El Mundo de la practica

実践知の世界

El Mundo de la practica

田辺繁治『生き方の人類学』講談社・現代新書[→文化 人類学、はじめの一歩;人類学の最前線]ノート

*真理=「それ以外の仕方ではありえない」

*それ以外の仕方でもありうる=さまざまな選択や思慮をめぐらして行われる活動。

・ポイエーシスとプラークシス

〈ポイエーシス〉:制作する人の好意自体の中に目的はなし

〈プラークシス〉:それをおこなう人の人格と一体となったもの:倫理的な卓越性(アレテー)が込められる。

※【質問】ところで、人格とは人にやどるものなのか、それとも人が生み出した結果なのだ ろうか?

■自由な市民

・〈プラークシス〉=一切の労働から解放された自律的で自由な市民が、言説と討議をもっておこなう

都市国家(ポリス)の公共的な活動であり、政治的活動そのもの。

・〈ポイエーシス〉=建築、錬金術、醫術、占い、呪術/〈キネーシス〉に属する技能(テク ネー=技術知)

テクネーは、西洋近代的技術のことではない。

・「テクネーは西欧近代の技術概念とは正反対であり、あくまで自然あるいは素材に潜在す る力を巧みに引き出して利用する、限界をもった活動」(p.33)。

※古代ギリシャの自由人は、自然に働きかけて力を引き出すというこのテクネーという行為 を蔑んでいた(→近代における〈労働〉の概念と著しく対比をなす)。

■メティス(策略知=狡知[こうち])

まず、プラトニズム批判をとおしての〈知〉のあり方の復権という学問的文脈が登場する。

(→煎じ詰めれば、ヴィーコやヘルダーが主張した知のあり方へと繋がる)

・醫術、航海術、軍事戦略、修辞学、職人の技芸、政治戦術

・メティスは「巨大な力に対抗して変転する状況に繊細かつ機敏に対応し決断する知性であり、 最小をもって最大を支配し圧倒するソフィスト的能力でもある」(p.34)。

[→技能巧みなサーファーを想起せよ。サイバネティクス、サイバーパンク]

・論理的な推論ではなく、勘やコツによる近似的な推論行為

■プロネーシス(知慮 practical wisdom)=本書では〈実践知〉としている

・『ニコマコス倫理学』第6巻に登場。

〈プロネーシス〉=「「人間にとっての諸般の善と悪に関しての、ことわりを具えて真を失 わない実践可能の状態」にある知的構え」(p.36)。

・「プロネーシスこそはプラークシスを支える実践知である。・・・・プロネーシスは正しい目 標をめざす倫理的卓越性とその目標に臨機応変に到達する技法の結合である」(p.36)。

・倫理的卓越性(アレテー)という徳: プロニスモ=知慮ある人

※「プラトニズムによって過度に純化されたプラークシスを修正し、メティス的なプロネー シスが実践の核心にあるという考え方を導入していた」(37頁)という発言は、田辺の勇み足か?

・メティスとプロネーシスの関係についての田辺の見解(p.37)。

・〈ソープロシュネー〉(節制):よく生きること=正しくおこなうこと。後期フーコー流に言 うと、「節制をわきまえ、自らを統治できる自由状態をそなえた主体の一つの存在形式である」(田辺の表現、p.37)。

【コメント】

アリストテレスによる徳の二分法

- (1)知的なもの(→ソフィア、プロネーシス)

- (2)倫理的なもの(→正義、節制、気前よさ)

日本語で実践知とは何かを考えてみる(→リンク先)

アリストテレスの実践知入 門(池田光穂)

■実践知の衰退

まず藤沢令夫の「実践と観想」論:近代の科学技術はプロネーシスを排除することにより成立す る。ん〜ん? この主張はどこまで正当性をもつのか?

・アリストテレス的プロネーシス復権の2つの契機:

・〈実証主義〉=自然科学的な法則性(論拠:鷲田清一『人称と行為』)

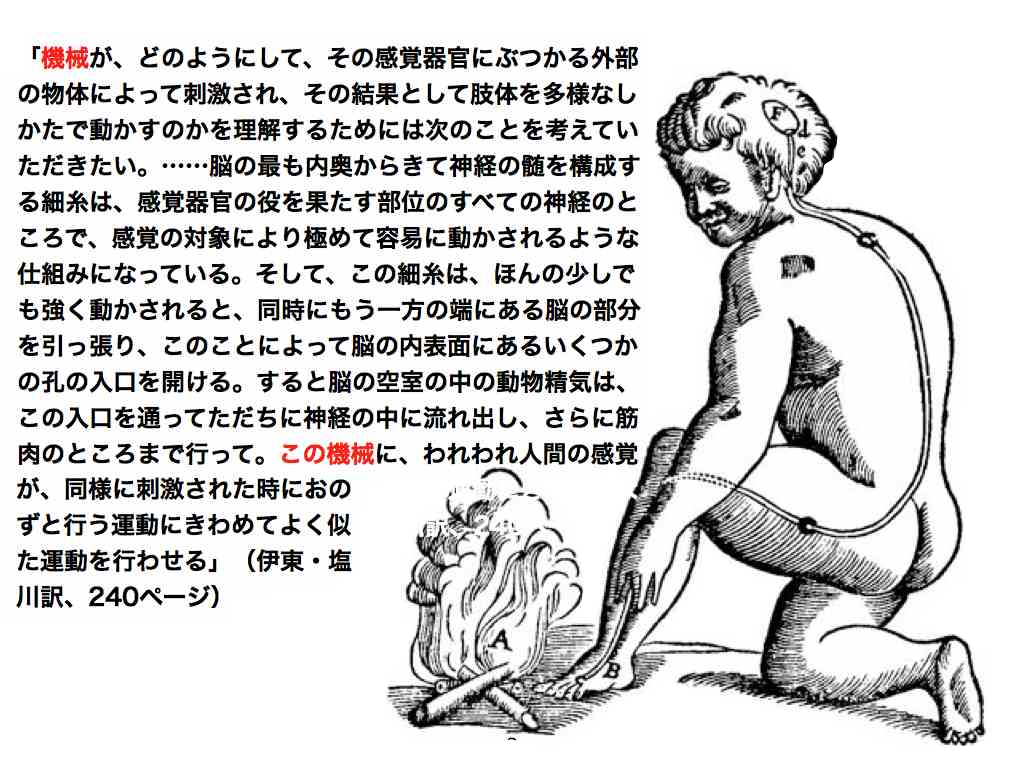

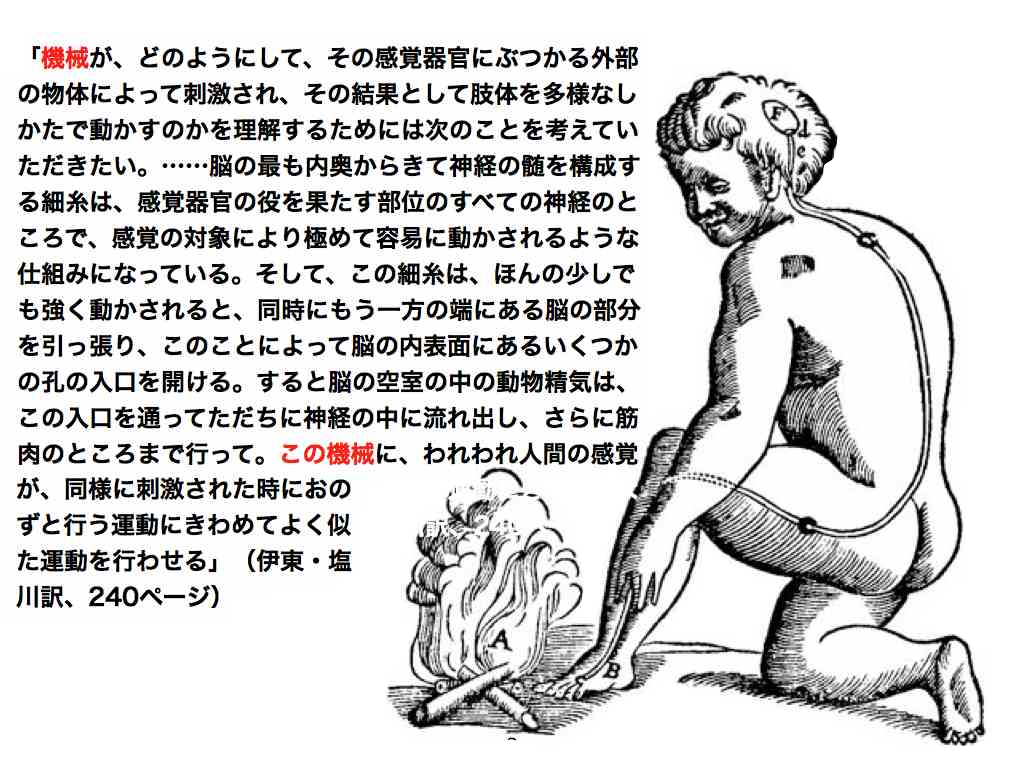

■ 機械の中の幽霊

・デカルトの、内的に省察する自己のドグマ(身体=機械から切り離された内省する自己=幽 霊)批判(G・ライル)『心の概念』1949年。

つまり、デカルトは心(res cogitance)と身体(res extensa)をわけ、前者に、直観、自由、分割不能、破壊不能そして自由意志という特権的な立場を与え、自己としての同一性の根拠も心にある ものとして扱われる。にもかかわらず、我々は心と身体の両方をもつ存在としてある。あるいは、他方で、私というものは、私の身体と関連づけられてはじめて 意味をもつ。

このようなデカルトの人間観を嘲笑して、ギルバート・ライルは、我々は機械(身体)の中に住 む幽霊(心)なのだと表現した。[→機械の中の幽霊]

・幽霊の知=内省する知性という批判とは、すなわち、身体から峻別される特権的な知の存在を 批判するということなの?

・日常言語学派の批判:知るという言葉の用法には、少なくとも以下の2つの用法があり、それ らはお互いに同じ行為を指し示すのではない、という指摘(批判)である。

・やり方を知ること(方法知 knowing how)/事実や真理を知ること(事実知 knowing what)、の峻別。

方法知:やり方、方法、手続きに関わる知識

事実知:事実や命題、規則などの知識

・方法知=理知的で実践にかかわることがら。

「ライルにとって、実践とは理知的に行われる行為であり、それはある規準を満たしている のみならず、それを自ら適用し、さらに自らの行為を規制しながら行うことである」(p.41)。

フィードバックと繰り返しによって可能にしている知、常に状況に応じて変化する知・・・ などなど。

■慣習化された行為(ライル)

・自分の行為に反省的ではなく、反射的であり、以前行われた行為の反復にすぎない。 (opp. 方法知に導かれた理知的な実践)

■慣習と方法知を区別せよ

方法知の例としての〈訓練〉:「自分が何をしているのかを考えながら行為を遂行することを学 ぶ」(p.43)。

「方法知とは、正しく行う規則が何であるかを頭の中で考えることなく、しかしその規則を遵守 し、かつその場にふさわしい論理的な推論に従いながら作業を首尾よくこなしてゆくことである」(p.44)。[→モードゥス・オペランディ]

L・Wはこのような二分法には執着しない(ppp.54-5)。

※参考:マイケル・ポラニーの暗黙知[→仮想医療人類学辞典「暗黙知」]

■傾向性(disposition)

行為のやり方に習熟しているひとは性格のような傾向性をもつ。

・ライルは、この慣習化された行為/理知的な実践の二分法に陥る。実践知を方法知として特権 化する必要はないということである(cf. p.55)。

※英単語を覚えること:

反復的な暗記(=慣習化された行為)、読解や作文で覚えた英単語を使うこと(=慣習化さ れた行為+理知的な実践)、実際の会話の現場で覚えた英単語を使ってコミュニケーションする際に用法を覚えること(=理知的な実践)、覚えた単語が自然に 出てくること(=慣習化された行為)、違う用法に出会ったり用法を他者から修正されたときに新たに学習すること(=理知的な実践)。

・上記のようなプロセスは、単に慣習化された行為から理知的な行為を峻別するだけでは、現実 の生活実践をより深く理解することはできないことを示唆。このことはL・W(そして田辺)により批判。

・ライル批判についてはpp.45-47に列挙(ライルの方法論的アリストテレス主義批 判)。さらに慣習的反復行為/訓練による理知的行為の二分法は54-55頁あたりで批判される。

■ modus operandi :方法知の本質

・modus operandi(やり方, operational mode?)は「作業の手順やスタイルに関わる様式であり、完成された作品(opus operatum, operated works?)を生みだすまでにとられる方法の集合」(p.45)。

■L・Wの後期哲学

なぜか、冒頭にL・Wの伝記の紹介がある。

・前期哲学(1918構想、1922公刊):「言語にはただ一つの本質的論理があることを証

明するために、言語と世界、命題と事実とのつながりが〈表示関係〉にあり、ある言葉(名)の意味はその言葉が表示する対象であること」を提示した

(p.48)。

・35年後の死後公刊『探究』(1953)

■治療のメタファー

・〈哲学による治療〉というメタファーは、日常言語学派のもの? で、L・Wはその系譜に入れられ

ない(なぜ?)。

・単一の本質的論理に統合された前期の言語観の放棄。

■言語ゲームの解説

・(狭義の)言語ゲームとは?:「子どもが本や椅子があるということを学ぶとき、それは同時 に本を取りに行ったり、椅子に座ることを学ぶという活動であり、それが言語ゲームである。すなわち、語(発話)と行為が一体となった活動の全過程」 (p.50)がそれである。

・(広義の)言語ゲーム:「言語と、言語の織りこまれたさまざまな活動の総体」 (p.50)。

「言語ゲームとは、語とその対象といった固定された対応関係から解放された概念であり、それ 自体に多義性を含んでいる。しかし、しばしば批判されてきたその多義性、あいまいさそのものが、根源的に本質主義の対極にある人間の実践の多様な場面をと らえるのにふさわしいのである」(p.51)。

多義性は限界にあらず、可能性にある、ということか。

・ソシュールの概念からの跳躍:語とその対象といった固定化された対応関係から解放された概 念(p.51)。

・実例:命令、記述、報告、推論、仮説検証、実験とその結果の提示、物語、演劇、輪唱、なぞ なぞ、冗談、算数の応用問題、翻訳、感謝、呪い、あいさつ。

・評価:「言語ゲームは言語使用に限らず、マルクスの〈労働〉に匹敵しうる、人間活動のすべ てに対して開かれた概念」(p.52)。

※なぜ、労働の概念がすごいのか?、今村仁司の本を導きとしてマルクスをよむべし、とい うことか。

■規則と行動の関係

・規則と行動の間には一致も矛盾も存在しない。

・規則が行動を規定するときに解釈が必要となり、その解釈の解釈が必要となり、その・・・という繰り返し(「規則に従うことをいかに理解するかという問題

のパラドクス」(p.52))。

田辺が引用する『探究』第1部201:「われわれのパラドクスは、ある規則がいかなる行動の しかたも決定できないだろう。なぜなら、どのような行動もその規則と一致させることができるからということだった。その答えは、どのような行動の仕方も規 則と規則と一致させることができるのなら、矛盾させることもできる、ということであった。それゆえ、ここには、一致も矛盾も存在しないのであろう」 (pp.52-3)。

■(つまり)我々がもつ規則概念の根本的な誤り(p.53)がある

(1)規則が強制的で、規範的なものという主観的な感覚をもっている

(2)規則が自分の外にあり、客観的な公準である、という見解がある

■慣習と訓練が規則にしたがう実践を生む(pp.54-)

「規則を作りあげているのは私たちが生きている場における公共的、集合的な規則の使用であ り、規則に従うことは、そこにおける慣習や訓練によって形成されてきた実践であるといえる」(p.54)。

ここで反復による規則行為と訓練による理知的な行為を区分するライルが批判される。

◎LWの次の命題の講釈

LW「ある文相を理解するとは、ある言語を理解することである。ある言語を理解すると は、ある技術を習得することである」『探究』第1部199、本書55頁

田辺「言語を理解することは語とそれが指示する記号的な関係を知っていることではなく、 あくまで言語を道具のように器用に使いこなす行為である。・・理解とは人があたかも心のなかで内面的におこなう過程ではなく、行為と一体となった技法に習 熟していることだ・・」55頁

※私ゃErving Goffman のPresentation of self, 1956を思い出したでぇ。

反復による慣習行為が実践を生み出す。「規則に従う実践が生みだされるのは、すでにそう行為 するように慣習としてつねに訓練されているからである。規則に従って生みだされる実践は、過去から積みかさねられてきた訓練がもたらす成果だ・・」56 頁。

■ 生活様式(pp.56-)

LWの生活様式とは?:「社会的存在としての人間が、言語や非言語的な行為を含めたさまざま な活動にともなう傾向性を共有していることである」56頁。「生活様式とは、概念図式、つまり考え方、知覚の仕方、行為のやり方を共有していることであ る」56-57頁。

生活様式からコミュニティ概念へ!:「ウィトゲンシュタインの哲学が生活様式と言うとき、そ れはかならずしも社会学で言われてきたような社会関係の集合体、あるいは「共同体」を指していない」(57頁)。

■ 心的過程の否定(pp.57-)

「言語ゲームは公共性、協働性をもつ枠組みであり、その慣習に従った/訓練をとおして言語や さまざまな活動が生みだされる・・」57-8頁

「つまり、私たちは言語ゲームを拡大適用しながら、これまで人類学や社会学があつかってきた さまざまな社会制度あるいは階級などといった社会的枠組みを、とりあえず協働性をもって慣習としてくりかえし訓練が行われている場として見直せばよい」 58頁。

■ 言語ゲームの多様性(pp.59-)

なにをもって社会的な現象の分析と見なすのか?

ーー具体的な実践を観察することによって、言語ゲームとしての規則と慣習的な訓練の存在、あ るいはそれを支えている概念図式の一致を証明すること(59頁)

ーー複数の言語ゲーム間の関係性と類似性(→家族類似性)という、私たちの社会性世界を貫い ている共時的な動態(59頁)

■ 言語ゲームの差異化(pp.60-)

「私たちは家族類似性という概念によって、包括的な分類に含まれる複数の言語ゲームは同質的 な規則や実践を共有しているのではなく、実は複雑に差異化する多様性に満ちている・・」60頁。

言語ゲームにおける境界性の概念:

外部決定されないと同時に外部をもつ? ここから、田辺のいうコミュニティ概念が引き出 される。

「一つの言語ゲームが外部世界の何ものにも制約されずに、その内部で自己決定するかのよ うに語る。つまり、協働性に基づく慣習としての言語ゲームは外部決定されない。しかし、他方では、複数の類似する言語ゲームが共時的に関/係しあい差異化 していると強調する。つまり、言語ゲームは外部性をもっていて、そこには多様な言語ゲームが連鎖している。この2つの見方は何ら矛盾するものではない、す なわち、言語ゲームとは、慣習の同一性と差異化を合わせもった〈コミュニティ〉にほかならない」60-61頁。

人類学的な新しいコミュニティ像!(61頁)

そのコミュティは古代の都市のように、迷路でできた複雑な路地裏であると同時に、郊外を 走る直線の道路でもある(文中では「ゲームに移行して実践を生みだす」と表現する。61頁)

このことを可能にするのは、無藤隆『協同するからだともの』で語られる、こどもの遊びに みられるゲームの移行あるいはスイッチである。そこには、アバウトな論理や、移行期における2つのゲームの存在がある。

■ 言語ゲームの歴史性(pp.63-)

おっと、ここでウィトゲンシュタイン的人類学の構想が出てくる。これまでの「共時的な差異化 と移行の視点」と「通時的な変化」見渡す必要性。後者が、この節で言われる歴史性である。

事例「二世紀以上にわたって形成されてきたアメリカのブラック・コミュニティや・・・難民の 事例を考えれば、そうしたゲームの移行の考えによって文化的な移行を説明することが可能であろう」63頁。

LWも、言語ゲームの内部で規則の変化がおきることを『確実性の問題』で構想していたふしが あるとのことだ。だが、これは1951年の彼の死により中断(放棄?)される。したがってLWに期待するのはやめておこう。人類学が自力で考えるべきこと だというわけだ。

言語ゲームの本質的な一貫性について思いをめぐらすのではなく、その歴史性(時間的経過のこ とではなく、行為者の実践による経時的ないしは偶発的な変化のことらしい)について配慮することが重要であると示唆して、この第二章は終わる。

☆言語ゲーム

| A language-game

(German: Sprachspiel) is a philosophical concept developed by Ludwig

Wittgenstein, referring to simple examples of language use and the

actions into which the language is woven. Wittgenstein argued that a

word or even a sentence has meaning only as a result of the "rule" of

the "game" being played. Depending on the context, for example, the

utterance "Water!" could be an order, the answer to a question, or some

other form of communication. |

言語ゲーム(ドイツ語:

Sprachspiel)とは、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインが提唱した哲学的概念である。これは言語使用の単純な例や、言語が織り込まれた行動を

指す。ウィトゲンシュタインは、単語や文でさえも、その「ゲーム」の「ルール」が機能した結果としてのみ意味を持つと主張した。文脈によって、「水だ!」

という発話は命令でも、質問への答えでも、あるいは他の何らかの意思疎通の形にもなり得る。 |

| Philosophical Investigations Main article: Philosophical Investigations In his work Philosophical Investigations (1953), Ludwig Wittgenstein regularly referred to the concept of language-games.[1] Wittgenstein rejected the idea that language is somehow separate from and corresponding to reality, and he argued that concepts do not need clarity for meaning.[2] Wittgenstein used the term "language-game" to designate forms of language simpler than the entirety of a language itself, "consisting of language and the actions into which it is woven"[3] and connected by family resemblance (Familienähnlichkeit). The concept was intended "to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life,"[4] which gives language its meaning. Wittgenstein develops this discussion of games into the key notion of a language-game. He introduces the term using simple examples,[3] but intends it to be used for the many ways in which we use language.[4] In one language-game, a word might be used to stand for (or refer to) an object, but in another the same word might be used for giving orders, or for asking questions, and so on. The famous example is the meaning of the word "game". We speak of various kinds of games: board games, betting games, sports, "war games". These are all different uses of the word "games". Wittgenstein also gives the example of "Water!", which can be used as an exclamation, an order, a request, or an answer to a question.[5] The meaning of the word depends on the language-game within which it is being used. Another way Wittgenstein puts the point is that the word "water" has no meaning apart from its use within a language-game. One might use the word as an order to have someone else bring you a glass of water. But it can also be used to warn someone that the water has been poisoned. Wittgenstein does not limit the application of his concept of language games to word-meaning. He also applies it to sentence-meaning. For example, the sentence "Moses did not exist"[6] can mean various things. Wittgenstein argues that, independently of use in a particular context, the sentence does not 'say' anything. It is 'meaningless' because it is not used for a particular purpose. The sentence is meaningful only when it is used to say something. For instance, it can be used to say that no person fits the set of descriptions attributed to the person that goes by the name of "Moses". But it can also mean that the leader of the Israelites was not called Moses. Or that no one accomplished all that the Bible relates of Moses, etc. What the sentence means thus depends on the context in which it is used. The term 'language-game' is used to refer to: Fictional examples of language use that are simpler than our own everyday language.[7] Simple uses of language with which children are first taught language (training in language). Specific regions of our language with their own grammars and relations to other language-games. All of a natural language seen as comprising a family of language-games. These meanings are not separated from each other by sharp boundaries, but blend into one another (as suggested by the idea of family resemblance). The concept is based on the following analogy: The rules of language are analogous to the rules of games; thus saying something in a language is analogous to making a move in a game. The analogy between a language and a game demonstrates that words have meaning depending on the uses made of them in the various and multiform activities of human life. (The concept is not meant to suggest that there is anything trivial about language, or that language is "just a game".) |

『哲学探究』 主な記事: 哲学探究 ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインは、その著作『哲学探究』(1953年)において、言語ゲームという概念を頻繁に言及した[1]。ウィトゲンシュタイ ンは、言語が現実とは何らかの形で分離し、それに対応しているという考えを拒否し、概念は意味のために明晰さを必要としないと主張した[2]。ウィトゲン シュタインは「言語ゲーム」という用語を用いて、言語全体よりも単純な言語の形態を指し示した。それは「言語と、それに織り込まれた行動から成り立つ」 [3]ものであり、家族的類似性(Familienähnlichkeit)によって結びつけられている。この概念は「言語を話すことが活動の一部、ある いは生活様式の一部であるという事実を顕著にする」[4]ことを意図しており、それが言語に意味を与えるのである。 ウィトゲンシュタインはこのゲーム論を言語ゲームの核心概念へと発展させる。彼は単純な例を用いてこの用語を導入するが[3]、言語使用の多様な様態全般 に適用することを意図している[4]。ある言語ゲームでは単語が対象を表す(または指す)ために用いられるが、別のゲームでは同じ単語が命令や質問などに 用いられる。有名な例が「ゲーム」という言葉の意味だ。我々は様々な種類のゲームについて語る:ボードゲーム、賭け事、スポーツ、「戦争ゲーム」。これら は全て「ゲーム」という言葉の異なる用法である。ウィトゲンシュタインは「水だ!」という例も挙げる。これは感嘆詞として、命令として、要求として、ある いは質問への答えとして用いられる。[5] 語の意味は、それが用いられている言語ゲームに依存する。ウィトゲンシュタインが別の形で示したように、「水」という言葉は言語ゲーム内での使用を離れて は意味を持たない。誰かに水のグラスを持ってくるよう命令する際にこの言葉を使うこともあれば、水が毒されていると警告する際に使うこともある。 ウィトゲンシュタインは言語ゲーム概念の適用を単語の意味に限定しない。文の意味にも適用する。例えば「モーゼは存在しなかった」[6]という文は様々な 意味を持ち得る。ウィトゲンシュタインは、特定の文脈での使用とは独立して、この文は「何も述べていない」と主張する。特定の目的で使われていないため 「無意味」なのだ。この文が意味を持つのは、何かを言うために使われる時だけだ。例えば、「モーゼ」という名で呼ばれる人格に当てはまる一連の記述に、誰 一人として適合しないと言うために使える。しかし同時に、イスラエル人の指導者がモーゼと呼ばれていなかったという意味にもなり得る。あるいは、聖書が モーゼについて記す全てのことを成し遂げた人格は存在しなかったという意味にもなり得る。つまりこの文の意味は、それが使われる文脈に依存するのだ。 「言語ゲーム」という用語は以下の意味で使用される: 日常言語より単純な、言語使用の架空の例。[7] 子供に最初に言語を教える際の単純な言語使用(言語訓練)。 固有の文法と他の言語ゲームとの関係を持つ、言語の特定領域。 言語ゲーム群の集合として捉えられた自然言語全体。 これらの意味は明確な境界で区切られているわけではなく、互いに混ざり合っている(家族的類似性の概念が示唆するように)。この概念は次の類推に基づいて いる:言語の規則はゲームの規則に類似している。したがって、言語で何かを言うことはゲームで手番を行うことに類似している。言語とゲームの類推は、言葉 の意味が人間の生活の多様で多形的な活動における使用法に依存することを示している。(この概念は、言語に些細な点があるとか、言語が「単なるゲーム」だ ということを示唆するものではない。) |

| Examples The classic example of a language-game is the so-called "builder's language" introduced in §2 of the Philosophical Investigations: The language is meant to serve for communication between a builder A and an assistant B. A is building with building-stones: there are blocks, pillars, slabs and beams. B has to pass the stones, in the order in which A needs them. For this purpose they use a language consisting of the words "block", "pillar" "slab", "beam". A calls them out; — B brings the stone which he has learnt to bring at such-and-such a call. Conceive this as a complete primitive language.[7][8] Later "this" and "there" are added (with functions analogous to the function these words have in natural language), and "a, b, c, d" as numerals. An example of its use: builder A says "d — slab — there" and points, and builder B counts four slabs, "a, b, c, d..." and moves them to the place pointed to by A. The builder's language is an activity into which is woven something we would recognize as language, but in a simpler form. This language-game resembles the simple forms of language taught to children, and Wittgenstein asks that we conceive of it as "a complete primitive language" for a tribe of builders. |

例 言語ゲームの一つの典型的な例は、『哲学探究』第2節で導入されたいわゆる「建築者の言語」である: この言語は、建築者Aと助手Bの間の意思疎通のために用いられる。Aは建築用石材で建造物を建てている。そこにはブロック、柱、スラブ、梁がある。BはA が必要とする順序で石材を渡さねばならない。この目的のために、彼らは「ブロック」「柱」「板」「梁」という単語から成る言語を使う。Aがそれらを呼び出 すと、Bはそれぞれの呼び出しに対応する石を持ってくる。これを完全な原始言語と考えるのだ。[7] [8] 後に「こちら」「あちら」が追加される(自然言語におけるこれらの単語の機能に類似した機能を持つ)。また「a, b, c, d」が数字として追加される。使用例:建築者Aが「d ― スラブ ― そこ」と言い指さすと、建築者Bは四枚のスラブを「a, b, c, d…」と数え、Aが指さした場所へ移動させる。建築者の言語とは、我々が言語と認識する要素が織り込まれた活動であるが、より単純な形態である。この言語 ゲームは、子供に教えられる単純な言語形式に似ており、ウィトゲンシュタインはこれを「建築者の部族のための完全な原始言語」として捉えるよう求めてい る。 |

| Semiotics – Study of meaning-making and communication Worldview, also known as Weltanschauung – Fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society Speech act – Utterance that serves a performative function Neopragmatism – Philosophical position that sees language as a problem-solving tool |

記号論 – 意味形成とコミュニケーションの研究 世界観、別名ヴェルトアンシャウング – 個人や社会の根本的な認知的指向性 発話行為 – 実行的機能を果たす発話 新実用主義 – 言語を問題解決の道具と見る哲学的立場 |

| 1. Biletzki, Anat (2009) [2002]. "Ludwig Wittgenstein". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved April 4, 2012. Jago 2007, p. 55. 2. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell. §7. ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 3. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell. §23. ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 4. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell. §27. ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 5. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell. §79. ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 6. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell. §2. ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 7. Foord, Michael. "Wittgenstein Philosophical Investigations - Aphorisms 1-10". Voidspace.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-10-14. Retrieved 2013-12-12. |

1. ビレツキ、アナト(2009年)[2002年]。「ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン」。スタンフォード哲学百科事典。2012年4月4日取得。 ジャゴ 2007, p. 55. 2. ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ(1958年)。『哲学探究』。バジル・ブラックウェル。§7。ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 3. ヴィトゲンシュタイン, ルートヴィヒ (1958). 『哲学探究』. ベーシル・ブラックウェル. §23. ISBN 0-631-11900-0. 4. ヴィトゲンシュタイン, ルートヴィヒ (1958). 『哲学探究』. ベーシル・ブラックウェル. §27. ISBN 0-631-11900-0。 5. ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ(1958)。『哲学探究』。バジル・ブラックウェル。§79。ISBN 0-631-11900-0。 6. ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ(1958)。『哲学探究』。バジル・ブラックウェル。§2。ISBN 0-631-11900-0。 7. フォード、マイケル。「ウィトゲンシュタイン『哲学探究』-格言1-10」。Voidspace.org.uk。2014年10月14日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年12月12日に取得。 |

| Jago, Mark (2007). Wittgenstein. Humanities-Ebooks. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell. Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1942). Blue and Brown Books. Harper Perennial. |

ジャゴ、マーク(2007)。『ウィトゲンシュタイン』。ヒューマニティーズ・イーブックス。 ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ(1953)。『哲学探究』。ブラックウェル。 ウィトゲンシュタイン、ルートヴィヒ(1942)。『青と茶の本』。ハーパー・ペレニアル。 |

| Pukhaev, Andrey (2023).

"Understanding Wittgenstein's positive philosophy through

language‐games: Giving philosophy peace". Philosophical Investigations.

46 (3): 376–394. doi:10.1111/phin.12373. ISSN 0190-0536. Nicolas Xanthos (2006), "Wittgenstein's Language Games", in Louis Hébert (dir.), Signo (online), Rimouski (Quebec, Canada) Language-games and Family Resemblance A description of language-games in the entry for Ludwig Wittgenstein in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Logico-linguistic modeling. This is an application of the language-game concept in the area of information systems and knowledge-based system design. Gálvez, Jesús Padilla; Gaffal, Margit, eds. (15 September 2011). Forms of Life and Language Games. Aporia. Vol. 5. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag [de]. doi:10.1515/9783110321906. ISBN 978-3-11-032159-3. |

プカエフ、アンドレイ(2023)。「言語ゲームを通じてウィトゲンシュタインの積極的哲学を理解する:哲学に安息を与える」。『哲学探究』。46巻3号:376–394頁。doi:10.1111/phin.12373。ISSN 0190-0536。 ニコラス・ザンソス(2006)、「ウィトゲンシュタインの言語ゲーム」、ルイ・エベール編、『シグノ』(オンライン)、リムースキ(ケベック州、カナダ) 言語ゲームと家族的類似性スタンフォード哲学百科事典のルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの項目における言語ゲームの説明 論理言語学的モデリング。これは情報システムおよび知識ベースシステム設計の分野における言語ゲーム概念の応用である。 ガルベス、ヘスス・パディージャ;ガッファル、マルギット編(2011年9月15日)。『生命の形態と言語ゲーム』。アポリア。第5巻。フランクフルト: オントス・ヴェルラグ[ドイツ]。doi:10.1515/9783110321906。ISBN 978-3-11-032159-3。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_game_(philosophy) |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099