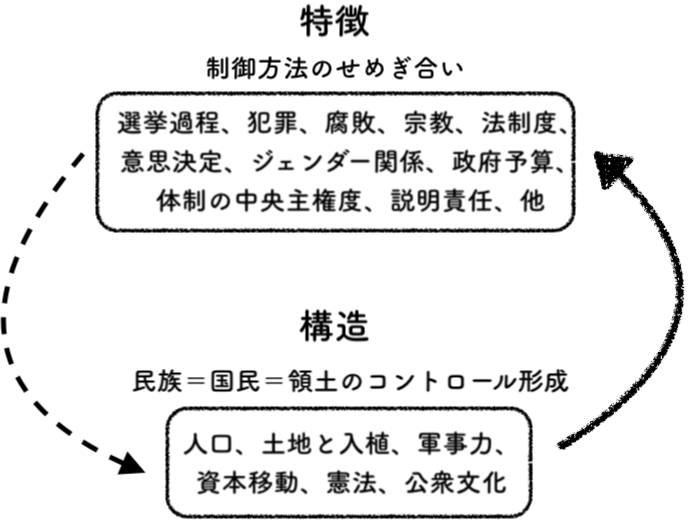

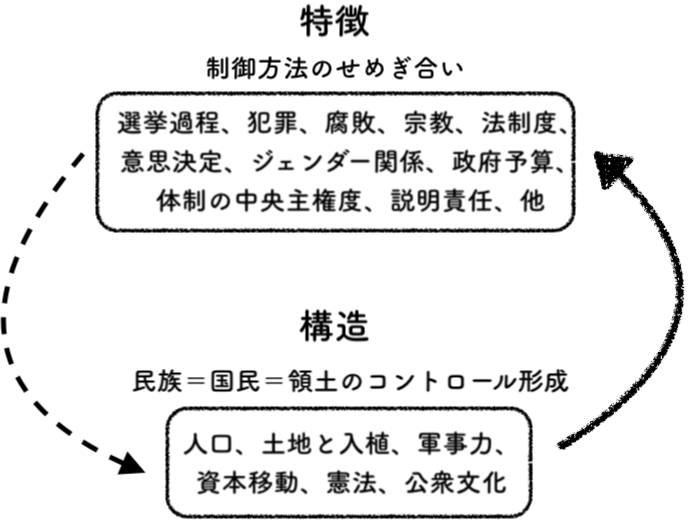

エスノクラシー(民族統治)

Ethnocracy

エスノクラシー(Ethnocracy)とは、レイシズム(人種主義)のイデオロギーに支 えられた、支配的な民 族集団(またはグループ)によって、その利益、権力、資源を促進するために国家機関が支配されている政治構造のひとつのタイプである。

| An ethnocracy

is a type of political structure in which the state apparatus is

controlled by a dominant ethnic group (or groups) to further its

interests, power and resources. Ethnocratic regimes typically display a

'thin' democratic façade covering a more profound ethnic structure, in

which ethnicity (race, religion, language etc) – and not citizenship –

is the key to securing power and resources. An ethnocratic society

facilitates the ethnicization of the state by the dominant group,

through the expansion of control likely accompanied by conflict with

minorities or neighbouring states. A theory of ethnocratic regimes was

developed by critical geographer Oren Yiftachel during the 1990s and

later developed by a range of international scholars. |

エ

スノクラシーとは、支配的な民族集団(またはグループ)によって、その利益、権力、資源を促進するために国家機関が支配されている政治構造の一種である。

エスノクラシー政権は通常、「薄い」民主主義的な外見で、より深い民族的構造を覆い隠しており、市民権ではなく民族性(人種、宗教、言語など)が権力と資

源を確保するカギとなる。民族統治的(エスノクラティック)な社会は、少数民族や近隣国家との紛争を伴う可能性の高い支配の拡大を通じて、支配集団による

国家の民族化(ethnicization)を促進させる。エスノクラティックな体制に関する理論は、1990年代に批判的地理学者であるオーレン・イフ

トハルによって構築され、その後、様々な国際的学者によって発展してきた。 |

| In

the 20th century, a few states passed (or attempted to pass)

nationality laws through efforts that share certain similarities. All

took place in countries with at least one national minority that sought

full equality in the state or in a territory that had become part of

the state and in which it had lived for generations. Nationality laws

were passed in societies that felt threatened by these minorities'

aspirations of integration and demands for equality, resulting in

regimes that turned xenophobia into major tropes. These laws were

grounded in one ethnic identity, defined in contrast to the identity of

the other, leading to persecution of and codified discrimination

against minorities. Research shows that several spheres of control are vital for ethnocratic regimes, including of the armed forces, police, land administration, immigration and economic development. These powerful government instruments may ensure domination by the leading ethnic groups and the stratification of society into 'ethnoclasses' (exacerbated by 20th century capitalism’s typically neo-liberal policies). Ethnocracies often manage to contain ethnic conflict in the short term by effective control over minorities and by effectively using the 'thin' procedural democratic façade. However, they tend to become unstable in the longer term, suffering from repeated conflict and crisis, which are resolved by either substantive democratization, partition, or regime devolution into consociational arrangements. Alternatively, ethnocracies that do not resolve their internal conflict may deteriorate into periods of long-term internal strife and the institutionalization of structural discrimination (such as apartheid). In ethnocratic states, the government is typically representative of a particular ethnic group, which holds a disproportionately large number of posts. The dominant ethnic group (or groups) uses them to advance the position of their particular ethnic group(s) to the detriment of others. Other ethnic groups are systematically discriminated against and may face repression or violations of their human rights at the hands of state organs. Ethnocracy can also be a political regime instituted on the basis of qualified rights to citizenship, with ethnic affiliation (defined in terms of race, descent, religion, or language) as the distinguishing principle.[7] Generally, the raison d'être of an ethnocratic government is to secure the most important instruments of state power in the hands of a specific ethnic collectivity. All other considerations concerning the distribution of power are ultimately subordinated to this basic intention.[citation needed] Ethnocracies are characterized by their control system – the legal, institutional, and physical instruments of power deemed necessary to secure ethnic dominance. The degree of system discrimination will tend to vary greatly from case to case and from situation to situation. If the dominant group (whose interests the system is meant to serve and whose identity it is meant to represent) constitutes a small minority (typically 20% or less) of the population within the state territory, substantial institutionalized suppression will probably be necessary to sustain its control. |

20

世紀には、いくつかの国家が、ある共通点をもった取り組みによって国籍法を制定した(あるいは制定しようとした)。いずれも、国家または国家の一部となり

何世代にもわたって暮らしてきた領土において完全な平等を求める少数民族が少なくとも一人はいる国で行われた。国籍法は、こうした少数民族の統合への願望

や平等への要求に脅威を感じた社会で成立し、その結果、外国人嫌いを主要なテーマとする政権が誕生したのである。これらの法律は、ある民族のアイデンティ

ティーを根拠とし、他の民族のアイデンティティーと対比して定義され、少数民族に対する迫害と成文化された差別につながった。 調査によれば、軍隊、警察、土地管理、移民、経済開発など、いくつかの支配領域がエスノクラティック政権にとって不可欠であることが分かっている。これら の強力な政府手段は、有力な民族集団による支配と「民族階級」への社会の階層化(20世紀資本主義の典型的な新自由主義政策によって悪化した)を確実にす る可能性がある。エスノクラシーは、マイノリティを効果的にコントロールし、「薄い」手続き的民主主義のファサードを効果的に利用することによって、短期 的には民族紛争を封じ込めることができる場合が多い。しかし、長期的には不安定になり、紛争と危機が繰り返され、実質的な民主化、分割、またはコンソシア ティブな取り決めへの体制移行によって解決される傾向がある。あるいは、内部紛争を解決できない民族国家は、長期にわたる内部抗争や構造的差別の制度化 (アパルトヘイトなど)へと悪化することもある。 エスノクラティックな国家では、通常、政府は特定の民族グループの代表であり、そのグループが不当に多くのポストを占めている。支配的な民族集団(または グループ) は、自分たちの特定の民族集団(またはグループ)の地位を向上させ、他の民族を不利にするためにそれらを利用します。他の民族は組織的に差別され、国家機 関の手による弾圧や人権侵害に直面することがあります。また、エスノクラシーは、民族的所属(人種、世系、宗教、言語などの観点から定義される)を際立た せる原理として、市民権に対する資格に基づき制定された政治体制である場合もある[7]。一般に、エスノクラシー政府の存在意義は、特定の民族集団の手に 国家権力の最も重要な道具を確保することである。権力の分配に関する他のすべての考慮事項は、最終的にこの基本的な意図に従属させられる。 エスノクラシーは、その支配システム、すなわち民族的優位性を確保するために必要とみなされる法的、制度的、物理的な権力手段によって特徴づけられる。シ ステムの差別の程度は、ケースバイケース、状況によって大きく異なる傾向がある。支配的な集団(その集団の利益とアイデンティティを代表するための制度) が国家領域内の人口の少数派(通常20%以下)である場合、その支配を維持するためには、おそらく相当な制度的抑圧が必要となる。 |

| One view is that the most

effective means of eliminating ethnic discrimination vary depending on

the specific situation. In the Caribbean, a "rainbow nationalism" type

of non-ethnic, inclusive civic nationalism has been developed as a way

to eliminate ethnic power hierarchies over time. (Although Creole

peoples are central in the Caribbean, Eric Kauffman warns against

conflating the presence of a dominant ethnicity in such countries with

ethnic nationalism.) Andreas Wimmler notes that a non-ethnic federal system without minority rights has helped Switzerland to avoid ethnocracy but that this did not help in overcoming ethnic discrimination when introduced in Bolivia. Likewise, ethnic federalism "produced benign results in India and Canada" but did not work in Nigeria and Ethiopia. Edward E. Telles notes that anti-discrimination legislation may not work as well in Brazil as in the U.S. at addressing ethnoracial inequalities, since much of the discrimination that occurs in Brazil is class-based, and Brazilian judges and police often ignore laws that are intended to benefit non-elites. |

20世紀には、いくつかの国家が、ある共通点をもった取り組みによって

国籍法を制定した(あるいは制定しようとした)。20世紀には、少なくとも1つの少数民族が完全な平等を求める国々で国籍法が制定された。カリブ海諸国で

は、非民族的で包括的な市民ナショナリズムである「虹のナショナリズム」が、時間をかけて民族の権力階層を排除する方法として発展してきた。(カリブ海で

はクレオール民族が中心であるが、Eric

Kauffmanはこのような国々における支配的なエスニックの存在をエスニックナショナリズムと混同しないように警告している)。 Andreas Wimmlerは、少数民族の権利を持たない非民族連邦制がスイスのエスノクラシー回避に役立ったが、ボリビアで導入された際には民族差別の克服に役立た なかったと指摘している。同様に、民族連邦制は「インドとカナダでは良質の結果をもたらした」が、ナイジェリアとエチオピアではうまくいかなかったとい う。Edward E. Tellesは、ブラジルで起きている差別の多くが階級に基づくものであり、ブラジルの裁判官や警察はしばしば非エリートの利益を意図した法律を無視する ため、民族的不平等を解決するために差別禁止法が米国ほど機能しないかもしれないと指摘している。 |

| Israel has been labeled an

ethnocracy by scholars such as: Alexander Kedar, Shlomo Sand, Oren

Yiftachel, Asaad Ghanem, Haim Yakobi, Nur Masalha and Hannah Naveh. However, scholars such as Gershon Shafir, Yoav Peled and Sammy Smooha prefer the term ethnic democracy to describe Israel, which is intended to represent a "middle ground" between an ethnocracy and a liberal democracy. Smooha in particular argues that ethnocracy, allowing a privileged status to a dominant ethnic majority while ensuring that all individuals have equal rights, is defensible. His opponents reply that insofar as Israel contravenes equality in practice, the term 'democratic' in his equation is flawed. |

イスラエルは、次のような学者たちによってエスノクラシーと呼ばれてい

る。Alexander Kedar、Shlomo Sand、Oren Yiftachel、Asaad Ghanem、Haim

Yakobi、Nur Masalha、Hannah Navehといった学者たち。 しかし、Gershon Shafir、Yoav Peled、Sammy Smoohaなどの学者は、イスラエルを表現するのに民族(エスニック)民主主義という言葉を好んでいる。これは、民族民主主義と自由民主主義の間の「中 間領域」を表現するためのものである。特にスモーハは、多数派を支配する民族に特権的な地位を認めつつ、すべての個人の権利を平等に確保する民族民主主義 は擁護できると主張する。スモーハの反論は、イスラエルが実際には平等に反している以上、彼の方程式に含まれる「民主主義」という言葉には欠陥がある、と いうものである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnocracy |

|

|

◎途上国の多民族社会におけるエスノクラ

ティックな動き(抵抗運動や暴力による暴発)

| And this dialectic, variously expressed, is a generic characteristic of new-state politics. In Indonesia, the establishment of an indigenous unitary state made the fact that the thinly populated but mineral-rich Outer Islands produced the bulk of the country's foreign-exchange earnings, while densely populated, resource-poor Java consumed the bulk of its income, painfully apparent in a way it could never become in the colonial era, and a pattern of regional jealousy developed and hardened to the point of armed revolt.24 In Ghana, hurt Ashanti pride burst into open separatism when, in order to accumulate development funds, Nkrumah's new national government fixed the cocoa price lower than what Ashanti cocoa growers wished it to be.25 In Morocco, Riffian Berbers, offended when their substantial military contribution to the struggle for independence was not followed by greater governmental assistance in the form of schools, jobs, improved communications facilities, and so on, revived a classic pattern of tribal insolence--refusal to pay taxes, boycott of marketplaces, retreat to a predatory mountain life-in order to gain Rabat's regard.26 In Jordan, Abdullah's desperate attempt to strengthen his newly sovereign civil state through the annexation of Cis-Jordan, negotiation with Israel, and modernization of the army provoked his assassination by an ethnically humiliated pan-Arab Palestinian.27 Even in those new states where such discontent has not progressed to the point of open dissidence, there has almost universally arisen around the developing struggle for governmental power as such a broad penumbra of primordial strife. Alongside of, and interacting with, the usual politics of party and parliament, cabinet and bureaucracy, or monarch and army, there exists, nearly everywhere a sort of parapolitics of clashing public identities and quickening ethnocratic aspirations. | そして、この弁証法は、さまざまに表現されるが、新国家政治の一般的な

特徴である。インドネシアでは、土着の単一国家が成立したことで、人口が少ないが鉱

物資源の豊富な外島が国の外貨収入の大部分を生産し、人口が密集し資源

の乏しいジャワ島がその大部分を消費するという事実が植民地時代にはありえない形で痛感され、地域の嫉妬が生まれ、武装反乱にまで硬化してしまったの

だ。

ガーナでは、ンクルマ新政権が開発資金を集めるために、アシャンティ地方のカカオ生産者が望むよりもカカオ価格を低く設定したため、傷ついたアシャンティ

のプライドが公然と分離主義に発展した。モロッコでは、独立闘争への多大な軍事的貢献の後に、学校、雇用、通信設備の改善といった形での政府の援助がな

かったことに腹を立てたリフィア・ベルベル人が、ラバトの評価を得るために、納税拒否、市場のボイコット、略奪的山間生活への後退といった部族の横暴の典

型的パターンを復活させている。ヨルダンでは、シスヨルダンの併合、イスラエルとの交渉、軍隊の近代化を通じて、新たに主権を得た市民国家を強化しようと

したアブドラの必死の試みが、民族的に屈辱を受けた汎アラブ系パレスチナ人による彼の暗殺を誘発したのである。このような不満が公然の反乱にまで発展しない新しい国家においても、政府権力をめぐる闘争の展

開の周辺には、ほぼ例外なく、このような原初的な争いの広い陰影(penumbra)が生まれている。政党と議会、内閣と官僚、あるいは君主と軍隊といった通常の政治と並行し

て、また相互作用しながら、ほぼすべての場所で、衝突する公的アイデンティティと加速する民族統治(ethnocratic)的願望という一種のパラポリ

ティクスが存在するのである。 |

| The

integrative revolution , by Clifford Geertz, 1963 |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

sa

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099