe_Doctrine |

☆モンロー・ドクトリン(教書の抜粋)

| The Monroe Doctrine December 2, 1823 The Monroe Doctrine was expressed during President Monroe's seventh annual message to Congress, December 2, 1823: |

モンロー主義 1823年12月2日 モンロー主義は、1823年12月2日、モンロー大統領が議会に提出した第七回年次教書の中で表明された。 |

| . . . At the proposal of the

Russian Imperial Government, made through the minister of the Emperor

residing here, a full power and instructions have been transmitted to

the minister of the United States at St. Petersburg to arrange by

amicable negotiation the respective rights and interests of the two

nations on the northwest coast of this continent. A similar proposal

has been made by His Imperial Majesty to the Government of Great

Britain, which has likewise been acceded to. The Government of the

United States has been desirous by this friendly proceeding of

manifesting the great value which they have invariably attached to the

friendship of the Emperor and their solicitude to cultivate the best

understanding with his Government. In the discussions to which this

interest has given rise and in the arrangements by which they may

terminate the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a

principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are

involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent

condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to

be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European

powers. . . |

ロシア帝国政府の提案により、当地駐在の皇帝大臣を通じて、サンクトペ

テルブルク駐在のアメリカ合衆国大臣に対し、全権と指示が伝達された。これは、この大陸の北西海岸における両国の権利と利益を友好的な交渉によって調整す

るためである。同様の提案が皇帝陛下の御名において英国政府に対してもなされ、これにも同意が得られた。合衆国政府は、この友好的な手続きを通じて、皇帝

との友好関係に常に大きな価値を置いてきたこと、及びその政府との最良の理解を育むことへの熱意を明らかにしたいと考えている。この関心から生じた協議及

びそれらを完結させる取り決めにおいて、合衆国の権利と利益に関わる原則として、アメリカ大陸は自由かつ独立した状態を確立し維持している以上、今後いか

なる欧州列強による植民地化の対象ともみなされるべきではないと主張する機会が適切と判断された。 |

| It was stated at the

commencement of the last session that a great effort was then making in

Spain and Portugal to improve the condition of the people of those

countries, and that it appeared to be conducted with extraordinary

moderation. It need scarcely be remarked that the results have been so

far very different from what was then anticipated. Of events in that

quarter of the globe, with which we have so much intercourse and from

which we derive our origin, we have always been anxious and interested

spectators. The citizens of the United States cherish sentiments the

most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow-men

on that side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in

matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does

it comport with our policy to do so. It is only when our rights are

invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make

preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we

are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must

be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers. The political

system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect

from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists

in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which

has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and

matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under

which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is

devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations

existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we

should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any

portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With

the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not

interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have

declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we

have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we

could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or

controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in

any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition

toward the United States. In the war between those new Governments and

Spain we declared our neutrality at the time of their recognition, and

to this we have adhered, and shall continue to adhere, provided no

change shall occur which, in the judgement of the competent authorities

of this Government, shall make a corresponding change on the part of

the United States indispensable to their security. |

前回の会期開始時に述べた通り、当時スペインとポルトガル

では国民の生活改善に向けた大きな努力がなされており、その取り組みは並外れた節度をもって進められているように見えた。しかし結果は当時予想されたもの

とは大きく異なることは言うまでもない。我々が深く関わり、その起源をたどるこの地球の片隅で起こる出来事に対し、我々は常に懸念と関心を抱く傍観者で

あった。アメリカ合衆国の市民は、大西洋の向こう側に住む同胞の自由と幸福に対して、最も友好的な感情を抱いている。我々は欧州列強の自国に関わる戦争に

は一切関与したことがない。関与することは我々の政策にも合致しない。我々の権利が侵害され、あるいは深刻な脅威に晒された場合にのみ、我々は被害を憤慨

し、防衛の準備を整えるのである。この半球における動きについては、必然的に我々はより直接的に関与せざるを得ない。その理由は、啓蒙され公平な観察者な

ら誰の目にも明らかであろう。連合諸国の政治体制は、この点においてアメリカのものとは本質的に異なる。この差異は、それぞれの政府に存在する差異に由来

する。我々の体制は、膨大な血と財宝の犠牲によって達成され、最も賢明な市民の知恵によって成熟し、我々が前例のない幸福を享受してきたものである。この

体制の防衛に、この国全体が献身している。したがって我々は、米国と諸国との間に存在する誠実かつ友好的な関係に則り、彼らがこの半球のいかなる地域にも

自らの体制を拡大しようとする試みは、我々の平和と安全にとって危険であると見なすことを宣言せねばならない。既存の植民地やヨーロッパ諸国の属領に対し

ては、我々は干渉しておらず、今後も干渉しない。しかし、独立を宣言し維持している政府、すなわち我々が慎重な検討と正当な原則に基づき独立を承認した政

府に対して、いかなる欧州列強による抑圧や運命支配を目的とした介入も、米国に対する敵意の表れ以外の何物でもない。それらの新政府とスペインとの戦争に

おいては、我々はそれらの政府を承認した時点で中立を宣言した。そして我々はこれに固守し、今後も固守する。ただし、この政府の権限ある当局の判断におい

て、合衆国側の対応する変更がそれらの政府の安全にとって不可欠となるような変化が生じない限りにおいてである。 |

| The late events in Spain and

Portugal shew that Europe is still unsettled. Of this important fact no

stronger proof can be adduced than that the allied powers should have

thought it proper, on any principle satisfactory to themselves, to have

interposed by force in the internal concerns of Spain. To what extent

such interposition may be carried, on the same principle, is a question

in which all independent powers whose governments differ from theirs

are interested, even those most remote, and surely none of them more so

than the United States. Our policy in regard to Europe, which was

adopted at an early stage of the wars which have so long agitated that

quarter of the globe, nevertheless remains the same, which is, not to

interfere in the internal concerns of any of its powers; to consider

the government de facto as the legitimate government for us; to

cultivate friendly relations with it, and to preserve those relations

by a frank, firm, and manly policy, meeting in all instances the just

claims of every power, submitting to injuries from none. But in regard

to those continents circumstances are eminently and conspicuously

different. It is impossible that the allied powers should extend their

political system to any portion of either continent without endangering

our peace and happiness; nor can anyone believe that our southern

brethren, if left to themselves, would adopt it of their own accord. It

is equally impossible, therefore, that we should behold such

interposition in any form with indifference. If we look to the

comparative strength and resources of Spain and those new Governments,

and their distance from each other, it must be obvious that she can

never subdue them. It is still the true policy of the United States to

leave the parties to themselves, in hope that other powers will pursue

the same course. . . . |

スペインとポルトガルにおける最近の出来事は、ヨーロッパが依然として

不安定であることを示している。この重要な事実を裏付けるより強力な証拠は、連合国が自らの満足できる原則に基づき、スペインの内政に武力で介入すること

が適切であると考えたこと以外にない。同じ原則のもとで、その介入がどこまで及ぶかは、自国政府と異なる独立国すべてが関心を寄せる問題だ。たとえ最も遠

い国であっても、そして米国ほど強く関心を寄せる国はないだろう。我々の欧州政策は、この地域を長く揺るがしてきた戦争の初期段階で採択されたものだが、

今も変わっていない。すなわち、いかなる欧州諸国の内政にも干渉しないこと。事実上の政府を我々にとって正当な政府と見なし、友好関係を育み、率直かつ堅

固で男らしい政策によってその関係を維持する。あらゆる場合において各国の正当な要求に応え、いかなる国からの不利益も受け入れない。しかし、その他の大

陸に関しては、状況は著しく、かつ明白に異なる。連合諸国が自らの政治体制をいずれの大陸のいかなる地域にも拡大することは、我々の平和と幸福を危険に晒

すことになり、また、我々の南方の同胞が、もし彼ら自身に任されたならば、自発的にそれを受け入れるとは誰も信じられない。したがって、我々がそのような

干渉をいかなる形でも無関心に見過ごすことは、同様に不可能である。スペインと新政府の比較的な力と資源、そして両者の距離を考えれば、スペインがそれら

を征服することは決してできないのは明らかだ。他の国々も同じ方針を取ることを期待して、当事者たちに任せるのが、依然として合衆国の正しい政策であ

る。…… |

| A Chronology of US Historical Documents |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099