メタモルフォシスとアナモルフォシス

Between metamorphosis and Anamorphosis

人間以外の事物・動物を、人間界に包摂しようとする 擬人化に対して、人間そのものが、事物や動物になろうとする発想ないしは哲 学という ものがある。先に挙げた、擬猫化/擬犬化が、それである。ここではそれを擬動物化(Theriomorphism, animalization)と 呼ん でおこう――これらの造語は私のオリジナルである。擬動物化はかれらの形態を模倣ないしは同一化ということからなりたつので、人間が動物に変化した後には 人間語の使用はそれほどみられない。現在のところ、私たちが知っている擬動物化の技法は、変身=変態(metamorphosis)と異種扮装 (anamorphosis)である。言い換えると、変身=変態は「メタモルフォシス」であり、異種扮装は「アナモルフォシス」である。変態=メタモル フォシスは身体が変形して元の身体とは別の身体に組織編成することであるのに対して、後者の異種扮装=アナモルフォシスには、例えば人間が コスプレで虎になるのだと称して、虎縞の毛皮のビキニを着て、つけ鼻をつけ、鼻の横に髭を描けば、それは立派な異種扮装になる。ちなみに、完全に変態した り、異種扮装でも変身が完璧になれば、もはやそれは動物の擬態ではなく、動物そのものになることは言うまでもない。

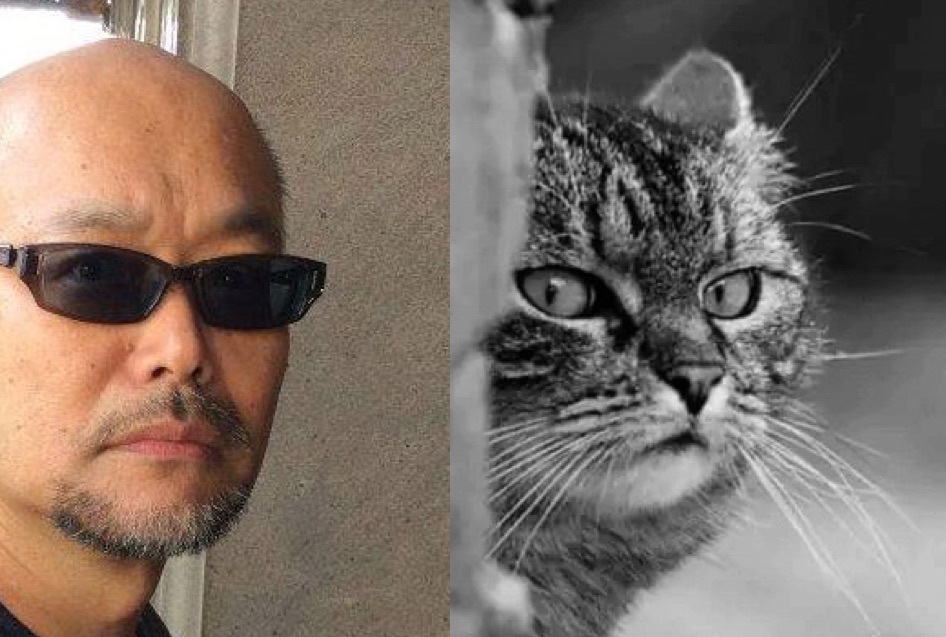

人間がアナモルフォシスを試みる理由は様々である。 まず、鹿を生け捕りにする猟師が鹿に変身することを想起してみよう。実際の例である。カサス・グランデスのこの老狩猟師は動物の衣装を身 に纏った時に、どれだけアンテロープの「気分」になっている(=まさに変心)してるのだろうか?カール・ロムホルツ(1902)『知られざるメキシコ』か らの記述である。

The plains of San Diego used to swarm with antelopes, and even at the time of my visit herds of them could be seen now and then. One old hunter near Casas Grandes resorted to an ingenious device for decoying them. He disguised himself as an antelope, by means of a cloak of cotton cloth (manta) painted to resemble the colouring of the animal. This covered his body, arms, and legs. On his head he placed the antlers of a stag, and by creeping on all fours he could approach the antelopes quite closely and thus successfully shoot them. The Apaches, according to the Mexicans, were experts at hunting antelopes in this manner.(p.84)- Unknown Mexico, Carl Lumholtz (1902).

サンディエゴの平原にはかつてアンテロープが群れを

なしており、私が訪れた当時も、時折その群れを見ることができた。カサス・グランデス近郊のある老猟師は、カモシカをおびき寄せるために巧妙な工夫をし

た。カモシカの色に似せた綿布(マンタ)のマントで、カモシカに変装したのだ。胴体、腕、脚を覆っている。四つん這いになってアンテロープに近づくと、う

まく撃つことができた。メキシコ人によれば、アパッチ(族)はこの方法でアンテロープを狩る専門家であったという。

それに添えられた写真である。キャプションにはこう書かれてある:A DEER disguised by old deer hunter of San Diego - Unknown Mexico, Carl Lumholtz(1902)

▲▲右の図像は、良源=

元三大師と角大師(『天明改正 元三大師御鬮繪抄』1785年仙鶴堂発行、であるが、元三大師(諡号:慈恵大師)観音の化身とも言われており、観音はあら

ゆる衆生を救うために33の姿に化身する。また、2本の角を持ち骨と皮とに痩せさらばえた夜叉の像を表したものと、眉毛が角のように伸びたものの2つの表

象化されている。『元三大師縁起』によると、良源が夜叉の姿に化しているのは、疫病

神そのものになったわけでなく、本物の疫病神になったわけでなく(中身

は大師のまま)本物の疫病を追い払った時の像であるという。最後は、The Transfigured Christ (1513)

by Andrea

Previtali.

▲▲▲右の最後の絵画は、アンドレア・プレヴィタリ の作品で、キリストの処刑・埋葬後の復活を意味するが、絵画の表題は『姿を変えるキリスト』とある。キリストは生前生きたままの姿として弟子たちの前にあ らわれるが、そのことは誰も気がつかなかった。なぜなら、キリストの死とその骸(むくろ)の崩壊を、キリストの使徒たちは疑っていなかったからだ。正確に 言えば、使徒を含めて、誰もキリストが生前の姿をとどめて「復活」することなど信じなかった。それゆえに、キリストの復活のテーマは、聖母マリアの処女懐 胎のように、非現実的でシュールレアリズム的なものとしてしか、現世の我々は「解釈」する他はないのである。したがって、この場合の『姿を変えるキリス ト』は、後の信徒たちが「そうなったらいいな」という希望的願望であり、多くのキリスト教会は、常識では考えられない処女懐胎とキリストの復活を、みずか らの信条告白(=パフォーマティブな言語行為)として受け入れている。

★アナモルフォシス、例えば、アマゾンのシャーマン が、裸体に黒い複数の●を描きこんでジャガーと一体化するのに、我々それを未開で原始的なものだと思えるだろうか。我々は、中に人がいるだろうが、獅子舞 の獅子に子供のあたまを齧らせて我が子の健勝を祈らないだろうか。もっと卑近でユニークな例がある。アマゾンやユニクロの潜入取材で、秀逸なルポルター ジュを書いた横田増生氏は、ユニクロに潜入取材を行っている最中に、職場での制服化しているユニクロの服を着たいと思わなかった。それは、取材先のユニク ロのブラックさを暴きたいという取材魂から着ている。しかし、そんな彼も心を変える。ブラックさを客体化するではなく、ユニクロの企業文化を生きるとはど のようなものかと、考え直した時である。次の横田氏の発言はとても示唆に富む。

「当初、私はユニクロで働くときだけ、ユニクロの商 品を着るようにし、それ以外は、絶対に着るもんかと思っていた。しかし、働いている間中、ユニクロを私服としてきるのはおもしろい、とすぐに思い直した。 働くだけでなく、消費者の視点からもユニクロという企業を見ることができると考え方からだ」(横田 2017:71)

それに対する、バイト先の店長の様子はこうだったという:(/は改行)「翌日、布袋店長は私 が前日買った服を着ているのを見て、/『うん、似合う、似合う』とご満悦の様子」( ibid.)

衣装を着るという人間のアナモルフォシスが、その着

る人の内的アイデンティティ(inner identity)の外部表象(outer

representation)として機能したり、文化人類学(民族誌学)の調査のように、対象民族や文化(=この場合はユニクロ・カルチャー)と

同一化することを通した「さらなるステップ」へと進むことを示している。

| Metamorphosis is a

biological process by which an animal physically develops including

birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and

relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell

growth and differentiation.[1] Some insects, fish, amphibians,

mollusks, crustaceans, cnidarians, echinoderms, and tunicates undergo

metamorphosis, which is often accompanied by a change of nutrition

source or behavior.[2] Animals can be divided into species that undergo

complete metamorphosis ("holometaboly"), incomplete metamorphosis

("hemimetaboly"), or no metamorphosis ("ametaboly").[3] Scientific usage of the term is technically precise, and it is not applied to general aspects of cell growth, including rapid growth spurts. Generally organisms with a larval stage undergo metamorphosis, and during metamorphosis the organism loses larval characteristics. [4] References to "metamorphosis" in mammals are imprecise and only colloquial, but historically idealist ideas of transformation and morphology, as in Goethe's Metamorphosis of Plants, have influenced the development of ideas of evolution. |

変態(へんたい、英:

metamorphosis)とは、動物が物理的に成長する生物学的プロセスのことで、出生時の変化や孵化を含み、細胞の成長と分化によって動物の身体構

造が顕著かつ比較的急激に変化することをいう。

[1]昆虫、魚、両生類、軟体動物、甲殻類、刺胞動物、棘皮動物、被殻動物などの一部が変態し、栄養源や行動の変化を伴うことが多い[2]

動物は、完全変態(「holometaboly」)をする種、不完全変態(「hemimetaboly」)、変態しない(「ameraboly」)に分け

ることができる[3] 。 この用語の科学的な使用は技術的に正確であり、急成長を含む細胞成長の一般的な側面には適用されない。一般に幼生期のある生物は変態し、変態の過程で幼生 期の特徴を失っていく。[哺乳類における「変態」への言及は不正確で口語的なものに過ぎないが、ゲーテの『植物の変態』のように、歴史的に変態や形態に関 する理想主義の考え方は、進化に関する考え方の発展に影響を与えたと言える。 |

| Etymology The word metamorphosis derives from Ancient Greek μεταμόρφωσις, "transformation, transforming",[5] from μετα- (meta-), "after" and μορφή (morphe), "form".[6] |

語源について メタモルフォーゼの語源は、古代ギリシャ語のμεταμόρφωσις「変容、変形」であり、μετα-(meta-)の「後」とμορφή (morphe)の「形」に由来する[5]。 |

| Hormonal control In insects, growth and metamorphosis are controlled by hormones synthesized by endocrine glands near the front of the body (anterior). Neurosecretory cells in an insect's brain secrete a hormone, the prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) that activates prothoracic glands, which secrete a second hormone, usually ecdysone (an ecdysteroid), that induces ecdysis (shedding of the exoskeleton).[7] PTTH also stimulates the corpora allata, a retrocerebral organ, to produce juvenile hormone, which prevents the development of adult characteristics during ecdysis. In holometabolous insects, molts between larval instars have a high level of juvenile hormone, the moult to the pupal stage has a low level of juvenile hormone, and the final, or imaginal, molt has no juvenile hormone present at all.[8] Experiments on firebugs have shown how juvenile hormone can affect the number of nymph instar stages in hemimetabolous insects.[9][10] Metamorphosis is iodothyronine-induced and an ancestral feature of all chordates.[11] |

ホルモンの制御 昆虫の成長や変態は、体の前方にある内分泌腺で合成されるホルモンによって制御されている。昆虫の脳の神経分泌細胞は、前胸腺を活性化する前胸腺刺激ホル モン(PTTH)を分泌し、前胸腺は第二のホルモン、通常はエクジソン(エクジステロイド)を分泌し、脱皮(外骨格の脱落)を誘導する[7]。PTTH は、後頭部器官のアラタ体も刺激してジュビナイルホルモンを分泌し、脱皮中に大人の特徴が発達しないよう促す。半翅目昆虫では、幼虫期の脱皮は幼若ホルモ ンが多く、蛹期への脱皮は幼若ホルモンが少なく、最後の脱皮(想像脱皮)は幼若ホルモンが全くない[8]。ヒグラシを使った実験では、半翅目昆虫のニンフ 期の数に幼若ホルモンがいかに影響するかが示されています[9][10]。 変態はヨードサイロニンによって誘導され、すべての脊索動物の祖先的特徴である[11]。 |

| Insects All three categories of metamorphosis can be found in the diversity of insects, including no metamorphosis ("ametaboly"), incomplete or partial metamorphosis ("hemimetaboly"), and complete metamorphosis ("holometaboly"). While ametabolous insects show very little difference between larval and adult forms (also known as "direct development"), both hemimetabolous and holometabolous insects have significant morphological and behavioral differences between larval and adult forms, the most significant being the inclusion, in holometabolus organisms, of a pupal or resting stage between the larval and adult forms. |

昆虫 昆虫の変態には、変態しないもの(「アメトーーク」)、不完全・部分変態(「ヘミメタボ」)、完全変態(「ホロメタボ」)の3種類があり、いずれも多様性 がある。アメフラシは幼虫と成虫の間にほとんど差がない(「直接発生」ともいう)のに対し、ヘミメタボとホロメタボは幼虫と成虫の間に形態的・行動的に大 きな差があり、ホロメタボでは幼虫と成虫の間に蛹期や休息期を持つことが最も重要である。 |

| Development and terminology In hemimetabolous insects, immature stages are called nymphs. Development proceeds in repeated stages of growth and ecdysis (moulting); these stages are called instars. The juvenile forms closely resemble adults, but are smaller and lack adult features such as wings and genitalia. The size and morphological differences between nymphs in different instars are small, often just differences in body proportions and the number of segments; in later instars, external wing buds form. The period from one molt to the next is called a stadium.[12] In holometabolous insects, immature stages are called larvae and differ markedly from adults. Insects which undergo holometabolism pass through a larval stage, then enter an inactive state called pupa (called a "chrysalis" in butterfly species), and finally emerge as adults.[13] |

展開と用語 半変態の昆虫では、未熟な段階をニンフと呼びます。成長期と脱皮期を繰り返しながら発達し、その段階を「齢」という。幼虫は成虫によく似ているが、小さ く、翅や生殖器などの成虫の特徴もない。幼虫の大きさや形態的な違いは小さく、体の比率や節数の違いだけであることが多く、幼虫の後半には外翅芽が形成さ れる。ある脱皮から次の脱皮までの期間をスタミナと呼ぶ[12]。 ホロメタボリックな昆虫では、未熟な段階は幼虫と呼ばれ、成虫とは顕著に異なる。ホロメタボリズムをとる昆虫は、幼虫期を経て、蛹(蝶の仲間では「さな ぎ」と呼ばれる)と呼ばれる不活性状態になり、最後に成虫として出てくる[13]。 |

| Evolution The earliest insect forms showed direct development (ametabolism), and the evolution of metamorphosis in insects is thought to have fuelled their dramatic radiation (1,2). Some early ametabolous "true insects" are still present today, such as bristletails and silverfish. Hemimetabolous insects include cockroaches, grasshoppers, dragonflies, and true bugs. Phylogenetically, all insects in the Pterygota undergo a marked change in form, texture and physical appearance from immature stage to adult. These insects either have hemimetabolous development, and undergo an incomplete or partial metamorphosis, or holometabolous development, which undergo a complete metamorphosis, including a pupal or resting stage between the larval and adult forms.[14] A number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the evolution of holometaboly from hemimetaboly, mostly centering on whether or not the intermediate stages of hemimetabolous forms are homologous in origin to the pupal stage of holometabolous forms. |

進化 昆虫の初期形態は直接発生(アメトーーク)であり、昆虫の変態進化が昆虫の飛躍的な成長を促したと考えられている(1,2)。初期のアメフラシを持つ「真 正昆虫」の中には、現在でもブリキムシやシルバーフィッシュのようなものが存在する。ヘミメタボリックな昆虫には、ゴキブリ、バッタ、トンボ、真性昆虫な どがいる。系統的には、翼手類に属するすべての昆虫は、未熟な段階から成虫になるまで、形態や質感、体裁が著しく変化する。これらの昆虫は、半代謝性発達 で不完全または部分的な変態をするか、全代謝性発達で幼虫と成虫の間の蛹または休息期を含む完全な変態をするかである[14]。 ヘミメタボリックからホロメタボリックへの進化を説明するために多くの仮説が提案されているが、その多くは、ヘミメタボリックの中間段階がホロメタボリッ クの蛹の段階と相同な起源であるかどうかが中心である。 |

| Recent research According to research from 2008, adult Manduca sexta is able to retain behavior learned as a caterpillar.[16] Another caterpillar, the ornate moth caterpillar, is able to carry toxins that it acquires from its diet through metamorphosis and into adulthood, where the toxins still serve for protection against predators.[17] Many observations published in 2002, and supported in 2013 indicate that programmed cell death plays a considerable role during physiological processes of multicellular organisms, particularly during embryogenesis, and metamorphosis.[18][19] Additional research in 2019 found that both autophagy and apoptosis, the two ways programmed cell death occur, are processes undergone during insect metamorphosis. [20] Below is the sequence of steps in the metamorphosis of the butterfly (illustrated): Metamorphosis of butterfly (PSF) 1 – The larva of a butterfly 2 – The pupa is now spewing the thread to form chrysalis 3 – The chrysalis is fully formed 4 – Adult butterfly coming out of the chrysalis |

最近の研究 2008年の研究によると、マンドゥカ・セクスタの成虫は、イモムシのときに学んだ行動を保持することができる[16]。別のイモムシ、オナガイモムシ は、食事から得た毒素を変態を経て成虫まで運ぶことができ、毒素は捕食者から守るためにまだ役立つ[17]。 2002年に発表され、2013年に支持された多くの観察結果は、プログラムされた細胞死が多細胞生物の生理的過程、特に胚形成と変態の間にかなりの役割 を果たすことを示している[18][19] 2019年の追加研究により、プログラムされた細胞死を起こす二つの方法であるオートファジーとアポトーシスは両方とも、昆虫の変態中に受ける過程である ことがわかった。[20] 以下は、蝶の変態の一連の流れです(図解): 蝶の変態(PSF) 1 - 蝶の幼虫 2 - 蛹が糸を吐いて蛹を形成する段階 3 - さなぎが完全に形成される 4 - 成虫が蛹から出てくるところ |

| Chordata Amphioxus In cephalochordata, metamorphosis is iodothyronine-induced and it could be an ancestral feature of all chordates.[11] Fish Some fish, both bony fish (Osteichthyes) and jawless fish (Agnatha), undergo metamorphosis. Fish metamorphosis is typically under strong control by the thyroid hormone.[21] Examples among the non-bony fish include the lamprey. Among the bony fish, mechanisms are varied. The salmon is diadromous, meaning that it changes from a freshwater to a saltwater lifestyle. Many species of flatfish begin their life bilaterally symmetrical, with an eye on either side of the body; but one eye moves to join the other side of the fish – which becomes the upper side – in the adult form. The European eel has a number of metamorphoses, from the larval stage to the leptocephalus stage, then a quick metamorphosis to glass eel at the edge of the continental shelf (eight days for the Japanese eel), two months at the border of fresh and salt water where the glass eel undergoes a quick metamorphosis into elver, then a long stage of growth followed by a more gradual metamorphosis to the migrating phase. In the pre-adult freshwater stage, the eel also has phenotypic plasticity because fish-eating eels develop very wide mandibles, making the head look blunt. Leptocephali are common, occurring in all Elopomorpha (tarpon- and eel-like fish). Most other bony fish undergo metamorphosis initially from egg to immotile larvae known as sac fry (fry with a yolk sac), then to motile larvae (often known as fingerlings due to them roughly reaching the length of a human finger) that have to forage for themselves after the yolk sac resorbs, and then to the juvenile stage where the fish progressively start to resemble adult morphology and behaviors until finally reaching sexual maturity.[22][23] |

脊索動物門 両生類 頭索動物では、変態はヨードサイロニンによって誘導され、それはすべての脊索動物の祖先の特徴である可能性がある[11]。 魚類 魚類の中には、骨魚類(Osteichthyes)と無顎類(Agnatha)の両方が変態をするものがある。魚類の変態は、一般的に甲状腺ホルモンによ る強い制御下にある[21]。 非骨魚類の例としては、ヤツメウナギが挙げられる。硬骨魚類では、その仕組みはさまざまである。 サケはディアドロマス性で、淡水から海水へと生活様式を変えることを意味する。 ヒラメの多くの種は、最初は体の左右に目がある左右対称の生活をしているが、成魚になると片方の目が移動して反対側(上側となる)に合流する。 ヨーロッパウナギは、幼生期からレプトセファルス期、大陸棚の端でシラスウナギに素早く変態し(ニホンウナギは8日間)、淡水と海水の境界で2ヶ月、シラ スウナギがエルバーに素早く変態し、その後長い成長期を経てより緩やかに変態し移動する段階と、多くの変態を繰り返している。成体前の淡水期では、魚食性 のウナギは大あごが非常に広くなり、頭部が鈍重に見えるため、表現型の可塑性も持っています。レプトセファリは一般的で、すべてのElopomorpha (タウナギやウナギに似た魚)で発生する。 他のほとんどの骨魚は、卵からサックフライ(卵黄嚢を持つ稚魚)と呼ばれる不動性の幼生に始まり、卵黄嚢が吸収された後に自給自足しなければならない運動 性の幼生(人間の指の長さに達することからフィンガーリングと呼ばれることが多い)、そして徐々に大人の形態や行動に似てくる幼生期へと変態を遂げ、最後 に性成熟に至ります [22] [23] 。 |

| Amphibians In typical amphibian development, eggs are laid in water and larvae are adapted to an aquatic lifestyle. Frogs, toads, and newts all hatch from the eggs as larvae with external gills but it will take some time for the amphibians to interact outside with pulmonary respiration. Afterwards, newt larvae start a predatory lifestyle, while tadpoles mostly scrape food off surfaces with their horny tooth ridges. Metamorphosis in amphibians is regulated by thyroxin concentration in the blood, which stimulates metamorphosis, and prolactin, which counteracts its effect. Specific events are dependent on threshold values for different tissues. Because most embryonic development is outside the parental body, development is subject to many adaptations due to specific ecological circumstances. For this reason tadpoles can have horny ridges for teeth, whiskers, and fins. They also make use of the lateral line organ. After metamorphosis, these organs become redundant and will be resorbed by controlled cell death, called apoptosis. The amount of adaptation to specific ecological circumstances is remarkable, with many discoveries still being made. Frogs and toads With frogs and toads, the external gills of the newly hatched tadpole are covered with a gill sac after a few days, and lungs are quickly formed. Front legs are formed under the gill sac, and hindlegs are visible a few days later. Following that there is usually a longer stage during which the tadpole lives off a vegetarian diet. Tadpoles use a relatively long, spiral‐shaped gut to digest that diet. Recent studies suggest tadpoles don't have a balanced homeostatic feedback control system until the beginning stages of metamorphosis. At this point, their long gut shortens and begins favoring the diet of insects.[24] Rapid changes in the body can then be observed as the lifestyle of the frog changes completely. The spiral‐shaped mouth with horny tooth ridges is resorbed together with the spiral gut. The animal develops a big jaw, and its gills disappear along with its gill sac. Eyes and legs grow quickly, a tongue is formed, and all this is accompanied by associated changes in the neural networks (development of stereoscopic vision, loss of the lateral line system, etc.) All this can happen in about a day, so it is truly a metamorphosis. It is not until a few days later that the tail is reabsorbed, due to the higher thyroxin concentrations required for tail resorption. |

両生類 典型的な両生類の発生では、卵は水中に産み落とされ、幼虫は水中での生活に適応するようになります。カエル、ヒキガエル、イモリはすべて外鰓を持つ幼生と して卵から孵化しますが、両生類が肺呼吸で外界と交流するようになるまでにはしばらく時間がかかります。その後、イモリの幼虫は捕食生活を始め、オタマ ジャクシは主に角質のある歯の隆起で表面から食べ物を削り取る。 両生類の変態は、変態を促す血中チロキシン濃度と、その効果を打ち消すプロラクチンによって制御されている。具体的な事象は、各組織の閾値に依存する。胚 の発達のほとんどは親の体外で行われるため、発達は特定の生態的状況による多くの適応を受ける。このため、オタマジャクシは歯、ヒゲ、ヒレのための角質の 隆起を持つことができる。また、側線器官を利用することもある。変態後、これらの器官は冗長になり、アポトーシスと呼ばれる制御された細胞死によって吸収 される。特定の生態環境に適応する量の多さには目を見張るものがあり、今も多くの発見がなされている。 カエルとヒキガエル カエルやヒキガエルでは、孵化したばかりのオタマジャクシの外側のエラは、数日後に鰓嚢で覆われ、肺が急速に形成されます。前足は鰓嚢の下で形成され、数 日後には後脚が見えるようになる。その後、オタマジャクシが菜食で生活する期間が長くなるのが普通である。オタマジャクシは、比較的長い螺旋状の腸を使っ て食事を消化する。最近の研究では、オタマジャクシは変態の初期段階まで、バランスのとれた恒常性フィードバック制御システムを持っていないことが示唆さ れています。この時点で、長い腸が短くなり、昆虫の食事を好むようになる[24]。 その後、カエルのライフスタイルが完全に変化するにつれて、体の急激な変化が観察されます。角質の歯の隆起がある螺旋状の口は、螺旋状の腸と一緒に吸収さ れる。大きな顎ができ、鰓嚢(えらのう)と共に鰓が消失する。目や足が急速に成長し、舌が形成され、それに伴う神経ネットワークの変化(立体視の発達、側 線システムの喪失など)が起こる。尾の再吸収に必要なチロキシン濃度が高くなるため、尾が再吸収されるのは数日後である。 |

| Salamanders Salamander development is highly diverse; some species go through a dramatic reorganization when transitioning from aquatic larvae to terrestrial adults, while others, such as the axolotl, display pedomorphosis and never develop into terrestrial adults. Within the genus Ambystoma, species have evolved to be pedomorphic several times, and pedomorphosis and complete development can both occur in some species.[21] Newts In newts, metamorphosis occurs due to the change in habitat, not a change in diet, because newt larvae already feed as predators and continue doing so as adults. Newts' gills are never covered by a gill sac and will be resorbed only just before the animal leaves the water. Adults can move faster on land than in water.[25] Newts often have an aquatic phase in spring and summer, and a land phase in winter. For adaptation to a water phase, prolactin is the required hormone, and for adaptation to the land phase, thyroxin. External gills do not return in subsequent aquatic phases because these are completely absorbed upon leaving the water for the first time. Caecilians Basal caecilians such as Ichthyophis go through a metamorphosis in which aquatic larva transition into fossorial adults, which involves a loss of the lateral line.[26] More recently diverged caecilians (the Teresomata) do not undergo an ontogenetic niche shift of this sort and are in general fossorial throughout their lives. Thus, most caecilians do not undergo an anuran-like metamorphosis.[27] |

サンショウウオ類 サンショウウオの発生は非常に多様で、水棲の幼生から陸棲の成体に移行する際に劇的な再編成を行う種もあれば、アキアカネなどのように変態を示し、陸棲の 成体に移行しないものもある。アンビストマ属では、種が何度も変態進化しており、種によっては変態と完全発達の両方が起こることがある[21]。 イモリ イモリの場合、イモリの幼虫はすでに捕食者として餌を食べ、成体になってもそれを続けるため、変態は食性の変化ではなく、生息環境の変化により起こる。イ モリのエラは鰓嚢に覆われることはなく、水から離れる直前にのみ再吸収される。成虫は水中よりも陸上の方が速く移動できる[25]。イモリは春から夏にか けて水棲期を、冬には陸棲期を持つことが多い。水相への適応にはプロラクチンが、陸相への適応にはサイロキシンが必要なホルモンである。外鰓は、初めて水 から出たときに完全に吸収されるため、その後の水棲期には戻ってこない。 アシナガバチ類 イクチオフィスなどの基部型アシナガバチは、水棲幼虫から化石成虫に移行する変態を行い、側線は失われる[26]が、最近分岐したアシナガバチ(テレソマ タ)は、この種の先天性ニッチシフトを行わず、生涯を通じて化石であることが一般的。したがって、ほとんどのアシナガバチは無尾類のような変態をしない [27]。 |

| Developmental biology – Study of

how organisms develop and grow Direct development – Growth to adulthood without metamorphosis Gosner stage – System of describing stages of development in anurans Hypermetamorphosis – High variability forms of complete metamorphosis Morphogenesis – Biological process that causes an organism to develop its shape |

発生生物学 - 生物がどのように発生し、成長するかを研究する。 直接発生 - 変態せずに成体まで成長すること。 ゴスナー期 -無尾類の発生段階を記述するシステム 超変態 - 完全変態の高変態形態。 形態形成 - 生物がその形を形成する生物学的プロセス |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metamorphosis |

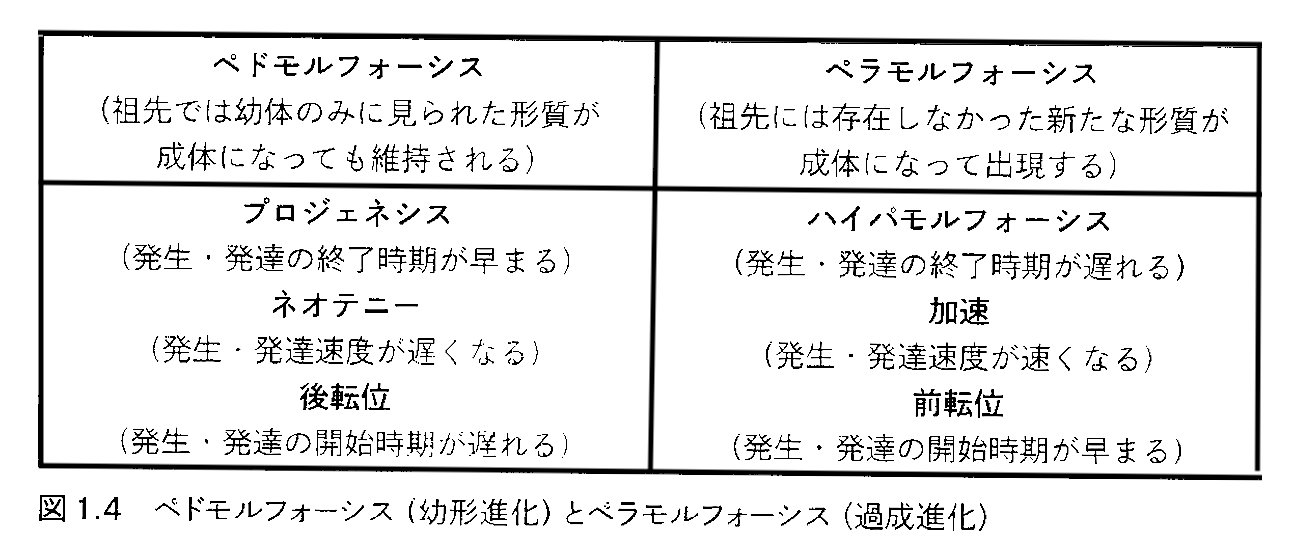

出典:家畜化という進化 : 人間はいかに動物を変えたか / リチャード・C・フランシス著 ; 西尾香苗訳, 白揚社 , 2019, p.32

★フランツ・カフカ「メタモルフォシス」

| The Metamorphosis

(German: Die Verwandlung), also translated as The Transformation,[2] is

a novella by Franz Kafka published in 1915. One of Kafka's best-known

works, The Metamorphosis tells the story of salesman Gregor Samsa, who

wakes to find himself inexplicably transformed into a huge insect

(German: ungeheueres Ungeziefer, lit. "monstrous vermin") and struggles

to adjust to this condition, as does his family. The novella has been

widely discussed among literary critics, who have offered varied

interpretations. In popular culture and adaptations of the novella, the

insect is commonly depicted as a cockroach. About 70 printed pages, it is the longest of the stories Kafka considered complete and published during his lifetime. It was first published in 1915 in the October issue of the journal Die weißen Blätter under the editorship of René Schickele. The first edition in book form appeared in December 1915 in the series Der jüngste Tag, edited by Kurt Wolff.[3] |

『変身』(ドイツ語: Die

Verwandlung)は、フランツ・カフカが1915年に発表した中編小説である。カフカを代表する作品の一つで、行商人グレゴール・ザムザが目を覚

ますと、不可解なことに巨大な虫(ドイツ語: ungeheueres

Ungeziefer、直訳すると「巨大な害虫」)へと変身していることに気づく物語である。彼自身も家族もこの状態に適応しようと苦闘する。この小説は

文学批評家の間で広く議論され、様々な解釈がなされてきた。大衆文化や小説の翻案においても、この虫は「巨大な害虫」として描かれ、主人公とその家族がこ

の状態に適応しようと苦闘する様子が描かれている。「巨大な害虫」)に変身したことに気づき、この状態に適応しようと苦闘する様子と、家族がそれに直面す

る様子を描いている。この短編小説は文学批評家の間で広く議論され、様々な解釈がなされてきた。ポピュラー・カルチャーやこの作品の翻案では、昆虫は一般

的にゴキブリとして描かれることが多い。 約70ページに及ぶこの作品は、カフカが生前に完成させ出版した作品の中で最長である。1915年10月、レネ・シッケレ編集の雑誌『白い葉』に初めて掲載された。単行本としての初版は1915年12月、クルト・ヴォルフ編集のシリーズ『最後の審判』で刊行された。 |

| Plot Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a "monstrous vermin". He initially considers the transformation to be temporary and slowly ponders the consequences of his metamorphosis. Stuck on his back and unable to get up and leave the bed, Gregor reflects on his job as a traveling salesman and cloth merchant, which he characterizes as being "plagued with ... the always changing, never enduring human exchanges that don't ever become intimate".[4] He sees his employer as a despot and would quickly quit his job if he were not his family's sole breadwinner and working off his bankrupt father's debts. While trying to move, Gregor finds that his office manager, the chief clerk, has shown up to check on him, indignant about Gregor's unexcused absence. Gregor attempts to communicate with both the manager and his family, but all they can hear from behind the door is incomprehensible vocalizations. Gregor laboriously drags himself across the floor and opens the door. The clerk, upon seeing the transformed Gregor, flees the apartment. Gregor's family is horrified, and his father drives him back towards his room. Gregor is injured when he tries to force himself through the narrow doorway but gets unstuck when his father shoves him through. With Gregor's unexpected transformation, his family is deprived of financial stability. They keep Gregor locked in his room, and he begins to accept his new identity and adapt to his new body. His sister Grete is the only one willing to bring him food, which she finds Gregor likes only if it is rotten. He spends much of his time crawling around on the floor, walls, and ceiling. Upon discovering Gregor's new pastime, Grete decides to remove his furniture to give him more space. She and her mother begin to empty the room of everything, except the sofa under which Gregor hides whenever anyone comes in. He finds their actions deeply distressing, fearing that he might forget his past as a human, and desperately tries to save a particularly loved portrait on the wall of a woman clad in fur. His mother loses consciousness at the sight of him clinging to the image to protect it. When Grete rushes out of the room to get some aromatic spirits, Gregor follows her and is slightly hurt when she drops a medicine bottle and it breaks. Their father returns home and angrily hurls apples at Gregor, one of which becomes lodged in his back, severely wounding him. Gregor suffers from his injuries and eats very little. His father, mother, and sister all get jobs and increasingly begin to neglect him, and they use his room for storage. For a time, his family leaves Gregor's door open in the evenings so he can listen to them talk to each other, but this happens less frequently once they rent a room in the apartment to three male tenants, who are not told about Gregor. One day, the charwoman, who briefly looks in on Gregor each day when she arrives and before she leaves, neglects to close his door fully. Attracted by Grete's violin-playing in the living room, Gregor crawls out and is spotted by the unsuspecting tenants, who complain about the apartment's unhygienic conditions and say they are leaving, will not pay anything for the time they have already stayed, and may take legal action. Grete, who is tired of taking care of Gregor and realizes the burden his existence puts on each member of the family, tells her parents they must get rid of "it" or they will all be ruined. Gregor, understanding that he is no longer wanted, laboriously makes his way back to his room and dies of starvation before sunrise. His body is discovered by the charwoman, who alerts his family and then disposes of the corpse. The relieved and optimistic father, mother, and sister all take the day off work. They travel by tram into the countryside and make plans to move to a smaller apartment to save money. During the short trip, Mr. and Mrs. Samsa realize that, despite the hardships that have brought some paleness to her face, Grete has grown up into a pretty young lady with a good figure and they think about finding her a husband. |

プロット ある朝、グレゴール・ザムザは目を覚ますと、自分が「巨大な害虫」に変身していることに気づいた。彼は当初、この変身は一時的なものだと考え、徐々に変身 の結果について考えを巡らせる。仰向けで動けず、ベッドから起き上がれないグレゴールは、営業マン兼布商人としての仕事を振り返る。彼はその仕事を「常に 変化し、決して持続せず、親密になることのない人間関係に悩まされる」と表現する。[4] 彼は雇い主を専制君主と見なし、家族の大黒柱であり、破産した父親の借金を返済している立場でなければ、すぐにでも仕事を辞めたいと考えていた。動こうとするグレゴールは、上司である主任事務員が、無断欠勤に憤慨しながら様子を見に来たことに気づく。 グレゴールは上司と家族に意思疎通を図ろうとするが、扉の向こうで聞こえるのは理解不能な声だけだ。グレゴールは床を這うように移動し、ようやく扉を開け る。変貌したグレゴールを見た主任はアパートから逃げ出した。家族は恐怖に震え、父親はグレゴールを部屋へ押し戻そうとする。狭い戸口を無理に抜けようと したグレゴールは傷を負うが、父親が押し込んだことでようやく抜け出せた。 グレゴールが突然変身したことで、家族は経済的安定を失った。彼らはグレゴールを部屋に閉じ込め、彼は新しい身分を受け入れ、新しい体に適応し始める。妹 のグレーテだけが彼に食べ物を運ぶことを厭わず、腐ったものだけがグレゴールの好物だと気づく。彼は床や壁、天井を這い回る時間を多く過ごす。 グレーテの新たな趣味を知ったグレーテは、彼のためにより広い空間を作るべく家具を撤去することを決める。母と共に部屋から全てを片付け始めるが、誰かが 部屋に入るとグレーテが隠れるソファだけは残された。グレーテは彼らの行動に深い苦痛を感じ、人間だった過去を忘れてしまうのではないかと恐れ、壁にか かった毛皮をまとった女性の肖像画を必死に守ろうとする。母親は、彼がその絵を護ろうと必死にしがみついている姿を見て気を失った。 グレテが芳香剤を取りに部屋を飛び出した時、グレゴールは彼女を追いかけた。するとグレテが薬瓶を落として割ったため、彼は軽く傷ついた。父親が帰宅すると、怒ってリンゴをグレゴールに投げつけた。その一つが背中に刺さり、彼は重傷を負った。 傷に苦悩するグレゴールはほとんど食べなくなった。父も母も妹も仕事を得て次第に彼を顧みず、部屋は物置と化した。しばらくの間、家族は夜になるとグレ ゴールの部屋の扉を開け、彼に会話が聞こえるようにしていたが、アパートに三人の男性下宿人を借り入れてからは、その頻度も減った。下宿人たちはグレゴー ルの存在を知らされていない。 ある日、掃除婦が到着時と退去時に毎日少しだけグレゴールを覗いていたが、その日はドアを完全に閉め忘れた。居間でグレテがバイオリンを弾く音に誘われ て、グレゴールは這い出てきて、不意を突かれた下宿人たちに発見される。彼らはアパートの衛生状態を苦情として挙げ、退去すると宣言し、既に滞在した期間 分の家賃は支払わないと告げ、法的措置を取る可能性もあると言った。 グレーテは、グレゴールを世話するのに疲れ、彼の存在が家族一人ひとりに負担をかけていることに気づいた。彼女は両親に「あれ」を処分しなければ、家族全 員が破滅すると告げる。グレゴールは自分がもはや必要とされていないことを理解し、苦労して自分の部屋に戻り、夜明け前に餓死した。その死体は掃除婦に よって発見され、彼女は家族に知らせた後、遺体を処分した。 安堵と楽観に満ちた父、母、妹は全員仕事を休む。路面電車で郊外へ出かけ、節約のため小さなアパートへ引っ越す計画を立てる。短い旅の途中、ザムザ夫妻 は、苦労で顔色は悪いものの、グレーテが美しい若い女性へと成長し、スタイルも良くなったことに気づき、彼女に夫を見つけることを考える。 |

| Characters Gregor Samsa "Gregor Samsa" redirects here. For other uses, see Gregor Samsa (disambiguation). Gregor is the main character of the story. He works as a traveling salesman in order to provide money for his sister and parents. He wakes up one morning finding himself transformed into an insect. After the metamorphosis, Gregor becomes unable to work and is confined to his room for most of the remainder of the story. This prompts his family to begin working once again. Gregor is depicted as isolated from society and often both misunderstands the true intentions of others and is misunderstood. Grete Samsa Grete is Gregor's younger sister, and she becomes his caretaker after his metamorphosis. They initially have a close relationship, but this quickly fades. At first, she volunteers to feed him and clean his room, but she grows increasingly impatient with the burden and begins to leave his room in disarray out of spite. Her initial decision to take care of Gregor may have come from a desire to contribute and be useful to the family, since she becomes angry and upset when the mother cleans his room. It is made clear that Grete is disgusted by Gregor, as she always opens the window upon entering his room to keep from feeling nauseous and leaves without doing anything if Gregor is in plain sight. She plays the violin and dreams of going to the conservatory to study, a dream Gregor had intended to make happen; he had planned on making the announcement on Christmas Day. To help provide an income for the family after Gregor's transformation, she starts working as a salesgirl. Grete is also the first to suggest getting rid of Gregor, which causes Gregor to plan his own death. At the end of the story, Grete's parents realize that she has become beautiful and full-figured and decide to consider finding her a husband.[5] Mr. Samsa Mr. Samsa is Gregor's father. After the metamorphosis, he is forced to return to work in order to support the family financially. His attitude towards his son is harsh. He regards the transformed Gregor with disgust and possibly even fear and attacks Gregor on several occasions. Even when Gregor was human, Mr. Samsa regarded him mostly as a source of income for the family. Gregor's relationship with his father is modelled after Kafka's own relationship with his father. The theme of alienation becomes quite evident here.[6] Mrs. Samsa Mrs. Samsa is Gregor's mother. She is portrayed as a submissive wife. She suffers from asthma, which is a constant source of concern for Gregor. She is initially shocked at Gregor's transformation, but she still wants to enter his room. However, it proves too much for her and gives rise to a conflict between her maternal impulse and sympathy and her fear and revulsion at Gregor's new form.[7] The Charwoman The charwoman is an old widowed lady who is employed by the Samsa family after their previous maid begs to be dismissed on account of the fright she experiences owing to Gregor's new form. She is paid to take care of their household duties. Apart from Grete and her father, the charwoman is the only person who is in close contact with Gregor, and she is unafraid in her dealings with Gregor. She does not question his changed state; she seemingly accepts it as a normal part of his existence. She is the one who notices Gregor has died and disposes of his body. |

登場人物 グレゴール・ザムザ 「グレゴール・ザムザ」はここへ転送される。その他の用法についてはグレゴール・ザムザ (曖昧さ回避)を参照のこと。 グレゴールはこの物語の主人公である。彼は妹と両親の生活費を稼ぐため、行商人として働いている。ある朝目覚めると、自分が虫に変身していることに気づ く。変身後、グレゴールは働けなくなり、物語の大半を自分の部屋に閉じこもって過ごす。これにより家族は再び働き始める。グレゴールは社会から孤立し、他 人の真意を誤解することもあれば、自身も誤解されることが描かれている。 グレーテ・ザムザ グレーテはグレゴールの妹であり、彼の変身後は介護者となる。当初は親密な関係だったが、それは急速に冷めていく。最初は自ら進んで餌を与え部屋を掃除し たが、次第に負担に苛立ち、意地悪から部屋を散らかしたまま放置するようになる。グレーテがグレゴールを世話しようと決めたのは、家族に貢献し役に立ちた いという思いからだったかもしれない。母親が彼の部屋を掃除すると、彼女は怒りと動揺を見せたからだ。グレテがグレゴールに嫌悪感を抱いていることは明ら かだ。彼の部屋に入ると必ず窓を開けて吐き気を抑え、グレゴールが視界に入ると何もせずに立ち去る。彼女はバイオリンを弾き、音楽院で学ぶ夢を抱いてい る。これはグレゴールが実現させようとしていた夢であり、彼はクリスマスにその発表を計画していた。グレゴールの変身後、家族の収入を支えるため、彼女は 販売員として働き始める。またグレテは最初にグレゴールを処分することを提案し、それがグレゴール自身の死を計画させるきっかけとなる。物語の終盤、両親 はグレテが美しく豊満な体つきになったことに気づき、彼女に夫を探すことを検討し始める。[5] ザムザ氏 ザムザ氏はグレゴールの父親である。変身後、彼は家族を養うために仕事に復帰せざるを得なかった。息子に対する彼の態度は厳しい。変身したグレゴールを嫌 悪し、おそらく恐怖さえ抱いており、幾度となくグレゴールを攻撃する。グレゴールが人間の頃でさえ、ザムザ氏は彼を主に家族の収入源と見なしていた。グレ ゴールと父親の関係は、カフカ自身の父親との関係をモデルにしている。疎外感というテーマがここで明らかになる。[6] ザムザ夫人 ザムザ夫人はグレゴールの母親である。従順な妻として描かれている。喘息を患っており、これがグレゴールにとって絶え間ない心配の種となる。グレゴールの 変身に最初は衝撃を受けるが、それでも彼の部屋に入ろうとする。しかし、それは彼女にとって耐え難いものであり、母性的な衝動や同情と、グレゴールの新形 態に対する恐怖や嫌悪との間で葛藤を生む。[7] 掃除婦 掃除婦は年老いた未亡人で、以前のメイドがグレゴールの新形態に恐怖を感じて辞職を願い出た後、ザムザ家に雇われた。彼女は家事を請け負うために雇われて いる。グレーテと父親を除けば、掃除婦はグレゴールと密接に接する唯一の人格であり、彼との関わりにおいて全く恐れを見せない。彼女は彼の変貌を疑問視せ ず、それが彼の存在の当然の一部であるかのように受け入れている。グレゴールの死に気づき、その遺体を処理するのも彼女である。 |

| Interpretations Like much of Kafka's work, The Metamorphosis tends to be given a religious (Max Brod) or psychological interpretation. It has been particularly common to read the story as an expression of Kafka's father complex, as was first done by Charles Neider in his The Frozen Sea: A Study of Franz Kafka (1948). Besides the psychological approach, interpretations focusing on sociological aspects, which see the Samsa family as a portrayal of general social circumstances, have also gained a large following.[8] Vladimir Nabokov rejected such interpretations, noting that they do not live up to Kafka's art. He instead chose an interpretation guided by the artistic detail but excluded any symbolic or allegoric meanings. Arguing against the popular father-complex theory, he observed that it is the sister more than the father who should be considered the cruelest person in the story, since she is the one backstabbing Gregor. In Nabokov's view, the central narrative theme is the artist's struggle for existence in a society replete with narrow-minded people who destroy him step by step. Commenting on Kafka's style, he writes, "The transparency of his style underlines the dark richness of his fantasy world. Contrast and uniformity, style and the depicted, portrayal and fable are seamlessly intertwined".[9] In 1989, Nina Pelikan Straus wrote a feminist interpretation of The Metamorphosis, noting that the story is not only about the metamorphosis of Gregor but also about the metamorphosis of his family and, in particular, his younger sister Grete. Straus suggested that the social and psychoanalytic resonances of the text depend on Grete's role as a woman, daughter, and sister, and that prior interpretations failed to recognize Grete's centrality to the story.[10] In 1999, Gerhard Rieck pointed out that Gregor and his sister, Grete, form a pair, which is typical of many of Kafka's texts: it is made up of one passive, rather austere, person and another active, more libidinal, person. The appearance of figures with such almost irreconcilable personalities who form couples in Kafka's works has been evident since he wrote his short story "Description of a Struggle" (e.g. the narrator/young man and his "acquaintance"). They also appear in "The Judgment" (Georg and his friend in Russia), in all three of his novels (e.g. Robinson and Delamarche in Amerika) as well as in his short stories "A Country Doctor" (the country doctor and the groom) and "A Hunger Artist" (the hunger artist and the panther). Rieck views these pairs as parts of one single person (hence the similarity between the names Gregor and Grete) and in the final analysis as the two determining components of the author's personality. Not only in Kafka's life but also in his oeuvre does Rieck see the description of a fight between these two parts.[11] Reiner Stach argued in 2004 that no elucidating comments were needed to illustrate the story and that it was convincing by itself, self-contained, even absolute. He believes that there is no doubt the story would have been admitted to the canon of world literature even if we had known nothing about its author.[12] According to Peter-André Alt (2005), the figure of the insect becomes a drastic expression of Gregor Samsa's deprived existence. Reduced to carrying out his professional responsibilities, anxious to guarantee his advancement and vexed with the fear of making commercial mistakes, he is the creature of a functionalistic professional life.[13] In 2007, Ralf Sudau wrote that particular attention should be paid to the motifs of self-abnegation and disregard for reality. Gregor's earlier behavior was characterized by self-renunciation and his pride in being able to provide a secure and leisured existence for his family. When he finds himself in need of assistance and in danger of becoming a parasite, he does not want to admit this to himself and be disappointed by the treatment he receives from his family, which is becoming more and more careless and even hostile to him. According to Sudau, Gregor engages in self-denial by hiding his nauseating appearance under the sofa and gradually famishing, thereby complying with the more or less blatant wish of his family. His gradual emaciation and "self-reduction" shows signs of a fatal hunger strike (which on the part of Gregor is unconscious and unsuccessful, and on the part of his family not understood or ignored). Sudau also lists the names of selected interpreters of The Metamorphosis (e.g. Beicken, Sokel, Sautermeister and Schwarz)[14] to whom the narrative is a metaphor for the suffering resulting from leprosy, an escape into the disease or a symptom onset, an image of an existence which is defaced by the career, or a revealing staging which cracks the veneer and superficiality of everyday circumstances and exposes its cruel essence. Sudau further notes that Kafka's representational style is on one hand characterized by an idiosyncratic interpenetration of realism and fantasy, a worldly mind, rationality, and clarity of observation, and on the other hand by folly, outlandishness, and fallacy. He also points to the grotesque and tragicomical, silent film-like elements.[15] Fernando Bermejo-Rubio (2012) argues that the story is often unjustly viewed as inconclusive. He reads the descriptions of Gregor and his family environment in The Metamorphosis to contradict each other. Diametrically opposed versions exist of Gregor's back, his voice, of whether he is ill or already undergoing the metamorphosis, whether he is dreaming or not, which treatment he deserves, of his moral point of view (false accusations made by Grete), and whether his family is blameless or not. Bermejo-Rubio emphasizes that Kafka ordered in 1915 that there should be no illustration of Gregor. He argues that it is exactly this absence of a visual narrator that is essential for Kafka's project, for he who depicts Gregor would stylize himself as an omniscient narrator. Another reason why Kafka opposed such an illustration is that the reader should not be biased in any way before reading. That the descriptions are not compatible with each other indicates that the opening statement is not to be trusted. If the reader is not hoodwinked by the first sentence and still thinks of Gregor as a human being, he will see that the story is conclusive and realize that Gregor is a victim of his own degeneration.[16] Volker Drüke (2013) believes that a crucial metamorphosis in the story is that of Grete, and the title of the story may be directed at her as well as Gregor. Gregor's metamorphosis is followed by his languishing and ultimately dying. Grete, by contrast, matures as a result of the new family circumstances and assumes responsibility. In the end – after the brother's death – the parents also notice that their daughter, "who was getting more animated all the time, ... had recently blossomed into a pretty and shapely girl", and they want to look for a partner for her. From this standpoint Grete's metamorphosis from a girl into a woman, is a subtextual theme of the story.[17] Allan Beveridge (2009) believes that the story shows the isolating effects of being different from others around you. He states that the story "shows how easy it is for carers and psychiatric staff to be unintentionally cruel to sufferers."[18] The reaction of the family to Gregor's suffering can be viewed as a metaphor for the presence of a disabled individual in the family and the challenges that come along with it, not only to the individual but to the family itself. |

解釈 カフカの作品の多くと同様に、『変身』は宗教的(マックス・ブロート)あるいは心理的な解釈が与えられる傾向がある。特にチャールズ・ナイダーが『凍った 海:フランツ・カフカ研究』(1948年)で初めて行ったように、この物語をカフカの父親コンプレックスの表現として読むことが一般的であった。心理学的 アプローチに加え、ザムザ一家を一般的な社会状況の描写と見なす社会学的側面に焦点を当てた解釈も、多くの支持を得ている。[8] ウラジーミル・ナボコフはこうした解釈を退け、それらはカフカの芸術に見合うものではないと指摘した。代わりに彼は、芸術的細部に導かれた解釈を選択した が、象徴的・寓意的な意味合いは一切排除した。広く受け入れられた父コンプレックス説に反論し、物語の中で最も残酷な人格は父親ではなく妹であると論じ た。なぜなら妹こそがグレゴールを裏切る存在だからだ。ナボコフの見解では、物語の中心テーマは、偏狭な人間に満ちた社会で芸術家が段階的に破壊されなが ら生き残ろうとする闘争である。カフカの文体について彼はこう記している。「その透明な文体は、幻想世界の暗く豊かな深みを際立たせる。対比と均質性、文 体と描写対象、描写と寓話がシームレスに絡み合っている」。[9] 1989年、ニーナ・ペリカン・シュトラウスは『変身』のフェミニスト的解釈を著し、この物語がグレゴールの変身だけでなく、彼の家族、特に妹グレテの変 身をも描いていると指摘した。シュトラウスは、この作品の社会的・精神分析的共鳴は、グレテが女性、娘、姉妹として果たす役割に依存しており、従来の解釈 はグレテが物語の中心的存在であることを認識していなかったと示唆した。[10] 1999年、ゲルハルト・リークは、グレゴールと妹グレーテが対をなすことを指摘した。これはカフカの多くの作品に見られる典型的な構図である。すなわ ち、受動的でやや厳格な人格と、能動的でよりリビドー的な人格から成る対である。このようなほぼ相容れない個人的な性格を持つ人物がカップルを形成する現 象は、カフカの短編『闘争の描写』(例:語り手/青年とその「知人」)の執筆時から明らかであった。また『審判』(ゲオルクとロシアの友人)、三つの長編 小説(『アメリカ』のロビンソンとデラマルシュ)、短編『田舎の医者』(田舎の医者と花婿)、『飢餓芸術家』(飢餓芸術家と豹)にも現れる。リーケはこれ らの対を単一の作者の人格(故にグレゴールとグレーテの名の類似性)と見なし、究極的には作者の個人的な人格を決定づける二要素と解釈する。リーケによれ ば、カフカの生涯だけでなく作品群においても、この二つの要素の闘争描写が存在する。[11] ライナー・シュタッハは2004年、この物語を説明するために解明的な解説は不要であり、物語自体が説得力があり、完結しており、絶対的であると主張し た。彼は、たとえ作者について何も知らなくても、この物語が世界文学の正典に認められたことに疑いの余地はないと考えている。[12] ピーター=アンドレ・アルト(2005)によれば、昆虫の姿はグレゴール・ザムザの剥奪された存在を劇的に表現している。職業的責任の遂行に還元され、昇進を保証することに不安を抱き、商業的失敗への恐怖に苛まれる彼は、機能主義的な職業生活の産物である。[13] 2007年、ラルフ・ズダウは自己犠牲と現実無視のモチーフに特に注目すべきだと記した。グレゴールは以前、自己犠牲的な行動と、家族に安定した安楽な生 活を保障できるという自負心によって特徴づけられていた。援助を必要とし、寄生者となる危険に直面した時、彼はこの事実を自ら認めたくなく、家族からの扱 いに失望したくなかった。家族は彼に対してますます無関心になり、敵意さえ抱き始めていたのだ。ズダウによれば、グレゴールはソファの下に吐き気を催す姿 を隠し、徐々に飢え死にを選ぶことで自己否定を行う。これは家族の露骨な願望に順応する行為だ。彼の漸進的な衰弱と「自己縮小」は、致命的なハンガースト ライキの兆候を示している(グレゴール側では無意識で失敗に終わり、家族側では理解されないか無視される)。スダウはまた、『変身』の選りすぐりの解釈者 たち(例えばバイケン、ゾケル、ザウターマイスター、シュヴァルツ)[14]の名を列挙する。彼らにとってこの物語は、ハンセン病による苦悩の隠喩、病へ の逃避あるいは症状発現、キャリアによって損なわれた存在のイメージ、あるいは日常状況の表層と虚飾を割ってその残酷な本質を暴く暴露的な演出である。ス ダウはさらに、カフカの表現様式は一方で現実主義と幻想の特異な相互浸透、世俗的な知性、合理性、観察の明晰性によって特徴づけられ、他方で愚かさ、奇妙 さ、誤謬によって特徴づけられると指摘する。またグロテスクで悲喜劇的な、無声映画的な要素にも言及している。[15] フェルナンド・ベルメホ=ルビオ(2012)は、この物語がしばしば不当に未解決と見なされていると論じる。彼は『変身』におけるグレゴールとその家族環 境の描写が互いに矛盾していると読み解く。グレゴールの背中、声、彼が病気なのか変身過程にあるのか、夢を見ているのか否か、受けるべき処遇、道徳的立場 (グレーテによる虚偽の告発)、家族の無罪性などについて、正反対の解釈が存在する。ベルメホ=ルビオは、カフカが1915年にグレゴールの挿絵を一切描 くなと指示したことを強調する。彼は、まさにこの視覚的語り手の不在こそがカフカの企てにとって不可欠だと論じる。なぜなら、グレゴールを描く者は自らを 全知の語り手として様式化してしまうからだ。カフカがそのような挿絵に反対したもう一つの理由は、読者が読む前にいかなる偏見も持たないようにするためで ある。描写が互いに整合しないことは、冒頭の主張が信用できないことを示している。読者が最初の文に騙されず、なおグレゴールを人間として捉えるならば、 物語の結末が必然的であることに気づき、グレゴールが自らの退化の犠牲者だと理解するだろう。[16] フォルカー・ドルケ(2013)は、物語における決定的な変容はグレテのものであり、物語のタイトルはグレゴールだけでなく彼女にも向けられている可能性 があると考える。グレゴールの変身は衰弱と死へと続く。対照的にグレーテは新たな家庭環境の中で成長し、責任を担うようになる。結局――兄の死後――両親 も娘が「次第に活気づき…最近では美しくすらりとした娘に成長していた」ことに気づき、彼女に相手を探そうとする。この観点から、グレテが少女から女性へ と変容する過程は、物語の隠された主題と言える。[17] アラン・ベベリッジ(2009)は、この物語が周囲と異なることがもたらす孤立効果を描いていると指摘する。彼は「介護者や精神科スタッフが、いかに容易 に無意識のうちに苦悩へ残酷な行為を働くかを示している」と述べている。[18] グレゴールが苦悩することに対する家族の反応は、家族内に障害者が存在すること、そしてそれが個人だけでなく家族全体にもたらす困難の隠喩として捉えられ る。 |

| Translations of the opening sentence The Metamorphosis has been translated into English more than twenty times. In Kafka's original, the opening sentence is "Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheuren Ungeziefer verwandelt". In their 1933 translation of the story – the first into English – Willa Muir and Edwin Muir rendered it as "As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect". In Middle High German, Ungeziefer literally means "unclean animal not suitable for sacrifice"[19] and is sometimes used colloquially to mean "bug", with the connotation of "dirty, nasty bug". It can also be translated as "vermin".[20][21] In a note in his translation of the story, Mark Harman writes: The compact phrase, "ungeheueres Ungeziefer, with its resonant double "un," defies translation and makes it hard to determine precisely what kind of creature Gregor has become. The possible meanings of ungeheuer—the opposite of geheuer (familiar)—range from "monstrous" to "huge." Etymologically complex, Ungeziefer could denote a number of small verminous creatures that can be either mammals or insects. While the indeterminacy of this term seems quite deliberate, Kafka is somewhat more precise in an April 1913 letter to Kurt Wolff in which he calls Gregor Samsa an "insect" (Insekt).[22] The phrase ungeheuren Ungeziefer, describing the creature into which Gregor Samsa transforms, has been translated in at least sixteen different ways.[23][20] These include the following: "gigantic insect" (Willa and Edwin Muir, 1933) "some monstrous kind of vermin" (A. L. Lloyd, London: The Parton Press, 1937; New York: The Vanguard Press, as Metamorphosis, 1946) "monstrous vermin" (Stanley Corngold, 1972; Joachim Neugroschel, 1993; Donna Freed, 1996) "giant bug" (J. A. Underwood, 1981) "monstrous insect" (Malcolm Pasley, 1992; Richard Stokes, 2002; Katja Pelzer, 2017; Mark Harman, 2024[24]) "enormous bug" (Stanley Appelbaum, 1996) "gargantuan pest" (M. A. Roberts, 2005; revised 2008)[25] "monstrous cockroach" (Michael Hofmann, 2007) "monstrous verminous bug" (Ian Johnston, 2007) "a vile insect, one of gigantic proportions" (Philip Lundberg, 2007) "some kind of monstrous vermin" (Joyce Crick, 2009) "horrible vermin" (David Wyllie, 2011; Karen Reppin, 2023[26]) "some sort of monstrous insect" (Susan Bernofsky, 2014)[27] "some kind of monstrous bedbug" (Christopher Moncrieff, 2014) "huge verminous insect" (John R. Williams, 2014)[28] "a kind of giant bug" (William Aaltonen, 2023) What kind of bug or vermin Kafka envisaged remains a debated mystery.[23][29][30] Kafka had no intention of labeling Gregor as any specific thing, but instead was trying to convey Gregor's disgust at his transformation. In his letter to his publisher of 25 October 1915, in which he discusses his concern about the cover illustration for the first edition, Kafka does use the term Insekt, though, saying "The insect itself is not to be drawn. It is not even to be seen from a distance."[31] Indeed, a "conspicuous lack of naming is a characteristic of Kafka's writing, and its aim is arguably far more ingenious than to inspire readers to speculate on species classification.... To seek to locate the animal in the encyclopedia is, in many ways, antithetical to the way Kafka's stories are constructed and incorporate ambiguity."[32] Vladimir Nabokov, who was a lepidopterist as well as a writer and literary critic, concluded from details in the text that Gregor was not a cockroach, but a beetle with wings under his shell, and capable of flight. Nabokov left a sketch annotated "just over three feet long" on the opening page of his English teaching copy. In his accompanying lecture notes, he discusses the type of insect Gregor has been transformed into. Noting that the cleaning lady addressed Gregor as "dung beetle" (Mistkäfer), e.g., "Come here for a bit, old dung beetle!" or "Hey, look at the old dung beetle!", Nabokov remarks that this was just her friendly way of addressing him, and that Gregor "is not, technically, a dung beetle. He is merely a big beetle."[33] Translations of other passages Paul Reitter, a professor of German Languages and Literature, compares three translations of a passage early in the novella, after Gregor awakes and wonders why he didn't hear his alarm clock: the Muirs', Susan Bernofsky's, and Mark Harman's.[34] |

冒頭の文の翻訳 『変身』は英語に二十回以上翻訳されている。カフカの原典における冒頭の文は「ある朝、グレゴール・ザムザが不安な夢から目を覚ますと、彼は自分のベッド の中で巨大な害虫に変身していた」である。1933年にウィラ・ミューアとエドウィン・ミューアが初めて英語に翻訳した際、彼らはこれを「ある朝、グレ ゴール・ザムザが不安な夢から目覚めると、彼は自分のベッドの中で巨大な虫に変身していることに気づいた」と訳した。中世高ドイツ語では、 Ungeziefer は文字通り「犠牲にふさわしくない不浄な動物」[19] を意味し、口語では「虫」を意味することもあり、「汚くて嫌な虫」という含意がある。また、「害虫」と訳すこともできる。[20][21] この物語の翻訳に関する注記の中で、マーク・ハーマンは次のように書いている。 「ungeheueres Ungeziefer」というコンパクトなフレーズは、響きのある二重の「un」を含み、翻訳が難しく、グレゴールがどのような生き物になったのかを正確 に判断することを困難にしている。ungeheuer(geheuer(見慣れた)の反対)の考えられる意味は、「巨大な」から「巨大な」まで多岐にわた る。語源的に複雑な「Ungeziefer」は、哺乳類でも昆虫でもありうる、いくつかの小さな害虫を指す可能性がある。この用語の不確定性はかなり意図 的なものと思われるが、カフカは1913年4月にクルト・ヴォルフに宛てた手紙の中で、グレゴール・ザムザを「昆虫(Insekt)」と呼んでおり、やや 正確である。[22] グレゴール・ザムザが変身した生物を形容する「ungeheuren Ungeziefer」という表現は、少なくとも16通りの異なる訳語が存在する。[23][20] その中には以下のようなものがある: 「巨大な昆虫」(ウィラ&エドウィン・ミューア訳、1933年) 「ある種の怪物的な害虫」(A. L. ロイド、ロンドン:パートン・プレス、1937年;ニューヨーク:ヴァンガード・プレス『変身』として、1946年) 「怪物的な害虫」(スタンリー・コーンゴールド、1972年;ヨアヒム・ノイグロシェル、1993年;ドナ・フリード、1996年) 「巨大な虫」(J. A. アンダーウッド、1981年) 「怪物のような昆虫」(マルコム・パスリー、1992年、リチャード・ストークス、2002年、カティア・ペルツァー、2017年、マーク・ハーマン、2024年[24]) 「巨大な虫」(スタンリー・アペルバウム、1996年) 「巨大な害虫」(M. A. ロバーツ、2005年、2008年改訂)[25] 「巨大なゴキブリ」(マイケル・ホフマン、2007年) 「巨大な害虫」(イアン・ジョンストン、2007年) 「巨大な、卑劣な昆虫」(フィリップ・ランドバーグ、2007年) 「ある種の巨大な害虫」(ジョイス・クリック、2009年) 「恐ろしい害虫」(デイヴィッド・ウィリー、2011年、カレン・レッピン、2023年[26]) 「ある種の巨大な昆虫」(スーザン・バーノフスキー、2014年) [27] 「ある種の怪物的なトコジラミ」(クリストファー・モンクリフ、2014年) 「巨大な害虫」(ジョン・R・ウィリアムズ、2014年)[28] 「一種の巨大な虫」(ウィリアム・アアルトネン、2023年) カフカがどんな虫や害虫を想定していたかは、今も議論の的となっている謎だ。[23][29][30] カフカはグレゴールを特定の何かに分類する意図はなく、むしろ変身への嫌悪感を伝えようとしていた。1915年10月25日の出版社宛ての手紙で初版表紙 絵への懸念を述べる際、カフカは確かに「昆虫」という語を用いている。「昆虫そのものは描いてはならない。遠くからでも見えてはならない」と記している。 [31] 実際、「名称の顕著な欠如はカフカの作風の特徴であり、その目的は読者に種分類を推測させることよりもはるかに巧妙だと言える。…この動物を百科事典で特 定しようとする行為は、多くの点でカフカの物語が構築され曖昧さを内包する手法と相反する」[32]。 作家であり文学評論家でもある一方で蝶類学者でもあったウラジーミル・ナボコフは、本文の詳細からグレゴールがゴキブリではなく、甲羅の下に羽根を持ち飛 行可能な甲虫であると結論づけた。ナボコフは自身の英語教材用コピーの表紙に「ちょうど三フィート強の長さ」と注釈を添えたスケッチを残している。付随す る講義ノートでは、グレゴールが変身した昆虫の種類について論じている。掃除婦がグレゴールを「糞虫(Mistkäfer)」と呼んだこと(例:「ちょっ とこっちへ来い、この糞虫め!」「おい、あの糞虫めを見てみろ!」)について、ナボコフはこれが単なる親しみを込めた呼び方であり、グレゴールは「厳密に は糞虫ではない。単なる大きな甲虫に過ぎない」と指摘している。[33] 他の箇所の翻訳 ドイツ語・ドイツ文学の教授であるポール・ライターは、グレゴールが目を覚まし、なぜ目覚まし時計の音が聞こえなかったのか不思議に思う、小説の序盤の3つの箇所について、ミュア夫妻、スーザン・バーノフスキー、マーク・ハーマンの3人の翻訳を比較している。[34] |

| Translation of the title The Translation Website states: The German title, Die Verwandlung, can be translated as either The Transformation or The Metamorphosis. The most frequent choice is metamorphosis, but this word has the disadvantage of being more "literary" and less commonly used in English than verwandlung is in German. The appearance of this word in the title perhaps too quickly alerts the reader to the strangeness of the story to follow; it doesn't really fit with the much more "ordinary" tone in which the story is narrated. Another problem is that those readers familiar with the word may know it primarily as a biological term referring to a caterpillar's transformation into a butterfly, not at all the type of transformation that the story describes. But despite these disadvantages, most contemporary translations use The Metamorphosis as the title of the story — mainly because it's the title that was most often used in earlier translations and therefore the one most familiar to English-language readers.[35] Mark Harman explains why he chose the title The Transformation for his translation of the story: Although that story is commonly known as "The Metamorphosis," Kafka, who had as a schoolboy not only read Ovid's Metamorphoses, that classic tale of "forms changed into new bodies," but also translated a portion of it from the Latin, could have entitled his story Die Metamorphose, but he did not do so. His decision to call the story "Die Verwandlung" certainly deserves to be respected in translation....[36] Although M. A. Roberts titled his 2005 translation The Metamorphosis, he notes that "Kafka's title actually translates as The Transformation".[37] In the afterword to her translation, Susan Bernofsky defends her choice of The Metamorphosis for the title: Unlike the English "metamorphosis," the German word Verwandlung does not suggest a natural change of state associated with the animal kingdom such as the change from a caterpillar to a butterfly. Instead, it is a word from fairytales used to describe the transformation, say, of a girl's seven brothers into swans. But the word "metamorphosis" refers to this, too; its first definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is "The action or process of changing in form, shape, or substance; esp. transformation by supernatural means." This is the sense in which it's used, for instance, in translations of Ovid. As a title for this rich, complex story, it strikes me as the most luminous, suggestive choice.[38] |

タイトルの翻訳 翻訳サイトによれば: ドイツ語のタイトル『Die Verwandlung』は『変身』または『変容』と訳し得る。最も一般的な訳は変容だが、この語は「文学的」な響きが強いため、ドイツ語における 「verwandlung」ほど英語では日常的に使われていないという欠点がある。この言葉がタイトルに現れることで、読者は物語の奇妙さに早々に気づか されるかもしれない。物語が語られる「ごく普通の」口調とはあまり合っていないのだ。別の問題として、この言葉を知っている読者も、主に生物学用語とし て、つまり幼虫が蝶へ変わる過程を指す言葉として認識している可能性が高い。物語が描写する変容とは全く異なるものだ。しかし、こうした欠点があるにもか かわらず、現代の翻訳のほとんどは、この物語のタイトルを「The Metamorphosis」としている。その主な理由は、このタイトルが、初期の翻訳で最もよく使われていたものであり、したがって英語圏の読者にとっ て最も馴染み深いものだからである。[35] マーク・ハーマンは、この物語の翻訳に「The Transformation」というタイトルを選んだ理由を次のように説明している。 この物語は一般に「変身」として知られているが、学生時代にオウィディウスの『変身物語』という「形が新しい体へと変わる」という古典的な物語を読んだだ けでなく、その一部をラテン語から翻訳したカフカは、この物語のタイトルを『Die Metamorphose』とすることもできたが、そうはしなかった。この物語を「Die Verwandlung」と呼ぶという彼の決定は、翻訳において確かに尊重されるに値するものである。[36] M. A. ロバーツは、2005年の翻訳に『The Metamorphosis』というタイトルを付けたが、「カフカのタイトルは、実際には『変身』と訳される」と述べている。[37] スーザン・バーノフスキーは、彼女の翻訳のあとがきで、タイトルを The Metamorphosis とすることの選択を擁護している。 英語の「metamorphosis」とは異なり、ドイツ語の Verwandlung は、毛虫が蝶に変わるような、動物界に関連する自然な状態の変化を意味しない。その代わりに、それは、例えば、少女の 7 人の兄弟が白鳥に変わるような、おとぎ話で使われる変容を表す言葉である。しかし「メタモルフォーゼ」という言葉もまた、この意味を指す。オックスフォー ド英語辞典におけるその第一義的な定義は「形態、形状、または物質の変化の作用または過程。特に超自然的な手段による変容」である。これは例えばオウィ ディウスの翻訳において用いられる用法だ。この豊かで複雑な物語の題名として、この言葉は最も輝かしく示唆に富む選択だと私は思う。[38] |

| In popular culture Main article: The Metamorphosis in popular culture |

ポピュラー・カルチャーにおいて メイン記事: ポピュラー・カルチャーにおける変身 |

| References 1. Kafka, Franz (1915). Die Verwandlung. Der Jüngste Tag. Leipzig: K. Wolff. 2. Malcolm Pasley (tr.), Kafka, Franz, The Transformation and Other Stories, Penguin Books, 1992; Mark Harman (tr.), Kafka, Franz, Selected Stories, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024. In a note on page 235 of his translation, Harman writes, "When the Muirs' remarkably elegant and highly influential translation of this story appeared in London in 1949, it did so under the appropriately plain title 'Transformation.' Unfortunately, however, all subsequent editions of their translation bear the flowery — and stylistically less apt — title 'The Metamorphosis.'" 3. Nitschke, Claudia (January 2008). "Peter-André Alt, Franz Kafka. Der ewige Sohn. 2005". Arbitrium. 26 (1). doi:10.1515/arbi.2008.032. ISSN 0723-2977. S2CID 162142676. 4. Harman, Mark, ed. and trans. Selected Stories: Franz Kafka. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (2024), p. 86. 5. "The character of Grete Samsa in The Metamorphosis from LitCharts | The creators of SparkNotes". LitCharts. Retrieved 31 October 2017. 6. "The character of Father in The Metamorphosis from LitCharts | The creators of SparkNotes". LitCharts. Retrieved 31 October 2017. 7. "The Metamorphosis: Mother Character Analysis". LitCharts. 8. Abraham, Ulf. Franz Kafka: Die Verwandlung. Diesterweg, 1993. ISBN 3-425-06172-0. 9. Nabokov, Vladimir V. Die Kunst des Lesens: Meisterwerke der europäischen Literatur. Austen – Dickens – Flaubert – Stevenson – Proust – Kafka – Joyce. Fischer Taschenbuch, 1991, pp. 313–52. ISBN 3-596-10495-5. 10. Straus, Nina Pelikan. "Transforming Franz Kafka's 'Metamorphosis'", Signs, 14:3 (Spring 1989), The University of Chicago Press, pp. 651–667. 11. Rieck, Gerhard. Kafka konkret – Das Trauma ein Leben. Wiederholungsmotive im Werk als Grundlage einer psychologischen Deutung. Königshausen & Neumann, 1999, pp. 104–25. ISBN 978-3-8260-1623-3. 12. Stach, Reiner. Kafka. Die Jahre der Entscheidungen, p. 221. 13. Alt, Peter-André. Franz Kafka: Der Ewige Sohn. Eine Biographie. C. H .Beck, 2008, p. 336. 14. Sudau, Ralf. Franz Kafka: Kurze Prosa / Erzählungen. Klett, 2007, pp. 163–164. 15. Sudau, Ralf. Franz Kafka: Kurze Prosa / Erzählungen. Klett, 2007, pp. 158–162. 16. Bermejo-Rubio, Fernando: "Truth and Lies about Gregor Samsa. The Logic Underlying the Two Conflicting Versions in Kafka's Die Verwandlung", in Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, Volume 86, Issue 3 (2012), pp. 419–479. 17. Drüke, Volker. "Neue Pläne Für Grete Samsa". Übergangsgeschichten. Von Kafka, Widmer, Kästner, Gass, Ondaatje, Auster Und Anderen Verwandlungskünstlern, Athena, 2013, pp. 33–43. ISBN 978-3-89896-519-4. 18. Beveridge, Allan (November 2009). "Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 15 (6): 459–461. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.109.007146. ISSN 1355-5146. 19. Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. 1993. p. 1486. ISBN 3423325119. 20. Bernofsky, Susan (14 January 2014). "On Translating Kafka's "The Metamorphosis"". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 16 May 2024. 21. Barker, Andrew (July 2021). "Giant Bug or Monstrous Vermin? Translating Kafka's Die Verwandlung in its Cultural, Social, and Biological Contexts". Translation and Literature. 30 (2): 198–208. doi:10.3366/tal.2021.0463. ISSN 0968-1361. 22. Harman, Mark, in Kafka, Franz, Selected Stories. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024, p. 236 n.2. 23. Gooderham, WB (13 May 2015). "Kafka's Metamorphosis and its mutations in translation". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. 24. Leeder, Karen, "An unsettling vision: Franz Kafka reconsidered, 100 years after his death", TLS, May 31, 2024. 25. Roberts states, "Pest could also be vermin", p. 13, n.2. 26. The Reppin translation is also used in Metamorphosis and The Trial, Page Publications, 2023, ISBN 978-1-64833-704-8, and William Collins, 2023, ISBN 9780008110567 27. In the afterword to her translation, Bernofsky writes that she added "some sort of" "to blur the borders of the somewhat too specific 'insect'; I think Kafka wanted us to see Gregor's new body and condition with the same hazy focus with which Gregor himself discovers them". Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis (Susan Bernofsky, tr.). New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014, p. 122. 28. Gooderham, WB (13 May 2015). "Kafka's Metamorphosis and its mutations in translation". The Guardian, errs in stating that John R. Williams translates "ungeheuren Ungeziefer" as "large verminous insect". Metamorphosis and Other Stories 29. "BBC Radio 4 - Archive on 4, The Entomology of Gregor Samsa". BBC. Retrieved 16 May 2024. 30. Onder, Csaba (2018). "THE LAYOUT: NABOKOV AND FRANZ KAFKA'S "THE METAMORPHOSIS"". Americana. XIV (1). Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2022. 31. "Briefe und Tagebücher 1915 (Franz Kafka) – ELibraryAustria". Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2006. 32. Warodell, Johan Adam (2023). "The Absence of Animals in Kafka's Fiction". MLN. 138 (3): 1121, 1122 – via Project MUSE. 33. Nabokov, Vladimir (1980). Lectures on Literature. New York, New York: Harvest. p. 260. 34. Reitter, Paul (Summer 2025). "The Kafka Challenge: Translating the Inimitable". The Hedgehog Review. 27 (2). Charlottesville, Virginia: 54–63. 35.Translation: What Difference Does it Make?: The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka 36. Kafka, Franz (2024). Selected Stories, translated and edited by Mark Harman. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 34. ISBN 978-0674737983. 37. Kafka, Franz, The Metamorphosis (M. A. Roberts, tr.). Clayton, Delaware: Prestwick House, 2005, p. 13, n.1 38. Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis (Susan Bernofsky, tr.). New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014, p. 126. |

参考文献 1. カフカ、フランツ (1915)。『変身』。『最後の審判』。ライプツィヒ:K. Wolff。 2. マルコム・パスリー(訳)、カフカ、フランツ、『変身とその他の物語』、ペンギンブックス、1992年、マーク・ハーマン(訳)、カフカ、フランツ、『選 集』、ハーバード大学出版局ベルナッププレス、2024年。ハーマンは、その翻訳の 235 ページにある注釈で、「1949 年、ロンドンで、ミュア夫妻によるこの物語の非常に優雅で影響力の大きい翻訳が発表されたとき、それは『変身』という適切で簡潔なタイトルで出版された。 しかし、残念ながら、その後のすべての版では、華やかではあるが、文体の点ではあまり適切ではない『変身』というタイトルが付けられている」と書いてい る。 3. ニッチケ、クローディア(2008年1月)。「ピーター・アンドレ・アルト、フランツ・カフカ。Der ewige Sohn。2005年」。Arbitrium。26 (1)。doi:10.1515/arbi.2008.032。ISSN 0723-2977。S2CID 162142676。 4. ハーマン、マーク、編、訳。選集:フランツ・カフカ。ハーバード大学出版局ベルナッププレス (2024)、86 ページ。 5. 「変身」のグレーテ・ザムザのキャラクター LitCharts | SparkNotes の制作者たち。LitCharts。2017年10月31日取得。 6. 「変身」の父親のキャラクター分析 LitCharts | SparkNotes の制作者たち。LitCharts。2017年10月31日取得。 7. 「変身:母親のキャラクター分析」。LitCharts。 8. アブラハム、ウルフ。フランツ・カフカ:Die Verwandlung。Diesterweg、1993年。ISBN 3-425-06172-0。 9. ナボコフ、ウラジーミル・V. 『読書の技術:ヨーロッパ文学の傑作たち。オースティン – ディケンズ – フローベール – スティーブンソン – プルースト – カフカ – ジョイス』. フィッシャー・タッシェンブフ, 1991, pp. 313–52. ISBN 3-596-10495-5. 10. ストラウス、ニーナ・ペリカン. 「フランツ・カフカの『変身』の変容」、『サインズ』14巻3号(1989年春)、シカゴ大学出版局、pp. 651–667。 11. リック、ゲルハルト。『カフカを具体的に―トラウマとしての生涯。作品における反復モチーフを心理学的解釈の基盤として』。ケーニヒスハウゼン&ノイマン、1999年、 pp. 104–25. ISBN 978-3-8260-1623-3. 12. シュタッハ、ライナー。カフカ。決断の年々、p. 221。 13. アルト、ペーター=アンドレ。フランツ・カフカ:永遠の息子。伝記。C. H. ベック、2008年、p. 336。 14. ズダウ、ラルフ。『フランツ・カフカ:短編小説/物語集』。クレット社、2007年、163–164頁。 15. ズダウ、ラルフ。『フランツ・カフカ:短編小説/物語集』。クレット社、2007年、158–162頁。 16. ベルメホ=ルビオ、フェルナンド:「グレゴール・ザムザに関する真実と虚偽。カフカの『変身』における二つの矛盾する解釈の根底にある論理」、『ドイツ文学・精神史季刊』第86巻第3号(2012年)、pp. 419–479。 17. ドルケ、フォルカー。「グレーテ・ザムザのための新たな計画」。『変身物語。カフカ、ヴィドマー、ケストナー、ガス、オンダッジェ、オースター、その他の変身芸術家たち』アテナ社、2013年、pp. 33–43。ISBN 978-3-89896-519-4。 18. ベヴァリッジ、アラン(2009年11月)。「フランツ・カフカの『変身』」。『精神医学治療の進歩』。15巻6号:459–461頁。doi:10.1192/apt.bp.109.007146。ISSN 1355-5146。 19. Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen. ミュンヘン: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. 1993. p. 1486. ISBN 3423325119. 20. バーノフスキー、スーザン (2014年1月14日). 「カフカの『変身』の翻訳について」. ニューヨーカー. ISSN 0028-792X。2024年5月16日取得。 21. バーカー、アンドルー(2021年7月)。「巨大な虫か、恐ろしい害虫か?カフカの『変身』を文化的、社会的、生物学的文脈で翻訳する」。翻訳と文学。 30 (2): 198–208。doi:10.3366/tal.2021.0463. ISSN 0968-1361. 22. ハーマン、マーク、カフカ、フランツ、『選集』ハーバード大学出版局ベルナッププレス、2024年、236ページ注2。 23. グッダーハム、WB(2015年5月13日)。「カフカの『変身』とその翻訳における変容」。ガーディアン。ISSN 0261-3077。 24. リーダー、カレン、「不安を煽るビジョン:死後100年を経て再考するフランツ・カフカ」、TLS、2024年5月31日。 25. ロバーツは、「害虫は害獣でもある」と述べている、p. 13、n.2。 26. レッピン訳は、『変身』および『審判』でも使用されている、Page Publications、2023年、ISBN 978-1-64833-704-8、およびウィリアム・コリンズ、2023年、ISBN 9780008110567 27. 彼女の翻訳のあとがきで、ベルノフスキーは「やや具体的すぎる『昆虫』という表現の境界を曖昧にするために『ある種の』という表現を追加した。カフカは、 グレゴール自身が自分の新しい体と状態を発見したときと同じ、ぼんやりとした焦点で、私たちにもそれを見てほしかったのだと思う」と書いている。カフカ、 フランツ。『変身』(スーザン・ベルノフスキー訳)。ニューヨーク・ロンドン:W. W. ノートン社、2014年、122頁。 28. グッダーハム、W. B. (2015年5月13日). 「カフカの『変身』とその翻訳における変異」. ガーディアン紙は、ジョン・R・ウィリアムズが「ungeheuren Ungeziefer」を「大型の害虫」と訳したと誤って記載している。変身とその他の物語 29. 「BBCラジオ4 - アーカイブ・オン・4、グレゴール・ザムザの昆虫学」. BBC. 2024年5月16日閲覧。 30. オンデル、チャバ(2018年)。「レイアウト:ナボコフとフランツ・カフカの『変身』」. Americana. XIV (1). 2023年4月22日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年1月3日閲覧。 31. 「Briefe und Tagebücher 1915 (Franz Kafka) – ELibraryAustria」. 2008年1月12日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2006年10月30日閲覧。 32. ワロデル、ヨハン・アダム (2023). 「カフカの小説における動物の不在」. MLN. 138 (3): 1121, 1122 – Project MUSE経由. 33. ナボコフ、ウラジーミル (1980). 『文学講義』. ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク: ハーベスト. p. 260. 34. ライター、ポール(2025年夏)。「カフカへの挑戦:模倣不可能なものの翻訳」。The Hedgehog Review。27 (2)。バージニア州シャーロッツビル:54–63。 35.翻訳:それはどんな違いをもたらすのか?:フランツ・カフカ『変身』 36. カフカ、フランツ(2024)。『選集』マーク・ハーマン訳・編集。ハーバード大学出版局ベルナッププレス、34ページ。ISBN 978-0674737983。 37. カフカ、フランツ、『変身』(M. A. ロバーツ訳)。デラウェア州クレイトン:プレストウィック・ハウス、2005年、13ページ、注1 38. カフカ、フランツ。『変身』(スーザン・バーノフスキー訳)。ニューヨークおよびロンドン:W. W. ノートン&カンパニー、2014年、126ページ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Metamorphosis |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆