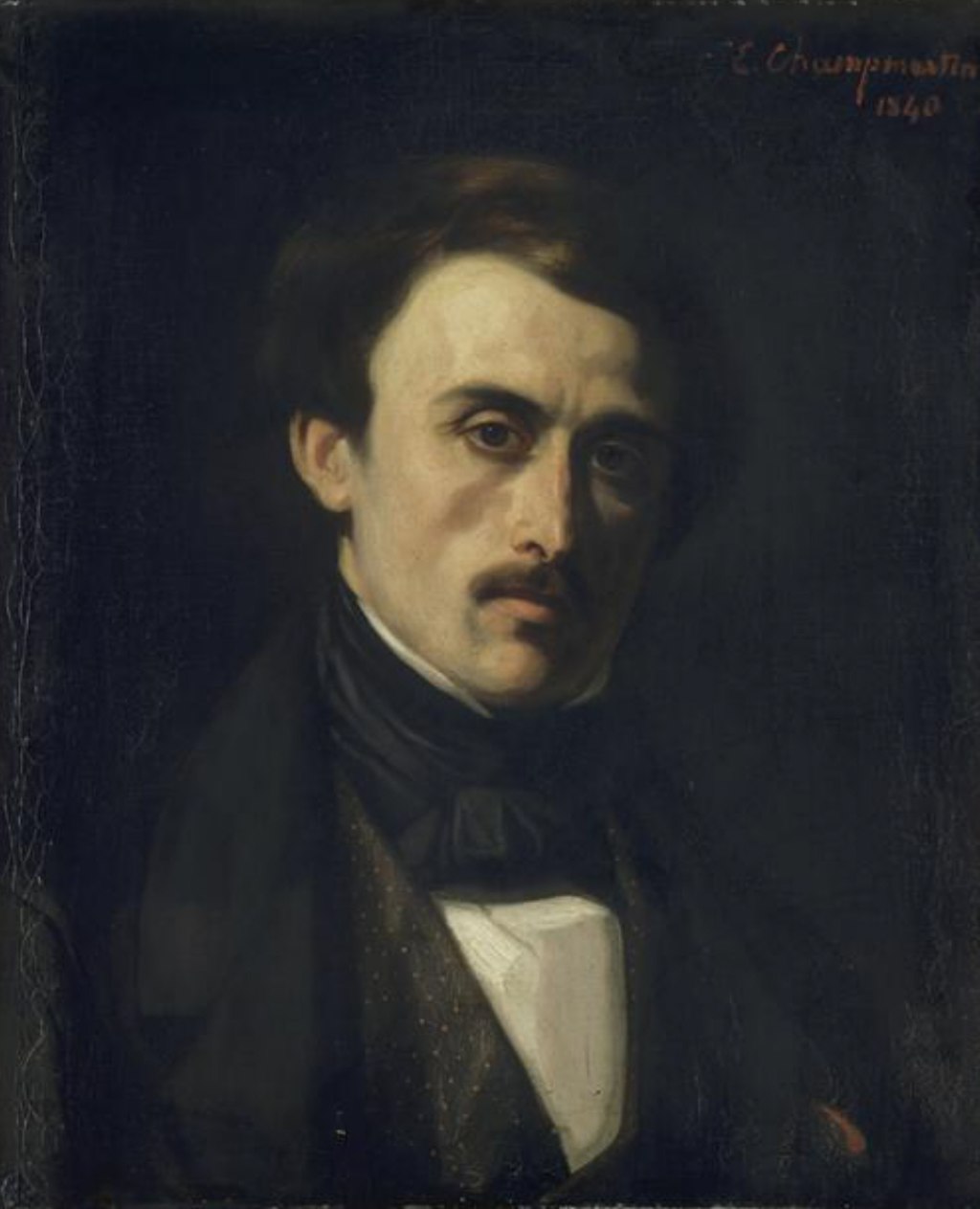

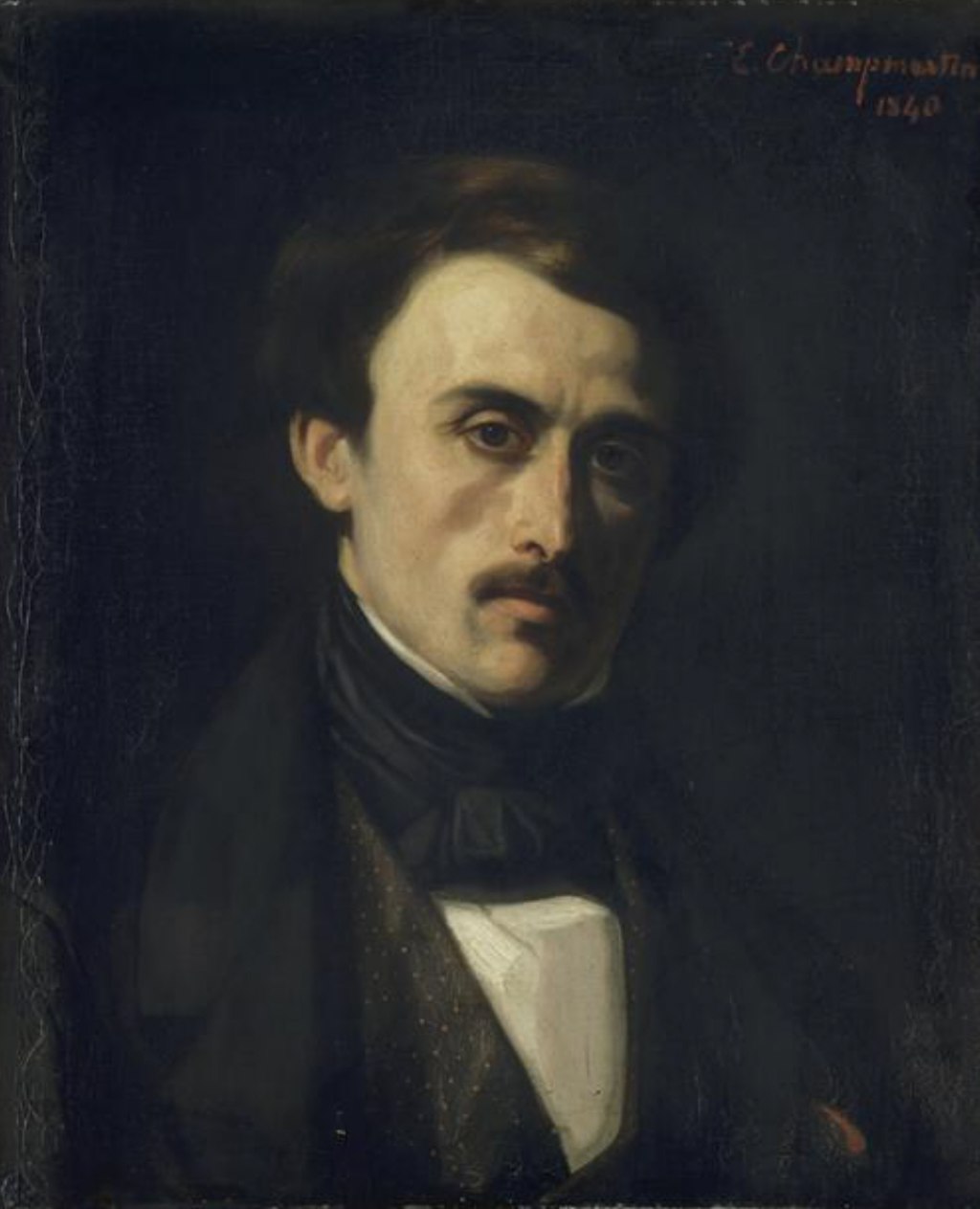

アルチュール・ド・ゴビノー

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, 1816-1882

解説:池田光穂

アルチュール・ド・ゴビノー

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, 1816-1882

解説:池田光穂

★ジョゼフ・アルチュール・ド・ゴビノー(1816年7月14日 - 1882年10月13日)はフランスの貴族で、科学的人種論と「人種人口学」を用いて人種差別の正当化に貢献し、アーリア人の支配者民族論を展開したこと で知られる。小説家、外交官、旅行作家として同時代の人々に知られた彼は、エリート主義者であり、1848年の革命直後に『人類の不平等に関する試論』を 書いた。その中で彼は、貴族は平民より優れており、貴族は劣等人種との交雑が少ないため、アーリア人の遺伝的特徴をより多く持っていると主張した。ゴビ ノーの著作は、ジョサイア・C・ノットやヘンリー・ホッツェのような白人至上主義者で奴隷制を支持するアメリカ人によってすぐに賞賛され、彼らは彼の 著書を英語に翻訳した。彼らは原著の約1,000ページを省略し、その中にはアメリカ人を人種的に混合された集団として否定的に記述した部分も含まれてい た。ドイツでゴビニズムと名付けられた社会運動に刺激を与えた彼の著作は、リヒャルト・ワーグナー、ワーグナーの義理の息子ヒューストン・スチュワート・ チェンバレン、ルーマニアの政治家A・C・クーザ教授、ナチ党の指導者といった著名な反ユダヤ主義者たちにも影響を与え、彼らは後に彼の著作を編集し、再 出版した(→彼の人種論については「アルチュール・ド・ゴビノーの人種論」を参照してください)。

| Joseph Arthur

de Gobineau

(French: [ɡɔbino]; 14 July 1816 – 13 October 1882) was a French

aristocrat who is best known for helping to legitimise racism by the

use of scientific race theory and "racial demography", and for

developing the theory of the Aryan master race. Known to his

contemporaries as a novelist, diplomat and travel writer, he was an

elitist who, in the immediate aftermath of the Revolutions of 1848,

wrote An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. In it he argued

that aristocrats were superior to commoners and that aristocrats

possessed more Aryan genetic traits because of less interbreeding with

inferior races. Gobineau's writings were quickly praised by white supremacist, pro-slavery Americans like Josiah C. Nott and Henry Hotze, who translated his book into English. They omitted around 1,000 pages of the original book, including those parts that negatively described Americans as a racially mixed population. Inspiring a social movement in Germany named Gobinism,[1] his works were also influential on prominent antisemites like Richard Wagner, Wagner's son-in-law Houston Stewart Chamberlain, the Romanian politician Professor A. C. Cuza, and leaders of the Nazi Party, who later edited and re-published his work. |

ジョゼフ・アルチュール・ド・ゴ

ビノー(仏: [ɡɔbino]; 1816年7月14日 -

1882年10月13日)はフランスの貴族で、科学的人種論と「人種人口学」を用いて人種差別の正当化に貢献し、アーリア人の支配者民族論を展開したこと

で知られる。小説家、外交官、旅行作家として同時代の人々に知られた彼は、エリート主義者であり、1848年の革命直後に『人類の不平等に関する試論』を

書いた。その中で彼は、貴族は平民より優れており、貴族は劣等人種との交雑が少ないため、アーリア人の遺伝的特徴をより多く持っていると主張した。 ゴビノーの著作は、ジョサイア・C・ノットやヘンリー・ホッツェのような白人至上主義者で奴隷制を支持するアメリカ人によってすぐに賞賛され、彼らは彼の 著書を英語に翻訳した。彼らは原著の約1,000ページを省略し、その中にはアメリカ人を人種的に混合された集団として否定的に記述した部分も含まれてい た。ドイツでゴビニズムと名付けられた社会運動に刺激を与えた彼の著作は、リヒャルト・ワーグナー、ワーグナーの義理の息子ヒューストン・スチュワート・ チェンバレン、ルーマニアの政治家A・C・クーザ教授、ナチ党の指導者といった著名な反ユダヤ主義者たちにも影響を与え、彼らは後に彼の著作を編集し、再 出版した。 |

| Early life and writings Origins Gobineau came from an old well-established aristocratic family.[2] His father, Louis de Gobineau (1784–1858), was a military officer and staunch royalist.[3] His mother, Anne-Louise Magdeleine de Gercy, was the daughter of a non-noble royal tax official. The de Gercy family lived in the French Crown colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti) for a time in the 18th century. Gobineau always feared he might have black ancestors on his mother's side.[4] Reflecting his hatred of the French Revolution, Gobineau later wrote: "My birthday is July 14th, the date on which the Bastille was captured-which goes to prove how opposites may come together".[5] As a boy and young man, Gobineau loved the Middle Ages, which he saw as a golden age of chivalry and knighthood much preferable to his own time.[6] Someone who knew Gobineau as a teenager described him as a romantic, "with chivalrous ideas and a heroic spirit, dreaming of what was most noble and most grand".[6] Gobineau's father was committed to restoring the House of Bourbon and helped the royalist Polignac brothers to escape from France.[7] As punishment he was imprisoned by Napoleon's secret police but was freed when the Allies took Paris in 1814.[7] During the Hundred Days the de Gobineau family fled France. After Napoleon's final overthrow following the Battle of Waterloo, Louis de Gobineau was rewarded for his loyalty to the House of Bourbon by being made a captain in the Royal Guard of King Louis XVIII.[7] The pay for a Royal Guardsman was very low, and the de Gobineau family struggled on his salary.[7] Magdeleine de Gobineau abandoned her husband for her children's tutor Charles de La Coindière. Together with her lover she took her son and two daughters on extended wanderings across eastern France, Switzerland and the Grand Duchy of Baden.[8] To support herself, she turned to fraud (for which she was imprisoned). His mother became a severe embarrassment to Gobineau, who never spoke to her after he turned twenty.[9] For the young de Gobineau, committed to upholding traditional aristocratic and Catholic values, the disintegration of his parents' marriage, his mother's open relationship with her lover, her fraudulent acts, and the turmoil imposed by being constantly on the run and living in poverty were all very traumatic.[9] Adolescence Gobineau spent the early part of his teenage years in the town of Inzligen where his mother and her lover were staying. He became fluent in German.[8] As a staunch supporter of the House of Bourbon, his father was forced to retire from the Royal Guard after the July Revolution of 1830 brought House of Orléans King Louis-Philippe, Le roi citoyen, ("the Citizen King") to power. He promised to reconcile the heritage of the French Revolution with the monarchy.[10] Given his family's history of supporting the Bourbons, the young Gobineau regarded the July Revolution as a disaster for France.[11] His views were those of a Legitimist committed to a Catholic France ruled over by the House of Bourbon.[12] In 1831, de Gobineau's father took custody of his three children, and his son spent the rest of his adolescence in Lorient, in Brittany.[13] Black and white sketch of Antoine Galland  The Orientalist tales of Antoine Galland (pictured) had a strong influence on Gobineau in his youth. Gobineau disliked his father, whom he dismissed as a boring and pedantic army officer incapable of stimulating thought.[9] Lorient had been founded in 1675 as a base for the French East India Company as King Louis XIV had grand ambitions for making France the dominant political and economic power in Asia.[13] As those ambitions were unrealized, Gobineau developed a sense of faded glory as he grew up in a city that had been built to be the dominant hub for Europe's trade with Asia. This dream went unrealized, as India became part of the British and not the French empire.[13] As a young man, Gobineau was fascinated with the Orient, as the Middle East was known in Europe in the 19th century.[14] While studying at the Collège de Bironne in Switzerland, a fellow student recalled: "All of his aspirations were towards the East. He dreamt only of mosques and minarets; he called himself a Muslim, ready to make the pilgrimage to Mecca".[14] Gobineau loved Oriental tales by the French translator Antoine Galland, often saying he wanted to become an Orientalist. He read Arab, Turkish and Persian tales in translation, becoming what the French call a "un orientaliste de pacotille" ("rubbish orientalist").[15] In 1835, Gobineau failed the entrance exams to the St. Cyr military school.[13] In September 1835, Gobineau left for Paris with fifty francs in his pocket aiming to become a writer.[13] He moved in with an uncle, Thibaut-Joseph de Gobineau, a Legitimist with an "unlimited" hatred of Louis-Philippe.[16] Reflecting his tendency towards elitism, Gobineau founded a society of Legitimist intellectuals called Les Scelti ("the elect"), which included himself, the painter Guermann John (German von Bohn) and the writer Maxime du Camp.[17] Early writings In the later years of the July Monarchy, Gobineau made his living writing serialized fiction (romans-feuilletons) and contributing to reactionary periodicals.[18] He wrote for the Union Catholique, La Quotidienne, L'Unité, and Revue de Paris.[5] At one point in the early 1840s, Gobineau was writing an article every day for La Quotidienne to support himself.[5] As a writer and journalist, he struggled financially and was forever looking for a wealthy patron willing to support him.[18] As a part-time employee of the Post Office and a full-time writer, Gobineau was desperately poor.[17] His family background made him a supporter of the House of Bourbon, but the nature of the Legitimist movement dominated by factious and inept leaders drove Gobineau to despair, leading him to write: "We are lost and had better resign ourselves to the fact".[19] In a letter to his father, Gobineau complained of "the laxity, the weakness, the foolishness and—in a word—the pure folly of my cherished party".[5] At the same time, he regarded French society under the House of Orléans as corrupt and self-serving, dominated by the "oppressive feudalism of money" as opposed to the feudalism of "charity, courage, virtue and intelligence" held by the ancien-régime nobility.[11] Gobineau wrote about July Monarchy France: "Money has become the principle of power and honour. Money dominates business; money regulates the population; money governs; money salves consciences; money is the criterion for judging the esteem due to men".[20] In this "age of national mediocrity" as Gobineau described it, with society going in a direction he disapproved of, the leaders of the cause to which he was committed being by his own admission foolish and incompetent, and the would-be aristocrat struggling to make ends meet by writing hack journalism and novels, he became more and more pessimistic about the future.[20] Gobineau wrote in a letter to his father: "How I despair of a society which is no longer anything, except in spirit, and which has no heart left".[17] He complained the Legitimists spent their time feuding with one another while the Catholic Church "is going over to the side of the revolution".[17] Gobineau wrote: Our poor country lies in Roman decadence. Where there is no longer an aristocracy worthy of itself, a nation dies. Our Nobles are conceited fools and cowards. I no longer believe in anything nor have any views. From Louis-Philippe we shall proceed to the first trimmer who will take us up, but only in order to pass us on to another. For we are without fibre and moral energy. Money has killed everything.[17] Gobineau struck up a friendship and had voluminous correspondence with Alexis de Tocqueville.[21][22][23][24] Tocqueville praised Gobineau in a letter: "You have wide knowledge, much intelligence, and the best of manners".[25] He later gave Gobineau an appointment in the Quai d'Orsay (the French foreign ministry) while serving as foreign minister during the Second Republic of France.[26] Breakthrough with Kapodistrias article In 1841, Gobineau scored his first major success when an article he submitted to Revue des deux Mondes was published on 15 April 1841.[18] Gobineau's article was about the Greek statesman Count Ioannis Kapodistrias. At the time, La Revue des Deux Mondes was one of the most prestigious journals in Paris, and being published in it put Gobineau in the same company as George Sand, Théophile Gautier, Philarète Chasles, Alphonse de Lamartine, Edgar Quinet and Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve who were all published regularly in that journal.[18] On international politics Gobineau's writings on international politics were generally as negative as his writings on France. He depicted Britain as a nation motivated entirely by hatred and greed and the extent of the British Empire around the globe as a source of regret.[27] Gobineau often attacked King Louis-Phillipe for his pro-British foreign policy, writing that he had "humiliated" France by allowing the British Empire to become the world's dominant power.[28] However, reports on the poor economic state of Ireland were a source of satisfaction for Gobineau as he asserted: "It is Ireland which is pushing England into the abyss of revolution".[27] According to Gobineau, the growing power and aggressiveness of Imperial Russia were a cause for concern. He regarded the disastrous retreat from Kabul by the British during the First Anglo-Afghan War with Afghanistan as a sign Russia would be the dominant power in Asia, writing: "England, an aging nation, is defending its livelihood and its existence. Russia, a youthful nation, is following its path towards the power that it must surely gain ... The empire of the Tsars is today the power which seems to have the greatest future ... The Russian people are marching steadfastly towards a goal that is indeed known but still not completely defined".[29] Gobineau regarded Russia as an Asian power and felt the inevitable triumph of Russia was a triumph of Asia over Europe.[29] He had mixed feelings about the German states, praising Prussia as a conservative society dominated by the Junkers. But he worried increasing economic growth promoted by the Zollverein (the German Customs Union) was making the Prussian middle-class more powerful.[30] Gobineau was critical of the Austrian Empire, writing that the House of Habsburg ruled over a mixed population of ethnic Germans, Magyars, Italians, Slavic peoples, etc., and it was inevitable such a multi-ethnic society would go into decline, while the "purely German" Prussia was destined to unify Germany.[31] Gobineau was also pessimistic about Italy, writing: "Shortly after the condottieri disappeared everything that had lived and flourished with them went too; wealth, gallantry, art and liberty, there remained nothing but a fertile land and an incomparable sky".[32] Gobineau denounced Spain for rejecting "a firm and natural authority, a power rooted in national liberty", predicting that without order imposed by an absolute monarchy, she was destined to sink into a state of perpetual revolution.[33] He was dismissive of Latin America, writing with references to the wars of independence: "The destruction of their agriculture, trade and finances, the inevitable consequence of long civil disorder, did not at all seem to them a price too high to pay for what they had in view. And yet who would want to claim that the half-barbarous inhabitants of Castile or the Algarve or the gauchos on the River Plate really deserve to sit as supreme legislators, in the places which they have contested against their masters with such pleasure and energy".[34] About the United States, Gobineau wrote: "The only greatness is that of wealth, and as everyone can acquire this, its ownership is independent of any of the qualities reserved to superior natures".[35] Gobineau wrote the United States lacked an aristocracy, with no sense of noblesse oblige ("nobility obligates") as existed in Europe. The American poor suffered worse than the European poor, causing the United States to be a violent society, where greed and materialism were the only values that counted.[36] In general Gobineau was hostile towards people in the Americas, writing that who in the Old World does not know "that the New World knows nothing of kings, princes and nobles?-that on those semi-virgin lands, in human societies born yesterday and scarcely yet consolidated, no one has the right or the power to call himself any greater than the very least of its citizens?"[35] Marriage  Departmental Museum of the Oise, Portrait of Gobineau's wife, Clémence, by Ary Scheffer (1850) In 1846, Gobineau married Clémence Gabrielle Monnerot. She had pressed for a hasty marriage as she was pregnant by their mutual friend Pierre de Serre who had abandoned her. As a practicing Catholic, she did not wish to give birth to an illegitimate child.[4] Monnerot had been born in Martinique. As with his mother, Gobineau was never entirely certain if his wife, and hence his two daughters had black ancestors or not, as it was a common practice for French slave masters in the Caribbean to take a slave mistress.[4] Gobineau's opposition to slavery, which he held always resulted in harmful miscegenation to whites, may have stemmed from his own personal anxieties that his mother or his wife might have African ancestry.[ |

生い立ちと著作 出自 父ルイ・ド・ゴビノー(1784-1858)は軍人であり、熱心な王党派であった[3]。 母アンヌ=ルイーズ・マグドレーヌ・ド・ジェルシーは、非貴族の王室租税官吏の娘であった。ド・ジェルシー家は18世紀にフランス王室の植民地であったサ ン=ドマング(現在のハイチ)に住んでいた時期がある。ゴビノーは母方の先祖に黒人がいるのではないかと常に恐れていた[4]。 フランス革命を憎んでいたゴビノーは、後に「私の誕生日は7月14日で、バスティーユが捕らえられた日である。 [5]少年時代から青年時代にかけて、ゴビノーは中世を愛し、騎士道と騎士階級の黄金時代は自分の時代よりもはるかに好ましいと考えた[6]。10代の頃 のゴビノーを知る人物は、彼を「騎士道精神と英雄的精神を持ち、最も高貴で壮大なものを夢見る」ロマンチストと評した[6]。 ゴビノーの父親はブルボン家の再興に尽力し、王党派のポリニャック兄弟のフランス脱出を助けた[7]。ワーテルローの戦いの後、ナポレオンが最終的に打倒 されると、ルイ・ド・ゴビノーはブルボン家への忠誠に報いられ、国王ルイ18世の王室衛兵隊長に任命された[7]。王室衛兵の給料は非常に低く、ド・ゴビ ノー家は彼の給料で苦労した[7]。 マグドレーヌ・ド・ゴビノーは、子供たちの家庭教師シャルル・ド・ラ・コワンディエールのために夫を捨てた。彼女は恋人と一緒に息子と2人の娘を連れてフ ランス東部、スイス、バーデン大公国を放浪した[8]。母親はゴビノーにとってひどく厄介な存在となり、ゴビノーは20歳を過ぎてからは一度も口をきかな かった[9]。 伝統的な貴族とカトリックの価値観を守ることに熱心だった若きゴビノーにとって、両親の結婚生活の崩壊、母親と愛人との公然の関係、母親の詐欺行為、そし て常に逃亡し貧困にあえぐことによる混乱は、すべて大きなトラウマとなった[9]。 青年期 ゴビノーは10代の前半を母親とその恋人が滞在していたインズリゲンの町で過ごした。ブルボン家の強固な支持者であった父は、1830年の7月革命によっ てオルレアン家の王ルイ=フィリップ(「市民王」)が権力を握った後、王宮衛兵を退くことを余儀なくされた。彼はフランス革命の遺産と王政の融和を約束し た[10]。ブルボン家を支持した一族の歴史から、若きゴビノーは7月革命をフランスにとっての災厄とみなした[11]。 彼の考えは、ブルボン家が支配するカトリックのフランスにコミットする正統派のものであった[12]。1831年、ド・ゴビノーの父親は3人の子供を引き 取り、息子はブルターニュのロリアンで残りの青春時代を過ごした[13]。 アントワーヌ・ギャランの白黒スケッチ  アントワーヌ・ガランのオリエンタリズムの物語(写真)は、少年時代のゴビノーに強い影響を与えた。 ゴビノーは父を嫌っており、退屈で衒学的な陸軍将校は思考を刺激することができないと見下していた[9]。ルイ14世がフランスをアジアにおける政治的・ 経済的支配者にするという壮大な野望を抱いていたため、ロリアンはフランス東インド会社の拠点として1675年に建設された[13]。インドがフランス帝 国ではなくイギリス帝国の一部となったため、この夢は実現しなかった[13]。 若い頃のゴビノーは、19世紀のヨーロッパで中東が知られていたように、オリエントに魅了されていた[14]: 「彼の願望はすべて東洋に向けられていた。ゴビノーはフランスの翻訳家アントワーヌ・ガランの東洋の物語が大好きで、しばしば東洋学者になりたいと言って いた。1835年、ゴビノーはサン=シール士官学校の入学試験に落ちた[13]。 1835年9月、ゴビノーは作家になることを目指し、50フランをポケットに入れてパリに向かった[13]。叔父のティボー・ジョゼフ・ド・ゴビノーの家 に身を寄せたが、彼はルイ=フィリップを「限りなく」憎む正統主義者であった。 [16]ゴビノーは、彼のエリート主義的傾向を反映して、レ・セルティ(「選民」)と呼ばれる正統派の知識人の協会を設立し、その中には彼自身、画家のグ エルマン・ジョン(ドイツ語でフォン・ボーン)、作家のマキシム・デュ・カンプが含まれていた[17]。 初期の著作 7月王政の後期、ゴビノーは連載小説(romans-feuilletons)を書き、反動的な定期刊行物に寄稿して生計を立てていた[18]。 [1840年代初頭のある時期、ゴビノーは自活のために毎日『ラ・コティディエンヌ』に記事を書いていた[5]。作家でありジャーナリストであったゴビ ノーは経済的に苦しく、自分を支援してくれる裕福なパトロンを探し続けていた。 家柄からブルボン家の支持者であったが、内紛に明け暮れ、無能な指導者が支配する正統派運動の本質に絶望し、ゴビノーはこう書く: 「父に宛てた手紙の中で、ゴビノーは「私の大切な党のいい加減さ、弱さ、愚かさ、そして一言で言えば純粋な愚かさ」[5]を訴えた。 同時に彼は、オルレアン家のもとでのフランス社会は腐敗し、利己的であり、アンシャン・レジーム時代の貴族が持っていた「慈愛、勇気、美徳、知性」の封建 主義とは対照的な「金の圧制的封建主義」に支配されていると考えていた[11]: 「金が権力と名誉の原理となった。貨幣が権力と名誉の原理となった。貨幣がビジネスを支配し、貨幣が人口を統制し、貨幣が統治し、貨幣が良心を癒し、貨幣 が人間に対する敬意を判断する基準となった」[20]。 ゴビノーが言うところの「国民的凡庸さの時代」、社会は彼が認めない方向に進み、彼が献身していた大義の指導者たちは彼自身が認めるように愚かで無能であ り、貴族になろうとする者はにわかジャーナリズムや小説を書くことで生活費を稼ぐのに苦労している、このような状況の中で、彼はますます将来を悲観するよ うになった[20]: ゴビノーは父に宛てた手紙の中で次のように書いている。「もはや精神以外は何もなく、心も残っていない社会に、私はどれほど絶望していることだろう」 [17] ゴビノーは、カトリック教会が「革命の側に回っている」一方で、正統主義者たちは互いに反目することに時間を費やしていると不満を述べた: 私たちの貧しい国はローマの退廃の中にある。もはやそれ自体に値する貴族がいないところでは、国家は滅びる。わが貴族はうぬぼれた愚か者であり、臆病者で ある。私はもはや何も信じていないし、何の見解も持っていない。ルイ=フィリップから、われわれを引き上げてくれる最初のトリマーのところに行こう。われ われには繊維も道徳的エネルギーもない。金がすべてを殺したのだ」[17]。 ゴビノーはアレクシス・ド・トクヴィルと親交を結び、膨大な書簡を交わしていた[21][22][23][24]。 トクヴィルは手紙の中でゴビノーを賞賛している: 「後にトクヴィルは、フランス第二共和政時代に外務大臣を務めていたゴビノーにオルセー(フランス外務省)への任命を与えた[26]。 カポディストリアスの記事でブレイク 1841年、ゴビノーはRevue des deux Mondesに投稿した記事が1841年4月15日に掲載され、最初の大きな成功を収めた[18]。当時、「第二月曜日」誌はパリで最も権威のある雑誌の ひとつであり、ゴビノーは同誌に掲載されたことで、同誌に定期的に掲載されていたジョージ・サンド、テオフィル・ゴーティエ、フィラレット・シャスル、ア ルフォンス・ド・ラマルティーヌ、エドガー・キネ、シャルル・オーギュスタン・サント=ブーヴらと肩を並べることになった[18]。 国際政治について ゴビノーの国際政治に関する著作は、フランスに関する著作と同様、概して否定的であった。ゴビノーはしばしばルイ=フィリップ国王の親英外交政策を攻撃 し、大英帝国が世界の支配的な大国となることを許してフランスに「屈辱を与えた」と書いている[28]。しかし、アイルランドの経済状態の悪さに関する報 告は、ゴビノーにとって満足のいくものであった: 「イングランドを革命の奈落の底に突き落とそうとしているのはアイルランドだ」[27]。 ゴビノーによれば、帝政ロシアの力の増大と攻撃性は憂慮すべきものであった。彼は、アフガニスタンとの第一次アングロ・アフガン戦争でのイギリスによるカ ブールからの悲惨な撤退を、ロシアがアジアで支配的な力を持つようになる兆候とみなし、こう書いている: 「年老いたイギリスは、自国の生活と存在を守ろうとしている。若い国家であるロシアは、必ず手に入れなければならない権力への道を歩んでい る......。ツァーリ皇帝の帝国は今日、最も偉大な未来があると思われる大国である。ロシア人民は、確かに知られてはいるが、まだ完全には定義されて いない目標に向かって着実に行進している」[29]。ゴビノーはロシアをアジアの大国とみなし、ロシアの必然的な勝利はヨーロッパに対するアジアの勝利で あると感じていた[29]。 プロイセンはユンカーによって支配された保守的な社会であると賞賛していた。ゴビノーはオーストリア帝国に批判的で、ハプスブルク家が支配していたのはド イツ人、マジャール人、イタリア人、スラヴ人などの混血であり、このような多民族社会が衰退していくのは避けられないが、「純粋なドイツ人」であるプロイ センはドイツを統一する運命にあると書いている[31]。 ゴビノーはイタリアについても悲観的で、こう書いている: 「コンドッティエリが姿を消した直後、彼らとともに生き、栄えたものはすべて消え去った。富、勇敢さ、芸術、自由、そこには肥沃な土地と比類なき空しか残 らなかった」[32] ゴビノーは、「確固とした自然な権威、国民の自由に根ざした権力」を拒否したスペインを非難し、絶対君主制による秩序がなければ、スペインは永遠の革命状 態に沈む運命にあると予言した[33] 彼はラテンアメリカにも否定的で、独立戦争を引き合いに出して書いている: 「長い内乱の必然的な帰結である農業、貿易、財政の破壊は、彼らにとって、自分たちが考えていることのために支払うには高すぎる代償とはまったく思えな かった。それなのに、カスティーリャやアルガルヴェ、あるいは平原河のガウチョの半分野蛮な住民が、そのような喜びとエネルギーをもって主人と争ってきた 場所で、本当に最高立法者として座るに値すると主張したいと思う者がいるだろうか」[34]。 アメリカについてゴビノーは、「唯一の偉大さは富であり、誰もがこれを手に入れることができるため、その所有は優れた本性に留保された資質とは無関係であ る」と書いている[35]。ゴビノーは、アメリカには貴族階級が存在せず、ヨーロッパに存在するようなノブレス・オブリージュ(「貴族は義務を負う」)の 意識はないと書いている。一般的にゴビノーはアメリカ大陸の人々に敵対的であり、旧世界の誰が「新世界が王も王子も貴族も何も知らないことを知らないの か、それらの半処女的な土地では、昨日生まれ、まだほとんど統合されていない人間社会では、誰もその市民の中で最も劣った者よりも偉いと自称する権利も力 もないことを」知らないと書いている[36]。 結婚  オワーズ県立博物館、アリ・シェフェールによるゴビノーの妻クレマンスの肖像画(1850年) 1846年、ゴビノーはクレマンス・ガブリエル・モンヌローと結婚した。共通の友人ピエール・ド・セールに捨てられ、その子を身ごもったクレマンスは、早 急な結婚を迫った。モンヌローはマルティニークで生まれた。母親と同様、ゴビノーは妻、ひいては彼の2人の娘が黒人の先祖を持つかどうか完全には確信が持 てなかった。ゴビノーは、奴隷制度は常に白人に有害な混血をもたらすとして反対していたが、それは母親や妻がアフリカ人の先祖を持つのではないかという個 人的な不安からきていたのかもしれない[4]。 |

| Early diplomatic work and

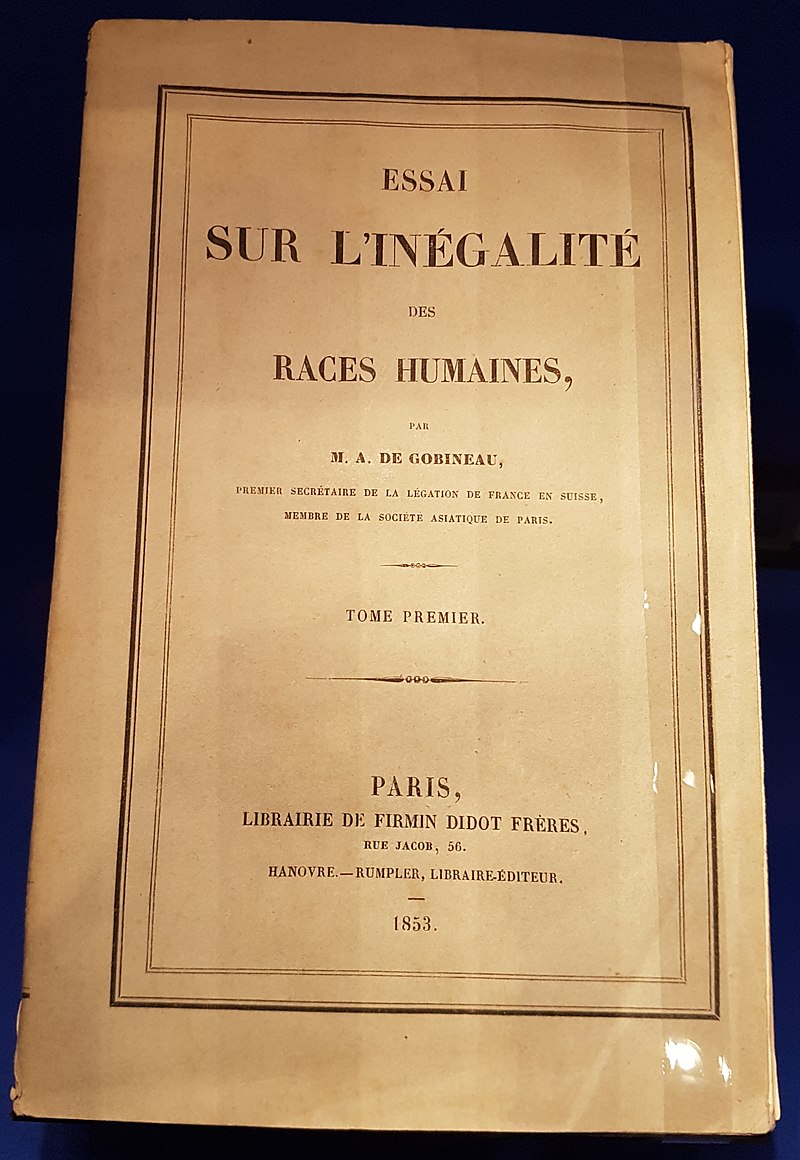

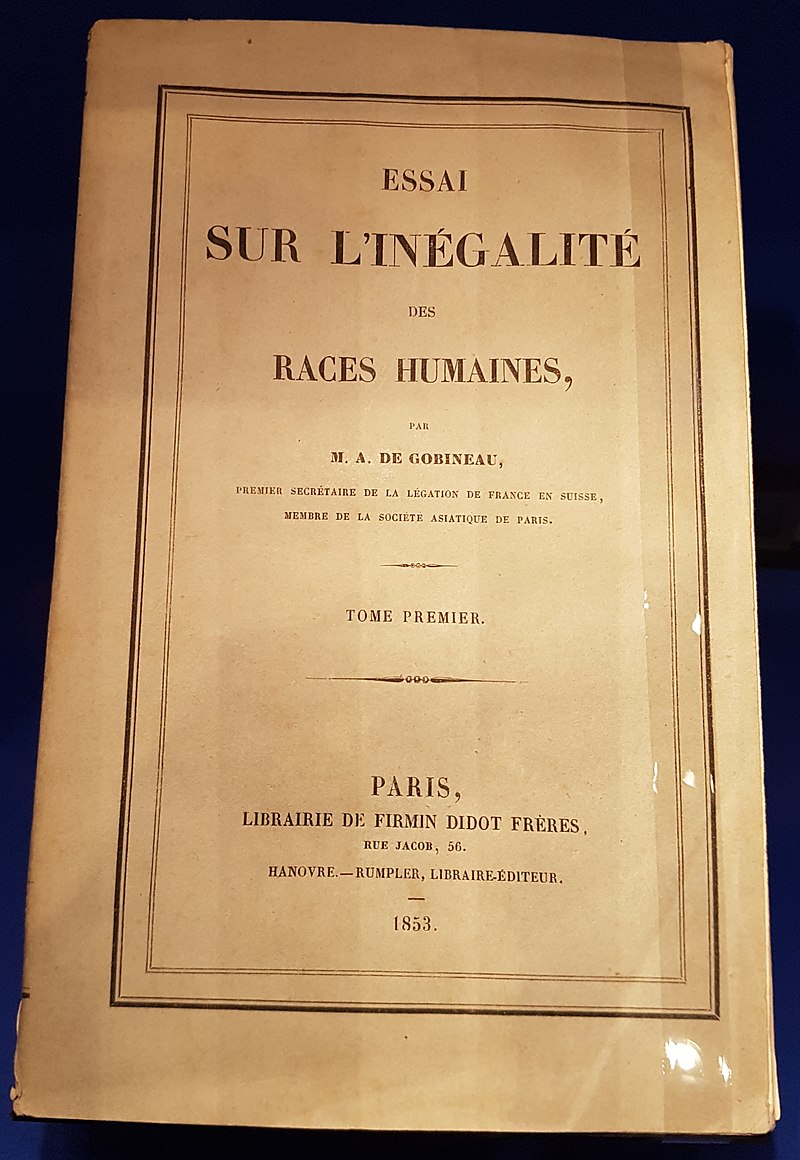

theories on race Main article: Social thinking of Arthur de Gobineau Embittered royalist Gobineau's novels and poems of the 1830s–40s were usually set in the Middle Ages or the Renaissance with aristocratic heroes who by their very existence uphold all of the values Gobineau felt were worth celebrating like honor and creativity against a corrupt, soulless middle class.[37] His 1847 novel Ternove was the first time Gobineau linked class with race, writing "Monsieur de Marvejols would think of himself, and of all members of the nobility, as of a race apart, of a superior essence, and he believed it criminal to sully this by mixture with plebeian blood."[38] The novel, set against the backdrop of the Hundred Days of 1815, concerns the disastrous results when an aristocrat Octave de Ternove unwisely marries the daughter of a miller.[39] Gobineau was horrified by the Revolution of 1848 and disgusted by what he saw as the supine reaction of the European upper classes to the revolutionary challenge. Writing in the spring of 1848 about the news from Germany he noted: "Things are going pretty badly ... I do not mean the dismissal of the princes—that was deserved. Their cowardice and lack of political faith make them scarcely interesting. But the peasants, there they are nearly barbarous. There is pillage, and burning, and massacre—and we are only at the beginning."[40] As a Legitimist, Gobineau disliked the House of Bonaparte and was displeased when Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte was elected president of the republic in 1848.[41] However, he came to support Bonaparte as the best man to preserve order, and in 1849, when Tocqueville became Foreign Minister, his friend Gobineau became his chef de cabinet.[42] Racial theories and aristocrats Shocked by the Revolution of 1848, Gobineau first expressed his racial theories in his 1848 epic poem Manfredine. In it he revealed his fear of the revolution being the beginning of the end of aristocratic Europe, with common folk descended from lesser breeds taking over.[43] Reflecting his disdain for ordinary people, Gobineau said French aristocrats like himself were the descendants of the Germanic Franks who conquered the Roman province of Gaul in the fifth century AD, while common French people were the descendants of racially inferior Celtic and Mediterranean people. This was an old theory first promoted in a tract by Count Henri de Boulainvilliers. He had argued that the Second Estate (the aristocracy) was of "Frankish" blood and the Third Estate (the commoners) were of "Gaulish" blood.[44] Born after the French Revolution had destroyed the idealized Ancien Régime of his imagination, Gobineau felt a deep sense of pessimism regarding the future.[44] For him the French Revolution, having destroyed the racial basis of French greatness by overthrowing and in many cases killing the aristocracy, was the beginning of a long, irresistible process of decline and degeneration, which could only end with the utter collapse of European civilization.[45] He felt what the French Revolution had begun the Industrial Revolution was finishing; industrialization and urbanization were a complete disaster for Europe.[45] Like many other European romantic conservatives, Gobineau looked back nostalgically at an idealized version of the Middle Ages as an idyllic agrarian society living harmoniously in a rigid social order.[45] He loathed modern Paris, a city he called a "giant cesspool" full of les déracinés ("the uprooted")—the criminal, impoverished, drifting men with no real home. Gobineau considered them to be the monstrous products of centuries of miscegenation ready to explode in revolutionary violence at any moment.[46] He was an ardent opponent of democracy, which he stated was mere "mobocracy"—a system that allowed the utterly stupid mob the final say on running the state.[47] Time in Switzerland and Germany From November 1849 to January 1854 Gobineau was stationed at the French legation in Bern as the First Secretary.[48] During his time in Switzerland Gobineau wrote the majority of the Essai.[48] He was stationed in Hanover in the fall of 1851 as acting Chargé d'Affaires, and was impressed by the "traces of real nobility" he said he saw at the Hanoverian court.[49] Gobineau especially liked the blind King George V whom he saw as a "philosopher-king" and to whom he dedicated the Essais.[49] He praised the "remarkable character" of Hanoverian men and likewise commended Hanoverian society as having "an instinctive preference for hierarchy" with the commoners always deferring to the nobility, which he explained on racial grounds.[50] Reflecting his lifelong interest in the Orient, Gobineau joined the Société Asiatique in 1852 and got to know several French Orientalists, like Julius von Mohl, very well.[15] In January 1854, Gobineau was sent as First Secretary to the French legation at the Free City of Frankfurt.[51] Of the Federal Convention of the German Confederation that sat in Frankfurt—also known as the "Confederation Diet"—Gobineau wrote: "The Diet is a business office for the German bureaucracy—it is very far from being a real political body".[51][52] Gobineau hated the Prussian representative at the Diet, Prince Otto von Bismarck, because of his advances towards Madame Gobineau.[53] By contrast, the Austrian representative, General Anton von Prokesch-Osten became one of Gobineau's best friends.[51] He was a reactionary Austrian soldier and diplomat who hated democracy and saw himself as a historian and orientalist, and for all these reasons Gobineau bonded with him.[53] It was during these periods that Gobineau began to write less often to his old liberal friend Tocqueville and more often to his new conservative friend Prokesch-Osten.[53] Gobineau's racial theories In his own lifetime, Gobineau was known as a novelist, a poet and for his travel writing recounting his adventures in Iran and Brazil rather than for the racial theories for which he is now mostly remembered.[54] However, he always regarded his book Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines (An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races) as his masterpiece and wanted to be remembered as its author.[54] A firm reactionary who believed in the innate superiority of aristocrats over commoners—whom he held in utter contempt—Gobineau embraced the now-discredited doctrine of scientific racism to justify aristocratic rule over racially inferior commoners.[43] Racial magnum opus: An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races  Photograph of the cover of the original edition of An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races Cover of the original edition of An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races In his An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, published in 1855, Gobineau ultimately accepts the prevailing Christian doctrine that all human beings shared the common ancestors Adam and Eve (monogenism as opposed to polygenism). He suggests, however, that "nothing proves that at the first redaction of the Adamite genealogies the colored races were considered as forming part of the species"; and, "We may conclude that the power of producing fertile offspring is among the marks of a distinct species. As nothing leads us to believe that the human race is outside this rule, there is no answer to this argument."[55] Gobineau stated he was writing about races, not individuals: examples of talented black or Asian individuals did not disprove his thesis of the supposed inferiority of the black and Asian races. He wrote: "I will not wait for the friends of equality to show me such and such passages in books written by missionaries or sea captains, who declare some Wolof is a fine carpenter, some Hottentot a good servant, that a Kaffir dances and plays the violin, that some Bambara knows arithmetic … Let us leave aside these puerilities and compare together not men, but groups."[56] Gobineau argued that race was destiny, declaring rhetorically: So the brain of a Huron Indian contains in undeveloped form an intellect which is absolutely that same as an Englishman or a Frenchman! Why then, in the course of the ages has he not then invented printing or steam power? Gobineau's primary thesis was that European civilization flowed from Greece to Rome, and then to Germanic and contemporary civilization. He thought this corresponded to the ancient Indo-European culture, which earlier anthropologists had misconceived as "Aryan"—a term that only Indo-Iranians are known to have used in ancient times.[57] This included groups classified by language like the Celts, Slavs and the Germans.[58][59] Gobineau later came to use and reserve the term Aryan only for the "Germanic race", and described the Aryans as la race germanique.[60] By doing so, he presented a racist theory in which Aryans—that is Germanic people—were all that was positive.[61] Reaction to Gobineau's essay The Essai attracted mostly negative reviews from French critics, which Gobineau used as a proof of the supposed truth of his racial theories, writing "the French, who are always ready to set anything afire—materially speaking—and who respect nothing, either in religion or politics, have always been the world's greatest cowards in matters of science".[62] However, events such as the expansion of European and American influence overseas and the unification of Germany led Gobineau to alter his opinion to believe the "white race" could be saved. The German-born American historian George Mosse argued that Gobineau projected his fear and hatred of the French middle and working classes onto Asian and Black people.[63] Summarizing Mosse's argument, Davies argued that: "The self-serving, materialistic oriental of the Essai was really an anti-capitalist's portrait of the money-grubbing French middle class" while "the sensual, unintelligent and violent negro" that Gobineau portrayed in the Essai was an aristocratic caricature of the French poor.[64] In his writings on the French peasantry, Gobineau characteristically insisted in numerous anecdotes, which he said were based on personal experience, that French farmers were coarse, crude people incapable of learning, indeed of any sort of thinking beyond the most rudimentary level of thought. As the American critic Michelle Wright wrote, "the peasant may inhabit the land, but they are certainly not part of it".[65] Wright further noted the very marked similarity between Gobineau's picture of the French peasantry and his view of blacks.[66] Time in Persia In 1855, Gobineau left Paris to become the first secretary at the French legation in Tehran, Persia (modern Iran). He was promoted to chargé d'affaires the following year.[67] The histories of Persia and Greece had played prominent roles in the Essai and Gobineau wanted to see both places for himself.[68] His mission was to keep Persia out of the Russian sphere of influence, but he cynically wrote: "If the Persians ... unite with the western powers, they will march against the Russians in the morning, be defeated by them at noon and become their allies by evening".[68] Gobineau's time was not taxed by his diplomatic duties, and he spent time studying ancient cuneiform texts and learning Persian. He came to speak a "kitchen Persian" that allowed him to talk to Persians somewhat. (He was never fluent in Persian as he said he was.)[67] Despite having some love for the Persians, Gobineau was shocked they lacked his racial prejudices and were willing to accept blacks as equals. He criticized Persian society for being too "democratic". Gobineau saw Persia as a land without a future destined to be conquered by the West sooner or later. For him this was a tragedy for the West. He believed Western men would all too easily be seduced by the beautiful Persian women causing more miscegenation to further "corrupt" the West.[67] However, he was obsessed with ancient Persia, seeing in Achaemenid Persia a great and glorious Aryan civilization, now sadly gone. This was to preoccupy him for the rest of his life.[69] Gobineau loved to visit the ruins of the Achaemenid period as his mind was fundamentally backward looking, preferring to contemplate past glories rather than what he saw as a dismal present and even bleaker future.[69] His time in Persia inspired two books: Mémoire sur l'état social de la Perse actuelle (1858) ("Memoire on the Social State of Today's Persia") and Trois ans en Asie (1859) ("Three Years in Asia").[69] Gobineau was less than complimentary about modern Persia. He wrote to Prokesch-Osten that there was no "Persian race" as modern Persians were "a breed mixed from God knows what!". He loved ancient Persia as the great Aryan civilization par excellence, however, noting that Iran means "the land of the Aryans" in Persian.[70] Gobineau was less Eurocentric than one might expect in his writings on Persia, believing the origins of European civilization could be traced to Persia. He criticized western scholars for their "collective vanity" in being unable to admit to the West's "huge" debt to Persia.[70] Josiah C. Nott and Henry Hotze  Sepia photograph of Josiah C. Nott looking to his left Josiah C. Nott  Photograph of Henry Hotzel looking at the casmera Henry Hotze In 1856, two American "race scientists", Josiah C. Nott and Henry Hotze, both ardent white supremacists, translated Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines into English. Champions of slavery, they found in Gobineau's anti-black writings a convenient justification for the "peculiar institution".[71] Nott and Hotze found much to approve of in the Essai such as: "The Negro is the most humble and lags at the bottom of the scale. The animal character imprinted upon his brow marks his destiny from the moment of his conception".[71] Much to Gobineau's intense annoyance, Nott and Hotze abridged the first volume of the Essai from 1,600 pages in the French original down to 400 in English.[72] At least part of the reason for this was because of Gobineau's hostile picture of Americans. About American white people, Gobineau declared: They are a very mixed assortment of the most degenerate races in olden-day Europe. They are the human flotsam of all ages: Irish, crossbreed Germans and French and Italians of even more doubtful stock. The intermixture of all these decadent ethnic varieties will inevitably give birth to further ethnic chaos. This chaos is no way unexpected or new: it will produce no further ethnic mixture which has not already been, or cannot be realized on our own continent. Absolutely nothing productive will result from it, and even when ethnic combinations resulting from infinite unions between Germans, Irish, Italians, French and Anglo-Saxons join us in the south with racial elements composed of Indian, Negro, Spanish and Portuguese essence, it is quite unimaginable that anything could result from such horrible confusions, but an incoherent juxtaposition of the most decadent kinds of people.[73] Highly critical passages like this were removed from The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races, as the Essai was titled in English. Nott and Hotze retained only the parts relating to the alleged inherent inferiority of blacks.[74] Likewise, they used Gobineau as a way of attempting to establish that white America was in mortal peril despite the fact that most American blacks were slaves in 1856. The two "race scientists" argued on the basis of the Essai that blacks were essentially a type of vicious animal, rather than human beings, and would always pose a danger to whites.[75] The passages of the Essai where Gobineau declared that, though of low intelligence, blacks had certain artistic talents and that a few "exceptional" African tribal chiefs probably had a higher IQ than those of the stupidest whites were not included in the American edition. Nott and Hotze wanted nothing that might give blacks admirable human qualities.[76] Beyond that, they argued that nation and race were the same, and that to be American was to be white.[77] As such, the American translators argued in their introduction that just as various European nations were torn apart by nationality conflicts caused by different "races" living together, likewise ending slavery and granting American citizenship to blacks would cause the same sort of conflicts, but only on a much vaster scale in the United States.[78] Time in Newfoundland In 1859, an Anglo-French dispute over the French fishing rights on the French Shore of Newfoundland led to an Anglo-French commission being sent to Newfoundland to find a resolution to the dispute. Gobineau was one of the two French commissioners dispatched to Newfoundland, an experience that he later recorded in his 1861 book Voyage à Terre-Neuve ("Voyage to Newfoundland"). In 1858, the Foreign Minister Count Alexandre Colonna-Walewski had tried to send Gobineau to the French legation in Beijing. He objected that as a "civilized European" he had no wish to go to an Asian country like China.[79] As punishment, Walewski sent Gobineau to Newfoundland, telling him he would be fired from the Quai d'Orsay if he refused the Newfoundland assignment.[80] Gobineau hated Newfoundland, writing to a friend in Paris on 26 July 1859: "This is an awful country. It is very cold, there is almost constant fog, and one sails between pieces of floating ice of enormous size."[81] In his time in St. John's, a city largely inhabited by Irish immigrants, Gobineau deployed virtually every anti-Irish cliché in his reports to Paris. He stated the Irish of St. John's were extremely poor, undisciplined, conniving, obstreperous, dishonest, loud, violent, and usually drunk.[82] He described several of the remote fishing settlements he visited in Utopian terms, praising them as examples of how a few hardy, tough people could make a living under very inhospitable conditions.[83] Gobineau's praise for Newfoundland fishermen reflected his viewpoint that those who cut themselves off from society best preserve their racial purity.[84] Despite his normal contempt for ordinary people, he called the Newfoundland fishermen he met "the best men that I have ever seen in the world".[85] Gobineau observed that in these remote coastal settlements, there were no policemen as there was no crime, going on to write: I am not sorry to have seen once in my life a sort of Utopia. [...] A savage and hateful climate, a forbidding countryside, the choice between poverty and hard dangerous labour, no amusements, no pleasures, no money, fortune and ambition being equally impossible—and still, for all this, a cheerful outlook, a kind of domestic well-being of the most primitive kind. [...] But this is what succeeds in enabling men to make use of complete liberty and to be tolerant of one another.[85] |

人種に関する初期の外交活動と理論 主な記事 アルチュール・ド・ゴビノーの社会思想 苦悩する王党派 1830年代から40年代にかけてのゴビノーの小説や詩は、たいてい中世やルネサンスを舞台にしたもので、腐敗した魂のない中産階級に対して、名誉や創造 性といった、ゴビノーが称賛に値すると感じた価値観のすべてを、その存在そのものによって支持する貴族の英雄が登場する。 [1847年の小説『テルヌーヴ』は、ゴビノーが初めて階級と人種を結びつけた作品であり、「ムッシュー・ド・マルヴェジョルスは、自分自身を、そして貴 族のすべての構成員を、別個の種族、優れた本質を持つものとして考えており、平民の血との混血によってこれを汚すことは犯罪的であると信じていた」と書い ている[38]。 ゴビノーは1848年の革命に恐怖し、革命の挑戦に対するヨーロッパの上流階級の無関心な反応に嫌悪感を抱いていた。1848年の春、彼はドイツからの ニュースについてこう書いている: 「事態はかなり悪化している。諸侯の解任という意味ではない。彼らの臆病さと政治的信念の欠如は、彼らをほとんど興味深い存在にしていない。しかし農民た ちは、ほとんど野蛮だ。略奪があり、焼き討ちがあり、虐殺があり、まだ始まったばかりである」[40]。 正統主義者であったゴビノーはボナパルト家を嫌っており、1848年にルイ=ナポレオン・ボナパルトが共和国大統領に選出された際には不快感を抱いた [41]。 しかし、秩序を維持するためにはボナパルトが最適であるとしてボナパルトを支持するようになり、1849年にトクヴィルが外相に就任すると、友人のゴビ ノーは彼の内閣官房長官に就任した[42]。 人種論と貴族 1848年の革命に衝撃を受けたゴビノーは、1848年に発表した叙事詩『マンフレディーヌ』で初めて人種論を表明した。その中で彼は、革命がヨーロッパ の貴族の終わりの始まりであり、劣等人種の末裔である庶民が支配するようになることを恐れていたことを明らかにしている[43]。庶民を軽蔑していたゴビ ノーは、自分のようなフランス貴族は紀元5世紀にローマ帝国のガリア地方を征服したゲルマン系フランク人の末裔であり、庶民であるフランス人は人種的に劣 等なケルト人や地中海沿岸の人々の末裔であると述べた。これは、アンリ・ド・ブーランヴィリエ伯爵の小冊子で最初に唱えられた古い説である。彼は、第二身 分(貴族)は「フランク人」の血を引いており、第三身分(平民)は「ガリア人」の血を引いていると主張していた[44]。フランス革命が彼の想像上の理想 化されたアンシャン・レジームを破壊した後に生まれたゴビノーは、未来に対して深い悲観を感じていた[44]。 彼にとって、フランス革命は、貴族階級を打倒し、多くの場合、貴族階級を殺すことによって、フランスの偉大さの人種的基盤を破壊し、ヨーロッパ文明の完全 な崩壊によってのみ終わることができる、衰退と退化の長く、抗いがたいプロセスの始まりであった[45]。 彼は、フランス革命が始めたことを産業革命が終わらせようとしていると感じていた。 他の多くのヨーロッパのロマンチックな保守主義者と同様に、ゴビノーは、厳格な社会秩序の中で調和して生活する牧歌的な農耕社会として理想化された中世を ノスタルジックに振り返った[45]。 彼は、レ・デラシネ(「根こそぎ奪われた者たち」)-犯罪者、貧困にあえぎ、本当の家を持たずに漂流する男たち-で溢れる「巨大な掃き溜め」と呼ばれる現 代のパリを嫌悪した。ゴビノーは彼らを、何世紀にもわたる混血の産物であり、今にも革命的暴力が爆発しそうな怪物だと考えていた[46]。 彼は民主主義に熱烈に反対しており、民主主義は単なる「モボクラシー」(まったく愚かな暴徒に国家運営の最終決定権を与える制度)だと述べていた [47]。 スイスとドイツでの生活 1849年11月から1854年1月まで、ゴビノーは一等書記官としてベルンのフランス公使館に駐在した[48]。 1851年秋、臨時代理公使としてハノーファーに駐在し、ハノーファーの宮廷で目にした「本物の高貴さの痕跡」に感銘を受けた[49]。ゴビノーは特に盲 目の国王ジョージ5世を気に入り、「哲学者王」と見なし、エセーを献呈した[49]。 [49]彼はハノーヴァー朝の男性の「驚くべき性格」を賞賛し、同様にハノーヴァー朝の社会が「本能的な上下関係の好み」を持っており、平民は常に貴族に 従順であったことを賞賛し、それを人種的な理由から説明した[50]。 ゴビノーは東洋への生涯の関心を反映して、1852年にアジア協会に入会し、ジュリウス・フォン・モールのような何人かのフランス人東洋学者と親交を深め た[15]。 1854年1月、ゴビノーは自由都市フランクフルトのフランス公使館に一等書記官として派遣された[51]。フランクフルトで開催されたドイツ盟約者団の 連邦会議(「盟約者団議会」としても知られる)について、ゴビノーは「議会はドイツ官僚のためのビジネスオフィスであり、真の政治機関とはほど遠い」と書 いている[51][52]。 [これとは対照的に、オーストリア代表のアントン・フォン・プロケシュ=オステン将軍はゴビノーの親友の一人となった[51]。彼は民主主義を憎む反動的 なオーストリアの軍人であり外交官であり、自らを歴史家であり東洋学者であると考えていた。 ゴビノーの人種論 ゴビノーは生前、小説家、詩人として、またイランやブラジルでの冒険を綴った旅行記で知られていたが、現在では人種論でよく知られている。 [54]平民に対する貴族の生来の優越性を信じる確固とした反動主義者であったゴビノーは、人種的に劣る平民に対する貴族の支配を正当化するために、科学 的人種主義という今では信用されなくなった教義を受け入れた[43]。 人種主義の大作:人種の不平等に関する試論』(原題:An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races)  人種不平等論』初版表紙の写真 人種不平等論』原版表紙 1855年に出版された『人類の不平等に関する試論』の中で、ゴビノーは最終的に、すべての人類は共通の祖先アダムとイヴを共有しているというキリスト教 の一般的な教義を受け入れている(多系統主義に対する単系統主義)。しかし彼は、「アダムの系図が最初に書き直されたとき、有色人種が種の一部であると考 えられていたことを証明するものは何もない」とし、「繁殖力のある子孫を残す力は、別個の種の印のひとつであると結論づけることができる」と述べている。 人類がこの規則から外れていると信じるに足るものは何もないので、この議論に対する答えはない」[55]。 ゴビノーは、自分が書いているのは人種についてであって、個人についてではないと述べている。有能な黒人やアジア人の例は、黒人やアジア人が劣っていると いう彼のテーゼを反証するものではなかった。彼はこう書いている: 「私は、宣教師や船長によって書かれた本の中の、あるウォロフ人は優れた大工であり、あるホッテントット人は優れた使用人であり、あるカフィール人は踊 り、ヴァイオリンを弾き、あるバンバラは算数を知っている......というような文章を、平等の友人たちが私に見せてくれるのを待つつもりはない。 ゴビノーは人種は運命であると主張し、修辞的にこう宣言した: つまり、ヒューロン系インディアンの脳は、未発達の状態で、イギリス人やフランス人とまったく同じ知性を秘めている!では、なぜ時代の流れの中で、彼は印 刷や蒸気を発明しなかったのか? ゴビノーの主要なテーゼは、ヨーロッパ文明はギリシャからローマへ、そしてゲルマン文明、現代文明へと流れていくというものだった。彼はこれが古代のイン ド・ヨーロッパ文化に対応すると考えたが、それ以前の人類学者はこれを「アーリア人」と誤解していた。 [58][59]ゴビノーは後にアーリア人という言葉を「ゲルマン民族」に対してのみ使用し留保するようになり、アーリア人をla race germanique(ゲルマン民族)と表現した[60]。そうすることで、彼はアーリア人、つまりゲルマン民族が肯定的なものすべてであるという人種主 義理論を提示した[61]。 ゴビノーのエッセイに対する反応 エッセイはフランスの批評家たちからほとんど否定的な批評を集めたが、ゴビノーはそれを自分の人種論が真実であることの証明として利用し、「フランス人 は、物質的なことに関しては常に何にでも火をつける用意があり、宗教においても政治においても何ものをも尊重しないが、科学の問題に関しては常に世界一の 臆病者である」と書いた[62]。ドイツ生まれのアメリカ人歴史家ジョージ・モッセは、ゴビノーはフランスの中産階級と労働者階級に対する恐怖と憎悪をア ジア人と黒人に投影したと論じている[63]。 モッセの議論を要約して、デイヴィスは次のように主張した:「エッサイの利己的で物質主義的な東洋人は、実のところ、反資本主義者が描いた金食い虫のフラ ンス中産階級の肖像」であり、ゴビノーがエッサイで描いた「官能的で、知性がなく、暴力的な黒人」はフランス貧困層の貴族的戯画であった。 [ゴビノーは、フランスの農民に関する著作の中で、フランスの農民は粗野で粗野な人々であり、学問を学ぶことも、初歩的な思考を超える思考をすることもで きないと、個人的な経験に基づくとした数々の逸話で主張している。アメリカの批評家ミシェル・ライトが書いたように、「農民はその土地に住んでいるかもし れないが、その土地の一部ではない」[65]。ライトはさらに、ゴビノーの描くフランスの農民像と彼の黒人観との間に非常に顕著な類似性があることを指摘 している[66]。 ペルシャ時代 1855年、ゴビノーはパリを離れ、ペルシャのテヘラン(現在のイラン)にあるフランス公使館の一等書記官となる。ペルシャとギリシアの歴史はエッサイの 中で重要な役割を担っており、ゴビノーはこの2つの地を自分の目で確かめたいと考えていた[68]。 ゴビノーの時間は外交任務のために割かれることはなく、古代の楔形文字のテキストを研究したり、ペルシア語を学んだりして過ごした。彼はペルシア人と多少 会話ができる「台所ペルシア語」を話すようになった。(ペルシャ人に対しては好意を持っていたが、ゴビノーは彼らが自分のような人種的偏見を持たず、黒人 を対等に受け入れてくれることに衝撃を受けた。彼はペルシャ社会があまりにも「民主的」であると批判した。 ゴビノーはペルシャを、遅かれ早かれ西洋に征服される運命にある未来なき土地と見ていた。彼にとって、これは西洋にとっての悲劇だった。しかし、彼は古代 ペルシアに執着し、アケメネス朝ペルシアに、今は亡き偉大で輝かしいアーリア文明を見ていた。ゴビノーはアケメネス朝時代の遺跡を訪れるのが好きで、彼の 心は基本的に後ろ向きであり、悲惨な現在やさらに暗い未来を見るよりも、過去の栄光に思いを馳せることを好んだからである[69]。 ペルシアでの生活は2冊の著作に影響を与えた: Mémoire sur l'état social de la Perse actuelle (1858)』(「今日のペルシアの社会状態に関する覚書」)と『Trois ans en Asie (1859)』(「アジアでの3年間」)である[69]。 ゴビノーは現代のペルシャをあまり褒めていなかった。彼はプロケシュ=オステンに、現代のペルシャ人は「神のみぞ知る混血種」であり、「ペルシャ民族」は 存在しないと書いた。しかし、彼は古代ペルシャを偉大なアーリア文明の最高峰として愛し、イランがペルシャ語で「アーリア人の土地」を意味することを指摘 した[70]。ゴビノーはペルシャに関する著作の中で、ヨーロッパ文明の起源はペルシャに遡ることができると考えており、思ったよりもヨーロッパ中心主義 的ではなかった。彼は西洋の学者たちが西洋のペルシャに対する「莫大な」負債を認めることができないという「集団的虚栄心」を批判した[70]。 ジョサイア・C・ノットとヘンリー・ホッツェ  左を向いているジョサイア・C・ノットのセピア写真 ジョサイア・C・ノット  カスメラを見るヘンリー・ホッツェルの写真 ヘンリー・ホッツェ 1856年、熱心な白人至上主義者であったジョサイア・C・ノットとヘンリー・ホッツェの2人のアメリカ人「人種科学者」が、『Essai sur l'inégalité des races humanaines』を英訳した。奴隷制の支持者であった彼らは、ゴビノーの反黒人的な著作の中に、「特殊な制度」を正当化する都合のよい理由を見出し た[71]: 「黒人は最も謙虚で、秤の底辺にいる。ノットとホッツェは、ゴビノーの激しい苛立ちのために、『エセー』第1巻をフランス語原文の1,600ページから英 語版の400ページに要約した[72]。その理由の少なくとも一部は、ゴビノーのアメリカ人に対する敵対的なイメージにあった。アメリカの白人について、 ゴビノーはこう宣言した: 彼らは昔のヨーロッパで最も退化した人種の非常に混じった寄せ集めである。彼らはあらゆる時代の人間の漂流物である: アイルランド人、混血のドイツ人、フランス人、さらに疑わしい家系のイタリア人。これらすべての退廃的な民族の混血は、必然的にさらなる民族の混沌を生む だろう。このカオスは決して予期せぬものでも、新しいものでもない。私たちの大陸でまだ実現されていない、あるいは実現できないような、さらなる民族的混 血を生み出すことはないだろう。ドイツ人、アイルランド人、イタリア人、フランス人、アングロサクソン人の間の無限の結合から生じる民族的結合が、インド 人、黒人、スペイン人、ポルトガル人の本質からなる人種的要素とともに南方でわれわれに加わるときでさえ、このような恐ろしい混乱から生じるものは、最も 退廃的な種類の人々の支離滅裂な並置以外には、まったく想像できないのである[73]。 このような極めて批判的な文章は、『人種の道徳的・知的多様性』から削除された。同様に、彼らはゴビノーを、1856年当時アメリカの黒人のほとんどが奴 隷であったという事実にもかかわらず、白人のアメリカが致命的な危機に瀕していることを立証しようとする手段として利用した[74]。二人の「人種科学 者」はエッセイに基づいて、黒人は本質的に人間というよりもむしろ凶暴な動物の一種であり、白人にとって常に危険な存在であると主張した[75]。ゴビ ノーがエッセイの中で、知能は低いが黒人にはある種の芸術的才能があり、少数の「例外的な」アフリカの部族長はおそらく最も愚かな白人よりも高いIQを 持っていると宣言した箇所は、アメリカ版には収録されなかった。ノットとホッツェは、黒人に立派な人間的資質を与える可能性のあるものは何も求めなかった [76]。それ以上に、彼らは国家と人種は同じであり、アメリカ人であることは白人であることだと主張した[77]。そのため、アメリカの翻訳者たちは序 文で、ヨーロッパのさまざまな国家が異なる「人種」が一緒に暮らすことによって引き起こされた国籍紛争によって引き裂かれたように、同様に奴隷制を終わら せ、黒人にアメリカの市民権を与えることは、同じような紛争を引き起こすだろうが、アメリカではより大きな規模になるだけだと主張した[78]。 ニューファンドランドでの時間 1859年、ニューファンドランドのフレンチ・ショアにおけるフランス人の漁業権をめぐる英仏間の紛争が起こり、その解決策を探るために英仏委員会が ニューファンドランドに派遣された。ゴビノーは、ニューファンドランドに派遣された2人のフランス人委員のうちの1人であり、その時の体験を後に1861 年の著書『Voyage à Terre-Neuve』(「ニューファンドランドへの航海」)に記している。1858年、外務大臣アレクサンドル・コロンナ=ワレフスキー伯爵は、ゴビ ノーを北京のフランス公使館に派遣しようとした。ワレフスキは罰としてゴビノーをニューファンドランドに送り、ニューファンドランドへの赴任を拒否すれば オルセーをクビにすると告げた[80]。 ゴビノーはニューファンドランドを嫌い、1859年7月26日にパリの友人にこう書いている: 「ここはひどい国だ。非常に寒く、霧が絶えず発生し、巨大な浮氷の間を航行する」[81] 。アイルランド系移民が多く住むセントジョンズでの滞在中、ゴビノーはパリへの報告の中で、事実上あらゆる反イリッシュの決まり文句を展開した。彼は、セ ント・ジョンズのアイルランド人は非常に貧しく、規律がなく、狡猾で、強情で、不正直で、大声で、暴力的で、たいてい酔っぱらっていたと述べている [82]。彼は、彼が訪れた辺境の漁村のいくつかをユートピア的な言葉で描写し、少数のたくましくタフな人々が、非常に人を寄せ付けない条件下でいかに生 計を立てることができるかを示す例として賞賛した。 [ゴビノーのニューファンドランドの漁民に対する賞賛は、社会から自らを切り離す者が最も人種的純潔を保てるという彼の視点を反映したものであった [84]。普段は普通の人々を軽蔑していたにもかかわらず、彼は出会ったニューファンドランドの漁民を「私がこれまで世界で見た中で最高の男たち」と呼ん だ[85]: 私は人生で一度だけ、ユートピアのようなものを見たことがある。[...)野蛮で憎むべき気候、禁断の田園地帯、貧困か厳しい危険な労働かの二者択一、娯 楽も楽しみもなく、金もなく、富も野心も等しく不可能であり、それでもなお、このような状況にもかかわらず、陽気な展望、最も原始的な一種の家庭的幸福を 見ることができた。[しかし、これこそが、人が完全な自由を活用し、互いに寛容であることを可能にすることに成功しているのである[85]。 |

| Ministerial career Minister to Persia In 1861, Gobineau returned to Tehran as the French minister[69] and lived a modest, ascetic lifestyle. He became obsessed with ancient Persia. This soon got out of control as he sought to prove ancient Persia was founded by his much admired Aryans, leading him to engage in what Irwin called "deranged" theories about Persia's history.[69] In 1865 Gobineau published Les religions et les philosophies dans l'Asie centrale ("Religions and Philosophies in Central Asia"), an account of his travels in Persia and encounters with the various esoteric Islamic sects he discovered being practiced in the Persian countryside.[86] His mystical frame of mind led him to feel in Persia what he called "un certain plaisir" ("a certain pleasure") as nowhere else in the world did he feel the same sort of joy he felt when viewing the ruins of Persia.[69] Gobineau had a low opinion of Islam, a religion invented by the Arab Mohammed. He viewed him as part of the "Semitic race", unlike the Persians whose Indo-European language led him to see them as Aryans.[86] Gobineau believed that Shia Islam was part of a "revolt" by the Aryan Persians against the Semitic Arabs, seeing a close connection between Shia Islam and Persian nationalism.[86] His understanding of Persia was distorted and confused. He mistakenly believed Shi'ism was practiced only in Persia, and that in Shi'ism the Imam Ali is much more venerated than Muhammad. He was unaware that Shia Islam only became the state religion of Persia under the Safavids.[86] Based on his own experiences, Gobineau believed the Persians did not really believe in Islam, with the faith of the Prophet being a cover over a society that still preserved many pre-Islamic features.[86] Gobineau also described the savage persecution of the followers of Bábism and of the new religion of the Baháʼí Faith by the Persian state, which was determined to uphold Shia Islam as the state religion.[86] Gobineau approved of the persecution of the Babi. He wrote they were "veritable communists" and "true and pure supporters of socialism", as every bit as dangerous as the French socialists. He agreed the Peacock Throne was right to stamp out Bábism.[87] Gobineau was one of the first Westerners to examine the esoteric sects of Persia. Though his work was idiosyncratic, he did spark scholarly interest in an aspect of Persia that had been ignored by Westerners until then.[88] His command of Persian was average, his Arabic was worse. Since there were few Western Orientalists who knew Persian, however, Gobineau was able to pass himself off for decades as a leading Orientalist who knew Persia like no one else.[89] Criticism of Gobineau's Persian work Only with his studies in ancient Persia did Gobineau come under fire from scholars.[88] He published two books on ancient Persia, Lectures des textes cunéiformes (1858) ("Readings of Cuneiform Texts") and Traité des écritures cunéiformes (1864) ("Treatise of Cuneiform Fragments").[88] Irwin wrote: "The first treatise is wrong-headed, yet still on this side of sanity; the second later and much longer work shows many signs of the kind of derangement that is likely to infect those who interest themselves too closely in the study of occultism."[88] One of the principal problems with Gobineau's approach to translating the cuneiform texts of ancient Persia was that he failed to understand linguistic change and that Old Persian was not the same language as modern Persian.[90] His books met with hostile reception from scholars who argued that Gobineau simply did not understand the texts he was purporting to translate.[90] Gobineau's article attempting to rebut his critics in the Journal asiatique was not published, as the editors had to politely tell him his article was "unpublishable" as it was full of "absurd" claims and vitriolic abuse of his critics.[90] During his second time in Persia, Gobineau spent much time working as an amateur archeologist and gathering material for what was to become Traité des écritures cunéiformes, a book that Irwin called "a monument to learned madness".[90] Gobineau was always very proud of it, seeing the book as a magnum opus that rivaled the Essai.[90] Gobineau had often traveled from Tehran to the Ottoman Empire to visit the ruins of Dur-Sharrukin at Khorsabad, near Mosul in what is now northern Iraq.[90] The ruins of Khorsabad are Assyrian, built by King Sargon II in 717 BC, but Gobineau decided the ruins were actually Persian and built by Darius the Great some two hundred years later.[91]  Painted portrait of Paul Émile Botta looking at the artist. French archaeologist Paul-Émile Botta (pictured) regarded Gobineau's Persian work as nonsense. French archeologist Paul-Émile Botta published a scathing review of Traité des écritures cunéiformes in the Journal asiatique. He wrote the cuneiform texts at the Dur-Sharrukin were Akkadian, that Gobineau did not know what he was talking about, and the only reason he had even written the review was to prove that he had wasted his time reading the book.[92] As Gobineau insistently pressed his thesis, the leading French Orientalist, Julius von Mohl of the Société asiatique, was forced to intervene in the dispute to argue that Gobineau's theories, which were to a large extent based on numerology and other mystical theories, lacked "scientific rigor", and the most favorable thing he could say was that he admired the "artistry" of Gobineau's thesis.[93] Continuing his Persian obsession, Gobineau published Histoire des Perses ("History of the Persians") in 1869.[93] In it he did not attempt to distinguish between Persian history and legends treating the Shahnameh and the Kush Nama (a 12th-century poem presenting a legendary story of two Chinese emperors) as factual, reliable accounts of Persia's ancient history.[93] As such, Gobineau began his history by presenting the Persians as Aryans who arrived in Persia from Central Asia and conquered the race of giants known to them as the Diws.[93] Gobineau also added his own racial theories to the Histoire des Perses, explaining how Cyrus the Great had planned the migration of the Aryans into Europe making him responsible for the "grandeur" of medieval Europe.[94] For Gobineau, Cyrus the Great was the greatest leader in history, writing: "Whatever we ourselves are, as Frenchmen, Englishmen, Germans, Europeans of the nineteenth century, it is to Cyrus that we owe it", going on to call Cyrus as "the greatest of the great men in all human history".[95] Minister to Greece In 1864, Gobineau became the French minister to Greece.[96] During his time in Athens, which with Tehran were the only cities he was stationed in that he liked, he spent his time writing poetry and learning about sculpture when not traveling with Ernest Renan in the Greek countryside in search of ruins.[96] Gobineau seduced two sisters in Athens, Zoé and Marika Dragoumis, who became his mistresses; Zoé remained a lifelong correspondent.[97] However great his enthusiasm for ancient Greece, Gobineau was less than complimentary about modern Greece. He wrote that due to miscegenation the Greek people had lost the Aryan blood responsible for "the glory that was Greece". Now the Greeks had a mixture of Arab, Bulgarian, Turkish, Serbian and Albanian blood.[98] In 1832, although nominally independent, Greece had become a joint Anglo-French-Russian protectorate. As such the British, French and Russian ministers in Athens had the theoretical power to countermand any decision of the Greek cabinet. Gobineau repeatedly advised against France exercising this power, writing Greece was "the sad and living evidence of European ineptness and presumptuousness". He attacked the British attempt to bring Westminster-style democracy to Greece as bringing about "the complete decay of a barbarous land" while the accusing the French of being guilty of introducing the Greeks to "the most inept Voltairianism".[99] About the "Eastern Question", Gobineau advised against French support for the irredentist Greek Megali Idea, writing the Greeks could not replace the Ottoman Empire, and if the Ottoman Empire should be replaced with a greater Greece, only Russia would benefit.[100] Gobineau advised Paris: The Greeks will not control the Orient, neither will the Armenians nor the Slav nor any Christian population, and, at the same time, if others were to come—even the Russians, the most oriental of them all—they could only submit to the harmful influences of this anarchic situation. [...] For me [...] there is no Eastern Question and if I had the honour of being a great government I should concern myself no longer with developments in these areas."[97] In the spring of 1866, Christian Greeks rebelled against the Ottoman Empire on the island of Crete. Three emissaries arrived in Athens to ask Gobineau for French support for the uprising, saying it was well known that France was the champion of justice and the rights of "small nations".[101] As France was heavily engaged in the war in Mexico Gobineau, speaking for Napoleon III, informed the Cretans to expect no support from France—they were on their own in taking on the Ottoman Empire.[101] He had no sympathy with the Greek desire to liberate their compatriots living under Ottoman rule; writing to his friend Anton von Prokesch-Osten he noted: "It is one rabble against another".[100] Recall to France as a result of Cretan uprising Gobineau called the Cretan uprising "the most perfect monument to lies, mischief and impudence that has been seen in thirty years".[102] During the uprising, a young French academic Gustave Flourens, noted for his fiery enthusiasm for liberal causes, had joined the Cretean uprising and had gone to Athens to try to persuade the Greek government to support it.[103] Gobineau had unwisely shown Flourens diplomatic dispatches from Paris showing both the French and Greek governments were unwilling to offend the Ottomans by supporting the Cretan uprising, which Flourens then leaked to the press.[99] Gobineau received orders from Napoleon III to silence Flourens.[99] On 28 May 1868, while Flourens was heading for a meeting with King George I, he was intercepted by Gobineau who had him arrested by the legation guards, put into chains and loaded onto the first French ship heading for Marseille.[103] L'affaire Flourens became a cause célèbre in France with novelist Victor Hugo condemning Gobineau in an opinion piece in Le Tribute on 19 July 1868 for the treacherous way he had treated a fellow Frenchman fighting for Greek freedom.[103] With French public opinion widely condemning the minister in Athens, Gobineau was recalled to Paris in disgrace.[103] Minister to Brazil In 1869, Gobineau was appointed the French minister to Brazil.[104] At the time, France and Brazil did not have diplomatic relations at an ambassadorial level, only legations headed by ministers. Gobineau was unhappy the Quai d'Orsay had sent him to Brazil, which he viewed as an insufficiently grand posting.[104] Gobineau landed in Rio de Janeiro during the riotously sensual Carnival, which disgusted him. From that moment on he detested Brazil, which he saw as a culturally backward and unsanitary place of diseases. He feared falling victim to the yellow fever that decimated the population of Brazil on a regular basis.[104] Gobineau's major duties during his time in Brazil from March 1869 to April 1870 were to help mediate the end of the Paraguayan War and seek compensation after Brazilian troops looted the French legation in Asunción. He did so and was equally successful in negotiating an extradition treaty between the French Empire and the Empire of Brazil. He dropped hints to Emperor Pedro II that French public opinion favored the emancipation of Brazil's slaves.[105] As slavery was the basis of Brazil's economy, and Brazil had the largest slave population in the Americas, Pedro II was unwilling to abolish slavery at this time. As most Brazilians have a mixture of Portuguese, African and Indian ancestry, Gobineau saw the Brazilian people, whom he loathed, as confirming his theories about the perils of miscegenation.[104] He wrote to Paris that Brazilians were "a population totally mixed, vitiated in its blood and spirit, fearfully ugly ... Not a single Brazilian has pure blood because of the pattern of marriages among whites, Indians and Negroes is so widespread that the nuances of color are infinite, causing a degeneration among the lower as well the upper classes".[104] He noted Brazilians are "neither hard-working, active nor fertile".[104] Based on all this, Gobineau reached the conclusion that all human life would cease in Brazil within the next 200 years on the grounds of "genetic degeneracy".[104] Gobineau was unpopular in Brazil. His letters to Paris show his complete contempt for everybody in Brazil, regardless of their nationality (except for the Emperor Pedro II), with his most damning words reserved for Brazilians.[104] He wrote about Brazil: "Everyone is ugly here, unbelievably ugly, like apes".[106] His only friend during his time in Rio was Emperor Pedro II, whom Gobineau praised as a wise and great leader, noting his blue eyes and blond hair as proof that Pedro was an Aryan.[104] The fact Pedro was of the House of Braganza left Gobineau assured he had no African or Indian blood. Gobineau wrote: "Except for the Emperor there is no one in this desert full of thieves" who was worthy of his friendship.[107] Gobineau's attitudes of contempt for the Brazilian people led him to spend much of his time feuding with the Brazilian elite. In 1870 he was involved in a bloody street brawl with the son-in-law of a Brazilian senator who did not appreciate having his nation being put down.[107] As a result of the brawl, Pedro II asked Paris to have his friend recalled, or he would declare him persona non-grata.[107] Rather than suffer the humiliation of this happening to the French minister the Quai d'Orsay promptly recalled Gobineau.[107] Return to France In May 1870 Gobineau returned to France from Brazil.[108] In a letter to Tocqueville in 1859 he wrote, "When we come to the French people, I genuinely favor absolute power", and as long as Napoleon III ruled as an autocrat, he had Gobineau's support.[109] Gobineau had often predicted France was so rotten the French were bound to be defeated if they ever fought a major war. At the outbreak of the war with Prussia in July 1870, however, he believed they would win within a few weeks.[110] After the German victory, Gobineau triumphantly used his own country's defeat as proof of his racial theories.[110] He spent the war as the maire (mayor) of the little town of Trie in Oise department.[111] After the Prussians occupied Trie, Gobineau established good relations with them and was able to reduce the indemnity imposed on Oise department.[112] Later, Gobineau wrote a book Ce qui est arrivé à la France en 1870 ("What Happened to France in 1870") explaining the French defeat was due to racial degeneration, which no publisher chose to publish.[113] He argued the French bourgeoisie were "descended from Gallo-Roman slaves", which explained why they were no match for an army commanded by Junkers.[114] Gobineau attacked Napoleon III for his plans to rebuild Paris writing: "This city, pompously described as the capital of the universe, is in reality only the vast caravanserai for the idleness, greed and carousing of all Europe."[114] In 1871, poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt who met Gobineau described him thus: Gobineau is a man of about 55, with grey hair and moustache, dark rather prominent eyes, sallow complexion, and tall figure with brisk almost jerky gait. In temperament he is nervous, energetic in manner, observant, but distrait, passing rapidly from thought to thought, a good talker but a bad listener. He is a savant, novelist, poet, sculptor, archaeologist, a man of taste, a man of the world."[115] Despite his embittered view of the world and misanthropic attitudes, Gobineau was capable of displaying much charm when he wanted to. He was described by historian Albert Sorel as "a man of grace and charm" who would have made a perfect diplomat in Ancien Régime France.[116] Minister to Sweden In May 1872, Gobineau was appointed the French minister to Sweden.[117] After arriving in Stockholm, he wrote to his sister Caroline: "This is the pure race of the North—that of the masters", calling the Swedes "the purest branch of the Germanic race".[117] In contrast to France, Gobineau was impressed with the lack of social conflict in Sweden, writing to Dragoumis: "There is no class hatred. The nobility lives on friendly terms with the middle class and with the people at large".[117] Gobineau argued that because of Sweden's remote location in Scandinavia, Aryan blood had been better preserved as compared to France. Writing about the accession of Oscar II to the Swedish throne in 1872 he said: "This country is unique ... I have just seen one king die and another ascend the throne without anyone doubling the guard or alerting a soldier".[118] The essential conservatism of Swedish society also impressed Gobineau as he wrote to Pedro II: "The conservative feeling is amongst the most powerful in the national spirit and these people relinquish the past only step by step and with extreme caution".[118] Sweden presented a problem for Gobineau between reconciling his belief in an Aryan master race with his insistence that only the upper classes were Aryans. He eventually resolved this by denouncing the Swedes as debased Aryans after all.[119] He used the fact King Oscar allowed Swedish democracy to exist and did not try to rule as an absolute monarch as evidence the House of Bernadotte were all weak and cowardly kings.[119] By 1875, Gobineau was writing, "Sweden horrifies me" and wrote with disgust about "Swedish vulgarity and contemptibility".[119] In 1874, Gobineau met the homosexual German diplomat Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, in Stockholm and became very close to him.[120] Eulenburg was later to recall fondly how he and Gobineau had spent hours during their time in Sweden under the "Nordic sky, where the old world of the gods lived on in the customs and habits of the people as well in their hearts."[120] Gobineau later wrote that only two people in the entire world had ever properly understood his racist philosophy, namely Richard Wagner and Eulenburg.[120]  From a 1924 edition – illustration by Maurice Becque An illustration from Gobineau's novel Nouvelle Asiatiques, published while he was in Sweden. The book reflected his long-standing interest in Persia and the Orient. Gobineau encouraged Eulenburg to promote his theory of an Aryan master-race, telling him: "In this way you will help many people understand things sooner."[120] Later, Eulenburg was to complain all of his letters to Gobineau had to be destroyed because "They contain too much of an intimately personal nature".[121] During his time in Sweden, Gobineau became obsessed with the Vikings and became intent on proving he was descended from the Norse.[122] His time in Stockholm was a very productive period from a literary viewpoint. He wrote Les Pléiades ("The Pleiades"), Les Nouvelles Asiatiques ("The New Asians"), La Renaissance, most of Histoire de Ottar Jarl, pirate norvégien conquérant du pays de Bray en Normandie et de sa descendance ("History of Ottar Jarl, Norwegian Pirate and Conqueror of Normandy and his Descendants") and completed the first half of his epic poem Amadis while serving as minister to Sweden.[122] In 1879, Gobineau attempted to prove his own racial superiority over the rest of the French with his pseudo-family history Histoire de Ottar Jarl. It begins with the line "I descend from Odin", and traces his supposed descent from the Viking Ottar Jarl.[123] As the de Gobineau family first appeared in history in late 15th century Bordeaux, and Ottar Jarl—who may or may not have been a real person—is said to have lived in the 10th century, Gobineau had to resort to a great deal of invention to make his genealogy work.[123] For him, the Essai, the Histoire des Perses and Histoire de Ottar Jarl comprised a trilogy, what the French critic Jean Caulmier called "a poetic vision of the human adventure", covering the universal history of all races in the Essai, to the history of the Aryan branch in Persia in Histoire des Perses to his own family's history in Histoire de Ottar Jarl.[124] During his time in Sweden, although remaining outwardly faithful to the Catholic Church, Gobineau privately abandoned his belief in Christianity. He was very interested in the pagan religion of the Vikings, which seemed more authentically Aryan to him.[125] For him, maintaining his Catholicism was a symbol of his reactionary politics and rejection of liberalism, and it was for these reasons he continued to nominally observe Catholicism.[125] Gobineau told his friend the Comte de Basterot that he wanted a Catholic burial only because the de Gobineaus had always been buried in Catholic ceremonies, not because of any belief in Catholicism.[126] For leaving his post in Stockholm without permission to join the Emperor Pedro II on his European visit, Gobineau was told in January 1877 to either resign from the Quai d'Orsay or be fired; he chose the former.[127][128] Gobineau spent his last years living in Rome, a lonely and embittered man whose principal friends were the Wagners and Eulenburg.[129] He saw himself as a great sculptor and attempted to support himself by selling his sculpture.[129] |

大臣歴 ペルシア公使 1861年、ゴビノーはフランス公使としてテヘランに戻り[69]、慎ましく禁欲的な生活を送った。彼は古代ペルシアに夢中になった。1865年、ゴビ ノーは『中央アジアの宗教と哲学』(Les religions et les philosophies dans l'Asie centrale)を出版した。これは、ペルシアを旅行し、ペルシアの田舎で行われている様々な秘教的なイスラム宗派との出会いを綴ったものである。 [ペルシャの遺跡を見たときに感じたような喜びは、世界のどこにもなかったからである[69]。 ゴビノーはアラブのモハメッドによって創始された宗教であるイスラム教を低く評価していた。ゴビノーは、シーア派イスラム教はセム系アラブ人に対するアー リア系ペルシア人の「反乱」の一部であり、シーア派イスラム教とペルシアのナショナリズムには密接な関係があると考えた[86]。彼はシーア派がペルシャ でのみ信仰されており、シーア派ではイマーム・アリーがムハンマドよりも崇拝されていると誤解していた。彼は、シーア派イスラム教がペルシアの国教となっ たのはサファヴィー朝の時代であることを知らなかった[86]。ゴビノーは自身の体験に基づき、ペルシア人はイスラム教を実際には信じておらず、預言者の 信仰はイスラム教以前の多くの特徴を残す社会を覆っていると考えていた。 [86]ゴビノーはまた、シーア派イスラム教を国教とするペルシャ国家による、バービズムの信者やバハー教という新しい宗教への野蛮な迫害についても述べ ている。ゴビノーはバビの迫害を認め、彼らは「真の共産主義者」であり、「社会主義の真の純粋な支持者」であり、フランスの社会主義者と同じくらい危険で あると書いた。ゴビノーは、ペルシアの秘教宗派を調査した最初の西洋人の一人であった[87]。彼の研究は特異なものであったが、それまで西洋人に無視さ れていたペルシアの一面に対する学問的関心を呼び起こした[88]。しかし、ペルシア語を知っている西洋のオリエンタリストはほとんどいなかったため、ゴ ビノーは何十年もの間、他の誰よりもペルシアを知っている一流のオリエンタリストとして自らを売り込むことができた[89]。 ゴビノーのペルシア語研究に対する批判 ゴビノーは古代ペルシアの研究においてのみ、学者たちから非難を浴びることになった[88]。 彼は古代ペルシアに関する2冊の本、Lectures des textes cunéiformes (1858)(「楔形文字のテキストの読み方」)とTraité des écritures cunéiformes (1864)(「楔形文字の断片の論考」)を出版した。 [アーウィンは次のように書いている。「最初の論考は間違っているが、まだ正気の側にある。2番目の後の、はるかに長い著作には、オカルティズムの研究に あまりに密接に関心を持つ人々に感染しやすい種類の錯乱の兆候が多く見られる。 「88] 古代ペルシアの楔形文字テキストを翻訳するゴビノーのアプローチの主な問題のひとつは、彼が言語的変化を理解しておらず、古ペルシア語が現代ペルシア語と 同じ言語ではないということであった。 ゴビノーは『Journal asiatique』誌で批評家たちに反論しようと試みたが、編集者たちから「不合理な」主張と批評家たちへの激しい罵倒に満ちているため「掲載不可能」 であると丁重に告げられ、掲載されることはなかった[90]。2度目のペルシア滞在中、ゴビノーはアマチュアの考古学者として多くの時間を費やし、アー ウィンが「学問的狂気の記念碑」と呼んだ『Traité des écritures cunéiformes』となるための資料を集めた。 [90]ゴビノーはこの本をエッセイに匹敵する大著とみなし、常に非常に誇りに思っていた[90]。ゴビノーはテヘランからオスマン帝国にしばしば足を運 び、現在のイラク北部のモスル近郊にあるホルサバードのドゥル・シャルルキン遺跡を訪れていた。 [90]コルサバードの遺跡は紀元前717年にサルゴン2世によって建設されたアッシリア時代のものであるが、ゴビノーはこの遺跡が実際にはペルシャ時代 のものであり、約200年後にダレイオス大王によって建設されたと判断した[91]。  画家を見つめるポール・エミール・ボッタの肖像画。 フランスの考古学者ポール=エミール・ボッタ(写真)は、ゴビノーのペルシャの作品をナンセンスとみなした。 フランスの考古学者ポール=エミール・ボッタは、『Journal asiatique』に『Traité des écritures cunéiformes』の酷評を発表した。彼は、ドゥル・シャルルキンの楔形文字テキストはアッカド語であり、ゴビノーは自分が何を言っているのか分 かっておらず、書評を書いたのは自分がこの本を読んで時間を無駄にしたことを証明するためだと書いた。 [ゴビノーが執拗に自分の論文を押し通すので、フランスを代表する東洋学者であるアジア学会のジュリウス・フォン・モールは、数秘術やその他の神秘的な理 論に大きく基づいているゴビノーの理論は「科学的厳密さ」を欠いていると主張するために、この論争に介入せざるを得なくなった。 ペルシアへの執着を続けたゴビノーは、1869年に『ペルシア人の歴史』(Histoire des Perses)を出版した[93]。その中で彼はペルシアの歴史と伝説を区別しようとせず、『シャハメ』と『クシュ・ナマ』(中国の2人の皇帝の伝説的な 物語を描いた12世紀の詩)をペルシアの古代史の事実で信頼できる記述として扱った[93]。 [ゴビノーは、ペルシア人を中央アジアからペルシアに到着し、ディウス族として知られる巨人族を征服したアーリア人とすることでその歴史を始めた [93]。ゴビノーはまた、『ペルシア史』に独自の人種論を加え、キュロス大王がいかにアーリア人のヨーロッパへの移住を計画し、中世ヨーロッパの「壮大 さ」の責任を彼に負わせたかを説明した[94]: 「私たち自身がフランス人、イギリス人、ドイツ人、19世紀のヨーロッパ人としてどうであれ、それはキュロスのおかげである」と書き、キュロスを「全人類 史における偉大な人物の中で最も偉大な人物」と呼んだ[95]。 ギリシャ公使 1864年、ゴビノーはフランスの駐ギリシャ公使となった[96]。アテネでの滞在中、彼が気に入った都市はテヘランだけであったが、エルネスト・ルナン と共に遺跡を求めてギリシャの田舎を旅していないときは、詩作と彫刻の勉強に時間を費やした。 [96] ゴビノーはアテネで2人の姉妹、ゾエとマリカ・ドラグミスを誘惑し、愛人とした。彼は、混血のためにギリシア人は「ギリシアであった栄光」の原因である アーリア人の血を失ったと書いている。現在、ギリシャ人はアラブ人、ブルガリア人、トルコ人、セルビア人、アルバニア人の血が混ざっている[98]。 1832年、名目上は独立していたものの、ギリシャはイギリス、フランス、ロシアの共同保護領となっていた。そのため、アテネのイギリス、フランス、ロシ アの閣僚は、ギリシャ内閣のいかなる決定をも反故にする理論的権限を持っていた。ゴビノーはフランスがこの権力を行使することに繰り返し忠告し、ギリシャ は「ヨーロッパの無策と僭越の悲しく生きた証拠」であると書いた。彼はギリシャにウェストミンスター式の民主主義をもたらそうとするイギリスの試みを「野 蛮な土地の完全な衰退」をもたらすと攻撃し、一方でフランスがギリシャ人に「最も無能なヴォルタイアニズム」を紹介した罪を犯していると非難した [99]。 東方問題」に関して、ゴビノーは、ギリシャ人がオスマン帝国に取って代わることはできず、オスマン帝国がより大きなギリシャに取って代わられるなら、ロシ アだけが利益を得るだろうと書き、フランスが独立主義的なギリシャのメガリ構想を支持することに反対するようパリに忠告した[100]: ギリシャ人はオリエントを支配することはできないし、アルメニア人もスラヴ人もキリスト教徒も支配することはできない。[私にとっては[......]東 方問題は存在せず、もし私が偉大な政府であることを光栄に思うならば、これらの地域の発展にはもはや関心を持たないはずである」[97]。 1866年の春、クレタ島でキリスト教徒であるギリシア人がオスマン帝国に反旗を翻した。3人の使者がアテネに到着し、フランスが正義と「小国」の権利の 擁護者であることはよく知られているとして、ゴビノーに蜂起に対するフランスの支援を要請した[101]。 [フランスはメキシコ戦争に深く関与していたため、ゴビノーはナポレオン3世の代弁者として、フランスからの支援を期待しないようクレタ人に伝えた: 「一人の暴徒が他の暴徒に対抗しているのだ」[100]。 クレタ蜂起によるフランスへの帰還 ゴビノーはクレタ蜂起を「この30年間で見た中で最も完璧な嘘と悪ふざけと不謹慎の記念碑」と呼んだ[102]。 蜂起の最中、リベラルな大義に対する熱狂的な情熱で知られるフランスの若き学者ギュスターヴ・フルーランスはクレタ蜂起に参加し、ギリシャ政府を説得する ためにアテネに向かった。 [ゴビノーは、フランスとギリシャの両政府がクレタ島の蜂起を支援することでオスマン帝国を怒らせることを望んでいないことを示すパリからの外交文書を不 用意にフルレンスに見せたが、フルレンスはそれをマスコミにリークした[99]。ゴビノーはナポレオン3世からフルレンスを黙らせるよう命令を受けた。 1868年5月28日、国王ジョージ1世との会談に向かったフルレンスだったが、ゴビノーに妨害され、公使館の衛兵に逮捕され、鎖につながれ、マルセイユ に向かう最初のフランス船に積み込まれた[103]。 [小説家ヴィクトル・ユーゴーが1868年7月19日付の『ル・トリビュート』誌のオピニオン・ピースで、ゴビノーがギリシャの自由のために戦う仲間のフ ランス人を裏切り者として扱ったことを非難した[103]。フランスの世論がアテネの公使を広く非難したため、ゴビノーは不名誉な形でパリに呼び戻された [103]。 ブラジル公使 1869年、ゴビノーはフランスの駐ブラジル公使に任命された[104]。当時、フランスとブラジルは大使レベルの外交関係を持っておらず、公使が率いる 公使館のみであった。ゴビノーは、ケ・ドルセーからブラジルに派遣されたことを不満に思っており、ブラジルへの赴任は壮大さに欠けるものだと考えていた [104]。その時から彼は、文化的に後進的で不衛生な病気が蔓延しているブラジルを嫌悪した。1869年3月から1870年4月までブラジルに滞在した ゴビノーの主な任務は、パラグアイ戦争の終結を仲介することと、ブラジル軍がアスンシオンのフランス公使館を略奪した後に補償を求めることであった [104]。彼はこれを実現し、フランス帝国とブラジル帝国との間の犯罪人引き渡し条約の交渉にも成功した。奴隷制度はブラジル経済の基盤であり、ブラジ ルはアメリカ大陸最大の奴隷人口を有していたため、ペドロ2世はこの時期に奴隷制度を廃止することを望まなかった。 ほとんどのブラジル人はポルトガル人、アフリカ人、インディアンの混血であるため、ゴビノーは、混血の危険性に関する彼の理論を裏付けるものとして、彼が 嫌悪するブラジル人を見た[104]。白人、インディアン、黒人の間の結婚のパターンが蔓延しているため、色のニュアンスは無限であり、上流階級だけでな く下層階級の間でも退化を引き起こしている」[104]。 ゴビノーはブラジルでは不人気だった。パリに宛てた彼の手紙には、国籍に関係なく(皇帝ペドロ2世を除く)ブラジルのすべての人を完全に軽蔑していたこと が記されており、ブラジル人に対しては最も非難的な言葉を残している[104]: 「ゴビノーは、ペドロがアーリア人である証拠として、彼の青い目と金髪に注目し、賢明で偉大な指導者であると賞賛した[104]。 ペドロがブラガンザ家の出身であることから、ゴビノーは彼がアフリカ人やインディアンの血を引いていないことを確信した。ゴビノーは「皇帝を除けば、泥棒 だらけのこの砂漠に友情に値する人物はいない」と書いている[107]。 ブラジル人を侮蔑するゴビノーの態度は、ブラジル人エリートとの確執に多くの時間を費やすことになった。1870年、彼は自国を貶められることを快く思わ ないブラジル上院議員の義理の息子と血みどろの路上乱闘に巻き込まれた[107]。乱闘の結果、ペドロ2世はパリに彼の友人を呼び戻すよう要請し、さもな くば彼をペルソナ・ノン・グラータ(非人格的存在)にすると宣言した[107]。 フランスの大臣にこのようなことが起こるという屈辱を味わうよりも、オルセー美術館は速やかにゴビノーを呼び戻した[107]。 フランスへの帰還 1859年にトクヴィルに宛てた手紙の中で、彼は「フランス国民の前に現れたとき、私は純粋に絶対的な権力を支持する」と書いており、ナポレオン3世が独 裁者として統治する限り、彼はゴビノーを支持していた[109]。ゴビノーはしばしば、フランスは腐っており、フランスが大きな戦争をすれば敗北するに違 いないと予測していた。しかし、1870年7月にプロイセンとの戦争が勃発すると、彼は数週間以内にプロイセンが勝利すると信じていた[110]。 ドイツの勝利の後、ゴビノーは自国の敗北を人種理論の証拠として勝ち誇った[110]。 彼は戦争をオワーズ県の小さな町トリィのメール(町長)として過ごした[111]。 その後、ゴビノーは『1870年のフランスに起こったこと』(Ce qui est arrivé à la France en 1870)を執筆し、フランスの敗戦は人種の退化によるものであると説明したが、どの出版社も出版を選ばなかった[113]。 彼はフランスのブルジョワジーが「ガロ・ローマ人の奴隷の子孫」であると主張し、ユンカーが指揮する軍隊に敵わなかった理由を説明した[114]: 「この都市は、誇らしげに宇宙の首都と称されているが、その実態は全ヨーロッパの怠惰、貪欲、放蕩のための広大なキャラバンサライにすぎない」 [114]。 1871年、ゴビノーに会った詩人のウィルフリッド・スコウェン・ブラントは彼をこう評した: ゴビノーは55歳くらいの男で、白髪と口ひげがあり、どちらかといえば黒目がちで、顔色は浅黒く、背が高く、ほとんどぎこちない歩き方をしている。気性は 神経質で、エネルギッシュな物腰で、観察力はあるが、思考から思考へと素早く移り変わり、話し上手だが聞き下手である。彼は博識で、小説家であり、詩人で あり、彫刻家であり、考古学者であり、趣味の人であり、世界の人である」[115]。 袂を分かったような世界観と人間嫌いの態度にもかかわらず、ゴビノーはその気になれば多くの魅力を発揮することができた。彼は歴史家アルベール・ソレルに 「気品と魅力のある人物」と評され、アンシャン・レジーム期のフランスでは完璧な外交官となったであろう[116]。 スウェーデン公使 1872年5月、ゴビノーはフランスのスウェーデン公使に任命された[117]。ストックホルムに到着後、彼は妹カロリーヌに手紙を書いた: 「フランスとは対照的に、ゴビノーはスウェーデンの社会的対立のなさに感銘を受け、ドラグーミスに次のように書き送っている。ゴビノーは、スウェーデンが スカンディナヴィアの辺境に位置するため、アーリア人の血がフランスに比べてよりよく保存されていると主張した[117]。1872年にスウェーデンの王 位にオスカル2世が即位したことについて、彼はこう書いている: 「この国はユニークだ。スウェーデン社会の本質的な保守主義もまたゴビノーに感銘を与え、ペドロ2世に宛てて「保守的な感情は国民精神の中で最も強力なも ののひとつであり、この国民は一歩一歩、細心の注意を払いながらしか過去を放棄しない」と書いている[118]。 スウェーデンはゴビノーにとって、アーリア人の主人種という信念と、上流階級だけがアーリア人であるという主張との間で、両立させることができないという 問題を提示した。彼は結局のところ、スウェーデン人を堕落したアーリア人として糾弾することによってこれを解決した[119]。 彼はオスカル王がスウェーデンの民主主義の存在を許し、絶対君主として統治しようとしなかったことを、ベルナドット家がすべて弱く臆病な王であったことの 証拠として用いた[119]。 1875年までには、ゴビノーは「スウェーデンは私をぞっとさせる」と書き、「スウェーデンの低俗さと卑劣さ」について嫌悪感をもって書いていた [119]。 1874年、ゴビノーはストックホルムで同性愛者のドイツ人外交官オイレンブルク公フィリップと出会い、非常に親しくなった[120]。オイレンブルクは 後に、ゴビノーとスウェーデン滞在中に「北欧の空の下で、神々の古い世界が人々の習慣や風習の中にも心の中にも生き続けている」スウェーデンで過ごした時 間を懐かしく思い出すことになる。 「120]ゴビノーは後に、全世界で彼の人種差別思想を正しく理解したのはリヒャルト・ワーグナーとオイレンブルクの二人だけだと書いている[120]。  1924年版より - モーリス・ベックによる挿絵 ゴビノーがスウェーデン滞在中に出版した小説『Nouvelle Asiatiques』の挿絵。ペルシャとオリエントに対するゴビノーの長年の関心が反映されている。 ゴビノーはオイレンブルクに、アーリア人の支配者民族説を広めるよう勧め、こう言った: 「後にオイレンブルグは、ゴビノーに宛てた手紙は「あまりにも個人的な内容が多い」ため、すべて破棄しなければならないと不満を漏らすことになる [121]。 ストックホルムでの生活は、文学的に非常に生産的な時期であった。彼は『プレアデス』(Les Pléiades)、『新アジア人』(Les Nouvelles Asiatiques)、『ルネサンス』(La Renaissance)、『ノルマンディーの海賊ブレイとその子孫の歴史』(Histoire de Ottar Jarl, pirate norvégien conquérant du pays de Bray en Normandie et de sa descendance)の大半を執筆し、スウェーデン公使を務めながら叙事詩『アマディス』(Amadis)の前半を完成させた[122]。 1879年、ゴビノーは擬似家族史『Histoire de Ottar Jarl』で、他のフランス人に対する自身の人種的優位性を証明しようとした。ドゥ・ゴビノー家が歴史に登場するのは15世紀末のボルドーであり、オッ タール・ヤールは実在の人物であったかどうかは不明だが、10世紀には生きていたと言われている。 [彼にとって、『エッセイ』、『ペルシア史』、『オッタル・ヤール史』は、フランスの批評家ジャン・コールミエが「人間の冒険の詩的ヴィジョン」と呼んだ 三部作を構成しており、『エッセイ』ではすべての民族の普遍的な歴史を、『ペルシア史』ではペルシアにおけるアーリア支族の歴史を、『オッタル・ヤール 史』では彼自身の家族の歴史を扱っている[124]。 スウェーデン滞在中、ゴビノーは表向きはカトリック教会に忠実であったが、内心ではキリスト教への信仰を捨てていた。ゴビノーにとって、カトリックの信仰 を維持することは、彼の反動的な政治と自由主義に対する拒絶の象徴であり、名目上カトリックの信仰を守り続けたのはこうした理由からであった[125]。 ゴビノーは友人のバステロ伯爵に、カトリックの埋葬を望んでいるのは、ゴビネオー家が常にカトリックの儀式で埋葬されてきたからであり、カトリックの信仰 があったからではないと語っている[126]。 1877年1月、皇帝ペドロ2世のヨーロッパ訪問に同行するためにストックホルムの赴任地を許可なく離れたことで、ゴビノーはオルセーを辞職するか解雇さ れるかのどちらかを選ぶように言われた。 ゴビノーは晩年をローマで過ごし、ワグネル夫妻とオイレンブルクを主な友人とする孤独で袂を分かった人物であった[129]。彼は自らを偉大な彫刻家と見 なし、彫刻を売ることで自活しようとした[129]。 遺産と影響 主な記事 ゴビニズム ゴビノーの思想は、生前も死後も多くの国、特にルーマニア、オスマン帝国、ドイツ、ブラジルに影響を与えた。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_de_Gobineau |

|

| ︎▶︎帝国主義と人種主義▶︎︎アーリア人種▶︎ゴビノーの人種理論(→「アルチュール・ド・ゴビノーの人種論」に移転▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ |

|

★ゴビノー関係の著作

●ゴビノーの人種理論(→「アルチュール・ド・ゴビノーの人種論」に移転)

●ゴビノー年譜

1816 7月14日オー=ド=セーヌ県ヴィル=ダ ヴレーで生 まれる

父親は官僚で強硬な君主論者。母親アンヌ=ルイー

ズ・マドレーヌ・ド・ジェルシは王室税務官の娘でサントドミンゴ生まれのクレオール女性であり、ポーリーヌ・ボナパルトの女官を務め、感傷的な長篇小説

Marguerite d'Alby(1821年)や回想録Une Vie de femme, liée aux événements de

l'époque(1835年)を著した。

1821 母マドレーヌ・ド・ジェルシは感傷的な長 篇小説(Marguerite d'Alby)を書く

1830

駆け落ちした母に連れられてスイスで数年間を過ご し、アルチュールはこの地で東洋趣味への興味を育む。7月29日にフランスで勃発した7月革命の後、オルレアン家のルイ・フィリップ()を国王とした立憲君主制の王政がはじまる(〜1848年2月 24日)

Louis-Philippe, King of the French from 1830 to 1848 (July Monarchy)

フィリップ・エガリテの

対外政策の功績→「対外政策においては、後のフランス帝国主義政策に先鞭をつけた。北アフリカでは、1830年に始まるアルジェリア出兵を引き継ぎ、

1834年にはアルジェリアを併合した。また、ナポレオン戦争期から続く青壮年男性人口の減少・伸び悩みを踏まえ、アルジェリア出兵による自国民の死傷者

を軽減するため、今に続くフランス外人部隊の設立勅書を1831年に出した。ラテンアメリカでは、当時政情不安定であったメキシコに介入し、1838年に

菓子戦争を起こして勝利した。極東では、アヘン戦争で敗れた清に対して1844年に黄埔条約を自国に有利な形で締結し、海禁政策を採るインドシナの阮朝大

南国に対しては1847年にダナン港を砲撃して圧力をかけた。一方、2度のエジプト・トルコ戦争ではいずれもエジプトを支持して地中海地域への影響力の強

化を狙ったが、1840年のロンドン条約で列強にこれを阻止されるなど、ヨーロッパでは東方問題をめぐって国際的に孤立した」ルイ・フィリップ)

1831 de Gobineau's

father took custody of his three children, and his son spent the rest

of his adolescence in Lorient, in Brittany.

1832 六月暴動または「1832年のパリ蜂起(Insurrection

républicaine à Paris en juin 1832)June Rebellion」

があるが失敗する。

1835

母マドレーヌ・ド・ジェルシ回想録(Une

Vie de femme, liée aux événements de l'époque)を書く。Gobineau

failed the entrance exams to the St. Cyr military school. Gobineau

failed the entrance exams to the St. Cyr military school.

パリにて、シルヴェストル・ド・サシー、ビュヌフ・ウジーヌ、エティエンヌ=マルク・カトルメールなどの東洋学者との交流や私淑がつづく。

1848 二月革命

1849 トクヴィルが外相に就任し、ゴビノーを外

務大臣室長に任命する。11月トクヴィルが辞任し、外相代理はドプール将軍に就任し、ゴビノーはベルン・フランス大使館第一書記に。

1852 カーシャーンのハッジ・ミルザ・ジャー

ン、ペルシャ官憲により殺害(オリエンタリストとしてのゴビノーはミルザ・ジャーン『バーブ教勃興史』の完全版を入手した)

1853, 1855 Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines(『諸人種の不平等に関する試論』)

この間、ハノーヴァー、フランクフルトで、フランス

大使

1855 Trois ans en Asie (de 1855 à 1858)

1858 Lecture des textes

cunéiformes

1866 Les religions et

les philosophies dans l'Asie centrale. 2. ed

1874 "Les Pléiades(長編小説)

1877 La Renaissance(戯曲)この年以降、ローマに住む。

1879 Histoire d'Ottar