主体と権力

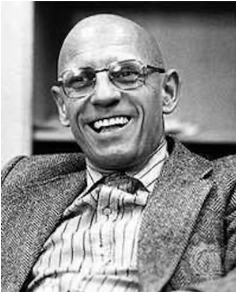

The Subject and Power by Michel Foucault

★ 「主体と権力について考えること」(→「ミッシェル・フーコーの2つの権力論」)

1) なぜ『権力論』を学ぶのか?

2) 主体の問題

3) 権力の次元は拡大されなければならない。

4) 権力はどのように行使されるのか?

5) 権力の特質とは何だろうか?

6) 権力関係を分析するにはどうすればよいのか?

7)

権力関係と戦略関係

☆ミッシェル・フーコー(Paul-Michel Foucault, 1926-1984)の権力概念——生産的権力論

「私 は、権力関係の新たなエコノミーをさ らに推し進めるための別の方法を提案したい。それは、より経験的で、より直接的に現在の状況に関連しており、理論と 実践の間のより多くの関係を暗示するものである。それは、さまざまな権力形態に対する抵抗の形態を起点とするものである。別のメタファーを用いるなら、こ の抵抗 を化学反応における触媒として利用し、権力関係を明らかにし、その位置を特定し、その適用点と使用される手法を見つけ出すことである。権力をその内部の合 理性という観 点から分析するのではなく、権力関係を戦略の対立を通じて分析することである。権力行使の定義に戻ろう。それは、ある行動が他の可能な行動 の領域を構造化 する方法である。したがって、権力関係にふさわしいのは、行動に対する行動様式である。つまり、権力関係は社会の結びつきに深く根ざしており、社会の上に 再構成されることはない。社会の上に再構成されることは、おそらく根本的な消滅を夢見ることができる補足的な構造としてではない。いずれにせよ、社会で生 きるということは、他の行動に対する行動が可能であるように生きるということであり、実際、進行中である。権力関係のない社会は、抽象的な ものにすぎな い。これは、特定の社会における権力関係の分析、その歴史的形成、強さや脆さの源泉、一部を変革したり、他を廃止したりするために必要な条件を、より政治 的に必要とするものである。権力関係のない社会はありえないとい う主張は、確立された権力関係が必然であるとか、あるいは、いかなる場合でも権力が社会の 中心に宿命として存在し、それを弱めることができないという主張ではない。むしろ、権力関係の分析、精査、そして権力関係と自由の非直線性との間の「対 立」を問題視することは、あらゆる社会的存在に内在する永続的な政治的課題であると言えるだろう。実際、権力関係と闘争の戦略の間には、相互に惹きつけ合 い、絶え間なく結びつき、そして絶え間なく反転し合うという関係がある。権力関係は、つねに二つの敵対者間の対立となる可能性がある。同様に、社会におけ る敵対者間の関係は、つねに権力のメカニズムが作動する余地がある。この不安定さの結果、同じ出来事や同じ変容を、闘争の歴史の内側から、あるいは権力関 係の観点から解読できる能力が生まれる。その結果生じる解釈は、同じ歴史的背景を参照しているとはいえ、同じ意味の要素や同じつながり、同じ種類の理解可 能性から構成されるものではない。また、2つの分析はそれぞれ、もう一方を参照していなければならない。実際、2つの解釈の相違こそが、多数の人間社会に 存在する「支配」の根本的な現象を明らかにするのである。」

☆フーコーによれば主体や個人は、人為的に構築されてきた概念であり、道徳、法、主権、合理性、責任、正気、性という概念と結びついているものである。

| The Subject and

Power [pdf] with password Michel Foucault Critical Inquiry 8 (4):777-795 (1982) Copy BIBTEX Abstract I would like to suggest another way to go further toward a new economy of power relations, a way which is more empirical, more directly related to our present situation, and which implies more relations between theory and practice. It consists of taking the forms of resistance against different forms of power as a starting point. To use another metaphor, t consists of using this resistance as a chemical catalyst so as to bring to light power relations, locate their position, and find out their point of application and the methods used. Rather than analyzing power from the point of view of its internal rationality, it consists of analyzing power relations through the antagonism of strategies.[…]Let us come back to the definition of the exercise of power as a way in which certain actions may structure the field of other possible actions. What, therefore, would be proper to a relationship of power is that it be a mode of action upon actions. That is to say, power relations are rooted deep in the social nexus, not reconstituted "above" society as a supplementary structure whose radical effacement one could perhaps dream of. In any case, to live in a society is to live in such a way that action upon other actions is possible-- and in fact ongoing. A society without power relations can only be an abstraction. Which, be it said in passing, makes all the more politically necessary the analysis of power relations in a given society, their historical formation, the source of their strength or fragility, the conditions which are necessary to transform some or to abolish others. For to say that there cannot be a society without power relations is not to say either that those which are established are necessary or, in any case, that power constitutes a fatality at the heart of societies, such that it cannot be undermined. Instead, I would say that the analysis, elaboration, and bringing into question of power relations and the "agonism" between power relations and the instransitivity of freedom is a permanent political task inherent in all social existence.[…]In effect, between a relationship of power and a strategy of struggle there is a reciprocal appeal, a perpetual linking and a perpetual reversal. At every moment the relationship of power may become a confrontation between two adversaries. Equally, the relationship between adversaries in society may, at every moment, give place to the putting into operation of mechanisms of power. The consequence of this instability is the ability to decipher the same events and the same transformations either from inside the history of struggle or from the standpoint of the power relationships. The interpretations which result will not consist of the same elements of meaning or the same links or the same types of intelligibility, although they refer to the same historical fabric, and each of the two analyses must have reference to the other. In fact, it is precisely the disparities between the two readings which make visible those fundamental phenomena of "domination" which are present in a large number of human societies.Michel Foucault has been teaching at the Collège de France since 1970. His works include Madness and Civilization , The Birth of the Clinic , Discipline and Punish , and History of Sexuality , the first volume of a projected five-volume study |

主体と権力 ミシェル・フーコー クリティカル・インクワイアリー 8 (4):777-795 (1982) BIBTEXのコピー 要約 私は、権力関係の新たなエコノミーをさらに推し進めるための別の方法を提案したい。それは、より経験的で、より直接的に現在の状況に関連しており、理論と 実践の間のより多くの関係を暗示するものである。それは、さまざまな権力形態に対する抵抗の形態を起点とするものである。別の比喩を用いるなら、この抵抗 を化学触媒として利用し、権力関係を明らかにし、その位置を特定し、その適用点と使用される手法を見つけ出すことである。権力をその内部の合理性という観 点から分析するのではなく、権力関係を戦略の対立を通じて分析することである。権力行使の定義に戻ろう。それは、ある行動が他の可能な行動の領域を構造化 する方法である。したがって、権力関係にふさわしいのは、行動に対する行動様式である。つまり、権力関係は社会の結びつきに深く根ざしており、社会の上に 再構成されることはない。社会の上に再構成されることは、おそらく根本的な消滅を夢見ることができる補足的な構造としてではない。いずれにせよ、社会で生 きるということは、他の行動に対する行動が可能であるように生きるということであり、実際、進行中である。権力関係のない社会は、抽象的なものにすぎな い。これは、特定の社会における権力関係の分析、その歴史的形成、強さや脆さの源泉、一部を変革したり、他を廃止したりするために必要な条件を、より政治 的に必要とするものである。権力関係のない社会はありえないという主張は、確立された権力関係が必然であるとか、あるいは、いかなる場合でも権力が社会の 中心に宿命として存在し、それを弱めることができないという主張ではない。むしろ、権力関係の分析、精査、そして権力関係と自由の非直線性との間の「対 立」を問題視することは、あらゆる社会的存在に内在する永続的な政治的課題であると言えるだろう。実際、権力関係と闘争の戦略の間には、相互に惹きつけ合 い、絶え間なく結びつき、そして絶え間なく反転し合うという関係がある。権力関係は、つねに二つの敵対者間の対立となる可能性がある。同様に、社会におけ る敵対者間の関係は、つねに権力のメカニズムが作動する余地がある。この不安定さの結果、同じ出来事や同じ変容を、闘争の歴史の内側から、あるいは権力関 係の観点から解読できる能力が生まれる。その結果生じる解釈は、同じ歴史的背景を参照しているとはいえ、同じ意味の要素や同じつながり、同じ種類の理解可 能性から構成されるものではない。また、2つの分析はそれぞれ、もう一方を参照していなければならない。実際、2つの解釈の相違こそが、多数の人間社会に 存在する「支配」の根本的な現象を明らかにするのである。ミシェル・フーコーは1970年よりコレージュ・ド・フランスで教鞭をとっている。著書に『狂気 と文明』、『臨床の誕生』、『監獄の誕生』、『性の歴史』などがある。『性の歴史』は5巻からなる研究計画の第1巻である。 |

| https://philpapers.org/rec/FOUTSA |

|

| Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Critical Inquiry

8, no. 4 (1982): 777–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343197 Also published as an Afterword to Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, eds. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983) [This Introduction has been significantly amended as of 20 July 2019. The previous version may be accessed here.] “My objective, instead, has been to create a history of the different modes [of objectification] by which, in our culture, human beings are made subjects.” p. 777. If this statement is accessible to you, you can skip this rather protracted introduction (to the first section of the article). If not, do not proceed without first reading this. This introduction is aimed at clarifying the meaning and importance of the word “subject” and its derivatives — especially subjectivation (or sometimes, subjectification). Lack of clarity on this would render the article inaccessible. The word “subject” has many meanings. (Check out this extensive list of meanings recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary.) When Foucault talks about the subject, or about subjectivation, he means to convey two different notions simultaneously. The first alludes to a well known philosophical tradition in which the subject as the center of experience is of central import. To explain this very crudely, I must first explain what is known as the subject-object dichotomy in philosophy. A subject is conscious and an object is unconscious. The subject experiences, feels, or thinks (or, in other words, is conscious). To use jargon, subjects possess subjectivity. Objects, on the other hand, do not. Rather, they are experienced, felt, thought about. Put another way, subjects perceive and objects are perceived. Put yet another way, subjects are active, i.e., they have agency, while objects are passive. (This is precisely the grammatical distinction made between active and passive voice!) The subject in this sense — the subject as the active, perceiving thing possessing agency — is the first notion that Foucault is referencing when he talks of the subject. The origin of this connotation (and also in the senses in which it is understood in grammar and logic) goes back to (the Latin translation of) a Greek term coined by Aristotle. This notion of the subject (otherwise called the “self”) has been particularly influential in modern philosophy. Particularly, the idea that this subject is free and untethered has informed much of modern liberal thought. But I digress. To get at the second aspect, we will have to complicate the picture a little more. We can start thus: we, humans, as conscious beings, are subjects. But how do we become subjects? If I have certain political opinions, behave a certain way, have certain preferences of food, etc. how do I come to have those opinions, behaviour, and preferences. A whole host of agencies/forces have a bearing on me: the family, the church, the state, the economy, even myself. This is the second notion that Foucault is bringing into the word “subject”. Grammatically, it would be used as a verb. This is the meaning conveyed by such phrases as “subject to the authority of the king”. This is the sense in which people are “subjects” in monarchies — in that they are subjected to the authority of the king — only that the authority of the king is replaced in contemporary times by a whole host of agencies which are listed above. The origin of this connotation is, the Oxford Dictionary informs us, Middle English. The implication is that we we do not automatically and autonomously become subjects in sense outlined above. We are subjects because we are subjected. Now, the complication. At the same time that I am a subject in this second sense, from the perspective of the family or the church or the state or even a part of myself (say my rational, true, authentic self — that self which wants me to be the best I can be), I am an object that needs to be moulded into a certain shape, having certain opinions, behaviour and preferences. So that when I try to alter my behaviour to become a better me, I am treating myself as an object. When the church uses its doctrines to make me a truer Christian, it is treating me as an object. And when the science of medicine does research on me, it is treating me as an object. When Foucault talks of the subject, he means all of these and when he talks of subjectivation, he means the process by which we are (and are made) subjects in all these senses. To wrap up this introduction, let us consider the sentence that I opened with: “My (i) objective, instead, has been to create a history of the different modes [of (ii) objectification] by which, in our culture, human beings are made (iii) subjects.” p. 777. (i) Objective means purpose in this context. That’s obvious. (ii) By modes of objectification, Foucault is referring to the ways in which my agency, self-knowledge, or individuality of the subject i.e. my subjectivity, is determined or controlled by family, the state, the church, or even by the subjects themselves. In short, he means the ways in which I am made an object. (iii) But at the end of all this, human beings still remain subjects in the sense that they have agency and also in the sense that this agency will be determined by other forces (by subjection). |

ミシェル・フーコー、「主体と権力」、Critical

Inquiry 8, no. 4 (1982): 777–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343197 また、ミシェル・フーコー著『構造主義と解釈学を超えて』の「あとがき」としても出版されている。 編集:Hubert L. Dreyfus、Paul Rabinow(シカゴ大学出版局、1983年) [この序文は2019年7月20日現在、大幅に修正されている。以前のバージョンは、こちらからアクセスできる。] 「私の目的は、むしろ、私たちの文化において人間が主体となるさまざまな様式(客観化)の歴史を創り出すことだった。」p. 777. この記述が理解できる場合は、このかなり長文の序文(記事の最初のセクション)を飛ばしていただいて構わない。理解できない場合は、まずこれを読まずに進 まないでいただきたい。 この序論の目的は、「主体」という言葉の意味と重要性、およびその派生語(特に「主観化(または「主観化」)」を明確にすることである。この点が明確でな いと、本記事は理解しがたいものとなる。「主体」という言葉には多くの意味がある。(オックスフォード英語辞典が記録している意味の広範なリストを参照の こと。)フーコーが「主体」や「主観化」について語る際には、同時に2つの異なる概念を伝えようとしている。 第一のものは、経験の中心としての主題が重要な意味を持つという、よく知られた哲学の伝統を暗示している。これを非常に大まかに説明すると、まず哲学にお ける主客二元論と呼ばれるものを説明しなければならない。主題は意識的であり、対象は無意識的である。主題は経験し、感じ、考える(つまり意識的であ る)。専門用語を使うと、主題は主観性を持つ。一方、対象は持たない。むしろ、経験され、感じられ、考えられる。別の言い方をすれば、主体は知覚し、客体 は知覚される。さらに別の言い方をすれば、主体は能動的であり、すなわち主体には意思があるが、客体は受動的である。(これは能動態と受動態の文法上の区 別とまさに一致する!)この意味での主体、すなわち能動的で知覚する主体、意思を持つ主体こそ、フーコーが主体について語る際に参照している最初の概念で ある。この含意の起源(また、文法や論理学で理解される意味においても)は、アリストテレスが作り出したギリシャ語の用語のラテン語訳にまで遡る。この 「主体」の概念(「自己」とも呼ばれる)は、特に近代哲学に大きな影響を与えてきた。特に、この主体は自由で縛りがないという考え方は、近代のリベラル思 想の多くに影響を与えてきた。しかし、話がそれてしまった。 第二の側面を理解するためには、もう少し話を複雑にしなければならない。 まず、人間は意識を持つ存在であり、主体である。 しかし、私たちはどのようにして主体となるのだろうか? もし私がある政治的意見を持ち、特定の行動を取り、特定の食べ物の好みを持っているとしたら、それらの意見や行動、好みはどのようにして生まれたのだろう か。私には、家族、教会、国家、経済、そして自分自身さえも、さまざまな機関や力が影響を及ぼしている。これが、フーコーが「主体」という言葉に持ち込ん だ2つ目の概念である。文法上は、動詞として用いられる。「王の権威に従属する」といった表現が伝える意味である。これは、君主制における「臣民」の意味 であり、つまりは王の権威に従属しているという意味である。ただし、現代では王の権威は、上述したさまざまな機関に置き換わっている。この意味の起源は、 オックスフォード辞典によると中英語である。この含意は、私たちは自動的かつ自律的に上述の意味での臣民になるわけではないということである。私たちは従 属しているからこそ、臣民なのである。 さて、ややこしい話になる。私がこの2番目の意味での主体であると同時に、家族や教会、国家、あるいは自分自身の一部(例えば、理性的で真実で本物の自 分、つまり、自分が最善を尽くせるようにと望む自分)から見ると、私は特定の意見や行動、好みを持つように形作られるべき対象でもある。そのため、より良 い自分になるために自分の行動を変えようとするとき、私は自分を物として扱っていることになる。教会がその教義を用いて私をより真のキリスト教徒にしよう とするとき、それは私を物として扱っていることになる。そして、医学という科学が私に対して研究を行うとき、それは私を物として扱っていることになる。 フーコーが主体について語る場合、彼はこれらすべてを意味しており、主体化について語る場合、彼はこれらのすべての意味において、私たちが主体となる(ま たは主体となるようにされる)プロセスを意味している。 この序文を締めくくるにあたり、冒頭の文章を考えてみよう。「私の(i)目的は、それどころか、私たちの文化において人間が(iii)主体となるさまざま な様式(ii)による客観化の歴史を創り出すことだった。」p. 777。 (i)目的とは、この文脈では目的を意味する。それは明らかだ。 (ii) 客観化の様式について、フーコーは、私の行動力、自己認識、あるいは主体の個性、すなわち私の主観が、家族、国家、教会、あるいは主体自身によって決定ま たは管理される様式について言及している。要するに、彼は私がどのようにして客体化されるかについて言及しているのだ。 (iii) しかし、こうしたことをすべて経ても、人間は依然として主体である。すなわち、人間には意思決定能力があるという意味でも、また、この意思決定能力が他の 力(従属)によって決定されるという意味でも、人間は主体である。 |

| Why Study Power? The Question of the Subject My goal has been to analyse the ways in which human beings are made subjects. There have been three modes of objectification which have made this transformation possible. First, there are the sciences such as grammar, philology and linguistics, economics, and biology whose classificatory endeavours have objectified the speaking subject, the labourer and the very living being. Second, there are dividing practices which have objectified subjects by dividing them within or from others. Consider the division between the mad and the sane, the sick and the healthy, the criminals and the “good boys”. Third, there is the process of subjectification whereby humans turn their very selves into subjects. Consider the identification of people with certain forms of sexuality. The general theme of my work thus has been “the question of the subject”. But I have had to “study power” because the existing legal model (the question of what legitimises power) and institutional model (the question of what is the state) of understanding power were insufficient to account for the objectification of the subject. The dimensions of power have to be expanded. It is important in this regard to start from forms of resistance against power and analyse power relations through the “antagonism of strategies”. “For example, to find out what our society means by sanity, perhaps we should investigate what is happening in the field of insanity. And what we mean by legality in the field of illegality.” “As a starting point, let us take a series of oppositions which have developed over the last few years: opposition to the power of men over women, of parents over children, of psychiatry over the mentally ill, of medicine over the population, of administration over the ways people live.” These struggles cut across state boundaries. They are against the effects of power as such as opposed to the exercise of power. They are immediate struggles — both temporally and spatially. They assert individuality. They are opposed to the privileges of knowledge and forms of imposition on people. They ask “Who are we?”, i.e., they are directed towards determining ones own subjectivity. “To sum up, the main objective of these struggles is … to attack a technique, a form of power. This form of power applies itself to immediate everyday life which categorizes the individual, marks him by his own individuality, attaches him to his own identity, imposes a law of truth on him which he must recognize and which others have to recognize in him. It is a form of power which makes individuals subjects. There are two meanings of the word ‘subject’: subject to someone else by control and dependence; and tied to his own identity by a conscience or self-knowledge. Both meanings suggest a form of power which subjugates and makes subject to.” “Generally, it can be said that there are three types of struggles: either against forms of domination; against forms of exploitation which separate individuals from what they produce; or … against subjection, against forms of subjectivity and submission.” While the struggles against forms of subjection have become salient, struggles against domination and exploitation have not disappeared. They reason why this form of struggle has become salient in this century is the rise of the modern state. The state totalises its power in the sense that it seeks to look after the totality of its subjects, i.e., the population. [For more on this aspect, see his essay “Governmentality”, summarised here.] But it also individualises. Never, I think, in the history of human societies ... has there been such a tricky combination in the same political structures of individualization techniques and of totalization procedures. In saying that the state power is individualising, I mean that the state exercises a form of power which is seeks the production of truth of the individual. This is a form of power that is analogous to the role played by pastors in Christianity, and hence may be called pastoral power. Pastoral power, in its religious context, aims at salvation, is sacrificial, is oriented towards the individual, and demands that the individual reveal his conscience and his innermost secrets. The modern state exercises secularised versions of these aspects of pastoral power. The welfare state with its commitment to the health and well-being of its citizens is engaged in ensuring worldly salvation. The surveillance state with its hunger for data on its citizens is analogous to the Catholic priest who has access to the innermost details of those who come to confession. The conclusion would be that the political, ethical, social, philosophical problem of our days is not to try to liberate the individual from the state and from the state's institutions but to liberate us both from the state and from the type of individualization which is linked to the state. We have to promote new forms of subjectivity through the refusal of this kind of individuality which has been imposed on us for several centuries. |

なぜ『権力論』を学ぶのか? 主体の問題 私の目標は、人間がどのようにして主題とされるのかを分析することである。この変容を可能にした客観化の様式は3つある。 第一に、文法、文献学、言語学、経済学、生物学といった学問がある。これらの学問の分類上の試みは、話す主体、労働者、そしてまさに生きている存在を客観 化してきた。第二に、他者との内面的または外面的な差異によって主体を客体化する分断の実践がある。正気と狂気、病気と健康、犯罪者と「善良な少年」の間 の境界を考えてみよう。第三に、人間が自分自身をまさに主体へと変える主体化のプロセスがある。ある種のセクシュアリティと人々を同一視する例を考えてみ よう。 私の作品の主題は、このように「主体の問題」であった。しかし、権力を「研究」せざるを得なかったのは、権力を理解するための既存の法的モデル(権力を正 当化するものは何かという問題)や制度的モデル(国家とは何かという問題)では、主体の客体化を説明するには不十分だったからだ。 権力の次元は拡大されなければならない。 この点において、権力に対する抵抗の形態から出発し、「戦略の対立」を通じて権力関係を分析することが重要である。「例えば、私たちの社会が正気というも のをどう考えているのかを理解するには、おそらく狂気という分野で何が起こっているのかを調査すべきだろう。そして、違法という分野における合法性とは何 を意味するのか。 「出発点として、ここ数年で発展してきた一連の対立を取り上げよう。それは、男性の権力に対する女性の対立、親の権力に対する子供の対立、精神医学の権力 に対する精神疾患患者の対立、医学の権力に対する人々の対立、行政の権力に対する人々の生き方の対立である。 これらの闘争は国家の境界を越えている。それは権力の行使に対するものではなく、権力そのものの影響に対するものだ。それは時間的にも空間的にも即時的な 闘争である。個性を主張する闘争であり、知識の特権や人々への押し付けの形式に反対する闘争である。「私たちは誰なのか?」という問いかけであり、すなわ ち、自己の主観を決定することに向けられている。 「要約すると、これらの闘争の主な目的は…技術、権力の形式を攻撃することである。この権力の形式は、個々人を分類し、その個々人の個性によって特徴づ け、その個々人のアイデンティティに結びつけ、その個々人が認識しなければならない、また他の人々もその個々人に対して認識しなければならない真実の法則 を押し付ける、即時的な日常生活に適用される。これは、個々人を主体化する権力の形式である。「主体」という言葉には2つの意味がある。すなわち、他者に よる支配や依存によって他者に従属すること、そして、良心や自己認識によって自己のアイデンティティに縛られることである。どちらの意味も、従属させ、従 属させるような権力の形を示唆している。 「一般的に、闘争には3つのタイプがあると言える。支配の形態に対する闘争、個人がその生産物から切り離される搾取の形態に対する闘争、あるいは…従属、 主観性、服従の形態に対する闘争である。従属の形態に対する闘争が顕著になっている一方で、支配や搾取に対する闘争が消滅したわけではない。 彼らは、この世紀にこの種の闘争が顕著になった理由として、近代国家の台頭を挙げる。国家は、その主権者である国民全体を統括しようとするという意味で、 その権力を集約する。この点についてさらに詳しく知りたい方は、彼の論文「統治性」を参照されたい。 私は、人類社会の歴史において、このような厄介な組み合わせが、個人化の技術と全体化の手続きが同じ政治構造の中で共存したことは一度もないと思う。 国家権力が個人化しているという表現は、国家が個々人の真実の生産を求める一形態の権力を行使していることを意味する。これはキリスト教における牧師の役 割に類似した権力形態であり、したがって「牧会的権力」と呼ぶことができる。宗教的文脈における牧会的権力は、救済を目的とし、犠牲的であり、個人に向け られ、個人が自らの良心と最も内密な秘密を明らかにすることを求める。現代国家は、これらの牧会的権力の世俗化されたバージョンを行使している。国民の健 康と幸福に献身する福祉国家は、現世での救済を保証することに携わっている。国民に関するデータを貪欲に収集する監視国家は、告解に訪れる人々の最も内密 な詳細にアクセスできるカトリックの司祭に類似している。 結論としては、現代の政治的、倫理的、社会的、哲学的問題は、国家や国家の制度から個人を解放しようとするのではなく、国家と国家につながる個人主義の両 方から私たちを解放することである。私たちは、数世紀にわたって押し付けられてきたこの種の個性を拒否することで、新しい主観性を推進しなければならな い。 |

| How Is Power Exercised? Analyses of the question of the “how” of power are generally limited to inventorying its manifestations. But are not these manifestations or effects of power linked to its origin and basic nature? The “how” I have in mind is not the question of how power manifests itself but the question of the means by which power is exercised. Power implies an objective capacity to exert force over things and the ability to modify, use, consume, or destroy them. Power also implies relationships between individuals or groups in that in any discussion of the mechanisms of power, we suppose that certain persons exercise power over others. There are relationships of communication, i.e., transmission of information by means of a language, a system of signs, or any other symbolic medium, through which persons act upon others. However, if the objectives or consequences of such relationships have results in the realm of power, it is only incidental. The point is that objective capacities, power relations, and relationships are not to be confused for one another. At the same time, they are not to be treated as three separate domains. In fact, they “always overlap one another, support one another reciprocally, and use each other mutually as means to an end”. The application of objective capacities in their most elementary forms implies relationships of communication (whether in the form of previously acquired information or of shared work); it is tied also to power relations (whether they consist of obligatory tasks, of gestures imposed by tradition or apprenticeship, of subdivisions and the more or less obligatory distribution of labor). Relationships of communication imply finalized activities (even if only the correct putting into operation of elements of meaning) and, by virtue of modifying the field of information between partners, produce effects of power. Across different societies, the coordination or relation between these three types of relationships is neither uniform nor constant. Rather, there are diverse specific models. “But there are also ‘blocks’ in which the adjustment of abilities, the resources of communication, and power relations constitute regulated and concerted systems.” Consider an educational institution whose constituents constitute a block of capacity–communication–power. “The activity which ensures apprenticeship and the acquisition of aptitudes or types of behavior is developed there by means of a whole ensemble of regulated communications (lessons, questions and answers, orders, exhortations, coded signs of obedience, differentiation marks of the ‘value’ of each person and of the levels of knowledge) and by the means of a whole series of power processes (enclosure, surveillance, reward and punishment, the pyramidal hierarchy).” Blocks like this constitute a ‘discipline’. Disciplines provide a view into the ways in which the constituents components — the capacity–communication–power triad — are welded together as well as the varied ways in which their interrelationships are articulated. “To approach the theme of power by an analysis of ‘how’ is therefore to introduce several critical shifts in relation to the supposition of a fundamental power. It is to give oneself as the object of analysis power relations and not power itself.” |

権力はどのように行使されるのか? 権力の「方法」に関する問題の分析は、一般的にその表出の目録作成に限定される。しかし、権力の表出や影響は、その起源や本質と結びついていないのだろう か? 私が念頭に置いている「どのように」とは、権力がどのようにして自らを現すかという問題ではなく、権力が行使される手段の問題である。権力は、物事に対し て力を及ぼす客観的な能力、およびそれらを修正、利用、消費、あるいは破壊する能力を意味する。また、権力は個人または集団間の関係も意味する。なぜな ら、権力のメカニズムに関するあらゆる議論において、私たちは特定の人物が他の人々に対して権力を行使していると想定しているからだ。 すなわち、言語、記号体系、その他の象徴的メディアによる情報の伝達、つまりコミュニケーションの関係によって、ある人物が他の人物に影響を与える。しか し、そのような関係の目的や結果が権力の領域に帰結するとしても、それはあくまで付随的なものである。重要なのは、客観的能力、権力関係、関係性を混同し てはならないということである。同時に、それらを3つの別個の領域として扱うべきではない。実際、それらは「常に互いに重なり合い、互いに相互に支え合 い、互いに相互に目的達成のための手段として利用し合う」のである。 客観的諸能力の最も初歩的な形態での適用は、コミュニケーションの関係(それが以前に獲得された情報や共同作業の形をとるかどうかに関わらず)を意味す る。また、それは権力関係(それが義務的な作業、伝統や徒弟制度によって課される身振り、細分化、および多かれ少なかれ義務的な労働分配からなるかどうか に関わらず)にも結びついている。コミュニケーションの関係は、完成された活動(たとえ意味の要素が正しく機能しているだけでも)を意味し、パートナー間 の情報分野を変化させることによって、権力の影響を生み出す。 異なる社会の間では、これら3つのタイプの関係の調整や関連性は、均一でも一定でもない。むしろ、多様な特定のモデルがある。 「しかし、能力、コミュニケーションのリソース、権力関係の調整が、規制された協調的なシステムを構成する『ブロック』もある。」能力、コミュニケーショ ン、権力のブロックを構成する要素を持つ教育機関を考えてみよう。「徒弟制度や適性、行動様式の習得を保証する活動は、一連の規制されたコミュニケーショ ン(授業、質問と回答、命令、訓戒、服従の暗号化されたサイン、各人の「価値」や知識レベルの差異化マーク)と、一連の権力プロセス(囲い込み、監視、報 酬と罰、ピラミッド型の階層)によってそこで展開される。 このようなブロックは「規律」を構成する。規律は、構成要素である能力、コミュニケーション、権力の3つの要素がどのように結びつけられているか、また、 それらの相互関係がどのように表現されているかについて、さまざまな見解を提供する。 「権力というテーマを『どのように』という分析によってアプローチすることは、したがって、根本的な権力の想定に関連して、いくつかの重要な変化をもたら すことになる。それは、権力関係を分析の対象として自らを位置づけることであり、権力そのものではない。」 |

| What constitutes the specific

nature of power? “[S]omething called Power, with or without a capital letter, which is assumed to exist universally in a concentrated or diffused form, does not exist. Power exists only when it is put into action.” That’s to say that power exists as a relation. What defines this relationship is that it is a mode of action which acts only indirectly; it is an action upon an action, on existing actions or on those which may arise in the present or the future. This requires that the one over whom power is exercised be thoroughly recognized and maintained to the very end as a person who acts, i.e., as a subject. In itself the exercise of power is not violence; nor is it a consent which, implicitly, is renewable. It is a total structure of actions brought to bear upon possible actions; it incites, it induces, it seduces, it makes easier or more difficult; in the extreme it constrains or forbids absolutely; it is nevertheless always a way of acting upon an acting subject or acting subjects by virtue of their acting or being capable of action. A set of actions upon other actions. The specificities of power relations can be better understood through the word conduct which means both (as a verb) to lead others and (as a noun) a way of behaving. The question of power is a question of government. Government in this sense refers not only to political structures or to the management of states but also the structuring of the possible field of action of others. To understand power in this way — as a mode of action upon the actions of others, or as the government of men by other men — is to presuppose free subjects over whom power is exercised, and that too, only insofar as they are free subjects. [S]lavery is not a power relationship when man is in chains. (In this case it is a question of a physical relationship of constraint.) Consequently, there is no face-to-face confrontation of power and freedom, which are mutually exclusive (freedom disappears everywhere power is exercised), but a much more complicated interplay. In this game freedom may well appear as the condition for the exercise of power (at the same time its precondition, since freedom must exist for power to be exerted, and also its permanent support, since without the possibility of recalcitrance, power would be equivalent to a physical determination). “At the very heart of the power relationship, and constantly provoking it, are the recalcitrance of the will and the intransigence of freedom. Rather than speaking of an essential freedom [then], it would be better to speak of an ‘agonism’ — of a relationship which is at the same time reciprocal incitation and struggle, … [of] a permanent provocation.” |

権力の特質とは何だろうか? 「大文字で書こうが小文字で書こうが、集中した形であれ拡散した形であれ、普遍的に存在すると想定される『力』と呼ばれるものは存在しない。力はそれが行 使された時にのみ存在する。」つまり、力は関係として存在するということだ。この関係を定義するのは、間接的にしか作用しない作用様式であるということ だ。それは、既存の作用に対する作用、あるいは現在または将来において生じる可能性のある作用に対する作用である。このため、権力が行使される対象は、最 後まで徹底的に、行動する者、すなわち主体として認識され、維持されなければならない。 権力の行使それ自体は暴力ではない。また、暗黙のうちに更新される同意でもない。それは、可能な行動に対して行使される行動の全体的な構造である。それは 扇動し、誘い、誘惑し、容易にしたり困難にしたりする。極端な場合には、強制したり、完全に禁止したりする。しかし、それは常に、行動する主体または行動 する主体たちに対して、彼らの行動または行動能力に基づいて行動する方法である。他の行動に対する一連の行動。 権力関係の特殊性は、他者を導くという意味の動詞と、行動様式という名詞の両方の意味を持つ「行動」という言葉によって、よりよく理解することができる。 権力の問題は、統治の問題である。この意味での統治とは、政治構造や国家の管理だけでなく、他者の行動の可能性の領域の構造化をも指す。 このように権力を理解するとは、すなわち他者の行動に対する行動様式として、あるいは他の人間による人間の統治として理解することであり、それは権力が行 使される自由な主体を前提としている。そして、それはあくまでも彼らが自由な主体である限りにおいてである。 人間が鎖につながれている場合、奴隷制は権力関係ではない。(この場合、それは物理的な拘束関係の問題である。)したがって、相互に排他的な権力と自由の 直接対決はなく(権力が行使されるところでは自由は消滅する)、はるかに複雑な相互作用がある。このゲームにおいて、自由は権力の行使の条件として現れる かもしれない(同時に、自由が存在しなければ権力を行使できないため、その前提条件でもある。また、抵抗の可能性がなければ、権力は物理的な決定と同等に なるため、自由は恒久的な支えでもある)。 「権力関係のまさに中心にあり、絶えずそれを引き起こしているのは、意志の反抗と自由の強情さである。本質的な自由について語るよりも、むしろ『アゴニズ ム』について語る方が良いだろう。それは、相互に刺激し合い、闘争する関係であり、…永続的な挑発である。」 |

| How is one to analyze the power

relationship? [This section has extracts only.] “One can analyze such relationships … by focusing on carefully defined institutions. [Institutions] constitute a privileged point of observation, diversified, concentrated, put in order, and carried through to the highest point of their efficacy. It is here that, as a first approximation, one might expect to see the appearance of the form and logic of their elementary mechanisms. “The analysis of power relations demands that a certain number of points be established concretely: The system of differentiations which permits one to act upon the actions of others: differentiations determined by the law or by traditions of status and privilege; economic differences … The types of objectives pursued by those who act upon the actions of others: the maintenance of privileges, the accumulation of profits … The means of bringing power relations into being: according to whether power is exercised by the threat of arms, by the effects of the word, by means of economic disparities, by more or less complex means of control … Forms of institutionalization: these may mix traditional predispositions, legal structures, phenomena relating to custom or to fashion (e.g., a family); they can also take the form of an apparatus closed in upon itself, with its specific loci, its own regulations, its hierarchical structures which are carefully defined, a relative autonomy in its functioning (e.g., military institutions); they can also form very complex systems endowed with multiple apparatuses (e.g., the state) … The degrees of rationalization: [to what extent the play of] power relations as action in a field of possibilities [are] more or less elaborate in relation to the effectiveness of the instruments and the certainty of the results … “[Thus,] one sees why the analysis of power relations within a society cannot be reduced to the study of a series of institutions, not even to the study of all those institutions which would merit the name ‘political’. Power relations are rooted in the system of social networks. … In referring here to the restricted sense of the word ‘government’, one could say that power relations have been progressively governmentalized, that is to say, elaborated, rationalized, and centralized in the form of, or under the auspices of, state institutions. |

権力関係を分析するにはどうすればよいのか? [このセクションは抜粋のみ] 「このような関係は、慎重に定義された制度に焦点を当てることで分析することができる。制度は、多様化され、集中され、秩序づけられ、その効力が最大限に 発揮されるという特権的な観察点となる。ここで、最初の近似値として、その基本的なメカニズムの形式と論理の兆候が見られると期待できる。 「権力関係の分析には、いくつかの点を具体的に設定することが必要である。 他者の行動に影響を与えることを可能にする差異化のシステム:地位や特権に関する法律や伝統によって決定される差異化、経済的な差異… 他者の行動に影響を与える人々が追求する目的の種類:特権の維持、利益の蓄積など 権力関係を生み出す手段:武力による威嚇、言葉による影響、経済格差、より複雑な支配手段など 制度化の形態:これらは伝統的な素因、法的構造、慣習や流行(例えば家族)に関連する現象が混在している可能性がある。また、特定の拠点、独自の規則、慎 重に定義された階層構造、機能における相対的な自律性(例えば軍事組織)を備えた、自己完結的な装置の形態を取る可能性もある。また、複数の装置を備えた 非常に複雑なシステム(例えば国家)を形成する可能性もある。 合理化の程度:可能性の領域における行動としての権力関係が、手段の有効性や結果の確実性と比較して、どの程度精巧に構築されているか。 「このように、社会における権力関係の分析が、一連の制度の研究に還元されることはなく、ましてや『政治的』という名称に値するすべての制度の研究に還元 されることはない理由がわかる。権力関係は社会ネットワークのシステムに根ざしている。…ここで「政府」という言葉の限定的な意味に言及するならば、権力 関係は徐々に政府化されてきた、つまり、国家機関の形態で、あるいは国家機関の支援の下で、精巧化、合理化、中央集権化されてきた、と言うことができる。 |

| Relations of power and relations

of strategy “The word ‘strategy’ is currently employed in three ways. First, to designate the means employed to attain a certain end… . Second, to designate the manner in which a partner in a certain game acts with regard to what he thinks should be the action of the others and what he considers the others think to be his own… . Third, to designate the procedures used in a situation of confrontation to deprive the opponent of his means of combat and to reduce him to giving up the struggle… . These three meanings come together in situations of confrontation … where the objective is to act upon an adversary in such a manner as to render the struggle impossible for him. … But it must be borne in mind that this is a very special type of situation and that there are others in which the distinctions between the different senses of the word ‘strategy’ must be maintained.” (emphasis added) There can be no relationship of power without the potential for a strategy of struggle. This is because, to quote again what has been said before, “at the very heart of the power relationship, and constantly provoking it, are the recalcitrance of the will and the intransigence of freedom”. A capacity for struggle (for freedom) is the precondition of power. This relationship of confrontation between power and struggle is an unstable one and if it attains stability, it would mean that one of the two has won out. When the confrontation is stabilised, the power relationship becomes at once its (the confrontation’s) target, fulfillment, and suspension while the strategy of struggle becomes a limit, a frontier for the relationship of power. Which is to say that every strategy of confrontation dreams of becoming a relationship of power, and every relationship of power leans toward the idea that, if it follows its own line of development and comes up against direct confrontation, it may become the winning strategy. |

権力関係と戦略関係 「戦略」という言葉は現在、3つの意味で用いられている。第一に、ある目的を達成するために採用される手段を指す場合。第二に、あるゲームにおけるパート ナーが、他者が取るべき行動と、他者が自分の行動をどう考えていると考えるかに関して、どのように行動するかを指す場合。第三に、対決の状況で用いられ る、相手から戦闘手段を奪い、降参させるための手順を指す。この3つの意味は、対立の状況において結びつく。その目的は、敵対者に闘争を不可能にするよう な方法で働きかけることである。しかし、これは非常に特殊な状況であり、他にも「戦略」という言葉の異なる意味の区別を維持しなければならない状況がある ことを念頭に置かなければならない。(強調部分) 闘争の戦略の可能性なしに権力の関係はありえない。なぜなら、以前にも引用したように、「権力関係のまさに中心には、絶えずそれを引き起こす、意志の反抗 心と自由の強情さがある」からだ。闘争(自由のための)の能力は、権力の前提条件である。 権力と闘争の対立関係は不安定なものであり、もし安定を獲得したとすれば、それは2つのうちの1つが勝利したことを意味する。対立が安定すると、権力関係 はたちまちその(対立の)目標となり、成就し、中断する。一方で、闘争の戦略は権力関係の限界、フロンティアとなる。 つまり、対立のあらゆる戦略は権力関係になることを夢見ているし、あらゆる権力関係は、独自の展開路線に従い、直接対立に突き当たれば、勝利戦略になるか もしれないという考えに傾く。 |

| https://x.gd/SBeVa |

|

☆Knowldge/Power

| The problem for me

is how to avoid this question, central

to the theme of right, regarding sovereignty and the

obedience of individual subjects in order that I may substitute

the problem of domination and subjugation for that

of sovereignty and obedience. Given that this was to be the

general line of my analysis, there were a certain number of

methodological precautions that seemed requisite to its

pursuit. In the very first place, it seemed important to accept

that the analysis in question should not concern itself with

the regulated and legitimate forms of power in their central

locations, with the general mechanisms through which they

operate, and the continual effects of these. On the contrary,

it should be concerned with power at its extremities, in its

ultimate destinations, with those points where it becomes

capillary, that is, in its more regional and local forms and

institutions. Its paramount concern, in fact, should be with

the point where power surmounts the rules of right which

organise and delimit it and extends itself beyond them,

invests itself in institutions, becomes embodied in techniques,

and equips itself with instruments and eventually

even violent means of material intervention. To give an

example: rather than try to discover where and how the

right of punishment is founded on sovereignty, how it is

presented in the theory of monarchical right or in that of

democratic right, I have tried to see in what ways punishment

and the power of punishment are effectively embodied in a certain

number of local, regional, material institutions,

which are concerned with torture or imprisonment, and to

place these in the climate-at once institutional and

physical, regulated and violent-of the effective apparatuses

of punishment. In other words, one should try to locate

power at the extreme points of its exercise, where it is

alwa ys less legal in character. Pp.96-97 |

私にとっての問題は、主権と服従という問題を、主権と服従という問題に

置き換えるために、権利の主題の中核をなすこの問い――主権と個人の服従に関する問い――をどう回避するかである。これが私の分析の大筋となる以上、その

追求には一定の方法論的注意が必要と思われた。まず第一に、問題の分析が、権力の中心的な領域における規範化された正当な形態、その一般的な作用メカニズ

ム、そしてそれらの持続的な効果に関わるべきではないと認めることが重要だと思われた。むしろ、権力の末端、究極的な到達点、すなわち毛細血管のように細

分化された地点、つまりより地域的・局所的な形態や制度に関わるべきだ。実際、その最優先の関心は、権力が自らを組織化し限定する法の規則を乗り越え、そ

れらを超えて拡張し、制度に投資し、技術に具現化し、道具を装備し、最終的には暴力的な物質的介入手段さえも獲得する地点にあるべきだ。例を挙げれば:

罰する権利が主権にどこでどのように基盤を置くのか、君主制の権利理論や民主的権利理論においてどのように提示されるのかを探ろうとするよりも、私は、拷

問や投獄に関わる特定の地方的・地域的・物質的制度において、罰と罰する権力が実際にどのように具現化されているかを考察し、それらを制度的かつ物理的、

規制されながらも暴力的であるという、実効的な罰の装置の環境の中に位置づけることを試みてきた。言い換えれば、権力は常に法的性格が希薄となる、その行

使の極限点において位置づけられるべきである。 |

| A second methodological

precaution urged that the

analysis should not concern itself with power at the level of

conscious intention or decision; that it should not attempt to

consider power from its internal point of view and that it

should refrain from posing the labyrinthine and unanswerable

question: 'Who then has power and what has he in

mind? What is the aim of someone who possesses power?'

Instead, it is a case of studying power at the point where its

intention, if it has one, is completely invested in its real and

effective practices. What is needed is a study of power in its

external visage, at the point where it is in direct and

immediate relationship with that which we can provisionally

call its object, its target, its field of application, there- that

is to say-where it installs itself and produces its real effects. p.97 |

第二の方法論的注意として、分析は意識的な意図や決定のレベルにおける 権力に関与すべきではない。権力をその内部的観点から考察しようと試みるべきではな く、また「では誰が権力を持ち、その者は何を考えているのか?権力を持つ者の目的は何か?」という迷宮的で答えようのない問いを提起することを控えるべき だ。むしろ、権力がもし意図を持つならば、その意図が完全に現実的かつ実効的な実践に注ぎ込まれる地点において権力を研究することである。必要なのは、権 力が外部に現れる様相、すなわち我々が暫定的にその対象、標的、適用領域と呼べるものとの直接的かつ即時的な関係にある地点、つまり権力が自らを位置づ け、現実の効果を生み出す地点における権力の研究である。 |

| Let us not, therefore, ask why

certain people want to

dominate, what they seek, what is their overall strategy. Let

us ask, instead, how things work at the level of on-going

SUbjugation, at the level of those continuous and uninterrupted

processes which subject our bodies, govern our

gestures, dictate our behaviours etc. In other words, rather

than ask ourselves how the sovereign appears to us in his

lofty isolation, we should try to discover how it is that

subjects are gradually, progressively, really and materially

constituted through a multiplicity of organisms, forces,

energies, materials, desires, thoughts etc. We should try to

grasp subjection in its material instance as a constitution of

subjects. This would be the exact opposite of Hobbes'

project in Leviathan, and of that, I believe, of all jurists for

whom the problem is the distillation of a single will-or

rather, the constitution of a unitary, singular body animated

by the spirit of sovereignty - from the particular wills of a

multiplicity of individuals. Think of the scheme of Leviathan:

insofar as he is a fabricated man, Leviathan is no other than

the amalgamation of a certain number of separate individualities, who

find themselves reunited by the complex

of elements that go to compose the State~ but at the heart of

the State, or rather, at its head, there exists something

which constitutes it as such, and this is sovereignty, which

Hobbes says is precisely the spirit of Leviathan. Well, rather

than worry about the problem of the central spirit, I believe

that we must attempt to study the myriad of bodies which

are constituted as peripheral subjects as a result of the effects

of power. Pp.97-98 |

したがって、なぜ特定の人間が支配を望むのか、彼らが何を求めているの

か、彼らの全体的な戦略は何か、といった問いはすべきではない。代わりに問うべきは、継続的な服従のレベルで、つまり私たちの身体を従属させ、身振りを支

配し、行動を規定するといった途切れることのない連続的なプロセスにおいて、物事がどのように機能しているかである。言い換えれば、高みから孤立した君主

が我々にどう見えるかではなく、主体がどのようにして、多様な有機体・力・エネルギー・物質・欲望・思考などを通じて、漸進的かつ実質的に形成されるのか

を探るべきだ。主体化を、主体の構成という物質的実例として把握しようとするべきである。これは『リヴァイアサン』におけるホッブズの構想とは正反対であ

り、また、複数の個人の個別的な意志から単一の意志——より正確には、主権の精神によって生気を与えられた単一で唯一無二の身体——を抽出すること(ある

いはむしろ、それを構成すること)を問題とする全ての法学者たちの構想とも正反対であると私は考える。『リヴァイアサン』の構想を考えてみよう。リヴァイ

アサンが人工的に造られた存在である限り、それは国家を構成する諸要素の複合体によって再統合された、ある数の分離した個別性の融合に他ならない。しかし

国家の中心、あるいはその頂点には、国家を国家たらしめる何かが存在する。それが主権であり、ホッブズによれば、まさにリヴァイアサンの精神そのものだと

いう。さて、中心的な精神の問題を心配するよりも、権力の影響によって周辺的な主体として構成される無数の身体を研究しようと試みるべきだと考える。 |

| A third methodological

precaution relates to the fact that

power is not to be taken to be a phenomenon of one

individual's consolidated and homogeneous domination

over others, or that of one group or class over others. What,

by contrast, should always be kept in mind is that power, if

we do not take too distant a view of it, is not that which

makes the difference between those who exclusively possess

and retain it, and those who do not have it and submit to it.

Power must by analysed as something which circulates, or

rather as something which only functions in the form of a

chain. It is never localised here or there, never in anybody's

hands, never appropriated as a commodity or piece of

wealth. Power is employed and exercised through a net-like

organisation. And not only do individuals circulate between

its threads; they are always in the position of simultaneously

undergoing and exercising this power. They are not only its

inert or consenting target; they are always also the elements

of its articulation. In other words, individuals are the

vehicles of power, not its points of application. p.98 |

第三の方法論的注意点は、権力が単一の個人が他者を統合的かつ均質に支

配する現象、あるいは単一の集団や階級が他者を支配する現象と見なされるべきではないという事実に関わる。対照的に常に留意すべきは、権力をあまり遠回し

に見ない限り、それは権力を独占的に保持する者と、権力を持たずそれに服従する者との差異を生むものではないということだ。権力は循環するもの、あるいは

むしろ連鎖の形態でしか機能しないものとして分析されねばならない。権力は決してここに局在せず、誰かの手に握られることもなく、商品や富として独占され

ることもない。権力は網の目のような組織を通じて行使され運用される。そして個人は、その糸の間を循環するだけでなく、常にこの権力を同時に受けつつ行使

する立場にある。彼らは単なる受動的・同意的な対象ではなく、常に権力の関節を構成する要素でもある。言い換えれば、個人は権力の適用点ではなく、権力の

媒体なのである。 |

| The individual is not to be

conceived as a sort of elementary

nucleus, a primitive atom, a multiple and inert material

on which power comes to fasten or against which it happens

to strike, and in so doing subdues or crushes individuals. In

fact, it is already one of the prime effects of power that

certain bodies, certain gestures, certain discourses, certain

desires, come to be identified and constituted as individuals.

The individual, that is, is not the vis-a-vis of power; it is, I

believe, one of its prime effects. The individual is an effect of

power, and at the same time, or precisely to the extent to

which it is that effect, it is the element of its articulation.

The individual which power has constituted is at the same

time its vehicle. p.98 |

個人は、権力が付着したり衝突したりする、ある種の素核や原始的な原

子、あるいは無機質な物質の集合体として捉えられるべきではない。そうすることで権力は個人を服従させたり押し潰したりするのだ。実際、特定の身体や動

作、言説、欲望が個人として識別され構成されること自体が、すでに権力の主要な効果の一つなのである。つまり個人は権力の対峙物ではない。むしろ権力の主

要な効果の一つであると考える。個人は権力の効果であると同時に、あるいはまさにその効果である限りにおいて、権力の構造要素でもある。権力が構成した個

人は、同時に権力の媒体でもあるのだ。 |

| There is a fourth methodological precaution that follows

from this: when I say that power establishes a network

through which it freely circulates, this is true only up to a

certain point. In much the same fashion we could say that

therefore we all have a fascism in our heads, or, more

profoundly, that we all have a power in our bodies. But I do

not believe that one should conclude from that that power is

the best distributed thing in the world, although in some

sense that is indeed so. We are not dealing with a sort of

democratic or anarchic distribution of power through

bodies. That is to say, it seems to me-and this then would

be the fourth methodological precaution - that the important

thing is not to attempt some kind of deduction of power

starting from its centre and aimed at the discovery of the

extent to which it permeates into the base, of the degree to

which it reproduces itself down to and including the most

molecular elements of society. One must rather conduct an

ascending analysis of power, starting, that is, from its

infinitesimal mechanisms, which each have their own

history, their own trajectory, their own techniques and

tactics, and then see how these mechanisms of power have

been - and continue to be- invested, colonised, utilised,

involuted, transformed, displaced, extended etc., by ever

more general mechanisms and by forms of global domination.

It is not that this global domination extends itself

right to the base in a plurality of repercussions: I believe

that the manner in which the phenomena, the techniques

and the procedures of power enter into play at the most

basic levels must be analysed, that the way in which these

procedures are displaced, extended and altered must

certainly be demonstrated; but above all what must be

shown is the manner in which they are invested and annexed

by more global phenomena and the subtle fashion in which

more general powers or economic interests are able to

engage with these technologies that are at once both

relatively autonomous of power and act as its infinitesimal

elements. In order to make this clearer, one might cite the

example of madness. The descending type of analysis, the

one of which I believe one ought to be wary, will say that the

bourgeoisie has, since the sixteenth or seventeenth century,

been the dominant class; from this premise, it will then set out to deduce the internment of the insane. One can always

make this deduction, it is always easily done and that is

precisely what I would hold against it. It is in fact a simple

matter to show that since lunatics are precisely those

persons who are useless to industrial production, one is

obliged to dispense with them. One could argue similarly in

regard to infantile sexuality- and several thinkers, including

Wilhelm Reich have indeed sought to do so up to a

certain point. Given the domination of the bourgeois class,

how can one understand the repression of infantile sexuality?

Well, very simply - given that the human body had become

essentially a force of production from the time of the

seventeenth and eighteenth century, all the forms of its

expenditure which did not lend themselves to the constitution

of the productive forces - and were therefore exposed

as redundant- were banned, excluded and repressed.

These kinds of deduction are always possible. They are

simultaneously correct and false. Above all they are too

glib, because one can always do exactly the opposite and

show, precisely by appeal to the principle of the dominance

of the bourgeois class, that the forms of control of infantile

sexuality could in no way have been predicted. On the

contrary, it is equally plausible to suggest that what was

needed was sexual training, the encouragement of a sexual

precociousness, given that what was fundamentally at stake

was the constitution of a labour force whose optimal state,

as we well know, at least at the beginning of the nineteenth

century, was to be infinite: the greater the labour force, the

better able would the system of capitalist production have

been to fulfil and improve its functions. pp.99-100. |

ここから導か

れる第四の方法論的注意がある。権力が自由に循環するネットワークを構築すると言うとき、それはある点までしか真実ではない。同じように、我々皆の頭の中

にはファシズムがある、あるいはより深く言えば、我々皆の身体には権力があると言えるだろう。しかし、そこから権力が世界で最も均等に分配されているもの

だと結論づけるべきではないと考える。ある意味では確かにそうだが。我々が扱っているのは、身体を通じて民主的あるいは無政府的に分配された権力などでは

ない。つまり、第四の方法論的注意として、重要なのは権力の中心から出発し、それが基盤に浸透する範囲や、社会の分子レベルの要素に至るまで自己複製する

度合いを発見しようとするような、権力の何らかの演繹を試みることではないと私には思える。むしろ権力の底辺から始まる上昇的な分析を行わねばならない。

つまり、それぞれ独自の歴史、軌跡、技術、戦術を持つ無限小のメカニズムから出発し、これらの権力メカニズムが、より普遍的なメカニズムやグローバルな支

配形態によって、いかに投資され、植民地化され、利用され、内包され、変容し、置換され、拡張されてきたか――そして現在もされ続けているか――を検証す

るのだ。このグローバルな支配が、複数の反響を通じて基盤レベルにまで直接的に拡大するわけではない。むしろ、権力の現象や技術、手続きが最も基礎的なレ

ベルでどのように作用するかを分析すべきであり、これらの手続きがどのように置き換えられ、拡張され、変容するかを確かに示す必要がある。しかし何よりも

明らかにすべきは、よりグローバルな現象によってそれらが投資され併合される様相、そしてより普遍的な権力や経済的利害が、権力から相対的に自律しつつも

その無限小の要素として機能するこれらの技術と、いかに巧妙に関与し得るかという点である。これを明確にするため、狂気の例を挙げてみよう。私が警戒すべ

きだと思う下降型の分析は、ブルジョアジーが16世紀あるいは17世紀以来支配階級であったと主張し、この前提から精神病患者の収容を導き出そうとする。

この推論は常に可能であり、容易に成し遂げられる。まさにその点こそが私の批判の的だ。実際、狂人とは産業生産に役立たない人格たちである以上、彼らを排

除せざるを得ないことを示すのは容易い。幼児的性欲についても同様の議論が可能であり、ヴィルヘルム・ライヒを含む幾人かの思想家が実際にその試みを一定

程度行ってきた。ブルジョワ階級の支配下において、幼児的性欲の抑圧をどう理解すべきか?非常に単純だ——17、18世紀以降、人間の身体が本質的に生産

力となった以上、生産力形成に寄与しないあらゆる消費形態——つまり余剰と断じられたものは——禁止され、排除され、抑圧されたのだ。こうした類推は常に

可能である。それは同時に正しくも誤りでもある。何よりも、それらはあまりにも安易だ。なぜなら、まったく逆の主張を常に展開し、まさにブルジョワ階級の

支配という原理に訴えることで、幼児期の性に対する統制の形態が予測不可能であったことを示せるからだ。むしろ、必要なのは性教育であり、性的な早熟を奨

励することだったと主張することも同様に妥当である。なぜなら、根本的に問題となっていたのは労働力の形成であり、少なくとも19世紀初頭においては、そ

の最適な状態は無限であることが周知の事実だったからだ。労働力が大きければ大きいほど、資本主義的生産システムはその機能をより良く果たし、改善するこ

とができたのである。 |

| Power/knowledge : selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977 [pdf] |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099