ナイト・ オブ・ザ・リビングデッド

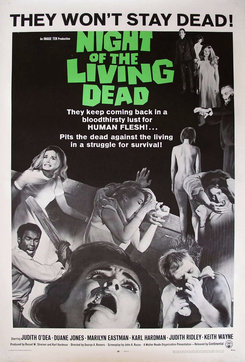

Night of the Living Dead, 1968, directed by George A. Romero

Living dead Karen

Cooper, eating her father's corpse

★『ナイト・ オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(Night of the Living Dead)は、ジョージ・A・ロメロが監督・撮影・編集、ロメロとジョン・ルッソが脚本、ラッセル・ストリーナーとカール・ハードマンが製作、 デュアン・ ジョーンズとジュディス・オディアが主演した1968年のアメリカのインディペンデント・ホラー映画。ストーリーは、ペンシルベニアの田舎町の農家に閉じ 込められた7人が、生き返った死体に襲われるというもの。この映画に登場する肉食モンスターは「グール」と呼ばれているが、大衆文化におけるゾンビの現代 的な描写を広めた代表作と言われている。

☆ 人類学的ゾンビとは、[実在する?クソ実証主義的に]ゾンビを研究する「ゾンビ の人類学(anthropology of Zombies)」のことではない。そうではなく、(α)「人類学はゾンビ的本性を もった存在である(Anthropology has the entitity of the natur of Zombie)」ということを探求する研究上のジャンルのことである。しかし、その前 に、(Β)「ゾンビとは何か(what kind of the nature of the Zombie?)」について、我々は知らないといけない。ゾンビを 理解するには、1968年を分水嶺にして、2つの意味の使い分けをしなればならない。まず、(1)古典的で保守的なゾンビ(classical Zombie per se)である。それはハイチのブードゥー信仰 の中にでてくる実態や伝承としてのゾンビである。そして、グローバリゼーションをとげた、現在我々が理解しているゾンビは1968年のホラー映画『生きる 屍の夜(Night of the Living Dead)』以降の大衆文化や映画あるいはゲームの(2)キャラクター[あるいは哲学的実体(philosophical entity)]としてのゾンビである。もちろ ん、現在ゾンビとして、理解されているものは、圧倒的に後者の意味——ないしは語用——が主である。

★ 『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(Night of the Living Dead)を民族誌(エスノグラフィー)として読む

Night of the Living Dead

is a 1968 American independent horror film directed, photographed, and

edited by George A. Romero, written by Romero and John Russo, produced

by Russell Streiner and Karl Hardman, and starring Duane Jones and

Judith O'Dea. The story follows seven people trapped in a farmhouse in

rural Pennsylvania, under assault by reanimated corpses. Although the

flesh-eating monsters that appear in the film are referred to as

"ghouls", they are credited with popularizing the modern portrayal of

zombies in popular culture. Night of the Living Dead

is a 1968 American independent horror film directed, photographed, and

edited by George A. Romero, written by Romero and John Russo, produced

by Russell Streiner and Karl Hardman, and starring Duane Jones and

Judith O'Dea. The story follows seven people trapped in a farmhouse in

rural Pennsylvania, under assault by reanimated corpses. Although the

flesh-eating monsters that appear in the film are referred to as

"ghouls", they are credited with popularizing the modern portrayal of

zombies in popular culture.Having gained experience creating television commercials, industrial films, and Mister Rogers' Neighborhood segments through their production company The Latent Image, Romero, Russo, and Streiner decided to make a horror film to capitalize on interest in the genre. Their script primarily drew inspiration from Richard Matheson's 1954 novel I Am Legend. Principal photography took place between July 1967 and January 1968, mainly on location in Evans City, Pennsylvania. Romero used guerrilla filmmaking techniques he had honed in his commercial and industrial work to complete the film on a budget of approximately US$100,000. Without the budget for a proper set, they rented a condemned farmhouse to destroy during the course of filming. Night of the Living Dead premiered in Pittsburgh on October 1, 1968. It grossed US$12 million domestically and US$18 million internationally, earning more than 250 times its budget and making it one of the most profitable film productions ever made at the time. Released shortly before the adoption of the Motion Picture Association of America rating system, the film's explicit violence and gore were considered groundbreaking, leading to controversy and negative reviews. It eventually garnered a cult following and critical acclaim and has appeared on lists of the greatest and most influential films by such outlets as Empire, The New York Times, and Total Film. Frequently identified as a touchstone in the development of the horror genre, retrospective scholarly analysis has focused on its reflection of the social and cultural changes in the United States during the 1960s, with particular attention towards the casting of Jones, an African-American, in the leading role.[5] In 1999, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[6][7][8] Night of the Living Dead created a successful franchise that includes five sequels released between 1978 and 2009, all directed by Romero. Due to an error when titling the original film, it entered the public domain upon release,[9] resulting in numerous adaptations, remakes, and a lasting legacy in the horror genre. An official remake, written by Romero and directed by Tom Savini, was released in 1990. |

『ナイト・

オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(Night of

the Living

Dead)は、ジョージ・A・ロメロが監督・撮影・編集、ロメロとジョン・ルッソが脚本、ラッセル・ストリーナーとカール・ハードマンが製作、

デュアン・

ジョーンズとジュディス・オディアが主演した1968年のアメリカのインディペンデント・ホラー映画。ストーリーは、ペンシルベニアの田舎町の農家に閉じ

込められた7人が、生き返った死体に襲われるというもの。この映画に登場する肉食モンスターは「グール」と呼ばれているが、大衆文化におけるゾンビの現代

的な描写を広めたと言われている。 『ナイト・

オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(Night of

the Living

Dead)は、ジョージ・A・ロメロが監督・撮影・編集、ロメロとジョン・ルッソが脚本、ラッセル・ストリーナーとカール・ハードマンが製作、

デュアン・

ジョーンズとジュディス・オディアが主演した1968年のアメリカのインディペンデント・ホラー映画。ストーリーは、ペンシルベニアの田舎町の農家に閉じ

込められた7人が、生き返った死体に襲われるというもの。この映画に登場する肉食モンスターは「グール」と呼ばれているが、大衆文化におけるゾンビの現代

的な描写を広めたと言われている。ロメロ、ルッソ、ストレイナーの3人は、制作会社ザ・レイテント・イメージを通じて、テレビコマーシャル、産業映画、ミスター・ロジャースの隣人コーナー などの制作経験を積み、このジャンルへの関心を生かすためにホラー映画の制作を決意した。彼らの脚本は、主にリチャード・マシスンの1954年の小説『ア イ・アム・レジェンド』からインスピレーションを得た。主要撮影は1967年7月から1968年1月にかけて、主にペンシルベニア州エバンス・シティで行 われた。ロメロは、商業や工業の仕事で磨いたゲリラ映画製作のテクニックを駆使し、約10万米ドルの予算でこの映画を完成させた。まともなセットを作る予 算がなかったため、撮影中に破壊するために廃墟となった農家を借りた。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は1968年10月1日にピッツバーグでプレミア上映された。国内興行収入は1,200万米ドル、海外興行収入は 1,800万米ドルで、予算の250倍以上を稼ぎ出し、当時最も収益性の高い映画作品のひとつとなった。アメリカ映画協会のレーティング制度が導入される 直前に公開されたため、その露骨な暴力描写とゴア描写は画期的とされ、賛否両論と否定的な批評を招いた。最終的にはカルト的な人気と批評家の絶賛を集め、 『Empire』、『The New York Times』、『Total Film』などが選ぶ最も偉大で影響力のある映画のリストに登場した。ホラー・ジャンルの発展における試金石とされることが多く、回顧的な学術的分析で は、1960年代のアメリカにおける社会的・文化的変化の反映に焦点が当てられており、特にアフリカ系アメリカ人であるジョーンズを主役に起用したことに 注目が集まっている[5]。1999年、この映画は米国議会図書館によって「文化的、歴史的、または美学的に重要」とみなされ、ナショナル・フィルム・レ ジストリに保存されることになった[6][7][8]。 『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は、1978年から2009年にかけて公開された5本の続編を含むフランチャイズとして成功を収めた。原作のタイトル 付けのミスにより、公開と同時にパブリックドメインとなり[9]、その結果、数多くの映画化、リメイクがなされ、ホラージャンルにおける永続的な遺産と なった。ロメロ脚本、トム・サヴィーニ監督の公式リメイクが1990年に公開された。 |

| Plot Duration: 1 hour, 35 minutes and 53 seconds.1:35:53Subtitles available.CC Night of the Living Dead (full film) Siblings Barbra and Johnny drive to a cemetery in rural Pennsylvania to visit their father's grave, where a pale man in a tattered suit kills Johnny and attacks Barbra. She flees to a nearby farmhouse but finds the resident's corpse lying half-eaten on the stairs. A growing horde of ghouls soon surround the house as a stranger, Ben, arrives and initially mistakes Barbra for the homeowner. After driving back several ghouls, he boards the windows and doors. While searching the home for supplies, he locates a lever-action rifle. A nearly catatonic Barbra is surprised to find people already taking shelter in the home's cellar. Harry, his wife Helen, and their young daughter Karen fled there after a group of the same monsters overturned their car and bit Karen on the arm, leaving her seriously ill. A couple, Tom and Judy, took shelter after hearing an emergency broadcast about a series of brutal killings. Tom and Ben secure the farmhouse while Harry protests that it is unsafe aboveground before returning to the cellar. Ghouls continue to besiege the farmhouse in increasing numbers. The refugees listen to radio and television reports of an army of cannibalistic corpses committing mass murder across the East Coast of the United States and of the posses of armed men patrolling the countryside to exterminate the living dead. Reports confirm that the ghouls can die again from heavy blows to the head, bullets to the brain, or being burned. Various rescue centers offer refuge and safety, and scientists theorize that radiation from an exploding space probe returning from Venus caused the reanimations.  Judy peers from an open truck window. Judith Ridley as Judy, near the gas pump Ben devises a plan to obtain medical supplies for Karen and transport the group to a rescue center by refueling his truck at a pump on the farm. Ben, Tom, and Judy drive there together, holding the ghouls off with torches and Molotov cocktails. However, the gas from the pump spills and causes the truck to catch fire and explode, killing Tom and Judy. Ben returns and breaks down the door when Harry does not let him in. The remaining survivors attempt to figure a way out. They pause their discussion to watch the 3 a.m. news update until the power cuts out. The ghouls soon break through the doors and windows of the unlit home. In the chaos, Harry grabs Ben's gun but is disarmed and shot by Ben. Harry staggers down to the cellar and dies next to his daughter. Karen dies from her injuries, becomes a ghoul, and eats her father's remains. She stabs her mother to death with a masonry trowel. Barbra tries to help Ben keep the ghouls out, but a reanimated Johnny drags her away. As the horde breaks in, Ben takes refuge in the cellar, where he shoots Harry's and Helen's ghouls. In the morning, an armed posse arrives to dispatch the remaining ghouls. Awoken by their gunfire and sirens, Ben emerges from the cellar, but they shoot him, mistaking Ben for a ghoul. His body is thrown onto a bonfire and burned with the rest of the ghouls. Cast  Ben holds a rifle in the farmhouse living room. Ben, played by Duane Jones The low-budget film included no well-known actors,[10] but propelled the careers of some cast members.[11] Two independent film companies from Pittsburgh—Hardman Associates and director George A. Romero's The Latent Image—combined to form Image Ten, a production company chartered only to create Night of the Living Dead.[12] The cast consisted of members of Image Ten, actors previously cast for their commercials, acquaintances of Romero, and Pittsburgh stage actors.[13] Duane Jones as Ben. The casting was potentially controversial in 1968 when it was rare for a black man to be cast as the hero of an American film primarily composed of white actors, but Romero said that Jones performed the best in his audition.[14] Jones went on to appear in other films, including Ganja & Hess (1973) and Beat Street (1984),[15] but worried that people only recognized him as Ben.[16] Judith O'Dea as Barbra. A 23-year-old commercial and stage actress, O'Dea previously worked for Hardman and Eastman in Pittsburgh. O'Dea was in Hollywood seeking entry to the movie business when contacted about the role.[17] O'Dea expressed surprise at the film's cultural impact and the renown it brought her.[18] Karl Hardman as Harry Cooper. President of Hardman Associates, Karl Hardman, played the hostile father. Cooper's wife was played by Hardman's real-life business and romantic partner Marilyn Eastman.[19][20] Marilyn Eastman as Helen Cooper.[21] Vice president of Hardman Associates, Marilyn Eastman played the doomed mother Helen Cooper and the unnamed, bug-eating zombie. She later appeared in Santa Claws (1996), directed by John Russo.[20][22] Kyra Schon as Karen Cooper. Hardman's daughter in real life,[23] 9-year-old Schon also portrayed the mangled corpse on the house's upstairs floor that Ben drags away.[24] Keith Wayne as Tom. "Keith Wayne" was Ronald Keith Hartman's stage name.[24] After this lone acting role, Wayne went on to work as a singer, dancer, musician, and night-club owner.[25][24] Wayne became a successful chiropractor in North Carolina.[25] Wayne explained the change in careers during a 1992 interview, "I am not that person anymore. [...] I got to a point in my life where I wanted to have some control. I didn't want to wake up at 40 or 50 and not be in control."[26] In 1995, he took his own life at age 50.[27][28] Judith Ridley as Judy. The 19-year-old receptionist from Hardman Associates auditioned for Barbra without any acting experience and was given the less-demanding role of Judy.[29] Ridley starred in Romero's unsuccessful second feature There's Always Vanilla (1971).[30] Bill Hinzman, who played the first ghoul encountered by Barbra and Johnny in the cemetery, went on to work on a number of horror films including The Majorettes (1986) and Flesheater (1988).[31][32] George Kosana as Sheriff McClelland. Kosana also served as the film's production manager.[33] Bill "Chilly Billy" Cardille as himself.[34] Cardille was well known in Pittsburgh as a TV presenter who hosted a horror film anthology series, Chiller Theatre.[35] His daughter Lori would go on to star in Romero's Day of the Dead (1985).[36][37] |

プロット 上映時間 1時間35分53秒1:35:53字幕あり.CC ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド バーブラとジョニーの兄妹は父の墓参りのためペンシルベニア州の墓地に向かうが、そこでボロボロのスーツを着た青白い男がジョニーを殺し、バーブラを襲 う。彼女は近くの農家に逃げ込むが、階段に半殺しの住人の死体が転がっているのを発見する。やがてグールの大群が家を取り囲み、そこに見知らぬ男ベンが現 れ、バーブラを家主と間違える。数人のグールを追い返した後、彼は窓とドアに板を貼る。家の中に物資がないか探していると、レバーアクション式のライフル を見つける。 ほとんど緊張状態のバーブラは、すでに家の地下室に避難している人々を見つけ驚く。ハリーと妻のヘレン、そして幼い娘のカレンは、同じ怪物の集団に車を横 転され、カレンの腕に噛みついて重病になった後、そこに逃げ込んだ。トムとジュディの夫婦は、一連の残忍な殺人事件に関する緊急放送を聞いて避難した。ト ムとベンは農家を確保し、ハリーは地下室に戻る前に地上は危険だと抗議する。グールは農家を包囲し続け、その数は増えていく。 避難民たちはラジオやテレビで、アメリカ東海岸で大量殺人を犯している人食いの死体の軍団や、生ける屍を駆除するために田舎をパトロールしている武装した 男たちの報告に耳を傾ける。報告書によれば、グールたちは頭部への激しい打撃、脳への銃弾、火傷で再び死ぬことがある。さまざまなレスキューセンターが避 難場所と安全を提供し、科学者たちは、金星から帰還した宇宙探査機の爆発による放射線が、生き返りを引き起こしたという説を唱える。  開いたトラックの窓から覗き込むジュディ。 ジュディ役のジュディス・リドリー、ガソリンスタンドの近くで ベンはカレンのために医薬品を調達し、農場内の給油所でトラックに給油して一行を救助センターに運ぶ計画を立てる。ベン、トム、ジュディの3人は、松明と 火炎瓶でグールたちを食い止めながら、一緒にそこへ車を走らせる。しかし、ポンプからガスがこぼれ、トラックが炎上・爆発し、トムとジュディが死亡する。 ベンが戻り、ハリーが中に入れてくれないのでドアを壊す。 残された生存者たちは出口を探そうとする。停電になるまで、彼らは午前3時のニュースを見るために話し合いを中断する。やがてグールたちが明かりのない家 のドアや窓を破って侵入してくる。混乱の中、ハリーはベンの銃を奪うが、武装を解かれ、ベンに撃たれる。ハリーはよろめきながら地下室に下り、娘の隣で息 を引き取る。 カレンは怪我から死に、グールとなって父の亡骸を食べる。母親を石工用のこてで刺し殺す。バーブラはベンがグールを追い出すのを手伝おうとするが、生き 返ったジョニーに引きずられる。大群が押し寄せる中、ベンは地下室に避難し、そこでハリーとヘレンのグールを撃ち殺す。 朝になると、武装した警官隊が残りのグールを退治しにやってくる。銃声とサイレンで目を覚ましたベンは地下室から出てくるが、彼らはベンをグールと間違え て撃ってしまう。彼の遺体は焚き火に投げ込まれ、残りのグールたちと共に焼かれる。 キャスト  農家の居間でライフルを構えるベン。 デュアン・ジョーンズ演じるベン ピッツバーグの2つの独立系映画会社-ハードマン・アソシエイツとジョージ・A・ロメロ監督のザ・レイテント・イマージュ-が合体し、『ナイト・オブ・ ザ・リビング・デッド』を製作するためだけに設立された製作会社イメージ・テンが設立された[12]。キャストはイメージ・テンのメンバー、以前コマー シャルで起用された俳優、ロメロの知人、ピッツバーグの舞台俳優で構成された[13]。 ベン役のドゥエイン・ジョーンズ 白人俳優が中心のアメリカ映画で黒人が主人公に起用されることが珍しかった1968年当時、このキャスティングは物議を醸す可能性があったが、ロメロは ジョーンズがオーディションで最高の演技をしたと語っている[14]。 ジョーンズはその後、『ガンジャ&ヘス』(1973年)や『ビート・ストリート』(1984年)など他の映画にも出演したが[15]、人々にベンとしてし か認識されないことを心配していた[16]。 バーブラ役のジュディス・オディア 23歳の商業・舞台女優だったオディアは、以前はピッツバーグのハードマン&イーストマンに勤めていた。オディアは、この役について連絡を受けたとき、ハ リウッドで映画業界への参入を模索していた[17]。 ハリー・クーパー役のカール・ハードマン ハードマン・アソシエイツ社長のカール・ハードマンが敵対する父親を演じた。クーパーの妻を演じたのは、ハードマンの実生活でのビジネスパートナーであ り、恋愛パートナーでもあったマリリン・イーストマンだった[19][20]。 ヘレン・クーパー役のマリリン・イーストマン[21] ハードマン・アソシエイツの副社長であるマリリン・イーストマンは、破滅的な母親ヘレン・クーパーと無名の虫食いゾンビを演じた。後にジョン・ルッソ監督 の『サンタの爪』(1996年)に出演[20][22]。 カレン・クーパー役のカイラ・ショーン 実生活ではハードマンの娘であり[23]、9歳のショーンは、ベンが引きずっていく家の2階にあるバラバラになった死体も演じた[24]。 トム役のキース・ウェイン 「キース・ウェイン」はロナルド・キース・ハートマンの芸名であった[24]。この唯一の俳優役の後、ウェインは歌手、ダンサー、ミュージシャン、ナイト クラブのオーナーとして働くようになった[25][24]。ウェインはノースカロライナでカイロプラクターとして成功した[25]。ウェインは1992年 のインタビューでキャリアの変化について「僕はもうそんな人間じゃない。[僕はもうそういう人間じゃないんだ。1995年、彼は50歳で自ら命を絶った [27][28]。 ジュディ役ジュディス・リドリー ハードマン・アソシエイツの19歳の受付嬢は、演技経験なしでバーブラのオーディションを受け、要求の少ないジュディ役を与えられた[29]。リドリー は、ロメロの失敗作となった2作目の長編『ゼアズ・オールウェイズ・バニラ』(1971年)に主演した[30]。 墓地でバーブラとジョニーが遭遇した最初のグールを演じたビル・ヒンズマンは、『マジョレッツ』(1986年)や『フレッシュ・シーター』(1988年) など、数多くのホラー映画に出演した[31][32]。 マクレランド保安官役のジョージ・コサナ。コサナは本作のプロダクション・マネージャーも務めた[33]。 ビル・"チリー・ビリー"・カーディル役[34] カーディルはホラー映画のアンソロジー・シリーズ『チラー劇場』の司会を務めるTV司会者としてピッツバーグでは有名だった[35] 彼の娘ロリはロメロ監督の『死者の日』(1985年)に出演することになる[36][37]。 |

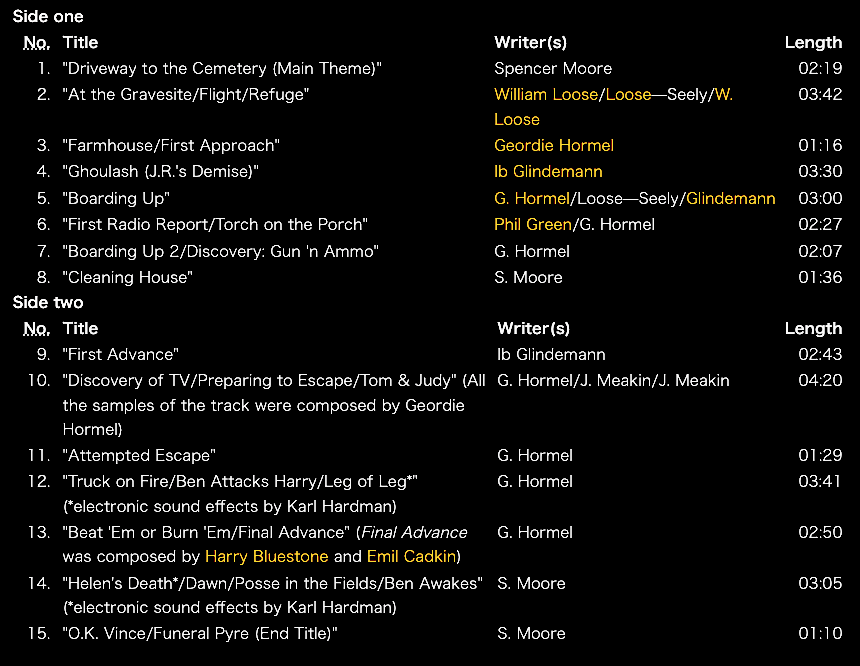

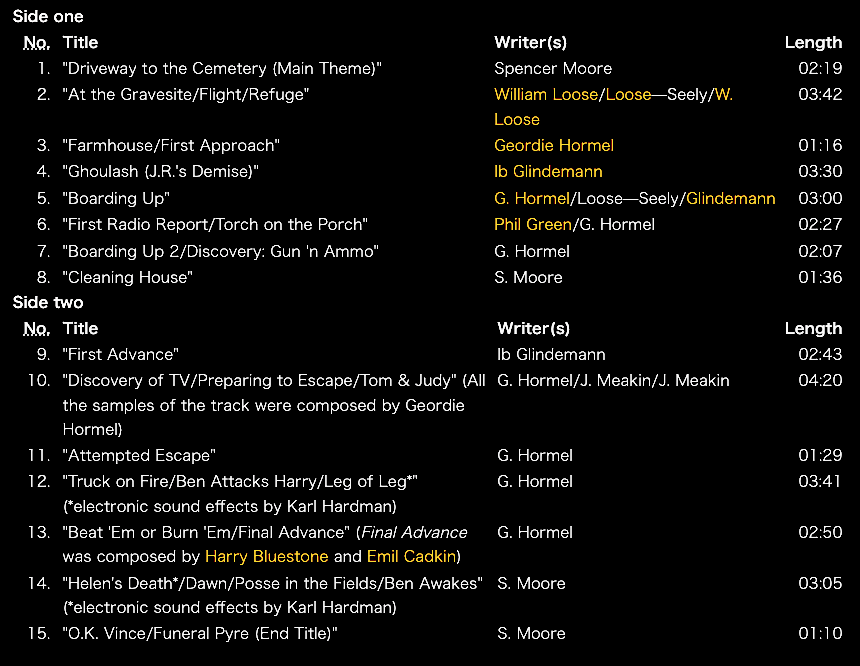

| Production Development and pre-production External videos video icon The Calgon Story. The creation of a high-budget television commercial for Calgon brand detergent spurred the film's producers to create a horror movie.[38] George Romero embarked upon his career in the film industry while attending Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.[39] He directed and produced television commercials and industrial films for The Latent Image, a company he co-founded with his friend Russell Streiner.[40] The Latent Image started small, but after producing a high-budget Calgon commercial spoofing Fantastic Voyage (1966), Romero felt that The Latent Image had the experience and equipment to produce a feature film.[38] They wanted to capitalize on the film industry's "thirst for the bizarre", according to Romero.[41] He, Streiner, and John A. Russo contacted Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman, president, and vice president respectively, of a Pittsburgh-based industrial film firm called Hardman Associates, Inc. The Latent Image pitched their idea for a then-untitled horror film.[42] These discussions led to the creation of Image Ten, a production company chartered to produce a single feature film. The initial budget was $6,000;[12] each member of the production company invested $600 for a share of the profits.[43][b] Ten more investors contributed another $6,000, but this was still insufficient.[44] Production stopped multiple times during filming while Romero used early footage to persuade additional investors.[45] Image Ten eventually raised approximately $114,000 for the budget ($959,000 today).[46][44] Writing  A group of actors in zombie makeup shamble across the unlit lawn of the farmhouse. Ghouls swarm around the house, searching for living human flesh. The script was co-written by Russo and Romero. They abandoned an early horror comedy concept about adolescent aliens,[47] after realizing they would not have the budget to create a convincing spaceship.[48] Russo proposed a more constrained narrative where a young man runs away from home and discovers aliens harvesting human corpses for food in a cemetery.[49][50] Romero combined this idea with an unpublished short story about flesh-eating ghouls,[51] and they began filming with an incomplete script.[45][47] According to Russo, the screenplay written prior to filming only covered events up to the emergence of the Cooper family.[52] Russo completed the script while filming and Romero later expanded the final pages of his short story into the sequels Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985).[53] Romero drew inspiration from Richard Matheson's I Am Legend (1954),[54][c] a horror novel about a plague that ravages a futuristic Los Angeles. The infected in I Am Legend become vampire-like creatures and prey on the uninfected.[55][44][56] Matheson described Romero's interpretation as "kind of cornball",[57] and more theft than homage.[58] In an interview, Romero contrasted Night of the Living Dead with I Am Legend. He explained that Matheson wrote about the aftermath of a complete global upheaval; Romero wanted to explore how people would respond to that kind of disaster as it developed.[59] Much of the dialogue was altered, rewritten, or improvised by the cast.[60] Lead actress Judith O'Dea told an interviewer, "I don't know if there was an actual working script! We would go over what basically had to be done, then just did it the way we each felt it should be done".[18] One example offered by O'Dea concerns a scene where Barbra tells Ben about Johnny's death. O'Dea said that the script vaguely had Barbra talk about riding in the car with Johnny before they were attacked. She described Barbra's dialogue for the scene as entirely improv.[61] Eastman modified the scenes written for Helen and Harry Cooper in the cellar.[42] Karl Hardman attributed Ben's lines to lead actor Duane Jones. Ben was an uneducated truck driver in the script until Jones began to rewrite his character.[62][42] The lead role was initially written for a white actor, but upon casting black actor Duane Jones, Romero intentionally did not alter the script to reflect this.[63] The film appeared in theaters at a time when very few black actors played leading roles. The rare exceptions, like the consciously black heroes played by Sidney Poitier, were written as subservient to make those characters palatable to white audiences.[64][65] Asked in 2013 if he took inspiration from the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in the same year that the movie was made, Romero responded in the negative, noting that he only heard about the shooting when he was on his way to find distribution for the finished film.[63] Filming Principal photography Color photograph of tombstones from the film.  Evans City Cemetery in 2007 Color photograph of the cemetery chapel seen in the film, now with all windows boarded over.  Cemetery Chapel in 2009 The small budget dictated much of the production process.[42][66] Scenes were filmed near Evans City, Pennsylvania, 30 miles (48 km) north of Pittsburgh in rural Butler County;[67] the opening sequence was shot at the Evans City Cemetery on Franklin Road, south of the borough.[68][d] Lacking the money to build or purchase a house for the main set, the filmmakers rented a nearby farmhouse scheduled for demolition. Though it lacked running water, some crew members slept there during the shooting, taking baths in a nearby creek.[71] The building's neglected cellar was not a viable location for filming, so the few basement scenes were shot beneath The Latent Image offices.[72] The basement door shown in the film was cut into a wall by the production team and led nowhere.[73] Props and special effects were simple and limited by the budget. The blood, for example, was Bosco Chocolate Syrup drizzled over cast members' bodies.[74] The human flesh consumed by ghouls consisted of meat and offal donated by an investor's butcher shop.[75][76] Zombie makeup varied during the film. Initially, makeup was limited to white skin with blackened eyes. As filming progressed, mortician's wax simulated wounds and decaying flesh.[77] Filming took place between July 1967 and January 1968 under various titles. Work began under the generic working title Monster Flick, was changed to Night of Anubis after Romero's short story that provided the basis for the script, and was completed as Night of the Flesh Eaters, a title not used in the final release due to a potential conflict with a similarly named film.[78][79][80] The small budget led Romero to shoot on 35 mm black-and-white film. The completed film ultimately benefited from the decision, as film historian Joseph Maddrey describes the black-and-white filming as "guerrilla-style", resembling "the unflinching authority of a wartime newsreel". He found the exploitation film to resemble a documentary on social instability.[81] Directing  Karen Cooper leans over her father's bloody corpse holding two handfuls of meat in a still from the film. Living dead Karen Cooper, eating her father's corpse Night of the Living Dead was the first feature-length film directed by George A. Romero. His initial work involved filming advertisements, industrial films, and shorts for Pittsburgh public broadcaster WQED's children's series Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.[82][83][84] Romero's decision to direct Night of the Living Dead launched his career as a horror director. He took the helm of the sequels as well as Season of the Witch (1972), The Crazies (1973), Martin (1978), Creepshow (1982) and The Dark Half (1993).[85][86] Critics saw the influence of the horror and science-fiction films of the 1950s in Romero's directorial style. Stephen Paul Miller, for instance, witnessed "a revival of fifties schlock shock ... and the army general's television discussion of military operations in the film echoes the often inevitable calling-in of the army in fifties horror films". Miller admits that "Night of the Living Dead takes greater relish in mocking these military operations through the general's pompous demeanor" and the government's inability to source the zombie epidemic or protect the citizenry.[87] Romero described the film's intended mood as a downward arc from near hopelessness to complete tragedy. Film historian Carl Royer praised the film's sophistication—especially considering Romero's limited experience—and noted the use of chiaroscuro (film noir style) lighting to create a mood of increasing alienation.[88] While some critics dismissed Romero's film because of the graphic scenes, writer R. H. W. Dillard claimed that the "open-eyed detailing" of taboo heightened the film's success. He asked, "What girl has not, at one time or another, wished to kill her mother? And Karen, in the film, offers a particularly vivid opportunity to commit the forbidden deed vicariously."[89] Romero featured social taboos as key themes, especially cannibalism. Film historian Robin Wood interprets the flesh-eating scenes of Night of the Living Dead as a late-1960s critique of American capitalism. Wood argues that the zombies' consumption of people represents the logical endpoint of human interactions under capitalism.[90] Post-production Members of Image Ten were involved in filming and post-production, participating in loading camera magazines, gaffing, constructing props, recording sounds and editing.[91] Production stills were shot and printed by Karl Hardman, assisted by a "production line" of other cast members.[42] Upon completion of post-production, Image Ten found it difficult to secure a distributor willing to show the film with the gruesome scenes intact. Columbia rejected the film for its lack of color, and American International Pictures declined after requests to soften it and re-shoot the final scene were rejected by producers.[45] The Walter Reade Organization agreed to show the film uncensored but changed the title from Night of the Flesh Eaters to Night of the Living Dead because of an existing film with a similar title. While changing the title, the copyright notice was accidentally deleted from the early releases of the film.[9][92] Soundtrack Duration: 14 minutes and 27 seconds.14:27 Drawn from pre-existing recordings, the music in Night of the Living Dead appears in many other films. The composition from the end credits previously appeared during this 1959 nuclear fallout public service video.[93] FALLOUT: WHEN AND HOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF AGAINST IT (USA 1959, produziert von Creative Arts Studio Inc. im Auftrag des Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization) The film's music consisted of existing pieces that were mixed or modified for the film. Much of the soundtrack had been used by previous films.[e] Romero selected tracks from the Hi-Q music library, and Hardman cut them to match the scenes and augmented them with electronic effects.[94][42] A soundtrack album featuring music and dialogue cues from the film was compiled and released on LP by Varèse Sarabande in 1982. In 2008, the recording group 400 Lonely Things released the album Tonight of the Living Dead, an instrumental album with music and sounds sampled from the 1968 film.[95]  |

プロダクション 開発およびプリプロダクション 外部ビデオ ビデオアイコン『カルゴン物語』 カルゴンブランドの洗剤の高予算テレビコマーシャルの制作が、この映画のプロデューサーをホラー映画制作へと駆り立てた[38]。 ジョージ・ロメロは、ピッツバーグのカーネギーメロン大学在学中に映画業界でのキャリアをスタートさせた[39]。 彼は友人のラッセル・ストリーナーと共同で設立した会社、レイテント・イメージでテレビコマーシャルや産業映画の監督と製作を担当した[40]。レイテン ト・イメージは小規模にスタートしたが、『ファンタスティック・ヴォヤッジ』(1966年)をもじった高予算のカルゴンのコマーシャルを製作した後、ロメ ロはレイテント・イメージが長編映画を製作する経験と機材を持っていると感じた。 [ロメロによれば、彼らは映画業界の「奇妙なものへの渇望」を利用したいと考えていた[41]。彼とストレイナー、ジョン・A・ルッソは、ハードマン・ア ソシエイツというピッツバーグを拠点とする産業映画会社の社長カール・ハードマンと副社長マリリン・イーストマンに連絡を取った。ラテント・イメージは、 当時タイトル未定のホラー映画のアイデアを売り込んだ[42]。 この話し合いが、1本の長編映画を製作するために設立された製作会社、イメージ・テンの設立につながった。当初の予算は6,000ドルで、[12]制作会 社の各メンバーは利益の分け前のために600ドルを出資した[43][b]。さらに10人の出資者が6,000ドルを出資したが、それでもまだ不十分だっ た[44]。ロメロが初期の映像を使って追加の出資者を説得する間、撮影中に何度も制作が中断された[45]。イメージ・テンは最終的に予算として約 114,000ドル(現在では959,000ドル)を集めた[46][44]。 脚本  ゾンビのメイクをした俳優たちが、農家の明かりのない芝生を横切る。 グールたちが家の周りに群がり、生きた人肉を探す。 脚本はルッソとロメロの共同執筆。彼らは、説得力のある宇宙船を作る予算がないことに気づき、思春期のエイリアンを題材にした初期のホラー・コメディの構 想を断念した[47]。ルッソは、青年が家を飛び出し、墓地で食料として人間の死体を収穫しているエイリアンを発見するという、より制約の多い物語を提案 した[48]。 [49][50]ロメロはこのアイデアを肉を食べるグールについての未発表の短編小説と組み合わせ[51]、彼らは未完成の脚本で撮影を開始した[45] [47]。ルッソによれば、撮影前に書かれた脚本はクーパー一家の出現までの出来事しかカバーしていなかった[52]。ルッソは撮影中に脚本を完成させ、 ロメロは後に短編小説の最後のページを続編の『ドーン・オブ・ザ・デッド』(1978年)と『デイ・オブ・ザ・デッド』(1985年)に拡大した [53]。 ロメロはリチャード・マシスンの『アイ・アム・レジェンド』(1954年)からインスピレーションを得た[54][c]。ロメロはインタビューで、『ナイ ト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』と『アイ・アム・レジェンド』を対比させている。彼はマシスンが完全な世界的大混乱の余波について書いたと説明し、ロメロ はそのような災害が発生したときに人々がどのように反応するかを探りたかったと述べた[59]。 主演女優のジュディス・オディアはインタビュアーに、「実際の作業台本があったかどうかはわからない!オディアが提示した一例は、バーブラがジョニーの死 についてベンに話すシーンに関するものだ。オディアによると、脚本ではバーブラが襲われる前にジョニーと車に乗っていたことを漠然と話していたという。 イーストマンは、地下室のヘレンとハリー・クーパーのために書かれたシーンを修正した[42]。ベンは、ジョーンズが彼のキャラクターを書き直し始めるま で、脚本では無学なトラック運転手だった[62][42]。 主役は当初白人俳優のために書かれていたが、黒人俳優のドゥエイン・ジョーンズを起用した際、ロメロは意図的に脚本を変更しなかった[63]。シドニー・ ポワチエが演じた意識的に黒人のヒーローのような稀な例外は、それらのキャラクターを白人の観客に受け入れやすくするために従属的なものとして書かれた [64][65]。 2013年に、この映画が製作された同じ年に起きたマーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアの暗殺からインスピレーションを得たかどうか尋ねられたロメロ は、否定的な回答をし、完成した映画の配給先を探す途中で銃撃事件のことを聞いただけだと述べた[63]。 撮影 主要撮影 映画に登場する墓石のカラー写真。  2007年のエヴァンス市墓地 映画に登場した墓地の礼拝堂のカラー写真。  2009年の墓地礼拝堂 低予算のため、製作過程の多くが指示された[42][66]。シーンはバトラー郡の田舎にあるピッツバーグの北30マイル(48キロ)のペンシルバニア州 エバンズシティ近郊で撮影され[67]、冒頭のシークエンスは自治区の南にあるフランクリン・ロードのエバンズシティ墓地で撮影された[68][d]。水 道はなかったが、何人かのクルーは撮影中にそこで寝泊まりし、近くの小川で入浴した[71]。 小道具や特殊効果はシンプルで、予算によって制限された。例えば、血はボスコ・チョコレート・シロップをキャストの体に垂らしたものであった[74]。 グールが食べる人肉は、投資家の肉屋から提供された肉と内臓で構成されていた[75][76]。当初、メイクは白い肌に黒ずんだ目だけだった。撮影が進む につれて、死神の蝋で傷や腐った肉をシミュレートするようになった[77]。一般的な作業タイトルである『Monster Flick(邦題:怪物フリック)』で始まり、脚本のベースとなったロメロの短編小説にちなんで『Night of Anubis(邦題:アヌビスの夜)』に変更され、『Night of the Flesh Eaters(邦題:肉を喰らう者たちの夜)』として完成した。映画史家のジョセフ・マドリーは、モノクロ撮影を「ゲリラ・スタイル」と表現し、「戦時中 のニュース映画のような淡々とした威厳」に似ていると述べている。彼は、この搾取映画が社会不安定のドキュメンタリーに似ていることを発見した[81]。 監督  父親の血まみれの死体に寄りかかり、両手に肉を持つカレン・クーパー。 父親の死体を食べる生ける屍カレン・クーパー ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は、ジョージ・A・ロメロが初めて監督した長編映画である。最初の仕事は広告、産業映画、ピッツバーグの公共放送局 WQEDの子供向けシリーズ『Mister Rogers' Neighborhood』の短編を撮影することだった[82][83][84]。続編のほか、『魔女の季節』(1972年)、『クレイジーズ』 (1973年)、『マーティン』(1978年)、『クリープショー』(1982年)、『ダーク・ハーフ』(1993年)でもメガホンをとった[85] [86]。批評家たちは、ロメロの演出スタイルに1950年代のホラー映画やSF映画の影響を見ていた。例えば、スティーヴン・ポール・ミラーは、「50 年代のシュロックショックのリバイバル......そして、映画の中で陸軍大将が軍事作戦についてテレビで議論するのは、50年代のホラー映画でしばしば 避けられない軍隊の招集と呼応している」と目撃している。ミラーは、「『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は、将軍の尊大な態度を通して、こうした軍事 作戦を嘲笑することに喜びを感じている」と認めており、ゾンビの蔓延を防ぎ、市民を保護する政府の無能さも認めている[87]。ロメロは、この映画の意図 したムードを、絶望に近い状態から完全な悲劇へと下降する弧であると説明した。映画史家のカール・ロイヤーは、特にロメロの限られた経験を考慮すると、こ の映画の洗練さを賞賛し、疎外感を増大させるムードを作り出すためにキアロスクーロ(フィルム・ノワール風)照明を使用していることを指摘した[88]。 生々しいシーンのためにロメロの映画を否定する批評家もいたが、作家のR.H.W.ディラードは、タブーの「率直な細部描写」がこの映画の成功を高めたと 主張した。母親を殺したいと思ったことのない少女がいるだろうか?そしてこの映画のカレンは、禁じられた行為を身をもって体験する、とりわけ鮮烈な機会を 提供している」[89]。ロメロは社会的タブーを重要なテーマとして取り上げ、とりわけカニバリズムを取り上げた。映画史家のロビン・ウッドは、『ナイ ト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』の肉食シーンを、1960年代後半のアメリカ資本主義批判として解釈している。ウッドによれば、ゾンビによる人間の消費 は、資本主義の下での人間関係の論理的終着点を表しているという[90]。 ポスト・プロダクション イメージ・テンのメンバーは撮影とポストプロダクションに参加し、カメラマガジンの装填、ギャフィング、小道具の組み立て、音声の録音、編集に参加した [91]。プロダクション・スチルはカール・ハードマンによって撮影・印刷され、他のキャスト・メンバーによる「プロダクション・ライン」によって支援さ れた。コロンビアはカラーでないことを理由にこの映画を拒否し、アメリカン・インターナショナル・ピクチャーズはラストシーンを和らげたり撮り直したりす る要求をプロデューサーに拒否された後に拒否した[45]。ウォルター・リード・オーガニゼーションはこの映画をノーカットで上映することに同意したが、 同じようなタイトルの既存の映画があったため、タイトルを『ナイト・オブ・ザ・フレッシュイーターズ』から『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』に変更し た。タイトルを変更する際、初期に公開された作品から著作権表示が誤って削除された[9][92]。 サウンドトラック 収録時間 14分27秒.14:27 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』の音楽は、既存の録音から引用されており、他の多くの映画にも登場している。エンドクレジットの作曲は以前、この 1959年の核放射性降下物の公共サービスビデオに登場した[93]。 FALLOUT: WHEN AND HOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF AGAINST IT (USA 1959, produziert von Creative Arts Studio Inc. im Auftrag des Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization). この映画の音楽は、映画用にミックスされたり変更されたりした既存の楽曲で構成されている。ロメロはハイキューの音楽ライブラリから楽曲を選択し、ハード マンはシーンに合わせてそれらをカットし、電子効果で補強した[94][42]。1982年にヴァレーズ・サラバンドから、この映画の音楽と台詞のキュー を収録したサウンドトラック・アルバムがLPでリリースされた。2008年には、レコーディング・グループの400 Lonely Thingsが、1968年の映画からサンプリングされた音楽とサウンドを収録したインストゥルメンタル・アルバム『Tonight of the Living Dead』をリリースした[95]。  |

| Release Premiere controversy Duration: 1 minute and 50 seconds.1:50 Night of the Living Dead trailer highlighting the film's gore and violence. Night of the Living Dead premiered on October 1, 1968, at the Fulton Theater in Pittsburgh.[21] Nationally, it was a Saturday afternoon matinée—typical for horror films at the time—and attracted the usual horror film audience of mainly pre-teens and adolescents.[96][97][98] The MPAA film rating system was not in place until the following month, so children were able to purchase tickets. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times chided theater owners and parents who allowed children access to a film they were entirely unprepared for. Ebert noted that the children in the audience initially displayed typical reactions to '60s horror films, including shouting when ghouls appeared on the screen. He said that the atmosphere in the theater shifted to grim silence as the protagonists each began to fail, die, and be consumed—either by fire or the undead.[98] The deaths of Ben, Barbra, and the supporting cast showed audiences an uncomfortable, nihilistic outlook that was unusual for the genre.[99] According to Ebert: The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying ... It's hard to remember what sort of effect this movie might have had on you when you were six or seven. But try to remember. At that age, kids take the events on the screen seriously, and they identify fiercely with the hero. When the hero is killed, that's not an unhappy ending but a tragic one: Nobody got out alive. It's just over, that's all.[98] A review in Variety denounced the movie as a moral failing of the film's makers, the horror genre, and regional cinema. The reviewer claimed that the "unrelieved orgy of sadism" was effectively pornography due to its extreme violence.[100] These early denouncements would not limit the film's commercial success or later critical recognition.[101] Critical reception  The neon marquee of a theater lists several notable cult films including Donnie Darko, Reanimator, and Night of the Living Dead. Decades after its initial release, a theater runs a midnight showing of the cult classic Despite the controversy, five years after the premiere Paul McCullough of Take One observed that Night of the Living Dead was the "most profitable horror film ever ... produced outside the walls of a major studio".[102] In the decade after its release, the film grossed over $15 million at the U.S. box office. It was translated into over 25 languages.[103] The Wall Street Journal reported that it was the top-grossing film in Europe in 1968.[89][89] In a 1971 Newsweek article, Paul D. Zimmerman noted that the film had "become a bona fide cult movie for a burgeoning band of blood-lusting cinema buffs".[104] Decades after its release, the film enjoys a reputation as a classic and still receives positive reviews.[105][106][107] In 2008, the film was ranked by Empire magazine No. 397 of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[108] The New York Times also placed the film on their Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[109] In January 2010, Total Film included the film on its list of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[110] Rolling Stone named Night of the Living Dead one of The 100 Maverick Movies in the Last 100 Years.[111] Reader's Digest found it to be the 12th scariest movie of all time.[112] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 95% of 84 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "George A. Romero's debut set the template for the zombie film, and features tight editing, realistic gore, and a sly political undercurrent."[113] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 89 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[114] Night of the Living Dead was awarded two distinguished honors decades after its debut. The Library of Congress added the film to the National Film Registry in 1999 with other films deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[6][33][115][116] In 2001, the film was ranked No. 93 by the American Film Institute on their AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills list, a list of America's most heart-pounding movies.[117] The zombies in the picture were also a candidate for AFI's AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes & Villains, in the villains category, but failed to make the official list.[118] The Chicago Film Critics Association named it the 5th scariest film ever made.[119] The film also ranked No. 9 on Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[120] New Yorker critic Pauline Kael called the film "one of the most gruesomely terrifying movies ever made – and when you leave the theatre you may wish you could forget the whole horrible experience. ... The film's grainy, banal seriousness works for it – gives it a crude realism".[121] A Film Daily critic commented, "This is a pearl of a horror picture that exhibits all the earmarks of a sleeper."[122] While Roger Ebert criticized the matinée screening, he admitted that he "admires the movie itself".[98] Critic Rex Reed wrote, "If you want to see what turns a B movie into a classic ... don't miss Night of the Living Dead. It is unthinkable for anyone seriously interested in horror movies not to see it."[123] Copyright status and home media In the United States, Night of the Living Dead was mistakenly released into the public domain because the original distributor failed to replace the copyright notice when changing the film's name.[9][124] Image Ten displayed a notice on the title frames of the film beneath the original title, Night of the Flesh Eaters, but the Walter Reade Organization removed it when changing the title.[9][125] At that time, United States copyright law held that public dissemination required copyright notice to maintain a copyright.[126] Several years after the film's release, its creators discovered that the original prints distributed to theaters had no copyright protection.[124] Because Night of the Living Dead was not copyrighted, it has received hundreds of home video releases on VHS, Betamax, DVD, Blu-ray, and other formats.[127] Over two hundred distinct versions of the film have been released on tapes alone.[128] Numerous versions of the film have appeared on DVD, Blu-ray, and LaserDisc with varying quality.[129] The original film is available to view or download for free on many websites.[f] As of February 2024, it is the Internet Archive's third most-viewed film, with over 3.5 million views.[138] The film received a VHS release in 1993 through Tempe Video.[139] The next year, a THX certified 25th anniversary Laserdisc was released by Elite Entertainment. It features special features, including commentary, trailers, gallery files, and more.[140] In 1999, Russo's revised version of the film, Night of the Living Dead: 30th Anniversary Edition, was released on VHS and DVD by Anchor Bay Entertainment.[139] In 2002, Elite Entertainment released a special edition DVD featuring the original cut.[139] Dimension Extreme released a restored print of the film on DVD.[139] This was followed by a 4K restoration Blu-ray released by The Criterion Collection on February 13, 2018, sourced from a print owned by the Museum of Modern Art and acquired by Janus Films.[141][142] This release also features a workprint edit of the film under the title of Night of Anubis, in addition to various bonus materials.[143] In February 2020, Netflix took down Night of the Living Dead from its streaming service in Germany following a legal request in 2017 because "a version of the film is banned in that country."[144][145] Revisions There are numerous revised versions of the film with content added, deleted, rearranged, or more heavily modified. From its initial release into the public domain, Night of the Living Dead was widely screened from inferior prints in grindhouse theaters, a trend that continued among the bottom-tier home video companies. The first major revisions of Night of the Living Dead involved colorization by home video distributors. Hal Roach Studios released a colorized version in 1986 that featured ghouls with pale green skin.[146][147] Another colorized version appeared in 1997 from Anchor Bay Entertainment with grey-skinned zombies.[148] In 2009, Legend Films co-produced a colorized 3D version of the film with PassmoreLab, a company that converts 2-D film into 3-D format.[149] The film was theatrically released on October 14, 2010.[150] According to Legend Films founder Barry Sandrew, Night of the Living Dead is the first entirely live action 2-D film to be converted to 3-D.[151] In 1999, co-writer Russo released a modified version called Night of the Living Dead: 30th Anniversary Edition.[152] He filmed additional scenes and recorded a revised soundtrack composed by Scott Vladimir Licina. In an interview with Fangoria magazine, Russo explained that he wanted to "give the movie a more modern pace".[153] Russo took liberties with the original script. The additions are neither clearly identified nor even listed. Entertainment Weekly reported "no bad blood" between Russo and Romero. The magazine quoted Romero as saying, "I didn't want to touch Night of the Living Dead".[154] Critics disliked the revised film, notably Harry Knowles of Ain't It Cool News, who promised to permanently ban anyone from his publication who offered positive criticism of the film.[155][156] A collaborative animated project known as Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated was screened at several film festivals[157] and was released onto DVD on July 27, 2010, by Wild Eye Releasing.[158][159] This project aims to "reanimate" the 1968 film by replacing Romero's celluloid images with animation done in a wide variety of styles by artists from around the world, laid over the original audio from Romero's version.[160] Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated was nominated in the category of Best Independent Production (film, documentary or short) for the 8th Annual Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards.[161] Starting in 2015, and working from the original camera negatives and audio track elements, a 4K digital restoration of Night of the Living Dead was undertaken by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and The Film Foundation.[162] The fully restored version was shown in November 2016 as part of To Save and Project: The 14th MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation.[163][164] This same restoration was released on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection on February 13, 2018,[141] and on Ultra HD Blu-ray on October 4, 2022.[165] |

リリース プレミア論争 上映時間 1分50秒.1:50 映画『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』のゴアと暴力を強調した予告編. ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は1968年10月1日、ピッツバーグのフルトン・シアターでプレミア上映された[21]。全国的には、当時のホラー 映画としては典型的な土曜日の午後のマチネであり、主に10代前と青少年という通常のホラー映画の観客を惹きつけた。シカゴ・サンタイムズ紙のロジャー・ エバート記者は、子どもたちにまったく準備のない映画を鑑賞させた映画館のオーナーや親たちを非難した。エバートは、観客の子供たちが最初、スクリーンに グールが現れると叫ぶなど、60年代のホラー映画に対する典型的な反応を示したと指摘した。ベン、バーブラ、そして脇役たちの死は、このジャンルには珍し い、不快で虚無的な見通しを観客に示した[99]: 観客の子供たちは唖然としていた。ほとんど完全に沈黙していた。映画は途中から楽しく怖がるのをやめ、予想外に恐ろしくなっていた。通路を挟んで私の向か い側に、たぶん9歳くらいの小さな女の子がいた。あなたが6歳か7歳の頃、この映画があなたにどんな影響を与えたかを思い出すのは難しい。しかし、思い出 してみてほしい。その年頃の子供たちは、スクリーンの中の出来事を真剣に受け止め、主人公に激しく共感する。主人公が殺されたとき、それは不幸な結末では なく、悲劇的な結末なのだ: 誰も生きて帰れなかった。ただ終わった、それだけだ」[98]。 バラエティ』誌の批評は、映画の製作者、ホラー・ジャンル、地域映画の道徳的失敗としてこの映画を非難した。この批評家は、「サディズムの乱痴気騒ぎ」は その極端な暴力のために事実上ポルノであると主張した[100]。 これらの初期の非難は、この映画の商業的成功や後の批評家の評価を制限することはなかった[101]。 批評家の評価  映画館のネオンマーキーには、『ドニー・ダーコ』、『リアニメーター』、『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』など、有名なカルト映画がいくつかリスト アップされている。 初公開から数十年後、ある映画館ではこのカルト的名作を深夜に上映している。 賛否両論あったものの、公開から5年後、テイク・ワンのポール・マッカローは、『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド』は「メジャースタジオ以外で製作さ れたホラー映画の中で最も収益性の高い作品」であると評価した[102]。ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙は、1968年にヨーロッパで最も興行収入 を上げた映画であると報じた[89][89]。 1971年のニューズウィークの記事で、ポール・D・ジマーマンは、この映画が「血に飢えた映画ファンの急成長中の一団にとって、正真正銘のカルト映画と なった」と指摘した[104]。 公開から数十年経った今でも、この映画は古典的作品として高い評価を得ており、好意的な評価を得ている[105][106][107]。 2008年、この映画は『Empire』誌によって「史上最高の映画500本」の397位にランク付けされた[108]。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙もこの映画を「史上最高の映画1000本」のリストに入れた[109]。 2010年1月、『Total Film』はこの映画を「史上最高の映画100本」のリストに加えた。 [110] ローリング・ストーン誌は『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』を「過去100年間で最も革新的な映画100本」のひとつに選んだ[111] リーダーズ・ダイジェスト誌は、この映画を史上12番目に怖い映画だと評価した[112] レビュー集計サイト「ロッテン・トマト」では、84人の批評家のレビューのうち95%が肯定的で、平均評価は8.9/10。同サイトのコンセンサスはこう だ: 「ジョージ・A・ロメロのデビュー作はゾンビ映画の雛形を作り、タイトな編集、リアルなゴア、そしてずる賢い政治的な裏の顔を特徴としている」 [113]。加重平均を用いるメタクリティックでは、17人の批評家に基づき100点満点中89点を与え、「普遍的な称賛」を示している[114]。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』はデビューから数十年後、2つの栄誉に輝いた。アメリカ議会図書館は1999年、「文化的、歴史的、美学的に重要」と みなされた他の映画とともに、この映画をナショナル・フィルム・レジストリに加えた[6][33][115][116] 2001年、この映画はアメリカ映画協会によって、アメリカで最も胸躍る映画のリストであるAFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrillsの93位にランク付けされた。 [シカゴ映画批評家協会は、この映画を史上最も怖い映画の第5位に選んだ[119] 。 ニューヨーカーの批評家ポーリン・ケールは、この映画を「これまでに作られた映画の中で最も残酷で恐ろしい映画のひとつであり、劇場を出るときには、その 恐ろしい体験のすべてを忘れてしまいたいと願うかもしれない」と評した。... この映画の粒状で平凡なシリアスさが功を奏し、粗野なリアリズムを与えている」と評した[121]。 フィルム・デイリー紙の批評家は「これは、スリーパーのすべての兆候を示す真珠のようなホラー映画だ」とコメントした[122]。 ロジャー・エバートはマチネー上映を批評する一方で、「映画そのものを賞賛している」と認めた[98]。批評家レックス・リードが「B級映画を古典に変え るものを見たいなら......『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』を逃すな。ホラー映画に真剣に興味がある人なら、これを見ないことは考えられない」 [123]。 著作権の状態と家庭用メディア アメリカでは、『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド』はオリジナルの配給会社が映画名を変更する際に著作権表示を差し替えなかったため、誤ってパブリッ クドメインとして公開された[9][124]。イメージ・テンは原題『Night of the Flesh Eaters』の下にある映画のタイトル枠に通知を表示したが、ウォルター・リード・オーガニゼーションはタイトルを変更する際にそれを削除した。 [9][125]当時、アメリカの著作権法では、著作権を維持するためには、公衆への普及には著作権表示が必要であるとされていた[126]。 映画の公開から数年後、製作者たちは、劇場に配布されたオリジナルプリントには著作権保護がないことを発見した[124]。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は著作権保護されていなかったため、VHS、ベータマックス、DVD、Blu-ray、その他のフォーマットで何百も のホームビデオがリリースされている[127]。 この映画の200以上の異なるバージョンがテープだけでリリースされている[128]。 この映画の多数のバージョンがDVD、Blu-ray、レーザーディスクで様々な品質で登場している[129]。 翌年、エリート・エンターテインメントからTHX認証25周年記念レーザーディスクが発売された。1999年、ルッソの改訂版『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビン グデッド:30周年記念版』がアンカー・ベイ・エンターテインメントからVHSとDVDでリリースされた[139]。2002年、エリート・エンターテイ ンメントがオリジナル・カットを収録した特別版DVDをリリース。 [139]これに続き、2018年2月13日にクライテリオン・コレクションから、近代美術館が所有し、ヤヌス・フィルムズが入手したプリントを使用した 4K復元ブルーレイがリリースされた[141][142]。 このリリースでは、様々なボーナス素材に加え、『アヌビスの夜』のタイトルで映画のワークプリント編集も収録されている[143]。 2020年2月、Netflixは2017年の法的要請を受け、「映画のバージョンがその国で禁止されている」[144][145]ことを理由に、ドイツ のストリーミングサービスから『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド』を削除した。 改訂版 この映画には、内容の追加、削除、再配置、またはより大きく変更された多数の改訂版がある。公開当初から、『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド』は劣悪 なプリントで広くグラインドハウスで上映され、その傾向は底辺のホームビデオ会社の間で続いた。ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』の最初の大きな改訂 は、ホームビデオ配給会社によるカラー化だった。ハル・ローチ・スタジオは1986年に淡い緑色の肌のグールをフィーチャーしたカラー化版をリリースした [146][147]。1997年にはアンカー・ベイ・エンターテイメントからグレーの肌のゾンビをフィーチャーした別のカラー化版が登場した [148]。2009年、レジェンド・フィルムズは2Dフィルムを3Dフォーマットに変換する会社であるパスモア・ラボとこの映画のカラー化3D版を共同 製作した。 [149]この映画は2010年10月14日に劇場公開された[150]。レジェンド・フィルムズの創設者であるバリー・サンドリューによれば、『ナイ ト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド』は3-Dに変換された初の完全な実写2-D映画である[151]。 1999年、共同脚本家であるルッソは『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド:30周年記念版』と呼ばれる修正版をリリースした[152]。 Fangoria』誌のインタビューで、ルッソは「映画に現代的なペースを与えたかった」と説明している[153]。ルッソはオリジナルの脚本を自由に変 更した。Entertainment Weekly誌は、ルッソとロメロの間に「悪縁はない」と報じた。同誌はロメロの「『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』には触れたくなかった」という言 葉を引用している[154]。批評家たちは改訂された映画を嫌っており、特に『エイント・イット・クール・ニュース』のハリー・ノウルズは、この映画につ いて肯定的な批評をした者を自身の出版物から永久追放すると約束した[155][156]。 Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated』として知られる共同アニメーションプロジェクトは、いくつかの映画祭で上映され[157]、2010年7月27日にWild Eye ReleasingからDVDでリリースされた[158][159]。このプロジェクトは、ロメロのセル画を世界中のアーティストによる様々なスタイルの アニメーションに置き換え、ロメロ版のオリジナル音声に重ねることで、1968年の映画を「再アニメ化」することを目的としている。 [160]『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド:リアニメイテッド』は、第8回ロンド・ハットン・クラシック・ホラー・アワードの最優秀インディペンデン ト作品(映画、ドキュメンタリー、短編)部門にノミネートされた[161]。 2015年に開始され、オリジナルのカメラネガとオーディオトラックの要素から作業された『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』の4Kデジタル修復は、近 代美術館(MoMA)とフィルム財団によって行われた[162] 完全修復版は、2016年11月に「To Save and Project」の一環として上映された: 第14回MoMA国際映画保存フェスティバル[163][164]この同じ修復は、2018年2月13日にクライテリオン・コレクションによってBlu- rayでリリースされ[141]、2022年10月4日にUltra HD Blu-rayでリリースされた[165]。 |

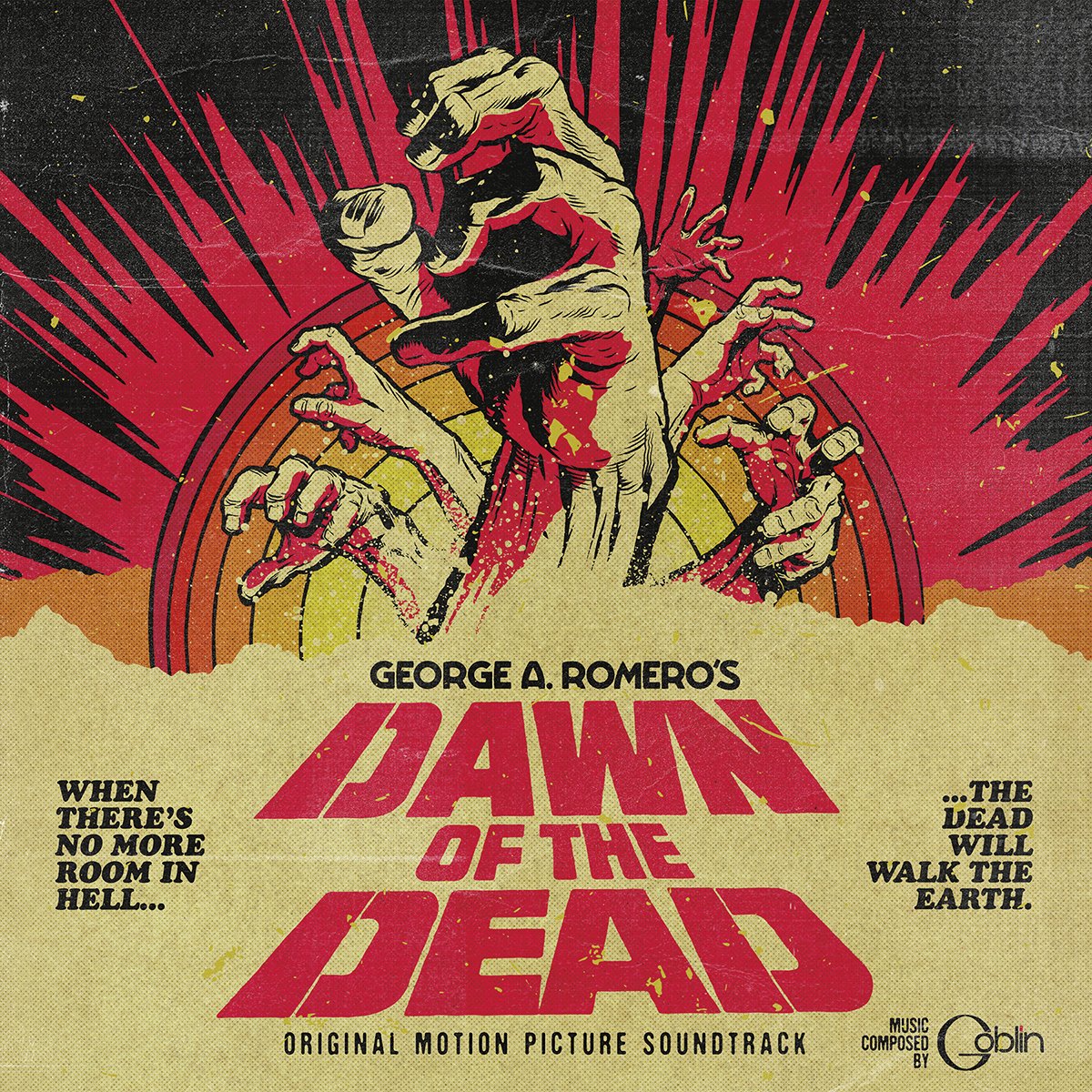

| Related works Romero's Dead films Main article: Night of the Living Dead (film series) An album with illustrations of hands bursting through the ground, above the words "When there's no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth."  Cover for Dawn of the Dead album Night of the Living Dead is the first of six ... of the Dead films directed by George Romero. Following the 1968 film, Romero released Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Land of the Dead, Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead.[166] Each film traces the evolution of the living dead epidemic in the United States and humanity's desperate attempts to cope with it. As in Night of the Living Dead, Romero peppered the other films in the series with critiques specific to the periods in which they were released.[167][168][169] Romero died with several "Dead" projects unfinished, including the posthumously completed novel The Living Dead[170] and the upcoming film The Twilight of the Dead.[171] Return of the Living Dead series Main article: Return of the Living Dead (film series) The Return of the Living Dead series takes place in an alternate continuity where both the original film and the titular living dead exist. The series has a complicated relationship with Romero's Dead films.[172] Co-writer John Russo wrote the novel Return of the Living Dead (1978) as a sequel to the original film and collaborated with Night alumni Russ Streiner and Rudy Ricci on a screenplay under the same title. In 1981, investment banker Tom Fox bought the rights to the story. Fox brought in Dan O'Bannon to direct and rewrite the script, changing nearly everything but the title.[173][174] O'Bannon's The Return of the Living Dead arrived in theaters in 1985 alongside Day of the Dead. Romero and his associates attempted to block Fox from marketing his film as a sequel and demanded the name be changed. In a previous court case, Dawn Associates v. Links (1978), they had prevented Illinois-based film distributor William Links from re-releasing an unrelated film under the title Return of the Living Dead. Fox was forced to cease his advertising campaign but allowed to retain the title.[175][174][176][177] Rise of the Living Dead George Cameron Romero, the son of director George A. Romero, wrote a prequel to his father's classic, under the working titles Origins and Rise of the Living Dead. George Cameron Romero said that he created Rise of the Living Dead as an homage to his father's work, a glimpse into the political turmoil of the mid-to-late 1960s, and a bookend piece to his father's original story. Despite raising funds for the film on Indiegogo in 2014,[178] as of 2023 the film has yet to go into production.[179] In April 2021, Heavy Metal magazine published the first issue of a graphic novel adaptation of the story titled The Rise from Romero's script and with art by Diego Yapur.[180][181] Remakes and other related films Many remakes have attempted to reimagine the original film's story, most notably the 1990 remake written by Romero and directed by special effects artist Tom Savini. Savini had planned to work on the 1968 film before being drafted into the Vietnam War,[182][183] and, after the war, worked with Romero on the sequels.[184] The remake was based on the original screenplay but included a revised plot that portrayed Barbra (Patricia Tallman) as a capable and active heroine.[185] Film historian Barry Grant interprets the new Barbara as a reversal of the original film's portrayal of feminine passivity.[186] He explores how the 1990 Barbra embodies—arguably masculine—virtuous professionalism, as depicted in the works of classic Hollywood director Howard Hawks, a major influence on Romero.[187] Grant describes her as the film's only Hawksian professional. After changing from a mousy outfit that mirrors the original into the visually militaristic clothing she discovers in the farmhouse, Barbra is the lone character able to separate her emotions from the objective necessity to exterminate the living dead.[188] According to Grant, Romero is able to offer one of the most important feminist outlooks in horror because the undead disrupt all traditional values including patriarchy.[189] The second remake was in 3-D and released in September 2006 under the title Night of the Living Dead 3D, directed by Jeff Broadstreet. Unlike Savini's film, Broadstreet's project was not affiliated with Romero.[190] Broadstreet's film was followed in 2012 by a prequel, Night of the Living Dead 3D: Re-Animation.[191] On September 15, 2009, it was announced that Simon West was producing a 3D animated retelling of the original film, originally titled Night of the Living Dead: Origins 3D and later re-titled Night of the Living Dead: Darkest Dawn.[192][193] The movie is written and directed by Zebediah de Soto. The voice cast includes Tony Todd as Ben, Danielle Harris as Barbra, Joseph Pilato as Harry Cooper, Alona Tal as Helen Cooper, Bill Moseley as Johnny, Tom Sizemore as Chief McClellan and newcomers Erin Braswell as Judy and Michael Diskint as Tom.[194][195][196][197][198][199] Director Doug Schulze's 2011 film Mimesis: Night of the Living Dead relates the story of a group of horror film fans who become involved in a "real-life" version of the 1968 film.[200][201] Due to its public domain status, several independent producers have created remakes. Night of the Living Dead: Resurrection (2012): British filmmaker James Plumb directed this Wales-set remake.[202] A Night of the Living Dead (2014): Shattered Images Films and Cullen Park Productions released a remake with new twists and characters, written and directed by Chad Zuver.[203] Rebirth (formerly Night of the Living Dead: Rebirth) (2021):[204] Rising Pulse Productions' updated take on the classic film was released in June 2021 and brings to light present issues that impact modern society such as religious bigotry, homophobia and the influence of social media.[205] Night of the Animated Dead (2021): Warner Bros. Home Entertainment announced in June 2021 that they were in production of an animated adaptation. Directed by Jason Axinn (To Your Last Death) and featuring the voices of Dulé Hill (Ben), Katharine Isabelle (Barbra), Josh Duhamel (Harry Cooper), James Roday Rodriguez (Tom), Katee Sackhoff (Judy), Will Sasso (Sheriff McClelland), Jimmi Simpson (Johnny) and Nancy Travis (Helen Cooper), it was released via video on demand on September 21, 2021.[206] A Night of the Undead (2022) was released to select theaters in October 2022.[207] In January 2023, the film saw wider release. Directed by Kenny Scott Guffey, Jake C. Young and stars Denny Kidd, Briana Phipps-Stotts, and Mason Johnson.[208] Night of the Living Dead II: In June 2021, director Marcus Slabine debuted information about his secretly filmed sequel.[209] The film stars Lori Cardille, Terry Alexander and Jarlath Conroy of Day of the Dead.[210] As of 2024, the film has still not been released.[211] Festival of the Living Dead: In May 2023, the Soska sisters announced an in-universe followup taking place half a century after the events of the 1968 film, starring Ashley Moore and Camren Bicondova. It was set to be released on Tubi in fall 2023, but will now premiere in April 2024.[212][213] In other media At the suggestion of Bill Hinzman (the actor who played the zombie that first attacks Barbra in the graveyard and kills her brother Johnny at the beginning of the original film), composers Todd Goodman and Stephen Catanzarite composed an opera Night of the Living Dead based on the film.[214] The Microscopic Opera Company produced its world premiere, which was performed at the Kelly-Strayhorn Theater in Pittsburgh, in October 2013.[215] The opera was awarded the American Prize for Theater Composition in 2014.[216] A play called Night of the Living Dead Live! was published in 2017[217] and has been performed in major cities including Toronto, Leeds and Auckland.[218][219][220] |

関連作品 ロメロのデッド映画 主な記事 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(映画シリーズ) "地獄に空きがなくなると、死者が地上を歩くようになる "という文字の上に、地面から破裂する手のイラストが描かれたアルバム。  アルバム『ドーン・オブ・ザ・デッド』のジャケット ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は、ジョージ・ロメロが監督した6本の『死霊のはらわた』映画のうちの1本目である。1968年の作品に続き、ロメロ は『ドーン・オブ・ザ・デッド』、『デイ・オブ・ザ・デッド』、『ランド・オブ・ザ・デッド』、『ダイアリー・オブ・ザ・デッド』、『サバイバル・オブ・ ザ・デッド』を発表した。ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』のように、ロメロはシリーズの他の作品に、それらが公開された時代特有の批評を散りばめてい る[167][168][169]。ロメロは、死後に完結した小説『リビング・デッド』[170]や公開予定の映画『トワイライト・オブ・ザ・デッド』 [171]など、いくつかの「デッド」プロジェクトを未完のまま死去した。 生ける屍の帰還』シリーズ 主な記事 生ける屍の帰還』シリーズ 生ける屍の帰還』シリーズは、オリジナルの映画と主人公の生ける屍の両方が存在する別の連続性を舞台としている。共同脚本家のジョン・ルッソはオリジナル 映画の続編として小説『Return of the Living Dead』(1978年)を書き、同タイトルの脚本を『ナイト』出身のラス・ストリーナーとルディ・リッチと共同で執筆した。1981年、投資銀行家のト ム・フォックスが物語の権利を購入。フォックスはダン・オバノンを監督に迎え、脚本を書き直し、タイトル以外のほぼすべてを変更した[173] [174]。ロメロと彼の仲間は、フォックスが彼の映画を続編として販売するのを阻止しようとし、名前を変更するよう要求した。以前の裁判「ドーン・アソ シエイツ対リンクス」(1978年)では、イリノイ州に本拠を置く映画配給会社ウィリアム・リンクスが、無関係の映画を『リターン・オブ・ザ・リビング デッド』のタイトルで再公開するのを阻止していた。フォックスは広告キャンペーンの中止を余儀なくされたが、タイトルの保持は許可された[175] [174][176][177]。 ライズ・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド ジョージ・A・ロメロ監督の息子であるジョージ・キャメロン・ロメロは、父の名作の前日譚を『Origins』と『Rise of the Living Dead』という作業タイトルで執筆した。ジョージ・キャメロン・ロメロは、父の作品へのオマージュとして、1960年代半ばから後半の政治的混乱を垣間 見る作品として、また父の原作へのブックエンド作品として、『ライズ・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』を制作したと語っている。2014年に Indiegogoで映画のための資金を集めたにもかかわらず[178]、2023年現在、映画はまだ製作に取り掛かっていない[179]。2021年4 月、Heavy Metal誌は、ロメロの脚本とディエゴ・ヤプールのアートによる『The Rise』と題された物語のグラフィック小説の翻案の創刊号を出版した[180][181]。 リメイクとその他の関連映画 ロメロが脚本を書き、特殊効果アーティストのトム・サヴィーニが監督した1990年のリメイクは特に有名である。サヴィーニはベトナム戦争に徴兵される前 に1968年の作品に携わる予定だったが[182][183]、戦後はロメロと共に続編に携わった[184]。リメイク版はオリジナルの脚本に基づいてい たが、バーブラ(パトリシア・トールマン)を有能で活動的なヒロインとして描くプロットの改訂が含まれていた。 [185]映画史家のバリー・グラントは、新しいバーバラを、オリジナル映画の女性的受動性の描写の逆転として解釈している[186]。彼は、1990年 のバーバラが、ロメロに大きな影響を与えた古典的ハリウッド監督ハワード・ホークスの作品に描かれているような、間違いなく男性的で高潔なプロフェッショ ナリズムをどのように体現しているかを探求している。原作を反映したねっとりとした服装から、農家で発見した視覚的に軍国主義的な服装に着替えたバーブラ は、生ける屍を絶滅させるという客観的な必要性から感情を切り離すことができる唯一のキャラクターである[188]。 グラントによれば、アンデッドが家父長制を含むあらゆる伝統的な価値観を崩壊させるため、ロメロはホラーにおいて最も重要なフェミニズムの展望のひとつを 提示することができたという[189]。 2度目のリメイクは3Dで、ジェフ・ブロードストリート監督による『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド 3D』というタイトルで2006年9月に公開された。サヴィーニの映画とは異なり、ブロードストリートのプロジェクトはロメロとは無関係だった [190]。ブロードストリートの映画は2012年に前日譚である『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビング・デッド 3D』が公開された: 再アニメ化[191]。 2009年9月15日、サイモン・ウェストがオリジナル映画の3Dアニメーションを製作することが発表され、当初は『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド: オリジン3D』と題され、後に『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド:ダーケスト・ドーン』と改題された[192][193]。声の出演はベン役のトニー・ トッド、バーブラ役のダニエル・ハリス、ハリー・クーパー役のジョセフ・ピラト、ヘレン・クーパー役のアローナ・タル、ジョニー役のビル・モーズリー、マ クレラン署長役のトム・サイズモア、そしてジュディ役のエリン・ブラズウェルとトム役のマイケル・ディスキントが新たに加わった[194][195] [196][197][198][199]。 ダグ・シュルツ監督の2011年の映画『ミメシス』: ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』は、1968年の映画の「実写版」に巻き込まれたホラー映画ファンのグループの物語を描いている[200] [201]。 パブリックドメインであるため、いくつかの独立系プロデューサーがリメイクを制作している。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド:リザレクション』(2012年): イギリスの映画監督ジェームズ・プラムがウェールズを舞台にしたこのリメイクを監督した[202]。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(2014年): Shattered Images FilmsとCullen Park Productionsは、チャド・ズーヴァーが脚本と監督を務めた、新たなひねりと登場人物を加えたリメイクを発表した[203]。 Rebirth (formerly Night of the Living Dead: Rebirth) (2021):[204] Rising Pulse Productionsによる古典的な映画の最新版は2021年6月に公開され、宗教的偏見、同性愛嫌悪、ソーシャルメディアの影響など、現代社会に影響 を与える現在の問題を浮き彫りにした[205]。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・アニメイテッド・デッド』(2021年): ワーナー・ブラザース・ホームエンターテイメントは2021年6月、アニメ化作品の製作を発表した。監督は『最後の死へ』のジェイソン・アクシン、声の出 演はデュレ・ヒル(ベン)、キャサリン・イザベル(バーブラ)、ジョシュ・デュアメル(ハリー・クーパー)、ジェームズ・ロデイ・ロドリゲス(トム)、ケ イティ・サッコフ(ジュディ)、ウィル・サッソ(マクレランド保安官)、ジミ・シンプソン(ジョニー)、ナンシー・トラヴィス(ヘレン・クーパー)で、 2021年9月21日にビデオ・オン・デマンドでリリースされた[206]。 アンデッドの夜』(2022年)は2022年10月に一部の劇場で公開された[207]。 2023年1月、この映画はより広い公開を見た。監督はケニー・スコット・グフィー、ジェイク・C・ヤング、主演はデニー・キッド、ブリアナ・フィップ ス・ストッツ、メイソン・ジョンソン[208]。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッドII:2021年6月、監督のマーカス・スレイバインは秘密裏に撮影された続編についての情報を公開した[209]。 この映画にはロリ・カーディル、テリー・アレクサンダー、『デイ・オブ・ザ・デッド』のジャーラス・コンロイが出演している[210]。2024年現在、 この映画はまだ公開されていない[211]。 フェスティバル・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド:2023年5月、ソスカ姉妹はアシュリー・ムーアとカムレン・ビコンドヴァ主演の、1968年の映画の出来事 の半世紀後を舞台とした、ユニバース内の続編を発表した。2023年秋にTubiで公開される予定だったが、2024年4月に公開されることになった [212][213]。 他のメディアでは ビル・ヒンズマン(オリジナル映画の冒頭で、墓地で最初にバーブラを襲い、彼女の弟ジョニーを殺すゾンビを演じた俳優)の提案により、作曲家のトッド・ グッドマンとスティーヴン・カタンザライトは、映画を基にオペラ『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』を作曲した[214]。 ミクロスコピック・オペラ・カンパニーが世界初演を制作し、2013年10月にピッツバーグのケリー・ストレイホーン劇場で上演された[215]。 ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド・ライブ!』という戯曲が2017年に出版され[217]、トロント、リーズ、オークランドなどの主要都市で上演されて いる[218][219][220]。 |

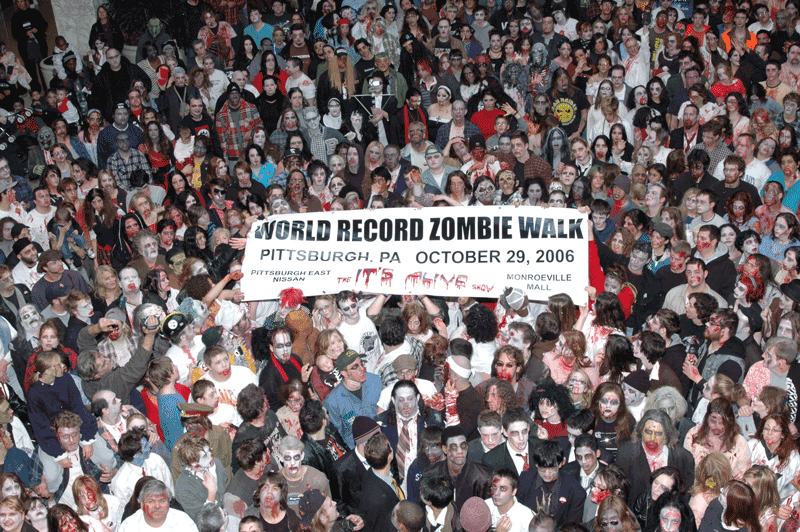

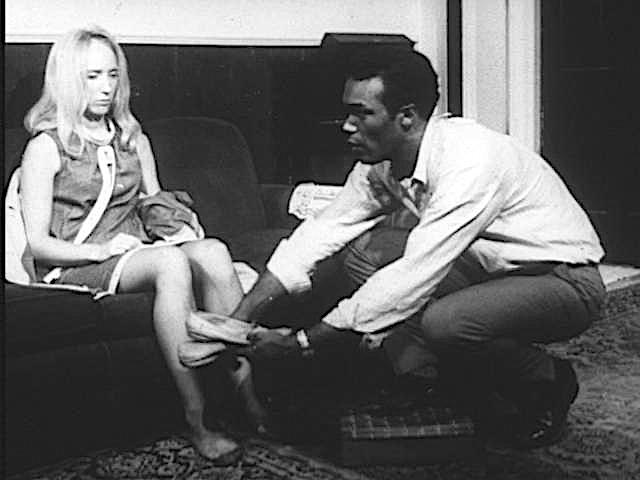

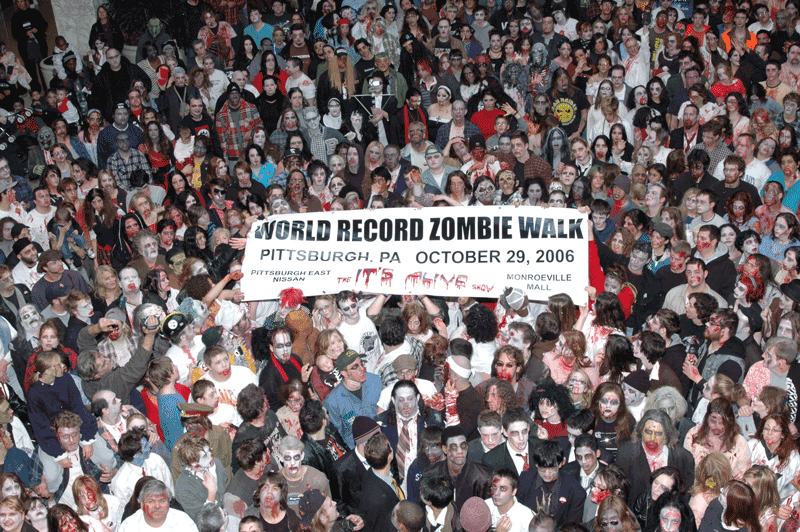

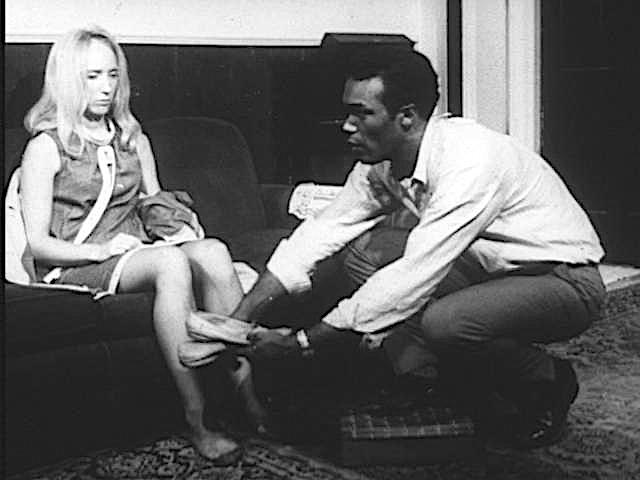

| Legacy See also: Zombie  A packed crowd in zombie makeup hold a banner reading, "World Record Zombie Walk, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 26, 2006, The It's Alive Show, Pittsburgh East Nissan, Monroeville Mall" A zombie walk in Monroeville Mall, the setting of Romero's Dawn of the Dead Romero revolutionized the horror film genre with Night of the Living Dead; according to Almar Haflidason of the BBC, the film represented "a new dawn in horror film-making".[221] The film ushered in the splatter film subgenre. Earlier horror films had largely involved rubber masks, costumes, cardboard sets, and mysterious figures lurking in the shadows. They were set in locations far removed from rural and suburban America.[222] Romero revealed the power behind exploitation and setting horror in ordinary, unexceptional locations and offered a template for making an effective film on a small budget.[223] Night spawned countless imitators in cinema, television, and video gaming.[7] According to author Barry Keith Grant, the slasher films of the 1970s and 1980s such as John Carpenter's Halloween (1978), Sean S. Cunningham's Friday the 13th (1980), and Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) are indebted to Romero's use of gore in a familiar setting.[224] The film is regarded as one of the launching pads for the modern zombie movie,[225] and effectively redefined the "zombie".[226] Before the film's release, the term "zombie" described a concept from Haitian folklore whereby a bokor could reanimate a corpse into an insensate slave.[227] Early zombie films like White Zombie (1932) combined this with racial and postcolonial anxieties.[228] Romero never used the word "zombie" in the 1968 film or its script—using instead, ghoul—because he said that his flesh-eaters were something new.[21][229][230][63] The term "zombie" was retroactively applied to Night after its cannibalistic undead became the dominant zombie concept in the United States,[231] to such an extent that zombie has become a byword for concepts that failed to "die".[232] According to professor of religious studies Kim Paffenroth, Romero's antagonists broke with earlier traditions of "voodoo zombies" by having no human villain in control of the zombie and thus no potential to ever restore the monsters' humanity.[233] Compared to the vampires and Haitian zombies that served as inspiration, Romero's antagonists derive more horror from abjection, the disgust that arises from an inability to separate clean from corrupt. While the vampire myth offers a potential escape from mundane life, the zombie offers an infinite decay more abject than conventional death.[234] Cultural critic Steven Shaviro has remarked that—unlike with other movie characters—audiences cannot identify with the zombies because there is no identity left within their bodies, and that they instead provide audiences a combination of disgust and fascinated attraction.[226][235] Critical analysis  Ben crouches to give shoes to Barbra who is sitting on the couch barefoot Barbra and Ben after their first meeting Since its release, many critics and film historians have interpreted Night of the Living Dead as a subversive film that critiques 1960s American society, international Cold War politics and domestic racism.[65] Film historian Robin Wood organized "The American Nightmare"—a sixty-film retrospective combining screenings and director interviews to frame horror in terms of oppression and repression—for the 1979 Toronto International Film Festival. His essay from the program notes, "An Introduction to the American Horror Film", was highly influential, especially in film criticism where horror as a genre had not previously been considered a topic for serious analysis.[236][237] Wood interprets notable horror films including Night through a psychoanalytic framework.[238] He discusses how traits deemed unacceptable are repressed on the personal level or when not repressed, oppressed on the societal level.[238] He identifies repressed taboos and othered groups as the psychological basis for horror monsters.[238] Wood and later critics used this framework to discuss Night as a commentary on repressed sexuality, the marginalized groups of 1960s America, and the disruption to societal norms resulting from the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.[239][240] Elliot Stein of The Village Voice sees the film as an ardent critique of American involvement in the Vietnam War, arguing that it "was not set in Transylvania, but Pennsylvania – this was Middle America at war, and the zombie carnage seemed a grotesque echo of the conflict then raging in Vietnam".[241] Film historian Sumiko Higashi concurs, arguing that Night of the Living Dead draws from the visual vocabulary the media used to report on the war, noting especially that the photographs of the napalm girl and the execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém would be fresh in the minds of the film's creators and audience.[242] She points to aspects of the Vietnam War paralleled in the film: grainy black-and-white newsreels, search and destroy operations, helicopters, and graphic carnage.[243] In 1968, the news was still broadcast in black and white, and the graphic photographs that appear during the closing credits resemble the contemporary Vietnam War photojournalism.[65] Critics have compared the shooting of the film's black protagonist to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[65][244][245] Stein explains, "In this first-ever subversive horror movie, the resourceful black hero survives the zombies only to be surprised by a redneck posse".[241] In 2018, on the film's 50th anniversary, Mark Lager of CineAction noted a clear parallel between the killing and destruction of Ben's body by white police and the violence directed at African Americans during the civil rights movement. Lager described it as a more honest exploration of 1960s America than anything produced by Hollywood.[246] Film historian Gregory Waller identifies broad-ranging critiques of American institutions including the nuclear family, private homes, media, government, and "the entire mechanism of civil defense".[247] Film historian Linda Badley explains that the film was so horrifying because the monsters were not creatures from outer space or some exotic environment, but rather that "They're us."[248] In the 2009 documentary film Nightmares in Red, White and Blue, the zombies in the film are compared to the "silent majority" of the U.S. in the late 1960s.[249] |

レガシー こちらも参照: ゾンビ  "世界記録ゾンビ・ウォーク、ペンシルベニア州ピッツバーグ、2006年10月26日、イッツ・アライブ・ショー、ピッツバーグ・イースト・ニッサン、モ ンロービル・モール "と書かれた横断幕を掲げるゾンビメイクをした大勢の観客。 ロメロ監督の『ドーン・オブ・ザ・デッド』の舞台となったモンロービル・モールでのゾンビ・ウォーク ロメロは『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』でホラー映画のジャンルに革命を起こした。BBCのアルマー・ハフリダソンによれば、この映画は「ホラー映 画製作における新たな夜明け」を象徴している[221]。それまでのホラー映画は、ゴム製のマスク、衣装、段ボール製のセット、物陰に潜む謎の人物などが 主だった。ロメロは搾取の背後にある力を明らかにし、ホラーを普通の、特別でない場所に設定し、低予算で効果的な映画を作るためのテンプレートを提供した [223]。 [7]作家のバリー・キース・グラントによれば、ジョン・カーペンター監督の『ハロウィン』(1978年)、ショーン・S・カニンガム監督の『13日の金 曜日』(1980年)、ウェス・クレイヴン監督の『エルム街の悪夢』(1984年)といった1970年代と1980年代のスラッシャー映画は、ロメロが身 近な設定でゴア表現を用いたことに負っている[224]。 この映画は現代のゾンビ映画の出発点のひとつとみなされており[225]、効果的に「ゾンビ」を再定義した[226]。 この映画の公開以前は、「ゾンビ」という用語は、ボコールが死体を無感覚な奴隷に生き返らせることができるというハイチの民間伝承の概念を表していた [227]。 [228]ロメロは1968年の映画やその脚本で「ゾンビ」という言葉を使わず、代わりにグール(Ghoul)を使っていた。 宗教学のキム・パフェンロス教授によれば、ロメロの敵役たちは、ゾンビをコントロールする人間の悪役を持たず、したがってモンスターの人間性を回復する可 能性を持たないことによって、以前の「ブードゥー教ゾンビ」の伝統を打ち破った[233]。 インスピレーションとなった吸血鬼やハイチのゾンビと比較すると、ロメロの敵役たちは、清潔と腐敗を切り離すことができないことから生じる嫌悪感であるア ブジェクションから、より多くの恐怖を導き出す。吸血鬼神話が平凡な生活からの潜在的な逃避を提供するのに対して、ゾンビは従来の死よりも忌まわしい無限 の腐敗を提供する[234]。文化批評家のスティーヴン・シャヴィロは、他の映画のキャラクターとは異なり、ゾンビの身体にはアイデンティティが残されて いないため、観客はゾンビと同一化することができず、代わりに観客に嫌悪感と魅惑的な魅力の組み合わせを提供すると述べている[226][235]。 批判的分析  裸足でソファに座るバーブラに靴を渡そうとしゃがむベン。 初対面のバーブラとベン 公開以来、多くの批評家や映画史家は『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』を、1960年代のアメリカ社会、国際冷戦政治、国内人種差別を批評する破壊的 な映画として解釈してきた[65]。映画史家のロビン・ウッドは、1979年のトロント国際映画祭で、抑圧と抑圧という観点からホラーを構成するために、 上映と監督インタビューを組み合わせた60本の回顧上映会「アメリカの悪夢」を企画した。プログラムノートに掲載された彼のエッセイ「アメリカン・ホラー 映画入門」は、特に、それまでホラーというジャンルが本格的な分析の対象として考えられていなかった映画批評に大きな影響を与えた[236][237]。 ウッドは、『夜』を含む著名なホラー映画を精神分析の枠組みを通して解釈している[238]。 彼は、受け入れがたいとみなされる特徴が、どのように個人レベルで抑圧されるか、抑圧されていない場合は社会レベルで抑圧されるかについて論じている。 [238]彼は抑圧されたタブーや他者集団をホラー・モンスターの心理的基盤として同定している。 ウッドや後の批評家たちはこの枠組みを用いて、抑圧されたセクシュアリティ、1960年代のアメリカの疎外された集団、公民権運動やベトナム戦争から生じ た社会規範の崩壊についての解説として『ナイト』を論じた[239][240]。 ヴィレッジ・ヴォイスのエリオット・スタインは、この映画をベトナム戦争へのアメリカの関与に対する熱烈な批評として見ており、「トランシルヴァニアでは なくペンシルヴァニアが舞台であり、これは戦争中の中米であり、ゾンビの殺戮は当時ベトナムで激化していた紛争のグロテスクな反響のように見えた」と論じ ている。 [241]映画史家の東すみ子も同意見で、『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』はメディアが戦争を報道する際に使用した視覚的語彙を利用しており、特に ナパーム・ガールの写真とグエン・ヴァン・レムの処刑は映画の制作者と観客の記憶に新しいと指摘する。 [1968年当時、ニュースはまだ白黒で放送されており、エンディング・クレジットに登場する生々しい写真は、現代のベトナム戦争のフォトジャーナリズム に似ている[65]。 批評家たちは、この映画の黒人主人公の射殺をマーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアの暗殺と比較している[65][244][245]。スタインは「こ の史上初の破壊的ホラー映画では、機知に富んだ黒人主人公はゾンビから生き延びるが、レッドネックの一団に驚かされるだけである」と説明する。 [241] 2018年、この映画の50周年に際して、シネアクションのマーク・ラガーは、白人警察によるベンの殺害と遺体の破壊と、公民権運動中のアフリカ系アメリ カ人に向けられた暴力との間に明確な並行関係があると指摘した。ラガーはこの映画を、ハリウッドが製作したどの作品よりも、1960年代のアメリカを正直 に描いた作品だと評した[246]。 映画史家のグレゴリー・ウォラーは、核家族、個人宅、メディア、政府、そして「市民防衛の仕組み全体」を含むアメリカの制度に対する広範な批評を明らかに している[247]。 [247]映画史家のリンダ・バドリーは、モンスターが宇宙や異国の環境から来た生き物ではなく、むしろ「彼らは私たちである」ため、この映画はとても恐 ろしいと説明している[248]。2009年のドキュメンタリー映画『赤と白と青の悪夢』では、映画のゾンビは1960年代後半のアメリカの「サイレン ト・マジョリティ」と比較されている[249]。 |

| List of American films of 1968 List of films in the public domain in the United States https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_of_the_Living_Dead |

|

| Book review Philippe Charlier, Zombies: An Anthropological Investigation of the Living Dead. Translated by Richard J. Gray II. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017. 160 pp. (Paper US$ 18.95) Philippe Charlier, a forensic medical examiner and paleopathologist affiliated with Raymond Poincaré University Hospital and Paris’s Descartes University, has appeared on French television and led notable European archaeological digs, earning him the title of the “Indiana Jones of the graveyards.” His Zombis: Enquete sur les morts-vivants (Tallandier, 2015) explores the zombie phenomenon and poudre zombie—zombie powder—via a novelistic travel memoir. In addition to the translation of the text itself by Richard Gray II, this new English edition includes Charlier’s author’s preface; an afterword by Alain Forment of the Musée de l’ Homme in Paris; a glossary of Haitian Creole terms, including some from Creole-language scholar Benjamin Hebblethwaite’s Vodou Songs in Haitian Creole and English (2012); and two appendices—one explaining the basic lwas found in Haitian Vodou along with their syncretistic Catholic saint links, and the other a list of clinical symptoms of tetrodotoxin poisoning, all of which drape the text with the aura of serious scholarship. In an August 28, 2017 article that appeared on the “Richland Source” website, Gray suggested that his translation “will be of interest … to scholars of Francophile studies as well as to professionals in the field of forensic science.” The University Press of Florida, an important publisher of scholarly work on Afro-Caribbean religion, such as Karen Richman’s Migration and Vodou (2005) and Toni Pressley-Sanon’s Itswa Across the Water, has published this most unscholarly text. Although Charlier’s intention to share his investigation with the masses can be admired, he has merely produced another sensationalized portrait of Haitian cultural traditions along the lines of William Seabrook’s fantastical travel memoir, The Magic Island, (1928). The most famous Haitian memoir, Wade Davis’s 1985 bestseller, The Serpent and the Rainbow: A Harvard Scientist’s Astonishing Journey into the Secret Societies of Haitian Voodoo, Zombis, and Magic, was marketed, like Charlier’s, as an Indiana Jones-type adventure. Both Davis and Seabrook report observing Vodou rituals, meeting “zombies,” and discovering “zombie powder,” a narrative that seems always to feature a cadre of professional Vodouists who cater to foreigners or outsiders in search of a “mysterious” Haiti. These memoir-styled travelogues sustain a long fascination by North American media culture with the Caribbean Other. Indeed, Charlier acknowledges that “zombies quickly become a cut-and-paste of the vampire myth, and spread widely throughout the continent of North America … as evidenced by the abundance of films and television series featuring the phenomenon of zombies, especially from the American film industry, … the television series The Walking Dead (five seasons in all, and a worldwide success), etc.” (p. 1). And Gray writes in his afterword about the way North American films such as Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) and the late George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) “encapsulated the public’s curiosity for the mysticism of Haitian Vodou” (p. 133). Unfortunately, this book falls short of its goal to provide insight from Vodou practitioners (as opposed to the professional Vodouists who cater to foreigners’ fantasies), and it does not succeed in linking the anthropological approach to everyday Vodou beliefs. Charlier tries to tackle the phenomenon through scientific questioning (a collaborative effort with Haitian sociologist, Laennec Hurbon of France’s National Center for Scientific Research). But crucially, both agree that they “are not trying to find out whether or not zombies exist,” instead discussing psychological, or maybe mystical, explanations of Vodou beliefs in life and death, and the idea that the “trauma of the slave trade has played a significant role in this phenomenon” (p. 7). Charlier shows a lack of familiarity with Haitian culture, religion, and scholarship and is unaware of the Creole orthography established decades ago (for example, spelling loa instead of lwa and houngan, instead of oungan). He returns to Davis’s sources, including the late oungans Erol Josue and Max Beauvoir, as well as Davis’s questionable discussions of zombification, sorcery, and toxic poisons, without adding anything new. This book is an undistinguished exploration of Vodou, “zombie powder,” and the question of whether “zombies” are “real,” or a metaphor for “living.” It continues a pattern in the production of travel memoirs from an outsider perspective on Haiti and Vodou masquerading as a serious anthropological work. |

書評 フィリップ・シャルリエ『ゾンビ』: 生ける屍の人類学的調査。リチャード・J・グレイ2世訳。Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017. 160ページ。(ペーパー US$18.95)。 レイモン・ポアンカレ大学病院とパリのデカルト大学に所属する法医解剖医で古病理学者のフィリップ・シャルリエは、フランスのテレビに出演し、ヨーロッパ の著名な考古学的発掘を指揮し、"墓場のインディ・ジョーンズ "の称号を得ている。彼の『Zombis: Enquete sur les morts-vivants』(Tallandier, 2015)は、ゾンビ現象とプードル・ゾンビ(ゾンビの粉)を小説的な旅行記を通して探求している。この新しい英語版には、リチャード・グレイ2世による 本文の翻訳に加え、シャルリエによる著者序文、パリ人間博物館のアラン・フォルマンによるあとがき、クレオール語学者ベンジャミン・ヘブレスウェイトの 『ハイチ・クレオール語と英語によるブードゥーの歌』(2012年)の一部を含むハイチ・クレオール語の用語集が収録されている; そして2つの付録、1つはハイチのブードゥーに見られる基本的なルワをカトリックの聖人とのシンクレティズム的な関連とともに説明したもの、もう1つはテ トロドトキシン中毒の臨床症状のリストで、これらすべてがこのテキストを真面目な学問のオーラで覆っている。 「リッチランド・ソース」のウェブサイトに掲載された2017年8月28日の記事で、グレイは彼の翻訳が "法医学分野の専門家だけでなく、フランコフィル研究の研究者にとっても......興味深いものになるだろう "と示唆した。フロリダ大学出版局は、カレン・リッチマンの『Migration and Vodou』(2005年)やトニ・プレスリー=サノンの『Itswa Across the Water』(2005年)など、アフロ・カリビアン宗教に関する学術研究の重要な出版社であるが、この最も学術的でないテキストを出版した。大衆と調査 を共有しようとするシャルリエの意図は賞賛に値するが、彼は単に、ウィリアム・シーブルックの幻想的な旅行記『魔法の島』(1928年)に沿って、ハイチ 文化伝統のセンセーショナルな肖像画をまた生み出したにすぎない。最も有名なハイチの回顧録は、ウェイド・デイヴィスの1985年のベストセラー『蛇と 虹』である: The Serpent and Rainbow: A Harvard Scientist's Astonishing Journey into the Secret Societies of Haitian Voodoo, Zombis, and Magic)は、シャルリエのものと同様、インディ・ジョーンズ的冒険として売り出された。デイヴィスもシーブルックも、ブードゥーの儀式を見学し、「ゾ ンビ」に会い、「ゾンビ・パウダー」を発見したと報告している。この物語には、「神秘的な」ハイチを求める外国人や部外者を相手にするプロのヴォドゥイス トの幹部が常に登場するようだ。こうした回顧録風の旅行記は、カリブ海の他者に対する北米のメディア文化の長い憧憬を支えている。実際、シャルリエは「ゾ ンビはすぐに吸血鬼神話の切り貼り版となり、北米大陸に広く普及した......特にアメリカ映画界がゾンビ現象をフィーチャーした映画やテレビシリーズ を数多く制作していることからもわかるように、......テレビシリーズ『ウォーキング・デッド』(全5シーズン、世界的な成功を収めた)など」と認め ている。(p. 1). そしてグレイはあとがきで、北米映画『Children Shouldn't Play with Dead Things』(1972年)や故ジョージ・ロメロ監督の『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド』(1968年)が「ハイチのヴォドゥーの神秘主義に対する 大衆の好奇心を凝縮した」(p.133)と書いている。 残念ながら本書は、(外国人の空想に便宜を図るプロのブー ドゥー論者と は対照的に)ブードゥーの実践者からの洞察を提供するという目標には 程遠く、人類学的アプローチを日常的なブードゥー信仰に結びつけるこ とには成功していな い。シャルリエは、科学的な質問を通してこの現象に取り組もうとしている(フランス国立科学研究センターのハイチ人社会学者ラエンネック・ ウルボンとの共同作業)。しかし決定的に重要なのは、両者とも「ゾンビが存在するかどうかを調べようとしているのではない」という点である。その代わり に、生と死に関するヴォドゥ信仰の心理学的、あるいは神秘学的な説明や、「奴隷貿易のトラウマがこの現象に重要な役割を果たしている」(p.7)という考 えについて論じている。 シャルリエはハイチの文化、宗教、学問に精通しておらず、数十年前に確立されたクレオール語の正書法を知らない(例えば、lwaの代わりにloa、 ouganの代わりにhounganと綴る)。彼はデイヴィスの情報源(故エロル・ジョスエやマックス・ボーヴォワールなど)に立ち戻り、またデイヴィス のゾンビ化、魔術、有毒毒物に関する疑問のある議論にも立ち戻るが、新しいことは何も付け加えていない。 本書は、ブードゥー、「ゾンビパウダー」、そして「ゾンビ」は「本物」なのか、それとも「生きること」のメタファーなのかという疑問についての、特筆すべ き点のない探求である。ハイチとブードゥーに関するアウトサイダー的視点からの旅行記が、まじめな人類学的作品に見せかけるというパターンを続けている。 |

***

★ゾンビの美学 : 植民地主義・ジェンダー・ポストヒューマン / 福田安佐子著, 人文書院 , 2024

『恐 怖城(ホワイト・ゾンビ)』『私はゾンビと歩いた!』から、ジョージ・A・ロメロを経て『バイオハザード』『ワールド・ウォー・Z』まで、ヴードゥー呪 術、噛みつき、ウィルス感染など、多様な原因で人間ならざるものへと変化し、およそ100年にもわたり増殖し続けるゾンビと作品の数々。恐怖の対象として 類を見ないその存在に託されたものは何か。本書では、ゾンビの歴史を通覧し、おもに植民地主義、ジェンダー、ポストヒューマニズムの視点から重要作に映る ものを仔細に分析する。アガンベンの生権力論を援用し、ゾンビに現代および近未来の人間像をみる力作。博士論文「ゾンビの美学 : 植民地主義・「人に似たもの」・ポストヒューマニズム 」(京都大学, 2021年提出) を加筆・修正したもの。参考文献: p256-266

序 章

第 1章 『恐怖城(ホワイト・ゾンビ)』とゾンビの誕生

第 2章 『私はゾンビと歩いた!』と呪われた人形

第 3章 近代におけるゾンビ―グロテスクなものか「人に似たもの」か

第 4章 ゾンビ映画におけるヒロインと女ゾンビ

第 5章 『ワールド・ウォー・Z』における新しいゾンビ

終

章

| 序章 |

|

| 第1章 『恐怖城(ホワイト・ゾンビ)』とゾンビの誕生 | |

| 第2章 『私はゾンビと歩いた!』と呪われた人形 | |

| 第3章 近代におけるゾンビ―グロテスクなものか「人に似たもの」か | |

| 第4章 ゾンビ映画におけるヒロインと女ゾンビ | |

| 第5章 『ワールド・ウォー・Z』における新しいゾンビ | |

| 終章 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Death

visits the Miser. Hieronymous Bosch 1494 or later.

☆

☆

☆