形而上学的必然性

Metaphysical necessity

Ananke

(/əˈnæŋkiː/; Ancient Greek: Ἀνάγκη), from the common noun ἀνάγκη

("force, constraint, necessity"), is the Orphic personification of

inevitability, compulsion and necessity.

☆ 哲学において、形而上学的必然性(広義の論理的必然性と呼ばれることもある; metaphysical necessity)[1]は、論理的必然性と名辞学的必然性(または物理的必然性)の中間に位置 し、論理的必然性は形而上学的必然性を伴うがその逆ではなく、形而上学的必然性は物理的必然性を伴うがその逆ではないという意味で、多くの異なる種類の必 然性の一つである。ある命題は、その命題がそうでなかったことがあり得ないならば、必然的であると言われる。名辞的必然性とは物理学の法則に従った必然性 であり、論理的必然性とは論理学の法則に従った必然性である。どのような事実が形而上学的に必要なのか、また、どのような根拠に基づいてある事実を形而上 学的には必要だが論理的には必要ではないとみなすことができるのかは、現代の哲学における実質的な議論の対象である。

★決定論▶︎自由意志▶文化決定論︎︎▶︎環境決定論▶非決定論▶偶然と偶発性︎▶

| In philosophy, metaphysical necessity,

sometimes called broad logical necessity,[1] is one of many different

kinds of necessity, which sits between logical necessity and

nomological (or physical) necessity, in the sense that logical

necessity entails metaphysical necessity, but not vice versa, and

metaphysical necessity entails physical necessity, but not vice versa.

A proposition is said to be necessary if it could not have failed to be

the case. Nomological necessity is necessity according to the laws of

physics and logical necessity is necessity according to the laws of

logic, while metaphysical necessities are necessary in the sense that

the world could not possibly have been otherwise. What facts are

metaphysically necessary, and on what basis we might view certain facts

as metaphysically but not logically necessary are subjects of

substantial discussion in contemporary philosophy. The concept of a metaphysically necessary being plays an important role in certain arguments for the existence of God, especially the ontological argument, but metaphysical necessity is also one of the central concepts in late 20th century analytic philosophy. Metaphysical necessity has proved a controversial concept, and criticized by David Hume, Immanuel Kant, J. L. Mackie, and Richard Swinburne, among others. |

哲

学において、形而上学的必然性(広義の論理的必然性と呼ばれることもある)[1]は、論理的必然性と名辞学的必然性(または物理的必然性)の中間に位置

し、論理的必然性は形而上学的必然性を伴うがその逆ではなく、形而上学的必然性は物理的必然性を伴うがその逆ではないという意味で、多くの異なる種類の必

然性の一つである。ある命題は、その命題がそうでなかったことがあり得ないならば、必然的であると言われる。名辞的必然性とは物理学の法則に従った必然性

であり、論理的必然性とは論理学の法則に従った必然性である。どのような事実が形而上学的に必要なのか、また、どのような根拠に基づいてある事実を形而上

学的には必要だが論理的には必要ではないとみなすことができるのかは、現代の哲学における実質的な議論の対象である。 形而上学的に必然的な存在という概念は、神の存在を論じるある種の議論、特に存在論的議論において重要な役割を果たしているが、形而上学的必然性は20世 紀後半の分析哲学においても中心的な概念の一つである。形而上学的必然性は論争の的となる概念であり、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、イマニュエル・カント、 J.L.マッキー、リチャード・スウィンバーンなどによって批判されてきた。 |

| Types of necessity Metaphysical necessity is contrasted with other types of necessity. For example, the philosophers of religion John Hick[2] and William L. Rowe[3] distinguished the following three: 1. factual necessity (existential necessity): a factually necessary being is not causally dependent on any other being, while any other being is causally dependent on it. 2. causal necessity (subsumed by Hick under the former type): a causally necessary being is such that it is logically impossible for it to be causally dependent on any other being, and it is logically impossible for any other being to be causally independent of it. 3. logical necessity: a logically necessary being is a being whose non-existence is a logical impossibility, and which therefore exists either timeless or eternally in all possible worlds. |

必然性の種類 形而上学的必然性は他の必然性と対比される。例えば、宗教哲学者であるジョン・ヒック[2]とウィリアム・L・ロウ[3]は以下の3つを区別した: 1.事実的必然性(実存的必然性):事実的に必然的な存在は、他のいかなる存在にも因果的に依存しないが、他のいかなる存在もそれに因果的に依存する。 2.因果的必然性(ヒックは前者の類型に包含される):因果的に必要な存在は、それが他のいかなる存在にも因果的に依存することは論理的に不可能であり、他のいかなる存在もそれと因果的に独立することは論理的に不可能である。 3.論理的必然性:論理的に必然的な存在とは、存在しないことが論理的に不可能な存在であり、したがって、すべての可能な世界において時間を超越して存在するか、永遠に存在するかのいずれかである。 |

| Hume's dictum Hume's dictum is a thesis about necessary connections between distinct entities. Its original formulation can be found in David Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature: "There is no object, which implies the existence of any other if we consider these objects in themselves".[4] Hume's intuition motivating this thesis is that while experience presents us with certain ideas of various objects, it might as well have presented us with very different ideas. So when I perceive a bird on a tree, I might as well have perceived a bird without a tree or a tree without a bird. This is so because their essences do not depend upon another.[4] David Lewis follows this line of thought in formulating his principle of recombination: "anything can coexist with anything else, at least provided they occupy distinct spatiotemporal positions. Likewise, anything can fail to coexist with anything else".[5] Hume's dictum has been employed in various arguments in contemporary metaphysics. It can be used, for example, as an argument against nomological necessitarianism, the view that the laws of nature are necessary, i.e. are the same in all possible worlds.[6][7] To see how this might work, consider the case of salt being thrown into a cup of water and subsequently dissolving.[8] This can be described as a series of two events, a throwing-event and a dissolving-event. Necessitarians hold that all possible worlds with the throwing-event also contain a subsequent dissolving-event. But the two events are distinct entities, so according to Hume's dictum, it is possible to have one event without the other. An even wider application is to use Hume's dictum as an axiom of modality to determine which propositions or worlds are possible based on the notion of recombination.[9][10] |

ヒュームの独断 ヒュームの独断は、異なる実体間の必要なつながりに関するテーゼである。その原型はデイヴィッド・ヒュームの『人間本性論』にある: 「このテーゼの動機となるヒュームの直観は、経験は私たちに様々な対象についてのある種の観念を与えるが、それは私たちに全く異なる観念を与えるかもしれ ないということである。つまり、私が木の上にいる鳥を認識するとき、私は木がなくても鳥を認識したかもしれないし、鳥がなくても木を認識したかもしれな い。これは、それらの本質が別の本質に依存していないためである[4]。デイヴィッド・ルイスは、彼の組み換えの原理を定式化する際に、この考え方に従っ た: 「どんなものでも、少なくともそれらが時空間的に異なる位置を占めていれば、他の何かと共存することができる。同様に、何ものも他の何ものとも共存できな いことがある」[5]。 ヒュームの独断は、現代の形而上学における様々な議論に用いられている。例えば、自然法則は必要である、すなわちすべての可能な世界において同じであると いう見解である名辞的必然主義に対する議論として用いることができる。必然論者は、投擲事象のあるすべての可能世界は、それに続く溶解事象も含むと考え る。しかし、この2つの事象は別個のものなので、ヒュームの独断によれば、一方の事象がなくても他方の事象を持つことは可能である。さらに広い応用とし て、ヒュームの独言をモダリティの公理として用いて、どの命題や世界が組み換えの概念に基づいて可能であるかを決定することができる[9][10]。 |

| A posteriori and necessary truths In Naming and Necessity,[11] Saul Kripke argued that there were a posteriori truths, such as "Hesperus is Phosphoros", or "Water is H2O", that were nonetheless metaphysically necessary. Necessity in theology While many theologians (e.g. Anselm of Canterbury, René Descartes, and Gottfried Leibniz) considered God to be a logically or metaphysically necessary being, Richard Swinburne argued for factual necessity, and Alvin Plantinga argues that God is a causally necessary being. Because a factually or causally necessary being does not exist by logical necessity, it does not exist in all logically possible worlds.[12] Therefore, Swinburne used the term "ultimate brute fact" for the existence of God.[13] |

事後的真理と必要真理 ソール・クリプキは『名付けと必然性』[11]の中で、「ヘスペロスはフォスフォロスである」や「水はH2Oである」といった事後的真理が存在するが、それは形而上学的に必然であると主張した。 神学における必然性 多くの神学者(カンタベリーのアンセルム、ルネ・デカルト、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツなど)が、神は論理的または形而上学的に必要な存在であると考え たが、リチャード・スウィンバーンは事実的必然性を主張し、アルヴィン・プランティンガは、神は因果的に必要な(必然な)存在であると主張している。事実 上または因果的に必要な存在は論理的必然性によって存在するわけではないので、論理的に可能なすべての世界において存在するわけではない。 |

| Ananke Modal logic Platonism A priori and a posteriori |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysical_necessity |

|

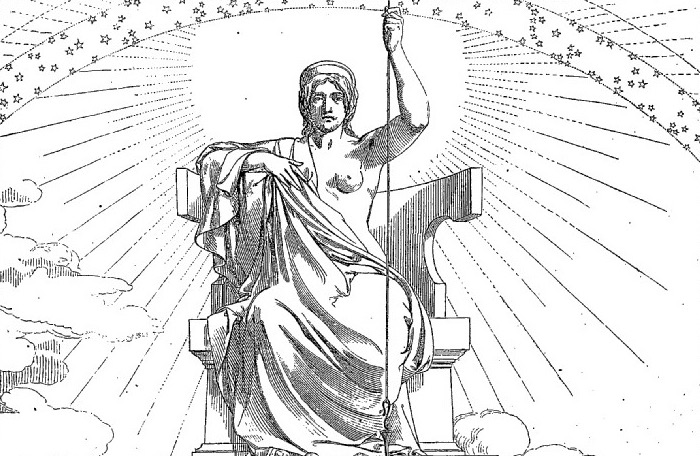

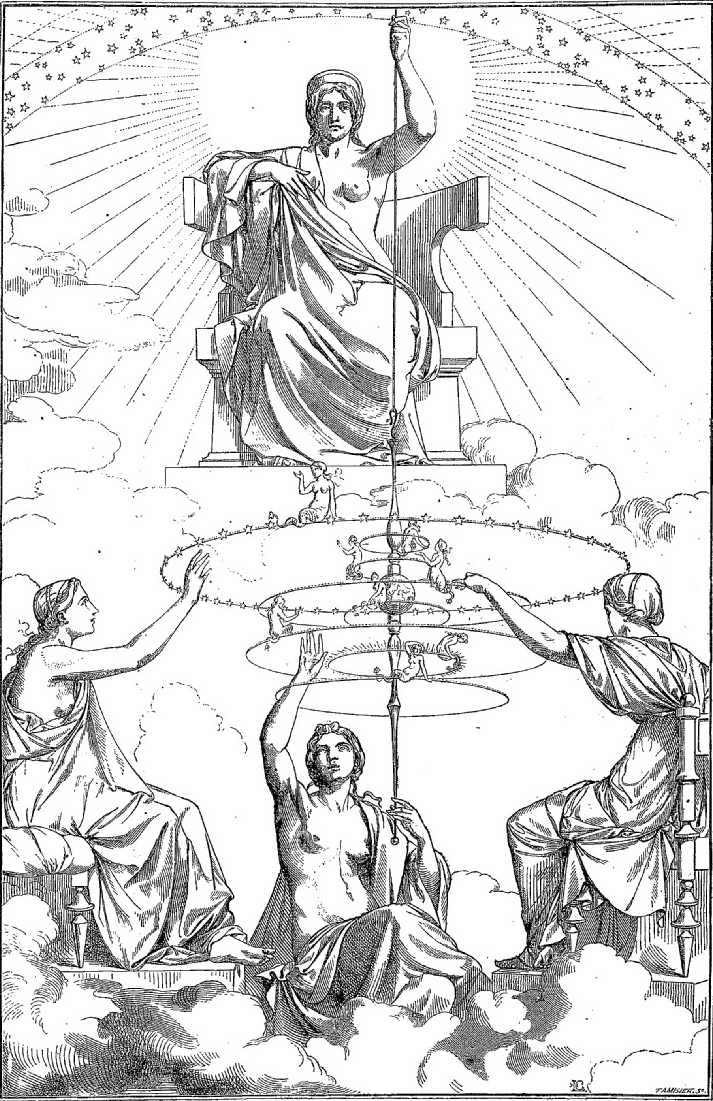

| In

ancient Greek religion, Ananke (/əˈnæŋkiː/; Ancient Greek: Ἀνάγκη),

from the common noun ἀνάγκη ("force, constraint, necessity"), is the

Orphic personification of inevitability, compulsion and necessity. She

is customarily depicted as holding a spindle. One of the Greek

primordial deities, the births of Ananke and her brother and consort,

Chronos (the personification of time, not to be confused with the Titan

Cronus), were thought to mark the division between the eon of Chaos and

the beginning of the cosmos. Ananke is considered the most powerful

dictator of fate and circumstance. Mortals and gods alike respected her

power and paid her homage. She is also considered the mother of the

Fates, hence she is thought to be the only being to overrule their

decisions[1] (according to some sources, excepting Zeus also).

According to Daniel Schowalter and Steven Friesen, she and the Fates

"are all sufficiently tied to early Greek mythology to make their Greek

origins likely."[2] The ancient Greek traveller Pausanias wrote of a temple in ancient Corinth where the goddesses Ananke and Bia (meaning force, violence or violent haste) were worshiped together in the same shrine. Ananke is also frequently identified or associated with Aphrodite, especially Aphrodite Urania, the representation of abstract celestial love; the two were considered to be related, as relatively unanthropomorphised powers that dictated the course of life.[3][4][5][6] Her Roman counterpart is Necessitas ("necessity").[7] Etymology "Ananke" is derived from the common Ancient Greek noun ἀνάγκη (Ionic: ἀναγκαίη anankaiē), meaning "force, constraint or necessity." The common noun itself is of uncertain etymology.[8] Homer refers to her being as necessity, often abstracted in modern translation (ἀναγκαίη πολεμίζειν, "it is necessary to fight") or force (ἐξ ἀνάγκης, "by force").[9] In Ancient Greek literature the word is also used meaning "fate" or "destiny" (ἀνάγκη δαιμόνων, "fate by the daemons or by the gods"), and by extension "compulsion or torture by a superior."[10] She appears often in poetry, as Simonides does: "Even the gods don't fight against ananke".[11] The pre-modern is carried over and translated (by reduction) into a more modern philosophical sense as "necessity", "logical necessity",[12] or "laws of nature".[13] Mythology In Orphic mythology, Ananke is a self-formed being who emerged at the dawn of creation with an incorporeal, serpentine form, her outstretched arms encompassing the cosmos. Ananke and Chronos are mates, mingling together in serpent form as a tie around the universe. Together, they have crushed the primal egg of creation of which constituent parts became earth, heaven and sea to form the ordered universe.[14] Ananke is the mother (or another identity) of Adrasteia, the distributor of rewards and punishments.[15] In the Orphic hymns, Aphrodite Urania is described as the mother of Ananke and ruler of the three Moirai: Ourania, illustrious, laughter-loving queen, sea-born, night-loving, of an awful mien; Crafty, from whom Ananke first came, producing, nightly, all-connecting dame: 'Tis thine the world with harmony to join, for all things spring from thee, O pow'r divine. The triple Moirai are rul'd by thy decree, and all productions yield alike to thee — Orphic hymn LIV.[16] Mother of the Moirai The Greek philosopher Plato in his Republic discussed the parentage of the Moirai or the Fates in the following lines:[17]  And there were another three who sat round about at equal intervals, each one on her throne, the Moirai (Moirae, Fates), daughters of Ananke, clad in white vestments with filleted heads, Lakhesis (Lachesis), and Klotho (Clotho), and Atropos (Atropus), who sang in unison with the music of the Seirenes, Lakhesis singing the things that were, Klotho the things that are, and Atropos the things that are to be . . . Lakhesis, the maiden daughter of Ananke (Necessity). Ananke the personification of Necessity, above the Moirai, the Fates. Aeschylus, the famous tragedian, gave an account in his Prometheus Bound where the Moirai were called the helmsman of the goddess Ananke along with the three Erinyes:[18] Prometheus: Not in this way is Moira (Fate), who brings all to fulfillment, destined to complete this course. Only when I have been bent by pangs and tortures infinite am I to escape my bondage. Skill is weaker by far than Ananke (Necessity). Chorus: Who then is the helmsman of Ananke (Necessity)? Prometheus: The three-shaped (trimorphoi) Moirai (Moirae, Fates) and mindful (mnêmones) Erinyes (Furies). Chorus: Can it be that Zeus has less power than they do? Prometheus: Yes, in that even he cannot escape what is foretold. Chorus: Why, what is fated for Zeus except to hold eternal sway? Prometheus: This you must not learn yet; do not be over-eager. Chorus: It is some solemn secret, surely, that you enshroud in mystery. Here Prometheus speaks of a secret prophecy, rendered ineluctable by Ananke, that any son born of Zeus and Thetis would depose the god. (In fact, any son of Thetis was destined to be greater than his father.) |

古

代ギリシアの宗教では、アナンケ(/əˈnæŋː; Ancient Greek: Ἀνάγκη)は普通名詞Ἀνάγκη("force,

constraint,

necessity")に由来し、必然性、強制、必然性を擬人化したものである。彼女は紡錘を持つ姿で描かれるのが通例である。ギリシャ神話の根源的な神

々の一人で、アナンケとその兄弟であり妃であるクロノス(時間の擬人化で、タイタンのクロノスと混同されないように)の誕生は、カオスの時代と宇宙の始ま

りの間の分裂を示すと考えられていた。アナンケは運命と状況の最も強力な独裁者と考えられている。人間も神々も彼女の力を尊敬し、敬意を払った。また、彼

女は運命の母とも考えられており、それゆえ、運命の決定を覆すことができる唯一の存在であると考えられている[1](いくつかの資料によれば、ゼウスも除

く)。ダニエル・ショウォルターとスティーヴン・フリーセンによれば、彼女と運命の女神たちは「その起源がギリシアである可能性が高いほど、すべて初期の

ギリシア神話と十分に結びついている」[2]。 古代ギリシアの旅行家パウサニアスは、古代コリントの神殿で、アナンケとビア(力、暴力、激しい急ぎを意味する)の女神が同じ神殿で共に崇拝されていたこ とを記している。アナンケはまた、アフロディーテ、特に抽象的な天上の愛の象徴であるアフロディーテ・ウラニアとしばしば同一視されたり関連づけられたり する。この2つは、人生の行く末を決定する比較的擬人化されていない力として、関連していると考えられていた[3][4][5][6]。 語源 「アナンケ」は、「力、制約、必然」を意味する古代ギリシア語の普通名詞Āνάγκη(Ionic: ἀναγκαίη anankaiē)に由来する。ホメロスは彼女の存在を必然性(現代語訳ではἀναγκαίη πολεμίζειν、「戦うことが必要である」)または力(ἐξ ἀνάγκης、「力によって」)として抽象化している[8]。 [9] 古代ギリシア文学では、この言葉は「運命」や「宿命」(ἀνάγκη δαιμόνων、「デーモンや神々による宿命」)、ひいては「上位者による強制や拷問」の意味でも使われる[10]。 前近代的なものは「必然性」、「論理的必然性」[12]、「自然の法則」[13]として引き継がれ、より近代的な哲学的な意味に(還元によって)翻訳される。 神話 オルフェウス神話では、アナンケは天地創造の夜明けに現れた自己形成された存在であり、無身の蛇のような姿をしており、彼女の伸ばした腕は宇宙を包んでい る。アナンケとクロノスは仲間であり、蛇の姿で宇宙を取り囲むように混じり合っている。アナンケは、報酬と罰の分配者であるアドラステイアの母(あるいは 別の正体)である[15]。 オルフィック讃歌では、アフロディーテ・ウラニアはアナンケの母であり、3つのモイライの支配者であると記述されている: オウラニア、輝かしい、笑いを愛する女王、海で生まれ、夜を愛し、恐ろしい形相を持つ; アナンケの最初の出自である狡猾な女王は、夜な夜な、すべてを結びつける女傑を生み出す: 世界は汝のものであり、調和をもたらすものである。 三重のモイライは汝の命令によって支配され、全ての生産物は汝に等しく帰する。 - オルフィック讃歌LIV.[16]。 モイライの母 ギリシアの哲学者プラトンは『共和国』の中で、モイライあるいは運命の親について次のように論じている[17]。  アナンケの娘たちであるモイライ(モイライ、運命の女神)は、白い衣を身にまとい、頭には切り身をつけた、ラケシス(ラケシス)、クロト(クロト)、アト ロポス(アトロポス)が、セイレネスの音楽に合わせて歌い、ラケシスは昔のことを、クロトは今のことを、アトロポスはこれからのことを歌った。ラケシスは アナンケ(必要)の乙女である。 アナンケは、モイライ(運命)よりも上位に位置する「必要性」の擬人化である。 有名な悲劇家であるアイスキュロスは、『プロメテウスの契り』の中で、モイライが3人のエリニュスとともに女神アナンケの操舵手と呼ばれていることを説明している[18]。 プロメテウスよ: プロメテウス:すべてを成就させるモイラ(運命)は、この道を完成させる運命にある。私が苦痛と拷問によって無限に曲げられたときにのみ、私は束縛から逃れられる。技はアナンケ(必然)よりはるかに弱い。 コーラス アナンケ(必要性)の舵取りは誰だ? プロメテウス: 3つの形をしたモイライ(モイライ、運命)と、心あるエリニュス(エリニュス、怒り)だ。 コーラス ゼウスの力は彼らより弱いのですか? プロメテウス: 予言されたことから逃れることはできない。 合唱:どうして?ゼウスは永遠の権力を握っているのですか? プロメテウス: まだ学ぶべきではない、思い上がるな。 合唱: それはきっと、あなたが謎に包む厳粛な秘密なのでしょう。 ここでプロメテウスは、アナンケによって不可避とされた、ゼウスとテティスの間に生まれた息子が神を退位させるという秘密の予言について語る。(実際、テティスの息子は誰でも父親より偉大になる運命にあった)。 |

| In philosophical thought In the Timaeus, Plato has the character Timaeus (not Socrates) argue that in the creation of the universe, there is a uniting of opposing elements, intellect ('nous') and necessity ('ananke'). Elsewhere, Plato blends abstraction with his own myth making: "For this ordered world (cosmos) is of a mixed birth: it is the offspring of a union of Necessity and Intellect. Intellect prevailing over Necessity by persuading (from Peitho, goddess of persuasion) it to direct most of the things that come to be toward what is best, and the result of this subjugation of Necessity to wise persuasion is the initial formation of the universe".[19] In Victor Hugo's novel Notre-Dame of Paris, the word "Ananke" is written upon a wall of Notre-Dame by the hand of Dom Claude Frollo. In his Toute la Lyre, Hugo also mentions Ananke as a symbol of love. In 1866, he wrote: Religion, society, nature; these are the three struggles of man. These three conflicts are, at the same time, his three needs: it is necessary for him to believe, hence the temple; it is necessary for him to create, hence the city; it is necessary for him to live, hence the plow and the ship. But these three solutions contain three conflicts. The mysterious difficulty of life springs from all three. Man has to deal with obstacles under the form of superstition, under the form of prejudice, and under the form of the elements. A triple "ananke" (necessity) weighs upon us, the "ananke" of dogmas, the "ananke" of laws, and the "ananke" of things. In Notre Dame de Paris the author has denounced the first; in Les Misérables he has pointed out the second; in this book (Toilers of the Sea) he indicates the third. With these three fatalities which envelop man is mingled the interior fatality, that supreme ananke, the human heart. Hauteville House, March, 1866. Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea, 1866, p. 5[20] — Victor Hugo Sigmund Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents (p. 140) said: "We can only be satisfied, therefore, if we assert that the process of civilization is a modification which the vital process experiences under the influence of a task that is set it by Eros and instigated by Ananke — by the exigencies of reality; and that this task is one of uniting separate individuals into a community bound together by libidinal ties." Wallace Stevens, in a poem of the 1930s, writes: "The sense of the serpent in you, Ananke, / And your averted stride / Add nothing to the horror of the frost / That glistens on your face and hair."[21] This connects with Stevens's sense of necessity or fate in his later work, especially in the collection The Auroras of Autumn. Robert Bird's essay "Ancient Terror",[22] inspired by Léon Bakst's painting Terror Antiquus, speculates on the evolution of Greek religion, tracing it to an original belief in a single, supreme goddess. Vyacheslav Ivanov suggests that the ancients viewed all that is human and all that is revered as divine as relative and transient: "Only Fate (Eimarmene), or universal necessity (Ananke), the inevitable 'Adrasteia,' the faceless countenance and hollow sound of unknown Destiny, was absolute." Before the goddess, who is both indestructible Force of Love and absolute Fate the Destroyer, Life-Giver and Fate-Death, as well as incorporating Mnemosyne (Memory) and Gaia (Mother Earth), masculine daring and warring are impotent and transient, and the masculine order imposed by Zeus and the other Olympian Gods is artificial.[23] |

哲学思想において プラトンは『ティマイオス』において、(ソクラテスではなく)ティマイオスという登場人物に、宇宙の創造には知性(「ヌース」)と必然性(「アナンケ」) という相反する要素の統合があると主張させている。また、プラトンは抽象化と神話作りを融合させている: 「この秩序ある世界(コスモス)は混合して生まれたものである。知性は、(説得の女神であるペイトーに由来する)説得することによって、必要性に打ち勝 ち、存在するようになる物事のほとんどを最良のものへと向かわせた。ヴィクトル・ユーゴーの小説『パリのノートルダム』では、ドム・クロード・フローロの 手によってノートルダムの壁に「アナンケ」という言葉が書かれている。また、ユゴーは『抒情詩』の中で、アナンケを愛の象徴として挙げている。1866 年、彼はこう書いている: 宗教、社会、自然。これらは人間の3つの闘争である。この3つの葛藤は、同時に人間の3つの欲求でもある。人間にとって必要なのは、信じることであり、そ れゆえ寺院であり、人間にとって必要なのは、創造することであり、それゆえ都市であり、人間にとって必要なのは、生きることであり、それゆえ鋤と船であ る。しかし、この3つの解決策には3つの矛盾がある。人生の神秘的な困難は、この3つすべてに起因している。人間は、迷信という形、偏見という形、そして 元素という形の障害に対処しなければならない。教義の "ananke"、法律の "ananke"、そして物事の "ananke "である。ノートルダム・ド・パリ』で著者は第一の「アナンケ」を糾弾し、『レ・ミゼラブル』で第二の「アナンケ」を指摘し、本書(『海の徒食者たち』) では第三の「アナンケ」を示している。人間を包むこれら3つの宿命と混じり合っているのが、内なる宿命、すなわち人間の心という至高のアナンケである。 オートヴィル邸、1866年3月。ヴィクトル・ユーゴー『海の労働者たち』1866年、5頁[20]。 - ヴィクトル・ユーゴー ジークムント・フロイトは『文明とその不満』(140頁)の中でこう述べている: 「したがって、文明の過程とは、エロスによって設定され、アナンケによって扇動された課題、つまり現実の緊急性によって、生命的な過程がその影響下で経験 する修正であり、この課題とは、別個の個人をリビドー的な絆によって結ばれた共同体に統合することである、と断言するならば、われわれは満足するしかな い」。 ウォレス・スティーヴンスは1930年代の詩の中でこう書いている。「アナンケ、あなたの中にある蛇の感覚は/あなたの避けられた歩幅は/あなたの顔と髪 に輝く霜の恐ろしさに/何の足しにもならない」[21]。これは、スティーヴンスの後期の作品、特に『秋のオーロラ』集における必然や運命の感覚とつな がっている。 ロバート・バードのエッセイ「古代の恐怖」[22]は、レオン・バクストの絵画『Terror Antiquus』に触発され、ギリシアの宗教の進化を推測し、それを単一の至高の女神への原初的な信仰へとたどっている。ヴャチェスラフ・イヴァノフ は、古代人は人間的なものすべてと神として崇められるものすべてを相対的で儚いものと見なしていたと示唆する: 運命(アイマルメーネ)、あるいは普遍的な必然(アナンケ)、必然的な「アドラステイア」、未知の運命の顔のない表情と空虚な音だけが絶対的なものであっ た。不滅の愛の力であると同時に、破壊者であり、生命を与え、宿命と死である絶対的な運命であり、またムネモシネ(記憶)とガイア(母なる大地)を内包す る女神の前では、男性的な大胆さと戦争は無力で一過性のものであり、ゼウスと他のオリュンポスの神々によって押しつけられた男性的な秩序は人為的なもので ある[23]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ananke |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆