ニコライ・レスコフ

Nikolai Leskov, 1831-1895

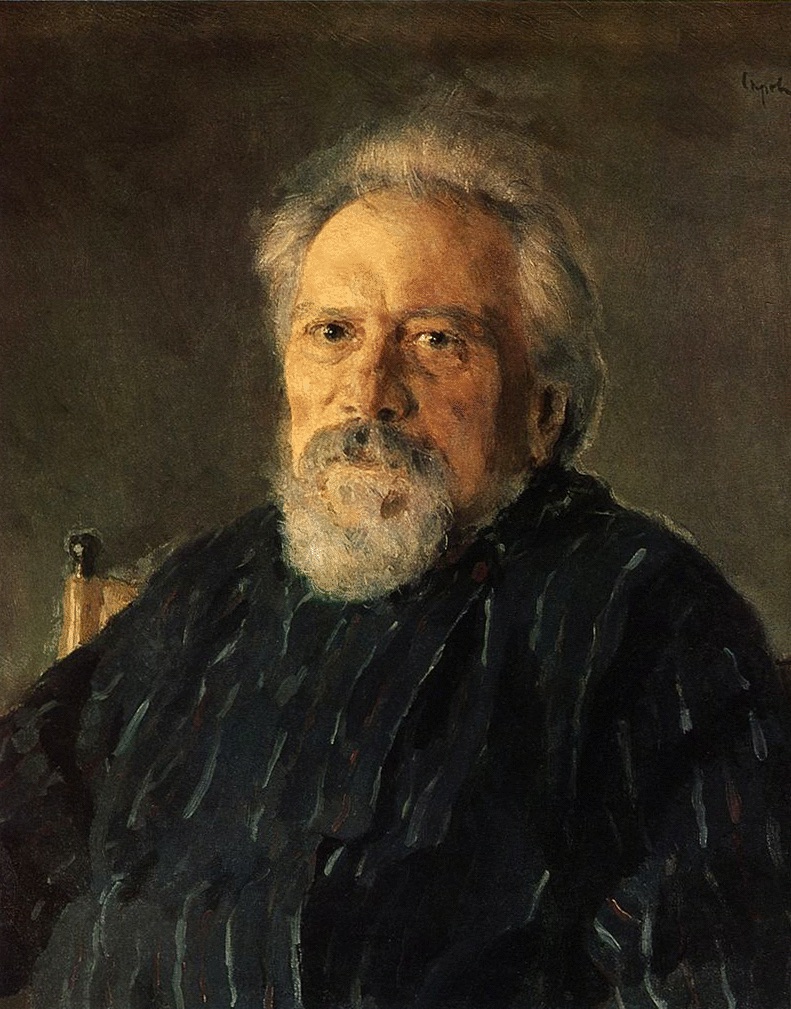

Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov by Ilya Repin, 1888–89

ニコライ・レスコフ

Nikolai Leskov, 1831-1895

■ 「物語作者(Erzähler)は——この名称が私たちにいかに親しい響きをもってい ようとも ——現在、生き生きと活動する存在では必ずしもない。物語作者は、私たちにとってすで に遠くなってしまったもの、そしていまなおさらに遠ざかりつつあるものだ。レスコフの ような作家を物語作者として描くことは、彼を私たちに近づけるものではなく、むしろ逆 に、彼との距離を大きくしようとするものである。一定の距離をおいて考察したときには じめて、物語作者の明瞭で大きな特徴が彼のなかで優位を占めてくるのだ。もっと分かり やすい比鳴を使うなら、正しい距離と適切な角度から観ると、岩の表面に人の顔や動物の 体が見えてくることがあるように、距離をおいてはじめて、物語作者の特徴が彼のなかに 現われてくる。このような距離や視角を私たちに教えてくれるのは、私たちがほとんど毎 日のように接する機会のある、ある種の経験である。この経験は私たちに、物語る技術が いま終駕に向かいつつあることを告げている。まともに何かを物語ることができる人に出 会うことは、ますますまれになってきている。そして、なにか物語をしてほしいという戸 があがると、その周囲に戸惑いの気配が広がっていくことがしばしばである。まるで、私 たちから失われることなどありえないと思われていた能力、確かなもののなかでも最も確 かだと思われていたものが、私たちから奪われていくかのようだ。すなわち、経験を交換 するという能力がある」——ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(浅井健二郎編訳 1996:284-285)(→「経験を交換する能力としての《物 語》」)

★

| Nikolai

Semyonovich

Leskov (Russian: Никола́й Семёнович Леско́в; 16 February

[O.S. 4

February] 1831 – 5 March [O.S. 21 February] 1895) was a Russian

novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist, who also

wrote under the pseudonym M. Stebnitsky. Praised for his unique writing

style and innovative experiments in form, and held in high esteem by

Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky among others, Leskov is

credited with creating a comprehensive picture of contemporary Russian

society using mostly short literary forms.[1] His major works include

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (1865) (which was later made into an opera by

Shostakovich), The Cathedral Folk (1872), The Enchanted Wanderer

(1873), and "The Tale of Cross-eyed Lefty from Tula and the Steel Flea"

(1881).[2] |

ニコライ・セミョーノヴィチ・レスコフ(ロシア語。Никола́й

Семёнович Леско́в;

1831年2月16日[西暦2月4日]-1895年3月5日[西暦2月21日])は、ロシアの小説家、短編作家、劇作家、ジャーナリストで、M・ステブニ

ツキーというペンネームでも執筆している。トルストイ、チェーホフ、マクシム・ゴーリキーらから高く評価され、独自の文体と革新的な形式的試みで、主に短

編小説を用いて現代ロシア社会の全体像を描き出したとされる[1]。

[主な作品に『ムツェンスクのマクベス夫人』(1865年)(後にショスタコーヴィチによってオペラ化)、『聖堂の民』(1872年)、『魅惑の放浪者』

(1873年)、『トゥーラの左目と鉄蚤の物語』(1881年)など[2] がある。] |

| Leskov received his formal

education at the Oryol Lyceum. In 1847 Leskov joined the Oryol criminal

court office, later transferring to Kiev, where he worked as a clerk,

attended university lectures, mixed with local people, and took part in

various student circles. In 1857 Leskov quit his job as a clerk and

went to work for the private trading company Scott & Wilkins owned

by Alexander Scott, his aunt's Scottish husband. |

レスコフはオリョール・リセウムで正規の教育を受けた。1847年、レ

スコフはオリョール刑事裁判所事務所に入り、その後キエフに移り、そこで書記官として働きながら大学の講義を受け、地元の人々と交流し、さまざまな学生

サークルに参加した。1857年、レスコフは書記官を辞め、叔母のスコットランド人の夫アレクサンダー・スコットが経営する民間貿易会社スコット&ウィル

キンス社で働くことになった。 |

| His literary career began in the

early 1860s with the publication of his short story The Extinguished

Flame (1862), and his novellas Musk-Ox (May 1863) and The Life of a

Peasant Woman (September, 1863). His first novel No Way Out was

published under the pseudonym M. Stebnitsky in 1864. From the mid-1860s

to the mid-1880s Leskov published a wide range of works, including

journalism, sketches, short stories, and novels. Leskov's major works,

many of which continue to be published in modern versions, were written

during this time. A number of his later works were banned because of

their satirical treatment of the Russian Orthodox Church and its

functionaries. Leskov died on 5 March 1895, aged 64, and was interred

in the Volkovo Cemetery in Saint Petersburg, in the section reserved

for literary figures. |

1860年代初頭、短編小説『消えた炎』(1862年)、小説『ムス

ク・オックス』(1863年5月)、『ある農婦の生活』(1863年9月)を発表し、彼の文学的キャリアは始まった。1864年にはM.ステブニツキーの

ペンネームで処女作『出口なし』が出版された。1860年代半ばから1880年代半ばにかけて、レスコフはジャーナリズム、スケッチ、短編小説、小説など

幅広い作品を発表している。現在も現代版として出版されているレスコフの主要作品の多くは、この時期に書かれたものである。また、ロシア正教会やその関係

者を風刺した作品は、後に発禁処分を受けることになる。1895年3月5日、64歳で死去。サンクトペテルブルクのヴォルコヴォ墓地にある文学者用の区画

に埋葬された。 |

| Early life Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov was born on 4 February 1831, in Gorokhovo, Oryol Gubernia, to Semyon Dmitrievich Leskov (1789–1848), a respected criminal investigator and local court official, and Maria Petrovna Leskova (née Alferyeva; 1813–1886),[3] the daughter of an impoverished Moscow nobleman, who first met her future husband at a very young age, when he worked as a tutor in their house. Leskov's ancestors on his father's side were all clergymen in the village of Leska in Oryol Gubernia, hence the name Leskov. Semyon Dmitrievich was a well-educated man; friends referred to him as a "homegrown intellectual".[4][5] One of Nikolai's aunts on his mother's side was married to a rich Oryol landlord named Strakhov who owned the village of Gorokhovo ("a beautiful, wealthy and well-groomed estate... where the hosts lived in luxury," according to Leskov)[6] another was the wife of an Englishman, the chief steward for several local estates and a large trade company owner.[7] Leskov spent his first eight years in Gorokhovo, where his grandmother lived and where his mother was only an occasional guest. He acquired his early education in the house of Strakhov, who employed tutors from Germany and France for his own children.[1] As the German teacher started to praise Leskov for his gifts, his life became difficult, due to the jealousy of his hosts. At his grandmother's request, his father took Nikolai back to Oryol where he settled in the family house at 3 Dvoryanskaya Street.[3] |

生い立ち ニコライ・セミョノビッチ・レスコフは1831年2月4日、オリョール・グベルニアのゴロホヴォで、犯罪捜査官で地元の裁判所職員として尊敬されていたセ ミョン・ドミトリエヴィッチ・レスコフ(1789-1848)と、モスクワの貧しい貴族の娘であり、幼い頃に家庭教師をした際に初めて未来の夫に会ったマ リア・ペトロヴナ・レスコヴァ(旧姓アルフェリエヴァ、1813-1886)の間に生まれる[3]。レスコフの父方の先祖はいずれもオリョールグベルニア のレスカ村の聖職者であったため、レスコフという名がついた。ニコライの母方の叔母は、ゴロホヴォ村(「美しく、裕福で、よく手入れされた地所...そこ で主人たちは贅沢に暮らしていた」)を所有するストラホフというオリョールの金持ち地主と結婚していた。レスコフによれば、「ホストたちが贅沢に暮らして いた」[6])、もう一人はイギリス人の妻で、地元のいくつかの領地の執事長や大きな貿易会社のオーナーだった[7]。レスコフは最初の8年間をゴロホボ で過ごし、祖母はそこに住んでいたが、母は時々客として来ていただけであった。レスコフはストラホフの家で幼児教育を受けたが、ストラホフは自分の子供の ためにドイツやフランスから家庭教師を雇っていた[1]。ドイツ人教師がレスコフの才能を褒めるようになると、受け入れ側の嫉妬によりレスコフの生活は苦 しくなった。祖母の要請により、父親はニコライをオリョールに連れ帰り、ドヴォーリャンスカヤ通り3番地の実家に居を構えた[3]。 |

| In 1839 Semyon Leskov lost his

job through a row and intrigue, having brought upon himself the wrath

of the governor himself. "So we left our house in Oryol, sold what we

had in the city and bought a village with 50 peasants in the Kromy

region from general A. I. Krivtsov. The purchase was made mostly on

credit, for mother was still hoping to get her five thousand off of

Strakhov which never came. The tiny village father had bought was

eventually sold for debts," Leskov later remembered.[6] What the

Leskovs, with their three sons and two daughters, were left with was a

small Panin khutor, one very poor house, a watermill, a garden, two

peasants' houses and 40 dessiatins of land. This is where Nikolai had

his first experiences with oral folklore and the 'earthy' Russian

dialecticisms he would later become famous for reviving in his literary

work.[8] |

1839年、セミョン・レスコフは騒動と陰謀によって職を失い、自ら総

督の怒りを買ってしまった。「それでオリョールの家を出て 市内にあるものを売り払い」 「クリブツォフ将軍からクロミー地方に

50人の農民が住む村を買い取った

母は、ストラホフから5千ドルもらえると思っていたが、結局もらえなかったからである。父が買った小さな村は、結局、借金で売られてしまった」とレスコフ

は後に回想している[6]。3人の息子と2人の娘を持つレスコフ家に残されたのは、小さなパニンフートル、非常に貧しい家1軒、水車、庭、小作人の家2

軒、土地40デシアチンであった。ニコライはここで初めて口承民俗学や、後に文学作品の中で復活させたことで有名になる「土臭い」ロシアの弁証法を体験す

ることになる[8]。 |

| In August 1841 Leskov began his

formal education at the Oryol Lyceum.[8] After five years of poor

progress all he could manage was a two-year graduation certificate.

Later, scholar B. Bukhstab, comparing Leskov's school failures with

those of Nikolay Nekrasov who had had similar problems, argued that,

"...apparently, in both cases the reasons were – on the one hand, the

lack of a guiding hand, on the other – [both young men's] loathing for

the tiresome cramming routine and the deadly dumbness of state

education, both having lively temperaments and an eagerness to learn

more of real life".[7] |

1841年8月、レスコフはオリョール・リセウムで正規の教育を受け始

めた[8]。5年間成績が振るわず、なんとか2年間の卒業証書を手にすることができただけだった。後に学者のB.ブフスタブは、レスコフの学校での失敗

を、同様の問題を抱えたニコライ・ネクラソフの失敗と比較しながら、「...明らかに、どちらの場合も、その理由は-一方では指導者の欠如、他方では(二

人の若者の)退屈な詰め込み式教育と国家教育の致命的な間抜けさを嫌い、どちらも活発な気質と実生活をもっと学びたいという熱意をもっていたから」[7]

だと論じている。 |

| In June 1847 Leskov joined the

Oryol criminal court office, where Sergey Dmitrievich had once worked.

In May 1848 Leskov's family's property was destroyed by a fire.[9] In

July of the same year Leskov's father died from cholera.[8] In December

1849 Leskov asked his superiors for a transfer to Kiev, where he joined

the local government treasury chamber as an assistant clerk and settled

with his maternal uncle, S. P. Alferyev, a professor of medicine.[5] |

1847年6月、レスコフはかつてセルゲイ・ドミトリエヴィチが勤務し ていたオリョール刑事裁判所事務所に入所する。1848年5月、レスコフの家族の財産が火事で消失し[9]、同年7月にはレスコフの父親がコレラで死亡し た[8]。 1849年12月にレスコフはキエフへの異動を上司に願い出、地方政府の財務局に書記官補佐として入り、医学の教授である母方の叔父S・P・アルファリエ フのところに身を寄せた[5]。 |

| In Kiev he attended lectures at

the University as an auditor student, studied the Polish and Ukrainian

languages and the art of icon-painting, took part in the religious and

philosophical circles of the students, and met pilgrims, sectarians and

religious dissenters. Dmitry Zhuravsky, an economist and critic of

serfdom in Russia, was said to be one of his major influences.[10] In

1853 Leskov married Olga Smirnova; they had one son, Dmitry (who died

after only a year), and a daughter, Vera.[11] |

キエフでは聴講生として大学の講義を受け、ポーランド語やウクライナ

語、イコン画を学び、学生たちの宗教的・哲学的サークルに参加し、巡礼者や宗派、宗教的異端者たちと知り合うことになった。1853年、レスコフはオル

ガ・スミルノワと結婚し、一男のドミトリー(1年で死去)と一女のヴェラをもうけた[11]。 |

| In 1857 Leskov quit his job in

the office and joined the private trading company Scott & Wilkins

(Шкотт и Вилькенс) owned by Alexander Scott,[12] his aunt Polly's

Scottish husband. Later he wrote of this in one of his short

autobiographical sketches: "Soon after the Crimean War I was infected

with a then popular heresy, something I've been reproaching myself for

since. I abandoned the state official career which seemed to be

starting promisingly and joined one of the newly-born trade

companies."[3] |

1857年、レスコフは会社を辞め、叔母ポリーのスコットランド人の夫

アレクサンダー・スコットが経営する民間貿易会社スコット&ウィルキンス(Шкот и

Вилькенс)に入社する[12]。後に彼は、短い自伝的スケッチの中でこのことを書いている。「クリミア戦争の直後、私は当時流行していた異端に感

染し、それ以来ずっと自分を責めている。私は前途有望に見えた国家公務員のキャリアを捨て、新しく生まれた貿易会社の一つに入社した」[3]。 |

| In May 1857 Leskov moved with

his family to Raiskoye village in Penza Governorate where the Scotts

were based, and later that month embarked upon his first business trip,

involving the transportation of the Oryol-based serfs of Count Perovsky

to the Southern Russian steppes, not entirely successfully, as he later

described in his autobiographical short story "The Product of

Nature".[8][13] While working for this company, which, in Leskov's

words, "was eager to exploit whatever the region could provide," he

derived valuable experience, making him an expert in numerous branches

of industry and agriculture. The firm employed him as an agent envoy;

while travelling through the remote regions of Russia, the young man

learned local dialects and became keenly interested in the customs and

ways of the different ethnic and regional groups of Russian peoples.

Years later, when asked what the source of the endless stream of

stories that seemed to pour out of him ceaselessly was, Leskov said,

pointing at his forehead: "From this trunk. Here pictures from the six

or seven years of my commercial career are being kept, from the times

when I travelled across Russia on business trips. Those were the best

years of my life. I saw a lot and life was easy for me."[7] |

1857年5月、レスコフは家族とともにスコッツ社の拠点であるペンザ 州のライスコエ村に移り住み、その月の終わりにはペロフスキー伯爵のオリョール人農奴を南ロシアの草原に運ぶという初めての出張に乗り出したが、後に彼の 自伝的短編「自然の産物」で描写されたように完全に成功とはいかなかった。 [レスコフの言葉を借りれば「この地域から得られるものは何でも利用しようとする」この会社で働きながら、彼は貴重な経験を積み、産業と農業の多くの分野 の専門家となった。この会社は彼を代理大使として雇い、ロシアの辺境を旅しながら方言を学び、ロシアのさまざまな民族や地域集団の習慣ややり方に強い関心 を抱くようになった。後年、レスコフは、自分から絶え間なく溢れ出るような物語の源泉は何かと問われ、自分の額を指差してこう言った。このトランクから だ」。このトランクには、私が商業界で活躍した6、7年間、ロシア各地に出張したときの写真が保管されている。私の人生の中で一番いい時代だった。いろい ろなものを見たし、人生も楽だった」[7]。 |

| In Russian Society in Paris he

wrote: "I think I know the Russian man down to the very bottom of his

nature but I give myself no credit for that. It's just that I've never

tried to investigate the 'people's ways' by having conversations with

Petersburg's cabmen. I just grew up among common people."[14] Up until

1860 Leskov resided with members of his family (and that of Alexander

Scott) in Raisky, Penza Governorate. In the summer of 1860, when Scott

& Wilkins closed, he returned to Kiev to work there as a journalist

for a while, then in the end of the year moved to Saint Petersburg.[7] |

『パリのロシア社会』の中で彼はこう書いている。「私はロシア人をその

本性の底まで知っているつもりだが、そのことを自分の手柄にするつもりはない。ただ、ペテルブルグのタクシーマンと会話して『民衆の道』を調べようとした

ことがないだけだ。1860年までレスコフは家族(とアレクサンドル・スコット)と共にペンザ県ライスキーに住んでいた。1860年の夏、スコット&ウィ

ルキンスの閉鎖に伴い、キエフに戻ってしばらくジャーナリストとして働き、その年の終わりにサンクトペテルブルクに移った[7]。 |

| Journalism Leskov began writing in the late 1850s, making detailed reports to the directors of Scott & Wilkins, and recounting his meetings and contracts in personal letters to Scott. The latter, marveling at his business partner's obvious literary gift, showed them to writer Ilya Selivanov who found these pieces "worthy of publication".[15] Leskov considered his long essay "Sketches on Wine Industry Issues", written in 1860 about the 1859 anti-alcohol riots and first published in a local Odessa newspaper, then in Otechestvennye Zapiski (April 1861), to be his proper literary debut.[8] |

ジャーナリズム レスコフは1850年代後半から執筆を始め、スコット&ウィルキンスの取締役に詳細な報告を行い、スコットへの私信で会合や契約の様子を語っている。 1859年の反アルコール暴動について1860年に書かれ、オデッサの地方紙に掲載された後、『Otechestvennye Zapiski』(1861年4月)に掲載された長編エッセイ『Sketches on Wine Industry Issues』が彼の正式な文学デビューとみなされた[8]。 |

| In May 1860 he returned with his

family to Kiev, and in the summer started to write for both the

Sankt-Peterburgskye Vedomosty newspaper and the Kiev-based Sovremennaya

Meditsina (where he published his article "On the Working Class", and

several essays on medical issues) and the Ukazatel Ekonomitchesky

(Economic Guide). His series of October 1860 articles on corruption in

the sphere of police medicine ("Some Words on the Police Medics in

Russia") led to confrontations with colleagues and his being fired from

Sovremennaya Meditsina. In 1860 his articles started to appear

regularly in the Saint Petersburg-based paper Otechestvennye Zapiski

where he found a friend and mentor in the Oryol-born publicist S. S.

Gromeko.[7] |

1860年5月、彼は家族とともにキエフに戻り、夏には『サンクトペテ

ルブルグスキー・ヴェドモスチ』紙とキエフの『ソヴレメンナーヤ・メディツィーナ』紙(『労働者階級について』や医療問題に関するいくつかのエッセーを掲

載)、『ウカーザーテル・エコノミチェスキー(経済ガイド)』に執筆するようになる。1860年10月、警察医学の腐敗に関する一連の記事(「ロシアの警

察医学者についてのいくつかの言葉」)は、同僚との対立を招き、ソヴレメナヤ・メディツィーナを解雇された。1860年、サンクトペテルブルクの『オテ

チェストヴェーヌ・ザピスキー』紙に定期的に記事を掲載するようになり、オリョール出身の宣伝家S・S・グロメコに友人と師匠を見出す[7]。 |

| In January 1861 Leskov moved to

Saint Peterburg where he stayed at Professor Ivan Vernadsky's along

with Zemlya i volya member Andrey Nechiporenko[16] and met Taras

Shevchenko. For a short while he moved to Moscow and started to work

for the Russkaya Retch newspaper, all the while contributing to

Otechestvennye Zapiski. In December he left Russkaya Retch (for

personal, rather than ideological reasons) and moved back to Saint

Peterburg where in January 1862 he joined the staff of the Northern Bee

(Severnaya ptchela), a liberal newspaper edited by Pavel Usov. There

Leskov met journalist Arthur Benni, a Polish-born British citizen, with

whom he forged a great friendship and later came to defend, as leftist

radicals in Petersburg started to spread rumours about his being "an

English spy" and having links with the 3rd Department.[8] For Severnaya

ptchela Leskov (now writing as M. Stebnitsky, a pseudonym he used in

1862–1869)[7] became the head of the domestic affairs department,[1]

writing sketches and articles on every possible aspect of everyday

life, and also critical pieces, targeting what was termed nihilism and

"vulgar materialism". He had some support at the time, from several

prominent journalists, among them Grigory Eliseev, who wrote in the

April 1862, Sovremennik issue: "Those lead columns in Ptchela make one

pity the potential that is being spent there, still unrealised

elsewhere."[8] At a time of intense public excitement, as D. S. Mirsky

pointed out, Leskov was "absorbed by the public interest as much as

anyone, but his eminently practical mind and training made it

impossible for him to join unreservedly any of the very impractical and

hot-headed parties of the day. Hence his isolation when, in the spring

of 1862, an incident occurred that had a lasting effect on his

career."[2] |

1861年1月、レスコフはサンピエトロブルクに移り、ゼムリア・イ・

ヴォリヤのメンバーであるアンドレイ・ネチポレンコとともにイワン・ヴェルナドスキー教授の家に滞在し[16]、タラス・シェフチェンコと知り合う。しば

らくはモスクワに移り、『ルースカヤ・レッチ』紙で働き始め、その間『オテチェストヴェニェ・ザピスキー』紙に寄稿していた。1862年1月、ウソフが編

集する自由主義的な新聞『北の蜂』(Severnaya

ptchela)のスタッフになった。そこでレスコフは、ポーランド生まれのイギリス人ジャーナリスト、アーサー・ベニと出会い、大きな友情を築き、後に

ペテルブルグの左翼急進派が、レスコフを「イギリスのスパイ」であり、第3局と関係があるという噂を流し始めたので、彼を擁護するようになる[8]。

[セヴェルナヤ・プチェラ』では、レスコフ(現在は、1862年から1869年まで使用していたペンネーム、M・ステブニツキー)は内政部の部長となり

[1]、日常生活のあらゆる側面に関するスケッチや記事を書き、またニヒリズムや「低俗物質主義」と呼ばれていたものをターゲットにした批評も書いていた

[8]。当時、彼は著名なジャーナリストたちから一定の支持を得ていたが、中でもグリゴリー・エリセーエフは1862年4月の『ソヴレメニク』誌に次のよ

うに書いている。「D. S.

ミルスキーが指摘するように、世間が激しく騒いでいた頃、レスコフは「誰よりも公共の利益に夢中になっていたが、彼の極めて実用的な精神と訓練のおかげ

で、当時の非常に非現実的で熱狂的な政党のいずれにも無条件に参加することは不可能であった」[8]。それゆえ、1862年の春、彼のキャリアに永続的な

影響を与える事件が起きたとき、彼は孤立してしまったのである」[2]。 |

| On 30 May 1862, Severnaya

ptchela published an article by Leskov on the issue of the fires that

started on 24 May, lasting for six days and destroying a large part of

the Apraksin and Schukin quarters of the Russian capital,[3] which

popular rumour imputed to a group of "revolutionary students and Poles"

that stood behind the "Young Russia" proclamation. Without supporting

the rumour, the author demanded that the authorities should come up

with a definitive statement which would either confirm or confute those

allegations. The radical press construed this as being aimed at

inciting the common people against the students and instigating police

repressions.[2] On the other hand, the authorities were unhappy too,

for the article implied that they were doing little to prevent the

atrocities.[17] The author's suggestion that "firemen sent to the sites

would do anything rather than idly stand by" angered Alexander II

himself, who reportedly said: "This shouldn't have been allowed, this

is a lie."[18][19] |

1862年5月30日、Severnaya

ptchelaは、5月24日に始まった火災が6日間続き、ロシアの首都のアプラクシン地区とシューキン地区の大部分を破壊した問題についてのレスコフの

記事を掲載した[3]

その噂は「若いロシア」の宣言の背後にいた「革命的な学生とポーランド人」のグループによるものとされた。この噂を裏付けることなく、著者は当局に対し

て、これらの疑惑を肯定するか否定するかのどちらかの決定的な声明を出すよう要求している。一方、当局は、この記事によって、残虐行為を防ぐためにほとん

ど何もしていないことを示唆され、不満だった[17]。

著者は、「現場に送られた消防士は、黙って見ているよりも何でもする」と提案し、アレクサンドル2世自身が怒り、言ったとされる。「こんなことは許される

べきではない、これは嘘だ」[18][19]と述べたという。 |

| Frightened, Severnaya ptchela

sent its controversial author on a trip to Paris as a correspondent,

making sure the mission was a long onе.[1][20] After visiting Wilno,

Grodno and Belostok, in November 1862 Leskov arrived in Prague where he

met a group of Czech writers, notably Martin Brodsky, whose arabesque

You Don't Cause Pain he translated. In December Leskov was in Paris,

where he translated Božena Němcová's Twelve Months (A Slavic

Fairytale), both translations were published by Severnaya ptchela in

1863.[8] On his return to Russia in 1863 Leskov published several

essays and letters, documenting his trip.[10] |

1862年11月、ヴィルノ、グロドノ、ベロストクを訪問した後、プラ

ハに到着し、チェコの作家たちと出会うが、特にマルティン・ブロスキーは、そのアラベスク「You Don't Cause

Pain」を翻訳した。12月にはパリに滞在し、ボジェナ・ニェムコヴァーの『十二月(A Slavic

Fairytale)』を翻訳し、両訳書は1863年にSevernaya

ptchelaから出版された[8]。1863年にロシアに戻ってからは、旅の記録としていくつかの随筆や手紙などを出版している[10]。 |

| Literary career- Debut |

文筆家としてのキャリア-デビュー |

| 1862 saw the launch of Leskov's

literary career, with the publication of "The Extinguished Flame"

(later re-issued as "The Drought") in the March issue of Vek magazine,

edited by Grigory Eliseev,[1] followed by the short novels Musk-Ox (May

1863) and The Life of a Peasant Woman (September, 1863).[8][21] In

August the compilation Three stories by M. Stebnitsky came out. Another

trip, to Riga in summer, resulted in a report on the Old Believers

community there, which was published as a brochure at the end of the

year.[8] In February 1864 Biblioteka Dlya Chteniya magazine began serially publishing his debut novel No Way Out (the April and May issues of the magazine, stopped by the censors, came out in June). The novel bore "every sign of haste and literary incompetence," as its author later admitted,[22] but proved to be a powerful debut in its own way. No Way Out, which satirized nihilist communes on the one hand and praised the virtues of the common people and the powers of Christian values on the other, scandalized critics of the radical left who discovered that for most of the characters real life prototypes could be found, and its central figure, Beloyartsev, was obviously a caricature of author and social activist Vasily Sleptsov.[10] All this seemed to confirm the view, now firmly rooted in the Russian literary community, that Leskov was a right-wing, 'reactionary' author. In April Dmitry Pisarev wrote in his review "A Walk In the Garden of Russian Literature" (Russkoye Slovo, 1865, No.3): "Can any other magazine be found anywhere in Russia, besides The Russian Messenger, that would venture to publish anything written by and signed as, Stebnitsky? Could one single honest writer be found in Russia who would be so careless, so indifferent regarding his reputation, as to contribute to a magazine that adorns itself with novels and novellas by Stebnitsky?"[3] The social democrat-controlled press started spreading rumours that No Way Out had been 'commissioned' by the Interior Ministry's 3rd Department. What Leskov condemned as "a vicious libel" caused great harm to his career: popular journals boycotted him, while Mikhail Katkov of the conservative The Russian Messenger greeted him as a political ally.[10] |

1862年には、グリゴリー・エリセーエフが編集した雑誌『ヴェク』の

3月号に『消えた炎』(後に『干ばつ』として再発行)を発表し、短編小説『ムスク・オクス』(1863年5月)と『農婦の生活』(1863年9月)が続く

など、レスコフの文学活動が始まる[8][21]。また、夏にリガを旅行し、そこの旧信者共同体についてのレポートを作成し、年末にパンフレットとして出

版された[8]。 1864年2月、Biblioteka Dlya Chteniya誌がデビュー作『No Way Out』の連載を開始した(検閲でストップした4、5月号は6月に発売された)。この小説は、後に作者が認めたように「あらゆる急ぎと文学的無能のしる し」を帯びていたが[22]、それなりに力強いデビュー作であることが証明された。一方ではニヒリズムのコミューンを風刺し、他方では庶民の美徳とキリス ト教的価値観の力を賞賛する『ノー・ウェイ・アウト』は、登場人物のほとんどに実在の人物像が見られること、また中心人物のベロイアルツェフは明らかに作 家で社会活動家のヴァシリー・スレプトソフの風刺であることを知った急進左派の批評家を顰蹙させる[10]。このことは、今やロシアの文学界にしっかりと 根付いた、レスコフが右派で「反動」作家だという見方が確認できるようなものだった[10]。4月、ドミトリー・ピサレフは「ロシア文学の庭を歩く」 (Russkoye Slovo, 1865, No.3)という評論で次のように書いている。ロシア・メッセンジャー』以外に、ステブニツキーが書き、ステブニツキーと署名したものを出版しようとする 雑誌がロシアのどこかにできるだろうか?ステブニツキーの小説や短編で飾られた雑誌に投稿するほど無頓着で、自分の評判に無頓着な誠実な作家がロシアに一 人でもいるだろうか」[3] 社会民主主義者が支配する新聞は、『出口なし』が内務省第3局から「依頼」されたという噂を流布しはじめた。レスコフは「悪質な中傷」と非難し、彼のキャ リアに大きな損害を与えた。大衆雑誌は彼をボイコットし、保守的な「The Russian Messenger」のミハイル・カトコフは彼を政治的味方として迎え入れた[10]。 |

| Major works Leskov's novel, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (written in Kiev in November 1864 and published in Dostoevsky's Epoch magazine in January 1865) and his novella The Amazon (Otechestvennye zapiski, No.7, 1866), both "pictures of almost unrelieved wickedness and passion",[2] were ignored by contemporary critics but were praised decades later as masterpieces, containing powerful depictions of highly expressive female characters from different classes and walks of life.[7] Both, marked by a peculiar "Leskovian" sense of humour, were written in the skaz manner, a unique folk-ish style of writing, which Leskov, along with Gogol, was later declared an originator of. Two more novellas came out at this time: Neglected People (Oboydyonnye; Otechestvennye Zapiski, 1865) which targeted Chernyshevsky's novel What's to Be Done?,[21] and The Islanders (1866), about the everyday life of Vasilyevsky Island's German community. It was in these years that Leskov debuted as a dramatist. The Spendthrift (Rastratchik), published by Literaturnaya biblioteka in May 1867, was staged first at the Alexandrinsky Theatre (as a benefit for actress E. Levkeeva), then in December at Moscow's Maly Theater (with E. Chumakovskaya in the lead).[8] The play was poorly received for "conveying pessimism and asocial tendencies."[10] All the while Leskov was working as a critic: his six-part series of essays on the St. Petersburg Drama Theater was completed in December 1867. In February 1868 Stories by M.Stebnitsky (Volume 1) came out in Saint Petersburg to be followed by Volume 2 in April;[8] both were criticized by the leftist press, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin in particular.[1] In 1870 Leskov published the novel At Daggers Drawn, another attack aimed at the nihilist movement which, as the author saw it, was quickly merging with the Russian criminal community. Leskov's "political" novels (according to Mirsky) were not among his masterpieces, but they were enough to turn him into "a bogey figure for all the radicals in literature and made it impossible for any of the influential critics to treat him with even a modicum of objectivity."[23] Leskov would later refer to the novel as a failure and blamed Katkov's incessant interference for it. "His was the publication in which literary qualities were being methodically repressed, destroyed, or applied to serve specific interests which had nothing to do with literature," he later insisted.[24] Some of his colleagues (Dostoevsky among them) criticized the novel from the technical point of view, speaking of the stiltedness of the "adventure" plot and the improbability of some of its characters.[7] The short novel Laughter and Grief (Sovremennaya letopis, March–May, 1871), a strong social critique focusing on the fantastic disorganization and incivility of Russian life and commenting on the sufferings of individuals in a repressive society[1] proved to be his last; from then on Leskov avoided the genre of the orthodox novel.[10] In November 1872, though, he adapted Victor Hugo's Toilers of the Sea for children. Five years later Józef Ignacy Kraszewski's The Favourites of King August came out, translated from the Polish and edited by Leskov.[8] |

主な作品 レスコフの小説『ムツェンスク郡のマクベス夫人』(1864年11月にキエフで執筆、1865年1月にドストエフスキーの雑誌『エポック』に掲載)と小説 『アマゾン』(Otechestvennye zapiski, No.7, レスコーフ独特のユーモアのセンスが際立つこの2作は、スカズ文法という独特の民衆的な文体で書かれており、後にゴーゴリと並んでレスコーフがその創始者 とされる[7]。この頃、さらに2つの小説が発表された。チェルヌィシェフスキーの小説『何をなすべきか』を題材にした『放置された人々』 (Oboydyonnye; Otechestvennye Zapiski, 1865)と、ヴァシリエフスキー島のドイツ人コミュニティの日常を描いた『島民』(1866)である。レスコフが劇作家としてデビューしたのもこの頃で ある。1867年5月にリテラトウルナヤ図書館から出版された『浪費家』(Rastratchik)は、まずアレクサンドリンスキー劇場で(女優E・レフ キーバのために)上演され、12月にはモスクワのマリー劇場で(E・チュマコフスカヤが主役を務めた)上演された[8]。 [この間、レスコフは批評家として活動し、1867年12月にサンクトペテルブルク劇場にまつわる6部構成のエッセイを完成させた[10]。1868年2 月にはサンクトペテルブルクで『M.Stebnitskyの物語』(第1巻)が出版され、4月には第2巻が出版された[8]が、いずれも左派の新聞、特に ミハイル・サルティコフ-シェドリンによって批判された[1]。 1870年、レスコフは小説『At Daggers Drawn』を発表したが、これもニヒリズム運動に対する攻撃であり、著者の見るところ、ロシアの犯罪社会と急速に融合しつつあった。レスコフの「政治 的」小説は(ミルスキーによれば)彼の代表作の一つではなかったが、彼を「文学界のすべての急進派にとって厄介な存在となり、影響力のある批評家の誰も彼 をわずかでも客観的に扱うことを不可能にした」[23]。レスコフは後に、この小説が失敗であると言い、カトコフの絶え間ない干渉を非難した。「彼の出版 物は、文学的特質が整然と抑圧され、破壊され、あるいは文学とは関係のない特定の利害のために適用されていた」と後に主張した[24]。 彼の同僚の一部(ドストエフスキーも含む)は、「冒険」プロットの陳腐さや一部のキャラクターのありえなさを話し、技術面から小説を批評した[7]。 1872年11月には、ヴィクトル・ユーゴーの『海の労働者たち』を子供向けに改作した[10]が、その翌年にはヨゼフ・イグナシー・クラシェフスキの 『八月王の寵愛』が出版された[8]。その5年後、ポーランド語から翻訳されたヨゼフ・イグナシー・クラシェフスキの『八月王の寵愛』が出版され、レスコ フが編集を担当した[8]。 |

| The Cathedral Folk

(Soboryane), published in 1872, is a compilation of stories and

sketches which form an intricate tapestry of thinly drawn plotlines.[7]

It was seen as a turning point in the author's career; a departure from

political negativism. According to Maxim Gorky, after Daggers,

his "evil novel", Leskov's "craft became more of a literary

icon-painting: he began to create a gallery of saints for the Russian

iconostases."[10] Leskov's miscellaneous sketches on the lives and

tribulations of the Russian small-scale priesthood and rural nobility

gradually gravitated (according to critic V. Korovin) into a cohesive,

albeit frameless tapestry of a battlefield where "good men" (Tuberozov,

Desnitsyn, Benefaktov, all of them priests) were fighting off a bunch

of crooks and scoundrels; nihilists and officials.[10] Soboryane,

published by The Russian Messenger in 1872, had for its major theme the

intrinsic, unbridgeable gap between the "down to earth", Christianity

of the people and the official, state-sponsored corrupt version; it

riled both the state and church authorities, was widely debated and had

great resonance.[7] In the summer of 1872 Leskov travelled to Karelia

and visited the Valaam monastery in Lake Ladoga; the result of this

trip was his Monastic Isles cycle of essays published in Russky mir in

1873. In October 1872 another collection, Small Belle-lettres Works by

Leskov-Stebnitsky came out. These were the months of his short-lived

friendship with Aleksey Pisemsky; Leskov greatly praised his novel In

the Vortex and in August 1872 visited Pisemsky in Moscow.[8] |

1872

年に出版された『聖堂の民』(Soboryane)は、物語やスケッチをまとめたもので、薄く描かれたプロットの複雑なタペストリーを形成している

[7]。これは、著者のキャリアにおける転機と見なされ、政治的否定主義からの出発であった。

マクシム・ゴーリキーによれば、「邪悪な小説」である『短剣』の後、レスコフは「工芸は文学的なイコン画のようになり、ロシアのイコノスタスのための聖人

たちのギャラリーを作り始めた」[10]という。コロヴィンによれば)「善人」(ツベローゾフ、デスニツィン、ベネファクトフ、いずれも司祭)がペテン師

や悪党、虚無主義者や役人の一団と戦う戦場の、枠なしとはいえまとまったタペスト

リーのような作品に

仕上がっていった。 [1872年にThe Russian

Messengerから出版された『Soboryane』は、民衆の「地に足の着いた」キリスト教と国家が支援する公式の腐敗したバージョンの間の本質的

で埋められないギャップを主要テーマとし、国家と教会の両方の当局を怒らせ、広く議論され大きな反響を呼んだ[7]。

1872年の夏にレスコフはカレリアに行き、ラドーガ湖のヴァラム僧院を訪れた。この旅の結果は、1873年にRussky

mirに出版した一連の論考Monastic

Islesだった。1872年10月には、レスコーフ=ステブニツキーの作品集『小ベルレトル作品集』が出版された。この時期は、アレクセイ・ピセムス

キーとの短い交友の時期であり、レスコフは彼の小説『渦中』を大いに賞賛し、1872年8月にモスクワにピセムスキーを訪ねた[8]。 |

| At the same time, Leskov was

working on two of his "Stargorod Chronicles", later regarded as part of

a trilogy, along with The Cathedral Folk, Old Years in Plodomasovo

(1869) and A Decayed Family (1873), each featuring a strong female

character: virtuous, courageous, noble and "reasonably humane". Both

works bore signs of being unfinished. It later transpired that the

second work was ill-received by Mikhail Katkov, and that Leskov, having

lost all interest, simply refused to complete what otherwise might have

been developed into a full-blown novel. Both chronicles were thinly

veiled satires on certain aspects of the Orthodox church, especially

those incongruities it had with intrinsic Christian values which had

made it impossible (according to the author) for the latter to take

root firmly in the Russian soil.[10] On 16 November 1874, Leskov wrote

to Ivan Aksakov: "The second part of A Decayed Family which appeared in

god-awful shape, became the last straw for me."[7] It was in the course

of the publication of this second part that Katkov told one of his

associates, Voskoboynikov: "We've made a mistake: this man is not one

of us."[25] |

同じ頃、レスコフは『スタゴロド年代記』(後に『聖堂の人々』『プロド

マソヴォの老年』(1869)『朽ちた家族』(1873)と並ぶ三部作の一つとされる)の執筆に取り組んでおり、いずれも高潔で勇気があり、気高い、「適

度に人間的」な強い女性を主人公にした作品である。どちらの作品も未完成の形跡がある。2作目はミハイル・カトコフに不評で、レスコフは興味を失い、本格

的な小説になるはずの作品の完成を拒んだだけだと、後に判明している。どちらの年代記も、正教会のある側面、特にキリスト教の本質的な価値観との不一致を

薄く風刺したもので、(著者によれば)正教会がロシアの土壌にしっかりと根付くことを不可能にしてしまったのである。

[1874年11月16日、レスコフはイワン・アクサコフに宛てて次のように書いている:「ひどい形で現れた『朽ちた家族』の第二部は、私にとって最後の

藁となった」[7]

この第二部の出版の過程で、カトコフは彼の仲間の一人、ヴォスコボイニコフに言ったのである。「この男は我々の仲間ではない」[25]。 |

| In

1873 The Sealed Angel came out, about a miracle which caused an Old

Believer community to return to the Orthodox fold.[10] Influenced by

traditional folk tales, it is regarded in retrospect one of Leskov's

finest works, employing his skaz technique to the fullest effect.

The Sealed Angel turned out to be the only story that avoided being

heavily cut by The Russian Messenger because, as Leskov later wrote,

"it slipped through, in the shadows, what with them being so busy."[26]

The story, rather critical of the authorities, resonated in high places

and was read, reportedly, at the Court.[7] |

1873

年に発表された『封印された天使』は、旧信者のコミュニティが正教徒に戻る原因となった奇跡を描いたものである[10]。伝統的な民話に影響を受けたこの

作品は、スカズの手法を最大限に活用し、レスコフの最も優れた作品の1つであると振り返って評価されている。封印された天使』は、後にレス

コフが書いたように、「彼らがとても忙しかったので、影ですり抜けた」ため、『ロシアの使者』による大幅なカットを免れた唯一の物語となった[26]。当

局をかなり批判したこの物語は上層部に共鳴し、宮中で読まれたとされる[7]。 |

| Inspired by his 1872 journey to

Lake Ladoga,[8] The Enchanted Wanderer (1873) was an amorphous, loosely

structured piece of work, with several plotlines intertwined – the form

Leskov thought the traditional novel was destined to be superseded by.

Decades later scholars praised the story, comparing the character of

Ivan Flyagin to that of Ilya Muromets, as symbolizing "the physical and

moral duress of the Russian man in times of trouble,"[10] but the

response of contemporary critics was lukewarm, Nikolay Mikhaylovsky

complaining of its general formlessness: "details stringed together

like beads, totally interchangeable."[27] While all of Leskov's

previous works were severely cut, this was the first one to be rejected

outright; it had to be published in the odd October and November issues

of the Russky mir newspaper .[7] In December 1873 Leskov took part in

Skladchina, the charity anthology aimed at helping victims of famine in

Russia.[8] |

1872年のラドガ湖への旅から着想を得た『魅惑のさすらい人』

(1873)は、いくつかのプロットが絡み合う、不定形で緩やかな構成の作品であり、レスコフは伝統的な小説が取って代わられる運命にあると考えていた。

数十年後、学者たちはこの物語を賞賛し、イワン・フライヤーギンのキャラクターをイリヤ・ムロメッツのそれと比較し、「困難な時代におけるロシア人男性の

肉体的・精神的強迫」を象徴しているとした[10]が、現代の批評家の反応は生ぬるく、ニコライ・ミハイロフスキーはその全体的な形のなさに不満を漏らし

た。レスコフのこれまでの作品はすべて厳しくカットされたが、これは完全に拒絶された最初の作品であり、『Russky

mir』新聞の奇妙な10月号と11月号に掲載されなければならなかった[7]

1873年12月にレスコフは、ロシアの飢饉の犠牲者を助けることを目的とした慈善アンソロジー、Skladchinaに参加する[8]。 |

| Having severed ties with The

Russian Messenger, Leskov found himself in serious financial trouble.

This was relieved to an extent by his invitation in January 1874 to

join the Scholarly Committee of the Ministry of Education (for this he

owed much to the Empress consort Maria Alexandrovna who was known to

have read The Cathedral Folk and spoke warmly to it),[3] where his duty

was to choose literature for Russian libraries and atheneums for a

meager wage of one thousand rubles per year.[7] In 1874 Leskov began

writing Wandering Lights: A Biography of Praotsev which was soon halted

and later printed as Early Years: From Merkula Praotsev’s Memoirs. It

was during the publication of this work that the author made a comment

which was later seen as his artistic manifesto: "Things

pass by us and I'm not going to diminish or boost their respective

significance; I won't be forced into doing so by the unnatural,

man-made format of the novel which demands the rounding up of fabulas

and the drawing together of plotlines to one central course. That's not

how life is. Human life runs on in its own way and that's how I'm going

to treat the roll of events in my works."[7] |

ロシアン・メッセンジャー』との関係を絶ったレスコフは、深刻な財政難

に陥っていた。1874年1月に文部省の学術委員会に招かれ(このことは、『聖堂の民衆』を読んだことで知られる女帝マリア・アレクサンドロヴナのおかげ

である)、年間千ルーブルという薄給でロシアの図書館やアテネウムに置く文学作品を選ぶことが彼の任務となり、ある程度は緩和された[7]。プラウツェフ

の伝記』を書き始めたが、すぐに中断され、後に『Early Years』として印刷された。From Merkula Praotsev's

Memoirs』として印刷された。この作品の出版時に、作者は後に彼の芸術的マニフェストとされるコメントを残している。「私

は、小説という不自然で人工的な形式によって、ファブラを丸め、筋を一つの中心的なコースにまとめることを要求されても、それを強制されることはない。人

生とはそういうものではないのだ。人間の人生はそれなりに続いていくし、私の作品でもそうやって出来事の展開を扱っていこうと思っています」[7]。 |

| In the spring of 1875 Leskov

went abroad, first to Paris, then to Prague and Dresden in August. In

December his novella "At the Edge of the World" was published in

Grazhdanin (1875, No. 52).[8] All the while he continued to work on a

set of stories which would later form his cycle Virtuous Ones. Some

critics found Leskov's heroes virtuous beyond belief, but he insisted

they were not fantasies, but more like reminiscences of his earlier

encounters. "I credit myself with having some ability for analyzing

characters and their motives, but I'm hopless at fantasizing. Making up

things is hard labour for me, so I've always felt the need for having

before me real faces which could intrigue me with their spirituality;

then they get hold of me and I infuse them with new life, using some

real-life stories as a basis," he wrote later in the Varshavsky Dnevnik

newspaper.[28] Years of confrontation with critics and many of his

colleagues have taken their toll. "Men of letters seem to recognize my

writing as a force, but find great pleasure in killing it; in fact they

have all but succeeded in killing it off altogether. I write nothing –

I just can't!", he wrote to Pyotr Schebalsky in January 1876.[8] |

1875年の春、レスコフはまずパリに、8月にはプラハとドレスデンに

留学した。12月には小説「世界の果てで」が『グラズダーニン』誌(1875年、第52号)に掲載された[8]

その間も、後に『高潔な者たち』シリーズとなる一連の物語に取り組み続けた。しかし、レスコーフは、それが空想ではなく、むしろ以前の出会いの回想のよう

なものだと主張している。「私は、登場人物やその動機を分析する能力はあると自負しているが、空想するのは苦手だ。だから、精神性をそそるような実在の人

物の顔が目の前にあることの必要性をいつも感じていた。そして、その人物は私になつき、私は現実の話をもとにして、新しい命を吹き込む」と、後にヴァル

シャフスキー・ドネヴニク紙に書いている[28]。評論家や多くの同僚と長年対立してきたことが、その犠牲になっている。「文人たちは私の文章を力として

認めているようだが、それを殺すことに大きな喜びを見出している。事実、彼らはそれを完全に殺すことに成功した。私は何も書かない-どうしてもできな

い!」と、1876年1月にピョートル・シェバルスキーに宛てて書いている[8]。 |

| In October 1881 Rus magazine

started publishing "The

Tale of Cross-eyed Lefty from Tula and the Steel Flea", which is seen

in retrospect as Leskov's finest piece of work, bringing out the best

in him as an ingenious storyteller and stylistic virtuoso whose skaz

style is rich in word play and full of original neologisms, each

carrying not only humorous but satirical messages. In Lefty the

author's point of view is engaged in lively interplay with that of the

main (grotesquely naive, simple-minded) character. "Some people argued

that I had done little to distinguish between the good and the bad, and

that it was difficult to make out who was a helper and who put wrenches

in the works. This can be explained by the intrinsic deceitfulness of

my own character," Leskov later wrote.[29] Most deceitful (according to

critic B. Bukhstab) was the author's treatment of the character ataman

Platov, whose actions, even as they are described in a grotesquely

heroic manner by the simple-minded protagonist, are openly ridiculed by

the author.[7] What would later come to be seen as one of the gems of

Russian literature was fiercely attacked both from the left (who

accused Leskov of propagating jingoistic ideas) and the right, who

found the general picture of the common people's existence as depicted

in the story a bit too gloomy for their taste.[7] |

1881年10月、『ルス』誌に「トゥー

ラの十字架目レフティと鋼鉄のノミの物語」が掲載された。この作品は、今にして思えばレスコフの最高傑作であり、独創的なストーリーテラーと文体の名手と

しての彼の良さが引き出されている。スカズ文体は言葉遊びに富み、独自の新語が多く、それぞれにユーモアだけでなく風刺のメッセージが入っている。

『レ

フティ』では、作者の視点と主人公(グロテスクなまでにナイーブで単純な性格)の視点が、生き生きと交錯しているのである。「私が善玉と悪玉の区別をほと

んどしていない、誰が協力者で誰が邪魔者なのか見分けがつかない、と言う人もいた。これは私自身の性格の本質的な欺瞞性によって説明できる」と後にレスコ

フは書いている[29]。最も欺瞞的だったのは(評論家のB・ブフスタブによれば)アタマン・プラトフという人物の扱いであり、彼の行動は、単純思考の主

人公によってグロテスクに英雄的に描写されていても、作者によって公然と馬鹿にされているのであった[7]。

[後にロシア文学の珠玉の一編とみなされることになるこの作品は、左派(レスコフはジンゴイズムの宣伝をしていると非難)、右派(物語に描かれた庶民の存

在の全体像は、彼らの好みには少し陰鬱すぎると感じた)の両方から猛烈な攻撃を受けている[7] 。 |

| "Leftie" premiered publicly in

March 1882 at the literary and musical evening of The Pushkin Circle;

on 16 April it came out in book form. The collection of sketches called

Pechersky Antics was written in December, and published by Kievskaya

Starina, in its February and April issues. By this time a large Russian

Antics cycle began to take shape, in which Leskov implemented, as he

saw it, Nikolai Gogol's idea (formulated in the Selected Passages from

Correspondence with Friends) of "extoling modest working men." "It is

wrong and unworthy to pick out the worst in the soul of the Russian

man, so I embarked on my own journey looking for virtuous ones. Whoever

I asked would reply to the effect that they knew no such saints, and

that all of us were sinful, but they had met some decent men... and I

just started writing about them," he wrote in the preface to one such

story ("Singlethought", Odnodum, 1879). A similar cycle of short

stories involved legends of early Christianity, with plot lines taken

from the "prologues" and Byzantine stories of the 10th and 11th

centuries. The fact that some of these pieces ("Pamphalone", "Beautiful

Azu") were translated into German and praised by publishers, made

Leskov immensely proud. What was new to the Russian reader in them was,

as Mirsky noted, "a boldly outspoken treatment of sensual episodes";

some critics accused the author of "treating his moral subjects as

nothing but pretexts for the display of voluptuous and sensual

scenes."[2] |

「レフティ」は1882年3月、プーシキン・サークルの文学と音楽の夕

べで公に初演され、4月16日には書籍として出版された。12月には「ペチェルスキー・アンチックス」と呼ばれるスケッチ集が書かれ、キエフスカヤ・スタ

リナから2月号と4月号に掲載された。この頃までには、レスコフは、ニコライ・ゴーゴリの「控えめな労働者を賞賛する」という考え(「友人との手紙の中か

ら選ばれた一節」で定式化されている)をそのまま実行した、大きな「ロシア風刺」サイクルが形成され始めていたのである。「ロシア人の魂から最悪のものを

選び出すのは間違っているし、ふさわしくないので、私は徳の高い人を探す旅に出た。誰に聞いても、そんな聖人は知らない、人間はみな罪深いが、まともな人

間には会ったことがある...だから、その人たちのことを書き始めた」と、そうした物語の序文に書いている(「一念」、Odnodum、1879年)。同

じように、初期キリスト教の伝説を扱った短編集もあり、プロローグや10~11世紀のビザンチン時代の物語からプロットを取っている。これらの作品の一部

(「パンファローネ」、「美しいアズ」)がドイツ語に翻訳され、出版社から賞賛されたことは、レスコフの大きな誇りであった。これらの作品の中でロシアの

読者にとって新鮮だったのは、ミルスキーが指摘するように、「官能的なエピソードを大胆に露骨に扱っていること」だった。一部の批評家は、この作家を「道

徳的テーマを、官能的で豊満な場面を見せるための口実にしか扱っていない」と非難している[2]。 |

| Later years In February 1883 the essay "Leap-frog in Church and Local Parish Whimsies" (based on an officially documented episode concerning the outrageous behaviour of a drunken pastor and deacon at a church in a provincial town) was published by Istorichesky vestnik.[7] It caused a scandal and cost its author his job at the Ministry of Education. Minister Delyanov suggested that Leskov should sign a retirement paper, but the latter refused. "What do you need such a firing for?" the Minister reportedly asked. "For a decent obituary," Leskov retorted. In April he informed the director of the Oryol lyceum that he was sending him a gold medal he had received from the Ministry "to be given to the poorest of that year's graduates."[8] |

晩年 1883年2月、エッセイ「教会と地方教区の気まぐれにおける跳び箱」(地方都市の教会で酔っ払った牧師と助祭の非道な振る舞いに関する公式記録のエピ ソードに基づく)がIstorichesky vestnikから出版された[7]。この論文はスキャンダルを引き起こし、著者は文部省での仕事を失うことになる。デリヤノフ大臣はレスコフに退職届に サインするよう勧めたが、レスコフは拒否した。「デリヤノフ大臣は、レスコフに退職願にサインするよう勧めたが、レスコフはこれを拒否した。と大臣が聞く と、「ちゃんとした死亡記事を書くためだ」とレスコフは言い返した。4月、彼はオリョール大学の学長に、「その年の卒業生の中で最も貧しい者に贈るため に、省から受け取った金メダルを送る」と告げた[8]。 |

| By this time the Russian

Orthodox Church had become the major target of Leskov's satire. In an

1883 letter, remembering The Cathedral Folk, he confessed: "These days

I wouldn't do them, I'd rather have written Notes of a Defrocked

Priest... to show how all of the Crucified One's commandments are being

corrupted and falsified... [My position] would be defined as Tolstoyan

these days, while things that have nothing to do with Christ's teaching

would be termed Orthodoxy. I wouldn't oppose the term, I'd just say,

Christianity this is not."[30] Leskov's religious essays of the early

1880s continued the same line of sympathetically supporting poor

clergymen and ridiculing the hypocrisy of the Russian Orthodoxy's

higher ranks.[1] In "Count Tolstoy and F. M. Dostoyevsky as

Heresiarchs" and "The Golden Age", both 1883) he defended both from the

criticism of Konstantin Leontiev. Leskov never became a Tolstoyan, but

his later works were impregnated with the idea of "new Christianity"

which he himself identified with Leo Tolstoy, whom he became close with

in the mid-1880s and was inevitably influenced by. On 18 April 1887,

Leskov wrote a letter to Tolstoy asking for permission to visit him in

Moscow so as to fulfill a "long-standing desire." On 25 April the two

authors met. "What a bright and original man," Tolstoy later wrote in a

letter to Chertkov. Leskov spent January 1890 with Chertkov and Tolstoy

at Yasnaya Polyana, where Tolstoy read to them his own play The Fruits

of Enlightenment.[8] |

この頃、ロシア正教会はレスコフの風刺の主要な標的になっていた。

1883年、『聖堂の人々』を回想する手紙の中で、彼はこう告白している。「十字架につけられた者のすべての戒律がいかに堕落し、偽られているかを示すた

めに...。[私の立場は)最近ではトルストイ的と定義され、キリストの教えとは無関係なものは正統派と呼ばれるようになった。1880年代前半のレスコ

フの宗教エッセイは、貧しい聖職者を同情的に支援し、ロシア正教の上層部の偽善を嘲笑するという同じ路線を続けていた[1]

。レスコフはトルストイ派にはならなかったが、その後の作品には、1880年代半ばに親しくなったレオ・トルストイと彼自身が同一視し、必然的に影響を受

けた「新しいキリスト教」の思想が滲み出ている。1887年4月18日、レスコフはトルストイに手紙を書き、「長年の願望」を実現するためにモスクワを訪

問する許可を得た。4月25日、二人の作家は面会した。トルストイは後にチェルトコフに宛てた手紙の中で、「なんと明るく独創的な男だろう」と書いてい

る。レスコフは1890年1月、チェルトコフ、トルストイとともにヤスナヤ・ポリャーナで過ごし、トルストイは自作の戯曲『啓蒙の果実』を読んで聞かせた

[8]。 |

| In July 1883 the first four

chapters of the novel As the Falcon Flies were published by Gazeta

Gatsuka, followed by chapters five through eight, then chapters nine

and ten; at this point the publication ceased due to interference by

the censors.[8] In January 1884 the publication of Notes of a Stranger

began in Gazeta Gatsuka (No. 2) to be stopped in April, again by the

censors. In the summer of 1884, while Leskov was on a trip through

Warsaw, Dresden, Marienbad, Prague and Vienna, a special censorship

order came out, demanding withdrawal of 125 books from Russian

libraries, Leskov's collection Trifles from the Life of Archbishops

(1878–79) included. In November 1884, Nov magazine began publishing the

novel The Unseen Trail: it was banned after chapter 26 and has never

been completed.[8] In November 1888 the novella Zenon the Goldsmith was

written for Russkaya mysl and promptly banned. By this time, according

to Bukhstab, Leskov found himself in isolation again. The right treated

him as a dangerous radical, while the left, under pressure from the

Russian government, were too scared to publish radical prose.[7] Leskov

himself referred to the stories of his later years as "cruel". "The

public doesn't like them because they're cynical and in your face. But

I don't want to please the public, I want to torture it and flog it,"

he wrote.[31] |

1883年7月、『ガゼッタ・ガツカ』から小説『鷹が飛ぶように』の最

初の4章が、次いで5章から8章、9章と10章が出版されたが、検閲官の妨害によりこの時点で出版が中止された[8]。1884年1月には『見知らぬ人の

ノート』(第2号)の出版がガゼッタ・ガツカから始まり、4月には再び検閲官によって中止された。1884年夏、レスコフがワルシャワ、ドレスデン、マリ

エンバート、プラハ、ウィーンを旅行中に、検閲の特別命令が出され、ロシアの図書館から125冊の本を取り上げるよう要求され、レスコフのコレクション

『大司教の生活からのトリフルス』(1878-79)が含まれる。1884年11月、雑誌『ノーヴ』が小説『見知らぬ道』の出版を開始したが、第26章で

発禁となり、未完に終わった[8]。1888年11月、小説『金細工師ゼノン』が『ルースキー・ミスル』に書かれたが、すぐに発禁となった。ブフスタブに

よれば、この頃、レスコフは再び孤立状態に陥っていた。右派は彼を危険な過激派として扱い、左派はロシア政府の圧力により、怖くて過激な散文を発表できな

かった[7]。

レスコフ自身、晩年の物語を「残酷」だと言っている[8]。レスコフ自身、晩年の物語を「残酷」だと言っている[7]。「世間は、シニカルで顔に出るから

嫌がるんだ。しかし、私は大衆を喜ばせたいのではなく、大衆を拷問し、鞭打ちにしたいのだ」と書いている[31]。 |

| In August, November and December

1887 respectively, the first three volumes of the collection Novellas

and Short Stories by N. S. Leskov were published. At the 1888 New Year

party at Alexei Suvorin's, Leskov met Anton Chekhov for the first time.

Soon Ilya Repin became Leskov's friend and illustrator. Several months

later in a letter, asking Leskov to sit for him, Repin explained his

motives: "Not only me but the whole of enlightened Russia loves you as

an outstanding, distinguished writer and as a thinking man." The

sittings early the next year were aborted: Leskov was unwilling to have

his portrait seen at a forthcoming exhibition of Repin's works.[8] |

1887年8月、11月、12月にそれぞれ、N. S.

レスコフの小説・短編集の最初の3巻が出版された。1888年、アレクセイ・スヴォーリンの家で開かれた新年会で、レスコフは初めてアントン・チェーホフ

に会った。まもなくイリヤ・レーピンがレスコフの友人となり、挿絵画家となった。数ヵ月後、レーピンはレスコフに代役を依頼する手紙の中で、その動機を説

明している。「私ばかりでなく、覚醒したロシア全体が、あなたを優れた作家として、また思想家として愛しているのです」。翌年早々の座談会は頓挫した。

レーピンの展覧会で自分の肖像画を見せることをレスコフが嫌がったからだ[8]。 |

| In September 1888 Pyotr Bykov

published a full bibliography of Leskov's works (1860–1887) which

intrigued publishers. In 1889 Alexei Suvorin's publishing house began

publishing the Complete Leskov in 12 volumes (which contained mostly

fiction). By June 1889, the fourth and fifth volumes had been issued,

but in August volume six, containing some anti-Eastern Orthodox satires

was stopped. On 16 August, Leskov suffered his first major heart attack

on the stairs of Suvorin's house, upon learning the news. The

publication of his works continued with volume seven, generating

considerable royalties and greatly improving the author's financial

situation.[7] A different version of volume six came out in 1890.[8] |

1888年9月、ピョートル・ビコフはレスコフの作品

(1860~1887年)の全書誌を発表し、出版社の興味をそそった。1889年、アレクセイ・スヴォーリンの出版社から『レスコフ全集』全12巻(ほと

んどがフィクション)が刊行されることになった。1889年6月までに第4巻と第5巻が発行されたが、8月には反東方正教会の風刺を含む第6巻が発行中止

となった。8月16日、その知らせを受けたレスコフは、スヴォーリンの家の階段で最初の大きな心臓発作を起こした。作品の出版は第7巻まで続き、かなりの

印税が得られ、著者の財政状況は大きく改善された[7]。 1890年には第6巻の別バージョンが出版された[8]。 |

| In January 1890 the publication

of the novel The Devil Dolls (with Tsar Nikolai I and Karl Bryullov as

the prototypes for the two main characters) started in Russkaya Mysl,

but was stopped by censors. In 1891 Polunochniki (Night Owls), a thinly

veiled satire on the Orthodox Church in general and Ioann Kronshtadsky

in particular, was published in Severny vestnik and caused an uproar.

The 1894 novella The Rabbit Warren about a clergyman who'd been

honoured for reporting people to the authorities and driving a police

official into madness by his zealousness (one of "his most remarkable

works and his greatest achievement in concentrated satire," according

to Mirsky)[2] was also banned and came out only in 1917 (in Niva

magazine).[32] The process of having his works published, which had

always been difficult for Leskov, at this late stage became, in his own

words, "quite unbearable".[7] |

1890年1月、『ルースカヤ・マイスル』誌上で小説『悪魔の人形』

(ニコライ1世とカール・ブリュロフを主人公の2人が原型)の出版が始まったが、検閲で中止された。1891年、正教会全般とイオアン・クロンシタスキー

を薄く風刺した『ポルノチニキ(夜ふかし)』がSeverny

vestnikに掲載され、騒動になった。1894年の小説『ウサギの戦場』は、当局に通報したことで表彰された聖職者がその熱心さで警察官を発狂させる

という内容(ミルスキーによれば「彼の最も注目すべき作品の一つで、集中風刺における最大の成果」[2])で、これも発禁となり、1917年に初めて(雑

誌『ニヴァ』で)発表された。

レスコフにとって常に困難だった作品の出版作業はこの時期、彼自身の言葉で「かなり耐え難い」ものになってしまった[7]。 |

| In his last years Leskov

suffered from angina pectoris and asthma.[10] There were also rumours,

whose accuracy and substantiation have been questioned, that he had

been diagnosed with male breast cancer. In early 1894 he caught a

severe cold; by the end of the year his general condition had

deteriorated. Responding to Pavel Tretyakov's special request, Leskov

(still very ill) agreed to pose for Valentin Serov, but in February

1895, when the portrait was exhibited in the Tretyakovskaya Gallery, he

felt utterly upset both by the portrait and the black frame. |

晩年は狭心症や喘息に悩まされ[10]、また男性乳癌との噂もあった

が、その正確性や信憑性には疑問が持たれている[11]。1894年初頭、彼はひどい風邪を引き、年末には全身状態が悪化した。1895年2月、トレチャ

コフ画廊で肖像画が公開されると、レスコフは肖像画と黒い額縁にひどく動揺した。 |

| On 5 March 1895, Leskov died,

aged 64. The funeral service was held in silence, in accordance with

the writer's December 1892 will, forbidding any speeches to be held

over his dead body. "I know I have many bad things in me and do not

deserve to be praised or pitied," he explained.[33] Leskov was interred

in the Literatorskiye Mostki necropolis at the Volkovo Cemetery in

Saint Petersburg (the section reserved for literary figures).[8] Due to

Leskov's purportedly difficult nature (he has been described as

despotic, vindictive, quick-tempered and prone to didacticism), he

spent the last years of his life alone, his biological daughter Vera

(from his first marriage) living far away and never visiting; his son

Andrey residing in the capital but avoiding his father.[7] |

1895年3月5日、レスコフは64歳で死去した。葬儀は、1892年

12月の作家の遺書に従い、遺体の前で演説をすることを禁じられたため、静かに行われた。「レスコフはサンクトペテルブルクのヴォルコヴォ墓地の文学者墓

地(文学者のための区画)に埋葬された[33]。

[レスコフの気難しい性格(専制的、執念深い、短気、教訓主義に陥りやすいと言われている)のため、晩年は一人で過ごし、実の娘ヴェラ(最初の結婚相手)

は遠くに住んでいて訪れることはなく、息子のアンドレイは首都に住んでいるが父親を避けていた[7]。 |

| Marriages and children On 6 April 1853 Leskov married Olga Vasilyevna Smirnova (1831–1909), the daughter of an affluent Kiev trader. Their son Dmitry was born on 23 December 1854 but died in 1855. On 8 March 1856, their daughter Vera Leskova was born. She married Dmitry Noga in 1879 and died in 1918. Leskov's marriage was an unhappy one; his wife suffered from severe psychological problems and in 1878 had to be taken to the St. Nicholas Mental Hospital in Saint Petersburg. She died in 1909.[34] |

結婚と子ども 1853年4月6日、レスコフはキエフの裕福な貿易商の娘オルガ・ワシリエヴナ・スミルノヴァ(1831-1909)と結婚した。1854年12月23日 に息子のドミトリーが生まれたが、1855年に死亡した。1856年3月8日、娘のヴェーラ・レスコヴァが生まれる。彼女は1879年にドミトリー・ノガ と結婚し、1918年に死去した。レスコフの結婚は不幸なものであった。妻は深刻な精神的問題を抱え、1878年にはサンクトペテルブルグの聖ニコラス精 神病院に収容されることになった。1909年に死去した[34]。 |

| In 1865 Ekaterina Bubnova (née

Savitskaya), whom he met for the first time in July 1864, became

Leskov's common-law wife. Bubnova had four children from her first

marriage; one of whom, Vera (coincidentally the same name as Leskov's

daughter by his own marriage) Bubnova, was officially adopted by

Leskov, who took care that his stepdaughter got a good education; she

embarked upon a career in music. In 1866 Bubnova gave birth to their

son, Andrey (1866–1953).[3] In August 1878 Leskov and Bubnova parted,

and, with Andrey, Nikolai moved into the Semyonov house at the corner

of Kolomenskaya St. and Kuznechny Lane, in Saint Petersburg. Bubnova

suffered greatly at having her son taken away from her, as her letters,

published many years later, attested.[35] In November 1883 Varya Dolina (daughter of E.A. Cook)[who?] joined Leskov and his son, first as a pupil and protege, soon becoming another of Leskov's adopted daughters.[8][34] |

1864年7月に初めて会ったエカテリーナ・ブブノワ(旧姓サヴィツカ

ヤ)は、1865年にレスコフの内縁の妻となった。ブブノワは最初の結婚で4人の子供をもうけたが、そのうちの一人、ヴェラ(偶然にもレスコフの娘と同じ

名前)はレスコフの正式な養子になり、彼は継娘が良い教育を受けられるように気を配り、彼女は音楽の道に進むことになる。1866年、ブブノワは息子のア

ンドレイ(1866-1953)を出産した[3]。1878年8月、レスコフとブブノワは別れ、ニコライはアンドレイを連れてサンクト・ペテルブルグのコ

ロメンスカヤ通りとクズネチニー通りの角にあるセミョーノフ家に移り住むことになった。ブブノワは息子を奪われたことに大変苦しみ、そのことは何年も後に

出版された彼女の手紙に証明されている[35]。 1883年11月、ヴァーリャ・ドリーナ(E.A.クックの娘)[誰?]がレスコフと彼の息子に加わり、最初は弟子として、すぐにレスコフのもうひとりの 養女になった[8][34]。 |

| Andrey Leskov made a career in

the military. From 1919 to 1931 he served as a staff officer on the

Soviet Army's North-Western frontier and retired with the rank of

Lieutenant-General.[33] By this time he had become an authority on his

father's legacy, praised by Maxim Gorky among many others and regularly

consulted by specialists. Andrey Leskov's The Life of Nikolai Leskov, a

comprehensive book of memoirs (which had its own dramatic story:

destroyed in the 1942 Siege of Leningrad by a bomb, it was

reconstructed from scratch by the 80-plus year old author after the

War, and finished in 1948).[36] It was first published by Goslitizdat

in Moscow (1954); in 1981 it was re-issued in two volumes by Prioksky

publishers in Tula.[33] |

アンドレイ・レスコフは軍でキャリアを積んだ。1919年から1931

年までソビエト軍の北西辺境で参謀として働き、中将の階級で退役した[33]。この時までに彼は父の遺産に関する権威となり、マキシム・ゴーリキーや他の

多くの人々から賞賛され、専門家から常に相談されるようになった。アンドレイ・レスコフの『ニコライ・レスコフの生涯』(1942年のレニングラード包囲

で爆弾により破壊され、戦後80歳を超えた著者がゼロから再構築し、1948年に完成させたという劇的な物語がある)。モスクワのゴスリチダートから最初

に出版(1954)、1981年にトゥーラのPrikosk出版から2巻で再発行された[33]。 |

| Legacy Nikolai Leskov, now widely regarded as a classic of Russian literature,[7][11] had an extremely difficult literary career, marred by scandals which resulted in boycotts and ostracism.[3] Describing the Russian literary scene at the time Leskov entered it, D. S. Mirsky wrote: |

レガシー ニコライ・レスコフは、現在ではロシア文学の古典として広く認められているが[7][11]、スキャンダルによってボイコットや追放に遭い、非常に困難な 文学キャリアを送った。 レスコフが参入した当時のロシア文学界について、D・S・ミルスキーは次のように記述している。 |

| It

was a time of intense party strife, when no writer could hope to be

well received by all critics and only those who identified themselves

with a definite party could hope for even partial recognition. Leskov

had never identified himself with any party and had to take the

consequences. His success with the reading public was considerable but

the critics continued to neglect him. Leskov's case is a striking

instance of the failure of Russian criticism to do its duty.[2] |

当

時は党派争いが激しく、どの作家もすべての批評家から好評を得ることはできず、特定の党派に属する者だけが部分的にでも評価を得ることができる時代であっ

た。レスコフはどの党派にも属さず、その結果を受け止めなければならなかった。レスコフは、どの党派にも属さず、その結果、読書家としてはかなりの成功を

収めたが、批評家からは無視され続けた。レスコフのケースは、ロシアの批評がその義務を果たせなかったことの顕著な例である[2]。 |

| After his 1862 article on the

"great fires" and the 1864 novel No Way Out, Leskov found himself in

total isolation which in the 1870s and 1880s was only partially

relieved. Apollon Grigoriev, the only critic who valued him and

approved of his work, died in 1864 and, according to Mirsky, "Leskov

owed his latter popularity to the good taste of that segment of the

reading public who were beyond the scope of the 'directing'

influences". In the 1870s things improved but, according to Brockhaus

and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, "Leskov's position in his last 12 to

15 years was ambivalent, old friends distrusting him, new ones being

still wary. For all his big name, he wasn't a centerpiece literary

figure and critics all but ignored him. This didn't prevent the huge

success of the Complete Leskov."[37] After the 10th volume of this

collection was published, critic Mikhail Protopopov came up with an

essay called "The Sick Talent". Crediting Leskov as a superb

psychologist and a master of "reproducing domestic scenes," he rated

him equal to Melnikov-Pechesky and Mikhail Avdeev. What prevented

Leskov from getting any higher, the critic argued, were "his love of

hyperbole" and what he termed "an overload of spices."[38] At the time

of his death in 1895 Leskov "had few friends in literary circles but a

great many readers all over Russia," according to Mirsky.[23] |

1862年の「大火」についての論文と1864年の小説『出口なし』の

後、レスコフは完全に孤立し、1870年代と1880年代には部分的にしか解放されないことに気づく。レスコフを評価し、彼の作品を認めていた唯一の批評

家アポロン・グリゴリエフは1864年に亡くなり、ミルスキーによれば、「レスコフの後年の人気は、『演出』の影響を受けなかった読者層の趣味のよさに負

うところが大きい」。1870年代には状況が好転したが、ブロックハウスとエフロン百科事典によれば、「最後の12年から15年のレスコフの立場は両義的

で、旧友は彼を不信に思い、新しい友人はまだ警戒している。レスコフは大物であるにもかかわらず、文学の中心人物ではなく、批評家も彼を無視するように

なった。しかし、『レスコフ全集』の大成功を阻むことはできなかった」[37]

この全集の第10巻が出版された後、評論家ミハイル・プロトポポフは「病める才能」というエッセイを発表した。レスコフは優れた心理学者であり、「家庭の

情景を再現する」名手であるとし、メルニコフ・ペチェスキーやミハイル・アヴデーエフと同等に評価したのである。1895年の死の際、レスコフは「文学界

に友人はほとんどいなかったが、ロシア全土に非常に多くの読者がいた」とミルスキーは述べている[23]。 |

| In 1897 The Adolf Marks

publishing house re-issued the 1889–1893 12-volume series and in

1902–1903 released the 36-volume version of it, expanded with essays,

articles and letters.[39] This, along with Anatoly Faresov's memoirs,

Against the Grain (1904), caused a new wave of interest in Leskov's

legacy. In 1923 three volumes of Nikolai Leskov's selected works came

out in Berlin, featuring an often-quoted rapturous preface by Maxim

Gorky (who called Leskov "the wizard of wording"), and was re-issued in

the USSR in early 1941.[36] |

1897年にアドルフ・マークス社が1889年から1893年の12巻

のシリーズを再出版し、1902年から1903年にはエッセイ、論文、書簡を追加した36巻のシリーズを発表した[39]。これは、アナトリー・ファレソ

フの回想録『穀物に対して』(1904)と共に、レスコフの遺産に対する新しい関心の波となった。1923年にベルリンでニコライ・レスコフの3冊の著作

が出版され、マクシム・ゴーリキー(彼はレスコフを「言葉の魔術師」と呼んだ)がしばしば引用する熱烈な序文を掲載し、1941年初めにソ連で再出版され

た[36]。 |

| For

decades after his death the attitude of critics toward Leskov and his

legacy varied. Despite the fact that some of his sharpest satires could

be published only after the 1917 Revolution, Soviet literary propaganda

found little of use in Leskov's legacy, often labeling the author a

"reactionary" who had "denied the possibility of social revolution,"

placing too much attention on saintly religious types. For

highlighting the author's 'progressive' inclinations "Leftie" (a

"glorification of Russian inventiveness and talent") and "The Toupee

Artist" (a "denunciation of the repressive nature of Tsarist Russia")

were invariably chosen.[36] "He is a brilliant author, an insightful

scholar of our ways of life, and still he's not being given enough

credit", Maxim Gorky wrote in 1928, deploring the fact that after the

1917 Revolution Leskov was still failing to gain ground in his homeland

as a major classic.[40] |

レ

スコフの死後数十年間、レスコフとその遺産に対する批評家の態度はさまざまであった。彼の最も鋭い風刺のいくつかは、1917年の革命後にのみ出版するこ

とができたにもかかわらず、ソ連の文学プロパガンダは、レスコフの遺産にほとんど役に立たないと考え、しばしばこの作家を「社会革命の可能性を否定した」

「反動的」であるとし、聖なる宗教的タイプに過剰な注意を払うようになった。著者の「進歩的」な傾向を強調するために、「レフティ」(「ロ

シアの発明と才能の美化」)と「トゥーピーの芸術家」(「帝政ロシアの抑圧的な性質を非難する」)が常に選ばれた[36]。 [36]

「彼は素晴らしい作家であり、我々の生活様式についての洞察に満ちた学者であるが、未だに十分な評価を得ていない」とマクシム・ゴーリキーは1928年に

書いており、1917年の革命の後、レスコフが主要な古典として母国でまだ地位を確立できていないことを嘆いている[40]。 |

| The inability of the new

literary ideologists to counterbalance demands of propaganda with

attempts at objectivity was evidenced in the 1932 Soviet Literary

Encyclopedia entry, which said: "In our times when the

problem-highlighting type of novel has gained prominence, opening up

new horizons for socialism and construction, Leskov's relevancy as a

writer, totally foreign to the major tendencies of our Soviet

literature, naturally wanes. The author of "Lefty", though, retains

some significance as a chronicler of his social environment and one of

the best masters of Russian prose."[41] Nevertheless, by 1934 Dmitry

Shostakovich had finished his opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk

District, which caused a furore at home and abroad (to be eventually

denounced in 1936 by Pravda).[42] Before that, in 1929, Ivan Shyshov's

opera The Toupee Artist (after Leskov's story of the same name) had

been published and successfully staged.[43] |

新しい文学者たちが、プロパガンダの要求と客観性の試みとのバランスを とることができないことは、1932年のソビエト文学百科事典の項目で証明されている。「問題提起型の小説が脚光を浴び、社会主義や建設の新しい地平を切 り開いた現代では、わがソ連文学の主要な傾向とは全く異質の作家としてのレスコフの妥当性は当然薄れている。しかし、『左翼』の作者は、彼の社会環境の記 録者として、またロシア散文の最高の巨匠の一人として、ある程度の意義を保っている」[41] にもかかわらず、ドミトリー・ショスタコーヴィチは1934年までにオペラ『ムツェンスク郡のマクベス夫人』を完成させており、これは国内外で騒動となっ た(最終的には1936年にプラウダに非難される)[42] 。 [それ以前の1929年には、イワン・シショフのオペラ『髪結い芸人』(レスコフの同名の物語にちなむ)が出版され、上演に成功している[43]。 |

| In the post-World War II USSR

the interest in Leskov's legacy was continually on the rise, never

going, though, beyond certain censorship-set limits. Several scholarly

essays came out and then an extensive biography by the writer's son

Andrey Leskov was published in 1954. In 1953 the Complete Gorky series

featured his 1923 N. S. Leskov essay which became the object of lively

academic discussion.[36] The 11-volume 1956–1958 (and then 6 volume

1973–1974) Complete Leskov editions were obviously incomplete: one of

his political "anti-nihilistic" novels At Daggers Drawn, was missing,

included essays and letters carefully selected. Yet, in fifty years'

time things changed radically. While in 1931, on Leskov's 100th

Anniversary, critics wrote of the "scandalous reputation which followed

Leskov's literary life from beginning to the end," by 1981 Leskov,

according to the critic Lev Anninsky, was regarded as a first rank

Russian classic and academic essays on him had found their place in the

Moscow University's new course between those on Dostoevsky and Leo

Tolstoy.[36] In 1989 Ogonyok re-issued the 12-volume Leskov collection

in which At Daggers Drawn appeared for the first time in the USSR.[44] |

第二次世界大戦後のソ連では、レスコフの遺産に対する関心が絶えず高

まっていたが、検閲で決められた一定の限度を超えることはなかった。いくつかの学術的なエッセイが出版され、1954年には作家の息子アンドレイ・レスコ

フによる広範な伝記が出版された。1953年の『ゴーリキー全集』では、1923年のN. S.

レスコフのエッセイが取り上げられ、活発な学術的議論の対象となった[36]。1956年から1958年の11巻(その後1973年から1974年の6

巻)のレスコフ全集は明らかに不完全で、彼の「反ニヒリズム」の政治小説のひとつ『ダガー・ドレイン』が欠けていたほか、随筆や手紙も慎重に選ばれてい

る。しかし、50年後、状況は一変する。1931年、レスコフの100周年記念日

に、批評家たちは「レスコフの文学人生の最初から最後までつきまとったスキャンダラスな評判」について書いたが、1981年には、評論家レフ・アニンス

キーによれば、レスコフは第一級のロシアの古典とみなされ、彼に関する学術論文はモスクワ大学の新しいコースでドストエフスキーとレオ・トルストイに関す

る論文の間に位置づけられた[36]. [1989年、オゴニョクは『At Daggers

Drawn』が収録されたレスコフ全12巻をソ連で初めて再出版した[44]。 |

| In 1996 the Terra publishing

house in Russia started a 30 volume Leskov series, declaring the

intention to include every single work or letter by the author, but by

2007 only 10 volumes of it had come out. The Literaturnoye nasledstvo

publishers started the Unpublished Leskov series: book one (fiction)

came out in 1991, book two (letters and articles) – in 2000; both were

incomplete, and the volume six material, which had been banned a

century ago and proved to be too tough for the Soviet censors, was

again neglected.[45] All 36 volumes of the 1902 Marks Complete Leskov

were re-issued in 2002 and Moshkov's On-line Library gathered a

significant part of Leskov's legacy, including his most controversial

novels and essays.[46] |

1996年、ロシアのテラ出版がレスコフの全作品、全書簡を収録すると

宣言して30巻のシリーズを始めたが、2007年までに出たのは10巻だけであった。リテラトゥルノエ・ナスレドストヴォ出版社は未刊行レスコフシリーズ

を開始し、第1巻(小説)は1991年に、第2巻(手紙と論文)は2000年に刊行されたが、いずれも不完全で、第6巻は1世紀前に禁止されソ連の検閲官

にとって厳しいことが判明し、再び放置されることになった。 [2002年に『1902 Marks Complete

Leskov』全36巻が再発行され、モシュコフのオンライン図書館には、最も議論を呼んだ小説やエッセイなど、レスコフの遺産のかなりの部分が集められ

ている[46]。 |

| Social and religious stance In retrospect, the majority of Leskov's legacy, documentary in essence, could be seen as part of the 19th century raznochintsy literature which relied upon the 'real life sketch' as a founding genre. But, while Gleb Uspensky, Vasily Sleptsov and Fyodor Reshetnikov were preaching "the urgent need to study the real life of the common people," Leskov was caustic in his scorn: "Never could I understand this popular idea among our publicists of 'studying' the life of the common people, for I felt it would be more natural for a writer to 'live' this kind of life, rather than 'study' it," he remarked.[1] With his thorough knowledge of the Russian provinces, competence in every nuance of the industrial, agricultural and religious spheres, including obscure regional, sectarian or ethnic nuances, Leskov regarded his colleagues on the radical left as cabinet theoreticians, totally rootless in their "studies".[1] Leskov was not indifferent to social injustice, according to Bukhstab. "It was just that he viewed social problems as a strict practitioner for whom only personal experience was worthy of trust while none of the theories based on philosophical doctrines held water. Unlike the Social Democrats, Leskov neither believed in the possibility of an agrarian revolution in Russia, nor wanted it to happen, seeing education and enlightenment, often of religious nature, as the factors for social improvement," wrote the biographer.[7] |

社会的・宗教的スタンス 振り返ってみると、レスコフの遺産の大部分は、本質的にドキュメンタリーであり、「実生活のスケッチ」を建前とする19世紀のラズノッチ文学の一部と見る ことができるだろう。しかし、グレブ・ウスペンスキー、ワシーリー・スレプトソフ、フョードル・レシェトニコフらが「庶民の実生活を研究することが急務 だ」と説く中、レスコフは苛烈に軽蔑した。私は、作家は庶民の生活を "研究 "するよりも "生活 "する方が自然だと思うからだ」と述べている[1]。 [レスコフは、ロシアの地方を知り尽くし、産業、農業、宗教の各分野のあらゆるニュアンスに通じており、地域、宗派、民族の曖昧なニュアンスも含めて、急 進左派の同僚を、「研究」に全く根ざさない内閣理論家だと考えていた[1] ブフスタブによれば、レスコフは社会正義に対して無関心だったわけではないそうである。ただ、哲学的教義に基づく理論が何一つ通用しない中で、個人的な経 験のみが信頼に値する厳格な実践家として社会問題を捉えていたのである」[2]。社会民主党とは異なり、レスコフはロシアにおける農地革命の可能性を信じ ておらず、またそれを望んでおらず、教育や啓蒙(しばしば宗教的な性質を持つ)を社会改善の要因として捉えていた」と伝記作家は書いている[7]。 |

| On the other hand, he had very

little in common with Russian literary aristocrats. According to D. S.

Mirsky, Leskov was "one of those Russian writers whose knowledge of

life was not founded on the possession of serfs, to be later modified

by university theories of French or German origin, like Turgenev's and

Tolstoy's, but on practical and independent experience. This is why his

view of Russian life is so unconventional and so free from that

attitude of condescending and sentimental pity for the peasant which is

typical of the liberal and educated serf-owner." Mirsky expressed

bewilderment at how Leskov, after his first novel No Way Out, could

have been seriously regarded as a 'vile and libelous reactionary', when

in reality (according to the critic) "the principal socialist

characters in the book were represented as little short of saints."[2] |

その一方で、彼はロシアの文学貴族たちとはほとんど共通点がない。D.

S.

ミルスキーによれば、レスコフは「ロシアの作家の一人で、生活についての知識は、ツルゲーネフやトルストイのようなフランスやドイツ由来の大学の理論に

よって後で修正される農奴の所有に基づくものではなく、実際的で独立した経験に基づくものであった。だから、彼のロシア生活観は型破りで、自由主義的で教

養ある農奴所有者にありがちな、農奴を見下し感傷的に憐れむ態度とは無縁なのだ」。ミルスキーは、最初の小説『出口なし』の後、どうしてレスコフが「下劣

で中傷的な反動主義者」と真剣にみなされたのか、困惑を表明した。現実には(この評論家によれば)「この本の中の社会主義の主要人物は、聖人に近い存在と

して表現されている」[2]。 |

| Some modern scholars argue that,

contrary to what his contemporary detractors said, Leskov had not held

"reactionary" or even "conservative" sensibilities and his outlook was

basically that of a democratic enlightener, who placed great hopes upon

the 1861 social reform and became deeply disillusioned soon afterwards.

The post-serfdom anachronisms that permeated Russian life in every

aspect, became one of his basic themes. Unlike Dostoevsky, who saw the

greatest danger in the development of capitalism in Russia, Leskov

regarded the "immovability of Russia's 'old ways' as its main

liability," critic Viduetskaya insisted. Leskov's attitude towards

'revolutionaries' was never entirely negative, this critic argued; it's

just that he saw them as totally unprepared for the mission they were

trying to take upon themselves, this tragic incongruity being the

leitmotif of many of his best known works; (The Musk-Ox, Mystery Man,

The Passed By, At Daggers Drawn).[1] |

1861年の社会改革に大きな期待をかけ、その直後に深い幻滅を覚えた

レスコフは、「反動的」どころか「保守的」な感性さえ持ち合わせていなかったと主張する現代人もいる。ロシア人の生活のあらゆる面に浸透している時代錯誤

は、彼の基本的なテーマのひとつとなった。ロシアにおける資本主義の発展に最大の危機を見出したドストエフスキーとは異なり、レスコフは「ロシアの『古い

やり方』の不動性を最大の負債と考えた」と評論家のヴィドゥエツカヤは主張する。レスコフの「革命家」に対する態度は、決して全面的に否定的なものではな

かった。 |

| In 1891, after Mikhail

Protopopov's article "The Sick Talent" was published, Leskov responded

with a letter of gratitude, pointing out: "You've judged me better than

those who wrote of me in the past. Yet historical context should be

taken into account too. Class prejudices and false piety, religious

stereotypes, nationalistic narrow-mindedness, what with having to

defend the state with its glory... I grew up amidst all of this, and I

was sometimes abhorred by it all... still I couldn't see the [true

Christianity's guiding] light."[7][47] |

1891年、ミハイル・プロトポポフの論文「病気の才能」が発表された

後、レスコフは感謝の手紙を出して、次のように指摘した。「あなたは、過去に私のことを書いた人たちよりも、私のことをよく判断してくれました。しかし、

歴史的な背景も考慮しなければならない。階級的偏見や偽りの信心深さ、宗教的固定観念、民族的偏狭さ、栄光ある国家を守らなければならないこ

と......。私はこうしたものの中で育ち、時にはそのすべてに忌み嫌われた......それでも私は(真のキリスト教の)指針を見ることができなかっ

たのです」[7][47]と述べている。 |

| Like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky,

Leskov saw the Gospel as the moral codex for humanity, the guiding

light of its development and an ideological basis for any progress. His

"saintly" gallery of characters propagated the same idea of

"multiplying what was good all over the land."[1] On the other hand,

the author often used religious plots to highlight contemporary

problems, often in the most frivolous manner. Some of his stories,

Christian on the face of it, were, according to Viduetskaya, "pagan in

spirit, especially next to the ascetic Tolstoy's prose of the similar

kind." Intrigued by the Raskol movement with its history and current

trends, Leskov never agreed with those of his collaugues (Afanasy

Shchapov among them) who saw Raskol communities as a potentially

revolutionary force and shared the views of Melnikov-Pechersky

concerning Old Believers.[1] |

トルストイやドストエフスキーと同様に、レスコフは福音書を人類の道徳

的規範、発展の指針、あらゆる進歩のための思想的基礎とみなした。彼の「聖人君子」のような登場人物たちは、「善いものを国中に増殖させる」という同じ考

えを宣伝した[1]。その一方で、作者はしばしば宗教的なプロットを使って、最も軽薄な方法で現代の問題を強調することもあった。ヴィドゥーツカヤによれ

ば、彼の物語のいくつかは、一見キリスト教的だが、「精神的には異教徒であり、特に禁欲的なトルストイの同種の散文に比べれば」である。レスコフは、その

歴史と現在の傾向を持つラスコー運動に興味を持ったが、ラスコー共同体を潜在的な革命勢力と見なし、旧信者に関するメルニコフ=ペチェルスキーの見解を共

有する彼の仲間たち(その中のアファナシー・シャポフ)には賛成しなかった[1]。 |

| In his latter years Leskov came

under the influence of Leo Tolstoy, developing the concept of "new

Christianity" he himself identified with the latter. "I am in total

harmony with him, and there's not a single person in the whole world

who's more dear to me. Things I don't share with him never bother me;

what I cherish is the general state of his soul, as it were, and his

mind's frightful insightfulness," Leskov wrote in another letter, to

Vladimir Chertkov.[48] As D.S. Mirsky[who?] pointed out, Leskov's Christianity, like that of Tolstoy, was "anti-clerical, undenominational and purely ethical." But there, the critic argued, the similarities ended. "The dominant ethical note is different. It is the cult not of moral purity and of reason, but of humility and charity. "Spiritual pride", self-conscious righteousness is for Leskov the greatest of crimes. Active charity is for him the principal virtue, and he attaches very little value to moral purity, still less to physical purity... [The] feeling of sin as the necessary soil for sanctity and the condemnation of self-righteous pride as a sin against the Holy Ghost is intimately akin to the moral sense of the Russian people and of the Eastern church, and very different from Tolstoy's proud Protestant and Luciferian ideas of perfection", Mirsky wrote.[2] |

晩年はトルストイの影響を受け、「新キリスト教」の概念を展開し、彼自

身もトルストイと同一視していた。「私は彼と完全に調和しており、私にとってこれほど大切な人はこの世に一人もいない。私が大切にしているのは、いわば彼

の魂の一般的な状態と、彼の心の恐ろしいほどの洞察力です」とレスコフはウラジーミル・チェルトコフ宛ての別の手紙に書いている[48]。 D.S.ミルスキー[誰?]が指摘するように、レスコフのキリスト教は、トルストイのそれと同様に、"反教会的、無教派的、純粋に倫理的 "なものであった。しかし、この批評家は、類似点はそこで終わっていると主張した。「支配的な倫理観が違うのだ。道徳的な純粋さや理性ではなく、謙虚さと 慈愛を崇拝しているのだ。レスコフにとって、「精神的な高慢さ」「自意識過剰な正義感」は最大の罪である。積極的な慈愛は彼にとって主要な美徳であり、道 徳的な純粋さにはほとんど価値を置かず、肉体的な純粋さはなおさらである......。[罪が聖なるものに必要な土壌であるという感覚と、独善的なプライ ドを聖霊に対する罪として非難することは、ロシアの人々や東方教会の道徳感覚と密接に関連しており、トルストイのプロテスタントやルシファー派の高慢な完 全性の考え方とは全く異なっている」とミルスキーは書いている[2]。 |

| Style and form Not long before his death, Leskov reportedly said: "Now they read me just for the intricacies of my stories, but in fifty years' time the beauty of it all will fade and only the ideas my books contain will retain value." That, according to Mirsky, was an exceptionally ill-judged forecast. "Now more than ever Leskov is being read and praised for his inimitable form, style and manner of speech," the critic wrote in 1926.[23] Many critics and colleagues of Leskov wrote about his innovative style and experiments in form. Anton Chekhov called him and Turgenev his two "tutors in literature."[7] |

スタイルとフォーム レスコフは死の直前、次のように語ったという。「今は物語の複雑さだけで読まれているが、50年後にはその美しさは消え去り、私の本に含まれる考えだけが 価値を持つようになるだろう」。ミルスキーに言わせれば、これは極めて不見識な予測であった。「レスコフの多くの批評家や同僚は、彼の革新的な文体や形式 上の実験について書いている。アントン・チェーホフは彼とツルゲーネフの2人を「文学の家庭教師」と呼んだ[7]。 |

| According to Bukhstab, it was

Leskov whose works Chekhov used as a template for mastering his

technique of constructing short stories, marveling at their density and

concentration, but also at their author's ability to make a reader

share his views without imposing them, using subtle irony as an

instrument. Tellingly, Leskov was the first of the major Russian

authors to notice Chekhov's debut and predict his future rise.[49] Leo

Tolstoy (while still expressing reservations as to the "overabundance

of colours") called Leskov "a writer for the future."[15][50] |

ブフスターブによれば、チェーホフはレスコフの作品を雛形として、短編

小説の構成技術を習得し、その密度と集中力に驚嘆するとともに、微妙な皮肉を道具として、自分の意見を押しつけることなく読者に共感させる作者の能力に感

嘆したという。レオ・トルストイは、(「色彩の過多」に関してまだ留保を表明しつつも)レスコフを「未来の作家」と呼んだ[15][50]。 |

| Maxim Gorky was another great

admirer of Leskov's prose, seeing him as one of the few figures in 19th

century Russian literature who had both ideas of their own and the

courage to speak them out loud. Gorky linked Leskov to the elite of

Russian literary thinkers (Dostoyevsky, Pisemsky, Goncharov and

Turgenev) who "formed more or less firm and distinct views on the

history of Russia and developed their own way of working within its

culture."[51] 20th century critics credited Leskov with being an

innovator who used the art of wording in a totally new and different

manner, increasing the functional scope of phrasing, making it a

precision instrument for drawing the nuances of human character.

According to Gorky, unlike Tolstoy, Gogol, Turgenev or Goncharov who

created "portraits set in landscapes," Leskov painted his backgrounds

unobtrusively by "simply telling his stories," being a true master of

"weaving a nervous fabric of lively Russian common talk," and "in this

art had no equals."[52] |

マクシム・ゴーリキーもレスコフの散文を高く評価しており、19世紀の

ロシア文学において、独自の思想とそれを声高に語る勇気を併せ持った数少ない人物の一人だと考えている。ゴーリキーはレスコフを「ロシアの歴史について多

かれ少なかれ確固とした明確な見解を形成し、その文化の中で独自の活動方法を展開した」ロシア文学思想家のエリートたち(ドストエフスキー、ピセムス

キー、ゴンチャロフ、ツルゲーネフ)と結びつけた[51]。20世紀の評論家は、レスコフが全く新しい、異なる方法で表現技術を用いた革新者で、言い回し