コウモリであるとはどういうことなのか?

What Is It Like to Be a Bat?

Townsend's big-eared bat

☆ 「コウモリになるとはどういうことか"What Is It Like to Be a Bat?"」 は、アメリカの哲学者トーマス・ネーゲルによる論文で、1974年10月に『The Philosophical Review』に発表され、その後『Mortal Questions』(1979年)に収録された。この論文では、「人間の概念の及ばない事実」に起因する心身問題の解決不可能性、客観性と還元主義の限 界、主観的経験の「現象学的特徴」、人間の想像力の限界、特定の意識的なものであることの意味など、意識がもたらすいくつかの困難が提示されている。ダニ エル・デネットは、コウモリの意識はアクセスできないというネーゲルの主張を否定し、コウモリの意識の「興味深い、あるいは理論的に重要な」特徴であ れば、第三者による観察が可能であると主張している。 例えば、コウモリが数メートル以上離れた物体を検知できないのは、エコロケーションの範囲が限られているからである。デネットは、その経験に類似した側面 があれば、さらなる科学的実験によって得ることができると考えている。彼はまた、ネーゲルの議論と疑問は新しいものではなく、1950年にB.A.ファレ ルが『マインド』誌の論文「経験」において述べていたものであると指摘 している。

| "What

Is It Like to Be a Bat?" is a paper by American philosopher Thomas

Nagel, first published in The Philosophical Review in October 1974, and

later in Nagel's Mortal Questions (1979). The paper presents several

difficulties posed by consciousness, including the possible

insolubility of the mind–body problem owing to "facts beyond the reach

of human concepts", the limits of objectivity and reductionism, the

"phenomenological features" of subjective experience, the limits of

human imagination, and what it means to be a particular, conscious

thing.[1] Nagel famously asserts that "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism—something it is like for the organism."[2] This assertion has achieved special status in consciousness studies as "the standard 'what it's like' locution."[3] Daniel Dennett, while sharply disagreeing on some points, acknowledged Nagel's paper as "the most widely cited and influential thought experiment about consciousness."[4]: 441 Nagel argues you cannot compare human consciousness to that of a bat. |

コ

ウモリであるとはどういうことか」は、アメリカの哲学者トーマス・ネーゲルによる論文で、1974年10月に『The Philosophical

Review』に発表され、その後『Mortal

Questions』(1979年)に収録された。この論文では、「人間の概念の及ばない事実」に起因する心身問題の解決不可能性、客観性と還元主義の限

界、主観的経験の「現象学的特徴」、人間の想像力の限界、特定の意識的なものであることの意味など、意識がもたらすいくつかの困難が提示されている

[1]。 ネーゲルは「ある生物が意識的な心的状態を持つのは、その生物であることのようなもの、つまりその生物にとってそのようなものであるようなものが存在する 場合のみである」と主張している[2]。この主張は意識研究において「標準的な『それがどのようなものであるか』という言い回し」[3]として特別な地位 を獲得している。ダニエル・デネットはいくつかの点で激しく意見を異にしながらも、ネーゲルの論文を「意識に関する最も広く引用され、影響力のある思考実 験」[4]として認めている: 441 ネーゲルは人間の意識をコウモリのそれと比較することはできないと主張している。 |

Thesis "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" was written by Thomas Nagel (pictured)  Nagel challenges the possibility of explaining "the most important and characteristic feature of conscious mental phenomena" by reductive materialism (the philosophical position that all statements about the mind and mental states can be translated, without any loss or change in meaning, into statements about the physical). For example, a reductive physicalist's solution to the mind–body problem holds that whatever "consciousness" is, it can be fully described via physical processes in the brain and body.[5] Nagel begins by assuming that "conscious experience is a widespread phenomenon" present in many animals (particularly mammals), even though it is "difficult to say [...] what provides evidence of it." Thus, Nagel sees consciousness not as something exclusively human, but as something shared by many, if not all, organisms. Nagel must be speaking of something other than sensory perception, since objective facts and widespread evidence show that organisms with sensory organs have biological processes of sensory perception. In fact, what all organisms share, according to Nagel, is what he calls the "subjective character of experience" defined as follows: "An organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism – something that it is like for the organism."[1] The paper argues that the subjective nature of consciousness undermines any attempt to explain consciousness via objective, reductionist means. The subjective character of experience cannot be explained by a system of functional or intentional states. Consciousness cannot be fully explained if the subjective character of experience is ignored, and the subjective character of experience cannot be explained by a reductionist; it is a mental phenomenon that cannot be reduced to materialism.[6] Thus, for consciousness to be explained from a reductionist stance, the idea of the subjective character of experience would have to be discarded, which is absurd. Neither can a physicalist view, because in such a world, each phenomenal experience had by a conscious being would have to have a physical property attributed to it, which is impossible to prove due to the subjectivity of conscious experience. Nagel argues that each and every subjective experience is connected with a "single point of view", making it infeasible to consider any conscious experience as "objective". Nagel uses the example of bats to clarify the distinction between subjective and objective concepts. Because bats are mammals, they are assumed to have conscious experience. Nagel was inspired to use a bat for his argument after living in a home where the animals were frequent visitors. Nagel ultimately used bats for his argument because of their highly evolved and active use of a biological sensory apparatus that is significantly different from that of many other organisms. Bats use echolocation to navigate and perceive objects. This method of perception is similar to the human sense of vision. Both sonar and vision are regarded as perceptual experiences. While it is possible to imagine what it would be like to fly, navigate by sonar, hang upside down and eat insects like a bat, that is not the same as a bat's perspective. Nagel claims that even if humans were able to metamorphose gradually into bats, their brains would not have been wired as a bat's from birth; therefore, they would only be able to experience the life and behaviors of a bat, rather than the mindset.[7] Such is the difference between subjective and objective points of view. According to Nagel, "our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience", meaning that each individual only knows what it is like to be them (subjectivism). Objectivity requires an unbiased, non-subjective state of perception. For Nagel, the objective perspective is not feasible, because humans are limited to subjective experience. Nagel concludes with the contention that it would be wrong to assume that physicalism is incorrect, since that position is also imperfectly understood. Physicalism claims that states and events are physical, but those physical states and events are only imperfectly characterized. Nevertheless, he holds that physicalism cannot be understood without characterizing objective and subjective experience. That is a necessary precondition for understanding the mind-body problem. |

論文 "コウモリであるとはどのようなことか?"はトーマス・ネーゲル(写真)によって書かれた。  ネーゲルは、「意識的な精神現象の最も重要で特徴的な特徴」を説明する可能性について、還元的唯物論(心や精神状態に関する記述はすべて、意味の損失や変 化なしに、物理学的な記述に翻訳できるという哲学的立場)に異議を唱えている。例えば、心身問題に対する還元的唯物論者の解答は、「意識」が何であれ、そ れは脳と身体における物理的プロセスによって完全に記述できるというものである[5]。 ネーゲルは、「意識的経験は、多くの動物(特に哺乳類)に存在する広範な現象である」と仮定することから始める。このように、ネーゲルは意識を人間だけの ものとしてではなく、すべてではないにせよ、多くの生物に共通するものとして捉えている。感覚器官を持つ生物は、感覚知覚の生物学的プロセスを持っている ことを、客観的事実と広範な証拠が示しているからである。実際、ネーゲルによれば、すべての生物に共通するのは、彼が「経験の主観的性格」と呼ぶもので、 次のように定義されている: 「ある生物が意識的な精神状態を持つのは、その生物であることのようなもの、つまりその生物にとってそのようなもの、が存在する場合に限られる」[1]。 この論文では、意識の主観的な性質が、客観的で還元主義的な手段によって意識を説明しようとする試みを台無しにすると論じている。経験の主観的な性質は、 機能的状態や意図的状態のシステムで説明することはできない。体験の主観的な性格を無視すれば、意識を完全に説明することはできないし、体験の主観的な性 格は還元主義者によって説明されることはない。なぜなら、そのような世界では、意識的存在によって経験されるそれぞれの現象的経験に物理的性質が帰属しな ければならないが、それは意識的経験の主観性のために証明不可能だからである。ネーゲルは、主観的な経験のひとつひとつが「単一の視点」と結びついてお り、意識的な経験を「客観的」とみなすことは不可能だと主張する。 ネーゲルは主観的概念と客観的概念の区別を明確にするために、コウモリを例に挙げる。コウモリは哺乳類であるため、意識的経験を持つと仮定される。ナーゲ ルは、コウモリが頻繁に訪れる家に住んでいたことから、コウモリを議論に使うことを思いついた。ナゲルがコウモリを論証に用いたのは、他の多くの生物とは 大きく異なる、高度に進化した生物学的感覚装置を積極的に使っているからである。コウモリはエコーロケーション(反響定位)を使って移動し、物体を認識す る。この知覚方法は人間の視覚に似ている。ソナーも視覚も知覚的な体験とみなされる。コウモリのように空を飛んだり、ソナーで航行したり、逆さにぶら下 がったり、昆虫を食べたりすることがどのようなものかを想像することは可能だが、それはコウモリの視点とは違う。ネーゲルは、たとえ人間がコウモリに徐々 に変態できたとしても、彼らの脳は生まれたときからコウモリのように配線されているわけではないので、考え方ではなく、コウモリの生活や行動を体験できる に過ぎないと主張している[7]。 これが主観的視点と客観的視点の違いである。ネーゲルによれば、「私たち自身の精神活動こそが、私たちの経験における唯一疑いようのない事実」であり、つ まり各個人は、自分が自分であることがどのようなものであるかしか知らない(主観主義)。客観性には、偏りのない、主観的でない知覚状態が必要である。 ネーゲルにとって、人間は主観的な経験に限定されるため、客観的な視点は実現不可能である。 ネイゲルは、物理主義もまた不完全に理解されているので、物理主義が正しくないと仮定するのは間違っているという主張で締めくくっている。物理主義は状態 や出来事が物理的であると主張するが、それらの物理的な状態や出来事は不完全にしか特徴づけられていない。にもかかわらず、物理主義は客観的・主観的経験 を特徴づけることなしには理解できないとしている。それが心身問題を理解するための必要条件である。 |

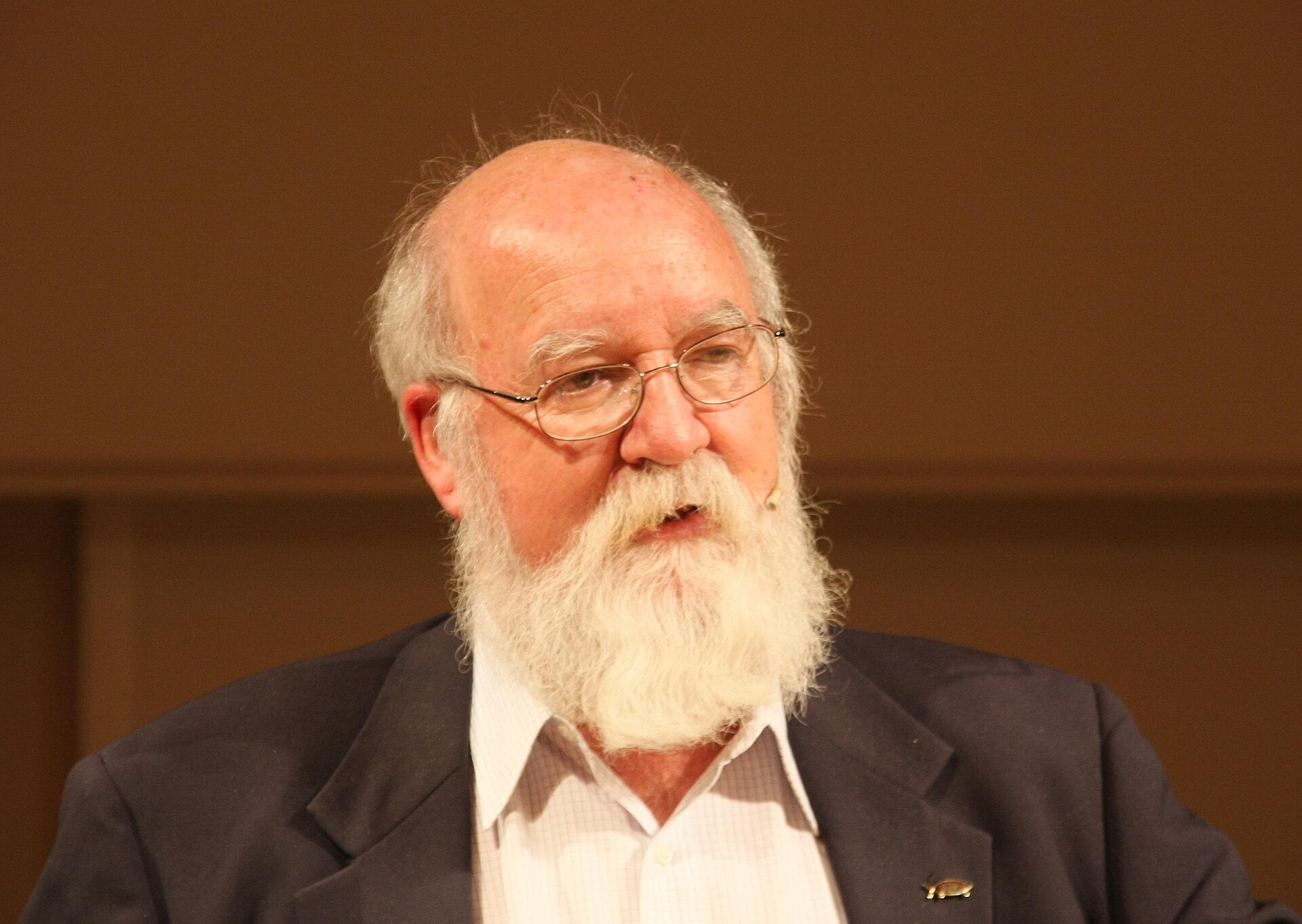

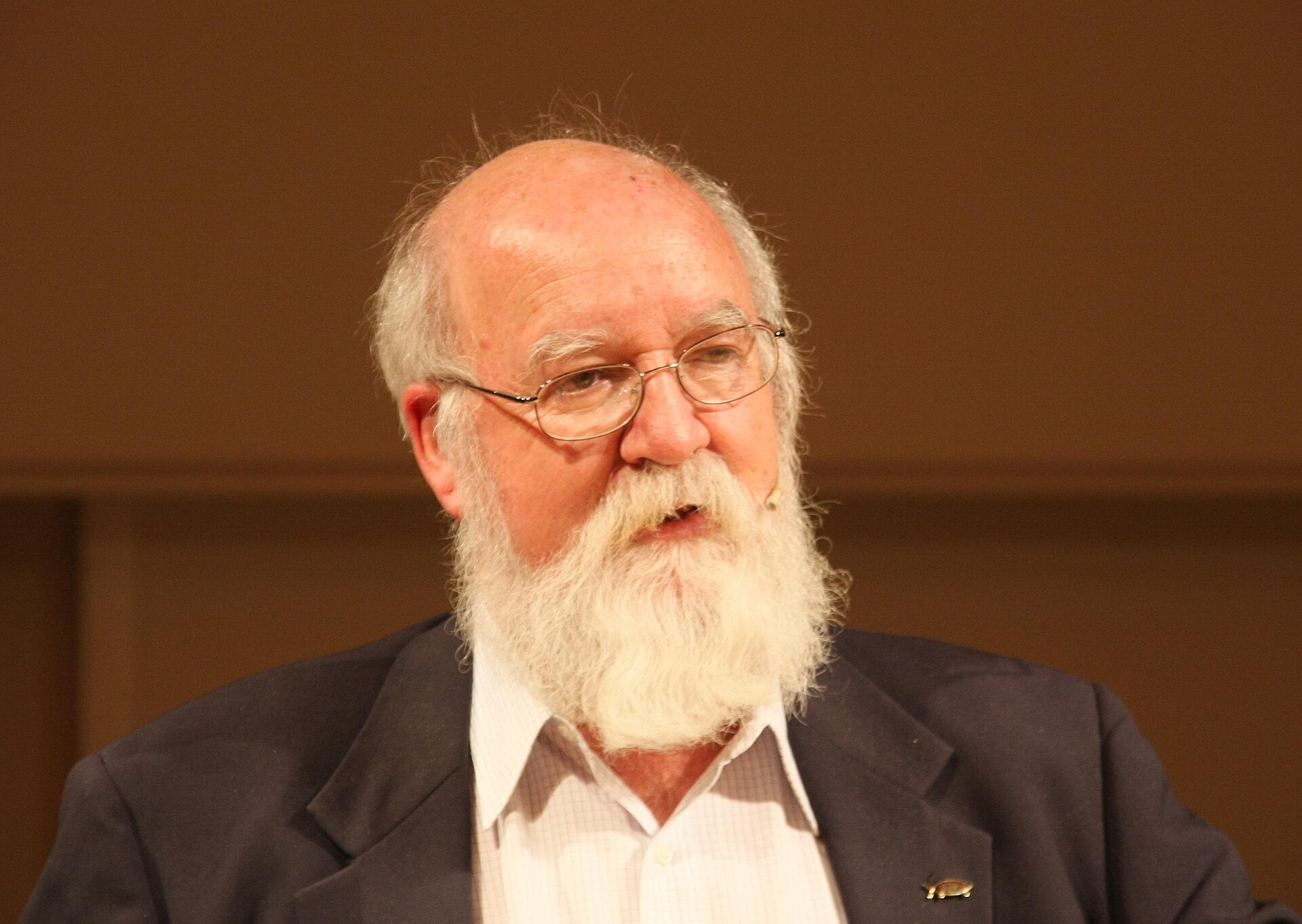

Criticisms Daniel Dennett (pictured) has been a vocal critic of the paper's assertions Daniel Dennett denies Nagel's claim that the bat's consciousness is inaccessible, contending that any "interesting or theoretically important" features of a bat's consciousness would be amenable to third-person observation.[4]: 442 For instance, it is clear that bats cannot detect objects more than a few meters away because echolocation has a limited range. Dennett holds that any similar aspects of its experiences could be gleaned by further scientific experiments.[4]: 443 He has also pointed out[8] that Nagel's argument and question were not new, but had previously been stated by B. A. Farrell in an article "Experience", in the journal Mind, in 1950.[9] Kathleen Akins similarly argued that many questions about a bat's subjective experience hinge on unanswered questions about the neuroscientific details of a bat's brain (such as the function of cortical activity profiles), and Nagel is too quick in ruling these out as answers to his central question.[10][11] Peter Hacker analyzes Nagel's statement as not only "malconstructed" but philosophically "misconceived" as a definition of consciousness,[12] and he asserts that Nagel's paper "laid the groundwork for…forty years of fresh confusion about consciousness."[13]: 13 Eric Schwitzgebel and Michael S. Gordon have argued that, contrary to Nagel, normal sighted humans do use echolocation much like bats - it is just that it is generally done without one's awareness. They use this to argue that normal people in normal circumstances can be grossly and systematically mistaken about their conscious experience.[14] |

批判 ダニエル・デネット(写真)はこの論文の主張を声高に批判している。 ダニエル・デネットは、コウモリの意識はアクセスできないというネーゲルの主張を否定し、コウモリの意識の「興味深い、あるいは理論的に重要な」特徴であ れば、第三者による観察が可能であると主張している[4]: 442 例えば、コウモリが数メートル以上離れた物体を検知できないのは、エコロケーションの範囲が限られているからである。デネットは、その経験に類似した側面 があれば、さらなる科学的実験によって得ることができると考えている[4]: 443 彼はまた、ネーゲルの議論と疑問は新しいものではなく、1950年にB.A.ファレルが『マインド』誌の論文「経験」において述べていたものであると指摘 している[8]。 キャスリーン・エイキンズも同様に、コウモリの主観的経験に関する多くの疑問は、コウモリの脳の神経科学的な詳細(皮質活動プロファイルの機能など)に関 する未解決の疑問に依存しており、ネーゲルは自分の中心的な疑問に対する答えとしてこれらを除外するのが早すぎると論じている[10][11]。 ピーター・ハッカーはネーゲルの声明を意識の定義として「誤った構成」であるだけでなく、哲学的に「誤った考え」であると分析しており[12]、彼はネーゲルの論文が「意識に関する40年にわたる新鮮な混乱の基礎を築いた」と断言している[13]: 13 エリック・シュヴィッツゲーベルとマイケル・S・ゴードンは、ネーゲルとは逆に、普通の目の見える人間はコウモリと同じようにエコロケーションを使ってい ると主張した。彼らはこのことを利用して、普通の状況にいる普通の人は、意識的な経験について重大かつ組織的な間違いを犯す可能性があると論じている [14]。 |

| Animal consciousness Intersubjectivity Qualia Umwelt |

動物意識 間主観性 クオリア 環世界 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/What_Is_It_Like_to_Be_a_Bat%3F | |

| コウモリであるとはどのようなことか / トマス・ネーゲル著 ; 永井均訳, 勁草書房 , 2023 | |

| 死、性、戦争、意識など人間の生にかかわる多様な問いを、明晰な表現と誠実な態度で論じる。89年の刊行から長く読まれ続けてきたロングセラーの哲学書に、古田徹也と永井均による新たな解説2篇を収録。 死 人生の無意味さ 道徳における運の問題 性的倒錯 戦争と大量虐殺 公的行為における無慈悲さ 優先政策 平等 価値の分裂 生物学の埓外にある倫理学 大脳分離と意識の統一 コウモリであるとはどのようなことか 汎心論 主観的と客観的 |

|

| Thomas Nagel

(/ˈneɪɡəl/; born July 4, 1937) is an American philosopher. He is the

University Professor of Philosophy and Law Emeritus at New York

University,[3] where he taught from 1980 until his retirement in

2016.[4] His main areas of philosophical interest are political

philosophy, ethics and philosophy of mind.[5] Nagel is known for his critique of material reductionist accounts of the mind, particularly in his essay "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" (1974), and for his contributions to liberal moral and political theory in The Possibility of Altruism (1970) and subsequent writings. He continued the critique of reductionism in Mind and Cosmos (2012), in which he argues against the neo-Darwinian view of the emergence of consciousness. |

トー

マス・ネーゲル(/ˈne↪Ll_26A;

1937年7月4日生まれ)はアメリカの哲学者である。ニューヨーク大学名誉哲学・法学部教授であり[3]、1980年から2016年に退職するまで教鞭

をとっていた[4]。主な哲学的関心領域は政治哲学、倫理学、心の哲学である[5]。 ネーゲルは、特に彼のエッセイ 「What Is It Like to Be a Bat?」(1974年)における物質還元主義的な心の説明に対する批判で知られている。(1974)、『利他主義の可能性』(1970)およびその後の 著作におけるリベラルな道徳・政治理論への貢献で知られる。Mind and Cosmos』(2012年)では還元主義への批判を続け、意識の発生に関するネオ・ダーウィン的見解に反論している。 |

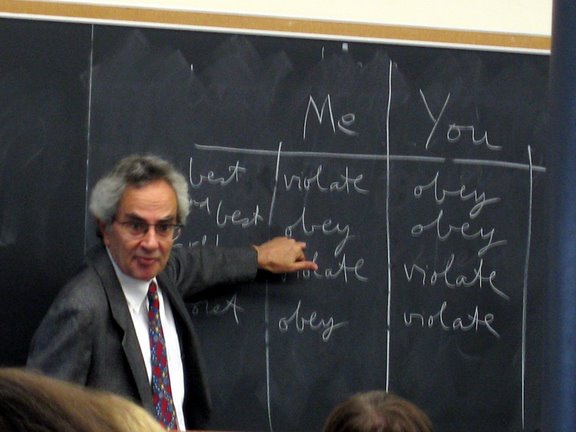

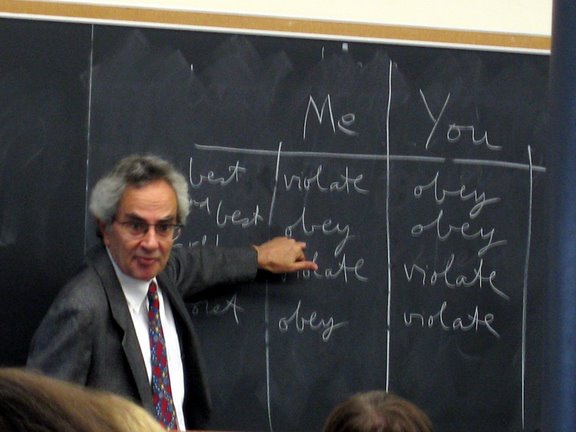

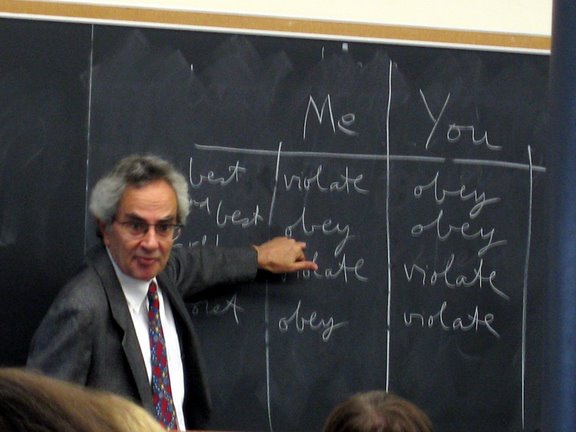

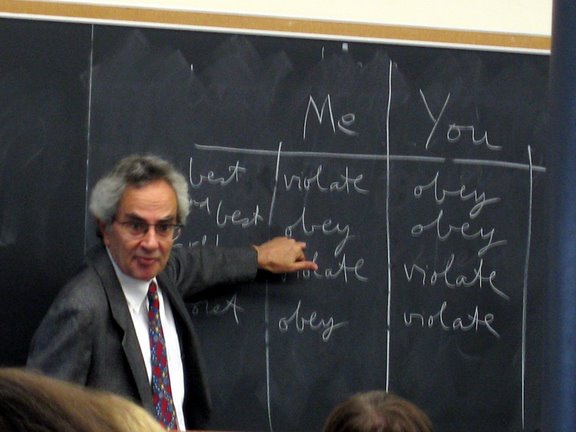

Life and career Nagel in 2008, teaching ethics Nagel was born on July 4, 1937, in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia), to German Jewish refugees Carolyn (née Baer) and Walter Nagel.[6][7] He arrived in the US in 1939, and was raised in and around New York.[7] He had no religious upbringing, but regards himself as a Jew.[8] Nagel received a Bachelor of Arts degree in philosophy from Cornell University in 1958, where he was a member of the Telluride House and was introduced to the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. He then attended the University of Oxford on a Fulbright Scholarship and received a BPhil in philosophy in 1960; there, he studied with J. L. Austin and Paul Grice. He received his Doctor of Philosophy degree in philosophy from Harvard University in 1963.[4][9] At Harvard, Nagel studied under John Rawls, whom Nagel later called "the most important political philosopher of the twentieth century."[10] Nagel taught at the University of California, Berkeley (from 1963 to 1966) and at Princeton University (from 1966 to 1980), where he trained many well-known philosophers, including Susan Wolf, Shelly Kagan, and Samuel Scheffler, the last of whom is now his colleague at New York University. Nagel is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a corresponding fellow of the British Academy, and in 2006 was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.[11] He has held fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.[11] In 2008 he was awarded a Rolf Schock Prize for his work in philosophy,[12] the Balzan Prize,[13] and the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters from the University of Oxford.[14] |

人生とキャリア 2008年、倫理学を教えるネーゲル ネーゲルは1937年7月4日、ユーゴスラビア(現セルビア)のベオグラードで、ドイツ系ユダヤ人難民のキャロリン(旧姓バール)とヴァルター・ネーゲル の間に生まれた[6][7]。1939年にアメリカに渡り、ニューヨークとその周辺で育った[7]。宗教的な教育は受けていないが、自らをユダヤ人とみな している[8]。 ネーゲルは1958年にコーネル大学で哲学の学士号を取得し、テルライド・ハウスのメンバーとしてルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの哲学に触れた。そ の後、フルブライト奨学金を得てオックスフォード大学に進学し、1960年に哲学の学士号を取得した。オックスフォード大学では、J・L・オースティンと ポール・グライスに師事した。ハーバード大学では、後にネーゲルが「20世紀で最も重要な政治哲学者」と呼ぶジョン・ロールズに師事した[10]。 ネーゲルはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校(1963年から1966年まで)とプリンストン大学(1966年から1980年まで)で教鞭をとり、スーザン・ウルフ、シェリー・ケーガン、サミュエル・シェフラーら多くの著名な哲学者を育てた。 ネーゲルはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローであり、英国アカデミーの準フェローである。 |

| Overview Nagel began to publish philosophy at age 22; his career now spans over 60 years of publication. He thinks that each person, owing to their capacity to reason, instinctively seeks a unified world view, but if this aspiration leads one to believe that there is only one way to understand our intellectual commitments, whether about the external world, knowledge, or what our practical and moral reasons ought to be, one errs. For contingent, limited and finite creatures, no such unified world view is possible, because ways of understanding are not always better when they are more objective. Like the British philosopher Bernard Williams, Nagel believes that the rise of modern science has permanently changed how people think of the world and our place in it. A modern scientific understanding is one way of thinking about the world and our place in it that is more objective than the commonsense view it replaces. It is more objective because it is less dependent on our peculiarities as the kinds of thinkers that people are. Our modern scientific understanding involves the mathematicized understanding of the world represented by modern physics. Understanding this bleached-out view of the world draws on our capacities as purely rational thinkers and fails to account for the specific nature of our perceptual sensibility. Nagel repeatedly returns to the distinction between "primary" and "secondary" qualities—that is, between primary qualities of objects like mass and shape, which are mathematically and structurally describable independent of our sensory apparatuses, and secondary qualities like taste and color, which depend on our sensory apparatuses. Despite what may seem like skepticism about the objective claims of science, Nagel does not dispute that science describes the world that exists independently of us. His contention, rather, is that a given way of understanding a subject matter should not be regarded as better simply for being more objective. He argues that scientific understanding's attempt at an objective viewpoint—a "view from nowhere"—necessarily leaves out something essential when applied to the mind, which inherently has a subjective point of view. As such, objective science is fundamentally unable to help people fully understand themselves. In "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" and elsewhere, he writes that science cannot describe what it is like to be a thinker who conceives of the world from a particular subjective perspective. Nagel argues that some phenomena are not best grasped from a more objective perspective. The standpoint of the thinker does not present itself to the thinker: they are that standpoint. One learns and uses mental concepts by being directly acquainted with one's own mind, whereas any attempt to think more objectively about mentality would abstract away from this fact. It would, of its nature, leave out what it is to be a thinker, and that, Nagel believes, would be a falsely objectifying view. Being a thinker is to have a subjective perspective on the world; if one abstracts away from this perspective one leaves out what he sought to explain. Nagel thinks that philosophers, over-impressed by the paradigm of the kind of objective understanding represented by modern science, tend to produce theories of the mind that are falsely objectifying in precisely this kind of way. They are right to be impressed—modern science really is objective—but wrong to take modern science to be the only paradigm of objectivity. The kind of understanding that science represents does not apply to everything people would like to understand. As a philosophical rationalist, Nagel believes that a proper understanding of the place of mental properties in nature will involve a revolution in our understanding of both the physical and the mental, and that this is a reasonable prospect that people can anticipate in the near future. A plausible science of the mind will give an account of the stuff that underpins mental and physical properties in such a way that people will simply be able to see that it necessitates both of these aspects. Now, it seems to people that the mental and the physical are irreducibly distinct, but that is not a metaphysical insight, or an acknowledgment of an irreducible explanatory gap, but simply where people are at their present stage of understanding. Nagel's rationalism and tendency to present human nature as composite, structured around our capacity to reason, explains why he thinks that therapeutic or deflationary accounts of philosophy are complacent and that radical skepticism is, strictly speaking, irrefutable.[clarification needed] The therapeutic or deflationary philosopher, influenced by Wittgenstein's later philosophy, reconciles people to the dependence of our worldview on our "form of life". Nagel accuses Wittgenstein and American philosopher of mind and language Donald Davidson of philosophical idealism.[15] Both ask people to take up an interpretative perspective to making sense of other speakers in the context of a shared, objective world. This, for Nagel, elevates contingent conditions of our makeup into criteria for what is real. The result "cuts the world down to size" and makes what there is dependent on what there can be interpreted to be. Nagel claims this is no better than more orthodox forms of idealism in which reality is claimed to be made up of mental items or constitutively dependent on a form supplied by the mind. |

概要 ネーゲルは22歳で哲学の出版を始め、そのキャリアは60年以上に及ぶ。しかし、この願望が、外的世界や知識、あるいは実践的・道徳的な理由がどうあるべ きかを問わず、私たちの知的コミットメントを理解する唯一の方法があると信じ込ませるのであれば、それは誤りである。偶発的で、限定的で、有限な生き物に とって、そのような統一された世界観はありえない。 イギリスの哲学者バーナード・ウィリアムズのように、ネーゲルは近代科学の台頭が、人々の世界に対する考え方とその中での私たちの立場を永久に変えたと考 えている。近代的な科学的理解は、世界とその中での私たちの立場について考える一つの方法であり、それに取って代わる常識的な見方よりも客観的である。よ り客観的であるのは、私たち人間の思考者としての特殊性にあまり左右されないからである。現代の科学的理解には、現代物理学に代表される数学化された世界 の理解が含まれる。この漂白された世界観を理解することは、純粋に合理的な思考者としての私たちの能力を引き出すものであり、私たちの知覚的感性の特異な 性質を説明するものではない。ネーゲルは繰り返し、「一次的な」性質と「二次的な」性質の区別に立ち戻る。つまり、質量や形状のような、われわれの感覚装 置とは無関係に数学的・構造的に記述可能な物体の一次的な性質と、味や色のような、われわれの感覚装置に依存する二次的な性質の区別である。 科学の客観的主張に対する懐疑のように見えるかもしれないが、ネーゲルは、科学が我々とは無関係に存在する世界を記述することに異議を唱えているのではな い。彼の主張はむしろ、ある主題を理解するある方法が、より客観的であるというだけで、より優れていると見なすべきではないということである。彼は、科学 的理解が客観的な視点、つまり 「どこからでもないところからの視点 」を持つという試みは、主観的な視点を本質的に持つ心に適用する場合、本質的な何かを欠落させることになると主張する。そのため、客観的な科学は根本的 に、人が自分自身を完全に理解するのを助けることができないのである。蝙蝠になるとはどういうことか』などで彼は、科学は、個別主義的な視点から世界を構 想する思想家がどのようなものであるかを記述することはできないと書いている。 ネーゲルは、ある種の現象は、より客観的な視点から把握するのが最善ではないと主張する。思考者の立場は、思考者自身に提示されるのではなく、思考者自身 がその立場なのである。人は自分の心を直接知ることで、心的概念を学び、使うのである。ネーゲルは、思考者であることが何であるかを排除することは、誤っ た客観化であると考える。思想家であるということは、世界に対して主観的な視点を持つことである。この視点を抽象化してしまうと、彼が説明しようとしたこ とが抜け落ちてしまう。 ネーゲルは、近代科学に代表されるような客観的理解のパラダイムに過剰な感銘を受けた哲学者たちが、まさにこのような虚偽の客観化を行う心の理論を生み出 しがちだと考えている。近代科学が本当に客観的であることに感銘を受けるのは正しいが、近代科学が客観性の唯一のパラダイムであると考えるのは間違ってい る。科学が象徴するような理解は、人々が理解したいと思うものすべてに当てはまるわけではない。 哲学的合理主義者であるネーゲルは、自然界における精神的性質の位置づけを正しく理解することは、物理的なものと精神的なものの両方の理解における革命を 伴うものであり、それは人々が近い将来に予期しうる妥当な見通しであると考えている。もっともらしい心の科学は、精神的性質と物理的性質の根底を支えるも のについて、人々が単純にそれがこれらの側面の両方を必要とすることを理解できるような説明を与えるだろう。現在、精神と身体は不可逆的に区別されている ように人々には見えるが、それは形而上学的な洞察や不可逆的な説明の隔たりを認めることではなく、単に人々の現在の理解段階にあるのだ。 ネーゲルの合理主義や、人間の本性を理性的な能力を中心に構成された複合的なものとして提示する傾向は、彼が哲学の治療的あるいはデフレ的な説明は自己満 足であり、急進的懐疑主義は厳密に言えば反論の余地がないと考える理由を説明している[clarification needed]。治療的あるいはデフレ的な哲学者は、ヴィトゲンシュタインの後期の哲学の影響を受け、我々の世界観が我々の「生活の形態」に依存している ことを人々に和解させる。ネーゲルはウィトゲンシュタインとアメリカの心と言語の哲学者ドナルド・デイヴィッドソンを哲学的観念論で非難している。ネーゲ ルにとってこのことは、私たちが作り上げる偶発的な条件を、何が現実であるかの基準へと昇華させるものである。その結果、「世界は縮小され」、そこにある ものは、そこにあると解釈されるものに依存するようになる。ネーゲルは、これでは、現実が心的なものから構成されているとか、心によって供給される形式に 構成的に依存していると主張する、より正統的な観念論と変わらないと主張する。 |

| Philosophy of mind What is it like to be a something Further information: What Is It Like to Be a Bat? Nagel is probably most widely known in philosophy of mind as an advocate of the idea that consciousness and subjective experience cannot, at least with the contemporary understanding of physicalism, be satisfactorily explained with the concepts of physics. This position was primarily discussed by Nagel in one of his most famous articles: "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" (1974). The article's title question, though often attributed to Nagel, was originally asked by Timothy Sprigge. The article was originally published in 1974 in The Philosophical Review, and has been reprinted several times, including in The Mind's I (edited by Daniel Dennett and Douglas Hofstadter), Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology (edited by Ned Block), Nagel's Mortal Questions (1979), The Nature of Mind (edited by David M. Rosenthal), and Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings (edited by David J. Chalmers). In "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?", Nagel argues that consciousness has essential to it a subjective character, a what it is like aspect. He writes, "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism—something it is like for the organism."[16] In the 50th-anniversary republication of his article in book form, Nagel writes that he "tried to show that the irreducible subjectivity of consciousness is an obstacle to many proposed solutions to the mind-body problem."[17] His critics[who?] have objected to what they see as a misguided attempt to argue from a fact about how one represents the world (trivially, one can only do so from one's point of view) to a false claim about the world, that it somehow has first-personal perspectives built into it. On that understanding, Nagel is a conventional dualist about the physical and the mental. This is, however, a misunderstanding[according to whom?]: Nagel's point is that there is a constraint on what it is to possess the concept of a mental state, namely, that one be directly acquainted with it. Concepts of mental states are only made available to a thinker who can be acquainted with their own states; clearly, the possession and use of physical concepts has no corresponding constraint. Part of the puzzlement here is because of the limitations of imagination: influenced by his Princeton colleague Saul Kripke, Nagel believes that any type identity statement that identifies a physical state type with a mental state type would be, if true, necessarily true. But Kripke argues that one can easily imagine a situation where, for example, one's C-fibres are stimulated but one is not in pain and so refute any such psychophysical identity from the armchair. (A parallel argument does not hold for genuine theoretical identities.) This argument that there will always be an explanatory gap between an identification of a state in mental and physical terms is compounded, Nagel argues, by the fact that imagination operates in two distinct ways. When asked to imagine sensorily, one imagines C-fibres being stimulated; if asked to imagine sympathetically, one puts oneself in a conscious state resembling pain. These two ways of imagining the two terms of the identity statement are so different that there will always seem to be an explanatory gap, whether or not this is the case. (Some philosophers of mind[who?] have taken these arguments as helpful for physicalism on the grounds that it exposes a limitation that makes the existence of an explanatory gap seem compelling, while others[who?] have argued that this makes the case for physicalism even more impossible as it cannot be defended even in principle.) Nagel is not a physicalist because he does not believe that an internal understanding of mental concepts shows them to have the kind of hidden essence that underpins a scientific identity in, say, chemistry. But his skepticism is about current physics: he envisages in his most recent work that people may be close to a scientific breakthrough in identifying an underlying essence that is neither physical (as people currently think of the physical), nor functional, nor mental, but such that it necessitates all three of these ways in which the mind "appears" to us. The difference between the kind of explanation he rejects and the kind he accepts depends on his understanding of transparency: from his earliest work to his most recent Nagel has always insisted that a prior context is required to make identity statements plausible, intelligible and transparent. |

心の哲学 何かになるとはどういうことか さらに詳しい情報 コウモリになるとはどういうことか? ネーゲルは心の哲学において、意識と主観的経験は、少なくとも現代の物理主義の理解では、物理学の概念では満足に説明できないという考えの提唱者として、 おそらく最も広く知られている。この立場は、ネーゲルが最も有名な論文のひとつで主に論じている: 「コウモリになるとはどういうことか?"(1974年)である。(1974). この論文のタイトルの問いは、ネーゲルのものとされることが多いが、もともとはティモシー・スプリッゲの問いであった。この論文は1974年に『The Philosophical Review』に掲載された後、『The Mind's I』(ダニエル・デネット、ダグラス・ホフスタッター編)、『Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology』(ネッド・ブロック編)、『Nagel's Mortal Questions』(1979年)、『The Nature of Mind』(デイヴィッド・M・ローゼンタール編)、『Philosophy of Mind』(心の哲学)などに再録されている: Classical and Contemporary Readings』(デイヴィッド・J・チャルマーズ編)などがある。 ネーゲルは『コウモリであることはどのようなものか』の中で、意識には主観的な性格、つまり「どのようなものであるか」という側面が不可欠であると論じて いる。彼は、「ある生物が意識的な心的状態を持つのは、その生物であることのようなもの、つまりその生物にとってそのようなものがある場合に限られる」と 書いている。 「17]彼の批評家[誰?]は、世界をどのように表現するかという事実(些細なことだが、人は自分の視点からしかそうすることができない)から、世界には 何らかの形で一人称的な視点が組み込まれているという、世界についての誤った主張へと論証しようとする誤った試みであるとみなし、異議を唱えている。その ように理解すれば、ネーゲルは物理的なものと精神的なものについての従来の二元論者である。しかし、これは誤解である: ネーゲルが言いたいのは、精神状態の概念を所有するとはどういうことなのか、つまりそれを直接知っているという制約があるということである。心的状態の概 念は、それ自身の状態を知ることができる思考者のみが利用できる。 プリンストン大学の同僚であるソール・クリプキの影響を受け、ネーゲルは、物理的状態の種類と精神的状態の種類を同一視するような型同一性声明は、真であ れば必然的に真になると考えている。しかしクリプキは、例えばC線維が刺激されても痛みを感じないような状況を容易に想像することができ、そのような精神 物理学的同一性を肘掛け椅子から反駁することができると主張する(同じような議論は、真の理論的同一性については成り立たない)。精神的状態と身体的状態 の同一性の間には常に説明的ギャップが存在するというこの議論は、想像力が2つの異なる方法で作用するという事実によって、ネーゲルはさらに複雑になって いると主張する。感覚的に想像せよと言われれば、C線維が刺激される様子を想像し、共感的に想像せよと言われれば、痛みに似た意識状態に身を置く。この2 つの想像の仕方は、同一性宣言の2つの用語があまりに異なるため、そうであるかどうかにかかわらず、常に説明のギャップがあるように思われる。(心の哲学 者[誰?]の中には、説明的ギャップの存在を説得力のあるものに見せる限界を露呈しているという理由で、これらの議論を物理主義に役立つものとする者もい れば、原理的にさえ擁護できないので、物理主義のケースをさらに不可能なものにすると主張する者[誰?]もいる)。 ネーゲルが物理主義者でないのは、精神概念の内的理解が、例えば化学における科学的同一性を支えるような隠された本質を持っていることを示すとは信じてい ないからである。しかし、彼の懐疑論は現在の物理学に関するものである。彼は最新の研究で、(現在人々が考えるような)物理的でもなく、機能的でもなく、 精神的でもなく、心が私たちに「見える」これら3つの方法すべてを必要とするような、根底にある本質を特定する科学的ブレークスルーに人々が近づいている 可能性を想定している。ネーゲルが否定する説明と受け入れる説明の異なる点は、透明性についての彼の理解にかかっている。ネーゲルは、初期の研究から最新 の研究まで、同一性の記述をもっともらしく、理解しやすく、透明なものにするためには、事前の文脈が必要だと常に主張してきた。 |

| Natural selection and consciousness Further information: Mind and Cosmos In his 2012 book Mind and Cosmos, Nagel argues against a materialist view of the emergence of life and consciousness, writing that the standard neo-Darwinian view flies in the face of common sense.[18]: 5–6 He writes that mind is a basic aspect of nature, and that any philosophy of nature that cannot account for it is fundamentally misguided.[18]: 16ff He argues that the principles that account for the emergence of life may be teleological, rather than materialist or mechanistic.[18]: 10 Despite Nagel's being an atheist and not a proponent of intelligent design (ID), his book was "praised by creationists", according to the New York Times.[4] Nagel writes in Mind and Cosmos that he disagrees with both ID defenders and their opponents, who argue that the only naturalistic alternative to ID is the current reductionist neo-Darwinian model.[18]: 12 Nagel has argued that ID should not be rejected as non-scientific, for instance writing in 2008 that "ID is very different from creation science," and that the debate about ID "is clearly a scientific disagreement, not a disagreement between science and something else."[19] In 2009, he recommended Signature in the Cell by the philosopher and ID proponent Stephen C. Meyer in The Times Literary Supplement as one of his "Best Books of the Year."[20] Nagel does not accept Meyer's conclusions but endorsed Meyer's approach, and argued in Mind and Cosmos that Meyer and other ID proponents, David Berlinski and Michael Behe, "do not deserve the scorn with which they are commonly met."[18]: 10 |

自然淘汰と意識 さらに詳しい情報 心と宇宙 ネーゲルは2012年に出版した『Mind and Cosmos(心と宇宙)』の中で、生命と意識の発生に関する唯物論的見解に反対し、標準的なネオ・ダーウィン的見解は常識に反していると書いている [18]: 5-6 心は自然の基本的な側面であり、それを説明できない自然哲学は根本的に間違っていると書いている[18]: 16ff 生命の発生を説明する目的論は、唯物論的・機械論的なものではなく、むしろ目的論的なものであるかもしれないと主張している[18]: 10 ネーゲルは無神論者であり、インテリジェント・デザイン(ID)の支持者ではないにもかかわらず、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙によれば、彼の著書は「創造論 者によって賞賛された」[4]。ネーゲルは『Mind and Cosmos』の中で、IDの唯一の自然主義的な代替案は現在の還元主義的なネオ・ダーウィン・モデルであると主張するID擁護派とその反対派の両方に同 意できないと書いている[18]: 12 ネーゲルはIDを非科学的なものとして否定すべきではないと主張しており、例えば2008年には「IDは創造科学とは大きく異なる」と書き、IDに関する 議論は「科学とそれ以外のものとの間の不一致ではなく、明らかに科学的な不一致である」と述べている[19]。ネーゲルはマイヤーの結論を受け入れてはい ないが、マイヤーのアプローチを支持しており、『Mind and Cosmos』において、マイヤーや他のID提唱者であるデイヴィッド・バーリンスキーやマイケル・ベーエは「一般的に言われているような軽蔑に値しな い」と論じている[18]: 10 |

| Ethics Nagel's Rawlsian approach Nagel has been highly influential in the related fields of moral and political philosophy. Supervised by John Rawls, he has been a longstanding proponent of a Kantian and rationalist approach to moral philosophy. His distinctive ideas were first presented in the short monograph The Possibility of Altruism, published in 1970. That book seeks by reflection on the nature of practical reasoning to uncover the formal principles that underlie reason in practice and the related general beliefs about the self that are necessary for those principles to be truly applicable to us. Nagel defends motivated desire theory about the motivation of moral action. According to motivated desire theory, when a person is motivated to moral action it is indeed true that such actions are motivated, like all intentional actions, by a belief and a desire. But it is important to get the justificatory relations right: when a person accepts a moral judgment they are necessarily motivated to act. But it is the reason that does the justificatory work of justifying both the action and the desire. Nagel contrasts this view with a rival view which believes that a moral agent can only accept that they have a reason to act if the desire to carry out the action has an independent justification. An account based on presupposing sympathy would be of this kind.[21] The most striking claim of the book is that there is a very close parallel between prudential reasoning in one's own interests and moral reasons to act to further the interests of another person. When one reasons prudentially, for example about the future reasons that one will have, one allows the reason in the future to justify one's current action without reference to the strength of one's current desires. If a hurricane were to destroy someone's car next year, at that point they will want their insurance company to pay them to replace it: that future reason gives them a reason to take out insurance now. The strength of the reason ought not to be hostage to the strength of one's current desires. The denial of this view of prudence, Nagel argues, means that one does not really believe that one is one and the same person through time. One is dissolving oneself into distinct person-stages.[22] |

倫理学 ネーゲルのロールズ的アプローチ ネーゲルは道徳哲学と政治哲学の関連分野で大きな影響力を持っている。ジョン・ロールズに師事した彼は、道徳哲学におけるカント的・合理主義的アプローチ を長年提唱してきた。彼の独特な考え方は、1970年に出版された短い単行本『利他主義の可能性』で初めて紹介された。この本は、実践的推論の本質を考察 することによって、実践における理性の根底にある形式的原理と、それらの原理が真に私たちに適用されるために必要な、自己に関する関連した一般的信念を明 らかにしようとするものである。ネーゲルは道徳的行為の動機づけについて動機づけられた欲求理論を擁護している。動機づけられた欲望理論によれば、人格が 道徳的行動に動機づけられるとき、そのような行動は、すべての意図主義的行動と同様に、信念と欲望によって動機づけられることは確かに事実である。しか し、正当化関係を正しく理解することが重要である。人格が道徳的判断を受け入れるとき、彼らは必然的に行動を動機づけられる。しかし、行為と欲求の両方を 正当化するのは理性である。ネーゲルはこの見方を、道徳的行為者は、その行為を遂行しようとする欲求が独立した正当性を持っている場合にのみ、自分には行 為する理由があると受け入れることができると考える対立的な見方と対比している。共感を前提とした説明はこの種のものである。 本書で最も印象的な主張は、自分自身の利益のためのプルデンシャルな理由付けと、他人の利益を促進するために行動する道徳的理由付けの間には、非常に密接 な並行関係があるということである。プルデンシャルな理由付けをするとき、例えば将来自分が持つことになる理由については、自分の現在の欲望の強さを参照 することなく、将来の理由によって現在の行動を正当化することができる。例えば、来年ハリケーンによって車が壊された場合、その時点で保険会社に車を買い 替える費用を支払ってもらいたいと思うだろう。理由の強さは、現在の欲望の強さの人質になってはならない。ネーゲルは、このような思慮分別の見方を否定す ることは、自分が時間を通じて同一の人格であると信じていないことを意味すると主張する。人は自分自身を別個の人格段階に分解しているのである[22]。 |

| Altruistic action This is the basis of his analogy between prudential actions and moral actions: in cases of altruistic action for another person's good that person's reasons quite literally become reasons for one if they are timeless and intrinsic reasons. Genuine reasons are reasons for anyone. Like the 19th-century moral philosopher Henry Sidgwick, Nagel believes that one must conceive of one's good as an impersonal good and one's reasons as objective reasons. That means, practically, that a timeless and intrinsic value generates reasons for anyone. A person who denies the truth of this claim is committed, as in the case of a similar mistake about prudence, to a false view of themself. In this case the false view is that one's reasons are irreducibly theirs, in a way that does not allow them to be reasons for anyone: Nagel argues this commits such a person to the view that they cannot make the same judgments about their own reasons third-personally that they can make first-personally. Nagel calls this "dissociation" and considers it a practical analogue of solipsism (the philosophical idea that only one's own mind is sure to exist). Once again, a false view of what is involved in reasoning properly is refuted by showing that it leads to a false view of people's nature. |

利他的行動 他人のために利他的な行動をとる場合、その人格の理由が時間を超越した本質的な理由であれば、文字通りその人の理由になる。本源的な理由は、誰にとっても 理由となる。19世紀の道徳哲学者ヘンリー・シジウィックのように、ネーゲルは自分の善を非人間的な善と考え、自分の理由を客観的な理由と考えなければな らないと考えている。つまり現実的には、時間を超越した本質的な価値が誰にでも理由を生み出すということだ。この主張の真理を否定する人格は、慎重さにつ いての同様の間違いの場合と同様に、自分自身について誤った見方をしていることになる。この場合、誤った見解とは、自分の理由が誰の理由にもなりえないよ うな形で、不可逆的に自分のものであるというものである: ネーゲルは、このような人格は、自分自身の理由について、一人称的に下すことができる判断と同じ判断を三人称的に下すことはできないという見解に陥ってし まうと主張する。ネーゲルはこれを「解離」と呼び、独我論(自分の心だけが確実に存在するという哲学的な考え方)の実際的な類型だと考えている。もう一度 言うが、適切な推論をするためには何が必要かという誤った見方は、人の本質に対する誤った見方につながることを示すことで反論されている。 |

| Subjective and objective reasons Nagel's later work on ethics ceases to place as much weight on the distinction between a person's personal or "subjective" reasons and their "objective" reasons. Earlier, in The Possibility of Altruism, he took the stance that if one's reasons really are about intrinsic and timeless values then, qua subjective reason, one can only take them to be the guise of the reasons that there really are: the objective ones. In later discussions, Nagel treats his former view as an incomplete attempt to convey the fact that there are distinct classes of reasons and values, and speaks instead of "agent-relative" and "agent-neutral" reasons. In the case of agent-relative reasons (the successor to subjective reasons), specifying the content of the reason makes essential reference back to the agent for whom it is a reason. An example of this might be: "Anyone has a reason to honor his or her parents." By contrast, in the case of agent-neutral reasons (the successor to objective reasons) specifying the content of the reason does not make any essential reference back to the person for whom it is a reason. An example of this might be: "Anyone has a reason to promote the good of parenthood." |

主観的理由と客観的理由 ネーゲルの後期の倫理学研究では、人格の個人的な理由、つまり「主観的」な理由と、人格の「客観的」な理由との区別にそれほど重きを置かなくなっている。 それ以前の『利他主義の可能性』では、もし自分の理由が本当に本質的で時間を超越した価値に関するものであるならば、主観的な理由としては、本当に存在す る理由、すなわち客観的な理由の見せかけに過ぎないという立場をとっていた。後の議論においてネーゲルは、かつての見解を、理由と価値には別個の類型があ るという事実を伝える不完全な試みとみなし、その代わりに「主体相対的」な理由と「主体中立的」な理由について語っている。主体関係的理由(主観的理由の 後継)の場合、理由の内容を特定することで、それが理由である主体への言及が不可欠となる。例えば、次のようなものである: 「誰でも自分の両親を敬う理由がある"。対照的に、エージェント中立的理由(客観的理由の後継)の場合、理由の内容を特定することで、それが理由である人 格を本質的に参照することはない。例えば、次のようなものである: 「誰にでも子育ての善を促進する理由がある"。 |

| Objective reasons The different classes of reasons and values (i.e., agent-relative and agent-neutral) emphasized in Nagel's later work are situated within a Sidgwickian model in which one's moral commitments are thought of objectively, such that one's personal reasons and values are simply incomplete parts of an impersonal whole. The structure of Nagel's later ethical view is that all reasons must be brought into relation to this objective view of oneself. Reasons and values that withstand detached critical scrutiny are objective, but more subjective reasons and values can nevertheless be objectively tolerated. However, the most striking part of the earlier argument and of Sidgwick's view is preserved: agent-neutral reasons are literally reasons for anyone, so all objectifiable reasons become individually possessed no matter whose they are. Thinking reflectively about ethics from this standpoint, one must take every other agent's standpoint on value as seriously as one's own, since one's own perspective is just a subjective take on an inter-subjective whole; one's personal set of reasons is thus swamped by the objective reasons of all others. |

客観的な理由 ネーゲルの後期の著作で強調されている理由と価値観の異なるクラス(すなわち、主体相対的なものと主体中立的なもの)は、自分の道徳的コミットメントを客 観的に考えるシドグウィック・モデルの中に位置づけられる。ネーゲルの後期倫理観の構造は、すべての理由がこの客観的な自己観と関連づけられなければなら ないというものである。分離された批判的精査に耐える理由や価値観は客観的であるが、より主観的な理由や価値観も客観的には許容されうる。しかし、先の議 論とシジウィックの見解の最も印象的な部分は維持されている。主体中立的な理由は、文字通り誰にとっても理由であるため、客観化可能な理由はすべて、誰で あろうと個々人が所有するものとなる。この立場から倫理について反省的に考えると、人は価値に関する他のすべてのエージェントの立場を自分の立場と同じよ うに真剣に受け止めなければならない。なぜなら、自分の立場は主観的な全体に対する主観的な受け止め方に過ぎないからである。 |

| World agent views This is similar to "world agent" consequentialist views in which one takes up the standpoint of a collective subject whose reasons are those of everyone. But Nagel remains an individualist who believes in the separateness of persons, so his task is to explain why this objective viewpoint does not swallow up the individual standpoint of each of us. He provides an extended rationale for the importance to people of their personal point of view. The result is a hybrid ethical theory of the kind defended by Nagel's Princeton PhD student Samuel Scheffler in The Rejection of Consequentialism. The objective standpoint and its demands have to be balanced with the subjective personal point of view of each person and its demands. One can always be maximally objective, but one does not have to be. One can legitimately "cap" the demands placed on oneself by the objective reasons of others. In addition, in his later work, Nagel finds a rationale for so-called deontic constraints in a way Scheffler could not. Following Warren Quinn and Frances Kamm, Nagel grounds them on the inviolability of persons. |

世界代理人論 これは「世界代理人」の結果論的見解に似ており、その理由はすべての人のものであるという集団的主体の立場に立つものである。しかしネーゲルは依然として 人格の分離を信じる個人主義者であり、彼の仕事は、この客観的視点がなぜ私たち一人ひとりの個人的視点を飲み込まないのかを説明することである。彼は、人 格にとって個人的視点が重要であることの根拠を拡大解釈する。その結果、ネーゲルのプリンストン大学の博士課程の学生であったサミュエル・シェフラーが 『帰結主義の否定』で擁護したような、ハイブリッドな倫理理論が生まれる。客観的な立場とその要求は、各人の主観的な個人的視点とその要求とバランスを取 らなければならない。人は常に格律であることはできるが、そうである必要はない。人は、他人の客観的な理由によって自分に課された要求を、合法的に 「キャップ」することができるのである。さらに、ネーゲルは後年の著作において、シェフラーにはできなかった方法で、いわゆるデオン的制約の根拠を見出し ている。ウォーレン・クインとフランシス・カムに倣い、ネーゲルは人格の不可侵性にその根拠を置く。 |

| Political philosophy The extent to which one can lead a good life as an individual while respecting the demands of others leads inevitably to political philosophy. In the Locke lectures published as the book Equality and Partiality, Nagel exposes John Rawls's theory of justice to detailed scrutiny. Once again, Nagel places such weight on the objective point of view and its requirements that he finds Rawls's view of liberal equality not demanding enough. Rawls's aim to redress, not remove, the inequalities that arise from class and talent seems to Nagel to lead to a view that does not sufficiently respect the needs of others. He recommends a gradual move to much more demanding conceptions of equality, motivated by the special nature of political responsibility. Normally, people draw a distinction between what people do and what people fail to bring about, but this thesis, true of individuals, does not apply to the state, which is a collective agent. A Rawlsian state permits intolerable inequalities and people need to develop a more ambitious view of equality to do justice to the demands of the objective recognition of the reasons of others. For Nagel, honoring the objective point of view demands nothing less. |

政治哲学 他者の要求を尊重しながら、個人としてどこまで善良な生活を送ることができるかということは、必然的に政治哲学につながる。ネーゲルは『平等と偏愛』とし て出版されたロックの講義の中で、ジョン・ロールズの正義論を詳細に検証している。ネーゲルは再び、客観的視点とその要件に重きを置き、ロールズの自由主 義的平等観が十分に要求されていないことに気づく。ロールズが目指すのは、階級や才能から生じる不平等を取り除くことではなく、是正することであり、ネー ゲルには、他者のニーズを十分に尊重しない考え方につながっているように見える。彼は、政治的責任の特別な性質に動機づけられた、より厳しい平等概念への 段階的な移行を勧めている。通常、人は人が行うことと、人がもたらさなかったことを区別するが、このテーゼは個人に当てはまるものであり、集合的主体であ る国家には当てはまらない。ロールズ的な国家は耐え難い不平等を容認しており、人々は他者の理由を客観的に認めるという要求を正当化するために、より野心 的な平等観を発展させる必要がある。ネーゲルにとって、客観的な視点を尊重することは、それ以下のものを要求するものではない。 |

| Atheism In Mind and Cosmos, Nagel writes that he is an atheist: "I lack the sensus divinitatis that enables—indeed compels—so many people to see in the world the expression of divine purpose as naturally as they see in a smiling face the expression of human feeling."[18] In The Last Word, he wrote, "I want atheism to be true and am made uneasy by the fact that some of the most intelligent and well-informed people I know are religious believers. It isn't just that I don't believe in God and, naturally, hope that I'm right in my belief. It’s that I hope there is no God! I don’t want there to be a God; I don’t want the universe to be like that."[23] |

無神論 ネーゲルは『Mind and Cosmos』の中で、自分は無神論者であると書いている。「私には、多くの人々が、微笑む顔に人間の感情の表出を見るように、自然に神の目的の表出を世 界に見ることを可能にする、いや、そうせざるを得ないような、神に対する感覚が欠けている」[18]。私は神を信じていないし、当然、自分の信念が正しい ことを願っている。神などいないことを望んでいるのだ!私は神が存在することを望んでおらず、宇宙がそのようなものであることを望んでいない」[23]。 |

| Experience itself as a good Nagel has said, "There are elements which, if added to one's experience, make life better; there are other elements which if added to one's experience, make life worse. But what remains when these are set aside is not merely neutral: it is emphatically positive. ... The additional positive weight is supplied by experience itself, rather than by any of its consequences."[24][25] |

善としての経験 ネーゲルはこう言っている。「経験に加えれば人生をより良くする要素があり、経験に加えれば人生をより悪くする要素もある。しかし、それらが脇に置かれた ときに残るものは、単に中立的なものではなく、強調的に肯定的なものである。... さらに肯定的な重みを与えるのは、経験そのものであり、むしろその結果である」[24][25]。 |

| Personal life Nagel married Doris Blum in 1954, divorcing in 1973. In 1979, he married Anne Hollander, who died in 2014.[6] |

私生活 ネーゲルは1954年にドリス・ブルムと結婚し、1973年に離婚した。1979年にアン・ホランダーと結婚し、2014年に死去した[6]。 |

| Awards Nagel received the 1996 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay for Other Minds (1995). He has also been awarded the Balzan Prize in Moral Philosophy (2008), the Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (2008) and the Distinguished Achievement Award of the Mellon Foundation (2006).[4] |

受賞歴 ネーゲルは、1996年PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel賞(エッセイ芸術部門)を『Other Minds』(1995年)で受賞している。また、道徳哲学におけるバルザン賞(2008年)、スウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの論理学・哲学におけるロ ルフ・ショック賞(2008年)、メロン財団の特別功労賞(2006年)を受賞している[4]。 |

| Selected publications Books Nagel, Thomas (1970). The possibility of altruism. Princeton, N.J: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780691020020. (Reprinted in 1978, Princeton University Press.) Nagel, Thomas; Held, Virginia; Morgenbesser, Sidney (1974). Philosophy, morality, and international affairs: essays edited for the Society for Philosophy and Public Affairs. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195017595. Nagel, Thomas (1979). Mortal questions. London: Canto. ISBN 9780521406765. Nagel, Thomas (1986). The view from nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195056440. Nagel, Thomas (1987). What does it all mean?: a very short introduction to philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195174373. Nagel, Thomas (1991). Equality and partiality. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195098396. Nagel, Thomas (1997). The last word. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195149838.[26] Nagel, Thomas (1999). Other minds: critical essays, 1969–1994. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195132465. Nagel, Thomas; Murphy, Liam (2002). The myth of ownership : taxes and justice. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176568. Nagel, Thomas (2002). Concealment and exposure: and other essays. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195152937. Nagel, Thomas (2010). Secular philosophy and the religious temperament: essays 2002–2008. Oxford New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195394115. Nagel, Thomas (2012). Mind and Cosmos: why the materialist neo-Darwinian conception of nature is almost certainly false. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199919758 Articles 1959, "Hobbes's Concept of Obligation", Philosophical Review, pp. 68–83. 1959, "Dreaming", Analysis, pp. 112–6. 1965, "Physicalism", Philosophical Review, pp. 339–56. 1969, "Sexual Perversion", Journal of Philosophy, pp. 5–17 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1969, "The Boundaries of Inner Space", Journal of Philosophy, pp. 452–8. 1970, "Death", Nous, pp. 73–80 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1970, "Armstrong on the Mind", Philosophical Review, pp. 394–403 (a discussion review of A Materialist Theory of the Mind by D. M. Armstrong). 1971, "Brain Bisection and the Unity of Consciousness", Synthese, pp. 396–413 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1971, "The Absurd", Journal of Philosophy, pp. 716–27 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1972, "War and Massacre", Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 1, pp. 123–44 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1973, "Rawls on Justice", Philosophical Review, pp. 220–34 (a discussion review of A Theory of Justice by John Rawls). 1973, "Equal Treatment and Compensatory Discrimination", Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 2, pp. 348–62. 1974, "What Is it Like to Be a Bat?", Philosophical Review, pp. 435–50 (repr. in Mortal Questions). Online text 1976, "Moral Luck", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supplementary vol. 50, pp. 137–55 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1979, "The Meaning of Equality", Washington University Law Quarterly, pp. 25–31. 1981, "Tactical Nuclear Weapons and the Ethics of Conflict", Parameters: Journal of the U.S. Army War College, pp. 327–8. 1983, "The Objective Self", in Carl Ginet and Sydney Shoemaker (eds.), Knowledge and Mind, Oxford University Press, pp. 211–232. 1987, "Moral Conflict and Political Legitimacy", Philosophy & Public Affairs, pp. 215–240. 1994, "Consciousness and Objective Reality", in R. Warner and T. Szubka (eds.), The Mind-Body Problem, Blackwell. 1995, "Personal Rights and Public Space", Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 83–107. 1997, "Assisted Suicide: The Philosophers' Brief" (with R. Dworkin, R. Nozick, J. Rawls, T. Scanlon, and J. J. Thomson), New York Review of Books, March 27, 1997. 1998, "Reductionism and Antireductionism", in The Limits of Reductionism in Biology, Novartis Symposium 213, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 3–10. 1998, "Concealment and Exposure", Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 3–30. Online text 1998, "Conceiving the Impossible and the Mind-Body Problem", Philosophy, vol. 73, no. 285, pp. 337–352. Online PDF Archived 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine 2000, "The Psychophysical Nexus", in Paul Boghossian and Christopher Peacocke (eds.) New Essays on the A Priori, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 432–471. Online PDF Archived 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine 2003, "Rawls and Liberalism", in Samuel Freeman (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Rawls, Cambridge University Press, pp. 62–85. 2003, "John Rawls and Affirmative Action", The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 39, pp. 82–4. 2008, "Public Education and Intelligent Design", Philosophy and Public Affairs 2009, "The I in Me", a review article of Selves: An Essay in Revisionary Metaphysics by Galen Strawson, Oxford, 448 pp, ISBN 0-19-825006-1, lrb.co.uk 2021, Thomas Nagel, "Types of Intuition: Thomas Nagel on human rights and moral knowledge", London Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 11 (3 June 2021), pp. 3, 5–6, 8. Deontology, consequentialism, utilitarianism. 2023: "Leader of the Martians" (review of M.W. Rowe, J.L. Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer, Oxford, May 2023, ISBN 978 0 19 870758 5, 660 pp.), London Review of Books, vol. 45, no. 17 (7 September 2023), pp. 9–10. "I [the reviewer, Thomas Nagel] was one of Austin's last students..." (p. 10.) A quotation from J.L. Austin: "Is it not possible that the next century may see the birth... of a true and comprehensive science of language? Then we shall have rid ourselves of one more part of philosophy... in the only way we ever can get rid of philosophy, by kicking it upstairs." (p. 10.) |

主な出版物 著書 ネーゲル,トーマス (1970). 利他主義の可能性. Princeton, N.J.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780691020020. (1978年プリンストン大学出版局より再版) ネーゲル, トーマス; ヘルド, ヴァージニア; モルゲンベッサー, シドニー (1974). Philosophy, morality, and international affairs: essays edited for the Society for Philosophy and Public Affairs. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 9780195017595. ネーゲル, トーマス (1979). Mortal questions. ロンドン: Canto. ISBN 9780521406765. ネーゲル, トーマス (1986). The view from nowhere. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 9780195056440. ネーゲル, トーマス (1987). What does it all mean?: a very short introduction to philosophy. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 9780195174373. ネーゲル, トーマス (1991). 平等と偏愛. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195098396. ネーゲル, トーマス (1997). 最後の言葉 New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195149838.[26]. ネーゲル, トーマス (1999). Other minds: critical essays, 1969-1994. New York Oxford: オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 9780195132465. Neagel, Thomas; Murphy, Liam (2002). 所有の神話 : 税と正義. Oxford University Press: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176568. ネーゲル, トーマス (2002). Concealment and exposure: and other essays. Oxford New York: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 9780195152937. ネーゲル, トーマス (2010). Secular philosophy and the religious temperament: essays 2002-2008. Oxford New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195394115. ネーゲル, トーマス (2012). Mind and Cosmos: Why the materialist neo-Darwinian conception of nature is almost sure false. Oxford New York: オックスフォード大学出版局, ISBN 9780199919758 論文 1959年、「ホッブズの義務概念」、『哲学評論』、68-83頁。 1959年、「夢想」、『分析』、112-6頁。 1965年、「物理主義」、『哲学評論』、339-56頁。 1969, 「Sexual Perversion」, Journal of Philosophy, pp.5-17 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1969, 「The Boundaries of Inner Space」, Journal of Philosophy, pp.452-8. 1970, 「Death」, Nous, pp. 73-80 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1970, 「Armstrong on the Mind」, Philosophical Review, pp.394-403 (D. M. Armstrong著『A Materialist Theory of the Mind』の論評). 1971, 「Brain Bisection and the Unity of Consciousness」, Synthese, pp.396-413 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1971, 「The Absurd」, Journal of Philosophy, pp.716-27 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1972年、「戦争と虐殺」、『哲学と公共』第1巻、123-44頁(『死すべき問題』所収の再録)。 1973, 「Rawls on Justice」, Philosophical Review, pp. 220-34 (a discussion review of A Theory of Justice by John Rawls). 1973年、「平等待遇と代償的差別」、『哲学と公共』第2巻、348-62頁。 1974年、「コウモリになるとはどういうことか」、『哲学評論』、435-50頁(『死すべき問題』所収)。オンラインテキスト 1976, 「Moral Luck」, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supplementary vol. 50, pp.137-55 (repr. in Mortal Questions). 1979, 「The Meaning of Equality」, Washington University Law Quarterly, pp.25-31. 1981年、「戦術核兵器と紛争の倫理」、Parameters: Journal of the U.S. Army War College, pp.327-8. 1983, 「The Objective Self」, Carl Ginet and Sydney Shoemaker (eds.), Knowledge and Mind, Oxford University Press, pp. 1987, 「Moral Conflict and Political Legitimacy」, Philosophy & Public Affairs, pp.215-240. 1994年、「意識と客観的現実」、R. ワーナー、T. スブカ編『心身問題』、ブラックウェル。 1995年、「人格権と公共空間」、『哲学と公共』24巻2号、83-107頁。 1997年、「自殺幇助: 1997年、「自殺幇助:哲学者ブリーフ」(R.ドウォーキン、R.ノージック、J.ロールズ、T.スカンロン、J.J.トムソンと共著)、『ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』1997年3月27日号。 1998年、「還元主義と反還元主義」、『生物学における還元主義の限界』、ノバルティスシンポジウム213号、ジョン・ワイリー&サンズ、3-10頁。 1998年、「隠蔽と暴露」、『哲学と公共』27巻1号、3-30頁。オンラインテキスト 1998年、「不可能の観念と心身問題」、『哲学』、73巻、285号、337-352頁。オンラインPDF アーカイブ 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine 2000, 「The Psychophysical Nexus」, Paul Boghossian and Christopher Peacocke (eds.) New Essays on the A Priori, Oxford: クラレンドン・プレス、432-471頁。オンラインPDF アーカイブ 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine 2003, 「Rawls and Liberalism」, サミュエル・フリーマン(編)The Cambridge Companion to Rawls, Cambridge University Press, pp.62-85. 2003, 「John Rawls and Affirmative Action」, The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 39, pp. 2008年、「公共教育とインテリジェント・デザイン」、『哲学と公共問題』誌 2009年、「私の中の私」、『自我』の書評論文: 2009年、「私のなかの私」、『自我:修正形而上学のエッセイ』(ゲイレン・ストローソン著、オックスフォード、448頁、ISBN 0-19-825006-1, lrb.co.uk)の書評論文。 2021年、トーマス・ネーゲル「直観のタイプ」: Thomas Nagel on human rights and moral knowledge」, London Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 11 (3 June 2021), pp. 義務論、帰結主義、功利主義。 2023: 「火星人のリーダー"(書評:M.W. Rowe, J.L. Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer, Oxford, May 2023, ISBN 978 0 19 870758 5, 660頁)、『ロンドン・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』第45巻第17号(2023年9月7日)、9-10頁。「私(評者トーマス・ネーゲル)はオースティ ンの最後の教え子の一人である。(p.10.)J.L.オースティンからの引用:「次の世紀には、真の包括的な言語科学が誕生する可能性はないだろうか。 そうなれば、我々は哲学のもう一つの部分を取り除くことができるだろう...哲学を取り除く唯一の方法は、哲学を二階に蹴り上げることだ。(p. 10.) |

| American philosophy List of American philosophers New York University Department of Philosophy David Chalmers Frank Jackson Galen Strawson Hard problem of consciousness Knowledge argument Phenomenology Neutral monism |

アメリカ哲学 アメリカの哲学者一覧 ニューヨーク大学哲学科 デイビッド・チャルマーズ フランク・ジャクソン ガレン・ストローソン 意識の難問 知識の議論 現象学 中立的一元論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Nagel |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

くまさんであるとはどーいうことなのか?

☆

☆

☆