スピノザ『神学政治論』

Tractatus

Theologico-Politicus, 1670

Joannes

van

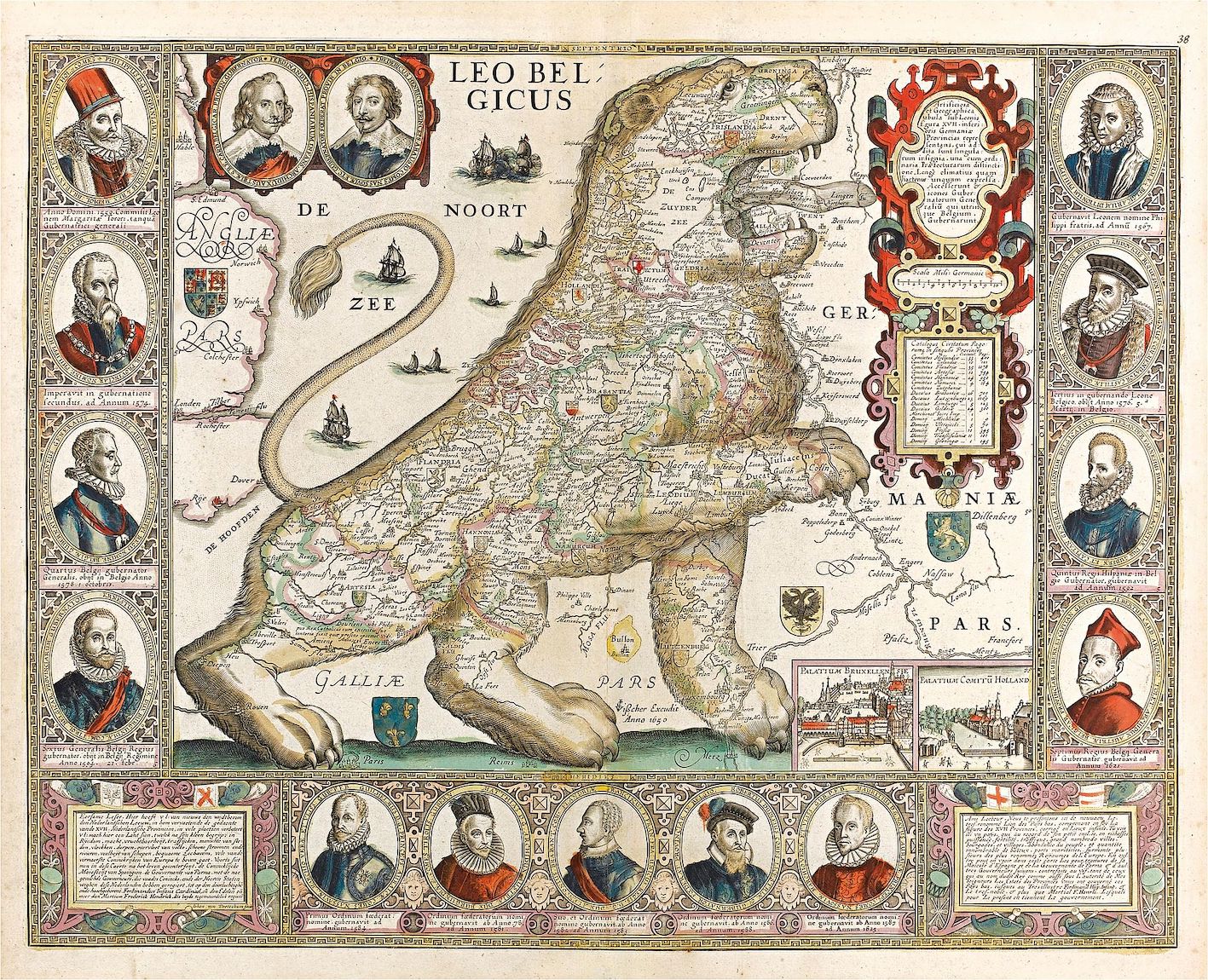

Deutecum, Claes Jansz Visscher, Leo Belgicus

『神学政治論』(Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, TTP)は、1670 年にベネディクトゥス(バルーフ)・スピノザが著した書物。『聖書』批判を通し た、政治論で、今日における政教分離や、デモクラシーの考え方を支持する点で、当時とし ては、過激で、宗教界ならびに世俗政治の観点からも危険思想と見なされた書物。出版地と著者を偽って出版したが、誰が出版したかが、ほぼほぼ理解されてい た書物。スピノザが生前に出版した唯一の書物。この出版は、後の啓蒙思想家たちのアイディアを刺激し、(1)無神論ないしは汎神論、(2)デモクラシーの 思想的基盤を準備した、(3)聖書を真理のテキストではなく人間にとって考えることを要求する書物、すなわちテキストよりも信仰者各人の心の問題である、 と位置付けた、ほとんど最初の著作だと言われている。

Writing and

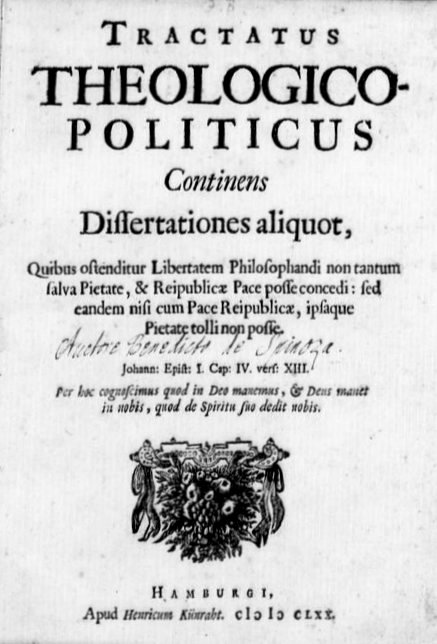

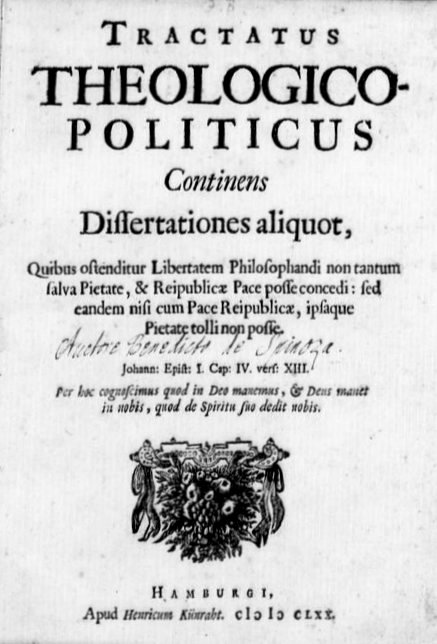

publication history Portrait of Baruch Spinoza, 1665. Spinoza had been working on his magnum opus, the Ethics, when he put it aside to write the TTP. Unlike the abstract composition of that work as a mathematical proof, the TTP is more discursive and accessible to readers of Latin. He wrote to Henry Oldenburg, Secretary of the Royal Society, who had visited him in the Netherlands and they continued the connection via letters, telling him about the new work. Oldenburg was surprised and Spinoza wrote his justifications for the diversion from metaphysics. The TTP is a frontal assault on the power of theologians underpinned by Scripture. Spinoza wanted to defend himself against charges of atheism. He sought the freedom to philosophize, unhindered by religious authority.[7] The treatise was published anonymously in 1670 by Jan Rieuwertsz in Amsterdam. In order to protect the author and publisher from political retribution, the title page identified the city of publication as Hamburg and the publisher as Henricus Künraht. Spinoza wrote in Neo-Latin, the language of European scholars of the era. To reach beyond the scholarly readership in the Dutch Republic, publication in Dutch was the next step. Jan Hendriksz Glazemaker, Spinoza's Dutch translator and a Collegiant freethinker, prepared the edition by 1671 and sent it to the publisher; Spinoza himself intervened to prevent its printing for the moment, since the translation could have put Spinoza and his circle of supporters in increased danger with authorities.[8] |

執筆および出版履歴 1665年のバルーフ・スピノザの肖像画。 スピノザは、偉大な作品である『エチカ』を執筆していたが、TTPを書くためにそれを中断した。数学的な証明としてのその作品の抽象的な構成とは異なり、 TTPはより論理的でラテン語の読者にも理解しやすいものだった。スピノザは、オランダを訪れた王立協会の書記ヘンリー・オルデンバーグに手紙を書き、そ の後も手紙で連絡を取り合い、新しい作品について彼に伝えた。オルデンブルクは驚き、スピノザは形而上学からの転向の正当性を書いた。TTPは、聖書に裏 打ちされた神学者の権力に対する正面からの攻撃である。スピノザは無神論の罪状から身を守ろうとした。彼は宗教的権威に邪魔されることなく哲学する自由を 求めた。 この論文は1670年にアムステルダムのヤン・リューベルトスによって匿名で出版された。著者と出版者を政治的な報復から守るため、タイトルページには出 版地をハンブルク、出版者をヘンリクス・クンラートと記載した。スピノザは当時のヨーロッパの学者たちが用いた新ラテン語で執筆した。オランダ共和国の学 術的な読者層を超えて広めるためには、オランダ語での出版が次のステップであった。スピノザのオランダ語訳者であり、コレギウムの自由思想家でもあったヤ ン・ヘンドリクス・グラスメーカーは、1671年までに版を準備し、それを出版社に送った。スピノザ自身は、翻訳によってスピノザと彼を支持する人々が当 局からさらに危険な立場に置かれる可能性があるとして、その時点では印刷を差し止めるよう介入した。[8] |

| tructure of the work The work comprises 20 named chapters preceded by a preface. The majority of chapters deal with aspects of religion, with the last five concerning aspects of the state. The following list gives shortened chapter titles, taken from the full titles, in the 2007 edition of the TTP edited by Jonathan I. Israel.[9] Preface. Chapter 1. On prophecy. Chapter 2. On the prophets. Chapter 3. On the vocation of the Hebrews. Chapter 4. On the divine law. Chapter 5. On ceremonies and narratives. Chapter 6. On miracles. Chapter 7. On the interpretation of Scripture. Chapter 8. Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings. Chapter 9. Further queries about the same books. Chapter 10. Remaining Old Testament books. Chapter 11. Apostles and prophets. Chapter 12. Divine law and the word of God. Chapter 13. The teachings of Scripture. Chapter 14. Faith and philosophy. Chapter 15. Theology and reason. Chapter 16. Foundations of the state. Chapter 17. The Hebrew state in the time of Moses. Chapter 18. The Hebrew state and its history. Chapter 19. Sovereign powers and religion. Chapter 20. A free state. |

作品の構成 この作品は序文に続いて20の章から構成されている。大半の章は宗教の側面を扱っており、最後の5章は国家の側面を扱っている。以下のリストは、ジョナサ ン・I・イスラエル編集による2007年版『TTP』の完全なタイトルから取られた短縮された章のタイトルである。 序文。 第1章 預言について。 第2章 預言者について。 第3章 ヘブライ人の天職について。 第4章 神の律法について。 第5章 儀式と物語について。 第6章 奇跡について。 第7章 聖書の解釈について。 第8章 五書、ヨシュア記、士師記、ルツ記、サムエル記、列王記。 第9章 同じ書籍に関するさらなる質問 第10章 残りの旧約聖書の書籍 第11章 使徒と預言者 第12章 神の法と神の言葉 第13章 聖書の教え 第14章 信仰と哲学 第15章 神学と理性 第16章 国家の基礎 第17章 モーセの時代のヘブライ人の国家 第18章 ヘブライ人の国家とその歴史 第19章 国家権力と宗教 第20章 自由な国家 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractatus_Theologico-Politicus |

| The

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (TTP) or Theologico-Political

Treatise, is a 1670 work of philosophy written in Latin by the Dutch

philosopher Benedictus Spinoza (1632–1677). The book was one of the

most important and controversial texts of the early modern period. Its

aim was "to liberate the individual from bondage to superstition and

ecclesiastical authority."[3] In it, Spinoza expounds his views on

contemporary Jewish and Christian religion and critically analyses the

Bible, especially the Old Testament, which underlies both. He argues

what the best roles for state and religion should be and concludes that

a degree of democracy and freedom of speech and religion works best,

such as in Amsterdam, while the state remains paramount within reason.

The goal of the state is to guarantee the freedom of citizens.

Religious leaders should not interfere in politics. Spinoza interrupted

his writing of his magnum opus, the Ethics, to respond to the

increasing intolerance in the Dutch Republic, directly challenging

religious authorities and their power over freedom of thought. He

published the work anonymously, in Latin, rightly anticipating harsh

criticism and vigorous attempts by religious leaders and conservative

secular authorities to suppress his work entirely. He halted the

publication of a Dutch translation. One described it as being "Forged

in hell by the apostate Jew working together with the devil".[4] The

work has been characterized as "one of the most significant events in

European intellectual history", laying the groundwork for ideas about

liberalism, secularism, and democracy.[5] |

『神学・政治論』(TTP)または『神学・政治論』は、オランダの哲学

者ベネデクトゥス・デ・スピノザ(1632年 -

1677年)が1670年にラテン語で著した哲学書である。この本は、近世初期における最も重要かつ物議を醸したテキストのひとつである。その目的は「迷

信と教会権威の束縛から個人を解放すること」であった。[3]

その中でスピノザは、当時のユダヤ教とキリスト教の宗教に関する自身の考えを展開し、聖書、特にその両方の根底にある旧約聖書を批判的に分析している。彼

は、国家と宗教にとって最善の役割とは何かを論じ、アムステルダムのように、国家が合理的な範囲内で最優先される一方で、ある程度の民主主義と信教の自由

が最も効果的であると結論づけている。国家の目的は市民の自由を保証することである。宗教指導者は政治に干渉すべきではない。スピノザは、オランダ共和国

で高まりつつあった不寛容な風潮に反論するため、代表作『エチカ』の執筆を中断し、宗教的権威とその思想の自由に対する権力に直接的に異議を唱えた。彼

は、宗教指導者や保守的な世俗的権威者たちから厳しい批判を受け、作品を完全に弾圧しようとする激しい動きが起こることを予期して、この作品をラテン語で

匿名で出版した。彼はオランダ語訳の出版を中止した。ある批評家は、この作品を「背教者のユダヤ人が悪魔と共謀して地獄で作り上げたもの」と評した。

[4]

この作品は「ヨーロッパの知的歴史における最も重要な出来事のひとつ」と評され、自由主義、世俗主義、民主主義に関する思想の基礎を築いた。[5] |

| Historical context Further information: Dutch Golden Age The vaunted religious tolerance of the Dutch Republic was under strain in the mid-seventeenth century. War with England over trade and imperial dominance affected the Northern Netherlands' prosperity. The conservative leaders of the Dutch Reformed Church put pressure on civil authorities to curtail freedom of expression and the circulation of ideas to which they objected. In the political sphere conservatives sought to restore the position of stadholder, or head of state, with a member of the House of Orange. During the First Stadtholderless period (1650–1672) Johan de Witt functioned as head of state and was in favor of policies of religious toleration, which had helped fuel prosperity. Jews could practice their religion openly and were an integral part of the commercial sector. There were also a great number of Christian sects that contributed to the religious and intellectual ferment of the Republic. Some dissenters began openly challenging religious authorities and religion itself, as Spinoza had done, leading to his expulsion from the Jewish community in Amsterdam in 1656. A like-minded friend and kindred intellectual spirit, Adriaan Koerbagh (1633–1669), had published two works scathing of religion. Because they were published in Dutch rather than Latin, and therefore accessible to a much wider readership, he quickly came to the attention of religious authorities, arrested, and thrown into prison, where he quickly died. His death was a hard blow for Spinoza and his reaction was to commence writing in 1665 what became the TTP.[6] Heeding the danger of writing in Dutch, Spinoza's treatise is in Latin. Unlike the dense text of the Ethics, the TTP is much more accessible and deals with religion and politics rather than metaphysics. Scholars have suggested that the text of the TTP incorporates the Apologia ("defense") he had written in Spanish after his expulsion from the Jewish community in 1656. |

歴史的背景 詳細情報:オランダ黄金時代 17世紀半ば、オランダ共和国の誇る宗教的寛容さは大きな試練に直面していた。貿易と帝国支配をめぐるイギリスとの戦争は、北部ネーデルラントの繁栄に影 響を与えた。オランダ改革派教会の保守派指導者たちは、自分たちが反対する思想の表現や流通の自由を制限するよう、市民当局に圧力をかけた。政治面では、 保守派はオレンジ公の一族から総督(国家元首)を選出する制度の復活を求めた。 第一次オランジュリー総督不在時代(1650年~1672年)には、ヨハン・デ・ウィットが国家元首として宗教的寛容政策を推進し、これが繁栄の追い風と なった。 ユダヤ人は公然と宗教を実践することができ、商業部門の重要な一部を担っていた。また、キリスト教の宗派も数多く存在し、共和国の宗教的、知的な活気の一 因となっていた。一部の反対派は、スピノザのように宗教的権威や宗教そのものを公然と批判し始め、1656年にはアムステルダムのユダヤ人社会から追放さ れるに至った。同じ考えを持つ友人であり、類まれな知性を持つアドリアーン・クーバーグ(1633-1669)は、宗教を痛烈に批判する著作を2冊発表し ていた。それらの著作はラテン語ではなくオランダ語で出版されたため、より幅広い読者層に読まれることとなり、彼はたちまち宗教当局の目に留まり、逮捕さ れて投獄され、間もなく死亡した。彼の死はスピノザにとって大きな打撃であり、1665年にTTPとなる著作の執筆を開始した。オランダ語で執筆すること の危険性を考慮し、スピノザの論文はラテン語で書かれている。『倫理学』の難解な文章とは異なり、『TTP』はより理解しやすく、形而上学よりも宗教や政 治について論じている。学者たちは、『TTP』の文章は、1656年にユダヤ人社会から追放された後にスペイン語で書かれた『アポロギア』(弁明)を組み 込んでいると指摘している。 |

| Treatment of religion In the treatise, Spinoza put forth his most systematic critique of Judaism, and all organized religion in general. Spinoza argued that theology and philosophy must be kept separate, particularly in the reading of scripture. Whereas the goal of theology is obedience, philosophy aims at understanding rational truth. Scripture does not teach philosophy and thus cannot be made to conform with it, otherwise the meaning of scripture will be distorted. Conversely, if reason is made subservient to scripture, then, Spinoza argues, "the prejudices of a common people of long ago... will gain a hold on his understanding and darken it." Spinoza argued that purportedly supernatural occurrences, namely prophecy and miracles, have in fact natural explanations. He argued that God acts solely by the laws of his own nature and rejected the view that God acts for a particular purpose or telos. For Spinoza, those who believe that God acts for some end are delusional and projecting their hopes and fears onto the workings of nature. |

宗教の扱い スピノザはこの論考の中で、ユダヤ教、そして組織化された宗教全般に対する最も体系的な批判を打ち出した。スピノザは、神学と哲学は、特に聖典の読解にお いて、分離しておかなければならないと主張した。神学の目標が服従であるのに対し、哲学は合理的な真理を理解することを目的としている。聖書は哲学を教え ないので、哲学に合わせると、聖書の意味が歪んでしまう。逆に理性を聖典に従わせると、"大昔の庶民の偏見が...彼の理解を支配し、暗くしてしまう "とスピノザは主張するのである。 スピノザは、予言や奇跡といった超自然的と称される出来事には、実は自然的な説明がつくと主張した。スピノザは、予言や奇跡といった超自然的な現象は、実 は自然的な説明によるものだと主張し、神は自らの自然の法則によってのみ行動すると主張し、神が特定の目的やテロスのために行動するという見方を否定し た。スピノザにとって、神が何らかの目的のために行動すると信じる者は妄想であり、自分の希望や恐怖を自然の働きに投影しているのである。 |

| Scriptural interpretation Spinoza was not only the real father of modern metaphysics and moral and political philosophy, but also of the so-called higher criticism of the Bible. He was particularly attuned to the idea of interpretation; he felt that all organized religion was simply the institutionalized defense of particular interpretations. He rejected in its entirety the view that Moses composed the first five books of the Bible, called the Pentateuch by Christians or Torah by Jews. He provided an analysis of the structure of the Bible which demonstrated that it was essentially a compiled text with many different authors and diverse origins; in his view, it was not "revealed" all at once. His Tractatus Theologico-Politicus undertook to show that Scriptures properly understood gave no authority for the militant intolerance of the clergy who sought to stifle all dissent by the use of force. To achieve his object, Spinoza had to show what is meant by a proper understanding of the Bible, which gave him occasion to apply criticism to the Bible. His approach stood in stark contrast to contemporaries like John Bunyan, Manasseh ben Israel, and militant clerics. Spinoza, who permitted no supernatural rival to Nature and no rival authority to the civil government of the state, rejected also all claims that Biblical literature should be treated in a manner entirely different from that in which any other document is treated that claims to be historical. His contention that the Bible "is in parts imperfect, corrupt, erroneous, and inconsistent with itself, and that we possess but fragments of it"[3] roused great storm at the time, and was mainly responsible for his evil repute for a century at least.[4] Nevertheless, many have gradually adopted his views, agreeing with him that the real "word of God", or true religion, is not something written in books but "inscribed on the heart and mind of man".[5] Many scholars and ministers of religion now praise Spinoza's services in the correct interpretation of Scripture as a document of first rate importance in the progressive development of human thought and conduct.[4] |

聖書解釈 スピノザは、近代形而上学、道徳哲学、政治哲学の実の父であると同時に、いわゆる聖書の高等批評の父である。彼は特に解釈の問題に関心を持ち、組織化され た宗教はすべて特定の解釈を制度的に擁護しているに過ぎないと考えていた。モーセが聖書の最初の5冊を書いたとする説(キリスト教では五書、ユダヤ教では トーラーと呼ばれる)を全面的に否定した。また、聖書は多くの著者と多様な起源を持つ編集されたテキストであり、一度に「啓示」されたものではない、とい う構造的な分析も行った。 また、『政治神学論』は、聖書を正しく理解することが、武力によって異論を封じ込めようとする聖職者の過激な不寛容に何の根拠も与えないということを示す ものであった。この目的を達成するために、スピノザは聖書の正しい理解とは何かを示す必要があり、そのために彼は聖書に批判を加える機会を得た。ス ピノザのアプローチは、同時代のジョン・バニヤン、マナセ・ベン・イスラエル、過激派聖職者らとは対照的であった。スピノザは、自然に対して超自然的な対 抗を認めず、国家という市民的な政府に対して対抗する権威を認めず、聖書文学を、歴史的であると主張する他の文書の扱いとはまったく異なる方法で扱うべき という主張もすべて否定した。聖書は部分的に不完全であり、腐敗し、誤りがあり、それ自身と矛盾しており、我々はその断片しか持っていない」という彼の主 張は、当時大きな反響を呼び、少なくとも1世紀にわたる彼の悪評の主因となった[3]。 [4] それにもかかわらず、多くの人が徐々に彼の見解を採用し、真の「神の言葉」、すなわ ち真の宗教は書物に書かれたものではなく、「人間の心と精神に刻まれたもの」であるという彼の意見に同意した[5]。 多くの学者や宗教相が、聖書の正しい解釈におけるスピノザの功績を、人間の思想と行動の進歩的発展において第一級の重要性を持つ文書として賞賛するように なった[4]。 |

| Treatment of Judaism Though of Jewish ancestry, Spinoza does not refer to himself as Jewish at all through the treatise. He only speaks of "the Hebrews" or "the Jews" in third person. The treatise also rejected the Jewish notion of "chosenness"; to Spinoza, all peoples are on par with each other, as God has not elevated one over the other. Spinoza also offered a sociological explanation as to how the Jewish people had managed to survive for so long, despite facing relentless persecution. In his view, the Jews had been preserved due to a combination of Gentile hatred and Jewish separatism. He also gave one final, crucial reason for the continued Jewish presence, which in his view, was by itself sufficient to maintain the survival of the nation forever: circumcision. It was the ultimate anthropological expression of bodily marking, a tangible symbol of separateness which was the ultimate identifier. Spinoza also posited a novel view of the Torah; he claimed that it was essentially a political constitution of the ancient state of Israel. In his view, because the state no longer existed, its constitution could no longer be valid. He argued that the Torah was thus suited to a particular time and place; because times and circumstances had changed, the Torah could no longer be regarded as a valid document. |

ユダヤ教の扱い スピノザはユダヤ人の家系でありながら、論考を通じて自らをユダヤ人であるとは全く言っていない。ヘブライ人」あるいは「ユダヤ人」という三人称で語るの みである。この論文では、ユダヤ人の「神からの召命」の概念も否定している。スピノザは、神がある民族を他の民族より高くしていないため、すべての民族は 互いに同等であると考えたのである。さらにスピノザは、ユダヤ人が執拗な迫害を受けながらも長い間生き延びることができた理由を、社会学的に説明した。そ れは、異邦人の憎悪とユダヤ人の分離主義が相まって、ユダヤ人が生き延びることができたというのである。 そして、ユダヤ人が存在し続けた最後の決定的な理由として、それだけで民族の存続を永遠に維持するのに十分であると彼は考えていた。割礼は人類学的に究極 の身体的マーキングの表現であり、究極の識別子である分離の具体的なシンボルであった。 スピノザはまた、律法について、古代イスラエル国家の政治的憲法であるという新しい見解を示した。国家が存在しない以上、その憲法はもはや有効でないと考 えたのである。そして、『トーラー』はある特定の時代と場所に適したものであり、時代と環境が変われば、『トーラー』は有効な文書とは見なされなくなる、 と主張した。 |

| Spinoza's political theory Spinoza agreed with Thomas Hobbes that if each man had to fend for himself, with nothing but his own right arm to rely upon, then the life of man would be "nasty, brutish, and short".[6] The truly human life is only possible in an organised community, that is, a state or commonwealth. The state ensures security of life, limb and property; it brings within reach of every individual many necessaries of life which he could not produce by himself; and it sets free sufficient time and energy for the higher development of human powers. Now the existence of a state depends upon a kind of implicit agreement on the part of its members or citizens to obey the sovereign authority which governs it. In a state no one can be allowed to do just as he pleases. Every citizen is obliged to obey its laws; and he is not free even to interpret the laws in a special manner. This looks at first like a loss of freedom on the part of the individuals, and the establishment of an absolute power over them. Yet that is not really so. In the first place, without the advantages of an organised state the average individual would be so subject to dangers and hardships of all kinds and to his own passions that he could not be called free in any real sense of the term, least of all in the sense that Spinoza used it. Man needs the state not only to save him from others but also from his own lower impulses and to enable him to live a life of reason, which alone is truly human. In the second place, state sovereignty is never really absolute. It is true that almost any kind of government is better than none, so that it is worth bearing much that is irksome rather than disturb the peace. But a reasonably wise government will even in its own interest endeavour to secure the good will and cooperation of its citizens by refraining from unreasonable measures, and will permit or even encourage its citizens to advocate reforms, provided they employ peaceable means. In this way the state really rests, in the last resort, on the united will of the citizens, on what Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who read Spinoza, subsequently called the "general will".[4] Spinoza sometimes writes as if the state upheld absolute sovereignty. But that is due mainly to his determined opposition to every kind of ecclesiastical control over it. Though he is prepared to support what may be called a state religion, as a kind of spiritual cement, yet his account of this religion is such as to make it acceptable to the adherents of any one of the historic creeds, to deists, pantheists and all others, provided they are not fanatical believers or unbelievers. It is really in the interest of freedom of thought and speech that Spinoza would entrust the civil government with something approaching absolute sovereignty in order to effectively resist the tyranny of the militant churches.[5] |

スピノザの政治理論 スピノザはトマス・ホッブズと同じように、もし各人が自分の右腕だけを頼りに自活しなければならないとしたら、人間の生活は「厄介で、残忍で、短い」もの になるだろうと考えた[6]。 真に人間らしい生活は組織された共同体、つまり国家や連邦においてのみ可能なのである。国家は、生命、身体、財産の安全を保証し、各個人が自分で生産する ことができない多くの生活必需品を手の届くところにもたらし、人間の力をより高く発展させるために十分な時間とエネルギーを自由にさせるのである。さて、 国家の存在は、その構成員または市民の側が、それを統治する主権的権威に従うという一種の暗黙の了解に依存している。国家においては、誰も自分の好きなよ うにすることはできない。すべての市民はその法律に従う義務があり、法律を特別な方法で解釈する自由さえない。これは一見、個人の自由が失われ、個人に対 する絶対的な権力が確立されたように見える。しかし、実際にはそうではない。第一に、組織化された国家の利点がなければ、平均的な個人はあらゆる種類の危 険と苦難にさらされ、自らの情熱に支配されることになり、本当の意味で自由とは呼べない。少なくともスピノザが使った意味においてはそうである。人間は、 他者からだけでなく、自分自身の低次の衝動からも救い、真に人間らしい理性の生活を送れるようにするために、国家を必要とするのである。第二に、国家主権 は決して絶対的なものではない。ほとんどどんな種類の政府でも、ないよりはましであることは事実であり、平和を乱すよりは、不愉快なことをたくさん我慢す るほうが価値がある。しかし、合理的に賢明な政府は、自らの利益のためにさえ、不合理な手段を控えることによって市民の善意と協力を確保しようと努力し、 市民が平和的手段を用いる限り、改革を主張することを許可し、奨励さえするだろう。このように国家は最終的には市民の団結した意志、スピノザを読んだジャ ン=ジャック・ルソーが後に「一般意志」と呼んだものに実質的に依存しているのである[4]。 スピノザは時に国家が絶対的な主権を保持しているかのように書くことがある。しかし、それは主として、国家に対するあらゆる種類の教会的統制に断固として 反対するためである。彼は一種の精神的な聖域として国家宗教と呼ばれるものを支持する用意があるが、この宗教についての彼の説明は、狂信的な信者や不信仰 者でない限り、歴史的信条のいずれかの信奉者、神学者、汎神論者、その他すべての人に受け入れられるようなものであった。スピノザが、過激な教会の専制に 効果的に対抗するために、絶対的な主権に近いものを市民政府に委ねたのは、本当に思想と言論の自由のためなのである[5]。 |

| Human power consists in strength

of mind and intellect One of the most striking features in Spinoza's political theory is his basic principle that "right is might." This principle he applied systematically to the whole problem of government, and seemed rather pleased with his achievement, inasmuch as it enabled him to treat political theory in a scientific spirit, as if he were dealing with applied mathematics. The identification or correlation of right with power has caused much misunderstanding. People supposed that Spinoza reduced justice to brute force. But Spinoza was very far from approving Realpolitik. In the philosophy of Spinoza the term "power" (as should be clear from his moral philosophy) means a great deal more than physical force. In a passage near the end of his Political Treatise he states explicitly that "human power chiefly consists in strength of mind and intellect" — it consists in fact, of all the human capacities and aptitudes, especially the highest of them. Conceived correctly, Spinoza's whole philosophy leaves ample scope for ideal motives in the life of the individual and of the community.[7] |

人間の力は精神と知性の強さからなる スピノザの政治理論で最も顕著な特徴の一つは、"権利は力である "という彼の基本原理である。この原理を政府の問題全体に体系的に適用し、あたかも応用数学を扱うかのような科学的精神で政治理論を扱うことができたの で、彼はその成果にむしろ満足しているようであった。権利と権力との同一視や相関は多くの誤解を引き起こした。人々はスピノザが正義を野蛮な力に還元した と思っていた。しかし、スピノザは現実の政治を承認することから非常に遠いところにいた。スピノザの哲学において、「力」という言葉は(彼の道徳哲学から 明らかなように)物理的な力よりもはるかに大きな意味をもっている。スピノザは『政治学論考』の末尾の一節で、「人間の力は主として心と知性の強さにあ る」と明言し、実際、人間のすべての能力と適性、特にその中でも最高のものからなるとしている。スピノザの哲学全体は、個人と共同体の生活において、理想 的な動機のための十分な余地を残していると正しく考えられている[7]。 |

| Monarchy, Aristocracy, and

Democracy Spinoza discusses the principal kinds of states, or the main types of government, namely, Monarchy, Aristocracy, and Democracy. Each has its own peculiarities and needs special safeguards, if it is to realise the primary function of a state. Monarchy may degenerate into Tyranny unless it is subjected to various constitutional checks which will prevent any attempt at autocracy. Similarly, Aristocracy may degenerate into Oligarchy and needs analogous checks. On the whole, Spinoza favours Democracy, by which he meant any kind of representative government. In the case of Democracy the community and the government are more nearly identical than in the case of Monarchy or Aristocracy; consequently a democracy is least likely to experience frequent collisions between the people and the government and so is best adapted to secure and maintain that peace, which it is the business of the state to secure.[4] |

君主制、貴族制、民主制 スピノザは、国家の主要な種類、すなわち君主制、貴族制、民主制を論じている。スピノザは、国家の主要な機能を実現するためには、それぞれに特徴があり、 特別な保護措置が必要であるとしている。君主制は、独裁の試みを阻止する様々な憲法 上のチェックに従わなければ、専制政治に堕落する可能性がある。同様に、貴族制度は寡頭制に堕落する可能性があり、同様のチェックが必要である。全体と して、ス ピノザは民主主義を支持し、それはあらゆる種類の代表することができる政府を意味する。民主主義の場合、共同体と政府は君主制や貴族制の場合よりもほぼ同 一であり、その結果、民主主義は国民と政府の間で頻繁に衝突する可能性が最も低く、国家の仕事である平和を確保し維持するために最も適合している[4]。 |

| Reception and influence It is unlikely that Spinoza's Tractatus ever had political support of any kind, with attempts being made to suppress it even before Dutch magistrate Johan de Witt's murder in 1672. In 1673, it was publicly condemned by the Synod of Dordrecht (1673) and banned officially the following year.[citation needed] Harsh criticism of the TTP began to appear almost as soon as it was published. One of the first, and most notorious, critiques was by Leipzig professor Jakob Thomasius in 1670.[8][9] The British philosopher G. E. Moore suggested to Ludwig Wittgenstein that he title one of his works "Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus" as a homage to Spinoza's treatise.[10] |

受容と影響 スピノザの『政治神学論』は、1672年にオランダの行政官ヨハン・デ・ウィットが殺害される以前から弾圧の試みがなされており、政治的な支持を受けたと は考え にくい。1673年、ドルドレヒトのシノドスによって公に非難され、翌年には公式に禁止された[citation needed] TTPに対する厳しい批判は、出版されるとほぼ同時に現れはじめた。最初の、そして最も悪名高い批評の1つは1670年にライプチヒの教授ヤコブ・トマシ ウスによるものだった[8][9]。 イギリスの哲学者G・E・ムーアはルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインにスピノザ の論文へのオマージュとして彼の作品の1つを「論理哲学概論」と題するよ うにと提案している[10]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractatus_Theologico-Politicus |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Some English translations 1862 by Robert Willis with introduction and notes (Trübner & Co., London). See below for the full text in Wikisource. 1883 by R. H. M. Elwes in the first volume of The Chief Works of Spinoza (George Bell & Sons, London). 1958 by A. G. Wernham in The Political Works of Spinoza, an abriged version, with introduction and notes, that includes the full text of the Tractatus Politicus (Clarendon Press, Oxford). 1982 by Samuel Shirley, with an introduction by B. S. Gregory (Brill, Leiden). Latter added to his translation of the Complete Works, with introduction and notes by Michael L. Morgan (Hacket Publications, 2002). 2007 by Jonathan Israel and Michael Silverthorne with introduction and notes also by Israel in the Cambridge Texts in History of Philosophy series. 2016 by Edwin Curley in the second volume of The Collected Works of Spinoza (Princeton University Press; first volume issued in 1985). |

一部の英語訳 1862年、ロバート・ウィリス著、序文と注釈付き(Trübner & Co.、ロンドン)。ウィキソースの全文は下記を参照。 1883年、R. H. M. エルウズ著、『スピノザの主要著作』第1巻(ジョージ・ベル・アンド・サンズ、ロンドン)。 1958年、A. G. ウェルナムによる『スピノザの政治的著作』は、要約版であり、序文と注釈付きで、『政治学論集』の全文が含まれている(オックスフォード、Clarendon Press)。 1982年、サミュエル・シャーリーによるもの。B. S. グレゴリーによる序文付き(ライデン、ブリル社)。後者は、マイケル・L・モーガンによる序文と注釈付きの全集の翻訳に追加された(ハケット出版、2002年)。 2007年、ジョナサン・イスラエルとマイケル・シルバーソーンによる序文と注釈付きで、ケンブリッジ・テキスト・イン・ヒストリー・オブ・フィロソフィーシリーズに収録。 2016年、エドウィン・カーリーによるスピノザ全集第2巻(プリンストン大学出版、第1巻は1985年発行)に収録。 |

| Thomas Hobbes Moses Maimonides Abraham ibn Ezra Demythologization Toleration Tractatus Politicus |

トマス・ホッブズ モーゼス・マイモニデス アブラハム・イブン・エズラ 脱神話化 寛容 政治学論文集 |

| Further reading Israel, Jonathan I. Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650-1750. Oxford University Press: 2001. ISBN 0-19-925456-7 ______. Spinoza, Life and Legacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2023. ISBN 9780198857488 Melamed, Yitzhak and Michael Rosenthal, eds. Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise: A Critical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2010. Nadler, Steven. A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2011. ISBN 9780691139890 Pines, Shlomo."Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus and the Jewish Philosophical Tradition" in Jewish Thought in the Seventeenth Century. Ed. Isadore Twersky and Bernard Septimus. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1987. Smith, Steven B. Spinoza, Liberalism, and the Question of Jewish Identity. New Haven: Yale University Press 1997. ISBN 0-300-06680-5 |

参考文献 イスラエル、ジョナサン I. 『急進的な啓蒙思想:哲学と近代性の形成、1650年~1750年』オックスフォード大学出版局:2001年。ISBN 0-19-925456-7 ______. 『スピノザ、その生涯とその遺産』オックスフォード大学出版局:2023年。ISBN 9780198857488 Melamed, Yitzhak and Michael Rosenthal, eds. Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise: A Critical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2010. Nadler, Steven. A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2011. ISBN 9780691139890 パインズ、ショロモ著「スピノザの『神学・政治論』とユダヤ哲学の伝統」『17世紀のユダヤ思想』編者:イサドア・トウェルスキー、バーナード・セプティマス、ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、1987年。 スミス、スティーブン・B.『スピノザ、リベラリズム、そしてユダヤ人アイデンティティの問題』ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版、1997年。ISBN 0-300-06680-5 |

A Theologico-Political Treatise by

Benedict de SPINOZA Part 1/2 | Full Audio Book

Preface to Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise, read in Latin with English subtitles

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆