クラウゼヴィッツ『戦争論』

On War, Vom Kriege, 1816-1830

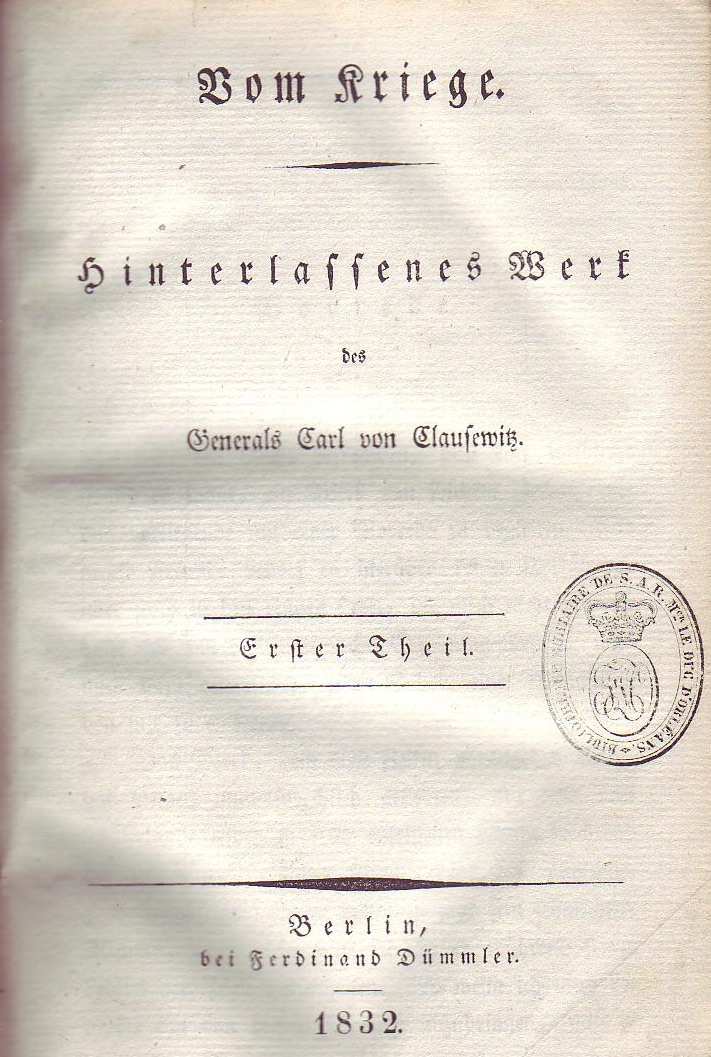

Carl

von Clausewitz, while in Prussian service, painted by Wilhelm Wach in

early 1830s./ Title page of the original German edition Vom Kriege,

published in 1832./ Marie von Clausewitz (née, Countess von Brühl)

☆ 『戦争論(ヴォム・クリーゲ)』(ドイツ語発音: [fɔm ˈkʁˈə])は、プロイセンの将軍カール・フォン・クラウゼヴィッツ(1780-1831)による戦争と軍事戦略に関する書物であり、主にナポレオン戦 争後の1816年から1830年の間に書かれ、1832年に妻のマリー・フォン・ブリュールによって死後に出版された。 政治的・軍事的分析と戦略に関する最も重要な論考のひとつであり、論争的であると同時に戦略的思考に影響を与え続けている。Vom KriegeはOn Warとして何度か英訳されている。『戦争論』は未完の作品である。クラウゼヴィッツは1827年に溜め込んだ原稿の改訂に着手したが、その作業を終える まで生きられなかった。彼の妻が彼の著作集を編集し、1832年から1835年にかけて出版した。 10巻からなる彼の著作集には、プロイセン国家における重要な政治的、軍事的、知的、文化的指導者たちとの膨大な往復書簡や短い論文こそ収録されていない ものの、彼の大規模な歴史的、理論的著作のほとんどが収められている。『戦争論(あるいは戦争について)』は最初の3巻で構成され、彼の理論的探求を表し ている。

| Vom Kriege (German

pronunciation: [fɔm ˈkʁiːɡə]) is a book on war and military strategy by

Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), written mostly after

the Napoleonic wars, between 1816 and 1830, and published posthumously

by his wife Marie von Brühl in 1832.[1] It is one of the most important

treatises on political-military analysis and strategy ever written, and

remains both controversial and influential on strategic thinking.[1][2] Vom Kriege has been translated into English several times as On War. On War is an unfinished work. Clausewitz had set about revising his accumulated manuscripts in 1827, but did not live to finish the task. His wife edited his collected works and published them between 1832 and 1835.[3] His ten-volume collected works contain most of his larger historical and theoretical writings, though not his shorter articles and papers or his extensive correspondence with important political, military, intellectual and cultural leaders in the Prussian state. On War is formed by the first three volumes and represents his theoretical explorations. |

『戦争論(ヴォム・クリーゲ)』(ドイツ語発音: [fɔm

ˈkʁˈə])は、プロイセンの将軍カール・フォン・クラウゼヴィッツ(1780-1831)による戦争と軍事戦略に関する書物であり、主にナポレオン戦

争後の1816年から1830年の間に書かれ、1832年に妻のマリー・フォン・ブリュールによって死後に出版された。

[1]政治的・軍事的分析と戦略に関する最も重要な論考のひとつであり、論争的であると同時に戦略的思考に影響を与え続けている[1][2]。 Vom KriegeはOn Warとして何度か英訳されている。『戦争論』は未完の作品である。クラウゼヴィッツは1827年に溜め込んだ原稿の改訂に着手したが、その作業を終える まで生きられなかった。彼の妻が彼の著作集を編集し、1832年から1835年にかけて出版した[3]。 10巻からなる彼の著作集には、プロイセン国家における重要な政治的、軍事的、知的、文化的指導者たちとの膨大な往復書簡や短い論文こそ収録されていない ものの、彼の大規模な歴史的、理論的著作のほとんどが収められている。『戦争について』は最初の3巻で構成され、彼の理論的探求を表している。 |

| History Clausewitz was among those intrigued by the manner in which the leaders of the French Revolution, especially Napoleon, changed the conduct of war through their ability to motivate the populace and gain access to the full resources of the state, thus unleashing war on a greater scale than had previously been seen in Europe. Clausewitz believed that moral forces in battle had a significant influence on its outcome. Clausewitz was well-educated and had strong interests in art, history, science, and education. He was a professional soldier who spent a considerable part of his life fighting against Napoleon. In his lifetime, he had experienced both the French Revolutionary Army's (1792—1802) zeal and the conscripted armies employed by the French crown. The insights he gained from his political and military experiences, combined with a solid grasp of European history, provided the basis for his work.[1][3][4] A wealth of historical examples is used to illustrate its various ideas. Napoleon and Frederick the Great figure prominently for having made very efficient use of the terrain, movement and the forces at their disposal. |

歴史 クラウゼヴィッツは、フランス革命の指導者たち、特にナポレオンが、民衆の意欲をかき立て、国家の全資源を利用する能力によって戦争遂行を変え、ヨーロッ パでそれまで見られなかったような大規模な戦争を引き起こしたことに興味を抱いた一人であった。クラウゼヴィッツは、戦闘における道徳的な力がその結果に 大きな影響を及ぼすと考えていた。クラウゼヴィッツは教養があり、芸術、歴史、科学、教育に強い関心を持っていた。彼は職業軍人であり、人生のかなりの部 分をナポレオンとの戦いに費やした。生前、彼はフランス革命軍(1792~1802年)の熱狂とフランス王室が採用した徴兵制の両方を経験している。その 政治的、軍事的経験から得た洞察と、ヨーロッパ史の確かな把握が、彼の著作の基礎となった[1][3][4]。 その様々なアイデアを説明するために、豊富な歴史的事例が用いられている。ナポレオンとフリードリヒ大王は、地形、移動、そして自由に使える戦力を非常に 効率的に利用したことで突出している。 |

Clausewitz's theory An operational map for Napoleon's military expedition to Italy, 1796. Map from Clausewitz: Vom Kriege, 1857. Definition of war Clausewitz argued that war theory cannot be a strict operational advice for generals.[5] Instead, he wanted to highlight general principles that would result from the study of history and logical thinking. He contended that military campaigns could be planned only to a very small degree because incalculable influences or events, so-called friction, would quickly make any too-detailed planning in advance obsolete. Military leaders must be capable to make decisions under time pressure with incomplete information since in his opinion "three quarters of the things on which action is built in war" are concealed and distorted by the fog of war.[6] In his 1812 Bekenntnisschrift ("Notes of Confession"), he presents a more existential interpretation of war by envisioning war as the highest form of self-assertion by a people. That corresponded in every respect with the spirit of the time when the French Revolution and the conflicts that arose from it had caused the evolution of conscript armies and guerrillas. The people's armies supported the idea that war is an existential struggle.[7][8] During the following years, however, Clausewitz gradually abandoned this exalted view and concluded that the war served as a mere instrument: "Thus, war is an act of violence in order to force our will upon the enemy."[9] Purpose, goal and means Clausewitz analyzed the conflicts of his time along the line of the categories Purpose, Goal and Means. He reasoned that the Purpose of war is one's will to be enforced, which is determined by politics. The Goal of the conflict is therefore to defeat the opponent in order to exact the Purpose. The Goal is pursued with the help of a strategy, that might be brought about by various Means such as by the defeat or the elimination of opposing armed forces or by non-military Means (such as propaganda, economic sanctions and political isolation). Thus, any resource of the human body and mind and all the moral and physical powers of a state might serve as Means to achieve the set goal.[10] One of Clausewitz's best-known quotes summarizes that idea: "War is the continuation of policy with other means."[9] That quote in itself allows for the interpretation that the military will take over from politics as soon as war has begun, as, for example, the German General Staff did during World War I. However, Clausewitz had postulated the primacy of politics and in this context elaborated: "[...], we claim that war is nothing more than a continuation of the political process by applying other means. By applying other means we simultaneously assert that the political process does not end with the conclusion of the war or is being transformed into something entirely different, but that it continues to exist and proceed in its essence, regardless of the means, it might make use of."[11] According to Azar Gat, the "general message" of the book was that "the conduct of war could not be reduced to universal principles [and is] dominated by political decisions and moral forces."[12][13] These basic conclusions are essential to Clausewitz's theory: War must never be seen as having any purpose in itself but should be seen as a political instrument: "War is not merely a political act, but a real political instrument, a continuation of the political process, an application by other means."[14] The military objectives in war that support one's political objectives fall into two broad types: "war to achieve limited aims" and war to "disarm" the enemy: "to render [him] politically helpless or militarily impotent." All else being equal, the course of war will tend to favor the party with the stronger emotional and political motivations, especially the defender.[1] Some of the key ideas (not necessarily original to Clausewitz or even to his mentor, Gerhard von Scharnhorst) discussed in On War include[15] (in no particular order of importance): the dialectical approach to military analysis the methods of "critical analysis" the uses and abuses of historical studies the nature of the balance-of-power mechanism the relationship between political objectives and military objectives in war the asymmetrical relationship between attack and defense the nature of "military genius" the "fascinating trinity" (Wunderliche Dreifaltigkeit) of war philosophical distinctions between "absolute or ideal war," and "real war" in "real war," the distinctive poles of a) limited war and b) war to "render the enemy helpless" "war" belongs fundamentally to the social realm, rather than the realms of art or science "strategy" belongs primarily to the realm of art "tactics" belongs primarily to the realm of science the essential unpredictability of war simplicity: Everything is very simple in war, but the simplest thing is difficult. These difficulties accumulate.[16] The strength of any strategy lies in its simplicity.[17] the "fog of war" "friction" strategic and operational "centres of gravity" the "culminating point of the offensive" the "culminating point of victory" Clausewitz used a dialectical method to construct his argument, which led to frequent modern misinterpretation because he explores various often-opposed ideas before he came to conclusions. Modern perceptions of war are based on the concepts that Clausewitz put forth in On War, but they have been diversely interpreted by various leaders (such as Moltke, Vladimir Lenin, Dwight Eisenhower, and Mao Zedong), thinkers, armies, and peoples. Modern military doctrine, organization, and norms are all still based on Napoleonic premises, but whether the premises are necessarily also "Clausewitzian" is debatable.[18] The "dualism" of Clausewitz's view of war (that wars can vary a great deal between the two "poles" that he proposed, based on the political objectives of the opposing sides and the context) seems to be simple enough, but few commentators have been willing to accept that crucial variability[citation needed]. They insist that Clausewitz "really" argued for one end of the scale or the other. On War has been seen by some prominent critics as an argument for "total war".[a] It has been blamed for the level of destruction involved in the First and the Second World Wars, but it seems rather that Clausewitz, who did not actually use the term "total war", had merely foreseen the inevitable development that started with the huge, patriotically motivated armies of the Napoleonic wars[citation needed]. They resulted (though the evolution of war has not yet ended) in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with all the forces and capabilities of the state devoted to destroying forces and capabilities of the enemy state (thus "total war"). Conversely, Clausewitz has also been seen as "The preeminent military and political strategist of limited war in modern times".[19] Clausewitz and his proponents have been severely criticized by other military theorists, like Antoine-Henri Jomini[20] in the 19th century, B. H. Liddell Hart[21] in the mid-20th century, and Martin van Creveld[22] and John Keegan[23] more recently.[24] On War is a work rooted solely in the world of the nation state, states historian Martin van Creveld, who alleges that Clausewitz takes the state "almost for granted", as he rarely looks at anything before the Peace of Westphalia, and mediaeval warfare is effectively ignored in Clausewitz's theory.[22] He alleges that Clausewitz does not address any form of intra/supra-state conflict, such as rebellion and revolution, because he could not theoretically account for warfare before the existence of the state.[25] Previous kinds of conflict were demoted to criminal activities without legitimacy and not worthy of the label "war". Van Creveld argues that "Clausewitzian war" requires the state to act in conjunction with the people and the army, the state becoming a massive engine built to exert military force against an identical opponent. He supports that statement by pointing to the conventional armies in existence throughout the 20th century. However, revolutionaries like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels derived some inspiration from Clausewitzian ideas.[25] |

クラウゼヴィッツの理論 1796年、ナポレオンのイタリア遠征の作戦地図。クラウゼヴィッツの地図: Vom Kriege, 1857. 戦争の定義 クラウゼヴィッツは、戦争論は将軍に対する厳密な作戦上の助言にはなり得ないと主張した[5]。 その代わりに、彼は歴史の研究と論理的思考から生じる一般原則を強調したかったのである。クラウゼヴィッツは、軍事作戦はごく小規模にしか計画できないと 主張した。なぜなら、計り知れない影響や出来事、いわゆる摩擦は、事前にあまりに詳細な計画を立ててもすぐに陳腐化してしまうからである。彼の意見によれ ば、「戦争において行動の基礎となる事柄の4分の3」は戦争の霧によって隠され、歪曲されるため、軍事指導者は不完全な情報のもとで時間的なプレッシャー のもとで意思決定を行う能力がなければならない[6]。 1812年の『告白ノート』(Bekenntnisschrift)では、戦争は民族による自己主張の最高の形であるとすることで、戦争のより実存的な解 釈を示している。それは、フランス革命とそこから生じた紛争が徴兵軍やゲリラの進化をもたらした当時の精神とあらゆる点で一致している。人民軍は、戦争は 実存的な闘いであるという考えを支持した[7][8]。 しかし、その後の数年間で、クラウゼヴィッツはこの高尚な見解を徐々に放棄し、戦争は単なる道具としての役割を果たすと結論づけた: 「このように、戦争とは敵に我々の意志を強制するための暴力行為である」[9]。 目的、目標、手段 クラウゼヴィッツは当時の紛争を目的、目標、手段というカテゴリーに沿って分析した。クラウゼヴィッツは、戦争の目的とは、政治によって決定される自分の 意志を強制することであるとした。したがって、紛争の目的は、目的を達成するために相手を打ち負かすことである。目的は戦略の助けを借りて追求されるが、 それは、相手の軍隊の敗北や排除、あるいは非軍事的手段(プロパガンダ、経済制裁、政治的孤立など)など、さまざまな手段によってもたらされる。したがっ て、人間の肉体や精神、国家の道徳的・物理的な力のあらゆる資源が、設定された目標を達成するための手段として機能する可能性がある[10]。 クラウゼヴィッツの最もよく知られた名言の一つは、この考えを要約したものである。 しかし、クラウゼヴィッツは政治の優位性を仮定しており、その文脈で次のように述べている: 「戦争とは、政治的プロセスを他の手段で継続することにほかならない。他の手段を適用することによって、我々は同時に、政治的プロセスが戦争の終結によっ て終わるのでもなく、全く異なるものに変容されるのでもなく、その本質において、どのような手段を用いようとも、存在し続け、進行し続けることを主張す る」[11]。 アザール・ガットによれば、この本の「一般的なメッセージ」は、「戦争の遂行は普遍的な原則に還元することはできず、政治的な決定と道徳的な力によって支配される」[12][13]というものであった: 戦争は、それ自体に何らかの目的があると見なしてはならず、政治的道具として見なすべきである: 「戦争は単なる政治的行為ではなく、真の政治的手段であり、政治的プロセスの継続であり、他の手段による応用である」[14]。 政治的目的を支援する戦争における軍事的目的は、大きく2つのタイプに分類される: 「限定された目的を達成するための戦争」と、敵を「武装解除」するための戦争である。 他の条件がすべて同じであれば、戦争の行方は感情的・政治的動機の強い側、特に防衛側に有利になる傾向がある[1]。 クラウゼヴィッツやその師であるゲルハルト・フォン・シャルンホルストのオリジナルであるとは限らないが、『戦争論』で論じられている重要な考え方には以下のようなものがある[15](重要度の高い順ではない): 軍事分析への弁証法的アプローチ 批判的分析」の方法 歴史研究の利用と悪用 勢力均衡メカニズムの本質 戦争における政治的目的と軍事的目的の関係 攻撃と防衛の非対称的関係 軍事的天才」の本質 戦争の「魅力的な三位一体」(Wunderliche Dreifaltigkeit) 絶対戦争または理想戦争」と「現実の戦争」の哲学的区別 現実の戦争」においては、a) 限定戦争と b) 「敵を無力化」するための戦争という特徴的な両極がある。 「戦争」は、芸術や科学の領域ではなく、基本的に社会的領域に属する。 「戦略」は主として芸術の領域に属する。 「戦術」は主に科学の領域に属する。 戦争の本質的な予測不可能性 単純さ: 戦争ではすべてが非常に単純だが、最も単純なことが難しい。このような困難が積み重なっていくのである[16]。あらゆる戦略の強みは、その単純さにある[17]。 戦争の霧 「摩擦」 戦略上および作戦上の 「重心」 「攻勢の頂点」 勝利の頂点 クラウゼヴィッツは弁証法的な方法を用いて議論を組み立てたが、結論に至るまでにしばしば対立するさまざまな考えを探求したため、現代ではしばしば誤った解釈がなされるようになった。 現代の戦争認識は、クラウゼヴィッツが『戦争論』で提示した概念に基づいているが、さまざまな指導者(モルトケ、ウラジーミル・レーニン、ドワイト・アイ ゼンハワー、毛沢東など)、思想家、軍隊、民族によって多様に解釈されてきた。現代の軍事ドクトリン、組織、規範はすべて依然としてナポレオン的な前提に 基づいているが、その前提が必ずしも「クラウゼヴィッツ的」であるかどうかは議論の余地がある[18]。 クラウゼヴィッツの戦争観の「二元論」(戦争は対立する側の政治的目的と文脈に基づいて、クラウゼヴィッツが提唱した2つの「極」の間で大きく変化しうる ということ)は単純なことのように思えるが、その決定的な変動性を受け入れようとする論者はほとんどいない[要出典]。彼らは、クラウゼヴィッツが「本当 に」どちらか一方を主張していたと主張する。戦争論』は、著名な批評家の中には「総力戦」を主張するものと見なす者もいる[a]。 第一次世界大戦と第二次世界大戦における破壊のレベルについて非難されているが、実際には「総力戦」という言葉を使わなかったクラウゼヴィッツはむしろ、 ナポレオン戦争[要出典]における愛国心に突き動かされた巨大な軍隊から始まった必然的な発展を予見していたに過ぎないように思われる。その結果(戦争の 進化はまだ終わっていないが)、広島と長崎への原爆投下が実現し、国家のあらゆる力と能力が敵国家の力と能力を破壊することに捧げられた(したがって「総 力戦」)。逆に、クラウゼヴィッツは「近代における限定戦争の卓越した軍事的・政治的戦略家」ともみなされている[19]。 クラウゼヴィッツとその支持者は、19世紀にはアントワーヌ=アンリ・ジョミニ[20]、20世紀半ばにはB・H・リデル・ハート[21]、最近ではマー ティン・ヴァン・クレーヴェルド[22]やジョン・キーガン[23]のような他の軍事理論家によって厳しく批判されてきた。 [クラウゼヴィッツが反乱や革命のような国家内/超国家間の紛争を扱っていないのは、国家が存在する以前の戦争を理論的に説明することができなかったから である[25]。 それ以前の紛争は「戦争」というレッテルを貼るに値しない正当性のない犯罪行為に降格された。ヴァン・クレーベルトは、「クラウゼヴィッツ的戦争」には国 家が国民や軍隊と連携して行動することが必要であり、国家は同一の相手に対して軍事力を行使するために構築された巨大なエンジンになると主張する。彼は、 20世紀を通じて存在した従来の軍隊を指摘することで、その主張を支持している。しかし、カール・マルクスやフリードリヒ・エンゲルスのような革命家たち は、クラウゼヴィッツの思想からいくらかのインスピレーションを得ていた[25]。 |

| English translations 1873. Graham, J.J. translator. Republished 1908 with extensive commentary and notes by Victorian imperialist F.N. Maude.[26] 1943. O. J. Matthijs Jolles, translator (New York: Random House, 1943). This is viewed by some modern scholars[who?] as the most accurate existing English translation. 1968. Edited with introduction by Anatol Rapoport. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044427-0. 1976/1984. Michael Howard and Peter Paret, editors and translators. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05657-9. 1989. Michael Howard and Peter Paret, editors and translators. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01854-6. |

英語訳 1873年。J.J. グラハム訳。1908年に、ビクトリア朝の帝国主義者 F.N. モードによる広範な解説と注釈を加えて再出版された。[26] 1943年。O. J. Matthijs Jolles 訳(ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス、1943年)。一部の現代学者[誰?] は、これを現存する最も正確な英語訳と評価している。 1968年。Anatol Rapoport による序文付き編集版。Viking Penguin。ISBN 0-14-044427-0。 1976/1984年。マイケル・ハワードとピーター・パレット、編集者および翻訳者。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 0-691-05657-9。 1989年。マイケル・ハワードとピーター・パレット、編集者および翻訳者。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-01854-6。 |

| Concepts List of military theorists Philosophy of war Realpolitik Books Achtung - Panzer! by Heinz Guderian Anabasis and Hellenica by Xenophon The Art of War by Niccolò Machiavelli Commentarii de Bello Gallico by Gaius Julius Caesar Epitoma rei militaris by Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus Infanterie Greift An by Erwin Rommel Mes Rêveries by Maurice de Saxel Storm of Steel by Ernst Jünger Strategikon of Maurice by Byzantine Emperor Maurice Tactica of Emperor Leo VI the Wise Truppenführung by Helmuth von Moltke the Elder The Utility of Force by General Sir Rupert Smith The Influence of Sea Power upon History by Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan |

概念 軍事理論家のリスト 戦争哲学 現実政治 著書 ハインツ・グデーリアン著『アハトゥング・パンツァー!』 クセノフォン著『アナバシス』と『ヘレニカ』 ニコロ・マキアヴェッリ著『戦争術』 ガイアス・ユリウス・カエサル著『ベロ・ガリコ注解』 『エピトマ・レイ・ミリタリス 』by プブリウス・フラウィウス・ヴェゲティウス・レナトゥス エルヴィン・ロンメル著『インファンテリー・グライフト・アン』 モーリス・ド・ザクセルの「私の夢 鋼鉄の嵐 by エルンスト・ユンガー ビザンツ皇帝モーリスのストラテジコン 賢帝レオ6世のタクティカ ヘルムート・フォン・モルトケ長老の『戦線離脱』 ルパート・スミス将軍著『武力の効用』 アルフレッド・セイヤー・マハン提督著『シーパワーの歴史への影響力』 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_War | |

| 本

書が執筆された時期は主にナポレオン戦争終結後の1816年から1830年にかけてであり、クラウゼヴィッツが陸軍大学校の学校長として勤務している時期

に大部分が書かれた。1827年に原稿に大規模な修正を加えて整理しているが、未完成のまま死去したことから妻のマリー・フォン・ブリュール(ドイツ語

版、英語版)が遺稿と断片的なまま残されていた最終的な2つの章を編集した。マリーが出版した遺稿集としての『戦争論』全十巻は[1]、第2版から第15

版までマリーの兄ブリュールが内容を改ざんしている[2]。第16版以降、ハールヴェークが初版に依拠し直したものとなっている。 戦争論の内容は8篇から構成されている: 第1篇「戦争の本質について」 - 戦争の本性、理論の戦争と現実の戦争の相違、戦争の目的と手段などを論じる 第2編「戦争の理論について」 - 軍事学のあり方やその方法論を論じる 第3編「戦略一般について」 - 戦略を定義し、従来の時間・空間・戦力の戦闘の基本的な三要素だけではなく、精神的要素を考察の対象として分析する 第4編「戦闘」 - 戦闘の一般的性質や勝敗の決定について物質的側面と精神的側面から分析する 第5編「戦闘力」 - 戦闘力の構成や環境との一般的関係を論じる 第6編「防御」 - 防御の戦術的性格や種類、戦略的な位置づけを論じる 第7編「攻撃」 - 攻撃の戦術的性格、勝利の極限点を論じる 第8編「作戦計画」- 理論の戦争と現実の戦争の関係を述べた上で、戦争計画の要点を論じる 戦争 戦争がどのような本質を持つのかを明らかにするためには戦争の多様な在り方を説明できるような理論が必要である。そこでまず戦争における暴力性に着目する ところからクラウゼヴィッツは議論を始める。そもそも戦争の内在的な本質とは単純化すれば敵対する二者による決闘の性質がある。そこで「戦争とは、敵を強 制してわれわれの意志を遂行させるために用いられる暴力行為である」として戦争を単純に捉えた場合、戦争の本質は暴力の行使であり、またその目標は敵の戦 闘力の粉砕にあるということが分かる。戦争におけるこのような暴力の行使には 敵に敵対的感情を抱く相互作用 敵の戦闘力を粉砕しようとする相互作用 敵の戦闘力に応じた我の戦闘力を準備しようとする相互作用 の3つの相互作用が認められる。これらの相互作用によって戦争における暴力の行使は原理的に拡大しようとする。 しかしながら、現実世界のあらゆる戦争において暴力が極限的に行使されていると考えることはできない。クラウゼヴィッツはここで暴力性ではなく戦争におけ る政治性に着眼点を移す。つまり戦争は孤立的行為ではなく、また一度の決戦で成立することも、戦争の戦果が絶対的なものではないと考える。ここで改めて戦 争における政治的目的が見直されることになる。そもそも敵に対して要求する犠牲を小さくすれば、敵の抵抗は小さくなり、したがって我が支出すべき努力も小 さくなる。政治的目的が戦争において支配的であるために軍事行動はその暴力の極限性を弱化させ、皆殺しの戦争からにらみ合い状態までさまざまな種類の激し さを伴う戦争が生じることになる。 さらに戦争における政治の蓋然性の法則と暴力の極限性の法則を以って戦争の多様な形態を説明できたとしても、これだけではまだ説明することができない事態 がありうることをクラウゼヴィッツは指摘する。それは戦争においてしばしば生じる軍事行動の停止という事態である。そもそも戦争における両軍の将軍の利害 は完全に対立するものとして考えられるが、これは戦場における両極性と考えることができる。言い換えれば戦闘は片方が勝利すればもう片方が原理的に敗北す ることになるという一般的な性質が存在する。 しかし戦場における両極性は一つではない。これは軍事行動の攻撃と防御がそれぞれに両極性を持つことによるものである。つまり攻撃を行うことを決心しよう とするならば、防御の利益を超える攻撃の利益が約束されなければならないということである。軍事行動の停止はこの攻撃と防御の損得の相違による二種類の両 極性の法則の結果である[3]。 クラウゼヴィッツは戦争をカメレオンに例えてその規模・形態・情勢が変動していくものと考えた。そしてその戦争の全体を支配している諸傾向を概観すると、 主に国民による憎悪や暴力性をもたらす傾向 主に軍隊による自由な精神活動としての傾向 主に政府による従属的傾向 の3つから三位一体が成り立っているとまとめている。この三位一体の各要素はそれぞれに固有の役割を持っており、これらの主体や相互の関係を無視して現実の戦争を見ることは不可能であると論じている。 戦略 クラウゼヴィッツにとって戦略とは戦争目的のために戦闘を使用する教義であり、戦略の対象となるものは戦闘である。戦略においてまず全ての軍事行動にその 目的に合致した目標を設定する必要がある。そして戦略に従って戦争計画を立案し、個々の戦役に対する見通しを以って個々の戦闘を位置づける。戦略における 問題は科学的な形式や課題を発見することではなく、そこに作用している精神的な諸力を把握することである。 戦略においてあらゆるものごとが単純であることと、その実践が容易であるとは限らない。達成すべき目標を設定したとしても無数の要因によって方針を転換す ることなく、計画を完遂するためには自信と知性が必要である。戦略においては戦術と異なってあらゆることが緩やかに進行するためその状況判断は推測に依存 せざるをえず、したがって決断不能な状況に陥りやすい。 戦略において考察される諸要素は以下の5点に集約できる。 精神的要素 - 戦闘における将軍の才能、武徳、国民精神などの精神的特性とその作用を含む、 物理的要素 - 戦闘力の量的な大小や質的な組成を含む 数学的要素 - 作戦線の角度、空間や時間における兵力集中や節約に関する 地理的要素 - 制高地点・山岳・河川・森林・道路など 統計的要素 - 兵站や休養を含む これら諸要素は相互に連関したものである。 戦闘 戦闘とはクラウゼヴィッツによれば本来の軍事行動によって遂行される闘争であり、これは敵の撃滅や征服を目的とするものである。したがって戦闘における敵 とは我に対抗する相手の戦闘力である。戦争の目的は諸々の戦闘によって構成されており、それぞれの戦闘は特殊な目標を持ちながら戦争全体と結合している。 したがってあらゆる戦略的な行動は戦闘と密接な関係を持っている。 戦闘の一般的目標とは敵の撃滅であるが、それが敵の死傷によるものであるか、また敵の戦闘意思の放棄によるものかは問わない。とにかく戦闘によって敵の戦 闘力の損耗が我のそれよりも比較的に大であり、また巧妙な部隊の配備によって敵を不利な状況に追い込むことで退却を強いることなどによって勝敗を決定す る。つまり戦闘における勝利の概念とは、敵が物理的諸力において我よりも大きな損失を被っており、精神的諸力についても同様であり、さらに敵が戦闘継続の 意思を放棄することで上記のに条件を承認することによって獲得することができる。 戦闘の一般的な記述だけでなく、多種多様な形態に着目すると戦闘を分類する必要がある。そこでクラウゼヴィッツは防御戦闘と攻撃戦闘に大別する: 防御戦闘 - 敵戦闘力の撃滅、ある地点の防御またはある地点の防御が狙い 攻撃戦闘 - 敵戦闘力の撃滅、ある地点の略取またはある物件の略取が狙い このことから防御の目標は常に消極的なものであり、他の積極的行動を容易にする以外には間接的に有用であるだけである。したがって防御戦闘が頻繁に実施されることは、戦略的情勢の悪化を意味している。 防御と攻撃 防御と攻撃の関係についてクラウゼヴィッツはその行動の受動性と能動性から区分する。防御という戦闘行動とは敵の進撃の撃退であり、攻撃は逆に敵を積極的 に求める戦闘方式である。戦争において一方的な防御はありえず、防御と攻撃は彼我の双方向の戦闘行動によって相対化する。ただし防御の目的とは攻撃の奪取 に比較して維持であるため、その実施は容易である。そのためクラウゼヴィッツは防御形式は本来的に攻撃形式よりも有利であると考える[4]。しかし攻撃を 行わなければ敵の戦闘力を打倒するという戦闘の目的は達成することはできない。 つまり攻撃と防御とは交代しながら行われるものである。その理由には攻撃と防御のそれぞれの戦術的性質が異なっているだけでなく、戦闘力の一般的な性質か らも考察できる。戦力の衰弱をもたらす要因としては、決戦後にも継続される戦闘、後方支援の確保、戦闘における損害、根拠地と前線の距離の増大、要塞の攻 囲、労苦の増大、同盟軍の戦線離脱の要因がある。このような要因による戦闘力の総量の消耗は敵の精神的、物質的な戦闘力の損耗によって相対的に解消される ものであり、戦術的勝利はこの戦闘力の均衡において圧倒的な優位があるために獲得されるものである。 しかしながら戦争において勝利者が軍事的努力によって一名残らず殲滅できるとは限らないだけでなく、戦闘力は勝利後も既に述べたさまざまな要素によって次 第に減退していくものである。攻撃を行うことは常に戦闘の目的である敵戦闘力の打破に寄与するものであるが、攻撃によって獲得した戦果は時間の経過ととも に逓減していくものだと理解できる。ここで攻撃によってのみ得られる戦果の限界量を導入することが可能となり、これを攻撃の限界点とクラウゼヴィッツは命 名する。この攻撃の本質的性格を考慮すれば、防御とはこの攻撃の内在的な欠点を補うため、つまり攻撃の限界点においてそれまで獲得してきた戦果を保存する ため、状況に応じて選択される戦闘行動として位置づけることができる。 戦争計画 クラウゼヴィッツは戦争計画の章では戦争の総括的問題を解明し、本来の戦略とその重要事項について論じている。戦争計画は軍事行動のすべてが総合されたも のであり、計画中のさまざまな目標は戦争目的と関係付けられる。戦争は国家の知性である政治家と軍人によって発起され、戦争において、また戦争によって達 成すべき目標を決定する。しかしクラウゼヴィッツの戦争理論によって既に明らかにされたように、戦争には純粋な暴力の相互作用の原理が機能する絶対戦争と 現実的形態として諸々の抑制が加わる現実の戦争がある。つまり戦争は二種類の目的が設定されうるものであり、敵の完全な打倒という戦争目標と敵国の国土の 一部を攻略占領という制限された戦争目標が考えられる。 さらに戦争は政治の道具であり、政治的交渉は戦争においても継続され、また同時に戦争行動は政治的交渉を構成するという見解がクラウゼヴィッツの基本的立 場である。つまり戦争が政治に内部的に従属するため、政治の戦争意思が強大になるに従って戦争は絶対的形態へと移行する。また政治の戦争意思が弱小になる に従って、戦争本来の姿から生じる厳しい結果を避け、遠い将来の成果よりも近くの結果に関心が集中する。戦争に必要な主要計画は全て政治的事情に対する考 察が必要であり、政府と統帥部の意志が統一されなければならない。その方法の一つとして内閣の一員に最高司令官を加えることを挙げている。クラウゼヴィッ ツは、攻勢的戦争、防御的戦争それぞれにおいて重要な点を述べている。 クラウゼヴィッツが提案する戦争計画の原則は二つの原則から成り立っている。それは次のように定式化される。 可能な限り集中的に行動する 可能な限り迅速的に行動する 集中的行動の原則をクラウゼヴィッツは次のように説明する。敵の戦闘力を集中させ、その点に対して我の戦闘力を集中することが必要である。しかし戦闘力の 最初の配置や参戦諸国や交戦地域の地理的環境などによっては分割も可能である。しかし戦闘の勝敗が重要でない地域に戦闘力を分散する場合にはこの原則に従 うことが困難になる場合もある。したがってこの集中の原則は主要な戦闘を必要とする方面に対してのみ攻撃を、その他の方面に対しては防御を実施することが 合理的であると考えられる。さらに迅速の原則において時間の浪費は戦力の消耗であり、また時間の要素は奇襲の条件を構成する。したがって戦争においては常 に敵の完全な打倒を狙いながら前進し続けることだけが望ましいのであり、一度でも停止すると敵に対する有効な攻撃前進を再開することは不可能となる。 https://x.gd/RwGk6 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆