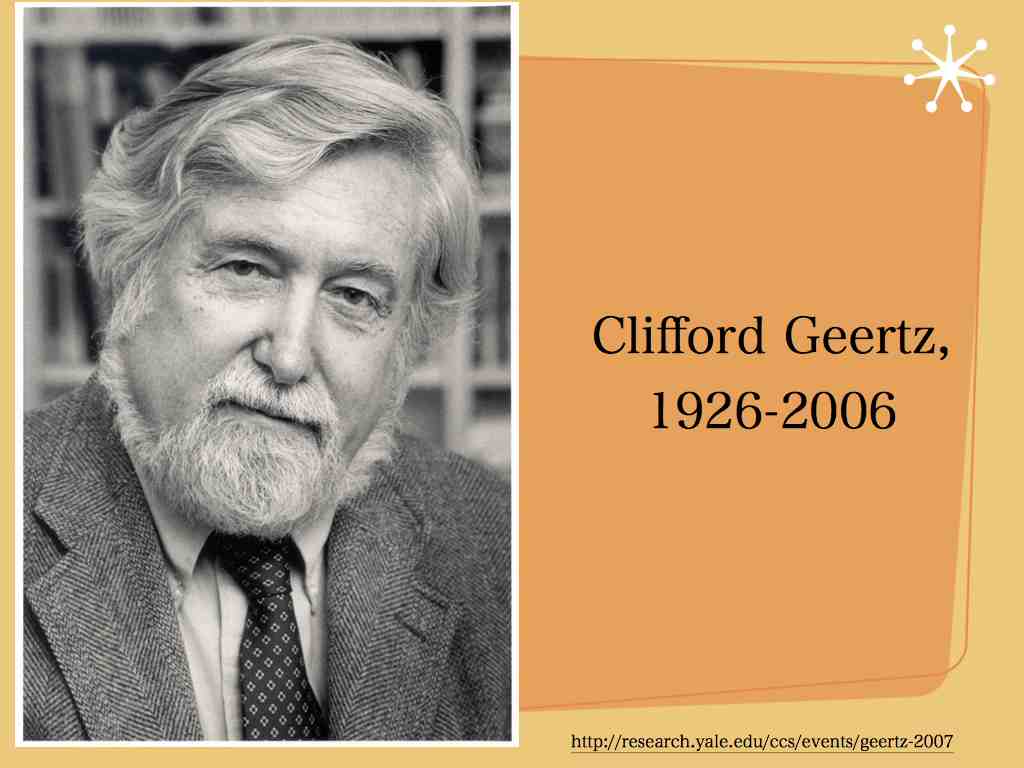

Ideology As a Cultural System, from Introduction to Geertz' Interpretation of Culture, 1973

文化体系としてのイデオロギー

Ideology As a Cultural System, from Introduction to Geertz' Interpretation of Culture, 1973

解説:池田光穂

『文化の解釈』(邦訳:文化の解釈学)[The Interpretation of Cultures, 1973.]は、1973年のクリフォード・ギアーツの著書、から「文化としての政治」について考える

8.文化体系としてのイデオロギー(邦

訳, pp.3-) Ideology As a Cultural System

| I | 3 |

・イデオロギーが「おとろしい」用語と

して使われてきたわけ ・イデオロギーの言わば自己言及性(マンハイム) ・それゆえマンハイムは「価値判断を含まないイデオロギー概念」の探求(構築)に着手する、pp.4-5 ・ゼノンのパラドクスと、マンハイムのパラドクスとの類似(脱色しても脱色しても無垢の差は縮まらない) ・イデオロギーのイデオロギー概念を解消しようと努力するマンハイム、または「イデオロギーの終焉」終焉。 ・イデオロギー抜きの社会科学は「客観性」への到達願望か? ・イデオロギー抜きの社会科学は、自分の探求している内容や手法が「洗練」されていない、というコンプレックスによるのか?(7) ・イデオロギーが社会学的分析を拒む(分析が不適切だから?) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 1)社会科学は、価値判断を含まないイデオロギー概念を手にしてない 2)その理由は方法論的な欠如ではなく、理論的な不備による 3)社会的心理的文脈を吟味するのではなく、イデオロギーを象徴的に取り扱うときに、このようなジレンマが生じる 4)意味というものを巧妙に扱う概念装置を完成させるべき 5)研究対象をより正確にとらえること(そうでないと)「おとなしい嫁」を探せと言われて死骸をもちかえる愚かな少年(ジャワの民話)にならないように (7) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++ |

| II |

・イデオロギー概念のほとんどは価値判

断的=侮蔑的である(8)。 ・スタークの議論を引きながら、イデオロギーという用語にはさまざまなマイナスのイメージが付与されていることを指摘。 ・つまり、イデオロギー研究とは、知識社会学とは異なり、その知的誤謬をしてきすることにあると認識されている(9) ・シルズにおいても、その扱いは同様(10) ・あの慎重なタルコット・パーソンズも同じような路線を主張する(11)——有害な「二次的」選択性—— ・社会科学の分析に、イデオロギーほど中傷されているのに、なぜそれが残留しているのかは謎のまま(12) ・レイモン・アーロンの「知識人の阿片」でも同様 ・シルズのイデオロギーに対する病理的な嫌悪は、異端審問官の異端に対する態度に通底する(13) ・イデオロギーがもつ先験的な虚偽性の意味を保持させるのは、論点先取的な誤 りにも覚える(14) |

|

| III |

14 |

・イデオロギーの病理解剖的な様相にス

トーリーはすすむ。とりわけ、社会心理的な説明。 ・イデオロギーの社会的決定要因は、利益説と緊張説(15) ・利益説には多くを踏み込まない(15) ・利益説の問題は、心理的には貧困であり、社会学的には骨太すぎること(16) ・果てしのない闘争史観(17) ・利益説も、緊張説も、両方とも、心理的であり、社会的説明でもある(18) ・緊張説の出発点は、社会の「慢性的な不統合状態」からはじまる(18-19) ・社会的摩擦が個人的摩擦に反映される(19)そして絶望状態を産む(20) ・イデオロギー的思想は、この絶望に対する(ある種の)反応である(20)——象徴的はけ口など ・この表現は、病理的(医学的)に説明=表現される(20) ・以下、洗浄(カタルシス)論的、意欲論的、団結論的、弁護論的 ・洗浄=カタルシス論は、安全弁論的で、スケープゴート的(21) ・意欲論 ・団結論(21) ・弁護論(22) +++++++++ ・緊張説とそのの限界(24-25) ・いずれせよ、社会と心理の関連を関連づけて説明するイデオロギー説明説の問題点が列挙されている(26) |

| IV |

26 |

・社会科学理論は、マルクス主義、ダー

ウィニズム、功利主義、観念論、フロイト学説、行動主義、実証主義、操作主義など、主知的な運動から影響をうけてきた(26) ・(他方)生態学、動物行動学、比較心理学、ゲーム理論、サイバネティクス、統計学の方法論的革新から影響をうけてこなかった。 ・例外のひとつバークの「象徴行為」論。 ・哲学者の仕事も、文芸批評家の仕事も影響を与えていない(26)。 ・比喩言語を理解できないので、イデオロギーの手の込んだ苦痛の叫びに還元してみることとなる(27) ・サットンの「タフト・ハートレー法」の理解。組織労働者は「奴隷労働法」とラベル(28)。 ・奴隷労働者を見下すような見解が(事例引用)には含まれている。(29-) ・それは比喩の企て(30-) ・奴隷労働という表現は、複雑な象徴的行為であることを示唆(33-34) |

| V |

34 |

・人間の思考は公共的活動であり……

(34) ・思考が外にあるアプローチ=外在説 ・象徴モデルと世界の状態の過程と付き合わせる活動(35) ・引用、想像的思考とは……(35) ・引用、象徴モデルとは……(37) ・人間を政治的動物とするのは(41) ・イデオロギーの説明に(41-) ・エドマンド・バークのイデオロギー論(批判) ・「教えられざる感性の人」(42)——エドマンド・バーク ・【イデオロギーは大衆の政治的緊張への反応だ】 「イデオロギーの機能とは、政治 を意味あるものとするような権威ある概念を与えることによって、すなわち政治を理解し得るような 形で把握する手段としての説得力あるイメージを与えることによって、自律的な政治を可能とするこ とである。事実ある政治体系が、受け入れられてきた伝統の無媒介的支配から、すなわち一方で宗教 的ないし哲学的規律の直接的で細部にまでわたる導きから、他方で慣習的道徳の省みられることのな い教えからまさに自らを解放し始めるとき、形式化されたイデオロギーが最初に現われ根を張る傾向 にある。自律的政体が分佑することは、政治的行為について、独立しった文化的モデルが分化す ることをも意味する。なぜなら政治的行為に特定しない古いモデルは、そうした政治体系が要請する ようなたぐいの導きを与えるには、あまりに包括的にすぎるか、具体的にすぎるか、だからである。そう/ したモデルは、超越的な意味を負わせて政治的行動を束縛するか、習慣的判断のうつろな現実主義に 縛り付けて政治的理念を窒息させるかである。ある社会の最も広汎な文化的方向付けも、最も実際的 で「実用的な」方向付けも、ともに政治過程の妥当なイメージを与えるに充分でなくなったときに、 イデオロギーは社会的政治的な意味と姿勢の源泉として決定的重要性を帯び始める」(42-43) ・イデオロギーの積極的解釈(44)★ |

| VI |

45 |

・イデオロギーの醸成の場はどこにあ

る?(45)——イデオロギーの跋扈は途上国(=ギアツの言葉では「新生国家」)にある ・ラマルティーヌの詩(46)——このあたりの解説はベネディクト・アンダーソンの表現に似ている? ・インドネシア近代国家における適応と失敗のプロセス(47) ・ヒンドゥ時代のジャワ(48) ・イスラムとヒンドゥ(49) ・パンチャシラ(51) ・マニポル・ウスデク(54) ・イデオロギーとリアル・ポリテークが混乱したインドネシアの分析(56-57) ・インドネシアは政治的実験の場 ・ ・イデオロギーの科学的研究の出発点(58) |

| VII |

58 |

・なぜ、ケネス・バークの引用からこの

セクションははじまるのか?(58-59) ・【批判的想像的作品】 「批判的想像的作品とは、それが生まれた状況により提示された問題に対する解答である。それは単 なる解答ではなく、戦略的解答であり様式化された解答である。というのは同じ「はい」と言うにし ても、「よかった!」を意味する調子の時と「残念!」を意味する調子の時とでは、様式や戦略に違 いがあるからである。そこで私はさしあたっての作業上、「戦略」と「状況」の間に区別を設けるこ とによって、批判的ないし想像的性格の作品とは……状況を包囲するために様々な戦略を用いること である……と考えることにしたい。こうした戦略は状況を測り、状況の構造とその目立った内容物に// 名前を付けるが、それらに対する姿勢を含むような形で名前を付けるのである。/ このような見方をしても、いかなる意味でも個人的ないし歴史的主観主義にくみすることにはなら ない。こうした状況は本物である。それらを処理するための戦略には公共の内容がある。状況が個人 と個人の間で、あるいはある時代と時代の間で重なり合う限り、その戦略には普遍的意味がある ——ケネス・バーグ『文学形式の哲学(Philosophy of Literary Form)』」(58-59) ・科学とイデオロギーの差異の解説(60-61) ・「ヒットラーが自国民の悪魔的自己嫌悪を、聖書に依拠して呪術的に腐敗するユダヤ 人像に映し描 いたとき、彼はドイツ人の意識を歪めていたのではなかった。彼は単にそれを客体化していたのであ る——広くみられた個人的神経症を、強力な社会的力へと変容させていたのである」(ギアーツ(下)1987:62)。 ・言説により人を動員させる機能がイデオロギーであるが、それを働かせるためには、言説のシンボル的操作が必要だということか?(62-63) ・【科学とイデオロギーの関係】——イデオロギーと「科学(あるいは常識)の共犯関係?を最後に描写するギアーツ。でも科学を信じているギアーツの別の姿 がある。 +++++++ ・「しかし、科学とイデオロギーが相異なる企てであったとしても、相互に関連してい ないわけではな い。イデオロギーは確かに社会の条件と方向について経験に基づく主張 を行なうが、評価を行なうの は科学の(そして科学的知識が欠如する場合には常識の)役目である。イデオロギーに対するものとし ての科学の社会機能とは、まずイデオロギ——それが何であるか、それがどのように機能するか、 それを生むものは何か——を理解すること、次にそれを批判し、それに現実との妥協(必ずしも降伏/ ではない)を強いることである。社会問題の科学的分析という欠くべからざる伝統が存 在することは、 極端なイデオロギーを生まない保証として最も効果が大きいものの一つである。なぜなら科学的分析 というものには、政治的理念が依存し尊重すべき実証的知識の源泉として、比類のない信頼性がある からである。科学的分析はそうした阻止機構として唯一のものではない。既に述べたように、当該社 会の他の強力な集団が奉ずる競合的イデオロギーの存在もまた、少なくとも同じくらい重要である。 また全体的権力の夢がそこでは明らかに幻想としかなり得ない自由な政治体系も、また伝統的期待が 常に裏切られるわけではなく伝統的思想が根源的に無能力であるわけでもない安定した社会条件も、 同じくまた重要である。しかし自らの見解については静かに妥協を拒む科学的分析は、おそらくその どれよりも不屈である」(62-63) |

●追記:マイケル・オークショット——こ

れには、ギアーツ先生がいう否定的な意味は込められていない。具体的な経験とは別物であるという定義が

素晴らしい。

「私の理解するかぎりでは、政治的イデオロギーとは、ある抽象的な原理または諸原理の関連せる組合せを意味し、 あらかじめ個々の経験から独立に考案されたものである。それは、社会を整序することに関わる行動に先んじて、追 求されるべき目的を定式化し、そうすることによって、いっそう鼓舞されるべき諸要求と抑圧または修正されるべき ものとを、区別する手段を提供してくれる」(翻訳 p.134)

"As I understand it, a political ideology purports to be an

abstract

principle, or set of related abstract principles, which has been

independently

premeditated. It supplies in advance of the activity of

attending to the arrangements of a society a formulated end to be

pursued, and in so doing it provides a means of distinguishing

between those desires which ought to be encouraged and those

which ought to be suppressed or redirected." (Oakeshott 1962:116)

| Ideology

as a Cultural System. Clifford Geertz I. It is one of the minor ironies of modern intellectual history that the term "ideology" has itself become thoroughly ideologized. A concept that once meant but a collection of political proposals, perhaps somewhat intellectualistic and impractical but at any rate idealistic--"social romances as someone, perhaps Napoleon, called them--has now become, to quote Webster's, "the integrated assertions, theories, and aims constituting a politico-social program, often with an implication of factitious propagandizing; as, Fascism was altered in Germany to fit the Nazi ideology"--a much more formidable proposition. Even in works that, in the name of science, profess to be using a neutral sense of the term, the effect of its employment tends nonetheless to be distinctly polemical in Sutton, Harris, Kaysen, and Tobin's in many ways excellent The American Business Creed, for example, an assurance that "one has no more cause to feel dismayed or aggrieved by having his own views described as 'ideology' than had Moliere's famous character by the discovery that all his life he had been talking prose,"1 is followed immediately by the listing of the main characteristics of ideology as bias, oversimplification, emotive language, and adaption to public prejudice No one, at least outside the Communist bloc, where a somewhat distinctive conception of the role of thought in society is institutionalized, would call himself an ideologue or consent unprotestingly to be called one by others. Almost universally now the familiar parodic paradigm applies: "I have a social philosophy; you have political opinions; he has an ideology." The historical process by which the concept of ideology came to be itself a part of the very subject matter to which it referred has been traced by Mannheim; the realization (or perhaps it was only an admission) that sociopolitical thought does not grow out of disembodied reflection but "is always bound up with the existing life situation of the thinker" seemed to taint such thought with the vulgar struggle for advantage it had professed to rise above.2 But what is of even more immediate importance is the question of whether or not this absorption into its own referent has destroyed its scientific utility altogether, whether or not having become an accusation, it can remain an analytic concept. In Mannheim's case, this problem was the animus of his entire work--the construction, as he put it, of a "nonevaluative conception of ideology.' But the more he grappled with it the more deeply he became engulfed in its ambiguities until, driven by the logic of his initial assumptions to submit even his own point of view to sociological analysis, he ended, as is well known, in an ethical and epistemological relativism that he himself found uncomfortable. And so far as later work in this area has been more than tendentious or mindlessly empirical, it has involved the employment of a series of more or less ingenious methodological devices to escape from what may be called (because, like the puzzle of Achilles and the tortoise, it struck at the very foundations of rational knowledge) Mannheim's Paradox. As Zeno's Paradox raised (or, at least, articulated) unsettling questions about the validity of mathematical reasoning, so Mannheim's Paradox raised them with respect to the objectivity of sociological analysis. Where, if anywhere, ideology leaves off and science begins has been the Sphinx's Riddle of much of modern sociological thought and the rustless weapon of its enemies. Claims to impartiality have been advanced in the name of disciplined adherence to impersonal research procedures of the academic man's institutional insulation from the immediate concerns of the day and his vocational commitment to neutrality, and of deliberately cultivated awareness of and correction for one's own biases and interests. They have been met with denial of the impersonality (and the effectiveness) of the procedures, of the solidity of the insulation, and of the depth and genuineness of the self-awareness. "I am aware," a recent analyst of ideological preoccupations among American intellectuals concludes, somewhat nervously, "that many readers will claim that my position is itself ideological."3 Whatever the fate of his other predlctions, the validity of this one is certain. Although the arrival of a scientific sociology has been repeatedly proclaimed, the acknowledgment of its existence is far from universal even among social scientists themselves; and nowhere is resistance to claims to objectivity greater than in the study of ideology. A number of sources for this resistance have been cited repeatedly in the apologetic literature of the social sciences. The valueladen nature ot the subject matter is perhaps most frequently invoked: men do not care to have beliefs to which they attach great moral significance examined dispassionately, no matter for how pure a purpose; and if they are themselves highly ideologized, they may find it simply impossible to believe that a disinterested approach to critical matters of social and political conviction can be other than a scholastic sham. The inherent elusiveness of ideological thought, expressed as it is in intricate symbolic webs as vaguely defined as they are emotionally charged; the admitted fact that ideological special pleading has, from Marx forward, so often been clothed in the guise of "scientific sociology"; and the defensiveness of established intellectual classes who see scientific probing into the social roots of ideas as threatening to their status, are also often mentioned. And, when all else fails, it is always possible to point out once more that sociology is a young science, that it has been so recently founded that it has not had time to reach the levels of institutional solidity necessary to sustain its claims to investigatory freedom in sensitive areas. All these arguments have, doubtless, a certain validity. But what--by a curious selective omission the unkind might well indict as ideological--is not so often considered is the possibility that a great part of the problem lies in the lack of conceptual sophistication within social science itself, that the resistance of ideology to sociological analysis is so great because such analyses are in fact fundamentally inadequate; the theoretical framework they employ is conspicuously incomplete. I shall try in this essay to show that such is indeed the case: that the social sciences have not yet developed a genuinely nonevaluative conception of ideology; that this failure stems less from methodological indiscipline than from theoretical clumsiness; that this clumsiness manifests itself mainly in the handling of ideology as an entity in itself --as an ordered system of cultural symbols rather than in the discrimination of its social and psychological contexts (with respect to which our ana Iytical machinery is very much more refined); and that the escape from Mannheim's Paradox lies, therefore, in the perfection of a conceptual apparatus capable of dealing more adroitly with meaning. Bluntly, we need a more exact apprehension of our object of study, lest we find ourselves in the position of the Javanese folk-tale figure, "Stupid Boy," who, having been counseled by his mother to seek a quiet wife, returned with a corpse. |

イデオロギーとしての文化システム クリフォード・ギアーツ I. 「イデオロギー」という用語自体が徹底的にイデオロギー化されてしまったことは、現代の知的歴史における些細な皮肉のひとつである。かつては政治的提案の 集合体を意味していた概念、おそらくはいくらか観念的で非現実的ではあるが、いずれにせよ理想主義的な概念――「社会的なロマン主義」と、おそらくナポレ オンは呼んだ――は、現在ではウェブスターの言葉を引用すれば、「政治的社会的なプログラムを構成する統合された主張、理論、目的であり、しばしば人為的 なプロパガンダの含みを持つ。例えば、ファシズムはドイツでナチスのイデオロギーに合うように変化した」という、より強力な命題となっている。科学の名の もとに、用語を中立的に使用していると主張する作品においても、その使用が論争的な効果をもたらす傾向にあることに変わりはない。サットン、ハリス、ケイ セン、トビンの『The American Business Creed』は、多くの点で優れた作品である。例えば、「自分の意見が『イデオロギー』と表現されたからといって落胆したり、不当に扱われたと感じる理由 は、モリエールの 「自分の生涯をかけて散文を語っていたことを発見したモリエールの有名な登場人物よりも、自分の意見が『イデオロギー』と表現されたことで落胆したり不当 に扱われたりする理由などない」という主張が続きます。1 そのすぐ後に、イデオロギーの主な特徴として、偏見、単純化、感情的な表現、そして大衆の偏見への順応が挙げられています。少なくとも社会における思想の 役割について、ある程度独特な概念が制度化されている共産圏以外の地域では、自らをイデオローグと称する者や、他人からそう呼ばれることに異議を唱えない 者はいないでしょう。今ではほぼ世界中で、おなじみのパロディ的なパラダイムが適用されている。「私は社会哲学を持っている。あなたは政治的意見を持って いる。彼はイデオロギーを持っている」 イデオロギーという概念が、それ自体がまさにその概念が指し示す主題の一部となるに至った歴史的過程は、マンハイムによって明らかにされている。社会政治 思想は、身体から切り離された思索から生じるのではなく、「常に思想家の既存の生活状況と結びついている」という認識(あるいは、それは単なる承認にすぎ なかったかもしれない)は、 。しかし、より差し迫った問題は、この参照対象への吸収が科学的実用性を完全に破壊してしまったかどうか、告発の対象となってしまった以上、分析的概念で あり続けることができるかどうかという問題である。マンハイムの場合、この問題は彼の全作品の動機となった。すなわち、彼が言うところの「価値判断を伴わ ないイデオロギーの概念」の構築である。しかし、彼がこの問題に取り組めば取り組むほど、その曖昧さに深く巻き込まれていった。そして、当初の仮定の論理 に駆られて、自身の視点さえも社会学的分析に委ねるようになった彼は、周知の通り、自らを不快に感じた倫理的・認識論的相対主義に陥った。この分野におけ るその後の研究が、偏見に満ちたものや、無分別な経験主義的なものに留まらない限り、それは、マンハイムのパラドックスと呼ばれるもの(アキレスと亀のパ ズルのように、合理的知識の根幹を揺るがすもの)から逃れるために、さまざまな独創的な方法論的工夫を駆使したものとなっている。 ゼノンのパラドックスが数学的推論の妥当性について不安を掻き立てるような疑問を提起した(あるいは少なくとも明確にした)ように、マンハイムのパラドッ クスは社会学分析の客観性について同様の疑問を提起した。イデオロギーがどこで終わり、科学が始まるのかは、近代社会学思想の多くにおけるスフィンクスの 謎であり、その敵の錆びない武器であった。公平性への主張は、学術的な人間の、その時代の差し迫った関心事から隔離された制度上の非個人的研究手順への規 律ある厳守、および職業上の中立性への献身、そして、自らの偏見や利害に対する意識を意図的に養い、修正するという名目で進められてきた。これらは、手順 の非個人的性質(および有効性)、隔離の堅固さ、自己認識の深さと真実性の否定に直面してきた。「私は自覚している」と、最近のアメリカ知識人のイデオロ ギー的関心についての分析者は、やや神経質な調子で結論づけている。「多くの読者は、私の立場自体がイデオロギー的であると主張するだろう」3。彼の他の 予測の運命がどうであれ、この予測の妥当性は確実である。科学的社会学の到来は繰り返し宣言されてきたが、その存在の認知は社会科学者自身の間でも普遍的 とは程遠い。そして、客観性への主張に対する抵抗は、イデオロギーの研究において最も大きい。 この抵抗の要因については、社会科学の弁明的な文献で繰り返し挙げられている。この主題の価値を伴う性質は、おそらく最も頻繁に引き合いに出されるもので ある。人間は、いかに純粋な目的であっても、道徳的に大きな意義を付与した信念を冷静に検証されることを望まない。また、もし人間自身が高度にイデオロ ギー化されている場合、社会や政治的な信念の重要な問題に対して、利害関係のないアプローチが学問的な偽善以外の何者でもないと考えることは、単に不可能 であるかもしれない。感情を揺さぶるようなあいまいな定義の複雑な象徴の網として表現されるイデオロギー的思考の本質的な捉えどころのなさ、マルクス以 降、イデオロギー的特別弁護が「科学的社会学」という仮面を被ることが非常に多かったという認められた事実、そして、アイデアの社会的ルーツを科学的に探 ることを自分たちの地位を脅かすものとして捉える確立された知識階級の防衛的な姿勢も、よく言及される。そして、他に手段がない場合には、社会学はまだ歴 史の浅い学問であり、最近になってようやく確立されたばかりであるため、デリケートな分野における調査の自由を主張し続けるために必要な制度的な強固さを 獲得するだけの時間がなかった、ということを再び指摘することが常に可能である。これらの議論には、確かに一定の妥当性がある。しかし、興味深い選択的省 略によって、不親切な人々からイデオロギー的だと非難される可能性があるが、あまり考慮されていないのは、問題の大部分が社会科学自体の概念的な洗練度の 欠如にあるという可能性である。社会学的な分析に対するイデオロギーの抵抗が非常に大きいのは、そのような分析が実際には根本的に不適切であるためであ り、彼らが用いる理論的枠組みは著しく不完全である。 本稿では、社会科学がまだイデオロギーに対する真に評価的でない概念を発展させていないこと、この失敗は方法論の無規律さよりも理論的な不器用さから生じ ていること、この不器用さは主にイデオロギーをそれ自体の存在として取り扱う際に現れること --社会や心理的文脈の区別(これに関しては、私たちの分析的機械ははるかに洗練されている)よりも、むしろ文化的なシンボルの秩序あるシステムとして、 というように。そして、マンハイムのパラドックスからの脱却は、意味をより巧みに扱うことのできる概念的装置の完成にある。端的に言えば、私たちは研究対 象をより正確に把握する必要がある。さもなければ、ジャワの民話に登場する「愚かな少年」の立場に立たされることになる。母親から「おとなしい妻をめとる ように」と助言された愚かな少年は、死体を抱えて戻ってきた。 |

| II. That the conception of ideology now regnant in the social sciences is a thoroughly evaluative (that is, pejorative) one is readily enough demonstrated. " [The study of ideology] deals with a mode of thinking which is thrown off its proper course," Werner Stark informs us; "ideological thought is . . . something shady, something that ought to be overcome and banished from our mind." It is not (quite) the same as lying, for, where the liar at least attains to cynicism, the ideologue remains merely a fool: "Both are concerned with untruth, but whereas the liar tries to falsify the thought of others while his own private thought is correct, while he himself knows well what the truth is, a person who falls for an ideology is himself deluded in his private thought, and if he misleads others, does so unwillingly and unwittingly."4 A follower of Mannheim, Stark holds that all forms of thought are socially conditioned in the very nature of things, but that ideology has in addition the unfortunate quality of being psychologically "deformed" ("warped," "contaminated," "falsified," "distorted," "clouded") by the pressure of personal emotions like hate, desire, anxiety, or fear. The sociology of knowledge deals with the social element in the pursuit and perception of truth, its inevitable confinement to one or another existential perspective. But the study of ideology--an entirely different enterprise--deals with the causes of intellectual error: Ideas and beliefs, we have tried to explain. can be related to reality in a double way: either to the facts of reality, or to the strivings to which this reality, or rather the reaction to this reality, gives rise. Where the former connection exists, we find thought which is, in principle, truthful; where the latter relation obtains, we are faced with ideas which can be true only by accident. and which are likely to be vitiated by bias. the word taken in the widest possible sense. The former type of thought deserves to be called theoreticai; the latter must be characterized as paratheoretical. Perhaps one might also describe the former as rational, the latter as emotionally tinged--the former as purely cognitive, the latter as evaluative. To borrow Theodor Geiger's simile . . . thought determined by social fact is like a pure stream. crystal-clear, transparent; ideological ideas like a dirty river, muddied and polluted by the impurities that have flooded into it. From the one it is healthy to drink; the other is poison to be avoided.5 This is primitive, but the same confinement of the referent of the term "ideology" to a form of radical intellectual depravity also appears in contexts where the political and scientific arguments are both far more sophisticated and infinitely more penetrating. In his seminal essay on "Ideology and Civility," for example, Edward Shils sketches a portrait of "the ideological outlook," which is, if anything, even grimmer than Stark's.6 Appearing "in a variety of forms, each alleging itself to be unique"--Italian Fascism, German National Socialism, Russian Bolshevism, French and Italian COmmunism, the Action Francaise, the British Union of Fascists, "and their fledgling American kinsman, 'McCarthyism,' which died in infancy"--this outlook "encircled and invaded public life in the Western countries during the 19th century and in the 20th century. . . threatened to achieve universal domination." It consists, most centrally, of "the assumption that politics should be conducted from the standpoint of a coherent, comprehensive set of beliefes which must override every other consideration." Like the politics it supports, it is dualistic, opposing the pure "we" to the evil "they," proclaiming that he who is not with me is against me. It is alienative in that it distrusts, attacks, and works to undermine established political institutions. It is doctrinaire in that it claims complete and exclusive possession of political truth and abhors compromise. It is totalistic in that it aims to order the whole of social and cultural life in the image of its Ideals, futuristic in that it works toward a utopian culmination of history in which such an ordering will be realized. It is, in short, not the sort of prose any good bourgeois gentleman (or even any good democrat) is likely to admit to speaking. Even on more abstract and theoretical levels, where the concern is more purely conceptual, the notion that the term "ideology" properly applies to the views of those "stiff in opinions, and always in the wrong" does not disappear. In Talcott Parsons's most recent contemplation of Mannheim's Paradox, for example, "deviations from [social scientific objectivity" emerge as the "essential criteria of an ideology": "The problem of ideology arises where there is a discrepancy between what is believed and what can be [established as] scientifically correct."7 The "deviations" and "discrepancies" involved are of two general sorts. First, where social science, shaped as is all thought by the overall values of the society within which it is contained, is selective in the sort of questions it asks, the particular problems it chooses to tackle, and so forth, ideologies are subject to a further, cognitively more pernicious "secondary" selectivity, in that they emphasize some aspects of social reality--that reality, for example, as revealed by current social scientific knowledge--and neglect or even suppress other aspects. "Thus the business ideology, for instance, substantially exaggerates the contribution of businessmen to the national welfare and underplays the contribution of scientists and professional men. And in the current ideology of the 'intellectual,' the importance of social pressures to conformity' is exaggerated and institutional factors in the freedom of the individual are ignored or played down." Second, ideological thought, not content with mere overselectivity, positively distorts even those aspects of social reality it recognizes, distortion that becomes apparent only when the assertions involved are placed against the background of the authoritative findings of social science. "The criterion of distortion is that statements are made about society which by social-scientific methods can be shown to be positively in error, whereas selectivity is; involved where the statements are, at the proper level, 'true,' but do not constitute a balanced account of the available truth." That in the eyes of . the world there is much to choose between being positively in error and rendering an unbalanced account of the available truth seems, however, rather unlikely. Here, too, ideology is a pretty dirty river. Examples need not be multiplied, although they easily could be. Nlore important is the question of what such an egregiously loaded concept is doing among the analytic tools of a social science that, on the basis of a claim to cold-blooded objectivity, advances its theoretical mterpretations as "undistorted" and therefore normative visions of social reality. If the critical power of the social sciences stems from their disinterestedness, is not this power compromised when the analysis of political thought is governed by such a concept, much as the analysis of religious thought would be (and, on occasion, has been) compromised when cast in terms of the study of "superstition"? The analogy is not farfetched. In Raymond Aron's The Opium of the Intellectuals, for example, not only the title--ironically echoic of Marx's bitter iconoclasm--but the entire rhetoric of the argument ("political myths," "the idolatry of history," "churchmen and faithful "secular clericalism," and so forth)8 reminds one of nothing so much as the literature of militant atheist Shils's tack of invoking the extreme pathologies of ideological thought -- Nazism, Bolshevism, or whatever --as its paradigmatic forms is reminiscent of the tradition in which the Inquisition, the personal depravity of Renaissance popes, the savagery of Reformation wars, or the primitiveness of Bible belt fundamentalism Is offered as an archetype of religious belief and behavior. And Parsons's view that ideology is defined by its cognitive insufficiencies vis-a-vis science is perhaps not so distant as it might appear from the Comtean view that religion is characterized by an uncritically figurative conception of reality, which a sober sociology, purged of metaphor, win soon render obsolete: We may wait as long for the "end of ideology" as the positivists have waited for the end of religion. Perhaps it is even not too much to suggest that, as the militant atheism of the Enlightenment and after was a response to the quite genuine horrors of a spectacular outburst of religious bigotry, persecution, and strife (and to a broadened knowledge of the natural world), so the militantly hostile approach to ideology is a similar response to the political holocausts of the past halfcentury (and to a broadened knowledge of the social world). And, if this suggestion is valid, the fate of ideology may also turn out to be similar -- isolation from the mainstream of social thought.9 Nor can the issue be dismissed as merely a semantic one. One is, naturally, free to confine the referent of the term "ideology" to "something shady" if one wishes; and some sort of historical case for doing so can perhaps be made. But if one does so limit it, one cannot then write works on the ideologies of American businessmen, New York "literary" intellectuals, members of the British Medical Association, industrial laborunion leaders, or famous economists and expect either the subjects or interested bystanders to credit them as neutral.'10 Discussions of sociopolitical ideas that indict them ab initio, in terms of the very words used to name them, as deformed or worse, merely beg the questions they pretend to raise. It is also possible, of course, that the term "ideology" should simply be dropped from scientific discourse altogether and left to its polemical fate--as "superstition" in fact has been. But, as there seems to be nothing at the moment with which to replace it and as it is at least partially established in the technical lexicon of the social sciences, it seems more advisable to proceed with the effort to defuse it.11 |

II. 社会科学で現在支配的なイデオロギーの概念が徹底的に評価的な(つまり、軽蔑的な)ものであることは、容易に証明できる。「イデオロギーの研究は、本来の 道筋を逸脱した思考様式を扱うものである」と、ヴェルナー・シュタールは私たちに教えている。「イデオロギー的な思考は...何か怪しげなものであり、克 服し、私たちの心から追放すべきものである。」 それは(まったく)嘘と同じではない。なぜなら、嘘つきは少なくともシニシズムを獲得するが、イデオローグは単なる愚か者のままであるからだ。「両者とも 虚偽に関わるが、嘘つきは他人の考えを改ざんしようとする一方で、自分の個人的な考えは正しい。一方で、彼自身は真実が何であるかをよく理解している。一 方、イデオロギーに陥った人は、自分の個人的な考えを誤解しており、他人を欺く場合でも、不本意かつ無意識のうちにそうしている。」4 マンハイムの信奉者であるスタークは、あらゆる思考形態は物事の本質において社会的に条件付けられているが、イデオロギーにはさらに、憎悪、欲望、不安、 恐怖などの個人的な感情の圧力によって心理的に「変形」(「ゆがむ」、「汚染される」、「偽造される」、「歪曲される」、「曇る」)するという不運な性質 がある、と主張している。知識社会学は、真実の追求と認識における社会的要素、すなわち、真実が必然的に存在論的観点のひとつに限定されることを扱う。し かし、イデオロギーの研究は、まったく異なる分野であるが、知的誤りの原因を扱う。 我々は、思想と信念について説明しようとしてきた。思想と信念は、現実に対して2つの方法で関連している可能性がある。すなわち、現実の事実、または現 実、あるいは現実への反応が生み出す努力のいずれかである。前者の関係が存在する場所では、原則として真実である思考が見出される。後者の関係が存在する 場所では、偶然にのみ真実となりうる考えに直面する。そして、それは偏見によって台無しにされる可能性が高い。この言葉は、可能な限り広い意味で捉えられ る。前者の思考は理論的と呼ぶにふさわしく、後者は傍論的と特徴づけられるべきである。おそらく、前者は合理的、後者は感情的と表現することもできるだろ う。前者は純粋に認識的、後者は評価的である。テオドール・ガイガーの例えを借りれば、社会的事実によって決定づけられた思考は、澄んだ小川のようなもの である。一方、思想は、不純物が流れ込み濁って汚染された汚い川のようなものである。前者は健康に良いので飲むことができるが、後者は避けるべき毒であ る。 これは原始的であるが、「イデオロギー」という用語の参照対象が急進的な知的堕落の一形態に限定されていることは、政治的および科学的議論がはるかに洗練 され、はるかに深く突き刺さるような文脈においても見られる。例えば、エドワード・シールズは「イデオロギーと礼節」に関する画期的な論文の中で、「イデ オロギー的展望」の肖像を描いているが、それはスタークのそれよりもさらに陰鬱なものである。6 「それぞれが唯一無二であると主張する、さまざまな形態で現れる」――イタリアのファシズム、ドイツの国民社会主義、ロシアのボリシェヴィズム フランスおよびイタリアの共産主義、フランス行動党、イギリスのファシスト同盟、「そして、その未熟なアメリカ人の親戚である『マッカーシズム』」が挙げ られる。この見解は、「19世紀から20世紀にかけて、西洋諸国の公共生活を包囲し、侵略した。... 普遍的な支配を達成しようと脅かした。」それは、最も中心的な部分では、「政治は、あらゆる他の考慮事項を上回る、首尾一貫した包括的な信念体系の観点か ら行われるべきである」という前提から成り立っている。それを支える政治と同様に、それは二元論的であり、純粋な「私たち」と邪悪な「彼ら」を対立させ、 「私」に同調しない者は「私」の敵であると宣言する。それは、既存の政治制度を不信し、攻撃し、弱体化させようとするという点で疎外的なものである。政治 的真理の独占的な所有を主張し、妥協を嫌うという点で、それは教条主義的である。社会生活と文化的生活のすべてをその理想のイメージ通りに秩序立てること を目指すという点で、全体主義的である。そのような秩序が実現される歴史のユートピア的な集大成に向けて活動するという点で、未来志向的である。つまり、 それは、良きブルジョワ紳士(あるいは良き民主主義者)が口にするような言葉ではない。 より抽象的で理論的なレベル、つまりより純粋に概念的な関心事においても、「頑固な意見を持ち、常に間違っている」人々の見解に「イデオロギー」という用 語が適切に当てはまるという考え方は消えない。例えば、タルコット・パースンズがマンハイムのパラドックスについて最近考察した中で、「社会科学的な客観 性からの逸脱」が「イデオロギーの本質的な基準」として浮上している。「イデオロギーの問題は、信じられていることと科学的に正しいとされることとの間に 食い違いがある場合に生じる」7。関与する「逸脱」と「食い違い」には、一般的に2つの種類がある。まず、社会科学は、それが含まれる社会全体の価値観に よって形作られるため、問いかける質問の種類、取り組む特定の問題などにおいて選択的になるが、イデオロギーは、社会の現実のいくつかの側面を強調し、他 の側面を無視したり、場合によっては抑圧するという、さらに認知的に有害な「二次的」選択性を帯びる。「例えば、ビジネス思想は、ビジネスマンが国民の福 祉に貢献している度合いを実際以上に誇張し、科学者や専門家の貢献を過小評価する。そして、現在の「知識人」のイデオロギーにおいては、社会的な同調圧力 の重要性が誇張され、個人の自由に関する制度的な要因は無視されたり、軽視されたりしている。」 第二に、イデオロギー的な思考は、単なる選択の偏りだけでは満足せず、認識している社会の現実の側面さえも積極的に歪曲する。この歪曲は、関連する主張が 社会科学の権威ある調査結果を背景に置かれた場合にのみ明らかになる。「歪曲の基準は、社会についてなされた主張が、社会科学的手法によって間違いである ことが証明できる場合である。一方、選択性は、主張が適切なレベルで『真実』であるものの、利用可能な真実のバランスの取れた説明を構成しない場合に含ま れる。」しかし、世界の見方では、間違いであることと、利用可能な真実のバランスの取れていない説明をすることの間には、多くの選択肢があるように思われ る。ここでも、イデオロギーはかなり汚い川である。 例を挙げる必要はないが、簡単に挙げることができる。それよりも重要なのは、このようなひどく偏った概念が、冷酷な客観性を主張し、理論的解釈を「歪みの ない」ものとして、したがって社会現実の規範的なビジョンとして提示する社会科学の分析ツールの中で、どのような役割を果たしているかという問題である。 社会科学の批判力がその無関心さから生じているとすれば、政治思想の分析がそのような概念によって支配されている場合、その批判力は損なわれるのではない か。宗教思想の分析が「迷信」の研究という観点から損なわれることがあるように(そして、時には実際に損なわれているように)。 この類推は的外れではない。例えば、レイモンド・アロン著『知識人のアヘン』では、皮肉にもマルクスの辛辣な偶像破壊主義を想起させるタイトルだけでな く、論旨全体(「政治的迷信」、「歴史の偶像崇拝」、「聖職者と敬虔な信者による世俗的聖職者主義」など)が、8 。ナチズム、ボルシェビズム、その他、イデオロギー思想の極端な病理を典型的な形態として引き合いに出すという、好戦的な無神論者シルズの手法は、宗教的 信念と行動の典型として、異端審問、ルネサンス期の教皇の個人的堕落、宗教改革戦争の残虐性、聖書ベルトの原理主義の原始性といった伝統を想起させる。そ して、科学に対する認識の不十分さによってイデオロギーが定義されるというパーソンズの考え方は、宗教が現実を批判的に考えずに比喩的に捉えるという特徴 を持つというコントの考え方と、それほどかけ離れたものではないかもしれない。宗教は、比喩を排除した冷静な社会学によってすぐに時代遅れになるだろう。 「イデオロギーの終焉」を待つのは、実証主義者が宗教の終焉を待っていたのと同じくらい長い時間になるかもしれない。啓蒙主義以降の過激な無神論が、宗教 的偏見、迫害、争いの大規模な勃発という極めて深刻な恐怖(および自然界に関する知識の拡大)への反応であったように、イデオロギーに対する過激な敵対的 アプローチも、過去半世紀の政治的ホロコースト(および社会世界に関する知識の拡大)への同様の反応であると主張するのは、おそらく行き過ぎではないだろ う。そして、この提案が妥当であるならば、イデオロギーの運命もまた同様である可能性がある。すなわち、社会思想の主流から孤立することである。9 また、この問題を単に意味論的なものとして片付けることもできない。もちろん、必要であれば「イデオロギー」という用語の参照対象を「怪しげなもの」に限 定することは自由である。そして、そうする歴史的な事例もある程度は作れるだろう。しかし、もしそう限定するならば、アメリカのビジネスマン、ニューヨー クの「文学的」知識人、英国医師会の会員、産業労働組合のリーダー、あるいは著名な経済学者のイデオロギーに関する著作を書いたとしても、その主題や 彼らを中立的なものとみなすことを、主題や利害関係者から信用されることを期待することはできない。10 彼らを非難する社会政治的な考えについて、それらを指名するために使われる言葉そのものについて、当初から議論することは、単に彼らが提起しようとしてい る問題を先送りするだけである。もちろん、「イデオロギー」という用語を科学的な議論から完全に排除し、その論争的な運命に委ねることも可能である。実 際、「迷信」という用語はそう扱われてきた。しかし、現時点ではそれに代わる用語は見当たらないし、少なくとも部分的には社会科学の専門用語として定着し ているため、この用語を廃止する努力を続ける方が望ましいと思われる。11 |

| III. As the flaws hidden in a tool show up when it is used, so the intrinsic weaknesses of the evaluative concept of ideology reveal themselves when it is used. In particular, they are exposed in the studies of the social sources and consequences of ideology, for in such studies this concept is coupled to a highly developed engine of social--and personalitysystem analysis whose very power only serves to emphasize the lack of a similar power on the cultural (that is, the symbolsystem) side. In investigations of the social and psychological contexts of ideological thought (or at least the "good" ones), the subtlety with which the contexts are handled points up the awkwardness with which the thought is handled, and a shadow of imprecision is cast over the whole discussion, a shadow that even the most rigorous methodological austerity cannot dispel. There are currently two main approaches to the study of the social determinants of ideology: the interest theory and the strain theory.12 For the first, ideology is a mask and a weapon; for the second, a symptom and a remedy. In the interest theory, ideological pronouncements are seen against the background of a universal struggle for advantage; in the strain theory, against the background of a chronic effort to correct sociopsychological disequilibrium. In the one, men pursue power; in the other, they flee anxiety. As they may, of course, do both at the same time--and even one by means of the other -- the two theories are not necessarily contradictory; but the strain theory (which arose in response to the empirical difficulties encountered by the interest theory), being less simplistic, is more penetrating, less concrete, more comprehensive. The fundamentals of the interest theory are too well known to need review; developed to perfection of a sort by the Marxist tradition, they are now standard intellectual equipment of the man-in-the-street, who is only too aware that in political argumentation it all comes down to whose ox is gored. The great advantage of the interest theory was and is its rooting of cultural idea-systems in the solid ground of social structure, through emphasis on the motivations of those who profess such systems and on the dependence of those motivations in turn upon social position, most especially social class. Further, the interest theory welded political speculation to political combat by pointing out that ideas are weapons and that an excellent way to institutionalize a particular view of reality -- that of one's group, class, or party--is to capture political power and enforce it. These contributions are permanent; and if interest theory has not now the hegemony it once had, it is not so much because it has been proved wrong as because its theoretical apparatus turned out to be too rudimentary to cope with the complexity of the interaction among social, psychological, and cultural factors it itself uncovered. Rather like Newtonian mechanics, it has not been so much displaced by subsequent developments as absorbed into them. The main defects of the interest theory are that its psychology is too anemic and its sociology too--muscular. Lacking a developed analysis of motivation, it has been constantly forced to oscillate between a narrow and superficial utilitarianism that sees men as impelled by rational calculation of their consciously recognized personal advantage and a broader, but no less superficial, historicism that speaks with a studied vagueness of men's ideas as somehow "reflecting," "expressing," "corresponding to," "emerging from," or "conditioned by" their social commitments. Within such a framework, the analyst is faced with the choice of either revealing the thinness of his psychology by being so specific as to be thoroughly implausible or concealing the fact that he does not have any psychological theory at all by being so general as to be truistic. An argument that for professional soldiers "domestic [governmental] policies are important mainly as ways of retaining and enlarging the military establishment [because] that is their business; that is what they are trained for" seems to do scant justice to even so uncomplicated a mind as the military mind is reputed to be; while an argument that American oil men "cannot very well be pure-and-simple oil men" because "their interests are such" that "they are also political men" is as enlightening as the theory (also from the fertile mind of M. Jourdain) that the reason opium puts you to sleep is that it has dormitive powers13 On the other hand, the view that social action is fundamentally an unending struggle for power leads to an unduly Machiavellian view of ideology as a form of higher cunning and, consequently, to a neglect of its broader, less dramatic social functions. The battlefield image of society as a clash of interests thinly disguised as a clash of principles turns attention away from the role that ideologies play in defining (or obscuring) social categories, stabilizing (or upsetting) social expectations. maintaining (or undermining) social norms, strengthening (or weakening) social consensus, relieving (or exacerbating) social tensions. Reducing ideology to a weapon in a guerre de plume gives to its analysis a warming air of militancy, but it also means reducing the intellectual compass within which such analysis may be conducted to the constrictcd realism of tactics and strategy. The intensity of interest theory is --to adapt a figure from Whitehead--but the reward of its narrowness. As "interest," whatever its ambiguities, is at one and the same time a psychological and sociological concept--referring both to a felt advantage of an individual or group of individuals and to the objective structure of opportunity within which an individual or group moves--so also is strain," for it refers both to a state of personal tension and to a condition of societal dislocation. The difference is that with "strain" both the motivational background and the social structural context are more systematically portrayed, as are their relations with one another. It is, in fact, the addition of a developed conception of personality systems (basically Freudian), on the one hand, and of social systems (basically Durkheimian) on the other, and of their modes of interpenetration-- the Parsonian addition--that transforms interest theory into strain theory.14 The clear and distinct idea from which strain theory departs is the chronic malintegration of society. No social arrangement is or can be completely successful in coping with the functional problems it inevitably faces. All are riddled with insoluble antinomies: between liberty and pohtical order, stability and change, efficiency and humanity, precision and flexibility, and so forth. There are discontinuities between norms in different sectors of the society --the economy, the polity, the family, and so on. There are discrepancies between goals within the different sectors -- between the emphases on profit and productivity in business firms or between extending knowledge and disseminating it in universitics. for example. And there are the contradictory role expectations of which so much has been made in recent American sociological literature on the foreman, the working wife, the artist, and the politician. Social friction is as pervasive as is mechanical friction--and as irremovable. Further, this friction or social strain appears on the level of the individual personality--itself an inevitably malintegrated system of conflicting desires, archaic sentiments, and improvised defenses--as psychological strain. What is viewed collectively as structural inconsistency is felt individually as personal insecurity, for it is in the experience of the social actor that the imperfections of society and contradictions of character meet and exacerbate one another. But at the same time, the fact that both society and personality are, whatever their shortcomings, organized systems, rather than mere congeries of institutions or clusters of motives, means that the sociopsychological tensions they induce are also systematic, that the anxieties derived from social interaction have a form and order of their own. In the modern world at least, most men live lives of patterned desperation. Ideological thought is, then, regarded as (one sort of) response to this desperation: "Ideology is a patterned reaction to the patterned strains of a social role."15 It provides a "symbolic outlet" for emotional disturbances generated by social disequilibrium. And as one can assume that such disturbances are, at least in a general way, common to all or most occupants of a given role or social position, so ideological reactions to the disturbances will tend to be similar, a similarity only reinforced by the presumed commonalities in "basic personality structure" among members of a particular culture, class, or occupational category. The model here is not military but medical: An ideology is a malady (Sutton, et al., mention nail-chewing, alcoholism, psychosomatic disorders and "crotchets" among the alternatives to it) and demands a diagnosis. "The concept of strain is not in itself an explanation of ideological patterns but a generalized label for the kinds of factors to look for in working out an explanation."16 But there is more to diagnosis, either medical or sociological, than the identification of pertinent strains; one understands symptoms not merely etiologically but teleologically--in terms of the ways in which they act as mechanisms, however unavailing, for dealing with the disturbances that have generated them. Four main classes of explanation have been most frequently employed: the cathartic, the morale, the solidarity, and the advocatory. By the "cathartic explanation" is meant the venerable safetyvalve or scapegoat theory. Emotional tension is drained off by being displaced onto symbolic enemies ("The Jews," "Big Business," "The Reds," and so forth). The explanation is as simpleminded as the device; but that, by providing legitimate objects of hostility (or, for that matter, of love), ideology may ease somewhat the pain of being a petty bureaucrat, a day laborer, or a small-town storekeeper is undeniable. By the "morale explanation" is meant the ability of an ideology to sustain individuals (or groups) in the face of chronic strain, either by denying it outright or by legitimizing it in terms of higher values. Both the struggling small businessman rehearsing his boundless confidence in the inevitable justness of the American system and the neglected artist attributing his failure to his maintenance of decent standards in a Philistme world are able, by such means, to get on with their work. Ideology bridges the emotional gap between things as they are and as one would have them be, thus insuring the performance of roles that might otherwise be abandoned in despair or apathy. By the "solidarity explanation" is meant the power of ideology to knit a social group or class together. To the extent that it exists, the unity of the labor movement, the business community, or the medical profession obviously rests to a significant degree on common ideological orientation; and the South would not be The South without the existence of popular symbols charged with the emotions of a pervasive social predicament. Finally, by the "advocatory explanation" is meant the action of ideologies (and ideologists) in articulating, however partially and indistinctly, the strains that impel them, thus forcing them into the public notice. "Ideologists state the problems for the larger society, take sides on the issues involved and 'present them in the court' of the ideological market place."17 Although ideological advocates (not altogether unlike their legal counterparts) tend as much to obscure as to clarify the true nature of the problems involved, they at least call attention to their existence and, by polarizmg issues, make continued neglect more difficult. Without Marxist attack, there would have been no labor reform; without Black Nationalists, no deliberate speed. It is here, however, in the investigation of the social and psychological roles of ideology, as distinct from its determinants, that strain theory itself begins to creak and its superior incisiveness, in comparison with interest theory, to evaporate. The increased precision in the location of the springs of ideological concern does not, somehow, carry over into the discrimination of its consequences, where the analysis becomes, on the contrary, slack and ambiguous. The consequences envisaged, no doubt genuine enough in themselves, seem almost adventitious, the accidental byproducts of an essentially nonrational, nearly automatic expressive process initially pointed in another direction --as when a man stubbing his toe cries an involuntary "ouch!" and incidentally vents his anger, signals his distress, and consoles himself with the sound of his own voice; or as when, caught in a subway crush, he issues a spontaneous "damn!" of frustration and, hearing similar oaths from others. gains a certain perverse sense of kinship with fellow sufferers. This defect, of course, can be found in much of the functional analysis in the social sciences: a pattern of behavior shaped by a certain set of forces turns out, by a plausible but nevertheless mysterious coincidence, to serve ends but tenuously related to those forces. A group of primitives sets out, in all honesty, to pray for rain and ends by strengthening its social solidarity; a ward politician sets out to get or remain near the trough and ends by mediating between unassimilated immigrant groups and an impersonal governmental bureaucracy; an ideologist sets out to air his grievances and finds himself contributing, through the diversionary power of his illusions, to the continued viability of the very system that grieves him. The concept of latent function is usually invoked to paper over this anomalous state of affairs, but it rather names the phenomenon (whose reality is not in question) than explains it; and the net result is that functional analyses --and not only those of ideology--remain hopelessly equivocal. The petty bureaucrat's anti-Semitism may indeed give him something to do with the bottled anger generated in him by constant toadying to those he considers his intellectual inferiors and so drain some of it away; but it may also simply increase his anger by providing him with something else about which to be impotently bitter. The neglected artist may better bear his popular failure by invoking the classical canons of his art; but such an invocation may so dramatize for him the gap between the possibilities of his environment and the demands of his vision as to make the game seem unworth the candle. Commonality of ideological perception may link men together, but it may also provide them, as the history of Marxian sectarianism demonstrates, with a vocabulary by means of which to explore more exquisitely the differences among them. The clash of ideologists may bring a social problem to public attention, but it may also charge it with such passion that any possibility of dealing with it rationally is precluded. Of all these possibilities, strain theorists are, of course, very well aware. Indeed they tend to stress negative outcomes and possibilities rather more than the positive, and they but rarely think of ideology as more than a faute de mieux stopgap--like nailchewing. But the main point is that, for all its subtlety in ferreting out the motives of ideological concern, strain theory's analysis of the consequences of such concern remains crude, vacillatory, and evasive. Diagnostically it is convincing; functionally it is not. The reason for this weakness is the virtual absence in strain theory (or in interest theory either) of anything more than the most rudimentary conception of the processes of symbolic formulation. There is a good deal of talk about emotions "finding a symbolic outlet" or "becoming attached to appropriate symbols" -- but very little idea of how ffi the trick is really done. The link between the causes of ideology and its | effects seems adventitious because the connecting element--the autono| mous process of symbolic formulation--is passed over in virtual silence. Both interest theory and strain theory go directly from source analysis to consequence analysis without ever seriously examining ideologies as systems of interacting symbols, as patterns of interworking meanings. Themes are outlined, of course; among the content analysts, they are even counted. But they are referred for elucidation, not to other themes nor to any sort of semantic theory, but either backward to the effect they presumably mirror or forward to the social reality they presumably distort. The problem of how, after all, ideologies transform sentiment into significance and so make it socially available is short-circuited by the crude device of placing particular symbols and particular strains (or interests) side by side in such a way that the fact that the first are derivatives of the second seems mere common sense--or at least post-Freudian, post-Marxian common sense. And so, if the analyst be deft enough, it does.18 The connection is not thereby explained but merely educed. The nature of the relationship between the sociopsychological stresses that incite ideological attitudes and the elaborate symbolic structures through which those attitudes are given a public existencc is much too complicated to be comprehended in terms of a vague and unexamined notion of emotive resonance. |

III. 道具に隠された欠陥が使用される際に明らかになるように、評価的な観念としてのイデオロギーの本質的な弱点も、それが使用される際に明らかになる。特に、 イデオロギーの社会的源泉と結果の研究において、それらは露呈する。なぜなら、そのような研究では、この概念は高度に発達した社会分析および性格分析のエ ンジンと結びついているが、そのエンジンが持つ力は、文化(すなわち、記号体系)の側における同様の力の欠如を強調するだけだからである。イデオロギー思 想の社会的・心理的背景(少なくとも「良い」もの)を調査する際、その背景が扱われる際の繊細さによって、その思想が扱われる際のぎこちなさが浮き彫りに なり、議論全体に不正確さの影が投げかけられる。その影は、最も厳格な方法論的厳格さをもってしても払拭することはできない。 イデオロギーの社会的決定要因の研究には現在、主に2つのアプローチがある。関心理論と緊張理論である。12 前者は、イデオロギーを仮面と武器と見なし、後者は、症状と治療法と見なす。関心理論では、イデオロギー的宣言は、普遍的な優位性獲得競争を背景として見 られる。緊張理論では、社会心理的不均衡を是正しようとする慢性的努力を背景として見られる。一方では、人間は権力を追い求め、他方では不安から逃れよう とする。もちろん、同時に両方を行うことも、一方を他方の手段として行うこともあり得るが、この2つの理論は必ずしも矛盾するものではない。しかし、緊張 理論(これは利害理論が経験的に直面する困難に対応して生まれたもの)は、より単純化されておらず、より洞察力に富み、より具体的ではなく、より包括的で ある。 利害理論の基礎は周知の事実であり、再検討する必要はない。マルクス主義の伝統によってある種の完成度にまで発展したこの理論は、今では一般市民の標準的 な知的装備となっている。一般市民は、政治的な議論においては、すべてが「どちらの牛が角で突かれたか」という問題に帰着することをよく理解している。利 害理論の大きな利点は、そのシステムを信奉する人々の動機や、その動機が社会的な地位、特に社会階級に依存していることを強調することで、文化的な思想体 系を社会構造という確固たる基盤に根付かせたことである。さらに、利益理論は、思想は武器であり、特定の現実の捉え方(自分のグループ、階級、政党のそ れ)を制度化する優れた方法とは、政治権力を掌握し、それを強制することであると指摘することで、政治的思索と政治闘争を結びつけた。これらの貢献は永続 的なものであり、もしも関心理論がかつての覇権を現在も保持していないとすれば、それはその理論が誤りであることが証明されたからというよりも、その理論 的装置が、関心理論自身が明らかにした社会的、心理学的、文化的な要因の相互作用の複雑さに対処するにはあまりにも初歩的すぎることが判明したからであ る。むしろニュートン力学のように、関心理論はそれ以降の進展によって駆逐されたというよりも、それらに吸収されたのである。 関心理論の主な欠点は、その心理学が貧弱すぎ、社会学が強すぎることである。動機に関する発展した分析を欠いているため、人間を意識的に認識された個人的 利益の合理的な計算によって動かされていると見る狭く表面的な功利主義と、人間の考え方を「反映」、「表現」、「対応」、「発生」、あるいは「条件付け」 するものとして、わざと曖昧に語るより広範だが、これまた表面的な歴史主義との間で、常に揺れ動かざるを得なかった。そのような枠組みの中で、分析者は、 あまりにも特定しすぎてまったくありそうもないものにしてしまうことで、その人物の心理の薄っぺらさを明らかにするか、あまりにも一般化しすぎてありふれ たものにしてしまうことで、その人物が心理理論をまったく持っていないという事実を隠蔽するか、という選択に直面する。職業軍人にとって「国内政策は、軍 事組織を維持し拡大する方法として重要である。なぜなら、それが彼らの仕事であり、そのために訓練されているからだ」という主張は、軍人の心はそれほど単 純ではないにもかかわらず、その心に正当な評価を与えていないように思われる。一方、「 アメリカの石油業界の人間は「純粋な石油業界の人間であるはずがない」という主張は、「彼らの利益がそうだから」であり、「彼らは政治的な人間でもある」 という主張は、アヘンが人を眠らせるのは、それが催眠作用を持つからだという理論(これもM. Jourdainの豊かな発想から生まれたもの)と同様に、啓発的である。 一方、社会運動とは本質的に終わりのない権力闘争であるという見方は、イデオロギーを高度な策略の一形態とみなす行き過ぎたマキャベリズム的な見方につな がり、その結果、より広範で劇的ではない社会機能が軽視されることになる。社会を、利益の衝突を理念の衝突と見せかけた戦場と見なすことは、イデオロギー が社会的カテゴリーの定義(または曖昧化)、社会的期待の安定化(または混乱)、社会的規範の維持(または弱体化)、社会的合意の強化(または弱体化)、 社会的緊張の緩和(または悪化)において果たす役割から目を背けさせる。イデオロギーを「筆による戦争」における武器に還元することは、その分析に好戦的 な雰囲気を与えるが、同時に、そのような分析が実施される知的コンパスを、戦術と戦略の狭いリアリズムに還元することでもある。関心理論の強度は、ホワイ トヘッドの言葉を借りれば、その狭さの報酬である。 「利害」は、その曖昧さに関わらず、同時に心理学的および社会学的な概念である。すなわち、個人または個人の集団が感じる優位性と、その個人または集団が 動く機会の客観的構造の両方を指す。「緊張」も同様である。なぜなら、それは個人の緊張状態と社会的な混乱状態の両方を指すからだ。違いは、「緊張」では 動機づけの背景と社会構造の文脈の両方がより体系的に描かれ、両者の関係も描かれていることである。実際、パーソンズ理論の追加によって、関心理論は緊張 理論へと変化する。14 緊張理論の出発点となる明確かつ明瞭な考えは、社会の慢性的な機能不全である。社会のあらゆる仕組みは、必然的に直面する機能上の問題に対処する上で、完 全に成功しているわけではないし、また、完全に成功することはありえない。自由と政治的秩序、安定と変化、効率性と人間性、正確性と柔軟性など、あらゆる ものに解決不能な二律背反が存在する。社会の異なる分野、すなわち経済、政治、家族などにおける規範の間には不連続性がある。異なる分野における目標の間 にも相違がある。例えば、企業における利益や生産性の重視、あるいは大学における知識の拡大と普及などである。そして、最近アメリカ社会学の文献で多く取 り上げられている、監督者、働く妻、芸術家、政治家などに対する矛盾した役割期待もある。社会的摩擦は機械的摩擦と同じくらい広範囲に広がっており、取り 除くことができない。 さらに、この摩擦や社会的緊張は、個人の人格レベルで現れる。人格自体が、相反する欲求、古風な感情、即興的な防御という、必然的に統合不良を起こすシス テムである。構造的不整合として総体的に捉えられるものは、個々人にとっては個人的な不安として感じられる。なぜなら、社会の不完全さと性格の矛盾がぶつ かり合い、互いに悪化するのは、社会的な行動者の経験においてだからである。しかし同時に、社会も個性も、その欠点が何であれ、単なる制度の集合体や動機 の集まりではなく、組織化されたシステムであるという事実がある。つまり、社会心理的な緊張は体系的なものであり、社会的な相互作用から生じる不安には独 自の形と秩序があるということである。少なくとも現代社会では、ほとんどの人は型にはまった絶望的な生活を送っている。 したがって、イデオロギー思想は、この絶望に対する反応(の一種)とみなされる。「イデオロギーとは、社会的な役割の型にはまった緊張に対する型にはまっ た反応である。」15 イデオロギーは、社会的不均衡によって生じる感情的な混乱に対して「象徴的な出口」を提供する。そして、こうした障害は少なくとも一般的な意味では、特定 の役割や社会的地位にある人々のすべてまたはほとんどに共通していると想定できるため、障害に対するイデオロギー的な反応も同様のものになる傾向がある。 この類似性は、特定の文化、階級、職業カテゴリーに属する人々の「基本的な性格構造」に共通性があるという想定によって、さらに強調される。ここでモデル となるのは軍事ではなく医学である。イデオロギーとは病である(Sutton らは、その代替案として、爪を噛む、アルコール依存症、心身症、そして「クローチェット」を挙げている)。そして、診断を必要とする。「緊張の概念は、そ れ自体がイデオロギーのパターンを説明するものではなく、説明を導き出すために探す要因の種類を一般化したラベルである。」16 しかし、医学的であれ社会学的であれ、診断には関連する緊張の特定以上のものがある。人は症状を単に病因論的にではなく、目的論的に理解する。つまり、そ れらが、たとえ役に立たないとしても、それらを生み出した障害に対処するためのメカニズムとして作用する方法という観点から理解する。最も頻繁に用いられ てきた説明は、主に4つのカテゴリーに分類される。すなわち、浄化、モラル、連帯、提唱である。「下剤的説明」とは、由緒ある安全弁理論またはスケープ ゴート理論を意味する。感情的な緊張は、象徴的な敵(「ユダヤ人」、「大企業」、「赤」など)に転嫁されることによって解消される。この説明は、その手法 と同様に単純である。しかし、敵意の正当な対象(あるいは愛情の対象)を提供することで、イデオロギーが、小役人や日雇い労働者、あるいは小さな町の店主 の苦痛をいくらか和らげる可能性があることは否定できない。「士気に関する説明」とは、イデオロギーが慢性的なストレスに直面する個人(または集団)を支 える能力を意味する。それは、ストレスを全面的に否定するか、より高い価値観の観点からそれを正当化することによってである。アメリカというシステムの必 然的な正しさを信じて疑わない小規模事業主も、俗世の中でまともな基準を維持しようとして挫折した芸術家も、そうした手段によって仕事を続けることができ る。イデオロギーは、あるがままのものとそうあってほしいものとの間の感情的なギャップを埋める。それによって、さもなければ絶望や無気力によって放棄さ れてしまうかもしれない役割の遂行が保証される。「連帯の説明」とは、イデオロギーが社会集団や階級を結びつける力を意味する。労働運動、企業、医療業界 などの団結は、その存在の程度において、明らかに共通のイデオロギー的志向に大きく依存している。また、広範な社会的な苦境の感情を担う大衆的なシンボル が存在しなければ、南部は南部ではなくなってしまうだろう。最後に、「擁護的説明」とは、イデオロギー(およびイデオローグ)が、部分的であれ不明瞭であ れ、それらを推進する要因を明確に表現する行為を意味し、それによってそれらを公に認知せざるを得ない状況に追い込む。「イデオローグは、より大きな社会 の問題を提起し、関連する問題について立場を明らかにし、イデオロギー市場という『法廷』にそれを提示する」17。イデオロギーの擁護者(法律上の擁護者 とまったく同じではないが)は、問題の真の性質を明らかにするのと同じくらい、それを不明瞭にする傾向があるが、少なくともその存在に注意を喚起し、問題 を二極化することで、継続的な無視をより困難にしている。マルクス主義者の攻撃がなければ労働改革は起こらなかっただろうし、ブラック・ナショナリストが いなければ意図的なスピードは実現しなかっただろう。 しかし、決定要因とは異なるイデオロギーの社会的および心理的役割の調査において、緊張理論そのものが軋み始め、利害理論と比較してその優れた洞察力が消 え失せる。イデオロギー的関心の源泉の特定精度が向上しても、その帰結の識別には何らかの形でそれが反映されるわけではなく、むしろ分析は緩慢で曖昧なも のとなる。想定される帰結は、それ自体は疑いなく十分に本物であるが、ほとんど偶発的であり、本質的に非理性的でほぼ自動的な表現プロセスの副産物である ように思われる。このプロセスは、当初は別の方向を向いていた。例えば、つま先をぶつけて思わず「痛っ!」と叫び、ついでに怒りをぶちまけ、 苦痛を訴え、自分の声の響きに自らを慰める。あるいは、地下鉄の押しつぶされそうになる混雑に巻き込まれたとき、自発的に「ちくしょう!」と不満を口に し、他の人々からも同じような悪態を耳にする。そして、苦痛を共有する人々との間に、ある種の歪んだ親近感を覚える。 もちろん、この欠陥は社会科学における機能分析の多くに見られる。ある特定の力によって形作られた行動パターンが、もっともらしいが不可解な偶然によっ て、その力とはほとんど関係のない目的を果たすことになる。原始人の一団が、正直に雨乞いをしようとして、結局は社会的な連帯感を強めることになる。区の 政治家が、権力の近くに行こうとして、あるいは権力の近くに留まろうとして、結局は未同化移民グループと非人格的な政府官僚機構との仲介役を担うことにな る。イデオローグが、自分の不満を訴えようとして、幻想の転換力によって、自分自身が、自分を悩ませているまさにそのシステムの存続に貢献していることに 気づく。 潜在機能という概念は、通常、この異常な状態を覆い隠すために持ち出されるが、それは現象を説明するのではなく、現象を名指すだけである(その現実性は疑 いの余地がない)。そして、最終的な結果は、機能分析(イデオロギーの機能分析に限らない)が絶望的に曖昧なままであるということだ。小役人の反ユダヤ主 義は、彼が知的劣等者とみなす人々に対して常にへつらうことで彼の中にたまった怒りを何かにぶつけることができ、その怒りの一部を解消できるかもしれな い。しかし、それは単に、彼に無力な苦々しさを感じる別の対象を与えることで、彼の怒りを増大させるだけかもしれない。無視された芸術家は、自身の芸術に おける古典的な規範を引用することで、自身の人気喪失をよりうまく耐えることができるかもしれない。しかし、そのような引用は、自身の環境の可能性と自身 のビジョンが求めるものとの間のギャップを、その芸術家にとって劇的に強調し、そのゲームがろうそくの火に似て価値がないと思わせるかもしれない。イデオ ロギーの認識における共通性は、人々を結びつけるかもしれないが、同時に、マルクス主義の宗派主義の歴史が示すように、人々の間の相違をより繊細に探求す るための語彙をも提供するかもしれない。イデオロギー論者の衝突は、社会問題を人々の注意に訴えるかもしれないが、同時に、その問題に情熱を注ぎ込み、理 性的に対処する可能性を排除してしまうかもしれない。これらの可能性について、もちろん、緊張理論の論者はよく理解している。実際、彼らは肯定的なものよ りも否定的な結果や可能性を強調する傾向があり、イデオロギーを一時しのぎの策以上のものとして考えることはほとんどない。しかし、重要なのは、イデオロ ギー的関心の動機を突き止めるための繊細な手法とは裏腹に、その関心の結果に対するストレイン理論の分析は粗野で、不安定で、回避的であるということだ。 診断としては説得力があるが、機能的にはそうではない。 この弱点の理由は、緊張理論(あるいは利害理論でも)には、象徴的定式化のプロセスに関する最も初歩的な概念以上のものがほとんど見られないことにある。 感情が「象徴的な出口を見つける」とか「適切な象徴に結びつく」といった話はたくさんあるが、そのトリックが実際にどのように行われるのかについての考え はほとんどない。イデオロギーの原因と影響の間のつながりは、その結合要素である象徴的定式化の自律的プロセスがほとんど無視されているため、偶発的なも ののように思われる。関心理論も緊張理論も、相互作用する象徴の体系、相互に作用する意味のパターンとしてイデオロギーを真剣に検討することなく、原因分 析から結果分析へと直接進む。テーマは、もちろん概説される。内容分析家の間では、テーマの数が数えられることさえある。しかし、それらは解明のために参 照されるのであって、他のテーマや意味論の類に参照されるわけではない。参照されるのは、おそらく反映しているであろう影響を遡って、あるいはおそらく歪 めているであろう社会的現実を前方に参照するのである。結局のところ、イデオロギーが感情を意義へと変え、社会的に利用可能にする方法の問題は、特定のシ ンボルと特定の系統(または利害)を並置するという粗野な手法によって回避される。その手法では、前者が後者の派生物であるという事実が、単なる常識であ るかのように見える。少なくとも、フロイトやマルクス以降の常識であるかのように見える。したがって、分析者が十分に巧妙であれば、そのように見える。 18 そのつながりは説明されているわけではなく、単に導き出されているだけである。イデオロギー的態度を煽り立てる社会心理的ストレスと、そうした態度に公的 な存在意義を与える精巧な象徴構造との関係性は、感情的な共鳴という漠然とした未検証の概念で理解するにはあまりにも複雑である。 |

| IV. It is of singular interest in this connection that, although the general stream of social scientific theory has been deeply influenced by almost every major intellectual movement of the last century and a half-- Marxism, Darwinism, Utilitarianism, Idealism, Freudianism, Behaviorism, Positivism, Operationalism--and has attempted to capitalize on virtually every important field of methodological innovation from ecology, ethology, and comparative psychology to game theory, cybernetics, and statistics, it has, with very few exceptions, been virtually untouched by one of the most important trends in recent thought: the effort to construct an independent science of what Kenneth Burke has called "symbolic action." 19 Neither the work of such philosophers as Peirce, Wittgenstein, Cassirer, Langer, Ryle, or Morris nor of such literary critics as Coleridge, Eliot, Burke, Empson, Blackmur, Brooks, or Auerbach seems to have had any appreciable impact on the general pattern of social scientific analysis.20 Aside from a few more venturesome (and largely programmatic) linguists--a Whorf or a Sapir-- the question of how symbols symbolize, how they function to mediate meanings has simply been bypassed. 'The embarrassing fact," the physician cum novelist Walker Percy has written, "is that there does not exist today-- a natural empirical science of symbolic behavior as such.... Sapir's gentle chiding about the lack of a science of symbolic behavior and the need of such a science is more conspicuously true today than it was thirty-five years ago."21 It is the absence of such a theory and in particular the absence of any analytical framework within which to deal with figurative language that have reduced sociologists to viewing ideologies as elaborate cries of pain. With no notion of how metaphor, analogy, irony, ambiguity, pun, paradox, hyperbole, rhythm, and all the other elements of what we Iamely call "style" operate -- even, in a majority --of cases, with no recognition that these devices are of any importance in casting personal attitudes into public form, sociologists lack the symbolic resources out of which to construct a more incisive formulation. At the same time that the arts have been establishing the cognitive power of "distortion" and philosophy has been undermining the adequacy of an emotivist theory of meaning, social scientists have been rejecting the first and embracing the second. It is not therefore surprising that they evade the problem of construing the import of ideological assertions by simply failing to recognize it as a problem.22 In order to make explicit what I mean, let me take an example that is, I hope, so thoroughly trivial in itself as both to still any suspicions that I have a hidden concern with the substance of the political issue involved and, more important, to bring home the point that concepts developed for the analysis of the more elevated aspects of culture--poetry, for example--are applicable to the more lowly ones without in any way blurring the enormous qualitative distinctions between the two. In discussing the cognitive inadequacies by which ideology is defined for them, Sutton et al. use as an example of the ideologist's tendency to "oversimplify" the denomination by organized labor of the Taft-Hartley Act as a "slave labor law": Ideology tends to be simple and clear-cut. even where its simplicity and clarity do less than justice to the subject under discussion. The ideological picture uses sharp lines and contrasting blacks and whites. The ideologist exaggerates and caricatures in the fashion of the cartoonist. In contrast, a scientific description of social phenomena is likely to be fuzzy and indistinct. [n recent labor ideology the Taft-Hartley Act has been a "slave labor act." By no dispassionate examination does the Act merit this label. Any detached assessment of the Act would have to consider its many provisions individually. On any set of values, even those of trade unions themselves, such an assessment would yield a mixed verdict. But mixed verdicts are not the stuff of ideology. They are too complicated, too fuzzy. Ideology must categorize the Act as a whole with a symbol to rally workers, voters and legislators to action.23 Leaving aside the merely empirical question of whether or not it is in fact true that ideological formulations of a given set of social phenomena are inevitably "simpler" than scientific formulations of the same phenomena, there is in this argument a curiously depreciatory--one might even say "oversimple"--view of the thought processes of laborunion leaders on the one hand and "workers, voters and legislators" on the other. It is rather hard to believe that either those who coined and disseminated the slogan themselves believed or expected anyone else to believe that the law would actually reduce (or was intended to reduce) the American worker to the status of a slave or that the segment of the public for whom the slogan had meaning perceived it in any such terms. Yet it is precisely this flattened view of other people's mentalities that leaves the sociologist with only two interpretations, both inadequate, of whatever effectiveness the symbol has: either it deceives the uninformed (according to interest theory), or it excites the unreflective (according to strain theory). That it might in fact draw its power from its capacity to grasp, formulate, and communicate social realities that elude the tempered language of science, that it may mediate more complex meanings than its literal reading suggests, is not even considered. "Slave labor act" may be, after all, not a label but a trope. More exactly, it appears to be a metaphor or at least an attempted metaphor. Although very few social scientists seem to have read much of it, the literature on metaphor--"the power whereby language, even with a small vocabulary, manages to embrace a multimillion things"-- is vast and by now in reasonable agreements.24 In metaphor one has, of course, a stratification of meaning, in which an incongruity of sense on one level produces an influx of significance on another. As Percy has pointed out, the feature of metaphor that has most troubled philosophers (and, he might have added, scientists) is that it is "wrong": "It asserts of one thing that it is something else." And, worse yet, it tends to be most effective when most "wrong."25 The power of a metaphor derives precisely from the interplay between the discordant meanings it symbolically coerces into a unitary conceptual framework and from the degree to which that coercion is successful in overcoming the psychic resistance such semantic tension inevitably generates in anyone in a po8: sition to perceive it. When it works, a metaphor transforms a false identification (for example, of the labor policies of the Republican Party and of those of the Bolsheviks) into an apt analogy; when it misfires, it is a mere extravagance. That for most people the "slave labor law" figure was, in fact, pretty: much a misfire (and therefore never served with any effectiveness as "a symbol to rally workers, voters and legislators to action") seems evident enough, and it is this failure, rather than its supposed clear-cut simplicity, that makes it seem no more than a cartoon. The semantic tension between the image of a conservative Congress outlawing the closed shop and of the prison camps of Siberia was--apparently--too great to be resolved into a single conception, at least by means of so rudimentary a stylistic device as the slogan. Except (perhaps) for a few enthusiasts, the analogy did not appear; the false identification remained false. But failure is not inevitable, even on such an elementary level. Although, a most unmixed verdict, Sherman's "War is hell" is no social-science proposition, even Sutton and his associates would probably not regard it as either an exaggeration or a caricature. More important, however, than any assessment of the adequacy of the two tropes as such is the fact that, as the meanings they attempt to spark against one another are after all socially rooted, the success or failure of the attempt is relative not only to the power of the stylistic mechanisms employed but also to precisely those sorts of factors upon which strain theory concentrates its attention. The tensions of the Cold War, the fears of a labor movement only recently emerged from a bitter struggle for existence, and the threatened eclipse of New Deal liberalism after two decades of dominance set the sociopsychological stage both for the appearance of the "slave labor" figure and--when it proved unable to work them into a cogent analogy--for its miscarriage The militarists of 1934 Japan who opened their pamphlet on Basic Theory Or National Defense and Suggestions for Its Strengthening with the resounding familial metaphor, "War is the father of creation and the mother of culture," would no doubt have found Sherman's maxim as unconvincing as he would have found theirs.26 They were energetically preparing for an imperialist war in an ancient nation seeking its footing in the modern world; he was wearily pursuing a civil war in an unrealized nation torn by domestic hatreds. It is thus not truth that varies with social, psychological, and cultural contexts but the symbols we construct in our unequally effective attempts to grasp it. War is hell and not the mother of culture, as the Japanese eventually discovered--although no doubt they express the fact in a grander idiom. The sociology of knowledge ought to be called the sociology of meaning, for what is socially determined is not the nature of conception but the vehicles of conception. In a community that drinks its coffee blacks Henle remarks, to praise a girl with "You're the cream in my coffee would give entirely the wrong impression; and, if omnivorousness were regarded as a more significant characteristic of bears than their clumsy roughness, to call a man "an old bear" might mean not that he was crude, but that he had catholic tastes.27 Or, to take an example from Burke, since in Japan people smile on mentioning the death of a dose friend, the semantic equivalent (behaviorally as well as verbally) into American English is not "He smiled," but "His face fell"; for, with such a rendering, we are "translating the accepted social usage of Japan into the corresponding accepted social usage of the West."28 And. closer to the ideological realm, Sapir has pointed out that the chairmanship of a committee has the figurative force we give it only because we hold that "administrative functions somehow stamp a person as superior to those who are being directed"; "should people come to feel that administrative functions are little more than symbolic automatism th. chairmanship of a committee would be recognized as little more than a petrified symbol and the particular value that is now felt to inhere in it would tend to disappear."29 The case is no different for "slave labor law." If forced labor camps come, for whatever reasons, to play a lesprominent role in the American image of the Soviet Union, it will not be the symbol's veracity that has dissolved but its very meaning, its capacity to be either true or false. One must simply frame the argument--that the Taft-Hartley Act is a mortal threat to organized labor--in some other way. In short, between an ideological figure like "slave labor act" and the social realities of American life in the midst of which it appears, there exists a subtlety of interplay, which concepts like "distortion," "selectivity," or "oversimplification" are simply incompetent to formulated Not only is the semantic structure of the figure a good deal more complex than it appears on the surface, but an analysis of that structure forces one into tracing a multiplicity of referential connections between it and social reality, so that the final picture is one of a configuration of dissimilar meanings out of whose interworking both the expressive power and the rhetorical force of the final symbol derive. This interworking is itself a social process, an occurrence not "in the head" but in that public world where "people talk together, name things, make assertions, and to a degree understand each other."31 The study of symbolic action is no less a sociological discipline than the study of small groups, bureaucracies, or the changing role of the American woman; it is only a good deal less developed. |

IV. この点において特筆すべきは、社会科学理論の一般的な流れは、過去1世紀半のほぼすべての主要な知的運動――マルクス主義、ダーウィニズム、功利主義、観 念論、フロイト主義、行動主義、実証主義、操作主義――に深く影響を受け、 生態学、動物行動学、比較心理学からゲーム理論、サイバネティクス、統計学に至るまで、方法論の革新におけるほぼすべての重要な分野を活用しようとしてき たが、ごく一部の例外を除いて、最近の思想における最も重要な傾向のひとつである、ケネス・バークが「象徴的行為」と呼ぶものの独立した科学を構築する試 みには、ほとんど手をつけていない。19 ピアス、ウィトゲンシュタイン、カッシーラー、ランガー、ライル、モリスといった哲学者の業績も、コールリッジ、エリオット、バーク、エンプソン、ブラッ クマー、ブルックス、オーエブリーといった文学評論家の業績も、 社会科学的分析の一般的なパターンに著しい影響を与えた人物はいない。20 ウォーフやサピアのような、より大胆な(そしてほとんどがプログラム的な)言語学者を除いては、記号がどのように記号化するか、意味を媒介する機能として どのように機能するかという問題は、単純に回避されてきた。医師であり小説家でもあるウォーカー・パーシーは、「恥ずべき事実」として、「今日、記号行動 に関する自然な経験科学は存在しない」と書いている。記号行動の科学が存在しないこと、そしてそのような科学が必要であることについて、サピアが優しく叱 責していることは、35年前よりも今日の方がより顕著に真実である。」21 このような理論の欠如、特に比喩的な言語を扱うための分析的枠組みの欠如が、社会学者をイデオロギーを痛切な叫び声として捉えるように追いやってきた。た とえ大半のケースにおいて、比喩、類推、皮肉、曖昧性、ダジャレ、逆説、誇張、リズム、そして私が「スタイル」と呼ぶものの他のすべての要素がどのように 作用するのかについての概念がなく、また、これらの手法が個人の態度を公的な形に定着させる上で重要であるという認識がないために、社会学者は、より鋭い 定式化を構築するための象徴的なリソースを欠いている。芸術が「歪曲」の認知力を確立し、哲学が感情論的な意味論の妥当性を損なってきたのと同時に、社会 科学者は前者を拒絶し、後者を受け入れてきた。したがって、彼らがイデオロギー的主張の含意を解釈するという問題を、単にそれを問題として認識しないこと によって回避しているとしても、驚くには当たらない。 私が言わんとすることを明確にするために、私は、私が政治問題の本質について隠された関心を持っているのではないかという疑いを晴らすと同時に、より重要 なこととして、文化のより高尚な側面(例えば詩)の分析のために開発された概念が、より卑しいものにも適用可能であり、両者の間に存在する質的な大きな違 いをぼやかせることは一切ないという点を理解してもらうために、完全に些細な例を挙げてみようと思う。サットンらは、イデオロギーが認知上の不十分さに よって定義されることを論じる中で、労働組合による「タフト・ハートレー法」を「奴隷労働法」として「単純化しすぎる」イデオロギー論者の傾向を例として 挙げている。 イデオロギーは単純かつ明確である傾向がある。その単純性や明瞭性が、議論の対象に対して正当な評価を下していない場合でもである。イデオロギー的な描写 は、鋭い線と黒と白のコントラストを使用する。イデオロギー論者は、漫画家の手法で誇張や風刺を行う。それに対して、社会現象の科学的描写は、あいまいか つ不明瞭である傾向がある。最近の労働イデオロギーでは、タフト・ハートレー法は「奴隷労働法」である。この法律がこのレッテルに値するかどうかは、冷静 な検討によっては判断できない。この法律を客観的に評価するには、その多くの規定を個別に検討しなければならない。どのような価値観に照らしても、労働組 合自身でさえ、そのような評価は賛否両論となるだろう。しかし、賛否両論はイデオロギーの対象ではない。それはあまりにも複雑で、あいまいすぎる。イデオ ロギーは、労働者、有権者、議員を結集して行動を起こさせるシンボルとともに、この法律全体を分類しなければならない。 特定の社会現象をイデオロギー的に定式化することは、同じ現象を科学的に定式化するよりも「より単純」であるということが実際に真実であるかどうかとい う、単に経験的な問題はさておき、この議論には、労働組合のリーダーと「労働者、有権者、議員」の思考プロセスに対する、奇妙なほどに否定的な見方、ある いは「単純すぎる」とさえ言える見方がある。このスローガンを考案し広めた人々が、法律が実際にアメリカの労働者を奴隷の地位にまで引き下げる(あるいは 引き下げる意図がある)と信じていた、あるいは他の誰かが信じることを期待していたとは、なかなか信じがたい。また、このスローガンが意味を持つ人々も、 それをそのような言葉で捉えていたとは思えない。しかし、他者の心理をこのように単純化して見ることこそが、そのシンボルが持つ効果について、社会学者が 2つの不適切な解釈しか持てない原因となっている。すなわち、無知な人々を欺く(利害理論による)か、思慮のない人々を刺激する(緊張理論による)か、の どちらかである。実際には、科学の洗練された言語では捉えきれない社会の現実を把握し、体系化し、伝達する能力からその力が引き出されている可能性がある こと、また、その文字通りの意味よりも複雑な意味合いを媒介している可能性があることについては、まったく考慮されていない。「奴隷労働行為」は、結局の ところ、レッテルではなく修辞法であるのかもしれない。 より正確に言えば、それは比喩であるか、少なくとも比喩の試みであるように見える。社会科学者のほとんどがこの文献をあまり読んだことがないようだが、比 喩に関する文献は膨大であり、今では妥当な合意が得られている。24 比喩には、もちろん、意味の層がある。あるレベルでの意味の不調和が、別のレベルでの意義の流入を生み出す。パーシーが指摘しているように、哲学者(そし て、彼が付け加えるなら科学者)を最も悩ませてきた比喩の特徴は、「誤り」である。「あるものを、それとは別のものだと主張する」ということである。さら に悪いことに、比喩は最も「間違っている」場合に最も効果的になる傾向がある。25 比喩の力は、まさに、比喩が象徴的に単一の概念的枠組みに無理やり押し込める不調和な意味の相互作用と、その強制が、比喩を認知する立場にある誰もが必然 的に生み出す意味論的な緊張から生じる心理的抵抗を克服する上で成功する度合いから生じる。うまく機能すれば、隠喩は誤った同一視(例えば、共和党の労働 政策とボルシェビキの労働政策の同一視)を適切な類似性に変える。しかし、誤った場合には、単なる贅沢に過ぎない。 ほとんどの人々にとって、「奴隷労働法」という表現は、実際にはかなり見当はずれであった(したがって、「労働者、有権者、議員を行動に駆り立てるシンボ ル」として有効に機能することは決してなかった)ことは明らかである。そして、この失敗こそが、その明快な単純性という想定よりも、この表現を単なる漫画 のように見せているのだ。クローズドショップを違法とする保守的な議会とシベリアの強制収容所のイメージの間の意味論的な緊張は、少なくともスローガンと いう初歩的なスタイルの手法では、ひとつの概念に解決するにはあまりにも大きすぎた。熱狂的な一部の人々を除いて、その類似性は見出されなかった。誤った 同一視は誤ったままであった。しかし、このような初歩的なレベルにおいても、失敗は避けられないわけではない。 純粋な評決を下すならば、シャーマンの「戦争は地獄だ」は社会科学的な命題ではないが、サットンや彼の仲間たちも、おそらくそれを誇張や風刺とは見なさな いだろう。 しかし、この2つの表現の適切さの評価よりも重要なのは、これらの表現が互いに呼び起こそうとする意味が結局は社会的に根ざしているという事実であり、そ の試みの成否は、用いられた表現上のメカニズムの力だけでなく、まさに緊張理論が注目するそれらの要因にも相対的なものとなる。冷戦の緊張、苦しい生存競 争からようやく脱した労働運動の不安、そして20年にわたって支配的であったニューディール自由主義が失墜の危機に瀕していたことが、社会心理的な舞台を 整え、「奴隷労働」という概念の登場を促した。そして、その概念が説得力のある類推として機能しないことが明らかになると、その概念は頓挫した。1934 年の日本の軍国主義者たちは、 あるいは国防とその強化に関する提言』というパンフレットを「戦争は創造の父であり、文化の母である」という衝撃的な家族的な比喩で開いた1934年の日 本の軍国主義者たちは、シャーマンの格言を自分たちのものと同じくらい説得力のないものと感じたに違いない。26 彼らは、近代世界での足場を模索する古代の国家で帝国主義戦争に精力的に備えていた。一方、彼は、国内の憎悪に引き裂かれた未開の国家で、内戦を疲れ果て て追っていた。したがって、真実が社会、心理、文化の文脈によって変化するのではなく、真実を把握しようとする私たちの不均等な試みの中で構築されるシン ボルこそが変化するのだ。戦争は地獄であり、文化の母ではない。日本人は最終的にこの事実を発見したが、彼らは間違いなく、この事実をより壮大なイディオ ムで表現するだろう。 社会的に決定されるのは概念の本質ではなく、概念の手段であるため、知識社会学は意味社会学と呼ぶべきである。コーヒーをブラックで飲むようなコミュニ ティでは、ヘンレは「君は僕のコーヒーのクリームだ」と褒めるのはまったく間違った印象を与えると述べている。また、雑食性が熊の不器用な粗野さよりも重 要な特徴であるとみなされる場合、「年取った熊」という表現は、その人が粗野であるという意味ではなく、趣味が幅広いという意味になるかもしれない。27 あるいは、バークの例を挙げると、 日本では友人の死を聞いて人々が微笑むことから、アメリカ英語における意味上の同等物(行動上および言語上)は「He smiled(彼は微笑んだ)」ではなく「His face fell(彼の顔が曇った)」となる。なぜなら、このような表現では「日本の社会で受け入れられている慣習を、西洋の社会で受け入れられている慣習に翻訳 している」ことになるからだ。28 そして、イデオロギーの領域により近いところで、サピアは、委員会の委員長という役職が比喩的な力をもつのは、 「管理機能が、管理される人々よりも優れた人物であることを何らかの形で刻印する」という考え方があるからこそ、私たちは委員会の議長職に比喩的な力を与 えている。「もし人々が管理機能が象徴的な自動的なものにすぎないと考えるようになった場合、委員会の議長職は単なる象徴の固まりとして認識され、今では そこに内在すると感じられている特別な価値は消え去る傾向にあるだろう」29。「奴隷労働法」の場合も事情は変わらない。強制労働収容所が、どのような理 由であれ、ソ連に対するアメリカのイメージの中でより目立つ役割を果たすようになった場合、そのシンボルの真実性が失われるのではなく、その意味、つまり 真実であるか偽りであるかの能力が失われることになるだろう。タフト・ハートレー法は組織労働者にとって致命的な脅威であるという主張を、別の方法で展開 しなければならない。 つまり、「奴隷労働法」のような観念的な概念と、それが現れるアメリカ社会の現実との間には、微妙な相互作用が存在する。「歪曲」、「選択」、「単純化」 といった概念では、それを表現することはできない。この概念の持つ意味構造は 表面的に見えるよりもはるかに複雑であるだけでなく、その構造の分析は、その象徴と社会的現実との間の参照関係の多様性をたどることを余儀なくさせる。そ の結果、最終的な象徴の表現力と修辞力は、その相互作用から生じる異質な意味の構成の1つとなる。この相互作用自体が社会的プロセスであり、それは「頭の 中」ではなく、「人々が共に話し、物事を名指し、主張し、ある程度お互いを理解する」31公共の世界で起こるものである。象徴的行為の研究は、小集団、官 僚制、あるいはアメリカ女性の役割の変化の研究に劣らず社会学的な分野である。しかし、その発展度はかなり劣る。 |