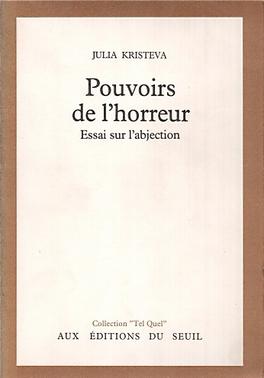

クリステヴァ『恐怖の力:アブジェクション= 卑賤に関するエッセー』(1980)

Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection

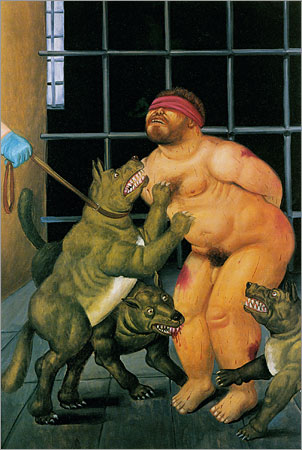

フェルナンド・ボテロの「アルグレイブ刑務所」を題材にした作品群より

☆ 恐怖の力: フランス語: Pouvoirs de l'horreur. Essai sur l'abjection)は、ジュリア・クリステヴァによる1980年の著作である。ジークムント・フロイトとジャック・ラカンの理論を引用し、恐怖、疎 外、去勢、男根、「私/私でない者」の二分法、エディプス・コンプレックス、追放、その他フェミニズム批評やクィア理論にふさわしい概念について考察して いる。 クリステヴァによれば、禁忌は象徴秩序における意味づけから逃れた「原初的秩序」を示すものであり、この用語は、主体と客体、あるいは自己と他者の区別が 失われることによって引き起こされる、意味の崩壊の危機に対する人間の反応(恐怖、嘔吐)を指すのに用いられる。

Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (French: Pouvoirs de l'horreur. Essai sur l'abjection) is a 1980 book by Julia Kristeva. The work is an extensive treatise on the subject of abjection,[1] in which Kristeva draws on the theories of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan to examine horror, marginalization, castration, the phallic signifier, the "I/Not I" dichotomy, the Oedipal complex, exile, and other concepts appropriate to feminist criticism and queer theory. According to Kristeva, the abject marks a "primal order" that escapes signification in the symbolic order; the term is used to refer to the human reaction (horror, vomit) to a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object, or between the self and the other. |

恐怖の力: フランス語: Pouvoirs de

l'horreur. Essai sur

l'abjection)は、ジュリア・クリステヴァによる1980年の著作である。ジークムント・フロイトとジャック・ラカンの理論を引用し、恐怖、疎

外、去勢、男根、「私/私でない者」の二分法、エディプス・コンプレックス、追放、その他フェミニズム批評やクィア理論にふさわしい概念について考察して

いる。 クリステヴァによれば、禁忌は象徴秩序における意味づけから逃れた「原初的秩序」を示すものであり、この用語は、主体と客体、あるいは自己と他者の区別が 失われることによって引き起こされる、意味の崩壊の危機に対する人間の反応(恐怖、嘔吐)を指すのに用いられる。  |

| Compared to Lacan Kristeva's understanding of the "abject" provides a helpful term to contrast to Lacan's objet petit a (or the "object - cause of desire"). Whereas the objet petit a allows a subject to coordinate his or her desires, thus allowing the symbolic order of meaning and intersubjective community to persist, the abject "is radically excluded and," as Kristeva explains, "draws me toward the place where meaning collapses".[2] It is neither object nor subject; the abject is situated, rather, at a place before we entered into the symbolic order. (On the symbolic order, see, in particular, the Lacan module on psychosexual development.) As Kristeva puts it, "Abjection preserves what existed in the archaism of pre-objectal relationship, in the immemorial violence with which a body becomes separated from another body in order to be".[3] The abject marks what Kristeva terms a "primal repression," one that precedes the establishment of the subject's relation to its objects of desire and of representation, before even the establishment of the opposition between consciousness and the unconscious. Kristeva refers, instead, to the moment in our psychosexual development when we established a border or separation between human and animal, between culture and that which preceded it. On the level of archaic memory, Kristeva refers to the primitive effort to separate ourselves from the animal: "by way of abjection, primitive societies have marked out a precise area of their culture in order to remove it from the threatening world of animals or animalism, which were imagined as representatives of sex and murder".[4] On the level of our individual psychosexual development, the abject marks the moment when we separated ourselves from the mother, when we began to recognize a boundary between "me" and other, between "me" and "(m)other." (See the Kristeva Module on Psychosexual Development.) The abject is "a precondition of narcissism".[5] which is to say, a precondition for the narcissism of the mirror stage, which occur after we establish these primal distinctions. The abject thus at once represents the threat that meaning is breaking down and constitutes our reaction to such a breakdown: a reestablishment of our "primal repression." The abject has to do with "what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules".[6]and, so, can also include crimes like Auschwitz. Such crimes are abject precisely because they draw attention to the "fragility of the law".[6] |

ラカンと比較する クリステヴァの「アブジェクト」理解は、ラカンのオブジェ・プティ・ア(あるいは「欲望の対象-[a])と対比させるのに有用な用語を提供する。オブ ジェ・プティ・アは主体が自分の欲望を調整することを可能にし、その結果、意味と主体間共同体の象徴的秩序が存続することを可能にするのに対し、アブジェ クトはクリステヴァが説明するように、「根本的に排除され、意味が崩壊する場所へと私を引き寄せる」[2]。オブジェでも主体でもなく、アブジェクトはむ しろ、私たちが象徴的秩序に入る前の場所に位置している。(象徴的秩序については、特に精神性愛の発達に関するラカンのモジュールを参照のこと)。クリス テヴァが言うように、「アブジェクトは、身体が存在するために別の身体から切り離される太古の暴力において、オブジェクティブな関係以前のアルカイズムに 存在していたものを保存する」[3]。アブジェクトは、クリステヴァが言うところの「原初的抑圧」を示すものであり、欲望と表象の対象に対する主体の関係 の確立に先立つものであり、意識と無意識の対立の確立にさえ先立つものである。 クリステヴァはその代わりに、私たちが心理的な発達において、人間と動物、文化とそれ以前のものとの間に境界線や分離を確立した瞬間を指している。古代の 記憶のレベルでは、クリステヴァは自分たちを動物から切り離そうとする原始的な努力に言及している。「原始社会は、性と殺人の代表として想像されていた動 物やアニマリズムの脅威的な世界から自分たちの文化を排除するために、アブジェクトという方法で、自分たちの文化の正確な領域をマークした」[4]。(ア ブジェクトは「ナルシシズムの前提条件」[5]であり、言い換えれば、私たちがこうした原初的な区別を確立した後に起こる鏡の段階のナルシシズムの前提条 件である。こうしてアブジェクトは、意味が崩壊しつつあるという脅威を表すと同時に、そのような崩壊に対するわれわれの反応、すなわち「原初的抑圧」の再 確立を構成する。アブジェクトは「アイデンティティ、システム、秩序を乱すもの」と関係している。国境、立場、規則を尊重しないもの」[6]であり、アウ シュビッツのような犯罪も含まれる。このような犯罪は、まさに「法の脆さ」に注意を喚起するものであるからこそ、abjectなのである[6]。 |

| Eruption of the Real More specifically, Kristeva associates the abject with the eruption of the Real into our lives. In particular, she associates such a response with our rejection of death's insistent materiality. Our reaction to such abject material recharges what is essentially a pre-lingual response. Kristeva, therefore, is quite careful to differentiate knowledge of death or the meaning of death (both of which can exist within the symbolic order) from the traumatic experience of being actually confronted with the sort of materiality that traumatically shows one's own death: "A wound with blood and pus, or the sickly, acrid smell of sweat, of decay, does not signify death. In the presence of signified death—a flat encephalograph, for instance—I would understand, react, or accept. No, as in true theater, without makeup or masks, refuse and corpses show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live. These body fluids, this defilement, this shit are what life withstands, hardly and with difficulty, on the part of death. There, I am at the border of my condition as a living being."[7] The corpse especially exemplifies Kristeva's concept since it literalizes the breakdown of the distinction between subject and object that is crucial for the establishment of identity and for our entrance into the symbolic order. What we are confronted with when we experience the trauma of seeing a human corpse (particularly the corpse of a friend or family member) is our own eventual death made palpably real. As Kristeva puts it, "The corpse, seen without God and outside of science, is the utmost of abjection. It is death infecting life. Abject".[6] |

現実の噴出 より具体的に言えば、クリステヴァは、アブジェクトを私たちの生活への現実の噴出と結びつけている。特に彼女は、このような反応を、死の執拗な物質性への 拒絶と結びつけている。そのような禁忌的な物質に対する私たちの反応は、本質的に言語以前の反応であるものを充電する。それゆえクリステヴァは、死につい ての知識や死の意味(どちらも象徴秩序の中に存在しうる)と、自らの死をトラウマ的に示すような物質性に実際に直面するというトラウマ的な経験とを区別す ることに細心の注意を払っている: 「血や膿のついた傷や、汗や腐敗の病的で刺激的な匂いは、死を意味しない。血と膿のついた傷や、汗のような、腐敗のような、病的で刺激的な匂いは、死を意 味しない。そうではなく、真の演劇のように、化粧も仮面もない状態で、私が生きるために恒久的に脇へ追いやってきたものを、ゴミや死体が見せてくれるの だ。これらの体液、穢れ、糞は、生が死の側で、ほとんど、そして困難にも耐えるものなのだ。そこでは、私は生物としての条件の境界にいる」[7]。 死体は、アイデンティティの確立と象徴秩序への参入にとって重要な、主体と客体の区別の崩壊を文字化するものであるため、クリステヴァの概念を特に例証し ている。人間の死体(特に友人や家族の死体)を見るというトラウマを経験するとき、私たちが直面するのは、私たち自身の最終的な死が明白に現実化すること である。クリステヴァが言うように、「神もなく、科学もない死体は、拒絶の極致である。それは生に感染する死である。拒絶」である[6]。 |

| Comparison with desire The abject must also be distinguished from desire (which is tied up with the meaning-structures of the symbolic order). It is associated, rather, with both fear and jouissance. In phobia, Kristeva reads the trace of a pre-linguistic confrontation with the abject, a moment that precedes the recognition of any actual object of fear: "The phobic object shows up at the place of non-objectal states of drive and assumes all the mishaps of drive as disappointed desires or as desires diverted from their objects".[8] The object of fear is, in other words, a substitute formation for the subject's abject relation to drive. The fear of, say, heights really stands in the place of a much more primal fear: the fear caused by the breakdown of any distinction between subject and object, of any distinction between ourselves and the world of dead material objects (reference page?). Kristeva also associates the abject with jouissance: "One does not know it, one does not desire it, one joys in it [on en jouit]. Violently and painfully. A passion".[9] This statement appears paradoxical, but what Kristeva means by such statements is that we are, despite everything, continually and repetitively drawn to the abject (much as we are repeatedly drawn to trauma in Freud's understanding of repetition compulsion). To experience the abject in literature carries with it a certain pleasure but one that is quite different from the dynamics of desire. Kristeva associates this aesthetic experience of the abject, rather, with poetic catharsis: "an impure process that protects from the abject only by dint of being immersed in it".[10] |

欲望との比較 アブジェクトは、欲望(象徴秩序の意味構造と結びついている)とも区別されなければならない。それはむしろ、恐怖とユイサンスの両方に関連づけられてい る。恐怖症においてクリステヴァは、実際の恐怖の対象が認識される以前の瞬間、つまり言語以前の対象との対峙の痕跡を読み取る。「恐怖症の対象は、欲動の 非対象的な状態の場所に現れ、欲動のすべての災難を失望した欲望として、あるいは欲望がその対象から逸脱したものとして引き受ける」[8]。例えば高所恐 怖は、本当はもっと原初的な恐怖、つまり主体と客体との間のあらゆる区別、自分自身と死滅した物質的対象の世界との間のあらゆる区別の崩壊によって引き起 こされる恐怖の代わりに立っているのである(参考ページ)。 クリステヴァはまた、「禁忌」をユイサンスと結びつけている: 「人はそれを知らず、それを望まず、その中で歓喜する[on en jouit]。暴力的に、痛烈に。この発言は逆説的に見えるが、クリステヴァがこのような発言で意味しているのは、私たちは何事にもかかわらず、絶えず繰 り返し、アブジェクトに引き寄せられるということである(フロイトの反復強迫の理解において、私たちがトラウマに繰り返し引き寄せられるのと同じよう に)。文学の中で抽象を体験することは、ある種の喜びを伴うが、それは欲望の力学とはまったく異なるものである。クリステヴァはこの美学的なアブジェクト の経験を、むしろ詩的なカタルシスと結びつけている。「アブジェクトに没頭することによってのみ、アブジェクトから身を守る不純なプロセス」である [10]。 |

| Purifying the abject The abject for Kristeva is, therefore, closely tied both to religion and to art, which she sees as two ways of purifying the abject: "The various means of purifying the abject—the various catharses—make up the history of religions, and end up with that catharsis par excellence called art, both on the far and near side of religion".[11] According to Kristeva, the best modern literature (Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Marcel Proust, Jorge Luis Borges, Antonin Artaud, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Franz Kafka, etc.) explores the place of the abject, a place where boundaries begin to break down, where people are confronted with an archaic space before such linguistic binaries as self/other or subject/object. The transcendent or sublime, for Kristeva, is really our effort to cover over the breakdowns (and subsequent reassertion of boundaries) associated with the abject; and literature is the privileged space for both the sublime and abject: "On close inspection, all literature is probably a version of the apocalypse that seems to me rooted, no matter what its sociohistorical conditions might be, on the fragile border (borderline cases) where identities (subject/object, etc.) do not exist or only barely so—double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject".[12] According to Kristeva, literature explores the way that language is structured over a lack, a want. She privileges poetry, in particular, because of poetry's willingness to play with grammar, metaphor and meaning, thus laying bare the fact that language is at once arbitrary and limned with the abject fear of loss: "Not a language of the desiring exchange of messages or objects that are transmitted in a social contract of communication and desire beyond want, but a language of want, of the fear that edges up to it and runs along its edges".[13][14] |

禁忌を浄化する したがって、クリステヴァにとってのアブジェクトは、宗教と芸術の両方と密接に結びついている: 「様々なカタルシスという、忌まわしきものを浄化する様々な手段が宗教の歴史を構成し、宗教の遠景と近景の両方において、芸術と呼ばれる卓越したカタルシ スに行き着く」[11]。 [11]クリステヴァによれば、最高の近代文学(フョードル・ドストエフスキー、マルセル・プルースト、ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘス、アントナン・アル トー、ルイ=フェルディナン・セリーヌ、フランツ・カフカなど)は、境界線が壊れ始める場所、人々が自己/他者や主体/客体といった言語的二項対立以前の 古風な空間に直面する場所である、「禁忌」の場所を探求している。 クリステヴァにとって、超越的なもの、崇高なものとは、実際には、抽象的なものに関連する崩壊(そしてそれに続く境界の再確立)を覆い隠そうとする私たち の努力であり、文学は崇高なものと抽象的なものの両方にとって特権的な空間である: 「よく観察してみると、すべての文学はおそらく、その社会史的条件がどうであれ、アイデンティティ(主体/客体など)が存在しないか、あるいはかろうじて そうであるにすぎない、二重、あいまい、異質、動物的、変成、変質、禁忌といった脆弱な境界(境界例)に根ざした黙示録のヴァージョンである」[12]。 クリステヴァによれば、文学は言語が欠乏や欲求の上に構造化される方法を探求する。クリステヴァは特に詩を高く評価するが、その理由は詩が文法、隠喩、意 味と戯れることを厭わないためであり、その結果、言語が恣意的であると同時に、喪失の忌まわしい恐怖によって制限されているという事実をむき出しにする: 「欲望を超えたコミュニケーションと欲望の社会的契約において伝達されるメッセージやオブジェクトの欲望的交換の言語ではなく、欲望の言語であり、欲望に 縁を寄せ、その縁に沿って走る恐怖の言語である」[13][14]。 |

| Felluga, Dino Franco (31 January

2011). "Modules on Kristeva: On the abject". Introductory guide to

critical theory. West Lafayette, Indiana, USA: Purdue University. Fletcher, J.; Benjamin, A. (2012). Abjection, Melancholia and Love: The Work of Julia Kristeva. Routledge Library Editions: Women, Feminism and Literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-32187-0. Kristeva, Julia (15 April 1982). Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. European Perspectives. Translated by Roudiez, Leon Samuel. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05347-1. |

Felluga, Dino Franco (31 January

2011). 「クリステヴァのモジュール: 禁忌について」. 批評理論入門ガイド。West Lafayette, Indiana, USA:

Purdue University. Fletcher, J.; Benjamin, A. (2012). Abjection, Melancholia and Love: The Work of Julia Kristeva. Routledge Library Editions: 女性、フェミニズム、文学。Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-32187-0. Kristeva, Julia (15 April 1982). Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. European Perspectives. Roudiez, Leon Samuel訳。コロンビア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-231-05347-1. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Powers_of_Horror |

|

| Kristeva, Julia (15 April 1982). Powers of Horror: An Essay on

Abjection. European Perspectives. Translated by Roudiez, Leon Samuel.

Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05347-1.[pdf] Translator's Note vii I. Approaching Abjection i 2. Something To Be Scared Of 32 3- From Filth to Defilement 56 4- Semiotics of Biblical Abomination 90 5- . . . Qui Tollis Peccata Mundi 113 6. Celine: Neither Actor nor Martyr • 133 7- Suffering and Horror 140 8. Those Females Who Can Wreck the Infinite 157 9- "Ours To Jew or Die" 174 12 In the Beginning and Without End . . . 188 11 Powers of Horror 207 Note |

恐怖の権力 : 「アブジェクシオン」試論 / ジュリア・クリステヴァ [著] ; 枝川昌雄訳, 東京 : 法政大学出版局 ,

1984.7. - (叢書・ウニベルシタス ; 137) 1. アブジェクションへのアプローチ 1 2. 何を怖がるか 3. 汚れから穢れへ 4. 聖書における嫌忌の記号論 5. 汝、世の罪を拭い去る者よ 6. セリーヌ:喜劇役者でも殉教者でもなく 7. 苦痛/恐怖 8. 無限を食いつぶす女たち 9. ユダヤ化するかそれとも死ぬか 10. はじめに、そして終わりなく 11. 恐怖の権力 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆