ロバート・ストレンジ・マクナマラ

Robert "Strange" McNamara;1916-2009

解説:池田光穂

| Robert Strange

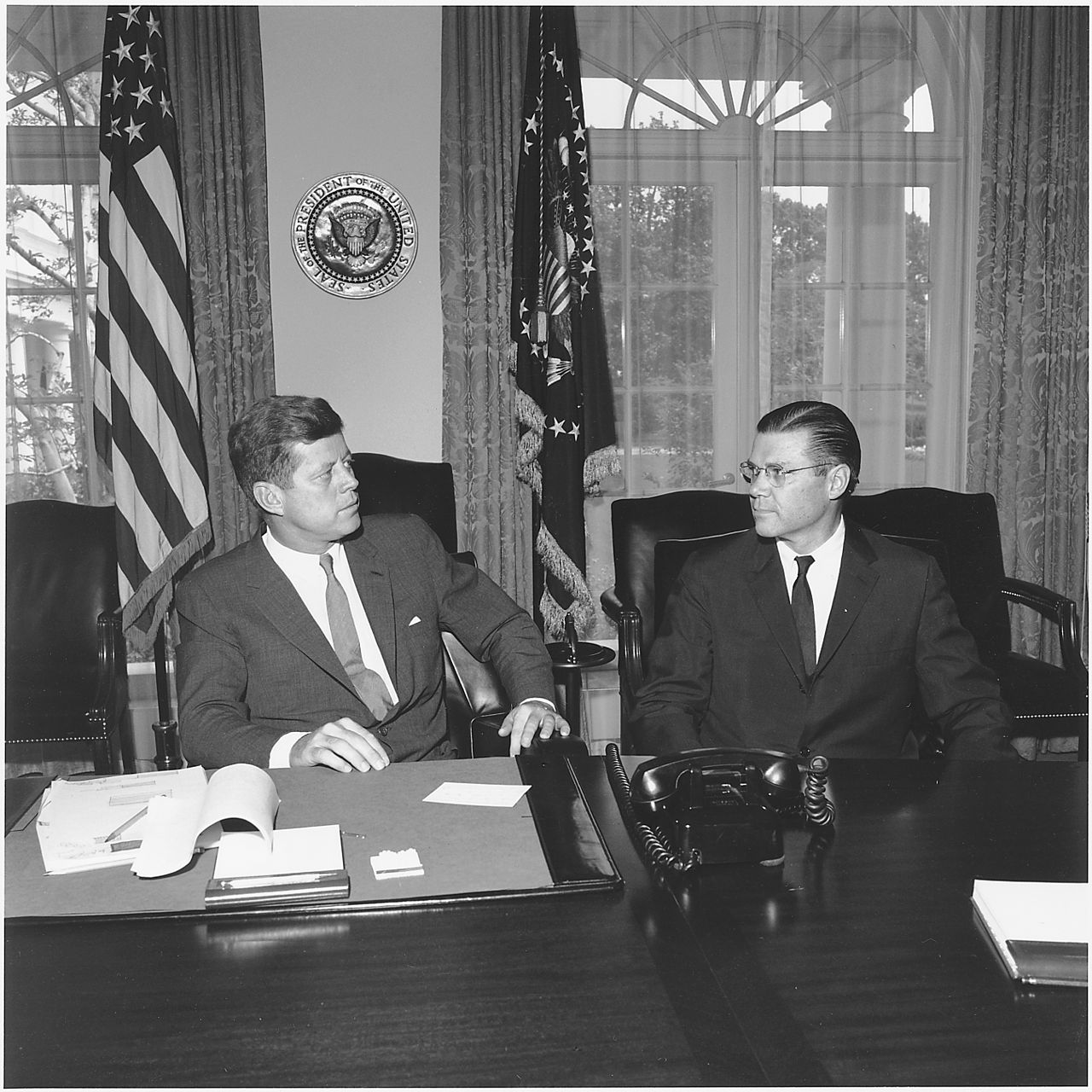

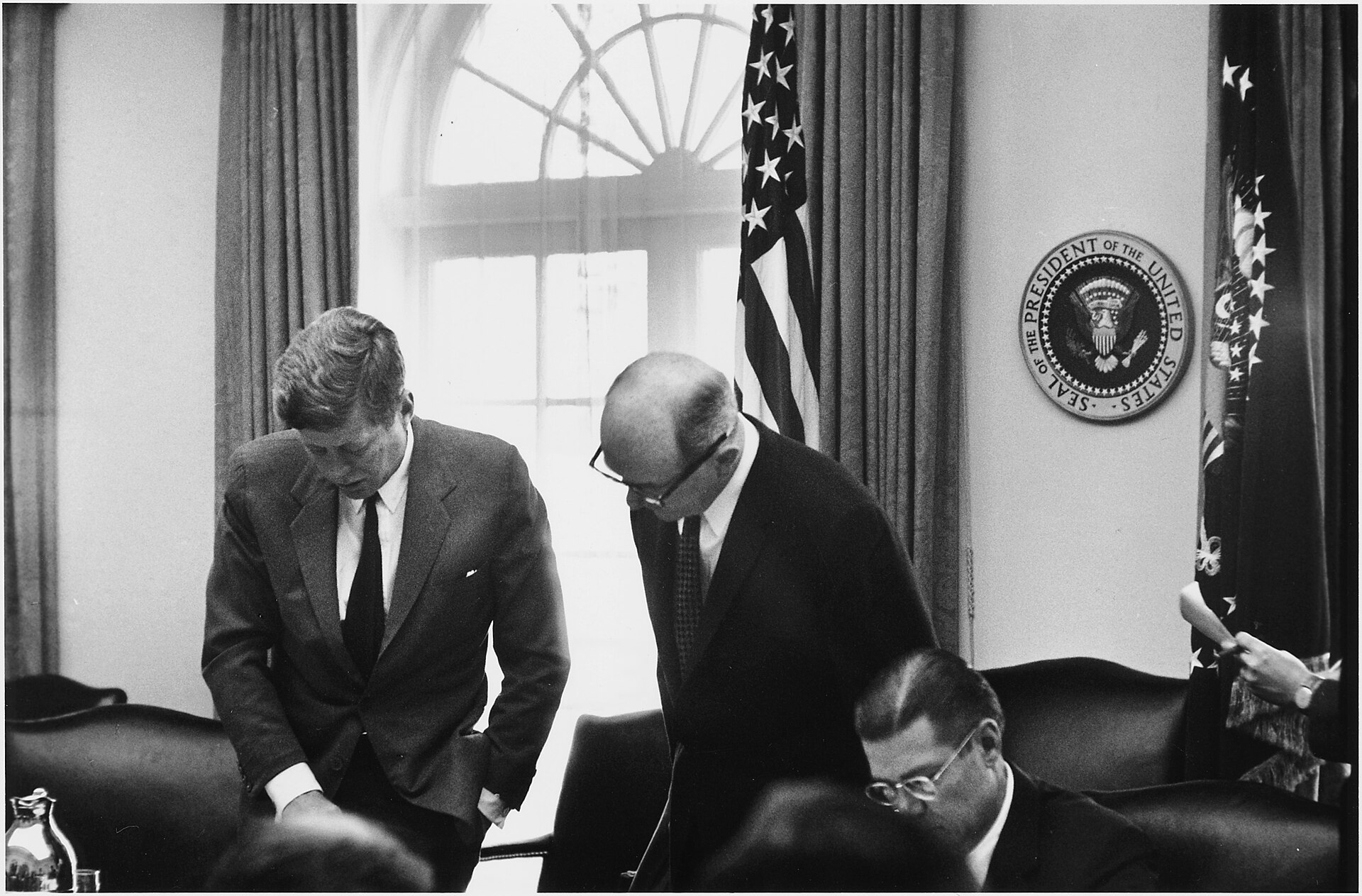

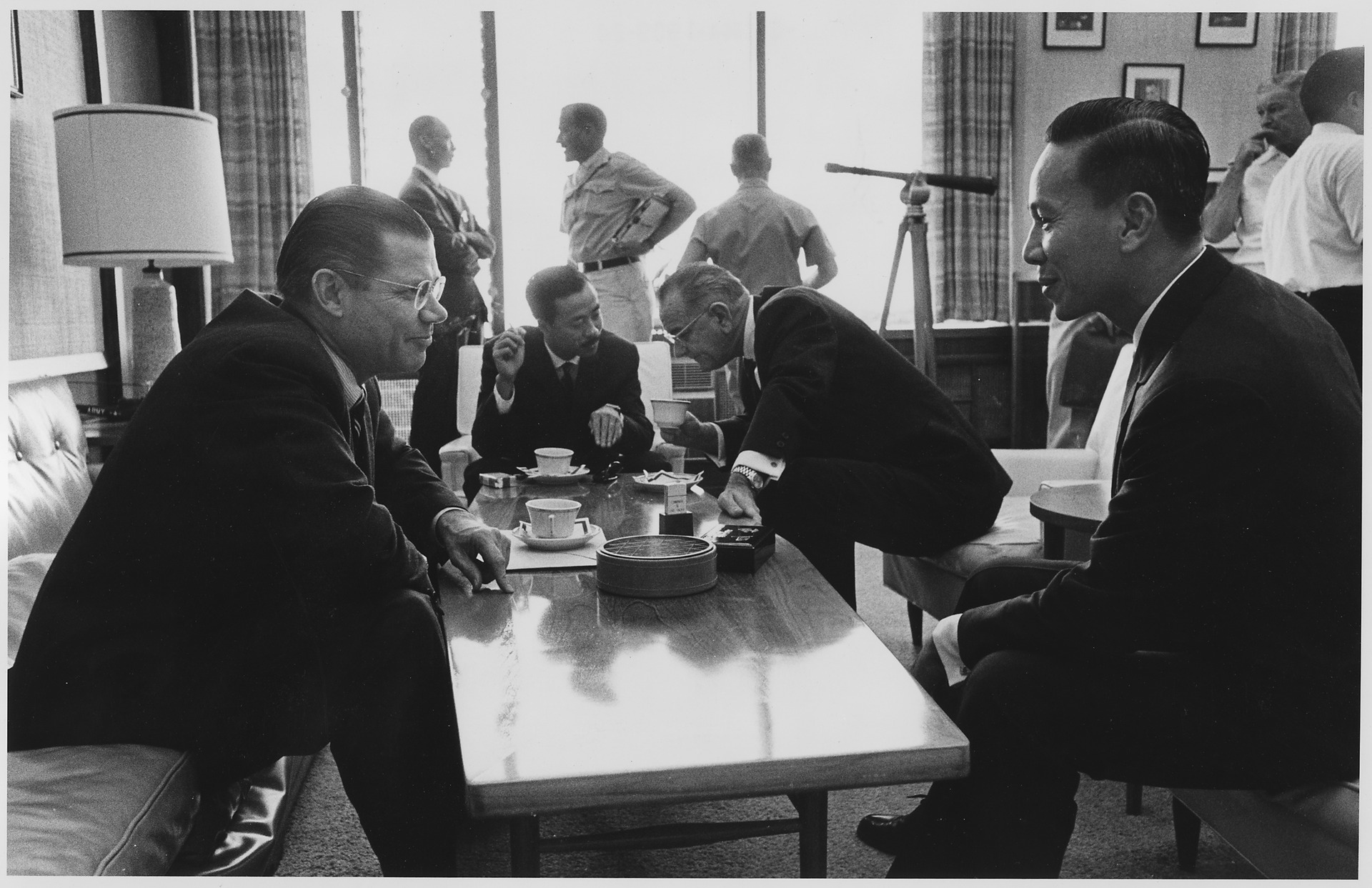

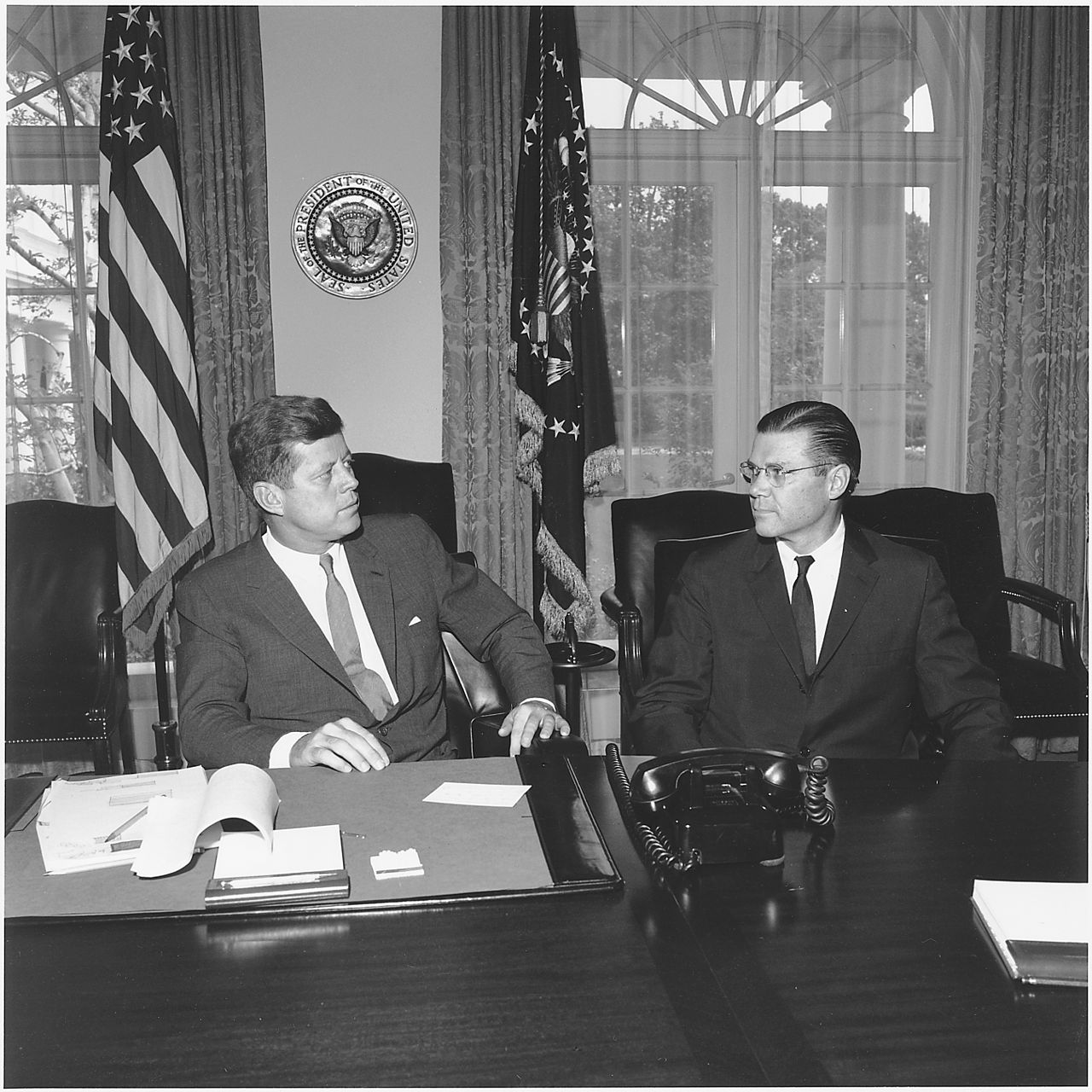

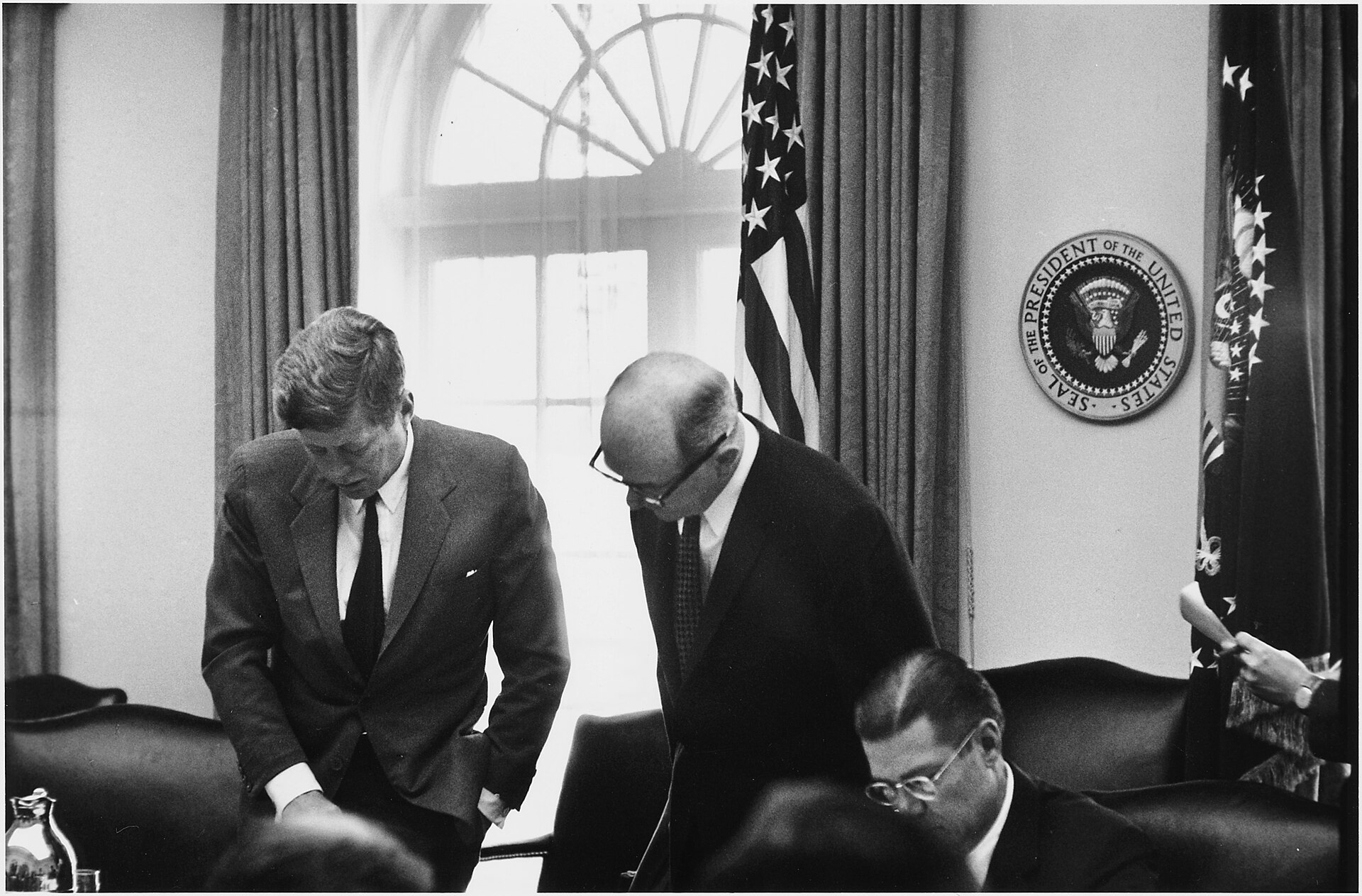

McNamara (/ˈmæknəmærə/; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American

businessman and government official who served as the eighth United

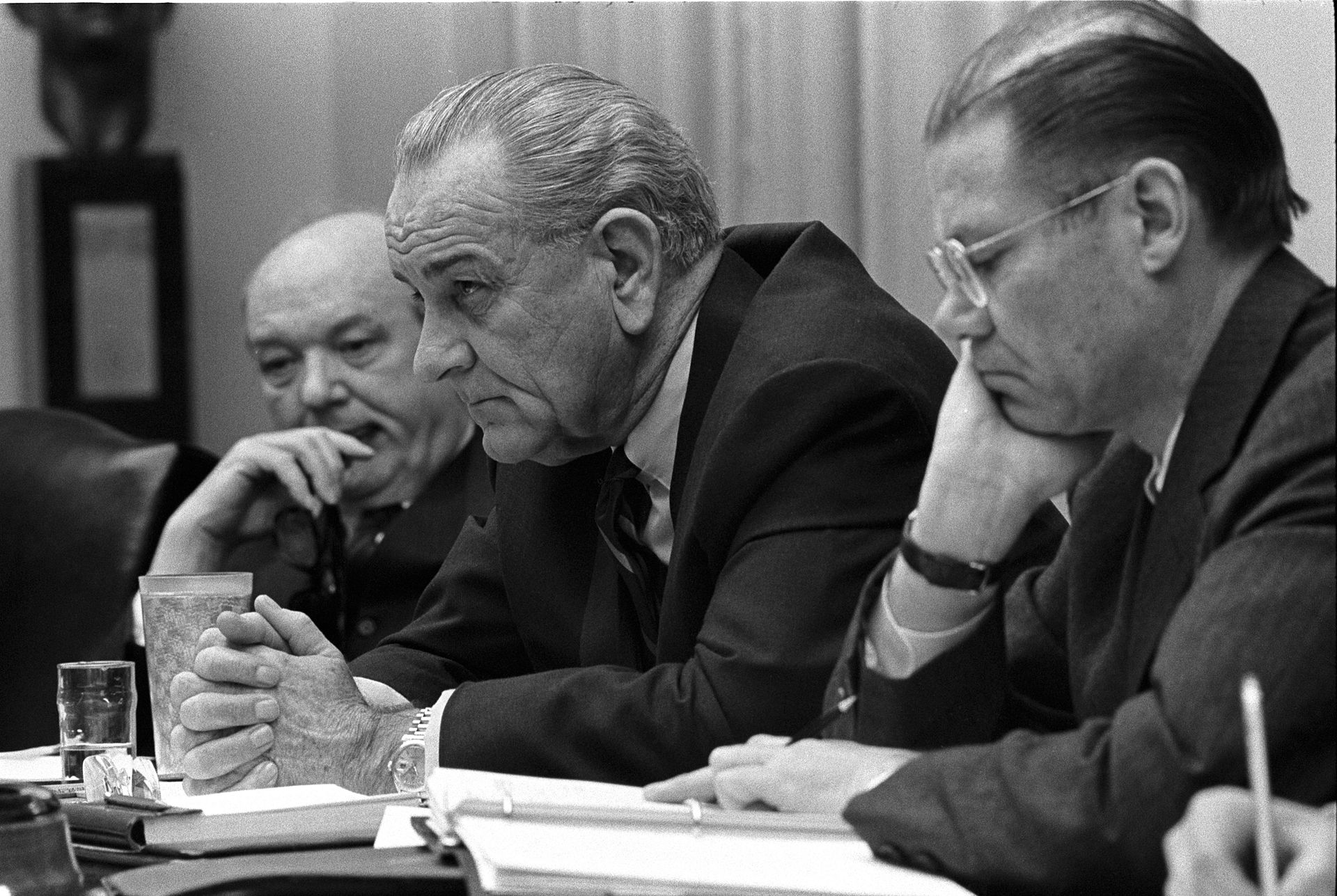

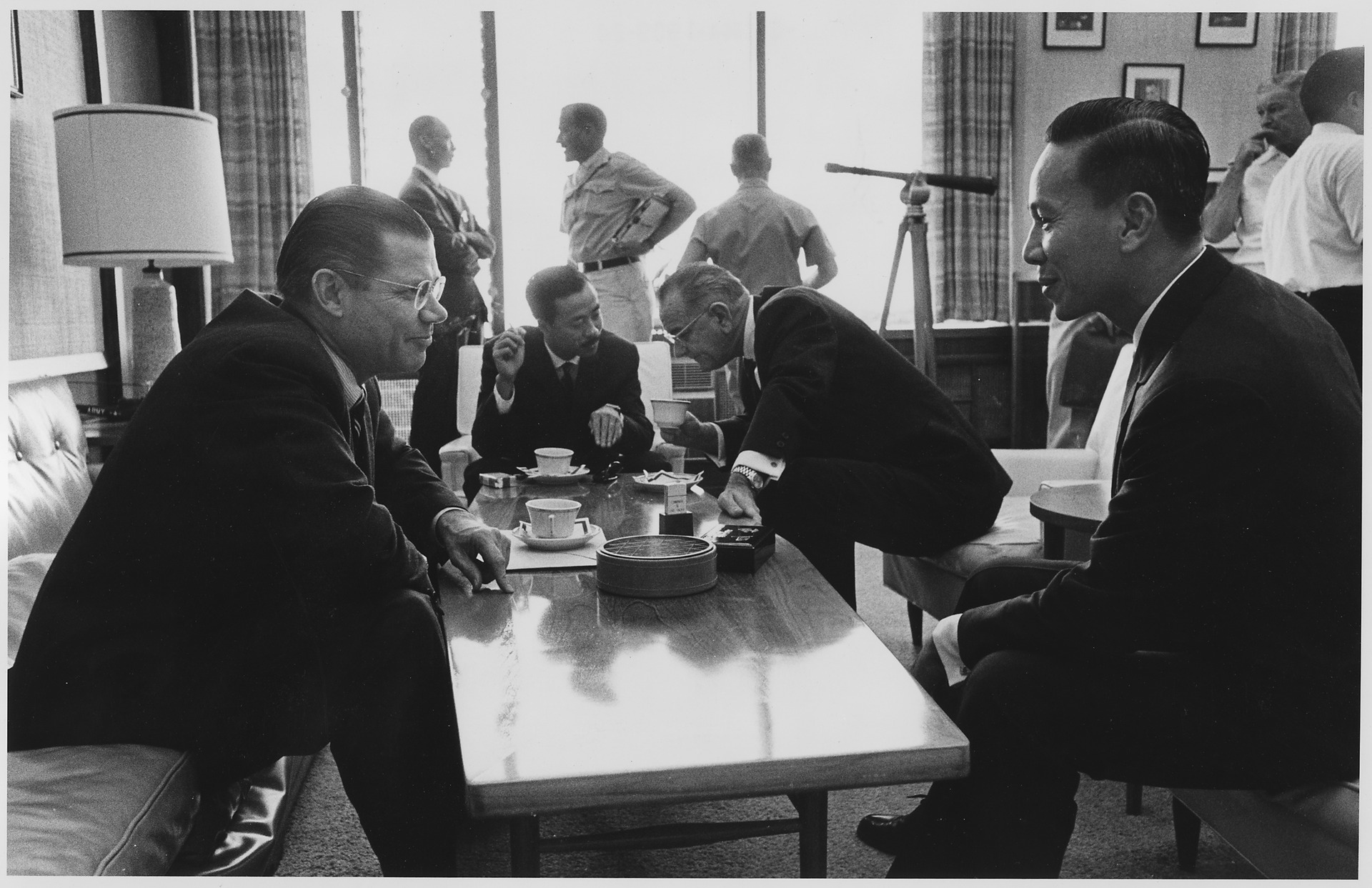

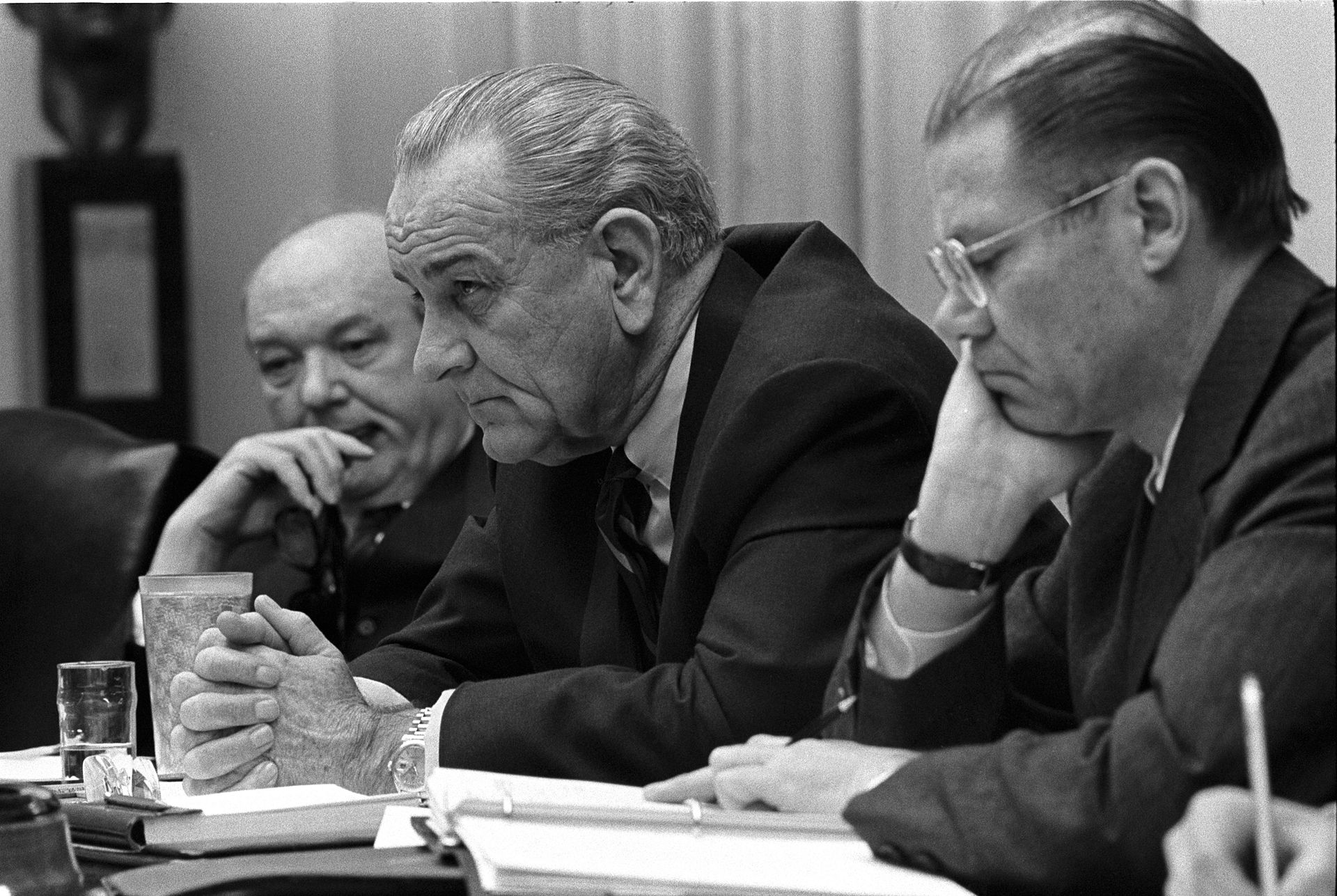

States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F.

Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson at the height of the Cold War. He remains

the longest-serving secretary of defense, having remained in office

over seven years. He played a major role in promoting the U.S.'s

involvement in the Vietnam War.[3] McNamara was responsible for the

institution of systems analysis in public policy, which developed into

the discipline known today as policy analysis.[4] McNamara was born in San Francisco, California, and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley and Harvard Business School.[5] He served in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. After World War II, Henry Ford II hired McNamara and a group of other Army Air Force veterans to work for Ford Motor Company. These "Whiz Kids" helped reform Ford with modern planning, organization, and management control systems. After briefly serving as Ford's president, McNamara accepted appointment as secretary of defense. McNamara became a close adviser to Kennedy and advocated the use of a blockade during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kennedy and McNamara instituted a Cold War defense strategy of flexible response, which anticipated the need for military responses short of massive retaliation. McNamara consolidated intelligence and logistics functions of the Pentagon into two centralized agencies: the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Defense Supply Agency. During the Kennedy administration, McNamara presided over a build-up of U.S. soldiers in South Vietnam. After the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident, the number of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam escalated dramatically. McNamara and other U.S. policymakers feared that the fall of South Vietnam to a Communist regime would lead to the fall of other governments in the region. McNamara grew increasingly skeptical of the efficacy of committing U.S. troops to South Vietnam. In 1968, he resigned as secretary of defense to become president of the World Bank. He served as president until 1981, shifting the focus of the World Bank from infrastructure and industrialization towards poverty reduction. After retiring, he served as a trustee of several organizations, including the California Institute of Technology and the Brookings Institution. In his later writings and interviews, he expressed regret for the decisions he made during the Vietnam War. |

ロバート・ストレンジ・マクナマラ(Robert Strange

McNamara、/ˈmæknəmærə/、1916年6月9日 -

2009年7月6日)は、冷戦の最中であった1961年から1968年まで、ジョン・F・ケネディ、リンドン・B・ジョンソンの両大統領の下で第8代アメ

リカ国防長官を務めたアメリカの実業家、政府高官である。国防長官在任期間が7年を超える最長記録を保持している。

彼は、米国のベトナム戦争への介入を推進する上で重要な役割を果たした。[3]

マクナマラは、公共政策におけるシステム分析の導入に責任があり、それは今日では政策分析として知られる学問分野へと発展した。[4] マクナマラはカリフォルニア州サンフランシスコで生まれ、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校とハーバード・ビジネス・スクールを卒業した。[5] 第二次世界大戦中はアメリカ陸軍航空軍に従軍した。 第二次世界大戦後、ヘンリー・フォード2世はマクナマラと他の陸軍航空軍退役軍人のグループをフォード・モーター社に採用した。 この「ウィズキッズ」と呼ばれるグループは、近代的な計画、組織、管理統制システムによりフォード社の改革を支援した。フォード社の社長を短期間務めた 後、マクナマラは国防長官に任命された。 マクナマラはケネディの側近となり、キューバ危機の際には海上封鎖を主張した。ケネディとマクナマラは、大規模報復に及ばない程度の軍事的対応の必要性を 予見した柔軟対応戦略という冷戦下の防衛戦略を打ち出した。マクナマラは国防総省の諜報および後方支援機能を2つの中央機関、国防情報局と国防供給庁に統 合した。ケネディ政権下で、マクナマラは南ベトナムにおける米兵の増派を指揮した。1964年のトンキン湾事件の後、ベトナム駐留米兵の数は劇的に増加し た。マクナマラをはじめとする米国の政策立案者たちは、南ベトナムが共産主義政権に陥落すれば、その地域の他の政府も陥落するのではないかと危惧した。 マクナマラは、南ベトナムに米軍を投入することの有効性についてますます疑念を深めていった。1968年、彼は国防長官を辞任し、世界銀行総裁に就任し た。彼は1981年まで総裁を務め、世界銀行の重点をインフラ整備や工業化から貧困削減へと移行させた。引退後は、カリフォルニア工科大学やブルッキング ス研究所など、複数の組織の理事を務めた。晩年には、著述やインタビューで、ベトナム戦争中の自身の決断を後悔していると述べた。 |

| Early life and career Robert McNamara was born in San Francisco, California.[3] His father was Robert James McNamara, sales manager of a wholesale shoe company, and his mother was Clara Nell (Strange) McNamara.[6][7][8] His father's family was Irish and, in about 1850, following the Great Irish Famine, had emigrated to the U.S., first to Massachusetts and later to California.[9] He graduated from Piedmont High School in Piedmont, California in 1933, where he was president of the Rigma Lions boys club[10] and earned the rank of Eagle Scout. McNamara attended the University of California, Berkeley and graduated in 1937 with a B.A. in economics with minors in mathematics and philosophy. He was a member of the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity,[11] was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in his sophomore year, and earned a varsity letter in crew. Before commissioning into the Army Air Force, McNamara was a Cadet in the Golden Bear Battalion at U.C. Berkeley.[12] McNamara was also a member of the UC Berkeley's Order of the Golden Bear, a fellowship of students and leading faculty members formed to promote leadership within the student body. He then attended Harvard Business School, where he earned an MBA in 1939. Immediately thereafter, McNamara worked for a year at Price Waterhouse, a San Francisco accounting firm. He returned to Harvard in August 1940 to teach accounting in the Business School and became the institution's highest-paid and youngest assistant professor at that time.[13] |

生い立ちとキャリア ロバート・マクナマラはカリフォルニア州サンフランシスコで生まれた。[3] 父親は卸売靴会社の営業部長ロバート・ジェームズ・マクナマラ、母親はクララ・ネル(ストレンジ)・マクナマラであった。[6][7][8] 父方の家系はアイルランド系で、 大飢饉を逃れてアメリカに移住し、最初はマサチューセッツ州、後にカリフォルニア州に移り住んだ。[9] 1933年にカリフォルニア州ピードモントのピードモント高校を卒業し、在学中はライオンズクラブの少年クラブの会長を務め、イーグルスカウトの称号を得 た。マクナマラはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校に進学し、1937年に経済学の学士号を取得して卒業した。副専攻は数学と哲学であった。彼はファイ・ガ ンマ・デルタ友愛会の会員であり[11]、2年生の時にファイ・ベータ・カッパに選出され、ボート競技で代表選手として活躍した。陸軍航空軍に入隊する 前、マクナマラはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校のゴールデン・ベア大隊の士官候補生であった[12]。マクナマラはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の ゴールデン・ベア勲章の会員でもあり、学生と指導的な教授陣の親睦団体で、学生間のリーダーシップを促進するために結成された。その後、ハーバード・ビジ ネス・スクールに進学し、1939年にMBAを取得した。 その後すぐに、マクナマラはサンフランシスコの会計事務所プライス・ウォーターハウスで1年間働いた。1940年8月にハーバードに戻り、ビジネススクー ルで会計学を教え、当時、同校で最も報酬が高く、かつ最年少の助教授となった。[13] |

| World War II Following his involvement in a Harvard program to teach analytical approaches used in business to officers of the United States Army Air Forces, McNamara entered the USAAF as a captain in early 1943, serving most of World War II with its Office of Statistical Control. One of his major responsibilities was the analysis of U.S. bombers' efficiency and effectiveness, especially the B-29 forces commanded by Major General Curtis LeMay in India, China, and the Mariana Islands.[14] McNamara established a statistical control unit for the XX Bomber Command and devised schedules for B-29s doubling as transports for carrying fuel and cargo over the Hump. He left active duty in 1946 with the rank of lieutenant colonel and with a Legion of Merit. |

第二次世界大戦 ハーバード大学のプログラムで、アメリカ陸軍航空軍の将校たちにビジネスで用いられる分析的アプローチを教えた後、マクナマラは1943年初頭に大尉とし てアメリカ陸軍航空軍に入隊し、統計管理室で第二次世界大戦の大半を過ごした。彼の主な任務のひとつは、米国の爆撃機の効率性と有効性の分析であり、特に カーチス・ルメイ少将が指揮するB-29部隊のインド、中国、マリアナ諸島における分析であった。マクナマラは第20爆撃軍団の統計管理部門を設立し、B -29が輸送機としても機能し、フッド諸島(現ミャンマー)の「ハンプ」地域に燃料や貨物を輸送するスケジュールを考案した。彼は1946年に大佐の階級 とレジオン・オブ・メリット勲章を授与されて現役を退いた。 |

| Ford Motor Company See also: Whiz Kids (Ford) In 1946, Tex Thornton, a colonel under whom McNamara had served, put together a group of former officers from the Office of Statistical Control to go into business together. Thornton had seen an article in Life magazine portraying the Ford Motor Company as being in dire need of reform. Henry Ford II, himself a World War II veteran from the Navy, hired the entire group of ten, including McNamara. They helped the money-losing company reform its chaotic administration through modern planning, organization, and management control systems. Because of their youth, combined with asking many questions, Ford employees initially and disparagingly referred to them as the "Quiz Kids". The Quiz Kids rebranded themselves as the "Whiz Kids". Starting as manager of planning and financial analysis, McNamara advanced rapidly through a series of top-level management positions. McNamara had Ford adopt computers to construct models to find the most efficient, rational means of production, which led to much rationalization.[15] McNamara's style of "scientific management" with his use of spreadsheets featuring graphs showing trends in the auto industry were regarded as extremely innovative in the 1950s and were much copied by other executives in the following decades.[15] In his 1995 memoirs, McNamara wrote: "I had spent fifteen years as a manager [at Ford] identifying problems and forcing organizations—often against their will—to think deeply and realistically about alternative courses of action and their consequences".[15] He was a force behind the Ford Falcon sedan, introduced in the fall of 1959—a small, simple and inexpensive-to-produce counter to the large, expensive vehicles prominent in the late 1950s. McNamara placed a high emphasis on safety: the Lifeguard options package introduced the seat belt (a novelty at the time), padded visor, and dished steering wheel, which helped to prevent the driver from being impaled on the steering column during a collision.[16][17] After the Lincoln line's very large 1958, 1959, and 1960 models proved unpopular, McNamara pushed for smaller versions, such as the 1961 Lincoln Continental. On November 9, 1960, McNamara became the first president of the Ford Motor Company from outside the Ford family since John S. Gray in 1906.[18] |

フォード・モーター・カンパニー 関連情報: ウィズキッズ(フォード) 1946年、マクナマラが仕えていたテキサス・ソーントン大佐は、統計管理事務所の元役員たちを集め、一緒に事業を始めることにした。ソーントンは、 フォード・モーター・カンパニーが改革を切実に必要としていると描いた記事をライフ誌で目にした。自身も第二次世界大戦の海軍退役軍人であるヘンリー・ フォード2世は、マクナマラを含む10人のグループ全員を雇った。 彼らは、赤字経営に陥っていた同社を、近代的な計画、組織、管理統制システムによって、混乱した経営状態から改革した。若かった彼らは、多くの質問を投げ かけたため、フォードの従業員たちは当初、彼らを「クイズ・キッズ」とあざけりをもって呼んだ。クイズ・キッズたちは、自らを「ウィズ・キッズ」と改名し た。 マクナマラは、企画および財務分析のマネージャーとしてキャリアをスタートさせ、その後、一連の最高経営責任者職を短期間で務めた。マクナマラは、フォー ドにコンピュータを導入し、最も効率的で合理的な生産手段を見つけるためのモデルを構築した。これにより、合理化が大幅に進んだ。[15] マクナマラの「科学的経営」スタイルは、自動車業界の傾向を示すグラフを特徴とするスプレッドシートの使用により、1950年代には非常に革新的とみなさ れ、その後の数十年間、他の経営者たちに多く模倣された。[15] 1995年の回顧録で、マクナマラは次のように書いている。 「私はフォードで15年間、問題を特定し、組織に(時には組織の意に反して)代替案とその結果について深く現実的に考えさせることを強いてきた」と記して いる。[15] 彼は、1959年秋に発売されたフォード・ファルコンセダンの推進力となった。これは、1950年代後半に目立っていた大型で高価な車に対する小型でシン プル、かつ生産コストの低い車であった。マクナマラは安全性を重視し、オプションパッケージ「ライフガード」でシートベルト(当時としては目新しい装備) やパッド付きバイザー、衝突時にステアリングコラムに刺さるのを防ぐディッシュ型ステアリングホイールを導入した。[16][17] リンカーン・ラインの1958年、1959年、1960年の非常に大型のモデルが不評だった後、マクナマラは1961年型リンカーン・コンチネンタルのよ うな小型モデルを推し進めた。 1960年11月9日、マクナマラは1906年のジョン・S・グレイ以来となる、フォード家以外からフォード・モーター・カンパニーの社長となった。 [18] |