There is no such thing as society !!

池田光穂

オックスフォード英語辞典(OED)の「社会 (Society)」の最初の定義はこのように書いてある。

Association with one's fellow men, esp. in a friendly or intimate manner; companionship or fellowship. Also rarely of animals (quot. 1774).

【翻訳】ある人の仲間と共にある、とりわけ友好的な いしは親密な流儀での、連合(アソシーエション)のこと。仲間付き合い、親睦的結社。時には(人間以外の)動物にもみられる。[以上の用例は 1774年の下記]。

1774 Goldsm. Nat. Hist. (1776) V. 153 As Nature has formed the rapacious class for war, so she seems equally to have fitted these for peace, rest, and society.

【翻訳】1776年に出版されたオリバー・ゴールド スミス(Oliver Goldsmith, 1730-1774)『地球と生きている自然に関する歴史(An History of the Earth and Animated Nature)』5巻153ページからの用例:「自然は闘争のための強欲な階級を造ったがゆえに、自然は同様に、平和と休息と社会のための階級をも併せて もつようになった」。

OEDはそれよりも140年ほど古い用例を示してい るが、この現代的用法の起源は18世紀後半の博物学者ゴールドスミスのものに依拠させている。

さて、ではこのことは、何を意味するのだろうか? 私の考えでは、社会というものの用例は、啓蒙主義にもとづく市民社会の登場と深い関係があるのではないかということである。これは古い用法では、社会の語 源となったラテン語の形容詞 socius(主格・男性形)——意味は分有している・加盟している・家族親族である・連盟している——の用法の対象の範囲が狭かったの対して、国家を構 成するメンバーである市民の啓蒙時代における「急速な拡張」のせいで、社会というものの定義が想定する範囲がきわめて大きなものになったということに他な らない。すなわち、現代の我々の社会が想像する一番大きな集団は、まさに市民社会(civil society)そのものなのである。

市民社会の確立は、あるいはそのような権利主張が公

共のものになる根拠は、市民からの代表者が政治権力を司る民主主義(democracy)——人民による権力掌握(demos+cracia)——という

考え方が確立しつつあったということである。この最たる力の行使の結果がブルジョア革命である。

今日における社会の概念は、市民による共同性を前提 にしているが、それが古代から引き継いだ親密性の範疇=親密圏(intimate sphere)と公共性の範疇=公共圏(public sphere)との重なりや、時代的取り扱いについては、さまざまな議論がある。

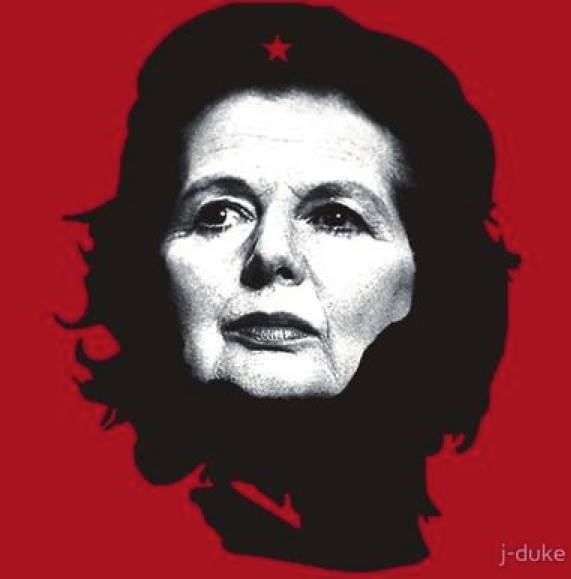

■マーガレット・サッチャーさん(Margaret Hilda Thatcher, 1925-2013)の「社会はない」発言(1987年)の出典は?

| The phrase "there is

no such thing as society" was famously uttered by former UK Prime

Minister Margaret Thatcher in a 1987 interview, meaning individuals and

families must first look out for themselves, not expect the government

to solve all problems, a statement rooted in her emphasis on

self-reliance and limited government. While critics saw it as callous,

Thatcher argued she meant people should care for themselves and

neighbors, not solely rely on the state, a point often lost in the

truncated quote, which stresses individual responsibility over

collective dependence on government. |

「社会など存在しない」という発言は、1987年のインタビューで元英

国首相マーガレット・サッチャーが有名に口にしたものだ。これは個人や家族がまず自らを守らねばならず、政府が全ての問題を解決するのを期待すべきではな

いという意味であり、彼女の自立と小さな政府を重視する姿勢に根ざした主張である。批判派はこれを冷酷な発言と捉えたが、サッチャーは「人々は国家だけに

頼るのではなく、自分自身と隣人を支えるべきだ」という意味だと主張した。この核心は、政府への集団的依存よりも個人の責任を強調するこの引用句が省略さ

れることで、しばしば見失われてしまうのである。 |

| Thatcher's View: She believed

society was made up of individuals and families, and people should

prioritize self-sufficiency before looking to the state for solutions,

a core tenet of her conservative, individualistic ideology. |

サッチャーの見解: 彼女は社会は個人と家族で構成されており、人々は国家に解決策を求める前に自立を優先すべきだと信じていた。これは彼女の保守的で個人主義的なイデオロギーの中核をなす信条である。 |

| The Full Quote: "I think we've

been through a period where too many people have been given to

understand that if they have a problem, it's the government's job to

cope with it... And, you know, there is no such thing as society. There

are individual men and women, and there are families, and no government

can do anything except through people, and people must look to

themselves first. It's our duty to look after ourselves and then, also,

to look after our neighbour". |

完全な引用文:「我々は、問題があれば政府が対処するのが当然だと考え

させられてきた時代を経験してきたと思う…

そして、社会なんてものは存在しない。個々の男女がいて、家族がいて、政府は人々を通じてしか何もできない。人々はまず自分自身を見なければならない。自

分自身の面倒を見るのが義務であり、そして隣人の面倒も見なければならないのだ」 |

| Political Interpretation: The

statement aimed to shift focus from state welfare to personal

responsibility, but was widely interpreted as promoting selfishness and

undermining community. |

政治的解釈:この声明は、国家による福祉から個人的な責任へと焦点を移すことを目的としていたが、広く利己主義を助長し共同体を損なうものと解釈された。 |

| Impact and Reactions Criticism: Many found the statement heartless, suggesting it encouraged neglecting the needy. |

影響と反応 批判:多くの人々がこの声明を冷酷だと感じ、困窮者を顧みないことを助長していると指摘した。 |

| Support & Nuance: Supporters

argued it was taken out of context, emphasizing personal

responsibility, similar to John F. Kennedy's "ask not what your country

can do for you". |

支持とニュアンス:支持者たちは文脈から切り離された主張だと反論し、個人的な責任を強調した。これはジョン・F・ケネディの「国が君のために何ができるかではなく、君が国のために何ができるかを問え」と同様の主張である。 |

| Political Legacy: The phrase

became iconic of Thatcherism, influencing subsequent political

discussions on individualism versus collectivism, with later leaders

like David Cameron proposing "Big Society" initiatives to foster

community action. |

政治的遺産:この言葉はサッチャー主義の象徴となり、個人主義と集団主義をめぐる後の政治議論に影響を与えた。デイヴィッド・キャメロンのような後任の指導者たちは、地域社会の活動を促進する「ビッグ・ソサエティ」構想を提唱した。 |

ウィキペディア(英語)によりますと1987年の Woman's Own 誌において、下記のようなインタビューへの返答をしています。

"I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand "I have a problem, it is the Government's job to cope with it!" or "I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!" "I am homeless, the Government must house me!" and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing!"

つまり、

「…彼ら(=政府に文句を言う人たち)は、自分たち の問題を社会のせいにするのです、 誰が社会なのでしょうか? そんなものは存在しないのです!」 と言い、「個々の男たちと女たちがおり、家族がいます、そして人々を通してしか政府はなにも為しえないのです、人々はまず自分たち自身を省みなければなり ません(people look to themselves first)」を含む次のような言葉が続きます。

There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour and life is a reciprocal business and people have got the entitlements too much in mind without the obligations." (この出典は、"Interview for Woman's Own ("no such thing as society") with journalist Douglas Keay". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 23 September 1987.)

個人として男も女もいるし、家族もいる。政府は人々を通じてでなければ何もできない。そして人々はまず自分自身を顧みる。自分自身の面倒を見るのが義務であり、隣人の面倒を見る手助けもする。人生は相互扶助の営みだ。人々は義務を顧みず、権利ばかりを過度に意識している。

"During her tenure as

Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher oversaw a number of neoliberal

reforms, including tax reduction,

exchange rate reform, deregulation, and privatisation.These

reforms were continued and supported by her successor John Major.

Although opposed by the Labour Party, the reforms were largely left

unaltered when Labour returned to power in 1997. Indeed, the Labour

government under Tony Blair even implemented a variety of privatisation

and deregulation measures that had not been completed under prior

governments." - neoliberalism

■さて、サッチャーの「社会などない」発言よりも 29年前に、マルクス主義文芸批評家・社会学者のレイモンド・ウィリアムズは、『文化と社会』(1958年——ただし私が参照したのは1960年版)のな かで、こう喝破しています。

「大衆は存在しない。人びとを大衆とみなす方法があ

るだけだ」と。There are in fact no masses; there are only ways of seeing

people as masses (Williams 1960:319).

■大衆と社会に関するレイモンド・ウィリアムズの主 張

F. R, Leavis, in the

pamphlet Mass Civilization and Minority Culture published in 1930,

を論じるなかで、

What, in fact, do we mean by 'mass'? Do we mean a democracy dependent

on universal suffrage, or a culture dependent on universal education,

or a reading public dependent on universal literacy? If we find the

products of mass-civilization so repugnant, are we to identify the

suffrage or the education or the literacy as the agents of decay? Or,

alternatively, do we mean by mass-civilization an industrial

civilization, dependent on machine production and the factory system?

Do we find institutions like the popular press and advertising to be

the necessary consequences of such a system of production? Or, again,

do we find both the machine-civilization and the institutions to be

products of some great change and decline in human minds? Such

questions, which are the common places of our generation, inevitably

underlie the detailed judgements. And Leavis, though he has never

claimed to offer a theory of such matters, has in fact, in a number of

ways, committed himself to certain general attitudes which amount to a

recognizable attitude towards modern history and society.

(Williams 1960:275-276)

では、我々が「大衆」という言葉で何を意味しているのか。それは普通選挙に依存する民主主義なのか、普遍的教育に依存する文化なのか、それとも普遍的識字

能力に依存する読者層なのか。もし大衆文明の産物がそれほど嫌悪すべきものだと感じるなら、衰退の要因として選挙権や教育や識字能力を特定すべきなのか。

あるいは、大衆文明とは機械生産と工場制度に依存する産業文明を指すのか。大衆向け新聞や広告といった制度は、そのような生産体制の必然的帰結だと考える

のか。あるいは、機械文明も制度も、人間の精神における何らかの大きな変化と衰退の産物だと考えるのか。こうした問いは我々の世代にとって当たり前のこと

であり、詳細な判断の根底に必ず横たわっている。そしてリーヴィスは、こうした事柄について理論を提示したことは一度もないが、実際には様々な形で、現代

の歴史と社会に対する認識可能な態度に帰着する特定の一般的な姿勢を自らに課してきたのである。

if the working people are really in this helpless condition, that they

alone cannot go beyond 'trade-union consciousness' (that is, a negative

reaction to capitalism rather than a positive reaction towards

socialism) , they can be regarded as 'masses' to be captured, the

objects rather than the subjects of power. Almost anything can then be

justified.(p.303)

もし労働者階級が本当にこの無力な状態にあり、彼ら

自身だけでは「労働組合意識」(つまり社会主義への積極的反応ではなく資本主義への消極的反応)を超えられないのなら、彼らは掌握すべき「大衆」と見なさ

れ、権力の主体ではなく対象となる。そうなれば、ほとんど何でも正当化できるのだ。(p.303)

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the same point is clear, and the terms are now

direct, The hated politicians are in charge, while the dumb mass of

'peoples' goes on in very much its own ways, protected by its very

stupidity. The only dissent comes from a rebel intellectual: the exile

against the whole system. Orwell puts the case in these terms because

this is how he really saw present society, and Nineteen Eighty Four is

desperate because Orwell recognized that on such a construction the

exile could not win, and then there was no hope at all. (Pp.312-313)

『1984年』でも同じ点が明確で、表現はより直接

的だ。憎むべき政治家たちが権力を握り、愚かな大衆は愚かさゆえに守られながら、相変わらず自分たちのやり方で生きている。異論を唱えるのは反逆的な知識

人だけだ。体制全体に抗う亡命者である。オーウェルがこうした表現を用いたのは、当時の社会をまさにそう見ていたからだ。『1984年』が絶望的なのは、

オーウェルがこうした構造では亡命者が勝てず、結局は全く希望がないと悟ったからである。(pp.312-313)

Masses was a new word for mob, and it is a very significant word. It

seems probable that three social tendencies joined to confirm its

meaning. First, there was the concentration of population in the

industrial towns, a physical massing of persons which the great

increase in total population accentuated, and which has continued with

continuing urbanization. Second, there was the concentration of workers

into factories: again, a physical massing, made necessary by

machine-production; also, a social massing, in the work-relations made

necessary by the development of large scale collective production.

Third, there was the conse quent development of an organized and

self-organizing working class: a social and political

massing.(Pp.316-317)

大衆とは群衆を指す新語であり、極めて重要な言葉である。その意味を確固たるものにしたのは、三つの社会的傾向が結びついた結果だろう。第一に、工業都市

への人口集中があった。これは物理的な人の集積であり、総人口の急増によって顕著になり、都市化の進展と共に継続している。第二に、労働者が工場に集中し

た。これもまた物理的な集積であり、機械生産によって必要とされた。同時に、大規模な集団生産の発展によって必要とされた労働関係における社会的集積でも

あった。第三に、その結果として組織化された、そして自己組織化する労働者階級が発展した。これは社会的・政治的な集積であった。(pp.316-

317)

The masses are always the others, whom we don't know, and can't know.(p.319)

大衆とは常に他者であり、我々が知らず、知り得ない

者たちである。(p.319)

■

リンク

- Neoliberalism︎▶︎社会▶社会学的想像力と現代社会︎︎▶︎社会的事実のつくられ方▶︎︎社会など存在しない▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

- 文化と社会 / ウィリアムズ [著] ; 若松繁信, 長谷川光昭訳,京都 : ミネルヴァ書房 , 1968

- Culture and society, 1780-1950 / Raymond Williams, New York, Anchor Books, 1960(https://archive.org/details/culturesociety17001850mbp)

- George Herbert Mead, Mind, Self and Society, 1934.

その他の情報