自然主義

Naturalism

☆哲学において、自然主義(naturalism)

とは宇宙において作用するのは自然法則と自然力のみ(超自然的な力とは対照的に)という考え方である。[1]

主要な意味において[2]、それは存在論的自然主義、形而上学的自然主義、純粋自然主義、哲学的自然主義、反超自然主義とも呼ばれる。「存在論的」とは、

存在するものについての哲学的研究である存在論を指す。哲学者はしばしば自然主義を物理主義や唯物論と同等と見なすが、これらの哲学間には重要な相違点が

ある。

例えば哲学者ポール・カーツは、自然は物質的原理を参照することで最もよく説明されると主張した。これらの原理には、科学界で認められている質量、エネル

ギー、その他の物理的・化学的特性が含まれる。さらにこの自然主義の観念は、精霊、神々、幽霊は実在せず、自然には「目的」が存在しない(非目的論)と考

える。このより強固な自然主義の定式化は、一般的に形而上学的自然主義と呼ばれる[3]。一方、自然主義が厳密な形而上学的意味において真実かどうかをさ

らに検討することなく、現在のパラダイムとして作業方法において自然主義を仮定すべきだというより穏健な見解は、方法論的自然主義と呼ばれる。[4]

汎神論者(自然は神性と同等であると信じつつ、明確な個人的擬人化された神を認めない者)を除き、有神論者は自然が現実の全てを含むという考えに異議を唱

える。一部の有神論者によれば、自然法則は神々の二次的原因と見なされる可能性がある。

| In philosophy,

naturalism is the idea that only natural laws and forces (as opposed to

supernatural ones) operate in the universe.[1] In its primary sense,[2]

it is also known as ontological naturalism, metaphysical naturalism,

pure naturalism, philosophical naturalism and antisupernaturalism.

"Ontological" refers to ontology, the philosophical study of what

exists. Philosophers often treat naturalism as equivalent to

physicalism or materialism, but there are important distinctions

between the philosophies. For example, philosopher Paul Kurtz argued that nature is best accounted for by reference to material principles. These principles include mass, energy, and other physical and chemical properties accepted by the scientific community. Further, this sense of naturalism holds that spirits, deities, and ghosts are not real and that there is no "purpose" in nature as in dysteleology. This stronger formulation of naturalism is commonly referred to as metaphysical naturalism.[3] On the other hand, the more moderate view that naturalism should be assumed in one's working methods as the current paradigm, without any further consideration of whether naturalism is true in the robust metaphysical sense, is called methodological naturalism.[4] With the exception of pantheists – who believe that nature is identical with divinity while not recognizing a distinct personal anthropomorphic god – theists challenge the idea that nature contains all of reality. According to some theists, natural laws may be viewed as secondary causes of God(s). In the 20th century, Willard Van Orman Quine, George Santayana, and other philosophers argued that the success of naturalism in science meant that scientific methods should also be used in philosophy. According to this view, science and philosophy are not always distinct from one another, but instead form a continuum. "Naturalism is not so much a special system as a point of view or tendency common to a number of philosophical and religious systems; not so much a well-defined set of positive and negative doctrines as an attitude or spirit pervading and influencing many doctrines. As the name implies, this tendency consists essentially in looking upon nature as the one original and fundamental source of all that exists, and in attempting to explain everything in terms of nature. Either the limits of nature are also the limits of existing reality, or at least the first cause, if its existence is found necessary, has nothing to do with the working of natural agencies. All events, therefore, find their adequate explanation within nature itself. But, as the terms nature and natural are themselves used in more than one sense, the term naturalism is also far from having one fixed meaning". — Dubray 1911 |

哲学において、自然主義とは宇宙において作用するのは自然法則と自然力

のみ(超自然的な力とは対照的に)という考え方である。[1]

主要な意味において[2]、それは存在論的自然主義、形而上学的自然主義、純粋自然主義、哲学的自然主義、反超自然主義とも呼ばれる。「存在論的」とは、

存在するものについての哲学的研究である存在論を指す。哲学者はしばしば自然主義を物理主義や唯物論と同等と見なすが、これらの哲学間には重要な相違点が

ある。 例えば哲学者ポール・カーツは、自然は物質的原理を参照することで最もよく説明されると主張した。これらの原理には、科学界で認められている質量、エネル ギー、その他の物理的・化学的特性が含まれる。さらにこの自然主義の観念は、精霊、神々、幽霊は実在せず、自然には「目的」が存在しない(非目的論)と考 える。このより強固な自然主義の定式化は、一般的に形而上学的自然主義と呼ばれる[3]。一方、自然主義が厳密な形而上学的意味において真実かどうかをさ らに検討することなく、現在のパラダイムとして作業方法において自然主義を仮定すべきだというより穏健な見解は、方法論的自然主義と呼ばれる。[4] 汎神論者(自然は神性と同等であると信じつつ、明確な個人的擬人化された神を認めない者)を除き、有神論者は自然が現実の全てを含むという考えに異議を唱 える。一部の有神論者によれば、自然法則は神々の二次的原因と見なされる可能性がある。 20世紀において、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインやジョージ・サンタヤナら哲学者たちは、科学における自然主義の成功は、哲学においても科学的 方法を用いるべきことを意味すると主張した。この見解によれば、科学と哲学は常に互いに区別されるものではなく、むしろ連続体を形成している。 「自然主義は特定の体系というより、多くの哲学的・宗教的体系に共通する視点や傾向である。明確に定義された肯定的・否定的教義の集合というより、多くの 教義に浸透し影響を与える態度や精神だ。名称が示す通り、この傾向の本質は、存在する全てのものの唯一の元来かつ根本的な源として自然を捉え、あらゆるも のを自然の観点から説明しようとする点にある。自然の限界こそが現実世界の限界であるか、あるいは存在が必要とされる第一原因は自然作用の働きとは無関係 である。したがってあらゆる事象は自然そのものの中に十分な説明を見出す。しかし「自然」や「自然的」という言葉自体が複数の意味で用いられるため、「自 然主義」という用語もまた単一の意味を持つとは程遠い」。 — デュブレ 1911 |

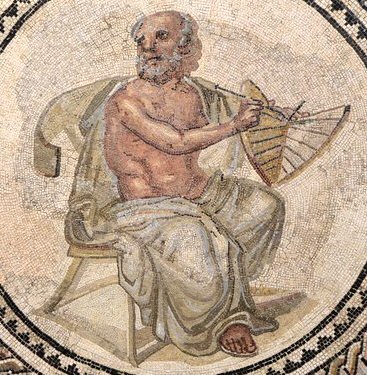

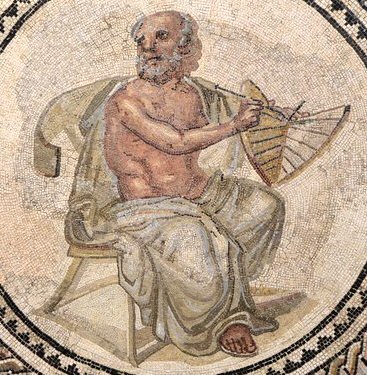

| History See also: History of materialism and History of metaphysical realism Ancient and medieval philosophy Naturalism is most notably a Western phenomenon, but an equivalent idea has long existed in the East. Naturalism was the foundation of two out of six orthodox schools and one heterodox school of Hinduism.[5][6] Samkhya, one of the oldest dualist schools of Indian philosophy puts nature (Prakriti) as the primary cause of the universe, without assuming the existence of a personal God or Ishvara. The Carvaka, Nyaya, Vaisheshika schools originated in the 7th, 6th, and 2nd century BCE, respectively.[7] Similarly, though unnamed and never articulated into a coherent system, one tradition within Confucian philosophy embraced a form of Naturalism dating to the Wang Chong in the 1st century, if not earlier, but it arose independently and had little influence on the development of modern naturalist philosophy or on Eastern or Western culture.  Ancient Roman mosaic showing Anaximander, a contributor to naturalism in ancient Greek philosophy Western metaphysical naturalism originated in ancient Greek philosophy. The earliest pre-Socratic philosophers, especially the Milesians (Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes) and the atomists (Leucippus and Democritus), were labeled by their peers and successors "the physikoi" (from the Greek φυσικός or physikos, meaning "natural philosopher" borrowing on the word φύσις or physis, meaning "nature") because they investigated natural causes, often excluding any role for gods in the creation or operation of the world. This eventually led to fully developed systems such as Epicureanism, which sought to explain everything that exists as the product of atoms falling and swerving in a void.[8] Aristotle surveyed the thought of his predecessors and conceived of nature in a way that charted a middle course between their excesses.[9] Plato's world of eternal and unchanging Forms, imperfectly represented in matter by a divine Artisan, contrasts sharply with the various mechanistic Weltanschauungen, of which atomism was, by the fourth century at least, the most prominent ... This debate was to persist throughout the ancient world. Atomistic mechanism got a shot in the arm from Epicurus ... while the Stoics adopted a divine teleology ... The choice seems simple: either show how a structured, regular world could arise out of undirected processes, or inject intelligence into the system. This was how Aristotle… when still a young acolyte of Plato, saw matters. Cicero… preserves Aristotle's own cave-image: if troglodytes were brought on a sudden into the upper world, they would immediately suppose it to have been intelligently arranged. But Aristotle grew to abandon this view; although he believes in a divine being, the Prime Mover is not the efficient cause of action in the Universe, and plays no part in constructing or arranging it ... But, although he rejects the divine Artificer, Aristotle does not resort to a pure mechanism of random forces. Instead he seeks to find a middle way between the two positions, one which relies heavily on the notion of Nature, or phusis.[10] With the rise and dominance of Christianity in the West and the later spread of Islam, metaphysical naturalism was generally abandoned by intellectuals. Thus, there is little evidence for it in medieval philosophy. |

歴史 関連項目: 唯物論の歴史、形而上学的実在論の歴史 古代および中世の哲学 自然主義は主に西洋の現象だが、同等の思想は東洋にも古くから存在する。ヒンドゥー教の六正派のうち二派と一異端派の基礎を自然主義が成していた。[5] [6] インド哲学最古の二元論学派の一つであるサンキヤは、個人的な神やイシュヴァラの存在を仮定せず、自然(プラクリティ)を宇宙の第一原因とする。カルヴァ カ、ニャーヤ、ヴァイシェーシカ各学派はそれぞれ紀元前7世紀、6世紀、2世紀に起源を持つ。[7] 同様に、名称を持たず体系化されることもなかったが、儒教哲学の一伝統は王充(1世紀)以前に遡る自然主義の一形態を包含していた。ただしこれは独立して 発生したものであり、近代自然主義哲学の発展や東西文化への影響はほとんどなかった。  古代ギリシャ哲学における自然主義の先駆者アナクシマンドロスを描いた古代ローマのモザイク 西洋の形而上学的自然主義は古代ギリシャ哲学に起源を持つ。初期のソクラテス以前の哲学者たち、特にミレトス学派(タレス、アナクシマンドロス、アナクシ メネス)と原子論者(レウキッポス、デモクリトス)は、自然原因を研究し、世界の創造や運営における神々の役割をしばしば排除したことから、同時代人や後 継者たちによって「フィシコイ(physikoi)」 (ギリシャ語のφυσικός、すなわち「自然哲学者」を意味する。これは φύσις、すなわち「自然」を意味する語に由来する)と呼ばれた。彼らは自然の原因を調査し、世界の創造や営みにおける神々の役割をしばしば排除したか らだ。これは最終的に、存在するすべてのものを虚空の中で落下し、軌道を変える原子の産物として説明しようとするエピクロス主義のような、完全に発達した 体系へとつながった。 アリストテレスは先人たちの思想を総括し、彼らの極端な主張の中間路線を歩む形で自然観を構築した。[9] プラトンの永遠不変のイデア世界は、神聖な工匠によって物質界に不完全な形で再現されるが、これは様々な機械論的世界観と鋭く対照的である。少なくとも4 世紀までに原子論が最も顕著な機械論的世界観となった…この論争は古代世界全体にわたり持続することになる。原子論的機械論はエピクロスによって勢いづい た…一方ストア学派は神による目的論を採用した…選択は単純に見える:無秩序な過程から構造化された規則的な世界が如何に生じうるかを示すか、あるいはシ ステムに知性を注入するか。これがアリストテレスが…プラトンの若き弟子であった頃、事態を捉えた方法であった。キケロはアリストテレス自身の洞窟の比喩 を伝えている:もし洞窟の住人を突然地上世界へ連れ出せば、彼らは即座にそれが知性によって整えられたと推測するだろう。しかしアリストテレスはこの見解 を後に放棄した。彼は神的存在を信じるものの、第一動因は宇宙における作用の効率的原因ではなく、その構築や配置には一切関与しない... しかし、神的な創造主を否定する一方で、アリストテレスは純粋な無作為な力による機械論に頼ることもなかった。代わりに彼は、二つの立場の中間的な道、す なわち「自然(phusis)」という概念に大きく依拠する立場を模索したのである。[10] 西洋におけるキリスト教の台頭と支配、そして後のイスラム教の広がりにより、形而上学的自然主義は知識人によって概ね放棄された。したがって、中世哲学においてその痕跡はほとんど見られない。 |

| Modern philosophy It was not until the early modern era of philosophy and the Age of Enlightenment that naturalists like Benedict Spinoza (who put forward a theory of psychophysical parallelism), David Hume,[11] and the proponents of French materialism (notably Denis Diderot, Julien La Mettrie, and Baron d'Holbach) started to emerge again in the 17th and 18th centuries. In this period, some metaphysical naturalists adhered to a distinct doctrine, materialism, which became the dominant category of metaphysical naturalism widely defended until the end of the 19th century. Thomas Hobbes was a proponent of naturalism in ethics who acknowledged normative truths and properties.[12] Immanuel Kant rejected (reductionist) materialist positions in metaphysics,[13] but he was not hostile to naturalism. His transcendental philosophy is considered to be a form of liberal naturalism.[14] In late modern philosophy, Naturphilosophie, a form of natural philosophy, was developed by Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling[15] and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel[15] as an attempt to comprehend nature in its totality and to outline its general theoretical structure. A version of naturalism that arose after Hegel was Ludwig Feuerbach's anthropological materialism,[16] which influenced Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels's historical materialism, Engels's "materialist dialectic" philosophy of nature (Dialectics of Nature), and their follower Georgi Plekhanov's dialectical materialism.[17] Another notable school of late modern philosophy advocating naturalism was German materialism: members included Ludwig Büchner, Jacob Moleschott, and Carl Vogt.[18][19] The current usage of the term naturalism "derives from debates in America in the first half of the 20th century. The self-proclaimed 'naturalists' from that period included John Dewey, Ernest Nagel, Sidney Hook, and Roy Wood Sellars."[20] |

近代哲学 自然主義者たちが再び現れ始めたのは、近世哲学と啓蒙時代である。17世紀から18世紀にかけて、ベネディクト・スピノザ(心身並行説を提唱)、デイ ヴィッド・ヒューム[11]、そしてフランス唯物論の提唱者たち(特にデニス・ディドロ、ジュリアン・ラ・メトリー、ドルバック男爵)が台頭した。この時 期、一部の形而上学的自然主義者は物質主義という独自の教義を堅持し、これが19世紀末まで広く擁護された形而上学的自然主義の主流派となった。 トマス・ホッブズは倫理学における自然主義の提唱者であり、規範的真理と特性を認めていた[12]。イマヌエル・カントは形而上学における(還元主義的) 物質主義的立場を拒否したが[13]、自然主義に対して敵対的ではなかった。彼の超越論的哲学は自由主義的自然主義の一形態と見なされている[14]。 近代後期哲学において、自然哲学の一形態である自然哲学(Naturphilosophie)は、フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨーゼフ・フォン・シェリ ング[15]とゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル[15]によって、自然をその全体性において理解し、その一般的な理論的構造を概説しよう とする試みとして発展した。 ヘーゲル以後に現れた自然主義の一形態が、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの人類学的唯物論である[16]。これはカール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エン ゲルスの歴史的唯物論、エンゲルスの自然哲学における「唯物弁証法」(『自然弁証法』)、そして彼らの後継者ゲオルギー・プレハーノフの弁証法的唯物論に 影響を与えた。[17] 自然主義を主張した近代後期哲学のもう一つの注目すべき学派はドイツ唯物論である。そのメンバーにはルートヴィヒ・ビュヒナー、ヤコブ・モレショット、カール・フォクトらが含まれる。[18][19] 「自然主義」という用語の現在の用法は「20世紀前半のアメリカにおける論争に由来する。この時期の自称『自然主義者』には、ジョン・デューイ、アーネスト・ネーゲル、シドニー・フック、ロイ・ウッド・セラーズらが含まれる」[20]。 |

| Contemporary philosophy Currently, metaphysical naturalism is more widely embraced than in previous centuries, especially but not exclusively in the natural sciences and the Anglo-American, analytic philosophical communities. While the vast majority of the population of the world remains firmly committed to non-naturalistic worldviews, contemporary defenders of naturalism and/or naturalistic theses and doctrines today include Graham Oppy, Kai Nielsen, J. J. C. Smart, David Malet Armstrong, David Papineau, Paul Kurtz, Brian Leiter, Daniel Dennett, Michael Devitt, Fred Dretske, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Mario Bunge, Jonathan Schaffer, Hilary Kornblith, Leonard Olson, Quentin Smith, Paul Draper and Michael Martin, among many other academic philosophers.[citation needed] According to David Papineau, contemporary naturalism is a consequence of the build-up of scientific evidence during the twentieth century for the "causal closure of the physical", the doctrine that all physical effects can be accounted for by physical causes.[21] By the middle of the twentieth century, the acceptance of the causal closure of the physical realm led to even stronger naturalist views. The causal closure thesis implies that any mental and biological causes must themselves be physically constituted, if they are to produce physical effects. It thus gives rise to a particularly strong form of ontological naturalism, namely the physicalist doctrine that any state that has physical effects must itself be physical. From the 1950s onwards, philosophers began to formulate arguments for ontological physicalism. Some of these arguments appealed explicitly to the causal closure of the physical realm (Feigl 1958, Oppenheim and Putnam 1958). In other cases, the reliance on causal closure lay below the surface. However, it is not hard to see that even in these latter cases the causal closure thesis played a crucial role. — Papineau 2007 In contemporary continental philosophy, Quentin Meillassoux proposed speculative materialism, a post-Kantian return to David Hume which can strengthen classical materialist ideas.[22] This speculative approach to philosophical naturalism has been further developed by other contemporary thinkers including Ray Brassier and Drew M. Dalton. |

現代哲学 現在、形而上学的自然主義は、過去数世紀よりも広く受け入れられている。特に、自然科学や英米の分析哲学界で顕著である。世界の大半の人々は依然として非 自然主義的な世界観を固く信じているが、現代の自然主義や自然主義的な論文・学説の擁護者には、グラハム・オッピー、カイ・ニールセン、J. J. C. スマート、デイヴィッド・マレット・アームストロング、デイヴィッド・パピノー、ポール・カーツ、ブライアン・ライター、ダニエル・デネット、マイケル・ デヴィット、フレッド・ドレツキー、ポール&パトリシア・チャーチランド、マリオ・バンジ、ジョナサン・シェイファー、ヒラリー・コーンブリス、レナー ド・オルソン、クエンティン・スミス、ポール・ドレイパー、マイケル・マーティンなど、その他多くの学術哲学者たちが挙げられる。 デイヴィッド・パピノーによれば、現代の自然主義は、20 世紀における「物理的因果閉鎖」の科学的証拠の蓄積の結果である。物理的因果閉鎖とは、すべての物理的効果は物理的原因によって説明できるとする学説である。[21] 20世紀半ばまでに、物理的領域の因果的閉鎖性の受容は、さらに強力な自然主義的見解につながった。因果的閉鎖性の説は、あらゆる精神的および生物学的原 因が物理的効果を生み出すためには、それ自体が物理的に構成されていなければならないことを意味する。したがって、これは特に強力な形の存在論的自然主 義、すなわち、物理的効果を持つあらゆる状態はそれ自体が物理的でなければならないという物理主義の教義を生み出す。1950年代以降、哲学者たちは存在 論的物理主義を支持する議論を構築し始めた。これらの議論の一部は、物理的領域の因果的閉鎖性を明示的に訴えた(Feigl 1958, Oppenheim and Putnam 1958)。他のケースでは、因果的閉鎖性への依存は表層下にあった。しかし、後者のケースでさえ因果的閉鎖性命題が重要な役割を果たしていたことは容易 に理解できる。 — Papineau 2007 現代の大陸哲学において、クエンティン・メイラスーは思弁的唯物論を提唱した。これはポスト・カント的なデイヴィッド・ヒューム回帰であり、古典的唯物論 思想を強化し得るものである[22]。この哲学的自然主義への思弁的アプローチは、レイ・ブラッシエやドリュー・M・ダルトンを含む他の現代思想家によっ てさらに発展させられている。 |

| Etymology The term "methodological naturalism" is much more recent, though. According to Ronald Numbers, it was coined in 1983 by Paul de Vries, a Wheaton College philosopher. De Vries distinguished between what he called "methodological naturalism", a disciplinary method that says nothing about God's existence, and "metaphysical naturalism", which "denies the existence of a transcendent God".[23] The term "methodological naturalism" had been used in 1937 by Edgar S. Brightman in an article in The Philosophical Review as a contrast to "naturalism" in general, but there the idea was not really developed to its more recent distinctions.[24] |

語源 「方法論的自然主義」という用語は、はるかに新しいものである。ロナルド・ナンバーズによれば、この言葉は1983年にウィートン大学の哲学者ポール・ デ・フリースによって造語された。デ・フリースは、神の存在について何も語らない学問的方法である「方法論的自然主義」と、「超越的な神の存在を否定す る」という「形而上学的自然主義」とを区別した。[23] 「方法論的自然主義」という用語は、1937年にエドガー・S・ブライトマンが『フィロソフィカル・レビュー』誌の論文で、一般的な「自然主義」との対比 として使用していた。しかしそこでは、この概念は近年の区別まで発展させていなかった。[24] |

Description Hubble Ultra-Deep Field  Flammarion engraving A 21st century image of the universe and a 1888 illustration of the cosmos According to Steven Schafersman, naturalism is a philosophy that maintains that; 1. "Nature encompasses all that exists throughout space and time; 2. Nature (the universe or cosmos) consists only of natural elements, that is, of spatio-temporal physical substance – mass –energy. Non-physical or quasi-physical substance, such as information, ideas, values, logic, mathematics, intellect, and other emergent phenomena, either supervene upon the physical or can be reduced to a physical account; 3. Nature operates by the laws of physics and in principle, can be explained and understood by science and philosophy; 4. The supernatural does not exist, i.e., only nature is real. Naturalism is therefore a metaphysical philosophy opposed primarily by supernaturalism".[25] Or, as Carl Sagan succinctly put it: "The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be."[26] In addition Arthur C. Danto states that naturalism, in recent usage, is a species of philosophical monism according to which whatever exists or happens is natural in the sense of being susceptible to explanation through methods which, although paradigmatically exemplified in the natural sciences, are continuous from domain to domain of objects and events. Hence, naturalism is polemically defined as repudiating the view that there exists or could exist any entities which lie, in principle, beyond the scope of scientific explanation.[27][28] Arthur Newell Strahler states: "The naturalistic view is that the particular universe we observe came into existence and has operated through all time and in all its parts without the impetus or guidance of any supernatural agency."[29] "The great majority of contemporary philosophers urge that reality is exhausted by nature, containing nothing 'supernatural', and that the scientific method should be used to investigate all areas of reality, including the 'human spirit'." Philosophers widely regard naturalism as a "positive" term, and "few active philosophers nowadays are happy to announce themselves as 'non-naturalists'". "Philosophers concerned with religion tend to be less enthusiastic about 'naturalism'" and that despite an "inevitable" divergence due to its popularity, if more narrowly construed, (to the chagrin of John McDowell, David Chalmers and Jennifer Hornsby, for example), those not so disqualified remain nonetheless content "to set the bar for 'naturalism' higher."[30] |

説明 ハッブル・ウルトラディープ・フィールド  フラマリオンの版画 21世紀の宇宙像と1888年の宇宙図 スティーブン・シェイファーズマンによれば、自然主義とは次のように主張する哲学である: 1. 「自然とは時空に存在する全てのものを包含する」 2. 「自然(宇宙)は自然的要素、すなわち時空間的物理的実体―質量・エネルギー―のみで構成される。情報、観念、価値、論理、数学、知性、その他の創発的現象といった非物理的または準物理的実体は、物理的実体に付随するか、物理的説明に還元可能である」 3. 自然は物理法則によって作用し、原理的には科学と哲学によって説明・理解可能である。 4. 超自然的なものは存在せず、つまり自然のみが実在する。したがって自然主義は、主に超自然主義と対立する形而上学的哲学である」。[25] あるいはカール・セーガンが簡潔に述べたように:「宇宙は、存在するもの、かつて存在したもの、そしてこれから存在するものすべてである」。[26] さらにアーサー・C・ダントは、近年の用法における自然主義とは、あらゆる存在や事象が自然的であるとする哲学的一元論の一種だと述べる。ここで自然的と は、自然科学に典型的に見られる手法によって説明可能であり、対象や事象の領域を超えて連続しているという意味である。したがって、自然主義は論争的に定 義され、科学的な説明の範囲を原理的に超える実体が存在し得るという見解を否定するものだと言われる。[27][28] アーサー・ニューウェル・ストララーはこう述べている:「自然主義的見解とは、我々が観察する特定の宇宙が、いかなる超自然的な力の働きかけや導きもな く、存在し始め、あらゆる時間とあらゆる部分において作用してきたという見解である。」[29] 「現代の哲学者の大多数は、現実とは自然によって尽くされ、「超自然的な」ものは何も含まれておらず、「人間の精神」を含む現実のあらゆる領域を調査する には科学的方法を用いるべきだと主張している。哲学者たちは自然主義を「肯定的な」用語と広く見なしており、「今日、自らを『非自然主義者』と公言するこ とを喜ぶ現役の哲学者はほとんどいない」。「宗教に関心を持つ哲学者は『自然主義』にあまり熱心ではない」傾向があり、その人気による「避けられない」相 違があるにもかかわらず、より狭義に解釈した場合(例えば、ジョン・マクダウェル、デヴィッド・チャーマーズ、ジェニファー・ホーンズビーはこれを残念に 思っている)、それほど失格ではない者たちは、それにもかかわらず「『自然主義』のハードルをより高く設定する」ことに満足している。[30] |

| Providing assumptions required for science According to Robert Priddy, all scientific study inescapably builds on at least some essential assumptions that cannot be tested by scientific processes;[31] that is, that scientists must start with some assumptions as to the ultimate analysis of the facts with which it deals. These assumptions would then be justified partly by their adherence to the types of occurrence of which we are directly conscious, and partly by their success in representing the observed facts with a certain generality, devoid of ad hoc suppositions."[32] Kuhn also claims that all science is based on assumptions about the character of the universe, rather than merely on empirical facts. These assumptions – a paradigm – comprise a collection of beliefs, values and techniques that are held by a given scientific community, which legitimize their systems and set the limitations to their investigation.[33] For naturalists, nature is the only reality, the "correct" paradigm, and there is no such thing as supernatural, i.e. anything above, beyond, or outside of nature. The scientific method is to be used to investigate all reality, including the human spirit.[34] Some[who?] claim that naturalism is the implicit philosophy of working scientists, and that the following basic assumptions are needed to justify the scientific method:[35] 1. That there is an objective reality shared by all rational observers.[35][36] "The basis for rationality is acceptance of an external objective reality."[37] "Objective reality is clearly an essential thing if we are to develop a meaningful perspective of the world. Nevertheless its very existence is assumed."[38] "Our belief that objective reality exist is an assumption that it arises from a real world outside of ourselves. As infants we made this assumption unconsciously. People are happy to make this assumption that adds meaning to our sensations and feelings, than live with solipsism."[39] "Without this assumption, there would be only the thoughts and images in our own mind (which would be the only existing mind) and there would be no need of science, or anything else."[40][self-published source?] 2. That this objective reality is governed by natural laws;[35][36] "Science, at least today, assumes that the universe obeys knowable principles that don't depend on time or place, nor on subjective parameters such as what we think, know or how we behave."[37] Hugh Gauch argues that science presupposes that "the physical world is orderly and comprehensible."[41] 3. That reality can be discovered by means of systematic observation and experimentation.[35][36] Stanley Sobottka said: "The assumption of external reality is necessary for science to function and to flourish. For the most part, science is the discovering and explaining of the external world."[40][self-published source?] "Science attempts to produce knowledge that is as universal and objective as possible within the realm of human understanding."[37] 4. That Nature has uniformity of laws and most if not all things in nature must have at least a natural cause.[36] Biologist Stephen Jay Gould referred to these two closely related propositions as the constancy of nature's laws and the operation of known processes.[42] Simpson agrees that the axiom of uniformity of law, an unprovable postulate, is necessary in order for scientists to extrapolate inductive inference into the unobservable past in order to meaningfully study it.[43] "The assumption of spatial and temporal invariance of natural laws is by no means unique to geology since it amounts to a warrant for inductive inference which, as Bacon showed nearly four hundred years ago, is the basic mode of reasoning in empirical science. Without assuming this spatial and temporal invariance, we have no basis for extrapolating from the known to the unknown and, therefore, no way of reaching general conclusions from a finite number of observations. (Since the assumption is itself vindicated by induction, it can in no way "prove" the validity of induction — an endeavor virtually abandoned after Hume demonstrated its futility two centuries ago)."[44] Gould also notes that natural processes such as Lyell's "uniformity of process" are an assumption: "As such, it is another a priori assumption shared by all scientists and not a statement about the empirical world."[45] According to R. Hooykaas: "The principle of uniformity is not a law, not a rule established after comparison of facts, but a principle, preceding the observation of facts ... It is the logical principle of parsimony of causes and of economy of scientific notions. By explaining past changes by analogy with present phenomena, a limit is set to conjecture, for there is only one way in which two things are equal, but there are an infinity of ways in which they could be supposed different."[46] 5. That experimental procedures will be done satisfactorily without any deliberate or unintentional mistakes that will influence the results.[36] 6. That experimenters won't be significantly biased by their presumptions.[36] 7. That random sampling is representative of the entire population.[36] A simple random sample (SRS) is the most basic probabilistic option used for creating a sample from a population. The benefit of SRS is that the investigator is guaranteed to choose a sample that represents the population that ensures statistically valid conclusions.[47] |

科学に必要な前提条件の提供 ロバート・プリディによれば、あらゆる科学的研究は、科学的手法では検証できない本質的な前提条件を少なくともいくつか必然的に基盤としている。[31] つまり、科学者は扱う事実の究極的な分析に関する何らかの前提条件から始めざるを得ない。これらの前提は、一部では我々が直接意識する事象の類型への適合 性によって、また一部では特定の一般性をもって観察事実を表現する成功(その過程で場当たり的な仮定を排除する)によって正当化される。[32] クーンもまた、あらゆる科学は単なる経験的事実ではなく、宇宙の性質に関する前提に基づいていると主張する。これらの仮定―パラダイム―とは、特定の科学 コミュニティが共有する信念・価値観・技法の集合体であり、彼らの体系を正当化し、研究の限界を設定するものである[33]。自然主義者にとって、自然こ そが唯一の現実であり「正しい」パラダイムであり、超自然的なもの―すなわち自然を超越した、自然を超えた、自然の外にあるもの―は存在しない。科学的メ ソッドは、人間の精神を含むあらゆる現実を調査するために用いられるべきである。[34] 一部の[誰?]は、自然主義が現役科学者の暗黙の哲学であり、科学的方法を正当化するには以下の基本前提が必要だと主張する。[35] 1. すべての理性的な観察者が共有する客観的現実が存在する。[35] [36] 「合理性の基盤は、外部の客観的現実の受容にある。」[37]「世界に対する意味ある視点を構築するには、客観的現実が明らかに不可欠である。しかしなが ら、その存在自体が前提とされている。」[38]「客観的現実が存在するという我々の信念は、それが我々自身の外にある現実世界から生じるという前提に基 づいている。幼児期に我々はこの前提を無意識に受け入れた。人々は、この仮定によって感覚や感情に意味が加わることを喜んで受け入れ、独我論の中で生きる よりはましだと考える。」[39]「この仮定がなければ、存在するのは自らの心の中にある思考やイメージ(それが唯一の存在する心となる)だけであり、科 学やその他の何ものも必要とされなくなる。」[40][自費出版の出典?] 2. この客観的現実は自然法則によって支配されているという前提;[35][36] 「少なくとも今日の科学は、宇宙が時間や場所、あるいは我々の思考・知識・行動といった主観的要素に依存しない、認識可能な原理に従うと仮定している。」[37] ヒュー・ゴーチは、科学が「物理的世界は秩序正しく理解可能である」と前提していると論じる。[41] 3. 現実とは体系的な観察と実験によって発見され得るものである。[35][36] スタンリー・ソボトカは言う:「外部現実の前提は、科学が機能し発展するために必要である。科学の大部分は、外部世界の発見と説明である。」 [40][自己出版の出典?]「科学は、人間の理解の範囲内で可能な限り普遍的かつ客観的な知識を生み出そうとする」[37]。 4. 自然界には法則の均一性があり、自然界のほとんど、あるいはすべての事象には少なくとも自然的な原因が存在する。[36] 生物学者スティーブン・ジェイ・グールドは、これら密接に関連する二つの命題を「自然法則の不変性」と「既知のプロセスの作用」と呼んだ。[42] シンプソンも、法則の均一性という公理(証明不可能な仮定)が、科学者が帰納的推論を観察不可能な過去に外挿し、意味ある研究を行うために必要だと同意し ている。[43] 「自然法則の空間的・時間的不変性という仮定は、決して地質学に特有のものではない。なぜならそれは帰納的推論の根拠となるものであり、ベーコンが約 400年前に示したように、経験科学における基本的な推論様式だからだ。この空間的・時間的不変性を仮定しなければ、既知から未知への外挿を行う根拠がな く、したがって有限の観察から一般的な結論に到達する方法もない。(この前提自体が帰納によって正当化される以上、帰納法の有効性を「証明」することは到 底不可能である。この試みは、ヒュームが2世紀前にその無益さを示して以来、事実上放棄されている) [45] R. フーイカースによれば:「均一性の原理は法則でもなければ、事実の比較後に確立された規則でもない。それは事実の観察に先行する原理である…これは原因の 節約と科学的概念の経済性という論理的原理である。過去の変化を現在の現象との類推によって説明することで、推測に制限が設けられる。なぜなら、二つのも のが等しいと言える方法は一つしかないが、それらが異なるという仮定ができる方法は無限にあるからだ。」[46] 5. 実験手順が、結果に影響を与えるような熟議または非意図的な誤りなく、満足のいく形で実施されること。[36] 6. 実験者が自身の仮定によって著しく偏らないこと。[36] 7. ランダムサンプリングが母集団全体を代表すること。[36] 単純無作為抽出(SRS)は、母集団から標本を作成するために用いられる最も基本的な確率的手法である。SRSの利点は、調査者が母集団を代表し統計的に有効な結論を保証する標本を選択することが保証される点にある。[47] |

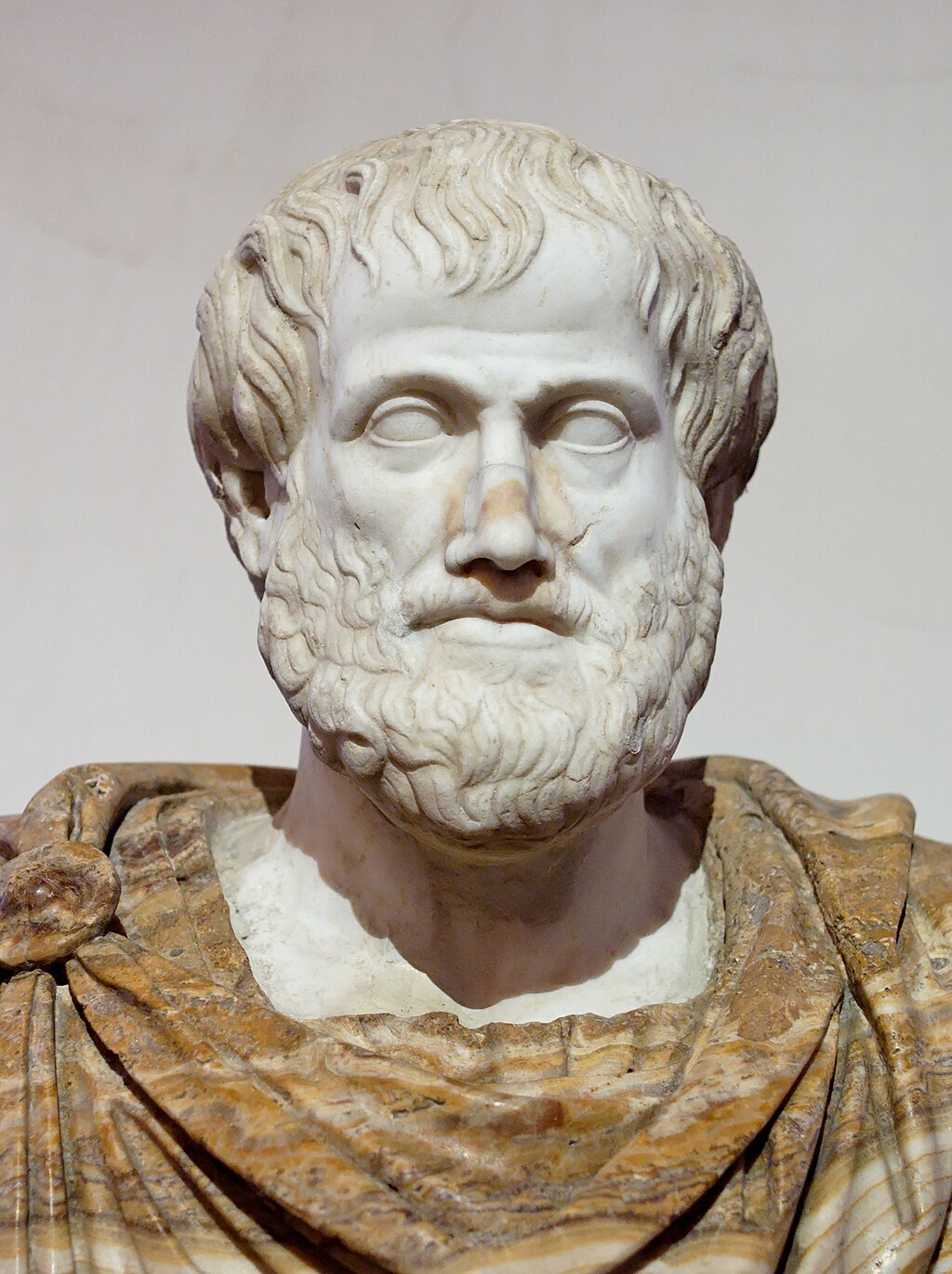

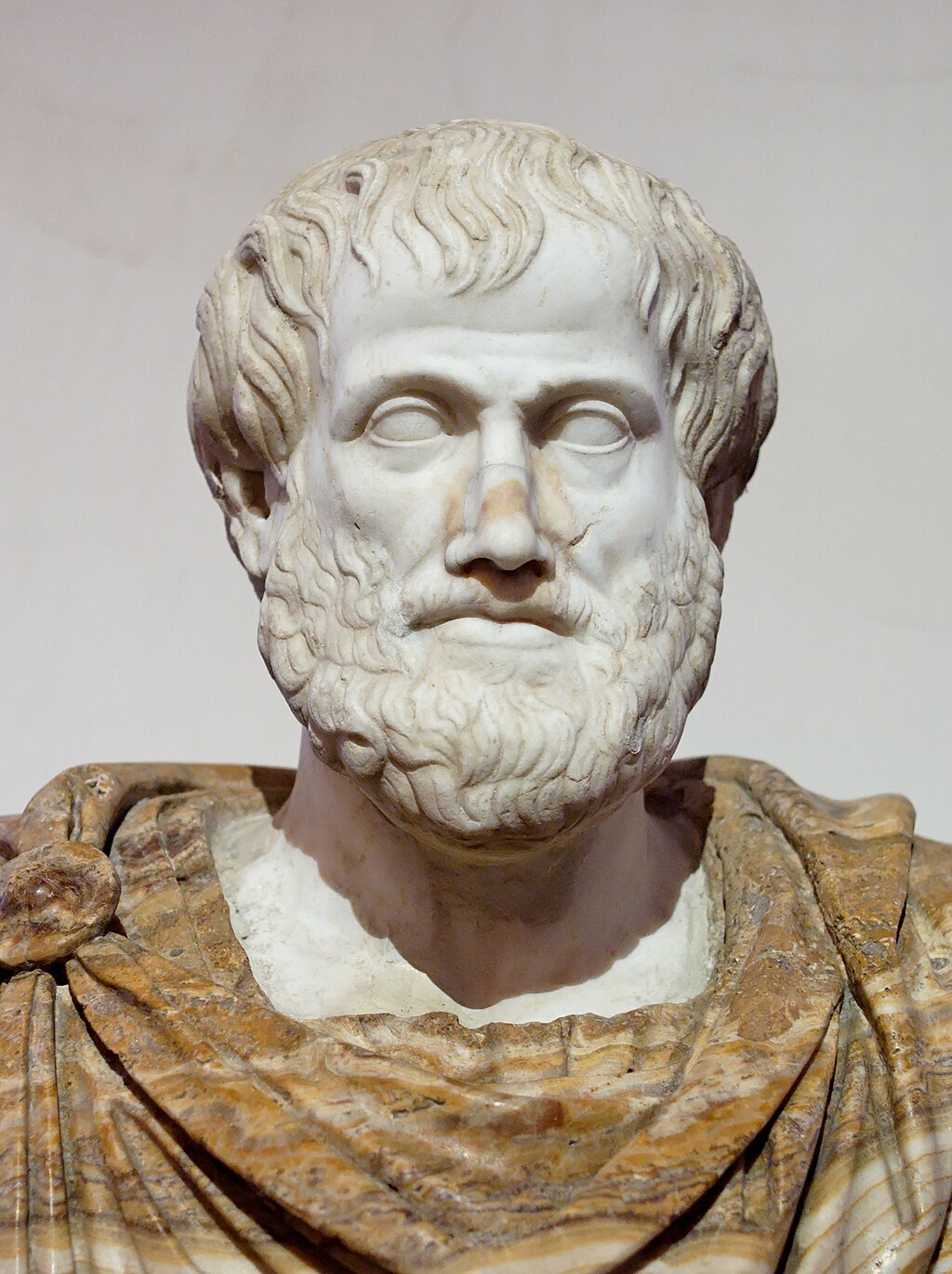

Methodological naturalism Aristotle, one of the philosophers behind the modern day scientific method used as a central term in methodological naturalism Methodological naturalism, the second sense of the term "naturalism", (see above) is "the adoption or assumption of philosophical naturalism … with or without fully accepting or believing it."[25] Robert T. Pennock used the term to clarify that the scientific method confines itself to natural explanations without assuming the existence or non-existence of the supernatural.[48] "We may therefore be agnostic about the ultimate truth of [philosophical] naturalism, but nevertheless adopt it and investigate nature as if nature is all that there is."[25] According to Ronald Numbers, the term "methodological naturalism" was coined in 1983 by Paul de Vries, a Wheaton College philosopher.[23] Both Schafersman and Strahler assert that it is illogical to try to decouple the two senses of naturalism. "While science as a process only requires methodological naturalism, the practice or adoption of methodological naturalism entails a logical and moral belief in philosophical naturalism, so they are not logically decoupled."[25] This “[philosophical] naturalistic view is espoused by science as its fundamental assumption."[29] But Eugenie Scott finds it imperative to do so for the expediency of deprogramming the religious. "Scientists can defuse some of the opposition to evolution by first recognizing that the vast majority of Americans are believers, and that most Americans want to retain their faith." Scott apparently believes that "individuals can retain religious beliefs and still accept evolution through methodological naturalism. Scientists should therefore avoid mentioning metaphysical naturalism and use methodological naturalism instead."[49] "Even someone who may disagree with my logic … often understands the strategic reasons for separating methodological from philosophical naturalism—if we want more Americans to understand evolution."[50] Scott's approach has found success as illustrated in Ecklund's study where some religious scientists reported that their religious beliefs affect the way they think about the implications – often moral – of their work, but not the way they practice science within methodological naturalism.[51] Papineau notes that "Philosophers concerned with religion tend to be less enthusiastic about metaphysical naturalism and that those not so disqualified remain content "to set the bar for 'naturalism' higher."[30] In contrast to Schafersman, Strahler, and Scott, Robert T. Pennock, an expert witness[48] at the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial and cited by the Judge in his Memorandum Opinion,[52] described "methodological naturalism" stating that it is not based on dogmatic metaphysical naturalism.[53] Pennock further states that as supernatural agents and powers "are above and beyond the natural world and its agents and powers" and "are not constrained by natural laws", only logical impossibilities constrain what a supernatural agent cannot do. In addition he says: "If we could apply natural knowledge to understand supernatural powers, then, by definition, they would not be supernatural." "Because the supernatural is necessarily a mystery to us, it can provide no grounds on which one can judge scientific models." "Experimentation requires observation and control of the variables.... But by definition we have no control over supernatural entities or forces." The position that the study of the function of nature is also the study of the origin of nature is in contrast with opponents who take the position that functioning of the cosmos is unrelated to how it originated. While they are open to supernatural fiat in its invention and coming into existence, during scientific study to explain the functioning of the cosmos, they do not appeal to the supernatural. They agree that allowing "science to appeal to untestable supernatural powers to explain how nature functions would make the scientist's task meaningless, undermine the discipline that allows science to make progress, and would be as profoundly unsatisfying as the ancient Greek playwright's reliance upon the deus ex machina to extract his hero from a difficult predicament."[54] |

方法論的自然主義 方法論的自然主義の中心概念として用いられる現代科学的方法の背景にある哲学者の一人、アリストテレス 方法論的自然主義は、「自然主義」という用語の第二の意味(上記参照)であり、「哲学的自然主義の採用または仮定…それを完全に受け入れ信じているか否か を問わない」ものである。[25] ロバート・T・ペノックはこの用語を用いて、科学的方法が超自然的存在の有無を仮定せず、自然的な説明に限定されることを明確にした[48]。「したがっ て我々は[哲学的]自然主義の究極的真実について不可知論的立場を取っても、それを採用し、自然が存在する全てであるかのように自然を調査することができ る」[25]。 ロナルド・ナンバーズによれば、「方法論的自然主義」という用語は1983年にウィートン大学の哲学者ポール・デ・フリースによって造語された[23]。 シェーファーズマンとストララーは共に、自然主義の二つの意味を分離しようとする試みは非論理的だと主張する。「科学というプロセスは方法論的自然主義の みを要求するが、方法論的自然主義の実践や採用は、哲学的自然主義への論理的・道徳的信念を伴う。ゆえに両者は論理的に切り離せない」[25]。この 「[哲学的]自然主義的見解は、科学が根本的前提として支持するものである」[29]。 しかしユージニー・スコットは、宗教的思考を脱洗脳する便宜上、これを分離することが不可欠だと考える。「科学者はまず、アメリカ人の大多数が信者であ り、その大半が信仰を保持したいと望んでいることを認識することで、進化論への反対の一部を和らげられる」。スコットは明らかに「個人は宗教的信念を保持 しつつ、方法論的自然主義を通じて進化論を受け入れられる」と考えている。したがって科学者は形而上学的自然主義に言及せず、方法論的自然主義を用いるべ きだ[49]。「たとえ私の論理に同意しない者でさえ…より多くのアメリカ人に進化論を理解させたいなら、方法論的自然主義と哲学的自然主義を区別する戦 略的理由を理解することが多い」[50] スコットのアプローチはエックランドの研究で実証されたように成功を収めている。そこでは一部の宗教的科学者が、自身の宗教的信念が研究の帰結(しばしば 道徳的帰結)への考え方には影響を与えるが、方法論的自然主義内での科学実践方法には影響を与えないと報告している。[51] パピノーは「宗教に関わる哲学者たちは形而上学的自然主義に熱心でない傾向があり、そうではない者たちも『自然主義』の基準を高く設定することに満足して いる」と指摘している。[30] シェイファーズマン、ストララー、スコットとは対照的に、キッツミラー対ドーバー地区学区裁判における専門家証人[48]であり、判事の意見書[52]で も引用されたロバート・T・ペノックは、「方法論的自然主義」について、それは教条的な形而上学的自然主義に基づくものではないと説明している。[53] ペノックはさらに、超自然的な存在や力は「自然界とその作用や力を超越した存在」であり「自然法則に制約されない」ため、超自然的な存在にできないことを 制約するのは論理的不可能のみだと述べる。加えて彼はこう言う:「もし自然界の知識を応用して超自然的な力を理解できるなら、定義上、それは超自然的なも のではなくなる」 「超自然的なものは必然的に我々にとって謎であるため、科学的モデルを判断する根拠を提供し得ない。」「実験には変数の観察と制御が必要だ。…しかし定義 上、我々は超自然的な存在や力を制御できない。」 自然の機能の研究が同時に自然の起源の研究でもあるという立場は、宇宙の機能はその起源と無関係だとする反対派の立場とは対照的だ。彼らは宇宙の創造と存 在の起源において超自然的な意志を認めるが、宇宙の機能を説明する科学的探究においては超自然的なものに訴えない。彼らは「科学が自然の機能を説明するた めに検証不可能な超自然的な力に訴えることは、科学者の任務を無意味にし、科学の進歩を可能にする規律を損ない、古代ギリシャの劇作家が困難な状況から主 人公を救うためにデウス・エクス・マキナに依存したのと同じくらい深く不満足なものになる」という点で同意している。[54] |

| Views on methodological naturalism W. V. O. Quine Main article: Naturalized epistemology W. V. O. Quine describes naturalism as the position that there is no higher tribunal for truth than natural science itself. In his view, there is no better method than the scientific method for judging the claims of science, and there is neither any need nor any place for a "first philosophy", such as (abstract) metaphysics or epistemology, that could stand behind and justify science or the scientific method. Therefore, philosophy should feel free to make use of the findings of scientists in its own pursuit, while also feeling free to offer criticism when those claims are ungrounded, confused, or inconsistent. In Quine's view, philosophy is "continuous with" science, and both are empirical.[55] Naturalism is not a dogmatic belief that the modern view of science is entirely correct. Instead, it simply holds that science is the best way to explore the processes of the universe and that those processes are what modern science is striving to understand.[56] Karl Popper Karl Popper equated naturalism with inductive theory of science. He rejected it based on his general critique of induction (see problem of induction), yet acknowledged its utility as means for inventing conjectures. A naturalistic methodology (sometimes called an "inductive theory of science") has its value, no doubt. ... I reject the naturalistic view: It is uncritical. Its upholders fail to notice that whenever they believe to have discovered a fact, they have only proposed a convention. Hence the convention is liable to turn into a dogma. This criticism of the naturalistic view applies not only to its criterion of meaning, but also to its idea of science, and consequently to its idea of empirical method. — Karl R. Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery, (Routledge, 2002), pp. 52–53, ISBN 0-415-27844-9. Popper instead proposed that science should adopt a methodology based on falsifiability for demarcation, because no number of experiments can ever prove a theory, but a single experiment can contradict one. Popper holds that scientific theories are characterized by falsifiability. Alvin Plantinga Alvin Plantinga, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Notre Dame, and a Christian, has become a well-known critic of naturalism.[57][failed verification] He suggests, in his evolutionary argument against naturalism, that the probability that evolution has produced humans with reliable true beliefs, is low or inscrutable, unless the evolution of humans was guided (for example, by God). According to David Kahan of the University of Glasgow, in order to understand how beliefs are warranted, a justification must be found in the context of supernatural theism, as in Plantinga's epistemology.[58][59][60] (See also supernormal stimuli). Plantinga argues that together, naturalism and evolution provide an insurmountable "defeater for the belief that our cognitive faculties are reliable", i.e., a skeptical argument along the lines of Descartes' evil demon or brain in a vat.[61] Take philosophical naturalism to be the belief that there aren't any supernatural entities – no such person as God, for example, but also no other supernatural entities, and nothing at all like God. My claim was that naturalism and contemporary evolutionary theory are at serious odds with one another – and this despite the fact that the latter is ordinarily thought to be one of the main pillars supporting the edifice of the former. (Of course I am not attacking the theory of evolution, or anything in that neighborhood; I am instead attacking the conjunction of naturalism with the view that human beings have evolved in that way. I see no similar problems with the conjunction of theism and the idea that human beings have evolved in the way contemporary evolutionary science suggests.) More particularly, I argued that the conjunction of naturalism with the belief that we human beings have evolved in conformity with current evolutionary doctrine ... is in a certain interesting way self-defeating or self-referentially incoherent. — Alvin Plantinga, Naturalism Defeated?: Essays on Plantinga's Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism, "Introduction"[61] The argument is controversial and has been criticized as seriously flawed, for example, by Elliott Sober.[62][63] Robert T. Pennock Robert T. Pennock states that as supernatural agents and powers "are above and beyond the natural world and its agents and powers" and "are not constrained by natural laws", only logical impossibilities constrain what a supernatural agent cannot do. He says: "If we could apply natural knowledge to understand supernatural powers, then, by definition, they would not be supernatural." As the supernatural is necessarily a mystery to us, it can provide no grounds on which one can judge scientific models. "Experimentation requires observation and control of the variables.... But by definition we have no control over supernatural entities or forces." Science does not deal with meanings; the closed system of scientific reasoning cannot be used to define itself. Allowing science to appeal to untestable supernatural powers would make the scientist's task meaningless, undermine the discipline that allows science to make progress, and "would be as profoundly unsatisfying as the ancient Greek playwright's reliance upon the deus ex machina to extract his hero from a difficult predicament."[64] Naturalism of this sort says nothing about the existence or nonexistence of the supernatural, which by this definition is beyond natural testing. As a practical consideration, the rejection of supernatural explanations would merely be pragmatic, thus it would nonetheless be possible for an ontological supernaturalist to espouse and practice methodological naturalism. For example, scientists may believe in God while practicing methodological naturalism in their scientific work. This position does not preclude knowledge that is somehow connected to the supernatural. Generally however, anything that one can examine and explain scientifically would not be supernatural, simply by definition. Mousavirad Seyyed Jaaber Mousavirad distinguishes between epistemological and methodological naturalism. While he accepts that knowledge is not limited to sense perception and experimentation, he views methodological naturalism as a practical convention for pursuing universal science. Referring to Michael Ruse’s claim that science must exclude references to God[65], Mousavirad challenges the implication that empirical methods are the only valid path to knowledge. He argues that although natural sciences, by consensus, rely solely on sensory and empirical data, they cannot assert that empirical knowledge is the only form of factual knowledge. Natural science can report only on what is observable; it must remain neutral regarding metaphysical influences. Thus, while methodological naturalism is valid as a shared scientific approach, it cannot justify or refute knowledge from non-empirical source.[66] |

方法論的自然主義に関する見解 W. V. O. クワイン 主な記事: 自然化された認識論 W. V. O. クワインは、自然主義を「真理のより高い審判機関は自然科学そのもの以外に存在しない」という立場と定義する。彼の見解では、科学の主張を判断する上で科 学的方法に勝る手法はなく、科学や科学的方法を背後から支え正当化するような(抽象的な)形而上学や認識論といった「第一哲学」は必要もなければ存在意義 もない。 したがって、哲学は自らの探求において科学者の発見を自由に利用すると同時に、それらの主張が根拠を欠き、混乱し、あるいは矛盾している場合には自由に批 判を加えるべきである。クワインの見解では、哲学は科学と「連続的」であり、両者とも経験的である[55]。自然主義は、現代の科学観が完全に正しいとい う独断的な信念ではない。むしろ、科学が宇宙のプロセスを探求する最良の方法であり、それらのプロセスこそが現代科学が理解しようとしている対象であると 単純に主張するものである。[56] カール・ポパー カール・ポパーは自然主義を帰納的科学理論と同一視した。彼は帰納法に対する一般的な批判(帰納法の問題参照)に基づいてこれを拒否したが、仮説を構築する手段としての有用性は認めていた。 自然主義の方法論(時に「帰納的科学理論」と呼ばれる)には確かに価値がある。...しかし私は自然主義的見解を拒否する。それは批判的でないからだ。そ の支持者たちは、事実を発見したと信じるたびに、実際には単なる慣習を提案しているに過ぎないことに気づいていない。ゆえにその慣習は教条へと変質する危 険性がある。この自然主義的見解への批判は、その意味の基準だけでなく、科学の概念、ひいては経験的方法の概念にも当てはまる。 — カール・R・ポパー『科学的発見の論理』(Routledge, 2002年)、52–53頁、ISBN 0-415-27844-9。 ポパーは代わりに、科学は区別のために反証可能性に基づく方法論を採用すべきだと提案した。なぜなら、いかなる数の実験も理論を証明することは決してでき ないが、たった一つの実験が理論と矛盾する可能性があるからだ。ポパーは、科学的理論は反証可能性によって特徴づけられると主張する。 アルヴィン・プランティンガ ノートルダム大学名誉哲学教授でありキリスト教徒であるアルヴィン・プランティンガは、自然主義の著名な批判者となっている。[57][検証失敗] 彼は自然主義に対する進化論的論証において、進化が信頼できる真の信念を持つ人間を生み出した確率は、人間の進化が何らかの導き(例えば神による)を受け なかった限り、低い、あるいは不可解であると示唆している。グラスゴー大学のデイヴィッド・カハンによれば、信念がどのように正当化されるかを理解するた めには、プランティンガの認識論のように、超自然的な有神論の文脈において正当化の根拠を見出さねばならない。[58][59][60](超常刺激も参照 のこと)。 プランティンガは、自然主義と進化論が相まって「我々の認知能力が信頼できるという信念に対する克服不可能な反駁」を提供する、すなわちデカルトの悪意ある悪魔や脳槽の脳のような懐疑的論証をもたらすと論じる。[61] 哲学的自然主義とは、超自然的な実体は存在しないという信念である。例えば神という人格はおろか、他の超自然的な実体も、神に似たものも一切存在しないと いう立場だ。私の主張は、自然主義と現代の進化論は深刻な矛盾を抱えているというものだ。後者が通常、前者の構造を支える主要な支柱の一つと考えられてい るにもかかわらず、である。(もちろん、進化論そのものやその周辺を攻撃しているわけではない。むしろ、自然主義と「人類がそのような形で進化した」とい う見解の結合を攻撃しているのだ。神の存在を信じる立場と、現代の進化論が示唆する形で人類が進化したという考えの結合には、同様の問題は見当たらな い。) より具体的には、自然主義と、私たち人間は現在の進化論に従って進化したという信念との結びつきは、ある興味深い意味で、自己矛盾あるいは自己参照的に一 貫性を欠いていると私は主張した。 —アルヴィン・プランティンガ、『自然主義は敗北したか?:プランティンガの自然主義に対する進化論的議論に関するエッセイ』「序文」[61] この議論は物議を醸しており、エリオット・ソバーなどから重大な欠陥があると批判されている。 ロバート・T・ペノック ロバート・T・ペノックは、超自然的な存在や力は「自然界やその存在や力を超えた存在」であり、「自然法則に制約されない」ため、超自然的な存在ができな いことを制約するのは論理的に不可能なことだけだと述べている。彼はこう言う。「もし自然界の知識を適用して超自然的な力を理解できるなら、それは定義 上、超自然的な力ではないだろう」。超自然的なものは必然的に私たちにとって謎であるため、科学的なモデルを判断するための根拠は提供できない。「実験に は変数の観察と制御が必要だ...。しかし、定義上、私たちは超自然的な存在や力を制御することはできない」。科学は意味を扱うものではない。閉じた科学 的な推論のシステムは、それ自体を定義するために使用することはできない。科学が検証不可能な超自然的力に訴えることを許せば、科学者の任務は無意味とな り、科学の進歩を可能にする規律を損ない、「古代ギリシャの劇作家が困難な状況から主人公を救うためにデウス・エクス・マキナに依存したのと同じくらい深 く不満足なものとなるだろう」[64]。 この種の自然主義は、超自然的存在の有無について何も語らない。定義上、それは自然的検証を超越しているからだ。実用的な観点から言えば、超自然的説明の 拒絶は単なる実用主義に過ぎない。したがって、存在論的超自然主義者が方法論的自然主義を支持し実践することは依然として可能である。例えば、科学者は神 を信じつつ、科学研究においては方法論的自然主義を実践しうる。この立場は、何らかの形で超自然と結びついた知識を排除しない。しかし一般的に、科学的に 検証・説明可能なものは、定義上、超自然的ではない。 ムサヴィラッド セイェド・ジャアバー・ムサヴィラッドは認識論的自然主義と方法論的自然主義を区別する。彼は知識が感覚的知覚や実験に限定されないことを認めつつも、方 法論的自然主義を普遍的科学を追求するための実用的な慣習と見なす。マイケル・ルースの「科学は神への言及を排除すべきだ」という主張[65]に言及し、 ムサヴィラッドは経験的手法が唯一の有効な知識への道であるという含意に異議を唱える。彼は、自然科学が合意に基づき感覚的・経験的データのみに依拠する とはいえ、経験的知識が唯一の事実的知識形態だと断言できないと論じる。自然科学は観察可能な事象のみを報告でき、形而上学的な影響については中立を保た ねばならない。したがって方法論的自然主義は共有された科学的アプローチとして有効だが、非経験的源からの知識を正当化も反駁もできないのだ[66]。 |

| Atheism Clockwork universe Deism Empiricism Hylomorphism Legal naturalism Naturalist computationalism Naturalistic fallacy Naturalistic pantheism Philosophy of nature Physicalism Platonized naturalism Poetic naturalism Religious naturalism Scientism Sociological naturalism Spiritual naturalism Transcendental naturalism |

無神論 時計仕掛けの宇宙 自然神論 経験論 物質形態論 法的自然主義 自然主義的計算主義 自然主義的誤謬 自然主義的汎神論 自然哲学 物理主義 プラトン化された自然主義 詩的自然主義 宗教的自然主義 科学主義 社会学的自然主義 精神的自然主義 超越的自然主義 |

| References |

|

| References Audi, Robert (1996). "Naturalism". In Borchert, Donald M. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy Supplement. USA: Macmillan Reference. pp. 372–374. Carrier, Richard (2005). Sense and Goodness without God: A defense of Metaphysical Naturalism. AuthorHouse. p. 444. ISBN 1-4208-0293-3. Chen, Christina S. (2009). Larson, Thomas (ed.). "Atheism and the Assumptions of Science and Religion". Lyceum (2): 1–10. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Danto, Arthur C. (1967). "Naturalism". In Edwards, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: The Macmillan. pp. 448–450. Dubray, Charles Albert (1911). "Naturalism" . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Durak, Antoine Berke (6 June 2008). "The nature of reality and knowledge". Gauch, Hugh G. (2002). Scientific Method in Practice. Cambridge University Press. Gould, S. J. (1965). "Is uniformitarianism necessary?". American Journal of Science. 263 (3): 223–228. Bibcode:1965AmJS..263..223G. doi:10.2475/ajs.263.3.223. Gould, Stephen J. (1984). "Toward the vindication of punctuational change in catastrophes and earth history". In Bergren, W. A.; Van Couvering, J. A. (eds.). Catastrophes and Earth History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Gould, Stephen J. (1987). Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 119. Heilbron, John L., ed. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195112290. Hooykaas, R. (1963). The principle of uniformity in geology, biology, and theology (2nd ed.). London: E.J. Brill. Kurtz, Paul (1990). Philosophical Essays in Pragmatic Naturalism. Prometheus Books. Lacey, Alan R. (1995). "Naturalism". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 604–606. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0. Post, John F. (1995). "Naturalism". In Audi, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 517–518. Rea, Michael (2002). World Without Design: The Ontological Consequences of Naturalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924760-9. Sagan, Carl (2002). Cosmos. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50832-5. Schafersman, Steven D. (1996). "Naturalism is Today An Essential Part of Science". Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2010. Simpson, G. G. (1963). "Historical science". In Albritton, C. C. Jr. (ed.). Fabric of geology. Stanford, California: Freeman, Cooper, and Company. Sobottka, Stanley (2005). "Consciousness" (PDF). Strahler, Arthur N. (1992). Understanding Science: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues. Buffalo: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9780879757243. Stone, J.A. (2008). Religious Naturalism Today: The Rebirth of a Forgotten Alternative. G – Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. State University of New York Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7914-7537-9. LCCN 2007048682. Whitehead, A.N. (1997) [1920]. Science and the Modern World. Lowell Lectures. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-83639-3. LCCN 67002244. |

参考文献 アウディ、ロバート(1996)。「自然主義」。ドナルド・M・ボーチャート編『哲学百科事典補遺』。アメリカ:マクミラン・リファレンス。372–374頁。 キャリヤー、リチャード(2005)。『神なき感覚と善:形而上学的自然主義の擁護』。オーサーハウス。444頁。ISBN 1-4208-0293-3。 チェン、クリスティーナ・S.(2009)。ラーソン、トーマス(編)。「無神論と科学・宗教の前提」。『ライセウム』第2号:1–10頁。2014年3月26日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。 ダント、アーサー・C.(1967)。「自然主義」。エドワーズ、ポール(編)。『哲学百科事典』。ニューヨーク:マクミラン。pp. 448–450。 デュブレ、シャルル・アルベール (1911). 「自然主義」. ハーバーマン、チャールズ (編). 『カトリック百科事典』. 第10巻. ニューヨーク: ロバート・アップルトン社. デュラック、アントワーヌ・ベルケ (2008年6月6日). 「現実と知識の本質」. ゴーシュ、ヒュー・G. (2002). 『実践における科学的方法』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 グールド、S. J. (1965). 「均一説は必要か?」。『アメリカン・ジャーナル・オブ・サイエンス』263巻3号: 223–228頁。Bibcode:1965AmJS..263..223G. doi:10.2475/ajs.263.3.223. Gould, Stephen J. (1984). 「大災害と地球史における断続的変化の正当化に向けて」. In Bergren, W. A.; Van Couvering, J. A. (eds.). 『大災害と地球史』. ニュージャージー州プリンストン: プリンストン大学出版局. Gould, Stephen J. (1987). 『時の矢、時の循環:地質学的时间発見における神話と隠喩』. マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局. pp. 119. ハイルブロン, ジョン・L. 編 (2003). 『オックスフォード近代科学史事典』. オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0195112290. フーイカース、R.(1963)。『地質学、生物学、神学における均一性の原理』(第2版)。ロンドン:E.J.ブリル。 カーツ、ポール(1990)。『実用自然主義の哲学的エッセイ』。プロメテウス・ブックス。 レイシー、アラン・R.(1995)。「自然主義」. テド・ホンデリッチ編『オックスフォード哲学事典』. オックスフォード大学出版局. pp. 604–606. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0. ポスト, ジョン・F. (1995). 「自然主義」. ロバート・オーディ編『ケンブリッジ哲学辞典』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. pp. 517–518. レア、マイケル(2002)。『設計なき世界:自然主義の存在論的帰結』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 0-19-924760-9。 セーガン、カール(2002)。『コスモス』。ランダムハウス。ISBN 978-0-375-50832-5。 シェイファーズマン、スティーブン D. (1996). 「自然主義は今日の科学に欠かせない要素である」. 2019年7月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2010年11月3日取得。 シンプソン、G. G. (1963). 「歴史科学」. アルバリットン、C. C. Jr. (編). 地質学の構造。カリフォルニア州スタンフォード:フリーマン、クーパー、アンド・カンパニー。 ソボッカ、スタンリー (2005). 「意識」 (PDF). ストララー、アーサー N. (1992). 科学を理解する:概念と問題の紹介。バッファロー:プロメテウス・ブックス。ISBN 9780879757243. ストーン、J.A. (2008). 『今日の宗教的自然主義:忘れられた選択肢の復活』 G – 参考資料、情報、学際的テーマシリーズ。ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7914-7537-9. LCCN 2007048682. ホワイトヘッド、A.N.(1997)[1920]。『科学と現代世界』。ローウェル講義。フリープレス。ISBN 978-0-684-83639-3。LCCN 67002244。 |

| Further reading Mario De Caro and David Macarthur (eds) Naturalism in Question. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2004. Mario De Caro and David Macarthur (eds) Naturalism and Normativity. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010. Friedrich Albert Lange, The History of Materialism, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co Ltd, 1925, ISBN 0-415-22525-6 David Macarthur, "Quinean Naturalism in Question," Philo. vol 11, no. 1 (2008). Sander Verhaeg, Working from Within: The Nature and Development of Quine's Naturalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. |

追加文献(さらに読む) マリオ・デ・カロ、デイヴィッド・マッカーサー編『自然主義の問い』ケンブリッジ(マサチューセッツ州):ハーバード大学出版局、2004年。 マリオ・デ・カロ、デイヴィッド・マッカーサー編『自然主義と規範性』ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局、2010年。 フリードリヒ・アルベルト・ラング『唯物論の歴史』ロンドン:キーガン・ポール・トレンチ・トラブナー社、1925年、ISBN 0-415-22525-6 デイヴィッド・マッカーサー「クワイン的自然主義の問い」『Philo』第11巻第1号(2008年) サンダー・フェルヘーグ『内側から働く:クワインの自然主義の本質と発展』ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局、2018年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naturalism_(philosophy) |

Double

rainbow at Yosemite National Park. According to naturalism, the causes

of all phenomena are to be found within the universe and not

transcendental factors beyond it.

ヨセミテ国立公園の二重の虹。自然主義によれば、あらゆる現象の原因は宇宙の内部に求められ、それを超えた超越的な要因にはない。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099