egemonia(伊), hegemony(英), hegemmonie(独)

ヘゲモニー

egemonia(伊), hegemony(英), hegemmonie(独)

解説:池田光穂

☆マルクス主義が人々のこころを捉えてい た時代には、「デコンストラクション」や「知の考古学」は「効力」をもっていた。だが、しかし、……。懐疑論的相対主義、複数の言語ゲーム(公共的合意の 概念)、美学的な現状肯定、経験論的歴史主義、カルスタなどサブカルチャー重視は、(冷戦の終焉以降/共産主義の終焉以降)支配思想すなわちヘゲモニック な階級が利用する思想になった(柄谷 2004:8)

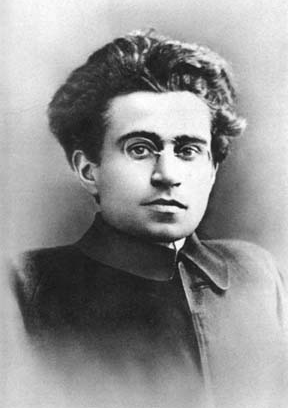

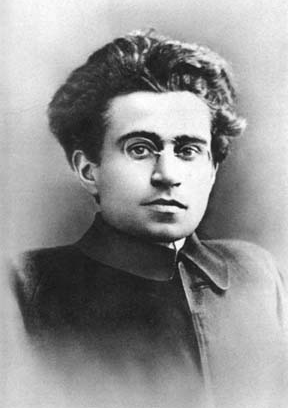

ヘゲモニーとは、人々による合意にもとづ いた覇権や支配権のことをさす。この言葉の語源はギリシャ語のヘーゲスタイつまり、都市国家による別の 国家や農村の支配のことをさしていた。イタリアのマルクス主義思想家・運動家のアントニオ・グラムシ(Antonio Gramsci, 1891-1937)は、強制や恐怖による権力支配とは異なり、人々の合意による権力掌握のことについて指摘し、それをヘゲモニーとして称した。

ヘゲモニーは覇権という意味もあるので、

グラムシのそれを覇権と区別するために「文化的ヘゲモニー・文化的覇権」と呼ぶ場合がある。「マ

ルクス主義哲学において、文化的覇権とは、支配階級の世界観が文化的規範として受け入れられるように、その社会の文化(信念や説明、認識、価値観、風俗)

を形成する支配階級によって、文化的に多様な社会が支配されることである。普遍的な支配イデオロギーとして、支配階級の世界観は、社会的、政治的、経済的

現状を、支配階級のみに利益をもたらす人為的な社会構成としてではなく、あらゆる社会階級に利益をもたらす自然で必然的で永続的な社会状況として誤って表

現する。

哲学や社会学において、文化的ヘゲモニーという用語の意味合いや含蓄は、ヘゲモニーのリーダーシップや体制を示す古代ギリシャ語のヘゲモニア

(ἡγεμονία)に由来している。

[政治学においては、覇権は帝国によって行使される地政学的な支配であり、覇権国家(リーダー国家)は、直接的な支配(軍事的侵略、占領、領土の併合)の

脅威ではなく、権力の暗黙の手段である介入の脅威によって帝国の従属国家を支配している。」

さて、グラムシによるヘゲモニー理論のこ とを理解するためには、彼の政治的信条と実践の原理であったマルクス主義(共産主義)と、当時の共産主 義の状況、さらにはイタリアのファシスト政権の樹立などのことを考慮すればわかりやすい。

マルクス『ゴータ綱領批判』(1875) では、革命の過渡期における「労働者階級=プロレタリアート」が権力を掌握し、政治支配を確立する統治 のアイディアが構想された。いわゆるプロレタリアート独裁についての考え方である。

この政治支配は、ロシア革命の政治権力の 確立のプロセスにおいてにおいてウラジミール・I・レーニン(1870-1924)により一種のドグマ 的正当化に成功した。ここで興味ふかいことは、レーニンはヘゲモニー(ギリシャ語的語源のとおり「政治的支配」)をプロレタリアート独裁と同義語として 使っていたということであり、この用語法はやがて使わなくなる。しかし1918年にはドイツのK.カウツキー(1854-1938)は、プロレタリアート 独裁は、ソビエトによる一党独裁にすぎないことを喝破して(=今からみれば当然の批判のことながら「革命の遂行」という使命感に燃えていたソビエトからみ れば裏切りと思われ、レーニンは口汚く批判した)、カウツキーは社会民主主義の立場を明確にした。

他方、グラムシは、イタリア社会党を経由 して、1921年にイタリア共産党の結成にかかわり、翌年から1年ほどモスクワに滞在し、その直後亡命 先でイタリア共産党書記長になる。ファシスト=ムッソリーニ政権下で下院議員に選出されると、議員は逮捕を免れるという特権を利用して帰国するが、最終的 にはその特権が剥奪されて1926年より禁固刑に処され、1937年まで収監される。

グラムシは、獄中での論文等の執筆が許さ れ、そのなかでサバルタンや ヘゲモニーに関する論考の断片が記されることになる。グラムシによれば—— 自分の足元を掬ったファシスト政権の存在もあり——イタリアにおける政治支配の問題は、ロシアほど単純であるとは思われず、[共産主義者のみならず反共産 主義の勢力の]支配の形態は複雑であった。つまり、政治を通して支配関係を確立するということは、力ずくの暴力だけではなく(=この点はプロレタリアート 独裁における単純な暴力観からは離礁している)、文化、道徳さらには教育というプロセス、さらには市民社会の確立や民主主義という政治制度(=この点では レーニンよりもカウツキー的な社会民主主義的な政治権力掌握の概念に近い)が関係していると理解した。

ただし、グラムシのヘゲモニーに関する議 論は、むしろさまざまなノートの断片のなかに登場し、彼自身も(学位論文のように)一つのまとまった議 論としてまとめる(ブルジョア的?)という気持ちもなかったようで、グラムシのテキストのどこかに「グラムシのヘゲモニー論」があると期待すると失望する ことになる。また後のグラムシ研究者がヘゲモニー論として、その価値を取り出そうとする議論の多くは、贔屓の引き倒しのものが多いので、ノートから読者の 創造的解釈によってヘゲモニー論に新しい生命を与えるほうがより生産的であろう。

ヘゲモニーの理論では、主体性をもつ人々 が、なぜ意見を異にする勢力や権力に従属するのかということについて明らかにする。すなわち同意をもと に活動に参加していると感じている主体は、その活動がもつイデオロギーを実践を通して内面化し、全体の活動に「従属」するということが可能になるというこ とだ。これは、強制的な権力により従属していることでもなく、また処罰や恐怖によって主体性のある人をあることに従わせることでもない。

大衆動員が、参加者全員による合理的な理 解によって可能になっているのではなく、その動員を正当化するイデオロギーに対し て合意しているのだと いう共同体感のみによって従っているかも知れない。

政治的支配や統治について、文化、道徳お よび教育が深く関わるというアイディアは、のちにルイ・アルチュセール(Louis Althusser, 1918-1990)「国家と国家イデオロギー装置」の議論で興味深い展開を遂げる。

また、文化研究(カルチュラルスタディー ズ, Cultural Studies)において、スチュアート・ホール(Stuart Hall, 1932-)は、この研究領域における重要な鍵概念として、としてグラムシのヘゲモニーと、アルチュセールのイデオロギー論をあげている。

★「ヘゲモニーと暴力の位相」はこちら。

| In Marxist

philosophy, cultural

hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the

ruling class who shape the culture of that society—the beliefs and

explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of

the ruling class becomes the accepted cultural norm.[1] As the

universal dominant ideology, the ruling-class worldview misrepresents

the social, political, and economic status quo as natural, inevitable,

and perpetual social conditions that benefit every social class, rather

than as artificial social constructs that benefit only the ruling

class.[2][3] In philosophy and in sociology, the denotations and the connotations of term cultural hegemony derive from the Ancient Greek word hegemonia (ἡγεμονία), which indicates the leadership and the régime of the hegemon.[4] In political science, hegemony is the geopolitical dominance exercised by an empire, the hegemon (leader state) that rules the subordinate states of the empire by the threat of intervention, an implied means of power, rather than by threat of direct rule—military invasion, occupation, and territorial annexation.[5][6] |

マルクス主義哲学において、文化的覇権とは、支配階級の世界観が文化的

規範として受け入れられるように、その社会の文化(信念や説明、認識、価値観、風俗)を形成する支配階級によって、文化的に多様な社会が支配されることで

ある[1]。普遍的な支配イデオロギーとして、支配階級の世界観は、社会的、政治的、経済的現状を、支配階級のみに利益をもたらす人為的な社会構成として

ではなく、あらゆる社会階級に利益をもたらす自然で必然的で永続的な社会状況として誤って表現する[2][3]。 哲学や社会学において、文化的ヘゲモニーという用語の意味合いや含蓄は、ヘゲモニーのリーダーシップや体制を示す古代ギリシャ語のヘゲモニア (ἡγεμονία)に由来している。 [政治学においては、覇権は帝国によって行使される地政学的な支配であり、覇権国家(リーダー国家)は、直接的な支配(軍事的侵略、占領、領土の併合)の 脅威ではなく、権力の暗黙の手段である介入の脅威によって帝国の従属国家を支配している[5][6]。 |

| In 1848, Karl Marx proposed that

the economic recessions and practical contradictions of a capitalist

economy would provoke the working class to proletarian revolution,

depose capitalism, restructure social institutions (economic,

political, social) per the rational models of socialism, and thus begin

the transition to a communist society. Therefore, the dialectical

changes to the functioning of the economy of a society determine its

social superstructures (culture and politics). To that end, Antonio Gramsci proposed a strategic distinction between the politics for a War of Position and for a War of Manœuvre. The war of position is an intellectual and cultural struggle wherein the anti-capitalist revolutionary creates a proletarian culture whose native value system counters the cultural hegemony of the bourgeoisie. The proletarian culture will increase class consciousness, teach revolutionary theory and historical analysis, and thus further develop revolutionary organisation among the social classes.[7] After winning the war of position, socialist leaders would then have the necessary political power and popular support to realise the war of manœuvre, the political praxis of revolutionary socialism. Political economy As Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony analyses the functions of economic class within the base and superstructure, from which Gramsci developed the functions of social class within the social structures created for and by cultural domination. In the practise of imperialism, cultural hegemony occurs when the working and the peasant classes believe and accept that the prevailing cultural norms of a society (the dominant ideology imposed by the ruling class) realistically describes the natural order of things in society. In the war for position, the working-class intelligentsia politically educate the working classes to perceive that the prevailing cultural norms are not natural and inevitable social conditions, and to recognize that the social constructs of bourgeois culture function as instruments of socio-economic domination, e.g. the institutions (state, church, and social strata), the conventions (custom and tradition), and beliefs (religions and ideologies), etc. That to realise their own working-class culture the workers and the peasants, by way of their own intellectuals, must perform the necessary analyses of their culture and national history in order for the proletariat to transcend the old ways of thinking about the order of things in a society under the cultural hegemony of an imperial power. Social domination Gramsci said that cultural and historical analyses of the "natural order of things in society" established by the dominant ideology, would allow common-sense men and women to intellectually perceive the social structures of bourgeois cultural hegemony. In each sphere of life (private and public) common sense is the intellectualism with which people cope with and explain their daily life within their social stratum within the greater social order; yet the limits of common sense inhibit a person's intellectual perception of the exploitation of labour made possible with cultural hegemony. Given the difficulty in perceiving the status quo hierarchy of bourgeois culture (social and economic classes), most people concern themselves with private matters, and so do not question the fundamental sources of their socio-economic oppression, individual and collective.[8] |

1848年、カール・マルクスは、資本主義経済の経済不況と現実的矛盾

が労働者階級をプロレタリア革命へと駆り立て、資本主義を退け、社会主義の合理的モデルに従って社会制度(経済、政治、社会)を再構築し、共産主義社会へ

の移行を開始すると提唱した。したがって、社会の経済の機能に対する弁証法的変化は、その社会の上部構造(文化と政治)を決定する。 そのために、アントニオ・グラムシは、「陣地戦争」のための政治と「作戦戦争」のための政治を戦略的に区別することを提案した。陣地戦争とは、反資本主義 革命家が、ブルジョアジーの文化的ヘゲモニーに対抗する固有の価値体系を持つプロレタリア文化を創造する知的・文化的闘争である。プロレタリア文化は、階 級意識を高め、革命理論と歴史分析を教え、社会階級間の革命的組織をさらに発展させる。 政治経済 マルクス主義哲学として、文化的覇権は、基層と上部構造における経済階級の機能を分析し、そこからグラムシは、文化的支配のために、また文化的支配によっ て生み出された社会構造における社会階級の機能を発展させた。帝国主義の実践において、文化的ヘゲモニーは、労働者階級と農民階級が、社会の一般的な文化 規範(支配階級が押し付ける支配的イデオロギー)が社会の自然な秩序を現実的に記述していると信じ、受け入れるときに生じる。 労働者階級の知識層は、地位争奪戦の中で、労働者階級を政治的に教育し、一般的な文化規範が自然で必然的な社会状況ではないことを認識させ、ブルジョア文 化の社会的構成要素が社会経済的支配の道具として機能していることを認識させる。労働者と農民は、自らの労働者階級の文化を実現するために、自らの知識人 たちによって、帝国権力の文化的ヘゲモニー下にある社会における物事の秩序についての古い考え方をプロレタリアートが超越するために、自分たちの文化と国 民史について必要な分析を行わなければならない。 社会的支配 グラムシは、支配的イデオロギーによって確立された「社会における物事の自然な秩序」の文化的・歴史的分析によって、常識的な男女がブルジョア文化ヘゲモ ニーの社会構造を知的に認識できるようになると述べた。しかし、常識の限界は、文化的ヘゲモニーによって可能になった労働搾取に対する知的認識を阻害す る。ブルジョア文化(社会的・経済的階級)の現状階層を認識することが困難であることから、ほとんどの人々は私的な事柄に関心を持ち、個人的・集団的な社 会経済的抑圧の根本的な原因を問うことはない[8]。 |

| Intelligentsia To perceive and combat ruling-class cultural hegemony, the working class and the peasant class depend upon the moral and political leadership of their native intelligentsia, the scholars, academics, and teachers, scientists, philosophers, administrators et al. from their specific social classes; thus Gramsci's political distinction between the intellectuals of the bourgeoisie and the intellectuals of the working class, respectively, the men and women who are the proponents and the opponents of the cultural status quo: Since these various categories of traditional intellectuals experience through an esprit de corps their uninterrupted historical continuity, and their special qualifications, they thus put themselves forward as autonomous and independent of the dominant social group. This self-assessment is not without consequences in the ideological and political fields; consequences of wide-ranging import. The whole of idealist philosophy can easily be connected with this position, assumed by the social complex of intellectuals, and can be defined as the expression of that social utopia, by which the intellectuals think of themselves as "independent" [and] autonomous, [and] endowed with a character of their own, etc. — Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (1971), pp. 7–8.[9] The traditional and vulgarized type of the intellectual is given by the Man of Letters, the philosopher, and the artist. Therefore, journalists, who claim to be men of letters, philosophers, artists, also regard themselves as the "true" intellectuals. In the modern world, technical education, closely bound to industrial labour, even at the most primitive and unqualified level, must form the basis of the new type of intellectual. . . . The mode of being of the new intellectual can no longer consist of eloquence, which is an exterior and momentary mover of feelings and passions, but in active participation in practical life, as constructor [and] organizer, as "permanent persuader", not just simple orator. — Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (1971), pp. 9–10.[10] |

知識階級 支配階級の文化的ヘゲモニーを認識し、それに対抗するために、労働者階級と農民階級は、固有の社会階級出身の知識人、学者、学者、教師、科学者、哲学者、 行政官などの道徳的・政治的指導力に依存している。したがって、グラムシは、ブルジョアジーの知識人と労働者階級の知識人を政治的に区別し、それぞれ文化 的現状の支持者と反対者である男女を区別している: これらの伝統的知識人のさまざまなカテゴリーは、エスプリ・ド・コルプス(団結心)を通じて、途切れることのない歴史的連続性と特別な資格を体験している ため、支配的な社会集団から自立し、独立した存在として自らを前面に押し出している。このような自己評価は、イデオロギーや政治的な分野に影響を及ぼさな いわけではない。観念論哲学の全体は、知識人の社会的複合体によって想定されるこの立場と容易に結びつけることができ、知識人が自分たちを「独立した」 [自律した][独自の性格を備えた]存在であるなどと考える、この社会的ユートピアの表現として定義することができる。 - アントニオ・グラムシの獄中ノートからの選択』(1971年)、7-8頁[9]。 知識人の伝統的で低俗なタイプは、文学者、哲学者、芸術家によって与えられる。したがって、文学者、哲学者、芸術家を自称するジャーナリストもまた、自ら を「真の」知識人とみなしている。現代世界では、最も原始的で無資格のレベルであっても、産業労働と密接に結びついた技術教育が、新しいタイプの知識人の 基礎を形成しなければならない。. . . 新しい知識人の在り方は、もはや、感情や情念を外面的かつ瞬間的に動かす雄弁ではなく、建設者[および組織者]として、単なる弁舌家ではなく「永続的な説 得者」として、実践生活に積極的に参加することである。 - アントニオ・グラムシ『獄中ノート』(1971年)より抜粋、9-10頁[10]。 |

After Gramsci In 1968, Rudi Dutschke, a leader of the German student movement, the "68er-Bewegung", said that changing the bourgeois society of West Germany required a long march through the society's institutions, in order to identify and combat cultural hegemony.[11] German student movement In 1967, regarding the politics and society of West Germany, the leader of the German Student Movement, Rudi Dutschke, applied Gramsci's analyses of cultural hegemony using the phrase the "Long March through the Institutions" to describe the ideological work necessary to realise the war of position. The allusion to the Long March (1934–35) of the Chinese People's Liberation Army indicates the great work required of the working-class intelligentsia to produce the working-class popular culture with which to replace the dominant ideology imposed by the cultural hegemony of the bourgeoisie.[12][11] State apparatuses of ideology In Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (1970), Louis Althusser describes the complex of social relationships among the different organs of the State that transmit and disseminate the dominant ideology to the populations of a society.[13] The ideological state apparatuses (ISA) are the sites of ideological conflict among the social classes of a society; and, unlike the military and police forces, the repressive state apparatuses (RSA), the ISA exist as a plurality throughout society. Despite the ruling-class control of the RSA, the ideological apparatuses of the state are both the sites and the stakes (the objects) of class struggle, because the ISA are not monolithic social entities, and exist amongst society. As the public and the private sites of continual class struggle, the ideological apparatuses of the state (ISA) are overdetermined zones of society that are composed of elements of the dominant ideologies of previous modes of production, hence the continual political activity in: the religious ISA (the clergy) the educational ISA (the public and private school systems) the family ISA (patriarchal family) the legal ISA (police and legal, court and penal systems) the political ISA (political parties) the company union ISA the mass communications ISA (print, radio, television, internet, cinema) the cultural ISA (literature, the arts, sport, etc.)[14] The parliamentary structures of the State, by which elected politicians exercise the will of the people also are an ideological apparatus of the State, given the State's control of which populations are allowed to participate as political parties. In itself, the political system is an ideological apparatus, because citizens' participation involves intellectually accepting the ideological "fiction, corresponding to a 'certain' reality, that the component parts of the [political] system, as well as the principle of its functioning, are based on the ideology of the 'freedom' and 'equality' of the individual voters and the 'free choice' of the people's representatives, by the individuals that 'make up' the people".[15] |

グラムシ以後 1968年、ドイツの学生運動 「68er-Bewegung 」の指導者であったルディ・ドゥチュケは、西ドイツのブルジョア社会を変えるには、文化的ヘゲモニーを特定し、それに対抗するために、社会の制度を通して 長い行進をする必要があると述べた[11]。 ドイツの学生運動 1967年、西ドイツの政治と社会に関して、ドイツ学生運動の指導者ルディ・ドゥチュケは、グラムシの文化的ヘゲモニーに関する分析を適用し、「制度を貫 く長征」という言葉を用いて、陣地戦争を実現するために必要なイデオロギー的作業を説明した。中国人民解放軍の長征(1934-35年)への言及は、ブル ジョアジーの文化的ヘゲモニーによって押しつけられた支配的なイデオロギーに取って代わる労働者階級の大衆文化を生み出すために労働者階級の知識人に要求 される偉大な仕事を示している[12][11]。 イデオロギーの国家機構 ルイ・アルチュセールは『イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家装置』(1970年)の中で、支配的イデオロギーを社会の住民に伝達し広める国家のさまざまな 機関の間の複雑な社会的関係を描写している。 RSAの支配階級的な統制にもかかわら ず、国家のイデオロギー装置は、階級闘争の場であると ともに杭(対象)である。なぜなら、ISAは一枚岩の社 会的実体ではなく、社会の中に存在するからである。継続的な階級闘争の公の場と私的な場として、国家のイデオロギー装置(ISA)は、以前の生産様式の支 配的イデオロギーの要素で構成される社会の過剰決定されたゾーンであり、それゆえ、以下のような政治的活動が継続的に行われている: 宗教ISA(聖職者) 教育ISA(公立・私立学校制度) 家族ISA(家父長的家族) 法的ISA(警察、法律、裁判所、刑罰制度) 政治ISA(政党) 企業組合ISA マス・コミュニケーションISA(印刷物、ラジオ、テレビ、インターネット、映画) 文化ISA(文学、芸術、スポーツなど)[14]。 選挙で選ばれた政治家が民意を行使するための国家の議会構造も、どのような集団が政党として参加することを許されるかを国家が統制していることからすれ ば、国家のイデオロギー的装置である。国民の参加は、[政治]システムの構成部分とその機能原理が、個々の有権者の「自由」と「平等」、そして国民の代表 者の「自由な選択」というイデオロギーに基づくという、イデオロギー的な「『ある』現実に対応する虚構」を、国民を『構成する』個人によって知的に受け入 れることを含むからである」[15]。 |

| Behavioral contagion –

Spontaneous, unsolicited and uncritical imitation of another's behavior Collective action problem – Type of social dilemma Cultural capital – Concept of social status and social mobility Cultural conflict – Clash of beliefs or values Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990), by James C. Scott Focal point (game theory) – Concept in game theory Hegemonic masculinity – Concept in gender studies Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe Herd behavior – Behavior of individuals acting in a group "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses" (1970), by Louis Althusser Marxist cultural analysis – Anti-capitalist cultural critique Marx's theory of alienation – Social theory claiming that capitalism alienates workers from their humanity Nicos Poulantzas – Marxist political sociologist and philosopher (1936–1979) Organic crisis – scenario of complete instability of a system Passive revolution – Years-long change in political order, in Gramscian discourse Political consciousness Posthegemony – Concept in political philosophy Sheeple Social capital – Networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society Soft power – Concept developed by Joseph Nye Southern strategy – 20th century Republican electoral strategy for the Southern US Subaltern (postcolonialism) – Concept from critical theory and post-colonial studies The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1962), by Jürgen Habermas |

行動伝染 - 自発的、無許可的、無批判的な他人の行動の模倣 集団行動問題 - 社会的ジレンマの一種 文化資本 - 社会的地位と社会的流動性の概念 文化的対立 - 信念や価値観の衝突 支配と抵抗の芸術 ジェームス・C・スコット著『隠された記録』(1990年 フォーカルポイント(ゲーム理論) - ゲーム理論における概念 覇権的男性性 - ジェンダー研究における概念 覇権と社会主義戦略』(1985年)エルネスト・ラクロー、シャンタル・ムフ著 群衆行動 - 集団で行動する個人の行動 「イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家機構」(1970年)ルイ・アルチュセール著 マルクス主義的文化分析 - 反資本主義的文化批判 マルクスの疎外論 - 資本主義が労働者を人間性から疎外すると主張する社会理論 ニコス・プーランザス - マルクス主義の政治社会学者、哲学者(1936-1979年) 有機的危機 - 体制が完全に不安定になるシナリオ 受動的革命 - グラムス的言説における、政治秩序の数年にわたる変化 政治意識 ポストヘゲモニー - 政治哲学における概念 羊 ソーシャル・キャピタル(社会関係資本) - 特定の社会で生活し、働く人々の間の関係のネットワーク ソフトパワー - ジョセフ・ナイが提唱した概念 南部戦略 - 20世紀のアメリカ南部における共和党の選挙戦略 サバルタン(ポストコロニアリズム) - 批評理論およびポストコロニアル研究における概念 公共圏の構造転換: ユルゲン・ハーバーマス著『公共圏の構造的変容:ブルジョア社会のあるカテゴリーへの探究』(1962年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_hegemony |

★

| Hegemony

(/hɛˈdʒɛməni/ ⓘ, UK also /hɪˈɡɛməni/, US also /ˈhɛdʒəmoʊni/) is the

political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other

states, either regional or global.[1][2][3] In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the hegemon city-state over other city-states.[4] In the 19th century, hegemony denoted the "social or cultural predominance or ascendancy; predominance by one group within a society or milieu" and "a group or regime which exerts undue influence within a society".[5] In theories of imperialism, the hegemonic order dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the subordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence, either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government. The term hegemonism denoted the geopolitical and the cultural predominance of one country over other countries, e.g. the hegemony of the Great Powers established with European colonialism in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.[6] In International Relations theories, hegemony is distinguished from empire as ruling only external but not internal affairs of other states.[7] |

覇権(ヘゲモニー、/hɛˈ, 英: /hʒɛməni/, 英:

/hɪˈɪˈ, 米: /hɛɛməni/

)は、ある国家が他の国家に対して政治的・経済的・軍事的に優位に立つことであり、地域的または世界的なものである[1][2][3]。 古代ギリシャ(紀元前8世紀頃~紀元後6世紀頃)では、覇権国家が他の都市国家に対して政治的・軍事的に優位に立つことを指していた[4]。 19世紀においては、覇権は「社会的または文化的な優位性、上昇性、社会や環境におけるある集団による優位性」、「社会内で不当な影響力を行使する集団や 体制」を指していた[5]。 帝国主義の理論においては、覇権的秩序は、覇権的影響圏を構成する従属国家の内政と社会的性格を、内部の後援政府または外部の設置政府によって規定する。 覇権主義という用語は、アフリカ、アジア、ラテンアメリカにおけるヨーロッパの植民地主義によって確立された大国の覇権のように、ある国が他の国に対して 地政学的、文化的に優位に立つことを示すものであった。 |

| In

the historical writing of the 19th century, the denotation of hegemony

extended to describe the predominance of one country upon other

countries; and, by extension, hegemonism denoted the Great Power

politics (c. 1880s – 1914) for establishing hegemony (indirect imperial

rule), that then leads to a definition of imperialism (direct foreign

rule). In the early 20th century, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci used the idea of hegemony to talk about politics within a given society. He developed the theory of cultural hegemony, an analysis of economic class (including social class) and how the ruling class uses consent as well as force to maintain its power. Hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analysed the social norms that established the social structures to impose their Weltanschauung (world view)—justifying the social, political, and economic status quo—as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs beneficial solely to the ruling class.[4][6][64] From the Gramsci analysis derived the political science denotation of hegemony as leadership; thus, the historical example of Prussia as the militarily and culturally predominant province of the German Empire (1871–1918); and the personal and intellectual predominance of Napoleon Bonaparte upon the French Consulate (1799–1804).[65] Contemporarily, in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe defined hegemony as a political relationship of power wherein a sub-ordinate society (collectivity) perform social tasks that are culturally unnatural and not beneficial to them, but that are in exclusive benefit to the imperial interests of the hegemon, the superior, ordinate power; hegemony is a military, political, and economic relationship that occurs as an articulation within political discourse.[66] Beyer analysed the contemporary hegemony of the United States at the example of the Global War on Terrorism and presented the mechanisms and processes of American exercise of power in 'hegemonic governance'.[67] |

19世紀に書かれた歴史書では、覇

権主義(ヘゲモニー)という概念は、ある国が他の国に対して優位に立つことを表すために拡張され、ひいては、覇権主義(間接的な帝国支配)を確立するため

の大国政治(1880年代~1914年頃)を表し、それが帝国主義(直接的な外国支配)の定義につながる。 20世紀初頭、イタリアのマルクス主義哲学者アントニオ・グラムシは、ある社会内の政治について語るために覇権の考えを用いた。彼は、経済階級(社会階級 を含む)の分析である文化的覇権論を展開し、支配階級が権力を維持するために力だけでなく同意をどのように利用するかを論じた。したがって、文化的覇権の 哲学的・社会学的理論は、支配階級にのみ有益な人為的な社会構成としてではなく、むしろすべての社会階級にとって自然で必然的で有益なものとして、彼らの 世界観(Weltanschauung)を押し付けるための社会構造を確立した社会規範を分析した[4][6][64]。 グラムシの分析から、リーダーシップとしての覇権という政治学的な定義が導き出された。したがって、ドイツ帝国の軍事的・文化的に優勢な州としてのプロイ セン(1871年~1918年)の歴史的な例や、フランス領事館におけるナポレオン・ボナパルト(1799年~1804年)の個人的・知的優位が挙げられ る。 [同時期に、エルネスト・ラクローとシャンタル・ムフは『ヘゲモニーと社会主義戦略』(1985年)において、ヘゲモニーとは、従属社会(パフォーマティ ビティ)が文化的に不自然で彼らにとって有益ではないが、ヘゲモニーである上位の順列的権力の帝国的利益に排他的な利益をもたらす社会的課題を遂行する権 力の政治的関係であり、ヘゲモニーは政治的言説の中で明瞭なものとして生じる軍事的、政治的、経済的関係であると定義している。 [66]バイヤーは、世界規模の対テロ戦争を例にアメリカの現代の覇権を分析し、「覇権的ガバナンス」におけるアメリカの権力行使のメカニズムとプロセス を提示している[67]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hegemony |

|

リンク

権威と権力の合致こそがヘゲモニーの確立 を意味する(→ハンナ・アーレント 暴力論)。

リンク

文献

(※コンパクトにまとまったグラムシの思想のアンソロジー で安価で手に入る点もすばらしい。にもかかわらず用語索引がないのが残念——吉見俊哉のカルスタ講釈を聞かされるよりも、そのページに索引を載せて欲し かった。この点は平凡社にルサンチマンをぶちまけたい——紹介者より)

池田光穂「世界医療システム」(ヘゲモニー概念を医療システム批判に応用した 実例)

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆