physical anthropology

自然人類学

physical anthropology

解説:池田光穂

自然人類学 しぜん・じんるいがく anthropology

人間を研究する学問が人類学。人類 (ギリシャ語でanthropos)と学問(同じく logos)の 合成語がこの言語である。自然人類学は形質人類学ともいう。人類学が現在の学問の体勢として出発する以前から、この用語は〈人間学〉という用語と学問(=哲学)で呼ばれていたが、人類学と は別物であり、また直接の先祖というわけではない。自然人類学は、人間の生物学的な側面から 中心に、人類の成り立ち、進化、あるいは霊長類としての 人間の研究として霊長類学(primatology)なども隣接関連分野として研究する領域のことである。自然人類学あるいは形質人類学(共にphysical anthropology)は、21世紀に入って生物人類学(biological anthropology)と呼ばれるようになった(→「生物人類学」)。

● 現代の標準的な「自然人類学」教科書の章立ての紹介(Molnar, Stephen. Human Variation: Races, Typesm and Ethnic Group. 6th ed., Prentice Hall. 2006.)——まだレイス(人種)の用語を使っていますが?!

1. 生物学的多様性と人種の概念

2. 人間の多様性のための生物学的基 礎

3. シンプルな遺伝的形質について (1):血液型のグループとタンパク質

4. シンプルな遺伝的形質について(2):ヘモグロビ ンの多様性とDNAマーカー

5. 複雑な遺伝形質とその適応(1)

6. 複雑な遺伝形質とその適応(2)

7. 人間の変異性、行動、人種主義 (レイシズム)

8. 人間の生物多様性の分布

9. 健康の諸相と人間の多様性:人種 概念の影響

10. 人間の種の変貌する次元

+++

Chapter 1 Biological Diversity and the Race Concept: An Introduction Human Variation: Its Discovery and Classification Anthropometry: The Measures of Human Variation Eugenics Racial Boundaries: Fact or Fiction? Race, Geography, and Origins Confusions and Contradictions of Human Classification Human Biological Variability: A Perspectiive

Chapter 2 The Biological Basis for Human Variation Principles of Inheritance Formal Human Genetics Factors of Variation and Evolution The Gene, DNA, and the "Code of Life," Chromosomes at the Molecular Level Gene Clusters and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLPs) Y-Chromosome DNA Polymorphisms Mitochondrial DNA Genes and Populations: A Summary

Chapter 3 Traits of Simple Inheritance I: Blood Groups and Proteins Blood Components and Inherited Traits The Blood Groups The Blood Groups: An Overview White Blood Cell (WBC) Antigens Polymorphisms of Serum Proteins Inborn Errors of Metabolism Other Polymorphisms of Anthropological Interest Traits of Simple Inheritance: Some Conclusions

Chapter 4 Traits of Simple Inheritance II: Hemoglobin Variants and DNA Markers Hemoglobins: Normal and Abnormal Distribution of Hemoglobin S Malaria and Natural Selection Other Abnormal Hemoglobins The Enzyme G6PD (Glucose 6 Phosphate Dehydrogenase) Distribution of Red-Cell Variants in Sardinian Populations Gene Frequency Changes and African Americans DNA Markers of Human Variation Genetic Markers at the DNA Level: Some Conclusions

Chapter 5 Traits of Complex Inheritance and Their Adaptations: I The Structure and Function of Skin Skin Color and Evolution Craniofacial Traits Eye Color and Hair Color Human Form and Its Variability Body Size and Form: Perspectives of Heredity

Chapter 6 Traits of Complex Inheritance and Their Adaptations: II Characteristics of Growth and Development Nutritional Influences Adaptations to Cold or Hot Environments High Altitude Environments: Stresses and Responses Conclusions: Complex Traits and Their Adaptations

Chapter 7 Human Variability, Behavior, and Racism Race, Nations, and Racism Intelligence Quotient: A Measure of Mental Ability? Behavior and Inheritance or Inheritance of Behavior Class and Caste Genetics, Intelligence, and the Future

Chapter 8 Distribution of Human Biodiversity Some Factors Contributing to Gene Distribution Races, Ethnic Groups, or Breeding Populations Breeding Populations Clinal Distribution of Traits Breeding Populations versus Clines

Chapter 9 Perspectives of Health and Human Diversity: Influences of the Race Concept Epidemiiological Transition: The Distribution and Type of Disease The Developing World and Epidemiological Transitions A New World, but Old Diseases What Is a Race? Genes, Races, Environments, and Diseases: Some Conclusions

Chapter 10 Changing Dimensions of the Human Species Population Size and Growth: Historical Perspectives Factors of Population Change Empowerment of Women Fertility Differences and Population Composition Demographic Balances Regional Changes and World Populations Races, Types, and Ethnic Groups: Where Are We?

| Biological

anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a social

science

discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of

human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human

primates, particularly from an evolutionary perspective.[1] This

subfield of anthropology systematically studies human beings from a

biological perspective. |

生物人類学は、身体的人類学(形質人類学・自然人類学)とも呼ば

れ、人

間、絶滅したヒト属の祖先、および関連する非ヒト霊長類の生物学的および行動学的側面を、特に進化論的観点から研究する社会科学分野である。[1]

この人類学のサブフィールドは、生物学的観点から人間を体系的に研究する。 |

| Branches As a subfield of anthropology, biological anthropology itself is further divided into several branches. All branches are united in their common orientation and/or application of evolutionary theory to understanding human biology and behavior. Bioarchaeology is the study of past human cultures through examination of human remains recovered in an archaeological context. The examined human remains usually are limited to bones but may include preserved soft tissue. Researchers in bioarchaeology combine the skill sets of human osteology, paleopathology, and archaeology, and often consider the cultural and mortuary context of the remains. Evolutionary biology is the study of the evolutionary processes that produced the diversity of life on Earth, starting from a single common ancestor. These processes include natural selection, common descent, and speciation. Evolutionary psychology is the study of psychological structures from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify which human psychological traits are evolved adaptations – that is, the functional products of natural selection or sexual selection in human evolution. Forensic anthropology is the application of the science of physical anthropology and human osteology in a legal setting, most often in criminal cases where the victim's remains are in the advanced stages of decomposition. Human behavioral ecology is the study of behavioral adaptations (foraging, reproduction, ontogeny) from the evolutionary and ecologic perspectives (see behavioral ecology). It focuses on human adaptive responses (physiological, developmental, genetic) to environmental stresses. Human biology is an interdisciplinary field of biology, biological anthropology, nutrition and medicine, which concerns international, population-level perspectives on health, evolution, anatomy, physiology, molecular biology, neuroscience, and genetics. Paleoanthropology is the study of fossil evidence for human evolution, mainly using remains from extinct hominin and other primate species to determine the morphological and behavioral changes in the human lineage, as well as the environment in which human evolution occurred. Paleopathology is the study of disease in antiquity. This study focuses not only on pathogenic conditions observable in bones or mummified soft tissue, but also on nutritional disorders, variation in stature or morphology of bones over time, evidence of physical trauma, or evidence of occupationally derived biomechanic stress. Primatology is the study of non-human primate behavior, morphology, and genetics. Primatologists use phylogenetic methods to infer which traits humans share with other primates and which are human-specific adaptations. |

分科 生物人類学は、人類学のサブフィールドとして、さらにいくつかの分科に分けられる。すべての分科は、人間生物学と行動の理解に、進化論の方向性や応用を共 通して取り入れている。 1)生物考古学は、考古学的文脈で発見された人骨の調査を通じて過去の人間の文化を研究する学問である。調査対象となる人骨は通常骨に限られるが、保存状 態のよい軟組織が含まれる場合もある。生物考古学の研究者は、人類骨学、古病理学、考古学のスキルを組み合わせ、人骨の文化的および埋葬の背景を考慮する ことが多い。 2)進化生物学は、単一の共通祖先から始まり、地球上の生命の多様性を生み出した進化の過程を研究する学問である。これらのプロセスには、自然淘汰、共通 の祖先、種分化などが含まれる。 進化心理学は、現代の進化論的観点から心理構造を研究する学問である。進化心理学では、人間の心理的特性のうち、進化によって適応されたもの、すなわち、 人間の進化における自然淘汰または性淘汰の機能的産物であるものを特定しようとする。 3)法医学人類学は、法的な状況下で自然人類学および人骨学の科学を応用するものであり、多くの場合、被害者の遺体が高度に腐敗した段階にある犯罪事件で 用いられる。 4)人間行動生態学は、進化論的および生態学的な観点から行動適応(採餌、繁殖、個体発生)を研究する学問である(行動生態学を参照)。環境ストレスに対 する人間の適応反応(生理学的、発達学的、遺伝学的)に焦点を当てている。 5)人間生物学は、生物学、生物人類学、栄養学、医学の学際的な分野であり、健康、進化、解剖学、生理学、分子生物学、神経科学、遺伝学に関する国際的 な、集団レベルの視点に関わるものである。 古生物学は、人類の進化に関する化石の証拠を研究する学問であり、主に絶滅したヒト科やその他の霊長類の化石を用いて、人類の系統における形態学的および 行動学的変化、および人類の進化が起こった環境を解明する。 6)古病理学は、古代の疾病を研究する学問である。この研究では、骨やミイラ化した軟組織に観察できる病原状態だけでなく、栄養障害、時代による身長や骨 の形態の変化、外傷の痕跡、職業に起因する生体力学的ストレスの証拠にも焦点を当てている。 7)霊長類学は、ヒト以外の霊長類の行動、形態、遺伝学を研究する学問である。霊長類学者は、人類が他の霊長類と共有する特徴と、ヒト特有の適応は何かを 推測するために、系統発生学的手法を用いる。 |

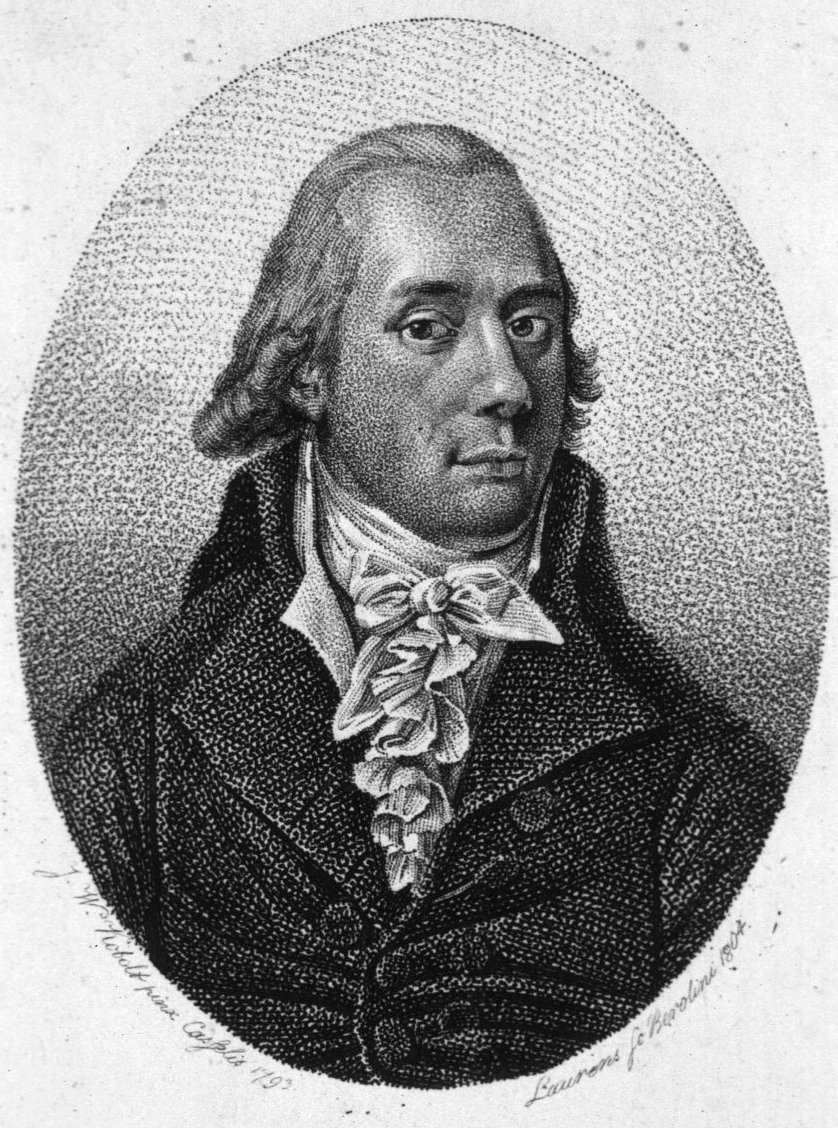

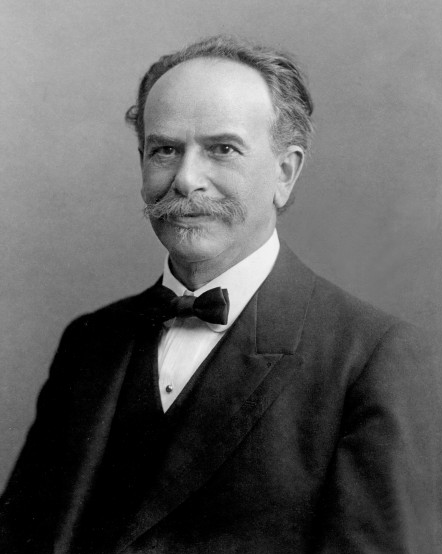

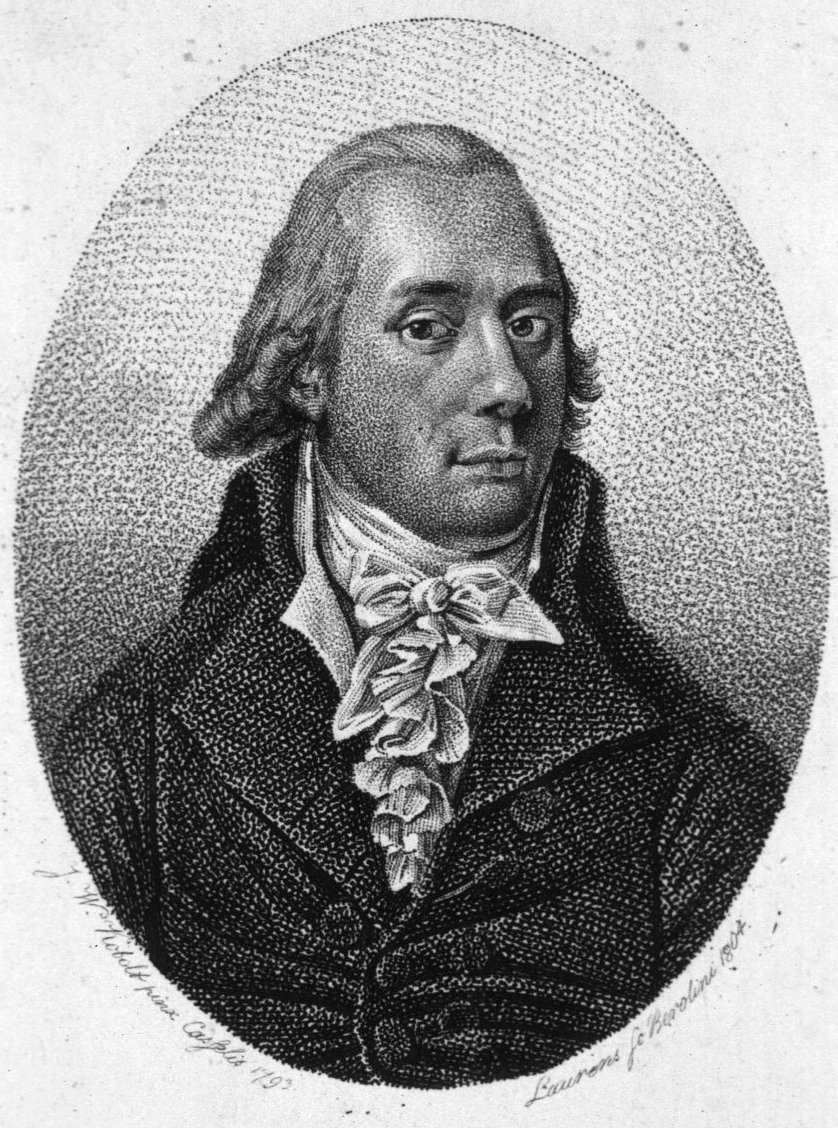

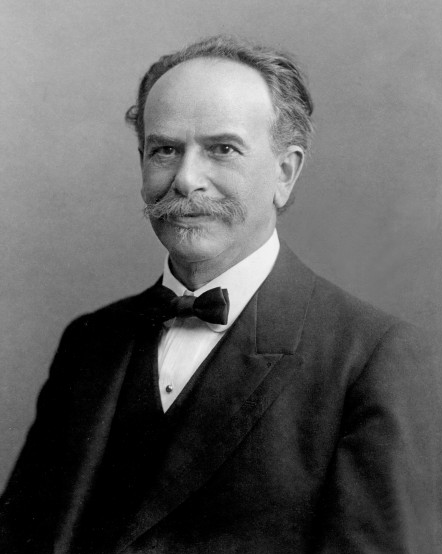

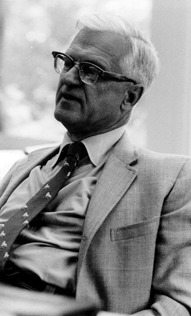

| History Origins   Johann Friedrich Blumenbach  Franz Boas Biological Anthropology looks different today from the way it did even twenty years ago. Even the name is relatively new, having been 'physical anthropology' for over a century, with some practitioners still applying that term.[2] Biological anthropologists look back to the work of Charles Darwin as a major foundation for what they do today. However, if one traces the intellectual genealogy back to physical anthropology's beginnings—before the discovery of much of what we now know as the hominin fossil record—then the focus shifts to human biological variation. Some editors, see below, have rooted the field even deeper than formal science. Attempts to study and classify human beings as living organisms date back to ancient Greece. The Greek philosopher Plato (c. 428–c. 347 BC) placed humans on the scala naturae, which included all things, from inanimate objects at the bottom to deities at the top.[3] This became the main system through which scholars thought about nature for the next roughly 2,000 years.[3] Plato's student Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC) observed in his History of Animals that human beings are the only animals to walk upright[3] and argued, in line with his teleological view of nature, that humans have buttocks and no tails in order to give them a soft place to sit when they are tired of standing.[3] He explained regional variations in human features as the result of different climates.[3] He also wrote about physiognomy, an idea derived from writings in the Hippocratic Corpus.[3] Scientific physical anthropology began in the 17th to 18th centuries with the study of racial classification (Georgius Hornius, François Bernier, Carl Linnaeus, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach).[4] The first prominent physical anthropologist, the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840) of Göttingen, amassed a large collection of human skulls (Decas craniorum, published during 1790–1828), from which he argued for the division of humankind into five major races (termed Caucasian, Mongolian, Aethiopian, Malayan and American).[5] In the 19th century, French physical anthropologists, led by Paul Broca (1824–1880), focused on craniometry[6] while the German tradition, led by Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902), emphasized the influence of environment and disease upon the human body.[7] In the 1830s and 40s, physical anthropology was prominent in the debate about slavery, with the scientific, monogenist works of the British abolitionist James Cowles Prichard (1786–1848) opposing[8] those of the American polygenist Samuel George Morton (1799–1851).[9] In the late 19th century, German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858–1942) strongly impacted biological anthropology by emphasizing the influence of culture and experience on the human form. His research showed that head shape was malleable to environmental and nutritional factors rather than a stable "racial" trait.[10] However, scientific racism still persisted in biological anthropology, with prominent figures such as Earnest Hooton and Aleš Hrdlička promoting theories of racial superiority[11] and a European origin of modern humans.[12]  "New physical anthropology" In 1951 Sherwood Washburn, a former student of Hooton, introduced a "new physical anthropology."[13] He changed the focus from racial typology to concentrate upon the study of human evolution, moving away from classification towards evolutionary process. Anthropology expanded to include paleoanthropology and primatology.[14] The 20th century also saw the modern synthesis in biology: the reconciling of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and Gregor Mendel's research on heredity. Advances in the understanding of the molecular structure of DNA and the development of chronological dating methods opened doors to understanding human variation, both past and present, more accurately and in much greater detail. |

歴史 起源   ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハ  フランツ・ボアズ 生物人類学は、20年前とは異なる様相を呈している。この名称自体も比較的新しく、1世紀以上も「自然人類学」と呼ばれていた時期があり、現在でもその名 称を使用している研究者もいる。生物人類学者は、今日行っている研究の主要な基礎として、チャールズ・ダーウィンの研究を振り返っている。しかし、知的系 譜を物理人類学の始まりまで遡り、現在ホミニンの化石記録として知られているものの多くが発見される以前までさかのぼると、焦点は人間の生物学的多様性に シフトする。一部の編集者は、この分野を正式な科学よりもさらに深く根付いていると見ている。 人間を生物として研究し分類しようとする試みは古代ギリシャにまで遡る。ギリシャの哲学者プラトン(紀元前428年頃 - 紀元前347年頃)は、人間を「スカラ・ナチュレ(自然の階梯)」に位置づけた。スカラ・ナチュレには、無生物を底辺とし、神々を頂点とするあらゆるもの が含まれていた。[3] これが、学者たちが自然について考える主な体系となり、その後およそ2000年にわたって続いた。[3] プラトンの プラトンの弟子アリストテレス(紀元前384年頃-322年頃)は著書『動物誌』の中で、人間は直立歩行する唯一の動物であると述べ[3]、人間には尻が あり尾がないのは、立ちつづけて疲れたときに座って休めるようにするためであると主張した。これは、アリストテレスの目的論的な自然観に沿った主張であ る。彼は、 気候の違いによるものだと説明した。また、ヒポクラテスの著作から派生した観相学についても記述している。 著名な最初の自然人類学者であるゲッティンゲンのドイツ人医師ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハ(1752年-1840年)は、膨大な数の人間の頭 蓋骨のコレクション(『頭蓋骨十組』、1790年から1828年の間に出版)を収集し、それをもとに人類を5 つの主要な人種(コーカソイド、モンゴロイド、エチオピア 。[5] 19世紀には、ポール・ブローカ(1824年-1880年)が率いるフランスの自然人類学者たちは頭蓋計測学に重点を置き[6]、ルドルフ・ウィルヒョー (1821年-1902年)が率いるドイツの伝統では、人体に対する環境や疾患の影響が強調された。[7] 1830年代から40年代にかけて、奴隷制度に関する論争では自然人類学が優勢となり、イギリスの奴隷制度廃止論者ジェームズ・カウルズ・プリチャード (1786年~1848年)の科学的単一起源説の著作が、アメリカ人の多起源説者サミュエル・ジョージ・モートン(1799年~1851年)の著作に反対 した。 19世紀後半には、ドイツ系アメリカ人の人類学者フランツ・ボアズ(1858年 - 1942年)が、人間の形に対する文化や経験の影響を強調することで、生物人類学に大きな影響を与えた。彼の研究は、頭部の形状は安定した「人種」の特徴 というよりも、環境や栄養状態の影響を受けやすいことを示した。[10] しかし、生物人類学においては、アーネスト・フートンやアレシュ・ハルディチカといった著名な人物が人種優越論[11]や現生人類のヨーロッパ起源説 [12]を唱えるなど、科学的な人種差別が依然として根強く残っていた。  「新しい自然人類学」 1951年、フートンの元学生であったシャーウッド・ウォッシュバーンは 「新しい自然人類学」を導入した。[13] 彼は人類進化の研究に焦点を絞り、人種類型論から人類進化の研究へと重点を移し、分類から進化プロセスへと方向転換した。人類学は、古生物学や霊長類学を 含むまでに拡大した。[14] 20世紀には、生物学の分野でも現代の総合説が誕生した。すなわち、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論とグレゴール・メンデルの遺伝学の研究を調和させたも のである。DNAの分子構造の理解が進み、年代測定法が開発されたことで、過去と現在の両方における人間の変異を、より正確に、より詳細に理解することが 可能になった。 |

| 続きは「生物人類学」で!! |

|

| Zeresenay Alemseged John Lawrence Angel George J. Armelagos William M. Bass Caroline Bond Day Jane E. Buikstra William Montague Cobb Carleton S. Coon Robert Corruccini Raymond Dart Robin Dunbar Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt Linda Fedigan A. Roberto Frisancho Robert Foley Jane Goodall Joseph Henrich Earnest Hooton Aleš Hrdlička Sarah Blaffer Hrdy Anténor Firmin Dian Fossey Birute Galdikas Richard Lynch Garner Colin Groves Yohannes Haile-Selassie Ralph Holloway William W. Howells Donald Johanson Robert Jurmain Melvin Konner Louis Leakey Mary Leakey Richard Leakey Frank B. Livingstone Owen Lovejoy Ruth Mace Jonathan M. Marks Robert D. Martin Russell Mittermeier Desmond Morris Douglas W. Owsley David Pilbeam Kathy Reichs Alice Roberts Pardis Sabeti Robert Sapolsky Eugenie C. Scott Meredith Small Chris Stringer Phillip V. Tobias Douglas H. Ubelaker Frans de Waal Sherwood Washburn David Watts Tim White Milford H. Wolpoff Richard Wrangham Teuku Jacob Biraja Sankar Guha |

ゼレンセイ・アレムセゲド ジョン・ローレンス・エンジェル ジョージ・J・アーメラゴス ウィリアム・M・バス キャロライン・ボンド・デイ ジェーン・E・バイクストラ ウィリアム・モンゴメリー・コブ カールトン・S・クーン ロバート・コルリッチーニ レイモンド・ダート ロビン・ダンバー エゴン・フォン・アイクシュテット リンダ・フェディガン A・ロベルト・フリサンチョ ロバート・フォーリー ジェーン・グドール ジョセフ・ヘンリッヒ アーネスト・フートン アレシュ・ハルディチカ サラ・ブレイファー・ハーディ アンテノール・ファーマン ダイアン・フォッシー ビルート・ガルディカス リチャード・リンチ・ガーナー コリン・グローブス ヨハネス・ハイレ・セラシエ ラルフ・ホロウェイ ウィリアム・W・ハウエルズ ドナルド・ジョハンソン ロバート・ジャーマイン メルヴィン・コナー ルイス・ルキー メアリー・ルキー リチャード・ルキー フランク・B・リヴィングストン オーエン・ラブジョイ ルース・メイス ジョナサン・M・マークス ロバート・D・マーティン ラッセル・ミッターマイヤー デズモンド・モリス ダグラス・W・オウスリー デビッド・ピルビーム キャシー・ライヒス アリス・ロバーツ パルディス・サベティ ロバート・サポルスキー ユージニー・C・スコット メレディス・スモール クリス・ストリンガー フィリップ・V・トビアス ダグラス・H・ウベイラー フラン・ド・ワール シャーウッド・ウォッシュバーン デビッド・ワッツ ティム・ホワイト ミルフォード・H・ウォルポフ リチャード・ランガム テウク・ジェイコブ ビラジャ・サンカル・グハ |

| Anthropometry, the measurement

of the human individual Biocultural anthropology Ethology Evolutionary anthropology Evolutionary biology Evolutionary psychology Human evolution Paleontology Primatology Race (human categorization) Sociobiology |

人体計測学、人間の個体の測定 生物文化人類学 動物行動学 進化人類学 進化生物学 進化心理学 人類の進化 古生物学 霊長類学 人種(人間の分類) 社会生物学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biological_anthropology |

リンク

︎猿にもわかる文化人類学▶︎文化人類学入門▶人 類学︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆