儀礼

Ritual

☆

儀式とは、身振り、言葉、行動、または崇敬対象物を含む一連の活動のことである[1][2]。儀式は、宗教的共同体を含む共同体の伝統によって規定される

ことがある。儀式は、形式主義、伝統主義、不変性、ルール・ガバナンス、聖なる象徴主義、パフォーマンスによって特徴づけられるが、定義されるわけではな

い[3]。

儀礼には、組織化された宗教やカルトの礼拝儀礼や秘跡だけでなく、通過儀礼、贖罪や浄化の儀礼、忠誠の誓い、奉納儀礼、戴冠式や大統領就任式、結婚、葬儀

なども含まれる。握手や挨拶のような一般的な行為でさえ、儀式と呼べるかもしれない。

儀式研究の分野では、この用語の定義がいくつも対立している。キリアキディスによる一つの定義は、儀式とは、部外者にとっては非合理的、非連続的、あるい

は非論理的に見える一連の活動(あるいは一連の行為)に対する部外者の、あるいは「エティック」なカテゴリーである、というものである。この用語は、この

活動が不慣れな傍観者にはそのように見えることを認めるものとして、内部者または「エミック」なパフォーマティによっても使用されることがある[5]。

心理学では、儀式という用語は、不安を中和または予防するために人が体系的に用いる反復的な行動に対して専門的な意味で用いられることがある。強迫性障害

の症状であることもあるが、強迫的儀式的行動は一般的に孤立した活動である。

| A ritual is a

sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or revered

objects.[1][2] Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a

community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized,

but not defined, by formalism, traditionalism, invariance,

rule-governance, sacral symbolism, and performance.[3] Rituals are a feature of all known human societies.[4] They include not only the worship rites and sacraments of organized religions and cults, but also rites of passage, atonement and purification rites, oaths of allegiance, dedication ceremonies, coronations and presidential inaugurations, marriages, funerals and more. Even common actions like hand-shaking and saying "hello" may be termed as rituals. The field of ritual studies has seen a number of conflicting definitions of the term. One given by Kyriakidis is that a ritual is an outsider's or "etic" category for a set activity (or set of actions) that, to the outsider, seems irrational, non-contiguous, or illogical. The term can be used also by the insider or "emic" performer as an acknowledgement that this activity can be seen as such by the uninitiated onlooker.[5] In psychology, the term ritual is sometimes used in a technical sense for a repetitive behavior systematically used by a person to neutralize or prevent anxiety; it can be a symptom of obsessive–compulsive disorder but obsessive-compulsive ritualistic behaviors are generally isolated activities. |

儀式とは、身振り、言葉、行動、または崇敬対象物を含む一連の活動のこ

とである[1][2]。儀式は、宗教的共同体を含む共同体の伝統によって規定されることがある。儀式は、形式主義、伝統主義、不変性、ルール・ガバナン

ス、聖なる象徴主義、パフォーマンスによって特徴づけられるが、定義されるわけではない[3]。 儀礼には、組織化された宗教やカルトの礼拝儀礼や秘跡だけでなく、通過儀礼、贖罪や浄化の儀礼、忠誠の誓い、奉納儀礼、戴冠式や大統領就任式、結婚、葬儀 なども含まれる。握手や挨拶のような一般的な行為でさえ、儀式と呼べるかもしれない。 儀式研究の分野では、この用語の定義がいくつも対立している。キリアキディスによる一つの定義は、儀式とは、部外者にとっては非合理的、非連続的、あるい は非論理的に見える一連の活動(あるいは一連の行為)に対する部外者の、あるいは「エティック」なカテゴリーである、というものである。この用語は、この 活動が不慣れな傍観者にはそのように見えることを認めるものとして、内部者または「エミック」なパフォーマティによっても使用されることがある[5]。 心理学では、儀式という用語は、不安を中和または予防するために人が体系的に用いる反復的な行動に対して専門的な意味で用いられることがある。強迫性障害 の症状であることもあるが、強迫的儀式的行動は一般的に孤立した活動である。 |

| Etymology The English word ritual derives from the Latin ritualis, "that which pertains to rite (ritus)". In Roman juridical and religious usage, ritus was the proven way (mos) of doing something,[6] or "correct performance, custom".[7] The original concept of ritus may be related to the Sanskrit ṛtá ("visible order)" in Vedic religion, "the lawful and regular order of the normal, and therefore proper, natural and true structure of cosmic, worldly, human and ritual events".[8] The word "ritual" is first recorded in English in 1570, and came into use in the 1600s to mean "the prescribed order of performing religious services" or more particularly a book of these prescriptions.[9] |

語源 英語のritualはラテン語のritualis「儀式に関わるもの(ritus)」に由来する。ローマ時代の法学的・宗教的な用法では、ritusは何 かを行うための証明された方法(mos)であり[6]、「正しい実行、習慣」であった[7]。ritusの元の概念は、ヴェーダ宗教におけるサンスクリッ ト語の↪L_1E5B↩(「目に見える秩序」)、「宇宙的、世俗的、人間的、儀式的な出来事の、通常の、したがって適切で自然で真の構造の、合法的で規則 的な秩序」に関連していると考えられる。 [8]「儀式」という言葉は1570年に初めて英語で記録され、1600年代には「宗教的な儀式を行うための規定された順序」、より詳細には「これらの規 定が書かれた本」を意味する言葉として使われるようになった[9]。 |

| Characteristics There are hardly any limits to the kind of actions that may be incorporated into a ritual. The rites of past and present societies have typically involved special gestures and words, recitation of fixed texts, performance of special music, songs or dances, processions, manipulation of certain objects, use of special dresses, consumption of special food, drink, or drugs, and much more.[10][11][12] Catherine Bell argues that rituals can be characterized by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism and performance.[13] Formalism  Priests performing a mass. The use of Latin in a Tridentine Catholic Mass is an example of a "restricted code". Ritual uses a limited and rigidly organized set of expressions which anthropologists call a "restricted code" (in opposition to a more open "elaborated code"). Maurice Bloch argues that ritual obliges participants to use this formal oratorical style, which is limited in intonation, syntax, vocabulary, loudness, and fixity of order. In adopting this style, ritual leaders' speech becomes more style than content. Because this formal speech limits what can be said, it induces "acceptance, compliance, or at least forbearance with regard to any overt challenge". Bloch argues that this form of ritual communication makes rebellion impossible and revolution the only feasible alternative. Ritual tends to support traditional forms of social hierarchy and authority, and maintains the assumptions on which the authority is based from challenge.[14] Traditionalism The First Thanksgiving 1621, oil on canvas by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863–1930). The painting shows common misconceptions about the event that persist to modern times: Pilgrims did not wear such outfits, and the Wampanoag are dressed in the style of Plains Indians.[15] Rituals appeal to tradition and are generally continued to repeat historical precedent, religious rite, mores, or ceremony accurately. Traditionalism varies from formalism in that the ritual may not be formal yet still makes an appeal to the historical trend. An example is the American Thanksgiving dinner, which may not be formal, yet is ostensibly based on an event from the early Puritan settlement of America. Historians Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger have argued that many of these are invented traditions, such as the rituals of the British monarchy, which invoke "thousand year-old tradition" but whose actual form originate in the late nineteenth century, to some extent reviving earlier forms, in this case medieval, that had been discontinued in the meantime. Thus, the appeal to history is important rather than accurate historical transmission.[16] Invariance Catherine Bell states that ritual is also invariant, implying careful choreography. This is less an appeal to traditionalism than a striving for timeless repetition. The key to invariance is bodily discipline, as in monastic prayer and meditation meant to mold dispositions and moods. This bodily discipline is frequently performed in unison, by groups.[17] Rule-governance Rituals tend to be governed by rules, a feature somewhat like formalism. Rules impose norms on the chaos of behavior, either defining the outer limits of what is acceptable or choreographing each move. Individuals are held to communally approved customs that evoke a legitimate communal authority that can constrain the possible outcomes. Historically, war in most societies has been bound by highly ritualized constraints that limit the legitimate means by which war was waged.[18] Sacral symbolism  Ritual practitioner on Inwangsan Mountain, Seoul South Korea Activities appealing to supernatural beings are easily considered rituals, although the appeal may be quite indirect, expressing only a generalized belief in the existence of the sacred demanding a human response. National flags, for example, may be considered more than signs representing a country. The flag stands for larger symbols such as freedom, democracy, free enterprise or national superiority.[19] Anthropologist Sherry Ortner writes that the flag does not encourage reflection on the logical relations among these ideas, nor on the logical consequences of them as they are played out in social actuality, over time and history. On the contrary, the flag encourages a sort of all-or-nothing allegiance to the whole package, best summed [by] 'Our flag, love it or leave.'[20] Particular objects become sacral symbols through a process of consecration which effectively creates the sacred by setting it apart from the profane. Boy Scouts and the armed forces in any country teach the official ways of folding, saluting and raising the flag, thus emphasizing that the flag should never be treated as just a piece of cloth.[21] Performance The performance of ritual creates a theatrical-like frame around the activities, symbols and events that shape participant's experience and cognitive ordering of the world, simplifying the chaos of life and imposing a more or less coherent system of categories of meaning onto it.[22] As Barbara Myerhoff put it, "not only is seeing believing, doing is believing."[23] |

特徴 儀式に取り入れることのできる行為には、ほとんど制限がない。過去と現在の社会における儀式は、一般的に、特別な身振りや言葉、決まった文章の朗読、特別 な音楽や歌や踊りの演奏、行列、特定の物体の操作、特別な服装の使用、特別な食べ物や飲み物や薬物の摂取などを含んでいる[10][11][12]。 キャサリン・ベルは、儀式は形式主義、伝統主義、不変性、規則統治、聖なる象徴主義、パフォーマンスによって特徴づけられると論じている[13]。 形式主義  ミサを執り行う神父たち。 カトリックのトリデンタイン式ミサにおけるラテン語の使用は、「制限されたコード」の一例である。 儀式は、人類学者が「制限されたコード」(より開かれた「精緻化されたコード」に対して)と呼ぶ、限定的で厳格に組織化された一連の表現を用いる。モーリ ス・ブロッホは、儀礼は参加者に、イントネーション、構文、語彙、声の大きさ、秩序の固定性において制限された、この形式的な弁論スタイルを使用すること を義務づけていると論じている。このスタイルを採用することで、儀式の指導者の発話は、内容よりもスタイルが重視されるようになる。このような形式的な発 話は、発言できる内容を制限するため、「いかなるあからさまな挑戦に対しても、受容、遵守、少なくとも忍耐」を誘発する。ブロッホは、このような儀礼的コ ミュニケーション形態が反抗を不可能にし、革命が唯一実現可能な代替案であると主張する。儀式は伝統的な社会階層と権威の形態を支持し、権威の基礎となっ ている前提を挑戦から維持する傾向がある[14]。 伝統主義  ジャン・レオン・ジェローム・フェリス(1863-1930)作、油彩・キャンバス。この絵は、現代まで続いているこの出来事に関する一般的な誤解を示している: 巡礼者はそのような服装をしておらず、ワンパノアグ族は平原インディアンのスタイルで着飾っている[15]。 儀式は伝統に訴えるものであり、一般的に歴史的な先例、宗教的儀式、風習、儀式を正確に繰り返すために継続される。伝統主義は形式主義とは異なり、儀式は 形式的でなくても歴史的な傾向に訴えかけるものである。例えば、アメリカの感謝祭の晩餐会は、正式な儀式ではないかもしれないが、表向きは初期のピューリ タン入植時代の行事に基づいている。歴史家エリック・ホブズボームとテレンス・レンジャーは、こうした伝統の多くは創作された伝統であると主張している。 たとえば、イギリス君主制の儀式は「千年来の伝統」を引き合いに出しているが、実際の形式は19世紀後半に生まれたものであり、その間に途絶えていた以前 の形式(この場合は中世)をある程度復活させたものである。このように、正確な歴史的伝承よりも歴史へのアピールが重要なのである[16]。 不変性 キャサリン・ベルは、儀式もまた不変であり、注意深い振り付けを意味すると述べている。これは伝統主義への訴えというよりも、時代を超えた反復への努力で ある。不変性の鍵は、修道院での祈りや瞑想のように、気質や気分を形成するための身体の鍛錬である。この身体的鍛錬は、集団で一斉に行われることが多い [17]。 規則性 儀式は規則に支配される傾向があり、これは形式主義にやや似た特徴である。ルールは行動の混沌に規範を課し、何が許容されるかの外枠を定義したり、それぞ れの動きを振り付けたりする。個人は共同体として承認された慣習に縛られ、それが正当な共同体の権威を呼び起こし、起こりうる結果を制約することができ る。歴史的に、ほとんどの社会における戦争は、戦争が行われる正当な手段を制限する高度に儀式化された制約に縛られてきた[18]。 聖なる象徴  韓国ソウルの仁王山で儀式を行う修行者 超自然的な存在に訴える活動は儀式と見なされやすいが、その訴えは極めて間接的で、人間の反応を求める聖なるものの存在に対する一般化された信念を表現し ているにすぎない場合もある。例えば、国民旗は国を象徴する標識以上のものと考えられる。国旗は、自由、民主主義、自由企業、あるいは国民の優越性といっ た、より大きなシンボルを象徴している。 国旗は、これらの観念の間の論理的な関係や、時間や歴史の中で社会的現実の中で展開されるそれらの論理的な結果についての考察を促すものではない。それど ころか国旗は、「われわれの国旗よ、それを愛するか、去るか」[20]で最もよく要約されるように、パッケージ全体に対するある種のオール・オア・ナッシ ングの忠誠を促している。 特定の物体は、聖別というプロセスを通じて神聖なシンボルとなる。ボーイスカウトや軍隊はどの国でも、国旗の折り方、敬礼の仕方、掲揚の仕方を公式に教えており、国旗を単なる布切れとして扱ってはならないことを強調している[21]。 パフォーマティビティ 儀式のパフォーマンスは、参加者の経験や世界に対する認知的秩序を形成する活動、シンボル、出来事の周囲に演劇的なフレームを作り出し、人生の混沌を単純 化し、多かれ少なかれ首尾一貫した意味の範疇の体系をその上に押し付ける[22]。 バーバラ・マイヤーホフが言うように、「見ることは信じることであるだけでなく、行うことは信じることである」[23]。 |

| Genres For simplicity's sake, the range of diverse rituals can be divided into categories with common characteristics, generally falling into one three major categories: rites of passage, generally changing an individual's social status; communal rites, whether of worship, where a community comes together to worship, such as Jewish synagogue or Mass, or of another character, such as fertility rites and certain non-religious festivals; rites of personal devotion, where an individual worships, including prayer and pilgrimages, pledges of allegiance, or promises to wed someone. However, rituals can fall in more than one category or genre, and may be grouped in a variety of other ways. For example, the anthropologist Victor Turner writes: Rituals may be seasonal, ... or they may be contingent, held in response to an individual or collective crisis. ... Other classes of rituals include divinatory rituals; ceremonies performed by political authorities to ensure the health and fertility of human beings, animals, and crops in their territories; initiation into priesthoods devoted to certain deities, into religious associations, or into secret societies; and those accompanying the daily offering of food and libations to deities or ancestral spirits or both. — Turner (1973) Rites of passage Main article: Rites of passage A rite of passage is a ritual event that marks a person's transition from one status to another, including adoption, baptism, coming of age, graduation, inauguration, engagement, and marriage. Rites of passage may also include initiation into groups not tied to a formal stage of life such as a fraternity. Arnold van Gennep stated that rites of passage are marked by three stages:[24] 1. Separation Wherein the initiates are separated from their old identities through physical and symbolic means. 2. Transition Wherein the initiated are "betwixt and between". Victor Turner argued that this stage is marked by liminality, a condition of ambiguity or disorientation in which initiates have been stripped of their old identities, but have not yet acquired their new one. Turner states that "the attributes of liminality or of liminal personae ("threshold people") are necessarily ambiguous".[25] In this stage of liminality or "anti-structure" (see below), the initiates' role ambiguity creates a sense of communitas or emotional bond of community between them. This stage may be marked by ritual ordeals or ritual training. 3. Incorporation Wherein the initiates are symbolically confirmed in their new identity and community.[26] Rites of affliction Further information: Shamanism, Exorcism, and Ritual purification Anthropologist Victor Turner defines rites of affliction actions that seek to mitigate spirits or supernatural forces that inflict humans with bad luck, illness, gynecological troubles, physical injuries, and other such misfortunes.[27] These rites may include forms of spirit divination (consulting oracles) to establish causes—and rituals that heal, purify, exorcise, and protect. The misfortune experienced may include individual health, but also broader climate-related issues such as drought or plagues of insects. Healing rites performed by shamans frequently identify social disorder as the cause, and make the restoration of social relationships the cure.[28] Turner uses the example of the Isoma ritual among the Ndembu of northwestern Zambia to illustrate. The Isoma rite of affliction is used to cure a childless woman of infertility. Infertility is the result of a "structural tension between matrilineal descent and virilocal marriage" (i.e., the tension a woman feels between her mother's family, to whom she owes allegiance, and her husband's family among whom she must live). "It is because the woman has come too closely in touch with the 'man's side' in her marriage that her dead matrikin have impaired her fertility." To correct the balance of matrilinial descent and marriage, the Isoma ritual dramatically placates the deceased spirits by requiring the woman to reside with her mother's kin.[29] Shamanic and other ritual may effect a psychotherapeutic cure, leading anthropologists such as Jane Atkinson to theorize how. Atkinson argues that the effectiveness of a shamanic ritual for an individual may depend upon a wider audiences acknowledging the shaman's power, which may lead to the shaman placing greater emphasis on engaging the audience than in the healing of the patient.[30] Death, mourning, and funerary rites Further information: Funeral [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) Many cultures have rites associated with death and mourning, such as the last rites and wake in Christianity, shemira in Judaism, the antyesti in Hinduism, and the antam sanskar in Sikhism. These rituals often reflect deep spiritual beliefs and provide a structured way for communities to grieve and honor the deceased. In Buddhism, for example, the bardo rituals guide the soul through the stages of death and rebirth. In Islam, the Janazah prayer is an essential communal act that underscores the unity of the Muslim community in life and death. Indigenous cultures may have unique practices, such as the Australian Aboriginal smoking ceremony, intended to cleanse the spirit of the departed and ensure a safe journey to the afterlife.  Aztec ritual human sacrifices, Codex Mendoza Calendrical and commemorative rites See also: Liturgical calendar and Wheel of the Year Calendrical and commemorative rites are ritual events marking particular times of year, or a fixed period since an important event. Calendrical rituals give social meaning to the passage of time, creating repetitive weekly, monthly or yearly cycles. Some rites are oriented towards a culturally defined moment of change in the climatic cycle, such as solar terms or the changing of seasons, or they may mark the inauguration of an activity such as planting, harvesting, or moving from winter to summer pasture during the agricultural cycle.[27] They may be fixed by the solar or lunar calendar; those fixed by the solar calendar fall on the same day (of the Gregorian, Solar calendar) each year (such as New Year's Day on the first of January) while those calculated by the lunar calendar fall on different dates (of the Gregorian, Solar calendar) each year (such as Chinese lunar New Year). Calendrical rites impose a cultural order on nature.[31] Mircea Eliade states that the calendrical rituals of many religious traditions recall and commemorate the basic beliefs of a community, and their yearly celebration establishes a link between past and present, as if the original events are happening over again: "Thus the gods did; thus men do."[32] Rites of sacrifice, exchange, and communion  Deva yajna performed during Durga Puja in Bangladesh This genre of ritual encompasses forms of sacrifice and offering meant to praise, please or placate divine powers. According to early anthropologist Edward Tylor, such sacrifices are gifts given in hope of a return. Catherine Bell, however, points out that sacrifice covers a range of practices from those that are manipulative and "magical" to those of pure devotion. Hindu puja, for example, appear to have no other purpose than to please the deity.[33] According to Marcel Mauss, sacrifice is distinguished from other forms of offering by being consecrated, and hence sanctified. As a consequence, the offering is usually destroyed in the ritual to transfer it to the deities. Rites of feasting, fasting, and festivals  Masquerade at the Carnival of Venice Rites of feasting and fasting are those through which a community publicly expresses an adherence to basic, shared religious values, rather than to the overt presence of deities as is found in rites of affliction where feasting or fasting may also take place. It encompasses a range of performances such as communal fasting during Ramadan by Muslims; the slaughter of pigs in New Guinea; Carnival festivities; or penitential processions in Catholicism.[34] Victor Turner described this "cultural performance" of basic values a "social drama". Such dramas allow the social stresses that are inherent in a particular culture to be expressed and worked out symbolically in a ritual catharsis; as the social tensions continue to persist outside the ritual, pressure mounts for the ritual's cyclical performance.[35] In Carnival, for example, the practice of masking allows people to be what they are not, and acts as a general social leveller, erasing otherwise tense social hierarchies in a festival that emphasizes play outside the bounds of normal social limits. Yet outside carnival, social tensions of race, class and gender persist, hence requiring the repeated periodic release found in the festival.[36] Water rites Further information: Water and religion, Holy water, and Water Communion A water rite is a rite or ceremonial custom that uses water as its central feature. Typically, a person is immersed or bathed as a symbol of religious indoctrination or ritual purification. Examples include the Mikveh in Judaism, a custom of purification; misogi in Shinto, a custom of spiritual and bodily purification involving bathing in a sacred waterfall, river, or lake; the Muslim ritual ablution or Wudu before prayer; baptism in Christianity, a custom and sacrament that represents both purification and initiation into the religious community (the Christian Church); and Amrit Sanskar in Sikhism, a rite of passage (sanskar) that similarly represents purification and initiation into the religious community (the khalsa). Rites that use water are not considered water rites if it is not their central feature. For example, having water to drink during or after ritual is common, but does not make thar ritual a water ritual unless the drinking of water is a central activity such as in the Church of All Worlds waterkin rite. Fertility rites This section is an excerpt from Fertility rite.[edit] Fertility rites or fertility cult are religious rituals that are intended to stimulate reproduction in humans or in the natural world.[37] Such rites may involve the sacrifice of "a primal animal, which must be sacrificed in the cause of fertility or even creation".[38] Sexual rituals This section is an excerpt from Sexual ritual.[edit] Sexual rituals fall into two categories: culture-created, and natural behaviour, the human animal having developed sex rituals from evolutionary instincts for reproduction, which are then integrated into society, and elaborated to include aspects such as marriage rites, dances, etc.[39] Sometimes sexual rituals are highly formalized and/or part of religious activity, as in the cases of hieros gamos, the hierodule, and Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.). Political rituals  Parade through Macao, Latin City (2019). The Parade is held annually on December 20th to mark the anniversary of Macao's Handover to China. According to anthropologist Clifford Geertz, political rituals actually construct power; that is, in his analysis of the Balinese state, he argued that rituals are not an ornament of political power, but that the power of political actors depends upon their ability to create rituals and the cosmic framework within which the social hierarchy headed by the king is perceived as natural and sacred.[40] As a "dramaturgy of power" comprehensive ritual systems may create a cosmological order that sets a ruler apart as a divine being, as in "the divine right" of European kings, or the divine Japanese Emperor.[41] Political rituals also emerge in the form of uncodified or codified conventions practiced by political officials that cement respect for the arrangements of an institution or role against the individual temporarily assuming it, as can be seen in the many rituals still observed within the procedure of parliamentary bodies. Ritual can be used as a form of resistance, as for example, in the various Cargo Cults that developed against colonial powers in the South Pacific. In such religio-political movements, Islanders would use ritual imitations of western practices (such as the building of landing strips) as a means of summoning cargo (manufactured goods) from the ancestors. Leaders of these groups characterized the present state (often imposed by colonial capitalist regimes) as a dismantling of the old social order, which they sought to restore.[42] Rituals may also attain political significance after conflict, as is the case with the Bosnian syncretic holidays and festivals that transgress religious boundaries.[43] |

ジャンル 簡略化のため、多様な儀式は共通の特徴を持つカテゴリーに分けることができ、一般的には次の3つのカテゴリーに大別される: 通過儀礼:一般的に個人の社会的地位を変える; 共同体の儀式:ユダヤ教のシナゴーグやミサなど、共同体が集まって礼拝するもの、あるいは豊穣の儀式や特定の非宗教的な祭りなど、別の性格のもの; 祈りや巡礼、忠誠の誓い、結婚の約束など、個人が礼拝する個人的な献身の儀式。 しかし、儀式は複数のカテゴリーやジャンルに分類されることもあり、他にもさまざまな方法でグループ分けされることがある。たとえば、人類学者のヴィクター・ターナーはこう書いている: 儀式は季節的なものかもしれないし、......個人的あるいは集団的な危機に対応して行われる偶発的なものかもしれない。... その他の儀式には、占いの儀式、領土内の人間、動物、作物の健康と豊穣を保証するために政治当局が行う儀式、特定の神々に献身する神職への入会、宗教団体 への入会、秘密結社への入会、神々や祖先の霊、あるいはその両方への日々の食物や献杯に伴う儀式などがある。 - ターナー (1973) 通過儀礼 主な記事 通過儀礼 通過儀礼とは、養子縁組、洗礼、成人式、卒業式、就任式、婚約、結婚など、ある身分から別の身分への移行を示す儀式のことである。通過儀礼には、友愛会の ような人生の正式な段階に縛られないグループへの入会も含まれる。アーノルド・ヴァン・ゲンネップは、通過儀礼は次の3つの段階によって特徴付けられると 述べている[24]。 1. 分離 イニシエーションは物理的、象徴的な手段によって、古いアイデンティティから分離される。 2. 移行 イニシエイトが 「間に挟まれた 」状態である。ヴィクター・ターナーは、この段階は、イニシエイトたちが古いアイデンティティを剥奪されたものの、まだ新しいアイデンティティを獲得して いない曖昧さや見当識障害の状態である「限界性」によって特徴づけられると主張した。ターナーは「限界性あるいは限界的なペルソナ(「閾値の人々」)の属 性は必然的に曖昧である」と述べている[25]。この限界性あるいは「反構造」(下記参照)の段階では、イニシエートたちの役割の曖昧さが、彼らの間にコ ミュニタスあるいは感情的な共同体の絆の感覚を生み出す。この段階は儀式的試練や儀式的訓練によって特徴づけられるかもしれない。 3. 組み入れ ここでイニシエートたちは新しいアイデンティティと共同体において象徴的に確認される[26]。 苦難の儀式 さらなる情報 シャーマニズム、エクソシズム、儀式の浄化 人類学者のヴィクター・ターナーは、不運、病気、婦人科系のトラブル、肉体的な怪我、その他のそのような災難を人間に与える霊や超自然的な力を軽減しよう とする行為を苦難の儀式と定義している[27]。これらの儀式には、原因を確立するための霊の占い(神託に相談する)の形式や、癒し、浄化、祓い、保護す る儀式が含まれる。経験する災難には、個人の健康だけでなく、干ばつや昆虫の疫病など、気候に関連する広範な問題も含まれる。シャーマンが行う癒しの儀式 は、社会的混乱が原因であると特定し、社会的関係の回復を治療とすることが多い[28]。 ターナーは、ザンビア北西部のンデンブ族におけるイソマの儀式を例に挙げて説明する。イソマの苦難の儀式は、子供のいない女性の不妊を治すために用いられ る。不妊症は、「母系血統と処女婚の間の構造的緊張」(つまり、女性が忠誠を誓う母親の家族と、彼女が生きなければならない夫の家族の間に感じる緊張)の 結果である。女性が結婚生活で 「男側 」と密接に接触しすぎたために、死んだ母系家族に生殖能力が損なわれてしまったのである」。母系血統と結婚のバランスを正すために、イソマの儀式は、女性 が母親の親族のもとに住むことを要求することによって、亡くなった霊を劇的になだめる[29]。 シャーマンやその他の儀式は心理療法的な治癒をもたらす可能性があり、ジェーン・アトキンソンなどの人類学者はその方法を理論化している。アトキンソン は、個人に対するシャーマンの儀式の有効性は、シャーマンの力をより多くの聴衆が認めるかどうかにかかっており、シャーマンは患者の治癒よりも聴衆を惹き つけることに重きを置くようになるかもしれないと論じている[30]。 死、弔い、葬送儀礼 さらに詳しい情報 葬儀 [アイコン]. このセクションは拡張が必要である。追加することで手助けができる。(2022年3月) キリスト教における最後の儀式や通夜、ユダヤ教におけるシェミラ、ヒンドゥー教におけるアンティスティ、シーク教におけるアンタムサンスカールなど、多く の文化には死と弔いに関連する儀式がある。これらの儀式はしばしば深い精神的信念を反映し、共同体が故人を悼み、敬うための体系化された方法を提供する。 例えば仏教では、バルドの儀式が死と再生の段階を通して魂を導く。イスラム教では、ジャナザの祈りは、生と死におけるイスラム共同体の結束を強調する、共 同体にとって不可欠な行為である。先住民の文化には、オーストラリア先住民の喫煙儀式のように、亡くなった人の魂を清め、死後の世界への安全な旅を保証す ることを目的とした独特の慣習がある。  アステカの人身御供の儀式、メンドーサ写本 暦と記念の儀式 こちらも参照のこと: 典礼暦と年輪 暦と記念の儀式は、1年の特定の時期、または重要な出来事から一定期間を示す儀式行事である。暦に基づく儀式は、時間の経過に社会的な意味を与え、週単 位、月単位、年単位で繰り返されるサイクルを作り出す。ある種の儀礼は、太陽節や季節の変わり目など、気候サイクルが変化する文化的に定義された瞬間に向 けられたものであったり、植え付け、収穫、農業サイクルにおける冬から夏への牧草地の移動など、ある活動の開始を示すものであったりする。 [太陽暦で定められたものは毎年(グレゴリオ暦、太陽暦の)同じ日に行われる(1月1日の元旦など)が、太陰暦で定められたものは毎年(グレゴリオ暦、太 陽暦の)異なる日に行われる(中国の旧正月など)。ミルチェア・エリアーデは、多くの宗教的伝統における暦の儀式は、共同体の基本的な信念を想起させ、そ れを記念するものであり、その年ごとの祝祭は、あたかも元の出来事が再び起こっているかのように、過去と現在を結びつけるものであると述べている: 「神々はこのように行い、人はこのように行う」[32]。 犠牲、交換、交わりの儀式  バングラデシュのドゥルガ・プージャで行われるデーヴァ・ヤジュナ このジャンルの儀式には、神の力を賛美したり、喜ばせたり、なだめたりするための犠牲や捧げ物の形式が含まれる。初期の人類学者エドワード・タイラーによ れば、このような犠牲は見返りを期待して捧げられる贈り物である。しかし、キャサリン・ベルは、生け贄には操作的で「魔術的」なものから、純粋な献身に基 づくものまで、さまざまな慣習が含まれると指摘する。たとえばヒンドゥー教の法会は、神を喜ばせること以外に目的がないように見える[33]。 マルセル・モースによれば、生贄は聖別され、それゆえに神聖化されることによって、他の供物の形態と区別される。その結果、供え物は通常、神々に移すために儀式の中で破壊される。 饗宴、断食、祭りの儀式  ヴェネツィアのカーニバルでの仮面舞踏会 饗宴と断食の儀式は、饗宴や断食が行われることもある苦難の儀式に見られるような神々のあからさまな存在ではなく、共同体が基本的な宗教的価値を共有して いることを公に表現するものである。イスラム教徒によるラマダン中の共同断食、ニューギニアにおける豚の屠殺、カーニバルのお祭り、カトリックにおける懺 悔の行列など、さまざまなパフォーマンスが含まれる[34]。ビクター・ターナーは、この基本的価値観の「文化的パフォーマンス」を「社会的ドラマ」と表 現した。このようなドラマは、特定の文化に内在する社会的ストレスを、儀式のカタルシスにおいて象徴的に表現し、解決することを可能にする。例えば、カー ニバルでは、仮面をかぶるという行為は、人々がありのままの自分になることを可能にし、通常の社会的限界の枠外で遊ぶことを強調する祭りの中で、そうでな ければ緊迫した社会的階層を消し去り、一般的な社会的平準化の役割を果たす。しかし、カーニバルの外では、人種、階級、ジェンダーの社会的緊張が根強く 残っており、それゆえ、祭りで見られる定期的な解放を繰り返す必要がある[36]。 水の儀式 さらに詳しい情報 水と宗教、聖水、水の聖体拝領 水の儀式とは、水を中心的な特徴とする儀式や儀礼的習慣のことである。一般的には、宗教的教化や儀式の浄化の象徴として、人が水に浸かったり入浴したりす る。例えば、ユダヤ教におけるミクヴェ、神聖な滝や川、湖で沐浴する神道における禊(みそぎ)、イスラム教における礼拝前の沐浴(ウドゥ)などがある; キリスト教における洗礼は、浄化と宗教共同体(キリスト教会)への入信の両方を表す習慣であり秘跡である。シーク教におけるアムリット・サンスカールも同 様に、浄化と宗教共同体(カルサ)への入信を表す通過儀礼(サンスカール)である。水を使う儀式は、それが中心的な特徴でなければ、水の儀式とはみなされ ない。例えば、儀式の最中や後に水を飲むことは一般的だが、万国教会のウォーターキンの儀式のように水を飲むことが中心的な活動でない限り、サーの儀式を 水の儀式とはしない。 豊穣の儀式 このセクションは豊穣の儀式[編集]からの抜粋である。 豊穣の儀式または豊穣のカルトは、人間または自然界における生殖を刺激することを意図した宗教的儀式である[37]。このような儀式は、「豊穣、あるいは創造のために犠牲にされなければならない原始的な動物」の犠牲を伴うことがある[38]。 性的儀式 このセクションは性的儀式からの抜粋である[編集]。 性的儀式は、文化によって創造されたものと、自然行動という2つのカテゴリーに分類される。ヒトという動物は、生殖のための進化的本能から性儀式を発達さ せ、それが社会に統合され、結婚儀式や舞踊などの側面を含むように精巧化された[39]。時には、性的儀式は、ヒエロスガモス、ヒエロデュール、オルド・ テムプリ・オリエンティス(O.T.O.)の場合のように、高度に形式化され、かつ/または宗教活動の一部である。 政治的儀式  マカオ、ラテン都市を練り歩くパレード(2019年)。パレードは毎年12月20日、マカオの中国返還記念日に行われる。 人類学者のクリフォード・ギアーツによれば、政治的儀式は実際に権力を構築するものである。つまり、バリの国家を分析した彼は、儀式は政治権力の飾りでは なく、政治的行為者の権力は儀式を創造する能力と、王を頂点とする社会階層が自然で神聖なものとして認識される宇宙的枠組みによって決まると主張した。 [40] 「権力のドラマトゥルギー」として、包括的な儀式システムは、ヨーロッパの王の「神権」や日本の天皇の神格化のように、支配者を神的存在として際立たせる 宇宙論的秩序を生み出すことがある[41]。政治的儀式はまた、一時的にそれを引き受ける個人に対して、制度や役割の取り決めに対する敬意を固めるため に、政治的役人によって実践される成文化されていない、あるいは成文化された慣習の形でも現れる。 例えば、南太平洋で植民地権力に対抗して発展した様々なカーゴ・カルトのように、儀式は抵抗の形として使われることもある。このような宗教的・政治的運動 では、島民は祖先から貨物(製造品)を呼び寄せる手段として、西洋の慣習(着陸帯の建設など)を儀式的に模倣した。これらのグループの指導者たちは、(し ばしば植民地資本主義体制によって押しつけられた)現在の状態を古い社会秩序の解体として特徴づけ、それを回復しようとした[42]。宗教の境界を越えた ボスニアのシンクレティックな祝日や祭りの場合のように、儀礼はまた紛争後に政治的な意義を獲得することもある[43]。 |

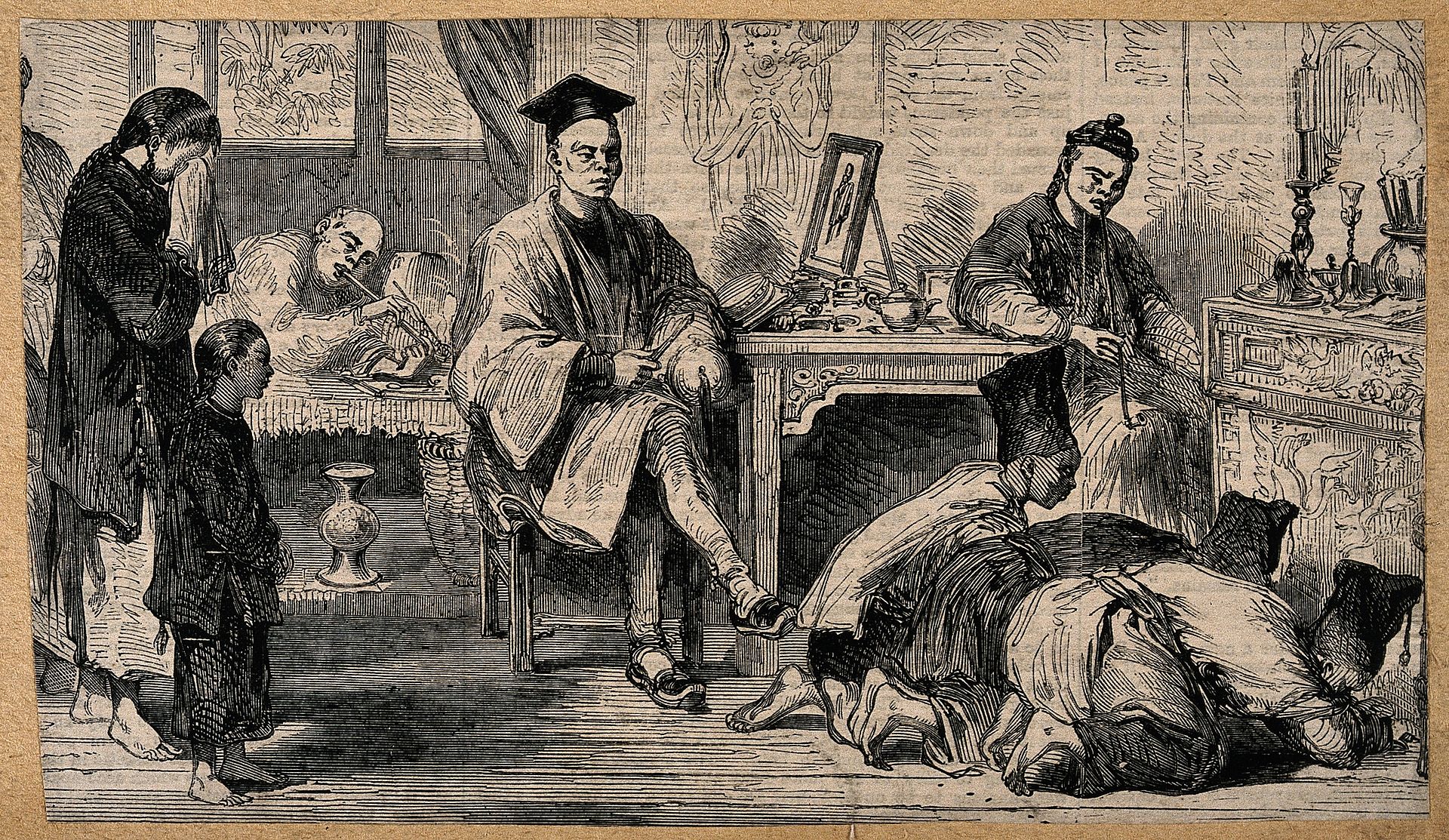

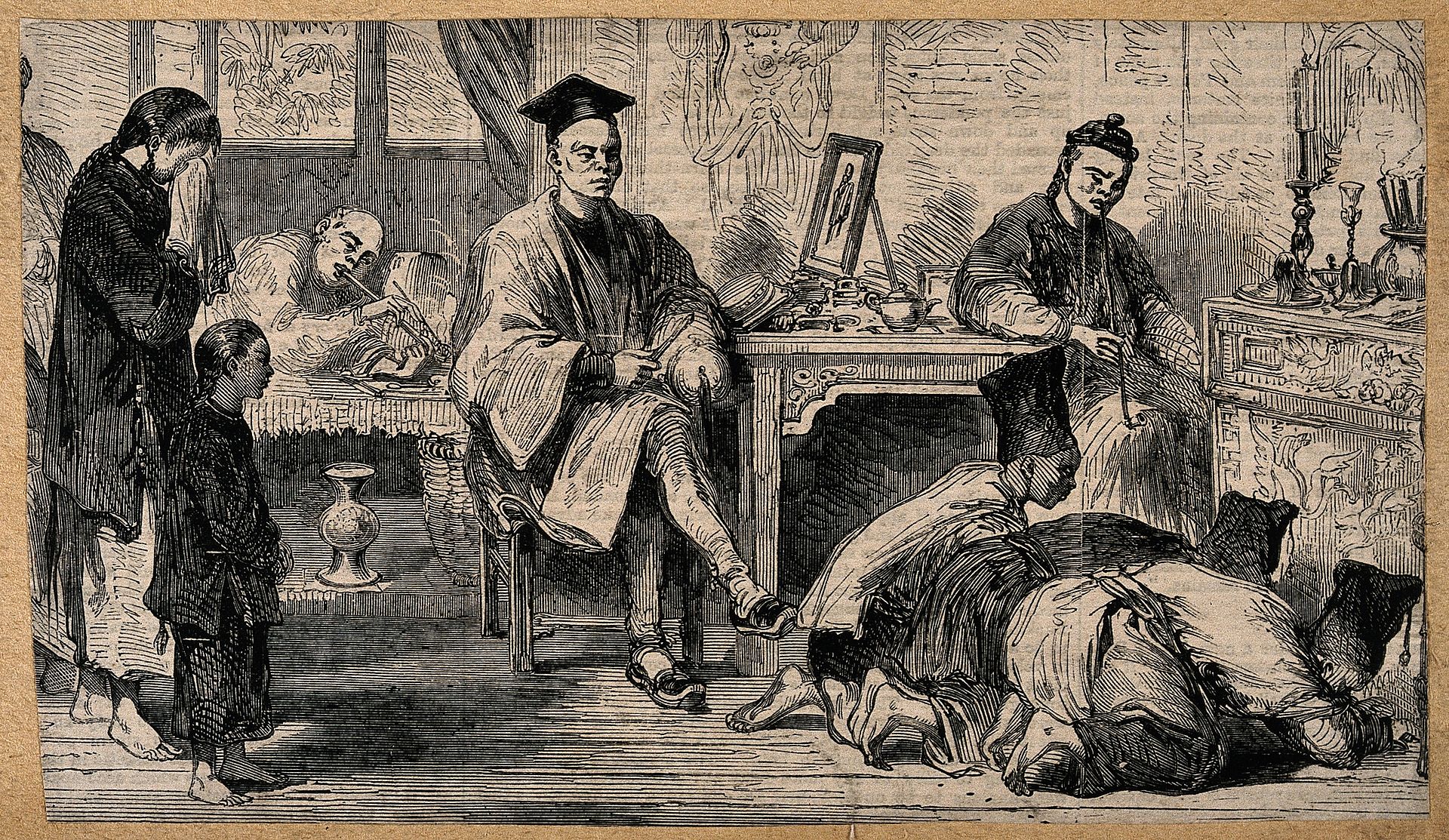

| Anthropological theories See also: Ritology Functionalism  A priest elevates the host during a Catholic Mass, one of the most widely performed rituals in the world.[44] Main article: Structural functionalism Nineteenth century "armchair anthropologists" were concerned with the basic question of how religion originated in human history. In the twentieth century their conjectural histories were replaced with new concerns around the question of what these beliefs and practices did for societies, regardless of their origin. In this view, religion was a universal, and while its content might vary enormously, it served certain basic functions such as the provision of prescribed solutions to basic human psychological and social problems, as well as expressing the central values of a society. Bronislaw Malinowski used the concept of function to address questions of individual psychological needs; A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, in contrast, looked for the function (purpose) of the institution or custom in preserving or maintaining society as a whole. They thus disagreed about the relationship of anxiety to ritual.[45]  Kowtowing in a court, China, before 1889 Malinowski argued that ritual was a non-technical means of addressing anxiety about activities where dangerous elements were beyond technical control: "magic is to be expected and generally to be found whenever man comes to an unbridgeable gap, a hiatus in his knowledge or in his powers of practical control, and yet has to continue in his pursuit.".[46] Radcliffe-Brown in contrast, saw ritual as an expression of common interest symbolically representing a community, and that anxiety was felt only if the ritual was not performed.[45] George C. Homans sought to resolve these opposing theories by differentiating between "primary anxieties" felt by people who lack the techniques to secure results, and "secondary (or displaced) anxiety" felt by those who have not performed the rites meant to allay primary anxiety correctly. Homans argued that purification rituals may then be conducted to dispel secondary anxiety.[47] A.R. Radcliffe-Brown argued that ritual should be distinguished from technical action, viewing it as a structured event: "ritual acts differ from technical acts in having in all instances some expressive or symbolic element in them."[48] Edmund Leach, in contrast, saw ritual and technical action less as separate structural types of activity and more as a spectrum: "Actions fall into place on a continuous scale. At one extreme we have actions which are entirely profane, entirely functional, technique pure and simple; at the other we have actions which are entirely sacred, strictly aesthetic, technically non-functional. Between these two extremes we have the great majority of social actions which partake partly of the one sphere and partly of the other. From this point of view technique and ritual, profane and sacred, do not denote types of action but aspects of almost any kind of action."[49] As social control  Balinese rice terraces regulated through ritual See also: social control The functionalist model viewed ritual as a homeostatic mechanism to regulate and stabilize social institutions by adjusting social interactions, maintaining a group ethos, and restoring harmony after disputes. Although the functionalist model was soon superseded, later "neofunctional" theorists adopted its approach by examining the ways that ritual regulated larger ecological systems. Roy Rappaport, for example, examined the way gift exchanges of pigs between tribal groups in Papua New Guinea maintained environmental balance between humans, available food (with pigs sharing the same foodstuffs as humans) and resource base. Rappaport concluded that ritual, "...helps to maintain an undegraded environment, limits fighting to frequencies which do not endanger the existence of regional population, adjusts man-land ratios, facilitates trade, distributes local surpluses of pig throughout the regional population in the form of pork, and assures people of high quality protein when they are most in need of it".[50] Similarly, J. Stephen Lansing traced how the intricate calendar of Hindu Balinese rituals served to regulate the vast irrigation systems of Bali, ensuring the optimum distribution of water over the system while limiting disputes.[51] Rebellion While most Functionalists sought to link ritual to the maintenance of social order, South African functionalist anthropologist Max Gluckman coined the phrase "rituals of rebellion" to describe a type of ritual in which the accepted social order was symbolically turned on its head. Gluckman argued that the ritual was an expression of underlying social tensions (an idea taken up by Victor Turner), and that it functioned as an institutional pressure valve, relieving those tensions through these cyclical performances. The rites ultimately functioned to reinforce social order, insofar as they allowed those tensions to be expressed without leading to actual rebellion. Carnival is viewed in the same light. He observed, for example, how the first-fruits festival (incwala) of the South African Bantu kingdom of Swaziland symbolically inverted the normal social order, so that the king was publicly insulted, women asserted their domination over men, and the established authority of elders over the young was turned upside down.[52] Structuralism Main article: Structuralism Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French anthropologist, regarded all social and cultural organization as symbolic systems of communication shaped by the inherent structure of the human brain. He therefore argued that the symbol systems are not reflections of social structure as the Functionalists believed, but are imposed on social relations to organize them. Lévi-Strauss thus viewed myth and ritual as complementary symbol systems, one verbal, one non-verbal. Lévi-Strauss was not concerned to develop a theory of ritual (although he did produce a four-volume analysis of myth) but was influential to later scholars of ritual such as Mary Douglas and Edmund Leach.[53] Structure and anti-structure Victor Turner combined Arnold van Gennep's model of the structure of initiation rites, and Gluckman's functionalist emphasis on the ritualization of social conflict to maintain social equilibrium, with a more structural model of symbols in ritual. Running counter to this emphasis on structured symbolic oppositions within a ritual was his exploration of the liminal phase of rites of passage, a phase in which "anti-structure" appears. In this phase, opposed states such as birth and death may be encompassed by a single act, object or phrase. The dynamic nature of symbols experienced in ritual provides a compelling personal experience; ritual is a "mechanism that periodically converts the obligatory into the desirable".[54] Mary Douglas, a British Functionalist, extended Turner's theory of ritual structure and anti-structure with her own contrasting set of terms "grid" and "group" in the book Natural Symbols. Drawing on Levi-Strauss' Structuralist approach, she saw ritual as symbolic communication that constrained social behaviour. Grid is a scale referring to the degree to which a symbolic system is a shared frame of reference. Group refers to the degree people are tied into a tightly knit community. When graphed on two intersecting axes, four quadrants are possible: strong group/strong grid, strong group/weak grid, weak group/weak grid, weak group/strong grid. Douglas argued that societies with strong group or strong grid were marked by more ritual activity than those weak in either group or grid.[55] (see also, section below) Anti-structure and communitas Main article: Communitas In his analysis of rites of passage, Victor Turner argued that the liminal phase - that period 'betwixt and between' - was marked by "two models of human interrelatedness, juxtaposed and alternating": structure and anti-structure (or communitas).[56] While the ritual clearly articulated the cultural ideals of a society through ritual symbolism, the unrestrained festivities of the liminal period served to break down social barriers and to join the group into an undifferentiated unity with "no status, property, insignia, secular clothing, rank, kinship position, nothing to demarcate themselves from their fellows".[57] These periods of symbolic inversion have been studied in a diverse range of rituals such as pilgrimages and Yom Kippur.[58] Social dramas Beginning with Max Gluckman's concept of "rituals of rebellion", Victor Turner argued that many types of ritual also served as "social dramas" through which structural social tensions could be expressed, and temporarily resolved. Drawing on Van Gennep's model of initiation rites, Turner viewed these social dramas as a dynamic process through which the community renewed itself through the ritual creation of communitas during the "liminal phase". Turner analyzed the ritual events in 4 stages: breach in relations, crisis, redressive actions, and acts of reintegration. Like Gluckman, he argued these rituals maintain social order while facilitating disordered inversions, thereby moving people to a new status, just as in an initiation rite.[59] Symbolic approaches to ritual Arguments, melodies, formulas, maps and pictures are not idealities to be stared at but texts to be read; so are rituals, palaces, technologies, and social formations. — Geertz (1980), p. 135 Clifford Geertz also expanded on the symbolic approach to ritual that began with Victor Turner. Geertz argued that religious symbol systems provided both a "model of" reality (showing how to interpret the world as is) as well as a "model for" reality (clarifying its ideal state). The role of ritual, according to Geertz, is to bring these two aspects – the "model of" and the "model for" – together: "it is in ritual – that is consecrated behaviour – that this conviction that religious conceptions are veridical and that religious directives are sound is somehow generated."[60] Symbolic anthropologists like Geertz analyzed rituals as language-like codes to be interpreted independently as cultural systems. Geertz rejected Functionalist arguments that ritual describes social order, arguing instead that ritual actively shapes that social order and imposes meaning on disordered experience. He also differed from Gluckman and Turner's emphasis on ritual action as a means of resolving social passion, arguing instead that it simply displayed them.[61] As a form of communication Whereas Victor Turner saw in ritual the potential to release people from the binding structures of their lives into a liberating anti-structure or communitas, Maurice Bloch argued that ritual produced conformity.[62] Maurice Bloch argued that ritual communication is unusual in that it uses a special, restricted vocabulary, a small number of permissible illustrations, and a restrictive grammar. As a result, ritual utterances become very predictable, and the speaker is made anonymous in that they have little choice in what to say. The restrictive syntax reduces the ability of the speaker to make propositional arguments, and they are left, instead, with utterances that cannot be contradicted such as "I do thee wed" in a wedding. These kinds of utterances, known as performatives, prevent speakers from making political arguments through logical argument, and are typical of what Weber called traditional authority instead.[63] Bloch's model of ritual language denies the possibility of creativity. Thomas Csordas, in contrast, analyzes how ritual language can be used to innovate. Csordas looks at groups of rituals that share performative elements ("genres" of ritual with a shared "poetics"). These rituals may fall along the spectrum of formality, with some less, others more formal and restrictive. Csordas argues that innovations may be introduced in less formalized rituals. As these innovations become more accepted and standardized, they are slowly adopted in more formal rituals. In this way, even the most formal of rituals are potential avenues for creative expression.[64] As a disciplinary program  Scriptorium monk at work. "Monks described this labor of transcribing manuscripts as being 'like prayer and fasting, a means of correcting one's unruly passions.'"[65] In his historical analysis of articles on ritual and rite in the Encyclopædia Britannica, Talal Asad notes that from 1771 to 1852, the brief articles on ritual define it as a "book directing the order and manner to be observed in performing divine service" (i.e., as a script). There are no articles on the subject thereafter until 1910, when a new, lengthy article appeared that redefines ritual as "...a type of routine behaviour that symbolizes or expresses something".[66] As a symbolic activity, it is no longer confined to religion, but is distinguished from technical action. The shift in definitions from script to behavior, which is likened to a text, is matched by a semantic distinction between ritual as an outward sign (i.e., public symbol) and inward meaning.[67] The emphasis has changed to establishing the meaning of public symbols and abandoning concerns with inner emotional states since, as Evans-Pritchard wrote "such emotional states, if present at all, must vary not only from individual to individual, but also in the same individual on different occasions and even at different points in the same rite."[68] Asad, in contrast, emphasizes behavior and inner emotional states; rituals are to be performed, and mastering these performances is a skill requiring disciplined action. In other words, apt performance involves not symbols to be interpreted but abilities to be acquired according to rules that are sanctioned by those in authority: it presupposes no obscure meanings, but rather the formation of physical and linguistic skills. — Asad (1993), p. 62 Drawing on the example of Medieval monastic life in Europe, he points out that ritual in this case refers to its original meaning of the "...book directing the order and manner to be observed in performing divine service". This book "prescribed practices, whether they had to do with the proper ways of eating, sleeping, working, and praying or with proper moral dispositions and spiritual aptitudes, aimed at developing virtues that are put 'to the service of God.'"[69] Monks, in other words, were disciplined in the Foucauldian sense. The point of monastic discipline was to learn skills and appropriate emotions. Asad contrasts his approach by concluding: Symbols call for interpretation, and even as interpretive criteria are extended so interpretations can be multiplied. Disciplinary practices, on the other hand, cannot be varied so easily, because learning to develop moral capabilities is not the same thing as learning to invent representations. — Asad (1993), p. 79 As a form of social solidarity Ethnographic observation shows ritual can create social solidarity. Douglas Foley Went to North Town, Texas, between 1973 and 1974 to study public high school culture. He used interviews, participant observation, and unstructured chatting to study racial tension and capitalist culture in his ethnography Learning Capitalist Culture. Foley refers to football games and Friday Night Lights as a community ritual. This ritual united the school and created a sense of solidarity and community on a weekly basis involving pep rallies and the game itself. Foley observed judgement and segregation based on class, social status, wealth, and gender. He described Friday Night Lights as a ritual that overcomes those differences: "The other, gentler, more social side of football was, of course, the emphasis on camaraderie, loyalty, friendship between players, and pulling together".[70] In his ethnography Waiting for Elijah: Time and Encounter in a Bosnian Landscape, anthropologist Safet HadžiMuhamedović suggests that shared festivals like St George's Day and St Elijah's Day structure interfaith relationships and appear as acts of solidarity against ethno-nationalist purifications of territory in Bosnia.[43] Ritualization Main article: Ritualization Asad's work critiqued the notion that there were universal characteristics of ritual to be found in all cases. Catherine Bell has extended this idea by shifting attention from ritual as a category, to the processes of "ritualization" by which ritual is created as a cultural form in a society. Ritualization is "a way of acting that is designed and orchestrated to distinguish and privilege what is being done in comparison to other, usually more quotidian, activities".[71] Sociobiology and behavioral neuroscience Anthropologists have also analyzed ritual via insights from other behavioral sciences. The idea that cultural rituals share behavioral similarities with personal rituals of individuals was discussed early on by Freud.[72] Dulaney and Fiske compared ethnographic descriptions of both rituals and non-ritual doings, such as work to behavioral descriptions from clinical descriptions of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[73] They note that OCD behavior often consists of such behavior as constantly cleaning objects, concern or disgust with bodily waste or secretions, repetitive actions to prevent harm, heavy emphasis on number or order of actions etc. They then show that ethnographic descriptions of cultural rituals contain around 5 times more of such content than ethnographic descriptions of other activities such as "work". Fiske later repeated similar analysis with more descriptions from a larger collection of different cultures, also contrasting descriptions of cultural rituals to descriptions of other behavioral disorders (in addition to OCD), in order to show that only OCD-like behavior (not other illnesses) shares properties with rituals.[74] The authors offer tentative explanations for these findings, for example that these behavioral traits are widely needed for survival, to control risk, and cultural rituals are often performed in the context of perceived collective risk. Other anthropologists have taken these insights further, and constructed more elaborate theories based on the brain functions and physiology. Liénard and Boyer suggest that commonalities between obsessive behavior in individuals and similar behavior in collective contexts possibly share similarities due to underlying mental processes they call hazard precaution. They suggest that individuals of societies seem to pay more attention to information relevant to avoiding hazards, which in turn can explain why collective rituals displaying actions of hazard precaution are so popular and prevail for long periods in cultural transmission.[75] Ritual as a methodological measure of religiosity Further information: Theories about religions According to the sociologist Mervin Verbit, ritual may be understood as one of the key components of religiosity. And ritual itself may be broken down into four dimensions; content, frequency, intensity and centrality. The content of a ritual may vary from ritual to ritual, as does the frequency of its practice, the intensity of the ritual (how much of an impact it has on the practitioner), and the centrality of the ritual (in that religious tradition).[76][77][78] In this sense, ritual is similar to Charles Glock's "practice" dimension of religiosity.[79] |

人類学理論 こちらも参照のこと: 律動論 機能主義  世界で最も広く行われている儀式の一つであるカトリックのミサで、司祭が聖体を高く掲げる[44]。 主な記事 構造機能主義 19世紀の「腕利きの人類学者」は、宗教が人類の歴史の中でどのように生まれたのかという基本的な問題に関心を寄せていた。20世紀になると、彼らの推測 に基づく歴史は、その起源にかかわらず、これらの信仰や実践が社会に何をもたらしたかという問題をめぐる新たな関心に取って代わられた。この考え方では、 宗教は普遍的なものであり、その内容は千差万別かもしれないが、人間の基本的な心理的・社会的問題に対する所定の解決策を提供したり、社会の中心的な価値 観を表現したりするなど、一定の基本的な機能を果たしていた。ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーは、個人の心理的欲求の問題に対処するために機能という概念を 用いたが、対照的にA.R.ラドクリフ=ブラウンは、社会全体の維持や維持における制度や慣習の機能(目的)に注目した。そのため、彼らは儀式と不安の関 係について意見が対立していた[45]。  宮廷でのお辞儀(中国、1889年以前 マリノフスキーは、儀式は危険な要素が技術的に制御できない活動に対する不安に対処するための非技術的な手段であると主張した: 「魔法は、人間がその知識や実践的な制御の力において、埋めがたい隔たりや裂け目に遭遇し、それでもなお追求を続けなければならないときには必ず期待され るものであり、一般に見出されるものである」[46]。対照的に、ラドクリフ=ブラウンは、儀式を共同体を象徴的に表す共通の関心の表現とみなし、儀式が 行われない場合にのみ不安が感じられるとした。 [45] ジョージ・C・ホーマンズは、結果を確保するための技術を欠いている人々が感じる「一次的な不安」と、一次的な不安を和らげるための儀式を正しく行ってい ない人々が感じる「二次的な(あるいはずれた)不安」とを区別することによって、これらの対立する理論を解決しようとした。ホーマンズは、二次的不安を払 拭するために浄化の儀式が行われることがあると主張した[47]。 A.R.ラドクリフ=ブラウンは、儀式を構造化された出来事として捉え、儀式を技術的行為と区別すべきだと主張した: 「儀式的行為は技術的行為とは異なり、すべての場合において何らかの表現的要素や象徴的要素を持っている」[48]。対照的にエドモンド・リーチは、儀式 的行為と技術的行為を構造的なタイプの別個の活動としてではなく、むしろスペクトルとして捉えている。一方の極には、完全に俗悪で、完全に機能的で、純粋 かつ単純な技術的行為があり、他方の極には、完全に神聖で、厳密に美的で、技術的に非機能的な行為がある。この両極の間に、一方の領域を部分的に、他方の 領域を部分的に取り入れた社会的行為の大多数がある。この観点からすると、技術と儀式、俗と聖は行為の種類を示すのではなく、ほとんどあらゆる種類の行為 の側面を示すのである」[49]。 社会的統制として  儀式によって調整されるバリの棚田 社会的統制も参照のこと。 機能主義モデルは、儀式を、社会的相互作用を調整し、集団のエートスを維持し、紛争の後に調和を回復することによって、社会制度を調整し安定させる恒常性維持メカニズムとみなした。 機能主義モデルはすぐに取って代わられたが、後の「新機能主義」理論家たちは、儀式がより大きな生態系システムを調整する方法を検討することで、そのアプ ローチを採用した。例えばロイ・ラパポートは、パプアニューギニアの部族グループ間で豚の贈与交換が行われることによって、人間、利用可能な食料(豚は人 間と同じ食料を共有している)、資源基盤の間の環境バランスが保たれていることを調査した。Rappaportは、儀式は「...劣化していない環境を維 持するのに役立ち、戦闘を地域人口の存続を脅かさない頻度に制限し、人と土地の比率を調整し、貿易を促進し、豚肉の形で地域人口全体に豚の地域余剰を分配 し、人々がそれを最も必要とするときに高品質のタンパク質を保証する」と結論づけた[50]。 [同様に、J.スティーヴン・ランシングは、ヒンドゥー教のバリの儀式の複雑な暦が、バリの広大な灌漑システムを調整し、紛争を制限しながら、システム上 の水の最適な配分を保証するのに役立っていたことを追跡した[51]。 反乱 ほとんどの機能主義者が儀式を社会秩序の維持に結びつけようとする一方で、南アフリカの機能主義人類学者マックス・グラックマンは、受け入れられている社 会秩序が象徴的に覆されるタイプの儀式を表現するために、「反逆の儀式」という言葉を作り出した。グルックマンは、儀式は根底にある社会的緊張の表現であ り(この考えはヴィクター・ターナーによって取り上げられた)、儀式は制度的な圧力弁として機能し、このような周期的なパフォーマティビティを通じてその 緊張を和らげると主張した。儀式は、実際の反乱につながることなく緊張を表現できる限りにおいて、最終的には社会秩序を強化するために機能したのである。 カーニバルも同じように捉えられている。例えば、南アフリカのバントゥー系スワジランド王国の初穂祭(incwala)が、通常の社会秩序を象徴的に反転 させ、王が公然と侮辱され、女性が男性に対する支配を主張し、若者に対する年長者の確立された権威がひっくり返されたことを観察した[52]。 構造主義 主な記事 構造主義 フランスの人類学者クロード・レヴィ=ストロースは、すべての社会的・文化的組織を、人間の脳に内在する構造によって形成されたコミュニケーションの象徴 体系とみなした。したがって彼は、象徴体系は機能主義者が信じていたような社会構造の反映ではなく、社会関係を組織化するために社会関係に課せられたもの であると主張した。こうしてレヴィ=ストロースは、神話と儀式を、一方は言語的、他方は非言語的な、相補的な象徴体系とみなしたのである。レヴィ=スト ロースは儀礼の理論を発展させることには関心がなかったが(彼は神話について4巻からなる分析を行ったが)、メアリー・ダグラスやエドモンド・リーチと いった後の儀礼の研究者たちに影響を与えた[53]。 構造と反構造 ヴィクター・ターナーは、アーノルド・ヴァン・ゲネップによるイニシエーション儀礼の構造モデルと、社会的均衡を維持するための社会的対立の儀式化に関す るグルックマンの機能主義的強調を、儀礼における象徴のより構造的なモデルと結合させた。儀式内の構造化された象徴的対立を強調するこの考え方に対抗する ものとして、彼は通過儀礼の限界段階、すなわち「反構造」が現れる段階を探求した。この段階では、誕生と死のような対立する状態が、ひとつの行為、物体、 フレーズによって包括されることがある。儀式において経験される象徴の動的な性質は、説得力のある個人的な経験を提供する。儀式は「義務的なものを望まし いものに定期的に変換するメカニズム」である[54]。 イギリスの機能主義者であるメアリー・ダグラスは、『ナチュラル・シンボル(Natural Symbols)』という本の中で、「グリッド(grid)」と「グループ(group)」という彼女自身の対照的な用語を用いて、儀式の構造と反構造に 関するターナーの理論を拡張した。レヴィ=ストロースの構造主義的アプローチを引きながら、彼女は儀式を社会的行動を制約する象徴的コミュニケーションと 見なした。グリッドとは、象徴体系が参照枠として共有される度合いを示す尺度である。グループとは、人々が緊密に結びついた共同体に結びついている度合い を指す。交差する2つの軸でグラフ化すると、強い集団/強いグリッド、強い集団/弱いグリッド、弱い集団/弱いグリッド、弱い集団/強いグリッドの4象限 が可能である。ダグラスは、強い集団や強いグリッドを持つ社会は、集団やグリッドのいずれかが弱い社会よりも、より多くの儀式活動によって特徴づけられる と主張した[55](以下のセクションも参照)。 反構造とコミュニタス 主な記事 コミュニタス ヴィクター・ターナーは、通過儀礼の分析において、リミナルな段階、つまり「狭間と狭間」の期間は、「並置され交互に繰り返される人間の相互関係の2つの モデル」、すなわち構造と反構造(あるいはコミュニタス)によって特徴付けられると主張した。 [56]儀礼が儀礼的象徴主義を通じて社会の文化的理想を明確に表現する一方で、限界期の奔放な祝祭は社会的障壁を取り払い、「地位、財産、記章、世俗的 な衣服、階級、親族的地位、仲間から自分たちを区別するものは何もない」[57]、集団を未分化な一体化へと結合させる役割を果たしていた。こうした象徴 的逆転の時期は、巡礼やヨム・キプールなどの多様な儀礼において研究されてきた[58]。 社会的ドラマ マックス・グラックマンの「反抗の儀式」という概念に始まり、ヴィクター・ターナーは、多くの種類の儀式が、構造的な社会的緊張が表現され、一時的に解決 される「社会的ドラマ」としても機能していると主張した。ターナーは、ヴァン・ジェンネプの入信儀礼のモデルを引きながら、こうした社会的ドラマを、「限 界段階」におけるコミュニタスの儀礼的創造を通じて共同体が自己を更新していくダイナミックなプロセスとしてとらえた。ターナーは儀式を4つの段階に分け て分析した:関係の断絶、危機、抑圧的行為、再統合の行為である。グルックマンと同様に、彼はこれらの儀式が社会秩序を維持する一方で、無秩序な逆転を促 進し、それによって、ちょうど入信儀礼におけるように、人々を新たな地位へと移行させると主張した[59]。 儀式への象徴的アプローチ 議論、メロディ、公式、地図、絵は、見つめられるべき理想ではなく、読まれるべきテキストである。 - ギアーツ(1980)、135ページ。 クリフォード・ギアーツもまた、ヴィクター・ターナーから始まった儀式への象徴的アプローチを発展させた。ギアーツは、宗教的象徴体系は現実の「モデル」 (世界をありのままに解釈する方法を示す)であると同時に、現実の「モデル」(理想的な状態を明らかにする)でもあると主張した。ゲアーツによれば、儀式 の役割は、この2つの側面--「模範の模範」と「模範のための模範」--を結びつけることである: 「宗教的な観念が真実であり、宗教的な指示が健全であるという確信が何らかの形で生み出されるのは、儀式において、つまり聖別された行動においてである」 [60]。 ゲーツのような象徴人類学者は、儀式を文化システムとして独自に解釈されるべき言語のようなコードとして分析していた。ゲアーツは儀式が社会秩序を記述す るという機能主義的な議論を否定し、その代わりに儀式が社会秩序を積極的に形成し、無秩序な経験に意味を付与すると主張した。彼はまた、社会的な情熱を解 決する手段としての儀式行為に重きを置くグラックマンやターナーとは異なっており、その代わりに儀式は単にそれらを表示するだけであると主張していた [61]。 コミュニケーションの形式として ヴィクター・ターナーが儀式に、人々を生活の束縛構造から解放する反構造やコミュニタスへと解放する可能性を見出していたのに対して、モーリス・ブロッホは儀式が適合性を生み出すと主張していた[62]。 モーリス・ブロッホは、儀礼的コミュニケーションは、特殊で制限された語彙、少数の許容されるイラストレーション、制限された文法を用いるという点で異例 であると論じていた。その結果、儀式の発話は非常に予測可能なものとなり、話し手は何を言うべきかほとんど選択できないという点で匿名的なものとなる。制 限的な構文は、話し手が命題的な議論をする能力を低下させ、その代わりに、結婚式における「私は汝に結婚式を挙げます」のような、矛盾することのない発話 が残される。パフォーマティビティとして知られるこの種の発話は、話し手が論理的な議論を通じて政治的な主張をすることを妨げ、ウェーバーが代わりに伝統 的な権威と呼んだものの典型である[63]。 ブロッホの儀式言語のモデルは創造性の可能性を否定している。これに対してトマス・チョルダスは、儀礼的言語がどのように革新のために使用されうるかを分 析している。ソルダスは、パフォーマティヴな要素を共有する儀式のグループ(「詩学」を共有する儀式の「ジャンル」)に注目している。これらの儀式は形式 的なスペクトルに沿って分類され、より形式的でないものもあれば、より形式的で制限的なものもある。Csordasは、あまり形式化されていない儀式に革 新が導入される可能性があると論じている。これらの革新が受け入れられ、標準化されるにつれて、より正式な儀式に徐々に採用されるようになる。このよう に、最もフォーマルな儀式でさえも、創造的な表現のための潜在的な手段なのである[64]。 規律プログラムとして  作業中のスクリプトリウムの僧侶。僧侶たちは、写本を書き写すというこの労働を、「祈りや断食のようなものであり、自分の手に負えない情熱を正す手段である」と表現している[65]。 Encyclopædia Britannicaにおける儀式と儀礼に関する記事の歴史的分析において、Talal Asadは、1771年から1852年まで、儀式に関する簡潔な記事は、儀式を「神聖な礼拝を行う際に遵守すべき順序と方法を指示する書物」(すなわち、 台本)として定義していると指摘している。その後、1910年に儀式を「...何かを象徴したり表現したりする日常的な行動の一種」と再定義する長文の記 事が登場するまで、この主題に関する記事はない[66]。象徴的な活動として、儀式はもはや宗教に限定されるものではなく、技術的な行動とは区別される。 テキストになぞらえられるスクリプトから行動への定義のシフトは、外面的な記号(すなわち公的なシンボル)としての儀式と内面的な意味との間の意味論的な 区別によって一致している[67]。 エバンス=プリチャードが書いているように、「そのような感情状態は、もし存在するとしても、個人によって異なるだけでなく、同じ個人においても、異なる機会において、さらには同じ儀式において異なる時点においてさえも、変化するはずである」[68]からである。 言い換えれば、適切なパフォーマティビティとは、解釈されるべきシンボルではなく、権威者によって承認されたルールに従って獲得されるべき能力なのである。 - アサド(1993)62ページ ヨーロッパにおける中世の修道院生活の例を引きながら、この場合の儀式とは、「神の奉仕を行う際に守るべき秩序と方法を指示する書物」という本来の意味を 指していると指摘する。この書物は、「食事、睡眠、労働、祈りの適切な方法に関するものであれ、適切な道徳的気質や精神的適性に関するものであれ、『神に 仕える』徳を身につけることを目的とした実践を規定していた」[69]。修道僧の訓練のポイントは、技術と適切な感情を学ぶことにあった。アサドは彼のア プローチとは対照的に、次のように結論づける: シンボルは解釈を求めるものであり、解釈の基準が拡大されるにつれて、解釈も拡大される。他方、道徳的能力を開発するための学習は、表象を発明するための学習と同じではないからである。 - Asad (1993), p. 79 社会的連帯の一形態として 民族誌的観察によれば、儀式は社会的連帯を生み出すことができる。ダグラス・フォーリーは1973年から1974年にかけてテキサス州ノースタウンに赴 き、公立高校の文化を研究した。彼はインタビュー、参与観察、構造化されていないおしゃべりを用いて、人種間の緊張と資本主義文化を研究し、そのエスノグ ラフィー『資本主義文化を学ぶ』(Learning Capitalist Culture)にまとめた。フォーリーは、フットボールの試合やフライデーナイトライツを共同体の儀式と呼んでいる。この儀式は学校を団結させ、壮行会 や試合そのものを含む連帯感や共同体意識を毎週生み出していた。フォーリーは、階級、社会的地位、裕福さ、性別による判断と分離を観察した。彼はフライ デーナイトライツを、そうした違いを克服する儀式だと表現した: 「フットボールのもうひとつの、より穏やかで社会的な側面は、もちろん、仲間意識、忠誠心、選手間の友情、団結を強調することだった」[70]: 人類学者のサフェット・ハジムハメドヴィッチは、『Waiting for Elijah: Time and Encounter in a Bosnian Landscape』の中で、聖ジョージ記念日や聖エリヤ記念日のような共有の祭りが宗教間の関係を構造化し、ボスニアにおける民族主義的な領土の浄化に 対する連帯の行為として現れることを示唆している[43]。 儀式化 主な記事 儀式化 アサドの研究は、儀式の普遍的な特徴があらゆるケースに見られるという考え方を批判した。キャサリン・ベルは、カテゴリーとしての儀式から、儀式が社会に おける文化的形態として生み出される「儀式化」のプロセスに注意を移すことによって、この考えを拡張した。儀式化とは、「他の、通常はより日常的な活動と 比較して、行われていることを区別し、特権化するためにデザインされ、組織化された行動様式」のことである[71]。 社会生物学と行動神経科学 人類学者はまた、他の行動科学からの洞察によって儀式を分析してきた。DulaneyとFiskeは、儀式と非儀式的な行為、例えば仕事に関する民族誌的 記述を、強迫性障害(OCD)の臨床的記述から得られた行動記述と比較している。そして、文化的儀式に関する民族誌的記述には、「仕事」のような他の活動 に関する民族誌的記述の約5倍、このような内容が含まれていることを示している。フィスクは後に、より多くの異なる文化圏の記述を用いて同様の分析を繰り 返し、文化的儀式に関する記述を(OCDに加えて)他の行動障害に関する記述と対比させることで、OCDに似た行動のみが(他の病気ではなく)儀式と特性 を共有していることを示した[74]。著者らはこれらの知見について、例えば、これらの行動特性は生存のために広く必要とされ、リスクをコントロールする ために必要であり、文化的儀式は知覚された集団的リスクの文脈で行われることが多いといった暫定的な説明を提示している。 他の人類学者はこれらの洞察をさらに推し進め、脳の機能や生理学に基づいてより精巧な理論を構築した。LiénardとBoyerは、個人における強迫的 な行動と集団的な文脈における同様の行動の共通点は、彼らが危険予知と呼ぶ精神的なプロセスが根底にあるために共通点がある可能性を示唆している。彼ら は、社会の個人は危険の回避に関連する情報により注意を払うようであることを示唆しており、このことは、危険予防の行動を示す集団的儀式が文化的伝播の中 で非常に人気があり、長期間にわたって広まっている理由を説明することができる[75]。 宗教性の方法論的尺度としての儀式 さらなる情報 宗教に関する理論 社会学者のマーヴィン・ヴァービットによれば、儀式は宗教性の重要な構成要素の一つとして理解される。儀式そのものは、内容、頻度、強度、中心性の4つの 次元に分けることができる。儀式の内容は、儀式によって異なるかもしれないし、儀式の実践頻度、儀式の強度(儀式が実践者にどれほどの影響を与えるか)、 儀式の中心性(その宗教的伝統における)も異なるかもしれない[76][77][78]。 この意味において、儀式はチャールズ・グロックの宗教性の「実践」次元と類似している[79]。 |

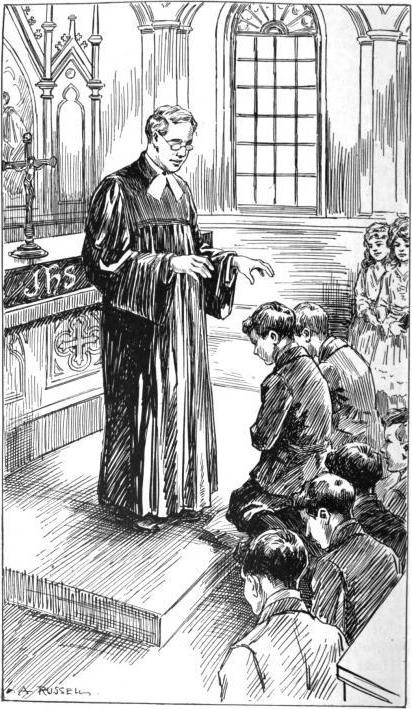

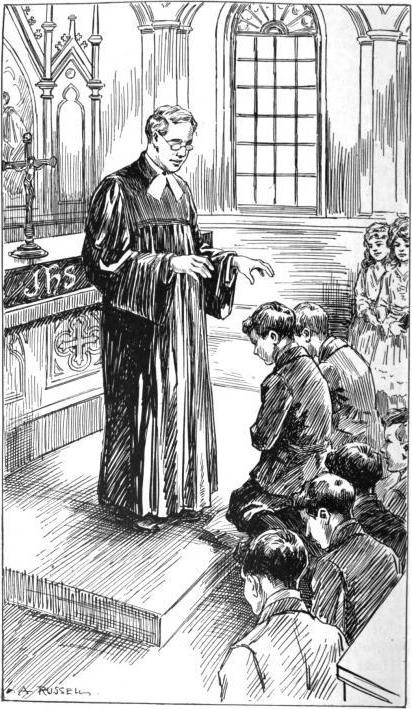

| Religious perspectives Further information: Myth and ritual In religion, a ritual can comprise the prescribed outward forms of performing the cultus, or cult, of a particular observation within a religion or religious denomination. Although ritual is often used in context with worship performed in a church, the actual relationship between any religion's doctrine and its ritual(s) can vary considerably from organized religion to non-institutionalized spirituality, such as ayahuasca shamanism as practiced by the Urarina of the upper Amazon.[80] Rituals often have a close connection with reverence, thus a ritual in many cases expresses reverence for a deity or idealized state of humanity. Christianity  This Lutheran pastor administers the rite of confirmation on youth confirmands after instructing them in Luther's Small Catechism. Main article: Rite (Christianity) In Christianity, a rite is used to refer to a sacred ceremony (such as anointing of the sick), which may or may not carry the status of a sacrament depending on the Christian denomination (in Roman Catholicism, anointing of the sick is a sacrament while in Lutheranism it is not). The word "rite" is also used to denote a liturgical tradition usually emanating from a specific center; examples include the Roman Rite, the Byzantine Rite, and the Sarum Rite. Such rites may include various sub-rites. For example, the Byzantine Rite (which is used by the Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Lutheran, and Eastern Catholic churches) has Greek, Russian, and other ethnically based variants. Islam For daily prayers, practicing Muslims must perform a ritual recitation from the Quran in Arabic while bowing and prostrating. Quranic chapter 2 prescribes rituals such as the direction to face for prayers (qiblah); pilgrimage (Hajj), and fasting in Ramadan.[81] Iḥrām is a state of ritual purity in preparation for pilgrimage in Islam.[82] Hajj rituals include circumambulation around the Kaʿbah.[83]... and show us our rites[84] - these rites (manāsik) are presumed the rituals of ḥajj.[83] Truly Ṣafā and Marwah are among the rituals of God[85] Saʿy is the ritual travel, partway between walking and running, seven times between the two hills.[86] |

宗教的視点 さらに詳しい情報 神話と儀式 宗教において儀式とは、ある宗教や宗派の中で、特定の観察対象であるカルトゥス(教団)を実行するために定められた外見上の形式を指す。儀式は教会で行わ れる礼拝との関連で使われることが多いが、宗教の教義と儀式との実際の関係は、組織化された宗教から、アマゾン上流のウラリナ族が実践するアヤワスカ・ シャーマニズムのような非組織化されたスピリチュアリティまで、実にさまざまである[80]。儀式はしばしば敬虔さと密接な関係があるため、多くの場合、 儀式は神や人間の理想的な状態に対する敬虔さを表現している。 キリスト教  このルター派の牧師は、ルターの小カテキズムを指導した後、青少年の確認者に確認の儀式を行う。 主な記事 儀式(キリスト教) キリスト教では、儀式は神聖な儀式(病者の塗油など)を指すのに使われ、キリスト教の宗派によって聖餐式の地位を持つ場合と持たない場合がある(ローマ・ カトリックでは病者の塗油は聖餐式だが、ルター派では聖餐式ではない)。また、「儀式」という言葉は、通常、特定の中心から発せられる典礼の伝統を示すた めにも使われる。その例としては、ローマ儀式、ビザンチン儀式、サルム儀式などがある。そのような儀式には、さまざまな下位儀式が含まれることがある。例 えば、ビザンツ典礼(東方正教会、東方ルーテル教会、東方カトリック教会で使用されている)には、ギリシャ語、ロシア語、その他の民族的なバリエーション がある。 イスラム教 毎日の礼拝では、パフォーマティビティのあるイスラム教徒は、アラビア語でコーランを朗読し、お辞儀と平伏をしなければならない。クルアーン第2章では、 礼拝に向かう方角(キブラ)、巡礼(ハッジ)、ラマダンの断食などの儀式が規定されている[81]。イフラームとは、イスラム教における巡礼に備えた儀式 的な純潔の状態のことである[82]。 ハッジの儀式にはカームバを一周することが含まれる[83]......そして私たちの儀式を見せてください[84] - これらの儀式(マナーシク)はハッジの儀式と推定される[83] Ṣとマルワーは神の儀式のひとつである[85] サフュイとは、歩くことと走ることの中間の儀式で、2つの丘の間を7回移動することである[86]。 |

| Freemasonry Main articles: Masonic ritual and symbolism and List of Masonic rites In Freemasonry, rituals are scripted words and actions which employ Masonic symbolism to illustrate the principles espoused by Freemasons. These rituals are progressively taught to entrusted members during initiation into a particular Masonic rite comprising a series of degrees conferred by a Masonic body.[87] The degrees of Freemasonry derive from the three grades of medieval craft guilds; those of "Entered Apprentice", "Journeyman" (or "Fellowcraft"), and "Master Mason". In North America, Freemasons who have been raised to the degree of "Master Mason" have the option of joining appendant bodies that offer additional degrees to those, such as those of the Scottish Rite or the York Rite. |

フリーメーソン 主な記事 メーソンの儀式と象徴主義、メーソンの儀式一覧 フリーメーソンにおいて儀式とは、フリーメーソンが信奉する原則を説明するためにメーソンの象徴を用いた台本化された言葉や行動のことである。これらの儀 式は、メーソン団体によって授与される一連の学位から成る特定のメーソン儀式への入会の際に、委託された会員に徐々に教え込まれる[87]。フリーメイソ ンの学位は、中世の工芸ギルドの3つの等級、すなわち「入門見習い」、「ジャーニーマン」(または「フェロークラフト」)、「マスターメイソン」に由来す る。北米では、「マスター・メーソン」の学位に昇格したフリーメイソンは、スコティッシュ・ライトやヨーク・ライトのような、さらなる学位を提供する付属 団体に加入する選択肢がある。 |

| Behavioral script – Play of the visualization Builders' rites – Ceremonies associated with construction Chinese ritual mastery traditions – Chinese folk religious order Confucianism § Rite and centring – Chinese ethical and philosophical system Gut (ritual) – Korean shamanic rite Kagura – Type of ceremonial dance in Shinto ritual List of substances used in rituals Nabichum – type of dance Nuo rituals – Indigenous Chinese religion Process art – Art movement Processional walkway – Structure Religious symbolism – Icon representing a particular religion Ritualism in the Church of England – Emphasis on the rituals and liturgical ceremony of the church Symbolic boundaries – theory of how people form social groups proposed by cultural sociologists Taiping Qingjiao – Taoist festival The Rite of Spring – 1913 ballet by Igor Stravinsky |

行動台本 - 視覚化の遊び 建設者の儀式 - 建設に関連する儀式 中国の儀式習得の伝統 - 中国の民間宗教秩序 儒教 § 儀式と中心 - 中国の倫理・哲学体系 ガット(儀式) - 韓国のシャーマン儀式 神楽 - 神道儀礼における儀式舞踊の一種 儀式に使われる物質のリスト ナビチュム - 舞の一種 ヌオの儀式 - 中国先住民族の宗教 プロセスアート - 芸術運動 参道 - 構造物 宗教的象徴 - 特定の宗教を象徴するアイコン 英国国教会の儀式主義 - 教会の儀式と典礼儀式を重視する。 シンボリック・バウンダリー - 文化社会学者が提唱した、人々がどのように社会集団を形成するかについての理論 太平青射 - 道教の祭り 春の祭典 - イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーによる1913年のバレエ作品 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritual |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099