ビーグル号航海記

The Voyage of the Beagle

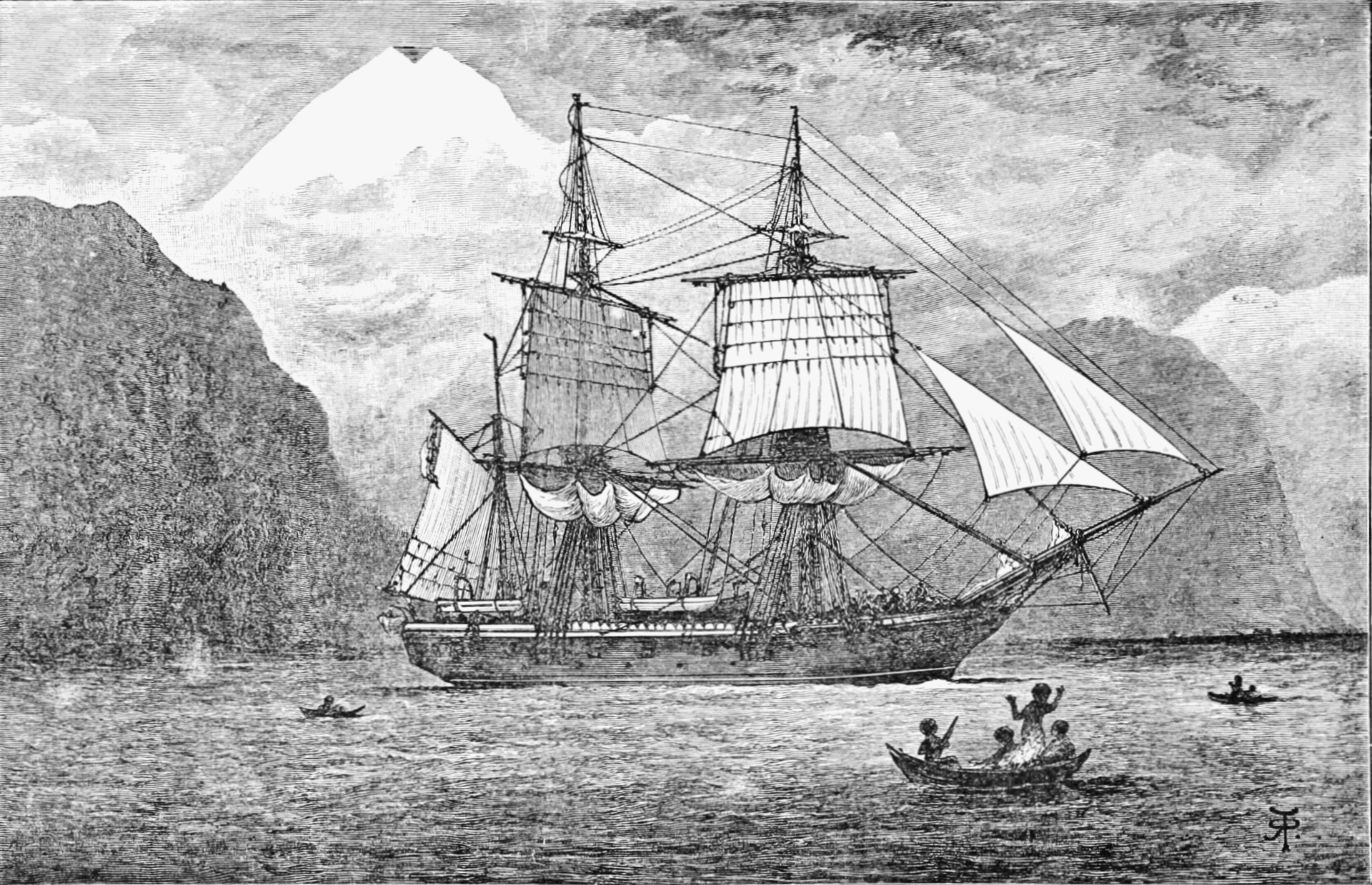

Reproduction

of frontispiece by Robert Taylor Pritchett from the first Murray

illustrated edition, 1890: HMS Beagle in the Straits of Magellan at

Monte Sarmiento in Chile.

☆ 『ビーグル号航海記』は、チャールズ・ダーウィンが著し、1839年に『日記と覚書』として出版された本に最もよく付けられるタイトルであり、この本に よってダーウィンは多大な名声と尊敬を集めた。これは『英国王立船アドベンチャー号およびビーグル号航海記』の第3巻であり、他の巻は船の指揮官によって 執筆または編集された。『日記と覚書』は、HMSビーグル号の2回目の測量遠征におけるダーウィンの役割を扱っている。ダーウィンの記述の人気により、 1839年に出版社が『ダーウィンの研究日誌』として再版し、1845年に出版された改訂第2版ではこのタイトルが使用された。1905年に再版された本 書は、『ビーグル号航海記』というタイトルで紹介され、現在ではこのタイトルで広く知られている。 ビーグル号は、ロバート・フィッツロイ船長の指揮下、1831年12月27日にプリマス湾を出航した。当初は2年間の予定であったが、実際には5年近くか かり、ビーグル号が帰港したのは1836年10月2日であった。この間、ダーウィンはほとんどの時間を陸上での探検に費やした(陸上で3年3ヶ月、海上で 18ヶ月)。この本は、生き生きとした旅行記であると同時に、生物学、地質学、人類学を網羅した詳細な科学フィールド日誌であり、西欧諸国が世界全体を探 検し、地図を作成していた時代に書かれたもので、ダーウィンの鋭い観察力を示すものとなっている。 ダーウィンは探検中にいくつかの地域を再訪したが、この本の章は、日付ではなく場所や位置に基づいて整理されているため、わかりやすい。 航海中に付けられたダーウィンのメモには、種の固定性に対する彼の考えが変化していることを示唆するコメントが含まれている。帰国後、彼はこれらのメモに 基づいてこの本を書いた。この時期、彼は共通の祖先と自然淘汰による進化論の最初の理論を構築していた。この本には、特に1845年の第2版に、彼の考え のいくつかの示唆が含まれている。

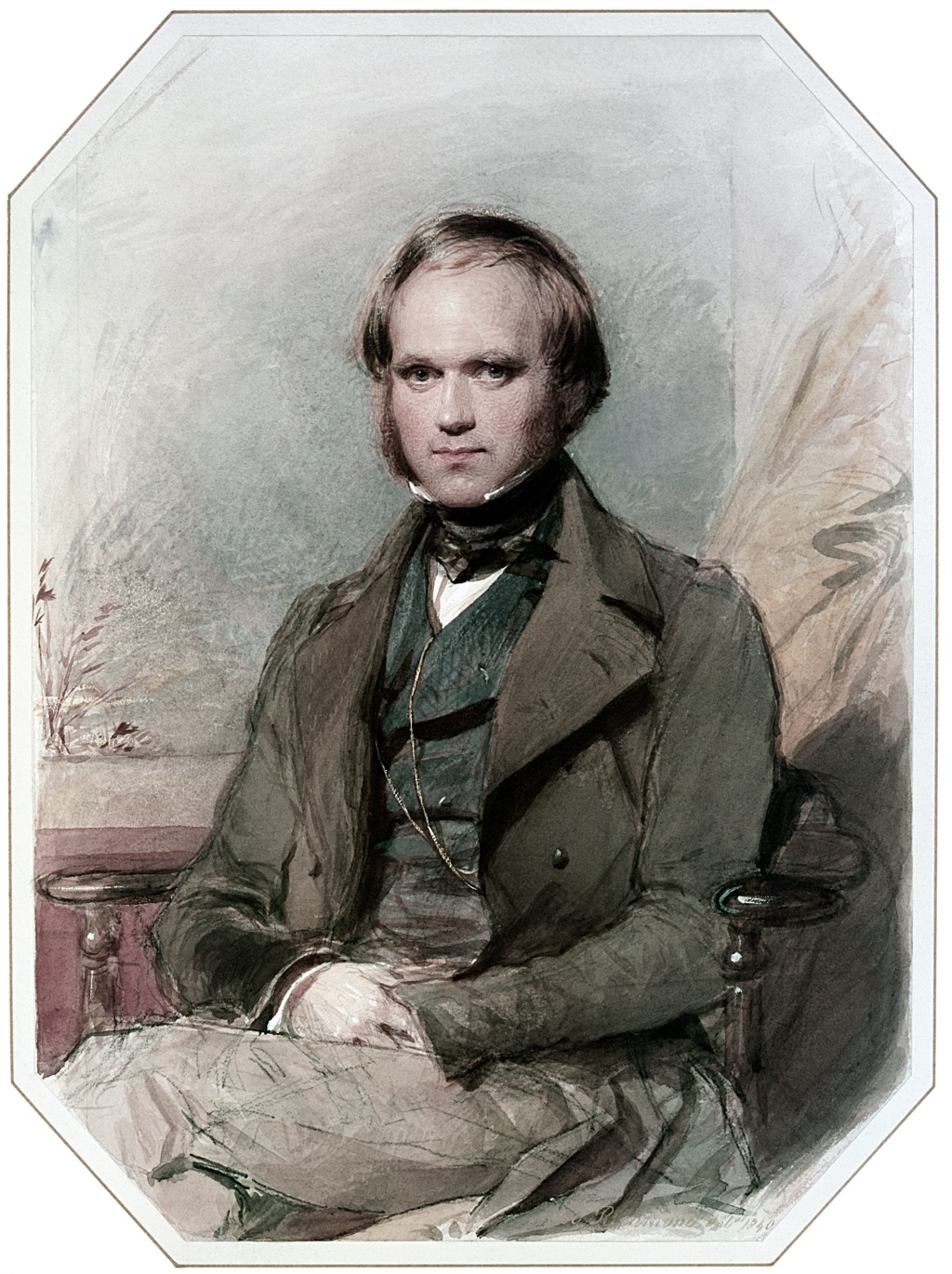

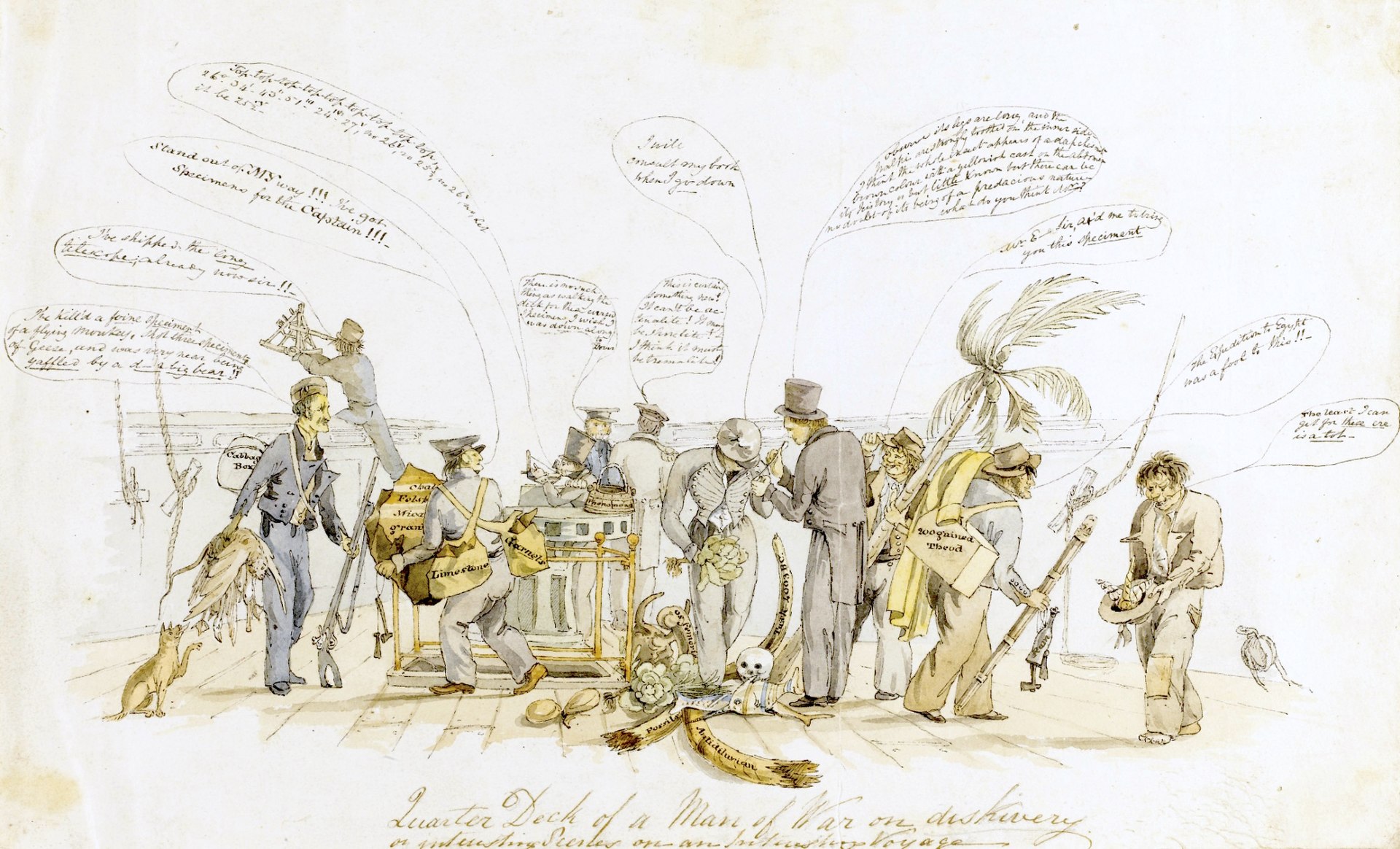

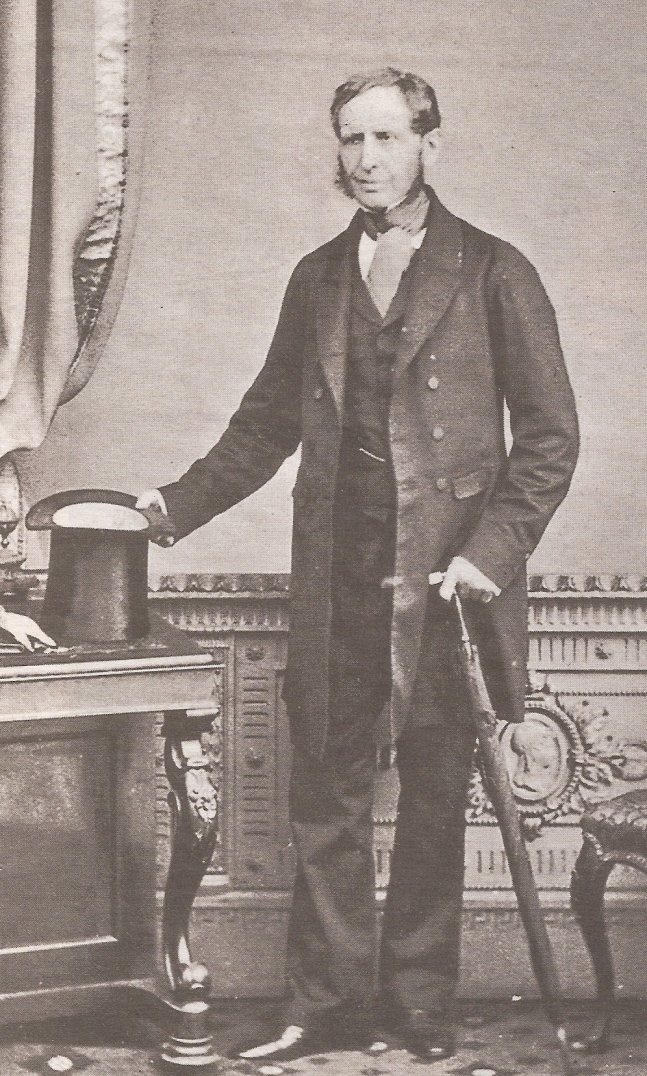

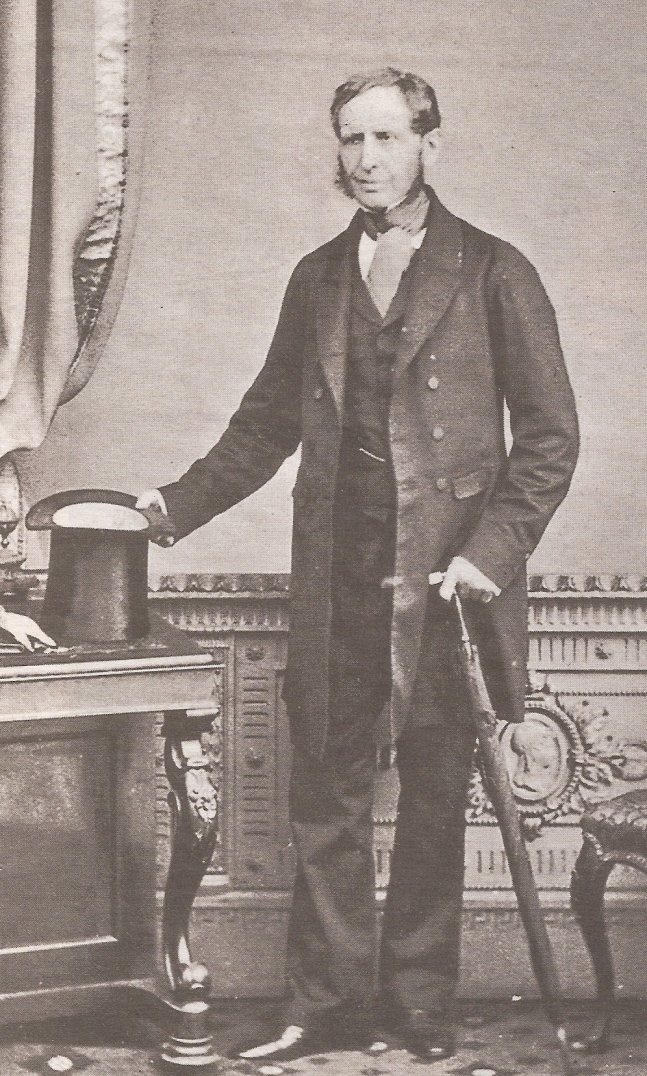

水 彩画[部分]1840年当時/ ロバート・フィッツロイ, 1805-1865, ヘルマン・ヨハン・シュミット(1872-1959)による肖像リトグラフの写真複製[ca.1850]

The

Voyage of the

Beagle is the title most commonly given to the book written by

Charles

Darwin and published in 1839 as his Journal and Remarks, bringing him

considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of The

Narrative of the Voyages of H.M. Ships Adventure and Beagle, the other

volumes of which were written or edited by the commanders of the ships.

Journal and Remarks covers Darwin's part in the second survey

expedition of the ship HMS Beagle. Due to the popularity of Darwin's

account, the publisher reissued it later in 1839 as Darwin's Journal of

Researches, and the revised second edition published in 1845 used this

title. A republication of the book in 1905 introduced the title The

Voyage of the "Beagle", by which it is now best known.[2] Robert FitzRoy, 1805-1865, Photographic copy of a portrait lithograph made by Herman John Schmidt (1872-1959) Beagle sailed from Plymouth Sound on 27 December 1831 under the command of Captain Robert FitzRoy. While the expedition was originally planned to last two years, it lasted almost five—Beagle did not return until 2 October 1836. Darwin spent most of this time exploring on land (three years and three months on land; 18 months at sea). The book is a vivid travel memoir as well as a detailed scientific field journal covering biology, geology, and anthropology that demonstrates Darwin's keen powers of observation, written at a time when Western Europeans were exploring and charting the whole world. Although Darwin revisited some areas during the expedition, for clarity the chapters of the book are ordered by reference to places and locations rather than by date. Darwin's notes made during the voyage include comments hinting at his changing views on the fixity of species. On his return, he wrote the book based on these notes, at a time when he was first developing his theories of evolution through common descent and natural selection. The book includes some suggestions of his ideas, particularly in the second edition of 1845. |

『ビーグル号航海記』は、チャールズ・ダーウィンが著し、1839年に

『日記と覚書』として出版された本に最もよく付けられるタイトルであり、この本によってダーウィンは多大な名声と尊敬を集めた。これは『英国王立船アドベ

ンチャー号およびビーグル号航海記』の第3巻であり、他の巻は船の指揮官によって執筆または編集された。『日記と覚書』は、HMSビーグル号の2回目の測

量遠征におけるダーウィンの役割を扱っている。ダーウィンの記述の人気により、1839年に出版社が『ダーウィンの研究日誌』として再版し、1845年に

出版された改訂第2版ではこのタイトルが使用された。1905年に再版された本書は、『ビーグル号航海記』というタイトルで紹介され、現在ではこのタイト

ルで広く知られている。 ロバート・フィッツロイ, 1805-1865, ヘルマン・ヨハン・シュミット(1872-1959)による肖像リトグラフの写真複製 ビーグル号は、ロバート・フィッツロイ[Robert FitzRoy] 船長の指揮下、1831年12月27日にプリマス湾を出航した。当初は2年間の予定であったが、実際には5年近くか かり、ビーグル号が帰港したのは1836年10月2日であった。この間、ダーウィンはほとんどの時間を陸上での探検に費やした(陸上で3年3ヶ月、海上で 18ヶ月)。この本は、生き生きとした旅行記であると同時に、生物学、地質学、人類学を網羅した詳細な科学フィールド日誌であり、西欧諸国が世界全体を探 検し、地図を作成していた時代に書かれたもので、ダーウィンの鋭い観察力を示すものとなっている。 ダーウィンは探検中にいくつかの地域を再訪したが、この本の章は、日付ではなく場所や位置に基づいて整理されているため、わかりやすい。 航海中に付けられたダーウィンのメモには、種の固定性に対する彼の考えが変化していることを示唆するコメントが含まれている。帰国後、彼はこれらのメモに 基づいてこの本を書いた。この時期、彼は共通の祖先と自然淘汰による進化論の最初の理論を構築していた。この本には、特に1845年の第2版に、彼の考え のいくつかの示唆が含まれている。 |

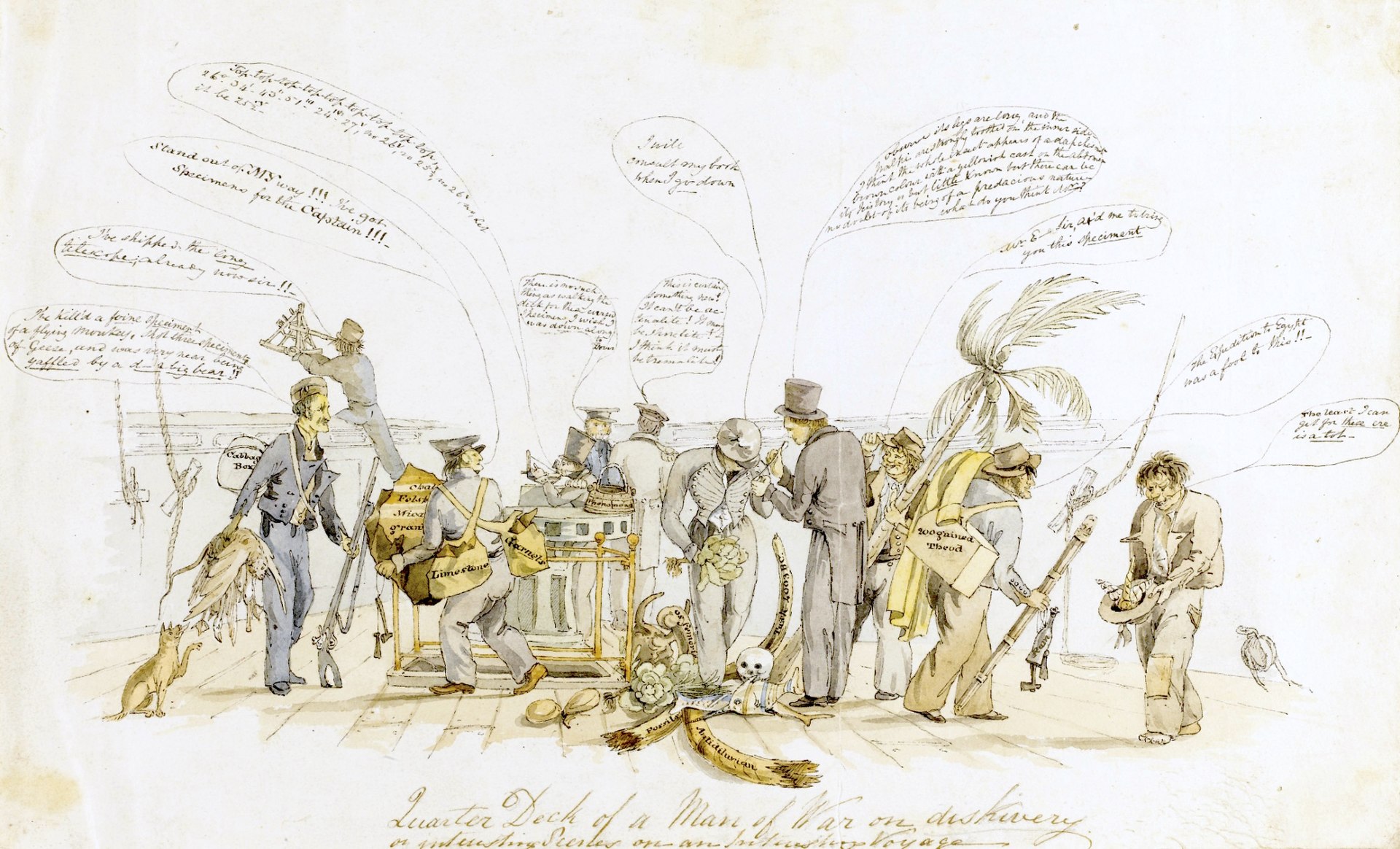

| Context In May 1826 two ships left Plymouth to survey the southern coasts of South America. The senior officer of the expedition was Phillip Parker King, Commander and Surveyor of HMS Adventure, and under his orders Pringle Stokes was Commander and Surveyor of HMS Beagle. In August 1828 Stokes died after shooting himself. In December Robert FitzRoy was given command of the ship and continued the survey. In January 1830 FitzRoy noted in his journal the need for expertise in mineralogy or geology, on a future expedition he would "endeavour to carry out a person qualified to examine the land; while the officers, and myself, would attend to hydrography." Both ships returned to Plymouth in August 1830.[3] King was in poor health, and retired from the Navy (he moved back to his home in Australia in 1832).[4][5] In August 1831, while Beagle was being readied, FitzRoy's offer of a place for a self-funded naturalist was raised with University of Cambridge professors.[6] Henslow passed it on to Darwin who was well qualified and, enthused by reading Humboldt's Personal Narrative, was on a short study tour with geologist Adam Sedgwick in preparation for a planned visit with friends to Tenerife. Darwin read the letters when he got home, and was eager to join the voyage.[7][8] Darwin's diary / journal On board the ship, Darwin began a day-to-day record of activities in the form of a diary, which he commonly called "my Journal". Darwin wrote entries, in ink, while on the ship or when staying for a period in a house on shore. When travelling on land, he left the manuscript on the ship, and made pencil notes in pocket books to record details of his excursions along with his field notes on geology and natural history. He then wrote up his diary entries from these notes or from memory, sometimes several weeks after the event.[9] Pages 1 and 2, dated 16 December 1831, outline events from Darwin arriving home on 29 August to his arrival at Devonport on 24 October.[10] From page 3 onwards he adopts a consistent layout, with month, the year and place in a heading at the top, page number in a top corner, and the day of the month in the margin at each entry. After delays and false starts due to weather, they set off on 27 December. Darwin suffered seasickness, and his entry for that date starts "I am now on the 5th of Jan.y writing the memoranda of my misery for the last week".[9][11] In April, a month after reaching South America, he wrote to his sister Caroline that he was struggling to write letters, partly due to "writing everything in my journal".[12] A few weeks later at Botafogo, tired and short of time, he sent her "in a packet, my commonplace Journal.— I have taken a fit of disgust with it & want to get it out of my sight, any of you that like may read it.— a great deal is absolutely childish: Remember however this, that it is written solely to make me remember this voyage, & that it is not a record of facts but of my thoughts". He invited criticisms.[13] In reply, his sister Catherine praised his "interesting and entertaining" descriptions, "Susan read the Journal aloud to Papa, who was interested, and liked it very much". His Wedgwood relatives had asked to see it at Maer Hall. Darwin left that "entirely in your hands.— I suspect the first part is abominaly childish, if so do not send it to Maer.— Also, do not send it by the Coach, (it may appear ridiculous to you) but I would as soon loose a piece of my memory as it.— I feel it is of such consequence to my preserving a just recollection of the different places we visit."[14] By 14 July 1833 Darwin had sent more of his diary. On 28 October Caroline gave the requested critical assessment – in the first part Darwin had "probably from reading so much of Humboldt, got his phraseology & occasionly made use of the kind of flowery french expressions which he uses, instead of your own simple straight forward & far more agreeable style. I have no doubt you have without perceiving it got to embody your ideas in his poetical language & from his being a foreigner it does not sound unnatural in him". However, "the greatest part I liked exceedingly & could find no fault". In July 1834, Darwin agreed that these points were "perfectly just", and continued to update his diary carefully.[15][16] As Beagle headed homewards in April 1836, Darwin told Caroline that FitzRoy too was busy with writing "the account of the Voyage". This "Book" might be "rather diffuse", but otherwise good: "his style is very simple & excellent. He has proposed to me, to join him in publishing the account, that is, for him to have the disposal & arranging of my journal & to mingle it with his own. Of course I have said I am perfectly willing, if he wants materials; or thinks the chit-chat details of my journal are any ways worth publishing. He has read over the part, I have on board, & likes it." Darwin asked his family about this idea,[17] but would be aware the custom of the Navy was that the captain had a right to first use of papers.[18][19] Journal and remarks Soon after Darwin's return, he was at a party hosted by Fanny and Hensleigh Wedgwood for their relatives on 4 December 1836. They agreed to review his journal. The physician and travel writer Henry Holland looked at some pages and "thought that it would not be worth while to publish it alone, as it would be partly going over the same ground with the Captain", leaving Darwin "more perplexed" but "becoming rather inclined to the plan of mixing up long passages with Capt Fitzroy." He would "go on with the geology and let the journal take care of itself",[20][19] but Emma Wedgwood did not think Holland "any judge as to what is amusing or interesting", and like Catherine thought it should be published by itself, not "mixed up with Capt. FitzRoy's".[21] Fanny and Hensleigh found the "Journal so interesting, that it is quite difficult to stop to criticize".[22] Though "not in general a good reader of travels", he "found no part of yours tedious." They had "read a great deal of it aloud too" as a more severe test, and concluded it had "more variety and a greater number of interesting portions" than other travel books, "the less it is mixed up with the Captains the better."[23] After advice from Broderip, FitzRoy wrote on 30 December that "One volume might be for King—another for you—and a third for me. The profits if any, to be divided into three equal portions—What think you of such a plan?" Darwin agreed, and began work on his volume.[24][25] In March he told Fox "I am now hard at work and give up every thing else for it. Our plan is as follows.— Capt. FitzRoy writes two volumes, out of the materials collected during both the last voyage under Capt. King to T. del Fuego and during our circumnavigation.— I am to have the third volume, in which I intend giving a kind of journal of a naturalist, not following however always the order of time, but rather the order of position.— The habits of animals will occupy a large portion, sketches of the geology, the appearance of the country, and personal details will make the hodge-podge complete.— Afterwards I shall write an account of the geology in detail, and draw up some Zoological papers.— So that I have plenty of work, for the next year or two, and till that is finished I will have no holidays."[26] |

背景 1826年5月、2隻の船がプリマスを出航し、南米の南岸の測量を行った。遠征隊の最高責任者はフィリップ・パーカー・キング(HMSアドベンチャーの艦 長兼測量官)であり、その指揮下にプリングル・ストークス(HMSビーグルの艦長兼測量官)がいた。1828年8月、ストークスは自殺し死亡した。12月 にはロバート・フィッツロイが船の指揮を任され、測量を続けた。1830年1月、フィッツロイは航海日誌に、今後の遠征では「陸地の調査に適した人物を同 行させるよう努める。その間、士官と私は水路学の調査にあたる」と記し、鉱物学または地質学の専門家の必要性を指摘した。両船は1830年8月にプリマス に戻った。[3] キングは健康状態が悪く、海軍を退役した(1832年にオーストラリアの自宅に戻った)。[4][5] 1831年8月、ビーグル号の準備が進む中、フィッツロイは自費で参加する自然史研究者のための席をケンブリッジ大学の教授たちに提供した。[6] ヘンズローは、そのことを適任であるダーウィンに伝えた。フンボルトの『パーソナル・ナラティブ』を読み、熱狂したダーウィンは、友人たちとテネリフェ島 を訪れる予定に備え、地質学者のアダム・セジウィックとともに短期間の研究旅行に出かけていた。ダーウィンは帰宅後に手紙を読み、航海への参加を強く希望 した。[7][8] ダーウィンの日記 船上で、ダーウィンは日々の活動を日記というかたちで記録し始めた。彼はそれを「私の日記」と呼んでいた。ダーウィンは船上で、あるいは陸上の家に滞在し ている間、インクで日記を書いた。陸上を移動しているときは原稿を船に残し、ポケットブックに鉛筆でメモをとり、地質学や自然史のフィールドノートととも に遠出の詳細を記録した。 その後、これらのメモや記憶をもとに、時には出来事から数週間後に日記の項目を書き上げた。[9] 1831年12月16日付けの1ページ目と2ページ目は、8月29日にダーウィンが帰宅してから10月24日にデボンポートに到着するまでの出来事を概説 している。[10] 3ページ目以降は、見出しに月、年、場所、ページの上隅にページ番号、各項目の余白にその月の日付を記載するという一貫したレイアウトを採用している。天 候による遅延や出発の失敗を経て、彼らは12月27日に船出した。 ダーウィンは船酔いに苦しみ、その日の日記には「私は今、1月5日である。先週の悲惨な出来事を書き留めるために、このメモを書いている」と記している。 [9][11] 南米に到着してから1か月後の4月、彼は姉のキャロラインに手紙を書き、手紙を書くのに苦労していると伝えた。その理由の一部は、「日記にすべてを書き記 している」ことによるものだった。[12] 数週間後、ボタフォゴで疲れ果て、時間も足りない中、 時間のないボタフォゴで、彼は姉のキャロラインに「平凡な日記を包みに入れて送る。私はそれに嫌気がさして、自分の視界から消し去りたいと思っている。も し気に入ったら、誰でも読んでくれて構わない。大部分はまったく子供じみていて、 しかし、これはあくまでこの航海を忘れないために書くものであり、事実の記録ではなく、私の考えを記したものだということを覚えておいてほしい。彼は批判 を求めた。[13] それに対して、姉のキャサリンは彼の「興味深く、楽しい」描写を賞賛し、「スーザンは日記をパパに音読した。パパは興味を持って、とても気に入った」と述 べた。ウェッジウッドの親戚たちは、メア・ホールで日記を見たいと申し出た。ダーウィンは「すべてお任せします。最初の部分はひどく幼稚だと思いますが、 もしそうであればメアに送らないでください。また、馬車では送らないでください(あなたにはばかばかしく見えるかもしれませんが)。私は、私たちが訪れた さまざまな場所について、正しい記憶を保つことが非常に重要だと感じています。」と伝えた。[14] 1833年7月14日までに、ダーウィンはさらに日記を送っていた。10月28日、キャロラインは要求されていた批判的な評価を述べた。その最初の部分 で、ダーウィンは「おそらくフンボルトの著作を読み過ぎたせいか、ダーウィンは、あなた自身のシンプルで率直かつはるかに心地よい文体ではなく、フンボル トが使うような、時に詩的なフランス語表現を時折用いている。あなたがそれに気づかずに、彼の詩的な言葉で自分の考えを表現していることは疑いがない。ま た、彼が外国人であることから、彼の言葉に不自然な響きが感じられることもない」しかし、「私が非常に気に入って、欠点を見つけることができなかった部分 が大部分を占めていた」1834年7月、ダーウィンはこれらの指摘が「完全に正当である」と同意し、日記の更新を慎重に続けた。 1836年4月、ビーグル号が帰路につくと、ダーウィンはキャロラインにフィッツロイも航海記の執筆に忙しくしていると伝えた。この「本」は「かなり散 漫」かもしれないが、それ以外は良いものだ。「彼の文体は非常にシンプルで素晴らしい。彼は私に、航海記の出版に彼と協力してほしいと申し出てきた。つま り、私の日記を彼が管理し、彼自身のものと混ぜ合わせるというのだ。もちろん、彼が資料を欲しがっているなら、あるいは、私の日記の些細な雑談が出版に値 すると考えているなら、私は喜んで協力すると伝えた。彼は私が船上に持っている部分を読み、それを気に入っている。」ダーウィンはこの考えについて家族に 尋ねたが、海軍の慣習では船長が最初に論文を使用する権利を有していたことを知っていた。 日記と発言 ダーウィンが帰国して間もなく、1836年12月4日にファニーとヘンスリー・ウェッジウッドが親族のために主催したパーティーに出席した。彼らは彼の日 記を検討することに同意した。医師であり旅行作家でもあるヘンリー・ホランドは、いくつかのページに目を通し、「単独で出版する価値はないだろうと考え た。なぜなら、それは船長と同じ内容を繰り返すことになるからだ」と述べ、ダーウィンを「より当惑」させたが、「フィッツロイ大佐との長い文章を混ぜ合わ せるという計画にむしろ傾倒するようになった」 彼は「地質学を続け、日記は日記として扱う」つもりだったが、[20][19] エマ・ウェッジウッドはホランドを「何が面白く、興味深いかを判断できる人物」とは思っておらず、キャサリンと同じように、それは単独で出版されるべきで あり、「 フィッツロイ大尉のものと混ぜ合わせる」のではなく、単独で出版すべきだと考えていた。[21] ファニーとヘンスリーは、「『日記』をとても面白く感じ、批判を止めるのはかなり難しい」と述べた。[22] 彼は「旅行記の読み手としては一般的ではない」が、「あなたの文章の退屈な部分は見つからなかった」と述べた。さらに厳しいテストとして「かなりの部分を 声に出して読んだ」が、結論として「他の旅行記よりもバラエティに富み、興味深い部分が多い」とし、「船長たちの話が混ざっていなければ、なお良い」と述 べた。[23] ブロデリップの助言を受けて、フィッツロイは12月30日に「1巻はキング船長に、もう1巻はあなたに、そして3巻目は私に」と書いた。もし利益が出た場 合は、それを3等分する。このような計画について、あなたはどう思うか?」と尋ねた。ダーウィンはこれに同意し、自身の巻の執筆に取り掛かった。[24] [25] 3月、ダーウィンはフォックスに「私は今、仕事に熱中しており、それ以外のことはすべて放棄している。私たちの計画は以下の通りである。— キング船長の指揮下でトド・デル・フエゴ島へ向かった前回の航海と、私たちの世界周航の間に収集した資料をもとに、フィッツロイ船長が2巻を執筆する。— 私は第3巻を担当し、そこでは一種の自然史家の日記のようなものを書くつもりである。ただし、常に時系列に従うのではなく、むしろ位置に従う。— 動物の習性についてはかなりの部分を割くつもりだ。地質学のスケッチ、その国の様子、個人的な詳細を書き加えることで、寄せ集めが完成するだろう。その 後、地質学について詳しく記述し、いくつかの動物学論文を執筆するつもりだ。来年の1、2年は仕事がたくさんあり、それが終わるまでは休暇を取るつもりは ない。」[26] |

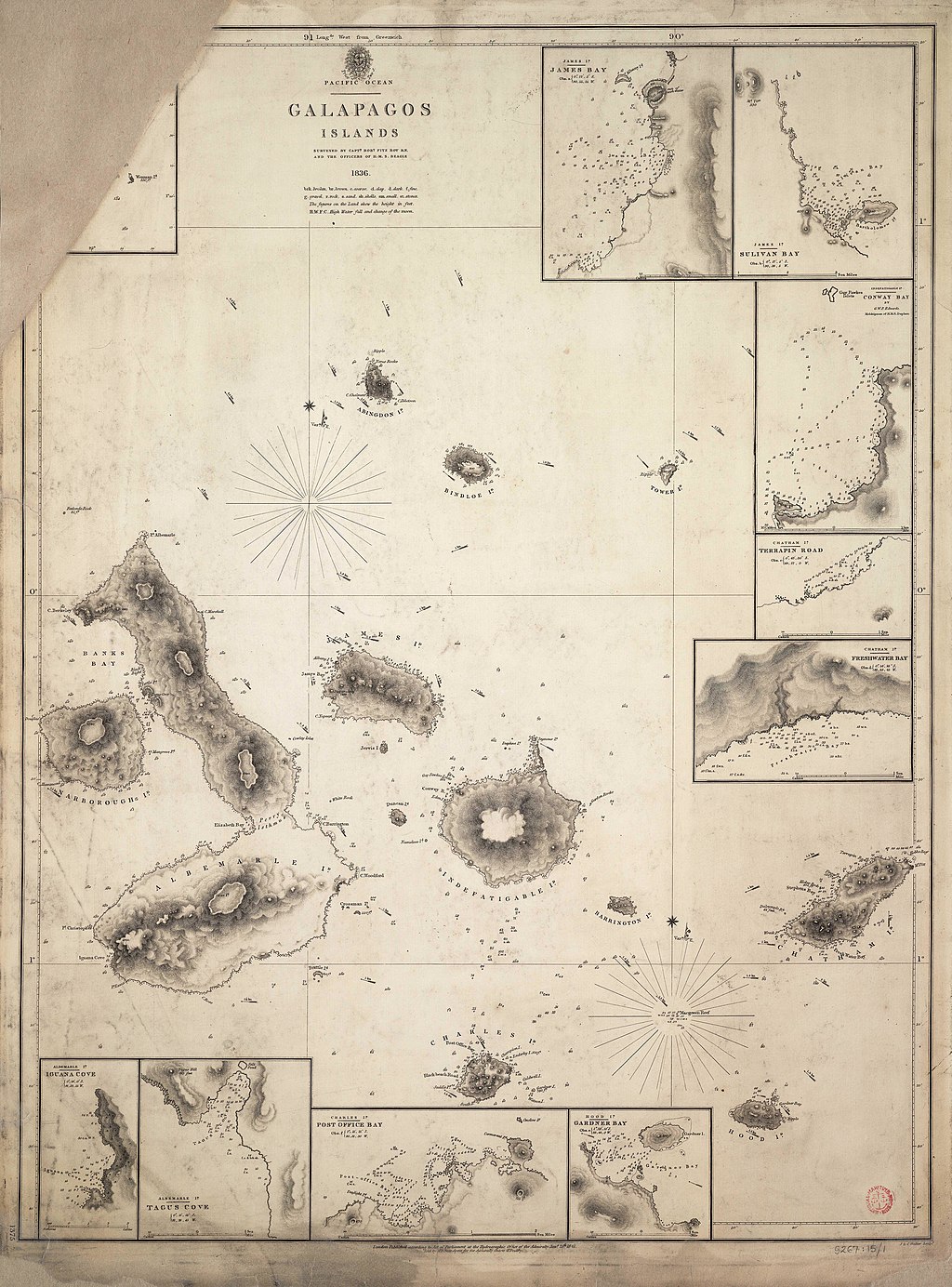

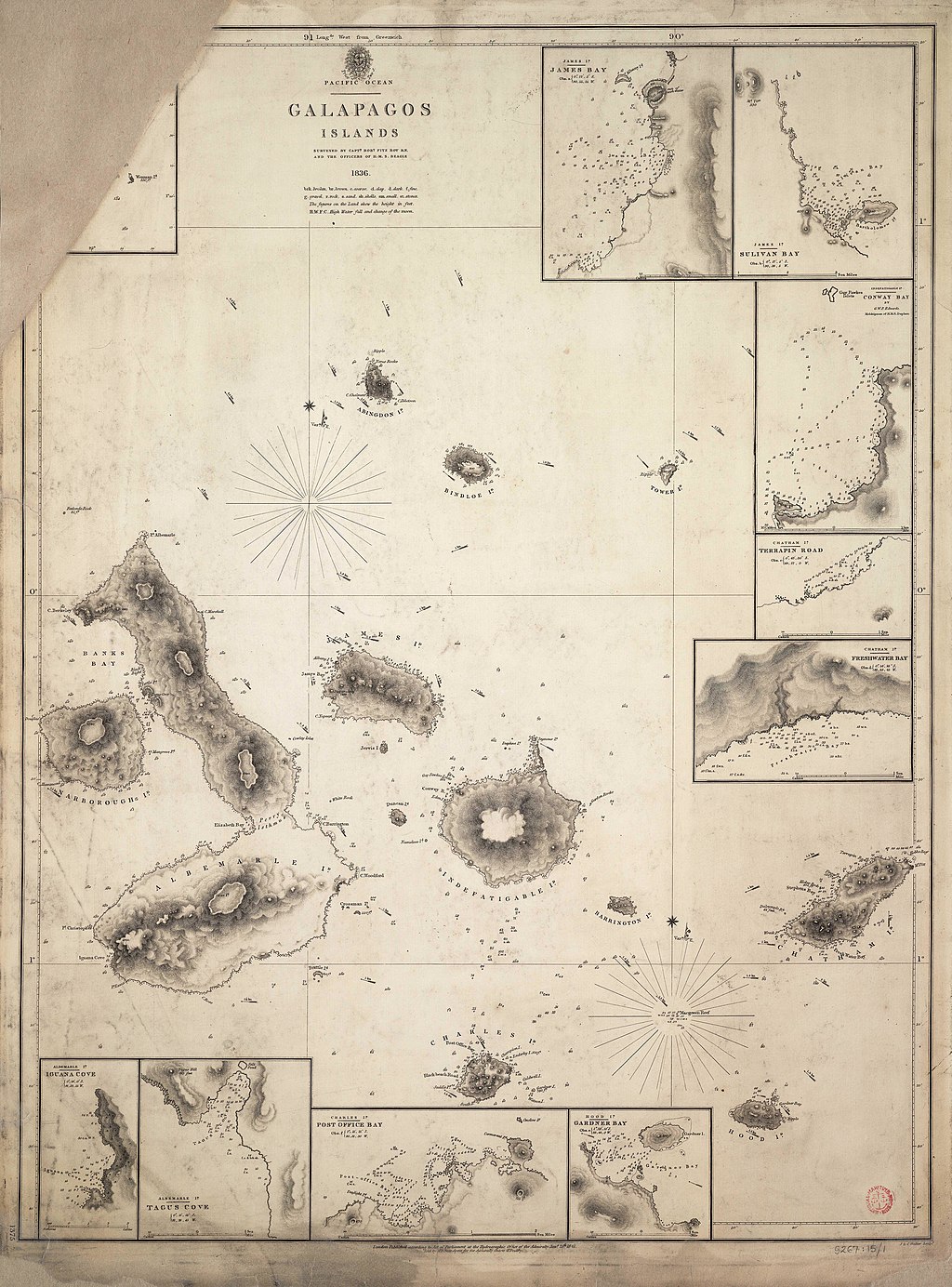

| Publication of FitzRoy's

narrative and Darwin's book Darwin reorganised his diary, trimmed parts, and incorporated scientific material from his field notes. He passed his writing to the publisher Henry Colburn, and in August 1837 had the first proofs back from the printer. Henslow helped check them; on 4 November, Darwin wrote to him that "If I live till I am eighty years old I shall not cease to marvel at finding myself an author". Part of it was printed, "the smooth paper and clear type has a charming appearance, and I sat the other evening gazing in silent admiration at the first page of my own volume, when I received it from the printers!"[27] FitzRoy had to edit King's account of the first voyage, adding extracts from the journal of the previous captain of Beagle and his own journal when he took over, as well as write his own account of the second voyage. In mid-November 1837, he took offence that Darwin's preface to volume III (and a similar preface to the first part of The Zoology) lacked, in his view, enough acknowledgement of the help given by FitzRoy and other officers; the problem was overcome. By the end of February 1838, King's Narrative (volumes I) and Darwin's Journal (volume III) had been printed, but FitzRoy was still hard at work on volume II.[27][28] The Narrative was completed and published as a four-volume set in May 1839,[29] as the Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle, describing their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the Beagle's Circumnavigation of the Globe, in three volumes.[30] Volume one covers the first voyage under Commander Phillip Parker King, volume two is FitzRoy's account of the second voyage. Darwin's Journal and Remarks, 1832–1835 forms the third volume, and the fourth volume is a lengthy appendix.[2] The publication was reviewed as a whole by Basil Hall in the July 1839 issue of the Edinburgh Review.[31] Volume two includes FitzRoy's Remarks with reference to the Deluge in which he recanted his earlier interest in the geological writings of Charles Lyell and his remarks to Darwin during the expedition that sedimentary features they saw "could never have been effected by a forty days' flood", asserting his renewed commitment to a literal reading of the Bible.[32] He had married on the ship's return, and his wife was very religious.[33] Darwin's contribution proved remarkably popular and the publisher, Henry Colburn of London, announced on 15 August a separate volume of Darwin's text,[29] published with a new title page as Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the various countries visited by H.M.S. Beagle.[2][34] The Publishers‘ Circular of 2 September carried an advertisement for this volume, as well as a separate advertisement for the other volumes,[29] as listed at William Broderip's article in the Quarterly Review.[34] This was apparently done without seeking Darwin's permission or paying him a fee. Second edition: changing ideas on evolution  Illustration from Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology The second edition of 1845 incorporated extensive revisions made in the light of interpretation of the field collections and developing ideas on evolution. This edition was commissioned by the publisher John Murray, who actually paid Darwin a fee of £150 for the copyright. The full title was modified to Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world.[2] In the first edition, Darwin remarks in regard to the similarity of Galápagos wildlife to that on the South American continent, "The circumstance would be explained, according to the views of some authors, by saying that the creative power had acted according to the same law over a wide area". (This was written in a reference to Charles Lyell's ideas of "centres of creation".) Darwin notes the gradations in size of the beaks of species of finches, suspects that species "are confined to different islands", "But there is not space in this work, to enter into this curious subject." Later editions hint at his new ideas on evolution: Considering the small size of these islands, we feel the more astonished at the number of their aboriginal beings, and at their confined range... within a period geologically recent the unbroken ocean was here spread out. Hence, both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near to that great fact – that mystery of mysteries – the first appearance of new beings on this earth. Speaking of the finches with their gradations in size of beaks, he writes "one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends." In 1890, John Murray published an illustrated edition of the book, at the suggestion of the artist Robert Taylor Pritchett, who was already known for accompanying voyages of the RYS Wanderer and Sunbeam, and producing pictures used in books on these cruises.[35] In his foreword to this edition of Journal and Researches, Murray said that most "of the views given in this work are from sketches made on the spot by Mr. Pritchett, with Mr. Darwin's book by his side", and the illustrations had been "chosen and verified with the utmost care and pains".[1] |

フィッツロイの航海日誌とダーウィンの著書の出版 ダーウィンは日記を整理し、一部を削除し、フィールドノートから科学的な内容を盛り込んだ。彼は原稿を出版社のヘンリー・コルバーンに渡し、1837年8 月には最初の校正刷りが印刷業者から戻ってきた。ヘンズローが校正を手伝い、11月4日、ダーウィンは彼に「もし私が80歳まで生き延びたとしても、自分 が著者であることに驚きを禁じ得ないだろう」と書き送った。その一部が印刷された。「滑らかな紙と鮮明な活字は魅力的な外観で、先日、印刷所から受け取っ た自分の本の最初のページを、私は夕べ、静かに感嘆のまなざしで見つめていた」[27] フィッツロイは、キングによる最初の航海の報告を編集し、引き継いだ際にビーグル号の前船長の航海日誌と自身の航海日誌からの抜粋を付け加え、さらに自身 による第2回航海の報告も執筆しなければならなかった。1837年11月中旬、彼はダーウィンが第3巻の序文(および『動物学』第1部の序文)で、フィッ ツロイや他の士官たちの貢献を十分に評価していないことに憤慨した。1838年2月末には、キングの『航海記』(第1巻)とダーウィンの『日記』(第3 巻)が印刷されていたが、フィッツロイはまだ第2巻の執筆に励んでいた。[27][28] 『航海記』は1839年5月に4巻本として完成し、出版された。[29] 3巻本として、国王の船アドベンチャー号とビーグル号による南米南岸の調査とビーグル号による世界一周航海について記述されている。[30] 第1巻はフィリップ・パーカー・キング船長による最初の航海について、第2巻はフィッツロイによる2度目の航海について書かれている。第3巻は『チャール ズ・ダーウィンの航海日誌と見解、1832年~1835年』で、第4巻は長い付録となっている。[2] この出版物は、1839年7月の『エディンバラ・レビュー』誌で、バジル・ホールによって全体的に評価された。[31] 第2巻には、フィッツロイがチャールズ・ライエルの地質学に関する著作への関心を撤回し、また、彼らが目にした堆積の特徴は「決して40日間の洪水によっ て生じたものではない」と、遠征中にダーウィンに述べたことについて言及した「フィッツロイの注釈」が含まれている。彼は船の帰還中に結婚しており、彼の 妻は非常に信心深かった。 ダーウィンの寄稿は非常に好評を博し、ロンドンのヘンリー・コルバーンという出版社は8月15日、ダーウィンの文章を別の巻として発表した。[29] 新しいタイトルページとともに、HMSビーグル号が訪れたさまざまな国の地質学と自然史の研究誌として出版された。[ 2][34] 9月2日付の出版社の広告には、この巻の広告とともに、他の巻の広告も掲載されていた。[29] これは、ウィリアム・ブロデリップの『クォータリー・レビュー』の記事に記載されている通りである。[34] これは明らかに、ダーウィンの許可を得ることなく、また彼に報酬を支払うことなく行われた。 第2版:進化論に関する考え方の変化  『ビーグル号航海記』の図版 1845年の第2版では、現地での収集品の解釈と進化論に関する考え方の発展を踏まえて、大幅な修正が加えられた。この版は、出版社ジョン・マレーの依頼 により出版されたもので、実際にはマレーがダーウィンに著作権使用料として150ポンドを支払った。正式タイトルは『ビーグル号世界一周航海中に訪問した 各国の自然史と地質学に関する研究』に変更された。 初版において、ダーウィンはガラパゴス諸島の野生生物と南米大陸の生物の類似性について、「この状況は、一部の著者の見解によれば、創造の力が広範囲にわ たって同じ法則に従って作用した結果であると説明できるだろう」と述べている。(これは、チャールズ・ライエルの「創造の中心地」という考え方を参照して 書かれたものである。) ダーウィンはフィンチ類のくちばしの大きさの変化に注目し、種が「異なる島々に限定されている」のではないかと疑った。「しかし、この作品では、この興味 深いテーマについて詳しく述べるスペースがない。 」 後の版では、進化に関する彼の新しい考えが示唆されている。 これらの島々の小ささを考慮すると、私たちは、その原住民の数と限られた範囲に、より驚かされる。地質学的に最近では、途切れることなく海が広がってい た。したがって、空間的にも時間的にも、私たちはその大きな事実、すなわち、この地球上に新たな生物が最初に現れたという謎の謎に、いくらか近づいたよう に思われる。 嘴の大きさが段階的に変化しているフィンチについて、彼は「この列島では元々鳥類が少なかったため、ある種が捕獲され、異なる目的のために改良されたので はないか」と書いている。 1890年、ジョン・マレーは、RYSの探検船ワンダラー号とサンビーム号の航海に同行し、これらのクルーズに関する書籍の挿絵を描いていたことで既に知 られていた画家ロバート・テイラー・プリチェットの提案を受け、図版付きの版を出版した。[35] この『日誌と研究』の版の序文で、マレーは 『日誌と研究』の序文で、マレーは「この作品で紹介されている景色のほとんどは、ダーウィン著の書籍を傍らに置き、プリチェット氏がその場で描いたスケッ チによるものである」と述べ、挿絵は「最大限の注意と労力を払って厳選され、確認された」ものであると述べている。[1] |

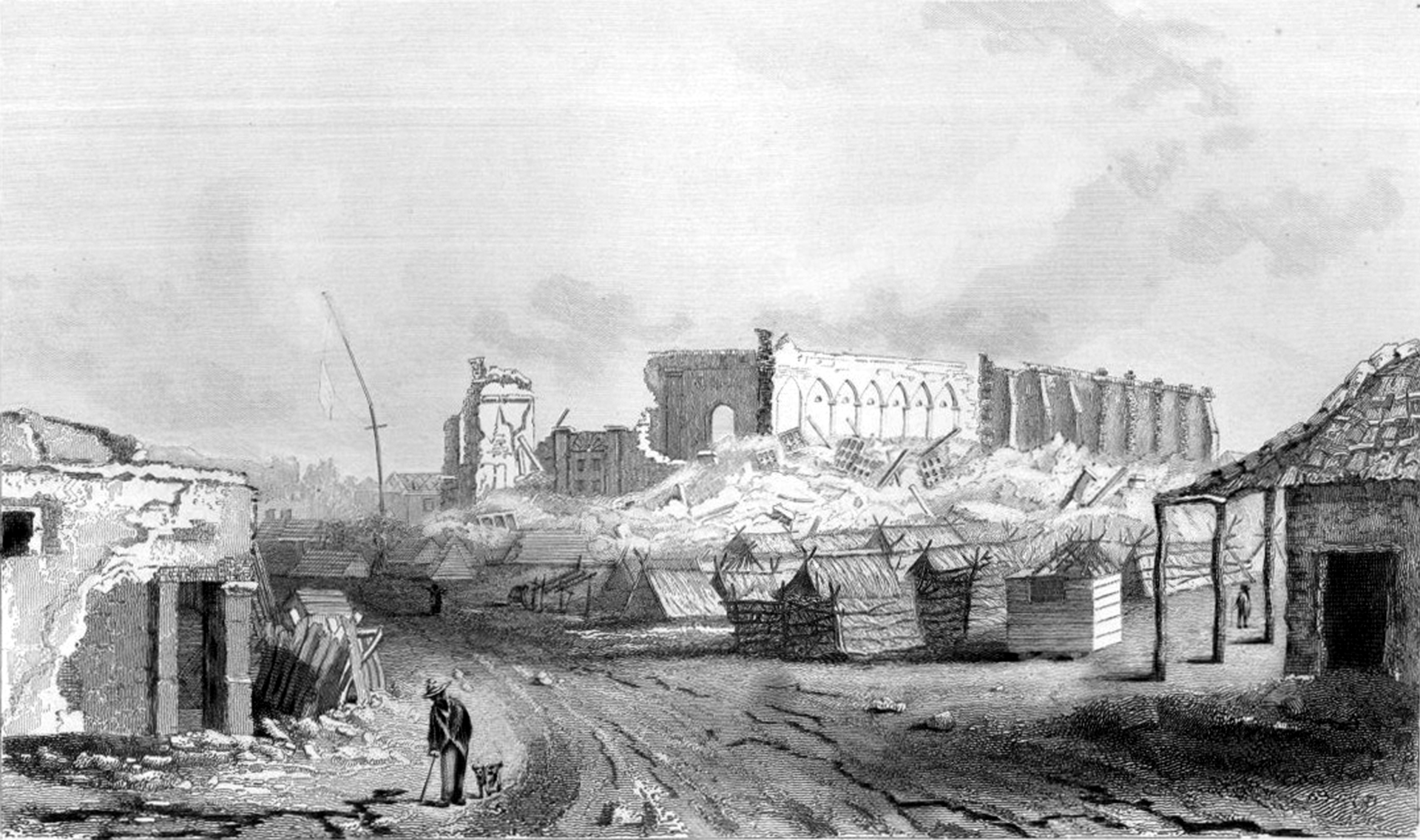

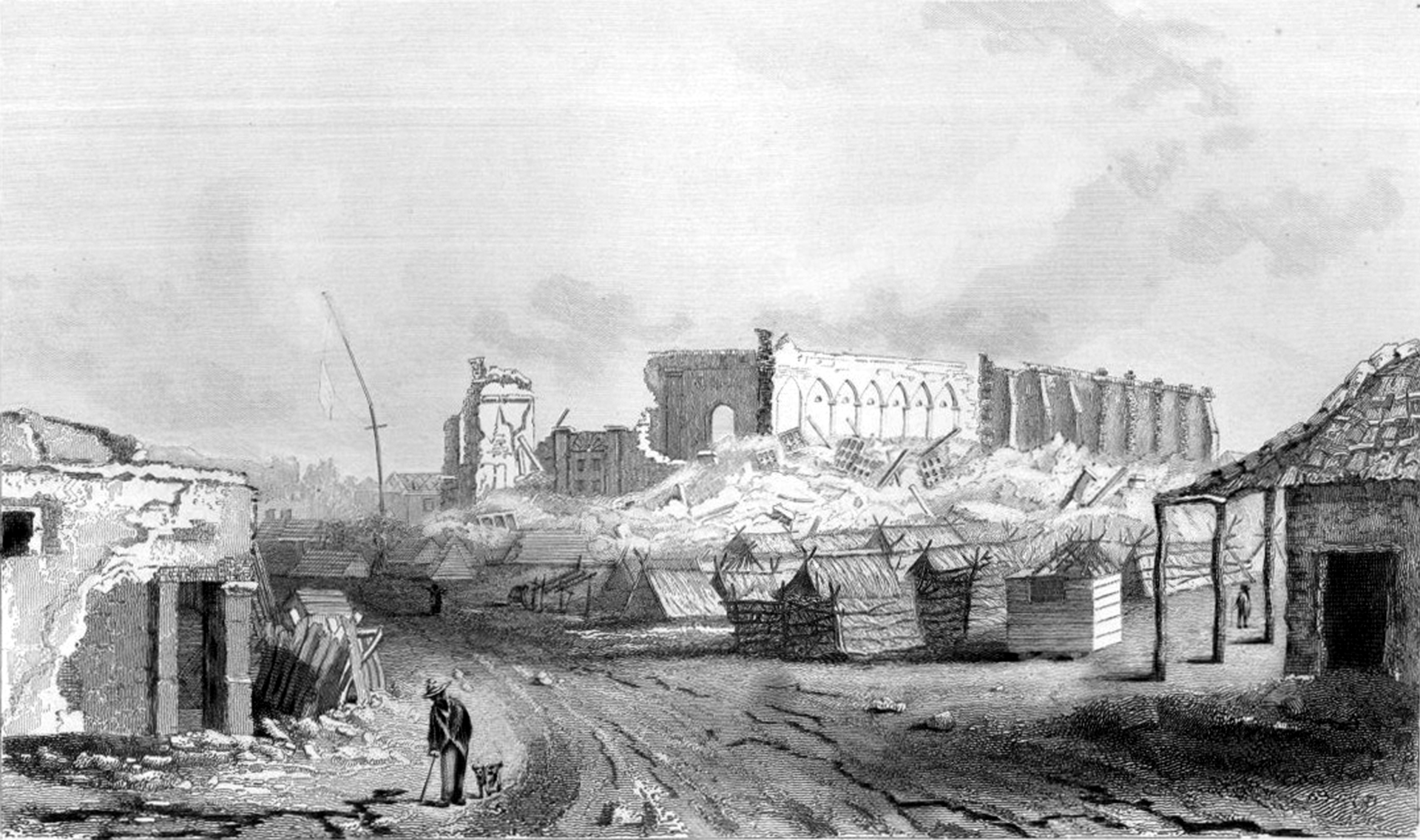

| Contents – places Darwin visited For readability, the chapters of the book are arranged geographically rather than in an exact chronological sequence of places Darwin visited or revisited.[36] The main headings (and in some cases subheadings) of each chapter give a good idea of where he went, but not the exact sequence. See second voyage of HMS Beagle for a detailed synopsis of Darwin's travels. The contents list in the book also notes topics discussed in each chapter, not shown here for simplicity. Names and spellings are those used by Darwin. The list below is based on the Journal and Remarks of 1839. Preface Chapter I: St. Jago–Cape de Verde Islands (St. Paul's Rocks, Fernando Noronha, 20 Feb.., Bahia, or San Salvador, Brazil, 29 Feb..) Chapter II: Rio de Janeiro Chapter III: Maldonado Chapter IV: Río Negro to Bahia Blanca Chapter V: Bahía Blanca Chapter VI: Bahia Blanca to Buenos Aires Chapter VII: Buenos Aires to St. Fe Chapter VIII: Banda Oriental Chapter IX: Patagonia Chapter X: Santa Cruz–Patagonia Chapter XI: Tierra del Fuego Chapter XII: The Falkland Islands Chapter XIII: Strait of Magellan Chapter XIV: Central Chile Chapter XV: Chiloe and Chonos Islands Chapter XVI: Chiloe and Concepcion Chapter XVII: Passage of Cordillera Chapter XVIII: Northern Chile and Peru Chapter XIX: Galapagos Archipelago Chapter XX: Tahiti and New Zealand Chapter XXI: Australia (Van Diemen's Land) Chapter XXII: Coral Formations (Keeling or Cocos Islands) Chapter XXIII: Mauritius to England In the second edition, the Journal of Researches of 1845, chapters VIII and IX were merged into a new chapter VIII on "Banda Oriental and Patagonia", and chapter IX now included "Santa Cruz, Patagonia and The Falkland Islands". After chapter X on Tierra del Fuego, chapter XI had the revised heading "Strait of Magellan–Climate of the Southern Coasts". The following chapters were renumbered accordingly. Chapter XIV was given the revised heading "Chiloe and Concepcion: Great Earthquake", and chapter XX had the heading "Keeling Island:–Coral Formations", with the concluding chapter XXI keeping the heading "Mauritius to England". https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Voyage_of_the_Beagle |

内容 - ダーウィンが訪れた場所 読みやすさを考慮して、この本の章は、ダーウィンが訪れた場所や再訪した場所を正確な年代順ではなく、地理的に配列されている。[36] 各章の主な見出し(場合によっては小見出し)は、彼がどこを訪れたかをよく表しているが、正確な順序ではない。ダーウィンの旅の詳細な概要については、 HMSビーグル号の第2回航海を参照のこと。この本の目次には、各章で論じられたトピックも記載されているが、ここでは簡略化のため省略する。人名および 綴りはダーウィンによる表記に従っている。以下のリストは、1839年の『日記』および『覚書』に基づくものである。 序文 第1章:サンチャゴ島 - カーボベルデ諸島(サン・パウロ岩礁、フェルナンド・ノローニャ、2月20日、ブラジル、バイアまたはサンサルバドル、2月29日) 第2章:リオデジャネイロ 第3章:マルドナド 第4章:リオネグロからバイアブランカ 第5章:バイアブランカ 第6章:バイアブランカからブエノスアイレス 第7章:ブエノスアイレスからセントフェ 第8章:バンダ・オリエンタル 第9章:パタゴニア 第10章:サンタ・クルス~パタゴニア 第11章:ティエラ・デル・フエゴ 第12章:フォークランド諸島 第13章:マゼラン海峡 第14章:チリ中央部 第15章:チロエ島およびチョノス諸島 第16章:チロエ島およびコンセプシオン 第17章:コルディレラ通過 第18章:チリ北部およびペルー 第19章:ガラパゴス諸島 第20章:タヒチおよびニュージーランド 第21章:オーストラリア(ヴァン・ダイマンの土地 第22章:サンゴ礁(キーリング島またはココス諸島 第23章:モーリシャスからイングランド 第2版である1845年の『研究日誌』では、第8章と第9章が「バンダ・オリエンタルとパタゴニア」という新しい第8章に統合され、第9章には「サンタ・ クルス、パタゴニア、フォークランド諸島」が追加された。ティエラ・デル・フエゴに関する第10章の後に、第11章は「マゼラン海峡 - 南岸の気候」という見出しに変更された。それに伴い、その後の章も順に番号が変更された。第14章は「チロエ島とコンセプシオン:大地震」という見出しに 変更され、第20章は「キーリング島:サンゴの形成」という見出しとなり、最終章である第21章は「モーリシャスからイングランド」という見出しが維持さ れた。 |

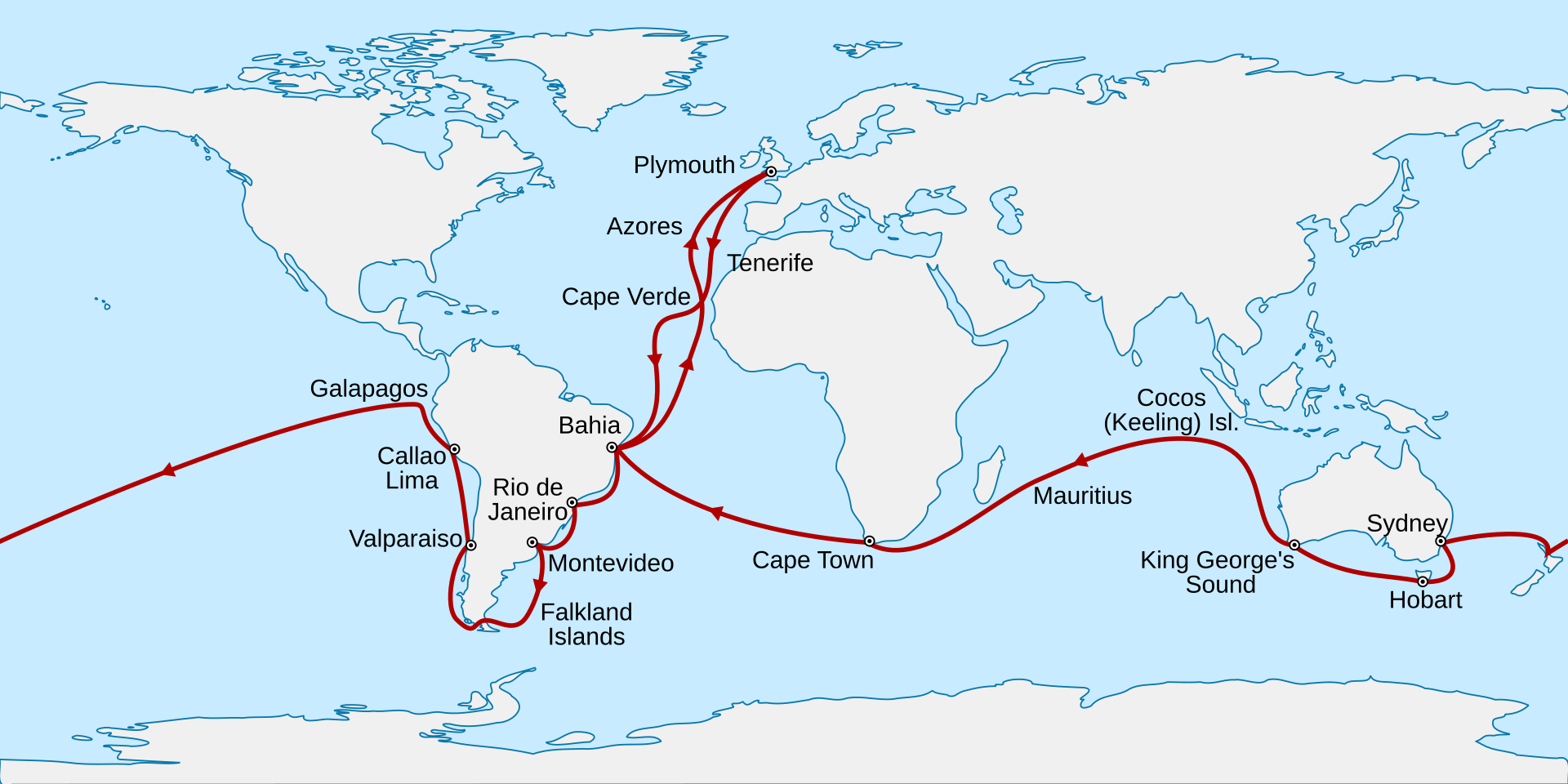

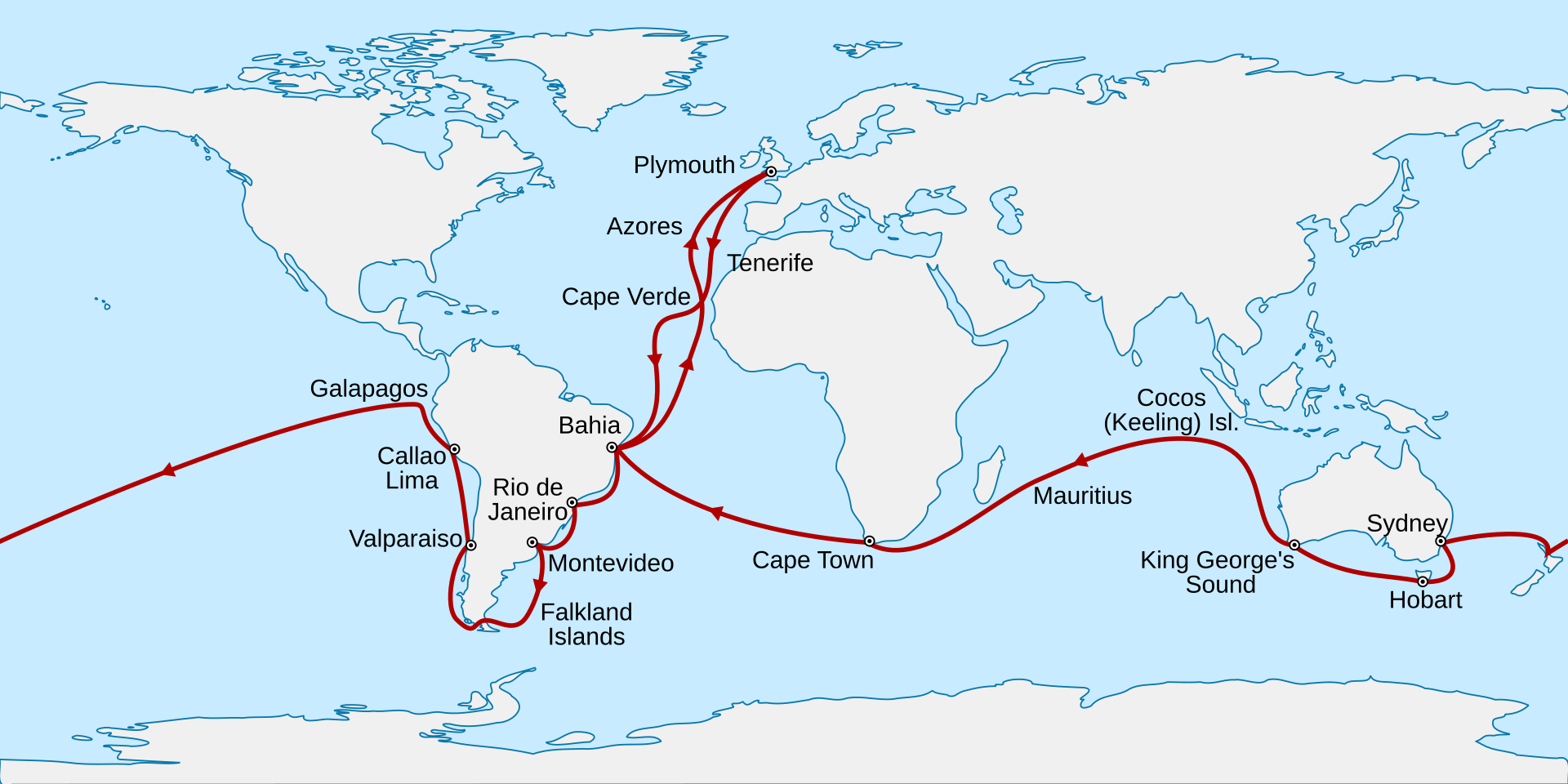

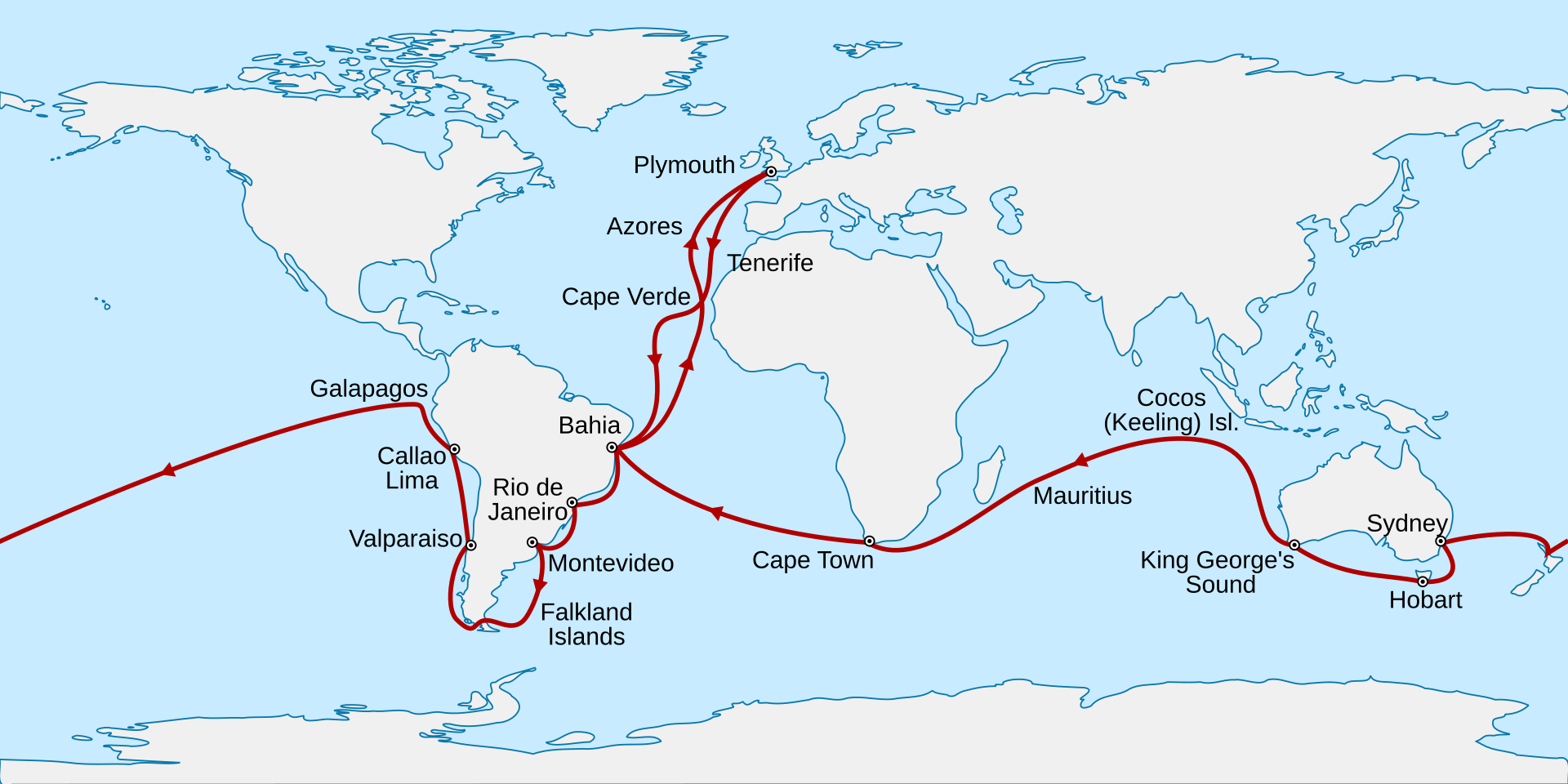

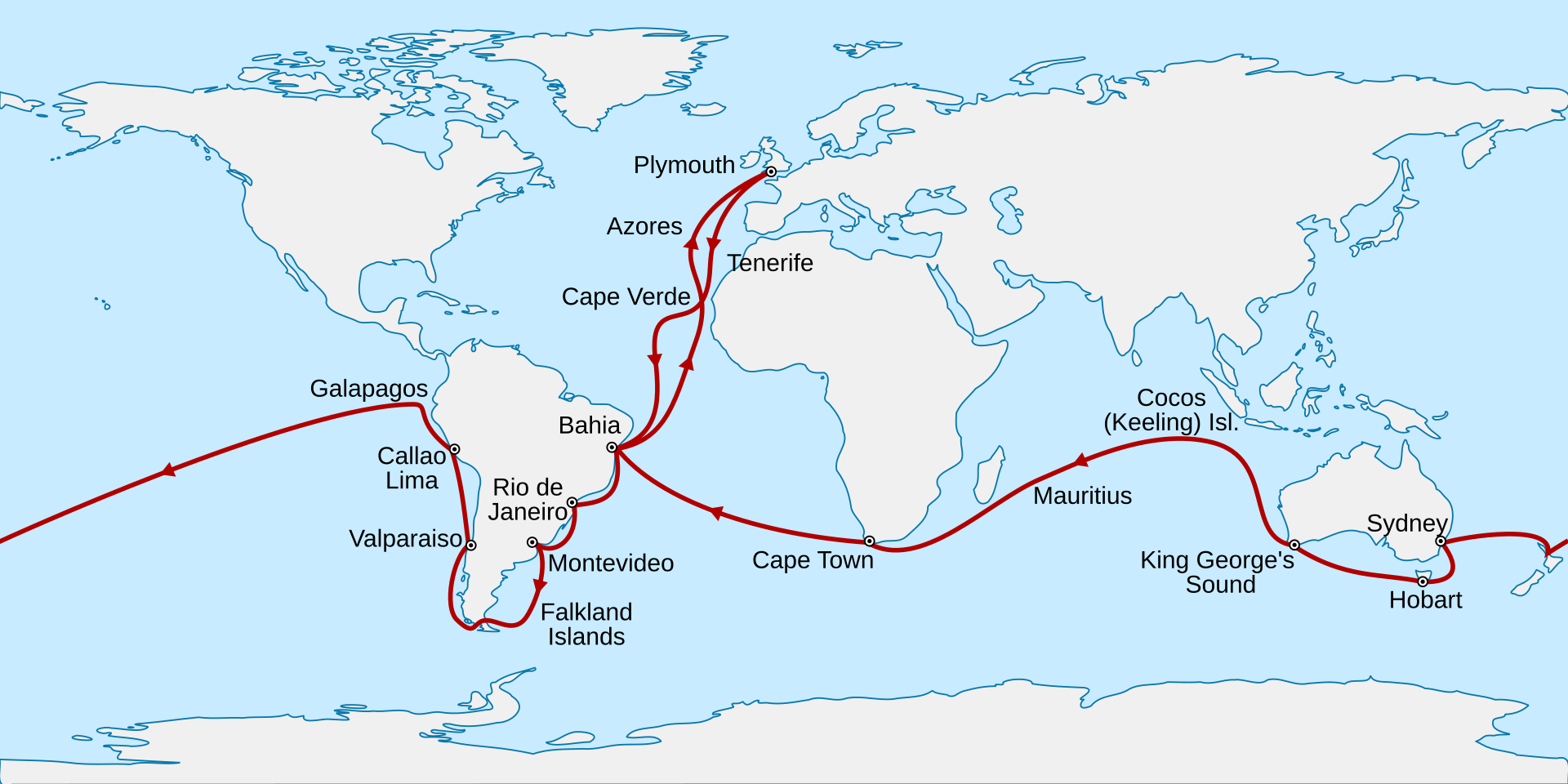

HMS Beagle at Tierra del Fuego (painted by Conrad Martens). HMS Beagle in the seaways of Tierra del Fuego, painting by Conrad Martens during the voyage of the Beagle (1831-1836), from The Illustrated Origin of Species by Charles Darwin, abridged and illustrated by Richard Leakey  Map of the Voyage of the Beagle, a circumnavigation travel with Charles Darwin. |

ティエラ・デル・フエゴのHMS ビーグル号(コンラッド・マルテンス画)。ティエラ・デル・フエゴの海上のHMS ビーグル号(コンラッド・マルテンス画、ビーグル号の航海中(1831年~1836年)の『種の起源』より、チャールズ・ダーウィン著、リチャード・リー キー編、図版  チャールズ・ダーウィンによる世界一周旅行「ビーグル号の航海」の地図。 |

| Sources Darwin, Charles (June 1960), "Darwin as a Traveller", The Geographical Journal, 126 (2): 129–136, Bibcode:1960GeogJ.126..129D, doi:10.2307/1793952, JSTOR 1793952 Retrieved on 15 December 2006 Browne, E. Janet (1995), Charles Darwin: vol. 1 Voyaging, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 1-84413-314-1 Browne, E. Janet (2002), Charles Darwin: vol. 2 The Power of Place, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0-7126-6837-3 Darwin, Charles (1835), Extracts from letters to Professor Henslow. Cambridge, [printed by the Cambridge University Press for private distribution] Retrieved on 30 April 2007 Darwin, Charles (1887), Darwin, F (ed.), The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter., London: John Murray (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin) Retrieved on 15 December 2006 Darwin, Charles (1958), Barlow, N (ed.), The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand-daughter Nora Barlow., London: Collins (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin) Retrieved on 15 December 2006 Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991), Darwin, London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group, ISBN 0-7181-3430-3 Freeman, R. B. (1977), The Works of Charles Darwin: An Annotated Bibliographical Handlist (Second ed.), Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd Retrieved on 30 April 2007 Gordon, Robert; Thomas, Deborah (20–21 March 1999), "Circumnavigating Darwin", Darwin Undisciplined Conference, Sydney. Retrieved on 15 December 2006 Keynes, Richard (2001), Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary, Cambridge University Press, retrieved 24 October 2008 Rookmaaker, Kees; van Wyhe, eds. (March 2021), Transcription of Darwin, C. R. [Beagle diary (1831-1836)]. EH88202366, Darwin Online Thomson, Keith S. (2003), HMS Beagle : the story of Darwin's ship, London: Phoenix, ISBN 978-0-7538-1733-9, OCLC 52143718 van Wyhe, John (2006), Charles Darwin: gentleman naturalist: A biographical sketch Retrieved on 15 December 2006 |

出典 ダーウィン、チャールズ(1960年6月)、「旅行者としてのダーウィン」、『地理学雑誌』、126巻2号:129–136頁、Bibcode: 1960GeogJ.126..129D、 doi:10.2307/1793952, JSTOR 1793952 2006年12月15日取得 ブラウン, E. ジャネット (1995), 『チャールズ・ダーウィン: 第1巻 航海』, ロンドン: ジョナサン・ケープ, ISBN 1-84413-314-1 ブラウン、E. ジャネット(2002)、『チャールズ・ダーウィン:第2巻 場所の力』、ロンドン:ジョナサン・ケープ、ISBN 0-7126-6837-3 ダーウィン、チャールズ(1835)、『ヘンズロー教授への手紙からの抜粋』。ケンブリッジ、[ケンブリッジ大学出版局による私的配布用印刷]2007年 4月30日取得 ダーウィン、チャールズ(1887)、ダーウィン、F(編)、『チャールズ・ダーウィンの生涯と書簡、自伝的章を含む』、ロンドン:ジョン・マレー (『チャールズ・ダーウィンの自伝』)2006年12月15日取得 ダーウィン、チャールズ (1958)、バーロウ、N (編)、『チャールズ・ダーウィンの自伝 1809–1882』。 原本の欠落部分を復元。 孫娘ノラ・バーロウによる編集、付録および注釈付き。ロンドン:コリンズ (『チャールズ・ダーウィンの自伝』) 2006年12月15日取得 デズモンド、エイドリアン; ムーア、ジェームズ (1991)、ダーウィン、ロンドン:マイケル・ジョセフ、ペンギン・グループ、ISBN 0-7181-3430-3 フリーマン、R. B. (1977)、チャールズ・ダーウィンの作品:注釈付き書誌ハンドリスト(第 2 版)、キャノン・ハウス・フォークストーン、ケント、イングランド:Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd 2007年4月30日取得 ゴードン、ロバート;トーマス、デボラ(1999年3月20日-21日)、「ダーウィンを巡る航海」、ダーウィン・アンディシプリンド会議、シドニー。 2006年12月15日取得 キーンズ、リチャード(2001)、『チャールズ・ダーウィンのビーグル号航海日誌』、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2008年10月24日取得 ルークマカー、キース; ファン・ワイヘ、編 (2021年3月), 『ダーウィン、C. R. [ビーグル号航海日誌 (1831-1836)]』の転写. EH88202366, ダーウィン・オンライン トムソン、キース・S.(2003)、『HMSビーグル号:ダーウィンの船の物語』、ロンドン:フェニックス、ISBN 978-0-7538-1733-9、OCLC 52143718 ヴァン・ワイエ、ジョン(2006)、『チャールズ・ダーウィン:紳士自然学者:伝記的概説』、2006年12月15日取得 |

| Bibliography of original

publications Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, Volume I – King, P. Parker (1839), Proceedings of the first expedition, 1826–30, under the command of Captain P. Parker King, R.N., F.R.S, Great Marlborough Street, London: Henry Colburn Retrieved on 30 April 2007 Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, Volume II – FitzRoy, Robert (1839), Proceedings of the second expedition, 1831–36, under the command of Captain Robert Fitz-Roy, R.N., Great Marlborough Street, London: Henry Colburn Retrieved on 15 December 2006 Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, Volume III – Darwin, Charles (1839), Journal and remarks. 1832–1836., London: Henry Colburn (The Voyage of the Beagle) Retrieved on 30 April 2007 Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, Appendix – FitzRoy, Robert (1839b), Appendix, Great Marlborough Street, London: Henry Colburn Retrieved on 15 December 2006 Darwin, Charles (1845), Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. (Second ed.), London: John Murray (The Voyage of the Beagle) Retrieved on 30 April 2007 Darwin, Charles (1890), Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the various countries visited by H.M.S. Beagle etc. (First Murray illustrated ed.), London: John Murray (The Voyage of the Beagle) Retrieved on 3 August 2014 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Voyage_of_the_Beagle |

原典文献目録 アドベンチャー号とビーグル号の航海、第1巻 – キング、P. パーカー (1839)、第1次探検隊の記録、1826–30年、P. パーカー・キング海軍大佐、王立協会会員指揮下、ロンドン・グレート・マールボロ通り:ヘンリー・コルバーン刊 2007年4月30日取得 アドベンチャー号とビーグル号の航海、第2巻 – フィッツロイ、ロバート (1839)、第2次探検の記録、1831–36年、ロバート・フィッツロイ海軍大尉指揮下、ロンドン、グレート・マールボロ・ストリート:ヘンリー・コ ルバーン、2006年12月15日取得 アドベンチャー号とビーグル号の航海、第3巻 – ダーウィン、チャールズ (1839)、航海日誌と所見。1832–1836年、ロンドン:ヘンリー・コルバーン (『ビーグル号の航海』) 2007年4月30日取得 アドベンチャー号とビーグル号の航海、付録 – フィッツロイ、ロバート (1839b)、付録、ロンドン、グレート・マールボロ・ストリート:ヘンリー・コルバーン、2006年12月15日取得 ダーウィン、チャールズ(1845)、『H.M.S.ビーグル号世界周航における訪問諸国の自然史および地質学に関する研究日誌』(第二版)、ロンドン: ジョン・マレー(『ビーグル号航海記』)2007年4月30日取得 ダーウィン、チャールズ(1890年)、『H.M.S.ビーグル号が訪問した諸国の自然史および地質学に関する研究日誌』(初版マレー社図版付)、ロンド ン:ジョン・マレー(『ビーグル号航海記』)2014年8月3日取得 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Voyage_of_the_Beagle |

| The

second voyage of HMS Beagle,

from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836, was the second survey

expedition of HMS Beagle, made under her newest commander, Robert

FitzRoy. (During Beagle's first voyage, Captain Pringle Stokes had died

by suicide. The expedition's leader appointed Beagle's 1st Lieutenant,

W. G. Skyring, as her acting commander. Roughly three months later,

Admiral Otway decided to give Beagle to his flag lieutenant, FitzRoy.)

FitzRoy had thought of the advantages of having someone onboard who

could investigate geology, and sought a naturalist to accompany them as

a supernumerary. At the age of 22, the graduate Charles Darwin hoped to

see the tropics before becoming a parson, and accepted the opportunity.

He was greatly influenced by reading Charles Lyell's Principles of

Geology during the voyage. By the end of the expedition, Darwin had

made his name as a geologist and fossil collector, and the publication

of his journal (later known as The Voyage of the Beagle) gave him wide

renown as a writer. Beagle sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, and then carried out detailed hydrographic surveys around the coasts of southern South America, returning via Tahiti and Australia, after having circumnavigated the Earth. The initial offer to Darwin told him the voyage would last two years; it lasted almost five. Darwin spent most of this time exploring on land: three years and three months land, 18 months at sea.[1] Early in the voyage, Darwin decided that he could write a geology book, and he showed a gift for theorising. At Punta Alta in Argentina, he made a major find of gigantic fossils of extinct mammals, then known from very few specimens. He collected and made detailed observations of plants and animals. His findings undermined his belief in the doctrine that species are fixed, and provided the basis for ideas which came to him when back in England, leading to his theory of evolution by natural selection. |

1831年

12月27日から1836年10月2日までの間に行われたHMSビーグル号の2度目の航海は、ロバート・フィッツロイを艦長として行われた2度目の調査探

検であった。(ビーグル号の最初の航海中、プリングル・ストークス船長は自殺していた。遠征隊のリーダーは、ビーグル号の第一副官W. G.

スカイリングを臨時船長に任命した。およそ3ヵ月後、オトウェイ提督はビーグル号を旗艦としてフィッツロイに与えることを決めた。)フィッツロイは、地質

学の調査ができる人物を乗船させることの利点を考え、その任務に就くナチュラリストを同行させることを求めた。当時22歳だったチャールズ・ダーウィンは

牧師になる前に熱帯地方を見てみたいと考えており、この機会に喜んで乗船した。航海中、チャールズ・ライエルの著書『地質学原理』を読み、大きな影響を受

けた。この探検を終える頃には、ダーウィンは地質学者および化石収集家として名を馳せ、航海日誌(後に『ビーグル号航海記』として出版)を著したことで作

家としても広く知られるようになった。 ビーグル号は大西洋を横断し、南米南部の海岸一帯で詳細な水路測量を実施した。その後、タヒチとオーストラリアを経由して地球を一周し、帰路についた。 当初、航海は2年で終わる予定だったが、実際には5年近くかかった。 この間、ダーウィンは陸上で3年3ヶ月、海上で18ヶ月を過ごした。[1] 航海の初期に、ダーウィンは地質学に関する本を書くことができると判断し、理論化する才能を示した。アルゼンチンのプンタ・アルタで、彼は当時ごく少数の 標本でしか知られていなかった絶滅した巨大な哺乳類の化石を発見した。彼は植物や動物を収集し、詳細な観察を行った。 その発見は、種は固定されているという彼の信念を揺るがすものであり、後にイギリスに戻った際に彼に浮かんだ考えの基礎となり、自然淘汰による進化論へと つながった。 |

Aims of the expedition Ship's chronometer from HMS Beagle made by Thomas Earnshaw. British Museum, London. When the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the Pax Britannica saw seafaring nations competing in colonisation and rapid industrialisation. The logistics of supply and growing commerce needed reliable information about sea routes, but existing nautical charts were incomplete and inaccurate. Spanish American wars of independence ended Spain's monopoly over trade,[2][3] and the UK's 1825 commercial treaty with Argentina recognised its independence, increasing the naval and commercial significance of the east coast of South America.[4] The Admiralty instructed Commander King to make an accurate hydrographic survey of "the Southern Coasts of the Peninsula of South America, from the southern entrance of the River Plata, round to Chilóe; and of Tierra del Fuego".[5][6] As Darwin wrote of his voyage, "The object of the expedition was to complete the survey of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, commenced under Captain King in 1826 to 1830—to survey the shores of Chile, Peru, and of some islands in the Pacific—and to carry a chain of chronometrical measurements round the World."[7][6] The expeditions also had diplomatic objectives, visiting disputed territories.[2] An Admiralty memorandum set out the detailed instructions. The first requirement was to resolve disagreements in the earlier surveys about the longitude of Rio de Janeiro, which was essential as the base point for meridian distances. The accurate marine chronometers needed to determine longitude, had only become affordable since 1800; Beagle carried 22 chronometers to allow corrections. The ship was to stop at specified points for a four-day rating of the chronometers and to check them by astronomical observations: it was essential to take observations at Porto Praya and Fernando de Noronha to calibrate against the previous surveys of William Fitzwilliam Owen and Henry Foster. It was important to survey the extent of the Abrolhos Archipelago reefs, shown incorrectly in Albin Roussin's survey, then proceed to Rio de Janeiro to decide the exact longitude of Villegagnon Island.[8] The real work of the survey was then to commence south of the Río de la Plata, with return trips to Montevideo for supplies; details were given of priorities, including surveying Tierra del Fuego and approaches to harbours on the Falkland Islands. The west coast was then to be surveyed as far north as time and resources permitted. The commander would then determine his own route west: season permitting, he could survey the Galápagos Islands. Then, Beagle was to proceed to Point Venus, Tahiti, and on to Port Jackson, Australia, which were known points to verify the chronometers.[9] No time was to be wasted on elaborate drawings; charts and plans should have notes and simple views of the land as seen from the sea showing measured heights of hills. Continued records of tides and meteorological conditions were also required. An additional suggestion was for a geological survey of a circular coral atoll in the Pacific Ocean including its profile and of tidal flows, to investigate the formation of such coral reefs.[10] |

遠征の目的 トーマス・アーンショウが製作したHMSビーグル号の船用クロノメーター。 大英博物館(ロンドン)。 1815年にナポレオン戦争が終結すると、大英帝国の平和(パックス・ブリタニカ)のもと、海洋国家が植民地化と急速な工業化を競い合うようになった。 物資の供給と拡大する商業活動には、海路に関する信頼できる情報が必要であったが、当時の海図は不完全で不正確であった。スペイン領アメリカ独立戦争によ りスペインの貿易独占は終わりを告げた[2][3] 。また、1825年に英国がアルゼンチンと結んだ通商条約ではアルゼンチンの独立が認められ、南米東海岸の海軍および商業上の重要性が高まった[4]。海 軍本部はキング司令官に「南米大陸南岸、ラプラタ川南口からチロエ島を回り、ティエラ・デル・フエゴまで」の正確な水路測量を行うよう指示した [5][6] ダーウィンは航海について次のように記している。「この遠征の目的は、1826年から1830年にかけてキング船長が着手したパタゴニアとティエラ・デ ル・フエゴの測量調査を完了すること、チリ、ペルー、および太平洋のいくつかの島の海岸を測量すること、そして世界を一周してクロノメーターによる一連の 測定を行うことだった」[7][6] この遠征には外交的な目的もあり、係争中の領土も訪問した。[2] 海軍省の覚書には詳細な指示が記載されていた。最初の要件は、経度測定の基点として不可欠なリオデジャネイロの経度について、過去の調査で生じた意見の相 違を解決することだった。経度測定に必要な正確なマリンクロノメーターは、1800年以降になって初めて入手可能になった。ビーグル号には、補正を行うた めに22個のクロノメーターが搭載された。船は特定の地点に4日間停泊し、クロノメーターの精度を評価し、天体観測によってそれらをチェックすることに なっていた。ウィリアム・フィッツウィリアム・オーウェンとヘンリー・フォスターによる過去の調査と照らし合わせるために、ポルト・プラヤとフェルナン ド・デ・ノローニャで観測を行うことが不可欠であった。アルビン・ルッシンの調査で不正確に示されたアブロルホス諸島のサンゴ礁の範囲を調査し、その後リ オ・デ・ジャネイロに進んでヴィラガノンの島の正確な経度を決定することが重要であった。[8] 実際の測量作業は、リオ・デ・ラ・プラタの南から開始され、物資補給のためにモンテビデオへの往復が行われた。ティエラ・デル・フエゴの測量やフォークラ ンド諸島の港への接近を含む詳細な優先事項が示された。その後、時間と資源が許す限り、西海岸を北に向かって測量することになっていた。指揮官は、その 後、西に向かう航路を独自に決定することになっていた。季節が許せば、ガラパゴス諸島を測量することも可能であった。その後、ビーグル号は、クロノメー ターの精度を検証する既知の地点である、タヒチのヴィーナス岬、オーストラリアのポートジャクソンへと進むことになっていた。 緻密な図面を描くために時間を費やすことはなく、海図や設計図には、海から見た陸地の簡単な見取り図と、丘陵の正確な標高を記載すべきであった。潮汐と気 象条件の継続的な記録も必要とされた。さらに、太平洋の環状のサンゴ環礁の地質調査、その輪郭と潮汐流の調査を行い、このようなサンゴ礁の形成を調査する ことが提案された。[10] |

| Context and preparations The previous survey expedition to South America involved HMS Adventure and HMS Beagle under the overall command of the Australian Commander Phillip Parker King. During the survey, Beagle's captain, Pringle Stokes, committed suicide and command of the ship was given to the young aristocrat Robert FitzRoy, a nephew of George FitzRoy, 4th Duke of Grafton. When a ship's boat was taken by the natives of Tierra del Fuego, FitzRoy tried taking some of them hostage, and after this failed he got occupants of a canoe to put another on the ship in exchange for buttons. He brought four of them back to England to be given a Christian education, with the idea that they could eventually become missionaries. One died of smallpox.[11][12] After Beagle's return to Devonport dockyard on 14 October 1830, Captain King retired.[13]  Robert FitzRoy The 27-year-old FitzRoy had hopes of commanding a second expedition to continue the South American survey, but when he heard that the Lords of the Admiralty no longer supported this, he grew concerned about how to return the Fuegians. He made an agreement with the owner of a small merchant-vessel to take himself and five others back to South America, but a kind uncle heard of this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon afterwards, FitzRoy heard that he was to be appointed commander of HMS Chanticleer to go to Tierra del Fuego, but due to her poor condition, Beagle was substituted. On 27 June 1831, FitzRoy was commissioned as commander of the voyage, and Lieutenants John Clements Wickham and Bartholomew James Sulivan were both appointed.[14] Captain Francis Beaufort, the Hydrographer of the Admiralty, was invited to decide on the use that could be made of the voyage to continue the survey, and he discussed with FitzRoy plans for a voyage of several years, including a continuation of the trip around the world to establish median distances. Beagle was commissioned on 4 July 1831, under the command of Captain FitzRoy, who promptly spared no expense in having Beagle extensively refitted. Beagle was immediately taken into dock for extensive rebuilding and refitting. As she required a new deck, FitzRoy had the upper-deck raised considerably, by 8 inches (200 mm) aft and 12 inches (300 mm) forward.[15] The Cherokee-class brig-sloops had the reputation of being "coffin brigs", which handled badly and were prone to sinking.[16] By helping the decks to drain more quickly with less water collecting in the gunnels, the raised deck gave Beagle better handling and made her less liable to become top-heavy and capsize. Additional sheathing to the hull added about seven tons to her burthen and perhaps fifteen to her displacement.[15] The ship was one of the first to test the lightning conductor invented by William Snow Harris. FitzRoy obtained five examples of the Sympiesometer, a kind of mercury-free barometer patented by Alexander Adie and favoured by FitzRoy as giving the accurate readings required by the Admiralty.[15] In addition to its officers and crew, Beagle carried several supernumeraries, passengers without an official position. FitzRoy employed a mathematical instrument maker to maintain his 22 marine chronometers kept in his cabin, as well as engaging the artist/draughtsman Augustus Earle to go in a private capacity.[15] The three Fuegians taken on the previous voyage were going to be returned to Tierra del Fuego on Beagle together with the missionary Richard Matthews.[14][17] Naturalist and geologist For Beaufort and the leading Cambridge "gentlemen of science", the opportunity for a naturalist to join the expedition fitted with their drive to revitalise British government policy on science. This elite disdained research done for money and felt that natural philosophy was for gentlemen, not tradesmen. The officer class of the Army and Navy provided a way to ascend this hierarchy; the ship's surgeon often collected specimens on voyages, and Robert McCormick had secured the position on Beagle after taking part in earlier expeditions and studying natural history. A sizeable collection had considerable social value, attracting wide public interest, and McCormick aspired to fame as an exploring naturalist.[18] Collections made by the ship's surgeon and other officers were government property, though the Admiralty was not consistent on this,[19] and went to important London establishments, usually the British Museum.[20] The Admiralty instructions for the first voyage had required officers "to use their best diligence in increasing the Collections in each ship: the whole of which must be understood to belong to the Public", but on the second voyage this requirement was omitted, and the officers were free to keep all the specimens for themselves.[19][21] FitzRoy's journal written during the first voyage noted that, while investigating magnetic rocks near the Bárbara Channel, he regretted "that no person in the vessel was skilled in mineralogy, or at all acquainted with geology", to make use of the opportunity of "ascertaining the nature of the rocks and earths" of the areas surveyed. FitzRoy decided that on any similar future expedition, he would "endeavour to carry out a person qualified to examine the land; while the officers, and myself, would attend to hydrography."[22] This indicated a need for a naturalist qualified to examine geology, who would spend considerable periods onshore away from the ship. McCormick lacked expertise in geology and had to attend to his duties on the ship.[23] FitzRoy knew that commanding a ship could involve stress and loneliness. He was aware of his uncle Viscount Castlereagh's suicide due to stress from overwork, as well as Captain Stokes's suicide.[24] This was to be the first time that FitzRoy would be fully in charge of a ship with no commanding officer or second captain to consult. It has been suggested that he felt the need for a gentleman companion who shared his scientific interests and could dine with him as an equal,[25] although there is no direct evidence to support this. Professor John Stevens Henslow described the position "more as a companion than a mere collector", but this was an assurance that FitzRoy would treat his guest as a gentleman naturalist. Several other ships at this period carried unpaid civilians as naturalists.[26] Early in August, FitzRoy discussed this position with Beaufort, who had a scientific network of friends at the University of Cambridge.[27] At Beaufort's request, mathematics lecturer George Peacock wrote from London to Henslow about this "rare opportunity for a naturalist", saying that an "offer has been made to me to recommend a proper person to go out as a naturalist with this expedition", and suggesting the Reverend Leonard Jenyns.[28][29] Though Jenyns nearly accepted and even packed his clothes, he had concerns about his obligations as vicar of Swaffham Bulbeck and about his health, therefore Jenyns declined the offer. Henslow briefly thought of going, but his wife "looked so miserable" that he quickly dropped the idea.[30] Both recommended bringing the 22-year-old Charles Darwin, who was on a geology field trip with Adam Sedgwick. He had just completed the ordinary Bachelor of Arts degree which was a prerequisite for his intended career as a parson.[27] Offer of place to Darwin  Darwin in 1840, after the voyage and publication of his Journal and Remarks Darwin fitted well the expectations of a gentleman natural philosopher and was well trained as a naturalist.[31] When he had studied geology in his second year at Edinburgh, he had found it dull, but from Easter to August 1831, he learned a great deal with Sedgwick and developed a strong interest during their geological field trip.[32] On 24 August Henslow wrote to Darwin: ...that I consider you to be the best qualified person I know of who is likely to undertake such a situation— I state this not on the supposition of yr. being a finished Naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, & noting any thing worthy to be noted in Natural History. Peacock has the appointment at his disposal & if he can not find a man willing to take the office, the opportunity will probably be lost— Capt. F. wants a man (I understand) more as a companion than a mere collector & would not take any one however good a Naturalist who was not recommended to him likewise as a gentleman. ... The Voyage is to last 2 yrs. & if you take plenty of Books with you, any thing you please may be done ... there never was a finer chance for a man of zeal & spirit... Don't put on any modest doubts or fears about your disqualifications for I assure you I think you are the very man they are in search of.[33] The letter went first to George Peacock, who quickly forwarded it to Darwin with further details, confirming that the "ship sails about the end of September". Peacock had discussed the offer with Beaufort, "he entirely approves of it & you may consider the situation as at your absolute disposal".[34] When Darwin returned home from the field trip late on 29 August and opened the letters,[35] his father objected strongly to the voyage so, the next day, he wrote declining the offer[36] and left to go shooting at the estate of his uncle Josiah Wedgwood II. With Wedgwood's help, Darwin's father was persuaded to relent and fund his son's expedition, and on Thursday 1 September, Darwin wrote to Beaufort accepting the offer.[37] That day, Beaufort wrote to tell FitzRoy that his friend Peacock had "succeeded in getting a 'Savant' for you—A Mr Darwin grandson of the well known philosopher and poet—full of zeal and enterprize and having contemplated a voyage on his own account to S. America".[38] On Friday Darwin left for Cambridge, where he, the next day, got advice on preparations of the voyage and references to experts by Henslow.[30] Alexander Charles Wood (an undergraduate whose tutor was Peacock) wrote from Cambridge to his cousin FitzRoy to recommend Darwin.[39] Around midday on Sunday 4 September, Wood received FitzRoy's response, "straightforward and gentlemanlike" but strongly against Darwin joining the expedition; both Darwin and Henslow then "gave up the scheme". Darwin went to London anyway, and next morning met FitzRoy, who explained that he had promised the place to his friend Mr. Chester (possibly the novelist Harry Chester), but Chester had turned it down in a letter received not five minutes before Darwin arrived. FitzRoy emphasised the difficulties, including cramped conditions and plain food.[40][41] Darwin would be on the Admiralty's books to get provisions (worth £40 a year) and, like the ship's officers and captain, would pay £30 a year towards the mess bill.[42] Including outfitting, the cost to him was unlikely to reach £500.[40] The ship would sail on 10 October, and would probably be away for three years. They talked and dined together, and soon found each other agreeable.[41] The Tory FitzRoy had been cautious at the prospect of companionship with this unknown young gentleman of Whig background, and later admitted that his letter to Wood was "to throw cold water on the scheme" in "a sudden horror of the chances of having somebody he should not like on board". He half-seriously told Darwin later that, as "an ardent disciple of Lavater", he had nearly rejected Darwin on the phrenological basis that the shape (or physiognomy) of Darwin's nose indicated a lack of determination.[43][44] Darwin's preparations While he continued to get acquainted with FitzRoy, going shopping together, Darwin rushed around to arrange his supplies and equipment.[45] He took advice from experts on specimen preservation including William Yarrell at the Zoological Society of London, Robert Brown at the British Museum, Captain Phillip Parker King who led the first expedition, and invertebrate anatomist Robert Edmond Grant who had tutored Darwin at Edinburgh.[46] Yarrell gave invaluable advice and bargained with shopkeepers, so Darwin paid £50 for two pistols and a rifle, while FitzRoy had spent £400 on firearms.[44] On Sunday, 11 September, FitzRoy and Darwin took the steam packet for Portsmouth.[47] Darwin was not seasick and had a pleasant "sail of three days". For the first time, he saw the "very small" cramped ship, met the officers,[48] and was glad to get a large cabin, shared with the assistant surveyor John Lort Stokes. On Friday, Darwin rushed back to London, "250 miles in 24 hours",[49] and on via Cambridge and St. Albans, travelling on the Wonder coach all day on 22 September to arrive in Shrewsbury that evening, then after a last brief visit to family and friends left for London on 2 October.[47][50] Delays to Beagle gave Darwin an extra week to consult experts and complete packing his baggage.[51] After sending his heavy goods down by steam packet, he took the coach along with Augustus Earle and arrived at Devonport on 24 October.[52] The geologist Charles Lyell asked FitzRoy to record observations on geological features such as erratic boulders. Before they left England, FitzRoy gave Darwin a copy of the first volume of Lyell's Principles of Geology which explained features as the outcome of a gradual process taking place over extremely long periods of time.[53] In his autobiography, Darwin recalled Henslow giving advice at this time to obtain and study the book, "but on no account to accept the views therein advocated".[54] Darwin's position as a naturalist on board was as a self-funded guest with no official appointment, and he could leave the voyage at any suitable stage. At the outset, George Peacock had advised that "The Admiralty are not disposed to give a salary, though they will furnish you with an official appointment & every accomodation [sic]: if a salary should be required however I am inclined to think that it would be granted". Far from wanting this,[34][55] Darwin's concern was to maintain control over his collection. He was even reluctant to be on the Admiralty's books for victuals until he got assurances from FitzRoy and Beaufort that this would not affect his rights to assign his specimens.[19][42] Beaufort initially thought specimens ought to go to the British Museum, but Darwin had heard of many left waiting to be described, including botanical specimens from the first Beagle voyage. Beaufort assured him that he "should have no difficulty" as long as he "presented them to some public body" such as the Zoological or Geological societies. Henslow had set up the small Cambridge Philosophical Society museum, Darwin told him that new finds should go to the "largest & most central collection" rather than a "Country collection, let it be ever so good",[45][56] but soon expressed "hope to be able to assist the Philosoph. Society" with some specimens.[57] FitzRoy arranged transport of specimens to England as official cargo on the Admiralty Packet Service, at no cost to Darwin even though it was his private collection.[58][59] Henslow agreed to store them at Cambridge, and Darwin confirmed with him arrangements for land carriage from the port,[60] to be funded by Darwin's father.[57] Darwin's work on the expedition The captain had to record his survey in painstaking paperwork, and Darwin too kept a daily log as well as detailed notebooks of his finds and speculations, and a diary which became his journal. Darwin's notebooks show complete professionalism that he had probably learnt at the University of Edinburgh when making natural history notes while exploring the shores of the Firth of Forth with his brother Erasmus in 1826 and studying marine invertebrates with Robert Edmund Grant for a few months in 1827.[61] Darwin had also collected beetles at Cambridge, but he was a novice in all other areas of natural history. During the voyage, Darwin investigated small invertebrates while collecting specimens of other creatures for experts to examine and describe once Beagle had returned to England.[32] More than half of his carefully organised zoology notes deal with marine invertebrates. The notes also record closely reasoned interpretations of what he found about their complex internal anatomy while dissecting specimens under his microscope and small experiments on their response to stimulation. His onshore observations included intense, analytical comments on possible reasons for the behaviour, distribution, and relation to their environment of the creatures he saw. He made good use of the ship's excellent library of books on natural history but continually questioned their correctness.[62] Geology was Darwin's "principal pursuit" on the expedition, and his notes on that subject were almost four times larger than his zoology notes, although he kept extensive records on both. During the voyage, he wrote to his sister that "there is nothing like geology; the pleasure of the first days partridge shooting or first days hunting cannot be compared to finding a fine group of fossil bones, which tell their story of former times with almost a living tongue". To him, investigating geology brought reasoning into play and gave him opportunities for theorising.[61] |

背景と準備 南米への前回の調査遠征には、オーストラリア人指揮官フィリップ・パーカー・キングの指揮下にHMSアドベンチャーとHMSビーグルが参加した。調査中、 ビーグル号の船長プリングル・ストークスが自殺し、船の指揮はジョージ・フィッツロイ第4代グラフトン公爵の甥である貴族の青年ロバート・フィッツロイに 委ねられた。船のボートがティエラ・デル・フエゴの原住民に奪われた際、フィッツロイは彼らの一部を人質にとろうとし、それが失敗に終わると、今度はカ ヌーの乗員に別のカヌーを船に引き渡すようボタンと交換で要求した。彼は最終的に宣教師になれるかもしれないと考え、4人の原住民をキリスト教の教育を受 けさせるためにイギリスに連れ帰った。1人は天然痘で死亡した。[11][12] 1830年10月14日にビーグルがデボンポートのドックに戻ると、キング船長は引退した。[13]  ロバート・フィッツロイ 27歳のフィッツロイは、南米調査を継続するための第2回探検隊の指揮官になることを希望していたが、海軍卿がもはやこれを支援しないことを知ると、彼は フォークランド諸島民をどうやって帰すかについて懸念を抱くようになった。彼は小型商船の船主と、自分と他の5人を南米に連れて帰るという契約を結んだ が、このことを耳にした親切な伯父が海軍卿に連絡した。その後まもなく、フィッツロイはHMSチャントクレア号の指揮官に任命され、ティエラ・デル・フエ ゴに向かうことになったが、チャントクレア号の状態が悪かったため、ビーグル号に変更された。1831年6月27日、フィッツロイは航海の指揮官に任命さ れ、ジョン・クレメンツ・ウィッカム中尉とバーソロミュー・ジェームズ・サリバン中尉が任命された。 海軍本部水路部長のフランシス・ビューフォート大佐が、測量継続のための航海の活用法を決定するために招待され、フィッツロイと数年にわたる航海計画につ いて話し合った。その中には、中距離を確定するための世界一周航海の継続も含まれていた。ビーグル号は1831年7月4日に就航し、フィッツロイ大佐の指 揮下に入った。フィッツロイ大佐は、ビーグル号を徹底的に修理させるため、すぐに費用を惜しまなかった。ビーグルはすぐにドックに入れられ、大規模な改修 と再装備が行われた。新しい甲板が必要だったため、フィッツロイは上甲板をかなり高くし、後方に8インチ(200mm)、前方に12インチ(300mm) 高くした。チェロキー級のブリッグスループは、 「棺のブリッグ」という不名誉な異名を持ち、操縦性が悪く、沈没しやすいとされていた。[16] 甲板の排水を促進し、舷窓にたまる水を減らすことで、甲板を高くしたことでビーグルの操縦性が向上し、トップヘビーになって転覆しにくくなった。船体に追 加の被覆材を施したことで、船の積載量は約7トン、排水量は15トンほど増加した。[15] この船は、ウィリアム・スノウ・ハリスが発明した避雷針を最初に試験した船のひとつであった。フィッツロイは、アレクサンダー・アディーが特許を取得し、 海軍省が必要とする正確な測定値を得るのに適しているとしてフィッツロイが好んだ水銀を使用しない気圧計の一種であるシンピエソメーターを5つ入手した。 ビーグル号には、士官や乗組員に加えて、公式な役職を持たない乗客である数人の余剰人員が乗船していた。フィッツロイは、自分の船室に保管されていた22 個のマリンクロノメーターをメンテナンスするために、数学機器メーカーを雇い、また、芸術家兼製図家オーガスタス・アールを個人的な立場で雇った。 [15] 前回の航海で採用された3人のフエゴ島民は、宣教師リチャード・マシューズとともにビーグル号でティエラ・デル・フエゴに送り返されることになっていた。 [14][17] 博物学者および地質学者 ボフォートとケンブリッジの一流の「科学者」たちにとって、博物学者が遠征に参加する機会は、英国政府の科学政策を活性化させようという彼らの意欲にぴっ たりだった。このエリートたちは金銭目的の研究を軽蔑しており、自然哲学は商人ではなく紳士の為にあると考えていた。陸軍と海軍の士官階級は、このヒエラ ルキーを上昇する手段を提供していた。航海中の船医はしばしば標本を収集し、ロバート・マコーミックは以前の探検に参加し、自然史を研究した後にビーグル 号のポジションを確保していた。膨大なコレクションは社会的価値が高く、広く人々の関心を惹き、マコーミックは探検家兼博物学者として名を馳せることを望 んでいた。[18] 船医やその他の士官が収集したコレクションは政府の所有物であったが、海軍省は一貫した方針を持っておらず、[19] 通常は大英博物館などロンドンの重要な施設に送られた。 20] 最初の航海における海軍省の指示では、各船の収集品を増やすために「最大限の努力を払うこと」が士官たちに求められていた。収集品はすべて公有物とみなさ れるべきである」とされていたが、2回目の航海ではこの要件は削除され、士官たちはすべての標本を自由に持ち帰ることができた。 フィッツロイの航海日誌には、バルバラ海峡付近で磁鉄鉱を調査中に、「船内に鉱物学に精通した人物が一人もいないこと、あるいは地質学にまったく通じてい ないこと」を残念に思ったと記されている。調査地域の「岩石や土壌の性質を明らかにする」機会を活用するためである。フィッツロイは、今後同様の探検を行 う際には、「土地の調査に適した人物を同行させるよう努める。その間、私と士官たちは水路学の調査にあたる」と決めていた。[22] これは、船から離れて陸地でかなりの期間を過ごすことになる地質学の調査に適したナチュラリストが必要であることを示していた。マコーミックは地質学の専 門知識を持っていなかったため、船での任務に専念せざるを得なかった。[23] フィッツロイは、船の指揮にはストレスや孤独が伴うことを知っていた。彼は、ストークス船長の自殺だけでなく、過労によるストレスが原因で叔父のカスルレ イ子爵が自殺したことも知っていた。[24] フィッツロイが、相談できる航海長や副船長もいない船の指揮を完全に執るのは、これが初めてのことだった。フィッツロイは、科学的な関心を共有し、対等の 立場で食事を共にできる紳士的な仲間を必要としていたという説があるが、これを裏付ける直接的な証拠はない。ジョン・スティーヴン・ヘンズロー教授は、こ の役職を「単なる収集家というよりも仲間」と表現したが、これはフィッツロイがゲストを紳士的な自然科学者として扱うことを保証するものであった。この時 期、他のいくつかの船でも無給の民間人が自然科学者として乗船していた。 8月初旬、フィッツロイは、ケンブリッジ大学に科学分野の友人ネットワークを持つビューフォートとこの件について話し合った。[27] ビューフォートの依頼により、ロンドンからヘンズローに宛てて、数学講師のジョージ・ピーコックが「自然史家にとっての貴重な機会」について書き送った。 ピーコックは、「 この探検に自然科学者として参加する適任者を推薦するようにとの申し出があった」と述べ、レナード・ジェイニンス牧師を推薦した。[28][29] ジェイニンスはほぼ承諾し、荷造りまでしていたが、スワフハム・バルベックの牧師としての義務と健康状態に懸念があったため、結局申し出を断った。ヘンズ ローは一時は出席を検討したが、妻が「あまりにもみじめな様子」であったため、すぐにその考えを断念した。[30] 2人とも、アダム・セジウィックと地質学の野外調査に出かけていた22歳のチャールズ・ダーウィンを連れてくることを勧めた。ダーウィンは、牧師になるた めの必須条件である通常の文学士号を取得したばかりであった。[27] ダーウィンへの乗船許可  1840年、航海と『日記』および『考察』の出版を経て ダーウィンは紳士的な自然哲学者としての期待にぴったりと当てはまり、自然学者として十分に訓練されていた。[31] 彼はエディンバラ大学2年目の時に地質学を学んだ際には退屈だと感じていたが、1831年の復活祭から8月にかけて、セジウィックのもとで多くのことを学 び、地質学の野外実習中に強い興味を抱くようになった。[32] 8月24日、ヘンズローはダーウィンに手紙を書き、 ... 私は、あなたがそのような任務を引き受ける可能性がある人物として、私が知る限り最も適任であると考える。これは、あなたがすでにナチュラリストとして完 成しているという仮定に基づいて述べているのではなく、自然史において注目に値するものを収集、観察、記録するのに十分な資格があるという意味である。 ピーコックは自由に予定を組むことができる。もし彼がその職を引き受けることを望む人物を見つけられない場合、その機会は失われるだろう。F大尉は、単な る収集家というよりも仲間として、より有能な人物を求めている。そして、紳士として同様に推薦されていない限り、どんなに有能な博物学者であっても採用し ないだろう。航海は2年続く。本がたくさんあれば、どんなことでもできるだろう。熱意と行動力のある人にとってこれほど素晴らしいチャンスはない。自分の 能力不足について、謙虚に疑問や不安を抱く必要はない。私は断言するが、君はまさに彼らが探している人物だ。 手紙はまずジョージ・ピーコックに送られ、彼はすぐに詳細を付け加えてそれをダーウィンに転送し、「船は9月末頃に出航する」ことを確認した。ビュー フォートは、この申し出について「彼は完全に賛成しており、状況は完全にあなたの自由裁量で決めることができます」と述べていた。[34] 8月29日の夜遅く、遠征から戻ったダーウィンが手紙を開封すると、[35] 父親は航海に強く反対したため、翌日、ダーウィンは申し出を断る手紙を書き[36]、叔父ジョサイア・ウェッジウッド2世の屋敷で狩猟に出かけた。ウェッ ジウッドの助力により、ダーウィンの父親は考えを変え、息子の探検に資金援助することに同意し、9月1日木曜日、ダーウィンはビューフォートにその申し出 を受け入れる旨の手紙を書いた。[37] その日、ビューフォートはフィッツロイに手紙を書き、友人ピーコックが「 フィッツロイの友人である著名な哲学者であり詩人でもあるダーウィンの孫にあたる人物で、熱意と進取の気性に富み、自費で南米への航海を計画している」と フィッツロイに伝えた。[38] 金曜日、ダーウィンはケンブリッジに向けて出発し、翌日、ヘンズローから航海の準備と専門家の紹介に関する助言を得た。[30] アレクサンダー・チャールズ・ウッド(ピーコックが家庭教師をしていた学生)は、ダーウィンを推薦する手紙を従兄弟のフィッツロイに送った。9月4日 (日)の正午頃、ウッドはフィッツロイからの返事を受け取った。「率直で紳士的な」返事だったが、ダーウィンが遠征に参加することには強く反対していた。 ダーウィンとヘンズローは「計画を諦めた」。それでもダーウィンはロンドンに向かい、翌朝フィッツロイと会った。フィッツロイは、その場所を友人のチェス ター氏(小説家ハリー・チェスターの可能性もある)に約束してしまったと説明したが、チェスターはダーウィンが到着する5分前に受け取った手紙で断りを入 れていた。フィッツロイは、手狭な環境や粗末な食事など、困難な状況を強調した。[40][41] ダーウィンは、海軍省から食料(年間40ポンド相当)の支給を受けることになり、船の士官や船長と同様に、 年間30ポンドの食事代を支払うことになっていた。[42] 艤装を含めても、彼が負担する費用は500ポンドに達することはなかったと思われる。[40] 船は10月10日に出航し、おそらく3年間は不在となるだろう。彼らは一緒に話し、食事をし、すぐに意気投合した。[41] 保守党員のフィッツロイは、このホイッグ党出身の無名の紳士との交友関係に慎重な姿勢を示していたが、後にウッドへの手紙は「船に気に入らない人物が乗る かもしれないという突然の恐怖感から、計画に水を差すため」だったと認めた。彼は後に、ダーウィンに「ラヴァーターの熱心な弟子」として、ダーウィンの鼻 の形(または人相)が不決断を示しているという頭蓋学上の根拠から、彼を拒絶しかけたと冗談めかして語った。 ダーウィンの準備 フィッツロイと親交を深め、一緒に買い物に出かける一方で、ダーウィンは急いで必要な物資や装備の手配を行った。[45] 彼は、ロンドン動物学会のウィリアム・ヤレル、大英博物館のロバート・ブラウン、第一次探検隊を率いたフィリップ・パーカー・キング大佐、エディンバラで ダーウィンに指導した無脊椎動物学者のロバート・エドモンド・グラントといった標本保存の専門家から助言を受けた。 46] ヤレルは非常に貴重なアドバイスを与え、店主たちと値引き交渉もしたため、ダーウィンは2丁のピストルとライフル銃を合わせて50ポンドで購入することが できたが、フィッツロイは銃器に400ポンドも費やしていた。[44] 9月11日(日)、フィッツロイとダーウィンは蒸気船でポーツマスに向かった。[47] ダーウィンは船酔いすることもなく、3日間の快適な船旅を楽しんだ。初めて「非常に狭い」窮屈な船を目にし、士官たちと会い、[48] 大きなキャビンを確保できたことを喜んだ。そのキャビンは、測量助手のジョン・ロート・ストークスと共有するものだった。金曜日、ダーウィンは「24時間 で250マイル」[49]を急いでロンドンに戻り、ケンブリッジとセント・オールバンズを経由し、9月22日の1日中ワンダー号のバスで移動し、その日の 夜にシュルーズベリーに到着した。その後、家族や友人を最後に短時間訪問した後、10月2日にロンドンに向けて出発した 10月2日にロンドンに向けて出発した。[47][50] ビーグル号の遅延により、ダーウィンは専門家と相談し、荷物の梱包を完了させるために1週間余分に時間を取ることができた。[51] 重量のある荷物を蒸気船で送った後、彼はオーガスタス・アールとともに馬車で出発し、10月24日にデボンポートに到着した。 地質学者チャールズ・ライエルはフィッツロイに、漂石などの地質学的特徴の観察記録を依頼した。フィッツロイは、イギリスを出発する前に、ダーウィンに、 非常に長い時間をかけて徐々に起こる過程の結果として特徴が形成されることを説明したライエルの『地質学原理』の第1巻のコピーを渡した。[53] ダーウィンは自伝の中で、ヘンズローがこのとき、その本を入手して研究するよう助言したが、「その本で唱えられている見解を決して受け入れるな」と付け加 えたことを思い出したと述べている。[54] 乗船した博物学者としてのダーウィンの立場は、公的な任命のない自費での客であり、航海のどの段階でも下船できる立場であった。当初、ジョージ・ピーコッ クは「海軍本部は給与を支給するつもりはないが、公的な任命とあらゆる便宜は提供するつもりだ。しかし、もし給与が必要であれば、支給される可能性もあ る」と助言していた。これとは対照的に、[34][55] ダーウィンの関心は自身の収集品を管理することにあった。 フィッツロイとビューフォートから、標本を譲渡する権利に影響しないという保証を得るまでは、海軍省の食糧費の負担になることさえ嫌がった。[19] [42] ビューフォートは当初、標本は大英博物館に送られるべきだと考えていたが、ダーウィンはビーグル号の最初の航海で採取された植物標本を含め、記載を待って いる標本が数多くあることを知っていた。ビューフォートは、動物学協会や地質学協会などの「何らかの公的機関」に提出する限り、「何ら問題はない」と保証 した。ヘンズローはケンブリッジ哲学協会の小さな博物館を設立していたが、ダーウィンは新しい発見は「田舎のコレクション」ではなく、「最大かつ最も中心 的なコレクション」に送るべきだと彼に告げた。[45][56] しかし、すぐに「哲学協会にいくつかの標本を提供し、支援できることを願っている」と述べた。[57] フィッツロイは、これらの標本を海軍便の公式貨物としてイングランドに輸送する手配をした。これは、ダーウィンの個人的なコレクションであったにもかかわ らず、ダーウィンに費用負担をさせることなく行われた。[58][59] ヘンズローはケンブリッジでの保管を承諾し、ダーウィンは港からの陸路輸送の手配をヘンズローと確認した。[60] 輸送費はダーウィンの父親が負担することになっていた。[57] ダーウィンの遠征での仕事 船長は、綿密な書類作成で測量記録を残さなければならず、ダーウィンもまた、日誌を付け、発見や思索の詳細を詳細なノートに記録し、後に彼のジャーナルと なる日記もつけていた。ダーウィンのノートには、1826年に兄のエラスムスと共にフォース湾沿岸を探検し、1827年に数か月間ロバート・エドマンド・ グラントと共に海洋無脊椎動物を研究していた時に、おそらくエディンバラ大学で学んだであろう、完璧なまでのプロ意識が表れている。[61] ダーウィンはケンブリッジでも甲虫を収集していたが、それ以外の自然史の分野では素人同然であった。航海中、ダーウィンは他の生物の標本を収集する一方 で、小型の無脊椎動物を調査した。ビーグル号がイギリスに戻った後、専門家がそれらの標本を調査し、記述することになっていた。[32] ダーウィンが慎重にまとめた動物学のメモの半分以上は、海洋無脊椎動物に関するものだった。メモには、顕微鏡で標本を観察しながら、それらの複雑な内部構 造について発見したことや、刺激に対するそれらの反応に関する小規模な実験について、綿密に推論した解釈も記録されている。陸上での観察では、目にした生 物の行動、分布、環境との関係について、その理由を推測した詳細な分析的なコメントが含まれている。彼は船内の優れた自然史に関する蔵書を十分に活用した が、その正確性を常に疑っていた。 地質学は、この探検におけるダーウィンの「主な研究対象」であり、このテーマに関する彼のメモは動物学のメモの4倍近くに及んだが、彼は両方について広範 な記録を残している。航海中、彼は妹に宛てた手紙の中で、「地質学に勝るものはない。最初の数日間のウズラ狩りや狩猟の楽しみは、化石の骨格群を見つけ、 その骨格がまるで生きているかのように太古の昔を物語っていることにはかなわない」と書いている。彼にとって、地質学を調査することは論理を働かせること につながり、理論を構築する機会を与えてくれた。[61] |