ナチ・ジェノサイドを学ぶ人のために

For Students learning on Nazi genocide

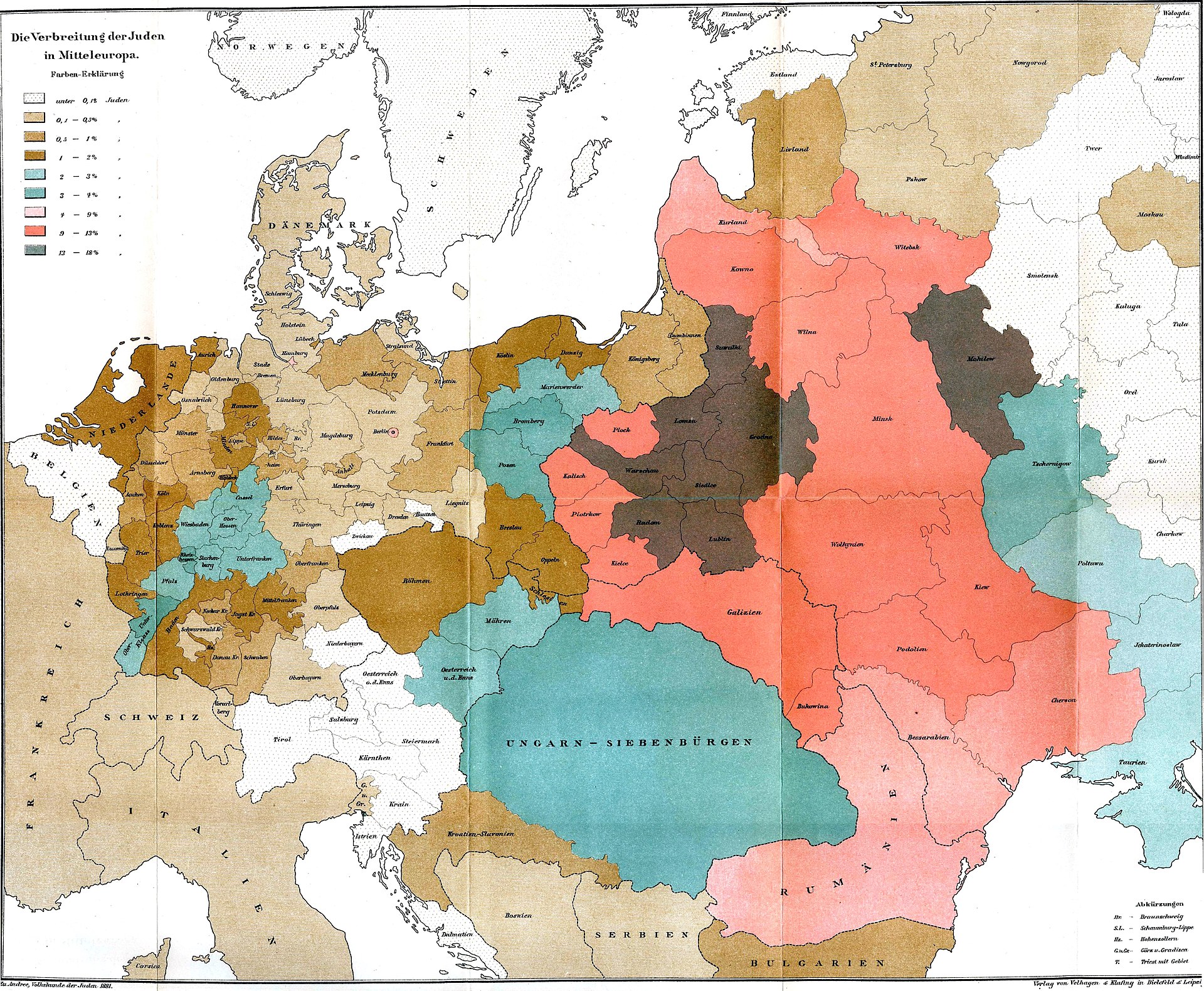

European Jewish population distribution, ca. 1881; percentage of Jews (in German)

「「genocide」(ジェノサイド)という言葉は、1944年より前には存在しませんで した。これは非常に特定的な言葉で、あるグループの存在を抹消することを目的として行われる暴力的な犯罪行為を意味します。 米国の権利章典や1948年に採択された国連世界人権宣言で述べられている人権は、個人の権利に関するものです。1944年、ポーランド系ユダヤ人の弁護 士であるラファエル・レムキン(Raphael Lemkin, 1900~1959)は、ヨーロッパ在住ユダヤ人の抹殺を含む、ナチスの組織的殺戮政策を記録しようと努めました。 彼は、人種や部族を意味するギリシャ語の「geno-」と、殺人を意味するラテン語の「-cide」を組み合わせて「genocide」という言葉を創り ました。 この新しい言葉を提案するにあたり、レムキンは「集団そのものの絶滅を目的とした、国民的集団の生命に不可欠な基盤を破壊するためのさまざまな行動の組織 的な計画」を考えていました。 その翌年、ドイツのニュルンベルクで行われた国際軍事裁判において、ナチス幹部は「人道に対する罪」で告発されました。 「ジェノサイド」という言葉は起訴状に含まれていますが、説明的なものであり、法律用語ではありませんでした。1948年12月9日、ホロコーストの余韻 がまだ冷めない中、レムキン自身のたゆまぬ努力もあって、国際連合はジェノサイド犯罪の防止と処罰に関する条約(The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention)を採択しました。 この条約により「ジェノサイド」は国際犯罪と定められ、締約国は「防止と処罰を行う義務」を負うことになりました。 これによると、「ジェノサイド」とは、国民的、民族的、人種的、または宗教的な集団の全体もしくは一部を破壊す る意図をもって取られる次のような行動と定義されています。 (a) 集団の構成員を殺害すること (b) 集団の構成員に重大な肉体的または精神的な危害を加えること (c) 全体または一部の肉体的な破壊をもたらすような危害を集団の生活条件に故意に与えること (d) 集団内での出生を妨げることを意図とした措置を講ずること (e) 集団の子供を別の集団に強制的に移送すること」という意味になる」「ジェ ノサイドとは」ホロコースト百科事典)

| 絶滅収容所とホロコースト |

絶

滅収容所(Extermination camp; Vernichtungslager) とは、アウシュヴィッツ=ビルケナウ強制収容所(Das

Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau)、ヘ ウムノ強制収容所(KZ

Chełmno)、ベウジェツ強制収容所(Konzentrationslager Belzec)、ルブリン強制収容所(Majdanek,

Konzentrationslager Lublin)、ソビボル強制収容所(Vernichtungslager

Sobibor)、トレブリンカ強制収容所(Konzentrationslager

Treblinka)、以上6つの強制収容所を指す言葉である。絶滅収容所を正式名称とした施設は存在せず、また、当時のドイツ政府の公式文書に絶滅収容

所という言葉は存在しない。 これはホ

ロコーストを目的として、ナチス・ドイツが第二次世界大戦中に設立した。絶滅収容所は大戦中に絶滅政策の総仕上げとして建てられた。犠牲者の遺体

は、通常は焼却処分ないし集団墓地に埋められて処理された。こうした収容所によってナチスが絶滅させようとしたのは、主にヨーロッパのユダヤ人とロマ(当

時はジプシーと呼ばれた)であった。しかし、ソ連軍の捕虜や同性愛者、ときにはポーランド人も含まれていた。 |

| ア

ウシュビッツに医学=医療はあったのか? |

ナ

チ管理下のアウシュビッツ強制収容所に、おびただ

しい数のナチの軍医(医者)や看護師が働いていたはずだ。問題は、アウシュビッツに言葉の正しい意味での「医学=医療(medicine)」はあったのか

ということだ。ポーランドにかって、Medical Review - Auschwitz (Przegląd Lekarski –

Oświęcim)という、ノーベル平和賞の候補にもなった 医学ジャーナルがあったらしい。同サイトからの引用である。 |

| ハイドリヒとユダヤ人絶滅政策 |

ラ

インハルト・ハイドリヒとは、「ドイツの政治家、軍人。最終階級は親衛隊大将 (SS-Obergruppenführer)

および警察大将(General der Polizei)。国家保安本部(RSHA, Reichssicherheitshauptamt der

SS)の事実上の初代長官(27 Sep, 1939-4 June,

1942)。ドイツの政治警察権力を一手に掌握し、ハインリヒ・ヒムラーに次ぐ親衛隊の実力者となった。ユダヤ人問題の最終的解決計画の実質的な推進者で

あった。その冷酷さから親衛隊の部下たちから「金髪の野獣(Die blonde

Bestie)」と渾名された。1942年1月20日のヴァンゼー会議の

主宰者。戦時中にはベーメン・メーレン保護領(チェコ)の統治にあたっていたが、大英帝国政府およびチェコスロバキア亡命政府が送

りこんだチェコ人部隊により暗殺された(エンスラポイド作戦)」。 |

| ヴァ

ンゼー会議 |

ヴァ

ンゼー会議( Wannseekonferenz, Wannsee

Conference)とは、15名のヒトラー政権の高官が会同して、ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の移送と殺害について分担と連携を討議した会議である。会議の

前年の7月31日ハイドリッヒはゲーリングから「ユダヤ人問題の最終的解

決」(ユダヤ人の絶滅政策)の委任(下記、手紙文書参照)を受け、この権限に基づき、ヴァンゼー会議を企画、翌年実現。会議は1942年1月20日にベル

リンの高級住宅地、ヴァンゼー湖畔にある親衛隊の所有する邸宅で開催された。しかしながら、会議が開かれる以前からアイ

ンザッツグルッペン(Einsatzgruppen)という部隊は占領下の東ヨーロッパやソ連においてヨーロッパユダヤ人を組織的に殺戮していた。ナチス

政権は広大な占領地域に分散し居住

する多数のヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人を絶滅させるために必要な官僚組織の協調体制を確立できずにいた。官僚組織は異なる省庁に属し、それらはしばしば互いに競

合していたからである。よってナチス政権は「ホロコースト計画完遂の阻害要因は、各省庁がヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の抹殺を必ずしも優先事項として取り扱わな

かったことにある」と考えた。そこで、ヨーロッパユダヤ人の絶滅を優先事項とすることを再確認し、関係省庁の上層幹部に必要な権限を取り戻し、複雑に絡み

合う官僚組織の多くが最終的解決を共同して実行できるようにするためにヴァンゼー会議が開催された。 |

| ポライモス |

ロ

マネス語のPorajmos

[pʰoɽmos](ポライモス、ドイツ語:「食い尽くす」)とは、国家社会主義時代に行われたヨーロッパのロマ人の大量虐殺のことである。長い間の差別

と迫害の歴史の集大成である。犠牲者の人数は不明である。さまざまな推計によると、幅はあるものの、10万人オーダーの数字になっている。 |

| アドルフ・アイヒマン |

オッ

トー・アドルフ・アイヒマン

は1942年1月のヴァンゼー会議に参加し、ユダヤ人問題に対する大量虐殺的最終解決策の実施を計画した。その後、ラインハルト・ハイドリヒ親衛隊大将

から、ドイツ占領下のヨーロッパ全土で数百万人のユダヤ人をナチスのゲットーやナチスの絶滅収容所に大量に強制送還するための後方支援と管理を任された。

彼は1945年に連合国に捕らえられ拘束されたが、逃亡し、最終的にアルゼンチンに定住した。1960年5月、彼はイスラエルのモサド情報機関によって追

跡・拉致され、イスラエル最高裁判所で裁判にかけられた。大々的に報道されたアイヒマン裁判の結果、彼はエルサレムで有罪判決を受け、1962年に絞首刑

で処刑された。 |

◎ホロ

コースト研究の先人たち

| H.G.アドラー |

Hans Günther Adler,

1910-1988 |

ア

ドラーは1946年の後に、フリーランスの作家、研究者となり、歴史、社会学、哲学、詩などに関する26冊の本を著し、ホロコーストに関するノンフィク

ションやフィクションを中心に、いくつかの自伝的著作もある。サイモン・シャマは、『フィナンシャル・タイムズ』紙に寄稿し、アドラーの作品はプリモ・

レーヴィやソルジェニーツィンといった20世紀の強制収容所の目撃者と並ぶにふさわしいと述べている。 |

| マックス・ヴァインライヒ |

Max Weinreich,

1894-1969 |

マッ

クス・ヴァインライヒ(Max Weinreich, Макс Вайнрайх,

1893年/1894年 ロシア帝国クールラント県ゴールディンゲン Goldingen (現ラトビア・クルディーガ Kuldīga) -

1969年 ニューヨーク市)は、クールラント出身のユダヤ教徒のイディッシュ語学・言語学者 |

| レオン・ポリアコフ |

Léon Poliakov,

1910-1997 |

レ

オン・ポリアコフ(ロシア語:Лев Поляков、1910年11月25日サンクトペテルブルク -

1997年12月8日オルセー)は、フランスの歴史学者で、ホロコーストと反ユダヤ主義について幅広く執筆し、『アーリア神話』を著した。

ロシア系ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれ、イタリア、ドイツで暮らした後、フランスに移住した。

第二次世界大戦中のユダヤ人迫害に関する資料を収集するために設立された「現代ユダヤ人資料センター」を共同設立した。また、ニュルンベルク裁判ではエド

ガー・フォールに協力した。

ポリアコフは1954年から1971年まで国立科学研究センター(Centre national de la recherche

scientifique)で研究部長を務めた[1]。

歴史家のジョス・サンチェスによれば、ポリアコフはホロコーストに関連する諸問題について教皇ピウス12世の処分を批判的に評価した最初の学者である

[citation needed]

1950年11月、ポリアコフは影響力のあるユダヤ人雑誌『コメンタリー』に「バチカンと『ユダヤ人問題』-ヒトラー時代の記録-そしてその後」を執筆し

ている。この論文は、第二次世界大戦とホロコーストにおけるローマ教皇庁の態度を考察した最初のものであったが、この分野におけるポリアコフの最初の調査

が世界的に重要な意味を持つようになったのは、1963年にドイツの劇作家ロルフ・ホフートが劇『Der

Stellvertreter』を発表して以来のことであった。

当時はほとんど注目されていなかったが、ポリアコフの1951年の

『Breviaire de la

haine』(「憎しみの収穫」)は、ラウル・ヒルバーグの『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の滅亡』より10年も早く、大量虐殺に関する最初の主要著作となった[2]。

ポリアコフは、画期的な著作が出版された1951年当時、出版にふさわしくないとされた「ジェノサイド」という言葉さえ使うのを控えたと『メモワール』の

中で述べている[3]。 |

| テオドール・アーベル |

Theodore Fred

Abel, 1896-1988 |

テオドール・フレッド・アーベル(1896-1988)はアメリカの社

会学教授で、ヒトラーの国家社会主義運動に参加した人々の一人称の証言を集めた最大の単独アーカイブを作成した。男性の証言集は、1938年に『ヒトラー

はなぜ権力を握ったのか』という本として出版された。女性の証言は、後日出版される予定であった。その後、フロリダ州立大学の3人の教授の計らいで、転

写、翻訳、デジタル化が行われた[1]。 |

| オイゲン・コーゴン(コゴン) |

Eugen Kogon, 1903-1987 |

『Der SS-Staat: 1946年に出版された『SS

国家:ドイツ強制収容所のシステム』は、ナチスの犯罪に関する基本的な文献として、現在も残っている。 収容所内売春という事柄は、オイゲン・コゴンの『SS 国家』、ヘルマン・ラングバインの『アウシュヴィッツの人間』、1972年のハインツ・ヘーガー(en:Heinz Heger)の初の著作[8]などによって仄めかされていた。しかしながら女性研究者が沈黙を破る90年代中ごろまでは、戦後の英雄も当時囚人であった事 などから、ナチズムの研究においてタブー視されていた[9][10]。 1994年にクリスタ・パウルが『ナチズムと強制売春』を[11]、2009年にロベルト・ゾンマー(Robert Sommer)が『Das KZ-Bordell: sexuelle Zwangsarbeit in nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslagern. (強制収容所の売春施設:ナチス強制収容所での性的強制労働』(Paderborn)を発表した[3]。 彼女ら"非社会的"とされて収容された者たちが国家社会主義体制の被害者として正式に認知されるようになったのは1990年代に入ってからのことである。 [1]p,55 |

| ラ

ウル・ヒルバーグ |

Raul Hilberg,

1926-2007 |

ラ

ウル・ヒルバーグは、ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人への国家社会主義の犯罪を扱うさいに、 1)4つの権力集団(官僚・軍・産業・政党)の官僚的な集合体 = 絶滅機構 2)ゆるやかな措置がその後につづくさらに厳しい処置を遂行するために先行条件となる= 絶滅過程 を前提し、完成されたユダヤ人の絶滅計画が最初からあったわけではなかったが、どの地域でも同じように段階的に順番通りに作戦が実行された事実を説明しよ うとした。 ナチズム研究では、ユダヤ人絶滅政策におけるヒトラーの意図を重視する「意図主義 Intentionalism」と、独ソ戦以降の特異な状況の中で部 分的な絶滅作戦が、徐々に全面的なものへとエスカレートしていったとする「機能主義 Functionalism」の立場がある。ヒルバー グは、ヒトラーをユダヤ人絶滅への推進力として前提としているので「意図主義者」と考えられる。しかし、ヒルバーグの描く「絶滅過程」は、一ドイツ人の悪 意によって一挙に創造されたものではない。官僚たちはユダヤ人たちを「憎悪」してはいなかった。ヒルバーグの示す絶滅過程での現場の状況では、4つの権力集団は自分たちの決断がどこに導くか を知らないまま独自に行動し、ある時には互いの仕事をさえぎり、ある時には調整し合い、前人未踏の犯罪へと邁進していく。これは「機能主 義」による解釈に酷似している。ここでの主犯は一人ではなく、ドイツ官僚全体に及ぶ。 さらにヒルバーグは、(1)ユダヤ人の絶滅は「国策」であり、ドイツ全体が国を挙げ て荷担した事業である、(2)ドイツ人が行政面で通達に従順にしたが うユダヤ人に頼り、ユダヤ人は自らの絶滅の共謀者になった、という2つの重大な指摘を行い、特に後者の結論を譲らなかったことで論争を招 く。これはヒルバーグがユダヤ人評議会をドイツ官僚機構の延長ととらえていたことからして、不可避の結論だった。さらに進んで彼は「神・王・法律・契約を信頼するユダヤ人の伝統」に言及しないわけにいかなかった し、「経済的に利用価値のあるものを遂行者が破壊することはあるまいというユダヤ人の計算」についても熟考しないわけにいかなかった。ヒルバーグは、いち 早く難を逃れた安全なアメリカからユダヤ人評議会の「加害責任」を問うたこ とで糾弾される。 ヒルバーグのホロコースト研究は時代に先駆けて発表され、論争に巻きこまれた当時は挑発的でさえあったが、現在ではこの分野で彼の業績は評価されている。 |

| ジョージ・モッセ |

George Lachmann Mosse,

1918-1999 |

ゲ

ルハルト・"ジョージ"・ラッハマン・モッセ(Gerhard "George" Lachmann Mosse、1918年9月20日 -

1999年1月22日)は、ナチス・ドイツからイギリス、そしてアメリカに移住したアメリカの歴史学者。アイオワ大学、ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校、

イスラエルのエルサレム・ヘブライ大学で歴史学の教授を務めた[1]。ナチズムの研究で最も知られ、憲法史、プロテスタント神学、男性性の歴史など、さま

ざまなテーマについて25冊以上の著作がある。1966年、ウォルター・ラカーとともに『現代史ジャーナル』を創刊。 |

| ヘンリー・エゴン・フリードランダー |

Henry

Friedlander, ursprünglich

Heinz Egon Friedländer, 1930-2012 |

ヘ

ンリー・エゴン・フリードランダー[1](1930年9月24日-2012年10月17日)は、ドイツ系アメリカ人のユダヤ人ホロコースト史家であり、ホ

ロコーストの犠牲者の範囲を広げることを支持する主張で知られる。ドイツのベルリンでユダヤ人の家庭に生まれたフリードランダーは、アウシュビッツの生存

者として1947年に渡米し[2]、1953年にテンプル大学で歴史学の学士号を、1954年と1968年にペンシルベニア大学で修士号と博士号を取得し

た[3]。1975年から2001年に退職するまで、ニューヨーク市立大学ブルックリン・カレッジのユダヤ学科教授を務めた。 |

著作と理論紹介

| George Mosse's

first published work was a 1947 paper in the Economic History Review

describing the Anti-Corn Law League. He claimed that this was the first

time the landed gentry had tried to organize a mass movement in order

to counter their opponents. In The Holy Pretence (1957), he suggested

that a thin line divides truth and falsehood in Puritan casuistry.

Mosse declared that he approached history not as narrative, but as a

series of questions and possible answers. The narrative provides the

framework within which the problem of interest can be addressed. A

constant theme in his work is the fate of liberalism. Critics pointed

out that he had made Lord Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke, the chief

character of his book The Struggle for Sovereignty in England (1950),

into a liberal long before liberalism had come into existence.

Reviewers noted that the sub-text in his The Culture of Western Europe

(1961) was the triumph of totalitarianism over liberalism. His most well-known book, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (1964), analyzes the origins of the nationalist belief system. Mosse claimed, however, that it was not until his book The Nationalization of the Masses (1975), which dealt with the sacralization of politics, that he began to put his own stamp upon the analysis of cultural history. He started to write it in the Jerusalem apartment of the historian Jacob Talmon, surrounded by the works of Rousseau. Mosse sought to draw attention to the role played by myth, symbol, and political liturgy in the French Revolution. Rousseau, he noted, went from believing that "the people" could govern themselves in town meetings, to urging that the government of Poland invent public ceremonies and festivals in order to imbue the people with allegiance to the nation. Mosse argued that there was a continuity between his work on the Reformation and his work on more recent history. He claimed that it was not a big step from Christian belief systems to modern civic religions such as nationalism. In The Crisis of German Ideology, he traced how the "German Revolution" became anti-Jewish, and in Toward the Final Solution (1979) he wrote a general history of racism in Europe. He argued that although racism was originally directed towards blacks, it was subsequently applied to Jews. In Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectable and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe (1985), he claimed that there was a link between male eros, the German youth movement, and völkisch thought. Because of the dominance of the male image in so much nationalism, he decided to write the history of that stereotype in The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity (1996). |

モッセの最初の著作は、1947年に『経済史研究』誌に発表した反コー

ン法同盟に関する論文である。彼は、土地持ちの貴族が敵対者に対抗するために大衆運動を組織しようとしたのはこれが初めてだと主張している。また、『聖な

るふり』(1957年)では、ピューリタンの詭弁には真実と虚偽を分ける細い線があることを示唆している。モッセは、歴史を物語としてではなく、一連の問

いと可能な答えとしてアプローチすることを宣言した。物語は、関心のある問題に取り組むことができる枠組みを提供する。彼の作品に一貫して見られるテーマ

は、リベラリズムの運命である。批評家たちは、彼が『イングランドにおける主権への闘い』(1950年)の主人公であるエドワード・コーク卿を、自由主義

が生まれるずっと前に自由主義者に仕立て上げたことを指摘している。彼の著書『西ヨーロッパの文化』(1961年)のサブテキストは、自由主義に対する全

体主義の勝利であると評者は指摘する。 彼の最も有名な著書は、『ドイツ・イデオロギーの危機』(The Crisis of German Ideology)である。Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (1964) は、民族主義的な信念体系の起源を分析したものである。しかし、モッセは、文化史の分析に自分の刻印を押すようになったのは、政治の神聖化を扱った『大衆 の国家化』(1975年)以降だと主張している。彼は、歴史家ヤコブ・タルモンのエルサレムのアパートで、ルソーの著作に囲まれながら執筆を開始した。 モッセは、フランス革命において神話、象徴、政治的典礼が演じた役割に注目しようとした。ルソーは、「民衆」は町の集会で自分たちを統治できると信じてい たのが、ポーランド政府に対して、民衆に国家への忠誠心を持たせるために公的な儀式や祭りを発明するように促したと指摘した。モッセは、宗教改革に関する 仕事と最近の歴史に関する仕事との間には連続性があると主張した。彼は、キリスト教の信仰体系からナショナリズムのような近代市民宗教への移行は大きなス テップではない、と主張した。 ドイツ・イデオロギーの危機』では、「ドイツ革命」がどのように反ユダヤ主義になったかを追跡し、『最終解決に向けて』(1979)では、ヨーロッパにお ける人種差別の一般史を書いている。人種差別はもともと黒人に向けられたものであったが、その後ユダヤ人にも適用されるようになったと主張した。ナショナ リズムとセクシュアリティ』では ナショナリズムとセクシュアリティ: Respectable and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe (1985)では、男性のエロス、ドイツの青年運動、そしてフェルキッシュ思想の間に関連性があると主張している。多くのナショナリズムにおいて男性像が 支配的であったため、彼はそのステレオタイプの歴史を『人間のイメージ』に書くことにしたのである。The Creation of Modern Masculinity (1996)』を出版した。 |

| Mosse saw nationalism, which

often includes racism, as the chief menace of modern times. As a Jew,

he regarded the rejection of the Age of Enlightenment in Europe as a

personal threat, as it was the Enlightenment spirit which had liberated

the Jews. He noted that European nationalism had initially tried to

combine patriotism, human rights, cosmopolitanism, and tolerance. It

was only later that France and then Germany came to believe that they

had a monopoly on virtue. In developing this view Mosse was influenced

by Peter Viereck, who argued that the turn towards aggressive

nationalism first arose in the era of Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Ernst

Moritz Arndt. Mosse traced the origins of Nazism in völkisch ideology

back to a 19th-century organicist worldview that fused

pseudo-scientific nature philosophy with mystical notions of a "German

soul". The Nazis made völkisch thinking accessible to the broader

public via potent rhetoric, powerful symbols, and mass rituals. Mosse

demonstrated that antisemitism drew on stereotypes that depicted the

Jew as the enemy of the German Volk, an embodiment of the urban,

materialistic, scientific culture that was supposedly responsible for

the corruption of the German spirit. In Toward the Final Solution, he claimed that racial stereotypes were rooted in the European tendency to classify human beings according to their closeness or distance from Greek ideals of beauty. Nationalism and Sexuality: Middle-Class Morality and Sexual Norms in Modern Europe extended these insights to encompass other excluded or persecuted groups: Jews, homosexuals, Romani people, and the mentally ill. Many 19th-century thinkers relied upon binary stereotypes that categorized human beings either as "healthy" or "degenerate", "normal" or "abnormal", "insiders" or "outsiders". In The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity, Mosse argued that middle-class male respectability evoked "counter-type" images of men whose weakness, nervousness, and effeminacy threatened to undermine an ideal of manhood. Mosse's upbringing attuned him to both the advantages and the dangers of a humanistic education. His book German Jews beyond Judaism (1985) describes how the German-Jewish dedication to Bildung, or cultivation, helped Jews to transcend their group identity. But it also argues that during the Weimar Republic, Bildung contributed to a blindness toward the illiberal political realities that later engulfed Jewish families. Mosse's liberalism also informed his supportive but critical stance toward Zionism and the State of Israel. In an essay written on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Zionism, he wrote that the early Zionists envisioned a liberal commonwealth based on individualism and solidarity, but a "more aggressive, exclusionary and normative nationalism eventually came to the fore." Historian James Franklin argues that: as a teacher and scholar, George Mosse has posed challenging questions about what it means to be an intellectual engaged in the world. The central problem Mosse has examined throughout his career is: how do intellectuals relate their ideas to reality or to alternative views of that reality?.... Mosse has chosen to focus on intellectuals and the movements with which they were often connected at their most intemperate.... For Mosse, the role of the historian is one of political engagement; he or she must delineate the connections (and disconnections) between myth and reality.[13] |

モッセは、人種差別を含むナショナリズムを現代の最大の脅威とみなし

た。ユダヤ人である彼は、ヨーロッパにおける啓蒙時代の否定を、個人的な脅威と考えた。なぜなら、ユダヤ人を解放したのは啓蒙の精神であったからだ。彼

は、ヨーロッパのナショナリズムは、当初、愛国心、人権、コスモポリタニズム、寛容を結びつけようとしていた、と指摘した。フランスやドイツが、自分たち

の美徳は自分たちで独占できると考えるようになったのは、その後のことである。モッセは、ペーター・ヴィーレックの影響を受け、攻撃的ナショナリズムへの

転向は、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテとエルンスト・モーリッツ・アルントの時代に初めて生じたと主張している。モッセは、ナチズムの起源をフェルキッ

シュ思想に求め、疑似科学的な自然哲学と「ドイツ魂」の神秘的観念を融合させた19世紀の有機主義的世界観に遡る。ナチスは、強力なレトリック、強力なシ

ンボル、大衆的な儀式を通じて、フェルキッシュの考え方をより多くの大衆に理解させたのである。モッセは、反ユダヤ主義が、ユダヤ人をドイツ民族の敵、す

なわちドイツ精神の腐敗の原因とされる都市的、物質的、科学的文化の体現者として描くステレオタイプに基づくものであることを示した。 彼は『最終的解決に向けて』のなかで、人種的ステレオタイプは、ギリシャの美の理想に近いか遠いかによって人間を分類しようとするヨーロッパの傾向に根ざ していると主張している。ナショナリズムとセクシュアリティ ナショナリズムとセクシュアリティ:近代ヨーロッパにおける中産階級の道徳と性的規範』は、こうした洞察を、排除され迫害されている他のグループにも広げ ている。ユダヤ人、同性愛者、ロマ人、精神病患者などである。19世紀の思想家の多くは、人間を「健康」か「退廃」か、「正常」か「異常」か、「内部者」 か「外部者」かに分類する二項対立的な固定観念に依拠した。人間のイメージ モッセは、中流階級の男性の立派さが、弱さ、神経質さ、女々しさといった、男らしさの理想を損なうような「カウンタータイプ」の男性像を呼び起こすと主張 した。 モッセは、人文主義的な教育の利点と危険性の両方に敏感な生い立ちであった。彼の著書『ユダヤ教を超えたドイツ系ユダヤ人』(1985年)は、ドイツ系ユ ダヤ人のビルドゥングス(教養)への傾倒が、いかにユダヤ人の集団アイデンティティーを超越するのに役立ったかを描いている。しかし、ワイマール共和国時 代には、ビルドゥングが、後にユダヤ人家族を巻き込むことになる非自由主義的な政治的現実に対する盲目につながったとも論じている。モッセのリベラリズム は、シオニズムとイスラエル国家に対する支持と批判の姿勢にも反映されている。シオニズム100周年を記念して書かれたエッセイの中で、彼は、初期のシオ ニストは個人主義と連帯に基づく自由な共同体を構想していたが、「より攻撃的、排他的、規範的なナショナリズムがやがて前面に出てきた」と書いている。 歴史家のジェームズ・フランクリンは、次のように論じている。 ジョージ・モッセは教師として、また学者として、世界と関わる知識人であることの意味について、挑戦的な問いを投げかけている。モッセがそのキャリアを通 じて考察してきた中心的な問題は、「知識人は自分の考えを現実やその現実に対する別の見解にどのように関連付けるのか」ということである。モッセは、知識 人と、彼らが最も激越な状態で関与していた運動に焦点を当てることにした。モッセにとって、歴史家の役割は政治的関与の一つであり、神話と現実の間の接続 (および切断)を明確にしなければならない[13]。 |

| The Destruction of the European Jews, by Raul Hilberg | 『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の絶滅』1961, 1985 |

| The Destruction of the European

Jews is a 1961 book by historian Raul Hilberg. Hilberg revised his work

in 1985, and it appeared in a new three-volume edition. It is largely

held to be the first comprehensive historical study of the Holocaust.

According to Holocaust historian, Michael R. Marrus (The Holocaust in

History), until the book appeared, little information about the

genocide of the Jews by Nazi Germany had "reached the wider public" in

both the West and the East, and even in pertinent scholarly studies it

was "scarcely mentioned or only mentioned in passing as one more

atrocity in a particularly cruel war". Hilberg's "landmark synthesis, based on a masterful reading of German documents", soon led to a massive array of writings and debates, both scholarly and popular, on the Holocaust. Two works which preceded Hilberg's by a decade, but remained little known in their time, were Léon Poliakov's Bréviaire de la haine (Harvest of Hate), published in 1951, and Gerald Reitlinger's The Final Solution, published in 1953.[1] Discussing the writing of Destruction in his autobiography, Hilberg wrote: "No literature could serve me as an example. The destruction of the Jews was an unprecedented occurrence, a primordial act that had not been imagined before it burst forth. The Germans had no model for their deed, and I did not have one for my narrative."[2] |

『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の絶滅』は、歴史家ラウル・ヒルバーグが

1961年に発表した著作である。1985年に改訂され、全3巻の新装版として刊行された。ホロコーストに関する最初の包括的な歴史的研究書とされること

が多い。ホロコースト史家のマイケル・R・マラス(The Holocaust in

History)によれば、この本が出版されるまで、ナチス・ドイツによるユダヤ人虐殺については、西洋でも東洋でも「広く一般に知られる」ことはほとん

どなく、適切な学術研究においても「ほとんど言及されなかったか、特に残虐な戦争における一つの残虐行為としてわずかに言及するにすぎなかった」という。 ヒルバーグの「ドイツ語文献の見事な読解に基づく画期的な総合」は、やがてホロコーストに関する膨大な数の著作と議論を、学者と一般市民の双方から生み出 すことになった。ヒルバーグに10年先行しながら、当時はほとんど知られていなかったのが、1951年に出版されたレオン・ポリアコフの 『Bréviaire de la haine(憎しみの収穫)』と1953年に出版されたジェラルド・ライトリンガー『The Final Solution』であった[1]。 自伝の中で『絶滅』の執筆について論じたヒルバーグは、「どんな文学も私の手本となることはできなかった」と書いている。ユダヤ人の破壊は前代未聞の出来 事であり、それがはじける前には想像もつかなかった原初的な行為であった。ドイツ人はその行為の手本となるものを持たなかったし、私も自分の物語の手本と なるものを持たなかった」[2]。 |

| Written with support, published

with difficulties Hilberg began his study of the Holocaust leading to The Destruction while stationed in Munich in 1948 for the U.S. Army's War Documentation Project. He proposed the idea for the work as a PhD. dissertation and was supported in this by his doctoral advisor, Columbia University professor Franz Neumann. While the dissertation won a prize, Columbia University Press, Princeton University Press, Oklahoma University Press, as well as Yad Vashem all declined to publish it. It was eventually published by a small publishing company, Quadrangle Books. This first edition was published in an unusually small type. Much of the page count increase of later versions is due to being published in a conventional type size. This was not the end of Hilberg's publishing woes. It was not translated until 1982, when Ulf Wolter of the small leftist publishers Olle & Wolter in Berlin published a German translation. For this purpose the work was enlarged by about 15%, so that Hilberg spoke of a "second edition", "solid enough for the next century". |

支えられて書き、苦労して出版 ヒルバーグは、『絶滅』につながるホロコーストの研究を、1948年に米軍の戦争記録プロジェクトのためにミュンヘンに駐留していたときに始めた。博士論 文としてこの作品の構想を提案し、博士課程の指導教官であったコロンビア大学のフランツ・ノイマン教授がこれを支援した。 この論文は賞をもらったが、コロンビア大学出版局、プリンストン大学出版局、オクラホマ大学出版局、ヤド・ヴァシェムは出版を断念した。結局、小さな出版 社であるクアドラングル・ブックスから出版されることになった。この初版は、異常に小さな活字で出版された。後の版でページ数が増えているのは、従来の大 きさの活字で出版されたためである。ヒルバーグの出版の苦労はこれで終わりではなかった。1982年にベルリンの小さな左翼系出版社オルレ&ウォルターの ウルフ・ウォルターがドイツ語訳を出版するまで、この作品は翻訳されることはなかった。このため、作品は15%ほど増補され、ヒルバーグは「次の世紀にも 通用するほどしっかりした」「第二版」と語っている。 |

| Opposition from Hannah Arendt In his autobiography, Hilberg reveals learning that Hannah Arendt advised Princeton University Press against publishing The Destruction. This may have been due to the first chapter, which she later described as "very terrible" and betraying little understanding of German history.[3] She did, however, base her account of the Final Solution (in Eichmann in Jerusalem) on Hilberg's history, as well as sharing his controversial characterisation of the Judenrat. Hilberg strongly criticized Arendt's "banality of evil" thesis which appeared shortly after The Destruction, to be published with her articles for The New Yorker with respect to Adolf Eichmann's trial (Eichmann in Jerusalem). He still defended Arendt's right to have her views aired upon being condemned by the Anti-Defamation League. In fact, David Cesarani writes that Hilberg "defended her several arguments at a bitter debate organised by Dissent magazine which drew an audience of hundreds".[4] In a letter to the German philosopher Karl Jaspers, Arendt went on to write that: [Hilberg] is pretty stupid and crazy. He babbles now about a "death wish" of the Jews. His book is really excellent, but only because it is a simple report. A more general, introductory chapter is beneath a singed pig.[5] Hilberg also goes on to claim that Nora Levin heavily borrowed from The Destruction without acknowledgment in her 1968 The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry, and that historian Lucy Davidowicz not only ignored The Destruction's findings in her 1975 The War against the Jews, 1933–1945 but also went on to exclude mention of him, along with a galaxy of other leading Holocaust scholars, in her 1981 historiographic work, The Holocaust and the Historians. "She wanted preeminence", Hilberg writes.[6] |

ハンナ・アーレントからの反対意見 ヒルバーグは自伝の中で、ハンナ・アーレントがプリンストン大学出版局に『絶滅』の出版を進言したことを知ったことを明かしている[3]。しかし、最終的 解決(『エルサレムのアイヒマン』)については、ヒルバーグの歴史に基づき、ユダヤ人部会(Judenrat)についての論議を呼ぶような彼の性格を共有 することになった[3]。ヒルバーグは、『破壊』の直後に、アーレントが『ニューヨーカー』に寄稿したアドルフ・アイヒマン裁判に関する論文(『エルサレ ムのアイヒマン』)とともに発表した「悪の陳腐さ」論文を強く批判した。彼は、Anti-Defamation Leagueから非難されたアーレントが自分の意見を放送される権利を持つことを、今でも擁護している。事実、デイヴィッド・セサラニは、ヒルバーグが 「ディセント誌が主催し、数百人の聴衆を集めた辛辣な討論会で彼女のいくつかの議論を弁護した」と書いている[4]。ドイツの哲学者カール・ヤスパースに 宛てた手紙の中で、アーレントは続けて次のように書いている。 [ヒルバーグはかなり愚かで、狂っています。彼は今、ユダヤ人の「死の願望」についてしゃべっている。彼の本は実に素晴らしいが、それは単純な報告書であ るからにほかならない。もっと一般的な、入門的な章は歌われた豚の下にあるのだ[5]。 ヒルバーグはまた、ノーラ・レヴィンが1968年の『ホロコースト』の中で、『破壊』から謝意もなく大きく借用したと主張している。歴史家ルーシー・ダ ヴィドヴィッチは、1975年に出版した『ユダヤ人に対する戦争、1933-1945』において『破壊』の所見を無視しただけでなく、1981年に出版し た歴史学の著作『ホロコーストと歴史家』において、他の主要なホロコースト学者たちとともに『破壊』についての言及を排除している。「彼女は優位に立ちた かったのだ」とヒルバーグは書いている[6]。 |

| Opposition from Yad Vashem Hilberg's work received a hostile reception from Yad Vashem, particularly over his treatment of Jewish resistance to the perpetrators of the Holocaust in the book's concluding chapter. Hilberg argued that "The reaction pattern of the Jews is characterized by almost complete lack of resistance...[T]he documentary evidence of Jewish resistance, overt or submerged, is very slight". Hilberg attributed this lack of resistance to the Jewish experience as a minority: "In exile, the Jews... had learned that they could avert danger and survive destruction by placating and appeasing their enemies...Thus over a period of centuries the Jews had learned that in order to survive they had to restrain from resistance". Yad Vashem's scholars, including Josef Melkman and Nathan Eck, did not feel that Hilberg's characterizations of Jewish history were correct, but they also felt that by using Jewish history to explain the reaction of the Jewish community to the Holocaust, Hilberg was suggesting that some responsibility for the extent of the destruction fell on the Jews themselves, a position that they found unacceptable. The 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, and the subsequent publication by Hannah Arendt and Bruno Bettelheim of works that were more critical of Jewish actions during the Holocaust than Hilberg had been, inflamed the controversy. In 1967, Nathan Eck wrote a sharply critical review of Hilberg, Arendt, and Bettelheim's claims in Yad Vashem Studies, the organization's research journal, titled "Historical Research or Slander".[7][8][9][10] Hilberg eventually reached a reconciliation with Yad Vashem, and participated in international conferences organized by the institution in 1977 and 2004.[9][11] In 2012 Yad Vashem held a symposium marking the translation of his book into Hebrew.[12][13][14] |

ヤド・ヴァシェムからの反対意見 ヒルバーグの著作は、ヤド・ヴァシェムから敵意をもって迎えられた。特に、この本の最終章における、ホロコーストの加害者に対するユダヤ人の抵抗の扱いを めぐってである。ヒルバーグは、「ユダヤ人の反応パターンは、ほとんど完全な抵抗の欠如によって特徴づけられている...ユダヤ人の抵抗の証拠書類は、あ からさまなものも、水面下のものも、きわめてわずかである」と論じている。ヒルバーグはこの抵抗の欠如を、少数派としてのユダヤ人の経験に起因するとして いる。「亡命中のユダヤ人は...敵をなだめ、宥めることで危険を回避し、破壊を生き延びることができると学んだ...したがって、ユダヤ人は何世紀にも わたって、生き延びるためには抵抗を控えなければならないことを学んできたのである」。ヨゼフ・メルクマンやナタン・エックなどヤド・ヴァシェムの研究者たちは、ヒルバーグのユダヤ 史の記述が正しいとは思っていなかったが、ユダヤ史を用いてホロコーストに対するユダヤ人社会の反応を説明することは、破壊の程度に対する何らかの責任が ユダヤ人自身にあることを示唆しており、受け入れがたい立場であるとも感じていたのである。1961年にアドルフ・アイヒマンが裁判にかけ られ、その後ハンナ・アーレントやブルーノ・ベッテルハイムがヒルバーグ以上にホロコースト中のユダヤ人の行動を批判する著作を発表したため、論争が高 まった。1967年、ナタン・エックはヤド・ヴァシェムの研究誌『ヤド・ヴァシェム・スタディーズ』に「歴史研究か誹謗か」と題してヒルバーグ、アーレン ト、ベッテルハイムの主張に対する鋭い批判を書き下ろした[7][8][9][10]。 ヒルバーグは最終的にヤド・ヴァシェムと和解し、1977年と2004年に同機関が主催した国際会議に参加した[9][11]。 2012年にヤド・ヴァシェムは彼の本のヘブライ語への翻訳を記念してシンポジウムを開催した[12][13][14]。 |

| Against overstating the heroism

of Jewish victims A key reason as to why notable Jews and organizations were hostile to Hilberg's work was that The Destruction relied most of all on German documents, whereas Jewish accounts and sources were featured far less prominently. This, argued Hilberg's opponents, trivialized the suffering Jews endured under Nazism. For his part, Hilberg maintains that these sources simply could not have been central to a systematic, social-scientific reconstruction of the destruction process. Another important factor for this hostility by many in the Jewish community (including some Holocaust survivors) is that Hilberg refused to view the vast majority of Jewish victims' "passivity" as a form of heroism or resistance (in contrast to those Jews who actively resisted, waging armed struggle against the Nazis). Equally controversially, he provided an analysis for this passivity in the context of Jewish history. The Jews, Hilberg argued, were convinced "the persecutor would not destroy what he could economically exploit." Hilberg calculated the economic value of Jewish slave labor to the Nazis as being several times the entire value of confiscated Jewish assets, and used this as evidence that the destruction of Jews continued irrespective of economic considerations. Additionally, Hilberg estimated the total number of Germans killed by Jews during World War II as less than 300, an estimate that is not conducive to an image of heroic struggle. Hilberg, therefore, disagreed with what he termed a "campaign of exaltation", explains historian Mitchell Hart, and with Holocaust historians such as Martin Gilbert who argued that "[e]ven passivity was a form of resistance[,] to die with dignity was a form of resistance." According to Hilberg, his own approach was crucial for grasping the Nazi genocide of Jews as a process. Hart adds that: This sort of "inflation of resistance" is dangerous because it suggests that the Jews truly did present the Nazis with some sort of "opposition" that was not just a horrible figment of their antisemitic imaginations.[15] |

ユダヤ人犠牲者の英雄的行為を誇張することへの反発 ヒルバーグの著作に著名なユダヤ人や団体が敵対した大きな理由は、『絶 滅』がドイツ側の資料に最も依拠しており、ユダヤ人の記録や資料があまり大きく取り 上げられていないことであった。これは、ナチズムのもとでユダヤ人が受 けた苦しみを矮小化するものだと、ヒルバーグは反対した。一方、ヒルバーグは、これらの資料は、破壊の過程を社会科学的に体系的に再現するための中心的存 在にはなり得なかったと主張している。 ユダヤ人社会の多くの人々(一部のホロコースト生存者を含む)がこうした敵意を抱いたもう一つの重要な要因は、ヒルバーグが大多数のユダヤ人犠牲者の「受動性」を(ナチスに対して武装闘争を行い積極的に抵 抗したユダヤ人とは対照的に)英雄主義や抵抗とみなすのを拒否したことである。また、ユダヤ人の受動性をユダヤ史の文脈で分析したことも問題であった。 ヒルバーグは、ユダヤ人は「迫害者が経済的に利用できるものを破壊することはない」と確信していたと主張した。ヒルバーグは、ナチスにとってのユダヤ人奴 隷労働の経済的価値を、没収されたユダヤ人資産の全価値の数倍と計算し、これを証拠に、経済的考慮とは無関係にユダヤ人の破壊が続けられたとしたのであ る。また、ヒルバーグは、第二次世界大戦中にユダヤ人に殺されたドイツ人の総数を300人以下と推定し、英雄的闘争のイメージとは無縁の推定をしている。 したがって、ヒルバーグは、彼が「高揚キャンペーン」と呼んだもの、また、マーティン・ギルバートのようなホロコースト史家が主張した [「受け身も抵抗の一種、威厳をもって死ぬのも抵抗の一種 」に反対したのだと歴史家ミッチェル・ハートは説明している。ヒルバーグによれば、彼自身のアプローチは、ナチスのユダヤ人大量虐殺をプロセスとして把握 するために極めて重要であったという。ハートはこう付け加えている。 このような「抵抗のインフレ」は、ユダヤ人が本当にナチスにある種の「反対」を提示しており、それは彼らの反ユダヤ的想像力の恐ろしい産物に過ぎなかった ということを示唆するので、危険である[15]」と述べている。 |

| The Destruction of the Jews as a

historically explicable event This problem underscores a more fundamental question: whether the Holocaust can (or to what extent it should) be made explicable through a social-scientific, historical account. Speaking against what he terms a "quasi mystical association," historian Nicolas Kinloch writes that "with the publication of Raul Hilberg's monumental book," the subject had risen to be considered "an event requiring more, rather than less, stringent historical analysis."[16] Citing Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer's statement that "if the Holocaust was caused by humans, then it is as understandable as any other human event", Kinloch finally concludes that this "will itself help to make any repetition of the Nazi genocide less likely".[17] One danger, however, from this attempt to "demystify", argues Arno Lustiger, can lead to another mystification proffering "clichés about the behaviour of the doomed Jews [which depict] their alleged cowardliness, compliance, submission, collaboration and lack of passive or armed resistance". He goes on to echo the early critics of (the no longer marginalized) Hilberg, stating that: "it is about time to publish researched testimonies of the victims and survivors [as opposed to those] documentations and books, based solely on German documents."[18] An altogether different argument challenged the view that since the Nazis destroyed massive sets of sensitive documents pertaining to the Holocaust upon the arrival of Soviet and Western Allied troops, no truly comprehensive, verifiable historical reconstruction could be achieved. This, however, argues Hilberg, demonstrates an ignorance as to the structure and scope of the Nazi bureaucracy. While it is true that many sensitive documents were destroyed, the bureaucracy nonetheless was so immense and so dispersed, that most pertinent materials could be reconstructed either from copies or from a vast array of more peripheral ones. From these documents, The Destruction proceeds to outline the treatment of the Jews by the Nazi State through a succession of very different stages, each one more extreme, more dehumanizing than that which preceded it, eventually leading to the final stage: the physical destruction of the European Jews. |

歴史的に説明可能な出来事としてのユダヤ人の滅亡 この問題は、ホロコーストを社会科学的、歴史的に説明することができるのか(あるいは、どの程度まで説明する必要があるのか)という、より根本的な問題を 浮き彫りにしている。歴史家のニコラス・キンロックは、彼が「準神秘的な関連」と呼 ぶものに対して、「ラウル・ヒルバーグの記念碑的な本の出版によって、このテーマは「より厳しい歴史分析を要する出来事」と見なされるようになった」と書 いている[16]。 「ホロコーストの歴史家イェフダ・バウアーの「ホロコーストが人間によって引き起こされたのであれば、それは他の人間の出来事と同様に理解できる」という 発言を引用して、キンロクは最後に、このことは「それ自体がナチスの大量虐殺の繰り返しをより起こりにくくする助けになるだろう」と結論づけている[17]。 しかし、この「解明」の試みから生じる一つの危険は、アルノ・ルスティガーが主張するように、「運命にあるユダヤ人の行動についての決まり文句(それは彼 らが主張する臆病、遵守、服従、協力、受動的あるいは武装した抵抗の欠如を描いている)」を提供する別の神秘化につながる可能性があることだ。さらに彼 は、(もはや疎外されている)ヒルバーグに対する初期の批判に倣って、次のように述べている。「ドイツの文書だけに基づいた文書や書籍とは対照的に)被害 者や生存者の研究された証言を出版する時が来たのだ」[18]と述べている。 まったく別の議論では、ナチスがソ連軍と西側連合軍の到着とともにホロコーストに関する大量の機密文書を破棄したため、真に包括的で検証可能な歴史の再構 築はできないという見解に異議を唱えた。しかし、これは、ナチスの官僚機構の構造と範囲に対する無知を示すものであるとヒルバーグは主張している。多くの 機密文書が破棄されたのは事実だが、それでも官僚機構は非常に巨大で、分散していたため、ほとんどの関連資料はコピーか、より周辺的な膨大な資料から再構 成することができたのである。 これらの文書から、『破壊』は、ナチス国家によるユダヤ人の扱いを、それぞれがその前の段階よりも極端で非人間的な、非常に異なる段階を経て、最終的に ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の物理的破壊という最終段階に至るまで、概説していく。 |

| Stages leading to the

destruction process In The Destruction, Hilberg established what today has become orthodoxy in Holocaust historiography: the increasingly intensifying historical stages leading to genocide. Nazi Germany's persecution of Jews, Hilberg argued, began relatively mildly through political-legal discrimination and the appropriation of Jewish assets (1933–39). Ghettoization followed: the isolation of Jews in and their confinement to Ghettoes (1939–41). The final stage, Hilberg concluded, was the destruction itself, the continental annihilation of European Jews (1941–45). In the early stages, Nazi policies targeting Jews (whether directly or through aryanization) treated them as sub-human, but with a right to live under such conditions that this status affords. In the later stages, policy was formulated to define the Jews as anti-human, with extermination being viewed as an increasingly urgent necessity. The growing Nazi momentum of destruction, began with the murdering of Jews in German and German-annexed and occupied countries, and then intensified into a search for Jews to either exterminate or use as forced labour from countries allied with Nazi Germany as well as neutral countries. The more sophisticated and organized, less clandestine part of the Nazi machinery of destruction tended to murder Jews not fit for intense manual labour immediately; later in the destruction process, more and more Jews initially labelled productive were also murdered. Eventually, Nazi compulsion for the eradication of the Jews became total and absolute, with any potentially available Jews being actively sought solely for the purpose of destruction. The seamless transformation from yet inextricable distinction between these stages, could be realized only through and put into practice by this very compounding process of an ever-growing dehumanization. As demonized as the Jews were, it seems highly unlikely that the destruction process of the later stage could take place during the time line of the stage which preceded it. |

破壊に至る段階 ヒルバーグは『絶滅』の中で、今日ホロコースト歴史学の正統となった、大量殺戮に至る歴史的段階が次第に激化していくことを立証した。ナチス・ドイツのユ ダヤ人迫害は、政治的・法的差別とユダヤ人資産の横領という比較的穏やかな形で始まった(1933-39年)。そして、ユダヤ人をゲットーに隔離するゲッ トー化(1939-41年)である。最終段階は破壊そのものであり、ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の大陸的な消滅であるとヒルバーグは結論付けている(1941- 45年)。 初期段階では、ナチスのユダヤ人政策は(直接的にせよ、アーリア化を通じてせよ)ユダヤ人を人間以下の存在として扱い、その地位がもたらす条件の下で生き る権利を与えるものであった。後期には、ユダヤ人を反人間的な存在として定義する政策がとられ、絶滅がますます急務とされた。ナチスの破壊の勢いは、ドイ ツおよびドイツに併合・占領された国々でのユダヤ人殺害に始まり、ナチス・ドイツの同盟国や中立国から絶滅させるか強制労働に利用するためのユダヤ人を探 し出すことに激化していったのである。 ナチスの破壊装置のうち、より洗練され組織化され、密かに行われない部分は、激しい肉体労働に適さないユダヤ人を直ちに殺害する傾向があり、破壊プロセス の後半では、最初は生産的とされたユダヤ人もどんどん殺害されていきました。最終的に、ナチスのユダヤ人撲滅のための強制は完全かつ絶対的なものとなり、 利用可能なユダヤ人はすべて破壊の目的だけのために積極的に探されるようになったのである。 このような段階間の区別のない転換は、まさに人間性の喪失という複合的な過程によってのみ実現され、実行に移されることができた。ユダヤ人が悪魔化された 以上、後の段階の破壊プロセスが、その前の段階の時間軸の中で行われる可能性は極めて低いと思われる。 |

| An intentional destruction This dynamic reveals a spontaneity which many historians belonging to the functionalist school, following Hilberg's elaborate description, relied upon. These historians point to the more clandestine mass murder of Jews (principally in the East) and, as stated by notable functionalist, Martin Broszat, because "no general all encompassing directive for the extermination had existed." Unlike many later scholars, The Destruction does not emphasize and focus on the role of Hitler, though on this, Hilberg has shifted more towards the centre, with the third edition pointing at a less direct and systemic, more erratic and sporadic, but nonetheless pivotal, involvement by Hitler in his support for the destruction process. Hitler was a crucial impetus for the genocide, Hilberg claimed, but the role played by the organs of the State and the Nazi Party should not be understated. Hitler, therefore, intended to eradicate the Jews, an intent he sometimes phrased in concrete terms, but often this intent on the part of Hitler was interpreted by rather than dictated to those at the helm of the bureaucratic machinery of destruction which administered and carried out the genocide of the Jews. |

意図的な破壊 このダイナミズムは、機能主義学派に属する多くの歴史家が、ヒルバーグの精緻な記述に倣って、依拠した自発性を明らかにするものである。これらの歴史家 は、(主に東洋での)より密かなユダヤ人の大量殺戮を指摘し、著名な機能主義者マルティン・ブロスザットが述べたように、「絶滅のための包括的な指令は存 在しなかった」ためであるとしている。 多くの後発学者とは異なり、『破壊』はヒトラーの役割を強調し、重視していないが、この点に関して、ヒルバーグはより中央寄りにシフトしており、第三版で は、破壊プロセスを支援するヒトラーの直接的、組織的な関与は少なく、より不規則で散発的だが、それでも極めて重要な関与があったと指摘している。 ヒトラーは大量殺戮の決定的な推進力であったが、国家機関とナチ党が果たした役割も過小評価されるべきではないとヒルバーグは主張している。ヒトラーはユ ダヤ人の根絶を意図し、その意図を具体的な言葉で表現することもあったが、ヒトラーのこの意図は、ユダヤ人の大量虐殺を管理・実行する官僚的破壊装置の指 揮を執る人々に指示されたというよりも、むしろ彼らによって解釈された場合が多い。 |

| An estimated destruction of 5.1

million Jews Within a death toll often viewed as ranging from a low estimate of five million to a high estimate of seven million, Hilberg's own detailed breakdown in The Destruction reveals a total estimated death toll of 5.1 million Jews. Only for the death toll at Belzec does Hilberg provide a precise figure, all the others are rounded. When these rounding factors are taken into account a range of 4.9 million to 5.4 million deaths emerges. It is instructive to note that the discrepancy in total figures among Holocaust researchers is often overshadowed by that between Soviet and Western scholarship. One striking example can be seen in the Auschwitz State Museum's significant reduction of the estimated death toll in Auschwitz. On May 12, 1945, a few months after the liberation of Auschwitz, a Soviet State Commission reported that no fewer than four million people were murdered there.[19] Although few scholars west of the Iron Curtain accepted this report, this number was displayed on a plaque at the Auschwitz State Museum until the fall of communism in 1991, when it could be revised to 1.1 million.[20] Hilberg's own original estimate for the death toll in Auschwitz was examined although, Piper noted, this estimate fails to account for those not appearing in the records, especially those murdered immediately upon arrival. This extreme example does not, however, mean that the total death toll should be lowered by three million. Rather, the four million figure should be regarded as Soviet propaganda; following a correct distribution, the total death toll still amounts to conventionally held figures.[21] The role played by The Destruction in shaping widely held views as to the distribution of and the evidence for these, has for decades been, and arguably remains, almost canonical in Holocaust historiography. |

510万人のユダヤ人破壊の推定値 500万人という低い見積もりから700万人という高い見積もりまでの死者数の中で、ヒルバーグ自身が『破壊』の中で詳細に説明しているのは、510万人 のユダヤ人の推定死者数である。ヒルバーグが正確な数字を提示しているのはベルゼクでの死者数だけであり、他はすべて四捨五入されている。この四捨五入を 考慮すると、490万人から540万人の死亡者数の幅が現れる。 ホロコースト研究者のあいだの総数の食い違いは、ソ連と西側の研究者のあいだの食い違いと比べて、しばしば影が薄くなっていることは示唆に富んでいる。一 つの顕著な例は、アウシュヴィッツ国立博物館がアウシュヴィッツでの推定死亡者数を大幅に引き下げたことに見ることができる。1945年5月12日、アウ シュビッツ解放の数ヵ月後、ソ連の国家委員会は、400万人を下らない人々がそこで殺害されたと報告した[19]。鉄のカーテンの西側ではこの報告を受け 入れる学者はほとんどいなかったが、この数字は、1991年の共産主義崩壊までアウシュビッツ国立博物館のプレートに掲げられ、その後100万人に修正す ることもできた[20]。 ヒルバーグ自身のアウシュビッツでの死者数の推定が検討されたが、パイパーが指摘するように、この推定は記録にない人々、特に到着後すぐに殺された人々を 考慮できていない。しかし、この極端な例は、総死亡者数を300万人引き下げるべきだということを意味するものではない。むしろ、400万人という数字は ソ連のプロパガンダとみなすべきであり、正しい分布に従えば、総死者数は依然として従来から言われている数字になる[21]。これらの分布とその証拠に関 して広く認められている見解を形成する上で『破壊』が果たした役割は、何十年にもわたって、ホロコースト歴史学においてほぼ正典であり、間違いなく今もそ うであり続けている。 |

| Wide acclamation as seminal Reviewing the book just after publication, Guggenheim Fellow Andreas Dorpalen[22] wrote that Hilberg had "covered his topic with such thoroughness that his book will long remain a basic source of information on this tragic subject."[23] Today, The Destruction has achieved a highly distinguished level of prestige amongst Holocaust historians. While its ideas have been modified (including by Hilberg himself) and criticized throughout four decades, few in the field dispute its being a monumental work, in both originality and scope.[citation needed] Reviewing the appreciably expanded 1,440-page second edition, Holocaust historian Christopher Browning noted that Hilberg "has improved a classic, not an easy task."[24] And while Browning maintains that, with the exception of Hitler's role, there are no fundamental changes to the work's principal findings, he nevertheless states that: If one measure of a book's greatness is its impact, a second is its longevity. For 25 years The Destruction has been recognized as the unsurpassed work in its field. While monographic studies of particular aspects of the Final Solution, utilizing archival sources and court records not available to Hilberg before 1961, have extended our knowledge in many areas, The Destruction of the European Jews still stands as the preeminent synthesis, the book that put it all together in the framework of an overarching and unified analysis. The controversies surrounding Hilberg's book were perhaps the main reason why its Polish translation was released only after the collapse of the Soviet union, five decades after its original publication. The year Hilberg died, he refused an offer to have a shortened version published in translation, insisting that particularly in Poland, where so much of the Holocaust took place, only the full text of his work would suffice. The complete three-volume edition translated by Jerzy Giebułtowski was released in Poland in 2013. Dariusz Libionka from IPN, who led the book launch seminars in various cities, noted that the stories of defiance so prevalent in Poland can no longer be told without his perspective which includes the viewpoint of Holocaust bureaucracy. Reportedly, the last document Hilberg signed before his death was the release form allowing for the use of the word annihilation (as opposed to destruction) in the Polish title.[25][26] |

精選された本として広く称賛される 出版直後の書評で、グッゲンハイムフェローのアンドレアス・ドルパレン[22]は、ヒルバーグが「自分のテーマを徹底して網羅しているので、彼の本はこの 悲劇的テーマに関する基本的な情報源として長く残るだろう」と書いている[23]。今日、『破壊』はホロコースト史家の間で非常に優れた権威のレベルを獲 得している。その考え方は、40年間を通じて(ヒルバーグ自身によるものも含めて)修正され、批判されてきたが、その独創性と範囲の両方において記念碑的 作品であることに異議を唱える者はこの分野ではほとんどいない[citation needed] 1,440 ページのかなり拡大した第2版をレビューして、ホロコースト史家のクリストファー・ブラウニングは、ヒルバーグは「古典を改良したが、簡単ではなかった」 [24]、また、ヒトラーの役割を除いて、作品の主たる発見に対する根本的変更はないとして、それでも彼は次のように述べている。 本の偉大さを測る一つの尺度がそのインパクトであるとすれば、第二はその長寿である。『破壊』は25年間、この分野で最も優れた著作として認められてき た。1961年以前にヒルバーグが入手できなかった文書資料や裁判記録を利用した最終解決の特定の側面に関する単行本の研究が、多くの分野で我々の知識を 広げたが、『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』は依然として傑出した総合書として、包括的かつ統一的な分析の枠内ですべてをまとめた本として位置づけられてい る。 ヒルバーグの本をめぐる論争は、ポーランド語訳がソビエト連邦の崩壊後、原著の出版から50年経ってから発表された主な理由であったろう。ヒルバーグは亡 くなった年、短縮版の翻訳出版の申し出を断り、特にホロコーストの舞台となったポーランドでは、自分の著作の全文だけで十分だと主張したのである。 2013年、イェジー・ジェブウォトフスキの翻訳による全3巻の完全版がポーランドで発売された。各都市で開催された出版記念セミナーを担当したIPNの ダリウス・リビオンカ氏は、ポーランドに蔓延する反抗の物語は、ホロコースト官僚の視点を含む彼の視点なしにはもはや語れないと指摘する。伝えられるとこ ろによれば、ヒルバーグが生前に最後にサインした文書は、ポーランド語のタイトルに(破壊ではなく)殲滅という言葉を使うことを許可する承諾書であったと いう[25][26]。 |

| Alleged mistakes According to Henry Friedlander, Hilberg's 1961 and 1985 editions[27] of Destruction mistakenly overlooked what Friedlander called "the most elaborate [Nazi] subterfuge" involving the disabled.[28] This involved the collection of Jewish patients at various hospitals before being transported elsewhere and killed during the summer and autumn of 1940. The destination officially provided for these transports was the Government General of Poland and, although they never reached Poland, fraudulent letters informed the relatives that they had died at the Chelm mental hospital in the Lublin region. This deception was so successful that it was not even uncovered at Nuremberg, was accepted by most postwar historians, and continues even today to mislead researchers. In fact, these Jewish patients, the first Jewish victims of Nazi genocide, were all murdered in the T4 killing centers located inside the borders of the German Reich.[29] Friedlander discusses this ruse in Chapter 13 of his Origins of Nazi Genocide (1995). According to Lithuanian-American scholar Saulius Sužiedėlis, Hilberg misinterpreted a document regarding Algirdas Klimaitis, "a small-time journalist and killer shunned by even pro-Nazi Lithuanian elements and unknown to most Lithuanians". This resulted in Klimaitis being inadvertently "transformed into the head of the 'anti-Soviet partisans'".[30] |

疑惑の誤り ヘンリー・フリードランダーによれば、ヒルバーグの1961年と1985年の『破壊』[27]は、フリードランダーが障害者に関わる「最も手の込んだ(ナ チの)裏技」と呼んだものを誤って見落としていた[28]。 これは、1940年の夏から秋にかけて、ユダヤ人患者を様々な病院に集めてから別の場所に移送して殺害するというものである。 これらの輸送のために公式に提供された目的地はポーランド政府であり、彼らはポーランドに到着しなかったが、詐欺的な手紙は彼らがルブリン地域のチェルム 精神病院で死亡したと親族に知らせた。この欺瞞は非常にうまくいったので、ニュルンベルクでは発覚せず、戦後のほとんどの歴史家に受け入れられ、今日でも 研究者を惑わし続けている。実際には、ナチスの大量虐殺の最初のユダヤ人犠牲者であるこれらのユダヤ人患者は、すべてドイツ帝国の国境内にあるT4殺害セ ンターで殺害されたのである[29]。 フリードランダーは、『ナチスの大量虐殺の起源』(1995年)の第13章でこの策略について論じている。 リトアニア系アメリカ人の学者であるSaulius Sužiedėlisによれば、ヒルバーグはアルギルダス・クリマイティスに関する文書を誤って解釈しており、「親ナチのリトアニア人にさえ敬遠され、ほ とんどのリトアニア人に知られていない小物のジャーナリスト兼殺人者」であった。この結果、クリマイティスは不注意にも「『反ソ連パルチザン』の長に変身 させられた」[30]。 |

| Henry Friedlander argued that

three groups should be considered victims of the Holocaust, namely

Jews, Romani, and the mentally and physically disabled,[6] noting that

the latter were Nazism's first victims.[7] His opinions concerning the

inclusion of both the disabled and the Romani as victims of the

Holocaust often gave rise to intense debates with other scholars, such

as the Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer, who argued that only Jews should

be considered victims of the Holocaust.[citation needed] Like Friedlander, Sybil Milton supported a more expansive, inclusive definition of the Holocaust, arguing against the "exclusivity of emphasis on Judeocide in most Holocaust literature [that] has generally excluded Gypsies (as well as blacks and the handicapped) from equal consideration",[8] and exchanging views on the topic with Yehuda Bauer.[9] According to Friedlander, the origins of the Holocaust can be traced back to the coming together of two lines of Nazi policies: the antisemitic policies of the Nazi regime, and its "racial cleansing" policies that led to the Action T4 program.[citation needed] Arguing that the ultimate origins of the Holocaust came from the Action T4 program, he pointed to the fact that both the poison gas and the crematoria were originally deployed at the start of the Action T4 program in 1939.[citation needed] It was only later, in 1941, that the experts from the T4 program were imported by the SS to help design, and later run, the death camps for the Jews of Europe.[citation needed] Friedlander did not deny the importance of the Nazi's antisemitic ideology, but, in his view, the T4 program was the crucial seed that gave birth to the Holocaust. |

ヘンリー・フリードランダーは、ユダヤ人、ロマ人、心身障害者の3つのグループをホロコーストの犠牲者とみなすべきだと主張し、

後者がナチズムの最初の犠牲者であると指摘した[7]。障害者とロマ人をホロコーストの犠牲者に含めることに関する彼の意見は、ユダヤ人のみをホロコース

トの犠牲者とみなすべきだと主張するイスラエルの歴史家イェフダ・バウアーなど他の学者としばしば激しい議論を引き起こした[引用者註:必要]。 フリードランダーと同様に、シビル・ミルトンはホロコーストをより拡大的、包括的に定義することを支持し、「ほとんどのホロコースト文学においてユダヤ人 を強調する排他性(それは一般にジプシー(黒人や障害者と同様)を平等な考察から排除してきた)」に反対し、このテーマについてイェフダ・バウアーと意見 を交換している[8]。 ホロコーストの起源は、ナチス政権の反ユダヤ政策と行動T4計画につながる「人種浄化」政策の2つの路線が一緒になったところにあるとフリードランダーは 主張している[citation needed]。ホロコーストの究極の起源は行動T4計画にあると主張する彼は、毒ガスも火葬場ももともと行動T4計画が始まった1939年に配置された と指摘している[citation needed]. これは、ホロコーストの起源は、ナチスとその人種浄化政策の2つのラインは、初めにアクションT4プログラム、1939年初頭の、オランダでの実施につな がったからである(This comes from the Origins of the Holocaust is the Two lines of Nazi and its racial cleansing policies that led to the Action T4 Programs in the beginning,1939, the Netherlands, and the Netherlands.)フリードランダーは、ナチスの反ユダヤ主義的イデオロギーの重要性を否定しているわけではないが、彼の見解では、T4計画はホ ロコーストを生み出す決定的な種なのである。 |

| Eugen Kogon, 1903-1987 | |

| An avowed opponent of Nazism,

Kogon was arrested by the Gestapo in 1936 and again in March 1937,

charged with, among other things, "work[ing] for anti-national

socialist forces outside the territory of the Reich". In March 1938, he

was arrested a third time and, in September 1939, was deported to

Buchenwald, where he spent the next six years as "prisoner number

9093".[citation needed] At Buchenwald, Kogon spent part of his time working as a clerk for camp doctor Erwin Ding-Schuler, who headed up the typhus experimentation ward there. According to Kogon's own statements, he was able to develop a relationship bordering on trust with Ding-Schuler, after becoming his clerk in 1943. In time, they had conversations about family concerns, the political situation and events at the front. According to Kogon, through his influence on Ding-Schuler, he was able to save the lives of many prisoners,[3][4] including Stéphane Hessel, Edward Yeo-Thomas, and Harry Peulevé by exchanging their identities with those of prisoners who had died of typhus.[5] In early April 1945, Kogon and the head prisoner nurse in the typhus experimentation ward, Arthur Dietzsch, found out from Ding-Schuler that their names were on a list of 46 prisoners whom the SS wanted to execute shortly before the expected liberation of the camp. Ding-Schuler saved Kogon's life at the end of the war by arranging to hide him in a crate, then smuggling him out of Buchenwald[6] to his own home in Weimar.[7] Right after being liberated in 1945, Kogon again began working as a journalist. He worked as a volunteer historian for the United States Army at Camp King and began writing his book Der SS-Staat: Das System der deutschen Konzentrationslager ("The SS-State: The System of the German Concentration Camps"), first published in 1946, which still stands as the basic reference on Nazi crimes. The book was translated into several languages. The German language version alone sold 500,000 copies.[citation needed] Despite this intensive involvement with the past, Kogon primarily chose to look ahead, toward building a new society—one that would blend with Kogon's convictions of Christianity and socialism. Kogon had already spoken about his ideas in Buchenwald with fellow prisoner Kurt Schumacher. However, the rapid growth of the Social Democratic Party hindered the proposed alliance of right-wing social democrats and the Centre Party into a "Labour Party" after the British model. |

ナチズムに反対することを公言していたコゴンは、1936年にゲシュタ

ポに逮捕され、1937年3月には「帝国の領域外で反民族社会主義勢力のために働いた」等の罪で再び逮捕された。1938年3月に3度目の逮捕を受け、

1939年9月にブッヘンヴァルトに送還され、「囚人番号9093」としてその後6年間を過ごした[citation needed]。 ブッヘンヴァルトでは、コゴンは、チフス実験病棟の責任者である収容所医師エルヴィン・ディング・シュラーの事務員として勤務していた時期がある。コゴン 自身の供述によると、1943年に丁度彼の事務員になってから、信頼に近い関係を築くことができたようです。やがて、家族の問題や政治情勢、前線での出来 事について会話を交わすようになった。コゴンによれば、ディン=シューラーへの影響力によって、ステファン・ヘッセル、エドワード・ヨ=トーマス、ハ リー・ペウルヴェなど多くの捕虜の命を救うことができた[3][4]といい、彼らの身分をチフスで死んだ捕虜のものと交換することができたという。 [1945年4月初旬、コゴンとチフス実験病棟の看護師長アーサー・ディーツシュは、ディンシュラーから、SSが収容所解放の直前に処刑しようとしている 46名の囚人のリストに自分たちの名前があることを知らされた。ディンシュラーは終戦時にコゴンを木箱の中に隠し、ブッヘンヴァルトからワイマールの自宅 まで密航させ、命を救った[6]。 1945年に解放された直後、コゴンは再びジャーナリストとして働き始めた。彼は、キャンプ・キングでアメリカ軍のボランティア歴史家として働き、 『Der SS-Staat: 1946年に出版された『SS 国家:ドイツ強制収容所のシステム』は、ナチスの犯罪に関する基本的な文献として、現在も残っている。この本は数ヶ国語に翻訳された。ドイツ語版 だけでも50万部を売り上げた[citation needed]。 このように過去と深く関わりながらも、コゴンは、キリスト教と社会主義というコゴンの信念と調和する新しい社会の構築に向けて、主に前を向くことを選択し た。コゴンは、ブッヘンヴァルトで同じ囚人のクルト・シューマッハと自分の考えをすでに話していた。しかし、社会民主党の急成長により、右派社会民主党と 中央党の連合によるイギリス型の「労働党」の構想は頓挫した。 |

★ジェノサイド条約

集団殺害罪の防止および処罰に関する条約(しゅうだんさつがいざいのぼうしおよびしょばつに かんするじょうやく、フランス語: Convention pour la prévention et la répression du crime de génocide、英語: Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide)は、集団殺害を国際法上の犯罪とし、防止と処罰を定めるための条約。「ジェノサイド」(「種族」(genos)と「殺害」(cide) の合成語)を定義し、前文および19カ条から構成される。通称は、ジェノサイド条約(ジェノサイドじょうやく、Genocide Convention)。

ユダヤ系ポーランド人の法律家ラファエル・レムキンによって新しく造られた「ジェノサイド」

は、レムキンの活動でもあって、ニュルンベルク裁判でナチス・ドイツが行ったユダヤ人の大量虐殺(ホロコースト)に対して公式に使用された。さらにレムキ

ンは、これを法的な規制とすることを望み、新設された国際連合に国際的な条約とすることを積極的に働きかけた。

ジェノサイド条約では「国民的、人種的、民族的または宗教的集団」への破壊行為と定義されたが、初期草案には「社会・政治集団」の字句も盛り込まれていた

[1]。しかし、ソビエト連邦をはじめ、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、ドミニカ共和国、イラン、南アフリカ共和国などは、国内の政治反乱を鎮圧すればジェノサ

イドとして弾劾される可能性を恐れ、これを削除させた[1]。

その後、ジェノサイド再発防止のためのジェノサイド条約が、1948年12月9日、第3回国際連合総会決議260A(III)にて全会一致で採択され、

1951年1月12日に発効された。締約国は、152カ国(2023年4月現在)である。

日本はこの条約を批准していない。本条約が採択された1948年時点ではいまだ国際連合に未

加盟であった。国連事務総長は1949年12月に非加盟国に対して署名を促す招請を行ったが、この時も日本が含まれなかった経緯がある[2]。すでに国連

機関の国際電気通信連合に加盟し万国郵便連合にも復帰していた[2]が、サンフランシスコ平和条約の批准前で日本国は主権は回復せず占領下に置かれてい

た。極東国際軍事裁判で中華民国の判事を務めた梅汝璈は1955年、アメリカによる広島、長崎の住民に対する原子爆弾投下はジェノサイドに相当すると指摘

している[3]。

本条約は加盟国に、犯罪者処罰のための国内法整備を求めているが、日本の憲法21条で広く保障されている表現の自由の権利と、本条約が求める「集団殺害の

扇動」での処罰とは規定が衝突しているという指摘がある。[4][5]。

他に、南京事件は本条約以前の事件だが(条約は不遡及の原則により過去の事件には原則適用されない)、批准しようとすると、南京事件には適用しないという

留保宣言が発生し得たりすることが議論を巻き起こしたり、その事件への反省が求められるなどの懸念から加盟をしないのではという指摘もある。[6][7]

6条の留保

第6条は多数の国が留保しているため機能不全に陥っていると指摘される。ジェノサイド条約の 批准にあたり過去起こした事件、これから起こりうる事件に関して留保宣言をすることが各国で横行したためである。条約の根幹部分についての留保や、留保条 項を用意していないジェノサイド条約での留保により条約を骨抜きにすることが果たして良いのか、国連総会が国際司法裁判所に国際司法裁判所#勧告的意見を 求めた例がある。[8] 国際司法裁判所としては、留保の内容により個別に判断されるべきで、留保規定がなくとも留保はできて、また批准国が多いほど多数国間条約としての効き目が ある以上、留保そのものは禁止されるものではないという。

条文抜粋

第一条

締約国は、集団殺害が平時に行われるか戦時に行われるかを問わず、国際法上の犯罪であることを確認し、これを、防止し処罰することを約束する。

第二条

この条約では、集団殺害とは、国民的、人種的、民族的又は宗教的集団を全部又は一部破壊する意図をもつて行われた次の行為のいずれをも意味する。

(a) 集団構成員を殺すこと。

(b) 集団構成員に対して重大な肉体的又は精神的な危害を加えること。

(c) 全部又は一部に肉体の破壊をもたらすために意図された生活条件を集団に対して故意に課すること。

(d) 集団内における出生を防止することを意図する措置を課すること。

(e) 集団の児童を他の集団に強制的に移すこと。

第三条

次の行為は、処罰する。

(a) 集団殺害

(b) 集団殺害を犯すための共同謀議

(c) 集団殺害を犯すことの直接且つ公然の教唆

(d) 集団殺害の未遂

(e) 集団殺害の共犯

第四条

集団殺害又は第三条に列挙された他の行為のいずれかを犯す者は、憲法上の責任のある統治者であるか、公務員であるか又は私人であるかを問わず、処罰す

る。

第五条

締約国は、各の憲法に従つて、この条約の規定を実施するために、特に集団殺害又は第三条に列挙された他の行為のいずれかの犯罪者に対する有効な処罰を規

定するために、必要な立法を行うことを約束する。

第六条

集団殺害又は第三条に列挙された他の行為のいずれかについて告発された者は、行為がなされた地域の属する国の権限のある裁判所により、又は国際刑事裁判

所の管轄権を受理する締約国に関しては管轄権を有する国際刑事裁判所により審理される。

第七条

集団殺害及び第三条に列挙された他の行為は、犯罪人引渡しについては政治的犯罪と認めない。

締約国は、この場合、自国の実施中の法理及び条約に従つて、犯罪人引渡しを許すことを誓約する。

第八条

締約国は、国際連合の権限のある機関が集団殺害又は第三条に列挙された他の行為のいずれかを防止し又は抑圧するために適当と認める国際連合憲章に基く措

置を執るように、これらの機関に要求することができる。

第九条

この条約の解釈、適用又は履行に関する締約国間の紛争は、集団殺害又は第三条に列挙された他の行為のいずれかに対する国の責任に関するものを含め、紛争

当事国のいずれかの要求により国際司法裁判所に付託する。

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099