和辻哲郎

Tetsuro

WATSUJI, 1889-1960

☆「だが(著作の)修正をいうことによって、何を拒絶したのか。和辻とともにその後継者も解説者も、1945年の日本の挫折に直面することを拒否したのである。拒否されたのは日本の国家的挫折であるとともに、和辻倫理学の挫折でもあったであろう」(子安 2010:29)。

★和辻 哲郎(わつじてつろう、1889年〈明治22年〉3月1日 - 1960年〈昭和35年〉12月26日)は、日本の哲学者・倫理学者・文化史家・日本思想史家。『古寺巡礼』『風土』などの著作で知られ、その倫理学の体 系は和辻倫理学と呼ばれる。法政大学教授・京都帝国大学教授・東京帝国大学教授を歴任。日本倫理学会会員。文化勲章受章。 兵庫県出身。東大哲学科卒。ニーチェなど西洋哲学を研究。奈良の寺院建築や仏像の美を再発見し、『古寺巡礼』(1919年)も人気を博す。『人間の学とし ての倫理学』(1934年)で新しい倫理学の体系を構築。『風土』(1935年)、『面とペルソナ』(1937年)も名高い。なお、本文和辻の以下の情報 はすべて、ウィキペディアから のものである。

| Watsuji was born in

Himeji, Hyōgo Prefecture to a physician. During his youth he enjoyed

poetry and had a passion for Western literature. For a short time he

was the coeditor of a literary magazine and was involved in writing

poems and plays. His interests in philosophy came to light while he was

a student at First Higher School in Tokyo, although his interest in

literature would always remain strong throughout his life.

In his early writings (between 1913 and 1915) he introduced the work of

Søren Kierkegaard to Japan, as well as working on Friedrich Nietzsche,

but in 1918 he turned against this earlier position, criticizing

Western philosophical individualism, and attacking its influence on

Japanese thought and life. This led to a study of the roots of Japanese

culture, including Japanese Buddhist art, and notably the work of the

medieval Zen Buddhist Dōgen. Watsuji was also interested in the famous

Japanese writer Natsume Sōseki, whose books were influential during

Watsuji's early years. |

和辻は兵庫県姫路市の医師の家に生まれた。少年時代は詩を好み、西洋文

学に傾倒していた。一時期、文芸誌の共同編集長を務め、詩や戯曲の執筆に携わったこともある。第一高等学校在学中に哲学に目覚めるが、文学への関心は終生

変わらなかった。1913年から1915年にかけての著作では、キルケゴールの著作を日本に紹介し、ニーチェの著作も手がけたが、1918年になると、そ

れまでの立場とは逆に、西洋哲学的個人主義を批判し、日本の思想や生活への影響を攻撃するようになった。その結果、日本の仏教美術、特に中世の禅僧である

道元の作品など、日本文化のルーツとなるものを研究することになった。また、夏目漱石にも関心を持ち、その著書は和辻の若い頃に大きな影響を与えた。 |

| In the early 1920s Watsuji

taught at Toyo, Hosei and Keio universities, and at Tsuda Eigaku-juku

(now, Tsuda University).[1]

The issues of hermeneutics attracted his attention,[2] especially the

hermeneutics of August Böckh

and Dilthey.[3]

In March 1925, Watsuji became a lecturer at Kyoto Imperial University,

joining the other leading philosophers of the time, Nishida Kitaro and

Tanabe Hajime. In July, he was promoted to associate professor of

ethics.

In January 1927, it was decided that he would go to Germany for 3 years

for his research on the history of moral thought. He departed on 17th

February and finally arrived in Berlin in early April. In the beginning

of summer, he read Heidegger’s Being and Time which had just come

out.[4] He then went to Paris. He left Paris in early December and

arrived in Genoa on the 12th of that month.

From January to March 1928, he travelled to Rome, Naples, Sicily,

Florence, Bologna, Ravenna, Padua and Venice. He then cut his trip

short, returning to Japan in early July. So his stay in Europe only

lasted for roughly a year.

In March 1931, he was promoted to full professor at Kyoto Imperial

University.

He then moved to the Tokyo Imperial University in July 1934 and held

the chair in ethics until his retirement in March 1949.[5]

During World War II his theories (which claimed the superiority of

Japanese approaches to and understanding of human nature and ethics,

and argued for the negation of self) provided support for Japanese

nationalism, a fact which, after the war, he said that he regretted.

Watsuji died at the age of 71. |

1920年代前半、和辻は東洋大学、法政大学、慶応義塾大学、津田塾大

学で教鞭をとっていた。和辻の関心は、解釈学の問題、特にベックやディルタイの解釈学に注がれていた。1925年3月、和辻は京都帝国大学の講師とな

り、西田幾多郎、田辺一ら当時の代表的な哲学者たちと一緒に教鞭をとることになった。7月には、倫理学の助教授に昇格した。1927年1月、道徳思想史の

研究のため、3年間ドイツに行くことが決定された。2月17日に出発し、4月上旬にようやくベルリンに到着した。初夏には、出たばかりのハイデガー『存在

と時間』を読んだ。その後、パリに向かう。12月上旬にパリを出発し、同月12日にジェノバに到着した。1928年1月から3月にかけて、ローマ、ナポ

リ、シチリア、フィレンツェ、ボローニャ、ラヴェンナ、パドヴァ、ヴェニスなどを旅している。そして、7月上旬に日本に帰国している。ヨーロッパ滞在は1

年程度であった。1931年3月、京都帝国大学の正教授に昇進した。1934年7月、東京帝国大学に移り、1949年3月に退官するまで倫理学の講座を担

当した。第二次世界大戦中は、日本人の人間観・倫理観の優位性を主張し、自己の否定を主張した彼の学説が、日本のナショナリズムの支えとなったが、戦後、

彼はそのことを悔やんでいたという。和辻は71歳で亡くなった。 |

| Watsuji's

three main works were his two-volume 1954 History of Japanese Ethical

Thought, his three-volume Ethics, first published in 1937, 1942, and

1949, and his 1935 Climate. The last of these develops his most

distinctive thought. In it, Watsuji argues for an essential

relationship between climate and other environmental factors and the

nature of human cultures, and he distinguished three types of culture:

pastoral, desert, and monsoon.[6]

Watsuji wrote that Kendo involves raising a struggle to a

life-transcending level by freeing oneself from an attachment to

life.[7] |

和辻は、1954年に出版した

『日本倫理思想史』2巻、1937年、1942年、1949年に出版した『倫理学』3巻、1935年の『風土』の3冊を主著としている。このうち、最後の

『風土』は、彼の最も特徴的な思想を展開したものである。この中で和辻は、気候やその他の環境要因と人間文化の本質的な関係を論じ、牧歌的文化、砂漠文

化、モンスーン文化の3種類を区別している。和辻は、剣道とは、生への執着から解放されることによって、闘争を生を超越するレベルまで高めることであると

書いた。 |

| https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator#en/ |

|

August Böckh or Boeckh[5] (German: [bœk]; 24 November

1785 – 3 August 1867) was a German classical scholar and antiquarian. August Böckh or Boeckh[5] (German: [bœk]; 24 November

1785 – 3 August 1867) was a German classical scholar and antiquarian.Life He was born in Karlsruhe, and educated at the local gymnasium; in 1803 he left for the University of Halle, where he studied theology. F. A. Wolf was teaching there, and creating an enthusiasm for classical studies; Böckh transferred from theology to philology, and became the best of Wolf's scholars. In 1807, he established himself as Privatdozent in the University of Heidelberg and was shortly afterwards appointed professor extraordinarius, becoming professor two years later. [6] The common misconception of Böckh's forenames being Philipp August originated in Heidelberg where staff of the university misread the abbreviation 'Dr phil' (doctor philosophiae) as 'Dr Philipp August Böckh'.[7] In 1811, he moved to the new University of Berlin, where he had been appointed professor of eloquence and classical literature. He remained there till his death. He was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences of Berlin in 1814, and for a long time acted as its secretary. Many of the speeches contained in his Gesammelte kleine Schriften were delivered in this latter capacity.[6] He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1853.[8] Böckh died in Berlin in 1867, aged 81. Works Böckh worked out the ideas of Wolf in regard to philology and illustrated them by his practice. Discarding the old idea that philology consisted in a minute acquaintance with words and the exercise of the critical art, he regarded it as the entire knowledge of antiquity (totius antiquitatis cognitio), historical and philosophical. He divides philology into five parts: first, an inquiry into public acts, with a knowledge of times and places, into civil institutions, and also into law; second, an inquiry into private affairs; third, an exhibition of the religions and arts of the ancient nations; fourth, a history of all their moral and physical speculations and beliefs, and of their literatures; and fifth, a complete explanation of the language.[6] Böckh set forth these ideas in a Latin oration delivered in 1822 (Gesammelte kleine Schriften, i.). In his speech at the opening of the congress of German philologists in 1850, he defined philology as the historical construction of the entire life – therefore, of all forms of culture and all the productions of a people in its practical and spiritual tendencies. He allows that such a work is too great for any one person; but the very infinity of subjects is the stimulus to the pursuit of truth, and scholars strive because they have not attained. An account of Böckh's division of philology will be found in Freund's Wie studiert man Philologie?[6] From 1806, till his death Böckh's literary activity was unceasing. His principal works include an edition of Pindar, the first volume of which (1811) contains the text of the Epinician odes; a treatise, De Metris Pindari, in three books; and Notae Criticae: the second (1819) contains the Scholia; and part ii. of volume ii. (1821) contains a Latin translation, a commentary, the fragments and indices. It was for a long time the most complete edition of Pindar. But it was especially the treatise on the metres which placed Böckh in the first rank of scholars. This treatise forms an epoch in the treatment of the subject. In it the author threw aside all attempts to determine the Greek metres by mere subjective standards, pointing out at the same time the close connection between the music and the poetry of the Greeks. He investigated minutely the nature of Greek music as far as it can be ascertained, as well as all the details regarding Greek musical instruments; and he explained the statements of the ancient Greek writers on rhythm. In this manner he laid the foundation for a scientific treatment of Greek metres.[6] His Die Staatshaushaltung der Athener (1817; 2nd ed. 1851, with a supplementary volume Urkunden über das Seewesen des attischen Staats; 3rd ed. 1886) was translated into English under the title of The Public Economy of Athens. In it he investigated a subject of peculiar difficulty with profound learning. He amassed information from the whole range of Greek literature, carefully appraised the value of the information given, and shows throughout every portion of it rare critical ability and insight. A work of a similar kind was his Metrologische Untersuchungen über Gewichte, Münzfüsse, und Masse des Alterthums (1838).[6] In regard to the taxes and revenue of the Athenian state he derived a great deal of his most trustworthy information from inscriptions, many of which are given in his book. When the Berlin Academy of Sciences projected the plan of a Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, Böckh was chosen as the principal editor. This work (1828–1877) is in four volumes, the third and fourth volumes being edited by J. Franz, E. Curtius, A. Kirchhoff and H. Röhl.[6] Böckh's activity was continually digressing into widely different fields. He gained for himself a foremost position amongst the investigators of ancient chronology, and his name occupies a place by the side of those of Ideler and Mommsen. His principal works on this subject were: Zur Geschichte der Mondcyclen der Hellenen (1855); Epigraphisch-chronologische Studien (1856); Über die vierjährigen Sonnenkreise der Alten (1863), and several papers which he published in the Transactions of the Berlin Academy. Böckh also occupied himself with philosophy. One of his earliest papers was on the Platonic doctrine of the world, De Platonica corporis mundani fabrica et de vera Indole, Astronomiae Philolaice (1810), to which may be added Manetho und die Hundsternperiode (1845).[6] In opposition to Otto Gruppe, he denied that Plato affirmed the diurnal rotation of the earth (Untersuchungen über das kosmische System des Platon, 1852), and when in opposition to him Grote published his opinions on the subject (Plato and the Rotation of the Earth), Böckh was ready with his reply. Another of his earlier papers, and one frequently referred to, was Commentatio Academica de simultate quae Platoni cum Xenophonte intercessisse fertur (1811). Other philosophical writings were Commentatio in Platonis qui vulgo fertur Minoem (1806), and Philolaos des Pythagoreers Lehren nebst den Bruchstücken (1819), in which he endeavoured to show the genuineness of the fragments.[6] Besides his edition of Pindar, Böckh published an edition of the Antigone of Sophocles (1843) with a poetical translation and essays. An early and important work on the Greek tragedians is his Graecae Tragoediae Principum ... num ea quae supersunt et genuine omnia sint et forma primitive servata (1808).[6] The smaller writings of Böckh began to be collected in his lifetime. Three of the volumes were published before his death, and four after (Gesammelte kleine Schriften, 1858–1874). The first two consist of orations delivered in the university or academy of Berlin, or on public occasions. The third, fourth, fifth and sixth contain his contributions to the Transactions of the Berlin Academy, and the seventh contains his critiques. Böckh's lectures, delivered from 1809-1865, were published by Bratusehek under the title of Encyklopädie und Methodologie der philologischen Wissenschaften[9] (1877; 2nd ed. Klussmann, 1886). His philological and scientific theories are set forth in Elze, Über Philologie als System (1845), and Reichhardt, Die Gliederung der Philologie entwickelt (1846). His correspondence with Karl Otfried Müller appeared at Leipzig in 1883. John Paul Pritchard has made an abridged translation of Böckh's Encyclopädie und Methodologie der philologischen Wissenschaften: August Boeckh, On Interpretation and Criticism, University of Oklahoma Press, 1968. |

アウグスト・ベック(August Böckh)またはボエック(Boeckh)[5](ドイツ語:

[bœk]; 1785年11月24日 - 1867年8月3日)は、ドイツの古典学者、古文書学者である。 アウグスト・ベック(August Böckh)またはボエック(Boeckh)[5](ドイツ語:

[bœk]; 1785年11月24日 - 1867年8月3日)は、ドイツの古典学者、古文書学者である。生涯 カールスルーエで生まれ、地元のギムナジウムで教育を受けた。1803年、ハレ大学に進学し、神学を学んだ。そこで教鞭をとっていたF.A.ヴォルフは古 典研究に熱中しており、ベッヒは神学から文献学に転じ、ヴォルフの最高の研究者となった。 1807年、彼はハイデルベルク大学のPrivatdozentとなり、まもなく特別教授に任命され、2年後には教授となった。[6]ベッヒの姓がフィ リップ・アウグストであるという一般的な誤解は、ハイデルベルクで大学の職員が「Dr phil」(doctor philosophiae)という略称を「Dr Philipp August Böckh」と読み間違えたことに由来する[7]。 1811年、彼は雄弁と古典文学の教授に任命された新しいベルリン大学に移った。死ぬまでそこに留まった。1814年にはベルリン科学アカデミーの会員に 選ばれ、長い間その幹事を務めた。1853年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの外国人名誉会員に選ばれた[8]。 1867年、81歳でベルリンで死去した。 作品 ベッヒはヴォルフのフィロロギーに関する考えを実践によって明らかにした。ベッヒは、フィロロジーを言葉に関する微細な知識と批評の技術から成るという古 い考えを捨て、フィロロジーを歴史的・哲学的な古代の知識全体(totius antiquitatis cognitio)とみなした。彼は言語学を5つの部分に分けている。第1に、時代と場所、市民制度、法律に関する知識を伴う公的行為に関する調査、第2 に、私的な事柄に関する調査、第3に、古代国民の宗教と芸術の展示、第4に、国民のあらゆる道徳的・物理的な思索と信仰、文学の歴史、第5に、言語の完全 な説明である[6]。 ベッヒは1822年に行ったラテン語の演説の中で、これらの考えを述べている(Gesammelte kleine Schriften, i.)。1850年に開催されたドイツ言語学者会議の開会式での演説で、彼は言語学とは、生活全体、したがって、ある民族の実践的・精神的傾向におけるあ らゆる文化形態とあらゆる生産物の歴史的構築であると定義した。しかし、対象が無限であるからこそ、真理を追求する刺激となり、学者たちは到達できないか らこそ努力するのである。ベッヒの文献学の区分については、フロイントの『Wie studiert man Philologie? 1806年から亡くなるまで、ベッヒの文学活動は絶えることがなかった。彼の主な著作には、ピンダール版(その第一巻(1811年)にはエピニキア語の オードのテキストが収められている)、三巻からなる論文『De Metris Pindari』、『Notae Criticae』があり、第二巻(1819年)には『Scholia』、第二巻の第二部(1821年)にはラテン語訳、注釈、断片、索引が収められてい る。これは長い間、ピンダルの最も完全な版であった。しかし、ベッヒを学者として第一の地位に押し上げたのは、とりわけメートル法に関する論考であった。 この論考は、この主題の扱いにおけるエポックを形成している。この論文の中で著者は、単なる主観的な基準によってギリシア語の音律を決定しようとするすべ ての試みを捨て去り、同時にギリシア人の音楽と詩の間に密接な関係があることを指摘した。また、ギリシア音楽の性質や、ギリシア楽器に関するあらゆる詳細 について詳細に調査し、リズムに関する古代ギリシアの作家たちの記述についても説明した。このようにして、彼はギリシアの音律を科学的に扱う基礎を築いた [6]。 彼のDie Staatshaushaltung der Athener(1817年、第2版1851年、補巻Urkunden über das Seewesen des attischen Staats、第3版1886年)は、The Public Economy of Athensというタイトルで英訳された。この本では、彼は深い学識をもって、独特の難題を研究した。彼はギリシア文学のあらゆる範囲から情報を収集し、 与えられた情報の価値を注意深く評価し、そのあらゆる部分に稀有な批評能力と洞察力を示している。同じような種類の著作に、『Metrologische Untersuchungen über Gewichte, Münzfüsse, und Masse des Alterthums』(1838年)がある[6]。 アテネ国家の税と収入に関して、彼は最も信頼できる多くの情報を碑文から得ており、その多くは彼の著書に記載されている。ベルリン科学アカデミーが『グラ エカルム碑文集』(Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum)の出版を計画したとき、ベッヒは編集長に選ばれた。この著作(1828年~1877年)は全4巻で、第3巻と第4巻はJ.フランツ、 E.クルティウス、A.キルヒホフ、H.レールが編集した[6]。 ベ ッ ク の 活 動 は 、絶 え ず 広 く 異 な る 分 野 へ と 展 開 し て い た 。彼は古代年代学の研究者の中で第一人者の地位を獲得し、その名はイデラーやモムゼンと並び称されるようになった。彼の主な著作は以下の通りである: ヘレニズムの年代史』(1855年)、『書誌年代学研究』(1856年)、『古代人の14年間の年表』(1863年)、およびベルリン・アカデミー紀要に 発表したいくつかの論文である。ベッヒは哲学にも没頭した。彼の最も初期の論文のひとつは、プラトン的な世界の教義に関するもので、『De Platonica corporis mundani fabrica et de vera Indole, Astronomiae Philolaice』(1810年)であり、これに『Manetho und die Hundsternperiode』(1845年)を加えることができる[6]。 オットー・グルッペに対抗して、彼はプラトンが地球の日周運動を肯定していることを否定し(Untersuchungen über das kosmische System des Platon, 1852)、それに対抗してグローテがこのテーマに関する自分の意見(Plato and the Rotation of the Earth)を発表すると、ベッヒはすぐに反論した。彼の初期の論文のもう一つで、よく言及されるものに、Commentatio Academica de simultate quae Platoni cum Xenophonte intercessisse fertur (1811)がある。その他の哲学的著作としては、Commentatio in Platonis qui vulgo fertur Minoem (1806)、Philolaos des Pythagoreers Lehren nebst den Bruchstücken (1819)があり、断片の真正性を示そうと努めた[6]。 ベッヒはピンダール版の他に、詩的翻訳とエッセイを添えたソフォクレスの『アンティゴネー』の版(1843年)を出版した。ギリシア悲劇に関する初期の重 要な著作に、『ギリシア悲劇劇原 理...........................................................................num ea quae supersunt et genuine omnia sint et forma primitive servata』(1808)がある[6]。 ベッヒの小規模な著作は、彼が存命中に収集され始めた。そのうちの3冊は生前に、4冊は死後に出版された(Gesammelte kleine Schriften, 1858-1874)。最初の2冊は、ベルリンの大学やアカデミー、あるいは公の場で行われた演説から成っている。第3、4、5、6集にはベルリン・アカ デミー紀要への寄稿が、第7集には評論が収められている。1809年から1865年にかけて行われたベッヒの講義は、ブラトゥセーヘクによって Encyklopädie und Methodologie der philologischen Wissenschaften[9] (1877; 2nd ed. Klussmann, 1886)というタイトルで出版された。彼の言語学的・科学的理論はElze, Über Philologie als System (1845)とReichhardt, Die Gliederung der Philologie entwickelt (1846)に述べられている。カール・オットフリート・ミュラーとの書簡は1883年にライプツィヒで出版された。 ジョン・パウル・プリチャードがベッヒのEncyclopädie und Methodologie der philologischen Wissenschaftenを抄訳している: August Boeckh, On Interpretation and Criticism, University of Oklahoma Press, 1968. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/August_B%C3%B6ckh |

1889 兵庫県神崎郡砥堀村(とほりむら)仁豊野(にぶの)(現:姫路市仁豊野)にて誕 生。

1909 第一高等学校卒業。

1912 東京帝国大学文科大学哲学科卒業、同大学院進学。高瀬照と結婚。阿部次郎との親密な交流が始まる、また安倍能成とも終生交流した。

1917 奈良を旅行し、古寺を巡る

1919 『古寺巡礼』

1920 東洋大学講師。

1920 『思想』の編集に参画

1922 法政大学教授

1925 京都帝国大学助教授

1927 (道徳思想史の 研究のため)ヨーロッパ遊学。林達夫は、岩波書店の雑誌『思想』の編集 に関与するようになる。

1928

1929 岩波書店『思想』誌に1929年「風土」論の第1章が発表、以降間欠的に連載され

る。

1931 京都帝国大学教授

1932 京都大学より文学博士号取得「原始仏教の実践哲学」

1934 東京帝国大学文学部倫理学講座教授

1935

『風土』1935年3月に「牧場」の章が完成。

1935年9月に岩波書店から『風土:人間学的考察』として刊行された。

1943

1944 『風土』改訂12刷。『日

本の臣道・アメリカの国民性』

1945 雑誌『世界』の創刊に関わる

1949 定年退官。日本学士院会員

1950 日本倫理学会を創設し会長に就任(死去ま で)

1951 『鎖国』

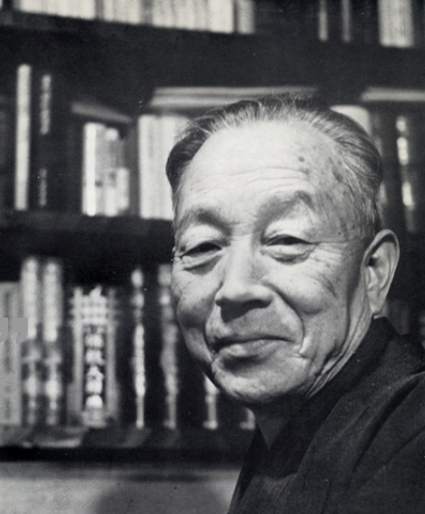

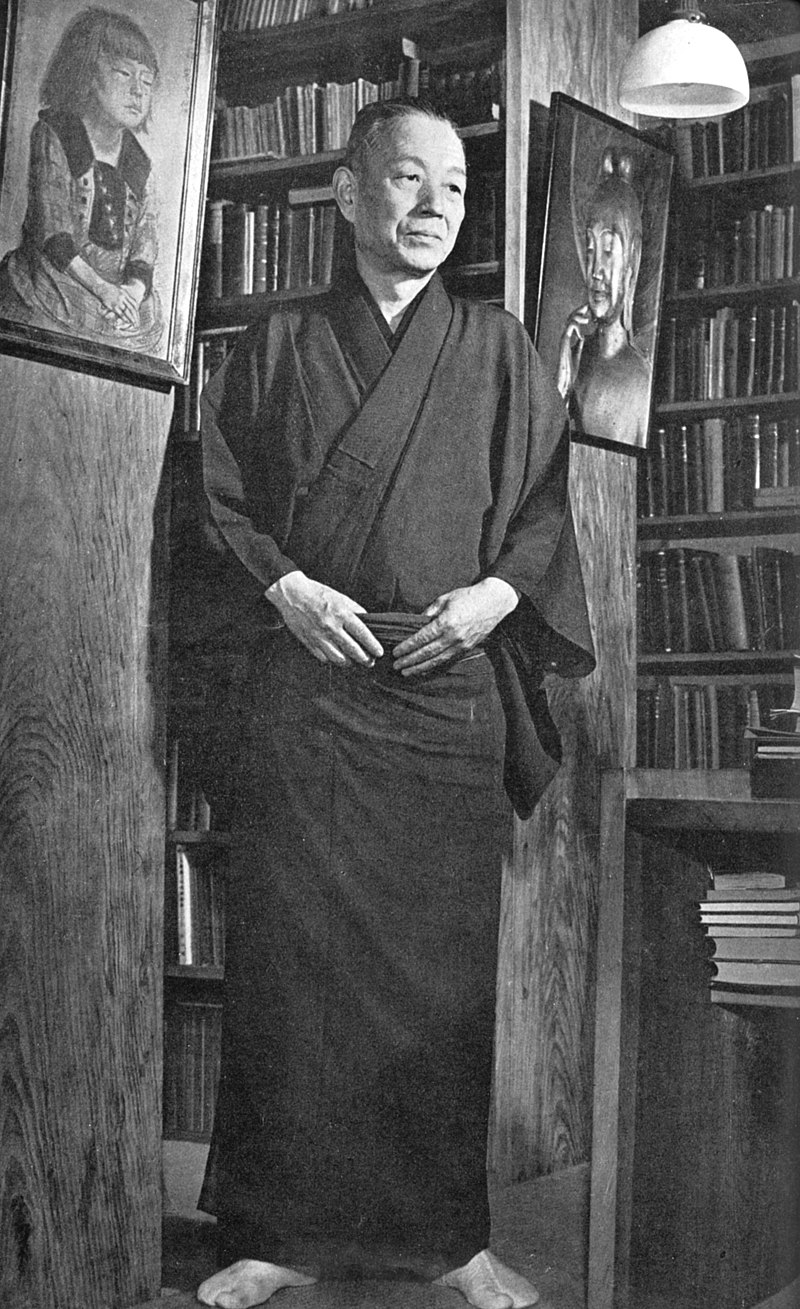

田村茂撮影 『現代日本の百人』 文芸春秋新社、1953年。

1953 『日本倫理思想史』

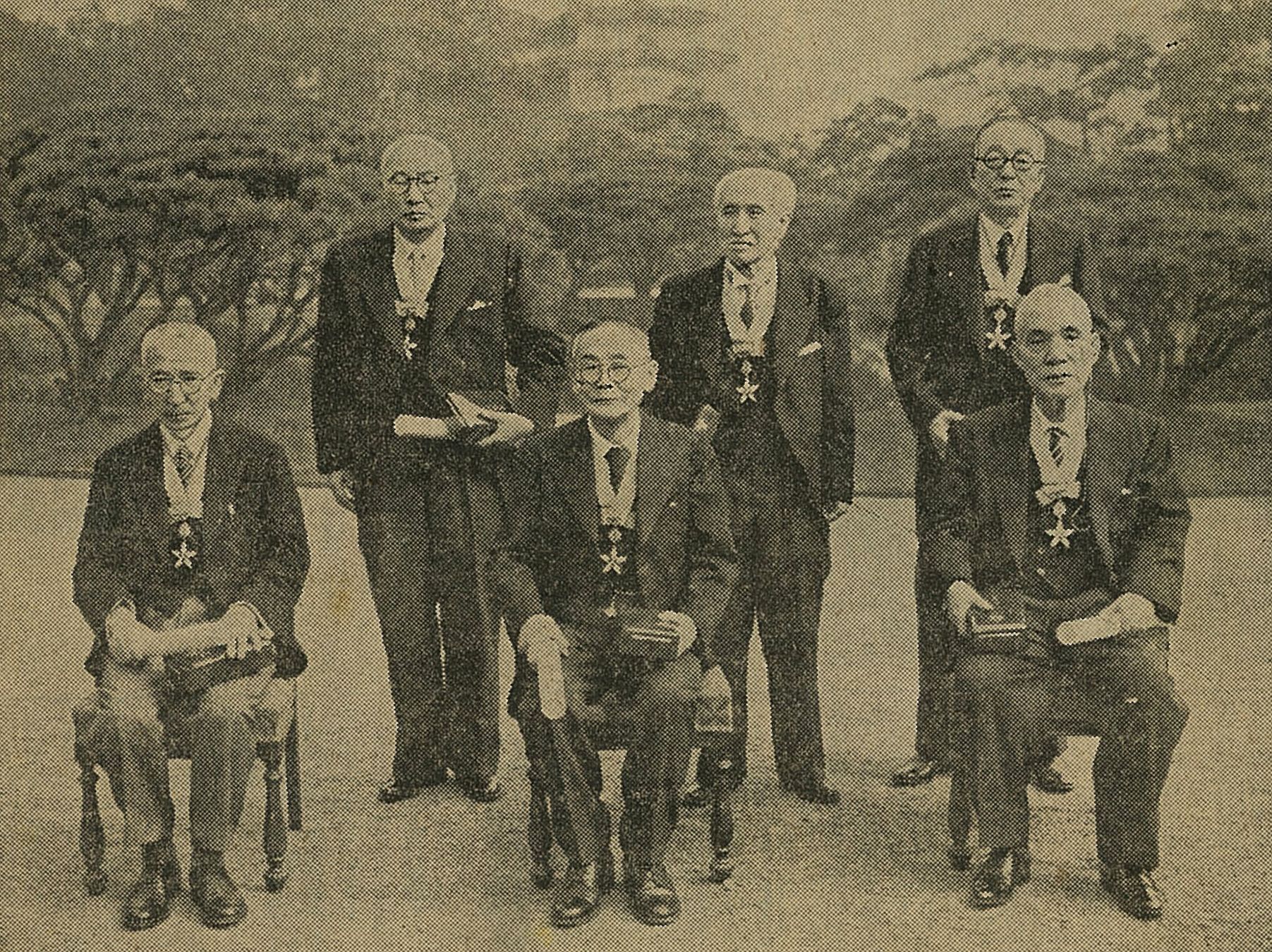

1955 毎日新聞社「毎日グラフ(1955年11月2日号)

1960 死去(71歳)

1961 A climate : a philosophical study / by Watsuji Tetsuro ; translated by Geoffrey Bownas, Tokyo : Printing Bureau, Japanese Govt.

| 和辻 哲郎(わつじ

てつろう、1889年〈明治22年〉3月1日 -

1960年〈昭和35年〉12月26日)は、日本の哲学者・倫理学者・文化史家・日本思想史家。『古寺巡礼』『風土』などの著作で知られ、その倫理学の体

系は和辻倫理学と呼ばれる。法政大学教授・京都帝国大学教授・東京帝国大学教授を歴任。日本倫理学会会員。文化勲章受章。 兵庫県出身。東大哲学科卒。ニーチェなど西洋哲学を研究。奈良の寺院建築や仏像の美を再発見し、『古寺巡礼』(1919年)も人気を博す。『人間の学とし ての倫理学』(1934年)で新しい倫理学の体系を構築。『風土』(1935年)、『面とペルソナ』(1937年)も名高い。 経歴 1889年 - 兵庫県神崎郡砥堀村(とほりむら)仁豊野(にぶの)(現:姫路市仁豊野)にて誕生。 出身校である姫路市立砥堀小学校には和辻の『ちから』の碑[3][4]が建つ。 1906年 - 旧制姫路中学校(現:兵庫県立姫路西高校)卒業。 1909年 - 第一高等学校卒業。 同年、後藤末雄、大貫晶川、木村荘太、谷崎潤一郎、芦田均らとともに同人誌、第二次『新思潮』に参加、第一号に載せたのは戯曲「常盤」。以後も、バーナー ド・ショーの翻訳などをするが、次第に文学から遠ざかる。谷崎の才能に及ばないと感じたからといわれる。 1912年 - 東京帝国大学文科大学哲学科卒業、同大学院進学。ラファエル・ケーベルを尊敬し、卒論を読んでもらいたいが為に英語で執筆した[注 1]。 静かな環境のもとで卒論に取り組むため、高座郡藤沢町(現:藤沢市)鵠沼にあった後輩高瀬弥一邸の離れを借りて執筆する。卒論完成と同時に高瀬弥一の妹、 照に求婚した。 同年、高瀬照と結婚。阿部次郎との親密な交流が始まる、また安倍能成とも終生交流した。 1913年 - 紹介を得て夏目漱石の漱石山房を訪れるようになる。『ニイチェ研究』を出版。 漱石の『倫敦塔』に強い感銘を受けた和辻は、熱烈な敬慕の情をしたためた手紙を書き送った[5]。 1915年 - 藤沢町鵠沼の妻・照の実家の離れに1918年まで住む。 この間、別の離れに安倍能成、阿部次郎も住み、交流。小宮豊隆・森田草平・谷崎潤一郎・芥川龍之介らの来訪を受ける。 1916年 - 漱石および岳父高瀬三郎の死。この時期、日本文化史に深い関心を寄せ始める。 1917年 - 奈良を旅行し、古寺を巡る。 1918年 - 東京市芝区に転居。 1919年 - 『古寺巡礼』を出版。 1920年 - 東洋大学講師 1921年 - 雑誌『思想』の編集に参画を始める。 1922年 - 法政大学教授 1925年 - 京都帝国大学助教授。京都市左京区に転居。 1927年 - ドイツ留学。(~1928年) 1928年 - 絶交事件(留学で留守中に阿部次郎が照夫人へ横恋慕したとして、阿部と絶交する) 1929年 - 龍谷大学講師兼務。 1931年 - 京都帝国大学教授[注 2] 1932年 - 大谷大学教授兼務、京都大学より文学博士号取得 「原始仏教の実践哲学」。 1934年 - 東京帝国大学文学部倫理学講座教授。東京市本郷区に転居。 1936年 - 『国体の本義』編纂委員を務める[7]。 1943年 - 宮中にて進講、講題は「尊皇思想とその伝統」。 1945年 - 雑誌『世界』の創刊に関わる。文部省が設置した公民教育刷新委員会の委員に就任[8]。 1949年 - 定年退官。日本学士院会員。 1950年 - 日本倫理学会を創設し会長に就任(死去まで)。 1951年 - 『鎖国』で読売文学賞。賞金は倫理学会に寄贈した。 1953年 - 『日本倫理思想史』で毎日出版文化賞  文化勲章授与式、後列右側が和辻哲郎[6]1955年 1955年 - 秋に文化勲章受章。 1958年 - 皇太子妃となる正田美智子の妃教育の講師を務めた。 1960年 - 心筋梗塞により練馬区南町の自宅で死去(71歳)。墓所は鎌倉市山ノ内の東慶寺。戒名は明徳院和風良哲居士[9]。 |

|

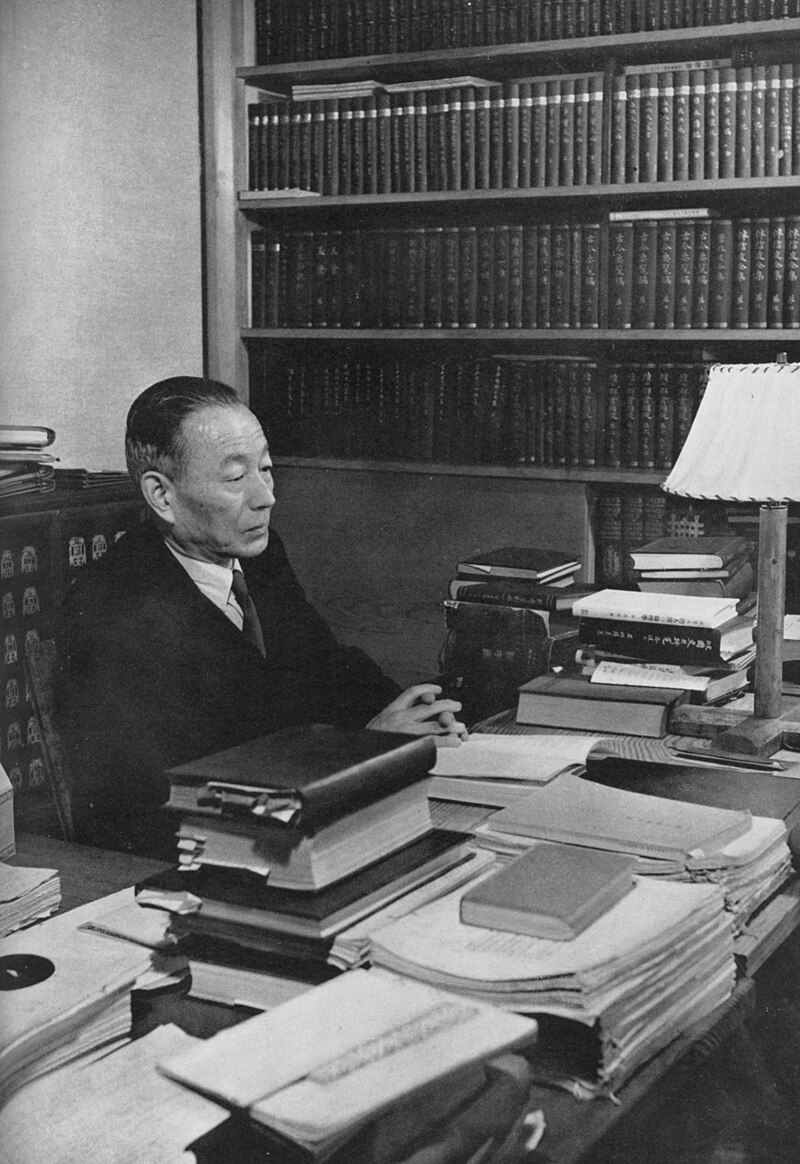

人物 着物姿の和辻(田村茂撮影) 日本的な思想と西洋哲学の融合、あるいは止揚とでもいうべき境地を目指した稀有な哲学者と評価される。主著の『倫理学』は、近代日本における独創性を備え た最も体系的な哲学書の一つであると言われている。 西田幾多郎などと同じく日本独自の哲学体系を目指した京都学派の一人として扱われることがある一方で、東京帝国大学文学部倫理学教室教授でもあり、相良 亨、金子武蔵、湯浅泰雄らを始め後進を多く育てた。現在でも高校倫理の教科書では、『風土』の「モンスーン型」や『日本倫理思想史』の「祀る神・祀られる 神」といった、和辻倫理学に基づいた記述がなされている[1]。 1988年度より(生誕百年記念を期し)姫路市の主催で和辻哲郎文化賞が、人文系著作に毎年授与されている。 和辻の全蔵書は、1961年に多くの仕事を共にした谷川徹三(法政大学教授ほか)の仲介で法政大学に寄贈された。長らく未整備だったが、1985年に法政 大学図書館長となった浜田義文が中心となり、整理が開始され、1994年に「法政大学和辻哲郎文庫目録」がまとめられた。浜田は「和辻文庫の生命は、和辻 の読んだ書物への書き込みにあるといって過言でない」と述べている。 『和辻哲郎全集』は校訂の際、旧字体から新字体、旧仮名遣いから現代仮名遣いへ改められ、読みやすくなった一方で学術書[2]としては批判を受けている。  1949年(土門拳撮影) |

|

| 業績 倫理学 『人間の学としての倫理学』では、西洋哲学の個人主義を批判し、人間という字が本来意味するように、それは間柄的存在であるといい、個人と社会の相互作用 が不調に陥ると全体主義・個人主義が台頭すると述べた。 『倫理学』も日本倫理学を打ち立てようとするものだったが途中で破綻し、戦後はあまり注目されなくなった。倫理は「個人意識」ではなく、他者との間の「実 験的行為的連関」の中で働いている。「間柄」の中で集団から個人への強制、個人の集団からの自立の往復が倫理を支える原理で、そのバランスがよい状態が行 為の善さである。善悪の基準は「人倫的組織」のなかで人々が常識として共有する「行為の仕方」である。その組織は家族、親族、地縁共同体、経済的組織、文 化共同体、国家で、それぞれに「行為の仕方」がある。こうした組織を外から「力」によって支えるのが「人倫的組織の人倫的組織」である国家である。「文化 共同体」は「言語の共同の範囲」であり、国家もその範囲となる。人倫的組織を「外護」する国家の法を守り従軍義務を果たすのが臣民の義務である。政府が人 倫的組織の存続を保証する「正義」(「仁政」)は「国家自身の根本的な行為の仕方」である。問題点も多く、臣民の戦争動員、倫理が国家内部にしか通用しな いため国際犯罪が倫理的問題にできないと言う「民族」の範囲の問題や、「間柄」のなかで果たす役割(「資格」)がないと人間がただの物体となってしまうよ うな人間観の問題がある[20]。 倫理思想史 『日本倫理思想史』では、古代から明治までの倫理思想を描き出した。倫理学は仏教や朱子学など体系性を持った外来思想であり、中国の思想になってしまうた め、倫理思想という言葉で日本の倫理思想史を題材にした。戦前に出版された『尊皇思想とその伝統』を大幅に増補したものであり、和辻の持つナショナリズ ム、天皇観が現れている。戦後、和辻は象徴天皇制論を発表した。 戦後間もなく刊行した『鎖国 日本の悲劇』では、江戸時代の鎖国により西洋の文物を輸入できなかったために、日本の近代化が遅れたとする。 風土 『風土』は欧州留学中、ハイデッガーの『存在と時間』に示唆を受け、時間ではなく空間的に人間考察をおこなったもの。1935年に初刊。第二次世界大戦後 に盛んになった日本文化論の先駆的な作品ともいえる。風土をモンスーン(日本も含む)、砂漠、牧場に分け、それぞれの風土と文化、思想の関連を追究した。 『風土』の中に見られる「風土が人間に影響する」という思想は、悪しき環境決定論であるという批判や、天皇制肯定論になっているという批判がある。一方で この風土という考え方こそが、グローバリゼーションの弊害をとどめる積極的な方法論である、とする評価(オギュスタン・ベルク)もある。 古寺巡礼 詳細は「古寺巡礼 (和辻哲郎)」を参照 |

|

| 著作 『ニイチェ研究』(内田老鶴圃、1913年、筑摩書房(新編)、1942年)- 権力意思を中心にニーチェを論じる。世界的に見ても先進的な解釈を展開。 『ゼエレン・キエルケゴオル』(内田老鶴圃、1915年、筑摩書房(新編)、1947年)- 日本初のキルケゴール研究 『偶像再興』(岩波書店、1918年)- 随想、短編論文集 『古寺巡礼』(岩波書店、1919年、改稿版1947年)- 飛鳥奈良の仏教美術を紹介し、古寺巡りの先駆となった。 『日本古代文化』(岩波書店、1920年、改稿版1942年、新稿版1951年)- 和辻哲郎自身が最も愛し、自信を持っていたという。 『日本精神史研究』(岩波書店、1926年、改版1970年)- 沙門道元、源氏物語について ほか 『原始基督教の文化史的意義』(岩波書店、1926年) 改版『原始キリスト教の文化史的意義』(1971年) 『原始佛教の実践哲学』(岩波書店、1927年、改訂版1948年、改版1970年、復刊1986年) 『人間の学としての倫理学』(岩波書店、1934年、岩波全書(新編)、1949年、改版1971年、新版1981年) 『続 日本精神史研究』(岩波書店、1935年) - 日本の文芸と仏教思想ほか 『風土 人間学的考察』(岩波書店、1935年、改版1967年) 『カント 実践理性批判』(「大思想文庫18」岩波書店、1935年、復刊1985年) 『面とペルソナ』(岩波書店、1937年、復刊1984年)- 随想、短篇論文集 『倫理学』(岩波書店(上中下)、1937年 - 1949年/改版(上下)1965年)- ※戦後重版に際し一部記述が改稿 『人格と人類性』(岩波書店、1938年) 『孔子』(「大教育家文庫1」岩波書店、1938年、復刊1984年/植村書店、1948年/角川文庫、1955年) 『尊皇思想とその傳統』(岩波書店〈日本倫理思想史 第1卷〉、1943年) 『日本の臣道 アメリカの國民性』[21](筑摩書房、1944年) - 占領期ではGHQ発禁図書に指定 『ホメーロス批判』(要書房、1946年) 『國民統合の象徴』(勁草書房、1948年)- 皇室論、国体論で「象徴天皇制」を擁護 『ポリス的人間の倫理学』(白日書院、1948年、岩波書店、1971年) 『ギリシア倫理学史』(要書房〈要選書〉、1951年) 『ケーベル先生』(弘文堂〈アテネ文庫〉、1948年)- 小冊子 『イタリア古寺巡礼』(要書房、1950年、角川文庫[22]、1956年)- 1920年代半ばの欧州留学先からの手紙を元にした。 『鎖國 日本の悲劇』(筑摩書房、1950年、筑摩叢書、1964年)- 後者は現行の仮名表記 『近代歴史哲学の先駆者』(弘文堂〈アテネ新書〉、1950年)- ヴィーコの先駆的紹介 『埋もれた日本』 (新潮社、1951年、新潮文庫、1980年)- 「新潮」等に戦後に著した随想や追悼記 『日本倫理思想史』(岩波書店(上下)、1952年、改訂版1959年、復刊1986年ほか) - 武士道等の論文集 『日本藝術史研究 歌舞伎と操浄瑠璃』(岩波書店、1955年、改版1971年、再版1979年) 『桂離宮 製作過程の考察』(中央公論社、1955年)- 写真渡辺義雄 『桂離宮 様式の背後を探る』(新書判:中央公論社、1958年)- 建築史家太田博太郎に考証の誤りを指摘され大幅に書き換えた 『自叙傳の試み』(中央公論社、1961年)「中央公論」に連載。一高時代までの未完作 『故国の妻へ』(角川書店、1965年) 『妻 和辻照への手紙』(講談社学術文庫(上下)、1977年) 『黄道』(角川書店、1965年)- 晩年の随想、短編論文集 『初旅の記』(新潮社、1972年)- 若き日の日記など 『仏教倫理思想史』(岩波書店、1985年)-「全集19」の単行版 『沙門道元』(隆文館「現代仏教名著全集」[23]、1987年) 全集 『和辻哲郎全集』(岩波書店 全20巻、1961-1963年)- 現行での仮名表記 第二次(1976年-1978年)、最終20巻目のみ増補、冊子判の「全集補遺」も同時刊行 増補版(全25巻・別巻2、1989-1992年)- 生誕100年を期に刊行、新たに小篇・書簡集・ノート等を収録 ニイチェ研究、ゼエレン・キェルケゴオル(金子武蔵解説) 古寺巡礼、桂離宮、人物埴輪の眼、麦積山塑像の示唆するもの(谷川徹三解説) 日本古代文化、埋もれた日本(古川哲史解説) 日本精神史研究、続 日本精神史研究(古川哲史解説) 原始仏教の実践哲学、仏教哲学の最初の展開(中村元解説) ケーベル先生、ホメーロス批判、孔子、近代歴史哲学の先駆者(古川哲史解説) 原始キリスト教の文化的意義、ポリス的人間の倫理学(金子武蔵解説) 風土、イタリア古寺巡礼(谷川徹三解説) 人間の学としての倫理学、カント 実践理性批判、人格と人類性(金子武蔵解説) 倫理学(上) 倫理学(下)(金子武蔵解説) 日本倫理思想史(上) 日本倫理思想史(下)(古川哲史解説) 尊皇思想とその伝統、日本の臣道、国民統合の象徴(古川哲史解説) 鎖国(古川哲史解説) 歌舞伎と操り浄瑠璃(古川哲史解説) 偶像再興、面とペルソナ、アメリカの国民性(古川哲史解説) 自叙伝の試み(安倍能成解説) 仏教倫理思想史(中村元解説) - 24. 各・小篇 全5巻 25. 書簡(18歳より、没時の71歳までの書簡) 別巻1(資料「講義ノート」) 選集 『昭和文學全集50 和辻哲郎集』(古川哲史解説、角川書店、1954年) 『現代知性全集36 和辻哲郎集』(日本書房、1961年) 復刻版『日本人の知性5 和辻哲郎』(学術出版会、2010年) 『現代日本思想大系28 和辻哲郎』(唐木順三編[24]、筑摩書房、1963年) 『近代日本思想大系25 和辻哲郎集』(梅原猛編、筑摩書房、1974年) 『京都哲学撰書 第8巻 人間存在の倫理学』(米谷匡史編・解説、燈影舎(一燈園)、2000年) 『京都哲学撰書 第24巻 新編 日本精神史研究』(藤田正勝編・解説、燈影舎、2002年) 『和辻哲郎仏教哲学読本 1・2』(書肆心水、2011年) 『和辻哲郎日本古代文化論集成』(書肆心水、2012年) 別巻2(講演筆記 未定稿 断片・メモ 公文書等 補遺) |

|

| 文庫・選書判 『古寺巡礼』(岩波文庫、1979年、改版2009年、ワイド版1991年、改版2010年) 『風土 人間学的考察』(岩波文庫、1979年、改版2010年、ワイド版1991年) 『鎖国 日本の悲劇』(岩波文庫(上・下)、1982年) 『孔子』(岩波文庫、1988年、ワイド版1994年) 『イタリア古寺巡礼』(岩波文庫、1991年) 『日本精神史研究』(岩波文庫、1992年、ワイド版2005年) 『和辻哲郎随筆集』(岩波文庫、1995年)- 坂部恵編・解説 『倫理学』(岩波文庫(全4巻)、2007年)- 熊野純彦注・解説 『人間の学としての倫理学』(岩波文庫、2007年) 『日本倫理思想史』(岩波文庫(全4巻)、2011-2012年)- 木村純二注・解説 『道元』(河出文庫、2011年) 『偶像再興・面とペルソナ 和辻哲郎感想集』(講談社文芸文庫、2007年) 『初版 古寺巡礼』(ちくま学芸文庫、2012年) - 衣笠正晃解説 『初稿 倫理学』(ちくま学芸文庫、2017年) - 苅部直編・解説 『桂離宮 様式の背後を探る』(中公文庫、1991年、改版2011年) 『自叙伝の試み』(中公文庫、1992年) 『日本語と哲学の問題』(景文館書店、2016年)- 小冊子 『新編 国民統合の象徴』(中公クラシックス、2019年)- 苅部直解説、佐々木惣一との国体論争も収録 翻訳・校訂 バーナード・ショー『恋をあさる人』(現代社、1913年) 『ニイチエ書簡集』(岩波書店、1917年) カアル・ラムプレヒト『近代歴史学』(岩波書店、1919年) サミュエル・H・ブチァー『希臘天才の諸相』(田中秀央共訳、岩波書店、1923年) 『ギリシア精神の様相』田中・寿岳文章共訳、岩波文庫、1940年 - 度々復刊 『ストリントベルク全集 第2 或魂の発展』岩波書店、1924年 『ストリントベルク全集 第4 痴人の告白』林達夫共訳、岩波書店、1924年 ニーチェ『愛する人々へ 書簡集』 手塚富雄共訳、要書房「要選書」、1950年 『正法眼蔵随聞記』懐奘編、岩波文庫、1929年、改版(中村元補訂)、1982年 『葉隠』 古川哲史共校訂、岩波文庫(上中下)、1940年 - 度々再版 夫人・友人らによる回想、伝記、対談 『和辻哲郎の思ひ出』 和辻照編[25]、岩波書店 1963年。前年に私家版刊 和辻照『和辻哲郎とともに』新潮社 1966年、再版1976年 高坂正顕『西田幾多郎と和辻哲郎』新潮社 1964年 『和辻哲郎座談』中公文庫、2020年。苅部直解説、対話5編・座談5編の計10編 弟子たちの研究、伝記 吉沢伝三郎『和辻哲郎の面目』 筑摩書房 1994年/平凡社ライブラリー 2006年 湯浅泰雄『和辻哲郎』 ミネルヴァ書房 1981年/ちくま学芸文庫 1995年 『和辻哲郎研究 湯浅泰雄全集13 日本哲学・思想史VI』 白亜書房 2008年(のちBNP) 『和辻哲郎 人と思想』 湯浅泰雄編、三一書房 1973年。討論+論集 勝部真長『和辻倫理学ノート』 東京書籍〈東書選書〉 1979年 勝部真長『若き日の和辻哲郎』 中公新書 1987年/PHP文庫 1995年 近年刊行の研究書 熊野純彦『和辻哲郎-文人哲学者の軌跡』 岩波新書 2009年 苅部直『光の領国 和辻哲郎』 創文社〈現代自由学芸叢書〉 1995年/岩波現代文庫 2010年 宮川敬之『和辻哲郎-人格から間柄へ 〈再発見日本の哲学〉』 講談社 2008年/講談社学術文庫 2015年 坂部恵『和辻哲郎-異文化共生の形』 岩波書店〈20世紀の思想家〉 1986年/岩波現代文庫 2001年 小牧治『和辻哲郎 人と思想』 清水書院〈Century books〉 1986年、新装版2015年。入門書(新書判) 小堀桂一郎『和辻哲郎と昭和の悲劇』 PHP新書、2017年。副題「伝統精神の破壊に立ちはだかった知の巨人」 三嶋輝夫『和辻哲郎-建築と風土』 ちくま新書、2022年 子安宣邦『和辻倫理学を読む』 青土社 2010年 牧野英二『和辻哲郎の書き込みを見よ! 和辻倫理学の今日的意義』 法政大学出版局 2009年、増補版2010年 「蔵書」書き込みの調査・検証で、前者は生誕120年記念企画展の「解説・図録」 市倉宏祐『和辻哲郎の視圏』 春秋社 2005年 仲正昌樹『〈日本哲学〉入門講義 西田幾多郎と和辻哲郎』 作品社 2015年 『和辻哲郎の人文学』 木村純二・吉田真樹 編、ナカニシヤ出版 2021年 犬飼裕一『和辻哲郎の社会学』 八千代出版、2016年 飯嶋裕治『和辻哲郎の解釈学的倫理学』 東京大学出版会 2019年 ハンス・リーダーバッハ『ハイデガーと和辻哲郎』 平田裕之訳、新書館 2006年 荘子邦雄『和辻哲郎の実像』 良書普及会 1998年 『甦る和辻哲郎』 佐藤康邦、清水正之、田中久文、〈叢書倫理学のフロンティア5〉ナカニシヤ出版 1999年 根来司『和辻哲郎-国語国文学への示唆』 有精堂出版 1990年 津田雅夫『和辻哲郎研究-解釈学・国民道徳・社会主義』(青木書店 2001年、増補版2014年) 「第4章 大正教養派のイタリア―写真で見た名画 和辻哲郎」末永航 -『イタリア、旅する心-大正教養世代のみた都市と文化』より(青弓社、2005年) 「第7章 和辻哲郎『風土』成立の時空と欧州航路」稲賀繁美 -『欧州航路の文化誌』より(橋本順光・鈴木禎宏編、青弓社、2017年) 『理想 No.677号 特集和辻哲郎』(理想社 2006年) 「和辻哲郎と濱田義文」(笠原賢介「法政哲学」 2005年) |

|

◎『風土』のウィキペディア(日本語)の短い解説 (→池田の2015年のノート「和辻哲郎『風土』1929-1935」)

「風土論が展開されていく中で見逃せないのが日本の

哲学者・和辻哲郎が著した『風土』(1935年)である。サブタイトルに『人間学的考察』とありハイデッガーの哲学に示唆を受け、歴史への視点を場所に移

して論じたものである。和辻によると「風土」は単なる自然現象ではなく、その中で人間が自己を見出すところの対象であり、文芸、美術、宗教、風習などあら

ゆる人間生活の表現が見出される人間の「自己了解」の方法であるという。そしてこうした規定をもとに具体的な研究例として1.モンスーン(南アジア・東ア

ジア地域)2.砂漠(西アジア地域)3.牧場(西ヨーロッパ地域)を挙げ、[3→

後の版にはこれに4.ステップ(ロシア・モンゴル地域)5.アメリカを加えている]それぞれの類型地域における人間と文化のあり方を把握

しようとした。和辻の風土論はユニークなものとして受け入れられ、各方面に与えた影響も大きく後の比較文化論などに影響を与えた。」

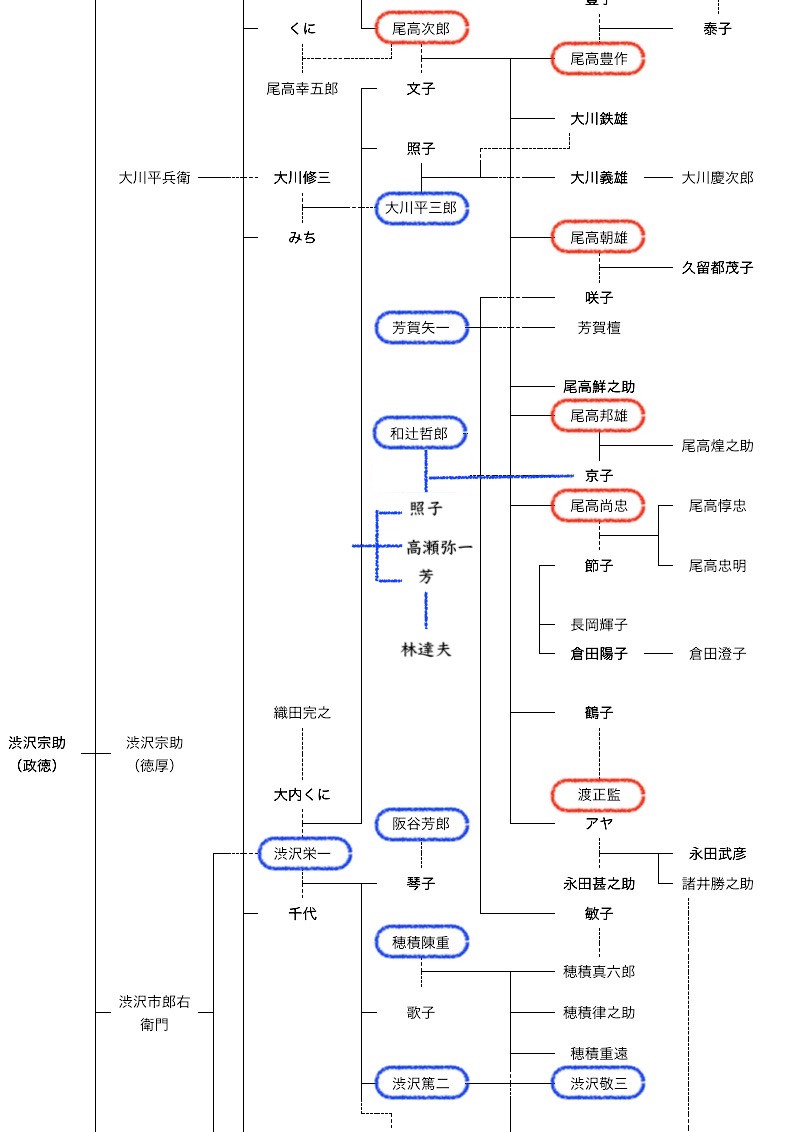

◎妻・照子の姉妹の夫の林達夫(1896-1984)の『思想』編集への関与は、1927年からは じまる

親族

『春の来た日に和辻哲郎ここに生まれる』

和辻哲郎生家の碑(姫路市仁豊野、国道312号沿い)[3]

父親は神崎郡砥堀村仁豊野(現:姫路市仁豊野)の医師・和辻瑞太郎で、和辻家は代々続く医家の家系であった[10]。瑞太郎は「医は仁術」を体現したよう

な人物で、明治に入っても東京に出ていこうともせず、丹羽篠山の山奥で農民の医療に生涯を捧げた[11]。瑞太郎の弟に京都大学医学部耳鼻咽喉科初代教授

の和辻春次がおり、その子供には大阪商船専務、京都市長、造船協会理事長などを務めた和辻春樹(船舶工学者)と、朝日新聞記者の和辻廣樹(歌手のロミ・山

田の実父)、岡山医大学長・田中文夫に嫁いだ娘のみつがいる[10][12][13]。母親のまさは印南郡神吉村の庄屋の娘で、その甥に最高裁判所判事の

田中二郎がいる[10]。

妻の照子(1889年 -

1977年)は横浜の貿易商・高瀬三郎の娘で、友人高瀬弥一の妹である。結婚時に持参金として照子の父から鵠沼の土地1万坪を贈られる[14]。長女の京

子(1914年 -

2013年)は社会学者の尾高邦雄に嫁し、経済学者の尾高煌之助をもうけた。京子は幼少のころ中勘助に偏愛されたことでも知られる。邦雄の兄尾高朝雄は東

京帝国大学法学部を出たあと、和辻在任中の京都大学哲学科で学んでいる。長男の夏彦(1921年 -

1979年)は武蔵高等学校中学校教師(倫理)[15]、目白学園女子短期大学教授などを務めた。夏彦の妻の和辻雅子(1926年 -

2013年)は夫の没後、東宮女官として美智子妃に仕え[16]、1985年からは宮内庁御用掛や侍従職御用掛として紀宮に仕えた[17]。和辻との共訳

書もある林達夫は和辻と相婿の義兄弟(妻の妹の夫)である。

和辻夫妻が暮らした練馬の自宅は神奈川県秦野にあった江戸時代後期の民家を移築したもので、1961年に川喜多長政・かしこ夫妻が購入して鎌倉に再移築

し、来日した映画関係者を迎える場として使われた[18][19]。映画『東京画』(1985年)の撮影にも使用された。その後鎌倉市の所有となり、

2000年には景観重要建造物に指定され、春夏に公開されている[18]。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099