生物人類学

生物人類学

biological anthropology

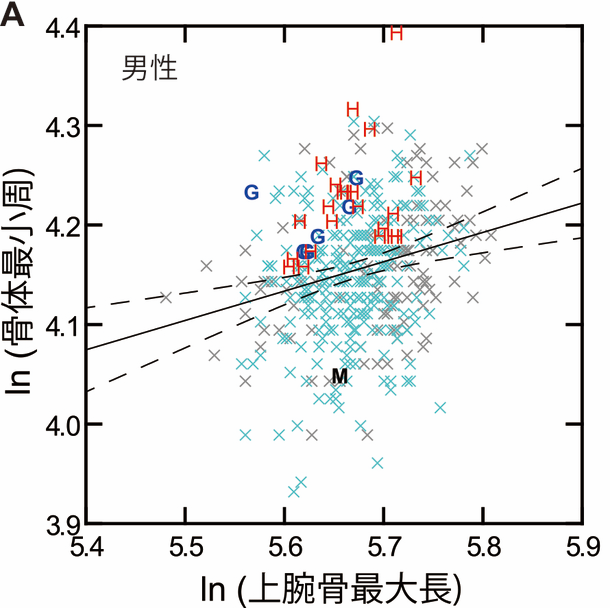

「図の

縦軸は「上腕骨の周径」、横軸は「上腕骨の長さ」に相当します。骨が長ければその分太くなる傾向があるため、こうして“長さでコントロールした太さ”を比

較します」。サンプルは縄文(水色の×)及び弥生・古墳時代人(グレーの×)の男性の上腕骨で、図中の斜めの実線は全サンプルに基づく回帰直線、つまり

「ある長さなら周の平均的状態はこれくらい」ということを表示します。回帰直線の上に来る個体は「平均以上に太い」とみなせます(出典:国立科学

博物館)。

解説:池田光穂

生物人類学とは、人類の生物学的あるいは医学的な問題関心にひきつけて、人類のありようを研究す る学問のことである。前世紀(20世紀)には、自然人類学と 呼ばれていた。人間を研究する学問が人類学。人類 (ギリシャ語でanthropos)と学問(同じく logos)の 合成語がこの言語である。人類学が現在の学問の体勢として出発する以前から、この用語は〈人間学〉という用語と学問(=哲学)で呼ばれていたが、人類学と は別物であり、また直接の先祖というわけではない。

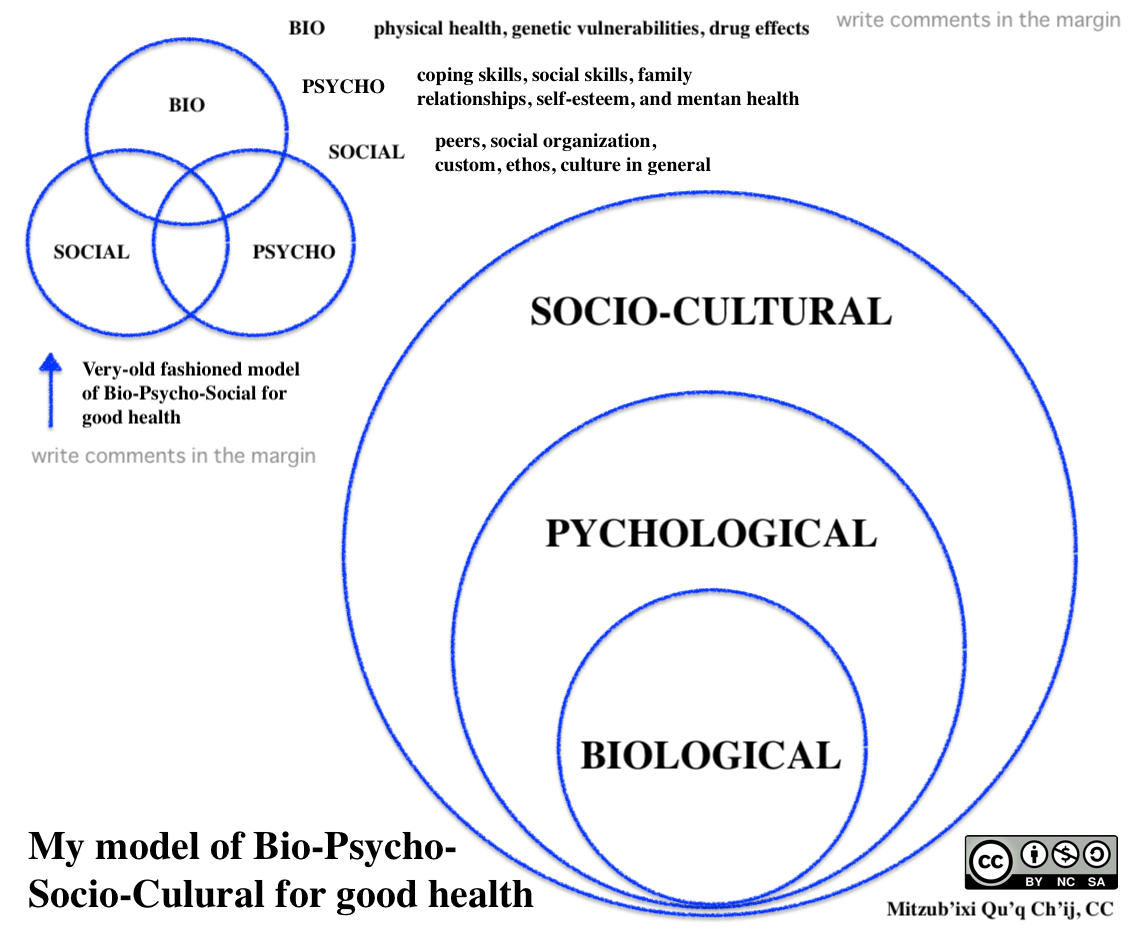

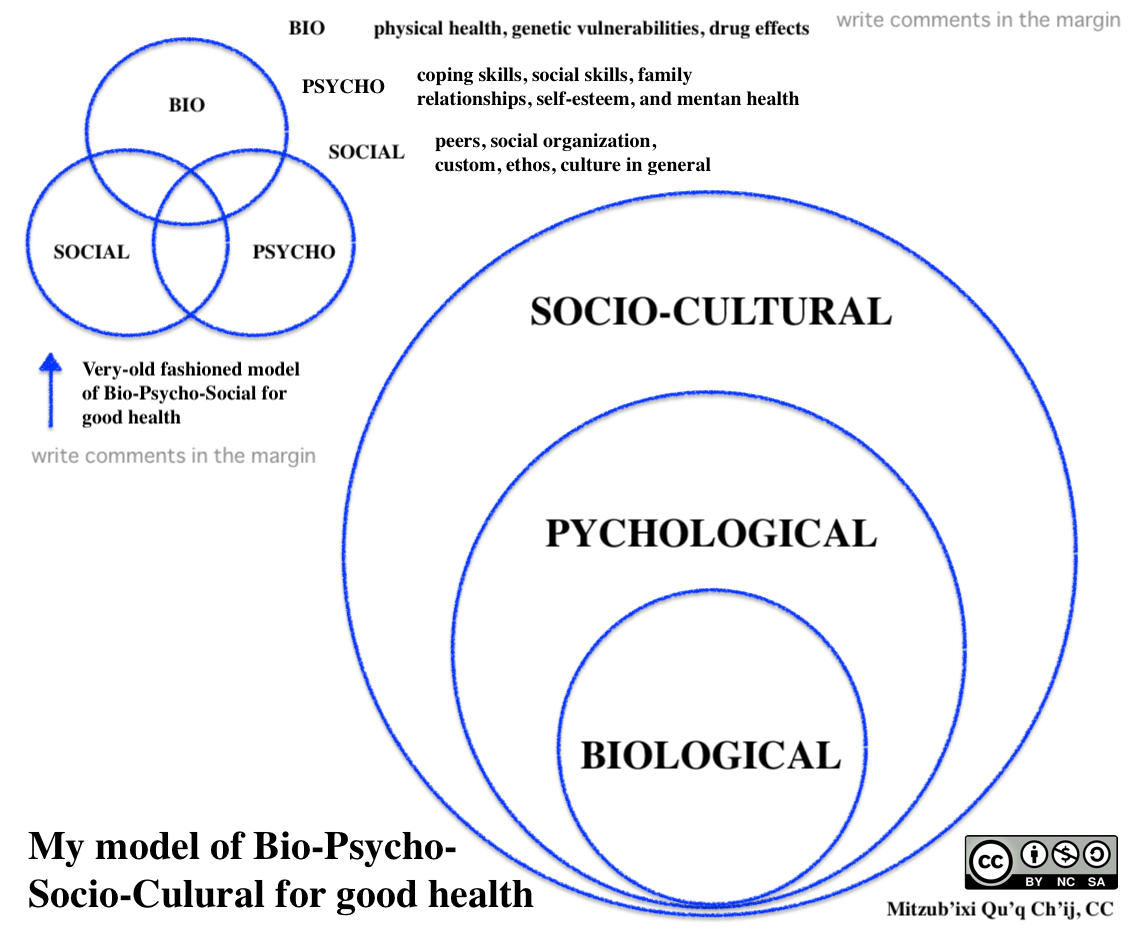

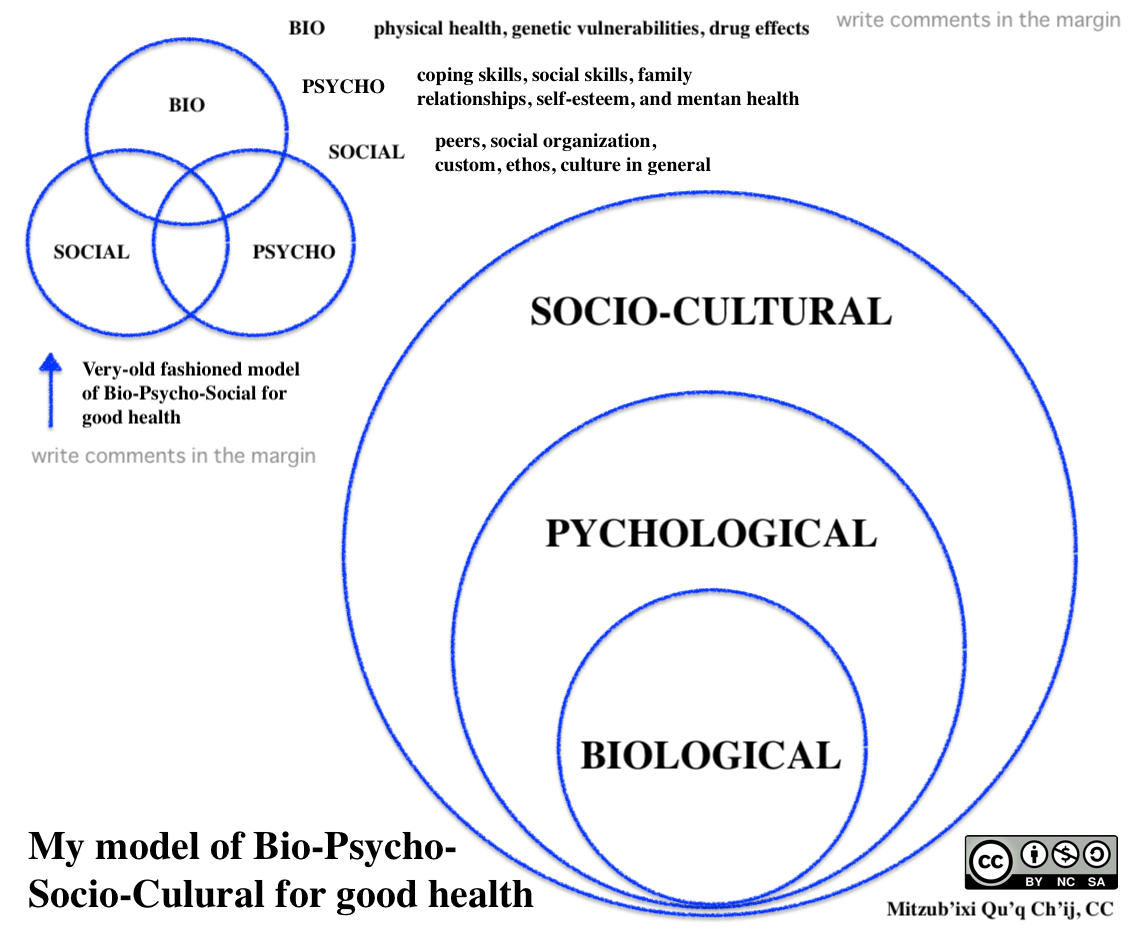

進化学的な生物人類学は、人間の生物学的な側面から中心に、人類の成り立ち、進化、あるいは霊長類としての 人間の研究として霊長類学(primatology)なども隣接関連分野として研究する領域のことである。しかし、人類進化のことだけを論じる生物人類学 者がいたら、それは、あまりにも人類学の歴史を知らなすぎる。人間存在のありようは、生物=心理=社会的なものからなりたっているからだ(→「生物心理社会モデル」)。そのために、生物人類学は、もう2つの関連領 域の活動と深い関係をもっている。すなわち、生物考古学(Bioarchaeology) と、医療人類学(Medical anthropology)である(→「生物人類学者のための生物考古学」 「生物人類学者のための医療人類学」)。

☆生物人類学と関連する学問分野の布置(画像のクリックで拡大)

| Biological

anthropology deals with the evolution of humans, their variability, and

adaptations to environmental stresses. Using an evolutionary

perspective, we examine not only the physical form of humans - the

bones, muscles, and organs - but also how it functions to allow

survival and reproduction. Within the field of biological anthropology there are many different areas of focus. Paleoanthropology studies the evolution of primates and hominids from the fossil record and from what can be determined through comparative anatomy and studies of social structure and behavior from our closest living relatives. Primatologists study prosimians, monkeys and apes, using this work to understand the features that make each group distinct and those that link groups together. Skeletal biology concentrates on the study of anatomically modern humans, primarily from archaeological sites, and aims to understand the diseases and conditions these past people experienced prior to dying. Forensic anthropologists use the study of skeletal biology to assist in the identification and analysis of more recently deceased individuals. Such cases often involve complex legal considerations. Human biologists concentrate on contemporary humans, examining not only their anatomy and physiology but also their reproduction and the effects of social status and other factors on their growth and development. Because these studies take place within an understanding of the context of human behavior and culture, biological anthropology stands as a unique link between the social and biological sciences. https://anthro.ucsc.edu/about/sub-fields/biological-anthro.html +++++++++++++++++++++ Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an evolutionary perspective.[1] This subfield of anthropology systematically studies human beings from a biological perspective. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biological_anthropology |

スタンフォード大学の生

物人類学のページでの解説はこうである。 生物人類学は、ヒトの進化、その多様性、環境ストレスへの適応を扱いま す。進化の観点から、骨、筋肉、臓器といった人間の身体的形態だけでなく、生存と生殖を可能にするためにどのように機能しているかを調べます。 生物人類学の分野では、さまざまな分野に焦点が当てられています。古人類学は、化石記録から霊長類やヒト科動物の進化を研究し、比較解剖学や社会構造・行 動の研究を通じて、最も近縁の現生人類から判断することができます。霊長類学者は、徘徊動物、サル、類人猿を研究し、それぞれのグループを特徴づける特徴 やグループ同士を結びつける特徴を理解するために使われます。骨格生物学は、主に遺跡から採取した解剖学的に現代人の研究に重点を置き、過去の人々が死ぬ 前に経験した病気や状況を理解することを目的としています。法人類学者は、骨格生物学の研究を利用して、最近死亡した人物の身元確認や分析に役立てていま す。このようなケースでは、しばしば複雑な法的考察が必要となります。人類学者は、現代の人間を対象に、解剖学や生理学だけでなく、生殖や社会的地位など が成長や発達に与える影響についても研究しています。 これらの研究は、人間の行動や文化の背景を理解した上で行われるため、生物人類学は、社会科学と生物科学をつなぐユニークな存在といえます。 https://anthro.ucsc.edu/about/sub-fields/biological-anthro.html +++++++++++++++++++++ 生物人類学は、物理人類学としても知られ、特に進化の観点から、ヒト、絶滅したヒト科の祖先、および関連するヒト以外の霊長類の生物学的および行動学的側 面に関する科学分野である[1]。 人類学のこのサブフィールドは、人間を生物学的観点から体系的に研究する。 |

|

|

| Branches As a subfield of anthropology, biological anthropology itself is further divided into several branches. All branches are united in their common orientation and/or application of evolutionary theory to understanding human biology and behavior. Bioarchaeology is the study of past human cultures through examination of human remains recovered in an archaeological context. The examined human remains usually are limited to bones but may include preserved soft tissue. Researchers in bioarchaeology combine the skill sets of human osteology, paleopathology, and archaeology, and often consider the cultural and mortuary context of the remains. Evolutionary biology is the study of the evolutionary processes that produced the diversity of life on Earth, starting from a single common ancestor. These processes include natural selection, common descent, and speciation. Evolutionary psychology is the study of psychological structures from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify which human psychological traits are evolved adaptations – that is, the functional products of natural selection or sexual selection in human evolution. Forensic anthropology is the application of the science of physical anthropology and human osteology in a legal setting, most often in criminal cases where the victim's remains are in the advanced stages of decomposition. Human behavioral ecology is the study of behavioral adaptations (foraging, reproduction, ontogeny) from the evolutionary and ecologic perspectives (see behavioral ecology). It focuses on human adaptive responses (physiological, developmental, genetic) to environmental stresses. Human biology is an interdisciplinary field of biology, biological anthropology, nutrition and medicine, which concerns international, population-level perspectives on health, evolution, anatomy, physiology, molecular biology, neuroscience, and genetics. Paleoanthropology is the study of fossil evidence for human evolution, mainly using remains from extinct hominin and other primate species to determine the morphological and behavioral changes in the human lineage, as well as the environment in which human evolution occurred. Paleopathology is the study of disease in antiquity. This study focuses not only on pathogenic conditions observable in bones or mummified soft tissue, but also on nutritional disorders, variation in stature or morphology of bones over time, evidence of physical trauma, or evidence of occupationally derived biomechanic stress. Primatology is the study of non-human primate behavior, morphology, and genetics. Primatologists use phylogenetic methods to infer which traits humans share with other primates and which are human-specific adaptations. |

部門 人類学の一分野である生物人類学は、さらにいくつかの分野に分かれている。どの分野も、人間の生物学と行動を理解するために進化理論を適用するという共通 の方向性を持っている点で共通している。 生物考古学(Bioarchaeology)とは、考古学的な文脈から出土した人骨の調査を通して、過去の人類の文化を研究する学問である。調査される遺 骨は通常骨に限られるが、保存された軟組織を含むこともある。生物考古学の研究者は、人骨学、古病理学、考古学のスキルを組み合わせ、遺骨の文化的背景や 遺体安置の背景を考慮することが多い。 進化生物学は、地球上の生物の多様性を生み出した進化の過程を研究する学問である。これらの過程には、自然選択、共通子孫、種分化などが含まれる。 進化心理学とは、現代の進化的観点から心理構造を研究する学問である。どのような人間の心理的特徴が進化した適応であるか、つまり人間の進化における自然 淘汰または性淘汰の機能的産物であるかを明らかにしようとするものである。 法医人類学とは、身体人類学と人体骨学の科学を法的な場面で応用することであり、多くの場合、被害者の遺骨が腐敗の進行段階にある刑事事件において行われ る。 ヒト行動生態学は、進化学的および生態学的観点から行動適応(採食、繁殖、個体発生)を研究する学問である(行動生態学を参照)。環境ストレスに対する人 間の適応反応(生理的、発達的、遺伝的)に焦点を当てている。 ヒト生物学は、生物学、生物人類学、栄養学、医学の学際的分野で、健康、進化、解剖学、生理学、分子生物学、神経科学、遺伝学に関する国際的、集団レベル の視点に関わる。 古人類学(Paleoanthropology)とは、ヒトの進化を示す化石の証拠を研究する学問であり、主に絶滅したヒト科やその他の霊長類の遺骨を用 いて、ヒトの系統における形態学的・行動学的変化や、ヒトの進化が起こった環境を明らかにする。 古病理学とは、古代における疾病の研究である。この研究では、骨やミイラ化した軟部組織で観察可能な病的状態だけでなく、栄養障害、身長や骨の形態の経年 変化、身体的外傷の証拠、職業に由来する生体力学的ストレスの証拠にも焦点を当てる。 霊長類学は、ヒト以外の霊長類の行動、形態、遺伝を研究する学問である。霊長類学者は系統学的手法を用いて、ヒトが他の霊長類とどの特徴を共有し、どれが ヒト特有の適応であるかを推論する。 |

| History Origins  Johann Friedrich Blumenbach  Franz Boas Biological Anthropology looks different today than it did even twenty years ago. The name is even relatively new, having been 'physical anthropology' for over a century, with some practitioners still applying that term.[2] Biological anthropologists look back to the work of Charles Darwin as a major foundation for what they do today. However, if one traces the intellectual genealogy back to physical anthropology's beginnings—before the discovery of much of what we now know as the hominin fossil record—then the focus shifts to human biological variation. Some editors, see below, have rooted the field even deeper than formal science. Attempts to study and classify human beings as living organisms date back to ancient Greece. The Greek philosopher Plato (c. 428–c. 347 BC) placed humans on the scala naturae, which included all things, from inanimate objects at the bottom to deities at the top.[3] This became the main system through which scholars thought about nature for the next roughly 2,000 years.[3] Plato's student Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC) observed in his History of Animals that human beings are the only animals to walk upright[3] and argued, in line with his teleological view of nature, that humans have buttocks and no tails in order to give them a cushy place to sit when they are tired of standing.[3] He explained regional variations in human features as the result of different climates.[3] He also wrote about physiognomy, an idea derived from writings in the Hippocratic Corpus.[3] Scientific physical anthropology began in the 17th to 18th centuries with the study of racial classification (Georgius Hornius, François Bernier, Carl Linnaeus, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach).[4] The first prominent physical anthropologist, the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840) of Göttingen, amassed a large collection of human skulls (Decas craniorum, published during 1790–1828), from which he argued for the division of humankind into five major races (termed Caucasian, Mongolian, Aethiopian, Malayan and American).[5] In the 19th century, French physical anthropologists, led by Paul Broca (1824-1880), focused on craniometry[6] while the German tradition, led by Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902), emphasized the influence of environment and disease upon the human body.[7] In the 1830s and 1840s, physical anthropology was prominent in the debate about slavery, with the scientific, monogenist works of the British abolitionist James Cowles Prichard (1786–1848) opposing[8] those of the American polygenist Samuel George Morton (1799–1851).[9] In the late 19th century, German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942) strongly impacted biological anthropology by emphasizing the influence of culture and experience on the human form. His research showed that head shape was malleable to environmental and nutritional factors rather than a stable "racial" trait.[10] However, scientific racism still persisted in biological anthropology, with prominent figures such as Earnest Hooton and Aleš Hrdlička promoting theories of racial superiority[11] and a European origin of modern humans.[12] "New Physical Anthropology" In 1951 Sherwood Washburn, a former student of Hooton, introduced a "new physical anthropology."[13] He changed the focus from racial typology to concentrate upon the study of human evolution, moving away from classification towards evolutionary process. Anthropology expanded to include paleoanthropology and primatology.[14] The 20th century also saw the modern synthesis in biology: the reconciling of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and Gregor Mendel's research on heredity. Advances in the understanding of the molecular structure of DNA and the development of chronological dating methods opened doors to understanding human variation, both past and present, more accurately and in much greater detail. |

歴史 起源  ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハ  フランツ・ボアズ 生物人類学は、20年前と今では様相が異なっている。生物人類学者たちは、チャールズ・ダーウィンの業績が、今日彼らが行っていることの主要な基盤である と振り返っている[2]。しかし、その知的系譜を身体人類学の始まり、つまり現在ヒトの化石記録として知られているものの多くが発見される前まで遡ると、 焦点はヒトの生物学的変異へと移っていく。後述するように、この分野を正式な科学よりもさらに深く根付かせた編集者もいる。 人間を生物として研究し分類しようとする試みは、古代ギリシャにまでさかのぼる。ギリシアの哲学者プラトン(紀元前428年頃-347年頃)は、ヒトを無 生物から神々に至るまですべてのものを含む自然尺度(scala naturae)に位置づけた[3]。 プラトンの弟子であるアリストテレス(紀元前384年頃~紀元前322年頃)は、『動物誌』の中で、直立歩行する動物は人間だけであることを観察し [3]、彼の目的論的な自然観に沿って、人間には尻尾がなく臀部があるのは、立つのに疲れたときに座るための楽な場所を与えるためであると主張した [3]。 [3]彼はまた、人相学についても書いており、これは『ヒポクラテス書』の記述に由来する考えであった。 科学的な身体人類学は17世紀から18世紀にかけて、人種分類の研究(ゲオルギウス・ホルニウス、フランソワ・ベルニエ、カール・リンネ、ヨハン・フリー ドリヒ・ブルーメンバッハ)から始まった[4]。 最初の著名な身体人類学者であるゲッティンゲンのドイツ人医師ヨハン・フリードリッヒ・ブルーメンバッハ(1752年-1840年)は、人間の頭蓋骨の大 規模なコレクション(Decas craniorum、1790年-1828年に出版)を集め、そこから人類を5つの主要人種(コーカソイド、モンゴル、アエチオピア、マレー、アメリカ) に分けることを主張した。 [5]19世紀には、ポール・ブロカ(1824-1880)を中心とするフランスの身体人類学者が頭蓋測定に焦点を当て[6]、ルドルフ・ヴィルヒョー (1821-1902)を中心とするドイツの伝統は、環境や病気が人体に及ぼす影響を強調した[7]。 1830年代から1840年代にかけて、身体人類学は奴隷制に関する議論において顕著であり、イギリスの奴隷廃止論者ジェームズ・カウルズ・プリチャード (James Cowles Prichard、1786-1848)の科学的で一遺伝子論的な著作は、アメリカの多遺伝子論者サミュエル・ジョージ・モートン(Samuel George Morton、1799-1851)の著作と対立していた[8]。 19世紀後半、ドイツ系アメリカ人の人類学者フランツ・ボアズ(1858-1942)は、文化や経験が人間の体型に与える影響を強調し、生物人類学に強い 影響を与えた。彼の研究は、頭の形が安定した「人種的」特徴ではなく、環境や栄養的要因によって変化することを示した[10]。しかし、アーネスト・フー トンやアレシュ・ハードリチカのような著名人が、人種的優越性[11]や現生人類のヨーロッパ起源説[12]を推進したため、科学的人種差別主義は依然と して生物人類学に根強く残っていた。 "新しい身体人類学/形質人類学" 1951年、フートンの元教え子であったシャーウッド・ウォッシュバーンは「新しい自然人類学」[13]を導入した。人類学は、古人類学や霊長類学を含む までに拡大した[14]。20世紀には、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論とグレゴール・メンデルの遺伝研究の和解という、生物学における近代的統合も起 こった。DNAの分子構造の理解や年代測定法の開発が進み、過去と現在の人類の変異をより正確に、より詳細に理解する道が開かれた。 |

| Notable biological

anthropologists Zeresenay Alemseged John Lawrence Angel George J. Armelagos William M. Bass Caroline Bond Day Jane E. Buikstra William Montague Cobb Carleton S. Coon Robert Corruccini Raymond Dart Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt Linda Fedigan A. Roberto Frisancho Jane Goodall Earnest Hooton Aleš Hrdlička Sarah Blaffer Hrdy Anténor Firmin Dian Fossey Birute Galdikas Richard Lynch Garner Colin Groves Yohannes Haile-Selassie Ralph Holloway William W. Howells Donald Johanson Robert Jurmain Melvin Konner Louis Leakey Mary Leakey Richard Leakey Frank B. Livingstone Owen Lovejoy Jonathan M. Marks Robert D. Martin Russell Mittermeier Desmond Morris Douglas W. Owsley David Pilbeam Kathy Reichs Alice Roberts Pardis Sabeti Robert Sapolsky Eugenie C. Scott Meredith Small Phillip V. Tobias Douglas H. Ubelaker Sherwood Washburn David Watts Tim White Milford H. Wolpoff Richard Wrangham Teuku Jacob Biraja Sankar Guha |

著名な生物人類学者 ゼレンセイ・アレムセゲド ジョン・ローレンス・エンジェル ジョージ・J・アーマレガス ウィリアム・M・バス キャロライン・ボンド・デイ ジェーン・E・バイクストラ ウィリアム・モンゴメリー・コブ カールトン・S・クーン ロバート・コルリッチーニ レイモンド・ダート エゴン・フォン・アイクシュテット リンダ・フェディガン A・ロベルト・フリサンチョ ジェーン・グドール アーネスト・フートン アレシュ・フルディチカ サラ・ブレイファー・ハーディ アンテル・フィルミン ダイアン・フォッシー ビルートゥ・ガルディカス リチャード・リンチ・ガーナー コリン・グローブス ヨハネス・ハイレ・セラシエ ラルフ・ホロウェイ ウィリアム・W・ハウエルズ ドナルド・ジョハンソン ロバート・ジャーマイン メルヴィン・コナー ルイス・リーキー メアリー・リーキー リチャード・リーキー フランク・B・リヴィングストン オーエン・ラブジョイ ジョナサン・M・マークス ロバート・D・マーティン ラッセル・ミッターマイヤー デズモンド・モリス ダグラス・W・オウスリー デビッド・ピルビーム キャシー・ライヒス アリス・ロバーツ パリス・サベティ ロバート・サポルスキー ユージン・C・スコット メレディス・スモール フィリップ・V・トビアス ダグラス・H・ウベラカー シャーウッド・ウォッシュバーン デビッド・ワッツ ティム・ホワイト ミルフォード・H・ウォルポフ リチャード・ランガム テウク・ジェイコブ ビラジャ・サンカル・グーハ |

| The term bioarchaeology

has been attributed to British archaeologist Grahame Clark who, in

1972, defined it as the study of animal and human bones from

archaeological sites. Redefined in 1977 by Jane Buikstra,

bioarchaeology in the United States now refers to the scientific study

of human remains from archaeological sites, a discipline known in other

countries as osteoarchaeology, osteology or palaeo-osteology. Compared

to bioarchaeology, osteoarchaeology is the scientific study that solely

focus on the human skeleton. The human skeleton is used to tell us

about health, lifestyle, diet, mortality and physique of the past.[1]

Furthermore, palaeo-osteology is simple the study of ancient bones.[2] In contrast, the term bioarchaeology is used in Europe to describe the study of all biological remains from archaeological sites. Although Clark used it to describe just human remains and animal remains (zoology/archaeozoology/zooarchaeology), increasingly modern archaeologists also include botanical remains (botany/archaeobotany/paleobotany/paleoethnobotany).[3] Bioarchaeology was largely born from the practices of New Archaeology, which developed in the United States in the 1970s as a reaction to a mainly cultural-historical approach to understanding the past. Proponents of New Archaeology advocated using processual methods to test hypotheses about the interaction between culture and biology, or a biocultural approach. Some archaeologists advocate a more holistic approach to bioarchaeology that incorporates critical theory and is more relevant to modern descent populations.[4] If possible, human remains from archaeological sites are analyzed to determine sex, age, and health. The results are used to determine patterns relevant to human behavior at the site. |

生物考

古学という用語は、1972

年にイギリスの考古学者グラヘイム・クラークが、遺跡から出土した動物や人骨の研究であると定義したことに由来する。1977年、ジェーン・ビュイクスト

ラによって再定義された米国におけるバイオ考古学は、現在では遺跡から出土した人骨の科学的研究を指す。生物考古学に比べ、骨考古学は人間の骨格のみに焦

点を当てた科学的研究である。骨格は、過去の健康状態、生活様式、食生活、死亡率、体格などを知るために用いられる[1]。 対照的に、生物考古学(bioarchaeology)という用語は、ヨーロッパでは、遺跡から出土したすべての生物学的遺物の研究を表すために使用され ている。クラークは、人間の遺体や動物の遺体(動物学/古生動物学/動物考古学)だけを説明するために用いていたが、現代の考古学者は、植物の遺体(植物 学/古植物学/古脊椎動物学)も含めるようになってきている[3]。 バイオ考古学は、1970年代に米国で発展したニュー考古学の実践から生まれた。ニュー考古学は、過去を理解するための文化史的アプローチが中心であった ことへの反動として発展した。ニュー・アーケオロジーの提唱者は、文化と生物学の相互作用に関する仮説を検証するために過程的な方法を用いること、つまり 生物文化的アプローチを提唱した。考古学者の中には、批評的理論を取り入れ、現代の子孫集団により関連した、より総合的な生物考古学のアプローチを提唱す る者もいる[4]。 可能であれば、遺跡から出土した人骨を分析し、性別、年齢、健康状態を特定する。その結果は、遺跡における人間の行動に関連するパターンを決定するために 使用される。 |

| Paleodemography Paleodemography is the field that attempts to identify demographic characteristics from the past population. The information gathered is used to make interpretations.[5] Bioarchaeologists use paleodemography sometimes and create life tables, a type of cohort analysis, to understand the demographic characteristics (such as risk of death or sex ratio) of a given age cohort within a population. Age and sex are crucial variables in the construction of a life table, although this information is often not available to bioarchaeologists. Therefore, it is often necessary to estimate the age and sex of individuals based on specific morphological characteristics of the skeleton. Age estimation The estimation of age in bioarchaeology and osteology actually refers to an approximation of skeletal or biological age-at-death. The primary assumption in age estimation is that an individual's skeletal age is closely associated with their chronological age. Age estimation can be based on patterns of growth and development or degenerative changes in the skeleton.[6] Many methods tracking these types of changes have been developed using a variety of skeletal series. For instance, in children age is typically estimated by assessing their dental development, ossification and fusion of specific skeletal elements, or long bone length.[7] For children, the different points of time at which different teeth erupt from the gums are best known for telling a child's age down to the exact year. But once the teeth are fully developed, age is hard to determine using teeth.[8] In adults, degenerative changes to the pubic symphysis, the auricular surface of the ilium, the sternal end of the 4th rib, and dental attrition are commonly used to estimate skeletal age.[9][10][11] When using bones to determine age, there might be problems that you might face. Until the age of about 30, the human bones are still growing. Different bones are fusing at different points of growth.[12] Some bones might not follow the correct stages of growth which can mess with your analysis. Also, as you get older there is wear and tear on the humans' bones and the age estimate becomes less precise as the bone gets older. The bones then become categorized as either 'young' (20–35 years), 'middle' (35–50 years), or 'old' (50+ years).[8] Sex determination Differences in male and female skeletal anatomy are used by bioarchaeologists to determine the biological sex of human skeletons. Humans are sexually dimorphic, although overlap in body shape and sexual characteristics is possible. Not all skeletons can be assigned a sex, and some may be wrongly identified as male or female. Sexing skeletons is based on the observation that biological males and biological females differ most in the skull and pelvis; bioarchaeologists focus on these parts of the body when determining sex, although other body parts can also be used. The female pelvis is generally broader than the male pelvis, and the angle between the two inferior pubic rami (the sub-pubic angle) is wider and more U-shaped, while the sub-pubic angle of the male is more V-shaped and less than 90 degrees.[13] Phenice[14] details numerous visual differences between the male and female pelvis. In general, the male skeleton is more robust than the female skeleton because of the greater muscles mass of the male. Males generally have more pronounced brow ridges, nuchal crests, and mastoid processes. It should be remembered that skeletal size and robustness are influenced by nutrition and activity levels. Pelvic and cranial features are considered to be more reliable indicators of biological sex. Sexing skeletons of young people who have not completed puberty is more difficult and problematic than sexing adults, because the body has not had time to develop fully.[13] Bioarchaeological sexing of skeletons is not error-proof. In reviewing the sexing of Egyptian skulls from Qua and Badari, Mann[15] found that 20.3% could be assigned to a different sex than the sex indicated in the archaeological literature. A re-evaluation of Mann's work showed that he did not understand the tomb numbering system of the old excavation and assigned wrong tomb numbers to the skulls. The sexing of the bone material was actually quite correct.[16] However, recording errors and re-arranging of human remains may play a part in this great incidence of misidentification. Direct testing of bioarchaeological methods for sexing skeletons by comparing gendered names on coffin plates from the crypt at Christ Church, Spitalfields, London to the associated remains resulted in a 98 percent success rate.[17] Sex-based differences are not inherently a form of inequality, but become an inequality when members of one sex are given privileges based on their sex. This stems from society investing differences with cultural and social meaning.[18] Gendered work patterns may make their marks on the bones and be identifiable in the archaeological record. Molleson[19] found evidence of gendered work patterns by noting extremely arthritic big toes, a collapse of the last dorsal vertebrae, and muscular arms and legs among female skeletons at Abu Hureyra. She interpreted this sex-based pattern of skeletal difference as indicative of gendered work patterns. These kinds of skeletal changes could have resulted from women spending long periods of time kneeling while grinding grain with the toes curled forward. Investigation of gender from mortuary remains is of growing interest to archaeologists.[20] |

古人口学 古人口学とは、過去の人口から人口統計学的特徴を特定しようとする分野である。生物考古学者は時に古デモグラフィーを利用し、コホート分析の一種である生 命表を作成することで、集団内のある年齢コホートの人口統計学的特徴(死亡リスクや男女比など)を理解する。年齢と性別は生命表を作成する上で極めて重要 な変数であるが、この情報はしばしば生物考古学者には入手できない。そのため、多くの場合、骨格の特定の形態学的特徴に基づいて個人の年齢と性別を推定す る必要がある。 年齢の推定 生物考古学や骨考古学における年齢推定とは、実際には骨格や生物学的な死亡時年齢の近似値を指す。年齢推定における第一の前提は、個人の骨格年齢は年代と 密接に関連しているということである。年齢推定は、成長・発育のパターンや骨格の退行性変化に基づいて行うことができる[6]。例えば、子供の場合、歯の 発育、特定の骨格要素の骨化および癒合、または長骨の長さを評価することによって年齢を推定するのが一般的である[7]。成人では、恥骨結合、腸骨の耳介 表面、第4肋骨の胸骨端、および歯の萎縮の退行性変化が、骨格年齢を推定するために一般的に使用される[9][10][11]。 骨を使って年齢を決定する場合、直面するかもしれない問題があります。約30歳まで、人間の骨はまだ成長している。異なる骨が異なる成長段階で融合してい るため[12]、いくつかの骨は正しい成長段階をたどっていない可能性があり、分析が混乱する可能性があります。また、年を取るにつれて、人間の骨には摩 耗や損傷が生じ、年齢推定は骨が古くなるにつれて正確ではなくなります。そのため、骨は「ヤング」(20~35歳)、「ミドル」(35~50歳)、「オー ルド」(50歳以上)のいずれかに分類されます[8]。 性別の決定 男性骨格と女性骨格の解剖学的な違いは、生物考古学者が人骨の生物学的性別を決定するために用いられる。ヒトは性的に二型であるが、体型と性的特徴の重複 はあり得る。すべての骨格に性別を割り当てることができるわけではなく、中には誤って男性または女性と同定されるものもある。骨格標本の性別判定は、生物 学的男性と生物学的女性では頭蓋骨と骨盤が最も異なるという観察に基づいている。女性の骨盤は一般的に男性の骨盤よりも広く、2つの下恥骨稜の間の角度 (恥骨下角)はより広く、よりU字形であるのに対し、男性の恥骨下角はよりV字形で90度未満である[13]。 一般的に、雄の骨格は雌の骨格よりも頑丈であるが、これは雄の方が筋肉量が多いためである。一般的に、雄の方が眉尾根、くびれ、乳様突起が顕著である。骨 格の大きさと頑健さは栄養と活動レベルに影響されることを忘れてはならない。骨盤と頭蓋の特徴は、生物学的性別の指標としてより信頼できると考えられてい る。思春期を終えていない若者の骨格の性判定は、身体が十分に発達する時間がないため、成人の性判定よりも困難で問題が多い[13]。 生物考古学的な骨格標本の性格付けは、間違いのないものではない。マン[15]は、クアとバダリから出土したエジプト人の頭蓋骨の性別を検討した結果、 20.3%が考古学文献に示されている性別とは異なる性別に割り当てられる可能性があることを発見した。マンの研究を再評価したところ、彼は古い発掘調査 の墓番号システムを理解しておらず、頭蓋骨に誤った墓番号を割り当てていたことがわかった。しかし、記録ミスや遺骨の再配置が、このような誤認の多発に一 役買っている可能性がある。 ロンドンのスピタルフィールズにあるクライスト・チャーチの地下納骨堂から出土した棺のプレートに記された性別と、関連する遺骨を比較することで、骸骨の 性別を決定するための生物考古学的手法を直接検証したところ、成功率は98パーセントであった[17]。 性差は本来不平等の一形態ではないが、ある性の成員がその性に基づく特権を与えられたときに不平等となる。これは、社会が差異に文化的・社会的な意味を与 えることに起因する[18]。ジェンダー化された労働形態は、骨にその痕跡を残し、考古学的記録で識別できるかもしれない。モレソン[19]は、アブ・フ レイラの女性骨格に見られる極度の関節炎を伴う外反母趾、最終背椎の崩壊、筋肉質な腕と脚に注目し、性別による労働パターンの証拠を発見した。彼女は、こ の性差による骨格の違いは、性別による労働パターンを示していると解釈した。このような骨格の変化は、女性が穀物を挽くときにつま先を前に丸めて膝をつい て長時間過ごしたために生じた可能性がある。遺体からジェンダーを調査することは、考古学者の関心を高めている[20]。 |

| Non-specific stress indicators Dental non-specific stress indicators Enamel hypoplasia Enamel hypoplasia refers to transverse furrows or pits that form in the enamel surface of teeth when the normal process of tooth growth stops, resulting in a deficit of enamel. Enamel hypoplasias generally form due to disease and/or poor nutrition.[13] Linear furrows are commonly referred to as linear enamel hypoplasias (LEHs); LEHs can range in size from microscopic to visible to the naked eye. By examining the spacing of perikymata grooves (horizontal growth lines), the duration of the stressor can be estimated,[21] although Mays argues that the width of the hypoplasia bears only an indirect relationship to the duration of the stressor. Studies of dental enamel hypoplasia are used to study child health. Unlike bone, teeth are not remodeled, so they can provide a more reliable indicator of past health events as long as the enamel remains intact. Dental hypoplasias provide an indicator of health status during the time in childhood when the enamel of the tooth crown is being formed. Not all of the enamel layers are visible on the surface of the tooth because enamel layers that are formed early in crown development are buried by later layers. Hypoplasias on this part of the tooth do not show on the surface of the tooth. Because of this buried enamel, teeth record stressors form a few months after the start of the event. The proportion of enamel crown formation time represented by this buried in enamel varies from up to 50 percent in molars to 15-20 percent in anterior teeth.[13] Surface hypoplasias record stressors occurring from about one to seven years, or up to 13 years if the third molar is included.[22] Skeletal non-specific stress indicators Porotic hyperostosis/cribra orbitalia It was long assumed that iron deficiency anemia has marked effects on the flat bones of the cranium of infants and young children. That as the body attempts to compensate for low iron levels by increasing red blood cell production in the young, sieve-like lesions develop in the cranial vaults (termed porotic hyperostosis) and/or the orbits (termed cribra orbitalia). This bone is spongy and soft.[4] It is however, highly unlikely that iron deficiency anemia is a cause of either porotic hyperostosis or cribra orbitalia.[23] These are more likely the result of vascular activity in these areas and are unlikely to be pathological. The development of cribra orbitalia and porotic hyperostosis could also be attributed to other causes besides an iron deficiency in the diet, such as nutrients lost to intestinal parasites. However, dietary deficiencies are the most probable cause.[24] Anemia incidence may be a result of inequalities within society, and/or indicative of different work patterns and activities among different groups within society. A study of iron-deficiency among early Mongolian nomads showed that although overall rates of cribra orbitalia declined from 28.7 percent (27.8 percent of the total female population, 28.4 percent of the total male population, 75 percent of the total juvenile population) during the Bronze and Iron Ages, to 15.5 percent during the Hunnu (2209–1907 BP) period, the rate of females with cribra orbitalia remained roughly the same, while the incidence of cribra orbitalia among males and children declined (29.4 percent of the total female population, 5.3 percent of the total male population, and 25 percent of the juvenile population had cribra orbitalia).[25] Bazarsad posits several reasons for this distribution of cribra orbitalia: adults may have lower rates of cribra orbitalia than juveniles because lesions either heal with age or lead to death. Higher rates of cribia orbitalia among females may indicate lesser health status, or greater survival of young females with cribia orbitalia into adulthood. Harris lines Harris lines form before adulthood, when bone growth is temporarily halted or slowed down due to some sort of stress (either disease or malnutrition).[26] During this time, bone mineralization continues, but growth does not, or does so at very reduced levels. If and when the stressor is overcome, bone growth will resume, resulting in a line of increased mineral density that will be visible in a radiograph.[24] If there is not recovery from the stressor, no line will be formed.[27] Hair The stress hormone cortisol is deposited in hair as it grows. This has been used successfully to detect fluctuating levels of stress in the later lifespan of mummies.[28] Mechanical stress and activity indicators Examining the effects that activities and workload has upon the skeleton allows the archaeologist to examine who was doing what kinds of labor, and how activities were structured within society. The division of labor within the household may be divided according to gender and age, or be based on other hierarchical social structures. Human remains can allow archaeologists to uncover patterns in the division of labor. Living bones are subject to Wolff's law, which states that bones are physically affected and remodeled by physical activity or inactivity.[29] Increases in mechanical stress tend to produce bones that are thicker and stronger. Disruptions in homeostasis caused by nutritional deficiency or disease[30] or profound inactivity/disuse/disability can lead to bone loss.[31] While the acquisition of bipedal locomotion and body mass appear to determine the size and shape of children's bones,[32][33][34] activity during the adolescent growth period seems to exert a greater influence on the size and shape of adult bones than exercise later in life.[35] Muscle attachment sites (also called entheses) have been thought to be impacted in the same way causing what were once called musculoskeletal stress markers, but now widely named entheseal changes.[36][37] These changes were widely used to study activity-patterns,[38] but research has shown that processes associated with aging have a greater impact than occupational stresses.[39][40][41][42][43][44] It has also been shown that geometric changes to bone structure (described above) and entheseal changes differ in their underlying cause with the latter poorly affected by occupation.[45][46] Joint changes, including osteoarthritis, have also been used to infer occupations but in general these are also manifestations of the aging process.[38] Markers of occupational stress, which include morphological changes to the skeleton and dentition as well as joint changes at specific locations have also been widely used to infer specific (rather than general) activities.[47] Such markers are often based on single cases described in clinical literature in the late nineteenth century.[48] One such marker has been found to be a reliable indicator of lifestyle: the external auditory exostosis also called surfer's ear, which is a small bony protuberance in the ear canal which occurs in those working in proximity to cold water.[49][50] One example of how these changes have been used to study activities is the New York African Burial Ground in New York. This provides evidence of the brutal working conditions under which the enslaved labored;[51] osteoarthritis of the vertebrae was very common, even among the young. The pattern of osteoarthritis combined with the early age of onset provides evidence of labor that resulted in mechanical strain to the neck. One male skeleton shows stress lesions at 37 percent of 33 muscle or ligament attachments, showing he experienced significant musculoskeletal stress. Overall, the interred show signs of significant musculoskeletal stress and heavy workloads, although workload and activities varied among different individuals. Some individuals show high levels of stress, while others do not. This references the variety of types of labor (e.g., domestic vs. carrying heavy loads) labor that enslaved individuals were forced to perform. Injury and workload Fractures to bones during or after excavation will appear relatively fresh, with broken surfaces appearing white and unweathered. Distinguishing between fractures around the time of death and post-depositional fractures in bone is difficult, as both types of fractures will show signs of weathering. Unless evidence of bone healing or other factors are present, researchers may choose to regard all weathered fractures as post-depositional.[13] Evidence of perimortal fractures (or fractures inflicted on a fresh corpse) can be distinguished in unhealed metal blade injuries to the bones. Living or freshly dead bones are somewhat resilient, so metal blade injuries to bone will generate a linear cut with relatively clean edges rather than irregular shattering.[13] Archaeologists have tried using the microscopic parallel scratch marks on cut bones in order to estimate the trajectory of the blade that caused the injury.[52] Diet and dental health Caries Dental caries, commonly referred to as cavities or tooth decay, are caused by localized destruction of tooth enamel, as a result of acids produced by bacteria feeding upon and fermenting carbohydrates in the mouth.[53] Subsistence based upon agriculture is strongly associated with a higher rate of caries than subsistence based upon foraging, because of the higher levels of carbohydrates in diets based upon agriculture.[27] For example, bioarchaeologists have used caries in skeletons to correlate a diet of rice and agriculture with the disease.[54] Females may be more vulnerable to caries compared to men, due to lower saliva flow than males, the positive correlation of estrogens with increased caries rates, and because of physiological changes associated with pregnancy, such as suppression of the immune system and a possible concomitant decrease in antimicrobial activity in the oral cavity.[55] |

非特異的ストレス指標歯科的非特異的ストレス指標 エナメル質低形成 エナメル質低形成とは、歯の正常な成長過程が停止してエナメル質が欠損した場合に、歯のエナメル質表面に形成される横溝またはピットを指す。エナメル質低 形成は一般に、疾患および/または栄養不良が原因で形成される。[13] 線状の溝は一般に線状エナメル質低形成(LEH)と呼ばれ、LEHの大きさは顕微鏡的なものから肉眼で確認できるものまで様々である。Maysは、低形成 の幅はストレスの持続時間と間接的な関係しか持たないと主張しているが、歯周溝(水平成長線)の間隔を調べることにより、ストレスの持続時間を推定するこ とができる。 歯のエナメル質低形成の研究は、子供の健康の研究に利用されている。骨とは異なり、歯はリモデリングされないので、エナメル質が無傷である限り、過去の健 康事象についてより信頼性の高い指標を提供することができる。歯の低形成は、歯冠のエナメル質が形成される小児期の健康状態の指標となる。歯冠形成の初期 に形成されたエナメル質層は後の層に埋もれてしまうため、すべてのエナメル質層が歯の表面に見えるわけではありません。この部分の低形成は歯の表面には現 れません。このようにエナメル質が埋もれているため、歯はストレスの記録は、その事象が始まってから数ヵ月後に形成される。エナメル冠形成時間のうち、こ の埋伏エナメル質が占める割合は、大臼歯で最大50%、前歯で15~20%とさまざまである[13]。表面低形成は、約1~7年、第3大臼歯を含めると最 大13年の間に発生したストレス因子を記録する[22]。 骨格の非特異的ストレス指標 多孔性過骨症/篩骨性眼窩 鉄欠乏性貧血は、乳幼児の頭蓋の扁平骨に著しい影響を及ぼすと長い間考えられてきた。低年齢児の赤血球産生を増加させることによって、身体が鉄レベルの低 下を補おうとするため、頭蓋の穹窿部(多孔性骨過剰症と呼ばれる)および/または眼窩(篩骨性眼窩と呼ばれる)にふるい状の病変が発生するのである。この 骨はスポンジ状で柔らかい。 しかし、鉄欠乏性貧血が多孔性過骨症や篩骨篩骨症の原因である可能性は非常に低い。クリブラオールビタニアおよび多孔性骨過形成症の発症は、腸内寄生虫に よって失われた栄養素など、食事中の鉄欠乏以外の原因による可能性もある。しかし、食事欠乏が最も可能性の高い原因である。 貧血の罹患率は、社会内の不平等の結果である可能性があり、また社会内の異なる集団間で異なる作業パターンや活動を示している可能性がある。初期のモンゴ ル遊牧民の鉄欠乏症の調査によると、眼窩擦過症の全体的な割合は、青銅器時代と鉄器時代には28.7%(女性総人口の27.8%、男性総人口の 28.4%、少年総人口の75%)であったが、匈奴時代には15.5%に減少した。 5%であった。 このような篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨篩骨の分布について、バザルサド氏はいくつかの理由を挙げ ている。メスで篩骨性眼窩炎の割合が高いのは、健康状態があまり良くないか、篩骨性眼窩炎を持つ若いメスの成体までの生存率が高いことを示しているのかも しれない。 ハリス線 ハリス線は、何らかのストレス(疾患または栄養不良)により骨の成長が一時的に停止または鈍化した場合に、成人になる前に形成される[26]。この間、骨 のミネラル化は継続するが、成長は継続しないか、またはそのレベルが非常に低下する。ストレス因子が克服されると、骨の成長が再開し、X線写真で確認でき るミネラル密度の増加線が形成される[24]。 毛髪 ストレスホルモンであるコルチゾールは、成長とともに毛髪に沈着する。これを利用して、ミイラの後期寿命におけるストレスレベルの変動を検出することに成 功している[28]。機械的ストレスと活動指標 活動や仕事量が骨格に与える影響を調べることで、考古学者は、誰がどのような種類の労働をしていたのか、また、社会の中で活動がどのように構成されていた のかを調べることができる。家庭内での労働の分担は、性別や年齢によって分けられていたり、その他の階層的な社会構造に基づいていたりする。人骨は、分業 のパターンを考古学者に明らかにさせることができる。 生きている骨はウォルフの法則に従う。ウォルフの法則とは、骨は身体活動や運動不足によって物理的な影響を受け、リモデリングされるというものである [29]。栄養欠乏や疾患[30]、または深い運動不足/運動不能/運動障害によって引き起こされる恒常性の乱れは、骨量の減少につながる可能性がある [31]。二足歩行の獲得と体格が子どもの骨の大きさと形を決定するように見える一方で[32][33][34]、思春期の成長期の活動は、成人後の運動 よりも成人後の骨の大きさと形に大きな影響を及ぼすようである[35]。 筋付着部(靭帯とも呼ばれる)も同じように影響を受け、かつては筋骨格系ストレスマーカーと呼ばれていたが、現在では広く靭帯変化と呼ばれているものを引 き起こしていると考えられている[36][37]。これらの変化は活動パターンの研究に広く利用されていたが[38]、加齢に伴う過程の方が職業的ストレ スよりも大きな影響を及ぼすことが研究により明らかになっている。 [39歳][40歳][41歳][42歳][43歳][44歳] また、骨構造の幾何学的変化(上述)と内反骨の変化は、その根本的な原因が異なり、後者は職業による影響を受けにくいことが示されている[45歳][46 歳] 変形性関節炎を含む関節の変化も職業を推測するために使用されてきたが、一般的にこれらも老化プロセスの現れである[38歳]。 骨格や歯列の形態学的変化や特定部位の関節変化を含む職業性ストレスのマーカーもまた、特定の(一般的ではなく)活動を推測するために広く使用されている [47]。 [48]このようなマーカーの1つは、生活習慣の信頼できる指標であることが判明している。外耳外骨腫は、サーファーズイヤーとも呼ばれ、冷たい水の近く で働く人に発生する外耳道の小さな骨隆起である[49][50]。 このような変化がどのように活動の研究に利用されてきたかの一例が、ニューヨークのニューヨーク・アフリカ埋葬地である。これは、奴隷が労働していた残酷 な労働条件の証拠となるものであり、[51]脊椎の変形性関節症は、若者の間でさえ非常に一般的であった。変形性脊椎症のパターンと発症年齢の早さから、 頸部に機械的な負担がかかる労働が行われていたことがわかる。ある男性の骨格では、33箇所の筋肉や靭帯の37%にストレス性病変が見られ、かなりの筋骨 格系ストレスを経験していたことがわかる。全体として、被葬者は著しい筋骨格系ストレスと重労働の徴候を示しているが、仕事量と活動は個人によって異な る。高いレベルのストレスを示す者もいれば、そうでない者もいる。これは、奴隷にされた人々が強いられた労働の種類が多様であったことを物語っている。 負傷と労働負荷 発掘中または発掘後の骨の骨折は比較的新鮮に見え、骨折した表面は白く風化していないように見える。どちらの骨折も風化の兆候が見られるため、死亡前後の 骨折と発掘後の骨折の区別は難しい。骨癒合の証拠やその他の要因が存在しない限り、研究者は風化骨折をすべて死後骨折とみなすことを選択することがある [13]。 死後周囲の骨折(または新鮮な死体に加えられた骨折)の証拠は、骨に加えられた治癒していない金属刃の損傷で見分けることができる。生きている骨や死んだ ばかりの骨はある程度弾力性があるため、骨への金属刃による損傷は、不規則な粉砕ではなく、比較的きれいなエッジを持つ直線的な切断を生じる[13]。考 古学者たちは、損傷を引き起こした金属刃の軌跡を推定するために、切断された骨にある微視的な平行傷跡を利用しようと試みている[52]。 食生活と歯の健康 う蝕 う蝕は、一般に虫歯または齲蝕と呼ばれ、口腔内の炭水化物を食べて発酵させる細菌によって産生される酸の結果、歯のエナメル質が局所的に破壊されることに よって引き起こされる[53]。農業に基づく自給自足は、採食に基づく自給自足よりもう蝕の発生率が高いことと強く関連している。 [例えば、生物考古学者は、骨格標本のう蝕を利用して、米食や農耕食とう蝕の関連性を明らかにしている[54]。唾液の分泌量が男性よりも少ないこと、エ ストロゲンがう蝕率の増加と正の相関関係があること、免疫系の抑制やそれに伴う口腔内の抗菌活性の低下といった妊娠に伴う生理的変化のため、女性は男性に 比べてう蝕にかかりやすいと考えられる[55]。 |

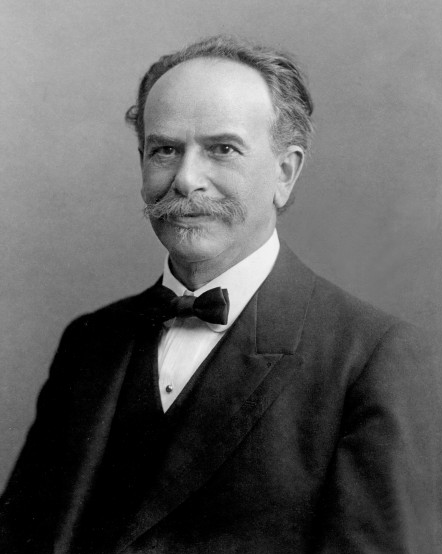

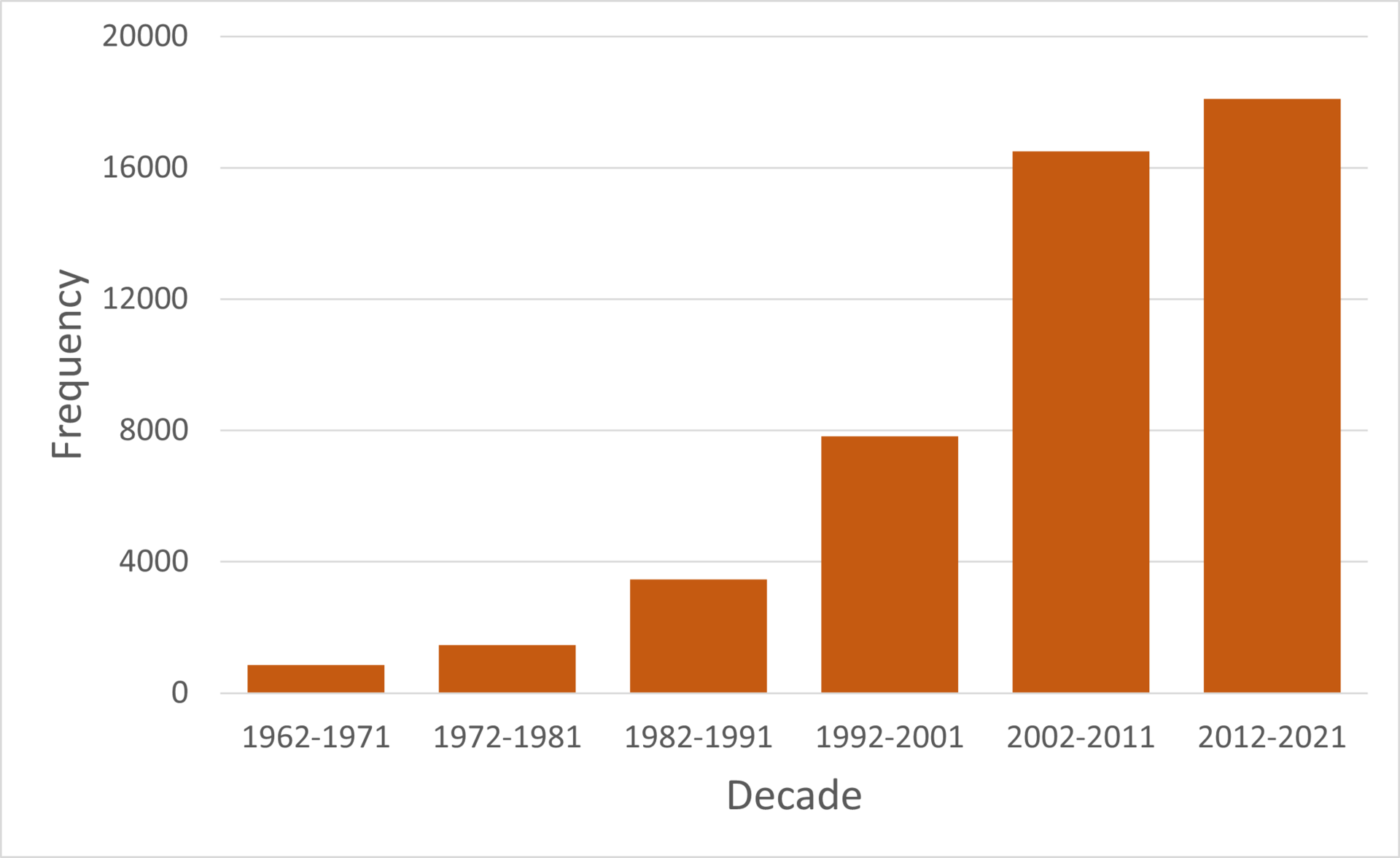

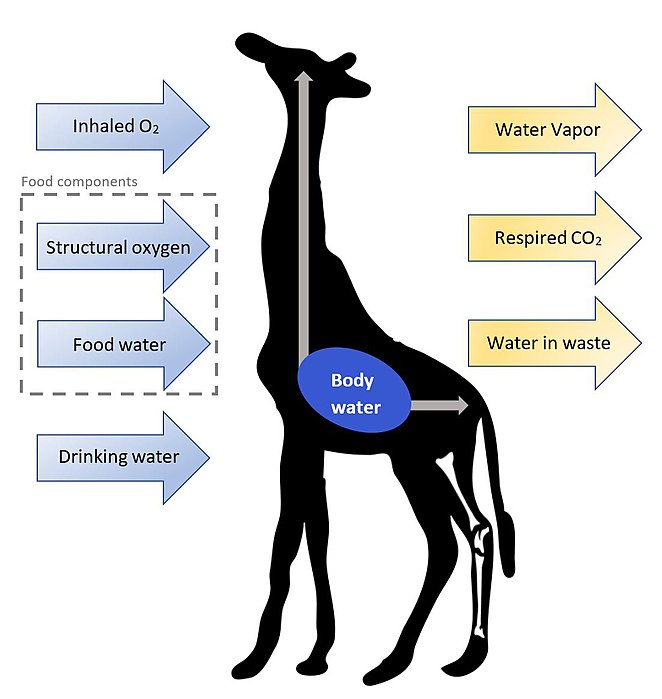

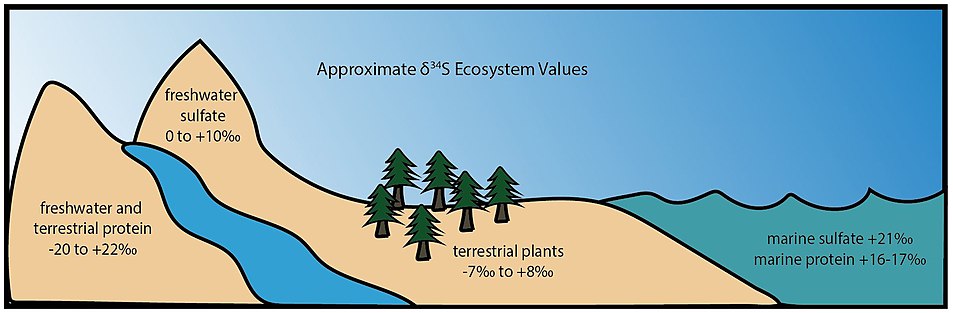

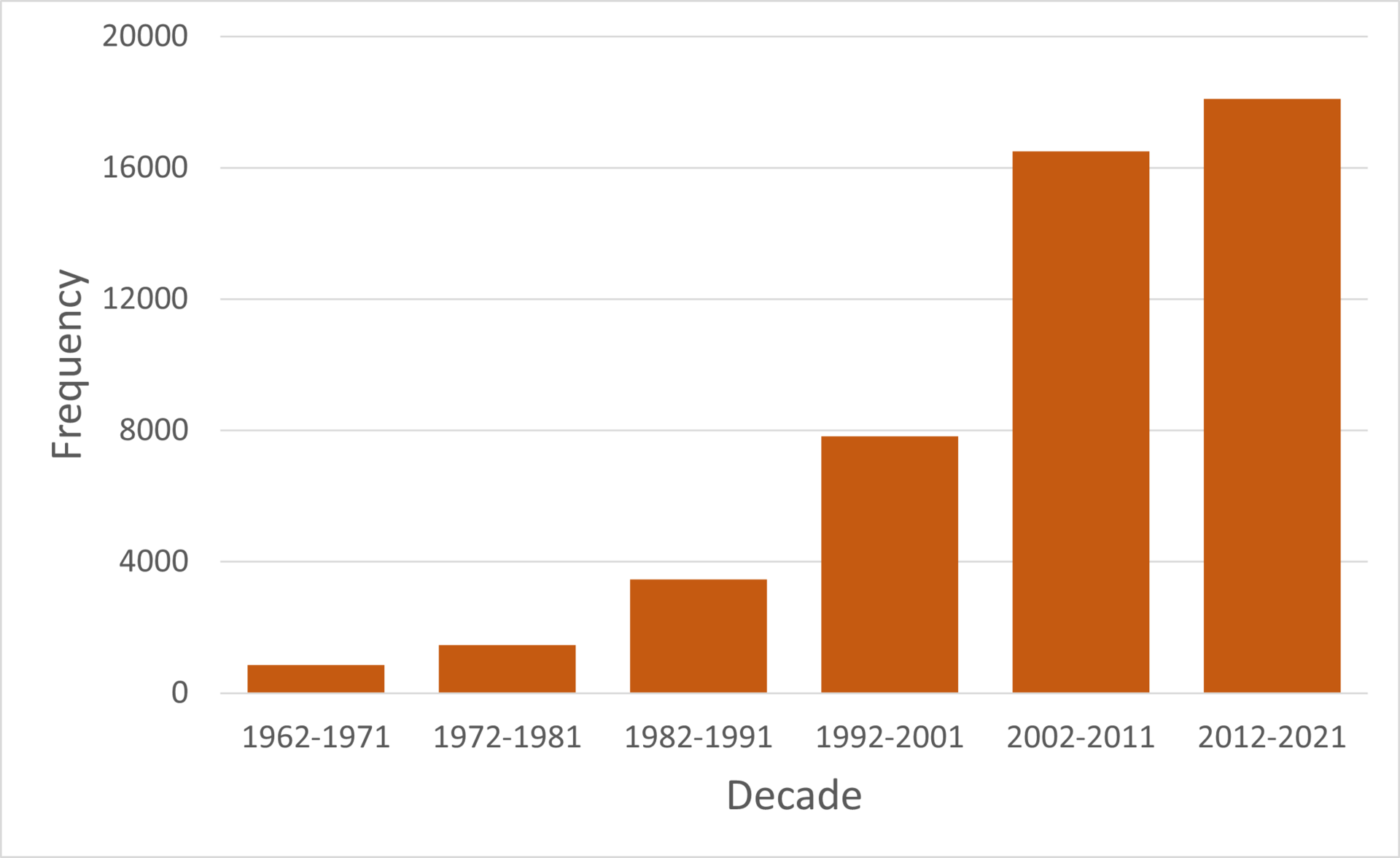

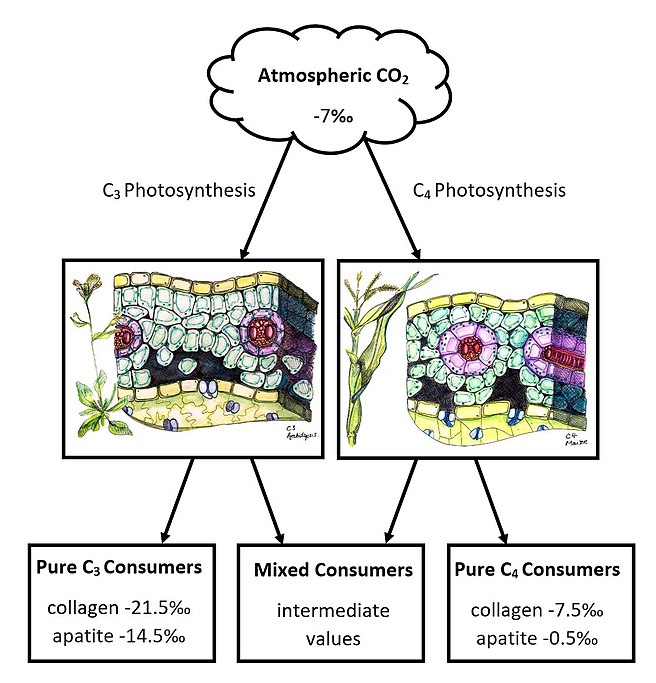

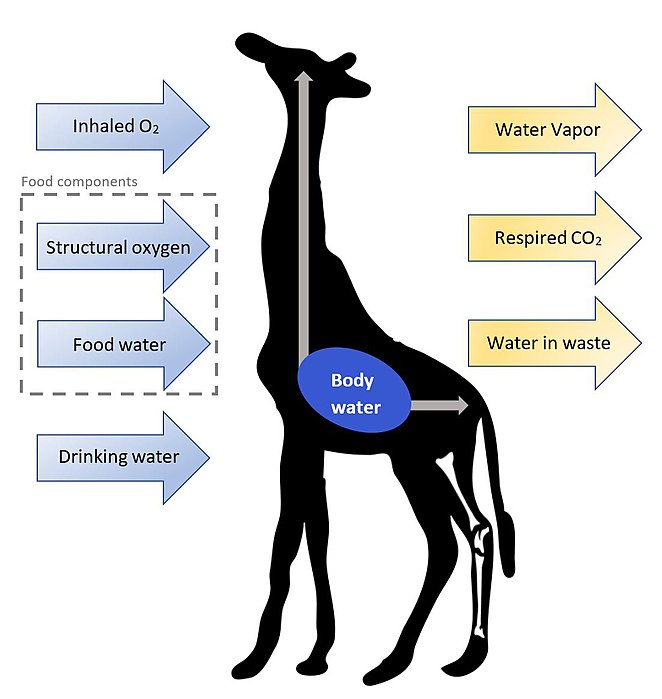

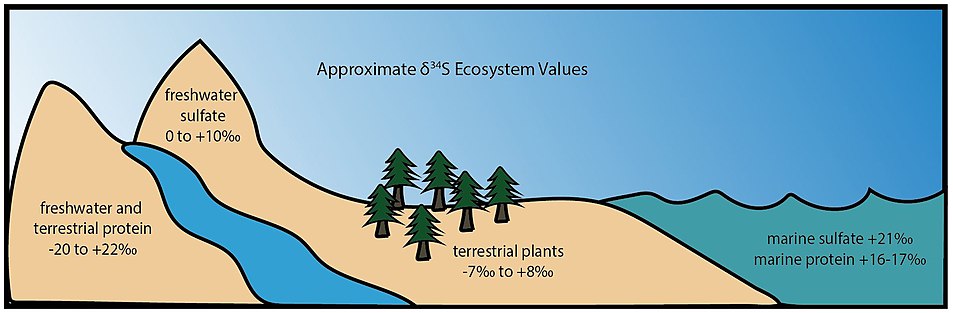

Stable isotope analysis Google scholar mentions of "isotope" and "archaeology" in publications over the past decades Overview Stable isotope biogeochemistry is a powerful tool that utilizes variations in isotopic signatures and relates them to biogeochemical processes. The science is based on the preferential fractionation of lighter or heavier isotopes, which results in enriched and depleted isotopic signatures compared to a standard value. Essential elements for life such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur are the primary stable isotope systems used to interrogate archeological discoveries. Isotopic signatures from multiple systems are typically used in tandem to create a comprehensive understanding of the analyzed material. These systems are most commonly used to trace the geographic origin of archaeological remains and investigate the paleodiets, mobility, and cultural practices of ancient humans.[56][57] Over the past few decades the use of isotope geochemistry in the context of archaeology has dramatically increased. System Applications Carbon Stable isotope analysis of carbon in human bone collagen allows bioarchaeologists to carry out dietary reconstruction and to make nutritional inferences. These chemical signatures reflect long-term dietary patterns, rather than a single meal or feast. Isotope ratios in food, especially plant food, are directly and predictably reflected in bone chemistry,[58] allowing researchers to partially reconstruct recent diet using stable isotopes as tracers.[59][60] Stable isotope analysis monitors the ratio of carbon 13 to carbon 12 (13C/12C), which is expressed as parts per mil (per thousand) using delta notation (δ13C).[61] The 13C and 12C ratio is either depleted (more negative) or enriched (more positive) relative to an international standard.[62] The original standard used in carbon stable isotope analysis is Pee Dee Belemnite (PDB), though this material has since been exhausted and replaced. 12C and 13C occur in a ratio of approximately 98.9 to 1.1.[62]  The composition of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere influences the isotopic values of C3 and C4 plants, which then impacts the δ13C of consumer collagen and apatite based on their diets.[63] The values in this diagram are average δ13C compositions for the respective categories based on Fig 11.1 in Staller et al. (2010). The ratio of carbon isotopes in consumers varies according to the types of plants digested with different photosynthesis pathways. The three photosynthesis pathways are C3 carbon fixation, C4 carbon fixation and Crassulacean acid metabolism. C4 plants are mainly grasses from tropical and subtropical regions, and are adapted to higher levels of radiation than C3 plants. Corn, millet[64] and sugar cane are some well-known C4 domesticates, while all trees and shrubs use the C3 pathway.[65] C4 carbon fixation is more efficient when temperatures are high and atmospheric CO2 concentrations are low.[66] C3 plants are more common and numerous than C4 plants as C3 carbon fixation is more efficient in a wider range of temperatures and atmospheric CO2 concentrations.[65] The different photosynthesis pathways used by C3 and C4 plants cause them to discriminate differently towards 13C leading to distinctly different ranges of δ13C. C4 plants range between -9 and -16‰, and C3 plants range between -22 and -34‰.[59] The isotopic signature of consumer collagen is close the δ13C of dietary plants, while apatite , a mineral component of bones and teeth, has an ~14‰ offset from dietary plants due fractionation associated with mineral formation.[66] Stable carbon isotopes have been used as tracers of C4 plants in paleodiets. For example, the rapid and dramatic increase in 13C in human collagen after the adoption of maize agriculture in North America documents the transition from a C3 to a C4 (native plants to corn) diet by 1300 CE.[67][68] Skeletons excavated from the Coburn Street Burial Ground (1750 to 1827 CE) in Cape Town, South Africa, were analyzed using stable isotope data in order to determine geographical histories and life histories of the interred.[69] The people buried in this cemetery were assumed to be slaves and members of the underclass based on the informal nature of the cemetery; biomechanical stress analysis[70] and stable isotope analysis, combined with other archaeological data, seem to support this supposition. Based on stable isotope levels, eight Cobern Street Burial Ground individuals consumed a diet based on C4 (tropical) plants in childhood, then consumed more C3 plants, which were more common at the Cape later in their lives. Six of these individuals had dental modifications similar to those carried out by peoples inhabiting tropical areas known to be targeted by slavers who brought enslaved individuals from other parts of Africa to the colony. Based on this evidence, it was argued that these individuals represent enslaved persons from areas of Africa where C4 plants are consumed and who were brought to the Cape as laborers.[69] These individuals were not assigned to a specific ethnicity, but it is pointed out that similar dental modifications are carried out by the Makua, Yao, and Marav peoples.[69] Four individuals were buried with no grave goods, in accordance with Muslim tradition, facing Signal Hill, which is a point of significance for local Muslims. Their isotopic signatures indicate that they grew up in a temperate environment consuming mostly C3 plants, but some C4 plants. Many of the isotopic signatures of interred individuals indicate that they Cox et al. argue that these individuals were from the Indian Ocean area. They also suggest that these individuals were Muslims. It was argued that stable isotopic analysis of burials, combined with historical and archaeological data can be an effective way in of investigating the worldwide migrations forced by the African Slave Trade, as well as the emergence of the underclass and working class in the colonial Old World.[69] Nitrogen The nitrogen stable isotope system is based on the relative enrichment or depletion of 15N in comparison to 14N in an analyzed material (δ15N). Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analyses are complementary in paleodiet studies. Nitrogen isotopes in bone collagen are ultimately derived from dietary protein, while carbon can be contributed by protein, carbohydrate, or fat in the diet.[71] δ13C values help distinguish between dietary protein and plant sources while systematic increases in δ15N values as you move up in trophic level helps determine the position of protein sources in the food web.[57][72][73] 15N increases about 3-4% with each trophic step upward.[74][75] It has also been suggested that the relative difference between human δ15N values and animal protein values scales with the proportion of that animal protein in the consumer's diet,[76] though this interpretation has been questioned due to contradictory views on the impact of nitrogen intake through protein consumption and nitrogen loss through waste release on 15N enrichment in the body.[73] When interpreting δ15N values of human remains, variations in nitrogen values within the same trophic level are also considered.[77] Nitrogen variations in plants, for example, can be caused by plant-specific reliance on nitrogen gas which causes the plant to mirror atmospheric nitrogen isotopic values.[77] Enriched or higher δ15N values can be achieved in plants that grew in soil fertilized by animal waste.[77] Nitrogen isotopes have been used to estimate the relative contributions of legumes verses nonlegumes, as well as terrestrial versus marine resources to the diet.[74][59][78] While other plants have δ15N values that range from 2 to 6‰,[74] legumes have lower 14N/15N ratios (close to 0‰, i.e. atmospheric N2) because they can fix molecular nitrogen, rather than having to rely on nitrates and nitrites in the soil.[71][77] Therefore, one potential explanation for lower δ15N values in human remains is an increased consumption of legumes or animals that eat them. 15N values increase with meat consumption, and decrease with legume consumption. The 14N/15N ratio could be used to gauge the contribution of meat and legumes to the diet. Oxygen  The oxygen stable isotope system is based on the 18O/16O (δ18O) in a given material, which is either enriched or depleted relative to a standard. The field typically normalizes to both Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) and Standard Light Antarctic Precipitation (SLAP).[79] This system is famous for its use in paleoclimatic studies but it also a prominent source of information in bioarchaeology. Variations in δ18O values in skeletal remains are directly related to the isotopic composition of the consumer's body water. The isotopic composition of mammalian body water is primarily controlled by consumed water.[79] δ18O values of freshwater drinking sources vary due to mass fractionations related to mechanisms of the global water cycle.[80] Evaporated water vapor will be more enriched in 16O (isotopically lighter; more negative delta value) compared to the body of water left behind which is now depleted in 16O (isotopically heavier; more positive delta value).[79][80] An accepted first-order approximation for the isotopic composition of animal drinking water is local precipitation, though this is complicated to varying degrees by confounding water sources like natural springs or lakes.[79] The baseline δ18O used in archaeological studies is modified depending on the relevant environmental and historical context of surrounding water sources.[79] δ18O values of bioapatite in human skeletal remains are assumed to have formed in equilibrium with body water, thus providing a species-specific relationship to oxygen isotopic composition of body water.[81] The same cannot be said for human bone collage, as δ18O values in collagen seem to be impacted by drinking water, food water, and a combination of metabolic and physiological processes.[82] While δ18O values from bone minerals are essentially an averaged isotopic signature throughout the entire life of the individual, dental enamel reflects isotopic signatures specific to early life since enamel is not biologically remodeled.[83] While carbon and nitrogen are used primarily to investigate the diets of ancient humans, oxygen isotopes offer insight into body water at different stages in a consumer's life. δ18O values are used to understand drinking behaviors,[84] animal husbandry,[85] and track mobility.[86] 97 burials from the ancient Maya citadel of Tikal were studied using oxygen isotopes.[87] Results from tooth enamel identified statistically different individuals, interpreted to be individuals from Maya lowlands, Guatemala, and potentially Mexico.[87] Historical context combined with the isotopic data from the burials is used to argue that migrant individuals were a part of lower and higher social classes within Tikal.[87] It is further suggested that the female migrants who arrived in Tikal during Early Classic period could have been the brides of Maya elite.[87] Sulfur  The sulfur stable isotope system is based on small, mass-dependent fractionations of sulfur isotopes in an analyzed material. These fractionations are then reported relative to Canyon Diablo Troilite (V-CDT), the agreed upon standard for the field. The ratio of the most abundant sulfur isotope, 32S, compared to rarer isotopes such as, 33S, 34S, and 36S, is used to characterize biological signatures and geological reservoirs. The fractionation of 34S (δ34S) is particularly useful since it is the most abundant of the rare sulfur isotopes, allowing the fractionations to be biogeochemically meaningful and analytically resolvable. This system is less commonly used on its own and typically acts as a secondary source of information that complements isotopic values of carbon and nitrogen.[88][89] In bioarchaeology, the sulfur system has been used to investigate consumer paleodiets and spatial behaviors through the analysis of hair and bone collagen.[90] Dietary proteins incorporated into living organisms tend to determine the stable isotope values of their organic tissues. Methionine and cysteine are the two canonical sulfur-containing amino acids. Of the two, δ34S values of methionine are considered to better reflect isotopic compositions of dietary sulfur, since cysteine values are impacted by diet and internal cycling.[90] While other stable isotope systems have significant trophic shifts, there is only a small shift (~0.5‰) observed between the δ34S values.[90] Figure 3 Illustration of different ecosystems with associated ranges of sulfur isotopic signatures. Consumers yield isotopic signatures that reflect the sulfur reservoir(s) of the dietary protein source. These characteristic values are determined by the isotopic nature of sulfate in the environment. Animal proteins sourced from marine ecosystems tend to have δ34S values between +16 and +17‰,[67][90][91] terrestrial plants range from -7‰ to +8‰, and proteins from freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems are highly variable.[88] The sulfate content of the modern ocean is very well-mixed with a δ34S of approximately +21‰,[92] while riverine water is heavily influenced by the sulfur-bearing minerals in surrounding bedrock and terrestrial plants are influenced by the sulfur content of local soils.[88][90] Estuarian ecosystems have increased complexity due to seawater and river inputs.[88][90] The extreme range of δ34S values for freshwater ecosystems often interferes with terrestrial signals, making it difficult to use the sulfur system as the sole tool in paleodiet studies.[88] Various studies have analyzed the isotopic ratios of sulfur in mummified hair.[93][94][95] Hair is a good candidate for sulfur studies as it typically contains at least 5% elemental sulfur.[90] One study incorporated sulfur isotope ratios into their paleodietary investigation of four mummified child victims of Incan sacrificial practices.[96] δ34S values helped them determine that the children had not been eating marine protein before their death. Historical insight coupled with consistent sulfur signatures for three of the children suggests that they were living in the same location 6 months prior to the sacrificial ceremony.[96] Studies have also measured δ34S values of bone collagen, though the interpretation of these values was not reliable until quality criteria for the analysis was published in 2009.[97] Though bone collagen is abundant in skeletal remains, less than 1% of the tissue is made of sulfur, making it imperative that these studies carefully assess the meaning of bone collagen δ34S values.[90] |

安定同位体分析 Google scholarによる過去数十年間の出版物における「アイソトープ」と「考古学」の言及数 概要安定同位体生物地球化学は、同位体シグネチャーの変動を利用し、それを生物地球化学プロセスに関連付ける強力なツールである。この科学は、軽い同位体 や重い同位体の優先的な分別に基づいており、その結果、標準値と比較して同位体標識が濃縮されたり、枯渇したりする。炭素、窒素、酸素、硫黄のような生命 に不可欠な元素は、考古学的発見を調査するために使用される主要な安定同位体系である。分析された物質を包括的に理解するために、複数のシステムからの同 位体標識が併用されるのが一般的である。これらのシステムは、考古学的遺跡の地理的起源を追跡し、古代人の古環境、移動性、文化的慣習を調査するために最 も一般的に使用されている[56][57]。過去数十年の間に、考古学の文脈における同位体地球化学の使用は劇的に増加している。 システムの応用 炭素 ヒトの骨コラーゲン中の炭素の安定同位体分析により、生物考古学者は食事の再構築を実施し、栄養学的推論を行うことができる。これらの化学的徴候は、単一 の食事や饗宴ではなく、長期的な食事パターンを反映しています。食物、特に植物性食物の同位体比は、骨の化学的性質に直接かつ予測可能に反映されるため [58]、研究者はトレーサーとして安定同位体を用いて最近の食生活を部分的に復元することができる[59][60]。安定同位体分析では、炭素13と炭 素12の比(13C/12C)をモニターしており、これはデルタ表記(δ13C)を用いてparts per mil(千分の一)で表される[61]。 [61]13Cと12Cの比率は、国際的な標準に対して、枯渇(より負)または濃縮(より正)のいずれかである[62]。炭素安定同位体分析で使用される 元の標準は、ピーディーベレムナイト(PDB)であるが、この材料はその後枯渇し、置き換えられている。12Cと13Cは約98.9対1.1の比率で存在 する[62]。  大気中の二酸化炭素の組成は、C3植物とC4植物の同位体値に影響を与え、その結果、消費者のコラーゲンとアパタイトのδ13Cに影響を与える。この図の 値は、Staller他(2010)のFig 11.1に基づく、それぞれのカテゴリーの平均δ13C組成である[63]。消費者の炭素同位体の比率は、異なる光合成経路で消化される植物の種類によっ て異なる。3つの光合成経路とは、C3炭素固定、C4炭素固定、カラスムギ酸代謝である。C4植物は主に熱帯・亜熱帯地域のイネ科植物で、C3植物よりも 高いレベルの放射に適応している。トウモロコシ、キビ[64]、サトウキビはよく知られたC4家畜であるが、すべての樹木と低木はC3経路を使用している [65]。C4炭素固定は、温度が高く、大気中のCO2濃度が低い場合に効率的である[66]。C3炭素固定は、より広い範囲の温度と大気中のCO2濃度 でより効率的であるため、C3植物はC4植物よりも一般的で数が多い[65]。 C3植物とC4植物が使用する光合成経路が異なるため、13Cに対する識別が異なり、δ13Cの範囲が明確に異なる。C4植物のδ13Cは-9~- 16‰、C3植物のδ13Cは-22~-34‰である[59]。消費者のコラーゲンの同位体比シグネチャーは食餌性植物のδ13Cに近いが、骨や歯のミネ ラル成分であるアパタイトは、ミネラル形成に伴う分画のため、食餌性植物から~14‰オフセットしている[66]。安定炭素同位体は、古環境におけるC4 植物のトレーサーとして使用されてきた。例えば、北米でトウモロコシ農業が採用された後のヒトのコラーゲン中の13Cの急速かつ劇的な増加は、 1300CEまでにC3からC4(在来植物からトウモロコシ)への食生活の移行を記録している[67][68]。 南アフリカのケープタウンにあるコバーン・ストリート埋葬地(1750年~1827年)から発掘された骸骨は、埋葬された人々の地理的な歴史や生活史を決 定するために安定同位体データを用いて分析された[69]。この墓地に埋葬された人々は、墓地の非公式な性質から奴隷や下層階級の人々であったと推測され ている。 安定同位体レベルに基づくと、コバーン・ストリート埋葬地の8人の個体は、幼少期にはC4(熱帯)植物をベースとした食事を摂取し、その後、岬でより一般 的であったC3植物をより多く摂取していた。このうち6人は、アフリカの他の地域から植民地へ奴隷として連れてきた奴隷商人がターゲットとしていたことで 知られる熱帯地域に住む民族が行ったのと同じような歯の修正を受けていた。この証拠に基づき、これらの個体はアフリカのC4植物が消費される地域から労働 者としてケープに連れてこられた奴隷であると主張された[69]。これらの個体は特定の民族に分類されなかったが、同様の歯の修正がマクア族、ヤオ族、マ ラブ族によって行われていることが指摘されている[69]。4人の個体は、地元のイスラム教徒にとって重要な地点であるシグナル・ヒルに面し、イスラム教 徒の伝統に従って、墓用品を持たずに埋葬された。彼らの同位体比の特徴から、彼らは温帯環境で育ち、主にC3植物を摂取していたが、一部C4植物も摂取し ていたことがわかる。埋葬された個体の同位体比シグネチャーの多くは、彼らがインド洋地域出身であることを示している。また、イスラム教徒であったことも 示唆している。埋葬品の安定同位体分析は、歴史的・考古学的データと組み合わせることで、アフリカ奴隷貿易によって強制された世界的な移住や、植民地時代 の旧世界における下層階級や労働者階級の出現を調査するための効果的な手段となり得ると主張した[69]。 窒素 窒素の安定同位体システムは、分析された物質中の14Nと比較した15Nの相対的な濃縮または減少(δ15N)に基づいている。炭素と窒素の安定同位体分 析は、古ダイエット研究において補完的な役割を果たす。骨コラーゲン中の窒素同位体は最終的に食餌性タンパク質に由来し、炭素は食餌中のタンパク質、炭水 化物、または脂肪に寄与する可能性がある[71]。δ13C値は食餌性タンパク質源と植物源を区別するのに役立つ一方、栄養段階が上がるにつれてδ15N 値が系統的に増加するため、食物網におけるタンパク質源の位置を決定するのに役立つ[57][72][73]。 [74][75]また、ヒトのδ15N値と動物性タンパク質値の相対的な差は、消費者の食事におけるその動物性タンパク質の割合に比例することが示唆され ているが[76]、この解釈は、タンパク質の消費による窒素摂取と老廃物の放出による窒素喪失が体内の15N濃縮に与える影響に関する矛盾した見解のため に疑問視されている[73]。 人間の遺体のδ15N値を解釈する際には、同じ栄養段階内の窒素値の変動も考慮される[77]。例えば、植物における窒素の変動は、植物が大気中の窒素同 位体値を反映する原因となる窒素ガスへの植物特有の依存によって引き起こされる可能性がある[77]。 [他の植物のδ15N値が2~6‰であるのに対し[74]、マメ科の植物は14N/15N比が低い(0‰に近い、つまり大気中のN2)。 したがって、ヒトの遺体におけるδ15N値が低いことの説明として考えられるのは、マメ科植物またはそれを食べる動物の消費量の増加である。15N値は肉 の消費によって増加し、豆類の消費によって減少する。14N/15N比は、食餌における肉類と豆類の寄与を測定するために使用できる。 酸素  酸素の安定同位体システムは、ある物質中の18O/16O(δ18O)に基づいており、標準物質に対して濃縮または減耗している。この分野は通常、ウィー ン標準海洋水(VSMOW)と標準光南極降水量(SLAP)の両方に正規化される[79]。このシステムは古気候学における使用で有名であるが、生物考古 学においても重要な情報源である。 骨格標本中のδ18O値の変動は、消費者の体内水の同位体組成に直接関係している。哺乳類の体内水の同位体組成は、主に消費された水によって制御されてい る[79]。淡水の飲用水源のδ18O値は、地球規模の水循環のメカニズムに関連する質量分画によって変化する[80]。蒸発した水蒸気は、16Oに枯渇 した(同位体的に重い;正のデルタ値)残された水と比較して、16Oに富んでいる(同位体的に軽い;負のデルタ値)。 [79][80]動物の飲料水の同位体組成の一次近似値として認められているのは、その地域の降水量であるが、これは自然の湧水や湖のような交絡する水源 によって、程度の差こそあれ複雑になっている[79]。 ヒトの骨格に含まれるバイオアパタイトのδ18O値は、体内水と平衡状態で形成されたと仮定されるため、体内水の酸素同位体組成との種特異的な関係が得ら れる[81]。 [82]。骨鉱物からのδ18O値は、基本的に個人の全生涯を通して平均化された同位体シグネチャーであるが、歯のエナメル質は生物学的にリモデリングさ れないため、初期生特有の同位体シグネチャーを反映する[83]。 炭素と窒素は主に古代人の食生活を調査するために使用されるが、酸素同位体は消費者の人生のさまざまな段階における体内の水分に関する洞察を提供する。 δ18O値は、飲酒行動[84]、家畜飼育[85]、移動追跡[86]を理解するために使用される。古代マヤのティカル城塞から出土した97の埋葬品が酸 素同位体を用いて研究された[87]。歯のエナメル質から得られた結果から、統計的に異なる個体が同定され、マヤの低地、グアテマラ、そして潜在的にはメ キシコの個体であると解釈された。 [87]さらに、古典期前期にティカルに到着した女性移住者は、マヤのエリートの花嫁であった可能性が示唆されている[87]。 硫黄  硫黄の安定同位体システムは、分析された物質中の硫黄同位体の質量に依存する小さな分画に基づいている。これらの分画は、この分野で合意された標準物質で あるキャニオン・ディアブロ・トロイライト(V-CDT)との相対値で報告される。最も豊富な硫黄同位体である32Sと、33S、34S、36Sなどの希 少同位体との比は、生物学的特徴や地質貯留層の特徴付けに使用される。34Sの分画(δ34S)は、希少硫黄同位体の中で最も豊富であるため、特に有用で ある。生物考古学では、毛髪や骨のコラーゲンの分析を通じて、消費者の古地理や空間行動を調査するために硫黄系が使用されている[90]。生物に取り込ま れた食餌性タンパク質は、その有機組織の安定同位体値を決定する傾向がある。メチオニンとシステインは、2つの典型的な含硫アミノ酸である。この2つのう ち、メチオニンのδ34S値は食餌性硫黄の同位体組成をよりよく反映していると考えられているが、システインの値は食餌や体内循環の影響を受けるためであ る[90]。他の安定同位体系では栄養学的なシフトが大きいのに対し、δ34S値の間にはわずかなシフト(~0.5‰)しか観察されない[90]。 図3 硫黄同位体比シグネチャーの範囲に関連するさまざまな生態系の図解。 消費者は、食物タンパク質源の硫黄リザーバーを反映する同位体比シグネチャーを得る。これらの特徴的な値は、環境中の硫酸塩の同位体の性質によって決ま る。海洋生態系に由来する動物性タンパク質は、δ34S値が+16から+17‰の間にある傾向があり[67][90][91]、陸上植物は-7‰から+ 8‰の範囲にある。 [一方、河川水は周囲の岩盤に含まれる硫黄含有鉱物の影響を大きく受け、陸上植物はその地域の土壌の硫黄含有量の影響を受ける。 [88][90]河口生態系は、海水や河川の流入によって複雑さを増している。[88][90]淡水生態系のδ34Sの値の極端な範囲は、しばしば陸域の シグナルと干渉し、古ダイエット研究において硫黄系を唯一のツールとして使用することを困難にしている。 様々な研究が、ミイラ化した毛髪中の硫黄の同位体比を分析している[93][94][95]。毛髪は一般的に少なくとも5%の元素状硫黄を含むため、硫黄 研究の良い候補である[90]。ある研究では、インカ帝国の生け贄の犠牲となった4人のミイラ化した子供の古食調査に硫黄同位体比を組み込んだ[96]。 歴史的洞察と3人の子供の一貫した硫黄の特徴から、彼らは生贄儀式の6ヶ月前に同じ場所で生活していたことが示唆された[96]。骨コラーゲンのδ34S 値を測定した研究もあるが、分析の品質基準が2009年に発表されるまで、これらの値の解釈は信頼できなかった[97]。 |

| Archaeological uses of DNA aDNA analysis of past populations is used by archaeology to genetically determine the sex of individuals, determine genetic relatedness, understand marriage patterns, and investigate prehistoric population movements.[98] An example of Archaeologists using DNA to find evidence, in 2012 archaeologists found skeletal remains of an adult male. He was buried under a car park in England. with the use of DNA evidence, the archaeologists were able to confirm that the remains belonged to Richard III, the former king of England who died in the Battle of Bosworth.[99] In 2021, Canadian researchers used DNA analysis on skeletal remains found on King William Island, identifying them as belonging to Warrant Officer John Gregory, an engineer serving aboard HMS Erebus in the ill-fated 1845 Franklin Expedition. He was the first expedition member to be identified by DNA analysis.[100] |

DNAの考古学的利用 過去の集団のaDNA分析は、個人の性別の遺伝学的決定、遺伝的血縁関係の決定、婚姻パターンの理解、先史時代の集団移動の調査に考古学で使用されている [98]。 2012年、考古学者が成人男性の骨格を発見した。彼はイングランドの駐車場の下に埋められていた。DNAの証拠を使って、考古学者たちはその遺骨がボズ ワースの戦いで死んだ元イングランド王、リチャード3世のものであることを確認することができた[99]。 2021年、カナダの研究者はキング・ウィリアム島で発見された骸骨のDNA分析を行い、1845年の不運なフランクリン探検でHMSエレバスに乗船して いた技師、ジョン・グレゴリー准尉のものであることを突き止めた。彼はDNA分析によって特定された最初の探検隊員であった[100]。 |

| Bioarchaeological treatments of

equality and inequality Aspects of the relationship between the physical body and socio-cultural conditions and practices can be recognized through the study of human remains. This is most often emphasized in a "biocultural bioarchaeology" model.[101] It has often been the case that bioarchaeology has been regarded as a positivist, science-based discipline, while theories of the living body in the social sciences have been viewed as constructivist in nature. Physical anthropology and bioarchaeology have been criticized for having little to no concern for culture or history. Blakey[102][103] has argued that scientific or forensic treatments of human remains from archaeological sites construct a view of the past that is neither cultural nor historic, and has suggested that a biocultural version of bioarchaeology will be able to construct a more meaningful and nuanced history that is more relevant to modern populations, especially descent populations. By biocultural, Blakey means a type of bioarchaeology that is not simply descriptive, but combines the standard forensic techniques of describing stature, sex and age with investigations of demography and epidemiology in order to verify or critique socioeconomic conditions experienced by human communities of the past. The incorporation of analysis regarding the grave goods interred with individuals may further the understanding of the daily activities experienced in life. Currently, some bioarchaeologists are coming to view the discipline as lying at a crucial interface between the science and the humanities; as the human body is non-static, and is constantly being made and re-made by both biological and cultural factors.[104] Buikstra[105] considers her work to be aligned with Blakey's biocultural version of bioarchaeology because of her emphasis on models stemming from critical theory and political economy. She acknowledges that scholars such as Larsen[106][107] are productive, but points out that his is a different type of bioarchaeology that focuses on quality of life, lifestyle, behavior, biological relatedness, and population history. It does not closely link skeletal remains to their archaeological context, and is best viewed as a "skeletal biology of the past."[108] Inequalities exist in all human societies, even so-called “egalitarian” ones.[109] It is important to note that bioarchaeology has helped to dispel the idea that life for foragers of the past was “nasty, brutish and short”; bioarchaeological studies have shown that foragers of the past were often quite healthy, while agricultural societies tend to have increased incidence of malnutrition and disease.[110] However, based on a comparison of foragers from Oakhurst to agriculturalists from K2 and Mapungubwe, Steyn[111] believes that agriculturalists from K2 and Mapungubwe were not subject to the lower nutritional levels expected for this type of subsistence system. Danforth argues that more “complex” state-level societies display greater health differences between elites and the rest of society, with elites having the advantage, and that this disparity increases as societies become more unequal. Some status differences in society do not necessarily mean radically different nutritional levels; Powell did not find evidence of great nutritional differences between elites and commoners, but did find lower rates of anemia among elites in Moundville.[112] An area of increasing interest among bioarchaeologists interested in understanding inequality is the study of violence.[113] Researchers analyzing traumatic injuries on human remains have shown that a person's social status and gender can have a significant impact on their exposure to violence.[114][115][116] There are numerous researchers studying violence, exploring a range of different types of violent behavior among past human societies. Including intimate partner violence,[117] child abuse,[118] institutional abuse,[119] torture,[120][121] warfare,[122][123] human sacrifice,[124][125] and structural violence.[126][127] |

平等と不平等に関する生物考古学的研究 身体と社会文化的条件や慣習との関係の側面は、遺骨の研究を通じて認識することができる。このことは「生物文化的生物考古学」モデルにおいて最もよく強調 されている[101]。生物考古学が実証主義的で科学に基づく学問分野とみなされてきたのに対し、社会科学における生体の理論は構成主義的なものとみなさ れてきた。身体人類学と生物考古学は、文化や歴史に対する関心がほとんどないとして批判されてきた。ブレイキー[102][103]は、遺跡から出土した 人骨の科学的あるいは法医学的な処理が、文化的でも歴史的でもない過去の見解を構築していると主張し、生物文化的なバージョンの生物考古学が、現代の集 団、特に子孫集団により関連した、より有意義でニュアンスのある歴史を構築することができると示唆している。ブレイキーが言う「生物文化的考古学」とは、 単に記述的なものではなく、身長、性別、年齢を記述する標準的な法医学的手法と、人口統計学や疫学の調査を組み合わせて、過去の人類社会が経験した社会経 済的状況を検証・批判するものである。個人と一緒に埋葬された墓用品に関する分析を取り入れることで、人生で経験した日常的な活動の理解を深めることがで きるかもしれない。 現在、一部のバイオ考古学者は、この学問を科学と人文学の間の極めて重要な接点に位置するものとして捉えるようになってきている。 ブイクストラ[105]は、批判的理論と政治経済学に由来するモデルを重視しているため、自身の研究はブレイキーのバイオカルチュラル・バージョンのバイ オ考古学に沿ったものであると考えている。彼女は、ラーセン[106][107]のような学者が生産的であることは認めるが、彼の研究は生活の質、ライフ スタイル、行動、生物学的関連性、集団の歴史に焦点を当てた異なるタイプのバイオ考古学であると指摘している。骨格と考古学的コンテクストを密接に結びつ けることはなく、「過去の骨格生物学」として捉えるのが最適である[108]。 いわゆる「平等主義」社会であっても、すべての人間社会には不平等が存在する[109]。生物考古学は、過去の採集民の生活が「厄介で、残忍で、短命」で あったという考えを払拭するのに役立っていることに注目することは重要である。生物考古学の研究によれば、過去の採集民は非常に健康であったことが多く、 一方、農業社会では栄養失調や疾病の発生率が増加する傾向にある。 [しかし、オークハーストの採集民とK2やマプングブウェの農耕民との比較から、ステイン[111]はK2やマプングブウェの農耕民はこの種の自給自足シ ステムで予想されるような低栄養レベルではなかったと考えている。 Danforthは、より「複雑な」国家レベルの社会では、エリート層とそれ以外の社会との間で健康状態の差が大きく、エリート層が有利であり、この格差 は社会がより不平等になるにつれて大きくなると主張している。パウエルはエリート層と平民層との間に栄養面で大きな差があったという証拠を発見していない が、マウンドヴィルではエリート層における貧血の割合が低いことを発見している[112]。 不平等を理解することに関心のある生物考古学者の間で関心が高まっている分野は、暴力の研究である[113]。人骨の外傷を分析する研究者は、人の社会的 地位や性別が暴力への曝露に大きな影響を及ぼす可能性があることを示している[114][115][116]。暴力を研究する研究者は数多くおり、過去の 人類社会における様々な種類の暴力行為を探求している。親密なパートナーからの暴力、[117]児童虐待、[118]施設内虐待、[119]拷問、 [120][121]戦争、[122][123]人身御供、[124][125]構造的暴力などが含まれる[126][127]。 |

| Archaeological ethics There are ethical issues with bioarchaeology that revolve around treatment and respect for the dead.[4] Large-scale skeletal collections were first amassed in the US in the 19th century, largely from the remains of Native Americans. No permission was ever granted from surviving family for study and display. Recently, federal laws such as NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) have allowed Native Americans to regain control over the skeletal remains of their ancestors and associated artifacts in order to reassert their cultural identities. NAGPRA passed in 1990. At this time, many archaeologists underestimated the public perception of archaeologists as non-productive members of society and grave robbers.[128] Concerns about occasional mistreatment of Native American remains are not unfounded: in a Minnesota excavation 1971, White and Native American remains were treated differently; remains of White people were reburied, while remains of Native American people were placed in cardboard boxes and placed in a natural history museum.[128] Blakey[102] relates the growth in African American bioarchaeology to NAGPRA and its effect of cutting physical anthropologist off from their study of Native American remains. Bioarchaeology in Europe is not as affected by these repatriation issues as American bioarchaeology but regardless the ethical considerations associated with working with human remains are, and should, be considered.[4] However, because much of European archaeology has been focused on classical roots, artifacts and art have been overemphasized and Roman and post-Roman skeletal remains were nearly completely neglected until the 1980s. Prehistoric archaeology in Europe is a different story, as biological remains began to be analyzed earlier than in classical archaeology. |

考古学の倫理バイオ考古学には、死

者の扱いや尊重をめぐる倫理的な問題がある[4] 。遺族から研究や展示の許可を得ることはなかった。近年、NAGPRA(Native

American Graves Protection and Repatriation

Act:アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と返還に関する法律)のような連邦法によって、アメリカ先住民は自分たちの文化的アイデンティティを再確認するために、

自分たちの祖先の骸骨とそれに関連する遺物の管理を取り戻すことができるようになった。 1990年にNAGPRAが成立した。1971年のミネソタ州の発掘調査では、白人の遺骨とアメリカ先住民の遺骨は異なる扱いを受け、白人の遺骨は改葬さ れたが、アメリカ先住民の遺骨は段ボール箱に入れられ、自然史博物館に保管された[128]。 [Blakey[102] は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の生物考古学の成長とNAGPRAの関係、そしてNAGPRAが身体人類学者をネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨研究から切り離した 影響について述べている。 ヨーロッパのバイオ考古学は、アメリカのバイオ考古学ほどこのような本国送還の問題に影響されることはないが、それにもかかわらず、遺骨を扱うことに伴う 倫理的配慮は必要であり、また考慮されるべきである[4]。しかし、ヨーロッパの考古学の多くが古典的なルーツに焦点を当ててきたため、遺物や美術品が過 度に重視され、ローマ時代以降の骨格遺物は1980年代までほとんど無視されてきた。ヨーロッパにおける先史時代の考古学は事情が異なり、生物学的遺物の 分析が古典考古学よりも早く始まっている。 |

| Ancient DNA Biocultural anthropology Odontometrics Osteoarchaeology Paleopathology Zooarchaeology |

Anthropometry, the measurement

of the human individual Biocultural anthropology Ethology Evolutionary anthropology Evolutionary biology Evolutionary psychology Human evolution Paleontology Primatology Race (human categorization) Sociobiology |

| Medical anthropology for Bioanthropologists |

生物人類学者のための医療人類学 |

| Medical

anthropology

studies "human health and disease, health care systems, and biocultural

adaptation".[1] It views humans from multidimensional and ecological

perspectives.[2] It is one of the most highly developed areas of

anthropology and applied anthropology,[3] and is a subfield of social

and cultural anthropology that examines the ways in which culture and

society are organized around or influenced by issues of health, health

care and related issues. The term "medical anthropology" has been used since 1963 as a label for empirical research and theoretical production by anthropologists into the social processes and cultural representations of health, illness and the nursing/care practices associated with these.[4] Furthermore, in Europe the terms "anthropology of medicine", "anthropology of health" and "anthropology of illness" have also been used, and "medical anthropology", was also a translation of the 19th century Dutch term "medische anthropologie". This term was chosen by some authors during the 1940s to refer to philosophical studies on health and illness.[5] |

医

療人類学は、「人間の健康と病気、ヘルスケアシステム、生物文化的適応」を研究する学問であり[1]、人間を多面的かつ生態学的な視点から捉える[2]。

人類学および応用人類学の中で最も高度に発展した分野の一つであり[3]、文化や社会が健康やヘルスケア、関連する問題を中心に組織される、あるいはその

影響を受ける方法を研究する社会・文化人類学の一分野である。 医療人類学」という用語は、1963年以来、人類学者による、健康、病気、およびこれらに関連する看護/ケア実践の社会的プロセスと文化的表象に関する実 証的研究と理論的生産のためのラベルとして使用されている[4]。 さらにヨーロッパでは、「医療人類学」、「健康人類学」、「疾病人類学」という用語も使用されており、「医療人類学」は19世紀のオランダ語 「medische anthropologie」の翻訳でもある。この用語は、1940年代に健康と病気に関する哲学的研究を指すために一部の著者によって選択された [5]。 |

| Historical background The relationship between anthropology, medicine and medical practice is well documented.[6] General anthropology occupied a notable position in the basic medical sciences (which correspond to those subjects commonly known as pre-clinical). However, medical education started to be restricted to the confines of the hospital as a consequence of the development of the clinical gaze and the confinement of patients in observational infirmaries.[7][8] The hegemony of hospital clinical education and of experimental methodologies suggested by Claude Bernard relegate the value of the practitioners' everyday experience, which was previously seen as a source of knowledge represented by the reports called medical geographies and medical topographies both based on ethnographic, demographic, statistical and sometimes epidemiological data. After the development of hospital clinical training the basic source of knowledge in medicine was experimental medicine in the hospital and laboratory, and these factors together meant that over time mostly doctors abandoned ethnography as a tool of knowledge. Most, not all because ethnography remained during a large part of the 20th century as a tool of knowledge in primary health care, rural medicine, and in international public health. The abandonment of ethnography by medicine happened when social anthropology adopted ethnography as one of the markers of its professional identity and started to depart from the initial project of general anthropology. The divergence of professional anthropology from medicine was never a complete split.[9] The relationships between the two disciplines remained constant during the 20th century, until the development of modern medical anthropology in the 1960s and 1970s. A large number of contributors to 20th Century medical anthropology had their primary training in medicine, nursing, psychology or psychiatry, including W. H. R. Rivers, Abram Kardiner, Robert I. Levy, Jean Benoist, Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán and Arthur Kleinman. Some of them share clinical and anthropological roles. Others came from anthropology or social sciences, like George Foster, William Caudill, Byron Good, Tullio Seppilli, Gilles Bibeau, Lluis Mallart, Andràs Zempleni, Gilbert Lewis, Ronald Frankenberg, and Eduardo Menéndez. A recent book by Saillant & Genest describes a large international panorama of the development of medical anthropology, and some of the main theoretical and intellectual actual debates.[10][11] Some popular topics that are covered by medical anthropology are mental health, sexual health, pregnancy and birth, aging, addiction, nutrition, disabilities, infectious disease, non-communicable diseases (NCDs), global epidemics, disaster management and more. |

歴史的背景 人類学、医学、医療実践の関係はよく知られている[6]。一般的な人類学は、基礎医学(一般に前臨床と呼ばれる科目に相当)において重要な位置を占めてい た。クロード・ベルナールによって提案された病院臨床教育と実験的方法論の覇権は、以前は民族誌的、人口統計学的、統計学的、時には疫学的データに基づく メディカル・ジオグラフィやメディカル・トポグラフィと呼ばれる報告書に代表される知識源とみなされていた開業医の日常経験の価値を後退させた。病院での 臨床研修が発達してからは、医学における知識の基本的な源泉は病院や研究室での実験医学であり、これらの要因が相まって、時間の経過とともに、ほとんどの 医師が知識の道具としてのエスノグラフィーを放棄するようになった。というのも、20世紀の大部分は、プライマリーヘルスケアや農村医療、国際的な公衆衛 生において、エスノグラフィが知識の道具として残っていたからである。医学がエスノグラフィを放棄したのは、社会人類学がエスノグラフィを専門家としての アイデンティティの標識の一つとして採用し、一般人類学の当初のプロジェクトから逸脱し始めたときである。専門的な人類学と医学の乖離は、決して完全な分 裂ではなかった。W・H・R・リヴァース、アブラム・カーディナー、ロバート・I・レヴィ、ジャン・ブノワ、ゴンサロ・アギーレ・ベルトラン、アーサー・ クラインマンなど、20世紀の医療人類学に貢献した多くの人たちが、医学、看護学、心理学、精神医学で主な訓練を受けた。彼らの中には、臨床と人類学の役 割を分担している者もいる。また、ジョージ・フォスター、ウィリアム・コーディル、バイロン・グッド、トゥリオ・セッピリ、ジル・ビボー、リュイス・マ ジャール、アンドラス・ゼンプレニ、ギルバート・ルイス、ロナルド・フランケンバーグ、エドゥアルド・メネンデスのように、人類学や社会科学から来た者も いる。SaillantとGenestによる最近の本では、医療人類学の発展に関する国際的な大パノラマと、主要な理論的・知的な実際の議論のいくつかが 記述されている[10][11]。 医療人類学が扱う人気のあるトピックは、メンタルヘルス、性の健康、妊娠・出産、加齢、中毒、栄養、障害、感染症、非感染性疾患(NCDs)、世界的な伝 染病、災害管理などである。 |

| Medical sociology Peter Conrad notes that medical sociology studies some of the same phenomena as medical anthropology but argues that medical anthropology has different origins, originally studying medicine within non-western cultures and using different methodologies.[12]: 91–92 He argues that there was some convergence between the disciplines, as medical sociology started to adopt some of the methodologies of anthropology such as qualitative research and began to focus more on the patient, and medical anthropology started to focus on western medicine. He argued that more interdisciplinary communication could improve both disciplines.[12] |

医療社会学 ピーター・コンラッドは、医療社会学は医療人類学と同じ現象のいくつかを研究しているが、医療人類学の起源は異なっており、もともとは非西洋文化の中で医 学を研究し、異なる方法論を用いていたと主張している[12]: 91-92 .彼は、医療社会学が質的調査など人類学の方法論のいくつかを採用し始め、より患者に焦点を当て始めたこと、そして医療人類学が西洋医学に焦点を当て始め たことから、両分野の間にはいくつかの収束があったと主張している。彼は、より学際的なコミュニケーションが両分野を改善する可能性があると主張した。 |

| Popular medicine and medical

systems For much of the 20th century, the concept of popular medicine, or folk medicine, has been familiar to both doctors and anthropologists. Doctors, anthropologists, and medical anthropologists used these terms to describe the resources, other than the help of health professionals, which European or Latin American peasants used to resolve any health problems. The term was also used to describe the health practices of aborigines in different parts of the world, with particular emphasis on their ethnobotanical knowledge. This knowledge is fundamental for isolating alkaloids and active pharmacological principles. Furthermore, studying the rituals surrounding popular therapies served to challenge Western psychopathological categories, as well as the relationship in the West between science and religion. Doctors were not trying to turn popular medicine into an anthropological concept, rather they wanted to construct a scientifically based medical concept which they could use to establish the cultural limits of biomedicine.[13][14] Biomedicine is the application of natural sciences and biology to the diagnosis of a disease. Often in the Western culture, this is ethnomedicine. Examples of this practice can be found in medical archives and oral history projects.[15] The concept of folk medicine was taken up by professional anthropologists in the first half of the twentieth century to demarcate between magical practices, medicine and religion and to explore the role and the significance of popular healers and their self-medicating practices. For them, popular medicine was a specific cultural feature of some groups of humans which was distinct from the universal practices of biomedicine. If every culture had its own specific popular medicine based on its general cultural features, it would be possible to propose the existence of as many medical systems as there were cultures and, therefore, develop the comparative study of these systems. Those medical systems which showed none of the syncretic features of European popular medicine were called primitive or pretechnical medicine according to whether they referred to contemporary aboriginal cultures or to cultures predating Classical Greece. Those cultures with a documentary corpus, such as the Tibetan, traditional Chinese or Ayurvedic cultures, were sometimes called systematic medicines. The comparative study of medical systems is known as ethnomedicine, which is the way an illness or disease is treated in one's culture, or, if psychopathology is the object of study, ethnopsychiatry (Beneduce 2007, 2008), transcultural psychiatry (Bibeau, 1997) and anthropology of mental illness (Lézé, 2014).[16] Under this concept, medical systems would be seen as the specific product of each ethnic group's cultural history. Scientific biomedicine would become another medical system and therefore a cultural form that could be studied as such. This position, which originated in the cultural relativism maintained by cultural anthropology, allowed the debate with medicine and psychiatry to revolve around some fundamental questions: The relative influence of genotypical and phenotypical factors in relation to personality and certain forms of pathology, especially psychiatric and psychosomatic pathologies. The influence of culture on what a society considers to be normal, pathological or abnormal. The verification in different cultures of the universality of the nosological categories of biomedicine and psychiatry. The identification and description of diseases belonging to specific cultures that have not been previously described by clinical medicine. These are known as ethnic disorders and, more recently, as culture-bound syndromes, and include the evil eye and tarantism among European peasants, being possessed or in a state of trance in many cultures, and nervous anorexia, nerves and premenstrual syndrome in Western societies. Since the end of the 20th century, medical anthropologists have had a much more sophisticated understanding of the problem of cultural representations and social practices related to health, disease and medical care and attention.[17] These have been understood as being universal with very diverse local forms articulated in transactional processes. The link at the end of this page is included to offer a wide panorama of current positions in medical anthropology. |