ナラティブ調査

Narrative inquiry

☆ ナラティブ調査(Narrative inquiry)、 あるいはナラティヴ・インクワイアリーまたはナラティヴ・アナリシスは、20世紀初頭に質的研究という広範な分野の中から一つの学問分野として登場し、こ の手法が心理学や社会学で用いられた証拠が存在する。ナラティヴ・インクワイアリーは、物語、自伝、日記、フィールドノート、手紙、会話、インタビュー、 家族の物語、写真(およびその他の人工物)、人生経験などのフィールドテキストを分析単位として用い、人々が人生の中で意味を創り出す方法をナラティヴと して研究し理解する。 ナラティヴ・インクワイアリーは、認知科学、組織学、知識理論、応用言語学、社会学、職業科学、教育学などの分野で分析のツールとして採用されている。他 のアプローチとしては、断片化された逸話的資料によって捕捉される大量の量や、捕捉の時点で自己記号化または指標化されたものに基づく定量的手法やツール の開発がある。ナラティブ・インクワイアリーは、定量的/根拠のあるデータ収集の背後にある哲学に挑戦し、「客観的」データの考え方に疑問を投げかけてい る。 応用言語学のような学問分野では、この理論を使用する学問分野に十分な臨界量の研究が存在し、その適用を導くための枠組みを開発することができると指摘さ れている。

| Narrative inquiry or

narrative analysis emerged as a discipline from within the broader

field of qualitative research in the early 20th century,[1] as evidence

exists that this method was used in psychology and sociology.[2]

Narrative inquiry uses field texts, such as stories, autobiography,

journals, field notes, letters, conversations, interviews, family

stories, photos (and other artifacts), and life experience, as the

units of analysis to research and understand the way people create

meaning in their lives as narratives.[3] Narrative inquiry has been employed as a tool for analysis in the fields of cognitive science, organizational studies, knowledge theory, applied linguistics, sociology, occupational science and education studies, among others. Other approaches include the development of quantitative methods and tools based on the large volume captured by fragmented anecdotal material, and that which is self signified or indexed at the point of capture.[4] Narrative Inquiry challenges the philosophy behind quantitative/grounded data-gathering and questions the idea of “objective” data; however, it has been criticized for not being “theoretical enough."[5][6] In disciplines like applied linguistics, scholarly work has pointed out that enough critical mass of studies exists in the discipline that uses this theory, and that a framework can be developed to guide its application.[7] |

ナラティヴ・インクワイアリーまたはナラティヴ・アナリシスは、20世

紀初頭に質的研究という広範な分野の中から一つの学問分野として登場し[1]、この手法が心理学や社会学で用いられた証拠が存在する[2]。ナラティヴ・

インクワイアリーは、物語、自伝、日記、フィールドノート、手紙、会話、インタビュー、家族の物語、写真(およびその他の人工物)、人生経験などのフィー

ルドテキストを分析単位として用い、人々が人生の中で意味を創り出す方法をナラティヴとして研究し理解する[3]。 ナラティヴ・インクワイアリーは、認知科学、組織学、知識理論、応用言語学、社会学、職業科学、教育学などの分野で分析のツールとして採用されている。他 のアプローチとしては、断片化された逸話的資料によって捕捉される大量の量や、捕捉の時点で自己記号化または指標化されたものに基づく定量的手法やツール の開発がある[4]。ナラティブ・インクワイアリーは、定量的/根拠のあるデータ収集の背後にある哲学に挑戦し、「客観的」データの考え方に疑問を投げか けている。 「5][6]応用言語学のような学問分野では、この理論を使用する学問分野に十分な臨界量の研究が存在し、その適用を導くための枠組みを開発することがで きると指摘されている[7]。 |

| Background Narrative inquiry is a form of qualitative research, that emerged in the field of management science and later also developed in the field of knowledge management, which shares the sphere of Information Management.[8] It has been noted the narrative case studies were used by Freud in the field of psychology, and biographies were used in sociology in the early twentieth century.[2] Thus Narrative Inquiry focuses on the organization of human knowledge more than merely the collection and processing of data. It also implies that knowledge itself is considered valuable and noteworthy even when known by only one person. Knowledge management was coined as a discipline in the early 1980s as a method of identifying, representing, sharing, and communicating knowledge.[9] Knowledge management and Narrative Inquiry share the idea of Knowledge transfer, a theory which seeks to transfer unquantifiable elements of knowledge, including experience. Knowledge, if not communicated, becomes arguably useless, literally unused. Philosopher Andy Clark speculates that the ways in which minds deal with narrative (second-hand information) and memory (first-hand perception) are cognitively indistinguishable. Narrative, then, becomes an effective and powerful method of transferring knowledge. More recently, there has been a "narrative turn" in social science in response to the criticism against the paradigmatic methods of research.[2] It has also been forecasted that soon narrative inquiry will emerge as an independent research method as opposed to being an extension of the qualitative method.[7] |

背景 ナラティブ・インクワイアリーは質的研究の一形態であり、経営科学の分野で生まれ、後に情報マネジメントと同じ領域を共有するナレッジ・マネジメントの分 野でも発展した[8]。20世紀初頭には、心理学の分野でフロイトがナラティブ・ケース・スタディーを用い、社会学では伝記が用いられたことが指摘されて いる[2]。また、知識そのものは、たとえ一人しか知らないとしても、価値があり、注目に値するものであると考えられている。 ナレッジ・マネジメントは、知識を特定し、表現し、共有し、伝達する方法として、1980年代初頭に学問分野として造語された[9]。ナレッジ・マネジメ ントとナラティブ・インクワイアリーは、経験を含む知識の定量化不可能な要素を伝達しようとする理論である知識伝達(Knowledge transfer)の考え方を共有している。知識は、もし伝達されなければ、議論の余地なく役に立たなくなり、文字通り使われなくなる。 哲学者のアンディ・クラークは、物語(二次情報)と記憶(直接知覚)を扱う方法は、認知的に区別できないと推測している。そうなると、語りは知識を伝達する効果的で強力な方法となる。 さらに最近では、パラダイム的な研究手法に対する批判を受けて、社会科学において「ナラティブ・ターン」が起こっている[2]。また、近い将来、ナラティブな探究は、質的手法の延長線上にあるのではなく、独立した研究手法として登場するだろうと予測されている[7]。 |

| Narrative ways of knowing Narrative is a powerful tool in the transfer, or sharing, of knowledge, one that is bound to cognitive issues of memory, constructed memory, and perceived memory. Jerome Bruner discusses this issue in his 1990 book, Acts of Meaning, where he considers the narrative form as a non-neutral rhetorical account that aims at “illocutionary intentions,” or the desire to communicate meaning.[10] This technique might be called “narrative” or defined as a particular branch of storytelling within the narrative method. Bruner's approach places the narrative in time, to “assume an experience of time” rather than just making reference to historical time.[11] This narrative approach captures the emotion of the moment described, rendering the event active rather than passive, infused with the latent meaning being communicated by the teller. Two concepts are thus tied to narrative storytelling: memory and notions of time; both as time as found in the past and time as re-lived in the present.[12] A narrative method accepts the idea that knowledge can be held in stories that can be relayed, stored, and retrieved.[13] There is also a view that a critical event can play an important role as creating the context of a narrative to be captured.[7] |

ナラティヴな知の方法 語りは、知識の伝達や共有において強力なツールであり、記憶、構築された記憶、知覚された記憶といった認知的な問題と結びついている。ジェローム・ブルー ナーは1990年の著書『Acts of Meaning(意味の行為)』の中でこの問題について論じており、そこでは物語形式を「非中立的な修辞学的説明」、つまり「illocutionary intentions(意図の伝達)」、つまり意味を伝えたいという願望を目的としたものとみなしている[10]。この技法は「ナラティブ」と呼ばれるか もしれないし、物語法の中の特定の一分野として定義されるかもしれない。ブルーナーのアプローチは、単に歴史的な時間に言及するのではなく、「時間の経験 を想定する」ために、物語を時間の中に置く[11]。 このナラティブ・アプローチは、語られる瞬間の感情を捉え、出来事を受動的ではなく能動的なものとし、語り手によって伝達される潜在的な意味を吹き込む。つまり、記憶と時間の概念である。過去に見出される時間と、現在に再体験される時間の両方である[12]。 ナラティヴ・メソッドでは、知識は物語の中に保持され、それが伝達され、保存され、検索されうるという考え方を受け入れている[13]。また、重要な出来事が、捉えるべき物語の文脈を作り出すという重要な役割を果たしうるという見解もある[7]。 |

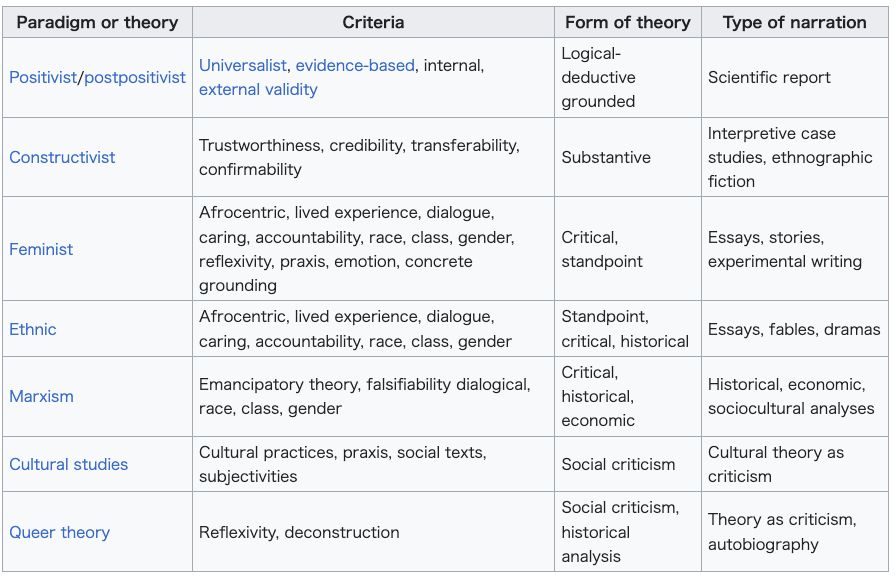

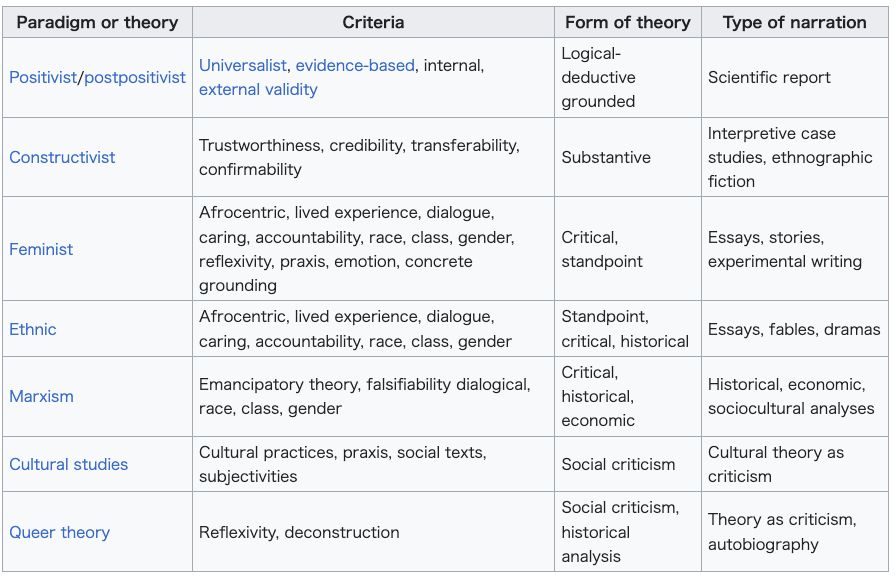

| Method 1. Develop a research question A qualitative study seeks to learn why or how, so the writer's research must be directed at determining the why and how of the research topic. Therefore, when crafting a research question for a qualitative study, the writer will need to ask a why or how question about the topic.[14] 2. Select or produce raw data The raw data tend to be interview transcriptions, but can also be the result of field notes compiled during participant observation or from other forms of data collection that can be used to produce a narrative.[15] 3. Organize data According to psychology professor Donald Polkinghorne, the goal of organizing data is to refine the research question and separate irrelevant or redundant information from that which will be eventually analyzed, sometimes referred to as "narrative smoothing."[16] Some approaches to organizing data are as follows: (When choosing a method of organization, one should choose the approach best suited to the research question and the goal of the project. For instance, Gee's method of organization would be best if studying the role language plays in narrative construction whereas Labov's method would more ideal for examining a certain event and its effect on an individual's experiences.)[17][18] Labov's: Thematic organization[19] or Synchronic Organization. This method is considered useful for understanding major events in the narrative and the effect those events have on the individual constructing the narrative.[20] The approach utilizes an "evaluation model" that organizes the data into an abstract (What was this about?), an orientation (Who? What? When? Where?), a complication (Then what happened?), an evaluation (So what?), a result (What finally happened?), and a coda (the finished narrative).[21] Said narrative elements may not occur in a constant order; multiple or reoccurring elements may exist within a single narrative.[21] Polkinghorne's: Chronological Organization or Diachronic Organization also related to the sociology of stories approach that focuses on the contexts in which narratives are constructed. This approach attends to the "embodied nature" of the person telling the narrative, the context from which the narrative is created, the relationships between the narrative teller and others within the narrative, historical continuity, and the chronological organization of events.[22] A story with a clear beginning, middle, and end is constructed from the narrative data. Polkinghorne makes the distinction between narrative analysis and analysis of narratives.[23] Narrative analysis utilizes "narrative reasoning" by shaping data in a narrative form and doing an in-depth analysis of each narrative on its own, whereas analysis of narratives utilizes paradigmatic reasoning and analyzes themes across data that take the form of narratives.[23] Bruner's functional approach focuses on what roles narratives serve for different individuals. In this approach, narratives are viewed as the way in which individuals construct and make sense of reality as well as the ways in which meanings are created and shared.[24] This is considered a functional approach to narrative analysis because the emphasis of the analysis is focused on the work that the narrative serves in helping individuals make sense of their lives, particularly through shaping random and chaotic events into a coherent narrative that makes the events easier to handle by giving them meaning.[24] The focus of this form of analysis is on the interpretations of events related in the narratives by the individual telling the story.[24] Gee's approach of structural analysis focuses on the ways in which the narrative is conveyed by the speaker with particular emphasis given to the interaction between the speaker and the listener.[25] In this form of analysis, the language that the speaker uses is the focus. This includes the language, the pauses in speech, discourse markers, and other similar structural aspects. In this approach, the narrative is divided into stanzas and each stanza is analyzed by itself and also in the way in which it connects to the other pieces of the narrative.[26] Jaber F. Gubrium's form of narrative ethnography features the storytelling process as much as the story in analyzing narrativity. Moving from text to field, he and his associate James A. Holstein present an analytic vocabulary and procedural strategies for collecting and analyzing narrative material in everyday contexts, such as families and care settings. In their view, the structure and meaning of texts cannot be understood separate from the everyday contexts of their production. Their two books--"Analyzing Narrative Reality" and "Varieties of Narrative Analysis" provide dimensions of an institutionally-sensitive, constructionist approach to narrative production. There are a multitude of ways of organizing narrative data that fall under narrative analysis; different types of research questions lend themselves to different approaches.[27] Regardless of the approach, qualitative researchers organize their data into groups based on various common traits.[22] 4. Interpret data Some paradigms/theories that can be used to interpret data:  While interpreting qualitative data, researchers suggest looking for patterns, themes, and regularities as well as contrasts, paradoxes, and irregularities.[21] (The research question may have to change at this stage if the data does not offer insight to the inquiry.) The interpretation is seen in some approaches as co-created by not only the interviewer but also with help from the interviewee, as the researcher uses the interpretation given by the interviewee while also constructing their own meaning from the narrative. With these approaches, the researcher should draw upon their own knowledge and the research to label the narrative.[25] According to some qualitative researchers, the goal of data interpretation is to facilitate the interviewee's experience of the story through a narrative form.[23] Narrative forms are produced by constructing a coherent story from the data and looking at the data from the perspective of one's research question.[16] |

方法 1. 研究課題を設定する 質的研究は、「なぜ」「どのように」を学ぼうとするものであるため、執筆者の研究は、研究トピックの「なぜ」「どのように」を決定することに向けられなけ ればならない。したがって、質的研究のためのリサーチクエスチョンを作成する場合、執筆者はトピックについてなぜ、またはどのように質問する必要がある [14]。 2. 生データを選択または作成する 生データはインタビューの記録であることが多いが、参加者観察中にまとめられたフィールドノートや、ナラティブを作成するために使用できる他の形式のデータ収集の結果であることもある[15]。 3. データを整理する 心理学教授のドナルド・ポルキングホーンによると、データを整理する目的は、リサーチクエスチョンを洗練させ、最終的に分析する情報から無関係な情報や冗長な情報を分離することであり、「ナラティブ・スムージング」と呼ばれることもある[16]。 データ整理のアプローチには以下のようなものがある: (整理方法を選択する際は、リサーチクエスチョンとプロジェクトの目標に最も適したアプローチを選ぶべきである)。例えば、物語構築において言語が果たす 役割を研究するのであれば、ジーの整理法が最適であるのに対し、ある出来事とそれが個人の経験に与える影響を調べるのであれば、ラボフの方法がより理想的 である)[17][18]。 ラボフの 主題構成[19]または共時的構成。 この方法は物語における主要な出来事とそれらの出来事が物語を構築している個人に与える影響を理解するのに有用であると考えられている[20]。このアプ ローチでは、データを抽象的なもの(これは何についての出来事であったか)、方向性(誰が?いつ、どこで、誰が、何をしたのか)、複雑さ(それから何が起 こったのか)、評価(だから何なのか)、結果(最終的に何が起こったのか)、コーダ(完成した物語)[21]にデータを整理する「評価モデル」を利用す る。 ポルキングホーンの 時系列的組織または通時的組織 物語が構築される文脈に焦点を当てる物語社会学のアプローチとも関連している。このアプローチでは、語りを語る人物の「身体化された性質」、語りが創造さ れる文脈、語り手と語りの中の他者との関係、歴史的連続性、出来事の時系列的構成に注意を払う[22]。ポルキングホーンはナラティブ分析とナラティブ分 析を区別している[23]。ナラティブ分析は、データをナラティブの形で形成し、それぞれのナラティブを単独で詳細に分析することによって「ナラティブ推 論」を利用するのに対し、ナラティブ分析はパラダイム推論を利用し、ナラティブの形をとるデータ全体のテーマを分析する[23]。 ブルーナーの機能的アプローチは、ナラティブが様々な個人にとってどのような役割を果たすかに焦点を当てている。このアプローチでは、ナラティブは個人が 現実を構 築し、理解する方法、また意味が創造され共有される方法と見なされる。 [分析の重点は、特にランダムで混沌とした出来事を首尾一貫した物語に形成することで、その出来事に意味を与えることにより、その出来事を扱いやすくする ことを通して、物語が個人の人生の意味づけを助けるという働きに焦点を当てているため、これは物語分析に対する機能的アプローチと考えられている [24]。 ジーの構造分析のアプローチでは、話し手と聞き手の間の相互作用に特に重点を置きながら、話し手によって語りが伝達される方法に焦点を当てる[25]。こ れには、言葉遣い、話の間、談話標識、その他同様の構造的側面が含まれる。このアプローチでは、語りはスタンザに分割され、各スタンザはそれ自体で分析さ れるだけでなく、語りの他の部分とのつながり方でも分析される[26]。 ジャベール・F・グブリアムのナラティヴ・エスノグラフィの形態は、 物語性を分析する上で、物語と同様に物語のプロセスを特徴としている。テキストからフィールドへと移動し、彼と彼の共同研究者であるジェイム ズ・A・ホルスタインは、家族や介護環境といった日常的なコンテク ストにおける物語素材を収集・分析するための分析語彙と手続き的戦 略を提示している。彼らの見解によれば、テクストの構造と意味は、その制作の日常的な文脈と切り離して理解することはできない。彼らの2冊の本--『ナラ ティブ・リアリティの分析』と『ナラティブ分析の多様性』--は、制度に敏感で、ナラティブ生産に対する構築主義的アプローチの次元を提供している。 ナラティブ分析に該当するナラティブデータの整理方法は多数あり、研究課題のタイプによって適したアプローチは異なる[27]。アプローチにかかわらず、質的研究者は様々な共通の特徴に基づいてデータをグループに整理する[22]。 4. データを解釈する データを解釈するために使用できるいくつかのパラダイム/理論がある:  質的データを解釈する際、研究者はパターン、テーマ、規則性だけでなく、対比、逆説、不規則性を探すことを推奨している[21]。 (データが調査に対する洞察を提供しない場合は、この段階でリサーチクエスチョンを変更する必要があるかもしれない)。 解釈は、インタビュアーだけでなく、インタビュイーの助けも借りて共同で作成するアプローチもある。 このようなアプローチでは、研究者は自分自身の知識と調査に基づいて、語りにラベル付けをする必要がある[25]。 一部の質的研究者によると、データ解釈の目的は、物語形式を通じて、インタビュー対象者のストーリー体験を促進することである[23]。 物語形式は、データから首尾一貫したストーリーを構築し、研究課題の観点からデータを見ることによって生み出される[16]。 |

| Interpretive research The idea of imagination is where narrative inquiry and storytelling converge within narrative methodologies. Within narrative inquiry, storytelling seeks to better understand the “why” behind human action.[29] Story collecting as a form of narrative inquiry allows the research participants to put the data into their own words and reveal the latent “why” behind their assertions. “Interpretive research” is a form of field research methodology that also searches for the subjective "why."[30] Interpretive research, using methods such as those termed “storytelling” or “narrative inquiry,” does not attempt to predefine independent variables and dependent variables, but acknowledges context and seeks to “understand phenomena through the meanings that people assign to them.”[31] Two influential proponents of a narrative research model are Mark Johnson and Alasdair MacIntyre. In his work on experiential, embodied metaphors, Johnson encourages the researcher to challenge “how you see knowledge as embodied, embedded in a culture based on narrative unity,” the “construct of continuity in individual lives.”[32] The seven “functions of narrative work” as outlined by Riessman[33] 1. Narrative constitutes past experiences as it provides ways for individuals to make sense of the past. 2. Narrators argue with stories. 3. Persuading. Using rhetorical skill to position a statement to make it persuasive/to tell it how it “really” happened. To give it authenticity or ‘truth’. 4. Engagement, keeping the audience in the dynamic relationship with the narrator. 5. Entertainment. 6. Stories can function to mislead an audience. 7. Stories can mobilize others into action for progressive change.[33] |

解釈的研究 想像力という考え方は、ナラティブ手法の中でナラティブ探究とストーリーテリングが収束するところである。ナラティブ探究の一形態としてのストーリー収集 は、調査参加者がデータを自分の言葉に置き換えて、彼らの主張の背後にある潜在的な「なぜ」を明らかにすることを可能にする。 「解釈的研究」もまた、主観的な「なぜ」を探求するフィールドリサーチの方法論の一形態である[30]。「ストーリーテリング」や「ナラティブ・インクワ イアリー」と呼ばれるような方法を用いた解釈的研究では、独立変数や従属変数をあらかじめ定義しようとせず、文脈を認め、「人々がそれらに付与する意味を 通して現象を理解する」ことを目指す[31]。 ナラティブ研究モデルの有力な支持者は、マーク・ジョンソンとアラスデア・マッキンタイアの2人である。ジョンソンは、経験的で身体化されたメタファーに 関す る研究の中で、研究者に「物語的な統一性に基づく文化に埋め込まれ た、身体化されたものとして知識をどのように見るか」、「個々の生 活における連続性の構成」[32]に挑戦するよう促している。 Riessman[33]が概説する7つの「ナラティブの機能」 1. 個人が過去を理解する方法を提供することで、語りは過去の経験を構成する。2. 語り手は物語で議論する。3. 説得する。説得力を持たせるために、あるいは「実際に」起こったことを伝えるために、修辞学的な技巧を駆使して発言を位置づける。信憑性や「真実」を与え る。4. 観客を語り手とダイナミックな関係に保つ。5. 娯楽性。6. ストーリーは観客を惑わす働きをすることがある。7. ストーリーは、進歩的変化のための行動に他者を動員することができる[33]。 |

| Practices Narrative analysis therefore can be used to acquire a deeper understanding of the ways in which a few individuals organize and derive meaning from events.[22] It can be particularly useful for studying the impact of social structures on an individual and how that relates to identity, intimate relationships, and family.[34] For example: Feminist scholars have found narrative analysis useful for data collection of perspectives that have been traditionally marginalized. The method is also appropriate to cross-cultural research. As Michael Brecher and Frank P. Harvey advocate, when asking unusual questions it is logical to ask them in an unusual manner.[35] Developmental psychology utilizes narrative inquiry to depict a child's experiences in areas such as self-regulation, problem-solving and development of self.[20] Personality uses the narrative approach in order to illustrate an individual's identity over a lifespan.[36] Social movements have used narrative analysis in their persuasive techniques.[37] Political practices. Stories are connected to the flow of power in the wider world. Some narratives serve different purposes for individuals and others, for groups. Some narratives overlap both individual experiences and social.[38] Promulgation of a culture: Narratives and storytelling are used to remember past events, reveal morals, entertain, relate to one another, and engage a community. Narrative inquiry helps to create an identity and demonstrate/carry on cultural values/traditions. Stories connect humans to each other and to their culture. These cultural definitions aid to make social knowledge accessible to people who are unfamiliar with the culture/situation. An example of this is how children in a given society learn from their parents and the culture around them.[38] |

実践 したがってナラティブ分析は、少数の個人が出来事を組織化し、そこから意味を導き出す方法をより深く理解するために用いることができる[22]: フェミニスト研究者は、ナラティブ分析が伝統的に疎外されてきた視点のデータ収集に有用であることを見出している。また、この方法は異文化研究にも適して いる。マイケル・ブレイチャーとフランク・P・ハーヴェイが提唱しているように、通常とは異なる質問をする際には、通常とは異なる方法で質問をすることが 論理的である[35]。 発達心理学では、自己調整、問題解決、自己の発達などの領域における子どもの経験を描写するために、ナラティブ・アプローチを利用している[20]。 パーソナリティは、生涯にわたる個人のアイデンティティを説明するためにナラティブ・アプローチを使用している[36]。 社会運動では、説得の手法にナラティブ分析が用いられている[37]。 政治的実践。物語はより広い世界における権力の流れと結びついている。物語には、個人にとって異なる目的を果たすものもあれば、集団にとって異なる目的を果たすものもある。個人的な経験と社会的な経験の両方に重なる物語もある[38]。 文化の伝播: ナラティブやストーリーテリングは、過去の出来事を思い出したり、モラルを明らかにしたり、楽しませたり、互いに関係を持ったり、コミュニティに関与した りするために使用される。物語の探究は、アイデンティティを創造し、文化的価値観や伝統を実証/継承するのに役立つ。物語は人間同士を結びつけ、文化と結 びつける。こうした文化的定義は、その文化や状況に馴染みのない人々が社会的知識にアクセスできるようにする助けとなる。この例として、ある社会の子ども たちが両親や周囲の文化からどのように学ぶかが挙げられる[38]。 |

| D. Jean Clandinin Qualitative research Content analysis Frame analysis Thematic analysis Narrative Narrative psychology Narratology Knowledge management Knowledge transfer Organizational storytelling Reflective practice Storytelling Hermeneutics Praxis intervention |

D. ジャン・クランディニン 質的研究 内容分析 フレーム分析 主題分析 物語 物語心理学 ナラトロジー 知識管理 知識伝達 組織のストーリーテリング リフレクティブ・プラクティス ストーリーテリング 解釈学 実践的介入 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrative_inquiry |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆