「人種」概念の歴史

Race as human

categorization

☆人種(Race is a categorization of humans)の言葉としての定義:人 種とは、身体的または社会的な共通性に基づいて人間をカテゴリー分けし、特定の社会において一般的に異なるものと見なされる集団に分類することである。 この用語は16世紀に一般的に使用されるようになったが、当時は近親関係によって特徴づけられるものを含む、さまざまな種類の集団を指すために使用されて いた。17世紀には、この用語は身体的(表現型の)特徴を指すようになり、その後、国民的帰属を指すようになった(→「社会は防衛しなければならない」)。 現代の科学では、人種は社会的な構築物であ り、社会が定めた規則に基づいて割り当てられるアイデンティティであるとみなされている。人種は集団内の身体的類似性に基づく部分もあるが、本質的な身体 的または生物学的意味合いを持つものではない。人種という概念は、ある人種が他の人種よりも優れているという理由で人間を区別できるという信念である人種 差別主義の基礎となっている。

★︎人種▶︎人種理論▶人種と遺伝学︎︎▶人種主義(レイシズム)︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| Race is a categorization of humans

based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally

viewed as distinct within a given society.[1] The term came into common

usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of

various kinds, including those characterized by close kinship

relations.[2] By the 17th century, the term began to refer to physical

(phenotypical) traits, and then later to national affiliations. Modern

science regards race as a social construct, an identity which is

assigned based on rules made by society.[3][4][5] While partly based on

physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent

physical or biological meaning.[1][6][7] The concept of race is

foundational to racism, the belief that humans can be divided based on

the superiority of one race over another. Social conceptions and groupings of races have varied over time, often involving folk taxonomies that define essential types of individuals based on perceived traits.[8] Modern scientists consider such biological essentialism obsolete,[9] and generally discourage racial explanations for collective differentiation in both physical and behavioral traits.[10][11][12][13][14] Even though there is a broad scientific agreement that essentialist and typological conceptions of race are untenable,[15][16][17][18][19][20] scientists around the world continue to conceptualize race in widely differing ways.[21] While some researchers continue to use the concept of race to make distinctions among fuzzy sets of traits or observable differences in behavior, others in the scientific community suggest that the idea of race is inherently naive[10] or simplistic.[22] Still others argue that, among humans, race has no taxonomic significance because all living humans belong to the same subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens.[23][24] Since the second half of the 20th century, race has been associated with discredited theories of scientific racism, and has become increasingly seen as a largely pseudoscientific system of classification. Although still used in general contexts, race has often been replaced by less ambiguous and/or loaded terms: populations, people(s), ethnic groups, or communities, depending on context.[25][26] Its use in genetics was formally renounced by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2023.[27] |

人種(Race is a categorization of humans)

とは、身体的または社会的な共通性に基づいて人間をカテゴリー分けし、特定の社会において一般的に異なるものと見なされる集団に分類することである。

[1]

この用語は16世紀に一般的に使用されるようになったが、当時は近親関係によって特徴づけられるものを含む、さまざまな種類の集団を指すために使用されて

いた。[2]

17世紀には、この用語は身体的(表現型の)特徴を指すようになり、その後、国民的帰属を指すようになった。現代の科学では、人種は社会的な構築物であ

り、社会が定めた規則に基づいて割り当てられるアイデンティティであるとみなされている。[3][4][5]

人種は集団内の身体的類似性に基づく部分もあるが、本質的な身体的または生物学的意味合いを持つものではない。[1][6][7]

人種という概念は、ある人種が他の人種よりも優れているという理由で人間を区別できるという信念である人種差別主義の基礎となっている。 人種に対する社会的概念やグループ分けは時代とともに変化しており、しばしば、知覚された特徴に基づいて個人の本質的なタイプを定義する民間分類学 (folk taxonomies)が関わっている。[8] 現代の科学者は、このような生物学的本質論(biological essentialism)は時代遅れであると考えている。[9] また、身体的および行動的特徴における集団的差異を人種によって説明することに一般的に否定的である。[10][11][12][13][14] 人種に関する本質論的および類型的概念は受け入れられないという科学的な合意が広く存在しているにもかかわらず[15][16][17][18][19] [20]、世界中の科学者たちは依然として人種をさまざまな方法で概念化し続けている。[21] 一部の研究者はあいまいな 形質や行動の観察可能な差異のあいまいな集合を区別するために人種概念を使い続けている研究者もいる一方で、科学界の一部では、人種という概念は本質的に 単純[10]または単純化しすぎている[22]と指摘する者もいる。さらに、人間の間では、すべての人間は同じ亜種であるホモ・サピエンス・サピエンスに 属しているため、人種には分類学上の重要性はないと主張する者もいる[23][24]。 20世紀後半以降、人種は科学的根拠のない人種差別理論と関連付けられ、疑似科学的な分類体系であると見なされることが多くなっている。一般的に使用され ているとはいえ、人種という用語は、文脈に応じて、より曖昧さの少ない、あるいは偏りのない用語(集団、国民、民族、コミュニティなど)に置き換えられる ことが多くなっている。[25][26] 遺伝学における人種の使用は、2023年に米国科学アカデミー、工学アカデミー、医学アカデミーによって正式に放棄された。[27] |

| Defining race Modern scholarship views racial categories as socially constructed, that is, race is not intrinsic to human beings but rather an identity created, often by socially dominant groups, to establish meaning in a social context. Different cultures define different racial groups, often focused on the largest groups of social relevance, and these definitions can change over time. Historical race concepts have included a wide variety of schemes to divide local or worldwide populations into races and sub-races. Across the world, different organizations and societies choose to disambiguate race to different extents: In South Africa, the Population Registration Act, 1950 recognized only White, Black, and Coloured, with Indians added later.[28] The government of Myanmar recognizes eight "major national ethnic races". The Brazilian census classifies people into brancos (Whites), pardos (multiracial), pretos (Blacks), amarelos (Asians), and indigenous (see Race and ethnicity in Brazil), though many people use different terms to identify themselves. Legal definitions of whiteness in the United States used before the civil rights movement were often challenged for specific groups. Furthermore, the United States Census Bureau proposed but then withdrew plans to add a new category to classify Middle Eastern and North African peoples in the 2020 U.S. census, due to a dispute over whether this classification should be considered a white ethnicity or a separate race.[29] The establishment of racial boundaries often involves the subjugation of groups defined as racially inferior, as in the one-drop rule used in the 19th-century United States to exclude those with any amount of African ancestry from the dominant racial grouping, defined as "white".[1] Such racial identities reflect the cultural attitudes of imperial powers dominant during the age of European colonial expansion.[6] This view rejects the notion that race is biologically defined.[30][31][32][33] According to geneticist David Reich, "while race may be a social construct, differences in genetic ancestry that happen to correlate to many of today's racial constructs are real".[34] In response to Reich, a group of 67 scientists from a broad range of disciplines wrote that his concept of race was "flawed" as "the meaning and significance of the groups is produced through social interventions".[35] Although commonalities in physical traits such as facial features, skin color, and hair texture comprise part of the race concept, this linkage is a social distinction rather than an inherently biological one.[1] Other dimensions of racial groupings include shared history, traditions, and language. For instance, African-American English is a language spoken by many African Americans, especially in areas of the United States where racial segregation exists. Furthermore, people often self-identify as members of a race for political reasons.[1] When people define and talk about a particular conception of race, they create a social reality through which social categorization is achieved.[36] In this sense, races are said to be social constructs.[37] These constructs develop within various legal, economic, and sociopolitical contexts, and may be the effect, rather than the cause, of major social situations.[clarify][38] While race is understood to be a social construct by many, most scholars agree that race has real material effects in the lives of people through institutionalized practices of preference and discrimination.[39] Socioeconomic factors, in combination with early but enduring views of race, have led to considerable suffering within disadvantaged racial groups.[40] Racial discrimination often coincides with racist mindsets, whereby the individuals and ideologies of one group come to perceive the members of an outgroup as both racially defined and morally inferior.[41] As a result, racial groups possessing relatively little power often find themselves excluded or oppressed, while hegemonic individuals and institutions are charged with holding racist attitudes.[42] Racism has led to many instances of tragedy, including slavery and genocide.[43] In some countries, law enforcement uses race to profile suspects. This use of racial categories is frequently criticized for perpetuating an outmoded understanding of human biological variation, and promoting stereotypes. Because in some societies racial groupings correspond closely with patterns of social stratification, for social scientists studying social inequality, race can be a significant variable. As sociological factors, racial categories may in part reflect subjective attributions, self-identities, and social institutions.[44][45] Scholars continue to debate the degrees to which racial categories are biologically warranted and socially constructed.[46] For example, in 2008, John Hartigan Jr. argued for a view of race that focused primarily on culture, but which does not ignore the potential relevance of biology or genetics.[47] Accordingly, the racial paradigms employed in different disciplines vary in their emphasis on biological reduction as contrasted with societal construction. In the social sciences, theoretical frameworks such as racial formation theory and critical race theory investigate implications of race as social construction by exploring how the images, ideas and assumptions of race are expressed in everyday life. A large body of scholarship has traced the relationships between the historical, social production of race in legal and criminal language, and their effects on the policing and disproportionate incarceration of certain groups. |

人種の定義 現代の学術研究では、人種カテゴリーは社会的に構築されたものと見なされている。つまり、人種は人間の本質的なものではなく、むしろ社会的な文脈において 意味を確立するために、しばしば社会的に支配的なグループによって作り出されたアイデンティティである。異なる文化は異なる人種グループを定義し、しばし ば社会的に関連性の高い最大のグループに焦点を当てるが、これらの定義は時代とともに変化する可能性がある。 歴史的に人種という概念には、地域的または世界的な人口を人種や亜人種に分類するさまざまな方式が含まれてきた。世界中で、さまざまな組織や団体が異なる程度の人種を明確に定義している。 南アフリカでは、1950年の人口登録法では白人、黒人、カラードのみを認め、後にインド人が追加された。[28] ミャンマー政府は8つの「主要国民民族」を認めている。 ブラジル国勢調査では、ブラジル国民は、ブランコ(白人)、パルド(混血)、プレト(黒人)、アマレロ(アジア人)に分類されるが、多くの国民は異なる用語で自らを識別している。 公民権運動以前のアメリカ合衆国における白人の法的定義は、特定のグループに対してしばしば疑問が呈されていた。 さらに、アメリカ合衆国国勢調査局は、2020年の国勢調査で中東および北アフリカの人々を分類する新たなカテゴリーを追加する計画を提案したが、この分類を白人種として考えるか、あるいは別の人種として考えるかについての論争により、計画は撤回された。 人種的境界線の設定には、しばしば人種的に劣っていると定義された集団の従属が伴う。例えば、19世紀のアメリカ合衆国で、アフリカ系の人々を「白人」と 定義された支配的な人種グループから排除するために用いられた「ワン・ドロップ・ルール」のようにである。。[1] このような人種的アイデンティティは、ヨーロッパの植民地拡大時代に優勢だった帝国主義国の文化的態度を反映している。[6] この見解は、人種が生物学的に定義されるという考え方を否定している。[30][31][32][33] 遺伝学者のデビッド・ライヒによると、「人種は社会的に構築されたものであるかもしれないが、今日の多くの人種的構築物と偶然相関する遺伝的祖先の違いは 現実である」[34]。ライヒに対して、幅広い分野の科学者67名からなるグループは、彼の「人種」の概念は「欠陥がある」とし、「集団の意味と重要性は 社会的な介入によって作り出される」と書いた。[35] 顔の特徴、肌の色、髪質などの身体的特徴の共通性は人種の概念の一部を構成するが、この関連性は本質的に生物学的なものではなく、むしろ社会的区別であ る。[1] 人種的グループのその他の次元には、共有の歴史、伝統、言語が含まれる。例えば、アフリカ系アメリカ人の英語は、特に人種隔離政策が存在した米国の地域に おいて、多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人が話す言語である。さらに、人々は政治的理由から自らを特定の民族に属するものとみなすことが多い。[1] 人々が特定の民族観を定義し、それについて語る場合、社会的カテゴリー化が達成されるような社会的現実を作り出すことになる。[36] この意味において、民族は社会的構築物であると言われる。[37] これらの構築物は、さまざまな法的、経済的、社会政治的状況の中で発展し、 むしろ、主要な社会状況の結果である可能性が高い。[明確化] [38] 人種は社会構築物であると理解されているが、ほとんどの学者は、人種は優先や差別といった制度化された慣行を通じて人々の生活に現実的な物質的な影響を及 ぼしていることに同意している。[39] 社会経済的要因と、初期から根強く残る人種観が組み合わさることで、不利な立場にある人種集団に大きな苦痛をもたらしている。[40] 人種差別はしばしば人種差別的な考え方と一致しており、ある集団の個人やイデオロギーが、他集団のメンバーを人種的に 定義され、道徳的にも劣っているとみなすようになる。[41] その結果、相対的に権力を持たない人種集団は、しばしば排除されたり抑圧されたりする。一方で、覇権的な個人や機関は、人種差別的な態度を持っていると非 難される。[42] 人種差別は、奴隷制度や大量虐殺など、多くの悲劇的な事例を引き起こしてきた。[43] 一部の国では、法執行機関が容疑者のプロファイリングに人種を用いている。このような人種カテゴリーの使用は、人間の生物学的多様性に関する時代遅れの理 解を永続させ、固定観念を助長するとして、たびたび批判されている。一部の社会では人種による区分が社会階層化のパターンと密接に対応しているため、社会 的不平等を研究する社会科学者にとっては、人種は重要な変数となりうる。社会学的な要因として、人種カテゴリーは主観的な帰属、自己同一性、社会制度を部 分的に反映している可能性がある。 学者たちは、人種カテゴリーが生物学的にどの程度裏付けられているか、また社会的にどの程度構築されているかについて、議論を続けている。[46] 例えば、2008年にジョン・ハーティガン・ジュニアは、文化を主に重視するものの、生物学や遺伝学の潜在的な関連性を無視しない人種観を主張した。 [47] それゆえ、異なる分野で採用されている人種パラダイムは、社会構築論と対比される生物学的な還元論の強調の度合いが異なる。 社会科学では、人種形成理論や批判的人種理論などの理論的枠組みが、人種に関するイメージ、考え、想定が日常生活でどのように表現されているかを調査する ことで、人種が社会的構築物であることの含意を研究している。多くの学術研究が、法や犯罪に関する言語における人種の歴史的、社会的生産と、特定の集団に 対する警察活動や不均衡な投獄への影響との関係を追跡している。 |

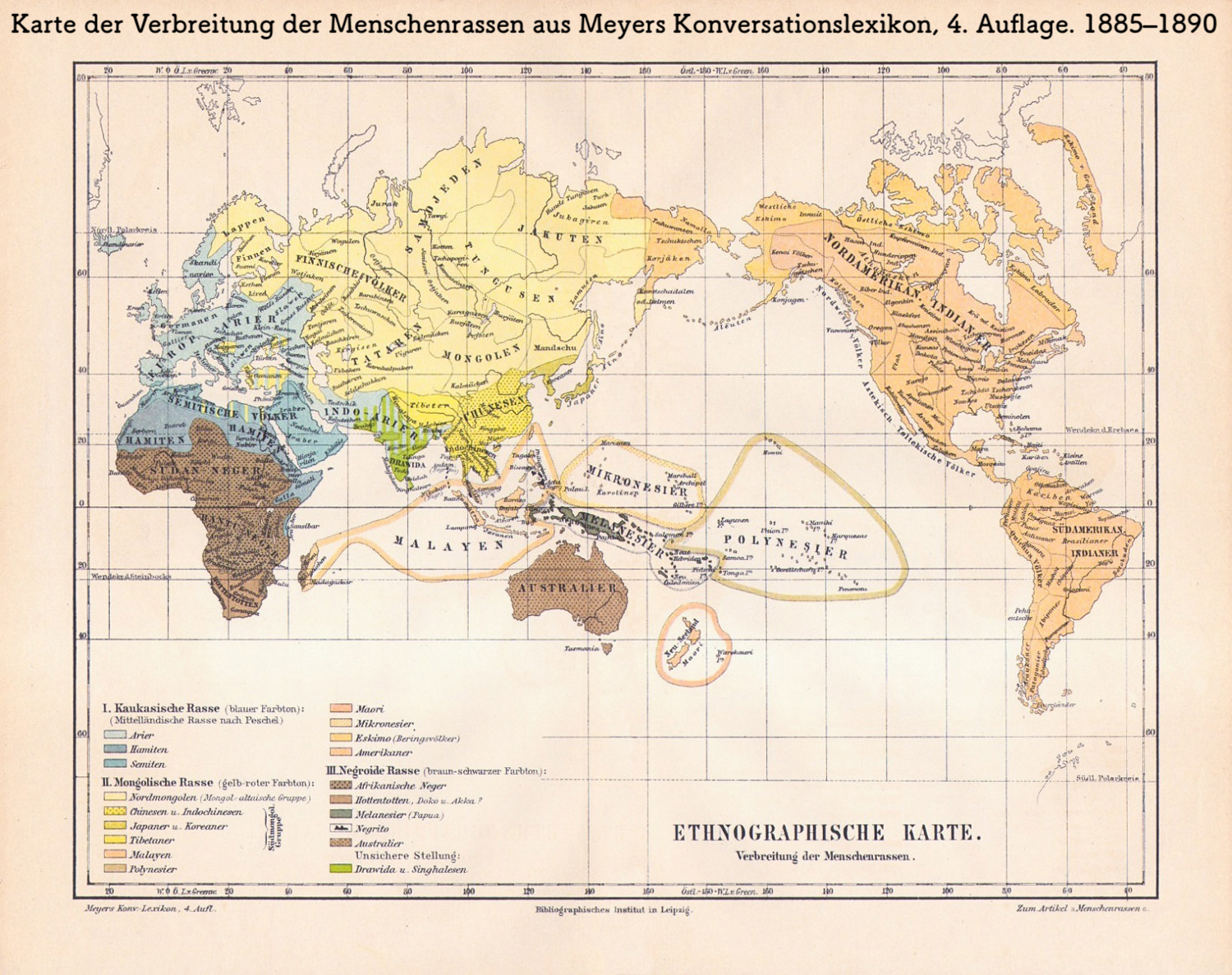

| Historical origins of racial classification See also: Historical race concepts and Scientific racism  The "three great races" according to Meyers Konversations-Lexikon of 1885–90. The subtypes are: Mongoloid race, shown in yellow and orange tones Caucasoid race, in light and medium grayish spring green-cyan tones Negroid race, in brown tones Dravidians and Sinhalese, in olive green and their classification is described as uncertain The Mongoloid race sees the widest geographic distribution, including all of the Americas, North Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the entire inhabited Arctic as well as most of Central Asia and the Pacific Islands.  "Races humaines" according to Pierre Foncins La deuxième année de géographie of 1888. White race, shown in rose, Yellow (Mongoloid) race, shown in yellow, Negroid race, shown in brown, "Secondary races" (Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Australian aboriginals, Samoyedic peoples, Hungarians, Malayans and others) are shown in orange Groups of humans have always identified themselves as distinct from neighboring groups, but such differences have not always been understood to be natural, immutable and global. These features are the distinguishing features of how the concept of race is used today. In this way the idea of race as we understand it today came about during the historical process of exploration and conquest which brought Europeans into contact with groups from different continents, and of the ideology of classification and typology found in the natural sciences.[48] The term race was often used in a general biological taxonomic sense,[25] starting from the 19th century, to denote genetically differentiated human populations defined by phenotype.[49][50] The modern concept of race emerged as a product of the colonial enterprises of European powers from the 16th to 18th centuries which identified race in terms of skin color and physical differences. Author Rebecca F. Kennedy argues that the Greeks and Romans would have found such concepts confusing in relation to their own systems of classification.[51] According to Bancel et al., the epistemological moment where the modern concept of race was invented and rationalized lies somewhere between 1730 and 1790.[52] Colonialism According to Smedley and Marks the European concept of "race", along with many of the ideas now associated with the term, arose at the time of the scientific revolution, which introduced and privileged the study of natural kinds, and the age of European imperialism and colonization which established political relations between Europeans and peoples with distinct cultural and political traditions.[48][53] As Europeans encountered people from different parts of the world, they speculated about the physical, social, and cultural differences among various human groups. The rise of the Atlantic slave trade, which gradually displaced an earlier trade in slaves from throughout the world, created a further incentive to categorize human groups in order to justify the subordination of African slaves.[54] Drawing on sources from classical antiquity and upon their own internal interactions – for example, the hostility between the English and Irish powerfully influenced early European thinking about the differences between people[55] – Europeans began to sort themselves and others into groups based on physical appearance, and to attribute to individuals belonging to these groups behaviors and capacities which were claimed to be deeply ingrained. A set of folk beliefs took hold that linked inherited physical differences between groups to inherited intellectual, behavioral, and moral qualities.[56] Similar ideas can be found in other cultures,[57] for example in China, where a concept often translated as "race" was associated with supposed common descent from the Yellow Emperor, and used to stress the unity of ethnic groups in China. Brutal conflicts between ethnic groups have existed throughout history and across the world.[58] Early taxonomic models The first post-Graeco-Roman published classification of humans into distinct races seems to be François Bernier's Nouvelle division de la terre par les différents espèces ou races qui l'habitent ("New division of Earth by the different species or races which inhabit it"), published in 1684.[59] In the 18th century the differences among human groups became a focus of scientific investigation. But the scientific classification of phenotypic variation was frequently coupled with racist ideas about innate predispositions of different groups, always attributing the most desirable features to the White, European race and arranging the other races along a continuum of progressively undesirable attributes. The 1735 classification of Carl Linnaeus, inventor of zoological taxonomy, divided the human species Homo sapiens into continental varieties of europaeus, asiaticus, americanus, and afer, each associated with a different humour: sanguine, melancholic, choleric, and phlegmatic, respectively.[60][61] Homo sapiens europaeus was described as active, acute, and adventurous, whereas Homo sapiens afer was said to be crafty, lazy, and careless.[62] The 1775 treatise "The Natural Varieties of Mankind", by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach proposed five major divisions: the Caucasoid race, the Mongoloid race, the Ethiopian race (later termed Negroid), the American Indian race, and the Malayan race, but he did not propose any hierarchy among the races.[62] Blumenbach also noted the graded transition in appearances from one group to adjacent groups and suggested that "one variety of mankind does so sensibly pass into the other, that you cannot mark out the limits between them".[63] From the 17th through 19th centuries, the merging of folk beliefs about group differences with scientific explanations of those differences produced what Smedley has called an "ideology of race".[53] According to this ideology, races are primordial, natural, enduring and distinct. It was further argued that some groups may be the result of mixture between formerly distinct populations, but that careful study could distinguish the ancestral races that had combined to produce admixed groups.[58] Subsequent influential classifications by Georges Buffon, Petrus Camper and Christoph Meiners all classified "Negros" as inferior to Europeans.[62] In the United States the racial theories of Thomas Jefferson were influential. He saw Africans as inferior to Whites especially in regards to their intellect, and imbued with unnatural sexual appetites, but described Native Americans as equals to whites.[64] Polygenism vs monogenism In the last two decades of the 18th century, the theory of polygenism, the belief that different races had evolved separately in each continent and shared no common ancestor,[65] was advocated in England by historian Edward Long and anatomist Charles White, in Germany by ethnographers Christoph Meiners and Georg Forster, and in France by Julien-Joseph Virey. In the US, Samuel George Morton, Josiah Nott and Louis Agassiz promoted this theory in the mid-19th century. Polygenism was popular and most widespread in the 19th century, culminating in the founding of the Anthropological Society of London (1863), which, during the period of the American Civil War, broke away from the Ethnological Society of London and its monogenic stance, their underlined difference lying, relevantly, in the so-called "Negro question": a substantial racist view by the former,[66] and a more liberal view on race by the latter.[67] |

人種分類の歴史的起源 参照:歴史的な人種概念と科学的人種主義  1885年から1890年に出版されたMeyers Konversations-Lexikonによる「三大人種」。その亜種は以下の通りである。 黄色とオレンジ色で示されたモンゴロイド 明るい灰色と中程度の灰色がかった春緑色・青緑色で示されたコーカソイド 茶色で示されたネグロイド ドラヴィダ人とシンハラ人はオリーブグリーンで、その分類は不確かであると説明されている。 モンゴロイドは、南北アメリカ、北アジア、東アジア、東南アジア、北極圏全域、中央アジアの大部分、太平洋諸島を含む最も広範囲に分布している。  1888年のPierre Foncins著『La deuxième année de géographie』によると、「人種」は次のとおりである。白人はピンク、黄色人種(モンゴロイド)は黄色、ネグロイドは茶色で示されている。「二次 人種」(アメリカ大陸の先住民、オーストラリアのアボリジニ、サモエド人、ハンガリー人、マレー人など)はオレンジ色で示されている 人類の集団は常に、近隣の集団とは異なるものとして自らを認識してきたが、そうした違いが常に自然で不変かつ普遍的なものと理解されてきたわけではない。 こうした特徴は、今日の人種概念の用いられ方における特徴的なものである。このように、今日私たちが理解している人種の概念は、ヨーロッパ人が異なる大陸 の集団と接触した歴史的な探検と征服の過程、および自然科学に見られる分類と類型論のイデオロギーの中で生まれたものである。[48] 人種という用語は、19世紀以降、生物分類学の一般的な意味で頻繁に使用され、表現型によって定義された遺伝的に分化したヒト集団を指すようになった。 [49][50] 現代の「人種」概念は、16世紀から18世紀にかけてのヨーロッパ列強による植民地事業の結果として登場したもので、肌の色や身体的特徴によって人種を識 別するものである。著者のレベッカ・F・ケネディは、ギリシア人とローマ人は、自分たちの分類体系との関連で、そのような概念を混乱させるものと感じたで あろうと論じている。[51] バンセルらによると、人種に関する近代的概念が考案され、合理化された認識論的な瞬間は、1730年から1790年の間である。[52] 植民地主義 スミドリーとマークスによると、ヨーロッパの「人種」概念は、現在ではその用語と関連付けられている多くの概念とともに、自然種の研究を導入し、それを優 先した科学革命の時代に生まれた。また、ヨーロッパの帝国主義と植民地化の時代に ヨーロッパ人と、明確な文化・政治的伝統を持つ人々との間に政治的な関係を築いた。[48][53] ヨーロッパ人が世界のさまざまな地域の人々と遭遇するにつれ、彼らはさまざまな人類集団の身体的、社会的、文化的な違いについて推測するようになった。大 西洋奴隷貿易の台頭は、徐々にそれ以前の世界中の奴隷貿易を駆逐し、アフリカ人奴隷の従属を正当化するために人類集団を分類するさらなる動機を生み出し た。[54] 古典古代の資料や、自分たち自身の内部での相互作用(例えば、イングランド人とアイルランド人の間の敵対関係は、初期のヨーロッパ人の人々の違いに関する 考え方に強い影響を与えた[55])を基に、ヨーロッパ人は自分たちや他者を外見によってグループ分けし、そのグループに属する個々人には、そのグループ に深く根付いているとされる行動や能力があるとみなすようになった。集団間の遺伝的な身体的差異を、知性、行動、道徳的資質といった遺伝的要素と結びつけ る民間信仰が定着した。[56] 類似した考え方は他の文化にも見られ、例えば中国では、「人種」と訳される概念が黄帝の子孫という共通の起源と結び付けられ、中国における民族の団結を強 調するために用いられてきた。民族間の残忍な紛争は、歴史を通じて世界中で存在してきた。[58] 初期の分類モデル ギリシャ・ローマ時代以降に発表された人類の分類で、人種による分類が最初と思われるのは、1684年に発表されたフランソワ・ベルニエの著書『地球の新 しい区分:そこに生息する異なる種または人種による』である。[59] 18世紀には、人類集団間の相違が科学的な調査の対象となった。しかし、表現型の多様性に関する科学的な分類は、しばしば異なる集団の生得的な素因に関す る人種差別的な考えと結びついており、常に最も望ましい特徴を白色人種に帰し、他の人種を望ましくない属性が徐々に増していく連続体として位置づけてい た。動物分類学の発明者であるカール・フォン・リンネによる1735年の分類では、ヒトの種であるホモ・サピエンスは、ユーロパエウス、アジアティクス、 アメリカヌス、アフェルという大陸別の種類に分けられ、それぞれ異なる体液(サングイヌス、メランコルス それぞれ、多血質、憂鬱質、胆汁質、粘液質と関連付けられた。[60][61] ホモ・サピエンス・ヨーロッパエは活動的、鋭敏、冒険的であると描写されたが、一方ホモ・サピエンス・アフエは狡猾、怠惰、不注意であるとされた。 [62] 1775年に発表されたヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハの論文「人類の自然な種類」では、コーカソイド、モンゴロイド、エチオピア人(後にネグロ イドと呼ばれる)、アメリカインディアン、マレー人の5つの主要な人種が提案されたが、 彼は人種間の序列を提案することはなかった。[62] また、ブローネンバッハは、あるグループから隣接するグループへの外見の段階的な移行に注目し、「人類の一形態が他の形態へと非常に自然に移行しており、 その境界を明確に区別することはできない」と示唆した。[63] 17世紀から19世紀にかけて、集団間の違いに関する民間信仰と、それらの違いに関する科学的説明が融合し、スメドリーが「人種観」と呼ぶものが生まれ た。[53] この人種観によると、人種は原始的で、自然で、永続的で、かつ明確なものである。さらに、一部の集団はかつては別個の集団であったものが混血した結果であ る可能性もあるが、慎重に研究すれば混血集団を生み出した祖先の集団を区別できる、とも主張された。[58] ジョルジュ・ビュフォン、ペトルス・カンペル、クリストフ・マイナーズによるその後の影響力のある分類では、いずれも「ネグロイド」はヨーロッパ人よりも 劣っていると分類された。[62] アメリカ合衆国では、トーマス・ジェファーソンの人種理論が影響力を持っていた。彼は、アフリカ人は特に知性において白人より劣り、不自然な性的欲求に駆 られているとみなしたが、アメリカ先住民は白人と同等の存在であると述べた。 多系統説 vs 一系統説 18世紀の最後の20年間、多系統説(異なる人種は各大陸で別々に進化し、共通の祖先を持たないという説)は、イギリスでは歴史家のエドワード・ロングと 解剖学者のチャールズ・ホワイト、ドイツでは民族誌学者のクリストフ・マイナーズとゲオルク・フォースター、フランスではジュリアン=ジョゼフ・ヴィレー によって提唱された。米国では、サミュエル・ジョージ・モートン、ジョシア・ノット、ルイ・アガシーが19世紀半ばにこの理論を推進した。多系説は19世 紀に広く普及し、ロンドン人類学会(1863年)の設立で頂点に達した。同学会は南北戦争のさなかにロンドン民族学会から独立し、単系説を打ち出したが、 両者の違いは、特に「黒人問題」と呼ばれるものにあった。。その相違点は、前者による実質的な人種差別的見解と、後者による人種に関するよりリベラルな見 解にあった。 |

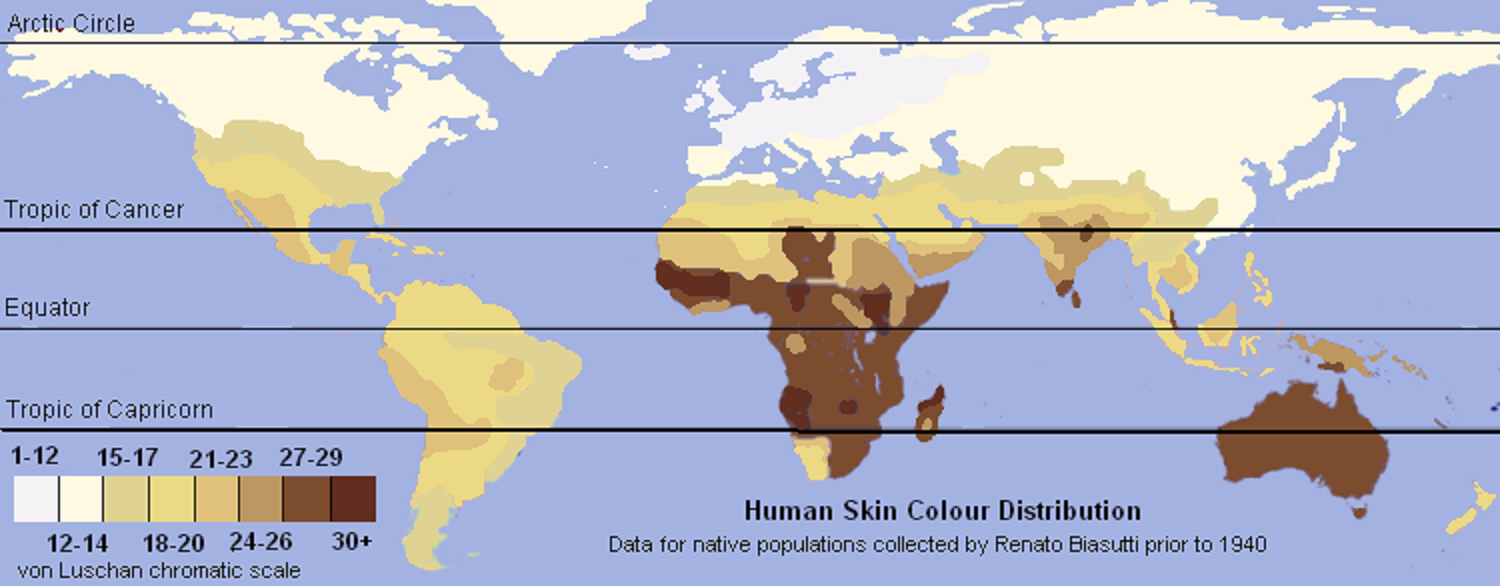

| Modern scholarship Models of human evolution See also: Multiregional hypothesis and Recent single origin hypothesis Today, all humans are classified as belonging to the species Homo sapiens. However, this is not the first species of homininae: the first species of genus Homo, Homo habilis, evolved in East Africa at least 2 million years ago, and members of this species populated different parts of Africa in a relatively short time. Homo erectus evolved more than 1.8 million years ago, and by 1.5 million years ago had spread throughout Europe and Asia. Virtually all physical anthropologists agree that Archaic Homo sapiens (A group including the possible species H. heidelbergensis, H. rhodesiensis, and H. neanderthalensis) evolved out of African H. erectus (sensu lato) or H. ergaster.[68][69] Anthropologists support the idea that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved in North or East Africa from an archaic human species such as H. heidelbergensis and then migrated out of Africa, mixing with and replacing H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis populations throughout Europe and Asia, and H. rhodesiensis populations in Sub-Saharan Africa (a combination of the Out of Africa and Multiregional models).[70][verification needed] Biological classification Further information: Race (biology), Species, Subspecies, Systematics, Phylogenetics, and Cladistics In the early 20th century, many anthropologists taught that race was an entirely biological phenomenon and that this was core to a person's behavior and identity, a position commonly called racial essentialism.[71] This, coupled with a belief that linguistic, cultural, and social groups fundamentally existed along racial lines, formed the basis of what is now called scientific racism.[72] After the Nazi eugenics program, along with the rise of anti-colonial movements, racial essentialism lost widespread popularity.[73] New studies of culture and the fledgling field of population genetics undermined the scientific standing of racial essentialism, leading race anthropologists to revise their conclusions about the sources of phenotypic variation.[71] A significant number of modern anthropologists and biologists in the West came to view race as an invalid genetic or biological designation.[74] The first to challenge the concept of race on empirical grounds were the anthropologists Franz Boas, who provided evidence of phenotypic plasticity due to environmental factors,[75] and Ashley Montagu, who relied on evidence from genetics.[76] E. O. Wilson then challenged the concept from the perspective of general animal systematics, and further rejected the claim that "races" were equivalent to "subspecies".[77] Human genetic variation is predominantly within races, continuous, and complex in structure, which is inconsistent with the concept of genetic human races.[78] According to the biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks,[48] By the 1970s, it had become clear that (1) most human differences were cultural; (2) what was not cultural was principally polymorphic – that is to say, found in diverse groups of people at different frequencies; (3) what was not cultural or polymorphic was principally clinal – that is to say, gradually variable over geography; and (4) what was left – the component of human diversity that was not cultural, polymorphic, or clinal – was very small. A consensus consequently developed among anthropologists and geneticists that race as the previous generation had known it – as largely discrete, geographically distinct, gene pools – did not exist. Subspecies The term race in biology is used with caution because it can be ambiguous. Generally, when it is used it is effectively a synonym of subspecies.[79] (For animals, the only taxonomic unit below the species level is usually the subspecies;[80] there are narrower infraspecific ranks in botany, and race does not correspond directly with any of them.) Traditionally, subspecies are seen as geographically isolated and genetically differentiated populations.[81] Studies of human genetic variation show that human populations are not geographically isolated.[82] and their genetic differences are far smaller than those among comparable subspecies.[83] In 1978, Sewall Wright suggested that human populations that have long inhabited separated parts of the world should, in general, be considered different subspecies by the criterion that most individuals of such populations can be allocated correctly by inspection. Wright argued: "It does not require a trained anthropologist to classify an array of Englishmen, West Africans, and Chinese with 100% accuracy by features, skin color, and type of hair despite so much variability within each of these groups that every individual can easily be distinguished from every other."[84] While in practice subspecies are often defined by easily observable physical appearance, there is not necessarily any evolutionary significance to these observed differences, so this form of classification has become less acceptable to evolutionary biologists.[85] Likewise this typological approach to race is generally regarded as discredited by biologists and anthropologists.[86][17] Ancestrally differentiated populations (clades) In 2000, philosopher Robin Andreasen proposed that cladistics might be used to categorize human races biologically, and that races can be both biologically real and socially constructed.[87] Andreasen cited tree diagrams of relative genetic distances among populations published by Luigi Cavalli-Sforza as the basis for a phylogenetic tree of human races (p. 661). Biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks (2008) responded by arguing that Andreasen had misinterpreted the genetic literature: "These trees are phenetic (based on similarity), rather than cladistic (based on monophyletic descent, that is from a series of unique ancestors)."[88] Evolutionary biologist Alan Templeton (2013) argued that multiple lines of evidence falsify the idea of a phylogenetic tree structure to human genetic diversity, and confirm the presence of gene flow among populations.[33] Marks, Templeton, and Cavalli-Sforza all conclude that genetics does not provide evidence of human races.[33][89] Previously, anthropologists Lieberman and Jackson (1995) had also critiqued the use of cladistics to support concepts of race. They argued that "the molecular and biochemical proponents of this model explicitly use racial categories in their initial grouping of samples". For example, the large and highly diverse macroethnic groups of East Indians, North Africans, and Europeans are presumptively grouped as Caucasians prior to the analysis of their DNA variation. They argued that this a priori grouping limits and skews interpretations, obscures other lineage relationships, deemphasizes the impact of more immediate clinal environmental factors on genomic diversity, and can cloud our understanding of the true patterns of affinity.[90] In 2015, Keith Hunley, Graciela Cabana, and Jeffrey Long analyzed the Human Genome Diversity Project sample of 1,037 individuals in 52 populations,[91] finding that diversity among non-African populations is the result of a serial founder effect process, with non-African populations as a whole nested among African populations, that "some African populations are equally related to other African populations and to non-African populations", and that "outside of Africa, regional groupings of populations are nested inside one another, and many of them are not monophyletic".[91] Earlier research had also suggested that there has always been considerable gene flow between human populations, meaning that human population groups are not monophyletic.[81] Rachel Caspari has argued that, since no groups currently regarded as races are monophyletic, by definition none of these groups can be clades.[92] Clines One crucial innovation in reconceptualizing genotypic and phenotypic variation was the anthropologist C. Loring Brace's observation that such variations, insofar as they are affected by natural selection, slow migration, or genetic drift, are distributed along geographic gradations or clines.[93] For example, with respect to skin color in Europe and Africa, Brace writes:[94] To this day, skin color grades by imperceptible means from Europe southward around the eastern end of the Mediterranean and up the Nile into Africa. From one end of this range to the other, there is no hint of a skin color boundary, and yet the spectrum runs from the lightest in the world at the northern edge to as dark as it is possible for humans to be at the equator. In part, this is due to isolation by distance. This point called attention to a problem common to phenotype-based descriptions of races (for example, those based on hair texture and skin color): they ignore a host of other similarities and differences (for example, blood type) that do not correlate highly with the markers for race. Thus, anthropologist Frank Livingstone's conclusion was that, since clines cross racial boundaries, "there are no races, only clines".[95] In a response to Livingstone, Theodore Dobzhansky argued that when talking about race one must be attentive to how the term is being used: "I agree with Dr. Livingstone that if races have to be 'discrete units', then there are no races, and if 'race' is used as an 'explanation' of the human variability, rather than vice versa, then the explanation is invalid." He further argued that one could use the term race if one distinguished between "race differences" and "the race concept". The former refers to any distinction in gene frequencies between populations; the latter is "a matter of judgment". He further observed that even when there is clinal variation: "Race differences are objectively ascertainable biological phenomena ... but it does not follow that racially distinct populations must be given racial (or subspecific) labels."[95] In short, Livingstone and Dobzhansky agree that there are genetic differences among human beings; they also agree that the use of the race concept to classify people, and how the race concept is used, is a matter of social convention. They differ on whether the race concept remains a meaningful and useful social convention.   Skin color (above) and blood type B (below) are nonconcordant traits since their geographical distribution is not similar. In 1964, the biologists Paul Ehrlich and Holm pointed out cases where two or more clines are distributed discordantly – for example, melanin is distributed in a decreasing pattern from the equator north and south; frequencies for the haplotype for beta-S hemoglobin, on the other hand, radiate out of specific geographical points in Africa.[96] As the anthropologists Leonard Lieberman and Fatimah Linda Jackson observed, "Discordant patterns of heterogeneity falsify any description of a population as if it were genotypically or even phenotypically homogeneous".[90] Patterns such as those seen in human physical and genetic variation as described above, have led to the consequence that the number and geographic location of any described races is highly dependent on the importance attributed to, and quantity of, the traits considered. A skin-lightening mutation, estimated to have occurred 20,000 to 50,000 years ago, partially accounts for the appearance of light skin in people who migrated out of Africa northward into what is now Europe. East Asians owe their relatively light skin to different mutations.[97] On the other hand, the greater the number of traits (or alleles) considered, the more subdivisions of humanity are detected, since traits and gene frequencies do not always correspond to the same geographical location. Or as Ossorio & Duster (2005) put it: Anthropologists long ago discovered that humans' physical traits vary gradually, with groups that are close geographic neighbors being more similar than groups that are geographically separated. This pattern of variation, known as clinal variation, is also observed for many alleles that vary from one human group to another. Another observation is that traits or alleles that vary from one group to another do not vary at the same rate. This pattern is referred to as nonconcordant variation. Because the variation of physical traits is clinal and nonconcordant, anthropologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries discovered that the more traits and the more human groups they measured, the fewer discrete differences they observed among races and the more categories they had to create to classify human beings. The number of races observed expanded to the 1930s and 1950s, and eventually anthropologists concluded that there were no discrete races.[98] Twentieth and 21st century biomedical researchers have discovered this same feature when evaluating human variation at the level of alleles and allele frequencies. Nature has not created four or five distinct, nonoverlapping genetic groups of people. Genetically differentiated populations Main articles: Race and genetics and Human genetic variation Another way to look at differences between populations is to measure genetic differences rather than physical differences between groups. The mid-20th-century anthropologist William C. Boyd defined race as: "A population which differs significantly from other populations in regard to the frequency of one or more of the genes it possesses. It is an arbitrary matter which, and how many, gene loci we choose to consider as a significant 'constellation'".[99] Leonard Lieberman and Rodney Kirk have pointed out that "the paramount weakness of this statement is that if one gene can distinguish races then the number of races is as numerous as the number of human couples reproducing".[100] Moreover, the anthropologist Stephen Molnar has suggested that the discordance of clines inevitably results in a multiplication of races that renders the concept itself useless.[101] The Human Genome Project states "People who have lived in the same geographic region for many generations may have some alleles in common, but no allele will be found in all members of one population and in no members of any other."[102] Massimo Pigliucci and Jonathan Kaplan argue that human races do exist, and that they correspond to the genetic classification of ecotypes, but that real human races do not correspond very much, if at all, to folk racial categories.[103] In contrast, Walsh & Yun reviewed the literature in 2011 and reported: "Genetic studies using very few chromosomal loci find that genetic polymorphisms divide human populations into clusters with almost 100 percent accuracy and that they correspond to the traditional anthropological categories."[104] Some biologists argue that racial categories correlate with biological traits (e.g. phenotype), and that certain genetic markers have varying frequencies among human populations, some of which correspond more or less to traditional racial groupings.[105] Distribution of genetic variation The distribution of genetic variants within and among human populations are impossible to describe succinctly because of the difficulty of defining a population, the clinal nature of variation, and heterogeneity across the genome (Long and Kittles 2003). In general, however, an average of 85% of statistical genetic variation exists within local populations, ≈7% is between local populations within the same continent, and ≈8% of variation occurs between large groups living on different continents.[106][107] The recent African origin theory for humans would predict that in Africa there exists a great deal more diversity than elsewhere and that diversity should decrease the further from Africa a population is sampled. Hence, the 85% average figure is misleading: Long and Kittles find that rather than 85% of human genetic diversity existing in all human populations, about 100% of human diversity exists in a single African population, whereas only about 60% of human genetic diversity exists in the least diverse population they analyzed (the Surui, a population derived from New Guinea).[108] Statistical analysis that takes this difference into account confirms previous findings that "Western-based racial classifications have no taxonomic significance".[91] Cluster analysis A 2002 study of random biallelic genetic loci found little to no evidence that humans were divided into distinct biological groups.[109] In his 2003 paper, "Human Genetic Diversity: Lewontin's Fallacy", A. W. F. Edwards argued that rather than using a locus-by-locus analysis of variation to derive taxonomy, it is possible to construct a human classification system based on characteristic genetic patterns, or clusters inferred from multilocus genetic data.[110][111] Geographically based human studies since have shown that such genetic clusters can be derived from analyzing of a large number of loci which can assort individuals sampled into groups analogous to traditional continental racial groups.[112][113] Joanna Mountain and Neil Risch cautioned that while genetic clusters may one day be shown to correspond to phenotypic variations between groups, such assumptions were premature as the relationship between genes and complex traits remains poorly understood.[114] However, Risch denied such limitations render the analysis useless: "Perhaps just using someone's actual birth year is not a very good way of measuring age. Does that mean we should throw it out? ... Any category you come up with is going to be imperfect, but that doesn't preclude you from using it or the fact that it has utility."[115] Early human genetic cluster analysis studies were conducted with samples taken from ancestral population groups living at extreme geographic distances from each other. It was thought that such large geographic distances would maximize the genetic variation between the groups sampled in the analysis, and thus maximize the probability of finding cluster patterns unique to each group. In light of the historically recent acceleration of human migration (and correspondingly, human gene flow) on a global scale, further studies were conducted to judge the degree to which genetic cluster analysis can pattern ancestrally identified groups as well as geographically separated groups. One such study looked at a large multiethnic population in the United States, and "detected only modest genetic differentiation between different current geographic locales within each race/ethnicity group. Thus, ancient geographic ancestry, which is highly correlated with self-identified race/ethnicity – as opposed to current residence – is the major determinant of genetic structure in the U.S. population."[113] Witherspoon et al. (2007) have argued that even when individuals can be reliably assigned to specific population groups, it may still be possible for two randomly chosen individuals from different populations/clusters to be more similar to each other than to a randomly chosen member of their own cluster. They found that many thousands of genetic markers had to be used in order for the answer to the question "How often is a pair of individuals from one population genetically more dissimilar than two individuals chosen from two different populations?" to be "never". This assumed three population groups separated by large geographic ranges (European, African and East Asian). The entire world population is much more complex and studying an increasing number of groups would require an increasing number of markers for the same answer. The authors conclude that "caution should be used when using geographic or genetic ancestry to make inferences about individual phenotypes".[116] Witherspoon, et al. concluded: "The fact that, given enough genetic data, individuals can be correctly assigned to their populations of origin is compatible with the observation that most human genetic variation is found within populations, not between them. It is also compatible with our finding that, even when the most distinct populations are considered and hundreds of loci are used, individuals are frequently more similar to members of other populations than to members of their own population."[116] Anthropologists such as C. Loring Brace,[117] the philosophers Jonathan Kaplan and Rasmus Winther,[118][119][120][121] and the geneticist Joseph Graves,[122] have argued that the cluster structure of genetic data is dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the influence of these hypotheses on the choice of populations to sample. When one samples continental groups, the clusters become continental, but if one had chosen other sampling patterns, the clustering would be different. Weiss and Fullerton have noted that if one sampled only Icelanders, Mayans and Maoris, three distinct clusters would form and all other populations could be described as being clinally composed of admixtures of Maori, Icelandic and Mayan genetic materials.[123] Kaplan and Winther therefore argue that, seen in this way, both Lewontin and Edwards are right in their arguments. They conclude that while racial groups are characterized by different allele frequencies, this does not mean that racial classification is a natural taxonomy of the human species, because multiple other genetic patterns can be found in human populations that crosscut racial distinctions. Moreover, the genomic data underdetermines whether one wishes to see subdivisions (i.e., splitters) or a continuum (i.e., lumpers). Under Kaplan and Winther's view, racial groupings are objective social constructions (see Mills 1998[124]) that have conventional biological reality only insofar as the categories are chosen and constructed for pragmatic scientific reasons. In earlier work, Winther had identified "diversity partitioning" and "clustering analysis" as two separate methodologies, with distinct questions, assumptions, and protocols. Each is also associated with opposing ontological consequences vis-a-vis the metaphysics of race.[125] Philosopher Lisa Gannett has argued that biogeographical ancestry, a concept devised by Mark Shriver and Tony Frudakis, is not an objective measure of the biological aspects of race as Shriver and Frudakis claim it is. She argues that it is actually just a "local category shaped by the U.S. context of its production, especially the forensic aim of being able to predict the race or ethnicity of an unknown suspect based on DNA found at the crime scene".[126] Clines and clusters in genetic variation Recent studies of human genetic clustering have included a debate over how genetic variation is organized, with clusters and clines as the main possible orderings. Serre & Pääbo (2004) argued for smooth, clinal genetic variation in ancestral populations even in regions previously considered racially homogeneous, with the apparent gaps turning out to be artifacts of sampling techniques. Rosenberg et al. (2005) disputed this and offered an analysis of the Human Genetic Diversity Panel showing that there were small discontinuities in the smooth genetic variation for ancestral populations at the location of geographic barriers such as the Sahara, the Oceans, and the Himalayas. Nonetheless, Rosenberg et al. (2005) stated that their findings "should not be taken as evidence of our support of any particular concept of biological race ... Genetic differences among human populations derive mainly from gradations in allele frequencies rather than from distinctive 'diagnostic' genotypes." Using a sample of 40 populations distributed roughly evenly across the Earth's land surface, Xing & et al. (2010, p. 208) found that "genetic diversity is distributed in a more clinal pattern when more geographically intermediate populations are sampled". Guido Barbujani has written that human genetic variation is generally distributed continuously in gradients across much of Earth, and that there is no evidence that genetic boundaries between human populations exist as would be necessary for human races to exist.[127] Over time, human genetic variation has formed a nested structure that is inconsistent with the concept of races that have evolved independently of one another.[128] Social constructions Main article: Race and society As anthropologists and other evolutionary scientists have shifted away from the language of race to the term population to talk about genetic differences, historians, cultural anthropologists and other social scientists re-conceptualized the term "race" as a cultural category or identity, i.e., a way among many possible ways in which a society chooses to divide its members into categories. Many social scientists have replaced the word race with the word "ethnicity" to refer to self-identifying groups based on beliefs concerning shared culture, ancestry and history. Alongside empirical and conceptual problems with "race", following the Second World War, evolutionary and social scientists were acutely aware of how beliefs about race had been used to justify discrimination, apartheid, slavery, and genocide. This questioning gained momentum in the 1960s during the civil rights movement in the United States and the emergence of numerous anti-colonial movements worldwide. They thus came to believe that race itself is a social construct, a concept that was believed to correspond to an objective reality but which was believed in because of its social functions.[129] Craig Venter and Francis Collins of the National Institute of Health jointly made the announcement of the mapping of the human genome in 2000. Upon examining the data from the genome mapping, Venter realized that although the genetic variation within the human species is on the order of 1–3% (instead of the previously assumed 1%), the types of variations do not support the notion of genetically defined races. Venter said, "Race is a social concept. It's not a scientific one. There are no bright lines (that would stand out), if we could compare all the sequenced genomes of everyone on the planet. ... When we try to apply science to try to sort out these social differences, it all falls apart."[130] Anthropologist Stephan Palmié has argued that race "is not a thing but a social relation";[131] or, in the words of Katya Gibel Mevorach, "a metonym", "a human invention whose criteria for differentiation are neither universal nor fixed but have always been used to manage difference".[132] As such, the use of the term "race" itself must be analyzed. Moreover, they argue that biology will not explain why or how people use the idea of race; only history and social relationships will. Imani Perry has argued that race "is produced by social arrangements and political decision making",[133] and that "race is something that happens, rather than something that is. It is dynamic, but it holds no objective truth."[134] Similarly, in Racial Culture: A Critique (2005), Richard T. Ford argued that while "there is no necessary correspondence between the ascribed identity of race and one's culture or personal sense of self" and "group difference is not intrinsic to members of social groups but rather contingent o[n] the social practices of group identification", the social practices of identity politics may coerce individuals into the "compulsory" enactment of "prewritten racial scripts".[135] |

現代の学説 人類進化のモデル 多地域進化説および単一起源説も参照 今日、すべてのヒトはホモ・サピエンス(Homo sapiens)という種に属すると分類されている。しかし、これはヒト亜科(ヒト科)の最初の種ではない。属ホモ(Homo)の最初の種であるホモ・ハ ビリス(Homo habilis)は、少なくとも200万年前に東アフリカで進化し、この種の個体は比較的短期間のうちにアフリカの各地に広がった。ホモ・エレクトスは 180万年以上前に進化し、150万年前にはヨーロッパとアジア全域に広がっていた。ほぼすべての自然人類学者が、旧人類(H. heidelbergensis、H. rhodesiensis、H. neanderthalensisなどの可能性がある種を含むグループ)は、アフリカのH. erectus(広義)またはH. ergasterから進化したという見解で一致している。[68][69] 人類学者は、解剖学的に現生人類(ホモ・サピエンス)が 北または東アフリカでH. heidelbergensisなどの旧人種から進化した後、アフリカを離れ、ヨーロッパとアジア全域のH. heidelbergensisとH. neanderthalensisの集団、およびサハラ以南のアフリカのH. rhodesiensisの集団と混血し、それらに取って代わったという考えを支持している(「アフリカ単一起源説」と「多地域進化説」の組み合わせ)。 [70][要検証] 生物学的分類 詳細情報:人種(生物学)、種、亜種、分類学、系統発生学、分岐分類学 20世紀初頭には、多くの人類学者が人種は完全に生物学的な現象であり、それが個人の行動やアイデンティティの中核であると教えた。この立場は一般に人種 本質論と呼ばれている。[71] 言語的、文化的、社会的集団は基本的に人種別に存在するという信念と相まって、これが現在では科学的人種主義と呼ばれるものの基礎を形成した。[72] ナチスの優生学プログラムの後、 反植民地運動の高まりとともに、人種本質論は広く支持されなくなった。[73] 文化に関する新たな研究や、始まったばかりの集団遺伝学の分野が、人種本質論の科学的地位を脅かし、人類人類学者が表現型の変異の要因に関する結論を修正 するに至った。[71] 西洋の現代人類学者や生物学者の相当数が、人種を遺伝学的あるいは生物学的に無効な区分とみなすようになった。[74] 人種という概念を実証的な根拠に基づいて初めて疑問視したのは、環境要因による表現型の可塑性を証明した人類学者フランツ・ボアズ(Franz Boas)と、遺伝学上の証拠を根拠としたアシュレイ・モンタギュー(Ashley Montagu)であった。[76] その後、E. O. ウィルソン(E. O. Wilson)が動物一般の系統学の観点から人種概念に疑問を呈し、「人種」と「亜種」が同義であるという主張をさらに否定した。[77] 人間の遺伝的多様性は主に人種内に存在し、連続的で、構造は複雑である。これは、遺伝的人種という概念と矛盾している。[78]生物人類学者ジョナサン・マークスによると、[48] 1970年代までに、(1)人間の差異のほとんどは文化的なものであること、(2)文化的なものでないものは主に多型であること、つまり、異なる頻度でさ まざまな人々の集団に存在すること、(3) 文化や多型ではないものは、主に地理的変動性である。つまり、地理的に徐々に変化するということである。そして、残ったもの、つまり文化でも多型でも地理 的変動性でもない人間の多様性の要素は、ごくわずかである。 その結果、人類学者や遺伝学者の間では、以前の世代が知っていたような人種、つまり地理的に離れた、遺伝子プールとして大きく異なる人種は存在しないというコンセンサスが生まれた。 亜種 生物学における「人種」という用語は、曖昧な可能性があるため、慎重に使用される。一般的に、この用語が使用される場合、それは事実上「亜種」と同義であ る。(動物の場合、種レベル以下の唯一の分類単位は通常亜種である。植物学には亜種よりもさらに細かい分類単位があるが、「人種」はそれらとは直接対応し ない。従来、亜種は地理的に孤立し、遺伝的に分化した個体群と見なされてきた。[81] ヒトの遺伝的多様性に関する研究では、ヒトの個体群は地理的に孤立していないことが示されている。[82] また、ヒトの遺伝的差異は、同等の亜種間の差異よりもはるかに小さい。[83] 1978年、ソール・ライトは、世界の離れた地域に長年生息してきた人類集団は、一般的に、その集団のほとんどの個体が観察によって正しく割り当てられる という基準によって、異なる亜種としてみなされるべきであると提案した。ライトは次のように主張した。「訓練を受けた人類学者でなくとも、イギリス人、西 アフリカ人、中国人といった集団を、それぞれの集団内で個体ごとに容易に識別できるほど多様性があるにもかかわらず、特徴、肌の色、髪のタイプによって 100%正確に分類できる」[84] 実際には、亜 亜種はしばしば容易に観察可能な外見によって定義されるが、これらの観察された差異には必ずしも進化上の重要性があるわけではないため、この種の分類は進 化生物学者には受け入れられにくくなっている。[85] 同様に、人種に対するこの類型論的アプローチは、一般的に生物学者や人類学者には信用されていないとみなされている。[86][17] 祖先的に分化した集団(クレード) 2000年、哲学者のロビン・アンドレアセンは、生物学的観点から人種を分類するのに分岐分類学が使用できる可能性を提案し、人種は生物学的に実在するも のであり、かつ社会的に構築されたものであると主張した。アンドレアセンは、ルイージ・カヴァッリ・スフォルツァが発表した集団間の相対的遺伝的距離を示 す樹形図を、人種進化の系統樹の根拠として引用した(p. 661)。生物人類学者のジョナサン・マークス(2008年)は、アンドレアセンが遺伝学の文献を誤って解釈していると反論した。「これらの系統樹は、単 系統進化(単一の祖先からの系列)に基づく系統樹ではなく、むしろ(類似性に基づく)表現型である」[88] 進化生物学者のアラン・テンプルトン(2013年)は、複数の証拠が ヒトの遺伝的多様性に関する系統樹構造の考え方を否定し、集団間の遺伝子流動の存在を裏付ける。[33] マークス、テンプルトン、カヴァッリ=スフォルツァは、いずれも遺伝学は人種に関する証拠を提供しないと結論づけている。[33][89] また、人類学者のリバーマンとジャクソン(1995年)も、人種概念を裏付けるための分岐分類学の利用を批判していた。彼らは、「このモデルの分子生物化 学的提唱者は、サンプルの初期グループ分けにおいて人種カテゴリーを明確に使用している」と主張した。例えば、東インド人、北アフリカ人、ヨーロッパ人と いった大規模で多様性に富むマクロ民族集団は、DNA変異の分析に先立って、白人としてひとまとめにされている。彼らは、この先験的なグループ分けが解釈 を制限し歪め、他の系統関係を不明瞭にし、ゲノムの多様性に対するより直接的な臨床環境要因の影響を軽視し、真の親和性のパターンに対する我々の理解を曇 らせる可能性があると主張した。[90] 2015年、キース・ハンレー、グラシエラ・カバナ、ジェフリー・ロングは、52集団1,037人のヒトゲノム多様性プロジェクトサンプルを分析し、 [91] 非アフリカ集団の多様性は連続的創始者効果のプロセスによるものであり、非アフリカ集団全体がアフリカ集団の中に位置づけられること、また「一部のアフリ カ集団は、他のアフリカ集団および非アフリカ集団と同等に近縁である」こと、そして「 アフリカ以外の地域では、地域ごとに集団が互いに内包されており、その多くは単系統ではない」という結果であった。[91] 以前の研究でも、人類集団の間では常にかなりの遺伝子流動があったことが示唆されており、つまり、人類集団は単系統ではないということである。[81] レイチェル・キャスパーは、現在人種と見なされている集団はどれも単系統ではないため、定義上、これらの集団はどれもクレードではないと主張している。 [92] クリネス 遺伝子型と表現型の変異を再概念化する上で重要な革新のひとつは、人類学者C. ローリング・ブレイスによる、自然淘汰、緩慢な移動、あるいは遺伝的浮動の影響を受ける限り、そのような変異は地理的勾配に沿って分布するという観察であ る。[93] 例えば、ヨーロッパとアフリカにおける肌の色に関して、ブレイスは次のように書いている。[94] 今日に至るまで、肌の色は地中海の東端のあたりから南に向かって、またナイル川を遡ってアフリカに向かって、ほとんど気づかないほど徐々に変化している。 この範囲の一方の端からもう一方の端まで、肌の色に境界があるような兆候はまったく見られないが、スペクトルは北の端の世界で最も明るい色から赤道の人間 が持つことのできる最も暗い色まで変化している。 これは、ある程度は距離による隔離が原因である。この指摘は、人種を表現する際に表現型に基づく方法(例えば、髪質や肌の色に基づく方法)に共通する問題 に注目を集めた。すなわち、人種を表すマーカーとあまり相関性のない他の多くの類似点や相違点(例えば、血液型)が無視されているという問題である。した がって、人類学者フランク・リビングストンの結論は、傾度(cline)は人種の境界を越えるため、「人種は存在せず、存在するのは傾度だけである」とい うものであった。[95] リビングストンの意見に対して、セオドア・ドブジャンスキーは、人種について語る際にはその用語がどのように使われているかに注意を払う必要があると主張 した。「人種が『離散的な単位』でなければならないのであれば、人種は存在しないということになる。また、『人種』が人間の多様性の『説明』として使われ るのであれば、その説明は無効である。さらに、彼は「人種の違い」と「人種概念」を区別するならば、人種という用語を使用してもよいと主張した。前者は集 団間の遺伝子頻度のあらゆる相違を指し、後者は「判断の問題」である。さらに、彼は臨床的変異がある場合でも、 「人種間の違いは客観的に確認できる生物学的現象であるが、人種的に異なる集団に人種(または亜種)のラベルを貼らなければならないというわけではない」 [95] つまり、リビングストンとドブジャンスキーは、人間の間には遺伝的な違いがあるという点では同意している。また、人々を分類するために人種概念を用いるこ と、および人種概念がどのように用いられるかは、社会的な慣習の問題であるという点でも同意している。人種概念が意味のある有用な社会的な慣習であり続け るかどうかについては、両者の意見は分かれている。   肌の色(上)と血液型B(下)は、地理的な分布が類似していないため、不調和形質である。 1964年、生物学者のポール・エールリッヒとホルムは、2つ以上の形質が不調和に分布している事例を指摘した。例えば、メラニンは赤道から南北に向かっ て減少するパターンで分布している。一方、βSヘモグロビンのハプロタイプの頻度は、 一方、β-S ヘモグロビンのハプロタイプの頻度はアフリカの特定の地理的地点から広がっている。[96] 人類学者レナード・リーバーマンとファティマ・リンダ・ジャクソンが観察したように、「不調和な異質性のパターンは、あたかも遺伝子型または表現型が均質 であるかのように、集団のいかなる記述をも偽る」のである。[90] 上述したような人間の身体的および遺伝的変異に見られるようなパターンは、記述された人種の数や地理的位置が、考慮された形質の重要性や量に大きく依存す るという結果をもたらしている。2万~5万年前に起こったと推定される肌の美白変異は、アフリカから北へ移動し、現在のヨーロッパに住むようになった人々 の肌の色が白くなった理由の一部である。東アジア人は、異なる変異により比較的色白の肌になった。[97] 一方、形質(または対立遺伝子)の数が増えるほど、人類の細分化がより多く検出される。なぜなら、形質と遺伝子頻度は常に同じ地理的位置に対応するわけで はないからだ。または、Ossorio & Duster (2005) の表現を借りれば、 人類学者は、はるか昔に、人間の身体的特徴は徐々に変化し、地理的に近接する集団ほど、地理的に離れた集団よりも類似性が高いことを発見した。この変化の パターンはクリナル変異として知られ、異なる人間集団間で変化する多くの対立遺伝子でも観察されている。もう一つの観察結果は、集団間で変化する特徴や対 立遺伝子は、同じ速度で変化するわけではないということである。このパターンは非一致型変異と呼ばれる。身体的特徴の変異が傾斜的かつ非一致型であるた め、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭の人類学者たちは、より多くの身体的特徴をより多くの人類集団で測定すればするほど、人種間の違いは少なくなり、人間を 分類するために作成しなければならないカテゴリーが増えることを発見した。1930年代から1950年代にかけて観察された人種の数は増加し、最終的に人 類学者たちは、明確な人種は存在しないという結論に達した。[98] 20世紀および21世紀の生物医学研究者は、対立遺伝子および対立遺伝子頻度のレベルで人間の変異を評価する際に、同様の特徴を発見した。自然は、重複し ない4つまたは5つの明確な遺伝的集団の人々を創造したわけではない。 遺伝的に分化した集団 詳細は「人種と遺伝」および「ヒトの遺伝的多型」を参照 集団間の相違を別の観点から見る方法としては、集団間の身体的相違ではなく遺伝的相違を測定するというものがある。20世紀半ばの人類学者ウィリアム・ C・ボイドは人種を次のように定義した。「ある集団が保有する遺伝子のうち、1つまたは複数の遺伝子の頻度に関して、他の集団と著しく異なる集団。どの遺 伝子座を、またどれくらいの数を、重要な『星座』として考慮するかは、恣意的な問題である」と定義した。[99] レナード・リーバーマンとロドニー・カークは、「この主張の最大の弱点は、もし1つの遺伝子によって人種を区別できるのであれば、人種の数は人間のカップ ルの数と同じくらい多くなるということだ」と指摘している。[100] さらに さらに、人類学者のスティーブン・モルナールは、傾度の不整合は必然的に人種の増加につながり、その概念自体が役に立たなくなるだろうと指摘している。 [101] ヒトゲノム・プロジェクトは、「同じ地理的地域に何世代にもわたって住み続けた人々は、いくつかの対立遺伝子を共有しているかもしれないが、ひとつの集団 のすべての構成員に共通する対立遺伝子は存在せず、また、他の集団の構成員にも共通する対立遺伝子は存在しない」と述べている。」[102] マッシモ・ピルイッチとジョナサン・カプランは、人種は存在し、それは生態型の遺伝的分類に対応するが、現実の人種は、民間伝承の人種カテゴリーにはほと んど、あるいはまったく対応しないと主張している。[103] これに対し、ウォルシュとユンは2011年の文献を再調査し、次のように報告している。「ごく少数の染色体座を用いた遺伝学的研究では、遺伝的多型によっ てヒト集団はほぼ100パーセントの精度でクラスターに分類され、それは従来の自然人類学上のカテゴリーに対応していることが分かっている」[104] 一部の生物学者は、人種カテゴリーは生物学的形質(例えば表現型)と相関しており、特定の遺伝子マーカーはヒト集団の間で異なる頻度で存在し、その一部は従来の人種グループ分けとほぼ一致していると主張している。[105] 遺伝的多様性の分布 集団の定義の難しさ、変異の臨床的性質、ゲノム全体の異質性などの理由により、ヒト集団内および集団間の遺伝的多型を簡潔に説明することは不可能である (Long & Kittles 2003)。しかし一般的に、統計上の遺伝的多様性の平均85%は地域集団内に存在し、約7%は同じ大陸内の地域集団間に存在し、約8%の多様性は異なる 大陸に居住する大きな集団間に存在する。[106][107] 人類の最近の起源がアフリカであるとする説によれば、アフリカには他の地域よりもはるかに多くの多様性が存在し、その多様性はアフリカから離れるほど減少 するはずである。したがって、平均85%という数値は誤解を招く。LongとKittlesは、全人類集団に存在する遺伝的多様性の85%ではなく、アフ リカの単一集団に存在する遺伝的多様性は約100%であることを見出した。一方、彼らが分析した中で最も多様性の低い集団(ニューギニアに由来するスルイ 族)には、人類の遺伝的多様性の約60%しか存在していないことが分かった。最も多様性の低い集団(ニューギニアに由来するスルイ族)では、わずか60% であることが分かった。[108] この違いを考慮した統計分析により、「西洋を基盤とする人種分類には分類学的な重要性がない」というこれまでの研究結果が裏付けられた。[91] クラスター分析 2002年のランダムな二対立遺伝子座の研究では、人間が明確な生物学的グループに分けられるという証拠はほとんど見つからなかった。[109] 2003年の論文「ヒトの遺伝的多様性:ルウォンティンの誤り」において、A. W. F. エドワーズは、分類を導き出すために遺伝子座ごとの変異分析を用いるのではなく、特徴的な遺伝子パターン、または多遺伝子座の遺伝子データから推定される クラスターに基づいて、ヒトの分類体系を構築することが可能であると論じた。[110][111] それ以降、地理学に基づくヒトの研究により、このような遺伝子クラスターは、 多数の遺伝子座を分析することで、従来の各大陸の民族グループに類似したグループにサンプル抽出された個体を分類できることが示されている。[112] [113] ジョアンナ・マウンテンとニール・リッシュは、遺伝子クラスターがいつの日かグループ間の表現型の変異に対応することが示される可能性はあるが、遺伝子と 複雑な形質との関係は依然として十分に理解されていないため、そのような想定は時期尚早であると警告している。[114] しかし、リッシュは、そのような限界があるからといって分析が役に立たないわけではないと否定している。「おそらく、実際の生年を単に用いるだけでは、年 齢を測る方法としてはあまり良くない。だからといって、それを捨て去るべきだというのだろうか?... あなたが考え出すカテゴリーはどれも不完全なものになるだろうが、だからといって、それを使ったり、それが有用であるという事実を否定することにはならな い」[115] 初期のヒト遺伝子クラスター分析の研究は、互いに極めて地理的に離れた場所に住む祖先集団から採取したサンプルを用いて実施された。このような広範囲にわ たる地理的距離は、分析でサンプリングされたグループ間の遺伝的変異を最大限に高め、各グループに特有のクラスターパターンを見つける可能性を最大限に高 めるだろうと考えられていた。 しかし、人類の移動(およびそれに対応する人類の遺伝子流動)が世界規模で歴史的に最近加速していることを踏まえ、遺伝子クラスター分析が、地理的に離れ たグループだけでなく、祖先的に特定されたグループをどの程度パターン化できるかを判断するためのさらなる研究が行われた。そのうちの1つの研究では、米 国の多民族集団を調査し、「各人種・民族集団内の異なる現在の地理的地域間では、わずかな遺伝的分化しか認められなかった。したがって、現在の居住地とは 対照的に、自己認識される人種・民族性と高い相関性を持つ古代の地理的祖先が、米国の人口における遺伝的構造の主な決定要因である」と結論づけている [113]。 Witherspoon ら(2007年)は、個人が特定の集団に確実に割り当てられる場合でも、異なる集団/クラスターからランダムに選んだ2人の個人が、同じクラスターからラ ンダムに選んだメンバーよりも互いに似ている可能性があることを論じている。彼らは、「異なる2つの集団からランダムに選ばれた2人の個体よりも、同じ集 団から選ばれた2人の個体の方が遺伝的に類似している可能性はどの程度あるか」という質問に対する答えが「決してない」となるためには、何千もの遺伝マー カーを使用しなければならないことを発見した。これは、広大な地理的範囲によって隔てられた3つの集団グループ(ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、東アジア)を想定 したものである。世界中の全人口ははるかに複雑であり、より多くの集団を研究するには、同じ回答を得るためにさらに多くのマーカーが必要となる。著者ら は、「地理的または遺伝的起源を基に個人の表現型を推論する際には、注意が必要である」と結論づけている。[116] Witherspoon らは次のように結論づけている。「十分な遺伝子データがあれば、個人はその起源となる集団に正しく割り当てられるという事実は、ほとんどのヒトの遺伝的多 様性が集団内に見られるのであって、集団間には見られないという観察結果と一致する。また、最も異なる集団が考慮され、数百の遺伝子座が使用された場合で も、個人は自身の集団のメンバーよりも、他の集団のメンバーとより類似していることが多いという我々の発見とも一致する」[116] 人類学者のC. ローリング・ブレイス(C. Loring Brace)[117]、哲学者のジョナサン・カプラン(Jonathan Kaplan)とラスムス・ヴィンター(Rasmus Winther)[118][119][120][121]、遺伝学者のジョセフ・グレイブス(Joseph Graves)[122]は、遺伝子データのクラスター構造は研究者の初期仮説に依存しており、その仮説が標本とする集団の選択に影響を与えると主張して いる。ある大陸グループをサンプリングすると、クラスターは大陸別になるが、他のサンプリングパターンを選択した場合、クラスタリングは異なるものにな る。WeissとFullertonは、アイスランド人、マヤ人、マオリ人のみをサンプリングした場合、3つの異なるクラスターが形成され、その他のすべ ての集団は、マオリ人、アイスランド人、マヤ人の遺伝物質の混合体として構成されているとみなすことができると指摘している。[123] したがって、KaplanとWintherは、このように見ると、LewontinとEdwardsの両方が主張していることは正しいと論じている。彼ら は、人種集団は異なる対立遺伝子頻度によって特徴づけられるが、人種分類がヒトの自然分類であることを意味するわけではないと結論づけている。なぜなら、 人種的区別を横断する複数の他の遺伝的パターンがヒト集団内で見られるからである。さらに、ゲノムデータは、細分化(すなわち分割論者)を望むか、連続体 (すなわち一括論者)を望むかによって、その解釈が異なる。カプランとウィンターの見解では、人種分類は客観的な社会的構築物(ミルズ 1998[124]を参照)であり、実用的な科学的理由からカテゴリーが選択され構築される限りにおいてのみ、従来の生物学的な現実性を持つ。ウィンター は以前の研究で、「多様性分割」と「クラスタリング分析」を、それぞれ異なる問題、仮定、プロトコルを持つ2つの別個の方法論として特定していた。また、 それぞれは人種の形而上学に対して相反する存在論的帰結をもたらすものである。[125] 哲学者のリサ・ガネットは、マーク・シュライバーとトニー・フルダキスが考案した生物地理学的祖先という概念は、シュライバーとフルダキスが主張するよう な人種の生物学的側面を客観的に測定するものではないと主張している。彼女は、それは実際には「特に犯罪現場で発見されたDNAから、身元不明の容疑者の 人種や民族性を予測できる法医学的な目的のために、米国の文脈によって形成されたローカルなカテゴリー」に過ぎないと主張している。[126] 遺伝的多様性における傾斜とクラスター 最近のヒト遺伝子クラスタリングの研究では、遺伝的多様性がどのように構成されているかについての議論が行われており、クラスターと傾斜が主な可能性のあ る順序付けとして挙げられている。Serre & Pääbo (2004) は、以前は人種的に均質であると考えられていた地域においても、先祖集団では滑らかな傾斜型の遺伝的多様性が見られると主張し、明らかなギャップはサンプ リング技術のアーティファクトであると結論付けた。これに対し、Rosenberg ら(2005)は、ヒト遺伝的多様性パネルの分析結果を示し、サハラ砂漠、海洋、ヒマラヤ山脈などの地理的障壁のある地域では、先祖の集団における滑らか な遺伝的変異に小さな不連続性があることを示した。 しかし、Rosenberg ら(2005)は、彼らの発見は「生物学的人種の特定の概念を支持する証拠として受け取られるべきではない」と述べている。人類集団間の遺伝的差異は、主 に「診断」用遺伝子型というよりも、対立遺伝子頻度の段階的変化に由来する」と述べている。 Xing & et al. (2010, p. 208) は、地球の陸地の表面にほぼ均等に分布する40の集団のサンプルを使用し、「地理的に中間的な集団をより多くサンプリングすると、遺伝的多様性はより連続 的なパターンで分布する」ことを発見した。 グイド・バルブザーニは、人間の遺伝的多様性は地球上の大部分において連続的に分布しており、人種が存在するために必要な人類集団間の遺伝的境界が存在するという証拠はないと述べている。[127] 長い年月をかけて、人間の遺伝的多様性は互いに独立して進化してきた人種という概念と矛盾する入れ子状の構造を形成してきた。[128] 社会的構築 詳細は「人種と社会」を参照 人類学者やその他の進化生物学者が、遺伝的差異について語る際に「人種」という言葉から「集団」という言葉へとシフトするにつれ、歴史家や文化人類学者、 その他の社会科学者は、「人種」という言葉を文化カテゴリーまたはアイデンティティとして再概念化し、すなわち、社会がその構成員をカテゴリーに分ける際 に選択する多くの可能な方法のうちの1つとして捉えるようになった。 多くの社会科学者は、共有する文化、祖先、歴史に関する信念に基づく自己認識グループを指すために、「人種」という言葉を「民族性」という言葉に置き換え ている。人種」に関する実証的および概念的な問題と並行して、第二次世界大戦後、進化論者や社会学者は、人種に関する信念が差別、アパルトヘイト、奴隷制 度、大量虐殺を正当化するためにいかに利用されてきたかを痛感していた。この疑問は、1960年代の米国における公民権運動や世界各地で勃発した多くの反 植民地運動の中で、さらに勢いを増した。 こうして、人種とは社会的に構築された概念であり、客観的な現実に対応するものと考えられていたが、その概念が信じられていたのは、それが社会的な機能を 有していたからであるという考え方が広まった。 2000年には、クレイグ・ベンターと米国立衛生研究所(NIH)のフランシス・コリンズが共同でヒトゲノムのマッピングを発表した。ベンターは、ゲノム マッピングのデータを調査した結果、ヒトの遺伝的多様性は1~3%程度(以前は1%と想定されていた)であるものの、その多様性の種類は遺伝的に定義され た人種の概念を裏付けるものではないことに気づいた。ベンターは、「人種は社会的概念である。科学的概念ではない。もし地球上のすべての人々のゲノム配列 を比較することができれば、際立った明確な境界線など存在しない。... 科学を適用してこうした社会的差異を解明しようとしても、すべてが崩れ去ってしまうのだ」[130] 人類学者のステファン・パルミーは、「人種とは『物』ではなく『社会的関係』である」と主張している。[131] あるいは、カーチャ・ギベル・メヴォラックの言葉を借りれば、「隠喩」であり、「差異化の基準が普遍的でも固定されたものでもなく、常に差異を管理するた めに用いられてきた、人間による発明」である。[132] したがって、「人種」という用語の使用自体を分析する必要がある。さらに、人々が人種という概念をなぜ、どのように使用するのかを生物学では説明できない と主張している。説明できるのは歴史と社会関係だけである。 イマニ・ペリーは、人種は「社会的な取り決めと政治的意思決定によって作り出される」ものであり[133]、「人種とは、存在するものではなく、起こるも のである。それは動的なものではあるが、客観的な真実性は持たない」と主張している。[134] 同様に、リチャード・T・フォードは『人種的文化: リチャード・T・フォードは、2005年の著書『人種文化:批判』の中で、「人種という帰属されたアイデンティティと、その人の文化や自己認識との間に は、必ずしも一致する関係はない」こと、また「集団間の相違は、その集団の構成員の本質的なものではなく、むしろ集団の識別という社会的慣習に起因するも のである」ことを論じている。さらに、アイデンティティ・ポリティクスの社会的慣習は、個人に対して「あらかじめ書かれた人種的台本」の「強制的な」実行 を強いる可能性があると主張している。[135] |

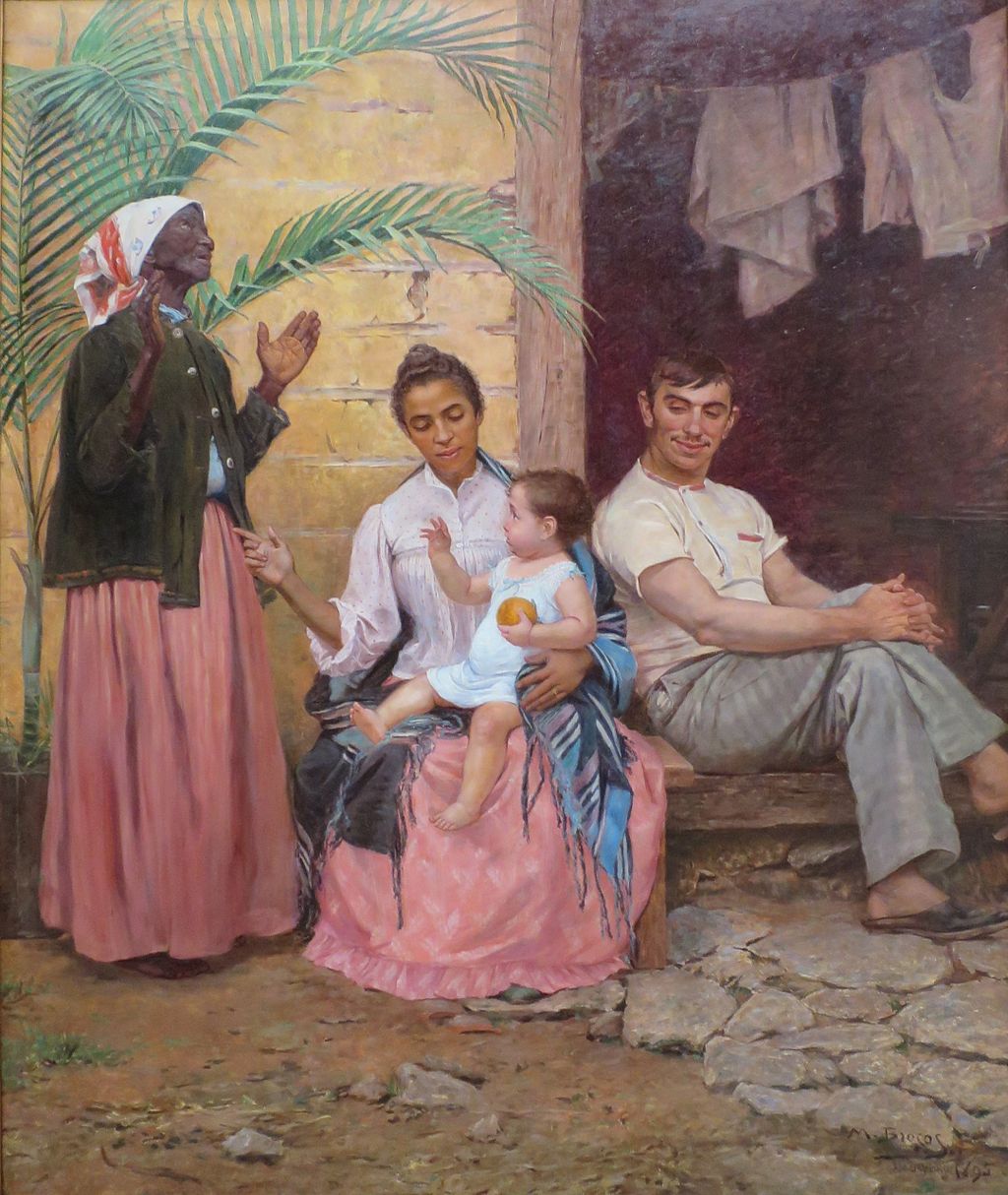

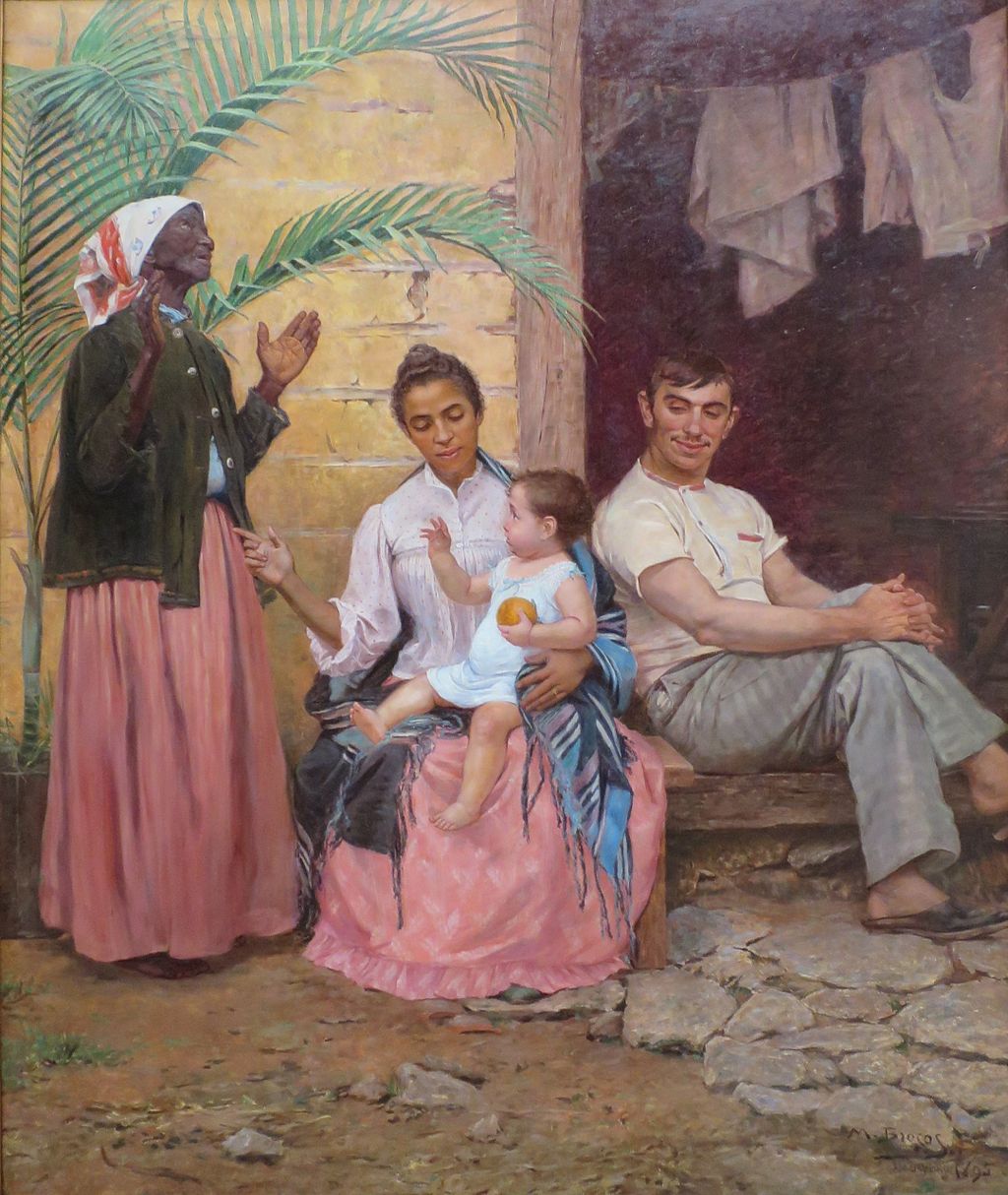

| Brazil Main article: Race in Brazil  Portrait "Redenção de Cam" (1895), showing a Brazilian family becoming "whiter" each generation Compared to 19th-century United States, 20th-century Brazil was characterized by a perceived relative absence of sharply defined racial groups. According to anthropologist Marvin Harris, this pattern reflects a different history and different social relations. Race in Brazil was "biologized", but in a way that recognized the difference between ancestry (which determines genotype) and phenotypic differences. There, racial identity was not governed by rigid descent rule, such as the one-drop rule, as it was in the United States. A Brazilian child was never automatically identified with the racial type of one or both parents, nor were there only a very limited number of categories to choose from,[136] to the extent that full siblings can pertain to different racial groups.[137]  Over a dozen racial categories would be recognized in conformity with all the possible combinations of hair color, hair texture, eye color, and skin color. These types grade into each other like the colors of the spectrum, and not one category stands significantly isolated from the rest. That is, race referred preferentially to appearance, not heredity, and appearance is a poor indication of ancestry, because only a few genes are responsible for someone's skin color and traits: a person who is considered white may have more African ancestry than a person who is considered black, and the reverse can be also true about European ancestry.[139] The complexity of racial classifications in Brazil reflects the extent of genetic mixing in Brazilian society, a society that remains highly, but not strictly, stratified along color lines. These socioeconomic factors are also significant to the limits of racial lines, because a minority of pardos, or brown people, are likely to start declaring themselves white or black if socially upward,[140] and being seen as relatively "whiter" as their perceived social status increases (much as in other regions of Latin America).[141] Fluidity of racial categories aside, the "biologification" of race in Brazil referred above would match contemporary concepts of race in the United States quite closely, though, if Brazilians are supposed to choose their race as one among, Asian and Indigenous apart, three IBGE's census categories. While assimilated Amerindians and people with very high quantities of Amerindian ancestry are usually grouped as caboclos, a subgroup of pardos which roughly translates as both mestizo and hillbilly, for those of lower quantity of Amerindian descent a higher European genetic contribution is expected to be grouped as a pardo. In several genetic tests, people with less than 60-65% of European descent and 5–10% of Amerindian descent usually cluster with Afro-Brazilians (as reported by the individuals), or 6.9% of the population, and those with about 45% or more of Subsaharan contribution most times do so (in average, Afro-Brazilian DNA was reported to be about 50% Subsaharan African, 37% European and 13% Amerindian).[142][143][144][145] If a more consistent report with the genetic groups in the gradation of genetic mixing is to be considered (e.g. that would not cluster people with a balanced degree of African and non-African ancestry in the black group instead of the multiracial one, unlike elsewhere in Latin America where people of high quantity of African descent tend to classify themselves as mixed), more people would report themselves as white and pardo in Brazil (47.7% and 42.4% of the population as of 2010, respectively), because by research its population is believed to have between 65 and 80% of autosomal European ancestry, in average (also >35% of European mt-DNA and >95% of European Y-DNA).[142][148][149][150] From the last decades of the Empire until the 1950s, the proportion of the white population increased significantly while Brazil welcomed 5.5 million immigrants between 1821 and 1932, not much behind its neighbor Argentina with 6.4 million,[151] and it received more European immigrants in its colonial history than the United States. Between 1500 and 1760, 700.000 Europeans settled in Brazil, while 530.000 Europeans settled in the United States for the same given time.[152] Thus, the historical construction of race in Brazilian society dealt primarily with gradations between persons of majority European ancestry and little minority groups with otherwise lower quantity therefrom in recent times.  |

ブラジル 詳細は「ブラジルの人種」を参照  肖像画「Redenção de Cam」(1895年)は、世代を経るごとに「白く」なっていくブラジル人家族を描いている 20世紀のブラジルは、19世紀のアメリカと比較すると、はっきりと定義された人種集団が相対的に存在しないという特徴があった。人類学者マーヴィン・ハリスによると、このパターンは異なる歴史と異なる社会関係を反映している。 ブラジルでは人種が「生物学化」されたが、それは遺伝子型を決定する先祖の違いと表現型の違いを認識するものであった。ブラジルでは、人種的アイデンティ ティは、米国における「一滴の血則」のような厳格な血統規則によって規定されることはなかった。ブラジルの子供は、自動的に親のどちらか一方または両方の 人種的タイプと同一視されることはなく、また、選択できるカテゴリーも非常に限られていた。[136] 完全な兄弟姉妹が異なる人種グループに属する場合もあるほどである。[137]  髪の色、髪質、目の色、肌の色など、考えられるすべての組み合わせに一致する12以上の人種カテゴリーが認められるだろう。これらのタイプはスペクトルの 色のように互いに移り変わり、どのカテゴリーも他のカテゴリーから著しく孤立しているわけではない。つまり、人種は外見を優先的に参照するものであり、遺 伝ではない。また、外見は先祖を推測するのに不適切な指標である。なぜなら、ある人の肌の色や特徴を決定する遺伝子はわずか数種類しかないからだ。白人と 考えられている人の方が、 黒人とされる人よりもアフリカ人の血統を多く受け継いでいる可能性があり、ヨーロッパ人の血統についても同様のことが言える。[139] ブラジルにおける人種分類の複雑さは、ブラジル社会における遺伝子混合の度合いを反映している。ブラジル社会は、厳密ではないにしても、依然として人種に よって厳格に階層化されている。こうした社会経済的要因は、人種の境界線の限界にも大きく影響している。なぜなら、パード(茶色の人々)の少数派は、社会 的に上昇すれば、自らを白人または黒人と主張し始める可能性が高く、また、彼らの社会的地位が相対的に高まるにつれ、より「白人」のように見られるからで ある(ラテンアメリカ地域の他の地域でも同様である)。 人種カテゴリーの流動性はさておき、ブラジルにおける人種の「生物学化」は、ブラジル人がアジア人と先住民を除いたIBGEの国勢調査における3つのカテ ゴリーから人種を選択すると仮定した場合、米国における現代の人種概念と非常に近いものとなる。同化されたアメリカインディアンや、アメリカインディアン の血統を非常に多く受け継ぐ人々は通常、混血人を意味する「カボクロ」として分類されるが、これは「メスチゾ」や「ヒルビリー」と訳される「パルド」のサ ブグループである。アメリカインディアンの血統が少ない人々については、ヨーロッパ人の遺伝的貢献度が高いと予想され、「パルド」として分類される。いく つかの遺伝子検査では、ヨーロッパ系が60~65%未満、アメリカインディアン系が5~10%の人は、通常、アフロブラジル人とグループ化される(本人の 申告による)か、人口の6.9%に該当し、 サブサハラの寄与が45%以上の場合はほとんどそうである(平均すると、アフリカ系ブラジル人のDNAはサブサハラアフリカが約50%、ヨーロッパが 37%、アメリカインディアンが13%であると報告されている)[142][143][144][145] 遺伝子混合の段階における遺伝子グループについて、より一貫性のある報告を考慮するならば(例えば、アフリカと非アフリカの祖先をバランスよく持つ人々 を、多民族国家ではなく黒人グループに分類するのではなく、ラテンアメリカではアフリカ系の人々が自分自身を混血と分類する傾向があるが、ブラジルではよ り多くの人々が白人および混血と報告するだろう( 2010年の時点でそれぞれ人口の47.7%と42.4%が白人および混血と自己申告している)。調査によると、ブラジル国民の平均的な常染色体上のヨー ロッパ人祖先の割合は65~80%であると考えられている(また、ヨーロッパ人のミトコンドリアDNAの35%以上、ヨーロッパ人のY染色体DNAの 95%以上でもある)[142][148][149][150] 帝国の最後の数十年から1950年代にかけて、ブラジルは1821年から1932年の間に550万人の移民を迎え入れ、隣国アルゼンチンの640万人には 及ばなかったものの、その割合は大幅に増加した。ブラジルは植民地時代にアメリカ合衆国よりも多くのヨーロッパ移民を受け入れた。1500年から1760 年の間に、70万人のヨーロッパ人がブラジルに移住した一方で、同じ期間に53万人のヨーロッパ人が米国に移住した。[152] したがって、ブラジル社会における人種の歴史的構築は、主にヨーロッパ系が大多数を占める人々と、その他少数派グループとの間の段階的変化を扱うものであ り、近年では、それ以外の人種は少数派である。  |

| European Union See also: Demographics of the European Union According to the Council of the European Union: The European Union rejects theories which attempt to determine the existence of separate human races. — Directive 2000/43/EC[153] The European Union uses the terms racial origin and ethnic origin synonymously in its documents and according to it "the use of the term 'racial origin' in this directive does not imply an acceptance of such [racial] theories".[153][154][full citation needed] Haney López warns that using "race" as a category within the law tends to legitimize its existence in the popular imagination. In the diverse geographic context of Europe, ethnicity and ethnic origin are arguably more resonant and are less encumbered by the ideological baggage associated with "race". In European context, historical resonance of "race" underscores its problematic nature. In some states, it is strongly associated with laws promulgated by the Nazi and Fascist governments in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, in 1996, the European Parliament adopted a resolution stating that "the term should therefore be avoided in all official texts".[155] The concept of racial origin relies on the notion that human beings can be separated into biologically distinct "races", an idea generally rejected by the scientific community. Since all human beings belong to the same species, the ECRI (European Commission against Racism and Intolerance) rejects theories based on the existence of different "races". However, in its Recommendation ECRI uses this term in order to ensure that those persons who are generally and erroneously perceived as belonging to "another race" are not excluded from the protection provided for by the legislation. The law claims to reject the existence of "race", yet penalize situations where someone is treated less favourably on this ground.[155] United States Main article: Race and ethnicity in the United States See also: Miscegenation § Admixture in the United States, and Historical racial and ethnic demographics of the United States The immigrants to the United States came from every region of Europe, Africa, and Asia. They mixed among themselves and with the indigenous inhabitants of the continent. In the United States most people who self-identify as African American have some European ancestors, while many people who identify as European American have some African or Amerindian ancestors. Since the early history of the United States, Amerindians, African Americans, and European Americans have been classified as belonging to different races. Efforts to track mixing between groups led to a proliferation of categories, such as mulatto and octoroon. The criteria for membership in these races diverged in the late 19th century. During the Reconstruction era, increasing numbers of Americans began to consider anyone with "one drop" of known "Black blood" to be Black, regardless of appearance. By the early 20th century, this notion was made statutory in many states. Amerindians continue to be defined by a certain percentage of "Indian blood" (called blood quantum). To be White one had to have perceived "pure" White ancestry. The one-drop rule or hypodescent rule refers to the convention of defining a person as racially black if he or she has any known African ancestry. This rule meant that those that were mixed race but with some discernible African ancestry were defined as black. The one-drop rule is specific to not only those with African ancestry but to the United States, making it a particularly African-American experience.[156] The decennial censuses conducted since 1790 in the United States created an incentive to establish racial categories and fit people into these categories.[157] The term "Hispanic" as an ethnonym emerged in the 20th century with the rise of migration of laborers from the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America to the United States. Today, the word "Latino" is often used as a synonym for "Hispanic". The definitions of both terms are non-race specific, and include people who consider themselves to be of distinct races (Black, White, Amerindian, Asian, and mixed groups).[158] However, there is a common misconception in the US that Hispanic/Latino is a race[159] or sometimes even that national origins such as Mexican, Cuban, Colombian, Salvadoran, etc. are races. In contrast to "Latino" or "Hispanic", "Anglo" refers to non-Hispanic White Americans or non-Hispanic European Americans, most of whom speak the English language but are not necessarily of English descent. |

欧州連合 関連項目:欧州連合の人口統計 欧州連合理事会によると: 欧州連合は、人種が別個に存在するという説を否定する。 — 指令2000/43/EC[153] 欧州連合は、その文書において「人種的起源」と「民族的起源」という用語を同義語として使用しており、それによると「この指令における『人種的起源』とい う用語の使用は、そのような(人種に関する)理論の受け入れを意味するものではない」[153][154][要出典]。Haney Lópezは、「人種」を法律上のカテゴリーとして使用することは、一般の人々の想像の中でその存在を正当化する傾向があると警告している。ヨーロッパの 多様な地理的背景においては、民族性や民族の出自の方がより共感を呼び、「人種」に関連するイデオロギー的な重荷に妨げられることは少ない。ヨーロッパの 文脈では、「人種」という言葉の歴史的な響きは、その問題のある本質を浮き彫りにしている。一部の国では、1930年代から1940年代にかけてヨーロッ パでナチスやファシスト政権が公布した法律と強く結びついている。実際、1996年には欧州議会が「したがって、この用語はすべての公式文書で使用を避け るべきである」という決議を採択している。[155] 人種的出自という概念は、人間は生物学的に異なる「人種」に分類できるという考えに基づいているが、この考えは科学界では一般的に否定されている。すべて の人間は同じ種に属しているため、ECRI(欧州人種主義・不寛容対策委員会)は異なる「人種」の存在を前提とする理論を否定している。しかし、ECRI の勧告では、この用語を使用することで、一般的に誤って「別の人種」に属すると認識されている人々が、法律で定められた保護の対象から除外されないように している。この法律は「人種」の存在を否定しているが、この理由で誰かが不利な扱いを受ける状況には罰則を科している。[155] アメリカ合衆国 詳細は「アメリカ合衆国における人種と民族」を参照 関連項目:混血 § アメリカ合衆国における混血、およびアメリカ合衆国の人種および民族の歴史的構成 アメリカ合衆国への移民はヨーロッパ、アフリカ、アジアのあらゆる地域からやってきた。彼らは互いに混血し、大陸の先住民とも混血した。アメリカ合衆国で は、アフリカ系アメリカ人と自己認識する人々のほとんどはヨーロッパ人の先祖を持ち、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人と自己認識する人々の多くはアフリカ人または アメリカインディアンの先祖を持つ。 アメリカ合衆国の初期の歴史以来、アメリカンインディアン、アフリカ系アメリカ人、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人は異なる人種として分類されてきた。異なる集団 間の混血を追跡する試みにより、混血種やオクトルーンなど、カテゴリーが次々と増えていった。これらの人種に属する基準は、19世紀後半に分岐した。再建 時代には、外見とは関係なく、知られている「黒人の血」が「一滴」でも混ざっている人なら誰でも黒人と見なすアメリカ人が増えていった。20世紀初頭まで に、この概念は多くの州で法律化された。アメリカ先住民は、今でも「インディアンの血」の一定割合(血統資格と呼ばれる)によって定義されている。白人で あるためには、知られている「純粋な」白人の先祖を持っていなければならない。一滴の血則または父系血統主義は、アフリカ系祖先が判明している場合、その 人物を人種的に黒人と定義する慣例を指す。この規則は、混血であってもアフリカ系祖先が判明している場合は黒人と定義されることを意味した。一滴の血則 は、アフリカ系祖先を持つ人々だけでなく、アメリカ合衆国にも特有のものであり、特にアフリカ系アメリカ人の経験となっている。 1790年以降、アメリカ合衆国で10年ごとに実施された国勢調査は、人種カテゴリーを確立し、人々をこれらのカテゴリーに当てはめるインセンティブを生み出した。 「ヒスパニック」という民族名称は、スペイン語を話すラテンアメリカ諸国からアメリカ合衆国への労働者の移住の増加に伴い、20世紀に登場した。今日、 「ラテン系」という言葉は「ヒスパニック」と同義語としてよく使われている。両者の定義は人種を特定するものではなく、自らを異なる人種(黒人、白人、ア メリカインディアン、アジア人、混血)であると考える人々も含む。[158] しかし、米国ではヒスパニック/ラテン系は人種であるという誤解が一般的である[159]。また、メキシコ人、キューバ人、コロンビア人、エルサルバドル 人など、国民の出自が人種であると考える場合さえある。「ラテン系」や「ヒスパニック系」に対して、「アングロ系」はヒスパニック系でない白人のアメリカ 人、またはヒスパニック系でないヨーロッパ系アメリカ人を指し、そのほとんどが英語を話すが、必ずしも英語を話す家系というわけではない。 |