シジフォス

Sisyphus, シーシュポス

Sisyphus by Titian (1548–49) , Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

☆ ギリシャ神話では、シシュフォス(/ˈsɪ Σίσυφος Sísyphos)はエフィラ(現在のコリントス)の創設者であり王であった。自分の権力を誇示するために訪問者を殺害した狡猾な暴君であった。この神聖 なもてなしの伝統(=歓待の伝統)に対する違反は、神々を大いに怒らせた。神々は彼を罰した。神々は彼に巨大な岩を転がして丘に登らせ、頂上に近づくたびに転がり落ちるよ うに仕向けた。古典が現代文化に与えた影響により、労多くして無益な仕事はシスフィアン(/sɪsɪˈfi-)と表現されるようになった。

| In Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos

(/ˈsɪsɪfəs/; Ancient Greek: Σίσυφος Sísyphos) was the founder and king

of Ephyra (now known as Corinth). He was a devious tyrant who killed

visitors to show off his power. This violation of the sacred

hospitality tradition greatly angered the gods. They punished him for

trickery of others, including his cheating death twice. The gods forced

him to roll an immense boulder up a hill only for it to roll back down

every time it neared the top, repeating this action for eternity.

Through the classical influence on modern culture, tasks that are both

laborious and futile are therefore described as Sisyphean

(/sɪsɪˈfiːən/).[2] |

ギ

リシャ神話では、シシュフォス(/ˈsɪ Σίσυφος

Sísyphos)はエフィラ(現在のコリントス)の創設者であり王であった。自分の権力を誇示するために訪問者を殺害した狡猾な暴君であった。この神聖

なもてなしの伝統に対する違反は、神々を大いに怒らせた。神々は彼を罰した。神々は彼に巨大な岩を転がして丘に登らせ、頂上に近づくたびに転がり落ちるよ

うに仕向けた。古典が現代文化に与えた影響により、労多くして無益な仕事はシスフィアン(/sɪsɪˈfi-)と表現されるようになった[2]。 |

| Etymology R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a pre-Greek origin and a connection with the root of the word sophos (σοφός, "wise").[3] German mythographer Otto Gruppe thought that the name derived from sisys (σίσυς, "a goat's skin"), in reference to a rain-charm in which goats' skins were used.[4] Family Sisyphus was formerly a Thessalian prince as the son of King Aeolus of Aeolia and Enarete, daughter of Deimachus.[5] He was the brother of Athamas, Salmoneus, Cretheus, Perieres, Deioneus, Magnes, Calyce, Canace, Alcyone, Pisidice and Perimede. Sisyphus married the Pleiad Merope by whom he became the father of Ornytion (Porphyrion[6]), Glaucus, Thersander and Almus.[7] He was the grandfather of Bellerophon through Glaucus;[8][9] and of Minyas, founder of Orchomenus, through Almus.[10] Another account related that Minyas was Sisyphus's son instead.[11] In other versions of the myth, Sisyphus was the true father of Odysseus by Anticleia instead of Laërtes.[12] |

語源 R. ドイツの神話学者オットー・グルッペは、ヤギの皮を使った雨のお守りにちなんで、シシス(σίσυς、「ヤギの皮」)に由来すると考えた[4]。 家族 シシフォスはかつてテッサリアの王子で、アイオリア王アイオロスとデイマコスの娘エナレテの息子であった[5]。アタマス、サルモネウス、クレテウス、ペリエレス、デイオネウス、マグネス、カリーチェ、カナーチェ、アルシオーネ、ピシディケ、ペリメデの兄弟であった。 シジフォスはプレアデス・メロペと結婚し、オルニシオン(ポルフィリオン[6])、グラウコス、テルサンデル、アルムスの父となった[7]。 グラウコスを通じてベレロフォンの祖父となり[8][9]、アルムスを通じてオルコメヌスの創始者ミニャスの祖父となった[10]。 神話の他のバージョンでは、シジフォスはラエルテスの代わりにアンティクリアによるオデュッセウスの本当の父親であった[12]。 |

| Reign Sisyphus was the founder and first king of Ephyra (supposedly the original name of Corinth).[8] King Sisyphus promoted navigation and commerce but was avaricious and deceitful. He killed guests and travelers in his palace, a violation of guest-obligations, which fell under Zeus' domain, thus angering the god. He took pleasure in these killings because they allowed him to maintain his iron-fisted rule. Conflict with Salmoneus Sisyphus and his brother Salmoneus were known to hate each other, and Sisyphus consulted the Oracle of Delphi on just how to kill Salmoneus without incurring any severe consequences for himself. From Homer onward, Sisyphus was famed as the craftiest of men. He seduced Salmoneus' daughter Tyro in one of his plots to kill Salmoneus, only for Tyro to slay their children when she discovered that Sisyphus was planning on using them to eventually dethrone her father. Cheating death Sisyphus betrayed one of Zeus' secrets by revealing the whereabouts of the Asopid Aegina to her father, the river god Asopus, in return for causing a spring to flow on the Corinthian acropolis.[8] Zeus ordered Thanatos to chain Sisyphus in Tartarus. Sisyphus was curious as to why Charon, whose job it was to guide souls to the underworld, had not appeared on this occasion. Sisyphus slyly asked Thanatos to demonstrate how the chains worked. As Thanatos was granting him his wish, Sisyphus seized the opportunity and trapped Thanatos in the chains instead. Once Thanatos was bound by the strong chains, no one died on Earth, causing an uproar. Ares, the god of war, became annoyed that his battles had lost their fun because his opponents would not die. The exasperated Ares intervened, freeing Thanatos, enabling deaths to happen again and turned Sisyphus over to him.[13] In some versions, Hades was sent to chain Sisyphus and was chained himself. As long as Hades was trapped, nobody could die. Consequently, sacrifices could not be made to the gods, and those that were old and sick were suffering. The gods finally threatened to make life so miserable for Sisyphus that he would wish he were dead. He then had no choice but to release Hades.[14] Before Sisyphus died, he had told his wife to throw his naked corpse into the middle of the public square (purportedly as a test of his wife's love for him). This caused Sisyphus to end up on the shores of the river Styx when he was brought to the underworld. Complaining to Persephone that this was a sign of his wife's disrespect for him, Sisyphus persuaded her to allow him to return to the upper world. Once back in Ephyra, the spirit of Sisyphus scolded his wife for not burying his body and giving it a proper funeral as a loving wife should. When Sisyphus refused to return to the underworld, he was forcibly dragged back there by Hermes.[15][16] In another version of the myth, Persephone was tricked by Sisyphus that he had been conducted to Tartarus by mistake, and so she ordered that he be released.[17] In Philoctetes by Sophocles, there is a reference to the father of Odysseus (rumoured to have been Sisyphus, and not Laërtes, whom we know as the father in the Odyssey) upon having returned from the dead.[clarification needed] Euripides, in Cyclops, also identified Sisyphus as Odysseus' father. Punishment in the underworld As a punishment for his crimes, Hades made Sisyphus roll a huge boulder endlessly up a steep hill in Tartarus.[8][18][19] The maddening nature of the punishment was reserved for Sisyphus due to his hubristic belief that his cleverness surpassed that of Zeus himself. Hades accordingly displayed his own cleverness by enchanting the boulder into rolling away from Sisyphus before he reached the top which ended up consigning Sisyphus to an eternity of useless efforts and unending frustration. Thus, pointless or interminable activities are sometimes described as "Sisyphean". Sisyphus was a common subject for ancient writers and was depicted by the painter Polygnotus on the walls of the Lesche at Delphi.[20] |

治世 シジフォス王はエフィラ(コリントの原名とされる)の創始者であり初代王であった[8]。シジフォス王は航海と商業を促進したが、欲深く欺瞞に満ちてい た。彼は自分の宮殿で客人や旅行者を殺したが、これはゼウスの支配下にある客人の義務違反であり、ゼウスを怒らせた。鉄拳支配を維持するため、彼はこのよ うな殺戮に喜びを感じていた。 サルモネウスとの対立 シジフォスと弟のサルモネウスは互いに憎み合っていたことが知られており、シジフォスはデルフォイの神託に、自分にとって深刻な結果を招くことなくサルモ ネウスを殺す方法を相談した。ホメロス以降、シジフォスは最も狡猾な男として名高い。彼はサルモネウスを殺す計画のひとつで、サルモネウスの娘ティロを誘 惑した。しかし、ティロは、シジフォスが最終的に父親を失脚させるために子供たちを使おうとしていることを知り、子供たちを殺してしまった。 死のごまかし シジフォスはゼウスの秘密を裏切り、コリントのアクロポリスに泉を湧かせる見返りに、彼女の父である河の神アソプスにアソピド・アエギナの居場所を明かした[8]。 ゼウスはタナトスに命じてシジフォスをタルタロスに鎖でつないだ。シジフォスは、魂を冥界に導くのが仕事であるカロンがなぜこの時に現れなかったのか不思 議に思った。シジフォスは狡猾にもタナトスに鎖の仕組みを教えてくれるように頼んだ。タナトスが願いを叶えようとしたとき、シジフォスはその機会をとら え、代わりにタナトスを鎖に閉じ込めた。タナトスが強力な鎖につながれると、地上では誰も死ななくなり、大騒ぎになった。戦いの神アレスは、相手が死なな いために戦いが面白くなくなったことに腹を立てた。苛立ったアレスは介入し、タナトスを解放して再び死が起こるようにし、シジフォスを彼に引き渡した [13]。 いくつかのバージョンでは、ハデスはシジフォスを鎖につなぐために送られ、自らも鎖につながれた。ハデスが囚われている限り、誰も死ぬことはできなかっ た。その結果、神々に生贄を捧げることができず、年老いた者や病気の者は苦しんでいた。神々はついに、シジフォスが死んだ方がましだと思うほど悲惨な人生 にしてやると脅した。そして彼は黄泉の国を解放するしかなかった[14]。 シジフォスは死ぬ前に、自分の裸の死体を広場の真ん中に投げ捨てるように妻に言っていた(妻の愛を試すためと言われている)。そのため、シジフォスは冥界 に連れて行かれるとき、三途の川の岸辺に行き着いた。これは妻が自分を軽んじている証拠だとペルセポネに訴えたシジフォスは、妻を説得して上の世界に戻る ことを許した。エフィラに戻ると、シジフォスの霊は、自分の遺体を埋葬せず、愛妻としてあるべき葬儀をしなかった妻を叱った。シジフォスが冥界に戻ること を拒否すると、彼はヘルメスによって強制的に引き戻された[15][16]。 神話の別のバージョンでは、ペルセポネはシジフォスが間違ってタルタロスに連れて行かれたと騙されたので、彼を解放するように命じた[17]。 ソフォクレスの『フィロクテテス』では、死から生還したオデュッセウスの父(『オデュッセイア』で父として知られるラエルテスではなく、シジフォスであっ たと噂されている)についての言及がある[要出典]。エウリピデスも『キュクロプス』の中で、シジフォスをオデュッセウスの父としている。 冥界での罰 その罪に対する罰として、ハデスはシジフォスにタルタロスの険しい丘の上で巨大な岩を延々と転がさせた。それに応じてハデスは、シジフォスが頂上に到達す る前に、シジフォスから転がり落ちるように玉石を魅惑することで、自らの賢さを見せつけ、結局、シジフォスは無駄な努力と終わりのない挫折を永遠に味わう ことになった。このように、無意味な活動や終わりのない活動は「シジフォス的」と表現されることがある。シジフォスは古代の作家にとって一般的な題材であ り、画家ポリグノトスによってデルフィのレシェの壁に描かれた[20]。 |

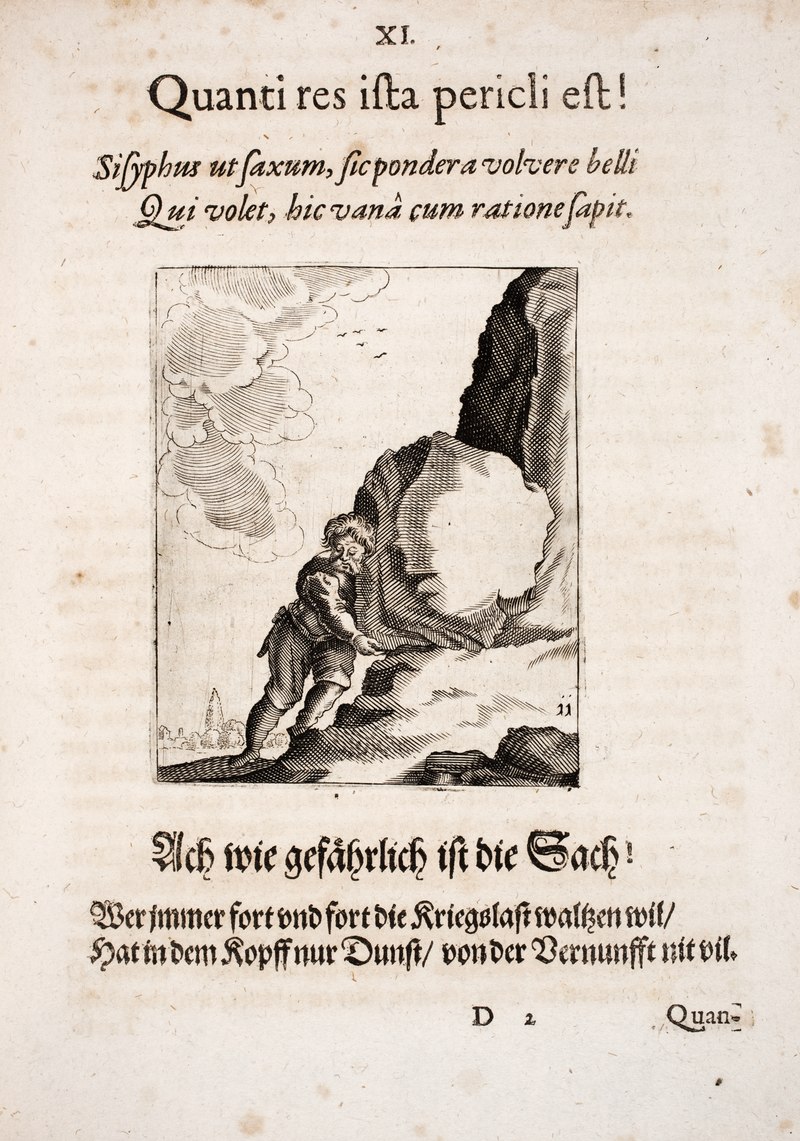

Interpretations Black and white etching of Sisyphus by Johann Vogel Sisyphus as a symbol for continuing a senseless war. Johann Vogel: Meditationes emblematicae de restaurata pace Germaniae, 1649 According to the solar theory, King Sisyphus is the disk of the sun that rises every day in the east and then sinks into the west.[21] Other scholars regard him as a personification of waves rising and falling, or of the treacherous sea.[21] The 1st-century BC Epicurean philosopher Lucretius interprets the myth of Sisyphus as personifying politicians aspiring for political office who are constantly defeated, with the quest for power, in itself an "empty thing", being likened to rolling the boulder up the hill.[22] Friedrich Welcker suggested that he symbolises the vain struggle of man in the pursuit of knowledge, and Salomon Reinach[23] that his punishment is based on a picture in which Sisyphus was represented rolling a huge stone Acrocorinthus, symbolic of the labour and skill involved in the building of the Sisypheum. Albert Camus, in his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus, saw Sisyphus as personifying the absurdity of human life, but Camus concludes "one must imagine Sisyphus happy" as "The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man's heart." More recently, J. Nigro Sansonese,[24] building on the work of Georges Dumézil, speculates that the origin of the name "Sisyphus" is onomatopoetic of the continual back-and-forth, susurrant sound ("siss phuss") made by the breath in the nasal passages, situating the mythology of Sisyphus in a far larger context of archaic (see Proto-Indo-European religion) trance-inducing techniques related to breath control. The repetitive inhalation–exhalation cycle is described esoterically in the myth as an up–down motion of Sisyphus and his boulder on a hill. In experiments that test how workers respond when the meaning of their task is diminished, the test condition is referred to as the Sisyphusian condition. The two main conclusions of the experiment are that people work harder when their work seems more meaningful, and that people underestimate the relationship between meaning and motivation.[25] |

解釈 シジフォスの白黒エッチング(ヨハン・フォーゲル作) 無意味な戦争を続ける象徴としてのシジフォス。ヨハン・フォーゲル:Meditationes emblematicae de restaurata pace Germaniae, 1649 太陽説によれば、シジフォス王は毎日東から昇り西に沈む太陽の円盤である[21]。 21] 紀元前1世紀のエピクロス派の哲学者ルクレティウスは、シジフォスの神話を、常に敗北する政治家を擬人化したものと解釈しており、権力を求めること自体が 「空しいこと」であり、玉石を転がして丘を登ることに例えられている[22]。 [フリードリッヒ・ウェルカーは、シシュフォスは知識を追い求める人間のむなしい闘争を象徴しているとし、サロモン・ライナッハは、シシュフォスの刑罰 は、シシュフェウム建設に関わる労働と技術を象徴する巨大な石アクロコリントスを転がすシシュフォスの絵に基づいているとした[23]。アルベール・カ ミュは、1942年のエッセイ『シジフォスの神話』の中で、シジフォスを人間の人生の不条理を擬人化したものと見ているが、カミュは、"高みに向かう闘い そのものが人の心を満たすのに十分である "として、"人はシジフォスの幸福を想像しなければならない "と結論づけている。より最近では、J.ニグロ・サンソネーゼ[24]がジョルジュ・デュメジルの研究を基に、「シジフォス」という名前の由来は、鼻腔内 の呼吸によって作られる連続的な往復音(「siss phuss」)の擬音語であると推測し、シジフォスの神話を、呼吸コントロールに関連する古代の(原始インド・ヨーロッパ宗教を参照)トランス誘発技術と いうはるかに大きな文脈の中に位置づけている。吸気と呼気を繰り返すサイクルは、神話ではシジフォスと丘の上の巨石の上下運動として難解に描写されてい る。 自分の仕事の意味が薄れたときに労働者がどう反応するかをテストする実験では、テスト条件はシジフォスの条件と呼ばれる。この実験の2つの主要な結論は、 自分の仕事がより有意義に見えるとき、人はより懸命に働くということと、人は意味とモチベーションの関係を過小評価しているということである[25]。 |

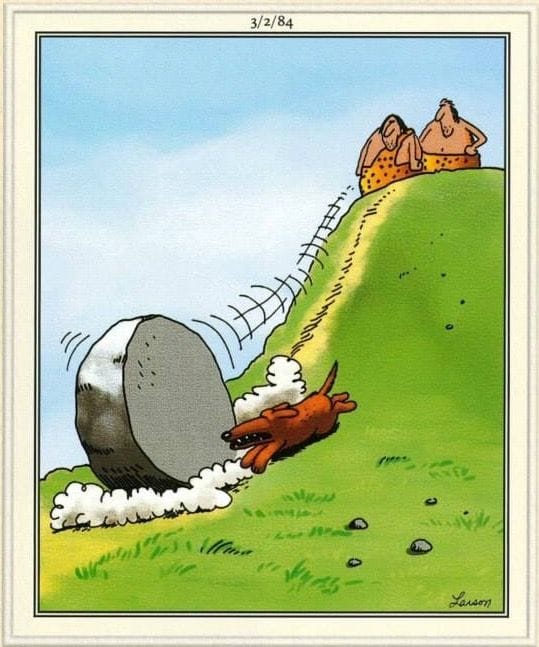

| Homer describes Sisyphus in both Book VI of the Iliad and Book XI of the Odyssey.[9][19] Ovid, the Roman poet, makes reference to Sisyphus in the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. When Orpheus descends and confronts Hades and Persephone, he sings a song so that they will grant his wish to bring Eurydice back from the dead. After this song is sung, Ovid shows how moving it was by noting that Sisyphus, emotionally affected for just a moment, stops his eternal task and sits on his rock, the Latin wording being inque tuo sedisti, Sisyphe, saxo ("and you sat, Sisyphus, on your rock").[26] In Plato's Apology, Socrates looks forward to the after-life where he can meet figures such as Sisyphus, who think themselves wise, so that he can question them and find who is wise and who "thinks he is when he is not."[27] Albert Camus, the French absurdist, wrote an essay entitled The Myth of Sisyphus, in which he elevates Sisyphus to the status of absurd hero. Franz Kafka repeatedly referred to Sisyphus as a bachelor; Kafkaesque for him were those qualities that brought out the Sisyphus-like qualities in himself. According to Frederick Karl: "The man who struggled to reach the heights only to be thrown down to the depths embodied all of Kafka's aspirations; and he remained himself, alone, solitary."[28] The philosopher Richard Taylor uses the myth of Sisyphus as a representation of a life made meaningless because it consists of bare repetition.[29] Wolfgang Mieder has collected cartoons that build on the image of Sisyphus, many of them editorial cartoons.[30] |

ホメロスは『イーリアス』第6巻と『オデュッセイア』第11巻の両方でシジフォスを描写している[9][19]。 ローマの詩人オヴィッドは、オルフェウスとエウリュディケの物語の中でシジフォスについて言及している。オルフェウスが黄泉とペルセポネと対決するとき、 彼はエウリュディケを死から蘇らせるという願いを叶えてもらうために歌を歌う。この歌が歌われた後、オヴィッドは、シジフォスがほんの一瞬感情的になって 永遠の仕事を止め、自分の岩の上に座ったことを記すことで、その歌がいかに感動的であったかを示している。 プラトンの『弁明』では、ソクラテスは死後の世界を楽しみにしており、そこでシジフォスのような自分を賢いと思っている人物に出会うことができる。 フランスの不条理主義者であるアルベール・カミュは、『シジフォスの神話』というエッセイを書き、その中でシジフォスを不条理な英雄の地位にまで高めている。 フランツ・カフカは、シジフォスを独身者として繰り返し言及した。彼にとってカフカ的とは、シジフォスのような資質を引き出す資質のことであった。フレデ リック・カールによれば、「高みに到達しようともがき、ただ深みに突き落とされる男は、カフカの願望のすべてを体現していた。 哲学者のリチャード・テイラーは、シジフォスの神話を、剥き出しの反復からなるために無意味な人生の表象として用いている[29]。 ヴォルフガング・ミーダーはシジフォスのイメージを基にした漫画を集めており、その多くは編集漫画である[30]。 |

| The Myth of Sisyphus, a 1942 philosophical essay by Albert Camus which uses Sisyphus' punishment as a metaphor for the absurd Sisyphus cooling, a cooling technique named after the Sisyphus myth Syzyfowe prace, a novel by Stefan Żeromski Comparable characters: Naranath Bhranthan, a willing boulder pusher in Indian folklore Jan Tregeagle, a Cornish magistrate who must empty Dozmary Pool with a limpet shell or weave sand into rope at Gwenor Cove Tantalus, who was similarly punished with a neverending toil Wu Gang – also tasked with the impossible: to fell a self-regenerating tree on the Moon |

シジフォスの神話、アルベール・カミュによる1942年の哲学的エッセイで、シジフォスの罰を不条理の比喩として用いている。 シジフォスの神話にちなんで名付けられた冷却技術。 Syzyfowe prace、ステファン・ジェロムスキーの小説。 類似の登場人物 ナラナート・ブランタン、インドの民話に登場する玉石を喜んで押す男。 ヤン・トレギーグル、コーンウォール地方の判事で、ドズマリー・プールの砂を足こぎ貝で空にしたり、グウェナー・コーブで砂を編んでロープにしたりしなければならない。 タンタロスも同様に、終わりのない苦役を課せられた。 呉剛(ウー・ギャング)もまた、月面で自己再生する木を伐採するという不可能を課せられた。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sisyphus |

|

|

Sisyphus Playing Dog by Gary Larson |

| Endgame,

by Samuel Beckett, is an absurdist, tragicomic one-act play about a

blind, paralyzed, domineering elderly man, his geriatric parents and

his doddering, dithering, harried, servile companion in an abandoned

house in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, who mention they are awaiting

some unspecified "end" which seems to be the end of their relationship,

death, and the end of the actual play itself. Much of the play's

content consists of terse, back and forth dialogue between the

characters reminiscent of bantering, along with trivial stage actions;

the plot is held together by the development of a grotesque

story-within-a-story that the character Hamm is relating. An

aesthetically profound part of the play is the way the

story-within-story and the actual play come to an end at roughly the

same time. The play's title refers to chess and frames the characters

as acting out a losing battle with each other or their fate. Originally written in French (entitled Fin de partie), the play was translated into English by Beckett himself [1] and was first performed on 3 April 1957 at the Royal Court Theatre in London in a French-language production. Written before but premiering after Waiting for Godot, it is arguably among Beckett's best works.[citation needed] The literary critic Harold Bloom called it the most original work of literature of the 20th century, saying that "[Other dramatists of the time] have no Endgame; to find a drama of its reverberatory power, you have to return to Ibsen."[2] Samuel Beckett considered it his masterpiece as the most aesthetically perfect, compact representation of his artistic views on human existence, and refers to it when speaking autobiographically through Krapp in Krapp's Last Tape when he mentions he had "already written the masterpiece". [citation needed]. Characters Hamm: Throughout the play remaining seated in an armchair fitted with castors, unable to stand, and blind. Hamm is dominating, acrimonious, banterous and comfortable in his misery. He claims to suffer, but his pessimism seems self-elected. He chooses to be isolated and self-absorbed. His relationships come off as parched of human empathy; he refers to his father as a "fornicator", refused to help his neighbor with oil for her lamp when she badly needed it, and has a fake pet dog which is a stuffed animal. Clov: Hamm's servant who is unable to sit. Taken in by Hamm as a child. Clov is wistful. He longs for something else, but has nothing to pursue. More mundane than Hamm, he reflects on his opportunities but takes little charge. Clov is benevolent, but weary. Nagg: Hamm's father who has no legs and lives in a dustbin. Nagg is gentle and fatherly, yet sorrowful and aggrieved in the face of his son's ingratitude. Nell: Hamm's mother who has no legs and lives in a dustbin next to Nagg. Reflective, she delivers a monologue about a beautiful day on Lake Como, and apparently dies during the course of the play. Samuel Beckett said that in his choice of character's names, he had in mind the word "hammer" and the word "nail" in English, French and German respectively, "clou" and "nagel". Beckett was an avid chess player, and the term endgame refers to the ending phase of a chess game. The play is dimly visible as a kind of metaphorical chess, albeit with limited symbolic meaning. Hamm at one point says "My kingdom for a knight-man!". Hamm, limited in his movement, resembles the king piece on a chess board, and Clov, who moves for him, a knight. |

サ

ミュエル・ベケット作の『エンドゲーム』は、黙示録的な荒地の廃屋で、盲目で半身不随の支配的な老人、老人の両親、おっちょこちょいでおっちょこちょいで

苛酷で下僕のような同伴者が、自分たちの関係の終わり、死、そして実際の劇そのものの終わりと思われる不特定の「終わり」を待っていると語る、不条理で悲

劇的な一幕劇である。戯曲の内容の多くは、雑談を思わせるような登場人物の間のつたない前後の会話と、些細な舞台上の行動で構成されている。プロットは、

登場人物のハムが語るグロテスクな物語の中の物語の展開によって支えられている。この戯曲の美学的に深い部分は、物語の中の物語と実際の戯曲がほぼ同時に

終わりを迎えることである。戯曲のタイトルはチェスを意味し、登場人物たちが互いに、あるいは運命との負け戦を演じているように組み立てられている。 原作はフランス語で書かれ(『Fin de partie』)、ベケット自身によって英訳され[1]、1957年4月3日にロンドンのロイヤル・コート劇場でフランス語上演された。文芸評論家のハロ ルド・ブルームはこの作品を20世紀で最も独創的な文学作品と呼び、「(当時の他の戯曲家には)『エンドゲーム』がない。 サミュエル・ベケットはこの作品を、人間存在に対する彼の芸術的見解を最も美学的に完璧に、コンパクトに表現したものとして自身の最高傑作とみなし、『ク ラップ最後のテープ』でクラップを通して自伝的に語る際に「すでに最高傑作を書いた」と言及した。[要出典)。 キャラクター ハム 劇中、キャスター付きの肘掛け椅子に座ったまま、立つこともできず、目も見えない。ハムは支配的で、険悪で、冗談好きで、自分の惨めさに安住している。彼 は苦しんでいると主張するが、その悲観主義は自ら選んだように見える。彼は孤立し、自己陶酔することを選ぶ。父親を 「姦淫者 」と呼び、隣人がランプの灯油を必要としているのに助けようとせず、ぬいぐるみのような偽のペットの犬を飼っている。 クロフ: ハムの使用人で、座ることができない。幼い頃にハムに引き取られる。切ない性格。他の何かに憧れているが、追い求めるものは何もない。ハムよりも平凡で、自分のチャンスについて考えるが、ほとんど主導権を握らない。慈悲深いが、疲れきっている。 ナグ: ハムの父親で、足がなくゴミ箱に住んでいる。ナグは穏やかで父親らしいが、息子の恩義を前に悲嘆にくれている。 ネル ハムの母親で足がなく、ナグの隣のゴミ箱に住んでいる。反省的で、コモ湖の美しい一日について独白するが、劇の途中で死んだらしい。 サミュエル・ベケットは、登場人物の名前を選ぶ際に、英語では「ハンマー」、フランス語では「釘」、ドイツ語ではそれぞれ「clou」と「nagel」を意識したと語っている。 ベケットは熱心なチェスプレイヤーであり、エンドゲームとはチェスの終局局面を指す。この戯曲は、象徴的な意味は限定的ではあるが、一種の比喩的なチェス としておぼろげながら見えてくる。ハムはある場面で「ナイトマンに私の王国を!」と言う。動きが制限されているハムはチェス盤のキングの駒に似ており、彼 のために動くクロフはナイトに似ている。 |

| Synopsis In a dreary, dim and nondescript room, Clov draws the curtains from the windows and prepares his master Hamm for his day. He says, "It's nearly finished," though it is not clear what he is referring to. He awakes Hamm by pulling a sheet from over him. After Hamm removes a bloodstained handkerchief from over his head and face, he says "It's time it ended." He summons Clov by means of a whistle, and they banter briefly. Eventually, Hamm's parents, Nell and Nagg, appear from inside two trash cans at the back of the stage. Hamm is as equally threatening, condescending and acrimonious with his parents as with his servant, though they still share a degree of mutual humor; Nell eventually sinks back into her bin, and Clov, examining her, says, "She has no pulse." Hamm tells his father he is telling a story and recites it partially to him, a fragment which treats on a derelict man who comes crawling on his belly to the narrator, who is putting up Christmas decorations, begging him for food for his starving boy sheltering in the wilderness. Clov returns, and they continue to banter in a way that is both quick-witted and comical yet with dark, overt existential undertones. Clov often threatens to leave Hamm, but it is made clear that he has nowhere to go as the world outside seems to be destroyed. Much of the stage action is intentionally banal and monotonous, including sequences where Clov moves Hamm's chair in various directions so that he feels himself to be in the right position, as well as moving him nearer to the window. By the end of the play, Clov finally seems intent on pursuing his commitment of leaving his cruel master Hamm. Clov tells him there is no more of the painkiller left, which Hamm has been insisting on getting his dose of throughout the play. Hamm finishes his dark, chilling story by having the narrator berate the collapsed man for the futility of trying to feed his son for a few more days when evidently their luck has run out (it becomes plain that the character of the narrator is Hamm himself, relating the events which brought Clov [the man's son] to him). Hamm believes Clov has left, being blind, but Clov re-enters and stands in the room silently with his coat on and carrying luggage, going nowhere. Hamm calls for his father, but receives no answer; he discards some of his belongings, and says that, though he has made his exit, his bloodstained handkerchief, which he replaces over his face and head, will "remain". |

あらすじ 薄暗く、何の変哲もない部屋で、クロフは窓のカーテンを引き、主人のハムの準備をする。彼は「もうすぐ終わる」と言う。彼はハムの上からシーツを引っ張 り、ハムを目覚めさせる。ハムが血まみれのハンカチを頭と顔から外した後、「そろそろ終わりにしよう 」と言う。彼は笛でクロヴを呼び出し、短い会話を交わす。 やがてハムの両親、ネルとナーグが舞台後方の2つのゴミ箱の中から現れる。ハムは使用人と同じように両親を脅し、見下し、険悪にする。その断片は、クリス マスの飾りつけをしているナレーターのもとに腹這いになってやってきて、荒野に避難している飢えた少年のために食料をねだる廃人について扱ったものだっ た。 クロヴが戻ってくると、二人は頭の回転が速くコミカルでありながら、暗くあからさまな実存的含みをもったやり方で談笑を続ける。クロフはしばしばハムのも とを去ると脅すが、外の世界が破壊されたように見えるため、彼には行き場がないことが明らかにされている。クロヴがハムの椅子をいろいろな方向に動かし て、自分が正しい位置にいると感じさせたり、ハムを窓の近くに移動させたりするシークエンスなど、舞台の動作の多くは意図的に平凡で単調なものになってい る。 劇の終盤になると、クロフはついに、残酷な主人ハムのもとを去るという決意を固めるようだ。クロフは、劇中ハムがずっと欲しがっていた鎮痛剤がもう残って いないことを告げる。ハムは、明らかに運が尽きたのに、あと数日も息子を養おうとするのは無駄だと、倒れた男を語り手に叱責させることで、暗く冷ややかな 物語を締めくくる(語り手のキャラクターはハム自身であり、クロフ[男の息子]を自分のところに連れてきた出来事を語っていることが明白になる)。ハム は、目が見えないクロフは出て行ったと思っていたが、クロフは再び部屋に入り、コートを着て荷物を持ち、どこにも行かずに黙って立っている。ハムは父を呼 ぶが返事はなく、持ち物をいくつか捨て、出て行ったが、顔と頭にかぶせた血に染まったハンカチは「残る」と言う。 |

| Possible themes in Endgame

include decay, insatiety and dissatisfaction, pain, monotony,

absurdity, humor, horror, meaninglessness, nothingness, existentialism,

nonsense, solipsism and people's inability to relate to or find

completion in one another, narrative or story-telling, family

relations, nature, destruction, abandonment, and sorrow. Hamm's story is broken up and told in segments throughout the play. It serves essentially as part of the climax of Endgame, albeit somewhat inconclusively. Hamm's story is gripping for how the narrative tone it is told in contrasts with the way the play the characters are in seems to be written or proceed. Whereas Endgame is somehow lurching, starting and stopping, rambling, unbearably impatient and sometimes incoherent, Hamm's story in some ways has a much more clear, liquid, fluid, descriptive narrative lens to it. In fact, in the way it uses run-of-the-mill literary techniques like describing the setting, facial expressions or an exchange of dialogue, in slightly bizarre ways, it almost seems like a parody of writing itself. Beckett's eerie, weird stories about people at their last gasp often doing or seeking something futile somehow seems to return again and again as central to his art. It could be taken to represent the inanity of existence, but it also seems to hint at mocking not only life but storytelling itself, inverting and negating the literary craft with stories that are idiotically written, anything from poorly to put-on and overwrought. Extremely characteristic Beckettian features in the work, represented by many lines throughout the work, are bicycles, a seemingly imaginary son, pity, darkness, a shelter, and a story being told. The play has postmodern features in that the characters recurrently hint that they are aware they are characters in a play. |

『エンドゲーム』で考えられるテーマには、腐敗、飽食と不満、苦痛、単調さ、不条理、ユーモア、恐怖、無意味、無、実存主義、ナンセンス、独在論と人々が互いに関わり合ったり、完成を見出したりできないこと、物語や物語り、家族関係、自然、破壊、放棄、悲しみなどがある。 ハムの物語は劇中、分割されて語られる。やや結論は出ないものの、基本的には『エンドゲーム』のクライマックスの一部として機能している。 ハムの物語は、それが語られる語り口調が、登場人物たちがいる芝居の書き方や進め方といかに対照的であるかという点で、手に汗握る。エンドゲーム』が、ど こかのらりくらりと、始まったり止まったり、とりとめもなく、耐え難いほどせっかちで、時に支離滅裂であるのに対し、ハムの物語は、ある意味で、より明確 で、流動的で、描写的な物語のレンズを持っている。実際、舞台設定や表情、台詞のやり取りを描写するようなありふれた文学的テクニックを、少し奇妙な方法 で使っている点で、それはほとんど文章そのもののパロディのように思える。ベケットの不気味で奇妙な物語は、最後の力を振り絞った人々が、しばしば無益な ことをしたり、求めたりするというものだが、なぜか彼の芸術の中心的存在として何度も繰り返されているように思える。それは存在の無意味さを表していると も取れるが、人生だけでなく物語そのものを嘲笑し、馬鹿馬鹿しく書かれた物語、稚拙なものから大げさなものまで、文学の技巧を反転させ、否定しているよう にも見える。 作品中の多くのセリフに代表される、この作品における極めて特徴的なベケット的特徴は、自転車、一見想像上の息子、同情、暗闇、シェルター、語られる物語である。 登場人物たちが、自分たちが芝居の登場人物であることを再三ほのめかすという点で、この戯曲はポストモダンの特徴を備えている。 |

| Production history The play was premiered on 3 April 1957 at the Royal Court Theatre, London, performed in French. The production was directed by Roger Blin, who also played Hamm, with Jean Martin as Clov, Georges Adet as Nagg and Christine Tsingos as Nell. Other early productions included a 1958 production at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York,[3] directed by Alan Schneider with Lester Rawlins as Hamm, Alvin Epstein as Clov, Nydia Westman as Nell and P. J. Kelly as Nagg (a recording of the play, with Gerald Hiken replacing Epstein, was released by Evergreen Records in 1958);[4] and at the Royal Court Theatre in London directed by George Devine who also played Hamm, with Jack MacGowran as Clov.[5] In the early 1960s, an English language production produced by Philippe Staib and directed by Beckett, with Patrick Magee and Jack MacGowran, was staged at the Studio des Champs-Elysees, Paris. After the Paris production, Beckett directed two other productions of the play: at the Schiller Theater Werkstatt, Berlin, 26 September 1967, with Ernst Schröder as Hamm and Horst Bollmann as Clov; and at the Riverside Studios, London, May 1980 with Rick Cluchey as Hamm and Bud Thorpe as Clov.[5] In 1984, JoAnne Akalaitis directed the play at the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The production featured music from Philip Glass and was set in a derelict subway tunnel. Grove Press, the owner of Beckett's work, took legal action against the theatre. The issue was settled out of court through the agreement of an insert into the program, part of which was written by Beckett: Any production of Endgame which ignores my stage directions is completely unacceptable to me. My play requires an empty room and two small windows. The American Repertory Theater production which dismisses my directions is a complete parody of the play as conceived by me. Anybody who cares for the work couldn't fail to be disgusted by this.[6] In 1985 Beckett directed "Waiting for Godot", "Krapp's Last Tape" and "Endgame" as stage pieces with the San Quentin Players. All three productions were grouped together under the title "Beckett Directs Beckett", and the production toured Europe and parts of Asia.[7] In 1991, a TV movie production was filmed with Stephen Rea as Clov, Norman Beaton as Hamm, Charlie Drake as Nagg and Kate Binchy as Nell.[8] In 1992, a videotaped production directed by Beckett, with Walter Asmus as the television director, was made as part of the Beckett Directs Beckett series, with Rick Cluchey as Hamm, Bud Thorpe as Clov, Alan Mandell as Nagg and Teresita Garcia-Suro as Nell.[9] A production with Michael Gambon as Hamm and David Thewlis as Clov and directed by Conor McPherson was filmed in 2000 as part of the Beckett on Film project. In 2004, a production with Michael Gambon as Hamm and Lee Evans as Clov was staged at London's Albery Theatre, directed by Matthew Warchus.[10] In 2005, Tony Roberts starred as Hamm in a production directed by Charlotte Moore at the Irish Repertory Theater in New York City with Alvin Epstein as Nagg, Adam Heller as Clov and Kathryn Grody as Nell.[11] In 2008 there was a brief revival staged at the Brooklyn Academy of Music starring John Turturro as Hamm, Max Casella as Clov, Alvin Epstein as Nagg and Elaine Stritch as Nell. New York theatre veteran Andrei Belgrader directed, replacing originally-sought Sam Mendes. In 2009, the British theatre company Complicite staged the play in London's West End with Mark Rylance as Hamm and Simon McBurney (who also directed the production) as Clov. The production also featured Tom Hickey as Nagg and Miriam Margolyes as Nell.[12] The production opened on 2 October 2009 at the Duchess Theatre.[12] Tim Hatley designed the set.[12] In 2010, Steppenwolf Theatre Company staged Endgame. It was directed by Frank Galati and starred Ian Barford as Clov, William Petersen as Hamm, Francis Guinan as Nagg, and Martha Lavey as Nell. James Schuette was responsible for set and scenic design.[13] In 2015, two of Australia's major state theatre companies staged the play. For Sydney Theatre Company, Andrew Upton directed the production, featuring Hugo Weaving as Hamm,[14] and for Melbourne Theatre Company, Colin Friels starred in a production directed by Sam Strong and designed by visual artist Callum Morton.[15] In 2016, Coronation Street actors David Neilson and Chris Gascoyne starred in a staging of the play at both the Citizens Theatre in Glasgow and HOME in Manchester. In 2019, the play was produced by Pan Pan Theatre at the Project Arts Centre in Dublin. The production was directed by Gavin Quinn and starred Andrew Bennett, Des Keogh, Rosaleen Linehan and Antony Morris. The production was designed by Aedin Cosgrove.[16] In 2020, the Old Vic in London staged a production directed by Richard Jones with Alan Cumming as Hamm, Daniel Radcliffe as Clov, Jane Horrocks as Nell and Karl Johnson as Nagg in a double bill with Rough for Theatre II.[17] Unfortunately, the production had to end its run two weeks earlier than its planned closing date of 28 March 2020 due to concerns over an outbreak of COVID-19.[18] Dublin's Gate Theatre staged the play in 2022. Directed by Danya Taymor, Hamm was played by Frankie Boyle and Clov by Robert Sheehan, with Seán McGinley and Gina Moxley as Nagg and Nell.[19][20] The French version was staged in 2022 at the Théâtre de l'Atelier in Paris. Jacques Osinski directed, Hamm was played by Frédéric Leidgens, Clov by Denis Lavant, Nagg and Nell by Peter Bonke and Claudine Delvaux.[21] A new production directed by Ciarán O'Reilly opened at the Irish Repertory Theater in New York City with previews beginning 25 January 2023 and an opening date of 2 February, with John Douglas Thompson as Hamm, Bill Irwin as Clov, Joe Grifasi as Nagg and Patrice Johnson Chevannes as Nell.[22] The production was originally scheduled to run until 12 March, but has now been extended until 9 April. |

製作経緯 初演は1957年4月3日、ロンドンのロイヤル・コート劇場でフランス語で上演された。演出はハム役のロジェ・ブラン、クロフ役はジャン・マルタン、ナーグ役はジョルジュ・アデ、ネル役はクリスティーヌ・シンゴスだった。 あ その他の初期のプロダクションとしては、1958年にニューヨークのチェリー・レーン劇場で、アラン・シュナイダーが演出し、ハム役をレスター・ローリン ズ、クロヴ役をアルヴィン・エプスタイン、ネル役をニディア・ウェストマン、ナーグ役をP・J・ケリーが演じたものがある[3]。 1960年代初頭には、フィリップ・スタイブがプロデュースし、ベケットが演出、パトリック・マギーとジャック・マクガウランが出演した英語版がパリの シャンゼリゼ劇場で上演された。1967年9月26日、ベルリンのシラー劇場でエルンスト・シュレーダーがハムを、ホルスト・ボルマンがクロヴを演じ、 1980年5月、ロンドンのリバーサイド・スタジオでリック・クルーシーがハムを、バド・ソープがクロヴを演じた[5]。 1984年、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジのアメリカン・レパートリー・シアターでジョアン・アカライティスが演出。この作品ではフィリップ・グラスの 音楽がフィーチャーされ、廃墟と化した地下鉄のトンネルが舞台となった。ベケットの作品の所有者であるグローブ・プレス社は、劇場に対して法的措置をとっ た。この問題は、ベケットが執筆したプログラムの一部を挿入するという合意によって、法廷外で解決された: 私の舞台演出を無視した『エンドゲーム』の上演は、私にとってまったく受け入れがたいものです。私の戯曲は空の部屋と2つの小さな窓を必要とする。私の演 出を無視したアメリカン・レパートリー・シアターのプロダクションは、私が考えた戯曲の完全なパロディだ。作品を大切に思う人なら誰でも、これに嫌悪感を 抱かないはずがない[6]。 1985年、ベケットはサン・クエンティン・プレイヤーズの舞台作品として『ゴドーを待ちながら』、『クラップの最後のテープ』、『エンドゲーム』を演出 した。この3つの作品は「ベケット演出のベケット」というタイトルでまとめられ、ヨーロッパとアジアの一部をツアーした[7]。 1991年には、スティーヴン・レアがクロフ役、ノーマン・ビートンがハム役、チャーリー・ドレイクがナグ役、ケイト・ビンチーがネル役を演じるテレビ映画作品が撮影された[8]。 1992年、「Beckett Directs Beckett」シリーズの一環として、ウォルター・アスマスをテレビディレクターに迎えたベケット演出のビデオテープ作品が制作され、ハム役にリック・ クルーシー、クロヴ役にバド・ソープ、ナッグ役にアラン・マンデル、ネル役にテレシータ・ガルシア=スーロが出演した[9]。 2000年には、ベケット・オン・フィルム・プロジェクトの一環として、マイケル・ガンボン(ハム役)とデヴィッド・ソーリス(クロヴ役)が出演し、コナー・マクファーソン(Conor McPherson)が監督した作品が撮影された。 2004年、マシュー・ウォーチャス演出のもと、ロンドンのアルベリーシアターで、ハム役にマイケル・ガンボン、クロヴ役にリー・エヴァンスによるプロダクションが上演された[10]。 2005年、ニューヨークのアイリッシュ・レパートリー・シアターで行われたシャーロット・ムーア演出のプロダクションでは、トニー・ロバーツがハム役で 主演し、アルヴィン・エプスタインがナーグ役、アダム・ヘラーがクロヴ役、キャサリン・グローディがネル役を演じた[11]。 2008年には、ブルックリン・アカデミー・オブ・ミュージックで、ハム役のジョン・タトゥーロ、クロヴ役のマックス・カセラ、ナーグ役のアルヴィン・エ プスタイン、ネル役のエレイン・ストリッチが出演する短期間のリバイバル公演が上演された。ニューヨーク演劇界のベテラン、アンドレイ・ベルグレーダー が、当初予定されていたサム・メンデスに代わって演出した。 2009年、イギリスの劇団Compliciteがロンドンのウェストエンドでこの作品を上演し、マーク・ライランスがハム役、サイモン・マクバーニー (演出も担当)がクロフ役を演じた。このプロダクションには、ナッグ役のトム・ヒッキーとネル役のミリアム・マーゴリーズも出演していた[12]。このプ ロダクションは、2009年10月2日にダッチェス劇場で開幕した[12]。 2010年、ステッペンウルフ・シアター・カンパニーが『Endgame』を上演。フランク・ガラティが演出し、クロフ役のイアン・バーフォード、ハム役 のウィリアム・ピーターセン、ナーグ役のフランシス・ギナン、ネル役のマーサ・ラヴィーが出演した。ジェームズ・シュエットがセットと舞台美術を担当した [13]。 2015年には、オーストラリアの2つの主要な州立劇団がこの作品を上演した。シドニー・シアター・カンパニーでは、アンドリュー・アプトンが演出し、ハ ム役のヒューゴ・ウィーヴィングが出演した[14]。メルボルン・シアター・カンパニーでは、コリン・フリエルズが主演し、サム・ストロングが演出、ビ ジュアル・アーティストのカラム・モートンがデザインを担当した[15]。 2016年には、コロネーションストリートの俳優デヴィッド・ニールソンとクリス・ガスコインが、グラスゴーの市民劇場とマンチェスターのHOMEの両方でこの劇の上演に主演した。 2019年には、ダブリンのプロジェクト・アート・センターでパンパン・シアターによって上演された。演出はギャヴィン・クイン、出演はアンドリュー・ベ ネット、デス・キョウ、ロザリーン・リネハン、アントニー・モリス。プロダクションのデザインはエーディン・コスグローブが担当した[16]。 2020年、ロンドンのオールド・ヴィックはリチャード・ジョーンズ演出によるプロダクションを上演し、アラン・カミングがハム役、ダニエル・ラドクリフ がクロフ役、ジェーン・ホロックスがネル役、カール・ジョンソンがナーグ役で、ラフ・フォー・シアターIIとのダブル・ビルで上演された[17]。残念な がら、このプロダクションはCOVID-19の流行が懸念されたため、予定されていた2020年3月28日の閉幕日より2週間早く上演を終了せざるを得な かった[18]。 ダブリンのゲート・シアターでは2022年に上演された。演出はダーニャ・テイモアで、ハムをフランキー・ボイル、クロヴをロバート・シーハンが演じ、ナグとネルをショーン・マッギンレーとジーナ・モックスレーが演じた[19][20]。 フランス版は2022年にパリのアトリエ劇場で上演された。ジャック・オシンスキーが演出し、ハムをフレデリック・レイドジェンス、クロヴをドゥニ・ラヴァン、ナーグとネルをピーター・ボンケとクローディーヌ・デルヴォーが演じた[21]。 シアラン・オライリー演出の新プロダクションがニューヨークのアイリッシュ・レパートリー・シアターで2023年1月25日からプレビューが始まり、2月 2日に開幕した。ハム役はジョン・ダグラス・トンプソン、クロヴ役はビル・アーウィン、ナーグ役はジョー・グリファシ、ネル役はパトリス・ジョンソン・ シュヴァネスである[22]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endgame_(play) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆