ネアンデルタール人の文化

Neanderthals' Culture

Neanderthal

mother with child depicted in the Anthropos Pavilion of the Moravian

Museum

☆ ネアンデルタール人は大型の獲物に挑戦する狩猟民族であり、小さな集団で生活していたた め、現代の狩猟採集社会に見られるような性的分業は存在しなかったと指摘されることがある。つまり、男性が狩りをし、女性と子どもが採集をするのではな く、男性も女性も子どもも狩りに参加しなければならなかったのだ。さらに、ネアンデルタール人の男女の歯の摩耗パターンから、彼らは一般的に物を運ぶため に歯を使用していたことが示唆されるが、男性は上の歯、女性は下の歯の摩耗が多く、作業における文化的な違いがあることが示唆されている[272]。 ネアンデルタール人の中には、ヒョウの皮や猛禽類の羽のような装飾的な衣服や宝飾品を身につけ、集団の中での地位の高さを誇示していたという説もあり、論 争を呼んでいる。ヘイデンは、発見されたネアンデルタール人の墓の数が少ないのは、現代の狩猟採集民の一部と同じように、高位のメンバーだけが手の込んだ 埋葬を受けたからだと仮定した[36]。トリンカウスは、死亡率が高いことから、高齢のネアンデルタール人は長生きするために特別な埋葬儀式を受けたと示 唆した[25]。 [あるいは、より多くのネアンデルタール人が埋葬を受けたが、その墓はクマに侵入され破壊された可能性もある[273]。4歳以下のネアンデルタール人の 墓が20基発見されていることからすると、発見されている墓の3分の1を超える。 トリンカウスは、いくつかの自然の岩のシェルターから回収されたネアンデルタール人の骨格を見て、ネアンデルタール人はいくつかの外傷に関連した傷害を 負っていることが記録されているが、どの人も脚に大きな外傷を負っておらず、動きが衰弱していたと述べている。トリンカウスは、ネアンデルタール人の文化 における自己の価値は、集団に食料を提供することに由来しており、衰弱した怪我はこの自己の価値をなくし、ほぼ即座に死に至ることになり、洞窟から洞窟へ と移動する間に集団についていけなくなった個体は取り残されることになると示唆した [25] 。 [25]しかし、非常に衰弱しやすい怪我をした個体が数年間看護された例があり、コミュニティ内で最も弱い立場にある個体の世話は、ハイデルベルゲンシス まで遡ることができる[47][254]。特に外傷率が高いことを考えると、このような利他的な戦略が、長い間種としての生存を保証していた可能性がある [47]。

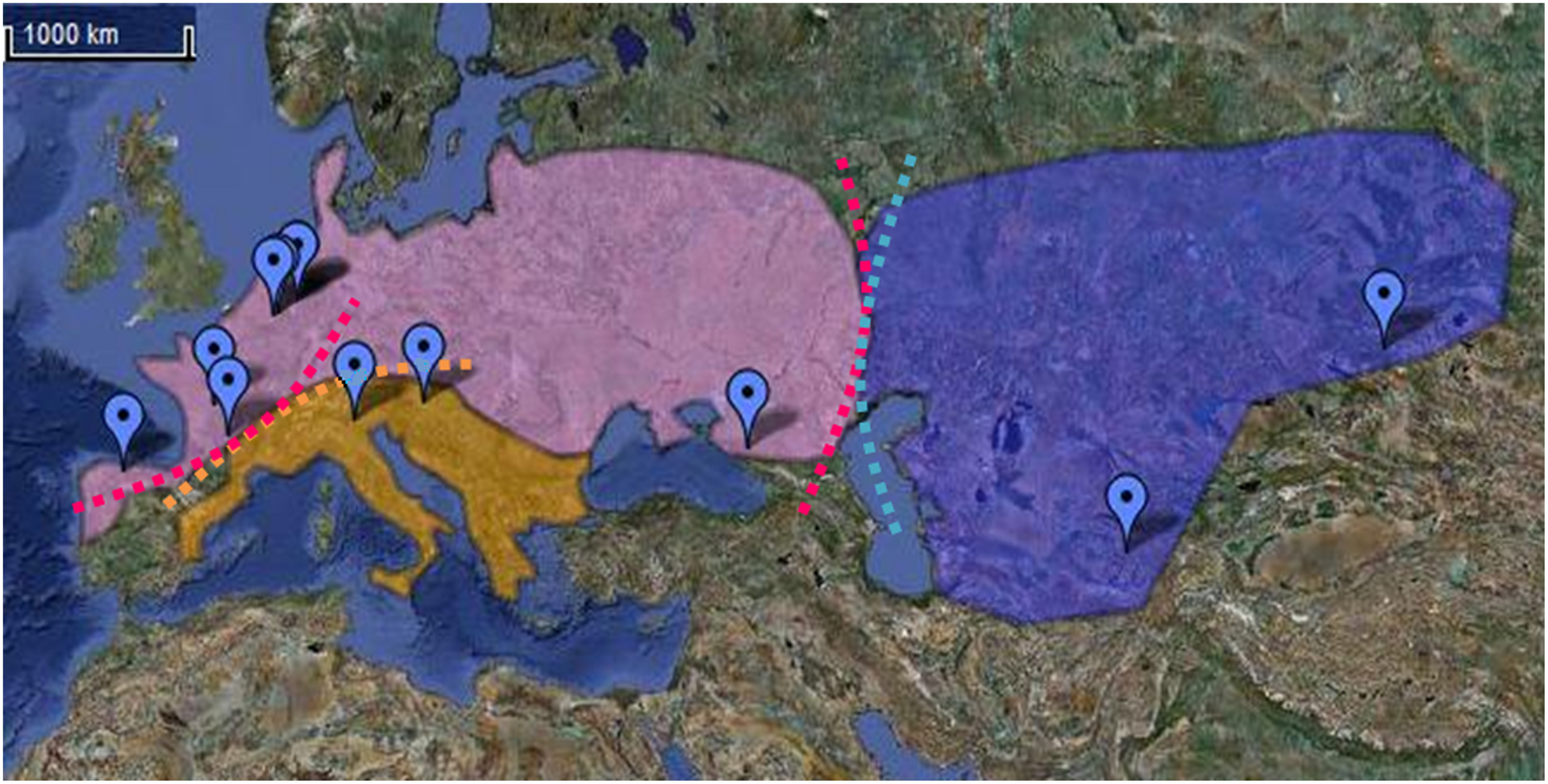

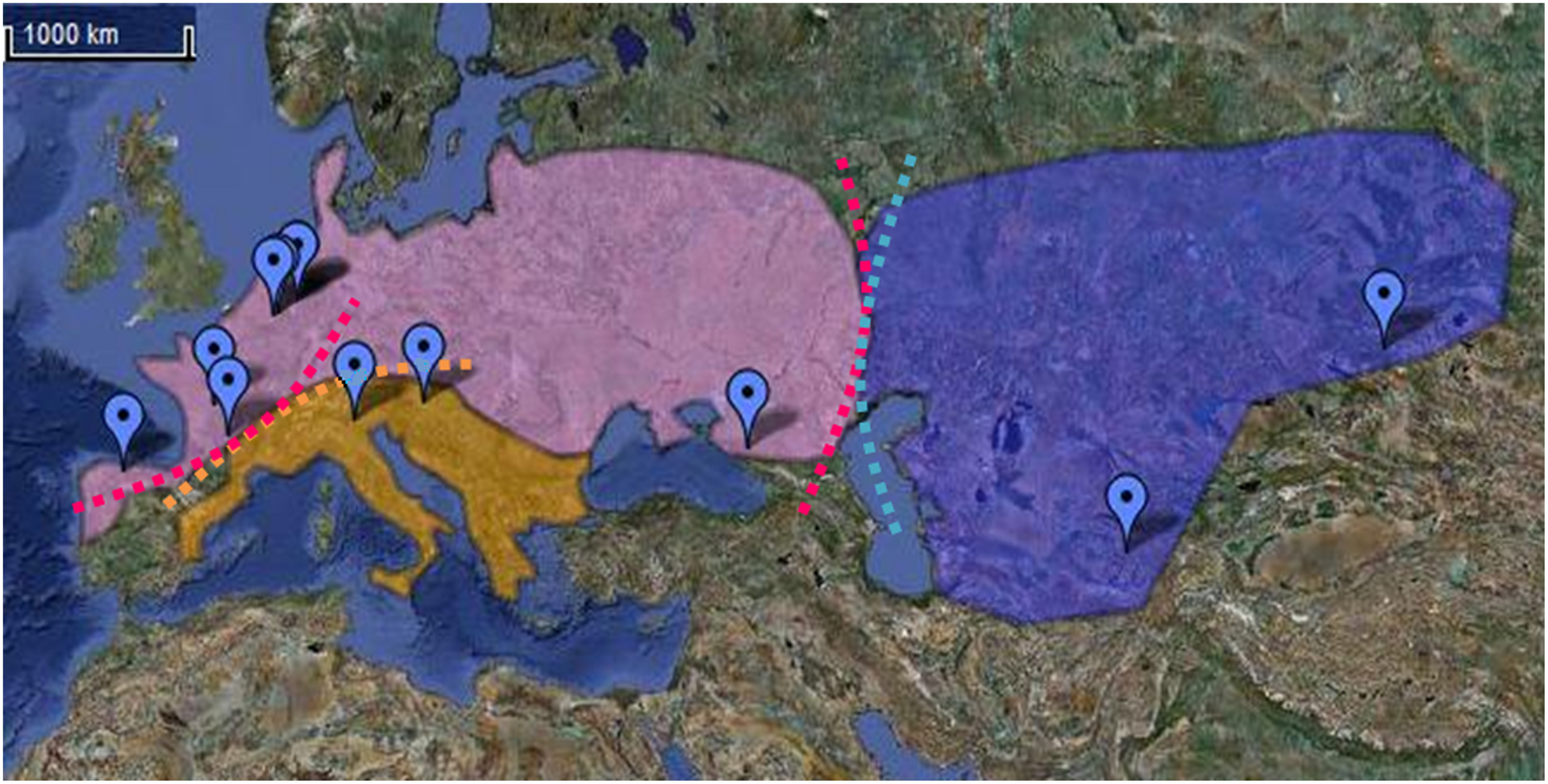

| Culture Main article: Neanderthal behavior Social structure Group dynamics  Skeleton of a Neanderthal child discovered in Roc de Marsal near Les Eyzies, France, on display at the Hall of Human Origins, Washington, D.C. Neanderthals likely lived in more sparsely distributed groups than contemporary modern humans,[176] but group size is thought to have averaged 10 to 30 individuals, similar to modern hunter-gatherers.[36] Reliable evidence of Neanderthal group composition comes from Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, and the footprints at Le Rozel, France:[188] the former shows 7 adults, 3 adolescents, 2 juveniles and an infant;[253] whereas the latter, based on footprint size, shows a group of 10 to 13 members where juveniles and adolescents made up 90%.[188] A Neanderthal child's teeth analysed in 2018 showed it was weaned after 2.5 years, similar to modern hunter gatherers, and was born in the spring, which is consistent with modern humans and other mammals whose birth cycles coincide with environmental cycles.[252] Indicated from various ailments resulting from high stress at a low age, such as stunted growth, British archaeologist Paul Pettitt hypothesised that children of both sexes were put to work directly after weaning;[183] and Trinkaus said that, upon reaching adolescence, an individual may have been expected to join in hunting large and dangerous game.[25] However, the bone trauma is comparable to modern Inuit, which could suggest a similar childhood between Neanderthals and contemporary modern humans.[254] Further, such stunting may have also resulted from harsh winters and bouts of low food resources.[252] Sites showing evidence of no more than three individuals may have represented nuclear families or temporary camping sites for special task groups (such as a hunting party).[36] Bands likely moved between certain caves depending on the season, indicated by remains of seasonal materials such as certain foods, and returned to the same locations generation after generation. Some sites may have been used for over 100 years.[255] Cave bears may have greatly competed with Neanderthals for cave space,[256] and there is a decline in cave bear populations starting 50,000 years ago onwards (although their extinction occurred well after Neanderthals had died out).[257][258] Neanderthals also had a preference for caves whose openings faced towards the south.[259] Although Neanderthals are generally considered to have been cave dwellers, with 'home base' being a cave, open-air settlements near contemporaneously inhabited cave systems in the Levant could indicate mobility between cave and open-air bases in this area. Evidence for long-term open-air settlements is known from the 'Ein Qashish site in Israel,[260][261] and Moldova I in Ukraine. Although Neanderthals appear to have had the ability to inhabit a range of environments—including plains and plateaux—open-air Neanderthals sites are generally interpreted as having been used as slaughtering and butchering grounds rather than living spaces.[29] In 2022, remains of the first-known Neanderthal family (six adults and five children) were excavated from Chagyrskaya Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia in Russia. The family, which included a father, a daughter, and what appear to be cousins, most likely died together, presumably from starvation.[262][263] Neanderthals, like contemporaneous modern humans, were most likely polygynous, based on their low second-to-fourth digit ratios, a biomarker for prenatal androgen effects that corresponds to high incidence of polygyny in haplorhine primates.[264] Inter-group relations  Neanderthal mother with child depicted in the Anthropos Pavilion of the Moravian Museum Canadian ethnoarchaeologist Brian Hayden calculated a self-sustaining population that avoids inbreeding to consist of about 450–500 individuals, which would necessitate these bands to interact with 8–53 other bands, but more likely the larger estimate given low population density.[36] Analysis of the mtDNA of the Neanderthals of Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, showed that the three adult men belonged to the same maternal lineage, while the three adult women belonged to different ones. This suggests a patrilocal residence (that a woman moved out of her group to live with her partner).[265] However, the DNA of a Neanderthal from Denisova Cave, Russia, shows that she had an inbreeding coefficient of 1⁄8 (her parents were either half-siblings with a common mother, double first cousins, an uncle and niece or aunt and nephew, or a grandfather and granddaughter or grandmother and grandson)[92] and the inhabitants of Cueva del Sidrón show several defects, which may have been caused by inbreeding or recessive disorders.[244] Considering most Neanderthal artefacts were sourced no more than 5 km (3.1 mi) from the main settlement, Hayden considered it unlikely these bands interacted very often,[36] and mapping of the Neanderthal brain and their small group size and population density could indicate that they had a reduced ability for inter-group interaction and trade.[204] However, a few Neanderthal artefacts in a settlement could have originated 20, 30, 100 and 300 km (12.5, 18.5, 60 and 185 mi) away. Based on this, Hayden also speculated that macro-bands formed which functioned much like those of the low-density hunter-gatherer societies of the Western Desert of Australia. Macro-bands collectively encompass 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi), with each band claiming 1,200–2,800 km2 (460–1,080 sq mi), maintaining strong alliances for mating networks or to cope with leaner times and enemies.[36] Similarly, British anthropologist Eiluned Pearce and Cypriot archaeologist Theodora Moutsiou speculated that Neanderthals were possibly capable of forming geographically expansive ethnolinguistic tribes encompassing upwards of 800 people, based on the transport of obsidian up to 300 km (190 mi) from the source compared to trends seen in obsidian transfer distance and tribe size in modern hunter-gatherers. However, according to their model Neanderthals would not have been as efficient at maintaining long-distance networks as modern humans, probably due to a significantly lower population.[266] Hayden noted an apparent cemetery of six or seven individuals at La Ferrassie, France, which, in modern humans, is typically used as evidence of a corporate group which maintained a distinct social identity and controlled some resource, trading, manufacturing and so on. La Ferrassie is also located in one of the richest animal-migration routes of Pleistocene Europe.[36]  Genetically, Neanderthals can be grouped into three distinct regions (above). Dots indicate sampled specimens.[28] Genetic analysis indicates there were at least three distinct geographical groups—Western Europe, the Mediterranean coast, and east of the Caucasus—with some migration among these regions.[28] Post-Eemian Western European Mousterian lithics can also be broadly grouped into three distinct macro-regions: Acheulean-tradition Mousterian in the southwest, Micoquien in the northeast, and Mousterian with bifacial tools (MBT) in between the former two. MBT may actually represent the interactions and fusion of the two different cultures.[27] Southern Neanderthals exhibit regional anatomical differences from northern counterparts: a less protrusive jaw, a shorter gap behind the molars, and a vertically higher jawbone.[267] These all instead suggest Neanderthal communities regularly interacted with neighbouring communities within a region, but not as often beyond.[27] Nonetheless, over long periods of time, there is evidence of large-scale cross-continental migration. Early specimens from Mezmaiskaya Cave in the Caucasus[139] and Denisova Cave in the Siberian Altai Mountains[90] differ genetically from those found in Western Europe, whereas later specimens from these caves both have genetic profiles more similar to Western European Neanderthal specimens than to the earlier specimens from the same locations, suggesting long-range migration and population replacement over time.[90][139] Similarly, artefacts and DNA from Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Caves, also in the Altai Mountains, resemble those of eastern European Neanderthal sites about 3,000–4,000 km (1,900–2,500 mi) away more than they do artefacts and DNA of the older Neanderthals from Denisova Cave, suggesting two distinct migration events into Siberia.[268] Neanderthals seem to have suffered a major population decline during MIS 4 (71–57,000 years ago), and the distribution of the Micoquian tradition could indicate that Central Europe and the Caucasus were repopulated by communities from a refuge zone either in eastern France or Hungary (the fringes of the Micoquian tradition) who dispersed along the rivers Prut and Dniester.[269] There is also evidence of inter-group conflict: a skeleton from La Roche à Pierrot, France, showing a healed fracture on top of the skull apparently caused by a deep blade wound,[270] and another from Shanidar Cave, Iraq, found to have a rib lesion characteristic of projectile weapon injuries.[271] |

文化 主な記事 ネアンデルタール人の行動 社会構造 集団力学  フランスのLes Eyzies近郊のRoc de Marsalで発見されたネアンデルタール人の子供の骨格。 ネアンデルタール人は現代の人類よりもまばらに分散した集団で生活していた可能性が高いが[176]、集団のサイズは現代の狩猟採集民と同様に平均 10~30人であったと考えられている。 [36]ネアンデルタール人の集団構成に関する信頼できる証拠は、スペインのクエバ・デル・シドロンとフランスのル・ロゼルの足跡から得られている [188]。前者では7人の大人、3人の青年、2人の幼年、1人の幼児が確認されており[253]、後者では足跡の大きさから10人から13人の集団が確 認されており、幼年と青年が90%を占めていた[188]。 2018年に分析されたネアンデルタール人の子供の歯は、現代の狩猟採集民と同様に2.5年後に離乳し、春に生まれたことを示しており、これは出生サイク ルが環境サイクルと一致する現代人や他の哺乳類と一致している。 イギリスの考古学者ポール・ペティットは、発育不全など低年齢時の高ストレスから生じる様々な病気から、男女の子どもは離乳後に直接働かされていたという 仮説を立て[183]、トリンカウスは、思春期に達すると、個体は大型で危険な狩猟に参加することが期待されていたかもしれないと述べている[25]。 [25]しかし、骨の外傷は現代のイヌイットに匹敵するものであり、ネアンデルタール人と現代の人類の間に同じような幼年期があったことを示唆している [254]。さらに、このような発育阻害は、厳しい冬や食糧資源の少ない時期にも起因していた可能性がある[252]。 3人以上の痕跡がある遺跡は、核家族であったか、特別なタスク・グループ(狩猟隊など)のための一時的なキャンプ地であった可能性がある[36]。特定の 食品などの季節的な材料の遺跡によって示されるように、バンドは季節によって特定の洞窟の間を移動し、世代を超えて同じ場所に戻ってきた可能性が高い。洞 窟クマは洞窟のスペースをネアンデルタール人と非常に競合していた可能性があり[256]、5万年前以降に洞窟クマの個体数が減少している(ただし、洞窟 クマの絶滅はネアンデルタール人が絶滅したかなり後に起こった)。 [257][258]ネアンデルタール人はまた、開口部が南に向いている洞窟を好んでいた[259]。ネアンデルタール人は一般的に洞窟居住者であり、 「本拠地」は洞窟であったと考えられているが、レバントの同時代に居住していた洞窟システムの近くに野外集落があったことは、この地域における洞窟と野外 の拠点間の移動を示している可能性がある。イスラエルのアイン・カシシュ遺跡[260][261]やウクライナのモルドバI遺跡からは、長期にわたる野外 居住の証拠が知られている。ネアンデルタール人は、平原や高原を含む様々な環境に居住する能力を持っていたようであるが、野外のネアンデルタール人遺跡は 一般的に、居住空間というよりもむしろ屠殺場や屠殺場として使われていたと解釈されている[29]。 2022年、ロシア、シベリア南部のアルタイ山脈にあるチャギルスカヤ洞窟から、初めて確認されたネアンデルタール人の家族(大人6人と子供5人)の遺骨 が発掘された。この家族には父親と娘、そして従兄弟と思われる者たちが含まれていたが、おそらく飢餓のために一緒に死亡した可能性が高い[262] [263]。 ネアンデルタール人は、同時代の現生人類と同様に、ハプロ霊長類における多夫多妻の高い発生率に対応する、出生前のアンドロゲン効果のバイオマーカーであ る低い2桁目から4桁目の比率に基づくと、多夫多妻であった可能性が高い[264]。 集団間の関係  モラヴィア博物館のアントロポス・パビリオンに展示されているネアンデルタール人の母親と子供。 カナダの民族考古学者であるブライアン・ヘイデンは、近親交配を回避して自立した集団を構成する個体数を約450~500と計算した。このことは、父系的 居住(女性がパートナーと暮らすために集団から移動したこと)を示唆している。 [265]しかし、ロシアのデニソワ洞窟で発見されたネアンデルタール人のDNAは、彼女の近親交配係数が1/8であることを示している(彼女の両親は共 通の母親を持つ異母兄妹、二重の第一いとこ、叔父と姪、叔母と甥、または祖父と孫娘、祖母と孫であった)[92]。 ヘイデンは、ネアンデルタール人の遺物のほとんどが主要な集落から5キロ(3.1マイル)以内しか離れていないことを考慮すると、これらの集団が頻繁に交 流していた可能性は低いと考えており[36]、ネアンデルタール人の脳のマッピングとその小さな集団サイズと人口密度は、彼らが集団間の交流や交易の能力 を低下させていたことを示している可能性がある[204] 。ヘイデンはまた、これに基づき、オーストラリアの西部砂漠の低密度狩猟採集社会と同じような機能を持つマクロバンドが形成されたと推測した。マクロバン ドは全体で13,000平方キロメートル(5,000平方マイル)をカバーし、各バンドは1,200~2,800平方キロメートル(460~1,080平 方マイル)を主張し、交配ネットワークのために、あるいは痩せた時代や敵に対処するために強固な同盟関係を維持していた。 [同様に、イギリスの人類学者Eiluned Pearceとキプロスの考古学者Theodora Moutsiouは、現代の狩猟採集民の黒曜石の移動距離と部族の規模に見られる傾向と比較して、黒曜石を原産地から300km(190マイル)まで輸送 することに基づいて、ネアンデルタール人は800人以上を含む地理的に広大な民族言語的部族を形成することが可能であった可能性があると推測した。しか し、彼らのモデルによれば、ネアンデルタール人は現代人ほど長距離ネットワークを維持する効率は高くなかったはずであり、その理由はおそらく人口が著しく 少なかったからであろう[266]。ヘイデンは、フランスのラ・フェラッシーに6、7人の墓地があったことを指摘している。これは現代人においては、通 常、明確な社会的アイデンティティを維持し、何らかの資源、交易、製造などを支配していた企業集団の証拠として用いられる。ラ・フェラッシーはまた、更新 世ヨーロッパの最も豊かな動物移動ルートのひとつに位置している[36]。  遺伝学的に、ネアンデルタール人は3つの異なる地域にグループ分けされる(上)。点はサンプリングされた標本を示す[28]。 遺伝学的分析によれば、少なくとも3つの異なる地理的グループ-西ヨーロッパ、地中海沿岸、コーカサス東部-が存在し、これらの地域間で若干の移動があっ たことが示されている[28]。ポスト・エマ紀の西ヨーロッパのムステリアン石器もまた、3つの異なるマクロ地域に大別することができる: 南西部のアシュレアン-伝統的モウステリアン、北東部のミコキエン、そして前2者の中間に位置するモウステリアン(MBT)である。MBTは、実際には2 つの異なる文化の相互作用と融合を表しているのかもしれない[27]。南部のネアンデルタール人は、北部のネアンデルタール人とは地域的な解剖学的差異を 示す:突出した顎が少なく、臼歯の後ろの隙間が短く、顎骨が垂直に高い。 それにもかかわらず、長期間にわたって、大陸を横断する大規模な移動の証拠がある。コーカサスのメズマイスカヤ洞窟[139]やシベリアのアルタイ山脈に あるデニソワ洞窟[90]で発見された初期の標本は、西ヨーロッパで発見された標本とは遺伝学的に異なっているが、これらの洞窟で発見された後期の標本 は、同じ場所で発見された初期の標本よりも西ヨーロッパのネアンデルタール人の標本に近い遺伝的プロファイルを持っている。 [同様に、同じくアルタイ山脈にあるチャギルスカヤ洞窟とオクラドニコフ洞窟の遺物やDNAは、デニソワ洞窟の古いネアンデルタール人の遺物やDNAより も、約3,000~4,000km(1,900~2,500マイル)離れた東ヨーロッパのネアンデルタール人の遺跡の遺物やDNAに似ており、シベリアへ の2つの異なる移動の出来事を示唆している。 [268]ネアンデルタール人はMIS 4(71-57,000年前)の間に大きな人口減少に見舞われたようであり、ミコキア人の伝統の分布は、中央ヨーロッパとコーカサスが、プルート川とドニ エステル川に沿って分散したフランス東部かハンガリー(ミコキア人の伝統の周縁部)のいずれかの避難地帯から再入植したことを示している可能性がある [269]。 フランスのラ・ロッシュ・ア・ピエロ(La Roche à Pierrot)から出土した骸骨には、刃物による深い傷によって引き起こされたと思われる頭蓋骨上部の治癒した骨折が見られ[270]、イラクのシャニ ダール洞窟から出土した骸骨には、投擲武器による傷害に特徴的な肋骨の病変が見られた[271]。 |

Social hierarchy Reconstruction of an elderly Neanderthal man and child in the Natural History Museum, Vienna It is sometimes suggested that, since they were hunters of challenging big game and lived in small groups, there was no sexual division of labour as seen in modern hunter-gatherer societies. That is, men, women and children all had to be involved in hunting, instead of men hunting with women and children foraging. However, with modern hunter-gatherers, the higher the meat dependency, the higher the division of labour.[36] Further, tooth-wearing patterns in Neanderthal men and women suggest they commonly used their teeth for carrying items, but men exhibit more wearing on the upper teeth, and women the lower, suggesting some cultural differences in tasks.[272] It is controversially proposed that some Neanderthals wore decorative clothing or jewellery—such as a leopard skin or raptor feathers—to display elevated status in the group. Hayden postulated that the small number of Neanderthal graves found was because only high-ranking members would receive an elaborate burial, as is the case for some modern hunter-gatherers.[36] Trinkaus suggested that elderly Neanderthals were given special burial rites for lasting so long given the high mortality rates.[25] Alternatively, many more Neanderthals may have received burials, but the graves were infiltrated and destroyed by bears.[273] Given that 20 graves of Neanderthals aged under 4 have been found—over a third of all known graves—deceased children may have received greater care during burial than other age demographics.[254] Looking at Neanderthal skeletons recovered from several natural rock shelters, Trinkaus said that, although Neanderthals were recorded as bearing several trauma-related injuries, none of them had significant trauma to the legs that would debilitate movement. He suggested that self worth in Neanderthal culture derived from contributing food to the group; a debilitating injury would remove this self-worth and result in near-immediate death, and individuals who could not keep up with the group while moving from cave to cave were left behind.[25] However, there are examples of individuals with highly debilitating injuries being nursed for several years, and caring for the most vulnerable within the community dates even further back to H. heidelbergensis.[47][254] Especially given the high trauma rates, it is possible that such an altruistic strategy ensured their survival as a species for so long.[47] |

社会階層 ウィーンの自然史博物館にあるネアンデルタール人の老人と子供の復元像 ネアンデルタール人は大型の獲物に挑戦する狩猟民族であり、小さな集団で生活していたため、現代の狩猟採集社会に見られるような性的分業は存在しなかった と指摘されることがある。つまり、男性が狩りをし、女性と子どもが採集をするのではなく、男性も女性も子どもも狩りに参加しなければならなかったのだ。さ らに、ネアンデルタール人の男女の歯の摩耗パターンから、彼らは一般的に物を運ぶために歯を使用していたことが示唆されるが、男性は上の歯、女性は下の歯 の摩耗が多く、作業における文化的な違いがあることが示唆されている[272]。 ネアンデルタール人の中には、ヒョウの皮や猛禽類の羽のような装飾的な衣服や宝飾品を身につけ、集団の中での地位の高さを誇示していたという説もあり、論 争を呼んでいる。ヘイデンは、発見されたネアンデルタール人の墓の数が少ないのは、現代の狩猟採集民の一部と同じように、高位のメンバーだけが手の込んだ 埋葬を受けたからだと仮定した[36]。トリンカウスは、死亡率が高いことから、高齢のネアンデルタール人は長生きするために特別な埋葬儀式を受けたと示 唆した[25]。 [あるいは、より多くのネアンデルタール人が埋葬を受けたが、その墓はクマに侵入され破壊された可能性もある[273]。4歳以下のネアンデルタール人の 墓が20基発見されていることからすると、発見されている墓の3分の1を超える。 トリンカウスは、いくつかの自然の岩のシェルターから回収されたネアンデルタール人の骨格を見て、ネアンデルタール人はいくつかの外傷に関連した傷害を 負っていることが記録されているが、どの人も脚に大きな外傷を負っておらず、動きが衰弱していたと述べている。トリンカウスは、ネアンデルタール人の文化 における自己の価値は、集団に食料を提供することに由来しており、衰弱した怪我はこの自己の価値をなくし、ほぼ即座に死に至ることになり、洞窟から洞窟へ と移動する間に集団についていけなくなった個体は取り残されることになると示唆した [25] 。 [25]しかし、非常に衰弱しやすい怪我をした個体が数年間看護された例があり、コミュニティ内で最も弱い立場にある個体の世話は、ハイデルベルゲンシス まで遡ることができる[47][254]。特に外傷率が高いことを考えると、このような利他的な戦略が、長い間種としての生存を保証していた可能性がある [47]。 |

| Food See also: Pleistocene human diet Hunting and gathering  Two red deer in a forest. One is facing the camera and the other is eating grass to its left Red deer, the most commonly hunted Neanderthal game[48][51] Neanderthals were once thought of as scavengers, but are now considered to have been apex predators.[274][275] In 1980, it was hypothesised that two piles of mammoth skulls at La Cotte de St Brelade, Jersey, at the base of a gulley were evidence of mammoth drive hunting (causing them to stampede off a ledge),[276] but this is contested.[277] Living in a forested environment, Neanderthals were likely ambush hunters, getting close to and attacking their target—a prime adult—in a short burst of speed, thrusting in a spear at close quarters.[71][278] Younger or wounded animals may have been hunted using traps, projectiles, or pursuit.[278] Some sites show evidence that Neanderthals slaughtered whole herds of animals in large, indiscriminate hunts and then carefully selected which carcasses to process.[279] Nonetheless, they were able to adapt to a variety of habitats.[56][277] They appear to have eaten predominantly what was abundant within their immediate surroundings,[58] with steppe-dwelling communities (generally outside of the Mediterranean) subsisting almost entirely on meat from large game, forest-dwelling communities consuming a wide array of plants and smaller animals, and waterside communities gathering aquatic resources, although even in more southerly, temperate areas such as the southeastern Iberian Peninsula, large game still featured prominently in Neanderthal diets.[280] Contemporary humans, in contrast, seem to have used more complex food extraction strategies and generally had a more diverse diet.[281] Nonetheless, Neanderthals still would have had to have eaten a varied enough diet to prevent nutrient deficiencies and protein poisoning, especially in the winter when they presumably ate mostly lean meat. Any food with high contents of other essential nutrients not provided by lean meat would have been vital components of their diet, such as fat-rich brains,[47] carbohydrate-rich and abundant underground storage organs (including roots and tubers),[282] or, like modern Inuit, the stomach contents of herbivorous prey items.[283] For meat, Neanderthals appear to have fed predominantly on hoofed mammals.[284] They primarily consumed red deer and reindeer, as these two were the most abundant game;[51][285] however, they also ate other Pleistocene megafauna such as chamois,[286] ibex,[287] wild boar,[286] steppe wisent,[288] aurochs,[286] Irish elk,[289] woolly mammoth,[290] straight-tusked elephant,[291] woolly rhinoceros,[292] Merck's rhinoceros[293] the narrow-nosed rhinoceros,[294] wild horse,[285] and so on.[30][52][295] There is evidence of directed cave and brown bear hunting both in and out of hibernation, as well as butchering.[296] Analysis of Neanderthal bone collagen from Vindija Cave, Croatia, shows nearly all of their protein needs derived from animal meat.[52] Some caves show evidence of regular rabbit and tortoise consumption. At Gibraltar sites, there are remains of 143 different bird species, many ground-dwelling such as the common quail, corn crake, woodlark, and crested lark.[56] Scavenging birds such as corvids and eagles were commonly exploited.[297] Neanderthals also exploited marine resources on the Iberian, Italian and Peloponnesian Peninsulas, where they waded or dived for shellfish,[56][298][299] as early as 150,000 years ago at Cueva Bajondillo, Spain, similar to the fishing record of modern humans.[300] At Vanguard Cave, Gibraltar, the inhabitants consumed Mediterranean monk seal, short-beaked common dolphin, common bottlenose dolphin, Atlantic bluefin tuna, sea bream and purple sea urchin;[56][301] and at Gruta da Figueira Brava, Portugal, there is evidence of large-scale harvest of shellfish, crabs and fish.[302] Evidence of freshwater fishing was found in Grotte di Castelcivita, Italy, for trout, chub and eel;[299] Abri du Maras, France, for chub and European perch; Payré, France;[303] and Kudaro Cave, Russia, for Black Sea salmon.[304] Edible plant and mushroom remains are recorded from several caves.[54] Neanderthals from Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, based on dental tartar, likely had a meatless diet of mushrooms, pine nuts and moss, indicating they were forest foragers.[249] Remnants from Amud Cave, Israel, indicates a diet of figs, palm tree fruits and various cereals and edible grasses.[55] Several bone traumas in the leg joints could possibly suggest habitual squatting, which, if the case, was likely done while gathering food.[305] Dental tartar from Grotte de Spy, Belgium, indicates the inhabitants had a meat-heavy diet including woolly rhinoceros and mouflon sheep, while also regularly consuming mushrooms.[249] Neanderthal faecal matter from El Salt, Spain, dated to 50,000 years ago—the oldest human faecal matter remains recorded—show a diet mainly of meat but with a significant component of plants.[306] Evidence of cooked plant foods—mainly legumes and, to a far lesser extent, acorns—was discovered at the Kebara Cave site in Israel, with its inhabitants possibly gathering plants in spring and fall and hunting in all seasons except fall, although the cave was probably abandoned in late summer to early fall.[45] At Shanidar Cave, Iraq, Neanderthals collected plants with various harvest seasons, indicating they scheduled returns to the area to harvest certain plants, and that they had complex food-gathering behaviours for both meat and plants.[53] Food preparation Neanderthals probably could employ a wide range of cooking techniques, such as roasting, and they may have been able to heat up or boil soup, stew, or animal stock.[49] The abundance of animal bone fragments at settlements may indicate the making of fat stocks from boiling bone marrow, possibly taken from animals that had already died of starvation. These methods would have substantially increased fat consumption, which was a major nutritional requirement of communities with low carbohydrate and high protein intake.[49][307] Neanderthal tooth size had a decreasing trend after 100,000 years ago, which could indicate an increased dependence on cooking or the advent of boiling, a technique that would have softened food.[308]  Small white flowers with a red-striped black bug sitting on top Yarrow growing in Spain At Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, Neanderthals likely cooked and possibly smoked food,[50] as well as used certain plants—such as yarrow and camomile—as flavouring,[49] although these plants may have instead been used for their medicinal properties.[44] At Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, Neanderthals may have been roasting pinecones to access pine nuts.[56] At Grotte du Lazaret, France, a total of twenty-three red deer, six ibexes, three aurochs, and one roe deer appear to have been hunted in a single autumn hunting season, when strong male and female deer herds would group together for rut. The entire carcasses seem to have been transported to the cave and then butchered. Because this is such a large amount of food to consume before spoilage, it is possible these Neanderthals were curing and preserving it before winter set in. At 160,000 years old, it is the oldest potential evidence of food storage.[48] The great quantities of meat and fat which could have been gathered in general from typical prey items (namely mammoths) could also indicate food storage capability.[309] With shellfish, Neanderthals needed to eat, cook, or in some manner preserve them soon after collection, as shellfish spoils very quickly. At Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the remains of edible, algae eating shellfish associated with the alga Jania rubens could indicate that, like some modern hunter gatherer societies, harvested shellfish were held in water-soaked algae to keep them alive and fresh until consumption.[310] |

食べ物 こちらも参照のこと: 更新世人類の食生活 狩猟と採集  森の中にいる2頭のアカシカ。1頭はカメラの方を向き、もう1頭はその左側で草を食べている。 ネアンデルタール人が最もよく狩猟したアカシカ[48][51]。 ネアンデルタール人はかつてスカベンジャーであったと考えられていたが、現在では頂点捕食者であったと考えられている[274][275]。 1980年、ジャージー州のラ・コット・ド・サン・ブレラードにある渓谷の底にある2つのマンモスの頭蓋骨の山は、マンモスの追い込み狩猟(岩棚から飛び 降りさせる)の証拠であるという仮説が立てられたが[276]、これには異論がある。 [277] 森林に囲まれた環境に住んでいたネアンデルタール人は、おそらく待ち伏せ狩猟者であり、ターゲットである素質のある成獣に接近し、至近距離から槍を突き刺 して、短時間のスピードで攻撃したのであろう[71][278]。 [278] いくつかの遺跡では、ネアンデルタール人が大規模な無差別狩猟で動物の群れ全体を屠殺し、その後どの死骸を処理するかを注意深く選んでいた証拠がある [279] 。 [草原に住む地域社会(一般に地中海沿岸以外の地域)では大型の狩猟動物の肉類を、森林に住む地域社会では多種多様な植物や小動物を、水辺に住む地域社会 では水生資源を、それぞれ食べていたようであるが、イベリア半島南東部のような南寄りの温帯地域でも、ネアンデルタール人の食生活には大型の狩猟動物が依 然として大きな比重を占めていた。 [280]。対照的に、現代人はより複雑な食物抽出戦略を用い、一般的にはより多様な食生活を送っていたようである[281]。それでもなお、ネアンデル タール人は、栄養不足やタンパク質中毒を防ぐために、特に赤身の肉を主に食べていたと推定される冬には、十分に多様な食生活を送っていたはずである。赤身 肉では供給されない他の必須栄養素を多く含む食品は、脂肪が豊富な脳[47]、炭水化物が豊富で豊富な地下貯蔵器官(根や塊茎を含む)[282]、あるい は現代のイヌイットのように草食性の獲物の胃の内容物[283]など、彼らの食事に不可欠な構成要素であったであろう。 肉については、ネアンデルタール人は主に蹄のある哺乳類を食べていたようである。 [284] ネアンデルタール人は主にアカシカとトナカイを食べていた; [51][285]しかし、シャモア、[286]アイベックス、[287]イノシシ、[286]ステップ・ワイゼント、[288]オーロックス、 [286]アイリッシュ・エルクといった他の更新世巨大動物も食べていた、 [289]ウーリーマンモス、[290]牙のまっすぐなゾウ、[291]ウーリーサイ、[292]メルクサイ[293]細鼻サイ、[294]野生馬、 [285]などがいる。 [30][52][295]冬眠中と冬眠明けの両方において、指示された洞窟やヒグマの狩猟の証拠があり、屠殺も行われていた[296]。 クロアチアのヴィンディヤ洞窟から出土したネアンデルタール人の骨のコラーゲンの分析によれば、彼らが必要としたタンパク質のほぼすべてが動物の肉に由来 していたことが示されている[52]。 いくつかの洞窟では、ウサギやカメを定期的に摂取していた証拠がある。ジブラルタルの遺跡では、143種の鳥類の遺骨が見つかっており、その多くはウズ ラ、ヤブサメ、キバシリ、ヒバリなどの地上に生息する鳥類であった。 [297]ネアンデルタール人もまたイベリア半島、イタリア半島、ペロポネソス半島で海洋資源を利用しており、そこでは徒渉したり潜水したりして貝類を 獲っていた。 [300] ジブラルタルのヴァンガード洞窟では、住民が地中海モンクアザラシ、コビレゴンドウ、バンドウイルカ、大西洋クロマグロ、タイ、ムラサキウニを消費してお り[56][301]、ポルトガルのグルータ・ダ・フィゲイラ・ブラバでは、貝類、カニ、魚類の大規模な収穫の証拠がある。 [302] イタリアのカステルチヴィータ洞窟ではマス、ハヤ、ウナギ、[299] フランスのアブリ・デュ・マラス洞窟ではハヤとヨーロッパスズキ、[303] フランスのペイレ洞窟、ロシアのクダロ洞窟では黒海のサケの淡水漁の証拠が発見されている[304]。 スペインのクエバ・デル・シドロン洞窟から出土したネアンデルタール人は、歯石から、キノコ、松の実、コケなどの肉を食べない食事をしていた可能性が高 く、森林の採食者であったことを示している[249]。イスラエルのアムード洞窟から出土した遺物は、イチジク、ヤシの木の実、様々な穀物、食用草などを 食べていたことを示している。 [55] 脚の関節にあるいくつかの骨の外傷は、おそらく習慣的にしゃがんでいたことを示唆する可能性があり、もしそうであれば、食料を集めていた可能性が高い [305] ベルギーのグロット・ド・スピーから出土した歯石は、住民がウーリーサイやムフロンヒツジなどの肉を多く食べる食生活を送っていたことを示す一方、キノコ も常食していたことを示している。 [249] スペインのエル・ソルトで5万年前に発見されたネアンデルタール人の糞便は、人類最古の糞便遺跡として記録されているが、主に肉を食べていたが、かなりの 割合で植物も食べていたことを示している[306] 。イスラエルのケバラ洞窟遺跡では、調理された植物性食品(主に豆類と、はるかに少ない程度ではあるがドングリ)の証拠が発見されており、この洞窟の住人 は春と秋に植物を採集し、秋以外の季節には狩猟を行っていた可能性があるが、洞窟は夏の終わりから秋の初めに放棄されたと考えられている。 [45] イラクのシャニダール洞窟では、ネアンデルタール人が様々な収穫期の植物を採集しており、特定の植物を収穫するためにその地域に戻ることを計画していたこ と、また肉と植物の両方に対して複雑な食物採集行動を持っていたことを示している[53]。 食物の準備 ネアンデルタール人は、おそらくローストなどの幅広い調理技術を用いることができ、スープ、シチュー、または動物のストックを温めたり、煮たりすることが できたかもしれない[49]。集落に動物の骨片が豊富にあったことから、おそらくすでに餓死した動物から採取した骨髄を煮て脂肪のストックを作っていたの かもしれない。これらの方法は、低炭水化物・高タンパク質摂取の共同体にとって主要な栄養要求であった脂肪の消費を大幅に増加させたであろう[49] [307]。ネアンデルタール人の歯の大きさは、10万年前以降減少傾向にあったが、これは調理への依存度が高まったこと、または食物を柔らかくする技術 である煮沸の出現を示す可能性がある[308]。  小さな白い花の上に赤い縞模様の黒い虫が座っている。 スペインに生育するヤロウ スペインのクエヴァ・デル・シドロンでは、ネアンデルタール人はおそらく食物を調理し、おそらく燻製にしていた[50]。 フランスのグロット・デュ・ラザレでは、合計23頭のアカシカ、6頭のアイベックス、3頭のオーロックス、1頭のノロジカが、発情期のために雌雄のシカの 群れが群れをなす秋の狩猟シーズンに狩猟されたようである。死骸はすべて洞窟に運ばれ、屠殺されたようだ。腐敗する前に消費するには大量の食料であるた め、ネアンデルタール人たちは冬が来る前にそれを保存していた可能性がある。16万年前というのは、食料貯蔵の証拠としては最も古いものである[48]。 典型的な獲物(すなわちマンモス)から一般的に集められた大量の肉と脂肪も、食料貯蔵能力を示している可能性がある[309]。貝類については、ネアンデ ルタール人は採取後すぐに食べるか、調理するか、何らかの方法で保存する必要があった。スペインのクエバ・デ・ロス・アビオネスでは、ジャニア・ルーベン スという藻類と結びついた、藻類を食べる食用貝類の遺跡が見つかっているが、これは、現代の狩猟採集社会と同じように、収穫した貝類を水に浸した藻類の中 に入れて、消費するまで新鮮な状態で保存していたことを示している可能性がある[310]。 |

Competition Cave hyena skeleton, head-on slightly angled view, in a walking position Cave hyena skeleton Competition from large Ice Age predators was rather high. Cave lions likely targeted horses, large deer and wild cattle; and leopards primarily reindeer and roe deer; which heavily overlapped with Neanderthal diet. To defend a kill against such ferocious predators, Neanderthals may have engaged in a group display of yelling, arm waving, or stone throwing; or quickly gathered meat and abandoned the kill. However, at Grotte de Spy, Belgium, the remains of wolves, cave lions and cave bears—which were all major predators of the time—indicate Neanderthals hunted their competitors to some extent.[57] Neanderthals and cave hyenas may have exemplified niche differentiation, and actively avoided competing with each other. Although they both mainly targeted the same groups of creatures—deer, horses and cattle—Neanderthals mainly hunted the former and cave hyenas the latter two. Further, animal remains from Neanderthal caves indicate they preferred to hunt prime individuals, whereas cave hyenas hunted weaker or younger prey, and cave hyena caves have a higher abundance of carnivore remains.[51] Nonetheless, there is evidence that cave hyenas stole food and leftovers from Neanderthal campsites and scavenged on dead Neanderthal bodies.[311] Similarly, evidence from the site of Payre in southern France shows that Neanderthals exhibited resource partitioning with wolves.[312] Cannibalism  Neandertal remains from the Troisième caverne of Goyet Caves (Belgium). The remains have scrape marks, indicating that they were butchered, with cannibalism being the "most parsimonious explanation".[313] There are several instances of Neanderthals practising cannibalism across their range.[314][315] The first example came from the Krapina, Croatia site, in 1899,[120] and other examples were found at Cueva del Sidrón[267] and Zafarraya in Spain; and the French Grotte de Moula-Guercy,[316] Les Pradelles, and La Quina. For the five cannibalised Neanderthals at the Grottes de Goyet, Belgium, there is evidence that the upper limbs were disarticulated, the lower limbs defleshed and also smashed (likely to extract bone marrow), the chest cavity disembowelled, and the jaw dismembered. There is also evidence that the butchers used some bones to retouch their tools. The processing of Neanderthal meat at Grottes de Goyet is similar to how they processed horse and reindeer.[314][315] About 35% of the Neanderthals at Marillac-le-Franc, France, show clear signs of butchery, and the presence of digested teeth indicates that the bodies were abandoned and eaten by scavengers, likely hyaenas.[317] These cannibalistic tendencies have been explained as either ritual defleshing, pre-burial defleshing (to prevent scavengers or foul smell), an act of war, or simply for food. Due to a small number of cases, and the higher number of cut marks seen on cannibalised individuals than animals (indicating inexperience), cannibalism was probably not a very common practice, and it may have only been done in times of extreme food shortages as in some cases in recorded human history.[315] |

競争 洞窟ハイエナの骨格、真正面からやや斜めに見た図、歩行姿勢 洞窟ハイエナの骨格 氷河期の大型捕食動物との競争はかなり激しかった。洞窟のライオンは馬、大型の鹿、野牛を、ヒョウは主にトナカイとノロ鹿を狙っていたと思われ、これらは ネアンデルタール人の食生活と重なる部分が多かった。このような獰猛な捕食者から獲物を守るために、ネアンデルタール人は大声で叫んだり、腕を振ったり、 石を投げたりする集団行動をとったかもしれない。しかし、ベルギーのスパイ洞窟では、当時の主要な捕食者であったオオカミ、洞窟ライオン、洞窟クマの遺骨 が見つかっており、ネアンデルタール人がある程度競争相手を狩っていたことを示している[57]。 ネアンデルタール人と洞窟ハイエナはニッチ分化の典型であり、積極的に競合を避けていたのかもしれない。両者は主にシカ、ウマ、ウシという同じグループの 生物を対象としていたが、ネアンデルタール人は主に前者を、洞窟ハイエナは主に後者2つを狩猟していた。さらに、ネアンデルタール人の洞窟から発見された 動物の遺体は、洞窟ハイエナが弱い獲物や若い獲物を狩るのに対して、ネアンデルタール人は優良な個体を好んで狩ったことを示しており、洞窟ハイエナの洞窟 にはより多くの肉食動物の遺骸がある[51]。それにもかかわらず、洞窟ハイエナがネアンデルタール人のキャンプ場から食料や残飯を盗んだり、ネアンデル タール人の死体をあさったりしていた証拠がある[311]。同様に、南フランスのペイユ遺跡から発見された証拠は、ネアンデルタール人がオオカミと資源の 分配を行っていたことを示している[312]。 カニバリズム  ゴイエ洞窟(ベルギー)のTroisième caverneから出土したネアンデルタール人の遺体。遺体には屠殺されたことを示す擦過痕があり、共食いが「最も穏当な説明」である[313]。 最初の例は1899年にクロアチアのクラピナで発見され[120]、その他の例はスペインのクエヴァ・デル・シドロン[267]とザファラヤ、フランスの ムーラ・ゲルシ洞窟、レ・プラデル洞窟、ラ・キナで発見されている[316]。ベルギーのGrottes de Goyetで食人された5頭のネアンデルタール人については、上肢が解体され、下肢が切断され、(おそらく骨髄を抽出するために)粉砕され、胸腔が解体さ れ、顎がバラバラにされたという証拠がある。また、肉屋が道具の手入れにいくつかの骨を使ったという証拠もある。グロット・ド・ゴワイエにおけるネアンデ ルタール人の肉の処理は、馬やトナカイを処理する方法と似ている[314][315]。フランスのマリラック=ル=フランのネアンデルタール人の約35% には明らかな屠殺の痕跡があり、消化された歯があることから、遺体は放置され、おそらくハイエナであろうスカベンジャーに食べられたことがわかる [317]。 これらの食人傾向は、儀式的な脱皮、埋葬前の脱皮(スカベンジャーや悪臭を防ぐため)、戦争行為、あるいは単に食用として説明されてきた。事例が少ないこ と、食人された個体に見られる切断痕の数が動物よりも多いこと(経験が浅いことを示している)から、食人はおそらくあまり一般的な習慣ではなく、記録され ている人類の歴史におけるいくつかの事例のように、極端な食糧不足の時にのみ行われていたのかもしれない[315]。 |

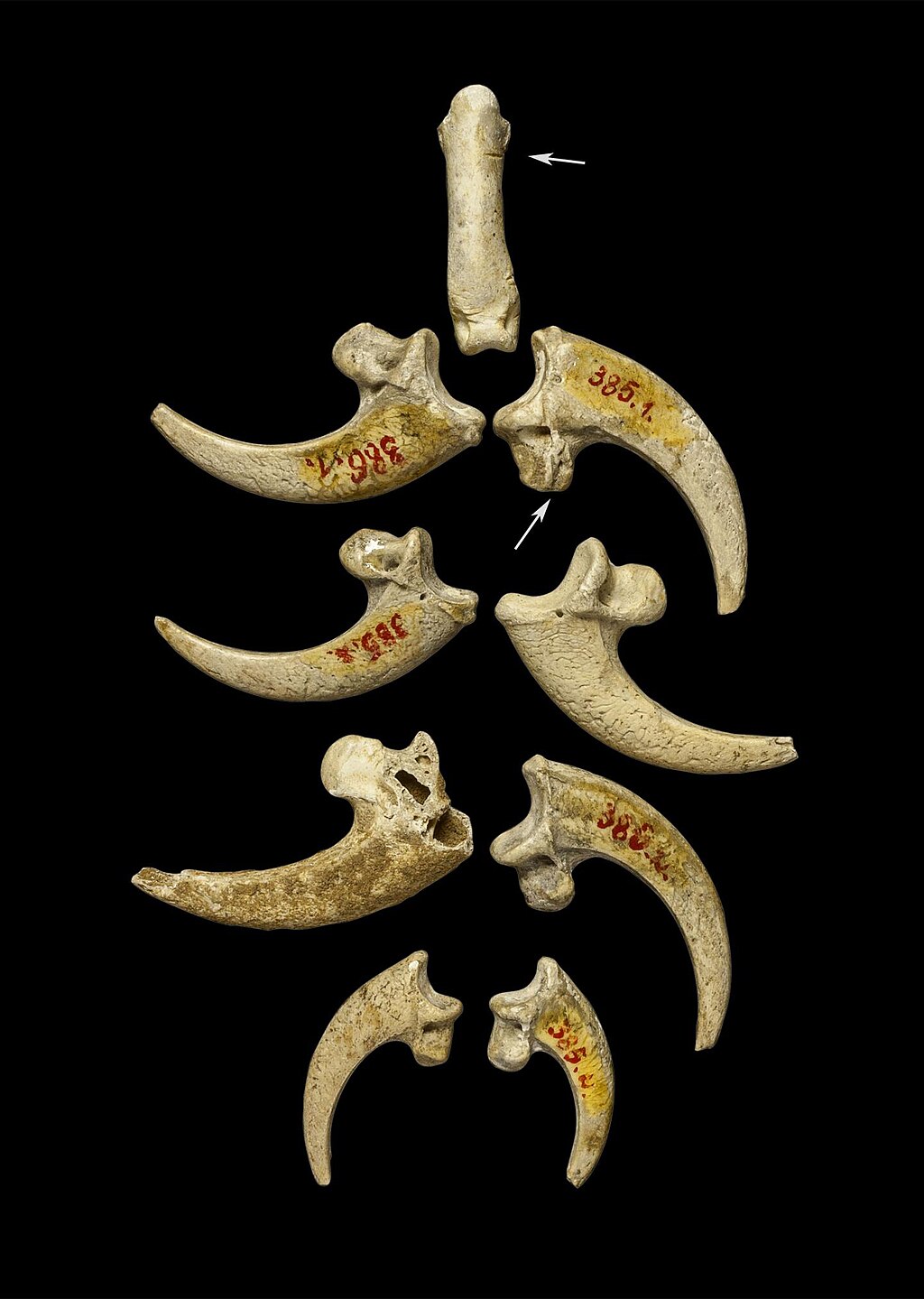

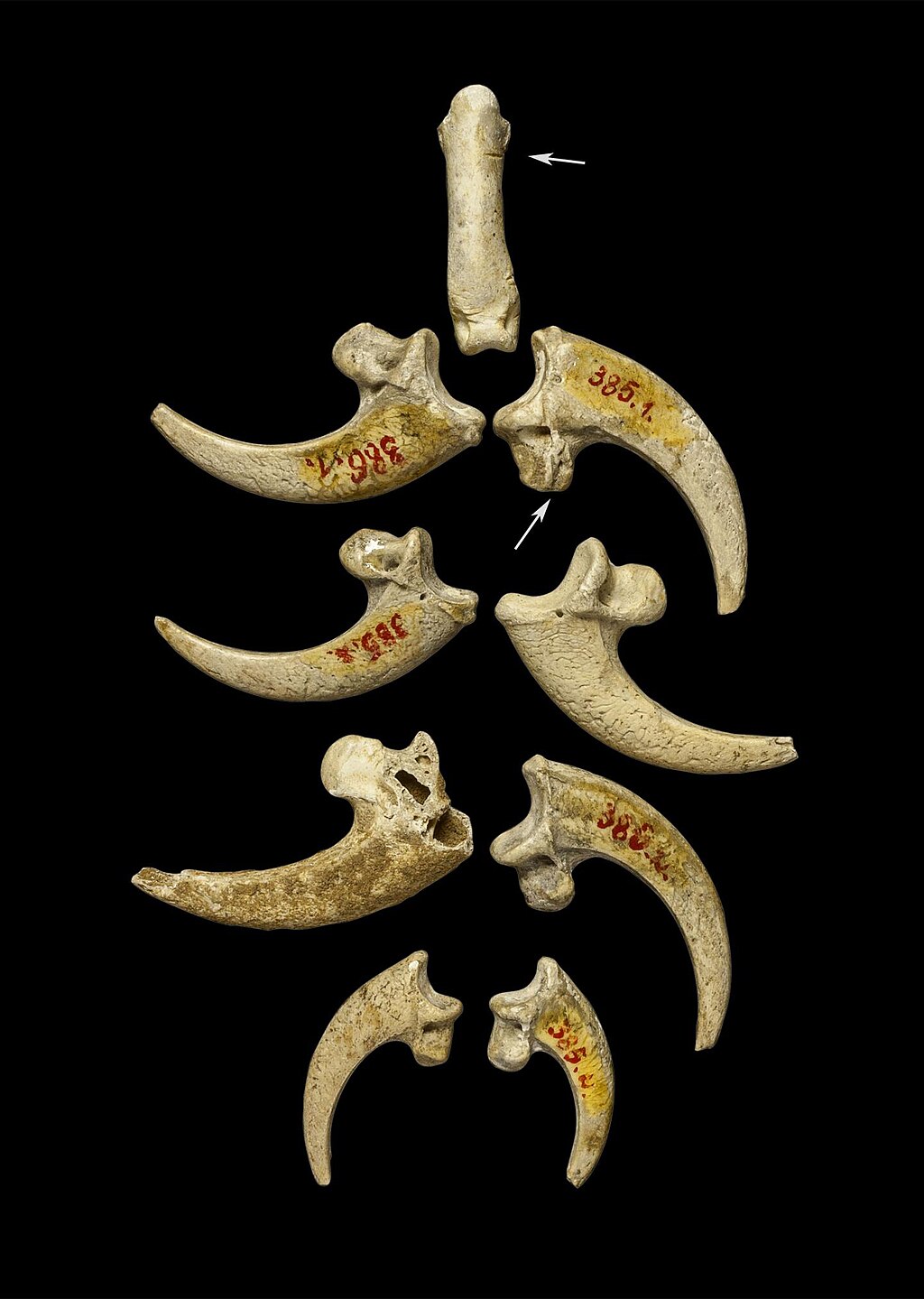

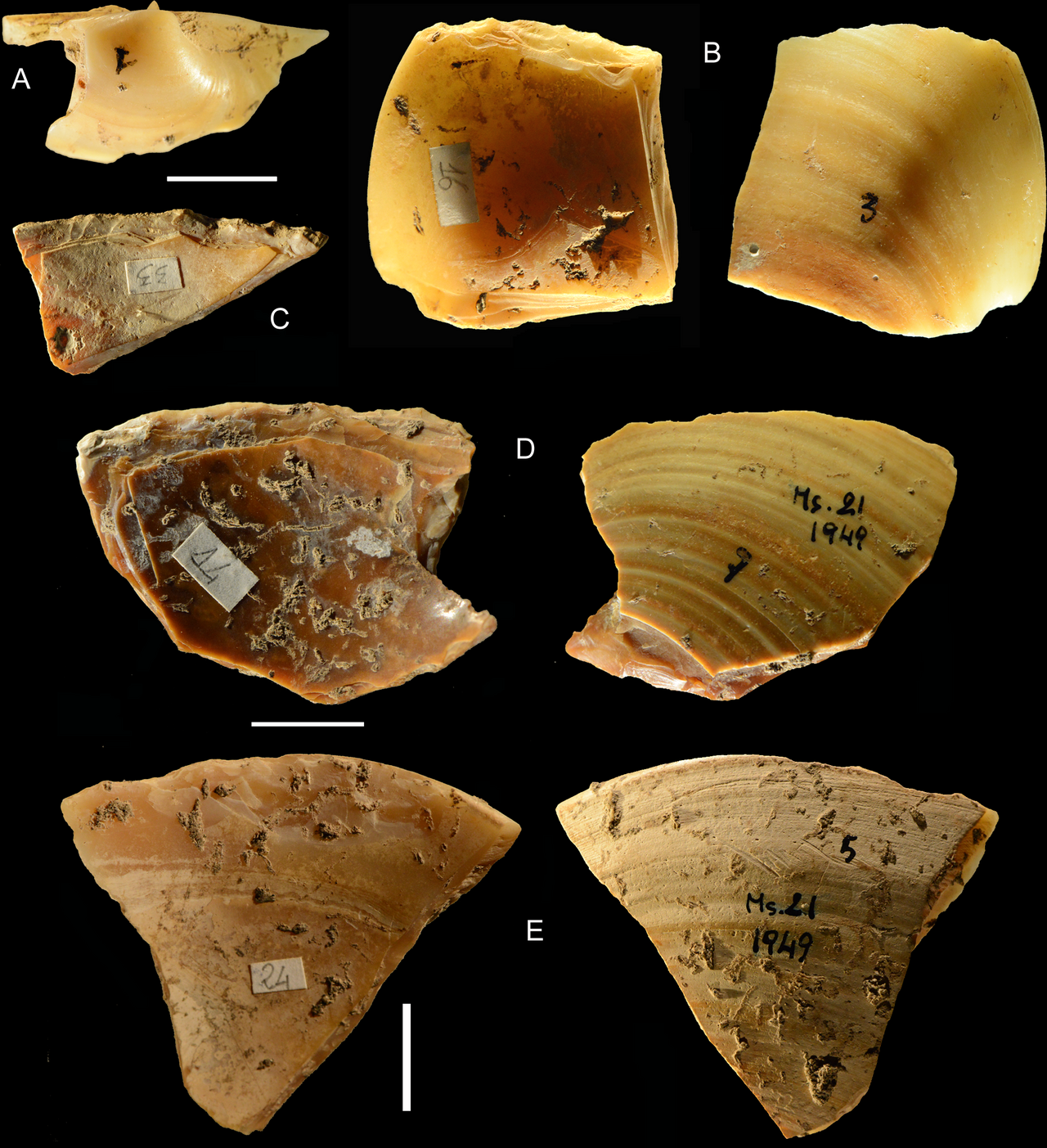

| The arts See also: Prehistoric art and Art of the Middle Paleolithic Personal adornment Neanderthals used ochre, a clay earth pigment. Ochre is well documented from 60 to 45,000 years ago in Neanderthal sites, with the earliest example dating to 250–200,000 years ago from Maastricht-Belvédère, the Netherlands (a similar timespan to the ochre record of H. sapiens).[318] It has been hypothesised to have functioned as body paint, and analyses of pigments from Pech de l'Azé, France, indicates they were applied to soft materials (such as a hide or human skin).[319] However, modern hunter gatherers, in addition to body paint, also use ochre for medicine, for tanning hides, as a food preservative, and as an insect repellent, so its use as decorative paint for Neanderthals is speculative.[318] Containers apparently used for mixing ochre pigments were found in Peștera Cioarei, Romania, which could indicate modification of ochre for solely aesthetic purposes.[320]  Decorated king scallop shell from Cueva Antón, Spain. Interior (left) with natural red colouration, and exterior (right) with traces of unnatural orange pigmentation Neanderthals collected uniquely shaped objects and are suggested to have modified them into pendants, such as a fossil Aspa marginata sea snail shell possibly painted red from Grotta di Fumane, Italy, transported over 100 km (62 mi) to the site about 47,500 years ago;[321] three shells, dated to about 120–115,000 years ago, perforated through the umbo belonging to a rough cockle, a Glycymeris insubrica, and a Spondylus gaederopus from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the former two associated with red and yellow pigments, and the latter a red-to-black mix of hematite and pyrite; and a king scallop shell with traces of an orange mix of goethite and hematite from Cueva Antón, Spain. The discoverers of the latter two claim that pigment was applied to the exterior to make it match the naturally vibrant inside colouration.[61][310] Excavated from 1949 to 1963 from the French Grotte du Renne, Châtelperronian beads made from animal teeth, shells and ivory were found associated with Neanderthal bones, but the dating is uncertain and Châtelperronian artefacts may actually have been crafted by modern humans and simply redeposited with Neanderthal remains.[322][323][324][325]  Speculative reconstruction of white-tailed eagle talon jewellery from Krapina, Croatia (arrows indicate cut marks) Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Clive and Geraldine Finlayson suggested that Neanderthals used various bird parts as artistic media, specifically black feathers.[326] In 2012, the Finlaysons and colleagues examined 1,699 sites across Eurasia, and argued that raptors and corvids, species not typically consumed by any human species, were overrepresented and show processing of only the wing bones instead of the fleshier torso, and thus are evidence of feather plucking of specifically the large flight feathers for use as personal adornment. They specifically noted the cinereous vulture, red-billed chough, kestrel, lesser kestrel, alpine chough, rook, jackdaw and the white tailed eagle in Middle Palaeolithic sites.[327] Other birds claimed to present evidence of modifications by Neanderthals are the golden eagle, rock pigeon, common raven and the bearded vulture.[328] The earliest claim of bird bone jewellery is a number of 130,000-year-old white tailed eagle talons found in a cache near Krapina, Croatia, speculated, in 2015, to have been a necklace.[329][330] A similar 39,000-year-old Spanish imperial eagle talon necklace was reported in 2019 at Cova Foradà in Spain, though from the contentious Châtelperronian layer.[331] In 2017, 17 incision-decorated raven bones from the Zaskalnaya VI rock shelter, Ukraine, dated to 43–38,000 years ago were reported. Because the notches are more-or-less equidistant to each other, they are the first modified bird bones that cannot be explained by simple butchery, and for which the argument of design intent is based on direct evidence.[59] Discovered in 1975, the so-called Mask of la Roche-Cotard, a mostly flat piece of flint with a bone pushed through a hole on the midsection—dated to 32, 40, or 75,000 years ago[332]—has been purported to resemble the upper half of a face, with the bone representing eyes.[333][334] It is contested whether it represents a face, or if it even counts as art.[335] In 1988, American archaeologist Alexander Marshack speculated that a Neanderthal at Grotte de L'Hortus, France, wore a leopard pelt as personal adornment to indicate elevated status in the group based on a recovered leopard skull, phalanges and tail vertebrae.[36][336] Abstraction  Giant deer bone of Einhornhöhle, Germany, c. 49,000 BC  The scratched floor of Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, c. 39,000 BC As of 2014, 63 purported engravings have been reported from 27 different European and Middle Eastern Lower-to-Middle Palaeolithic sites, of which 20 are on flint cortexes from 11 sites, 7 are on slabs from 7 sites, and 36 are on pebbles from 13 sites. It is debated whether or not these were made with symbolic intent.[63] In 2012, deep scratches on the floor of Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, were discovered, dated to older than 39,000 years ago, which the discoverers have interpreted as Neanderthal abstract art.[337][338] The scratches could have also been produced by a bear.[273] In 2021, an Irish elk phalanx with five engraved offset chevrons stacked above each other was discovered at the entrance to the Einhornhöhle cave in Germany, dating to about 51,000 years ago.[339] In 2018, some red-painted dots, disks, lines and hand stencils on the cave walls of the Spanish La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Doña Trinidad were dated to be older than 66,000 years ago, at least 20,000 years prior to the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe. This would indicate Neanderthal authorship, and similar iconography recorded in other Western European sites—such as Les Merveilles, France, and Cueva del Castillo, Spain—could potentially also have Neanderthal origins.[66][67][340] However, the dating of these Spanish caves, and thus attribution to Neanderthals, is contested.[65] Neanderthals are known to have collected a variety of unusual objects—such as crystals or fossils—without any real functional purpose or any indication of damage caused by use. It is unclear if these objects were simply picked up for their aesthetic qualities, or if some symbolic significance was applied to them. These items are mainly quartz crystals, but also other minerals such as cerussite, iron pyrite, calcite and galena. A few findings feature modifications, such as a mammoth tooth with an incision and a fossil nummulite shell with a cross etched in from Tata, Hungary; a large slab with 18 cupstones hollowed out from a grave in La Ferrassie, France;[62] and a geode from Peștera Cioarei, Romania, coated with red ochre.[341] A number of fossil shells are also known from French Neanderthals sites, such as a rhynchonellid and a Taraebratulina from Combe Grenal; a belemnite beak from Grottes des Canalettes; a polyp from Grotte de l'Hyène; a sea urchin from La Gonterie-Boulouneix; and a rhynchonella, feather star and belemnite beak from the contentious Châtelperronian layer of Grotte du Renne.[62] |

芸術 こちらも参照のこと: 先史時代の芸術と中期旧石器時代の芸術 装飾品 ネアンデルタール人は土の顔料である黄土を使っていた。オランダのマーストリヒト・ベルベデールの25-20万年前のものが最も古いものである(サピエン スの黄土色の記録と同じような時期である)[318]。ボディペイントとして機能していたという仮説があり、フランスのペッシュ・ド・ラゼの顔料の分析か ら、柔らかい素材(皮や人間の皮膚など)に塗られていたことが示されている。 [319]しかし、現代の狩猟採集民は、ボディペイントに加えて、黄土を薬に使ったり、皮のなめしに使ったり、食品の防腐剤として使ったり、虫除けとして 使ったりしているため、ネアンデルタール人の装飾塗料としての使用は推測の域を出ない[318]。ルーマニアのペシュテラ・シオアレイから黄土の顔料を混 ぜるために使われたと思われる容器が発見されているが、これはもっぱら美的目的のために黄土が改良されたことを示しているのかもしれない[320]。  スペイン、クエバ・アントンから出土した装飾が施されたホタテガイの貝殻。内部(左)は自然な赤色、外部(右)は不自然なオレンジ色の色素沈着の痕跡があ る。 ネアンデルタール人はユニークな形のものを収集し、それらをペンダントに加工していたと考えられている。例えば、イタリアのグロッタ・ディ・フマーネから 出土した、おそらく赤く塗られたアスパ・マルミナータ(Aspa marginata)の巻貝の化石は、約4万7,500年前に100km以上かけて運ばれたものである; [321] スペインのクエバ・デ・ロス・アビオネスから出土した、ザラガイ、グリシメリス・インスブリカ(Glycymeris insubrica)、スポンディルス・ゲデロプス(Spondylus gaederopus)の臍に穴の開いた約12万~11万5千年前の3つの貝殻、前者2つは赤と黄色の顔料、後者はヘマタイトと黄鉄鉱の赤と黒の混合物、 スペインのクエバ・アントンから出土した、ゲータイトとヘマタイトのオレンジ色の混合物の痕跡のあるキングホタテ貝殻。後者2つの発見者は、自然に鮮やか な内側の色と同じにするために外側に顔料が塗られたと主張している[61][310]。 [61][310]1949年から1963年にかけてフランスのレンヌ洞窟から発掘された動物の歯、貝殻、象牙から作られたシャテルペロン時代のビーズが ネアンデルタール人の骨と関連して発見されたが、年代は不確かであり、シャテルペロン時代の工芸品は実際には現代人によって作られ、単にネアンデルタール 人の遺骨と一緒に再堆積されたものかもしれない[322][323][324][325]。  クロアチアのクラピナから出土したオジロワシの爪の宝飾品の推定復元図(矢印は切断痕を示す) ジブラルタルの古人類学者であるクライヴ・フィンレイソンとジェラルディン・フィンレイソンは、ネアンデルタール人が様々な鳥の部位、特に黒い羽毛を芸術 的媒体として使用していたことを示唆した。 [326]2012年、フィンレイソン夫妻と同僚たちはユーラシア大陸の1,699の遺跡を調査し、猛禽類と貪食類、つまり人類が通常食用としない種が過 剰に存在し、より肉付きの良い胴体の代わりに翼の骨だけを加工していることから、個人的な装飾品として使用するために、特に大きな飛翔羽の羽毛を採取した 証拠であると主張した。彼らは特に中期旧石器時代の遺跡において、シロエリハゲワシ、アカハシガラス、チョウゲンボウ、レッサー・チョウゲンボウ、アルプ ス・チョウゲンボウ、ルーク、カシラダカ、オジロワシに注目している[327]。ネアンデルタール人による改造の証拠があると主張する他の鳥類は、イヌワ シ、イワバト、コモンレイヴン、ヒゲワシである。 328] 鳥の骨の宝飾品に関する最古の主張は、クロアチアのクラピナ近郊のキャッシュから発見された13万年前のオジロワシの爪の数々であり、2015年にネック レスであったと推測されている[329][330]。 [329][330] 2019年、スペインのコバ・フォラダで、論争となっているシャテルペロニアン層からではあるが、同様の39,000年前のスペイン帝国の鷲の爪のネック レスが報告された[331]。 2017年、ウクライナのザスカルナヤVI岩窟シェルターから、43-38,000年前と年代測定された17の切り込み装飾のあるカラスの骨が報告され た。切り込みは多かれ少なかれ互いに等距離にあるため、単純な屠殺では説明できず、直接的な証拠に基づいて設計意図の議論がなされる初めての改変された鳥 の骨である[59]。 1975年に発見されたいわゆる「ラ・ロッシュ・コタールの仮面」は、ほとんどが平らな火打石の破片で、中腹の穴から骨が押し出されており、32、40、 75,000年前[332]のものとされている。 [333][334]それが顔を表しているのかどうか、あるいはそれが美術品としてカウントされるのかどうかについては議論がある[335]。 1988年、アメリカの考古学者アレクサンダー・マーシャックは、回収されたヒョウの頭骨、指骨、尾椎に基づき、フランスのロルトゥス洞窟にいたネアンデ ルタール人が、集団内での地位の高さを示すために、身の回りの装飾品としてヒョウの毛皮を身に着けていたと推測している[36][336]。 抽象化  紀元前49,000年頃のドイツ、アインホルンヘーレの大鹿の骨  紀元前39,000年頃、ジブラルタル、ゴーラム洞窟の傷だらけの床 2014年現在、ヨーロッパと中東の後期~中期旧石器時代の27の遺跡から63の彫刻とされるものが報告されており、そのうち20は11の遺跡の火打ち石 皮質に、7は7の遺跡の石板に、36は13の遺跡の小石に刻まれている。2012年には、ジブラルタルにあるゴーラム洞窟の床面に、ネアンデルタール人の 抽象芸術と解釈される3万9000年以上前の深い傷が発見された[337][338]。 [337][338]この傷はクマによってつけられた可能性もある[273]。2021年、ドイツのアインホルンヘーレ洞窟の入口で、約5万1000年前 のものとされる、5つのオフセットされたシェブロンが重ねられたアイルランドのヘラジカのファランクスが発見された[339]。 2018年、スペインのラ・パシエガ、マルトラビエソ、ドーニャ・トリニダードの洞窟の壁に描かれたいくつかの赤く塗られた点、円盤、線、手の型紙は、西 ヨーロッパに現生人類が到着する少なくとも2万年前の66,000年前より古いものと年代測定された。これはネアンデルタール人が作者であることを示して おり、フランスのレ・メルヴェイユやスペインのクエバ・デル・カスティージョなど、西ヨーロッパの他の遺跡に記録されている同様の図像も、ネアンデルター ル人が起源である可能性がある[66][67][340]。しかし、これらのスペインの洞窟の年代測定、ひいてはネアンデルタール人によるものとすること には異論がある[65]。 ネアンデルタール人は、水晶や化石のような、機能的な目的もなく、使用による損傷の形跡もない、さまざまな珍しい物体を収集していたことが知られている。 これらの物体が単に美観のために拾われたのか、それとも何らかの象徴的な意味が込められていたのかは不明である。これらの遺物は主に水晶であるが、セリュ サイト、鉄黄鉄鉱、方解石、ガレナなどの他の鉱物も含まれている。ハンガリーのタタから出土した切込みのあるマンモスの歯や十字架が刻まれたヌンムライト の貝殻の化石、フランスのラ・フェラシーの墓から出土した18個のカップストーンがくり抜かれた大きな板[62]、ルーマニアのペシュテラ・シオアレイか ら出土した赤色黄土でコーティングされたジオードなど、いくつかの発見物は改変を特徴としている。 [341] フランスのネアンデルタール人遺跡からは、コンブ・グレナルから出土したリンコネリドやタラエブラチュリナ、グロット・デ・カナレットから出土したベレム ナイトのくちばし、グロット・デ・カナレットから出土したポリプなど、数多くの貝殻化石も発見されている; グロット・デ・リエーヌのポリプ、ラ・ゴンテリー・ブールーニュのウニ、レンヌ石窟のシャテルペルロニアン層から出土したリンチョネラ、フェザースター、 ベレムナイトのくちばしなどである。 [62] |

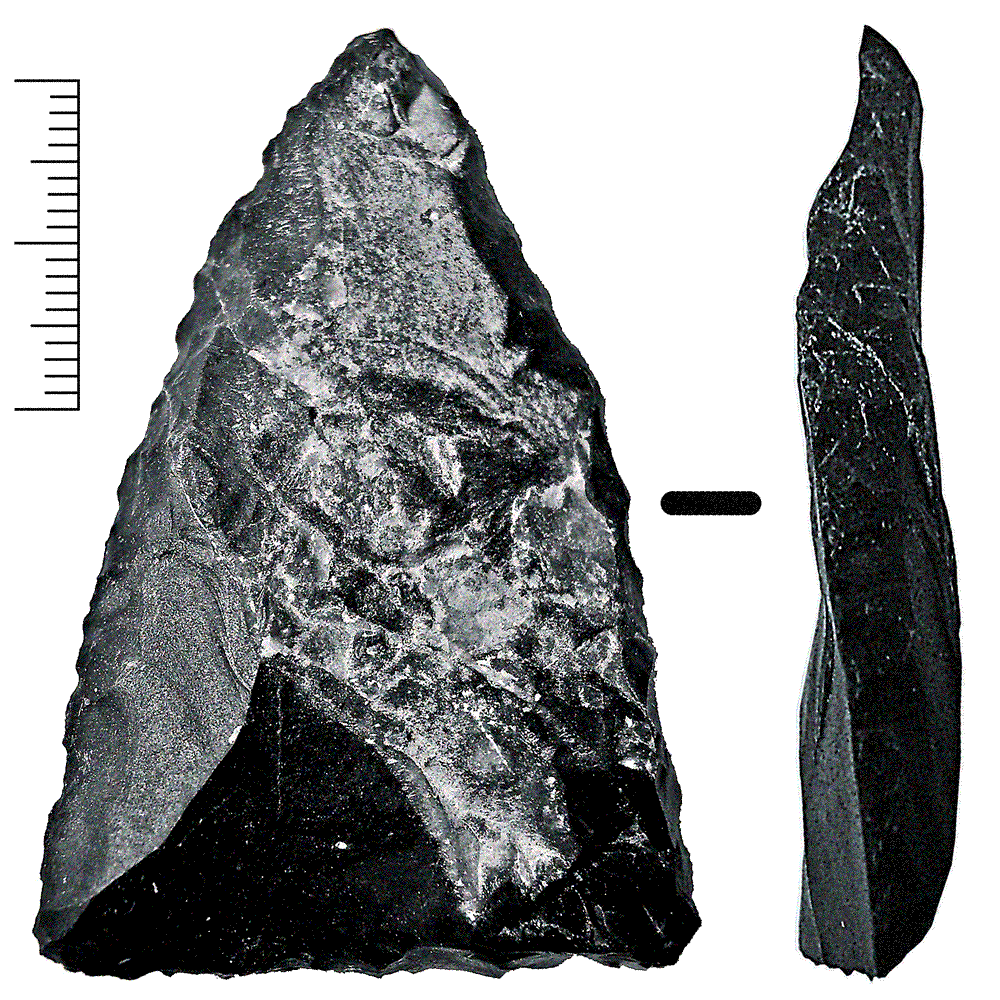

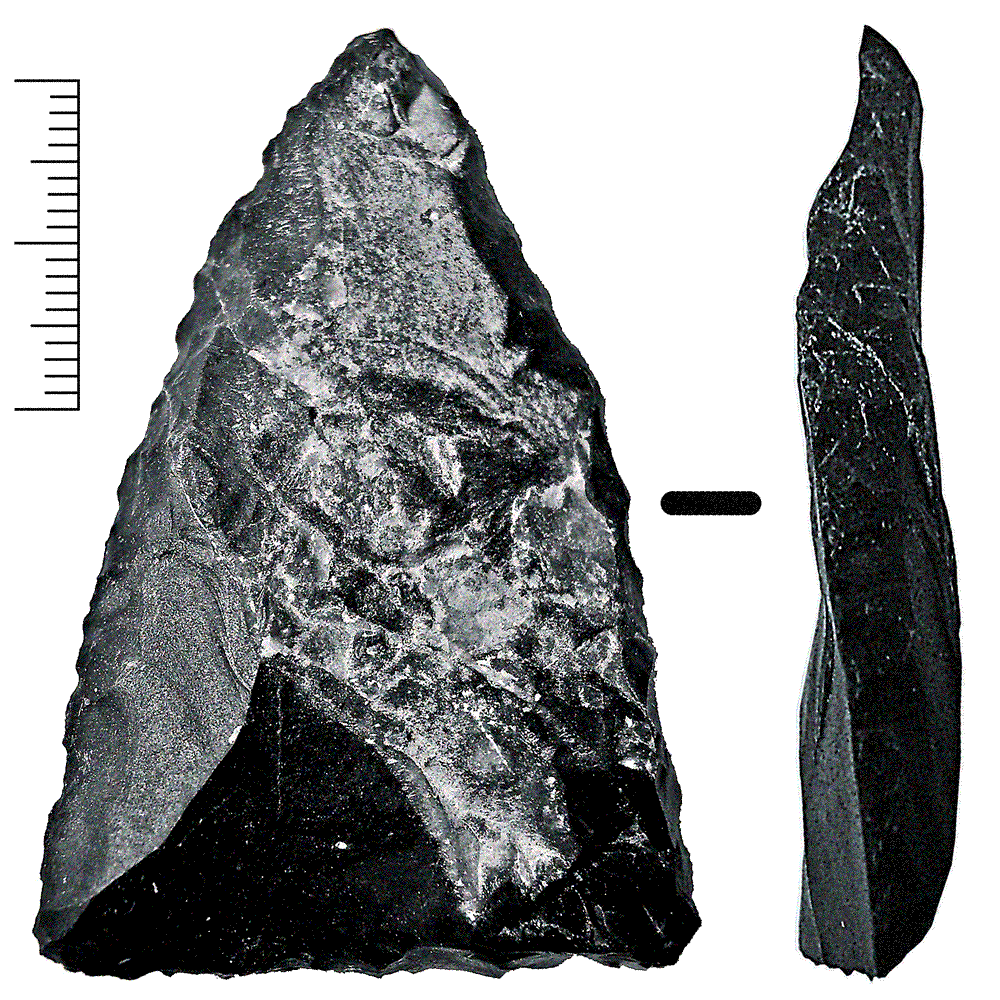

| Music See also: Prehistoric music  A hollow piece of bone with two circular holes The Divje Babe Flute in the National Museum of Slovenia Purported Neanderthal bone flute fragments made of bear long bones were reported from Potočka zijalka, Slovenia, in the 1920s, and Istállós-kői-barlang, Hungary,[342] and Mokriška jama, Slovenia, in 1985; but these are now attributed to modern human activities.[343][344] The 43,000-year-old Divje Babe flute from Slovenia, found in 1995, has been attributed by some researchers to Neanderthals, though its status as a flute is heavily disputed. Many researchers consider it to be most likely the product of a carnivorous animal chewing the bone,[345][344][346] but its discoverer Ivan Turk and other researchers have maintained an argument that it was manufactured by Neanderthal as a musical instrument.[64] Technology Despite the apparent 150,000-year stagnation in Neanderthal lithic innovation,[176] there is evidence that Neanderthal technology was more sophisticated than was previously thought.[69] However, the high frequency of potentially debilitating injuries could have prevented very complex technologies from emerging, as a major injury would have impeded an expert's ability to effectively teach a novice.[237] Stone tools  Mousterian projectile point  Levallois technique Neanderthals made stone tools, and are associated with the Mousterian industry.[32] The Mousterian is also associated with North African H. sapiens as early as 315,000 years ago[347] and was found in Northern China about 47–37,000 years ago in caves such as Jinsitai or Tongtiandong.[348] It evolved around 300,000 years ago with the Levallois technique which developed directly from the preceding Acheulean industry (invented by H. erectus about 1.8 mya). Levallois made it easier to control flake shape and size, and as a difficult-to-learn and unintuitive process, the Levallois technique may have been directly taught generation to generation rather than via purely observational learning.[33] There are distinct regional variants of the Mousterian industry, such as: the Quina and La Ferrassie subtypes of the Charentian industry in southwestern France, Acheulean-tradition Mousterian subtypes A and B along the Atlantic and northwestern European coasts,[349] the Micoquien industry of Central and Eastern Europe and the related Sibiryachikha variant in the Siberian Altai Mountains,[268] the Denticulate Mousterian industry in Western Europe, the racloir industry around the Zagros Mountains, and the flake cleaver industry of Cantabria, Spain, and both sides of the Pyrenees. In the mid-20th century, French archaeologist François Bordes debated against American archaeologist Lewis Binford to explain this diversity (the "Bordes–Binford debate"), with Bordes arguing that these represent unique ethnic traditions and Binford that they were caused by varying environments (essentially, form vs. function).[349] The latter sentiment would indicate a lower degree of inventiveness compared to modern humans, adapting the same tools to different environments rather than creating new technologies.[58] A continuous sequence of occupation is well documented in Grotte du Renne, France, where the lithic tradition can be divided into the Levallois–Charentian, Discoid–Denticulate (43,300 ±929 – 40,900 ±719 years ago), Levallois Mousterian (40,200 ±1,500 – 38,400 ±1,300 years ago) and Châtelperronian (40,930 ±393 – 33,670 ±450 years ago).[350] There is some debate if Neanderthals had long-ranged weapons.[351][352] A wound on the neck of an African wild ass from Umm el Tlel, Syria, was likely inflicted by a heavy Levallois-point javelin,[353] and bone trauma consistent with habitual throwing has been reported in Neanderthals.[351][352] Some spear tips from Abri du Maras, France, may have been too fragile to have been used as thrusting spears, possibly suggesting their use as darts.[303] |

音楽 こちらも参照のこと: 先史時代の音楽  2つの丸い穴が空いた骨の破片 スロベニア国民博物館のディヴィエ・ベーブ・フルート 熊の長い骨で作られたネアンデルタール人の骨製フルートの破片とされるものが、1920年代にスロヴェニアのポトチュカ・ジヤルカから、1985年にハン ガリーのイスタロス・キ・バーラン[342]とスロヴェニアのモクリシュカ・ジャマから報告されたが、これらは現在では現代人の活動に起因するものとされ ている[343][344]。 1995年にスロベニアで発見された43,000年前のディヴィエ・バベのフルートは、一部の研究者によってネアンデルタール人のものとされているが、フ ルートとしての地位は激しく議論されている。多くの研究者は、肉食動物が骨を噛んだ産物である可能性が高いとみなしているが[345][344] [346]、発見者のイヴァン・タークや他の研究者たちは、ネアンデルタール人が楽器として製造したものであるという主張を維持している[64]。 技術 ネアンデルタール人の石器技術革新が15万年間停滞していたにもかかわらず[176]、ネアンデルタール人の技術は以前考えられていたよりも洗練されてい たという証拠がある[69]。しかし、潜在的に衰弱させる可能性のある傷害の頻度が高かったため、非常に複雑な技術の出現が妨げられた可能性がある。 石器  ムステリアン尖頭器 レヴァロワ技法 ネアンデルタール人は石器を製造しており、モウステリアン産業と関連している[32]。モウステリアン産業は、早ければ31万5,000年前の北アフリカ のH.サピエンスとも関連しており[347]、中国北部では約4万7,000年~3万7,000年前に金石台や通天洞などの洞窟で発見されている [348]。レバロワはフレークの形と大きさを制御することを容易にし、習得が困難で直感的でないプロセスであるため、レバロワ技法は純粋な観察学習に よってではなく、世代から世代へと直接教えられた可能性がある[33]。  ムステリアン産業には、次のような明確な地域的変種がある: フランス南西部のシャレンティアンのクイナとラ・フェラシーの亜型、大西洋と北西ヨーロッパの海岸沿いのアシュレアン-伝統的なムーステリア亜型AとB、 [349]中欧と東欧のミコキエン産業、シベリアのアルタイ山脈の関連するシビリャチカの亜型などである、 [268]、西ヨーロッパの歯状モステリアン産業、ザグロス山脈周辺のラクロワール産業、スペインのカンタブリアとピレネー山脈両岸の薄片薙刀産業などが ある。20世紀半ば、フランスの考古学者フランソワ・ボルドは、この多様性を説明するためにアメリカの考古学者ルイス・ビンフォードと論争し(「ボルド- ビンフォード論争」)、ボルドはこれらが独自の民族的伝統を表していると主張し、ビンフォードはそれらが環境の違いによって引き起こされたものであると主 張した(本質的には、形態対機能)[349]。後者の意見は、新しい技術を創造するのではなく、異なる環境に同じ道具を適応させるという、現代人に比べて 低い発明性の程度を示すものである。 [フランスのレンヌ洞では、石器がレヴァロワ・シャンティアン、ディスコイド・デンティキュレート(43,300±929年前~40,900±719年 前)、レヴァロワ・モウステリアン(40,200±1,500年前~38,400±1,300年前)、シャテル・ペロニアン(40,930±393年前 ~33,670±450年前)に分類される。 ネアンデルタール人が遠距離武器を持っていたかどうかについては議論がある[351][352]。シリアのウム・エル・トレルにいたアフリカの野ろばの首 の傷は、重いルヴァロワ・ポイントの槍によって負わされた可能性が高く[353]、ネアンデルタール人においても習慣的な投擲と一致する骨外傷が報告され ている。 [351][352]フランスのアブリ・デュ・マラスから出土したいくつかの槍の穂先は、突き刺す槍として使用するにはもろすぎ、おそらくダーツとして使 用されたことを示唆しているのかもしれない[303]。 |

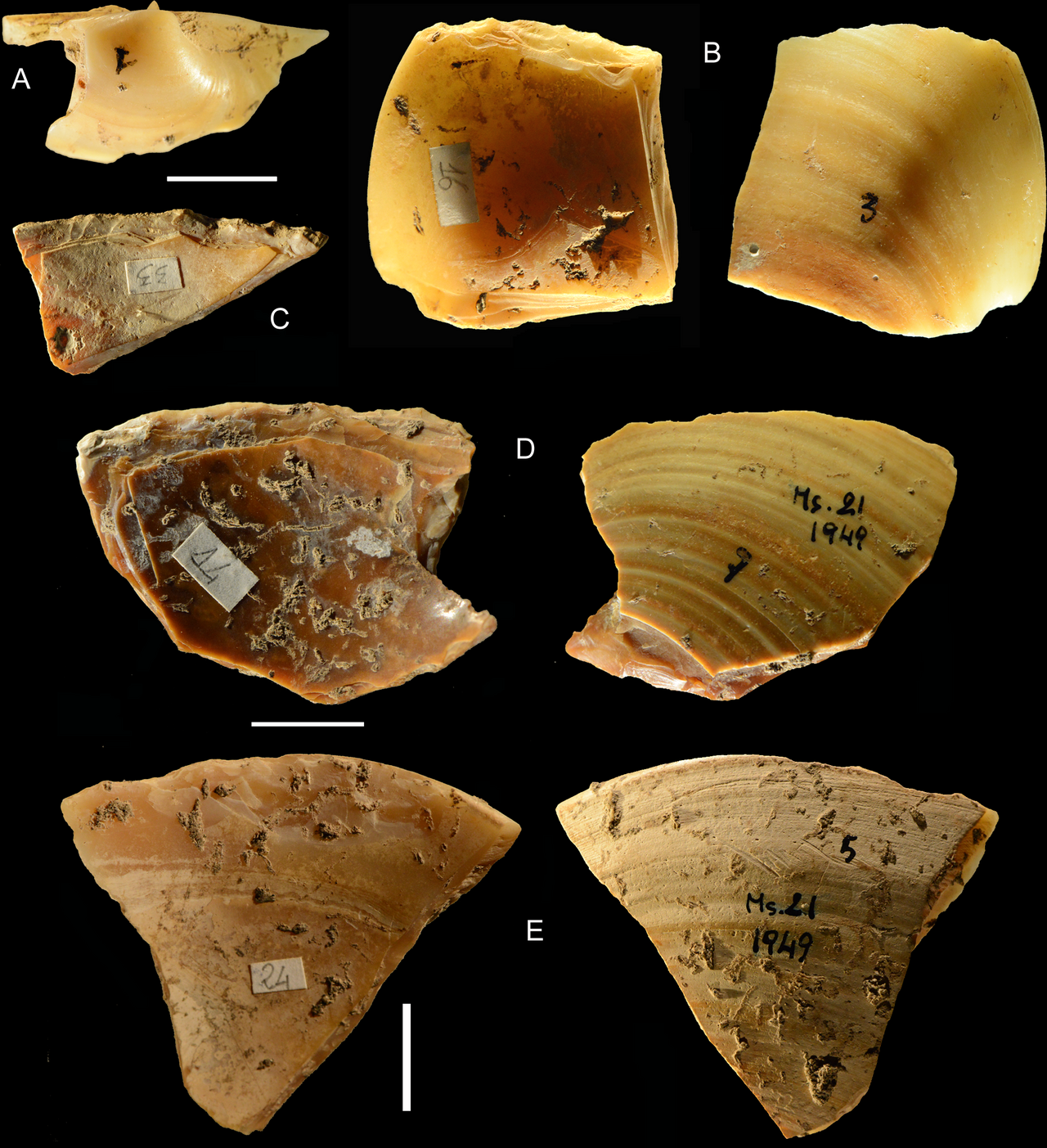

| Organic tools The Châtelperronian in central France and northern Spain is a distinct industry from the Mousterian, and is controversially hypothesised to represent a culture of Neanderthals borrowing (or by process of acculturation) tool-making techniques from immigrating modern humans, crafting bone tools and ornaments. In this frame, the makers would have been a transitional culture between the Neanderthal Mousterian and the modern human Aurignacian.[354][355][356][357][358] The opposing viewpoint is that the Châtelperronian was manufactured by modern humans instead.[359] Abrupt transitions similar to the Mousterian/Châtelperronian could also simply represent natural innovation, like the La Quina–Neronian transition 50,000 years ago featuring technologies generally associated with modern humans such as bladelets and microliths. Other ambiguous transitional cultures include the Italian Uluzzian industry,[360] and the Balkan Szeletian industry.[361] Before immigration, the only evidence of Neanderthal bone tools are animal rib lissoirs—which are rubbed against hide to make it more supple or waterproof—although this could also be evidence for modern humans immigrating earlier than expected. In 2013, two 51,400- to 41,100-year-old deer rib lissoirs were reported from Pech-de-l'Azé and the nearby Abri Peyrony in France.[356][100][100] In 2020, five more lissoirs made of aurochs or bison ribs were reported from Abri Peyrony, with one dating to about 51,400 years ago and the other four to 47,700–41,100 years ago. This indicates the technology was in use in this region for a long time. Since reindeer remains were the most abundant, the use of less abundant bovine ribs may indicate a specific preference for bovine ribs. Potential lissoirs have also been reported from Grosse Grotte, Germany (made of mammoth), and Grottes des Canalettes, France (red deer).[362]  Smooth clam shell scrapers from Grotta dei Moscerini, Italy The Neanderthals in 10 coastal sites in Italy (namely Grotta del Cavallo and Grotta dei Moscerini) and Kalamakia Cave, Greece, are known to have crafted scrapers using smooth clam shells, and possibly hafted them to a wooden handle. They probably chose this clam species because it has the most durable shell. At Grotta dei Moscerini, about 24% of the shells were gathered alive from the seafloor, meaning these Neanderthals had to wade or dive into shallow waters to collect them. At Grotta di Santa Lucia, Italy, in the Campanian volcanic arc, Neanderthals collected the porous volcanic pumice, which, for contemporary humans, was probably used for polishing points and needles. The pumices are associated with shell tools.[299] At Abri du Maras, France, twisted fibres and a 3-ply inner-bark-fibre cord fragment associated with Neanderthals show that they produced string and cordage, but it is unclear how widespread this technology was because the materials used to make them (such as animal hair, hide, sinew, or plant fibres) are biodegradable and preserve very poorly. This technology could indicate at least a basic knowledge of weaving and knotting, which would have made possible the production of nets, containers, packaging, baskets, carrying devices, ties, straps, harnesses, clothes, shoes, beds, bedding, mats, flooring, roofing, walls and snares, and would have been important in hafting, fishing and seafaring. Dating to 52–41,000 years ago, the cord fragment is the oldest direct evidence of fibre technology, although 115,000-year-old perforated shell beads from Cueva Antón possibly strung together to make a necklace are the oldest indirect evidence.[41][303] In 2020, British archaeologist Rebecca Wragg Sykes expressed cautious support for the genuineness of the find, but pointed out that the string would have been so weak that it would have had limited functions. One possibility is as a thread for attaching or stringing small objects.[363] The archaeological record shows that Neanderthals commonly used animal hide and birch bark, and may have used them to make cooking containers. However, this is based largely on circumstantial evidence, as neither fossilises well.[308] It is possible that the Neanderthals at Kebara Cave in Israel, used the shells of the spur-thighed tortoise as containers.[364] At the Italian Poggetti Vecchi site, there is evidence that they used fire to process boxwood branches to make digging sticks, a common implement in hunter-gatherer societies.[365] The Schöningen spears are a collection of wooden spears probably made by early Neanderthals found in Germany, dating to around 300,000 years ago. They were likely both thrown and used as handheld thrusting spears. The tools were specifically made of spruce, (or possibly larch in some specimens) and pine despite their uncommonness in the environment, suggesting that they had been deliberately selected for their material properties. The spears had been deliberately debarked, followed by the ends being sharpened using cutting and scraping. Other wooden tools made of split wood were also found at the site, some rounded and some pointed, which may have functioned for domestic tasks, like serving as awls (used to make holes) and hide smoothers for the pointed and rounded types respectively. The wooden artefacts show evidence of being repurposed and reshaped.[366] |

有機的な道具 フランス中部とスペイン北部のシャテルペロニアンは、モウステリアンとは異なる産業であり、ネアンデルタール人が、移住してきた現生人類から道具製作技術 を借りて(あるいは、その馴化の過程で)、骨の道具や装飾品を製作した文化であるという仮説が論争を呼んでいる。354][355][356][357] [358]反対意見は、シャテルペロニアンは現代人が代わりに製造したものであるというものである。 [359] モウステリアン/シャテルペロニアンのような突然の遷移は、5万年前のラ・キナ-ネロニアンの遷移のように、ブレードレットやマイクロリスのような、一般 的に現生人類に関連する技術を特徴とする、単なる自然な技術革新を表す可能性もある。他の曖昧な過渡期の文化には、イタリアのウルジア産業[360]やバ ルカンのセレティア産業[361]がある。 ネアンデルタール人が移住する以前には、ネアンデルタール人の骨の道具の唯一の証拠は、動物の肋骨のリソール(皮にこすりつけてしなやかさや防水性を高め るもの)であった。2013年には、フランスのペッシュ=ド=ラゼとその近くのアブリ=ペイロニーから、51,400~41,100年前のシカの肋骨で作 られたリソワールが2つ報告された[356][100]。2020年には、アブリ=ペイロニーからさらに5つのオーロックスまたはバイソンの肋骨で作られ たリソワールが報告され、1つは約51,400年前、他の4つは47,700~41,100年前のものであった。これは、この技術がこの地域で長い間使わ れていたことを示している。トナカイの遺骨が最も多く出土していることから、出土量の少ない牛の肋骨が使用されているのは、牛の肋骨が特別に好まれたこと を示しているのかもしれない。ドイツのグロッセ・グロット(マンモス製)、フランスのグロット・デ・カナレット(アカシカ製)からも潜在的なリスソワール が報告されている[362]。  イタリア、モッセリーニ洞窟から出土した滑らかな貝殻のスクレイパー イタリアの10の海岸遺跡(すなわちグロッタ・デル・カヴァッロとグロッタ・デイ・モッセリーニ)とギリシャのカラマキア洞窟のネアンデルタール人は、滑 らかな貝殻を使ってスクレーパーを作り、おそらくそれを木製の柄に取り付けていたことが知られている。おそらく、最も丈夫な貝殻を持つこの種の貝を選んだ のだろう。グロッタ・デイ・モッセリーニでは、貝殻の約24%が海底から生きたまま採取されたもので、ネアンデルタール人が貝殻を集めるために浅瀬を歩い たり潜ったりしたことを意味している。イタリアのカンパニア火山弧にあるグロッタ・ディ・サンタ・ルチアでは、ネアンデルタール人が多孔質の火山軽石を採 取した。軽石は貝の道具と関連している[299]。 フランスのアブリ・デュ・マラスでは、ネアンデルタール人に関連する撚り合わされた繊維と3枚重ねの内皮繊維の紐片が、彼らが紐や紐類を生産していたこと を示しているが、その材料(動物の毛、皮、筋、植物繊維など)は生分解性で保存性が非常に低いため、この技術がどの程度普及していたのかは不明である。こ の技術は、網、容器、包装、籠、運搬具、紐、ストラップ、馬具、衣服、靴、ベッド、寝具、マット、床材、屋根材、壁、罠の生産を可能にし、筏作り、漁業、 航海において重要であったであろう。5万2,000~4万1,000年前のものとされるこの紐の断片は、繊維技術の最古の直接的証拠であるが、11万 5,000年前のクエバ・アントンから出土した、ネックレスを作るために繋ぎ合わされた可能性のある穴あき貝殻ビーズが最古の間接的証拠である[41] [303]。 2020年、イギリスの考古学者レベッカ・ウラッグ・サイクスは、この発見が真正であることに慎重な支持を表明したが、紐は非常に弱く、限られた機能しか 持たなかっただろうと指摘した。一つの可能性は、小さな物を取り付けたり紐を通したりするための糸である[363]。 考古学的な記録によれば、ネアンデルタール人は動物の皮や白樺の樹皮をよく使っており、調理容器を作るのに使っていた可能性がある。イスラエルのケバラ洞 窟にいたネアンデルタール人は、スッポンガメの甲羅を容器として使っていた可能性がある[308]。 イタリアのポゲッティ・ヴェッキ遺跡では、狩猟採集社会で一般的な道具である掘り棒を作るために、火を使ってツゲの枝を加工していた証拠がある [365]。 シェーニンゲンの槍は、ドイツで発見された初期のネアンデルタール人が作ったと思われる木製の槍のコレクションで、約30万年前のものである。投げ槍であ ると同時に、手持ちの突き槍としても使用されていたようである。これらの道具は、スプルース(標本によってはカラマツかもしれない)やマツで作られてお り、環境的には珍しいものであったにもかかわらず、その材料特性から意図的に選ばれたことを示唆している。槍は意図的に樹皮が剥がされ、切削と削り出しに よって先が研がれていた。割木で作られた他の木製の道具も出土したが、丸みを帯びたものと尖ったものがあり、尖ったものはアウル(穴を開けるのに使用)、 丸みを帯びたものはハイド・スムーサー(皮を磨く道具)として、それぞれ家事作業に使用された可能性がある。木製品は再利用され、形を変えられた形跡があ る[366]。 |

| Fire and construction Many Mousterian sites have evidence of fire, some for extended periods of time, though it is unclear whether they were capable of starting fire or simply scavenged from naturally occurring wildfires. Indirect evidence of fire-starting ability includes pyrite residue on a couple of dozen bifaces from late Mousterian (c. 50,000 years ago) northwestern France (which could indicate they were used as percussion fire starters), and collection of manganese dioxide by late Neanderthals which can lower the combustion temperature of wood.[34][35][367] They were also capable of zoning areas for specific activities, such as for knapping, butchering, hearths and wood storage. Many Neanderthal sites lack evidence for such activity perhaps due to natural degradation of the area over tens of thousands of years, such as by bear infiltration after abandonment of the settlement.[273] In a number of caves, evidence of hearths has been detected. Neanderthals likely considered air circulation when making hearths as a lack of proper ventilation for a single hearth can render a cave uninhabitable in several minutes. Abric Romaní rock shelter, Spain, indicates eight evenly spaced hearths lined up against the rock wall, likely used to stay warm while sleeping, with one person sleeping on either side of the fire.[36][37] At Cueva de Bolomor, Spain, with hearths lined up against the wall, the smoke flowed upwards to the ceiling, and led to outside the cave. In Grotte du Lazaret, France, smoke was probably naturally ventilated during the winter as the interior cave temperature was greater than the outside temperature; likewise, the cave was likely only inhabited in the winter.[37]  The ring structures in Grotte de Bruniquel, France In 1990, two 176,000-year-old ring structures, several metres wide, made of broken stalagmite pieces, were discovered in a large chamber more than 300 m (980 ft) from the entrance within Grotte de Bruniquel, France. One ring was 6.7 m × 4.5 m (22 ft × 15 ft) with stalagmite pieces averaging 34.4 cm (13.5 in) in length, and the other 2.2 m × 2.1 m (7.2 ft × 6.9 ft) with pieces averaging 29.5 cm (11.6 in). There were also four other piles of stalagmite pieces for a total of 112 m (367 ft) or 2.2 t (2.4 short tons) worth of stalagmite pieces. Evidence of the use of fire and burnt bones also suggest human activity. A team of Neanderthals was likely necessary to construct the structure, but the chamber's actual purpose is uncertain. Building complex structures so deep in a cave is unprecedented in the archaeological record, and indicates sophisticated lighting and construction technology, and great familiarity with subterranean environments.[368] The 44,000-year-old Moldova I open-air site, Ukraine, shows evidence of a 7 m × 10 m (23 ft × 33 ft) ring-shaped dwelling made out of mammoth bones meant for long-term habitation by several Neanderthals, which would have taken a long time to build. It appears to have contained hearths, cooking areas and a flint workshop, and there are traces of woodworking. Upper Palaeolithic modern humans in the Russian plains are thought to have also made housing structures out of mammoth bones.[29] Birch tar Neanderthal produced the adhesive birch bark tar, using the bark of birch trees, for hafting.[369] It was long believed that birch bark tar required a complex recipe to be followed, and that it thus showed complex cognitive skills and cultural transmission. However, a 2019 study showed it can be made simply by burning birch bark beside smooth vertical surfaces, such as a flat, inclined rock.[39] Thus, tar making does not require cultural processes per se. However, at Königsaue (Germany), Neanderthals did not make tar with such an aboveground method but rather employed a technically more demanding underground production method. This is one of our best indicators that some of their techniques were conveyed by cultural processes.[370] |

火と建築 ムステリアン時代の遺跡の多くには、火を使った形跡があり、長期間にわたって使われたものもあるが、火を起こす能力があったのか、単に自然発生した山火事 から調達したのかは不明である。火を起こす能力の間接的な証拠としては、フランス北西部の後期ムステリアン期(約5万年前)の数十本の二刀流に付着した黄 鉄鉱の残留物(これは打撃式の火起こし器として使用されたことを示している可能性がある)、後期ネアンデルタール人による木材の燃焼温度を下げることがで きる二酸化マンガンの採取などがある[34][35][367]。ネアンデルタール人の遺跡の多くは、おそらく集落を放棄した後に熊が侵入するなどして、 何万年もかけてその地域が自然劣化したために、そのような活動の証拠を欠いている[273]。 多くの洞窟で囲炉裏の証拠が発見されている。ネアンデルタール人は囲炉裏を作る際に空気の循環を考慮したと思われる。というのも、一つの囲炉裏に適切な換 気がないと、洞窟は数分で居住不可能になるからである。スペインのアブリク・ロマーニ岩窟では、岩壁に対して等間隔に並んだ8つの囲炉裏が確認されてお り、おそらく就寝中に暖をとるために使用され、火の両側に1人ずつ寝ていたと考えられる[36][37]。スペインのクエバ・デ・ボロモールでは、壁に対 して並んだ囲炉裏があり、煙は天井へと流れ、洞窟の外へとつながっていた。フランスのラザレ洞窟では、洞窟内部の温度が外気温よりも高かったため、煙はお そらく冬に自然換気された。  フランス、ブルニケル洞窟の環状構造物 1990年、フランス、ブルニケル洞窟の入り口から300メートル(980フィート)以上離れた大きな洞窟で、幅数メートル、割れた石筍の破片でできた 17万6000年前の2つの環状構造が発見された。一つのリングは6.7m×4.5m(22フィート×15フィート)で、長さは平均34.4cm (13.5インチ)、もう一つは2.2m×2.1m(7.2フィート×6.9フィート)で、長さは平均29.5cm(11.6インチ)であった。他にも4 つの石筍の山があり、合計112m(367フィート)、2.2トン(2.4ショートトン)相当の石筍の破片があった。火を使った証拠や焼けた骨も、人間の 活動を示唆している。ネアンデルタール人のチームがこの建造物を建設した可能性が高いが、実際の目的は不明である。洞窟の奥深くにこれほど複雑な構造物を 構築することは、考古学的記録では前例がなく、洗練された照明と建設技術、そして地下環境に精通していたことを示している[368]。 ウクライナの4万4,000年前のモルドバI野外遺跡には、数人のネアンデルタール人が長期にわたって居住するためにマンモスの骨で作られた7メートル× 10メートル(23フィート×33フィート)のリング状の住居の証拠が残されている。囲炉裏、調理場、火打石の作業場があったようで、木工の痕跡もある。 ロシア平原の後期旧石器時代の現生人類も、マンモスの骨で住居構造を作ったと考えられている[29]。 白樺のタール ネアンデルタール人は、白樺の樹皮を使い、斧を作るための接着剤である白樺の樹皮タールを生産していた[369]。白樺の樹皮タールは複雑なレシピに従う 必要があり、そのため複雑な認知能力と文化的伝達を示すと長い間信じられていた。しかし、2019年の研究では、平らで傾斜のある岩のような滑らかな垂直 面のそばで白樺の樹皮を燃やすだけでタールを作ることができることが示された[39]。しかし、ケーニッヒスーエ(ドイツ)では、ネアンデルタール人はそ のような地上での方法でタールを作っていたのではなく、むしろ技術的にもっと厳しい地下での生産方法を採用していた。これは、彼らの技術の一部が文化的プ ロセスによって伝えられたことを示す最良の指標の一つである[370]。 |

| Clothes Neanderthals were likely able to survive in a similar range of temperatures to modern humans while sleeping: about 32 °C (90 °F) while naked in the open and windspeed 5.4 km/h (3.4 mph), or 27–28 °C (81–82 °F) while naked in an enclosed space. Since ambient temperatures were markedly lower than this—averaging, during the Eemian interglacial, 17.4 °C (63.3 °F) in July and 1 °C (34 °F) in January and dropping to as a low as −30 °C (−22 °F) on the coldest days—Danish physicist Bent Sørensen hypothesised that Neanderthals required tailored clothing capable of preventing airflow to the skin. Especially during extended periods of travelling (such as a hunting trip), tailored footwear completely enwrapping the feet may have been necessary.[371]  Front and back views of two almost-triangular-shaped stones with a sharp edge running across the bottom side Two racloir side scrapers from Le Moustier, France Nonetheless, as opposed to the bone sewing-needles and stitching awls assumed to have been in use by contemporary modern humans, the only known Neanderthal tools that could have been used to fashion clothes are hide scrapers, which could have made items similar to blankets or ponchos, and there is no direct evidence they could produce fitted clothes.[40][372] Indirect evidence of tailoring by Neanderthals includes the ability to manufacture string, which could indicate weaving ability,[303] and a naturally-pointed horse metatarsal bone from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, which was speculated to have been used as an awl, perforating dyed hides, based on the presence of orange pigments.[310] Whatever the case, Neanderthals would have needed to cover up most of their body, and contemporary humans would have covered 80–90%.[372][373] Since human/Neanderthal admixture is known to have occurred in the Middle East, and no modern body louse species descends from their Neanderthal counterparts (body lice only inhabit clothed individuals), it is possible Neanderthals (and/or humans) in hotter climates did not wear clothes, or Neanderthal lice were highly specialised.[373] Seafaring Remains of Middle Palaeolithic stone tools on Greek islands indicate early seafaring by Neanderthals in the Ionian Sea possibly starting as far back as 200–150,000 years ago. The oldest stone artefacts from Crete date to 130–107,000 years ago, Cephalonia 125,000 years ago, and Zakynthos 110–35,000 years ago. The makers of these artefacts likely employed simple reed boats and made one-day crossings back and forth.[42] Other Mediterranean islands with such remains include Sardinia, Melos, Alonnisos,[43] and Naxos (although Naxos may have been connected to land),[374] and it is possible they crossed the Strait of Gibraltar.[43] If this interpretation is correct, Neanderthals' ability to engineer boats and navigate through open waters would speak to their advanced cognitive and technical skills.[43][374] Medicine Given their dangerous hunting and extensive skeletal evidence of healing, Neanderthals appear to have lived lives of frequent traumatic injury and recovery. Well-healed fractures on many bones indicate the setting of splints. Individuals with severe head and rib traumas (which would have caused massive blood loss) indicate they had some manner of dressing major wounds, such as bandages made from animal skin. By and large, they appear to have avoided severe infections, indicating good long-term treatment of such wounds.[47] Their knowledge of medicinal plants was comparable to that of contemporary humans.[47] An individual at Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, seems to have been medicating a dental abscess using poplar—which contains salicylic acid, the active ingredient in aspirin—and there were also traces of the antibiotic-producing Penicillium chrysogenum.[249] They may also have used yarrow and camomile, and their bitter taste—which should act as a deterrent as it could indicate poison—means it was likely a deliberate act.[44] At the Kebara Cave in Israel, plant remains which have historically been used for their medicinal properties were found, including the common grape vine, the pistachios of the Persian turpentine tree, ervil seeds and oak acorns.[45] |

衣服 ネアンデルタール人は寝ている間、現代人と同じような温度範囲で生き延びることができたと思われる。野外で裸のまま風速5.4km/hで約32℃(90° F)、または密閉された空間で裸のまま27~28℃(81~82°F)である。エマ紀間氷期の7月の平均気温は17.4℃、1月の平均気温は1℃であり、 最も寒い日には-30℃まで下がる。デンマークの物理学者ベント・ソーレンセンは、ネアンデルタール人は皮膚への気流を防ぐ仕立ての衣服を必要としていた のではないかと考えた。特に長時間の移動(狩猟旅行など)の際には、足を完全に包む仕立ての履物が必要であった可能性がある[371]。  底面を横切る鋭いエッジを持つ、ほぼ三角形の形をした2つの石の正面図と背面図 フランス、ル・ムスティエから出土した2つのラクロワールの側掻器 それにもかかわらず、現代の人類が使用していたと想定される骨の縫い針や縫い目アウルとは対照的に、ネアンデルタール人が衣服のファッションに使用できた 可能性のある道具として知られているのは、毛布やポンチョのようなものを作ることができた皮の削り器だけであり、ぴったりとした衣服を作ることができたと いう直接的な証拠はない。 [40][372]ネアンデルタール人による仕立ての間接的な証拠としては、織物の能力を示す可能性のある紐の製造能力[303]や、スペインのクエバ・ デ・ロス・アビオネスから出土した自然に先が尖った馬の中足骨があり、オレンジ色の色素の存在から、染色された皮革に穴を開けるアウルとして使用されたと 推測されている。 [310]いずれにせよ、ネアンデルタール人は身体の大部分を覆う必要があったはずであり、現代の人類は80~90%を覆っていたはずである[372] [373]。 ヒトとネアンデルタール人の混血は中東で起こったことが知られており、現代の身体シラミの種はネアンデルタール人のものから派生していない(身体シラミは 服を着た個体にのみ生息する)ことから、暑い気候のネアンデルタール人(および/またはヒト)が服を着ていなかった可能性もあるし、ネアンデルタール人の シラミが高度に特殊化したものであった可能性もある[373]。 海上生活 ギリシャの島々に残る中旧石器時代の石器は、ネアンデルタール人がイオニア海で20~15万年前から航海をしていたことを示している。クレタ島の最古の石 器は13~10万7000年前、セファロニア島は12万5000年前、ザキントス島は11~35万年前のものである。これらの工芸品の製作者たちは、おそ らく単純な葦船を使い、1日で往復していたのであろう[42]。このような遺跡がある他の地中海の島々には、サルデーニャ島、メロス島、アロニソス島 [43]、ナクソス島(ナクソス島は陸続きであったかもしれないが)があり[374]、彼らがジブラルタル海峡を渡っていた可能性もある[43]。この解 釈が正しければ、ネアンデルタール人が船を設計し、外洋を航行する能力は、彼らの高度な認識能力と技術力を物語っていることになる[43][374]。 医学 ネアンデルタール人は、その危険な狩猟生活と治癒に関する広範な骨格の証拠から、頻繁に外傷を負っては回復する生活を送っていたようである。多くの骨によ く治った骨折があることから、副木が使われていたことがわかる。頭部や肋骨にひどい外傷を負った個体(大量の出血を引き起こしただろう)は、動物の皮で 作った包帯など、大きな傷に何らかの包帯を巻いていたことを示している。概して、彼らは重度の感染症を避けていたようであり、そのような傷の長期的な治療 が良好であったことを示している[47]。 スペインのクエバ・デル・シドロンにいた人物は、アスピリンの有効成分であるサリチル酸を含むポプラを用いて歯槽膿漏を治療していたようであり、抗生物質 を産生するペニシリウム・クリソゲナムの痕跡もあった[47]。 [249] 彼らはヤロウやカモミールも使っていた可能性があり、その苦味は毒を示す可能性があるため、抑止力として働くはずである。 イスラエルのケバラ洞窟では、一般的なブドウのつる、ペルシャのトルコキキョウのピスタチオ、エルビルの種子、オークのドングリなど、歴史的に薬効がある として使われてきた植物の遺物が発見された[45]。 |

Language Reconstruction of the Kebara 2 skeleton at the Natural History Museum, London It is not known whether the Neanderthals had the capacity for advanced language, but some researchers have argued that a complex language—possibly using syntax—was probably necessary to survive in their harsh environment, with Neanderthals needing to communicate about topics such as locations, hunting and gathering, and tool-making techniques.[69][375][376] The FOXP2 gene in modern humans is associated with speech and language development. FOXP2 was present in Neanderthals,[377] but not the gene's modern human variant.[378] Neurologically, Neanderthals had an expanded Broca's area—operating the formulation of sentences, and speech comprehension, but out of a group of 48 genes believed to affect the neural substrate of language, 11 had different methylation patterns between Neanderthals and modern humans. This could indicate a stronger ability in modern humans than in Neanderthals to express language.[379] In 1971, cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman attempted to reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal tract and concluded that it was similar to that of a newborn and incapable of producing a large range of speech sounds, due to the large size of the mouth and the small size of the pharyngeal cavity (according to his reconstruction), thus no need for a descended larynx to fit the entire tongue inside the mouth. He claimed that they were anatomically unable to produce the sounds /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɔ/, /g/, and /k/ and thus lacked the capacity for articulate speech, though were still able to speak at a level higher than non-human primates.[380][381][382] However, the lack of a descended larynx does not necessarily equate to a reduced vowel capacity.[383] The 1983 discovery of a Neanderthal hyoid bone—used in speech production in humans—in Kebara 2 which is almost identical to that of humans suggests Neanderthals were capable of speech. Also, the ancestral Sima de los Huesos hominins had humanlike hyoid and ear bones, which could suggest the early evolution of the modern human vocal apparatus. However, the hyoid does not definitively provide insight into vocal tract anatomy.[70] Subsequent studies reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal apparatus as comparable to that of modern humans, with a similar vocal repertoire.[384] In 2015, Lieberman hypothesized that Neanderthals were capable of syntactical language, although nonetheless incapable of mastering any human dialect.[385] It is debated if behavioural modernity is a recent and uniquely modern human innovation, or if Neanderthals also possessed it.[60][376][386][387] |

言語 ロンドンの自然史博物館にあるケバラ2の骨格の復元像 ネアンデルタール人が高度な言語能力を持っていたかどうかは不明であるが、一部の研究者は、ネアンデルタール人は場所、狩猟採集、道具製作技術などの話題 についてコミュニケーションをとる必要があったため、おそらく複雑な言語(おそらく構文を使用する)が過酷な環境で生き残るために必要であったと主張して いる[69][375][376]。現代人のFOXP2遺伝子は音声と言語の発達に関連している。ネアンデルタール人にはFOXP2が存在したが [377]、この遺伝子の現代人変異型には存在しなかった[378]。神経学的には、ネアンデルタール人は文の形成や言語理解を司るブローカ野を拡大して いたが、言語の神経基盤に影響を及ぼすと考えられている48の遺伝子群のうち、11の遺伝子はネアンデルタール人と現代人とでメチル化パターンが異なって いた。これは、ネアンデルタール人よりも現生人類の方が、言語を表現する能力が強いことを示している可能性がある[379]。 1971年、認知科学者のフィリップ・リーバーマンはネアンデルタール人の声道を復元しようと試みたが、口が大きく、咽頭腔が小さい(彼の復元によれば) ため、舌全体を口の中に収めるために喉頭を下降させる必要がなく、新生児の声道に似ており、広い範囲の音声を発することができないと結論づけた。彼は、彼 らは解剖学的に/a/、/i/、/u/、/ɔ/、/g/、/k/の音を出すことができず、したがって明瞭な発話の能力を欠いているが、それでもヒト以外の 霊長類よりも高いレベルで話すことができると主張した。 [しかし、喉頭が下降していないことが必ずしも母音能力の低下と一致するわけではない。1983年にケバラ2世でネアンデルタール人の舌骨が発見された が、これはヒトの舌骨とほぼ同じものであり、ネアンデルタール人に発話能力があったことを示唆している。また、シマ・デ・ロス・ウエソス人の祖先は、ヒト に似た舌骨と耳の骨を持っており、これは現代人の発声器の初期の進化を示唆する可能性がある。2015年、リーバーマンは、ネアンデルタール人は構文言語 が可能であったが、ヒトの方言をマスターすることはできなかったと仮説を立てた[385]。 行動的現代性が最近の、現代人特有の革新的なものなのか、それともネアンデルタール人も持っていたのかは議論されている[60][376][386] [387]。 |

| Religion See also: Paleolithic religion and History of religion Funerals  A disarticulatedtle=Grave shortcomings: the evidence for Neandertal burial Reconstruction of the grave of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 at the Musée de La Chapelle-aux-Saints Although Neanderthals did bury their dead, at least occasionally—which may explain the abundance of fossil remains[58]—the behaviour is not indicative of a religious belief of life after death because it could also have had non-symbolic motivations, such as great emotion[388] or the prevention of scavenging.[389] Estimates made regarding the number of known Neanderthal burials range from thirty-six to sixty.[390][391][392][393] The oldest confirmed burials do not seem to occur before approximately 70,000 years ago.[394] The small number of recorded Neanderthal burials implies that the activity was not particularly common. The setting of inhumation in Neanderthal culture largely consisted of simple, shallow graves and pits.[395] Sites such as La Ferrassie in France or Shanidar in Iraq may imply the existence of mortuary centers or cemeteries in Neanderthal culture due to the number of individuals found buried at them.[395] The debate on Neanderthal funerals has been active since the 1908 discovery of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 in a small, artificial hole in a cave in southwestern France, very controversially postulated to have been buried in a symbolic fashion.[396][397][398] Another grave at Shanidar Cave, Iraq, was associated with the pollen of several flowers that may have been in bloom at the time of deposition—yarrow, centaury, ragwort, grape hyacinth, joint pine and hollyhock.[399] The medicinal properties of the plants led American archaeologist Ralph Solecki to claim that the man buried was some leader, healer, or shaman, and that "The association of flowers with Neanderthals adds a whole new dimension to our knowledge of his humanness, indicating that he had 'soul' ".[400] However, it is also possible the pollen was deposited by a small rodent after the man's death.[401] The graves of children and infants, especially, are associated with grave goods such as artefacts and bones. The grave of a newborn from La Ferrassie, France, was found with three flint scrapers, and an infant from Dederiyeh [de] Cave, Syria, was found with a triangular flint placed on its chest. A 10-month-old from Amud Cave, Israel, was associated with a red deer mandible, likely purposefully placed there given other animal remains are now reduced to fragments. Teshik-Tash 1 from Uzbekistan was associated with a circle of ibex horns, and a limestone slab argued to have supported the head.[254] A child from Kiik-Koba, Crimea, Ukraine, had a flint flake with some purposeful engraving on it, likely requiring a great deal of skill.[63] Nonetheless, these contentiously constitute evidence of symbolic meaning as the grave goods' significance and worth are unclear.[254] Cults It was once argued that the bones of the cave bear, particularly the skull, in some European caves were arranged in a specific order, indicating an ancient bear cult that killed bears and then ceremoniously arranged the bones. This would be consistent with bear-related rituals of modern human Arctic hunter-gatherers. However, the alleged peculiarity of the arrangement could also be sufficiently explained by natural causes,[68][388] and bias could be introduced as the existence of a bear cult would conform with the idea that totemism was the earliest religion, leading to undue extrapolation of evidence.[402] It was also once thought that Neanderthals ritually hunted, killed and cannibalised other Neanderthals and used the skull as the focus of some ceremony.[315] In 1962, Italian palaeontologist Alberto Blanc believed a skull from Grotta Guattari, Italy, had evidence of a swift blow to the head—indicative of ritual murder—and a precise and deliberate incising at the base to access the brain. He compared it to the victims of headhunters in Malaysia and Borneo,[403] putting it forward as evidence of a skull cult.[388] However, it is now thought to have been a result of cave hyaena scavengery.[404] Although Neanderthals are known to have practised cannibalism, there is unsubstantial evidence to suggest ritual defleshing.[314] In 2019, Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Stewart, Geraldine and Clive Finlayson and Spanish archaeologist Francisco Guzmán speculated that the golden eagle had iconic value to Neanderthals, as exemplified in some modern human societies because they reported that golden eagle bones had a conspicuously high rate of evidence of modification compared to the bones of other birds. They then proposed some "Cult of the Sun Bird" where the golden eagle was a symbol of power.[60][328] There is evidence from Krapina, Croatia, from wear use and even remnants of string, that suggests that raptor talons were worn as personal ornaments.[405] |

宗教 こちらも参照のこと: 旧石器時代の宗教と宗教の歴史 葬儀  解体されたtle=墓の欠点:ネアンデルタール人埋葬の証拠 ラ・シャペル・オー・サン博物館にあるラ・シャペル・オー・サン1の墓の復元図。 ネアンデルタール人は少なくとも時折死者を埋葬していたが、これは化石[58]の豊富さを説明するものかもしれないが、死後の生に対する宗教的信念を示す 行動ではない。 知られているネアンデルタール人の埋葬の数に関する推定は36から60の範囲に及ぶ[390][391][392][393]。確認されている最古の埋葬 は約7万年前以前には行われていないようである[394]。フランスのラ・フェラッシーやイラクのシャニダールのような遺跡は、ネアンデルタール文化にお ける霊安室や墓地の存在を示唆しているのかもしれない。 ネアンデルタール人の葬儀に関する議論は、1908年にフランス南西部の洞窟の小さな人工的な穴の中で発見されたラ・シャペル・オー・サン1号以来、活発 になっている。 [396][397][398]イラクのシャニダール洞窟にある別の墓は、埋葬されたときに咲いていたと思われるいくつかの花、すなわち、セイヨウノコギ リソウ、センダングサ、ゴギョウ、ブドウヒヤシンス、マツヨイグサ、タチアオイの花粉と関連していた。 [399] 植物の薬効成分から、アメリカの考古学者ラルフ・ソレッキは、埋葬された男は何らかの指導者、ヒーラー、あるいはシャーマンであり、「ネアンデルタール人 と花との結びつきは、彼の人間性についてのわれわれの知識にまったく新しい次元を加え、彼が『魂』を持っていたことを示している」と主張した[400] 。 特に子供や幼児の墓には、工芸品や骨などの墓用品が付随している。フランスのラ・フェラッシーから発見された新生児の墓には、3つの火打ち石があり、シリ アのデデリエ[ド]洞窟から発見された乳児の墓には、三角形の火打ち石が胸に置かれていた。イスラエルのアムド洞窟から発見された生後10ヶ月の乳児は、 アカシカの下顎骨と一緒に発見されたが、他の動物の遺骨が断片になっていることから、おそらく意図的にそこに置かれたのであろう。ウズベキスタンのテシ ク・タシュ1号は、アイベックスの角の輪と、頭部を支えたと主張される石灰岩の板と関連していた[254]。ウクライナのクリミア、キク・コバから出土し た子どもは、意図的な彫刻が施された火打ち石片を持っていたが、これは非常に熟練した技術を必要とした可能性が高い[63]。それにもかかわらず、墓用品 が持つ意味や価値は不明であるため、これらの争いは象徴的な意味の証拠となっている[254]。 カルト かつて、ヨーロッパの洞窟にあるホラアナグマの骨、特に頭蓋骨は特定の順序で並べられており、これはクマを殺して儀式的に骨を並べた古代のクマ崇拝を示す ものだと主張されたことがある。これは現代人の北極圏狩猟採集民の熊にまつわる儀式と一致するだろう。しかし、その配列の特殊性は自然的な原因でも十分に 説明することができ[68][388]、熊教団の存在はトーテミズムが最古の宗教であったという考え方に合致するため、証拠の不当な外挿につながるという バイアスが持ち込まれる可能性もある[402]。 1962年、イタリアの古生物学者アルベルト・ブランは、イタリアのグロッタ・ガタリから発見された頭蓋骨には、儀式による殺人を示す頭部への一撃と、脳 にアクセスするための正確かつ意図的な根元の切開の痕跡があると考えた。彼はこれをマレーシアやボルネオのヘッドハンターの犠牲者と比較し[403]、頭 蓋骨崇拝の証拠として提出した[388]。しかし、現在では洞窟のハイエナ漁の結果であったと考えられている[404]。 2019年、ジブラルタルの古人類学者スチュワート、ジェラルディン、クライヴ・フィンレイソンとスペインの考古学者フランシスコ・グズマンは、イヌワシ の骨は他の鳥類の骨と比較して、改造の痕跡が際立って高い割合で見られると報告していることから、ネアンデルタール人にとってイヌワシは、いくつかの現代 人社会で例証されているように、象徴的な価値を持っていたと推測した。そして彼らは、イヌワシが権力の象徴であった「太陽の鳥のカルト」を提唱した [60][328]。クロアチアのクラピナからは、摩耗の使用や紐の残骸から、猛禽類の爪が個人的な装飾品として着用されていたことを示唆する証拠がある [405]。 |