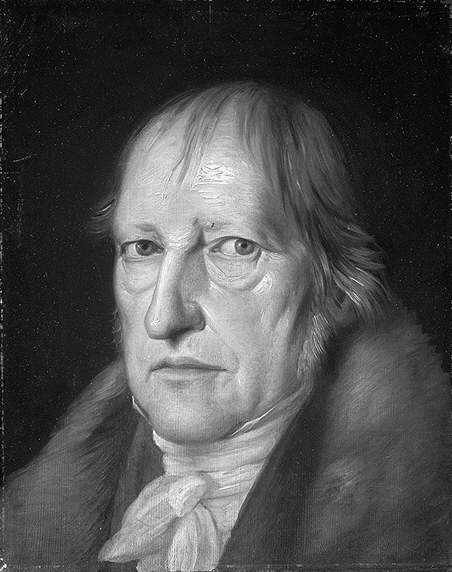

G.W.F.ヘーゲル『法の哲学』1821

Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831

1821 G.W.F. ヘーゲル『法の哲学(綱要)Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts/Elements of the Philosophy of Right』(『法の哲学』)の刊行。

本書『法の哲学』の目的は、複雑な社会を持つ近代国家が、個人の権利や個人の(主観的な)自由といった抽象概念を具体化する手段、すなわち客観的な内容を見出す手段であることを示すことであ

る。こうしてヘーゲルは、国家が具体的自由の実現、すなわち実行のた

めの卓越した場であることを示す1。

この目的のために、『原理』は「客観的精神」の概念を定義している。精神とは、主体(個人として、国家として、国民として、芸術作品における人物像とし

て、宗教において崇拝される神としてなど)を意味し、主体は、それ自体に客観的である複数の対象を統合することによって、その主体性を実現する。このよう

に、所有者は、仮にパルテス・エクストラ・パルテスで構成される土地を所有することによって、自分自身をそのように構成する限りにおいて精神である。精神

は、自分自身(自分の身体、自分の経験、自分の表象など)にのみ関係する個人である限り、主観的である。心が絶対的であるのは、その世界を主権的に支配す

る主体として公に姿を現すときである(たとえば、芸術的、宗教的表象においてそうである)。最後に、精神が客観的であるのは、公的に認知された規範を世界

に課すことによって、世界において自己を実現しようとするときである4。

ヘーゲルにとって、精神は自由、すなわち完全性を志向するものであり、それは精神がいかなる対象においても「くつろげる」ときに達成される。権利哲学の諸

原理』は、精神が自己を世界の中で十分に具現化しようとする努力を示している。しかし、客観的な心のレベルでは、主体と客体との間には解けがたい分裂があ

る。このため、精神は「あるべき姿」の様式、すなわち、侵犯されうる規範と争われうる特権においてのみ具現化される4。

時代背景

ナポレオンの没落(1821年5月5日にセントヘレナ島で死去)。1814-

1815年ウィーン会議。メッテルニヒの反動。産業革命たけなわ(ラッダイト運動

1811-1812年)。

構成

第1部 - 抽象的な権利ないし法、第2部 - 道徳、第3部 - 倫理からなる三部構成。

第1部の抽象法では、1)所有、2)契約、3)不法 が論じられる。

第2部の道徳では、1)故意と責任、2)意図と利 福、3)善と良心が論じられる。

第3部の倫理(人倫)では、1)家族(婚姻、家族の

資産、子供の教育と家族の解体)、2)市民社会(欲求のシステム、司法、行政と職業団体)、3)国家(国内法——君主権、統治権、立法;国際法——世界

史)が論じられる。

++

序文

緒論

第1部 - 抽象的な権利ないし法

第1章 - 自分のものとしての所有

A 占有所得

B 物件の使用

C 自分のものの外化、ないしは所有の放棄

所有から契約への移行

第2章 - 契約

第3章 - 不法

A 無邪気な不法

B 詐欺

C 強制と犯罪

権利ないし法から道徳への移行

第2部 - 道徳

第1章 - 企図と責任

第2章 - 意図と福祉

第3章 - 善と良心

道徳から倫理への移行

第3部 - 倫理

第1章 - 家族

A 婚姻

B 家族の資産

C 子どもの教育と家族の解体

家族から市民社会への移行

第2章 - 市民社会

※ヘーゲルは、市民社会を、家族——(市民社会)

——国家のあいだに位置付け、それを差異性(Differenz)の

段階だと位置付けている。

A 欲求の体系

a 欲求の仕方と満足の仕方

b 労働の仕方

c 資産

B 司法活動

a 法律としての法

b 法律の現存在

c 裁判

C 福祉行政と職業団体

a 福祉行政

b 職業団体

第3章 - 国家

A 国内公法

I. それ自身としての国家体制

a 君主権

b 統治権

c 立法権

II. 対外主権

B 国際公法

C 世界史

++

++

| Elements

of the

Philosophy of Right (German: Grundlinien der Philosophie des

Rechts) is

a work by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel published in 1820,[1] though

the book's original title page dates it to 1821. Hegel's most mature

statement of his legal, moral, social and political philosophy, it is

an expansion upon concepts only briefly dealt with in the Encyclopedia

of the Philosophical Sciences, published in 1817 (and again in 1827 and

1830). Law provides for Hegel the cornerstone of the modern state. As

such, he criticized Karl Ludwig von Haller's The Restoration of the

Science of the State, in which the latter claimed that law was

superficial, because natural law and the "right of the most powerful"

was sufficient. The absence of law characterized for Hegel despotism,

whether absolutist or ochlocracist. |

『法の哲学の諸要素』(ドイツ語: Grundlinien der

Philosophie des Rechts)は、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルが1820年に発表した著作であるが、[1]

書籍のオリジナルのタイトルページでは1821年となっている。ヘーゲルの法、道徳、社会、政治哲学に関する最も成熟した主張であり、1817年に出版さ

れた『哲学の科学の百科事典』(1827年と1830年に再版)で簡単にしか取り上げられなかった概念をさらに発展させたものである。ヘーゲルにとって、

法は近代国家の礎である。そのため、彼はカール・ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ハラーの著書『国家学の復興』を批判した。ハラーは、自然法と「最強者の権利」が

十分であるため、法は表面的なものであると主張していた。ヘーゲルにとって、法の不在は専制政治、すなわち絶対主義であれ衆愚政治であれ、専制政治の特徴

であった。 |

| Principes

de la philosophie du droit (en allemand, Grundlinien der

Philosophie des Rechts) est un ouvrage de philosophie publié par Georg

Hegel en octobre 1820 à l'usage de ses étudiants à l'université de

Berlin. Il s'agit tout à la fois d'un traité de philosophie politique,

de philosophie de l'esprit et de philosophie pratique, qui comprend

aussi bien une théorie juridique, politique et sociale qu'une éthique. Ce livre a exercé une influence considérable, non seulement en philosophie, mais aussi sur toute la théorie politique et sociale au xixe siècle comme au xxe siècle, qu'il s'agisse du marxisme, du socialisme, du libéralisme ou du fascisme. |

ゲオルク・ヘーゲルが1820年10月にベルリン大学の学生向けに出版

した哲学書である。政治哲学、心=精神の哲学、実践哲学に関する論考であり、法学、政治理論、社会理論、倫理学から構成されている。 本書は哲学のみならず、マルクス主義、社会主義、自由主義、ファシズムなど、19世紀から20世紀にかけてのあらゆる政治・社会理論に多大な影響を与え た。 |

| Historique de publication Genèse Professeur à l'université de Heidelberg, Georg Hegel donne une série de cours sur le droit et l'État en 18171. Il se fonde notamment sur des passages de son Encyclopédie des sciences philosophiques concernant l'« esprit objectif »1. L'année suivante, il donne un nouveau cours à Berlin, et décide d'approfondir la question du droit en rédigeant un livre dédié au sujet. Il donne un troisième cours lors de l'année universitaire 1819-1820, qui nourrit sa réflexion1. Les propositions qu'Hegel met en avant dans son livre sont inspirées ou reflètent en partie le débat politique de son temps. Les propositions de l'auteur pour une division du pouvoir bicamérale sont très similaires à celles proposées, peu avant la publication du livre, par Wilhelm von Humboldt (paragraphes 298 à 314)1. La proposition d'Hegel selon laquelle tous les citoyens doivent pouvoir devenir fonctionnaires ou militaires sur leur mérite et non sur la base de leur ascendance reflète une réforme avortée de Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom Stein qui avait cherché à supprimer la nécessité d'être d'ascendance noble pour servir dans l'armée (paragraphes 271, 277, 291)1. Rédaction Hegel travaille sur l'ouvrage, mais sa publication est retardée1. Alors que la prise de contrôle de la Prusse par Napoléon Ier avait conduit à l'émergence d'un fort courant libéral dans le pays, la victoire des conservateurs opposés aux réformes libérales en 1819 provoque la mise en place de la censure des publications d'intellectuels et d'enseignants d'université1. Des étudiants et des assistants d'Hegel sont arrêtés. Le philosophe décide alors de modifier des passages de son futur livre. Il rédige une nouvelle préface en juin 1820 avant que le livre ne soit publié cette année-là1. Publication Les Principes de la philosophie du droit paraissent en octobre 1820, à la Librairie Nicolai à Berlin. Son sous-titre est « Droit naturel et science de l'État en abrégé » (en allemand, Naturrecht und Staatswissenschaft im Grundrisse). Il s'agit d'un manuel de cours divisé en 360 paragraphes que Hegel commentait lors des cours qu'il consacrait à la philosophie du droit, mais il explique également dans la Préface qu'il entend toucher par son livre un plus large public. L'ouvrage a été soumis à la censure royale en 1820. La page de titre originale indique l'année 1821 car Hegel craignait que la publication ne soit retardée en raison de la censure. Le dernier chapitre des Principes de la philosophie du droit sur l'histoire font l'objet de développement dans La Raison dans l'histoire et dans les Leçons sur la philosophie de l'histoire. Réception Les premières critiques de l'ouvrage sont toutes négatives2. Hegel est accusé d'aller dans le sens du pouvoir en place et de la censure, et ce d'autant plus qu'il attaque Jakob Friedrich Fries dans sa préface, alors que ce dernier a été arrêté par la police prussienne2. Certaines phrases du livre sont interprétées comme une prise de position en faveur du régime, dont notamment, dans la préface, « Ce qui est rationnel est effectif, ce qui est effectif est rationnel »1. Fries écrit ainsi au sujet du livre que « Le champignon métaphysique d'Hegel ne tire pas ses racines dans les jardins de la science mais dans le fumier de la servilité »3. Après la première moitié des années 1820, Hegel délègue à son ancien élève Eduard Gans la tâche d'enseigner le contenu de la Philosophie du droit à l'université de Berlin1. |

出版の歴史 創始 18171年、ハイデルベルク大学の教授であったゲオルク・ヘーゲルは、法と国家に関する一連の講義を行い、特に『哲学諸科学百科事典』の「客観的精神」 1に関する箇所を引用した。翌年、彼はベルリンで別の講義を行い、このテーマで本を書くことで、法の問題をより深く掘り下げることにした。彼は1819年 から1820年にかけて第3回目の講義を行い、さらなる思考の材料を提供した1。 ヘーゲルが著書の中で提示した提案は、当時の政治的議論に触発されたものであり、また部分的にはそれを反映したものであった。二院制による権力の分割に関 する著者の提案は、本書が出版される少し前にヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトが提唱したものと非常によく似ている(第298段落から第314段落)1。 ヘーゲルが提案している、すべての国民が先祖の血筋ではなく、功績に基づいて公務員や軍人になれるようにすべきだという提案は、軍隊に所属するために貴族 の血筋である必要性を廃止しようとしていたハインリヒ・フリードリヒ・カール・フォン・シュタインによる頓挫した改革を反映している(271、277、 291項)1。 草稿 ヘーゲルはこの著作に取り組んだが、出版は遅れた1。ナポレオン1世がプロイセンを占領したことで、プロイセンでは強力な自由主義の潮流が生まれたが、 1819年に自由主義改革に反対する保守派が勝利したことで、知識人や大学教師の出版物に対する検閲が導入された1。ヘーゲルの学生や助手は逮捕された。 ヘーゲルはこのとき、将来出版する本のいくつかの箇所を修正することを決めた。1820年6月、ヘーゲルは新たな序文を書き、その年の出版にこぎつけた 1。 出版 『法哲学の原理』は1820年10月にベルリンのニコライ書店から出版された。副題は「自然法と国家科学」(ドイツ語ではNaturrecht und Staatswissenschaft im Grundrisse)であった。ヘーゲルが法哲学の講義で解説した360の段落に分かれた教科書であるが、序文で彼は、この本がより多くの読者に読まれ ることを意図していたとも説明している。 この本は1820年に王室の検閲を受けた。ヘーゲルは検閲のために出版が遅れることを恐れたためである。 歴史に関する『法哲学の原理』の最終章は、『歴史における理性』と『歴史哲学の教訓』の中で展開されている。 受容 この作品に対する最初の批判は、すべて否定的なものであった2。特に序文でヤコブ・フリードリッヒ・フリースを攻撃しており、フリースはプロイセン警察に 逮捕されていたにもかかわらず2。序文にある「合理的なものは効果的であり、効果的なものは合理的である」1。フリースはこの本について、「ヘーゲルの形 而上学的な菌は科学の庭に根を張るのではなく、隷属の肥溜めに根を張る」と書いている3。 1820年代前半以降、ヘーゲルはかつての弟子エドゥアルド・ガンスに、ベルリン大学で法哲学の内容を教える仕事を託した1。 |

| Objet L'ouvrage a pour objectif de démontrer que l'État moderne, avec sa société complexe, est ce par quoi les abstractions que sont les droits individuels et la liberté (subjective) d'un individu trouvent leur concrétisation, c'est-à-dire un contenu objectif. Hegel montre ainsi que l’État est le lieu par excellence de l'actualisation, c'est-à-dire de la mise en actes, de la liberté concrète1. Pour ce faire, les Principes définissent le concept de « l’esprit objectif ». L’esprit désigne le sujet (comme individu, comme État, comme peuple, comme figure d’une œuvre d’art, comme Dieu vénéré dans une religion, etc.), qui réalise sa subjectivité en intégrant l’objet multiple qui lui fait face et qui est, lui, objectif. Ainsi, un propriétaire est un esprit dans la mesure où il se constitue comme tel en faisant sien le terrain, par hypothèse constitué de partes extra partes dont il prend possession. L’esprit est subjectif en tant qu’individu qui ne se rapporte qu’à lui-même (à son corps, à son expérience propre, à ses représentations…). L'esprit est absolu quand il se manifeste publiquement en tant que sujet gouvernant souverainement son monde (comme c'est le cas, par exemple, dans les représentations artistiques et religieuses). Il est esprit objectif, enfin, quand il tend à se réaliser dans le monde en lui imposant des normes publiquement reconnues4. Pour Hegel, l’esprit tend vers la liberté, c’est-à-dire la complétude, laquelle se réalise quand il est « chez soi » en tout objet. Les Principes de la philosophie du droit présentent l’effort de l’esprit pour s’incarner adéquatement dans le monde. Toutefois, au niveau de l’esprit objectif, il y a une scission indépassable entre le sujet et l’objet. Pour cette raison, l’esprit ne s’incarne que sur le mode du « devoir-être », c’est-à-dire de normes pouvant être transgressées et de prérogatives pouvant être contestées4. |

主題 本書の目的は、複雑な社会を持つ近代国家が、個人の権利や個人の(主観的な)自由といった抽象概念を具体化する手段、すなわち客観的な内容を見出す手段で あることを示すことである。こうしてヘーゲルは、国家が具体的自由の実現、すなわち実行のための卓越した場であることを示す1。 この目的のために、『原理』は「客観的精神」の概念を定義している。精神とは、主体(個人として、国家として、国民として、芸術作品における人物像とし て、宗教において崇拝される神としてなど)を意味し、主体は、それ自体に客観的である複数の対象を統合することによって、その主体性を実現する。このよう に、所有者は、仮にパルテス・エクストラ・パルテスで構成される土地を所有することによって、自分自身をそのように構成する限りにおいて精神である。精神 は、自分自身(自分の身体、自分の経験、自分の表象など)にのみ関係する個人である限り、主観的である。心が絶対的であるのは、その世界を主権的に支配す る主体として公に姿を現すときである(たとえば、芸術的、宗教的表象においてそうである)。最後に、精神が客観的であるのは、公的に認知された規範を世界 に課すことによって、世界において自己を実現しようとするときである4。 ヘーゲルにとって、精神は自由、すなわち完全性を志向するものであり、それは精神がいかなる対象においても「くつろげる」ときに達成される。権利哲学の諸 原理』は、精神が自己を世界の中で十分に具現化しようとする努力を示している。しかし、客観的な心のレベルでは、主体と客体との間には解けがたい分裂があ る。このため、精神は「あるべき姿」の様式、すなわち、侵犯されうる規範と争われうる特権においてのみ具現化される4。 |

| Structure Toutes les traductions en langue française évoquées dans cette section et dans les sections suivantes sont celles de Jean-Louis Vieillard-Baron pour l'édition de l'ouvrage chez GF-Flammarion, 1999 (ISBN 978-2-0807-0664-5). Préface La préface défend le caractère spéculatif de la philosophie. La philosophie, dit Hegel, ne repose pas sur le « cœur » et l’« enthousiasme » (pensée immédiate, traduction Kervégan p. 96), ni sur le formalisme de la « définition », de la « classification » et du « syllogisme » (pensée réflexive, p. 92), mais elle considère le développement vivant et autonome de son objet. Il s’agit d’étudier « la différenciation déterminée des sphères de la vie publique », et comment l’organisation d’ensemble « fait naître la force du tout de l’harmonie de ses maillons » (p. 97). On trouve dans la préface la formule selon laquelle « ce qui est rationnel est effectif ; et ce qui est effectif est rationnel » (p. 104). Pour certains, cet énoncé exprime l’adhésion de Hegel au réel tel qu’il est, et notamment son allégeance au pouvoir prussien de l’époque5. En réalité, le contexte montre que Hegel, ici, tend à exclure du discours philosophique ce qui relèverait de l’injonction ou du vœu pieux. Pour lui, la philosophie ne doit pas être normative, elle doit se contenter de « penser ce qui est »6. Si l’on étudie le concept d’effectivité tel qu’il est présenté dans la Science de la logique, on constate, plus précisément, que l’effectivité désigne le réel en tant qu’il est régi par une règle immanente (ce qui le distingue de cette frange du réel que Hegel nomme le « phénomène ») et qu’un principe n’est rationnel que si, plutôt que de rester abstraitement « pur », il s’inscrit dans le réel. Par la formule sur l’identité du rationnel et de l’effectif, Hegel signifie donc que la philosophie du droit n’a pour tâche ni d’étudier les principes du droit seulement tels qu’ils devraient être, ni le détail infini des réalités juridiques, mais l’incarnation des principes juridiques généraux dans le réel. Première partie : Le droit abstrait Le droit abstrait porte sur l’appropriation des choses par l’homme – et cela dans son aspect à la fois factuel et légal. Pour Hegel, à l’époque post-antique, tout homme a le droit d’être propriétaire. Par la propriété, la volonté trouve à s’incarner dans le monde extérieur et ainsi se rend libre6. La propriété n’est donc pas un moyen pour satisfaire un besoin mais une fin en soi (§ 45). Le droit de propriété, pour Hegel, n’est pas dépendant de la qualité morale des individus ni du contexte socio-politique. En effet, il ne repose que sur la relation de l’homme et du bien appropriable – l’homme, pourvu d’une volonté, ayant par principe un droit « infini » sur la chose en tant qu’elle est sans volonté (§ 44). Le droit de propriété ne répond pas à la question de savoir ce qu’un individu déterminé doit posséder, il se borne à établir quelle forme prend la propriété valide (§ 37 et 38). C’est à ce titre qu’il est abstrait. 1. Dans un premier moment (« la propriété »), le droit du mien et du tien exprime le rapport que l’individu entretient avec une chose qui, par hypothèse, n’appartient encore à personne. Hegel évoque, entre autres, l’appropriation par la « saisie corporelle », la « mise en forme », et le « marquage » (§ 55-58). 2. Dans un deuxième moment (« le contrat »), la propriété procède du rapport intersubjectif des propriétaires qui contractent les uns avec les autres. Par le contrat, la propriété acquiert une existence dont la durée prolongée est garantie. C’est le processus où la volonté, originairement subjective, personnelle et arbitraire, devient une volonté objective d’ordre général, autrement dit une institution sociale7. 3. Dans un troisième moment (« l'injustice »), la propriété repose sur la contrainte juridictionnelle qui, à l’encontre d’une injustice commise, rétablit le bon droit (§ 93). La validité de la propriété ne repose plus ni sur le seul agir individuel, ni sur la série itérative des contrats individuels, mais sur le droit pénal commun à l’ensemble de la collectivité considérée. Il est à noter que Hegel dénie toute fonction préventive, éducative ou curative de la peine. Dans le cadre (immédiat, donc rudimentaire) du droit abstrait, il s’agit seulement d’une vengeance destinée à restaurer le bon droit8. Deuxième partie : La moralité (die Moralität) L’agir considéré dans le moment de la « moralité » vise l’accomplissement de buts particuliers. La section examine plus précisément les droits et les devoirs du sujet agissant tels qu’ils sont publiquement reconnus à l’époque post-antique. Pour Hegel le sujet a, alors, le droit de tirer de lui-même la maxime de son action. Il a également le droit ne se voir reprocher, parmi les effets de son action, que ce qu’il a effectivement voulu (§ 107). La maxime de l’action de type moral (qui peut être bonne ou mauvaise) ne procède d’aucune institution9. Pour cette raison, sa validité est toujours discutable : en fonction des circonstances, l’action peut avoir des effets malheureux ou être critiquable sous tel ou tel point de vue. L’action de type moral n’est pas une chimère, mais elle ne peut échapper à la contradiction et à l’insatisfaction (§ 108)10. On trouve dans cette section une discussion célèbre de la morale kantienne. Pour Hegel, dans la sphère de la moralité, aucune maxime n’est authentiquement universelle. En effet, dans la mesure où la maxime procède du seul sujet particulier, elle repose inévitablement sur des choix arbitraires (Remarque du § 135). Troisième partie : La réalité morale (die Sittlichkeit) La réalité morale (traduit aussi sous le terme : « La vie éthique » ou « L'éthicité ») désigne la sphère des organisations intersubjectives unifiées par une règle commune. Dans ces ensembles, les individus ont un comportement universel. « Universel », ici, n’est pas à entendre au sens où leur agir serait valable toujours et partout, mais au sens où, dans l’institution considérée, il assure le bien commun. Par exemple, l’individu agit en tant que membre de telle ou telle famille, de telle ou telle corporation, de tel ou tel peuple... Pour Hegel, être libre, c’est être « chez soi » dans son autre. Puisque l’institution unifie ses membres, elle est essentiellement libre et libérante (§ 149). La famille est la sphère des liens seulement « naturels ». Elle est certes une institution, mais une institution qui repose sur le sentiment (§ 158). Pour cette raison, il y a une multiplicité de familles, dont chacune n’a qu’une durée réduite (§ 177-178). La société civile bourgeoise est un moment de multiplicité. L’homme s’y rapporte à autrui non pas sur le mode de l’amour familial ni sur celui de la coappartenance à un même État, mais sur le mode de la concurrence et de la défense de ses intérêts égoïstes (§ 187). Hegel insiste sur les inégalités et les contradictions qu’implique la société civile, où l’on constate à la fois des phénomènes d’excès de fortune et la formation d’une « populace » misérable11. Mais la société n’est pas pour autant un état de nature, car en elle règne le droit. La société civile assure la production organisée et l’échange des biens, mais aussi la formation sociale des besoins. Par ailleurs, elle édicte et met en œuvre des lois. Enfin, elle s’organise en institutions à buts particuliers : les corporations et la police (la notion de « Polizei », dans le vocabulaire administratif classique allemand, désignant l’administration chargée non seulement du maintien de l’ordre, mais aussi de la régulation de la vie économique et sociale). L’État, enfin, représente l’achèvement de la vie éthique. Il ne repose ni sur le sentiment de l’amour (comme la famille), ni sur les intérêts égoïstes (comme la société civile) mais sur le patriotisme. Ses membres sont véritablement différents les uns des autres (comme dans la société civile), mais il les unifie (comme dans la famille). Le principe d’unification est alors la volonté délibérée d’obéir à la loi commune (Remarque du § 258). Cependant, l’État moderne ne se borne pas à conférer à ses membres une même disposition d’esprit civique (aspect d’identité). Il reconnaît également aux hommes le droit de poursuivre leurs buts individuels (aspect de différence). L’État ne prohibe nullement la défense des intérêts personnels des individus, mais ordonne ceux-ci au bien commun (§ 154). L’État se caractérise par une constitution au sens d’une organisation des pouvoirs. Dans l’État moderne, le pouvoir princier se distingue du pouvoir gouvernemental et du pouvoir parlementaire. En même temps, Hegel critique la théorie de la séparation des pouvoirs telle qu’on la trouve chez Montesquieu. À ses yeux, l’articulation des pouvoirs est « organique » au sens où chaque instance politique assume un aspect de la volonté politique, sans cependant borner les autres instances. Chaque instance est entièrement souveraine, mais elle ne prend en charge qu’une dimension particulière de la vie de l’État12. La fonction du prince a fait l’objet de controverses interprétatives. Il semble en effet y avoir une contradiction entre certains textes qui lui confèrent un rôle primordial (il est « le sommet et le commencement du tout »: cf. § 273) et d’autres qui, au contraire, en font un rouage subalterne de l'État (il se bornerait à contresigner les décrets préparés par le gouvernement: cf. Addition du § 279). Pour Karl Heinz Ilting, cette contradiction exprime deux modes d’expression de Hegel. L’un, exotérique (destiné au grand public) est celui des textes publiés. Il se caractérise par l’allégeance de Hegel au pouvoir en place. L’autre, ésotérique (destiné aux initiés) est celui des Leçons orales. Il se caractérise au contraire par le libéralisme politique13. Ce thème est aussi développé par Jacques D'Hondt. Pour Éric Weil, « le prince n’est pas le centre ni le rouage principal de l’État »14. Pour Bernard Bourgeois en revanche, le prince joue un rôle de premier plan dans l’État, car c’est justement le formalisme de sa décision qui lui confère une valeur absolue15. Pour Gilles Marmasse, l’évaluation par Hegel de la fonction princière est à rapporter au caractère « immédiat » de cette fonction. D’un côté, le prince est indispensable, car il est une composante de la volonté étatique. D’un autre côté, sa volonté est abstraite dans la mesure où elle ne porte pas sur le détail de la loi relativement aux individus (qui doit être déterminé par le parlement), ni sur son application aux affaires particulières (qui relève du gouvernement), mais sur son contenu relatif à l’État en général. Hegel minore donc bien la fonction du prince16. Hegel est favorable au caractère héréditaire de la monarchie. À ses yeux en effet, si le prince était élu, il serait dépendant de ses électeurs et ne serait pas véritablement souverain. Le prince est patriote. En outre, son appartenance à la dynastie régnante lui permet de s'élever au-dessus des intérêts particuliers, ce qui le rend apte à assumer sa fonction. Mais il faut souligner que cet éloge du prince est ambivalent : sa compétence n’est que naturelle, elle est donc en même temps inaboutie. Si le monarque décide, le gouvernement – au sens de l’administration d’État – prépare les lois et les met en œuvre. Sa fonction d’application consiste à subsumer les affaires particulières sous l’universel de la loi (§ 288). Il s’agit notamment de faire en sorte que les différentes activités de la société civile concourent à l’intérêt général. Hegel condamne la vénalité des charges : le fonctionnaire se comporte non en membre de la société civile mais en citoyen. Le pouvoir gouvernemental a une double caractéristique : la compétence et l’indépendance17. Le parlement examine les lois pour autant qu’elles se rapportent aux groupes socioprofessionnels différenciés mais soucieux de l’intérêt commun. La fonction du parlement est double : il précise le contenu de la loi et assure la formation de la disposition d’esprit de ses membres et finalement du peuple en général (§ 314). La publicité des débats parlementaires permet d’éduquer le public, de le faire passer d’une vision égocentrique et limitée à la vision d’ensemble de la communauté18. Pour Hegel, les relations entre États souverains sont essentiellement conflictuelles. Les États peuvent certes conclure des pactes les uns avec les autres, mais ces pactes sont inévitablement précaires. Hegel récuse notamment le programme kantien d’une paix perpétuelle fondée sur une Société des nations. L’histoire, pour Hegel, n’est pas celle de l’humanité en général mais celle des peuples. Chaque peuple, dans son évolution, tend à accéder à une conscience adéquate de lui-même, et à établir un État qui exprime sa conception propre de la liberté. D’un peuple à l’autre, il y a un progrès de la liberté. En effet, l’histoire commence avec le despotisme oriental. Elle se poursuit avec la « belle liberté » grecque (conditionnée cependant par l’esclavage et les oracles) et la liberté romaine (fondée sur le droit de propriété égal pour tous). Elle se conclut, enfin, avec la liberté de type germanique, selon laquelle chaque homme a une « valeur infinie ». À l’époque orientale, un seul est libre, à l’époque gréco-romaines, quelques-uns sont libres, et à l’époque germanique, dit Hegel, tous les hommes sont libres19. |

構造 本セクションおよび以下のセクションのフランス語訳はすべて、1999年GF-Flammarion版(ISBN 978-2-0807-0664-5)のJean-Louis Vieillard-Baronによるものである。 序文 序文は哲学の思弁的性格を擁護している。ヘーゲルは、哲学は「心」と「熱意」(即時的思考、ケルヴェガン訳、96頁)に基づくものではなく、「定義」、 「分類」、「シロギス」(反省的思考、92頁)の形式主義に基づくものでもなく、その対象の生きた自律的な発展を考察するものであると言う。それは、「公 共生活の諸領域の決定された分化」を研究する問題であり、全体的な組織が「そのつながりの調和から全体の強さをどのように生み出すか」(p.97)を研究 する問題である。 序文には、「合理的なものは効果的であり、効果的なものは合理的である」(p.104)という言葉がある。この言葉は、ヘーゲルが現実をありのままに堅持 していること、とりわけ当時のプロイセン権力に忠誠を誓っていることを表していると考える人もいる5。しかし実際には、ヘーゲルはここで哲学的言説から、 命令や敬虔な願望に等しいものを排除する傾向があることを示している。彼にとって、哲学は規定的であってはならず、「あるものについて考える」ことに満足 しなければならないのである6。 論理学の科学』で提示されている有効性の概念を研究してみると、より正確には、有効性とは、実在が内在的な規則に支配されている限りにおいて実在を指定す るものであり(これは、ヘーゲルが「現象」と呼ぶ実在の縁辺とは区別される)、原理とは、抽象的に「純粋」であるよりもむしろ、実在に刻み込まれている場 合にのみ合理的であることがわかる。したがって、合理的なものと現実的なものの同一性に関するヘーゲルの公式は、法哲学の課題が、あるべき姿としての法の 原理のみを研究することでも、法的現実の無限の細部を研究することでもなく、現実における一般的な法原理の具体化を研究することであることを意味してい る。 第一部:抽象法 抽象法は、人間による事物の充当を扱うものであり、これは事実的側面と法的側面の両方においてである。ヘーゲルにとって、ポスト・アンティーク時代におい て、すべての人間は財産を所有する権利を有する。所有することによって、意志は外界に具体化を見出し、自由となる6。したがって、所有権は必要を満たすた めの手段ではなく、それ自体が目的なのである(第45条)。 ヘーゲルにとって、所有権は個人の道徳的資質や社会政治的文脈に左右されるものではない。実際、それは人間と充当可能な事物との間の関係のみに基づくもの であり、意志を賦与された人間は、事物が意志を持たない限りにおいて、原理的にその事物に対して「無限の」権利を有するのである(第44条)。 所有権は、特定の個人が何を所有すべきかという問題に答えるものではなく、有効な所有権がどのような形式をとるかを定めているにすぎない(第 37、38 条)。所有権が抽象的であるのはこのためである。 1. 最初の瞬間(「所有権」)において、「私のもの」「あなたのもの」という権利は、仮説によれば、まだ誰のものでもない事物と個人の関係を表現している。 ヘーゲルはとりわけ、「身体的掌握」、「形づくり」、「マーキング」による充当について言及している(§55-58)。 2. 第二の瞬間(「契約」)において、所有権は、互いに契約する所有者の間主観的関係から生じる。契約を通じて、財産はその存続期間が保証された存在を獲得す る。これは、もともと主観的で個人的で恣意的であった意志が、一般的な秩序を持つ客観的な意志、言い換えれば社会的制度となる過程である7。 3. 第三の瞬間(「不公正」)において、財産は、行われた不公正に対して、権利を再確立する司法的制約に依拠する(第93条)。財産の有効性は、もはや個人の 行為のみ、あるいは個々の契約の反復的な連鎖に依拠するのではなく、対象となる集団全体に共通する刑法に依拠するのである。 ヘーゲルは刑罰の予防的、教育的、治療的機能を否定していることに留意すべきである。抽象的な法という(即物的な、したがって初歩的な)枠組みの中では、 刑罰は単に権利の回復を意図した復讐の問題にすぎない8。 第二部:道徳(die Moralität) 道徳」の文脈で考えられる行為は、特定の目標を達成することを目的としている。本節では、行為主体の権利と義務について、より具体的に考察する。ヘーゲル にとって、主体は自分の行為の極意を自分自身から導き出す権利を持っている。彼はまた、自分の行為の結果のうち、自分が実際に意志したことについてのみ非 難される権利を有する(107条)。 道徳的行為の極意(善であることも悪であることもある)は、いかなる制度にも由来しない9。このため、その妥当性には常に議論の余地がある。状況によって は、行為は不幸な結果をもたらすかもしれないし、ある観点からの批判を受けるかもしれない。道徳的行為はキメラではないが、矛盾や不満から逃れることはで きない(§108)10。 この節は、カント道徳の有名な議論を含んでいる。ヘーゲルにとって、道徳の領域におけるいかなる極意も、純粋に普遍的なものではない。実際、格言が特定の 主体のみから出発する限り、それは必然的に恣意的な選択にかかっている(135節の備考)。 第三部:道徳的現実(die Sittlichkeit) 道徳的現実(「倫理的生活」あるいは「倫理性」とも訳される)とは、共通の規則によって統一された間主観的組織の領域を指す。このような集団では、個人は 普遍的に行動する。ここでいう「普遍的」とは、彼らの行動がいつでもどこでも有効であるという意味ではなく、問題となっている組織において、それが共通善 を保証するという意味で理解される。例えば、個人はそのような家族の一員として、そのような企業の一員として、そのような人々の一員として行動する。ヘー ゲルにとって、自由であるということは、他のものの中で「くつろいでいる」ことである。制度はその成員を統合するものであるから、それは本質的に自由であ り、解放的である(§149)。 家族とは「自然な」結びつきだけの領域である。それは確かに制度であるが、感情に基づく制度である(§158)。このため、家族には多様性があり、それぞ れの家族の寿命は短い(§177-178)。 ブルジョア市民社会は多元性の瞬間である。そこでは、人間は、家族愛や同じ国家の一員という様式ではなく、競争や自己の利己的利益の擁護という様式で他者 と関係する(187条)。ヘーゲルは、市民社会が内包する不平等と矛盾を主張している。そこでは、富の過剰現象と悲惨な「暴徒」11の形成の両方が見られ る。 しかし、これは社会が自然状態であることを意味するものではない。市民社会は、商品の組織的な生産と交換を保証するだけでなく、ニーズの社会的形成も保証 する。また、法律を制定し、実施する。最後に、市民社会は、ギルドや警察(ドイツの古典的な行政用語で「ポリツァイ」とは、秩序の維持だけでなく、経済 的・社会的生活の規制にも責任を負う行政機関を指す)など、特定の目的をもった機関に組織される。 最後に、国家は倫理的生活の集大成である。それは(家族のような)愛や(市民社会のような)利己的な利益ではなく、愛国心に基づいている。その構成員は (市民社会のように)純粋に互いに異なるが、(家族のように)統一される。そして、その統一原理は、コモン・ローに従うという意図的な意志である(§ 258の備考)。 しかし、近代国家は、その構成員に同じ市民精神(アイデンティティの側面)の気質を与えることにとどまらない。国家はまた、人間が個々の目標を追求する権 利(差異の側面)も認めている。国家は、個人の個人的利益を擁護することを禁止するのではなく、それを共同の利益のために命ずる(154条)。 国家は、権力の組織化という意味での憲法によって特徴づけられる。近代国家では、君主権力は政府権力や議会権力と区別される。同時に、ヘーゲルはモンテス キューの三権分立論を批判する。ヘーゲルの見解では、三権分立は「有機的」なものであり、各政治的権力は政治的意思の一面を担うが、他の権力を制限するこ とはない。各権威は完全な主権者であるが、国家生活の特定の次元を担当しているにすぎない12。 王子の機能については、これまでさまざまな解釈がなされてきた。実際、彼に根源的な役割(彼は「全体の頂点であり、始まり」である:第 273 条を参照)を与えるある種のテキストと、逆に彼を国家の歯車の従属的な歯車(彼は政府によって作成された政令に連署すること に限定される:第 279 条の補足を参照)とする他のテキストとの間には矛盾があるように思われる。 カール・ハインツ・イルティングにとって、この矛盾はヘーゲルの二つの表現様式を表している。第一は、外典的な(一般大衆向けの)、出版されたテクストの 表現である。これはヘーゲルの権力者への忠誠によって特徴づけられる。もう一方の秘教的なもの(入門者向け)は、口伝である。これは政治的自由主義を特徴 としている13。このテーマはジャック・ドントも展開している。エリック・ワイルは、「王子は国家の車輪の中心でも主要な歯車でもない」と述べている 14。一方、ベルナール・ブルジョワにとっては、王子は国家において主導的な役割を果たすが、それはまさに彼の決断の形式主義が絶対的な価値を与えるから である15。 ジル・マルマスにとって、ヘーゲルによる王子の機能の評価は、その機能の「即時的」な性質に関係している。一方では、王子は国家の意志の構成要素であるた め、不可欠な存在である。他方で、彼の意志は、個人との関係における法の細部(これは議会によって決定されなければならない)や、特定の問題への適用(こ れは政府の問題である)に関わるものではなく、国家一般との関係におけるその内容に関わるものである限り、抽象的である。したがって、ヘーゲルは君子の機 能を弱体化している16。 ヘーゲルは君主制の世襲性を支持していた。彼の見解では、もし王子が選挙で選ばれるなら、王子は選挙人に依存することになり、真の主権者ではなくなる。王 子は愛国者である。さらに、王朝の一員であることが、特定の利害関係者の上に立つことを可能にし、それが王子の地位にふさわしいのである。しかし、このよ うな王子の賞賛は両義的なものであることを強調しておかなければならない。 君主が決定する一方で、政府(国家行政という意味で)は法律を準備し、それを実施する。その適用機能は、特定の事務を普遍的な法の下に服従させることにあ る(第288条)。これには、市民社会のさまざまな活動が一般的利益に貢献するようにすることも含まれる。 ヘーゲルは、公務員が市民社会の一員としてではなく、一市民としてふるまうことで、職務の悪徳性を非難している。政府の権力には、能力と独立性という2つ の特徴がある17。 国会は、社会的専門家集団に関係する限りにおいて、法律を審査する。社会的専門家集団は、分化しているが、共通の利益に関係している。国会の機能は2つあ り、法律の内容を特定することと、国会の構成員、ひいては国民一般の考え方の形成を保証することである(第314条)。議会での議論の公共性は、国民を教 育し、自己中心的で限定的なビジョンから共同体の全体的なビジョンへと移行させることを可能にする18。 ヘーゲルにとって、主権国家間の関係は本質的に対立的なものである。もちろん国家は互いに協定を結ぶことができるが、こうした協定は必然的に不安定なもの となる。特にヘーゲルは、国際連盟に基づく恒久平和というカント的な計画を否定している。 ヘーゲルにとって歴史とは、人類一般の歴史ではなく、民族の歴史である。それぞれの民族は、進化するにつれて、適切な自己認識を達成し、独自の自由の概念 を表現する国家を樹立する傾向がある。ある民族から次の民族へと、自由は進歩していく。実際、歴史は東洋の専制主義から始まる。ギリシャの「美しい自由」 (奴隷制と神託によって条件づけられていたとはいえ)、ローマの自由(すべての人に平等な財産を与える権利に基づく)と続く。そして最後に、すべての人間 が「無限の価値」を持つというゲルマン流の自由で締めくくられる。東洋の時代には、ただ一人が自由であり、グレコ・ローマの時代には、少数の人間が自由で あり、ゲルマンの時代には、すべての人間が自由であるとヘーゲルは言う19。 |

| Thèses La liberté comme action déterminée par soi dans l’État Hegel définit, dès la préface, la théorie éthique qui gouverne à tous les Principes de la philosophie du droit : le bien est, pour l'homme, son actualisation par lui-même de son esprit. L'esprit humain est liberté (§4), il porte vers la liberté. La liberté est non pas la possibilité d'agir, mais plutôt, l'agir humain même par lequel l'homme est déterminé par lui-même et par rien qui lui serait extérieur (§23)1. Il ne s'agit donc pas de la liberté assimilée au libre arbitre, qui n'est qu'une liberté de faire ce qui nous plaît (§15). La liberté consiste à agir en dépassant les particularités pour agir de manière universelle, c'est-à-dire objective (§23) ; cela exige de prendre en compte autrui pour l'intégrer à mon action, à mes projets1. L'homme est libre lorsque, dans le cadre de la vie éthique sociale, il s'identifie avec les institutions (les normes) de sa société, qu'il reconnaît légitimement comme lui correspondant et lorsqu'il se reconnaît comme en faisant partie. L'homme agit alors selon ses dispositions, qui sont alignées avec les besoins de la vie en société. Cela exige qu'au sein de l’État, les intérêts collectifs de l’État soient en harmonie avec les objectifs de vie des individus1. L'esprit subjectif et l'esprit objectif La psychologie humaine, en ce qu'elle a d'individuel (car liée à l'individualité de celui qui pense), relève de l'esprit subjectif. L'esprit objectif, lui, exige d'agir de manière rationnelle en-dehors de soi, en prenant en compte les autres ; la société rationnelle relève de l'esprit objectif1. La liberté est véritable lorsque les hommes agissent dans le cadre d'une société dont la rationalité se caractérise par le fait que chacun sait que ses institutions sont rationnelles, et que chacun agit en tant qu'il est lui-même, par lui-même, dans le cadre de ces institutions1. La vie éthique La vie éthique (Sittlichkeit, définie aux paragraphes 144 et 145) renvoie au système d'institutions sociales rationnelles dans lequel les individus vivent. La vie éthique objective réside dans ce système d'institutions rationnelles, c'est celle qui est ancrée dans ce système d'institutions. La vie éthique subjective est liée à la disposition d'un individu à agir dans le sens de ce que les institutions exigent (§146 et 148)1. Une société rationnelle est celle où la vie en société, avec ses institutions (normes de vie), n'oppresse pas les individus dans leurs besoins, mais où chacun agit selon son individualité, qui correspond à son devoir1. L'individu devient vraiment lui-même lorsqu'il prend conscience de ce que sa vie sociale est en adéquation avec son individualité, que les obligations éthiques qui sont les siennes ne sont pas des limitations à sa liberté mais au contraire son sa liberté en acte1. Ainsi, la vie éthique moderne ne conduit pas toujours au bonheur. Elle exige, pour rendre la personne satisfaite de son existence, de lui donner les moyens (les normes, les institutions) d'actualiser ses individualités, c'est-à-dire ses particularités dans la vie sociale (§187). Pour cela, l’État doit respecter le droit de chacun à déterminer les directions qu'il souhaite prendre dans sa vie et de lui fournir des institutions pour qu'il s'épanouisse dans son individualité (§185, 187, 206)1. Personnalité et subjectivité Hegel considère que la modernité libérale est telle que les individus ne se considèrent heureux que s'ils ont la capacité, dans la société dans laquelle ils vivent, d'agir selon leurs dispositions, c'est-à-dire d'être eux-mêmes. Toutefois, les institutions sociales ne sont appréciées, et la vie éthique accomplie, que lorsque les institutions (les normes) sociales nous permettent d'actualiser l'image que l'on se fait de soi, c'est-à-dire d'agir selon ce que l'on pense être notre individualité. Le signe de la modernité est donc que les individus se pensent comme des personnes, qui exigent d'exercer leur liberté arbitraire dans une sphère extérieure à eux-mêmes, à savoir leur propriété et non seulement leur corps (§41 à 47)1. Le philosophe soutient que la modernité est telle que les individus considèrent qu'ils donnent à eux-mêmes un sens singulier à leur existence par le biais des choix qu'ils réalisent au cours de leur vie, et qui expriment leur indépendante, leur faculté de libre choix. Les hommes sont donc des sujets de leur existence (§105-106) qui trouvent dans leur choix propre une « auto-satisfaction » (§105-106)1. Droit abstrait Le droit abstrait est le droit qui s'applique au domaine de la liberté arbitraire, c'est-à-dire de la liberté de l'individu d'agir comme il lui semble dans une sphère qui est la sienne, à savoir son corps et sa propriété. Ce droit est dit abstrait car il s'applique à l'individu non pas en tant qu'il est une personne (singulière), mais en tant que son individualité lui ouvre le droit à ces droits, indépendamment du contexte et de l'utilisation qu'il veut en faire1. Dans un État moderne, la rationalité de l’État exige qu'il protège ce droit abstrait par le biais des institutions judiciaires (§209)1. Droit positif Le droit positif a vocation à déterminer le droit, c'est-à-dire les règles de droit. Les droits que l'on suit en tant que personne ne sont valides dans une société que dès lors qu'ils sont transcrits en droit positif. Le droit positif qui ne procéderait pas de ce qui est juste, c'est-à-dire une règle votée par un Parlement qui serait contraire à la justice, n'oblige pas la personne ; ainsi des lois qui autoriseraient l'esclavage1. Le rôle de l’État Hegel distingue l'Etat en tant que société qui a une fin politique, et l’État en tant qu'institution politique (§267). L’État est la fin de l'individu non pas en tant que l’État est une institution politique, mais en tant qu'il est la société dans laquelle l'individu s'inscrit1. Il peut y agir librement en tant que membre de l’État : l'individu est alors « patriote », non pas en tant qu'il agit de manière héroïque pour son État, mais entant qu'il vit une vie de devoir éthique qui fait de la société la base de son action et en même temps sa fin (§268)1. Hegel s'oppose à la position des penseurs libéraux selon laquelle l’État, comme chez Johann Gottlieb Fichte, aurait pour utilité d'être le régulateur des droits de chacun, utilisant sa force pour superviser les actions des personnes. La véritable condition pour une vie éthique constituée dans un État, défend Hegel, est que les droits des personnes soient intégrés dans un système cohérent d'institutions qui assurent à chacun la liberté de vivre une vie conforme à leur personne1. La société civile Avec les Principes, Hegel donne à l'expression de société civile une nouvelle signification. Alors qu'elle était jusqu'à présent synonyme avec l’État, et permettait de distinguer la société au sens le plus large avec la société dite « naturelle » (la famille, avec laquelle nous sommes liés par des liens de nature et d'amour), Hegel utilise l'expression pour désigner l'espace intermédiaire entre l’État, qui est l'organisation de la communauté à des fins politiques, et la société naturelle, privée, de la famille. La société civile est ainsi définie comme la sphère d'existence dans laquelle l'individu, en tant qu'il est sujet de son existence et individualité, exerce son droit à mener sa vie comme il l'entend et à suivre ses intérêts subjectifs. Dans cette sphère, l'homme existe en tant qu'il est propriétaire1. La société civile permet l'économie de marché, où, par une ruse de la raison, les actions individuelles égoïstes contribuent à une rationalité non-intentionnelle qui harmonise les parties dans le tout. Toutefois, l'économie de marché est également un lieu de conflit entre les offreurs et les demandeurs (les producteurs et les consommateurs) et cause des déséquilibres néfastes. La société civile doit donc être régulée par l'État qui s'assure que la société ne soit ni contrôlée par lui-même, ni parfaitement libre commercialement1. Principe d'atomicité Les Principes de la philosophie du droit soutiennent la thèse selon laquelle la plus grande menace à la vie libre n'est pas tant l’État, mais plutôt le « principe d'atomicité », à savoir la propension des modernes à vivre une vie intégrée dans la société, où ils exercent leur subjectivité en accord avec la société. Il considère comme un danger la disposition qu'aurait la modernité à valoriser le fait pour l'individu de survaloriser sa personne en se retirant de la société ou en faisant passer sa subjectivité avant la société. Or, cela empêche ces individus de mener une vie authentique dans la société1. |

テーゼ 国家における自己決定行為としての自由 ヘーゲルは序文から、『権利の哲学』のすべての原理を支配する倫理理論を定義している:人間にとって、善とは精神の自己実現である。人間の精神は自由であ り(§4)、それは自由につながる。自由とは、行動の可能性ではなく、むしろ、人間が自分自身によって決定され、人間の外部の何ものによっても決定されな い人間の行動そのものである(§23)1。それは自由意志と同一視される自由ではなく、単に自分の思いのままに行動する自由である(§15)。自由とは、 普遍的に、すなわち客観的に行動するために、特殊性を超えて行動することである(§23)。 人間は、倫理的な社会生活の文脈において、社会の制度(規範)と同一視し、それが自分に対応するものであると合法的に認識し、自分が社会の一部であると認 識するとき、自由である。そして人間は、社会における生活の必要性に合致した自分の気質に従って行動する。そのためには、国家内において、国家の集団的利 益が個人の生活目標と調和していることが必要である1。 主観的な心と客観的な心 人間心理は、それが個人的である限り(思考者の個性と結びついているため)、主観的精神に属する。一方、客観的な心は、他者を考慮に入れながら、自分の外 側で合理的に行動することを要求する。真の自由が存在するのは、社会の制度が合理的であることを誰もが知っており、その制度の枠内で誰もが自分自身で行動 するという事実によって特徴づけられる社会の枠組みの中で人々が行動するときである1。 倫理的生活 倫理的生活(Sittlichkeit、第144、145項で定義)とは、個人が生活する合理的な社会制度の体系を指す。客観的な倫理的生活とは、この合 理的な制度体系の中に存在するものであり、この制度体系の中に固定されているものである。主観的倫理生活とは、制度が要求するように行動する個人の気質に 関するものである(§146、148)1。合理的な社会とは、制度(生活規範)を持つ社会における生活が、個人の必要を抑圧することなく、各個人が自分の 義務に対応する個性に従って行動する社会である1。個人が真に自分自身となるのは、自分の社会生活が自分の個性と一致しており、倫理的義務が自分の自由を 制限するものではなく、逆に行動の自由を制限するものであることに気づいたときである1。 現代の倫理的生活は、必ずしも幸福につながるとは限らない。人々が自己の存在に満足するためには、社会生活において自己の個性、すなわち自己の特殊性を実 現するための手段(規範、制度)が与えられる必要がある(§187)。この目的のために、国家は、各個人がその人生において進みたい方向を決定する権利を 尊重し、その個性を実現するための制度を与えなければならない(§185, 187, 206)1。 人格と主観性 ヘーゲルは、リベラルな近代性とは、個人が、自分の住む社会の中で、自分の気質に従って行動する能力、すなわち自分自身である能力を持っている場合にの み、自分自身を幸福であると考えるようなものであると考える。しかし、社会制度が評価され、倫理的生活が実現されるのは、社会制度(規範)によって自己イ メージが実現されるとき、つまり、自分の個性だと信じていることに従って行動できるときだけである。そして、近代の兆候は、個人が自分自身を個人として考 えることであり、その個人は、自分自身の外側の領域、すなわち、自分の身体だけでなく、自分の財産においても、恣意的な自由を行使することを要求するので ある(§41~47)1。 哲学者は、近代性とは、個人がその生活の過程で行う選択を通じて、自らの存在に特異な意味を与えるものであり、それは自らの独立性、自由選択能力を表現す るものであると考えるようなものである、と主張する。したがって、人は自らの選択に「自己満足」を見出す、自らの存在の主体である(§105-106) 1。 抽象法 抽象法とは、恣意的自由の領域に適用される法のことであり、すなわち、個人の身体と財産という自己の領域において、個人が思うままに行動する自由のことで ある。この権利が抽象的であると言われるのは、個人に適用されるのは、その個人が(単数の)人間である限りにおいてではなく、文脈やその利用方法のいかん にかかわらず、その個人性がこれらの権利を有する権利を与える限りにおいてであるからである1。近代国家においては、国家の合理性は、司法制度を通じてこ の抽象的権利を保護することを要求する(§209)1。 実定法 実定法の目的は、法、すなわち法の規則を定めることである。個人として従う権利は、それが実定法に転写されて初めて社会で有効となる。正義に基づかない正 法、すなわち正義に反する議会によって可決された規則は、個人を拘束するものではない。 国家の役割 ヘーゲルは、政治的目的をもつ社会としての国家と、政治的制度としての国家を区別している(§267)。国家が個人の目的であるのは、国家が政治的制度で ある限りにおいてではなく、国家が個人を包摂する社会である限りにおいてである1。そのとき、個人は「愛国者」であり、国家のために英雄的に行動するので はなく、社会を行動の基礎とし、同時にその目的とする倫理的義務に生きるのである(§268)1。 ヘーゲルは、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテのように、国家が個人の権利を規制し、個人の行動を監督するためにその権力を行使するという自由主義思想家の 立場に反対している。ヘーゲルは、国家の中で構成される倫理的生活の真の条件は、人々の権利が、すべての人がその人らしく生きる自由を保障する首尾一貫し た制度体系に統合されていることであると主張する1。 市民社会 ヘーゲルは「原理」によって、市民社会という表現に新しい意味を与えた。それまで市民社会は国家と同義であり、いわゆる「自然」社会(私たちが自然と愛の 絆で結ばれている家族)から広義の社会を区別することが可能であったが、ヘーゲルはこの表現を、政治的目的のために共同体を組織する国家と、家族という自 然で私的な社会との間の中間的な空間を指定するために用いる。こうして市民社会は、個人がその存在と個性の主体として、自分の人生を自分の思うように生 き、自分の主観的利益に従う権利を行使する存在領域と定義される。この領域では、人間は所有者として存在する1。 市民社会は市場経済を可能にし、そこでは、理性のいたずらによって、利己的な個人の行動が、全体の中で部分を調和させる意図せざる合理性に貢献する。しか し、市場経済は供給者と需要者(生産者と消費者)の対立の場でもあり、有害な不均衡を引き起こす。したがって、市民社会は国家によって規制されなければな らない。国家は、社会がそれ自体によってコントロールされることも、商業的に完全に自由であることも保証しない1。 原子性の原則 『法哲学の原理』は、自由な生活に対する最大の脅威は、国家というよりも「原子性の原理」、すなわち現代人が社会に統合された生活を送り、社 会に従って主体 性を発揮する傾向にあるというテーゼを支持している。彼は、社会から引き下がったり、社会よりも主体性を優先させたりすることで、個人を過大評価する近代 の傾向に危険性を見出している。このことは、こうした個人が社会の中で本物の人生を送ることを妨げている1。 |

| Débats et critiques Hegel comme partisan de l'absolutisme ou de l’État de droit L'ouvrage a été interprété par des courants libéraux prussiens comme le testament absolutiste de leur auteur. Le livre a ainsi amplifié l'image d'un Hegel en faveur du Machtstaat prussien1. Certains ont ainsi vu en ce livre, au début du XXe siècle, l'un des germes de l'impérialisme allemand, puis du national-socialisme20, quand bien même le philosophe attitré du Troisième Reich, Alfred Rosenberg, avait dénoncé Hegel comme contraire au nazisme1. Les hégéliens centristes interprètent l'ouvrage, depuis sa sortie, comme une tentative d'Hegel de fonder un État de droit. Les principaux spécialistes de l'auteur se rejoignent aujourd'hui sur cette analyse, rejetant le lieu commun d'un Hegel soutenant l'autoritarisme prussien1. Dans tout l'ouvrage, l'auteur se montre en faveur de réformes libérales modérées, sans se montrer ni radical, ni subversif1. Difficulté d'accès L'ouvrage a été été critiqué comme particulièrement difficiles d'accès, tout comme la Phénoménologie de l'esprit. Allen W. Wood écrit que du fait de la complexité de son style, et de « son écriture [...] difficile, même irritante, remplie de jargon impénétrable », Hegel est « débattu plus qu'il n'est compris »1. Eugène Fleischmann, dans son commentaire de l'ouvrage, La philosophie politique de Hegel, souligne également la difficulté d'accès de l’œuvre21. |

論争と批判 絶対主義あるいは法治主義の支持者としてのヘーゲル この本は、プロイセンの自由主義者たちによって、著者の絶対主義的遺言として解釈された。こうしてこの本は、ヘーゲルがプロイセンのマッハシュタット1 の支持者であるというイメージを増幅させた。20世紀初頭には、第三帝国の公式哲学者アルフレッド・ローゼンベルクがヘーゲルをナチズムに反するものとし て非難していたにもかかわらず、この本にドイツ帝国主義、後には国家社会主義の種を見出す者もいた20。 出版以来、中道派のヘーゲル研究者たちは、この著作をヘーゲルが立憲国家を創設しようとした試みであると解釈してきた。現在、著者の主要な研究者はこの分 析に同意しており、ヘーゲルがプロイセンの権威主義を支持したという通説を否定している1。作品全体を通して、著者は穏健な自由主義改革を支持しており、 急進的でも破壊的でもない1。 入手の難しさ 『精神現象学』と同様、この著作は特にアクセスしにくいと批判されている。アレン・W. ウジェーヌ・フライシュマン(Eugène Fleischmann)も、この著作の解説書『ヘーゲルの政治哲学』(Hegel's Political Philosophy)の中で、この著作の難解さを強調している21。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principes_de_la_philosophie_du_droit |

☆ヘーゲル「法の哲学」序文

| THE immediate

occasion for publishing these outlines is the need of placing in the

bands of my hearers a guide to my professional lectures upon the

Philosophy of Right. Hitherto I have used as lectures that portion of

the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophic Sciences (1817) which deals with

this subject. The present work covers the same ground in a more

detailed and systematic way. |

これらの概要を出版する直接の契機は、聴講者たちに『法の哲学』に関する専門講義の指針を提供する必要性にある。これまで私は、この主題を扱った『エンチクロペディ』(1817年)の一部を講義として用いてきた。本書は同じ内容をより詳細かつ体系的に扱っている。 |

| But now that these outlines are

to be printed and given to the general public, there is an opportunity

of explaining points which in lecturing would be commented on orally.

Thus the notes are enlarged in order to include cognate or conflicting

ideas, further consequences of the theory advocated, and the like.

These expanded notes will, it is hoped, throw light upon the more

abstract substance of the text, and present a more complete view of

some of the ideas current in our own time. Moreover, there is also

subjoined, as far as was compatible with the purpose of a compendium, a

number of notes, ranging over a still greater latitude. A compendium

proper, like a science, has its subject-matter accurately laid out.

With the exception, possibly, of one or two slight additions, its chief

task is to arrange the essential phases of its material. This material

is regarded as fixed and known, just as the form is assumed to be

governed by well-ascertained rules. A treatise in philosophy is usually

not expected to be constructed on such a pattern, perhaps because

people suppose that a philosophical product is a Penelope’s web which

must be started anew every day. |

しかし、これらの概要を印刷して一般に配布するにあたり、講義では口頭

で補足する程度の点についても説明する機会が生まれた。そこで、関連する概念や対立する思想、提唱する理論のさらなる帰結などを含めるため、ノートを拡充

した。この拡張版ノートが、より抽象的な本文の内容を解明し、現代に流通する諸思想のより包括的な見解を示すことを期待する。さらに、要約集としての目的

に沿う範囲で、より広範な領域にわたる注釈も付記した。科学と同様に、真の要約集はその主題を正確に整理するものである。おそらく一、二の軽微な追加を除

けば、その主たる任務は素材の本質的な側面を整理することにある。この素材は固定され既知のものと見なされ、形式が確立された規則に支配されていると仮定

されるのと同じである。哲学の論考が通常このような様式で構築されることは期待されない。おそらく人々は、哲学的産物はペネロペの織物のように毎日新たに

始めねばならないものだと考えているからだろう。 |

| This treatise differs from the

ordinary compendium mainly in its method of procedure. It must be

understood at the outset that the philosophic way of advancing from one

matter to another, the general speculative method, which is the only

kind of scientific proof available in philosophy, is essentially

different from every other. Only a clear insight into the necessity for

this difference can snatch philosophy out of the ignominious condition

into which it has fallen in our day. True, the logical rules, such as

those of definition, classification, and inference are now generally

recognised to be inadequate for speculative science. Perhaps it is

nearer the mark to say that the inadequacy of the rules has been felt

rather than recognised, because they have been counted as mere fetters,

and thrown aside to make room for free speech from the heart, fancy and

random intuition. But when reflection and relations of thought were

required, people unconsciously fell back upon the old-fashioned method

of inference and formal reasoning. In my Science of Logic I have

developed the nature of speculative science in detail. Hence in this

treatise an explanation of method will be added only here and there. In

a work which is concrete, and presents such a diversity of phases, we

may safely neglect to display at every turn the logical process, and

may take for granted an acquaintance with the scientific procedure.

Besides, it may readily be observed that the work as a whole, and also

the construction of the parts, rest upon the logical spirit. From this

standpoint, especially, is it that I would like this treatise to be

understood and judged. In such a work as this we are dealing with a

science, and in a science the matter must not be separated from the

form. |

この論考は、その進め方の点で通常の要約とは大きく異なる。まず理解す

べきは、哲学において唯一可能な科学的証明である、ある事柄から別の事柄へと進む哲学的手法、すなわち一般的な思索的方法が、他のあらゆる方法とは本質的

に異なるということだ。この差異の必要性を明確に洞察してこそ、現代において堕落した状態にある哲学を救い出せるのである。確かに、定義・分類・推論と

いった論理的規則が思弁科学には不十分であることは、今や広く認められている。むしろ、規則の不十分さは認識というより実感されてきたと言う方が適切だろ

う。なぜならそれらは単なる束縛と見なされ、心の自由な発言や空想、無作為な直感に道を譲るために捨て去られてきたからだ。しかし、思索や思考の関連性が

求められる場面では、人民は無意識のうちに、昔ながらの推論や形式的推論の方法に回帰した。私の『論理学の科学』では、思索的科学の本質を詳細に論じてい

る。したがって本論考では、方法論の説明は所々で補足するに留める。具体的で多様な局面を呈する著作においては、論理的過程を随所で示すことを省略しても

差し支えず、科学的処置への習熟を前提とすることができる。さらに、著作全体および各部分の構成が論理的精神に依拠していることは容易に観察できる。特に

この観点から、本論考を理解し評価してほしい。このような著作では科学を扱っており、科学においては内容を形式から切り離してはならないのである。 |

| Some, who are thought to be

taking a profound view, are heard to say that everything turns upon the

subject-matter, and that the form may be ignored. The business of any

writer, and especially of the philosopher, is, as they say, to

discover, utter, and diffuse truth and adequate conceptions. In actual

practice this business usually consists in warming up and distributing

on all sides the same old cabbage. Perhaps the result of this operation

may be to fashion and arouse the feelings; though even this small merit

may be regarded as superfluous, for “they have Moses and the prophets:

let them hear them.” Indeed, we have great cause to be amazed at the

pretentious tone of those who take this view. They seem to suppose that

up till now the dissemination of truth throughout the world has been

feeble. They think that the warmed-up cabbage contains new truths,

especially to be laid to heart at the present time. And yet we see that

what is on one side announced as true, is driven out and swept away by

the same kind of worn-out truth. Out of this hurly-burly of opinions,

that which is neither new nor old, but permanent, cannot be rescued and

preserved except by science. |

深遠な見解を持っていると思われる者の中には、全ては主題次第であり、

形式は無視してよいと言う者もいる。あらゆる書き手、特に哲学者の仕事は、彼らが言うように、真理と適切な概念を発見し、表明し、広めることだ。実際のと

ころ、この仕事は往々にして、同じ古いキャベツを温め直して四方八方に配ることに過ぎない。この操作の結果、感情を形作り喚起することもあるかもしれな

い。とはいえ、このささやかな功績さえも不要と見なされるかもしれない。「彼らにはモーセと預言者たちがいる。彼らに聞かせよ」と。実際、この見解を持つ

者たちの尊大な口調には驚かされる。彼らは、これまで世界中に真理を広める努力が弱々しかったとでも思っているようだ。彼らは温め直したキャベツに新たな

真理が含まれており、特に現代において心に留めるべきものだと考えている。しかし我々は、ある側で真実と宣言されたものが、同じ種類の陳腐な真理によって

駆逐され一掃されるのを目の当たりにする。この意見の喧噪の中から、新しくも古くもない、恒久的な真理を救い出し保存できるのは、科学によってのみであ

る。 |

| Further, as to rights, ethical

life, and the state, the truth is as old as that in which it is openly

displayed and recognised, namely, the law, morality, and religion. But

as the thinking spirit is not satisfied with possessing the truth in

this simple way, it must conceive it, and thus acquire a rational form

for a content which is already rational implicitly. In this way the

substance is justified before the bar of free thought. Free thought

cannot be satisfied with what is given to it, whether by the external

positive authority of the state or human agreement, or by the authority

of internal feelings, the heart, and the witness of the spirit, which

coincides unquestioningly with the heart. It is the nature of free

thought rather to proceed out of its own self, and hence to demand that

it should know itself as thoroughly one with truth. |

さらに、権利、倫理的生活、国家に関して言えば、その真理は、それが公

然と示され認識されるもの、すなわち法、道徳、宗教と同じくらい古い。しかし、思考する精神はこの単純な方法で真理を所有することに満足しないため、それ

を構想しなければならず、こうしてすでに暗黙のうちに合理的である内容に対して合理的な形式を獲得する。このようにして、実体は自由な思考の法廷において

正当化されるのだ。自由な思考は、与えられたものに満足することはできない。それが国家という外部の積極的権威によるものであれ、人間の合意によるもので

あれ、あるいは内面の感情、心、そして心に疑いなく一致する精神の証言という権威によるものであれ。むしろ自由な思考の本質は、自らの内から出発し、それ

ゆえに自らを真実と完全に一つであると知ることを要求することにある。 |

| The ingenuous mind adheres with

simple conviction to the truth which is publicly acknowledged. On this

foundation it builds its conduct and way of life. In opposition to this

naive view of things rises the supposed difficulty of detecting amidst

the endless differences of opinion anything of universal application.

This trouble may easily be supposed to spring from a spirit of earnest

inquiry. But in point of fact those who pride themselves upon the

existence of this obstacle are in the plight of him who cannot see the

woods for the trees. The confusion is all of their own making. Nay,

more: this confusion is an indication. that they are in fact not

seeking for what is universally valid in right and the ethical order.

If they were at pains to find that out, and refused to busy themselves

with empty opinion and minute detail, they would adhere to and act in

accordance with substantive right, namely the commands of the state and

the claims of society. But a further difficulty lies in the fact that

man thinks, and seeks freedom and a basis for conduct in thought.

Divine as his right to act in this way is, it becomes a wrong, when it

takes the place of thinking. Thought then regards itself as free only

when it is conscious of being at variance with what is generally

recognised, and of setting itself up as something original. |

純真な心は、公に認められた真実を単純な確信をもって固く信じる。この

基盤の上に、その行動と生き方を築くのだ。この素朴な見方に対抗して、無数の意見の異なる中において普遍的に適用できるものを発見することの難しさが持ち

上がる。この困難は、真剣な探究心から生じていると思われがちだ。しかし実際には、この障害の存在を誇りに思う者たちは、木を見て森を見ずの状態にある。

混乱はすべて彼ら自身が作り出したものだ。いや、それ以上に:この混乱は、彼らが実際には正義と倫理秩序において普遍的に有効なものを求めていない証拠

だ。もし彼らがそれを発見しようと努め、空虚な意見や細部に忙殺されることを拒むならば、実質的な正義、すなわち国家の命令と社会の要求に固執し、それに

従って行動するだろう。しかしさらなる困難は、人間が思考し、思考の中に自由と行動の基盤を求めるという事実に存在する。このように行動する権利は神聖な

ものだが、思考に取って代わる時、それは誤りとなる。思考は、一般に認められたものと相違し、自らを独創的なものと位置づけることを自覚した時のみ、自由

であると自認するのだ。 |

| The idea that freedom of thought

and mind is indicated only by deviation from, or even hostility to what

is everywhere recognised, is most persistent with regard to the state.

The essential task of a philosophy of the state would thus seem to be

the discovery and publication of a new and original theory. |

思想と精神の自由が、広く認められているものからの逸脱、あるいは敵意によってのみ示されるという考えは、国家に関して最も根強い。したがって国家哲学の本質的な課題は、新しく独創的な理論の発見と公表にあるように思われる。 |

| When we examine this idea and

the way it is applied, we are almost led to think that no state or

constitution has ever existed, or now exists. We are tempted to suppose

that we must now begin and keep on beginning afresh for ever. We are to

fancy that the founding of the social order has depended upon present

devices and discoveries. As to nature, philosophy, it is admitted, has

to understand it as it is. The philosophers’ stone must be concealed

somewhere, we say, in nature itself, as nature is in itself rational.

Knowledge must, therefore, examine, apprehend and conceive the reason

actually present in nature. Not with the superficial shapes and

accidents of nature, but with its eternal harmony, that is to say, its

inherent law and essence, knowledge has to cope. But the ethical world

or the state, which is in fact reason potently and permanently

actualised in self-consciousness, is not permitted to enjoy the

happiness of being reason at all. |

この考えとその適用方法を検証すると、これまで国家や憲法が存在したこ とも、現在存在するとも思えなくなる。我々は今こそ新たな出発を繰り返し続けねばならないと誘惑されるのだ。社会秩序の確立は、現在の工夫や発見に依存し てきたと想像せざるを得ない。自然に関しては、哲学はそれをあるがままに理解すべきだと認められている。我々は言う、自然そのものの中に、自然がそれ自体 合理的であるように、賢者の石は隠されているに違いないと。したがって知識は、自然の中に実際に存在する理性を検証し、把握し、概念化しなければならな い。知識が対処すべきは、自然の表層的な形や偶発的な事象ではなく、その永遠の調和、すなわち内在する法則と本質である。しかし倫理的世界、すなわち国家 は、実際には自己意識の中で強力かつ恒久的に実現された理性であるにもかかわらず、理性であるという幸福を享受することを許されていない。 |

| Footnote: There

are two kinds of laws, laws of nature and laws of right. The laws of

nature are simply there, and are valid as they are. They cannot be

gainsaid, although in certain cases they may be transgressed. In order

to know laws of nature, we must get to work to ascertain them, for they

are true, and only our ideas of them can be false. Of these laws the

measure is outside of us. Our knowledge adds nothing to them, and does

not further their operation. Only our knowledge of them expands. The

knowledge of right is partly of the same nature and partly different.

The laws of right also are simply there, and we have to become

acquainted with them. In this way the citizen has a more or less firm

hold of them as they are given to him, and the jurist also abides by

the same standpoint. But there is also a distinction. In connection

with the laws of right the spirit of investigation is stirred up, and

our attention is turned to the fact that the laws, because they are

different, are not absolute. Laws of right are established and handed

down by men. The inner voice must necessarily collide or agree with

them. Man cannot be limited to what is presented to him, but maintains

that he has the standard of right within himself. He may be subject to

the necessity and force of external authority, but not in the same way

as he is to the necessity of nature; for always his inner being says to

him how a thing ought to be, and within himself he finds the

confirmation or lack of confirmation of what is generally accepted. In

nature the highest truth is that a law is. In right a thing is not

valid because it is, since every one demands that it shall conform to

his standard. Hence arises a possible conflict between what is and what

ought to be, between absolute unchanging right and the arbitrary

decision of what ought to be right. Such division and strife occur only

on the soil of the spirit. Thus the unique privilege of the spirit

would appear to lead to discontent and unhappiness, and frequently we

are directed to nature in contrast with the fluctuations of life. But

it is exactly in the opposition arising between absolute right, and

that which the arbitrary will seeks to make right, that the need lies

of knowing thoroughly what right is. Men must openly meet and face

their reason, and consider the rationality of right. This is the

subject-matter of our science in contrast with jurisprudence, which

often has to do merely with contradictions. Moreover the world of today

has an imperative need to make this investigation. In ancient times,

respect and reverence for the law were universal. But now the fashion

of the time has taken another turn, and thought confronts everything

which has been approved. Theories now set themselves in opposition to

reality, and make as though they were absolutely true and necessary.

And there is now more pressing need to know and conceive the thoughts

upon right. Since thought has exalted itself as the essential form, we

must now be careful to apprehend right also as thought. It would look

as though the door were thrown open for every casual opinion, when

thought is thus made to supervene upon right. But true thought of a

thing is not an opinion, but the conception of the thing itself. The

conception of the thing does not come to us by nature. Every man has

fingers, and may have brush and colours, but he is not by reason of

that a painter. So is it with thought. The thought of right is not a

thing which every man has at first hand. True thinking is thorough

acquaintance with the object. Hence our knowledge must be scientific. |

脚注:法 には二種類ある。自然の法則と権利の法則だ。自然の法則はただそこにあるだけで、あるがままに有効だ。反論の余地はないが、特定の状況では破られることも ある。自然の法則を知るには、それを確かめるために働かねばならない。なぜならそれらは真実であり、誤り得るのは我々のそれに対する考えだけだからだ。こ れらの法則の尺度(基準)は我々の外にある。我々の知識はそれらに何も加えず、その作用を促進しない。ただ我々の知識がそれらについて広がるだけだ。権利 に関する知識は、部分的には同じ性質を持ち、部分的には異なる。権利の法則もまた単に存在するものであり、我々はそれらを知る必要がある。このようにして 市民は、与えられたままのそれらを多かれ少なかれ確固として把握し、法学者もまた同じ立場に立つ。しかし区別もある。権利の法則に関しては探究心が喚起さ れ、我々の注意は「法則が異なるゆえに絶対ではない」という事実に向けられる。権利の法則は人間によって制定され継承される。内なる声は必然的にそれらと 衝突するか、あるいは調和する。人間は提示されたものに限定されることはなく、自らの内に正義の基準を持つと主張する。外部の権威の必然性と力に服従する ことはあっても、自然の必然性に服従するのと同じようにはならない。なぜなら常に内なる存在が物事のあるべき姿を告げ、一般に受け入れられたものの正当性 あるいは不正当性を自らの内に見出すからだ。自然において最高の真理は、法則が存在するということだ。正義においては、あるものが存在するからといって正 当とはならない。なぜなら誰もが、それが自らの基準に合致することを求めるからだ。ここから、あるべき姿と現実の間の、絶対不変の正義と「正しいべきも の」の恣意的決定との間の、潜在的な対立が生じる。このような分裂と葛藤は、精神の領域においてのみ起こる。こうして精神の特権は不満と不幸をもたらすよ うに見え、人生の変動とは対照的に自然へと目を向けることがしばしばある。しかし絶対的正義と、恣意的な意志が正義としようとするものとの間に生じる対立 こそが、正義とは何かを徹底的に知る必要性を示している。人間は自らの理性に真正面から向き合い、正義の合理性を考察しなければならない。これが我々の学 問の主題であり、しばしば矛盾のみを扱う法学とは対照的である。さらに現代世界はこの探究を緊急に必要としている。古代においては法への敬意と畏敬が普遍 的であった。しかし今や時代の風潮は別の方向へ転じ、思考は承認されてきたあらゆるものに直面する。理論は現実に対抗し、あたかも絶対的真実かつ必然であ るかのように振る舞う。だからこそ、正義についての思考を知り、理解することが今ほど切実に求められている。思考が本質的な形式として自らを高めた以上、 我々は正義をも思考として捉えるよう注意しなければならない。思考がこのように正義に優先すると、あらゆる安易な意見に門戸が開かれたように見えるかもし れない。しかし、物事に対する真の思考とは意見ではなく、物事そのものの概念である。物事の概念は自然に我々に与えられるものではない。誰もが指を持ち、 筆や絵の具を持つかもしれないが、それゆえに画家になるわけではない。思考も同様だ。正義についての思考は、誰もが最初から持っているものではない。真の 思考とは対象との徹底的な親交である。ゆえに我々の知識は科学的でなければならない。 |

| On the contrary, the spiritual

universe is looked upon as abandoned by God, and given over as a prey

to accident and chance. As in this way the divine is eliminated from

the ethical world, truth must be sought outside of it. And since at the

same time reason should and does belong to the ethical world, truth,

being divorced from reason, is reduced to a mere speculation. Thus

seems to arise the necessity and duty of every thinker to pursue a

career of his own. Not that he needs to seek for the philosophers’

stone, since the philosophising of our day has saved him the trouble,

and every would-be thinker is convinced that he possesses the stone

already without search. But these erratic pretensions are, as it indeed

happens, ridiculed by all who, whether they are aware of it or not, are

conditioned in their lives by the state, and find their minds and wills

satisfied in it. These, who include the majority if not all, regard the

occupation of philosophers as a game, sometimes playful, sometimes

earnest, sometimes entertaining, sometimes dangerous, but always as a

mere game. Both this restless and frivolous reflection and also this

treatment accorded to it might safely be left to take their own course,

were it not that betwixt them philosophy is brought into discredit and

contempt. The most cruel despite is done when every one is convinced of

his ability to pass judgment upon, and discard philosophy without any

special study. No such scorn is heaped upon any other art or science. |

それどころか、精神的な世界は神に見捨てられ、偶然や運命の餌食に委ね

られていると見なされる。このようにして神聖なものは倫理的世界から消去法による排除を受けるため、真理はその外に求められねばならない。同時に理性は倫

理的世界に属すべきであり、また実際に属している。ゆえに理性から切り離された真理は、単なる思索に堕する。こうしてあらゆる思想家が独自の道を歩む必要

性と義務が生まれるように思われる。哲学者たちの石を探す必要はない。現代の思索がすでにその手間を省いており、自称思想家たちは皆、探さずともすでに石

を所有していると確信しているからだ。しかし、こうした気まぐれな主張は、実際にそうであるように、国家によって生活を規定され、その中に精神と意志の充

足を見出す者たち──自覚しているか否かを問わず──全員から嘲笑される。これらの人々(大多数、いやほぼ全員)は、哲学者の営みを遊びと見なす。時に戯

れ、時に真剣、時に娯楽、時に危険ではあるが、常に単なる遊びとして。この落ち着きのない軽薄な考察も、それに与えられる扱いも、哲学が信用を失い軽蔑さ

れる結果を招くのでなければ、そのまま放置しても差し支えなかっただろう。最も残酷な侮辱は、誰もが特別な研究なしに哲学を評価し捨て去る能力があると確

信する時に生じる。他のいかなる芸術や科学にも、これほどの軽蔑は浴びせられない。 |

| In point of fact the pretentious

utterances of recent philosophy regarding the state have been enough to

justify anyone who cared to meddle with the question, in the conviction

that he could prove himself a philosopher by weaving a philosophy out

of his own brain. Notwithstanding this conviction, that which passes

for philosophy has openly announced that truth cannot be known. The

truth with regard to ethical ideals, the state, the government and the

constitution ascends, so it declares, out of each man’s heart, feeling

and enthusiasm. Such declarations have been poured especially into the

eager ears of the young. The words “God giveth truth to his chosen in

sleep” have been applied to science ; hence every sleeper has numbered

himself amongst the chosen. But what he deals with in sleep is only the

wares of sleep. Mr. Fries, one of the leaders of this shallow-minded

host of philosophers, on a public festive occasion, now become

celebrated, has not hesitated to give utterance to the following notion

of the state and constitution: “When a nation is ruled by a common

spirit, then from below, out of the people, will come life sufficient

for the discharge of all public business. Living associations, united

indissolubly by the holy bond of friendship, will devote themselves to

every side of national service, and every means for educating the

people.” This is the last degree of shallowness, because in it science

is looked upon as developing, not out of thought or conception, but out

of direct perception and random fancy. Now the organic connection of

the manifold branches of the social system is the architectonic of the

state’s rationality, and in this supreme science of state architecture

the strength of the whole, is made to depend upon the harmony of all

the clearly marked phases of public life, and the stability of every

pillar, arch, and buttress of the social edifice. And yet the shallow

doctrine, of which we have spoken permits this elaborate structure to

melt and lose itself in the brew and stew of the “heart, friendship,

and inspiration.” Epicurus, it is said, believed that the world

generally should be given over to each individual’s opinions and whims

and according to the view we are criticising, the ethical fabric should

be treated in the same way. By this old wives’ decoction, which

consists in founding upon the feelings what has been for many centuries

the labour of reason and understanding, we no longer need the guidance

of any ruling conception of thought. On this point Goethe’s

Mephistopheles, and the poet is a good authority, has a remark, which I

have already used elsewhere: |

実際のところ、近年の哲学が国家について発した大げさな主張は、この問

題に関心を寄せる者なら誰でも、自らの頭脳から哲学を紡ぎ出すことで哲学者たることを証明できると確信するに足るものであった。この確信にもかかわらず、

哲学と称されるものは、真理は知り得ないと公然と宣言している。倫理的理想、国家、政府、憲法に関する真理は、各人の心、感情、熱意から湧き上がるものだ

と宣言する。こうした宣言は特に若者の熱心な耳に注がれてきた。「神は選ばれし者に眠りの中で真理を与える」という言葉が科学に適用されたため、眠る者は

皆、自らを選ばれし者と数えてきたのだ。だが眠りの中で扱うのは、眠りの産物に過ぎない。この浅はかな哲学者たちの指導者の一人であるフライス氏は、今や

有名な公の祝典の席で、国家と憲法について次のような見解を躊躇なく表明した。「国民が共通の精神によって統治される時、下から、すなわち人々の中から、

あらゆる公共事業を行うのに十分な生命力が湧き上がる。」

聖なる友情の絆で不可分に結ばれた生きた共同体が、国民奉仕のあらゆる側面と、人民を教育するあらゆる手段に身を捧げるだろう。」これは浅薄さの極みであ

る。なぜなら、この考えでは科学が思考や構想からではなく、直接的な知覚と気まぐれな空想から発展すると見なされているからだ。社会システムの多様な枝葉

の有機的連結こそが国家合理性の建築原理であり、この至高の国家建築学において、全体の強度は公共生活の明瞭な諸相の調和と、社会建築のあらゆる柱・アー

チ・支柱の安定性に依存する。しかし我々が論じた浅薄な教義は、この精巧な構造を「心、友情、霊感」という煮込み鍋の中で溶かし、失わせてしまう。エピク

ロスは世界全体を各個人の意見や気まぐれに委ねるべきだと主張したと言われるが、我々が批判する見解によれば、倫理の構造も同様に扱われるべきだというの

だ。この古い迷信の煮汁――何世紀にもわたる理性と理解の労作を感情に委ねるもの――によって、我々はもはや支配的な思想概念の導きを必要としない。この

点についてゲーテのメフィストフェレス(詩人は信頼できる権威だ)は、私が既に他所で引用した言葉を残している: |

| “Verachte nur Verstand und Wissenschaft, des Menschen allerhöchste Gaben - So hast dem Teufel dich ergeben und musst zu Grunde gehn.” |

「知性と科学を軽蔑するだけでいい、 それは人間にとって最高の賜物だ。 そうすれば悪魔に身を委ねることになり、 破滅するだろう。」 |

| It is no surprise that the view

just criticised should appear in the form of piety. Where, indeed, has

this whirlwind of impulse not sought to justify itself? In godliness

and the Bible it has imagined itself able to find authority for

despising order and law. And, in fact, it is piety of the sort which

has reduced the whole organised system of truth to elementary intuition

and feeling. But piety of the right kind leaves this obscure region,

and comes out into the daylight, where the idea unfolds and reveals

itself. Out of its sanctuary it brings a reverence for the law and

truth which are absolute and exalted above all subjective feeling. The particular kind of evil consciousness developed by the wishy-washy eloquence already alluded to, may be detected in the following way. It is most unspiritual, when it speaks most of the spirit. It is the most dead and leathern, when it talks of the scope of life. When it is exhibiting the greatest self-seeking and vanity it has most on its tongue the words “people” and “nation.” But its peculiar mark, found on its very forehead, is its hatred of law. Right and ethical principle, the actual world of right and ethical life are apprehended in thought, and by thought are given definite, general, and rational form, and this reasoned right finds expression in law. But feeling, which seeks its own pleasure, and conscience, which finds right in private conviction, regard the law as their most bitter foe. The right, which takes the shape of law and duty, is by feeling looked upon as a shackle or dead cold letter. In this law it does not recognise itself and does not find itself free. Yet the law is the reason of the object, and refuses to feeling the privilege of warming itself at its private hearth. Hence the law, as we shall occasionally observe, is the Shibboleth, by means of which are detected the false brethren and friends of the so-called people. Inasmuch as the purest charlatanism has won the name of philosophy, and has succeeded in convincing the public that its practices are philosophy, it has now become almost a disgrace to speak in a philosophic way about the state. Nor can it be taken ill, if honest men become impatient, when the subject is broached. Still less is it a surprise that the government has at last turned its attention to this false philosophising. With us philosophy is not practised as a private art, as it was by the Greeks, but has a public place, and should therefore be employed only in the service of the state. The government has, up till now, shown such confidence in the scholars in this department as to leave the subject matter of philosophy wholly in their hands. Here and there, perhaps, has been shown to this science not confidence - so much as indifference, and professorships have been retained as a matter of tradition. In France, as far as I am aware, the professional teaching of metaphysics at least has fallen into desuetude. In any case the confidence of the state has been ill requited by the teachers of this subject. Or, if we prefer to see in the state not confidence, but indifference, the decay of fundamental knowledge must be looked upon as a severe penance. Indeed, shallowness is to all appearance most endurable and most in harmony with the maintenance of order and peace, when it does not touch or hint at any real issue. |

批判された見解が敬虔という形で現れるのは当然だ。この衝動の旋風が自

らを正当化しようとしない場所などどこにあるというのか。敬虔と聖書の中に、秩序と法を軽んじる権威を見出せると想像してきたのだ。そして実際、この種の

敬虔こそが、真理の体系全体を初歩的な直感と感情に還元してきたのである。しかし正しい敬虔は、この曖昧な領域を離れ、思想が展開し自らを明らかにする日

光の下へ出る。その聖域から、あらゆる主観的感情を超越した絶対的かつ崇高な法と真理への畏敬をもたらすのだ。 先述した曖昧な雄弁によって育まれた悪しき意識の特質は、次のように見抜ける。それは最も精神を語る時、最も非精神的である。人生の意義を語る時、最も死 んだ革のようなものである。最大の自己追求と虚栄を露わにする時、その口に最も頻繁に上るのは「人々」と「国民」という言葉だ。しかしその額に刻まれた特 異な印は、法への憎悪である。 正義と倫理の原理、すなわち正義と倫理の実践的世界は、思考によって把握され、思考によって明確で普遍的かつ合理的な形を与えられる。そしてこの理性的な 正義は法として表現される。しかし、自らの快楽を求める感情と、私的な確信の中に正義を見出す良心は、法を最も憎むべき敵と見なす。法と義務の形をとる正 義は、感情によって束縛や冷たい文字の塊と見なされるのだ。この法の中に、感情は自らを認めず、自由を見出さない。しかし法は対象の理性であり、感情が私 的な炉辺で暖を取る特権を拒む。ゆえに法は、我々が時折観察するように、いわゆる民衆の偽りの兄弟や友人を暴くためのシボレト(見分けの言葉)なのであ る。 最も純粋なペテン師が哲学の名を勝ち取り、その行為が哲学であると公衆を説得することに成功した以上、国家について哲学的に語るのは今やほとんど恥辱と なった。誠実な人々がこの話題に触れると苛立つのも無理はない。ましてや政府がようやくこの偽りの哲学に目を向けたのは驚くに当たらない。 我々にとって哲学は、ギリシャ人のように私的な技芸として実践されるのではなく、公的な場を持つ。ゆえに国家の奉仕にのみ用いられるべきである。政府はこ れまで、この分野の学者たちに絶大な信頼を寄せ、哲学の主題を完全に彼らの手に委ねてきた。所々では、この学問に対して信頼というよりむしろ無関心が示さ れ、教授職は伝統として維持されてきたに過ぎない。フランスでは、少なくとも形而上学の専門教育は廃れつつあると承知している。いずれにせよ、国家の信頼 は、この分野の教師たちによって裏切られてきた。あるいは、国家の態度を信頼ではなく無関心と見做すならば、基礎的知識の衰退は厳しい罰と見なされねばな らない。実際、浅薄さは、いかなる本質的問題にも触れず、示唆さえしない限り、あらゆる見かけ上、最も耐えやすく、秩序と平和の維持に最も調和しているよ うに見えるのだ。 |

| Hence it would not be necessary

to bring it under public control, if the state did not require deeper

teaching and insight, and expect science to satisfy the need. Yet this

shallowness, notwithstanding its seeming innocence, does bear upon

social life, right and duty generally, advancing principles which are

the very essence of superficiality. These, as we have learned so

decidedly from Plato, are the principles of the Sophists, according to

which the basis of right is subjective aims and opinions, subjective

feeling and private conviction. The result of such principles is quite

as much the destruction of the ethical system, of the upright

conscience, of love and right, in private persons, as of public order

and the institutions of the state. The significance of these facts for

the authorities will not be obscured by the claim that the bolder of

these perilous doctrines should be trusted, or by the immunity of

office. The authorities will not be deterred by the demand that they should protect and give free play to a theory which strikes at the substantial basis of conduct, namely, universal principles, and that they should disregard insolence on the ground of its being the exercise of the teacher’s function. To him, to whom God gives office, He gives also understanding is a well-worn jest, which no one in our time would like to take seriously. In the methods of teaching philosophy, which have under the circumstances been reanimated by the government, the important element of protection and support cannot be ignored. The study of philosophy is in many ways in need of such assistance. Frequently in scientific, religious, and other works may be read a contempt for philosophy. Some, who have no conspicuous education and are total strangers to philosophy, treat it as a cast-off garment. They even rail against it, and regard as foolishness and sinful presumption its efforts to conceive of God and physical and spiritual nature. They scout its endeavour to know the truth. Reason, and again reason, and reason in endless iteration is by them accused, despised, condemned. Free expression, also, is given by a large number of those, who are supposed to be cultivating scientific research, to their annoyance at the unassailable claims of the conception. When we, I say, are confronted with such phenomena as these, we are tempted to harbour the thought that old traditions of tolerance have fallen out of use, and no longer assure to philosophy a, place and public recognition. |

したがって、国家がより深い教えと洞察を必要とせず、科学がその必要を

満たすと期待するのであれば、これを公的管理下に置く必要はない。しかしこの浅薄さは、一見無害に見えるにもかかわらず、社会生活や権利・義務全般に影響

を及ぼし、まさに表層性の本質である原理を推進するのだ。これらは、我々がプラトンから明らかに学んだ通り、ソフィストの原理である。すなわち、正義の基

盤は主体的な目的や意見、主体的な感情や私的な確信にあるとする原理だ。このような原理の結果は、個人の倫理体系や正しい良心、愛や正義を破壊するのと同

様に、公共秩序や国家の制度をも破壊する。これらの危険な教義を大胆に唱える者を信頼すべきだという主張や、職権による免責によって、権力者にとってのこ

れらの事実の重要性が覆い隠されることはない。 権力者は、行動の実質的基盤、すなわち普遍的原理を攻撃する理論を保護し自由に展開させるべきだという要求や、教師の職務の行使であるという理由で傲慢を 無視すべきだという要求によって、決して抑止されない。神が職位を与える者に理解も与えるというのは、よく使われる冗談であり、現代では誰も真剣に受け止 めようとはしない。 政府によって状況下で再活性化された哲学教育の方法においては、保護と支援という重要な要素を無視することはできない。哲学の研究は多くの点でそのような 支援を必要としている。科学や宗教などの著作において、哲学に対する軽蔑が頻繁に読み取れる。目立った教養もなく哲学とは無縁の人間が、哲学を古着のよう に扱う。彼らは哲学を罵倒し、神や物理的・精神的自然を構想しようとする哲学の試みを愚かさと罪深い傲慢と見なす。真理を知ろうとする哲学の努力を嘲笑す る。理性、そしてまた理性、果てしなく繰り返される理性が、彼らによって非難され、軽蔑され、断罪されるのだ。また、科学的研究を育むべきとされる多くの 人々が、この概念の揺るぎない主張に対する不快感を、自由に表現している。我々がこうした現象に直面する時、古くからの寛容の伝統が廃れ、哲学に居場所と 公的な認知をもはや保証していないのではないかと、考えを抱かずにはいられない。 |

| Footnote: The same finds

expression in a letter of Joh. v. Müller (Works, Part VIII., p. 56),

who, speaking of the condition of Rome in the year 1803, when the city

was under French rule, writes, “A professor, asked how the public

academies were doing, answered, ‘On les tolère comme les bordels!’”

Similarly the so-called theory of reason or logic we may still hear

commended, perhaps under the belief that it is too dry and unfruitful a

science to claim any one’s attention, or, if it be pursued here and

there, that its formulae are without content, and, though not of much

good, can be of no great harm. Hence the recommendation, so it is

thought, if useless, can do no injury. |

脚注:同様の表現がヨハン・フォン・ミュラーの手紙(著作集第VIII

巻56頁)にも見られる。彼は1803年、ローマがフランス支配下にあった当時の状況を語りながらこう記している。「ある教授が公立アカデミーの現状を尋

ねられ、『娼館のように黙認されている』と答えた」

同様に、いわゆる理性論や論理学の理論が今も称賛されることがある。おそらくそれは、あまりに乾燥して実りのない学問だから誰の関心も引かない、あるいは

所々で研究されてもその定式は中身がなく、大した益はないが害も大きくないという信念のもとでだろう。だから推奨されるのだ、役に立たないなら害もないだ

ろうと考えられて。 |

| These presumptuous utterances,

which are in vogue in our time, are, strange to say, in a measure

justified by the shallowness of the current philosophy. Yet, on the

other hand, they have sprung from the same root as that against which

they so thanklessly direct their attacks. Since that self-named

philosophising has declared that to know the truth is vain, it has

reduced all matter of thought to the same level, resembling in this way

the despotism of the Roman Empire, which equalised noble and slave,

virtue and vice, honour and dishonour, knowledge and ignorance. In such

a view the conceptions of truth and the laws of ethical life are simply

opinions and subjective convictions, and the most criminal principles,

provided only that they are convictions, are put on a level with these

laws. Thus, too, any paltry special object, be it never so flimsy, is

given the same value as au interest common to all thinking men and the