チャールズ・ダーウィン『種の起源について』1859年

On the Origin of Species

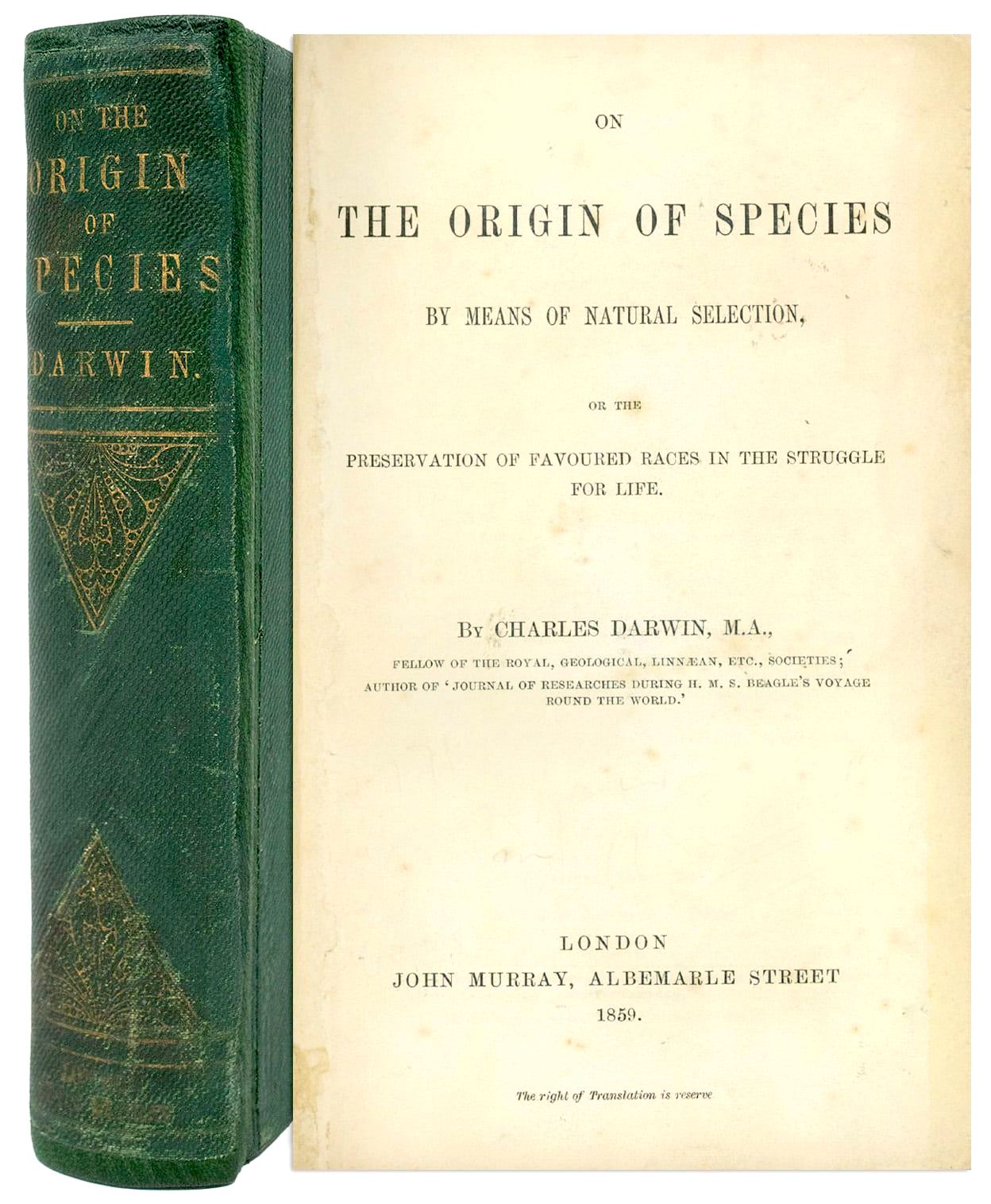

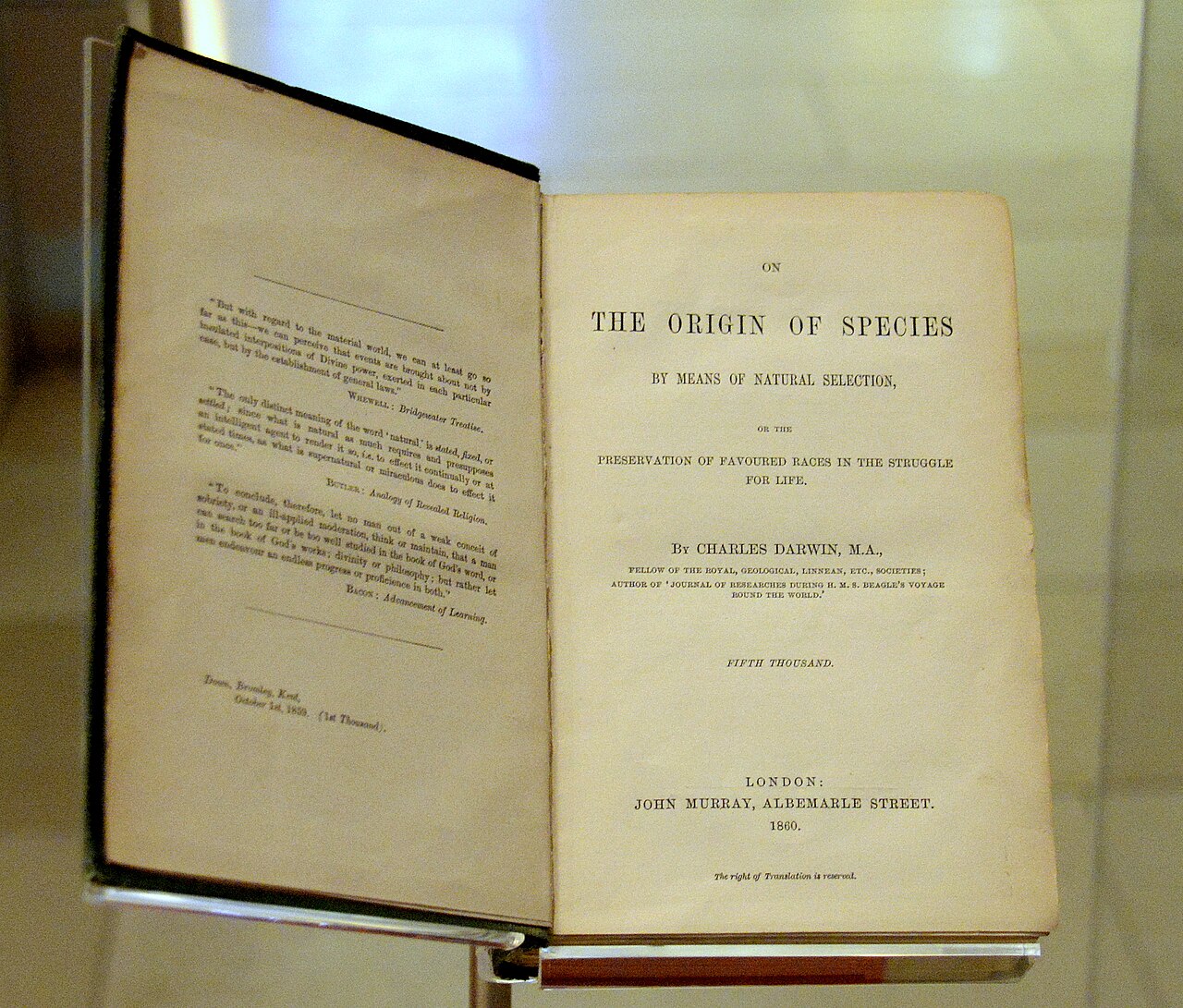

☆ 『種の起源について』("On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life")は、チャールズ・ダーウィン(1809-1882)による科学 文献で、進化生物学の基礎とされる。1859年11月24日に出版された。ダーウィンの著書は、自然淘汰の過程を通じて個体群が世代を経て進化するという 科学理論を紹介した。本書は、生命の多様性が進化の枝分かれパターンを通じた共通の子孫によって生じたという証拠の数々を提示した。ダーウィンは、 1830年代にビーグル号探検で収集した証拠や、その後の研究、書簡、実験から得た知見を盛り込んだ。

On the Origin of Species

(or, more completely, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural

Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for

Life)[3] is a work of scientific literature by Charles Darwin that is

considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology; it was

published on 24 November 1859.[4] Darwin's book introduced the

scientific theory that populations evolve over the course of

generations through a process of natural selection. The book presented

a body of evidence that the diversity of life arose by common descent

through a branching pattern of evolution. Darwin included evidence that

he had collected on the Beagle expedition in the 1830s and his

subsequent findings from research, correspondence, and

experimentation.[5] On the Origin of Species

(or, more completely, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural

Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for

Life)[3] is a work of scientific literature by Charles Darwin that is

considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology; it was

published on 24 November 1859.[4] Darwin's book introduced the

scientific theory that populations evolve over the course of

generations through a process of natural selection. The book presented

a body of evidence that the diversity of life arose by common descent

through a branching pattern of evolution. Darwin included evidence that

he had collected on the Beagle expedition in the 1830s and his

subsequent findings from research, correspondence, and

experimentation.[5]Various evolutionary ideas had already been proposed to explain new findings in biology. There was growing support for such ideas among dissident anatomists and the general public, but during the first half of the 19th century the English scientific establishment was closely tied to the Church of England, while science was part of natural theology. Ideas about the transmutation of species were controversial as they conflicted with the beliefs that species were unchanging parts of a designed hierarchy and that humans were unique, unrelated to other animals. The political and theological implications were intensely debated, but transmutation was not accepted by the scientific mainstream. The book was written for non-specialist readers and attracted widespread interest upon its publication. Darwin was already highly regarded as a scientist, so his findings were taken seriously and the evidence he presented generated scientific, philosophical, and religious discussion. The debate over the book contributed to the campaign by T. H. Huxley and his fellow members of the X Club to secularise science by promoting scientific naturalism. Within two decades, there was widespread scientific agreement that evolution, with a branching pattern of common descent, had occurred, but scientists were slow to give natural selection the significance that Darwin thought appropriate. During "the eclipse of Darwinism" from the 1880s to the 1930s, various other mechanisms of evolution were given more credit. With the development of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s, Darwin's concept of evolutionary adaptation through natural selection became central to modern evolutionary theory, and it has now become the unifying concept of the life sciences. |

『種

の起源について』("On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or

the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for

Life")は、チャールズ・ダーウィンによる科学文献で、進化生物学の基礎とされる。1859年11月24日に出版された。ダーウィンの著書は、自然淘

汰の過程を通じて個体群が世代を経て進化するという科学理論を紹介した。本書は、生命の多様性が進化の枝分かれパターンを通じた共通の子孫によって生じた

という証拠の数々を提示した。ダーウィンは、1830年代にビーグル号探検で収集した証拠や、その後の研究、書簡、実験から得た知見を盛り込んだ。 『種

の起源について』("On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or

the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for

Life")は、チャールズ・ダーウィンによる科学文献で、進化生物学の基礎とされる。1859年11月24日に出版された。ダーウィンの著書は、自然淘

汰の過程を通じて個体群が世代を経て進化するという科学理論を紹介した。本書は、生命の多様性が進化の枝分かれパターンを通じた共通の子孫によって生じた

という証拠の数々を提示した。ダーウィンは、1830年代にビーグル号探検で収集した証拠や、その後の研究、書簡、実験から得た知見を盛り込んだ。生物学における新たな発見を説明するために、すでに様々な進化論的な考え方が提案されていた。反体制派の解剖学者や一般市民の間では、このような考えを支 持する声が高まっていたが、19世紀前半のイギリスの科学界の体制は英国国教会と密接に結びついており、科学は自然神学の一部であった。種の転生に関する 考えは、種は設計された階層の不変の部分であり、人間は他の動物とは無関係な唯一無二の存在であるという信念と対立し、物議を醸した。政治的、神学的な影 響は激しく議論されたが、突然変異は科学の主流には受け入れられなかった。 この本は専門家以外の読者に向けて書かれ、出版と同時に広く関心を集めた。ダーウィンはすでに科学者として高く評価されていたため、彼の発見は真剣に受け 止められ、彼が提示した証拠は科学的、哲学的、宗教的な議論を引き起こした。この本をめぐる議論は、T・H・ハクスリーやXクラブの仲間たちによる、科学 的自然主義を推進することで科学を世俗化しようとする運動に貢献した。20年も経たないうちに、一般的な子孫の分岐パターンを持つ進化が起こったという科 学的合意が広まったが、科学者たちは、ダーウィンが適切と考えた自然淘汰の重要性を与えるのに時間がかかった。1880年代から1930年代までの "ダーウィニズムの蝕 "の間、進化の他のさまざまなメカニズムがより高く評価されるようになった。1930年代から1940年代にかけての現代進化総合学の発展により、自然選 択による進化的適応というダーウィンの概念が現代進化論の中心となり、現在では生命科学の統一概念となっている。 |

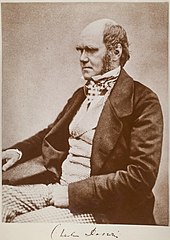

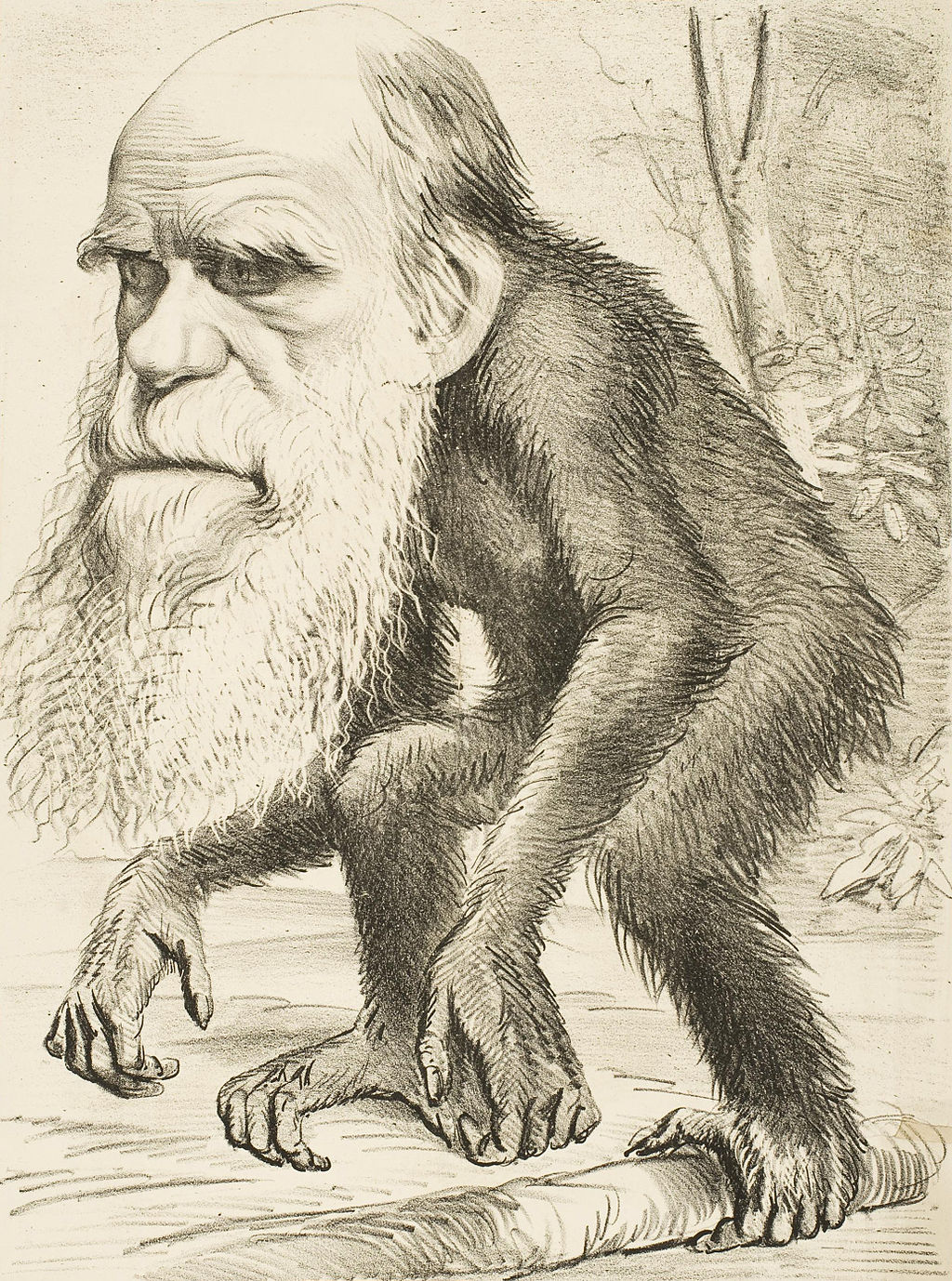

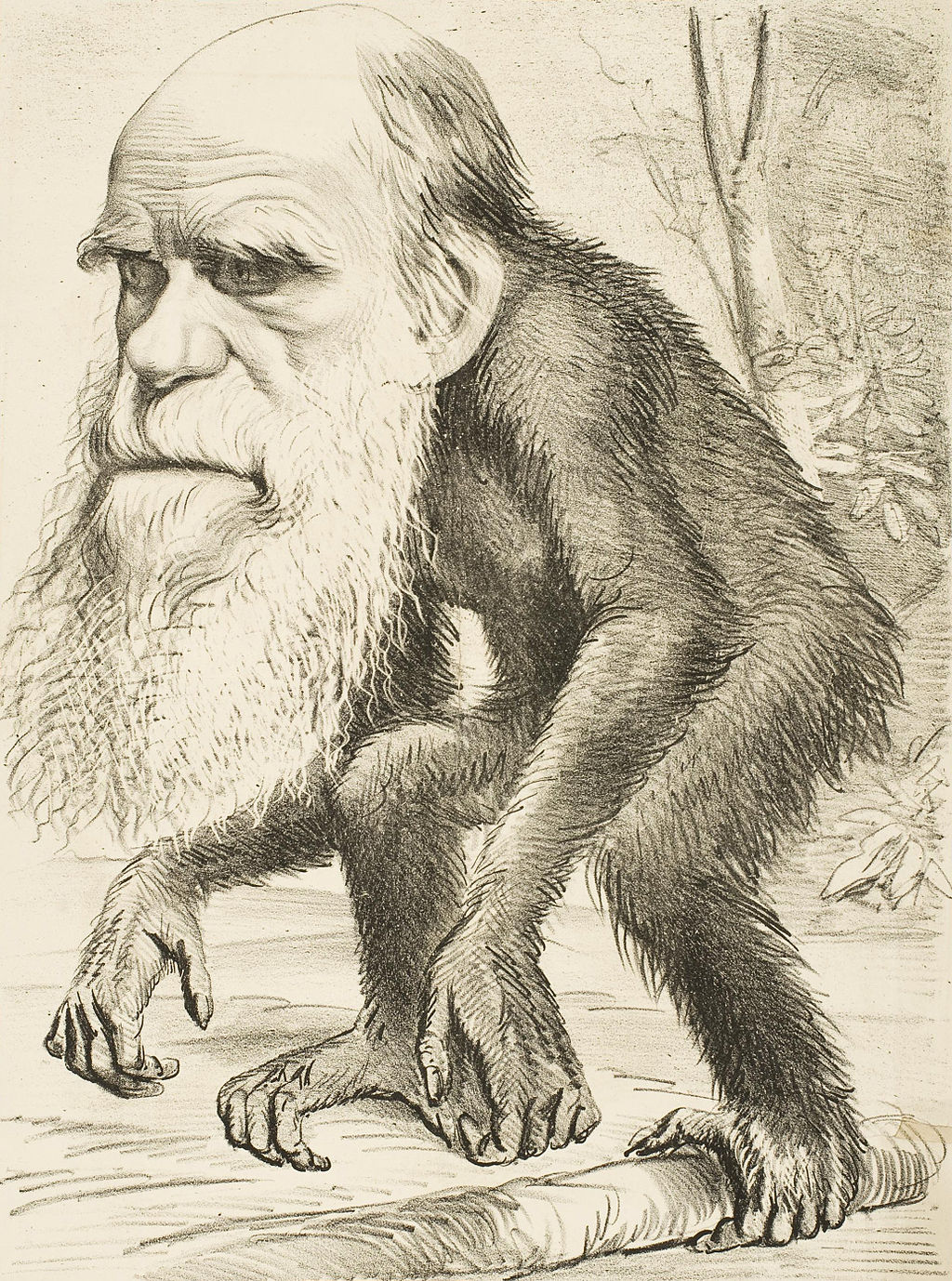

Summary of Darwin's theory Darwin pictured shortly before publication Darwin's theory of evolution is based on key facts and the inferences drawn from them, which biologist Ernst Mayr summarised as follows:[6] 1. Every species is fertile enough that if all offspring survived to reproduce, the population would grow (fact). 2. Despite periodic fluctuations, populations remain roughly the same size (fact). 3. Resources such as food are limited and are relatively stable over time (fact). 4. A struggle for survival ensues (inference). 5. Individuals in a population vary significantly from one another (fact). 6. Much of this variation is heritable (fact). 7. Individuals less suited to the environment are less likely to survive and less likely to reproduce; individuals more suited to the environment are more likely to survive and more likely to reproduce and leave their heritable traits to future generations, which produces the process of natural selection (fact). 8. This slowly effected process results in populations changing to adapt to their environments, and ultimately, these variations accumulate over time to form new species (inference). |

ダーウィン理論の概要 出版直前のダーウィン ダーウィンの進化論は、重要な事実とそこから導かれる推論に基づいており、生物学者エルンスト・マイヤーは次のように要約している[6]。 1. すべての種は繁殖可能であり、すべての子孫が繁殖のために生き残った場合、個体数は増加する(事実)。 2. 周期的な変動があるにもかかわらず、個体群の大きさはほぼ同じである(事実)。 3. 食料などの資源は限られており、長期にわたって比較的安定している(事実)。 4. 生存競争が起こる(推論)。 5. 集団内の個体は互いに大きく異なる(事実)。 6. この変異の多くは遺伝する(事実)。 7. 環境に適していない個体は生き残る可能性が低く、繁殖する可能性も低い。一方、環境に適している個体は生き残る可能性が高く、繁殖する可能性も高い(事実)。 8. このゆっくりとしたプロセスの結果、個体群は環境に適応するように変化し、最終的にこれらの変異が時間の経過とともに蓄積され、新しい種が形成される(推論)。 |

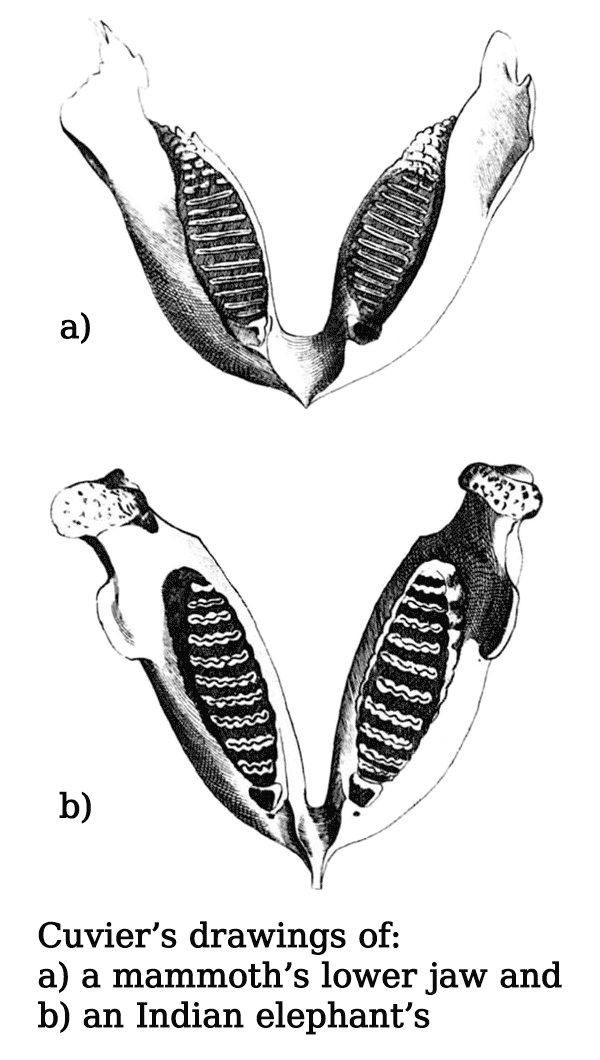

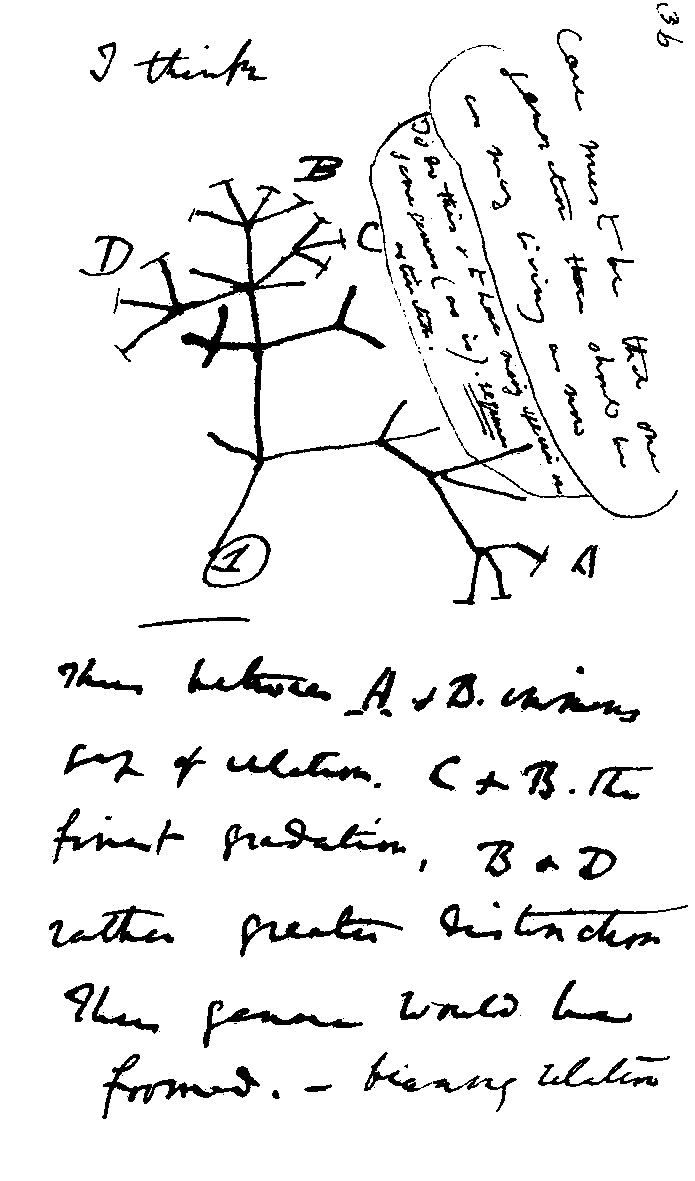

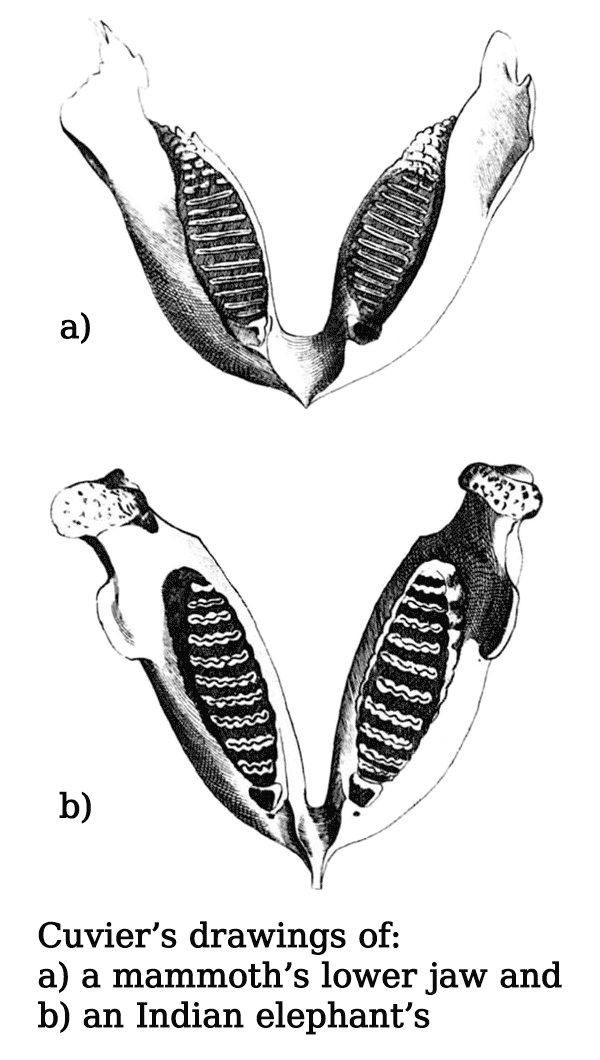

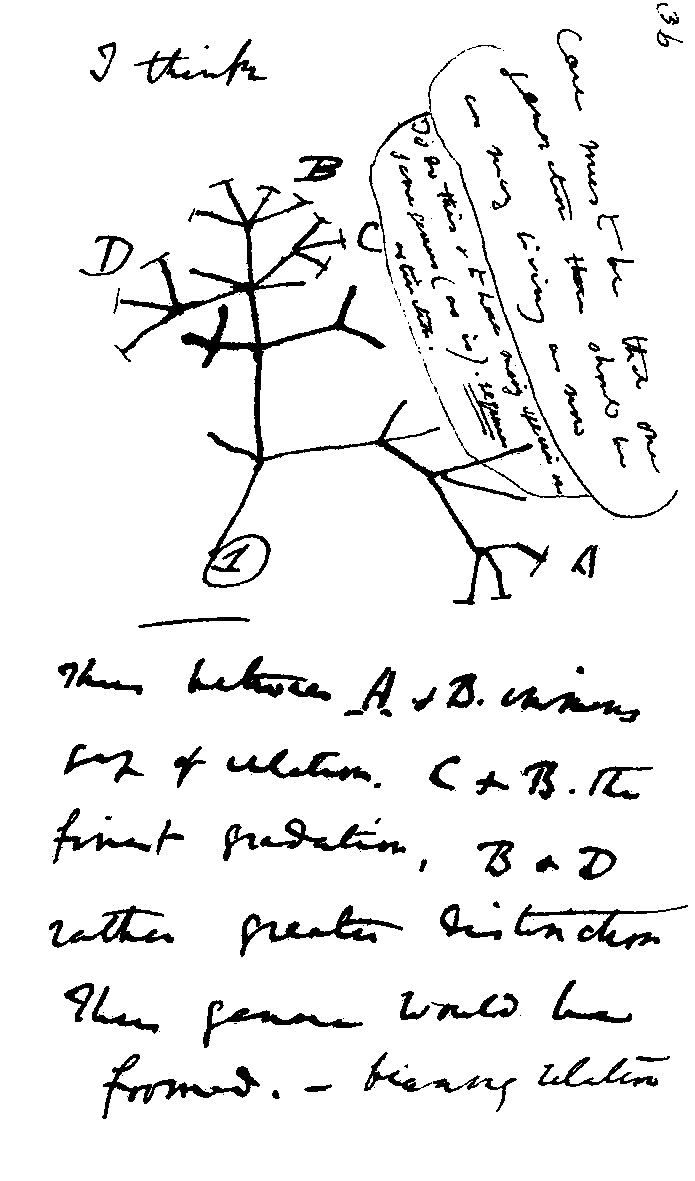

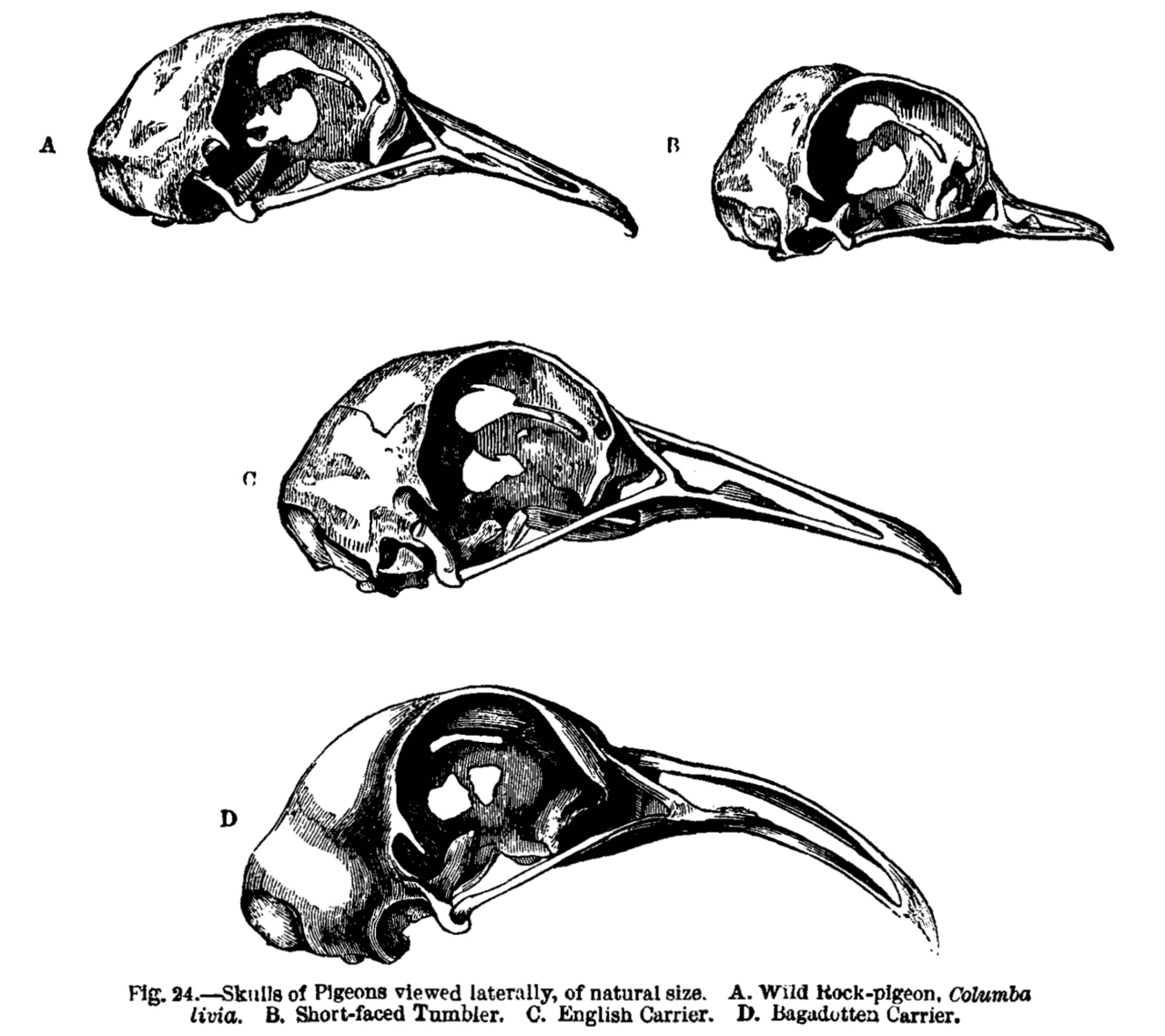

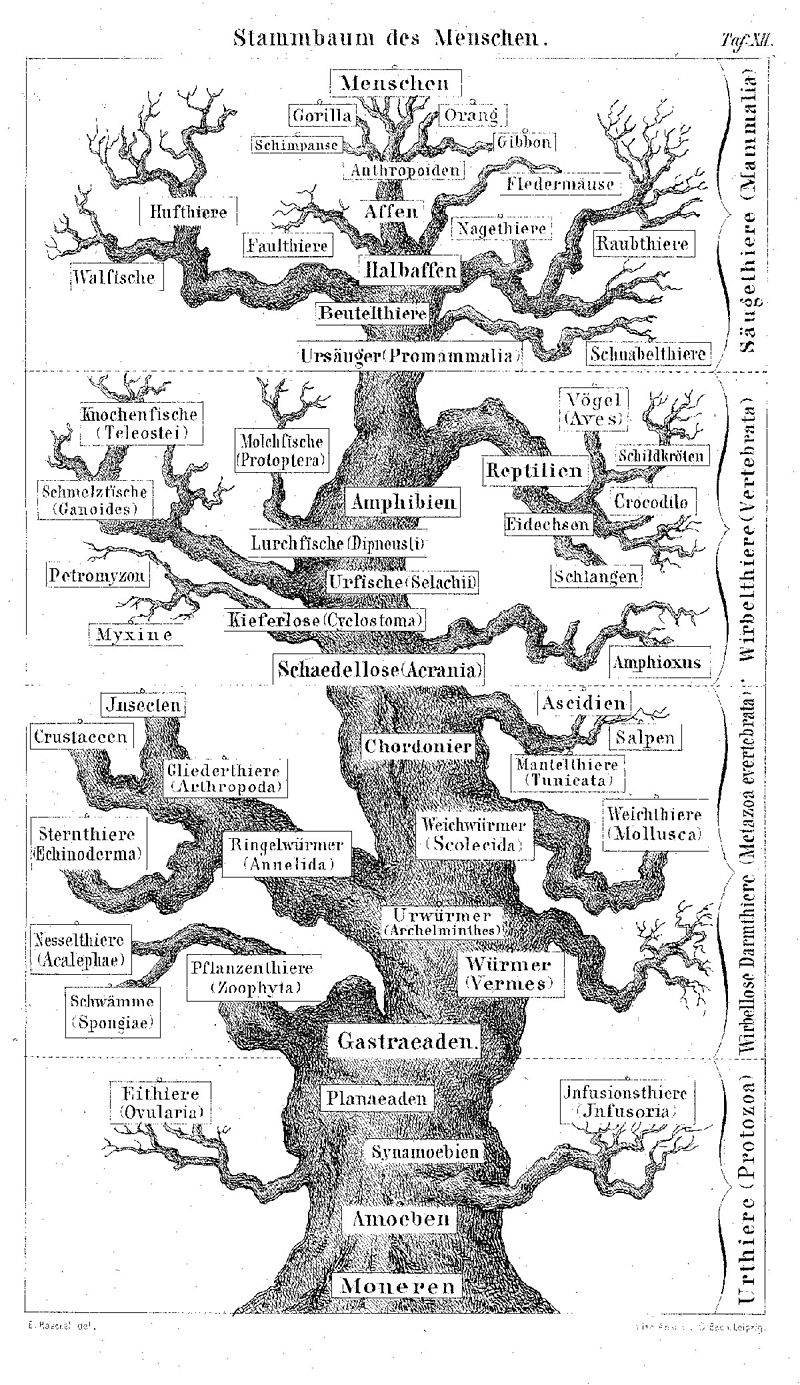

| Background See also: History of evolutionary thought and History of biology Developments before Darwin's theory In later editions of the book, Darwin traced evolutionary ideas as far back as Aristotle;[7] the text he cites is a summary by Aristotle of the ideas of the earlier Greek philosopher Empedocles.[8] Early Christian Church Fathers and Medieval European scholars interpreted the Genesis creation narrative allegorically rather than as a literal historical account;[9] organisms were described by their mythological and heraldic significance as well as by their physical form. Nature was widely believed to be unstable and capricious, with monstrous births from union between species, and spontaneous generation of life.[10]  Cuvier's 1799 paper on living and fossil elephants helped establish the reality of extinction. The Protestant Reformation inspired a literal interpretation of the Bible, with concepts of creation that conflicted with the findings of an emerging science seeking explanations congruent with the mechanical philosophy of René Descartes and the empiricism of the Baconian method. After the turmoil of the English Civil War, the Royal Society wanted to show that science did not threaten religious and political stability. John Ray developed an influential natural theology of rational order; in his taxonomy, species were static and fixed, their adaptation and complexity designed by God, and varieties showed minor differences caused by local conditions. In God's benevolent design, carnivores caused mercifully swift death, but the suffering caused by parasitism was a puzzling problem. The biological classification introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1735 also viewed species as fixed according to the divine plan, but did recognize the hierarchical nature of different taxa. In 1766, Georges Buffon suggested that some similar species, such as horses and asses, or lions, tigers, and leopards, might be varieties descended from a common ancestor. The Ussher chronology of the 1650s had calculated creation at 4004 BC, but by the 1780s geologists assumed a much older world. Wernerians thought strata were deposits from shrinking seas, but James Hutton proposed a self-maintaining infinite cycle, anticipating uniformitarianism.[11] Charles Darwin's grandfather Erasmus Darwin outlined a hypothesis of transmutation of species in the 1790s, and French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a more developed theory in 1809. Both envisaged that spontaneous generation produced simple forms of life that progressively developed greater complexity, adapting to the environment by inheriting changes in adults caused by use or disuse. This process was later called Lamarckism. Lamarck thought there was an inherent progressive tendency driving organisms continuously towards greater complexity, in parallel but separate lineages with no extinction.[12] Geoffroy contended that embryonic development recapitulated transformations of organisms in past eras when the environment acted on embryos, and that animal structures were determined by a constant plan as demonstrated by homologies. Georges Cuvier strongly disputed such ideas, holding that unrelated, fixed species showed similarities that reflected a design for functional needs.[13] His palæontological work in the 1790s had established the reality of extinction, which he explained by local catastrophes, followed by repopulation of the affected areas by other species.[14] In Britain, William Paley's Natural Theology saw adaptation as evidence of beneficial "design" by the Creator acting through natural laws. All naturalists in the two English universities (Oxford and Cambridge) were Church of England clergymen, and science became a search for these laws.[15] Geologists adapted catastrophism to show repeated worldwide annihilation and creation of new fixed species adapted to a changed environment, initially identifying the most recent catastrophe as the biblical flood.[16] Some anatomists such as Robert Grant were influenced by Lamarck and Geoffroy, but most naturalists regarded their ideas of transmutation as a threat to divinely appointed social order.[17] Inception of Darwin's theory See also: Charles Darwin's education and Inception of Darwin's theory Darwin went to Edinburgh University in 1825 to study medicine. In his second year he neglected his medical studies for natural history and spent four months assisting Robert Grant's research into marine invertebrates. Grant revealed his enthusiasm for the transmutation of species, but Darwin rejected it.[18] Starting in 1827, at Cambridge University, Darwin learnt science as natural theology from botanist John Stevens Henslow, and read Paley, John Herschel and Alexander von Humboldt. Filled with zeal for science, he studied catastrophist geology with Adam Sedgwick.[19][20]  In mid-July 1837 Darwin started his "B" notebook on Transmutation of Species, and on page 36 wrote "I think" above his first evolutionary tree. In December 1831, he joined the Beagle expedition as a gentleman naturalist and geologist. He read Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology and from the first stop ashore, at St. Jago, found Lyell's uniformitarianism a key to the geological history of landscapes. Darwin discovered fossils resembling huge armadillos, and noted the geographical distribution of modern species in hope of finding their "centre of creation".[21] The three Fuegian missionaries the expedition returned to Tierra del Fuego were friendly and civilised, yet to Darwin their relatives on the island seemed "miserable, degraded savages",[22] and he no longer saw an unbridgeable gap between humans and animals.[23] As the Beagle neared England in 1836, he noted that species might not be fixed.[24][25] Richard Owen showed that fossils of extinct species Darwin found in South America were allied to living species on the same continent. In March 1837, ornithologist John Gould announced that Darwin's rhea was a separate species from the previously described rhea (though their territories overlapped), that mockingbirds collected on the Galápagos Islands represented three separate species each unique to a particular island, and that several distinct birds from those islands were all classified as finches.[26] Darwin began speculating, in a series of notebooks, on the possibility that "one species does change into another" to explain these findings, and around July sketched a genealogical branching of a single evolutionary tree, discarding Lamarck's independent lineages progressing to higher forms.[27][28][29] Unconventionally, Darwin asked questions of fancy pigeon and animal breeders as well as established scientists. At the zoo he had his first sight of an ape, and was profoundly impressed by how human the orangutan seemed.[30] In late September 1838, he started reading Thomas Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population with its statistical argument that human populations, if unrestrained, breed beyond their means and struggle to survive. Darwin related this to the struggle for existence among wildlife and botanist de Candolle's "warring of the species" in plants; he immediately envisioned "a force like a hundred thousand wedges" pushing well-adapted variations into "gaps in the economy of nature", so that the survivors would pass on their form and abilities, and unfavourable variations would be destroyed.[31][32][33] By December 1838, he had noted a similarity between the act of breeders selecting traits and a Malthusian Nature selecting among variants thrown up by "chance" so that "every part of newly acquired structure is fully practical and perfected".[34] Darwin now had the basic framework of his theory of natural selection, but he was fully occupied with his career as a geologist and held back from compiling it until his book on The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs was completed.[35][36] As he recalled in his autobiography, he had "at last got a theory by which to work", but it was only in June 1842 that he allowed himself "the satisfaction of writing a very brief abstract of my theory in pencil".[37] Further development See also: Development of Darwin's theory Darwin continued to research and extensively revise his theory while focusing on his main work of publishing the scientific results of the Beagle voyage.[35] He tentatively wrote of his ideas to Lyell in January 1842;[38] then in June he roughed out a 35-page "Pencil Sketch" of his theory.[39] Darwin began correspondence about his theorising with the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker in January 1844, and by July had rounded out his "sketch" into a 230-page "Essay", to be expanded with his research results and published if he died prematurely.[40]  Darwin researched how the skulls of different pigeon breeds varied, as shown in his Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication of 1868. In November 1844, the anonymously published popular science book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, written by Scottish journalist Robert Chambers, widened public interest in the concept of transmutation of species. Vestiges used evidence from the fossil record and embryology to support the claim that living things had progressed from the simple to the more complex over time. But it proposed a linear progression rather than the branching common descent theory behind Darwin's work in progress, and it ignored adaptation. Darwin read it soon after publication, and scorned its amateurish geology and zoology,[41] but he carefully reviewed his own arguments after leading scientists, including Adam Sedgwick, attacked its morality and scientific errors.[42] Vestiges had significant influence on public opinion, and the intense debate helped to pave the way for the acceptance of the more scientifically sophisticated Origin by moving evolutionary speculation into the mainstream. While few naturalists were willing to consider transmutation, Herbert Spencer became an active proponent of Lamarckism and progressive development in the 1850s.[43] Hooker was persuaded to take away a copy of the "Essay" in January 1847, and eventually sent a page of notes giving Darwin much-needed feedback. Reminded of his lack of expertise in taxonomy, Darwin began an eight-year study of barnacles, becoming the leading expert on their classification. Using his theory, he discovered homologies showing that slightly changed body parts served different functions to meet new conditions, and he found an intermediate stage in the evolution of distinct sexes.[44][45] Darwin's barnacle studies convinced him that variation arose constantly and not just in response to changed circumstances. In 1854, he completed the last part of his Beagle-related writing and began working full-time on evolution. He now realised that the branching pattern of evolutionary divergence was explained by natural selection working constantly to improve adaptation. His thinking changed from the view that species formed in isolated populations only, as on islands, to an emphasis on speciation without isolation; that is, he saw increasing specialisation within large stable populations as continuously exploiting new ecological niches. He conducted empirical research focusing on difficulties with his theory. He studied the developmental and anatomical differences between different breeds of many domestic animals, became actively involved in fancy pigeon breeding, and experimented (with the help of his young son Francis) on ways that plant seeds and animals might disperse across oceans to colonise distant islands. By 1856, his theory was much more sophisticated, with a mass of supporting evidence.[44][46] |

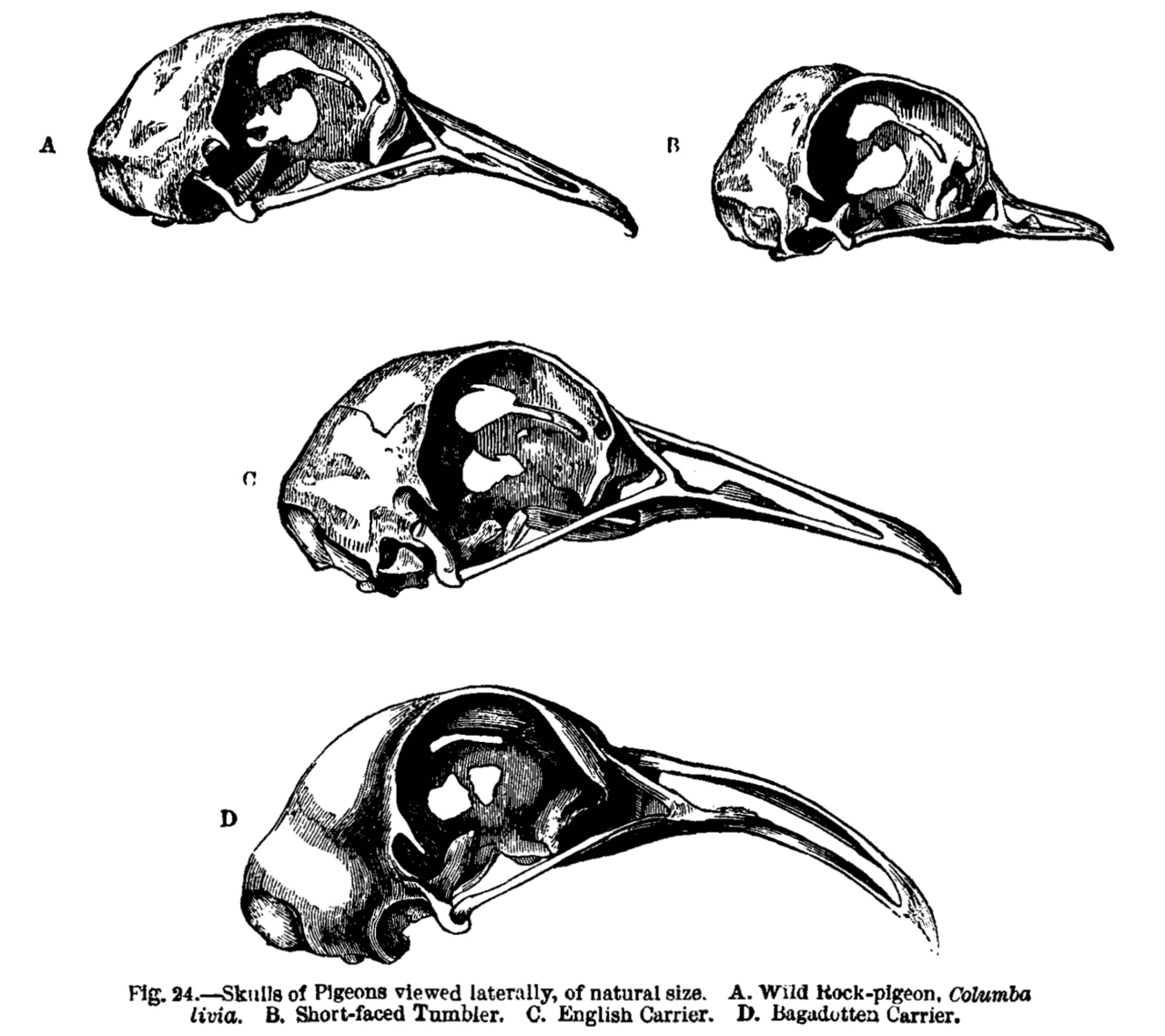

背景 こちらも参照: 進化思想史、生物学史 ダーウィンの理論以前の展開 ダーウィンが引用したテキストは、それ以前のギリシアの哲学者エンペドクレスの考えをアリストテレスが要約したものである[8]。初期キリスト教の教父や 中世ヨーロッパの学者たちは、創世記の天地創造の物語を文字通りの歴史的記述としてではなく、寓意的に解釈した[9]。自然は不安定で気まぐれであり、種 と種の結合による怪物のような誕生や生命の自然発生があると広く信じられていた[10]。  キュヴィエが1799年に発表した、生きているゾウと化石のゾウに関する論文は、絶滅の現実を立証する一助となった。 プロテスタント宗教改革は、ルネ・デカルトの機械的哲学やバコニアン法の経験主義に合致する説明を求める新興科学の知見と対立する創造の概念をもって、聖 書の文字通りの解釈を促した。イギリス内戦の混乱の後、王立協会は科学が宗教的・政治的安定を脅かすものではないことを示したかった。ジョン・レイは、合 理的秩序に関する影響力のある自然神学を発展させた。彼の分類学では、種は静的で固定されたものであり、その適応と複雑さは神によって設計されたものであ る。神の慈悲深い設計では、肉食動物は慈悲深く速やかに死をもたらすが、寄生による苦しみは不可解な問題であった。1735年にカール・リンネが導入した 生物学的分類もまた、神の計画に従って種が固定されたものとみなしたが、異なる分類群の階層的な性質は認識していた。1766年、ジョルジュ・ビュフォン は、馬と驢馬、ライオン、トラ、ヒョウなど、いくつかの類似種は共通の祖先から派生した品種である可能性を示唆した。1650年代のアッシャー年代記で は、天地創造は紀元前4004年とされていたが、1780年代には、地質学者たちはもっと古い世界を想定していた。ウェルネリアンは、地層は縮小する海か ら堆積したものだと考えていたが、ジェームズ・ハットンは、均一主義を先取りして、自己維持する無限のサイクルを提唱した[11]。 チャールズ・ダーウィンの祖父であるエラスマス・ダーウィンは、1790年代に種の転換の仮説を概説し、フランスの博物学者ジャン=バティスト・ラマルク は、1809年にさらに発展した理論を発表した。両者とも、自然発生が単純な生命体を生み出し、それが使用や不使用によって生じた成体の変化を受け継ぐこ とによって環境に適応し、徐々に複雑さを増していくと考えていた。このプロセスは後にラマルク主義と呼ばれるようになった。ジェフロワは、胚の発生は、環 境が胚に作用した過去の時代の生物の変化を再現しており、動物の構造は相同性によって示されるように一定の計画によって決定されると主張した。ジョル ジュ・キュヴィエはこのような考えに強く異論を唱え、関連性のない固定種は機能的な必要性のための設計を反映した類似性を示すとした[13]。1790年 代の彼の古生物学的研究は、絶滅の現実を確立し、彼はそれを局所的な大災害によって説明し、その後、影響を受けた地域に他の種が再繁殖した[14]。 イギリスでは、ウィリアム・ペイリーの自然神学が、自然法則を通して作用する創造主による有益な「デザイン」の証拠として適応を捉えていた。ロバート・グ ラントのような一部の解剖学者はラマルクやジェフロワの影響を受けていたが、ほとんどの自然主義者は彼らの突然変異の考えを、神が定めた社会秩序に対する 脅威とみなしていた[17]。 ダーウィン理論の始まり 以下も参照: チャールズ・ダーウィンの教育、ダーウィン理論の始まり ダーウィンは医学を学ぶために1825年にエジンバラ大学に入学した。2年目には医学をおろそかにして博物学を学び、ロバート・グラントの海洋無脊椎動物 の研究を4ヶ月間手伝った。1827年からケンブリッジ大学で、ダーウィンは植物学者ジョン・スティーヴンス・ヘンズローから自然神学としての科学を学 び、ペイリー、ジョン・ハーシェル、アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトを読んだ。科学への熱意に満たされた彼は、アダム・セジウィックのもとで破局主義 的な地質学を学んだ[19][20]。  1837年7月中旬、ダーウィンは種の変容に関するノート「B」を書き始め、36ページには最初の進化の木の上に「私は思う」と書いた。 1831年12月、彼は紳士博物学者、地質学者としてビーグル号探検隊に参加した。彼はチャールズ・ライエルの『地質学の原理』を読み、最初の寄港地であ るセント・ジェーゴでライエルの一様主義が地質学的景観史の鍵であることを知った。ダーウィンは巨大なアルマジロに似た化石を発見し、「創造の中心」を見 つけることを期待して、現代の種の地理的分布に注目した。 [21]探検隊がティエラ・デル・フエゴに帰還させた3人のフエギ人宣教師は友好的で文明的であったが、ダーウィンには島の彼らの親類が「惨めで劣悪な野 蛮人」に見え[22]、人間と動物との間にもはや埋めがたい隔たりがあるとは思えなかった[23]。1836年にビーグル号がイギリスに近づくにつれ、彼 は種が固定されていないかもしれないと指摘した[24][25]。 リチャード・オーウェンは、ダーウィンが南米で発見した絶滅種の化石が、同じ大陸に生息する現生種と同種であることを示した。1837年3月、鳥類学者 ジョン・グールドは、ダーウィンのレアは以前に記載されたレアとは別種であること(ただし、両者の生息域は重なっていた)、ガラパゴス諸島で採集された モッキンバードはそれぞれ特定の島に固有の3つの別種であること、そしてそれらの島で採集されたいくつかの別種の鳥はすべてフィンチとして分類されること を発表した[26]。 [26]ダーウィンは一連のノートの中で、これらの発見を説明するために、「ある種が別の種に変化する」という可能性について推測を始め、7月頃には、ラ マルクの独立した系統がより高い形態へと進歩していくことを捨てて、単一の進化樹の系図をスケッチした[27][28][29]。 ダーウィンは型破りにも、確立された科学者だけでなく、ファンシーなハトや動物の飼育者にも質問をした。動物園で彼は初めて類人猿を目にし、オランウータ ンがいかに人間的であるかに深い感銘を受けた[30]。 1838年9月下旬、ダーウィンはトマス・マルサスの『人口原理に関する試論』を読み始める。ダーウィンはこれを、野生動物の生存競争や植物学者ド・カン ドールの植物における「種の争い」と関連づけた。彼はすぐに、よく適応した変異を「自然の経済の隙間」に押し込む「10万のくさびのような力」を思い描い た。 [31][32][33]。1838年12月までにダーウィンは、育種家が形質を選択する行為と、マルサス的自然が「偶然」によって生み出された変種の中 から「新しく獲得された構造のあらゆる部分が完全に実用化され完成される」ように選択する行為との類似性に着目していた[34]。 ダーウィンは自然淘汰の理論の基本的な枠組みを手に入れたが、地質学者としてのキャリアで手一杯であったため、『サンゴ礁の構造と分布』に関する本が完成 するまで、その理論の編纂を控えていた[35][36]。 自伝の中で回想しているように、彼は「ついに仕事をするための理論を手に入れた」のであったが、「自分の理論のごく簡単な要旨を鉛筆で書くという満足感」 を得たのは1842年6月のことであった[37]。 さらなる発展 以下も参照: ダーウィン理論の発展 ダーウィンは、ビーグル号航海の科学的成果を出版するという主な仕事に集中しながら、自分の理論の研究と大幅な改訂を続けた[35]。 [39]ダーウィンは1844年1月に植物学者のジョセフ・ダルトン・フッカーと自分の理論について文通を始め、7月までに「スケッチ」を230ページの 「エッセイ」にまとめ、研究結果を加えて増補し、早死にした場合には出版する予定であった[40]。  ダーウィンは、1868年の『家畜化された動植物の変異(Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication)』に示されているように、異なる品種のハトの頭蓋骨がどのように変化するかを研究した。 1844年11月、スコットランドのジャーナリスト、ロバート・チェンバースによって匿名で出版された大衆科学書『天地創造の自然史』(Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation)は、種の転変という概念に対する人々の関心を広めた。Vestiges』は、化石記録や発生学から得られた証拠を用いて、生物は時間の 経過とともに単純なものからより複雑なものへと進歩してきたという主張を支持した。しかし、ダーウィンの進行中の研究の背後にある枝分かれする共通子孫説 ではなく、直線的な進行を提案し、適応を無視していた。ダーウィンは出版後すぐにこの本を読み、その素人じみた地質学と動物学を軽蔑したが[41]、アダ ム・セジウィックをはじめとする一流の科学者がその道徳性と科学的誤りを攻撃した後、彼自身の主張を慎重に見直した[42]。突然変異を考慮する自然学者 はほとんどいなかったが、ハーバート・スペンサーは1850年代にラマルク主義と漸進的発展の積極的な支持者となった[43]。 フッカーは、1847年1月に「エッセイ」のコピーを持ち帰るよう説得され、最終的にはダーウィンに必要なフィードバックを与えるメモのページを送った。 ダーウィンは分類学の専門知識がないことを思い知らされ、フジツボの研究を8年間始め、フジツボの分類の第一人者となった。ダーウィンは自分の理論を用い て、わずかに変化した体の部位が新しい条件に対応するために異なる機能を果たすことを示す相同性を発見し、明確な性の進化における中間段階を見出した [44][45]。 ダーウィンのフジツボの研究は、変化する状況に対応するだけでなく、絶えず変異が生じることを確信させた。1854年、ダーウィンはビーグル号関連の著作 の最後の部分を完成させ、進化に関する本格的な研究を開始した。彼は今、進化の分岐パターンは、適応を向上させるために絶えず働く自然淘汰によって説明で きることに気づいた。彼の考え方は、島嶼のように孤立した個体群でのみ種が形成されるという見解から、孤立を伴わない種分化に重点を置くものへと変化し た。つまり、彼は大規模で安定した個体群内で特殊化が進み、新しい生態学的ニッチを継続的に開拓していると考えたのである。彼は自身の理論の難点に焦点を 当てた実証的研究を行った。彼は多くの家畜の異なる品種間の発育や解剖学的差異を研究し、空想的な鳩の繁殖に積極的に関わり、植物の種子や動物が海を渡っ て分散し、遠くの島々を植民地化する方法について(幼い息子フランシスの助けを借りて)実験を行った。1856年までには、彼の理論はより洗練され、多く の裏付けとなる証拠が揃っていた[44][46]。 |

| Publication Main article: Publication of Darwin's theory Time taken to publish In his autobiography, Darwin said he had "gained much by my delay in publishing from about 1839, when the theory was clearly conceived, to 1859; and I lost nothing by it".[47] On the first page of his 1859 book he noted that, having begun work on the topic in 1837, he had drawn up "some short notes" after five years, had enlarged these into a sketch in 1844, and "from that period to the present day I have steadily pursued the same object."[48][49] Various biographers have proposed that Darwin avoided or delayed making his ideas public for personal reasons. Reasons suggested have included fear of religious persecution or social disgrace if his views were revealed, and concern about upsetting his clergymen naturalist friends or his pious wife Emma. Charles Darwin's illness caused repeated delays. His paper on Glen Roy had proved embarrassingly wrong, and he may have wanted to be sure he was correct. David Quammen has suggested all these factors may have contributed, and notes Darwin's large output of books and busy family life during that time.[50] A more recent study by science historian John van Wyhe has determined that the idea that Darwin delayed publication only dates back to the 1940s, and Darwin's contemporaries thought the time he took was reasonable. Darwin always finished one book before starting another. While he was researching, he told many people about his interest in transmutation without causing outrage. He firmly intended to publish, but it was not until September 1854 that he could work on it full-time. His 1846 estimate that writing his "big book" would take five years proved optimistic.[48] Events leading to publication: "big book" manuscript  A photograph of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) taken in Singapore in 1862 An 1855 paper on the "introduction" of species, written by Alfred Russel Wallace, claimed that patterns in the geographical distribution of living and fossil species could be explained if every new species always came into existence near an already existing, closely related species.[51] Charles Lyell recognised the implications of Wallace's paper and its possible connection to Darwin's work, although Darwin did not, and in a letter written on 1–2 May 1856 Lyell urged Darwin to publish his theory to establish priority. Darwin was torn between the desire to set out a full and convincing account and the pressure to quickly produce a short paper. He met Lyell, and in correspondence with Joseph Dalton Hooker affirmed that he did not want to expose his ideas to review by an editor as would have been required to publish in an academic journal. He began a "sketch" account on 14 May 1856, and by July had decided to produce a full technical treatise on species as his "big book" on Natural Selection. His theory including the principle of divergence was complete by 5 September 1857 when he sent Asa Gray a brief but detailed abstract of his ideas.[52][53] Joint publication of papers by Wallace and Darwin Darwin was hard at work on the manuscript for his "big book" on Natural Selection, when on 18 June 1858 he received a parcel from Wallace, who stayed on the Maluku Islands (Ternate and Gilolo). It enclosed twenty pages describing an evolutionary mechanism, a response to Darwin's recent encouragement, with a request to send it on to Lyell if Darwin thought it worthwhile. The mechanism was similar to Darwin's own theory.[52] Darwin wrote to Lyell that "your words have come true with a vengeance, ... forestalled" and he would "of course, at once write and offer to send [it] to any journal" that Wallace chose, adding that "all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed".[54] Lyell and Hooker agreed that a joint publication putting together Wallace's pages with extracts from Darwin's 1844 Essay and his 1857 letter to Gray should be presented at the Linnean Society, and on 1 July 1858, the papers entitled On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection, by Wallace and Darwin respectively, were read out but drew little reaction. While Darwin considered Wallace's idea to be identical to his concept of natural selection, historians have pointed out differences. Darwin described natural selection as being analogous to the artificial selection practised by animal breeders, and emphasised competition between individuals; Wallace drew no comparison to selective breeding, and focused on ecological pressures that kept different varieties adapted to local conditions.[55][56][57] Some historians have suggested that Wallace was actually discussing group selection rather than selection acting on individual variation.[58] Abstract of Species book Soon after the meeting, Darwin decided to write "an abstract of my whole work" in the form of one or more papers to be published by the Linnean Society, but was concerned about "how it can be made scientific for a Journal, without giving facts, which would be impossible." He asked Hooker how many pages would be available, but "If the Referees were to reject it as not strictly scientific I would, perhaps publish it as pamphlet."[59][60] He began his "abstract of Species book" on 20 July 1858, while on holiday at Sandown,[61] and wrote parts of it from memory, while sending the manuscripts to his friends for checking.[62] By early October, he began to "expect my abstract will run into a small volume, which will have to be published separately."[63] Over the same period, he continued to collect information and write large fully detailed sections of the manuscript for his "big book" on Species, Natural Selection.[59] Murray as publisher; choice of title  On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, 2nd edition. By Charles Darwin, John Murray, London, 1860. National Museum of Scotland. By mid-March 1859 Darwin's abstract had reached the stage where he was thinking of early publication; Lyell suggested the publisher John Murray, and met with him to find if he would be willing to publish. On 28 March Darwin wrote to Lyell asking about progress, and offering to give Murray assurances "that my Book is not more un-orthodox, than the subject makes inevitable." He enclosed a draft title sheet proposing An abstract of an Essay on the Origin of Species and Varieties Through natural selection, with the year shown as "1859".[64][65] Murray's response was favourable, and a very pleased Darwin told Lyell on 30 March that he would "send shortly a large bundle of M.S. but unfortunately I cannot for a week, as the three first chapters are in three copyists' hands". He bowed to Murray's objection to "abstract" in the title, though he felt it excused the lack of references, but wanted to keep "natural selection" which was "constantly used in all works on Breeding", and hoped "to retain it with Explanation, somewhat as thus",— Through Natural Selection or the preservation of favoured races.[65][66] On 31 March Darwin wrote to Murray in confirmation, and listed headings of the 12 chapters in progress: he had drafted all except "XII. Recapitulation & Conclusion".[67] Murray responded immediately with an agreement to publish the book on the same terms as he published Lyell, without even seeing the manuscript: he offered Darwin ⅔ of the profits.[68] Darwin promptly accepted with pleasure, insisting that Murray would be free to withdraw the offer if, having read the chapter manuscripts, he felt the book would not sell well[69] (eventually Murray paid £180 to Darwin for the first edition and by Darwin's death in 1882 the book was in its sixth edition, earning Darwin nearly £3000[70]). On 5 April, Darwin sent Murray the first three chapters, and a proposal for the book's title.[71] An early draft title page suggests On the Mutability of Species.[72] Murray cautiously asked Whitwell Elwin to review the chapters.[59] At Lyell's suggestion, Elwin recommended that, rather than "put forth the theory without the evidence", the book should focus on observations upon pigeons, briefly stating how these illustrated Darwin's general principles and preparing the way for the larger work expected shortly: "Every body is interested in pigeons."[73] Darwin responded that this was impractical: he had only the last chapter still to write.[74] In September the main title still included "An essay on the origin of species and varieties", but Darwin now proposed dropping "varieties".[75] With Murray's persuasion, the title was eventually agreed as On the Origin of Species, with the title page adding by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.[3] In this extended title (and elsewhere in the book) Darwin used the biological term "races" interchangeably with "varieties", meaning varieties within a species.[76][77] He used the term broadly,[78] and as well as discussions of "the several races, for instance, of the cabbage" and "the hereditary varieties or races of our domestic animals and plants",[79] there are three instances in the book where the phrase "races of man" is used, referring to races of humans.[80] Publication and subsequent editions On the Origin of Species was first published on Thursday 24 November 1859, priced at fifteen shillings with a first printing of 1250 copies.[81] The book had been offered to booksellers at Murray's autumn sale on Tuesday 22 November, and all available copies had been taken up immediately. In total, 1,250 copies were printed but after deducting presentation and review copies, and five for Stationers' Hall copyright, around 1,170 copies were available for sale.[2] Significantly, 500 were taken by Mudie's Library, ensuring that the book promptly reached a large number of subscribers to the library.[82] The second edition of 3,000 copies was quickly brought out on 7 January 1860,[83] and incorporated numerous corrections as well as a response to religious objections by the addition of a new epigraph on page ii, a quotation from Charles Kingsley, and the phrase "by the Creator" added to the closing sentence.[84] During Darwin's lifetime the book went through six editions, with cumulative changes and revisions to deal with counter-arguments raised. The third edition came out in 1861, with a number of sentences rewritten or added and an introductory appendix, An Historical Sketch of the Recent Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species.[85] In response to objections that the origin of life was unexplained, Darwin pointed to acceptance of Newton's law even though the cause of gravity was unknown, and Leibnitz had accused Newton of introducing "occult qualities & miracles".[86][87] The fourth edition in 1866 had further revisions. The fifth edition, published on 10 February 1869, incorporated more changes and for the first time included the phrase "survival of the fittest", which had been coined by the philosopher Herbert Spencer in his Principles of Biology (1864).[88] In January 1871, George Jackson Mivart's On the Genesis of Species listed detailed arguments against natural selection, and claimed it included false metaphysics.[89] Darwin made extensive revisions to the sixth edition of the Origin (this was the first edition in which he used the word "evolution" which had commonly been associated with embryological development, though all editions concluded with the word "evolved"[90][91]), and added a new chapter VII, Miscellaneous objections, to address Mivart's arguments.[2][92] The sixth edition was published by Murray on 19 February 1872 as The Origin of Species, with "On" dropped from the title. Darwin had told Murray of working men in Lancashire clubbing together to buy the fifth edition at 15 shillings and wanted it made more widely available; the price was halved to 7s 6d by printing in a smaller font. It includes a glossary compiled by W.S. Dallas. Book sales increased from 60 to 250 per month.[3][92] Publication outside Great Britain  American botanist Asa Gray (1810–1888) In the United States, botanist Asa Gray, an American colleague of Darwin, negotiated with a Boston publisher for publication of an authorised American version, but learnt that two New York publishing firms were already planning to exploit the absence of international copyright to print Origin.[93] Darwin was delighted by the popularity of the book, and asked Gray to keep any profits.[94] Gray managed to negotiate a 5% royalty with Appleton's of New York,[95] who got their edition out in mid-January 1860, and the other two withdrew. In a May letter, Darwin mentioned a print run of 2,500 copies, but it is not clear if this referred to the first printing only, as there were four that year.[2][96] The book was widely translated in Darwin's lifetime, but problems arose with translating concepts and metaphors, and some translations were biased by the translator's own agenda.[97] Darwin distributed presentation copies in France and Germany, hoping that suitable applicants would come forward, as translators were expected to make their own arrangements with a local publisher. He welcomed the distinguished elderly naturalist and geologist Heinrich Georg Bronn, but the German translation published in 1860 imposed Bronn's own ideas, adding controversial themes that Darwin had deliberately omitted. Bronn translated "favoured races" as "perfected races", and added essays on issues including the origin of life, as well as a final chapter on religious implications partly inspired by Bronn's adherence to Naturphilosophie.[98] In 1862, Bronn produced a second edition based on the third English edition and Darwin's suggested additions, but then died of a heart attack.[99] Darwin corresponded closely with Julius Victor Carus, who published an improved translation in 1867.[100] Darwin's attempts to find a translator in France fell through, and the translation by Clémence Royer published in 1862 added an introduction praising Darwin's ideas as an alternative to religious revelation and promoting ideas anticipating social Darwinism and eugenics, as well as numerous explanatory notes giving her own answers to doubts that Darwin expressed. Darwin corresponded with Royer about a second edition published in 1866 and a third in 1870, but he had difficulty getting her to remove her notes and was troubled by these editions.[99][101] He remained unsatisfied until a translation by Edmond Barbier was published in 1876.[2] A Dutch translation by Tiberius Cornelis Winkler was published in 1860.[102] By 1864, additional translations had appeared in Italian and Russian.[97] In Darwin's lifetime, Origin was published in Swedish in 1871,[103] Danish in 1872, Polish in 1873, Hungarian in 1873–1874, Spanish in 1877 and Serbian in 1878. By 1977, Origin had appeared in an additional 18 languages,[104] including Chinese by Ma Chün-wu who added non-Darwinian ideas; he published the preliminaries and chapters 1–5 in 1902–1904, and his complete translation in 1920.[105][106] |

出版 主な記事 ダーウィン理論の出版 出版に要した時間 ダーウィンは自伝の中で、「理論が明確に考え出された1839年頃から1859年まで出版が遅れたことによって多くのものを得たが、それによって失ったも のは何もない」と述べている[47]。 1859年の著書の最初のページでは、1837年にこのテーマについて研究を始め、5年後に「いくつかの短いメモ」を作成し、1844年にそれをスケッチ に拡大し、「その時期から今日まで、私は同じ目的を着実に追求してきた」と述べている[48][49]。 様々な伝記作家が、ダーウィンは個人的な理由から自分の考えを公にすることを避けたり、遅らせたりしたと提唱している。その理由としては、自分の考えが明 らかになった場合の宗教的迫害や社会的不名誉への恐れ、聖職者である博物学者の友人や敬虔な妻エマを動揺させることへの懸念などが指摘されている。チャー ルズ・ダーウィンの病気は度重なる遅れを引き起こした。グレン・ロイに関する彼の論文は恥ずかしくなるほど間違っていることが判明しており、彼は自分が正 しいことを確かめたかったのかもしれない。デイヴィッド・クァンメンは、これらすべての要因が関係している可能性を示唆し、その時期のダーウィンの大量の 著作と多忙な家庭生活を指摘している[50]。 科学史家ジョン・ファン・ワイエによるより最近の研究では、ダーウィンが出版を遅らせたという考えは1940年代にまでさかのぼるものであり、ダーウィン の同時代の人々は、ダーウィンが要した時間は妥当であると考えていた。ダーウィンはいつも1冊の本を書き終えてから別の本を書き始めた。ダーウィンは研究 している間、怒りを買うことなく、多くの人々に自分が転成に興味を持っていることを話した。ダーウィンは出版するつもりでいたが、1854年9月になって ようやく本格的に取り組むことができた。彼の「大著」の執筆には5年かかるという1846年の見積もりは楽観的であることが証明された[48]。 出版に至る経緯 「大著」の原稿  1862年にシンガポールで撮影されたアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレス(1823-1913)の写真。 1855年、アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスによって書かれた種の「導入」に関する論文は、すべての新種が常に既存の近縁種の近くで誕生した場合、現生 種と化石種の地理的分布のパターンが説明できると主張した[51]。ダーウィンは、完全で説得力のある説明をしたいという思いと、短い論文を早く書かなけ ればならないというプレッシャーとの間で葛藤した。彼はライエルに会い、ジョセフ・ドルトン・フッカーとの往復書簡の中で、学術雑誌に発表するために必要 な編集者による校閲に自分の考えをさらしたくはないと断言した。彼は1856年5月14日に「スケッチ」を書き始め、7月までに自然淘汰に関する「大著」 として、種に関する完全な技術的論文を執筆することを決めた。分岐の原理を含む彼の理論は、1857年9月5日にエイサ・グレイに彼のアイデアの簡潔だが 詳細な要約を送った時点で完成していた[52][53]。 ウォレスとダーウィンによる論文の共同出版 1858年6月18日、ダーウィンはマルク諸島(テルナテ島とギロロ島)に滞在していたウォレスから小包を受け取った。その小包には、ダーウィンの最近の 激励に対する返答として、進化のメカニズムを説明した20ページが同封されており、ダーウィンが価値があると思うならライエルに送るようにとの要請があっ た。そのメカニズムはダーウィン自身の理論に類似していた[52]。ダーウィンはライエルに、「あなたの言葉は復讐のように真実となり、......阻止 されました」と書き、ウォーレスが選んだ雑誌に「もちろん、すぐに手紙を書いて送ることを申し出ます」と述べ、「私の独創性は、それがどのようなものであ れ、すべて粉砕されるでしょう」と付け加えた[54]。 [ライエルとフッカーは、ウォレスのページにダーウィンの1844年の『エッセイ』と1857年のグレイへの手紙からの抜粋を加えた共同出版物をリンネ学 会で発表することで合意し、1858年7月1日にウォレスとダーウィンによる『品種が変種を形成する傾向について』と『自然淘汰による品種と種の永続につ いて』という論文がそれぞれ読み上げられたが、ほとんど反応はなかった。ダーウィンはウォレスの考えを彼の自然淘汰の概念と同じだと考えていたが、歴史家 はその違いを指摘している。ダーウィンは自然淘汰を動物の品種改良者によって行われる人為的淘汰に類似していると説明し、個体間の競争を強調したが、 ウォーレスは淘汰的品種改良とは比較せず、異なる品種を地域の条件に適応させておく生態学的圧力に焦点を当てた[55][56][57]。一部の歴史家 は、ウォーレスは実際には個体差に作用する淘汰ではなく、集団淘汰について議論していたと示唆している[58]。 種の本の要旨 会議の直後、ダーウィンはリンネ協会から出版される1つまたは複数の論文の形で「私の研究全体の要約」を書くことを決めたが、「事実を伝えることなく、 ジャーナル用に科学的なものにするにはどうすればよいか、それは不可能であろう」と懸念した。彼はフッカーに何ページが利用可能かを尋ねたが、「もし査読 者が厳密には科学的でないとして却下するのであれば、私はおそらくパンフレットとして出版するだろう」[59][60]。彼は1858年7月20日、サン ダウンでの休暇中に「種の本抄」を書き始め[61]、原稿を友人に送ってチェックしてもらいながら、その一部を記憶に基づいて書いた[62]。 10月初旬までに、彼は「私の抄録は小冊子になり、別に出版しなければならなくなるだろうと予想し始めた」[63]。同じ期間に、彼は情報収集を続け、種に関する「大著」である『自然淘汰』のための原稿の大きな、完全に詳細な部分を書き続けた[59]。 出版社としてのマレー、タイトルの選択  『自然淘汰による種の起源、あるいは生命争奪における有利な種族の保存』第2版。チャールズ・ダーウィン著、ジョン・マレー、ロンドン、1860年。スコットランド国立博物館 1859年3月中旬までに、ダーウィンの抄録は早期の出版を考える段階に達していた。ライエルは出版社ジョン・マレーを提案し、出版する意思があるかどう かを確認するために彼と会った。3月28日、ダーウィンはライエルに手紙を書き、進捗状況を尋ねるとともに、マレーに「私の本が、テーマからして必然的な ものである以上に、非正統的なものではない」ことを保証するよう申し出た。彼は、「自然淘汰による種と品種の起源に関する試論(An abstract of an Essay on the Origin of Species and Varieties Through natural selection)」というタイトルの草稿を同封し、年号は「1859」と記した[64][65]。 マレイの返事は好意的で、非常に満足したダーウィンは3月30日にライエルに「間もなく大量のM.S.の束を送りますが、第一章の3つが3人の写し手の手 に渡っているので、残念ながら1週間は送れません」と伝えた。3月31日、ダーウィンはマレーに確認の手紙を書き、現在執筆中の12章の見出しを列挙し た。マレーは原稿を見ることもなく、ライエルを出版したのと同じ条件で本を出版することに即座に同意し、ダーウィンに利益の⅔を提供すると返事をした。 [68]ダーウィンはすぐに快諾し、もし各章の原稿を読んで、この本が売れないと感じたら、マレーは自由に申し出を取り下げることができると主張した [69](最終的にマレーはダーウィンに初版180ポンドを支払い、1882年にダーウィンが亡くなるまでにこの本は第6版となり、ダーウィンは3000 ポンド近くを稼いだ[70])。 4月5日、ダーウィンは最初の3つの章と本のタイトルの案をマレーに送った[71]。初期のタイトル草稿は『種の変異性について』を示唆していた [72]。マレーは慎重にウィットウェル・エルウィンに章を見直すよう依頼した[59]。ライエルの提案により、エルウィンは「証拠なしに理論を述べる」 のではなく、ハトの観察に焦点を当て、それらがダーウィンの一般原則をどのように説明しているかを簡潔に述べ、間もなく期待される大作への道を準備するよ う勧めた: 「ダーウィンは、これは非現実的であり、まだ最後の章しか書くことがないと答えた[74]。9月、メインタイトルは依然として「種と品種の起源に関する小 論」を含んでいたが、ダーウィンは今度は「品種」を削除することを提案した[75]。 マーレイの説得により、タイトルは最終的に『種の起源』(On the Origin of Species)として合意され、タイトルページには「自然淘汰の手段によって、あるいは生命をめぐる闘争における有利な種族の保存」と付け加えられた [3]。この拡張されたタイトル(および本の他の場所)において、ダーウィンは生物学用語の「種族」を「品種」と互換的に使用し、種内の品種を意味した [76][77]。 [彼はこの用語を広義に使用しており[78]、「例えばキャベツのいくつかの種族」や「家畜や植物の遺伝的な品種や種族」[79]についての議論だけでな く、「人間の種族」という表現がこの本の中で3回使われており、人間の種族を指している[80]。 出版とその後の版 種の起源』は1859年11月24日(木)に初版が発行され、価格は15シリング、初版部数は1250部であった[81]。この本は11月22日(火)の マレイの秋のセールで書店に提供され、入手可能な部数はすべてすぐに売り切れた。合計で1250部が印刷されたが、贈呈用と批評用、そしてステーショナー ズ・ホールの版権用の5部を差し引くと、約1170部が販売可能であった[2]。重要なのは、500部がマディーズ・ライブラリーに持ち込まれたことで、 この本が図書館の多くの購読者に速やかに届けられたことであった。 [1860年1月7日、3,000部の第2版がすぐに出版され[83]、多くの修正が加えられるとともに、2ページに新しい碑文が追加され、チャールズ・ キングズレーからの引用が追加され、「創造主による」というフレーズが末尾に追加されるなど、宗教的な反対意見への対応がなされた[84]。ダーウィンが 存命中に、この本は6版を重ね、提起された反論に対処するために、累積的な変更と改訂が行われた。生命の起源が未解明であるという反論に対して、ダーウィ ンは、重力の原因が不明であるにもかかわらずニュートンの法則が受け入れられたこと、そしてライプニッツがニュートンに「オカルト的な性質と奇跡」を持ち 込んだと非難したことを指摘した[86][87]。1869年2月10日に出版された第5版では、さらに変更が加えられ、哲学者のハーバート・スペンサー が『生物学原理』(1864年)の中で造語した「適者生存」という言葉が初めて盛り込まれた[88]。 1871年1月、ジョージ・ジャクソン・ミヴァートの『種の創世記』(On the Genesis of Species)は自然淘汰に対する詳細な反論を列挙し、それが誤った形而上学を含んでいると主張した[89]。ダーウィンは『起原』第6版を大幅に改訂 し(これは、すべての版が「進化した」(evolved)という言葉で結ばれていたにもかかわらず、一般的に発生学的発生と関連付けられていた「進化」と いう言葉を彼が使用した最初の版であった[90][91])、ミヴァートの反論に対処するために新しい第7章「雑駁な反論」を追加した[2][92]。 第6版は1872年2月19日にマレーによって『種の起源』として出版され、タイトルから「On」が削除された。ダーウィンは、第5版を15シリングで買 うためにランカシャーで働く男たちが集まっていることをマレーに話し、より広く入手できるようにすることを望んだ。W.S.ダラスが編纂した用語集も含ま れている。書籍の売り上げは月60冊から250冊に増加した[3][92]。 イギリス国外での出版  アメリカの植物学者エイサ・グレイ(1810年-1888年) アメリカでは、ダーウィンの同僚であったアメリカ人の植物学者エイサ・グレイがボストンの出版社とアメリカ版の出版を交渉したが、ニューヨークの出版社2 社がすでに国際的な著作権がないことを利用して『Origin』の印刷を計画していることを知った。5月の手紙の中でダーウィンは2,500部の印刷部数 について言及しているが、その年は4部あったため、これが初版のみを指しているのかは定かでない[2][96]。 この本はダーウィンが生きている間に広く翻訳されたが、概念や比喩の翻訳に問題が生じ、翻訳者自身の意図によって偏った翻訳もあった[97]。彼は著名な 高齢の博物学者であり地質学者であったハインリッヒ・ゲオルク・ブロンを歓迎したが、1860年に出版されたドイツ語訳はブロン自身の考えを押し付け、 ダーウィンが意図的に省いた論争的なテーマを追加した。ブロンが「有利な種族」を「完成された種族」と訳し、生命の起源を含む問題についてのエッセイを加 え、ブロンがナチュール哲学を信奉していたこともあり、宗教的な意味合いについての最終章を追加した[98]。1862年、ブロンは第3版の英語版とダー ウィンが提案した追加を基に第2版を作成したが、その後心臓発作で亡くなった[99]。 [1862年に出版されたクレマンス・ロワイエによる翻訳には、宗教的啓示に代わるものとしてダーウィンの考えを賞賛し、社会的ダーウィニズムと優生学を 先取りした考えを促進する序文と、ダーウィンが表明した疑問に対する彼女自身の答えを示す多くの説明文が加えられた。ダーウィンは、1866年に出版され た第2版と1870年に出版された第3版についてロワイエとやり取りをしたが、彼女に註釈を削除させることは難しく、これらの版には悩まされた[99] [101]。 エドモン・バルビエによる翻訳が1876年に出版されるまで、彼は満足しないままであった。 [1864年までに、イタリア語とロシア語でも翻訳が出版された[97]。ダーウィンが存命中の1871年にはスウェーデン語、[103]1872年には デンマーク語、1873年にはポーランド語、1873年から1874年にはハンガリー語、1877年にはスペイン語、1878年にはセルビア語で『起原』 が出版された。1977年までに『起原』はさらに18の言語で出版され[104]、その中にはダーウィン以外の思想を加えた馬鈞武による中国語も含まれて いた。馬鈞武は1902年から1904年にかけて序章と第1章から第5章を出版し、1920年には全訳を出版した[105][106]。 |

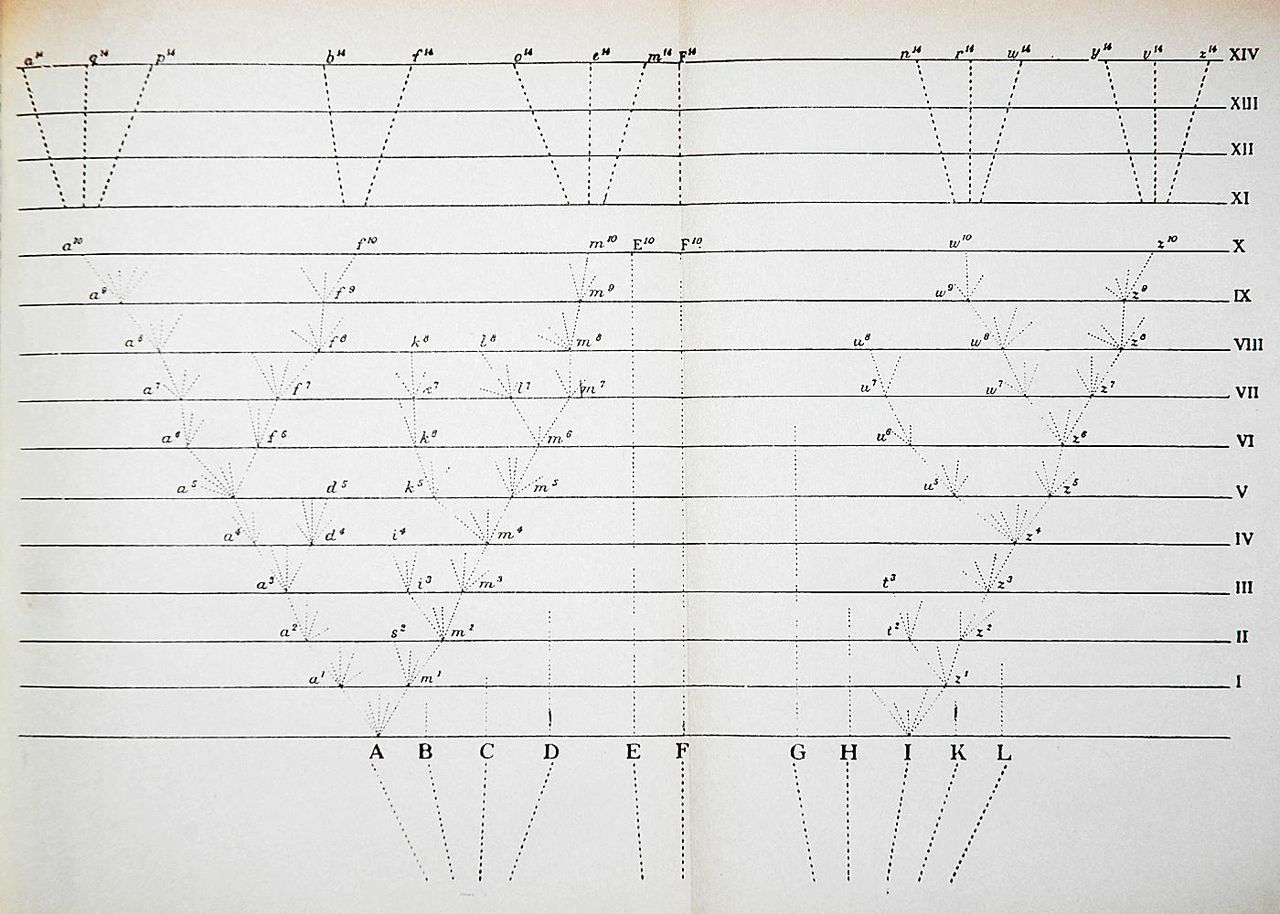

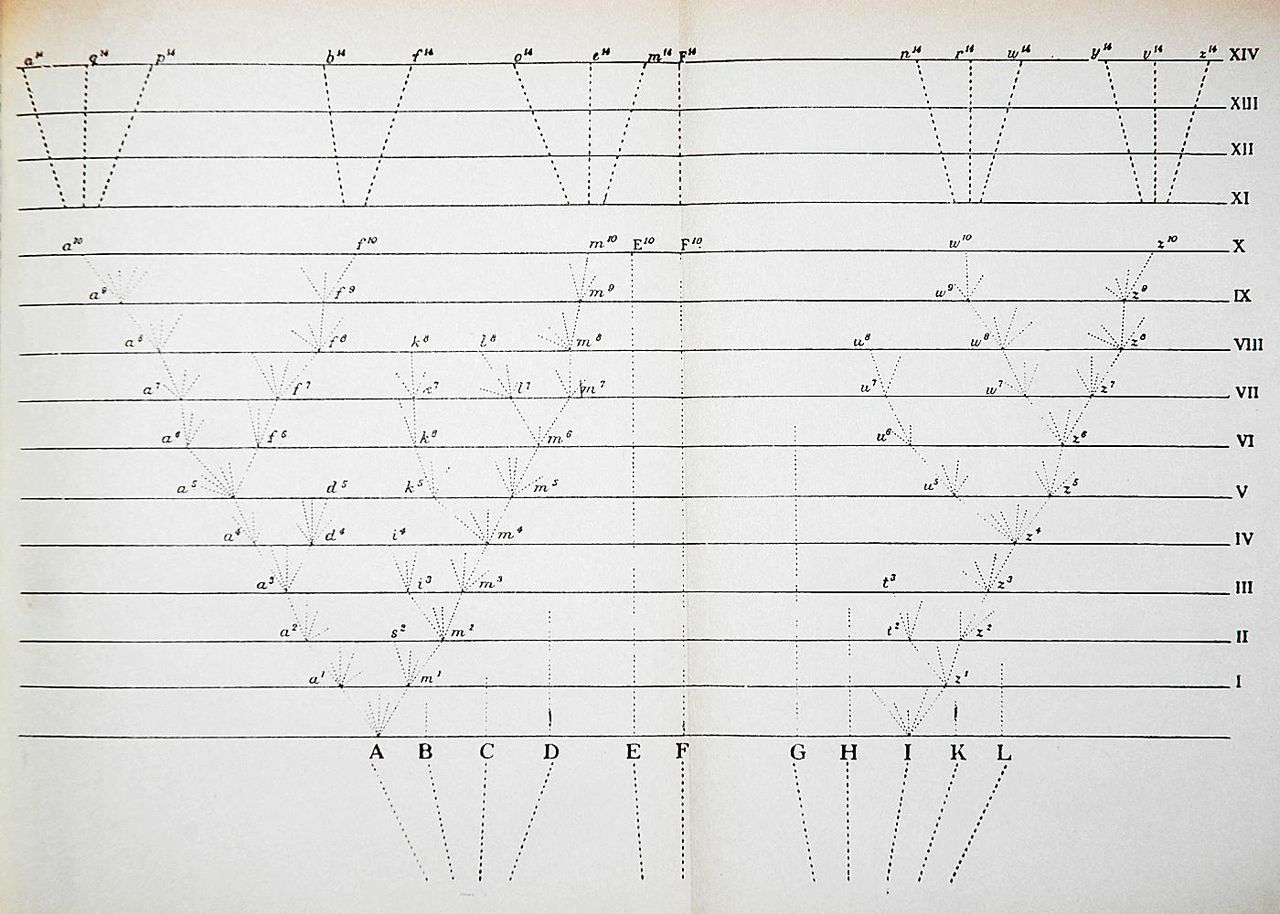

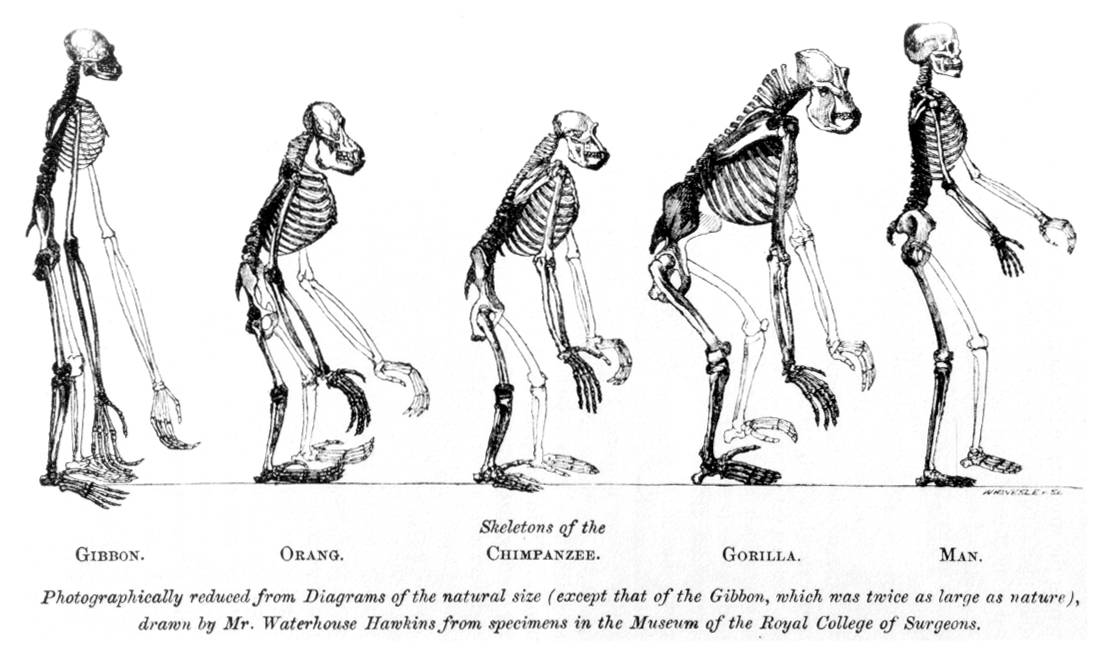

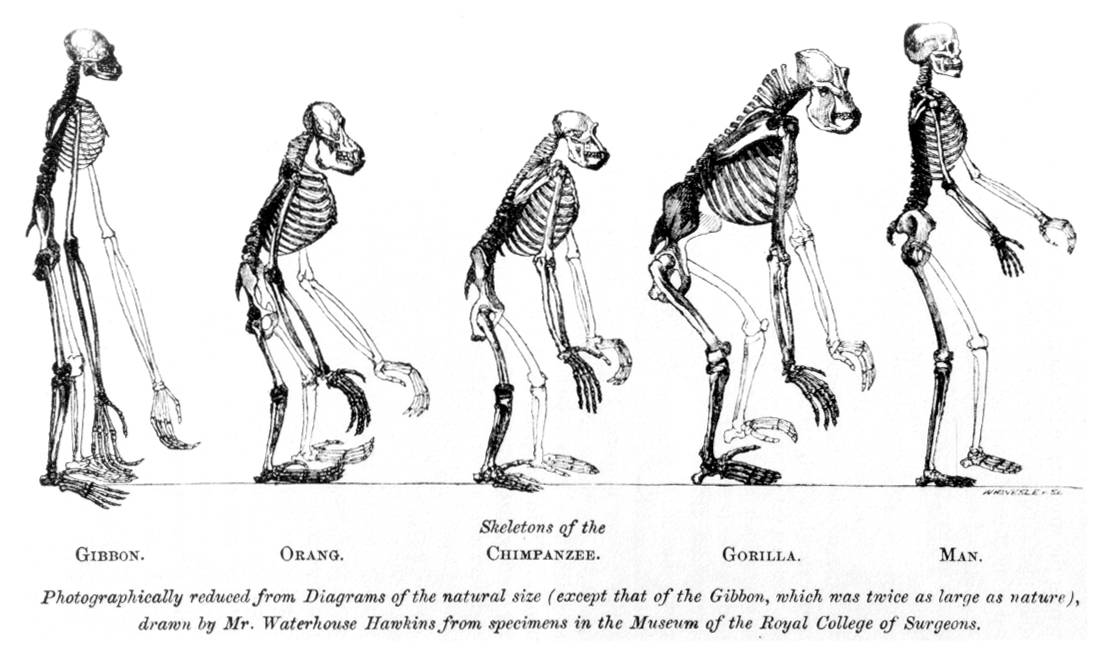

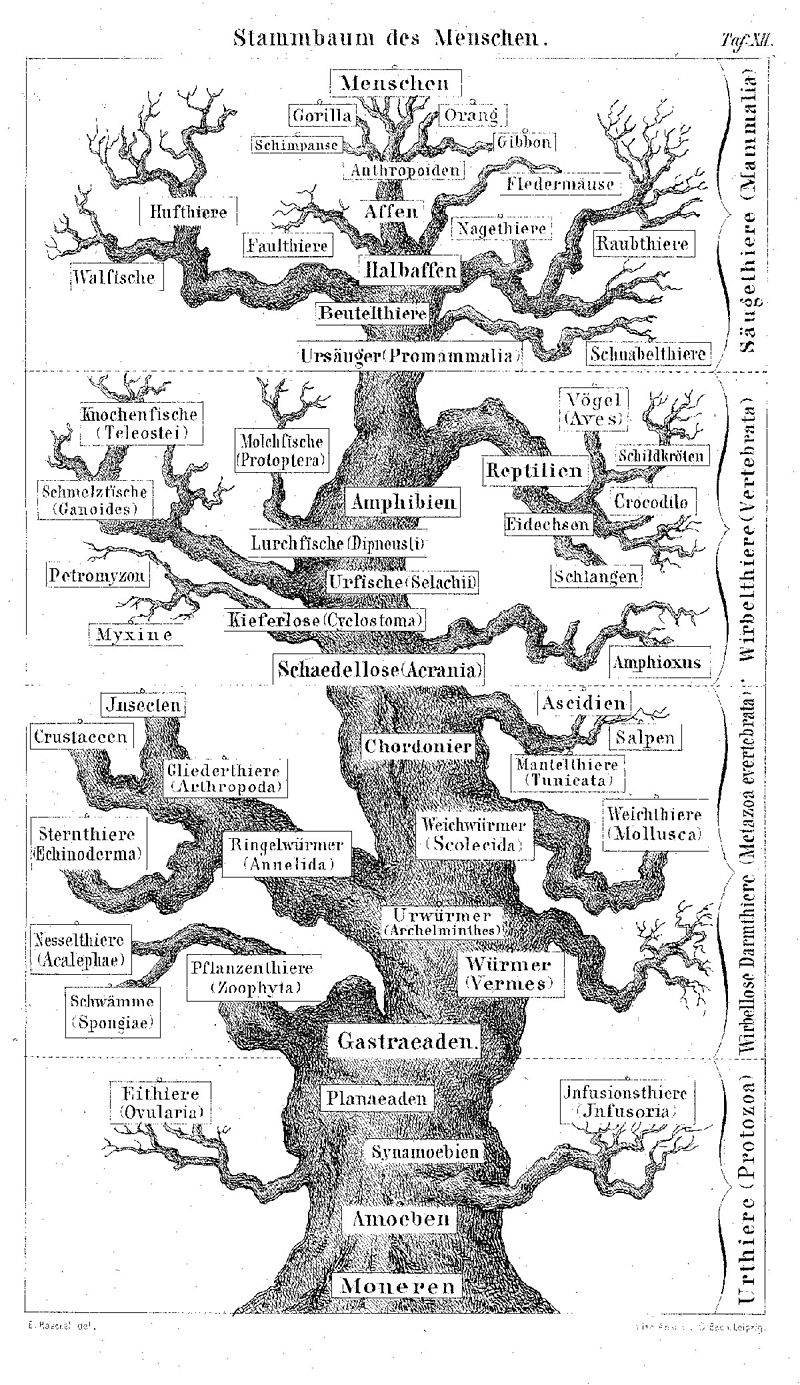

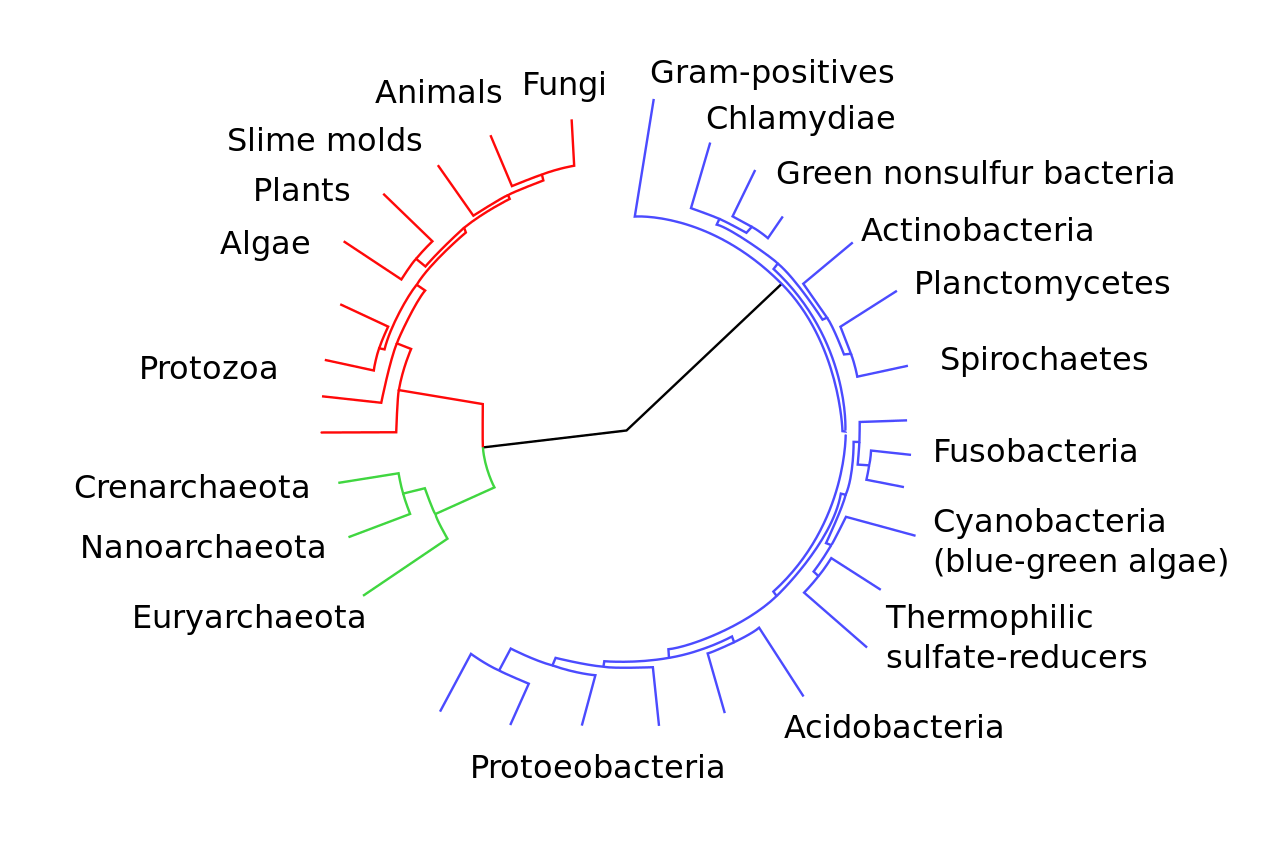

| Content Title pages and introduction  John Gould's illustration of Darwin's rhea was published in 1841. The existence of two rhea species with overlapping ranges influenced Darwin. Page ii contains quotations by William Whewell and Francis Bacon on the theology of natural laws,[107] harmonising science and religion in accordance with Isaac Newton's belief in a rational God who established a law-abiding cosmos.[108] In the second edition, Darwin added an epigraph from Joseph Butler affirming that God could work through scientific laws as much as through miracles, in a nod to the religious concerns of his oldest friends.[84] The Introduction establishes Darwin's credentials as a naturalist and author,[109] then refers to John Herschel's letter suggesting that the origin of species "would be found to be a natural in contradistinction to a miraculous process":[110] WHEN on board HMS Beagle, as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts in the distribution of the inhabitants of South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species—that mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers.[111] Darwin refers specifically to the distribution of the species rheas, and to that of the Galápagos tortoises and mockingbirds. He mentions his years of work on his theory, and the arrival of Wallace at the same conclusion, which led him to "publish this Abstract" of his incomplete work. He outlines his ideas, and sets out the essence of his theory: As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.[112] Starting with the third edition, Darwin prefaced the introduction with a sketch of the historical development of evolutionary ideas.[113] In that sketch he acknowledged that Patrick Matthew had, unknown to Wallace or himself, anticipated the concept of natural selection in an appendix to a book published in 1831;[114] in the fourth edition he mentioned that William Charles Wells had done so as early as 1813.[115] Variation under domestication and under nature Chapter I covers animal husbandry and plant breeding, going back to ancient Egypt. Darwin discusses contemporary opinions on the origins of different breeds under cultivation to argue that many have been produced from common ancestors by selective breeding.[116] As an illustration of artificial selection, he describes fancy pigeon breeding,[117] noting that "[t]he diversity of the breeds is something astonishing", yet all were descended from one species of rock pigeon.[118] Darwin saw two distinct kinds of variation: (1) rare abrupt changes he called "sports" or "monstrosities" (example: Ancon sheep with short legs), and (2) ubiquitous small differences (example: slightly shorter or longer bill of pigeons).[119] Both types of hereditary changes can be used by breeders. However, for Darwin the small changes were most important in evolution. In this chapter Darwin expresses his erroneous belief that environmental change is necessary to generate variation.[120] In Chapter II, Darwin specifies that the distinction between species and varieties is arbitrary, with experts disagreeing and changing their decisions when new forms were found. He concludes that "a well-marked variety may be justly called an incipient species" and that "species are only strongly marked and permanent varieties".[121] He argues for the ubiquity of variation in nature.[122] Historians have noted that naturalists had long been aware that the individuals of a species differed from one another, but had generally considered such variations to be limited and unimportant deviations from the archetype of each species, that archetype being a fixed ideal in the mind of God. Darwin and Wallace made variation among individuals of the same species central to understanding the natural world.[117] Struggle for existence, natural selection, and divergence In Chapter III, Darwin asks how varieties "which I have called incipient species" become distinct species, and in answer introduces the key concept he calls "natural selection";[123] in the fifth edition he adds, "But the expression often used by Mr. Herbert Spencer, of the Survival of the Fittest, is more accurate, and is sometimes equally convenient."[124] Owing to this struggle for life, any variation, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, in its infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to external nature, will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring ... I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection, in order to mark its relation to man's power of selection.[123] He notes that both A. P. de Candolle and Charles Lyell had stated that all organisms are exposed to severe competition. Darwin emphasizes that he used the phrase "struggle for existence" in "a large and metaphorical sense, including dependence of one being on another"; he gives examples ranging from plants struggling against drought to plants competing for birds to eat their fruit and disseminate their seeds. He describes the struggle resulting from population growth: "It is the doctrine of Malthus applied with manifold force to the whole animal and vegetable kingdoms." He discusses checks to such increase including complex ecological interdependencies, and notes that competition is most severe between closely related forms "which fill nearly the same place in the economy of nature".[125] Chapter IV details natural selection under the "infinitely complex and close-fitting ... mutual relations of all organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life".[126] Darwin takes as an example a country where a change in conditions led to extinction of some species, immigration of others and, where suitable variations occurred, descendants of some species became adapted to new conditions. He remarks that the artificial selection practised by animal breeders frequently produced sharp divergence in character between breeds, and suggests that natural selection might do the same, saying: But how, it may be asked, can any analogous principle apply in nature? I believe it can and does apply most efficiently, from the simple circumstance that the more diversified the descendants from any one species become in structure, constitution, and habits, by so much will they be better enabled to seize on many and widely diversified places in the polity of nature, and so be enabled to increase in numbers.[127] Historians have remarked that here Darwin anticipated the modern concept of an ecological niche.[128] He did not suggest that every favourable variation must be selected, nor that the favoured animals were better or higher, but merely more adapted to their surroundings.  This tree diagram, used to show the divergence of species, is the only illustration in the Origin of Species. Darwin proposes sexual selection, driven by competition between males for mates, to explain sexually dimorphic features such as lion manes, deer antlers, peacock tails, bird songs, and the bright plumage of some male birds.[129] He analysed sexual selection more fully in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). Natural selection was expected to work very slowly in forming new species, but given the effectiveness of artificial selection, he could "see no limit to the amount of change, to the beauty and infinite complexity of the coadaptations between all organic beings, one with another and with their physical conditions of life, which may be effected in the long course of time by nature's power of selection". Using a tree diagram and calculations, he indicates the "divergence of character" from original species into new species and genera. He describes branches falling off as extinction occurred, while new branches formed in "the great Tree of life ... with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications".[130] Variation and heredity In Darwin's time there was no agreed-upon model of heredity;[131] in Chapter I Darwin admitted, "The laws governing inheritance are quite unknown."[132] He accepted a version of the inheritance of acquired characteristics (which after Darwin's death came to be called Lamarckism), and Chapter V discusses what he called the effects of use and disuse; he wrote that he thought "there can be little doubt that use in our domestic animals strengthens and enlarges certain parts, and disuse diminishes them; and that such modifications are inherited", and that this also applied in nature.[133] Darwin stated that some changes that were commonly attributed to use and disuse, such as the loss of functional wings in some island-dwelling insects, might be produced by natural selection. In later editions of Origin, Darwin expanded the role attributed to the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Darwin also admitted ignorance of the source of inheritable variations, but speculated they might be produced by environmental factors.[134][135] However, one thing was clear: whatever the exact nature and causes of new variations, Darwin knew from observation and experiment that breeders were able to select such variations and produce huge differences in many generations of selection.[119] The observation that selection works in domestic animals is not destroyed by lack of understanding of the underlying hereditary mechanism. Breeding of animals and plants showed related varieties varying in similar ways, or tending to revert to an ancestral form, and similar patterns of variation in distinct species were explained by Darwin as demonstrating common descent. He recounted how Lord Morton's mare apparently demonstrated telegony, offspring inheriting characteristics of a previous mate of the female parent, and accepted this process as increasing the variation available for natural selection.[136][137] More detail was given in Darwin's 1868 book on The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, which tried to explain heredity through his hypothesis of pangenesis. Although Darwin had privately questioned blending inheritance, he struggled with the theoretical difficulty that novel individual variations would tend to blend into a population. However, inherited variation could be seen,[138] and Darwin's concept of selection working on a population with a range of small variations was workable.[139] It was not until the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s that a model of heredity became completely integrated with a model of variation.[140] This modern evolutionary synthesis had been dubbed Neo Darwinian Evolution because it encompasses Charles Darwin's theories of evolution with Gregor Mendel's theories of genetic inheritance.[141] Difficulties for the theory Chapter VI begins by saying the next three chapters will address possible objections to the theory, the first being that often no intermediate forms between closely related species are found, though the theory implies such forms must have existed. As Darwin noted, "Firstly, why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion, instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?"[142] Darwin attributed this to the competition between different forms, combined with the small number of individuals of intermediate forms, often leading to extinction of such forms.[143] Another difficulty, related to the first one, is the absence or rarity of transitional varieties in time. Darwin commented that by the theory of natural selection "innumerable transitional forms must have existed," and wondered "why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth?"[144] (For further discussion of these difficulties, see Speciation#Darwin's dilemma: Why do species exist? and Bernstein et al.[145] and Michod.[146]) The chapter then deals with whether natural selection could produce complex specialised structures, and the behaviours to use them, when it would be difficult to imagine how intermediate forms could be functional. Darwin said: Secondly, is it possible that an animal having, for instance, the structure and habits of a bat, could have been formed by the modification of some animal with wholly different habits? Can we believe that natural selection could produce, on the one hand, organs of trifling importance, such as the tail of a giraffe, which serves as a fly-flapper, and, on the other hand, organs of such wonderful structure, as the eye, of which we hardly as yet fully understand the inimitable perfection?[147] His answer was that in many cases animals exist with intermediate structures that are functional. He presented flying squirrels, and flying lemurs as examples of how bats might have evolved from non-flying ancestors.[148] He discussed various simple eyes found in invertebrates, starting with nothing more than an optic nerve coated with pigment, as examples of how the vertebrate eye could have evolved. Darwin concludes: "If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find out no such case."[149] In a section on "organs of little apparent importance", Darwin discusses the difficulty of explaining various seemingly trivial traits with no evident adaptive function, and outlines some possibilities such as correlation with useful features. He accepts that we "are profoundly ignorant of the causes producing slight and unimportant variations" which distinguish domesticated breeds of animals,[150] and human races. He suggests that sexual selection might explain these variations:[151][152] I might have adduced for this same purpose the differences between the races of man, which are so strongly marked; I may add that some little light can apparently be thrown on the origin of these differences, chiefly through sexual selection of a particular kind, but without here entering on copious details my reasoning would appear frivolous.[153] Chapter VII (of the first edition) addresses the evolution of instincts. His examples included two he had investigated experimentally: slave-making ants and the construction of hexagonal cells by honey bees. Darwin noted that some species of slave-making ants were more dependent on slaves than others, and he observed that many ant species will collect and store the pupae of other species as food. He thought it reasonable that species with an extreme dependency on slave workers had evolved in incremental steps. He suggested that bees that make hexagonal cells evolved in steps from bees that made round cells, under pressure from natural selection to economise wax. Darwin concluded: Finally, it may not be a logical deduction, but to my imagination it is far more satisfactory to look at such instincts as the young cuckoo ejecting its foster-brothers, —ants making slaves, —the larvæ of ichneumonidæ feeding within the live bodies of caterpillars, —not as specially endowed or created instincts, but as small consequences of one general law, leading to the advancement of all organic beings, namely, multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die.[154] Chapter VIII addresses the idea that species had special characteristics that prevented hybrids from being fertile in order to preserve separately created species. Darwin said that, far from being constant, the difficulty in producing hybrids of related species, and the viability and fertility of the hybrids, varied greatly, especially among plants. Sometimes what were widely considered to be separate species produced fertile hybrid offspring freely, and in other cases what were considered to be mere varieties of the same species could only be crossed with difficulty. Darwin concluded: "Finally, then, the facts briefly given in this chapter do not seem to me opposed to, but even rather to support the view, that there is no fundamental distinction between species and varieties."[155] In the sixth edition Darwin inserted a new chapter VII (renumbering the subsequent chapters) to respond to criticisms of earlier editions, including the objection that many features of organisms were not adaptive and could not have been produced by natural selection. He said some such features could have been by-products of adaptive changes to other features, and that often features seemed non-adaptive because their function was unknown, as shown by his book on Fertilisation of Orchids that explained how their elaborate structures facilitated pollination by insects. Much of the chapter responds to George Jackson Mivart's criticisms, including his claim that features such as baleen filters in whales, flatfish with both eyes on one side and the camouflage of stick insects could not have evolved through natural selection because intermediate stages would not have been adaptive. Darwin proposed scenarios for the incremental evolution of each feature.[156] Geological record Chapter IX deals with the fact that the geological record appears to show forms of life suddenly arising, without the innumerable transitional fossils expected from gradual changes. Darwin borrowed Charles Lyell's argument in Principles of Geology that the record is extremely imperfect as fossilisation is a very rare occurrence, spread over vast periods of time; since few areas had been geologically explored, there could only be fragmentary knowledge of geological formations, and fossil collections were very poor. Evolved local varieties which migrated into a wider area would seem to be the sudden appearance of a new species. Darwin did not expect to be able to reconstruct evolutionary history, but continuing discoveries gave him well-founded hope that new finds would occasionally reveal transitional forms.[157][158] To show that there had been enough time for natural selection to work slowly, he cited the example of The Weald as discussed in Principles of Geology together with other observations from Hugh Miller, James Smith of Jordanhill and Andrew Ramsay. Combining this with an estimate of recent rates of sedimentation and erosion, Darwin calculated that erosion of The Weald had taken around 300 million years.[159] The initial appearance of entire groups of well-developed organisms in the oldest fossil-bearing layers, now known as the Cambrian explosion, posed a problem. Darwin had no doubt that earlier seas had swarmed with living creatures, but stated that he had no satisfactory explanation for the lack of fossils.[160] Fossil evidence of pre-Cambrian life has since been found, extending the history of life back for billions of years.[161] Chapter X examines whether patterns in the fossil record are better explained by common descent and branching evolution through natural selection, than by the individual creation of fixed species. Darwin expected species to change slowly, but not at the same rate – some organisms such as Lingula were unchanged since the earliest fossils. The pace of natural selection would depend on variability and change in the environment.[162] This distanced his theory from Lamarckian laws of inevitable progress.[157] It has been argued that this anticipated the punctuated equilibrium hypothesis,[158][163] but other scholars have preferred to emphasise Darwin's commitment to gradualism.[164] He cited Richard Owen's findings that the earliest members of a class were a few simple and generalised species with characteristics intermediate between modern forms, and were followed by increasingly diverse and specialised forms, matching the branching of common descent from an ancestor.[157] Patterns of extinction matched his theory, with related groups of species having a continued existence until extinction, then not reappearing. Recently extinct species were more similar to living species than those from earlier eras, and as he had seen in South America, and William Clift had shown in Australia, fossils from recent geological periods resembled species still living in the same area.[162] Geographic distribution Chapter XI deals with evidence from biogeography, starting with the observation that differences in flora and fauna from separate regions cannot be explained by environmental differences alone; South America, Africa, and Australia all have regions with similar climates at similar latitudes, but those regions have very different plants and animals. The species found in one area of a continent are more closely allied with species found in other regions of that same continent than to species found on other continents. Darwin noted that barriers to migration played an important role in the differences between the species of different regions. The coastal sea life of the Atlantic and Pacific sides of Central America had almost no species in common even though the Isthmus of Panama was only a few miles wide. His explanation was a combination of migration and descent with modification. He went on to say: "On this principle of inheritance with modification, we can understand how it is that sections of genera, whole genera, and even families are confined to the same areas, as is so commonly and notoriously the case."[165] Darwin explained how a volcanic island formed a few hundred miles from a continent might be colonised by a few species from that continent. These species would become modified over time, but would still be related to species found on the continent, and Darwin observed that this was a common pattern. Darwin discussed ways that species could be dispersed across oceans to colonise islands, many of which he had investigated experimentally.[166] Chapter XII continues the discussion of biogeography. After a brief discussion of freshwater species, it returns to oceanic islands and their peculiarities; for example on some islands roles played by mammals on continents were played by other animals such as flightless birds or reptiles. The summary of both chapters says: ... I think all the grand leading facts of geographical distribution are explicable on the theory of migration (generally of the more dominant forms of life), together with subsequent modification and the multiplication of new forms. We can thus understand the high importance of barriers, whether of land or water, which separate our several zoological and botanical provinces. We can thus understand the localisation of sub-genera, genera, and families; and how it is that under different latitudes, for instance in South America, the inhabitants of the plains and mountains, of the forests, marshes, and deserts, are in so mysterious a manner linked together by affinity, and are likewise linked to the extinct beings which formerly inhabited the same continent ... On these same principles, we can understand, as I have endeavoured to show, why oceanic islands should have few inhabitants, but of these a great number should be endemic or peculiar; ...[167] Classification, morphology, embryology, rudimentary organs Chapter XIII starts by observing that classification depends on species being grouped together in a Taxonomy, a multilevel system of groups and sub-groups based on varying degrees of resemblance. After discussing classification issues, Darwin concludes: All the foregoing rules and aids and difficulties in classification are explained, if I do not greatly deceive myself, on the view that the natural system is founded on descent with modification; that the characters which naturalists consider as showing true affinity between any two or more species, are those which have been inherited from a common parent, and, in so far, all true classification is genealogical; that community of descent is the hidden bond which naturalists have been unconsciously seeking, ...[168] Darwin discusses morphology, including the importance of homologous structures. He says, "What can be more curious than that the hand of a man, formed for grasping, that of a mole for digging, the leg of the horse, the paddle of the porpoise, and the wing of the bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern, and should include the same bones, in the same relative positions?" This made no sense under doctrines of independent creation of species, as even Richard Owen had admitted, but the "explanation is manifest on the theory of the natural selection of successive slight modifications" showing common descent.[169] He notes that animals of the same class often have extremely similar embryos. Darwin discusses rudimentary organs, such as the wings of flightless birds and the rudiments of pelvis and leg bones found in some snakes. He remarks that some rudimentary organs, such as teeth in baleen whales, are found only in embryonic stages.[170] These factors also supported his theory of descent with modification.[31] Concluding remarks The final chapter, "Recapitulation and Conclusion", reviews points from earlier chapters, and Darwin concludes by hoping that his theory might produce revolutionary changes in many fields of natural history.[171] He suggests that psychology will be put on a new foundation and implies the relevance of his theory to the first appearance of humanity with the sentence that "Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[31][172] Darwin ends with a passage that became well known and much quoted: It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us ... Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.[173] Darwin added the phrase "by the Creator" from the 1860 second edition onwards, so that the ultimate sentence begins "There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one".[174] |