デイヴィッド・ロス『正義と善』1930

The Right and the Good, by David Ross

☆ 『正義と善』は、スコットランドの哲学者デイヴィッド・ロスによる1930年の著書である。この本の中で、ロスは一見したところの義務を基盤とした義務論 的多元主義を展開している。ロスは、道徳性についてはリアリストの立場、道徳的知識については直観主義者の立場を擁護している。『正義と善』は、20世紀 における倫理理論の最も重要な著作のひとつとして評価されている。[1][2]

| The Right and the Good

is a 1930 book by the Scottish philosopher David Ross. In it, Ross

develops a deontological pluralism based on prima facie duties. Ross

defends a realist position about morality and an intuitionist position

about moral knowledge. The Right and the Good has been praised as one

of the most important works of ethical theory in the twentieth

century.[1][2] |

『正

義と善』は、スコットランドの哲学者デイヴィッド・ロスによる1930年の著書である。この本の中で、ロスは一見したところの義務を基盤とした義務論的多

元主義を展開している。ロスは、道徳性についてはリアリストの立場、道徳的知識については直観主義者の立場を擁護している。『正義と善』は、20世紀にお

ける倫理理論の最も重要な著作のひとつとして評価されている。[1][2] |

| Summary As the title suggests, The Right and the Good is about rightness, goodness and their relation to each other.[3]: x Rightness is a property of acts while goodness concerns various kinds of things. According to Ross, there are certain features that both have in common: they are real properties, they are indefinable, pluralistic and knowable through intuition.[2] Central to rightness are prima facie duties, for example, the duty to keep one's promises or to refrain from harming others.[1] Of special interest for understanding goodness is intrinsic value: what is good in itself. Ross ascribes intrinsic value to pleasure, knowledge, virtue and justice.[2] It is easy to confuse rightness and goodness in the case of moral goodness. An act is right if it conforms to the agent's absolute duty.[3]: 28 Doing the act for the appropriate motive is not important for rightness but it is central for moral goodness or virtue.[4] Ross uses these considerations to point out the flaws in other ethical theories, for example, in G. E. Moore's ideal utilitarianism or in Immanuel Kant's deontology. |

要約 タイトルが示すように、『正義と善』は正しさ、善さ、そしてそれらの相互関係について論じている。[3]: x 正しさとは行為の性質であり、善さとはさまざまな事物に関わるものである。ロスによると、両者には共通する特徴がある。それは、実在する性質であり、定義 不可能で多元的であり、直観によって知ることができるというものである。[2] 正しさの中心となるのは、一見したところ義務である。例えば、約束を守る義務や他者を傷つけない義務などである。[1] 善を理解する上で特に興味深いのは、本質的価値である。すなわち、それ自体が善であるものは何かということである。ロスは、快楽、知識、美徳、正義に本質 的価値を帰属させている。[2] 道徳的な善の場合、正しさや善を混同しやすい。行為は、行為者の絶対的な義務に適合している場合、正しいとされる。[3]:28 適切な動機に基づいて行為を行うことは、正しいことにとっては重要ではないが、道徳的な善や美徳にとっては重要である。[4] ロスは、こうした考察を基に、他の倫理理論の欠陥を指摘している。例えば、G. E. ムーアの理想功利主義や、イマヌエル・カントの義務論などである。 |

| Realism and indefinability Ross defends a realist position about morality: the moral order expressed in prima facie duties is just as real as "the spatial or numerical structure expressed in the axioms of geometry or arithmetic".[3]: 29–30 Furthermore, the terms "right" and "good" are indefinable.[2] This means that various naturalistic theories trying to define "good" in terms of desire or "right" in terms of producing the most pleasure fail.[3]: 11–2 But this even extends to theories that characterize one of these terms through the other. Ross uses this line of thought to object to Moore's ideal utilitarianism, which defines "right" in terms of "good" by holding that an action is right if it produces the best possible outcome.[1][4] |

リアリズムと定義不可能性 ロスは道徳に関する現実主義の立場を擁護している。一見して義務として表現される道徳的秩序は、「幾何学や算術の公理で表現される空間的または数理的構 造」と同じくらい現実的である。[3]: 29–30 さらに、「正しい」や「良い」という用語は定義できない。[2] つまり、欲望という観点から「良い」を定義しようとしたり、最大の快楽を生み出すという観点から「正しい」を定義しようとしたりするさまざまな自然主義的 な理論は失敗する。[3]: 11–2 しかし、これは、これらの用語の一方を他方によって特徴づける理論にまで及ぶ。ロスは、この考え方を基に、最善の結果をもたらす行動は正しいとする「善」 の概念によって「正しさ」を定義するムーアの理想功利主義に異議を唱えている。[1][4] |

| The Right Ross, like Immanuel Kant, is a deontologist: he holds that rightness depends on adherence to duties, not on consequences.[1] But against Kant's monism, which bases ethics in only one foundational principle, the categorical imperative, Ross contends that there is a plurality of prima facie duties determining what is right.[2][3]: xii Some duties originate from our own previous actions, like the duty of fidelity (to keep promises and to tell the truth), and the duty of reparation (to make amends for wrongful acts). The duty of gratitude (to return kindnesses received) arises from the actions of others. Other duties include the duty of non-injury (not to hurt others), the duty of beneficence (to promote the maximum of aggregate good), the duty of self-improvement (to improve one's own condition) and the duty of justice (to distribute benefits and burdens equably).[3]: 21–5 [1] One problem the deontological pluralist has to face is that cases can arise where the demands of one duty violate another duty, so-called moral dilemmas.[5] For example, there are cases where it is necessary to break a promise in order to relieve someone's distress.[3]: 28 Ross makes use of the distinction between prima facie duties and absolute duty to solve this problem.[3]: 28 The duties listed above are prima facie duties; they are general principles whose validity is self-evident to morally mature persons. They are factors that do not take all considerations into account. Absolute duty, on the other hand, is particular to one specific situation, taking everything into account, and has to be judged on a case-by-case basis.[2][4] Various considerations are involved in such judgments, e.g. concerning which prima facie duties would be upheld or violated and how important they are in the given case.[1] Ross uses the comparison to physics, where various forces, e.g. due to gravitation or electromagnetism, affect the movement of bodies, but the overall movement is determined not by one single force component but by the total net force.[3]: 28–9 It is absolute duty that determines which acts are right or wrong. This way, the dilemmas posed by prima facie duties can be resolved.[3]: 21–2 [2] |

正義・正しさ ロスは、イマニュエル・カントと同様に、義務論者である。すなわち、正しさは義務の遵守に依存し、結果に依存するものではないと主張している。[1] しかし、倫理を唯一の基礎原則である定言命法のみに求めるカントの一元論に対して、ロスは、一見して正しいと判断できる義務には複数の種類があることを主 張している。[2][3]:xii いくつかの義務は、私たちの過去の行動に由来する。例えば、誠実さの義務(約束を守り、真実を語る)や )、賠償義務(不正行為の償い)などがある。感謝の義務(受けた親切に報いること)は他者の行動から生じる。その他の義務には、非侵害の義務(他者を傷つ けないこと)、善行の義務(総体的な善を最大限に促進すること)、自己改善の義務(自身の状態を改善すること)、正義の義務(利益と負担を公平に分配する こと)などがある。[3]: 21–5 [1] 義務論的多元論者が直面しなければならない問題のひとつは、ある義務の要求が別の義務に違反するというケースが生じうるということ、いわゆる道徳的ジレン マである。[5] 例えば、誰かの苦痛を和らげるために約束を破らなければならないケースがある。[3]: 28 ロスは、この問題を解決するために、一見したところの義務と絶対的な義務の区別を利用している。[3]: 28 上記に挙げた義務は一見したところの義務である。これらは道徳的に成熟した人格者にとっては自明の妥当性を有する一般原則である。これらはあらゆる考慮事 項を考慮に入れたものではない。一方、絶対的義務は特定の状況に特有のものであり、あらゆる要素を考慮した上で、個別に判断されるべきものである。[2] [4] このような判断には、例えば、どの一見の義務が支持されるか、あるいは違反されるか、また、その事例においてどの程度の重要性を持つかなど、さまざまな考 慮事項が関わってくる。[1] ロスは物理学との比較を用いており、そこでは、例えば重力や電磁気学によるさまざまな力が しかし、物体の動きは、単一の力ではなく、総合力によって決定される。[3]: 28-9 どの行為が正しいか、間違っているかを決定するのは、絶対的な義務である。このようにして、一見義務によって引き起こされるジレンマは解決できる。 [3]: 21-2 [2] |

| The Good The term "good" is used in various senses in natural language.[4] Ross points out that it is important for philosophy to distinguish between the attributive and the predicative sense.[3]: 65 In the attributive sense, "good" means skillful or useful, as in "a good singer" or "a good knife". This sense of good is relative to a certain kind: being good as something, like a person may be good as a singer but not good as a cook.[3]: 65–7 The predicative sense of good, on the other hand, as in "pleasure is good" or "knowledge is good" is not relative in this sense. Of main interest to philosophy is a certain type of predicative goodness: so-called intrinsic goodness. An intrinsically good thing is good in itself: it would be good even if it existed all by itself, it is not just good as a means because of its consequences.[3]: 67–8 [6] According to Ross, self-evident intuition shows that there are four kinds of things that are intrinsically good: pleasure, knowledge, virtue and justice.[1][4] "Virtue" refers to actions or dispositions to act from the appropriate motives, for example, from the desire to do one's duty.[2] "Justice", on the other hand, is about happiness in proportion to merit. As such, pleasure, knowledge and virtue all concern states of mind, in contrast to justice, which concerns a relation between two states of mind.[2] These values come in degrees and are comparable with each other. Ross holds that virtue has the highest value while pleasure has the lowest value.[4][5] He goes so far as to suggest that "no amount of pleasure is equal to any amount of virtue, that in fact virtue belongs to a higher order of value".[3]: 150 Values can also be compared within each category, for example, well-grounded knowledge of general principles is more valuable than weakly grounded knowledge of isolated matters of fact.[3]: 146–7 [2] |

善 「善」という語は自然言語においてさまざまな意味で用いられる。[4] ロスは、哲学において、属性的意味と述定的意味を区別することが重要であると指摘している。[3]: 65 属性的意味では、「善」は「上手な」あるいは「有用な」という意味であり、「上手な歌手」や「良いナイフ」のように用いられる。この「良い」という感覚は ある特定の種類の相対的なものである。例えば、ある人格は歌手としては優れていても、料理人としては優れていないかもしれない。[3]: 65–7 一方、「快楽は良い」や「知識は良い」というように、述語的な意味での「良い」は、この感覚においては相対的なものではない。哲学が主に興味を持っている のは、ある特定のタイプの述語的な善、すなわち、いわゆる本質的な善である。本質的に善いものはそれ自体で善い。それ自体で存在していても善い。それは、 結果として善いという理由で手段として善いというだけではない。[3]: 67–8 [6] ロスによると、自明の直観は、本質的に善であるものは4種類あることを示している。すなわち、快楽、知識、徳、正義である。[1][4] 「徳」とは、適切な動機、例えば義務を果たしたいという欲求から行動する、あるいは行動する傾向を指す。[2] 一方、「正義」とは、功績に比例した幸福を意味する。そのため、快楽、知識、徳はすべて心の状態に関係するが、正義は2つの心の状態の関係に関係する。 [2] これらの価値は段階的に存在し、互いに比較することができる。ロスは、徳が最高の価値を持ち、快楽が最低の価値を持つと主張している。[4][5] 彼はさらに、「快楽の量は徳の量に決して匹敵せず、実際、徳はより高次の価値に属する」とまで述べている。[3]:150 価値は各カテゴリー内でも比較でき、例えば、一般的な原則に関する根拠のしっかりした知識は、事実の個別事項に関する根拠の弱い知識よりも価値が高い。 [3]:146– 7[2] |

| Intuitionism According to Ross's intuitionism, we can know moral truths through intuition, for example, that it is wrong to lie or that knowledge is intrinsically good.[2] Intuitions involve a direct apprehension that is not mediated by inferences or deductions: they are self-evident and therefore not in need of any additional proof.[1] This ability is not inborn but has to be developed on the way to reaching mental maturity.[3]: 29 But in its fully developed form, we can know moral truths just as well as we can know mathematical truths like the axioms of geometry or arithmetic.[3]: 30 [7] This self-evident knowledge is limited to general principles: we can come to know the prima facie duties this way but not our absolute duty in a particular situation: what we should do all things considered.[3]: 19–20, 30 All we can do is consult perception to determine which prima facie duty has the highest normative weight in this particular case, even though this usually does not amount to knowledge proper due to the complexity involved in most specific cases.[2] |

直観主義 ロスの直観主義によれば、道徳的真理は直観によって知ることができる。例えば、嘘をつくことは悪いことであるとか、知識は本質的に善であるといったことで ある。[2] 直観とは、推論や演繹によって媒介されない直接的な把握を意味する。直観は自明であり、したがって追加の証明を必要としない。[1] この能力は生得的なものではなく、精神的に成熟する過程で開発されるものである。[3]: 29 しかし、その能力が完全に 完全に発達した形では、幾何学や算術の公理のような数学的真理を知るのと同じように、道徳的真理を知ることができる。[3]: 30 [7] この自明の知識は一般的な原則に限られる。一見したところの義務はこの方法で知ることができるが、特定の状況における絶対的な義務、つまりあらゆることを 考慮した上で何をすべきか、を知ることはできない。[3]: 19–20, 30 私たちにできるのは、 特定のケースにおいて、どの一応の義務が最も高い規範的価値を持つかを判断する。ただし、通常、特定のケースには複雑な要素が絡むため、これは適切な知識 にはならない。[2] |

| Objections to other theories Various arguments in The Right and the Good are directed against utilitarianism in general and Moore's version of it in particular. Ross acknowledges that there is a duty to promote the maximum of aggregate good, as utilitarianism demands. But, Ross contends, this is just one besides various other duties, which are ignored by the overly simplistic and reductive utilitarian outlook.[3]: 19 [1] Another fault of utilitarianism is that it disregards the personal character of duties, for example, due to fidelity and gratitude.[3]: 22 Ross argues that his deontological pluralism does a better job at capturing common-sense morality since it avoids these problems.[2] Ross objects to Kant's view that the rightness of actions depends on their motive. Such a view leads to a circular or even contradictory account of duty since "[t]hose who hold that our duty is to act from a certain motive usually ... hold that the motive from which we ought to act is the sense of duty".[3]: 5 So "it is my duty to do act A from the sense that it is my duty to do act A".[3]: 5 To avoid this problem, Ross suggests that moral goodness should be distinguished from moral rightness or moral obligation.[3]: 5 The moral value of an action depends on the motive but the motive is not relevant for whether the act is right or wrong.[4] |

他の理論に対する異論 『正義と善』におけるさまざまな議論は、功利主義一般、特にムーアの功利主義に対するものである。ロスは、功利主義が要求するように、集合的な善を最大限 に促進する義務があることを認めている。しかし、ロスは主張する。これは、あまりにも単純化され還元主義的な功利主義の見解によって無視されている、さま ざまな義務のほんの1つにすぎない。[3]:19[1] 功利主義のもう1つの欠点は、例えば誠実さや感謝といった義務の持つ人格的な側面を無視していることである。[3]:22 ロスは、義務論的多元主義はこれらの問題を回避できるため、常識的な道徳性をより適切に捉えることができると主張している。[2] ロスは、行動の善し悪しはその動機によって決まるというカントの見解に異議を唱えている。このような見解は、義務に関する循環論法、あるいは矛盾した説明 につながる。なぜなら、「私たちの義務は特定の動機に基づいて行動することであると考える人々は、通常...行動すべき動機は義務感であると考える」から である。[3]:5 したがって、「Aという行動を取ることが私の義務であるという感覚から、私はAという行動を取るべきである」ということになる。[3]:5 この問題を回避するために、ロスは道徳的な善は道徳的な正しさや道徳的な義務とは区別されるべきであると提案している 。ある行為の道徳的価値はその動機に依存するが、その行為が正しいか間違っているかについては動機は関係ない。[4] |

| Criticism Ross's intuitionism relies on our intuitions about what is right and what has intrinsic value as the source of moral knowledge. But it is questionable how reliable moral intuitions are. One worry is due to the fact that there is a lot of disagreement about fundamental moral principles.[2] Another doubt comes from an evolutionary perspective which holds that our moral intuitions are primarily shaped by evolutionary pressures and less by the objective moral structure of the world.[1][8] Utilitarians have defended their position against the accusations of being overly simplistic and out of touch with common-sense morality by pointing to flaws in Ross's arguments.[1] Many examples by Ross in favor of deontological pluralism seem to rely on a rather generic characterization of the cases. But filling in the particular details may show utilitarianism to be more in touch with common-sense than initially suggested.[9][2] Another criticism concerns Ross's term "prima facie duty". As Shelly Kagan has pointed out, this term is unfortunate since it implies a mere appearance as, for example, when someone is under the illusion of having a certain duty.[10] But what Ross tries to convey is that every prima facie duty has actual normative weight even though it may be overruled by other considerations. This would be better expressed by the term "pro tanto duty".[10][2] |

批判 ロスの直観主義は、何が正しく、何が道徳的知識の源としての本質的価値を持つかについての直観に依存している。しかし、道徳的直観がどの程度信頼できるか は疑問である。懸念のひとつは、根本的な道徳的原則について多くの意見の相違があるという事実によるものである。[2] もうひとつの疑問は、進化論的観点から、道徳的直観は主に進化上の圧力によって形作られ、世界の客観的な道徳構造によって形作られることは少ないというも のである。[1][8] 功利主義者は、ロスの議論の欠陥を指摘することで、自らの立場が単純化されすぎており、常識的な道徳観と乖離しているという非難に対して、その立場を擁護 してきた。[1] ロスが義務論的多元主義を支持するために挙げた多くの例は、かなり一般的な事例の性格づけに依存しているように見える。しかし、特定の詳細を埋めること で、功利主義が当初考えられていたよりも常識に即していることが示される可能性がある。[9][2] もう一つの批判は、ロスの用語「一見したところの義務(prima facie duty)」に関するものである。シェリー・ケーガンが指摘しているように、この用語は、例えば、ある義務があると錯覚している場合など、単なる外見を意 味するため、不適切である。[10]しかし、ロスが伝えようとしているのは、一見したところの義務は、他の考慮事項によって覆される可能性があるとして も、実際には規範的な重みを持っているということである。これは「pro tanto duty」という用語で表現した方が適切である。[10][2] |

| Influence Ross's deontological pluralism was a true innovation and provided a plausible alternative to Kantian deontology.[2] His ethical intuitionism found few followers among his contemporaries but has seen a revival by the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century. Among the philosophers influenced by The Right and the Good are Philip Stratton-Lake, Robert Audi, Michael Huemer, and C.D. Broad.[1] |

影響 ロスの義務論的多元主義は真の革新であり、カントの義務論に対する説得力のある代替案となった。[2] 彼の倫理直観論は同時代にはほとんど追随者がいなかったが、20世紀末から21世紀初頭にかけて復活した。『正義と善』に影響を受けた哲学者には、フィ リップ・ストラットン=レイク、ロバート・オーディ、マイケル・ヒューマー、C.D.ブロードなどがいる。[1] |

| Deontology Ethical intuitionism G. E. Moore Immanuel Kant Moral realism Utilitarianism |

義務論 倫理的直観論(→倫理学における直観主義) G. E. ムーア イマヌエル・カント 道徳的実在論 功利主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Right_and_the_Good |

☆ウィリアム・デイヴィド・ロス(William David Ross, 1877-1971)

| Sir William David Ross

KBE FBA (15 April 1877 – 5 May 1971), known as David Ross but usually

cited as W. D. Ross, was a Scottish Aristotelian philosopher,

translator, WWI veteran, civil servant, and university administrator.

His best-known work is The Right and the Good (1930), in which he

developed a pluralist, deontological form of intuitionist ethics in

response to G. E. Moore's consequentialist form of intuitionism. Ross

also critically edited and translated a number of Aristotle's works,

such as his 12-volume translation of Aristotle together with John

Alexander Smith, and wrote on other Greek philosophy. |

サー・ウィリアム・デイヴィッド・ロス KBE

FBA(1877年4月15日 - 1971年5月5日)は、デイヴィッド・ロスとして知られ、通常W.

D.ロスと表記される。スコットランドの哲学者、翻訳家、第一次世界大戦の退役軍人、公務員、大学管理者であった。彼の最も有名な著作は『正

義と善』

(1930年)であり、この著作では、G. E.

ムーアの結果主義的な直観主義に対して、多元的で義務論的な直観主義倫理を展開した。また、ロス氏は、ジョン・アレクサンダー・スミス氏とともにアリスト

テレスの12巻の翻訳など、アリストテレスの著作を数多く批判的に編集・翻訳し、その他のギリシャ哲学についても著述を行った。 |

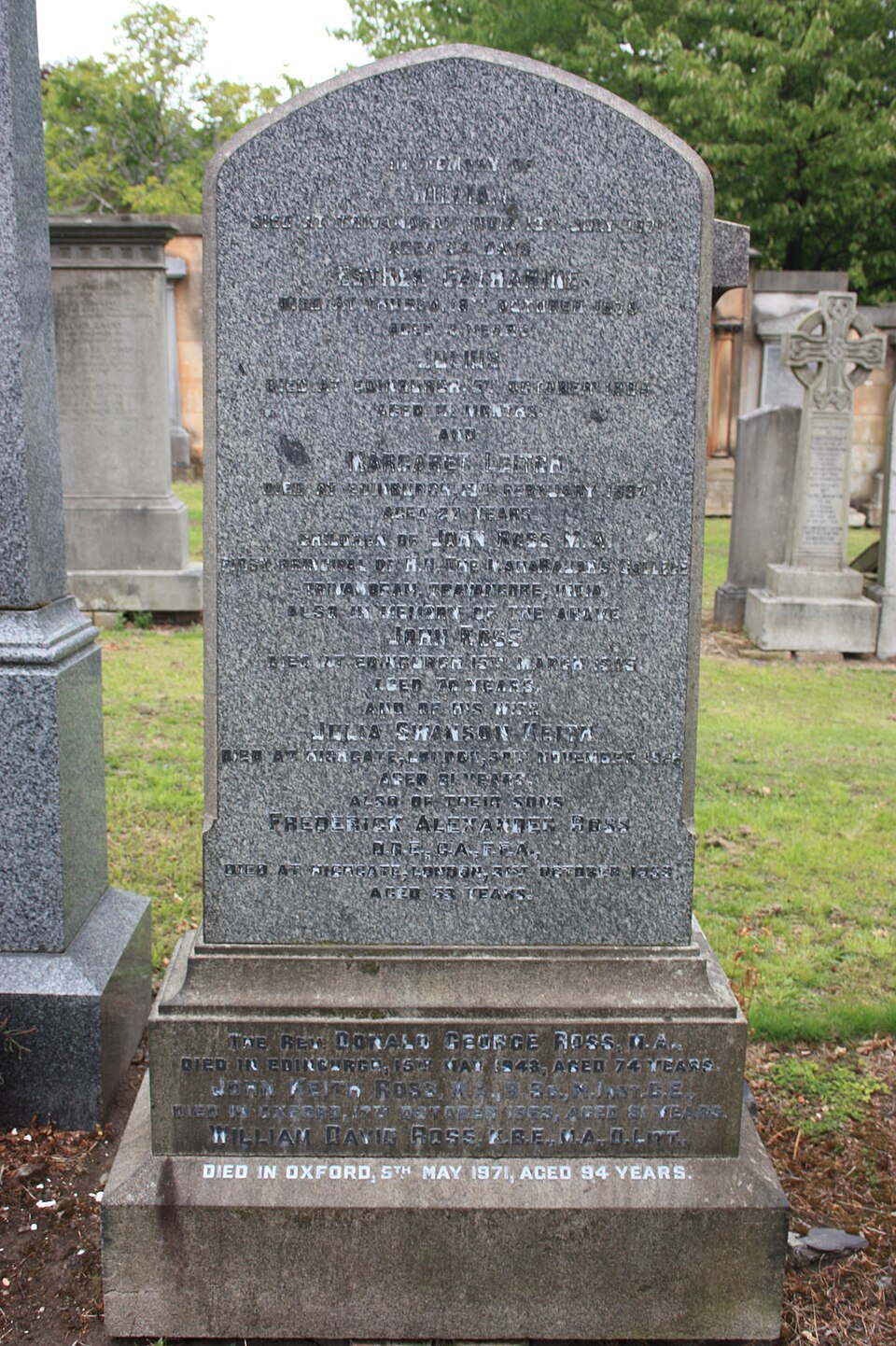

| Life William David Ross was born in Thurso, Caithness in the north of Scotland the son of John Ross (1835–1905).[3] He spent most of his first six years as a child in southern India.[4] He was educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh, and the University of Edinburgh. In 1895, he gained a first class MA honours degree in classics. He completed his studies at Balliol College, Oxford, with a First in Classical Moderations in 1898 and a First in Literae Humaniores ('Greats', a combination of philosophy and ancient history) in 1900.[5] He was made a Fellow of Merton College in 1900, a position he held until 1945;[6] he was elected to a tutorial fellowship at Oriel College in October 1902.[7] With the outbreak of World War I, Ross joined the army in 1915 with a commission on the special list.[8] He held a series of positions involved with the supply of munitions.[4] At the time of the armistice he held the rank of major and was Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Ministry of Munitions.[8] He was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1918 in recognition of his wartime service. For his post-war services to various public bodies he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1938.[8][4] Ross was White's Professor of Moral Philosophy (1923–1928), Provost of Oriel College, Oxford (1929–1947), Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford from 1941 to 1944 and Pro-Vice-Chancellor (1944–1947). He was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1939 to 1940. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy and was its president from 1936 to 1940.[8] Of the many governmental committees on which he served one was the Civil Service Tribunal, of which he was chairman. One of his two colleagues was Leonard Woolf, who thought that the whole system of fixing governmental remuneration should be on the same basis as the US model, dividing the civil service into a relatively small number of pay grades.[9] Ross did not agree with this radical proposal. In 1947 he was appointed chairman of the first Royal Commission on the Press, United Kingdom, elected an honorary fellow of Trinity College Dublin,[10] and elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society.[11] He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950.[12]  The Ross family grave, Grange Cemetery He died in Oxford on 5 May 1971. He is memorialised on his parents' grave in the Grange Cemetery in Edinburgh. |

生涯 ウィリアム・デイヴィッド・ロスは、スコットランド北部のケイスネス州サーソーで、ジョン・ロス(1835–1905)の子として生まれた。[3] 幼少期の最初の6年間の大半を南インドで過ごした。[4] エディンバラのロイヤル・ハイ・スクールとエディンバラ大学で教育を受けた。1895年、古典学で優等学位(一等)を取得した。オックスフォード大学ベリ オール・カレッジで学業を続け、1898年に古典学中級試験で一等、1900年にはリテラエ・ヒューマニオーレス(哲学と古代史の複合科目「グレート ス」)で一等を得た。[5] 1900年にマートン・カレッジのフェローに任命され、この地位は1945年まで保持した[6]。1902年10月にはオリエル・カレッジのチュートリア ル・フェローに選出された[7]。 第一次世界大戦勃発に伴い、ロスは大戦特別任官リストで1915年に陸軍に入隊した[8]。弾薬供給に関わる一連の職務を担当した。[4]休戦時には少佐 の階級で軍需省次官補を務めていた。[8]戦時中の功績が認められ、1918年に大英帝国勲章オフィサー(OBE)を受章。戦後の各種公共機関への貢献に より、1938年には大英帝国勲章ナイト・コマンダー(KCBE)に叙された。[8][4] ロスはホワイトズ道徳哲学教授(1923-1928年)、オックスフォード大学オリエル・カレッジ学長(1929-1947年)、オックスフォード大学副 総長(1941-1944年)、副総長補佐(1944-1947年)を務めた。1939年から1940年までアリストテレス協会の会長を務めた。英国学士 院のフェローに選出され、1936年から1940年までその会長を務めた。[8] 彼が務めた数多くの政府委員会の一つに公務員審判所があり、彼はその委員長を務めた。同僚の一人であるレナード・ウルフは、政府職員の報酬体系全体を米国 モデルと同様の基準で設定し、公務員を比較的少数の給与等級に分類すべきだと考えていた。[9] ロスはこのような急進的な提案には同意しなかった。1947年には英国初の王立報道委員会委員長に任命され、ダブリン大学トリニティ・カレッジの名誉フェ ローに選出された[10]。またアメリカ哲学協会の国際会員にも選出された[11]。1950年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの会員に選出されている。 [12]  ロス家の墓、グレンジ墓地 彼は1971年5月5日にオックスフォードで死去した。エディンバラのグレンジ墓地にある両親の墓に彼の記念碑が建てられている。 |

| Family His younger brother was minister Donald George Ross (1879–1943). He married Edith Ogden in 1906 and they had four daughters, Margaret (who married Robin Harrison), Eleanor, Rosalind (who married John Miller Martin), and Katharine. Edith died in 1953. He was a cousin of Berriedale Keith. |

家族 弟はドナルド・ジョージ・ロス(1879年~1943年)牧師だった。 1906年にエディス・オグデンと結婚し、4人の娘、マーガレット(ロビン・ハリソンと結婚)、エレノア、ロザリンド(ジョン・ミラー・マーティンと結婚)、キャサリンが生まれた。エディスは1953年に亡くなった。 彼はベリデール・キースのいとこだった。 |

| Ethical theory Ross was a moral realist, a non-naturalist, and an intuitionist.[13] He argued that there are moral truths. He wrote: The moral order ... is just as much part of the fundamental nature of the universe (and ... of any possible universe in which there are moral agents at all) as is the spatial or numerical structure expressed in the axioms of geometry or arithmetic.[14] Thus, according to Ross, the claim that something is good is true if that thing really is good. Ross also agreed with G. E. Moore's claim that any attempt to define ethical statements solely in terms of statements about the natural world commits the naturalistic fallacy. Furthermore, the terms right and good are "indefinable".[15] This means not only that they cannot be defined in terms of natural properties but also that it is not possible to define one in terms of the other. Ross rejected Moore's consequentialist ethics. According to consequentialist theories, what people ought to do is determined only by whether their actions will bring about the best. By contrast, Ross argues that maximising the good is only one of several prima facie duties (prima facie obligations) which play a role in determining what a person ought to do in any given case. |

倫理学理論 ロスは道徳的実在論者であり、非自然主義者であり、直観主義者であった[13]。彼は道徳的真理が存在すると主張した。彼はこう記している: 道徳秩序は…幾何学や算術の公理に表される空間的・数的な構造と同様に、宇宙(そして…道徳的主体が存在するあらゆる可能性のある宇宙)の基本的な性質の一部である。[14] したがってロスによれば、何かが善であるという主張は、そのものが実際 に善である場合に真となる。またロスもG・E・ムーアの主張に同意し、倫理的命題を自然界に関する命題のみで定義しようとする試みは自然主義的誤謬に陥る とした。さらに、「正しい」と「善い」という用語は「定義不可能」である[15]。これは、自然的性質によって定義できないだけでなく、一方を他方で定義 することも不可能であることを意味する。 ロスはムーアの帰結主義倫理学を拒否した。帰結主義理論によれば、人格 がすべきことは、その行動が最善をもたらすか否かによってのみ決定される。これに対し、ロスは、善を最大化することは、個々の事例において人格がすべきこ とを決定する役割を果たす、いくつかの表面的義務(prima facie obligations)の一つに過ぎないと主張する。 |

| Duties In The Right and the Good, Ross lists seven prima facie duties, without claiming his list to be exhaustive: fidelity; reparation; gratitude; justice; beneficence; non-maleficence; and self-improvement. In any given situation, any number of these prima facie duties may apply. In the case of ethical dilemmas, they may even contradict one another. Someone could have a prima facie duty of reparation, say, a duty to help people who helped you move house, move house themselves, and a prima facie duty of fidelity, such as taking one's children on a promised trip to the park, and these could conflict. Nonetheless, there can never be a true ethical dilemma, Ross argued, because one of the prima facie duties in a given situation is always the weightiest, and over-rules all the others. This is thus the absolute obligation or absolute duty, the action that the person ought to perform.[16] It is frequently argued, however, that Ross should have used the term pro tanto rather than prima facie. Shelly Kagan, for example, wrote: It may be helpful to note explicitly that in distinguishing between pro tanto and prima facie reasons I depart from the unfortunate terminology proposed by Ross, which has invited confusion and misunderstanding. I take it that – despite his misleading label – it is actually pro tanto reasons that Ross has in mind in his discussion of what he calls prima facie duties.[17] Explaining the difference between pro tanto and prima facie, Kagan wrote: "A pro tanto reason has genuine weight, but nonetheless may be outweighed by other considerations. Thus, calling a reason a pro tanto reason is to be distinguished from calling it a prima facie reason, which I take to involve an epistemological qualification: a prima facie reason appears to be a reason, but may actually not be a reason at all."[17] |

義務 『正 義と善』において、ロスは七つの表面上の義務を列挙している。ただし、このリストが網羅的であるとは主張していない。忠実、償い、感謝、正義、善行、不 害、自己研鑽である。特定の状況においては、これらの表面上の義務がいくつも適用される可能性がある。倫理的ジレンマの場合、それらが互いに矛盾すること さえある。例えば、誰かが「償いの義務」——引っ越しを手伝ってくれた人たちの引っ越しを助ける義務——と「忠実の義務」——約束した公園への子供連れ旅 行を実行する義務——を同時に負っている場合、これらは衝突しうる。しかしながらロスによれば、真の倫理的ジレンマは存在しえない。なぜなら特定の状況下 では、常に一つの義務が他を凌駕する重みを持つからだ。これが絶対的義務、すなわち人格が遂行すべき行動である。[16] しかしロスが「prima facie」ではなく「pro tanto」という用語を用いるべきだったと主張されることが多い。例えばシェリー・ケイガンはこう記している: 「プロ・タント」と「プリマ・フェイシー」の区別において、私はロスが提案した不適切な用語法から離れることを明示的に述べておくのが有益だろう。この用 語は混乱と誤解を招いてきた。私は、ロスの誤解を招く呼称にもかかわらず、彼が「プリマ・フェイシー義務」と呼ぶものの議論において、実際には「プロ・タ ント理由」を念頭に置いていると理解している。[17] プロ・タントとプリマ・フェイシーの違いについて、ケイガンは次のように説明している:「プロ・タント理由は真の重みを持つが、それでも他の考慮事項に よって上回る可能性がある。したがって、理由をプロ・タント理由と呼ぶことは、プリマ・フェイシー理由と呼ぶこととは区別される。後者は認識論的な留保を 含むと私は考える:プリマ・フェイシー理由は理由のように見えるが、実際には全く理由ではないかもしれない」[17] |

| Values and intuition According to Ross, self-evident intuition shows that there are four kinds of things that are intrinsically good: pleasure, knowledge, virtue and justice.[18][19] Virtue refers to actions or dispositions to act from the appropriate motives, for example, from the desire to do one's duty.[15] Justice, on the other hand, is about happiness in proportion to merit. As such, pleasure, knowledge and virtue all concern states of mind, in contrast to justice, which concerns a relation between two states of mind.[15] These values come in degrees and are comparable with each other. Ross holds that virtue has the highest value while pleasure has the lowest value.[19][20] He goes so far as to suggest that "no amount of pleasure is equal to any amount of virtue, that in fact virtue belongs to a higher order of value".[21]: 150 Values can also be compared within each category, for example, well-grounded knowledge of general principle is more valuable than weakly grounded knowledge of isolated matters of fact.[21]: 146–7 [15] According to Ross's intuitionism, we can know moral truths through intuition, for example, that it is wrong to lie or that knowledge is intrinsically good.[15] Intuitions involve a direct apprehension that is not mediated by inferences or deductions: they are self-evident and therefore not in need of any additional proof.[18] This ability is not inborn but has to be developed on the way to reaching mental maturity.[21]: 29 But in its fully developed form, we can know moral truths just as well as we can know mathematical truths like the axioms of geometry or arithmetic.[21]: 30 [22] This self-evident knowledge is limited to general principles: we can come to know the prima facie duties this way but not our absolute duty in a particular situation: what we should do all things considered.[21]: 19–20, 30 All we can do is consult perception to determine which prima facie duty has the highest normative weight in this particular case, even though this usually does not amount to knowledge proper due to the complexity involved in most specific cases.[15] |

価値と直観 ロスによれば、自明の直観は、本質的に善なるものが四種類存在することを示している。すなわち、快楽、知識、徳、そして正義である。[18][19] 徳とは、適切な動機、例えば義務を果たしたいという欲求から行動する行為や行動傾向を指す。[15] 一方、正義とは功績に見合った幸福を意味する。したがって快楽、知識、徳性は全て心の状態に関わるのに対し、正義は二つの心の状態間の関係に関わる。 [15] これらの価値は程度があり、互いに比較可能である。ロスは徳性が最も高い価値を持ち、快楽が最も低い価値を持つと主張する。[19][20] 彼はさらに「いかなる快楽も徳と同等ではなく、実際、徳はより高次の価値体系に属する」とまで示唆している。[21]: 150 価値は各カテゴリー内でも比較可能だ。例えば、一般原理に関する確固たる知識は、孤立した事実に関する脆弱な知識よりも価値が高い。[21]: 146–7 [15] ロスによる直観主義によれば、道徳的真理は直観によって知ることができる。例えば「嘘をつくことは間違っている」とか「知識は本質的に善である」といった ことだ。[15] 直観は推論や演繹を介さない直接的な把握を伴う。それらは自明であり、したがって追加の証明を必要としない。[18] この能力は生得的なものではなく、精神的成熟に達する過程で発達させなければならない。[21]: 29 しかし完全に発達した形態では、幾何学や算術の公理といった数学的真理を知るのと同じように、道徳的真理を知ることができる。[21]:30[22] この自明の知識は一般原理に限定される。つまり、この方法では表面上の義務は知り得るが、特定の状況における絶対的義務、すなわちあらゆる事情を考慮した 上での行動指針は知り得ない。[21]: 19–20, 30 私たちにできるのは、知覚を参照して、この特定の事例においてどの表面上の義務が規範的に最も重みを持つかを判断することだけだ。とはいえ、ほとんどの具 体的な事例は複雑であるため、これは通常、厳密な意味での知識には至らない。[15] |

| Criticism and influence A frequent criticism of Ross's ethics is that it is unsystematic and often fails to provide clear-cut ethical answers. Another is that "moral intuitions" are not a reliable basis for ethics, because they are fallible, can vary widely from individual to individual, and are often rooted in our evolutionary past in ways that should make us suspicious of their capacity to track moral truth.[23] Additionally there is no consideration of the consequence of the action undertaken, as with all deontological approaches.[24] Ross's deontological pluralism was a true innovation and provided a plausible alternative to Kantian deontology.[15] His ethical intuitionism found few followers among his contemporaries but has seen a revival by the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century. Among the philosophers influenced by The Right and the Good are Philip Stratton-Lake, Robert Audi, Michael Huemer, and C. D. Broad.[1 |

批判と影響 ロス倫理学に対する頻繁な批判は、体系化されておらず、明確な倫理的回答を提供できないことが多い点だ。別の批判は、「道徳的直観」が倫理の信頼できる基 盤とならないというものである。なぜならそれらは誤りやすく、個人間で大きく異なり、しばしば進化の過去に基づくため、道徳的真実を追跡する能力に疑念を 抱かせるべきだからだ。[23] さらに、義務論的アプローチ全般と同様に、実行される行為の結果が考慮されていない。[24] ロスの義務論的多元主義は真の革新であり、カントの義務論に対する説得力のある代替案を提供した。[15] 彼の倫理的直観主義は同時代人からはほとんど支持を得られなかったが、20世紀末から21世紀初頭にかけて再評価されている. 『正義と善』の影響を受けた哲学者には、フィリップ・ストラットン=レイク、ロバート・オーディ、マイケル・ヒューマー、C・D・ブロードらがいる。[1] |

| Selected works 1908: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W. D. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1923: Aristotle 1924: Aristotle's Metaphysics 1927: 'The Basis of Objective Judgments in Ethics'. International Journal of Ethics, 37:113–127. 1930: The Right and the Good 1936: Aristotle's Physics 1939: Foundations of Ethics 1949: Aristotle's Prior and Posterior Analytics 1951: Plato's Theory of Ideas 1954: Kant's Ethical Theory: A Commentary on the Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten, Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

選集 1908年:『ニコマコス倫理学』。W. D. ロス訳。オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プレス。 1923年:『アリストテレス』 1924年:『アリストテレスの形而上学』 1927年:「倫理における客観的判断の基礎」。『国際倫理学雑誌』37:113–127。 1930年:『正義と善』 1936年:『アリストテレスの物理学』 1939年:『倫理学の基礎』 1949年:『アリストテレスの優先分析学および後分析学』 1951年:『プラトンの観念論』 1954年:『カントの倫理学:道徳形而上学の基礎に関する解説』、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| References 1. "William David Ross" by David L. Simpson in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2012 2. A Simple Ethical Theory Based on W. D. Ross 3. Grave of John Ross, Grange Cemetery 4. Warnock, G., & Wiggins, D. (2004). "Ross, Sir (William) David (1877–1971), philosopher". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31629. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 12 April 2022. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.) 5. Oxford University Calendar 1905, Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1905, pp. 137, 182. 6. Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 18. 7. "University intelligence". The Times. No. 36902. London. 18 October 1902. p. 11. 8. G. N. Clark, 'Sir David Ross', Proceedings of the British Academy, 57 (1971), pp. 525–543 9. The Journey Not The Arrival Matters. Leonard Woolf, 1969. 10. Webb, D.A. (1992). J.R., Barlett (ed.). Trinity College Dublin Record Volume 1991. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin Press. ISBN 1-871408-07-5. 11. "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 16 March 2023. 12. "William David Ross". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. 10 February 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023. 13. Stratton-Lake, Philip (2002). "Introduction". In Stratton-Lake, Philip (ed.). The right and the good. Oxford: Clarendon Press. doi:10.1093/0199252653.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-153096-8. OCLC 302367339. 14. Ross, W. D. (2002). "What Makes Right Acts Right?" (PDF). The right and the good. Philip Stratton-Lake. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 29–30. doi:10.1093/0199252653.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-153096-8. OCLC 302367339. The moral order expressed in these propositions is just as much part of the fundamental nature of the universe (and, we may add, of any possible universe in which there were moral agents at all) as is the spatial or numerical structure expressed in the axioms of geometry or arithmetic. 15. Skelton, Anthony (2012). "William David Ross". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 12 January 2021. 16. Ross, William David (1930). The Right and the Good (1946 reprint ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 21. 17. Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989) p. 17n. 18. Simpson, David L. "William David Ross". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 January 2021. 19. Burgh, W. G. de (1931). "The Right and the Good. By W. D. Ross M.A., LL.D., Provost of Oriel College, Oxford. (Oxford: At the Clarendon Press. 1930. pp. vi, 176.)". Philosophy. 6 (22): 236–40. doi:10.1017/S0031819100045265. S2CID 170734138. 20. Borchert, Donald (2006). "Ross, William David". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Macmillan. 21. Ross, W. D. (2002) [1930]. The Right and the Good. Clarendon Press. 22. Craig, Edward (1996). "Ross, William David". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. 23. For a discussion of these and other common criticisms of Ross's ethics, see Simpson, "William David Ross". 24. Gaw, Allan (2011). On moral grounds : lessons from the history of research ethics. Michael H. J. Burns. Glasgow: SA Press. ISBN 978-0-9563242-2-1. OCLC 766246011. |

参考文献 1. 「ウィリアム・デイヴィッド・ロス」デイヴィッド・L・シンプソン著、インターネット哲学百科事典、2012年 2. W. D.ロスに基づく単純な倫理理論 3. ジョン・ロスの墓、グレンジ墓地 4. ワーノック、G.、ウィギンズ、D. (2004). 「ロス、サー(ウィリアム)デイヴィッド(1877–1971)、哲学者」 『オックスフォード国民伝記大辞典』(オンライン版)。オックスフォード大学出版局。doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31629。ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8。2022年4月12日取得。(購読、ウィキペディア図書館アクセス、または英国公共図書館の会員資格が必要だ。) 5. Oxford University Calendar 1905, Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1905, pp. 137, 182. 6. Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 18. 7. 「大学情報」. The Times. No. 36902. London. 18 October 1902. p. 11. 8. G. N. Clark, 「サー・デイヴィッド・ロス」, Proceedings of the British Academy, 57 (1971), pp. 525–543 9. The Journey Not The Arrival Matters. Leonard Woolf, 1969. 10. ウェブ、D.A. (1992)。J.R.、バートレット (編)。トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリン記録 1991年版。ダブリン:トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリン出版。ISBN 1-871408-07-5。 11. 「APS 会員履歴」。search.amphilsoc.org。2023年3月16日取得。 12. 「ウィリアム・デイヴィッド・ロス」。アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー。2023年2月10日。2023年3月16日取得。 13. ストラットン・レイク、フィリップ(2002)。「序文」。ストラットン・レイク、フィリップ(編)。『権利と善』。オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プ レス。doi:10.1093/0199252653.001.0001。ISBN 978-0-19-153096-8。OCLC 302367339。 14. Ross, W. D. (2002). 「正しい行為を正しいものにするものは何か?」 (PDF). 『権利と善』. Philip Stratton-Lake. オックスフォード: クラレンドン・プレス. pp. 29–30. doi:10.1093/0199252653.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-153096-8。OCLC 302367339。これらの命題に表現されている道徳的秩序は、幾何学や算術の公理に表現されている空間的または数値的構造と同様に、宇宙(そして、道 徳的行為者が存在するあらゆる可能な宇宙)の基本的な性質の一部である。 15. Skelton, Anthony (2012). 「ウィリアム・デイヴィッド・ロス」. 『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』. スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所. 2021年1月12日取得. 16. Ross, William David (1930). 『正義と善』 (1946年再版). ロンドン: オックスフォード大学出版局. p. 21. 17. Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989) p. 17n. 18. Simpson, David L. 「William David Ross」. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 January 2021. 19. バーグ、W. G. de (1931). 「正義と善。W. D. ロス M.A.、LL.D.、オックスフォード大学オリエル・カレッジ学長著。(オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プレス。1930年。vi、176 ページ。)」『哲学』6 (22): 236–40. doi:10.1017/S0031819100045265. S2CID 170734138. 20. Borchert, Donald (2006). 「Ross, William David」. Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Macmillan. 21. Ross, W. D. (2002) [1930]. The Right and the Good. Clarendon Press. 22. Craig, Edward (1996). 「ロス、ウィリアム・デイヴィッド」. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. 23. ロスの倫理学に対するこれらの批判やその他の一般的な批判についての議論については、Simpson, 「ウィリアム・デイヴィッド・ロス」を参照のこと。 24. ガウ、アラン(2011)。『道徳的根拠:研究倫理の歴史から学ぶ教訓』。マイケル・H・J・バーンズ。グラスゴー:SAプレス。ISBN 978-0-9563242-2-1。OCLC 766246011。 |

| Further reading G. N. Clark, 'Sir David Ross', Proceedings of the British Academy, 57 (1971), pp. 525–543 Phillips, David. Rossian Ethics: W. D. Ross and Contemporary Moral Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. Stout, A. K. 1967. 'Ross, William David'. In P. Edwards (ed.), The Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. New York: Macmillan: 216–217. Stratton-Lake, Philip. 2002. 'Introduction'. In Ross, W. D. 1930. The Right and the Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Timmons, Mark. 2003. 'Moral Writings and The Right and the Good'. [Book Review] Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews |

さらに読む G. N. Clark, 『Sir David Ross』, Proceedings of the British Academy, 57 (1971), pp. 525–543 Phillips, David. Rossian Ethics: W. D. Ross and Contemporary Moral Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. Stout, A. K. 1967. 「ロス、ウィリアム・デイヴィッド」 P. Edwards (編) The Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. New York: Macmillan: 216–217. ストラットン・レイク、フィリップ。2002年。「序文」。ロス、W. D. 1930年。『権利と善』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 ティモンズ、マーク。2003年。「道徳に関する著作と『権利と善』」。[書評] ノートルダム哲学評論 |

| Skelton, Anthony. "William David Ross". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._D._Ross |

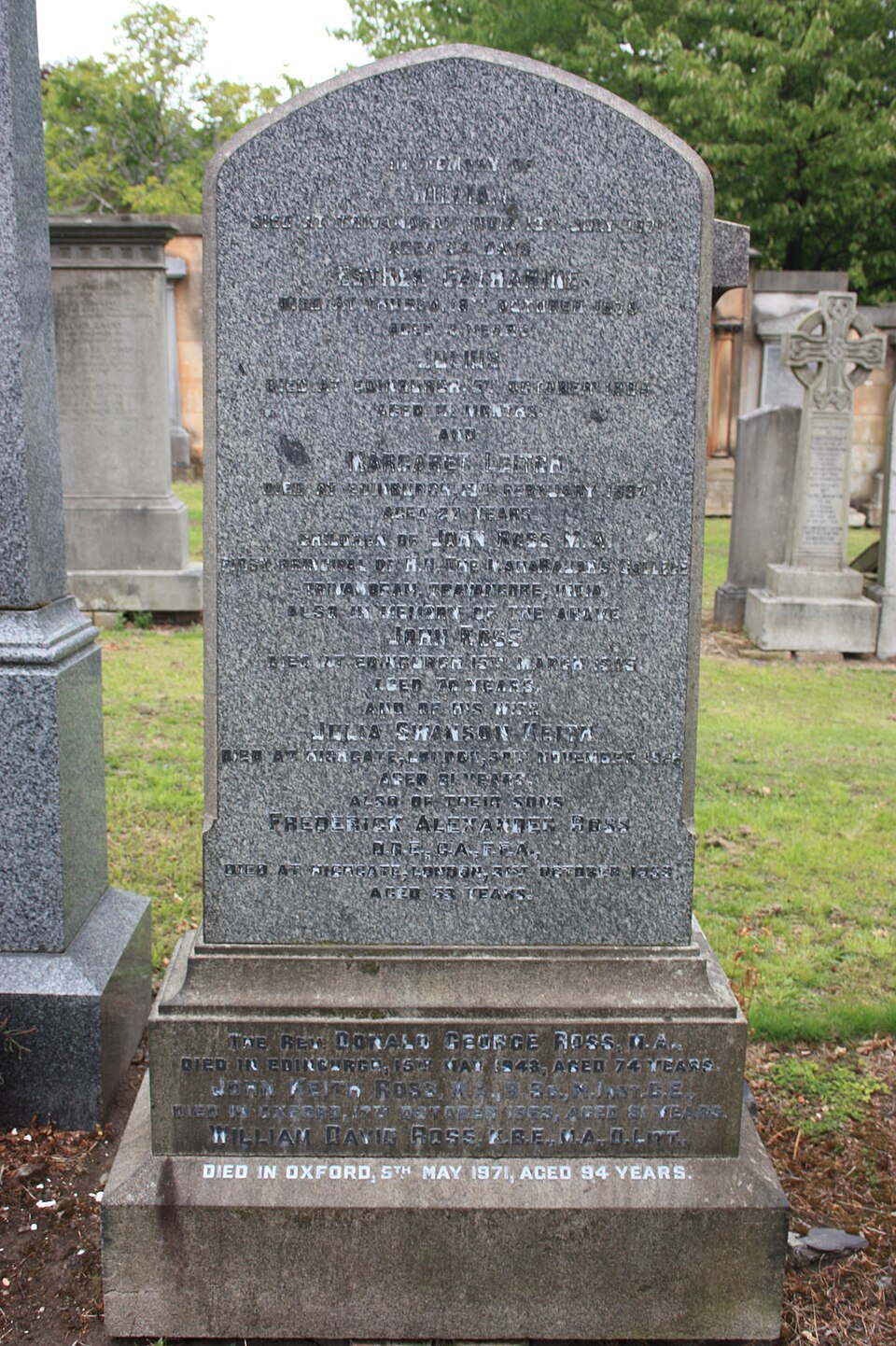

☆内在的価値

| 倫理学において、内在的価値(intrinsic value)

とは、それ自体で価値あるあらゆるものの性質である。内在的価値は、手段的価値(外在的価値とも呼ばれる)とは対照的であり、これは他の内在的価値を持つ

ものとの関係から価値を得るあらゆるものの特性である。[1]

本質的価値は常に、対象が「それ自体において」または「それ自体のために」持つものであり、本質的特性である。内在的価値を持つ対象は、目的、あるいはカ

ントの用語で言えば目的そのものと見なすことができる。[2] 「内在的価値」という用語は、価値(倫理学と美学の両方を含む)を研究する哲学の一分野である価値論で使用される。主要な規範倫理学理論はいずれも、何ら かのものを本質的に価値あるものと見なしている。例えば、徳倫理学者の場合、ユーダイモニア(人間の繁栄、時に「幸福」と訳される)には本質的価値がある 一方、幸福をもたらすもの(家族を持つことなど)は単なる手段的価値に過ぎない。同様に、結果主義者は、快楽、苦痛の欠如、および/または個人の選好の充 足に内在的価値を見出し、それらを生み出す行為は単なる手段的価値しか持たないと考える。一方、義務論的倫理学の支持者は、道徳的に正しい行動(他者に対 する道徳的義務を尊重する行動)は、その結果にかかわらず、常に本質的に価値があると主張する。 本質的価値の別称には、最終価値、本質的価値、原則的価値、あるいは究極的意義がある。[3] |

|

| 目的 哲学と倫理学において、目的、あるいはテロスとは、一連の段階における究極の目標を指す。例えば、アリストテレスによれば、あらゆる行為の目的は幸福であ る。これは、その目標達成を助ける手段とは対照的である。例えば、金銭や権力は幸福という目的への手段と言える。しかしながら、ある対象は目的と手段を同 時に兼ねることがある。 終了は、おおむね以下の概念と類似しており、しばしばそれらの同義語として用いられる: 目的 または 目標:最も一般的な意味で、行動を導く予期される結果。 目標 または 目的 とは、個人 または システム が達成または実現を計画または意図する、想定される状態を指す。  |

|

| 数量 本質的価値を持つものは、ゼロ個、一つ、あるいは複数個存在する可能性がある。[5] 本質的虚無主義、あるいは単に虚無主義(ラテン語nihil「無」に由来)は、本質的価値を持つものはゼロ個であると主張する。 本質的アリキディズム 詳細情報:倫理的価値平等 内在的アリキディズム、あるいは単にアリキディズム(ラテン語aliquid「何か」に由来)は、一つ以上の存在があると主張する。これは単一から全可能性に至る複数の量に及ぶ可能性がある。[6] 内在的一元論(ギリシャ語monos「単一」に由来)は、内在的価値を持つものは一つだけだと主張する。この見解は、この対象を内在的に価値あるものとして受け入れる生活態度のみを支持する可能性がある。 内在的多元主義(ラテン語multus「多数」に由来)は、内在的価値を持つものが多数存在すると主張する。言い換えれば、この見解は複数の生命姿勢の内在的価値を内在的に価値あるものと認める可能性がある。 内在的汎主義(ギリシャ語pan「全て」に由来)は、あらゆるものに内在的価値があると主張する。 複数の事物に内在的価値があると見なすアリキディスティックな人生観の支持者間では、それらが等しく内在的に価値あるものと見なされるか、あるいは不平等 に価値あるものと見なされるかがある。しかし実際には、それらの手段的価値が結果として不平等な全体的価値をもたらすため、いずれの場合でも不平等に評価 される可能性がある。 内在的多様主義 この見解は、複数の人生観の内在的価値をそれ自体として価値あるものと見なす。これは、複数の内在的価値を多かれ少なかれ手段的価値として扱う見解とは異 なる点に注意が必要だ。なぜなら、内在的一元論的見解も、自らが選んだ内在的価値以外の内在的価値を価値あるものと見なす場合があるが、それは他の内在的 価値が自らが選んだ内在的価値に間接的に寄与する範囲に限定されるからだ。 内在的多元論の最も単純な形態は、内在的二元論(ラテン語の「二つ」に由来)である。これは幸福と徳といった二つの対象が内在的価値を持つと主張する。ヒューマニズムは、複数の事物に内在的価値があると認める人生観の一例である。[5] 多元主義は、必ずしも内在的価値に否定的な側面(例えば、快楽と苦痛を異なるコインの表裏として内在的価値を持つと認める功利主義の特徴)を含むわけではない。 未特定のアリキディズム 詳細記事: イーツイズム イーツイズム(オランダ語: ietsisme、「何か主義」)とは、一方で「天と地の間には我々が知る以上の何かが存在する」と内心で疑い(あるいは実際に信じ)つつ、他方で特定の 宗教が提示する確立された信仰体系、教義、あるいは神の本質に関する見解を受け入れず、支持しない人々の持つ一連の信念を指す用語である。 この意味では、さらに特定しないアリキディズムと概ね見なせる。例えば、ほとんどの生命観は「何かが存在する」「人生に意味がある」「それ自体が目的であ る何か、あるいは存在に何かが加わる」といった受容を含み、様々な対象や「真実」を仮定する。一方、イーツイズムは「何かが存在する」という事実のみを受 け入れ、それ以上の仮定をしない。 総内的価値 対象の総内的価値とは、その平均内的価値、平均価値強度、価値持続時間の積である。これは絶対的価値でも相対的価値でもあり得る。総内的価値と総手段的価値を合わせると、対象の総全体価値となる。 |

|

| 具体的と抽象的 本質的な価値を持つ目的、つまり終点は、具体的な対象でも抽象的な対象でもあり得る。 具体的 具体的な対象が終点として受け入れられる場合、それは単一の個別対象であることもあれば、一つ以上の普遍的概念の全ての個別対象に一般化されることもあ る。しかし、大多数の生活態度は普遍的概念の全ての個別対象を終点として選ぶ。例えばヒューマニズムは、個々の人間を目的とは見なさず、人類全体を目的と する。 連続体 単一の普遍概念に属する複数の個別事例を一般化する際、目的が実際に個別事例なのか、それともむしろ抽象的な普遍概念なのかが明確でない場合がある。こうしたケースでは、人生観は具体的な目的と抽象的な目的の間の連続体として捉えられるかもしれない。 これにより、生命観は本質的に多元的であると同時に本質的に一元的であるという状態になり得る。しかし、このような量的矛盾は実践的にはさほど重要ではない。なぜなら、目的を複数の目的に分割すると全体の価値は減少するが、価値の強度が増すからである。 |

|

| 本質的価値の種類 絶対的と相対的 本質的価値に関して、絶対的倫理的価値と相対的倫理的価値の区別があるかもしれない。 相対的本質的価値は主観的であり、個人や文化の観念、あるいは個人の人生観の選択に依存する。一方、絶対的本質的価値は哲学的に絶対的であり、個人や文化の観念から独立している。また、その価値を持つ対象が発見されたか否かにも依存しない。 絶対的内在的価値が存在するかどうかについては、例えば実用主義において議論が続いている。実用主義において、ジョン・デューイ[7]の経験主義的アプ ローチは、内在的価値を物事の固有または永続的な特性として認めなかった。彼はそれを、目的を持つ存在としての我々の継続的な倫理的価値付け活動の幻想的 な産物と見なした。特定の状況に限定して保持される場合、デューイは善は状況に対してのみ相対的に内在的であると主張した。つまり、彼は相対的な内在的価 値のみを認め、絶対的な内在的価値は存在しないと考えた。あらゆる文脈において、善は対比される内在的善ではなく、手段的価値として理解するのが最善だと 主張した。言い換えれば、デューイによれば、内在的価値を持つのは貢献的な善のみである。 肯定的と否定的 内在的価値に関して、肯定的価値と否定的価値の両方が存在する可能性がある。肯定的内在的価値を持つものは追求され、あるいは最大化される。一方、否定的 内在的価値を持つものは回避され、あるいは最小化される。例えば功利主義では、快楽は肯定的内在的価値を持ち、苦悩は否定的内在的価値を持つ。 |

|

| 類似の概念 本質的価値は主に倫理学で使われるが、哲学においても同様の概念が用いられ、本質的には同じ概念を指す用語が存在する。 「究極的な重要性」として、それは生命体が人生観を構成するために結びつくものである。 これは人生の意味と同義であり、人生において意味あるものや価値あるものとして表現される[8]。ただし人生の意味はより曖昧で、他の用法も存在する。 中世哲学における至高の善(Summum bonum)は基本的にこれと同等である。 相対的内在的価値は概ね倫理的理想と同義である。 個人の経験が内在的価値である場合、固有価値は第一級の手段的価値と見なされることがある。 |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intrinsic_value_(ethics) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆