Gender as one of sociological categories

Gender Trouble

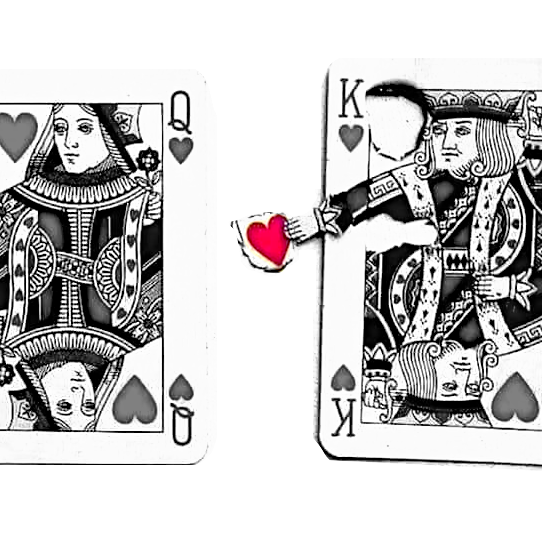

Gender as one of sociological categories

"●(1)Butler criticizes one of the central assumptions of feminist

theory: that there exists an identity and a subject that requires

representation in politics and language. For Butler, "women" and

"woman" are categories complicated by factors such as class, ethnicity,

and sexuality. Moreover, the universality presumed by these terms

parallels the assumed universality of the patriarchy, and erases the

particularity of oppression in distinct times and places. Butler thus

eschews identity politics in favor of a new, coalitional feminism that

critiques the basis of identity and gender. She challenges assumptions

about the distinction often made between sex and gender, according to

which sex is biological while gender is culturally constructed. Butler

argues that this false distinction introduces a split into the

supposedly unified subject of feminism. Sexed bodies cannot signify

without gender, and the apparent existence of sex prior to discourse

and cultural imposition is only an effect of the functioning of gender.

Sex and gender are both constructed.

●(2)Examining the work of the philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and

Luce Irigaray, Butler explores the relationship between power and

categories of sex and gender. For de Beauvoir, women constitute a lack

against which men establish their identity; for Irigaray, this

dialectic belongs to a "signifying economy" that excludes the

representation of women altogether because it employs phallocentric

language. Both assume that there exists a female "self-identical being"

in need of representation, and their arguments hide the impossibility

of "being" a gender at all. Butler argues instead that gender is

performative: no identity exists behind the acts that supposedly

"express" gender, and these acts constitute, rather than express, the

illusion of the stable gender identity. If the appearance of “being” a

gender is thus an effect of culturally influenced acts, then there

exists no solid, universal gender: constituted through the practice of

performance, the gender "woman" (like the gender "man") remains

contingent and open to interpretation and "resignification". In this

way, Butler provides an opening for subversive action. She calls for

people to trouble the categories of gender through performance.

●(3)Discussing the patriarchy, Butler notes that feminists have

frequently made recourse to the supposed pre-patriarchal state of

culture as a model upon which to base a new, non-oppressive society.

For this reason, accounts of the original transformation of sex into

gender by means of the incest taboo have proven particularly useful to

feminists. Butler revisits three of the most popular: the

anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss's anthropological structuralism, in

which the incest taboo necessitates a kinship structure governed by the

exchange of women; Joan Riviere's psychoanalytic description of

"womanliness as a masquerade" that hides masculine identification and

therefore also conceals a desire for another woman; and Sigmund Freud's

psychoanalytic explanation of mourning and melancholia, in which loss

prompts the ego to incorporate attributes of the lost loved one, in

which cathexis becomes identification.

●(4)Butler extends these accounts of gender identification in

order to emphasize the productive or performative aspects of gender.

With Lévi-Strauss, she suggests that incest is "a pervasive cultural

fantasy" and that the presence of the taboo generates these desires;

with Riviere, she states that mimicry and masquerade form the "essence"

of gender; with Freud, she asserts that "gender identification is a

kind of melancholia in which the sex of the prohibited object is

internalized as a prohibition" (63) and therefore that "same-sexed

gender identification" depends on an unresolved (but simultaneously

forgotten) homosexual cathexis (with the father, not the mother, of the

Oedipal myth). For Butler, "heterosexual melancholy is culturally

instituted as the price of stable gender identities" (70) and for

heterosexuality to remain stable, it demands the notion of

homosexuality, which remains prohibited but necessarily within the

bounds of culture. Finally, she points again to the productivity of the

incest taboo, a law which generates and regulates approved

heterosexuality and subversive homosexuality, neither of which exists

before the law.

●(5)In response to the work of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan

that posited a paternal Symbolic order and a repression of the

"feminine" required for language and culture, Julia Kristeva added

women back into the narrative by claiming that poetic language—the

"semiotic"—was a surfacing of the maternal body in writing,

uncontrolled by the paternal logos. For Kristeva, poetic writing and

maternity are the sole culturally permissible ways for women to return

to the maternal body that bore them, and female homosexuality is an

impossibility, a near psychosis. Butler criticizes Kristeva, claiming

that her insistence on a "maternal" that precedes culture and on poetry

as a return to the maternal body is essentialist: "Kristeva

conceptualizes this maternal instinct as having an ontological status

prior to the paternal law, but she fails to consider the way in which

that very law might well be the cause of the very desire it is said to

repress" (90). Butler argues the notion of "maternity" as the long-lost

haven for females is a social construction, and invokes Michel

Foucault's arguments in The History of Sexuality (1976) to posit that

the notion that maternity precedes or defines women is itself a product

of discourse.

●(6)Butler dismantles part of Foucault's critical introduction to

the journals he published of Herculine Barbin, an intersex person who

lived in France during the 19th century and eventually committed

suicide when she was forced to live as a man by the authorities. In his

introduction to the journals, Foucault writes of Barbin's early days,

when she was able to live her gender or "sex" as she saw fit as a

"happy limbo of nonidentity" (94). Butler accuses Foucault of

romanticism, claiming that his proclamation of a blissful identity

"prior" to cultural inscription contradicts his work in The History of

Sexuality, in which he posits that the idea of a "real" or "true" or

"originary" sexual identity is an illusion, in other words that "sex"

is not the solution to the repressive system of power but part of that

system itself. Butler instead places Barbin's early days not in a

"happy limbo" but along a larger trajectory, always part of a larger

network of social control. She suggests finally that Foucault's

surprising deviation from his ideas on repression in the introduction

might be a sort of "confessional moment", or vindication of Foucault's

own homosexuality of which he rarely spoke and on which he permitted

himself only once to be interviewed.

●(7)Butler traces the feminist theorist Monique Wittig's thinking

about lesbianism as the one recourse to the constructed notion of sex.

The notion of "sex" is always coded as female, according to Wittig, a

way to designate the non-male through an absence. Women, thus reduced

to "sex", cannot escape carrying sex as a burden. Wittig argues that

even the naming of the body parts creates a fiction and constructs the

features themselves, fragmenting what was really once "whole".

Language, repeated over time, "produces reality-effects that are

eventually misperceived as 'facts'" (115).

●(8)Butler questions the notion that "the body" itself is a

natural entity that "admits no genealogy", a usual given without

explanation: "How are the contours of the body clearly marked as the

taken-for-granted ground or surface upon which gender signification are

inscribed, a mere facticity devoid of value, prior to significance?"

(129). Building on the thinking of the anthropologist Mary Douglas,

outlined in her Purity and Danger (1966), Butler claims that the

boundaries of the body have been drawn to instate certain taboos about

limits and possibilities of exchange. Thus the hegemonic and homophobic

press has read the pollution of the body that AIDS brings about as

corresponding to the pollution of the homosexual's sexual activity, in

particular his crossing the forbidden bodily boundary of the perineum.

In other words, Butler's claim is that "the body is itself a

consequence of taboos that render that body discrete by virtue of its

stable boundaries" (133). Butler proposes the practice of drag as a way

to destabilize the exteriority/interiority binary, finally to poke fun

at the notion that there is an "original" gender, and to demonstrate

playfully to the audience, through an exaggeration, that all gender is

in fact scripted, rehearsed, and performed.

●(9)Butler attempts to construct a feminism (via the politics of

jurido-discursive power) from which the gendered pronoun has been

removed or not presumed to be a reasonable category. She claims that

even the binary of subject/object, which forms the basic assumption for

feminist practices—"we, 'women,' must become subjects and not

objects"—is a hegemonic and artificial division. The notion of a

subject is for her formed through repetition, through a "practice of

signification" (144). Butler offers parody (for example, the practice

of drag) as a way to destabilize and make apparent the invisible

assumptions about gender identity and the inhabitability of such

"ontological locales" (146) as gender. By redeploying those practices

of identity and exposing as always failed the attempts to "become"

one's gender, she believes that a positive, transformative politics can

emerge.

※(10)All page numbers are from the first edition: Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York, Routledge, 1990)." - Gender Trouble. Wiki

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Columbia, personification of the United States, wearing a warship

bearing the words "World Power" as her "Easter bonnet" on the cover of

Puck, 6 April 1901.