解説 池田光穂

★マナイズムは、メラネシアの宗

教概念を理解するための用語で、死霊(=死人の幽霊)や死んだ人のたましい(魂)には、多くのマナが含まれるという。マナという(物理的な力以外で)生き

ている人を苦しめたり、場合によっては助けたする。なぜなら、死霊や魂はちから、つまりマナをもっているからなのだと説明される、そのような信仰形態を、

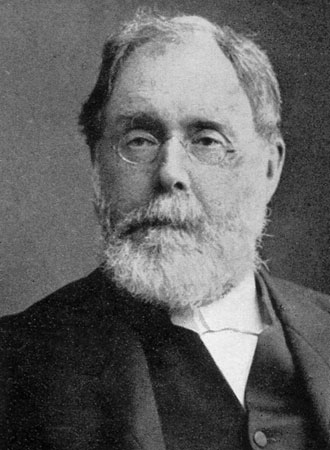

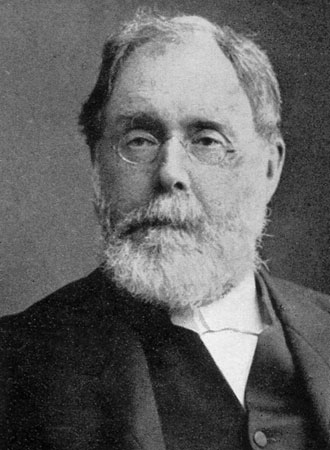

マナイズム(manaism, マナ信仰)という。ロバート・ヘンリー・コドリントン(Robert Henry Codrington,

1830-1922)が、この信仰について、最初に記述したので、そのように呼ばれる(→「マナイ

ズム・マナ信仰」)

| In Melanesian and

Polynesian cultures, mana

is

a supernatural force that permeates the universe.[1] Anyone or anything

can have mana. They believed it to be a cultivation or possession of

energy and power, rather than being a source of power.[1] It is an

intentional force.[1] Mana has been discussed mostly in relation to cultures of Polynesia, but also of Melanesia, notably the Solomon Islands[2][3] and Vanuatu.[4][5][6][7][8] In the 19th century, scholars compared mana to similar concepts such as the orenda of the Iroquois Indians and theorized that mana was a universal phenomenon that explained the origin of religions.[1] Etymology The reconstructed Proto-Oceanic word *mana is thought to have referred to "powerful forces of nature such as thunder and storm winds" rather than supernatural power.[9] As the Oceanic-speaking peoples spread eastward, the word started to refer instead to unseen supernatural powers.[9] |

メラネシアやポリネシアの文化では、マナは宇宙に浸透している超自然的

な力である[1]。彼らはマナを力の源というよりも、エネルギーや力の育成や所有であると信じていた[1]。 マナは主にポリネシアの文化に関連して論じられてきたが、メラネシア、特にソロモン諸島[2][3]やバヌアツでも論じられている[4][5][6] [7][8]。 19世紀、学者たちはマナをイロコイ・インディアンのオレンダなどの類似した概念と比較し、マナは宗教の起源を説明する普遍的な現象であると理論化した [1]。 語源 復元された原オセアニア語の*manaは、超自然的な力ではなく、「雷や暴風などの強力な自然の力」を指していたと考えられている[9]。オセアニア語を 話す民族が東に広がるにつれて、この単語は代わりに目に見えない超自然的な力を指すようになった[9]。 |

| Polynesian culture Mana is a foundation of Polynesian theology, a spiritual quality with a supernatural origin and a sacred, impersonal force. To have mana implies influence, authority, and efficacy: the ability to perform in a given situation. The quality of mana is not limited to individuals; peoples, governments, places and inanimate objects may also possess mana, and its possessors are accorded respect. Mana protects its protector and they depend on each other for growth both positive and negative. It depends on the person where he takes his mana.[citation needed] In Polynesia, mana was traditionally seen as a "transcendent power that blesses" that can "express itself directly" through various ways, but most often shows itself through the speech, movement, or traditional ritual of a "prophet, priest, or king."[10] Hawaiian and Tahitian culture In Hawaiian and Tahitian culture, mana is a spiritual energy and healing power which can exist in places, objects and persons. Hawaiians believe that mana may be gained or lost by actions, and Hawaiians and Tahitians believe that mana is both external and internal. Sites on the Hawaiian Islands and in French Polynesia are believed to possess mana—for example, the top rim of the Haleakalā volcano on the island of Maui and the Taputapuatea marae on the island of Raiatea in the Society Islands.[citation needed] Ancient Hawaiians also believed that the island of Molokaʻi possessed mana, compared with its neighboring islands. Before the unification of the Kingdom of Hawaii by King Kamehameha I, battles were fought for possession of the island and its south-shore fish ponds which existed until the late 19th century.[citation needed] A person may gain mana by pono (right actions). In ancient Hawaii, there were two paths to mana: sexual means or violence. In at least this tradition, nature is seen as dualistic, and everything has a counterpart. A balance between the gods Kū and Lono formed, through whom are the two paths to mana (ʻimihaku, or the search for mana). Kū, the god of war and politics, offers mana through violence; this was how Kamehameha gained his mana. Lono, the god of peace and fertility, offers mana through sexuality.[citation needed] Prayers were believed to have mana, which was sent to the akua at the end when the priest usually said "amama ua noa," meaning "the prayer is now free or flown."[11] Māori (New Zealand) culture Māori use In Māori culture, there are two essential aspects of a person's mana: mana tangata, authority derived from whakapapa (genealogy) and mana huaanga, defined as "authority derived from having a wealth of resources to gift to others to bind them into reciprocal obligations".[12] Hemopereki Simon, from Ngāti Tūwharetoa, asserts that there are many forms of mana in Maori beliefs.[13] The indigenous word reflects a non-Western view of reality, complicating translation.[14] This is confirmed by the definition of mana provided by Māori Marsden who states that mana is: Spiritual power and authority as opposed to the purely psychic and natural force — ihi.[15] According to Margaret Mutu, mana in its traditional sense means: Power, authority, ownership, status, influence, dignity, respect derived from the atua.[16][13] In terms of leadership, Ngāti Kahungunu legal scholar Carwyn Jones comments: "Mana is the central concept that underlies Māori leadership and accountability." He also considers mana as a fundamental aspect of the constitutional traditions of Māori society.[17] According to the New Zealand Ministry of Justice: Mana and tapu are concepts which have both been attributed single-worded definitions by contemporary writers. As concepts, especially Maori concepts they can not easily be translated into a single English definition. Both mana and tapu take on a whole range of related meanings depending on their association and the context in which they are being used.[18] A tribe with mana whenua must have demonstrated their authority over a territory. General English usage In contemporary New Zealand English, the word "mana" refers to a person or organisation of people of great personal prestige and character.[19] The increased use of the term mana in New Zealand society is the result of the politicisation of Māori issues stemming from the Māori Renaissance.[citation needed] |

ポリネシア文化 マナはポリネシア神学の根幹をなすもので、超自然的な起源を持つ霊的な性質であり、神聖で非人間的な力である。マナを持つということは、影響力、権威、効 力、つまり与えられた状況において実行する能力を意味する。マナの性質は個人に限定されるものではなく、民族、政府、場所、無生物もマナを持つことがあ り、マナを持つ者は尊敬される。マナはその保護者を守り、プラスとマイナスの両方の成長のために互いに依存し合う。マナをどこに持っていくかはその人次第 である[要出典]。 ポリネシアでは、マナは伝統的に「祝福する超越的な力」と見なされており、それは様々な方法を通じて「それ自身を直接表現する」ことができるが、最も多く の場合、「預言者、司祭、王」の話し方、動き、または伝統的な儀式を通じてそれ自身を示す[10]。 ハワイとタヒチの文化 ハワイとタヒチの文化では、マナは霊的なエネルギーであり、場所や物、人の中に存在する癒しの力である。ハワイ人は、マナは行動によって得たり失ったりす ると信じており、ハワイ人とタヒチ人は、マナは外的なものと内的なものの両方があると信じている。例えば、マウイ島のハレアカラ火山の頂上や、ソサエティ 諸島のライアテア島のタプタプアテア・マラエなどである[要出典]。 古代ハワイアンはまた、モロカイ島は近隣の島々に比べてマナがあると信じていました。カメハメハ大王がハワイ王国を統一する前は、島と南岸の養魚池の所有 権をめぐって戦いが繰り広げられ、19世紀後半まで存在した[要出典]。 人はポノ(正しい行い)によってマナを得ることができる。古代ハワイでは、マナを得るには性的手段と暴力の2つの道があった。少なくともこの伝統では、自 然は二元論的なものと見なされ、すべてのものには対応するものがある。クーとロノという神々の間で均衡が生まれ、彼らを通してマナへの2つの道(イミハ ク、またはマナの探求)が存在する。戦争と政治の神であるクーは、暴力によってマナを提供し、カメハメハはこうしてマナを得た。平和と豊穣の神であるロノ は、性愛を通してマナを提供する。[要出典]祈りにはマナがあると信じられており、そのマナは、司祭が通常「アママ・ウア・ノア」、つまり「祈りは今、自 由である、あるいは飛翔している」と言うときに、最後にアクアに送られる[11]。 マオリ(ニュージーランド)の文化 マオリの使用 マオリ文化では、人のマナには2つの本質的な側面がある。マナ・タンガタとは、ワカパパ(系譜)に由来する権威であり、マナ・フアンガとは、「互恵的な義 務を負わせるために他者に贈る豊かな資源を持つことに由来する権威」と定義される。 [12]トゥワレトア先住民のヘモペレキ・サイモンは、マオリの信仰には様々な形のマナが存在すると主張している[13]。この先住民の言葉は非西洋的な 現実観を反映しており、翻訳を複雑にしている[14]: 純粋に精神的で自然な力であるイヒとは対照的に、霊的な力と権威である[15]。 マーガレット・ムトゥによれば、伝統的な意味でのマナとは次のようなものである: 権力、権威、所有権、地位、影響力、威厳、アトゥアに由来する尊敬[16][13]。 リーダーシップに関して、ンガティ・カフングヌの法学者であるカーウィン・ジョーンズは次のようにコメントしている: 「マナはマオリのリーダーシップと説明責任を支える中心的な概念である。また、マナはマオリ社会の憲法上の伝統の基本的な側面であるとも考えている [17]。 ニュージーランド法務省によると マナ(Mana)とタプ(Tapu)は、現代の作家によって一言で定義されている概念である。概念として、特にマオリ族の概念として、単一の英語の定義に 簡単に翻訳することはできません。マナもタプも、その関連性や使用される文脈によって、様々な意味を持つのである[18]。 マナウィヌアを持つ部族は、領土に対する権威を示さなければならない。 一般的な英語の用法 現代のニュージーランド英語では、"mana "という単語は、個人的な威信と人格を持つ人または組織を指す[19]。 |

| Academic study Photo of a three-masted schooner  The 1891 Southern Cross, one of the ships at Norfolk Island's Melanesian Mission where Codrington taught and worked  Missionary Robert Henry Codrington traveled widely in Melanesia, publishing several studies of its language and culture. His 1891 book The Melanesians: Studies in their Anthropology and Folk-Lore contains the first detailed description of mana in English.[9] Codrington defines it as "a force altogether distinct from physical power, which acts in all kinds of ways for good and evil, and which it is of the greatest advantage to possess or control".[4] Pre-animism Describing pre-animism, Robert Ranulph Marett cited the Melanesian mana (primarily with Codrington's work): "When the science of Comparative Religion employs a native expression such as mana, it is obliged to disregard to some extent its original or local meaning. Science, then, may adopt mana as a general category ... ".[20]: 99 In Melanesia the animae are the souls of living men, the ghosts of deceased men, and spirits "of ghost-like appearance" or imitating living people. Spirits can inhabit other objects, such as animals or stones.[20]: 115–120 The most significant property of mana is that it is distinct from, and exists independently of, its source. Animae act only through mana. It is impersonal, undistinguished, and (like energy) transmissible between objects, which can have more or less of it. Mana is perceptible, appearing as a "Power of awfulness" (in the sense of awe or wonder).[20]: 12–13 Objects possessing it impress an observer with "respect, veneration, propitiation, service" emanating from the mana's power. Marett lists a number of objects habitually possessing mana: "startling manifestations of nature", "curious stones", animals, "human remains", blood,[20]: 2 thunderstorms, eclipses, eruptions, glaciers, and the sound of a bullroarer.[20]: 14–17 If mana is a distinct power, it may be treated distinctly. Marett distinguishes spells, which treat mana quasi-objectively, and prayers (which address the anima). An anima may have departed, leaving mana in the form of a spell which can be addressed by magic. Although Marett postulates an earlier pre-animistic phase, a "rudimentary religion" or "magico-religious" phase in which the mana figures without animae, "no island of pure 'pre-animism' is to be found."[20]: xxvi Like Tylor, he theorizes a thread of commonality between animism and pre-animism identified with the supernatural—the "mysterious", as opposed to the reasonable.[20]: 22 Durkheim's totemism In 1912, French sociologist Émile Durkheim examined totemism, the religion of the Aboriginal Australians, from a sociological and theological point of view, describing collective effervescence as originating in the idea of the totemic principle or Mana.[citation needed] Criticism In 1936, Ian Hogbin criticised the universality of Marett's pre-animism: "Mana is by no means universal and, consequently, to adopt it as a basis on which to build up a general theory of primitive religion is not only erroneous but indeed fallacious".[21] However, Marett intended the concept as an abstraction.[20]: 99 Spells, for example, may be found "from Central Australia to Scotland."[20]: 55 Early 20th-century scholars also saw mana as a universal concept, found in all human cultures and expressing fundamental human awareness of a sacred life energy. In his 1904 essay, "Outline of a General Theory of Magic", Marcel Mauss drew on the writings of Codrington and others to paint a picture of mana as "power par excellence, the genuine effectiveness of things which corroborates their practical actions without annihilating them".[22]: 111 Mauss pointed out the similarity of mana to the Iroquois orenda and the Algonquian manitou, convinced of the "universality of the institution";[22]: 116 "a concept, encompassing the idea of magical power, was once found everywhere".[22]: 117 Mauss and his collaborator, Henri Hubert, were criticised for this position when their 1904 Outline of a General Theory of Magic was published. "No one questioned the existence of the notion of mana", wrote Mauss's biographer Marcel Fournier, "but Hubert and Mauss were criticized for giving it a universal dimension".[23] Criticism of mana as an archetype of life energy increased. According to Mircea Eliade, the idea of mana is not universal; in places where it is believed, not everyone has it, and "even among the varying formulae (mana, wakan, orenda, etc.) there are, if not glaring differences, certainly nuances not sufficiently observed in the early studies".[24] "With regard to these theories founded upon the primordial and universal character of mana, we must say without delay that they have been invalidated by later research".[25] Holbraad[26] argued in a paper included in the volume "Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically" that the concept of mana highlights a significant theoretical assumption in anthropology: that matter and meaning are separate. A hotly debated issue, Holbraad suggests that mana provides motive to re-evaluate the division assumed between matter and meaning in social research. His work is part of the ontological turn in anthropology, a paradigm shift that aims to take seriously the ontology of other cultures.[27] |

学術研究 3本マストのスクーナー船  コドリントンが教鞭を執ったノーフォーク島メラネシア伝道所の船のひとつ、1891年サザンクロス号  宣教師ロバート・ヘンリー・コドリントンは、メラネシアを広く旅し、その言語と文化についていくつかの研究を発表した。彼の1891年の著書『The Melanesians: Studies in their Anthropology and Folk-Lore (メラネシア人の人類学と民間伝承の研究)』には、英語によるマナに関する最初の詳細な記述が含まれている[9]。コドリントンはマナを「物理的な力とは まったく異なる力であり、善と悪のためにあらゆる方法で作用し、それを所有または制御することが最大の利点である」と定義している[4]。 プレアニミズム ロバート・ラヌルフ・マレットはアニミズム以前について、メラネシアのマナを引き合いに出した(主にコドリントンの研究による): 「比較宗教学がマナのような土着の表現を用いる場合、その本来の意味や土地の意味をある程度無視せざるを得ない。そして科学は、マナを一般的なカテゴリー として採用することができる。「20]: 99 メラネシアでは、アニマエは生きている人間の魂、亡くなった人間の幽霊、「幽霊のような外見をした」、あるいは生きている人間を模した霊である。霊は動物 や石など他の物体に宿ることもある[20]: 115-120 マナの最も重要な性質は、マナがその源から区別され、独立して存在することである。アニマはマナを通してのみ作用する。マナは非人間的で区別がなく、(エ ネルギーと同様に)対象物の間で伝達可能であり、対象物はマナを多く持つことも少なく持つこともできる。マナは知覚可能であり、(畏怖や驚嘆という意味 で)「畏怖の力」として現れる[20]: 12-13 マナを持つ物体は、マナの力から発せられる「尊敬、崇敬、鎮魂、奉仕」を観察者に印象づける。マレットは習慣的にマナを持つ対象として、「驚くべき自然の 現れ」、「不思議な石」、動物、「人間の遺体」、血液、[20]: 2 雷雨、日食、噴火、氷河、牛の鳴き声などを挙げている[20]: 14-17 マナが別個の力であるならば、それは別個に扱われるかもしれない。マレットは、マナを準客観的に扱う呪文と、(アニマに働きかける)祈りを区別している。 アニマは呪文という形でマナを残し、魔法で対処できるようになった。マレットはアニマ以前の段階、すなわちマナがアニマなしで登場する「初歩的宗教」ある いは「魔術的宗教」段階を仮定しているが、「純粋な『前アニミズム』の島は発見されていない」[20]: xxvi。タイロールと同様に、彼はアニミズムと前アニミズムの間に、超自然的なもの、つまり合理的なものとは対照的な「神秘的なもの」と同定される共通 性の糸を理論化している[20]: 22。 デュルケムのトーテミズム 1912年、フランスの社会学者エミール・デュルケームは、オーストラリアのアボリジニの宗教であるトーテミズムを社会学的・神学的観点から考察し、集団 の発揚はトーテム原理またはマナの思想に由来すると述べた[要出典]。 批判 1936年、イアン・ホグビンはマレットのプレアニミズムの普遍性を批判した:「マナは決して普遍的なものではなく、その結果、原始宗教の一般的な理論を 構築するための基礎としてそれを採用することは誤りであるだけでなく、実に誤りである」[21] しかしながら、マレットはこの概念を抽象的なものとして意図していた[20]: 55 20世紀初頭の学者たちもまた、マナを普遍的な概念とみなし、あらゆる人類の文化に見られ、神聖な生命エネルギーに対する人間の根源的な意識を表現してい ると考えた。マルセル・モースは1904年に発表したエッセイ「魔術の一般理論の概要」の中で、コドリントンらの著作を引用し、マナとは「卓越した力、物 事を消滅させることなく、その実際的な作用を裏付ける、物事の真の有効性」であるとした[22]: 111 モースはマナがイロコイ族のオレンダやアルゴンキン族のマニトゥーに類似していることを指摘し、「制度の普遍性」を確信した[22]: 116 「魔術的な力という概念を包含する概念は、かつてあらゆる場所で見出された」[22]: 117 モースと彼の共同研究者であるアンリ・ユベールは、1904年に『魔術の一般理論概論』が出版されたとき、この立場から批判を受けた。「マナの概念の存在 に疑問を抱く者はいなかったが、ユベールとモースはマナに普遍的な次元を与えたとして批判された」とモースの伝記作家マルセル・フルニエは書いている。ミ ルチェア・エリアーデによれば、マナの観念は普遍的なものではなく、マナが信じられている場所において、すべての人がマナを持っているわけではなく、「様 々な公式(マナ、ワカン、オレンダなど)の中にさえ、顕著な違いはないにせよ、初期の研究では十分に観察されなかったニュアンスが確かに存在する」 [24]。 ホルブラード[26]は「Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically(人工物を民族誌的に理論化する)"に収録されている論文で、マナの概念は人類学における重要な理論的前提を浮き彫りに していると論じている。ホルブラードは、マナは社会調査において物質と意味の間に想定される区分を再評価する動機になると示唆している。彼の研究は、人類 学における存在論的転回、つまり他文化の存在論を真剣に受け止めることを目指すパラダイム・シフトの一環である[27]。 |

| Aṣẹ Barakah Chakra Charm The Force Guṇa Kami in Shinto Manitou Melanesian mythology Mysticism Occult Philippine shamans or Babaylan Prana Qi or Chi Quintessence or Aether Ritual Scientific skepticism Taboo Talisman Väki Wind Horse Yorishiro in Shinto |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mana_(Oceanian_cultures) |

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Source: La Abeja Medica, Barcelona