使徒パウロ

Paul the Apostle, ca. 5 - 64/65

Saint

Paul (c. 1611) by Peter Paul

Rubens.

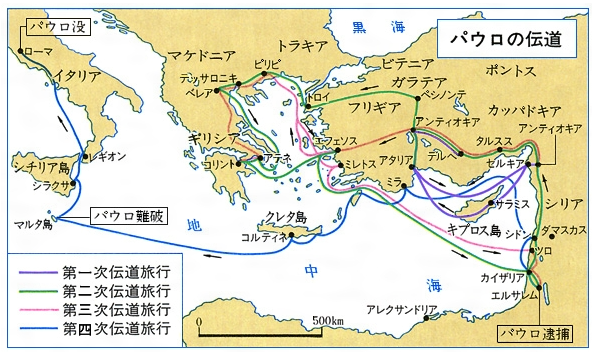

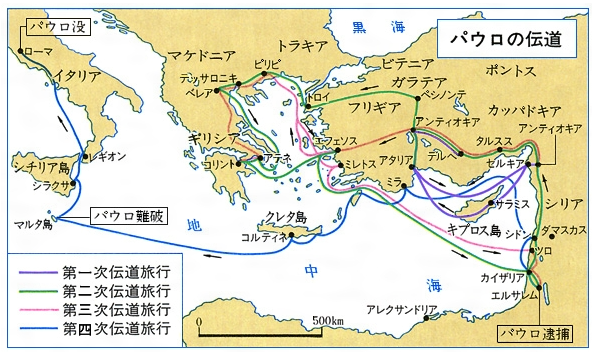

☆ パウロ( Paul) (タルソスのサウロとも呼ばれる、西暦5年頃-64/65年頃)は、一般に使徒パウロや聖パウロとして知られるキリスト教の使徒であり、1世紀の世 界にイエスの教えを広めた。新約聖書への貢献から、彼は一般に使徒時代の最も重要な人物の一人とみなされており、また西暦40年代半ばから50年代半ばに かけて小アジアとヨーロッパにいくつかのキリスト教共同体を創設した。 パウロの生涯と業績に関する主な情報源は、新約聖書の中の使徒言行録であり、その内容の約半分はパウロの記録である。パウロは十二使徒の一人ではなく、存 命中はイエスを知らなかった。使徒言行録によれば、パウロはパリサイ人として生活し、改宗前のエルサレム周辺において、キリスト教に改宗したヘレニズム化 したディアスポラ系ユダヤ人[12]であろうイエスの初期の弟子たちの迫害に参加していた。ステファノの処刑を承認した後しばらくして、パウロはダマスコ への道を旅していた。 真昼に、太陽よりも明るい光がパウロとパウロと一緒にいた人々を照らし、すべての人が地面に倒れ、復活したキリストが幻の中でパウロに迫害について口頭で 話しかけた盲目にされ、町に入るように命じられたパウロは、3日後にダマスコのアナニヤによって視力を回復した。これらの出来事の後、パウロは洗礼を受 け、すぐにナザレのイエスがユダヤ人の救世主であり、神の子であることを宣べ伝え始めた。使徒言行録に記されているように、彼は小アジア、アカイア、マケ ドニア、キプロスのギリシャ地方、ユダヤ、シリアの非ユダヤ人社会にキリスト教のメッセージを広めるために3回の宣教の旅をした。

☆年譜| 5年頃 ローマ属州キリキア州都タルソスにて、ユダヤ教ファリサイ派の家庭に誕生する。 18~30年頃 エルサレムのラビ・ガマリエル1世の元で学ぶ。 30~34年頃 キリスト教徒を激しく迫害する。 32年頃 最初のキリスト教殉教者ステファノの石打ちに立ち会う。 34年頃 ダマスコに向かう途中、降臨したイエスと会いキリスト教へ回心する。 34~36年 アラビア・エルサレム・ダマスコを巡る。 36年頃 聖バルナバの助けでエルサレムへ行き、ペトロやヤコブなどの使徒と会う。 36~44年 身の安全のため、故郷タルソスで暮らしながら説教する。 44~46年 バルナバとともにアンティオキアを拠点として布教活動を行なう。 46年頃 ユダヤで飢饉が起こり、バルナバとともにエルサレムへ救援物資を届ける。 46~48年 第1回宣教旅行として、キプロス島~小アジア南部(南ガラテア)方面を回る。 48年 使徒会議のため、エルサレムへ(エルサレム会議)。異邦人の割礼問題を解決する。 49年 アンティオキアにて、ユダヤの規律に関して使徒ペトロと衝突する。 49年 次の旅へのヨハネ・マルコの同伴を拒み、バルナバと衝突し仲違いする。 49~52年 第2次伝道旅行として、小アジア・マケドニア・ギリシア方面を回る。 50年頃 ルステラでテモテを弟子にし、旅に同行させる。 50年頃 港町トロアスで出会った医師ルカも旅に同行する。船でマケドニアへ。 50年頃 マケドニアのフィリピにてシラスとともに鞭打ちにされ投獄されるが、その晩に扉が開き解放される。テサロニケ、ベレアへと旅を続ける。ベレアにシラスとテモテを残し、アテネ・コリントへ。 50~51年 「テサロニケ人への手紙(第一、第二」」を執筆する。 51~52年 18ヶ月間、テント職人として働きながらコリントに滞在する。コリントにてシラス・テモテと合流する。 53年頃 エフェソへ。そこから海路でカイセリアとエルサレムを経由し、アンティオキアへ帰郷する。 53~58年 第3回宣教旅行として、小アジア・マケドニア・ギリシャを回る。 54~55年 宣教しながらテント職人として働き、2年間エフェソに滞在する。「コリントへの手紙」「ガラティア人への手紙」4通を執筆する。 56年 マケドニア、ギリシャ、エーゲ海の島々と沿岸地域を巡る。 57年 エルサレムに到着する。敵対するユダヤ人たちと暴動を起こし逮捕される。 58~59年 カイザリアに幽閉される。 59~60年 皇帝(カエサル)に上告するためローマへと護送されるも、マルタで船が難破する。 60~62年 ローマで自宅に軟禁される。「フィリピ人への手紙」「エフェソの信徒への手紙」「コロサイの信徒への手紙」「フィレモンへの手紙」を執筆する。 62~64年 ネロ帝により釈放され、スペイン方面への宣教を行なう。「テモテへの手紙」「ティトゥスへの手紙」を執筆する。 64年 ローマの大火が発生する。キリスト教徒大迫害が行なわれ、投獄される。 64~67年 ローマで殉教する。 出典:https://x.gd/ebWam |

★聖パウロ : 普遍主義の基礎 / アラン・バディウ [著] ; 長原豊, 松本潤一郎訳, 河出書房新社 , 2004(→「イデオロギーとしての倫理」)

1 パウロ—われらが同時代人

2 パウロとは誰のことか

3 テクストとコンテクスト

4 言説理論

5 主体の分割

6 死と復活の反弁証法

7 法に抗うパウロ

8 普遍的力—愛

9 希望

10 普遍性と差異の横断

11

結ぶ‐契るために

| Paul[a]

(also named

Saul of Tarsus;[b] c. 5 – c. 64/65 AD), commonly known as Paul the

Apostle[7] and Saint Paul,[8] was a Christian apostle who spread the

teachings of Jesus in the first-century world.[9] For his contributions

towards the New Testament, he is generally regarded as one of the most

important figures of the Apostolic Age,[8][10] and he also founded

several Christian communities in Asia Minor and Europe from the mid-40s

to the mid-50s AD.[11] The main source of information on Paul's life and works is the Acts of the Apostles book in the New Testament and approximately half of its content documents them. Paul was not one of the Twelve Apostles, and did not know Jesus during his lifetime. According to the Acts, Paul lived as a Pharisee and participated in the persecution of early disciples of Jesus, possibly Hellenised diaspora Jews converted to Christianity,[12] in the area of Jerusalem, prior to his conversion.[note 1] Some time after having approved of the execution of Stephen,[13] Paul was traveling on the road to Damascus so that he might find any Christians there and bring them "bound to Jerusalem".[14] At midday, a light brighter than the sun shone around both him and those with him, causing all to fall to the ground, with the risen Christ verbally addressing Paul regarding his persecution in a vision.[15][16] Having been made blind,[17] along with being commanded to enter the city, his sight was restored three days later by Ananias of Damascus. After these events, Paul was baptized, beginning immediately to proclaim that Jesus of Nazareth was the Jewish messiah and the Son of God.[18] He made three missionary journeys to spread the Christian message to non-Jewish communities in Asia Minor, the Greek provinces of Achaia, Macedonia, and Cyprus, as well as Judea and Syria, as narrated in the Acts. Fourteen of the 27 books in the New Testament have traditionally been attributed to Paul.[19] Seven of the Pauline epistles are undisputed by scholars as being authentic, with varying degrees of argument about the remainder. Pauline authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews is not asserted in the Epistle itself and was already doubted in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.[note 2] It was almost unquestioningly accepted from the 5th to the 16th centuries that Paul was the author of Hebrews,[21] but that view is now almost universally rejected by scholars.[21][22] The other six are believed by some scholars to have come from followers writing in his name, using material from Paul's surviving letters and letters written by him that no longer survive.[9][8][note 3] Other scholars argue that the idea of a pseudonymous author for the disputed epistles raises many problems.[24] Today, Paul's epistles continue to be vital roots of the theology, worship and pastoral life in the Latin and Protestant traditions of the West, as well as the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox traditions of the East.[25] Paul's influence on Christian thought and practice has been characterized as being as "profound as it is pervasive", among that of many other apostles and missionaries involved in the spread of the Christian faith.[9] |

パウロ[a](タルソスのサウロとも呼ばれる[b]、西暦5年頃-

64/65年頃)は、一般に使徒パウロ[7]や聖パウロ[8]として知られるキリスト教の使徒であり、1世紀の世界にイエスの教えを広めた[9]。新約聖

書への貢献から、彼は一般に使徒時代の最も重要な人物の一人とみなされており[8][10]、また西暦40年代半ばから50年代半ばにかけて小アジアと

ヨーロッパにいくつかのキリスト教共同体を創設した[11]。 パウロの生涯と業績に関する主な情報源は、新約聖書の中の使徒言行録であり、その内容の約半分はパウロの記録である。パウロは十二使徒の一人ではなく、存 命中はイエスを知らなかった。使徒言行録によれば、パウロはパリサイ人として生活し、改宗前のエルサレム周辺において、キリスト教に改宗したヘレニズム化 したディアスポラ系ユダヤ人[12]であろうイエスの初期の弟子たちの迫害に参加していた[注釈 1]。ステファノの処刑を承認した後しばらくして[13]、パウロはダマスコへの道を旅していた。 [14] 真昼に、太陽よりも明るい光がパウロとパウロと一緒にいた人々を照らし、すべての人が地面に倒れ、復活したキリストが幻の中でパウロに迫害について口頭で 話しかけた[15][16] 盲目にされ[17]、町に入るように命じられたパウロは、3日後にダマスコのアナニヤによって視力を回復した。これらの出来事の後、パウロは洗礼を受け、 すぐにナザレのイエスがユダヤ人の救世主であり、神の子であることを宣べ伝え始めた[18]。使徒言行録に記されているように、彼は小アジア、アカイア、 マケドニア、キプロスのギリシャ地方、ユダヤ、シリアの非ユダヤ人社会にキリスト教のメッセージを広めるために3回の宣教の旅をした。 新約聖書の27冊の書物のうち14冊は、伝統的にパウロによるものとされている[19]。ヘブライ人への手紙のパウロによる著者は、手紙自体では主張され ておらず、2~3世紀にはすでに疑問視されていた[注釈 2]。5世紀から16世紀にかけては、パウロがヘブライ人への手紙の著者であることはほぼ疑いなく受け入れられていた[21]が、現在ではその見解は学者 によってほぼ普遍的に否定されている。 [21][22]他の6つの書簡は、現存するパウロの書簡や、もはや残っていないパウロが書いた書簡から得た資料を用いて、パウロの名前で信奉者たちが書 いたものであると考える学者もいる[9][8][注釈 3]。 今日、パウロの書簡は、西洋のラテン語とプロテスタントの伝統、そして東洋のカトリックと正教会の伝統において、神学、礼拝、司牧生活の重要なルーツであ り続けている[25]。キリスト教の思想と実践に対するパウロの影響は、キリスト教信仰の普及に関与した他の多くの使徒や宣教師と同様に、「深遠であると 同時に広範である」と特徴づけられている[9]。 |

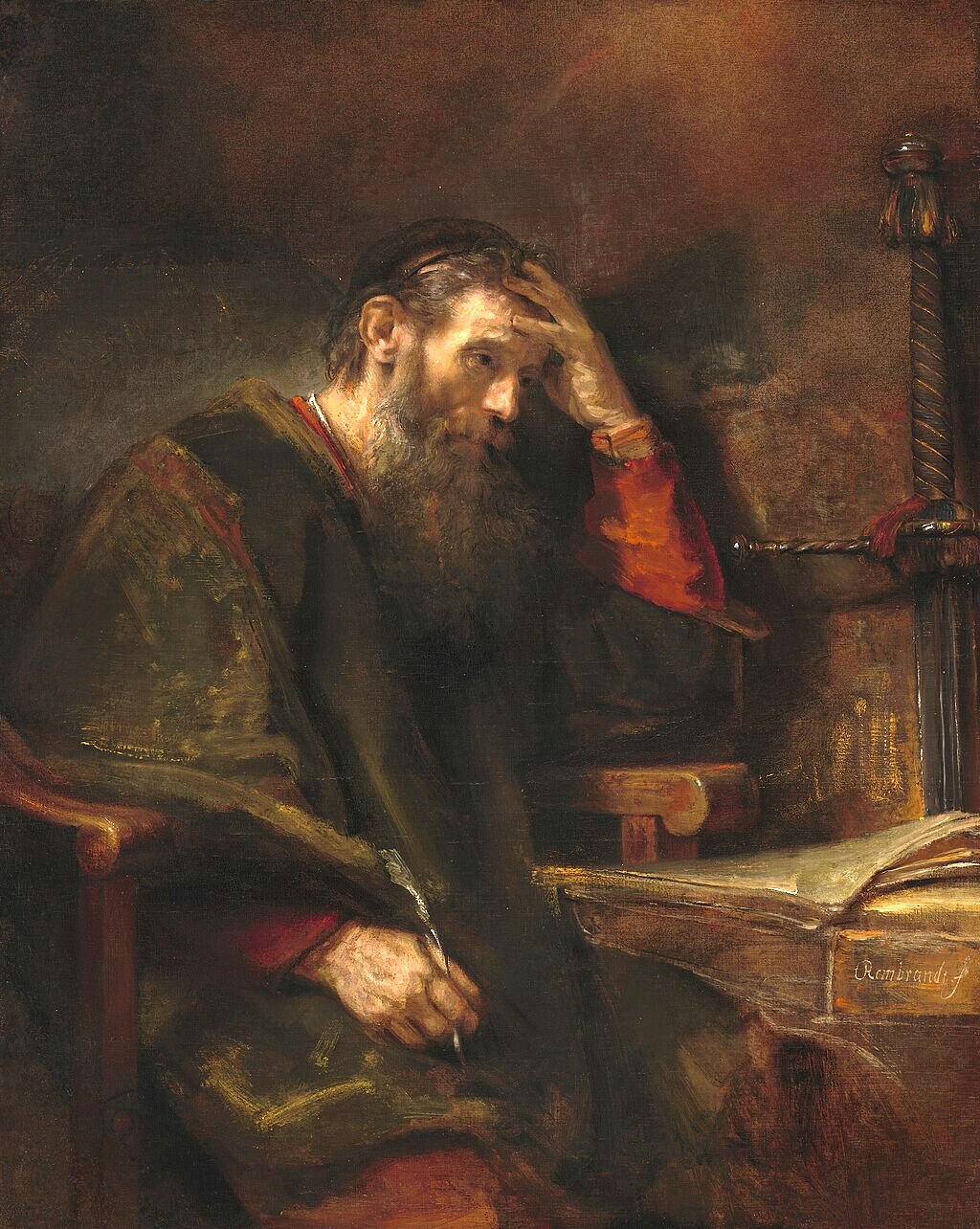

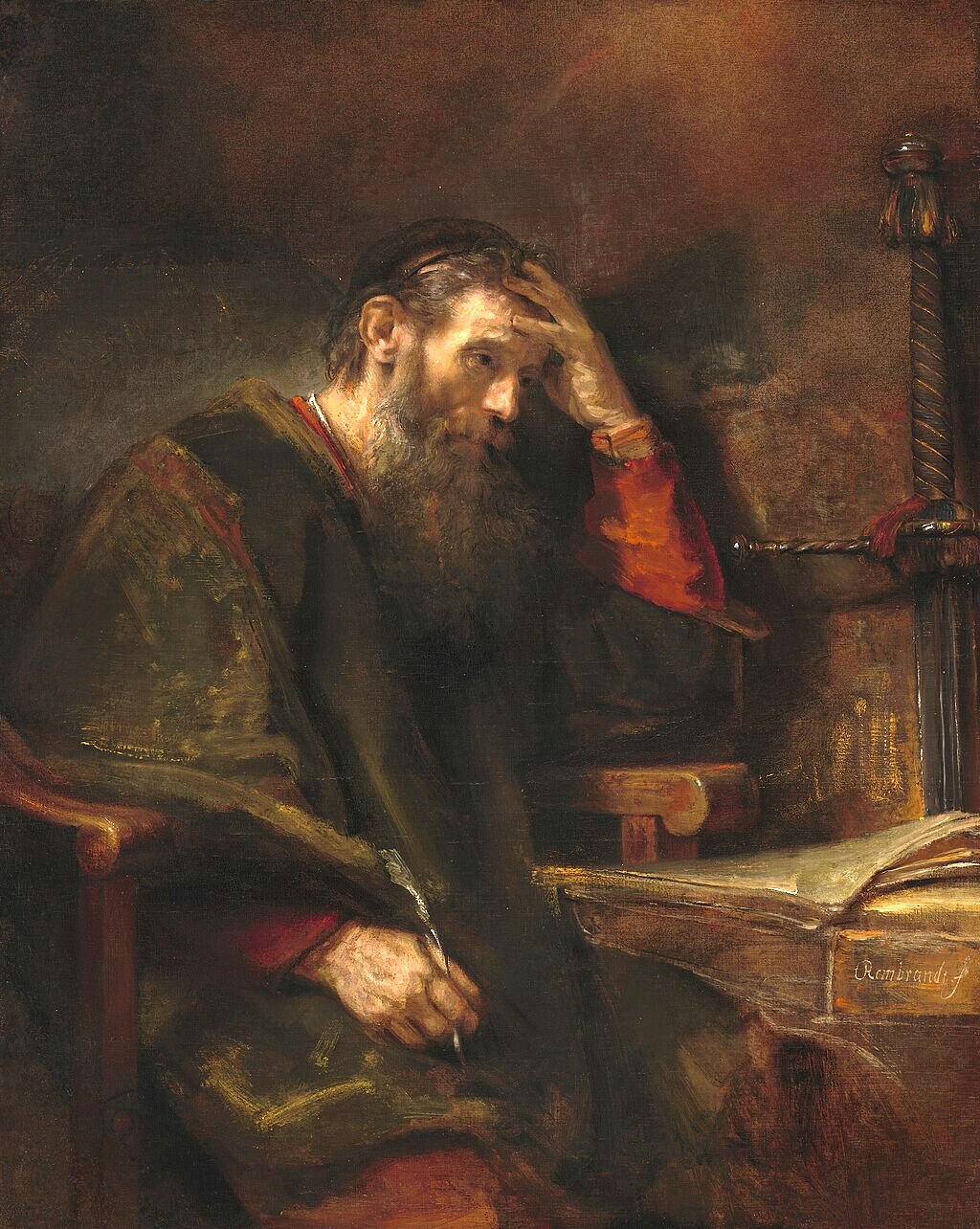

Names The Apostle Paul, portrait by Rembrandt (c. 1657) Paul's Jewish name was "Saul" (Hebrew: שָׁאוּל, Modern: Sha'ûl, Tiberian: Šā'ûl), perhaps after the biblical King Saul, the first king of Israel and, like Paul, a member of the Tribe of Benjamin; the Latin name Paulus, meaning small, was not a result of his conversion as is commonly believed but a second name for use in communicating with a Greco-Roman audience.[26][27] According to the Acts of the Apostles, he was a Roman citizen.[28] As such, he bore the Latin name Paulus, which translates in biblical Greek as Παῦλος (Paulos).[29][30] It was typical for the Jews of that time to have two names: one Hebrew, the other Latin or Greek.[31][32][33] Jesus called him "Saul, Saul"[34] in "the Hebrew tongue" in the Acts of the Apostles, when he had the vision which led to his conversion on the road to Damascus.[35] Later, in a vision to Ananias of Damascus, "the Lord" referred to him as "Saul, of Tarsus".[36] When Ananias came to restore his sight, he called him "Brother Saul".[37] In Acts 13:9, Saul is called "Paul" for the first time on the island of Cyprus, much later than the time of his conversion.[38] The author of Luke–Acts indicates that the names were interchangeable: "Saul, who also is called Paul." He refers to him as Paul through the remainder of Acts. This was apparently Paul's preference since he is called Paul in all other Bible books where he is mentioned, including those that he authored. Adopting his Roman name was typical of Paul's missionary style. His method was to put people at ease and approach them with his message in a language and style that was relatable to them, as he did in 1 Corinthians 9:19–23.[39][40] |

彼の名前 使徒パウロ、レンブラントによる肖像画(1657年頃) パウロのユダヤ名は「サウル」(ヘブライ語: שָׁ, 現代語: Sha'ûl, Tiberian: ラテン語名のパウルスは、一般に信じられているような改宗の結果ではなく、グレコ・ローマ人の聴衆とのコミュニケーションに使用するためのセカンドネーム であった。 [26][27] 使徒言行録によれば、彼はローマ市民であった[28]。そのため、彼はパウルスというラテン語名を名乗ったが、これは聖書ギリシア語ではΠαῦλος(パ ウロス)と訳される[29][30]。当時のユダヤ人にとって、ヘブライ語とラテン語またはギリシア語の二つの名前を持つことは典型的であった[31] [32][33]。 イエスは使徒言行録の中で、彼がダマスコへの道で回心するきっかけとなった幻を見たとき、彼を「ヘブライ語」で「サウル、サウル」[34]と呼んだ [35]。その後、ダマスコのアナニアへの幻の中で、「主」は彼を「タルソスのサウル」と呼んだ[36]。 使徒言行録13:9では、サウロはキプロス島で初めて「パウロ」と呼ばれているが、これは彼が回心した時よりもずっと後のことである[38]: 「サウロはパウロとも呼ばれる。ルカによる福音書-使徒言行録』の著者は、「サウロ、またパウロとも呼ばれる。パウロが言及されている他のすべての聖書 (パウロが執筆したものも含む)では、パウロはパウロと呼ばれているので、これは明らかにパウロの好みであった。ローマ名を用いるのは、パウロの宣教スタ イルの典型であった。彼の方法は、第一コリント9:19-23で行ったように、人々を安心させ、彼らに親しみやすい言葉とスタイルでメッセージを伝えるこ とであった[39][40]。 |

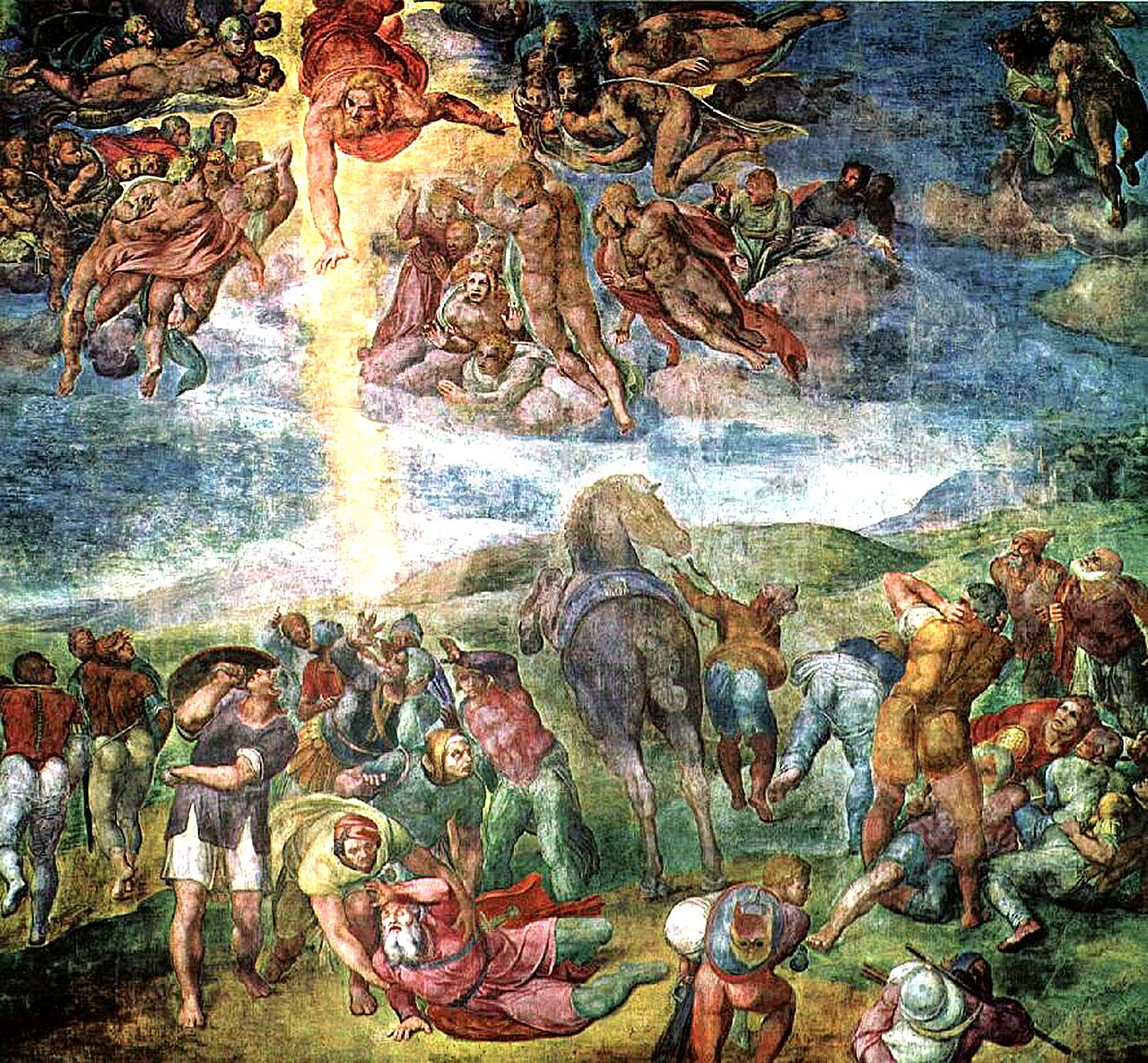

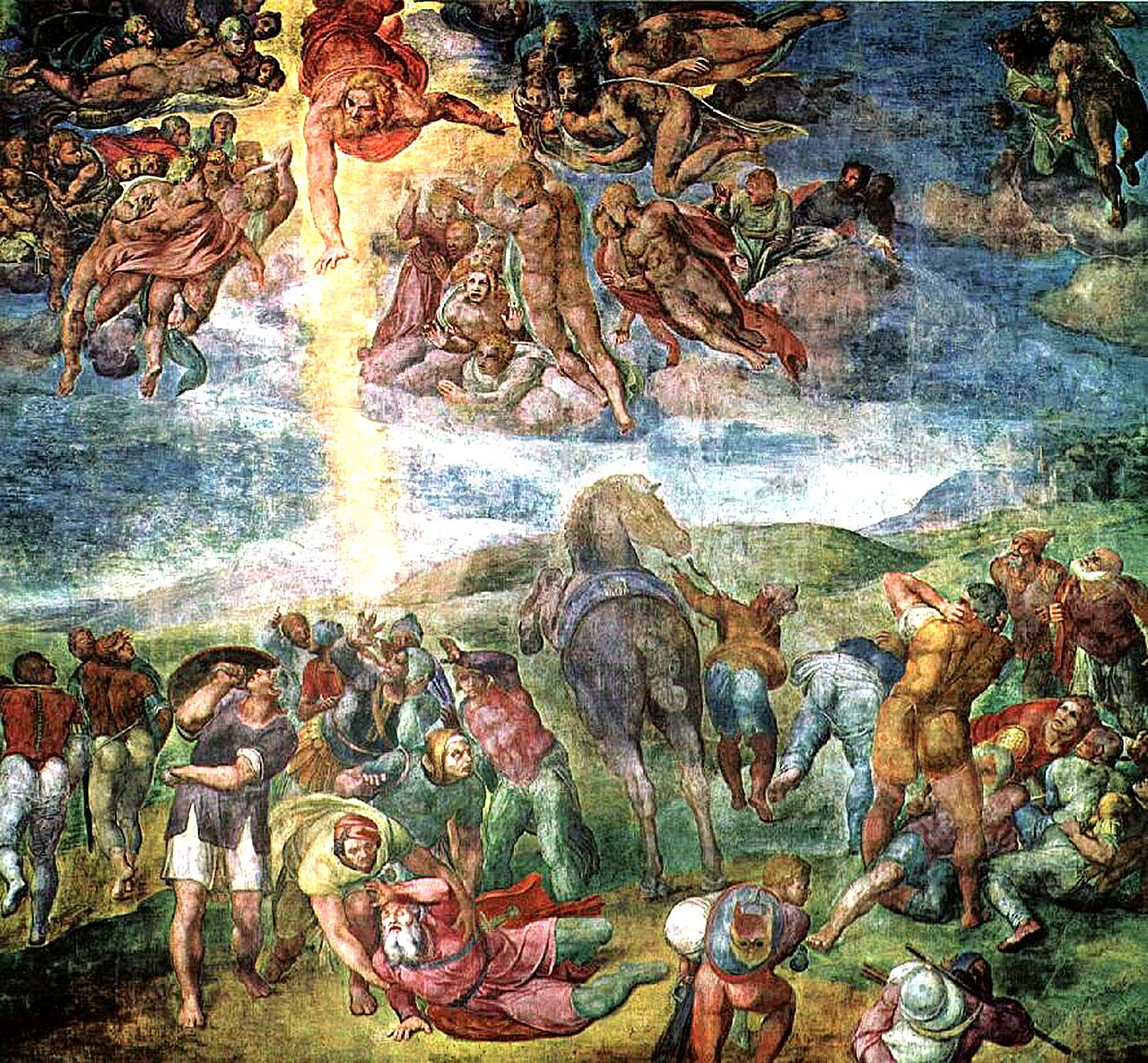

| Available sources Further information: Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles  The Conversion of Saul, a fresco by Michelangelo developed between 1542 and 1545 The main source for information about Paul's life is the material found in his epistles and in the Acts of the Apostles.[41] However, the epistles contain little information about Paul's pre-conversion past. The Acts of the Apostles recounts more information but leaves several parts of Paul's life out of its narrative, such as his probable but undocumented execution in Rome.[42] The Acts of the Apostles also appear to contradict Paul's epistles on multiple matters, in particular concerning the frequency of Paul's visits to the church in Jerusalem.[43][44] Sources outside the New Testament that mention Paul include: Clement of Rome's epistle to the Corinthians (late 1st/early 2nd century); Ignatius of Antioch's epistles to the Romans and to the Ephesians[45] (early 2nd century); Polycarp's epistle to the Philippians (early 2nd century); Eusebius's Historia Ecclesiae (early 4th century); The apocryphal Acts narrating the life of Paul (Acts of Paul, Acts of Paul and Thecla, Acts of Peter and Paul), the apocryphal epistles attributed to him (the Latin Epistle to the Laodiceans, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians, and the Correspondence of Paul and Seneca) and some apocalyptic texts attributed to him (Apocalypse of Paul and Coptic Apocalypse of Paul). These writings are all later, usually dated from the 2nd to the 4th century. |

入手可能な情報源 さらに詳しい情報 使徒言行録の歴史的信頼性  1542年から1545年にかけて描かれたミケランジェロのフレスコ画「サウロの改宗 パウロの生涯に関する主な情報源は、彼の書簡と使徒言行録にある資料である[41]が、書簡にはパウロの改宗前の過去に関する情報はほとんど含まれていな い。使徒言行録にはより多くの情報が記されているが、パウロがローマで処刑された可能性が高いが文書化されていないなど、パウロの生涯のいくつかの部分が 物語から省かれている[42]。使徒言行録はまた、特にパウロがエルサレムの教会を訪れる頻度に関する複数の事柄について、パウロの書簡と矛盾しているよ うに見える[43][44]。 新約聖書以外でパウロに言及している情報源には以下のものがある: ローマのクレメンスのコリント人への手紙(1世紀後半から2世紀初頭); アンティオキアのイグナティウスのローマ人への手紙とエフェソの信徒への手紙[45](2世紀初頭); ポリカープのフィリピの信徒への手紙(2世紀初頭); エウセビオスの『教会史』(4世紀初頭); パウロの生涯を物語るアポクリファルの使徒言行録(パウロの使徒言行録、パウロとテクラの使徒言行録、ペテロとパウロの使徒言行録)、パウロによるとされ るアポクリファルの書簡(ラテン語のラオディキアの信徒への手紙、コリントの信徒への手紙第三、パウロとセネカの書簡)、パウロによるとされるいくつかの 黙示録的テキスト(パウロの黙示録、コプト語のパウロの黙示録)。これらの著作はすべて後世のもので、通常2世紀から4世紀にかけてのものである。 |

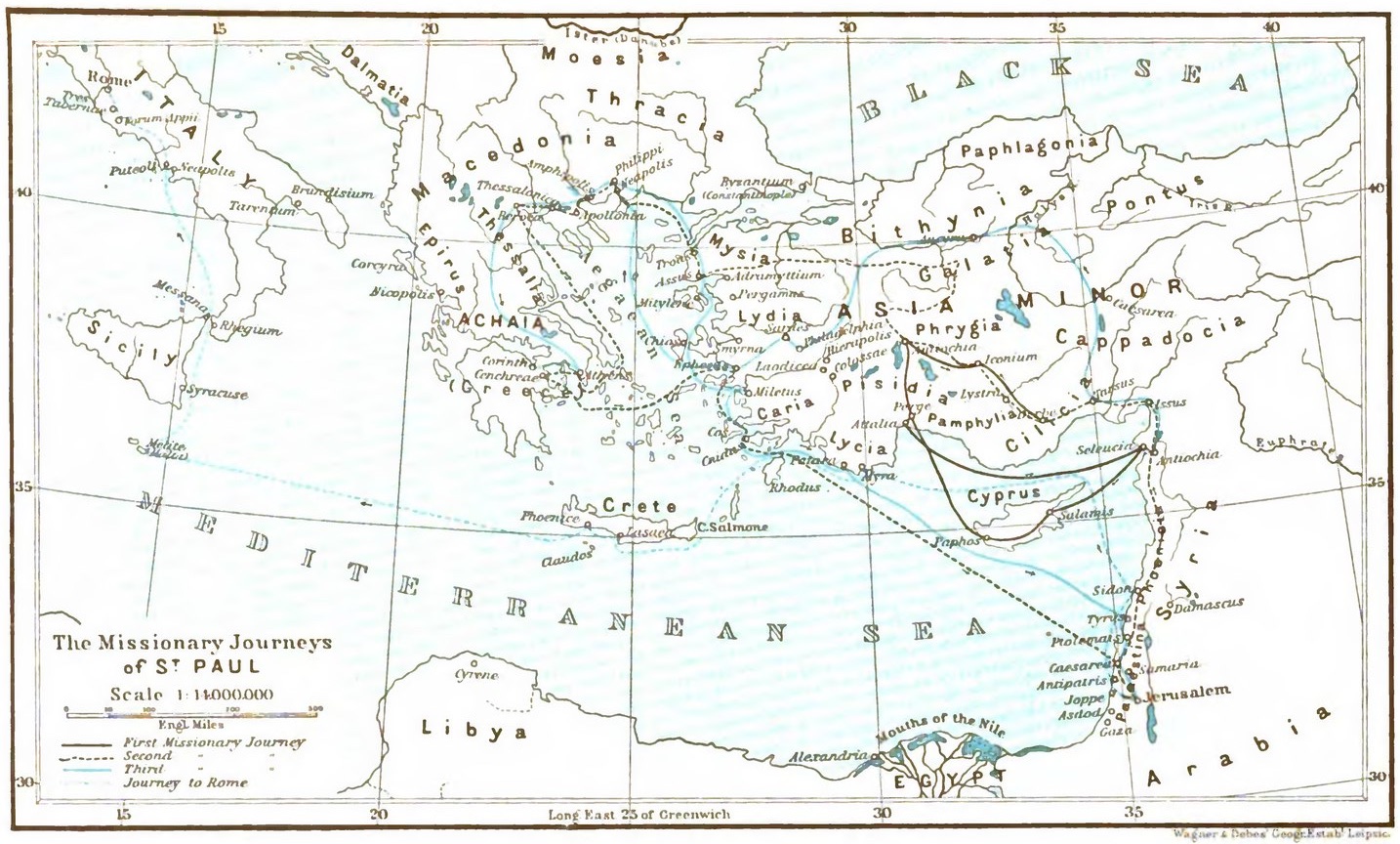

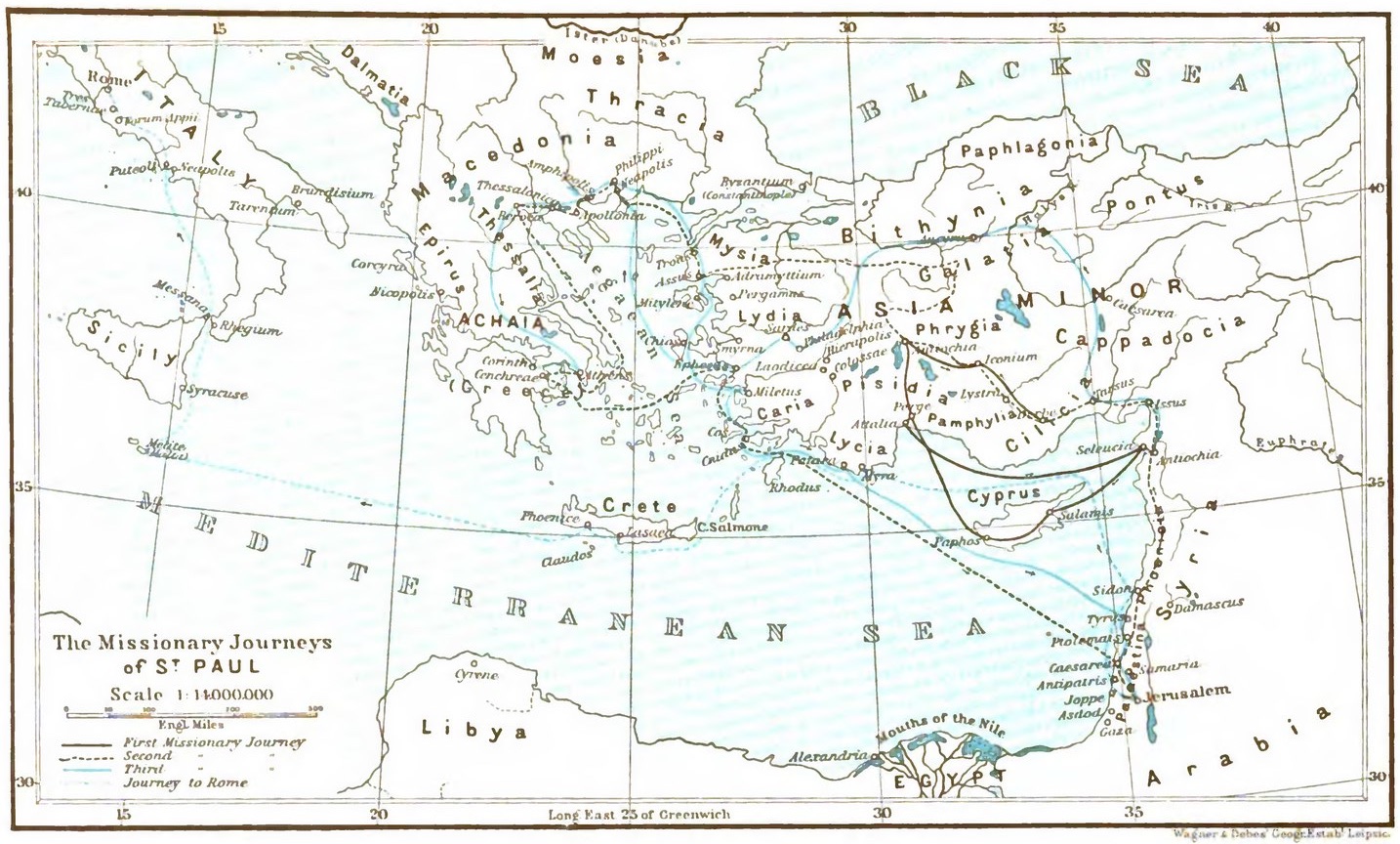

| Biography Early life  Geography relevant to Paul's life, stretching from Jerusalem to Rome  The two main sources of information that give access to the earliest segments of Paul's career are the Acts of the Apostles and the autobiographical elements of Paul's letters to the early Christian communities.[41] Paul was likely born between the years of 5 BC and 5 AD.[46] The Acts of the Apostles indicates that Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, but Helmut Koester takes issue with the evidence presented by the text.[47][48] He was from a devout Jewish family[49] based in the city of Tarsus.[26] One of the larger centers of trade on the Mediterranean coast and renowned for its university, Tarsus had been among the most influential cities in Asia Minor since the time of Alexander the Great, who died in 323 BC.[49] Paul referred to himself as being "of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a Pharisee".[50][51] The Bible reveals very little about Paul's family. Acts quotes Paul referring to his family by saying he was "a Pharisee, born of Pharisees".[52][53] Paul's nephew, his sister's son, is mentioned in Acts 23:16.[54] In Romans 16:7, he states that his relatives, Andronicus and Junia, were Christians before he was and were prominent among the Apostles.[55] The family had a history of religious piety.[56][note 4] Apparently, the family lineage had been very attached to Pharisaic traditions and observances for generations.[57] Acts says that he was an artisan involved in the leather crafting or tent-making profession.[58][59] This was to become an initial connection with Priscilla and Aquila, with whom he would partner in tentmaking[60] and later become very important teammates as fellow missionaries.[61] While he was still fairly young, he was sent to Jerusalem to receive his education at the school of Gamaliel,[62][51] one of the most noted teachers of Jewish law in history. Although modern scholarship agrees that Paul was educated under the supervision of Gamaliel in Jerusalem,[51] he was not preparing to become a scholar of Jewish law, and probably never had any contact with the Hillelite school.[51] Some of his family may have resided in Jerusalem since later the son of one of his sisters saved his life there.[54][26] Nothing more is known of his biography until he takes an active part in the martyrdom of Stephen,[63] a Hellenised diaspora Jew.[64] Some modern scholarship notes that while Paul was fluent in Koine Greek, the language he used to write his letters, his first language was probably Aramaic.[65] In his letters, Paul drew heavily on his knowledge of Stoic philosophy, using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile converts in their understanding of the Gospel and to explain his Christology.[66][67] Persecutor of early Christians  Conversion on the Way to Damascus, a 1601 portrait by Caravaggio Paul says that prior to his conversion,[68] he persecuted early Christians "beyond measure", more specifically Hellenised diaspora Jewish members who had returned to the area of Jerusalem.[69][note 1] According to James Dunn, the Jerusalem community consisted of "Hebrews", Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and "Hellenists", Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.[70] Paul's initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking "Hellenists" due to their anti-Temple attitude.[71] Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the "Hebrews" and their continuing participation in the Temple cult.[71] Conversion Main article: Conversion of Paul the Apostle  The Conversion of Saint Paul on the Way to Damascus, a c. 1889 portrait by José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior Paul's conversion can be dated to 31–36 AD[72][73][74] by his reference to it in one of his letters. In Galatians 1:16, Paul writes that God "was pleased to reveal his son to me."[75] In 1 Corinthians 15:8, as he lists the order in which Jesus appeared to his disciples after his resurrection, Paul writes, "last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also."[76] According to the account in the Acts of the Apostles, it took place on the road to Damascus, where he reported having experienced a vision of the ascended Jesus. The account says that "He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, 'Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?' He asked, 'Who are you, Lord?' The reply came, 'I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting'."[77] According to the account in Acts 9:1–22, he was blinded for three days and had to be led into Damascus by the hand.[78] During these three days, Saul took no food or water and spent his time in prayer to God. When Ananias of Damascus arrived, he laid his hands on him and said: "Brother Saul, the Lord, [even] Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost."[79] His sight was restored, he got up and was baptized.[80] This story occurs only in Acts, not in the Pauline epistles.[81] The author of the Acts of the Apostles may have learned of Paul's conversion from the church in Jerusalem, or from the church in Antioch, or possibly from Paul himself.[82] According to Timo Eskola, early Christian theology and discourse was influenced by the Jewish Merkabah tradition.[83] Similarly, Alan Segal and Daniel Boyarin regard Paul's accounts of his conversion experience and his ascent to the heavens (in 2 Corinthians 12) as the earliest first-person accounts that are extant of a Merkabah mystic in Jewish or Christian literature. Conversely, Timothy Churchill has argued that Paul's Damascus road encounter does not fit the pattern of Merkabah.[84] Post-conversion According to Acts: And immediately he proclaimed Jesus in the synagogues, saying, "He is the Son of God." And all who heard him were amazed and said, "Is not this the man who made havoc in Jerusalem of those who called upon this name? And has he not come here for this purpose, to bring them bound before the chief priests?" But Saul increased all the more in strength, and confounded the Jews who lived in Damascus by proving that Jesus was the Christ. — Acts 9:20–22[85] Early ministry  What is believed to be the house of Ananias of Damascus in Damascus  Bab Kisan, believed to be where Paul escaped from persecution in Damascus After his conversion, Paul went to Damascus, where Acts 9 states he was healed of his blindness and baptized by Ananias of Damascus.[86] Paul says that it was in Damascus that he barely escaped death.[87] Paul also says that he then went first to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus.[88][89] Paul's trip to Arabia is not mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, and some suppose he actually traveled to Mount Sinai for meditations in the desert.[90][91] He describes in Galatians how three years after his conversion he went to Jerusalem. There he met James and stayed with Simon Peter for 15 days.[92] Paul located Mount Sinai in Arabia in Galatians 4:24–25.[93] Paul asserted that he received the Gospel not from man, but directly by "the revelation of Jesus Christ".[94] He claimed almost total independence from the Jerusalem community[95] (possibly in the Cenacle), but agreed with it on the nature and content of the gospel.[96] He appeared eager to bring material support to Jerusalem from the various growing Gentile churches that he started. In his writings, Paul used the persecutions he endured to avow proximity and union with Jesus and as a validation of his teaching. Paul's narrative in Galatians states that 14 years after his conversion he went again to Jerusalem.[97] It is not known what happened during this time, but both Acts and Galatians provide some details.[98] Though a view is held that Paul spent 14 years studying the scriptures and growing in the faith. At the end of this time, Barnabas went to find Paul and brought him to Antioch.[99][100] The Christian community at Antioch had been established by Hellenised diaspora Jews living in Jerusalem, who played an important role in reaching a Gentile, Greek audience, notably at Antioch, which had a large Jewish community and significant numbers of Gentile "God-fearers."[101] From Antioch the mission to the Gentiles started, which would fundamentally change the character of the early Christian movement, eventually turning it into a new, Gentile religion.[102] When a famine occurred in Judea, around 45–46,[103] Paul and Barnabas journeyed to Jerusalem to deliver financial support from the Antioch community.[104] According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative center for Christians following the dispersion of the believers after the death of Stephen. It was in Antioch that the followers of Jesus were first called "Christians".[105] First missionary journey  Map of St. Paul's missionary journeys The author of Acts arranges Paul's travels into three separate journeys. The first journey,[106] for which Paul and Barnabas were commissioned by the Antioch community,[107] and led initially by Barnabas,[note 5] took Barnabas and Paul from Antioch to Cyprus then into southern Asia Minor, and finally returning to Antioch. In Cyprus, Paul rebukes and blinds Elymas the magician[108] who was criticizing their teachings. They sailed to Perga in Pamphylia. John Mark left them and returned to Jerusalem. Paul and Barnabas went on to Pisidian Antioch. On Sabbath they went to the synagogue. The leaders invited them to speak. Paul reviewed Israelite history from life in Egypt to King David. He introduced Jesus as a descendant of David brought to Israel by God. He said that his team came to town to bring the message of salvation. He recounted the story of Jesus' death and resurrection. He quoted from the Septuagint[109] to assert that Jesus was the promised Christos who brought them forgiveness for their sins. Both the Jews and the "God-fearing" Gentiles invited them to talk more next Sabbath. At that time almost the whole city gathered. This upset some influential Jews who spoke against them. Paul used the occasion to announce a change in his mission which from then on would be to the Gentiles.[110] Antioch served as a major Christian home base for Paul's early missionary activities,[4] and he remained there for "a long time with the disciples"[111] at the conclusion of his first journey. The exact duration of Paul's stay in Antioch is unknown, with estimates ranging from nine months to as long as eight years.[112] In Raymond E. Brown's An Introduction to the New Testament, published in 1997, a chronology of events in Paul's life is presented, illustrated from later 20th-century writings of biblical scholars.[113] The first missionary journey of Paul is assigned a "traditional" (and majority) dating of 46–49 AD, compared to a "revisionist" (and minority) dating of after 37 AD.[114] Council of Jerusalem Main article: Council of Jerusalem See also: Circumcision controversy in early Christianity A vital meeting between Paul and the Jerusalem church took place in the year 49 AD by traditional (and majority) dating, compared to a revisionist (and minority) dating of 47/51 AD.[115] The meeting is described in Acts 15:2[116] and usually seen as the same event mentioned by Paul in Galatians 2:1.[117][42] The key question raised was whether Gentile converts needed to be circumcised.[118][119] At this meeting, Paul states in his letter to the Galatians, Peter, James, and John accepted Paul's mission to the Gentiles. The Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, and also in Paul's letters.[120] For example, the Jerusalem visit for famine relief[121] apparently corresponds to the "first visit" (to Peter and James only).[122][120] F. F. Bruce suggested that the "fourteen years" could be from Paul's conversion rather than from his first visit to Jerusalem.[123] Incident at Antioch Main article: Incident at Antioch Despite the agreement achieved at the Council of Jerusalem, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter in a dispute sometimes called the "Incident at Antioch", over Peter's reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch because they did not strictly adhere to Jewish customs.[118] Writing later of the incident, Paul recounts, "I opposed [Peter] to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong", and says he told Peter, "You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?"[124] Paul also mentions that even Barnabas, his traveling companion and fellow apostle until that time, sided with Peter.[118] The outcome of the incident remains uncertain. The Catholic Encyclopedia suggests that Paul won the argument, because "Paul's account of the incident leaves no doubt that Peter saw the justice of the rebuke".[118] However, Paul himself never mentions a victory, and L. Michael White's From Jesus to Christianity draws the opposite conclusion: "The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as persona non grata, never again to return".[125] The primary source account of the Incident at Antioch is Paul's letter to the Galatians.[124] Second missionary journey  St. Paul in Athens delivering the Areopagus sermon in which he addressed early issues in Christology, depicted in a 1515 portrait by Raphael[126][127] Paul left for his second missionary journey from Jerusalem, in late Autumn 49 AD,[128] after the meeting of the Council of Jerusalem where the circumcision question was debated. On their trip around the Mediterranean Sea, Paul and his companion Barnabas stopped in Antioch where they had a sharp argument about taking John Mark with them on their trips. The Acts of the Apostles said that John Mark had left them in a previous trip and gone home. Unable to resolve the dispute, Paul and Barnabas decided to separate; Barnabas took John Mark with him, while Silas joined Paul. Paul and Silas initially visited Tarsus (Paul's birthplace), Derbe and Lystra. In Lystra, they met Timothy, a disciple who was spoken well of, and decided to take him with them. Paul and his companions, Silas and Timothy, had plans to journey to the southwest portion of Asia Minor to preach the gospel but during the night, Paul had a vision of a man of Macedonia standing and begging him to go to Macedonia to help them. After seeing the vision, Paul and his companions left for Macedonia to preach the gospel to them.[129] The Church kept growing, adding believers, and strengthening in faith daily.[130] In Philippi, Paul cast a spirit of divination out of a servant girl, whose masters were then unhappy about the loss of income her soothsaying provided.[131] They seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace before the authorities and Paul and Silas were put in jail. After a miraculous earthquake, the gates of the prison fell apart and Paul and Silas could have escaped but remained; this event led to the conversion of the jailor.[132] They continued traveling, going by Berea and then to Athens, where Paul preached to the Jews and God-fearing Greeks in the synagogue and to the Greek intellectuals in the Areopagus. Paul continued from Athens to Corinth. Interval in Corinth Around 50–52 AD, Paul spent 18 months in Corinth. The reference in Acts to Proconsul Gallio helps ascertain this date (cf. Gallio Inscription).[42] In Corinth, Paul met Priscilla and Aquila,[133] who became faithful believers and helped Paul through his other missionary journeys. The couple followed Paul and his companions to Ephesus and stayed there to start one of the strongest and most faithful churches at that time.[134] In 52, departing from Corinth, Paul stopped at the nearby village of Cenchreae to have his hair cut off, because of a vow he had earlier taken.[135] It is possible this was to be a final haircut prior to fulfilling his vow to become a Nazirite for a defined period of time.[136] With Priscilla and Aquila, the missionaries then sailed to Ephesus[137] and then Paul alone went on to Caesarea to greet the Church there. He then traveled north to Antioch, where he stayed for some time (Ancient Greek: ποιησας χρονον, "perhaps about a year"), before leaving again on a third missionary journey.[citation needed] Some New Testament texts[note 6] suggest that he also visited Jerusalem during this period for one of the Jewish feasts, possibly Pentecost.[138] Textual critic Henry Alford and others consider the reference to a Jerusalem visit to be genuine[139] and it accords with Acts 21:29,[140] according to which Paul and Trophimus the Ephesian had previously been seen in Jerusalem. Third missionary journey  The Preaching of Saint Paul at Ephesus, a 1649 portrait by Eustache Le Sueur[141] According to Acts, Paul began his third missionary journey by traveling all around the region of Galatia and Phrygia to strengthen, teach and rebuke the believers. Paul then traveled to Ephesus, an important center of early Christianity, and stayed there for almost three years, probably working there as a tentmaker,[142] as he had done when he stayed in Corinth. He is claimed to have performed numerous miracles, healing people and casting out demons, and he apparently organized missionary activity in other regions.[42] Paul left Ephesus after an attack from a local silversmith resulted in a pro-Artemis riot involving most of the city.[42] During his stay in Ephesus, Paul wrote four letters to the church in Corinth.[143] The Jerusalem Bible suggests that the letter to the church in Philippi was also written from Ephesus.[144] Paul went through Macedonia into Achaea[145] and stayed in Greece, probably Corinth, for three months[145] during 56–57 AD.[42] Commentators generally agree that Paul dictated his Epistle to the Romans during this period.[146] He then made ready to continue on to Syria, but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia because of some Jews who had made a plot against him. In Romans 15:19,[147] Paul wrote that he visited Illyricum, but he may have meant what would now be called Illyria Graeca,[148] which was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.[149] On their way back to Jerusalem, Paul and his companions visited other cities such as Philippi, Troas, Miletus, Rhodes, and Tyre. Paul finished his trip with a stop in Caesarea, where he and his companions stayed with Philip the Evangelist before finally arriving at Jerusalem.[150] Conjectured journey from Rome to Spain Among the writings of the early Christians, Pope Clement I said that Paul was "Herald (of the Gospel of Christ) in the West", and that "he had gone to the extremity of the west".[151] Where Lightfoot's translation has "had preached" below (in the "Church tradition" section), the Hoole translation has "having become a herald".[152] John Chrysostom indicated that Paul preached in Spain: "For after he had been in Rome, he returned to Spain, but whether he came thence again into these parts, we know not".[153] Cyril of Jerusalem said that Paul, "fully preached the Gospel, and instructed even imperial Rome, and carried the earnestness of his preaching as far as Spain, undergoing conflicts innumerable, and performing Signs and wonders".[154] The Muratorian fragment mentions "the departure of Paul from the city [of Rome] [5a] (39) when he journeyed to Spain".[155] |

略歴 初期の生活  エルサレムからローマまでのパウロの生涯に関連する地理  パウロの経歴の初期の部分にアクセスできる2つの主な情報源は、使徒言行録と初期キリスト教共同体に宛てたパウロの手紙の自伝的要素である[41]。使徒 言行録は、パウロが生まれながらにしてローマ市民であったことを示しているが[46]、ヘルムート・コーテルはこのテキストが示す証拠に異議を唱えている [47][48]。 地中海沿岸の交易の中心地のひとつであり、大学で有名なタルソスは、紀元前323年に亡くなったアレクサンドロス大王の時代から、小アジアで最も影響力の ある都市のひとつであった[49]。 パウロは自らを「イスラエルの家系、ベニヤミン族、ヘブライ人のヘブライ人、律法に関してはパリサイ人」[50][51]と称していた。使徒言行録には、 パウロが自分の家族について「パリサイ人から生まれたパリサイ人である」と述べていることが引用されている[52][53]。 使徒言行録23:16には、パウロの甥である妹の息子が言及されている[54]。 使徒言行録によれば、彼は革細工やテント作りの職人であった[58][59]。 このことは、彼がテント作りのパートナーとなり[60]、後に宣教師仲間として非常に重要なチームメイトとなるプリスキラとアキラとの最初のつながりと なった[61]。 パウロがまだかなり若いうちにエルサレムに送られ、歴史上最も著名なユダヤ律法の教師の一人であるガマリエルの学校で教育を受けた[62][51]。現代 の学問では、パウロがエルサレムでガマリエルの監督の下で教育を受けたという点で一致しているが[51]、彼はユダヤ法の学者になるための準備をしていた わけではなく、おそらくヒレライト学派と接触することはなかった[51]。 現代の研究では、パウロはコイネーギリシャ語(彼が手紙を書くのに用いた言語)に堪能であったが、彼の第一言語はおそらくアラム語であったと指摘している [65]。手紙の中でパウロはストア哲学の知識を多用し、新しい異邦人の改宗者が福音を理解するのを助け、彼のキリスト論を説明するためにストア哲学の用 語や比喩を用いた[66][67]。 初期キリスト教徒迫害者  カラヴァッジョによる1601年の肖像画『ダマスコ途上での回心』 ジェームズ・ダンによれば、エルサレムの共同体は、アラム語とギリシア語の両方を話すユダヤ人である「ヘブライ人」と、ギリシア語のみを話すユダヤ人であ る「ヘレニスト」で構成されており、おそらくエルサレムに再定住したディアスポラ・ユダヤ人であった。 [70]パウロの最初のキリスト教徒迫害は、おそらく彼らの反神殿的な態度のために、これらのギリシア語を話す「ヘレニスト」に向けられたものであった [71]。 改宗 主な記事 使徒パウロの改宗  ダマスコに向かう聖パウロの改宗(1889年頃、José Ferraz de Almeida Júniorによる肖像画 パウロが改宗したのは紀元31~36年頃と推定される[72][73][74]。ガラテヤ人への手紙1:16で、パウロは、神が「喜んで御子をわたしに現 された」と書いている[75]。コリント人への手紙第一15:8では、イエスが復活後に弟子たちに現れた順序を列挙しながら、パウロは、「最後に、まだ生 まれていない者のように、主はわたしにも現れた」と書いている[76]。 使徒言行録』の記述によると、それはダマスコへの道中、昇天したイエスの幻を見たと報告した場所で起こった。サウロ、サウロ、なぜ私を迫害するのか』と言 う声が聞こえた。すると、『あなたが迫害しているイエスである』という答えが返ってきた」[77]。 使徒言行録9:1-22の記述によると、彼は3日間目が見えなくなり、手を引かれてダマスコに入らなければならなかった[78]。この3日間、サウロは食 べ物も水もとらず、神への祈りに時間を費やした。ダマスコのアナニヤが到着すると、彼は彼に手を置いて言った: 「兄弟サウロ、あなたが来た道すがら、あなたに現れた主、すなわちイエスは、あなたが視力を得、聖霊に満たされるために、わたしを遣わされたのです」 [79] 視力は回復し、彼は立ち上がり、洗礼を受けた。 使徒言行録』の著者は、パウロの回心をエルサレムの教会から、あるいはアンティオキアの教会から、あるいはおそらくパウロ自身から知ったのかもしれない [82]。 同様に、アラン・シーガルとダニエル・ボヤリンは、パウロの回心体験と天上への昇天に関する記述(『コリントの信徒への手紙二12章』)を、ユダヤ教やキ リスト教の文献に現存するメルカバの神秘主義者に関する最古の一人称の記述とみなしている。逆にティモシー・チャーチルは、パウロのダマスカス街道での出 会いはメルカバのパターンには当てはまらないと主張している[84]。 改宗後 使徒言行録によると そしてすぐに、会堂でイエスを宣べ伝え、「この方は神の子です 」と言った。すると、彼の話を聞いた者はみな驚いて言った、「この人は、エルサレムでこの名を呼び求める人々を大混乱に陥れた人ではないか。祭司長たちの 前に彼らを縛りつけるために、この目的でここに来たのではないか。"と言った。しかし、サウロはますます力を増し、イエスがキリストであることを証明し て、ダマスコに住むユダヤ人たちを困惑させた。 - 使徒言行録9:20-22[85] 初期の宣教  ダマスコにあるダマスコのアナニヤの家とされる場所  パウロがダマスコの迫害から逃れた場所とされるバブ・キサン 使徒言行録9章によると、パウロはダマスコに行き、そこで失明をいやされ、ダマスコのアナニヤからバプテスマを受けた[86]。 [88][89]パウロのアラビアへの旅は聖書の他のどこにも記されておらず、彼が実際にシナイ山へ行き、砂漠で黙想したと推測する人もいる[90] [91]。彼はガラテヤの信徒への手紙の中で、回心してから3年後にエルサレムに行ったことを述べている。パウロはガラテヤ4:24-25で、シナイ山を アラビアに位置づけた[93]。 パウロは、福音を人からではなく、「イエス・キリストの啓示」によって直接受けたと主張した[94]。 彼はエルサレム共同体からのほぼ完全な独立を主張したが[95](おそらくセナクルにおいて)、福音の性質と内容についてはエルサレム共同体と一致した [96]。 彼は、自分が始めた様々な成長する異邦人教会からエルサレムに物質的な支援をもたらすことに熱心であったようだ。パウロはその著作の中で、自分が耐えた迫 害を、イエスとの接近と一致を宣言するため、また自分の教えを検証するために用いている。 ガラテヤの信徒への手紙』におけるパウロの叙述によれば、パウロは回心してから14年後に再びエルサレムに向かった[97]。この間に何が起こったのかは 定かではないが、『使徒言行録』と『ガラテヤの信徒への手紙』にはいくつかの詳細が記されている[98]。この時、バルナバはパウロを探しに行き、アン ティオキアに連れてきた[99][100]。アンティオキアのキリスト教共同体は、エルサレムに住んでいたヘレニズム化したディアスポラのユダヤ人たちに よって設立されたものであり、彼らは異邦人やギリシャ人の聴衆、特に大規模なユダヤ人社会とかなりの数の異邦人「神を畏れる者」を抱えていたアンティオキ アで、異邦人やギリシャ人の聴衆に福音を伝える重要な役割を果たした。 「アンティオキアから異邦人への伝道が始まり、それは初期キリスト教運動の性格を根本的に変えることになり、最終的には新しい異邦人の宗教となった [102]。 使徒言行録によると、アンティオキアは、ステファノの死後、信者が散り散りになった後、キリスト教徒の代替的な中心地となっていた。イエスを信奉する者た ちが初めて「クリスチャン」と呼ばれたのはアンティオキアであった[105]。 最初の宣教の旅  聖パウロの宣教旅行の地図 使徒言行録』の著者は、パウロの旅を3つの別々の旅に分類している。最初の旅は[106]、パウロとバルナバがアンティオキア共同体から依頼され [107]、最初はバルナバが率いた旅で[注釈 5]、バルナバとパウロはアンティオキアからキプロスに行き、その後小アジア南部に入り、最後にアンティオキアに戻った。キプロスでパウロは、彼らの教え を批判していた魔術師エリマス[108]を叱責し、盲目にする。 彼らはパンフィリアのペルガに向かった。ヨハネ・マルコは彼らのもとを去り、エルサレムに戻った。パウロとバルナバはピシディアのアンティオキアへ向かっ た。安息日に彼らは会堂に行った。指導者たちは彼らを招いて話をさせた。パウロはエジプトでの生活からダビデ王までのイスラエルの歴史を振り返った。彼 は、イエスが神によってイスラエルに連れて来られたダビデの子孫であると紹介した。パウロは、自分のチームは救いのメッセージを伝えるためにこの町に来た と言った。イエスの死と復活の物語を語った。彼はセプトゥアギンタ[109]を引用し、イエスが彼らに罪の赦しをもたらす約束のクリストスであると主張し た。ユダヤ人も「神を畏れる」異邦人も、次の安息日にもっと話をしようと彼らを招いた。その時、ほとんど全市民が集まった。このことで一部の有力なユダヤ 人たちは動揺し、彼らに反対する発言をした。パウロはこの機会を利用して、以後は異邦人に対する宣教に変更することを発表した[110]。 アンティオキアは、パウロの初期の宣教活動において主要なキリスト教の本拠地となり[4]、パウロは最初の旅が終わった後も「弟子たちとともに長い間」そ こに留まった[111]。パウロがアンティオキアに滞在した正確な期間は不明であり、9ヶ月から8年にも及ぶと推定されている[112]。 1997年に出版されたレイモンド・E・ブラウンの『新約聖書入門』では、パウロの生涯における出来事の年表が、20世紀後半に書かれた聖書学者の著作か ら図解されている[113]。 エルサレム公会議 主な記事 エルサレム公会議 参照 初期キリスト教における割礼論争 パウロとエルサレム教会の間で重要な会議が行われたのは、伝統的な年代測定法では紀元49年であったが、修正主義的な年代測定法では紀元47/51年で あった[115]。 [117][42]重要な問題は、異邦人が割礼を受ける必要があるかどうかということであった。118][119]この会議で、パウロはガラテヤの信徒へ の手紙の中で、ペテロ、ヤコブ、ヨハネがパウロの異邦人への宣教を受け入れたと述べている。 エルサレムの集会は使徒言行録やパウロの手紙にも言及されている[120]。例えば、飢饉救済のためのエルサレム訪問[121]は、明らかに「最初の訪 問」(ペテロとヤコブに対してのみ)に相当する[122][120]。 F・F・ブルースは、「14年間」というのは、エルサレムへの最初の訪問からではなく、パウロの回心からではないか、と示唆している[123]。 アンティオキアでの出来事 主な記事 アンティオキア事件 エルサレム公会議での合意にもかかわらず、パウロは、アンティオキアの異邦人クリスチャンがユダヤ教の習慣を厳格に守っていないことを理由に、ペテロが食 事を共にすることを嫌がったことをめぐって、後に「アンティオキアの事件」とも呼ばれる論争でペテロと公に対立したことを語っている[118]。 後にこの出来事について書いた文章で、パウロは「(ペテロが)明らかに間違っていたので、面と向かって反対した」と語り、ペテロにこう言ったと述べてい る。それなのに、どうして異邦人にユダヤ人の習慣に従うことを強要するのですか」[124]。パウロはまた、その時まで旅の仲間であり、使徒仲間であった バルナバでさえも、ペテロの味方をしたことにも触れている[118]。 この事件の結末はまだ定かではない。カトリック百科事典は、「パウロのこの出来事に関する記述から、ペテロが叱責の正当性を認めていたことは疑いない」 [118]として、パウロが論争に勝利したと示唆している。 しかし、パウロ自身は勝利に言及したことはなく、L.マイケル・ホワイトの『イエスからキリスト教へ』は逆の結論を導いている: 「ペテロとの一触即発は政治的虚勢の完全な失敗であり、パウロはすぐにペルソナ・ノン・グラータとしてアンティオキアを去り、二度と戻ることはなかった」 [125]。 アンティオキアでの事件に関する一次資料は、パウロのガラテヤの信徒への手紙である[124]。 第二次伝道の旅  アテネでアレオパゴスの説教を行う聖パウロ(ラファエロによる1515年の肖像画に描かれている)[126][127]。 割礼問題が議論されたエルサレム公会議が開かれた後、パウロは紀元49年晩秋、エルサレムから二度目の宣教の旅に出発した[128]。地中海をめぐる旅の 途中、パウロと同行のバルナバはアンティオキアに立ち寄り、そこでヨハネ・マルコを旅に同行させることについて鋭く議論した。使徒言行録によれば、ヨハ ネ・マルコは以前の旅で彼らのもとを去り、帰国したという。バルナバはヨハネ・マルコを連れて行き、シラスはパウロに加わった。 パウロとシラスは当初、タルソス(パウロの生まれ故郷)、デルベ、リストラを訪れた。リストラでは、評判の良い弟子テモテに出会い、彼を連れて行くことに した。パウロと同行のシラスとテモテは、福音を宣べ伝えるために小アジアの南西部に旅する計画だったが、夜中にパウロはマケドニヤの人が立っていて、自分 たちを助けるためにマケドニヤに行ってほしいと懇願する幻を見た。その幻を見た後、パウロとその仲間たちはマケドニアに福音を宣べ伝えるために出発した [129]。教会は成長し続け、信者を増やし、日々信仰を強めていった[130]。 ピリピでは、パウロは召使いの少女から占いの霊を追い出し、その主人たちは、彼女の占いによって収入がなくなることを不満に思った[131]。奇跡的な地 震の後、牢獄の門は崩れ落ち、パウロとシラスは逃げ出すことができたが、そのまま留まった。この出来事が看守の改心につながった[132]。彼らは旅を続 け、ベレヤを経てアテネに行き、パウロは会堂でユダヤ人と神を敬うギリシア人に、アレオパゴスでギリシアの知識人に説教した。パウロはアテネからコリント に向かった。 コリントでのインターバル 紀元50-52年頃、パウロはコリントで18ヶ月を過ごした。使徒言行録のプロコンスル・ガリオに関する記述は、この年代を確認するのに役立つ(ガリオ碑 文参照)[42]。コリントでパウロはプリスキラとアキラに出会い[133]、彼らは忠実な信者となり、パウロの他の宣教の旅を通してパウロを助けた。二 人はパウロとその仲間たちに従ってエペソに行き、そこにとどまって、当時最も強く信仰深い教会の一つを始めた[134]。 52年、コリントを出発したパウロは、近くのケンクレア村に立ち寄り、以前に立てた誓願のために髪を切った[135]。これは、定められた期間、ナジル人 になるという誓願を果たす前の最後の散髪であった可能性がある[136]。プリスキラとアキラとともに宣教師たちはその後、エフェソスに向けて出航し [137]、パウロ一人でカイザリアに向かい、そこの教会に挨拶した。その後、アンティオキアまで北上し、そこでしばらく滞在した後(古代ギリシア語: ποιησας χρονον、「おそらく約1年」)、再び三度目の宣教の旅に出た。 [138]テキスト批評家のヘンリー・アルフォードなどは、エルサレム訪問への言及は本物であり[139]、パウロとエペソ人トロフィモスが以前にエルサ レムで目撃されたという使徒言行録21:29[140]と一致していると考えている。 第三次伝道旅行  エフェソスでの聖パウロの説教、ユスターシュ・ル・スールによる1649年の肖像画[141]。 使徒言行録によると、パウロはガラテヤとフリギヤ地方を巡り、信徒たちを強め、教え、戒めることから第三次伝道旅行を始めた。その後、パウロは初期キリス ト教の重要な中心地であったエペソに行き、ほぼ3年間滞在し、おそらくコリントに滞在したときと同じように、そこで天幕職人として働いた[142]。パウ ロは多くの奇跡を行い、人々を癒し、悪霊を追い出したと言われており、他の地域での宣教活動を組織したようである[42]。地元の銀細工師の攻撃により、 街の大部分を巻き込んだ親アルテミス派の暴動が起こった後、パウロはエフェソを去った[42]。 エフェソ滞在中、パウロはコリントの教会に4通の手紙を書いた[143]。 パウロはマケドニアを通ってアカイアに行き[145]、紀元56年から57年の間、ギリシャ、おそらくコリントに3ヶ月間滞在した[42]。ローマ人への 手紙15:19[147]では、パウロはイリュリクムに行ったと書いているが、これは現在イリュリア・グラエカと呼ばれている[148]、当時ローマ帝国 のマケドニア地方の一部門であったイリュリアを指していたのかもしれない[149]。エルサレムに戻る途中、パウロとその仲間たちは、ピリピ、トロアス、 ミレトス、ロードス島、ティレなどの都市を訪れた。パウロはカイザリヤに立ち寄り、そこで福音書記者フィリポのもとに滞在し、最終的にエルサレムに到着し て旅を終えた[150]。 ローマからスペインへの旅 初期キリスト教徒の著作の中で、教皇クレメンス1世はパウロが「西方における(キリストの福音の)伝道者」であり、「西方の果てまで行った」と述べている [151]。 ライトフット訳では以下(「教会の伝統」の部分)で「宣教していた」となっているところ、フール訳では「宣教師となった」となっている[152]。ヨハ ネ・クリュソストムはパウロがスペインで宣教したことを示した: 「153]エルサレムのキュリロは、パウロが「完全に福音を宣べ伝え、帝政ローマでさえも指導し、その宣教の真剣さをスペインにまで伝え、無数の争いを受 け、しるしと不思議を行った」と述べている[154]。 ムラトリオの断片は、「パウロがスペインに旅立ったとき、(ローマの)町[5a](39)を出発したこと」に言及している[155]。 |

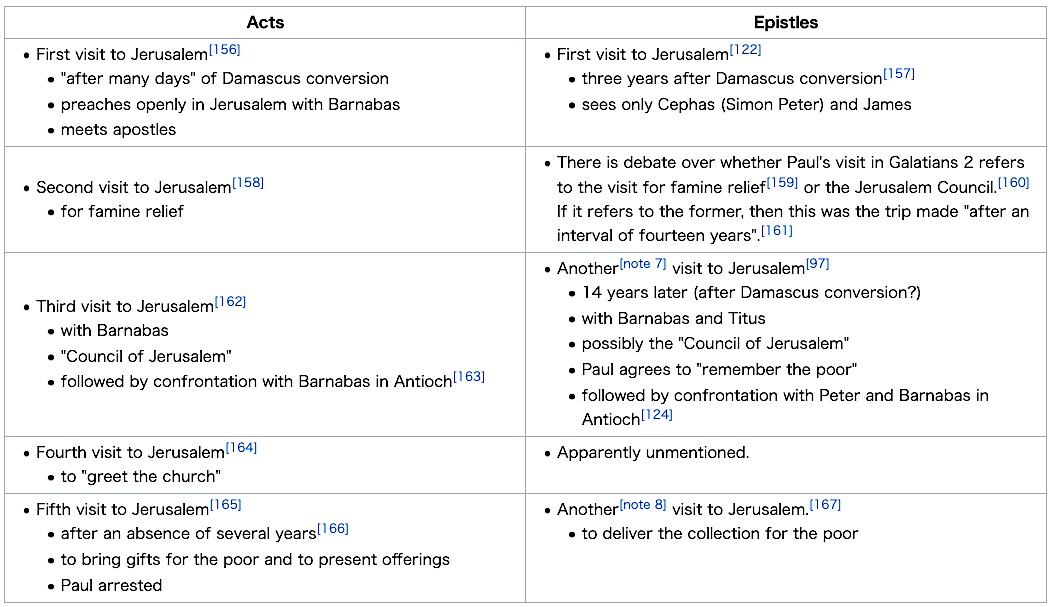

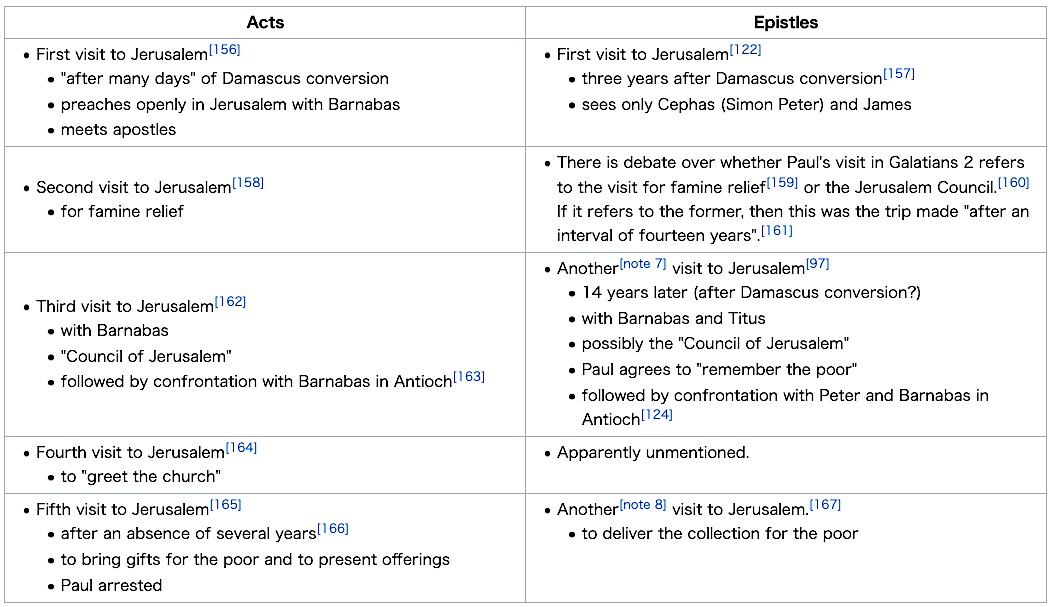

| Visits to Jerusalem in Acts and

the epistles The following table is adapted from the book From Jesus to Christianity by Biblical scholar L. Michael White,[120] matching Paul's travels as documented in the Acts and the travels in his Epistles but not agreed upon fully by all Biblical scholars.  |

使徒言行録と書簡におけるエルサレム訪問 以下の表は、聖書学者L.マイケル・ホワイトの著書『イエスからキリスト教へ』[120]から引用したもので、使徒言行録に記されているパウロの旅と書簡 に記されているパウロの旅を一致させているが、すべての聖書学者によって完全に合意されているわけではない。  |

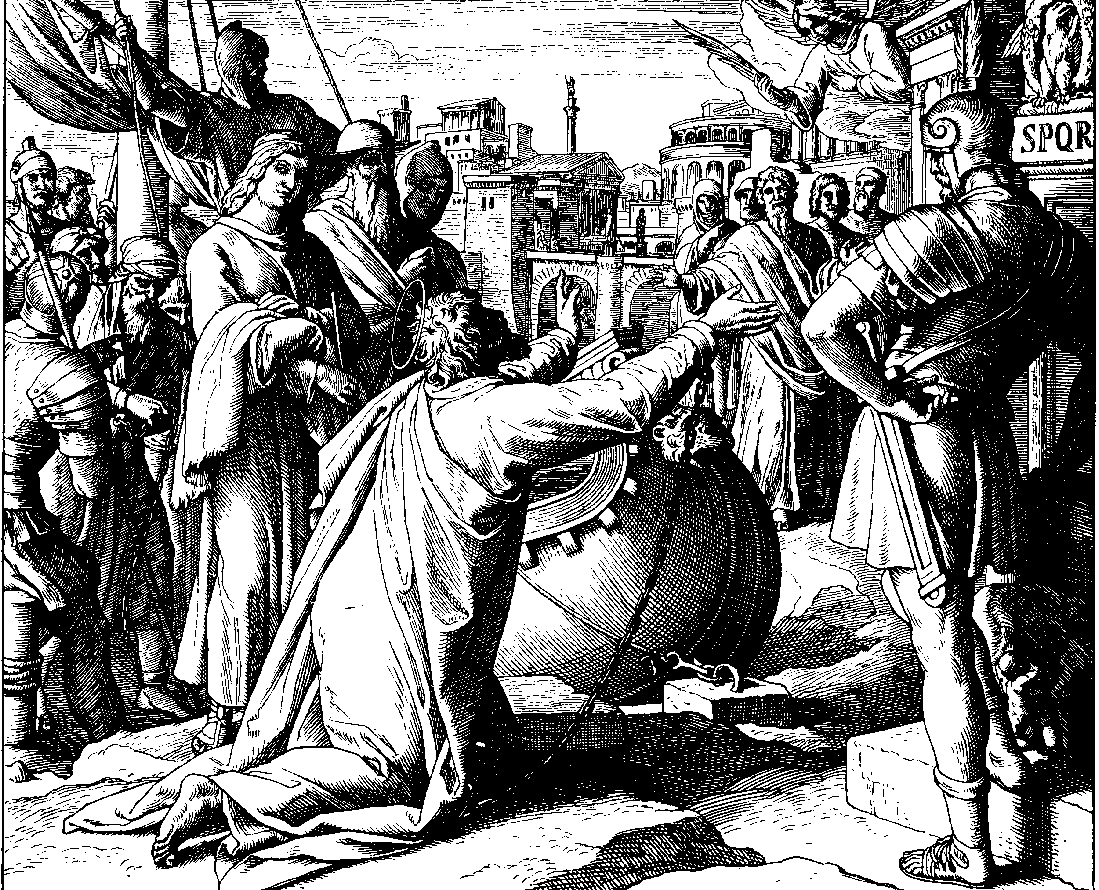

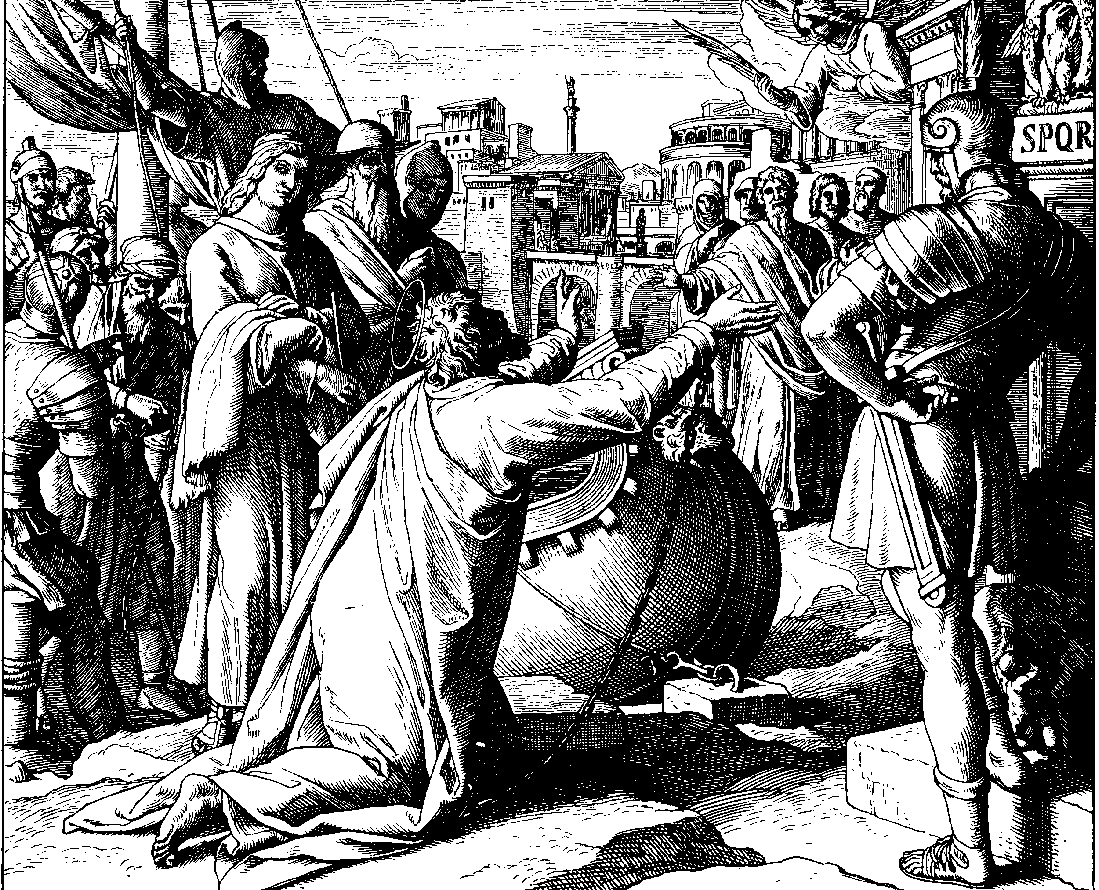

Last visit to Jerusalem and

arrest St. Paul's arrest depicted in an early 1900s Bible illustration  St. Paul's grotto in Rabat, Malta In 57 AD, upon completion of his third missionary journey, Paul arrived in Jerusalem for his fifth and final visit with a collection of money for the local community. The Acts of the Apostles reports that he initially was warmly received. However, Acts goes on to recount how Paul was warned by James and the elders that he was gaining a reputation for being against the Law, saying, "they have been told about you that you teach all the Jews living among the Gentiles to forsake Moses, and that you tell them not to circumcise their children or observe the customs."[168] Paul underwent a purification ritual so that "all will know that there is nothing in what they have been told about you, but that you yourself observe and guard the law."[169] When the seven days of the purification ritual were almost completed, some "Jews from Asia" (most likely from Roman Asia) accused Paul of defiling the temple by bringing gentiles into it. He was seized and dragged out of the temple by an angry mob. When the tribune heard of the uproar, he and some centurions and soldiers rushed to the area. Unable to determine his identity and the cause of the uproar, they placed him in chains.[170] He was about to be taken into the barracks when he asked to speak to the people. He was given permission by the Romans and proceeded to tell his story. After a while, the crowd responded. "Up to this point they listened to him, but then they shouted, 'Away with such a fellow from the earth! For he should not be allowed to live.'"[171] The tribune ordered that Paul be brought into the barracks and questioned by flogging. Paul asserted his Roman citizenship, which would prevent his flogging. The tribune "wanted to find out what Paul was being accused of by the Jews, the next day he released him and ordered the chief priests and the entire council to meet".[172] Paul spoke before the council and caused a disagreement between the Pharisees and the Sadducees. When this threatened to turn violent, the tribune ordered his soldiers to take Paul by force and return him to the barracks.[173] The next morning, 40 Jews "bound themselves by an oath neither to eat nor drink until they had killed Paul",[174] but the son of Paul's sister heard of the plot and notified Paul, who notified the tribune that the conspiracists were going to ambush him. The tribune ordered two centurions to "Get ready to leave by nine o'clock tonight for Caesarea with two hundred soldiers, seventy horsemen, and two hundred spearmen. Also provide mounts for Paul to ride, and take him safely to Felix the governor."[175] Paul was taken to Caesarea, where the governor ordered that he be kept under guard in Herod's headquarters. "Five days later the high priest Ananias came down with some elders and an attorney, a certain Tertullus, and they reported their case against Paul to the governor."[176] Both Paul and the Jewish authorities gave a statement "But Felix, who was rather well informed about the Way, adjourned the hearing with the comment, "When Lysias the tribune comes down, I will decide your case."[177] Marcus Antonius Felix then ordered the centurion to keep Paul in custody, but to "let him have some liberty and not to prevent any of his friends from taking care of his needs."[178] He was held there for two years by Felix, until a new governor, Porcius Festus, was appointed. The "chief priests and the leaders of the Jews" requested that Festus return Paul to Jerusalem. After Festus had stayed in Jerusalem "not more than eight or ten days, he went down to Caesarea; the next day he took his seat on the tribunal and ordered Paul to be brought." When Festus suggested that he be sent back to Jerusalem for further trial, Paul exercised his right as a Roman citizen to "appeal unto Caesar".[42] Finally, Paul and his companions sailed for Rome where Paul was to stand trial for his alleged crimes.[179] Acts recounts that on the way to Rome for his appeal as a Roman citizen to Caesar, Paul was shipwrecked on Melita, which is present-day Malta,[180] where the islanders showed him "unusual kindness" and where he was met by Publius.[181] From Malta, he travelled to Rome via Syracuse, Rhegium, and Puteoli.[182] Two years in Rome  Paul Arrives in Rome from Die Bibel in Bildern, published in the 1850s Paul finally arrived in Rome c. 60 AD, where he spent another two years under house arrest.[179] The narrative of Acts ends with Paul preaching in Rome for two years from his rented home while awaiting trial.[183] Irenaeus wrote in the 2nd century that Peter and Paul had been the founders of the church in Rome and had appointed Linus as succeeding bishop.[184] However, Paul was not a bishop of Rome, nor did he bring Christianity to Rome since there were already Christians in Rome when he arrived there;[185] Paul also wrote his letter to the church at Rome before he had visited Rome.[186] Paul only played a supporting part in the life of the church in Rome.[187] Death  The Beheading of Saint Paul, an 1887 portrait by Enrique Simonet Paul's death is believed to have occurred after the Great Fire of Rome in July 64 AD, but before the last year of Nero's reign, in 68 AD.[2] Pope Clement I writes in his Epistle to the Corinthians that after Paul "had borne his testimony before the rulers", he "departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance."[188] Ignatius of Antioch writes in his Epistle to the Ephesians that Paul was "martyred", without giving any further information.[189] Tertullian writes that Paul was 'crowned with an exit like John' (Paulus Ioannis exitu coronatur), although it is unclear which John he meant.[190] Eusebius states that Paul was killed during the Neronian Persecution[191] and, quoting from Dionysius of Corinth, argues that Peter and Paul were martyred "at the same time".[192] This is also reported by Sulpicius Severus, who claimed Peter was crucified while Paul was beheaded.[193] John Chrysostom provides an account of Nero imprisoning Paul, but not of his execution, and no mention of Peter.[194] Lactantius only mentioned '[It was Nero] who first persecuted the servants of God; he crucified Peter, and slew Paul' (Paulum interfecit).[195][196] Based on the letters attributed to Paul, Jerome claims Paul was imprisoned by Nero in 'the twenty-fifth year after our Lord's passion' (post passionem Domini vicesimo quinto anno), 'that is the second of Nero' (id est, secundo Neronis), 'at the time when Festus Procurator of Judea succeeded Felix, he was sent bound to Rome, (...) remaining for two years in free custody'. Jerome interpreted the Second Epistle to Timothy to indicate that 'Paul was dismissed by Nero' (Paulum a Nerone dimissum) 'that the gospel of Christ might be preached also in the West'; but 'in the fourteenth year of Nero' (quarto decimo Neronis anno) 'on the same day with Peter, [Paul] was beheaded at Rome for Christ's sake and was buried in the Ostian way, the thirty-seventh year after our Lord's passion' (anno post passionem Domini tricesimo septimo).[197][198][non-primary source needed] A legend later developed that his martyrdom occurred at the Aquae Salviae, on the Via Laurentina. According to this legend, after Paul was decapitated, his severed head rebounded three times, giving rise to a source of water each time that it touched the ground, which is how the place earned the name "San Paolo alle Tre Fontane" ("St Paul at the Three Fountains").[199][200] The apocryphal Acts of Paul also describe the martyrdom and the burial of Paul, but their narrative is highly fanciful and largely unhistorical.[201] Remains According to the Liber Pontificalis, Paul's body was buried outside the walls of Rome, at the second mile on the Via Ostiensis, on the estate owned by a Christian woman named Lucina.[202] It was here, in the fourth century, that the Emperor Constantine the Great built a first church. Then, between the fourth and fifth centuries, it was considerably enlarged by the Emperors Valentinian I, Valentinian II, Theodosius I, and Arcadius. The present-day Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls was built there in the early 19th century.[199] Caius in his Disputation Against Proclus (198 AD) mentions this of the places in which the remains of the apostles Peter and Paul were deposited: "I can point out the trophies of the apostles. For if you are willing to go to the Vatican or to the Ostian Way, you will find the trophies of those who founded this Church".[203] Writing on Paul's biography, Jerome in his De Viris Illustribus in 392 AD mentions that "Paul was buried in the Ostian Way at Rome".[204] In 2002, an 8-foot (2.4 m)-long marble sarcophagus, inscribed with the words "PAULO APOSTOLO MART", which translates as "Paul apostle martyr", was discovered during excavations around the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls on the Via Ostiensis. Vatican archaeologists declared this to be the tomb of Paul the Apostle in 2005.[citation needed] In June 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced excavation results on the tomb. The sarcophagus was not opened but was examined by a probe, which revealed pieces of incense, purple, and blue linen, and small bone fragments. The bone was radiocarbon dated to the 1st or 2nd century. According to the Vatican, these findings support the conclusion that the tomb is Paul's.[205][206] |

最後のエルサレム訪問と逮捕 1900年代初期の聖書の挿絵に描かれた聖パウロの逮捕  マルタのラバトにある聖パウロの洞窟 紀元57年、3度目の伝道旅行を終えたパウロは、5度目となる最後のエルサレム訪問のため、地元共同体のための募金を携えてエルサレムに到着した。使徒言 行録によれば、パウロは当初温かく迎えられた。しかし使徒言行録は、パウロがヤコブと長老たちから、彼が律法に反しているとの評判を得ていることを警告さ れたことを、次のように語っている。「あなたが異邦人の間に住んでいるすべてのユダヤ人に、モーセを捨てるように教え、子供に割礼を施さず、習慣を守らな いように言っていることが、あなたのことで伝えられています」[168]。 7日間の清めの儀式がほぼ終わったとき、「アジアから来たユダヤ人」(おそらくローマ・アジアから来たユダヤ人)たちが、パウロが異邦人を神殿に連れてき て汚したと訴えた。パウロは怒った群衆に捕らえられ、神殿から引きずり出された。この騒動を聞きつけた侍従長は、百人隊長や兵士たちとともにその場に駆け つけた。170]彼は兵営に連行されようとしたとき、人々に話をしたいと言った。彼はローマ人の許可を得て、自分の話をした。しばらくすると、群衆は答え た。「ここまでは彼の話に耳を傾けていたが、やがて彼らは叫んだ!パウロを兵営に連行し、鞭で打って尋問するよう命じた。パウロはローマ市民であることを 主張した。廷吏は「パウロがユダヤ人から訴えられていることを知りたいと思い、翌日、パウロを釈放し、祭司長たちと全評議会に集まるように命じた」 [172]。これが暴力に発展しそうになると、枢機卿は兵士たちにパウロを力ずくで連れて行き、兵営に戻すように命じた[173]。 翌朝、40人のユダヤ人たちが「パウロを殺すまでは飲食しないことを誓い」[174]、パウロの妹の息子がその陰謀を聞きつけ、パウロに知らせた。教皇は 二人の百人隊長に「今夜九時までに兵士二百人、騎兵七十人、槍兵二百人を率いてカイサリアに出発する準備をせよ」と命じた。また、パウロが乗る馬を用意 し、総督フェリクスのもとに無事に連れて行くように」[175]。 パウロはカイザリヤに連れて行かれ、総督はヘロデの本陣で警護するように命じた。五日後、大祭司アナニヤが何人かの長老と一人の弁護士テルトゥルスを連れ てやって来て、総督にパウロに対する訴えを報告した」[176] パウロとユダヤ当局の双方が陳述し、「しかし、フェリクスはむしろ道についてよく知っていたので、「廷吏リュシアスが下って来たら、私があなたの訴えを決 めます 」と言って、審理を休会させた」[177]。 マルクス・アントニウス・フェリクスは、百人隊長にパウロの身柄を拘束するよう命じたが、「パウロにはある程度の自由を与え、パウロの友人たちがパウロの 世話をするのを妨げないようにすること」[178]を命じ、新しい総督ポルシウス・フェストゥスが任命されるまで、パウロはフェリクスによって2年間そこ に拘束された。祭司長たちとユダヤ人の指導者たち」は、フェストゥスにパウロをエルサレムに戻すよう要求した。フェストゥスはエルサレムに滞在した後、 「8日か10日も経たないうちにカイサリアに下り、翌日、法廷に着き、パウロを連行するように命じた」。フェストゥスが、さらなる裁判のためにエルサレム に送り返すことを提案すると、パウロはローマ市民として「カイザルに上訴する」権利を行使した[42]。最終的に、パウロとその仲間たちは、パウロがその 罪の容疑で裁判を受けることになるローマに向けて出航した[179]。 使徒言行録によれば、ローマ市民としてカエサルに上訴するためにローマに向かう途中、パウロはメリタ(現在のマルタ島)で難破し[180]、そこで島民た ちはパウロに「並外れた親切」をし、パウロはプブリウスに出迎えられた[181]。 ローマでの2年間  ローマに到着したパウロ(1850年代に出版された『Die Bibel in Bildern』より 使徒言行録』の物語は、パウロが裁判を待つ間、借家から2年間ローマで説教するところで終わっている[179]。 イレナイオスは2世紀に、ペトロとパウロがローマ教会の創始者であり、リヌスを後継の司教に任命したと書いている[184]が、パウロはローマの司教では なかったし、彼がローマに到着したときにはすでにローマにはキリスト教徒がいたので、彼がローマにキリスト教をもたらしたわけでもなかった[185]。 死  聖パウロの斬首、エンリケ・シモネによる1887年の肖像画 パウロの死は、西暦64年7月のローマ大火の後、ネロの治世の最後の年である西暦68年以前に起こったと考えられている[2]。教皇クレメンス1世は、 『コリントの信徒への手紙』の中で、パウロが「支配者たちの前で証しをした」後、「忍耐強い忍耐の顕著な模範を見出されたので、世を去って聖なる場所に 行った」と書いている。 188]アンティオキアのイグナティウスは『エフェソの信徒への手紙』の中で、パウロが「殉教した」と書いているが、それ以上の情報は与えていない [189]。テルトゥリアヌスは、パウロが「ヨハネのような出口の冠を戴いた」(Paulus Ioannis exitu coronatur)と書いているが、どのヨハネを指しているのかは不明である[190]。 エウセビオスは、パウロはネロニア迫害の間に殺されたと述べ[191]、コリントのディオニシウスから引用して、ペトロとパウロは「同時に」殉教したと主 張している[192]。 [193]ヨハネ・クリュソストムは、ネロがパウロを投獄したことは記述しているが、その処刑については記述しておらず、ペトロについては言及していない [194]。ラクタンティウスは「最初に神のしもべたちを迫害したのはネロであり、彼はペトロを十字架につけ、パウロを殺した」(Paulum interfecit)とだけ述べている[195][196]。 パウロのものとされる手紙に基づき、ジェロームはパウロがネロによって投獄されたのは「主の受難後25年目」(post passionem Domini vicesimo quinto anno)、「ネロの2年目」(id est, secundo Neronis)であり、「ユダヤのフェストゥス総督がフェリクスの後を継いだとき、彼はローマに拘束されて送られ、(...)2年間自由に拘束された」 と主張している。ジェロームは、『キリストの福音が西方にも宣べ伝えられるように』とテモテへの第二の手紙を解釈し、『パウロはネロによって解任された』 (Paulum a Nerone dimissum)と述べている; しかし、「ネロの十四年」(quarto decimo Neronis anno)に、「ペトロと同じ日に、[パウロは]キリストのためにローマで斬首され、主の受難後三十七年目にオスティア式に葬られた」(anno post passionem Domini tricesimo septimo)。 [197][198][非一次資料が必要]。 後に、パウロの殉教はラウレンティーナ通りにあるアクアエ・サルビアエで起こったという伝説が生まれた。この伝説によると、パウロは首を切られた後、切断 された頭部が3回跳ね返り、地面に触れるたびに水源が生まれたことから、この地は 「San Paolo alle Tre Fontane」(「3つの泉の聖パウロ」)と呼ばれるようになった[199][200] アポクリファルの『パウロの使徒言行録』にもパウロの殉教と埋葬が描かれているが、その物語は非常に空想的で、ほとんど史実ではない。 遺骨 Liber Pontificalis』によると、パウロの遺体はローマの城壁の外、オスティエンシス通りの2マイル地点、ルキナというキリスト教徒の女性が所有する 土地に埋葬された[202]。その後、4世紀から5世紀にかけて、ヴァレンティニアヌス1世、ヴァレンティニアヌス2世、テオドシウス1世、アルカディウ ス帝によってかなり拡張された。現在の城壁外聖パウロ大聖堂は、19世紀初頭にそこに建てられた[199]。 カイウスは『プロクロスとの論争』(西暦198年)の中で、使徒ペトロとパウロの遺骸が安置された場所についてこう述べている: 「私は使徒たちの戦利品を指し示すことができる。ヴァチカンやオスティア街道へ行く気になれば、この教会を創立した人々の戦利品を見つけることができるか らである」[203]。 パウロの伝記について書いた西暦392年の『De Viris Illustribus』の中で、ジェロームは「パウロはローマのオスティア街道に埋葬された」と言及している[204]。 2002年、オスティエンシス通りの城壁外聖パウロ教会周辺の発掘調査で、「PAULO APOSTOLO MART」(パウロ使徒殉教者)と刻まれた長さ2.4メートルの大理石の石棺が発見された。バチカンの考古学者は2005年、これが使徒パウロの墓である と発表した[要出典]。2009年6月、教皇ベネディクト16世はこの墓の発掘結果を発表した。石棺は開封されなかったが、プローブによって調査され、 香、紫、青のリネンの破片と小さな骨片が発見された。骨は放射性炭素年代測定で1世紀か2世紀とされた。バチカンによれば、これらの発見はこの墓がパウロ のものであるという結論を裏付けるものである[205][206]。 |

Church tradition A Greek Orthodox mural painting of St. Paul Various Christian writers have suggested more details about Paul's life: 1 Clement, a letter written by the Roman bishop Clement of Rome around the year 90, reports this about Paul: By reason of jealousy and strife Paul by his example pointed out the prize of patient endurance. After that he had been seven times in bonds, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, had preached in the East and in the West, he won the noble renown which was the reward of his faith, having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the farthest bounds of the West; and when he had borne his testimony before the rulers, so he departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance. — Lightfoot 1890, p. 274, The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians, 5:5–6 Commenting on this passage, Raymond Brown writes that while it "does not explicitly say" that Paul was martyred in Rome, "such a martyrdom is the most reasonable interpretation".[207] Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote in the 4th century, states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero.[203] This event has been dated either to the year 64 AD, when Rome was devastated by a fire, or a few years later, to 67 AD. According to one tradition, the church of San Paolo alle Tre Fontane marks the place of Paul's execution. A Roman Catholic liturgical solemnity of Peter and Paul, celebrated on 29 June, commemorates his martyrdom, and reflects a tradition (preserved by Eusebius) that Peter and Paul were martyred at the same time.[203] The Roman liturgical calendar for the following day now remembers all Christians martyred in these early persecutions; formerly, 30 June was the feast day for St. Paul.[208] Persons or religious orders with a special affinity for St. Paul can still celebrate their patron on 30 June. The apocryphal Acts of Paul and the apocryphal Acts of Peter suggest that Paul survived Rome and traveled further west. Some think that Paul could have revisited Greece and Asia Minor after his trip to Spain, and might then have been arrested in Troas, and taken to Rome and executed.[209][note 4] A tradition holds that Paul was interred with Saint Peter ad Catacumbas by the via Appia until moved to what is now the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History, writes that Pope Vitalian in 665 gave Paul's relics (including a cross made from his prison chains) from the crypts of Lucina to King Oswy of Northumbria, northern Britain. The skull of Saint Paul is claimed to reside in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran since at least the ninth century, alongside the skull of Saint Peter.[210] The Feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul is celebrated on 25 January.[211] |

教会の伝統 ギリシャ正教の聖パウロの壁画 パウロの生涯については、さまざまなキリスト教作家がその詳細を示唆している: ローマの司教クレメンスが90年頃に書いた書簡『1クレメンス』は、パウロについてこう報告している: 嫉妬と争いのために、パウロはその模範によって、忍耐強く耐え忍ぶことの賞を指摘した。そして、支配者たちの前であかしをした後、世を去って聖なる所に行 き、忍耐の模範を見出したのである。 - ライトフット1890年、274頁、『コリントの信徒へのクレメンスの手紙』5:5-6 この箇所について、レイモンド・ブラウンは、パウロがローマで殉教したと「明言はしていない」が、「そのような殉教は最も妥当な解釈である」と書いている [207]。4世紀に書かれたカイザリアのエウセビオスは、パウロはローマ皇帝ネロの治世に斬首されたと述べている[203]。この出来事は、ローマが火 事で荒廃した西暦64年か、数年後の西暦67年とされている。ある伝承によると、サン・パオロ・アッレ・フォンターネ教会はパウロが処刑された場所を示し ている。6月29日に祝われるローマ・カトリックのペトロとパウロの典礼祭は、パウロの殉教を記念するものであり、ペトロとパウロが同時に殉教したという 伝承(エウセビオスによって保存されている)を反映している[203]。 アポクリファルの『パウロの使徒言行録』とアポクリファルの『ペテロの使徒言行録』は、パウロがローマを生き延びてさらに西へ旅したことを示唆している。 パウロはスペインへの旅の後、ギリシャと小アジアを再訪し、トロアスで逮捕され、ローマに連行されて処刑されたのではないかという説もある[209][注 4]。現在のローマの城壁外聖パウロ大聖堂に移されるまで、パウロはアッピア街道沿いのカタクンバスで聖ペトロとともに埋葬されたという伝承もある。ベデ は『教会史』の中で、665年に教皇ヴィタリアヌスがルキナの地下聖堂にあったパウロの聖遺物(牢獄の鎖で作られた十字架を含む)をブリテン北部のノーサ ンブリア王オズウィーに贈ったと記している。聖パウロの頭骨は、聖ペテロの頭骨と並んで、少なくとも9世紀以降、聖ヨハネ・ラテランの大修道院に保管され ていると主張されている[210]。 聖パウロの改宗の祝日は1月25日である[211]。 |

Feast days Paul the Apostle, detail of the mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, 6th century Roman Catholicism The Roman Martyrology commemorates Paul with a feast celebrating his conversion on 25 January.[212] The Roman Martyrology also commemorates Paul and Peter with a solemnity on 29 June.[213] Eastern Orthodoxy The Eastern Orthodox Church has several fixed days for the commemoration of Paul: 7 March – The Synaxis of the Saints of the Dodecanese Islands.[214] 29 June – The Apostles Peter and Paul.[215] 30 June – The Twelve Apostles.[216] 12 October – The Synaxis of the Saints of Athens.[217] The Eastern Orthodox Church also has numerous non-fixed days for the veneration of Paul: 21 Days before Pascha – Synaxis of the Saints of Rhodes.[218] 21 Days after Pascha – Synaxis of the Saints of Euboea.[219] First Sunday of May – Synaxis of the Saints of Gortyna and Arkadia in the island of Crete.[220][221] The Sunday between 16 and 22 August – Synaxis of the Saints of Lefkada.[222] The Church of England The Church of England celebrates the Conversion of Saint Paul on 25 January as a Festival.[223] Furthermore, along with Saint Peter, Paul is remembered by the Church of England with a Festival on 29 June.[223] Lutheran Church Missouri Synod The Lutheran Church Missouri Synod has two festivals for Saint Paul, the first being his conversion on 25 January, and the second being for Saints Peter and Paul on 29 June.[224] Patronage Paul is the Patron Saint of several locations. He is the Patron Saint of the island of Malta, which celebrates Paul's arrival to the island via shipwreck on 10 February. This day is a public holiday on the island.[225] Paul is also considered to be the Patron Saint of the city of London. Physical appearance  A facial composite of St. Paul created by experts of the Landeskriminalamt of North Rhine-Westphalia using historical sources The New Testament offers little if any information about the physical appearance of Paul, but several descriptions can be found in apocryphal texts. In the Acts of Paul[226] he is described as "A man of small stature, with a bald head and crooked legs, in a good state of body, with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked".[227] In the Latin version of the Acts of Paul and Thecla it is added that he had a red, florid face. In The History of the Contending of Saint Paul, his countenance is described as "ruddy with the ruddiness of the skin of the pomegranate".[228] The Acts of Saint Peter confirms that Paul had a bald and shining head, with red hair.[229] As summarised by Barnes,[230] Chrysostom records that Paul's stature was low, his body crooked and his head bald. Lucian, in his Philopatris, describes Paul as "corpore erat parvo, contracto, incurvo, tricubitali" ("he was small, contracted, crooked, of three cubits, or four feet six").[31] Nicephorus claims that Paul was a little man, crooked, and almost bent like a bow, with a pale countenance, long and wrinkled, and a bald head. Pseudo-Chrysostom echoes Lucian's height of Paul, referring to him as "the man of three cubits".[31] |

祝祭日 使徒パウロ、ラヴェンナ、サン・ヴィターレ聖堂のモザイクの詳細、6世紀 ローマ・カトリック ローマ殉教録は1月25日にパウロの回心を祝う祝祭日でパウロを記念している[212]。ローマ殉教録はまた6月29日にパウロとペテロを厳粛な祝祭日で 記念している[213]。 東方正教会 東方正教会はパウロを記念する日をいくつか定めている: 3月7日-ドデカネス諸島の聖人の祭日[214]。 6月29日 使徒ペトロとパウロ[215]。 6月30日-十二使徒[216]。 10月12日 - アテネの聖人のシナクシス[217]。 東方正教会には、パウロを崇敬するための固定されていない日が数多くある: パシュカの21日前-ロードス島の聖人の祭日[218]。 パシュカの21日後-エウボイアの聖人の祭日[219]。 5月の第1日曜日-クレタ島のゴルティナとアルカディアの聖人のシナクシス[220][221]。 8月16日から22日の間の日曜日-レフカダ島の聖人のシナクシス[222]。 イギリス国教会 イングランド国教会では、1月25日に聖パウロの改宗を祝う。[223] さらに、聖ペトロとともに、パウロもイングランド国教会では6月29日に祭りをもって記念される[223]。 ルーテル教会ミズーリ・シノッド ルーテル教会ミズーリ・シノドでは、聖パウロのための2つの祭りがあり、1つ目は1月25日の彼の回心、2つ目は6月29日の聖ペトロとパウロのためのも のである[224]。 守護聖人 パウロはいくつかの場所の守護聖人である。マルタ島の守護聖人であるパウロは、2月10日に難破船でマルタ島に到着したことを祝っている。また、パウロは ロンドン市の守護聖人でもある。 外見  ノルトライン=ヴェストファーレン州のLandeskriminalamtの専門家が歴史的資料を用いて作成した聖パウロの顔の合成写真。 新約聖書にはパウロの外見に関する情報はほとんどないが、アポクリファルのテキストにはいくつかの記述が見られる。パウロ行伝』[226]では、「小柄 で、頭は禿げ上がり、脚は曲がっており、体つきはよく、眉が合い、鼻はやや鉤鼻であった」と記述されている[227]。ラテン語版の『パウロとテクラ行 伝』では、赤ら顔で華やかであったと付け加えている。 聖ペテロ行伝』では、パウロが禿げ上がった輝く頭で、赤い髪をしていたことが確認されている[229]。 バーンズが要約しているように[230]、クリソストムはパウロの身長は低く、体は曲がっており、頭は禿げていたと記録している。ルキアヌスは『フィロパ トリス』(Philopatris)の中で、パウロを 「corpore erat parvo, contracto, incurvo, tricubitali」(「彼は小さく、縮こまっていて、曲がっていて、3キュビト、あるいは4フィート6であった」)と描写している[31]。 ニケフォロスは、パウロは小柄で、曲がっていて、ほとんど弓のように曲がっており、顔色が悪く、しわが長く、頭は禿げていたと主張している。偽クリソスト ムは、ルキアヌスのパウロの身長を「三キュビトの男」と呼んでいる[31]。 |

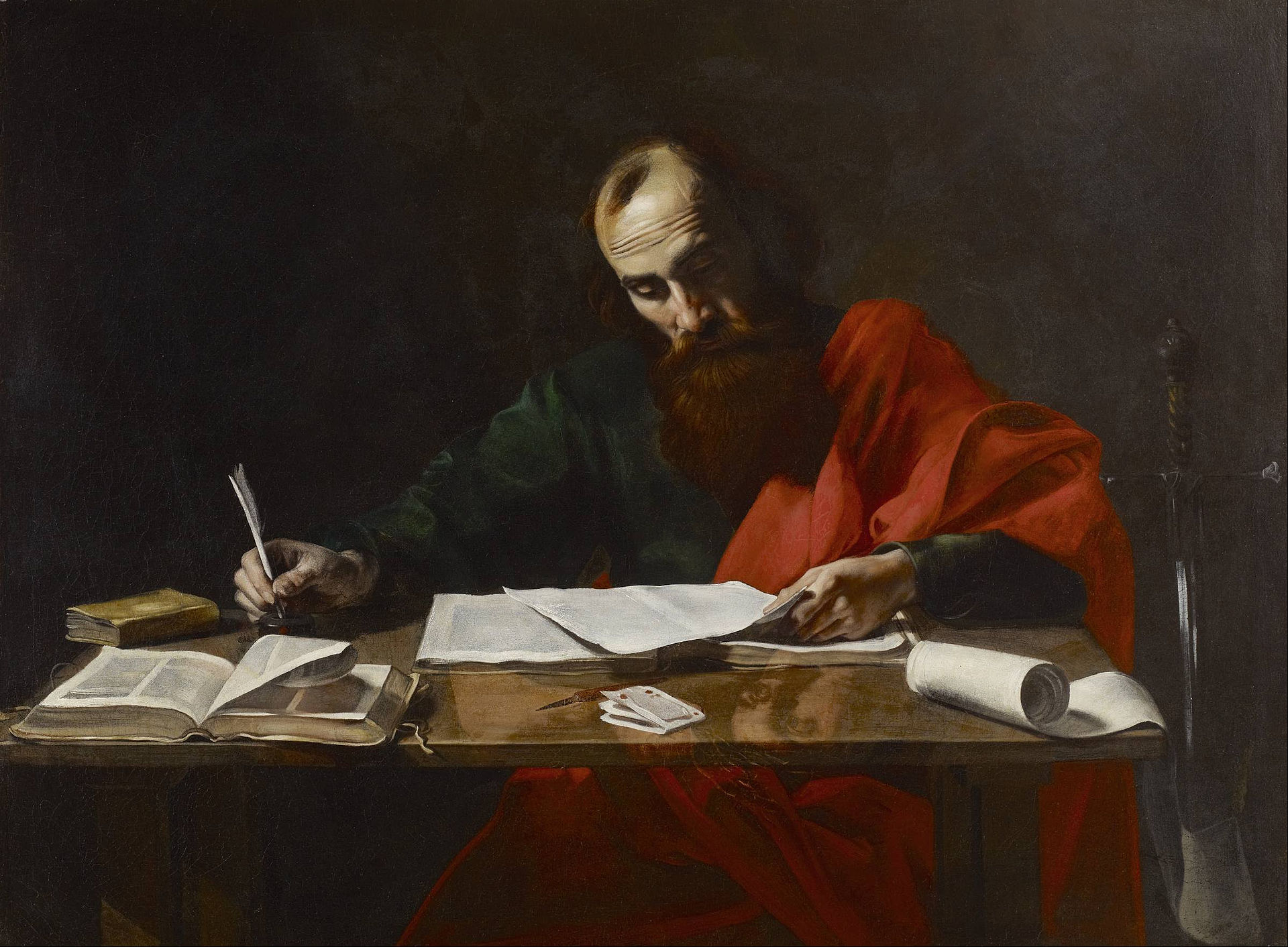

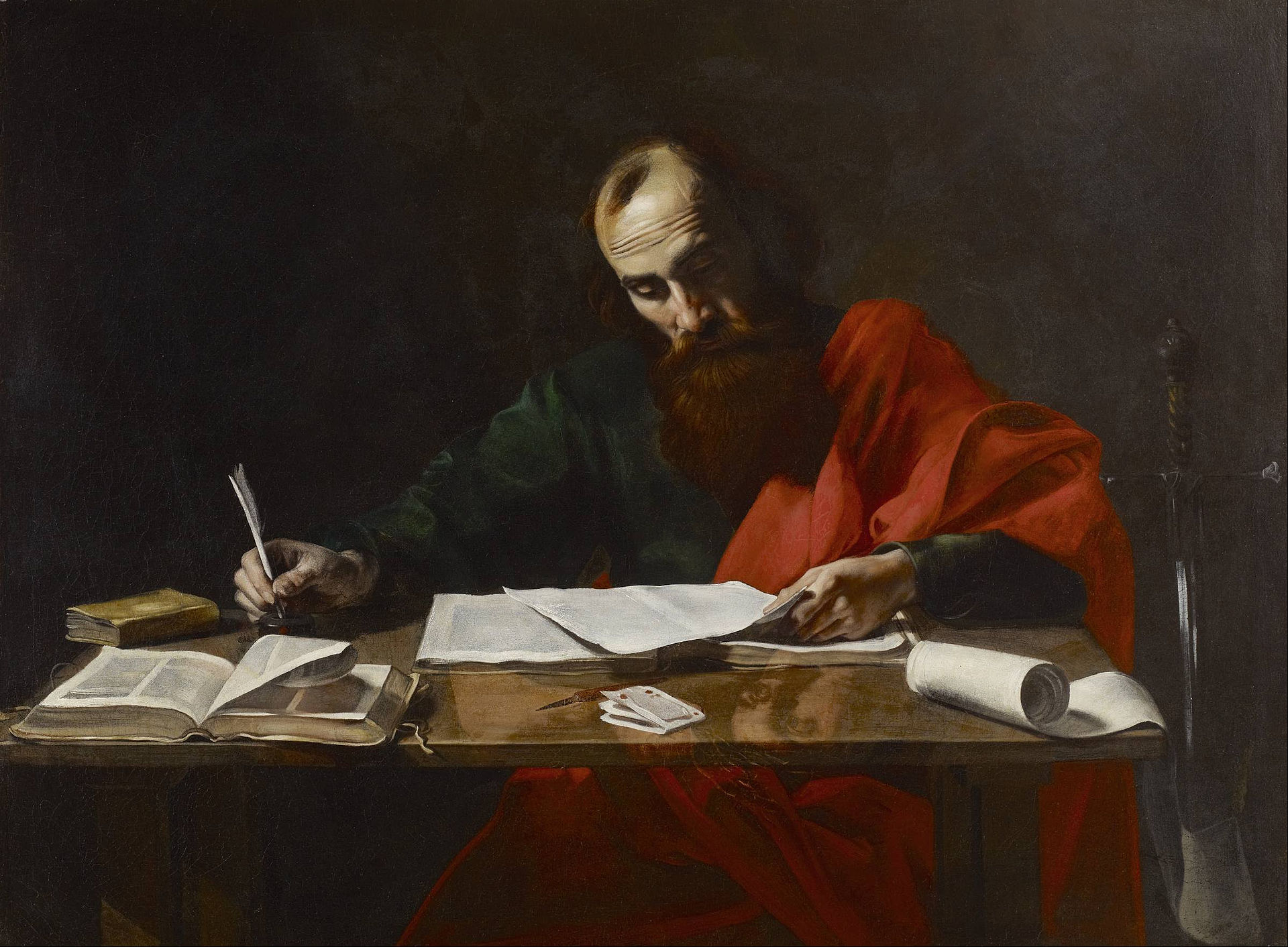

Writing  A statue of St. Paul in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran by Pierre-Étienne Monnot Of the 27 books in the New Testament, 13 identify Paul as the author; seven of these are widely considered authentic and Paul's own, while the authorship of the other six is disputed.[231][232][233] The undisputed letters are considered the most important sources since they contain what is widely agreed to be Paul's own statements about his life and thoughts. Theologian Mark Powell writes that Paul directed these seven letters to specific occasions at particular churches. As an example, if the Corinthian church had not experienced problems concerning its celebration of the Lord's Supper,[234] today it would not be known that Paul even believed in that observance or had any opinions about it one way or the other. Powell comments that there may be other matters in the early church that have since gone unnoticed simply because no crises arose that prompted Paul to comment on them.[235] In Paul's writings, he provides the first written account of what it is to be a Christian and thus a description of Christian spirituality. His letters have been characterized as being the most influential books of the New Testament after the Gospels of Matthew and John.[8][note 9] Date Paul's authentic letters are roughly dated to the years surrounding the mid-1st century. Placing Paul in this time period is done on the basis of his reported conflicts with other early contemporary figures in the Jesus movement including James and Peter,[236] the references to Paul and his letters by Clement of Rome writing in the late 1st century,[237] his reported issues in Damascus from 2 Corinthians 11:32 which he says took place while King Aretas IV was in power,[238] a possible reference to Erastus of Corinth in Romans 16:23,[239] his reference to preaching in the province of Illyricum (which dissolved in 80 AD),[240] the lack of any references to the Gospels indicating a pre-war time period, the chronology in the Acts of the Apostles placing Paul in this time, and the dependence on Paul's letters by other 1st-century pseudo-Pauline epistles.[241] Authorship Main article: Authorship of the Pauline epistles  Paul Writing His Epistles, a 17th portrait by Valentin de Boulogne  Russian Orthodox icon of the Apostle Paul, an 18th-century iconostasis of Jesus' transfiguration in the Kizhi Monastery in Karelia, Russia Seven of the 13 letters that bear Paul's name, Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon, are almost universally accepted as being entirely authentic and dictated by Paul himself.[8][231][232][233] They are considered the best source of information on Paul's life and especially his thought.[8] Four of the letters (Ephesians, 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus) are widely considered pseudepigraphical, while the authorship of the other two is subject to debate.[231] Colossians and 2 Thessalonians are possibly "Deutero-Pauline" meaning they may have been written by Paul's followers after his death. Similarly, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus may be "Trito-Pauline" meaning they may have been written by members of the Pauline school a generation after his death. According to their theories, these disputed letters may have come from followers writing in Paul's name, often using material from his surviving letters. These scribes also may have had access to letters written by Paul that no longer survive.[8] The authenticity of Colossians has been questioned on the grounds that it contains an otherwise unparalleled description (among his writings) of Jesus as "the image of the invisible God", a Christology found elsewhere only in the Gospel of John.[242] However, the personal notes in the letter connect it to Philemon, unquestionably the work of Paul. Internal evidence shows close connection with Philippians.[31] Ephesians is a letter that is very similar to Colossians but is almost entirely lacking in personal reminiscences. Its style is unique. It lacks the emphasis on the cross to be found in other Pauline writings, reference to the Second Coming is missing, and Christian marriage is exalted in a way that contrasts with the reference in 1 Corinthians.[243] Finally, according to R. E. Brown, it exalts the Church in a way suggestive of the second generation of Christians, "built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets" now past.[244] The defenders of its Pauline authorship argue that it was intended to be read by a number of different churches and that it marks the final stage of the development of Paul's thinking. It has been said, too, that the moral portion of the Epistle, consisting of the last two chapters, has the closest affinity with similar portions of other Epistles, while the whole admirably fits in with the known details of Paul's life, and throws considerable light upon them.[245] Three main reasons have been advanced by those who question Paul's authorship of 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus, also known as the Pastoral Epistles: They have found a difference in these letters' vocabulary, style, and theology from Paul's acknowledged writings. Defenders of the authenticity say that they were probably written in the name and with the authority of the Apostle by one of his companions, to whom he distinctly explained what had to be written, or to whom he gave a written summary of the points to be developed, and that when the letters were finished, Paul read them through, approved them, and signed them.[245] There is a difficulty in fitting them into Paul's biography as it is known.[246] They, like Colossians and Ephesians, were written from prison but suppose Paul's release and travel thereafter.[31] 2 Thessalonians, like Colossians, is questioned on stylistic grounds with, among other peculiarities, a dependence on 1 Thessalonians—yet a distinctiveness in language from the Pauline corpus. This, again, is explainable by the possibility that Paul requested one of his companions to write the letter for him under his dictation.[31] Acts Although approximately half of the Acts of the Apostles deals with Paul's life and works, Acts does not refer to Paul writing letters. Historians believe that the author of Acts did not have access to any of Paul's letters. One piece of evidence suggesting this is that Acts never directly quotes from the Pauline epistles. Discrepancies between the Pauline epistles and Acts would further support the conclusion that the author of Acts did not have access to those epistles when composing Acts.[247][248] British Jewish scholar Hyam Maccoby contended that Paul, as described in the Acts of the Apostles, is quite different from the view of Paul gleaned from his own writings. Some difficulties have been noted in the account of his life. Paul as described in the Acts of the Apostles is much more interested in factual history, less in theology; ideas such as justification by faith are absent as are references to the Spirit, according to Maccoby. He also pointed out that there are no references to John the Baptist in the Pauline Epistles, although Paul mentions him several times in the Acts of the Apostles. Others have objected that the language of the speeches is too Lukan in style to reflect anyone else's words. Moreover, George Shillington writes that the author of Acts most likely created the speeches accordingly and they bear his literary and theological marks.[249] Conversely, Howard Marshall writes that the speeches were not entirely the inventions of the author and while they may not be accurate word-for-word, the author nevertheless records the general idea of them.[250] F. C. Baur (1792–1860), professor of theology at Tübingen in Germany, the first scholar to critique Acts and the Pauline Epistles, and founder of the Tübingen School of theology, argued that Paul, as the "Apostle to the Gentiles", was in violent opposition to the original 12 Apostles. Baur considers the Acts of the Apostles were late and unreliable. This debate has continued ever since, with Adolf Deissmann (1866–1937) and Richard Reitzenstein (1861–1931) emphasising Paul's Greek inheritance and Albert Schweitzer stressing his dependence on Judaism. |

著作 ピエール=エティエンヌ・モノによる聖ヨハネ・ラテラノ大寺院の聖パウロ像 新約聖書の27の書物のうち、13の書物がパウロを著者としている。そのうちの7つの書簡はパウロ自身のものであり、真正であると広く考えられているが、 残りの6つの書簡の著者については論争がある[231][232][233]。神学者マーク・パウエルは、パウロはこれらの7つの手紙を特定の教会におけ る特定の機会に宛てて書いたと書いている。例えば、もしコリント教会が主の晩餐の祝いに関して問題を経験していなければ[234]、今日、パウロが主の晩 餐の儀式を信じていたことや、それについて何らかの意見を持っていたことすら知られていなかっただろう。パウエルは、パウロがそれについてコメントするよ うな危機が起こらなかったために、その後気づかれなくなった事柄が初代教会には他にもあるかもしれないとコメントしている[235]。 パウロの著作の中で、彼は、キリスト者であることが何であるか、したがってキリスト者の霊性についての最初の記述を提供している。彼の書簡は、マタイとヨ ハネの福音書に次いで新約聖書の中で最も影響力のある書物であると特徴づけられている[8][注釈 9]。 年代 パウロの真正な手紙の年代は、おおよそ1世紀半ば頃とされている。この時代にパウロを置くことは、ヤコブとペテロを含むイエス運動における他の初期の同時 代の人物との衝突の報告[236]、1世紀後半に書かれたローマのクレメンスによるパウロと彼の手紙への言及[237]、2コリント11:32からダマス コでの彼の報告された問題であり、それはアレタス4世が権力を握っていた時に起こったと彼が言っている[238]、ローマ16: ローマ人への手紙16章23節にあるコリントのエラストゥスへの言及の可能性、[239]イリュリクム州(紀元80年に解散)での説教への言及、 [240]戦前の時代であることを示す福音書への言及の欠如、パウロをこの時代に位置づける使徒言行録の年表、他の1世紀の偽パウロ書簡によるパウロの書 簡への依存。 [241] 作者 主な記事 パウロ書簡の著者について  書簡を書くパウロ、ヴァレンティン・ド・ブローニュによる17世紀の肖像画  ロシア正教の使徒パウロのイコン、ロシア、カレリアのキジ修道院にある18世紀のイエスの変容のイコノスタシス。 パウロの名を冠した13通の手紙のうち、ローマ人への手紙、第一コリント人への手紙、第二コリント人への手紙、ガラテヤ人への手紙、ピリピ人への手紙、第 一テサロニケ人への手紙、ピレモン人への手紙の7通は、パウロ自身が口述したものであり、すべて本物であるとほぼ普遍的に受け入れられている[8] [231][232][233]。 エペソ人への手紙、テモテへの手紙、テトスへの手紙の4通は偽書と広く考えられているが、他の2通の著者については議論がある[231]。同様に、テモテ への手紙一、テモテへの手紙二、テトスへの手紙は、パウロの死後、パウロ派の人々によって書かれた「トリト・パウロ的」なものである可能性がある。彼らの 説によれば、これらの論争の的になっている手紙は、パウロの名を借りて、しばしばパウロの現存する手紙から引用して書いた信奉者たちによって書かれた可能 性がある。また、これらの書記たちは、現存しないパウロが書いた書簡を入手していた可能性もある[8]。 コロサイの信徒への手紙の信憑性は、イエスが「目に見えない神のかたち」であるという(パウロの著作の中では)他に類を見ない記述を含んでいるという理由 で疑問視されてきた。内的証拠はピリピ人への手紙との密接な関係を示している[31]。 エフェソの信徒への手紙は、コロサイの信徒への手紙とよく似ているが、個人的な回想はほとんどない。その文体は独特である。他のパウロの手紙に見られるよ うな十字架の強調がなく、再臨への言及が欠けており、キリスト者の結婚が第一コリントの手紙の言及とは対照的な形で称揚されている[243]。最後に、 R.E.ブラウンによれば、この手紙は、過ぎ去った「使徒と預言者の土台の上に建てられた」第二世代のクリスチャンを示唆するような形で教会を称揚してい る[244]。 パウロの作者であることを擁護する人々は、この書が多くの異なる教会によって読まれることを意図しており、パウロの思想の発展の最終段階を示すものである と主張している。また、最後の2章からなるこの手紙の道徳的な部分は、他の手紙の同様の部分と最も親和性が高く、全体はパウロの生涯の既知の詳細と見事に 一致し、それらにかなりの光を投げかけていると言われている[245]。 牧会書簡としても知られているテモテへの手紙一、テモテへの手紙二、テトスへの手紙のパウロの著者に疑問を呈する人々によって、三つの主な理由が唱えられ てきた: それは、これらの書簡の語彙、文体、神学がパウロの著作と異なることである。真正性を擁護する人々は、これらの書簡はおそらく使徒の名において、また使徒 の権威のもとに、使徒の仲間の一人が書いたものであり、使徒はその一人に対して、書かなければならないことを明確に説明し、あるいは展開されるべきポイン トの要約を文書で与え、書簡が完成したときに、パウロはそれを通読し、承認し、署名したと述べている[245]。 コロサイ人への手紙』や『エペソ人への手紙』と同様に、獄中から書かれたものであるが、パウロが釈放され、その後旅に出たと仮定している[31]。 テサロニケ人への手紙二章は、コロサイ人への手紙二章と同様に、文体的な理由から疑問視されている。この点についても、パウロが仲間の一人に頼んで、口述 筆記で手紙を書かせたという可能性で説明できる[31]。 使徒言行録 使徒言行録の約半分はパウロの生涯と業績について書かれているが、使徒言行録にはパウロが手紙を書いたという記述はない。歴史家たちは、使徒言行録の著者 はパウロの手紙に接していなかったと考えている。それを示唆する証拠の一つは、使徒言行録がパウロの書簡を直接引用していないことである。パウロ書簡と使 徒言行録の間に食い違いがあることは、使徒言行録の作者が使徒言行録を作成する際にパウロ書簡に接していなかったという結論をさらに裏付けることになる [247][248]。 イギリスのユダヤ人学者ハイアム・マコビーは、使徒言行録に記述されているパウロは、彼自身の著作から得られたパウロ観とはかなり異なっていると主張し た。パウロの生涯に関する記述にはいくつかの難点が指摘されている。マコビーによれば、使徒言行録に記されているパウロは、事実に基づいた歴史に関心が高 く、神学的な記述は少ない。彼はまた、パウロは使徒言行録の中で何度もバプテスマのヨハネに言及しているにもかかわらず、パウロ書簡にはバプテスマのヨハ ネに関する記述がないことも指摘している。 また、演説の言葉がルカ風であり、他の誰の言葉でもないと反論する人もいる。さらに、ジョージ・シリントンは、使徒言行録の著者がこの演説を創作した可能 性が最も高く、彼の文学的、神学的な痕跡が残っていると書いている[249]。逆に、ハワード・マーシャルは、この演説は完全に著者の創作ではなく、一字 一句正確ではないかもしれないが、それでも著者は演説の一般的な考えを記録していると書いている[250]。 F. ドイツのチュービンゲン神学教授であり、使徒言行録とパウロの書簡を初めて批判した学者であり、チュービンゲン神学学派の創設者であるC.バウルは、パウ ロは「異邦人への使徒」として、本来の12使徒と激しく対立していたと主張した。バウルは使徒言行録は後世のものであり、信憑性に欠けると考えた。この論 争はその後も続き、アドルフ・ダイスマン(1866-1937)とリヒャルト・ライトゼンシュタイン(1861-1931)はパウロのギリシア人としての 遺伝を強調し、アルベルト・シュヴァイツァーはユダヤ教への依存を強調した。 |