ローレンス・コールバーグ

Lawrence Kohlberg,

1927-1987

☆ローレンス・コールバーグ(/ˈkoʊlbɜːrɡ/、1927年10月25日 - 1987年1月17日)は、道徳的発達段階説で最もよく知られるアメリカの心理学者である。

シカゴ大学心理学部およびハーバード大学教育大学院の教授を務めた。彼の時代には珍しいこととされていたが、彼は道徳的判断というテーマの研究を決意し、25年前にジャン・ピアジェが

発表した子どもの道徳的発達に関する研究をさらに発展させた。[1] 実際、コルバーグが 彼の見解に基づく論文を発表するまでに5年を要した。[1]

コルバーグの研究は、ピアジェの研究結果だけでなく、哲学者ジョージ・ハーバート・ミードとジェームズ・マーク・ボールドウィンの理論も反映し、さらに発

展させたものである。[2] 同時に、彼は心理学の分野に「道徳的発達」という新たな分野を創出した。

引用や認知など6つの基準を用いた実証的研究において、コルバーグは20世紀で30番目に著名な心理学者であると言われている。[3]

| Lawrence Kohlberg

(/ˈkoʊlbɜːrɡ/; October 25, 1927 – January 17, 1987) was an American

psychologist best known for his theory of stages of moral development. He served as a professor in the Psychology Department at the University of Chicago and at the Graduate School of Education at Harvard University. Even though it was considered unusual in his era, he decided to study the topic of moral judgment, extending Jean Piaget's account of children's moral development from 25 years earlier.[1] In fact, it took Kohlberg five years before he was able to publish an article based on his views.[1] Kohlberg's work reflected and extended not only Piaget's findings but also the theories of philosophers George Herbert Mead and James Mark Baldwin.[2] At the same time he was creating a new field within psychology: "moral development". In an empirical study using six criteria, such as citations and recognition, Kohlberg was found to be the 30th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.[3] |

ローレンス・コールバーグ(/ˈkoʊlbɜːrɡ/、1927年10

月25日 - 1987年1月17日)は、道徳的発達段階説で最もよく知られるアメリカの心理学者である。 シカゴ大学心理学部およびハーバード大学教育大学院の教授を務めた。 彼の時代には珍しいこととされていたが、彼は道徳的判断というテーマの研究を決意し、25年前にジャン・ピアジェが発表した子どもの道徳的発達に関する研 究をさらに発展させた。[1] 実際、コルバーグが 彼の見解に基づく論文を発表するまでに5年を要した。[1] コルバーグの研究は、ピアジェの研究結果だけでなく、哲学者ジョージ・ハーバート・ミードとジェームズ・マーク・ボールドウィンの理論も反映し、さらに発 展させたものである。[2] 同時に、彼は心理学の分野に「道徳的発達」という新たな分野を創出した。 引用や認知など6つの基準を用いた実証的研究において、コルバーグは20世紀で30番目に著名な心理学者であると言われている。[3] |

| Early life and education Lawrence Kohlberg was born in Bronxville, New York.[4] He was the youngest of four children of Alfred Kohlberg,[5] a Jewish German entrepreneur, and of his second wife, Charlotte Albrecht, a Christian German chemist.[6] His parents separated when he was four years old and divorced finally when he was 14. From 1933 to 1938, Lawrence and his three siblings rotated between their mother and father for six months at a time. This rotating custody of the Kohlberg children ended in 1938, when the children were allowed to choose the parent with whom they wanted to live.[6] Kohlberg attended high school at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and served in the Merchant Marine at the end of World War II.[7] He worked for a time with the Haganah on a ship smuggling Jewish refugees from Romania into Palestine through the British Blockade.[8][9] Captured by the British and held at an internment camp on Cyprus, Kohlberg escaped with fellow crew members. Kohlberg was in Palestine during the fighting in 1948 to establish the state of Israel, but refused to participate and focused on nonviolent forms of activism. He also lived on a kibbutz during this time, until he was able to return to America in 1948.[6] In the same year, he enrolled at the University of Chicago. At the time it was possible to gain credit for courses by examination, and Kohlberg earned his bachelor's degree in one year, 1948.[10] He then began study for his doctoral degree in psychology, which he completed at Chicago in 1958. In 1955 while beginning his dissertation, he married Lucille Stigberg, and the couple had two sons, David and Steven. In those early years he read Piaget's work. Kohlberg found a scholarly approach that gave a central place to the individual's reasoning in moral decision making. At the time this contrasted with the current psychological approaches of behaviorism and psychoanalysis that explained morality as simple internalization of external cultural or parental rules, through teaching using reinforcement and punishment or identification with a parental authority.[11] |

幼少期と教育 ローレンス・コールバーグはニューヨーク州ブロンクスビルで生まれた。[4] 彼はユダヤ系ドイツ人の実業家アルフレッド・コールバーグ[5]と、その2番目の妻であるキリスト教徒のドイツ人化学者シャーロット・アルブレヒト[6] の4人の子供のうちの末っ子であった。1933年から1938年にかけて、ローレンスと3人の兄弟姉妹は、6か月ごとに母親と父親の間を行き来していた。 このコルバーグ家の子供たちの交代制の親権は、子供たちが一緒に暮らしたい親を選ぶことが許された1938年に終了した。 コールバーグはマサチューセッツ州アンドーバーのフィリップス・アカデミーで高校に通い、第二次世界大戦末期には商船隊に所属していた。[7] 彼は一時、ハガナとともに、英国の封鎖をくぐり抜け、ルーマニアからパレスチナにユダヤ人難民を密航させる船で働いていた。[8][9] 英国に捕らえられ、キプロスの収容所に収容されていたが、コールバーグは他の乗組員とともに脱走した。1948年のイスラエル建国をめぐる戦闘中、パレス チナに滞在していたが、参加を拒否し、非暴力的な活動に専念した。1948年にアメリカに帰国できるまで、この間キブツで暮らしていた。[6] 同年、シカゴ大学に入学した。当時は試験で単位を取得することが可能であり、コルバーグは1948年という1年間で学士号を取得した。[10] その後、心理学の博士号取得に向けた研究を開始し、1958年にシカゴで博士号を取得した。1955年に博士論文の執筆を開始する一方で、ルシール・ス ティグバーグと結婚し、2人の息子、デビッドとスティーブンが生まれた。 初期の頃、彼はピアジェの研究を読んだ。コールバーグは、道徳的な意思決定における個人の推論を主軸とする学術的なアプローチを見出した。当時、これは、 強化や罰則、あるいは親権者の権威への同一視による教育を通じて、道徳性を外部の文化的または親の規則の単純な内面化として説明する行動主義や精神分析と いった心理学的アプローチとは対照的であった。[11] |

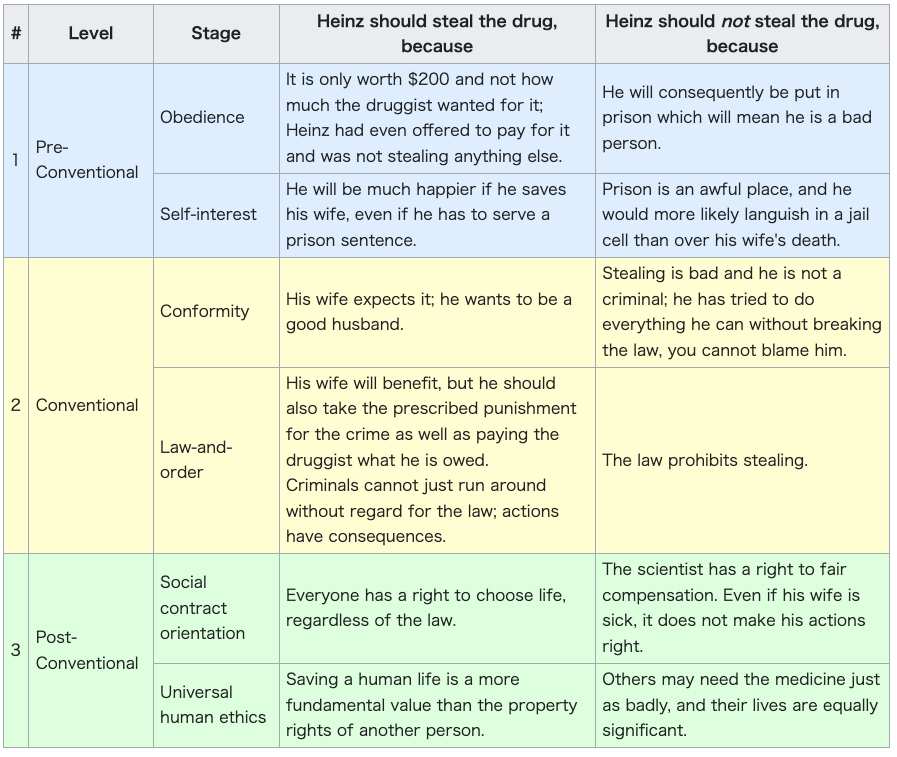

| Career This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Lawrence Kohlberg" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Kohlberg's first academic appointment was at Yale University, as an assistant professor of psychology, 1958–1961. [10] Kohlberg spent a year at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, in Palo Alto, California, 1961–1962, and then joined the Psychology Department of the University of Chicago as assistant, then associate professor of psychology and human development, 1962–1967. There he instituted the Child Psychology Training Program.[1] He held a visiting appointment at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, 1967–1968, and then was appointed Professor of Education and Social Psychology there, beginning 1968, where he remained until his death.[12] In 1969 he accepted Rebecca Shribman-Katz's invitation of the Society for Justice-Ethics-Morals (JEM) and visited Israel to study the morality of young people in that country. This was the beginning of the life-long cooperation between JEM and Kohlberg. JEM published many books in Hebrew under his supervision, merging Kohlberg's morality theory and Jewish morality and putting it into practice, in teaching justice, ethics and morals to judges, lawyers, teachers, police officers, prisoners and the young generation of Israel [1]. In 1978, Kohlberg invited Katz to participate in the conference of Law in a Free Society, which led to the research published in 1980 "Moral Education and Law-Related Education". Stages of moral development Main article: Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development In his unpublished 1958 dissertation, Kohlberg described what are now known as Kohlberg's stages of moral development.[13] These stages are planes of moral adequacy conceived to explain the development of moral reasoning. Created while studying psychology at the University of Chicago, the theory was inspired by the work of Jean Piaget and a fascination with children's reactions to moral dilemmas.[14] Kohlberg proposed a form of "Socratic" moral education and reaffirmed John Dewey's idea that development should be the aim of education.[15] He also outlined how educators can influence moral development without indoctrination and how public school can be engaged in moral education consistent with the United States Constitution.[1] Kohlberg's approach begins with the assumption that humans are intrinsically motivated to explore and become competent at functioning in their environments. In social development, this leads us to imitate role models we perceive as competent and to look to them for validation.[16] Thus our earliest childhood references on the rightness of our and others' actions are adult role models with whom we are in regular contact. Kohlberg also held that there are common patterns of social life, observed in universally occurring social institutions, such as families, peer groups, structures, and procedures for clan or society decision-making, and cooperative work for mutual defense and sustenance. Endeavoring to become competent participants in such institutions, humans in all cultures exhibit similar actions and thoughts concerning the relations of self, others, and the social world. Furthermore, the more one is prompted to have empathy for the other person, the more quickly one learns to function well in cooperative human interactions. [17] The sequence of stages of moral development thus corresponds to a sequence of progressively more inclusive social circles (family, peers, community, etc.) within which humans seek to operate competently. When those groups function well, oriented by reciprocity and mutual care and respect, growing humans adapt to larger and larger circles of justice, care, and respect. Each stage of moral cognitive development is the realization in conscious thought of the relations of justice, care, and respect exhibited in a wider circle of social relations, including narrower circles within the wider. Kohlberg's theory holds that moral reasoning, which is the basis for ethical behavior, has six identifiable developmental constructive stages – each more adequate at responding to moral dilemmas than the last.[18] Kohlberg suggested that the higher stages of moral development provide the person with greater capacities/abilities in terms of decision making and so these stages allow people to handle more complex dilemmas.[1] In studying these, Kohlberg followed the development of moral judgment beyond the ages originally studied earlier by Piaget,[19] who also claimed that logic and morality develop through constructive stages.[18] Expanding considerably upon this groundwork, it was determined that the process of moral development was principally concerned with justice and that its development continued throughout the life span,[13] even spawning dialogue of philosophical implications of such research.[20][21] His model "is based on the assumption of co-operative social organization on the basis of justice and fairness."[22] Kohlberg studied moral reasoning by presenting subjects with moral dilemmas. He would then categorize and classify the reasoning used in the responses, into one of six distinct stages, grouped into three levels: preconventional, conventional and postconventional.[23][24][25] Each level contains two stages. These stages heavily influenced others and have been utilized by others like James Rest in making the Defining Issues Test in 1979.[26] |

経歴 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない内容は、異議申し立てにより削除される場合があります。 出典: 「ローレンス・コールバーグ」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2018年1月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) コールバーグの最初の学術職は、1958年から1961年まで、イエール大学心理学部の助教授であった。 [10] コールバーグは1961年から1962年にかけて、カリフォルニア州パロアルトにある行動科学高等研究所で1年間を過ごし、その後、シカゴ大学心理学部の 助手、そして心理学・人間発達学部の准教授として1962年から1967年まで勤務した。そこで彼は児童心理学トレーニングプログラムを導入した。[1] 1967年から1968年にかけてハーバード大学教育大学院で客員教授を務め、1968年より同大学院の教育・社会心理学教授に就任し、死去するまでその職にあった。 1969年、彼はレベッカ・シュリブマン・カッツの招待を受け、正義・倫理・道徳学会(JEM)に参加し、イスラエルを訪問して、その国の若者の道徳性を 研究した。これが、JEMとコールバーグの生涯にわたる協力関係の始まりとなった。JEMは、コールバーグの道徳理論とユダヤ教の道徳を融合させ、それを 実践に移す形で、裁判官、弁護士、教師、警察官、受刑者、そしてイスラエルの若い世代に対して正義、倫理、道徳を教えるためのヘブライ語の書籍を多数出版 した[1]。 1978年、コールバーグはカッツを「自由社会における法」の会議に招待し、1980年に発表された「道徳教育と法関連教育」の研究につながった。 道徳的発達の段階 詳細は「ローレンス・コールバーグの道徳的発達段階」を参照 1958年の未発表の博士論文で、コールバーグは、現在ではコールバーグの道徳的発達段階として知られているものを説明した。[13] これらの段階は、道徳的推論の発達を説明するために考え出された道徳的適格性の段階である。シカゴ大学で心理学を学んでいる間に作成されたこの理論は、 ジャン・ピアジェの研究と、道徳的ジレンマに対する子どもの反応に対する関心から着想を得たものである。[14] コールバーグは「ソクラテス的」道徳教育の形式を提案し、 教育の目的は発達にあるというジョン・デューイの考えを再確認した。[15] また、教育者が教化することなく道徳的発達に影響を与える方法や、公立学校が合衆国憲法に則った道徳教育を行う方法についても概説した。[1] コールバーグのアプローチは、人間は本質的に、環境の中で探索し、その環境で有能になるように動機づけられているという仮定から始まる。社会的な成長にお いては、これは、有能であると認識するロールモデルを模倣し、その妥当性を確認するためにそのロールモデルに目を向けることを意味する。[16] したがって、自分や他者の行動の正しさについて、幼少期に最初に参照するのは、日常的に接触する大人たちのロールモデルである。コールバーグはまた、家 族、仲間集団、一族や社会の意思決定の構造や手続き、相互防衛や生活維持のための協同作業など、普遍的に存在する社会制度において観察される、社会生活に おける共通のパターンがあるとも考えた。そのような制度において有能な参加者となることを目指す中で、あらゆる文化の人々は、自己、他者、社会世界との関 係について、類似した行動や思考を示す。さらに、他者に対して共感を持つように促されるほど、人間は協調的な人間関係においてうまく機能する方法をより早 く習得する。[17] 道徳的発達段階の順序は、人間が有能に機能しようとする、より包括的な社会集団(家族、仲間、地域社会など)の順序に対応している。これらのグループが相 互依存と相互の思いやりと尊敬の念に基づいてうまく機能している場合、成長する人間は、正義、思いやり、尊敬の念の輪をより大きく広げていく。道徳的認知 発達の各段階は、より広い範囲の社会関係に示される正義、思いやり、尊敬の念の関係を、より広い範囲内のより狭い範囲も含めて、意識的に思考することに よって理解することである。 コールバーグの理論では、倫理的行動の基礎となる道徳的推論には、6つの明確な発達的構成段階があり、それぞれが前の段階よりも道徳的ジレンマへの対応に 適しているとされている。[18] コールバーグは、道徳的発達の上位段階では、意思決定能力が向上し、より複雑なジレンマに対処できるようになるとしている。[1] コールバーグは、ピアジェが以前に研究した年齢を超えて道徳的判断の発達を研究した。。コルバーグは、この基礎研究を大幅に拡張し、道徳的発達プロセスは 主に正義に関わるものであり、その発達は生涯を通じて継続するものであると結論づけた。[13] このような研究の哲学的含意に関する議論も巻き起こった。[20][21] 彼のモデルは「正義と公平を基盤とした協力的な社会組織という前提に基づいている」[22]。 コールバーグは、被験者に道徳的ジレンマを提示することで、道徳的推論を研究した。そして、被験者の回答で用いられた推論を分類し、6つの明確な段階の1 つに分類した。その段階は、3つのレベル(前慣習的、慣習的、後慣習的)にグループ化されている。[23][24][25] 各レベルには2つの段階がある。これらの段階は、他の研究者に大きな影響を与え、ジェームズ・レスト(James Rest)が1979年に「Defining Issues Test」を作成する際に利用された。[26] |

| Moral education Kohlberg is most well known among psychologists for his research in moral psychology, but among educators he is known for his applied work of moral education in schools. The three major contributions Kohlberg made to moral education were the use of Moral Exemplars, Dilemma Discussions, and Just Community Schools.[6] Kohlberg's first method of moral education was to examine the lives of moral exemplars who practiced principled morals such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Socrates, and Abraham Lincoln. He believed that moral exemplars' words and deeds increased the moral reasoning of those who watched and listened to them.[6] Kohlberg never tested to see if examining the lives of moral exemplars did in fact increase moral reasoning. Recent research in moral psychology has brought back the value of witnessing moral exemplars in action or learning about their stories.[27] Witnessing the virtuous acts of moral exemplars may not increase moral reasoning, but it has been shown to elicit an emotion known as moral elevation that can increase an individual's desire to be a better person and even has the potential to increase prosocial and moral behavior.[27][28][29][30] Although Kohlberg's hypothesis that moral exemplars could increase moral reasoning might be unfounded, his understanding that moral exemplars have an important place in moral education has growing support. Dilemma discussions in schools was another method proposed by Kohlberg to increase moral reasoning. Unlike moral exemplars, Kohlberg tested this method by integrating moral dilemma discussion into the curricula of school classes in humanities and social studies. Results of this and other studies using similar methods found that moral discussion does increase moral reasoning and works best if the individual in question is in discussion with a person who is using reasoning that is just one stage above their own.[6] The final method Kohlberg used for moral education was known as "just communities". In 1974, Kohlberg worked with schools to set up democracy-based programs, where both students and teachers were given one vote to decide on school policies.[31] The purpose of these programs were to build a sense of community in schools in order to promote democratic values and increase moral reasoning. Kohlberg's idea and development of "just communities" were greatly influenced by his time living on a kibbutz as a young adult in 1948 and when he was doing longitudinal cross-cultural research of moral development at Sasa, another kibbutz.[32] Writing Some of Kohlberg's most important publications were collected in his Essays on Moral Development, Vols. I and II, The Philosophy of Moral Development (1981) and The Psychology of Moral Development (1984), published by Harper & Row. Other works published by Kohlgainz or about Kohlberg's theories and research include Consensus and Controversy, The Meaning and Measurement of Moral Development, Lawrence Kohlberg's Approach to Moral Education and Child Psychology and Childhood Education: A Cognitive Developmental View.[33] |

道徳教育 コールバーグは道徳心理学の研究で心理学者の間で最もよく知られているが、教育者の間では学校における道徳教育の応用研究で知られている。コールバーグが 道徳教育に大きく貢献した3つの要素は、模範的人物の活用、ジレンマ・ディスカッション、正義のコミュニティ・スクールである。 コールバーグの道徳教育の最初の方法は、マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニア、ソクラテス、エイブラハム・リンカーンといった、原則に基づいた道徳を 実践した道徳的模範者の人生を調査することだった。彼は、道徳的模範者の言動は、彼らを見聞きした人々の道徳的推論を高めるという信念を持っていた。 [6] コールバーグは、道徳的模範者の人生を調査することが実際に道徳的推論を高めるかどうかを確かめるテストを行ったことはなかった。最近の道徳心理学の研究 では、模範的な人物の行動を目撃したり、その人物の物語を学んだりすることの価値が再び注目されている。[27] 模範的な人物の善行を目撃しても、道徳的推論能力は高まらないかもしれないが、道徳的高揚と呼ばれる感情を引き起こすことが示されており、この感情は個人 の「より良い人間になりたい」という願望を高める可能性がある より良い人間になりたいという願望を高め、さらには利他的行動や道徳的行動を増やす可能性もあることが示されている。[27][28][29][30] 模範的な道徳的行動が道徳的推論を高めるというコールバーグの仮説は根拠のないものかもしれないが、模範的な道徳的行動が道徳教育において重要な位置を占 めるという彼の理解は、支持を広げている。 学校におけるジレンマ・ディスカッションも、コールバーグが道徳的推論を高めるために提案した方法のひとつである。道徳的模範とは異なり、コールバーグ は、この方法を、人文科学や社会科学の授業カリキュラムに道徳的ジレンマ・ディスカッションを組み込むことで検証した。この研究と、同様の方法を用いた他 の研究の結果、道徳的ディスカッションは道徳的推論を高めることが判明し、対象となる個人が、自分より1段階上の推論を用いる人物とディスカッションを行 うと、最も効果的であることが分かった。 コールバーグが道徳教育に用いた最後の方法は、「公正な共同体」として知られている。1974年、コールバーグは学校と協力して、生徒と教師にそれぞれ1 票ずつ投票権を与え、学校の方針を決定するという、民主主義に基づくプログラムを立ち上げた。[31] これらのプログラムの目的は、学校にコミュニティ意識を育み、民主主義の価値観を促進し、道徳的推論を増やすことだった。コールバーグの「公正な共同体」 の概念と発展は、1948年に青年期にキブツで生活した経験と、同じくキブツであるササで道徳的発達に関する長期にわたる異文化研究を行っていた経験か ら、大きな影響を受けている。 著作 コールバーグの最も重要な著作の一部は、『道徳的発達に関する論文集』第1巻および第2巻( IとII、The Philosophy of Moral Development (1981年)およびThe Psychology of Moral Development (1984年)は、Harper & Row社から出版された。 コールバーグの理論と研究に関するその他の著作には、Consensus and Controversy、The Meaning and Measurement of Moral Development、Lawrence Kohlberg's Approach to Moral Education、Child Psychology and Childhood Education: A Cognitive Developmental Viewがある。[33] |

| Critiques Carol Gilligan, a fellow researcher of Kohlberg's in the studies of moral reasoning that led to Kohlberg's developmental stage theory, suggested that to make moral judgments based on optimizing concrete human relations is not necessarily a lower stage of moral judgment than to consider objective principles. Postulating that women may develop an empathy-based ethic with a different, but not lower structure than that Kohlberg had described, Gilligan wrote In a Different Voice, a book that founded a new movement of care-based ethics that initially found strong resonance among feminists and later achieved wider recognition. Kohlberg's response to Carol Gilligan's criticism was that he agreed with her that there is a care moral orientation that is distinct from a justice moral orientation, but he disagreed with her claim that women scored lower than men on measures of moral developmental stages because they are more inclined to use care orientation rather than a justice orientation.[34] Kohlberg disagreed with Gilligan's position on two grounds. Firstly, many studies measuring moral development of males and females found no difference between men and women, and when differences were found, they were attributable to differences in education, work experiences, and role-taking opportunities, but not gender.[34] Secondly, longitudinal studies of females found the same invariant sequence of moral development as previous studies that were of males only.[34] In other words, Gilligan's criticism of Kohlberg's moral development theory was centered on differences between males and females that did not exist. Kohlberg's detailed responses to numerous critics can be read in his book Essays on Moral Development: Vol.II. The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages. Another criticism against Kohlberg's theory was that it focused too much on reason at the expense of other factors. One problem with Kohlberg's focus on reason was that little empirical evidence found a relationship between moral reasoning and moral behavior. Kohlberg recognized this lack of a relationship between his moral stages and moral behavior. In an attempt to understand this, he proposed two sub-stages within each stage, to explain individual differences within each stage.[34] He then proposed a model of the relationship between moral judgments and moral action. According to Kohlberg,[34] an individual first interprets the situation using their moral reasoning, which is influenced by their moral stage and sub-stage. After interpretation individuals make a deontic choice and a judgment of responsibility, which are both influenced by the stage and sub-stage of the individual. If the individual does decide on a moral action and their obligation to do it, they still need the non-moral skills to carry out a moral behavior. If this model is true then it would explain why research was having a hard time finding a direct relationship between moral reason and moral behavior. Another problem with Kohlberg's emphasis on moral reasoning is growing empirical support that individuals are more likely to use intuitive "gut reactions" to make moral decisions than use reason-based thought.[35] The high use of intuition directly challenges the place of reason in moral experience. This expanding of the moral domain from reason has raised questions that perhaps morality research is entering areas of inquiry that are not considered real morality, which was a concern of Kohlberg when he first started his research.[35] Scholars such as Elliot Turiel and James Rest have responded to Kohlberg's work with their own significant contributions. |

批判 コールバーグの道徳的推論研究における共同研究者であるキャロル・ギリガンは、コールバーグの発達段階理論につながる研究において、具体的な人間関係を最 適化することを基盤とした道徳的判断は、客観的原則を考慮するよりも道徳的判断の段階が低いとは限らないと示唆した。ギリガンは、女性はコールバーグが述 べたものとは異なるが、それより劣るものではない共感に基づく倫理観を発達させる可能性があると仮定し、著書『声なき叫び』でケアに基づく倫理という新た な運動を創始した。この運動は当初フェミニストの間で強い共感を呼び、その後さらに広く認知されるようになった。 ギリアンによる批判に対するコールバーグの回答は、正義の道徳的志向とは異なる思いやりの道徳的志向が存在するという彼女の主張には同意するが、女性は正 義の道徳的志向よりも思いやりの道徳的志向を用いる傾向が強いため、道徳的発達段階の測定において男性よりも低いスコアになるという彼女の主張には反対す るというものであった。[34] コールバーグはギリアンの立場に反対する理由を2つ挙げている。第一に、男女の道徳的発達を測定した多くの研究では男女間に違いは見られず、違いが見られ た場合でも、それは教育、職業経験、役割取得の機会の違いによるもので、性別によるものではないことが分かっている。[34] 第二に、 女性を対象とした縦断的研究では、男性のみを対象とした過去の研究と同様の不変の道徳的発達の順序が発見された。[34] つまり、ギリアンによるコールバーグの道徳的発達理論への批判は、存在しない男女間の差異に焦点を当てたものだった。コールバーグによる数多くの批判への 詳細な回答は、著書『道徳的発達に関する研究:第2巻。道徳的発達の心理学:道徳的段階の性質と妥当性』で読むことができる。 コールバーグの理論に対する別の批判は、理性に焦点を当てすぎて他の要因を犠牲にしているというものだった。コールバーグが理性に焦点を当てたことによる 問題のひとつは、道徳的推論と道徳的行動の間に何らかの関係があることを示す実証的証拠がほとんど見つからなかったことである。コールバーグは、自身の道 徳的段階と道徳的行動の間にこの関係性がないことを認識していた。この点を理解しようと試みたコールバーグは、各段階における個人差を説明するために、各 段階内に2つのサブステージを提案した。[34] その後、コールバーグは道徳的判断と道徳的行動の関係性に関するモデルを提案した。コールバーグによると、[34] 個人はまず、自身の道徳的段階とサブステージに影響を受ける道徳的推論を用いて状況を解釈する。解釈の後、個人は義務論的な選択と責任の判断を行うが、こ れらは両方とも個人の段階と下位段階の影響を受ける。 個人が道徳的な行動とその義務を決定した場合でも、道徳的な行動を実行するには道徳的でないスキルが必要である。 このモデルが正しいとすれば、研究が道徳的理由と道徳的行動の直接的な関係を見出すのに苦労している理由を説明できるだろう。 コールバーグが道徳的推論を重視することによるもう一つの問題は、個人が道徳的判断を下す際に、理性に基づく思考よりも直感的な「本能的な反応」を用いる 可能性が高いという実証的な裏付けが強まっていることである。[35] 直感の多用は、道徳的経験における理性の役割に直接疑問を投げかける。この道徳領域が理性から拡大したことにより、おそらく道徳研究は真の道徳とは考えら れていない領域の研究に入り込んでいるのではないかという疑問が生じている。これは、コルバーグが研究を始めた当初から懸念していたことである。[35] エリオット・ツィーレルやジェームズ・レストなどの学者は、コルバーグの研究に独自の重要な貢献で応えている。 |

| Death While doing cross-cultural research in Belize in 1971, Kohlberg contracted a tropical parasitic infection,[36] causing him extreme abdominal pain. The long-term effects of the infection and the medications took their toll, and Kohlberg's health declined as he also engaged in increasingly demanding professional work, including "Just Community" prison and school moral education programs.[37] Kohlberg experienced depression as well. On January 17, 1987, Kohlberg parked at the end of a dead end street in Winthrop, Massachusetts, across from Boston's Logan Airport. He left his wallet with identification on the front seat of his unlocked car and apparently walked into the icy Boston Harbor. His car and wallet were found within a couple of weeks, and his body was recovered some time later, with the late winter thaw, in a tidal marsh across the harbor near the end of a Logan Airport runway.[31] After Kohlberg's body was recovered and his death confirmed, former students and colleagues published special issues of scholarly journals to commemorate his contribution to developmental psychology.[38] |

死 1971年にベリーズで異文化研究を行っていた際、コルバーグは熱帯寄生虫感染症に感染し、[36] 激しい腹痛に見舞われた。感染症と投薬治療の長期的な影響により、健康状態が悪化し、さらに「正義の共同体」刑務所・学校道徳教育プログラムなど、ますま す要求の厳しい専門業務に従事したため、健康状態はさらに悪化した。[37] コルバーグはうつ病も経験した。 1987年1月17日、コールバーグはマサチューセッツ州ウィンスロップの行き止まりの通りの突き当たりに車を停めた。彼は鍵を開けたままにした車のフロ ントシートに身分証明書入りの財布を置き、どうやら氷結したボストン港の水中に入水していった。彼の車と財布は数週間以内に見つかり、遺体はその後、晩冬 の雪解けとともに、ローガン空港の滑走路の端にある港の向こう側の干潟で発見された。 コールバーグの遺体が発見され、死亡が確認された後、彼の元学生や同僚たちは、発達心理学への彼の貢献を記念して学術誌の特別号を出版した。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_Kohlberg |

|

| The

Heinz dilemma is a frequently used example in many ethics and morality

classes. One well-known version of the dilemma, used in Lawrence

Kohlberg's stages of moral development, is stated as follows:[1] A woman was on her deathbed. There was one drug that the doctors said would save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to produce. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman's husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000 which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: “No, I discovered the drug and I'm going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man's laboratory to steal the drug for his wife. Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not? From a theoretical point of view, it is not important what the participant thinks that Heinz should do. Kohlberg's theory holds that the justification the participant offers is what is significant, the form of their response. Below are some of many examples of possible arguments that belong to the six stages:  |

ハインツのジレンマは、多くの倫理や道徳の授業で頻繁に用いられる例である。ローレンス・コールバーグの道徳発達段階理論で用いられる、よく知られたジレンマの1つのバージョンは、次のように述べられている。 ある女性が死の床にあった。医師が、彼女を救うことができると述べた薬があった。それは、同じ町に住む薬剤師が最近発見したラジウムの一形態であった。そ の薬の製造には費用がかかったが、薬剤師はその製造コストの10倍の価格を請求した。彼はラジウムに200ドルを支払い、薬の少量分に2,000ドルを請 求した。病気の女性の夫ハインツは、知り合いに金を借りようと頼み歩いたが、調達できたのは製造コストの半分にあたる1,000ドルほどだった。彼は薬剤 師に、妻が死にかけており、安く売ってほしい、あるいは後払いにしたいと頼んだ。しかし薬剤師は「いや、この薬を発見したのは私だ。私はこの薬で儲けるつ もりだ」と言った。そこでハインツは自暴自棄になり、妻のために薬を盗むために、その男の研究室に押し入った。ハインツは妻のために薬を盗むために研究室 に押し入るべきだったのだろうか?なぜ、あるいはなぜそうではないのか? 理論的な観点から見ると、参加者がハインツがすべきだと考えることは重要ではない。コールバーグの理論では、参加者が示す正当化こそが重要であり、その反応の形式であるとしている。以下に、6つの段階に属する可能性のある議論の例をいくつか挙げる。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099