プラークシスあるいは実践

praxis

☆ Praxis とは、理論、教訓、技能が制定され、具体化され、実現され、適用され、実践されるプロセスのことである。 "Praxis "はまた、アイデアに関与し、適用し、行使し、実現し、実践する行為を指すこともある。

| Praxis is the process

by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, embodied, realized,

applied, or put into practice. "Praxis" may also refer to the

act of engaging, applying, exercising, realizing, or practising ideas.

This has been a recurrent topic in the field of philosophy, discussed

in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, Francis Bacon,

Immanuel Kant, Søren Kierkegaard, Ludwig von Mises, Karl Marx, Antonio

Gramsci, Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, Jean-Paul Sartre, Paulo

Freire, Murray Rothbard, and many others. It has meaning in the

political, educational, spiritual and medical realms. ■人間の経験=知のあり方(アリストテレス)  |

Praxis

とは、理論、教訓、技能が制定され、具体化され、実現され、適用され、実践されるプロセスのことである。 "Praxis

"はまた、アイデアに関与し、適用し、行使し、実現し、実践する行為を指すこともある。プラトン、アリストテレス、聖アウグスティヌス、フランシス・ベー

コン、イマヌエル・カント、セーレン・キェルケゴール、ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼス、カール・マルクス、アントニオ・グラムシ、マルティン・ハイデ

ガー、ハンナ・アーレント、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、パウロ・フレイレ、マレー・ロスバード、その他多くの人々の著作で論じられている。政治的、教育

的、精神的、医学的な領域で意味を持つ。 ■人間の経験=知のあり方(アリストテレス)  |

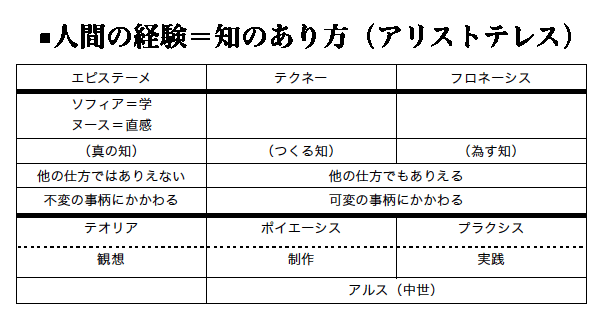

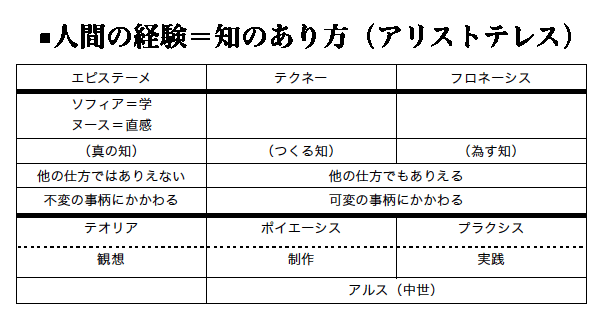

| Origins The word praxis is from Ancient Greek: πρᾶξις, romanized: praxis. In Ancient Greek the word praxis (πρᾶξις) referred to activity engaged in by free people. The philosopher Aristotle held that there were three basic activities of humans: theoria (thinking), poiesis (making), and praxis (doing). Corresponding to these activities were three types of knowledge: theoretical, the end goal being truth; poietical, the end goal being production; and practical, the end goal being action.[1] Aristotle further divided the knowledge derived from praxis into ethics, economics, and politics. He also distinguished between eupraxia (εὐπραξία, "good praxis")[2] and dyspraxia (δυσπραξία, "bad praxis, misfortune").[3] |

語源 プラクシス(praxis)という言葉は、古代ギリシャ語のπρǶξις(ローマ字表記:プラクシス)に由来する。古代ギリシャ語でプラクシス (πρǶξις)という言葉は、自由な人々が行う活動を指していた。哲学者アリストテレスは、人間には3つの基本的な活動、すなわちテオリア(考えるこ と)、ポイエーシス(作ること)、プラクシス(行うこと)があるとした。アリストテレスはさらに、プラクシスから得られる知識を倫理学、経済学、政治学に 分けた。彼はまた、eupraxia(εŐπραξία、「良いプラクシス」)[2]とdyspraxia(δυσπραξία、「悪いプラクシス、不 幸」)を区別した[3]。 |

| Marxism Young Hegelian August Cieszkowski was one of the earliest philosophers to use the term praxis to mean "action oriented towards changing society" in his 1838 work Prolegomena zur Historiosophie (Prolegomena to a Historiosophy).[4] Cieszkowski argued that while absolute truth had been achieved in the speculative philosophy of Hegel, the deep divisions and contradictions in man's consciousness could only be resolved through concrete practical activity that directly influences social life.[4] Although there is no evidence that Karl Marx himself read this book,[5] it may have had an indirect influence on his thought through the writings of his friend Moses Hess.[6][7]  Anarchist banner in Dresden, Germany, translating to "Solidarity must become praxis", 20 January 2020 Marx uses the term "praxis" to refer to the free, universal, creative and self-creative activity through which man creates and changes his historical world and himself.[8] Praxis is an activity unique to man, which distinguishes him from all other beings.[8] The concept appears in two of Marx's early works: the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and the Theses on Feuerbach (1845).[5] In the former work, Marx contrasts the free, conscious productive activity of human beings with the unconscious, compulsive production of animals.[5] He also affirms the primacy of praxis over theory, claiming that theoretical contradictions can only be resolved through practical activity.[5] In the latter work, revolutionary practice is a central theme: The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-change [Selbstveränderung] can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice. (3rd thesis)[9] All social life is essentially practical. All the mysteries which lead theory towards mysticism find their rational solution in human praxis and in the comprehension of this praxis. (8th thesis)[9] Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it. (11th thesis)[9] Marx here criticizes the materialist philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach for envisaging objects in a contemplative way. Marx argues that perception is itself a component of man's practical relationship to the world. To understand the world does not mean considering it from the outside, judging it morally or explaining it scientifically. Society cannot be changed by reformers who understand its needs, only by the revolutionary praxis of the mass whose interest coincides with that of society as a whole—the proletariat. This will be an act of society understanding itself, in which the subject changes the object by the very fact of understanding it.[10] Seemingly inspired by the Theses, the nineteenth century socialist Antonio Labriola called Marxism the "philosophy of praxis".[11] This description of Marxism would appear again in Antonio Gramsci's Prison Notebooks[11] and the writings of the members of the Frankfurt School.[12][13] Praxis is also an important theme for Marxist thinkers such as Georg Lukacs, Karl Korsch, Karel Kosik and Henri Lefebvre, and was seen as the central concept of Marx's thought by Yugoslavia's Praxis School, which established a journal of that name in 1964.[13] |

マルクス主義 若きヘーゲル主義者アウグスト・チエシュコフスキは、1838年に発表した『歴史哲学へのプロレゴメナ(Prolegomena zur Historiosophie)』において、「社会を変えるための行動」を意味する「プラクシス(praxis)」という言葉を最も早く用いた哲学者の一 人である。 [カール・マルクス自身がこの本を読んだという証拠はないが[5]、彼の友人モーゼス・ヘスの著作を通じて彼の思想に間接的な影響を与えた可能性がある [6][7]。  連帯はプラクシスとならなければならない」と訳されたドイツ、ドレスデンのアナキストの横断幕(2020年1月20日) マルクスは「プラクシス」という用語を、人間が歴史的世界と自分自身を創造し、変化させる、自由で普遍的で創造的で自己創造的な活動を指すのに用いている [8]。プラクシスは人間に固有の活動であり、人間を他のすべての存在から区別するものである[8]。この概念はマルクスの初期の著作の2つ、1844年 の『経済哲学手稿』と1845年の『フォイエルバッハに関するテーゼ』に登場する。 [前者の著作では、マルクスは人間の自由で意識的な生産活動を動物の無意識的で強制的な生産活動と対比している[5] : 状況の変化と人間の活動あるいは自己の変化[Selbstveränderung]の一致は、革命的実践としてのみ構想され、合理的に理解されうる。(第3テーゼ)[9]。 すべての社会生活は本質的に実践的である。理論を神秘主義へと導くすべての謎は、人間の実践とこの実践の理解のうちにその合理的解決を見出す。(第8テーゼ)[9] 哲学者はこれまで、世界をさまざまに解釈してきたにすぎない。(第11テーゼ)[9] マルクスはここで、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの唯物論哲学が対象を観照的に想定していることを批判している。マルクスは、認識それ自体が人間の世界 に対する実践的関係の構成要素であると主張する。世界を理解するということは、世界を外側から考察したり、道徳的に判断したり、科学的に説明したりするこ とではない。社会は、その必要性を理解する改革者たちによって変えられるのではなく、社会全体と利害が一致する大衆、すなわちプロレタリアートの革命的実 践によってのみ変えられるのである。これは、社会が自分自身を理解する行為であり、主体が対象を理解するというまさにその事実によって対象を変えるのであ る[10]。 このテーゼに触発されたかのように、19世紀の社会主義者アントニオ・ラブリオラはマルクス主義を「プラクティスの哲学」と呼んだ。 [12][13]プラクシスはゲオルク・ルカックス、カール・コルシュ、カレル・コシク、アンリ・ルフェーヴルといったマルクス主義の思想家にとっても重 要なテーマであり、1964年にその名の雑誌を創刊したユーゴスラビアのプラクシス学派によってマルクスの思想の中心的な概念とみなされていた[13]。 |

| Jean-Paul Sartre In the Critique of Dialectical Reason, Jean-Paul Sartre posits a view of individual praxis as the basis of human history.[14] In his view, praxis is an attempt to negate human need.[15] In a revision of Marxism and his earlier existentialism,[16] Sartre argues that the fundamental relation of human history is scarcity.[17] Conditions of scarcity generate competition for resources, exploitation of one over another and division of labor, which in its turn creates struggle between classes. Each individual experiences the other as a threat to his or her own survival and praxis; it is always a possibility that one's individual freedom limits another's.[18] Sartre recognizes both natural and man-made constraints on freedom: he calls the non-unified practical activity of humans the "practico-inert".[14] Sartre opposes to individual praxis a "group praxis" that fuses each individual to be accountable to each other in a common purpose.[19] Sartre sees a mass movement in a successful revolution as the best exemplar of such a fused group.[20] |

ジャン=ポール・サルトル ジャン=ポール・サルトルは『弁証法的理性批判』の中で、人間の歴史の基礎として個人のプラクシス(実践)という見方を提唱している。彼の見解では、プラ クシスとは人間の欲求を否定する試みである。サルトルは、マルクス主義とそれ以前の実存主義を修正し、人間の歴史の基本的な関係は欠乏であると主張する。 欠乏の状況は、資源をめぐる競争、ある者の他の者に対する搾取、分業を生み、それが階級間の闘争を生み出す。各個人は、他者を自らの生存と実践に対する脅 威として経験する。個人の自由が他者の自由を制限する可能性は常にある。サルトルは、自由に対する自然的な制約と人為的な制約の両方を認めている。彼は、 人間の非一元的な実践活動を「実践的不活性」と呼んでいる。サルトルは個人のプラクシスに対して、各個人が共通の目的の中で互いに説明責任を果たすように 融合する「集団のプラクシス」に反対する。サルトルは、成功した革命における大衆運動を、そのような融合した集団の最良の模範と見なしている。 |

| Hannah Arendt In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt argues that Western philosophy too often has focused on the contemplative life (vita contemplativa) and has neglected the active life (vita activa). This has led humanity to frequently miss much of the everyday relevance of philosophical ideas to real life.[21][22] For Arendt, praxis is the highest and most important level of the active life.[22] Thus, she argues that more philosophers need to engage in everyday political action or praxis, which she sees as the true realization of human freedom.[21] According to Arendt, our capacity to analyze ideas, wrestle with them, and engage in active praxis is what makes us uniquely human. In Maurizio Passerin d'Etreves's estimation, "Arendt's theory of action and her revival of the ancient notion of praxis represent one of the most original contributions to twentieth century political thought. ... Moreover, by viewing action as a mode of human togetherness, Arendt is able to develop a conception of participatory democracy which stands in direct contrast to the bureaucratized and elitist forms of politics so characteristic of the modern epoch."[23] |

ハンナ・アーレント ハンナ・アーレントは『人間の条件』の中で、西洋哲学はあまりにもしばしば観想的生活(vita contemplativa)に焦点を当て、活動的生活(vita activa)を軽視してきたと論じている。このため人類は、哲学的な考え方が現実の生活と日常的に関連することをしばしば見逃してきた。] アーレントにとって、プラクティスは活動的生活の最高かつ最も重要なレベルである。したがって彼女は、より多くの哲学者が日常的な政治的行動やプラクティ スに従事する必要があると主張する。アーレントによれば、思想を分析し、それと格闘し、能動的なプラクシス(実践)に取り組む能力こそが、人間を人間たら しめているのである。 マウリツィオ・パセリン・デトリーブスの評価では、「アーレントの行動論と、彼女が古くからあるプラクシスという概念を復活させたことは、20世紀の政治 思想における最も独創的な貢献のひとつである。... さらに、行動を人間の一体性の様式とみなすことによって、アーレントは参加型民主主義の概念を展開することができた。"それは、近代という時代に特徴的な 官僚主義的でエリート主義的な政治形態とは正反対のものである。 |

| Education Praxis is used by educators to describe a recurring passage through a cyclical process of experiential learning, such as the cycle described and popularised by David A. Kolb.[24] Paulo Freire defines praxis in Pedagogy of the Oppressed as "reflection and action directed at the structures to be transformed."[25] Through praxis, oppressed people can acquire a critical awareness of their own condition, and, with teacher-students and students-teachers, struggle for liberation.[26] In the British Channel 4 television documentary New Order: Play at Home,[27][28] Factory Records owner Tony Wilson describes praxis as "doing something, and then only afterwards, finding out why you did it". Praxis may be described as a form of critical thinking and comprises the combination of reflection and action. Praxis can be viewed as a progression of cognitive and physical actions: Taking the action Considering the impacts of the action Analysing the results of the action by reflecting upon it Altering and revising conceptions and planning following reflection Implementing these plans in further actions This creates a cycle which can be viewed in terms of educational settings, learners and educational facilitators. Scott and Marshall (2009) refer to praxis as "a philosophical term referring to human action on the natural and social world"[citation needed]. Furthermore, Gramsci (1999) emphasises the power of praxis in Selections from the Prison Notebooks by stating that "The philosophy of praxis does not tend to leave the simple in their primitive philosophy of common sense but rather to lead them to a higher conception of life". To reveal the inadequacies of religion, folklore, intellectualism and other such 'one-sided' forms of reasoning, Gramsci appeals directly in his later work to Marx's 'philosophy of praxis', describing it as a 'concrete' mode of reasoning. This principally involves the juxtaposition of a dialectical and scientific audit of reality; against all existing normative, ideological, and therefore counterfeit accounts. Essentially a 'philosophy' based on 'a practice', Marx's philosophy, is described correspondingly in this manner, as the only 'philosophy' that is at the same time a 'history in action' or a 'life' itself (Gramsci, Hoare and Nowell-Smith, 1972, p. 332). |

教育 プラクシスとは、デビッド・A・コルブによって記述され、一般化されたサイクルのような、経験的学習の循環的なプロセスを繰り返し通過することを表現するために教育者によって使用される[24]。 パウロ・フレイレは『被抑圧者の教育学』において、プラクシスとは「変革されるべき構造に向けられた反省と行動」であると定義している[25]。プラクシ スを通じて、抑圧された人々は自らの状態に対する批判的認識を獲得し、教師と生徒、生徒と教師とともに、解放のために闘うことができる[26]。 イギリスのチャンネル4のテレビドキュメンタリー『ニュー・オーダー』では、[27][28]: ファクトリー・レコードのオーナーであるトニー・ウィルソンは、プラクシスとは「何かをすること、そしてその後に初めて、なぜそれをしたのかを知ること」 であると述べている[27][28]。 プラクシスとは、批判的思考の一形態であり、内省と行動の組み合わせである。プラクシスとは、認知的行動と身体的行動の進行とみなすことができる: 行動を起こす 行動の影響を考える 行動を振り返り、その結果を分析する。 反省の結果、概念や計画を変更・修正する。 これらの計画をさらなる行動に移す このサイクルは、教育現場、学習者、教育ファシリテーターの観点から見ることができる。 ScottとMarshall(2009)は、プラクシス(praxis)を「自然および社会的世界に対する人間の行動を指す哲学用語」[要出典]と呼ん でいる。さらに、グラムシ(1999)は『獄中ノートからの選択』の中で、「プラクシスの哲学は、単純な人々を常識という原始的な哲学の中に置き去りにす るのではなく、むしろより高次の人生観へと導く傾向がある」と述べ、プラクシスの力を強調している。 宗教、民俗学、知識主義、その他の「一面的な」推論形態の不十分さを明らかにするために、グラムシは後の著作でマルクスの「実践哲学」に直接訴え、それを 「具体的な」推論様式と表現している。これは、主として、弁証法的かつ科学的な現実の監査を並置することを含む;既存のすべての規範的、イデオロギー的、 したがって偽造的な説明に対して。本質的に「実践」に基づく「哲学」であるマルクスの哲学は、このように、同時に「行動する歴史」あるいは「人生」そのも のである唯一の「哲学」である(Gramsci, Hoare and Nowell-Smith, 1972, p.332)。 |

| Spirituality See also: Praxis (Eastern Orthodoxy) Praxis is also key in meditation and spirituality, where emphasis is placed on gaining first-hand experience of concepts and certain areas, such as union with the Divine, which can only be explored through praxis due to the inability of the finite mind (and its tool, language) to comprehend or express the infinite. In an interview for YES! Magazine, Matthew Fox explained it this way: Wisdom is always taste—in both Latin and Hebrew, the word for wisdom comes from the word for taste—so it's something to taste, not something to theorize about. "Taste and see that God is good", the psalm says; and that's wisdom: tasting life. No one can do it for us. The mystical tradition is very much a Sophia tradition. It is about tasting and trusting experience, before institution or dogma.[29] According to Strong's Concordance, the Hebrew word ta‛am is, properly, a taste. This is, figuratively, perception and, by implication, intelligence; transitively, a mandate: advice, behaviour, decree, discretion, judgment, reason, taste, understanding. |

スピリチュアリティ こちらも参照のこと: プラクシス(東方正教会) 瞑想やスピリチュアリティにおいても、プラクティスは重要な鍵を握っている。そこでは、概念や、神との合一など、プラクティスを通じてのみ探求できる特定 の領域について、実体験を得ることが重視される。YES.誌のインタビューで、マシュー・フォックスはこのように説明している!誌のインタビューで、マ シュー・フォックスはこのように説明している: ラテン語でもヘブライ語でも、知恵の語源は味覚である。「神は良い方であることを味わって見よ」と詩篇にある。それは知恵であり、人生を味わうことである。神秘主義の伝統は非常にソフィアの伝統である。それは制度や教義よりも、経験を味わい、信頼することである[29]。 ストロングのコンコーダンスによれば、ヘブライ語のta‛amは正しくは「味」である。これは比喩的には知覚であり、暗示的には知性であり、推移的には命令である。 |

| Medicine Praxis is the ability to perform voluntary skilled movements. The partial or complete inability to do so in the absence of primary sensory or motor impairments is known as apraxia.[30] |

医学 プラクシスとは、自発的に熟練した動作を行う能力のことである。一次的な感覚障害や運動障害がないにもかかわらず、そのような動作が部分的または完全にできないことは、失行と呼ばれる[30]。 |

| Apraxia Christian theological praxis Hexis Lex artis Orthopraxy Praxeology Praxis Discussion Series Praxis (disambiguation) Praxis intervention Praxis school Practice (social theory) Theses on Feuerbach |

失行 キリスト教神学的実践 ヘクシス レクス・アーティス オーソプラクシス プラクセオロジー プラクシス討論シリーズ Praxis (曖昧さ回避) Praxis介入 Praxisスクール プラクティス(社会理論) フォイエルバッハに関するテーゼ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Praxis_(process) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆