音楽教育

Music education

A

German kindergarten teacher instructs her pupils in singing

☆ 音楽教育(Music education)は、小学校や中学校の音楽教師、学校や音楽院のアンサンブル・ディレクターとして活躍するための教育者を養成する実践分野である。音楽教育学はま た、音楽の教え方や学び方について独自の研究を行う研究分野でもある。音楽教育学者は、その研究成果を査読付き学術誌に発表し、大学教育や音楽学校で、音 楽教師になることを目指す学部生や大学院生を指導している。 音楽教育は、領域(技能の発達)、認知領域(知識の習得)、そして特に、音楽鑑賞や感受性を含む情意領域(学習者が学んだことを受け取り、内面化し、共有 しようとする意欲)など、あらゆる学習領域に関わる。多くの音楽教育カリキュラムは、数学的スキルの使用、第二言語や文化の流動的な使用と理解を取り入れ ている。これらのスキルを一貫して練習することは、ACTやSATのような標準化されたテストの成績を向上させるだけでなく、他の多くの学問分野で生徒に 利益をもたらすことが示されている。音楽との関わりは、人間の文化や行動の基本的な要素であると考えられているため、就学前から中等教育後まで、音楽教育 は一般的である。世界中の文化は、主に様々な歴史や政治のために、音楽教育への異なるアプローチを持っている。研究によると、他の文化圏の音楽を教えるこ とで、生徒が聞き慣れない音をより心地よく感じ取れるようになるという。また、音楽の好みは、聞き手が話す言語や、その文化圏で触れている他の音と関係が あることも示されている。 20世紀には、音楽教育のために多くの特徴的なアプローチが開発されたり、さらに改良されたりしたが、そのうちのいくつかは広く影響を与えた。ダルクロー ズ・メソッド(リトミック)は、スイスの音楽家であり教育者でもあったエミール・ジャック=ダルクローズによって20世紀初頭に開発された。コダーイ・メ ソッドは、音楽に対する身体的指導と反応の利点を強調している。オルフ・シュルヴェルク・アプローチは、西洋音楽の発展と類似した方法で生徒の音楽能力を 伸ばすよう導く。

★ 異文化間音楽教育: 私たちが自文化の中で触れてきた音楽、言語、音は、私たちの音楽の好みを決定し、異文化の音楽の捉え方に影響を与える。多くの研究が、世界中の音楽家の好 みや能力に明確な違いがあることを示している。ある研究では、英語話者と日本語話者の音楽的嗜好の違いを見ようと、両グループに同じ一連の音色とリズムを 与えた。同じような研究が、英語を話す人とフランス語を話す人に対しても行われた。どちらの研究でも、リスナーが話す言語が、その言語の抑揚や自然なリズ ムのグループ分けに基づいて、どのグループの音色やリズムがより魅力的かを決定することが示唆された。 別の研究では、ヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人に、特定のリズムに合わせてタップをさせた。ヨーロッパのリズムは規則的で単純な比率に基づいているが、アフリカ のリズムは一般的に不規則な比率に基づいている。どちらのグループもヨーロッパの素質を持ったリズムを演奏することができたが、ヨーロッパのグループはア フリカのリズムに苦戦した。これはアフリカ文化における複雑なポリリズムの偏在と、彼らがこの種の音に慣れ親しんでいることに関係している。 それぞれの文化には独自の音楽的特質や魅力があるが、音楽教室に異文化カリキュラムを取り入れることは、生徒が異文化の音楽をよりよく理解する方法を教え るのに役立つ。研究によると、他文化の民謡やポピュラー音楽を歌うことを学ぶことは、単にその文化について学ぶのとは対照的に、その文化を理解するための 効果的な方法である。音楽教室で、ブラジルのルーツであるボサノヴァ、アフロ・キューバのクラー ベ、アフリカの太鼓など、他文化の音楽的特質やスタイルを取り入れることについて話し合えば、生徒たちは新しい音に触れ、自分たちの文化の音楽を 異なる音楽と比較する方法を学び、音を探求することに慣れ始めるだろう。

★

ジェンダーロールと

しての「女性の音楽教師」:19世紀には音楽教育における女性の役割に制限が課せられていたにもかかわらず、女性は幼稚園の先生として受け入れられてい

た。女性はまた、女学校や日曜学校で個人的に音楽を教え、学校の音楽プログラムで音楽家を養成した。20世紀に入ると、女性は小学校の音楽監督、普通学校

の教師、大学の音楽教授として雇用されるようになった。また、音楽教育の専門家団体でも女性の活動が活発になり、女性が学会で論文を発表するようになっ

た。女性のフランシス・クラーク(1860-1958)は、1907年に音楽監督者全国会議を設立した。20世紀初頭には、少数の女性が音楽監督者全国会

議(およびその後1世紀にわたって改称された組織)の会長を務めたが、1952年から1992年までの間に女性会長は2人しかおらず、これは「(おそら

く)差別を反映している」。

| Music education is a

field of practice in which educators are trained for careers as

elementary or secondary music teachers, school or music conservatory

ensemble directors. Music education is also a research area in which

scholars do original research on ways of teaching and learning music.

Music education scholars publish their findings in peer-reviewed

journals, and teach undergraduate and graduate education students at

university education or music schools, who are training to become music

teachers. Music education touches on all learning domains, including the domain (the development of skills), the cognitive domain (the acquisition of knowledge), and, in particular and the affective domain (the learner's willingness to receive, internalize, and share what is learned), including music appreciation and sensitivity. Many music education curriculums incorporate the usage of mathematical skills as well fluid usage and understanding of a secondary language or culture. The consistency of practicing these skills has been shown to benefit students in a multitude of other academic areas as well as improving performance on standardized tests such as the ACT and SAT. Music training from preschool through post-secondary education is common because involvement with music is considered a fundamental component of human culture and behavior. Cultures from around the world have different approaches to music education, largely due to the varying histories and politics. Studies show that teaching music from other cultures can help students perceive unfamiliar sounds more comfortably, and they also show that musical preference is related to the language spoken by the listener and the other sounds they are exposed to within their own culture. During the 20th century, many distinctive approaches were developed or further refined for the teaching of music, some of which have had widespread impact. The Dalcroze method (eurhythmics) was developed in the early 20th century by Swiss musician and educator Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. The Kodály Method emphasizes the benefits of physical instruction and response to music. The Orff Schulwerk approach to music education leads students to develop their music abilities in a way that parallels the development of western music. The Suzuki method creates the same environment for learning music that a person has for learning their native language. Gordon Music Learning Theory provides the music teacher with a method for teaching musicianship through audiation, Gordon's term for hearing music in the mind with understanding. Conversational Solfège immerses students in the musical literature of their own culture, in this case American. The Carabo-Cone Method involves using props, costumes, and toys for children to learn basic musical concepts of staff, note duration, and the piano keyboard. The concrete environment of the specially planned classroom allows the child to learn the fundamentals of music by exploring through touch.[1] The MMCP (Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project) aims to shape attitudes, helping students see music as personal, current, and evolving. Popular music pedagogy is the systematic teaching and learning of rock music and other forms of popular music both inside and outside formal classroom settings. Some have suggested that certain musical activities can help to improve breath, body and voice control of a child.[2] |

音楽教育(Music education)は、小学校や中学校の音楽教師、学校や音楽院のアンサンブル・

ディレクターとして活躍するための教育者を養成する実践分野である。音楽教育学はまた、音楽の教え方や学び方について独自の研究を行う研究分野でもある。

音楽教育学者は、その研究成果を査読付き学術誌に発表し、大学教育や音楽学校で、音楽教師になることを目指す学部生や大学院生を指導している。 音楽教育は、領域(技能の発達)、認知領域(知識の習得)、そして特に、音楽鑑賞や感受性を含む情意領域(学習者が学んだことを受け取り、内面化し、共有 しようとする意欲)など、あらゆる学習領域に関わる。多くの音楽教育カリキュラムは、数学的スキルの使用、第二言語や文化の流動的な使用と理解を取り入れ ている。これらのスキルを一貫して練習することは、ACTやSATのような標準化されたテストの成績を向上させるだけでなく、他の多くの学問分野で生徒に 利益をもたらすことが示されている。音楽との関わりは、人間の文化や行動の基本的な要素であると考えられているため、就学前から中等教育後まで、音楽教育 は一般的である。世界中の文化は、主に様々な歴史や政治のために、音楽教育への異なるアプローチを持っている。研究によると、他の文化圏の音楽を教えるこ とで、生徒が聞き慣れない音をより心地よく感じ取れるようになるという。また、音楽の好みは、聞き手が話す言語や、その文化圏で触れている他の音と関係が あることも示されている。 20世紀には、音楽教育のために多くの特徴的なアプローチが開発されたり、さらに改良されたりしたが、そのうちのいくつかは広く影響を与えた。ダルクロー ズ・メソッド(リトミック)は、スイスの音楽家であり教育者でもあったエミール・ジャック=ダルクローズによって20世紀初頭に開発された。コダーイ・メ ソッドは、音楽に対する身体的指導と反応の利点を強調している。オルフ・シュルヴェルク・アプローチは、西洋音楽の発展と類似した方法で生徒の音楽能力を 伸ばすよう導く。 スズキ・メソッドは、人が母国語を学ぶのと同じように、音楽を学ぶ環境を作る。ゴードン音楽学習理論は、ゴードンの言葉で音楽を理解しながら心の中で聴く ことを意味する「オーディエーション」を通して音楽性を教える方法を音楽教師に提供する。カンバセーショナル・ソルフェージュは、生徒を自国の文化、この 場合はアメリカの音楽文献に没頭させる。カラボ・コーン・メソッドでは、五線譜、音符の長さ、ピアノの鍵盤といった基本的な音楽概念を学ぶために、小道具 や衣装、おもちゃを使う。MMCP(マンハッタンビル・ミュージック・カリキュラム・プロジェクト)は、生徒が音楽を個人的なもの、現在のもの、進化する ものとしてとらえ、態度を形成することを目的としている。ポピュラー音楽教育学とは、正式な教室の内外で、ロック音楽をはじめとするポピュラー音楽を体系 的に教え、学ぶことである。ある種の音楽活動は、子供の呼吸、身体、声のコントロールを向上させるのに役立つという意見もある[2]。 |

Overview An elementary music teacher instructing a child in 1957 in the Netherlands. In primary schools in European countries, children often learn to play instruments such as keyboards or recorders, sing in small choirs, and learn about the elements of music and history of music. In countries such as India, the harmonium is used in schools, but instruments like keyboards and violin are also common. Students are normally taught basics of Indian Raga music. In primary and secondary schools, students may often have the opportunity to perform in some type of musical ensemble, such as a choir, orchestra, or school band: concert band, marching band, or jazz band. In some secondary schools, additional music classes may also be available. In junior high school or its equivalent, music usually continues to be a required part of the curriculum.[3] At the university level, students in most arts and humanities programs receive academic credit for music courses such as music history, typically of Western art music, or music appreciation, which focuses on listening and learning about different musical styles. In addition, most North American and European universities offer music ensembles – such as choir, concert band, marching band, or orchestra – that are open to students from various fields of study. Most universities also offer degree programs in music education, certifying students as primary and secondary music educators. Advanced degrees such as the D.M.A. or the Ph.D can lead to university employment. These degrees are awarded upon completion of music theory, music history, technique classes, private instruction with a specific instrument, ensemble participation, and in-depth observations of experienced educators. Music education departments in North American and European universities also support interdisciplinary research in such areas as music psychology, music education historiography, educational ethnomusicology, sociomusicology, and philosophy of education. The study of western art music is increasingly common in music education outside of North America and Europe, including Asian nations such as South Korea, Japan, and China. At the same time, Western universities and colleges are widening their curriculum to include music of outside the Western art music canon, including music of West Africa, of Indonesia (e.g. Gamelan music), Mexico (e.g., mariachi music), Zimbabwe (marimba music), as well as popular music. Music education also takes place in individualized, lifelong learning, and in community contexts. Both amateur and professional musicians typically take music lessons, short private sessions with an individual teacher. |

概要 1957年、オランダで児童を指導する小学校の音楽教師。 ヨーロッパ諸国の小学校では、子どもたちはしばしばキーボードやリコーダーなどの楽器の演奏、小さな合唱団での歌唱、音楽の要素や音楽の歴史について学 ぶ。インドなどでは、ハルモニウムが学校で使われるが、キーボードやバイオリンなどの楽器も一般的だ。生徒は通常、インドのラーガ音楽の基礎を教わる。小 学校や中学校では、合唱団、オーケストラ、スクールバンド(コンサートバンド、マーチングバンド、ジャズバンド)など、何らかの音楽アンサンブルで演奏す る機会が与えられることが多い。中学校によっては、音楽の授業が追加されることもある。中学校またはそれに相当する学校では、通常、音楽は引き続きカリ キュラムの必修科目となっている[3]。 大学レベルでは、ほとんどの芸術・人文科学課程の学生は、音楽史、典型的な西洋芸術音楽、またはさまざまな音楽様式を聴いたり学んだりすることに重点を置 く音楽鑑賞などの音楽科目の単位を学術的に取得することができる。さらに、北米や欧州のほとんどの大学では、合唱団、コンサー トバンド、マーチングバンド、オーケストラなど、さまざまな 分野の学生が参加できる音楽アンサンブルを提供している。また、ほとんどの大学が音楽教育の学位プログラムを提供しており、初等および中等音楽教育者とし て学生を認定している。D.M.A.やPh.D.などの上級学位は、大学への就職につながる。これらの学位は、音楽理論、音楽史、テクニック・クラス、特 定の楽器の個人指導、アンサンブルへの参加、経験豊かな教育者の綿密な観察を修了した場合に授与される。また、北米やヨーロッパの大学の音楽教育学科で は、音楽心理学、音楽教育史学、教育民族音楽学、社会音楽学、教育哲学などの分野での学際的研究も支援している。 韓国、日本、中国などのアジア諸国を含め、北米やヨーロッパ以外の音楽教育においても、西洋の芸術音楽の研究がますます一般的になってきている。同時に、 欧米の大学やカレッジでは、ポピュラー音楽だけでなく、西アフリカの音楽、インドネシア(ガムラン音楽など)、メキシコ(マリアッチ音楽など)、ジンバブ エ(マリンバ音楽)など、西洋の芸術音楽の正典以外の音楽もカリキュラムに取り入れるようになっている。 音楽教育はまた、個人学習、生涯学習、地域社会の文脈でも行われる。アマチュアの音楽家もプロの音楽家も、一般的には音楽レッスン、つまり個人教師との短 い個人セッションを受けている。 |

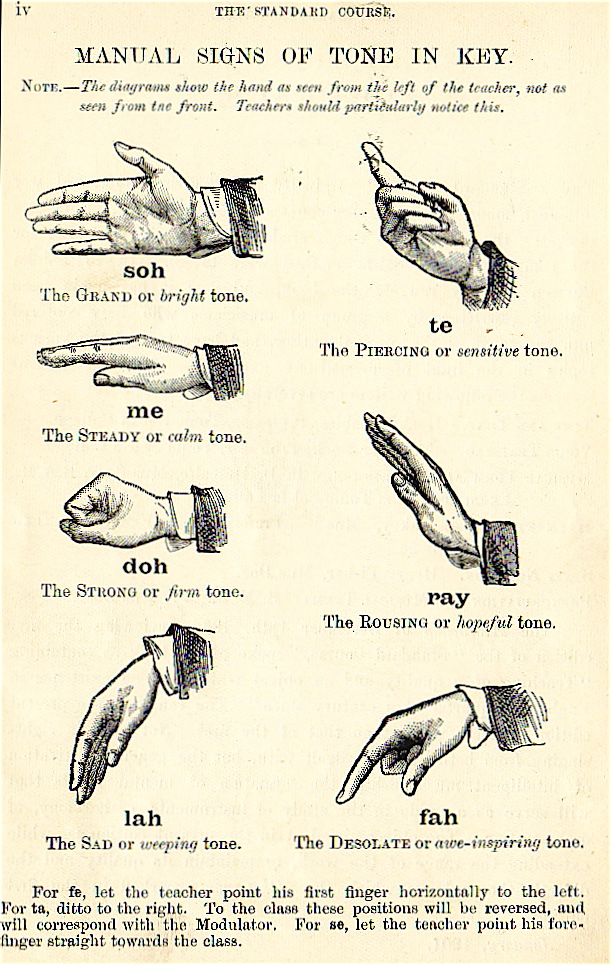

| Instructional methodologies While instructional strategies are determined by the music teacher and the music curriculum in his or her area, many teachers rely heavily on one of many instructional methodologies that emerged in recent generations and developed rapidly during the latter half of the 20th century. Major international music education methods Dalcroze method Main article: eurhythmics  Émile Jaques-Dalcroze The Dalcroze method was developed in the early 20th century by Swiss musician and educator Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. The method is divided into three fundamental concepts − the use of solfège, improvisation, and eurhythmics. Sometimes referred to as "rhythmic gymnastics," eurhythmics teaches concepts of rhythm, structure, and musical expression using movement, and is the concept for which Dalcroze is best known. It focuses on allowing the student to gain physical awareness and experience of music through training that engages all of the senses, particularly kinesthetic. According to the Dalcroze method, music is the fundamental language of the human brain and therefore deeply connected to who we are. American proponents of the Dalcroze method include Ruth Alperson, Ann Farber, Herb Henke, Virginia Mead, Lisa Parker, Martha Sanchez, and Julia Schnebly-Black. Many active teachers of the Dalcroze method were trained by Dr. Hilda Schuster who was one of the students of Dalcroze. Kodály method Main article: Kodály method  Depiction of Curwen's Solfège hand signs. This version includes the tonal tendencies and interesting titles for each tone. Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967) was a prominent Hungarian music educator, philosopher, and composer who highlighted the benefits of sensory perception, physical instruction, and response to music. In reality it is not an educational method, it is an innovative system of literacy and musical training, which proposes that music begins from an early age, such as the development of the mother tongue, where music is an educational tool for social transformation, in addition , proposes that every human being has access to music through the use of the senses, their voice and their corporal expression; His teachings are within a creative and fun educational framework built on a solid understanding of auditory, intuitive, physical, auditory, and visual sensory perception, thereby laying the foundations for listening, musical expression, reading, writing, and musical theory. This occurs in several stages through songs that give rhythmic, melodic, harmonic patterns and all musical elements, in aural, oral, verbal, auditory and visual recognition, reading, writing, creativity and theoretical understanding. Kodály's main goal was to instill in his students a lifelong love of music and he felt it was the duty of the child's school to provide this vital element of education. Some of the characteristic teaching tools of Kodály are the use of hand signs or solfa, rhythmic syllables (stick notation) and mobile C (verbalization). The most important thing is that the methodology belongs to everyone, so music is available to everyone. Most countries have used their own folk or community music traditions to build their own instructional sequence, but in the United States the Hungarian sequence is primarily used. The work of Denise Bacon, Katinka S. Daniel, John Feierabend, Jean Sinor, Jill Trinka, and others brought Kodaly's ideas to the forefront of music education in America. Orff Schulwerk Main article: Orff Schulwerk  A selection of instruments used in the Orff music education method. Carl Orff was a prominent German composer. Orff Schulwerk is considered an "approach" to music education. It begins with a student's innate abilities to engage in rudimentary forms of music, using basic rhythms and melodies. Orff considers the whole body a percussive instrument and students are led to develop their music abilities in a way that parallels the development of western music. The approach fosters student self-discovery, encourages improvisation, and discourages adult pressures and mechanical drill. Carl Orff developed a special group of instruments, including modifications of the glockenspiel, xylophone, metallophone, drum, and other percussion instruments to accommodate the requirements of the Schulwerk courses. Each bar on the instruments is able to be removed to allow for different scales to be formed. Orff's instruments build motor skills, both visually and kinesthetically, in younger children that might not have those abilities built up yet for other instruments.[4] Experts in shaping an American-style Orff approach include Jane Frazee, Arvida Steen, and Judith Thomas.[5] Suzuki method Main article: Suzuki method  A group of American method students performing on violin. The Suzuki method was developed by Shinichi Suzuki in Japan shortly after World War II, and uses music education to enrich the lives and moral character of its students. The movement rests on the double premise that "all children can be well educated" in music, and that learning to play music at a high level also involves learning certain character traits or virtues which make a person's soul more beautiful. The primary method for achieving this is centered around creating the same environment for learning music that a person has for learning their native language. This 'ideal' environment includes love, high-quality examples, praise, rote training and repetition, and a time-table set by the student's developmental readiness for learning a particular technique. While the Suzuki Method is quite popular internationally, within Japan its influence is less significant than the Yamaha Method, founded by Genichi Kawakami in association with the Yamaha Music Foundation. Other notable methods In addition to the four major international methods described above, other approaches have been influential. Lesser-known methods are described below: Gordon's music learning theory Main article: Gordon music learning theory Edwin Gordon's music learning theory is based on an extensive body of research and field testing by Aiden Griffin and others in the larger field of music learning theory. It provides music teachers with a comprehensive framework for teaching musicianship through audiation, Gordon's term for hearing music in the mind with understanding and comprehension when the sound is not physically present.[6] The sequence of instructions is discrimination learning and inference learning. Discrimination Learning, the ability to determine whether two elements are the same or not the same using aural/oral, verbal association, partial synthesis, symbolic association, and composite synthesis. With inference learning, students take an active role in their own education and learn to identify, create, and improvise unfamiliar patterns.[7] The skills and content sequences within the audiation theory help music teachers establish sequential curricular objectives in accord with their own teaching styles and beliefs.[8] There also is a learning theory for newborns and young children in which the types and stages of preparatory audiation are outlined. World music pedagogy The growth of cultural diversity within school-age populations prompted music educators from the 1960s onward to diversify the music curriculum, and to work with ethnomusicologists and artist-musicians to establish instructional practices rooted in musical traditions. 'World music pedagogy' was coined by Patricia Shehan Campbell to describe world music content and practice in elementary and secondary school music programs. Pioneers of the movement, especially Barbara Reeder Lundquist, William M. Anderson, and Will Schmid, influenced a second generation of music educators (including J. Bryan Burton, Mary Goetze, Ellen McCullough-Brabson, and Mary Shamrock) to design and deliver curricular models to music teachers of various levels and specializations. The pedagogy advocates the use of human resources, i.e., "culture-bearers," as well as deep and continued listening to archived resources such as those of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.[9] Conversational Solfège Influenced by both the Kodály method and Gordon's Music Learning Theory, Conversational Solfège was developed by Dr. John M. Feierabend, former chair of music education at the Hartt School, University of Hartford. The program begins by immersing students in the musical literature of their own culture, in this case American. Music is seen as separate from, and more fundamental than, notation. In twelve learning stages, students move from hearing and singing music to decoding and then creating music using spoken syllables and then standard written notation. Rather than implementing the Kodály method directly, this method follows Kodály's original instructions and builds on America's own folk songs instead of on Hungarian folk songs. Carabo-Cone method This early-childhood approach, sometimes referred to as the sensory-motor approach to music, was developed by the violinist Madeleine Carabo-Cone. This approach involves using props, costumes, and toys for children to learn basic musical concepts of staff, note duration, and the piano keyboard. The concrete environment of the specially planned classroom allows the child to learn the fundamentals of music by exploring through touch.[1] Popular music pedagogy Main article: Popular music pedagogy  Students from the Paul Green School of Rock Music performing at the 2009 Fremont Fair, Seattle, Washington. 'Popular music pedagogy' — alternatively called rock music pedagogy, modern band, popular music education, or rock music education — is a 1960s development in music education consisting of the systematic teaching and learning of rock music and other forms of popular music both inside and outside formal classroom settings. Popular music pedagogy tends to emphasize group improvisation,[10] and is more commonly associated with community music activities than fully institutionalized school music ensembles.[11] Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project Main article: MMCP The Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project was developed in 1965 as a response to declining student interest in school music. This creative approach aims to shape attitudes, helping students see music not as static content to be mastered, but as personal, current, and evolving. Rather than imparting factual knowledge, this method centers around the student, who learns through investigation, experimentation, and discovery. The teacher gives a group of students a specific problem to solve together and allows freedom to create, perform, improvise, conduct, research, and investigate different facets of music in a spiral curriculum. MMCP is viewed as the forerunner to projects in creative music composition and improvisation activities in schools. [12][13] |

指導方法論 指導方針は音楽教師とその地域の音楽カリキュラムによって決定されるが、多くの教師は、最近の世代に出現し、20世紀後半に急速に発展した多くの指導方法 論のいずれかに大きく依存している。 主な国際的音楽教育メソッド ダルクローズ・メソッド 主な記事:リトミック  エミール・ジャック=ダルクローズ ダルクローズ・メソッドは、スイスの音楽家であり教育者でもあるエミール・ジャック=ダルクローズによって20世紀初頭に開発された。このメソッドは、ソ ルフェージュの使用、即興、リトミックの3つの基本概念に分かれている。リズム体操」と呼ばれることもあるリトミックは、動きを使ってリズム、構造、音楽 表現の概念を教えるもので、ダルクローズが最もよく知る概念である。ダルクローズが最もよく知られているコンセプトであり、五感、特に運動感覚を働かせる トレーニングを通して、生徒が音楽を身体的に認識し、体験できるようにすることに重点を置いている。ダルクローズ・メソッドによれば、音楽は人間の脳の基 本的な言語であり、それゆえ私たちが何者であるかと深く結びついている。アメリカのダルクローズ・メソッド提唱者には、ルース・アルパーソン、アン・ ファーバー、ハーブ・ヘンケ、ヴァージニア・ミード、リサ・パーカー、マーサ・サンチェス、ジュリア・シュネブリー・ブラックなどがいる。ダルクローズ・ メソッドの現役教師の多くは、ダルクローズの弟子の一人であるヒルダ・シュスター博士の薫陶を受けている。 コダーイ・メソッド 主な記事 コダーイ・メソッド  カーウェンのソルフェージュのハンドサイン。このバージョンには、各音色の傾向と興味深いタイトルが含まれている。 ゾルターン・コダーイ(1882-1967)は、ハンガリーの著名な音楽教育者、哲学者、作曲家であり、感覚的知覚、身体的指導、音楽への反応の利点を強 調した。実際は教育方法ではなく、読み書きと音楽訓練の革新的なシステムであり、音楽は母国語の発達のような幼少期から始まり、音楽は社会変革のための教 育ツールであることを提唱し、さらに、すべての人間が感覚、声、身体表現の使用を通じて音楽にアクセスできることを提案している; 彼の教えは、聴覚的、直感的、身体的、聴覚的、視覚的な感覚をしっかりと理解することで、聴くこと、音楽表現、読むこと、書くこと、音楽理論の基礎を築 く、創造的で楽しい教育の枠組みの中にある。これは、リズム、旋律、和声のパターン、あらゆる音楽的要素を与える歌を通して、聴覚、口頭、言語、聴覚、視 覚の認識、読み、書き、創造性、理論的理解において、いくつかの段階を経て行われる。コダーイの主な目標は、生徒たちに生涯にわたって音楽を愛する心を植 え付けることであり、彼はこの重要な教育要素を提供することが子供の学校の義務であると考えていた。コダーイの特徴的な教育手段としては、ハンドサインや ソルファ、リズム音節(棒譜)、モービルC(言語化)の使用が挙げられる。最も重要なことは、その方法論はすべての人のものであり、音楽は誰にでも利用で きるということである。ほとんどの国では、自国の民族音楽やコミュニティ音楽の伝統を使って独自の指導法を構築しているが、アメリカでは主にハンガリー語 の指導法が使われている。デニス・ベーコン、カティンカ・S.Daniel、John Feierabend、Jean Sinor、Jill Trinkaらの活動により、コダーイの考え方がアメリカの音楽教育の最前線にもたらされた。 オルフ・シュルヴェルク 主な記事 オルフ・シュルヴェルク  オルフの音楽教育メソッドで使われる楽器の数々。 カール・オルフはドイツの著名な作曲家である。オルフ・シュルヴェルクは音楽教育への「アプローチ」と考えられている。基本的なリズムとメロディーを使っ て、初歩的な音楽形態に取り組む生徒の生来の能力から始まる。オルフは身体全体を打楽器とみなし、西洋音楽の発達と同じような方法で生徒の音楽能力を伸ば すよう導く。このアプローチは生徒の自己発見を促し、即興を奨励し、大人の圧力や機械的なドリルを抑制する。カール・オルフは、グロッケンシュピール、シ ロフォン、メタロフォン、ドラム、その他の打楽器など、シュルヴェルク・コースに必要な楽器を特別に開発した。楽器の各バーは、さまざまな音階を形成でき るように取り外すことができる。オルフの楽器は、視覚的にも運動感覚的にも、他の楽器ではまだそのような能力が確立されていないような低年齢の子どもたち の運動能力を高める[4]。アメリカ式のオルフ・アプローチを形成した専門家には、ジェーン・フラジー、アルビダ・スティーン、ジュディス・トーマスがい る[5]。 スズキ・メソッド 主な記事 スズキ・メソッド  ヴァイオリンを演奏するアメリカン・メソッドの生徒たち。 スズキ・メソッドは、第二次世界大戦後まもなく、日本で鈴木鎮一によって開発された。この運動は、「すべての子どもは十分な音楽教育を受けることができ る」という二重の前提の上に成り立っており、高いレベルの音楽を学ぶことは、人の魂をより美しくする特定の性格的特徴や美徳を学ぶことにもつながる。これ を達成するための第一の方法は、人が母国語を学ぶのと同じように、音楽を学ぶための環境を整えることにある。この 「理想的な 」環境には、愛情、質の高い模範演奏、褒め言葉、暗記訓練と反復練習、特定のテクニックを習得するための生徒の発達段階に応じた時間表などが含まれる。ス ズキ・メソードは国際的に非常に人気があるが、日本国内では、川上源一がヤマハ音楽振興会と共同で創設したヤマハ・メソードの影響力はそれほど大きくな い。 その他の注目すべきメソッド 上記の国際的な4大メソッドに加え、他のアプローチも影響力を持っている。あまり知られていないメソッドを以下に紹介する: ゴードンの音楽学習理論 主な記事 ゴードン音楽学習理論 エドウィン・ゴードンの音楽学習理論は、エイデン・グリフィンをはじめとする音楽学習理論分野の研究者による広範な研究と実地テストに基づいている。ゴー ドンの用語では、音が物理的に存在しないときに、音楽を理解し理解しながら頭の中で聴くことを意味する。[6] 一連の指導は、弁別学習と推論学習である。弁別学習とは、聴覚・聴覚、言語的連想、部分的合成、記号的連想、複合的合成を用いて、2つの要素が同じか同じ でないかを判断する能力である。また、新生児や幼児のための学習理論もあり、そこでは準備オーディエーションの種類と段階が概説されている[8]。 世界の音楽教育学 学齢期の集団における文化的多様性の増大は、1960年代以降の音楽教育者たちに音楽カリキュラムの多様化を促し、民族音楽学者やアーティスト・ミュージ シャンと協力して、音楽の伝統に根ざした指導法を確立するよう促した。世界音楽教育学」とは、パトリシア・シェハン・キャンベルによって作られた造語で、 小中学校の音楽課程における世界音楽の内容と実践を表すものである。この運動の先駆者たち、特にバーバラ・リーダー・ランドクイスト、ウィリアム・M・ア ンダーソン、ウィル・シュミッドは、第二世代の音楽教育者たち(J・ブライアン・バートン、メアリー・ゲッツェ、エレン・マッカロー・ブラブソン、メア リー・シャムロックなど)に影響を与え、様々なレベルや専門分野の音楽教師にカリキュラム・モデルをデザインし、提供している。この教育法は、スミソニア ン・フォークウェイズ・レコーディングスのようなアーカイブ・リソースを深く聴き続けるだけでなく、人的リソース、すなわち「文化を伝える人」を活用する ことを提唱している[9]。 会話型ソルフェージュ コダーイ・メソッドとゴードンの音楽学習理論に影響を受けたカンバセーショナル・ソルフェージュは、ハートフォード大学ハート・スクールの音楽教育学前教 授であるジョン・M・フィーラベンド博士によって開発された。このプログラムは、まず生徒が自国の文化、この場合はアメリカの音楽文献に浸ることから始ま る。音楽は記譜法とは別のものであり、記譜法よりも基本的なものである。12の学習段階を経て、生徒は音楽を聞いたり歌ったりすることから、音節を解読 し、話し言葉を使って音楽を創作すること、そして標準的な記譜法へと移行していく。コダーイ・メソッドをそのまま実践するのではなく、このメソッドはコ ダーイのオリジナルの指示に従い、ハンガリーの民謡ではなく、アメリカ独自の民謡を土台にしている。 カラボ・コーン・メソッド この幼児期のアプローチは、音楽への感覚運動的アプローチと呼ばれることもあり、ヴァイオリニストのマドレーヌ・カラボ=コーンによって開発された。この アプローチでは、五線譜、音符の長さ、ピアノの鍵盤といった基本的な音楽概念を学ぶために、小道具、衣装、おもちゃを使う。特別に計画された教室の具体的 な環境によって、子どもは触れながら探求し、音楽の基礎を学ぶことができる[1]。 ポピュラー音楽教育学 主な記事 ポピュラー音楽教育学  2009年、ワシントン州シアトルのフリーモント・フェアで演奏するポール・グリーン・スクール・オブ・ロック・ミュージックの生徒たち。 ポピュラー音楽教育学」-ロック音楽教育学、モダン・バンド、ポピュラー音楽教育、ロック音楽教育などとも呼ばれる-は、1960年代に音楽教育界で発展 したもので、正式な教室の内外でロック音楽をはじめとするポピュラー音楽を体系的に教え、学ぶものである。ポピュラー音楽教育学は、グループの即興演奏を 強調する傾向があり[10]、完全に制度化された学校の音楽アンサンブルよりも、コミュニティの音楽活動に関連することが一般的である[11]。 マンハッタンビル音楽カリキュラム・プロジェクト 主な記事 MMCP マンハッタンビル音楽カリキュラム・プロジェクトは、学校音楽に対する生徒の関心が低下していることへの対応として1965年に開発された。この創造的な アプローチは、生徒が音楽を、習得すべき静的な内容としてではなく、個人的で、現在進行形で、進化しているものとしてとらえ、態度を形成することを目的と している。このメソッドは、事実に基づいた知識を教えるのではなく、生徒を中心に据えたもので、生徒は調査、実験、発見を通して学んでいく。教師は、生徒 のグループに一緒に解決すべき特定の問題を与え、スパイラル・カリキュラムの中で、音楽のさまざまな側面を創造、演奏、即興、指揮、研究、調査する自由を 与える。MMCPは、学校における創造的な作曲・即興活動におけるプロジェクトの先駆けであると考えられている。[12][13] |

| Standards and assessment Achievement standards are curricular statements used to guide educators in determining objectives for their teaching. Use of standards became a common practice in many nations during the 20th century. For much of its existence, the curriculum for music education in the United States was determined locally or by individual teachers. In recent decades there has been a significant move toward adoption of regional and/or national standards. MENC: The National Association for Music Education, created nine voluntary content standards, called the National Standards for Music Education.[1] These standards call for: Singing, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music. Performing on instruments, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music. Improvising melodies, variations, and accompaniments. Composing and arranging music within specified guidelines. Reading and notating music. Listening to, analyzing, and describing music. Evaluating music and music performances. Understanding relationships between music, the other arts, and disciplines outside the arts. Understanding music in relation to history and culture. |

基準と評価 達成基準とは、教育者が教育目標を決定する際の指針となるカリキュラムの記述である。スタンダードの使用は、20世紀に多くの国で一般的に行われるように なった。アメリカでは、音楽教育のカリキュラムは、その存続期間の大部分において、地域や個々の教師によって決定されていた。ここ数十年、地域および/ま たは全国的な基準を採用する動きが顕著になっている。MENC:全米音楽教育協会は、全米音楽教育基準と呼ばれる9つの自主的な内容基準を作成した [1]: 単独で、または他の人と一緒に、さまざまなレパートリーの音楽を歌う。 単独で、または他の人と一緒に、さまざまなレパートリーの音楽を楽器で演奏する。 メロディー、変奏、伴奏を即興で演奏する。 指定されたガイドラインの範囲内で作曲や編曲をする。 楽譜を読み、記譜する 音楽を聴き、分析し、説明する。 音楽や演奏を評価する 音楽と他の芸術、芸術以外の分野との関係を理解する。 音楽を歴史や文化と関連づけて理解する。 |

Integration with other subjects Children in primary school are assembling a do-organ of Orgelkids Some schools and organizations promote integration of arts classes, such as music, with other subjects, such as math, science, or English, believing that integrating the different curricula will help each subject to build off of one another, enhancing the overall quality of education. One example is the Kennedy Center's "Changing Education Through the Arts" program. CETA defines arts integration as finding a natural connection(s) between one or more art forms (dance, drama/theater, music, visual arts, storytelling, puppetry, and/or creative writing) and one or more other curricular areas (science, social studies, English language arts, mathematics, and others) in order to teach and assess objectives in both the art form and the other subject area. This allows a simultaneous focus on creating, performing, and/or responding to the arts while still addressing content in other subject areas.[14]  Students with a music teacher Music in education is a way of incorporating music in teaching a subject. Music can be useful in education because, to play music it utilizes critical thinking and problem solving skills.[15][16]Depending on the subject, it offers a new way of learning information. For example, in literacy, it can explain different elements like metaphors, characters and setting. [16]Music teaches repetition which in turn benefits mathematical skills. For learning mathematics, the components of music are very helpful, simplifying concepts such as fractions and ratios.[15] This is because of the way music works. Music also involves frequency and sound waves which are beneficial to understanding concepts in science.[16] Understanding the different pitches in words and patterns in structure coincide with the way music structure is understood and read. [16] The European Union Lifelong Learning Programme 2007–2013 has funded three projects that use music to support language learning. Lullabies of Europe (for pre-school and early learners),[17] FolkDC (for primary),[18] and the recent PopuLLar (for secondary).[19] In addition, the ARTinED project is also using music for all subject areas.[20] Significance A number of researchers and music education advocates have argued that studying music enhances academic achievement,[21] such as William Earhart, former president of the Music Educators National Conference, who claimed that "Music enhances knowledge in the areas of mathematics, science, geography, history, foreign language, physical education, and vocational training."[22] Researchers at the University of Wisconsin suggested that students with piano or keyboard experience performed 34% higher on tests that measure spatial-temporal lobe activity, which is the part of the brain that is used when doing mathematics, science, and engineering.[23] A long-term study over twelve years at the University of Graz also found a change in the grey matter in the brain of children with music lessons.[24] An experiment by Wanda T. Wallace setting text to melody suggested that some music may aid in text recall.[25] She created a three verse song with a non-repetitive melody; each verse with different music. A second experiment created a three verse song with a repetitive melody; each verse had exactly the same music. A third experiment studied text recall without music. She found the repetitive music produced the highest amount of text recall, suggesting music can serve as a mnemonic device.[25] Smith (1985) studied background music with word lists. One experiment involved memorizing a word list with background music; participants recalled the words 48 hours later. Another experiment involved memorizing a word list with no background music; participants also recalled the words 48 hours later. Participants who memorized word lists with background music recalled more words demonstrating music provides contextual cues.[26] Citing studies that support music education's involvement in intellectual development and academic achievement, the United States Congress passed a resolution declaring that: "Music education enhances intellectual development and enriches the academic environment for children of all ages; and Music educators greatly contribute to the artistic, intellectual and social development of American children and play a key role in helping children to succeed in school."[27] Bobbett (1990) suggests that most public school music programs have not changed since their inception at the turn of the last century. "…the educational climate is not conducive to their continuance as historically conceived and the social needs and habits of people require a completely different kind of band program."[28] A 2011 study conducted by Kathleen M. Kerstetter for the Journal of Band Research found that increased non-musical graduation requirements, block scheduling, increased number of non-traditional programs such as magnet schools, and the testing emphases created by the No Child Left Behind Act are only some of the concerns facing music educators. Both teachers and students are under increased time restrictions"[29] Patricia Powers states, "It is not unusual to see program cuts in the area of music and arts when economic issues surface. It is indeed unfortunate to lose support in this area especially since music and the art programs contribute to society in many positive ways."[22] Comprehensive music education programs average $187 per pupil, according to a 2011 study funded by the NAMM Foundation.[30] The Texas Commission on Drugs and Alcohol Abuse Report noted that students who participated in band or orchestra reported the lowest lifetime and current use of all substances including alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs.[31] Teaching with music Studies have shown that music education can be used to enhance cognitive achievement in students. In the United States an estimated 30% of students struggle with reading, while 17% are reported as having a specific learning disability linked to reading.[32] Using intensive music curriculum as an intervention paired alongside regular classroom activities, research shows that students involved with the music curriculum show increases in reading comprehension, word knowledge, vocabulary recall, and word decoding.[33] According to the National Association for Music Education, in a study done in 2012, those who participated in musical activities scored higher on the SAT. These students scored an average of 31 points higher in reading and writing, and 23 points higher in math.[34] When a student is singing a melody with text, they are using multiple areas of their brain to multitask. Music affects language development, increases IQ, spatial-temporal skills, and improves test scores. Music education has also shown to improve the skills of dyslexic children in similar areas as mentioned earlier by focusing on visual auditory and fine motor skills as strategies to combat their disability.[35] Since research in this area is sparse, we cannot convincingly conclude these findings to be true, however the results from research done do show a positive impact on both students with learning difficulties and those who are not diagnosed. Further research will need to be done, but the positive engaging way of bringing music into the classroom cannot be forgotten, and the students generally show a positive reaction to this form of instruction.[36] Music education has also been noted to have the ability to increase someone's overall IQ, especially in children during peak development years.[37] Spatial ability, verbal memory, reading and mathematic ability are seen to be increased alongside music education (primarily through the learning of an instrument).[37] Researchers also note that a correlation between general attendance and IQ increases is evident, and due to students involvement in music education, general attendance rates increase along with their IQ. Fine motor skills, social behaviors, and emotional well-being can also be increased through music and music education. The learning of an instrument increases fine motor skills in students with physical disabilities. Emotional well being can be increased as students find meaning in songs and connect them to their everyday life.[38] Through social interactions of playing in groups like jazz and concert bands, students learn to socialize and this can be linked to emotional and mental well-being. There is evidence of positive impacts of participation in youth orchestras and academic achievement and resilience in Chile.[39] According to the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IAEEA),[40] "the world's top academic countries place a high value on music education. Hungary, Netherlands, and Japan have required music training at the elementary and middle school levels, both instrumental and vocal, for several decades." In contrast to previous experimental studies, a meta-analysis published in 2020 found a lack of evidence to support the claim that musical training positively impacts children’s cognitive skills and academic achievements, with the authors concluding that "researchers’ optimism about the benefits of music training is empirically unjustified and stems from misinterpretation of the empirical data and, possibly, confirmation bias."[41][42] Music advocacy In some communities – and even entire national education systems – music is provided little support as an academic subject area, and music teachers feel that they must actively seek greater public endorsement for music education as a legitimate subject of study. This perceived need to change public opinion has resulted in the development of a variety of approaches commonly called "music advocacy". Music advocacy comes in many forms, some of which are based upon legitimate scholarly arguments and scientific findings, while other examples controversially rely on emotion, anecdotes, or unconvincing data. Recent high-profile music advocacy projects include the "Mozart Effect", the National Anthem Project, and the movement in World Music Pedagogy (also known as Cultural Diversity in Music Education) which seeks out means of equitable pedagogy across students regardless of their race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic circumstance. The Mozart effect is particularly controversial as while the initial study suggested listening to Mozart positively impacts spatial-temporal reasoning, later studies either failed to replicate the results,[43][44] suggested no effect on IQ or spatial ability,[45] or suggested the music of Mozart could be substituted for any music children enjoy in a term called "enjoyment arousal."[46] Another study suggested that even if listening to Mozart may temporarily enhance a student's spatial-temporal abilities, learning to play an instrument is much more likely to improve student performance and achievement.[47] Educators similarly criticized the National Anthem Project not only for promoting the educational use of music as a tool for non-musical goals, but also for its links to nationalism and militarism.[48] Contemporary music scholars assert that effective music advocacy uses empirically sound arguments that transcend political motivations and personal agendas. Music education philosophers such as Bennett Reimer, Estelle Jorgensen, David J. Elliott, John Paynter, and Keith Swanwick support this view, yet many music teachers and music organizations and schools do not apply this line of reasoning into their music advocacy arguments. Researchers such as Ellen Winner conclude that arts advocates have made bogus claims to the detriment of defending the study of music,[49] her research debunking claims that music education improves math, for example.[50] Researchers Glenn Schellenberg and Eugenia Costa-Giomi also criticize advocates incorrectly associating correlation with causation, Giomi pointing out that while there is a "strong relationship between music participation and academic achievement, the causal nature of the relationship is questionable."[50][51] Philosophers David Elliott and Marissa Silverman suggest that more effective advocacy involves shying away from "dumbing down" values and aims through slogans and misleading data, energy being better focused into engaging potential supporters in active music-making and musical-affective experiences,[52] these actions recognizing that music and music-making are inherent to human culture and behavior, distinguishing humans from other species.[53] The focus is also on advocacy of music education as important, despite disparities in income and social status. Woodrow Wilson said "We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class of persons, a very much larger class of necessity in every society, to forgo the privilege of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks."[54] |

他教科との融合 小学生の子どもたちがオルゴールキッズのドゥオルガンを組み立てている。 異なるカリキュラムを統合することで、各教科が互いに高め合い、教育全体の質を高めることができると考え、音楽などの芸術科目と数学、科学、英語などの他 教科との統合を推進する学校や団体もある。 その一例が、ケネディセンターの「芸術を通して教育を変える」プログラムである。CETAでは、芸術の統合とは、1つまたは複数の芸術形式(ダンス、演 劇、音楽、ビジュアル・アート、ストーリーテリング、人形劇、クリエイティブ・ライティングなど)と、1つまたは複数の他のカリキュラム分野(科学、社会 科、英語、数学など)との間に自然なつながりを見つけ、芸術形式と他の教科分野の両方の目標を教え、評価することであると定義している。これにより、芸術 の創作、演奏、反応に同時に焦点を当てながら、他の教科の内容にも取り組むことができる[14]。  音楽教師のいる生徒 教育における音楽とは、教科の教育に音楽を取り入れる方法である。音楽を演奏することで、批判的思考や問題解決能力を活用することができるため、音楽は教 育に役立つことがある[15][16]。科目によっては、情報を学ぶ新しい方法を提供する。例えば、読み書きにおいては、比喩、登場人物、設定など、さま ざまな要素を説明することができる。[16]音楽は繰り返しを教え、それが数学的スキルに役立つ。数学の学習において、音楽の構成要素は非常に役に立ち、 分数や比といった概念を単純化する。また、音楽には周波数や音波が含まれており、科学の概念を理解するのに有益である[16]。言葉の中の異なる音程や構 造のパターンを理解することは、音楽の構造を理解し読み取る方法と一致する。[16] 欧州連合(EU)の生涯学習プログラム2007-2013は、音楽を使って言語学習を支援する3つのプロジェクトに資金を提供している。 Lullabies of Europe」(就学前・早期学習者向け)[17]、「FolkDC」(初等教育向け)[18]、そして最近の「PopuLLar」(中等教育向け)であ る[19]。さらに「ARTinED」プロジェクトも、すべての教科に音楽を活用している[20]。 意義 音楽教育者全国会議の元会長であるウィリアム・イヤハートは、「音楽は数学、科学、地理、歴史、外国語、体育、職業訓練の分野における知識を高める」と主 張している。 「ウィスコンシン大学の研究者は、ピアノやキーボードの経験がある学生は、数学、科学、工学を行うときに使用される脳の部分である空間-側頭葉の活動を測 定するテストで34%高い成績を示唆した[23] 。 ワンダ・T・ウォレスによる実験では、テキストをメロディに合わせることで、音楽がテキストの想起を助ける可能性が示唆された[25]。2つ目の実験で は、繰り返しのメロディーを持つ3つの詩の歌を作った。3つ目の実験では、音楽なしでテキストの想起を調べた。彼女は、反復的な音楽が最も多くのテキスト を想起させることを発見し、音楽が記憶装置として機能することを示唆した[25]。 スミス(1985)は、BGMと単語リストについて研究した。ある実験では、BGMとともに単語リストを暗記した。別の実験では、BGMなしの単語リスト を暗記した。BGM付きの単語リストを暗記した参加者は、より多くの単語を想起しており、音楽が文脈の手がかりとなることが実証された[26]。 音楽教育が知的発達と学業達成に関与していることを裏付ける研究を引用して、米国議会は次のように宣言する決議案を可決した: 「音楽教育は、あらゆる年齢の子どもたちの知的発達を高め、学業環境を豊かにする。音楽教育者は、アメリカの子どもたちの芸術的、知的、社会的発達に大き く貢献し、子どもたちが学校で成功するために重要な役割を果たしている」[27]。 Bobbett (1990)は、ほとんどの公立学校の音楽プログラムは、前世紀初頭の開始以来変わっていないことを示唆している。...教育環境は、歴史的に考えられて きたような継続を助長しておらず、人々の社会的ニーズや習慣は、まったく異なる種類のバンドプログラムを必要としている」[28] Kathleen M. KerstetterがJournal of Band Researchのために行った2011年の調査では、音楽以外の卒業要件の増加、ブロックスケジューリング、マグネットスクールなどの非伝統的プログラ ムの増加、および「落ちこぼれ防止教育法」によって作成されたテストの強調は、音楽教育者が直面している懸念の一部に過ぎないことがわかった。教師も生徒 も、時間的な制約が増えている」[29]。 パトリシア・パワーズは、「経済的な問題が表面化すると、音楽や芸術の分野でプログラムが削減されるのは珍しいことではない。NAMM財団が資金を提供し た2011年の調査によると、総合的な音楽教育プログラムは、生徒一人当たり平均187ドルである[30]。テキサス州薬物・アルコール乱用委員会報告書 は、バンドやオーケストラに参加している学生は、アルコール、タバコ、違法薬物を含むすべての物質の生涯および現在の使用量が最も少ないと報告したことを 指摘した[31]。 音楽を使った教育 音楽教育は、生徒の認知的達成を高めるために利用できることが、研究によって示されている。米国では、生徒の推定30%が読解に苦労しており、17%が読 解に関連する特定の学習障害を持っていると報告されている[32]。通常の教室での活動とペアになった介入として集中的な音楽カリキュラムを使用すると、 研究では、音楽カリキュラムに関与している生徒が読解力、単語の知識、語彙の想起、単語の解読の増加を示すことを示している[33]。全米音楽教育協会に よると、2012年に行われた研究では、音楽活動に参加した人は、SATでより高いスコアを獲得した。これらの学生は、読み書きで平均31点、数学で平均 23点高かった[34]。学生がテキストでメロディーを歌っているとき、脳の複数の領域をマルチタスクに使っている。音楽は言語の発達に影響を与え、IQ や空間的・時間的スキルを高め、テストの点数を向上させる。音楽教育はまた、障害に対抗する戦略として視覚聴覚と微細運動技能に焦点を当てることで、先に 述べたのと同様の分野で失読症児の技能を向上させることが示されている[35]。この分野の研究はまばらであるため、これらの知見が真実であると説得力を 持って結論づけることはできないが、行われた研究の結果は、学習障害のある生徒と診断されていない生徒の両方に良い影響を与えることを示している。さらな る研究が必要であるが、音楽を教室に取り入れる積極的な魅力的な方法は忘れることができず、生徒は一般的にこの指導形態に肯定的な反応を示している [36]。 音楽教育はまた、誰かの全体的なIQを増加させる能力を持っていることが指摘されている、特に発育のピークの年の子供たちである[37]。空間能力、言語 記憶、読書や数学の能力は、音楽教育(主に楽器の学習を通じて)と一緒に増加することが見られる[37]。 研究者はまた、一般的な出席率とIQの増加の間の相関関係が明らかであり、学生が音楽教育に関与するため、一般的な出席率は、彼らのIQと一緒に増加する ことに注意してください。 運動能力、社会的行動、情緒的幸福も、音楽や音楽教育を通じて高めることができる。楽器の学習は、身体障害を持つ生徒の細かい運動能力を向上させる。ジャ ズバンドやコンサートバンドのようなグループで演奏する社会的交流を通じて、生徒は社交性を学び、これが感情的・精神的幸福につながる。 国際教育到達度評価協会(IAEEA)[40]によると、「世界の学力上位国は音楽教育に高い価値を置いている。ハンガリー、オランダ、日本は、数十年前 から小中学校レベルで器楽と声楽の両方の音楽教育を義務づけている。」 これまでの実験的研究とは対照的に、2020年に発表されたメタアナリシスでは、音楽トレーニングが子どもの認知能力や学業成績にプラスの影響を与えると いう主張を支持する証拠が不足していることが判明し、著者は「音楽トレーニングの利点に関する研究者の楽観論は経験的に不当であり、経験的データの誤った 解釈と、おそらく確証バイアスから生じている」と結論づけている[41][42]。 音楽擁護 一部の地域社会、さらには国の教育制度全体においてさえ、音楽は学問分野としてほとんど支持されておらず、音楽教師は、音楽教育が正当な学問分野であると いう世論の支持を積極的に求めなければならないと感じている。世論を変える必要があると認識された結果、一般的に「音楽アドボカシー」と呼ばれる様々なア プローチが発展してきた。音楽擁護には様々な形態があり、正当な学術的論拠や科学的知見に基づくものもあれば、感情や逸話、説得力のないデータに頼る例も あり、物議を醸している。 最近注目されている音楽擁護プロジェクトには、「モーツァルト効果」、国歌プロジェクト、世界音楽教育学(音楽教育における文化的多様性とも呼ばれる)の 運動などがあり、人種、民族、社会経済的状況に関係なく、生徒全体に公平な教育法を模索するものである。モーツァルト効果は特に議論の的となっている。最 初の研究では、モーツァルトを聴くことが空間的・時間的推論にプラスの影響を与えることが示唆されたが、その後の研究では結果を再現できなかったり [43][44]、IQや空間的能力への影響がないことが示唆されたり[45]、「享楽的喚起」と呼ばれる用語で、モーツァルトの音楽が子供たちが楽しむ あらゆる音楽の代わりになることが示唆されたりした。 「別の研究では、モーツァルトを聴くことで生徒の空間的・時間的能力が一時的に高まったとしても、楽器を演奏することを学ぶ方が生徒の成績や達成度を向上 させる可能性がはるかに高いことが示唆されている[47]。教育者たちも同様に、国歌斉唱プロジェクトを、音楽を非音楽的な目的のためのツールとして教育 的に利用することを促進するだけでなく、ナショナリズムや軍国主義との関連性についても批判している[48]。 現代の音楽学者たちは、効果的な音楽擁護には、政治的動機や個人的な思惑を超越した、経験的に確かな論拠が用いられると主張している。ベネット・ライ マー、エステル・ヨルゲンセン、デビッド・J・エリオット、ジョン・ペインター、キース・スワンウィックといった音楽教育哲学者はこの見解を支持している が、多くの音楽教師や音楽団体・音楽学校は、音楽擁護の主張にこの筋道を適用していない。エレン・ウィナーなどの研究者は、芸術擁護派は音楽研究を擁護す る上で不利になるようなインチキ主張をしてきたと結論づけており[49]、彼女の研究は、例えば、音楽教育が数学を向上させるという主張を否定している [50]。 「哲学者のデビッド・エリオットとマリッサ・シルヴァーマンは、より効果的な擁護活動には、スローガンや誤解を招くようなデータを通じて価値観や目的を 「矮小化」することから遠ざかり、潜在的な支持者を積極的な音楽づくりや音楽的情緒的体験に引き込むことにエネルギーを集中させることが必要であると示唆 している[52]。これらの行動は、音楽や音楽づくりは人間の文化や行動に固有のものであり、人間を他の種から区別するものであると認識している [53]。ウッドロー・ウィルソンは、「我々は、ある一群の人間に教養教育を受けさせたいのであり、また別の一群の人間、すなわちあらゆる社会で必要とさ れる非常に大きな一群の人間には、教養教育の特権を放棄し、特定の困難な手作業を行うために自らを適合させたいのである」と述べている[54]。 |

| Cross-cultural

music education The music, languages, and sounds we are exposed to within our own cultures determine our tastes in music and affect the way we perceive the music of other cultures. Many studies have shown distinct differences in the preferences and abilities of musicians from around the world. One study attempted to view the distinctions between the musical preferences of English and Japanese speakers, providing both groups of people with the same series of tones and rhythms. The same type of study was done for English and French speakers. Both studies suggested that the language spoken by the listener determined which groupings of tones and rhythms were more appealing, based on the inflections and natural rhythm groupings of their language.[55] Another study had Europeans and Africans try to tap along with certain rhythms. European rhythms are regular and built on simple ratios, while African rhythms are typically based on irregular ratios. While both groups of people could perform the rhythms with European qualities, the European group struggled with the African rhythms. This has to do with the ubiquity of complex polyrhythm in African culture and their familiarity with this type of sound.[55] While each culture has its own musical qualities and appeals, incorporating cross-cultural curricula in our music classrooms can help teach students how to better perceive music from other cultures. Studies show that learning to sing folk songs or popular music of other cultures is an effective way to understand a culture as opposed to merely learning about it. If music classrooms discuss the musical qualities and incorporate styles from other cultures, such as the Brazilian roots of the Bossa Nova, the Afro-Cuban clave, and African drumming, it will expose students to new sounds and teach them how to compare their cultures’ music to the different music and start to make them more comfortable with exploring sounds.[56] |

異文化間音楽教育 私たちが自文化の中で触れてきた音楽、言語、音は、私たちの音楽の好みを決定し、異文化の音楽の捉え方に影響を与える。多くの研究が、世界中の音楽家の好 みや能力に明確な違いがあることを示している。ある研究では、英語話者と日本語話者の音楽的嗜好の違いを見ようと、両グループに同じ一連の音色とリズムを 与えた。同じような研究が、英語を話す人とフランス語を話す人に対しても行われた。どちらの研究でも、リスナーが話す言語が、その言語の抑揚や自然なリズ ムのグループ分けに基づいて、どのグループの音色やリズムがより魅力的かを決定することが示唆された[55]。 別の研究では、ヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人に、特定のリズムに合わせてタップをさせた。ヨーロッパのリズムは規則的で単純な比率に基づいているが、アフリカ のリズムは一般的に不規則な比率に基づいている。どちらのグループもヨーロッパの素質を持ったリズムを演奏することができたが、ヨーロッパのグループはア フリカのリズムに苦戦した。これはアフリカ文化における複雑なポリリズムの偏在と、彼らがこの種の音に慣れ親しんでいることに関係している[55]。 それぞれの文化には独自の音楽的特質や魅力があるが、音楽教室に異文化カリキュラムを取り入れることは、生徒が異文化の音楽をよりよく理解する方法を教え るのに役立つ。研究によると、他文化の民謡やポピュラー音楽を歌うことを学ぶことは、単にその文化について学ぶのとは対照的に、その文化を理解するための 効果的な方法である。音楽教室で、ブラジルのルーツであるボサノヴァ、アフロ・キューバのクラーベ、アフリカの太鼓など、他文化の音楽的特質やスタイルを 取り入れることについて話し合えば、生徒たちは新しい音に触れ、自分たちの文化の音楽を異なる音楽と比較する方法を学び、音を探求することに慣れ始めるだ ろう[56]。 |

| Role of women Main article: Women in music education A music teacher leading a music ensemble in an elementary school in 1943. While music critics argued in the 1880s that "...women [composers] lacked the innate creativity to compose good music" due to "biological predisposition",[57] later, it was accepted that women would have a role in music education, and they became involved in this field "...to such a degree that women dominated music education during the later half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century."[57]"Traditional accounts of the history of music education [in the US] have often neglected the contributions of women, because these texts have emphasized bands and the top leaders in hierarchical music organizations."[58] When looking beyond these bandleaders and top leaders, women had many music education roles in the "...home, community, churches, public schools, and teacher-training institutions" and "...as writers, patrons, and through their volunteer work in organizations."[58] Despite the limitations imposed on women's roles in music education in the 19th century, women were accepted as kindergarten teachers, because this was deemed to be a "private sphere". Women also taught music privately, in girl's schools, Sunday schools, and they trained musicians in school music programs. By the turn of the 20th century, women began to be employed as music supervisors in elementary schools, teachers in normal schools and professors of music in universities. Women also became more active in professional organizations in music education, and women presented papers at conferences. A woman, Frances Clarke (1860-1958) founded the Music Supervisors National Conference in 1907. While a small number of women served as President of the Music Supervisors National Conference (and the following renamed versions of the organization over the next century) in the early 20th century, there were only two female Presidents between 1952 and 1992, which "[p]ossibly reflects discrimination." After 1990, however, leadership roles for women in the organization opened up. From 1990 to 2010, there were five female Presidents of this organization.[59] Women music educators "outnumber men two-to-one" in teaching general music, choir, private lessons, and keyboard instruction .[59] More men tend to be hired as for band education, administration and jazz jobs, and more men work in colleges and universities.[59] According to Dr. Sandra Wieland Howe, there is still a "glass ceiling" for women in music education careers, as there is "stigma" associated with women in leadership positions and "men outnumber women as administrators."[59] |

女性の役割 主な記事 音楽教育における女性 1943年、小学校で音楽合奏を指導する音楽教師。 音楽批評家たちは1880年代、「...女性(の作曲家)には、生物学的な素質」によって「良い音楽を作曲するための生得的な創造性が欠けている」と主張 していたが[57]、その後、女性が音楽教育において役割を持つことが認められ、「...19世紀後半から20世紀にかけて、女性が音楽教育を支配するほ どまでに」この分野に関わるようになった。 「57][57]「従来の音楽教育史の記述では、楽団や階層的な音楽組織のトップリーダーを重視してきたため、女性の貢献が軽視されることが多かった」 [58]が、こうした楽団長やトップリーダー以外にも目を向けると、女性は「...家庭、地域社会、教会、公立学校、教員養成機関」において、また 「...作家として、後援者として、組織におけるボランティア活動を通じて」、多くの音楽教育の役割を担っていた[58]。 19世紀には音楽教育における女性の役割に制限が課せられていたにもかかわらず、女性は幼稚園の先生として受け入れられていた。女性はまた、女学校や日曜 学校で個人的に音楽を教え、学校の音楽プログラムで音楽家を養成した。20世紀に入ると、女性は小学校の音楽監督、普通学校の教師、大学の音楽教授として 雇用されるようになった。また、音楽教育の専門家団体でも女性の活動が活発になり、女性が学会で論文を発表するようになった。女性のフランシス・クラーク (1860-1958)は、1907年に音楽監督者全国会議を設立した。20世紀初頭には、少数の女性が音楽監督者全国会議(およびその後1世紀にわたっ て改称された組織)の会長を務めたが、1952年から1992年までの間に女性会長は2人しかおらず、これは「(おそらく)差別を反映している」。 しかし、1990年以降、組織における女性の指導的役割は開放された。1990年から2010年まで、この団体の女性会長は5人であった[59]。女性の 音楽教育者は、一般音楽、合唱、個人レッスン、鍵盤楽器指導において、「2対1で男性を上回っている」[59]。 バンド教育、管理、ジャズの仕事としては、より多くの男性が雇われる傾向があり、より多くの男性が大学で働く。 [59]サンドラ・ウィーランド・ハウ博士によると、指導的立場にある女性に関連する「汚名」があり、「管理者としては男性の方が女性よりも多い」 [59]ため、音楽教育のキャリアにおける女性のための「ガラスの天井」がまだある。 |

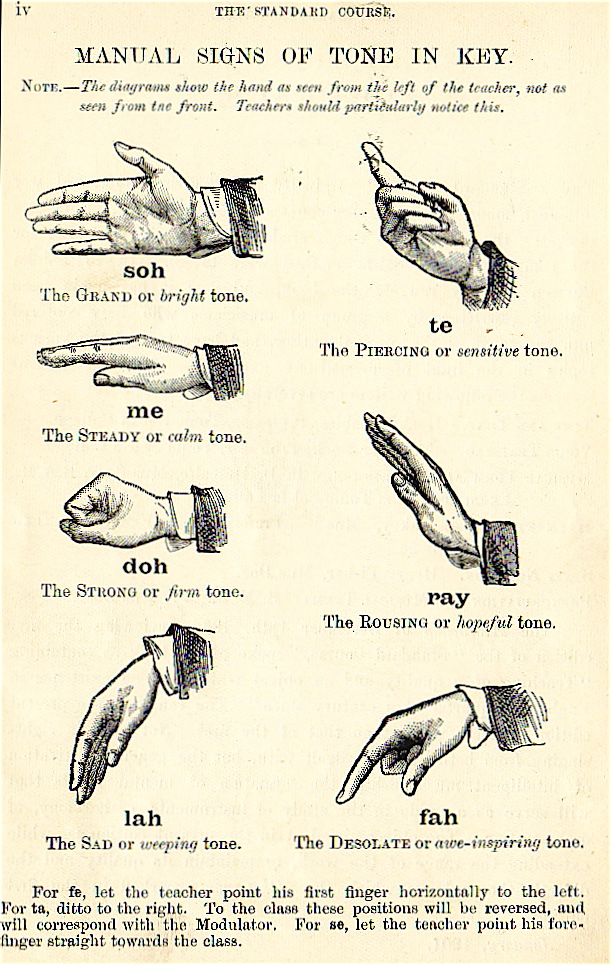

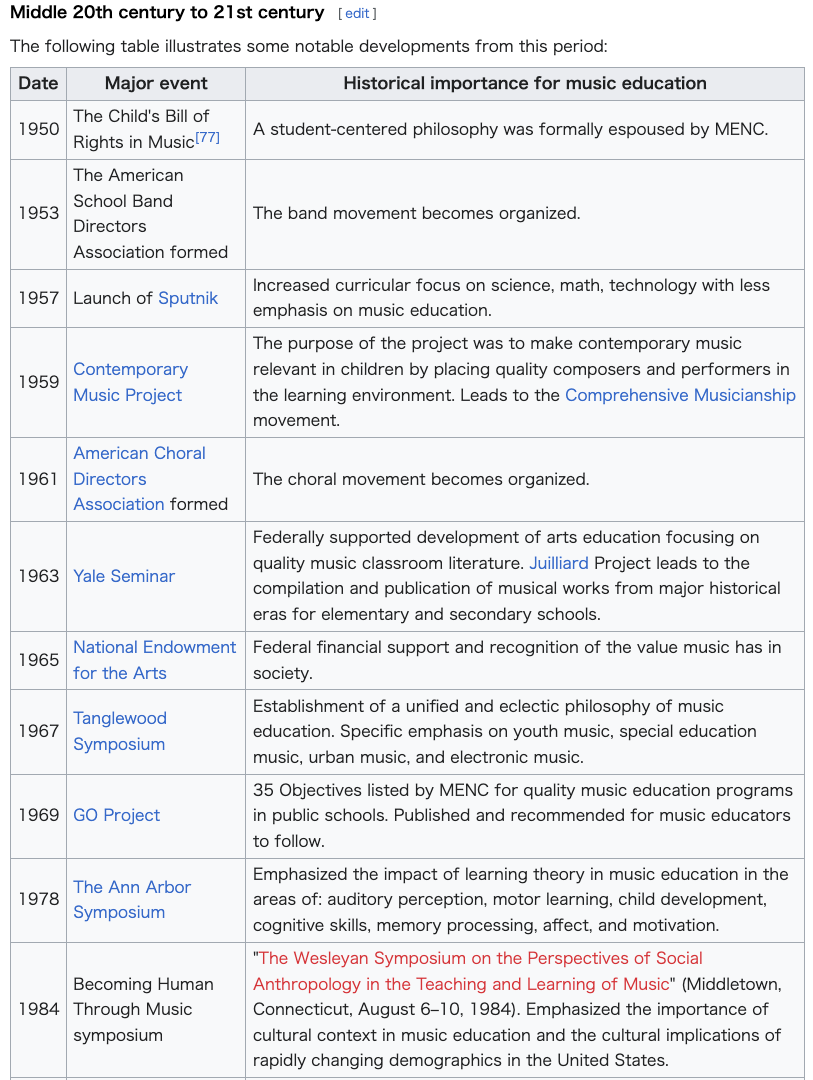

| Americas See also: Music education in Barbados Latin American musical traditions Historical aspects Among the Aztecs, a great variety of instruments were used for two main purposes: to curate and play - religious music (the purview of specialized priests; and to perform court music - (played daily for the Aztec ruling class.) [60] The education of Aztecs of all social ranks, were conducted in schools called calmecac, telpochcalli, and cuicacalli.[61] and was a requirement for all people. This emphasizes the great importance that music and dance played in the lives of the Aztecs.[60] In Mayan culture, musicians occupied a space between the elite and the common people. Music played a prominent role and professional musicians using a variety of wind instruments, drums and rattles to celebrate military victories. Music also played a prominent role in the funeral rites of the elite.[62]  Bonampak, Temple of the Murals, room 1, musicians With Spanish and Portuguese colonization, music began to be influenced by European ideas and principles.The Catholic Church used music education as a means to spread Christianity to local indigenous populations.[63] One example of an early educator is Esteban Salas considered the first Cuban native-born art music composer developed Santiago de Cuba into a center of music excellence in the country.[64] Salinas’ influence in the development of Cuban music includes a collection of over 100 music compositions that established him as the initiator of the Cuban art music tradition.[64] His legacy continues in modern-day Cuba where the Esteban Salas Early Music Festival is held every year in Havana. The festival attracts classical music artists from around the world to perform and teach music following the tradition of Esteban Salinas.[65] Since music was taught to the general public by rote, until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, very few people knew how to read music other than those who played instruments.[63] The development of music in Latin America mainly followed that of European development:[63] Choirs were formed to sing masses, chants, psalms; secular music also became more prevalent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and beyond.[66] Today Today,[when?] music education in Latin America places a large emphasis on folk music, masses, and orchestral music. Many schools teach their choirs to sing in their native language as well as in English. Several Latin American Schools, specifically in Puerto Rico and Haiti, believe music to be an important subject and are working on expanding their programs. In Puerto Rico, there is no official music education policy governing early childhood music instruction.[67] Outside of school, many communities form their own musical groups and organizations their performances being very popular with the local audiences. There are a few well-known Latin American choral groups, such as "El Coro de Madrigalistas" from Mexico. This famous choral group tours around Mexico, showing students around the country what a professional choral ensemble sounds like.[68] There is also evidence of the positive impact of participation in youth orchestras and academic achievement and resilience in Chile.[69] Music education can improve academic results in children.[70] In Colombia, the Medellin Music School network has been in operation for over two decades. It has been demonstrated that students involved in this music program have better academic achievement and are less inclined to participate in violence. The music program increases chances of graduation for participants.[71] Music education and indigenous cultures Beyond traditional choral music, young Latin American artists are now using hip-hop as a way to promote the revitalization of indigenous languages and celebrate traditions that originated before the Spanish Conquest.[72] Hip-hop in Latin America now acts as a voice of the oppressed, establishing this form of music as an expression of social revolution.[73] Throughout Latin America, young indigenous artists are now using hip hop as a way to express their struggle against poverty and injustice.[73] The new music coming out of Latin America all shows influences that go back to ancient Indigenous traditions.[72] Uchpa and Alborada are two successful Peruvian bands who have celebrated their indigenous roots.[74] From Chile, Jaas Newen's song "Inche Kay Che" calls for the defense of traditional Indigenous culture. The song "Koangagu" by Brazilian group Brô MC’s examines how Indigenous and modern Brazilian cultures can come together in music. "Presente y Combativo" by Parce MC, Mugre Sur, Sapín celebrates the life of a Bolivian rapper who was murdered in 2009.[72] United States Further information: Music education and programs within the United States 18th century After the preaching of Reverend Thomas Symmes, the first singing school was created in 1717 in Boston for the purposes of improving singing and music reading in the church. These singing schools gradually spread throughout the colonies. Music education continued to flourish with the creation of the Academy of Music in Boston. Reverend John Tufts published An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm Tunes Using Non-Traditional Notation which is regarded as the first music textbook in the colonies. Between 1700 and 1820, more than 375 tune books would be published by such authors as Samuel Holyoke, Francis Hopkinson, William Billings, and Oliver Holden.[75] Music began to spread as a curricular subject into other school districts. Soon after music expanded to all grade levels and the teaching of music reading was improved until the music curriculum grew to include several activities in addition to music reading. By the end of 1864 public school music had spread throughout the country. 19th century In 1832, Lowell Mason and George Webb formed the Boston Academy of Music with the purposes of teaching singing and theory as well as methods of teaching music. Mason published his Manuel of Instruction in 1834 which was based upon the music education works of Pestalozzian System of Education founded by Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. This handbook gradually became used by many singing school teachers. From 1837 to 1838, the Boston School Committee allowed Lowell Mason to teach music in the Hawes School as a demonstration. This is regarded as the first time music education was introduced to public schools in the United States. In 1838 the Boston School Committee approved the inclusion of music in the curriculum and Lowell Mason became the first recognized supervisor of elementary music. In later years Luther Whiting Mason became the Supervisor of Music in Boston and spread music education into all levels of public education (grammar, primary, and high school). During the middle of the 19th century, Boston became the model to which many other cities across the United States included and shaped their public school music education programs.[76] Music methodology for teachers as a course was first introduced in the Normal School in Potsdam. The concept of classroom teachers in a school that taught music under the direction of a music supervisor was the standard model for public school music education during this century. (See also: Music education in the United States) While women were discouraged from composing in the 19th century, "later, it was accepted that women would have a role in music education, and they became involved in this field...to such a degree that women dominated music education during the later half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century."[57] Early 20th century In the United States, teaching colleges with four-year degree programs developed from the Normal Schools and included music. Oberlin Conservatory first offered the Bachelor of Music Education degree. Osbourne G. McCarthy, an American music educator, introduced details for studying music for credit in Chelsea High School. Notable events in the history of music education in the early 20th century also include: Founding of the Music Supervisor's National Conference (changed to Music Educators National Conference in 1934, later MENC: The National Association for Music Education in 1998, and currently The National Association for Music Education – NAfME) in Keokuk, Iowa in 1907. Rise of the school band and orchestra movement leading to performance oriented school music programs. Growth in music methods publications. Frances Elliot Clark develops and promotes phonograph record libraries for school use. Carl Seashore and his Measures of Musical Talent music aptitude test starts testing people in music. Middle 20th century to 21st century The following table illustrates some notable developments from this period: |

アメリカ大陸 こちらも参照のこと: バルバドスの音楽教育 ラテンアメリカの音楽の伝統 歴史的側面 アステカでは、多種多様な楽器が2つの主な目的のために使用された。宗教音楽(専門の司祭の権限)と宮廷音楽(アステカの支配階級のために毎日演奏され た)である[60]。アステカのあらゆる社会階層の教育は、カルメカック、テルポッチカリ、クイカカリと呼ばれる学校で行われ[61]、すべての人々の必 須条件であった。60]。マヤ文化では、音楽家はエリートと庶民の間の空間を占めていた。音楽は重要な役割を果たし、プロの音楽家が様々な管楽器、太鼓、 ガラガラを使って軍事的勝利を祝った。音楽はまた、エリートの葬儀においても重要な役割を果たした[62]。  ボナンパク、壁画の神殿、第1室、音楽家たち スペインとポルトガルの植民地化によって、音楽はヨーロッパの思想や原則の影響を受け始めた。カトリック教会は、地元の先住民にキリスト教を広める手段と して音楽教育を利用した[63]。初期の教育者の一例として、キューバ初の生粋の芸術音楽作曲家とされるエステバン・サラスが、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバ をこの国の優れた音楽の中心地に発展させた。 [64]キューバ音楽の発展におけるサリナスの影響力には、キューバ芸術音楽の伝統の創始者としての地位を確立した100曲以上の作曲作品集が含まれる。 この音楽祭には、世界中からクラシック音楽のアーティストが集まり、エステバン・サリナスの伝統に則った音楽を演奏し、教えている[65]。 ラテンアメリカにおける音楽の発展は、主にヨーロッパの発展に倣ったものであった[63]。ミサ曲、聖歌、詩篇を歌うために合唱団が結成され、世俗音楽も17世紀から18世紀以降に普及した[66]。 今日 今日[いつ?]、ラテンアメリカの音楽教育は、民族音楽、ミサ曲、管弦楽に大きな重点を置いている。多くの学校では、合唱団が英語だけでなく母国語で歌う ことも教えている。ラテンアメリカのいくつかの学校、特にプエルトリコとハイチでは、音楽を重要な科目と考え、プログラムの拡大に取り組んでいる。プエル トリコでは、幼児期の音楽教育を規定する公式の音楽教育方針はない[67]。学校の外では、多くのコミュニティが独自の音楽グループや団体を結成し、その 演奏は地元の聴衆に非常に人気がある。メキシコの「エル・コーロ・デ・マドリガリスタ(El Coro de Madrigalistas)」など、ラテンアメリカの有名な合唱グループもいくつかある。この有名な合唱団は、メキシコ各地をツアーし、国内の学生にプ ロの合唱団がどのような音を奏でるかを見せている[68]。また、チリでは、青少年オーケストラへの参加が、学業成績や回復力にプラスの影響を与えるとい う証拠もある[69]。 コロンビアでは、メデジン音楽学校ネットワークが20年以上にわたって運営されている。この音楽プログラムに参加した生徒は、学業成績が向上し、暴力に参加する傾向が少ないことが実証されている。音楽プログラムは、参加者の卒業の可能性を高めている[71]。 音楽教育と先住民文化 伝統的な合唱音楽だけでなく、ラテンアメリカの若いアーティストたちは現在、先住民の言語の活性化を促進し、スペイン征服以前に生まれた伝統を祝う方法と してヒップホップを使用している[72]。 [ラテンアメリカ全体を通して、若い先住民アーティストたちは現在、貧困や不公正に対する闘いを表現する方法としてヒップホップを使用している[73]。 ラテンアメリカから出てくる新しい音楽はどれも、古代の先住民の伝統にさかのぼる影響を示している[72]。 ウチュパとアルボラーダは、先住民のルーツを讃え、成功を収めたペルーの2つのバンドである[74]。 チリからは、ジャース・ニューエンの曲「インチェ・ケイ・チェ」が、伝統的な先住民文化の擁護を呼びかけている。ブラジルのグループ、Brô MC'sの 「Koangagu 」という曲は、先住民文化とブラジルの現代文化が音楽の中でどのように融合できるかを考察している。Parce MC, Mugre Sur, Sapínの 「Presente y Combativo 」は、2009年に殺害されたボリビアのラッパーの人生を称えている[72]。 アメリカ さらなる情報 米国内の音楽教育とプログラム 18世紀 トーマス・シンメス牧師の説教の後、1717年にボストンで教会での歌唱と読譜の向上を目的とした最初の歌唱学校が設立された。こうした歌唱学校は、次第 に植民地全体に広がっていった。ボストンに音楽アカデミーが設立されたことで、音楽教育はさらに盛んになった。ジョン・タフツ牧師は、植民地初の音楽教科 書とされる『非伝統的記譜法を用いた詩篇の歌唱入門』を出版した。1700年から1820年の間に、サミュエル・ホリヨーク、フランシス・ホプキンソン、 ウィリアム・ビリングス、オリバー・ホールデンなどの著者によって375以上の曲集が出版された[75]。 音楽はカリキュラム科目として他の学区にも広がり始めた。やがて音楽は全学年に広がり、譜読みの指導は改善され、音楽カリキュラムは譜読みに加えていくつかの活動を含むまでになった。1864年末までに、公立学校の音楽は全国に広まった。 19世紀 1832年、ローウェル・メイソンとジョージ・ウェッブは、歌唱と理論の教育、および音楽の教授法を目的として、ボストン音楽アカデミーを設立した。メイ ソンは1834年に、スイスの教育者ヨハン・ハインリッヒ・ペスタロッチによって創設されたペスタロッチ教育システムの音楽教育著作を基にした『マニュエ ル・オブ・インストラクション』を出版した。このハンドブックは、次第に多くの歌唱学校の教師に使われるようになった。1837年から1838年にかけ て、ボストン教育委員会はローウェル・メイソンがホーズ・スクールでデモンストレーションとして音楽を教えることを許可した。これは、アメリカの公立学校 に音楽教育が導入された最初の例とされている。1838年、ボストン教育委員会はカリキュラムに音楽を取り入れることを承認し、ローウェル・メイスンは小 学校音楽の監督者として初めて認められた。後年、ルーサー・ホワイティング・メイスンがボストンの音楽監督となり、音楽教育をすべてのレベルの公教育(文 法学校、小学校、高校)に広めた。 19世紀中頃、ボストンは、全米の多くの都市が公立学校の音楽教育プログラムを取り入れ、形成するモデルとなった[76]。音楽監督者の指導の下で音楽を 教える学校のクラス担任というコンセプトは、この世紀の公立学校音楽教育の標準モデルであった。(参照:アメリカにおける音楽教育)19世紀には女性は作 曲をすることを敬遠されていたが、「その後、女性が音楽教育において役割を持つことが認められ、女性がこの分野に関わるようになり、...19世紀後半か ら20世紀にかけて女性が音楽教育を支配するほどになった」[57]。 20世紀初頭 アメリカでは、4年制の学位プログラムを持つ教育大学が師範学校から発展し、音楽も含まれるようになった。オバーリン音楽院が最初に音楽教育学士号を授与 した。アメリカの音楽教育者オズボーン・G・マッカーシーは、チェルシー高校で単位取得のために音楽を学ぶ詳細を紹介した。20世紀初頭の音楽教育史にお ける注目すべき出来事には、以下も含まれる: 1907年、アイオワ州キオクックで音楽監督者全国会議(1934年に音楽教育者全国会議と改称、その後1998年にMENC:全米音楽教育協会、現在は全米音楽教育協会-NAfME)が設立される。 スクールバンドとオーケストラの運動が高まり、演奏重視の学校音楽プログラムにつながる。 音楽メソッドの出版物が増える。 フランシス・エリオット・クラークが学校用の蓄音機レコード・ライブラリーを開発、普及させる。 カール・シーショアと彼の音楽適性検査が始まる。 20世紀半ばから21世紀 以下の表は、この時期の注目すべき動きを示している: |

Present Music course offerings and even entire degree programs in online music education developed in the first decade of the 21st century at various institutions, and the fields of world music pedagogy and popular music pedagogy have also seen notable expansion. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, social aspects of teaching and learning music came to the fore. This emerged as praxial music education,[80] critical theory,[81] and feminist theory.[82] Of importance are the colloquia and journals of the MayDay Group, "an international think tank of music educators that aims to identify, critique, and change taken-for-granted patterns of professional activity, polemical approaches to method and philosophy, and educational politics and public pressures that threaten effective practice and critical communication in music education."[83] With a new focus on social aspects of music education, scholars have analyzed critical aspects such as music and race,[84] gender,[85] class,[86] institutional belonging,[87] and sustainability.[88] |

現在 21世紀の最初の10年間は、様々な教育機関でオンライン音楽教育のコースや学位プログラム全体が発展し、世界音楽教育学や ポピュラー音楽教育学の分野も顕著に拡大した。 20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて、音楽を教え学ぶことの社会的側面が前面に押し出されるようになった。重要なのは、メイデーグループのコロキアムや ジャーナルである。メイデーグループは、「音楽教育者の国際的なシンクタンクであり、音楽教育における効果的な実践と批判的なコミュニケーションを脅か す、専門家としての活動の既成のパターン、方法論や哲学に対する極論的なアプローチ、教育政治や公的圧力を特定し、批判し、変革することを目的としてい る。 「音楽教育の社会的側面に新たに焦点を当て、学者たちは音楽と人種[84]、ジェンダー[85]、階級[86]、組織への帰属[87]、持続可能性 [88]などの重要な側面を分析している。 |

| Europe See also: Music education in Italy Music has been a prominent subject in schools and other learning institutions in Europe for many centuries. Such early institutions as the Sistine Chapel Choir and the Vienna Boys Choir offered important early models of choral learning, while the Paris Conservatoire later became influential for training in wind band instruments. Several instructional methods were developed in Europe that would later impact other parts of the world, including those affiliated with Zoltan Kodaly, Carl Orff, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, and ABRSM, to name but a few. Notable professional organizations on the continent now include the Europe regional branch of the International Society for Music Education, and the European Association of Conservatoires. In recent decades, Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe have tended to successfully emphasize classical music heritage, while the Nordic countries have especially promoted popular music in schools.[89] |

ヨーロッパ こちらも参照のこと: イタリアの音楽教育 音楽は、ヨーロッパの学校やその他の教育機関において、何世紀にもわたって重要な科目であった。システィーナ礼拝堂合唱団やウィーン少年合唱団といった初 期の教育機関は、合唱教育の重要な初期モデルとなった。ヨーロッパでは、ゾルタン・コダーイ、カール・オルフ、エミール・ジャック=ダルクローズ、 ABRSMなど、後に世界各地に影響を与えることになる指導法が開発された。ヨーロッパ大陸の著名な専門組織としては、国際音楽教育学会のヨーロッパ地域 支部、ヨーロッパ音楽院協会などがある。ここ数十年、中欧、南欧、東欧はクラシック音楽の伝統を重視する傾向にあり、北欧諸国は特に学校でのポピュラー音 楽の普及を推進している[89]。 |

| Asia See also: Music education in Turkey and Music education in Israel India Institutional music education was started in colonial India by Rabindranath Tagore after he founded the Visva-Bharati University. At present, most universities have a faculty of music with some universities specially dedicated to fine arts such as Indira Kala Sangeet University, Swathi Thirunal College of Music, Prayag Sangeet Samiti or Rabindra Bharati University.Indian classical music is based on the Guru-Shishya parampara system. The teacher, known as Guru, transmit the musical knowledge to the student, or shyshya. This is still the main system used in India to transmit musical knowledge. Although European art music became popularized in schools throughout much of the world during the twentieth century (East Asia, Latin America, Oceania, Africa), India remains one of the few highly populated nations in which non-European indigenous music traditions have consistently received relatively greater emphasis. That said, there is certainly much western influence in the popular music associated with Bollywood film scores. Indonesia The Indonesian island of Java is known for its rich musical culture, centered around gamelan music. The two oldest gamelan instrument sets, dating from the twelfth century, are housed in the kratons (palaces) in the cities of Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Gamelan music is an integral part of the Javanese culture: it is a part of religious ceremonies, weddings, funerals, palace activities, national holidays, and local community gatherings. In recent years, there has been an increasing market for gamelan associated tourism: several companies arrange visits for tourists wishing to participate in and learn gamelan.[90] Gamelan music has a distinct pedagogical approach. The term maguru panggul, translated means “teaching with the mallet” describes the master-apprentice approach that is used most often when teaching the music. The teacher demonstrates long passages of music at a time, without stopping to have the student demonstrate comprehension of the passage, as in a western music pedagogy. A teacher and student will frequently sit on opposite sides of a drum or mallet instrument, so that both can play it. This provides the teacher an easy way to demonstrate, and the student can study and mimic the teacher's actions. The teacher trains the kendang player, who is the leader of the ensemble. The teacher works one on one with them and repeats the parts as many times as necessary until the piece is rhythmically and stylistically accurate. The Kendang player is sometimes relied on to transmit the music to their fellow gamelan members.[91] Africa See also: Music education in Uganda The South African Department of Education and the ILAM Music Heritage Project SA teach African music using western musical framework. ILAM's Listen and Learn for students 11–14 is "unique" in teaching curriculum requirements for western music using recordings of traditional African music.[92] From the time that Africa was colonized up to 1994, indigenous music and arts being taught in schools was a rare occurrence. The African National Congress (ANC) attempted to repair the neglect of indigenous knowledge and the overwhelming emphasis on written musical literacy in schools. It is not well known that the learning of indigenous music actually has a philosophy and teaching procedure that is different from western “formal” training. It involves the whole community because indigenous songs are about the history of its people. After the colonization of Africa, music became more centered on Christian beliefs and European folk songs, rather than the more improvised and fluid indigenous music. Before the major changes education went through from 1994 to 2004, during the first decade of the democratic government, teachers were trained as classroom teachers and told that they would have to incorporate music into other subject areas. The few colleges with teaching programs that included instrumental programs held a greater emphasis on music theory, history of western music, western music notation, and less on making music. Up until 1999, most college syllabi did not include training in indigenous South African Music.[93] In African cultures, music is seen as a community experience and is used for social and religious occasions. As soon as children show some sign of being able to handle music or a musical instrument they are allowed to participate with the adults of the community in musical events. Traditional songs are more important to many people because they are stories about the histories of the indigenous peoples.[94] Australia Although the National Curriculum for schools includes music under its Arts component,[95] research published in 2005 and 2020 have shown that it varies widely from state to state and school to school, with some students receiving none at all. By state and territory: Queensland's state primary schools has enjoyed good music programs since the 1980s; South Australia's music education strategy and fund was formed in 2019; Victoria has a best practice framework; Tasmania, Western Australia, and the ACT employs specialist teachers in some primary schools; in New South Wales, generalist teachers are responsible for teaching the whole primary school curriculum in state schools. [96] In November 2018, ABC Television aired Don't Stop The Music, a three-part series which documented the launch and progress of a music program in a primary school in an underprivileged area of Perth, Western Australia. It showed the positive effects of the program on the students and their families, as well as the teachers. A broader project encouraged members of the public to donate musical instruments to disadvantaged schools, which led to Musica Viva Australia receiving over 4,500 instruments to process.[97] The series featured popular musician Guy Sebastian and researcher and music educator Anita Collins, and was also supported by the Salvation Army.[98] |

アジア こちらも参照のこと: トルコの音楽教育、イスラエルの音楽教育 インド 植民地時代のインドで、ラビンドラナート・タゴールがヴィスヴァ=バラティ大学を設立した後、音楽教育が始まった。現在、ほとんどの大学に音楽学部があ り、インディラ・カラ・サンゲート大学、スワティ・ティルナル音楽大学、プラヤーグ・サンゲート・サミティ、ラビンドラ・バーラティ大学など、美術に特化 した大学もある。インド古典音楽は、グル・シシヤ・パランパラ・システムに基づいている。グルと呼ばれる教師は、生徒(シシヤ)に音楽的知識を伝える。こ れは今でもインドで音楽知識を伝えるために使われている主なシステムだ。ヨーロッパの芸術音楽は、20世紀に世界中の多くの学校(東アジア、ラテンアメリ カ、オセアニア、アフリカ)で普及したが、インドは、ヨーロッパ以外の土着の音楽伝統が一貫して比較的重視されてきた、人口の多い数少ない国のひとつであ る。とはいえ、ボリウッドの映画音楽に関連するポピュラー音楽には、確かに西洋の影響が多く見られる。 インドネシア インドネシアのジャワ島は、ガムラン音楽を中心とした豊かな音楽文化で知られている。12世紀に作られた最古のガムラン楽器セットは、ジョグジャカルタと スラカルタにあるクラトン(宮殿)にある。ガムラン音楽はジャワ文化に不可欠な要素であり、宗教儀式、冠婚葬祭、宮殿での活動、祝祭日、地域コミュニティ の集まりの一部となっている。近年、ガムランに関連した観光市場が拡大しており、いくつかの会社が、ガムランに参加したり学んだりすることを希望する観光 客のための訪問を手配している[90]。 ガムラン音楽には独特の教育的アプローチがある。マグル・パングル(maguru panggul)という用語は、「槌で教える」という意味で、ガムラン音楽を教える際に最もよく使われる師弟関係を表している。西洋音楽の教育法のよう に、生徒がそのパッセージの理解度を示すために立ち止まることなく、教師は一度に長いパッセージを実演する。先生と生徒が太鼓やマレット楽器の反対側に座 り、両者が演奏できるようにすることもよくある。こうすることで、教師は実演しやすくなり、生徒は勉強して教師の動作を真似ることができる。先生は、アン サンブルのリーダーであるケンダン奏者を訓練する。先生は彼らと1対1で取り組み、曲がリズム的にも様式的にも正確になるまで、必要なだけ何度もパートを 繰り返す。ケンダン奏者は、仲間のガムラン・メンバーに音楽を伝えるために頼りにされることもある[91]。 アフリカ 以下も参照のこと: ウガンダの音楽教育 南アフリカ教育省とILAM Music Heritage Project SAは、西洋音楽の枠組みを使ってアフリカ音楽を教えている。ILAMの11~14歳の生徒を対象としたListen and Learnは、アフリカの伝統音楽の録音を用いて西洋音楽のカリキュラム要件を教えるという「ユニークな」ものである[92]。 アフリカが植民地化されてから1994年まで、土着の音楽や芸術が学校で教えられることは稀であった。アフリカ民族会議(ANC)は、学校において土着の 知識が軽視され、文字による音楽リテラシーが圧倒的に重視されていたことを修復しようと試みた。土着音楽の学習には、西洋的な 「正式な 」訓練とは異なる哲学と教授法があることはあまり知られていない。先住民の歌はその民族の歴史に関わるものだからだ。アフリカが植民地化された後、音楽は より即興的で流動的な土着音楽ではなく、キリスト教の信仰やヨーロッパの民謡が中心となった。1994年から2004年にかけて、民主政権の最初の10年 間に教育が大きく変わる前は、教師はクラス担任として訓練され、他の教科に音楽を取り入れなければならないと言われていた。器楽科を含む教職課程を持つ数 少ない大学では、音楽理論、西洋音楽史、西洋楽譜に重点が置かれ、音楽を作ることにはあまり重点が置かれていなかった。1999年まで、ほとんどの大学の シラバスには南アフリカ固有の音楽のトレーニングは含まれていなかった[93]。 アフリカの文化では、音楽はコミュニティでの体験とみなされ、社会的・宗教的な機会に使われる。子供たちが音楽や楽器を扱える兆候を見せるとすぐに、コ ミュニティの大人たちとともに音楽行事に参加することが許される。伝統的な歌は、先住民の歴史についての物語であるため、多くの人々にとってより重要であ る[94]。 オーストラリア 学校のナショナル・カリキュラムには、芸術の要素に音楽が含まれているが[95]、2005年と2020年に発表された調査によると、州や学校によってそ の内容は大きく異なり、まったく受けていない生徒もいる。州や準州によって異なる: クイーンズランド州の州立小学校は1980年代から優れた音楽プログラムを享受してきた。南オーストラリア州の音楽教育戦略と基金は2019年に設立され た。ビクトリア州にはベストプラクティスの枠組みがあり、タスマニア州、西オーストラリア州、ACT州は一部の小学校で専門教員を採用している。ニューサ ウスウェールズ州では、一般教員が州立学校の小学校カリキュラム全体の指導を担当している。[96] 2018年11月、ABCテレビは、西オーストラリア州パースの恵まれない地域の小学校における音楽プログラムの立ち上げと経過を記録した3部構成のシ リーズ『Don't Stop The Music』を放映した。この番組では、生徒とその家族、そして教師たちに、このプログラムが良い影響を与えていることが紹介された。このシリーズは、人 気ミュージシャンのガイ・セバスチャンと研究者で音楽教育者のアニタ・コリンズを起用し、救世軍の支援も受けた[98]。 |

| Jamey Aebersold Stefan Ammer Ysaye Barnwell Leonard Bernstein Edward Bailey Birge Nadia Boulanger Allen Britton Patricia Shehan Campbell F. Melius Christiansen Frances Elliott Clark Satis N. Coleman Julia Crane John Curwen Max Deutsch Peter W. Dykema Will Earhart Jacob Eisenberg David J. Elliott Sarah Ann Glover Edwin Gordon Lucy Green Philip C. Hayden David G. Hebert Paul Hindemith Jere T. Humphreys Émile Jaques-Dalcroze Dmitry Kabalevsky Zoltán Kodály Paul R. Lehman Charles Leonhard Joseph E. Maddy Michael Mark Ellis Marsalis, Jr. Wynton Marsalis Lowell Mason Luther Whiting Mason Lin Manuel Miranda James Mursell Carl Orff John Paynter Bennett Reimer R. Murray Schafer Christopher Small Shinichi Suzuki Lennie Tristano John Tufts Thomas Tyra Heitor Villa-Lobos |

ジャミー・エーバーソルド ステファン・バンティング イッセイ・バーンウェル レナード・バーンスタイン エドワード・ベイリー・ビルジ ナディア・ブーランジェ アレン・ブリトン パトリシア・シェハン・キャンベル F. メリウス・クリスチャンセン フランシス・エリオット・クラーク サティス N. コールマン ジュリア・クレーン ジョン・カーウェン マックス・ジャーマン ピーター・W・ダイクマ ウィル・アーハート ジェイコブ・アイゼンバーグ デビッド・J・エリオット サラ・アン・グローバー エドウィン・ゴードン ルーシー・グリーン フィリップ C. ヘイデン デヴィッド・G. ヘバート ポール・ヒンデミット ジェレ・T.ハンフリーズ エミール・ジャック=ダルクローズ ドミトリー・カバレフスキー ゾルターン・コダーイ ポール・R・リーマン チャールズ・レオンハルト ジョセフ・E. マディ マイケル・マーク エリス・マルサリスJr. ウィントン・マルサリス ローウェル・メイソン ルーサー・ホワイティング・メイソン リン・マニュエル・ミランダ ジェームズ・マーセル カール・オルフ ジョン・ペインター ベネット・ライマー R. マレー・シェーファー クリストファー・スモール 鈴木 真一 レニー・トリスターノ ジョン・タフツ トーマス・タイラ ハイター・ヴィラ=ロボス |

| American Choral Directors Association American Orff-Schulwerk Association American String Teachers Association International Association for Jazz Education[99] International Society for Music Education International Society for Philosophy of Music Education[100] National Association for Music Education (US-based: also called NafME, and previously MENC) Music Teachers National Association Nordic Network for Music Education (NNME) |

アメリカ合唱指揮者協会 米国オルフ・シュルヴェルク協会 米国弦楽指導者協会 国際ジャズ教育協会[99] 国際音楽教育学会 国際音楽教育哲学協会[100] 全米音楽教育協会(米国を拠点とし、NafMEとも呼ばれる。) 音楽教師全国協会 北欧音楽教育ネットワーク (NNME) |

| Basic Concepts in Music Education Colored music notation Musical Futures Music education for young children Music school Musicology Research in Music Education Timeline of jazz education Visual arts education Vocal coach |

音楽教育の基本概念 カラー楽譜 音楽の未来 幼児のための音楽教育 音楽学校 音楽学 音楽教育研究 ジャズ教育年表 視覚芸術教育 ヴォーカル・コーチ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_education |

|

| Basic Concepts in Music Education

is a landmark work published in 1958 as the Fifty-Seventh Yearbook of

the National Society for the Study of Education. In 1954, the Music

Educators National Conference (MENC) had formed its Commission on Basic

Concepts in an attempt to seek a more soundly-based philosophical

foundation. The work of the commission resulted in the publication of

Basic Concepts, which advocated an aesthetic justification for music

education. According to the aesthetic philosophy, music education

should be justified for its own sake rather than for its extra-musical

benefits. Contents Section I: Disciplinary Backgrounds Therber H. Madison, The Need for New Concepts in Music Education Foster McMurray, Pragmatism in Music Education Harry S. Broudy, A Realistic Philosophy of Music Education John H. Mueller, Music and Education: A Sociological Approach George Frederick McKay, The Range of Musical Experience James Mursell, Growth Processes in Music Education Louis P. Thorpe, Learning Theory and Music Teaching Allen Britton, Music in Early American Public Education: A Historical Critique Section II: Music in Schools C.A. Burnmeister, The Role of Music in General Education Robert House, Curriculum Construction in Music Education William C. Hartshorn, The Role of Listening E. Thayer Gaston, Functional Music Charles Leonhard, Evaluation in Music Education Oletta A. Benn, A Message for New Teachers Basic Concepts II Richard Colwell edited Basic Concepts in Music Education II in 1991. This volume included updates from the living authors of the original volume as well as new contributions from leaders in the field. References Henry, N. B. (Ed.). (1958). Basic Concepts in Music Education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Mark, M. L., & Gary, C. L. (1999). A history of American music education (2nd ed.). Reston, VA: MENC—The National Association for Music Education. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_Concepts_in_Music_Education |

『音楽教育の基本概念』

は、1958年に全国教育学会年鑑第五十七号として出版された画期的な著作である。1954年、音楽教育者全国会議(MENC)は、より健全な哲学的基盤