Genealogy of the South-Frontier

Discource, the Nanshin-ron, of the Empire of Japan

The main office of The

Oriental Development Company, in Seoul, Empire of Japan

Genealogy of the South-Frontier

Discource, the Nanshin-ron, of the Empire of Japan

The main office of The

Oriental Development Company, in Seoul, Empire of Japan

国家イデオロギー的南進論

1887 志賀重昂『南洋時報』

1888 菅沼貞風『新日本図南の夢』

1890 田口卯吉『南洋経略論』

1892 鈴木経勲(つねのり)『南洋探検実記』

1893 田口卯吉『南嶋巡航記』

1901 竹越与三郎『南国記』

●南進の二線(矢野暢『日本の南洋史観』『南進の系譜』)

矢野によると、南進論の特徴は次の7つにまとめられる(矢野 2009:43-44)。

後年に矢野の書籍の再編集本の「解題」で清水元(2009:353-354)は、この本は実証史学研究としては穴だらけであるが、それには ない「生々しい現実的な問題意識に貫かれた『なにものか』」と行為的に評価している。これは、近代日本の「知と権力」が南洋でむすびついた南進政策に他ならない、歴史イデオロギー分析の書であるとも評価することができるのではないか?

1)日本の海外進出は南方であることを強く強調する

2)「北進」論に強く対抗する

3)南洋の未開性、後進性を強調し、それを啓蒙解放するのは日本の使命であると自認する(→柳田の南方統治案)

4)南洋が西洋の勢力圏であることを否認する(あるいはその能力の欠如)

5)陸ではなく「海」の思想であることが強調される

6)日本人の南洋への関心の低さを慨嘆する

7)日本の南方関与により、国内の社会経済問題が解決すると考える

◎フレデリック・ターナーの「フロンティア学説」との比較(→植民行為が植民者のエートスをつくる)

「アメリカ合衆国の国勢調査局は、一平方マイルにつき人口(先住民は除く)が二人以上六人以下の地域をフロンティア(Frontier)と定めていた。この地帯の外辺がフロンティア・ラインである。白人入植者によるインディアンに対する征服が進むとともに、フロンティア・ラインは西部に漸次移動していき、1890年の国勢調査局長が、フロンティア・ラインと呼べるものがなくなったことを国勢調査報告書に記載した。これが「フロンティアの消滅」である。このフロンティア消滅をうけて、歴史家のフレデリック・ターナー(Frederick Jackson Turner, 1861-1932)は、フロンティアと合衆国の民主主義・国民性を関連づけて述べた(フロンティア学説)。アメリカの言う「フロンティア」とは実際には 「インディアンの掃討の最前線」であり、スー族に対する「ウーンデッド・ニーの虐殺」があった1890年に「インディアンの掃討が完了した。」として合衆 国政府は「フロンティアの消滅」とした。「フロンティアの消滅」と前後して、アメリカ合衆国は太平洋進出を始めていく」フロンティア); 「シカゴ万国博覧会開催中の1893年7月12日、ターナーはアメリカ歴史学会に投稿し出版された初出論文『アメリカ史におけるフロンティアの意義』の中 の「フロンティア学説」を主張した。その中では、アメリカ合衆国の精神と成功は直接この国の西方への拡張に結び付けられると述べている。ターナーに拠れ ば、特異でごつごつしたアメリカの独自性が形成されたのは、開拓者の文明と荒野の荒々しさとが出遭ったときに起こった。このことで新しいタイプの市民が生まれた。すなわち荒野を手なづける力のある者や荒野が力と個性を与えた者とした["The Old Frontiers" by Alan Taylor, The New Republic, May 7, 2008]。」

以下はテキスト(ウィキペディア「南進論(Nanshin-ron)」他に準拠)

| outline |

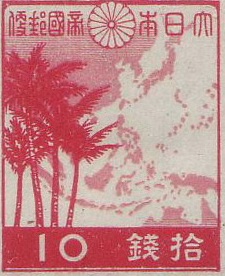

Nanshin-ron (南進論,

"Southern Expansion Doctrine" or "Southern Road") was a political

doctrine in the Empire of Japan that stated that Southeast Asia and the

Pacific Islands were Japan's sphere of interest and that their

potential value to the Empire for economic and territorial expansion

was greater than elsewhere.

The opposing political doctrine was Hokushin-ron (北進論, "Northern

Expansion Doctrine"); largely supported by the Imperial Japanese Army,

it stated the same but for Manchuria and Siberia. After military

setbacks at Nomonhan, Mongolia; the start of the Second Sino-Japanese

War; and negative Western attitudes towards Japanese expansionist

tendencies, the Southern Expansion Doctrine became predominant. Its

focus was to procure colonial resources in Southeast Asia and to

neutralize the threat posed by Western military forces in the Pacific.

The Army favored a "counterclockwise strike" while the Navy favored a

"clockwise strike."[1] |

南

進論(な

んしんろん、Southern Expansion

Doctrine)とは、東南アジアと太平洋諸島を日本の関心領域とし、経済的・領土的な拡張のために他の地域よりも大きな価値を持つとした大日本帝国の

政治理論である。これと対立するのが「北進論」であり、日本陸軍が中心となって、満州やシベリアについても同じように主張した。モンゴルのノモンハンでの

失敗、日中戦争の開始、日本の拡張主義的な傾向に対する欧米の否定的な態度などを経て、南方拡大論が優勢になった。東南アジアの植民地資源の確保と、太平

洋における欧米軍の脅威の排除を目的としたものである。陸軍は「反時計回りの攻撃」、海軍は「時計回りの攻撃」を支持した。 |

| Meiji-period genesis |

In Japanese historiography, the

term nanshin-ron is used to describe Japanese writings on the

importance to Japan of the South Seas region in the Pacific Ocean.[2]

Japanese interest in Southeast Asia can be observed in writings of the

Edo period (17th–19th centuries).[3]

During the final years of the Edo period, the leaders of the Meiji

Restoration determined that Japan needed to pursue a course of

imperialism in emulation of the European nations to attain equality in

status with the West, as European powers were laying claim to

territories ever closer to Japan.

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the nanshin-ron policy came to be

advanced with the southern regions as a focus for trade and

emigration.[3] During the early Meiji period, Japan derived economic

benefits from Japanese emigrants to Southeast Asia, among them, there

were prostitutes (Karayuki-san)[4] who worked in brothels in British

Malaya,[5] Singapore,[6] the Philippines,[7] the Dutch East Indies[8]

and French Indochina.[9] Nanshin-ron was advocated as a national policy

by a group of Japanese ideologues during the 1880s and the 1890s.[10]

Writings of the time often presented areas of Micronesia and Southeast

Asia as uninhabited or uncivilised and suitable for Japanese

colonisation and cultivation.[11] In its initial stages Nanshin-ron

focused primarily on Southeast Asia, and until the late 1920s, it

concentrated on gradual and peaceful Japanese advances into the region

to address what the Japanese saw as the twin problems of

underdevelopment and Western colonialism.[12] During the first decade

of the 20th century, private Japanese companies became active in trade

in Southeast Asia. Communities of emigrant Japanese merchants arose in

many areas and sold sundry goods to local customers, and Japanese

imports of rubber and hemp increased.[4] Large-scale Japanese

investment occurred especially in rubber, copra, and hemp plantations

in Malaya and in Mindanao in the southern Philippines. The Japanese

Foreign Ministry established consulates in Manila (1888), Singapore

(1889), and Batavia (1909).

With increasing Japanese industrialization came the realization that

Japan was dependent on the supply of many raw materials from overseas

locations outside its direct control and was hence vulnerable to that

supply's disruption. The Japanese need for the promotion of trade,

developing and protecting sea routes, and official encouragement of

emigration to ease overpopulation arose simultaneously with the

strengthening of the Imperial Japanese Navy, which gave Japan the

military strength to protect its overseas interests if diplomacy failed. |

日

本の歴史学では、太平洋の南洋地域の日本にとっての重要性を説いた文献を「南進論」と呼んでいる。東南アジアに対する日本の関心は、江戸時代(17〜19

世紀)の書物に見ることができる。江戸時代末期、明治維新の指導者たちは、ヨーロッパ列強が日本により近い領土を要求してきたため、日本は西洋と対等な地

位を得るためにヨーロッパ諸国を模倣した帝国主義を追求する必要があると判断した。1868年の明治維新後、南方地域を貿易や移住の中心とする南進論が進

められるようになった。明治初期、日本は東南アジアへの日本人移民から経済的利益を得ていた。その中には、イギリス領マラヤ、シンガポール、フィリピン、

オランダ領東インド、フランス領インドシナの売春宿で働く娼婦(からゆきさん)がいた。南進論は、1880年代から1890年代にかけて、日本の思想家た

ちによって国策として提唱された。当時の文章では、ミクロネシアや東南アジアの地域は、人が住んでいない未開の地であり、日本の植民地化、開墾に適した地

域であるとしばしば紹介されています。南信論は、初期の段階では主に東南アジアに焦点を当て、1920年代後半までは、日本人が考える低開発と西洋植民地

主義という2つの問題に対処するために、この地域に徐々に平和的に進出することに焦点を合わせていた。20世紀最初の10年間は、日本の民間企業が東南ア

ジアでの貿易に積極的に取り組んだ。日本から移住した商人たちは、各地で雑貨を販売し、ゴムや麻の輸入が増加した。特にマラヤやフィリピン南部のミンダナ

オ島では、ゴムやコプラ、麻のプランテーションに大規模な日本からの投資が行われた。日本外務省は、マニラ(1888)、シンガポール(1889)、バタ

ビア(1909)に領事館を設置した。日本の工業化が進むにつれて、日本は多くの原材料を海外からの供給に依存し、その供給が途絶えると脆弱になることが

分かってきた。貿易の促進、航路の開拓と保護、人口過剰を緩和するための公式な移民奨励の必要性は、同時に日本海軍の強化によって、外交が失敗した場合に

海外の利益を守るための軍事力を日本に与えることになった |

| Pacific islands |

The Japanese government began

pursuing a policy of overseas migration in the late 19th century as a

result of Japan's limited resources and increasing population. In 1875,

Japan declared its control over the Bonin Islands.[10] The formal

annexation and incorporation of the Bonin Islands and Taiwan into the

Japanese Empire can be viewed as first steps in implementation of the

"Southern Expansion Doctrine"

in concrete terms.

However, World War I had a profound impact on the "Southern Expansion

Doctrine" since Japan occupied vast areas in the Pacific that had been

controlled by the German Empire: the Caroline Islands, Mariana Islands,

Marshall Islands and Palau. In 1919, the island groups officially

became a League of Nations mandate of Japan and came under the

administration of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The focus of the

"Southern Expansion Doctrine" expanded to include the island groups

(the South Seas Mandate), whose economic and military development came

to be viewed as essential to Japan's security. |

日

本政府は、19世紀後半、日本の限られた資源と人口の増加を背景に、海外移住の政策を進めた。1875年、日本は小笠原諸島への支配を宣言した。小笠原諸

島と台湾の日本帝国への正式な併合と編入は、「南方拡大ドクトリン」を具体的に実行する第一歩と見ることができる。しかし、第一次世界大戦は、ドイツ帝国

が支配していた太平洋のカロリン諸島、マリアナ諸島、マーシャル諸島、パラオを

占領したため、「南方拡大ドクトリン」に大きな影響を与えることに

なった。1919年、これらの島々は正式に国際連盟の委任統治領となり、日本海軍の

管理下に置かれることになった。南方拡大ドクトリン」の対象が島嶼部(南洋群)に拡大され、経済・軍事の発展が日本の安全保障に不可欠とされるようになっ

たのである |

| Theoretical development |

Meiji-period nationalistic

researchers and writers pointed to Japan's relations with the Pacific

region from the 17th-century red seal ship trading voyages, and

Japanese immigration and settlement in Nihonmachi during the period

before the Tokugawa shogunate's national seclusion policies. Some

researchers attempted to find archeological or anthropological evidence

of a racial link between the Japanese of southern Kyūshū (the Kumaso)

and the peoples of the Pacific islands.

Nanshin-ron appeared in Japanese political discourse around the

mid-1880s.[13] In the late 19th century, the policy focused on the

adjacent China[14] with an emphasis on securing control of Korea and

expanding Japanese interests in Fujian. Russian involvement in

Manchuria at the turn of the century led to the policy being eclipsed

by hokushin-ron (the "Northern Expansion Doctrine"). The resulting

Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) produced territorial gains for Japan in

South Manchuria.[15] After the war, the expansionist aspects of

nanshin-ron became more developed, and the policy was incorporated into

national defence strategy in 1907.[16]

In the 1920s and the 1930s, the "Southern Expansion Doctrine" gradually

came to be formalized, largely through the efforts of the Imperial

Japanese Navy's "South Strike Group," a strategic think tank based in

the Taihoku Imperial University in Taiwan. Many professors at the

university were either active or former Navy officers, with direct

experience in the territories in question. The university published

numerous reports promoting the advantages of investment and settlement

in the territories under Navy control.

In the Navy, the Anti-Treaty Faction (han-joyaku ha) opposed the

Washington Treaty, unlike the Treaty Faction. The former set up a

"Study Committee for Policies towards the South Seas" (Tai Nan'yō

Hōsaku Kenkyū-kai) to explore military and economic expansion

strategies, and cooperated with the Ministry of Colonial Affairs

(Takumu-sho) to emphasize the military role of Taiwan and Micronesia as

advanced bases for further southern expansion. |

明

治期の国粋主義的な研究者や作家は、17世紀の朱印船貿易に始まる日本と太平洋地域との関係や、徳川幕府の鎖国政策以前の日本町への日本人移民・定住を指

摘し、「朱印船貿易と日本町への移民・定住は、日本が太平洋に進出するきっかけとなった」と述べている。また、南九州の日本人(熊襲)と太平洋の島々の人

々の間に人種的なつながりがあることを考古学的、人類学的に証明しようとする研究者もいた。南進論が日本の政治に登場するのは、1880年代半ば頃である。19世紀後半には、朝鮮半島の支配権の確保と福建省における日本の権益の拡大に重点を置き、隣接する中国に焦点を当てた政策

がとられた。しかし、19世紀末にロシアが満州に進出してくると、この政策は北進論に取って代わられることになる。その結果、日露戦争(1904-05)

で日本は南満州の領土を獲得することになった。日露戦後、

南進論はさらに発展し、1907年には国防政策に組み込まれた。1920年代から1930年代にかけて、日本海軍の「南方攻撃隊?」(台湾の台北帝国大学

に置かれた戦略シンクタンク)の努力によって、「南方拡大ドクトリン」は徐々に公式化されるようになった。同大学の教授陣の多くは現役の海軍将校や元海軍

将校であり、対象領土での直接の経験があった。同大学は、海軍の支配下にある領土への投資や入植の利点を宣伝するレポートを数多く発表した。海軍では、条

約派とは異なり、反条約派がワシントン条約に反対した。「対南洋方策研究会(Study Committee for Policies

towards the South

Seas)」を設置し、軍事的・経済的な拡張戦略を検討し、拓務省と協力して台湾やミクロネシアの軍事的役割を強調し、さらなる南方進出のための先進的な

拠点としたのである。 ・1901 糖業改良意見書 ・1908-1909 「日糖疑獄」事件 ・1914 日本委任統治領南洋群島(South Seas Mandate) ・1914 パラオで「モデグゲイ」新宗教運動が発生 |

| Economic development |

In 1920 the Foreign Ministry

convened the Nan-yo Boeki Kaigi (South Seas Trade Conference), to

promote South Seas commerce and published in 1928 Boeki, Kigyo oyobi

imin yori mitaru Nan'yo ("The South Seas in View of Trade and

Emigration"). The term Nan-yo kokusaku (National Policy towards the

South Seas) first appeared.

The Japanese government sponsored several companies, including the

Nan'yō Takushoku Kabushiki Kaisha (South Seas Colonization Company),

the Nan'yō Kōhatsu Kabushiki Kaisha (South Seas Development Company),

and the Nan'yō Kyōkai (South Seas Society) with a mixture of private

and government funds for development of phosphate mining, sugar cane

and coconut industries in islands and to sponsor emigrants. Japanese

Societies were established in Rabaul, New Caledonia, Fiji and New

Hebrides in 1932 and in Tonga in 1935.

The success of the Navy in the economic development of Taiwan and the

South Seas Mandate through alliances among military officers,

bureaucrats, capitalists, and right-wing and left-wing intellectuals

contrasted sharply with Army failures in the Chinese mainland. |

1920

年、外務省は南洋貿易を促進するために「南洋貿易会議」を開催し、1928年には『貿易事業及び移民より見たる南洋』を刊行した。南洋国策という言葉が初

めて登場した。日本政府は、南洋拓殖株式会社、南洋開発株式会社、南洋協会などいくつかの会社を私費と国費で設立し、島々のリン鉱石、サトウキビ、ココナ

ツなどの産業を発展させ、移民を奨励した。1932年にはラバウル、ニューカレドニア、フィジー、ニューヘブリディーズ諸島に、1935年にはトンガに日

本協会が設立された。台湾と南洋委任統治領の経済開発において、海軍が軍人、官僚、資本家、右翼・左翼の知識人の連携によって成功したことは、中国大陸で

の陸軍の失敗と好対照をなしている。 ・1922 1922年2月11日にミクロネシアに対する委任権が発効.3月南洋庁設 置(パラオ・コロール島)総理府 ・1924 南洋庁は外務省に移管 ・1929 拓務省(Ministry of Colonial Affairs)が発足 |

| Increasing militarization |

The Washington Naval Treaty had

restricted the size of the Japanese Navy and also stipulated that new

military bases and fortifications could not be established in overseas

territories or colonies. However, in the 1920s, Japan had already begun

the secret construction of fortifications in Palau, Tinian and Saipan.

To evade monitoring by the Western powers, they were camouflaged as

places to dry fishing nets or coconut, rice, or sugar-cane farms, and

Nan'yō Kohatsu Kaisha (South Seas Development Company) in co-operation

with the Japanese Navy, assumed responsibility for construction.

The construction increased after the even more restrictive London Naval

Treaty of 1930, and the growing importance of military aviation led

Japan to view Micronesia to be of strategic importance as a chain of

"unsinkable aircraft carriers" protecting Japan and as a base of

operations for operations in south-west Pacific.

The Navy also began examining the strategic importance of Papua and New

Guinea to Australia since it was aware that the Australian annexation

of those territories had been motivated in large part in an attempt to

secure an important defense line. |

ワ

シントン海軍条約は、日本海軍の規模を制限し、海外の領土や植民地には新たな軍事基地や要塞を設置しないことを定めていた。しかし、日本は1920年代に

すでにパラオ、テニアン、サイパンで秘密裏に要塞の建設に着手していた。欧米列強の監視を逃れるため、漁網を干す場所やヤシ、米、サトウキビなどの農場に

偽装し、南洋興発株式会社が日本海軍と共同で建設を担った。1930年のロンドン海軍条約以降、さらに建設が進み、軍事航空の重要性が高まったことから、

日本はミクロネシアを日本を守る「不沈空母」の列島として、また南西太平洋の作戦拠点として戦略的に重要視するようになった。また海軍は、豪州がパプア、

ニューギニアを併合したのは、重要な防衛線の確保が大きな動機で あったことを知り、豪州にとっての戦略的重要性を検討し始めた。 |

| Adoption as national policy |

In

1931, the "Five Ministers Meeting" defined the Japanese objective of

extending its influence in the Pacific but excluded areas such as the

Philippines, the Dutch East Indies and Java, which might provoke other

countries.[4] Nanshin-ron became official policy after 1935[16] and was

officially adopted as national policy with the promulgation of the Toa

shin Chitsujo (New Order in East Asia) in 1936 at the "Five Ministers

Conference" (attended by the Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Finance

Minister, Army Minister and the Navy Minister), with the resolution to

advance south peacefully.

By the start of World War II, the policy had evolved in scope to

include Southeast Asia.[16] The doctrine also formed part of the basis

of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, which was proclaimed by

Japanese Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro from July 1940. Resource-rich

areas of Southeast Asia were earmarked to provide raw materials for

Japan's industry, and the Pacific Ocean was to become a "Japanese

lake." In September 1940, Japan occupied northern French Indochina, and

in November, the Pacific Islands Bureau (Nan'yō Kyoku) was established

by the Foreign Ministry. The events of the Pacific War from December

1941 overshadowed further development of the "Southern Expansion

Doctrine", but the Greater East Asia Ministry was created in November

1942, and a Greater East Asia Conference was held in Tokyo in 1943.

During the war, the bulk of Japan's diplomatic efforts remained

directed at Southeast Asia. The "Southern Expansion Doctrine" was

brought to an end by the Japanese surrender at the end of the war. |

1931年の「五相会議」では、日本の目的は太平洋における影響力の拡大であるが、フィリピ

ン、オランダ領東インド、ジャワなど他国を刺激する可能性のある地域は除外されていることが明らかになった。南進論は1935年以降に公式な政策となり、1936年8月7日の広田弘毅内閣の「五相会議」(首

相、外相、蔵相、陸相、海軍大臣が出席)で平和的に南進することを決議し、「東亜新秩序」を公布して正式に国策として採用されることになった。第二次世界

大戦が始まる頃には、この政策は東南アジアを含む範囲に発展していた。このドクトリンは、1940年7月に近衛文麿首相が宣言した「大東亜共栄圏」の基礎

の一部にもなっている。東南アジアの資源豊富な地域は、日本の産業に原材料を提供するために予定されており、太平洋は「日本の湖」になるはずであった。

1940年9月、日本はフランス領インドシナ北部を占領し、11月には外務省に南洋局が設置された。1941年9月6日「帝国国策遂行要領」。

1941年12月からの太平洋戦争の影響で、「南方拡大ドクトリン」は影を潜めたが、1942年11月に大東亜省が創設され、1943年には東京で大東亜

会議が開かれた。戦時中の日本の外交努力の大部分は、東南アジアに向けられたままであった。南方拡大ドクトリン」は、終戦時の日本の降伏によって終焉を迎

えた。 ・1935年 国際連盟脱退/永田鉄山暗殺(相沢事件) ・1936年 東亜新秩序/二・二六事件 ・1937年 田河水泡『のらくろ総攻撃』 |

| Source: |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanshin-ron |

www.DeepL.com/Translator |

◎韓国興業

「日露戦争直後の1904年(明37)9月、朝鮮半島の農業改良事業を目的に渋沢栄一ら実業家の提唱により韓国興業が設立。1909年(明 42)韓国倉庫 を合併し倉庫業に進出、1910年(明43)には同様の拓殖事業を行っていた韓国拓殖を合併し事業を拡張する。同年の韓国併合により韓国興業は1913年 (大2)朝鮮興業と改称。各地に農場を配置し安定した農業経営にあたる。25年史は沿革と農業・倉庫・畜産事業等を記述した13章からなり、特に農業を詳 述。多数の事業写真と統計表を含む。[1945年(昭20)北緯38度線以南の耕作地は新韓公社が接収、それ以外の消息は不明]」朝鮮興業(株)『朝鮮興 業株式会社二十五年誌』(1929.10).」[渋沢社史デー タベース]

◎南洋殖産から南洋興発へ

「第一次世界大戦のドイツ帝国敗戦により、南洋の旧ドイツ領を国際連盟・委任統治領として日本が統治することになった。これを契機として日本内 地の資本が 次々と進出するが、大戦後の恐慌の影響を受けて初期の進出会社は経営に行き詰まった。1920年に南洋殖産、1921年には西村拓殖が倒産した。そして、 後には従業員である約1,000人の移民が取り残された[3][4][5]。残された労働者は飢餓に苦しみ、土着の住民の主要な食糧であるヤシがカイガラ ムシによる虫害を受け、彼らも食糧難に襲われていた[1]。これらの2社の倒産の同時期に、日本内地と台湾で製糖業に携わっていた松江春次は、移民の救済 と南洋での製糖業の将来性を主張していた[3]。これらの失業者の救済と南洋開発のため、松江春次を中心に設立されたのが南洋興発である。南洋興発株式会 社(なんようこうはつ、英語: Nanyo Kohatsu Kabushiki Kaisha)は、第一次世界大戦後に大日本帝国の委任統治領となった南洋群島サイパン島において、1920年代に東洋拓殖株式会社と実 業家の松江春次が中心になって設立した企業。第二次世界大戦終結時のポツダム宣言の受諾に伴い、1945年9月30日に閉鎖機関に指定されて解散した。南 洋興発は、満州を拠点とした南満州鉄道に対して南洋諸島を舞台に発展したため、「海の満鉄」[1]と呼ばれるほか、「北の満鉄、南の南興」[2]と並称さ れることもある。南洋庁(1922-1945)や日本海軍と密接な関係を持ち、南洋庁長官は南洋群島の統治に強い影響力を持つ南洋興発を「群島と興発会社 は共存共死、一蓮托 生の関係」と評した[2]。」(ウィキペディア「南洋興発」)

1917 西村製糖所サイパンに設立(西村惣四郎)

1919 西村拓殖会社(これが南洋興発の商法上の設立日1919.11.18)

1919-1920 西村拓殖会社、南洋殖産、喜多合名会社、などの先発会社の(世界恐慌の不況の)破綻

1922 松江春次(Haruji MATSUE, 1876-1954)は西村拓殖を買収して南洋興発を立ち上げ、南洋殖産のサイパン島、テニアン島における権利と事業を継承

1931 オランダ領ニューギニア島、1937年にセレベス島(スラウェシ島)とティモール島に進出

1932 南洋庁の歳入は約482万円であり、うち約309万円を南洋興発からの出港税が占める

1934 松江、蘭領ニュー

ギニア買収案を提唱(外務省国際問題を懸念して非公開文書になる)

1935 日本政府が実施した移民政策に従って南洋興発はミクロネシアの主要な島々に施設を建設、パラオ島にパイナップルの缶詰工場、ポンペイ 島に澱粉精製の工場建設

1940 7月26日第2次近衛文麿内閣の発足時の「基本国策要綱」に「大東亜新秩序」の建設が謳われる(「大東亜共栄園」)。

1941 1941年12月8日の日米開戦。

1941年「12月12日の閣議において、「今次戦争ノ呼称並ニ平戦時ノ分界時期等ニ付テ」が閣議決定された[8]。この閣議決定の第1項 で「今次ノ對米英戰爭及今後情勢ノ推移ニ伴ヒ生起スルコトアルヘキ戰爭ハ支那事變ヲモ含メ大東亞戰爭ト呼稱ス」と明記し、支那事変(日中戦争)と「対米英 戦争」を合わせた戦争呼称として「大東亜戦争」が公式に決定した」

1942 南洋興発は南洋貿易(NBK)と合併

1944 マリアナ諸島でマリアナ地区軍民協定が締結され、南洋興発は軍に全能力を提供する

1945 9月GHQにより閉鎖機関に指定され、解散

1950 南洋貿易、元南洋興発社長であった栗林徳一により再

建.

1954 閉鎖機関指定は解除

◎東洋拓殖

「東洋拓殖は、1908年(明治41年)12月18日制定の東洋拓殖株式会社法(東拓法,

明治41-昭和14に5回改正)を根拠法とし、日本統治時代の朝鮮における日本農民の植民事業を 推進することを目的として設立された[2]。

設立時の資本金は20万株で1000万円であった。韓国政府現物出資(土地)分6万株および役員持株千株を除く13万9000株が同年11月公募され、対

象とされた日朝両民族による応募額は、35倍を超える466万5000株に達した[3]。

東洋拓殖の歴史は殖民団体たる「東洋協会」の作成案(東拓設立要綱)にまでさかのぼることが出来る[2]。桂太郎が中心人物となったこの東洋協会の案が政

府内部で審議され始め、1908年2月に「東拓創立調査会」が発足。委員長の岡野敬次郎(内閣法制局長)、勝田主計(大蔵省理財局長)、児玉秀雄(総督府

書記官)の主導の下に骨格が作られた。この動きに対して韓国統監(当時)の伊藤博文が、東拓の役員・出資者に韓国人を入れることを旨とする大韓帝国政府と

の共同出資案を創立調査会に告げ、また韓国王室との日韓民間の半官半民資本の共同出資により設立され、初代総裁には宇佐川一正(陸軍中将)が赴任した。

設立委員会には豊川良平(三菱合資会社銀行部総裁)、中野武営(関西銀行総裁)、韓相龍(漢城銀行総務長)ら財界や韓国側からも参加して、国家資本輸出と

密着して植民地投資が展開されていく尖兵となった[4]。こうして政府が創立から8年間に毎年30万円の補助金交付、社債の保証を始めとした保護を含めた

国策会社となった」ウィキペディア「東洋拓殖」︎▶アマゾニア産業(アマゾ

ニア産業研究所)︎▶︎︎朝鮮鴨緑江水力発電・江界水力電気▶︎樺太開発▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

◎鈴木均『サイパン夢残 : 「玉砕」に潰えた「海の満鉄」』日本評論社 , 1993

︎▶︎プロローグ 一九七六年冬・サイパン︎▶

第1章 日本人と南洋群島︎▶

第2章 委任統治時代の開幕︎▶

第3章 サイパン・テニアンを耕す︎▶

第4章 大量移民の沖縄人︎▶

第5章 南興コンツェルンの実像︎▶

第6章 昭和期「南進」の組織と思想︎▶

第7章 「南の楽園」サイパンの最期▶

エピローグ 一九七九年初夏・パラオ

◎南洋経済研究所

「南洋経済研究所の沿革は、次のとおりである。1937(昭和 12)年 11 月 1 日、海 軍省の斡旋と指導により設立され、理事長に海軍少将の糟谷宗一(かすや・そうい ち、1885-1942)が就任した。1941 年 7 月には、財務基盤の強化のため、財団法人 の設立許可を受けた。国策企業である東洋拓殖株式会社の関連会社であった南洋興 発株式会社からの寄附金などを基に設立されたものである。1942 年 1 月に、糟谷 が没したため、常務理事の小西が経営の中心となる。本部は赤坂区表町 4 丁目 1 番 地(現、港区赤坂 8 丁目 1 番 19 号)、出版部は麹町区内幸町 2 丁目 3 番地(現、千 代田区内幸町 1 丁目 3 番 1 号)の幸ビル内に所在した。 同所の目的は「南洋資源ノ利用ノ即時実行可能ナル科学的研究ヲ行ヒ、以テ我ガ 国策ニ寄与スル」で、調査研究機構は、「研究所ヲ蘭印〔オランダ領東 インド〕、比 律賓〔フィリピン〕、馬来、仏印〔フランス領インドシナ〕及ビ泰ノ五班ニ分チ… …必要ノ調査研究ヲナス」[富樫 1941:400-401]のであった。事業は、「一、南洋 資源利用の科学的研究/二、南洋事情の調査研究/三、調査研究に基く参考資料の 刊行/四、其の他理事会に於て必要と認めたる事項」[大東亜省 1944:224]であ る。 幹部については、1944(昭和 19)年当時で、代表理事は小西干比古(こにし・たて ひこ)、理事は中堂観恵、柴勝男、棚木范、大波信夫、監事は鵜沢聡衛、評議員は 平出英夫、矢牧章、棚木范、大波信夫、主事は菊地淳であった。」大澤広嗣「対外謀略と経済調査に関わった仏教者:近代日タイ関係と佐藤政孝」『宗教学年 報』第33 輯2018 年 3 月 31 日発行(大正大学宗教学会), p.12.

◎東亜研究所年譜

◎拓務省年譜

1896 3月31日、拓殖務省官制(勅令)が公布され、4月2日、台湾総督府を監督し、内務省所管の北海道に関する政務を管理する目的で拓殖 務省(たくしょくむしょう)が設置

1897 行政整理により翌年の1897年(明治30年)9月2日に廃止。9月1日、内閣に台湾事務局をおく旨公布され(勅令)、以後、内務省 が台湾事務を担当

1910 6月22日、拓殖局官制が公布され(勅令)、内閣直属の所轄行政機関として拓殖局が新設

1917 7月31日、拓殖局官制が公布された(勅令)(初代長官白仁武)

1929 6月10日、拓務省官制が公布され(勅令)、拓務省が新設され、朝鮮総督府・台湾総督府・関東庁・樺太庁・南洋庁の統治事務の監督、および海外移民の募集や指導を行う

1942 大東亜省官制が公布され(勅令)、大東亜共栄圏を包括的に管理する大東亜省(Ministry of Greater East Asia)が設置されると、拓務省は、大東亜省・内務省・外務省などに分割

◎柳田国男は国際連盟常設委任統治委員会委員就任 「太平洋委任統治」報告書(岩本由輝『も う一つの遠野物語』刀水書房, 1994)(→村井紀『南島イ デオロギーの発生』ノート)

◎学知と南進

東亜経済研究所と南方軍政「1941年12月8日の日米開戦後、東京商大東亜経済研究所(現・一橋大学経済研究所)に集まった教員の中から 「南方占領地での軍政に協力しつつ自分たちの独自の研究を進めていこう」という声が高まり、当時の高瀬荘太郎学長が実弟(高瀬啓治陸軍大佐)を通じて軍部 に働きかけ、南方への調査団派遣が本決まりになった。東亜経済研究所の担当は昭南市(シンガポール)の南方軍軍政総監部(のちマライ軍政監部)の調査部付 として英領マラヤの民族・経済状況の調査を行うことであり、同研究所のスタッフを中心に赤松要教授を筆頭に石田龍次郎・小田橋貞寿・板垣与一(與一)・山田勇・山田秀雄・大野精三郎・宇津木正らの教員が南方に派遣された。派遣された教員たちは司政官として精力的な調査活動を行い、のちのUMNOにつながるクリス運動の発足に関わった板垣與一のように、軍政部の対マレー人工作に関与した者もいた」 ウィキペディア「東亜経済研究所と南方軍政」)

◎矢野暢「南進」の系譜 : 日本の南洋史観の章立て

第1部 「南進」の系譜

南方関与のはじまり

「南進論」の系譜

経済進出のパターン

在留邦人の生態

「大東亜共栄圏」の虚妄

戦後日本の東南アジア進出

第2部 日本の南洋史観

七人の「南進論」者

明治期の「南進論」の性格

大正期「南進論」の特質

「拠点」思想の基盤—台湾と南洋群島

「南進論」と庶民の関わり

昭和期における「南進論」の展開

◎松岡静雄年譜(Wikiwandによる)

松岡 静雄(まつおか しずお、1878年(明治11年)5月1日 - 1936年(昭和11年)5月23日)は、日本の海軍軍人、言語学者、民族学者。最終階級は海軍大佐。柳田國男の弟。

1878 兵庫県神東郡田原村辻川(現神崎郡福崎町)に儒者・松岡操、たけの七男として生まれる

1897 12月、海軍兵学校(25期)を首席[2]で卒業

1899 2月、海軍少尉任官

1904 日露戦争には「千代田」航海長として出征し、日本海海戦を戦った。その後、「八幡丸」「千歳」の各航海長、第2艦隊参謀、海兵監事、軍令部参謀などを歴任

1907 9月、海軍少佐に進級、オーストリア=ハンガリー大使館付武官となり、さらに「磐手」「朝日」「筑波」の各副長を務める

1914 12月、臨時南洋群島防備隊参謀の発令があったが病欠で赴任できず、横須賀鎮守府付の後、海軍省文庫主管を勤める

1916 海軍大佐に昇進

1918 予備役に編入

1921 5月に退役。神奈川県藤沢市(当時は藤沢町)鵠沼に居を移すが、直後に起こった関東大震災(1923年9月1日)では、遭難死し た東久邇宮師正王の遺骸を運ぶために軍艦を相模湾に回航させたり、遭難死した住民26体の遺骸を地元青年団が荼毘に付す際の指揮を執ったりしたという逸話 が残っている。

1923 震災後は鵠沼西海岸に居を構え、神楽舎(ささらのや)と名付けて言語学、民俗学を研究し、同じ軍人出身の「岡書院」店主岡茂雄の勧めもあり、十数年で多くの著作を残した。また、扇谷正造をはじめ多くの青年たちが訪れて学んだ。

1936 没後、弟子たちによって「松岡静雄先生之庵趾」という石碑が建てられ、現存する。言語学、民俗学における権威者()

◎中生勝美の「南洋群島」における人類学

| 第3章 南洋群島:委任統治と民族調査 | 「国 際連盟からの委任統治という植民地 の統治形態が、南洋群島の人類学調査と研究にいかなる影響を与えたのかという」関心( 中生 2016:190)。→「その意味で南洋群島は、国際連盟が委任統治領として、日本人に現地住民の福利厚生の促進や権利保護を主眼とする政策をとる義務を 負わせたこと、さらに国際連盟脱退後、日本が土地制度を改革する政策をとったことが、人類学的研究を推進させたということができよう」( 中生 2016:238)※これは矢野暢のイデオロギーに満ちてはいるが知と権力がむすびつく「土着的なオリエンタリズム批判」という観点からはかなり後退して いるものといえよう。 |

| 第1節 はじめに | |

| 第2節 南洋群島統治史 | 田代安定の先駆性 |

| 第3節 日本統治による調査事業 | |

| 第4節 松岡静雄のミクロネシア民族学 | 『ミクロネシア民族誌』 |

| 第5節 日本のゴーギャン:土方久功 | |

| 第6節 杉浦健一と土地旧慣調査 | |

| 第7節 おわりに |

リンク

リンク

文献

文献(南洋興発関連)復刻を含めた刊行年の新しい順

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099